Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Application of Image Processing Techniques in Rice Grain Phenotypic Analysis and Genome-Wide Association Studies

College of Engineering, Academy for Advanced Interdisciplinary Studies, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, 210095, China

* Corresponding Author: Jiexiong Xu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Enhancing Grain Yield: From Molecular Mechanisms to Sustainable Agriculture)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2365-2383. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.067124

Received 25 April 2025; Accepted 10 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Background: Rice grain morphology—including traits such as awn length, hull color, size, and shape—is of central importance to yield, quality, and domestication, yet comprehensive quantification at scale has remained challenging. A promising solution has been provided by the integration of high-throughput imaging with genomic analysis. Methods: A standardized 2D image-processing pipeline was established to extract four categories of traits—awn length, hull color, projected grain area, and shape descriptors via PCA of normalized contours—from high-resolution photographs of 229 Oryza sativa japonica landraces. Genome-wide association analyses were then performed using a mixed linear model to control for population structure and kinship. Results: Broad phenotypic diversity was evident in awn length, hull coloration, grain dimensions, and morphological shape, with the first principal component explaining the dominant axis of shape variation. Known awn regulators GAD1/OsRAE2 (chr 8; ) and An-1 (chr 4; ) were identified. The hull color gene Rd (chr 1; ) was detected. A novel locus on chr 12 at 8.75 Mb with Os12g0257600 (), and the known grain size gene FLO2 (chr 4; ) were associated with projected area. Shape PC1 was mapped to GLW7/OsSPL13 (chr 7; ), NAL2/OsWOX3A (chr 11; ), and OsGIF1 (chr 11; ). Conclusions: This study demonstrates that image-based phenotyping combined with genome-wide association studies (GWAS) can efficiently reveal both established and novel genetic determinants of rice grain morphology. These findings provide actionable targets for marker-assisted selection and genome editing to tailor grain traits in rice breeding programs.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileGrain morphology in rice (Oryza sativa L.) is considered a key agronomic and quality attribute, encompassing traits such as grain length, width, the presence and length of awns, and hull color. These traits influence grain yield, thousand-grain weight, milling quality, and consumer preferences [1]. Long and short grain types are preferred in different markets, and grain shape plays a role in packing density and appearance [2]. Awns, which are bristle-like extensions of the lemma, are involved in seed dispersal and protection in wild rice, but have often been selected against during domestication to facilitate harvesting and processing. Similarly, grain hull and seed-coat coloration—ranging from black or red to straw-white—have been subjects of human selection [3–5], with specific genes such as Bh4 for black hull and Rc for red pericarp determining these visible traits [6]. Understanding the genetic basis for such morphological diversity is essential for rice breeding and for gaining insights into how human selection has shaped rice phenotypes.

Traditional methods for phenotypic measurement of grain traits are labor-intensive and prone to human error or subjectivity. For example, awn length might be measured using a ruler, and grain dimensions might be determined with calipers, with each sample measured individually. Recent advances in plant phenomics have introduced digital imaging as an effective tool for measuring plant traits in a high-throughput and objective manner [7,8]. Two-dimensional (2D) image analysis has proven particularly effective for capturing rice grain size and shape traits in large populations. Previous studies have demonstrated that 2D digital image analysis can accurately measure grain length, width, area, and related shape indices. This approach provides high heritability estimates and aids in the identification of quantitative trait loci (QTL) for grain shape [9,10]. High-throughput phenotyping platforms have also been employed to automatically measure multiple traits, leading to the successful identification of numerous loci via genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [11–15]. These studies underscore the potential of image-based phenotyping to expedite genetic analyses of important traits.

Despite the widespread use of advanced phenotyping systems, there remains a need for accessible image analysis approaches that can capture a broader range of traits beyond basic length and width, even if not at ultra-high throughput [16,17]. Traits like awn length and hull color, which are rarely quantified in standard image-based studies, could provide additional insights into rice diversity and its genetic regulation [18–20]. Awns and color are often recorded as simple presence/absence or qualitative traits, but digital imaging enables their quantification, such as measuring awn length in centimeters and capturing color in an objective color space. Moreover, grain shape is a complex trait that cannot be fully described by length and width alone. Analyzing the grain outline using techniques such as principal component analysis (PCA) can capture subtle shape variations, such as grain curvature and oblong vs. round shapes, as quantitative descriptors.

GWAS offer several technical advantages over traditional bi-parental QTL mapping in dissecting rice grain morphology. Whereas linkage mapping in a bi-parental population is limited to detecting only two alleles per locus and yields low-resolution QTL intervals due to few recombination events [21], GWAS leverages the numerous historical recombination events accumulated in diverse rice germplasm to achieve much higher mapping resolution [22]. By scanning a broad panel of genetically diverse accessions, GWAS captures a wider spectrum of allelic diversity (including multiple haplotypes at a locus) than is typically achievable in a single biparental cross [23]. Importantly, because GWAS is conducted on natural or breeding populations, the identified loci correspond to naturally occurring variation, making the findings directly relevant to rice’s evolutionary and agronomic context [24]. These features enable GWAS to pinpoint genetic factors underlying complex traits like grain size and shape with far greater precision and relevance than classical QTL mapping [25].

In this study, 2D image processing was employed to extract a suite of phenotypic traits from rice grain images, which were then used to perform a genome-wide association study. The goal was to link image-derived phenotypic variation to specific genomic regions in a panel of rice landraces. The focus of the study was on applying image analysis for phenotype extraction, followed by a GWAS to identify loci associated with the observed variation. Four categories of traits were quantified from grain images: (1) Awn length (mm), the length of the longest awn on the grain; (2) Hull color in International Commission on Illumination

2.1 Plant Materials and Phenotypic Data Collection

A field experiment was conducted at the experimental farm of Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Nanjing, Jiangsu Province, China (

For each landrace, the harvested grains were spread in a single layer, and a rapid visual screening was performed to locate the modal—or most representative—kernel in terms of size, shape, and hull condition. One filled, mature grain (with hull and, if present, awn intact) was selected as the imaging target. All phenotypic traits were extracted from this representative image, and each landrace contributed a single composite data point to the downstream analysis.

Digital images of rice grains were captured using a high-resolution macro camera to enable phenotypic measurements. An Olympus TG-6 digital camera was employed under fixed lighting conditions to capture 229 sets of grain images. Each image was acquired at a resolution of 4000

2.2 Image Processing and Trait Extraction

All grain images were processed using a custom image analysis pipeline developed in Python, employing the OpenCV [27] and sci-kit-image libraries [28]. The general workflow consisted of several stages to extract quantitative phenotypic traits from each grain image. First, raw images were standardized by converting them to a consistent format and color space. Images were processed in true-color RGB mode (24-bit) for color-related traits. Given the planar imaging setup, geometric distortion corrections were unnecessary. The Segment Anything Model (SAM) [29] was applied to isolate the grain from the background, producing a binary mask outlining each grain. These masks were manually reviewed and refined using Labelme [30] to ensure accuracy, resulting in clean grain silhouettes suitable for downstream measurements.

Next, pixel-based dimensions were calibrated using the reference scale included in each image. For camera images, the number of pixels spanning a known length on the scale was used to compute a pixel-to-millimetre conversion factor, allowing all trait measurements to be expressed in physical units.

From each processed grain image, a set of phenotypic traits was extracted. Awn length was measured as the linear distance from the grain base to the tip of the awn, based on the longest protrusion from the main grain body in the binary mask. If a grain lacked an awn, the awn length was recorded as zero. Color fidelity was ensured by measuring all awned samples, which were visually inspected and verified.

Grain hull color was evaluated in the CIELAB color space, which quantifies color using three perceptual dimensions: lightness (

The projected grain area, reflecting the two-dimensional size of the grain (excluding the awn), was determined by counting the number of pixels within the binary mask and converting this to square millimetres using the calibration factor. This trait provided an integrated measure of grain size, combining aspects of both length and width.

A contour normalization and principal component analysis (PCA) approach was applied to characterize grain shapes beyond basic linear dimensions. First, the contour coordinates at pixel precision were extracted for each grain mask. An ellipse was fitted to the contour using image moments matching the grain’s second-order moments. The coordinates were then transformed through an affine transformation that normalized the fitted ellipse into a unit circle. Specifically, the grain’s centroid was translated to the origin, the contour was rotated to align the ellipse’s major axis with the

All grains in the dataset were thus represented by 36-dimensional shape vectors. These vectors were subjected to PCA after mean-centering each dimension. PCA identified orthogonal axes of variation in the shape space. The first five principal components (PC1 to PC5) were retained as shape descriptors because they captured the majority of the variation. PC1 typically represented elongation or slenderness, while subsequent components described increasingly subtle morphological patterns. The results of all phenotype extraction scripts were subject to manual inspection to ensure precise segmentation and reliable trait measurement.

