Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Differential Responses of Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) Cultivars to Exogenous Indole-3-Butyric Acid Application

Organic Agriculture Management of Department, Applied Technology and Management School of Silifke, Mersin University, Silifke/Mersin, 33900, Turkey

* Corresponding Author: Gülay Zulkadir. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Integrated Nutrient Management in Cereal Crops)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(7), 2117-2129. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.066762

Received 16 April 2025; Accepted 19 June 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) is a globally important legume crop valued for its nutritional content and adaptability. Establishing a robust root system during early growth is critical for optimal nutrient uptake, shoot development, and increased resistance to biotic stress. This study evaluated the effects of exogenous indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) on root and shoot development in two bean cultivars, Onceler-98 and Topcu, during the seedling stage. IBA was applied at four concentrations: 0 (control), 50, 100, and 150 μM. Morphological parameters measured included root length (RL), root fresh weight (RFW), root dry weight (RDW), root nodule number (RNN), shoot length (SL), shoot fresh weight (SFW), and shoot dry weight (SDW). The experiment followed a randomized complete block design with four replications. Significant (p ≤ 0.05) and highly significant (p ≤ 0.01) differences were observed across treatments and cultivars. The results indicated that Onceler-98 generally responded more favorably to IBA application, with optimal growth performance observed at 100 μM. In contrast, Topcu was less responsive to IBA overall, and high concentrations—particularly 150 μM—tended to suppress nodule formation.Keywords

Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), belonging to the Fabaceae family is an annual plant of the Phaseolus genus [1]. It is one of the most widely cultivated legumes worldwide due to its importance as a food and income source for producers. Bean seeds are high in protein, low in fat, and low in calories. They are also rich in mineral elements such as iron, calcium, magnesium, manganese, and potassium [2]. Due to their rich nutritional content, affordability as a protein source, and long shelf life, beans are particularly popular in developing countries [3]. However, their tolerance to various environmental conditions during growth directly affects yield.

Auxins are plant hormones that influence the growth, development, and stress tolerance of plants [4]. Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), one of the most important growth-promoting hormones, activates the ascorbate-glutathione cycle [5] and enhances plant defense against oxidative stress [6]. Additionally, it plays a crucial role in root elongation and growth [7]. Another important auxin is indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), which is converted to IAA, leading to increased nitric oxide production [8]. This elevated nitric oxide effectively reduces superoxide formation by facilitating peroxynitrite formation [9]. Numerous studies have investigated the effects of IAA on plant growth and development. However, despite its theoretical efficacy, IAA is unsuitable for practical applications due to its low stability and rapid degradation [10]. While an IAA solution degrades within 2 days, the stability of an IBA solution can exceed 28 days [11]. Nonetheless, the stability of IBA is affected by environmental factors such as heat and light. Moreover, IBA can be formulated as a more stable fertilizer when combined with alkylated choline cations [12].

Previous studies have shown that IBA, which is widely used especially in rooting processes, is converted to IAA through the HOMEBOX PROTEIN 24 (HB24) transcription factor and promotes root hair elongation in plants [13]. The hair-like structures formed by protrusions of root epidermal cells increase the contact surface between the root and the soil, thereby enhancing water and nutrient uptake [14]. These structures also provide a rapid and effective response to environmental stimuli [15]. Consequently, recent studies emphasize improving the root system to increase yield, resilience, and tolerance to nutrient deficiencies [16,17].

The known enhancement of root formation by the hormone IBA, through the stimulation of IAA, GA3, and total phenolics [18], suggests that the exogenous application of natural and/or synthetic auxins could be used to promote adventitious root production [19,20]. Based on their effectiveness in inducing adventitious roots, auxins including IAA and IBA have been widely reported by researchers to be commercially used for stimulating root formation in various plant species, such as Cotinus coggygria [21], Lens culinaris M. [22], Vitis vinifera [23], and Magnolia wufengensis [24]. In this context, IBA has been noted to exhibit higher efficacy in root induction due to its superior performance and greater stability under light exposure [25]. However, it has also been found that root formation and elongation vary depending on plant species and cultivars [21]. Considering above mentioned fact this study was conducted to investigate the potential effects of exogenously applied IBA on root structure, nodule formation, and subsequently, seedling characteristics in bean plants.

2.1 Plant Material and Growth Conditions

This trial was established on March 24, 2022, and terminated on April 28, 2022, at the Mersin University, Silifke School of Applied Technology and Business greenhouse. In the trial, varieties developed by the ‘Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry Transitional Zone Agricultural Research Institute (Eskisehir, Türkiye)’ were used.

The experiment was conducted using a randomized complete block design with a factorial arrangement and four replications. The first factor consisted of two bean cultivars, ‘Onceler-98’ and ‘Topcu’, while the second factor included four IBA concentrations: 0, 50, 100, and 150 μM. To evaluate adaptability to field conditions, 5-L pots were filled with field soil, and three bean seeds were sown in each pot.

After emergence, thinning was performed to leave only one plant per pot. Two weeks post-emergence, the prepared IBA solutions were applied to the respective pots as 200 mL of irrigation water. This application was repeated four times at three-day intervals. Observations were made on the 8th day after the last application, when flowering had begun. During the intervals without solution application, the plant’s water requirements were met with tap water. The concentrations applied to the cultivar Onceler-98 (0, 50, 100, and 150 μM IBA) were designated as O1, O2, O3, and O4, respectively, while the corresponding treatments for cultivar Topcu were labeled T1, T2, T3, and T4.

At the beginning of flowering, traits related to root and shoot systems were measured, including Shoot Length (SL), Shoot Fresh Weight (SFW), Shoot Dry Weight (SDW), Root Length (RL), Root Fresh Weight (RFW), Root Dry Weight (RDW), and Root Number of Nodules (RNN). Root and shoot lengths were measured directly using a measuring tape. Fresh weight of root and shoots were determined using a scale with a sensitivity of 0.05 mg. Dry weights were obtained by weighing the samples on the same scale after drying them in an oven at 60°C for 24 h.

Two-way ANOVA variance analysis was conducted using SAS 9.4 [26] software. Additionally, ANOVA analyses of bean cultivars × treatment interactions and Principal Component Analyses (PCA) were performed using JMP 17.0 software [27] to explore the relationships between root and shoot traits of the bean cultivars. Significance differences between means were evaluated at p < 0.05. The Tukey multiple comparison test was used to compare the means. Asterisks indicate the level of significance: **(p ≤ 0.01) denotes highly significant differences, *(p ≤ 0.05) denotes significant differences, and non-significant differences (p > 0.05) are indicated by “ns”.

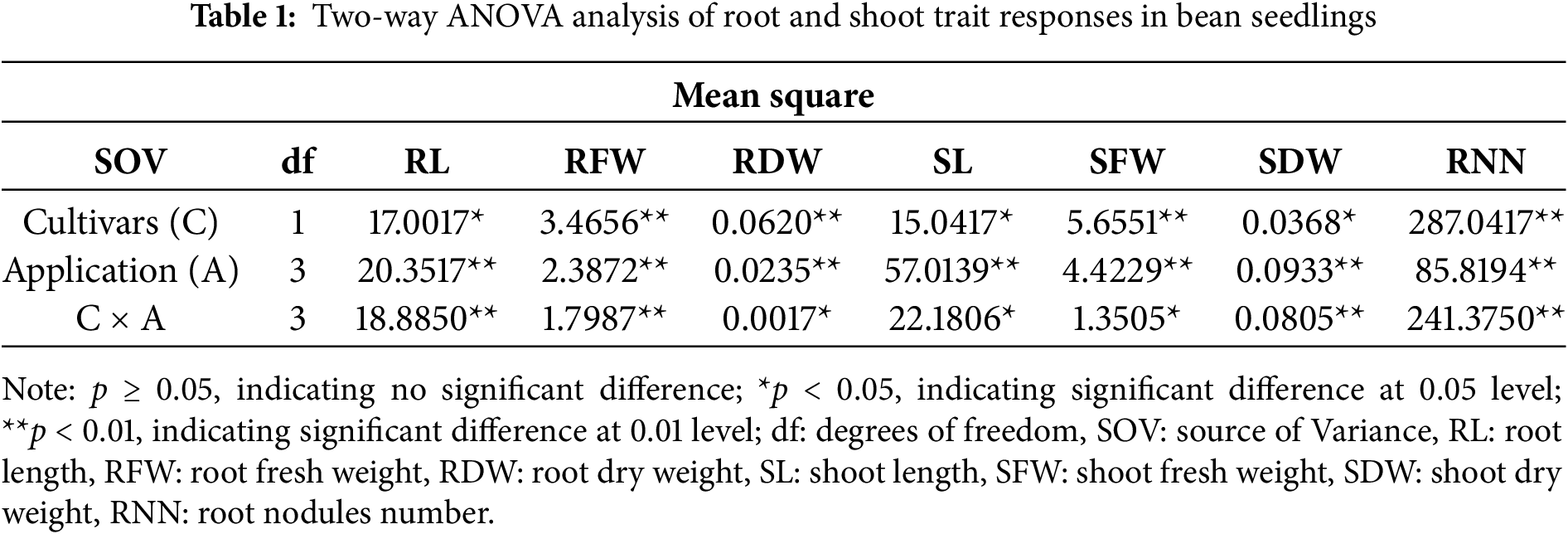

The two-way ANOVA revealed that all measured traits in bean seedlings were significantly influenced by cultivar (C), application (A), and their interaction (C × A). Application had the most consistent and pronounced effect across all traits, with highly significant differences (p < 0.01) observed for root length (RL), shoot length (SL), shoot fresh and dry weights (SFW, SDW), and root nodule number (RNN). Cultivar effects were also significant (p < 0.05 or p < 0.01) for all traits. The interaction between cultivar and application was significant for all traits, particularly for RNN, RL, SL and RFW, suggesting that the response to treatments was cultivar-dependent. These findings emphasize that both “cultivar” and “applied treatments” must be considered to effectively optimize root and shoot development in bean cultivation (Table 1). The variation in root and shoot structure of the samples is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Effects of different IBA doses on cultivars Onceler-98 and Topcu on root and shoot morphology

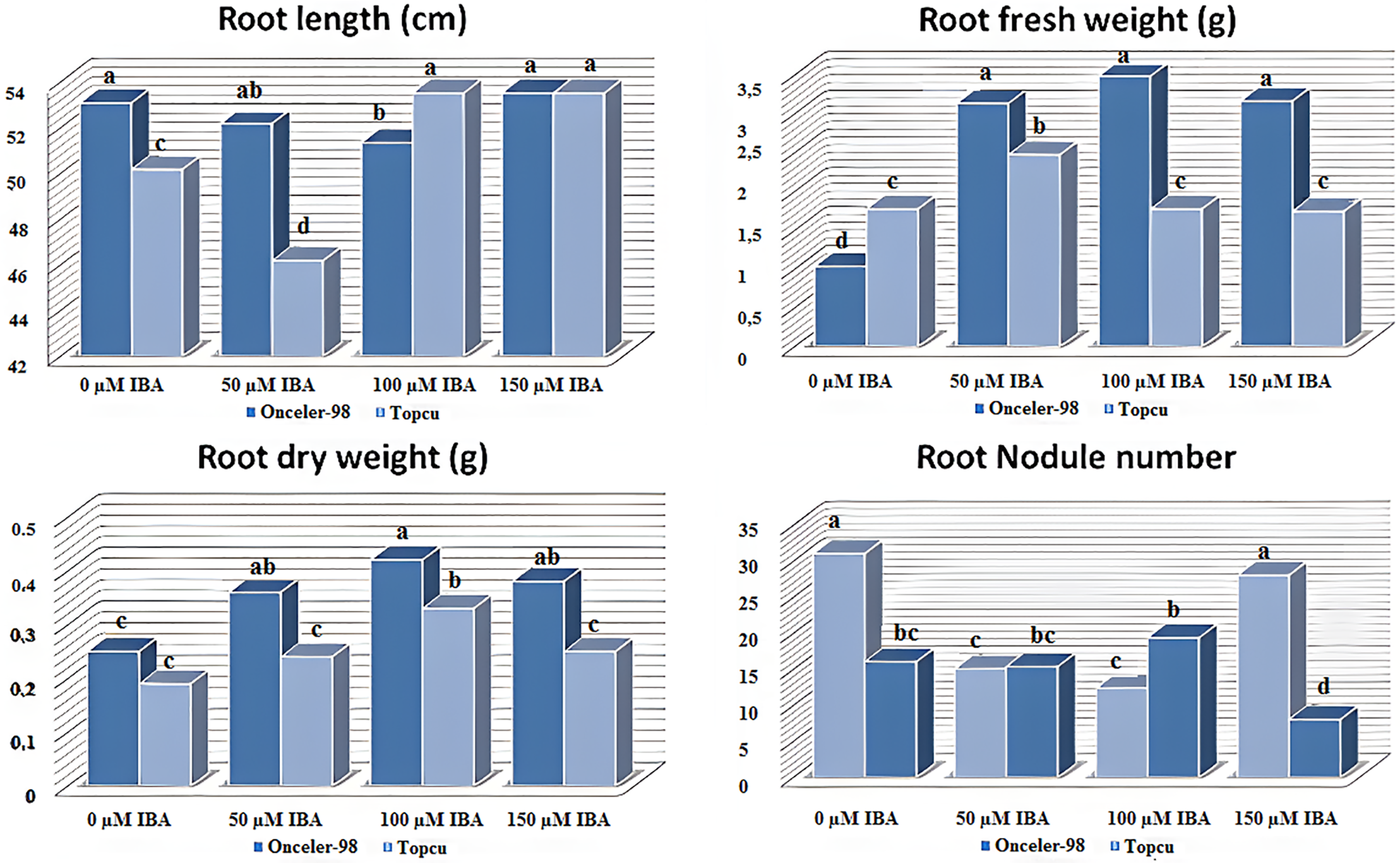

The effects of different indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) concentrations on root system traits in two bean cultivars are presented in Fig. 2. Application of IBA significantly influenced root length (RL), root fresh weight (RFW), root dry weight (RDW), and root nodule number (RNN), with cultivar-specific variations.

Figure 2: Effects of IBA concentrations on root morphology and nodulation in “Onceler-98” and “Topcu” bean cultivars. The lowercase letters show the distribution of averages due to the Tukey test to groups

In ‘Onceler-98’, the highest RL (53.50 cm) was recorded at 150 μM IBA (O4), closely followed by the control (0 μM, O1) at 53.07 cm. The lowest RL (49.17 cm) occurred at 50 μM IBA (O2). RFW peaked at 3.48 g under 100 μM IBA (O3), representing a 200% increase over the control (1.16 g). Similarly, RDW was highest at 100 μM (0.42 g), compared to the lowest value of 0.25 g in the control, reflecting a 68% increase. RNN was greatest in the control (30.00 nodules) but declined to 20.00 at 100 μM and 28.00 at 150 μM, indicating a 33.3% reduction at the intermediate concentration.

In ‘Topcu’, RL was highest (53.50 cm) at 100 μM IBA (T3), significantly greater than at 0 μM (T1: 50.17 cm) and 50 μM (T2: 46.17 cm), but statistically similar to 150 μM (T4: 53.50 cm). RFW reached a maximum (2.47 g) at 50 μM IBA, significantly higher than the control (1.77 g) and 150 μM (1.74 g). RDW peaked at 100 μM (0.33 g), whereas the lowest value (0.19 g) was observed in the control. Topcu exhibited the highest RNN at 100 μM (19.33 nodules) and the lowest at 150 μM (8 nodules), indicating a 43.5% decline in nodulation under higher auxin levels.

Comparing cultivars, ‘Onceler-98’ consistently exhibited stronger responses to IBA in terms of biomass accumulation: RFW increased by up to 200% in Onceler-98 vs. 63.2% in Topcu, and RDW increased by 50% vs. 32.1%, respectively. Root elongation was moderate, with a 3.3% increase in Onceler-98 and 5.0% in Topcu at 150 μM. However, nodulation was adversely affected in both cultivars, with more pronounced suppression in Topcu.

These results suggest that while IBA enhances root growth traits, it may concurrently reduce nodulation, particularly at intermediate to high concentrations. Onceler-98 appeared more responsive to IBA in promoting root development, whereas Topcu was more sensitive to its inhibitory effects on nodulation. Overall, indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) significantly affects root morphological traits and nodulation in bean cultivars, with responses varying by genotype and concentration. This suggests a trade-off between root development and symbiotic nitrogen fixation under auxin treatment, highlighting the importance of optimizing hormone concentrations according to cultivar-specific responses.

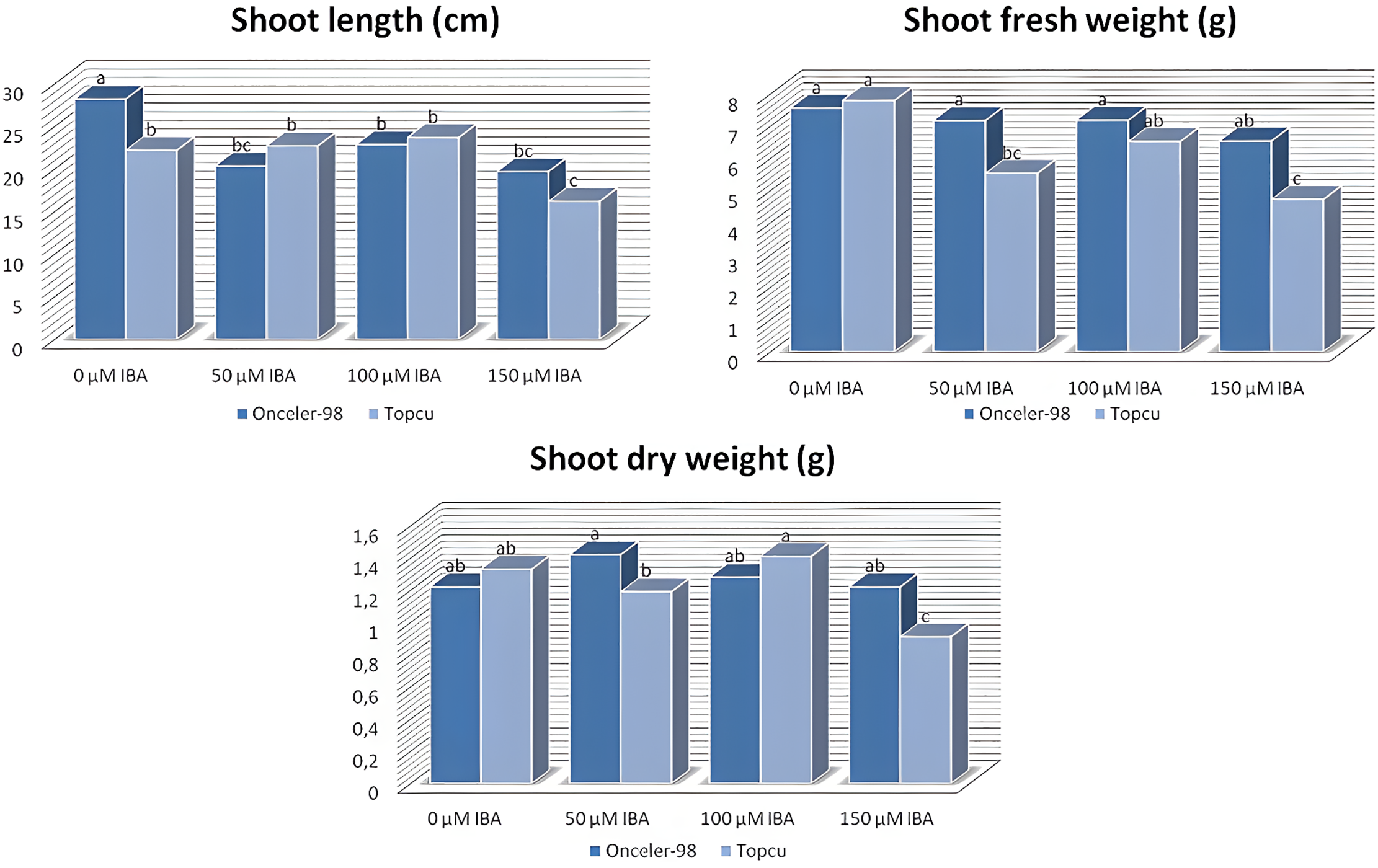

The effects of different indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) concentrations on shoot system traits in two bean cultivars are illustrated in Fig. 3. IBA application significantly influenced shoot length (SL), shoot fresh weight (SFW), and shoot dry weight (SDW), with variations depending on cultivar and concentration. The highest SL and SFW values were observed in the control group (25.17 cm and 7.67 g, respectively), followed by the 100 μM IBA treatment (23.25 cm and 6.85 g). The lowest values for both traits occurred at 150 μM IBA (17.92 cm for SL and 5.63 g for SFW), indicating a concentration-dependent decline. In contrast, SDW remained relatively stable across 0, 50, and 100 μM IBA (1.28, 1.31, and 1.34 g, respectively), with a significant decrease only at 150 μM (1.07 g).

Figure 3: Different IBA concentrations effect on Shoot system traits. The lowercase letters show the distribution of averages due to the Tukey test to groups

When considering the interaction between cultivar and IBA treatment, SL ranged from 16.17 cm to 28.17 cm, with the maximum observed in Onceler-98 under control conditions (O1) and the minimum in Topcu at 150 μM IBA (T4). SFW values varied between 4.72 g and 7.79 g, with the highest value recorded in Topcu control (T1). Treatments O1, O2, and O3 in Onceler-98 were statistically similar to T1, while T4 exhibited the lowest SFW. Regarding SDW, the highest value was obtained in O2 (1.42 g), followed closely by T3 (1.41 g), whereas the lowest was recorded in T4 (0.91 g). Except for T2, the other treatments clustered within a statistically indistinct intermediate group.

These results demonstrate that IBA affects shoot traits in a concentration- and genotype-dependent manner, consistent with the root trait findings. Moderate IBA levels (50–100 μM) tended to enhance SDW, particularly in Onceler-98, which showed a 16.4% increase at 50 μM. However, at 150 μM, both cultivars exhibited marked reductions in shoot growth, with Topcu being more sensitive (−39.4% in SFW and −31.6% in SDW). This suggests a physiological trade-off at higher IBA concentrations. Overall, the data highlight the importance of optimizing IBA levels to promote shoot and root development without negatively impacting key growth parameters and underscore the need for cultivar-specific hormonal management strategies.

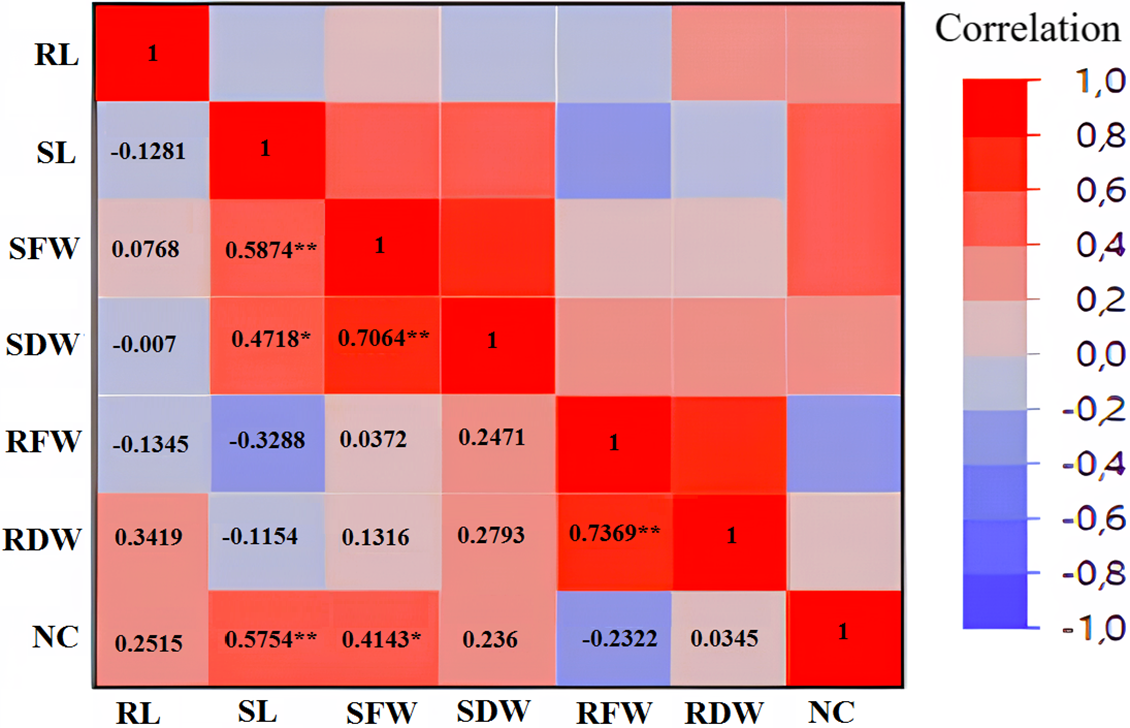

The results of the correlation analysis (Fig. 4) revealed several notable relationship among the measured traits. A moderate positive correlation was found between SL and NC (r = 0.5754), as well as between SL and SFW (r = 0.5874). Strong positive correlations were observed between SFW and SDW (r = 0.7064) and between RFW and RDW (r = 0.7369). In contrast, weak positive correlations were identified between SFW and NC (r = 0.4143) and between SL and SDW (r = 0.4718).

Figure 4: The correlation matrix heatmap shows the values of the Pearson correlation coefficient for all studied parameters, the positive values are in red, negative are in blue. The coefficient ranges from −1 (perfect negative linear relationship) to 1 (perfect positive linear relationship), while the value 0 indicates that there is no relationship between studied variables. *p < 0.05, indicating significant difference at 0.05 level; **p < 0.01, indicating significant difference at 0.01 level

The correlation matrix reveals several key relationships between root and shoot traits. A strong positive correlation between root fresh weight (RFW) and root dry weight (RDW) indicates that greater root biomass corresponds to increased dry matter accumulation. Similarly, RDW shows a strong positive correlation with shoot length (SL), suggesting coordinated growth between root development and shoot elongation. Shoot fresh weight (SFW) and shoot dry weight (SDW) are also highly correlated, reflecting the expected association between total shoot biomass and its dry component.

In contrast, correlations between root and shoot biomass traits tend to be weak or negative, implying that increases in root biomass do not necessarily correspond to proportional increases in shoot biomass, and vice versa. Notably, the number of nodules (RNN) exhibits weak correlations with all other traits, suggesting that nodulation is regulated independently of root and shoot morphological parameters.

Overall, these results indicate that biomass traits within the same organ are closely linked, while nodulation involves distinct regulatory mechanisms. This highlights the importance of considering separate physiological pathways when aiming to optimize both plant growth and symbiotic nitrogen fixation.

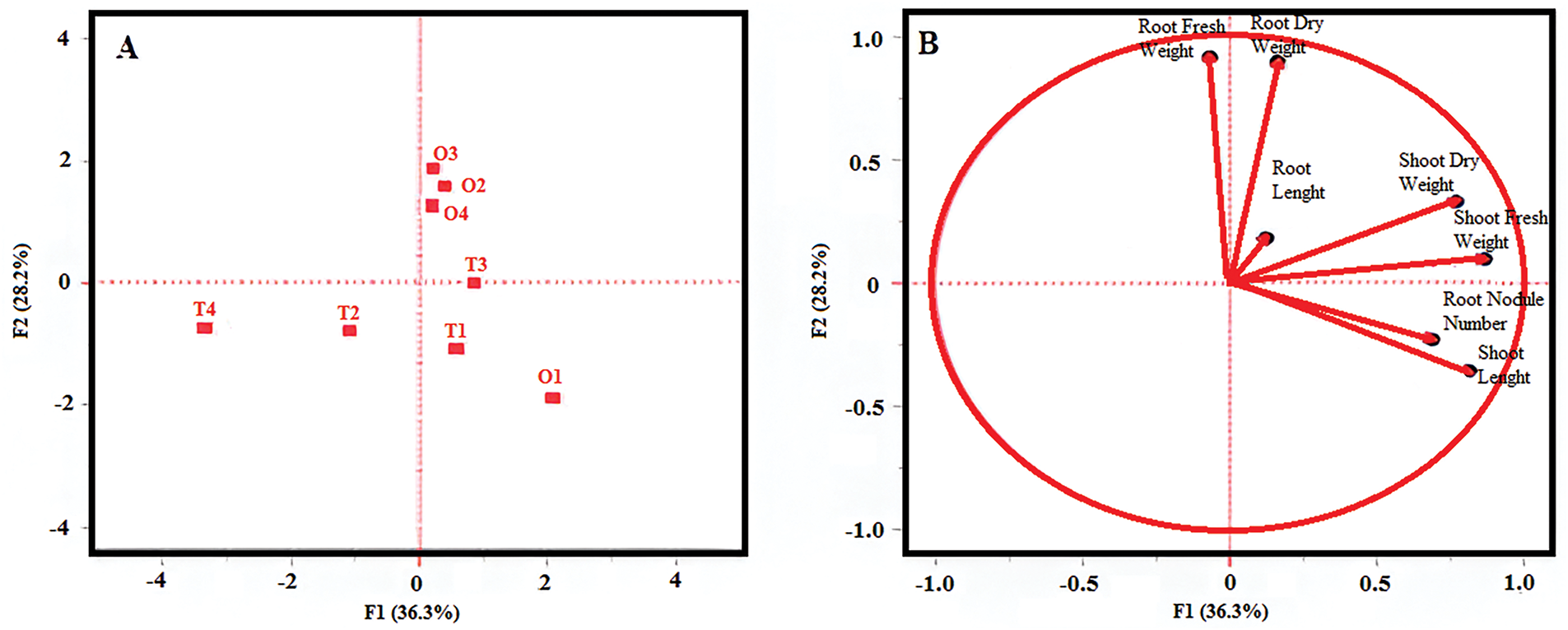

The Biplot and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) presented in Fig. 5A,B account for 64.5% of the total phenotypic variation observed. Fig. 5A highlights substantial variation between the shoot and root system parameters. In Fig. 5B, a very strong positive correlation is evident between shoot length and the number of root nodules, as well as between root dry weight and root fresh weight, and between shoot fresh weight and shoot dry weight. Additionally, root length exhibits positive relationship with both root and shoot fresh and dry weights. Moreover, shoot length, number of root nodules, shoot fresh weight, shoot dry weight, and root length collectively display positive associations, indicating coordinated development among these traits. Conversely, root dry and fresh weights show either negative correlation or no significant correlation with most other traits, except for root length and shoot dry weight. These results emphasize a particularly strong relationship between root length and overall shoot system development, suggesting that root elongation may play a pivotal role in supporting aboveground growth in bean cultivars.

Figure 5: Principal component analysis (PCA) of root/shoot systems traits. (A): Distribution due to C × A interaction; (B): Correlation-based representation of the examined features

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) identified root length as a primary factor influencing shoot system development, exhibiting strong positive correlations with both root traits and above-ground biomass components. In contrast, nodulation appeared to be largely independent of biomass-related parameters, suggesting that its regulation operates through distinct physiological pathways. These findings highlight the differential control mechanisms underlying root architecture and symbiotic nitrogen fixation, emphasizing the importance of tailored strategies when aiming to optimize both growth and nodulation in bean cultivation.

Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA), a widely recognized plant growth regulator, has been extensively utilized in agriculture to manage plant growth and development, particularly for stimulating adventitious root formation in plant cuttings [28]. Shi et al. [29] demonstrated that, akin to IBA, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) also modulates root architecture and enhances drought tolerance in plants. Li et al. [30] reported that exposure to 5 μM CdCl2 significantly inhibited root development, including adventitious roots. However, the addition of 10 μM IBA mitigated cadmium toxicity, enhancing root system resilience. Similarly, IBA improved drought and CdCl2 tolerance in bean seedlings by promoting root development.

In alignment with our findings, Jemaa et al. [31] observed that salt stress reduced root growth in Arabidopsis thaliana by 38%–68%, but the presence of auxins like IBA and IAA mitigated this reduction to as low as 20%. Ludwig-Müller et al. [32] further emphasized that adventitious root development in Arabidopsis is concentration-dependent with respect to auxins such as IBA and IAA. Parallel results were reported by Síposová et al. [33] in rice, where increasing IBA concentrations initially enhanced root length, fresh weight, and dry weight. However, at higher concentrations, IBA exerted inhibitory effects on root growth. Similarly, Khadr et al. [34] found that root length increased with IBA concentrations up to 100 μM, but significantly declined at 150 μM, confirming the biphasic nature of IBA’s effect on root development.

While 50 μM IBA generally produced the highest root fresh weight (RFW) across cultivars, further increases in concentration resulted in a decline in RFW. This response may reflect a physiological shift in the plant’s allocation of resources to root system development or, alternatively, the onset of auxin-induced toxicity at higher doses. For the ‘Onceler-98’ cultivar, the peak RFW was observed at 100 μM IBA, with the lowest value recorded in the control group. In contrast, the ‘Topcu’ cultivar exhibited the highest RFW at 50 μM IBA, followed by a concentration-dependent decline. Li et al. [30] reported that cadmium exposure reduced RFW in beans, but the inclusion of IBA in cadmium treatments mitigated this effect, enhancing root biomass. Similarly, Khadr et al. [34] studied carrot taproot responses to varying IBA concentrations (0, 50, 100, and 150 μM) and observed increases in xylem vessel number and area, although higher concentrations were associated with reduced expression of lignin biosynthesis genes. In maize, high IBA concentrations (10−7 M) reduced root length but increased root diameter, while lower concentrations (10−9 to 10−12 M) stimulated both traits [33]. Khadr et al. [34] also found that RFW increased between 0 and 100 μM IBA but declined significantly beyond that, a trend consistent with our findings. These results underscore the dose-dependent nature of IBA’s effects on root biomass and highlight the importance of optimizing concentration levels to maximize beneficial outcomes while avoiding phytotoxicity.

Both cultivars exhibited their highest root dry weight (RDW) values at the 100 μM IBA concentration, suggesting this dosage optimally promotes root biomass accumulation. An overall increase in RDW was observed with increasing IBA concentrations in both genotypes. The ‘Onceler-98’ cultivar consistently demonstrated higher RDW values than ‘Topcu’, particularly at 100 μM, where it achieved the most substantial increase relative to the control. Although ‘Topcu’ recorded lower average RDW values, it also responded positively to IBA, reaching its peak RDW at the same concentration as ‘Onceler-98’. These findings suggest a genotype-specific sensitivity to IBA, with both cultivars benefiting from moderate concentrations in terms of root dry biomass. Khadr et al. [34] reported that incremental increases in IBA concentrations (0, 50, and 100 μM) led to improvements in root length, which typically correlates with enhanced root fresh weight (RFW) and RDW. Similarly, Orhan et al. [35] found that RDW in Pistacia vera seedlings varied with IBA dosage, peaking at intermediate concentrations before declining at higher levels, further supporting the concentration-dependent nature of IBA efficacy.

Regarding nodulation, the highest number of nodules was recorded in the ‘Onceler-98’ cultivar. Notably, while IBA treatment initially reduced nodule number compared to the control, a partial recovery at higher concentrations was observed in ‘Onceler-98’, suggesting a non-linear response potentially influenced by hormonal balance and root development status. In contrast, the ‘Topcu’ cultivar showed a consistent and marked decline in nodulation, particularly at 150 μM IBA, indicating greater sensitivity to auxin-induced inhibition of symbiotic interactions. These observations point to possible genetic and physiological differences between the cultivars in terms of hormone sensitivity and nodule formation. The genotype-specific responses also highlight the necessity for extended field trials spanning multiple years and involving diverse genotypes and seed origins under replicated conditions to better understand the complex interplay between IBA concentration, root development, and nodulation. This will be essential for developing cultivar-specific management practices aimed at optimizing both vegetative growth and nitrogen fixation.

As shown in Fig. 3, the bean cultivar ‘Onceler-98’ generally outperformed ‘Topcu’ in shoot system traits. Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) application initially enhanced shoot length (SL), shoot fresh weight (SFW), and shoot dry weight (SDW), but these improvements plateaued or declined at higher concentrations, particularly at 150 μM IBA. The highest SL values for both cultivars were observed in the control (0 μM IBA), with an increase noted up to the 100 μM concentration, followed by a decrease at 150 μM, indicating a threshold beyond which IBA may exert inhibitory effects. While ‘Onceler-98’ displayed generally superior shoot performance, some traits at intermediate concentrations (50 and 100 μM IBA) were higher in the ‘Topcu’ cultivar. Specifically, ‘Topcu’ responded more favorably in SL at these concentrations, despite ‘Onceler-98’ having a stronger baseline performance under control conditions. This suggests differential sensitivity and optimal concentration ranges for each cultivar in terms of shoot development.

In contrast to these findings, Khadr et al. [34] observed a consistent increase in both shoot and total plant length in carrot plants across rising IBA concentrations (0–150 μM), highlighting the potential species-specific nature of auxin responses. The discrepancies between the current results and those of Khadr et al. may be attributed to genetic differences, as well as environmental and methodological factors such as light intensity and duration, potting media composition, irrigation regime, and potential additives in the IBA formulation. Similarly, Zalt [36] reported that increasing concentrations of IBA, alongside other auxins like naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), enhanced root and shoot development in blueberry cultivars under in vitro conditions. These results collectively underscore the importance of considering both species- and genotype-specific responses when applying exogenous auxins and optimizing concentration ranges for desired growth outcomes.

A comparable trend to shoot length (SL) was observed in shoot fresh weight (SFW), where increasing IBA concentrations led to an initial rise followed by a decline at 150 μM. The cultivar ‘Onceler-98’ consistently outperformed ‘Topcu’ in SFW, recording higher values across most concentrations. Notably, at 150 μM IBA, the decline in SFW was more pronounced in ‘Topcu’ (4.72 g) than in ‘Onceler-98’ (6.53 g), suggesting greater sensitivity to high auxin levels in the former. The increase in SFW is likely linked to enhanced photosynthetic activity, facilitated by expanded shoot biomass and green surface area. This aligns with the notion that IBA application, when kept below phytotoxic thresholds, can stimulate vegetative growth and biomass accumulation, ultimately contributing to higher yield potential. However, beyond the optimal range, IBA appears to exert inhibitory effects, possibly due to hormonal imbalance or toxicity. Interestingly, while root fresh weight (RFW) declined with increasing IBA concentrations beyond 100 μM, SFW showed a contrasting pattern, particularly in ‘Onceler-98’, where a substantial increase was still recorded. This divergence underscores the complexity of hormonal regulation, where above-ground and below-ground tissues may respond differently to the same auxin treatments. Supporting this, Xu et al. [37] demonstrated that the combined application of IBA and indole-3-acetyl aspartate (IBAA) improved early plant growth more effectively than either compound alone. Similarly, studies by Wiesman et al. [38], Li et al. [30], Ludwig-Müller [39], Xi et al. [40], and Sosnowski et al. [41] found that IBA positively influenced both shoot and root system development in bean plants, reinforcing the relevance of auxins in modulating growth dynamics.

Shoot dry weight (SDW) exhibited similar responses across treatments, with both cultivars showing improved SDW up to a certain concentration, followed by declines at higher IBA levels. ‘Onceler-98’ again displayed superior resilience, maintaining higher SDW values even at 150 μM IBA. This suggests a more robust physiological tolerance to elevated auxin levels compared to ‘Topcu’. Peak SDW in ‘Onceler-98’ occurred at 50 μM, whereas ‘Topcu’ reached its maximum at 100 μM IBA. Under salinity stress, the application of IBA has also been shown to mitigate sodium ion accumulation and promote shoot and root growth, as demonstrated in Vicia faba [42], further supporting IBA’s role in stress amelioration and growth stimulation. In general, shoot and root fresh weights are strongly correlated with their corresponding dry weights, which justifies the widespread practice of using one as a proxy for the other. However, as observed in this study and noted in the literature, root length does not always parallel fresh or dry root weight. This decoupling suggests that while root elongation may increase, it does not necessarily correspond to biomass accumulation, likely due to changes in tissue density or root architecture.

This study reveals substantial phenotypic variation between bean cultivars in terms of root and shoot development, as well as nodulation responses to exogenous indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) application. Among the tested concentrations, 100 μM IBA was found to consistently promote root growth traits,including root length, fresh weight, and dry weight, particularly in the ‘Onceler-98’ cultivar. This cultivar exhibited a notable capacity to tolerate higher auxin levels, maintaining robust shoot biomass and demonstrating a pronounced increase in root development. Conversely, the ‘Topcu’ cultivar exhibited a more moderate response to IBA, with high concentrations (especially 150 μM) leading to suppressed nodulation and a decline in shoot parameters. Notably, nodulation in ‘Onceler-98’ followed a biphasic pattern, with peak nodule numbers observed in both the absence of IBA and at high concentration, while intermediate levels were less conducive to nodulation. Furthermore, elevated IBA concentrations (150 μM) were associated with reduced shoot biomass and length in both cultivars, suggesting a trade-off where auxin-driven root stimulation may occur at the expense of shoot development. These results underscore a complex, genotype-dependent interaction between IBA-mediated root growth, nodulation dynamics, and shoot system sensitivity. Overall, this research highlights the importance of tailoring hormone treatments to specific cultivar responses. A nuanced understanding of auxin’s dual role in promoting root development while potentially suppressing above-ground growth and symbiotic efficiency can guide the strategic use of growth regulators in legume production. Such targeted interventions could improve plant health, enhance yield potential, and increase resilience under variable environmental conditions.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: All the data that supports the findings of this study are available in the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Xiong L, Liu C, Liu D, Yan Z, Yang X, Feng G. Optimization of an indirect regeneration system for common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2023;17(6):821–33. doi:10.1007/s11816-023-00830-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Lisciani S, Marconi S, Le Donne C, Camilli E, Aguzzi A, Gabrielli P, et al. Legumes and common beans in sustainable diets: nutritional quality, environmental benefits, spread and use in food preparations. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1385232. doi:10.3389/fnut.2024.1385232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Islam SS, Adhikary S, Mostafa M, Hossain MM. Vegetable beans: comprehensive insights into diversity, production, nutritional benefits, sustainable cultivation and future prospects. Online J Biol Sci. 2024;24(3):477–94. doi:10.3844/ojbsci.2024.477.494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Siposova K, Labancova E, Kucerova D, Kollarova K, Vivodova Z. Effects of exogenous application of indole-3-butyric acid on maize plants cultivated in the presence or absence of cadmium. Plants. 2021;10(11):2503. doi:10.3390/plants10112503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Bashri G, Prasad SM. Exogenous IAA differentially affects growth, oxidative stress and antioxidants system in Cd stressed Trigonella foenum-graecum L. seedlings: toxicity alleviation by up-regulation of ascorbate-glutathione cycle. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2016;132:329–38. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.06.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Khan MY, Prakash V, Yadav V, Chauhan DK, Prasad SM, Ramawat N, et al. Regulation of cadmium toxicity in roots of tomato by indole acetic acid with special emphasis on reactive oxygen species production and their scavenging. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;142(14):193–201. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.05.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Cakmakcı R, Mosber G, Milton AH, Alatürk F, Ali B. The effect of auxin and auxin-producing bacteria on the growth, essential oil yield, and composition in medicinal and aromatic plants. Curr Microbiol. 2020;77(4):564–77. doi:10.1007/s00284-020-01917-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Piacentini D, Della Rovere F, Sofo A, Fattorini L, Falasca G, Altamura MM. Nitric oxide cooperates with auxin to mitigate the alterations in the root system caused by cadmium and arsenic. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:553062. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.01182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Demecsova L, Zelinova V, Liptakova Ľ, Valentovicova K, Tamas L. Indole-3-butyric acid priming reduced cadmium toxicity in barley root tip via NO generation and enhanced glutathione peroxidase activity. Planta. 2020;252(3):1–16. doi:10.1007/s00425-020-03451-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Nordstrom AC, Jacobs FA, Eliasson L. Effect of exogenous indole-3-acetic acid and indole-3-butyric acid on internal levels of the respective auxins and their conjugation with aspartic acid during adventitious root formation in pea cuttings. Plant Physiol. 1991;96(3):856–61. doi:10.1104/pp.96.3.856. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Kaczmarek DK, Kleiber T, Wenping L, Niemczak M, Chrzanowski L, Pernak J. Transformation of indole-3-butyric acid into ionic liquids as a sustainable strategy leading to highly efficient plant growth stimulators. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2020;8(11):4676. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b06378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kaczmarek DK, Pacholak A, Burlaga N, Wojcieszak M, Materna K, Kruszka D, et al. Dicationic ionic liquids with an indole-3-butyrate anion-plant growth stimulation and ecotoxicological evaluations. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2023;11(36):13282–97. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c02286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhao H, Wang Y, Zhao S, Fu Y, Zhu L. HOMEOBOX PROTEIN 24 mediates the conversion of indole-3-butyric acid to indole-3-acetic acid to promote root hair elongation. New Phytol. 2021;232(5):2057–70. doi:10.1111/nph.17719. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Grierson C, Nielsen E, Ketelaarc T, Schiefelbein J. Root hairs. Arab Book. 2014;12:e0172. doi:10.1199/tab.0172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Liu M, Zhang H, Fang X, Zhang Y, Jin C. Auxin acts downstream of ethylene and nitric oxide to regulate magnesium deficiency-induced root hair development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59:1452–65. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcy078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ghanem ME, Hichri I, Smigocki AC, Albacete A, Fauconnier ML, Diatloff E, et al. Root-targeted biotechnology to mediate hormonal signaling and improve crop stress tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 2011;30(5):807–23. doi:10.1007/s00299-011-1005-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Colombi T, Torres LC, Walter A, Keller T. Feedback between soil penetration resistance, root architecture and water uptake limit water accessibility and crop growth—a vicious circle. Sci Total Environ. 2018;626:1026–35. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.01.129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. El-Banna MF, Farag NB, Massoud HY, Kasem MM. Exogenous IBA stimulated adventitious root formation of Zanthoxylum beecheyanum K. Koch stem cutting: histo-physiological and phytohormonal investigation. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023;197:107639. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.107639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Wise K, Gill H, Selby-Pham J. Willow bark extract and the biostimulant complex Root Nectar® increase propagation efficiency in chrysanthemum and lavender cuttings. Sci Hortic. 2020;263:109108. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2019.109108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Chen W, He L, Tian S, Masabni J, Xiong H, Zou F, et al. Factors involved in the success of Castanea henryi stem cuttings in different cutting mediums and cutting selection periods. J For Res. 2021;32(4):1627–39. doi:10.1007/s11676-020-01208-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ilczuk A, Jacygrad E. The effect of IBA on anatomical changes and antioxidant enzyme activity during the in vitro rooting of smoke tree (Cotinus coggygria Scop.). Sci Hortic. 2016;210(10):268–76. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2016.07.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Singh P, Pandey A, Khan A. Effect of seed priming on growth, physiology, and yield of lentil (Lens culinaris Medik) Cv. Ndl-1. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2017;1:717–9. [Google Scholar]

23. Daskalakis I, Biniari K, Bouza D, Stavrakaki M. The effect that indolebutyric acid (IBA) and position of cane segment have on the rooting of cuttings from grapevine rootstocks and from Cabernet franc (Vitis vinifera L.) under conditions of a hydroponic culture system. Sci Hortic. 2018;227(1):79–84. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2017.09.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang Y, Khan MA, Zhu Z, Hai T, Sang Z, Jia Z, et al. Histological, morpho-physiological, and biochemical changes during adventitious rooting induced by exogenous auxin in Magnolia wufengensis cuttings. Forests. 2022;13(6):925. doi:10.3390/f13060925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lakehal A, Bellini C. Control of adventitious root formation: insights into synergistic and antagonistic hormonal interactions. Physiol Plant. 2019;165(1):90–100. doi:10.1111/ppl.12823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 15.3 user’s guide. Cary, NC, USA: SAS Institute Inc.; 2023. [Google Scholar]

27. SAS Institute Inc. JMP®, Version 17. Cary, NC, USA: SAS Institute Inc.; 1989-2023. [Google Scholar]

28. Pacurar DI, Perrone I, Bellini C. Auxin is a central player in the hormone cross-talks that control adventitious rooting. Physiol Plant. 2014;151(1):83–96. doi:10.1111/ppl.12171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Shi H, Chen L, Ye T, Liu X, Ding K, Chan Z. Modulation of auxin content in Arabidopsis confers improved drought stress resistance. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2014;82:209–17. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.06.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Li SW, Zeng XY, Leng Y, Feng L, Kang XH. Indole-3-butyric acid mediates antioxidative defense systems to promote adventitious rooting in mung bean seedlings under cadmium and drought stresses. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2018;161:332–41. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.06.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Jemaa E, Saida A, Sadok B. Impact of indole-3-butyric acid and indole-3-acetic acid on the lateral roots growth of Arabidopsis under salt stress conditions. Aust J Agric Eng. 2011;2(1):18–24. [Google Scholar]

32. Ludwig-Müller J, Vertocnik A, Town CD. Analysis of indole-3-butyric acid-induced adventitious root formation on Arabidopsis stem segments. J Exp Bot. 2005;56(418):2095–105. doi:10.1093/jxb/eri208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Siposova K, Kollarova K, Liskova D, Vivodova Z. The effects of IBA on the composition of maize root cell walls. J Plant Physiol. 2019;239(822):10–7. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2019.04.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Khadr A, Wang GL, Wang YH, Zhang RR, Wang XR, Xu ZS, et al. Effects of auxin (indole-3-butyric acid) on growth characteristics, lignification, and expression profiles of genes involved in lignin biosynthesis in carrot taproot. PeerJ. 2020;8(2):e10492. doi:10.7717/peerj.10492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Orhan E, Esitken A, Ercisli S, Sahin F. Effects of indole-3-butyric acid (IBAbacteria and radicle tip-cutting on lateral root induction in Pistacia vera. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2007;82(1):2–4. doi:10.1080/14620316.2007.11512190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zalt N. The effect of auxins on rooting of blueberry in vitro [master’s thesis]. Adana, Türkiye: Cukurova University; 2024. [Google Scholar]

37. Xu Y, Zhang Y, Li Y, Li G, Liu D, Zhao M, et al. Growth promotion of Yunnan pine early seedlings in response to foliar application of IAA and IBA. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(5):6507–20. doi:10.3390/ijms13056507. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Wiesman Z, Riov J, Epstein E. Comparison of movement and metabolism of indole-3-acetic acid and indole-3-butyric acid in mung bean cuttings. Physiol Plant. 1988;74(3):556–60. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1988.tb02018.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ludwig-Müller J. Indole-3-butyric acid in plant growth and development. Plant Growth Regul. 2000;32(2/3):219–30. doi:10.1023/A:1010746806891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Xi Z, Zhang Z, Sun Y, Shi Z, Tian W. Determination of indole-3-acetic acid and indole-3-butyric acid in mung bean sprouts using high performance liquid chromatography with immobilized Ru(bpy)32+-KMnO4 chemiluminescence detection. Talanta. 2009;79(2):216–21. doi:10.1016/j.talanta.2009.03.031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Sosnowski J, Krol J, Truba M. The effects of indole-3-butyric acid and 6-benzyloaminopuryn on Fabaceae plants morphometrics. J Plant Interact. 2019;14(1):603–9. doi:10.1080/17429145.2019.1680753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Abdel Latef AAH, Akter A, Tahjib-Ul-Arif M. Foliar application of auxin or cytokinin can confer salinity stress tolerance in Vicia faba L. Agronomy. 2021;11(4):790. doi:10.3390/agronomy11040790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools