Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Synergistic Effect of Zinc Oxide, Magnesium Oxide and Graphene Nanomaterials on Fusarium oxysporum-Inoculated Tomato Plants

1 Maestría en Ciencias en Horticultura, Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Saltillo, 25315, México

2 Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias, Centro de Investigación Regional Noroeste, Campo Experimental Todos Santos, La Paz, 23070, México

3 Instituto Potosino de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica, A.C. (IPICYT), San Luis Potosí, 78216, México

4 Centro de Investigación en Química Aplicada, Saltillo, 25294, México

5 Departamento de Horticultura, Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Saltillo, 25315, México

6 Laboratorio Nacional Conahcyt de Ecofisiología Vegetal y Seguridad Alimentaria (LANCEVSA), Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Saltillo, 25315, México

7 Departamento de Botánica, Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro, Saltillo, 25315, México

* Corresponding Author: Antonio Juárez-Maldonado. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Metabolism Changes to Abiotic and Biotic Stresses: Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Responses and Possible Adaptations Strategies)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(7), 2097-2116. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.067092

Received 24 April 2025; Accepted 30 June 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

Tomato is an economically important crop that is susceptible to biotic and abiotic stresses, situations that negatively affect the crop cycle. Biotic stress is caused by phytopathogens such as Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici (FOL), responsible for vascular wilt, a disease that causes economic losses of up to 100% in crops of interest. Nanomaterials represent an area of opportunity for pathogen control through stimulations that modify the plant development program, achieving greater adaptation and tolerance to stress. The aim of this study was to evaluate the antimicrobial capacity of the nanoparticles and the concentrations used in tomato plants infected with FOL. To this end, a two-stage experiment was conducted. In Stage 1, the effects of the nanomaterials (Graphene nanoplatelets [GP], Zinc oxide nanoparticles [ZnO NPs], Magnesium oxide nanoparticles [MgO NPs]) were evaluated both alone and in combination to determine the most effective method of controlling FOL-induced disease. In Stage 2, the most effective combination of nanomaterials (ZnO+GP) was evaluated at four concentrations ranging from 100 to 400 mg L−1. To evaluate the effectiveness of the treatments, we determined the incidence and severity of the disease, agronomic parameters, as well as the following biochemical variables: chlorophylls, β-carotene, vitamin C, phenols, flavonoids, hydrogen peroxide, superoxide anion, and malondialdehyde. The results show various positive effects, highlighting the efficiency of the ZnO+GP at 200 mg L−1, which reduced the severity by approximately 20%, in addition to increasing agronomic variables and reducing reactive oxygen species. Moreover, the results show that the application of these nanomaterials increases vegetative development and defense against biotic stress. The use of nanomaterials such as zinc oxide, magnesium oxide and graphene can be an effective tool in the control of the severity of Fusarium oxysporum disease.Keywords

Solanum lycopersicum L. is a crop of great economic importance as a functional food that is widely used in cooking [1]. It is susceptible to several pathogens such as fungi, viruses, bacteria and oomycetes, which reduce the yield and quality of the vegetable [2]. These pathogens affect not only the morphological aspects but also the biochemical and molecular aspects [3].

Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici (FOL) is responsible for vascular wilt [4]. This pathogen invades the root, degrading the basal area of the stem, restricting plant growth and development, and causing low or zero yields [5]. It colonizes the xylem, restricting water transport and causing loss of turgor, chlorosis, wilting, and eventually death [6]. FOL is responsible for high annual losses of up to 100% in tomato crops [7].

Global food security is under threat from resistant pathogens and climate change. To strengthen crop resistance and achieve greener, more sustainable agriculture, we need sustainable strategies such as nanotechnology and plant microbiome management [8]. Pathogen control requires the application of sustainable, interdisciplinary tools that include plant protection, food safety, and environmental protection [9]. However, the conventional method for FOL control is of chemical origin and has several drawbacks, such as rapid release and degradation of the active ingredient, leading to over-application that not only induces resistance in the pathogen but also harms the environment [10]. Therefore, nanotechnology is promising as a biostimulant that induces tolerance to inappropriate abiotic or biotic stress situations [11]. Nanoparticles (NPs) and nanomaterials (NMs) can increase agricultural production and reduce damage caused by phytopathogens [12]. They delay the release of the active ingredient, are effective at low doses, and protect crops from fungal or bacterial diseases at low cost [13]. The use of NMs (such as zinc oxide and magnesium oxide) to control plant pathogens has excellent results [14]. One of the major advantages of this technology is that far fewer metals are released into the environment than with conventional metal fungicides. Unlike conventional chemicals, nanomaterials are more potent and effective at controlling pathogens at much lower doses. They can also maintain or even improve crop productivity [15,16].

Zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles emerge as a promising alternative to traditional pesticides, combining antimicrobial action with nutritional benefits. However, their mechanisms of action and potential adverse effects require further investigation [17]. ZnO NPs are effective against a wide range of pathogens [13]. It induces the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which transmit signals that activate physicochemical defense responses [18]. It is an essential nutrient for metabolism, plant development, genetic expression, biomolecular composition, in addition to participating in photosynthesis and being a cofactor of hormones (gibberellins, auxins, cytokinins, abscisic acid) and enzymes (hydrolases, ligases) [19]. On the other hand, MgO NPs control plant diseases by producing ROS that are toxic to microorganisms and activate signaling pathways such as salicylic acid [20]. A hormone that triggers defense responses such as activation of pathogen recognition (PR) genes, hypersensitive response (HR), and systemic acquired response (SAR) [21]. Finally, graphene is a carbon allotrope with chemical and mechanical stability, high surface area, and low toxicity. It facilitates the absorption of nutrients by acting as a carrier of essential elements [10]. It has antimicrobial potential because it can damage the cellular structure of pathogens, resulting in their death [22].

Based on the aforementioned properties, nanoparticles of zinc oxide (ZnO) and magnesium oxide (MgO) combined with graphene (GP) are presented as an economic opportunity with complementary properties that provide the nutrient and also exhibit antimicrobial capacities [23]. The functionality of the mixture is based on the ability of GP to act as a transporter of molecules such as ZnO and MgO, enhancing the properties of both materials [24]. This is due to the chemical compatibility they exhibit, achieving interaction with GP through the formation of covalent or non-covalent bonds between their functional groups [25]. Their nanometric size is effective in crops because they easily penetrate the cell, in addition to being efficiently absorbed and translocated [26]. They have a larger specific surface area, which increases the points of contact with microorganisms, cross the membrane by endocytosis, generate oxidative stress and cause cell death [27].

The NPs used in this research stimulate the immune system and positively modify the metabolic and adaptive performance of plants [28]. They alleviate stress, promote plant survival, and reduce the use of agrochemicals [29]. They are also highly transportable, easy to handle, efficient, and have a long shelf life, making them a practical technique with potential for improving food production systems [30].

Based on the above, this study aims to evaluate the effect of ZnO and MgO nanoparticles combined with GP on tomato plants inoculated with FOL, their ability to induce tolerance to the pathogen, as well as their effect on plant physiological behavior.

The tomatoes were grown in a greenhouse using ‘El Cid F1’ indeterminate saladette tomato seeds from Harris Moran (Davis, CA, USA). The plants were transplanted into 20 L black polyethylene containers filled with a 1:1 mixture of peat moss and perlite. Steiner’s solution [31] was used to provide the plants with nutrients. The plants were guided to a single stem.

This research was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, from March to May 2024, tomato plants were grown for 70 days and seven treatments were applied directly to the soil at a volume of 10 mL per plant and a concentration of 100 mg L−1 (where nanoparticle mixtures were evaluated, each was 50%). The treatments were as follows: 1) ZnO+GP: zinc oxide nanoparticles plus graphene inoculated with FOL; 2) MgO+GP: magnesium oxide nanoparticles plus graphene inoculated with FOL; 3) GP: graphene nanoparticles inoculated with FOL; 4) MgO: Magnesium oxide nanoparticles inoculated with FOL; 5) ZnO: Zinc oxide nanoparticles inoculated with FOL; 6) T+: Positive control inoculated with FOL; and 7) T0: Absolute control (no application or inoculation with FOL). To ensure adequate dispersion of the nanomaterials, the suspensions were sonicated for 30 min prior to treatment application. Treatment started at the time of transplantation and was applied every two weeks for a total of five times.

In the second stage, which ran from June to October 2024, tomato plants were grown for 14 weeks. The most effective treatment from the first stage was evaluated and applied at four different concentrations. The treatments evaluated were: 1) ZnO+GP at 100 mg L−1+FOL, 2) ZnO+GP at 200 mg L−1+FOL, 3) ZnO+GP at 300 mg L−1+FOL, 4) ZnO+GP at 400 mg L−1+FOL, 5) T+: positive control inoculated with FOL, 6) CC: chemical control (captan at 5 g L−1) + FOL, and 7) T0: Absolute control (no application or inoculation with FOL). The nanoparticle treatments were applied directly to the soil at a volume of 10 mL per plant; ZnO NPs and GP were added in a 1:1 ratio, with each component representing 50%. To ensure adequate dispersion of the nanomaterials, the suspensions were sonicated for 30 min prior to application. Treatment started at the time of transplantation and was applied every two weeks for a total of seven times.

2.2 Characterization of Nanoparticles

Graphene nanoplatelets (GP) with a thickness of 2–8 nm (three to six layers), a purity of 95% and a specific surface area of 500–1200 m2/g were used (CAS number: 7782-42-5, US Research Nanomaterials, Inc., Houston, TX, USA). Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) have a size of 10–30 nm, a purity of 99.8%, and a specific surface area of 30–50 m2/g (CAS number: 1314-13-2, SkySpring Nanomaterials, Inc., Houston, TX, USA). Magnesium oxide nanoparticles (MgO NPs) are 20 nm in size, 99% pure, and have a specific surface area of >60 m2/g (CAS number: 1309-48-4, US Research Nanomaterials, Inc., Houston, TX, USA).

2.3 F. oxysporum Inoculation, Analysis of Disease Incidence and Severity

F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici spores were propagated at 29°C for 15 days in Petri dishes containing potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium supplemented with ampicillin (100 mg L−1). The plants corresponding to the FOL treatments were inoculated at transplanting time by immersing the seedling roots in a conidial suspension at a concentration of 1 × 108 mL−1.

Disease incidence was determined visually when symptoms of FOL disease were observed. Plants showing no symptoms were assigned a value of zero, while those showing symptoms were assigned a value of one. Results are expressed as incidence percentages.

Disease severity was determined using a visual scale for each of the 20 plants per treatment, with the average being reported. The visual scale was assigned a value where: 0 = no symptoms; 1 = wilting of basal leaves; 2 = chlorosis of basal leaves and wilting of young leaves; 3 = wilting of most leaves, diffuse drying and yellowing; and 4 = dead plant. Disease severity was calculated as a percentage.

Measurements were taken to evaluate the growth and development of the tomato plants. The height and stem diameter of each plant were measured, and the number of leaves and clusters were counted.

At harvest, the fresh biomass was weighed. The dry biomass was obtained by drying the samples in a drying oven (DHG9240A model) at a constant temperature of 90°C for 72 h. Fruit yield was calculated as the total weight of the fruit harvested.

2.5 Sampling for Biochemical Analysis

The leaf samples used for the various biochemical analyses were collected 45 days after transplanting. Fully expanded young leaves (third or fourth leaf) were collected for sampling and placed on ice before being stored at −20°C. The samples were freeze-dried and ground into a fine powder, and stress biomarkers, secondary metabolites and photosynthetic pigments were then determined.

The content of chlorophylls (a and b) and β-carotene was determined according to the method of Nagata and Yamashita [32]. The lyophilized sample (10 mg) was mixed with 2 mL of hexane: acetone (3:2). Subsequently the samples were subjected to an ultrasonic bath for 5 min. They were then centrifuged at 15,000× g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed and the absorbance was read at 645 and 663 nm using a spectrophotometer. The obtained values were used in Eqs. (1) and (2) to calculate the chlorophyll content. For β-carotene, absorbances at 453, 505, 645 and 663 nm were measured and the obtained values were used in Eq. (3).

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was assessed according to the methodology described by Velikova et al. [33] and expressed as μmol g−1 DW. In total, 10 mg of lyophilized sample was homogenized with 1000 μL of cold trichloroacetic acid (0.1%). The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000× g for 15 min and 250 μL of the supernatant was added to 750 μL of potassium phosphate buffer (10 mM) (pH 7.0) and 1000 μL of potassium iodide (1 M). The absorbance of the supernatant was read at 390 nm. The content of H2O2 was given on a standard.

Superoxide anion (O2•−) production rate was measured by monitoring the nitrite formation from hydroxylamine in the presence of O2•− as described by Yang et al. [34] with some modifications. Lyophilized dried tissue (20 mg) were homogenized with 5 mg of polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), 1 mL of potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.8), and then centrifuged at 5000× g and 4°C for 15 min. The obtained supernatant (600 μL) was mixed with 550 μL of potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.8) and 60 μL of hydroxylamine hydrochloride (10 mM), homogenized in vortex, and then incubated for 30 min at 25°C. The incubated solution (650 μL) was added to 650 μL of 3-aminobenzenesulphonic acid (17 mM) and 1 mL 1-naphthylamine (7 mM), and then further kept for 20 min at 25°C. The absorbance was recorded at 530 nm. A standard curve with NO2 was used to calculate the O2•− production rate from the reaction equation of O2•− with hydroxylamine. The O2•− production rate was expressed as µmol 100 g−1 min−1 on a dry weight basis (µmol 100 g−1 DW min−1).

Malondialdehyde (MDA) was determined according to the methodology described by Velikova et al. [33] and expressed as nmol g−1 DW. In total, 50 mg of lyophilized sample was homogenized in 1000 μL of thiobarbituric acid (TBA) (0.1%). The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000× g for 20 min and 500 μL of the supernatant was added to 1000 μL of TBA (0.5%) in trichloroacetic acid (20%). The mixture was incubated in boiling water for 30 min, and the reaction was stopped by placing the reaction tube in an ice bath. Then, the sample was centrifuged at 10,000× g for 5 min, and the absorbance of supernatant was read at 532 nm. The amount of MDA–TBA complex (red pigment) was calculated from the extinction coefficient of 155 mM−1 cm−1.

Total phenols (mmol 100 g−1 DW) were obtained according to Yu and Dahlgren [35]. 100 mg of lyophilized tissue was extracted with 1 mL of a water/acetone solution (1:1) and the mixture was homogenized for 30 s. The sample tubes were centrifuged at 17,500× g for 10 min at 4°C. Then, 18 μL of the supernatant, 70 μL of the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, and 175 μL of 20% sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) were placed in a test tube, and 1750 μL of distilled water was added. The samples were placed in a water bath at 45°C for 30 min. Finally, the reading was taken at a wavelength of 750 nm on the UV-Vis spectrophotometer (UNICO Spectrophotometer, Model UV2150, Dayton, NJ, USA). Total phenols were expressed in mg equivalents of gallic acid per gram of dry weight (mg g−1 DW).

The flavonoid content was determined according to Arvouet-Grand et al. [36]. For extraction, 20 mg of lyophilized tissue was placed in a test tube to which 2 mL of reactive grade methanol was added, and this was homogenized for 30 s. The mixture was filtered using Whatman No. 1 paper. For quantification, 1 mL of the extract and 1 mL of 2% methanolic aluminum trichloride (AlCl3) solution were added to a test tube and allowed to stand for 20 min in darkness. The reading was taken at a wavelength of 415 nm on the UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UNICO Spectrophotometer, Model UV2150, Dayton, NJ, USA). The results are expressed in mg equivalents of quercetin per gram of dry weight (mg g−1 DW).

Vitamin C (mg g−1 DW) was determined by means of spectrophotometry as described by Hung and Yen [37]. Briefly, 10 mg of lyophilized tissue was extracted with 1 mL of 1% metaphosphoric acid (HPO3) and filtered with Whatman No. 1 filter paper. For quantification, 200 μL of extract was taken and mixed with 1800 μL of 2,6 dichlorophenol indophenol (100 mM), with absorbance measured at 515 nm on a UV–Vis spectrophotometer (UNICO Spectrophotometer, Model UV2150, Dayton, NJ, USA).

The experiment was conducted using a randomized complete block design with five replications. Each experimental unit contained four plants. An analysis of variance and Fisher’s LSD means test (p ≤ 0.05) were performed. In addition, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) and the Hotelling test (p ≤ 0.05) were performed on the variables of incidence and severity of disease caused by F. oxysporum. InfoStat software version 2020 was used.

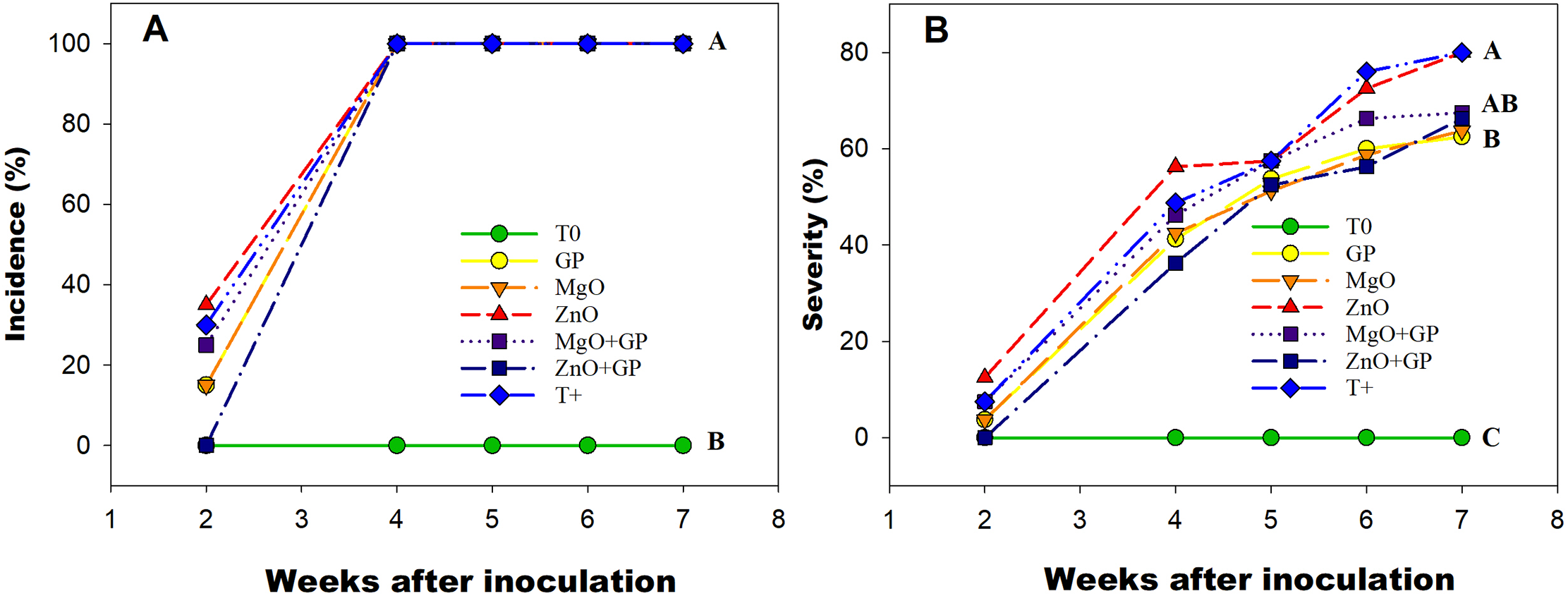

3.1 Incidence and Severity of Disease in the First Stage

In the first stage, significant differences were observed; two weeks after inoculation, the MgO+GP and GP treatments showed a 16% and 50% lower incidence, respectively, compared to T+, while ZnO+GP showed no incidence (Fig. 1A). The 100% incidence was manifested four weeks after inoculation. On the other hand, the severity of the disease decreased significantly with the application of nanomaterials. The treatment with the lowest severity since inoculation was ZnO+GP, which showed a 22% reduction compared to T+ at week 6. At week 7, GP, MgO, ZnO+GP, and MgO+GP decreased by 14%, 12%, 9%, and 7%, respectively, compared to T+ (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1: Incidence (A) and severity (B) of F. oxysporum disease in tomato plants from the second week after inoculation. T0: absolute control; GP: graphene+FOL; MgO: magnesium oxide nanoparticles+FOL; ZnO: zinc oxide nanoparticles+FOL; MgO+GP: magnesium oxide nanoparticles+graphene+FOL; ZnO+GP: zinc oxide nanoparticles+graphene+FOL; T+: plants inoculated with FOL. Treatments with the same letter are not significantly different according to Hotteling test (p ≤ 0.05)

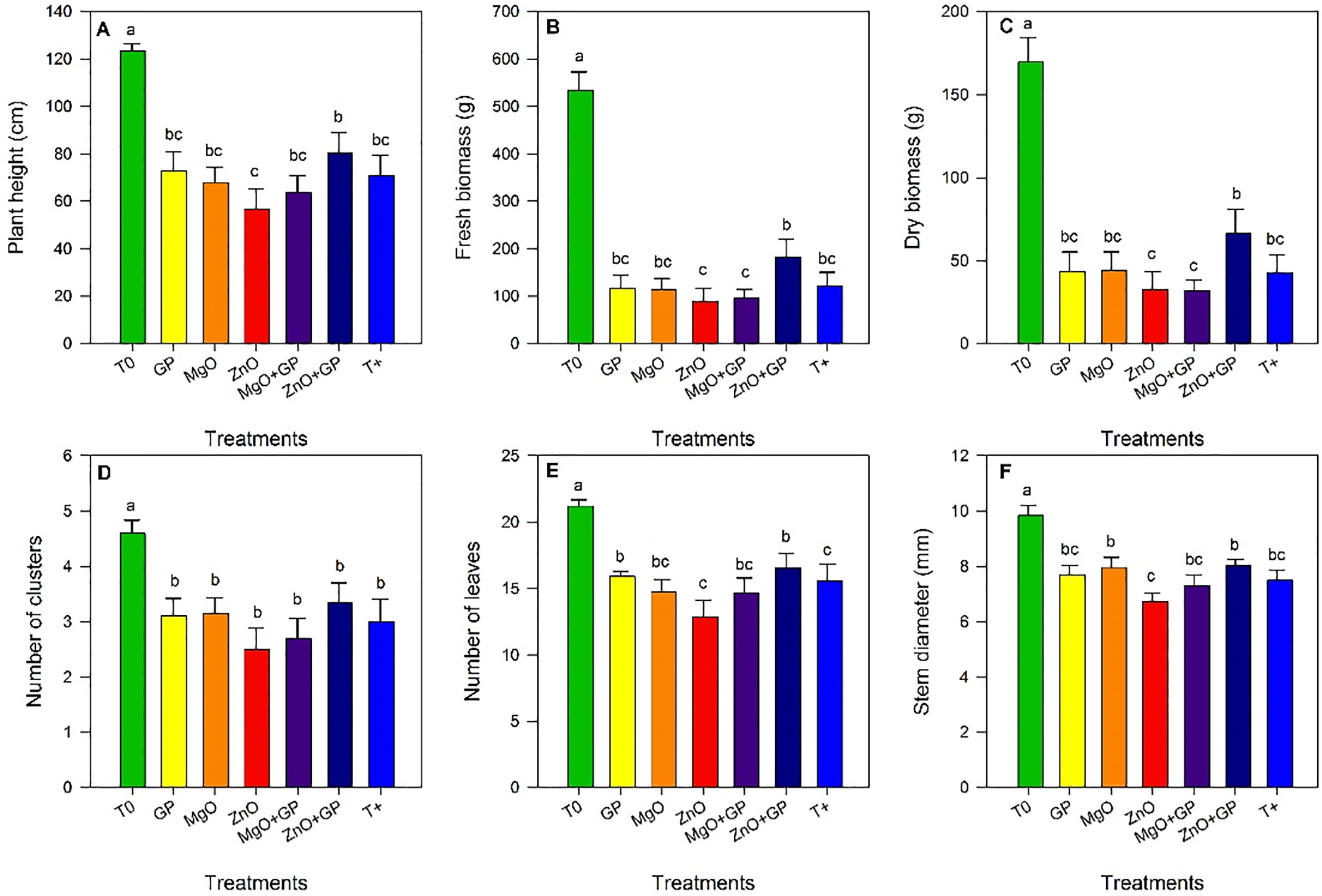

3.2 Agronomic Parameters of the First Stage

Significant differences were observed between the treatments. Plants in the T0 treatment showed greater height. Within the inoculated treatments, ZnO+GP exceeded the rest, increasing 41% compared to ZnO and 13.5% compared to T+ (Fig. 2A). In the case of fresh and dry biomass, T0 had the highest content and among the inoculated treatments, ZnO+GP exceeded the others (Fig. 2B,C). In the variable number of clusters, no significant differences were found among the inoculated treatments, with T0 being the best treatment (Fig. 2D). Significant differences were observed in the number of leaves, with T0 being the best treatment, while in the FOL treatments, ZnO+GP was the best (Fig. 2E). Significant differences were observed in stem diameter, with T0 increasing this variable compared to the rest of the treatments. However, the ZnO+GP and MgO treatments increased it by 7% and 6%, respectively, compared to T+ (Fig. 2F).

Figure 2: Plant height (A), fresh biomass (B), dry biomass (C), number of clusters (D), number of leaves (E), and stem diameter (F) of tomato plants. T0: absolute control; GP: graphene+FOL; MgO: magnesium oxide nanoparticles+FOL; ZnO: zinc oxide nanoparticles+FOL; MgO+GP: magnesium oxide nanoparticles+graphene+FOL; ZnO+GP: zinc oxide nanoparticles+graphene+FOL; T+: plants inoculated with FOL. Means with the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher’s LSD test (p ≤ 0.05)

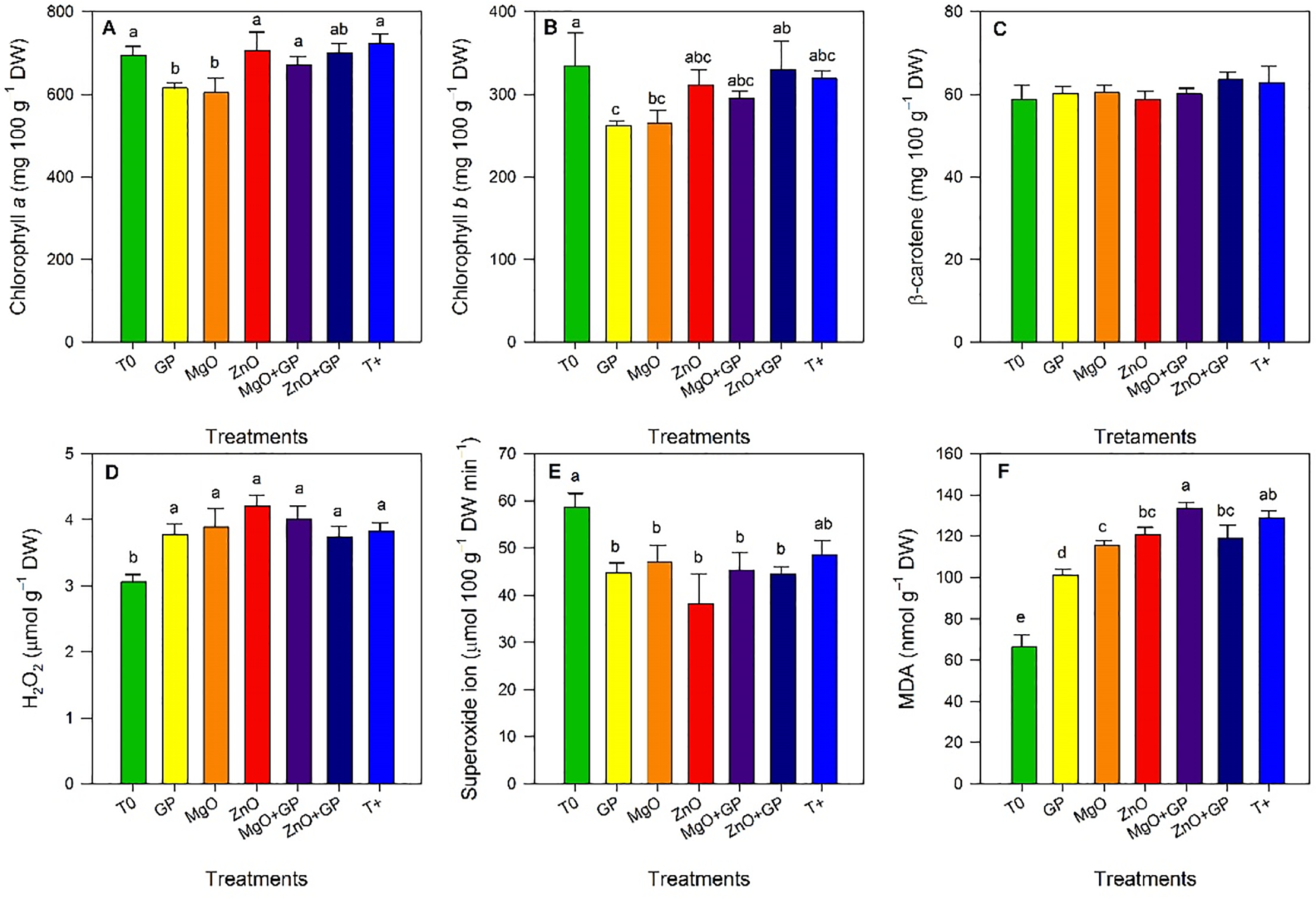

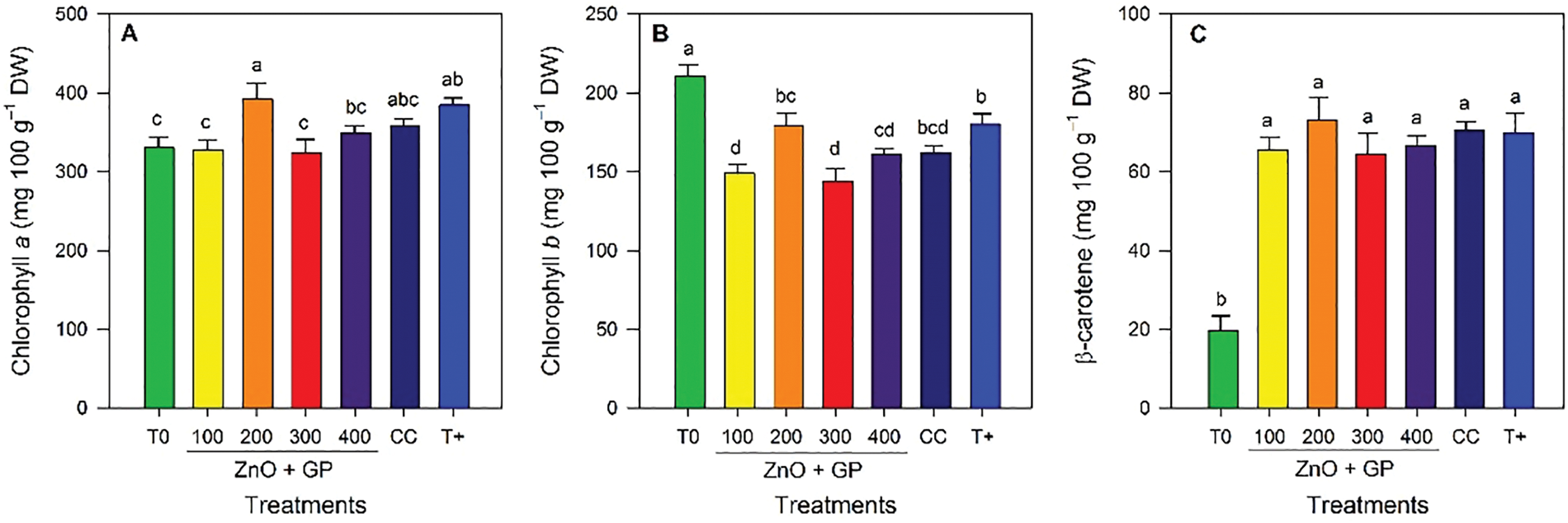

3.3 First-Stage Photosynthetic Pigments and Stress Biomarkers

Significant differences between treatments were observed for chlorophyll a content. ZnO, T+, MgO+GP and ZnO+GP showed the highest values for this variable, statistically comparable to T0. ZnO+GP exceeded GP and MgO by 14% and 16%, respectively (Fig. 3A). Significant differences were observed for chlorophyll b content. ZnO+GP was statistically comparable to T0 and exceeded GP and MgO by 20% (Fig. 3B). β-carotene content did not show significant differences between treatments (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3: Chlorophyll a (A), chlorophyll b (B), β-carotene (C), hydrogen peroxide (D), superoxide radical (E), and malondialdehyde (F) content in tomato plants. T0: absolute control; GP: graphene+FOL; MgO: magnesium oxide nanoparticles+FOL; ZnO: zinc oxide nanoparticles+FOL; MgO+GP: magnesium oxide nanoparticles+ graphene+FOL; ZnO+GP: zinc oxide nanoparticles+graphene+FOL; T+: plants inoculated with FOL. Means with the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher’s LSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Figures without letters in the bars do not show significant differences (p ≤ 0.05)

Results for hydrogen peroxide content showed no differences between treatments (Fig. 3D). Regarding the superoxide radical content, a reduction was observed with the application of ZnO, decreasing by 17% compared to T+; the nanoparticle treatments did not differ significantly from each other (Fig. 3E). The MDA content increased significantly in the T+ and MgO+GP treatments, by 95% and 101%, respectively, compared to T0. GP reduced this variable by 22% and 24% compared to T+ and MgO+GP, respectively (Fig. 3F).

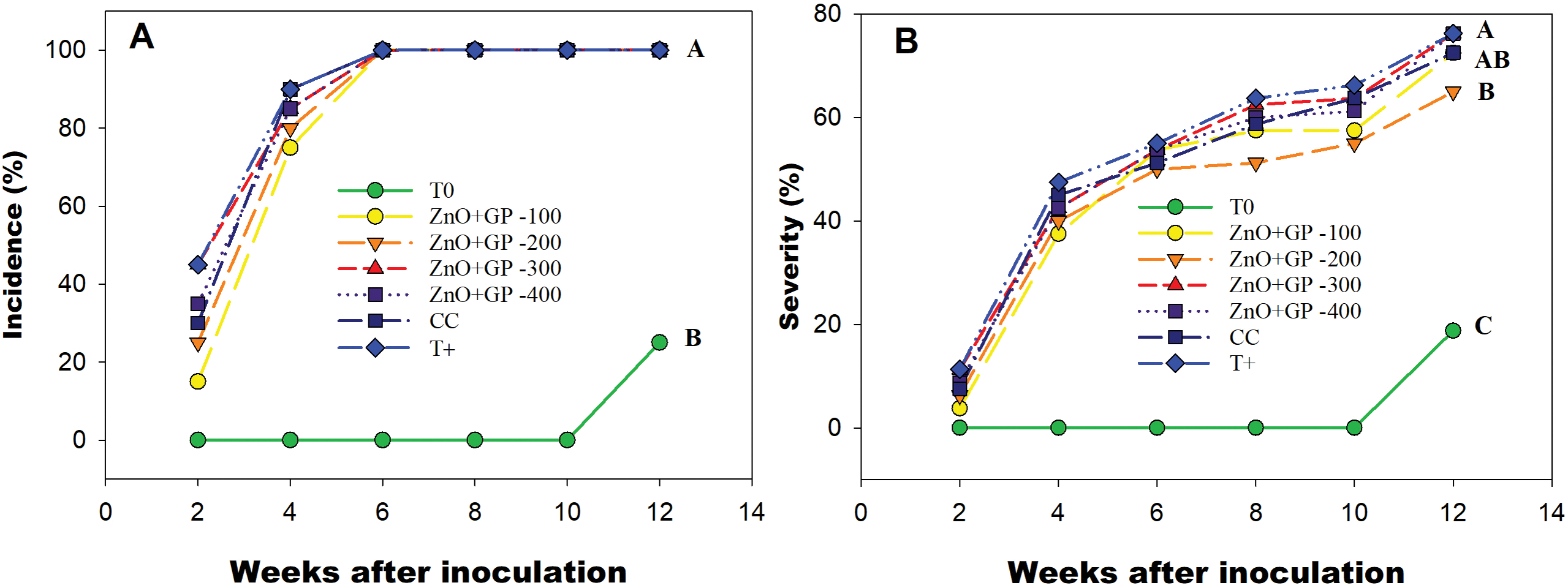

3.4 Incidence and Severity of Disease in the Second Stage

Highly significant differences were observed between treatments, with a significantly higher incidence each week after inoculation in T+. At week 5, the 200 mg L−1 treatment showed a 15% reduction in incidence compared to T+ and a 10% reduction compared to CC. However, by week 6, the incidence reached 100% in all treatments (Fig. 4A). Regarding disease severity, it was found that the application of ZnO+GP reduced symptoms at low concentrations, with 200 mg L−1 being the most effective, reducing disease by 15% and 10% compared to T+ and CC, respectively. The 100 mg L−1 concentration showed similar efficacy to the chemical control (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4: Incidence (A) and severity (B) of F. oxysporum disease in tomato plants, from the second week after inoculation. T0: absolute control; 1) ZnO+GP-100, 2) ZnO+GP-200, 3) ZnO+GP-300, 4) ZnO+GP-400: zinc oxide nanoparticles+graphene+FOL, applied at 4 different concentrations in mg L−1; CC: chemical control+FOL; T+: positive control inoculated with FOL. Treatments with the same letter are not significantly different according to Hotteling test (p ≤ 0.05)

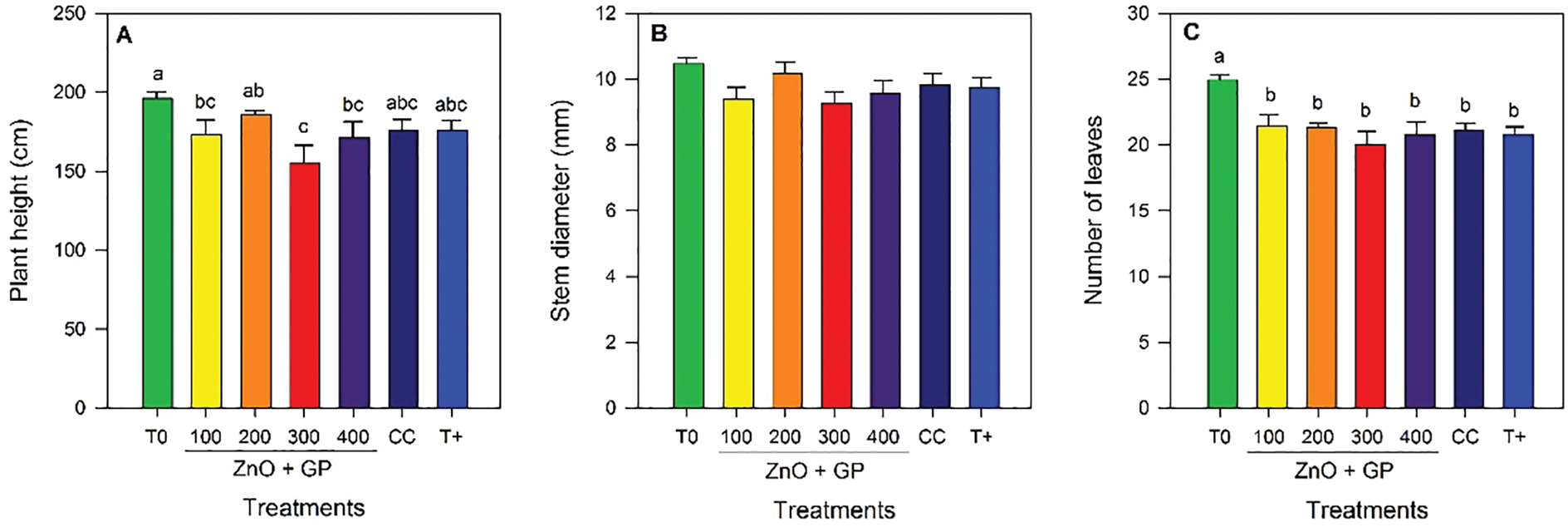

3.5 Agronomic Parameters of the Second Stage

Significant differences in plant height were observed among the different treatments. The application of ZnO+GP nanoparticles at a concentration of 200 mg L−1 stood out, statistically exceeding T0 and the 300 mg L−1 and 400 mg L−1 treatments by 16% and 8%, respectively (Fig. 5A). No significant differences were found between treatments for stem diameter (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5: Plant height (A), stem diameter (B), number of leaves (C), fresh biomass (D), dry biomass (E), and fruit yield (F) of tomato plants. T0: absolute control; 1) ZnO+GP-100, 2) ZnO+GP-200, 3) ZnO+GP-300, 4) ZnO+GP-400: zinc oxide nanoparticles+graphene+FOL, applied at 4 different concentrations in mg L−1; CC: chemical control+FOL; T+: positive control inoculated with FOL. Means with the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher’s LSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Figures without letters in the bars do not show significant differences (p ≤ 0.05)

Regarding the number of leaves, the application of nanoparticles did not alter this variable in the inoculated plants; however, T0 showed an increase compared to the other treatments (Fig. 5C).

Regarding biomass, the trend is similar, with the 200 mg L−1 concentration showing the highest content compared to the control T0. For dry biomass, the 300 mg L−1 concentration and the FOL control reduced dry weight by 23% compared to the 200 mg L−1 concentration (Fig. 5D,E).

Yield was higher in the ZnO+GP treatments at concentrations of 100 and 200 mg L−1, statistically equal to T0. However, these same treatments were not statistically different from CC and T+ (Fig. 5F).

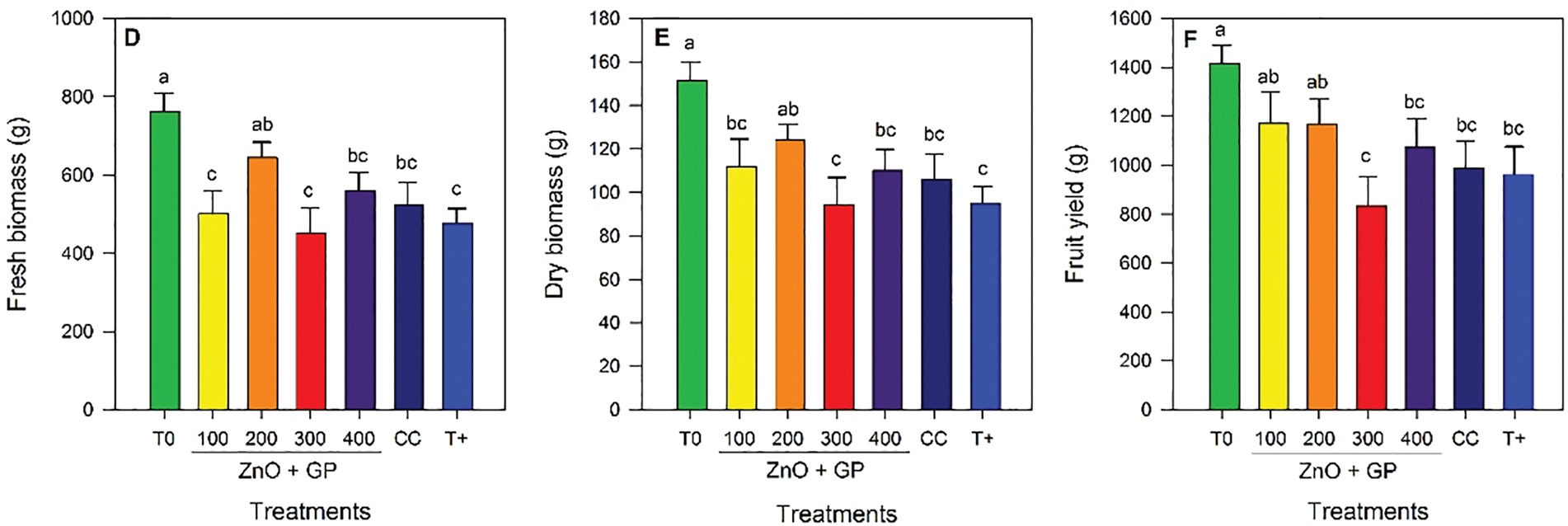

3.6 Photosynthetic Pigments and Stress Biomarkers of the Second Stage

Chlorophyll a content increased with the application of ZnO+GP at 200 mg L−1, a treatment statistically comparable to T+ and CC, exceeding T0 by 18% (Fig. 6A). In terms of chlorophyll b content, T0 had the highest mean value (Fig. 6B). For β-carotene content, the FOL inoculated treatments did not show significant differences among themselves, but all exceeded T0 (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6: Chlorophyll a (A), chlorophyll b (B), β-carotene (C), hydrogen peroxide (D), superoxide radical (E), and malondialdehyde (F) content in tomato plants. T0: absolute control; 1) ZnO+GP-100, 2) ZnO+GP-200, 3) ZnO+GP-300, 4) ZnO+GP-400: zinc oxide nanoparticles+graphene+FOL, applied at 4 different concentrations in mg L−1; CC: chemical control+FOL; T+: positive control inoculated with FOL. Means with the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher’s LSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Figures without letters in the bars do not show significant differences (p ≤ 0.05)

There were no significant differences in the mean hydrogen peroxide content, so the treatments were statistically equal (Fig. 6D). For superoxide anion, the inoculated treatments showed no significant differences among themselves; however, the absolute control had the lowest level of this radical (Fig. 6E). Regarding malondialdehyde content, significant differences were observed, with CC having the highest content of this compound. While concentrations of 100, 300 and 400 mg L−1 of ZnO+GP reduced the content of this compound by 27%, 37% and 23% with respect to CC (Fig. 6F).

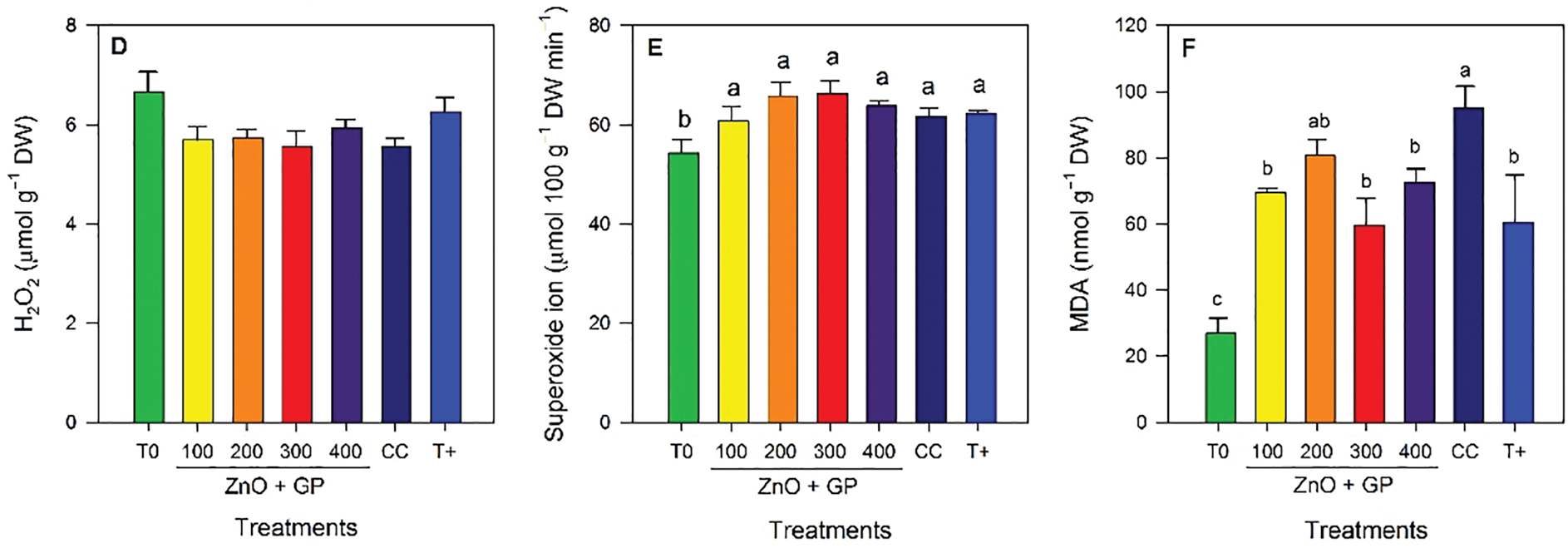

3.7 Second-Stage Antioxidant Compounds

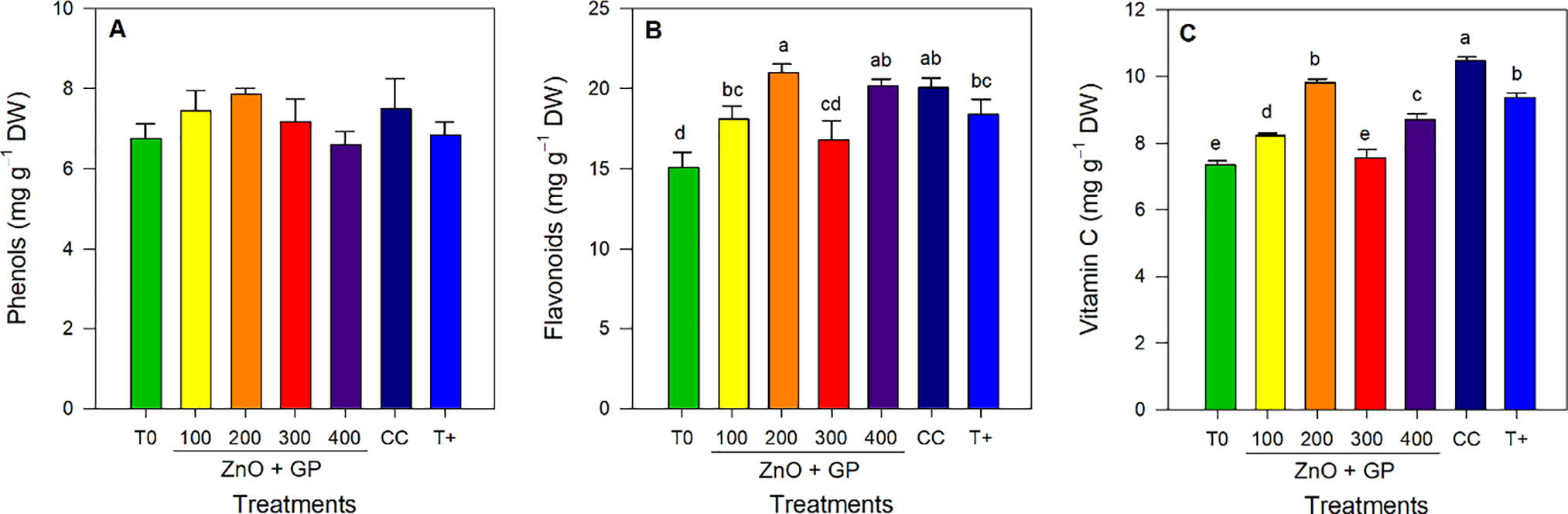

No significant differences were found between treatments for phenol content (Fig. 7A). Significant differences were observed between treatments for flavonoids; the 200 mg L−1 ZnO+GP treatment had the highest concentration of flavonoids, 28% and 12% more than T0 and T+, respectively (Fig. 7B). Differences were found between treatments for ascorbic acid content; CC had the highest average. However, the ZnO+GP-200 mg L−1 treatment had higher vitamin C contents than the other concentrations (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7: Phenols (A), flavonoids (B), vitamin C (C) content in tomato plants. T0: absolute control; 1) ZnO+GP-100, 2) ZnO+GP-200, 3) ZnO+GP-300, 4) ZnO+GP-400: zinc oxide nanoparticles+graphene+FOL, applied at 4 different concentrations in mg L−1; CC: chemical control+FOL; T+: positive control inoculated with FOL. Means with the same letter are not significantly different according to Fisher’s LSD test (p ≤ 0.05). Figures without letters in the bars do not show significant differences (p ≤ 0.05)

4.1 Plant Responses at the Morphological Level

FOL is an aggressive phytopathogen responsible for significant losses in the production and quality of various crops, so strategies are needed to mitigate the effects of different types of biotic stress. The application of nanoparticles is considered a viable, functional and economical option that has been shown to reduce the severity of FOL in tomato plants (Fig. 1A,B). This is related to the antimicrobial capacity of the compounds used [22]. When translocated from the root to the shoots through the xylem, it enters by endocytosis or directly penetrates the membrane and disperses in the cytoplasm [38]. Nanomaterials have a dual effect in controlling the development of pathogens, such as FOL. First, NMs have antimicrobial properties [22]. Additionally, NMs activate plant defense reactions, including the hypersensitive response and systemic acquired response, as well as the generation of secondary metabolites [39]. This in turn induces plant tolerance to pathogens such as FOL.

Graphene acts by direct contact, which is the most relevant mechanism of action on the microbial cell, causing rupture of the cell wall and membrane, oxidative stress, enzyme inhibition, changes in membrane fluidity, and decreased gene transcription [40]. ZnO and MgO NPs generate ROS, which damage microbial cell structures [20]. This results in structural damage and the loss of cell content, ultimately leading to cell decline [41]. Furthermore, they activate signalling pathways such as salicylic acid, thereby stimulating defence responses in plants, including the hypersensitive response, systemic acquired response and/or secondary metabolites [20,39].

Plant response to nanoparticles varies depending on size, shape, application method, and dose [42]. Their nanometric size and shape influence penetration and mobility. In other words, they are effective in crops because they easily penetrate cells and are absorbed and translocated efficiently [26]. Additionally, the nanoparticles have a larger surface area, increasing their points of contact with microorganisms and enhancing their interaction with pathogens [27].

In the first stage of this research the ZnO+GP mixture was the best (Fig. 1B). The ZnO+GP mixture was the most efficient thanks to the antimicrobial properties of both materials [13,22]. ZnO NPs induces the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which transmit signals and activate physicochemical defense responses [18]. On the other hand, the antimicrobial capacity of graphene is based on structural damage to the microbial cell wall or membrane (in addition to the oxidative stress it causes), which leads to cell death [22]. Additionally, graphene’s ability to carry molecules (such as ZnO and MgO) makes them more accessible and improves the properties of both materials [24]. In the second stage, we observed that lower concentrations increased resistance to infection (Fig. 4B). Since NPs are compounds that act under the principle of hormesis, a phenomenon in which low exposure to a substance stimulates it and higher concentrations damage or inhibit it [43], the key is to find the correct concentration-response relationship [44], resulting in adaptation and recovery to the plant’s inadequate situation [45].

The positive response of nanoparticles is due to the fact that they affect physiological processes by modulating metabolism, interacting with cytoplasmic proteins, membranes and organelles that influence gene expression and allow acclimation [46]. This has already been demonstrated in several studies. El-abeid et al. [47], show that the severity of FOL decreased in tomato and pepper plants after application of CuO NPs with reduced graphene oxide nanosheets (1 mg L−1 via soil). González-García et al. [48], reported a significant reduction in the incidence of FOL in tomato plants through the application of carbon nanomaterials, in addition to increasing other agronomic variables such as yield.

The inoculated treatment (T+) reduced growth, but the application of ZnO+GP and MgO NPs promoted the development of stems, leaves and fruits compared to T+ (Fig. 2). This was a consequence of the presence of Fusarium oxysporum, a pathogen that limits plant development by blocking water transport, resulting in minimal or even zero yields [5]. Several studies have shown that the presence of FOL affects plant growth, causing a reduction in height, stem size, number of leaves, yield and biomass [49]. In the second stage, ZnO+GP at 200 mg L−1 was shown to be the most efficient treatment in terms of growth, development and yield variables, while higher concentrations (300 and 400 mg L−1) significantly reduced plant development and yield compared to lower concentrations (Fig. 5). That is, the results follow a hormetic pattern in which the plant tolerates the stimulus up to a certain limit, after which the damage outweighs the benefit or no response is generated [50]. Chahardoli et al. [51] show in their results the growth inhibition through the use of TiO2 NPs, applying 1000 mg L−1 in black cumin plants (Nigella arvensis), while concentrations of 100 mg L−1 managed to positively stimulate the plant. These nanomaterials have a biostimulant function, causing morphological, biochemical, physiological, epigenomic, proteomic and transcriptomic changes that favorably alter the metabolic and adaptive performance of plants [28]. Allowing the increase of growth, yield and induction of tolerance to adverse situations [11]. Guo et al. [52] report an increase in auxin content when applying 50 and 100 mg L−1 graphene oxide, triggering an increase in growth of stems, roots, fruits and biomass. Likewise, El-Abeid et al. [53] reported the most significant reduction of Fusarium solani and better development in tomato plants by applying CuO NPs at a concentration of 250 mg L−1.

4.2 Plant Responses at the Biochemical Level

Photosynthetic pigments such as chlorophyll a, b, and β-carotene are essential for photosynthesis and are affected by pathogen infection, affecting plant physiology and health [54]. This is because photosynthetic efficiency is closely related to growth and yield by converting light energy into free energy needed for life [55]. The amount of chlorophyll can be affected by biotic or abiotic stress factors, affecting the plant’s ability to capture light or avoid harmful photooxidations [56]. Photosynthesis is reduced by the presence of pathogens when they affect leaf tissues, reducing the photosynthetic area, and although the plant can maintain its chlorophyll function with the remaining tissue, the overall development of the plant is affected as the infection progresses, initially chlorosis reduces the amount of chlorophyll per chloroplast and cell death reduces the number of photosynthetically active cells [57].

That is, the decrease in chlorophyll content is common in stressful situations, but within the group of inoculated treatments; T+, ZnO independent and combined with graphene (at concentrations of 100 and 200 mg L−1) presented the highest content of photosynthetic pigments, which may be a physiological adaptation to mitigate the stress condition (Figs. 3 and 6). As a consequence of the ability of graphene to facilitate electron transfer and ROS scavenging in photosystem II, as observed in rice plants [58]. Rai-Kalal and Jajoo [59] reported increases in chlorophyll content by foliar application of ZnO NPs to wheat at concentrations of 10 mg L−1.

ROS can damage cells by accumulating oxygen when these compounds exceed their degradation capacity [60]. The inoculated treatments showed higher levels of hydrogen peroxide as evidenced by the increase in MDA, a byproduct of lipid peroxidation. However, there was a significant reduction in MDA levels in the ZnO, GP, MgO, and ZnO+GP treatments (Fig. 3). In the second stage, the chemical control treatment had the highest MDA levels (Fig. 6), indicating increased oxidative stress that altered the redox balance. Research has reported an increase in H2O2 and MDA levels in tomato plants due to FOL infection [61].

On the other hand, the superoxide radical is a reactive oxygen species that can cause damage to proteins and DNA, minimizing development and productivity and even causing plant death [62]. O2•− decreased in the treatments inoculated with the application of nanoparticles, which is closely related to the ability of nanomaterials to activate the antioxidant defense system, increasing the reduction of this compound, so that the healthy control was able to present relatively high levels without causing significant damage. However, it is normal for ROS to increase in stressful situations [63]. This was observed in the second stage, where superoxide anion levels increased in the inoculated plants (Fig. 6B).

NMs act as elicitors by inducing defense responses in plants and stimulating the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites [64]. Stimulate the biosynthesis of non-enzymatic antioxidants, such as phenols, flavonoids, and vitamin C, as well as enzymatic antioxidants, such as catalase, peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase, which eliminate excess ROS [65,66]. These compounds convert ROS into less toxic substances, thereby reducing their harmful effects at the cellular level [67]. This is a consequence of the mild oxidative stress induced by NMs, which acts as a signal to activate defense mechanisms [20]. Reactive oxygen species cause an increase in the production of defense compounds in the cell in response to stress. This defense system converts oxidizing compounds into less toxic substances, thereby reducing their harmful effects [67].

Immunity to pathogen attack requires regulation of the defense system, generation of ROS, and production of secondary metabolites, especially polyphenolic compounds (phenols/flavonoids) that regulate redox balance. These are defense compounds that reduce the accumulation of mycotoxins and protect the cell from oxidative damage [68]. These compounds are part of the plant’s active response, limiting the progression of the disease and providing tolerance to infection [69]. By recognizing the stimulus, signaling and activating molecular and biochemical processes that protect against infection [70]. In the present work, an increase in the levels of metabolites such as flavonoids and ascorbic acid was observed (Fig. 7B,C). Flavonoids are bioactive compounds with antimicrobial properties that neutralize toxic or oxidizing substances, thereby reducing the risk of cell damage [71]. Ascorbic acid induces plant growth and is also a potent antioxidant that scavenges reactive oxygen species (H2O2) and reduces oxidative stress in plants [72]. González-García et al. [65] reported a significant increase in ascorbic acid and flavonoid content in tomato plants after foliar application of graphene at concentrations of 100 to 500 mg L−1.

4.3 Additional Factors to Consider When Using Nanomaterials

Currently, the cost of using chemicals to control pathogens in agriculture is lower than the cost of using nanomaterials. However, chemicals have several drawbacks, including the rapid release and degradation of the active ingredient and the development of pathogen resistance, which requires increased doses and the rotation of active ingredients. This results in higher economic costs and environmental risks [10,73]. In this sense, NMs can be a viable, efficient alternative to conventional products. For instance, studies have shown that nanofertilizers can be significantly more effective than traditional fertilizers, requiring lower doses [74].

However, excessive application of nanoparticles will inevitably impact the environment. Prolonged applications and high concentrations increase the probability of bioaccumulation in plant tissues [75]. Although not all nanomaterials are toxic, there is a lack of bioaccumulation studies [76], so more research is needed in this area. In this study, low concentrations were used (100–400 mg L−1, with 10 mL applied per plant), which is different from other studies. The research shows that nanoparticles accumulate in corn plants when 15,000 mg L−1 of ZnO is applied. The nanoparticles are found in the intercellular spaces, vacuoles, and cytoplasm with degenerated mitochondria. Lower concentrations do not show bioaccumulation [76].

The use of nanoparticles has grown significantly across various industries over the last decade. However, there is no comprehensive information on how nanoparticles interact with the environment. While some studies demonstrate the non-toxicity of these nanometric materials, others raise concerns about their potential impact on health and the environment [77]. Concerns are heightened, especially when using metallic nanoparticles, as they have been documented to damage microbial communities due to nanotoxicity [78]. Therefore, the biocidal capacity of metallic nanoparticles may pose a significant threat to non-pathogenic organisms [79]. Although nanotechnology has been experimented with in many areas, more research is needed to guarantee the safe application of these materials and understand their long-term effects and sustainability [78].

Application of zinc oxide and graphene nanoparticles to inoculated tomato plants reduced the incidence and severity of disease caused by FOL. It also increased agronomic variables such as plant height, stem diameter, leaf number, and bunch number, and even increased the content of photosynthetic pigments and reduced the content of stress biomarkers, allowing for plant growth and development.

The results confirm the effectiveness of these compounds in positively impacting agricultural crops by mitigating damage caused by pathogens. They are a viable, cost-effective option that stimulates the plants, activating defense responses and influencing fruit yield and quality in tomato.

In this research, different concentrations were evaluated with the aim of finding a more efficient and reliable standard, since the application of nanoparticles is an area with great potential in agriculture. However, it is still under development and requires research to define the optimal concentrations to achieve stimulation and guarantee safe and sustainable application.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Antonio Juárez-Maldonado and Yolanda González-García; methodology, Alejandra Sánchez-Reyna, Ángel Gabriel Alpuche-Solís, Gregorio Cadenas-Pliego and Adalberto Benavides-Mendoza; formal analysis, Alejandra Sánchez-Reyna, Yolanda González-García, Ángel Gabriel Alpuche-Solís, Gregorio Cadenas-Pliego, Adalberto Benavides-Mendoza and Antonio Juárez-Maldonado; writing—original draft preparation, Alejandra Sánchez-Reyna, Yolanda González-García, and Antonio Juárez-Maldonado; writing—review and editing, Alejandra Sánchez-Reyna, Yolanda González-García, Ángel Gabriel Alpuche-Solís, Gregorio Cadenas-Pliego, Adalberto Benavides-Mendoza and Antonio Juárez-Maldonado; supervision and project administration, Yolanda González-García and Antonio Juárez-Maldonado. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Glossary/Abbreviations

| FOL | Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| NMs | Nanomaterials |

| ZnO | Zinc oxide |

| MgO | Magnesium oxide |

| GP | Graphene |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| PR | Pathogen recognition genes |

| HR | Hypersensitive response |

| SAR | Systemic acquired response |

| DW | Dry weight |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| TBA | Thiobarbituric acid |

| T+ | Positive control inoculated with FOL |

| CC | Chemical control |

| LSD | Least Signifficant Difference |

| MANOVA | Multivariate analysis of variance |

References

1. Kiralan M, Ketenoglu O. Utilization of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) by-products: an overview. In: Mediterranean fruits bio-wastes: chemistry, functionality and technological applications. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 799–818. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-84436-3_34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Campos MD, Félix Mdo R, Patanita M, Materatski P, Varanda C. High throughput sequencing unravels tomato-pathogen interactions towards a sustainable plant breeding. Hortic Res. 2021;8(1):171. doi:10.1038/s41438-021-00607-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Kumar A, Verma JP. Does plant—microbe interaction confer stress tolerance in plants: a review? Microbiol Res. 2018;207(2):41–52. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2017.11.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Carmona SL, Burbano-David D, Gómez MR, Lopez W, Ceballos N, Castaño-Zapata J et al. Characterization of pathogenic and nonpathogenic Fusarium oxysporum isolates associated with commercial tomato crops in the Andean region of Colombia. Pathogens. 2020;9(1):70. doi:10.3390/pathogens9010070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Hanan Aref H. Biology and integrated control of tomato wilt caused by Fusarium oxysporum lycopersici: a comprehensive review under the light of recent advancements. J Bot Res. 2020;3(1):84–99. doi:10.36959/771/565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Singh VK, Singh HB, Upadhyay RS. Role of fusaric acid in the development of ‘Fusarium Wilt’ symptoms in tomato: physiological, biochemical and proteomic perspectives. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017;118(3):320–32. doi:10.1016/J.PLAPHY.2017.06.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Mcgovern RJ, Citar C. Management of tomato diseases caused by Fusarium oxysporum. Crop Prot. 2015;78(2):78–92. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2015.02.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Hussain M, Shakoor N, Adeel M, Ahmad MA, Zhou H, Zhang Z, et al. Nano-enabled plant microbiome engineering for disease resistance. Nano Today. 2023;48(11):101752. doi:10.1016/j.nantod.2023.101752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jeger M, Beresford R, Bock C, Brown N, Fox A, Newton A, et al. Global challenges facing plant pathology: multidisciplinary approaches to meet the food security and environmental challenges in the mid-twenty-first century. CABI Agric Biosci. 2021;2(1):1–18. doi:10.1186/s43170-021-00042-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Bhattacharya N, Cahill DM, Yang W, Kochar M. Graphene as a nano-delivery vehicle in agriculture—current knowledge and future prospects. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2023;43(6):851–69. doi:10.1080/07388551.2022.2090315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Juárez-Maldonado A, Ortega-Ortíz H, Morales-Díaz AB, González-Morales S, Morelos-Moreno Á, Cabrera-De la Fuente M, et al. Nanoparticles and nanomaterials as plant biostimulants. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(1):162. doi:10.3390/ijms20010162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Rana RA, Siddiqui MN, Skalicky M, Brestic M, Hossain A, Kayesh E, et al. Prospects of nanotechnology in improving the productivity and quality of horticultural crops. Horticulturae. 2021;7(10):332. doi:10.3390/horticulturae7100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Malandrakis AA, Kavroulakis N, Chrysikopoulos CV. Use of copper, silver and zinc nanoparticles against foliar and soil-borne plant pathogens. Sci Total Environ. 2019;670(2):292–9. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Kumar A, Choudhary A, Kaur H, Guha S, Mehta S, Husen A. Potential applications of engineered nanoparticles in plant disease management: a critical update. Chemosphere. 2022;295(4):133798. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.133798. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Khan MR, Siddiqui ZA, Fang X. Potential of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles in plant disease diagnostics and management: recent advances and challenges. Chemosphere. 2022;297(7):134114. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.134114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Elmer W, Ma C, White J. Nanoparticles for plant disease management. Curr Opin Environ Sci Health. 2018;6:66–70. doi:10.1016/j.coesh.2018.08.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Jiang Y, Zhou P, Zhang P, Adeel M, Shakoor N, Li Y, et al. Green synthesis of metal-based nanoparticles for sustainable agriculture. Environ Pollut. 2022;309(4):119755. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Calvo P, Nelson L, Kloepper JW. Agricultural uses of plant biostimulants. Plant Soil. 2014;383:3–41. doi:10.1007/s11104-014-2131-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hacisalihoglu G. Zinc (Znthe last nutrient in the alphabet and shedding light on Zn efficiency for the future of crop production under suboptimal Zn. Plants. 2020;9(11):1471. doi:10.3390/plants9111471. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Fujikawa I, Takehara Y, Ota M, Imada K, Sasaki K, Kajiharab H. Magnesium oxide induces immunity against fusarium wilt by triggering the jasmonic acid signaling pathway in tomato. J Biotechnol. 2021;324:100–8. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2020.11.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Wilson SK, Pretorius T, Naidoo S. Mechanisms of systemic resistance to pathogen infection in plants and their potential application in forestry. BMC Plant Biol. 2023;23(1):404. doi:10.1186/s12870-023-04391-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Azizi-Lalabadi M, Hashemi H, Feng J, Jafari SM. Carbon nanomaterials against pathogens; the antimicrobial activity of carbon nanotubes, graphene/graphene oxide, fullerenes, and their nanocomposites. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;284(4):102250. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2020.102250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Saqib S, Nazeer A, Zaman W, Younas M, Shahzad A. Catalytic potential of endophytes facilitates synthesis of biometallic zinc oxide nanoparticles for agricultural application. BioMetals. 2022;35(5):967–85. doi:10.1007/s10534-022-00417-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Salih E, Mekawy M, Hassan RYA, El-Sherbiny IM. Synthesis, characterization and electrochemical-sensor applications of zinc oxide/graphene oxide nanocomposite. J Nanostruct Chem. 2016;6(2):137–44. doi:10.1007/s40097-016-0188-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Premkumar T, Geckeler KE. Graphene-DNA hybrid materials: assembly, applications, and prospects. Prog Polym Sci. 2012;37(4):515–29. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.08.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sharma B, Tiwari S, Kumawat KC, Cardinale M. Nano-biofertilizers as bio-emerging strategies for sustainable agriculture development: potentiality and their limitations. Sci Total Environ. 2023;860(1):160476. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Draviana HT, Fitriannisa I, Khafid M, Krisnawati DI, Widodo, Lai C-H et al. Size and charge effects of metal nanoclusters on antibacterial mechanisms. J Nanobiotechnol. 2023;21(1):428. doi:10.1186/s12951-023-02208-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. González-Morales S, Solís-Gaona S, Valdés-Caballero MV, Juárez-Maldonado A, Loredo-Treviño A, Benavides-Mendoza A. Transcriptomics of biostimulation of plants under abiotic stress. Front Genet. 2021;12:583888. doi:10.3389/fgene.2021.583888. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Carletti P, García AC, Silva CA, Merchant A. Editorial: towards a functional characterization of plant biostimulants. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:677772. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.677772. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Hazarika A, Yadav M, Yadav DK, Yadav HS. An overview of the role of nanoparticles in sustainable agriculture. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2022;43(10):102399. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2022.102399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Steiner AA. A universal method for preparing nutrient solutions of a certain desired composition. Plant Soil. 1961;15(2):134–54. doi:10.1007/BF01347224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Nagata M, Yamashita I. Simple method for simultaneous determination of chlorophyll and carotenoids in tomato fruit. J Jpn Soc Food Sci Technol. 1992;39(10):925–8. doi:10.3136/nskkk1962.39.925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Velikova V, Yordanov I, Edreva A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants. Plant Sci. 2000;151(1):59–66. doi:10.1016/S0168-9452(99)00197-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yang H, Wu F, Cheng J. Reduced chilling injury in cucumber by nitric oxide and the antioxidant response. Food Chem. 2011;127(3):1237–42. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.02.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Yu Z, Dahlgren RA. Evaluation of methods for measuring polyphenols in conifer foliage. J Chem Ecol. 2000;26(9):2119–40. doi:10.1023/a:1005568416040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Arvouet-Grand A, Vennat B, Pourrat A, Legret P. Standardization of a propolis extract and identification of the main constituents. J Pharm Belg. 1994;49:462–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

37. Hung C-Y, Yen G-C. Antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds isolated from Mesona procumbens Hemsl. J Agric Food Chem. 2002;50(10):2993–7. doi:10.1021/jf011454y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Wang L, Ning C, Pan T, Cai K. Role of silica nanoparticles in abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in plants: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(4):1947. doi:10.3390/ijms23041947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Upadhyay R, Saini R, Shukla PK, Tiwari KN. Role of secondary metabolites in plant defense mechanisms: a molecular and biotechnological insights. Phytochem Rev. 2024;24(1):953–83. doi:10.1007/s11101-024-09976-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Maksimova YG. Microorganisms and carbon nanotubes: interaction and applications (review). Appl Biochem Microbiol. 2019;55(1):1–12. doi:10.1134/S0003683819010101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Kim MJ, Kim W, Chung H. Effects of silver-graphene oxide on seed germination and early growth of crop species. Plant Biol. 2020;8:e8387. doi:10.7717/peerj.8387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Rastogi A, Zivcak M, Sytar O, Kalaji HM, He X, Mbarki S, et al. Impact of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles on plant: a critical review. Front Chem. 2017;5:78. doi:10.3389/fchem.2017.00078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Jalal A, Oliveira Junior JC de, Ribeiro JS, Fernandes GC, Mariano GG, Trindade VDR et al. Hormesis in plants: physiological and biochemical responses. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;207(1):111225. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Calabrese EJ. Preconditioning is hormesis part I: documentation, dose-response features and mechanistic foundations. Pharmacol Res. 2016;110(5):242–64. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2015.12.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zulfiqar F, Ashraf M. Nanoparticles potentially mediate salt stress tolerance in plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;160(7141):257–68. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.01.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Khalid MF, Iqbal Khan R, Jawaid MZ, Shafqat W, Hussain S, Ahmed T, et al. Nanoparticles: the plant saviour under abiotic stresses. Nanomater. 2022;12(21):3915. doi:10.3390/nano12213915. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. El-Abeid SE, Ahmed Y, Daròs JA, Mohamed MA. Reduced graphene oxide nanosheet-decorated copper oxide nanoparticles: a potent antifungal nanocomposite against fusarium root rot and wilt diseases of tomato and pepper plants. Nanomater. 2020;10(5):1001. doi:10.3390/nano10051001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. González-García Y, Cadenas-Pliego G, Alpuche-Solís Á.G, Cabrera RI. Effect of carbon-based nanomaterials on fusarium wilt in tomato. Sci Hortic. 2022;291:110586. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2021.110586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Cota-Ungson D, González-García Y, Cadenas-Pliego G, Alpuche-Solís Á.G, Benavides-Mendoza A, Juárez-Maldonado A. Graphene-Cu nanocomposites induce tolerance against Fusarium oxysporum, increase antioxidant activity, and decrease stress in tomato plants. Plants. 2023;12(12):2270. doi:10.3390/plants12122270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Erofeeva EA. Hormesis in plants: its common occurrence across stresses. Curr Opin Toxicol. 2022;30(Pt B):100333. doi:10.1016/j.cotox.2022.02.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Chahardoli A, Sharifan H, Karimi N, Kakavand SN. Uptake, translocation, phytotoxicity, and hormetic effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2NPs) in Nigella arvensis L. Sci Total Environ. 2022;806:151222. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Guo X, Zhao J, Wang R, Zhang H, Xing B, Naeem M, et al. Effects of graphene oxide on tomato growth in different stages. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;162:447–55. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.03.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. El-Abeid SE, Mosa MA, El-Tabakh MAM, Saleh AM, El-Khateeb MA, Haridy MSA. Antifungal activity of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from Zizyphus spina leaf extract against Fusarium root rot disease in tomato plants. J Nanobiotechnol. 2024;22(1):28. doi:10.1186/s12951-023-02281-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Chauhan J, Prathibha MD, Singh P, Choyal P, Mishra UN, Saha D, et al. Plant Photosynthesis under abiotic stresses: damages, adaptive, and signaling mechanisms. Plant Stress. 2023;10(6):100296. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2023.100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Silva FMde O, Lichtenstein G, Alseekh S, Rosado-Souza L, Conte M, Suguiyama VF, et al. The genetic architecture of photosynthesis and plant growth-related traits in tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 2018;41(2):327–41. doi:10.1111/pce.13084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Ort DR, Merchant SS, Alric J, Zhu G, Los D. Redesigning photosynthesis to sustainably meet global food and bioenergy demand. Prog Nucl Energy 6 Biol Sci. 2015;112(28):8529–36. doi:10.1073/pnas.1424031112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Cheaib A, Killiny N. Photosynthesis responses to the infection with plant pathogens. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2024;38(1):9–29. doi:10.1094/MPMI-05-24-0052-CR. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Lu K, Shen D, Dong S, Chen C, Lin S, Lu S, et al. Uptake of graphene enhanced the photophosphorylation performed by chloroplasts in rice plants. Nano Res. 2020;13(12):3198–205. doi:10.1007/s12274-020-2862-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Rai-Kalal P, Jajoo A. Priming with zinc oxide nanoparticles improve germination and photosynthetic performance in wheat. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;160(2003):341–51. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.01.032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Linh TM, Mai NC, Hoe PT, Lien LQ, Ban NK, Hien LTT, et al. Metal-based nanoparticles enhance drought tolerance in soybean. J Nanomater. 2020;2020(6):1–13. doi:10.1155/2020/4056563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Maqsood A, Wu H, Kamran M, Altaf H, Mustafa A, Ahmar S, et al. Variations in growth, physiology, and antioxidative defense responses of two tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) cultivars after co-infection of Fusarium oxysporum and Meloidogyne incognita. Agronomy. 2020;10(2):159. doi:10.3390/agronomy10020159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Shah AA, Gupta A. Secondary metabolite basis of elicitor- and effector-triggered immunity in pathogen elicitation amid infections. Genet Manip Second Metab Med Plant. 2023;225–51. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-4939-7_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Sachdev S, Ansari SA, Ansari MI, Fujita M, Hasanuzzaman M. Abiotic stress and reactive oxygen species: generation, signaling, and defense mechanisms. Antioxidants. 2021;10(2):277. doi:10.3390/antiox10020277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Ghorbanpour M, Hadian J. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes stimulate callus induction, secondary metabolites biosynthesis and antioxidant capacity in medicinal plant Satureja khuzestanica grown in vitro. Carbon N Y. 2015;94:749–59. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2015.07.056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. González-García Y, López-Vargas ER, Cadenas-Pliego G, Benavides-Mendoza A, González-Morales S, Robledo-Olivo A, et al. Impact of carbon nanomaterials on the antioxidant system of tomato seedlings. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(23):5858. doi:10.3390/ijms20235858. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Faizan M, Faraz A, Yusuf M, Khan ST, Hayat S. Zinc oxide nanoparticle-mediated changes in photosynthetic efficiency and antioxidant system of tomato plants. Photosynthetica. 2018;56(2):678–86. doi:10.1007/s11099-017-0717-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Borges CV, Orsi RO, Maraschin M, Pace G, Lima P. Oxidative stress in plants and the biochemical response mechanisms. Plant Stress Mitigators. 2023;27:455–68. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-89871-3.00022-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Chrpová J, Orsák MPM, Trávní čková, JLM. Potential role and involvement of antioxidants and other secondary metabolites of wheat in the infection process and resistance to Fusarium spp. Agronomy. 2021;11(11):2235. doi:10.3390/agronomy11112235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Kaur S, Kumar M, Manoj S. How do plants defend themselves against pathogens-biochemical mechanisms and genetic interventions. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2022;28(2):485–504. doi:10.1007/s12298-022-01146-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Usman M, Aqeel M, Shahzad M, Jeelani G. Molecular regulation of antioxidants and secondary metabolites act in conjunction to defend plants against pathogenic infection. S Afr J Bot. 2023;161(8):247–57. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2023.08.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Tariq H, Asif S, Andleeb A, Hano C. Flavonoid production: current trends in plant metabolic engineering and De Novo microbial production. Metabolites. 2023;13(1):124. doi:10.3390/metabo13010124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Kanwal R, Maqsood MF, Shahbaz M, Naz N, Zulfiqar U, Ali MF, et al. Exogenous ascorbic acid as a potent regulator of antioxidants, osmo-protectants, and lipid peroxidation in pea under salt stress. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):247. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-04947-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Al-Shboul T, Sagala F, Nassar NN. Role of surfactants, polymers, nanoparticles, and its combination in inhibition of wax deposition and precipitation: a review. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2023;315(7):102904. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2023.102904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Cyriac J, Thomas B, Sreejit CM, Yuvaraj M, Joseph S. Chitosan zinc nanocomposite: a promising slow releasing zinc nano fertilizer. Mater Today Proc. 2023;5(4):11. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2023.11.062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Murali M, Gowtham HG, Singh SB, Shilpa N, Aiyaz M, Alomary MN, et al. Fate, bioaccumulation and toxicity of engineered nanomaterials in plants: current challenges and future prospects. Sci Total Environ. 2022;811:152249. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Alsuwayyid AA, Alslimah AS, Perveen K, Bukhari NA, Al-Humaid LA. Effect of zinc oxide nanoparticles on Triticum aestivum L. and bioaccumulation assessment using ICP-MS and SEM analysis. J King Saud Univ Sci. 2022;34(4):101944. doi:10.1016/j.jksus.2022.101944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Sun W, Dou F, Li C, Ma X, Ma LQ. Impacts of metallic nanoparticles and transformed products on soil health. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2021;51(10):973–1002. doi:10.1080/10643389.2020.1740546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Abishagu A, Kannan P, Sivakumar U, Manikanda Boopathi N, Senthilkumar M. Metal nanoparticles and their toxicity impacts on microorganisms. Biologia. 2024;79(9):2843–62. doi:10.1007/s11756-024-01760-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Mishra S, Yang X, Singh HB. Evidence for positive response of soil bacterial community structure and functions to biosynthesized silver nanoparticles: an approach to conquer nanotoxicity? J Environ Manage. 2020;253(11):109584. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.109584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools