Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Preliminary Study on Flower Bud Differentiation and Dynamic Changes in Endogenous Hormones in ‘Hongyang’ Kiwifruit

1 Key Laboratory of Coarse Cereal Processing, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Sichuan Province Engineering Technology Research Center of Coarse Cereal Industrialization, College of Food and Biological Engineering, Chengdu University, Chengdu, 610106, China

2 Sichuan Provincial Academy of Natural Resource Sciences, Sichuan Key Laboratory of Kiwifruit Breeding and Utilization, China-New Zealand Belt and Road Joint Laboratory on Kiwifruit, Chengdu, 610015, China

* Corresponding Author: Lihua Wang. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 3879-3892. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.073229

Received 13 September 2025; Accepted 07 November 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

To investigate endogenous hormone changes in “Hongyang” kiwifruit from overwintering buds to floral morphogenesis (bell-shaped flowering stage), systematic observations were conducted during the undifferentiated stage, axillary bud differentiation stage, and floral morphogenesis stage from late November 2023 to early April 2024. Paraffin sectioning was employed to examine floral bud morphology, while LC-MS targeted metabolomics quantified changes in 15 endogenous hormones across 8 classes. Results indicated floral bud differentiation commenced from late January to early February and concluded by mid-April, spanning approximately 70 days. Approximately 33 days after axillary bud initiation marked the axillary bud primordium differentiation stage, a critical phase for floral differentiation. The period from 33 to 61 days after axillary bud initiation constituted the key stage for female flower differentiation. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) levels remained consistently high and stable throughout the process. By the axillary bud primordium differentiation stage, abscisic acid (ABA), salicylic acid (SA), tylosterol (TY), and trans-zeatin riboside (tZR) levels significantly decrease, while 1-aminocyclopropane carboxylic acid (ACC), gibberellic acid (GA4), isopentenyladenine riboside (iPR), 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (12-OPDA), cis-zeatin (cZ), trans-zeatin (tZ), and cis-zeatin riboside (cZR) significantly increased. The study speculates that higher IAA levels may promote female flower differentiation; lower ABA levels favor floral bud differentiation; lower jasmonic acid (JA) levels may be associated with stamen abortion; lower SA levels favor female flower differentiation and development; and higher ACC and GA4 levels may promote female flower differentiation and flowering and subsequent development, respectively.Keywords

Kiwifruit belongs to the genus Actinidia Lindl. within the family Actinidiaceae. It is a perennial woody vine and is widely recognized as one of the four most successfully domesticated wild fruit trees of the 20th century [1]. Commercially cultivated kiwifruit varieties are currently classified into three types based on the color of their ripe flesh: green-fleshed, yellow-fleshed, and red-fleshed. Among these, red-fleshed kiwifruit is highly favored by consumers for its vibrant color. China, as the world’s largest kiwifruit grower by area, maintains a varietal structure where green-fleshed accounts for approximately 40%, while yellow-fleshed and red-fleshed each constitute about 30%. China is also currently the world’s largest producer of red-fleshed kiwifruit. ‘Hongyang’ (Actinidia chinensis Planch. var. rufopulpa C.F. Liang et A.R. Ferguson) was developed through seedling selection by the Sichuan Academy of Natural Resources Science. Approved by the Sichuan Provincial Agricultural Variety Certification in 1997, it became the world’s first red-fleshed kiwifruit variety. Subsequently, China employed methods such as seedling selection, bud sport selection, and hybrid breeding to develop a series of new red-fleshed kiwifruit varieties with excellent comprehensive traits. The development of these varieties (lines) has significantly enriched China’s kiwifruit germplasm resources. Notably, the vast majority of red-fleshed varieties developed to date utilize ‘Hongyang’ as a parent, indicating its status as the most central and pivotal parent in China’s red-fleshed kiwifruit breeding programs [2,3,4,5].

As the key reproductive organ of plants, flower bud differentiation represents the pivotal transition from vegetative to reproductive growth. This process is precisely regulated by genetic programs and relies on complex interactions between nutritional status and endogenous hormones [6,7,8]. At the molecular level, transcription factor families such as bHLH play pivotal roles in light signaling, hormone pathways, and flowering regulation. Members like MdbHLH (apple), SlbHLH (tomato), and PmbHLH (plum) have been demonstrated to participate in hormone integration, organ development, and stress response, respectively [9,10,11]. Recent studies indicate that endogenous hormones significantly influence floral differentiation in plants [12,13,14]. These hormones bind to specific protein receptors, enabling highly efficient regulation of floral differentiation processes, flowering timing, and floral organ quality at sub-optimal concentrations [15,16,17,18]. Currently, extensive research exists on hormone regulation mechanisms in various fruit trees, including Guava [13], Citrus [19], Apple [20], Persimmon [21], and Grape [22] Hormone regulation mechanisms in various fruit trees have been extensively studied. However, within the genus Actinidia, systematic research on flower bud differentiation and hormone dynamics remains scarce beyond preliminary investigations into flower bud development in Actinidia arguta [23,24]. In-depth exploration is urgently needed to provide theoretical foundations for flowering regulation and genetic improvement.

This study used ‘Hongyang’ kiwifruit as experimental material to systematically measure changes in multiple endogenous hormone levels during the development from overwintering bud differentiation to flower morphogenesis (bell-shaped flowers). Combined with paraffin section anatomical observations of morphological characteristics at key stages of flower bud differentiation, to investigate the physiological effects of endogenous hormones on ‘Hongyang’ flower bud differentiation and floral morphogenesis. This aims to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms underlying female flower formation in ‘Hongyang’, providing theoretical foundations for breeding research and flowering period management in production.

The experimental site is located at the Shifang Kiwifruit Research Base of the Sichuan Academy of Natural Resources Science (104°1′12.875″ E, 31°13′31.760″ N), situated within a subtropical humid climate zone. This flat-plain area exhibits a small annual temperature range, with an average annual temperature of 13°C–17°C. The climate is mild, rainfall is abundant, sunshine hours are relatively low, and the four seasons are distinct. The experimental material consists of mature female ‘Hongyang’ kiwifruit plants, aged 15–20 years, cultivated at this base and independently developed by the Sichuan Provincial Natural Resources Science Research Institute. Plants exhibiting vigorous growth and free from pests or diseases were selected for observation and sampling. For each sampling session, one-year-old vigorous shoots with consistent growth patterns and identical orientations were collected.

2.2 Observation of the Morphological Structure of Flower Bud Differentiation

From November 2023 to mid-April 2024, samples were collected periodically for paraffin sectioning based on growth and development. Specifically: From November 2023 to late February 2024: Samples collected approximately every 30 days; From March to April 2024: Samples collected approximately every 15 days; In April 2024, sampling will occur approximately every 7 days. A total of 7 sampling events will yield 9 samples. Material collection involves harvesting axillary buds from the leaf axils of 2–9 nodes on vigorous one-year-old shoots. Each sample will contain 3–6 axillary buds (collected before bud break; main flower buds will be collected after bud formation). Collected samples were placed in sampling tubes containing FAA solution [V(70% C2H6O):V(C2H4O2):V(CH2O) = 18:1:1] for fixation for over 24 h. Standard paraffin sectioning methods were employed, with section thickness of 5–7 μm. Sections were processed using Safranin-Fast Green counterstaining, followed by dehydration, clearing, wax immersion, embedding, sectioning, and mounting with resin. Observations were conducted using an Olympus BX251 optical microscope, and images were captured.

2.3 Measurement of Endogenous Hormones During Flower Bud Differentiation and Development

Sampling for endogenous hormone analysis must be synchronized with paraffin section sampling in terms of requirements, methods, and timing. Samples for endogenous hormone analysis should be transported back to the laboratory in ice packs, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored in an ultra-low temperature freezer at −80°C. Endogenous hormone content determination should be conducted uniformly according to requirements after all batches of sampling are completed. LC-MS-based targeted plant hormone metabolomics was employed to measure

Experimental procedures are as follows: (1) Metabolite extraction: Retrieve samples from −80°C. After grinding in liquid nitrogen, weigh 100 mg of sample. Add 1170 μL of acetonitrile-formic acid solution (80:19:1, v/v), followed by 10 μL ISMix-A and 20 μL ISMix-B. vortex for 60 s, cold-ultrasonicate in the dark for 25 min, and incubate at −20°C overnight. Centrifuge at 14,000 rcf at 4°C for 20 min. Transfer 900 μL supernatant to an Ostro 25 mg 96-well de-lipidized plate for positive-pressure filtration. Add 200 μL acetonitrile-formic acid solution (80:19:1, v/v) for elution. Blow-dry filtrate with liquid nitrogen. Store samples at −80°C. (2) Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Samples were separated using an Agilent 1290 Infinity LC ultra-high performance liquid chromatography system. Mass spectrometry analysis was performed on a 5500 QTRAP mass spectrometer (SCIEX) in both positive and negative ion modes. (3) Chromatographic peak areas and retention times were extracted using Multiquant 3.0.2 software. Retention times were calibrated using target compound standards for metabolite identification.

2.4 Data Processing and Analysis

Quantitative analysis was performed using the isotope internal standard method. The absolute content of the analyte was calculated based on the response abundance ratio (peak area ratio) between the analyte and the internal standard, along with the concentration of the internal standard. The quantitative procedure is as follows: First, derive the calibration curve equation from the mass spectrometry signal data of standard samples at different concentrations. Then, using the calibration curve, the software automatically calculates the concentration information of each metabolite in every sample. Finally, based on the initial mass or volume of the sample, the concentration information in the final sample is calculated in units of μmol/g or μmol/L.

Metabolite content in the sample (μmol/g or μmol/L) = C (measured) × V/(m or v) × n

Meaning of letters in the formula:

C (measured): Software-calculated concentration of component X in the sample;

V: Volume corresponding to the standard curve point;

m: Mass of the original sample weighed;

v: Volume of the original sample measured;

n: Dilution factor

To more accurately represent the content differences of each endogenous hormone across different time periods (groups), the average of three replicate measurements from samples taken at different time points was used as the quantitative content for each endogenous hormone. Bar charts were plotted for comparative analysis, with the horizontal axis representing the group and the vertical axis representing the content (ng/g). The upper error bar indicates the mean ± standard deviation, while the lower error bar indicates the mean − standard deviation. Data significance analysis was performed using SPSS 25 software, and bar charts were generated using Origin 2025 software.

3.1 Flower Bud Differentiation and Development Process of ‘Hongyang’

Using paraffin sectioning, we systematically observed the flower bud differentiation and development process of the female kiwifruit cultivar ‘Hongyang’, focusing on three stages: the undifferentiated stage (24 November 2023–31 January 2024), axillary bud differentiation and development stage (1 February–21 March, 2024), and floral morphogenesis stage (2–11 April 2024), spanning nearly 140 days. Results indicate axillary bud differentiation commenced on February 1, with this date serving as the reference point for calculating floral differentiation stages.

Undifferentiated Stage (I): By 31 January 2024, axillary bud growth remained slow with indistinct differentiation of axillary bud primordia. External morphology persisted in a dormant state showing no significant growth changes (Fig. 1I). However, sectioning revealed initial cellular differentiation and nascent germination within axillary buds (Fig. 2I), indicating the commencement of physiological activity.

Axillary Bud Differentiation and Development Stage (II–III): 33 days after the beginning of axillary bud differentiation (March 5) has entered the axillary bud primordium differentiation period. The overwintering buds began to sprout, with rust-colored villi on the top, and the mixed buds were obviously protruding (Fig. 1II); the section showed that the growth cone had obvious extension and expansion, and the young shoot (b) and the axillary bud primordium (a) began to differentiate. At this time, the top of the axillary bud primordium (a) was semi-spherical (Fig. 2II), which was the sign of the initial differentiation of the axillary inflorescence primordium. 49 days after the axillary buds began to differentiate (March 21), the axillary inflorescence primordium differentiation stage was entered. At this time, the outer scales of the overwintering buds had cracked, the top was greener and more and more rusty villi were exposed, gradually loose, close to the leaf expansion state (Fig. 1III); the sections clearly showed that the growth cone of the axillary inflorescence primordium (a1) changed from hemispherical to broad and flat, while the growth cone of the axillary leaf bud primordium (a2) was a thin tip triangle, and the morphological difference between the two was significant (Fig. 2III). At this time, the young shoots further differentiate and elongate, and the young shoots that form the axillary inflorescence primordium will develop into fruiting mother shoots.

Flower Morphogenesis Stage (IV–V): 61 days after axillary bud differentiation commenced (April 2), the plant entered the ovary and stamen differentiation stage. Young shoots elongated and unfurled leaves, with multiple flower buds of varying sizes developing at the shoot base (Fig. 1IV). Cross-sections of terminal flower buds reveal clearly differentiated structures: sepals (s), petals (e), stamen primordia (m), pistil primordia (p), ovary (v), and ovules (o). Sepals tightly enclose the outer layer, petals elongate centripetally and overlap, while stamen primordia encircle the pistil cluster. As the pistillary primordium develops, it indents downward to form a short, thick, hollow style. Its upper end features a radiating stigma, with ovules arranged in rows on the central axis placenta (Fig. 2IV). Seventy days after axillary bud differentiation (April 11), the plant entered the ovary and ovule formation stage. New shoots elongated significantly, unfurling 2–8 leaves per shoot. Multiple nodes emerged, each bearing inflorescences containing 1–3 flowers. Some flowers developed into bell-shaped flowers, nearing full bloom. Cross-section analysis of a bell flower (HY-20240411-3) revealed markedly enlarged ovaries (vi), further developed ovules (oi), significantly reduced stamens (mi), and shrunken anther sacs (Fig. 2(V-3)).

In production, it is generally accepted that pollen is fully mature during the bell-flower stage, when floral organ differentiation is complete. For the ‘Hongyang’ kiwifruit cultivar, the period from initial axillary bud differentiation in early February to the establishment of floral morphology (bell-flower stage) in mid-to-late April spans approximately 70 days. Due to regional and climatic differences, the phenological period and time required for flower bud differentiation are slightly different. The phenological period in Sichuan is not much different. The growth time will fluctuate according to the temperature change every year, but the process of flower bud development remains unchanged, which can be judged by combining external morphology and internal structure.

Figure 1: Different stages of flower bud differentiation and development in the female kiwifruit cultivar ‘Hongyang’. (I): Undifferentiated axillary bud stage; (II,III): Axillary bud differentiation stage; (IV,V): Floral morphogenesis stage.

Figure 2: Morphological Structure of Flower Bud Differentiation at Different Stages in the Female Kiwifruit Cultivar ‘Hongyang’. (I): Undifferentiated stage; (II): Axillary bud primordium differentiation stage; (III): Axillary inflorescence primordium differentiation stage; (IV). Ovary and stamen differentiation stage; (V-3): Ovary and ovule formation stage. a: Axillary bud primordia; b. Young shoot; a1. Axillary leaf bud primordia; a2. Axillary inflorescence primordia; bi. Developing young shoot; s. Sepals; e. Petals; p. Pistil primordia; m. Stamen cluster primordia; o. Ovule; v. Ovary; si. Developed calyx; ei. Developed petals; pi. Pistil; mi. Degenerated stamen; oi. Developed ovule; vi. Developed ovary.

3.2 Dynamic Changes in Endogenous Hormones During Flower Bud Differentiation and Development in ‘Hongyang’

The content of IAA in plants is low (usually 10–100 ng fresh weight) and concentrated in the vigorous growth parts. It can be seen from Fig. 3 that IAA remained at a high level (80.63–98.82 ng/g) during the differentiation and development of the morphogenesis of ‘Hongyang’ kiwifruit from overwintering buds to bell flowers, with little fluctuation, and only decreased during the bell flower period.

ABA can induce bud dormancy, inhibit growth, and promote organ abscission. As shown in Fig. 3, during the differentiation and development of ‘Hongyang’ from overwintering buds to bell-shaped flowers, ABA content was relatively high during the undifferentiated stage (I) (130.38–354.99 ng/g), exhibiting fluctuations alongside axillary bud priming; It then decreased significantly to 73.79–94.22 ng/g during the axillary bud differentiation and development stage (II–III). After entering the floral morphogenesis stage (IV–V), the content gradually increased, rising from 132.96 ng/g in the young bud stage to 445.11 ng/g in the bellflower stage.

1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC), as a precursor in ethylene biosynthesis, reflects ethylene synthesis levels. In this study (Fig. 3), ACC content exhibited distinct dynamic changes during the differentiation and development of ‘Hongyang’ kiwifruit from overwintering buds to bell-flower stage: ACC remained at relatively low levels (263.47–383.89 ng/g) during the undifferentiated stage (I); significantly increased during the axillary bud differentiation and development stage (II–III) (3733.74–6550.09 ng/g); and although it gradually decreased to 1968.85–3355.27 ng/g during the floral morphogenesis stage (IV–V), it remained significantly higher than the undifferentiated stage (I).

GA exists in numerous varieties and is widely distributed throughout plant tissues, particularly concentrated in tender parts such as shoot tips, root tips, and developing seeds. This experiment primarily measured the dynamic changes of GA4 (Fig. 3). During the differentiation and development of ‘Hongyang’ from overwintering buds to bell flowers, GA4 content was relatively low (9.79–12.41 ng/g) in the undifferentiated stage (I). significantly increased to 43.48 ng/g during the axillary bud primordia differentiation stage (II), reaching the peak level throughout the developmental stage; subsequently, it gradually decreased with the growth of young shoots and floral morphogenesis.

The dynamic changes of six cytokinins—cZ, tZ, cZR, tZR, iP, and iPR—were measured during the flower bud development of ‘Hongyang’ (Fig. 3). Except for tZR, which showed no obvious pattern, the other five exhibited discernible trends: iP maintained relatively low overall levels (0.61–1.71 ng/g) and gradually decreased with development; iPR, cZ, tZ, and cZR exhibited similar trends despite differing concentrations: all reached their lowest levels during the undifferentiated stage (I), significantly increased to peak levels during the axillary bud primordia differentiation stage (II), and then gradually decreased as flower morphology was established, though remaining higher than the undifferentiated stage (I) levels. Results indicate that all six CTKs (cZ, tZ, cZR, tZR, iP, iPR) participate in flower bud differentiation and morphogenesis in ‘Hongyang’, with most playing particularly crucial roles during the transition to flowering.

By monitoring changes in TY levels (Fig. 3), it was observed that during the differentiation and development of winter buds to bellflowers in ‘Hongyang’, the undifferentiated stage (I) exhibited higher concentrations (36.79–45.75 ng/g). Upon entering the axillary bud differentiation and development stage (II–III), levels significantly decreased to 18.96–21.07 ng/g. and remained at a low level (17.91–25.19 ng/g) with minimal fluctuation during the floral morphogenesis stage (IV–V).

3.2.7 Jasmonic Acid Derivatives (JAs)

As shown in Fig. 3, JA and JA-lle contents were extremely low during the undifferentiated stage (I) and axillary bud differentiation stage (II–III). They increased markedly during the ovary and stamen differentiation stage (IV) as flower development progressed, peaking in the smallest flower buds (V-1) (JA: 490.13 ng/g, JA-lle: 215.32 ng/g). Subsequently, they decreased significantly in larger flower buds (V-2) and nearly-opened bell-shaped flowers (V-3). 12-OPDA exhibited low levels during the undifferentiated stage (I) (393.85–1189.99 ng/g), increased markedly during the axillary bud primordia differentiation stage (II), and remained at high levels with a slight upward trend until the ovary and ovule formation stage (V), reaching a maximum of 5083.85 ng/g. Data from this experiment indicate that 12-OPDA, as an intermediate product in JA synthesis, exhibits significantly higher content levels than JA and JA-lle during axillary bud differentiation and flower development and morphogenesis in ‘Hongyang’. Furthermore, its production precedes that of JA and JA-lle. Additionally, JA-lle appears at roughly the same time as JA, with its content level slightly lower than that of JA.

SA participates in various biological processes, including seed germination, photosynthesis, respiration, flowering induction, and stress responses in plants. As shown in Fig. 3, SA content was relatively high during the undifferentiated stage (I) (453.09–505.08 ng/g). It then decreased sharply to 121.72–72.79 ng/g during the axillary bud differentiation and development stage (II–III). Subsequently, SA levels remained stable at a low level throughout flower development and morphogenesis.

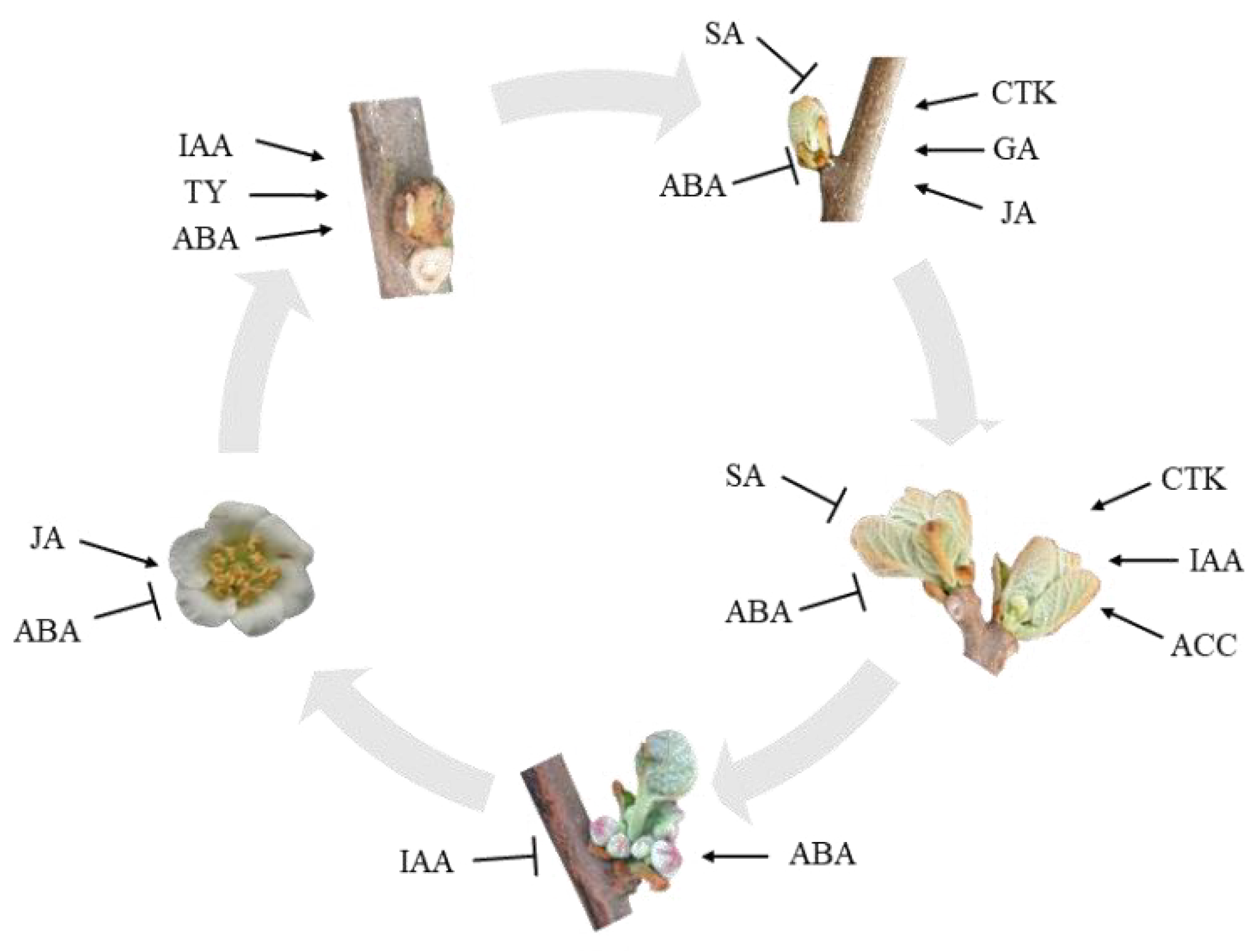

To more intuitively present the synergistic regulatory network of these multiple hormones during the critical stages of flower bud differentiation in ‘Hongyang’ Japanese quince, we have created a schematic diagram (Fig. 4). This diagram integrates the dynamic patterns of each hormone during different differentiation stages (I–V) and their inferred functions: During axillary bud primordia differentiation (Stage II), the rise of CTK, GA4, and IAA coupled with the decline of ABA jointly initiates floral differentiation; During the inflorescence and floral organ primordia differentiation stage (III–IV), elevated levels of IAA, ACC, and persistent BRs (e.g., TY) drive the formation of female-specific structures, while low levels of JAs and SA may promote stamen abortion; by the ovary and ovule formation stage (V), peak levels of ABA and JAs correlate with the flower senescence process.

Figure 3: Changes in Endogenous Hormone Content During Different Stages of Flower Development in the Female Kiwifruit Cultivar ‘Hongyang’. (a): Auxin: Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA); (b): Abscisic acid (ABA); (c): Ethylene: 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC); (d): Gibberellin-4 (GA4); (e): Cytokinins: Ionic adenine (iP), Ionic adenine riboside (iPR), cis-Z-cinnamoyl-L-alanine (cZ), trans-Z-cinnamoyl-L-alanine (tZ), cis-Z-cinnamoyl-L-alanine riboside (cZR), trans-Z-cinnamoyl-L-alanine riboside (tZR); (f): Brassinosteroids: Tylophorin (TY); (g): Jasmonic acid derivatives: Jasmonic acid (JA), Methyl jasmonate (JA-Ile), 12-Oxo-2-propenoic acid (12-OPDA); (h): Salicylic acid (SA).

Figure 4: Schematic diagram of hormone-induced flower bud differentiation in Kiwifruit trees.

Previous studies have indicated that the regulation of flower bud differentiation by endogenous hormones is not directly initiated by a single hormone, but rather results from the dynamic interplay of multiple hormones. In woody plants, GA is generally considered to inhibit flowering [16,25], though alternative perspectives have been proposed. For instance, Guo discovered that from the early to late stages of flower bud differentiation in Lycium ruthenicum Murr, the GA3 content in the buds significantly increased [26]; conversely, Looney reported that GA4 promotes flowering in apple trees [11,12]. In this study, following the differentiation stage (II) of axillary bud primordia in ‘Hongyang’ kiwifruit, GA4 content significantly increased as axillary inflorescence primordia began to differentiate. Although it subsequently decreased, it remained higher than the level during the undifferentiated stage (I). This suggests GA4 may partially promote female flower development in ‘Hongyang’, consistent with findings in Actinidia arguta by Li et al. [23]. Additionally, ABA levels reached their lowest point during axillary bud primordia differentiation stage (II), declining synchronously with primordia differentiation and potentially facilitating bud break and floral differentiation. During the formation of the ovary and ovule, ABA levels significantly rebounded, potentially promoting the flower senescence process (bell-shaped flowers take approximately 1–2 days to senesce). This pattern aligns with the findings reported by Li et al. in kiwifruit [23].

CTK is primarily distributed in regions of active cell division, where it promotes axillary bud growth [25] and induces floral meristem formation [27,28]. Li et al. [29] indicated that localized CTK synthesis in axillary buds or stems is crucial for bud activation and growth. Natural CTKs primarily include cis-tanzanin (cZ), isopentenyladenine (iP), and other forms, with tZ and iP being the most prevalent [8,30,31,32]. Previous studies indicate that high levels of CTK are required during flower bud differentiation to promote cell division and growth [33], whereas high concentrations of GA inhibit flower bud differentiation [34]. In this study, CTK levels significantly increased during the differentiation stage (II) of axillary bud primordia before gradually decreasing, consistent with previous reports [16,35].

A significant dynamic equilibrium exists between IAA and tZR, with decreased IAA levels often accompanied by increased tZR [36]. Most studies suggest IAA acts as a flower-inhibition factor [37], whose content rapidly declines during the physiological differentiation stage of flower buds in woody plants, thereby promoting the transition to morphological differentiation [16]. However, contrary findings exist. For instance, Wang [38] and Qiu et al. [39], respectively observed that high IAA concentrations favored morphological differentiation of flower buds in longan and apricot. Li et al. [23] also reported a sustained increase in IAA during female flower development in kiwifruit, suggesting it may promote the transition from bisexual to unisexual flowers. The present findings support these observations, indicating that elevated and stable IAA levels may participate in the differentiation of female flowers in ‘Hongyang’. Yang et al. [40] noted that sexual differentiation in Actinidia chinensis occurs during the early stage of pistil primordium differentiation (2–3 days after bud formation). In this experiment, ‘Hongyang’ exhibited bud formation 61 days after axillary bud differentiation initiation (April 2), indicating that the nearly 30-day period from axillary bud primordia differentiation stage (II) to ovary and stamen differentiation stage (IV) represents a critical phase for female flower differentiation. During this period, ACC maintained persistently elevated levels, potentially playing a significant role in this process.

Brassinosteroids (BRs), as the sixth class of plant hormones, encompass multiple types including brassinosterone BR2 (CS), brassinosterone-1-butyrate BR1 (BL), and tigrosteroin BR7 (TY) [41,42,43]. They promote cell division and participate in the regulation of floral bud differentiation, exhibiting higher concentrations in pollen and immature seeds [15,16]. This study speculates that TY may participate in the early stages of floral differentiation by enhancing photosynthesis, promoting cell division and elongation, and facilitating material accumulation and preparation processes [8,44]. JAs include cyclopentanone derivatives such as jasmonic acid (JA) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA). Among these, 12-OPDA serves as an intermediate in JA synthesis, while JA-lle represents its primary active form [45,46]. Research indicates JAs play crucial roles in stamen development, pollen maturation, and anther dehiscence. This study found that during the critical period of female flower differentiation (II–IV) in ‘Hongyang’, JA and JA-lle levels remained persistently low, particularly reaching extremely low levels before the ovary and stamen differentiation stage (IV). It is speculated that low JA concentrations may induce stamen abortion, consistent with studies in Arabidopsis and other plants [47,48]. In larger flower buds during the ovary and embryo sac formation stage (V), JA and JA-lle levels peaked, potentially related to promoting flower senescence, with a function similar to ABA [8]. The specific mechanism requires further investigation. Research on SA’s role in floral bud differentiation remains limited. Studies indicate SA inhibits female flower differentiation in cucumber [8]. In this study, SA levels remained low during the critical differentiation period of ‘Hongyang’ female flowers, suggesting low SA concentrations may favor differentiation and morphological establishment in these flowers.

Based on these findings, subsequent studies will systematically investigate the developmental dynamics of kiwifruit female and male flowers. By integrating the spatiotemporal patterns of endogenous hormones, we aim to elucidate the physiological and molecular mechanisms underlying floral bud differentiation. This research will identify critical developmental windows and core regulatory factors for floral organ differentiation, providing theoretical foundations and technical support for achieving precise control over floral bud differentiation.

This study preliminarily confirms that female flower bud differentiation in ‘Hongyang’ kiwifruit begins from late January to early February. By mid-to-late April (the bell flower stage), the morphological development of floral organs is largely complete, spanning approximately 70 days. This process primarily includes the differentiation of axillary inflorescence primordia, sepals primordia, petals primordia, apical/lateral flower bud primordia, pistil primordia (carpel cluster primordia), stamen cluster primordia, ovary/ovule formation, and stamen differentiation and degeneration. Among these, the period from 33 to 61 days after axillary bud differentiation initiation—spanning nearly 30 days—was identified as the critical phase for female flower differentiation in ‘Hongyang’. Paraffin section observations and endogenous hormone content measurements revealed that 33 days after axillary bud differentiation initiation, plants entered the axillary bud primordium differentiation stage (Stage II), a pivotal stage for flower bud differentiation. At this time, ABA content decreases, promoting bud emergence and floral differentiation in ‘Hongyang’. During the critical differentiation period, lower JAs levels may correlate with stamen abortion, while reduced SA concentrations favor female flower differentiation and morphogenesis. Conversely, elevated ACC and GA4 concentrations may accelerate female flower differentiation and subsequent flowering and development, respectively.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Sichuan Fruit Innovation Team Project (SCCXTD-2024-04), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2024YFHZ0227, 2025YFHZ0118, 2023YFN0005).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xiaoqin Zheng, Lihua Wang; data collection and experimentation: Yuqing Wan, Qian Zhang, Shihao Tang; data analysis and validation: Yuqing Wan, Qian Zhang; resources and technical support: Qiguo Zhuang, Liqin He. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| ‘Hongyang’ kiwifruit | |

| Indole-3-acetic acid | |

| Abscisic acid | |

| Ethylene | |

| Gibberellic acid | |

| Cytokinin | |

| Brassicasterols | |

| Tylosterol | |

| Jasmonic acid derivatives | |

| Salicylic acid | |

| 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid | |

| cis-12-Oxophytodienoic acid | |

| cis-Zeatin | |

| trans-Zeatin | |

| cis-Zeatin riboside | |

| trans-Zeatin riboside | |

| Isopentenyl adenosine | |

| Isopentenyl adenine |

References

1. Warrington IJ , Weston GC . Kiwifruit: science and management. Wellington, New Zealand: New Zealand Society for Horticultural Science; 1990. [Google Scholar]

2. Wang M , Li M , Wu B , Hou S . Study on the breed of new kiwi furlt cultlvar. Resour Dev Mark. 1996; 2: 51– 4. [Google Scholar]

3. Zheng XQ , He LQ , Zhang Q , Zhuang QG , Wang LH . Research progress on breeding of red-flesh kiwifruit. North Hortic. 2024; 1: 130– 5. (In Chinese). doi:10.11937/bfyy.20231991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Han ML , Zhang ZY , Zhao G , Chen LP , Li YD . Research advance and prospect of red-fleshed kiwifruit breeding in China. North Hortic. 2014; 1: 182– 7. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

5. Wang MZ . Sustainable breeding research of Actinidia chinensis var. rufopulpa. Resour Dev Mark. 2003; 19( 5): 309– 10. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

6. Fan L , Chen M , Dong B , Wang N , Yu Q , Wang X , et al. Transcriptomic analysis of flower bud differentiation in Magnolia sinostellata. Genes. 2018; 9( 4): 212. doi:10.3390/genes9040212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Theißen G , Melzer R , Rümpler F . MADS-domain transcription factors and the floral quartet model of flower development: linking plant development and evolution. Development. 2016; 143( 18): 3259– 71. doi:10.1242/dev.134080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang Z . Plant physiology. Beijing, China: China Agriculture Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

9. An JP , Xu RR , Wang XN , Zhang XW , You CX , Han Y . MdbHLH162 connects the gibberellin and jasmonic acid signals to regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis in apple. J Integr Plant Biol. 2024; 66( 2): 265– 84. doi:10.1111/jipb.13608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Waseem M , Li Z . Overexpression of tomato SlbHLH22 transcription factor gene enhances fruit sensitivity to exogenous phytohormones and shortens fruit shelf-life. J Biotechnol. 2019; 299: 50– 6. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2019.04.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wu Y , Wu S , Wang X , Mao T , Bao M , Zhang J , et al. Genome-wide identification and characterization of the bHLH gene family in an ornamental woody plant Prunus mume. Hortic Plant J. 2022; 8( 4): 531– 44. doi:10.1016/j.hpj.2022.01.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Julian C , Herrero M , Rodrigo J . Flower bud differentiation and development in fruiting and non-fruiting shoots in relation to fruit set in apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.). Trees. 2010; 24( 5): 833– 41. doi:10.1007/s00468-010-0453-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Huang WL , Zhang CK , Zhang DM , Zheng CL . Study on the morphological structure of flower bud differentiation and the dynamic changes of endogenous hormones in Psidium guajava L. South China Fruits. 2024; 53( 4): 80– 7. (In Chinese). doi:10.13938/j.issn.1007-1431.20230168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Tran LMH . The effect of phytohormones on the flowering of plants. Plant Sci Today. 2023; 10( 2): 138– 42. doi:10.14719/pst.2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Amasino R . Seasonal and developmental timing of flowering. Plant J. 2010; 61( 6): 1001– 13. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313x.2010.04148.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hoad GV . Hormonal regulation of fruit-bud formation in fruit trees. Flower Fruit Set Fruit Trees. 1983; 149: 13– 24. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.1984.149.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Niu F , Rehmani MS , Yan J . Multilayered regulation and implication of flowering time in plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2024; 213: 108842. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.108842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Freytes SN , Canelo M , Cerdán PD . Regulation of flowering time: when and where? Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2021; 63: 102049. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2021.102049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Koshita Y , Takahara T , Ogata T , Goto A . Involvement of endogenous plant hormones (IAA, ABA, GAs) in leaves and flower bud formation of satsuma mandarin (Citrus unshiu Marc.). Sci Hortic. 1999; 79( 3–4): 185– 94. doi:10.1016/S0304-4238(98)00209-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Milyaev A , Kofler J , Moya YAT , Lempe J , Stefanelli D , Hanke MV , et al. Profiling of phytohormones in apple fruit and buds regarding their role as potential regulators of flower bud formation. Tree Physiol. 2022; 42( 11): 2319– 35. doi:10.1093/treephys/tpac083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Sun P , Li J , Du G , Han W , Fu J , Diao S , et al. Endogenous phytohormone profiles in male and female floral buds of the persimmons (Diospyros kaki Thunb.) during development. Sci Hortic. 2017; 218: 213– 21. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2017.02.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Liu X , Yuan M , Dang S , Zhou J , Zhang Y . Comparative transcriptomic analysis of transcription factors and hormones during flower bud differentiation in ‘Red Globe’ grape under red‒blue light. Sci Rep. 2023; 13( 1): 8932. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-29402-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li XY , Wang ZX , Qin HY , Fan ST , Ai J . Dynamic variation of endogenous hormone during male and female flower buds development of Actinidia arguta. J Jilin Agric Univ. 2016; 38( 3): 281– 6. (In Chinese). doi:10.13327/j.jjlau.2015.2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Shi F , Li ZJ . Analysis of key hormones and mineral element content characteristics during the development of Ziziphus jujuba fruit. Xinjiang Farm Res Sci Technol. 2018; 41( 3): 29– 34. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-361X.2018.03.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Luo YW , Xie WH , Ma K . Correlation between endogenous hormones contents and flower bud differentiation stage of Ficus carica L. Acta Bot Boreali Occidentalia Sin. 2007; 27( 7): 1399– 404. (In Chinese). doi:10.3321/j.issn:1000-4025.2007.07.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Guo Y , An L , Yu H , Yang M . Endogenous hormones and biochemical changes during flower development and florescence in the buds and leaves of Lycium ruthenicum Murr. Forests. 2022; 13( 5): 763. doi:10.3390/f13050763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. D’Aloia M , Bonhomme D , Bouché F , Tamseddak K , Ormenese S , Torti S , et al. Cytokinin promotes flowering of Arabidopsis via transcriptional activation of the FT paralogue TSF. Plant J. 2011; 65( 6): 972– 9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04482.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Denay G , Chahtane H , Tichtinsky G , Parcy F . A flower is born: an update on Arabidopsis floral meristem formation. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2017; 35: 15– 22. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2016.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Li G , Tan M , Cheng F , Liu X , Qi S , Chen H , et al. Molecular role of cytokinin in bud activation and outgrowth in apple branching based on transcriptomic analysis. Plant Mol Biol. 2018; 98( 3): 261– 74. doi:10.1007/s11103-018-0781-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Osugi A , Sakakibara H . Q&A: how do plants respond to cytokinins and what is their importance? BMC Biol. 2015; 13: 102. doi:10.1186/s12915-015-0214-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhao Y . The role of local biosynthesis of auxin and cytokinin in plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2008; 11( 1): 16– 22. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2007.10.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Gajdosová S , Spíchal L , Kamínek M , Hoyerová K , Novák O , Dobrev PI , et al. Distribution, biological activities, metabolism, and the conceivable function of cis-zeatin-type cytokinins in plants. J Exp Bot. 2011; 62( 8): 2827– 40. doi:10.1093/jxb/erq457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Bartrina I , Otto E , Strnad M , Werner T , Schmülling T . Cytokinin regulates the activity of reproductive meristems, flower organ size, ovule formation, and thus seed yield in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2011; 23( 1): 69– 80. doi:10.1105/tpc.110.079079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ai J , Wang YP , Li CY , Guo XW , Li AM . The changes of three endogenous hormones during flower bud differentiation of Schisandga chinensis. China J Chin Mater Medica. 2006; 31( 1): 24– 6. [Google Scholar]

35. Wang D , Su P , Yang Z , Chen J , Liao R , Gao Y , et al. Combined analysis of metabolome and transcriptome in response to exogenous tZ treatment on axillary bud development in Eucommia ulmoides Oliver. Ind Crops Prod. 2025; 230: 121089. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2025.121089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Reig C , Mesejo C , Martínez-Fuentes A , Agustí M . In loquat (Eriobotrya japonica Lindl.) return bloom depends on the time the fruit remains on the tree. J Plant Growth Regul. 2014; 33( 4): 778– 87. doi:10.1007/s00344-014-9426-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Davies PJ . The plant hormones: their nature, occurrence, and functions. In: Plant hormones. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2010. p. 1– 15. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-2686-7_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wang W . Studies on the relationship of potassium chlorate (KCLO3) on off-Season flower-bud formation of longan and endogenous hormones and other growth substances [ dissertation]. Fuzhou, China: Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University; 2010. [Google Scholar]

39. Qiu XS , Liu GC , Lu DG , Zhang XZ , Li CM . Dynamic changes of endogenous hormonein leaf during the period of flower bud differentiation of apricot. J Anhui Agric Sci. 2006; 34( 9): 1798– 800. (In Chinese). doi:10.13989/j.cnki.0517-6611.2006.09.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Yang MX , Xiao DX , Liang H , Liu W . Cytomorphological observation on sex differentiation of Actinidia chinensis. Acta Hortic Sin. 2011; 38( 2): 257– 64. (In Chinese). doi:10.16420/j.issn.0513-353x.2011.02.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Li Z , He Y . Roles of brassinosteroids in plant reproduction. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21( 3): 872. doi:10.3390/ijms21030872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Baghel M , Nagaraja A , Srivastav M , Meena NK , Senthil Kumar M , Kumar A , et al. Pleiotropic influences of brassinosteroids on fruit crops: a review. Plant Growth Regul. 2019; 87( 2): 375– 88. doi:10.1007/s10725-018-0471-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Peres ALGL , Soares JS , Tavares RG , Righetto G , Zullo MAT , Mandava NB , et al. Brassinosteroids, the sixth class of phytohormones: a molecular view from the discovery to hormonal interactions in plant development and stress adaptation. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20( 2): 331. doi:10.3390/ijms20020331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Yang CJ , Zhang C , Lu YN , Jin JQ , Wang XL . The mechanisms of brassinosteroids’ action: from signal transduction to plant development. Mol Plant. 2011; 4( 4): 588– 600. doi:10.1093/mp/ssr020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Luo C , Qiu J , Zhang Y , Li M , Liu P . Jasmonates coordinate secondary with primary metabolism. Metabolites. 2023; 13( 9): 1008. doi:10.3390/metabo13091008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ruan J , Zhou Y , Zhou M , Yan J , Khurshid M , Weng W , et al. Jasmonic acid signaling pathway in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20( 10): 2479. doi:10.3390/ijms20102479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Ishiguro S , Kawai-Oda A , Ueda J , Nishida I , Okada K . The DEFECTIVE IN ANTHER DEHISCIENCE gene encodes a novel phospholipase A1 catalyzing the initial step of jasmonic acid biosynthesis, which synchronizes pollen maturation, anther dehiscence, and flower opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2001; 13( 10): 2191– 209. doi:10.1105/tpc.010192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Wang X , Wang J , Liu Z , Yang X , Chen X , Zhang L , et al. The R2R3 MYB gene TaMYB305 positively regulates anther and pollen development in thermo-sensitive male-sterility wheat with Aegilops kotschyi cytoplasm. Planta. 2024; 259( 3): 64. doi:10.1007/s00425-024-04339-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools