Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mapping of the Pepper Purple Fruit Gene and Development of Molecular Markers Based on BSA-Seq

1 Key Laboratory of Biology and Genetic Improvement of Horticultural Crops (South China), Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, College of Horticulture, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou, 510642, China

2 Dongguan Agricultural Scientific Research Center, Dongguan, 523086, China

* Corresponding Authors: Ting Ye. Email: ; Changming Chen. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Genetic Diversity and Evolution)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(6), 1695-1709. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.063349

Received 12 January 2025; Accepted 06 May 2025; Issue published 27 June 2025

Abstract

The color difference of capsicum fruit is closely related to the type and content of pigment in the peel, which is mainly determined by anthocyanins, chlorophyll, and carotenoids. This study used green “CA59” and purple “Z81” pepper fruits as parents to create the F2 generation. The fruit color of 466 F2 population was identified, and the extreme individuals from this population were selected for Bulked Segregant Analysis (BSA) using resequencing. Genetic analysis revealed that a pair of genes controls the expression of the purple fruit trait in capsicum. Using functional annotation, expression analysis, and sequencing analysis of candidate genes, it was determined that there were four genes in the region between InDel 67 and InDel 75 (185,664,068 BP-186,514,350 bp) on chromosome 10, that is the linkage interval for pepper purple fruit. There are 7 SNPs in the CaMYB1 gene (Capann_59V1aChr10g016200) in the pepper variety “Z81”. Of these, 4 SNPs are located in the gene’s coding region. These 4 SNPs lead to 2 mutations that do not change the amino acid sequence (synonymous mutations) and 2 mutations that do change the amino acid sequence (non-synonymous mutations). Additionally, the expression level of the CaMYB1 gene in the purple fruit of “Z81” is significantly higher than that in the green fruit of “CA59”. CaMYB1 is believed to be a crucial candidate gene in regulating anthocyanin production in purple capsicum fruit. A molecular marker, InDel 67, was successfully developed, with a total separation rate of 92.4%.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FilePeppers, belonging to the Solanaceae family, are widely cultivated in many regions across the globe [1–3]. As a significant cash crop belonging to the nightshade family, the color of its fruit is intricately associated with ripeness, and it serves as a crucial factor in capturing consumers’ interest [4]. The diversity in the color of capsicum fruit is attributed to variations in the types and concentrations of pigments in the peel [5]. The primary pigment in the green fruit of capsicum is chlorophyll, along with a small percentage of carotenoids [5,6]. On the other hand, the purple fruit is abundant in anthocyanins. Anthocyanins, a natural pigment, not only provide rich color to plant organs [6] but also attract insects and other animals for pollination and seed dissemination [7–10]. Additionally, anthocyanins can potentially enhance pepper resistance to abiotic stresses [11,12]. Furthermore, anthocyanins have been linked to numerous health advantages, including cardiovascular disease prevention, anti-cancer properties, liver protection, and enhanced vision [13]. These benefits have garnered significant interest in the realms of food, medicine, and other related fields. Anthocyanin synthesis is a complicated process influenced by various external factors, including light, pH, temperature, plant hormones, and metal ions, in addition to the internal regulation of structural and regulatory genes [14]. The primary determinants of anthocyanin synthesis are the structural genes, which mostly encode enzymes in their biosynthesis pathway. Early biosynthetic genes (EBGs) and late biosynthetic genes (LBGs) are two types of genes involved in the biosynthesis process [14]. The regulatory genes primarily consist of three transcription factor (TFs) types: MYB, bHLH, and WD40. These TFs typically interact with one another to form the MBW complex, which plays a crucial role in synthesizing and regulating plant anthocyanins [15]. On top of that, they can bind to the promoters of structural genes to control their expression [14].

The most prevalent anthocyanin in capsicum is delphinin-3-trans-coumarylrutin-5-glucoside, which accounts for around 89% of the content. Also, the content of delphinin-3-cis-coumarin-5-glucoside is 4.6% [16–18]. CaMYB1 and CaMYB2 mediated the biosynthesis of anthocyanins in cayenne pepper [19]. The A gene encoding the R2R3-MYB transcription factor, analogous to the PhAn2 gene of petunia and the SlAN2 gene of tomato, is the most well-known regulatory factor in chili peppers. It regulates the synthesis and accumulation of anthocyanins in chili peppers’ leaves, petals, and immature fruits [19,20].

With its high stability, high efficiency, and quick cycle, molecular marker technology—which is based on DNA polymorphism inheritance—offers several benefits over conventional breeding techniques [21]. Due to the progress in sequencing technology and decreased cost, molecular markers are becoming more commonly employed in crop breeding. Bulked Segregant Analysis (BSA) was first proposed to construct an extreme phenotypic hybridization library, analyze mutation frequency differences, and accurately screen molecular markers associated with target traits [22]. Researchers frequently use BSA in conjunction with whole-genome resequencing to identify differential genes [23,24]. The AFLP marker closely connected to the male sterile restorer line of pepper gene to quickly and accurately discover these types during hybridization and breeding [25]. To combat potato virus Y (PVY), researchers used BSA-seq to find the Pvr4 gene on chili pepper chromosome 10 and turn it into SCAR markers for quick PVY-resistant genotype identification [26]. The major locus governing capsaicin concentration on pepper chromosome 7, disclosing the genetic basis of spiciness [27]. These studies not only improve the breeding efficiency but also provide staunch support for the genetic and quality improvement of pepper.

This study involved using the green fruit inbred line CA59 as the maternal and the purple fruit inbred line pepper Z81 as the paternal to create the F2 population. Further, BSA-seq was used to determine the candidate interval and construct a genetic linkage map. The researchers could locate the specific genes related to anthocyanin biosynthesis in capsicum. Molecular markers closely linked to the anthocyanins in capsicum were developed. The findings above can serve as a basis for future-focused breeding efforts involving capsicum germplasm resources.

This study involved the hybridization of high-generation inbred lines of green fruit pepper CA59 (P1) and purple fruit pepper Z81 (P2), both of which had undergone more than 8 generations of breeding. The purpose was to create isolated populations of the F2 generation. A total of 466 individual F2 populations were examined to identify variations in fruit color. Extreme populations were then selected for resequenced-BSA analysis. The pepper materials used in this study were sourced exclusively from South China Agricultural University (Fig. S1). The pepper materials from the P1, P2, F1, and F2 generations were planted outdoors at the Guangzhou Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Nansha Headquarters). Standard field management practices were followed for all experimental materials.

Three pepper plants with normal growth were randomly selected from both parents and the F1 generation to assess the anthocyanin and chlorophyll content. Each pepper was harvested when it reached the green maturity stage, which is about 25–30 days after flowering. The spectrophotometer was used to measure the absorbance of all treated samples at 535 nm [28]. The anthocyanin content in the outer pericarp of both parents and F1 generation peppers was then estimated. The pigment was obtained through the direct immersion of plant tissues [29], and the absorbance of the extract was measured using the Cytation5 enzyme marker. Subsequently, the chlorophyll concentration in the outer pericarp of the parent plants and the F1 generation pepper was quantified separately.

2.3 Phenotypic Statistics and Identification

Upon reaching the green ripening stage, the peel color of 466 individuals belonging to the P1, P2, F1, and F2 generation isolated populations was examined. Next, the color segregation of the F2 generation pepper peel was analyzed using a ×2 goodness of fit test. The p value of the ×2 test was determined using the CHISQ test function in Microsoft Excel 2016.

2.4 BSA Mixed Pool Sequencing Analysis

Two parent pools were created by selecting 20 juvenile leaves from CA59 and Z81 peppers of equal sizes. Afterward, the peel color of the F2 generation isolated population was subjected to statistical analysis. From each plant, 50 purple and green fruit plants were chosen, and a young leaf of equal size was collected from each plant. These leaves were used to create two distinct groups: one consisting of “purple fruit” and the other consisting of “green fruit.” Wuhan Feisha Information Technology Co., Ltd. (China) successfully determined the extreme mixing pool’s DNA extraction and genome resequencing. Quality control of genome resequencing data from two parental pools and two extreme mixed pools of F2 generation was performed using SOAPnuke software [30]. Subsequently, the data that underwent quality control was aligned to the reference genome using the BWA-mem v0.7.17 [31]. The “CA59” pepper genome, produced by our research group [32], was used as the reference genome for this investigation. Once we had the comparison data, we utilized the MarkDuplicates tool in the web software Picard v2.25.7 to identify and eliminate PCR repetitions.

The bcftools v1.13 software was used to detect the variation of each pepper chromosome. The QTL-seqr tool [33] was employed to analyze and retrieve mutation information. Heterozygous mutant sites present in both parents were discarded. Next, the extreme mixed pool of purple fruit attributes’ SNP-index and Δ(SNP-index) were determined following [34]. To determine the average value of Δ(SNP-index) in each window, set the window length to 4 Mb and step size to 10 kb. The horizontal coordinate represents the physical position of the chromosome, while the vertical coordinate represents the average value. The distribution map of extreme mixed pool Δ(SNP-index) on all chromosomes of chili pepper was obtained using confidence levels of 95% and 99% as the criterion for interval existence. The significance level (α) for Grubbs detection is set to 0.001, and after that, the distribution of G′ values in the genome is obtained. Potential regions for candidate genes were selected based on the δ-index (SNP-index) values that exceeded the 95% threshold and the regions that exceeded the threshold in Grubbs tests.

2.5 Polymorphism InDel Marker Screening and Construction of Genetic Linkage Map

The differential Indel sites between parents were selected inward on both sides of the localized interval based on the location of the possible candidate interval provided by BSA-seq. The amplification primer was constructed using Primer Premier 5 software based on the sequences flanking the differential sites. The PCR products generated by this primer contain InDel sites with a length ranging from 150 to 350 base pairs. Primer synthesis was assigned to Beijing Qingke Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (China) (Tables S1 and S2). Polymorphism was confirmed in both parents, and the F2 population’s unique genotype was identified by selecting distinct and consistent markers. The genotyping results of InDel markers in the F2 generation population were analyzed in conjunction with the phenotypic data of the same population. The IciMapping software was utilized to predict the linkage interval associated with the purple fruit traits in pepper. A LOD value of 3.0 was used as the threshold to determine the presence of a linkage interval.

2.6 Functional Annotation and Variation Site Analysis of Interval Candidate Genes

Functional annotation was performed using CDS sequences of all genes in the reference genome. The software tools Diamond v2.0.9 [35] and BLAST v2.11 were utilized to compare the CDS sequences of the genes in the localization interval with the NT database, NR database, and Swissprot database. The annotation information for the gene is taken from the gene description found in the comparison result. The functional annotation data of the candidate genes was retrieved, and the candidate genes were subjected to preliminary screening and functional prediction. The snpEff v5.0e programme, developed by [36], was utilized to annotate the genetic variations of SNPs and InDels in the pigmentation of pepper peel. The gene names and annotation information of all genes within the candidate interval were extracted based on the genome annotation of the reference genome. The variation and mutation types of the candidate genes were determined by combining the mutation annotation file.

2.7 Analysis of Candidate Gene Expression

The cDNAs of different tissue parts (stem, leaf, petal, exocarp) of CA59 and Z81 were thinned to 200 ng/μL, and specific primes of genes in the candidate regions were designed. The ubiquitin extension protein gene CA12g20490 was used as the internal reference gene. The ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix, manufactured by Nanjing Nuovican Biotechnology Co., Ltd., was utilized for fluorescence quantitative PCR detection. Each tissue part sample had three biological replicates, and each biological replicate had three technical replicates. The formulation of the qRT-PCR reaction system is based on the information provided in Table S3. The reaction was conducted using the following temperature and time conditions: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 95°C for 10 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 20 s. This cycle was repeated 40 times. Fluorescence quantitative data was collected using BIO-RAD’s IQ5 software. The relative expression of the gene was computed using the 2−Δct technique. The data was then processed and mapped using GraphPad Prism 8.0.1.

2.8 Full-Length Cloning of CaMYB1 Gene

The CaMYB1 gene sequence and the 100 bp DNA sequences of the upstream and downstream were retrieved from the reference genome of “CA59” pepper. Customized primers were built using Primer Premier 5 software to clone the entire CaMYB1 gene (Table S4). The genomic DNA of capsicum CA59 and Z81 served as the template for cloning. The PCR reaction system is prepared based on the information provided in Table S5. The amplified PCR products were identified using gel electrophoresis using a 1% agarose gel at 145 volts for 15 min and visualized using gel imaging equipment.

2.9 Analysis of CaMYB1 Gene Promoter

To conduct promoter cis-element analysis, the 2000 bp upstream sequence of the CaMYB1 gene was taken from the reference genome of the “CA59” pepper. The promoter region of the CaMYB1 gene in this population had all the variation information for the two parents (CA59 and Z81). Afterward, both parents’ promoter sequences containing the CaMYB1 motif were uploaded to the PlantCARE website, where their respective cis-acting regions were analyzed.

3.1 Genetic Analysis of Purple Pepper Fruit

3.1.1 Determination of Pigment Content in the Outer Pericarp of Capsicum

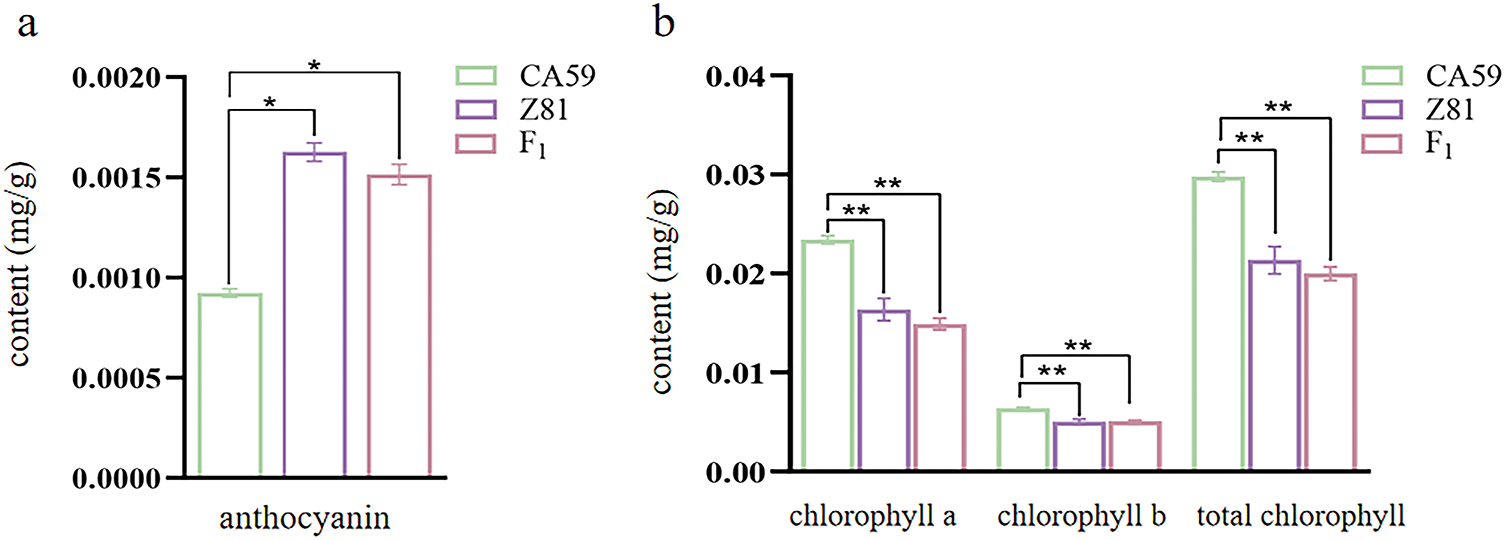

The concentration of anthocyanin in the outer pericarp of both the parents and the F1 generation peppers was measured (Fig. 1a). The anthocyanin content in the outer pericarp of CA59 pepper (P1) was 0.000923 mg/g, and in Z81 pepper (P2) was 0.001627 mg/g. The anthocyanin level in the outer pericarp of the Z81 pepper was approximately 1.76 times greater than that of the CA59 pepper. The anthocyanin content in the outer pericarp of F1 pepper was 0.001515 mg/g. The chlorophyll content in the outer pericarp of both parents and F1 generation was determined by the direct soaking method (Fig. 1b). The total chlorophyll content in the outer pericarp of CA59 (P1) was 0.030, and 0.021 mg/g in Z81 (P2). The total chlorophyll content of CA59 was significantly higher than that of Z81. The total anthocyanin content in the outer pericarp of the F1 generation pepper was 0.020 mg/g, which was also consistent with the results of anthocyanin content in the outer pericarp measured earlier.

Figure 1: Comparison of chlorophyll and anthocyanin contents in the outer pericarp of capsicum. (a): Contents of total chlorophyll and anthocyanins in parents and F1 generation exocarp. (b): Chlorophyll content in the outer pericarp of both parents and F1 generation capsicum. **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05

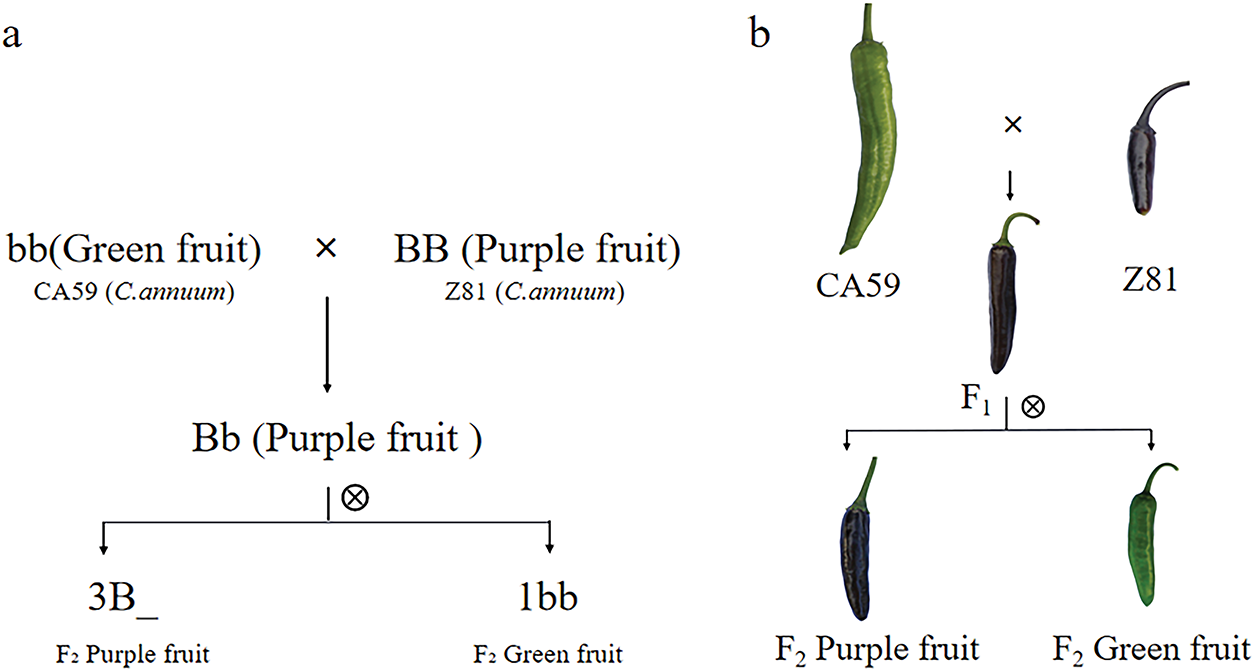

3.1.2 Statistical Analysis of Genetic Rules of Pepper Purple Fruit

As the plants reached the green maturity stage, all F1 and F2 generation isolated populations showed a field trait where an apparent purple color was seen on the pepper skins of the F1 (CA59 × Z81) generation plants. This demonstrates that the peppers’ purple outer pericarp characteristic is more dominant over the green. In the F2 generation of 466 individuals obtained from self-crossing F1, 363 individuals exhibited a purple outer peel color, while 103 individuals exhibited a green outer peel color. The Chi-square test results indicated that the ratio of purple to green individuals was approximately 3:1, the p-value of the chi-square test is 0.15, which is greater than 0.05, consistent with the genetic principle of single gene control (Fig. 2a,b).

Figure 2: Genetic map of purple fruit in CA59 × Z81 hybrid combination. (a): purple fruit genetic model map of CA59 × Z81 hybrid population. (b): genetic diagram of purple fruit in CA59 × Z81 hybrid population

3.2 Development of Molecular Markers Linked to Purple Fruit

The genomes of two sets of parents and two sets of mixed offspring from the F2 generation were sequenced, with distinct ‘green fruit’ and ‘purple fruit’ characteristics. The parental sequencing had a depth of 20×, whereas the mixed pool of purple and green fruit had a depth of 50×. The data collected indicates that 371.85 GB of data was produced, with 2,467,407,560 Reads being filtered sequences. The GC content was within the normal range, and the average values of Q20 and Q30 were 97.0% and 90.1%, respectively. This indicates that the data obtained by sequencing is sufficient and of high quality and can be used to analyze subsequent experiments (Table S6).

3.2.2 Preliminary Mapping of Purple Fruit Using BSA

A comparison was made between the genomes of the parents and the two extreme mixed-pool genomes to find SNP and InDel variations. This analysis yielded a total of 12,031,716 variance data points when compared to the reference genome. Afterward, the variation information acquired was refined using the bcftools software, resulting in 11,105,187 SNP sites and 919,023 InDel sites. To mitigate the impact of confounding population features, we eliminated heterozygous sites in both parents and did not exhibit polymorphism in either parent or extreme pool. After quality control, the SNP and InDel sites were utilized for further study.

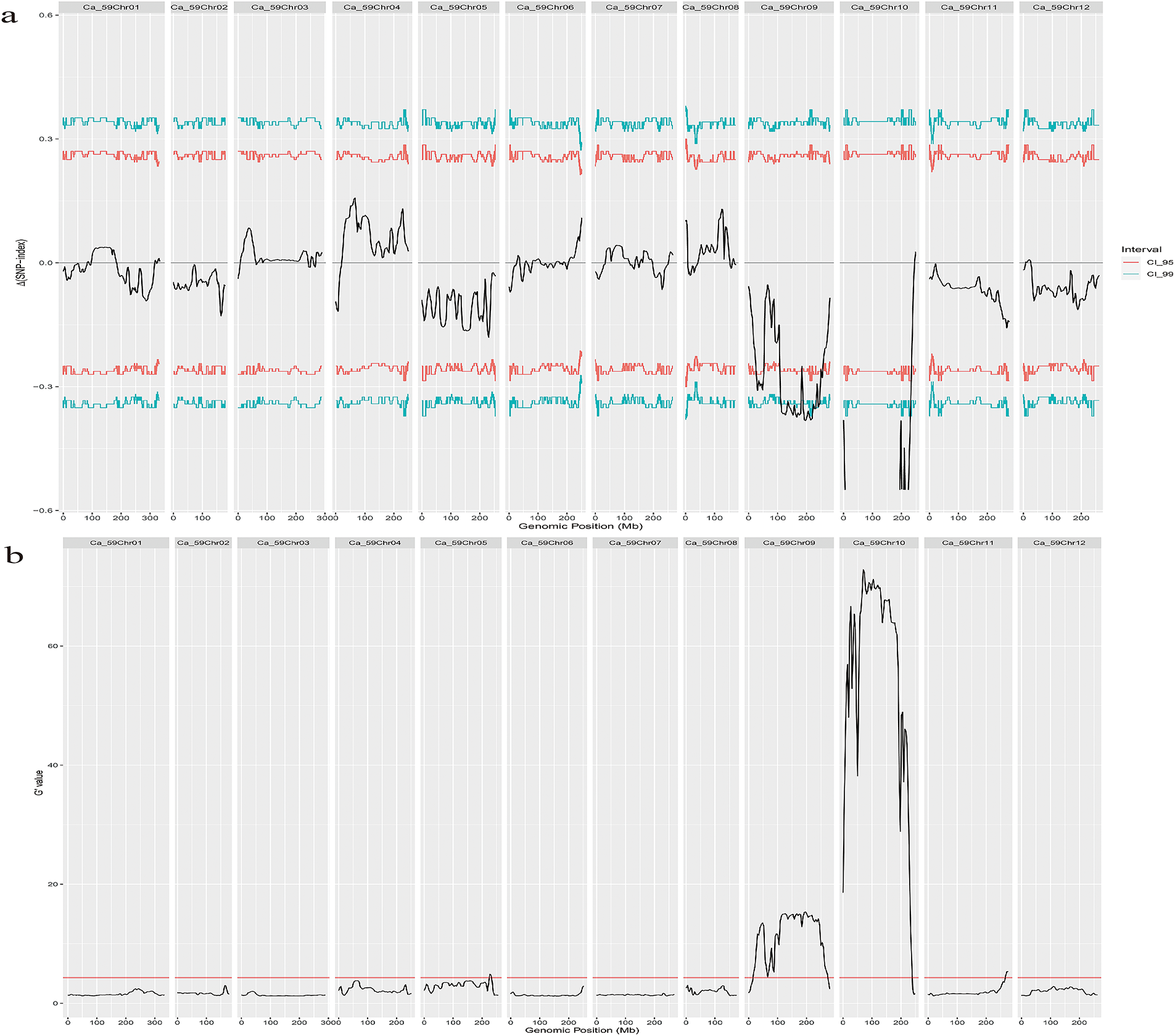

The SNP index and Gprime value were computed using a set of high-quality SNPs (10,571,690 SNPs) derived from a mixed pool of “purple fruit” and “green fruit” peppers. The Δ(SNP-index) value was then generated by calculating the difference. Gprime and Δ(SNP-index) distribution maps on chromosomes were created (Fig. 3a,b). The Δ(SNP-index) distribution map was used to filter candidate intervals, with the 95% confidence level used as the threshold. Notably, distinct peaks were observed on chromosome 9 and chromosome 10, respectively. A region of interest on chromosome 9 was identified, spanning the position from 19.1 to 267.3 Mb, with a length of 248.2 Mb. With a length of 238.23 Mb, the peak of chromosome 10 is between 7585 and 238,330,779 bp. These two peaks are potential regulators of the purple fruit trait in the capsicum population.

Figure 3: Preliminary location results of BSA-seq for purple fruit traits of pepper. (a): the distribution map of Δ(SNP-index) in all chromosomes of chili pepper, the black line is the fitting line, the red line is the 95% threshold line, and the green line is the 99% threshold line. (b): G′ value distribution map on chromosomes, red lines are threshold lines

3.2.3 Genetic Linkage Map of Pepper Purple Fruit Using InDel Markers

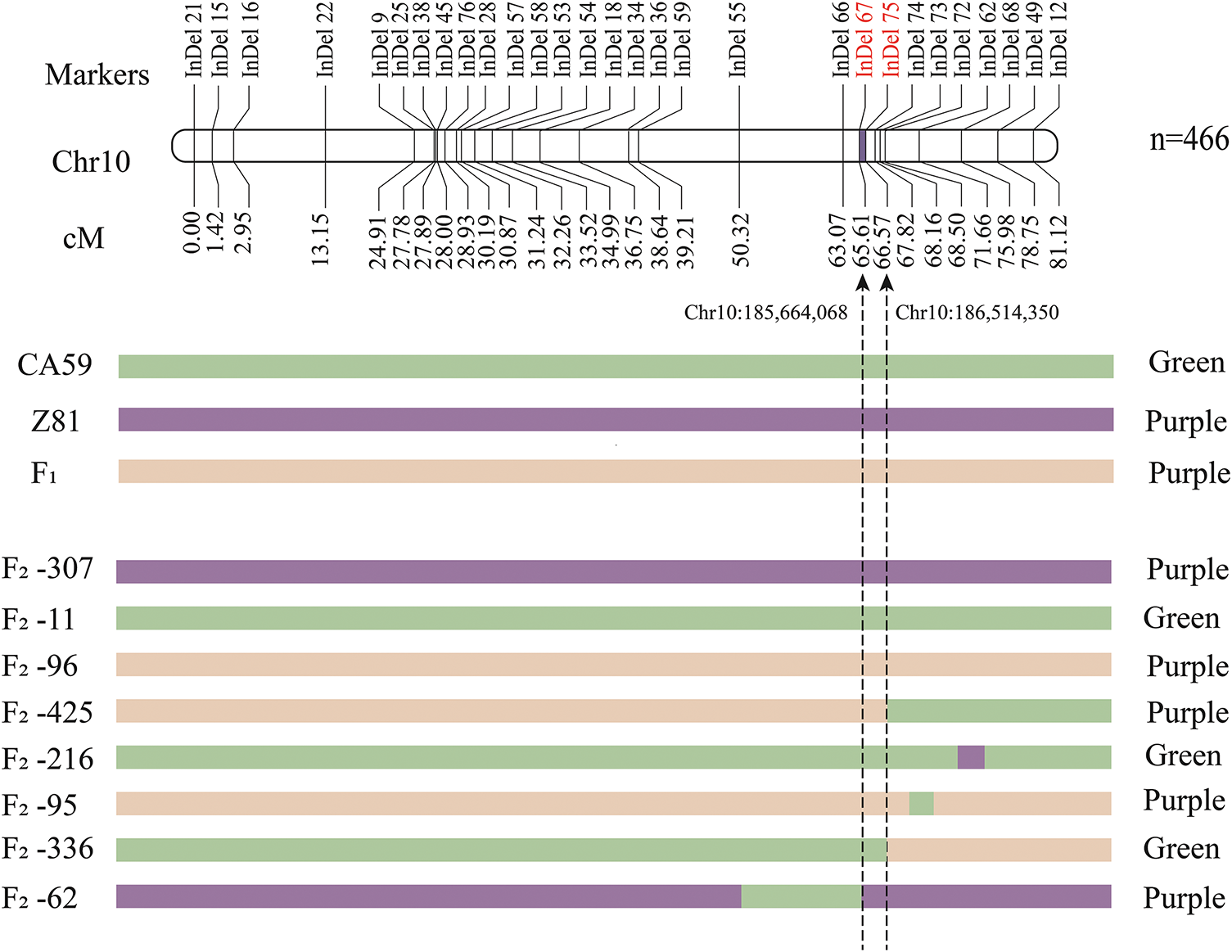

The preliminary mapping results of BSA-seq identified the potential areas associated with the purple fruit phenotype of capsicum at 19.1–267.3 Mb (248.2 Mb) on chromosome 9 and 7585–238,330,779 bp (238.23 Mb) on chromosome 10. To narrow down the potential link between capsicum purple fruit and its parent plants, we used the DNA of both parents, the F1 generation and 466 F2 generation plants. We analyzed the distribution of different types of bands in all F2 generation populations using statistical polymorphism InDel markers. Finally, we constructed a genetic linkage map using the QTL IciMapping software. Eight polymorphic markers were employed within the candidate region of chromosome 9. The findings revealed no association between this interval and purple fruit in peppers, therefore showing the absence of a linkage between chromosome 9 and pepper purple fruit. A total of 29 InDel markers exhibiting polymorphism were carefully chosen from the candidate region of chromosome 10 to create the genetic linkage map for capsicum purple fruit (Fig. 4). The findings indicated that the linkage gap spanned from InDel 67 to InDel 75, with a physical position ranging from 185,664,068 bp to 186,514,350 bp. The genetic distance measured 0.96 cM, the physical distance 850.28 kb, the LOD value 52.89, and the contribution rate 50.61%.

Figure 4: Genetic linkage map of purple fruit of pepper

3.2.4 Candidate Gene Sequence Analysis and Functional Annotation

The candidate genes in the region were compared to the results of variation found in the genome resequencing data. It was found that Capann_59V1aChr10g016200 had 7 SNPs, and Capann_59V1aChr10g016230 had 1 InDel. The full-length gene sequences of Capann_59V1aChr10g016210 and Capann_59V1aChr10g016220 in pepper varieties CA59 and Z81 were identical, with no InDel or SNP sites. It is speculated that the difference in skin color is caused by the Capann_59V1aChr10g016200 or Capann_59V1aChr10g016230 gene. The CDS sequences of 4 candidate genes inside the identified candidate region were compared to the NT, NR, and Swissport databases for functional annotation using Diamond and BLAST tools (Table S7). Examining genes associated with the biosynthesis of anthocyanin in capsicum revealed a specific transcription factor called CaMYB1 (Capann_59V1aChr10g016200). Therefore, it is considered a significant candidate gene that plays a crucial role in determining the purple fruit color in this population.

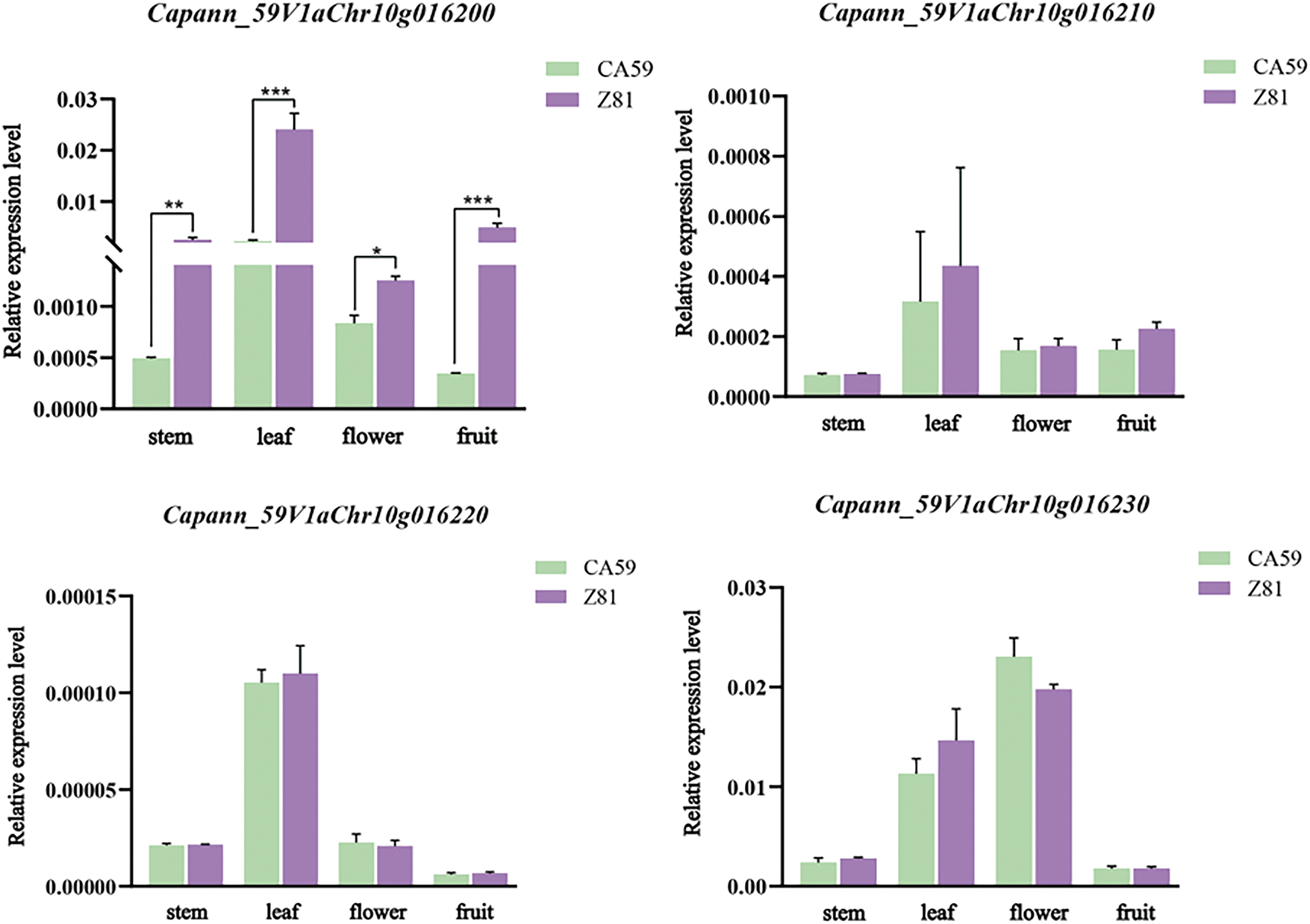

3.2.5 Expression Analysis of Candidate Gene Expression

The expression analysis of candidate genes was performed in the CA59 and Z81. The CaMYB1 (Capann_59V1aChr10g016200) had a significantly higher expression level in Z81 (purple fruit) than in CA59 (green fruit). At the same time, there was no significant difference in the relative expression levels of the other three genes (Fig. 5). It is fair to suggest the CaMYB1 (Capann_59V1aChr10g016200) is a key candidate gene controlling purple fruit traits in this population.

Figure 5: Relative expression levels of purple fruit trait candidate genes in different tissues of both parents. The expression level in stem, leaf, flower, and fruit was examined. Bars are the mean ± SD of three biological replicates

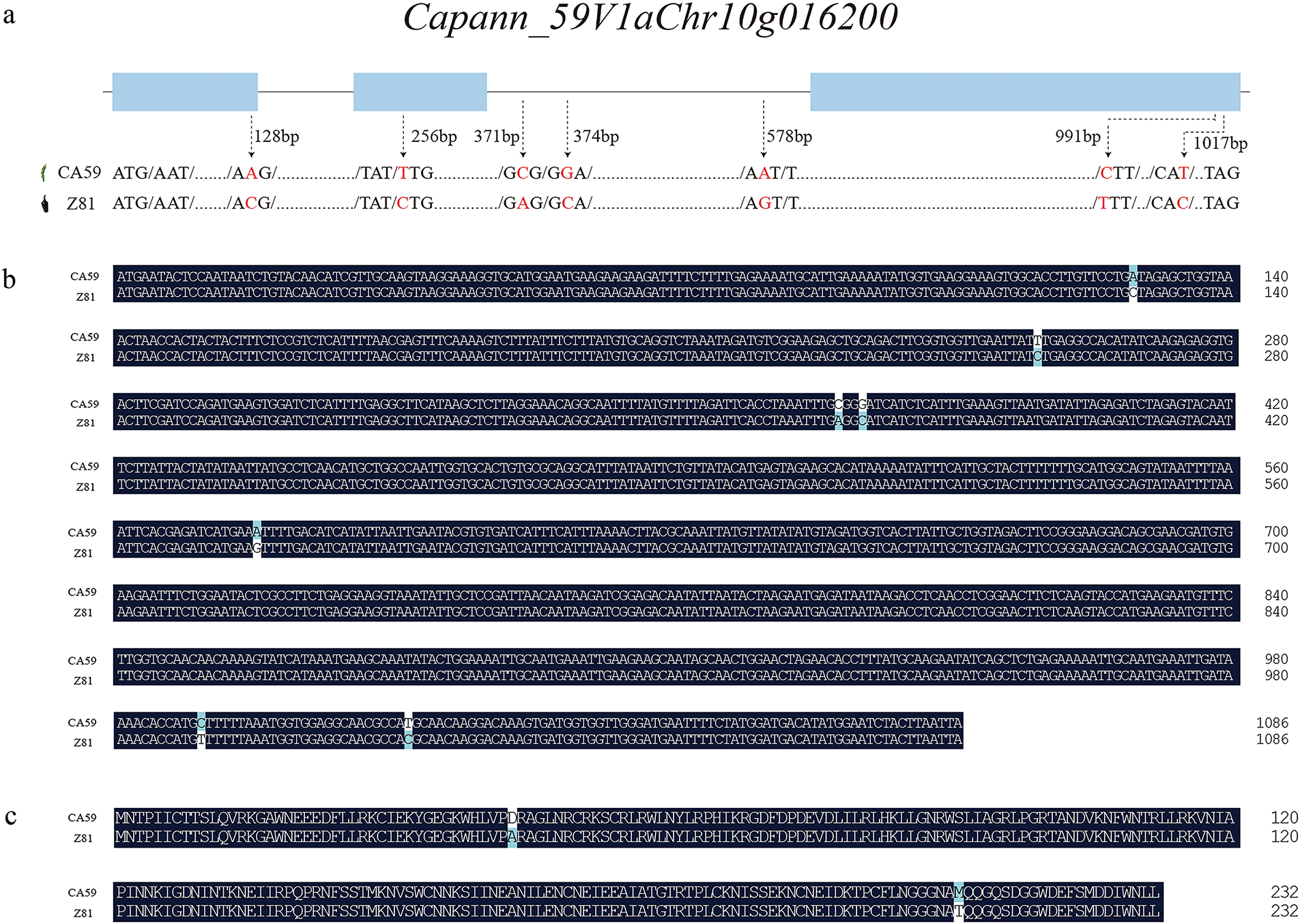

3.2.6 Sequence Analysis and Cloning of CaMYB1

The CaMYB1 gene is located at 185,765,157 Bp–185,766,243 bp on chromosome 10 and contains 3 exons with a coding length of 701 bp. Based on the genome resequencing of CA59 and Z81, it was found that the full-length CaMYB1 gene in pepper Z81 has a total of 7 SNPs. Out of these, 4 SNPs were found in the coding region of the gene, while 3 SNPs were found in the non-coding region (Fig. 6a).

Figure 6: Comparison of CaMYB1 gene sequences between CA59 and Z81. (a): Full-length sequence analysis of CaMYB1 gene. (b): Full-length DNA sequence comparison of CaMYB1 gene in capsicum CA59 and Z81. (c): Amino acid sequence comparison of CaMYB1 gene of capsicum CA59 and Z81

To confirm the validity of the SNP in the CaMYB1 gene sequence, the genomic DNA of capsicum CA59 and Z81 was amplified using PCR. The PCR products were subsequently recovered and purified, sequenced by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and the sequence was compared using DNAMAN software. Upon comparison, it was determined the Z81 had 7 SNPs at positions 128, 256, 371, 374, 578, 991, and 1017 bp when compared to CA59 (Fig. 6b). These SNPs led to 2 synonymous mutations and 2 non-synonymous mutations during the translation process (Fig. 6c).

3.2.7 Analysis of CaMYB1 Gene Promoter

The PlantCARE online database was used to examine the cis-acting elements present in the CaMYB1 promoter. The CaMYB1 promoter sequence had many cis-acting components, including CAAT-box and TATA-box, the basic promoter elements. Additionally, there are photoresponsive cis-acting elements, such as AE-box, Sp1, and salicylic acid-responsive cis-acting elements (TCA-element) (Table S8). An analysis of the promoter sequences of CaMYB1 in CA59 and Z81 in resequencing showed that pepper Z81 exhibited 11 Indel and 64 SNPs compared to pepper CA59 (Fig. S2). Consequently, alterations were observed in 15 cis-acting regions (Table S9). The CAAT-box, a fundamental promoter element, the meristem expression-related acting element, MYC, and the CTT motif decreased in numbers. Conversely, the salicylic acid-responsive cis-acting elements, TCA-element, and W box each increased by one. The presence of CAT-box and TGA-element, cis-acting elements connected with meristematic expression, was not observed in capsicum Z81. However, the presence of G-Box, two photoresponsive cis-acting elements not discovered in capsicum CA59, and ABRE, cis-acting elements implicated in the abscisic acid response, was observed.

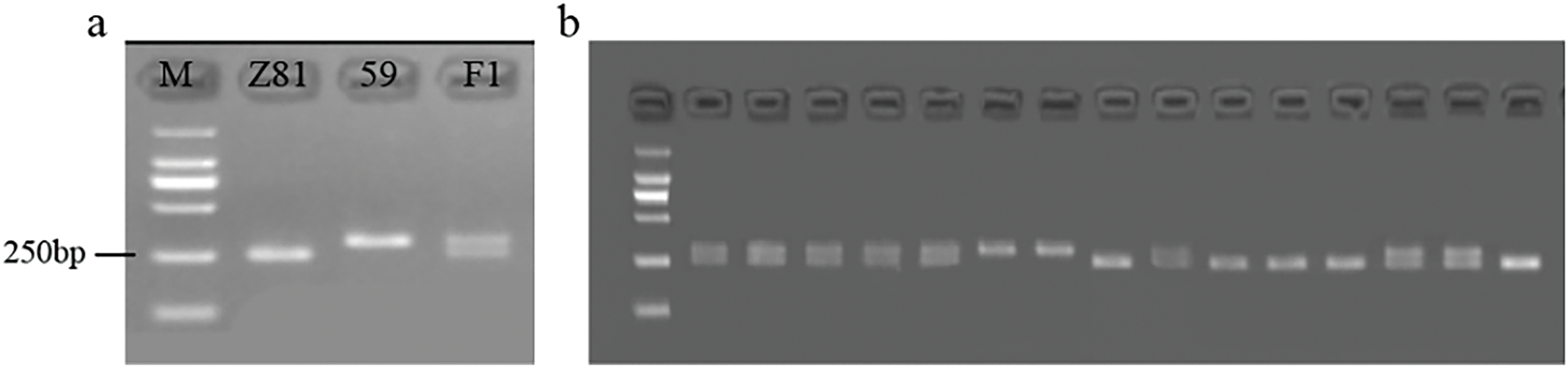

3.2.8 Molecular Marker Linked with Capsicum Purple Fruit

Upon conducting tests, it was discovered that InDel 67 exhibited polymorphism in both the parents and F1 generation (Fig. 7a). This polymorphism can be utilized to identify genotypes in the future F2 population. Additional investigation of 466 F2 individuals revealed that 105 had the same characteristics as the P1 strain (CA59). 126 individuals belonged to the same type as P2 (Z81). All 227 individuals exhibited identical characteristics as the F1 strain (Fig. 7b). In conjunction with the field phenotype, it was discovered that out of a population of 466 plants in the F2 generation, 462 plants exhibited known phenotypes. Among these, 427 plants were accurately classified phenotypically, resulting in a separation rate of 92.4%. This indicates that the molecular marker is strongly associated with the purple fruit characteristics of pepper and can effectively differentiate between purple fruit and green fruit plants.

Figure 7: Band distribution of InDel 67 markers in the population. (a): band type of InDel 67 in both parents and F1. (b): zonal distribution of InDel 67 in some plants in F2 generation

4.1 Genetic Analysis of Pepper Purple Fruit Traits

A significant quantity of anthocyanins accumulated during the green ripening stage of capsicum, resulting in the development of purple fruits in certain capsicum resources. The accumulation of anthocyanin is governed by the incomplete dominant A (Anthocyanin) gene and is additionally regulated by the MoA (Modifier of A) gene [15]. Previous research has demonstrated that the partial dominant features of purple to green and white can be observed in the outer pericarp of chili pepper [37]. The genetic population by crossbreeding purple pepper (HNUCA00054) with two green pepper varieties (HNUCA000233 and HNUCA00074) was created [37]. The P1, F1, and F2 fruit pigments were analyzed for their color at the green ripening stage using a chromometer. Using a mixed genetic model of major gene and polygene, multi-generation combination analysis was used to examine the genetic regularity of purple capsicum fruit in three hybrid populations. The study revealed that the variation in the L value and C value of the purple fruit color in young pepper is regulated by two pairs of major genes with additive-dominant-epistatic effects and an additive-dominant polygene model. Furthermore, the heritability of the major genes was shown to be at least 85.37%.

The presence of a purple color on the outer peel of capsicum is considered a quality attribute. Furthermore, purple dominates the green color on the outer peel [38]. A pepper variety named Chen12-4-1-1, which had purple stripes throughout the green ripening stage, and another pepper type called Zhongxian101-M-F9, which had green fruits [38]. These two varieties were employed to create an F2-generation isolated population. The research revealed that the ratio of purple-striped fruit to green fruit was 3:1, suggesting that a single dominant gene determines the presence of purple stripes [38]. The present investigation crossed plants bearing green and purple pepper fruits during the green ripening stage. The resultant F1 generation pepper fruits displayed purple color, and the F2 generation isolated population’s purple to green separation ratio was 3:1 (Fig. 2). This suggests that purple pepper was a dominant characteristic compared to green fruit, and a single gene governed it. These findings align with the outcomes of previous studies.

4.2 Gene Mapping of Pepper Purple Fruit Traits

The anthocyanin content of pepper leaves, petals, and pericarp was examined [39], along with the expression of structural, camyB1-like, and regulatory genes CaMYB113, CaMYB1, and CaMYB113. The findings indicated a positive correlation between structural genes and anthocyanin content in pepper leaves. Only CaMYB113 was expressed out of the three regulating genes. In this study, CaMYB1 was shown to be expressed in stems, leaves, petals, and fruits. The expression level in the Z81 pepper, which has purple leaves, petals, and fruits, was much higher than that of the CA59 pepper, which has green leaves, petals, and peel (Fig. 5). To find the gene CaAN3, which specifically causes the accumulation of anthocyanins in the pepper fruit, [40] utilized MAB2, characterized by purple fruits and green stems and leaves, and MAB1, characterized by green stems and leaves, to create an isolated population of the F2 generation. The BSR-seq analysis identified the target region of CaAN3 on chromosome 10, specifically within the 184.6–186.4 M range.

Among the candidate genes, Dem.v1.00043895 stood out as the strongest, CaMYB1. The expression level of CaMYB1 varied between the parents, and it was found to be specifically expressed in pepper fruit. This study utilized BSA-seq and genetic linkage map analysis to determine the location of the linkage interval associated with purple fruit in pepper. The interval was between InDel 67 and InDel 75 on chromosome 10, with a corresponding physical interval of 185,514,340–186,893,100 bp (Fig. 4). The LOD value for this linkage was 52.886. The rate of contribution was 50.61%. Within this region, there were a total of 4 genes. One of these genes, CaMYB1 (Capann_59V1aChr10g016200), was found in the candidate region and showed differential expression in both parents. This suggests that CaMYB1 is the crucial gene in the candidate region. Furthermore, the expression level of CaMYB1 in pepper Z81 was significantly higher than in pepper CA59.

This study diverges from prior research. Upon analyzing the amino acid sequence of the Dem. v1.00043895 gene in the parents and F2 generation of purple and green fruit plants, it was observed that at the 43rd amino acid residue of this gene, the green fruit plant had Alanine, whereas the purple fruit plant had Aspartic acid. However, unlike previous studies, the amino acid composition of green fruit (CA59) in this study is methionine (Met), while that of purple fruit (Z81) is threonine (Thr). Upon analyzing the promoter sequence of CaMYB1 (Capann_59V1aChr10g016200), it was discovered that there were multiple mutation sites in CA59 and Z81. These mutations did not follow a clear pattern, suggesting that the expression level of the CaMYB1 gene was low in the green immature pericarp of CA59. These events might have contributed to the elevated level of CaMYB1 expression in the purple immature pericarp of Z81.

Here, we measured the anthocyanin concentration in the outer pericarp of peppers Z81 and CA59. The anthocyanin concentration in Z81 was significantly higher than that in CA59 peppers. The genetic population was created from green fruit CA59 and purple fruit Z81. Capsicum purple fruit was linked to InDel 67 and 75 on chromosome 10, with a physical interval was 185,514,340 Bp–186,893,100 bp. The CaMYB1 (Capann_59V1aChr10g016200) gene in pepper Z81 had 7 SNPs, 4 of which were in the coding area, leading to 2 synonymous and 2 non-synonymous mutations. CaMYB1 is believed to be the primary candidate gene in the localized region. InDel 67 exhibits a high discerning power in distinguishing between purple and green fruit, achieving an overall separation rate of 92.4%. This finding holds significant potential in providing technical assistance for developing a molecular marker-assisted breeding system for purple fruit in peppers.

Acknowledgement: We are thankful to Aneesa Gul (Abdul Wali Khan University, Mardan, Pakistan) for revising the language of the manuscript.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A20230), the Guangdong Modern Vegetable Industry Technology System Project (2024CXTD08), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2024A1515010403), the Xizang Autonomous Region of Lhasa City Science and Technology Project (LSKJ202418) and the Guangdong Provincial Department of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (Selection and Breeding of New High-Yielding and High-Quality Pepper Varieties) (2024-NPY-00-020).

Author Contributions: Changming Chen and Ting Ye conceived and supervised the project. Rahat Sharif and Weiqin Mo provided some constructive suggestions for the research and revised the manuscript. Xinxin Liu, Yueyue Zhang and Rahat Sharif designed the study, performed key experiments, and wrote the manuscript. Zhenrong Li, Guiling Yang and Chao Song performed some experiments. Rahat Sharif, Xinxin Liu and Changming Chen revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.063349/s1.

Abbreviations

| Blast | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool |

| bp | Base pair |

| BSA | Bulked segregant analysis |

| BSA-seq | Bulked segregant analysis sequencing |

| cDNA | Complementary DNA |

| CDS | Coding-sequence |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| InDel | Insertion-Deletion |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| qRT-PCR | Real-time Quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

| QTL | Quantitative trait loci |

| SNP | Single nucleotide polymorphism |

References

1. Mondal A, Banerjee S, Terang W, Bishayee A, Zhang J, Ren L, et al. Capsaicin: a chili pepper bioactive phytocompound with a potential role in suppressing cancer development and progression. Phytother Res. 2024;38(3):1191–223. doi:10.1002/ptr.8107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Sharif R, Su L, Chen X, Qi X. Hormonal interactions underlying parthenocarpic fruit formation in horticultural crops. Hortic Res. 2022;9:uhab024. doi:10.1093/hr/uhab024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Sharif R, Raza A, Chen P, Li Y, El-Ballat EM, Rauf A, et al. HD-ZIP gene family: potential roles in improving plant growth and regulating stress-responsive mechanisms in plants. Genes. 2021;12(8):1256. doi:10.3390/genes12081256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Fei L, Liu J, Liao Y, Sharif R, Liu F, Lei J, et al. The CaABCG14 transporter gene regulates the capsaicin accumulation in Pepper septum. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;280:136122. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.136122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Marinov O, Nomberg G, Sarkar S, Arya GC, Karavani E, Zelinger E, et al. Microscopic and metabolic investigations disclose the factors that lead to skin cracking in chili-type pepper fruit varieties. Hortic Res. 2023;10(4):uhad036. doi:10.1093/hr/uhad036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Liu Z, Yang B, Zhang T, Sun H, Mao L, Yang S, et al. Full-length transcriptome sequencing of pepper fruit during development and construction of a transcript variation database. Hortic Res. 2024;11(9):uhae198. doi:10.1093/hr/uhae198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Thomas HR, Gevorgyan A, Hermanson A, Yanders S, Erndwein L, Norman-Ariztía M, et al. Graft incompatibility between pepper and tomato elicits an immune response and triggers localized cell death. Hortic Res. 2024;11(12):uhae255. doi:10.1093/hr/uhae255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Sun M, Voorrips RE, van Kaauwen M, Visser RGF, Vosman B. The ability to manipulate ROS metabolism in pepper may affect aphid virulence. Hortic Res. 2020;7(1):457. doi:10.1038/s41438-019-0231-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Yang Y, Li Y, Guang Y, Lin J, Zhou Y, Yu T, et al. Red light induces salicylic acid accumulation by activating CaHY5 to enhance pepper resistance against Phytophthora capsici. Hortic Res. 2023;10(11):uhad213. doi:10.1093/hr/uhad213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Ahmad S, Ali S, Shah AZ, Khan A, Faria S. Chalcone synthase (CHS) family genes regulate the growth and response of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) to Botrytis cinerea and abiotic stresses. Plant Stress. 2023;8(8):100159. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2023.100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhou H, Deng Q, Li M, Cheng H, Huang Y, Liao J, et al. R2R3-MYB transcription factor CaMYB5 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in pepper fruits. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;308:142450. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.142450. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Li Z, Ahammed GJ. Plant stress response and adaptation via anthocyanins: a review. Plant Stress. 2023;10(5):100230. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2023.100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Sandoval-Ramírez BA, Catalán Ú, Llauradó E, Valls RM, Salamanca P, Rubió L, et al. The health benefits of anthocyanins: an umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies and controlled clinical trials. Nutr Rev. 2022;80(6):1515–30. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuab086. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Lu Z, Wang X, Lin X, Mostafa S, Zou H, Wang L, et al. Plant anthocyanins: classification, biosynthesis, regulation, bioactivity, and health benefits. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2024;217(4):109268. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2024.109268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Sharma H, Sharma P, Kumar A, Chawla N, Dhatt AS. Multifaceted regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in plants: a comprehensive review. J Plant Growth Regul. 2024;43(9):3048–62. doi:10.1007/s00344-024-11306-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhou Y, Wu W, Sun Y, Shen Y, Mao L, Dai Y, et al. Integrated transcriptome and metabolome analysis reveals anthocyanin biosynthesis mechanisms in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) leaves under continuous blue light irradiation. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):210. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-04888-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhou Y, Mumtaz MA, Zhang Y, Shu H, Hao Y, Lu X, et al. Response of anthocyanin accumulation in pepper (Capsicum annuum) fruit to light days. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(15):8357. doi:10.3390/ijms23158357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wang Y, Liu S, Wang H, Zhang Y, Li W, Liu J, et al. Identification of the regulatory genes of UV-B-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in pepper fruit. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(4):1960. doi:10.3390/ijms23041960. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Ma X, Liang G, Xu Z, Lin C, Zhu B. CaMYBA-CaMYC-CaTTG1 complex activates the transcription of anthocyanin synthesis structural genes and regulates anthocyanin accumulation in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) leaves. Front Plant Sci. 2025;16:1538607. doi:10.3389/fpls.2025.1538607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Filyushin MA, Shchennikova AV, Kochieva EZ. The relationship between the anthocyanin content with the expression level of the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway regulatory and structural genes in pepper Capsicum L. Species Russ J Genet. 2023;59(9):900–10. doi:10.1134/s1022795423090041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang H, Liu Z, Wang Y, Mu S, Yue H, Luo Y, et al. A mutation in CsDWF7 gene encoding a delta7 sterol C-5(6) desaturase leads to the phenotype of super compact in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2024;137(1):20. doi:10.1007/s00122-023-04518-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang K, Li Y, Zhu W, Wei Y, Njogu MK, Lou Q, et al. Fine mapping and transcriptome analysis of virescent leaf gene v-2 in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:570817. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.570817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Song Z, Zhong J, Dong J, Hu F, Zhang B, Cheng J, et al. Mapping immature fruit colour-related genes via bulked segregant analysis combined with whole-genome re-sequencing in pepper (Capsicum annuum). Plant Breed. 2022;141(2):277–85. doi:10.1111/pbr.12997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wu L, Wang H, Liu S, Liu M, Liu J, Wang Y, et al. Mapping of CaPP2C35 involved in the formation of light-green immature pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) fruits via GWAS and BSA. Theor Appl Genet. 2022;135(2):591–604. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-894733/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kim DH, Kim BD. The organization of mitochondrial atp6 gene region in male fertile and CMS lines of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Curr Genet. 2006;49(1):59–67. doi:10.1007/s00294-005-0032-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Arnedo-Andrés M, Gil-Ortega R, Luis-Arteaga M, Hormaza J. Development of RAPD and SCAR markers linked to the Pvr4 locus for resistance to PVY in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Theor Appl Genet. 2002;105(6):1067–74. doi:10.1007/s00122-002-1058-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Blum E, Mazourek M, O’Connell M, Curry J, Thorup T, Liu K, et al. Molecular mapping of capsaicinoid biosynthesis genes and quantitative trait loci analysis for capsaicinoid content in Capsicum. Theor Appl Genet. 2003;108(1):79–86. doi:10.1007/s00122-003-1405-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Christodoulou MC, Orellana Palacios JC, Hesami G, Jafarzadeh S, Lorenzo JM, Domínguez R, et al. Spectrophotometric methods for measurement of antioxidant activity in food and pharmaceuticals. Antioxidants. 2022;11(11):2213. doi:10.3390/antiox11112213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Feng S, Zhou L, Sharif R, Diao W, Liu J, Liu X, et al. Mapping and cloning of pepper fruit color-related genes based on BSA-seq technology. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1447805. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1447805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Chen Y, Chen Y, Shi C, Huang Z, Zhang Y, Li S, et al. SOAPnuke: a MapReduce acceleration-supported software for integrated quality control and preprocessing of high-throughput sequencing data. GigaScience. 2017;7(1):gix120. doi:10.1093/gigascience/gix120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–60. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Liao Y, Wang J, Zhu Z, Liu Y, Chen J, Zhou Y, et al. The 3D architecture of the pepper genome and its relationship to function and evolution. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):3479. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-31112-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Mansfeld BN, Grumet R. QTLseqr: an R package for bulk segregant analysis with next-generation sequencing. Plant Genome. 2018;11(2):180006. doi:10.3835/plantgenome2018.01.0006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Majeed A, Johar P, Raina A, Salgotra RK, Feng X, Bhat JA. Harnessing the potential of bulk segregant analysis sequencing and its related approaches in crop breeding. Front Genet. 2022;13:944501. doi:10.3389/fgene.2022.944501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Buchfink B, Reuter K, Drost HG. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2021;18(4):366–8. doi:10.1038/s41592-021-01101-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Cingolani P, Platts A, le Wang L, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly. 2012;6(2):80–92. doi:10.4161/fly.19695. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Tan H, Li L, Tie M, Lu R, Pan S, Tang Y. Transcriptome analysis of green and purple fruited pepper provides insight into novel regulatory genes in anthocyanin biosynthesis. PeerJ. 2024;12:e16792. doi:10.7717/peerj.16792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Li N, Liu Y, Yin Y, Gao S, Wu F, Yu C, et al. Identification of CaPs locus involving in purple stripe formation on unripe fruit, reveals allelic variation and alternative splicing of R2R3-MYB transcription factor in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1140851. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1140851. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Li Z, Ahammed GJ. Hormonal regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis for improved stress tolerance in plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023;201:107835. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.107835. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Byun J, Kim TG, Lee J-H, Li N, Jung S, Kang BC. Identification of CaAN3 as a fruit-specific regulator of antho-cyanin biosynthesis in pepper (Capsicum annuum). Theor Appl Genet. 2022;135(7):2197–211. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1283047/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools