Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Regenerative Agriculture: A Sustainable Path for Boosting Plant and Soil Health

1 Regional Centre of Agricultural Research of Sidi Bouzid, Gafsa Road Km 6, B.P. 357, Sidi Bouzid, 9100, Tunisia

2 Research Laboratory of Agricultural Production Systems and Sustainable Development (LR03AGR02), Department of Agricultural Production, Higher School of Agriculture of Mogran, University of Carthage, Mogran Zaghouan, Tunis, 1121, Tunisia

3 Faculty of Sciences and Techniques of Sidi Bouzid, University of Kairouan, Kairouan, 3100, Tunisia

4 Agricultural Vocational Training Center Chott Meriem Agriculture Extension and Training Agency, Chott-Mariem, 4042, Tunisia

* Corresponding Authors: Lobna Hajji-Hedfi. Email: ,

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plants Abiotic and Biotic Stresses: from Characterization to Development of Sustainable Control Strategies)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2255-2284. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.066951

Received 21 April 2025; Accepted 11 August 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Fungal plant diseases are infections caused by pathogenic fungi that affect crops, ornamental plants, and trees. Symptoms of these diseases can include leaf spots, fruit rot, root rot, and generalized growth retardation. Fungal diseases can result in decreased quality and quantity of crops, which can have a negative economic impact on farmers and producers. Moreover, these diseases can cause environmental damage. Indeed, fungal diseases can directly affect crops by reducing plant growth and yield, as well as altering their quality and nutritional value. Although effective, the use of many chemical products is often harmful to health and the environment, and their use is increasingly restricted due to their high toxicity. To address this issue, it is becoming increasingly essential to replace these chemical products with products that respect the environment and human health, and for sustainable agriculture, such as regenerative agricultural practices. Regenerative agricultural practices such as crop rotation, intercropping, composting, and no-till farming techniques can offer sustainable solutions for the prevention and control of plant fungal diseases. These regenratives approaches not only help to control fungal plant disease by strengthening plant disease resistance, but also significantly contribute to the improvement of sustainable agriculture, by restoring soil health, increasing biodiversity and reducing the use of harmful chemicals to the environment and human health in order to keep a long-term ecosystem resilience, promote environmental sustainability, and support global food security. Using regenerative agricultural practices can provide a holistic and effective approach to controlling fungal plant diseases while improving the health and productivity of farming systems.Keywords

Among the most significant problems facing agriculture are plant diseases. It can lower agricultural product quality and yield losses and increase crop treatment expenses. A significant yield-limiting issue in agricultural production is plant diseases [1]. Of these diseases, 70%–80% are caused by pathogenic fungi. Plant-pathogenic fungi have adverse effects on crop growth and yield [2]. In recent years, fungal diseases of crops have become increasingly serious as they have severely affected crop yield and quality, and they have become an important bottleneck for the development of sustainable agriculture [3]. Some diseases are not caused by a single pathogen but rather are the result of the synergy of multiple pathogens [1]. For instance, Fusarium wilt is an important fungal disease affecting many crops (corn, wheat, tomato, and fruit trees), causing significant yield losses and reducing the quality of crops. Grey rot, caused by B. cinerea, is a fungal disease that affects many plants, including fruits, vegetables, flowers, and ornamental crops. It causes significant damage to crop and is considered one of the most damaging diseases for current agriculture [4].

Fungal diseases cause 70%–80% of all diseases that affect plants in general. Plants are damaged by killing cells and blocking transporters, as is the case with vascular fungi (such as Fusarium and Verticillium) that obstruct the movement of nutrients in vascular tissues [5,6]. Fungal diseases manifest in various ways in plant tissues. Some, like downy mildew, target leaves and vegetative structures. Others, like Botrytis fruit rot, cause decay and spotting on fruits. Additionally, fungal pathogens like Phytophthora can infect plant roots, leading to root rot [1,2].

To address these problems, various inputs are used to improve crop yields or eliminate harmful organisms. However, in recent years, consumers have become increasingly aware of the destructive effects of pesticides on the environment (water and soil quality) and their health. Chemical control remains very costly and could create numerous constraints (economically not feasible, increasing environmental pollution, the appearance of resistant isolates, etc.) [7].

The effects of synthetic pesticides on human health have sparked interest in finding an alternative way to control diseases that attack fruits and vegetables. To reduce dependence on synthetic pesticides, the use of regenerative agricultural practices can help manage phytopathogens as an alternative method for sustainable agriculture that is respectful of human health and the environment. Regenerative agricultural practice as a crop management procedure represents the oldest and most broadly applicable ecofriendly innovative approach with farmers for the prevention of losses in crops due to diseases and other causes despite the development of chemical methods; this approach has excellent promise for the future [3].

Although “regenerative agriculture” is a new concept, its practices are pegged on both recent research and ancient wisdom [8]. Regenerative agriculture draws considerable parallels with earlier concepts like organic farming, permaculture, indigenous knowledge, sustainable agriculture, and holistic management [9]. These more traditional approaches revolve around biodiversity, soil fertility, ecosystem health, and long-term sustainability [10,11]. Regenerative Agriculture goes further to emphasize such techniques that restore and enhance the ecosystems, like carbon sequestration, control of the water cycle, and increasing organic matter in the soil [11–14]. Being conscious of these historical underpinnings helps us understand the scope and potential of regenerative agriculture in finding solutions to present-day problems in food security and climate change [14,15].

Regenerative agriculture is based upon a philosophy that seeks to replicate the structure and function equivalent to natural systems in a design similar to biologically healthy and resilient farm systems [8,9]. Regenerative farming requires a mindset that is structured, system-based, place-based, and positive-outcome oriented [11]. Regenerative design is an approach where the output of a system improves the health and resiliency of that system over time [7,14]. Furthermore, regenerative agriculture is a farming practice that embraces the principles of sustainability and aims to restore degraded farmland to a state of health while sustaining its land-based income for those who depend on it for their livelihood [15]. This practice has been gaining popularity among farmers and consumers alike, as it offers a more natural approach to agriculture that is not only beneficial to the environment but also helps to improve the productivity and resilience of farms [3,9].

Regenerative agriculture is a farming method that aims to restore soil health and encourage biodiversity [9,14]. By using practices such as crop rotation [16], composting [17], fertilization [18], covering the soil [19], intercropping [20], soil solarization [21], and regenerative farmers can improve soil structure and promote the growth of healthy plants [10]. Additionally, these practices can also help prevent plant diseases [12]. Regenerative agricultural practices have a significant impact on soil health, which in turn has beneficial effects on plant diseases [10,14].

2 The Five Main Principles of Regenerative Agriculture

The term regenerative agriculture has gained increasing attention as a successful agricultural approach with great potential for regenerating and maintaining ecosystems. Regenerative agriculture (RA) is an agricultural strategy that uses natural processes to enhance soil health, restore landscape function, improve nutrient cycling, produce food and fiber, augment biological activity, deliver high productivity and high-quality food [22].

RA is often combined with agricultural practices and principles that draw on environmental science to work with and enhance natural processes. Principles focus on the processes associated with RA including supporting and promoting plant diversity, decreasing soil disturbance, and living root systems [14].

In the context of plant disease control, we discuss the 5 principles of RA which are (i) reducing soil disturbance, (ii) covering the soil, (iii) ensuring live roots in the soil all year round, (vi) practicing crop diversity, and (v) integrating livestock.

Industrial agriculture’s reliance on heavy tillage accelerates soil erosion, jeopardizing productivity and sustainability [23]. Regenerative agriculture offers a science-based solution, prioritizing minimal soil disturbance to promote a healthy microbiome and combat this challenge [24,25]. Minimizing tillage achieves three key goals: preserving soil structure for improved water retention and erosion resistance, nurturing beneficial microbes for nutrient cycling and disease suppression, and boosting organic matter content for enhanced fertility and water-holding capacity [26,27]. These mechanisms translate into tangible benefits like for example increased crop yields with reduced reliance on external inputs, efficient water management through improved drought tolerance, hence carbon sequestration mitigating climate change. Regenerative agriculture prioritizes soil health, leveraging natural processes to combat erosion, enhance productivity, and build resilience for a more sustainable future. Further research and implementation are crucial to maximize its potential and ensure widespread adoption [25,28–30].

Regenerative agriculture practices like minimum or no tillage aim to minimize soil disturbance. This approach promotes fungal growth, enhancing nutrient cycling within the soil. Conversely, conventional tillage practices disrupt the soil, increase carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and water resource depletion. Minimum tillage offers cost savings and reduces soil erosion risk. Additionally, some studies suggest conservation tillage methods can increase soil organic carbon (SOC) sequestration, potentially mitigating climate change [31,32].

The most effective strategy for boosting SOC appears to be minimum tillage combined with residue retention in double-cropping systems. Increased SOC concentration in topsoil enhances soil productivity, biological activity, and resilience to harsh weather. Studies suggest a potential increase of 4.6 Mg/ha in SOC stock within the upper 30 cm of soil under no-tillage compared to conventional tillage over a decade. However, SOC accumulation under continuous no-tillage farming might be insignificant in warm, semi-arid climates. Perennial pastures incorporated into crop rotations can promote slow SOC accumulation in such environments. Several factors influence SOC increase with conservation tillage, including precipitation, soil depth, crop yield, and decomposition rate [14,33].

Current practices in Southeast Australia are unlikely to increase SOC in the short term, but incorporating legume leys could restore soil organic matter (SOM) in the long term due to increased root biomass. Long-term tillage practices have a more significant impact on SOC than short-term practices. Additionally, clay content plays a role in SOM storage-tillage practices reduce carbon stabilization within micro aggregates in clayey soils but have minimal effect on sandy soils. Research suggests that tillage disrupts soil, leading to SOC loss, while switching to conservation tillage can promote substantial SOC sequestration, especially in North America [34,35].

No-till (NT) farming is another approach to improving soil biology. Studies show increased soil fertility (N, P, and K) and higher SOC levels under NT compared to conventional tillage (CT) in irrigated Mediterranean systems. This translates to higher biological activity and potentially increased soil productivity under NT. However, some experts argue that the role of no-till in mitigating climate change might be overestimated [14,36].

The impact of no-tillage on crop yields and profitability varies depending on region, crops, and soil properties. While some studies show benefits like increased barley yield (49%) in dry climates and reduced global warming potential [36], others report no significant yield differences compared to conventional tillage [37]. NT alone might not be sufficient, with practices like cover cropping improving soil’s physical properties [38]. Regional conditions influence carbon sequestration and yields. Arid regions might see a “win-win” with NT, while humid areas might only experience an increased SOC [39]. Furthermore, in the Mediterranean semi-arid system, it was reported that a no-till study was initiated in 1994 examined the long-term impact of conventional tillage compared to no tillage. This study focused on durum wheat and Vicia faba L. In the no-till (NT) system, SOC stocks in the top of 0-30 cm increased by approximately 23%, accompanied by significant increases in microbial DNA (dsDNA) and enzyme activities, strongly indicating improved soil health. It was concluded that, in semi-arid Mediterranean agricultural systems, crop residue rotation and reduced tillage can prevent carbon loss, preserve soil, and promote long-term sustainability [40].

Regenerative agriculture emphasizes keeping soil covered and maintaining living roots year-round. Cover crops are a key strategy, typically planted between main cash crops to maintain soil cover. This can be done by planting after harvest or under-seeding cash crops with perennials to take over post-harvest. Cover crops can be single-species or diverse mixes [41]. While single species are easier to manage, multi-species cover crops, including legumes, offer broader benefits: improving nitrogen fixation, microbial diversity, soil compaction, attracting beneficial insects, suppressing weeds, regulating soil temperature, and increasing water infiltration. In addition to improving soil fertility, cover crops contribute to carbon sequestration [42]. Their widespread adoption could reduce agricultural greenhouse gas emissions by 10%, comparable to no-tillage practices [43]. A key benefit is enhanced microbial biomass due to adding organic matter (SOM) to the soil [44]. However, significant increases in soil carbon take several years [45]. Studies show varied responses of cover crops to SOC accumulation across different global regions and climates. In a North American temperate humid region, cover cropping for six years out of eight increased surface SOC storage and improved soil function, but profitability depended on the production system. The exact mechanism of SOC storage with cover crops remains unclear, potentially involving both belowground and aboveground biomass inputs and root exudates [46].

Studies suggested a link between soil texture and cover crop effectiveness in increasing soil carbon. Clay soils appear to benefit more from cover crops in terms of SOC accumulation, as demonstrated by research in Argentina using both fine and coarse-textured soils [47]. Cover crops can also promote SOC accumulation in eroded soils with low initial carbon content [48]. However, the benefits are more pronounced under no-tillage practices due to slower residue decomposition than conventional tillage [49].

Plant diversity is crucial for maintaining soil productivity in both natural and agricultural systems. Crop diversification offers multiple benefits, including increased crop yield and biodiversity, pest and disease suppression, and improved water and soil quality. Legume cover crops, particularly when used without nitrogen fertilizers, can positively affect the subsequent cash crop’s yield [50].

The mechanisms by which cover crops influence subsequent crop yield vary considerably across cropping systems and environments, making it a complex topic with limited understanding [51]. Studies in Western Australia’s low-rainfall regions suggest cover crops can negatively affect gross margins [52]. Additionally, summer cover crops might deplete available moisture, potentially harming subsequent crops, especially during dry seasons [53]. However, some studies report yields improvements in corn and soybeans following cover crops, even in dry years [54]. Positive yield effects might be attributed to reduced soil compaction and temperature, increased soil aggregate stability, carbon and nitrogen content, and improved water retention [55].

Conversely, other studies report yields decline of up to 10% after cover cropping [51]. Cover crops might also harbor pests and diseases that could infect subsequent crops. However, mustard cover crops demonstrate a biofumigation effect, potentially reducing the impact of soil-borne pathogens. Careful management and selection of cover crop species are crucial to maximizing benefits and minimizing risks in dryland agriculture [56].

Cover crops benefit crop production systems regarding disease suppression, microbial host, erosion reduction, soil quality improvement, organic matter provision, and nutrient cycling facilitation [51]. Another role it may play is providing habitat for beneficial microorganisms, improving soil structure, and serving as a non-host crop for pathogens. Such attributes are beneficial in contributing to the overall health and sustainability of agricultural systems [57]. In fact, according to [58] a multi-omics analysis examined the impact of root exudates from four cover crop species of Sorghum bicolor, Vicia villosa, Brassica napus, and Secale cereal on soil microbial functionality. According to the study, different microbial metabolic reactions were induced by the distinctive exudate profiles produced by each species. Several microbial taxa that can produce phytohormones like IAA and GA4 were elevated in exudates from sorghum and cereal. The abundance of bacterial nitrite oxidizers was selectively increased by these exudates, suggesting a focused impact on nitrogen cycle activities. Furthermore, an overall mean change of 15.5%, meta-analysis data collected from international field studies comparing systems with and without cover crops demonstrated that the addition of cover crops considerably boosted SOC. While temperate regions demonstrated more noticeable gains (18.7%) than tropical climates (7.2%), fine-textured soils showed the largest increases (mean change of 39.5%). Additionally, cover crops raised levels of mineralizable carbon and nitrogen and decreased erosion and runoff, among other soil quality indicators. With an estimated mean carbon storage rate of 0.56 Mg ha−¹ yr−¹, cover crops might absorb over 0.16 ± 0.06 Pg C year, or around two percent of current fossil fuel emissions, if only 15% of cropland worldwide adopted them [59].

Regarding pathogen disease, the exact mechanisms by which cover crops suppress soilborne pathogens are not fully understood. However, several potential modes of action have been proposed. These include the production of phytochemicals toxic to pathogens [57], the provision of substrate for beneficial microorganisms such as Pseudomonas, Rhizobacteria, and Trichoderma species [56,60], allelopathic effects [61], and the reduction of pathogen dispersal via rain splash [59].

Cover crops can host arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, which can effectively reduce soilborne diseases [62]. This is supported by the abundance of mycorrhizal fungi in short-term cover crop-maize rotations and the use of forage oats as a fall cover crop [63]. Mycorrhizal fungi form a mat-like structure around plant roots, produce antagonistic chemicals, compete with pathogens, and solubilize nutrients [56].

The disease-suppressive effects of cover crops arise from multiple, often interconnected, mechanisms [64]. These can be broadly categorized into primary and secondary effects [35,27]. Primary mechanisms include the direct release of allelopathic compounds by cover crops, which can inhibit pathogen growth or germination. Complementing these are secondary, biologically-mediated mechanisms, such as the enhancement of beneficial microbial communities in the rhizosphere and bulk soil [61,41]. These microbial communities exert antagonism against pathogens through competition for resources, hyperparasitism, antibiosis, or induced systemic resistance in host plants [60,55,49]. Additionally, cover crops contribute to improved soil structure and water infiltration, indirectly creating an environment less conducive to disease development [53]. Understanding the interplay between these diverse mechanisms is crucial for optimizing cover crop selection and management for enhanced disease suppression [51].

2.3 Ensuring Live Roots in the Soil All-Year-Round

Regenerative agriculture hinges on maintaining continuous living roots in soil throughout the year. Cover crops, strategically chosen for their diverse benefits, play a crucial role in achieving this. Beyond mere soil protection, these plant communities offer a multitude of advantages as follows [14,65,66]:

Enhancing Organic Matter: Cover crops decompose, enriching soil with organic matter (OM), fostering soil microbiota, and increasing water retention. Improved OM content translates to enhanced soil structure, promoting root development and efficient nutrient cycling [14,65,66].

Efficient Nutrient Management: Nitrogen-fixing cover crops enrich soil fertility by converting atmospheric nitrogen into plant-usable forms, minimizing reliance on external fertilizers. Additionally, they efficiently capture residual nutrients from main crops, preventing leaching and pollution [14,65,66].

Weed Suppression and Erosion Control: Live cover effectively utilizes water and suppresses unwanted weed growth, minimizing competition with main crops. Their dense root networks bind soil particles, significantly reducing wind and water runoff erosion [14,65,66].

Microorganism Haven: Continuous root exudates from living cover crops nourish diverse soil microbial communities, including beneficial bacteria and fungi. These microbes enhance nutrient availability, improve plant disease resistance, and contribute to overall soil health [14,65,66].

Building Ecosystem Services: Cover crops act as “biological armor,” protecting the delicate surface layer from harsh weather. Their continuous photosynthesis fuels the base of the soil food web, fostering beneficial organisms that provide natural fertilization and pest control services for subsequent crops [14,65,66].

Regenerative agriculture emphasizes crop diversity as a key principle, advocating for varied plantings instead of monoculture reliance. This approach, achievable through cover crops, crop rotation, and intercropping, counters the detrimental effects of monoculture practices, which deplete soil nutrients and exacerbate erosion [67].

The scientific basis for crop diversity rests upon several vital benefits:

Balanced Nutrient Profile: Different crops uptake and mineralize unique nutrient profiles, enriching the soil with diverse organic matter. This fosters a “nutritional balance” within the soil ecosystem, promoting healthy plant growth and reducing reliance on external fertilizers [14].

Enhanced Soil Structure: Varied root systems from diverse crops contribute to improved soil structure. Deeper taproots from certain plants increase porosity and drainage, while fibrous shallow roots from others enhance water infiltration and surface stability. This combined effect fosters a robust soil architecture, crucial for nutrient cycling and water retention [68].

Reduced Pest and Disease Pressure: Monocultures create conditions for specific pests and diseases to thrive. Crop diversity disrupts this cycle by disrupting host availability and attracting beneficial insects that predate harmful ones. This natural pest control reduces the need for synthetic pesticides [69,70].

Improved Water Management: Diverse cover crops and rotations can optimize water infiltration and utilization. Deep-rooted plants access deeper water reserves, while shallow-rooted crops improve surface water absorption. This combined strategy enhances overall water efficiency and reduces erosion risk [65].

Resilient Agricultural Systems: By mimicking natural ecosystems, crop diversity fosters a more resilient farm system. The varied plant communities are better equipped to withstand environmental stressors like drought, extreme weather, and pest outbreaks, leading to more stable yields and reduced risk of crop failure [68].

Demonstrating the impact of this regenerative practice of crop diversity rotation, a 36-year field experiment in a temperate area that varied maize-soybean rotations by incorporating cover crops, including small grain cereals and cover crops under rainout shelters to simulate drought conditions. Rotation diversification, according to the study, mitigated plant water stress at both the leaf and canopy levels, reducing maize yield losses under drought by 17.1% ± 6.1% [71]. Furthermore, in field trials conducted with long-term crop rotation have demonstrated that boosting crop diversity, especially by using cover crops, can improve soil microbial communities with disease-suppressive characteristics. Beneficial bacteria carrying the prnD gene, associated with antifungal compound production, by approximately 9% compared to monocultures, highlighting how crop diversity can improve natural soil disease suppression and contribute to sustainable plant health management [72].

Therefore, incorporating crop diversity into regenerative agriculture fosters a holistic approach to soil health, pest management, and overall farm resilience. This scientifically sound approach contributes to a more sustainable and productive agricultural system in the long run [70].

Regenerative agriculture actively incorporates livestock into farming systems through practices like managed grazing, aiming to benefit the land, animals, humans, and the environment [73]. Beyond enhancing the previously mentioned principles, integrating livestock provides several scientifically recognized benefits:

Improved Soil Health: Animal manure directly adds organic matter to the soil, enriching the microbial community and enhancing nutrient cycling. The diversity of microbial life fostered by these additions improves soil fertility and overall health [74].

Enhanced Nutrient Cycling: Manure serves as a natural fertilizer, returning nutrients to the soil in forms readily available to plants. This reduces reliance on external fertilizers and promotes a more closed-loop system within the farm [75].

Reduced Soil Erosion: Managed grazing practices can combat erosion by promoting plant cover and distributing plant residues across the land. Animal hooves can further break down compacted soil, improving infiltration and water retention [76].

Improved Water Infiltration: Reduced compaction and increased soil aggregation, facilitated by controlled grazing, enhance water infiltration. This ensures efficient water utilization and promotes healthy plant growth [76].

Diversified Income and Protein Source: Integrating livestock provides farmers and local communities with additional income opportunities and access to protein sources, contributing to rural livelihoods and economic resilience [77].

Managed grazing forms the core of responsible livestock integration. Rotating animals through different pastures prevents overgrazing and allows for plant recovery, promoting plant growth and soil health in the end. In wheat crop, sheep rotational grazing was found to reduce cumulative CO2 emissions by up to 33% when compared to ungrazed controls, while also increasing soil organic carbon (SOC) by 23.5% and readily oxidized organic carbon by 7.7%. These findings demonstrate that, in addition to improving soil carbon storage, selective grazing can mitigate climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Therefore, integrating livestock into regenerative agriculture goes beyond mere animal rearing. It represents a scientifically grounded approach toward creating a more holistic, sustainable, and productive farming system that benefits the entire ecosystem and its stakeholders [77,78].

3 Disease Management Techniques in Regenerative Agriculture

Regenerative agricultural practices, such as crop rotation, cover cropping, and compost application, demonstrably enhance soil health and consequently bolster plant disease resistance. This effect is mediated by fostering a rich and diverse community of beneficial soil microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, and protozoa. These microbial allies thrive under the improved nutritional and environmental conditions created by regenerative practices, leading to several beneficial outcomes for plant health. Firstly, these microorganisms efficiently decompose organic matter, releasing essential nutrients readily accessible by plants. Secondly, they act as natural biocontrol agents by producing compounds that directly inhibit and even eradicate harmful plant pathogens. This targeted suppression of disease-causing organisms contributes to increased plant resilience against fungal diseases. In essence, regenerative agriculture fosters a vibrant microbial ecosystem within the soil, functioning as a potent natural defense mechanism for plant health [79].

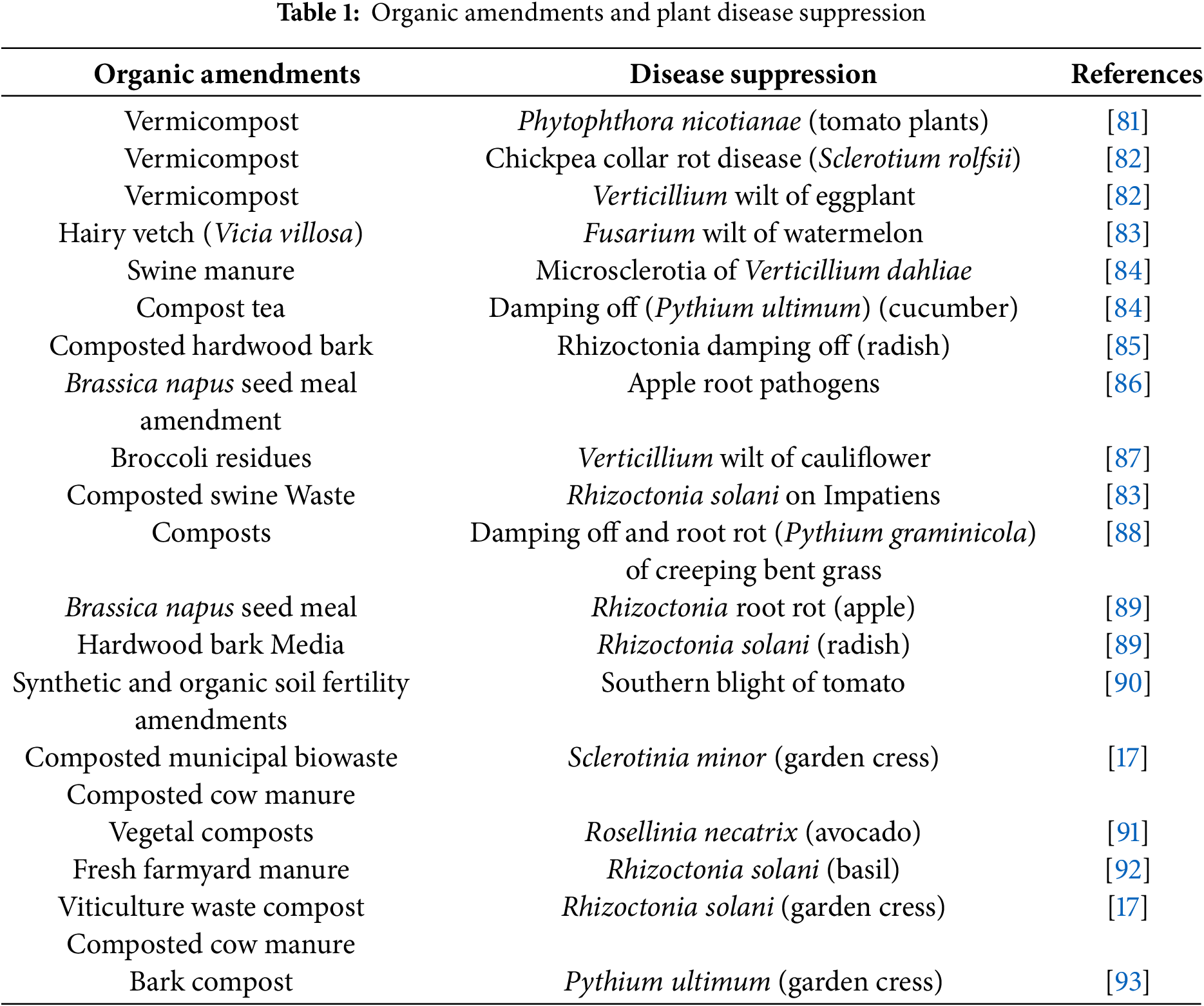

Organic amendments, encompassing diverse materials like cover crops, manure, and composts, hold exciting potential for boosting plant nutrition and suppressing soilborne pathogens. Their ability to enhance soil suppressiveness against various plant diseases across agricultural and horticultural crops is well established. However, realizing their full potential in disease control presents several challenges (Table 1) [79].

One key hurdle lies in the inherent variability of organic amendments themselves. Variations in chemical composition, composting methods, and resident microbial communities significantly affect their suppressive potential, leading to inconsistent results and hindering widespread adoption [80]. Additionally, organic amendments exert their disease-suppressive effects through diverse mechanisms, including fueling beneficial microbes, harboring antagonistic microorganisms, and promoting overall soil microbial activity (Table 1) [80].

Further complicating matters are the limited predictability observed with animal manures. While composts demonstrate consistent disease suppression, the impact of animal manures remains less reliable due to their variable composition and potential to harbor pathogens themselves [80].

Compost amendments enhance soil health through various mechanisms, ultimately leading to improved plant growth and disease resistance. By optimizing chemical, physical, and biological soil characteristics, composts create a more favorable environment for plants, reducing their stress levels and fostering resilience against pathogens. However, their positive impact extends beyond indirect effects. High-quality composts, rich in beneficial microorganisms, can promote plant health by harboring antagonistic microbes. These microbial allies actively combat soilborne pathogens through competition, parasitism, or inhibition, providing an additional layer of disease protection [80].

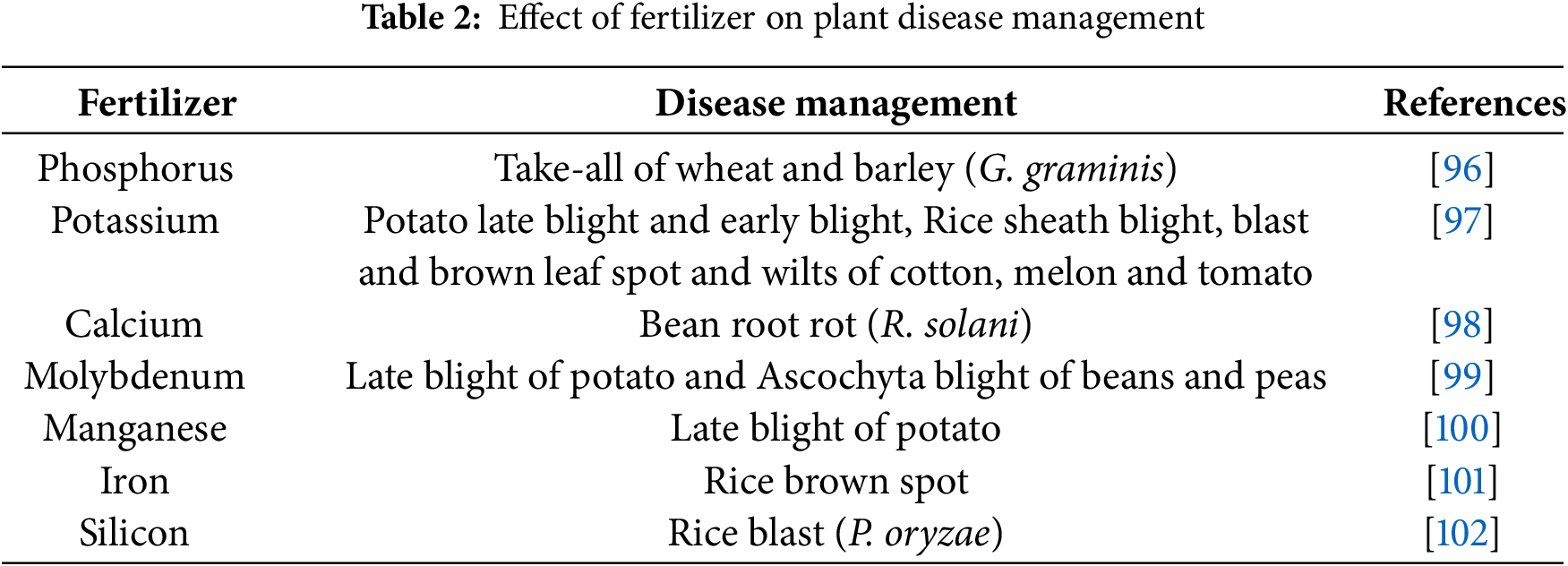

Plant nutritional status plays a crucial role in determining their susceptibility to disease [94]. Nutrient deficiencies can compromise plant defenses, making them more prone to pathogen attacks. Conversely, excessive fertilizer application can also create conditions favorable for pathogen growth, rendering the plant vulnerable. This complex interplay between nutrients and disease highlights the importance of balanced crop nutrition for managing plant health [95].

Two key strategies emerge from this understanding.

Avoiding nutrient stress: Maintaining optimal nutrient levels prevents deficiencies that weaken plant defenses, making them less susceptible to pathogen invasion [95].

Manipulating nutrient availability: Tailoring nutrient supply can create an environment disadvantageous for specific pathogens, hindering their growth and reproduction. Effectively employing these strategies empowers farmers to utilize nutrient management as a valuable tool for safeguarding crop health and promoting sustainable agricultural practices [95].

Plant diseases and nutrient deficiencies are intricately linked. Specific nutrient imbalances can predispose plants to specific diseases, highlighting the importance of balanced plant nutrition for disease management. For example, calcium deficiency increases wilting incidence in tomatoes, while zinc deficiency makes maize more susceptible to downy mildew [94]. Conversely, excessive nitrogen application can also have detrimental effects. High nitrogen in potatoes increases late blight susceptibility, while in wheat, it can exacerbate rusts, mildews, blight, and Karnal bunt [94]. These examples demonstrate the diverse ways nutrient imbalances can influence plant-pathogen interactions. Implementing appropriate nutrient management practices that address deficiencies and excesses holds significant potential for reducing disease frequency and promoting plant health [95].

While high nitrogen fertilizer application is suggested for controlling sugar beet root rot caused by Sclerotium rolfsii, the mechanism remains debatable. One proposed explanation attributes control to ammonia (NH3) accumulation and subsequent acidification of soil pH due to urea utilization [94,95]. Interestingly, Table 2 shows various instances where fertilizer application can decrease plant disease frequency. This diverse range of examples highlights the complex interplay between nutrients, plant health, and pathogen growth. Elucidating these intricate relationships and tailoring fertilizer strategies holds significant promise for developing sustainable disease management solutions in diverse crops [95].

Nitrogen, the cornerstone of plant growth, plays a surprisingly intricate role in disease development [103]. While abundance is a critical factor influencing disease susceptibility, research demonstrates inconsistent and poorly elucidated results. This complexity stems from several factors. Plants absorb nitrogen in two forms: nitrate (NO3-) and ammonium (NH4+). These forms influence disease differently, with NO3- often linked to increased susceptibility to obligate parasites (e.g., Puccinia graminis) which depend directly on living host cells for nutrients [100]. Obligate parasites, as mentioned above, have distinct nutritional needs compared to facultative parasites like Fusarium oxysporum, which can utilize dead or dying plant tissues. High nitrogen can decrease the severity of diseases caused by these facultative parasites [104]. Understanding these nutritional differences between pathogen types is crucial. Obligates rely on the plant’s metabolic machinery, often thriving in environments rich in available sugars and amino acids, both products of a nitrogen-rich environment. Conversely, facultative parasites can exploit alternative sources, making them less susceptible to nitrogen-related changes in the host plant [105,106].

Potassium (K) plays a multifaceted role in plant health, affecting stress response and disease resistance. Deficiencies manifest as weakened cell walls, diminished root systems, and accumulated sugars and nitrogen, all factors that compromise the plant’s ability to resist pathogen invasion. K fertilization emerges as a powerful tool, influencing not only insect infestations but also disease susceptibility across diverse host plants [105].

This influence stems from two key roles:

Metabolic Stress Protection: Adequate K levels bolster the plant’s resilience against metabolic stress, mitigating the negative impacts of various stressors that can leave it vulnerable to infection [107,108].

Enhanced Disease Resistance: K directly strengthens the plant’s defense mechanisms, up to an optimal level. Increasing the K amendment results in a decrease in plant resistance [107,108].

The effectiveness of K as a disease control agent is evident in Perrenoud’s comprehensive analysis of 2449 studies in 1990. The data paints a compelling picture. K application significantly decreased the occurrence of fungal (~70%), bacterial (~69%), viral (~41%), insect and mite (~63%), and nematode (~33%) diseases [97].

Phosphorus (P), second only to nitrogen in fertilizer application, plays a vital role in plant life. Beyond its fundamental role in RNA synthesis (Ribonucleic Acid) and numerous biochemical processes, P serves various purposes in agriculture. P finds unique applications as a fungicide, bactericide, and nematicide, directly targeting harmful pathogens in different formulations. P fertilizers are widely used to improve crop yields, addressing deficiencies that significantly hamper production [107].

Interestingly, the most promising application of P in disease control appears to be in seedling protection. Faster root development triggered by P allows seedlings to escape the vulnerable early stages where they are most susceptible to fungal diseases. Similarly, P application shows promise in reducing root rot in corn, especially in P-deficient soils, suggesting a synergy between optimal P levels and enhanced root health [108].

While the link between adequate phosphorus (P) supply and improved crop growth is well-established, its influence on disease resistance presents a more intricate picture. Studies reveal promising results with foliar application of phosphate salts, inducing disease resistance in diverse crops like cucumber, broad bean, grapevine, maize, and rice. This suggests that P may contribute to disease reduction, beyond its core role in plant growth [109].

While often overlooked, micronutrients play a crucial role beyond essential plant functions. Their involvement in plant physiology and biochemistry extends to influencing plant response to pathogens, offering valuable support in the fight against disease. This multi-pronged defense mechanism operates through three key pathways. Micronutrients can induce structural or physiological alterations within the plant itself, enhancing its resistance to pathogen invasion or hindering the spread of disease. For example, calcium strengthens cell walls, while silicon can form physical barriers against fungal penetration [108]. Some micronutrients exhibit direct toxicity towards specific pathogens, acting as natural antimicrobial agents. Copper ions, for instance, can disrupt essential metabolic pathways in fungal cells, while boron can inhibit spore germination [108]. Micronutrients can act as “fertilizers” for beneficial microbes inhabiting the plant’s rhizosphere or phyllosphere. These microbes, in turn, compete with or directly antagonize harmful pathogens, creating a natural biocontrol system [108].

While manganese (Mn) stands as the most intensely studied micronutrient for its influence on disease resistance, its practical application remains limited due to challenges with fertilizer efficacy and soil retention. Mn plays a crucial role in the biosynthesis of lignin and phenol compounds, vital components of plant cell walls. In Mn-deficient plants, compromised cell wall integrity weakens their ability to physically restrict fungal hyphae penetration, leaving them vulnerable to invasion. Conversely, adequate Mn nutrition facilitates the suppression of aminopeptidase enzymes within the plant, essential for fungal growth, and hinders the activity of pectin methylesterase, an enzyme used by fungi to break down host cell walls. These mechanisms collectively contribute to Mn’s potential in controlling pathogenic diseases [110–112].

Iron (Fe), an essential micronutrient for both plants and pathogens, presents a complex dilemma in their interactions. While vital for numerous biological processes, its ability to catalyze the formation of harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS) creates a double-edged sword. Plants can leverage this duality to their advantage, strategically manipulating local oxidative stress as a defense mechanism against invading pathogens. By limiting iron availability or compartmentalizing iron within cells, plants can create an environment unfavorable for pathogen growth and reproduction. Conversely, pathogens have evolved diverse strategies to overcome these iron limitations, employing mechanisms like siderophore production to chelate and acquire iron from the host or even directly damaging plant cells to access intracellular iron stores [113–115].

Though not classified as an essential nutrient, silicon (Si) stands out as a promising tool for mitigating disease severity in various crops, particularly within the Poaceae, Equisetaceae, and Cyperaceae families. This unique element exerts its protective effect through a multi-faceted approach. By accumulating in plant cell walls, Si forms a formidable barrier, hindering the penetration of fungal pathogens and reducing the effectiveness of their tissue-degrading enzymes. Si deposition strengthens cell walls, making them more resistant to mechanical stress and enzymatic degradation, further impeding pathogen invasion. Si triggers various physiological responses within the plant, activating defense genes and promoting the production of protective compounds, leading to a more robust immune system [116,117].

Numerous studies demonstrate the effectiveness of calcium application in reducing the incidence and severity of diverse plant diseases across various crops. From cereals and vegetables to legumes, fruit trees, and even post-harvest tubers and fruits, calcium offers a protective shield. For instance, it inhibits anthracnose in apples, minimizes post-harvest disease development in strawberries, and reduces Fusarium crown rot in tomatoes. However, the form of calcium application significantly influences its disease control mechanism. While lime primarily alters soil pH, affecting disease indirectly, calcium salts like propionate exhibit direct inhibitory action against pathogens [118,119].

Irrigation plays a complex role in agricultural systems, affecting soil health and disease incidence. Maintaining soil moisture can reduce erosion and enhance fertility through nutrient delivery, but it also directly or indirectly affects pathogen activity and disease development [120].

Optimum irrigation aims to provide enough water for root uptake of essential nutrients and moisture. However, excess water can have detrimental effects on disease dynamics. In the case of common potato scab caused by Streptomyces scabies, maintaining moist soil during tuber formation encourages antagonistic bacterial communities, suppressing disease development [121]. On a similar note, water stress and high soil temperatures favor the charcoal rot fungus Macrophomina phaseolina, making irrigation crucial for disease suppression by lowering the temperature and relieving stress on potato plants [122].

Excessive irrigation, particularly during a plant’s juvenile stage, can predispose it to Pythium attacks. To mitigate damping-off risks, frequent but low-volume irrigation is recommended. Similarly, cereal rusts thrive in wet soil conditions, highlighting the influence of soil moisture on various diseases. For example, club root in crucifers, silver scurf in potatoes, and Cercosporella in wheat worsen with wet soil, while white mold in onions, common scab in potatoes, and Fusarium diseases in cereals become more severe under dry conditions [120,121].

Understanding the specific needs of both the crop and the prevalent pathogens is crucial for effective irrigation management. Damping-off fungi like Pythium and Phytophthora rely on soil water for zoospore release and movement, making dry soil surfaces an effective control strategy [100]. Studies like Biles et al. [123] also demonstrate the potential benefits of targeted irrigation, with alternate-row irrigation significantly reducing root rot caused by P. capsici in chili peppers compared to full-row irrigation.

Therefore, irrigation practices should be carefully tailored to the specific crop, pathogen, and environmental conditions. Striking a balance between optimal water availability for plant growth and minimizing disease risks through strategic irrigation methods is critical for sustainable agricultural production [120].

Intercropping, the cultivation of two or more crops simultaneously, is gaining traction as a sustainable agricultural practice, particularly in regions with degraded soils [124]. This approach offers numerous advantages, including reduced land and water demands, making it particularly relevant in areas facing water scarcity. Importantly, intercropping contributes to economic sustainability for farmers by balancing overall yield and fostering yield stability across crops [97]. Intercropping offers an advantage through the concept of complementary resource utilization. Compared to monocultures, intercropped plants exhibit a more efficient strategy for sharing and maximizing access to available sunlight, water, and nutrients [107]. This optimized resource utilization translates into several beneficial outcomes for the intercropped system.

- Intercropping promotes better soil water retention and utilization, optimizing available resources [20].

- The diverse root systems of intercropped plants create favorable conditions for microorganism activity, leading to improved nitrogen fixation and nutrient cycling within the soil ecosystem [125].

Intercropping is not just an age-old tradition but also a powerful tool for modern agriculture. Beyond maximizing yield per unit area, it offers resilience against crop failure due to biotic or abiotic stressors [95]. Studies have documented its effectiveness in combating plant diseases, providing valuable protection for component crops. For example, intercropping pea with mustard, linseed, wheat, chickpea, or grain delays the onset and development of powdery mildew [95]. Similar reports have highlighted its disease-suppressing role in various cropping systems [106].

Many research showed reduced net blotch (Pyrenophora teres) on barley and ascochyta blight (Ascochyta pisi) on peas when intercropped with legumes. These observations suggest that intercropping disrupts pathogen lifecycles and creates an environment less conducive to disease establishment. While the exact mechanisms vary depending on the crops and pathogens involved, potential explanations, including [20,126,127]:

- Intermingled crops can physically hinder pathogen dispersal and spore landing on vulnerable hosts [120].

- Intercropping alters temperature, humidity, and light availability within the canopy, potentially making it less favorable for specific pathogens [20].

- Diverse root systems can compete for resources with soil-borne pathogens, limiting their access to nutrients and space [126].

- Intercropping fosters a more diverse soil microbiome, potentially harboring beneficial organisms that suppress pathogens [20,126].

Crop rotation, with its ancient origins [16], offers far more than just soil health maintenance and erosion control. It plays a critical role in suppressing plant diseases caused by soilborne pathogens [128]. Monoculture practices often lead to a buildup of specific pathogens in the soil, causing yield and quality decline [129]. Conversely, crop rotation with resistant or less susceptible crops disrupts this cycle, reducing pathogen populations through natural mortality and the antagonistic activity of beneficial soil microorganisms. This strategy is most effective against biotrophic pathogens requiring living hosts or those with limited survival capabilities [130]. However, pathogens with broad host ranges or persistent structures like sclerotia or oospores pose greater challenges [128].

Beyond pathogen-specific benefits, crop rotation can harness broader microbial communities. For example, clover-potato rotations revealed 25 shared bacterial species, constituting 73% of culturable bacteria from both crops. These endophytic bacteria even exhibited inhibitory activity against the potato pathogen R. solani, highlighting the potential for mutually beneficial relationships fostered by rotation [128]. Furthermore, crop rotation contributes to the overall disease suppressiveness of soil, evident in cases like take-all disease and Rhizoctonia solani infections in various crops [130]. While the exact mechanisms for Rhizoctonia disease decline remain unclear, research suggests both host crop and pathogen play a role [129]. Crop rotation transcends its role in simply improving yield. It is a crucial tool for sustaining and enhancing soil fertility, ultimately serving as an asset for agricultural productivity [129]. The core principle involves regularly cycling different crop types on the same land over time. This practice prevents the continuous depletion of specific nutrients by a single crop and allows for their replenishment through diverse root systems and residue contributions. Furthermore, crop rotation enhances soil moisture retention and improves texture by promoting organic matter accumulation and aggregation [130].

A significant benefit of crop rotation lies in its ability to manage weeds and pathogens. Rotating these crops can introduce these beneficial microbes into the soil, suppressing harmful pathogens and promoting plant growth [128,129]. Therefore, crop rotation extends beyond its immediate impact on yield by promoting a holistic approach to soil health and disease management. Its versatility and effectiveness position it as a cornerstone of sustainable agricultural practices [16]. Crop rotation stands as a powerful, natural tool for managing plant pathogens, serving as a form of “green” soil remediation. Its effectiveness stems from its impact on both pathogen populations and the broader soil environment [129].

By strategically rotating crops, we can disrupt the buildup of specific pathogens in crop residues, preventing the exponential growth that often leads to devastating disease outbreaks. This approach extends beyond individual pathogens, influencing broad ranges of soil characteristics, including biological, chemical, and physical aspects [129]. For specialized pathogens like Fusarium solani f. sp. phaseoli, which plague beans, crop rotation demonstrably reduces their populations within the soil. This highlights its efficacy in managing Fusarium root rot, a major threat to bean production [97].

3.6 Soil Solarization and Biofumigation/Biodisinfection

Soil solarization leverages solar energy to elevate soil temperatures, effectively controlling various plant pathogens. This hydrothermal process relies on two critical factors: temperature and moisture. Optimizing both, often through clear tarps and strategic irrigation, enhances its efficacy. Treatment duration is also crucial, with longer exposures generally leading to better disease control [21]. While not achieving complete microbial eradication, solarization selectively suppresses harmful pathogens. This shift in the microbial balance, favoring beneficial microorganisms like Bacillus spp., Pseudomonas spp., and Talaromyces flavus, fosters a healthier soil ecosystem [56].

A key advantage of solarization is its broad-spectrum activity against fungi, nematodes, bacteria, weeds, arthropod pests, and even unidentified agents. Moreover, its effects can persist for up to 3 years beyond treatment, likely due to reduced pathogen inoculum density and induced disease suppressiveness within the soil [131]. This long-lasting efficacy extends beyond direct pathogen reduction. This environment-friendly and cost-effective technique holds immense potential for integrated disease management in sustainable agriculture. Due to its broad-spectrum activity, persistent effects, and support of beneficial microbial communities, it offers a valuable strategy for promoting crop health and minimizing dependence on chemical controls [132].

Biofumigation, also known as disinfection, stands as a strategic tool for disease management in cooler regions. This technique relies on covering the soil with plastic mulch after incorporating fresh organic matter. Although the exact mechanisms remain under investigation, two key drivers are the anaerobic fermentation of the organic matter and the subsequent production of toxic metabolites under the plastic barrier [133]. These processes contribute to the inactivation or destruction of pathogenic fungi, offering a valuable alternative to chemical control methods. Biofumigation specifically harnesses the power of select plant species, like those from the Brassicaceae family, which produce naturally occurring toxic molecules known as glucosinolates. These molecules exhibit allelopathic effects, suppressing the growth or even eliminating various soilborne pathogens [134].

Biodisinfection, on the other hand, focuses on using large quantities of generic organic matter to create anaerobic conditions within the soil [133]. This environment favors the production of diverse toxic metabolites, ultimately leading to pathogen destruction. Understanding these distinctions and the underlying mechanisms of biofumigation/disinfection paves the way for optimizing this method for targeted disease control in cooler regions. This environment-friendly approach holds significant potential for promoting sustainable agriculture practices by reducing reliance on chemical fungicides [135].

The principles of regenerative agriculture emphasize continuous soil cover and maintaining living roots in the soil throughout the year. A key strategy to achieve this is the integration of cover crops into agricultural systems. Cover crops are intentionally planted between successive primary cash crops to ensure the soil remains covered and biologically active during fallow periods [136]. This can be done either by seeding cover crops after the harvest of the main crop or by intercropping cover crops (often perennials) with grain crops this allows the cover crops to establish and maintain soil cover following the grain harvest and into the next growing season. Cover crops can be single-species or diverse multi-species mixtures. While single-species cover crops offer ease of management, multi-species blends can potentially combine the diverse benefits of each included species [137,138]. Mixtures including legumes and other functional groups are believed to improve a multitude of ecosystem functions, such as:

- Biological nitrogen fixation: Legumes form symbiotic relationships with rhizobia, converting atmospheric nitrogen into plant-available forms [5].

- Enhanced soil microbial diversity: Multi-species cover crops to support a wider range of soil microbes [19].

- Reduced soil compaction: Diverse root systems help alleviate compaction [139].

- Attraction of beneficial insects: Flowering cover crops provide resources for pollinators and predatory insects [138].

- Weed suppression: Cover crops compete with weeds for resources [139].

- Regulation of soil temperature: Cover crops provide a physical barrier, mitigating temperature extremes [137].

- Increased water infiltration: Improved soil structure and root systems enhance water absorption [138].

- Enhanced soil structure: Cover crops improve soil aggregation through the action of root exudates and physical root presence, leading to better aeration, drainage, and water infiltration [5].

- Reduced reliance on synthetic chemicals: Cover crops compete with weeds for resources, suppressing their growth and potentially reducing the need for herbicides [136].

- Increased soil organic matter: Cover crop biomass decomposition contributes organic matter to the soil, enhancing its fertility and water-holding capacity [139].

- Nutrient cycling and supply: Some cover crops, particularly legumes, can fix atmospheric nitrogen, enriching the soil and providing a natural nitrogen source for subsequent crops [19].

- Improved soil moisture conservation: Cover crops act as a living mulch, reducing soil evaporation and enhancing water retention through improved soil structure [136].

- Reduced soil erosion: Cover crops provide soil cover, intercepting raindrops and mitigating the erosive force of wind and water [139].

- Enhanced disease suppression: Cover crops can harbor beneficial soil microbial communities that antagonize plant pathogens, potentially leading to a lower incidence of soilborne diseases in subsequent cash crops [100].

Beyond general soil health benefits, cover crops can also promote specific disease suppression by enhancing the abundance and efficacy of individual beneficial microorganisms. A prime example is the fungus Trichoderma harzianum, which suppresses various soilborne pathogens affecting beans and many other vegetable crops, including Pythium spp. and Fusarium spp. T. harzianum’s suppressive mechanism is primarily through competition for nutrients [5]. Its ability to aggressively colonize various cover crops, including annual ryegrass, red clover, hairy vetch, and winter wheat, is critical [136]. Cover crop success, including establishment, persistence, and subsequent crop colonization efficiency, is contingent upon species selection, termination timing, and prevailing environmental factors [139]. Research suggests that winter wheat and canola offer optimal carryover of Trichoderma populations [19].

Conservation tillage (CT) encompasses practices like minimum tillage or no-tillage and offers an alternative to conventional tillage (typically involving plowing and leaving more than 30% crop residue on the soil surface). CT has been widely adopted in sustainable agricultural systems to mitigate the adverse effects of conventional practices. Typical CT methods include no-tillage (NT), where the soil is left undisturbed, and reduced tillage, which minimizes soil disturbance [140].

These practices fundamentally alter soil properties, affecting the spatial distribution of soil organic matter and microbial populations within the soil profile. NT leads to increased carbon, nitrogen, and water accumulation near the soil surface compared to CT. This translates to higher enzyme activity and improved microbial resource use efficiency [140]. CT can also influence soil pH, which subsequently affects microbial diversity and overall soil suitability for specific crops. Furthermore, CT promotes the formation of fungal hyphal networks, bolstering fungal populations [141]. The size and diversity of soil microbial communities can be shaped by tillage practices alone [142], crop residue retention itself (Lupwayi et al. 2018), or the combined effects of both tillage and residue retention [143].

CT is a farming practice that minimizes soil disturbance; it provides several mechanisms that contribute to disease reduction or suppression [143]. Reduced tillage in this practice promotes an active and diverse soil microbial community, which can outcompete or suppress plant pathogens [142]. Increased organic matter resulting from crop residues improves the structure of the soil, nutrient cycling, and release of compounds inhibitory to pathogens [140]. Reduced soil disturbance preserves soilborne beneficial organisms and reduces the spread of pathogens. Crop residue cover, by being a physical barrier, tends to moderate soil temperature and further curtail pathogen development. The combined result is that the soil environment is more conducive to health, and plants will be inherently more resistant to their pathogens [141].

Defined as an integrated approach, sustainable agriculture seeks to address fundamental and practical ecological issues related to food production, utilizing biological, physical, chemical, and ecological principles to develop environmentally sensitive practices. The successful application of beneficial microbes holds a significant promise for maintaining soil health, increasing water-holding capacity, promoting carbon storage, enhancing root development, facilitating the availability and cycling of essential nutrients, filtering pollutants, and ultimately contributing to biodiversity conservation. It is important to recognize that while conventional agricultural practices can deplete soil microbes and overall soil health, various strategies can reverse this trend and promote soil quality improvement [138].

In contrast to chemical and organic fertilizers, biological fertilizers offer a unique approach by introducing beneficial bacteria and fungi to the soil, rather than directly supplying all necessary nutrients to crops [18]. These microorganisms play a crucial role in several key soil processes, including:

- Regulation of organic matter dynamics and decomposition: Breaking down organic matter releases essential nutrients for plant uptake [144].

- Enhancing plant nutrient availability: Microbial activity directly influences the availability of crucial plant nutrients like nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur [145,146].

Beyond enhancing nutrient availability, biofertilizers offer the additional benefit of promoting plant resistance. This augmented resistance can be attributed to several mechanisms, as outlined by Narendra Babu et al. [147]:

- Plant growth hormone production or modification: Biofertilizers can influence plant growth and induce systemic resistance (ISR) through the production or modification of plant hormones like gibberellic acid, indole acetic acid, cytokinins, and ethylene [148].

- Antimicrobial compound production: These microbial inoculants can synthesize and release volatile compounds including siderophores (facilitate iron acquisition), antibiotics (suppress harmful microbes), chitinases and β1,3-glucanases (enzymes that degrade fungal cell walls), and even cyanides (potent toxins against specific pathogens), creating a hostile environment for detrimental organisms [18,149].

- Nitrogen fixation: Certain biofertilizers harbor nitrogen-fixing bacteria that can convert atmospheric nitrogen into a plant-usable form, contributing to plant nutrition and potentially reducing reliance on synthetic nitrogen fertilizers [145].

- Nutrient solubilization: Specific biofertilizers harbor microbes capable of solubilizing phosphorus (p-minerals) and other sparingly soluble nutrients, making them more readily available for plant uptake [150].

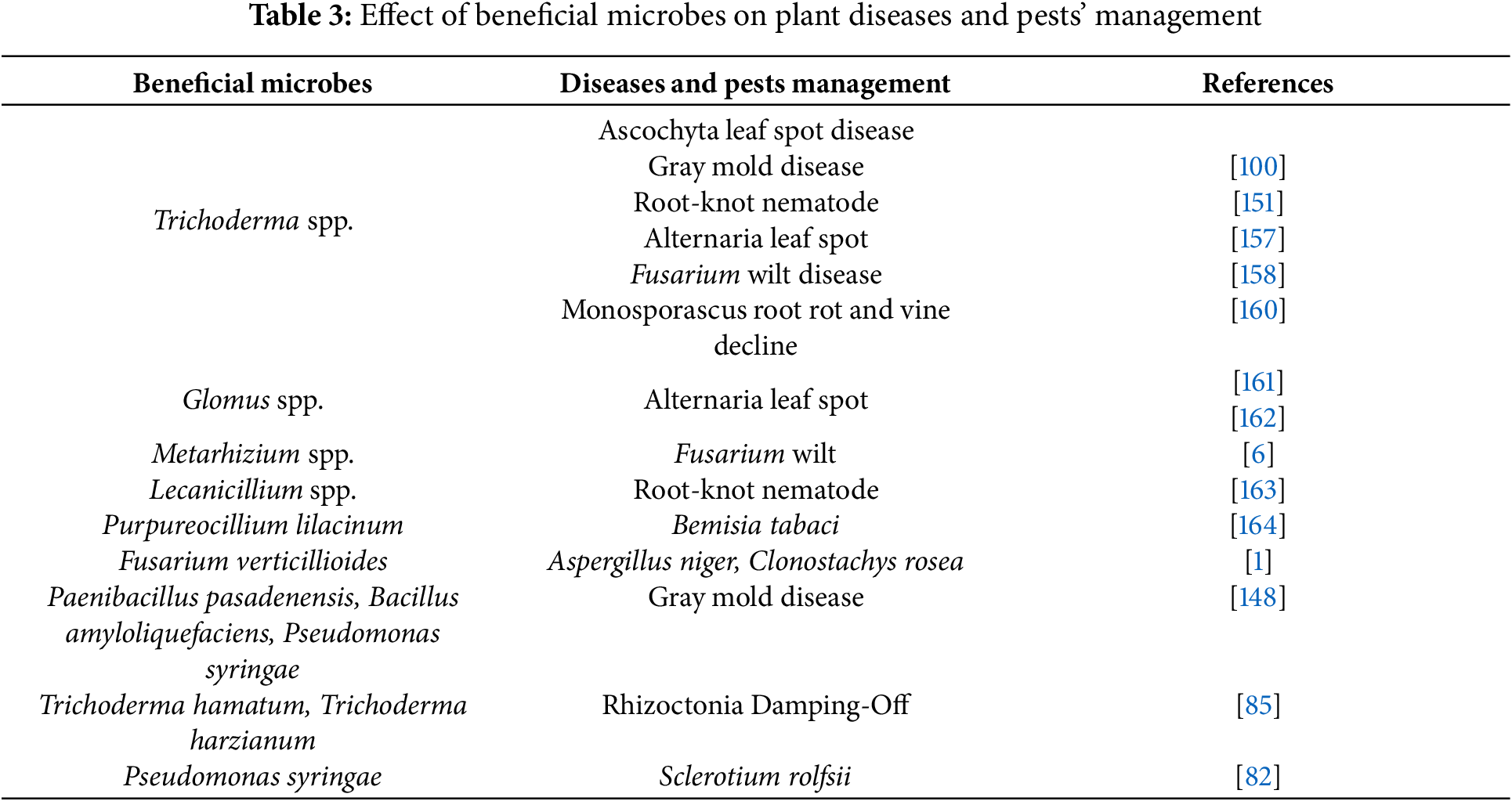

Beneficial microorganisms have become very vital to sustainable agriculture due to improved plant health and productivity, and they are commonly known as plant growth-promoting Rhizobacteria or plant growth-promoting fungi [145]. These microorganisms interact with plants through the colonization of their roots and eventually offer a wide array of benefits to them [18]. Among the chief roles undertaken by such organisms is nutrient acquisition: the solubilization and mineralization of critical nutrients like phosphorus and potassium into more available forms to plants. This reduces reliance on artificial fertilizers and allows more holistic cultivation of crops [150,151]. Besides, these microbes synthesize growth-promoting substances like hormones and vitamins, stimulating plant growth and development for increased yields and improved quality of crops. They also enhance the tolerance of the plant to stress factors such as biotic and abiotic factors, like drought and salinity, and pathogenic attack [6,152,153].

Trichoderma species offer a multifaceted approach to plant health, acting as both growth promoters and biocontrol agents [154]. Their beneficial effects can be summarized as follows:

- Enhanced nutrient acquisition: Trichoderma spp. act as antagonists against harmful soil microbes, improving the availability of nutrients for plant growth and their colonization [154]. Additionally, their root colonization facilitates the uptake of essential minerals like copper, iron, phosphorus, manganese, and sodium by plants, thereby promoting growth [155,156].

- Induction of plant defense mechanisms: Trichoderma species act as elicitors, triggering the activation of various plant defense genes, leading to both localized and systemic resistance against potential pathogens [157,158].

- Growth promotion: Beyond their direct antagonistic effects, Trichoderma spp. join a wider array of beneficial microbes like plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) from the Pseudomonas fluorescens-putida group, which can significantly colonize plant roots and directly enhance plant growth and yield [159]. Additionally, bacteria like Bacillus subtilis have been demonstrated to promote plant growth and protect against fungal pathogens (Table 3) [156].

Cultivar selection and planting are crucial components of any integrated disease control program. This strategy relies on utilizing plant varieties exhibiting resistance to specific pathogens. Plant resistance is defined as the host’s inherent ability to suppress or hinder the activity and progression of a pathogenic agent, ultimately reducing or eliminating disease symptoms [100]. This resistance can operate through various mechanisms, including:

- Pre-formed physical barriers: Plants may possess physical structures like thicker cell walls or waxy cuticles that hinder pathogen penetration [165].

- Antimicrobial compounds: Certain plants produce natural compounds with antimicrobial properties that can directly inhibit or kill invading pathogens [100].

- Hypersensitive response: In some cases, upon pathogen recognition, plants trigger a localized cell death response at the infection site, preventing further pathogen spread [166].

- Activation of defense signaling pathways: Pathogen recognition can trigger complex signaling pathways within the plant, leading to the production of defense enzymes, secondary metabolites, and other molecules that collectively impede pathogen growth and spread [167].

Resistant plant cultivars offer several distinct advantages within integrated disease control programs:

- Environmentally friendly: Unlike chemical control methods, utilizing resistant cultivars avoids introducing harmful chemicals into the environment, minimizing potential ecological disruption [87].

- Reduced reliance on chemical controls: The inherent resistance of these cultivars often translates to a reduced need for, or even complete elimination of, chemical fungicides or pesticides, contributing to a more sustainable agricultural approach [168,169].

- Compatibility with other control methods: The use of resistant cultivars can be seamlessly integrated with other disease management strategies targeting different pathogens, offering a multifaceted approach to disease control [165].

- Long-lasting resistance: In certain plant-pathogen systems, resistance can be remarkably stable over extended periods, with cultivars maintaining their resistance for many years [87]. This extended efficacy minimizes the need for frequent cultivar replacements and ensures long-term disease control benefits [170]. Although each of these regenerative inputs provides particular benefits, recent study also shows significant synergies and possible trade-offs when used in integrated systems. Synergistic advantages can result from integrating regenerative practices. For example, combining compost and cover crops in a long-term Mediterranean field study resulted in a remarkable 19 Mg C/ha increase in organic carbon soil down to 1 m depth when compared to systems that just utilized cover crops or mineral fertilizer [171]. The integration of compost offered nutrients and mobile carbon in this case, and root canals from cover crops improved water infiltration, allowing for deeper carbon storage. In intensive organic vegetable systems, applying compost and growing winter cover crops frequently have synergistic effects, but there are trade-offs as well. A long-term field study conducted in California revealed that frequent cover cropping more successfully enhanced labile carbon pools, such as permanganate oxidizable carbon (POX-C), which are intimately related to microbial activity and nutrient cycling, whereas compost primarily increased total soil organic carbon (SOC) stocks. This demonstrates that while cover crops increase nutrient availability and biological activity, compost helps to stabilize carbon sequestration. This suggests that both approaches target distinct soil health outcomes and should be carefully combined based on management objectives [172]. Careful management is necessary for that. Excessive use of high-nitrogen fertilizers or untreated manure might temporarily raise the risk of pathogens or cause nutrient imbalances, underscoring the significance of optimal integration to maximize benefits and minimize limitations [173,174].

Beyond soil amendments and microbial dynamics, plant resistance itself plays a critical role in disease suppression. Plant resistance encompasses a series of mechanisms that restrict or impede the development of a pathogen. These mechanisms manifest at various stages, starting as early as the infection phase and continuing to hinder pathogen progression within the plant. The ultimate effect of resistance is quantifiable by measuring either the reduction in symptom expression or the diminished development of disease epidemics [167]. It is important to distinguish resistance, which focuses on the plant’s direct impact on the pathogen, from other defense mechanisms like avoidance (preventing initial contact with the pathogen) and tolerance (a plant’s ability to tolerate a disease without significant yield or quality loss) [168]. This distinction ensures a focused understanding of resistance mechanisms employed by plants to combat pathogens [165].

4 Conclusions and Future Perspective

Regenerative agricultural practices offer a potential strategy for combating plant fungal diseases. By prioritizing crop diversification, soil health enhancement, integrated crop management strategies, and crop rotation techniques, these practices can facilitate a reduction in pesticide reliance and promote agricultural sustainability. The net effect of implementing regenerative agricultural practices includes a decrease in environmental impact, improvements in sustainability, and potential benefits to overall agricultural health for farmers, consumers, and the broader ecosystem. Additionally, these practices contribute to improved soil and ecosystem health, potentially resulting in enhanced crop yields and quality. In conclusion, regenerative agricultural practices hold promises for controlling plant fungal diseases while promoting sustainable agricultural practices. Future research efforts should prioritize the seamless integration of these practices into existing agricultural systems. Additionally, investigations are needed to identify optimal strategies for managing fungal diseases using regenerative approaches across diverse agricultural settings, accounting for variations in crop types and climatic conditions. By addressing these research gaps, we can unlock the full potential of regenerative agriculture for sustainable disease management and improved agricultural resilience.

The application of regenerative agricultural practices holds significant promise for the future of sustainable agriculture by fostering the control of plant fungal diseases. This approach prioritizes the restoration of soil health, promotes the diversification of biological communities within the agricultural ecosystem, and ultimately enhances the system’s capacity to withstand environmental pressures. By implementing techniques such as crop rotation, cover cropping, intercropping, and the incorporation of compost and disease-resistant plant varieties, farmers can achieve the dual benefit of reducing reliance on chemical fertilizers and pesticides while simultaneously improving both plant and soil health. This holistic strategy fosters a more balanced and resilient agricultural ecosystem, potentially mitigating the emergence and spread of plant fungal diseases.

Regenerative agricultural practices can mitigate the impact of fungal diseases on crops by enhancing overall plant health, diversifying crop species and rotations, promoting robust soil microbial communities, and increasing plant resilience to environmental stressors. These practices foster biodiversity, which in turn encourages the establishment of beneficial organisms (including natural fungal disease antagonists) within agricultural ecosystems.

While regenerative agricultural practices exhibit potential for mitigating fungal diseases, their large-scale adoption faces hurdles. These include the need for significant adjustments to existing production systems, alongside comprehensive farmer training and education initiatives. Additionally, robust research is necessary to elucidate the intricate interplay between these practices and various plant fungal diseases. This knowledge will be crucial for optimizing their application as a management strategy, ensuring efficacy across diversified crops and a range of climatic conditions.

To foster the widespread adoption of disease-suppressive and environmentally sound agricultural practices, policy interventions are crucial. Governments and agricultural organizations should consider implementing subsidy mechanisms to incentivize farmers for integrating beneficial practices such as cover cropping, reduced tillage, and diverse crop rotations. These financial incentives can offset initial adoption costs and demonstrate the long-term economic benefits of healthier soil ecosystems. Additionally, funding for research and extension services is vital to develop localized best practices and provide farmers with the knowledge and tools necessary to transition to regenerative systems. Establishing knowledge-sharing platforms and farmer-to-farmer networks can further accelerate the adoption of these practices, ensuring that proven strategies for disease suppression and improved soil health are widely disseminated and implemented across agricultural landscapes.

Supportive policy brief measures are necessary to increase the use of regenerative approaches for the management of fungal infections in plants. To guarantee successful implementation, it is also essential to invest in extension services, localized research, and farmer training. The adoption of these methods can be further accelerated by encouraging networks for information sharing and farmer-to-farmer learning. When combined, these research and policy initiatives can promote broad adoption, enhance plant and soil health, and create more robust agricultural systems.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to the review editor and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions to improve the clarity of the research paper.

Funding Statement: The financial support has been provided by SIRAM project within the framework of PRIMA, a program supported by H2020, the European Program for Research and Innovation and the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (MERS).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Validation: Lobna Hajji-Hedfi. Writing—original draft: Lobna Hajji-Hedfi, Omaima Bargougui, Abdelhak Rhouma. Writing—review & editing: Lobna Hajji-Hedfi, Takwa Wannassi, Amira Khlif, Samar Dali, Wafa Gamaoun. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All relevant data are within the paper.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Chatterjee S, Kuang Y, Splivallo R, Chatterjee P, Karlovsky P. Interactions among filamentous fungi Aspergillus niger, Fusarium verticillioides and Clonostachys rosea: fungal biomass, diversity of secreted metabolites and fumonisin production. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16(1):83–3. doi:10.1186/s12866-016-0698-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Li J, Gu F, Wu R, Yang J, Zhang K. Phylogenomic evolutionary surveys of subtilase superfamily genes in fungi. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):45456. doi:10.1038/srep45456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Marin-Menguiano M, Morenosanchez I, Barrales RR, Fernandezalvarez A, Ibeas JI. N-glycosylation of the protein disulfide isomerase Pdi1 ensures full Ustilago maydis virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2019;15(11):e1007687. doi:10.1101/571125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li Y, Chang SX, Tian LH, Zhang QP. Conservation agriculture practices increase soil microbial biomass carbon and nitrogen in agricultural soils: a global meta-analysis. Soil Biol Biochem. 2018;12:50–8. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.02.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Nascimento VD, Arf O, Alves MC, Souza EJD, Silva PRTD, Kaneko FH, et al. Mechanical chiseling and the cover crop effect on the common bean yield in the Brazilian Cerrado. Agriculture. 2022;12(5):616. doi:10.3390/agriculture12050616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Siqueira AC, Mascarin GM, Gonçalves CR, Marcon J, Quecine MC, Figueira A, et al. Multi-Trait biochemical features of metarhizium species and their activities that stimulate the growth of tomato plants. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2020;4:535160. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2020.00137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Stathatou PM, Corbin L, Meredith JC, Garmulewicz A. Biomaterials and regenerative agriculture: a methodological framework to enable circular transitions. Sustainability. 2023;15(19):14306. doi:10.3390/su151914306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wilson KR, Myers RL, Hendrickson MK, Heaton EA. Different stakeholders’ conceptualizations and perspectives of regenerative agriculture reveals more consensus than discord. Sustainability. 2022;14(22):15261. doi:10.3390/su142215261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Rempelos L, Kabourakis E, Leifert C. Innovative organic and regenerative agricultural production. Agronomy. 2023;13(5):1344. doi:10.3390/agronomy13051344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]