2.3 Genome-Wide Association Analysis

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) were performed for each trait—awn length, grain hull color, projected grain area, and five shape principal components (PC1–PC5)—using a mixed linear model (MLM) to account for genetic relatedness among the 229 rice landraces. The MLM is essential to mitigate spurious associations arising from population structure or familial relatedness, a widely adopted plant GWAS strategy. A total of 165,004 SNPs with a minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.05 were used for GWAS.

GWAS was performed using GEMMA version 0.98.5 [31] to identify genetic loci associated with the grain morphological traits. GEMMA employs the mixed linear model (MLM) for association with a kinship matrix to avoid confounding effects [32]. The model equation is:

where Y is the phenotypic value vector, X is the genotype matrix, and

For those traits that exhibited no SNP associations above the genome-wide threshold in the initial MLM scan, the genome-wide test was rerun with two more sensitive models available in rMVP v1.4: (i) a generalized linear model that included the first two genotypic principal components as fixed covariates (GLM + PCA) [33] and (ii) the Fixed and Random Model Circulating Probability Unification algorithm (FarmCPU) [34]. Signals detected solely by these supplementary models are regarded as exploratory leads; the MLM-based results constitute the primary set owing to their stricter control of type-I error.

The LD decay distance of the natural variant population of rice was approximately 200 kb [35], and since the Taihu landrace panel analysed here is identical to that used in earlier GWAS of the region’s germplasm [36], the same 200 kb window on either side of each lead SNP was adopted when defining association intervals. Gene annotations and public expression databases, such as RAP-DB and RiceXPro, were consulted to evaluate gene function and expression profiles for novel loci. Genes expressed in relevant tissues—such as developing panicles or grains—were flagged as plausible candidates for further study.

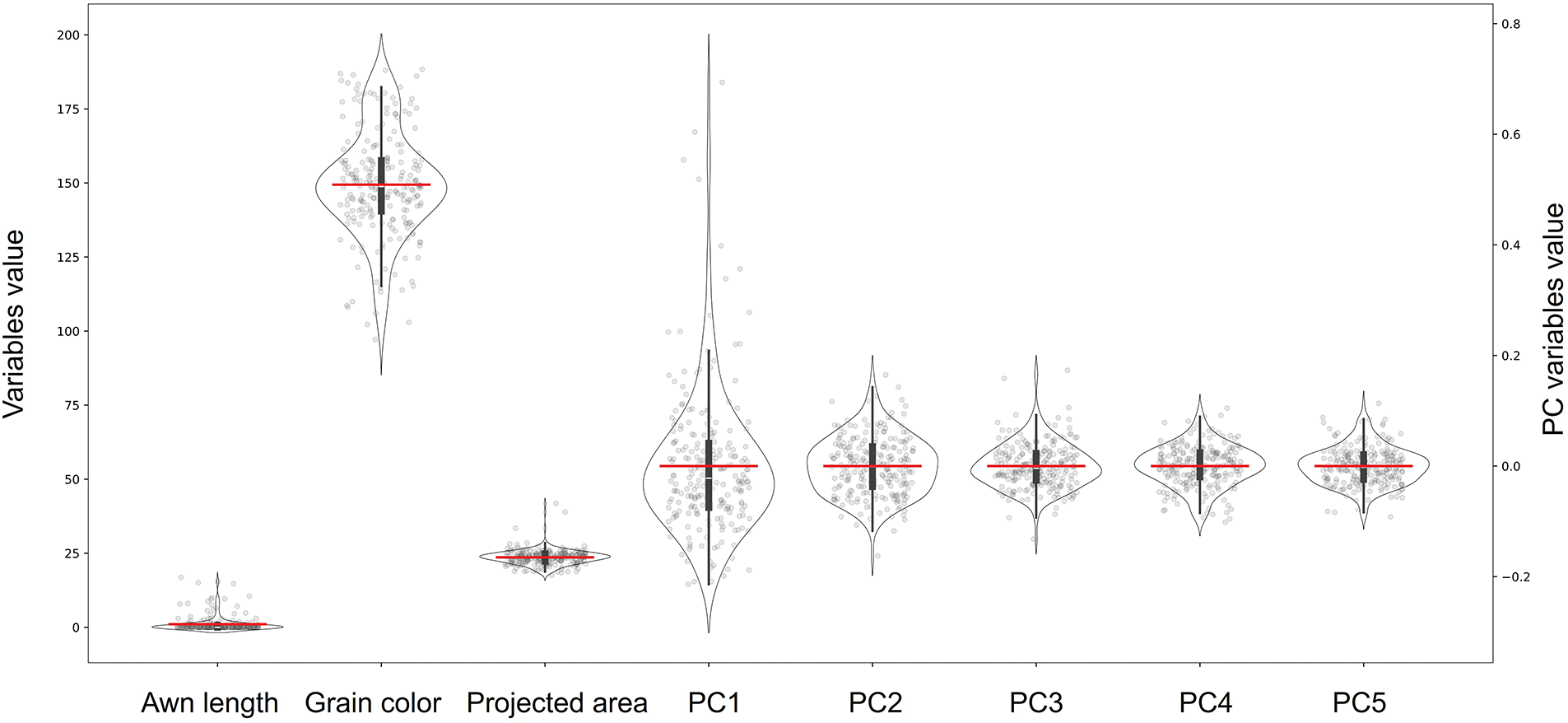

The GWAS results were visualized using Manhattan plots, in which SNP p-values were plotted against their genomic positions, and quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plots were used to compare observed and expected distributions of test statistics.

2.4 Pearson Correlation Analysis

To quantify pairwise relationships among the eight image-derived traits, Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficients (

3.1 Validation of Image-Based Phenotyping Accuracy

Manual validation was carried out to quantify the accuracy and reproducibility of the 2D image-processing pipeline. Because it is impractical to benchmark every extracted trait, two representative metrics—awn length and grain length—were selected for manual measurement on 20 randomly chosen landraces using a digital caliper (precision

Regression of image-derived traits against manual benchmarks showed strong correlations. Grain length exhibited an

3.2 Phenotypic Variation in Grain Traits among Rice Landraces

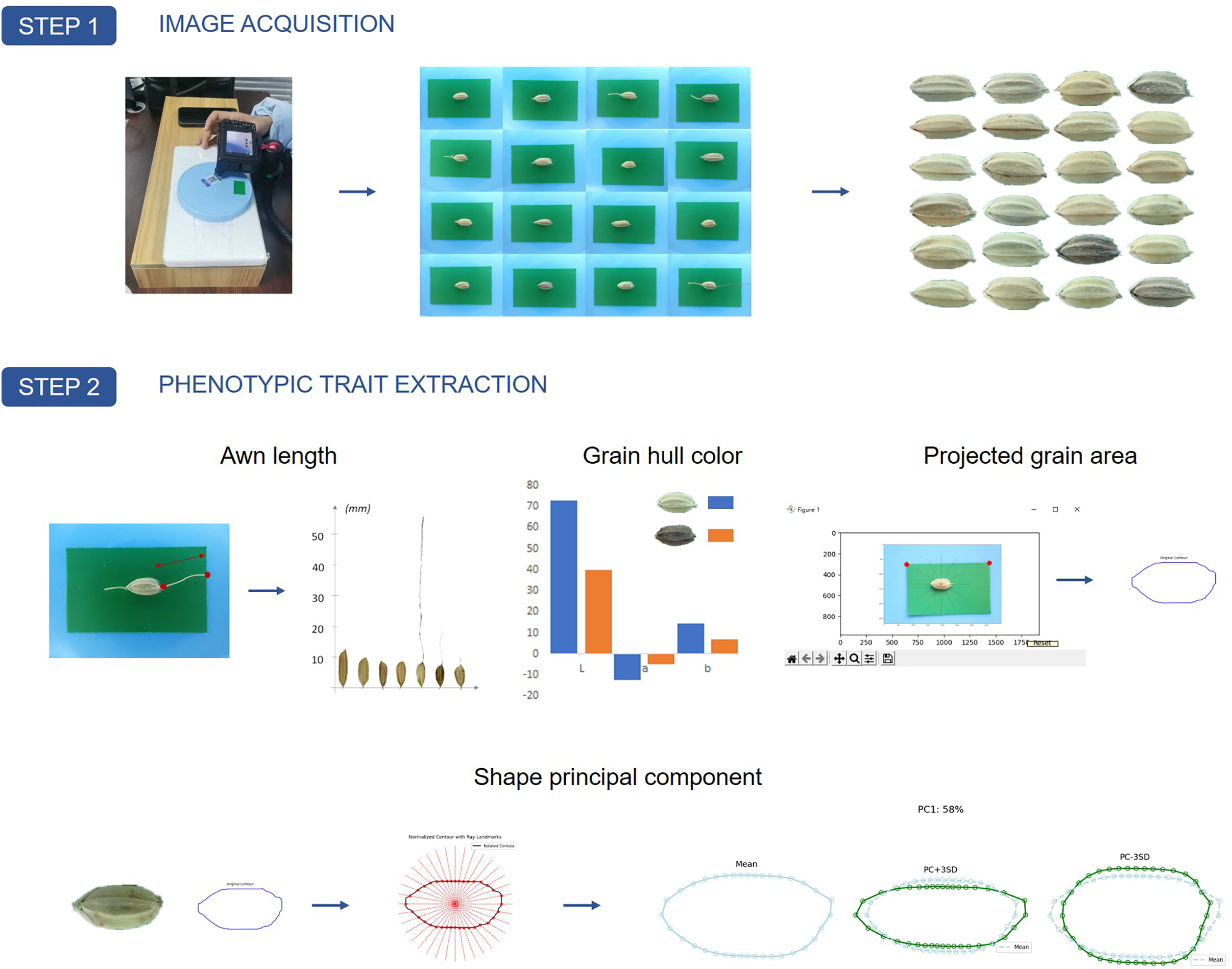

Substantial phenotypic diversity in grain morphology was exhibited in the rice landrace panel, as captured through the image-based phenotyping pipeline. An overview of the three-step workflow employed in this study is provided in Fig. 1. In Step 1, high-resolution images of rice grains were captured under standardized lighting and camera settings. In Step 2, key phenotypic traits—including awn length, hull color (quantified in the CIELAB color space), projected grain area, and shape attributes derived via principal component analysis—were automatically extracted from each grain image. Finally, in Step 3, these phenotypic data were integrated with high-density SNP information to perform a genome-wide association study (GWAS), generating Manhattan and Q-Q plots that revealed significant marker-trait associations (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Overview of the three-step workflow for image-based phenotyping and genome-wide association analysis of rice grain traits. In Step 1, high-resolution images of rice grains are captured under standardized lighting and camera settings. Step 2 involves extracting key phenotypic traits from each grain image—measuring awn length, quantifying hull color (e.g., in the CIELAB space), determining projected area, and performing shape analysis through principal feature extraction. Finally, in Step 3, a genome-wide association study (GWAS) is conducted using these phenotypic data and high-density SNP information, producing Manhattan and Q-Q plots that reveal significant marker

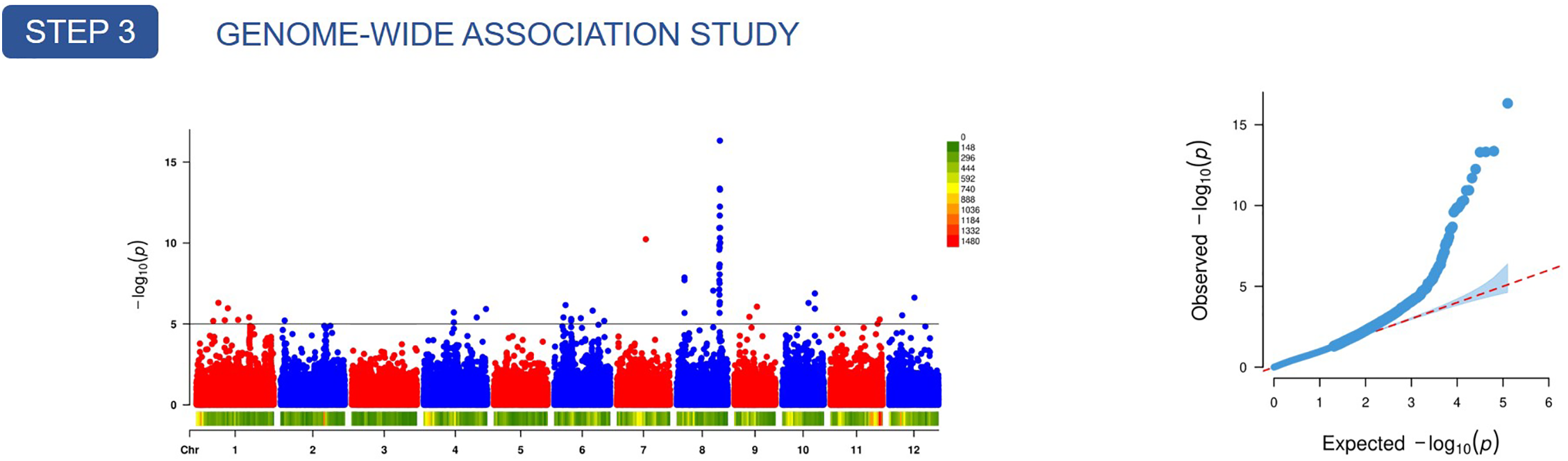

Prominent awns were exhibited by many traditional landraces, with the greatest length recorded in this study reaching approximately 16.83 mm. In contrast, the majority of japonica landraces displayed either very short awns or none at all, with completely awnless varieties having awn lengths recorded as zero (Fig. 2). The distribution of awn length was bimodal, reflecting the binary presence or absence of awns, although continuous variation was observed among the awned types. This pattern is consistent with the role of awn length as a domestication-related trait, shaped by major-effect genes responsible for awn suppression [37], along with additional polygenic variation influencing awn length among awned accessions [38].

Figure 2: Distribution of eight phenotypic traits (awn length, hull color, projected area, and shape principal components PC1–PC5) among the japonica landrace panel. Each violin plot illustrates the trait’s probability density, with individual data points shown as gray circles, and the red horizontal bar denoting the mean. Due to differences in scale, awn length, hull color, and projected area are plotted against the left

Grain hull color, quantified in the CIELAB color space [39], also exhibited considerable variation among landraces. Lightness (

Compared with

Grain size and shape traits also exhibited wide variation. Projected grain area ranged from about 17

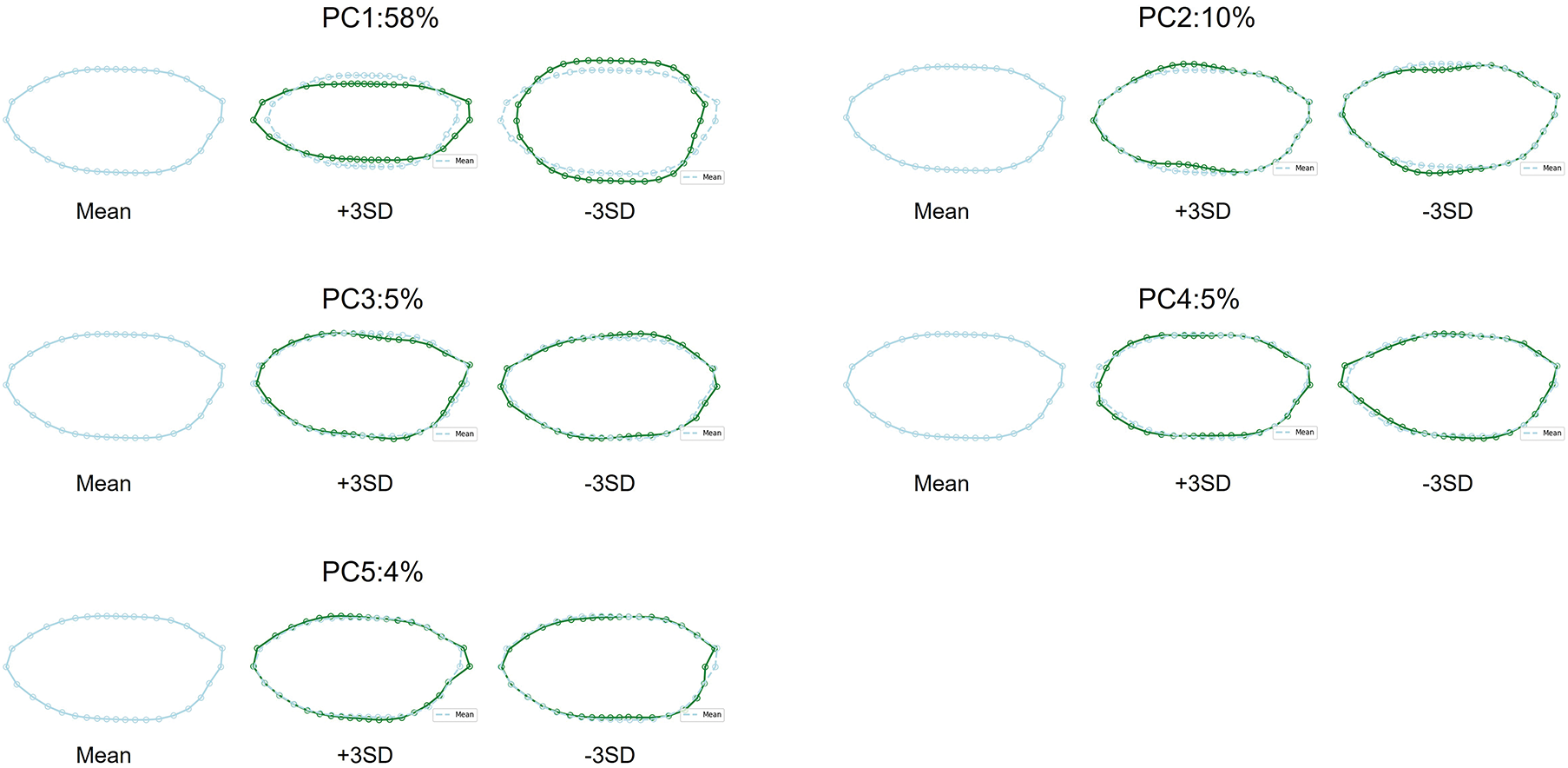

Figure 3: Mean grain contour (light blue) compared with

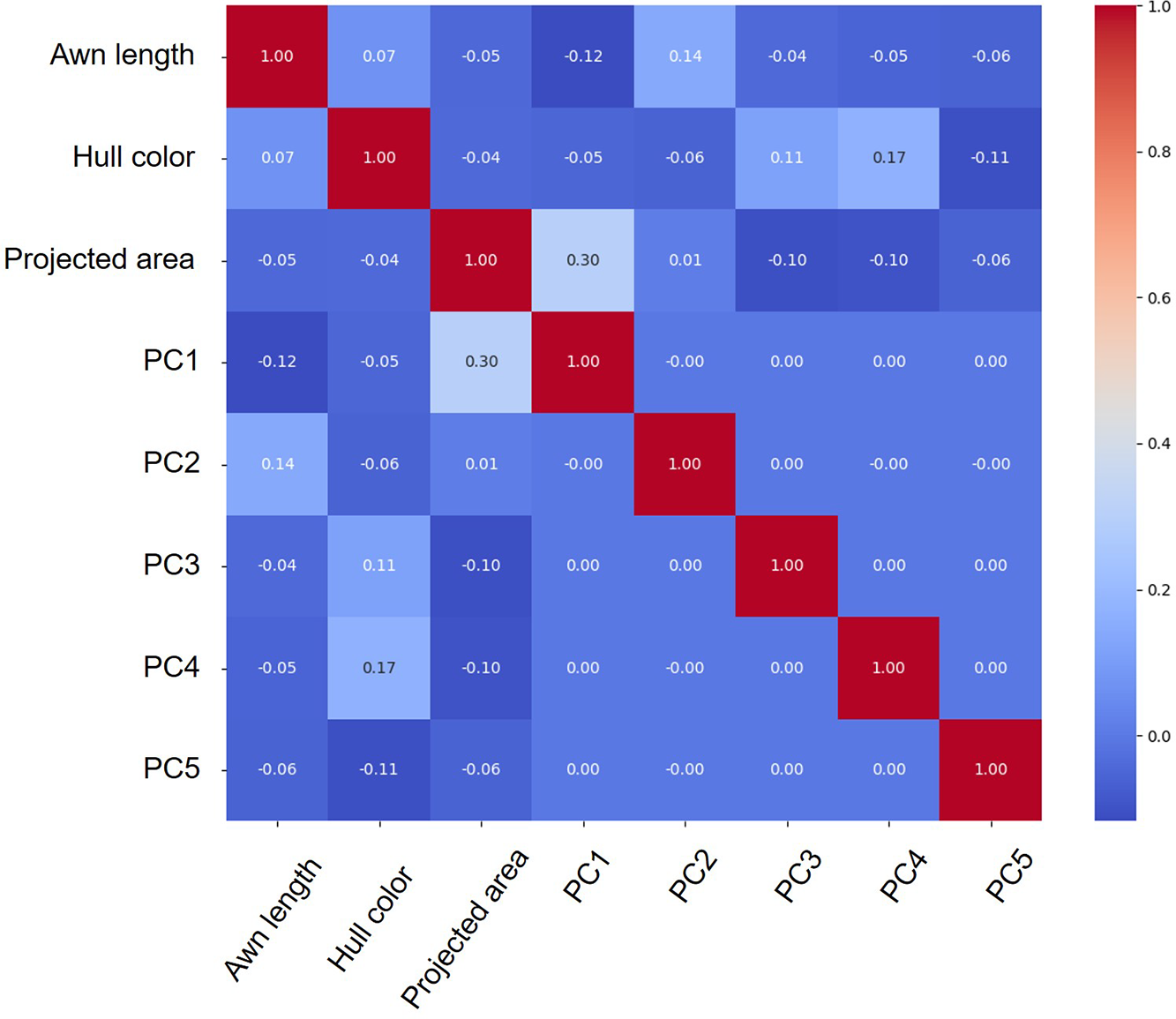

Pearson correlation analysis, based on two-tailed Pearson tests (

Figure 4: Correlation matrix illustrating the relationships among eight phenotypic traits—awn length, hull color, projected area, and shape principal components (PC1–PC5)—derived from the rice landrace panel. The heatmap’s color gradient indicates the magnitude and direction of the Pearson correlation coefficients (red for positive and blue for negative correlations), with each cell annotated with its corresponding value. Notably, projected area shows a moderate correlation with PC1 (r = 0.30), while the other principal components exhibit minimal intercorrelation with area and the remaining traits. These findings demonstrate that although some morphological traits are partially related, most traits vary independently, thereby reinforcing the reliability of the phenotype measurements for downstream GWAS analysis

3.3 Genome-Wide Association Studies of Different Morphological Traits

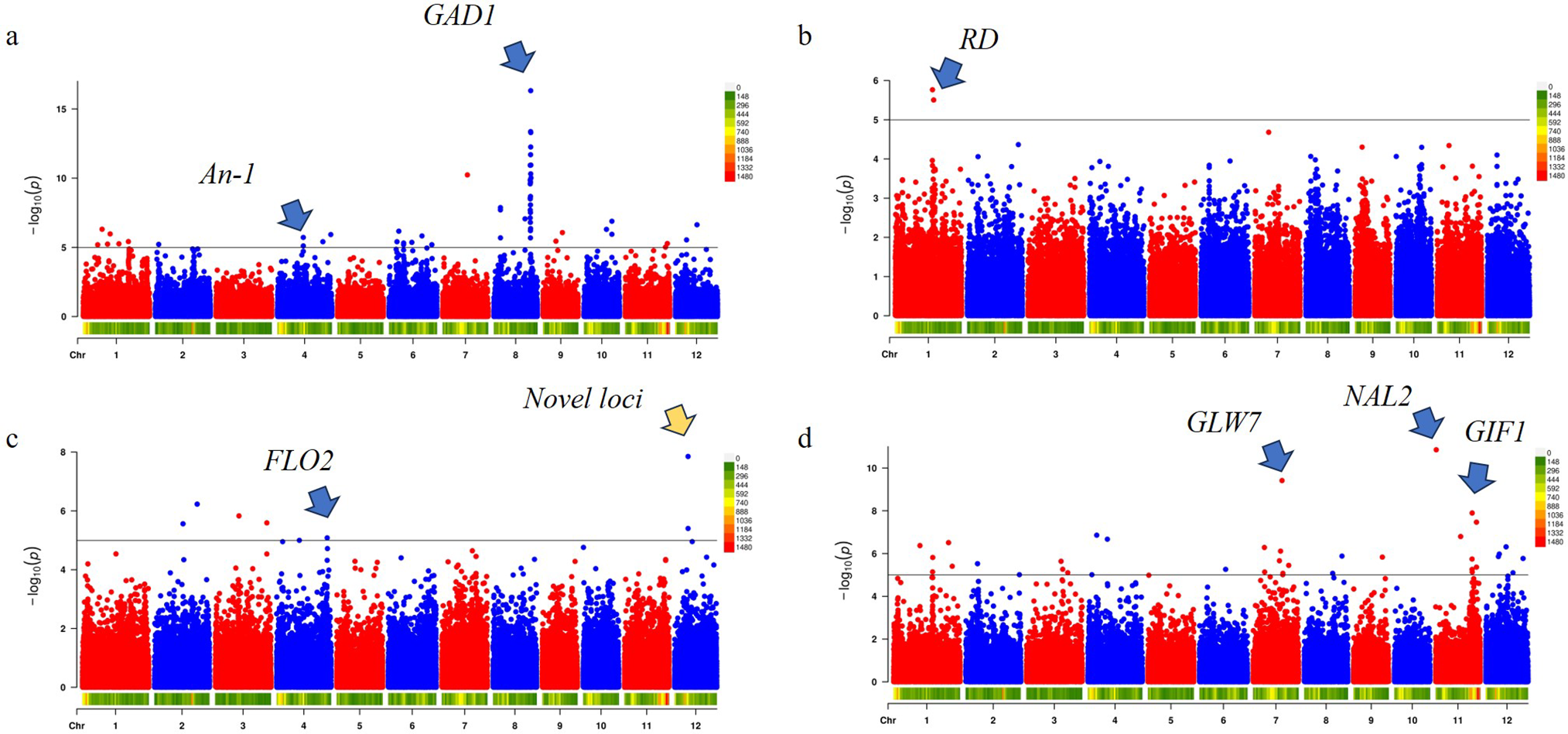

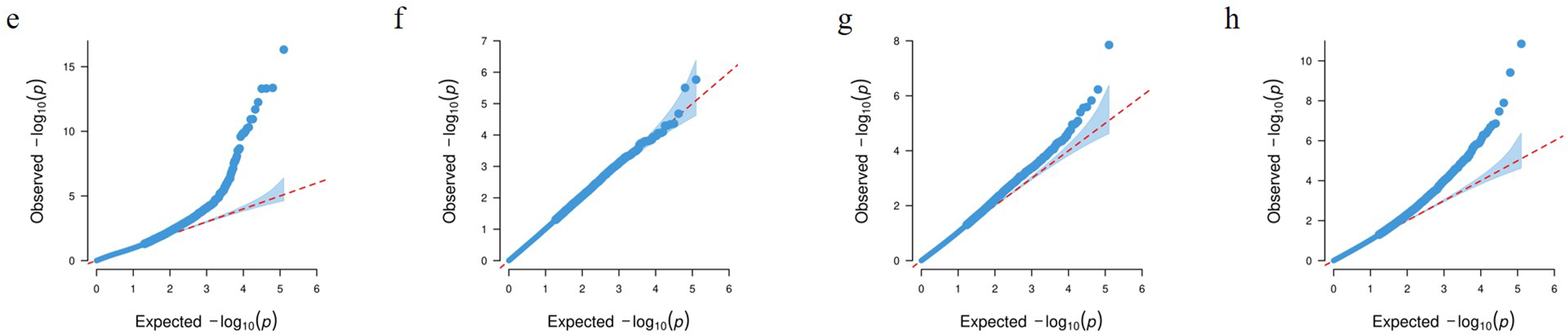

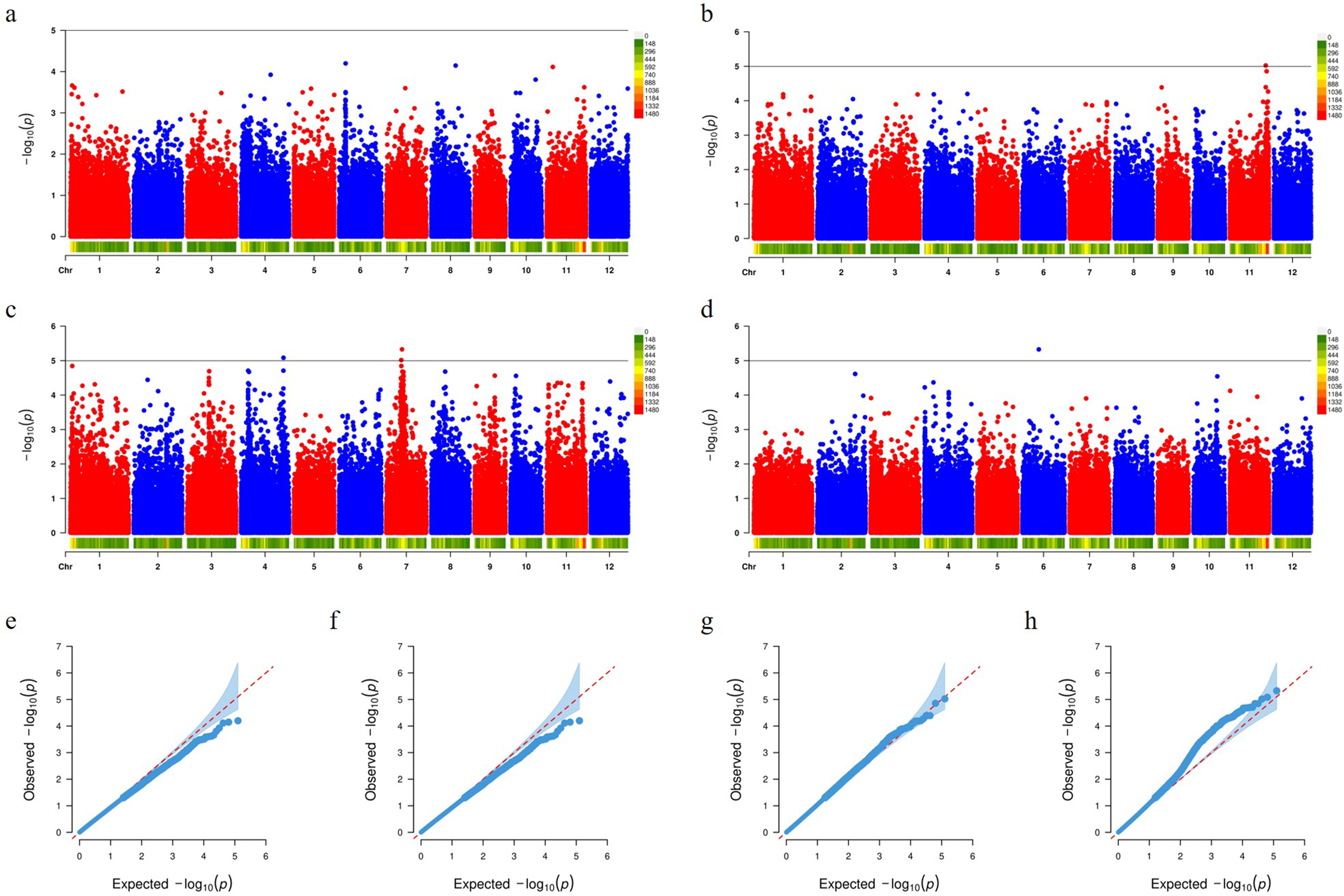

GWAS were performed for each of the key phenotypic traits (awn length, hull color, projected area, and shape PC1) using high-density SNP data and a mixed model to control for population structure (Fig. 5a–d). The genomic inflation factors for all GWAS analyses were found to be close to 1.0, indicating that population structure was adequately accounted for by the mixed linear model. The p-value distributions showed good alignment with expectations, except for an apparent deviation at the tails, which corresponded to true associations (Fig. 5e–h). Association signals that exceeded the significance threshold of

Figure 5: GWAS results for four key grain traits (a–d) and their corresponding Q-Q plots (e–h) in a panel of japonica landraces. Panels (a–d) are Manhattan plots of

A genome-wide association study for awn length was performed, identifying two distinct peaks that implicate different candidate genes involved in this complex trait. The most significant association was detected on chromosome 8 at position 24,042,077 (

Similarly, earlier genetic analyses using the near-isogenic line NIL-An-1 (wild An-1 allele introgressed into the awnless indica cultivar Guangluai 4) showed that An-1/OsRAE1 promotes awn and grain elongation while reducing grain number per panicle. A secondary association on chromosome 4 (chr4: 16,874,401;

A GWAS for rice hull color was performed identified a significant association on chromosome 1 at position 25,065,200 (

Subsequent studies demonstrated that Rd also operates in the C-S-A regulatory module governing hull pigmentation: myeloblastosis (MYB) factor C1 and bHLH factor S1 form a complex that directly activates Rd/A1 transcription in the lemma and palea. Only when all three genes are functional do hulls accumulate cyanidin 3-O-glucoside and appear purple, whereas loss of Rd diverts the pathway toward brown hues. The association signal detected in this study, therefore, supports Rd as a key structural gene influencing residual flavonoid deposition in the hulls of the japonica landrace panel, where upstream regulators (C1/S1) are largely inactive, and allelic variation at Rd modulates the remaining color intensity [54].

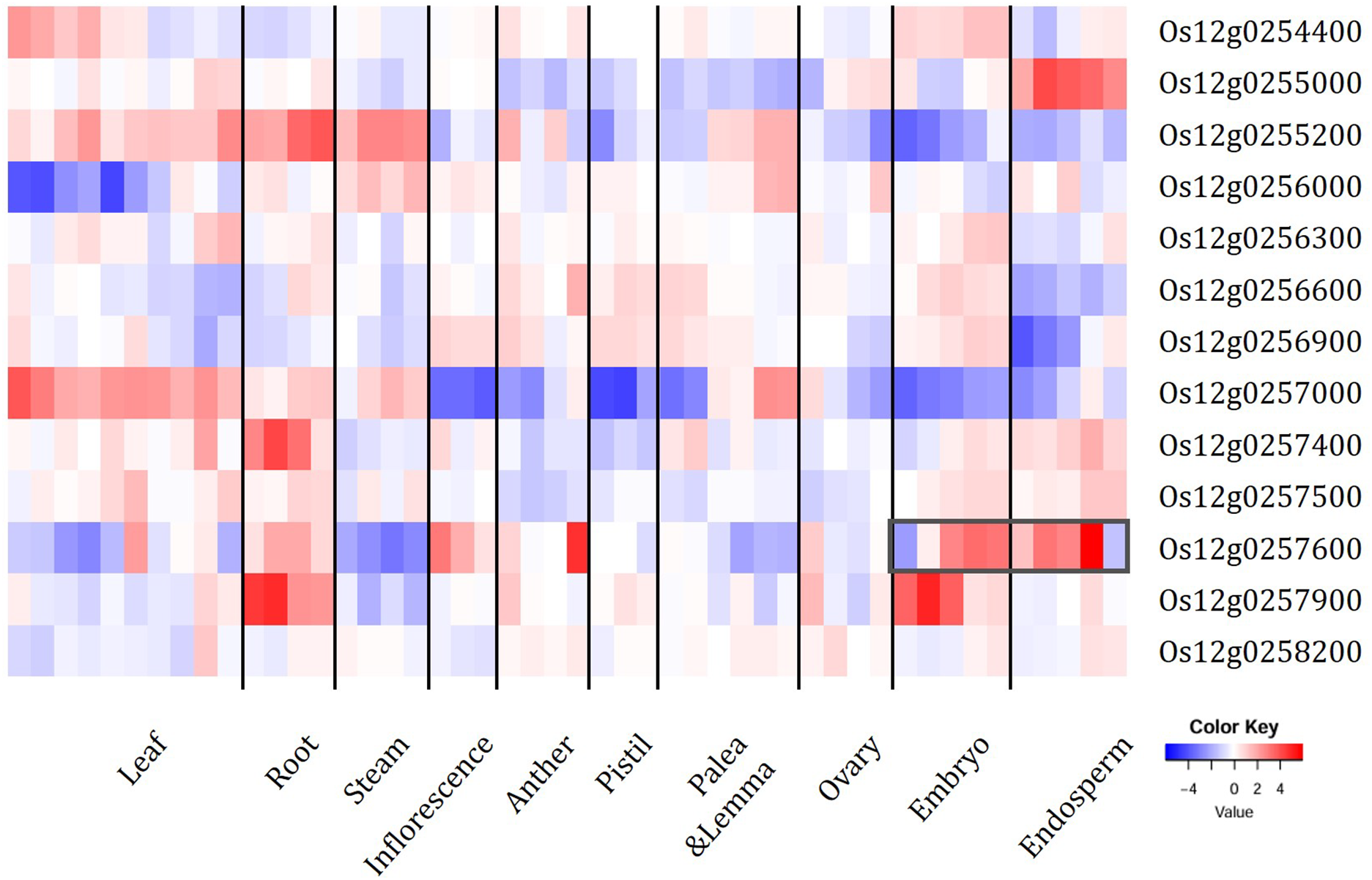

A genome-wide association study (GWAS) was performed for the projected grain area, identifying two main association peaks on chromosomes 12 and 4. The most significant signal (

Figure 6: Heatmap of spatiotemporal expression of the 13 genes in the region of interest (ROI) from microarray data (RiceXPro: https://ricexpro.dna.affrc.go.jp/, accessed on 9 July 2025). Z score, normalized expression. The heavy gray box indicates the high expression level of Os12g0257600 in embryo and endosperm

Notably, Os12g0255000 is annotated as a hypothetical gene with no conserved domains or functional reports, while Os12g0257900 belongs to the receptor-like kinase (RLK) super-family whose members are best known for roles in pathogen recognition and immune signalling rather than organ-size regulation in rice [55]. These features render both genes less plausible for controlling grain morphology.

Among these candidates, OsLAC28 is the most compelling. It encodes a multicopper oxidase-type laccase that belongs to sub-family V of the rice OsLAC gene family. Laccases participate in brassinosteroid (BR) signalling and cell-wall modification; in rice, the OsmiR397–OsLAC module controls cell proliferation in spikelet hulls, and down-regulation of OsLAC genes via OsmiR397 enlarges grain size and boosts yield by reducing BR sensitivity [56]. Taken together—(i) strong, seed-specific expression, (ii) biochemical annotation, and (iii) prior functional evidence—these observations nominate Os12g0257600(OsLAC28) as the causal gene underlying the chromosome 12 QTL for projected grain area.

In addition to the novel signal on chromosome 12, a second major peak (

3.4 Grain Shape Principal Component Analysis and GWAS

Among the five principal components (PCs) derived from the grain shape analysis, only PC1—which represents the grain length-width ratio—showed significant association signals (Fig. 5). Three major peaks were detected on chromosome 7 (position 18,875,985 bp;

The locus on chromosome 7 was co-localized with GLW7/OsSPL13 [58]. Previous studies have shown that the glw7 mutant exhibits significantly reduced grain length, grain width, and grain thickness relative to wild-type plants, whereas overexpression lines display marked increases in panicle length, the number of primary and secondary branches, grain size, and grain weight, ultimately leading to enhanced yield [58]. These phenotypic effects arise primarily through alterations in spikelet hull cell length and size, with minimal impact on plant height and tiller number. The association of PC1 with GLW7/OsSPL13 underscores that PC1 effectively captures the length-to-width dimension of grain shape variation. On chromosome 11, the strongest signal was mapped to 334,303 bp near NAL2/OsWOX3A, a gene implicated in lateral organ development [59]. Although nal2 or nal3 single mutants in rice have relatively normal leaves, nal2/3 double mutants exhibit notably narrow and rolled leaves, increased tillers, reduced lateral roots, and slender grains, while plant height remains nearly unchanged [59]. These pleiotropic effects suggest that allelic variation in OsWOX3A may influence leaf morphology and grain hull shape, contributing to the slenderness captured by PC1. A second association on chromosome 11 (23,794,924 bp) involved OsGIF1, which encodes a growth-regulating factor (GRF)-interacting factor. Overexpression of OsGIF1 enhances grain length, width, and thousand-grain weight by promoting both cell proliferation and elongation [60]. Notably, OsGIF1 emerged in the shape-based GWAS rather than in area-based analyses, suggesting that its natural allelic variations may exert a more pronounced effect on the relative proportions of the grain (e.g., length-to-width ratio) than on overall grain size alone.

For PC2–PC5, the mixed linear model (MLM) GWAS did not yield any associations that exceeded the genome-wide significance threshold, suggesting that these higher-order shape components (e.g., hull curvature and tip morphology) may be governed by highly polygenic architectures or that the allelic diversity for these traits is limited in the present panel (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: GWAS results for shape descriptors (PC2–PC5) and their corresponding Q-Q plots in a panel of japonica landraces. Panels (a–d) are Manhattan plots of

To assess whether the stringent correction in the MLM might have masked true associations for PC2–PC5, both a generalized linear model with the first two population-structure principal components included as fixed covariates (GLM + PCA) and FarmCPU (without PCA covariates) were applied. Under both approaches, a significant peak emerged on chromosome 6 at 19,629,938 bp for the PC5 trait, co-localizing with the known grain-size regulator OsUBR7. OsUBR7 encodes an E3 ubiquitin ligase responsible for histone H2B monoubiquitination (H2Bub1), exerting epigenetic control over genes involved in cell proliferation and organ development. Accessions carrying the associated allele show mildly reduced panicle length, grain width, grain length, and thousand-grain weight. Nevertheless, because MLM more effectively suppresses cryptic relatedness in a complex germplasm panel, the MLM results have been retained as the main findings, with the GLM + PCA (Fig. S2) and FarmCPU (Fig. S3) associations presented as supplementary evidence to highlight potentially interesting loci while ensuring robustness and reproducibility.

A two-dimensional (2D) image-processing pipeline was integrated with high-density genomic data in this study to dissect the genetic architecture underlying rice grain morphology in a diverse panel of japonica landraces. By standardizing image capture, segmentation, and feature extraction, key grain traits—including awn length, hull coloration, projected area, and multiple shape descriptors—were measured quickly and with high reproducibility. Subsequent genome-wide association studies (GWAS) uncovered both known and novel loci, highlighting the power of image-based phenotyping in identifying candidate genes related to agronomically important traits.

By leveraging a GWAS approach, multiple significant loci associated with diverse rice grain phenotypes, including awn length, hull color, projected area, and shape, were identified. Major-effect genes such as GAD1 (OsRAE2) [37,61] and An-1 [52] were detected for awn length, reflecting the evolutionary transition from long-awned wild rice to predominantly awnless cultivars. Regarding hull color, a strong association with Rd—encoding a key enzyme in the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway—was observed in darker-hulled accessions, while lighter-hulled lines were generally found to lack functional alleles at pigment-related loci [53]. A novel locus on chromosome 12 was uncovered regarding grain size, encompassing a plausible candidate gene (Os12g0257600(OsLAC28)) that shows seed-specific expression and functions as a multicopper-oxidase laccase involved in brassinosteroid signalling and cell-wall modification, thereby promoting cell proliferation during early grain development. An additional signal co-localized with FLO2 [57] on chromosome 4, corroborating its established role in starch accumulation and grain filling. Finally, shape variation, quantified via PCA, revealed that the primary length-to-width component (PC1) was mapped to loci containing genes such as GLW7 (OsSPL13) [58], NAL2 (OsWOX3A) [59], and OsGIF1 [60], all of which are implicated in cell proliferation and hull development. Collectively, these findings validate known regulators and illuminate novel candidate genes, providing a robust framework for understanding the genetic control of rice grain morphology and informing future breeding strategies.

Only four trait categories—awn length, hull color, projected area, and outline-derived shape—were analyzed because they can be quantified reliably from a single planar photograph. Important grain attributes such as kernel thickness, volume, bulk density, chalkiness and endosperm translucency require multi-view reconstruction, X-ray computed tomography (CT), laser scanning or destructive assays, and therefore lay outside the scope of the present pipeline. Recent reports using CT or structured-light scanning show that adding the third spatial dimension markedly improves the accuracy of thickness, density and volume estimates, but at the expense of throughput and equipment complexity [62,63]. Future work will explore low-cost 3-D solutions (e.g., stereo pairs or turn-table imaging) so that these complementary phenotypes can be integrated into the genotype-phenotype maps.

To benchmark the image-processing workflow, we manually measured grain length and awn length with a digital caliper in twenty randomly selected accessions. These two easily recorded linear traits offer a stringent, first-order check on segmentation accuracy and scale calibration. Independent ground-truth measurements were not collected for hull color, projected area, or the outline-derived shape descriptors; therefore, bias in these chromatic and morphometric traits cannot be ruled out. In future work we will design dedicated validation experiments—such as spectrally calibrated color targets and 3-D reference objects—to quantify, and where necessary correct, any residual phenotyping error.

4.3 Future Perspectives and Broader Implications

From a practical standpoint, integrating digital imaging with GWAS enables rapid, cost-effective phenotypic profiling at scale. The approach is readily adaptable to other plant species and trait sets (e.g., leaf shape, seed color in cereals and legumes, fruit size/shape in horticultural crops), facilitating precision phenomics in breeding pipelines. Further, the discovery of novel candidate genes underscores the potential for translational breeding applications: gene editing or marker-assisted selection targeting these loci could open avenues for tailoring grain attributes—such as size or color—to specific market demands or environmental conditions.

It is demonstrated in this work that high-quality, image-based phenotyping, combined with genome-wide association studies, can reveal both major-effect genes and novel candidate loci contributing to morphological diversity in rice grains. This approach not only refines the understanding of domestication-related changes (e.g., awn length) and quality traits (grain shape, hull pigmentation), but also paves the way for next-generation breeding strategies. Extending this framework to larger populations and integrating multi-omics data (e.g., transcriptomics, epigenomics) are expected to deepen insights into the intricate regulatory networks controlling grain development and further accelerate crop improvement.

Acknowledgement: I gratefully acknowledge the Institute of Germplasm Resources and Biotechnology at the Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences for providing the plant materials.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Jiexiong Xu, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.067124/s1.

References

1. Zhao D, Zhang C, Li Q, Liu Q. Genetic control of grain appearance quality in rice. Biotechnol Adv. 2022;60(2):108014. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2022.108014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Marris E. Geneticists reveal what makes great rice. Nature. 2015 Jul. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.17918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Fornasiero A, Wing RA, Ronald P. Rice domestication. Current Biology. 2022 Jan;32(1):R20–4. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.11.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wang Z, Guo Z, Zou T, Zhang Z, Zhang J, He P, et al. Substitution mapping and allelic variations of the domestication genes from O. rufipogon and O. nivara. Rice. 2023;16(1):38. doi:10.1186/s12284-023-00655-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Wambugu PW, Ndjiondjop MN, Henry R. Genetics and genomics of African Rice (Oryza glaberrima Steud) Domestication. Rice. 2021 Jan;14(1):6. doi:10.1186/s12284-020-00449-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Xia D, Zhou H, Wang Y, Li P, Fu P, Wu B, et al. How rice organs are colored: the genetic basis of anthocyanin biosynthesis in rice. Crop J. 2021 Jun;9(3):598–608. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2021.03.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lu Y, Wang J, Fu L, Yu L, Liu Q. High-throughput and separating-free phenotyping method for on-panicle rice grains based on deep learning. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1219584. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1219584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Sun J, Ren Z, Cui J, Tang C, Luo T, Yang W, et al. A high-throughput method for accurate extraction of intact rice panicle traits. Plant Phenomics. 2024;6(4):0213. doi:10.34133/plantphenomics.0213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Shin Y, Won YJ, Lee C, Cheon KS, Oh H, Lee GS, et al. Identification of grain size-related QTLs in Korean japonica rice using genome resequencing and high-throughput image analysis. Agriculture. 2022;12(1):51. doi:10.3390/agriculture12010051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Manzoor GA, Yin C, Zhang L, Wang J. Mapping and validation of quantitative trait loci on yield-related traits using bi-parental recombinant inbred lines and reciprocal single-segment substitution lines in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plants. 2025;14(1):43. doi:10.3390/plants14010043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Wang W, Guo W, Le L, Yu J, Wu Y, Li D, et al. Integration of high-throughput phenotyping, GWAS, and predictive models reveals the genetic architecture of plant height in maize. Mol Plant. 2023 Feb;16(2):354–73. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2022.11.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Zhang Z, Qu Y, Ma F, Lv Q, Zhu X, Guo G, et al. Integrating high-throughput phenotyping and genome-wide association studies for enhanced drought resistance and yield prediction in wheat. New Phytol. 2024 Jul;243(5):1758–75. doi:10.1111/nph.19942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Pinit S, Ruengchaijatuporn N, Sriswasdi S, Buaboocha T, Chadchawan S, Chaiwanon J. Hyperspectral and genome-wide association analyses of leaf phosphorus status in local Thai indica rice. PLoS One. 2022 Apr;17(4):e0267304. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0267304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Davis JM, Gaillard M, Tross MC, Shrestha N, Ostermann I, Grove RJ, et al. 3D reconstruction enables high-throughput phenotyping and quantitative genetic analysis of phyllotaxy. Plant Phenomics. 2025 Mar;7(1):100023. doi:10.1016/j.plaphe.2025.100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Dhanapal AP, York LM, Hames KA, Fritschi FB. Genome-wide association study of topsoil root system architecture in field-grown soybean [Glycinemax (L.) Merr.]. Front Plant Sci. 2021 Feb;11:590179. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.590179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Wang W, Mauleon R, Hu Z, Chebotarov D, Tai S, Wu Z, et al. Genomic variation in 3010 diverse accessions of Asian cultivated rice. Nature. 2018;557(7703):43–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

17. Xu J. GrainShape: a landmark-annotated image dataset of japonica rice grains for geometric morphometric analysis. Data Brief. 2025;61:111781. doi:10.1016/j.dib.2025.111781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wang N, Chen H, Qian Y, Liang Z, Zheng G, Xiang J, et al. Genome-wide association study of rice grain shape and chalkiness in a worldwide collection of xian accessions. Plants. 2023;12(3):419. doi:10.3390/plants12030419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Singh G, Jyoti SD, Uppalanchi P, Chepuri R, Mondal S, Harper CL, et al. Genomic regions associated with flag leaf and panicle architecture in rice (Oryzasativa L.). BMC Genomics. 2024;25(1):1200. doi:10.1186/s12864-024-11037-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Guo J, Wang W, Li W. Genome-wide association study reveals novel QTLs and candidate genes for panicle number in rice. Front Genet. 2024;15:1470294. doi:10.3389/fgene.2024.1470294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang P, Zhong K, Shahid MQ, Tong H. Association analysis in rice: from application to utilization. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

22. Cu ST, Warnock NI, Pasuquin J, Dingkuhn M, Stangoulis J. A high-resolution genome-wide association study of the grain ionome and agronomic traits in rice Oryza sativa subsp. indica. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):19230. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-98573-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Feng Y, Lu Q, Zhai R, Zhang M, Xu Q, Yang Y, et al. Genome wide association mapping for grain shape traits in indica rice. Planta. 2016;244(4):819–30. doi:10.1007/s00425-016-2548-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zhao K, Tung CW, Eizenga GC, Wright MH, Ali ML, Price AH, et al. Genome-wide association mapping reveals a rich genetic architecture of complex traits in Oryza sativa. Nat Commun. 2011;2(1):467. doi:10.1038/ncomms1467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Wang Q, Tang J, Han B, Huang X. Advances in genome-wide association studies of complex traits in rice. Theoret Appl Genetics. 2020;133(5):1415–25. doi:10.1007/s00122-019-03473-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Padmashree R, Barbadikar KM, Honnappa, Magar ND, Balakrishnan D, Lokesha R, et al. Genome-wide association studies in rice germplasm reveal significant genomic regions for root and yield-related traits under aerobic and irrigated conditions. Front Plant Sci. 2023 Jul;14:1143853. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1143853. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Xu C, Liu Y, Li Y, Xu X, Xu C, Li X, et al. Differential expression of GS5 regulates grain size in rice. J Exp Bot. 2015 Feb;66(9):2611–23. doi:10.1093/jxb/erv058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Li Y, Fan C, Xing Y, Jiang Y, Luo L, Sun L, et al. Natural variation in GS5 plays an important role in regulating grain size and yield in rice. Nat Genetics. 2011;43(12):1266–9. doi:10.1038/ng.977. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Kirillov A, Mintun E, Ravi N, Mao H, Rolland C, Gustafson L, et al. Segment anything. In: Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2023 Oct 2–6; Paris Convention Center, Paris, France. Piscataway, NJ, USA: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE); 2023. p. 4015–26. doi:10.1109/ICCV51070.2023.00371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Russell BC, Torralba A, Murphy KP, Freeman WT. LabelMe: a database and web-based tool for image annotation. Int J Comput Vis. 2007 Oct;77(1–3):157–73. doi:10.1007/s11263-007-0090-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhou X, Stephens M. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat Genet. 2012 Jun;44(7):821–4. doi:10.1038/ng.2310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Yu J, Pressoir G, Briggs WH, Vroh Bi I, Yamasaki M, Doebley JF, et al. A unified mixed-model method for association mapping that accounts for multiple levels of relatedness. Nat Genet. 2005 Dec;38(2):203–8. doi:10.1038/ng1702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genetics. 2006;38(8):904–9. doi:10.1038/ng1847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Liu X, Huang M, Fan B, Buckler ES, Zhang Z. Iterative usage of fixed and random effect models for powerful and efficient genome-wide association studies. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(2):e1005767. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Huang X, Wei X, Sang T, Zhao Q, Feng Q, Zhao Y, et al. Genome-wide association studies of 14 agronomic traits in rice landraces. Nat Genetics. 2010;42(11):961–7. doi:10.1038/ng.695. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Zheng H, Tang W, Yang T, Zhou M, Guo C, Cheng T, et al. Grain protein content phenotyping in rice via hyperspectral imaging technology and a genome-wide association study. Plant Phenomics. 2024;6(1):0200. doi:10.34133/plantphenomics.0200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Jin J, Hua L, Zhu Z, Tan L, Zhao X, Zhang W, et al. GAD1 encodes a secreted peptide that regulates grain number, grain length, and awn development in rice domestication. Plant Cell. 2016 Sep;28(10):2453–63. doi:10.1105/tpc.16.00379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Suganami M, Yoshida H, Yoshida S, Kawamura M, Koketsu E, Matsuoka M, et al. Redefining awn development in rice through the breeding history of Japanese awn reduction. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1370956. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1370956. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Schanda J. Colorimetry: understanding the CIE system. 1st ed. In: Wiley IS&T series in imaging science and technology. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2007. 496 p. doi:10.1002/9780470175637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Furukawa T, Maekawa M, Oki T, Suda I, Iida S, Shimada H, et al. The Rc and Rd genes are involved in proanthocyanidin synthesis in rice pericarp. Plant J. 2006 Dec;49(1):91–102. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313x.2006.02958.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Fan C, Xing Y, Mao H, Lu T, Han B, Xu C, et al. GS3, a major QTL for grain length and weight and minor QTL for grain width and thickness in rice, encodes a putative transmembrane protein. Theoreti Appl Genetics. 2006;112(6):1164–71. doi:10.1007/s00122-006-0218-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Huang X, Qian Q, Liu Z, Sun H, He S, Luo D, et al. Natural variation at the DEP1 locus enhances grain yield in rice. Nat Genetics. 2009;41(4):494–7. doi:10.1038/ng.352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Shomura A, Izawa T, Ebana K, Ebitani T, Kanegae H, Konishi S, et al. Deletion in a gene associated with grain size increased yields during rice domestication. Nat Genetics. 2008;40(8):1023–8. doi:10.1038/ng.169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Weng J, Gu S, Wan X, Gao H, Guo T, Su N, et al. Isolation and initial characterization of GW5, a major QTL associated with rice grain width and weight. Cell Res. 2008;18(12):1199–209. doi:10.1038/cr.2008.307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Wang S, Wu K, Yuan Q, Liu X, Liu Z, Lin X, et al. Control of grain size, shape and quality by OsSPL16 in rice. Nat Genetics. 2012;44(8):950–4. doi:10.1038/ng.2327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Zuo J, Li J. Molecular genetic dissection of quantitative trait loci regulating rice grain size. Ann Rev Genetics. 2014;48(1):99–118. doi:10.1146/annurev-genet-120213-092138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Wu Y, Wang Y, Mi XF, Shan JX, Li XM, Xu JL, et al. The QTL GNP1 encodes GA20ox1, which increases grain number and yield by increasing cytokinin activity in rice panicle meristems. PLoS Genetics. 2016;12(10):e1006386. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Ishimaru K, Hirotsu N, Madoka Y, Murakami N, Hara N, Onodera H, et al. Loss of function of the IAA-glucose hydrolase gene TGW6 enhances rice grain weight and increases yield. Nature Genetics. 2013;45(6):707–11. doi:10.1038/ng.2612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Wang J, Zhang Q, Wang Y, Huang J, Luo N, Wei S, et al. Analysing the rice young panicle transcriptome reveals the gene regulatory network controlled by TRIANGULAR HULL1. Rice. 2019;12(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12284-019-0265-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Tong X, Wang Y, Sun A, Bello BK, Ni S, Zhang J. Notched belly grain 4, a novel allele of dwarf 11, regulates grain shape and seed germination in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(12):4069. doi:10.3390/ijms19124069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Furuta T, Komeda N, Asano K, Uehara K, Gamuyao R, Angeles-Shim RB, et al. Convergent loss of awn in two cultivated rice species Oryza sativa and Oryza glaberrima is caused by mutations in different loci. G3 Genes Genomes Genetics. 2015;5(11):2267–74. doi:10.1534/g3.115.020834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Wang Z, Yang J, Huang T, Chen Z, Nyasulu M, Zhong Q, et al. Genetic analysis of the awn length gene in the rice chromosome segment substitution line CSSL29. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(4):1436. doi:10.3390/ijms26041436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Yang W, Chen L, Zhao J, Wang J, Li W, Yang T, et al. Genome-wide association study of pericarp color in rice using different germplasm and phenotyping methods reveals different genetic architectures. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:841191. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.841191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Sun X, Zhang Z, Chen C, Wu W, Ren N, Jiang C, et al. The C-S-A gene system regulates hull pigmentation and reveals evolution of anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway in rice. J Exp Bot. 2018 Jan;69(7):1485–98. doi:10.1093/jxb/ery001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Liang X, Zhou JM. Receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases: central players in plant receptor kinase-mediated signaling. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2018;69(1):267–99. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042817-040540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Zhang YC, Yu Y, Wang CY, Li ZY, Liu Q, Xu J, et al. Overexpression of microRNA OsmiR397 improves rice yield by increasing grain size and promoting panicle branching. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(9):848–52. doi:10.1038/nbt.2646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. She KC, Kusano H, Koizumi K, Yamakawa H, Hakata M, Imamura T, et al. A novel factor FLOURY ENDOSPERM2 is involved in regulation of rice grain size and starch quality. Plant Cell. 2010 Oct;22(10):3280–94. doi:10.1105/tpc.109.070821. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Si L, Chen J, Huang X, Gong H, Luo J, Hou Q, et al. OsSPL13 controls grain size in cultivated rice. Nat Genet. 2016 Mar;48(4):447–56. doi:10.1038/ng.3518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Cho S, Yoo S, Zhang H, Pandeya D, Koh H, Hwang J, et al. The rice narrow leaf2 and narrow leaf3 loci encode WUSCHEL-related homeobox 3A (OsWOX3A) and function in leaf, spikelet, tiller and lateral root development. New Phytol. 2013 Apr;198(4):1071–84. doi:10.1111/nph.12231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. He Z, Zeng J, Ren Y, Chen D, Li W, Gao F, et al. OsGIF1 positively regulates the sizes of stems, leaves, and grains in rice. Front Plant Sci. 2017 Oct;8:197. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.01730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Luo J, Amin B, Wu B, Wu B, Huang W, Salmen SH, et al. Blocking of awn development-related gene OsGAD1 coordinately boosts yield and quality of Kam Sweet Rice. Physiol Plant. 2024 Feb;176(2):482. doi:10.1111/ppl.14229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Huang X, Zheng S, Zhu N. High-throughput legume seed phenotyping using a handheld 3D laser scanner. Remote Sens. 2022;14(2):431. doi:10.3390/rs14020431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Griffiths M, Gautam B, Lebow C, Duncan K, Ding X, Handakumbura P, et al. Evaluation of 3D seed structure and cellular traits in-situ using X-ray microscopy. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):4532. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-88482-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools