Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Systematic Literature Review for Mechanisms and Costs of Plant Adaptation to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses

1 Department of Agricultural Biotechnology, Faculty of Agriculture, Atatürk University, Erzurum, 25000, Turkey

2 Department of Plant Protection, University of Anbar, Anbar, 31001, Iraq

3 Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, Atatürk University, Erzurum, 25000, Turkey

* Corresponding Author: Mohammed Majid Abed. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Ornamental Plants: Micropropagation, Plant Biotechnology, Chromosome Doubling, Mutagenesis, Plant Breeding, Environmental Stress Tolerance, and Postharvest Physiology)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 3845-3860. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.073163

Received 12 September 2025; Accepted 28 November 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

Plants are continuously exposed to abiotic and biotic stresses that threaten their growth, reproduction, and survival. Adaptation to these stresses requires complex regulatory networks that coordinate physiological, molecular, and ecological responses. However, such adaptation often incurs significant costs, including reduced growth, yield penalties, and altered ecological interactions. This review systematically synthesizes recent advances published between 2018 and 2025, following PRISMA criteria, on plant responses to abiotic and biotic stressors, with an emphasis on the trade-offs between adaptation and productivity. It also highlights major discrepancies in the literature and discusses strategies for enhancing plant stress tolerance in agriculture. By integrating findings from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, the review categorizes both mechanistic insights and ecological consequences. The findings underscore the need for multi-stress, systems-level, field-based research that connects molecular processes to ecological and agricultural outcomes. Accordingly, critical gaps are identified—particularly the scarcity of multi-stress and field-based studies—and future directions that integrate omics approaches, systems biology, and eco-physiological frameworks are proposed. Understanding the costs of adaptation is essential not only for breeding resilient, high-yielding crops but also for ensuring their successful incorporation into sustainable agricultural practices under changing climate conditions.Keywords

Plants, as living organisms, face various environmental challenges that threaten their growth and survival. Broadly, these challenges can be classified into two types: abiotic and biotic stresses. Abiotic stresses arise from factors such as drought, salinity, extreme temperatures, heavy metals, and nutritional imbalances, whereas biotic stresses are caused by various microorganisms, diseases, and pests. Abiotic stress factors resulting from environmental variables significantly affect plant metabolism, photosynthesis, and cellular homeostasis [1,2]. Stress factors induced by living organisms such as fungi, bacteria, viruses, nematodes, herbivores, and parasitic plants compromise plant health by depleting resources, altering tissues, and triggering immune responses. Unlike abiotic pressures, biotic challenges often involve co-evolutionary dynamics between plants and their antagonists, leading to highly specialized defense mechanisms, including gene-for-gene resistance and inducible secondary metabolite production [3,4].

Understanding the difference between abiotic and biotic stress is critical, and it is also essential to recognize that plants frequently encounter multiple pressures simultaneously in both natural and agricultural environments [5]. Adaptation to various stresses is crucial for survival, reproduction, and productivity, but it is not without associated costs. A review of previous literature revealed a predominant focus on specific stressors under controlled conditions, yielding findings such as osmotic adjustment in drought tolerance and hypersensitive responses in pathogen defense [6,7]. Recent advances in genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics have broadened the field to incorporate systems-level perspectives, revealing intricate signaling networks and trade-offs between plant growth and defense [8]. It has been found that plant responses are critical for maintaining cellular homeostasis, safeguarding reproductive success, and ensuring long-term survival; thus, survival under various conditions heavily relies on stress adaptation [9].

Accordingly, plants that are incapable of adjusting to abiotic or biotic stresses are eliminated from competition, influencing species distribution and community composition. Thus, a variety of adaptive mechanisms, such as drought-escape phenology and pathogen-specific resistance genes, determine ecological fitness and evolutionary success [10]. These adaptations not only ensure individual plant survival but also maintain biodiversity and environmental stability. In agriculture, abiotic stressors are estimated to reduce global crop yields by more than half, while biotic stresses cause additional losses that threaten food supply chains [11,12]. However, the costs of adaptation, such as reduced growth during constitutive defense activation, pose challenges to breeding efforts aimed at enhancing resilience without compromising yield [13]. Therefore, the present review seeks to synthesize existing knowledge on plant stress adaptation mechanisms, emphasize the trade-offs involved, and identify gaps in previous research that hinder the development of long-term solutions for agricultural and natural ecosystems. Furthermore, it aims to bridge the gap between fundamental plant science and crop improvement strategies.

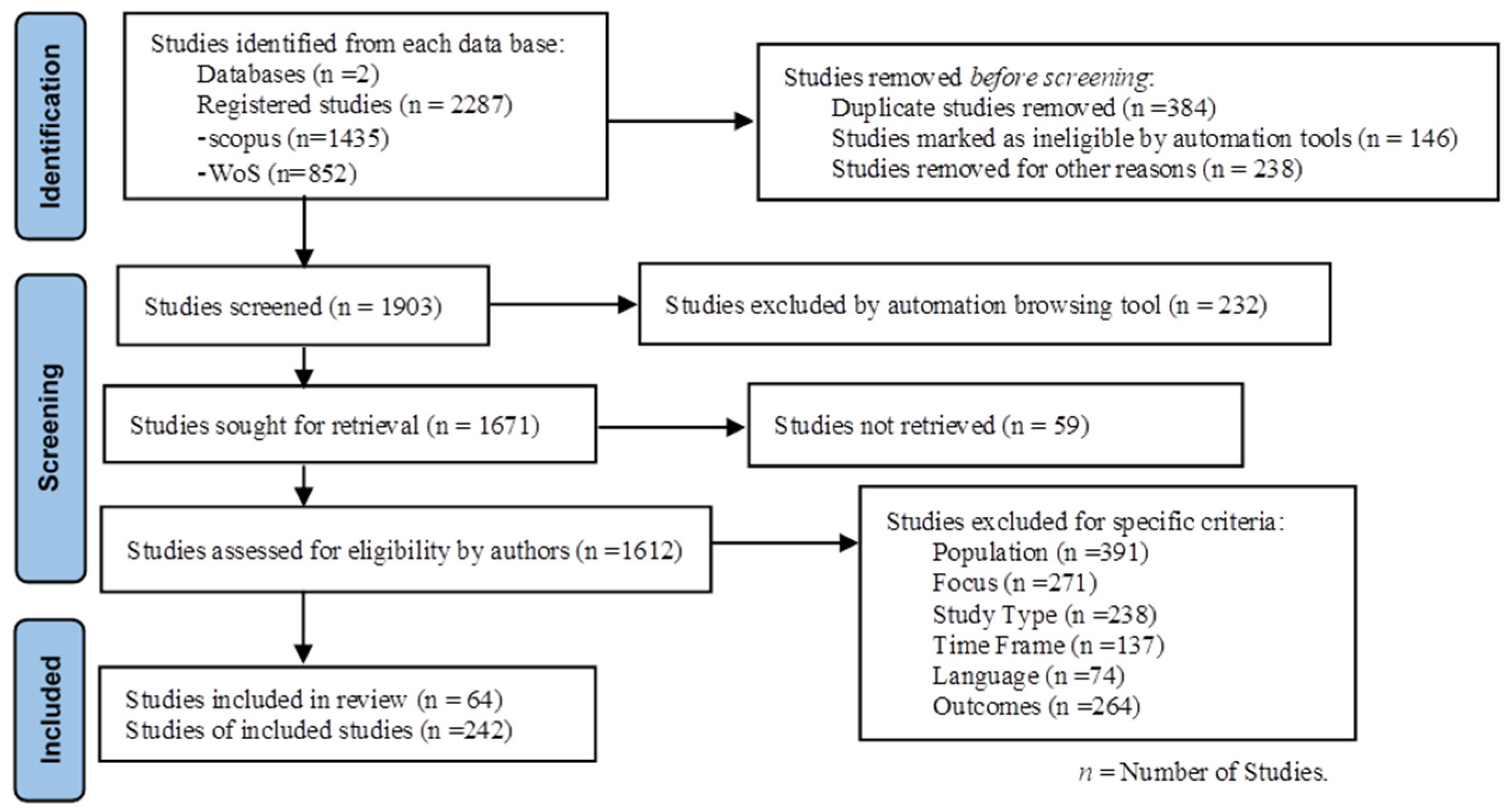

The review of current phenomena was conducted following the PRISMA 2021 standards for systematic reviews [14]. A comprehensive literature search was performed using systematic queries in the widely recognized databases Scopus and Web of Science, covering the period from 2018 to 2025, and employing keyword combinations related to plant adaptability, abiotic stress, biotic stress, trade-offs, and survival strategies. The procedures of the systematic literature review are illustrated in Fig. 1. Duplicate records were removed prior to screening titles and abstracts for relevance. Full-text screening was subsequently conducted to ensure that the studies met the objectives of the review. A total of 64 studies were included to address plant adaptation mechanisms to abiotic and/or biotic stress, as well as the associated costs or trade-offs.

Figure 1: Procedures of Systematic Literature Review.

In addition, the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the current review are presented in Table 1 and include: research conducted within the timeframe of 2018–2025; exclusion of non-English publications, conference abstracts without full papers, and articles that do not focus on plant adaptation processes. Both original research and review articles were evaluated to capture mechanistic insights as well as broader perspectives.

Table 1: Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Classification | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Studies on plants (model species and crops) under abiotic or biotic stress | Studies on non-plant organisms or unrelated biological systems |

| Intervention/Focus | Mechanisms of adaptation, tolerance, or trade-offs under stress conditions | Studies focused only on agronomy without mechanistic insights |

| Study Type | Peer-reviewed original research and review articles | Conference abstracts, editorials, or non-peer-reviewed materials |

| Timeframe | Published between 2018–2025 | Published before 2018 |

| Language | English | Non-English publications |

| Outcomes | Evidence of plant adaptation strategies, stress physiology, molecular mechanisms, or fitness costs | Studies not addressing adaptation, costs, or mechanisms |

3 Plant Responses to Abiotic Stress

Plants employ morphological, physiological, and molecular strategies to withstand severe abiotic conditions. The complex interactions between different abiotic stresses were not addressed in this study, which focused primarily on individual stressors in controlled environments. Furthermore, there has been limited research on stress memory and epigenetic regulation under field conditions.

3.1 Drought Stress and Water Deficit

Drought is one of the most significant abiotic stressors limiting plant growth and yield worldwide. Water deprivation alters cellular turgor, inhibits photosynthesis, and induces oxidative stress by increasing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). To cope with drought, plants employ various strategies, including drought escape (accelerated flowering and seed development); avoidance mechanisms (deep root growth, reduced leaf area, and cuticular wax deposition); and tolerance responses (osmotic adjustment through accumulation of proline, sucrose, and glycine betaine). Molecular processes also contribute, with ABA-mediated signaling pathways regulating stomatal closure, stress-responsive gene expression, and antioxidant enzyme activity [15,16].

Recent research advances confirm the interaction of drought responses with other signaling networks. It has been shown that plants can balance growth–defense trade-offs under prolonged water deficits, for example through interactions between ABA and other hormones, including ethylene, jasmonic acid, and salicylic acid [17]. Furthermore, transcriptomic studies have demonstrated that drought activates a complex regulatory network involving transcription factors such as the DREB, AREB/ABF, and NAC families, which coordinate downstream stress tolerance genes [18]. Nonetheless, despite these advances, drought adaptation remains highly genotype-specific, with significant knowledge gaps in translating molecular insights into sustained drought resistance under field conditions.

3.2 Salinity Stress and Ion Homeostasis

Soil salinity affects approximately 20% of irrigated land worldwide and is increasing due to poor irrigation management and climate-driven saltwater intrusion [19]. Elevated salt levels disrupt osmotic balance, induce ionic toxicity (excess Na+ and Cl−), and cause nutritional imbalances, leading to reduced plant growth and productivity [20]. Plants respond to salinity by employing ion compartmentalization, selective ion transport via high-affinity K+ transporters (HKT) and salt overly sensitive (SOS) signaling pathways, and the accumulation of osmoprotectants to maintain cellular homeostasis [21,22].

The review of current literature indicates that halophytes (salt-tolerant plants) possess highly effective mechanisms for salt exclusion and sequestration, providing valuable genetic resources for engineering tolerance in glycophytes (salt-sensitive crops). Functional genomics studies have identified critical regulatory genes involved in Na+ transport and ion homeostasis, including SOS1, NHX1, and HKT1;5 [23]. However, implementing these discoveries in crops remains challenging due to the complex interactions between salt stress and other abiotic factors, such as drought and heat [24]. Therefore, to effectively address salt stress, future research should focus on integrating molecular breeding, microbiome engineering, and sustainable agronomic practices.

3.3 Temperature Extremes: Heat and Cold Stress

Fluctuations in temperature, including heat waves and chilling or freezing events, pose significant threats to plants. Heat waves cause protein denaturation, membrane destabilization, and increased ROS generation, whereas cold stress reduces enzyme activity, alters membrane fluidity, and disrupts metabolic pathways. Plants respond to heat stress by activating heat shock proteins (HSPs), which function as molecular chaperones, producing antioxidants, and modifying lipid composition to stabilize membranes [25,26]. In contrast, plant responses to cold stress involve the accumulation of compatible solutes (such as sugars and proline), the induction of C-repeat binding factors (CBFs), and activation of the ICE-CBF-COR transcriptional cascade, which regulates cold-responsive (COR) genes. Additionally, epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation and histone changes, have been shown to contribute to stress memory, enhancing plant tolerance to repeated temperature extremes [27,28]. Despite these adaptive mechanisms, many crop species remain highly sensitive to climate-induced heat waves and frosts, underscoring the urgent need for integrative breeding and technological interventions.

3.4 Heavy Metals, Nutrient Deficiency, and Oxidative Stress

Other major abiotic constraints limiting plant growth and productivity include heavy metal pollution (e.g., cadmium, lead, and arsenic) and nutrient deficiencies (e.g., nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium). Heavy metals disrupt cellular redox balance, damage the photosynthetic apparatus, and increase ROS levels, whereas nutrient deficiencies alter metabolic pathways and limit biomass accumulation. Plants respond to these stresses by chelating metals through phytochelatins and metallothioneins, compartmentalizing them in vacuoles, increasing root exudation, and activating nutrient transporters [29,30]. Previous studies have emphasized the importance of plant–microbe interactions in mitigating these stresses. For example, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria enhance nutrient uptake and facilitate heavy metal sequestration, thereby improving plant resilience [31]. Furthermore, modern omics approaches have revealed stress-induced transcriptional reprogramming and signaling crosstalk between nutrient sensing and stress responses, with particular attention to novel molecular pathways for oxidative stress mitigation under metal exposure [10,32,33]. However, most of these studies are limited to model plants in controlled environments. Therefore, multi-stress evaluations are required to better understand the ecological and agricultural significance of these responses, highlighting the critical need for field-based investigations.

4 Plant Responses to Biotic Stress

Biotic stressors necessitate the recognition and activation of plant defenses, as they involve interactions with other living organisms. A survey of the literature indicates that model plants, such as Arabidopsis spp., are frequently the focus of studies with limited applicability to actual crops [34]. The preference for Arabidopsis is largely due to its short life cycle, small and fully sequenced genome, ease of genetic manipulation, and the availability of extensive genetic and molecular resources [35]. While these studies have provided important insights into basic defense mechanisms, their direct relevance to crops remains limited. Consequently, there is a gap between fundamental discoveries in model plants and their application to crop improvement, as few studies have examined biotic stress responses in agriculturally significant species. Despite the predominance of Arabidopsis research, translating these insights to crops has been restricted. Recent findings demonstrate integrated PTI–ETI signaling, viral defense through RNA silencing, and the ecological significance of herbivore-induced VOCs, highlighting both mechanistic understanding and evolutionary trade-offs [36].

4.1 Pathogen infection: Fungi, Bacteria, and Viruses

Plants are constantly exposed to pathogens, including fungi, bacteria, and viruses, which deplete host resources and reduce yield. In response, plants have evolved a multi-layered immune system. The first layer, pattern-triggered immunity (PTI), relies on pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to detect conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) [37]. PTI induces defense responses such as cell wall reinforcement, ROS generation, and the accumulation of antimicrobial metabolites [38]. The second layer, effector-triggered immunity (ETI), is mediated by nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat (NLR) proteins, which recognize pathogen effectors and often trigger localized cell death (hypersensitive response) to restrict pathogen spread [39].

Recent studies in plant pathology have revealed complex signaling crosstalk between PTI and ETI, indicating that these layers of immunity function as integrated networks rather than as entirely separate mechanisms. For example, fungal pathogens often suppress PTI through effectors, which in turn activate ETI [40]. Meanwhile, RNA silencing pathways are employed to counter viral infections, with short RNAs targeting viral genomes for degradation [41]. The discovery of integrated decoy domains in NLR proteins, along with the role of mobile defense signals, has advanced our understanding of pathogen recognition. Despite these advances, achieving long-term resistance in crops remains challenging due to pathogen evolution, highlighting the need for dynamic breeding strategies and molecular engineering approaches.

4.2 Herbivory and Plant–Insect Interactions

Insects that feed on plants impose an additional layer of biotic stress by reducing productivity through direct tissue consumption and by acting as vectors of plant diseases. Plants employ constitutive defenses (structural barriers such as trichomes, thorns, and wax layers) and inducible defenses (secondary metabolites, protease inhibitors, and volatile organic compounds [VOCs]) to deter herbivores or attract natural enemies [42]. The jasmonic acid (JA) signaling pathway regulates anti-herbivore responses and often interacts with the ethylene and salicylic acid (SA) pathways to fine-tune defense mechanisms [43]. Recent studies have highlighted the ecological and evolutionary dimensions of plant–insect interactions. For instance, some herbivores have evolved mechanisms to detoxify or even sequester plant defense compounds, leading to an evolutionary arms race between plants and insects. Additionally, VOC-mediated indirect defenses are increasingly recognized as critical ecological strategies, enabling plants to recruit parasitoids and herbivore predators [44]. However, the review indicates that trade-offs between growth and defense can constrain the scope of inducible responses, complicating efforts to develop insect-resistant crops without compromising productivity.

4.3 Parasitic Plants and Nematode Infestations

Parasitic plants, such as Striga and Cuscuta, pose unique biotic challenges by extracting water, nutrients, and photosynthates from host plants through specialized structures called haustoria. These interactions not only reduce host energy but also suppress resistance signaling, making them particularly detrimental to members of the Gramineae and Fabaceae families. Host plants defend against parasitic infection by producing germination inhibitors, reinforcing cell walls at penetration sites, or activating localized defense responses analogous to pathogen-triggered immunity [45]. Similarly, plant-parasitic nematodes, such as Meloidogyne spp. (root-knot nematodes) and Heterodera spp. (cyst nematodes), manipulate host physiology by secreting effectors that reprogram root growth and establish feeding sites. Plants counter these attacks through both PTI- and ETI-like responses, and certain resistance genes, such as Mi-1 in tomato, confer nematode resistance. However, nematodes exhibit substantial evolutionary potential to overcome resistance genes, and their concealed lifestyle within roots complicates detection [46]. The current research highlights the potential of RNA interference (RNAi)-based approaches and microbiome engineering for achieving durable nematode resistance.

5 Costs of Plant Adaptation to Stress

Although plant responses to stressful conditions enhance survival, they incur significant costs in terms of growth, reproduction, and metabolic efficiency. Few studies have quantified the energy budgets associated with stress responses or examined their long-term ecological consequences, particularly in natural or agricultural settings. The following sections analyze each of these costs based on a review of the relevant literature, thereby emphasizing a deeper understanding of these trade-offs and identifying gaps to guide future research and solutions.

5.1 Molecular Signaling and Defense Cost

A sophisticated signaling network involving phytohormones, transcription factors, and secondary messengers regulates plant responses to biotic stress. Salicylic acid (SA) is critical for systemic acquired resistance (SAR) against biotrophic pathogens, whereas jasmonic acid (JA) and ethylene (ET) mediate defenses against necrotrophic pathogens and herbivores, respectively [47]. Plants integrate signals from multiple pathways to prioritize defense according to the type of threat, but trade-offs arise because activation of one pathway can suppress another [48]. At the cellular level, defense signaling is amplified by calcium signaling, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascades, and bursts of ROS. Short RNAs regulate defense responses, while transcription factors such as WRKY, MYB, and ERF control downstream gene expression. Nevertheless, fitness costs are inherent in these systems, as defense responses consume resources that could otherwise support growth and reproduction. For example, JA-mediated defenses can reduce seed yield, and constitutive SA accumulation can impede development [17]. Consequently, one of the major challenges for long-term crop sustainability is identifying and mitigating these trade-offs.

5.2 Resource Allocation Trade-Offs

Plants have limited carbon, nitrogen, and energy resources; consequently, investment in defense or stress tolerance must be balanced against growth and reproduction. The classic growth–defense trade-off occurs when carbon skeletons and reducing power are redirected from primary metabolism (cell division, expansion, and yield formation) toward the biosynthesis of defensive metabolites (phenolics, terpenoids, alkaloids) and structural reinforcements (lignin, suberin) [49]. Conversely, under chronic abiotic stress (e.g., drought or salinity), plants allocate resources preferentially to root biomass, osmolyte accumulation, and protective proteins, which stabilize physiology while suppressing shoot growth and harvest index [50]. Similarly, in cereals, inherent resistance often compromises seed set and thousand-kernel weight, illustrating how survival-oriented traits can constrain reproduction (Long et al., 2024).

The overall distributional trade-offs vary with the environment: while investment in defense enhances fitness under stressful conditions, the same allocation in benign environments can reduce fitness compared with fast-growing genotypes [51]. This delicate balance is largely mediated by hormonal cross-talk among ABA, SA, JA, and ET. ABA promotes water conservation and stress tolerance while inhibiting cell expansion, whereas SA- and JA-driven immunity can restrict growth by altering transcriptional programs in primary metabolism [52]. For breeding programs aiming to combine resistance and productivity, quantifying these trade-offs across different genotypes and environmental conditions remains a critical challenge.

5.3 Metabolic Costs of Stress Responses

Plant responses to stress factors incur direct metabolic costs, as ATP, NAD(P)H, and amino acids are mobilized for the synthesis of stress proteins (e.g., HSPs, LEA proteins, and PR proteins), antioxidants (components of the ascorbate–glutathione cycle), and osmoprotectants (such as proline and glycine betaine). ROS management alone demands precise redox control and continuous investment in enzyme turnover (e.g., SOD, CAT, and APX), which can reduce carbon-use efficiency [53]. Similarly, maintaining ion gradients under salinity through SOS pathway components and NHX antiporters imposes a bioenergetic burden due to the activity of proton pumps and transport cycles [54]. Although induced defenses are less costly than constitutive ones, they still divert metabolism toward the phenylpropanoid and isoprenoid pathways. They also depend on nitrogen reserves for resistance proteins and can inhibit photosynthesis via stomatal and mesophyll adjustments [55]. Stress responses redirect resources to resistance-related transcripts, potentially limiting growth-related gene expression. These costs are not merely transient; prolonged activation leads to cumulative reductions in biomass accumulation, reproductive output, and resource-use efficiency.

5.4 Ecological and Evolutionary Costs

At both community and ecological scales, stress adaptation influences species cohabitation, competitive hierarchies, and biodiversity. Genotypes with high constitutive defenses may dominate in chronically harsh environments, but they are outcompeted in resource-rich habitats by faster-growing, less-defended rivals, resulting in spatial and temporal niche partitioning [56]. This dynamic generates intraspecific and interspecific variation in defense strategies, driven by variable selection pressures across habitats and years [57]. Defense traits can also shape herbivore populations and higher trophic interactions, thereby affecting ecological processes such as nutrient cycling [58]. Arms races with pathogens and herbivores promote rapid diversification of R genes and specialized metabolites, but this diversification can be constrained by pleiotropy and the costs of autoimmunity (e.g., overactive SA/ETI signaling leading to dwarfism and sterility) [59]. In crops, strong selection for yield under benign conditions can eliminate stress-resilience genes, reduce genetic diversity and increase susceptibility to emerging stresses a trade-off with clear evolutionary and food security implications.

Despite its conceptual clarity, quantitative accounting of stress-related costs remains limited. Few studies have integrated whole-plant carbon and nitrogen budgets with fluxomic and respiratory costs to estimate the total energy expenditure of specific defense modules or tolerance traits across developmental stages and environmental conditions [60]. Long-term, multi-season experiments that track lifetime fitness, seed bank dynamics, and transgenerational effects are also scarce, restricting our understanding of the evolutionary trajectories of costly defenses. Another critical gap lies in linking molecular processes to predicted phenotypes under realistic, multi-stress field conditions. Models that integrate hormonal cross-talk, redox signaling, and transport energetics with canopy photosynthesis and yield outcomes across varying climates are notably lacking. Fig. 2 summarizes plant abiotic and biotic stresses, along with their associated costs.

Figure 2: Plants’ mechanisms for adaptation and costs.

Since plants rarely encounter single stresses, adaptation depends on coordinated signaling and regulation. The current review identified limited knowledge of cross-talk between stress pathways, particularly at the systems biology level, and few studies linking molecular signaling to ecological outcomes. Plant hormones orchestrate adaptive responses through an integrated signaling network, with ABA, SA, JA, and ET playing central roles. ABA serves as the primary regulator of abiotic stress tolerance, especially drought and salinity, by modulating stomatal closure, osmolyte accumulation, and the expression of dehydration-responsive genes. However, ABA often suppresses SA- and JA-mediated immunity, affecting the balance between stress tolerance and defense [61]. Recent multi-omics studies reveal that hormonal cross-talk is highly context-dependent, influenced by stress intensity, timing, and tissue specificity. Emerging evidence also indicates that hub transcription factors, including WRKYs, NACs, and MYCs, function as integrators of multiple hormonal signals [62,63]. Systems-level analyses demonstrate that hormone cross-talk operates as a dynamic network rather than linear pathways, highlighting the importance of integrative modeling for predicting adaptive responses under multi-stress conditions. For instance, drought–pathogen interactions mediated by ABA–SA antagonism produces outcomes that cannot be predicted from single-stress studies, illustrating how multiple pathways converge to shape adaptation. Table 2 displays adaptation mechanisms of plants for abiotic and biotic stress.

Table 2: Plants’ adaptation mechanisms for stress factors.

| Category | Stress Factors | Adaptation Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|

| Abiotic Stress | - Drought - Salinity. - Temperature extremes (heat/cold). - Heavy metals. | - Morphological: deep roots, reduced leaf area. - Physiological: stomatal regulation, osmotic adjustment. - Biochemical: antioxidants, osmolytes. - Molecular: stress-responsive genes, transcription factors. |

| Biotic Stress | - Pathogens (fungi, bacteria, viruses). - Herbivores (insects, grazers). - Parasitic plants. | - Structural: cuticle thickening, trichomes, thorns. - Chemical: phytoalexins, secondary metabolites. - Molecular: hormone signaling (SA, JA, ET). - Symbiotic: beneficial microbes (e.g., mycorrhizae, endophytes). |

| Costs of Adaptation | N/A | - Cross-talk between abiotic and biotic pathways (synergy or antagonism). - Epigenetic stress memory. |

6.1 Hormonal Cross-Talk in Stress Adaptation

Plant hormones regulate adaptive responses through an integrated signaling network, with abscisic acid (ABA), salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET) playing central roles. ABA serves as the primary regulator of abiotic stress tolerance, particularly under drought and salinity, by modulating stomatal closure, osmolyte accumulation, and the expression of dehydration-responsive genes [64]. However, ABA often suppresses SA- and JA-mediated immunity, thereby influencing the balance between stress tolerance and defense [61]. Consequently, ABA can inhibit SA-dependent pathogen resistance, increasing susceptibility under conditions of water scarcity. Similarly, JA and ET cooperate to regulate defense against herbivores and necrotrophic pathogens, although ABA signaling may attenuate their activity during abiotic stress adaptation.

Recent multi-omics studies have demonstrated that hormonal cross-talk is highly context-dependent, influenced by stress intensity, timing, and tissue specificity [61]. Emerging evidence indicates that hub transcription factors, such as WRKYs, NACs, and MYCs, function as integrators of multiple hormonal signals. For example, WRKY70 modulates antagonism between SA and JA, whereas MYC2 coordinates ABA and JA pathways under drought and herbivore stress [62]. Systems-level analyses reveal that hormone cross-talk operates as a dynamic network rather than through linear pathways, highlighting the importance of integrative modeling for predicting adaptive responses under multi-stress conditions [65].

6.2 Genetic and Epigenetic Regulation in Plant Stress Responses

Genetic and epigenetic modifications provide plants with flexible and reversible mechanisms to fine-tune gene expression in response to stress. DNA methylation (5mC) can suppress stress-responsive genes or activate them via demethylation of promoter regions. Similarly, histone modifications, such as H3K4me3 (activation) and H3K27me3 (repression), modulate stress-induced transcriptional reprogramming [66]. Recent studies indicate that salt, drought, and pathogen infections trigger genome-wide re-patterning of methylation and histone marks, affecting pathways including ABA biosynthesis, ROS detoxification, and PR protein accumulation [17]. High-throughput sequencing has revealed stress-specific epigenetic signatures, suggesting that different stressors leave distinct ‘molecular marks’ on the chromatin landscape [67]. CRISPR/dCas9-based epigenome editing is being explored to manipulate these marks for developing stress-resistant crops without altering the DNA sequence [68]. This approach opens new avenues in crop improvement, complementing traditional breeding and transgenic strategies by harnessing natural epigenetic plasticity.

Furthermore, epigenetic memory enables plants to ‘recall’ previous stress exposures, resulting in faster or stronger responses upon re-exposure—a phenomenon known as stress priming. For instance, drought priming induces long-term modifications in DNA methylation and histone acetylation, enhancing tolerance across successive drought cycles [69]. Similarly, pathogen priming via SA signaling causes chromatin remodeling at defense gene loci, facilitating rapid transcriptional activation upon reinfection [27]. Remarkably, some of these epigenetic states are heritable, allowing offspring to exhibit greater tolerance even without direct exposure. For example, progeny of heat- or drought-stressed Arabidopsis plants display altered DNA methylation patterns that confer increased stress resilience [66,69]. However, the stability and predictability of stress memory across generations remain debated. Consequently, distinguishing environmentally induced epigenetic modifications from genetic variation is critical for effectively exploiting stress memory in crop breeding.

Plants in natural and agricultural ecosystems rarely experience a single stress in isolation; instead, they are exposed to combinations of stressors such as drought, heat, salinity, disease, flooding, and herbivory. These stress combinations often elicit novel responses that differ from single-stress effects, ranging from synergistic amplification to antagonistic suppression [70]. For example, drought–heat co-occurrence increases ROS accumulation and accelerates senescence, whereas drought–pathogen interactions can enhance disease susceptibility due to ABA–SA antagonism. Conversely, some stress combinations, such as cold–pathogen interactions, may confer cross-protection by improving overall resistance through shared signaling pathways (e.g., ROS and JA). Recent systems biology approaches demonstrate that multi-stress responses are not simply additive but involve nonlinear cross-talk among signaling networks. Transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses reveal stress-specific signals that cannot be predicted from single-stress studies [71]. These findings highlight the need to develop predictive models that incorporate network flexibility under combined stresses. Addressing these interactions is particularly important under climate change, as both abiotic and biotic pressures are expected to intensify.

Despite significant advances in research, a review of the current literature on plant stress and associated costs reveals substantial gaps in our understanding of integrative stress adaptation. First, most studies have focused on single hormone pathways or isolated stress types, whereas real-world scenarios involve dynamic interactions across hormonal, metabolic, and epigenetic levels [72]. There remains limited understanding of how ABA, SA, JA, and ET signaling networks are fine-tuned under combined stresses, and how trade-offs between growth and defense are mechanistically resolved at the whole-plant level. Moreover, although epigenetic processes such as stress memory and transgenerational inheritance have been extensively studied in model species like Arabidopsis, they remain largely unexplored in crops. Second, while omics technologies (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics) have generated vast datasets, their integration into systems biology frameworks is still limited. Few studies combine multi-omics data with computational modeling to predict stress effects across scales, from molecular signaling to field-level yield stability [65]. Additionally, field validation of laboratory findings remains scarce, raising concerns about ecological and agronomic applicability. To address these limitations and translate integrative insights into practical crop improvement strategies, future research must combine multi-omics, phenomics, and computational modeling with long-term, multi-stress field experiments.

7.1 Need for Multi-Stress Studies

Most contemporary research in plant stress biology focuses on single stressors; however, real-world conditions often expose plants to multiple simultaneous stresses, such as drought–heat or salinity–pathogen combinations. These interactions produce emergent responses that cannot be predicted from single-stress experiments. We hypothesize that multi-stress combinations activate distinct transcriptional and metabolic reprogramming nodes that are absent under individual stressors, with potential regulators located in stress-hub signaling proteins (e.g., MAPKs, SnRKs). Future studies should incorporate factorial stress experiments in both controlled and field environments, coupled with dynamic network modeling, to elucidate how signaling hierarchies are rewired. Such research may identify master regulators whose manipulation could generate crops tolerant to multiple concurrent stressors, rather than merely single-stress tolerance.

7.2 Systems Biology and Omics Approaches

Stress regulators have been identified through genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics, yet their isolated application limits the discovery of cross-scale interactions [73]. Most research remains confined to a single omics layer, constraining our ability to capture the full complexity of stress adaptation networks. We propose that integrating temporal multi-omics datasets with machine learning can reveal predictive indicators of stress “tipping points”, where plants transition from tolerance to collapse. Moving forward, systems biology approaches should combine multi-omics data with network modeling, machine learning, and predictive simulations to identify key regulators and stress indicators [8]. These strategies can help prioritize candidate genes for genome editing, pinpoint metabolic bottlenecks that constrain adaptation efficiency, and provide AI-driven simulations to elucidate mechanistic insights into the trade-offs between growth and defense.

7.3 Bridging Model and Crop Plant Research

Owing to their short generation times and genetic tractability, model species such as Arabidopsis thaliana and rice have been the focus of most stress biology research. While these models provide valuable mechanistic insights, they often fail to capture stress responses in agricultural crops, which differ substantially in genomic complexity, physiology, and ecological adaptability. It is plausible that stress adaptation mechanisms are only partially conserved between model species and crops, with particularly pronounced divergence in polyploid or clonally propagated species (e.g., wheat, potato). Future research should prioritize mapping stress-response gene families across crops and identifying lineage-specific innovations. Pan-genomics, crop-specific CRISPR/Cas technologies, and comparative multi-omics approaches will be essential for accelerating the translation of laboratory findings to agriculturally relevant species. Collaborative networks integrating fundamental plant biology, breeding, and field evaluation will be critical for bridging this persistent gap.

7.4 Linking Physiology to Ecology

A major gap in contemporary stress biology is the disconnect between cellular and molecular processes and their consequences at the population, community, and ecosystem levels. While physiological research has elucidated mechanisms such as stomatal closure, ROS detoxification, and hormonal crosstalk, it remains unclear how these responses scale to influence species interactions, competitive fitness, and ecosystem processes, including carbon cycling and nutrient flux. Molecular stress responses may serve as observable eco-physiological markers (e.g., canopy thermal imaging and isotopic carbon flow) that predict plant competitive fitness and ecosystem resilience. Likewise, pathogen defense mechanisms modulate plant–microbe–insect interactions, producing cascading effects on community structure. By integrating plant physiology, ecosystem modeling, and global climate projections, researchers can develop predictive frameworks linking individual adaptation processes to broader ecological and agricultural outcomes.

Laboratory-based research can provide valuable mechanistic insights, but it often fails to capture the complexities of field conditions, where stress intensity fluctuates dynamically across seasons and years. Long-term field studies are necessary to improve our understanding of stress tolerance over ecological and evolutionary timescales, particularly in perennial crops and wild plant populations. Such studies can determine whether adaptive processes identified in short-term experiments translate into long-term yield stability and ecological resilience. Moreover, longitudinal trials allow the assessment of transgenerational stress memory, shifts in microbial communities, and evolutionary adaptation, which single-season studies cannot capture. We hypothesize that prolonged exposure to variable stressors induces persistent epigenetic “stress memory”, enhancing resistance across generations through chromatin remodeling and small RNAs. Integrating field ecology with molecular biology will enable researchers to evaluate whether laboratory-defined mechanisms, such as epigenetic priming or hormonal cross-talk, function effectively under dynamic environmental conditions. This ecological perspective provides a more realistic foundation for breeding and management strategies in a changing climate.

Plants have evolved an impressive array of adaptations to survive and reproduce under diverse biotic and abiotic stressors. These adaptations span morphological, physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms, enabling plants to regulate water use, maintain ion homeostasis, detoxify harmful compounds, defend against pathogens and herbivores, and even modulate interactions with their microbiomes. Collectively, these strategies highlight the resilience of sessile organisms in dynamic and often hostile environments. However, stress adaptation is not without cost. Activating defense mechanisms requires substantial resource allocation, frequently diverting carbon, nitrogen, and energy away from growth and reproduction. These trade-offs influence plant fitness in both natural and agricultural systems, shaping ecological interactions, evolutionary trajectories, and crop yields. Understanding these costs is essential not only for explaining patterns of plant diversity in ecosystems but also for guiding breeding and biotechnological strategies aimed at enhancing agricultural sustainability.

Although significant progress has been made in understanding individual stress-response pathways, important gaps remain in previous research. Most current studies focus on single stressors under controlled conditions, overlooking the multi-stress reality of field environments. Developing predictive models of plant performance under complex scenarios requires integrative approaches that combine omics technologies, systems biology, and field-based validation. Moreover, bridging the gap between model species and crops, investigating the ecological consequences of stress adaptation, and considering the socioeconomic aspects of adoption are critical for translating research into practice. Looking forward, the challenge for plant science is not only to elucidate the molecular mechanisms of stress adaptation but also to apply these insights across scales from cells to ecosystems, and from the laboratory to the field. This approach will enable the development of crops and agricultural practices that are resilient, productive, and sustainable in the face of global climate change and environmental pressures.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Murat Aydin and Mohammed Majid Abed; Methodology, Esma Yiğider; Software, Mohammed Majid Abed; Investigation and Validation, Melek Ekinci; Writing—original draft preparation, Mohammed Majid Abed; Writing—review and editing, Ertan Yildirim and Melek Ekinci; Supervision, Murat Aydin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable, as this study is a narrative review based on previously published literature.

Ethics Approval: The study does not include human or animal subjects.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lesk C , Coffel E , Winter J , Ray D , Zscheischler J , Seneviratne SI , et al. Stronger temperature-moisture couplings exacerbate the impact of climate warming on global crop yields. Nat Food. 2021; 2( 9): 683– 91. doi:10.1038/s43016-021-00341-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Gupta B , Shrestha J . Editorial: abiotic stress adaptation and tolerance mechanisms in crop plants. Front Plant Sci. 2023; 14: 1278895. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1278895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cui H , Tsuda K , Parker JE . Effector-triggered immunity: from pathogen perception to robust defense. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2015; 66: 487– 511. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Dutta P , Mahanta M , Singh SB , Thakuria D , Deb L , Kumari A , et al. Molecular interaction between plants and Trichoderma species against soil-borne plant pathogens. Front Plant Sci. 2023; 14: 1145715. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1145715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Singh M , Jyoti , Kumar N , Singh H . Plant functional traits assisted crop adaptation to abiotic and biotic stress. In: Plant functional traits for improving productivity. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2024. p. 239– 55. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-1510-7_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Singh A , Mehta S , Yadav S , Nagar G , Ghosh R , Roy A , et al. How to cope with the challenges of environmental stresses in the era of global climate change: an update on ROS stave off in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23( 4): 1995. doi:10.3390/ijms23041995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ahmad U , Hassain M , Arshad Z , Ayub B . Harnessing potential of plant breeding strategies for climate smart agriculture. Theor Appl Plant Sci. 2023; 1: 72– 83. doi:10.62460/TBPS/2023.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Gupta S , Kaur R , Upadhyay A , Chauhan A , Tripathi V . Unveiling the secrets of abiotic stress tolerance in plants through molecular and hormonal insights. 3 Biotech. 2024; 14( 10): 252. doi:10.1007/s13205-024-04083-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kurepa J , Smalle JA . Plant hormone modularity and the survival-reproduction trade-off. Biology. 2023; 12( 8): 1143. doi:10.3390/biology12081143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kumar N , Lata C , Kaur G , Manjul AS . Brassinosteroid: a stress-reliever molecule for plants under abiotic stress. In: Plant growth regulators to manage biotic and abiotic stress in agroecosystems. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2024. p. 231– 56. doi:10.1201/9781003389507-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mekouar MA . 15. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Yearb Int Environ Law. 2023; 32( 1): 298– 304. doi:10.1093/yiel/yvac040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Raza A , Khare T , Zhang X , Rahman MM , Hussain M , Gill SS , et al. Novel strategies for designing climate-smart crops to ensure sustainable agriculture and future food security. J Sustain Agric Environ. 2025; 4( 2): e70048. doi:10.1002/sae2.70048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ramegowda V , Senthil A , Senthil-Kumar M . Stress combinations and their interactions in crop plants. Plant Physiol Rep. 2024; 29( 1): 1– 5. doi:10.1007/s40502-024-00785-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Page MJ , McKenzie JE , Bossuyt PM , Boutron I , Hoffmann TC , Mulrow CD , et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021; 372: n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kumari P , Joshi P , Kyum M , Ngure D , Batista LA . Advancements in functional genomics in exploring abiotic stress tolerance mechanisms in cereals. Omics and system biology approaches for delivering better cereals. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2024. p. 133– 75. doi:10.1201/9781032693385-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yin X , Leng G , Huang S , Peng J . Aggravation of global maize yield loss risk under various hot and dry scenarios using multiple types of prediction approaches. Int J Climatol. 2024; 44( 4): 1058– 73. doi:10.1002/joc.8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. He Z , Webster S , He SY . Growth–defense trade-offs in plants. Curr Biol. 2022; 32( 12): R634– 9. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.04.070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Uçarlı C . Drought stress and the role of NAC transcription factors in drought response. In: Drought stress. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2025. p. 295– 320. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-80610-0_11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Singh A . Soil salinity: a global threat to sustainable development. Soil Use Manag. 2022; 38( 1): 39– 67. doi:10.1111/sum.12772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zörb C , Geilfus CM , Dietz KJ . Salinity and crop yield. Plant Biol. 2019; 21( S1): 31– 8. doi:10.1111/plb.12884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. van Zelm E , Zhang Y , Testerink C . Salt tolerance mechanisms of plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2020; 71: 403– 33. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Awais M , Rasheed Z , Sadiq MT . Salinity stress Effects on nutrient uptake in plants and its influence on plant growth efficiency. Trends Anim Plant Sci. 2023; 1: 64– 72. doi:10.62324/TAPS/2023.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ashraf M , Munns R . Evolution of approaches to increase the salt tolerance of crops. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2022; 41( 2): 128– 60. doi:10.1080/07352689.2022.2065136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhou Y , Feng C , Wang Y , Yun C , Zou X , Cheng N , et al. Understanding of plant salt tolerance mechanisms and application to molecular breeding. Int J Mol Sci. 2024; 25( 20): 10940. doi:10.3390/ijms252010940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Hasanuzzaman M . Plant ecophysiology and adaptation under climate change: mechanisms and perspectives II: mechanisms of adaptation and stress amelioration. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-2172-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kan Y , Mu X , Gao J , Lin H , Lin Y . The molecular basis of heat stress responses in plants. Mol Plant. 2023; 16( 10): 1612– 34. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2023.09.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ramakrishnan M , Zhang Z , Mullasseri S , Kalendar R , Ahmad Z , Sharma A , et al. Epigenetic stress memory: a new approach to study cold and heat stress responses in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2022; 13: 1075279. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1075279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Janmohammadi M , Sabaghnia N . Proteome response of winter-hardy wheat to cold acclimation. Bot Serb. 2023; 47( 2): 317– 24. doi:10.2298/botserb2302317j. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sharma JK , Kumar N , Singh NP , Santal AR . Phytoremediation technologies and their mechanism for removal of heavy metal from contaminated soil: an approach for a sustainable environment. Front Plant Sci. 2023; 14: 1076876. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1076876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Mishra S , Levengood H , Fan J , Zhang C . Plants under stress: exploring physiological and molecular responses to nitrogen and phosphorus deficiency. Plants. 2024; 13( 22): 3144. doi:10.3390/plants13223144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Fasusi OA , Babalola OO , Adejumo TO . Harnessing of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in agroecosystem sustainability. CABI Agric Biosci. 2023; 4: 26. doi:10.1186/s43170-023-00168-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Bhatt D , Nath M , Badoni S , Joshi R . Preface. In: Current omics advancement in plant abiotic stress biology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2024. p. xxi– xxii. doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-21625-1.00033-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ahmad J , Ali-Dinar H , Munir M , Alqahtani N , Alyas T , Ahmad M , et al. Enhancing plant resilience to biotic and abiotic stresses through exogenously applied nanoparticles: a comprehensive review of effects and mechanism. Phyton. 2025; 94( 2): 281– 302. doi:10.32604/phyton.2025.061534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Uauy C , Nelissen H , Chan RL , Napier JA , Seung D , Liu L , et al. Challenges of translating Arabidopsis insights into crops. Plant Cell. 2025; 37( 5): koaf059. doi:10.1093/plcell/koaf059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Schreiber M , Jayakodi M , Stein N , Mascher M . Plant pangenomes for crop improvement, biodiversity and evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 2024; 25( 8): 563– 77. doi:10.1038/s41576-024-00691-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Tao L , Chen T . Special issue “plant responses to abiotic and biotic stresses”. Int J Mol Sci. 2025; 26( 19): 9651. doi:10.3390/ijms26199651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. DeFalco TA , Zipfel C . Molecular mechanisms of early plant pattern-triggered immune signaling. Mol Cell. 2021; 81( 17): 3449– 67. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2021.07.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ngou BPM , Wyler M , Schmid MW , Kadota Y , Shirasu K . Evolutionary trajectory of pattern recognition receptors in plants. Nat Commun. 2024; 15( 1): 308. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-44408-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Nguyen QM , Iswanto ABB , Son GH , Kim SH . Recent advances in effector-triggered immunity in plants: new pieces in the puzzle create a different paradigm. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22( 9): 4709. doi:10.3390/ijms22094709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Yu XQ , Niu HQ , Liu C , Wang HL , Yin W , Xia X . PTI-ETI synergistic signal mechanisms in plant immunity. Plant Biotechnol J. 2024; 22( 8): 2113– 28. doi:10.1111/pbi.14332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lozano-Durán R . Viral recognition and evasion in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2024; 75( 1): 655– 77. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-060223-030224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Mostafa S , Wang Y , Zeng W , Jin B . Plant responses to herbivory, wounding, and infection. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23( 13): 7031. doi:10.3390/ijms23137031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Erb M , Reymond P . Molecular interactions between plants and insect herbivores. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2019; 70: 527– 57. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-095910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Kansman JT , Jaramillo JL , Ali JG , Hermann SL . Chemical ecology in conservation biocontrol: new perspectives for plant protection. Trends Plant Sci. 2023; 28( 10): 1166– 77. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2023.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Mutuku JM , Cui S , Yoshida S , Shirasu K . Orobanchaceae parasite–host interactions. New Phytol. 2021; 230( 1): 46– 59. doi:10.1111/nph.17083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Sato K , Kadota Y , Shirasu K . Plant immune responses to parasitic nematodes. Front Plant Sci. 2019; 10: 1165. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.01165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Ghozlan MH , EL-Argawy E , Tokgöz S , Lakshman DK , Mitra A . Plant defense against necrotrophic pathogens. Am J Plant Sci. 2020; 11( 12): 2122– 38. doi:10.4236/ajps.2020.1112149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Spoel SH , Dong X . Salicylic acid in plant immunity and beyond. Plant Cell. 2024; 36( 5): 1451– 64. doi:10.1093/plcell/koad329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Ku YS , Liao YJ , Chiou SP , Lam HM , Chan C . From trade-off to synergy: microbial insights into enhancing plant growth and immunity. Plant Biotechnol J. 2024; 22( 9): 2461– 71. doi:10.1111/pbi.14360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Figueroa-Macías JP , García YC , Núñez M , Díaz K , Olea AF , Espinoza L . Plant growth-defense trade-offs: molecular processes leading to physiological changes. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22( 2): 693. doi:10.3390/ijms22020693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Watts S , Kaur S , Kariyat R . Revisiting plant defense-fitness trade-off hypotheses using Solanum as a model genus. Front Ecol Evol. 2023; 10: 1094961. doi:10.3389/fevo.2022.1094961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Khan N , Bano A , Ali S , Ali Babar M . Crosstalk amongst phytohormones from planta and PGPR under biotic and abiotic stresses. Plant Growth Regul. 2020; 90( 2): 189– 203. doi:10.1007/s10725-020-00571-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Fichman Y , Rowland L , Oliver MJ , Mittler R . ROS are evolutionary conserved cell-to-cell stress signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023; 120( 31): e2305496120. doi:10.1073/pnas.2305496120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Mendis CL , Padmathilake RE , Attanayake RN , Perera D . Learning from Salicornia: physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Int J Mol Sci. 2025; 26( 13): 5936. doi:10.3390/ijms26135936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Xu Y , Fu X . Reprogramming of plant central metabolism in response to abiotic stresses: a metabolomics view. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23( 10): 5716. doi:10.3390/ijms23105716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. López-Goldar X , Zas R , Sampedro L . Resource availability drives microevolutionary patterns of plant defences. Funct Ecol. 2020; 34( 8): 1640– 52. doi:10.1111/1365-2435.13610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Agrawal AA . A scale-dependent framework for trade-offs, syndromes, and specialization in organismal biology. Ecology. 2020; 101( 2): e02924. doi:10.1002/ecy.2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Abdala-Roberts L , Puentes A , Finke DL , Marquis RJ , Montserrat M , Poelman EH , et al. Tri-trophic interactions: bridging species, communities and ecosystems. Ecol Lett. 2019; 22( 12): 2151– 67. doi:10.1111/ele.13392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Deng YW , He ZH . The seesaw action: balancing plant immunity and growth. Sci Bull. 2024; 69( 1): 3– 6. doi:10.1016/j.scib.2023.11.051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Treves H , Küken A , Arrivault S , Ishihara H , Hoppe I , Erban A , et al. Carbon flux through photosynthesis and central carbon metabolism show distinct patterns between algae, C3 and C4 plants. Nat Plants. 2022; 8( 1): 78– 91. doi:10.1038/s41477-021-01042-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Ghosh P , Roychoudhury A . Molecular basis of salicylic acid–phytohormone crosstalk in regulating stress tolerance in plants. Braz J Bot. 2024; 47( 3): 735– 50. doi:10.1007/s40415-024-00983-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Zhou JM , Zhang Y . Plant immunity: danger perception and signaling. Cell. 2020; 181( 5): 978– 89. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Varadharajan V , Rajendran R , Muthuramalingam P , Runthala A , Madhesh V , Swaminathan G , et al. Multi-omics approaches against abiotic and biotic stress—a review. Plants. 2025; 14( 6): 865. doi:10.3390/plants14060865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Hussain Q , Asim M , Zhang R , Khan R , Farooq S , Wu J . Transcription factors interact with ABA through gene expression and signaling pathways to mitigate drought and salinity stress. Biomolecules. 2021; 11( 8): 1159. doi:10.3390/biom11081159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Raza A , Tabassum J , Fakhar AZ , Sharif R , Chen H , Zhang C , et al. Smart reprograming of plants against salinity stress using modern biotechnological tools. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2023; 43( 7): 1035– 62. doi:10.1080/07388551.2022.2093695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Lämke J , Bäurle I . Epigenetic and chromatin-based mechanisms in environmental stress adaptation and stress memory in plants. Genome Biol. 2017; 18( 1): 124. doi:10.1186/s13059-017-1263-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Chang YN , Zhu C , Jiang J , Zhang H , Zhu JK , Duan CG . Epigenetic regulation in plant abiotic stress responses. J Integr Plant Biol. 2020; 62( 5): 563– 80. doi:10.1111/jipb.12901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Chen JT . Genome and epigenome editing for stress-tolerant crops. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2025. doi:10.1002/9781394280049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Liu Y , Wang J , Liu B , Xu ZY . Dynamic regulation of DNA methylation and histone modifications in response to abiotic stresses in plants. J Integr Plant Biol. 2022; 64( 12): 2252– 74. doi:10.1111/jipb.13368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Pardo-Hernández M , García-Pérez P , Lucini L , Rivero RM . Multi-omics exploration of ABA involvement in identifying unique molecular markers for single and combined stresses in tomato plants. J Exp Bot. 2024; 76( 21): 6389– 409. doi:10.1093/jxb/erae372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Shaar-Moshe L , Peleg Z . Systems biology approach unfolds unique life-history strategies in response to abiotic stress combinations. In: Multiple abiotic stress tolerances in higher plants. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2023. p. 15– 23. doi:10.1201/9781003300564-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Sharma MK . Exploring the biochemical profiles of medicinal plants cultivated under stressful environmental conditions. Curr Agric Res J. 2024; 12( 1): 81– 103. doi:10.12944/carj.12.1.07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Raza A . Metabolomics: a systems biology approach for enhancing heat stress tolerance in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2022; 41( 3): 741– 63. doi:10.1007/s00299-020-02635-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools