Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Genome-Wide Identification and Functional Characterization of UGT Gene Family in Sorghum bicolor with Insights into SbUGT12’s Role in C4 Photosynthesis

1 College of Life Sciences, Hengshui University, Hengshui, 053000, China

2 Collaborative Innovation Center for Wetland Conservation and Green Development of Hebei Province, Hengshui University, Hengshui, 053000, China

3 Guizhou Key Laboratory of Biology and Breeding for Specialty Crops, College of Life Science, Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang, 550025, China

4 College of Life Sciences, Henan Normal University, Xinxiang, 453007, China

* Corresponding Authors: Xiaoli Guo. Email: ; Jianhui Ma. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 3893-3912. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.073736

Received 24 September 2025; Accepted 06 November 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGTs) play essential roles in plant secondary metabolism and stress responses, yet their composition and functions in Sorghum bicolor, a model C4 plant, remain inadequately characterized. This study identified 196 SbUGT genes distributed across all 10 chromosomes and classified them into 16 subfamilies (A–P) through phylogenetic analysis. Among these, 61.2% were intronless, and 10 conserved motifs, including the UGT-specific PSPG box, were identified. Synteny analysis using MCScanX revealed 12 segmental duplication events and conserved syntenic relationships with other Poaceae species (rice, maize, and barley). Promoter analysis uncovered 125 distinct cis-acting elements, predominantly associated with stress and hormone responses, as well as MYB/MYC binding sites. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) indicated that genes in cluster C2 were highly expressed in leaves and correlated with the C4 photosynthetic pathway. Within this cluster, SbUGT12 was identified as a hub gene, demonstrating strong binding affinity to UDP-glucose and forming a co-expression network with key C4 photosynthetic genes. Molecular docking further confirmed its binding capacity with four C4-related compounds. These findings provide insights into the evolution and function of the SbUGT family and suggest a regulatory role for SbUGT12 in C4 photosynthesis, offering genetic resources for improving stress tolerance and photosynthetic efficiency in sorghum.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe UGT gene family is one of the largest superfamilies in the plant kingdom [1]. It glycosylates diverse small molecule acceptors, such as hormones, secondary metabolites, and exogenous toxins, by transferring a sugar moiety from an activated UDP-sugar donor to these compounds during plant growth and development [2]. This modification plays a critical role in altering the water solubility, stability, subcellular localization, and bioactivity of the acceptor molecules [3,4]. Therefore, the UGT gene family significantly influence plant survival and adaptability.

Based on the high degree of conservation in their catalytic functions, UGT proteins can be systematically classified into distinct groups, such as groups A–P in Arabidopsis thaliana [5,6]. Although the number of UGT members varies considerably among plant species, this diversity often arises from gene duplication and functional divergence to facilitate plants adaptation to specific ecological pressures or stresses, thereby contributing to species-specific metabolic traits [5,6,7]. For instance, 122 and 163 UGT members have been identified in Arabidopsis and rice (Oryza sativa), respectively, with many involved in phytohormone homeostasis (e.g., auxin, ABA, MeJA and SA signaling) and flavonoid biosynthesis [6,7,8]. Specifically, Arabidopsis UGT75D1 regulates auxin homeostasis through conjugation with indole-3-acetic acid, influencing cotyledon development and stress responses during seed germination [9]. UGT71C5 glycosylates ABA to form ABA-glucose ester, contributing to ABA homeostasis, resulting in delayed seed germination and enhanced drought tolerance in Arabidopsis [10]. Similarly, UGT76B1 in Arabidopsis conjugates isoleucic acid and plays a critical role in regulating plant defense and senescence by mediating the crosstalk between SA and JA signaling pathways [6]. In Dendrobium catenatum, UGT708S6 functions as a bifunctional glycosyltransferase capable of catalyzing both C- and O-glycosylation of flavonoids, with key residue R271 playing a critical role in its catalytic activity and sugar donor preference [11].

Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) is a globally important C4 cereal crop, known for its high photosynthetic efficiency, strong drought resistance, and ability to grow in low-fertility soils. It is regarded as a key crop for ensuring food security and promoting sustainable agricultural development [12,13]. The C4 photosynthetic pathway in sorghum involves the spatial separation of carbon fixation and the Calvin cycle between mesophyll and bundle sheath cells, which significantly increases photosynthetic efficiency, particularly under conditions of high temperature, high light intensity, and water deficit [14]. As the primary organ for photosynthesis, the leaf plays a pivotal role in sustaining high photosynthetic activity in C4 crops. Therefore, the photosynthetic capacity of sorghum leaves is a fundamental determinant of overall photosynthetic performance and grain yield.

Moreover, sorghum exhibits considerable resilience to diverse abiotic stresses, including high temperature, osmotic stress, high-intensity light, UV radiation, and drought. This adaptability is closely linked to its abundant and specialized secondary metabolites. For instance, under combined osmotic and heat stress, sorghum cells employ distinct adaptive strategies involving reprogramming of the extracellular proteome, characterized by upregulation of ROS-scavenging enzymes and downregulation of ROS-generating peroxidases [15]. Under prolonged high-fluence UV exposure, the pericarp of black sorghum activates ROS accumulation and induces defense-related transcriptional networks mediated by MYB, NAC, and WRKY transcription factors, leading to the biosynthesis and cell wall accumulation of 3-deoxyanthocyanidins [16]. Under drought conditions, mutation of a brassinosteroid receptor gene, SbBRI1, alters regulation of the phenylpropanoid pathway, redirecting metabolic investment from lignin biosynthesis to flavonoid accumulation, thereby enhancing photosynthetic efficiency and drought resilience [17].

Certain UGT genes/proteins in sorghum play a central role in mediating environmental stress responses and secondary metabolism. Previous studies have demonstrated that UGT85B1 functions as a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucoside dhurrin. Its substrate specificity and stereoselectivity are determined by two critical amino acid residues, Ser391 and Arg201, located within its functional domains [18,19,20]. Knockout of UGT85B1 (also designated as the tcd2 mutant) disrupts cyanogenic glucoside synthesis, resulting in impaired plant growth and accumulation of toxic intermediates [21]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) further indicate that genetic polymorphisms in UGT85B1 are strongly correlated with cyanogenic glucoside content in sorghum leaves, a relationship modulated by nitrogen availability [22]. Additionally, sorghum UGTs contribute to drought stress response. ABA seed priming enhances drought tolerance by activating the IAA biosynthesis pathway, including YUCCA genes, which act synergistically with drought-induced ABA-inactivating genes (such as UGT and BGLU genes) to strengthen ABA–IAA signaling crosstalk [23]. Another sorghum UGT member, Sobic.010G120200, is implicated in the regulation of aerial root mucilage secretion, influencing sugar allocation and nitrogen fixation processes [24,25].

Despite the evident importance of UGT genes in sorghum, genome-wide identification, phylogenetic classification, and functional prediction of UGTs in this crop have not been comprehensively characterized, which limits the systematic understanding of this gene family’s roles. Therefore, the present study performed a genome-wide identification of the UGT gene family in sorghum and analyzed the chromosomal distributions, gene structures, conserved motifs, and evolutionary relationships of its members. Furthermore, cis-acting element analysis of SbUGT promoters and transcriptome profiling was performed to predict their potential biological functions. Finally, gene co-expression network analysis was applied to identify potential pathways associated with UGT genes in sorghum leaves. This study provides a foundation for further elucidating the biological functions of the UGT gene family in sorghum.

2.1 Identification of SbUGT Genes in Sorghum

Genomic data for sorghum were acquired from the Sorghum Genome Mapping Database (SGMD; https://sorghum.genetics.ac.cn/SGMD, accessed on 05 November 2025) [26]. Using the Arabidopsis UGT protein sequences as queries, local BLASTp searches were performed against the predicted protein sequences of the sorghum genome with an E-value threshold of 1 × 10−10. Concurrently, HMMER searches were carried out to verify the presence of the PSPG domain in sorghum proteins, applying an E-value cutoff of 1 × 10−5 [27]. All candidate sequences were further examined for the presence of complete conserved domains using the Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/) and SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de) databases. Sequences that were incomplete or lacked functional domains were discarded. A total of 196 SbUGT genes were identified in sorghum and designated SbUGT1 to SbUGT196.

2.2 Phylogenetic Analysis, Physicochemical Properties, and Subcellular Localization of SbUGT Proteins

A phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the full-length protein sequences of 196 sorghum UGT proteins and 122 Arabidopsis UGT proteins using MEGA X software [28]. Multiple sequence alignment was carried out with MUSCLE under default parameters [29]. A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was generated with IQ-TREE [30], employing 1000 bootstrap replicates to assess node support.

Physicochemical properties of the identified SbUGT proteins, including amino acid length, molecular weight, theoretical isoelectric point (pI), instability index, aliphatic index, and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), were calculated using the ProtParam tool available on the ExPASy server (https://web.expasy.org/protparam). Subcellular localization was predicted using WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/).

2.3 Chromosomal Distribution, Synteny Analysis and Prediction of Cis-Acting Elements in SbUGT Promoters

Chromosomal locations of the SbUGT genes were analyzed using TBtools [31]. Intraspecific synteny analysis was performed with MCScanX to identify segmentally duplicated gene pairs [32], and the results were visualized using TBtools. For interspecific synteny, comparative genomic analyses were conducted among rice, sorghum, Zea mays (maize), and Hordeum vulgare (barley) using JCVI to detect conserved syntenic blocks. Syntenic relationships were visualized to infer evolutionary rearrangements [33].

The 2000 bp sequences upstream of the transcription start sites of all 196 SbUGT genes were defined as promoter regions and extracted from the sorghum genome. Prediction of cis-acting regulatory elements was carried out using the PlantCARE database [34].

2.4 Analysis of Gene Structure, Protein Domains, and Conserved Motifs in SbUGTs

The exon-intron structures of SbUGT genes were analyzed based on the GFF annotation file of the sorghum genome and visualized using TBtools [31]. Conserved protein domains were predicted via NCBI Batch CD-search (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi), with particular emphasis on the glycosyltransferase (GT) domain. Conserved motifs were identified using the MEME suite under default parameters [35], and their distributions were visualized with TBtools [31].

2.5 Expression Profiling and Co-Expression Network Analysis of SbUGTs in Different Tissues

Tissue-specific expression data for SbUGT genes were obtained from transcriptome datasets of 13 sorghum tissues in SGMD (https://sorghum.genetics.ac.cn/SGMD) [26]. The tissues encompassed multiple developmental stages and organs, including: three seed developmental stages (filling-stage designated as seed 1, waxy-stage as seed 2, and 3-day germinated seeds as seed 3); root; whole seedling; leaf at the 2-week seedling stage (leaf 1); booting-stage samples comprising the top second leaf (leaf 2) and stem (stem 1); filling-stage samples including flag leaf (leaf 3), the top fourth leaf (leaf 4), and the top third stem (stem 2); and inflorescences before and after flowering (designated as inflorescence 1 and inflorescence 2, respectively) [26]. Genes with low expression were filtered out, retaining only those with FPKM ≥ 1 in at least one tissue, resulting in 151 SbUGTs. Expression values were log2(FPKM + 1) transformed for normalization. Heatmaps were generated using the R packages “ggplot2”, “pheatmap”, “reshape2”, and “factoextra” for hierarchical clustering [36].

A weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was performed using the top 50% genes based on median absolute deviation (MAD) to identify modules correlated with tissue types [37]. Parameters settings were as follows: softpower = 10, minimum module size = 30, module merge cut height = 0.25, and deep split = 2. Hub genes were selected based on the following criteria: top 10% intramodular connectivity, |KME| ≥ 0.8, and |GS| ≥ 0.2. Functional enrichment analysis of hub genes in KEGG pathways was conducted using KOBAS-i with default parameter [38]. Co-expression networks of the SbUGT12 and its associated genes were visualized using Cytoscape [39].

2.6 Molecular Docking of SbUGT12 with Potential Substrates

Molecular docking was employed to investigate the interactions between SbUGT12 and potential substrates. The three-dimensional structure of SbUGT12 was computationally modeled for use as the receptor. Ligand and structures, including malate (PubChem CID: 160434), pyruvate (CID: 107735), phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP; CID: 1005), oxaloacetate (CID: 970), and UDP-glucose (CID: 8629), were retrieved from the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/, accessed on 05 November 2025). Semi-flexible docking simulations were carried out using AutoDock Vina [40]. The binding site was defined as a grid box centered at coordinates (x = 15.6, y = 22.3, z = 18.9) with dimensions of 30 × 30 × 30 Å. The exhaustiveness parameter was set to 50. For each ligand-receptor complex, 20 independent docking runs were conducted. The conformation with the most favorable binding free energy was selected. Energy corrections were subsequently applied using the MM/PBSA method [41].

3.1 Identification, Physicochemical Properties, and Chromosomal Distribution of the UGT Gene Family in Sorghum

A total of 196 UGT genes were identified in the sorghum genome through a BLASTp search using the conserved PSPG domain (PF00201) as a query. These genes were designated SbUGT1 to SbUGT196. The encoded proteins ranged from 124 to 621 amino acids in length (average: 478 aa), with molecular weights between 14.06 and 68.34 kDa (average: 51.67 kDa). The theoretical pI values varied from 4.81 to 9.69 (average: 5.72), instability indices ranged from 28.47 to 56.92 (average: 43.87), aliphatic indices from 69.74 to 103.51 (average: 88.87), and GRAVY values from −0.44 to 0.25. Subcellular localization predictions indicated that the majority of SbUGTs were targeted to the chloroplast (118 genes) or cytoplasm (50 genes) (Table S1).

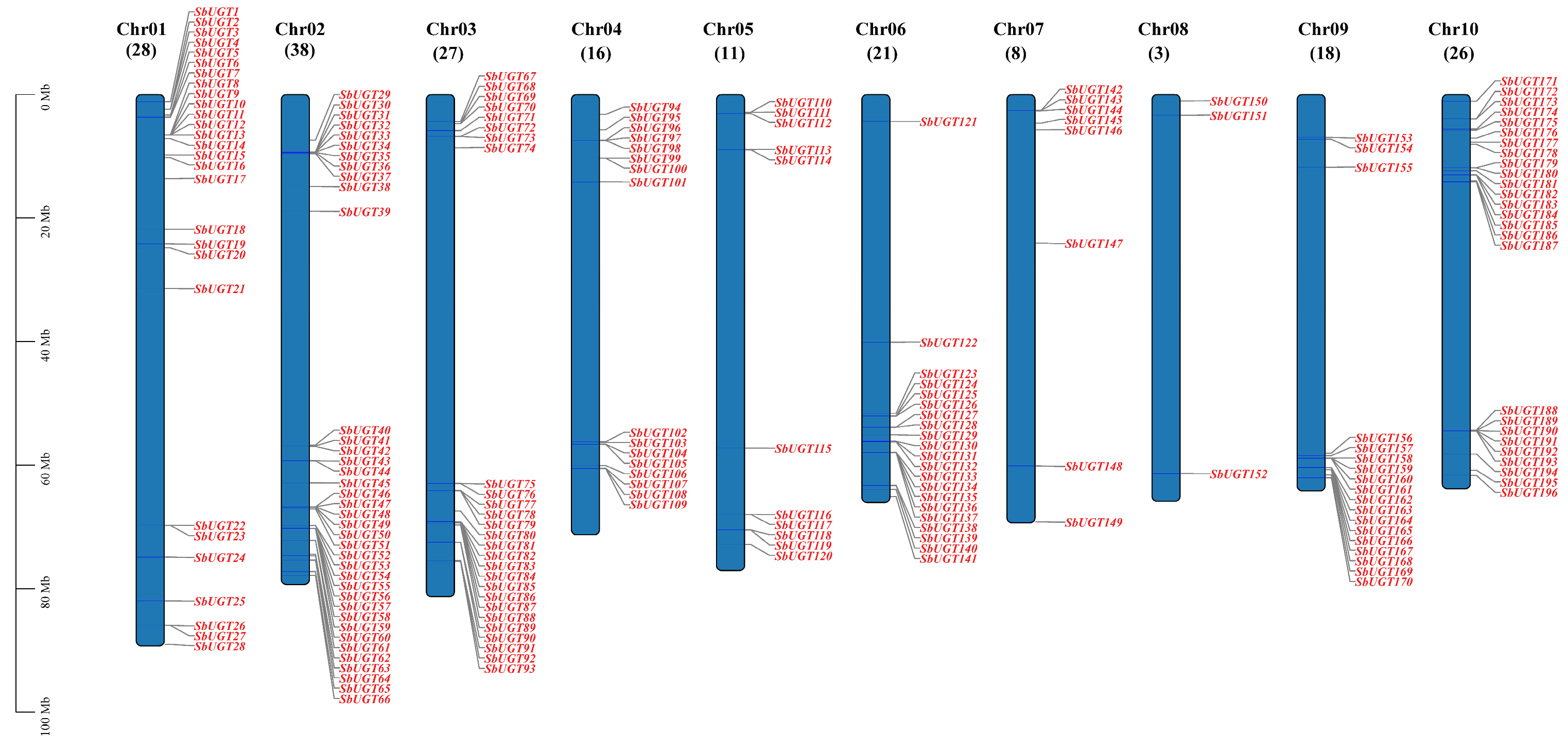

Chromosomal distribution analysis revealed the 196 SbUGT genes were non-uniformly distributed across all ten sorghum chromosomes (Chr01–Chr10; Fig. 1). Chromosome 2 harbored the largest number of genes (38 genes, 19.39%), followed by Chr01 (28 genes, 14.29%) and Chr03 (27 genes, 13.78%). In contrast, Chr08 contained the fewest SbUGT genes (3 genes, 1.53%), reflecting considerable heterogeneity in gene distribution among chromosomes. Notably, most SbUGTs formed dense clusters near chromosomal termini, suggesting the occurrence of tandem duplication events.

Figure 1: Chromosomal distribution of SbUGT genes. The number of genes located on each chromosome is indicated parentheses.

3.2 Phylogenetic Analysis and KEGG Functional Enrichment of the UGT Family

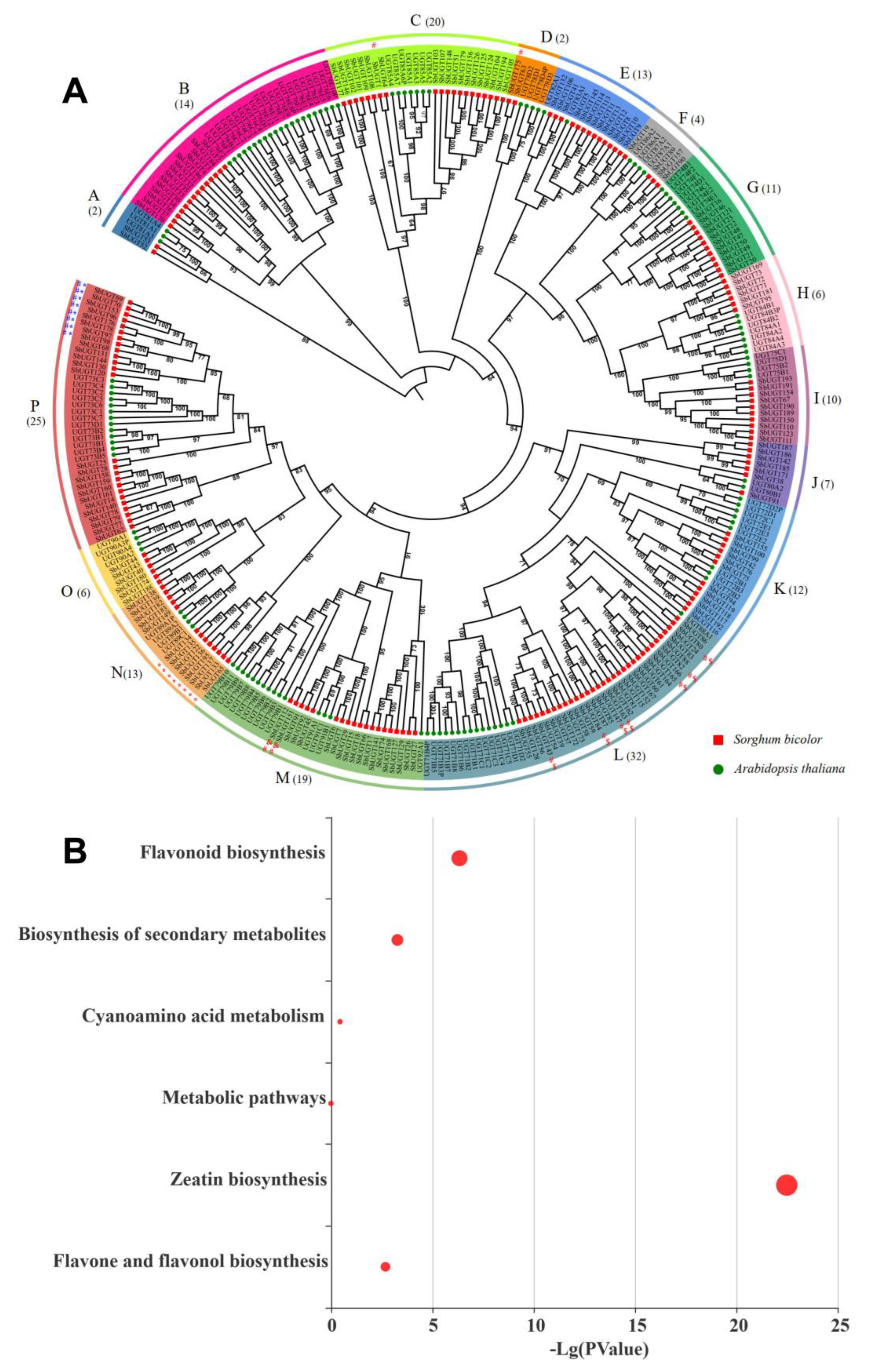

A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using 318 UGT protein sequences, including 196 from sorghum and 122 from Arabidopsis. The proteins were classified into 16 evolutionarily conserved subfamilies, designated A to P (Fig. 2A). The distribution of SbUGTs among these subfamilies was variable: subfamily L was the largest, containing 32 SbUGTs (16.33%), followed by subfamily P (25 genes, 12.76%) and subfamily C (20 genes, 10.20%). In contrast, subfamilies A and D each contained only two SbUGTs (1.02%).

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that 27 SbUGTs were associated with six metabolic pathways. Among these, four pathways were significantly enriched (p < 0.05, Fig. 2B): zeatin biosynthesis, flavonoid biosynthesis, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, and flavone and flavonol biosynthesis. These enriched pathways displayed distinct subfamily-specific distributions. For instance, the 16 SbUGTs enriched in zeatin biosynthesis were equally distributed between subfamilies N and P. All seven SbUGTs associated with flavonoid biosynthesis belonged to subfamily L. Of the 19 SbUGTs linked to secondary metabolite biosynthesis, the majority were located in subfamilies L (7 genes) and P (8 genes), with the remaining four distributed across subfamilies C, D, and M. The two SbUGTs implicated in flavone and flavonol biosynthesis were uniquely found in subfamily M.

Figure 2: Phylogenetic analysis and KEGG pathway enrichment of the UGT gene family. (A) Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree based on full-length UGT protein sequences from 196 SbUGTs and.122 AtUGTs. Subfamilies are labeled A–P. Numbers at the branch nodes represent bootstrap support values (%) based on 1000 replicates. Sorghum and Arabidopsis UGTs are marked with red squares and green circles, respectively. SbUGTs significantly enriched in KEGG pathways are indicated with symbols: zeatin biosynthesis (*), flavonoid biosynthesis ($), biosynthesis of secondary metabolites (#), and flavone and flavonol biosynthesis (&). (B) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of SbUGTs.

3.3 Analysis of Protein Motifs, Conserved Domains, and Gene Structures of SbUGTs

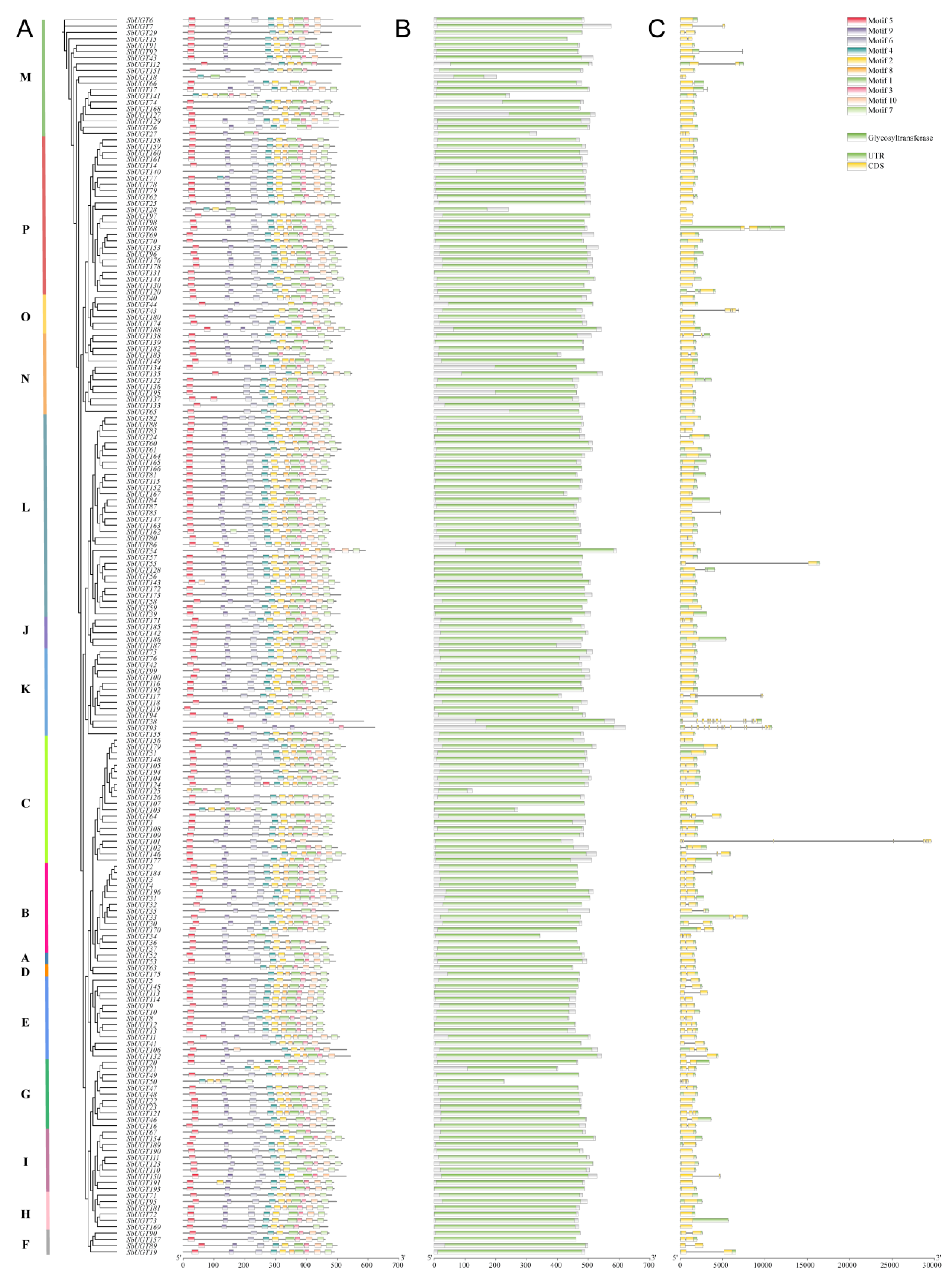

To investigate the conservation and diversification of SbUGT proteins, MEME suite analysis was employed and identified ten conserved motifs with distinct positional and subfamily-specific features (Fig. 3A). All SbUGT proteins contained the characteristic UGT-specific PSPG domain (Motif 1), located near the C-terminus. Motifs 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, and 10 were present in the majority of SbUGTs, indicating broad conservation. Among these, Motif 5 was predominantly located near the N-terminus, whereas Motif 7 was positioned toward the C-terminus. Subfamily-specific absence patterns suggested functional divergence: Motif 6 was completely absent in subfamily D and partially absent in subfamilies M and E, while Motif 9 was also entirely missing in subfamily D and partially absent in subfamilies M, N, K, F, and E. These findings imply evolutionary subfunctionalization among UGT subfamilies, potentially related to substrate specificity in sorghum glycosylation.

NCBI Batch CD-search confirmed that all 196 SbUGT proteins contain the GT domain (Fig. 3B). All members exhibited the conserved PSPG subdomain (PF00201) proximal to the C-terminus (Fig. 3A), validating their functional integrity and classification within the UGT superfamily.

Exon–intron structure analysis revealed significant diversity among SbUGT subfamilies (Fig. 3C). A total of 120 SbUGTs (61.22%) lacked introns and exhibited a single-exon structure; these were predominantly distributed in subfamilies M, P, O, N, L, J, K, I, H, and A. The remaining genes contained 1 to 13 introns and were enriched in subfamilies C, B, D, E, G, and F. Notably, SbUGT93 displayed the most complex structure, with 14 exons and 13 introns. Conserved structural patterns were observed within specific subfamilies. For example, all members of subfamilies B, D, E, and F shared a two-exon–one-intron structure, indicating strong evolutionary conservation of gene architecture that may correlate with functional specialization in glycosyltransferase activity.

Figure 3: Protein motifs, conservation domain and gene structure of sorghum UGT genes. (A) Conserved motif distribution across SbUGT subfamilies. (B) Conservation domain predicted by NCBI CD-search. Green bars, GT domain. (C) Exon-intron structures of SbUGTs. Yellow boxes: exons; grey lines: introns.

3.4 Intraspecific and Interspecific Synteny Analysis of SbUGTs

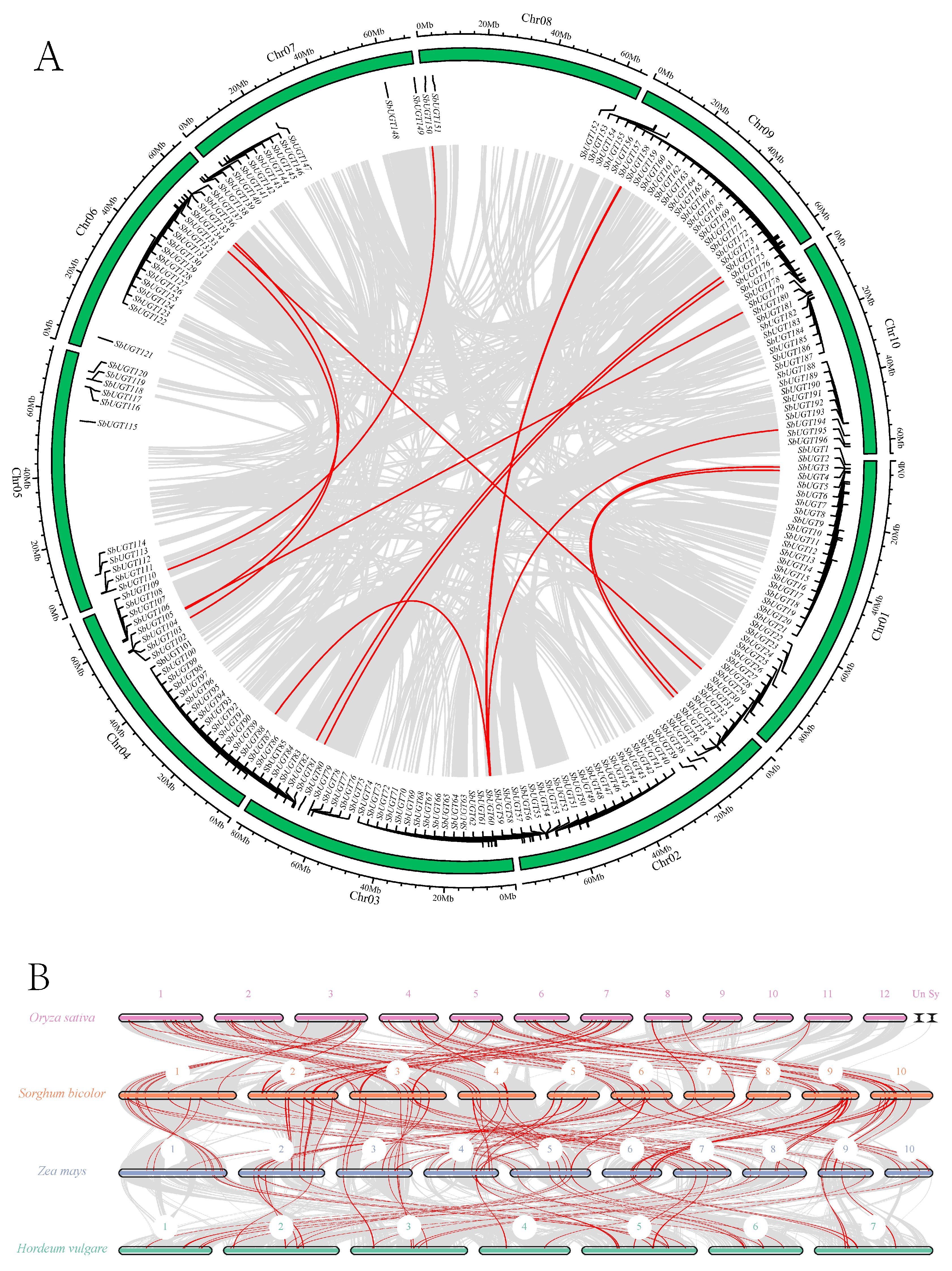

Chromosomal localization (Fig. 1) indicated that SbUGT genes were predominantly clustered near chromosome ends, suggesting the occurrence of tandem duplication events during evolution. To further investigate this, synteny analysis was performed, which identified 12 segmentally duplicated gene pairs involving 21 SbUGTs distributed across nine chromosomes (Fig. 4A). These syntenic pairs included:

| SbUGT2/SbUGT35, | SbUGT26/SbUGT129, | SbUGT68/SbUGT96, | SbUGT81/SbUGT162, |

| SbUGT89/SbUGT157, | SbUGT67/SbUGT154, | SbUGT68/SbUGT153, | SbUGT67/SbUGT189, |

| SbUGT103/SbUGT124, | SbUGT106/SbUGT132, | SbUGT107/SbUGT177, | and SbUGT110/SbUGT150. |

These results demonstrate that segmental duplication has played a significant role in the expansion of the SbUGT gene family.

Figure 4: Intraspecific (A) and interspecific (B) synteny networks of SbUGT genes. Gray lines indicate the overall syntenic blocks within or between genomes; red lines indicate syntenic UGT gene pairs. Chromosomes are labeled Chr01–Chr10 (A) and by number in (B).

Comparative synteny analysis of UGT genes among four Poaceae crops (rice, sorghum, maize, and barley) revealed both conserved genomic structures and lineage-specific chromosomal rearrangements (Fig. 4B). A total of 62 rice–sorghum, 83 sorghum–maize, and 40 maize–barley syntenic UGT pairs were identified, demonstrating strong macro-syntenic conservation. Multi-layered homologous relationships were observed: for example, UGT clusters on maize chromosome 7 (Zm07) were syntenic with sorghum chromosome 2 (Sb02), which in turn showed correspondences with both Zm02 and Zm07. Maize chromosome 2 (Zm02) also exhibited synteny with barley chromosome 2 (Hv02). Similar conservation was also observed on the UGTs located on rice chromosome 1 (Os01), sorghum chromosome 3 (Sb03), maize chromosome 3 (Zm03), and barley chromosome 2 (Hv02). These complex syntenic relationships suggest that the divergence of Poaceae species involved not only the conservation of ancestral genomic blocks harboring UGT clusters but also large-scale chromosomal rearrangements—including fissions, fusions, and inversions. These events followed a “block-wise” differentiation pattern, indicating that functionally associated chromosomal segments often evolved as cohesive units.

3.5 Analysis of Promoter Cis-Acting Elements in SbUGTs

Analysis of the 2000 bp promoter regions upstream of the 196 SbUGT genes identified a total of 26,609 cis-acting elements, representing 125 distinct types (Fig. 5A). In addition to core promoter elements such as TATA-box and CAAT-box, as well as several unnamed elements, the ten most abundant cis-acting elements were: Myb (923 occurrences), MYC (773), G-box (699), ABRE (629), CGTCA-motif (545), TGACG-motif (539), as-1 (539), STRE (449), ARE (313), and Box 4 (308). These elements were associated with diverse biological processes (Fig. 5B), including: methyl jasmonate (MeJA) responsiveness (1086 elements), abscisic acid (ABA) responsiveness (631), light responsiveness (761), salicylic acid (SA) responsiveness (103), anaerobic induction (315), low-temperature responsiveness (134), auxin-responsive elements (139), MYB binding sites (229), zein metabolism regulation (138), anoxic specific inducibility (68), gibberellin-responsive elements (104), seed-specific regulation (81), and defense and stress responsiveness (47 elements). The distribution patterns of these functional elements across individual SbUGT promoters revealed gene-specific regulatory profiles (Fig. 5C), suggesting that different SbUGT genes are likely regulated under distinct physiological or environmental conditions.

Figure 5: Prediction of cis-acting elements in the promoter regions of SbUGT genes. (A) Frequency distribution of the top cis-acting elements in SbUGT promoter. (B) Functional classification of cis-acting elements. (C) Distribution of cis-acting elements across SbUGT promoters.

3.6 Tissue-Specific Expression Profiling and Co-Expression Network Analysis of SbUGT Genes

Transcriptomic data from 13 developmental tissues of sorghum were analyzed, leading to the identification of 151 expressed SbUGT genes. Hierarchical clustering classified these into nine distinct expression clusters (C1–C9; Fig. 6A). Cluster C1 (11 SbUGTs) was preferentially expressed in photosynthetic tissues (seedling, leaf1/3/4); C2 (36 SbUGTs) was active across broad vegetative tissues (seedling, leaf1–4); C3 (9 SbUGTs) showed expression in both vegetative and reproductive tissues (seed1, inflorescence1/2, stem1/2); C4 (11 SbUGTs) was widely expressed in multiple tissues (including root, seedling, seed3, infloresscence1 and stem1), C5 (25 SbUGTs) was also widely expressed in multiple tissues (including root, seedling, seed3 and stem1), C6 (14 SbUGTs) exhibited seed-specific expression (seed1/2); C7 (13 SbUGTs) was predominantly expressed in root and seedling; C8 (15 SbUGTs) showed peak expression in seedling, seed3, and leaf1; and C9 (17 SbUGTs) was highly expressed in inflorescence1, with secondary expression in vegetative tissues (seedling, seed3, leaf1).

WGCNA using expression data from the 13 tissues identified 23 co-expression modules, ranging in size from 33 to 6290 genes (Fig. 6B). Significant correlations (p < 0.05) were detected between specific modules and tissues. The mediumpurple2 module (608 genes) correlated strongly with root (r = 0.70, p = 0.007). Six modules—brown (2720 genes), coral (557), ivory (1158), coral1 (785), antiquewhite2 (6290), and navajowhite4 (256 genes)—were significantly associated with leaf (r = 0.83, −0.59, −0.67, −0.69, −0.80, −0.63; p = 5 × 10−4, 0.03, 0.01, 0.009, 9 × 10−4, 0.02). Five modules—cyan (193 genes), darkseagreen (33), coral1 (785), navajowhite4 (256), and brown3 (74 genes)—exhibited positive correlation with inflorescence (r = 0.85, 0.74, 0.61, 0.81, 0.61; p = 2 × 10−4, 0.004, 0.03, 7 × 10−4, 0.03). Another five modules, coral (557 genes), darkseagreen2 (109), white (834), brown2 (88), and lightpink4 (184 genes), were linked to seed (r = −0.60, 0.65, −0.68, −0.88, −0.56; p = 0.03, 0.02, 0.01, 8 × 10−5, 0.04).

Among these, the antiquewhite2 and brown modules, both significantly associated with leaf tissues (p < 0.05), contained 32 and 28 SbUGTs, respectively, indicating their functional importance in leaf biology. Cluster analysis (Fig. 6A) revealed that within the antiquewhite2 module, 10 SbUGTs belonged to C5, 6 to C4, and the remainder were distributed across other clusters. In the brown module, 20 of the 28 SbUGTs clustered within C2, which was enriched in leaf tissues, confirming the leaf-specific role of brown module SbUGTs.

Notably, SbUGT12 (SbE048.01G084500) was identified as a hub gene (top 10% connectivity) within the brown module. A total of 127 hub genes were found to directly interact with SbUGT12, forming a 128-gene co-expression network (including SbUGT12 itself). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of these genes revealed significant enrichment (p < 0.05) in nine metabolic pathways (Fig. 6C): Carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms (map00710), Pyruvate metabolism (map00620), Carbon metabolism (map01200), One carbon pool by folate (map00670), Photosynthesis (map00195), Metabolic pathways (map01100), Plant hormone signal transduction (map04075), Photosynthesis— antenna proteins (map00196), and Porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism (map00860).

Among the top 10 genes with highest edge weights to SbUGT12 (Fig. 6D) were Ferredoxin-NADP reductase (SbE048.03G468800), NADP-dependent malate dehydrogenase (SbE048.07G188800), PPDK kinase/phosphatase (SbE048.02G338400), and a PDZ domain-containing protein (SbE048.07G054700)—all key components of the C4 photosynthetic pathway, highlighting their central role in photosynthetic metabolism in this C4 crop.

Figure 6: Tissue-specific expression profiling and co-expression network analysis of SbUGT genes. (A) Hierarchical clustering of 151 SbUGT genes across 13 developmental tissues. Nine expression clusters (C1–C9) were identified. (B) Module–tissue correlation analysis based on WGCNA. The heatmap depicts Pearson correlation coefficients (r) between 23 co-expression modules and 13 tissues. (C) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of 128 genes interacting with SbUGT12. (D) Co-expression subnetwork of SbUGT12 (highlighted in cyan) and its top 10 co-expressed genes (pink). Edge length is inversely proportional to TOM weight, indicating stronger co-expression associations. Gene annotations: SbE048.03G468800, Ferredoxin–NADP reductase; SbE048.04G109800, CIA30, NAD_binding_10; SbE048.07G054700, PDZ. domain-containing protein; SbE048.01G319900, PfkB; SbE048.01G425500, NifU; SbE048.08G036600, Abi; SbE048.02G338400, PPDK kinase/phosphatase; SbE048.07G188800, NADP-dependent malate dehydrogenase; SbE048.08G055100, 5-FTHF_cyc-lig; SbE048.09G211500, PsbW.

3.7 Molecular Docking Analysis of SbUGT12 with UDP-Glucose and C4 Photosynthetic Metabolites

Given the strong co-expression association between SbUGT12 and genes involved in the C4 photosynthetic pathway (Fig. 6C,D), molecular docking was performed to evaluate the binding potential of SbUGT12 with UDP-glucose and four key C4 photosynthetic intermediates: malate, pyruvate, PEP, and oxaloacetate (Fig. 7). The results demonstrated that SbUGT12 exhibited strong binding affinity for UDP-glucose, with a binding free energy (ΔG) of –10.24 kcal/mol, indicating a highly stable interaction under the simulation conditions (Fig. 7A). Additionally, spontaneous binding (ΔG < 0) was observed with all four C4 metabolites: malate (Fig. 7B), pyruvate (Fig. 7C), PEP (Fig. 7D), and oxaloacetate (Fig. 7E). The binding affinities, in descending order, were as follows: PEP (–5.61 kcal/mol) > oxaloacetate (–5.26 kcal/mol) > malate (–4.86 kcal/mol) > pyruvate (–4.42 kcal/mol). Analysis of the binding mode of PEP to SbUGT12 (Fig. 7D) revealed that its phosphate group formed conventional hydrogen bonds with active-site residues PHE A:247, VAL A:251, and GLN A:340, in addition to engaging in attractive charge interactions with residues such as GLU A:257. These interactions, comprising an extensive hydrogen-bond network and electrostatic forces, collectively stabilized the conformation of PEP within the binding pocket.

Figure 7: Molecular docking analysis of SbUGT12 with UDP-glucose. (A) and C4 photosynthetic metabolites: malate (B), pyruvate (C), PEP (D), and oxaloacetate (E).

This study provides an in-depth analysis of the UGT gene family in sorghum, providing important insights into its functional diversity and evolutionary dynamics. Compared to other plant species, the UGT family size in sorghum (196 genes) is larger than that in Arabidopsis (122 genes) [6], rice (163 genes) [7], wheat (179 genes) [42], barley (175 genes) [43], and maize (147 genes) [44], suggesting a possible gene family expansion in sorghum. This expansion may be driven by tandem duplication events, as evidenced by the clustered distribution of SbUGTs at chromosomal termini and 12 SbUGT segmental duplication pairs formed in sorghum genome. The expansion of the UGT gene family in sorghum may reflect its adaptation to specific metabolic demands, potentially linked to its resilience under diverse environmental stresses (e.g., drought and pathogen infection) [45,46], as well as its ability to synthesize a variety of secondary metabolites, such as sorghum-specific tannin [47,48].

Notably, a majority of SbUGTs (118 genes, 60.2%) are predicted to localize to the chloroplast, whose proportion appears larger than that in C3 species like rice and Arabidopsis. This finding is strongly associated with sorghum’s C4 nature, as chloroplasts are central to C4 photosynthesis, facilitating efficient carbon fixation through specialized compartmentalization. It potentially reflects an adaptation for optimizing photosynthetic-related processes, such as the glycosylation of photosynthetic intermediates or protective metabolites such as flavonoids, which might provide a shield against photooxidative damage—an essential adaptation for survival in high-light environments [49,50,51,52].

Phylogenetic analysis of UGT proteins from sorghum and Arabidopsis identified 16 evolutionarily conserved subfamilies (A–P), revealing both functional conservation and subfamily-specific functional divergence. The unequal distribution of SbUGTs across subfamilies, with expanded subfamilies (such as L and P) contrasting with smaller ones (such as A and D), suggests subfamily-specific expansion driven by metabolic requirements during sorghum evolution. This hypothesis is further supported by KEGG enrichment analysis: significantly enriched pathways exhibited distinct subfamily distribution. Notably, all SbUGTs involved in flavonoid biosynthesis were clustered in subfamily L, highlighting its functional conservation—consistent with previous reports that phylogenetically related UGTs often participate in similar metabolic pathways [53,54].

Furthermore, functional preferences of specific sorghum UGT subfamilies show both conservation and divergence compared to other species such as Arabidopsis and maize. While UGTs associated with flavonoid biosynthesis typically localize to subfamilies L and M in Arabidopsis and maize [5,55,56], this study confirms flavonoid biosynthesis enrichment in sorghum subfamily L, with flavone biosynthesis uniquely restricted to subfamily M. Crucially, unlike the enrichment of zeatin metabolism-related UGTs in subfamily O in poplar [57], sorghum zeatin biosynthesis involves in subfamilies N and P, and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites dominates subfamilies L and P. These findings demonstrate that while UGT functions are phylogenetically conserved, functional divergence can occur through species-specific metabolic adaptations, providing pivotal insights into the evolution of specialized metabolism in sorghum.

The analysis of conserved motifs, domains, and gene structures within the sorghum UGT family reveals both functional conservation and structural divergence among its subfamilies. All SbUGT proteins contain the specific C-terminal PSPG domain and share the glycosyltransferase GT domain, confirming their functional integrity as members of the UGT superfamily. Variation in motif composition, such as the absence of Motif 6 in subfamily D and partial loss in M and E, and Motif 9 in D, M, N, K, F, and E, suggests subfunctionalization during evolution, potentially linked to substrate specificity for UGT. Furthermore, exon–intron structural diversity supports evolutionary divergence: while 61.2% of SbUGTs are intronless and clustered in certain subfamilies, others contain up to 13 introns, with subfamilies B, D, E, and F uniformly exhibiting a two-exon–one-intron structure. These conserved gene structure patterns of SbUGTs imply that gene structure constraints may correlate with functional conservation in glycosylation activities. These findings may reflect how structural conservation and divergence among SbUGT subfamilies may underlie functional diversification, particularly in substrate recognition and catalytic specificity. The consistent presence of the PSPG and GT domains supports a conserved mechanism of glycosyl transfer, while variability in motif composition and gene structure offers insights into lineage-specific evolution [5,7,53,56,57,58]. This structural-functional correlation provides a foundation for further experimental investigation into the role of specific UGT subfamilies in sorghum secondary metabolism.

Cis-acting elements analysis in the promoter regions of 196 SbUGT genes revealed that, in addition to basic elements such as TATA-box and CAAT-box, a wide range of functional elements associated with various hormone responses (e.g., MeJA, ABA, SA), abiotic stresses (e.g., low temperature, hypoxia), and light responsiveness were also widely present. The diversity and high frequency of these elements suggest that the SbUGT gene family may broadly respond to hormonal signals such as MeJA and ABA, as well as environmental factors like photoperiod and low temperature, playing important roles particularly in stress response and growth regulation. Furthermore, the differences in these elements among different SbUGT gene promoters suggest that functional diversification within the sorghum UGT gene family. Certain genes are likely activated preferentially in specific tissues or under particular stress conditions, enabling spatiotemporal regulation of SbUGTs. This phenomenon has also been reported in other species. For instance, in Arabidopsis, the promoters of UGT73B3 and UGT73B5 are enriched in SA-responsive elements (early SAIGs) and participate in regulating redox status and general detoxification of ROS-reactive secondary metabolites during the hypersensitive response to Pst-AvrRpm1 [59]. In rice, UGT85E1 is significantly upregulated under drought stress and ABA treatment, and plays an important role in mediating plant responses to drought and oxidative stresses [60]. Additionally, UGT76E1, UGT76E2, UGT76E11, and UGT76E12 are involved in wound-induced synthesis of 12-O-glucopyranosyl-jasmonic acid in Arabidopsis [61]. These findings collectively indicate that the functional specificity and diversification of SbUGTs are achieved through diverse combinations of cis-elements in the promoter.

Through transcriptome analysis, we classified 151 expressed SbUGTs into 9 distinct expression clusters (C1–C9) based on their tissue-specific expression patterns, indicating that SbUGT genes exhibit high functional diversification and expression specificity during sorghum growth and development. For instance, genes in clusters C1 and C2 were highly expressed in photosynthetic and vegetative tissues, suggesting their potential involvement in glycosylation of the metabolites and compounds in leaves [58]. The seed-specific expression pattern of C6 implies that these ShUGTs may participate in storage compound synthesis such as tannie and phytohormones during seed development [10,47].

WGCNA co-expression network analysis revealed significant associations of six modules, including antiquewhite2, brown, and coral, with leaf tissues. Interestingly, the brown module contained 28 SbUGT genes, 20 of which belonged to C2 characterized by hierarchical clustering, genes in which were dominant expressed in leaf tissues than in other tissues. Furthermore, SbUGT12 was identified as a hub gene, whose interacting genes were significantly enriched in multiple metabolic pathways closely related to photosynthesis, and top co-expressed genes encode key enzymes in the C4 photosynthetic pathway. These includes ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase (FNR), NADP-dependent malate dehydrogenase, and PDZ domain-containing proteins, which play vital roles in photosynthetic carbon assimilation and metabolite transport between mesophyll and bundle sheath cells in C4 plants [62,63]. Subsequently, molecular docking verified that SbUGT12 spontaneously binds to four core C4 photosynthetic metabolites (PEP, oxaloacetate, malate, and pyruvate), providing direct evidence for its involvement in C4 photosynthetic metabolism. Therefore, we propose that SbUGT12 may participate in regulating C4 photosynthesis by glycosylating metabolic C4 photosynthetic metabolites.

It is worth mention that previous studies have primarily focused on the glycosylation modification and regulatory roles of UGT family members in secondary metabolism, such as in flavonoids and hormones [10,19,56,59]. In contrast, our study is the first to reveal a measurable binding capacity of SbUGT12 to primary metabolites involved in C4 photosynthesis. This finding not only expands our understanding of the functional diversity of UGTs but also provides new insights into the metabolic regulation of high photosynthetic efficiency in C4 crops. However, since these gene expression and molecular interactions are currently inferred from transcriptome data, computational simulations and binding free energy calculations, their biological functions require further experimental validation. This would include qRT-PCR analysis of gene expression, in vitro enzymatic activity assays investigating glycosylated product formation, as well as phenotypic analysis of gene knockout plants under photosynthetic conditions. Such studies would help clarify the specific role of SbUGT12 in photosynthetic carbon assimilation.

Another thing that is noteworthy is that this study is based on the reference genome of E048, a sweet sorghum variety. In contrast to grain sorghum (e.g., BTx623), which is cultivated primarily for seed production, sweet sorghum exhibits a distinct source-sink relationship, where photoassimilates are preferentially allocated and stored as sucrose in the stalk, making it a dominant sink organ. This difference fundamentally influences carbon partitioning strategies in C4 plants. Consequently, the functional implications for the UGT gene family, particularly for members like SbUGT12 potentially involved in pathways related to C4 photosynthesis, analyzed herein within the E048 context, should be interpreted considering this sweet sorghum-specific source-sink physiology. Extrapolating these findings to grain sorghum, where the seed acts as the major sink, requires caution and should be considered hypothetical pending validation. Future comparative genomics and functional studies utilizing the grain sorghum genomes will be crucial to elucidate the functional conservation and divergence of UGT genes across two different sorghum types.

In conclusion, this study identified and characterized 196 SbUGT genes in sorghum, classifying them into 16 phylogenetic subfamilies, of which 61.2% lack introns and contain conserved PSPG motifs. Evolutionary analyses highlighted the contribution of segmental duplication to the expansion of this gene family and revealed conserved syntenic relationships with other Poaceae species. Promoter analysis identified abundant stress- and hormone-responsive cis-elements, indicating a potential role for SbUGTs in environmental adaptation. Transcriptomic profiling demonstrated tissue-specific expression patterns, and co-expression analysis highlighted SbUGT12 as a hub gene associated with the C4 photosynthetic pathway in leaves. Molecular docking further confirmed that SbUGT12 binds spontaneously to four key C4 metabolites, supporting its putative involvement in photosynthetic metabolism. These findings provide fundamental insights into the molecular evolution and functional diversification of the SbUGT family and identify SbUGT12 as a crucial candidate for future research aimed at improving photosynthetic efficiency in sorghum.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Scientific Research Project of Hengshui University, grant number 2022XJZX59, Science Research Project of Hebei Education Department, grant number QN2022189, and the Guizhou Key Laboratory of Biology and Breeding for Specialty Crops, grant number QKHPT ZSYS [2025]026.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xiaoli Guo, Jianhui Ma; data collection: Zhangen Lu, Kuijing Liang, Lingbao Wang, Liran Shi; analysis and interpretation of results: Wenxiang Zhang, Juan Huang, Shanshan Wei; draft manuscript preparation: Wenxiang Zhang, Wenning Cui, Huifen Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Materials.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.073736/s1.

Abbreviations

| Glycosyltransferase | |

| UDP-glycosyltransferase | |

| Abscisic acid | |

| Methyl jasmonate | |

| Salicylic acid | |

| Weighted gene co-expression network analysis | |

| Grand average of hydropathicity | |

| Theoretical isoelectric point | |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate |

References

1. Bock KW . The UDP-glycosyltransferase (UGT) superfamily expressed in humans, insects and plants: animal-plant arms-race and co-evolution. Biochem Pharmacol. 2016; 99: 11– 7. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2015.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chen HY , Li X . Identification of a residue responsible for UDP-sugar donor selectivity of a dihydroxybenzoic acid glycosyltransferase from Arabidopsis natural accessions. Plant J. 2017; 89( 2): 195– 203. doi:10.1111/tpj.13271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Bowles D , Isayenkova J , Lim EK , Poppenberger B . Glycosyltransferases: managers of small molecules. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2005; 8( 3): 254– 63. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2005.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ross J , Li Y , Lim E , Bowles DJ . Higher plant glycosyltransferases. Genome Biol. 2001; 2( 2): Reviews3004. doi:10.1186/gb-2001-2-2-reviews3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li Y , Baldauf S , Lim EK , Bowles DJ . Phylogenetic analysis of the UDP-glycosyltransferase multigene family of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 2001; 276( 6): 4338– 43. doi:10.1074/jbc.M007447200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. von Saint Paul V , Zhang W , Kanawati B , Geist B , Faus-Kessler T , Schmitt-Kopplin P , et al. The Arabidopsis glucosyltransferase UGT76B1 conjugates isoleucic acid and modulates plant defense and senescence. Plant Cell. 2011; 23( 11): 4124– 45. doi:10.1105/tpc.111.088443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Shen Y , Li J , Cai X , Jin J , Li D , Wu H , et al. Investigation of the potential regulation of the UDP-glycosyltransferase genes on rice grain size and abiotic stress response. Gene. 2025; 933: 149003. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2024.149003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Meech R , Hu DG , McKinnon RA , Mubarokah SN , Haines AZ , Nair PC , et al. The UDP-Glycosyltransferase (UGT) superfamily: new members, new functions, and novel paradigms. Physiol Rev. 2019; 99( 2): 1153– 222. doi:10.1152/physrev.00058.2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang GZ , Jin SH , Jiang XY , Dong RR , Li P , Li YJ , et al. Ectopic expression of UGT75D1, a glycosyltransferase preferring indole-3-butyric acid, modulates cotyledon development and stress tolerance in seed germination of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol. 2016; 90( 1–2): 77– 93. doi:10.1007/s11103-015-0395-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu Z , Yan JP , Li DK , Luo Q , Yan Q , Liu ZB , et al. UDP-glucosyltransferase71c5, a major glucosyltransferase, mediates abscisic acid homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015; 167( 4): 1659– 70. doi:10.1104/pp.15.00053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yu L , He K , Wu Y , Hao K , Wang Y , Yao J , et al. UGT708S6 from Dendrobium catenatum, catalyzes the formation of flavonoid C-glycosides. BMC Biotechnol. 2024; 24( 1): 94. doi:10.1186/s12896-024-00923-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zheng H , Dang Y , Sui N . Sorghum: a multipurpose crop. J Agric Food Chem. 2023; 71( 46): 17570– 83. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.3c04942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Paterson AH , Bowers JE , Bruggmann R , Dubchak I , Grimwood J , Gundlach H , et al. The Sorghum bicolor genome and the diversification of grasses. Nature. 2009; 457( 7229): 551– 6. doi:10.1038/nature07723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wang Y , Bräutigam A , Weber AP , Zhu XG . Three distinct biochemical subtypes of C4 photosynthesis? A modelling analysis. J Exp Bot. 2014; 65( 13): 3567– 78. doi:10.1093/jxb/eru058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ngwenya SP , Moloi SJ , Shargie NG , Brown AP , Chivasa S , Ngara R . Regulation of proline accumulation and protein secretion in Sorghum under combined osmotic and heat stress. Plants. 2024; 13( 13): 1874. doi:10.3390/plants13131874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Schumaker B , Mortensen L , Klein RR , Mandal S , Dykes L , Gladman N , et al. UV-induced reactive oxygen species and transcriptional control of 3-deoxyanthocyanidin biosynthesis in black sorghum pericarp. Front Plant Sci. 2024; 15: 1451215. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1451215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Fontanet-Manzaneque JB , Laibach N , Herrero-Garcja I , Coleto-Alcudia V , Blasco-Escámez D , Zhang C , et al. Untargeted mutagenesis of brassinosteroid receptor SbBRI1 confers drought tolerance by altering phenylpropanoid metabolism in Sorghum bicolor. Plant Biotechnol J. 2024; 22( 12): 3406– 23. doi:10.1111/pbi.14461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Del Giudice R , Putkaradze N , Dos Santos BM , Hansen CC , Crocoll C , Motawia MS , et al. Structure-guided engineering of key amino acids in UGT85B1 controlling substrate and stereo-specificity in aromatic cyanogenic glucoside biosynthesis. Plant J. 2022; 111( 6): 1539– 49. doi:10.1111/tpj.15904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hansen KS , Kristensen C , Tattersall DB , Jones PR , Olsen CE , Bak S , et al. The in vitro substrate regiospecificity of recombinant UGT85B1, the cyanohydrin glucosyltransferase from Sorghum bicolor. PhytoChem. 2003; 64( 1): 143– 51. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00261-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Thorsøe KS , Bak S , Olsen CE , Imberty A , Breton C , Lindberg Møller B . Determination of catalytic key amino acids and UDP sugar donor specificity of the cyanohydrin glycosyltransferase UGT85B1 from Sorghum bicolor. Molecular modeling substantiated by site-specific mutagenesis and biochemical analyses. Plant Physiol. 2005; 139( 2): 664– 73. doi:10.1104/pp.105.063842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Blomstedt CK , O’Donnell NH , Bjarnholt N , Neale AD , Hamill JD , Møller BL , et al. Metabolic consequences of knocking out UGT85B1, the gene encoding the glucosyltransferase required for synthesis of dhurrin in Sorghum bicolor (L. Moench). Plant Cell Physiol. 2016; 57( 2): 373– 86. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcv153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Hayes CM , Burow GB , Brown PJ , Thurber C , Xin Z , Burke JJ . Natural variation in synthesis and catabolism genes influences dhurrin content in sorghum. Plant Genome. 2015; 8( 2): eplantgenome2014.09.0048. doi:10.3835/plantgenome2014.09.0048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Luhua Y , Yu N , Chunjie C , Wangdan X , Qiaoqiao G , Xinfeng J , et al. Unlocking the synergy: ABA seed priming enhances drought tolerance in seedlings of sweet sorghum through ABA-IAA crosstalk. Plant Cell Environ. 2025; 48( 8): 5952– 69. doi:10.1111/pce.15575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. McKinley B , Rooney W , Wilkerson C , Mullet J . Dynamics of biomass partitioning, stem gene expression, cell wall biosynthesis, and sucrose accumulation during development of Sorghum bicolor. Plant J. 2016; 88( 4): 662– 80. doi:10.1111/tpj.13269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Xu S , Li XQ , Guo H , Wu XY , Wang N , Liu ZQ , et al. Mucilage secretion by aerial roots in sorghum (Sorghum bicolor): sugar profile, genetic diversity, GWAS and transcriptomic analysis. Plant Mol Biol. 2023; 112( 6): 309– 23. doi:10.1007/s11103-023-01365-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chen C , Ge F , Du H , Sun Y , Sui Y , Tang S , et al. A comprehensive omics resource and genetic tools for functional genomics research and genetic improvement of sorghum. Mol Plant. 2025; 18( 4): 703– 19. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2025.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yu DS , Lee DH , Kim SK , Lee CH , Song JY , Kong EB , et al. Algorithm for predicting functionally equivalent proteins from BLAST and HMMER searches. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012; 22( 8): 1054– 8. doi:10.4014/jmb.1203.03050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Kumar S , Stecher G , Li M , Knyaz C , Tamura K . MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018; 35( 6): 1547– 9. doi:10.1093/molbev/msy096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Edgar RC . MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004; 32( 5): 1792– 7. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Nguyen LT , Schmidt HA , von Haeseler A , Minh BQ . IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015; 32( 1): 268– 74. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chen C , Wu Y , Li J , Wang X , Zeng Z , Xu J , et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol Plant. 2023; 16( 11): 1733– 42. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2023.09.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wang Y , Tang H , Wang X , Sun Y , Joseph PV , Paterson AH . Detection of colinear blocks and synteny and evolutionary analyses based on utilization of MCScanX. Nat Protoc. 2024; 19( 7): 2206– 29. doi:10.1038/s41596-024-00968-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Pelletier JF , Sun L , Wise KS , Assad-Garcia N , Karas BJ , Deerinck TJ , et al. Genetic requirements for cell division in a genomically minimal cell. Cell. 2021; 184( 9): 2430– 40. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Lescot M , Déhais P , Thijs G , Marchal K , Moreau Y , Van de Peer Y , et al. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002; 30( 1): 325– 7. doi:10.1093/nar/30.1.325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Bailey TL , Johnson J , Grant CE , Noble WS . The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43( W1): W39– 49. doi:10.1093/nar/gkv416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Huang J , Tang B , Ren R , Wu M , Liu F , Lv Y , et al. Understanding the potential gene regulatory network of starch biosynthesis in Tartary Buckwheat by RNA-Seq. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23( 24): 15774. doi:10.3390/ijms232415774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Langfelder P , Horvath S . WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform 2008; 9: 559. doi:10.1186/1471-2105-9-559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Bu D , Luo H , Huo P , Wang Z , Zhang S , He Z , et al. KOBAS-i: intelligent prioritization and exploratory visualization of biological functions for gene enrichment analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021; 49( W1): W317– 25. doi:10.1093/nar/gkab447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Shannon P , Markiel A , Ozier O , Baliga NS , Wang JT , Ramage D , et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003; 13( 11): 2498– 504. doi:10.1101/gr.1239303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Trott O , Olson AJ . AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J Comput Chem. 2010; 31( 2): 455– 61. doi:10.1002/jcc.21334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Rifai EA , van Dijk M , Vermeulen NPE , Yanuar A , Geerke DP . A comparative linear interaction energy and MM/PBSA study on SIRT1-ligand binding free energy calculation. J Chem Inf Model. 2019; 59( 9): 4018– 33. doi:10.1021/acs.jcim.9b00609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. He Y , Ahmad D , Zhang X , Zhang Y , Wu L , Jiang P , et al. Genome-wide analysis of family-1 UDP glycosyltransferases (UGT) and identification of UGT genes for FHB resistance in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biology. 2018; 18( 1): 67. doi:10.1186/s12870-018-1286-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Feng Z , Admas T , Cheng B , Meng Y , Pan R , Zhang W . UGT gene family identification and functional analysis of HvUGT1 under drought stress in wild barley. Physiol Mol Biol Plants Int J Funct Plant Biol. 2024; 30( 8): 1225– 38. doi:10.1007/s12298-024-01487-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Li Y , Li P , Wang Y , Dong R , Yu H , Hou B . Genome-wide identification and phylogenetic analysis of family-1 UDP glycosyltransferases in maize (Zea mays). Planta. 2014; 239( 6): 1265– 79. doi:10.1007/s00425-014-2050-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Vela S , Wolf ESA , Rollins JA , Cuevas HE , Vermerris W . Dual-RNA-sequencing to elucidate the interactions between sorghum and colletotrichum sublineola. Front Fungal Biol. 2024; 5: 1437344. doi:10.3389/ffunb.2024.1437344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Faye JM , Akata EA , Sine B , Diatta C , Cisse N , Fonceka D , et al. Quantitative and population genomics suggest a broad role of stay-green loci in the drought adaptation of sorghum. Plant Genome. 2022; 15( 1): e20176. doi:10.1002/tpg2.20176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Yanqing D , Yilin W , Jianxia X , Feng J , Wenzhen L , Qiaoling Z , et al. Short communication a telomere-to-telomere genome assembly of Hongyingzi, a sorghum cultivar used for Chinese Baijiu production. Crop J. 2024; 12( 2): 635– 40. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2024.02.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Wang F , Zhao Q , Li S , Sun R , Zang Z , Xiong AS , et al. Genetic mechanisms, biological function, and biotechnological advance in sorghum tannins research. Biotechnol Adv. 2025; 81: 108573. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2025.108573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Döring F , Streubel M , Bräutigam A , Gowik U . Most photorespiratory genes are preferentially expressed in the bundle sheath cells of the C4 grass Sorghum bicolor. J Exp Bot. 2016; 67( 10): 3053– 64. doi:10.1093/jxb/erw041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Liao B , Liu X , Li Y , Ge Y , Liang X , Liao Z , et al. Functional characterization of a highly efficient UDP-glucosyltransferase CitUGT72AZ4 involved in the biosynthesis of flavonoid glycosides in citrus. J Agric Food Chem. 2025; 73( 9): 5450– 64. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.4c07454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Ren C , Cao Y , Xing M , Guo Y , Li J , Xue L , et al. Genome-wide analysis of UDP-glycosyltransferase gene family and identification of members involved in flavonoid glucosylation in Chinese bayberry (Morella rubra). Front Plant Sci. 2022; 13: 998985. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.998985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Ferreyra MLF , Serra P , Casati P . Recent advances on the roles of flavonoids as plant protective molecules after UV and high light exposure. Physiol Plant. 2021; 173( 3): 736– 49. doi:10.1111/ppl.13543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Yang Q , Zhang Y , Qu X , Wu F , Li X , Ren M , et al. Genome-wide analysis of UDP-glycosyltransferases family and identification of UGT genes involved in abiotic stress and flavonol biosynthesis in Nicotiana tabacum. BMC Plant Biology. 2023; 23( 1): 204. doi:10.1186/s12870-023-04208-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Xu P , Li J , Chen C , Chen J , Yang M , Deng H , et al. Integrated transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses reveal tissue-specific accumulation and expression patterns of monoterpene glycosides, gallaglycosides, and flavonoids in Paeonia lactiflora Pall. BMC Genomics. 2025; 26( 1): 561. doi:10.1186/s12864-025-11750-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Dai X , Shi X , Yang C , Zhao X , Zhuang J , Liu Y , et al. Two UDP-glycosyltransferases catalyze the biosynthesis of bitter flavonoid 7-O-neohesperidoside through sequential glycosylation in tea plants. J Agric Food Chem. 2022; 70( 7): 2354– 65. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.1c07342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Petrich J , Alvarez CE , Gómez Cano L , Dewberry R , Grotewold E , Casati P , et al. Functional characterization of a maize UDP-glucosyltransferase involved in the biosynthesis of flavonoid 7-O-glucosides and di-O-glucosides. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2025; 221: 109583. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2025.109583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Song Y , Chen P , Xuan A , Bu C , Liu P , Ingvarsson PK , et al. Integration of genome wide association studies and co-expression networks reveal roles of PtoWRKY 42-PtoUGT76C1-1 in trans-zeatin metabolism and cytokinin sensitivity in poplar. New Phytol. 2021; 231( 4): 1462– 77. doi:10.1111/nph.17469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Vogt T , Jones P . Glycosyltransferases in plant natural product synthesis: characterization of a supergene family. Trends Plant Sci. 2000; 5( 9): 380– 6. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01720-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Simon C , Langlois-Meurinne M , Didierlaurent L , Chaouch S , Bellvert F , Massoud K , et al. The secondary metabolism glycosyltransferases UGT73B3 and UGT73B5 are components of redox status in resistance of Arabidopsis to Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 2014; 37( 5): 1114– 29. doi:10.1111/pce.12221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Liu Q , Dong GR , Ma YQ , Zhao SM , Liu X , Li XK , et al. Rice glycosyltransferase gene UGT85E1 is involved in drought stress tolerance through enhancing abscisic acid response. Front Plant Sci. 2021; 12: 790195. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.790195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Haroth S , Feussner K , Kelly AA , Zienkiewicz K , Shaikhqasem A , Herrfurth C , et al. The glycosyltransferase UGT76E1 significantly contributes to 12-O-glucopyranosyl-jasmonic acid formation in wounded Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. J Biol Chem. 2019; 294( 25): 9858– 72. doi:10.1074/jbc.RA119.007600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Sage RF , Christin PA , Edwards EJ . The C(4) plant lineages of planet Earth. J Exp Bot. 2011; 62( 9): 3155– 69. doi:10.1093/jxb/err048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Furbank RT . Walking the C4 pathway: past, present, and future. J Exp Bot. 2017; 68( 2): 4057– 66. doi:10.1093/jxb/erx006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools