Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Physiological and Molecular Mechanisms of Freezing in Plants

1 Crop and Horticultural Science Research Department, South Kerman Agricultural and Natural Resources Research and Education Center, AREEO, Jiroft, 78617-46411, Iran

2 Department of Agronomy and Plant Breeding, Agriculture Institute, Research Institute of Zabol, Zabol, 98613-35856, Iran

* Corresponding Author: Ali Salehi Sardoei. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Metabolic Mechanisms of Plant Responses to Stress)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(6), 1601-1630. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.064729

Received 22 February 2025; Accepted 26 May 2025; Issue published 27 June 2025

Abstract

The ability of plants to tolerate cold is a complex process. When temperatures drop or freeze, plant tissues can develop ice, which dehydrates the cells. However, plants can protect themselves by preventing ice formation. This intricate response to cold stress is regulated by hormones, photoperiod, light, and various factors, in addition to genetic influences. In autumn, plants undergo morphological, physiological, biochemical, and molecular changes to prepare for the low temperatures of winter. Understanding cellular stress responses is crucial for genetic manipulation aimed at enhancing cold resistance. Early autumn frosts or late spring chills can cause significant damage to plants, making it essential to adapt in autumn to survive winter conditions. While the general process of acclimatization is similar across many plant species, variations exist depending on the specific type of plant and regional conditions. Different plant organs exhibit varying degrees of damage from cold stress, and by applying agricultural principles, potential damage can be largely controlled. Timely reinforcement and stress prevention can minimize cold-related damage. Research has shown that in temperate climates, low temperatures restrict plant growth and yield. However, the intricate structural systems involved remain poorly understood. Over the past decade, studies have focused on the molecular mechanisms that enable plants to adapt to and resist cold stress. The gene signaling system is believed to play a crucial role in cold adaptation, and researchers have prioritized this area in their investigations. This study critically examines plant responses to cold stress through physiological adaptations, including calcium signaling dynamics, membrane lipid modifications, and adjustments in antioxidant systems. These mechanisms activate downstream gene expression and molecular functions, leading to key resistance strategies. Additionally, we explore the regulatory roles of endogenous phytohormones and secondary metabolites in cold stress responses. This review aims to enhance our foundational understanding of the mechanisms behind plant cold adaptation.Keywords

Abiotic stresses widely affect the growth and reproduction of plants. Following these stresses, morphological, biochemical, and molecular physiological changes occur in the plant, and through these steps, the plant will adapt to deal with the stress conditions [1]. High and low-temperature stresses are significant non-biological factors that influence plant cultivation and play a critical role in plant production. Low temperatures can adversely impact growth and yield, significantly reducing the harvest of various plants [2]. In general, the tolerance of plants in low temperatures (0°C–15°C) and freezing (below 0°C) are different [3]. Short-term cold exposure helps plants adapt to low temperatures; this process of developing a tolerance to cold is called cold adaptation [4]. The capacity of a plant to withstand low temperatures (0°C–15°C) without causing harm to its tissue is known as cold tolerance [5]. Biochemical and physiological changes occur during this process, leading to significant alterations in gene expression, membrane lipids, and the accumulation of small molecules [6]. When plants are subjected to freezing temperatures, their tolerance to physical and physicochemical changes will increase due to cold adaptation [7].

Plants employ key physiological strategies to mitigate freezing damage, emphasizing membrane stability and osmotic regulation. The plasma membrane, highly sensitive to temperature fluctuations, modifies its lipid composition by increasing the levels of unsaturated fatty acids. This adaptation helps preserve membrane fluidity and prevents rigidity in cold conditions [8,9]. Extracellular ice formation, a typical reaction to subzero temperatures, causes osmotic stress by extracting water from cells. This process can result in dehydration and may lead to membrane rupture [8]. Cold-acclimated plants address this challenge by accumulating osmolytes such as proline and sugars. These compounds help stabilize cellular structures and minimize ice crystal formation [9]. These adaptations work together to maintain membrane integrity and metabolic function in freezing conditions [8,9].

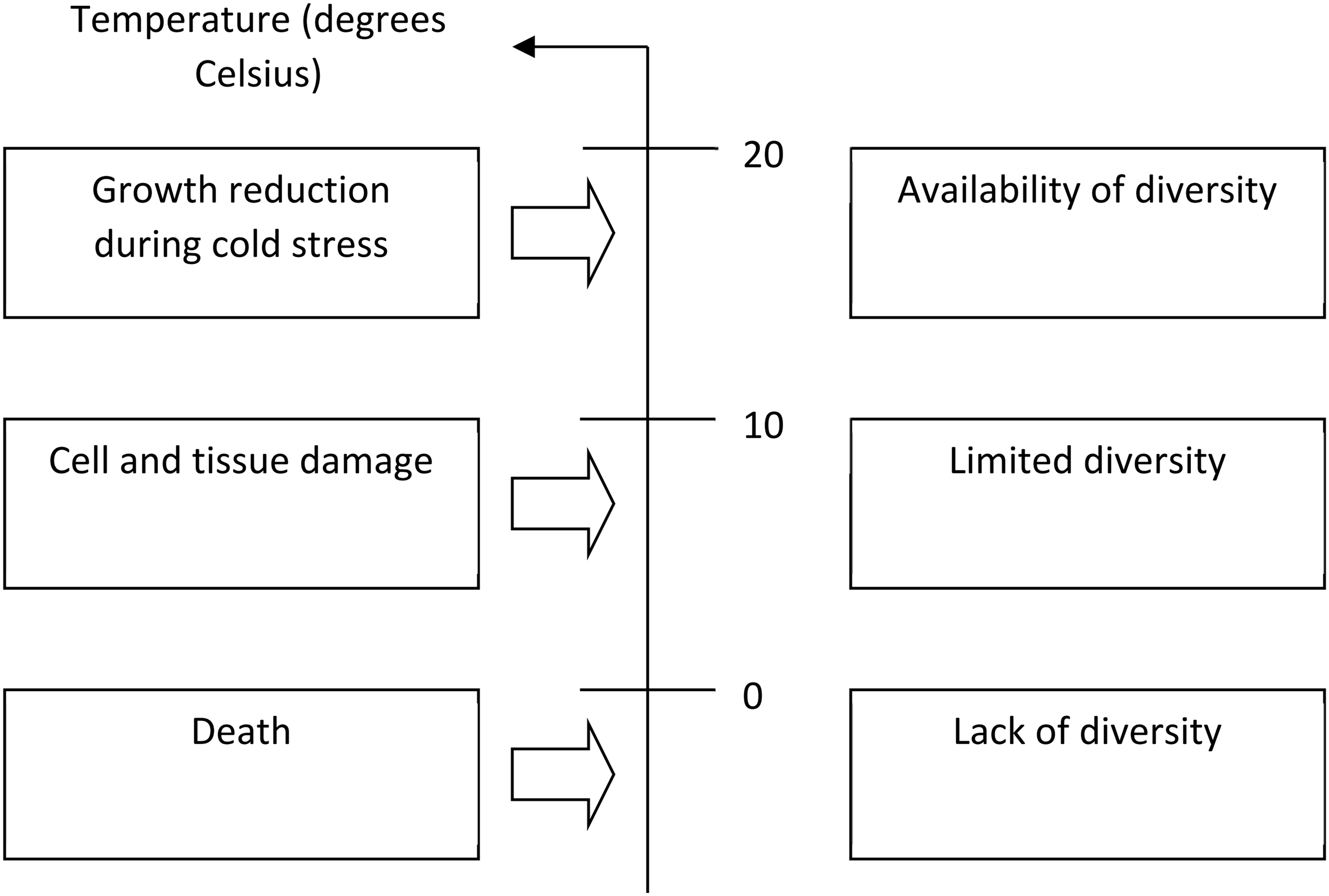

At the molecular level, plants initiate the ICE1-CBF-COR transcriptional cascade, a key pathway in their cold response. ICE1 activates CBF transcription factors, which then upregulate COR genes that encode cryoprotective proteins and enzymes [9]. At the same time, calcium signaling triggers downstream responses, such as MAPK cascades and mechanisms for maintaining ROS homeostasis, which help balance oxidative stress during freezing [10]. Phytohormones such as abscisic acid (ABA) and brassinosteroids (BRs) play a crucial role in modulating these pathways. ABA promotes stomatal closure and the synthesis of osmolytes, whereas BRs are involved in regulating CBF expression and the scavenging of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [9,10]. Epigenetic modifications and post-translational adjustments refine gene expression, allowing for precise control of cold adaptation mechanisms [9]. These interconnected networks facilitate coordinated molecular responses that help maintain plant viability under freezing stress. As temperatures fall below a certain threshold, the severity of growth retardation, metabolic dysfunction, and tissue damage increases (Fig. 1). Additionally, Fig. 1 shows that there is genetic variation in resistance and susceptibility throughout the entire temperature range below 20°C.

Figure 1: Diagram showing the levels of damage to plants at different temperatures from 0 to 20 degrees Celsius

Plants respond to freezing stress through a combination of physiological and molecular mechanisms aimed at stabilizing membranes, regulating osmotic balance, and modulating gene expression. Physiologically, cold acclimation triggers changes in membrane lipid composition, increasing unsaturated fatty acids to maintain fluidity and prevent damage from ice formation. Simultaneously, plants accumulate osmolytes, such as proline and sugars, to stabilize cellular structures and mitigate dehydration caused by ice forming outside the cells. At the molecular level, the ICE1-CBF-COR transcriptional cascade serves as a crucial regulatory pathway, activating cryoprotective genes that enhance freezing tolerance [9,11]. Calcium signaling and MAPK cascades enhance these responses, while phytohormones like ABA and jasmonic acid refine adaptive processes, including stomatal regulation and the production of antifreeze proteins (AFPs) [9,11,12]. Plant antifreeze proteins (AFPs), unlike their animal counterparts, demonstrate strong recrystallization inhibition due to their hydrophilic ice-binding domains, which effectively restrict ice crystal growth and minimize cellular damage [12]. Recent studies that combine field and laboratory experiments, including those on Camellia oleifera, have identified cold-responsive genes and highlighted the significance of cold acclimation in perennial species [13]. Advances in genetic engineering are now using these insights to create cold-resistant crops by integrating multi-omics data with findings from model systems to enhance stress resilience [9,13].

Recent advances in our understanding of the physiological and molecular mechanisms that allow plants to detect, respond to, and survive freezing temperatures have shed light on both their adaptations and regulatory networks. Key areas of research include membrane stability, lipid composition, antioxidant defenses, osmolyte accumulation, and the roles of phytohormones such as abscisic acid and brassinosteroids in cold adaptation. At the molecular level, attention is focused on the ICE1-CBF-COR transcriptional cascade and related signaling pathways that regulate gene expression in response to low temperatures, alongside the integration of epigenetic modifications and post-translational regulation [8,9]. This work makes novel contributions by synthesizing the latest findings in multi-omics and genetic engineering. It emphasizes the interactions between signaling networks, identifies new regulatory factors such as CAMTA and BZR1, and explores the practical application of these insights in breeding cold-tolerant crops. By integrating these emerging concepts, the review clarifies the complexity of plant freezing responses and suggests actionable strategies for enhancing crop resilience against climate change.

Because they lack systems to tolerate cold, tropical and subtropical plants are permanently damaged by low temperatures. Plants have a sophisticated process that involves many metabolic pathways in various cells to tolerate low temperatures [14].

Stress from low temperatures causes the expression of several genes at the molecular level. Cold-responsive genes are a set of genes that have been discovered and characterized as being involved in the processes of adaptation to low-temperature stress [15]. Expression of genes regulated by low temperature is effective both on cold tolerance and cold adaptation [16,17]. The activity of genes that regulate enzyme function and protein synthesis is essential for adaptation and tolerance to low temperatures. These genes activate at varying times and intensities in response to cold stress. Understanding the general mechanisms behind cold resistance can provide a foundation for applied research for scientists.

2 Mechanism of Cold Perception

Several primary sensors contribute to the perception of cold in plants. Each sensor can detect specific aspects of cold stress and may operate through distinct pathways for transmitting cold-related signals. Plants can sense low temperatures by detecting changes in the physical properties of their membranes, as membrane fluidity decreases under cold stress. The hardening of plasma membranes is enhanced by agents such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Even during natural and gradual temperature changes, increased membrane hardening can suppress the expression of COR genes. Conversely, the application of membrane fluidizers can prevent the induction of COR gene expression at low temperatures [18]. In Arabidopsis, the activation of diacylglycerol kinase (DAGK) is the first event that occurs in the first few seconds after exposure to cold. This shows that the activation of the DAGK pathway is correlated with changes in membrane fluidity. The stress-dependent activity of calcium ion mechanical stress-sensitive channel (MCC) increases at low temperatures and these calcium channels can be considered good candidates for calcium ion entry, which is necessary for the activation of the DAGK pathway. The cytoskeleton may also act as a low-temperature sensor [5].

The close relationship between the plasma membrane and the plant cytoskeleton provides a crucial framework for comprehending and directing signals. Several message transmission mechanisms, such as the cold stress message transmission pathway, ultimately target microtubules and microfilaments [6]. It seems that microtubules and actins play the main role in opening the calcium channel [19].

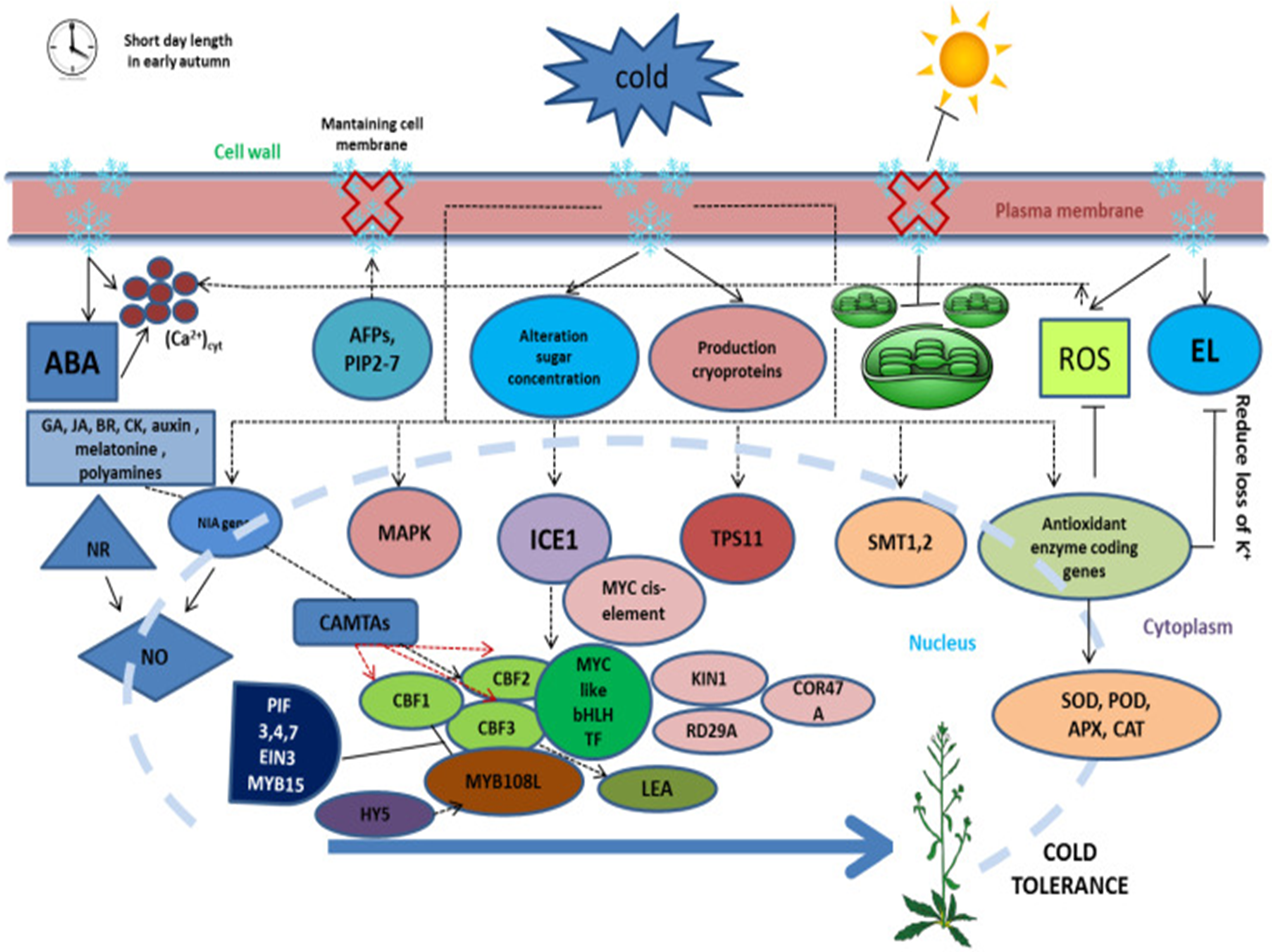

Phospholipase PLD (D) is also involved in directing the messages caused by stress. PLD is one of the plasma membrane proteins (Fig. 2). This protein may be responsible for connecting microtubules to the plasma membrane [20]. In tobacco and Arabidopsis, it functions as a structural connector and communication link between the plasma membrane and the cytoskeleton. Research has shown that the activation of certain COR genes is inhibited by the reduction of phosphatidic acid produced by phospholipase D (PLD). PLD plays a crucial role in stabilizing the cytoskeleton and its attachment to the plasma membrane through the stress-dependent calcium ion activation pathway [19].

Figure 2: Early autumnal short-day plants’ cold tolerance mechanism, which signals the beginning of cold stress [22]. This figure is distributed under CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Along with the plasma membrane, the chloroplast may contribute to sensing environmental temperature. In low-temperature conditions, an imbalance occurs between the chloroplast’s ability to capture light energy and the energy lost through metabolic activities. This imbalance increases pressure on photosystem II, ultimately leading to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [18,21]. Furthermore, plants may be able to sense low temperatures through the suppression of protein phosphatase activity and the phosphorylation of proteins in response to cold. The control of cold tolerance and cold message transmission is mediated by a group of MAPKs (Fig. 2).

MPK6 and MPK4 of Arabidopsis are phosphorylated by MKK2 when faced with cold, and the overexpression of MKK2 is necessarily activated in plants that exhibit cold tolerance and upregulation of CBF/DREBs [23]. Cold activation of alfalfa SAMK MPK requires membrane stiffening. Activation of SAMK at low temperatures is inhibited by blocking the intensity of extracellular calcium ion flow and stopped by CDPK antagonists. It has been found that membrane hardening requires calcium ion influx and CDPKs to activate the MAPK complex in winter rye plant [24]. Along with these results, several signaling pathways stimulate the production of COR protein [18].

Several theories have been proposed to explain the mechanism of frost damage. One primary theory suggests that frostbite occurs due to the accumulation of toxic and metabolic substances resulting from a metabolic imbalance induced by cold temperatures. While methods like intermittent heating, which help eliminate these accumulated toxins, have proven effective, no specific combination of frozen tissues has been identified to confirm the presence of particular toxic substances [25]. Another theory is the difference in lipids and types of fatty acids in plants, which causes differences in their sensitivity to freezing. It has been suggested that if membrane lipids are affected by cold temperatures, membrane permeability should increase. Liquid materials that leak from the cell cause part of the fruit to spoil, provide a suitable environment for the growth of pathogenic and non-pathogenic agents, and cause browning of the damaged tissue. Evaporation of water from damaged areas, especially if they are close to the epidermis, causes the epidermis to sink and create holes in the skin [24,25].

Direct cold injury or initial response to cold is physical. It is assumed that low temperatures cause changes in the physical properties of the cell membrane. This damage causes indirect damage [26].

In certain species sensitive to freezing, exposure to cold leads to changes in membrane fluidity. This alteration results in several secondary responses, including a loss of membrane stiffness, leakage of electrolytes, disruption of the internal structure of cells, and changes in enzyme activity [27]. These secondary responses eventually cause frostbite symptoms to appear.

4 Metabolic and Structural Changes during Cold Resistance

Plant tissues and cells go through a variety of modifications during cold acclimation that enable the cells to operate at low temperatures and tolerate freezing stress [6]. Adaptation to cold is associated with the reduction of tissue water and the accumulation of antifreeze compounds such as soluble carbohydrates and proteins [28]. Biochemical alterations in cell membranes include changes in protein quality concomitant with increased fluidity, phospholipid enrichment, and saturation of fatty acids [29]. The structural changes in the cell include the strengthening of the cytoplasm and a decrease in the size of the vacuole [30].

In stem bark cells of deciduous trees, chloroplasts accumulate throughout the cell instead of being uniformly distributed [31]. When Bartlett pear cell suspension culture is cold-acclimated to 2°C, changes in soluble intercellular polysaccharides will occur [32]. The accumulation of relatively small, neutral polysaccharides increased, while the levels of higher molecular weight pectic polysaccharides decreased. This reduction in pectic polysaccharides may result from inhibited synthesis or degradation at low temperatures. Additionally, callus deposition was observed in the cell wall, which helps stabilize this area against disturbances caused by freezing.

5 Effects of Cold Stress at the Cellular Level

The effects of cold stress and the changes caused by the occurrence of stress also occur at the cellular level, which is reflected in the higher levels of plant organs [33]. There is nearly unanimous agreement on the primary damage that cold stress inflicts on organelle surfaces and cell membranes. However, different cellular activities exhibit varying sensitivities to temperature. The lethal temperature threshold is a specific characteristic of each species and varies depending on the organ and plant tissue involved [34]. When the temperature reaches the threshold, the cell structures and their activities may be suddenly damaged, so that the protoplast is immediately destroyed, and cell death may occur due to damage to the membranes and disruption of the cell’s energy supply. Examining cellular reactions against cold shows phenomena such as loss of turgor pressure, vacuolization, reduction of cytoplasmic flow, and general disorder in organs [35].

Lowering the temperature by affecting the cell membrane, intracellular water, the activity of enzymes, and biochemical processes, affects the physiological activities of plants and causes less metabolic energy to be available to the plant [36]. In the presence of cold, the absorption of water and nutrients by the plant is limited, less biosynthesis occurs, and growth stops. The cell membrane is the first place that is exposed to adverse environmental factors [5,36]. In the conditions of cold stress, the activity of the structural parts of the membrane, including the activity of the enzymes that stick to the membrane and the enzymes that are present in the membrane and are considered the main part of the membrane structure, are disturbed [37].

The cell membrane has a special structure and chemical composition that can protect the cell from adverse environmental factors while understanding and identifying the conditions outside the cell [38]. To understand the effect of cold on the membrane, it is necessary to know the structure and composition of the cell membrane correctly and accurately. In terms of chemical composition, the cell membrane is mainly composed of proteins and phospholipids, but it also contains other compounds such as sterols, carbohydrates, and sulfolipids [23]. Sterols are also a part of the membrane structure, whose presence causes the stability of the hydrophobic part of the fat. The higher the number of sterols in the membrane, the higher the cold resistance of the plant [35].

Proteins constitute 50% of cell membrane composition, making their molecular stability crucial for maintaining membrane integrity. The transfer of substances and ions across the membrane relies on pumps, carriers, and channels, all of which are composed of proteins. The physical properties of fats within the membrane are significantly influenced by the activity of integral proteins, including those that form channels. These channel-forming proteins play a vital role in transporting ions and regulating soluble substances and enzymes associated with metabolism [39].

From the structural point of view, the proteins forming the channels in the membrane are seen indented inside the phospholipid layers. Phospholipids in the membrane are arranged in a bilayer facing each other in such a way that their non-polar ends are next to each other and their polar ends are far from each other and on both sides of the membrane [40]. Both sides of the membrane carry an electric charge. Calcium, being positively charged, forms a bond with the negative charges of proteins and phospholipids, acting as an electrical bridge that strengthens the cell membrane. The strength of the membrane directly influences its semi-permeability. In cold conditions, some calcium ions detach from the cell membrane, resulting in a loss of its semi-permeable properties [39,40].

Membrane proteins and phospholipids are not fixed in the membrane but are constantly moving and fluctuating. The movement speed of proteins is about 10,000 to 10,000 times lower than the movement of phospholipids [41]. Therefore, the cell membrane does not have a solid state and is in the form of a liquid crystal under normal conditions. This crystal has elasticity and acts as a fluid [42]. This movement of proteins increases the contact of the membrane with ions and hormones and plays an important role in the permeability and semi-permeability of the membrane [43].

The fluidity of a membrane is influenced by its chemical composition, particularly the ratio of saturated to unsaturated fatty acids, the types of chemical bonds present, and their locations. These factors are regulated by both plant genetic traits and environmental conditions. Research indicates that the disruption of the membrane caused by stress—especially as its intensity and duration increase—takes precedence over other cellular disorders. Consequently, during cold stress, the membrane transitions from a liquid crystal state to a solid-gel state, resulting in a loss of permeability [44]. In this condition, the physical state of the membrane changes, and as a result, the balance of the cell membrane is disturbed more often than in other cases. The change in the physical state of the membrane causes a decrease in the selective permeability of the membrane and its usual activity, leading to a disruption in the activities of cells and organs [45].

The most important hypothesis about cold damage is the hypothesis presented by Lyons Riesen based on the fluid state of the membrane and the effect of temperature reduction on the cell membrane. This theory is called the lipid phase change theory or Lyons-Riesen theory [46]. According to Lyons-Riesen theory or lipid phase change hypothesis, the first thermal sensor in the cell is the degree of fluidity of membrane lipids. Also, the first event that can happen in a cold-sensitive cell after being exposed to cold is a change in state or change in the molecular order of the lipid mass of that cell’s membrane [46]. According to this hypothesis, the damage caused by cold stress is somehow related to molecular changes in the order of membrane lipids, and these changes are also related to the way the membrane works [15,24]. Therefore, the rapid loss of water and leakage of ions as a result of cold damage can be the result of changing the state of plasma membrane lipids, which leads to an increase in membrane permeability. Probably, such changes are not related to critical limits and specific temperature thresholds but mostly occur in the range of stressful temperatures [22].

Fatty acids solidify at low temperatures due to either a decrease in the number of saturated bonds or an increase in chain length. The double-layer membrane’s lipid content has a significant impact on how it responds to temperature. The plant becomes less resistant to cold as the amount of unsaturated fatty acids in the membrane drops because this results in the membrane losing its fluid state and water permeability [47].

A decrease in cold resistance has been observed in several plant species due to a reduction in unsaturated fatty acids in their leaves. In cold-sensitive plants, the fatty acids in the membranes are more saturated, leading them to become semi-crystalline and solid at temperatures above zero degrees Celsius. This loss of membrane fluidity hampers the normal functioning of protein components, disrupting the transfer of soluble substances in and out of cells. As a result, energy transfer is impeded, and enzyme-dependent metabolism is negatively affected [5]. Therefore, the higher the degree of saturation of fatty acids in the membrane, the higher the temperature required to change the state in the membrane. Usually, plants from tropical regions have more saturated fatty acids compared to plants from colder regions [48]. Also, the amount of unsaturated fatty acids in the mitochondria of cold-resistant plants is higher compared to the mitochondria of cold-sensitive plants. The degree of resistance of cultivars to cold depends on their degree of leakage, so through the degree of permeability of the membrane of air cells of leaves and stems of plants, the degree of tolerance of different plant cultivars to cold stress can be determined [5].

A plant’s tolerance to cold decreases as its leakage rate increases. Conversely, a plant with a higher resistance of its membrane to transitioning from a liquid crystal to a solid-gel state is more resilient. When a plant experiences cold stress, the alteration in the membrane affects the activity of the enzymes present. These changes become more pronounced at temperatures that induce shifts in the state of the cell membrane [28]. Enzymes are active only in certain temperature ranges due to having a special temperature range. Outside the specific temperature range of a specific enzyme, proteins may accumulate in the plant cell, and tearing of the membranes destroys the cellular space [49]. This can cause a change in the kinetic energy or the allocation of the precursor of a key regulating enzyme, which itself causes damage caused by cold. The creation of these enzymatic changes can be independent of any change in fat state and therefore can be used as a primary approach in the development of damage [50].

6 Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are created when environmental stressors including low temperature, salt, and dryness cause molecular oxygen to decrease [51]. Reactive oxygen species are present as toxic products and message transfer molecules in plant biology [52]. At least 152 genes in Arabidopsis are part of a network involved in the synthesis of reactive oxygen species (ROS). This dynamic network encodes proteins responsible for both the production and degradation of ROS [53]. Evidence derived from cDNA microarray technology indicates that H2O2 of different reactive oxygen species increases the expression of certain genes while suppressing the expression of others [54]. The Arabidopsis frol mutant shows elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), reduced expression of COR genes, and heightened sensitivity to freezing and cold. The mitochondrial respiratory electron transport chain includes the iron-sulfur (Fe-S) component of the NADH dehydrogenase complex, which is encoded by the FRO1 gene. This condition leads to the production of high amounts of ROS [55].

Another Arabidopsis mutant called chy1, which lacks peroxisomal b-hydroxyisobutyryl-CoA hydrolase, is necessary for the buildup of elevated ROS levels, valine catabolism, and beta-oxidation of fatty acids. The chy2 mutant exhibited decreased CBF gene induction, which impairs freezing and cold tolerance [56,57]. ROS detection is linked to downstream signaling pathways involving calcium and calcium-binding proteins like calmodulin. Phosphatidic acid buildup [20] and the induction of unsaturated fatty acid peroxidation in membrane lipids [58] are caused by the activation of G-proteins and the transmission of phospholipid messages. Redox-responsive proteins like transcription factors and protein kinases can also be directly activated by ROS signals [55]. There is evidence of activated bipolar calcium channel upregulation in other investigations [59]. ROS is responsible for both the activation of the MAPK complex and Zat12. The majority of cellular functions, including the cold response, presumably use ROS as a metabolic signal [35].

Plants’ ability to cold stress tolerant depends on their defense mechanisms’ capacity to activate degrading enzymes more, as cold stress is linked to oxidative stress [35]. For instance, it has been demonstrated that when ROS build up, cytochrome C oxidase (COX) expression and activity decrease, while periodic oxidase (AOX) induction and activation increase [60]. It has been demonstrated that in Arabidopsis thaliana, overexpression of AOX lowers oxidative stress at low temperatures [61].

7 Growth Indicators Adapted to Cold

Many studies have evaluated cold tolerance in various plant species. A drop in temperature during the initial stage of seedling growth, followed by a decrease during the reproduction stage, leads to reduced establishment and lower seed production. Consequently, this results in diminished overall performance of the plants [62–64]. In general, a plant’s susceptibility to cold stress determines when cold symptoms will manifest, and this varies from plant to plant. After the plant is exposed to cold, it takes 48–72 h for the symptoms of cold damage to appear. The phenotypic symptoms of plants exposed to cold, such as reduced leaf area, wilting, and tissue necrosis (tissue death), are similar. Furthermore, plants’ ability to reproduce is hampered by cold stress, which results in sterile flowers [65].

Cold stress stops the germination, weak growth, and development of the seedling, turns the color of the leaves yellow, and causes the leaves to wither and wrinkle. The effect of cold on the reproductive stage of plants will cause a delay in the opening of the flower, followed by the sterility of the pollen (which seems to be one of the key factors in the yield of the crops) [14]. Low temperatures that can impact plant reproduction, specifically those above freezing at zero degrees Celsius, are referred to as the frost range. The effects of cold stress on plants vary depending on its intensity and duration. Cold damage is most apparent during the reproductive and flowering stages because reproductive tissues are particularly sensitive to low temperatures [35].

8 Physiological Indicators of Plants against Cold Stress

When exposed to cold temperatures, many plant species experience a variety of physiological or cellular alterations [66,67]. Plants attempt to preserve cell activity and function in cold environments; in particular, the integrity of the cell membrane and the structure of biologically active proteins are critical for survival in harsh environments. Ice forms in plant tissues when plants are exposed to below-freezing temperatures [22].

Since this portion of the plant has a higher freezing point due to larger concentrations of ice-forming nuclei in its apoplastic fluid, ice crystals develop in the intercellular gaps first. Water eventually escapes the cell as a result of this process, which lowers the apoplastic solution’s water potential. Thus, dehydration stress and freezing stress are typically linked in plants. Ice crystals cause modifications to the membrane’s lipid phase and increase ion leakage [68,69].

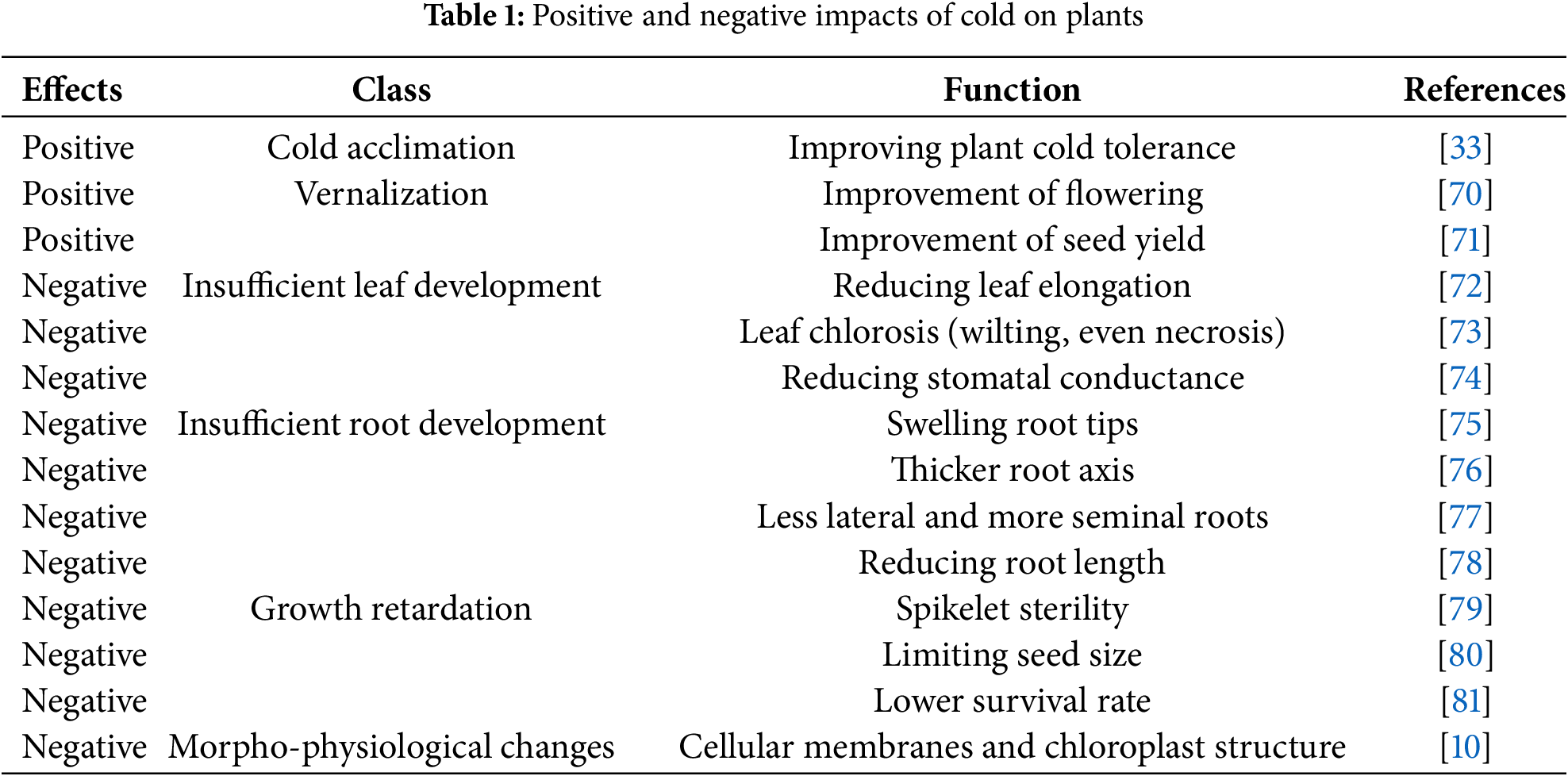

Osmotic stress leads to cell dehydration during freezing and encourages the formation of intracellular ice crystals. These ice crystals can rupture cells, cause cytosol leakage, and ultimately result in plant death in severe cases (Table 1). To enhance a plant’s tolerance to cold stress, it is crucial to inhibit the formation and growth of these intracellular ice crystals. Plants primarily employ a strategy known as cold adaptation to cope with cold conditions. This strategy allows them to store osmolytes, such as soluble carbohydrates and proline, along with cryoprotective polypeptides like COR15a [22]. Plants adapted to low temperatures often store more sugar (glucose, glucose 6-phosphate, amylose, starch, and maltose) in their underground tissues [44].

9 Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Response Cold Stress

One of the effects of frost damage on plants is necrosis, which is often brought on by a high level of reactive oxygen species (ROS). When under stress, a variety of intracellular elements, including the nucleus, cell walls, plasma, mitochondria, chloroplast, peroxisome, and endoplasmic reticulum, are naturally responsible for producing reactive oxygen species (ROS) [21]. The increase in H2O2 levels in plants under cold stress can be the result of oxygen production reactions in chloroplasts, which can lead to an increase in glycolate content. The harmful effects of ROS are due to the ability of these compounds to initiate a chain of autoxidation on unsaturated fatty acids. ROS can destroy unsaturated lipids and convert them into malondialdehyde (MDA), which is an active aldehyde, which ultimately leads to cell stress and damage to the plant [82].

In addition to increasing MDA, membrane permeability can increase the concentration of Ca in the cytosol. The physiological process of H2O2 toxicity can be reduced by developing efficient antioxidant defense systems and scavenging ROS.

10 Antioxidants during the Cold Stress Response

Plants have developed several antioxidant systems to mitigate the harmful effects of compounds like MDA on proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. These systems include natural antioxidants such as alpha-tocopherol, ascorbate, beta-carotene, flavonoids, and glutathione, as well as oxidant enzymes like catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and peroxidase (POX). Antioxidant enzymes play a crucial role in managing reactive oxygen species (ROS) by converting superoxide radicals (O2) produced by the SOD enzyme into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). Although the large amounts of H2O2 generated can be toxic to the plant, this compound can also serve as a secondary signal, triggering pathways that increase the activity of CAT, APX, and POD. These enzymes then detoxify H2O2, converting it into water [83,84].

Catalase mostly plays its role in peroxisome and cytoplasm, while glutathione peroxidase acts in wider parts such as cytoplasm, nucleus, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and extracellular. Several studies have shown that the level of activity of antioxidant enzymes and the expression of related genes in cold-sensitive cultivars is much lower than that of cold-resistant cultivars [41].

In addition, reactive oxygen species play an important role as secondary messengers in a variety of non-living stresses. In other words, plants need low concentrations of ROS as mediators of signal transmission. Low levels of ROS can increase the flow of calcium into the cytoplasm [85]. High calcium levels activate NADPH oxidase and convert superoxide radicals into H2O2 through the enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD). Therefore, the production of ROS is a process that is dependent on calcium, and the concentration of calcium is regulated through the concentrations of ROS caused by the activation of calcium channels in the plasma membrane [86]. Therefore, the coordinated communication of calcium and ROS regulates the activity of certain proteins that control the expression of certain genes in the nucleus. However, as previously stated, many other genes such as kinases and transcription factors are also involved in the response to environmental stresses.

Aquaporin AQP proteins are essential for maintaining membrane fluidity and permeability to water, as well as small molecules like glycerol and carbon dioxide. Their crucial role in plant stress responses has been confirmed. Plants that overexpress the genes responsible for producing these proteins have shown increased resistance to environmental stresses [7].

11 Cell Membrane Modifications under Low-Temperature Stress

The plasma membrane is recognized as the primary site of freezing-induced damage, prompting plants to prioritize membrane preservation mechanisms [87]. During cold acclimation, plant membranes undergo quantitative and qualitative alterations, particularly in lipid composition. These changes lower the threshold temperature for membrane damage in acclimatized plants compared to non-acclimatized individuals, as observed in plasma membranes and chloroplasts [37,88]. This adaptation is driven by increased membrane fluidity, achieved through a shift toward higher unsaturated fatty acid content [89].

Research indicates that changes in membrane fluidity prompt cytoskeletal reorganization, calcium ion influx, activation of the MAPK cascade, and the initiation of low-temperature responses [90]. Adapted plants exhibit modified lipid profiles in plasma membranes and chloroplast envelopes, reducing their susceptibility to cold-induced damage compared to non-adapted counterparts [91]. The elevated unsaturated fatty acid content enhances membrane fluidity [92], promoting structural stability (Fig. 3) and preventing cell death. Additionally, the adaptation process maintains protective mechanisms by sustaining enzyme activity critical for fluidity regulation [93].

Figure 3: Visual comparison of four citrus fruit varieties: Thomson orange (A), Japanese mandarin (B), Ruby Star grapefruit (C), Lisbon lemon (D) after the −8 degree Celsius treatment test (The figure belongs to the author)

12 Mechanisms of Plants against Cold Stress

Plants enhance their stress tolerance through physical adaptations and immediate cellular and molecular changes triggered by stress signals [85]. Plant sensing and defense against cold stress may be influenced by ROS production [63]. Biological macromolecules and membrane systems are hazardous to reactive oxygen species (ROS) [94]. Moreover, ROS damages DNA, lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates, which eventually results in oxidative stress in plants. Free radicals (superoxide radical O2-, hydroxyl radical OH-, per hydroxy radical HO2-, and alkoxy radicals RO-) and non-radical forms (hydrogen peroxide H2O2 and singlet oxygen) are examples of reactive oxygen species [95].

Photosystems I and II in chloroplasts (PSI and PSII) are the main site of the production of superoxide free radicals and singlet oxygen. ROS are produced in different organelles. Photosynthesizing plants are at high risk of oxidative damage due to the abundance of photosynthetic components and unsaturated fatty acids in their chloroplasts. In light, chloroplasts and peroxisomes are the main sources of ROS production [96].

Mitochondria are the main source of reactive oxygen species (ROS) when light is absent. In plants, both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant defense mechanisms create and regulate ROS, especially in high-stress environments. However, oxidative damage can occur if ROS levels rise and the antioxidant defenses are weakened [97]. Also, cold-resistant plants such as spinach can survive in cold conditions with a strong enzyme antioxidant defense system [98,99].

13 The Two Main Adaptive Strategies of Plants on Resistance Are Stress Resistance and Stress Avoidance

The method of resistance to frost damage depends on the temperature of the environment in which the plant grows [100]. Plants can avoid or tolerate extracellular freezing depending on the severity and duration of the freezing event [33]. There are two primary categories of plant tolerance techniques for freezing temperatures: First, freezing is avoided by supercooling; second, freezing is tolerated by extracellular ice production. In woody plants, both tolerance methods are present [30].

Plants exhibit two distinct responses to cold temperatures: resistance and avoidance. To prevent stress, it is essential to protect delicate tissues from freezing. Some plant species can retain heat during the day and gradually release it at night, thanks to their substantial tissue mass and high water content [68,101]. Annual grasses maintain their survival by keeping the organs and seeds dormant and covering the apical meristems with leaves [102,103].

Where there is more severe stress, tolerant plants have appeared that can adapt to the environment [104]. Although the change of structure and function and response to stress is not hereditary and by that, they increase their competence. Temperate plant species adapt to the weather during autumn. Once more, the metabolism of these organisms is focused on producing chemicals that provide protection against freezing temperatures. These molecules include soluble sugars like sucrose, raffinose, trehalose, and stachyose, sugar alcohols like sorbitol, ribitol, and inositol, and low molecular weight nitrogenous compounds like proline and betaine [24].

Many plants can increase their tolerance to extreme cold by being exposed to low temperatures above zero, this process is called cold acclimation [105]. Adaptation of plants to cold is the result of various biochemical and physiological changes, which result from changes in the expression of several genes responsible for tolerance to cold stress [106]. In response to cold, plants adapt themselves at the morphological, anatomical, physiological, and biochemical levels [105]. Plants that have adapted to cold affect the expression of many genes with the help of the changes they make in cellular adaptations, it also causes changes in membrane compositions and the accumulation of antioxidants and macromolecules induced by stress [51].

Depending on the genetic and physical variety of genotypes, the ideal temperature for plant adaptation differs between species and even within a species [106]. Plants require specialized survival strategies when exposed to cold temperatures. Typically, these plants are small-growing grasses, forages, and decorative shrubs with a high aerial/root ratio, low leaf area, and short height. Their vegetative habitat successfully maintains air temperatures near the soil surface by limiting cold at night and dispersing heat during the day [107]. Plants that are acclimated to cold often grow slowly, use C3 photosynthesis, and store sugar in subterranean tissues [108]. Plants adapt well to cold environments. The respiratory system has evolved to be efficient, which allows them to quickly prepare storage materials for storage during a short period of growth.

Tissues that rely on freezing avoidance show deep hypothermia, which implies that some cellular water remains liquid at temperatures below the freezing point. In terms of the supercooling range for pure water drops in emulsion, it was determined to be −1.38°C [109]. Freezing of supercooled water can be observed through thermal exotherms generated during the phase change from liquid to solid at low temperatures. In plants, a low-temperature exotherm was tested for its initiation between −39 and −55 degrees Celsius. Typically, certain tissues and organs in woody trees, such as the xylem cells of many hardwood species, as well as the flower buds and branches of conifers, avoid freezing [110]. Avoidance of freezing is found in plant species of regions where the intensity of freezing is moderate (temperatures slightly below zero) and its duration is also short. In olive trees, studies have also shown that olive leaves remain super-cold for a long time, which is a way to avoid freezing [110].

15 Frost Tolerance by Stagnation or Sleep

In temperate locations, perennial plants have special defense mechanisms to withstand seasonal variations in their surroundings [111]. As the growing season concludes, plants cease their growth and development, enter a dormant state, and develop frost resistance, which protects them from the sudden onset of winter. Distinguishing between the mechanisms of winter dormancy and cold tolerance is particularly challenging, as these processes overlap. Nonetheless, these strategies involve complex dynamic mechanisms that not only manage the development of freezing and stagnation tolerance but also ensure their proper initiation and conclusion [40]. These include the formation of specialized organs like buds, the temporary suspension of the apparent growth of any plant structure with a meristem, the reduction of photosynthetic system activity, respiration, and the loss of aerial organs in whole or in part. They also include the accumulation of substances that prevent frost [112].

16 Dormancy in Temperate Plants

To survive seasonal environmental fluctuations, temperate perennial plants have evolved specialized adaptive mechanisms [113]. As seasons transition, these plants halt growth and enter dormancy, concurrently activating frost tolerance to safeguard against abrupt winter onset [114]. While winter dormancy and frost tolerance are closely intertwined phenomena with overlapping processes, they involve intricate dynamic mechanisms that regulate their initiation, progression, and termination [115]. Key adaptations include: Morphological changes: Suspension of meristematic growth, aerial organ shedding, and formation of protective structures like buds. Physiological adjustments: Reduced photosynthetic activity, suppressed respiration, and biosynthesis of cryoprotective compounds.

17 Seasonal Fluctuations of Cold Resistance

Changes in cold resistance over the winter and spring are mostly dependent on the outside temperature. Plants’ short-term resistance variations directly correlate with temperature: at low temperatures, resistance levels rise, and at high temperatures, they fall [116]. On the other hand, temperature has an indirect effect on cold resistance through its effects on the annual growth cycle [117]. Woody plants respond more effectively to resistance boosters at the onset of winter than to excessively cold temperatures. During a deep recession, their resistance decreases in both directions. As winter draws to a close, plants quickly lose their resistance, but regaining it after the stagnation ends is more challenging. The effect of a consistent photoperiod on the transition from stasis to growth remains uncertain [38] the principles of actual, prospective, and minimal cold resistance to examine the dynamics of plant resistance. Potential cold resistance is the highest level of resistance that can be achieved, whereas actual cold resistance is the condition of the resistance at a specific moment in time.

The minimum resistance to cold is a crucial threshold at which a plant’s resistance remains consistent, even when exposed to extreme heat or treatments that induce brittleness. This resistance is influenced by the plant’s developmental stage, which determines both its potential and minimal resistance. It highlights the difference between the plant’s lowest resistance capacity and its potential resistance at any given time. Additionally, factors such as cell sap concentration, cell wall quantity, protoplasmic hydration, and overall water content significantly affect a plant’s ability to endure cold temperatures [118]. Water status may also have an indirect effect on cold resistance by reducing the respiration consumption of antifreeze sugars in dehydrated tissues [119].

More ice formation at low temperatures is the main cause of frost damage in small-leaf fruit trees [120]. During this stage, adaptation to a cold and subsequent increase in cold resistance is genetically controlled and includes several mechanisms that lead to the production of different metabolites, including polypeptides, amino acids, and sugars [121]. The temperature tolerance of a specific type of plant can vary. This is evidenced by its physiological response to cold, which triggers numerous physiological and biochemical changes. Some of these cold adaptation factors include an increase in sugar content, soluble proteins, antioxidant enzymes, proline, and chlorophyll fluorescence, as well as the emergence of new protein isoforms and alterations in membrane lipid composition [122].

Cell membranes are the main target of frostbite damage, which can be induced by a reduction in the surface area and concentration of soluble chemicals, protoplasmic dehydration, molecular packing of membrane components as a result of cell contraction, or a combination of these. Changes in ionic strength and pH also happen [123]. Frostbite causes the cell membrane to rupture, which increases the amount of soluble materials that leak out of the injured cells. This electrolyte leakage was initially employed in earlier studies on cold tolerance [124]. Because there was considerable variation in the total amount of electrolytes between the samples.

The concept that the proportion of total electrolytes released from a sample after heat killing serves as a measure of leakage has been presented [125]. Since the 1930s, the electrolytic leakage method has undergone extensive modifications and refinements. Electrical conductivity (EC) measurement is a simple, fast, effective, and reliable technique for selecting resistant cultivars. The accumulation of free proline is commonly observed in plants subjected to environmental stress and is linked to increased cold resistance. Cold-tolerant cultivars of P. communis were introduced to North America from Russia in 1879. The inheritance of frost resistance in pears is similar to that in apples and is primarily quantitative and additive [126].

One of the goals of genetic engineering is to achieve frost resistance by increasing the cytoplasmic levels of molecules such as (mannitol, fructans, proline, and glycine betaine) with osmotic protection properties [127]. Freezing affects the cell membrane and breaks it and increases the leakage of soluble substances from the damaged cells [128].

18 The Role of Plant Hormones and Secondary Metabolites in Coping with Stress

Cold, in addition to ABA, whose role was explained as an important regulator of cold adaptation, other growth regulators are also involved in this process [129]. Salicylic acid is another plant growth regulator that accumulates in plants due to cold, and its use has caused resistance to cold in different plants, it can cause plant resistance through the induction of relevant genes [130].

Gibberellin (GA) is another plant hormone whose amount changes in response to cold. It has been found that this hormone plays a role in the expression of the CRT/DRE-binding factor gene and ultimately resistance to drought, salinity, and cold [131–133]. GA is also involved in the balance between SA and JA in the CBF-driven response. Key components of gibberellin include nuclear DELLA proteins, which are transcription regulatory proteins containing aspartic acid, glutamic acid, leucine, leucine, and alanine at their N-terminal end, and function to inhibit plant growth. Research on the relationship between CBF1 and GA pathways shows that continuous expression of CBF1 results in reduced GA activity, ultimately causing stunted growth and delayed flowering in plants. RGL genes, which encode DELLA proteins, serve as growth inhibitors, while GA promotes growth by counteracting the inhibitory effects of DELLA [123].

The plant hormone jasmonic acid (JA) also acts as one of the auxiliary components in cold resistance and its exogenous application has caused cold resistance in a wide range of plants. In addition, inhibition of endogenous jasmonic acid causes sensitivity to cold. It has been found that jasmonic acid can increase the expression of CBF/DREB1 signaling genes [82,134].

Also, other plant hormones such as cytokinin and ethylene play roles in cold resistance, the use of cytokinin can cause cold resistance to some extent, but the exact role of this hormone in cold resistance has not yet been determined. It is also reported that the amount of ethylene increases during cooling in grapes [135]. Ethylene treatment in Arabidopsis increased cold resistance in this plant and physiological changes such as a decrease of MDA and an increase of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD, CAT, and POD [136].

In order to cope with cold stress, certain plants also produce substances known as secondary metabolites. By being incorporated into the cell wall, phenolic chemicals like lignin and suberin reinforce this section and can be produced more when exposed to cold treatment. While one of the mechanisms of cold resistance in cold-resistant trees is boosting the synthesis of chlorogenic acid. Furthermore, it has been shown that certain plants produce polyamines, which then develop into phenylamines and deactivate reactive oxygen species [137].

The cell membrane consists of lipids and proteins. Lipids can be categorized into two groups: saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. The ratio of these fatty acids influences the membrane’s fluidity. As ambient temperature changes, the membrane transitions from a semi-fluid state to a semi-crystalline state. Cold-sensitive plants typically contain a higher proportion of saturated fatty acids in their cell membranes, which means they are more likely to experience structural changes at elevated temperatures [138]. In comparison, more cold-resistant plants have more unsaturated fatty acids in their plasma membrane structure, and therefore, they will undergo membrane structural changes at lower temperatures [37].

Exposure to stress-inducing temperatures triggers a two-stage adjustment in cellular metabolism. In the first stage, the plant modifies its cellular processes to cope with low temperatures. This temperature stress alters not only the structural and catalytic properties of enzymes [16] but also the transport of metabolites across membranes. Consequently, the plant’s regulatory mechanisms are significantly activated to maintain metabolite levels and metabolic flow. In the second stage, the changes and improvements in metabolism in response to temperature stress are linked to adaptation mechanisms. Some metabolites play a crucial role in facilitating this adaptation and response to stress [139]. The metabolites that function as osmolytes in this instance have received particular attention. Osmolytes are involved in controlling the water balance inside cells and preventing cell dehydration. The stability of membranes, enzymes, and other cellular components is made possible by the uniform behavior of osmolytes. The re-formation of membrane lipids, which modifies the fluid and crystalline physical structure for appropriate membrane activity and energy sources, is greatly aided by osmolytes. These stress-responsive metabolites include soluble carbohydrates, amino acids, organic acids, polyamines, and lipids [42].

Protective chaperones, such as a group of proteins called late embryogenesis abundant (LEA), are active in protecting against membrane damage [122]. The available evidence shows that the damage to the membrane occurs with a decrease in temperature. With the existence of antioxidative mechanisms, the increase of the level in the apoplastic space and the stimulation of genes encoding chaperones are controlled [45]. Osmotic regulators including organic osmoprotectants (such as proline), other amines such as glycine betaine and polyamines, and various sugars and alcoholic sugars (such as mannitol, trehalose, and galactinol) play an active role in cold stress [138]. Cold shock proteins that bind to nucleic acid (CSS) act as anti-terminators or stimulators of transcription when the plant is exposed to stress conditions. This process is made possible by preventing the collapse of the RNA secondary structure (Jones, 1994). Zinc finger proteins that contain glycine-rich regions will also increase expression with cold stress [140].

The activity of osmotic genes responsive to cold stress (LOS) is necessary to send appropriate amounts of RNA types from the nucleus into the cytoplasm under stress conditions [56]. A crucial aspect of the cold acclimation process is stabilizing the membrane to prevent damage from low temperatures and inhibit the breakdown of membrane lipids. As late summer transitions into early autumn, plants prepare for colder conditions by undergoing a phase known as cold adaptation. This phase begins with decreasing temperatures and shorter daylight hours characteristic of this time of year. Proper timing for acclimatization is essential; if it occurs too early, it can shorten the plant’s growth period, while late acclimatization can lead to irreparable damage when the first autumn chills arrive. The acclimatization process consists of three stages [141–144]:

1. Adaptation to cold. Adaptation to cold includes a process that physiological changes occur inside the plant, which changes the nature of the plant from a sensitive plant to a tolerant plant.

2. Acquiring maximum tolerance to severe winter cold, at this stage the plant will have maximum tolerance to winter cold and will suffer minimal damage when faced with low temperatures.

3. The loss of adaptation, loss of adaptation is expressed as a decrease in the temperature tolerance of plants, and it depends on the temperature in the early stages. As the weather warms in the spring, plants lose their cold adaptation, and their dormant buds begin to grow. Plants may also respond to short periods of heat in winter and lose adaptation to cold, while they cannot respond to the return of cold periods quickly and show adaptation again, this process will lead to low-temperature damages [51,53].

Improper cold treatment or insufficient duration of any of the steps mentioned above limits the survival of the plant [46]. Several factors influence the adaptation of green space plants to cold, including regional climatic conditions, plant selection, and suitable agricultural practices. Cold-resistant trees and shrubs undergo adaptation in two stages. The first stage is triggered by the shortening of day length at the end of the growing season, which leads to partial resistance. When the day length falls below a certain threshold, it stimulates the completion of the plant’s aerial growth and initiates physiological and biochemical changes necessary for cold acclimatization. The second stage occurs when plants are exposed to low temperatures, resulting in maximum cold resistance. The geographical origin of plants within the same species significantly affects their cold adaptation. Research indicates variations in cold tolerance based on how different plants respond to changes in day length. Native plants from cold regions respond quickly to shorter days, allowing for rapid adaptation to cold. In contrast, plants from warmer regions require a longer duration of short days to begin their cold adaptation process. Generally, actively growing plants are less capable of adapting to cold [109].

19 The Type of Damage to the Plant

All sections of the plant, including the flowers, stems, leaves, and roots, are susceptible to cold damage. Typically, plants’ leaves and stems will show signs of cold damage sooner because ice crystals freeze and cause the plant’s tissues to lose moisture [145]. Because there are less dissolved chemicals in the apoplastic region, ice crystals develop more quickly there. The production of ice in the apoplastic space will cause a flow between the apoplastic and the surrounding cells because the vapor pressure of ice is lower than that of water at all temperatures. This will cause the cytoplasmic water gradient to move from the cytosol of the cell to the apoplastic region. The ice crystals formed in the apoplastic space will gain volume, which will put mechanical strain on the cell wall and plasma membrane and cause the cell to burst [47].

Ice formation within plant cells leads to cell death, resulting in leaves and stems changing color to a blackish-brown and becoming soft. While frost-tolerant plants have adapted sufficiently to survive, those that are not adapted may suffer damage that extends to the root system, potentially leading to death in cases of severe injury. Often, these injuries remain hidden until the following spring, when the plant fails to produce leaves. The inability to generate healthy buds and the lack of leaf formation in either the shoot branch or the entire plant are symptoms of cold temperature injuries. In spring, some plants may exhibit weak growth, produce flowers, and display unusual leaf formations, only to suddenly vanish at the onset of the hot season [53].

Most of the studies conducted on the mechanisms of cold damage have focused on the aerial parts of the plant, which is probably the reason for the difficulty of studying the roots in natural conditions and less concern for root damage in freezing conditions. Organs below the soil surface and above the soil both show different mechanisms in dealing with cold stress. So that in Arabidopsis, 86% of changes in the transcriptome level are not common between roots and shoots [40].

Studying the phenomenon of frostbite in plants from the cellular level to the appearance of symptoms in the plant organ will provide a suitable perspective to deal with this environmental phenomenon. Studying and familiarizing with the relevant physiological relationships can help prepare a comprehensive plan to control this phenomenon of damage in garden products.

20 Molecular Solutions to Low Temperatures

Physiological and molecular changes in cell membranes are key mechanisms that enable adaptation to low temperatures. These changes include an accumulation of cytosolic calcium (Ca2+), an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the activation of ROS receptor systems, as well as alterations in gene expression and transcription factors associated with low temperatures. Additionally, photosynthesis is affected by modifications in proline accumulation, sugar synthesis, and various metabolic processes [14]. In general, plants in temperate regions are more resistant to low temperatures compared to plants in tropical and subtropical regions and have different protective systems such as the ability to adapt to low temperatures [137]. Species with more northerly and colder geographical distribution show a higher ability to avoid frostbite and the formation of ice inside cells, which indicates genetic differences [35].

Classic genetic studies have shown that the ability of plants to adapt to cold climates is a quantitative trait controlled by several small genes [146]. The transfer of a gene responsible for changing the type of membrane lipids from Escherichia coli to Arabidopsis increased the percentage of saturated membrane lipids compared to unsaturated, and this increased sensitivity to heat [36]. A large number of physiological and biochemical changes occur during cold tolerance in plants, among which the activation of the expression of some genes and the silencing of others are of special importance [30]. The change in the expression of hundreds of genes in response to low-temperature results in the increase of thousands of metabolites, some of which have protective effects against the destructive effects of cold stress [147].

In recent years, many efforts have been made to identify and determine the nature of genes and determining their role in creating resistance to freezing and freezing [137]. Isolation and determination of the part of induced genes during cold tolerance, isolation and examination of mutants exposed to cold, and transcription analysis of these genes are among these efforts [148].

The main goal of studies related to cold adaptation includes identifying the genes involved in cold adaptation, determining the regulatory activity of these genes, and understanding the role of these genes in plant life, during exposure of plants to low temperatures [44,149]. Identifying the genes and gene networks involved in plant resistance to freezing, along with understanding their mechanisms, opens new opportunities to enhance the resistance of key agricultural products. These strategies can address the limitations of traditional breeding methods used to improve frost resistance. While significant progress has been made, it has become evident that cold resistance is governed by complex interactions involving multiple metabolic pathways. Consequently, the research gap in this area appears to be substantial [150].

Recent studies on complete plant genomes, along with the analysis of mutant and transgenic plants, have led to a better understanding of the transcription networks that are activated under cold stress [150]. Most of the studies conducted in the past were often limited to special genes or a small number of genes due to the weakness of facilities or methods [151]. But today, with the vast progress made in the field of genomic technologies, including the determination of gene expression patterns through methods such as microarray and in addition to that, various methods of analysis through bioinformatics and databases, it is possible to examine the genes encoding various traits on a large scale [2].

The examination of genes related to cold stress has also followed the same trend. In the latest research in this regard, the expression of 1300 genes related to cold stress in Arabidopsis was tested using microarray [152]. In 2002, Fuller and Thomas expanded their research to study the expression of approximately 8000 genes at various intervals after transferring plants from a warm to a cold environment. In 2005, to investigate the gene network that regulates cold stress resistance, Lee et al. analyzed the Arabidopsis genome transcriptome using an Affymetrix gene chip that included around 24,000 genes. A comparison of cold-responsive genes across the datasets from Fuller and Thomas with those from Lee et al. revealed that only 108 genes were shared among all three studies. These discrepancies may be attributed to variations in experimental conditions, such as differing temperature treatments and cultural environments. The genes common to these experiments are the most significant ones responding to low-temperature stress [153].

In a study, the complete genomes of grape, rice, Arabidopsis, and Tabrizi tree were subjected to bioinformatics analysis to find AP2/REF gene family homologs, which also include the CBF gene family [85].

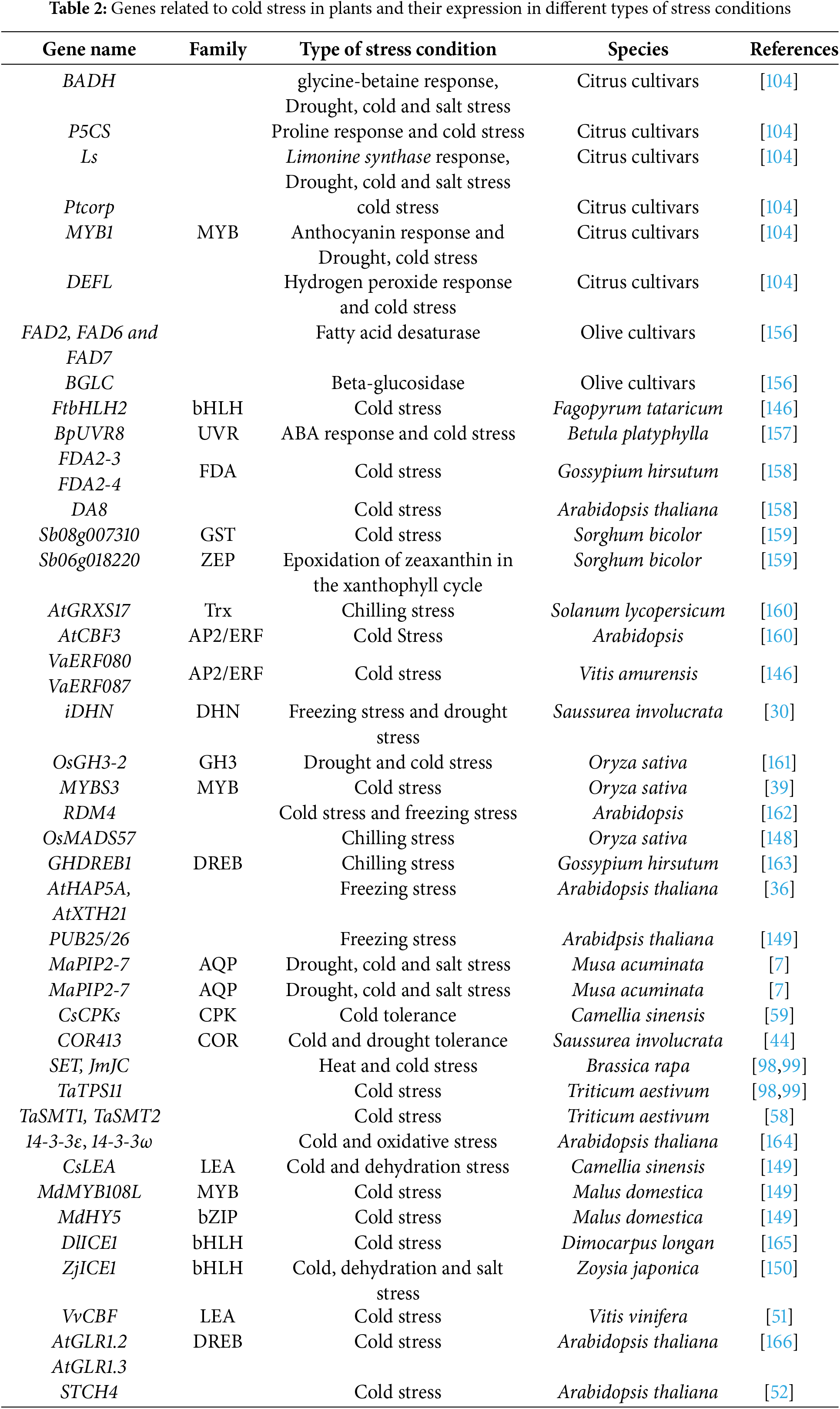

21 The Role of Regulatory Genes in Low-Temperature Response

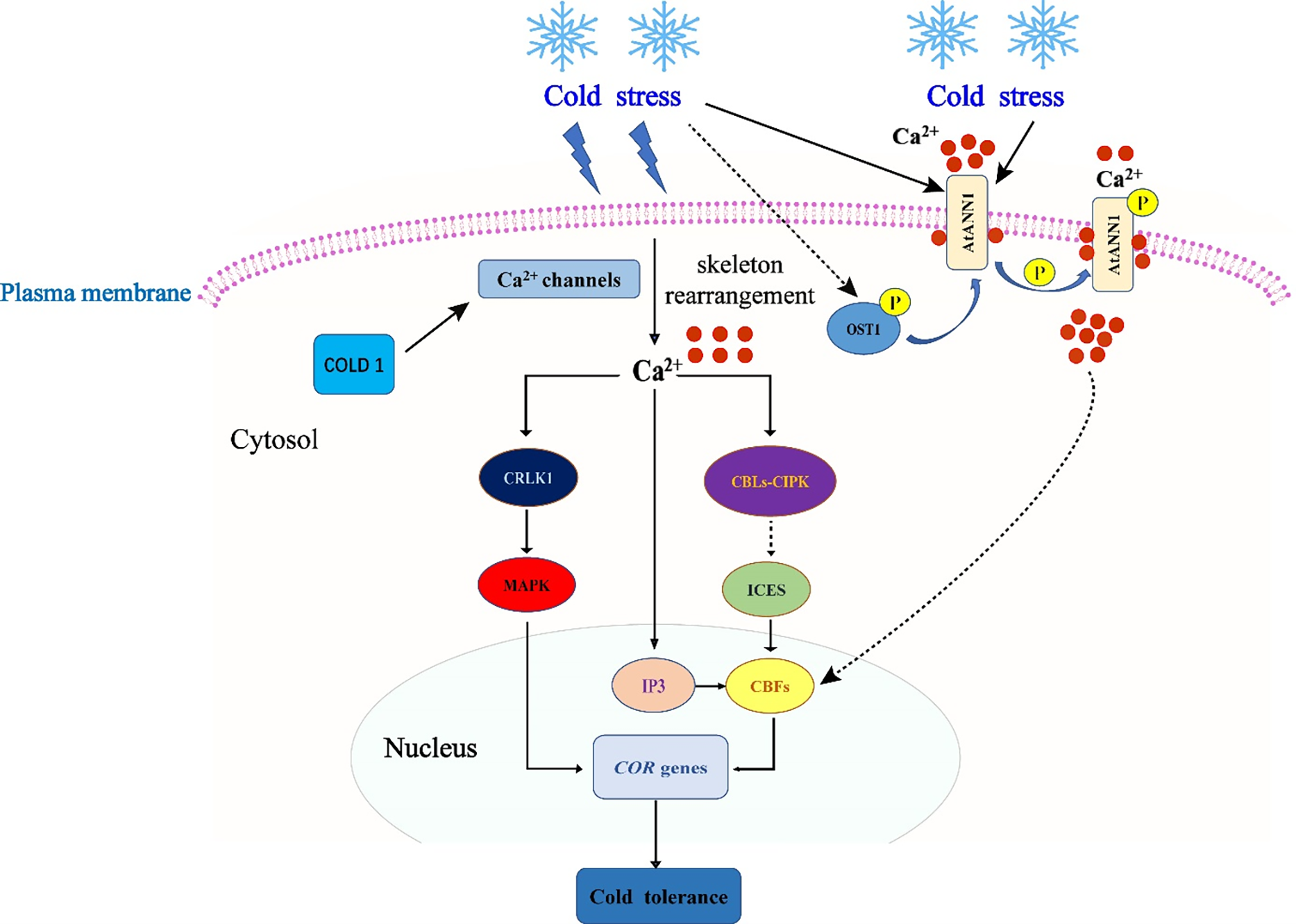

The capacity to withstand cold is a quantitative feature that manifests as transcriptional reprogramming in response to low temperatures, which alters the plant’s physiology and biochemistry in a number of ways [154]. Fig. 4 roughly depicts the collection of genes and molecular-biochemical processes involved in plants’ reactions to low temperatures.

Figure 4: The regulation of genes responding to cold [8]. This figure is distributed under CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Quick developments in our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms governing low-temperature stress tolerance, which are dependent on the expression of certain cold-regulated (COR) genes, might result in the development of instruments for the engineering of more tolerant plants [155]. Three primary categories include COR genes activated by cold exposure: 1. Genes that encode structural elements or enzymes thought to be directly involved in shielding cells against freezing damage (Table 2). 2. Genes that encode transcription factors and other proteins that regulate transcriptional or post-transcriptional reactions to low temperatures. 3. Genes connected to signaling cascades at low temperatures [55].

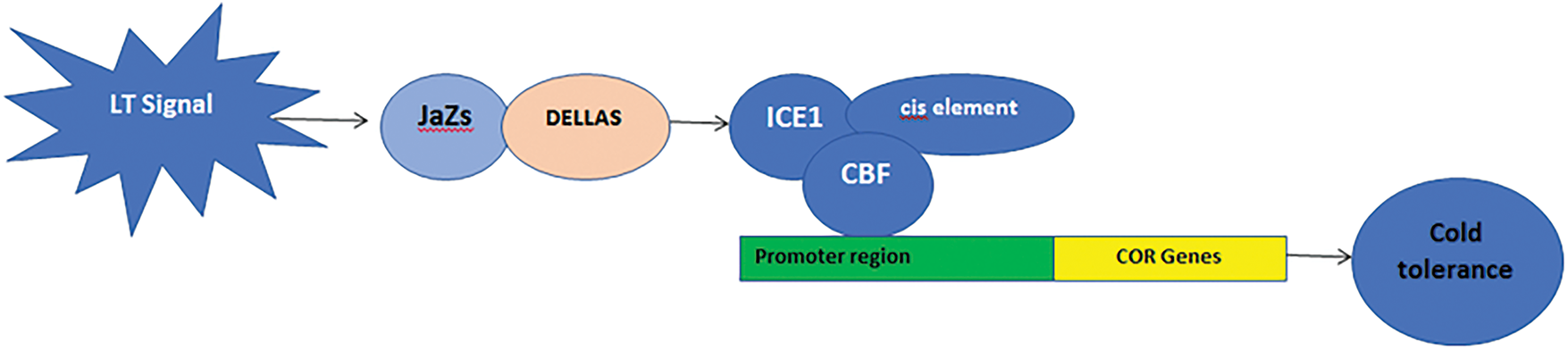

DELLA gene signaling and ICE1 induction are the primary mechanisms causing the production of the CBF transcription factor. By interacting with JaZs signaling, DELLAs induce the expression of CBF genes in response to cold [16,52,167]. Plants with higher cold tolerance are able to produce more COR genes due to CBFs binding to cis-elements in the promoter of these genes [160,167] (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: ICE-CBF-COR signaling pathways in plant tolerance to cold stress [22]. This figure is distributed under CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/)

Previous research has demonstrated that low temperature (LT)-induced constraints significantly hinder plant production in temperate regions. However, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear and complex. Over the past decade, studies have focused on how plants adapt to and tolerate cold stress. While our understanding of cold tolerance mechanisms has certainly advanced, several aspects still require further examination. The current investigation aims to explore the various mechanisms involved in the signaling pathways that contribute to cold resistance in plants [168–170].

Climate change has increased the impact of cold stress on agricultural productivity. A major future challenge is to combine insights from model systems with multi-omic and genetic datasets to create improved crop varieties and performance evaluation frameworks. At the same time, it is crucial to identify new natural sources of cold tolerance and understand their underlying mechanisms. Integrating these findings into breeding programs will be vital for developing resilient and sustainable global food systems.

Acknowledgement: This article was achieved based on the material and equipment of Research Institute of Zabol that the authors thank it.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Ali Salehi Sardoei. Data curation: Bahman Fazeli-Nasab. Formal analysis: Ali Salehi Sardoei. Investigation: Bahman Fazeli-Nasab. Methodology: Bahman Fazeli-Nasab. Project administration: Ali Salehi Sardoei. Resources: Bahman Fazeli-Nasab, Ali Salehi Sardoei. Supervision: Ali Salehi Sardoei. Validation: Bahman Fazeli-Nasab. Visualization: Bahman Fazeli-Nasab, Ali Salehi Sardoei. Writing—original draft: Ali Salehi Sardoei. Writing—reviewing & editing: Bahman Fazeli-Nasab. All authors had equal role in study design, work, statistical analysis and manuscript writing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All the data are embedded in the manuscript and the data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Fazeli-Nasab B, Rahmani AF. Microbial genes, enzymes, and metabolites: to improve rhizosphere and plant health management. In: Soni R, Suyal DC, Bhargava P, Goel R, editors. Microbiological activity for soil and plant health management. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2021. p. 459–506. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-2922-8_19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang F, Chen S, Liang D, Qu GZ, Chen S, Zhao X. Transcriptomic analyses of Pinus koraiensis under different cold stresses. BMC Genom. 2020;21(1):1–14. doi:10.1186/s12864-019-6401-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Wang H, Blakeslee JJ, Jones ML, Chapin LJ, Dami IE. Exogenous abscisic acid enhances physiological, metabolic, and transcriptional cold acclimation responses in greenhouse-grown grapevines. Plant Sci. 2020;293:110437. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2020.110437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Salehi-Sardoei A, Sharifani M, Sarmast MK, Ghasemnejhad M. Stepwise regression analysis of citrus genotype under cold stress. Gene Cell Tissue. 2023;10(2):e126518. doi:10.5812/gct-126518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yadav SK. Cold stress tolerance mechanisms in plants. A review. Agron Sustain Dev. 2010;30(3):515–27. doi:10.1051/agro/2009050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K, Shinozaki K. Transcriptional regulatory networks in cellular responses and tolerance to dehydration and cold stresses. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2006;57(1):781–803. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Xu Y, Hu W, Liu J, Song S, Hou X, Jia C, et al. An aquaporin gene MaPIP2-7 is involved in tolerance to drought, cold and salt stresses in transgenic banana (Musa acuminata L.). Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020;147:66–76. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.12.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Wang Y, Wang J, Sarwar R, Zhang W, Geng R, Zhu KM, et al. Research progress on the physiological response and molecular mechanism of cold response in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1334913. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1334913. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Zhou L, Ullah F, Zou J, Zeng X. Molecular and physiological responses of plants that enhance cold tolerance. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(3):1157. doi:10.3390/ijms26031157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Feng Y, Li Z, Kong X, Khan A, Ullah N, Zhang X. Plant coping with cold stress: molecular and physiological adaptive mechanisms with future perspectives. Cells. 2025;14(2):110. doi:10.3390/cells14020110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Qian Z, He L, Li F. Understanding cold stress response mechanisms in plants: an overview. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1443317. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1443317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang Z, Liu W, Huang Y, Li P. Research progress on plant anti-freeze proteins. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2024;93(6):1263–74. doi:10.32604/phyton.2024.050755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Xie H, Zhang J, Cheng J, Zhao S, Wen Q, Kong P, et al. Field plus lab experiments help identify freezing tolerance and associated genes in subtropical evergreen broadleaf trees: a case study of Camellia oleifera. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1113125. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1113125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Hannah MA, Heyer AG, Hincha DK. A global survey of gene regulation during cold acclimation in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2005;1(2):e26. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0010026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Rihan HZ, Al-Issawi M, Fuller MP. Advances in physiological and molecular aspects of plant cold tolerance. J Plant Interact. 2017;12(1):143–57. doi:10.1080/17429145.2017.1308568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Karimi M, Ebadi A, Mousavi SA, Salami SA, Zarei A. Comparison of CBF1, CBF2, CBF3 and CBF4 expression in some grapevine cultivars and species under cold stress. Sci Hortic. 2015;197(1–2):521–6. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2015.10.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Salehi Sardoei A, Sharifani M, Khoshhal Sarmast M, Ghasemnejad M. Screening citrus cultivars for freezing tolerance by reliable methods. Int J Hortic Sci Technol. 2024;11(1):25–34. doi:10.22059/ijhst.2023.349184.589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Miura K, Furumoto T. Cold signaling and cold response in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(3):5312–37. doi:10.3390/ijms14035312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Solanke AU, Sharma AK. Signal transduction during cold stress in plants. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2008;14(1–2):69–79. doi:10.1007/s12298-008-0006-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Huang GT, Ma SL, Bai LP, Zhang L, Ma H, Jia P, et al. Signal transduction during cold, salt, and drought stresses in plants. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39(2):969–87. doi:10.1007/s11033-011-0823-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Fazeli-Nasab B, Shahraki-Mojahed L, Sohail-Beygi G, Ghafari M. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of several medicinal plants against clinically isolated Staphylococcus aureus from humans and sheep. Gene Cell Tissue. 2022;9(2):e118752. doi:10.5812/gct.118752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ritonga FN, Chen S. Physiological and molecular mechanism involved in cold stress tolerance in plants. Plants. 2020;9(5):560. doi:10.3390/plants9050560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Baumann K. Stress responses: membrane-to-nucleus signals modulate plant cold tolerance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18(5):276–7. doi:10.1038/nrm.2017.38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Erath W, Bauer E, Fowler DB, Gordillo A, Korzun V, Ponomareva M, et al. Exploring new alleles for frost tolerance in winter rye. Theor Appl Genet. 2017;130(10):2151–64. doi:10.1007/s00122-017-2948-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Pareek A, Khurana A, Sharma AK, Kumar R. An overview of signaling regulons during cold stress tolerance in plants. Curr Genom. 2017;18(6):498–511. doi:10.2174/1389202918666170228141345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Ensminger I, Busch F, Huner NP. Photostasis and cold acclimation: sensing low temperature through photosynthesis. Physiol Plant. 2006;126(1):28–44. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.2006.00627.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yang Z, Han D, Wang L, Jin Z. Changes in photosynthetic parameters and antioxidant enzymatic activity of four tea varieties during a cold wave. Acta Ecol Sin. 2016;36(3):629–41. [Google Scholar]

28. Theocharis A, Clément C, Barka EA. Physiological and molecular changes in plants grown at low temperatures. Planta. 2012;235(6):1091–105. doi:10.1007/s00425-012-1641-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Shin H, Oh Y, Kim D. Differences in cold hardiness, carbohydrates, dehydrins and related gene expressions under an experimental deacclimation and reacclimation in Prunus persica. Physiol Plant. 2015;154(4):485–99. doi:10.1111/ppl.12293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Guo X, Zhang L, Zhu J, Liu H, Wang A. Cloning and characterization of SiDHN, a novel dehydrin gene from Saussurea involucrata Kar. et Kir. that enhances cold and drought tolerance in tobacco. Plant Sci. 2017;256:160–9. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.12.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Guo X, Liu D, Chong K. Cold signaling in plants: insights into mechanisms and regulation. J Integr Plant Biol. 2018;60(9):745–56. doi:10.1111/jipb.12706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wallner SJ, Wu MT, Anderson-Krengel SJ. Changes in extracellular polysaccharides during cold acclimation of cultured pear cells. J Am Soc Hortic Sci. 1986;111(5):769–73. doi:10.21273/jashs.111.5.769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Juurakko CL, Walker VK. Cold acclimation and prospects for cold-resilient crops. Plant Stress. 2021;2(1):100028. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2021.100028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Sandve SR, Kosmala A, Rudi H, Fjellheim S, Rapacz M, Yamada T, et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying frost tolerance in perennial grasses adapted to cold climates. Plant Sci. 2011;180(1):69–77. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.07.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Sanghera GS, Wani SH, Hussain W, Singh N. Engineering cold stress tolerance in crop plants. Curr Genom. 2011;12(1):30–43. doi:10.2174/138920211794520178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]