Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Floral Volatiles in Natural Populations of Paeonia lactiflora: Key Components and Cultivar Differential Analysis

1 College of Agriculture/Tree Peony, Henan University of Science and Technology, Luoyang, 471000, China

2 Peony Research Institute, Luoyang Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Luoyang, 471000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Xiaogai Hou. Email: ; Lili Guo. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Aromatic Plants: Application, Research and Breeding)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(6), 1921-1940. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.065738

Received 20 March 2025; Accepted 29 April 2025; Issue published 27 June 2025

Abstract

Floral scent serves as a key criterion for evaluating the ornamental value of flowering plants. Herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.), a traditional Chinese ornamental species, is valued for its vibrant coloration, intricate floral morphology, and positive cultural symbolism. In this study, dynamic headspace adsorption coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry was employed to analyze volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in flowers of 120 herbaceous peony cultivars at the half-opening stage. We detected 86 VOCs, comprising 25 aromatic compounds (79.70%), 21 hydrocarbons (10.51%), 29 terpenoids (8.37%), 7 fatty acid derivatives (1.03%), and 4 heterocyclic compounds (0.38%). The cultivar ‘Dr. Alexander Fleming’ demonstrated the highest total VOC content, followed by ‘Yuezhao Shanhe’ and ‘Daiyu’. The top five cultivars based on principal component analysis composite scores were ‘Shajin Guanding’, ‘Many Happy Returns’, ‘Edulis Superba’, ‘Huicui’, and ‘Madame de Verneville’. The volatile compositions of these cultivars showed statistically representative characteristics. Aroma activity value analysis revealed 22 key aroma components (e.g., 3-hexen-1-ol, acetate, (Z)-, limonene, (E)-β-ocimene) and 15 modifying components (e.g., methyl hexanoate, α-pinene, benzaldehyde). Domestic cultivars exhibited greater VOC diversity and higher content levels compared to introduced cultivars, with introduced cultivars demonstrating more pronounced compositional variation. Introduced cultivars primarily released nonanal and 1,4-dimethoxybenzene, associated with fruity-sweet notes, whereas domestic cultivars predominantly released 1,4-dimethoxybenzene and phenylethanol, characterized by sweet-floral aromas. Aromatic compounds primarily contributed to the overall aroma, with terpenoids as secondary contributors. This study systematically characterized the floral aroma components of herbaceous peony, providing a theoretical foundation for germplasm resource utilization in cut flower production, essential oil extraction, and aromatherapy applications.Keywords

Floral scents, released during flowering, comprise complex mixtures of lipophilic, low molecular weight volatile organic compounds (VOCs) with relatively high melting points [1]. These compounds play essential roles in plant survival, reproduction, and ecosystem dynamics [2–4]. Floral scent formation results from the combined effects of diverse floral VOCs. The distinct fragrance profiles originate from variations in VOC composition and concentration, resulting in unique scent characteristics. Based on their biosynthetic pathways, floral VOCs can be classified into three major groups: terpenoids, phenylpropanoids/benzenoids, and fatty acid derivatives [5]. Terpenoids represent the most diverse class of floral VOCs and play crucial roles in aroma formation [6]. These compounds are primarily biosynthesized through the mevalonate (MVA) and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways [7,8]. Phenylpropanoids/benzenoids compounds originate from the shikimic acid pathway and are widely present in plant floral fragrances, making them an important component of floral fragrances [9]. As the third major group of floral scent components, fatty acid derivatives are biosynthesized through the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway. These biologically active compounds often exhibit specific biological functions [10]. This classification of VOCs is not only taxonomically informative but also functionally relevant to our research. Terpenoids and phenylpropanoids/benzenoids compounds are particularly important in essential oil extraction due to their high volatility and aromatic properties, while fatty acid derivatives play a key role in determining the longevity and consumer appeal of cut flowers. By understanding the relative contributions of these VOC classes to fragrance quality, we can better identify cultivars with desirable aromatic profiles for both breeding programs and industrial applications. The commercial and ecological significance of floral VOCs has driven their extensive applications in food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries, consequently accelerating research progress [11].

Recent studies have primarily focused on fragrant ornamental plants, including herbaceous species such as Lilium [12], Lavandula angustifolia Mill. [13], Dianthus caryophyllus L. [14], Chrysanthemum × morifolium (Ramat.) Kitamura [15], and Tulipa gesneriana L. [16], as well as woody plants including Jasminum sambac [17], Paeonia sufruticosa [18], and Rosa rugosa [19]. These investigations have primarily focused on the VOCs of aromatic ornamental plants, the intensity of their fragrance, and how these factors influence consumer preferences. However, herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.), as a significant woody ornamental plant, has not had its unique floral scent characteristics and aromatic components adequately explored in these studies.

Herbaceous peony, a traditional Chinese ornamental species with a long cultivation history [20], is highly valued for its vibrant coloration and intricate floral morphology, possessing significant economic and cultural importance. Previous research on herbaceous peony has primarily focused on flower color [21–23], while floral scent studies remain limited. During breeding processes, floral fragrance traits have often been overlooked, resulting in most cultivars exhibiting faint or negligible aromas, with fragrant varieties being rare. To address market demands, enhancing floral fragrance traits and selecting aromatic cultivars have emerged as crucial objectives in herbaceous peony breeding. Recent years have witnessed progress in herbaceous peony floral fragrance research [24–28]. These investigations have primarily focused on preliminary identification of floral scent components and characterization of fragrance-related biosynthetic genes. However, existing studies are limited in their cultivar coverage. To comprehensively investigate herbaceous peony aroma profiles, this study systematically analyzed scent components across 120 cultivars, including 40 introduced varieties and 80 indigenous Chinese cultivars, significantly expanding the scope of floral scent research in herbaceous peony.

Accurate and effective methodologies are crucial for in-depth investigation of herbaceous peony aroma. Currently, headspace solid-phase microextraction (HS-SPME) and dynamic headspace sampling (DHS) are widely employed for aroma collection, while gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and automated thermal desorption-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (ATD-GC/MS) are commonly utilized for aroma analysis in herbaceous peony [29]. HS-SPME operates through adsorption of volatile components onto quartz fiber coatings, followed by thermal desorption at the GC inlet for component collection. DHS directly captures floral components from living plants, offering operational simplicity, minor contamination, and accurate representation of aromatic characteristics while avoiding issues associated with petal damage and aroma alteration. GC-MS enables rapid analysis of flavor compound composition and concentration, offering high efficiency, selectivity, and sensitivity. This technique has become a primary analytical tool in organic matter research. Lo et al. recommend the headspace method as the preferred approach for floral aroma collection, followed by GC-MS analysis for compound identification [30]. Building upon these methodological advantages in precise volatile component capture and efficient structural analysis, combined with previous research from our team on herbaceous peony floral scent, this study employed DHS coupled with GC-MS to analyze floral scent components across 120 herbaceous peony cultivars. This study analyzed the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) content and composition of different herbaceous peony cultivars, revealing significant differences in aromatic components among cultivars. Using principal component analysis (PCA), we identified superior cultivars with optimal aromatic component ratios. These findings provide breeders with critical insights for selecting high-VOC cultivars as parental material to develop new cultivars with stronger and longer-lasting fragrances, thereby improving breeding efficiency and shortening breeding cycles. Additionally, the results offer direct guidance for the herbaceous peony cut flower and essential oil industries. By selecting cultivars with high VOC content, cut flower producers can enhance product marketability, while essential oil extraction companies can optimize extraction efficiency and improve product quality. Furthermore, this study recommends prioritizing cultivars with higher proportions of aromatic and terpenoid compounds to achieve more desirable fragrance characteristics.

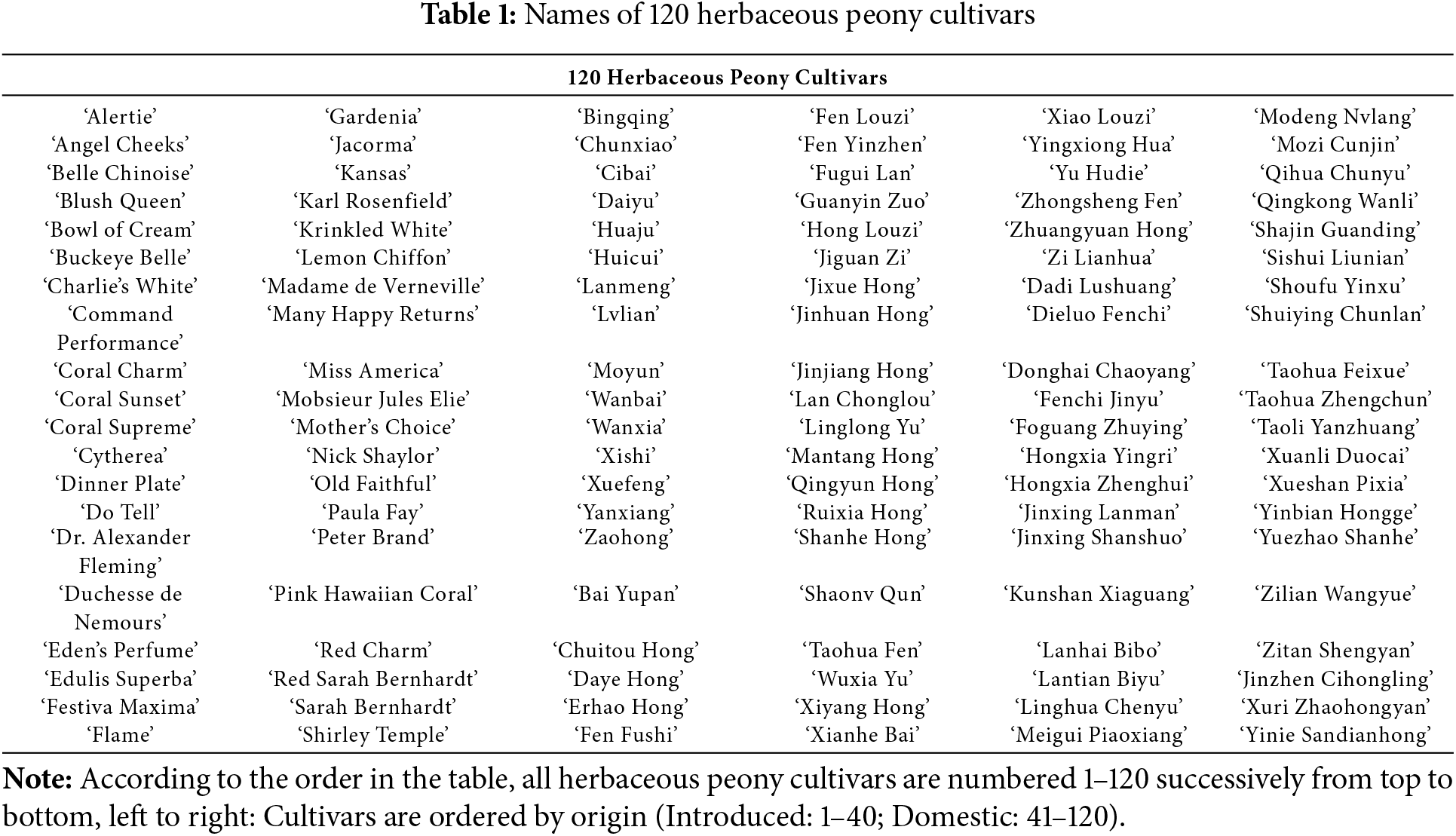

In this study, floral scent samples were collected from 120 herbaceous peony cultivars over two years (2023–2024). The majority (n = 116 cultivars, e.g., ‘Alertie’, ‘Angel Cheeks’, and ‘Belle Chinoise’) were sampled at the Luoyang Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences from mid-April to early May. Additionally, four cultivars (‘Dinner Plate’, ‘Nick Shaylor’, ‘Sarah Bernhardt’, and ‘Shirley Temple’) were collected in early June 2023 from the Beijing PEONY FARMER Cultivation Base. The Luoyang Academy of Agriculture and Forestry is located in Luoyang City, Henan Province (112°16′–112°37′ E, 34°35′–34°46′ N), while Beijing Peony Farmer Cultivation Base is situated in Yanqing District, Beijing (115°50′–116°29′ E, 40°26′–40°37′ N). Both locations experience a temperate continental monsoon climate, providing suitable environmental conditions for herbaceous peony growth. This climate type provides optimal light, thermal conditions, precipitation, and humidity for herbaceous peony development. However, Luoyang exhibits higher annual temperatures and greater precipitation compared to Yanqing, which experiences lower temperatures, larger diurnal temperature variations, and relatively less precipitation. The 120 herbaceous peony cultivars were systematically numbered from 1 to 120, with cultivars 1–40 representing introduced varieties from Europe and America, and cultivars 41–120 comprising indigenous Chinese varieties. Detailed information, including cultivar names and morphological characteristics at the half-opening stage, is presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1, respectively.

Figure 1: Morphological characteristics of 120 herbaceous peony cultivars at the half-opening stage. The order of the pictures is consistent with that of the 120 herbaceous peony varieties in Table 1

The floral scent collection method followed the protocol described by Wang et al. [28]. Floral scent samples were collected on clear, windless days to minimize environmental variability that could influence VOC profiles. The tested flowers were placed in an odorless, transparent sampling bag (250 mm × 380 mm, Huadr, Beijing, China) with both ends open. The upper end of the bag was connected to an activated charcoal tube, while the lower end was connected to a glass tube filled with Tenax TA adsorbent. Both ends were sealed with plastic clips, and the setup was connected to an atmospheric sampler (QC-1S model, manufactured by the Beijing Municipal Institute of Labour Protection, Beijing, China) via silicone tubing. The atmospheric sampler drew air from around the flowers, simulating the natural release of floral scent. Simultaneously, the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by the flowers were directed into the Tenax TA adsorption tube for collection. The air drawn by the sampler was purified through the activated charcoal tube to remove moisture and dust. The flow rate of the atmospheric sampler was set to 400 mL·min−1, and the collection time was 3 h. After collection, hexane was added to the adsorption tube to elute the adsorbent, yielding the eluate. The eluate samples were stored at −20°C until instrumental analysis.

Gas Chromatography conditions (Agilent 8890 gas chromatograph, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA): chromatographic column: HP-5MS flexible quartz capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm); carrier gas: high-purity helium at 0.8 mL·min−1; injection temperature: 250°C; column flow rate: 1.2 mL·min−1; column temperature: initiated temperature at 40°C (hold 1 min), followed by five sequential ramps: (1) 6°C·min−1 to 100°C, (2) 3°C·min−1 to 136°C, (3) 0.5°C·min−1 to 138°C, (4) 2°C·min−1 to 142°C, and (5) 12°C·min−1 to 250°C; injection mode: split injection (9:1 ratio); injection volume: 2 μL.

Mass Spectrometry conditions (Agilent 5977B mass spectrometer, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA): electron ionization: electron impact (EI) source, 70 eV; interface temperature: 250°C; ion source temperature: 230°C; quadrupole temperature: 150°C; EM voltage: 1247 V; mass range: 29–386 amu.

Qualitative Analysis: A 500 mg·L−1 N-alkane standard solution was diluted 50-fold with n-hexane and analyzed under the aforementioned GC-MS conditions. The retention times for individual n-alkanes were recorded, and the calculated retention indices (RIs) were compared with reference values from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) library. The RI calculation followed this formula:

where RI represents the retention index of the target analyte, n denotes the carbon number of the preceding n-alkane, tx indicates the retention time of the target analyte, tn corresponds to the retention time of the preceding n-alkane, and tn+1 refers to the retention time of the succeeding n-alkane, with tx falling between tn and tn+1 in the n-alkane series.

Quantitative analysis: A 69.32 mg·L−1 ethyl decanoate solution in ethyl acetate served as the internal standard. For each 80 μL sample, 0.4 μL of the internal standard solution was added, and the relative content of aroma components was calculated using the following formula:

Relative content of each component (μg·g−1) = [peak area of each component/peak area of internal standard] × internal standard concentration (mg·L−1) × internal standard volume (μL)/sample weight (g) × f (f is the correction factor of each component to the internal standard, f = 1).

Principal Component Analysis: The 19 volatile compounds with the highest content were selected as the objects of analysis, and the original data of their relative content were subjected to extreme value standardization. The standardized relative contents of selected floral VOCs were denoted as ZX1, ZX2, ZX3, ..., ZX19, comprising a total of 19 indicators. The coefficients for each indicator were obtained by dividing the corresponding eigenvector data in the principal component loading matrix by the square root of the respective initial eigenvalues. The calculation formula for the principal component composite score is as follows:

F1 = 0.234 ∗ ZX1 − 0.046 ∗ ZX2 − 0.039 ∗ ZX3 − 0.029 ∗ ZX4 − 0.025 ∗ ZX5 − 0.043 ∗ ZX6 − 0.064 ∗ ZX7 − 0.050 ∗ ZX8 − 0.067 ∗ ZX9 − 0.031 ∗ ZX10 − 0.077 ∗ ZX11 + 0.297 ∗ ZX12 + 0.343 ∗ ZX13 + 0.361 ∗ ZX14 + 0.361 ∗ ZX15 + 0.359 ∗ ZX16 + 0.351 ∗ ZX17 + 0.361 ∗ ZX18 + 0.269 ∗ ZX19

F2 = 0.055 ∗ ZX1 + 0.130 ∗ ZX2 + 0.493 ∗ ZX3 + 0.421 ∗ ZX4 + 0.102 ∗ ZX5 + 0.269 ∗ ZX6 − 0.050 ∗ ZX7 + 0.572 ∗ ZX8 − 0.171 ∗ ZX9 + 0.297 ∗ ZX10 − 0.157 ∗ ZX11 + 0.045 ∗ ZX12 + 0.000 ∗ ZX13 + 0.018 ∗ ZX14 + 0.030 ∗ ZX15 + 0.021 ∗ ZX16 + 0.025 ∗ ZX17 + 0.018 ∗ ZX18 − 0.015 ∗ ZX19

F3 = − 0.061 ∗ ZX1 + 0.196 ∗ ZX2 − 0.091 ∗ ZX3 − 0.129 ∗ ZX4 − 0.157 ∗ ZX5 + 0.326 ∗ ZX6 − 0.050 ∗ ZX7 + 0.112 ∗ ZX8 + 0.553 ∗ ZX9 + 0.368 ∗ ZX10 + 0.563 ∗ ZX11 + 0.105 ∗ ZX12 + 0.030 ∗ ZX13 + 0.051 ∗ ZX14 + 0.053 ∗ ZX15 + 0.045 ∗ ZX16 + 0.057 ∗ ZX17 + 0.054 ∗ ZX18 − 0.052 ∗ ZX19

F4 = 0.081 ∗ ZX1 − 0.181 ∗ ZX2 + 0.326 ∗ ZX3 + 0.380 ∗ ZX4 + 0.053 ∗ ZX5 − 0.429 ∗ ZX6 − 0.178 ∗ ZX7 + 0.096 ∗ ZX8 + 0.385 ∗ ZX9 − 0.442 ∗ ZX10 + 0.359 ∗ ZX11 − 0.083 ∗ ZX12 + 0.006 ∗ ZX13 + 0.016 ∗ ZX14 + 0.017 ∗ ZX15 + 0.022 ∗ ZX16 + 0.022 ∗ ZX17 + 0.013 ∗ ZX18 + 0.013 ∗ ZX19

F5 = 0.225 ∗ ZX1 + 0.569 ∗ ZX2 − 0.207 ∗ ZX3 + 0.019 ∗ ZX4 + 0.646 ∗ ZX5 − 0.153 ∗ ZX6 − 0.358 ∗ ZX7 − 0.076 ∗ ZX8 + 0.013 ∗ ZX9 + 0.056 ∗ ZX10 + 0.012 ∗ ZX11 − 0.058 ∗ ZX12 − 0.029 ∗ ZX13 + 0.001 ∗ ZX14 − 0.005 ∗ ZX15 − 0.019 ∗ ZX16 − 0.003 ∗ ZX17 − 0.012 ∗ ZX18 − 0.026 ∗ ZX19

Odor Activity Value Analysis: The formula for calculating the Odor Activity Value is as follows:

where Ci is the relative content of volatile compound i and OTi is the odor threshold of volatile compound i in water.

Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel (version 16.0) and IBM SPSS Statistics (version 21.0).

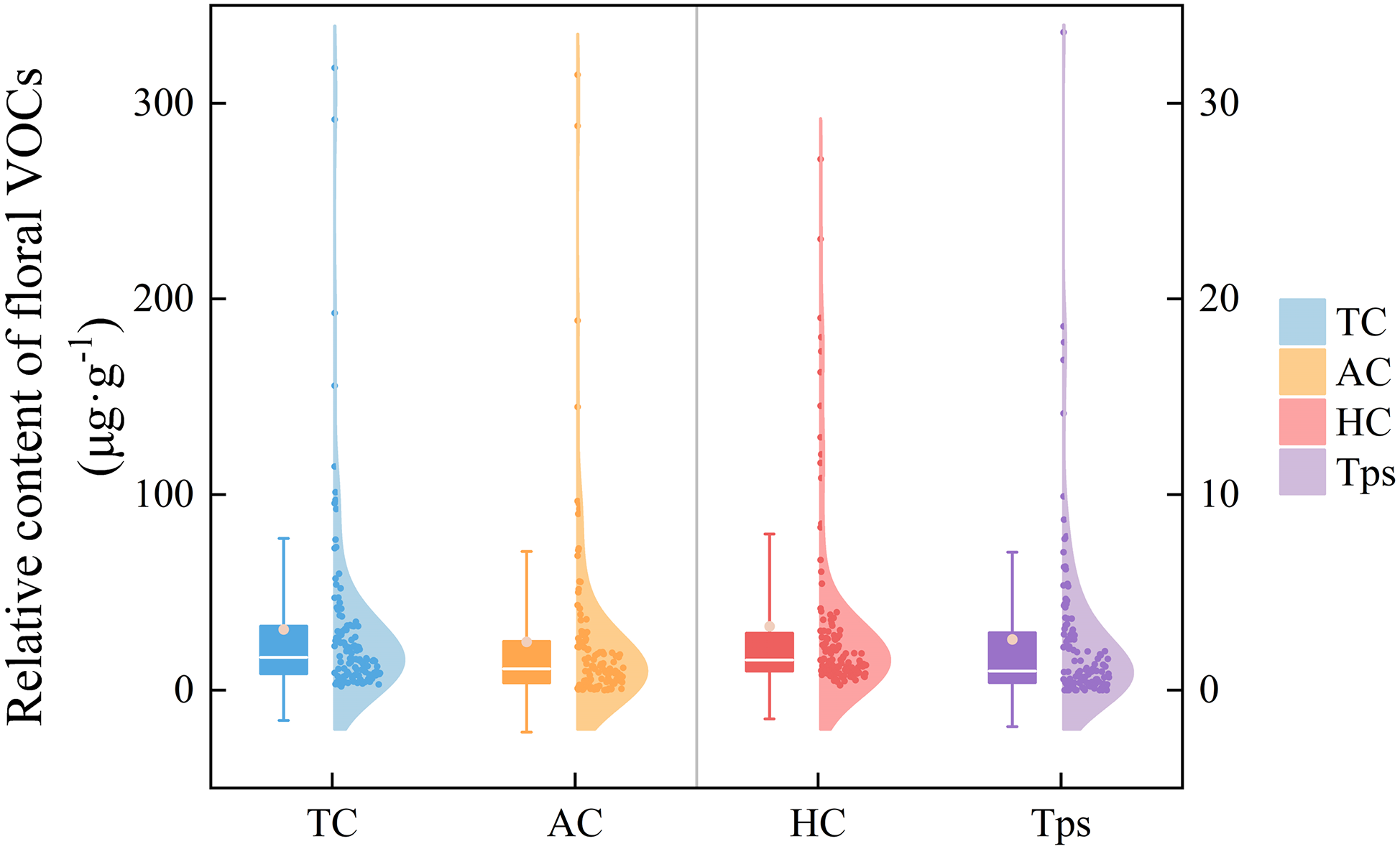

3.1 Major Floral VOCs Composition and Content from Herbaceous Peony Cultivars

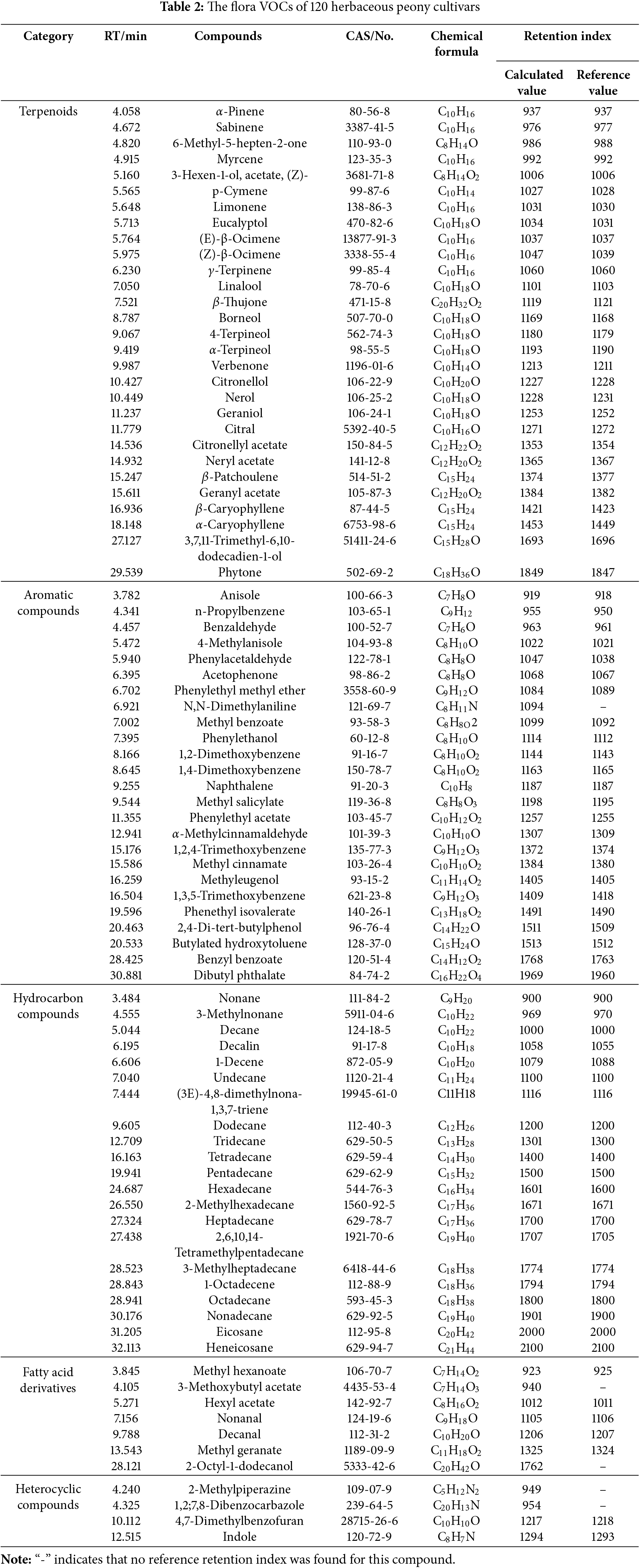

A total of 86 floral VOCs were identified, categorized into 29 terpenoids, 25 aromatic compounds, 21 hydrocarbons, 7 fatty acid derivatives, and 4 heterocyclic compounds (Table 2). Aromatic compounds constituted the largest proportion (79.70%), followed by hydrocarbons (10.51%) and terpenoids (8.37%), while fatty acid derivatives (1.03%) and heterocyclic compounds (0.38%) represented the smallest fractions. Comparative analysis of introduced and domestic cultivars revealed that aromatic compounds, hydrocarbons, and terpenoids predominated in both groups. However, introduced cultivars exhibited higher proportions of hydrocarbons relative to terpenoids, whereas the inverse pattern was observed in domestic cultivars.

The number of floral VOCs detected in each cultivar ranged from 4 to 38 across the studied herbaceous peony cultivars. ‘Hongxia Yingri’ and ‘Sishui Liunian’ contained the highest number of floral VOCs, while ‘Angel Cheeks’ and ‘Fenchi Jinyu’ contained the fewest. The distribution patterns of floral VOCs also varied substantially: nonane was universally detected across all cultivars, whereas γ-pinene and 4-terpineol were exclusively identified in ‘Hongxia Yingri’. Further analysis revealed that domestic cultivars contained 17 unique VOCs, significantly exceeding the four identified in introduced cultivars, highlighting the superior VOC diversity within domestic herbaceous peony germplasm.

3.2 Comparative Analysis of Total VOCs Contents among Herbaceous Peony Cultivars

Significant variation in total floral VOC contents were observed among herbaceous peony cultivars (Fig. 2). 37 cultivars, including ‘Coral Supreme’, ‘Command Performance’, and ‘Zitan Shengyan’, exhibited contents below 10 μg·g−1. 77 cultivars, such as ‘Yingxiong Hua’, ‘Ruixia Hong’, and ‘Chuitou Hong’, showed contents between 10 and 100 μg·g−1. Only six cultivars exceeded 100 μg·g−1: ‘Lvlian’, ‘Kansas’, ‘Modeng Nvlang’, ‘Daiyu’, ‘Yuezhao Shanhe’, and ‘Dr. Alexander Flaming’. ‘Dr. Alexander Flaming’ demonstrated the highest VOC content (318.06 ± 74.26 μg·g−1), followed by ‘Yuezhao Shanhe’ (291.74 ± 68.59 μg·g−1) and ‘Daiyu’ (192.75 ± 15.88 μg·g−1). The lowest contents were observed in ‘Zitan Shengyan’ (3.00 ± 0.97 μg·g−1), ‘Command Performance’ (2.82 ± 1.79 μg·g−1), and ‘Coral Supreme’ (1.95 ± 0.42 μg·g−1).

Figure 2: Relative content of floral VOCs in 120 herbaceous peony cultivars

Comparative analysis of introduced and domestic cultivars revealed similar content distributions, with most cultivars below 50 μg·g−1. 16 cultivars exceeded this threshold, comprising 6 introduced and 10 domestic cultivars. Introduced cultivars exhibited a mean content of 30.53 μg·g−1 (median: 15.29 μg·g−1), whereas domestic cultivars demonstrated a mean of 31.24 μg·g−1 (median: 20.12 μg·g−1). The elevated mean values relative to medians in both groups suggested right-skewed distributions. While most cultivars displayed relatively low contents, several exhibited exceptionally high values. The higher mean and median values of total VOC contents in domestic cultivars compared to introduced cultivars suggest superior overall floral aroma release capacity in domestic herbaceous peony germplasm. Furthermore, the greater discrepancy between median and mean values in introduced cultivars reflects more substantial inter-cultivar variability.

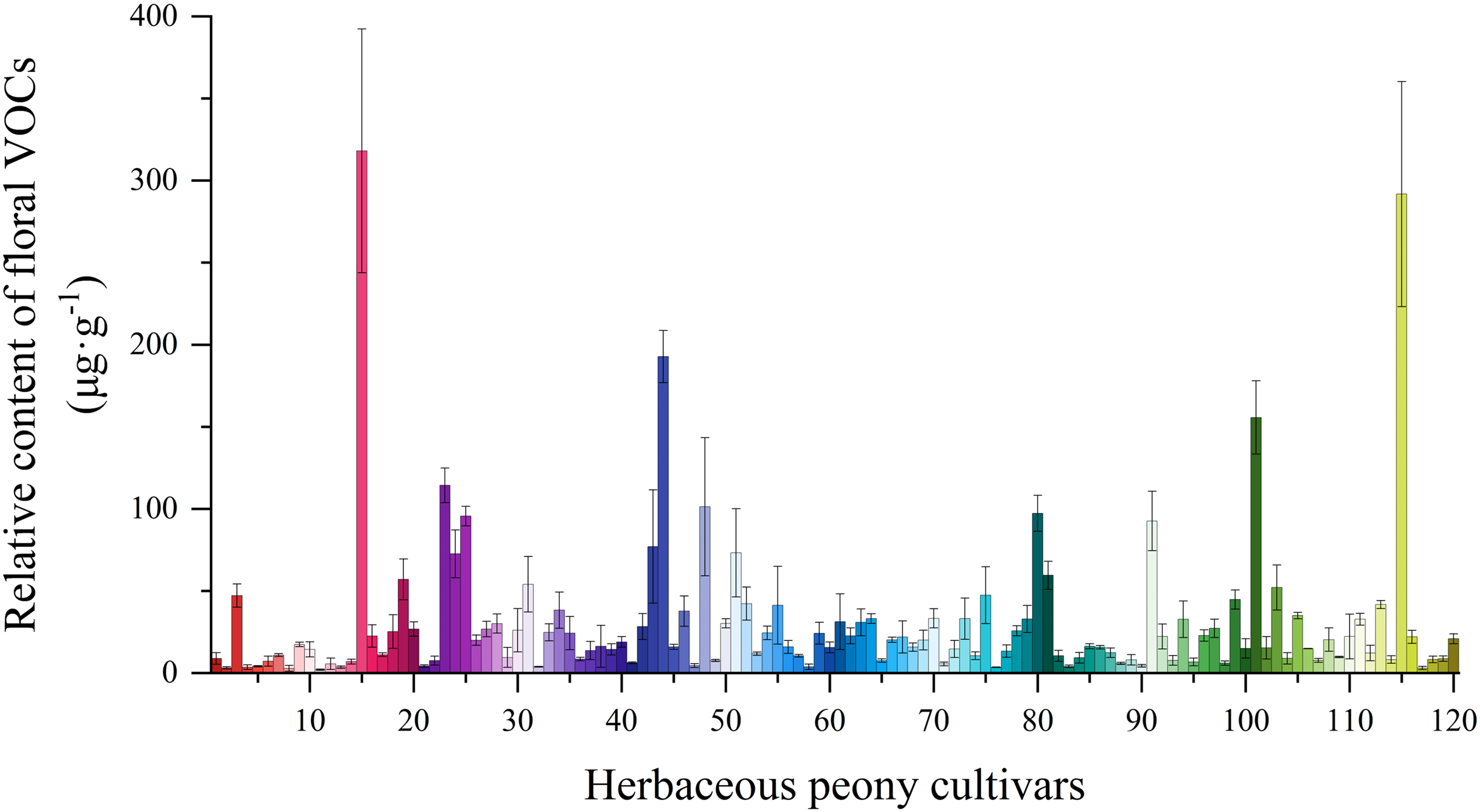

3.3 Comparative Analysis of Floral VOCs Categories among Herbaceous Peony Cultivars

Aromatic compounds, hydrocarbons and terpenoids were the three types of floral VOCs with the highest content in the aroma of herbaceous peony, so they were further analyzed and compared. Fig. 3 presents the distribution patterns of total VOCs contents and content of each VOCs categories. It can be seen that the fluctuation of the total content and the content of aromatic compounds therein showed a relatively obvious consistency. Similar to total VOC content, most cultivars exhibited low levels across all VOC categories, with only a few demonstrating exceptionally high concentrations.

Figure 3: Semi-violin-box plot of various floral fragrance VOCs of 120 herbaceous peony cultivars at the half-opening stage. From left to right, they are total content (TC), aromatic compounds (AC), hydrocarbon compounds (HC), and terpenoids (Tps). The relative contents of TC and AC are relatively high, corresponding to the left y-axis; while the relative contents of HC and Tps are relatively low, corresponding to the right y-axis. In the semi-violin-box plot, the mean values are presented in small dots inside the box bodies, the centre line represents the median. Violin edges show the 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers extend to 1.5× the interquartile range

Aromatic compounds were detected in all cultivars except ‘Linglong Yu’. ‘Dr. Alexander Fleming’ exhibited significantly higher aromatic compound contents (314.61 ± 73.13 μg·g−1), accounting for 98.92% of its total VOC content. The relative content of aromatic compounds ranged from 0 to 314.61 μg·g−1, with 85 cultivars showing >50% aromatic compound composition. Notably, phenylethanol and 1,4-dimethoxybenzene were widely distributed with high relative contents. While dibutyl phthalate, though present in 101 cultivars, showed lower contents.

Hydrocarbon compounds were universally present across all cultivars. ‘Shajin Guanding’ exhibited the highest hydrocarbon emissions (27.15 ± 1.37 μg·g−1), representing 77.66% of its total VOC content. The relative content of hydrocarbon compounds ranged from 0.25 to 27.15 μg·g−1, with 18 cultivars showing >50% hydrocarbon composition. Nonane was the most prevalent hydrocarbon, detected in all cultivars.

Comparative analysis of terpenoid content revealed their absence in 6 cultivars, including ‘Belle Chinoise’, ‘Charlie’s White’, and ‘Coral Sunset’. The cultivar ‘Qihua Chunyu’ exhibited the highest terpenoid emission (33.63 ± 8.47 μg·g−1), representing 64.62% of its total VOC content. The relative content of terpenoids ranged from 0 to 33.63 μg·g−1, with only 8 cultivars showing >50% terpenoid composition. Among the detected terpenoids, citronellol and geraniol showed high concents.

Analysis of dominant VOCs revealed distinct compositional patterns across cultivars. Aromatic compounds predominated in 90 cultivars, including ‘Belle Chinoise’, ‘Blush Queen’, and ‘Bowl of Cream’. Among these, 44 cultivars exhibited 1,4-dimethoxybenzene as their dominant volatile compound, while 42 cultivars showed phenylethanol as the primary volatile component. Methyl cinnamate was dominant in cultivars such as ‘Huaju’, ‘Ruixia Hong’, and ‘Jinzhen Cihongling’, whereas ‘Cytherea’ uniquely featured dibutyl phthalate. Hydrocarbon dominance was observed in 18 cultivars, including ‘Alertie’, ‘Angel Cheeks’, and ‘Charlie White’. Nonane served as the dominant volatile compound in 17 cultivars, while ‘Many Happy Returns’ uniquely exhibited heptadecane as its primary volatile component. Terpenoid dominance was identified in 11 cultivars, including ‘Bingqing’, ‘Moyun’, and ‘Xuefeng’. Geraniol served as the dominant volatile compound in 7 cultivars, while citronellol was the primary volatile component in 4 cultivars, including ‘Taohua Fen’ and ‘Qihua Chunyu’. Notably, ‘Barker’s Beauty’ was unique in having decanal, a fatty acid derivative, as its dominant VOC.

3.4 Principal Component Analysis of Major Floral VOCs

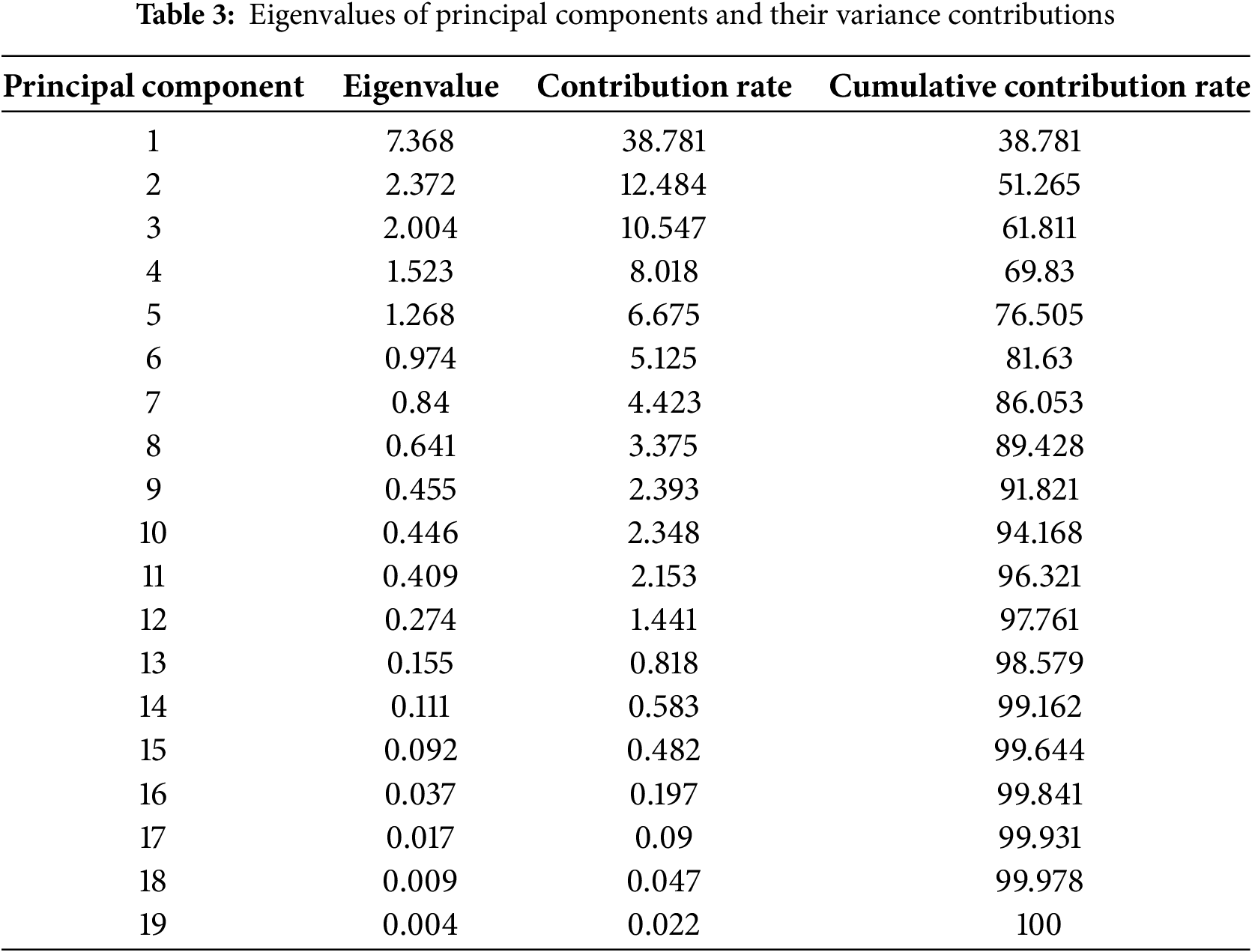

Principal component analysis (PCA) is a statistical dimensionality reduction technique that transforms original data into composite variables, facilitating more intuitive interpretation of complex datasets. To accurately identify key volatile components at the half-opening stage of herbaceous peony cultivars, 19 major floral VOCs—including nonane, (Z)-β-ocimene, and phenylethanol—were selected from 86 detected compounds for PCA. Data suitability for PCA was confirmed through SPSS analysis, with a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of 0.821 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity significance level <0.01. As shown in Table 3, the first five principal components had initial eigenvalues >1, collectively explaining 76.51% of the total variance, effectively representing the primary information of volatile components across 120 cultivars.

The first principal component (PC1) accounted for 38.78% of the total variance, with significant contributions from nonane, tetradecane, pentadecane, butylated hydroxytoluene, hexadecane, heptadecane, pentadecane, 2,6,10,14-Tetramethylpentadecane, octadecane, and dibutyl phthalate. PC2 explained 12.48% of the variance, primarily influenced by phenylethanol, 1,2-dimethoxybenzene, and phenylethyl acetate. PC3 contributed 10.55% of the variance, mainly driven by α-methylcinnamaldehyde and methyl cinnamate. PC4 represented 8.02% of the variance, with citronellol and citronellol acetate as the major contributors. Finally, PC5 accounted for 6.68% of the variance, predominantly influenced by (Z)-β-ocimene, 1,4-dimethoxybenzene, and geraniol.

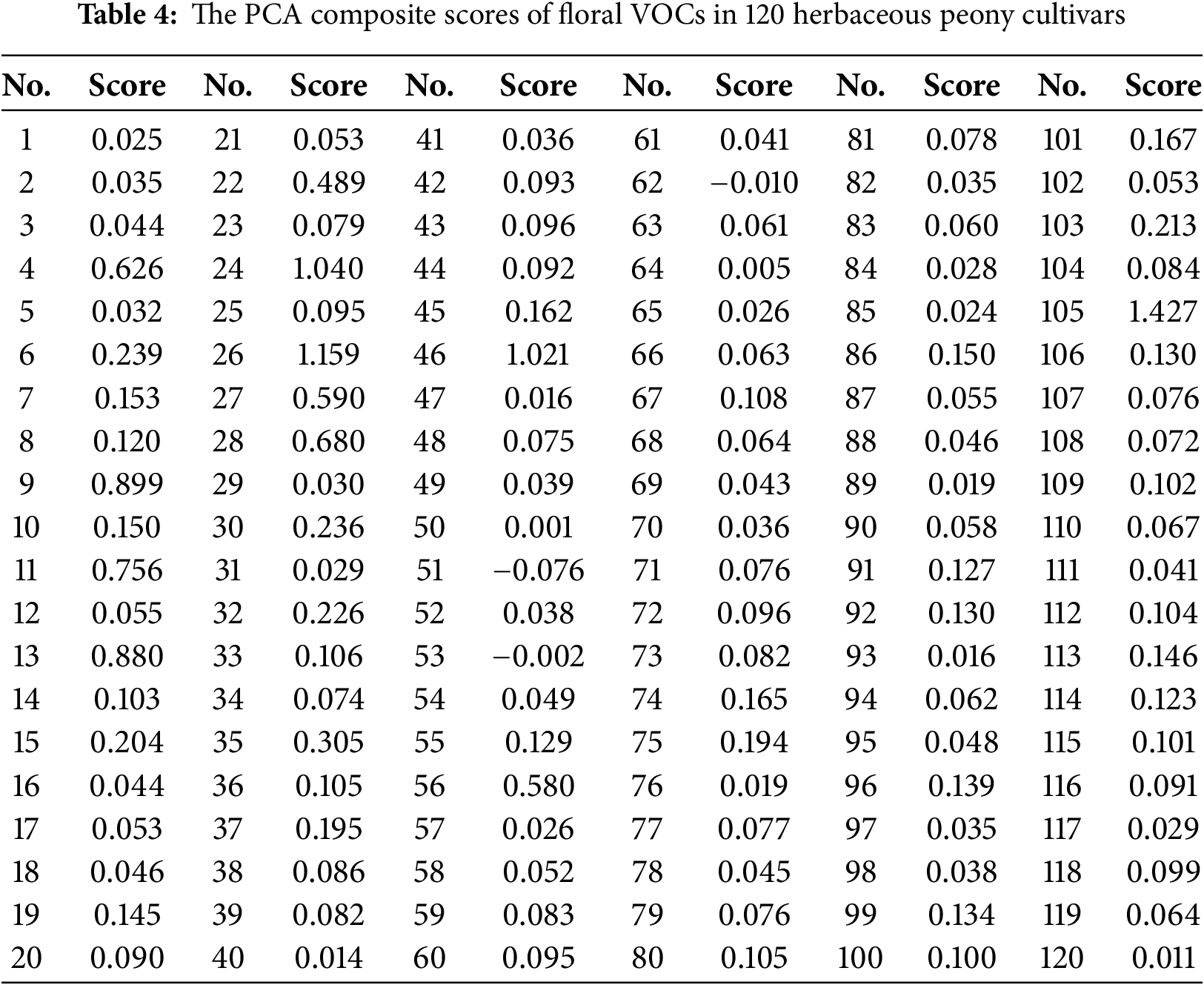

After calculating the principal component scores for the 120 herbaceous peony cultivars, these scores were weighted according to the ratio of the variance contribution rate of each principal component to the cumulative variance contribution rate. The weighted scores were then summed using the weighted sum method to obtain the composite score for each cultivar (Table 4). Based on the composite scores, the top five cultivars with the highest scores were identified: ‘Shajin Guanding’ (1.427), ‘Many Happy Returns’ (1.159), ‘Edulis Superba’ (1.040), ‘Huicui’ (1.021), and ‘Madame de Verneville’ (0.899). A comparison of the composite scores between domestic and introduced herbaceous peony cultivars revealed that 7 out of the top 10 cultivars and 21 out of the top 40 cultivars were introduced. Introduced cultivars dominated the higher rankings, with their overall distribution concentrated in the high-score segment, while most domestic cultivars were clustered in the middle- and low-score segments. These results indicate that, based on PCA composite scores, introduced cultivars generally outperform domestic cultivars.

3.5 Odor Classification and OAVs of Floral VOCs

The odor activity value (OAV) combines the relative content of volatile compounds with their odor thresholds, serving as a key indicator to evaluate the contribution of aroma components to the overall aroma profile. Generally, the higher the OAV of a volatile compound, the greater its contribution to the overall aroma. Volatile compounds with an OAV below 0.1 are considered to have a negligible impact on the aroma. Those with an OAV greater than 1 are regarded as modifying aroma components, while those with an OAV exceeding 10 are identified as key aroma components.

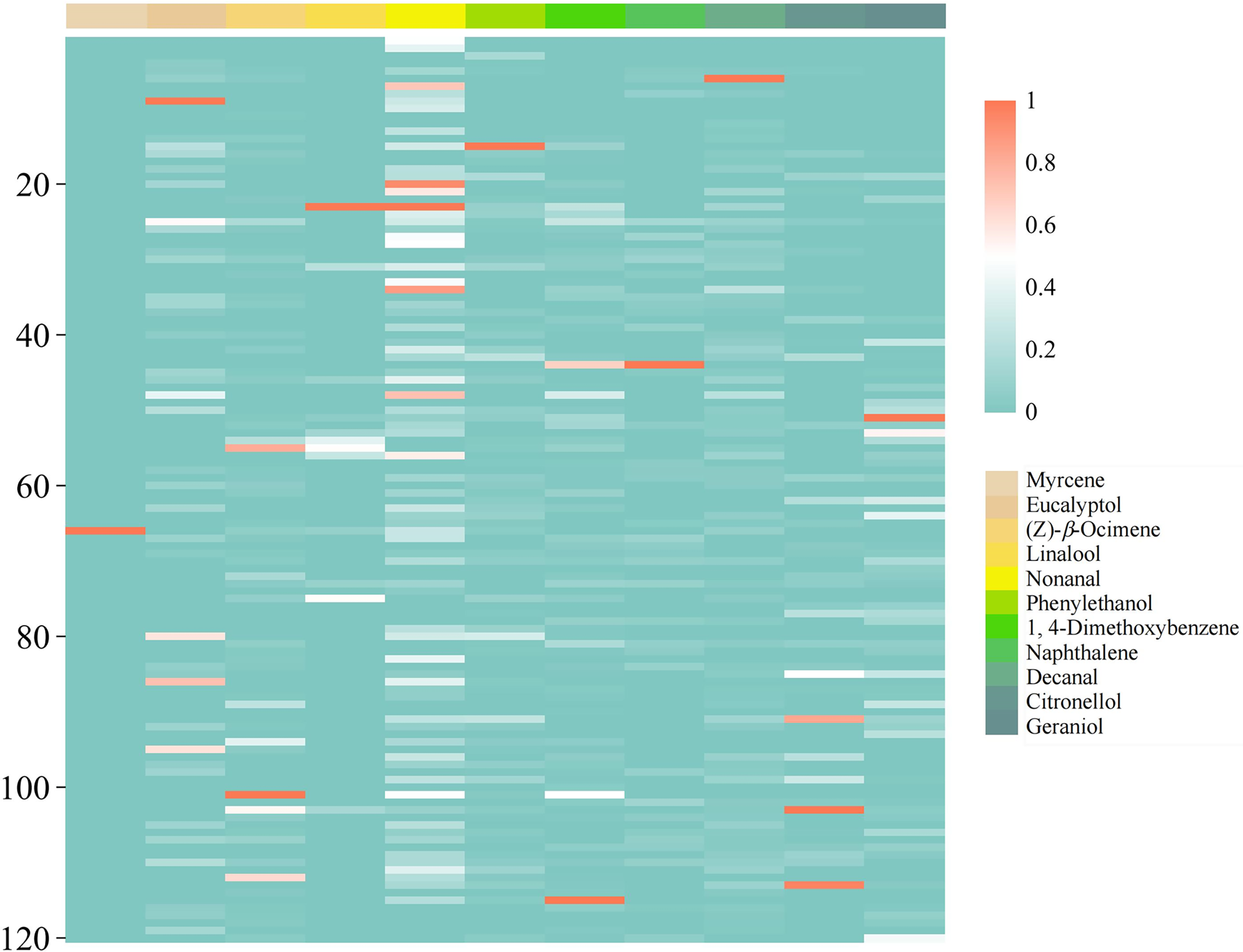

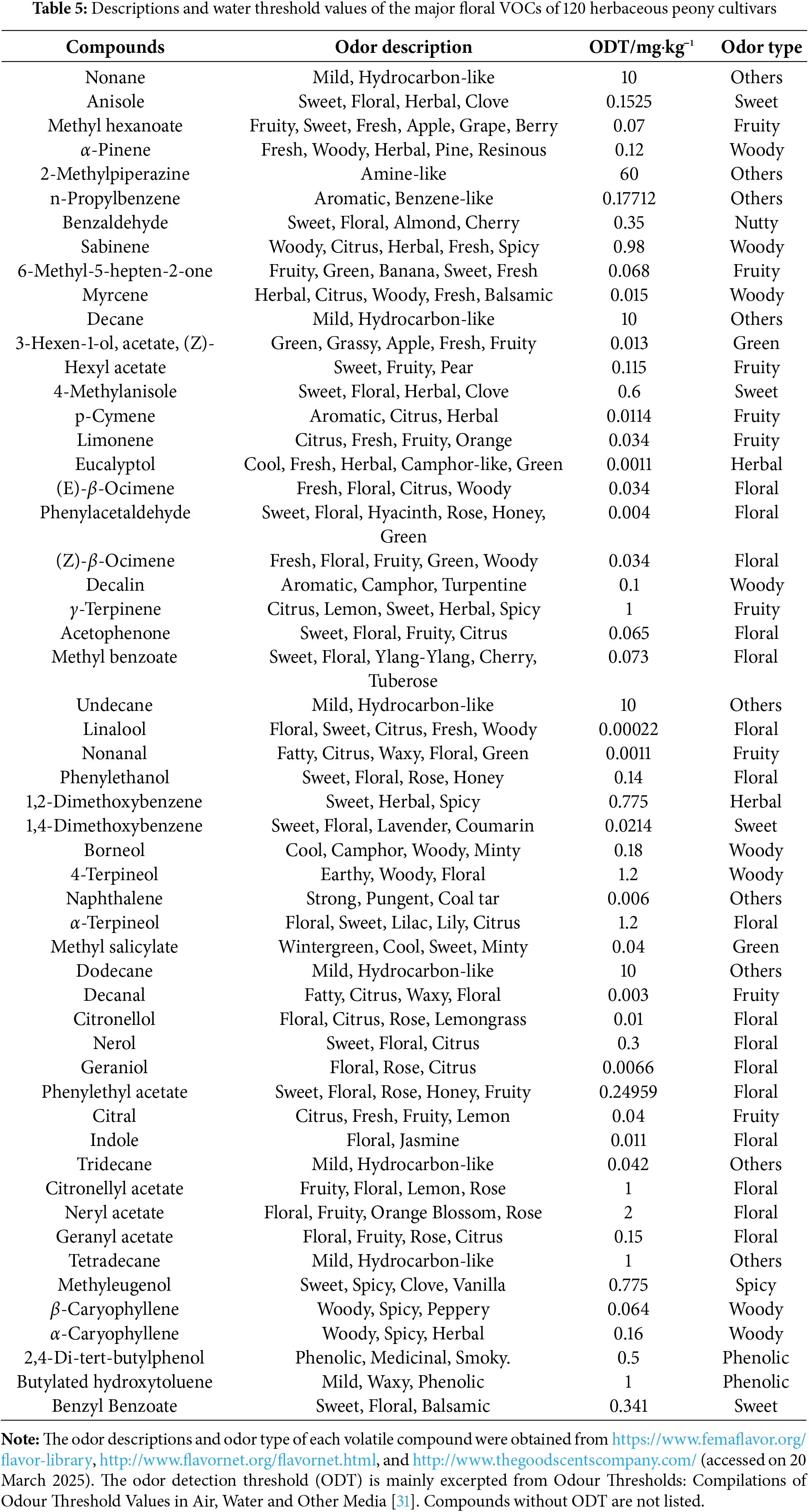

To investigate the contribution of floral VOCs to the overall aroma profile of herbaceous peony and to identify key aroma components, this study conducted a detailed analysis based on OAVs. Among the 86 identified floral VOCs, odor thresholds were obtained from the literature for only 54 VOCs; the remaining VOCs lacked available threshold data. The odor characteristics, odor thresholds, and aroma classifications of these 54 VOCs are summarized in Table 5. Through OAV analysis, 46 floral VOCs with OAVs greater than 0.1 were identified. Among these, 15 floral VOCs, including methyl hexanoate, α-pinene, and benzaldehyde, exhibited OAVs greater than 1 and were classified as modifying aroma components of the herbaceous peony floral scent. Additionally, 22 floral VOCs, such as 3-hexen-1-ol, acetate, (Z)-, limonene, and (E)-β-ocimene, had OAVs exceeding 10 and were identified as key aroma components. Within the key aroma components, 11 floral VOCs, including myrcene, eucalyptol, and (Z)-β-ocimene, showed OAVs greater than 100. These 11 VOCs comprised 6 terpenoids, 3 aromatic compounds, and 2 fatty acid derivatives, with their distribution characteristics illustrated in Fig. 4. Based on odor descriptions and aroma classifications, most floral VOCs exhibited floral, fruity, or woody notes. In the herbaceous peony floral scent, modifying aroma components were primarily sweet or woody, while key aroma components were predominantly floral, fruity, or woody.

Figure 4: Heatmap visualization of odor activity values for 11 floral VOCs (OAV > 100) across 120 herbaceous peony cultivars. OAV values were normalized per compound to a 0–1 scale using min-max transformation, where 1 represents the maximum OAV value within each compound and 0 indicates the minimum detectable level. Color gradient reflects min-max normalized OAV values per compound. Cultivars are ordered by origin (Introduced: 1–40; Domestic: 41–120)

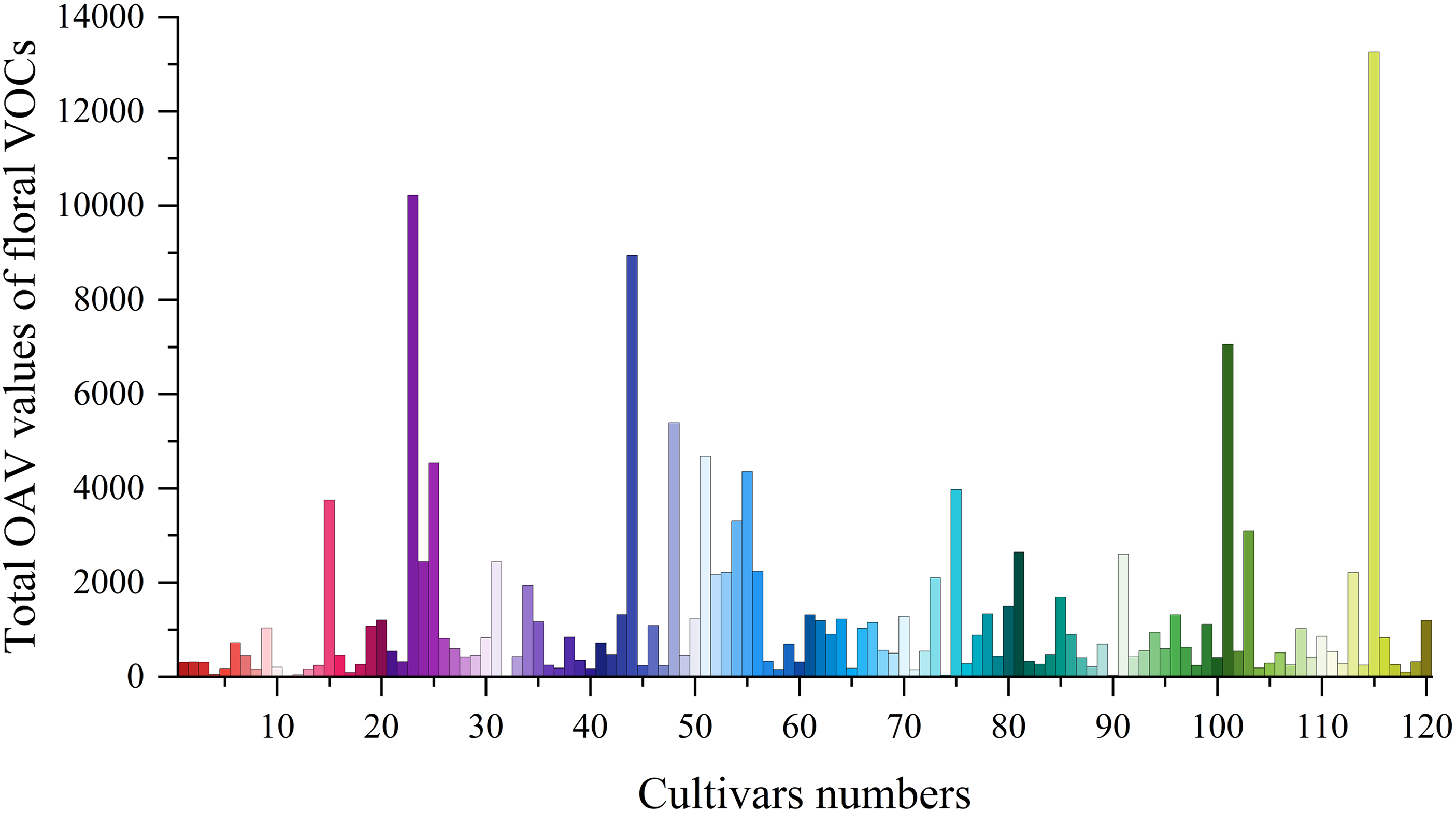

The sum of OAV values for each cultivar is shown in Fig. 5. The cultivar with the highest total OAV was ‘Yuezhao Shanhe’, followed by ‘Kansas’ and ‘Daiyu’. The lowest OAVs were observed in ‘Coral Supreme’, ‘Nick Shaylor’, and ‘Ruixia Hong’. By analyzing the highest-OAV aroma compounds in each herbaceous peony cultivar, aromatic compounds were found to contribute the most to the floral scent of 55 cultivars, including ‘Belle Chinoise’, ‘Coral Supreme’, and ‘Do Tell’. The highest-OAV aroma compounds in these cultivars were 1,4-dimethoxybenzene, phenylethanol, and naphthalene. terpenoids contributed the most to the floral aroma of 44 cultivars, such as ‘Blush Queen’, ‘Coral Charm’, and ‘Duchesse de Nemours’, with the highest-OAV aroma compounds including geraniol, citronellol, eucalyptol, and linalool. Fatty acid derivatives contributed the most to the floral aroma of 21 cultivars, such as ‘Alertie’, ‘Angel Cheeks’, and ‘Bowl of Cream’, with the highest-OAV aroma compounds being nonanal and decanal. The highest-OAV aroma compounds in introduced cultivars were primarily nonanal and 1,4-dimethoxybenzene, characterized by fruity and sweet aromas, while those in domestic cultivars were mainly 1,4-dimethoxybenzene and phenylethanol, dominated by sweet and floral aromas. Overall, aromatic compounds contributed the most to the overall aroma of herbaceous peony, followed by terpenoids. However, in introduced cultivars, fatty acid derivatives contributed more than terpenoids, which is a key factor in the aroma differences between domestic and introduced cultivars.

Figure 5: Total OAV values of floral VOCs in 120 herbaceous peony cultivars

In this study, the volatile components of flowers at the half-opening stage from 120 herbaceous peony cultivars were comprehensively identified and analyzed using multiple analytical methods, aiming to screen aromatic cultivars. The results demonstrated that aromatic compounds, hydrocarbons, and terpenoids constitute the primary components of the floral scent in herbaceous peony. The wide range of VOC diversity observed among herbaceous peony cultivars (from 4 to 38) provides breeders with a valuable resource for selecting parental material with desirable fragrance profiles. By prioritizing cultivars with high VOC diversity, breeders can develop new cultivars with unique fragrances.

Among all the floral scent VOCs, 1,4-dimethoxybenzene exhibited the highest relative content and the largest OAV. Specifically, 1,4-dimethoxybenzene ranked first in relative content among 44 cultivars and was identified as the highest-OAV aroma compound in 47 cultivars. In summary, based on the quantitative analysis and distribution characteristics across cultivars, it can be concluded that 1,4-dimethoxybenzene is the most critical aroma component in the floral scent of herbaceous peony. This conclusion aligns closely with the findings of Wang et al. [28]. 1,4-Dimethoxybenzene is widely present in the floral scents of various plant species and plays a significant role in attracting insect pollinators and facilitating fruit formation. 1,4-Dimethoxybenzene are particularly attractive to common pollinators, such as honeybees [32]. Furthermore, Hoepflinger et al. identified a novel O-methyltransferase, Cp4MP-OMT, which catalyzes the final step in the biosynthesis of 1,4-dimethoxybenzene [33]. This discovery provides critical insights into the biosynthetic pathway of 1,4-dimethoxybenzene.

As a simple and effective data processing method, PCA is widely utilized in the analysis of floral scent composition, as demonstrated in studies by Fu et al., Luo et al., and Zhou et al. [34–36]. In this study, 19 major volatile components, including nonane, (Z)-β-ocimene, and phenylethanol, were selected from the 86 identified floral VOCs for PCA. Five principal components were extracted, which effectively captured the primary information of the volatile components across the 120 herbaceous peony cultivars. The top 5 varieties with the combined scores of principal component analysis were ‘Shajin Guanding’ (1.427), ‘Many Happy Returns’ (1.159), ‘Edulis Superba’ (1.040), ‘Huicui’ (1.021) and ‘Madame de Verneville’ (0.899), and this result can provide parental choices with reference value for aroma breeding of herbaceous peony.

Aroma activity value analysis, a classical method widely applied in food flavor research [37], has gained increasing attention in floral scent studies in recent years [38–40]. Floral scent directly influences the human olfactory system, and the incorporation of odor threshold (ODT) data in the analysis of floral scent components enhances the credibility and persuasiveness of the results. By considering both the relative content of floral VOCs and their corresponding ODTs, it is evident that the contribution of floral VOCs to the overall aroma largely depends on their ODT levels. For instance, in the analysis of herbaceous peony floral scent, hydrocarbons exhibited higher relative content than terpenoids; however, terpenoids played a more critical role in shaping the floral aroma due to the typically higher ODTs of hydrocarbons, which reduced their aroma activity. Furthermore, the odor characterization of herbaceous peony floral VOCs revealed that they primarily exhibited floral, fruity, or woody aromas. The highest-OAV aroma compounds in introduced cultivars were predominantly nonanal and 1,4-dimethoxybenzene, exhibiting fruity and sweet aromas, while those in domestic cultivars were primarily 1,4-dimethoxybenzene and phenylethanol, characterized by sweet and floral aromas. Overall, aromatic compounds contributed the most to the overall aroma profile of herbaceous peony, followed by terpenoids. However, it should be noted that the limited availability of ODT data for many floral VOCs restricted this study to analyzing the aroma activity values of only a subset of floral VOCs. These findings underscore the necessity of further research to expand the ODT database for floral VOCs.

With advancements in science and technology, collection and analytical methods have become increasingly refined, driving rapid progress in floral scent research. Numerous genes associated with floral scent have been identified, establishing floral scent as a prominent research topic in plant sciences [41–43]. The findings of Peng et al. indicate that current floral scent research is progressively deepening, with perspectives expanding from microscopic to macroscopic levels, and research focuses now encompassing biosynthetic pathways, gene regulatory networks, ecological functions, and cultivar selection and breeding [44]. In this study, a systematic investigation of the floral scent composition of herbaceous peony was conducted. Dynamic headspace sampling was employed to collect floral VOCs from 120 herbaceous peony cultivars at the half-opening stage, followed by identification and analysis using GC-MS. The results not only clarified the main components of herbaceous peony floral scent but also analyzed the relative content and aroma activity of each component. These findings provide a solid theoretical foundation and data support for subsequent research on the regulatory mechanisms of herbaceous peony aroma, the identification of key genes controlling scent synthesis, the elucidation of biosynthetic pathways, and the targeted breeding of new aromatic herbaceous peony cultivars. However, it should be noted that this study did not account for environmental factors during VOC collection. Environmental changes can significantly impact plant physiology and VOC emissions [45]. High temperatures, for instance, can accelerate respiration and photosynthesis, altering VOC emission patterns. Increased CO2 concentrations can also affect stomatal conductance, influencing VOC release. These environmental factors collectively may importantly affect peony floral scent components. The exclusion of these factors may introduce some degree of bias into the results.

In this study, we systematically identified and analyzed the floral VOCs from flowers at the half-opening stage of 120 herbaceous peony cultivars using DHS-GC-MS. A total of 86 volatile compounds were identified, primarily categorized into five groups: aromatic compounds, hydrocarbons, terpenoids, fatty acid derivatives, and heterocyclic compounds. Among these, aromatic compounds, hydrocarbons, and terpenoids constituted the majority of the overall aroma profile. The top three cultivars with the highest total VOC release were ‘Dr. Alexander Fleming’, ‘Yuezhao Shanhe’, and ‘Daiyu’, which was significantly higher than that of other cultivars. PCA revealed that the top five cultivars, including ‘Shajin Guanding’, ‘Many Happy Returns’, ‘Edulis Superba’, ‘Huicui’, and ‘Madame de Verneville’, exhibited statistically representative aroma profiles, making them suitable candidates for aroma breeding. Based on OAV analysis, 15 floral VOCs, such as methyl hexanoate, α-pinene and benzaldehyde, were identified as modifying aroma components, while 22 floral VOCs, including 3-hexen-1-ol, acetate, (Z)-, limonene and (E)-β-ocimene, were recognized as key aroma constituents. The highest-OAV aroma compounds in introduced cultivars were primarily nonanal and 1,4-dimethoxybenzene, characterized by fruity and sweet aromas, while those in domestic cultivars were mainly 1,4-dimethoxybenzene and phenylethanol, dominated by sweet and floral aromas. Multivariate statistical analysis (PCA) and OAV evaluation demonstrated that aromatic compounds and terpenoids play a decisive role in shaping the overall aroma of herbaceous peony floral scent. The identification of 1,4-dimethoxybenzene as a key aroma component, characterized by its sweet, clove-like floral scent, underscores its potential as a target for aroma enhancement in herbaceous peony breeding. These findings not only provide a valuable research framework for analyzing the floral scent composition of other herbaceous peony cultivars but also lay the groundwork for the comprehensive development and utilization of herbaceous peony floral aroma in fields such as flavors and fragrances, cut flowers, and floral tea.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number U23A20211] and the Key Scientific Research Project of Higher Education Institutions in Henan Province [grant number 24A220001].

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Lili Guo; methodology, Meida Chen and Tongfei Niu; formal analysis, Meida Chen; investigation, Meida Chen, Tongfei Niu, Zhanxiang Tan and Yuxin Zhao; resources, Kai Gao, Xiaogai Hou and Lili Guo; data curation, Meida Chen; writing—original draft preparation, Meida Chen; writing—review and editing, Tongfei Niu, Xiaogai Hou and Lili Guo; visualization, Meida Chen and Tongfei Niu; supervision, Xiaogai Hou and Lili Guo; project administration, Tongfei Niu; funding acquisition, Lili Guo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Lili Guo, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mostafa S, Wang Y, Zeng W, Jin B. Floral scents and fruit aromas: functions, compositions, biosynthesis, and regulation. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:860157. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.860157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Vivaldo G, Masi E, Taiti C, Caldarelli G, Mancuso S. The network of plants volatile organic compounds. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):11050. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-10975-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Bisrat D, Jung C. Roles of flower scent in bee-flower mediations: a review. J Ecol Environ. 2022;46(1):18–30. doi:10.5141/jee.21.00075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Abbas F, O'Neill Rothenberg D, Zhou Y, Ke Y, Wang H. Volatile organic compounds as mediators of plant communication and adaptation to climate change. Physiol Plant. 2022;174(6):e13840. doi:10.1111/ppl.13840. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Knudsen JT, Gershenzon J. The chemical diversity of floral scent. In: Knudsen JT, Gershenzon J, editors. Biology of plant volatiles. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2020. p. 57–78. doi:10.1201/9780429455612-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Muhlemann JK, Klempien A, Dudareva N. Floral volatiles: from biosynthesis to function. Plant Cell Environ. 2014;37(8):1936–49. doi:10.1111/pce.12314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Dudareva N, Klempien A, Muhlemann JK, Kaplan I. Biosynthesis, function and metabolic engineering of plant volatile organic compounds. New Phytol. 2013;198(1):16–32. doi:10.1111/nph.12145. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Abbas F, Ke Y, Yu R, Yue Y, Amanullah S, Jahangir MM, et al. Volatile terpenoids: multiple functions, biosyn-thesis, modulation and manipulation by genetic engineering. Planta. 2017;246(5):803–16. doi:10.1007/s00425-017-2749-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Lv M, Zhang L, Wang Y, Ma L, Yang Y, Zhou X, et al. Floral volatile benzenoids/phenylpropanoids:biosyn-thetic pathway, regulation and ecological value. Hortic Res. 2024;11(10):uhae220. doi:10.1093/hr/uhae220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Osbourn AE, Lanzotti V. Plant-derived natural products—synthesis, function, and application. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2009. 597 p. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-85498-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Abbas F, Zhou Y, O'Neill RD, Alam I, Ke Y, Wang HC. Aroma components in horticultural crops: chemical diversity and usage of metabolic engineering for industrial applications. Plants. 2023;12(9):1748. doi:10.3390/plants12091748. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Du F, Wang T, Fan JM, Liu ZZ, Zong JX, Fan WX, et al. Volatile composition and classification of Lilium flower aroma types and identification, polymorphisms, and alternative splicing of their monoterpene synthase genes. Hortic Res. 2019;6(1):110. doi:10.1038/s41438-019-0192-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Guo X, Wang P. Aroma characteristics of lavender extract and essential oil from Lavandula angustifolia Mill. Molecules. 2020;25(23):5541. doi:10.3390/molecules25235541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Kishimoto K. Effect of temperature on scent emission from carnation cut flowers. Jpn Agric Res Q. 2022;56(2):163–70. doi:10.6090/jarq.56.163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wang Z, Zhao X, Tang X, Yuan Y, Xiang M, Xu Y, et al. Analysis of fragrance compounds in flowers of Chry-santhemum genus. Ornam Plant Res. 2023;3(1):12. doi:10.48130/OPR-2023-0012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ning K, Zhou T, Fan Y, El-Kassaby YA, Bian J. Discrimination of tulip cultivars with different floral scents using sensory assessment, electronic nose, and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;219(1):118996. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.118996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen G, Mostafa S, Lu Z, Du R, Cui J, Wang Y, et al. The jasmine (Jasminum sambac) genome and flower fragrances [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 24]. Available from: http://biorxiv.org/lookup/doi/10.1101/2020.12.17.420646. [Google Scholar]

18. Li R, Li Z, Leng P, Hu Z, Wu J, Dou D. Transcriptome sequencing reveals terpene biosynthesis pathway genes accounting for volatile terpene of tree peony. Planta. 2021;254(4):67. doi:10.1007/s00425-021-03715-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Cheng X, Feng Y, Chen D, Luo C, Yu X, Huang C. Evaluation of Rosa germplasm resources and analysis of floral fragrance components in R. rugosa. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1026763. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1026763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Yang Y, Sun M, Li S, Chen Q, Teixeira da Silva JA, Wang A, et al. Germplasm resources and genetic breeding of paeonia: a systematic review. Hortic Res. 2020;7(1):107. doi:10.1038/s41438-020-0332-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Bao M, Liu M, Zhang Q, Wang T, Sun X, Xu J. Factors affecting the color of herbaceous peony. J Amer Soc Hort Sci. 2020;145(4):257–66. doi:10.21273/JASHS04892-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wu Y, Hao Z, Tang Y, Zhao D. Anthocyanin accumulation and differential expression of the biosynthetic genes result in a discrepancy in the red color of herbaceous peony (Paeonia lactiflora Pall.) flowers. Horticulturae. 2022;8(4):349. doi:10.3390/horticulturae8040349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang D, Xie A, Yang X, Yang L, Shi Y, Dong L, et al. Analysis of physiological and biochemical factors af-fecting flower color of herbaceous peony in different flowering periods. Horticulturae. 2023;9(4):502. doi:10.3390/horticulturae9040502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang T, Xie A, Zhang D, Liu Z, Li X, Li Y, et al. Analysis of the volatile components in flowers of Paeonia lactiflora Pall. and Paeonia lactiflora Pall. var. Trichocarpa. Am J Plant Sci. 2021;12(01):146–62. doi:10.4236/ajps.2021.121009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhao Q, Gu L, Li Y, Zhi H, Luo J, Zhang Y. Volatile composition and classification of Paeonia lactiflora flower aroma types and identification of the fragrance-related genes. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(11):9410. doi:10.3390/ijms24119410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Zhao Q, Zhang M, Gu L, Yang Z, Li Y, Luo J, et al. Transcriptome and volatile compounds analyses of floral development provide insight into floral scent formation in Paeonia lactiflora ‘Wu Hua Long Yu’. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1303156. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1303156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Wang S, Luo Y, Niu T, Prijic Z, Markovic T, Guo D, et al. Comparative analysis of the volatile components of six herbaceous peony cultivars under ground-planted and vase-inserted conditions. Sci Hortic. 2024;334(2):113320. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wang A, Luo Y, Niu T, Gao K, Wang S, Zhao X, et al. Identification and content analysis of volatile compo-nents in 100 cultivars of Chinese herbaceous peony. Ornam Plant Res. 2024;4(1):e032. doi:10.48130/opr-0024-0029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Fan Y, Jin X, Wang M, Liu H, Tian W, Xue Y, et al. Flower morphology, flower color, flowering and floral fragrance in Paeonia L. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1467596. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1467596. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Lo MM, Benfodda Z, Molinié R, Meffre P. Volatile organic compounds emitted by flowers: ecological roles, production by plants, extraction, and identification. Plants. 2024;13(3):417. doi:10.3390/plants13030417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Van Gemert LJ. Odour thresholds: compilations of odour threshold values in air, water and other media. 2nd ed. Zeist, The Netherlands: Oliemans, Punter & Partners B.V; 2011. 378 p. [Google Scholar]

32. Dötterl S, Gershenzon J. Chemistry, biosynthesis and biology of floral volatiles: roles in pollination and other functions. Nat Prod Rep. 2023;40(12):1901–37. doi:10.1039/D3NP00024A. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Hoepflinger MC, Barman M, Dötterl S, Tenhaken R. A novel O-methyltransferase Cp4MP-OMT catalyses the final step in the biosynthesis of the volatile 1,4-dimethoxybenzene in pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo) flowers. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):294. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-04955-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Fu J, Hou D, Wang Y, Zhang C, Bao Z, Zhao H, et al. Identification of floral aromatic volatile compounds in 29 cultivars from four groups of Osmanthus fragrans by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Hortic Environ Biotechnol. 2019;60(4):611–23. doi:10.1007/s13580-019-00153-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Luo X, Yuan M, Li B, Li C, Zhang Y, Shi Q. Variation of floral volatiles and fragrance reveals the phylogenetic relationship among nine wild tree peony species. Flavour Fragr J. 2020;35(2):227–41. doi:10.1002/ffj.3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhou L, Yu C, Cheng B, Wan H, Luo L, Pan H, et al. Volatile compound analysis and aroma evaluation of tea-scented roses in China. Ind Crops Prod. 2020;155(3):112735. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Grosch W. Determination of potent odourants in foods by aroma extract dilution analysis (AEDA) and calculation of odour activity values (OAVs). Flavour Fragr J. 1994;9(4):147–58. doi:10.1002/ffj.2730090403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Yang YH, Zhao J, Du ZZ. Unravelling the key aroma compounds in the characteristic fragrance of Dendrobium officinale flowers for potential industrial application. Phytochemistry. 2022;200(2):113223. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2022.113223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Niu T, Ma H, Tan Z, Yu M, Wei D, Guo L, et al. Identification of floral fragrance components in 20 intersectional hybrids of paeonia in Luoyang region. Flavour Fragr J. 2024;40(2):190–204. doi:10.1002/ffj.3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang Y, Zhi H, Qu L, Su D, Luo J. Analysis of flower volatile compounds and odor classification of 17 tree peony cultivars. Sci Hortic. 2024;338:113665. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ramya M, Kwon OK, An HR, Park PM, Baek YS, Park PH. Floral scent: regulation and role of MYB transcription factors. Phytochem Lett. 2017;19:114–20. doi:10.1016/j.phytol.2016.12.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Sun M, Ren X, Liu Y, Yang J, Hui J, Zhang Y, et al. Genetic structure and selection signature in flora scent of roses by whole genome re-sequencing. Diversity. 2023;15(6):701. doi:10.3390/d15060701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ma H, Zhang C, Niu T, Chen M, Guo L, Hou X. Identification of floral volatile components and expression analysis of controlling gene in Paeonia ostii ‘Fengdan’ under different cultivation conditions. Plants. 2023;12(13):2453. doi:10.3390/plants12132453. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Peng Q, Zhang Y, Fan J, Shrestha A, Zhang W, Wang G. The development of floral scent research: a comprehensive bibliometric analysis (1987–2022). Plants. 2023;12(23):3947. doi:10.3390/plants12233947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Nawaz T, Nelson D, Fahad S, Saud S, Aaqil M, Adnan M, et al. Impact of elevated CO2 and temperature on overall agricultural productivity. In: Fahad S, Munir I, Nawaz T, Adnan M, Lal R, Saud S, editors. Challenges and solutions of climate impact on agriculture. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2025. p. 163–202. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-443-23707-2.00007-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools