Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Innovative Approaches in the Extraction, Identification, and Application of Secondary Metabolites from Plants

1 Ethnopharmacology and Pharmacognosy Team, Department of Biology, Faculty of Sciences and Technology, Errachidia, Moulay Ismaïl University, Meknes, 50000, Morocco

2 Laboratory of Applied Organic Chemistry, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Sciences and Technologies, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Route d’Imozzer, Fez, 30000, Morocco

3 Biotechnology, Environmental Technology and Valorization of Bio-Resources Team, Department of Biology, Laboratory of Research and Development in Engineering Sciences, Faculty of Sciences and Techniques Al-Hoceima, Abdelmalek Essaadi University, Tétouan, 93000, Morocco

4 Laboratory of Biotechnology, Conservation and Valorization of Natural Resources (LBCVNR), Faculty of Sciences Dhar EI Mehraz, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, B. P. 1796, Fez, 30000, Morocco

5 Laboratory of Functional Ecology and Environment, Faculty of Sciences and Technology, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Imouzzer Street, P.O. Box 2202, Fez, 30000, Morocco

* Corresponding Author: Amine Assouguem. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Vegetable Resources, Sustainable Plant Protection and Adaptation Strategies to Climate Change)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(6), 1631-1668. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.065750

Received 21 March 2025; Accepted 16 May 2025; Issue published 27 June 2025

Abstract

Unlike primary metabolites, secondary metabolites serve critical ecological functions, including plant protection, stress tolerance, and symbiosis. This review focuses on extracting, separating, and identifying the major classes of secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, terpenoids, phenolics, glycosides, saponins, and coumarins. It describes optimized methods regarding plant selection, extraction by solvents, and purification of the metabolites, highlighting the latest advancements in chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques. The review also describes some of the most important problems, such as the instability of the compounds or diversity of the structures, and discusses emerging technologies that solve these issues. Moreover, it examines the secondary roles of these metabolites in medicine, such as anticancer and antimicrobial drugs, sustainable agriculture biopesticides, and environmental ecology-also known as allelopathy and bioindicators. It combines traditional ethnobotanical approaches with contemporary science, demonstrating the vital need to protect biodiversity in key ecosystems such as tropical rainforests, mountain regions, coral reefs, and arid zones as a foundation for anticipatory bio-discoveries. It organizes the methodological frameworks and outlines the steps needed to enhance the extraction of bioactive compounds from natural sources.Keywords

Plants are key primary producers of ecosystems throughout the globe and serve as the bedrock of life on Earth. They can synthesize many biological and non-biological compounds representing raw metabolic processes [1,2]. These chemicals are often not regarded as mere metabolites; they are tailored to fulfill distinct functions, promoting survival. Among other things that plants synthesize, secondary metabolites stand out. While primary metabolites, which include carbohydrates, proteins, and nucleic acids, are vital to growth and reproduction, secondary metabolites have a much broader spectrum of specialized functions [3–5]. Alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids, tannins, and saponins are only a few examples of the thousands of secondary metabolites of structurally diverse nature. These compounds serve as a chemical barrier to herbivores and pathogens, and as attractants to pollinators or symbiotic organisms. They have additional functions in chemical warfare against neighboring plants. Furthermore, these compounds aid in coping with drought, salinity, and temperature extremes and enhance resilience against abiotic stresses [6,7]. The importance of secondary metabolites is not just limited to plant biology since their diverse biological activities have implications for humanity, agriculture, and industry [8–10]. Since ancient civilizations, plants have been used to treat several ailments and improve well-being. Unbeknownst to humans, they were using the plants’ secondary metabolites. Modern science has revealed the molecular structure of these compounds, resulting in the pharmacological inventions of many life-saving medications, notable examples include taxol (anticancer), vincristine (chemotherapy agent), quinine (antimalarial), galantamine (used in Alzheimer’s treatment), artemisinin (an antimalarial compound from Artemisia annua), morphine (a potent analgesic), and resveratrol (an antioxidant with cardioprotective properties). In agriculture, secondary metabolites are utilized to formulate biopesticides and growth-promoting substances to decrease the use of synthetic chemicals [11–13].

Exploring secondary metabolites may seem fruitful, but it has its challenges. The intricacy of plant matrices, the requirement of highly competent analytical tools, and the low concentrations of target compounds are some challenges one faces [14]. However, technological advances with interdisciplinary research have improved the way these molecules are isolated and characterized [15]. Thus, in this article, we shall attempt to rigorously investigate and analyze the various systems and techniques needed to isolate and characterize plant secondary metabolites to aid scientific discovery and innovation in multiple industries.

2 Importance of Secondary Metabolites

Secondary metabolites are organic molecules that, even though they are not directly engaged in the core processes supporting growth and reproduction, are important for a plant’s prosperity, ecological relationships, and utilization by humans [16]. These are produced through specialized pathways and are classified into three main classes based on their metabolic origins: alkaloids, terpenoids, and phenolics [17]. Their structures, biological activities, and uses vary significantly from each other. These metabolites are critical for the plants that produce them and the economies, ecosystems, and human societies that depend on them [18].

These secondary metabolites of amino acids are synthesized in various organisms, forming a large group of chemical compounds known for their wide-ranging ecological and medicinal purposes. Alkaloids also serve as a potent chemical defense mechanism because they are often toxic to microbes and herbivores. Some of the more popular examples include the following compounds:

Morphine is one of the most popular medicinal analgesics, which derives from the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum) plant as well. For many centuries now, morphine has been prescribed to dull pain, especially for injury or post-surgery recovery [19]. Modern medicine depicts morphine as a centerpiece of any pain management plans especially for terminal diseases like cancer. These unique plants are capable of providing unparalleled pain relief because of their ability to bind to opioid receptors within the human body. The isolation and discovery of morphine is not only a milestone in pharmacology, but also an important step in the isolation of other plant-derived compounds with high efficacy [20].

Quinine is one of the best antimalarials that have been used for centuries and is extracted from the bark of the Cinchona tree. Quinine kills malaria parasites through various mechanisms that interfere with their life cycle [21]. After establishing the infection, this involves inhibiting their growth and juga secara tidak langsung alright. This emphasizes its critical function in malaria management, especially before affordable synthetics emerged. The extraction of quinine led to the creation of synthetic antimalarial medicines and remains an important example of drug development motivated by natural sources. Furthermore, tonic water’s popularity has diverted its use from medicine to more quenching purposes [21].

Atropine is a chemical abundant in Atropa belladonna or deadly nightshade and has many uses in today’s medicine [22]. It is most commonly used for management of slow heartbeat (bradycardia) and as an antidote for organophosphate poisoning as well as mushroom poisoning [23]. Moreover, since atropine blocks the action of acetylcholine at muscarinic parasympathetic sites, it is extremely useful in general medicine. Additionally, atropine is an essential eye medicine that dilates pupils for an eye checkup. This application demonstrates the broad scope of alkaloids in the treatment of many different conditions [24]. The following illustrations show how alkaloids have found use in medicines and other industries due to their potent bioactivities. Their roles in plants are mainly used for deterring herbivores and providing protection from microbial infections. The ecological and economic importance of alkaloids is extremely high since they are some of the world’s most used plant-based compounds [25].

Terpenoids or isoprenoids are the largest and most structurally diverse class of natural products. They are made from isoprene units, and terpenoids perform a wide variety of functions and applications. They act as messengers, pigments, and building blocks for plants and help them survive [26]. Among them, sesquiterpene lactones comprising three isoprene units and a characteristic lactone ring are primarily found in the Asteraceae family. These compounds function in plant defense and display significant pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and antimicrobial effects. Notably, artemisinin, a sesquiterpene lactone from Artemisia annua, has been pivotal in antimalarial treatment, underscoring the therapeutic potential of this compound class.

Essential oils are aromatic compounds made from limonene and menthol, which have a number of applications, from perfumes to food additives and even traditional medicine. Their aroma makes them very desirable in fragrance and flavor-focused industries. They can provide a benefit for plants by acting as a natural pest deterrent, which helps protect the plants from herbivores and pathogens [27,28]. For instance, citronella oil is known for its ability to repel insects and is used as a natural insect repellent. Inhalation of essential oils stimulates the brain and makes the body feel more relaxed by reducing stress while improving mood. These compounds are used in aromatherapy. The psychological and physiological workings of these compounds are still being studied in wellness sciences [29].

Carotenoids are responsible for giving fruits and vegetables such as carrots, tomatoes, and peppers their vibrant colors. They include pigments such as beta-carotene and lycopene. These pigments help attract pollinators and seed dispersers and also protect the plants from damage caused by photooxidation [30]. Carotenoids have many benefits for human nutrition as they serve as precursors to vitamin A and antioxidants. Lack of carotenoids, and specifically vitamin A, can have dire health consequences, which illustrates its necessity in the diet. Carotenoids have also been associated with a decreased occurrence of chronic diseases, such as some cancers and cardiovascular diseases, which further demonstrates their importance for human health [31].

Plant and animal sources contribute to the formation of steroids, which are a class of intricate terpenoids. For instance, in plants, developmental and growth processes are modulated by steroids like brassinosteroids [32]. Various physiological activities, like cell membrane formation and hormone production, require cholesterol, which is a crucial component of steroid hormones. Their derivatives are foundational in human endocrinology. Among the plants, steroids obtained from some Dioscorea species have been employed for the development of drugs such as contraceptive pills and corticosteroids. This achievement emphasizes the potential of terpenoids in pharmacology [33]. The vast diversity of terpenoids underscores their significance in both natural ecosystems and human industries. Their roles in signaling, pigmentation, and defense highlight their ecological importance, while their utility in medicine and cosmetics showcases their economic value. From essential oils to life-saving drugs, terpenoids exemplify the multifunctional nature of secondary metabolites [34].

One or more hydroxyl functional groups attached to an aromatic ring is a defining characteristic of phenolic compounds [35]. Generally, phenolics are available in virtually all plants and have useful biological properties. Phenolics assist in maintaining plant structure and pigmentation as well as help in protecting plants from living and non-living threats [36].

Coumarins are widely distributed plant metabolites known for their defense allelochemical markers in plants. They are indisputably recognized for their biological importance as anticoagulants, antimicrobials, anti-inflammatories, and antioxidant agents [37,38]. A well-known example of a synthetic coumarin is warfarin, a frequently used anticoagulant. Natural coumarins such as umbelliferone and scopoletin exhibit marked biological activities and notable biomedicinal potentials [39]. In addition to pharmacology, coumarins are essential within the cosmetic and perfumer industries as fragrance compounds and filters for ultraviolet radiation. The ecological, medicinal, and industrial significance of these substances demands that adequate attention be devoted to research and conservation of biological diversity [40,41].

Flavonoids are one of the most investigated groups of phenolics due to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and cardiovascular advantages [38]. Various colorful fruits, vegetables, and even drinks such as tea and wine are rich sources of these compounds [42]. These compounds serve significant advantages in conjunction with a plant-based diet and aid in reducing oxidative stress within the body by neutralizing free radicals. Moreover, they enhance ecological activities by attracting pollinators and shielding plants from ultraviolet rays. This reveals how useful these compounds are in applied science and nature on a broader scale [43].

Tannins are classed as astringent compounds that can cover bark, leaves, and unripe fruits. Tannins bind proteins and other organic compounds, thus affecting their antimicrobial and astringent properties [44]. Tannins have wide applications in traditional medicine, most notably in wound and infection treatment. Such a wide application highlights their immense therapeutic potential. Tannins also find application in the leather industry through the tanning of animal hides to enhance the durability of leather. This application speaks to the economic value of phenolic compounds [45].

Lignans are regarded as phytoestrogens present in seeds and grains that carry out basic functions similar to those of estrogen, thereby aiding the human body in more ways than one. Most of their tasks are centered around hormone regulation and cancer prevention, especially breast and prostate cancers, due to their prevalence in all age groups. New research claims that cardiovascular health and metabolic function can also be improved using Lignans [46]. Plants utilize these compounds for structural support by strengthening the plant cell walls and emphasizing their ecological functions. Phenolics may check these and other compounds and other metabolites of the plant are important for plant defense and human health, which makes them important for both natural and applied perspectives. Their multifarious functions and versatility in structure continue to drive creativity in medicine, agriculture, and industry [36].

3 Applications and Implications

The analysis concerned with secondary metabolites has had an undeniable influence on pharmacology, agriculture, and even ecology. These substances have not only propelled technological advancements in medicine and farming, but they have also deepened our grasp of ecological systems and their complex interrelations.

The pharmacological exploration has undergone unprecedented changes, particularly within the field of botanicals and bioactive plant compounds. These compounds are the axis around which a range of therapies, from palliative care to oncology, are based.

Artemisinin, a sesquiterpene lactone compound extracted from the famous herb Artemisia annua L., 1753, belonging to the Asteraceae family, has been a well-known cornerstone of malaria treatment, especially in the case of drug-resistant malaria. The discovery of Artemisinin has saved millions of lives across the globe, bringing forth inspiration for synthetic analogs to be devised [47]. Taxol paclitaxel, extracted from the Pacific yew tree Taxus brevifolia Nutt., 1849, belonging to the Taxaceae family, has been a significant breakthrough in oncology. The mechanism of action of this compound, disrupting the microtubule functions of cancer cells, has transformed the treatment for a myriad of cancers, such as breast and ovarian [48]. Key chemotherapeutic alkaloids vincristine and vinblastine, derived from the Montana periwinkle, have been critical in cancer treatment, particularly in showcasing the importance of plant products in oncology [49]. Different secondary metabolites are being explored with the hopes of obtaining new components that can be used as medicine. New compounds are expected to be discovered as long as people progress in understanding the biological diversity of plants, fungi, and marine creatures, which serve as a rich source of potential chemicals but underline the need for conservation as well [50].

Metabolites such as phenolic compounds and terpenoids are essential in the agricultural industry because they can provide nonchemical methods to tackle issues such as pest control and weed invasion or even improve crop growth [18]. Chrysanthemum cinerariifolium Trevir., 1844, a member of the Asteraceae family, produces a class of compounds known as pyrethrins, which are one of the most potent organic pesticides as well as safe for vertebrates [51]. Their use allows for minimal impact on the environment while practicing agriculture [52]. Furthermore, metabolites such as juglone produced by the black walnut plant are naturally produced chemicals that aid in the suppression of weeds by stunting the growth of neighboring plants and reducing the need for synthetic pesticides that have been proven to be harmful [53]. In addition, terpenoid and phenolic-derived plant growth regulators aid in increasing stress tolerance, flowering, and germination in crops, along with changing climatic conditions, aid in improving the yield of crops. There are also positive impacts on soil due to secondary metabolites, such as increased soil health; for example, plant roots produce flavonoids that enhance nitrogen fixation in rhizobia, benefitting leguminous crops [54].

Secondary metabolites enable multi-dimensional interactions, impacting the dynamics among plants, microorganisms, and insects [55]. These compounds facilitate communication, defense, and adaptation. As with most other volatile organic compounds, some terpenoids immensely affect plant-insect relationships. During herbivory, it is common for plants to emit certain VOCs, which assist in attracting predatory insects or parasitoids that suppress the herbivores, thus minimizing damage [56]. The selective visual and odor stimuli provided by flowers’ phenolic compounds, especially flavonoids, help to attract particular pollinators. This selective attraction increases the overall effectiveness of pollination and assures human reproductive success. Toxic metabolites like alkaloids are harmful to herbivores and pathogens [57]. A classic example is tobacco, where nicotine acts as an insect repellent as well as an antimicrobial. Secondary metabolites also exhibit support for symbiotic relationships. Secondary metabolite signaling between mycorrhizal fungi and plant roots facilitates the transfer of nutrients, which promotes plant growth and nutrient absorption [58].

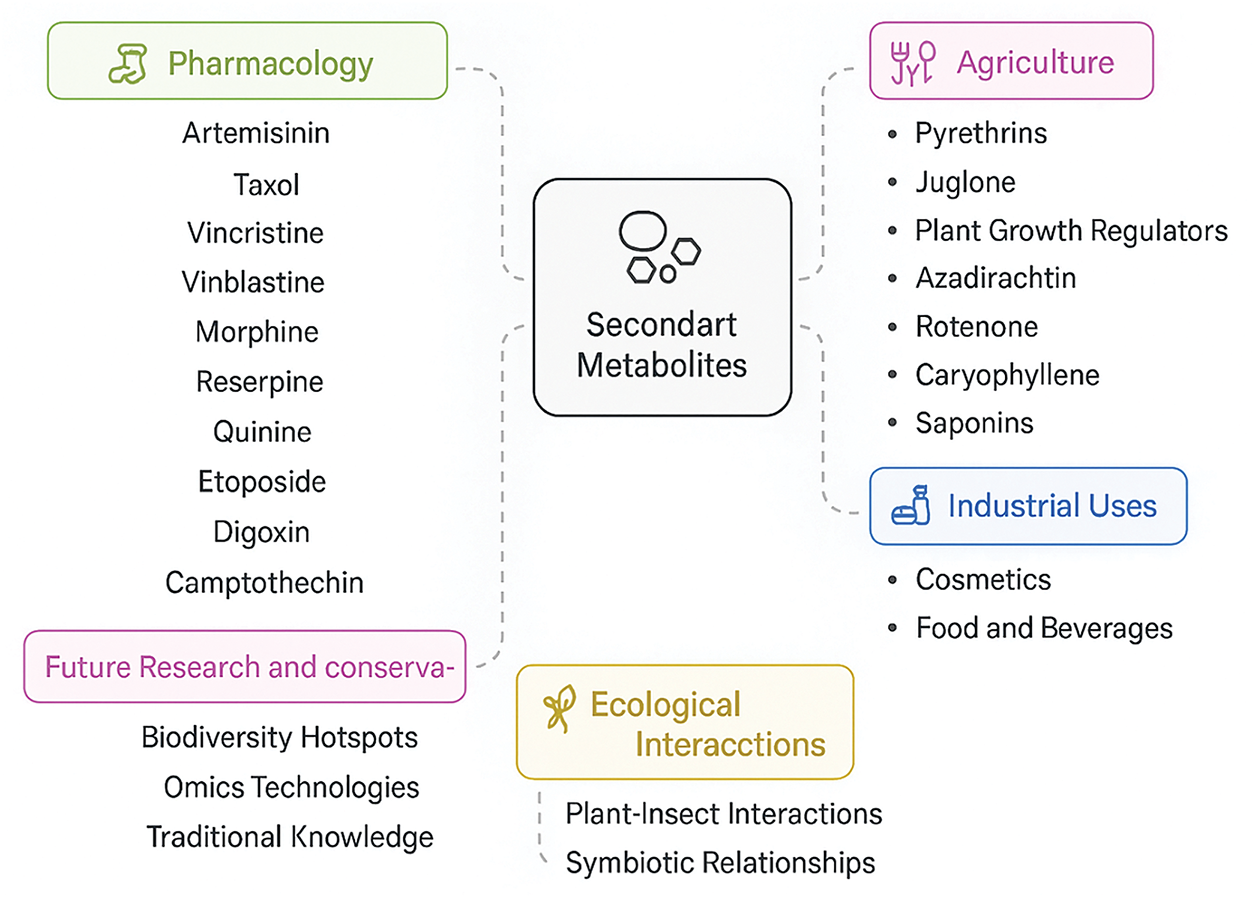

Secondary metabolites have industrial applications ranging from cosmetics to foods and beverages. Oils are common in perfumes, flavoring, and aromatherapy, and menthol is used extensively for both its flavoring and pharmaceutical properties [59]. Peppermint is a key source of menthol, and is essential for oral hygiene products and cooling agents. Resveratrol, polyphenols, and catechins derived from grapes and green teas, respectively, are used in nutraceuticals to provide anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects [60]. These compounds support cardiovascular health and may reduce the risk of chronic diseases. In secondary metabolite biotechnology can be an art of bioengineering. With the development of synthetic biology, complex metabolites like artemisinin are produced in microbial systems, which is a great scalable solution to global demand. With climate change, understanding secondary metabolites could help make crops that can withstand for climate (Fig. 1) [61]. These compounds are produced from metabolic pathways, and enhancing them can improve the plant’s stress tolerance, thus making agriculture more sustainable [12].

Figure 1: Applications and implications of secondary metabolites: pharmacology, agriculture, ecology, and beyond

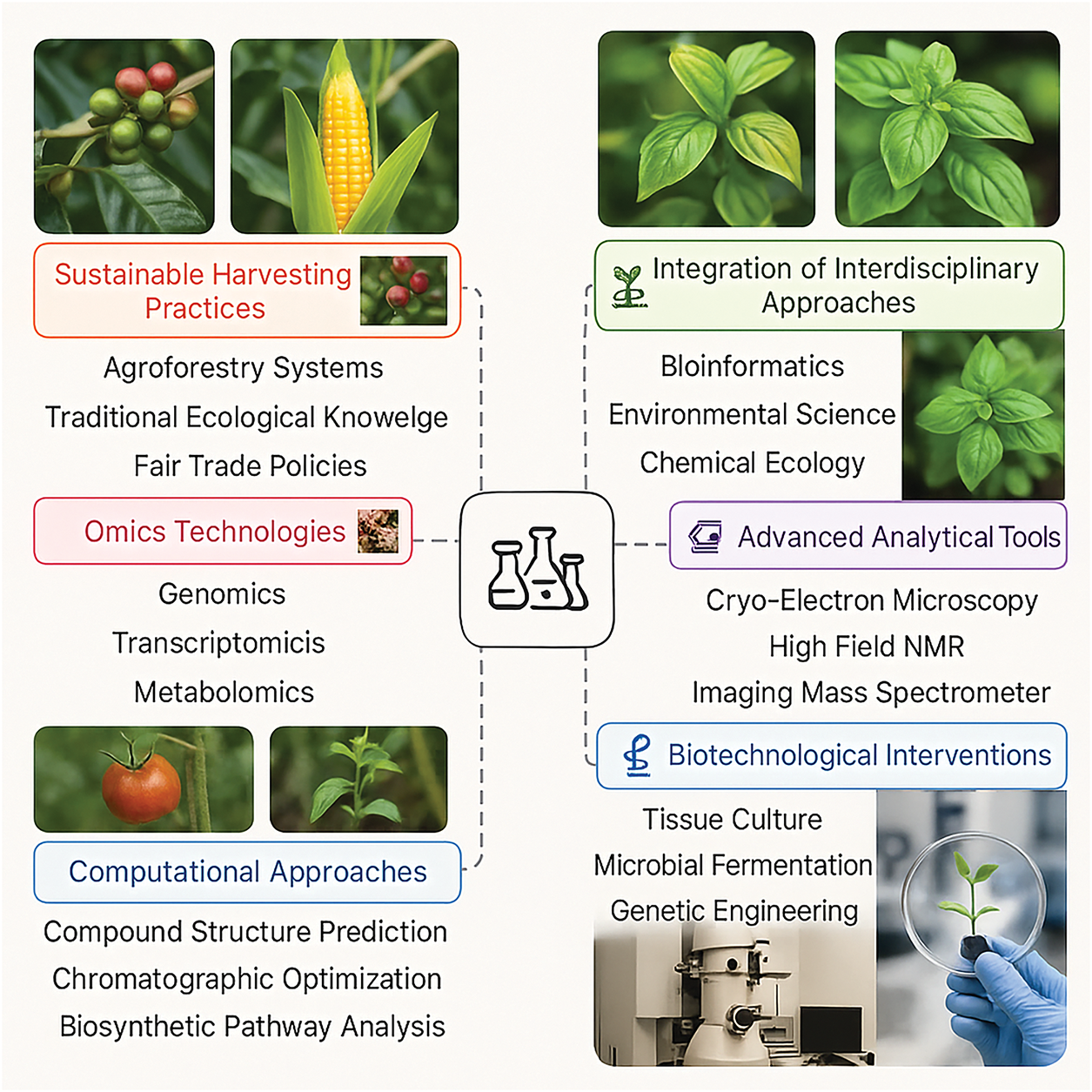

3.5 Future Research and Conservation

A massive collection of new secondary metabolites awaits discovery, so biodiversity should be maintained. Many secondary compounds have been found in diverse species of regions like coral reefs and tropical rainforests, which are biodiversity hot spots. These ecosystems, along with their chemical diversity, face the danger of being destroyed due to habitat destruction [62]. The discovery of novel and detailed characterization of secondary metabolites is seeing rapid growth with the emergence of omics technologies such as genomics, metabolomics, and proteomics [63]. Using these technologies, scientists can discover bioactive compounds and the associated biosynthetic pathways with much more efficacy. There is a possibility for much insight to be gained through the fusion of traditional knowledge and modern science to study the use of secondary metabolites. The indigenous knowledge of medicinal plants serves as a strong starting point for new drug discovery. The significance of secondary metabolites and their wide-ranging effects makes them extremely useful in overcoming the world’s entire gamut of challenges. Such technologies are helpful in medical science, agriculture, and several other fields [8].

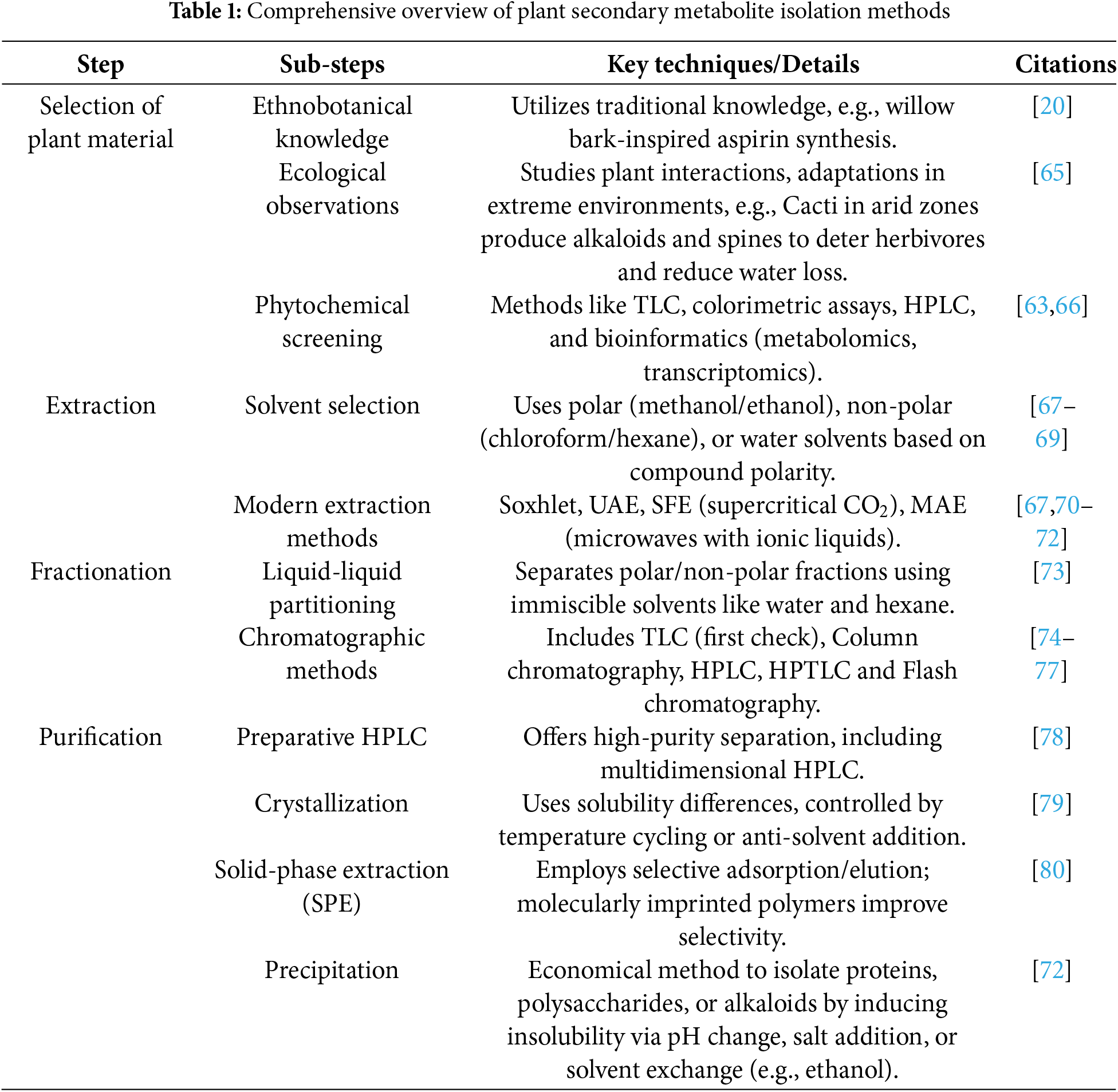

The extraction of secondary metabolites from plants involves different steps, each critical and needing precision while considering the chemicals’ properties. Below is a detailed breakdown of the workflow, expanded to incorporate more advanced insights.

4.1 Selection of Plant Material

Even within the same geographical area and climate, selecting plant species is of utmost importance regarding metabolite isolation. This choice is always guided by several aspects, which may include:

Ethnobotanical Knowledge: The cultural, medicinal, and nutritional practices that utilize specific plants suggest the possible existence of active compounds and, as such, do contain some form of bioactivity. For example, it is possible for plants used for treating inflammation to possess anti-inflammatory alkaloids or even flavonoids. Ethnobotany provides information on the cultures, foods, and medicinal practices inherited in the community. Modern scientific research greatly benefits from these traditional practices, as they frequently guide the discovery of important pharmacological agents. A classic example is the use of willow bark (Salix spp.) in traditional medicine to reduce pain and fever, eventually leading to the isolation of salicin and the development of aspirin [8–10]. Another important ethnobotanical breakthrough is quinine, derived from the bark of the Cinchona tree. Indigenous communities in South America used Cinchona bark for centuries to treat fever and malaria-like symptoms. This traditional knowledge caught the attention of European colonists and physicians, leading to the isolation of quinine in the 19th century. It became the first effective antimalarial treatment and paved the way for the development of synthetic derivatives and modern antimalarial drugs [8,20].

Ecological Observations: Secondary metabolites having antinutritional properties present in plants are particularly developed in those that survive in arid zones (deserts), extreme altitudes (Alpine), or rainforests as a means of adaptation [64]. For example, Cacti in arid zones produce alkaloids and spines to deter herbivores and reduce water loss. Alpine plants synthesize high levels of flavonoids, which act as UV protectants. In tropical rainforests, many trees produce tannins and saponins that inhibit fungal growth and microbial invasion in the humid environment. The resins of coniferous trees (e.g., pines and firs) are rich in terpenoids, acting as antimicrobial barriers and sealing wounds to prevent decay. Mustard plants produce glucosinolates, which serve both as herbivore deterrents and antimicrobial agents in the rhizosphere. These adaptations ensure plant survival in extreme ecosystems and highlight the ecological importance of secondary metabolites. Understanding these interactions requires detailed ecological studies that examine the relationships between plants, herbivores, pathogens, and neighboring flora [65].

Phytochemical Screening: Depending on the level of secondary metabolites in the species of plants in a collection, primary screening may include colorimetric assays such as the Folin-Ciocalteu method for total phenolics and thin-layer chromatography (TLC) to separate and visualize compound classes like alkaloids, flavonoids, or saponins [66]. Nevertheless, plant collections may also employ spectrophotometer bioinformatics for high-throughput screening as well as for further HPLC and other spectrometric plant assessment; for example, HPLC can separate and quantify curcumin in Curcuma longa or quercetin in onion extracts. Readying resources for the ethnobotanist ensures confidence for the plants deemed as the most useful. Advances in molecular biology, such as metabolomics and transcriptomics, have made phenolic compound screening easy, as results can be anticipated based on the expected biosynthesizing pathways [63].

Extraction is crucial for separating secondary metabolites from highly organized plant structures. Various factors influence the extraction selectivity and efficiency, including solvent choice, extraction method, and, most importantly, the temperature and time parameters.

The choice of solvent plays a crucial role in phytochemical extraction, as it determines the range and efficiency of metabolite recovery. Solvents can be broadly categorized into organic and inorganic types, each selected based on the polarity of the target compounds.

Methanol and Ethanol: These polar solvents are adequate for retrieving water-soluble compounds such as flavonoids, glycosides, and saponins. Ethanol is, along with methanol, widely used in the food and pharmaceutical industries because it is less harmful. Research suggests that ethanol-water mixtures are best for extracting various compounds because of their balance of polarity and solubility [67].

Acetone is useful for extracting a wide range of polar and semi-polar compounds, including phenolic acids and some alkaloids. It evaporates quickly, which helps in drying the extract faster. Acetonitrile: Often used in HPLC-grade extractions due to its excellent solubilizing capacity for polar compounds and compatibility with analytical instruments [67,68].

Chloroform and Hexane: Non-polar solvents such as chloroform and hexane are efficient for extracting lipophilic compounds, which include terms such as terpenoids, sterols, and some essential oils. When used with other solvents in sequential extraction, these non-polar solvents can yield a wider range of metabolites. Diethyl Ether: Suitable for extracting volatile oils and lipophilic flavonoids and often used with other solvents. Petroleum Ether: Commonly used to extract fats, oils, and waxes, particularly during the defatting stage before further phytochemical screening [68].

The water is frequently used for extracting hydrophilic compounds such as tannins, some alkaloids, and polysaccharides. In other cases, water extraction may be for co-extract unwanted substances such as starch or proteines. More advanced filtration systems can solve these problems and enhance the quality of the extract [69].

4.2.4 Modern Extraction Methods

Soxhlet Extraction: Builds on the traditional extraction principles but sets itself apart thanks to its exhaustive nature. This method does exhaust a lot of time. However, implementing automated systems has been shown to speed everything up and bring down the environmental impact. The traditional way of performing Soxhlet removably circulates the solvent effectively [67].

Ultrasonic-Assisted Extraction (UAE): Using ultrasound to extract is much more advanced than using traditional techniques and allows for amplifying metabolite release by destroying cell walls. UAE’s methods are also less prone to degradation which makes it a faster option with less solvent use than the traditional techniques [70].

Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE): Besides being one of the most effective methods for extracting nonpolar compounds, supercritical fluid extraction is also environmentally friendly. This is due to the method utilizing supercritical CO2 as a solvent, which leaves minimal residues on the extracted material. Changing the properties of CO2 by adjusting the pressure and temperature makes selective extraction possible [71].

Microwave-Assisted Extraction (MAE): Much like SFE, this method is also energy-saving due to using microwaves to evenly heat plant extracts. The combination of microwaves with ionic liquids is a significant advancement in the field of MAE and widens its range of use [72].

After extraction has been performed in any of these methods, the resulting crude extract typically contains a complex mixture of bioactive and non-bioactive constituents. The purpose of fractionation is to simplify these mixtures by separating compounds based on their distinct physical and chemical properties, such as polarity, molecular weight, and affinity for solvents. This step is essential for the efficient purification and identification of individual secondary metabolites [81].

4.3.1 Liquid-Liquid Partitioning (LLP)

Liquid-Liquid Partitioning: this approach takes advantage of the differing solubility of immiscible solvents, e.g., water and hexane. Separating polar and nonpolar fractions is possible, consequently facilitating efficient purification at later stages. Using several solvent pair combinations in Sequential partitioning improves fractionation efficacy and minimizes contamination [73].

4.3.2 Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE)

SPE involves passing the crude extract through a solid adsorbent material (usually a silica or polymer-based column), which retains specific compound classes based on adsorption and polarity. Solvents of increasing polarity are then used to elute fractions. SPE is widely used for pre-concentration, desalting, and clean-up before HPLC or LC-MS analysis. For example, it can separate flavonoid glycosides from phenolic acids [73].

Thin-Layer Chromatography (TLC): An easy and fast way to evaluate metabolites. Used as a first check to search for bioactive ingredients. Recent TLC devices with automated spotting and densitometry systems can simultaneously offer qualitative and quantitative data [74].

Column Chromatography: Separates mixtures based on the different affinity compounds have for the stationary and mobile phases. The stationary phase is often silica gel or alumina. The resolution of complicated mixtures has been enhanced by new methods, such as gradient elution [75].

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC): Highly effective method for separation as well as qualitative determination of metabolites. Combining HPLC with UV, fluorescence, or mass spectrometry analysis enhances resolution. The introduction of ultra-high performance liquid chromatography (UHPLC) has decreased analysis time while increasing resolution [76].

High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography (HPTLC)

HPTLC is an advanced form of TLC that offers improved resolution, reproducibility, and sensitivity. It incorporates automated sample application, controlled development chambers, and multi-wavelength scanning, allowing both qualitative and quantitative analysis [82,83]. HPTLC is particularly valuable for fingerprinting plant extracts, detecting adulterants, and standardizing herbal formulations. It serves as a complementary tool to HPLC in quality control and phytochemical profiling [84,85].

Flash Chromatography: one such is a preparative method that utilizes pressurized gas to hasten the separation process for the recovery of large amounts of extract. Systems with integrated detection and fraction collection increase the productivity of the process [77] (Table 1).

Isolation of the secondary metabolite is the goal for these individual compounds and, therefore, must be purified to remove any incidental agents.

Methods to Use

Preparative HPLC: It can isolate minute amounts of the highest purity compounds by offering great resolution separation. More advanced techniques, such as multidimensional HPLC, can isolate closely related isomers [78].

Crystallization: This method takes advantage of differences in solubility. Various compounds, such as certain alkaloids, are able to crystallize easily when subjected to certain solvents. Yield and purity are improved with controlled techniques such as temperature cycling and addition of anti-solvent [79].

Precipitation is a relatively simple and economical method. It occurs when, under certain conditions, a compound becomes insolubly and visible for separation through filtration or centrifugation. This method best serves proteins, polysaccharides, and, in some cases, even alkaloids. Selective precipitation can be triggered by acid-base adjustment, the addition of salt, or the exchange of solvents, such as putting Ethanol into an aqueous extract [86].

Membrane Filtration/ Ultrafiltration: These methods have a semi-permeable filter that can separate a mixture’s components. Ultrafiltration is geared more towards parent molecules like polysaccharides and getting rid of big unwanted materials sitting around in plant extracts. The method is mainly applied with enzymatic hydrolysis or dialysis [86]. Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE): This method employs selective adsorption and elution, which makes it convenient and straightforward. SPE makes it possible to pull metabolites from weak solutions easily. Using molecularly imprinted polymers in SPE enhances the selectivity, making it more useful [80].

Whether a compound is suitable for application in research, medicine, or industry depends greatly on the purity and identity of the isolated compounds. Considerable effort is implemented at a higher level of detail to check and ascertain the quality of the metabolites.

5.1 Methods of Quality Assessment

Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry LC-MS is a powerful technique widely used to analyze complex mixtures and confirm target compounds [77]. While the LC section separates the components in the mix, the MS section provides each component’s molecular weight and structure fragmentation [77]. This method is very valuable in confirming the compound’s identity and purity by providing both qualitative and quantitative analysis. It is also effective in detecting trace compounds and metabolite profiling applications. More detailed structure solutions can be made with tandem MS/MS techniques [79].

Spectral Analysis: Determining the structure and purity of a compound can be performed with characteristics of NMR, MS, and IR spectroscopy. For example, NMR gives detailed information about the molecular structure and the functional groups within a sample. More sophisticated NMR techniques, particularly sensitive low-concentration cryo-probes, are available [81]. The MS gives the molecular weight and fragmentation patterns of the sample. The precision measurement of mass distinguishes a high-resolution type of mass spectrometer commonly referred to as high-resolution MS (HR-MS), making it possible to determine the molecular formula with high accuracy [87]. Infrared spectroscopy is used for looking at a sample with a specific functional group by emphasizing the characteristic absorption bands of the group. Fourier-transform IR (FT-IR) is an infrared spectrometer that enhances the resolution and the speed of data collection [88].

Bioassays: Activity against a biological target fraction or oil extracts of an isolated compound is essential to bioassay test for its bioactivity. In drug discovery, agriculture, and cosmetics, these assays are important. Also, today cell-based assays are available with a possibility for a high-throughput screening platform, so evaluation of bioactivity is much easier [89].

5.2 Establishing a Link between Classical and Contemporary Styles

This link between classical and contemporary styles is critical in understanding the concept of secondary metabolite isolation as it is a dynamic and interdisciplinary process. With the blend of ethnobotanical knowledge and cultural practices, it becomes easier to choose which plants should be selected and studied further based on their therapeutic functions [90,91]. Within the context of scientific endeavors, these traditional methods of investigation follow the basics of efficient ethnobiology, where the best results are guaranteed. In conjunction with these theories, traditional methods have also changed, giving birth to modern methods such as extraction, purification, and analysis of secondary metabolites [92]. There are numerous extraction methods, but with supercritical fluid extraction, ultrasonic-assisted extraction, and microwave-assisted extraction, the guarantee of obtaining the best, efficient, and sustainable result with minimal solvent consumption and time is heightened [93,94]. Along with these are advanced methods of purification that were devised in the form of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), counter-current chromatography (CCC), and preparative chromatography, where the desired compounds are achieved in their purest forms [95]. These techniques of analysis are combined with mass spectrometry (MS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) to check the integrity and quality of the isolated compounds, making these multidisciplinary techniques advanced [96].

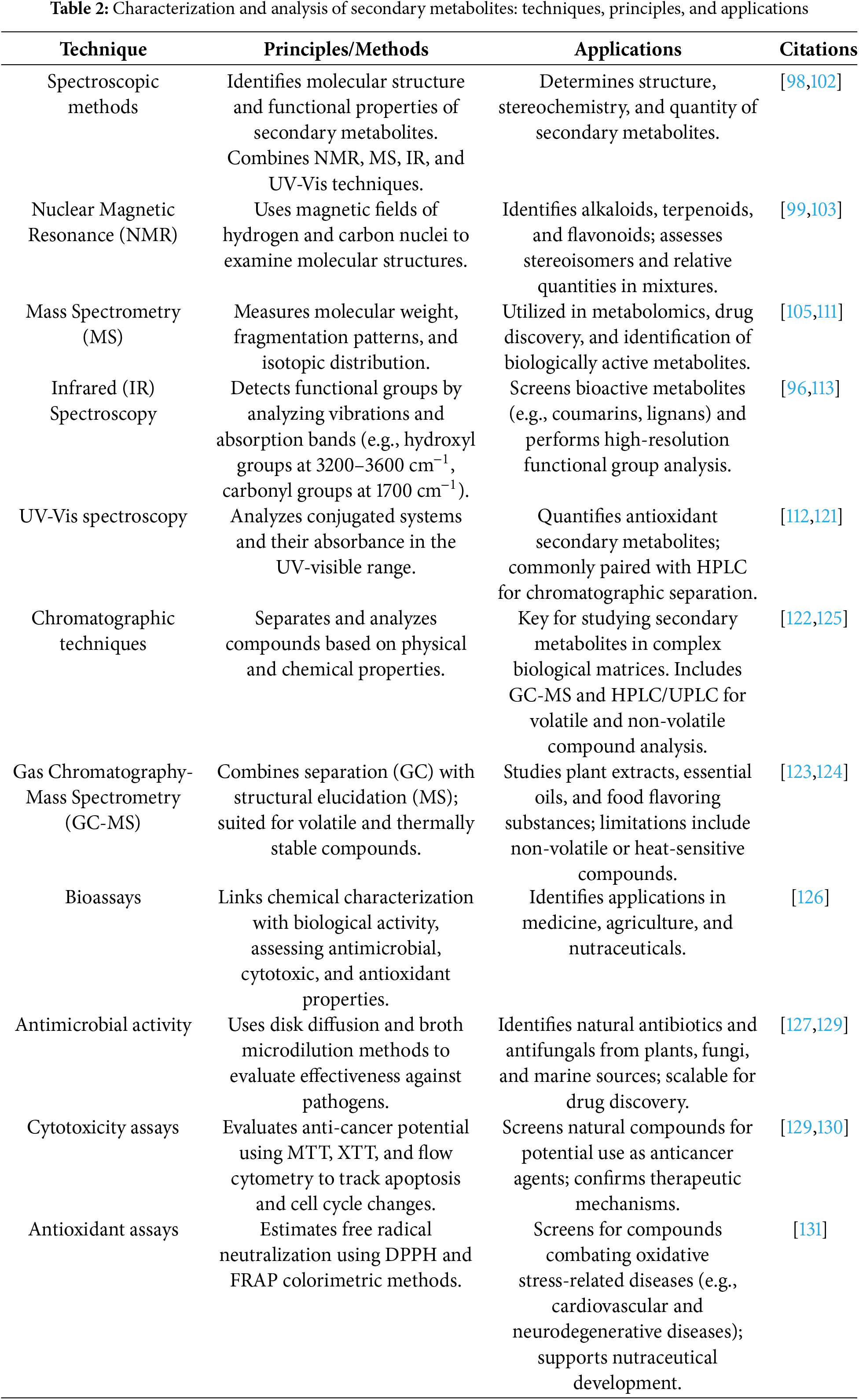

Secondary metabolites are important in diverse sectors, including pharmaceuticals and agriculture. These compounds are isolated and introduced into the method, where their structures, properties, and biological activity are determined. These involve different bioassays, chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques, which each provide differing information about the compounds and their possible uses [97]. This part analyzes the techniques, principles, and measures and explains why they are necessary for the study of secondary metabolites.

Spectroscopic techniques are central in identifying secondary metabolites’ molecular structure and functional properties. These methods provide comprehensive details about molecules in terms of the type of elements they include and the arrangement of the atoms. Each method has its advantages and disadvantages. Hence, it is necessary to use them in conjunction [98]. One of the most basic spectroscopic techniques is Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [99]. NMR chemistry is primarily used in biochemistry to determine the structure of compounds. It provides multi-dimensional NMR techniques such as two-dimensional doses to realize the blood composition structure. Regular steam proton NMR suggests basic biochemistry molecules contained within blood [100].

Generally speaking, the NMR examines the magnetic fields provided by hydrogen and carbon nuclei and the relative positions of these tissues in their environment, which results in very advanced methods for detecting [101].

Compounds such as alkaloids, terpenoids, flavonoids, and other biologically active compounds use Crescent NMR to determine dissolution’s stereoisomers in situations where they play a significant predominant role in the metabolism. Molecules often utilize submits as the Microwave through Buried NMR [102,103]. Combining areas of the peaks makes it possible to ascertain the relative quantities of various secondary metabolites present in a mixture [102].

Mass spectrometry is one of the important techniques in finding out:

Due to its sensitivity, accuracy, and versatility, mass spectrometry (MS) is an essential analytical technique in natural products and secondary metabolite research. It allows scientists to carefully untangle the chemical intricacy of plant extracts and other biological samples [104].

Determining Molecular Weight

MS is mainly known for its ability to determine molecular weight accurately. This technique is exceptionally beneficial at the preliminary steps of the metabolite detection process. High-resolution MS (HRMS) like Orbitrap or time-of-flight (TOF) systems enable exact mass determination, which greatly assists in calculating molecular formulas with high precision. As an example, the molecular ion peak [M+H]+ in the mass spectrum highlights the value of initiating structural elucidation where the protonated molecular weight of the compound is verified [105,106].

Fragmentation Patterns and Structural Elucidation

With the invention of more advanced MS techniques like tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), determining the substructure of a compound through its fragmentation pattern is much easier. Interpreting fragmentation—structural features of a molecule comprising its functional groups and their connections—through CID (collision-induced dissociation) provides numerous details. In the case of flavonoids, characteristic fragments like retro Diels-Alder cleavage products help in subclass differentiation [107]. Mass Frontier and MS-DIAL are examples of software that automate fragmentation interpretation [108].

Isotopic Pattern Analysis and Metabolic Tracing

Patterns of isotopes, which are helpful for isotope labeling studies, can now also be resolved by using high resolution MS. Through the use of isotopic labels (for example 13C, 15N), secondary metabolites can be tracked and their biosynthetic pathways elucidated in real time. This is very important for metabolic flux analysis and in studying how biosynthesis of metabolites changes in response to environmental or genetic perturbations [109,110].

Uses in Drug Development and Metabolomics

Mass spectrometry is integral in metabolomics, which studies minor molecule constituents termed metabolites. In botany, MS metabolomics is often performed to identify bioactive secondary metabolites like alkaloids, phenolics, terpenoids, and saponins. These compounds possess numerous therapeutic activities, such as anticancer, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory. For example, LC-MS was used to determine the presence of vincristine and vinblastine, two alkaloid-based anticancer drugs, in Catharanthus roseus [111]. Moreover, targeted MS techniques, such as multiple reaction monitoring (MRM), offer quantitative measurement of metabolites, which is essential in the QC of herbal medicines and phytopharmaceuticals [112].

6.1.2 Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy is an essential analytical technique for functional group detection within organic compounds. IR Absorption Spectroscopy can interrogate molecular bonds and identify the constituent parts of a compound by measuring the absorption of infrared radiation, which causes vibrational transitions in molecular bonds. The method is most suitable for the initial characterization of secondary metabolites owing to its rapidity, low sample requirement, and non-destructive nature [112].

Principle and Functional Group Detection

The functioning of IR spectroscopy is based on detecting vibrational movements of the covalent bonds of the molecules. Every bond has its unique vibrational frequency, depending on the types of atoms and the strength of the bond. If the infrared radiation corresponds to the natural vibrational energy of a bond, the bond would be broken, and an absorption band is formed in the IR spectrum. These absorptions are indicative of particular functional groups and enable the determination of the chemical identity of secondary metabolites.

Hydroxyl (-OH) Groups: Hydroxyl groups are frequent in phenolic compounds and flavonoids. Also known as the O-H stretching vibration, they tend to absorb energy in the 3200–3600 cm−1 range. The IR spectrum of quercetin, a well-known flavonoid, confirms the presence of phenolic hydroxyls as it shows a dominant broadband within this region [96].

Carbonyl (C=O) Groups: Aldehydes, ketones, esters, and carboxylic acids contain carbonyl groups with sharp absorption bands near 1700 cm−1 and C=O vibrations. The position may vary slightly due to hydrogen bonding. For instance, coumarin, an aromatic lactone derivative, possesses a strong carbonyl band at roughly 1715 cm−1, a hallmark of its lactone ring [88].

Uses for Analyzing Secondary Metabolites

IR spectroscopy is the most common method used for screening and confirming the structure of secondary metabolites from plants. IR is especially beneficial for the presence of major functional groups of compounds during secondary metabolite extraction since no extensive sample manipulation is needed.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: FTIR is another IR spectroscope with greater sensitivity and resolution. Despite their complexity, plant extracts can be tested using FTIR, and active constituents like lignans, tannins, and terpenoids can be targeted. FTIR also allows for multivariate chemometric models to be used for quantitative analysis.

Example: Lignans and Coumarins. FTIR spectra of lignans exhibit characteristic absorptions of methoxy groups (C-O stretching near 1100 cm−1), aromatic C=C stretching (around 1600 cm−1), and carbonyl positions (roughly 1700 cm−1). Coumarins, known for their bioactive anticoagulant and anti-inflammatory properties, exhibit combinations of carbonyl and aromatic ring vibrations, which aid in distinguishing simple coumarins from furanocoumarins [100].

6.1.3 Ultrviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy

Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy has become a standard approach for analyzing secondary metabolites of organisms, especially those possessing conjugated π-electron systems, such as flavonoids and phenolic and polyphenolic compounds. The technique uses UV and visible light from the electromagnetic spectrum, which ranges from 200–700 nm, to measure the amount of light absorbed by a sample, and this corresponds to certain electronic transitions, primarily π → π* and n → π* as well as others [113].

Principle and Analytical Relevance

Secondary metabolites with chromophores (the parts of molecules that contain an atom that can emit or absorb light) display characteristic absorbance spectra, exhibiting significance for both qualitative and quantitative assessments [41].

Conjugated Systems and Aromaticity: In compounds consisting of an extended conjugation, like resonance structures with several alternating double bonds or aromatic rings, they are most prominently visible for absorption in longer wavelengths. Take, for instance, flavonoids, such as quercetin, which have two leading absorption bands [114].

Band I (300–380 nm): Associated with the B-ring cinnamoyl system.

Band II (240–280 nm): Linked to the A-ring benzoyl system.

Other substituents, such as hydroxylation or glycosylation, help differentiate flavonoid subclasses by shifting these bands [115,116].

Quantitative Analysis

Secondary metabolites, and especially antioxidants, are quantitatively measured using UV-Vis spectroscopy. According to the Beer-Lambert Law, concentration can be calculated from absorbance (A) as shown in the relation A = εcl, where: A = absorbance; ε = molar absorptive; c = concentration, l = path length.

This method is appropriately used to determine TPC or TFC (phenolic and flavonoids content) with the reagents like samples: Reagents: Folin–Ciocalteu TPC (measured at about 760 nm) and Aluminum chloride (AlCl3) colorimetric assay for TFC (measured at about 415 nm) [102]. For phenolic content, gallic acid and catechin are standard references often employed [116,117].

Coupling with HPLC (HPLC-DAD/UV)

A Diode Array Detector (DAD) is used on the UV-Vis spectrophotometer, which is key in monitoring the performance of the HPLC system. Thus, real-time compound detection is possible as they elute from the chromatographic column accompanied by spectral collection [118]

For instance, during the polyphenol profiling of green tea (Camellia sinensis), catechins, too, were quantifiably separated using HPLC-UV. Intensely aromatic polyphenols, EGCG, and ECG were detected as expected at 280 nm. For instance, curcuminoids from Curcuma longa were quantifiably measured using UV detection at approximately 420 nm [119,120].

Uses in Antioxidant Studies and Natural Product Investigations

The evaluation of antioxidant activity is particularly facilitated by the use of UV-Vis spectrometry in conjunction with the following assays:

DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay (Absorbance at 517 nm),

ABTS Assay (Absorbance at 734 nm),

Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) (Absorbance at 593 nm).

These assays serve as rapid approaches in determining the antioxidant activity of secondary metabolites and plant extracts, which is essential in functional food and phytopharmaceutical research [118].

6.2 Chromatographic Techniques

There are different chromatographic methods for different physical and chemical properties of the target compounds, but chromatography is key for analyzing and separating secondary metabolites. The biological matrices are complex, but the versatility of the technique allows it to handle those with ease [121].

6.2.1 Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

GC-MS combines the powerful separation capacity of gas chromatography with the molecular identification ability of mass spectrometry, enabling both qualitative and quantitative analysis of volatile and thermally stable compounds. In GC, compounds are separated based on volatility and interaction with the column’s stationary phase; in MS, compounds are ionized and fragmented to generate characteristic mass spectra for identification [106,122].

Applications: Commonly used for analyzing essential oils, terpenoids, small organic acids, and volatile alkaloids. Widely applied in the food, fragrance, and pharmaceutical industries to profile aromatic compounds and plant volatiles. First example: GC-MS analysis of Lavandula angustifolia (lavender) oil reveals characteristic peaks for linalool and linalyl acetate, two bioactive volatile terpenes with calming effects. Second example: Screening of volatile constituents in Thymus vulgaris essential oil for antimicrobial studies [28,122].

Advantages: Merges separation power from gas chromatography and structural elucidation from mass spectrometry. Newer GC-MS systems also have automatic sample preparation and spectral compound libraries for quick identification [123].

Limitations: Not particularly useful for secondary metabolites that are non-volatile or heat sensitive, such as saponins.

6.2.2 High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC)

HPLC and its advanced form, UPLC are liquid-phase techniques suited for non-volatile, thermally sensitive, or polar secondary metabolites. Compounds are separated based on polarity, hydrophobicity, or ionic interactions using different stationary phases (e.g., reverse-phase C18 columns). Detection can be achieved using UV-Vis, DAD, fluorescence, or MS detectors [115,121].

Applications: Ideal for profiling alkaloids, phenolic acids, flavonoids, coumarins, and glycosides. First example: HPLC-DAD used in quantifying curcuminoids (e.g., curcumin, demethoxycurcumin) in Curcuma longa extracts at 420 nm. The second example is UPLC-MS/MS for high-speed profiling of ginsenosides in Panax ginseng.

Advantages: Provide high resolution, sensitivity, and reproducibility. UPLC significantly reduces analysis time (minutes instead of hours) with better peak capacity. It’s compatible with bioassay-guided fractionation of plant extracts [124,125].

Detectors & Enhancements: Diode Array Detectors (DAD) allow multi-wavelength detection, ideal for differentiating overlapping phenolic peaks. Fluorescence Detectors provide high sensitivity for compounds like alkaloids and polyphenols. HPLC-MS/MS is used in pharmacokinetics and metabolite identification studies.

Limitations: More expensive equipment and solvents, and requires careful optimization of mobile phase gradients and column types [41,72,112,121,126].

The importance of assessing the biological activity of secondary metabolites cannot be overemphasized, as it is critical in determining their chemical structure. Such compounds can indeed be useful in medicine, agriculture, and industry. These essays are meant to connect chemical characterization with application [127]. Secondary metabolites possess diverse biological activities with applications in medicine, agriculture, cosmetics, and biotechnology. Medicinally, they exhibit antimicrobial, anticancer, antioxidant, and neuroprotective properties, as seen with paclitaxel and artemisinin. In agriculture, they act as biopesticides and growth promoters, reducing reliance on synthetic chemicals. In cosmetics, flavonoids and phenolics offer anti-aging and UV-protective benefits. Additional effects include antidiabetic, hepatoprotective, and immunomodulatory actions. Their multifunctionality makes them valuable for sustainable solutions. Assessing biological activity alongside chemical structure is vital for discovering new therapeutic and industrial applications [81].

Purpose: Evaluate the effectiveness that varied secondary metabolites have against selected bacterial and fungal pathogens. Some certain naturally occurring compounds, such as some alkaloids and terpenoids, have antimicrobial activity and are of great importance in the fight against antibiotic resistance [128].

Methods: Each screening was performed using disk diffusion assays, which involved inoculating a microorganism on an agar plate and placing the compound in question on dialing wafers that had been cut into discs and placed on the agar plate. The size of the inhibition zone measured the power of the antimicrobial agent. The second method was broth microdilution techniques, which determine the MIC by evaluating the growth of microorganisms in liquid culture media [129].

Applications: The purpose of this assay may involve identifying sources of antibiotics, antifungal, and antibiofilm agents from other sources such as plants, fungi, and even marine organisms. The ability of compounds to inhibit or disrupt biofilm formation, which is a critical factor in microbial resistance and chronic infections, has become a key focus in recent screenings. Typically, these methods are scaled up for high-throughput screening in pharmaceutical pipelines during drug discovery and development [130].

Purpose: Use these assays to evaluate the anticancer potential of secondary metabolites. Because of the ability to alter the middle body parts of living organisms, some secondary metabolites like alkaloids and terpenoids demonstrate cytotoxic activity against cancer cells [130].

Methods: MTT and XTT assays for evaluating cell viability through estimating the metabolic activity of certain cells. Tracking of apoptosis and cell cycle alterations through flow cytometry yields an understanding of how cytotoxic secondary metabolites work within the cell. Uses: For screening natural resources for products with possible utility as anticancer agents with a focus on particular types and stages of cancer. In addition to cytotoxicity assays, the use of secondary metabolites is followed by confirming the therapeutic mechanisms through molecular approaches (Table 2) [131].

Goals: Estimate the capacity of secondary metabolites to neutralize free radicals that are associated with oxidative stress and the development of chronic ailments.

Protocol: Colorimetric methods that depend on DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) to estimate the radical scavenging ability of the tested sample.

The FRAP (Ferric reducing antioxidant power) assay quantifies the use of free electrons from the antioxidants to reduce ferric ions to ferrous ions.

ABTS assay (2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)): Generates the ABTS+ radical cation, which is neutralized by antioxidants; suitable for both hydrophilic and lipophilic compounds.

CUPRAC assay (Cupric Ion Reducing Antioxidant Capacity): Involves the reduction of Cu2+ to Cu+, forming a colored complex measured spectrophotometrically.

ORAC assay (Oxygen Radical Absorbance Capacity): Measures the inhibition of peroxyl-radical-induced oxidative degradation of a fluorescent molecule.

Uses: Screening for secondary metabolites that combat diseases associated with oxidative stress such as cardiovascular diseases and neurodegenerative diseases. Antioxidant assays lead nutrition scientists in formulating novel nutraceuticals and functional foods enriched with secondary metabolites [132].

7 Issues in the Isolation and Characterization of Secondary Metabolites

7.1 Plant Extracts Mixes Are Sophisticated

Many plants yield such extracts that are not pure and contain mixtures consisting of thousands of compounds, most of which are similar in their physical chemical attributes. This makes the extraction of individual secondary metabolites particularly challenging. Beyond the elementary obstacles, dealing with these problems sometimes involves tackling a series of such technical and methodological problems [133].

7.2 Comparable Physical Characteristics

Many secondary metabolites in an extract share the same solubility parameters and polarities or the same molecular weights. This poses a challenge for separation techniques like chromatography, which rely on a clear distinction between compounds, as it is hard to obtain. For example, high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC), and preparative scale separations usually require several steps to achieve purity. Moreover, the combination of chromatographic techniques and molecular tagging often leads to better separation of closely related compounds [124,125].

Another challenge is the choice of solvent, which can greatly affect the efficiency of the separation. A great amount of work is needed to find a suitable solvent or solvent mix to use; an ideal solvent is highly soluble in the compound but not retained well. In addition, new methods such as supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) and the use of green solvents have become popular and could be potential solutions to the traditional methods [134].

The co-elution of compounds that have similar retention times is one of the major challenges that are faced during isolation in chromatographic techniques. It is sometimes the case that a compound has similar behavior under different solvent conditions, which makes it essential to apply orthogonal separation techniques {LC-GC} rather than relying on gradient elution strategies. Detectors such as the multi-dimensional chromatography systems LC–MS/MS, or GC–GC–MS are some of the more advanced ones that are proving to be more effective in dealing with these types of co-elution problems as they enable the user to make finer distinctions based on chemical differences rather than physical ones [119].

Capillary electrophoresis and ion mobility spectrometry are the emerging technologies that are being explored to deal with co-elution problems. These methods provide the researchers with another tool as they allow differentiation based on charge and mobility [135]. Moreover, closely eluting compounds can further be investigated with the combination of high resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) and isotope labeling techniques [136].

Macromolecules, including polysaccharides, lipids, and extracts from plants, tend to interfere with isolation as these extracts often contain pigments [137]. These components make it difficult to identify and purify the compounds of interest as the target metabolites tend to mask of co-elute [138]. To reduce matrix effects, sample pre-treatment, selective precipitation, and membrane filtration techniques are often used. However, in some cases, these techniques tend to lead to loss of targeted compounds, which is unintentional [138].

In an effort to reduce matrix interferences, new techniques and novel adsorbent materials like molecular imprints have been invented [138]. For example, Specific metabolites may be captured by selective ligands coated upon magnetic nanoparticles, which reduces the background signal due to other interfering substances. In the same manner, solid-phase microextraction (SPME) methods are also being modified because of their characteristic of extracting metabolites out of complex matrices without much sample preparation [77].

Matrix modeling is another technique that shows strong potential. With the help of computer techniques, researchers may simulate the target compounds in complex mixtures of a sample. This simulation allows researchers to anticipate the interferences and enhance the separation techniques that can be used. When combined with sophisticated experimental techniques, this technique allows for a more focused and faster method of extraction of secondary metabolites [86].

7.5 Low Abundance of Target Metabolites

The production of secondary metabolites is often significantly low, especially in wild plants or in microorganisms cultivated in a lab environment. Such low yields makes it difficult to acquire enough substrates to analyze deeply into the material. This calls for the necessity of new and advanced methods and technology to overcome the challenges that the low yield poses [139].

7.5.1 Harvesting on a Large Scale

It is common for scientists to request vast amounts of plant tissue to balance low metabolite levels. This not only requires significant amounts of work, but it may also cause ecological damage through excessive collection of wild specimens [139]. Resourceful approaches like the cultivation of the source plant do take time and effort, but they are absolutely necessary. For instance, these plants can be grown using controlled techniques like hydroponic or aeroponic systems, which enhance the conditions for plant growth and consequently improve metabolite production [140]. One alternative is using endophytic microorganisms that can either produce or enhance the specific secondary metabolites needed. If these microorganisms can be isolated and cultured, then large-scale collection of plant tissues may be avoided. In addition, working with local communities for the collection of plant materials can promote ecologically safe practices [141].

The selection of certain methods for their achievement includes bioassay–guided fractionation, solid phase extraction, and solvent partitioning [142]. These methods have trade-offs because they may also result in the precipitation of compounds or contamination with other constituents. However, more recent developments, such as the automated liquid–liquid extraction with solvent extraction systems and new adsorbents like molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) have much better recovery rates for compounds [143]. Some advancements in ultrafiltration and nanofiltration enable researchers to selectively concentrate metabolites and remove unwanted matrix components. Integrating these techniques with online monitoring tools such as infrared spectroscopy improves the efficiency of enrichment processes and reduce material loss during alterations [144,145].

7.5.3 Sensitivity of Analytical Instruments

To detect those metabolites, majorly sensitive instruments such as mass spectrometers (MS) or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectrometers are. Even though some of these sophisticated devices SWIFT the highest level of development, they are not able to detect and quantify some compounds at picomolar or nanomolar concentration. Some Innovations The developments cryogenic NMR and Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FTICR-MS) have enhance the sensitivity of analytical techniques significantly [146]. Also, the implementation of microfluidic technologies into sample preparation procedures is servicing detection potential. These systems allow volumetric manipulation at the microliter scale, which lessens dilution and increases signal strength for minuscule components [14]. Certain methods like droplet-based microfluidics have been efficient in obtaining scarce metabolites from limited samples.

7.5.4 Progress in Syntehtic Biology and Metabolic Engineering

Similarly, there is active work in gene editing, and these technologies are considered powerful tools against the scarcity of most secondary metabolites. Constructing and manipulating biosynthetic pathways in microorganisms is a proven way to increase the yield of target compounds [147]. For example, gC9 mAb is designed to insert or delete specific genes from the microbial system to induce metabolic pathways of interest [148]. Besides, the growth of two or more microorganisms together in co-culture systems has demonstrated that interspecies relationships can promote metabolism and metabolite production. This improves productivity and increases the likelihood of obtaining compounds that would not be formed when grown alone [149].

Using a bioreactor has been crucial in increasing the scale of secondary metabolites. The invention of the fed-batch and continuous culture bioreactors allows for increased control of environmental factors like pH, temperature, and nutrient concentration, which may result in significant increases in the yield of metabolites. Moreover, encouraging results have been seen while using elicitors, which are defined as substances that result in signaling or stress response in the biological system to derive secondary metabolites within the bioreactors. Some of these examples can include the addition of jasmonic acid in plant cell cultures or antibiotics in microbial systems to induce biosynthetic processes [150].

7.5.6 High-Throughput Screening Methods

High-throughput screening (HTS) techniques help mitigate the free radical problem by counterfeiting the lack of metabolite abundance. These techniques utilize automated platforms to quickly screen thousands of samples to select the few that contain the targeted compounds in the highest concentration. In addition to advanced imaging technology, HTS enables much more detailed spatial and temporal examination of metabolite distribution [151].

7.5.7 Approaches Based on Computations and Machine Learning

An important contribution can be that machine learning approaches assist in the problem of sparse metabolites. These algorithms are capable of forecasting the most favorable conditions for metabolite biosynthesis, or genetic markers for elite phenotypes, through the analysis of big data obtained from omics studies. Metabolic network modeling similarly predicts bottlenecks in some biosynthetic pathways and these predictions can be used for strategic engineering [152]. Some of these methods are useful for the identification of cryptic gene clusters, which are genomic regions for secondary metabolites that are typically silent during laboratory cultivation. Using these algorithms, it is possible to predict the conditions or changes in the genome that would lead to the expression of otherwise silent clusters, thereby providing access to novel metabolites [153].

7.6 Characterization of the Structural Diversity of Secondary Metabolites

Diverse structural features of secondary metabolites pose a major challenge in their characterization. However, these features would need to be restructured to fully understand their activity in biology and their potential uses. This class of compounds is structurally complex, and a number of techniques and multi-disciplinary approaches will be needed to elucidate the structures and functions of these compounds [154].

7.6.1 Advanced Methods for Spectral Analysis

Several secondary metabolites are characterized by unique stereoisomeric structures with several chiral centers or functional groups, rendering structural elucidation quite difficult. Techniques such as NMR spectroscopy, X-ray crystallography, and advanced forms of mass spectrometry, including tandem MS and high resolution MS, are crucial, and indeed, techniques of these sorts require high-level computational power and special training owing to the complexities in data interpretation [155]. As an illustration, NMR spectroscopy yields high-quality data on a molecular level, but often requires the subject compounds to be isotopically labeled to increase sensitivity [154]. In spite of the above, X-ray crystallography is regarded as supremely accurate as long as the subject compounds can be crystallized, a process that is especially challenging for secondary metabolites that possess non-rigid multi-substituted frameworks [156]. New developments in electron diffraction techniques are emerging as suitable replacements for classic X-ray methods because they enable structure determination of microcrystals that are otherwise too small and unsuitable for traditional methods [157]. The adoption of mass spectrometry, especially in combination with ion mobility separation, tends to be essential when discussing secondary metabolites. This technique not only allows one to analyze mass-to-charge ratios with high resolution but also determines their fragmentation patterns, helping researchers determine the presence of different functional groups and their connectivity within the molecules. The application of these methods in combination with computational spectral deconvolution is proving very beneficial [158].

7.6.2 Stereoisomer Identification

If there are other stereoisomers like structural isomers, characterization may become further complex. For example, chiral enantiomers may differ in their biological activities and seem at times to be indistinguishable without the use of chiral separation procedures or highly sophisticated computational simulations [156]. One of the most convenient methods for resolving enantiomers chiral chromatography remains, but it is rather laborious and frequently requires significant method development [159]. New approaches such as vibrational circular dichroism (VCD) and electronic circular dichroism (ECD) are becoming more common as powerfulestablished techniques for stereochemstry [160]. They offer absolute configuration of the chiral compounds, and provide precise insight to the molecular chiral structures without any method of derivitation or separation. Also the application of more advanced quantum mechanial modeling increased the predict accuracy of determined stereochemical configuration, therefore decrease the experimental burden [156].

Stereoisomer identification is also getting easier with recent updates related to cryogenic electron microscopy (Cryo-EM). By keeping the molecules at cryogenic temperature, simliar to how atoms are frozen at mechanical rooms, the structure of the molecules does not suffer [161]. This method produces stunning visuals for the arrangement of stereoisomers that are globally complex and elaborate [156].

7.6.3 Degradation During Analysis

Some metabolites can undergo analysis-induced degradation, for instance, via light, heat, or solvent exposure. Degradation can cause inaccurate results, so strict control of experimental conditions is necessary [157]. Some of the most effective methods employed today for sample preparation include, temperature-controlled storage and transport, inert gas atmospheres, and stabilizers in the sample [162]. Using in situ flow-through NMR or microfluidic-based MS can examine the sample without removing it from controlled conditions, so the sample is not subjected to any environmental factors that could lead to degradation. These techniques have a lower sample preparation burden, significantly lessening the risk of sample degradation. Chemical modification of labile compounds that render them more stable is also becoming more common to increase the time these compounds can be preserved during testing. UV-active or sensitive metabolites present a different challenge wherein photodegradation can occur. Protective sample containers and UV-filtering solvents can be beneficial techniques that mitigate the issue [163]. Furthermore, techniques without a fixed frequency such as variable fluorescence have been used for studying kinetics of photodegradation [164].

7.6.4 Computational Tools and Structural Databases

The adoption of scientific methods and the development of comprehensive structural databases are increasingly evolving as the most effective ways to solve problems that stem from structural complexity [15]. Metabolite structures and their interactions with biological targets are better understood through molecular docking, quantum chemistry simulations, and machine learning applications [152]. These methods also make it possible to perform structure elucidation in a more efficient manner, as well as to develop hypotheses for compounds that have not yet been characterized [165].

For comparative analysis and spectral matching, freely available databases such as the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB) and METLIN are proving indispensable. Data of this nature enables the researcher to detect metabolites by experimentally acquired data and a library of known compounds. The steady growth and maintenance of sorts of databases is propelling the field single kidney forward significantly [166].

7.7 Environmental and Seasonal Variability

There are different factors ranging from climatic conditions, soil type, and exposure to sunlight that tend to affect secondary metabolite production [153,167]. There are also seasonal and geographical differences that further modify the quantity and quality of the metabolites produced. Accurately identifying and dealing with these variables is significant for reproducibility and consistency in research and industry [4].

Certain regions may have plants that possess distinct secondary metabolite profiles. This type of phenomenon is known as chemotypic variation, and it could make research and industrial applications much harder to replicate [168,169]. Soil characteristics like pH and mineral content, altitude, and climate should be considered in all aspects of metabolite profiling of plants. For instance, high altitudes plants may contain more alkaloIDs because of the increased exposure to UV rays [170]. To tackle these difficulties, researchers are combining geospatial mapping and metabolomics. Combining geographic information with metabolite profiling can allow for predicting and optimizing metabolite yields in a particular region [153]. Also, controlled transplanting experiments where plants are grown in several regions with some controls in place may reveal certain variables affecting metabolite profiling [171].

7.7.2 Seasonal Fluctuations Issues

Many other metabolic products are synthesized by certain species in response to stress or pathogen attack. Due to this, there may be an accumulation in certain months making it difficult to plan for the collection of raw materials [172]. The concentration of some phenolic compounds in some plant species can be high when water is scarce. In contrast, other compounds are produced when the plant is fed on or when fungal pathogens attack [65].

Through field work and seasonal monitoring of the changes coupled with metabolite profiling, researchers are beginning to understand these processes [172]. Moreover, phenological models that correlate changes in season with metabolite production are being designed. These models are particularly useful in understanding when certain compounds can be harvested for the maximum yield [173].

7.7.3 Controlled Cultivation Issues

There is always some degree of variability when using controlled cultivation approaches in the laboratory or greenhouse [174]. This, however, can be reduced by creating the environment needed for metabolite extraction [170]. In nature, certain conditions must be met, for instance light intensity, length of light exposure, nutrition, and the presence of other microbes within the environment have to be controlled. For instance, the generation of some flavonoids needs specific light wavelengths, while others require symbiosis with certain fungi or bacteria [140].

New technologies within precision agriculture and controlled-environment agriculture (CEA) allow these problems to be addressed [175]. Vertical farming, hydroponics, and automated climate control systems allow us to manipulate these parameters with great precision [176]. Furthermore, the application of elicitors, which are agents that induce stress responses in plants, is also being optimized for increased secondary metabolite production. The application of jasmonic acid and salicylic acid, to name a couple, is known to enhance the production of economically important alkaloids and phenolics in a variety of plant species [172].

7.7.4 Microbial and Symbiotic Influences

Increasing attention is given to the role that microbial communities play in the development of secondary metabolites. Various plants rely on their associated microbiota for regulating the synthesis of various metabolites through either direct biosynthetic processes or modulation of plant stress responses. For example, antimicrobial compounds within some plants can be produced naturally through the stimulation of endophytic fungi and bacteria [177].