Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Melatonin Priming Enhances Potassium Dichromate Stress Tolerance and Morpho-Physiological Performance via Genetic Modulation in Melon (Cucumis melo L.) Plant

1 Institute of Horticultural Science, Daqing Branch of Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Daqing, 163711, China

2 Mountain Horticultural Crops Research and Extension Center, Department of Horticultural Science, North Carolina State University, 455 Research Drive, Mills River, NC 28759, USA

* Corresponding Authors: Sikandar Amanullah. Email: ; Di Wang. Email:

# Tai Liu and Huichun Xu contributed equally as co-first authors to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Recent Research Trends in Genetics, Genomics, and Physiology of Crop Plants–Volume II)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 4117-4137. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.074131

Received 03 October 2025; Accepted 11 December 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

Heavy metal accumulation in agricultural soil is primarily driven by pesticides, polluted water, and industrial gas emissions, which pose threats to sustainable crop production. Chromium (Cr) stress has an adverse impact on plant development and metabolism, but approaches to reduce its toxicity and enhance plant resistance remain limited. Melatonin is a potent antioxidant involved in regulating various morpho-physiological functions of plants under different abiotic stresses. In this study, we investigated the impact of exogenous melatonin to mitigate the negative effects of potassium dichromate (PD) stress in melon plants and analyzed genetic modulation of morphological, physiological, and biochemical parameters. The obtained results revealed that melatonin treatment (100 µmol L−1) considerably improved seed germination rate, promoted plant growth, and stabilized chloroplast ultrastructure of leaves under PD-stress. This physiological resilience was similarly reflected by maintained photosynthetic efficiency and significantly stabilized photochemical parameters (e.g., Fv/Fm and NPQ). At the molecular level, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis confirmed that melatonin treatment maintained organelle integrity by upregulating primary metabolism indices and hindering Cr accumulation. Specifically, melatonin reduced the Cr-induced downregulation of chlorophyll biosynthesis genes [CmHEMA (MELO3C006296.2), CmGOGAT (MELO3C008481.2), and CmPOR (MELO3C016714.2)], restoring chlorophyll content by up to 5.08 mg·g−1, increased by 67.11%. The expression level of genes [CmSPS (MELO3C003715.2), CmPEPC (MELO3C018724.2), and CmRubisco (MELO3C012180.2)] showed an effective upsurge in carbohydrate synthesis. Moreover, melatonin significantly enhanced the antioxidant system [e.g., increasing SOD (46.13%), POD (35.85%), and APX (25.00%) activities] and promoted the accumulation of lignin and metallothionein [via upregulation of Cm4CL (MELO3C002346.2) and CmMet (MELO3C016513.2) genes], which restricted Cr translocation from the root to the shoot. To summarize, exogenous melatonin application could serve as an effective strategy for mitigating Cr-induced stress in melon by stabilizing basic photosynthetic processes and secondary metabolism through biochemical and molecular defensive mechanisms, thereby preventing Cr translocation by activating the accumulation of secondary metabolites (e.g., lignin and metallothionein) and photo-respiration elements. Our findings provided new perspective to understand melatonin as a viable, multidimensional bio-regulator for improving crop resilience in Cr-polluted agricultural systems.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileSince the onset of industrialization, the biosphere has experienced a significant accumulation of pollution from the presence of lethal heavy metals, for example, copper (Cu), cadmium (Cd), lead (Pb), and chromium (Cr) in soil, sediments, and groundwater. This pollution primarily results from various human activities, including mineral degradation, effluents from the textile dye, paper, and paint industries, urban sewage, and the use of agricultural chemicals [1,2]. In general, the toxicity mechanism of heavy metals is known for the main interaction process at the biotic and abiotic levels.

Cr is a hazardous heavy metal that negatively impacts plant development and significant growth factors, e.g., seed germination, photosynthetic capacity, and total biomass [3]. The chlorosis of leaves and necrosis of tissues are the primary morphological alterations induced by Cr stress, indicating its negative effect on plant growth that ultimately leads to plant death in severe cases [4,5]. This type of induced stress causes cytological changes in cellular organs and disrupts the ultrastructure of the chloroplast envelope as well as the degradation of membrane systems in plants [6]. The direct toxic effect of Cr on plants becomes continuous due to its persistent property, which will accumulate along the food chain and then cause irreversible damage [7]. Cr stress also kills plants by interfering with mineral element absorption by disturbing pigment production, as well as modifying the enzyme activity contributed to breakdown of glucose and antioxidant systems, resulting in disrupted photosynthesis and respiration [8,9]. Further, heavy metals have a negative impact on plants because they generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) and stimulate oxidative stresses [10,11].

Photosynthesis is an essential process for green pigmentation and relevant fluorescence indices in plants. It is the main source for the transformation of received light energy into chemical energy stored in organic compounds [4]. Photochemical parameters in plants are measures used to evaluate the efficiency and health of the photosynthetic machinery, particularly the Photosystem II (PSII) apparatus. The ratio of variable fluorescence (Fv) and maximum fluorescence (Fm) represents the major efficiency of light conversion in the photosynthetic reaction center II (PSII), whereas the quenching coefficient (qP) denotes the quantity of light energy absorbed for electron transfer in the PSII antenna pigment, which reflects the PSII reaction center’s activity. NPQ is the absorbed quantity of light energy received by the PSII pigmentation that is not utilized for photosynthetic electron transport and is converted into heat, which positively protects the photosynthetic apparatus [12].

Chloroplast is a main cell organelle of plants that performs photosynthesis activities and produces redox oxygen species (ROS) [13]. The accumulation of ROS under adverse environmental stress damages the stability and intrinsic function of complex internal structures and functional disorders, including the double membrane system [14,15]. The evolutionary resistive mechanism led to the maintenance of the plant membrane, which acts as a defensive barrier between the cytoplasm and exterior stress factor by retaining its components as well as organization through various membrane lipids. However, lipid composition frequently varies in response to environmental stresses, particularly the remodeling of the primary components of the green tissue membrane, e.g., monogalactosediacyl glycerol (MGDG) and digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG) [16]. Furthermore, increased metal chelation and lignification of cell walls favorably decreased heavy metal accumulation and restricted translocation inside plants [17,18].

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine), an endogenous indole tryptamine phytohormone, was discovered in plants in 1995. It is known to govern the positive regulation of several aspects of plant development, including root and leaf senescence and biomass output [19]. It is a free radical scavenger with substantial antioxidant characteristics, which is twice that of vitamin E, four times that of glutathione, and fourteen times that of mannitol [20,21,22]. The tiny size of the molecule, along with its high lipidicity and hydrophilicity, makes it simpler to penetrate cells and decrease hydrogen peroxide while minimizing oxidative damage under stressful conditions [23]. Further, exogenous melatonin treatment has been demonstrated to significantly increase pigment synthesis and photosystem II (PSII) performance, thereby increasing photosynthetic efficiency during stress [24]. Recently, the application of melatonin has emerged as a promising approach to coping with plants from different types of biotic and abiotic stresses.

Melon is widely regarded as a model plant for studying the complex biological processes that determine plant-specific traits [25]. In northeast China, agricultural black soil is rich in organic matter, which is strongly connected with specific heavy metal accumulations [26] and is extensively spread over the Songnen Plain. Due to the growth of the leather tanning industry in countries like China, Pakistan, and India, around 40 million liters of wastewater containing chromium (Cr) are being produced each year, damaging the texture of agricultural land [27]. In 2022, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China narrated in the Ecological Environment Bulletin that heavy metals are serious contaminants affecting the environmental quality of agricultural land [28]. However, there is a lack of knowledge on the identification of the metabolic processes involved in heavy metal resistance during plant growth dynamics in melon plants under Cr stress. The precise genetic and physiological role of melatonin in response to Cr stress is also crucial for understanding the evolution of melon species and their resilience to abiotic stresses.

2.1 Plant Materials and Experimental Treatments

An oriental melon variety (longqing) was chosen as experimental material based on its susceptibility to biotic and abiotic stresses and weaker plant growth during its lifespan. The varietal seeds were offered by the Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences (HAAS), Daqing Branch, China, and entire experiment was carried out in a controlled condition in the aseptic laboratory at HAAS. An exogenous melatonin treatment was checked on seed germination traits and morphological and physiological parameters of seedlings grown under heavy metal-induced stress. To sort out the treatments of melatonin and PD stress, a pre-experiment was conducted at small scale in lab and the actual experiment was conducted.

For evaluating the seed germination status and related parameters (sprout length, average diameter, and surface area), the seeds were gently sterilized in a solution of potassium permanganate (KMnO4, 10%) for one minute, then washed with double distilled water (ddH2O), and allowed to dry. Later, a total of 50 melon seeds were spread on a 9-cm-wide autoclaved petri dish having 4 layers of wet qualitative slow filter paper, and moisture was regularly retained with a total of 12 mL of test solution. Finally, a total of four treatment groups along with 3 replications of each treatment were used [e.g., (i) control with no stress (CK, just ddH2O), (ii) 100 μM of melatonin (M) application, (iii) 40 mg L−1 of potassium dichromate (PD) application as a stress, and (iv) melatonin treatment (M) + potassium dichromate stress (PD)]. The respective concentrations of potassium dichromate and melatonin treatment were referenced from previous research [29,30,31]. The treated melon seeds in petri dishes were incubated for 60 h at 28°C, and seed germination status as well as linked indices [sprout length (cm), average diameter (mm), and surface area (cm2)] were tested. The germination rate of 50 melon seeds of comparative treatments was calculated to determine the efficiency of melatonin using the equation as follows:

Seed germination rate = (germinated seeds-total seeds) × 100%; Melatonin efficiency = ([M + PD] rate-[PD] rate)/[PD] rate × 100%.2.2 Cultivation of Seedlings and Tissue Sampling

To cultivate proper melon seedlings and test the effect of exogenous melatonin treatment to mitigate the PD stress, the treated seeds were allowed to grow in sterilized plastic pots (diameter 6 cm and depth 7.5 cm) in controlled conditions using completely randomized design (CRD) geometry with three repetitions of each treatment. Briefly, seeds were put in muslin bags and allowed to germinate for two days at 28°C before being transferred to plastic pots filled with 3% organic matter soil and potting compost with a pH of 7–7.5. The characteristics of the compost are as follows: organic carbon (OC) = 20% (weight percentage on a dry product basis), organic nitrogen (ON) = 1%, organic matter (OM) = 35%, and pH = 6–7.

The emerging seedlings at the 4-true-leaf stage were divided into four groups. (i) spraying ddH2O as a control (without any stress), (ii) spraying 100 μM of melatonin (M), (iii) irrigating 40 mg L−1 of potassium dichromate solution as PD stress, and (iv) melatonin treatment (M) + potassium dichromate (PD) stress, each treatment was carried out with equal volume (40 mL) daily. The leaf samples from each treatment group were collected on the 1st day, 3rd day, and 5th day to determine the variation in physio-chemical indicators, as well as for transcriptional regulation through qPCR analysis; however, the morphological and ultrastructural observations were recorded on the 5th day.

2.3 Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

The leaf tissues of raised seedlings sampled from each treatment were checked for cytological observations using a transmission electron microscopy analysis at different magnification levels (1.5k×, 8k×, and 20k×), as reported in a previous study of Liu et al. [32]. Briefly, the true leaf tissues from normal (control, without stress) and stress-induced obvious symptoms were sampled from melon seedlings cultivated under four different treatments (above-mentioned). The sampled leaves were sliced into 2 mm-wide pieces and fixed with a 2.5% (v/v) solution containing 1% osmium tetroxide. Then, all samples were embedded in epoxy resin embedding medium (EMBed-812), sliced in thin sections, dried using acetone solutions, viewed with a high-resolution transmission electron microscope, and photographed.

2.4 Determination of Physiological and Biochemical Indices

A total of 1–2 g (g) of the fresh leaves from the top of the grown seedlings were randomly sampled from three biological repetitions of different treatment groups, and the physiological and biochemical indices [e.g., peroxidase (POD), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX)] were estimated based on the following instructions of commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits, Michy Biology Company (Suzhou, China). The level of PD-induced changes in membrane lipid peroxidation was also deliberated by quantifying the malondialdehyde (MDA) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) contents using ELISA test kits according to the briefed protocol. The lipid composition in the cell membrane of seedling leaves was checked through the electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectrometry method with a slight modification to the earlier reported protocol as Narayanan et al. [33].

The lignin content was determined using the same method as Shao et al. [34]. In short, the collected leaf tissues from various treatments and replications were standardized in a mortar with 10 mL of 95% ethanol (v/v) at 4°C, then centrifuged at a relative force of 5000× g for 4 min. The formed supernatant were separated and washed double with ethanol (80% v/v) and one time with acetone before being thoroughly dried in an oven at 60°C. The dry samples were incubated at 80°C for 2 h in a 4:1 (v/v) acetyl bromide (CH3COBr) and acetic acid (CH3COOH) before cooling to 25°C and being transferred to 50 mL glass bottles containing 5 mL of acetic acid and 2 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH). The reaction was ended through adding the 7.5 M hydroxylamine hydrochloride (NH2OH·HCl), and the final volume was adjusted with acetic acid. In the end, the lignin was measured using the absorbance rate at 480 nm. Metallothionein (Met) was measured through ELISA test kits, following the same technique of Zhang et al. [35].

2.5 Estimation of Total Chlorophyll Contents

Chlorophyll of the leaf samples taken for each treatment and replication were also measured using the ethanol-acetone extraction technique as Dong et al. [36]. Briefly, a sharp cutting razor was used to cut a total of 0.30 g of fresh weight (FW) leaf samples from the main vein of leaves joined at the same node. All samples were submerged in a 10 mL solution of ethanol and acetone (1:1) for 24 h. The NanoDrop™ One/OneC Microvolume UV Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Delaware, USA) was used to measure the extract’s absorbance rate at 440, 663, and 645 nm. Total chlorophyll was deliberated based on the formula:

Total chlorophyll (mg·g−1 FW) = (8.04 × A663 + 20.29 × A645) × V/W × 1000; W = weight, V = volume, and A = absorbance rate, individually.

2.6 Determination of Photosynthetic Fluorescence Indices

The chlorophyll fluorescence emission from the aerial surfaces of the intact plant leaves were monitored as described in a previous study [36]. The samples were collected from different treatment groups in slightly cloudy conditions, and the leaves were kept in fully dark conditions for 20 min prior to measuring fluorescence indices [e.g., light-adapted minimum fluorescence (F0), photochemical quenching coefficient (qP), maximum photochemical efficiency of PSII (Fv/Fm), and non-photochemical quenching coefficient (NPQ)].

2.7 Quantification of CR and Translocation Ratio

The samples of melon root, stalk, and leaf from different treatments were collected and completely dried. A 0.50 g (g) of every sample was homogenized with 7.50 mL of nitric acid (HNO3) and 2.50 mL of Perchloric Acid (HClO4) and kept overnight. Afterward, 5 mL of HNO3 was added to the mixture for full digestion and endogenous Cr was quantified by the same method of Zaheer et al. [37].

Translocation ratios of Cr in different organs were estimated based on the formulas of previous Luo et al. [38]: e.g., T roots to stalk (%) = Cstalk/Croots × 100 (1); T stalk to leaves (%) = Cleaves/Cstalk × 100 (2); T roots to leaves (%) = Cleaves/Croots × 100 (3), where Cleaves is concentration of Cr (μg/g) in leaves; Croots is in roots (μg/g); Cstalk is in stalk (μg/g).

2.8 Transcription Expression of Putative Genes

To investigate the genetic regulation mechanism of photosynthetic and physiological indices in melon, the annotated putative genes were obtained from previously reported studies, e.g., 4CL [34], HEMA [39], GOGAT [40], POR [41], PAO [42], SPS [43], PEPC [44], ruBisCo [45], PSB [46], Hcf136 [47], APX [48], POD [49], SOD [50], Met [51], and the housekeeping gene “Actin” [32], as shown in the Supplementary File. The functional annotation of selected genes was predicted in the referenced genome of melon [(v3.6.1, DHL92); Cucurbit Genomics Database, http://cucurbitgenomics.org].

The transcription expression of putative genes contributing in key metabolic pathways in melon plants were analyzed in response to melatonin treatment under PD-induced stress using qPCR verification. For the molecular experiment, total RNA was firstly extracted by RNAprep Pure Plant Kit (Tiangen Biotech, Beijing, China) according to the instructions, the integrity was checked through NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Delaware, USA), and the concentration index of A260/A230 ratio >2.0 was used for complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis. The first strand cDNA was synthesized by the PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) using 2 μL of total RNA. The cDNA products were diluted 5-fold with ddH2O before experimental use. For the qPCR analysis, a total of 10 µL of reaction mixture containing 1 µL of cDNA, 0.2 µL of primer, 5 µL of 2 × SYBR Green PCR Master Mixture, and 3.8 µL of ddH2O was used to examine expression level in the Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., California, USA) [32]. The detailed information about the molecular sequences (forward and reverse) of exported primers of predicted annotated genes in the melon genome and the referenced actin gene is available in the Supplementary File (Table S1).

All the experimental data was regularly collected, and the numerical values were computed using the Microsoft Excel Worksheet (v2019) [32]. The statistical differences among treatments within each measurement of time series data including physiological parameters were evaluated by two-factor repeated measures ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) and Tukey’s HSD (p < 0.05) using GraphPad Prism (v10.2.0), while one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s HSD (p < 0.05) was employed for the morphological parameters. The endogenous Cr quantification and translocation rates were compared using an independent samples t-test. The data were assessed for normality and homogeneity of variances prior to analysis.

3.1 Analysis of Seed Germination Status

We noticed that seed germination rate followed an S-shaped pattern under stress treatment, with an early slow phase followed by a rapid increase and a downward tendency at the end (Table 1). However, the observed S-shaped pattern varied between treatments. At the initial stage, the melatonin-treated seeds showed a quicker and higher germination rate (about 13.94%) during the first 36 h compared to the control (CK) group. However, as the time progressed, the germination rate differences decreased between the CK and melatonin-treated groups. It is noticeable that the saturation in germination under melatonin treatment is 12 h earlier than the control (CK), indicating that exogenous melatonin has the beneficial function of promoting the germination of seeds.

Table 1: The germination rate of melon seeds under different treatments and multiple time series; Mean ± SD (n = 3). Different uppercase letters (A, B, C, D) within a column indicate significant differences among treatments at given time points, whereas the lowercase letters (a, b, c, d) within a row denote significant differences among given time points within the same treatment (Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05).

| Treatments | Time Duration | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 h | 24 h | 36 h | 48 h | 60 h | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| CK | 26.00 ± 3.64dB | 55.33 ± 2.40cB | 81.33 ± 2.40bB | 92.67 ± 3.71aA | 96.00 ± 2.00aA |

| M | 35.33 ± 2.40cA | 63.33 ± 2.40bA | 92.67 ± 0.67aA | 96.67 ± 1.76aA | 98.67 ± 1.33aA |

| PD | 9.33 ± 1.33cC | 22.67 ± 1.33bD | 27.33 ± 2.67abD | 28.00 ± 3.06abC | 38.73 ± 2.91aC |

| M + PD | 25.33 ± 3.53cB | 48.00 ± 2.00bC | 64.67 ± 2.40aC | 67.33 ± 1.76aB | 71.33 ± 2.91aB |

The germination rate in PD-stress treated groups exhibited a sluggish trend, with the highest rate reaching only 38.73% at 60 h, which represents a 59.66% decrease relative to the CK group. However, exogenous melatonin application significantly alleviated the detrimental impact of potassium dichromate (PD)-stress on germination rate, which increased by 84.17%. PD stress significantly impaired the development condition of melon seed sprouts, as demonstrated by lower sprout length (27.59%), average diameter (19.54%), and surface area (37.50%) compared to the CK group (Fig. 1). However, exogenous melatonin treatment effectively reversed the negative effects of PD stress on these phenotypic parameters and even enhanced more when compared to CK treatment.

Figure 1: General observation of melon seed germination in response to different treatments of melatonin and PD stress. (A) Germination status and (B) Studied attributes associated with germination of melon seeds under different treatments. The graph bars represent the mean values, and error bars represent the Standard Deviations (SD) of the three replicates for each treatment, and dissimilar statistical letters (a, b, c) placed above the bars indicate the outcome of the Tukey’s HSD test, p < 0.05.

3.2 Analysis of Morphological and Cytological Observations

The inhibitory effect of PD stress and the enhancing effect of melatonin on the morphological characteristics of melon were evaluated. The treated seedlings exhibited typical stress symptoms, but melatonin showed the improved leaf morphology, as illustrated in the figure (Fig. 2A). Statistical analysis consistently showed that seedling growth and development were most severely affected under PD stress; however, extensive dehydration, chlorosis, and necrosis were observed on the leaf surfaces, indicating that PD stress induced significant osmotic stress and chlorophyll degradation in melon leaves compared to the melatonin and control (CK) treatment.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of the internal leaf organelles in melon seedlings subjected to various treatments revealed significant structural variations, as shown in the figure (Fig. 2B). PD-stressed samples exhibited swollen, spherical chloroplasts with indistinct and irregular thylakoid structures, supplemented by a reduced number of starch granules. In contrast, exogenous melatonin treatment effectively preserved the developmental integrity of melon leaves by stabilizing the chloroplast ultrastructure, maintaining normal thylakoid organization, and supporting regulated metabolic processes under stress.

Figure 2: Phenotypic and cytological appearance of melon seedling leaves under different treatments of melatonin and PD-stress. (A) Phenotypic observations of seedling leaves from three repetitions and (B) Cytological observations of endogenic chloroplast ultrastructure of sampled leaves at 60 h of time. Microscopic observation at dissimilar magnification levels of 1.5k×, 8k×, and 20k×. T, thylakoid; CM, chloroplast membrane; Chl, chloroplast; SG, starch granule; and GL, granal lamellae.

3.3 Analysis of Physiological Parameters

Regarding the physiological indices, PD-stressed samples exhibited substantially higher levels of MDA and H2O2 compared to the control (CK) on the 5th day, as shown in the figure (Fig. 3A,B). However, exogenous melatonin treatment effectively reduced MDA and H2O2 levels by 25.10% and 32.29% on the 3rd day, and by 35.72% and 21.98% on the 5th day, compared to PD-stressed samples. Additionally, SOD, POD, and APX activities increased by 88.94%, 105.26%, and 410.00% on the first day of PD stress compared to CK at the same time point, as illustrated in the figure (Fig. 3C–E).

As stress duration increased, the activity of these antioxidants significantly declined during anaphase, decreasing by 23.17%, 7.02%, and 9.43% on the 5th day compared to the 3rd day. In contrast, melatonin-treated samples exhibited continuous improvement, with antioxidant levels rising by 46.13%, 37.74%, and 25.00% relative to PD-stressed samples on the 5th day. Analysis of membrane lipid composition showed that the molar percentages of DGDG and MGDG accounted for over 60% of total leaf glycolipids. PD stress reduced MGDG and DGDG concentrations by 8.09% and 11.03%, respectively, while increasing the MGDG to DGDG ratio by 3.15%, indicating that PD stress adversely affected plastid membrane structure and composition, as illustrated in the figure (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3: Effects of melatonin and PD stress treatments on the physiological parameters of melon seedlings at different time points. (A) MDA content, (B) H2O2 content, (C) SOD activity, (D) POD activity, (E) APX activity, (F) Molar percentage of MGDG and DGDG content, and (G) Chlorophyll content. The graph bars represent the mean values, and error bars represent the Standard Deviations (SD) of the three replicates for each treatment, and dissimilar statistical letters (a, b, c, d) placed above the bars indicate the outcome of the Tukey’s HSD test, p < 0.05.

3.4 Analysis of Photosynthetic Status

In terms of photosynthetic-linked activity, total chlorophyll (Chl) contents were noticed to be decreased significantly by 29.82% on the 3rd day and 33.77% on the 5th day as shown in the figure (Fig. 3G), revealing the significant upsurge in superoxidative photosynthesis apparatus, implying that PD stress negatively affected the photosynthesis apparatus, so that caused the significant degradation of chlorophyll. On the other hand, exogenous melatonin application efficiently retained the Chl contents and homeostasis of MGDG and DGDG levels, which increased by 1.78% and 11.45% compared to PD-stressed samples on the 5th day, and lowered the MGDG to DGDG ratio by 9.17% at the same time period. It was also discovered that the protective mechanism of exogenous melatonin to chlorophyll synthesis is not limited to stabilizing the relative content under PD-stressed conditions, which increased by 47.71% on the third day and 67.11% on the 5th day; the chlorophyll content in melatonin-treated samples showed an obvious increasing trend, with improvements of 26.83% on the 3rd day and 27.02% on the 5th day, respectively.

3.5 Analysis of Chlorophyll Fluorescence Parameters

Chlorophyll-linked photosynthesis fluorescence parameters [F0 (minimal fluorescence yield of chlorophyll), Fv (variable fluorescence), and Fm (maximum fluorescence)] were checked to evaluate the PD stress-induced photoinhibition and the photoprotective function of melatonin. Chlf results showed that PD-stress induced a 17.38% reduction in F0 and 18.29% in Fv/Fm as compared to CK on the 5th day as shown in the figure (Fig. 4A,B), denoting the inhibited photosynthetic electron transport rate. Likewise, PD-stress caused a significant reduction in qP (18.01%) and NPQ (26.79%) (Fig. 4C,D), indicating the comprehensively restrained photochemical electron transfer under PD-induced stress treatment. However, the beneficial effect of melatonin on photosynthesis was further confirmed by the enhanced Chlf parameters, which increased 13.73% in F0, 18.65% in Fv/Fm, 12.81% in qP, and 30.26% in NPQ on the 5th day compared to that of the PD-stressed samples, respectively.

Figure 4: Effects of melatonin and PD stress treatments on chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of melon seedling leaves at different time points. (A) F0, (B) NPQ, (C) qP, and (D) Fv/Fm. The graph bars represent the mean values, and error bars represent the Standard Deviations (SD) of the three replicates for each treatment, and dissimilar statistical letters (a, b, c) placed above the bars indicate the outcome of the Tukey’s HSD test, p < 0.05.

3.6 Analysis of Met and Lignin Contents

The significant variations in metallothionein (Met) and lignin levels were observed across different tissues (leaf, stalk, and root) subjected to various treatments, with these differences becoming more evident as the duration of PD-stress treatment increased. In leaves, Met and lignin content surged by 26.98% and 4.64% on the 1st day and by 24.26% and 19.23% on the 5th day compared to CK, as shown in the figure (Fig. 5A,B). On the 1st day, Met and lignin contents increased by 23.33% and 2.52% under PD-stress, respectively, whereas there was a 37.84% and 14.03% increase on the 5th day, as shown in the figure (Fig. 5C,D). In roots, Met and lignin accumulation increased by 25.47% and 2.43% on the 1st day and by 29.90% and 23.80% on the 5th day, compared to CK treatment, as shown in the figure (Fig. 5E,F). Interestingly, Met content in lead, stalk, and root also increased by 8.57%, 1.69%, and 1.56% on the 5th day, compared to tissues under PD-stress; however, there was no obvious change at the initial stage. Additionally, the lignin content in the same tissues followed a similar increasing trend by 10.79%, 6.68%, and 2.54%, respectively.

Figure 5: Effects of melatonin and PD stress treatments on Met and lignin contents in different tissues of melon seedlings at different time points. (A,B) Met and lignin contents in leaf, (C,D) in stalk, and (E,F) in root. The graph bars represent the mean values, and error bars represent the Standard Deviations (SD) of the three replicates for each treatment, and dissimilar statistical letters (a, b, c, d) placed above the bars indicate the outcome of the Tukey’s HSD test, p < 0.05.

3.7 Analysis of Quantified Cr and Translocation Rate

We observed that exogenous melatonin treatment decreased endogenous Cr concentration (μg/g DW) in leaf, stalk, and root by 71.53%, 11.45%, and 2.43%, under PD-induced stress. Furthermore, the observed decreasing trend of Cr translocation rate (%) between various organs was consistent with the endogenous quantified Cr. However, exogenous melatonin treatment reduced Cr translocation rates by 9.28% and 67.71% from root to stalk and stalk to leaf, with the greatest inhibition rate seen in root to leaf, which dropped by 70.83% (Table 2).

Table 2: Effects of melatonin and PD stress treatments on Cr quantification and translocation ratio in various tissues (leaf, stalk, and root) of melon seedlings. CK, Control; M, Melatonin; PD, Potassium dichromate. “--” notation denotes the no stress treatment; Mean ± SD (n = 3). Dissimilar statistical letters within a column indicate the differences among the treatments using independent samples t-test (p < 0.05).

| Treatments | Endogenous Quantified Cr (μg/g DW) | Translocation Rate (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf | Stalk | Root | Root to Stalk | Stalk to Leaf | Root to Leaf | |

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

| CK | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| M | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| PD | 23.92 ± 1.65a | 110.26 ± 4.56a | 383.39 ± 2.76a | 28.77 ± 1.39a | 21.68 ± 0.88a | 6.24 ± 0.47a |

| M + PD | 6.81 ± 0.95b | 97.63 ± 3.20b | 374.06 ± 2.65b | 26.10 ± 0.89b | 7.00 ± 1.16b | 1.82 ± 0.26b |

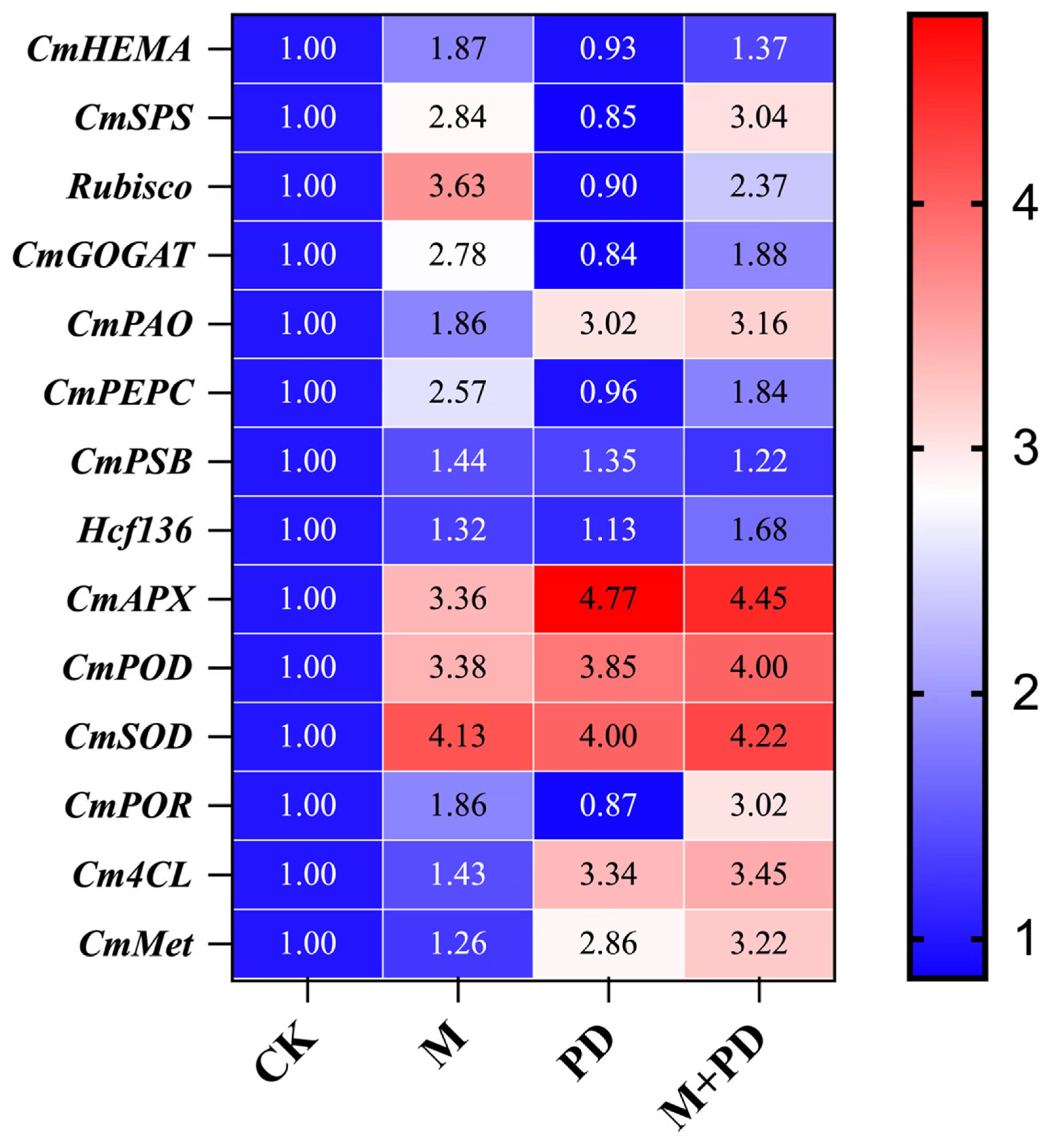

3.8 Analysis of Gene Transcriptional Regulation Trend

To investigate the genetic effectiveness of melatonin in alleviating the inhibitory effect of Cr stress, the transcriptional regulation trends of the selected putative melon genes associated closely with chlorophyll and carbohydrate synthesis and a series of key metabolism pathways were examined by qPCR analysis as shown in the figure (Fig. 6). We noticed that the expression trend of the GOGAT gene (MELO3C008481.2) encoding ferredoxin-dependent glutamate synthase 1 and the HEMA gene (MELO3C006296.2) encoding glutamyl-tRNA reductase (GluTR), which catalyzes the biosynthesis of glutamate and tetrapyrrole in plastid, triggering the chlorophyll biosynthesis, reduced by 16.00% and 7.00% under PD stress as compared with CK, indicating that the limited accessibility of the substrate for chlorophyll synthesis. Meanwhile, the upregulated PAO gene (MELO3C023571.2) induced by PD stress, which increased by 202.00%, was consistent with the ever-increasing chlorophyll degradation to its final product.

Similarly, the severely downregulated expression of the SPS gene (MELO3C003715.2) (15.00%), the PEPC gene (MELO3C018724.2) (4.00%), and the Rubisco gene (MELO3C012180.2) (10.00%), which catalyzed the sucrose synthesis and carbon fixation, further confirmed the reduced starch content. However, exogenous melatonin treatment showed the genetic improvement by increasing the expression level of the antioxidant-related genes, e.g., the POD gene (MELO3C002242.2, by 3.89%) and the SOD gene (MELO3C017624.2, by 5.50%) as compared with PD-stressed samples, and the Rubisco (MELO3C012180.2), HEMA, and SPS genes were upregulated by 163.33%, 47.31%, and 257.65%, respectively. Likewise, the expression level of the Met synthesis-related gene in melon (CmMet, MELO3C016513.2) and the lignin synthesis-related gene (Cm4CL, MELO3C002346.2) were also seemed to be enhanced by 3.29% and 12.59% under melatonin treatment. These results significantly showed the genetic improvement of photosynthetic, physiological, and biochemical traits of melon in response to different combination of treatments.

Figure 6: Heatmap of transcriptional expressions of the genes related to chlorophyll synthesis, antioxidant enzymes, metallothionein, and lignin synthesis in melon leaves under different treatments.

Melon is a commercial Cucurbitaceae fruit crop at global scale but numerous abiotic stress factors greatly affect its plant growth, development, yield, and productivity [25,32]. Chromium, one of the heavy metal elements used in modern industry, has exhibited a major threat to agricultural productivity, particularly in organic matter-rich areas that are positively associated with heavy metal ions [48,49,50,51,52]. The significant accumulation of high heavy metal concentrations produce a variety of deleterious effects on plants activities, including growth inhibition, metabolic issues, and reproductive disorders [53,54,55,56]. Understanding the genetic basis of plant stress responses is critical for generating improved stress-tolerant cultivars for sustainable agriculture.

Seed is the fundamental component of the plant life cycle; nevertheless, seed germination is a well-known early stage that is vulnerable to chemical and adverse rhizosphere conditions [57]. Although the seed coat can operate as a protective barrier against the detrimental effects of heavy metal ions, most seeds coat surface triggers the dormancy phase and exhibit a decrease in associated germination and vigor in response to heavy metal stress [58,59,60,61,62]. According to Parr et al. [63] and Samrana et al. [64], chromium suppresses the germination rate as well as physiological, cytological, biochemical, and molecular responses in cotton seeds and acacia beans. According to Akinci et al. [65], the rate of melon seed germination and early seedling development decreased as the Cr content increased. However, the use of melatonin has been used for its essential and protective potential in modulating stress-induced germination [21,24,38]. Lei et al. [66] found that melatonin improved seed germination by increasing reserve mobilization, enhancing scavenging, and lowering ROS generation under Cr stress conditions. Li et al. [67] discovered that exogenous priming with melatonin reduced Cr stress during rice (Oryza sativa) seed germination. In our experiment, 100 μM of melatonin treatment considerably increased the germination rate and related parameters of melon seeds under Cr-induced stress, which is a direct confirmation of melatonin’s role as a potent growth-promoting, an effective bio-regulator and stress-alleviating agent endowing the sprout with a larger surface area and longer sprout length, assuring better germination as shown in the figure (Fig. 1). These findings strongly imply that melatonin has high antioxidant characteristics for reducing the detrimental stress impacts on sprouting and its further growth while also positively promoting the germination rate and growth status of melon seeds.

Photosynthesis activity in plants serves as the primary process for plants growth activities and organic matter accumulation, and is regulated by various genes and enzymes, but this process is highly sensitive to Cr stress [68,69]. Fv/Fm, NPQ, and qP are photochemical parameters used to measure the efficiency and health of the chlorophyll fluorescence and photosynthetic process in plants. They are calculated from the fluorescence emitted by chlorophyll molecules within Photosystem II (PSII) [12,32,70]. In the present research, the Cr stress-induced hypoallergic plants showed a severe reduction in total chlorophyll content as shown in the figure (Fig. 3) and associated photochemical parameters (F0, Fv/Fm, and NPQ) as shown in the figure (Fig. 4), which broadly confirms the destruction level of photosynthetic efficiency as stated in the previous studies [37,70]. These abnormal events triggered endogenous physiological, molecular, and cytological (ultrastructural) changes in the chloroplast and thylakoid membrane as shown in the figure (Fig. 2) and similarly showed that Cr stress negatively affected the light-dependent photosynthetic reactions, as confirmed by the decreased MGDG and DGDG contents shown in the figure (Fig. 3), which are the primary components of the green tissue membrane [16]. However, the upregulated pheide a oxygenase (PAO) which catalyze the first step in the chlorophyll degradation pathway from pheide a to primary fluorescent chlorophyll catabolite along with the downregulated key genes (HEMA and GOGAT) catalyzed the synthesis of glutamate and tetrapyrrole in plastids, which trigger the total chlorophyll biosynthesis, as well as Rubisco and PEPC in the carbon fixation cycle, vastly limiting the substrate accessibility for chlorophyll synthesis and also causing degradable starch granules. In contrast, our application of melatonin significantly released the inhibitory effect on melon seedlings growth under Cr stress by continuing the leaf expansion and reducing leaf chlorosis as shown in results (Fig. 1, Table 1), preserved the intrinsic endogenic ultrastructure of melon leaves as shown in the figure (Fig. 2), and increased chlorophyll content at the molecular level, indicating a healthier chlorophyll cycle under stress. These results are consistent with the previous research findings [71,72,73], which demonstrated the protective role of melatonin in proper photosynthesis and pigmentation by retaining regular chloroplast structures and sustaining energy transfer efficiency under Cr stress.

It has been stated that the accumulation of Cr in melon seedlings is the initial stage of heavy metal ions entering the food chain, which requires great concern to find out effective methods in limiting Cr assimilation [74]. In our experiment, Cr accumulation occurred in the following organ sequence: root > stalk > leaf as shown in table (Table 2), possibly owing to its preferential property to accumulate in the root and the protective mechanism of shoots through hindering Cr mobility to aerial tissues of plant [2], but melatonin significantly reduced Cr concentration and translocation rate through root to shoot. These results are similar to the earlier findings in Oryza sativa and Zea mays cultivation under cadmium as well as chromium stress [75,76]. Besides, we assumed from our findings that the effectiveness of melatonin in reducing the toxicity of Cr is not limited to preventing the heavy metal ion transport but also relies on the specialization of cellular structure and detoxification protein by regulating primary and secondary metabolism. However, plants can reduce heavy metal permeation by immobilizing the cell wall when exposed to heavy metal stress.

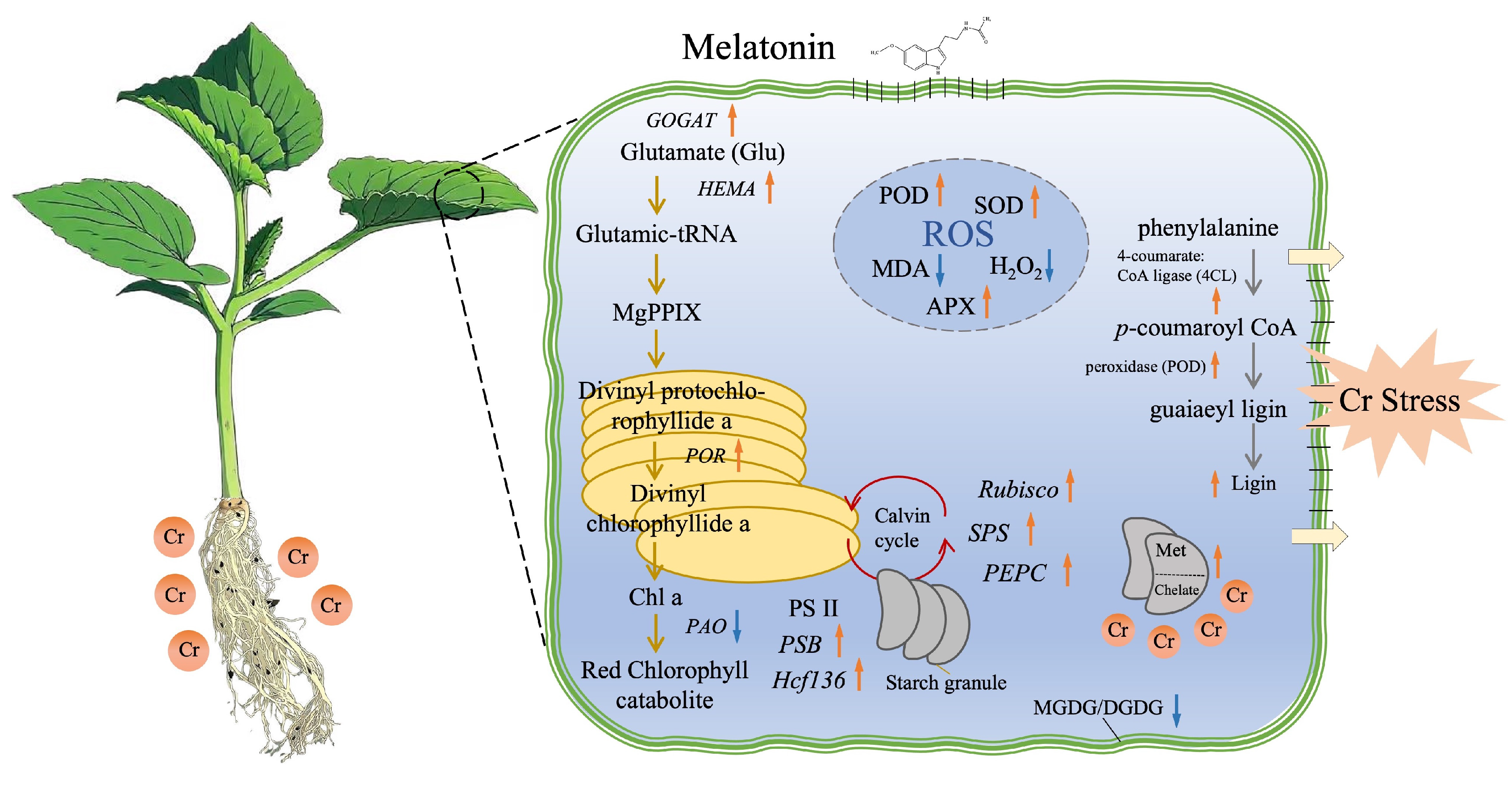

Lignin acts as a key component in maintaining cell wall integrity by thickening the walls to restrict the entry of heavy metal ions. Its synthesis primarily depends on the phenylpropanoid pathway [77]. This pathway begins with phenylalanine, which is catalyzed by phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) to initiate the reaction, followed by 4-coumarate CoA ligase (4CL), which provides substrates for subsequent reactions. These processes ultimately lead to the production of various phenylpropanoid compounds, including lignin, flavonoids, and isoflavones [78]. In this study, physiological and transcript-level analyses showed that melatonin treatment increased lignin content and upregulated the expression of the Cm4CL gene, potentially enhancing resistance to chromium toxicity by promoting the accumulation of secondary metabolites that reinforce the cell wall, as illustrated in Fig. 7. Metallothionein (Met), as a cysteine-rich protein, chelates heavy metals due to their thiol groups, which significantly form intracellular chelation and detoxification when exposed to heavy metal stress [78]. We also found that PD stress induced Met accumulation across all organs (leaves, roots, and stalks) of melon seedlings, but exogenous melatonin treatment alleviated the accumulated Met as shown in the figure (Fig. 5). This finding aligns with a previous report that melatonin application upsurges biosynthesis of Met in radish (Raphanus sativus L.) in response to cadmium stress [79]. Additionally, our melatonin application similarly mitigates the Cr toxicity through triggering the transcriptional level of the CmMet gene for biosynthesis of Met in melon as shown in the figure (Fig. 6), thereby restricting Cr transport within the plant organs.

SOD, POD, and APX are the main antioxidant enzymes protecting plants against stress-induced damages [32]. Most plants evolve defense mechanisms through the accumulation of antioxidant enzymes, which act as rapid protection mechanisms for scavenging excessive ROS under stress conditions [37]. Our study results exhibited the enhanced SOD, POD, and APX activities under Cr stress as shown in the figure (Fig. 3), especially for APX, increased 410.00% exceptionally exposed to PD stress on 1st day, reflecting an urgent and robust antioxidant response compared with SOD and POD, indicating that APX may be a priority antioxidant enzyme induced by PD stress, rapidly activating to mitigate acute oxidative damage in the early stress stage, which was similar to the previous researches [80,81]; however, the response of the antioxidants exposed to Cr stress differs by melatonin treatment. As the stress intensified, the antioxidant activities indicated a time-dependent reaction, with an initial upsurged followed by declined tendency.

MDA and H2O2 are the products of membrane lipid peroxidation under stress conditions, which also act as the vital signs to expose the peroxidation intensity induced through reactive oxygen species (ROS) as shown in the figure [82]. The overproduced ROS induced crucial oxidative destruction to the cell membrane is preliminary activity which happens in stressed plants. While in our study, application of melatonin significantly controlled the level of H2O2 and MDA by enhancing the antioxidant enzyme activities as results shown in the figure (Fig. 3), which may be indicative of the effectiveness of melatonin in releasing the adjust-limitation induced by Cr stress and strengthening the antioxidative defenses process to pursue ROS activity. This result also aligns with the previous research on melatonin application in mitigating oxidative stress in response to chromium and additional heavy metal-induced stresses [71,83]. Our current research evidence also suggested that the antioxidant property of these enzymes could act as a rapid response mechanism in plants to resist the stress conditions, while the application of exogenous melatonin serves as a supplementation that effectively enhances enzymatic activities to provide a continuous protective function to maintain metabolite homeostasis.

Additionally, the exogenous melatonin treatment enhanced the antioxidant activities, which is shown as attributed to the transcriptional regulation. Herein, our functional validation showed that the upregulated transcription levels of genes are catalyzing the biosynthesis of APX, SOD, and POD in response to increased Cr stress as shown in the figure (Fig. 6), which is related to the former results of Smeets et al. [84] and Zhang et al. [85]. Similarly, Altaf et al. [86] reported that exogenic melatonin can upregulate the antioxidant genes in pepper plant in response to chromium, nickel, cadmium, and vanadium-induced stress. Malik et al. [75] found that melatonin treatment enhanced the genetic modulation of antioxidant enzyme systems in response to Cr-induced stress in maize (Zea mays L.). The mechanism of melatonin treatment in controlling Cr concentration within melon seedlings is significant, while the efficiency of melatonin treatment varied between shoots and roots, and it is noteworthy that the protective property of melatonin to aboveground parts is more pronounced than to roots under PD stress [84,85,86]. In addition, our schematic diagram (Fig. 7) clearly illustrates the proposed model for morpho-physiological regulation via genetic modulation. It shows how melatonin alleviates chromium-induced oxidative damage by enhancing antioxidant enzyme activity and upregulating transcript levels. Meanwhile, the recent molecular evidences also provided new perspective for further exploring the mechanism of specific gene and pathways by genome editing and yeast-two-hybrid analysis to determine the hub gene in regulating Cr stress tolerance in crop plants [87,88].

Figure 7: The schematic diagram illustrates the proposed regulatory network mechanism through which melatonin treatment enhances chromium (Cr) stress tolerance in melon plants. Orange arrows indicate an increase, while purple arrows represent a decrease in the indicators and genes associated with metabolite production.

In summary, our findings demonstrate that melatonin treatment effectively alleviates heavy metal toxicity and induced stress in melon plants through transcriptional regulation of gene. This regulation enhances growth dynamics and membrane oxidative status, reduces oxidative damage, promotes lignification, and inhibits chromium uptake. Consequently, melatonin treatment presents a promising and sustainable strategy for mitigating heavy metal toxicity in agricultural soils. However, further comprehensive studies integrating breeding, molecular genetics, and omics approaches are essential to gain deeper insights into functionally validated hub genes involved in genetic regulatory networks.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Plan of Heilongjiang Province (Award number: SC2022ZX02C0202-06); the Heilongjiang Provincial Research Fund (Award number: CZKYF2025-1-B004); and the Heilongjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences Innovation Project (Award numbers: CX25YQ30 and CX24ZH10).

Author Contributions: All listed authors have substantially contributed to the manuscript and have approved the final submitted version. Conceptualization: Tai Liu and Sikandar Amanullah; data curation: Tai Liu and Huichun Xu; formal analysis: Tai Liu, Huichun Xu and Sikandar Amanullah; funding acquisition: Di Wang; investigation: Ye Che and Ling Zhang; methodology: Tai Liu, Huichun Xu, Sikandar Amanullah, Zeyu Jiang and Weiyi Bi; project administration: Di Wang; resources: Di Wang; software: Sikandar Amanullah and Lei Zhu; supervision: Sikandar Amanullah and Di Wang; validation: Tai Liu, Huichun Xu and Sikandar Amanullah; visualization: Tai Liu and Sikandar Amanullah; writing—original draft: Sikandar Amanullah; writing—review & editing: Sikandar Amanullah and Di Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data is available within the article or its Supplementary Materials.

Ethics Approval: No part of this research involved human or animal samples.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.074131/s1.

References

1. Swaminathan MS . Bio-diversity: an effective safety net against environmental pollution. Environ Pollut. 2003; 126( 3): 287– 91. doi:10.1016/s0269-7491(03)00241-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Shanker AK , Cervantes C , Loza-Tavera H , Avudainayagam S . Chromium toxicity in plants. Environ Int. 2005; 31( 5): 739– 53. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2005.02.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ullah A , Lin YJ , Zhang H , Yu XZ . Identification of the key genes involved in proline-mediated modification of cell wall components in rice seedlings under trivalent chromium exposure. Toxics. 2023; 12( 1): 4. doi:10.3390/toxics12010004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ahmad R , Ali S , Abid M , Rizwan M , Ali B , Tanveer A , et al. Glycinebetaine alleviates the chromium toxicity in Brassica oleracea L. by suppressing oxidative stress and modulating the plant morphology and photosynthetic attributes. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020; 27( 1): 1101– 11. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-06761-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zong H , Liu J , Wang F , Song N . Root morphological response of six peanut cultivars to chromium (VI) toxicity. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020; 27( 15): 18403– 11. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-08188-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Shahid M , Shamshad S , Rafiq M , Khalid S , Bibi I , Niazi NK , et al. Chromium speciation, bioavailability, uptake, toxicity and detoxification in soil-plant system: a review. Chemosphere. 2017; 178: 513– 33. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.03.074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Christou A , Georgiadou EC , Zissimos AM , Christoforou IC , Christofi C , Neocleous D , et al. Uptake of hexavalent chromium by Lactuca sativa and Triticum aestivum plants and mediated effects on their performance, linked with associated public health risks. Chemosphere. 2021; 267: 128912. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zeng F , Ali S , Qiu B , Wu F , Zhang G . Effects of chromium stress on the subcellular distribution and chemical form of Ca, Mg, Fe, and Zn in two rice genotypes. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci. 2010; 173( 1): 135– 48. doi:10.1002/jpln.200900134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Fan WJ , Feng YX , Li YH , Lin YJ , Yu XZ . Unraveling genes promoting ROS metabolism in subcellular organelles of Oryza sativa in response to trivalent and hexavalent chromium. Sci Total Environ. 2020; 744: 140951. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Hartley-Whitaker J , Ainsworth G , Meharg AA . Copper- and arsenate-induced oxidative stress in Holcus lanatus L. clones with differential sensitivity. Plant Cell Environ. 2001; 24( 7): 713– 22. doi:10.1046/j.0016-8025.2001.00721.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mittler R . Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002; 7( 9): 405– 10. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xia Q , Tang H , Fu L , Tan J , Govindjee G , Guo Y . Determination of F(v)/F(m) from chlorophyll a fluorescence without dark adaptation by an LSSVM model. Plant Phenomics. 2023; 5: 0034. doi:10.34133/plantphenomics.0034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Sairam R , Tyagi A . Physiology and molecular biology of salinity stress tolerance in plants. Curr Sci. 2004; 86: 407– 21. [Google Scholar]

14. Chaves MM , Miguel Costa J , Madeira Saibo NJ . Recent advances in photosynthesis under drought and salinity. In: Plant responses to drought and salinity stress—developments in a post-genomic era. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2011. p. 49– 104. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-387692-8.00003-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wang RL , Hua C , Zhou F , Zhou QC . Effects of NaCl stress on photochemical activity and thylakoid membrane polypeptide composition of a salt-tolerant and a salt-sensitive rice cultivar. Photosynthetica. 2009; 47( 1): 125– 7. doi:10.1007/s11099-009-0019-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Negi J , Munemasa S , Song B , Tadakuma R , Fujita M , Azoulay-Shemer T , et al. Eukaryotic lipid metabolic pathway is essential for functional chloroplasts and CO2 and light responses in Arabidopsis guard cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018; 115( 36): 9038– 43. doi:10.1073/pnas.1810458115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hossain A , Ahmad Z , Adeel M , Rahman MA , Alam MJ , Ahmed S , et al. Emerging roles of osmoprotectants in heavy metal stress tolerance in plants. In: Heavy metal toxicity in plants. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2021. p. 95– 110. doi:10.1201/9781003155089-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Han L , Gu H , Lu W , Li H , Peng WX , Ma NL , et al. Progress in phytoremediation of chromium from the environment. Chemosphere. 2023; 344: 140307. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hattori A , Migitaka H , Iigo M , Itoh M , Yamamoto K , Ohtani-Kaneko R , et al. Identification of melatonin in plants and its effects on plasma melatonin levels and binding to melatonin receptors in vertebrates. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1995; 35( 3): 627– 34. [Google Scholar]

20. Escames G , Guerrero JM , Reiter RJ , Garcia JJ , Munoz-Hoyos A , Ortiz GG , et al. Melatonin and vitamin E limit nitric oxide-induced lipid peroxidation in rat brain homogenates. Neurosci Lett. 1997; 230( 3): 147– 50. doi:10.1016/s0304-3940(97)00498-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Reiter RJ , Tan DX . Melatonin: an antioxidant in edible plants. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002; 957: 341– 4. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02938.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kükner AS , Kükner A , Naziroğlu M , Colakoğlu N , Celebi S , Yilmaz T , et al. Protective effects of intraperitoneal vitamin C, aprotinin and melatonin administration on retinal edema during experimental uveitis in the guinea pig. Cell Biochem Funct. 2004; 22( 5): 299– 305. doi:10.1002/cbf.1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Pan Y , Xu X , Li L , Sun Q , Wang Q , Huang H , et al. Melatonin-mediated development and abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2023; 14: 1100827. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1100827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Faizan M , Sultan H , Alam P , Karabulut F , Cheng SH , Rajput VD , et al. Melatonin and its cross-talk with other signaling molecules under abiotic stress. Plant Stress. 2024; 11: 100410. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2024.100410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Amanullah S , Gao P , Osae BA , Saroj A , Yang T , Liu S , et al. Genetic linkage mapping and QTLs identification for morphology and fruit quality related traits of melon by SNP based CAPS markers. Sci Hortic. 2021; 278: 109849. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ali MH , Mustafa AA , El-Sheikh AA . Geochemistry and spatial distribution of selected heavy metals in surface soil of Sohag, Egypt: a multivariate statistical and GIS approach. Environ Earth Sci. 2016; 75( 18): 1257. doi:10.1007/s12665-016-6047-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xie P , Liu Z , Li J , Ju D , Ding X , Wang Y , et al. Pollution and health-risk assessments of Cr-contaminated soils from a tannery waste lagoon, Hebei, North China: with emphasis on Cr speciation. Chemosphere. 2023; 317: 137908. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.137908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. MEEC (The Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China) . China Ecological Environment Bulletin [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2025 Dec 7]. Available from: https://www.mee.gov.cn/hjzl/sthjzk/zghjzkgb/202305/P020230529570623593284.pdf. [Google Scholar]

29. Kang Y , Lin YJ , Abid U , Zhang FF , Yu XZ . Trivalent chromium stress trigger accumulation of secondary metabolites in rice plants: integration of biochemical and transcriptomic analysis. Environ Technol Innov. 2024; 36: 103802. doi:10.1016/j.eti.2024.103802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang Q , Li A , Xu B , Wang H , Yu J , Liu J , et al. Exogenous melatonin enhances salt tolerance by regulating the phenylpropanoid biosynthesis pathway in common bean at sprout stage. Plant Stress. 2024; 14: 100589. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2024.100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Sun C , Xu L , Gao Q , Sun S , Liu X , Zhang Z , et al. Foliar spraying melatonin reduces the threat of chromium-contaminated water to wheat production by improving photosynthesis, limiting Cr translocation and reducing oxidative stress. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2025; 290: 117485. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2024.117485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Liu T , Amanullah S , Xu H , Gao P , Du Z , Hu X , et al. RNA-seq identified putative genes conferring photosynthesis and root development of melon under salt stress. Genes. 2023; 14( 9): 1728. doi:10.3390/genes14091728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Narayanan S , Vara Prasad PV , Welti R . Wheat leaf lipids during heat stress: II. Lipids experiencing coordinated metabolism are detected by analysis of lipid co-occurrence. Plant Cell Environ. 2016; 39( 3): 608– 17. doi:10.1111/pce.12648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Shao R , Zhang J , Shi W , Wang Y , Tang Y , Liu Z , et al. Mercury stress tolerance in wheat and maize is achieved by lignin accumulation controlled by nitric oxide. Environ Pollut. 2022; 307: 119488. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang D , Zhang Y , Zhou H , Wang H , Gao Y , Shao L , et al. Chalcogens reduce grain Cd accumulation by enhancing Cd root efflux and upper organ retention in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Environ Exp Bot. 2022; 201: 104975. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2022.104975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Dong Z , Men Y , Liu Z , Li J , Ji J . Application of chlorophyll fluorescence imaging technique in analysis and detection of chilling injury of tomato seedlings. Comput Electron Agric. 2020; 168: 105109. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2019.105109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zaheer IE , Ali S , Saleem MH , Imran M , Alnusairi GSH , Alharbi BM , et al. Role of iron-lysine on morpho-physiological traits and combating chromium toxicity in rapeseed (Brassica napus L.) plants irrigated with different levels of tannery wastewater. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020; 155: 70– 84. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.07.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Luo M , Wang D , Delaplace P , Pan Y , Zhou Y , Tang W , et al. Melatonin enhances drought tolerance by affecting jasmonic acid and lignin biosynthesis in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023; 202: 107974. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.107974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Zeng ZQ , Lin TZ , Zhao JY , Zheng TH , Xu LF , Wang YH , et al. OsHemA gene, encoding glutamyl-tRNA reductase (GluTR) is essential for chlorophyll biosynthesis in rice (Oryza sativa). J Integr Agric. 2020; 19( 3): 612– 23. doi:10.1016/S2095-3119(19)62710-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Guillamón JM , van Riel NA , Giuseppin ML , Verrips CT . The glutamate synthase (GOGAT) of Saccharomyces cerevisiae plays an important role in central nitrogen metabolism. FEMS Yeast Res. 2001; 1( 3): 169– 75. doi:10.1111/j.1567-1364.2001.tb00031.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Elango T , Jeyaraj A , Dayalan H , Arul S , Govindasamy R , Prathap K , et al. Influence of shading intensity on chlorophyll, carotenoid and metabolites biosynthesis to improve the quality of green tea: a review. Energy Nexus. 2023; 12: 100241. doi:10.1016/j.nexus.2023.100241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Christ B , Hörtensteiner S . Mechanism and significance of chlorophyll breakdown. J Plant Growth Regul. 2014; 33( 1): 4– 20. doi:10.1007/s00344-013-9392-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Zhang LH , Zhu LC , Xu Y , Lü L , Li XG , Li WH , et al. Genome-wide identification and function analysis of the sucrose phosphate synthase MdSPS gene family in apple. J Integr Agric. 2023; 22( 7): 2080– 93. doi:10.1016/j.jia.2023.05.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Feria AB , Ruíz-Ballesta I , Baena G , Ruíz-López N , Echevarría C , Vidal J . Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase kinase isoenzymes play an important role in the filling and quality of Arabidopsis thaliana seed. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2022; 190: 70– 80. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2022.08.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Liu LN . Advances in the bacterial organelles for CO2 fixation. Trends Microbiol. 2022; 30( 6): 567– 80. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2021.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. von Sydow L , Schwenkert S , Meurer J , Funk C , Mamedov F , Schröder WP . The PsbY protein of Arabidopsis Photosystem II is important for the redox control of cytochrome b559. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016; 1857( 9): 1524– 33. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Plücken H , Müller B , Grohmann D , Westhoff P , Eichacker LA . The HCF136 protein is essential for assembly of the photosystem II reaction center in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2002; 532( 1–2): 85– 90. doi:10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03634-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Shen L , Zhou Y , Yang X . Genome-wide identification of ascorbate peroxidase (APX) gene family and the function of SmAPX2 under high temperature stress in eggplant. Sci Hortic. 2024; 326: 112744. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Aleem M , Riaz A , Raza Q , Aleem M , Aslam M , Kong K , et al. Genome-wide characterization and functional analysis of class III peroxidase gene family in soybean reveal regulatory roles of GsPOD40 in drought tolerance. Genomics. 2022; 114( 1): 45– 60. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2021.11.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Noor J , Ullah A , Saleem MH , Tariq A , Ullah S , Waheed A , et al. Effect of Jasmonic Acid Foliar Spray on the Morpho-Physiological Mechanism of Salt Stress Tolerance in Two Soybean Varieties (Glycine max L.). Plants. 2022; 11( 5): 651. doi:10.3390/plants11050651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Chen J , Wen Y , Pan Y , He Y , Gong X , Yang W , et al. Analysis of the role of the rice metallothionein gene OsMT2b in grain size regulation. Plant Sci. 2024; 349: 112272. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2024.112272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Teng Y , Wu J , Lu S , Wang Y , Jiao X , Song L . Soil and soil environmental quality monitoring in China: a review. Environ Int. 2014; 69: 177– 99. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2014.04.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Ren S , Song C , Ye S , Cheng C , Gao P . The spatiotemporal variation in heavy metals in China’s farmland soil over the past 20?years: a meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2022; 806( Pt 2): 150322. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Zhang C , Cai X , Xia Z , Jin X , Wu H . Contamination characteristics of heavy metals in a small-scale tanning area of Southern China and their source analysis. Environ Geochem Health. 2023; 45( 8): 5655– 68. doi:10.1007/s10653-020-00732-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Rahman Z , Singh VP . The relative impact of toxic heavy metals (THMs) (arsenic (As), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr)(VI), mercury (Hg), and lead (Pb)) on the total environment: an overview. Environ Monit Assess. 2019; 191( 7): 419. doi:10.1007/s10661-019-7528-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Ertani A , Mietto A , Borin M , Nardi S . Chromium in agricultural soils and crops: a review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2017; 228( 5): 190. doi:10.1007/s11270-017-3356-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Hu Y , Liu X , Bai J , Shih K , Zeng EY , Cheng H . Assessing heavy metal pollution in the surface soils of a region that had undergone three decades of intense industrialization and urbanization. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2013; 20( 9): 6150– 9. doi:10.1007/s11356-013-1668-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Khan AG , Kuek C , Chaudhry TM , Khoo CS , Hayes WJ . Role of plants, mycorrhizae and phytochelators in heavy metal contaminated land remediation. Chemosphere. 2000; 41( 1–2): 197– 207. doi:10.1016/s0045-6535(99)00412-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Schützendübel A , Polle A . Plant responses to abiotic stresses: heavy metal-induced oxidative stress and protection by mycorrhization. J Exp Bot. 2002; 53( 372): 1351– 65. doi:10.1093/jexbot/53.372.1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Sharma RK , Agrawal M . Biological effects of heavy metals: an overview. J Environ Biol. 2005; 26( Suppl 2): 301– 13. [Google Scholar]

61. Gall JE , Rajakaruna N . The physiology, functional genomics, and applied ecology of heavy metal-tolerant Brassicaceae. In: Lang M , editor. Brassicaceae: characterization, functional genomics and health benefits. New York, NY, USA: Nova Science Pub Inc; 2013. p. 121– 48. [Google Scholar]

62. Bewley JD . Seed germination and dormancy. Plant Cell. 1997; 9( 7): 1055– 66. doi:10.1105/tpc.9.7.1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Dreyer Parr P , Taylor FG . Germination and growth effects of hexavalent chromium in Orocol TL (a corrosion inhibitor) on Phaseolus vulgaris. Environ Int. 1982; 7( 3): 197– 202. doi:10.1016/0160-4120(82)90105-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Samrana S , Ali A , Muhammad U , Azizullah A , Ali H , Khan M , et al. Physiological, ultrastructural, biochemical, and molecular responses of glandless cotton to hexavalent chromium (Cr6+) exposure. Environ Pollut. 2020; 266( Pt 1): 115394. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Akinci IE , Akinci S . Effect of chromium toxicity on germination and early seedling growth in melon (Cucumis melo L.). African J Biotechnol. 2010; 9( 29): 4589– 94. [Google Scholar]

66. Lei K , Sun S , Zhong K , Li S , Hu H , Sun C , et al. Seed soaking with melatonin promotes seed germination under chromium stress via enhancing reserve mobilization and antioxidant metabolism in wheat. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021; 220: 112241. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Li R , Zheng W , Yang R , Hu Q , Ma L , Zhang H . OsSGT1 promotes melatonin-ameliorated seed tolerance to chromium stress by affecting the OsABI5-OsAPX1 transcriptional module in rice. Plant J. 2022; 112( 1): 151– 71. doi:10.1111/tpj.15937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Manzoor N , Ahmed T , Noman M , Shahid M , Nazir MM , Ali L , et al. Iron oxide nanoparticles ameliorated the cadmium and salinity stresses in wheat plants, facilitating photosynthetic pigments and restricting cadmium uptake. Sci Total Environ. 2021; 769: 145221. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Ali S , Rizwan M , Waqas A , Hussain MB , Hussain A , Liu S , et al. Fulvic acid prevents chromium-induced morphological, photosynthetic, and oxidative alterations in wheat irrigated with tannery waste water. J Plant Growth Regul. 2018; 37( 4): 1357– 67. doi:10.1007/s00344-018-9843-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Maqbool A , Ali S , Rizwan M , Ishaque W , Rasool N , Rehman MZU , et al. Management of tannery wastewater for improving growth attributes and reducing chromium uptake in spinach through citric acid application. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018; 25( 11): 10848– 56. doi:10.1007/s11356-018-1352-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Ayyaz A , Farooq MA , Dawood M , Majid A , Javed M , Athar HUR , et al. Exogenous melatonin regulates chromium stress-induced feedback inhibition of photosynthesis and antioxidative protection in Brassica napus cultivars. Plant Cell Rep. 2021; 40( 11): 2063– 80. doi:10.1007/s00299-021-02769-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Chen F , Li Y , Zia-Ur-Rehman M , Hussain SM , Qayyum MF , Rizwan M , et al. Combined effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles and melatonin on wheat growth, chlorophyll contents, cadmium (Cd) and zinc uptake under Cd stress. Sci Total Environ. 2023; 864: 161061. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.161061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Yan F , Zhang J , Li W , Ding Y , Zhong Q , Xu X , et al. Exogenous melatonin alleviates salt stress by improving leaf photosynthesis in rice seedlings. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021; 163: 367– 75. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.03.058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Shetty BR , Jagadeesha PB , Salmataj SA . Heavy metal contamination and its impact on the food chain: exposure, bioaccumulation, and risk assessment. Cyta J Food. 2025; 23( 1): 2438726. doi:10.1080/19476337.2024.2438726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Malik Z , Afzal S , Dawood M , Abbasi GH , Khan MI , Kamran M , et al. Exogenous melatonin mitigates chromium toxicity in maize seedlings by modulating antioxidant system and suppresses chromium uptake and oxidative stress. Environ Geochem Health. 2022; 44( 5): 1451– 69. doi:10.1007/s10653-021-00908-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Huang J , Jing HK , Zhang Y , Chen SY , Wang HY , Cao Y , et al. Melatonin reduces cadmium accumulation via mediating the nitric oxide accumulation and increasing the cell wall fixation capacity of cadmium in rice. J Hazard Mater. 2023; 445: 130529. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.130529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Liu Q , Luo L , Zheng L . Lignins: biosynthesis and biological functions in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2018; 19( 2): 335. doi:10.3390/ijms19020335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Lam PY , Wang L , Lo C , Zhu FY . Alternative splicing and its roles in plant metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23( 13): 7355. doi:10.3390/ijms23137355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Yu XZ , Lin YJ , Zhang Q . Metallothioneins enhance chromium detoxification through scavenging ROS and stimulating metal chelation in Oryza sativa. Chemosphere. 2019; 220: 300– 13. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.12.119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Xu L , Zhang F , Tang M , Wang Y , Dong J , Ying J , et al. Melatonin confers cadmium tolerance by modulating critical heavy metal chelators and transporters in radish plants. J Pineal Res. 2020; 69( 1): e12659. doi:10.1111/jpi.12659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Yang X , Shi Q , Wang X , Zhang T , Feng K , Wang G , et al. Melatonin-induced chromium tolerance requires hydrogen sulfide signaling in maize. Plants. 2024; 13( 13): 1763. doi:10.3390/plants13131763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Ayala A , Muñoz MF , Argüelles S . Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014; 2014: 360438. doi:10.1155/2014/360438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Awan SA , Khan I , Rizwan M , Irshad MA , Wang X , Zhang X , et al. Reduction in the cadmium (Cd) accumulation and toxicity in pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L.) by regulating physio-biochemical and antioxidant defense system via soil and foliar application of melatonin. Environ Pollut. 2023; 328: 121658. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Smeets K , Opdenakker K , Remans T , Van Sanden S , Van Belleghem F , Semane B , et al. Oxidative stress-related responses at transcriptional and enzymatic levels after exposure to Cd or Cu in a multipollution context. J Plant Physiol. 2009; 166( 18): 1982– 92. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2009.06.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Zhang Y , Li Z , Peng Y , Wang X , Peng D , Li Y , et al. Clones of FeSOD, MDHAR DHAR genes from white clover and gene expression analysis of ROS-scavenging enzymes during abiotic stress and hormone treatments. Molecules. 2015; 20( 11): 20939– 54. doi:10.3390/molecules201119741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Altaf MA , Hao Y , Shu H , Ali Mumtaz M , Cheng S , Alyemeni MN , et al. Melatonin enhanced the heavy metal-stress tolerance of pepper by mitigating the oxidative damage and reducing the heavy metal accumulation. J Hazard Mater. 2023; 454: 131468. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Wang YX , Yu TF , Wang CX , Wei JT , Zhang SX , Liu YW , et al. Heat shock protein TaHSP17.4, a TaHOP interactor in wheat, improves plant stress tolerance. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023; 246: 125694. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Sohail H , Noor I , Hussain H , Zhang L , Xu X , Chen X , et al. Genome editing in horticultural crops: augmenting trait development and stress resilience. Hortic Plant J. 2025: 1– 18. doi:10.1016/j.hpj.2025.09.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools