Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Synergistic Effects of Melatonin and Methyl Jasmonate in Mitigating Drought-Induced Oxidative Stress in Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris)

1 Department of Crop Botany, Gazipur Agricultural University, Gazipur, 1706, Bangladesh

2 Department of Agronomy, Gazipur Agricultural University, Gazipur, 1706, Bangladesh

3 Department of Chemistry, State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, NY 13210, USA

* Corresponding Author: Mohammad Golam Mostofa. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants: Physio-biochemical and Molecular Mechanisms)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 3925-3943. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.073382

Received 17 September 2025; Accepted 18 December 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

The productivity of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), an economically important legume, is severely hindered by drought stress. While melatonin (Mel) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA) are known to alleviate abiotic stresses, their combined effects in mitigating drought-induced oxidative stress are unknown. Here, we examined the synergistic effects of Mel and MeJA in alleviating drought-associated oxidative damage in common bean. Compared with well-watered controls, drought stress caused a significant decline in plant biomass, photosynthetic pigments, and photosystem II efficiency (Fv/Fm). Drought also significantly increased hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) accumulation, which likely contributed to membrane lipid peroxidation, as indicated by elevated malondialdehyde (MDA) levels. Furthermore, drought stress substantially suppressed the activity of antioxidant enzymes, including catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD), and glutathione S-transferase (GST). In contrast, application of exogenous Mel and MeJA, particularly at 150 μM and 20 μM, respectively, significantly improved plant biomass, chlorophyll a (Chl a), chlorophyll b (Chl b), and Fv/Fm relative to drought-stressed plants only. Notably, the combined treatment with Mel and MeJA reduced H2O2 and MDA by 84.3% and 39.8%, respectively, while enhancing the activities of CAT (by 106.2%), POD (by 97.7%), and GST (by 54.2%) compared to drought-stressed plants only. Multivariate analyses further confirmed that Mel and MeJA effectively reduced the levels of H2O2 and MDA while enhancing antioxidant defense. These results suggest that the combined action of Mel and MeJA enhanced antioxidant defenses, restoring photosynthetic performance impaired by ROS in common bean. This synergy effectively mitigates drought-induced oxidative stress, highlighting their potential to improve resilience and support sustainable bean production for global food security.Keywords

Drought, a preeminent plant abiotic stressor, imposes catastrophic impacts on global crop production and food security. Drought has been lowering the crop yields at an alarming rate, with projected yield losses in arable lands up to 50% by 2050 [1]. Climate change exacerbated these losses through frequent, prolonged, and severe droughts with lower rainfall across agroecological zones [2,3]. Plant attributes, including growth, water and nutrient uptake, synthesis of photosynthetic pigments, and cellular and biochemical changes, including enzymatic activities, are greatly affected by drought stress, compromising yield significantly [4,5]. Drought causes cellular dehydration, leading to further osmotic and oxidative stress [6]. Severe drought stress in plants produces tremendous negative consequences on the plant’s photosynthesis by declining relative water content, stomatal conductance, intercellular CO2 concentration, transpiration rate, and functions of photosystem II (PSII) in terms of reducing the performance of electron transport and maximum quantum yield of PSII (FV/FM) [7]. However, drought triggers the development of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in plants, such as singlet oxygen (1O2), superoxide radical (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical (•OH), which are the primary constraints for plant growth and development [8,9].

To counter drought, plants deploy an array of morpho-physiological strategies, including modulation of root and shoot growth, water retention capacity, upregulation of photosynthetic pigments, and accumulation of osmolyte proline [10]. Moreover, plants deploy phytohormones for enhancing stress responsive proteins and antioxidant machineries (reviewed in [11]). Phytohormones play a crucial role in oxidative stress by modulating antioxidant defense and redox homeostasis in plants [12]. However, they modulate and orchestrate a complex signaling network by interacting with each other to enable the plant to survive in an extreme environment [13]. Drought stress in plants triggers ROS, which accelerates the level of lipid peroxidation product, malondialdehyde (MDA), enhances protein degradation, nucleic acid damage, and impairs the integrity of cell membranes [14,15]. In contrast, plants could reduce the toxicity of ROS by triggering a dynamic antioxidative defense system including enhanced activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and guaiacol peroxidase (GPX) [16,17,18].

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) (Mel), a ubiquitous growth regulator, has been stipulated as the potential modulator for plant growth, development, and abiotic stress acclimation processes, including drought [19,20]. Mel acts as the antioxidant itself and could alleviate the harmful effects of ROS by regulating other enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants [21]. Exogenous application of Mel has been reported in mitigating drought-induced oxidative damage of different crop species such as soybean [22], wheat [23], maize [24], and mung bean [25]. Mel has also emerged as a potential phytohormones modulating abiotic stress responses, including drought, by interacting and maintaining crosstalk with other phytohormones like auxin (AUX), cytokinins (CK), gibberellic acid (GA), abscisic acid (ABA), salicylic acid (SA), and jasmonic acid (JA) [13]. Alongside, methyl jasmonate (MeJA), a derivative of JA, can influence various processes of plant growth and development under drought stress [26]. MeJA has been known to alleviate drought stress by enhancing osmolyte proline, total protein, sugar content, and antioxidant activities [26]. MeJA also conferred drought tolerance in cowpeas by improving different physiological parameters [27]. Although the individual effects of Mel and MeJA are well known in drought tolerance, their interactive roles in drought mitigation in crop plants, particularly in legumes, remain unknown.

Phaseolus vulgaris L., commonly known as French bean or common bean, belonging to the Fabaceae family, is an annual bean species that has been cultivated as a popular legume crop across the globe [28]. The crop has been gaining popularity in South Asian countries, including Bangladesh, due to its potential nutritional and dietary values. Despite having this potential, about 60% of the common bean production area is greatly affected by prolonged drought worldwide [29]. Drought elicits profound morphological and biochemical disruptions of common bean, destabilizing the sustainable production system in developing countries. Even a short-term drought negatively affects the quality and yield of common bean [30]. More specifically, flowering, pod-bearing ability, and number of seeds are greatly affected by drought [31,32,33]. The country, like Bangladesh, where a dry climate persists in the winter season, shows a tremendous challenge to common bean production. Alongside, the gradual depletion of groundwater reserves exacerbates the growing condition. Therefore, exploring efficient drought tolerance strategies of common bean might resolve the problems and increase productivity. Recent research has demonstrated that the combined application of MeJA and salicylic acid (SA) enhances drought tolerance in common bean more effectively than their individual treatments [10], underscoring the potential of synergistic growth regulator use in stress mitigation. However, the interactive role of MeJA with other drought-alleviating molecules, such as Mel, remains largely unexplored. While our previous studies have indicated that both Mel and MeJA contribute to drought responses in common bean [34], the mechanisms by which these molecules mitigate drought-induced oxidative stress are still not fully understood. The potential synergistic effects of Mel and MeJA in reducing drought-related oxidative damage in legumes have yet to be investigated. Therefore, this study examined drought-stressed common bean plants treated with various Mel and MeJA combinations to assess their effectiveness in alleviating oxidative damage through morpho-physiological, biochemical, and multivariate analyses. We hypothesized that the co-application of Mel and MeJA would effectively mitigate drought-induced oxidative stress to restore the growth of common bean.

2.1 Plant Materials, Growth Conditions, Treatment Combinations, and Collection of Phenotypic Data

Common bean seeds (BARI Jharsheem-1) were procured from the Bangladesh Agricultural Research Institute (BARI), Gazipur, Bangladesh. Ten healthy seeds were sown in plastic pots (25 cm × 20 cm), maintaining uniform spacing in each pot with immediate light irrigation to ensure uniform germination. Each pot was filled with 9.5 kg of soil with the required dozes of fertilizers, and cow dung to ensure optimum fertility. The pots were subjected to ambient conditions (20–22°C and 50–60% relative humidity) by providing a shed to stop the interference of rainfall. Four uniform and healthy plants were retained in each pot. 15-day-old seedlings were treated with foliar spray of different concentrations of Mel (50, 100, and 150 μM) and 20 μM MeJA, the concentration of which was previously validated in common bean [10,34]. The plant, which was supposed to be only drought-stressed, was treated with the same amount of distilled water. After foliar spray, the plants were exposed to drought stress by stopping normal irrigation and maintaining 50% field capacity. The field capacity was maintained in the treated plants by regular monitoring of the moisture content (%) of the pot’s soil (at 15 cm depth) at 3-day intervals, as followed by Mohi-Ud-Din et al. [10]. The non-stress control plants were maintained by normal irrigation. The second spray of Mel and MeJA was applied 3 days after the first application. A completely randomized design (CRD) with three replications was set. Three plastic pots (replications) with 4 plants per each was set for each treatment. Therefore, a total of 15 pots with 60 plants (treatments × replications × plants; 5 × 3 × 4) was maintained. The treatment combinations were like T1; non stress control (C), T2; drought (D), T3; D + M (Mel) 50 μM + J (MeJA) 20 μM, T4; D + M 100 μM + J 20 μM, and T5; D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM. The phenotypic data were collected after 7 days of drought application when the plant showed drought effects by the appearance of chlorosis, drooping, and yellowing. To determine the physiological and biochemical assays, the fully matured leaves were collected. The collected leaf samples were either directly used for biochemical assay or stored at −80°C for further analyses.

2.2 Determination of Photosynthetic Pigments and Efficacy of Photosystem (PS) II

Photosynthetic pigments like chlorophyll a (Chl a) and chlorophyll b (Chl b) in the fully mature leaves were evaluated using 80% acetone according to the approaches of Porra et al. [35]. The quantification was done according to the formula of Lichtenthaler and Welburn [36]. In fresh leaf samples, the level of Chl fluorescence in terms of maximum quantum efficiency of photosystem II (Fv/Fm) was measured according to the method used by Yaghoubian et al. [37]. The minimum (F0) and maximum (Fm) fluorescence intensity in leaves were recorded after 15 min of dark acclimation using the Junior pulse-amplitude modulated (PAM) chlorophyll fluorometer (Heinz Walz GmbH, Effeltrich, Germany). The variable fluorescence (Fv) and maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm) were calculated using the equations: Fv = Fm − F0 and Fv/Fm = (Fm − F0)/Fm, respectively.

2.3 Measurement of H2O2 by Quantitative and Histochemical Assay, and Determination of Lipid Peroxidation Product (MDA)

For the determination of H2O2, fresh leaf tissue (0.1 g) was extracted using 0.1% Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) solution. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C, the supernatant was mixed with potassium iodide (1.0 M) and KP buffer (10 mM, pH 7.0) solution, followed by incubation at room temperature for 30 min. Finally, the absorbance of the mixture was read at 390 nm, and the content of H2O2 was measured as μmol g−1 FW [38]. The histochemical assay of H2O2 precipitation in the damaged leaf was followed by 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining [18]. The amount of MDA was determined following the procedure used by Siddiqui et al. [38] with slight modification. Briefly, the fresh leaf samples (0.1 g) were crushed in 0.1% TCA, followed by centrifugation at 11,500 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatants were mixed with Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) solution (0.5%, prepared in 20% TCA). The resultant solution was heated in a boiling water bath for 30 min at 95°C, then cooled quickly in an ice bath to terminate the reaction. Finally, the absorbance of the mixture was examined at 532 nm, and the content of MDA was measured as nmol g−1 FW.

2.4 Analysis of Total Protein and Enzymatic Antioxidants

Total protein was extracted from a fresh leaf sample (0.3 g) using an extraction buffer comprised of potassium chloride (100 mM), β-mercaptoethanol (5 mM), glycerol (10%), ascorbate (1 mM), and 50 mM ice-cold K-P buffer (pH 7.0) and centrifuged at 11,500 rpm at 4°C for 12 min. The protein concentration was determined as mg g−1 using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard and Bradford reagent [39]. The CAT activity was measured according to Aebi [40]. The CAT activity was computed with an extinction coefficient value of 39.4 M−1 cm−1 and calculated as μmol min−1 mg−1 protein. The methodology of Pütter’s [41] was followed to quantify the POD activity. The absorbance was measured using a spectrophotometer at 470 nm by maintaining the reaction kinetics for a minute. The activity was measured using an extinction coefficient, 26.6 mM−1 cm−1, and expressed as nmol min−1 mg−1 protein. Glutathione S-transferase (GST) activity was measured by following the procedure of Ghosh et al. [17]. The absorbance was measured using a spectrophotometer at 340 nm by maintaining the reaction kinetics for one minute. The extinction coefficient of 9.6 mM cm−1 was used to calculate the GST activity. The activity was determined as nmol min−1 mg−1 protein.

The experiment was followed by Completely Randomized Design (CRD) with three replications. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using the R program (R-4.1.0) for Windows (http://CRAN.R-project.org/). Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) was followed for the mean comparison test. For multivariate analysis, data were normalized using the z-score method in the R program. Pearson’s correlation was done using the R program (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/corrplot/vignettes/corrplot-intro.html, accessed on 01 September 2025). The library pheatmap was used for heatmap and hierarchical clusters analyses [42]. The libraries like ggplot2, factoextra, and FactoMineR were used for PCA analysis [43,44]. Robust Hierarchical Co-clustering was performed by following the methodology of Hasan et al. [45].

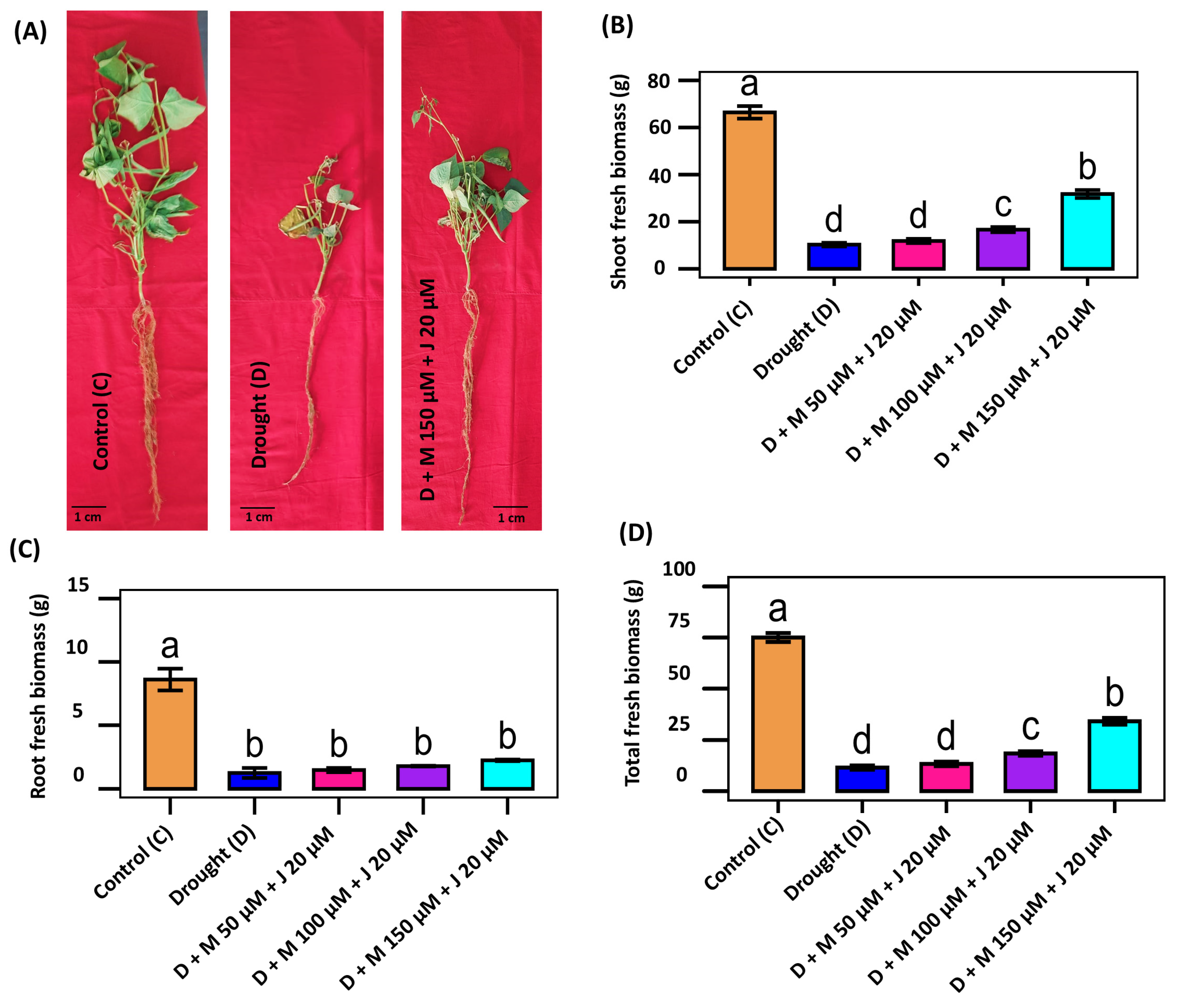

3.1 Mel and MeJA Restore Plant Growth under Drought Stress

Since drought causes inhibition in plant growth, we measured phenotypic growth while the plants treated with drought and drought with different combination of Mel and MeJA. Phenotypic appearance of the plant was greatly affected by drought stress, which was partially recovered by the combined application of Mel and MeJA (Fig. 1A). Drought affected plants showed significant impairment of growth. Shoot fresh biomass (SFBM), root fresh biomass (RFBM), and total fresh biomass (TFBM) were significantly reduced by 84.6%, 85.4% and 84.7%, respectively, when compared to the non-stress control plant (Fig. 1B–D). Non-stress control plants demonstrated the best performance in all the studied phenotypic characteristics. Exogenous application of Mel and MeJA was found to enhance plant biomass where the most notable results were observed with the treatment combination of D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM (Fig. 1). As compared to only drought-stressed plants, SFBM, RFBM and TFBM were increased by 209.7%, 79.5% and 195.5%, respectively by the treatment combination of D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM followed by 62.0%, 43.0%, and 59.9% by D + M 100 μM + J 20 μM (Fig. 1B–D). Although the treatment combination of D + M 50 μM + J 20 μM increased little biomass but there was no significant difference when compared to only drought-stressed plants. The results suggest that the combined application of Mel and MeJA could resume the growth of common bean under drought stress.

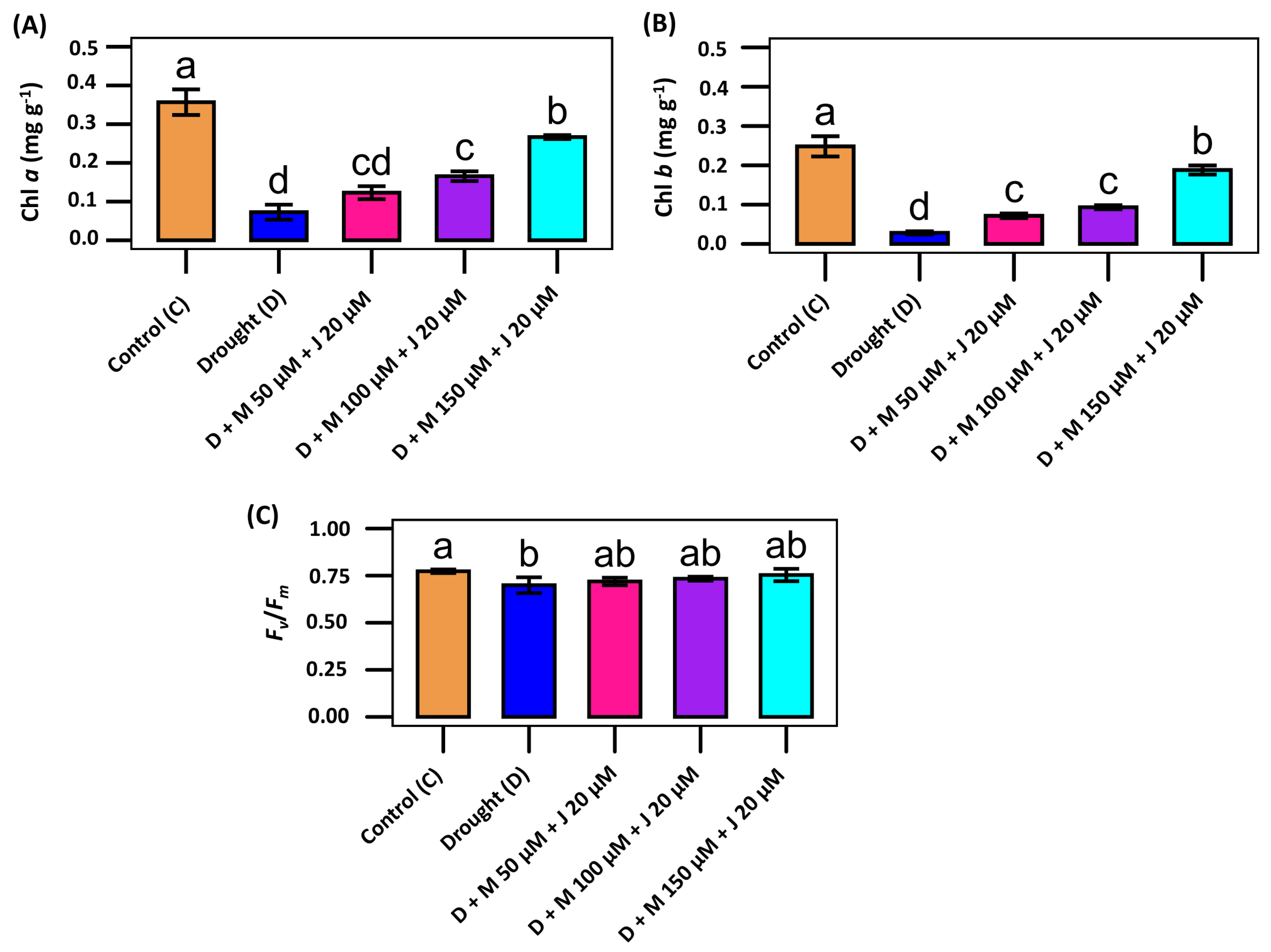

3.2 Mel and MeJA Repairs Plant’s Photosynthesis

Because drought reduces photosynthesis efficiency, we determined photosynthetic pigments in plants treated with different treatment combinations. Significant variations were observed in Chl a and Chl b content of common bean under different treatment conditions. The non-stress control plant showed the highest content of both Chl a and Chl b as compared to other treatment combinations. The Chl a and Chl b were reduced by 79.6% and 88.7% in drought-stressed plants as compared to non-stress control plants (Fig. 2A,B). Exogenous application of Mel and MeJA increased the synthesis of Chl a and Chl b irrespective of treatment combinations. As compared to only drought-stressed plants, those were increased by 266.6% and 568.9% when the plants were treated with D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM (Fig. 2A,B). Subsequently, we focused on the Chl fluorescence in terms Fv/Fm in the treated plants. Drought stress led to the reduction of 9.5% Fv/Fm value as compared to the control plant, whereas Mel and MeJA could restore up to 7.7% Fv/Fm value as compared with drought-stressed plants only (Fig. 2C). The results indicate the potentials of Mel and MeJA in restoring photosynthetic efficacy of common bean under drought stress.

Figure 1: Effects of combined application of melatonin (M) and methyl jasmonate (J) on the morphology and fresh biomass of common bean plants under drought (D) stress. Phenotypic appearance of common bean seedling as affected by the drought and combined application of growth regulators (A). Shoot fresh biomass (B), root fresh biomass (C), and total fresh biomass (D) of the plants grown under non-stress control (C), drought stress (D), D + M 50 μM + J 20 μM, D + M 100 μM + J 20 μM, and D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM conditions. Vertical bars represent +/− standard error (SE) values. Different letter(s) on the bar among the treatments denotes a significant difference at p ≤ 0.001. Scale bar represents 1 cm.

Figure 2: Modulation of photosynthetic pigments and efficacy of photosystem II (PSII) in common bean exposed to combined application of melatonin (M) and methyl jasmonate (J) followed by drought (D) stress. (A) Chlorophyll a (Chl a), (B) chlorophyll b (Chl b), and (C) maximum quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm) in the plants grown under non-stress control (C), drought stress (D), D + M 50 μM + J 20 μM, D + M 100 μM + J 20 μM, and D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM conditions. Vertical bars represent +/− standard error (SE) values. Different letter(s) on the bar denotes a significant difference at p ≤ 0.001 for Chl a and Chl b, and p ≤ 0.05 for Fv/Fm.

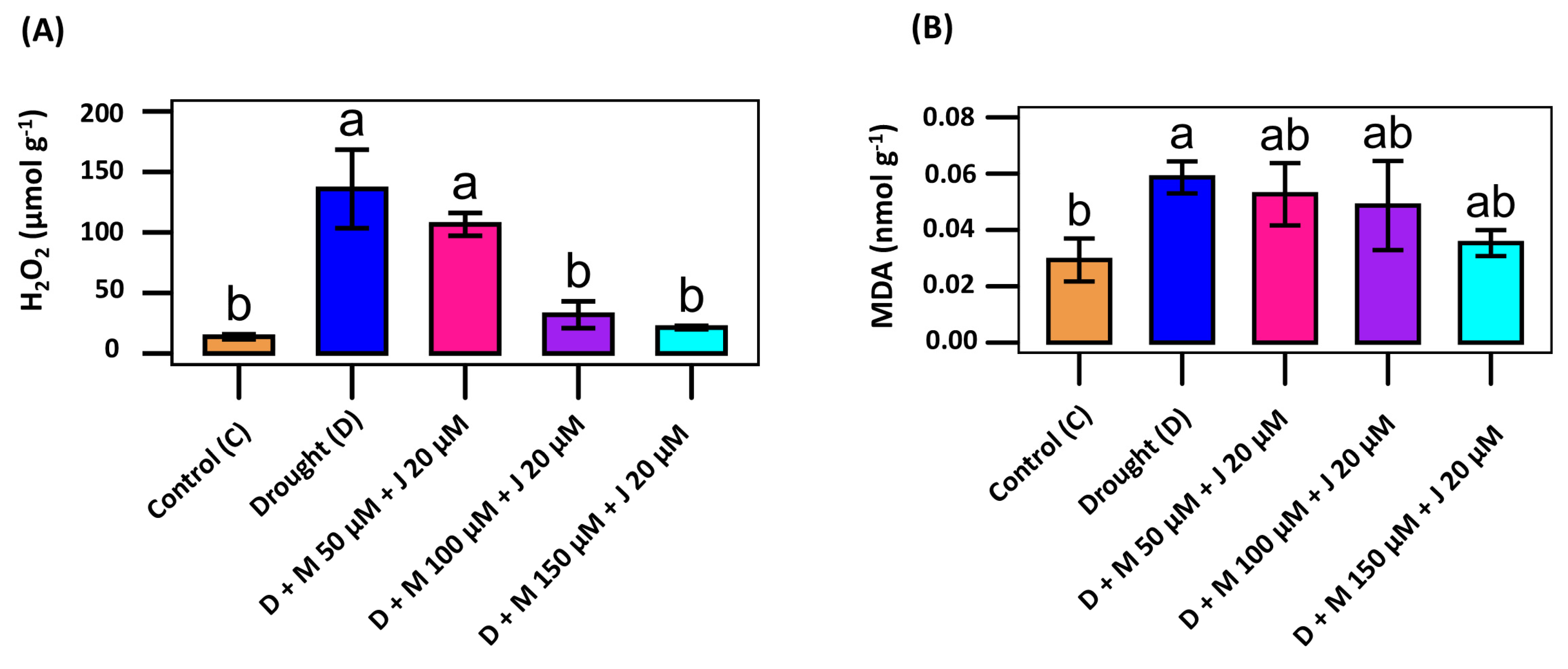

3.3 Mel and MeJA Reduces Drought-Induced Oxidative Damage

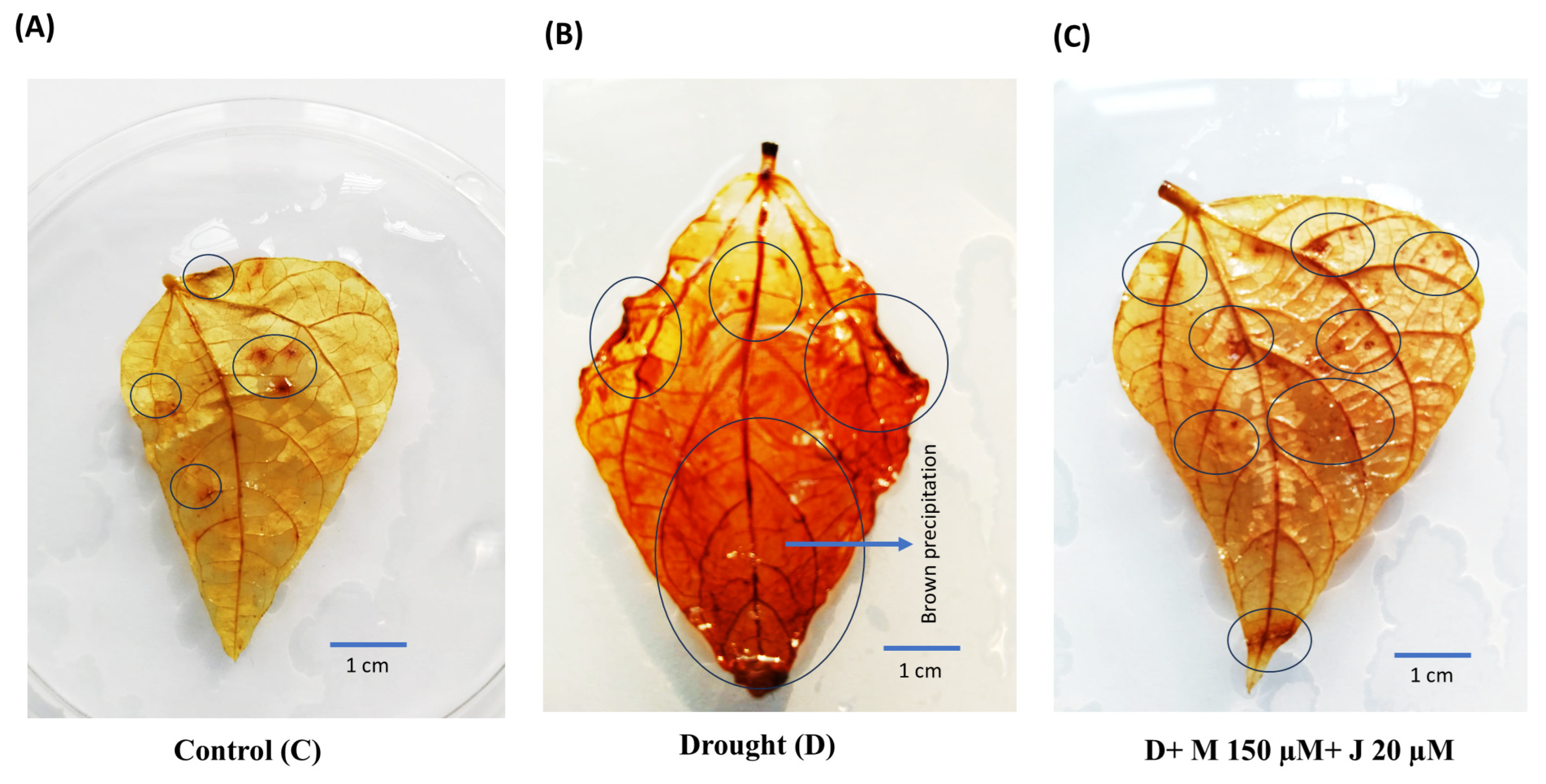

Since accumulation of ROS and thereafter lipid peroxidation products are the vital indicators for oxidative damage, we quantified levels of H2O2 and MDA in the leaf of common bean subjected to different treatment combinations. Drought stress led to increase accumulation of H2O2 by 885.4% compared to non-stress control (Fig. 3A). Consistently, drought stress induced tremendous tissue damage in the plant as reflected by the 100% induction of the lipid peroxidation product; MDA (Fig. 3B). Exogenous application of Mel and MeJA significantly reduced the incidence of H2O2 and MDA in drought-stressed plants. The incidence of H2O2 and MDA were reduced by 84.3% and 39.8%, respectively in plants treated with D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM compared to drought-stressed plants only. Those were also reduced by 76.5% and 17.0% by the treatment combination of D + M 100 μM + J 20 μM. To see the extent of H2O2 in the leaf, we also supposed common bean’s leaf to the histochemical analysis by DAB staining and found deep brown precipitation in the leaf treated with drought stress only as compared to non-stress control and plants treated with D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM (Fig. 4). More or less similar pattern of H2O2 in the leaf of non-stress control and plants treated with D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM reflects the reduction of oxidative damage by the combined application of Mel and MeJA.

Figure 3: Effect of combined application of melatonin (M) and methyl jasmonate (J) on oxidative stress indicators in common bean plant. The level of hydrogen peroxide, H2O2 (A) and lipid peroxidation product malondialdehyde, MDA (B) in the plants grown under non-stress control (C), drought stress (D), D + M 50 μM + J 20 μM, D + M 100 μM + J 20 μM, and D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM conditions. Vertical bars represent +/− standard error (SE) values. Different letter(s) on the bar denotes a significant difference at p ≤ 0.001 for H2O2 and p ≤ 0.05 for MDA.

Figure 4: Histochemical assay of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in common bean leaf by staining with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB). Brown spots indicate accumulation of H2O2 in the leaves of plants grown under control, C (A), drought, D (B) and D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM (C) conditions. Circle indicates brown precipitation. Scale bar represents 1 cm. M and J indicate melatonin ad methyl jasmonate, respectively.

3.4 Mel and MeJA Enhances Total Protein Content and Activity of Enzymatic Antioxidant

Because plants boost up cellular antioxidants to counter face drought effects, we determined the enzymatic antioxidants in the plants treated with different treatment combinations. The activity of CAT, POD, and GST were reduced by 63.9%, 56.2% and 54.3%, respectively, in drought-stressed plants as compared to non-stress control plants (Fig. 5A–C). Exogenous application of Mel and MeJA significantly triggered the activity of enzymatic antioxidants. As compared to only drought-stressed plants, the activity of CAT, POD, and GST was increased by 106.2%, 97.7% and 54.2%, respectively, while treated with D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM. The activity of those was promoted by 57.8%, 87.8% and 13.9% when treated with D + M 100 μM + J 20 μM. (Fig. 5A–C). Although total protein (TP) content was little increased in drought affected plants, it that was further triggered by 18.7% in D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM treated plants and 13.9% by D + M 100 μM + J 20 μM (Fig. 5D). The results indicate that both Mel and MeJA could upgrade enzymatic antioxidants to destabilize excess ROS produced in drought-stressed common bean.

Figure 5: Effects of combined application of melatonin (M) and methyl jasmonate (J) on the antioxidant defense in common bean. The activity of catalase, CAT (A), peroxidase, POD (B), glutathione S-transferase, GST (C), and total protein (D) in the plants grown under non-stress control (C), drought stress (D), D + M 50 μM + J 20 μM, D + M 100 μM + J 20 μM, and D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM conditions. Vertical bars represent +/− standard error (SE) values. Different letter(s) on the bar denotes a significant difference at p ≤ 0.001 for CAT and p ≤ 0.05 for POD, GST and TP.

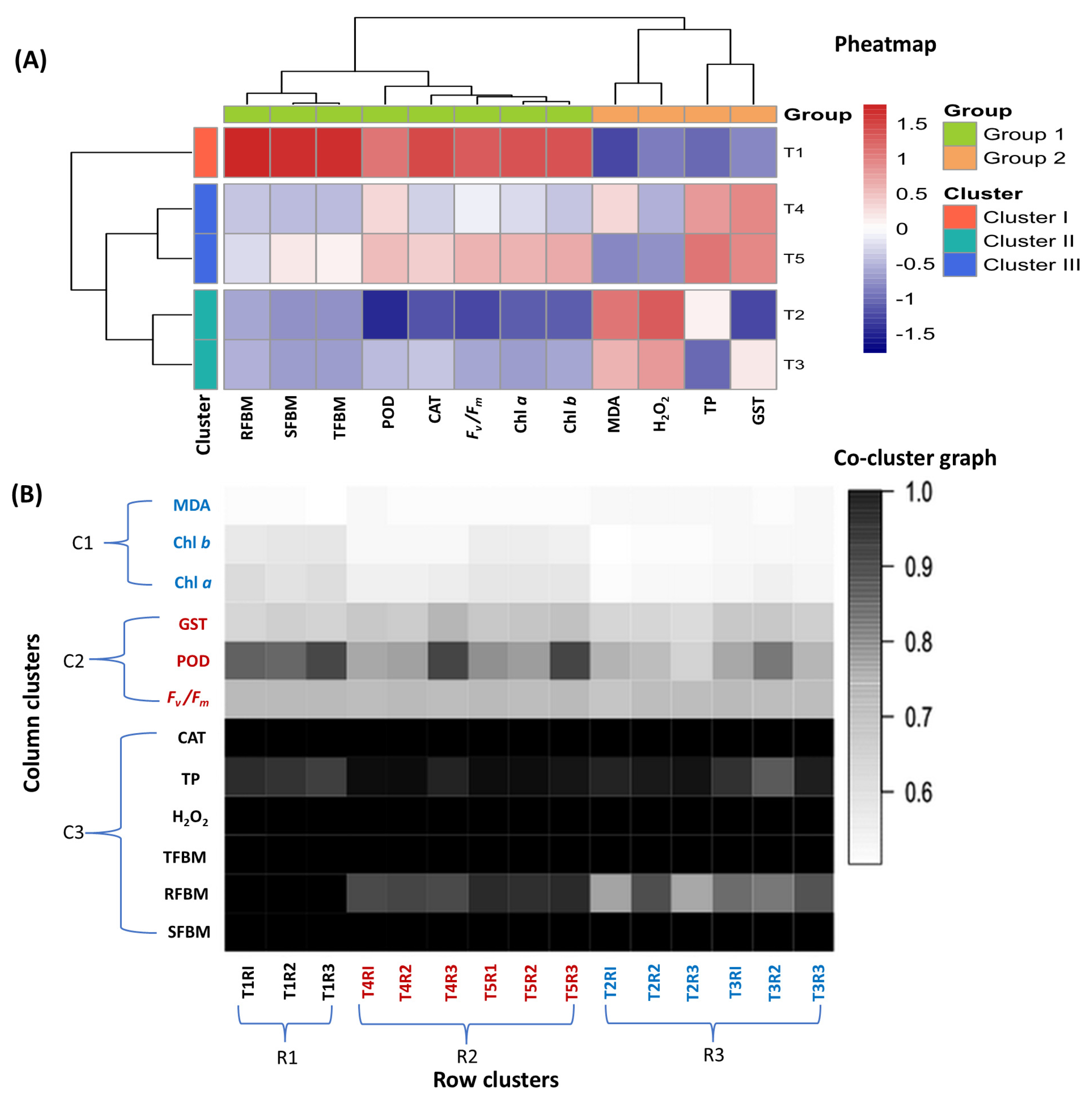

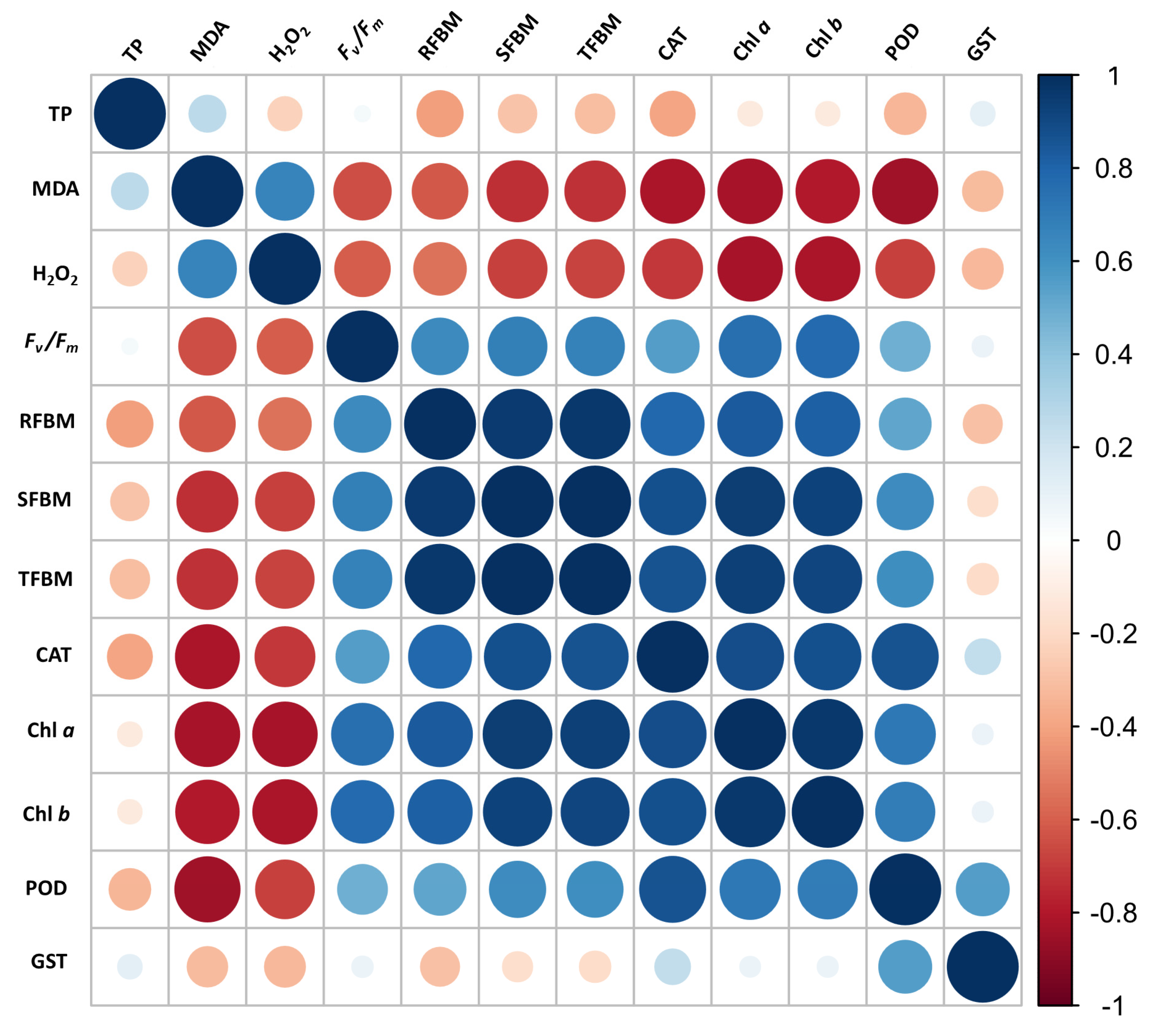

3.5 Multivariate Analyses Demonstrate the Significance of Mel and MeJA in Repairing Oxidative Damage

A correlogram was built to see the correlation among stress-responsive parameters studied in the experiments (Fig. A1). The parameters like Chl a, Chl b, Fv/Fm, RFBM, SFBM, TFBM, CAT, and POD showed positive correlation to each other as reflected by the intensity of blue color. Dark blue color indicated strong positive correlation between the traits. Oxidative stress indicators like H2O2 and MDA showed a strong negative relationship with most of the plant parameters, which were reflected by the intensity of red color. Analysis of the heatmap demonstrated two distinct groups of the studied parameters and three clusters of the treatment combinations used in this study (Fig. 6A). Group 1 included most of the studied parameters like RFBM, SFBM, TFBM, POD, CAT, Fv/Fm, Chl a, and Chl b whereas, H2O2, MDA, TP, and GST were included in group 2 (Fig. 6A). The non-stress control (T1) represented as cluster I and showed positive regulation to most of the studied parameters except oxidative stress indicators. The intensity of red and blue color reflected the extent of positive and negative regulation of the traits, respectively.

Although the treatment combinations of T4 (D + M 100 μM + J 20 μM) and T5 (D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM) shared the same cluster (III), T5 produced more positive impacts to the parameters. However, this combination strongly diminished the oxidative indicators like H2O2 and MDA. The cluster II comprised of T2 (Drought, D) and T3 (D + M 50 μM + J 20 μM) showed negative consequences to most of the studied parameters except H2O2, MDA, and TP. To validate the extent of regulation on the studied attributes by different treatment combinations, we also performed Robust Hierarchical Co-clustering (rHCoClust) analysis. The co-cluster analysis produced three column and three row clusters, respectively. The row cluster was exactly alike to the results of pheatmap. The co-cluster graph depicted that T1 and T5 strongly regulated most of the studied parameters as depicted by the intensity of black color (Fig. 6B). Along with that, the biplot made by principal component analysis (PCA) showed that, the regulation of the traits was followed by four principal components (PCs). Among those, principal component 1 (PC1) and principal component 2 (PC2) contributed 95% of the total variability (Fig. 7 and Fig. A2, Table A1). The major contributor was denoted as PC1, which accounts for 76.3% of the total variation. PC1 was followed by PC2, which accounts for 18.7% of the total variation (Fig. 7 and Fig. A2 and Table A1).

The parameters like GST, POD, CAT, Fv/Fm, Chl a, Chl b, SFBM, RFBM and TFBM showed positive contribution to PC1, whereas MDA, H2O2 and TP showed negative contribution to that PC. In contrast, GST, POD, Fv/Fm, Chl a, and Chl b made major contribution to PC2. Among the treatment combination, T5 positioning in separate quadrate showed its positive contribution to PC1 along with control (C) treatment. Whereas, T2 and T3 shared same quadrates and showing negative contribution to PC1. Thus, the results of pheatmap, rHCoClust and PCA analysis clearly demonstrated that exogenous Mel and MeJA strongly modulate the studied traits to diminish oxidative stress in common bean. However, more likely performances of T1 and T5 in regulating biochemical parameters reflecting that the combined application of M 150 μM + J 20 μM had best potential to alleviate drought-induced oxidative stress in common bean. Thus, our multivariate analyses reflect positive interaction between Mel and MeJA while regulating drought-induced stress markers.

Figure 6: Heatmap and hierarchical clustering of the studied plant’s parameters of common bean treated with T1 (non-stress control, C), T2 (drought stress, D), T3 (D + M 50 μM + J 20 μM), T4 (D + M 100 μM + J 20 μM) and T5 (D + M 150 μM + J 20 μM) (A). The intensity of red and blue color indicates positive and negative regulation, respectively. Here, root fresh biomass, RFBM; shoot fresh biomass, SFBM; total fresh biomass, TFBM; peroxidase, POD; catalase, CAT; maximum quantum yield of PSII, Fv/Fm; chlorophyl a, (Chl a); chlorophyll b, (Chl b); hydrogen peroxide, H2O2; malondialdehyde, MDA; glutathione-S-transferase, GST and total protein, TP. Robust Hierarchical Co-clustering analysis of the studied parameters (B). R in the treatment combinations indicates replication and R in cluster indicates row. Intensity of black color in the hierarchical clustering indicates strong regulation by the treatment combinations. C1, C2 and C2 indicate column cluster whereas R1, R2 and R3 indicate row cluster.

Figure 7: A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) showing the relationship between treatment combinations and observed parameters. Depending on their variation and divergence, plant parameters were categorized and distributed in different ordinate axes. The intensity of color and length of the vectors represented the extent of contribution of the studied parameters to PC1 and PC2. The angles between the vectors formed from the middle point of the biplots indicate the positive and negative interactions of the parameters studied. Additional details are given in the caption of Fig. 6.

Drought is one of the most severe abiotic stresses, causing substantial reductions in plant growth and sustainable productivity. Similar to other crops, drought markedly inhibited growth and biomass accumulation in common bean (Fig. 1), consistent with the previous findings [46]. In the present study, multivariate analyses clearly demonstrated the impact of drought-induced oxidative stress on the morpho-physiological and biochemical traits of common bean (Fig. 6, Fig. 7 and Fig. A1). Exogenous application of plant growth regulators, whether individually or in combination, has shown promise in alleviating drought stress in various crops. For example, the combined application of Mel and JA has been reported to enhance plant growth and yield under abiotic stresses, including drought [26,47,48,49]. These results align with the observations of Mohi-Ud-Din et al. [10], who reported improved growth and development of French bean under drought through both individual and combined application of Mel and SA. In our study, Mel and MeJA treatments similarly enhanced biomass accumulation in drought-stressed plants, further confirming the beneficial effects of their combined application in partially restoring common bean growth under drought conditions (Fig. 1). Drought has tremendous impacts in reducing photosynthesis capability in terms of impairing biosynthesis of photosynthetic pigments [50]. This study showed decreased Chl content and a lower level of maximum quantum yield of photosystem II (PSII) in terms of reduced Fv/Fm ratio, reflecting the suppression of Chl biosynthesis and PSII functioning in common bean under drought stress. Consistently, reduced synthesis of photosynthetic pigments under drought stress was supported by the previous studies with French bean [10,46]. Impairments of the synthesis of pigments could be happened by the photo-oxidation of pigment molecules led by excessive ROS [51]. Sole and combined application of Mel and JA have been shown to improve photosynthetic pigments and gas exchange parameters of different crop plants under a variety of environmental stresses [26,47,49,52]. Consistently, our findings showed significant induction of Chl a, Chl b, and Fv/Fm ratio in drought-stressed common bean plants by co-application of Mel and MeJA (Fig. 2), reflecting the potentials of those growth regulators in protecting photosynthetic machineries. Despite the sole application of JA or Mel could mitigate abiotic stresses, the combined application of those performed better in many cases. For instance, collective application of Mel and JA demonstrated significant recovery of plant’ photosynthesis under heat stress [53]. Further, JA and Mel in co-application significantly boosted the Chl synthesis in tomato under chromium stress [52]. Likely, MeJA in combination with SA repaired the synthesis of Chl pigments under drought stress [10]. The enhanced photosynthetic performance observed with Mel and MeJA treatment can be attributed to improved functionality of the photosynthetic apparatus, activation of key enzymes, and increased PSII efficiency, as reflected by the higher Fv/Fm ratio in Mel + MeJA-treated drought-stressed plants (Fig. 2C). Similarly, significant upregulation of PSII-associated genes (psbA and psbB) reported in heat-stressed wheat following exogenous Mel and JA application [47] supports our findings, where Mel + MeJA treatment elevated PSII efficiency under drought conditions.

Along with that, excess generation of ROS and synthesis of antioxidant enzymes are crucial to maintain redox balance under drought stress [10]. Drought-induced enhancement of H2O2 and MDA was recorded previously in a variety of crop plants, including common bean [10,46], soybean [54], mustard [55], and maize [56]. The findings of those are well corroborated by this finding where drought showed significant increment of ROS and MDA in common bean (Fig. 3). Although sole application of JA or Mel was found to reduce the regeneration of ROS under heat stress [53], the combined application of those produced better performances under drought stress in this study. Sole application of MeJA also showed comparatively lower performance in mitigating drought stress than combined application of MeJA and SA [10]. In complement to those, this findings regarding Mel + MeJA-mediated significant reduction of H2O2 and MDA reflecting the potentials of these growth regulators in mitigating oxidative damage in drought-affected common bean. The histochemical localization of H2O2 further confirmed the minimization of oxidative damage by those growth regulators in plants (Fig. 4). Our clustered correlogram and PCA analysis presented compelling evidence of the strong interrelationship among Mel + MeJA co-treated plant’s parameters (Fig. 6 and Fig. A1).

To combat excessive ROS accumulation, plants enhance the activities of enzymatic antioxidants—an inherent and evolutionarily conserved defense mechanism across terrestrial plants [17]. Among these enzymes, SOD serves as the first line of defense, followed by CAT and POD. Glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) also constitute a large and diverse enzyme family linked to enhanced tolerance against various abiotic stresses [57]. In this study, the activities of CAT, POD, and GST were markedly reduced under drought stress (Fig. 5A–C), consistent with earlier reports [10,17,58]. This decline likely results from ROS-induced damage to micro- and macromolecules, including vital enzymes. Previous studies have shown that exogenous application of Mel and JA can stimulate antioxidant enzyme activity under heat stress [53]. Similarly, MeJA and SA were reported to enhance antioxidant activities in French bean under drought, although their individual effects were not statistically significant [10]. Such improvements occur because phytohormones upregulate the expression of genes encoding antioxidant enzymes during stress. For example, melatonin induces the expression of APX1, APX2, CAT1, FSD1, CuZnSOD, and MnSOD under salt stress [59], while MeJA regulates genes encoding APX, CAT, and POD, thereby reducing oxidative damage [60]. Mel and JA have been widely reported to enhance antioxidant enzyme activities, helping plants neutralize excess ROS generated under various stress conditions [26,49,59]. In this study, the comparable activities of CAT, POD, and GST observed between non-stressed controls and Mel + MeJA-treated plants suggest that these phytomolecules effectively restored the drought-induced oxidative damage. This was further supported by the higher total protein content observed in drought-stressed plants treated with Mel and MeJA. Multivariate analyses reinforced these findings, showing that enzymatic antioxidants play a central role in suppressing ROS accumulation by reducing H2O2 and MDA levels (Fig. 6 and Fig. 7). Such effects likely result from the synergistic interactions between Mel and MeJA under drought stress. Although previous studies have reported synergistic crosstalk between Mel and JA in regulating drought tolerance [60], the molecular mechanisms underlying their interaction remain largely unknown. Transcriptomic evidence indicates that Mel-responsive genes under drought stress are predominantly associated with glutathione metabolism, calcium signaling, and JA biosynthesis [61]. Furthermore, Mel-induced upregulation of JA biosynthetic genes such as LOX1.5 and LOX2.1 supports this link [60]. Conversely, JA has been shown to induce Mel biosynthesis genes (SlSNAT and SlAMST) in tomato under cold stress [62], suggesting a positive feedback loop between Mel and JA signaling during abiotic stress responses.

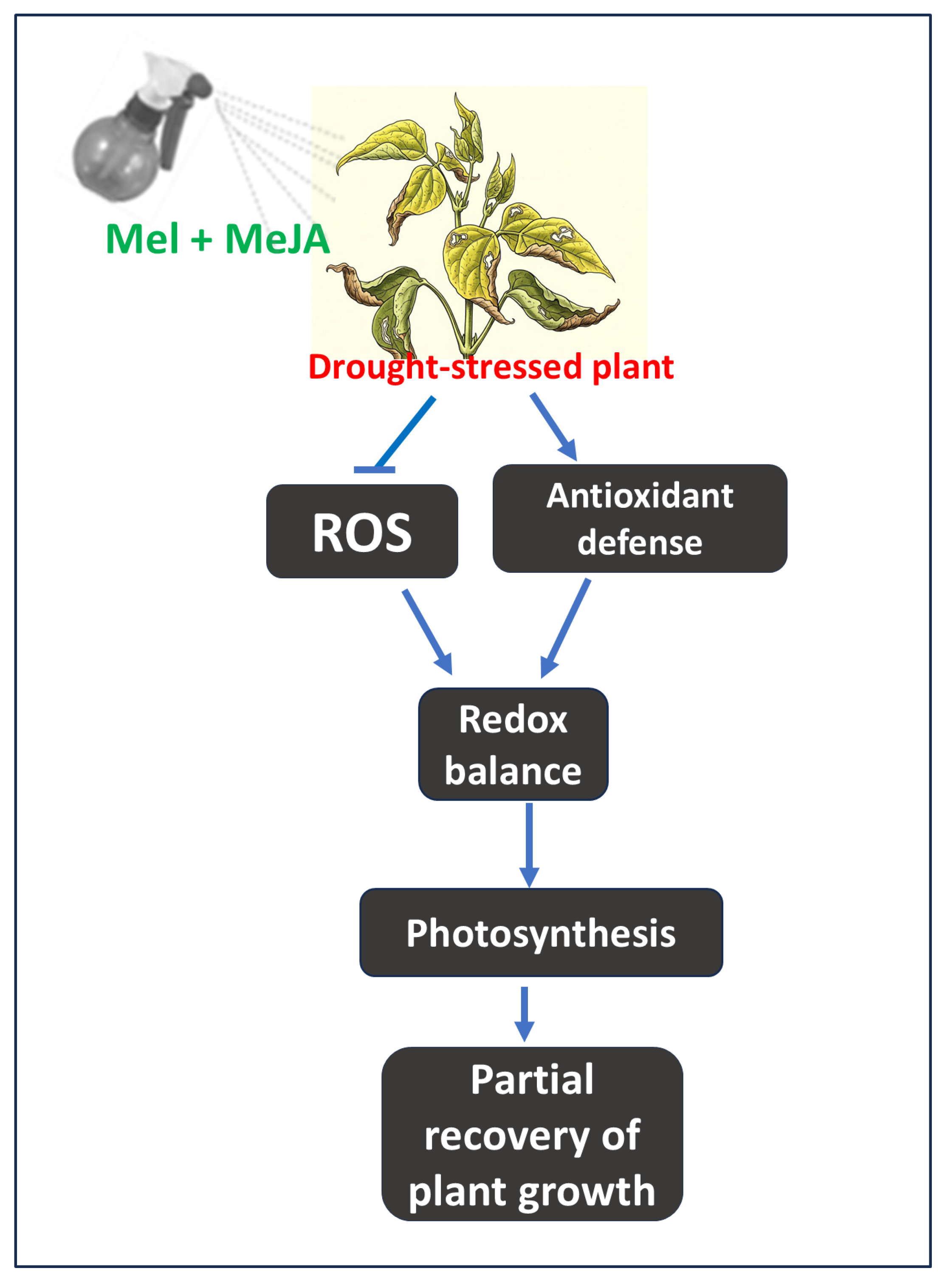

Among known growth regulator interactions, the strongest synergisms have been observed between Mel + SA and Mel + JA [13]. Mel + SA enhances stress tolerance by improving osmotic adjustment, maintaining redox homeostasis, promoting nutrient uptake, elevating polyamine levels, enhancing carbon assimilation and photosynthesis, and reducing methylglyoxal accumulation [10,63,64,65]. In contrast, Mel + JA synergy primarily functions through mutual enhancement of biosynthetic gene expression, improved osmotic regulation, and stabilization of photosynthetic pigments [34,60,62]. Whether Mel + MeJA co-application influences these biosynthetic pathways under drought in common bean remains to be determined. Recent findings in wheat have shown that Mel + MeJA protect against heat stress by synergistically activating antioxidant enzymes, optimizing ethylene biosynthesis, enhancing sulfur assimilation, and strengthening the ascorbate–glutathione (GSH) cycle [47]. This highlights the diverse stress-mitigating potential of the Mel + MeJA combination. In our study, Mel + MeJA treatment alleviated drought-induced oxidative stress in common bean by maintaining redox balance and enhancing photosynthetic pigment levels (Fig. 8). However, whether this involves regulation of ethylene biosynthesis and GSH metabolism warrants further investigation. Alongside, both Mel- and MeJA-mediated stress responses are closely linked to ABA signaling and the activation of stress-responsive transcription factors such as WRKY, AP2/ERF, MYB, and NAC [61,66,67,68]. This suggests that co-application of Mel and MeJA may regulate drought responses through phytohormonal and transcriptional networks. It is likely that Mel + MeJA mitigates drought-induced oxidative stress through multifaceted mechanisms involving crosstalk with other hormones, enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity, improved osmotic balance, and upregulation of hormone biosynthesis and stress-responsive genes. Nevertheless, further studies are needed to elucidate how Mel and MeJA co-regulate the expression of genes related to photosynthesis, ROS metabolism, and antioxidant defense in drought-stressed common bean.

Figure 8: Thematic model illustrating how combined melatonin (Mel) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA) treatment alleviates drought stress in common bean. Under drought conditions, Mel- and MeJA-treated plants exhibit enhanced antioxidant activity and reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation. This coordinated response helps maintain redox homeostasis and photosynthetic efficiency, leading to partial recovery of plant growth under drought stress.

Drought stress in common bean significantly reduced biomass, Chl content, and PSII efficiency while elevating H2O2 and MDA levels, indicating oxidative damage. Exogenous Mel and MeJA treatments alleviated these effects by enhancing photosynthetic performance, lowering oxidative markers, and boosting antioxidant enzyme activities (CAT, POD, and GST). Multivariate analyses confirmed their protective roles, with the combination of 150 μM Mel and 20 μM MeJA showing the highest efficacy. Overall, the co-application of Mel and MeJA effectively mitigated drought-induced oxidative stress and partially restored plant growth, offering a promising approach to improve drought resilience in legumes and support sustainable bean production. Future field trials, along with phytohormone profiling, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses, are warranted to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying Mel + MeJA synergism under drought stress.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The research was financed by the Research Management Wing, Gazipur Agricultural University, Bangladesh.

Author Contributions: Totan Kumar Ghosh: planned, designed, analyzed, edited and reviewed the manuscript; Md. Roushonuzzaman Rakib: performed experiments and wrote the manuscript; Munna: wrote and edited the manuscript; S. M. Zubair AL-Meraj: designed and reviewed the manuscript; Anika Nazran: designed and did experiments; Md. Moshiul Islam: edited and reviewed the manuscript; Mohammad Golam Mostofa: planned, edited and reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are available in the first and corresponding author of the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Figure A1: Pearson’s correlation analysis representing the relationship between studied parameters. Blue color indicates positive correlation between two parameters where deep blue color reflects strong positive relationship. Blank indicates insignificant relationship between the parameters. Additional details are given in the caption of Fig. 6.

Figure A2: Scree plot representing the contribution of four principal components where principal component 1 (PC1) and principal component 2 (PC2) showed 76.3% and 18.7% of total contribution, respectively.

Table A1: Eigen values, variances (%), and cumulative variance (%) of the principal component analysis (PCA) using studied parameters.

| Dimensions or Principal Components | Eigen Values | Variance (%) | Cumulative Variance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dim. 1 | 9.16 | 76.3 | 76.3 |

| Dim. 2 | 2.2 | 18.7 | 95.0 |

| Dim. 3 | 0.5 | 4.0 | 99.0 |

| Dim. 4 | 0.1 | 1.0 | 100.0 |

References

1. Fita A , Rodríguez-Burruezo A , Boscaiu M , Prohens J , Vicente O . Breeding and domesticating crops adapted to drought and salinity: a new paradigm for increasing food production. Front Plant Sci. 2015; 6: 978. doi:10.3389/fpls.2015.00978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Schwalm CR , Anderegg WRL , Michalak AM , Fisher JB , Biondi F , Koch G , et al. Global patterns of drought recovery. Nature. 2017; 548( 7666): 202– 5. doi:10.1038/nature23021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Trenberth KE , Dai A , van der Schrier G , Jones PD , Barichivich J , Briffa KR , et al. Global warming and changes in drought. Nature Clim Change. 2014; 4( 1): 17– 22. doi:10.1038/nclimate2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chen J , Li Y , Luo Y , Tu W , Wan T . Drought differently affects growth properties, leaf ultrastructure, nitrogen absorption and metabolism of two dominant species of Hippophae in Tibet Plateau. Acta Physiol Plant. 2018; 41( 1): 1. doi:10.1007/s11738-018-2785-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. He C , Wang W , Hou J . Plant growth and soil microbial impacts of enhancing licorice with inoculating dark septate endophytes under drought stress. Front Microbiol. 2019; 10: 2277. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.02277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ghosh S , Kamble NU , Verma P , Salvi P , Petla BP , Roy S , et al. Arabidopsis L-ISOASPARTYL METHYLTRANSFERASE repairs isoaspartyl damage to antioxidant enzymes and increases heat and oxidative stress tolerance. J Biol Chem. 2020; 295( 3): 783– 99. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA119.010779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Arab MM , Askari H , Aliniaeifard S , Mokhtassi-Bidgoli A , Estaji A , Sadat-Hosseini M , et al. Natural variation in photosynthesis and water use efficiency of locally adapted Persian walnut populations under drought stress and recovery. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023; 201: 107859. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.107859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Nadeem SM , Ahmad M , Tufail MA , Asghar HN , Nazli F , Zahir ZA . Appraising the potential of EPS-producing rhizobacteria with ACC-deaminase activity to improve growth and physiology of maize under drought stress. Physiol Plant. 2021; 172( 2): 463– 76. doi:10.1111/ppl.13212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jain M , Kataria S , Hirve M , Prajapati R . Water deficit stress effects and responses in maize. In: Plant abiotic stress tolerance. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2019. p. 129– 51. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-06118-0_5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mohi-Ud-Din M , Talukder D , Rohman M , Ahmed JU , Krishna Jagadish SV , Islam T , et al. Exogenous application of methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid mitigates drought-induced oxidative damages in French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Plants. 2021; 10( 10): 2066. doi:10.3390/plants10102066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Ali S , Ahmad Mir R , Haque MA , Danishuddin , Almalki MA , Alfredan M , et al. Exploring physiological and molecular dynamics of drought stress responses in plants: challenges and future directions. Front Plant Sci. 2025; 16: 1565635. doi:10.3389/fpls.2025.1565635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Khan DA , Ali Z , Iftikhar S , Amraiz D , Zaidi NS , Gul A , et al. Role of phytohormones in enhancing antioxidant defense in plants exposed to metal/metalloid toxicity. In: Plants under metal and metalloid stress. Singapore: Springer; 2018. p. 367– 400. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-2242-6_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Xu L , Zhu Y , Wang Y , Zhang L , Li L , Looi LJ , et al. The potential of melatonin and its crosstalk with other hormones in the fight against stress. Front Plant Sci. 2024; 15: 1492036. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1492036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Shi Y , Chang YL , Wu HT , Shalmani A , Liu WT , Li WQ , et al. OsRbohB-mediated ROS production plays a crucial role in drought stress tolerance of rice. Plant Cell Rep. 2020; 39( 12): 1767– 84. doi:10.1007/s00299-020-02603-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Singh M , Kushwaha BK , Singh S , Kumar V , Singh VP , Prasad SM . Sulphur alters chromium (VI) toxicity in Solanum melongena seedlings: role of sulphur assimilation and sulphur-containing antioxidants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017; 112: 183– 92. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.12.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Lotfi N , Vahdati K , Hassani D , Kholdebarin B , Amiri R . Peroxidase, guaiacol peroxidase and ascorbate peroxidase activity accumulation in leaves and roots of walnut trees in response to drought stress. Acta Hortic. 2010; 861( 861): 309– 16. doi:10.17660/actahortic.2010.861.42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ghosh TK , Tompa NH , Rahman MM , Mohi-Ud-Din M , Zubair Al-Meraj SM , Biswas MS , et al. Acclimation of liverwort Marchantia polymorpha to physiological drought reveals important roles of antioxidant enzymes, proline and abscisic acid in land plant adaptation to osmotic stress. PeerJ. 2021; 9: e12419. doi:10.7717/peerj.12419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Mostofa MG , Rahman A , Ansary MMU , Watanabe A , Fujita M , Tran LP . Hydrogen sulfide modulates cadmium-induced physiological and biochemical responses to alleviate cadmium toxicity in rice. Sci Rep. 2015; 5: 14078. doi:10.1038/srep14078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kabiri R , Hatami A , Oloumi H , Naghizadeh M , Nasibi F , Tahmasebi Z . Foliar application of melatonin induces tolerance to drought stress in Moldavian balm plants (Dracocephalum moldavica) through regulating the antioxidant system. Folia Hortic. 2018; 30( 1): 155– 67. doi:10.2478/fhort-2018-0016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zeng W , Mostafa S , Lu Z , Jin B . Melatonin-mediated abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2022; 13: 847175. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.847175 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Golding C , Lee H . Study and synthesis of melatonin as a strong antioxidant in plants. Biol Mol Chem. 2023; 1( 1): 35– 44. doi:10.22034/bmc.2023.417001.1006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wei W , Li QT , Chu YN , Reiter RJ , Yu XM , Zhu DH , et al. Melatonin enhances plant growth and abiotic stress tolerance in soybean plants. J Exp Bot. 2015; 66( 3): 695– 707. doi:10.1093/jxb/eru392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Anjum SA , Tanveer M , Hussain S , Tung SA , Samad RA , Wang L , et al. Exogenously applied methyl jasmonate improves the drought tolerance in wheat imposed at early and late developmental stages. Acta Physiol Plant. 2015; 38( 1): 25. doi:10.1007/s11738-015-2047-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Huang H , Ullah F , Zhou DX , Yi M , Zhao Y . Mechanisms of ROS regulation of plant development and stress responses. Front Plant Sci. 2019; 10: 800. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.00800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kuppusamy A , Alagarswamy S , Karuppusami KM , Maduraimuthu D , Natesan S , Ramalingam K , et al. Melatonin enhances the photosynthesis and antioxidant enzyme activities of mung bean under drought and high-temperature stress conditions. Plants. 2023; 12( 13): 2535. doi:10.3390/plants12132535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Abdelgawad ZA , Khalafaallah AA , Abdallah MM . Impact of methyl jasmonate on antioxidant activity and some biochemical aspects of maize plant grown under water stress condition. Agric Sci. 2014; 5( 12): 1077– 88. doi:10.4236/as.2014.512117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Sadeghipour O . Drought tolerance of cowpea enhanced by exogenous application of methyl jasmonate. Int J Mod Agric. 2018; 7: 51– 7. doi:10.17762/ijma.v7i4.77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Assefa T , Wu J , Beebe SE , Rao IM , Marcomin D , Claude RJ . Improving adaptation to drought stress in small red common bean: phenotypic differences and predicted genotypic effects on grain yield, yield components and harvest index. Euphytica. 2015; 203( 3): 477– 89. doi:10.1007/s10681-014-1242-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Beebe SE , Rao IM , Blair MW , Acosta-Gallegos JA . Phenotyping common beans for adaptation to drought. Front Physiol. 2013; 4: 35. doi:10.3389/fphys.2013.00035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ramirez-Vallejo P , Kelly JD . Traits related to drought resistance in common bean. Euphytica. 1998; 99( 2): 127– 36. doi:10.1023/A:1018353200015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Bonfil DJ , Goren O , Mufradi I , Lichtenzveig J , Abbo S . Development of early-flowering Kabuli chickpea with compound and simple leaves. Plant Breed. 2007; 126( 2): 125– 9. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0523.2007.01343.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Lesznyak M , Hunyadi Borbely E , Csajbok J . The role of nutrient-water-supply and the cultivation in the yield of pea (Pisum sativum L.). Cereal Res Commun. 2008; 36: 1079– 82. [Google Scholar]

33. Işik M , Önceler Z , Çakir S , Altay F . Effects of different irrigation regimes on the yield and yield components of dry bean (Phaseolus vulgaris). Acta Agron Hung. 2005; 52( 4): 381– 9. doi:10.1556/aagr.52.2004.4.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Rakib R , Anzuma A , Zubair Al Meraj SM , Munna , Khan HI , Nazran A , et al. Melatonin and methyl jasmonate-mediated morpho-physiological and biochemical adaptations to drought stress in French bean. Ann Bangladesh Agric. 2025; 28( 2): 37– 55. doi:10.3329/aba.v28i2.75969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Porra RJ , Thompson WA , Kriedemann PE . Determination of accurate extinction coefficients and simultaneous equations for assaying chlorophylls a and b extracted with four different solvents: verification of the concentration of chlorophyll standards by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta BBA Bioenerg. 1989; 975( 3): 384– 94. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(89)80347-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Lichtenthaler HK , Wellburn AR . Determinations of total carotenoids and chlorophylls a and b of leaf extracts in different solvents. Biochem Soc Trans. 1983; 11( 5): 591– 2. doi:10.1042/bst0110591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yaghoubian Y , Siadat SA , Moradi Telavat MR , Pirdashti H . Quantify the response of purslane plant growth, photosynthesis pigments and photosystem II photochemistry to cadmium concentration gradients in the soil. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2016; 63( 1): 77– 84. doi:10.1134/s1021443716010180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Siddiqui MN , Mostofa MG , Rahman MM , Tahjib-Ul-Arif M , Das AK , Mohi-Ud-Din M , et al. Glutathione improves rice tolerance to submergence: insights into its physiological and biochemical mechanisms. J Biotechnol. 2021; 325: 109– 18. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2020.11.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Bradford MM . A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976; 72: 248– 54. doi:10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Aebi H . Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzym. 1984; 105: 121– 6. doi:10.1016/s0076-6879(84)05016-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Pütter J . Peroxidases. In: Bergmeyer HU , editor. Methods of enzymatic analysis. New York, NY, USA: Verlag Chemie-Academic Press; 1974. p. 685– 90. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-091302-2.50033-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Kolde R . Pheatmap: Pretty Heatmaps, Version 1.0.12. rdrr.io 2019 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2025 Sep 1]. Available from: https://rdrr.io/cran/pheatmap/. [Google Scholar]

43. Lê S , Josse J , Husson F . FactoMineR: an R package for multivariate analysis. J Stat Soft. 2008; 25( 1): 1– 8. doi:10.18637/jss.v025.i01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Wickham H . Data analysis. In: ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2016. p. 189– 201. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-24277-4_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Hasan MN , Badsha MB , Mollah MNH . Robust hierarchical co-clustering for exploring toxicogenomic biomarkers and their chemical regulators. Sci Rep. 2025; 15( 1): 16676. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-99568-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Anzuma A , Hossain MM , Mohammed MU , Nazran A , Khan HI , Islam SM , et al. Enhancing drought tolerance in common bean by plant growth promoting rhizobacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Acta Agric Slov. 2024; 120( 3): 1– 10. doi:10.14720/aas.2024.120.3.18249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Sehar Z , Fatma M , Khan S , Mir IR , Abdi G , Khan NA . Melatonin influences methyl jasmonate-induced protection of photosynthetic activity in wheat plants against heat stress by regulating ethylene-synthesis genes and antioxidant metabolism. Sci Rep. 2023; 13( 1): 7468. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-34682-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Iqbal N , Fatma M , Gautam H , Umar S , Sofo A , D’Ippolito I , et al. The crosstalk of melatonin and hydrogen sulfide determines photosynthetic performance by regulation of carbohydrate metabolism in wheat under heat stress. Plants. 2021; 10( 9): 1778. doi:10.3390/plants10091778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Rahman MM , Mostofa MG , Keya SS , Ghosh PK , Abdelrahman M , Anik TR , et al. Jasmonic acid priming augments antioxidant defense and photosynthesis in soybean to alleviate combined heat and drought stress effects. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2024; 206: 108193. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.108193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Pandey HC , Baig MJ , Bhatt RK . Effect of moisture stress on chlorophyll accumulation and nitrate reductase activity at vegetative and flowering stage in Avena species. Agric Sci Res J. 2012; 2( 3): 111– 8. [Google Scholar]

51. Anjum SA , Xie X , Wang LC , Saleem MF , Man C , Lei W . Morphological, physiological and biochemical responses of plants to drought stress. Afr J Agric Res. 2011; 6( 9): 2026– 32. doi:10.5897/AJAR10.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Qin C , Lian H , Alqahtani FM , Ahanger MA . Chromium mediated damaging effects on growth, nitrogen metabolism and chlorophyll synthesis in tomato can be alleviated by foliar application of melatonin and jasmonic acid priming. Sci Hortic. 2024; 323: 112494. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Irfan M , Abou El-Yazied A , Sheeraz M , Hussain S , Sattar A , Ali Q , et al. Exogenous application of melatonin and jasmonic acid protects the sugar beet from heat stress by modulating the enzymatic antioxidants deference mechanism and accumulation of organic osmolytes. Acta Physiol Plant. 2025; 47( 3): 37. doi:10.1007/s11738-025-03784-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Razmi N , Ebadi A , Daneshian J , Jahanbakhsh S . Salicylic acid induced changes on antioxidant capacity, pigments and grain yield of soybean genotypes in water deficit condition. J Plant Interact. 2017; 12( 1): 457– 64. doi:10.1080/17429145.2017.1392623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Alam MM , Nahar K , Hasanuzzaman M , Fujita M . Exogenous jasmonic acid modulates the physiology, antioxidant defense and glyoxalase systems in imparting drought stress tolerance in different Brassica species. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2014; 8( 3): 279– 93. doi:10.1007/s11816-014-0321-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Tayyab N , Naz R , Yasmin H , Nosheen A , Keyani R , Sajjad M , et al. Combined seed and foliar pre-treatments with exogenous methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid mitigate drought-induced stress in maize. PLOS One. 2020; 15( 5): e0232269. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0232269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Dixon DP , Skipsey M , Edwards R . Roles for glutathione transferases in plant secondary metabolism. Phytochemistry. 2010; 71( 4): 338– 50. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.12.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Collado-González J , Piñero MC , Otálora G , López-Marín J , Del Amor FM . Effects of different nitrogen forms and exogenous application of putrescine on heat stress of cauliflower: photosynthetic gas exchange, mineral concentration and lipid peroxidation. Plants. 2021; 10( 1): 152. doi:10.3390/plants10010152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Gu Q , Xiao Q , Chen Z , Han Y . Crosstalk between melatonin and reactive oxygen species in plant abiotic stress responses: an update. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23( 10): 5666. doi:10.3390/ijms23105666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Luo M , Wang D , Delaplace P , Pan Y , Zhou Y , Tang W , et al. Melatonin enhances drought tolerance by affecting jasmonic acid and lignin biosynthesis in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023; 202: 107974. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.107974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Zhao C , Yang M , Wu X , Wang Y , Zhang R . Physiological and transcriptomic analyses of the effects of exogenous melatonin on drought tolerance in maize (Zea mays L.). Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021; 168: 128– 42. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.09.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Ding F , Ren L , Xie F , Wang M , Zhang S . Jasmonate and melatonin act synergistically to potentiate cold tolerance in tomato plants. Front Plant Sci. 2022; 12: 763284. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.763284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Talaat NB . Co-application of melatonin and salicylic acid counteracts salt stress-induced damage in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) photosynthetic machinery. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2021; 21( 4): 2893– 906. doi:10.1007/s42729-021-00576-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Talaat NB . Polyamine and nitrogen metabolism regulation by melatonin and salicylic acid combined treatment as a repressor for salt toxicity in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) plants. Plant Growth Regul. 2021; 95( 3): 315– 29. doi:10.1007/s10725-021-00740-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Kaya C , Ugurlar F , Ashraf M , Alyemeni MN , Ahmad P . Exploring the synergistic effects of melatonin and salicylic acid in enhancing drought stress tolerance in tomato plants through fine-tuning oxidative-nitrosative processes and methylglyoxal metabolism. Sci Hortic. 2023; 321: 112368. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Zhou M , Memelink J . Jasmonate-responsive transcription factors regulating plant secondary metabolism. Biotechnol Adv. 2016; 34( 4): 441– 9. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Zhao H , Zhang K , Zhou X , Xi L , Wang Y , Xu H , et al. Melatonin alleviates chilling stress in cucumber seedlings by up-regulation of CsZat12 and modulation of polyamine and abscisic acid metabolism. Sci Rep. 2017; 7( 1): 4998. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-05267-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Wang X , Li Q , Xie J , Huang M , Cai J , Zhou Q , et al. Abscisic acid and jasmonic acid are involved in drought priming-induced tolerance to drought in wheat. Crop J. 2021; 9( 1): 120– 32. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2020.06.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools