Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Early Spatiotemporal Dynamic of Green Fluorescent Protein-Tagged Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. batatas in Susceptible and Resistant Sweet Potato

1 Institute of Crop Sciences, Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Fuzhou, 350013, China

2 Scientific Observing and Experimental Station of Tuber and Root Crops in South China, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural

Affairs, Fuzhou, 350013, China

3 Department of Plant Pathology, The Ministry of Agriculture Key Laboratory of Pest Monitoring and Green Management and Joint International Research Laboratory of Crop Molecular Breeding, Ministry of Education, China Agricultural University, Beijing, 100193, China

* Corresponding Author: Sixin Qiu. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this article

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2479-2498. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.064850

Received 25 February 2025; Accepted 05 August 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Vascular wilt caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. batatas (Fob) is a devastating disease threatening global sweet potato production. To elucidate Fob’s pathogenicity mechanisms and inform effective control strategies, we generated a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged Fob strain to track infection dynamics in sweet potato susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua and resistant cultivar Xiangshu75-55, respectively. Through cytological observation, we found in the susceptible Xinzhonghua, Fob predominantly colonized stem villi, injured root growth points, and directly invaded vascular bundles through stem wounds. Spore germination peaked at 2–3 h post-inoculation (hpi), followed by cyclical mycelial expansion and sporulation within vascular tissues with sustaining infection. In contrast, the resistant Xiangshu75-55 exhibited strong suppression of Fob: spores rarely germinated in vascular bundles or on trichomes by 3 hpi, and mature hyphae were absent in stems at 24 hpi. Quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) confirmed significantly higher Fob biomass in Xinzhonghua than in Xiangshu75-55 by 16 hpi. Additionally, transcriptional profiling revealed distinct pathogen-host interactions during the compatible and incompatible reactions. In Xinzhonghua, Fob virulence genes FobPGX1, FobICL1, FobCTF2, FobFUB5 and FobFUB6 were upregulated within 16 hpi. Conversely, host defense genes IbMAPKK9, IbWRKY61, IbWRKY75, IbSWEET10, IbBBX24 and IbPIF4 were activated in Xiangshu75-55 during the same period. This study provides spatiotemporal cytological and molecular insights into Fob pathogenicity and host resistance, offering a foundation for early disease detection and improved Fusarium wilt management in sweet potato.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileFusarium oxysporum f. sp. batatas (Fob) is a soil-borne pathogenic fungus notorious for causing vascular discoloration, vine dehiscence, leaves yellowing and falling, and eventual wilt and death of sweet potato plants (Fig. S1) [1]. Particularly in South China, Fusarium wilt emerges as the most severe fungal disease affecting sweet potato cultivation [2]. However, critical aspects of Fob’s infection mechanisms in sweet potato, including its infection pattern and pivotal time points in the disease progression, remain unknown.

F. oxysporum is recognized as the 5th largest plant pathogen, and a worldwide distributed soil-borne pathogenic fungus that can cause devastating vascular diseases in plants [3]. F. oxysporum exhibits a broad host range and can infect more than 100 hosts, including globally important crops such as cotton, tomato, banana, and legumes [4]. Despite strains variations, the infection processes of F. oxysporum share commonalities. Generally, the spores initially recognize and adhere to plant roots, germinate to form mycelium, and penetrate the root epidermal cells or cell gaps, eventually enter the vascular bundles. The mycelium then expands upwards, blocks the vascular bundles, and leads to plant wilting, withering, and necrosis [5–7]. However, individual F. oxysporum strains infect plant species with host specificity, which is reflected in different process details [8]. Factors such as infection time, spore colonization regions, and the effect of root exudates on spore germination vary among strains [9].

In the quest for plant disease-resistant varieties against F. oxysporum, compatibility phenotypes between the pathogen and hosts were observed to screen resistant varieties [10]. Distinct resistance mechanisms have emerged among diverse plants. The compatibility differences are mainly reflected in the regions of pathogen colonization. Resistant banana cultivars restrict the movement and sporulation of the subtropical race 4 of F. oxysporum f. sp. cubense (Foc) in the rhizome [11]. Highly resistant grass pea germplasms exhibit a notable absence of F. oxysporum f. sp. pisi colonization in the vascular tissue, and partially resistant germplasms arrest fungal progression at the root level [12]. Tomato resistant cultivars with transmembrane R-proteins (I and I-3) or intracellular R-protein (I-2) show effective restriction of F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici proliferation and spread in the xylem [13]. While the strawberries resistant cultivar Festival impedes the germination and penetration of F. oxysporum f. sp. fragariae spores, and effectively confines fungal colonization within the root’s epidermal layer [14]. At the early stage of F. oxysporum f. sp. niveum infection of watermelon, the epidermal cells of the root hair area were infected by the pathogen in both resistant and susceptible cultivars. However, the pathogen failed to enter the interior of the primary root in the resistant cultivar [15].

In addition to the fungal colonization and infection regions, the colonization efficiency and infection rate could also differ [16]. During the initial phases of F. oxysporum f. sp. melonis race 1.2 infection in melons, mycelium colonizes the primary and secondary roots of both resistant and susceptible cultivars. However, the colonization efficiency and the rate of mycelium expansion in vascular bundles are significantly lower in the resistant cultivar compared to the susceptible one [17]. When F. oxysporum f. sp. ciceris infected resistant and susceptible chickpea cultivars, the fungus colonizes the host root surface irrespective of compatible or incompatible reaction. The rate and intensity of stem colonization are directly related to the compatibility between the pathogen races and the chickpea cultivars [18,19]. F. oxysporum f. sp. medicaginis colonizes the cortex and vascular bundles in both resistant and susceptible varieties of Medicago truncatula. However, distinctions between compatible and incompatible reaction were reflected in the reduction and delay of the disease symptom, but not significantly correlated with the colonization degree of the roots [20]. Similarly, F. oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum race 4 (FOV4) exhibits delayed infection, restricted growth, and impaired xylem colonization in resistant Pima cotton compared to susceptible varieties [21].

Resistance to F. oxysporum is usually a quantitative character, with varying degrees of symptom severity across different cultivars [22]. The real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) assay is a useful molecular tool to quantify the compatibility between the pathogen and host [23,24]. A reference-gene-based quantitative PCR method has been effectively employed to evaluate Fusarium resistance in wheat [25]. The quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) has also been utilized to quantify the Fusarium growth in resistant and susceptible M. truncatula accessions [26].

There are many studies on F. oxysporum infection of plants. However, the process of Fob infecting sweet potato and the differences in its manifestation among resistant and susceptible cultivars remain unknown. In this study, we constructed a GFP-tagged Fob to observe the Fob-GFP infection process in sweet potato susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua and resistant cultivar Xiangshu75-55, respectively. The key infection positions and time points in compatible reaction were demonstrated. Meanwhile, we quantified the Fob growth on both sweet potato cultivars by using qRT-PCR. Furthermore, we examined the differential expression levels of pathogenic-related genes of Fob and disease-resistance-related genes of sweet potatoes in compatible and incompatible reactions during the early stage of infection. This research provides a reference for early risk prediction for Fob, identification of plant disease resistance and formulating comprehensive control measures.

2.1 Fungus and Plant Materials

The Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. batatas strain Fob 3-1 used in this research was isolated from diseased sweet potato stems in Fujian province (Latitude: 26°03′41.00″ N, Longitude: 119°18′22.00″ E), China, and saved in Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Sweet potato cultivars Xinzhonghua [27] and Xiangshu75-55 [28] were selected due to their susceptibility and resistance to Fob, respectively.

2.2 Transformation of Fungal Spheroplasts

The transformation method was performed as described [29] with minor modifications. Fob 3-1 was inoculated and grown on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium at 28°C for 7 days. The mycelia at the edge of the colonies were cultivated in Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB) medium at 28°C for 14 h with 150 rpm. The Fob culture was filtered through sterile double-layered lens wiping paper. Mycelia were collected after washing with 0.8 M sterile NaCl. A total weight of 600 mg mycelia was resuspended in 4 mL Lysate buffer (1.2 M sorbitol, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM CaCl2, 20 mg/mL Driselase, 10 mg/mL Lysing Enzyme) for digestion at 28°C, 70 rpm for 3 h. The lysate was filtered through sterile double-layered lens wiping paper to collect the filtrate. The filtrate was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 min at room temperature, and the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was washed with 30 mL STC solution (1.2 M sorbitol, 10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 50 mM CaCl2). The final concentration of spheroplasts was adjusted to about 107 cells/mL with the STC solution.

Plasmid vector pCT74 was obtained from Dr. Ciuffetti (Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, USA) [30]. A total of 5 μg of pCT74 plasmid DNA was mixed with 200 μL Fob spheroplasts. After incubation at room temperature for 20 min, 1.25 mL PTC solution (STC with 40% PEG4000, Solarbio, Beijing, China) was added and mixed gently. Subsequently, the mixture was incubated at room temperature for 20 min. After that, transformants were incubated at 28°C for 5–7 days until the colonies became visible on Regeneration medium (200 g/L potato, 185 g/L sorbitol, 9 g/L agar) containing 50 μg/mL ampicillin (Solarbio, Beijing, China) and 100 μg/mL hygromycin B (Merck Ltd., Shanghai, China).

2.3 Morphological and Cultural Characteristics Observation

Fob transformants were screened by PDA medium supplemented with 100 μg/mL hygromycin B and subcultured for at least six generations. To examine the morphological traits and cultural characteristics of transformants, the microscope (Olympus IX73, Shanghai, China) with filter blocks for GFP (450 nm to 490 nm excitation, 590 nm long pass emission) was used for fluorescence detection. The selected transformants were further confirmed by confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica, SP5, Shanghai, China).

Ten stable expressing GFP transformants were cultured on PDA medium at 28°C. After 7 days, the spores were scraped from the medium surface, filtered with sterile filter paper, and suspended by sterile water. The spore suspension was adjusted to a final concentration of 5 × 105 spores/mL. The apical 20 cm of sweet potato seedlings were excised and immersed in the spore suspension for 20 min. Seedlings were then incubated in sterile water under a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod at 28°C. Seedlings inoculated with Fob wild type and sterile water were used as a positive control and a negative control, respectively. The disease index was counted in 3, 5, and 7 dpi. At least 10 seedlings were used as one replicate for each treatment and the experiment was repeated 3 times.

The assessment of disease symptoms was divided into six levels (Index = 0–5). Level “0” represents no evident disease symptoms; “1” represents the vascular bundle of the stem base is browning, but less than 3 cm, and the appearance of growth state is normal; “2” represents the growth state of the seedling is basically normal, nearly 1/4 of the stem vascular bundle is browning; “3” represents the leaves at the stem base turn yellow, and nearly 1/2 of the vascular bundle is browning; “4” represents most leaves turn yellow or fall off, the browning area of the stem vascular bundle expands to apical bud; and “5” represents the whole seedling is wilt and dead. The disease index (DI) was calculated based on the following formula as previously described [2]: DI (0.1 × n1 + 0.2 × n2 + 0.5 × n3 + 0.8 × n4 + 1.0 × n5)/N × 100. The “n” and “N” represent the number of diseased plants at each level and the total number of tested plants, respectively.

2.6 GFP-Tagged Fob Inoculation and Microscopic Examination

The spore suspension was adjusted to a final concentration of 5 × 105 spores/mL. The cut stems of sweet potato cultivars Xinzhonghua and Xiangshu75-55 were dipped into the spore suspension for 1, 2, 3, 8, 16 and 24 h, respectively. The treated stem samples were sectioned to 0.1–0.2 mm slices by using a double-edged razor blade, then observed with microscopy (Olympus IX73) and confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica SP5) equipped with the GFP filter (450- to 490-nm excitation, 500-nm emission).

2.7 RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from sweet potato seedlings using the Biospin Plant Total RNA Extraction Kit (Hangzhou Bioer Technology, Hangzhou, China). Reverse transcription of 1 μg RNA of each sample was performed by using the TransScript All-in-One First-Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix for qPCR and One-Step gDNA Removal (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). Three independent biological samples were collected and analyzed. Real-time PCR was performed by using PerfectStart Green qPCR SuperMix (TransGen Biotech, China) on the Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3 system. The relative expressions of genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method [31]. The primers used in the qRT-PCR analysis are listed in Table S1. Fob 28s ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and sweet potato IbActin were used as internal controls to normalize the data.

Differences in pathogenicity, relative Fob abundance, fold changes of expression levels of Fob and sweet potato genes were determined using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by least significant difference (LSD) tests tests for significant differences between two sweet potato cultivars or among all different treatments at the level p < 0.05. All data analysis and figures were performed using the GraphPad Prism 9.0 software. The values of samples are averages ± Standard error (SE) of three biological replicates.

3.1 Stable GFP-Tagged Fob Strain Generated by Spheroplast Transformation

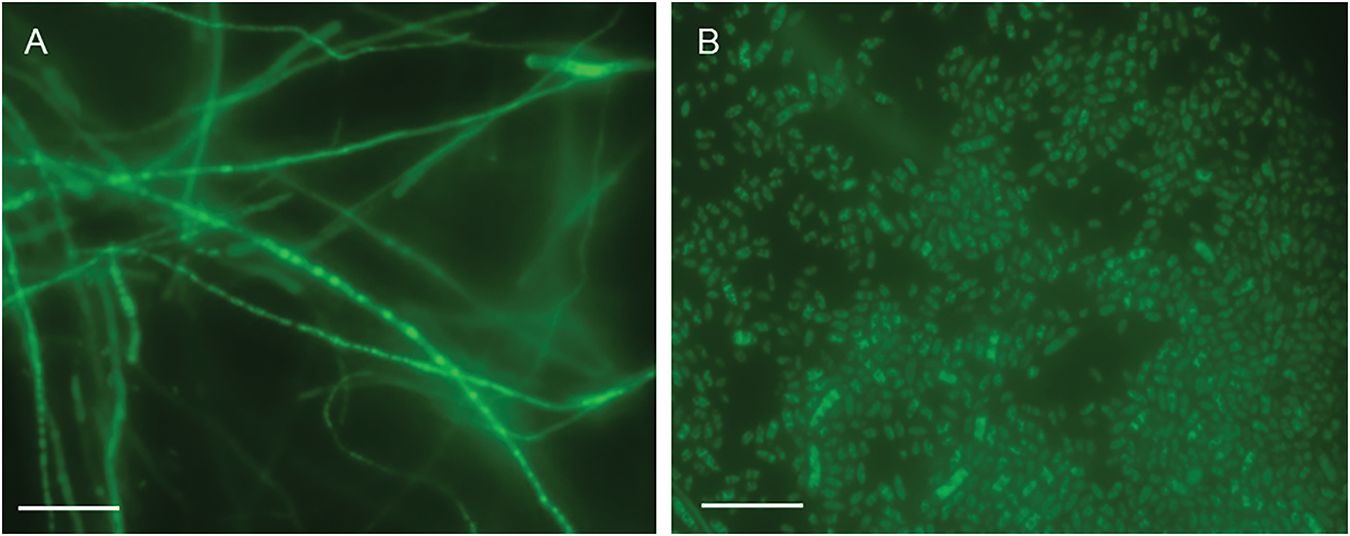

Spheroplasts were prepared by enzyme digestion from the Fob 3-1 strain, followed by spheroplast transformation induced by PEG with pCT74 plasmid [30]. The transformants were screened on PDA medium containing hygromycin B. After 7 d screening, 23 transformants were identified to exhibit green fluorescence. Moreover, the GFP fluorescence was still strongly detectable in 18 of the 23 strains after six generations screening (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: The 6th generation of GFP-expressing Fob by spheroplast transformation (100 μm scale bar). (A) Hyphae. (B) Spores

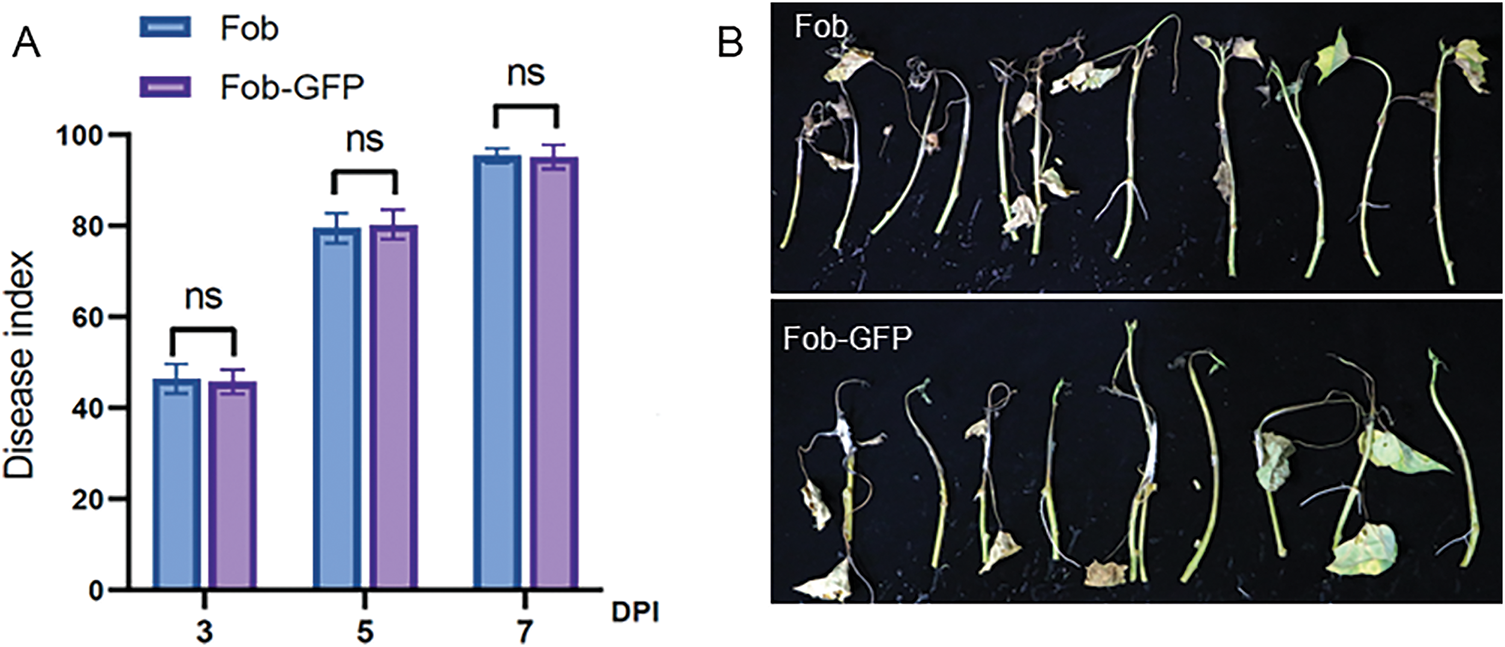

3.2 GFP-Tagged Fob Strain Has the Similar Pathogenicity as the Wild-Type Fob Strains

The GFP-tagged and wild-type strains were isolated using single spore method. Both strains were used to inoculate sweet potato susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua by soaking the excised stem in the spore suspension. Subsequently, the epidermis of the sweet potato stem was scraped, and the length of the browning vascular bundle was measured to calculate the disease index at 3, 5 and 7 days post inoculation (dpi), respectively. The result showed that the pathogenicity of the GFP-tagged strains was similar to that of the wild-type strain (Fig. 2A). Typical disease symptoms caused by Fob, such as stem cracking and leaf yellowing, were observed in both strains at 5 dpi. At 7 dpi, the stem and leaves were withered, the white mycelium was visible on the surface of stems (Fig. 2B). The results showed that the GFP-tagged strain still retained strong pathogenicity and was suitable for observing the infection process of Fob in sweet potato.

Figure 2: Pathogenicity of GFP-tagged and wild-type Fob. (A) The disease index at 3, 5 and 7 dpi of sweet potato susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua, “ns” indicates no significant difference at the 0.0001 probability levels, and n = 3. (B) The symptom of sweet potato Xinzhonghua at 7 dpi

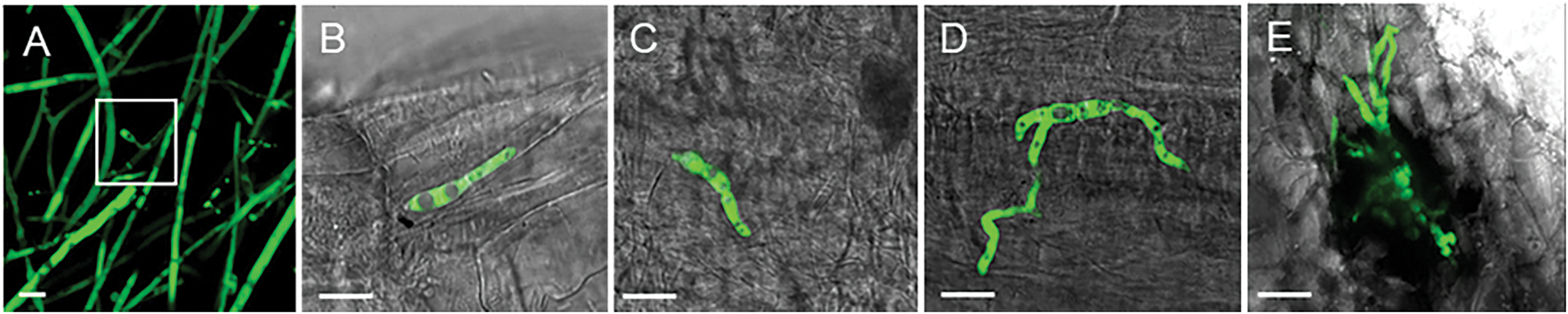

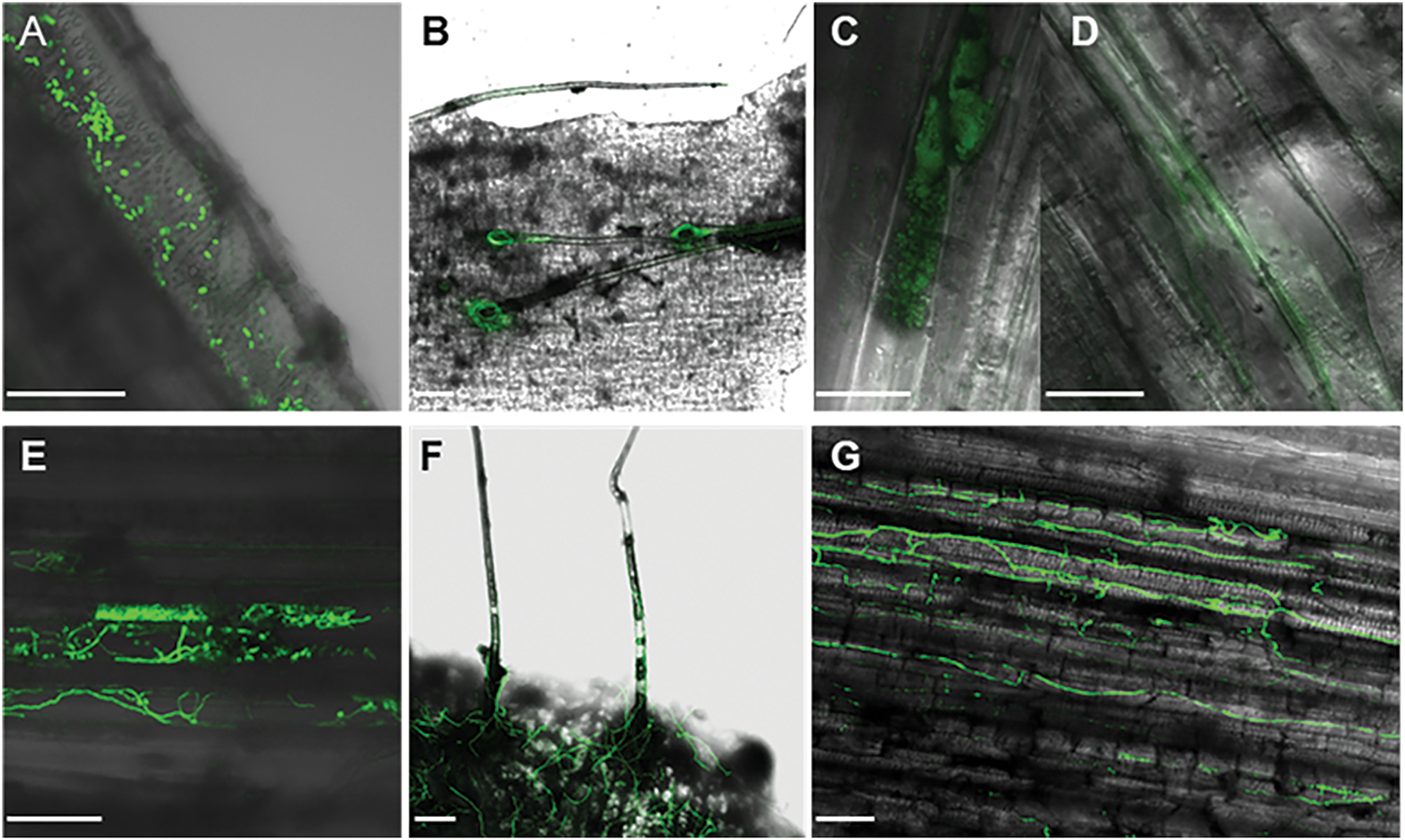

3.3 Visualization of GFP-Tagged Fob Sporulation and Spore Germination

During asexual propagation of the GFP-tagged Fob, the filamentous hyphae protruded outward to form conidiophore, and spores were produced at the apex of the conidiophore (Fig. 3A). In the spore suspension, the spores exhibited from zero to several septa. Non-septate spores were ellipsoidal and were the most prevalent morphological type. Spores tended to be sickle-shaped with increasing septa. In the infection process of susceptible sweet potato seedlings, the period between 2–3 hpi was crucial for spore germination on the plant surface. In this timeframe, a large number of spores began to germinate to form hyphae, and each spore segment could independently germinate outward to form hyphae (Fig. 3B–E).

Figure 3: The sporulation and spore germination process of GFP-tagged Fob (10 μm scale bar). (A) The sporulation, white rectangle indicates the spores produced at the apex of the conidiophore; (B) Spore germination from one cell; (C) Spore germination from two cells; (D) Spore germination from three cells; (E) Spore germination to multiple directions, forming the claw-like structure

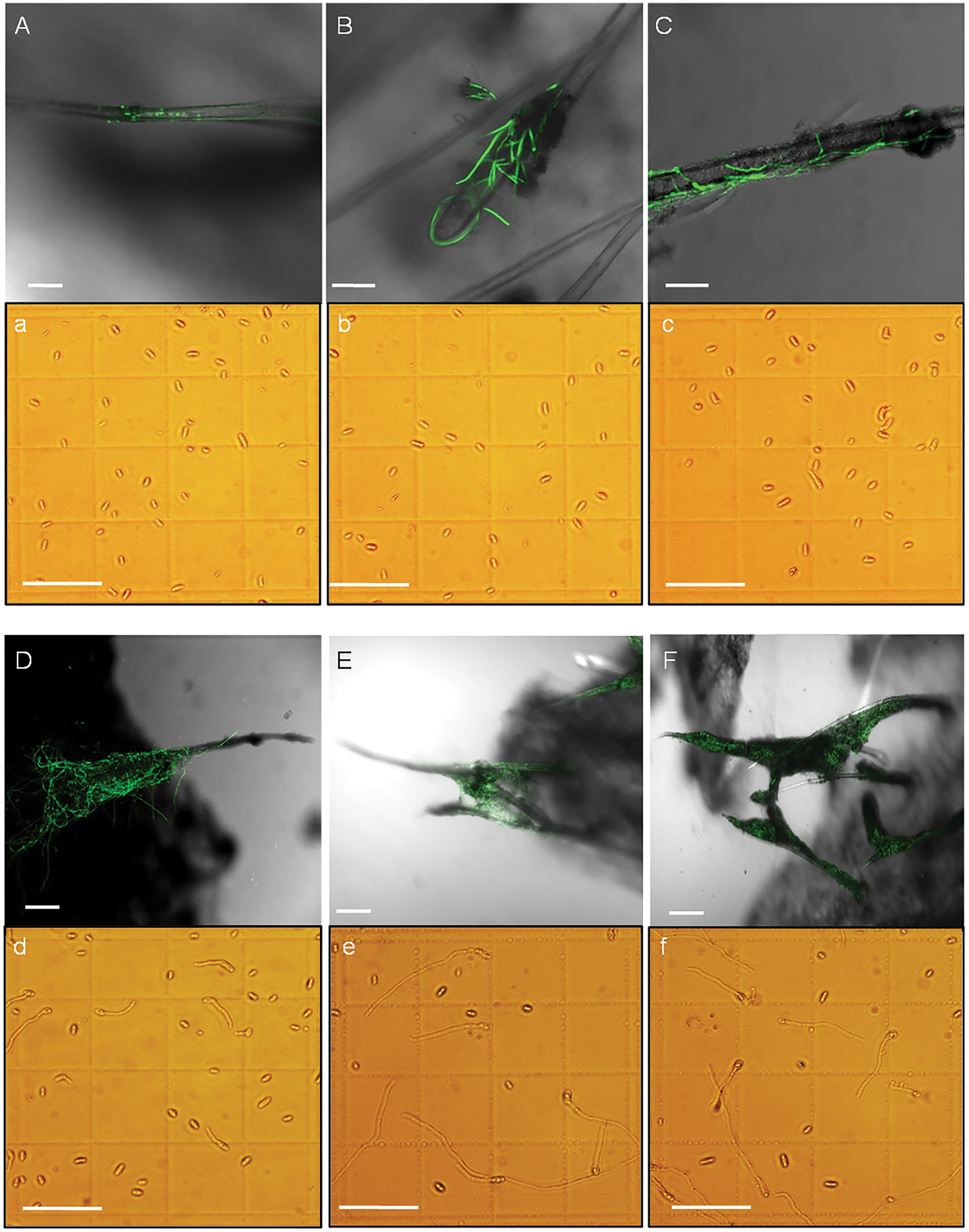

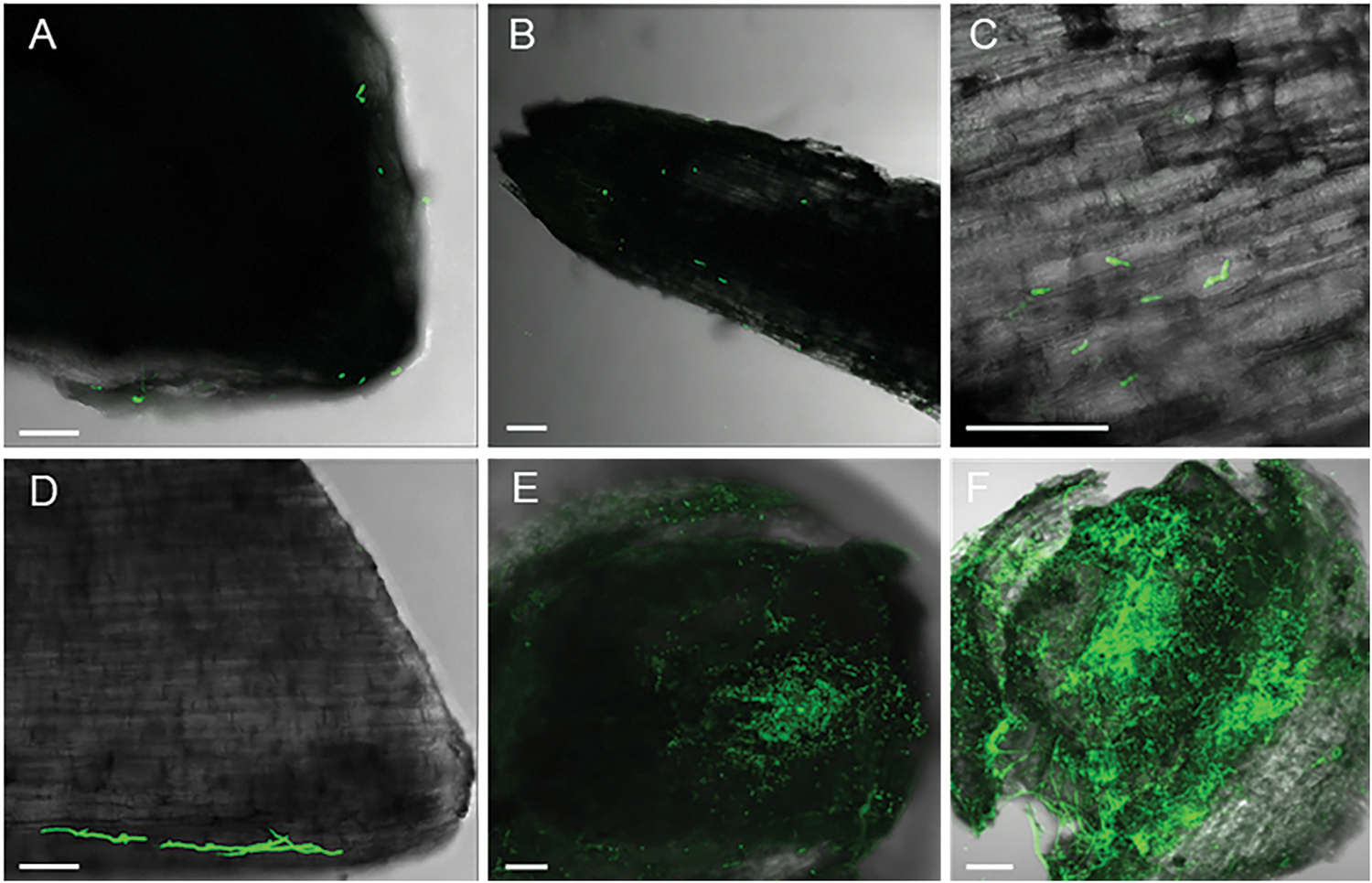

3.4 Colonization and Growth of GFP-Tagged Fob on the Surface of Susceptible Cultivar

To observe the colonization process, the stem base of sweet potato susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua was dipped in the GFP-tagged Fob spore suspension with a concentration of 5 × 105 spores/mL. At 1 hpi, spores gathered on the stem trichomes (Figs. 4 and 5A). At 2 hpi, spores began to germinate on the trichomes and form hyphae wrapping around them (Fig. 5B). The hyphae became dense at the base of the trichomes, then gradually elongated and branched to the tips at 3 hpi (Fig. 5C). The hyphae formed a dense network covering the trichomes at 8 hpi (Fig. 5D). Moreover, the mycelium not only developed on a single villus, but also joined adjacent trichomes at 16 and 24 hpi (Fig. 5E,F). The hyphae adhering to the base of the Xinzhonghua stem gradually diminished and were primarily localized near the internode root growth point at 24 hpi. In contrast, spores in suspension began to germinate later at 3 hpi (Fig. 5a–c), producing shorter and sparser hyphae (Fig. 5d–f). In suspension, the spore germination rate reached 5.7% at 8 hpi, 31.4% at 16 hpi, and 46.2% at 24 hpi (Fig. 5d–f).

Figure 4: The stem trichomes of sweet potato seedling. White rectangle indicates the growth points of nodes

Figure 5: Spore germination on the stem trichomes of sweet potato susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua (100 μm scale bar). (A–F) Spore germination and colonization on the trichomes at 1, 2, 3, 8, 16 and 24 hpi, respectively; (a–f) Spore germination in the static spore suspension at 1, 2, 3, 8, 16 and 24 hpi, respectively

On the root surface, the spores began to germinate at 3 hpi (Fig. 6A–D). Spore germination was faster on the root base, near the stem (Fig. 6D), compared to that on root tip and middle regions (Fig. 6A–C). On healthy roots, the spores did not aggregate or form dense mycelium. However, the spores congregated on injured roots (Fig. 6E). At 16 hpi, the hyphae predominantly extended, intertwined, forming a dense net at the injured root growth point, the joint site of the injured root and stem (Fig. 6F).

Figure 6: Colonization of the GFP-tagged Fob on the surface of sweet potato roots (100 μm scale bar). (A) Root tip at 3 hpi; (B) The middle of the root at 3 hpi; (C) Partial enlarged detail of the middle of the root at 3 hpi; (D) The base of the root at 3 hpi; (E) The injured root growth point at 3 hpi; (F) The injured root growth point at 16 hpi

3.5 Fob Infecting Sweet Potato Initiated at the Wounds of the Stem Base of Susceptible Cultivar

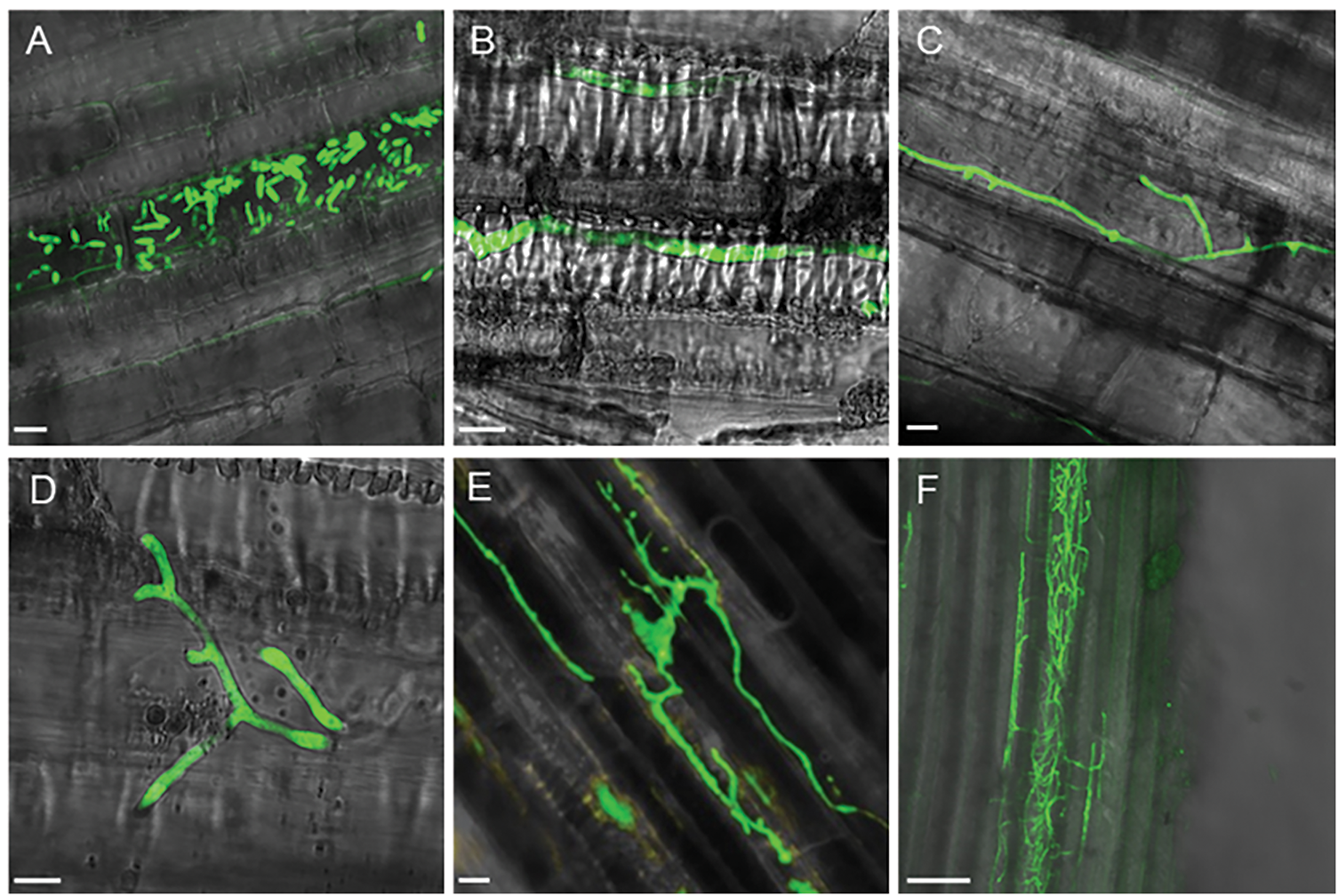

After immersing the excised stem base of Xinzhonghua in the spore suspension of 5 × 105 spores/mL concentration, a large number of spores were observed in the vascular bundle of stem base, initiating germination at 2 hpi (Fig. 7A). At 8 hpi, the hypha germinated from spores in the vascular bundle located 2 cm from the stem base (Fig. 7B). Subsequently, the mycelia branched extensively, expanding the infection area (Fig. 7C,D). Throughout mycelial growth, spores were continuously produced (Fig. 7E) and moved further away following the fluid in the vascular bundle. This cyclical infection process encompassed spore germination, mycelia formation, and spore production. Eventually, Fob spread horizontally in intercellular spaces and vertically within the vascular bundle, forming a dense mycelial network throughout the stem (Fig. 7F).

Figure 7: Colonization of the GFP-tagged Fob in the stem of sweet potato susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua. (A–E) 10 μm scale bar, (F) 100 μm scale bar. (A) Spores gathered and germinated in the vascular bundle at 2 hpi; (B) Mycelium extended in the vascular bundle at 8 hpi; (C,D) Mycelium branched at 8 and 16 hpi, respectively; (E) Sporulation in the vascular bundle at 24 hpi; (F) Dense mycelia net in the stem at 24 hpi

3.6 Distinct Colonization of Fob on Susceptible and Resistant Sweet Potato Cultivars

The resistant cultivar Xiangshu75-55 was subjected to the same inoculation method as for the susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua. At the early stage of infection, spores entered the vascular bundles of both susceptible and resistant sweet potato cultivars. However, Fob exhibited limited spore germination and mycelial expansion in Xiangshu75-55. At 3 hpi, both the germination of spores within the vascular bundles and the growth of mycelia around the stem trichomes were significantly reduced in Xiangshu75-55 (Fig. 8A,B), compared to Xinzhonghua (Fig. 8E,F). By 24 hpi, the vascular bundles of Xiangshu75-55 showed only dispersed spots (Fig. 8C) and sparse GFP signal in intercellular spaces without complete mycelial structure (Fig. 8D), whereas Xinzhonghua displayed a dense mycelial network (Fig. 8G).

Figure 8: Colonization of the GFP-tagged Fob on susceptible and resistant sweet potato cultivars (100 μm scale bar). (A–D) Sweet potato resistant cultivar Xiangshu75-55; (E–G) Sweet potato susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua; (A) Spores in the vascular bundle at 3 hpi; (B) Fob around the trichomes at 3 hpi; (C) Dispersion of GFP signal on the opaque area in sweet potato at 24 dpi; (D) Dispersion of GFP signal without complete mycelium appearing in the intercellular space of sweet potato cells at 24 hpi; (E) Spore germination in the vascular bundle at 3 hpi; (F) Extended mycelia around the trichomes at 3 hpi; (G) Dense mycelia net in the stem at 24 hpi

3.7 Quantification of Fob in Susceptible and Resistant Cultivars of Sweet Potato

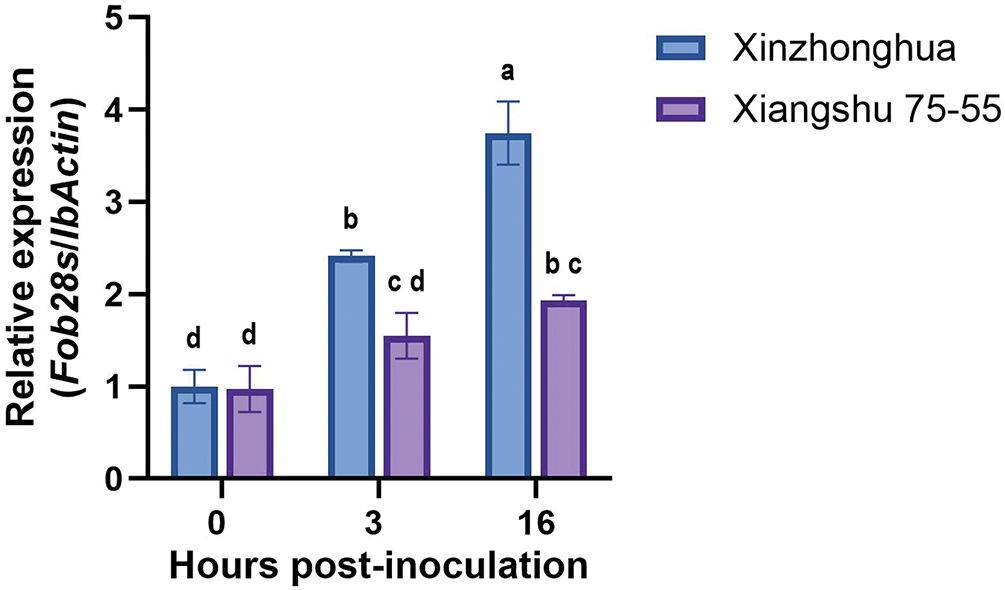

To quantify the disparity of Fob colonization between resistant and susceptible sweet potato cultivars, we compared the relative biomass of active Fob in the stems of the Xinzhonghua and Xiangshu75-55 cultivars during the initial stages of infection by qRT-PCR analysis. We calculated the expression quantity ratio of Fob28s rRNA to IbActin at 0, 3 and 16 hpi (Fig. 9). In the susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua, the stem colonization biomass of Fob exhibited a significant increase at 3 and 16 hpi. However, in the resistant cultivar Xiangshu75-55, no significant Fob biomass increase in the stem was observed over time. By 16 hpi, the biomass of Fob in Xinzhonghua stem was significantly higher than that in Xiangshu75-55 stem.

Figure 9: Relative Fob biomass in susceptible and resistant cultivars of sweet potato. The biomass of Fob was determined by qRT-PCR analysis of the gene expression level of Fob 28s rRNA relative to sweet potato IbActin at 0, 3 and 16 hpi between susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua and resistant cultivar Xiangshu75-55. Stem samples are averages ± SE of 3 biological replicates consisting of pools of 3 seedlings. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences at the 0.05 level of p value determined by the two-factor analysis of variance

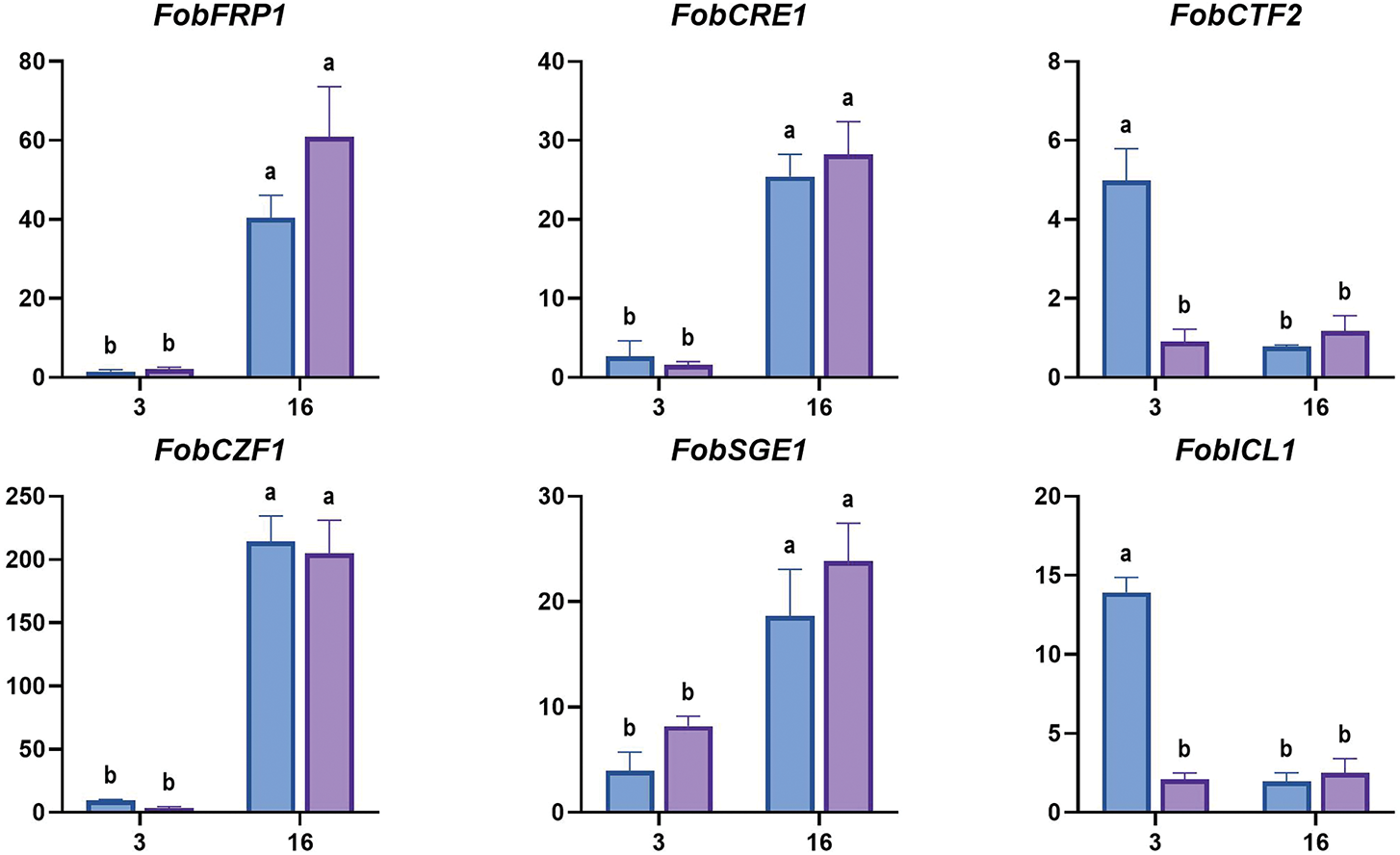

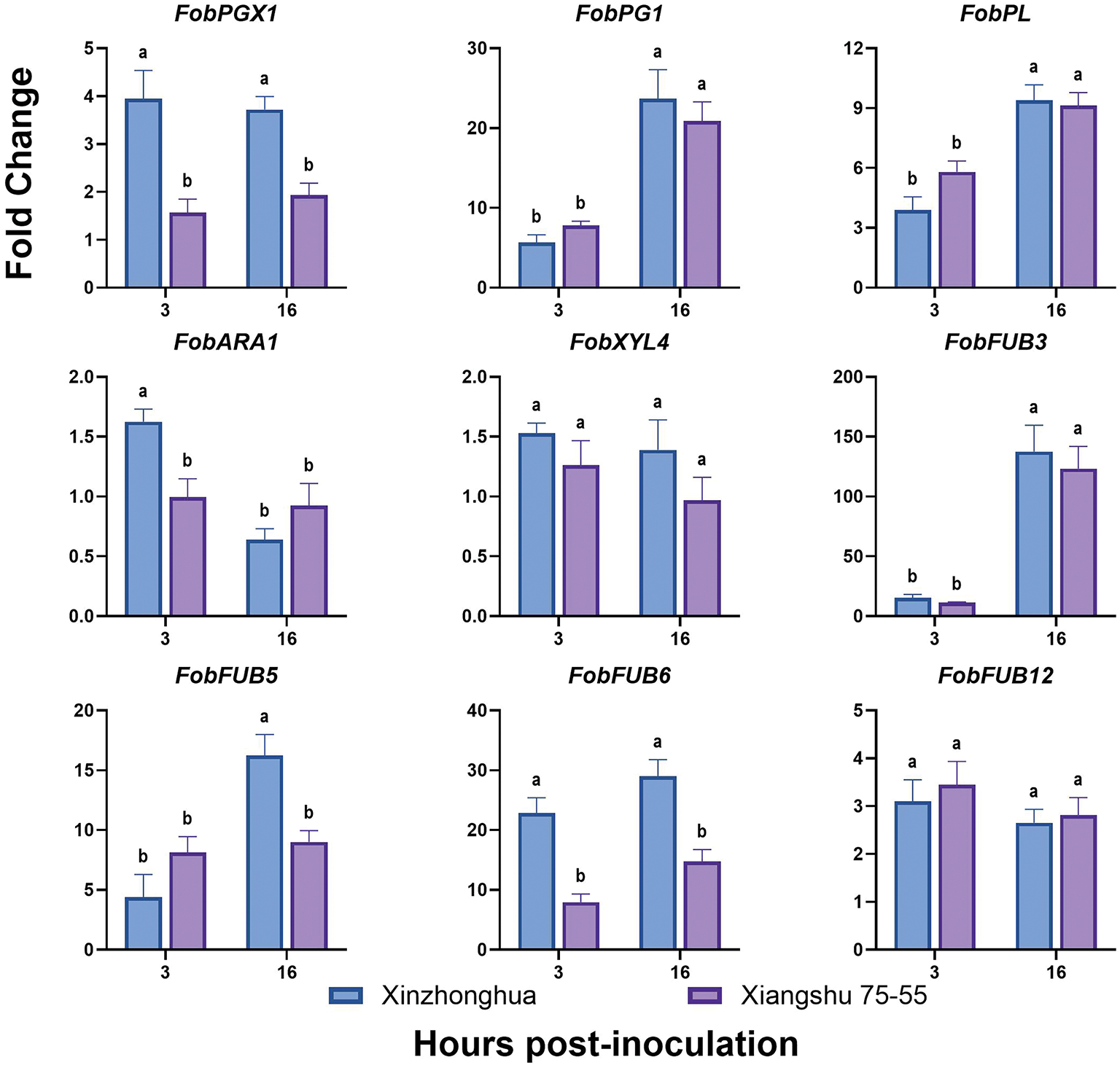

3.8 The Expression Differences of Pathogenic Genes of Fob in Susceptible and Resistant Cultivars of Sweet Potato

The infection process of F. oxysporum consists of host recognition, adhesion and colonization on the host surface, penetration into the plant tissues, and systemic expansion within the xylem vessels. The pathogen’s virulence is primarily determined by factors such as cell wall-degrading enzymes (CWDEs), phytotoxin, and effectors. Consequently, we analyzed the expression level of Fob pathogenic and related transcriptional regulatory genes at early infection time points of 0, 3, and 16 hpi. The transcriptional factors include CWDEs regulators FRP1 (F-box required for pathogenicity) and CRE1 (Carbon catabolite repression) [32], cutinases and lipases regulator CTF2 (Cutinase transcription factor) [33], conidiation and mycotoxin fusaric acid production regulator CZF1 (C2H2 zinc finger transcription factor) [34], SIX (Secreted in xylem) effectors and secondary metabolite biosynthesis regulator SGE1 (SIX gene expression) [35]. The pathogenic factors include CWDEs, such as ICL1 (Isocitrate lyase), PGX1 (Exo-polygalacturonase), ARA1 (Arabinanase), XYL4 (Xylanase), PL (Pectate lyase) [36], and FUBs (Fusaric acid biosynthetic) like FUB3, FUB5, FUB6 and FUB12 [37].

The qRT-PCR results showed that the expression level of FobPGX1 and FobFUB6 increased in susceptible cultivar and was higher than that in resistant cultivar at 3 hpi and 16 hpi. The expression levels of FobICL1 and FobCTF2 in susceptible cultivar increased at 3 hpi and were higher than that in resistant cultivar, then the expression levels declined at 16 hpi with no significant difference between the two cultivars. FobFUB5 showed higher expression in susceptible cultivar than in resistant cultivar at 16 hpi. The expression levels of FobFRP1, FobCRE1, Fob CZF1, FobSGE1, FobPG1, FobPL and FobFUB3 increased over time, and were significantly higher at 16 hpi than at 3 hpi, but no significant difference was found between susceptible and resistant cultivars. FobXYL4, FobFUB12 and FobARA1 showed no significant difference in expression between the two cultivars over time (Fig. 10).

Figure 10: The expression levels of Fob pathogenic genes in sweet potato susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua and resistant cultivar Xiangshu75-55 at early infection stage. The fold-change value represents the relative expression at 3 hpi and 16 hpi against that at 0 hpi measured by quantitative real-time PCR. The values of stem samples are averages ± SE of 3 biological replicates consisting of pools of 3 seedlings. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences at the 0.05 level of p value determined by the two-factor analysis of variance

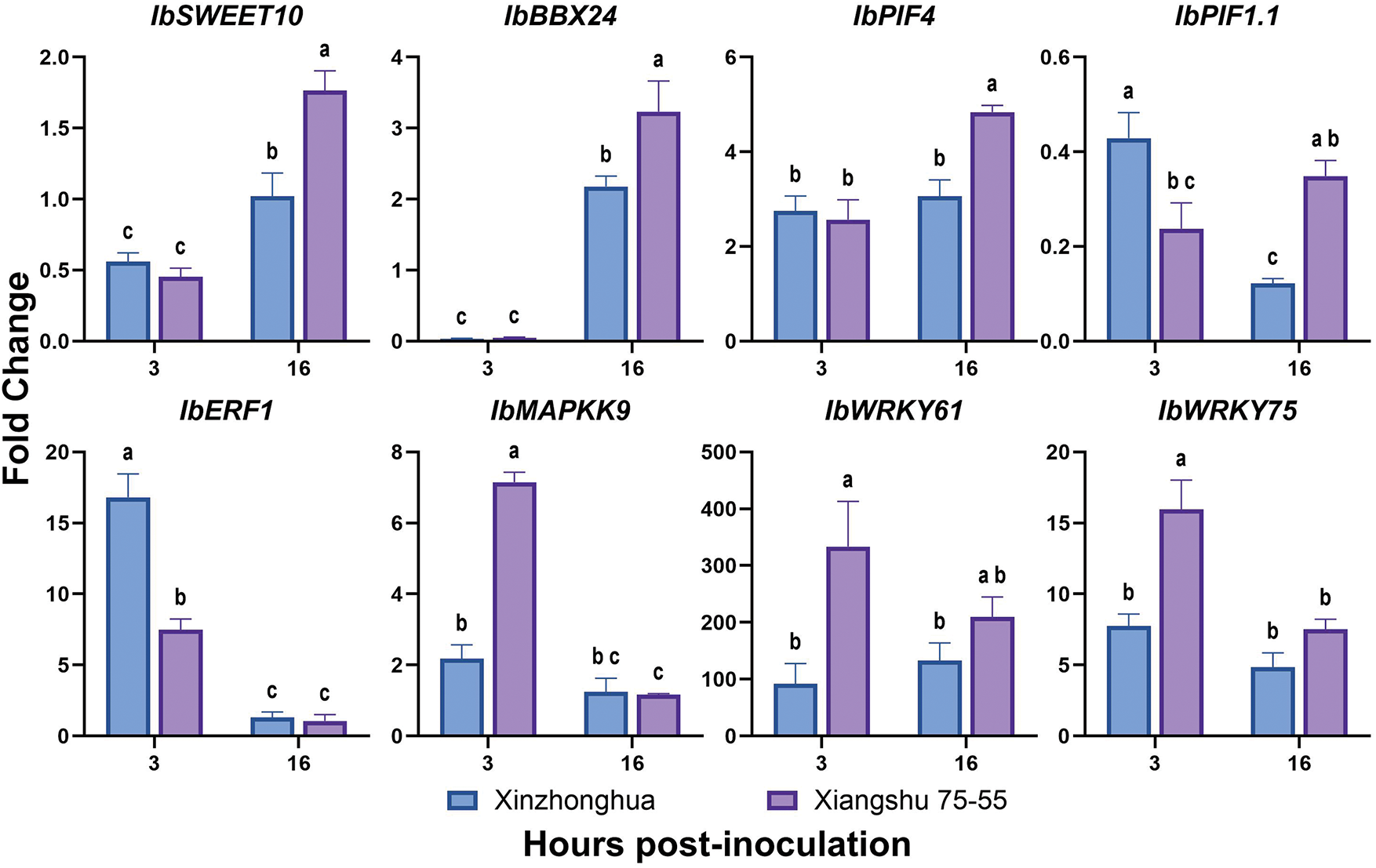

3.9 The Expression Differences of Sweet Potato Resistance Gene in Susceptible and Resistant Cultivars

It has been reported that the plasma membrane located sucrose transporter IbSWEET10 (Sugars will eventually be exported transporter) [38], JA (Jasmonic acid) pathway regulatory transcription factor IbBBX24 (B-box) [39], and the stress response factors IbPIFs (Phytochrome interacting factor) [40] can enhance Fusarium wilt resistance in sweet potato. In the resistant cultivar Eshu11, the expression of AP2/ERF (APETALA2/Ethylene-Responsive element binding Factor) family transcription factor coding gene IbERF1 (Ethylene responsive transcription factor) [41], and plant immune signal transduction related gene IbMAPKK9 (Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase) are up-regulated [42]. According to the transcriptome profile of sweet potato susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua and resistant cultivar Jinshan57 at 24 h post Fob infection, putative WRKY transcription factor genes WRKY75 (C52297) was up regulated in Jinshan57, and WRKY61(C55420) was up regulated in Xinzhonghua [27].

The qRT-PCR results revealed that the expression levels of IbMAPKK9, IbWRKY61 and IbWRKY75 were significantly increased in the resistant sweet potato cultivar Xiangshu75-55 compared to the susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua at 3 hpi. Conversely, IbERF1 was significantly up-regulated in susceptible cultivar than in resistant cultivar at 3 hpi. All the four genes showed no significant expression differences between the two cultivars at 16 dpi. IbSWEET10, IbBBX24 and IbPIF4 showed higher expression in resistant cultivar than in susceptible cultivar at 16 hpi. IbPIF1.1 was down-regulated in both cultivars within 16 hpi, with a more significant decline in the susceptible cultivar (Fig. 11).

Figure 11: The expression levels of sweet potato genes in susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua and resistant cultivar Xiangshu75-55. The fold-change value represents the relative expression at 3 hpi and 16 hpi against that at 0 hpi measured by quantitative real-time PCR. The values of stem samples are averages ± SE of 3 biological replicates consisting of pools of 3 seedlings. Lowercase letters indicate significant differences at the 0.05 level of p value determined by the two-factor analysis of variance

Understanding the early characteristics of Fob infection in sweet potato is of great significance for disease management and cost-saving. In this study, the GFP-tagged F. oxysporum f. s. batatas strains were initiatively generated to unveil the early spatiotemporal differences between the susceptible and resistant sweet potato cultivars by cytological and molecular biological methods.

GFP is a non-destructive widely used tool to shed light on the pathogenic process [43]. During the compatible reaction between Fob and sweet potato, the injured root growth points, the wound of cutting stem base, and the stem trichomes of the susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua were the pivotal positions for Fob early colonization. The critical period for the colonization and germination of spores was 2–3 hpi, which was much shorter than that of F. oxysporum f. sp. luffae (Folu) invading Luffa plants (7 dpi) [44], F. oxysporum f. sp. phaseoli (Fop) infecting common bean (6 dpi) [45], and F. oxysporum conidia germinating and adhering to succulent plants (2–3 dpi) [46]. The reason for this difference could be attributed to that sweet potato is a kind of vegetatively propagated crop, typically planted with excised stems with exposing wounds, facilitating direct entry of Fob into the vascular bundle. This result emphasized the necessity of implementing protective treatments for wounds prior to planting seedlings.

Many studies have demonstrated that the plant root is the primary site for F. oxysporum colonization and initial infection [47]. The root exudates can stimulate the germination of the spores [48] and enhance F. oxysporum infection in the rhizosphere [49]. F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici and F. oxysporum f. sp. lini exhibit a preference for colonizing and penetrating the root tips of tomato and flax, respectively [50,51]. However, in our observations of Fob infecting sweet potato seedlings, we noted that not root, but stem was the primary colonization site for Fob. Although spores could germinate on the root surface at 3 hpi, the germination rate at root tips was lower than root base near the stem. This is consistent with the findings of Olivain and Alabouvette, who reported that the root apex is not a common site of entry for F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici [52]. Further, aside from physically damaged roots, direct penetration of mycelia through the epidermis into the root vascular bundles in healthy roots has not been observed. Fob showed a significant colonization tendency on injured root growth points and trichomes on the stem.

The stem trichomes of sweet potato are morphologically similar to non-glandular trichomes that do not have globular secretory heads [53]. Trichomes, the outgrowths of epidermal cells, are generally thought to be beneficial structures physically protecting plants from biological stress [54]. However, in some cases, plant trichomes function as microbial habitats and infection sites that have detrimental effects on plants [55]. Plant trichomes provide a suitable environmental humidity for fungi, facilitate the adhesion of spores [56], and serve as preferred sites of penetration [57]. Fusarium graminearum, Fusarium proliferatum, and Fusarium verticillioides could immediately invade three types of trichomes on maize leaves, in which trichomes represent an entry point of infection [58]. Similarly, F. graminearum exploits wheat trichomes as primary colonization sites, secretes cell wall-degrading enzymes to breach their vulnerable bases, and invades lemma tissues through these entry points. The trichome density and base structure are critical determinants of Fusarium head blight susceptibility [59]. In this study, we observed preferential Fob colonization of trichomes. Spores adhered to trichomes and rapidly germinated, forming a dense hyphal network around trichomes by 8 hpi. However, there was no evidence of direct Fob invasion into trichomes or entering internal plant tissues from the trichomes. Noteworthily, we observed a novel phenomenon: the dynamic translocation of mycelia on trichomes. Mycelia transitioned from single villus colonization to forming interconnected networks among multiple trichomes within a day. At 24 hpi, mycelial accumulation mostly occurred on the trichomes and epidermis surrounding root growing points, aligning with hyphae predominant colonization at injured root growth points. We hypothesize that this mycelial aggregation and translocation on trichomes sustains fungal populations and facilitates efficient infection at root growth points.

In resistant cultivar Xiangshu75-55, the infection process of Fob was constrained. The resistant response was not reflected in blocking pathogen entry or changing localization preference, but in post-invasion containment. During the infection process, although the GFP fluorescence signals also appeared around the trichomes and in the vascular bundles in Xiangshu75-55, it was difficult to find the complete mycelium. Quantification of Fob biomass via qRT-PCR corroborated these observations, showing significantly lower fungal amount in Xiangshu75-55 by 16 hpi. The infection efficiency difference between compatible and incompatible reaction was similar to the process of F. oxysporum f. sp. melonis race 1.2 infecting melon cultivars [17], and F. oxysporum f. sp. ciceris invading chickpea cultivars [18]. For agricultural practice, the status of conidial germination on trichomes at 3 hpi, and Fob biomass in stem at 16 hpi could be rapid markers for evaluating sweet potato Fusarium wilt resistance.

The expression patterns of pathogen virulence genes and host resistance genes further profiled the early dynamic molecular differences between the compatible and incompatible reactions. Successful systemic infection of F. oxysporum in hosts requires several steps, including recognizing and adhering to the plant surface, degrading host tissues, and xylem colonization. During this process, the pathogenic factors of CWDEs, phytotoxins and effectors play crucial roles [60]. CWDEs enable pathogens to penetrate host tissues and achieve carbon sources. Transcription factor CTF regulates cutinases and lipases related gene expression, contributing to the hydrolysis of plant cuticular waxes [61]. In this research, elevated expression of FobPGX1 in susceptible plants at 3–16 hpi indicates enhanced pectin degradation. The transient upregulation of cutinase regulator FobCTF2 and FobICL1 at 3 hpi further suggests early cuticle modification and glyoxylate-cycle-driven energy metabolism during successful colonization. Notably, FobFRP1, FobCRE1, and FobPL increased similarly in both cultivars, implying their roles in basal infection rather than compatibility determination. Fusaric acid, a broad-spectrum phytotoxin in F. oxysporum, is essential for the early invasive growth of hyphae within host cells. In the F. oxysporum genome, there are generally 12 FUB genes arranged in clusters involved in the synthesis of fusaric acid [62]. During Fob infecting sweet potato, FobFUB5 and FobFUB6 were significantly upregulated in susceptible cultivar at 16 hpi, aligning with phytotoxin-mediated aggression during advanced colonization [63]. F. oxysporum secretes effector proteins to suppress the plant immunity [64]. SIX effector proteins represent major pathogenic effectors of F. oxysporum [65]. Transcription factor SGE1 is required for parasitic growth of the fungi and regulates expression of the SIX genes [35]. In Fob, we have not identified SIX genes, which may partly attribute to different formae speciales of F. oxysporum possess unique sets of SIX genes [66]. We examined the expression pattern of FobSGE1, which was up-regulated over time, but no significant difference between susceptible and resistant sweet potato cultivars.

Consistent with the cytological observation results, the triggered expression of sweet potato resistant genes indicated the mechanism of incompatible reaction more like active host defense rather than passive structural exclusion. Rapid induction of IbMAPKK9, IbWRKY61 and IbWRKY75 at 3 hpi in the resistant cultivar Xiangshu75-55 manifested immediate pathogen recognition and signal transduction. Afterwards, the upregulation of IbSWEET10, IbBBX24 and IbPIF4 at 16 hpi in Xiangshu75-55 highlighted a multi-layered strategy to restrict fungal growth. In accordance with the results, previous studies have revealed that these six genes are positively associated with plant resistance. MAPKKs are key components in the plant immune response signaling cascade (MAPKKK-MAPKK-MAPK) [67]. IbMAPKK9 is significantly up-regulated by Fob in the resistant sweet potato cultivar Eshu11 at 2–4 hpi [42]. Transcription factors IbBBX24 and WRKY75 enhance plant disease resistance by modulating the plant hormone signaling pathway. In sweet potato, IbBBX24 represses JA signaling pathway related gene IbJAZ10 expression, activates IbMYC2 expression, and the resistance to Fob of overexpression lines increase [39]. WRKY75 promotes JA-biosynthesis and signaling pathways mediated disease resistance in multiple plants, such as Arabidopsis and rapeseed [68,69]. MdWRKY61 positively regulates resistance to Colletotrichum siamense in apple [70]. SWEET proteins are membrane-localized sugar transporters that influence the accumulation of plant nutrients required by pathogens at colonization site [71]. In Arabidopsis, AtSWEET2 enhances hosts resistance to Pythium by reducing rhizosphere sugar availability [72]. In sweet potato, IbSWEET10 expression is significantly up-regulated during Fob infection, and transgenic lines overexpressing IbSWEET10 enhance resistance to Fob [38]. Previous study has shown that IbPIF1.1 and IbPIF4 are significantly induced by Fob in sweet potato at 0.5 dpi [40]. However, IbPIF1.1 in this study was down-regulated in both cultivars, which indicates the diverse functions and expression patterns of different IbPIFs across sweet potato cultivars. ERFs are transcription factors involved in plant defense responses. NbERF173 positively regulates the Nicotiana benthamiana disease resistance to Phytophthora parasitica [73]. IbERF1 expression in the resistant cultivar Eshu 11 was significantly induced by Fob at 2–4 hpi [41]. However, the expression level of IbERF1 in this study was higher in the susceptible cultivar at 3 hpi. This difference of IbERF1 expression patterns may be attributed to the diversity among various sweet potato cultivars, as well as the complex function of ERFs in dynamic regulating the plants response to biotic and abiotic stresses [74].

This study provides comprehensive cytological visualizations and gene expression profiles of the early spatiotemporal dynamics in both compatible and incompatible reactions between GFP-tagged Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. batatas (Fob) and sweet potato. In compatible reaction, Fob preferentially colonizes stem trichomes, injured root growth points, or directly enters the excised stem wound. Spore germination peaks at 2–3 hpi, followed by cyclic mycelium formation, proliferation and sporulation in the vascular bundle. The upregulation of Fob virulence genes FobPGX1, FobCTF2, FobICL1, FobFUB5 and FobFUB6 in susceptible cultivar Xinzhonghua within 16 hpi highlights the roles of cell wall degrading enzymes and fusaric acid in compatible reaction. During incompatible reaction, Fob spore germination, hyphal growth, and fungal biomass accumulation are restrained. Meanwhile, the expression levels of defense genes IbMAPKK9, IbWRKY61, IbWRKY75, IbSWEET10, IbBBX24 and IbPIF4 are elevated in resistant cultivar Xiangshu75-55 within 16 hpi, indicating early pathogen recognition, signal transduction, carbohydrate metabolism, and JA-mediated immunity in Fob resistance. These findings enhance the understanding of Fob’s pathogenic mechanisms and aid in developing effective disease control strategies, including early identification of sweet potato Fusarium wilt resistance.

Acknowledgement: We thank Dr. Ciuffetti (Oregon State University, USA) for providing the pCT74 plasmid. We also thank Dr. Xin Zhang (Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences, China) and Prof. Rongfeng Xiao (Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences, China) for their technical guidance on transformation of fungal spheroplasts.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the following grants, Earmarked fund for CARS-10-Sweet potato, High-quality development of agriculture “5511” collaborative innovation project (XTCXGC2021005), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian province (2021J01495), Basic Scientific Research Special Project for Fujian Provincial Public Research Institutes (2021R1031008), Science and Technology Innovation Team of Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CXTD2021012-1).

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the study conception and design. The corresponding author Sixin Qiu made substantial contributions to the design of the work and revised the manuscript. First author and co-first author, Hong Zhang, Ying Zhu and Xingyu Li had major roles in conducting the experiments and writing the first draft of the manuscript. Xingyu Li, Zhonghua Liu, Guoliang Li, Zhaomiao Lin, Yongxiang Qiu, Yongqing Xu and Shimin Lyu provided the materials, collaborated in the experiments and data analysis. Jiyang Wang improved test methods and revised the manuscript. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: Figure S1: Symptoms of sweet potato Fusarium wilt caused by of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. batatas (Fob). Table S1: Primer sequences used for qRT-PCR. The CDS sequences of the genes used to design the primers in this study. The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.064850/s1.

References

1. Li C, Wang L, Chai S, Xu Y, Wang C, Liu Y, et al. Screening of Bacillus subtilis HAAS01 and its biocontrol effect on Fusarium wilt in sweet potato. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2022;91(8):1779–93. doi:10.32604/phyton.2022.020192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yang Z, Lin Y, Chen H, Zou W, Wang S, Guo Q, et al. A rapid seedling assay for determining sweetpotato resistance to Fusarium wilt. Crop Sci. 2018;58(4):CSC2CROPSCI2017100600. doi:10.2135/cropsci2017.10.0600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Dean R, Van Kan JAL, Pretorius ZA, Hammond-Kosack KE, Di Pietro A, Spanu PD, et al. The top 10 fungal pathogens in molecular plant pathology. Mol Plant Pathol. 2012;13(4):414–30. doi:10.1111/j.1364-3703.2011.00783.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Li J, Fokkens L, Rep M. A single gene in Fusarium oxysporum limits host range. Mol Plant Pathol. 2021;22(1):108–16. doi:10.1111/mpp.13011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Czymmek KJ, Fogg M, Powell DH, Sweigard J, Park SY, Kang S. In vivo time-lapse documentation using confocal and multi-photon microscopy reveals the mechanisms of invasion into the Arabidopsis root vascular system by Fusarium oxysporum. Fungal Genet Biol. 2007;44(10):1011–23. doi:10.1016/j.fgb.2007.01.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Michielse CB, Rep M. Pathogen profile update: Fusarium oxysporum. Mol Plant Pathol. 2009;10(3):311–24. doi:10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00538.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Pietro AD, Madrid MP, Caracuel Z, Delgado-Jarana J, Roncero MIG. Fusarium oxysporum: exploring the molecular arsenal of a vascular wilt fungus. Mol Plant Pathol. 2003;4(5):315–25. doi:10.1046/j.1364-3703.2003.00180.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Sampaio AM, Rubiales D, Vaz Patto MC. Grass pea and pea phylogenetic relatedness reflected at Fusarium oxysporum host range. Crop Prot. 2021;141:105495. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2020.105495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Gordon TR. Fusarium oxysporum and the Fusarium wilt syndrome. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2017;55(1):23–39. doi:10.1146/annurev-phyto-080615-095919. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Sanogo S, Zhang J. Resistance sources, resistance screening techniques and disease management for Fusarium wilt in cotton. Euphytica. 2016;207(2):255–71. doi:10.1007/s10681-015-1532-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Chen A, Sun J, Matthews A, Armas-Egas L, Chen N, Hamill S, et al. Assessing variations in host resistance to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense race 4 in Musa species, with a focus on the subtropical race 4. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1062. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.01062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Sampaio AM, Vitale S, Turrà D, Di Pietro A, Rubiales D, van Eeuwijk F, et al. A diversity of resistance sources to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. pisi found within grass pea germplasm. Plant Soil. 2021;463(1):19–38. doi:10.1007/s11104-021-04895-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. van der Does HC, Constantin ME, Houterman PM, Takken FLW, Cornelissen BJC, Haring MA, et al. Fusarium oxysporumcolonizes the stem of resistant tomato plants, the extent varying with the R-gene present. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2019;154(1):55–65. doi:10.1007/s10658-018-1596-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Fang X, Kuo J, You MP, Finnegan PM, Barbetti MJ. Comparative root colonisation of strawberry cultivars camarosa and festival by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. fragariae. Plant Soil. 2012;358(1):75–89. doi:10.1007/s11104-012-1205-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lü G, Guo S, Zhang H, Geng L, Martyn RD, Xu Y. Colonization of Fusarium wilt-resistant and susceptible watermelon roots by a green-fluorescent-protein-tagged isolate of Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. niveum. J Phytopathol. 2014;162(4):228–37. doi:10.1111/jph.12174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Guo L, Yang L, Liang C, Wang G, Dai Q, Huang J. Differential colonization patterns of bananas (Musa spp.) by physiological race 1 and race 4 isolates of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense. J Phytopathol. 2015;163(10):807–17. doi:10.1111/jph.12378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zvirin T, Herman R, Brotman Y, Denisov Y, Belausov E, Freeman S, et al. Differential colonization and defence responses of resistant and susceptible melon lines infected by Fusarium oxysporum race 1·2. Plant Pathol. 2010;59(3):576–85. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3059.2009.02225.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jiménez-Fernández D, Landa BB, Kang S, Jiménez-Díaz RM, Navas-Cortés JA. Quantitative and microscopic assessment of compatible and incompatible interactions between chickpea cultivars and Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris races. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e61360. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0061360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Muche M, Yemata G. Epidemiology and pathogenicity of vascular wilt of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. ciceris, and the host defense responses. S Afr J Bot. 2022;151:339–48. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2022.10.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ramírez-Suero M, Khanshour A, Martinez Y, Rickauer M. A study on the susceptibility of the model legume plant Medicago truncatula to the soil-borne pathogen Fusarium oxysporum. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2010;126(4):517–30. doi:10.1007/s10658-009-9560-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhu Y, Abdelraheem A, Cooke P, Wheeler T, Dever JK, Wedegaertner T, et al. Comparative analysis of infection process in Pima cotton differing in resistance to Fusarium wilt caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. vasinfectum race 4. Phytopathology. 2022;112(4):852–61. doi:10.1094/PHYTO-05-21-0203-R. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Bani M, Rubiales D, Rispail N. A detailed evaluation method to identify sources of quantitative resistance to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. pisi race 2 within a Pisum spp. germplasm collection. Plant Pathol. 2012;61(3):532–42. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3059.2011.02537.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Haegi A, Catalano V, Luongo L, Vitale S, Scotton M, Ficcadenti N, et al. A newly developed real-time PCR assay for detection and quantification of Fusarium oxysporum and its use in compatible and incompatible interactions with grafted melon genotypes. Phytopathology. 2013;103(8):802–10. doi:10.1094/PHYTO-11-12-0293-R. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zhong X, Yang Y, Zhao J, Gong B, Li J, Wu X, et al. Detection and quantification of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum race 1 in plants and soil by real-time PCR. Plant Pathol J. 2022;38(3):229–38. doi:10.5423/PPJ.OA.03.2022.0039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Brunner K, Kovalsky Paris MP, Paolino G, Bürstmayr H, Lemmens M, Berthiller F, et al. A reference-gene-based quantitative PCR method as a tool to determine Fusarium resistance in wheat. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009;395(5):1385–94. doi:10.1007/s00216-009-3083-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Thatcher LF, Williams AH, Garg G, Buck SG, Singh KB. Transcriptome analysis of the fungal pathogen Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. medicaginis during colonisation of resistant and susceptible Medicago truncatula hosts identifies differential pathogenicity profiles and novel candidate effectors. BMC Genomics. 2016;17(1):860. doi:10.1186/s12864-016-3192-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Lin Y, Zou W, Lin S, Onofua D, Yang Z, Chen H, et al. Transcriptome profiling and digital gene expression analysis of sweet potato for the identification of putative genes involved in the defense response against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. batatas. PLoS One. 2017;12(11):e0187838. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187838. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Fang SM, Chen YS, Guo XD. Identifying and screening sweet potato varieties resistance to bacterial wilt and Fusarium wilt diseases. J Plant Genet Resour. 2001;2(1):37–9. (In Chinese). doi:10.13430/j.cnki.jpgr.2001.01.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Visser M, Gordon TR, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ, Viljoen A. Transformation of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense, causal agent of Fusarium wilt of banana, with the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene. Australas Plant Pathol. 2004;33(1):69–75. doi:10.1071/AP03084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Lorang JM, Tuori RP, Martinez JP, Sawyer TL, Redman RS, Rollins JA, et al. Green fluorescent protein is lighting up fungal biology. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67(5):1987–94. doi:10.1128/AEM.67.5.1987-1994.2001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Liu S, Li J, Zhang Y, Liu N, Viljoen A, Mostert D, et al. Fusaric acid instigates the invasion of banana by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense TR4. New Phytol. 2020;225(2):913–29. doi:10.1111/nph.16193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Jackson E, Li J, Weerasinghe T, Li X. The ubiquitous wilt-inducing pathogen Fusarium oxysporum—a review of genes studied with mutant analysis. Pathogens. 2024;13(10):823. doi:10.3390/pathogens13100823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Peng M, Wang J, Lu X, Wang M, Wen G, Wu C, et al. Functional analysis of cutinase transcription factors in Fusarium verticillioides. Phytopathol Res. 2024;6(1):48. doi:10.1186/s42483-024-00267-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Yun Y, Zhou X, Yang S, Wen Y, You H, Zheng Y, et al. Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici C2H2 transcription factor FolCzf1 is required for conidiation, fusaric acid production, and early host infection. Curr Genet. 2019;65(3):773–83. doi:10.1007/s00294-019-00931-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Ghosal D, Datta B. Molecular characterization of secreted in Xylem 1 (Six1) gene of Fusarium oxysporum causing wilt of potato (Solanum tuberosum). Plant Pathol. 2024;73(7):1847–58. doi:10.1111/ppa.13945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Duyvesteijn RGE, van Wijk R, Boer Y, Rep M, Cornelissen BJC, Haring MA. Frp1 is a Fusarium oxysporum F-box protein required for pathogenicity on tomato. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57(4):1051–63. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04751.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Dong X, Ling J, Li Z, Jiao Y, Zhao J, Yang Y, et al. Insights into the pathogenic role of fusaric acid in Fusarium oxysporum infection of Brassica oleracea through the comparative transcriptomic, chemical, and genetic analyses. J Agric Food Chem. 2025;73(16):9559–69. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.5c01032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Li Y, Wang Y, Zhang H, Zhang Q, Zhai H, Liu Q, et al. The plasma membrane-localized sucrose transporter IbSWEET10 contributes to the resistance of sweet potato to Fusarium oxysporum. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8(e44467):197. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zhang H, Zhang Q, Zhai H, Gao S, Yang L, Wang Z, et al. IbBBX24 promotes the jasmonic acid pathway and enhances Fusarium wilt resistance in sweet potato. Plant Cell. 2020;32(4):1102–23. doi:10.1105/tpc.19.00641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Nie N, Huo J, Sun S, Zuo Z, Chen Y, Liu Q, et al. Genome-wide characterization of the PIFs family in sweet potato and functional identification of IbPIF3.1 under drought and Fusarium wilt stresses. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4):4092. doi:10.3390/ijms24044092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Liu Y, Chen PR, Lei J, Wang LJ, Chai SS, Jin XJ, et al. Sequence and expression analysis of IbERF1 gene response to Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. batatas infection in Ipomoea batatas. Genom Appl Biol. 2022;41(1):175–84. (In Chinese). doi:10.13417/j.gab.014.000175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Jing XJ, Yang XS, Jin XJ, Liu Y, Lei J, Wang LJ, et al. Cloning and characterization of IbMAPKK9 gene associated with Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. batatas in sweet potato. Acta Agron Sin. 2023;49(12):3289–301. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

43. Guo X, Li R, Ding Y, Mo F, Hu K, Ou M, et al. Visualization of the infection and colonization process of Dendrobium officinale using a green fluorescent protein-tagged isolate of Fusarium oxysporum. Phytopathology. 2024;114:1791–801. doi:10.1094/phyto-12-23-0495-r.44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Namisy A, Chen SY, Huang JH, Unartngam J, Thanarut C, Chung WH. Histopathology and quantification of green fluorescent protein-tagged Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. luffae isolate in resistant and susceptible Luffa germplasm. Microbiol Spectr. 2024;12(2):e03127–23. doi:10.1128/spectrum.03127-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Batista RO, Leite TS, Nicoli A, Carneiro JES, Carneiro PCS, Paula Junior TJ, et al. Infection and colonization of common bean by EGFP transformants of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp phaseoli. Genet Mol Res. 2019;18(4):GMR18370. doi:10.4238/gmr18370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Yao J, Huang P, Chen H, Yu D. Fusarium oxysporum is the pathogen responsible for stem rot of the succulent plant Echeveria ‘Perle von Nürnberg’ and observation of the infection process. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2021;159(3):555–68. doi:10.1007/s10658-020-02186-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Edel-Hermann V, Lecomte C. Current status of Fusarium oxysporum formae speciales and races. Phytopathology. 2019;109(4):512–30. doi:10.1094/PHYTO-08-18-0320-RVW. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Tian D, Qin L, Verma KK, Wei L, Li J, Li B, et al. Transcriptomic and metabolomic differences between banana varieties which are resistant or susceptible to Fusarium wilt. PeerJ. 2023;11(5426):e16549. doi:10.7717/peerj.16549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Yuan F, Qiu F, Xie J, Fan Y, Zhang B, Zhang T, et al. Mechanism of action of Fusarium oxysporum CCS043 utilizing allelochemicals for rhizosphere colonization and enhanced infection activity in Rehmannia glutinosa. Plants. 2024;14(1):38. doi:10.3390/plants14010038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Bishop CD, Cooper RM. An ultrastructural study of root invasion in three vascular wilt diseases. Physiol Plant Pathol. 1983;22(1):15–IN13. doi:10.1016/S0048-4059(83)81034-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Turlier MF, Eparvier A, Alabouvette C. Early dynamic interactions between Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lini and the roots of Linum usitatissimum as revealed by transgenic GUS-marked hyphae. Can J Bot. 1994;72(11):1605–12. doi:10.1139/b94-198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Olivain C, Humbert C, Nahalkova J, Fatehi J, L’Haridon F, Alabouvette C. Colonization of tomato root by pathogenic and nonpathogenic Fusarium oxysporum strains inoculated together and separately into the soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(2):1523–31. doi:10.1128/AEM.72.2.1523-1531.2006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Wang X, Shen C, Meng P, Tan G, Lv L. Analysis and review of trichomes in plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21(1):70. doi:10.1186/s12870-021-02840-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Kang JH, Liu G, Shi F, Jones AD, Beaudry RM, Howe GA. The tomato odorless-2 mutant is defective in trichome-based production of diverse specialized metabolites and broad-spectrum resistance to insect herbivores. Plant Physiol. 2010;154(1):262–72. doi:10.1104/pp.110.160192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Kim KW. Plant trichomes as microbial habitats and infection sites. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2019;154(2):157–69. doi:10.1007/s10658-018-01656-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Calo L, García I, Gotor C, Romero LC. Leaf hairs influence phytopathogenic fungus infection and confer an increased resistance when expressing a Trichoderma α-1,3-glucanase. J Exp Bot. 2006;57(14):3911–20. doi:10.1093/jxb/erl155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Łaźniewska J, Macioszek VK, Kononowicz AK. Plant-fungus interface: the role of surface structures in plant resistance and susceptibility to pathogenic fungi. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2012;78(Suppl. 1):24–30. doi:10.1016/j.pmpp.2012.01.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Nguyen TTX, Dehne HW, Steiner U. Maize leaf trichomes represent an entry point of infection for Fusarium species. Fungal Biol. 2016;120(8):895–903. doi:10.1016/j.funbio.2016.05.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Sun Z, Zhu F, Chen X, Li T. The pivotal role of trichomes in wheat susceptibility to Fusarium head blight. Plant Pathol. 2024;73(7):1615–8. doi:10.1111/ppa.13933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Srivastava V, Patra K, Pai H, Aguilar-Pontes MV, Berasategui A, Kamble A, et al. Molecular dialogue during host manipulation by the vascular wilt fungus Fusarium oxysporum. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2024;62(1):97–126. doi:10.1146/annurev-phyto-021722-034823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Husaini AM, Sakina A, Cambay SR. Host-pathogen interaction in Fusarium oxysporum infections: where do we stand? Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2018;31(9):889–98. doi:10.1094/MPMI-12-17-0302-CR. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Brown DW, Lee SH, Kim LH, Ryu JG, Lee S, Seo Y, et al. Identification of a 12-gene fusaric acid biosynthetic gene cluster in Fusarium species through comparative and functional genomics. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2015;28(3):319–32. doi:10.1094/MPMI-09-14-0264-R. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. López-Díaz C, Rahjoo V, Sulyok M, Ghionna V, Martín-Vicente A, Capilla J, et al. Fusaric acid contributes to virulence of Fusarium oxysporum on plant and mammalian hosts. Mol Plant Pathol. 2018;19(2):440–53. doi:10.1111/mpp.12536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Brenes Guallar MA, Fokkens L, Rep M, Berke L, van Dam P. Fusarium oxysporum effector clustering version 2: an updated pipeline to infer host range. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1012688. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1012688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Yu DS, Outram MA, Smith A, McCombe CL, Khambalkar PB, Rima SA, et al. The structural repertoire of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici effectors revealed by experimental and computational studies. eLife. 2024;12:RP89280. doi:10.7554/eLife.89280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Jangir P, Mehra N, Sharma K, Singh N, Rani M, Kapoor R. Secreted in xylem genes: drivers of host adaptation in Fusarium oxysporum. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:628611. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.628611. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Sun T, Zhang Y. MAP kinase cascades in plant development and immune signaling. EMBO Rep. 2022;23(2):e53817. doi:10.15252/embr.202153817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Chen L, Zhang L, Xiang S, Chen Y, Zhang H, Yu D. The transcription factor WRKY75 positively regulates jasmonate-mediated plant defense to necrotrophic fungal pathogens. J Exp Bot. 2021;72(4):1473–89. doi:10.1093/jxb/eraa529. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Yu K, Zhang Y, Fei X, Ma L, Sarwar R, Tan X, et al. BnaWRKY75 positively regulates the resistance against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in ornamental Brassica napus. Hortic Plant J. 2024;10(3):784–96. doi:10.1016/j.hpj.2023.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Guo W, Chen W, Guo N, Zang J, Liu L, Zhang Z, et al. MdWRKY61 positively regulates resistance to Colletotrichum siamense in apple (Malus domestica). Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2022;117:101776. doi:10.1016/j.pmpp.2021.101776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Zhu Y, Tian Y, Han S, Wang J, Liu Y, Yin J. Structure, evolution, and roles of SWEET proteins in growth and stress responses in plants. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;263(Pt 2):130441. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130441. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Chen HY, Huh JH, Yu YC, Ho LH, Chen LQ, Tholl D, et al. The Arabidopsis vacuolar sugar transporter SWEET2 limits carbon sequestration from roots and restricts Pythium infection. Plant J. 2015;83(6):1046–58. doi:10.1111/tpj.12948. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Yu J, Chai C, Ai G, Jia Y, Liu W, Zhang X, et al. A Nicotiana benthamiana AP2/ERF transcription factor confers resistance to Phytophthora parasitica. Phytopathol Res. 2020;2(1):4. doi:10.1186/s42483-020-0045-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Zhang J, Wang D, Chen P, Zhang C, Yao S, Hao Q, et al. The transcriptomic analysis of the response of Pinus massoniana to drought stress and a functional study on the ERF1 transcription factor. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(13):11103. doi:10.3390/ijms241311103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools