Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Unraveling the Functional Diversity of MYB Transcription Factors in Plants: A Systematic Review of Recent Advances

1 Centre for Research in Biotechnology for Agriculture (CEBAR), Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

2 Institute for Advanced Studies, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

3 Department of Biotechnology, College of Science, Engineering and Technology, Osun State University, Osogbo, 210001, Nigeria

4 Department of Gastronomy, Faculty of Tourism, University of Kyrenia, Mersin 10, Girne, 99320, Türkiye

5 Institute of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

6 Department of Pharmaceutical Life Sciences, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Boon Chin Tan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Transcriptional Regulation and Signal Transduction Networks in Plant Growth, Development, Morphogenesis, and Environmental Responses)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2229-2254. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.067225

Received 27 April 2025; Accepted 14 July 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

Myeloblastosis (MYB) transcription factors (TFs) are evolutionarily conserved regulatory proteins that are crucial for plant growth, development, secondary metabolism, and stress adaptation. Recent studies have highlighted their crucial role in coordinating growth–defense trade-offs through transcriptional regulation of key biosynthetic and stress-response genes. Despite extensive functional characterization in model plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana, systematically evaluating the broader functional landscape of MYB TFs across diverse species and contexts remains necessary. This systematic review integrates results from 24 peer-reviewed studies sourced from Scopus and Web of Science, focusing on the functional diversity of MYB TFs, particularly in relation to abiotic stress tolerance, metabolic regulation, and plant developmental processes. Advances in genomic technologies, such as transcriptomics, genome editing, and comparative phylogenetics, have considerably enhanced our understanding of MYB-mediated regulatory mechanisms. These tools have facilitated the identification and functional characterization of MYB genes across model and non-model plant species. Key findings underscore the multifaceted roles of MYB TFs in enhancing stress resilience, modulating anthocyanin and flavonoid biosynthesis, and contributing to yield-related traits, thereby highlighting their potential applications in crop improvement and sustainable agriculture. However, critical gaps exist in understanding MYB interactions within complex regulatory networks, particularly in underrepresented plant species and ecological contexts. This review consolidates current knowledge as well as identifies research gaps and proposes future directions to advance the understanding and application of MYB TFs. The insights derived from this study underscore their transformative potential in addressing global challenges including food security and climate resilience through innovative agricultural practices.Keywords

Transcription factors (TFs) are master regulators of gene expression that are primarily involved in plant development, metabolism, and stress adaptation [1], which function by binding to local or distal cis-regulatory elements (also known as DNA-binding sites) in the promoters of target genes [2] and modulate transcription via activator or repressor domains [3]. Many TFs also contain additional domains that enable interactions with other proteins, such as co-regulators, signaling molecules, or other TFs, thereby expanding their functional versatility. Myeloblastosis (MYB) TFs are one of the largest and most functionally diverse groups among plant TF families. The increasing availability of genomic and transcriptomic tools facilitates large-scale identification, classification, and expression profiling of MYB TFs across model and non-model plant species. Over the past decade, MYB TFs have attracted considerable attention owing to their involvement in various physiological and molecular processes. These include cell cycle regulation, flowering, and fruit formation [4], as well as stress responses [5], such as drought tolerance, salinity, and pathogen resistance, making them potential targets for crop improvement. Functionally, MYB TFs have demonstrated practical applications in key agronomic traits. For example, Arabidopsis thaliana MYB proteins AtMYB60 and AtMYB96 regulate stomatal function and drought responses, highlighting their potential in developing stress-resilient crops [6,7]. Similarly, MYB TFs are important for anthocyanin biosynthesis in carrots [8] and improved stress tolerance in rice [9]. Consequently, MYB TFs are increasingly recognized as central regulators in plant physiological networks but also as key molecular targets for genetic strategies to enhance crop performance and resilience.

Despite considerable advancement, important knowledge gaps remain in our understanding of MYB TFs, particularly regarding their roles in non-model species of ecological and agronomic importance [10,11]. Although MYB TFs have been extensively characterized in model plants and associated with various physiological roles, our understanding remains fragmented in several key areas. To date, most studies have examined MYB functions in isolated contexts, such as development, metabolism, or stress response [12,13], without addressing how these regulatory activities intersect under real-world, multifactorial stress conditions. Moreover, functional investigations have predominantly focused on the R2R3-MYB subfamily, whereas other subfamilies such as 3R-MYBs have remained relatively unexplored, despite evidence of their unique contributions to cell cycle control and environmental signaling [14]. Studies on non-model species also remain limited, constraining the translational potential of MYB-based strategies in diverse crop systems. In addition, the integration of MYB TFs into broader signaling and regulatory frameworks, such as hormonal pathways, epigenetic modulation, and post-translational control, remains to be comprehensively explored. Addressing these gaps is essential for translating MYB research into practical strategies for enhancing crop resilience, productivity, and sustainability amidst global climate and food security challenges.

This review aims to bridge existing knowledge gaps by critically evaluating recent advances and integrating insights from structural classification, regulatory function, and biotechnological applications of MYB TFs. We highlight the role of MYB TFs as regulatory hubs that coordinate plant development, secondary metabolism, and environmental responses, thereby providing a strategic framework for future research and translational applications in crop biotechnology. The review focused on three main objectives: (1) elucidating structure-function relationships across MYB subfamilies, (2) mapping their roles in development and stress adaptation, and (3) identifying effective strategies to harness MYB networks for crop improvement. The review is structured as follows: Section 2 outlines the different classifications and functions of MYB TFs; Section 3 examines MYB regulatory roles in development and stress; Section 4 discusses the post-translational modifications of MYBs; Section 5 underscores the challenges in deciphering MYB interactomes and opportunities for translational research; Section 6 outlines the methodology for data collection and bibliometric analysis; and Section 7 concludes with future perspectives for MYB-driven sustainable agriculture.

2 Structural Classification and Functional Roles of MYB Transcription Factors

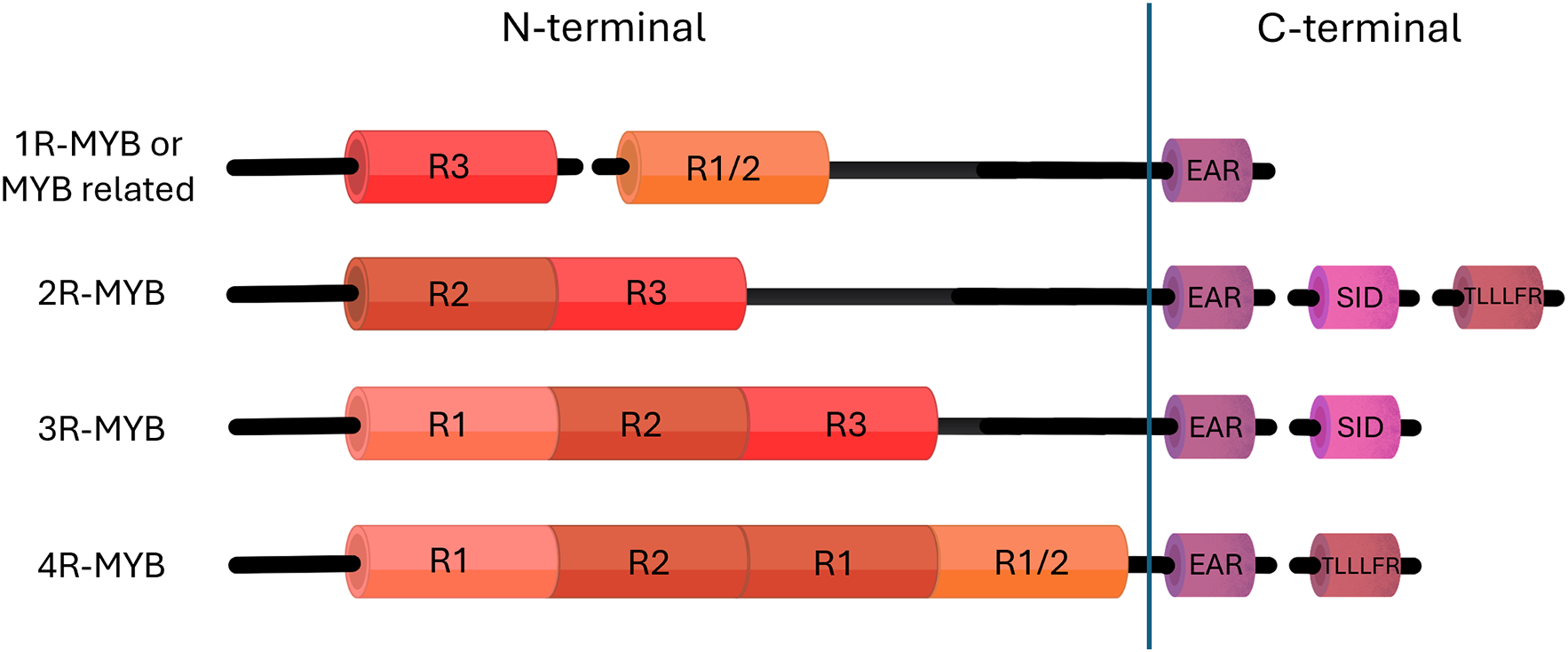

All MYB proteins have a conserved DNA-binding domain (DBD) located at the N-terminal region, which comprises one to four repeat units (1R, R2R3, 3R, or 4R-MYB; Fig. 1). These repeat motifs facilitate MYB proteins to recognize and bind to specific DNA sequences within gene promoter regions, thereby enabling them to modulate the transcription of target genes. Through this mechanism, MYB TFs regulate important biological functions, such as cell development, hormone signaling, secondary metabolite production, and the responses to various environmental stresses [15,16]. The DNA-binding domain consists of a highly conserved stretch of 50–53 amino acids that forms a helix-turn-helix (HTH) structure [17]. This shape, formed by the connection between the second and third helices [17], is crucial for the protein to attach to the major groove of the target DNA [18]. The function of MYB proteins is primarily determined by their C-terminal region, which varies in sequence and typically includes one or two specialized motifs. These include the ERF-associated amphipathic repression (EAR) [19], SID (interacts with the ABA- and drought-related protein SAD2) [20], and the TLLLFR motifs [15–17].

Figure 1: Structural classification of plant MYB transcription factors in plants. This figure shows the domain structure of MYB TFs based on the number and arrangement of MYB repeats in the N-terminal region: 1R-MYB (or MYB-related), 2R-MYB (R2R3), 3R-MYB, and 4R-MYB. The C-terminal contains specialized motifs such as EAR, SID, and TLLFR which contribute to transcriptional regulation and protein–protein interactions

Evolutionary diversification has classified MYB TFs into subfamilies based on structural motifs and sequence conservation, with R2R3-MYBs, lacking the first R-repeat, being the largest group in angiosperms [21]. In strawberry, Liu et al. [22] identified 393 R2R3-MYB genes, classifying them into 36 subgroups with four distinct subfamilies: 321 1R-MYB, 393 R2R3-MYB, 17 3R-MYB, and six 4R-MYB genes. The R2R3-MYBs accounted for 53.32% of FaMYB genes, highlighting their dominance. 1R-MYB TFs contain a single imperfect MYB repeat of approximately 51–52 amino acid residues, forming a DNA recognition helix that interacts with specific DNA sequences to regulate gene expression [23]. 1R-MYBs evolved through domain shuffling and contribute to functional diversification across plant taxa [24]. Their roles include regulating abiotic stress responses, such as drought tolerance [25], gene regulation, circadian rhythm control, and telomeric DNA binding [24]. For example, the overexpression of 1R-MYB genes enhances salt and cold stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis [23]. R3-MYB TFs, without the R1- and R2-repeats, function as inhibitors of MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) complexes and trichome development. They migrate from trichome precursor cells to neighbouring cells, where they interfere with R2R3-MYBs and disrupt MBW complex formation. These complexes promote trichome formation by inducing R3-MYB expression (excluding TCL1), helping maintain developmental balance. Additionally, R3-MYBs serve as negative regulators of flavonoid biosynthesis and other MBW-mediated processes by interacting with bHLH proteins, thereby inhibiting R2R3-MYB activity and adding an extra layer of regulatory control [26].

2R-MYBs represent the largest and most expanded MYB group in angiosperms, with over 170 members identified in A. thaliana [27], 116 in Capsicum [11], and 222 in Musa acuminata [28]. Overall, R2R3-MYB gene copy numbers are generally higher in seed plants than in ferns, and higher in ferns than in lycophytes [29]. R2R3-MYBs are defined by a conserved DNA-binding domain (DBD) containing two MYB repeats (R2 and R3) that interact with cis-elements in gene promoters to modulate gene expression (Fig. 1). Many activators and some repressors have a conserved bHLH-interacting motif in the first two helices of the R3 domain, facilitating the formation of the MBW transcriptional complex [15]. Although the N-terminal DBD is highly conserved, the C-terminal region is more variable and frequently contains functional motifs, including TLLLFR, SID, and C2/EAR [30], as well as conserved motifs such as C1, C3, C4, and C5. Functionally, R2R3-MYB proteins play a key role in regulating flavonoid accumulation. For example, PpMYB15 and PpMYBF1 in peach fruit [31] and VvMYBF1 in grapevine [32] promote anthocyanin production. Similarly, MYB10 and MYB1 in strawberry [33] and MdMYB23 in apples influence proanthocyanidin accumulation [34]. Additional functions include regulating the phenylpropanoid pathway, controlling stilbene biosynthesis in grapevine through TFs such as MYB14 and MYB15 [35], and the mediation of environmental responses such as cold tolerance and light-induced gene expression [34,36]. Kang et al. [5] investigated the expression levels of 20 Oryza sativa 2R-MYB genes under PEG (drought) and cadmium chloride (heavy metal stress) treatments and observed that some genes were upregulated, whereas others were downregulated in response to these stresses, indicating a functional role in stress adaptation.

The 3R-MYB TF family, characterized by the presence of three MYB repeats (R1, R2, and R3), represents a functionally and evolutionarily conserved group across various plant species. These TFs are key regulators of plant growth, cell cycle regulation, and responses to environmental stresses [14,37]. For example, CaMYB3R-5 from chili pepper has been associated with cell cycle processes and abiotic stress responses [11]. Similarly, expression levels of certain 3R-MYBs increase under temperature fluctuations and water stress [38,39]. From an applied perspective, understanding the roles of 3R-MYBs can support the development of genetically engineered crops with enhanced stress tolerance.

The 4R-MYB TFs represent the least common and least studied subgroup within the MYB family. These proteins are distinguished by having four conserved MYB-like repeats, enabling them to form complex structures that can interact with DNA to regulate various plant biological processes [40]. Phylogenetic evidence suggests that 4R-MYB proteins likely evolved from ancestral MYB genes through gene duplication events [14]. Despite their structural uniqueness, 4R-MYBs are extremely rare. A single 4R-MYB gene has been identified in O. sativa and two in A. thaliana [12,41]. Their biological roles remain largely unexplored. A notable exception is AtSNAPc4, a 4R-MYB protein in Arabidopsis, which functions as a component of the SNAP complex involved in snRNA gene transcription. It is essential for gametophyte and zygote development [42]. In medicinal plants, the 4R-MYB subfamily is similarly the smallest within the MYB family. For example, only two 4R-MYB genes have been identified in Dendrobium candidum, while only one is present in Jatropha curcas. This limited distribution further highlights the necessity for more comprehensive research to explore their functional diversity and evolutionary significance.

3 Integrative Insights and Applications of MYB Transcription Factors Based on Thematic Clusters

Understanding the multifaceted roles of MYB TFs requires a comprehensive approach that integrates functional, regulatory, and applied perspectives. In this section, we categorize and synthesize current findings into key thematic clusters to highlight the diverse and interconnected functions of MYB TFs. These clusters involve MYB-mediated responses to abiotic and biotic stresses, their involvement in secondary metabolism and nutritional enhancement, roles in plant development, interactions with hormonal signaling pathways, and the application of integrative omics and biotechnological tools for functional characterization (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Graphical representation of the thematic clusters highlighting the multifaceted roles of MYB TFs in plant biology and their implications for stress adaptation, metabolic regulation, and agricultural innovation

3.1 Stress Responses and Environmental Adaptation

Plants respond to abiotic stress by transducing environmental signals into internal responses through phytohormones and secondary messengers, which subsequently initiate the activation of TFs. In a genome-wide analysis of R2R3-MYB transcription factors in Ginkgo biloba, Liu et al. [43] identified 45 MYB genes and characterized their conserved motifs. Expression profiling under various abiotic stresses, such as salinity, cold, and heat, and phytohormone treatments such as ABA, methyl jasmonate (MeJA), salicylic acid (SA), and ethephon (ET) revealed distinct tissue-specific and stress-responsive expression patterns [43]. These findings suggest that G. biloba MYBs play important roles in coordinating developmental processes and adaptive responses to environmental stresses. Additionally, phylogenetic comparisons with Arabidopsis MYBs revealed both evolutionary conservation and potential functional divergence, underscoring the complex regulatory roles of MYBs in Ginkgo [43].

MYB TFs regulate abiotic stress responses by modulating plant hormone metabolism, including those involving ABA, jasmonic acid (JA), brassinosteroids (BR), and SA [44–46]. MYB TFs may also regulate antioxidant enzyme activities. For example, Zhang et al. [47] observed that ZmMYB-CC10 enhances drought tolerance in maize by mitigating oxidative damage through the activation of ZmAPX4, a key enzyme that scavenges reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), during drought stress. Similarly, Zhang et al. [48] identified ZmRL6 as a drought-inducible gene that regulates drought tolerance by reducing electrolyte leakage and malondialdehyde (MDA), which are indicators of membrane damage. ZmRL6 also increases proline levels and the activity of antioxidant enzymes, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), catalase (CAT), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and regulates key drought-related genes such as ZmLAX3, ZmCYP71B3, and ZmMYB4 [48].

MYB TFs can regulate anthocyanin biosynthesis through microRNA (miRNA) interactions, particularly under extreme environmental conditions. Sumbur et al. [49] identified 137 R2R3-MYB genes in Ammopiptanthus nanus, a dryland shrub, and demonstrated that the miR858-AnaMYB87 module mediates anthocyanin accumulation under osmotic stress. Under salt stress conditions, in which ionic toxicity is characterized by increased Na+ and reduced K+ concentrations, MYB TFs can directly regulate key ion transporters, such as NHX, SOS1, and HKT, which are crucial for mitigating Na+ toxicity [50]. By enhancing the expression of these ion transporters, MYB TFs play a critical role in maintaining cellular ion homeostasis, which is essential for plant survival under stress. For example, AtMYB42 alleviates ion toxicity by directly activating the expression of SOS2, a central regulator of Na+/K+ balance in roots [51]. In addition to regulating ion transporters, MYB TFs can also reduce ionic stress through alternative mechanisms. For example, ARS1 promotes stomatal closure to reduce transpirational water loss, facilitating increased Na+ transport and accumulation in shoots [52].

Li et al. [53] investigated the combined regulatory role of BHLH TF, PIF4, and the R2R3-MYB TF, MYB75 (PAP1), in seed germination under high glucose stress. Their findings showed that elevated glucose levels inhibit germination via the ABA signaling pathway, with PIF4 mediating this inhibition by activating ABI5 expression. Notably, PIF4 was observed to physically interact with PAP1, a key regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis. Further biochemical and physiological analyses revealed that PAP1 binds directly to the ABI5 promoter and represses its expression, thereby alleviating glucose-induced germination inhibition. The study concluded that PAP1 antagonizes PIF4 by competing for ABI5 regulation, ultimately promoting seed germination in the presence of high glucose stress. This study uncovers a previously unrecognized antagonistic interaction between PIF4 and PAP1 that fine-tunes ABI5 expression in response to glucose signaling.

3.2 Secondary Metabolism and Nutritional Enhancement

Flavonoids and terpenoids are two chemically diverse families of secondary metabolites that are crucial in plant adaptation to environmental stresses. Flavonoids, characterized by a C6–C3–C6 carbon skeleton, are divided into various groups: flavonols, flavones, isoflavones, dihydroflavonols, anthocyanins, and proanthocyanidins. MYB TFs have emerged as central regulators of both flavonoid and terpene biosynthesis, coordinating multiple branches of the flavonoid and polyphenol pathways. In Actinidia chinensis (kiwifruit), overexpression of MYB10 and MYB110 elevated anthocyanin levels [54], while in Camellia sinensis (tea plant), CsMYB8 and CsMYB99 are involved in flavonoid biosynthesis that affects tea flavor and quality [55]. JrMYB44 from Juglans regia (walnut) modulates polyphenol biosynthesis [56], and CsMYB59 in C. sinensis is a transcriptional activator of polyphenol oxidase (PPO) in tea plants, directly regulating CsPPO1, a key gene for black tea production [57].

Rather than functioning in isolated pathways, MYB TFs are involved in complex regulatory networks that coordinate multiple physiological processes simultaneously. A prominent example is their role in regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis, which contributes to pigmentation as well as to plant defense mechanisms under environmental stress. For example, Shi et al. [58] identified 102 R2R3-MYB genes in Solanum melongena (eggplant) and analyzed their expression under various abiotic stresses and hormone treatments. Notably, the overexpression of SmMYB75 led to a significant increase in anthocyanin and flavonoid accumulation, thereby improving the nutritional quality and potential stress resilience of eggplant fruits [58]. Similarly, in buckwheat, FeR2R3-MYB regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis by interacting with leucoanthocyanidin reductase and exhibits dynamic responsiveness to environmental signals such as light, drought, and cold [59]. In tobacco, NtMYB4a was identified as a dual-function TF, where its overexpression enhanced anthocyanin accumulation and abiotic stress tolerance, while knockout mutants exhibited reduced pigmentation and stress resistance [60].

MYB transcription factors achieve regulatory balance by activating promoters of stress-responsive genes, forming complexes with other TFs such as bHLH and WRKY, and integrating signals from hormonal pathways including ABA and JA. Many phenylpropanoid-related MYBs regulate downstream of ABA and JA, enabling context-dependent gene expression. However, not all MYB regulation is ABA-dependent. For example, Pardo-Hernandez et al. [61] showed that SlMYB50 and SlMYB86 regulate flavonoid production in tomato under combined salinity and heat stress even in ABA-deficient mutants, highlighting the existence of alternative regulatory mechanisms.

MYB TFs play a vital role in regulating plant growth and development by controlling gene expression involved in cell division, differentiation and organ formation. They influence key developmental processes, such as root and shoot growth, leaf and flower formation, and vascular tissue development. For example, 3R-MYBs are involved in controlling the cell cycle during mitosis by binding to mitosis-specific activator elements to facilitate cell cycle transitions [62]. However, despite their importance, the downstream targets of 3R-MYBs and the detailed molecular mechanisms by which they coordinate cell division and differentiation across various plant species remain insufficiently characterized. Conversely, Choi et al. [63] reported that five PgR2R3-MYBs in Panax ginseng were highly expressed in flower and leaf tissue compared to other tissues such as roots, suggesting that these MYB genes are directly involved in the growth and development of P. ginseng flowers and leaves.

Fruit ripening is a complex, tightly regulated process that determines harvest timing, fruit quality, and postharvest marketability. It involves a coordinated interplay of phytohormonal signaling, starch degradation, and cell wall remodeling. MYB TFs are crucial regulators throughout the ripening process by modulating hormone pathways and metabolic genes. For example, CsMYB77 contributes to delaying ripening in tomatoes and kumquats by modulating ABA and auxin signaling through the MYB77-SINAT4/PIN5-ABA/auxin regulatory pathway [64]. The breakdown of starch into soluble sugars is also critical for flavor development during ripening. In bananas, MaMYB3 and MaMYB16L are repressors of genes involved in starch degradation. Specifically, MaMYB3 inhibits the expression of MaGWD1 (glucan water dikinase), while MaMYB16L regulates MaDREB2, a dehydration-responsive element-binding TF [65,66]. These studies underscore the importance of MYB–hormone interactions in fruit maturation and quality standards. However, the dynamic cross-talk among different MYB TFs and hormone signaling pathways across diverse fruit crops remains insufficiently understood and requires further investigation.

In addition to their role in fruit ripening, MYB TFs, particularly the R2R3-MYB subfamily, are also involved in flower growth and development by regulating pigmentation, scent production, and floral organ morphology. Notable examples include six DlR2R3-MYB in Dimocarpus longan [67] and RhMYB17 in Rosa hybrida [68]. Additionally, MYBs notably contribute to vegetative growth through the control of stem elongation and lignification. In soybean, GmGAMYB promotes stem elongation via the gibberellin signaling pathway [69], while OsMPH1 in rice enhances plant height and grain yield by modulating internode development [70]. In pepper, silencing CaSLR1 results in stem lodging, reduced secondary wall thickness, and weaker mechanical strength, highlighting its role in maintaining structural integrity [71].

Regarding cell wall synthesis, MYB TFs are also upstream regulators of critical genes. For example, Zhang et al. [72] identified FfMYB13 in Flammulina filiformis as an upstream transcriptional regulator that activates four cell wall synthesis genes (FfKRE6, Ffgas1, FfHYD-1, and FfGFA1). They also suggest that FfMYB13 may help reduce tissue toughening by reducing oxidative damage through the activation of Ff-FeSOD1. Similarly, studies on AtMYB46 in Arabidopsis thaliana and RrMYB18 in Rosa rugosa show that both genes are induced by wounding and coordinate cell wall biosynthesis with cell cycle progression, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved mechanism linking stress response and growth [73]. These results indicate that the coordination of cell wall biosynthesis and cell cycle regulation by these MYBs is evolutionarily conserved, providing new insights into the connection between cell growth and cell cycle progression.

MYB TFs also play crucial roles in regulating structural adaptations under stress conditions, such as cuticle formation. The plant cuticle is a hydrophobic barrier that prevents water loss from aerial organs, particularly during drought. In Arabidopsis, MYB41 functions as a negative regulator of cutin biosynthesis by repressing genes, such as ATT1 and LACS2, whereas MYB30, MYB94, and MYB96 act as positive regulators of wax biosynthesis. Additionally, MYB16 and MYB106 contribute to the formation of cutin and wax formation [74]. MYB41, MYB94, and MYB96 are directly involved in drought response. MYB94 and MYB96 are activated under drought conditions and cooperatively enhance the expression of key wax biosynthetic genes, thereby reinforcing cuticular protection [74]. In contrast, MYB41 is induced by desiccation and ABA; however, its overexpression leads to abnormal cuticle development, reduced cell size, and increased leaf permeability, resulting in increased sensitivity to dehydration [75]. Although MYBs such as MYB41, MYB94, and MYB96 modulate wax biosynthesis, the balance between their positive and negative regulatory roles under varying environmental conditions remains insufficiently characterized.

3.4 Hormonal Signaling and Regulatory Networks

MYB TFs interact with key hormonal pathways, such as ABA, GA, and MeJA, to regulate stress responses and developmental processes. MYB TFs exert their regulatory effects through a mechanism that involves the degradation of Jasmonate ZIM-domain (JAZ) proteins. Under JA signaling, active JA-Ile complexes bind to the F-box protein COI-1 (Coronatine Insensitive-1), leading to the degradation of JAZ proteins. This degradation releases MYB TFs from repression, enabling them to activate target genes related to the plant’s defense and developmental responses [76]. JA is crucial for the regulation of defense responses and secondary metabolite accumulation. MYB TFs can modulate JA-induced pathways, influencing phenylpropanoid metabolism and flavonoid biosynthesis. For example, in Glycyrrhiza uralensis, R2R3-MYB members were induced by MeJA, leading to increased flavonoid levels, which are important for plant protection and attractiveness to pollinators [77]. Wu et al. [78] explored the genome-wide identification of R2R3-MYB TFs in Pueraria lobata var. thomsonii, focusing on puerarin biosynthesis and hormonal responses. Their study identified 209 PtR2R3-MYBs and established the regulatory connections between MYB TFs and structural genes involved in the phenylpropanoid pathway. They highlighted the responsiveness of specific MYB genes to MeJA and glutathione (GSH) treatments, further connecting hormonal signaling with secondary metabolite biosynthesis.

Several studies have highlighted the involvement of MYB TFs in hormonal signaling under abiotic stress. For example, Yao et al. [79] investigated the R2R3-MYB TF BnaMYB111L in rapeseed, revealing its role in ROS accumulation and hypersensitive-like cell death. The study demonstrated that BnaMYB111L activates target genes involved in ROS production, demonstrating its regulatory role in plant-pathogen interactions and abiotic stress through the ABA signaling pathway. ABA is a critical phytohormone involved in various plant processes and rapidly accumulates under environmental stress [80,81]. Stomatal opening and closing regulate gas and water exchange between plants and their environment, notably contributing to important attributes, such as drought tolerance [82]. Seo et al. [83] showed that the expression of the Arabidopsis gene AtMYB44 in soybean (Glycine max) improves drought and salt stress tolerance by positively regulating ABA signaling and inducing stomatal closure. Lim et al. [84] identified a MYB TF, CaDIM1 (Capsicum annuum 1), which is strongly upregulated in response to ABA and drought stress. Plants with silenced CaDIM1 exhibited reduced sensitivity to ABA, increased drought susceptibility, and decreased expression of stress-responsive genes.

MYB TFs may also interact with other hormonal pathways, such as gibberellins and jasmonates, to coordinate abiotic stress responses. For example, the MYB25 gene in Arabidopsis enhances salt stress tolerance by mediating ABA signaling [85]. MYB TFs are also integrated into complex signaling networks, forming novel interactions with proteins involved in multiple hormonal pathways to fine-tune plant responses to diverse stressors [86]. In potato, several StMYB genes are induced by ABA, GA, and IAA treatments [87]. Similarly, Liu et al. [88] revealed that a substantial number of HhMYBs in Hibiscus hamabo respond to ABA, SA, or MeJA, although their activation varies in timing and intensity depending on the specific hormonal stimulus.

A major unresolved question pertains to the specificity with which MYB TFs integrate signals from various hormonal pathways, including ABA, JA, and GA, to mediate distinct stress and developmental responses. Although many MYBs respond to multiple hormones, the mechanims influencing their pathway preference and the fine-tuning of their regulatory outputs under overlapping hormonal stimuli remain unclear. Additionally, the temporal and spatial dynamics of MYB-hormone interactions remain poorly understood. The timing, duration, and tissue-specific expression of hormone-induced MYB activity likely play essential roles in determining physiological outcomes; however, but these dynamics have yet to be systematically investigated.

3.5 Integrative Omics and Biotechnological Approaches for Unraveling MYB TF Functions

The applications of MYBs in genetic engineering and molecular breeding highlight their potential to revolutionize agricultural practices. Their role in abiotic stress tolerance and secondary metabolite production is particularly important. Omics technologies, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, have been progressively used to understand the roles of MYB TFs in various critical biological processes in plants. Genomics, through whole genome sequencing and annotation, facilitates the identification and classification of MYB gene families across numerous plant species. For example, Wang et al. [89] identified 440 MYB genes in cotton, revealing their involvement in abiotic and biotic stress responses, which has implications for improving cotton productivity. Another study by Luo et al. [59] demonstrated that FeR2R3-MYB in Fagopyrum esculentum plays a dual role in anthocyanin biosynthesis and drought tolerance. Molecular analysis revealed that FeR2R3-MYB interacts with leucoanthocyanidin reductase to enhance pigment production while responding to environmental stimuli. This study shows the functional versatility of MYB TFs, particularly their ability to mediate both metabolic and stress-related pathways in minor grain crops.

Integrative transcriptomic approaches enable comprehensive analysis of gene expression profiles across different developmental stages and under various abiotic stresses. These high-throughput datasets provide valuable insights into the dynamic regulation of MYB genes, presenting a powerful resource for elucidating their specific roles in abiotic stress responses and adaptive mechanisms. Functional characterization through plant transformation has become an essential subsequent step for validating transcriptome-based predictions. This approach enables researchers to experimentally confirm the regulatory roles of candidate MYB genes in mediating stress tolerance and developmental processes. For example, numerous studies have introduced specific MYB TFs into model plants, such as tobacco, to enhance abiotic stress resilience [90]. A notable example is the identification of MsMYB4 in alfalfa [91], in which transcriptomic profiling revealed its involvement in salinity tolerance by enhancing ROS scavenging via an ABA-dependent pathway. Subsequent functional assays demonstrated that MsMYB4 localizes to the nucleus and acts as a transcriptional activator, confirming its essential role in stress adaptation mechanisms. In addition to overexpression strategies, transcriptional repression techniques, such as RNA interference (RNAi), provide valuable tools for modulating MYB TF activity to achieve desirable phenotypic outcomes. RNAi can downregulate negative MYB regulators or fine-tune positive ones, thus enabling the engineering of crops with improved resilience to harsh environments. For example, Suprun et al. [92] employed RNAi to silence four MYB transcriptional repressors, SlMYBATV, SlMYB32, SlMYB76, and SlTRY in tomato plants. Silencing these repressors led to a significant upregulation of key anthocyanin biosynthesis genes, such as SlCHS1, SlCHS2, and SlANS, and resulted in enhanced anthocyanin accumulation in treated leaves. Collectively, integrative approaches combining transcriptomic profiling, transgenic expression, and gene silencing approaches contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of MYB TF function and provide potential approaches for engineering stress-resilient crops.

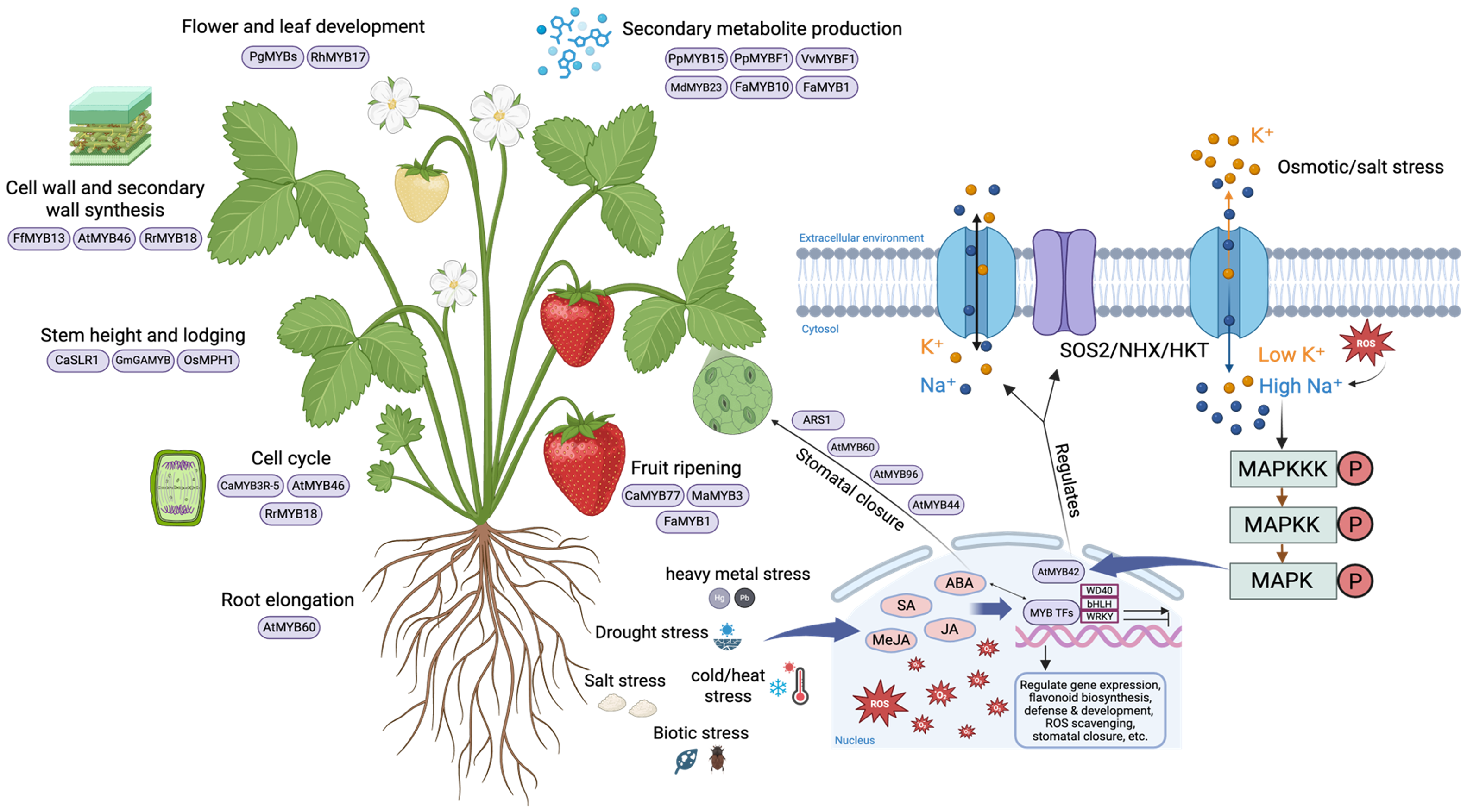

Proteomics has emerged as an effective tool for comprehensively analyzing protein structure, function, abundance, and interactions [93]. As proteins are the primary executors of most cellular activities, proteomics provides a notable advantage over other “omics” approaches by directly capturing the functional state of the cell [94]. Unlike genomics or transcriptomics, which measure potential outcomes, proteomics reveals real-time changes at the translational and post-translational levels, providing a comprehensive understanding of complex biological systems [95]. Proteomic analyses complement genomic and transcriptomic studies by providing insights into the protein levels, modifications, and interactions of MYB TFs. It enables direct assessment of MYB protein dynamics, including key regulatory post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and acetylation, which influence protein stability, subcellular localization, and transcriptional activity. These analyses also facilitate the identification of MYB-interacting partners, thereby providing a more comprehensive understanding of the role of MYBs within complex signaling and regulatory networks. For example, Wu et al. [78] characterized MYB-related proteins in A. thaliana, revealing their interactions with other key signaling molecules and confirming their involvement in critical plant regulatory pathways. Understanding MYB PTMs provides crucial insights into the regulation and activation of these proteins under specific stress conditions. For example, phosphorylation is a common PTM associated with TF regulation via the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade (Fig. 3), a signaling pathway that governs plant responses to growth and abiotic stress [96]. Thus, proteomics approaches enhance our functional understanding of MYB TF as well as elucidate the intricate regulatory mechanisms plants employ to adapt to environmental challenges.

Figure 3: Integrated roles of MYB transcription factors in plant development, metabolism, and abiotic stress responses. Specific MYB transcription factors from various species (Arabidopsis [AtMYB], Fragaria [FaMYB], Glycine max [GmMYB], and Oryza sativa [OsMYB]) regulate diverse biological processes across different tissues by integrating environmental signals, including abiotic stress, phytohormone signaling (ABA, SA, and MeJA), and MAPK cascades, to control gene expression related to flavonoid biosynthesis, cuticle development, ROS detoxification, and ion homeostasis. In the nucleus, MYBs interact with other transcriptional regulators to fine-tune plant responses for coordinated growth and stress resilience

Metabolomics, which focuses on profiling small metabolites produced during metabolic reactions, provides critical insights into the functional consequences of MYB TF modulation on primary and secondary metabolism. By analyzing the shifts in metabolite profiles, researchers can better understand the influence of MYB TFs on complex traits, such as pigment production, flavor, and stress responses. When integrated with gene-editing technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9, this approach enables the targeted enhancement or suppression of specific secondary metabolites, providing an effective strategy for precision crop improvement. For example, Yang et al. [97] applied this method in tomatoes to edit three fruit color-related genes: PSY1, MYB12, and SRG1. Becasue fruit color is determined by the accumulation of carotenoids, flavonoids, and chlorophyll degradation, targeted editing of these genes enabled the creation of novel tomato cultivars with various fruit colors, including brown, pink, yellow, light yellow, pink-brown, yellow-green, and light green. Similarly, targeted mutagenesis improves plant resistance to biotic stresses. In soybeans (G. max), Zhang et al. [98] used CRISPR/Cas9 to knock out the GmUGT gene involved in flavonoid biosynthesis, resulting in increased resistance to leaf-chewing insects. This study highlights how modifying secondary metabolite pathways can enhance both plant defense and crop resilience. Additionally, CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing is crucial for fine-tuning flavonoid biosynthesis in other crops. In grapevine (Vitis vinifera), Tu et al. [99] demonstrated that the knockout of the VvBZIP36 TF, a known repressor of anthocyanin biosynthesis, led to a significant increase in anthocyanin accumulation, thereby enhancing berry pigmentation. Collectively, metabolomics and gene-editing technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9 provide synergistic strategies to unravel and manipulate MYB TF-regulated metabolic networks, ultimately providing new opportunities for crop improvement and functional genomics research.

4 Post-Translational Modifications of MYB Transcription Factors

PTMs are critical in regulating MYB TFs in plants by fine-tuning their stability, activity, and interactions with other proteins. These modifications are dynamic control points that facilitate plants to rapidly adjust MYB TF function in response to developmental cues and environmental stimuli. Although studies in model species such as Arabidopsis thaliana have provided foundational insights into PTM-mediated regulation, extending this knowledge to non-model species is essential to thoroughtly understand the diversity and complexity of MYB regulation across plant lineages.

Phosphorylation is the most well-characterized PTM, often mediated by MAPK cascades. MAPKs are central regulators of various physiological processes, including plant growth, development, hormonal signaling, and responses to abiotiPhoc and biotic stress [100]. The functional specificity of MAPK pathways primarily depends on the identity of their substrate proteins, making the identification of these targets crucial for deciphering MAPK signaling networks [101]. For example, MPK4 plays a pivotal role in light-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis by directly interacting with and phosphorylating the MYB75 TF. This phosphorylation enhances MYB75 stability, thereby promoting the activation of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes [102]. Additionally, other MAP kinases, including MPK3, MPK6, and MPK11, phosphorylate MYB75, underscoring the broader involvement of the MPK–MYB75 module in flavonoid metabolism [103]. These findings demonstrate how MAPK-mediated phosphorylation acts as a key regulatory mechanism for modulating MYB function and linking environmental signals to metabolic and developmental responses in plants.

The regulatory role of MAPK-mediated phosphorylation in MYB function has also been demonstrated in fruit crops. In apple, a recent study [104] identified that MdMPK4, a MAP kinase homologous to Arabidopsis MPK4, directly interacts with and phosphorylates the R2R3-MYB TF MdMYB1 at serine residue 149. This phosphorylation considerably enhances MdMYB1’s transcriptional activation of structural genes, such as MdDFR and MdUFGT, both of which are essential for anthocyanin accumulation in the fruit skin. Functional characterization using site-directed mutants revealed that a non-phosphorylatable form of MdMYB1 (S149A) exhibited reduced activation of target genes, whereas a phospho-mimic form (S149D) significantly increased gene expression. Importantly, light exposure induced both MdMPK4 activity and MdMYB1 phosphorylation, linking environmental signals and metabolic regulation via the MAPK cascade. Moreover, silencing of MdMPK4 resulted in suppressed light-anthocyanin accumulation under light conditions, further confirming that phosphorylation of MdMYB1 is essential for regulating flavonoid biosynthesis [104].

Ubiquitination is another critical post-translational modification that regulates MYB TFs by modulating their stability and turnover. The ubiquitin/26S proteasome system is important in selective protein degradation, in which E3 ubiquitin ligases confer substrate specificity by attaching ubiquitin molecules to target proteins, thereby marking them for proteasomal degradation [105]. Several RING-type E3 ligases are key regulators of MYB protein stability. A well-characterized example is the RING-type E3 ligase constitutively photomorphogenic 1 (COP1), which modulates light-regulated anthocyanin biosynthesis by targeting MYB75 and MYB90/PAP2 for degradation in the dark. COP1 interacts with MYB75 and MYB90 and promotes their proteasome-dependent degradation, thus repressing anthocyanin accumulation under low-light conditions [106]. More recently, Xing et al. [107] demonstrated a similar regulatory mechanism in Camellia sinensis, in which the E3 ubiquitin ligase CsMIEL1 negatively regulates anthocyanin accumulation under low temperature. CsMIEL1 facilitates the ubiquitination of CsMYB75, a positive regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis, leading to its degradation via the 26S proteasome pathway. This degradation reduces the activation of downstream biosynthetic genes. The use of the proteasome inhibitor MG132 in the study further confirmed that CsMYB75 is degraded through this pathway. This represents a classic example of ubiquitin-mediated PTM, where environmental signals such as low temperature induce post-translational regulation of TFs to fine-tune secondary metabolite production. These findings underscore the pivotal role of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in controlling MYB TF function and plant adaptation through PTM-mediated proteostasis.

In addition to regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis, PTMs such as ubiquitination and SUMOylation also modulate MYB activity in hormonal signaling pathways. A well-characterized example is the regulation of MYB30, a key transcription factor in ABA signaling. Its stability is controlled by two antagonistic PTMs: ubiquitination, which promotes degradation, and SUMOylation, which enhances stability. The RING-H2 E3 ubiquitin ligase RHA2b targets MYB30 for degradation by ubiquitinating lysine 283 (Lys-283), directing it for proteolysis via the 26S proteasome. Arabidopsis plants deficient in RHA2b exhibit hypersensitivity to ABA, a phenotype that is suppressed in myb30 mutants, indicating that RHA2b functions upstream of MYB30 to modulate ABA responses during seed germination [108]. In contrast, the SUMO E3 ligase SIZ1 stabilizes MYB30 by adding SUMO at the same Lys-283 residue, which prevents ubiquitination and degradation. This SUMOylation enhances both the protein stability and transcriptional activity of MYB30 in the ABA signaling pathway [108,109]. Additionally, the SUMO protease ASP1 can reverse this modification, making MYB30 susceptible to ubiquitin-mediated turnover again. These findings highlight the intricate crosstalk between different PTMs in regulating MYB30 function and demonstrate how plants integrate environmental and hormonal signals through tightly regulated post-translational control mechanisms [110].

Recent comparative analyses across eudicot horticultural crops, including apple, grape, tomato, and kiwifruit, have revealed that post-translational modifications likely play a pivotal role in the functional diversification of anthocyanin-activating MYB TFs [111]. Although the DNA-binding domains of these MYBs remain highly conserved, their intrinsically disordered C-terminal regions exhibit considerable sequence variability. These variable regions frequently harbor predicted sites for phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and protein–protein interaction motifs, indicating that differential post-translational regulation, rather than differences in DNA binding, determines species-specific MYB functions. These modifications may modulate MYB protein stability, transcriptional activation potential, and interactions with other regulatory partners, thereby influencing pigmentation patterns and metabolic traits unique to each species. This insight highlights to a critical knowledge gap: the need for comprehensive, species-specific studies of PTM landscapes on MYB TFs to elucidate how these dynamic modifications drive functional diversity and adaptation in plants.

To complement the systematic literature review (SLR) and provide a broader perspective on the research landscape of MYB TFs in plants, this study incorporated a bibliometric analysis. Bibliometric analysis provides a quantitative approach to map the growth, trends, and influential contributors within the MYB TF research field. By examining publication patterns, citation networks, and keyword co-occurrences, this analysis highlights emerging hotspots, research gaps, and collaborative networks that may not be evident through qualitative review alone. The following sections detail the article selection process, inclusion criteria, and the methodology used to conduct the bibliometric analysis.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across prominent scientific databases, including Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/, accessed on 13 July 2025) and Web of Science (https://www.webofscience.com/, accessed on 13 July 2025). These were selected for their extensive coverage of biological and plant molecular research. The study adhered to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [112] to ensure a transparent and systematic article selection process. The review focused on peer-reviewed studies published between 2010 and 2024 to capture the latest advancements in MYB TF research while selectively including foundational studies predating this period for their notable contributions to the field.

A Boolean search strategy was employed using the following keywords:

(“MYB TFs” OR “MYB proteins”) AND (“plant stress response” OR “secondary metabolism” OR “developmental regulation”) AND (“functional diversity” OR “regulatory networks”) AND (“comparative analysis” OR “genomic studies”). [Search as of November 2024].

This approach ensured the inclusion of diverse studies addressing the multifaceted roles of MYB TFs across various plant species and conditions. Emphasis was placed on empirical studies that employed advanced methodologies such as transcriptomics, gene editing, and functional genomics. The articles were rigorously evaluated based on methodological quality, relevance, and their ability to address key themes, including the roles of MYB in stress tolerance, metabolic pathways, and developmental processes. The inclusion criteria prioritized studies exploring MYB TFs in model and non-model plant species, thereby identifying knowledge gaps and underrepresented areas in the literature. By synthesizing findings from diverse and high-quality studies, this review provides a comprehensive understanding of the regulatory mechanisms and evolutionary significance of MYB TFs.

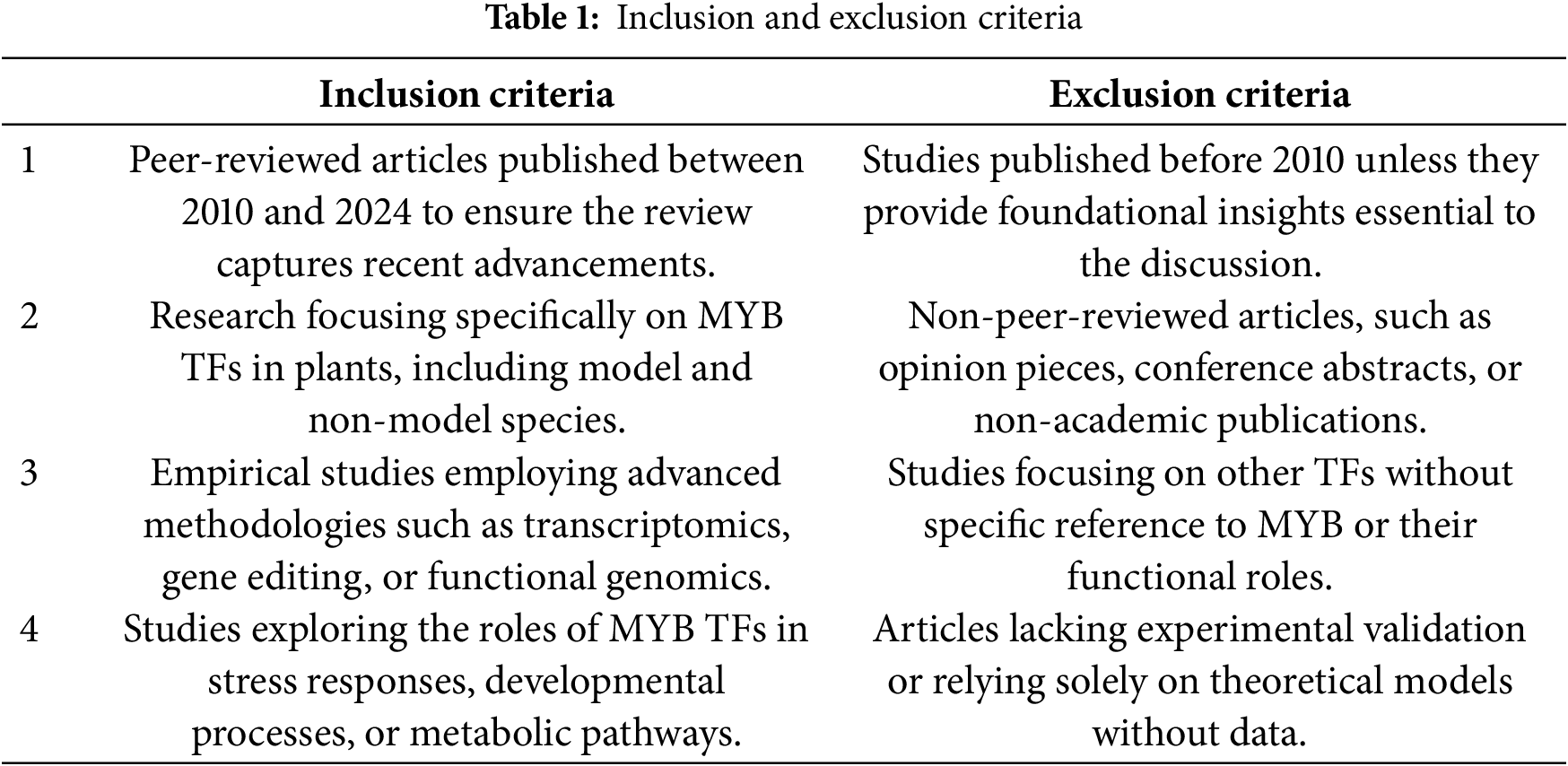

5.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Well-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to ensure a robust and systematic review of the functional diversity of MYB TFs in plants. These criteria were designed to identify high-quality, relevant studies that align with the review’s objectives while excluding those that did not meet methodological or thematic standards. By applying these parameters, the review prioritized the synthesis of comprehensive and reliable insights into the molecular mechanisms, regulatory pathways, and practical applications of MYB TFs. Table 1 presents the detailed specific inclusion and exclusion criteria.

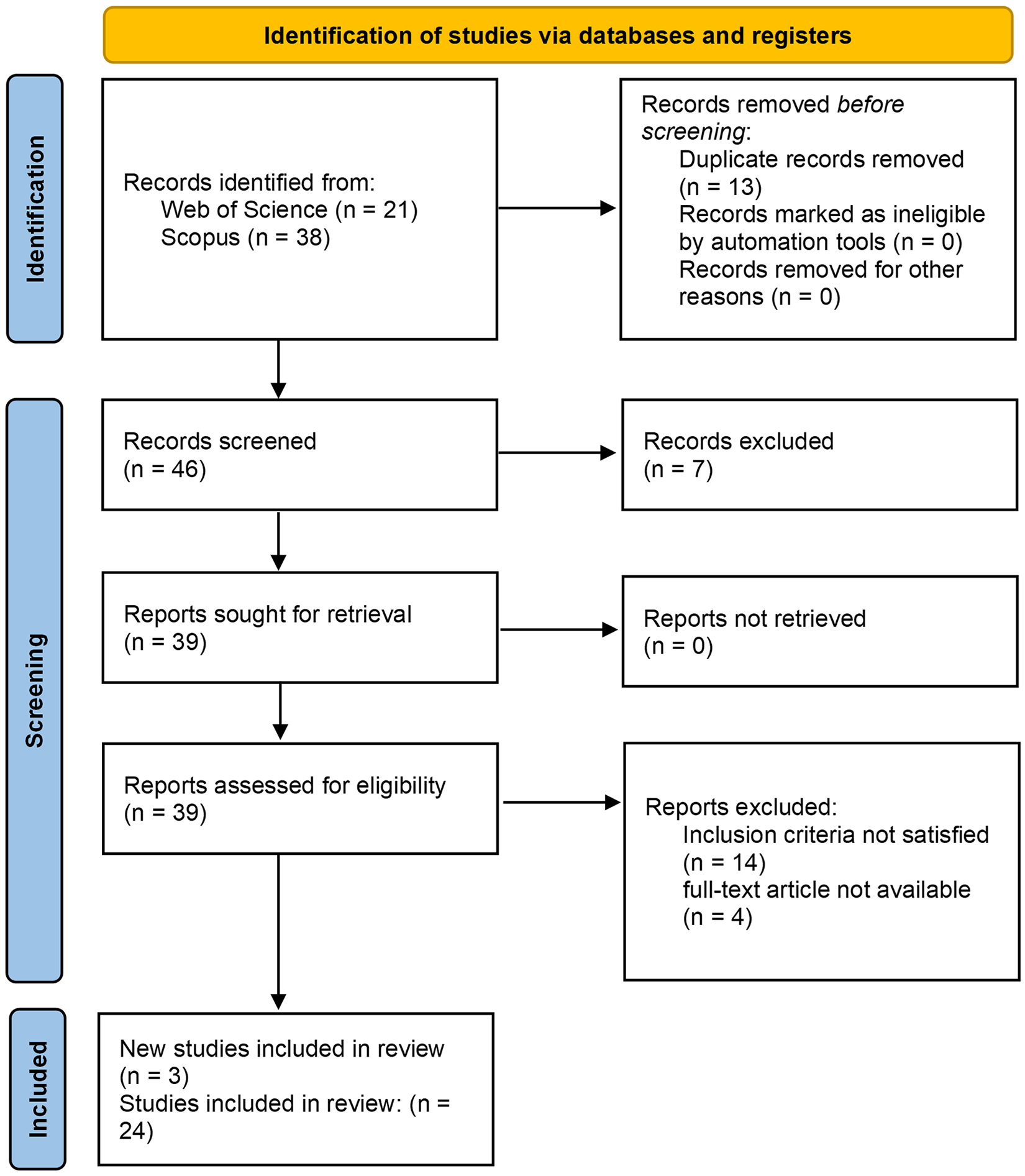

The article selection process (Fig. 4) started with a comprehensive search across prominent academic databases, including Scopus and Web of Science (WoS), to identify relevant studies on MYB TFs in plants. The initial search retrieved 59 records, of which 13 duplicates were removed, resulting in 46 unique articles for screening. Titles and abstracts were rigorously evaluated to assess relevance, focusing on the functional diversity, regulatory mechanisms, and applications of MYB TFs in plant biology. This step resulted in the exclusion of seven studies. The remaining 39 articles underwent a full-text review, during which 14 studies were excluded for failing to meet the predefined inclusion criteria, and four were inaccessible. To ensure the selection’s comprehensiveness, backward and forward citation tracking was performed, which identified three additional relevant studies. Ultimately, 24 peer-reviewed articles met the eligibility criteria and were included in this review.

Figure 4: Systematic review process based on PRISMA. From an initial pool of 59 records identified through Scopus and Web of Science, duplicates were removed (n = 13), and 46 studies underwent title/abstract screening. After removing irrelevant articles (n = 7), 39 full-text papers were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 14 were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria (lack of experimental validation) and four were unavailable. Backward/forward citation tracking yielded three additional studies, resulting in 24 peer-reviewed articles included in the final synthesis

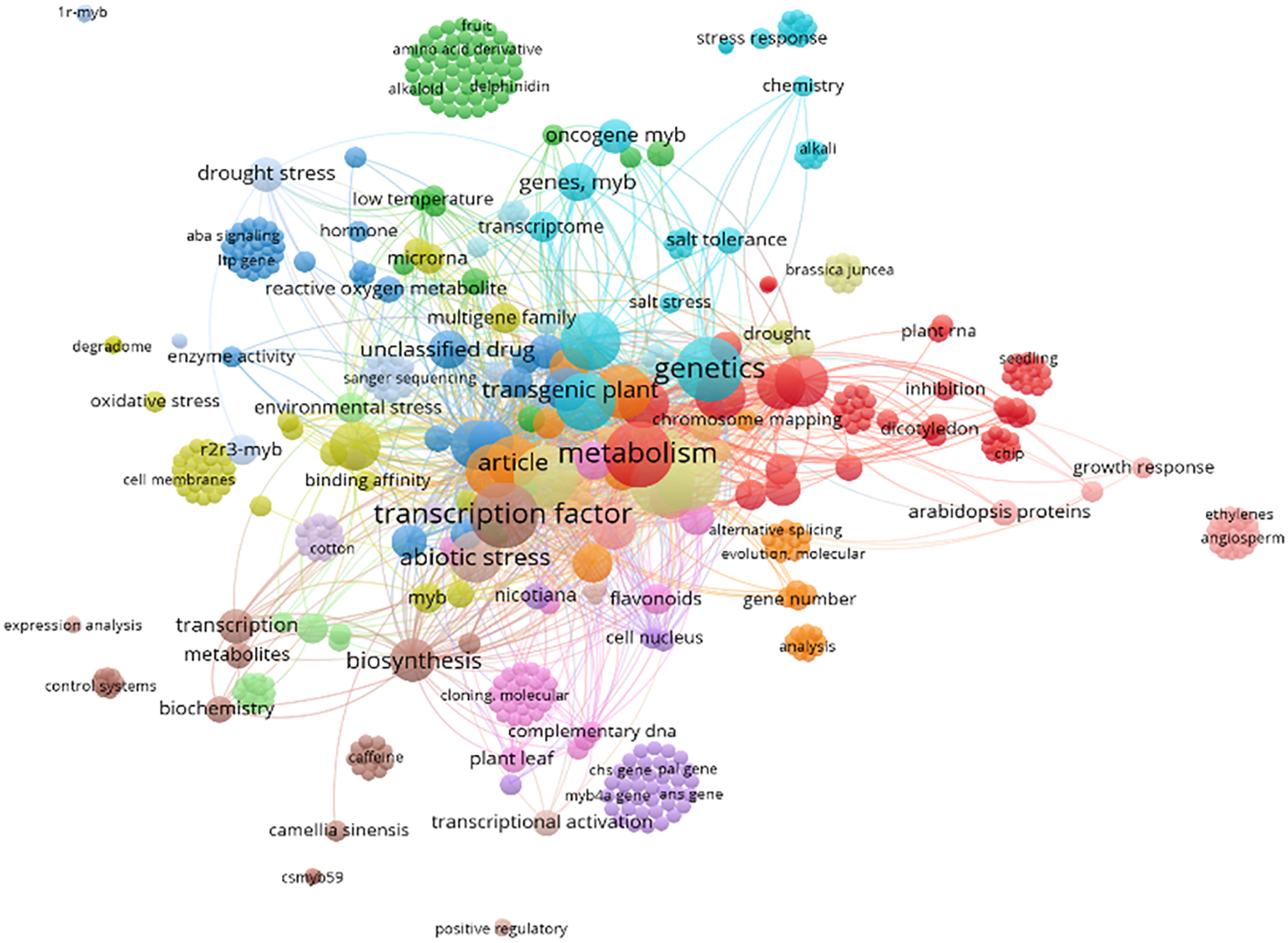

5.4 Co-Occurrence Network of Keywords

A bibliometric analysis was conducted using VOSviewer to elucidate the research landscape surrounding MYB TFs in plants [113,114]. This analysis examined the co-occurrence network of keywords in peer-reviewed literature, using data extracted from Scopus and WoS. The study aimed to identify trends, thematic clusters, and key research focal areas within MYB TF studies. The analysis revealed prominent research themes, including the roles of MYB proteins in abiotic stress responses, secondary metabolite biosynthesis, and plant development. Frequently co-occurring keywords such as “MYB TFs”, “drought tolerance”, “secondary metabolism”, and “gene expression regulation” underscored the centrality of these topics within the field.

The network analysis also highlighted emerging trends, such as the application of advanced genomic tools such as CRISPR-Cas9 and transcriptomics in elucidating MYB functions. Distinct clusters also underscored the evolutionary importance of MYB proteins and their regulatory influence in non-model plant species, which are increasingly recognized for their potential in agricultural biotechnology. By visualizing keyword interconnections, the analysis provided an enhanced understanding of the integration of MYB TFs into broader regulatory networks and their practical applications in improving crop resilience and productivity. These findings indicate the increasing scientific interest in elucidating the functional diversity of MYB TFs, providing valuable insights into future research directions and technological innovations in plant molecular biology.

The network map (Fig. 5) highlights key research themes centered on transcriptional regulation, stress responses, and plant metabolism, particularly focusing on MYB TFs and their multifaceted roles in plant biology. Prominent keywords such as “transcription factor,” “metabolism,” and “genetics” underscore the central focus on gene regulation and the molecular mechanisms underlying plant traits. The presence of “abiotic stress,” “drought stress,” and “salt tolerance” indicates a strong emphasis on plant responses to environmental challenges, particularly how MYB TFs mediate stress adaptation and resilience. These keywords, along with “low temperature” and “oxidative stress,” highlight the importance of studying plant adaptation mechanisms under adverse conditions, with MYB TFs playing a critical role in regulating these processes. The connection to “flavonoids,” “biosynthesis,” and “enzyme activity” indicates a considerable interest in secondary metabolite production and metabolic pathways, which are frequently linked to stress mitigation and agricultural applications. The inclusion of “reactive oxygen metabolites” further highlights the molecular intricacies of stress responses at the cellular level, revealing how plants manage oxidative damage under environmental pressures. Additionally, terms such as “transgenic plants,” “Arabidopsis proteins,” and “nicotiana” indicate the use of model organisms and genetic engineering approaches to explore gene function and validate the roles of MYB TFs in stress responses and metabolic regulation.

Figure 5: Keyword co-occurrence network related to MYB transcription factors, illustrating their functional diversity in plant growth, development, and stress responses. The network highlights major research themes, including abiotic stress tolerance, secondary metabolite biosynthesis, and evolutionary diversification. Data derived from Scopus (November 2024)

The network also highlights the application of advanced genomic tools, as evidenced by keywords such as “Sanger sequencing,” “chromosome mapping,” “expression analysis,” and “CRISPR.” These methodologies are crucial for elucidating the evolutionary trajectory of MYB proteins across plant lineages and for functional validation in model and transgenic species. Emerging terms such as “complementary DNA” and “evolution” reveal the increasing use of innovative technologies to enhance our understanding of MYB TFs and their regulatory networks. Peripheral clusters, including “flavonoids,” “reactive oxygen metabolites,” and “transcriptional activation,” show the breadth of MYB-mediated processes, from secondary metabolite production to cellular stress responses. The connections between “growth response,” “hormone signaling,” and “transcriptional activation” further underscore the diverse functional roles of MYB TFs in plant development and stress adaptation. However, the network also reveals gaps in current research, such as the underrepresentation of non-model species and limited exploration of MYB interactions within complex regulatory networks. Overall, the network map reveals a multidisciplinary approach, integrating genetics, biochemistry, and molecular biology to elucidate the complex interplay between genes, metabolites, and environmental stressors in plants. It underscores the multidimensional effect of MYB TFs on plant biology, comprising developmental regulation, stress adaptation, and metabolic pathways. These insights facilitate future studies aimed at utilizing MYB TFs to enhance crop resilience and productivity in a rapidly changing global climate.

6 Challenges and Future Research Directions

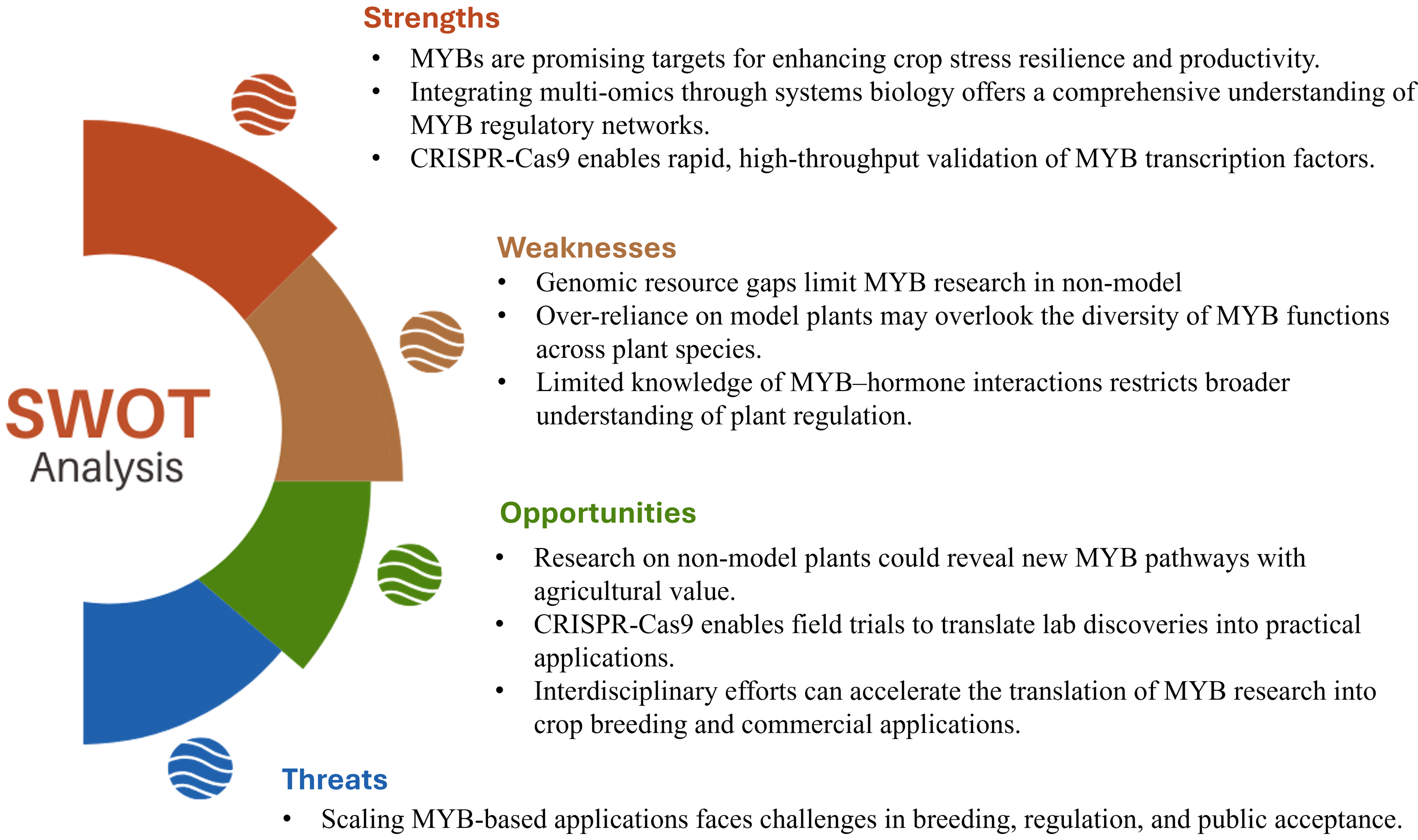

Despite notable advances in understanding MYB TFs, several challenges continue to impede the translation of their potential into agricultural applications (Fig. 6). A major limitation is the underrepresentation of non-model plant species and economically significant crops, such as buckwheat [59] and eggplant [115], which have unique stress-adaptive traits but lack comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic resources. For example, although MYB-mediated pathways in model plants such as Arabidopsis are well-characterized, studies on species such as Ammopiptanthus nanus [49] remain scarce. Addressing this gap requires prioritizing high-throughput sequencing and bioinformatics tools tailored to non-model systems, which can reveal novel MYB regulatory mechanisms and expand their biotechnological utility.

Figure 6: SWOT analysis of the functional diversity of MYB transcription factors in plants

A second challenge is deciphering the complexity of MYB interactions within broader regulatory networks. Although studies on MYB crosstalk with hormonal pathways such as ABA, GA, and MeJA and other TFs, including AtMYB7 [116] and PtR2R3-MYB [78], have provided foundational insights, our understanding remains fragmented. For example, MYB coordination with signaling molecules under dynamic environmental conditions, such as simultaneous drought and salinity stress, remains poorly resolved. Additionally, MYB functions frequently show contradictory roles across species. For example, R2R3-MYBs such as AtMYB75 (PAP1) and AtMYB90 (PAP2) in Arabidopsis are activators of anthocyanin biosynthesis [117]; however, their petunia ortholog, PhMYB27, is a repressor [118]. This functional divergence is influenced by species-specific pressures and context-dependent factors such as tissue-specific expression, interaction with cofactors (bHLH or WD40), and environmental signals (light and ABA).

The modular nature of MYB TFs further contributes to this divergence. For example, the structural variation in the C-terminal region determines whether a MYB functions as an activator or repressor; PhMYB27 harbors repression motifs, whereas AtMYB75 contains activation domains. Additionally, MYBs typically require bHLH and WD40 partners to form MBW complexes that activate flavonoid biosynthesis [118]; however, exceptions exist. SlAN2-like MYBs from wild tomato can activate anthocyanin biosynthesis independently of exogenous bHLH cofactors in heterologous systems, indicating partial bHLH-independence or utilization of endogenous partners [119,120]. Comparative analyses highlight both conserved and specialized functions across species: SmMYB75 in eggplant and FeR2R3-MYB in buckwheat both enhance anthocyanin accumulation, but they diverge in their integration with stress-response pathways: FeR2R3-MYB supports drought resilience, whereas SmMYB75 primarily influences flavonoid profiles and fruit coloration [59,115]. In contrast, 1R-MYBs, which are frequently involved in circadian rhythm regulation and telomeric DNA binding [24,121], exhibit less functional conservation and more species-specific variation.

Functional redundancy also complicates MYB characterization, particularly in model systems such as Arabidopsis, in which overlapping roles among PAP1, PAP2, MYB113, and MYB114 indicate that single-gene knockouts may not lead to a strong phenotype [117,122]. However, in species with high functional specialization, such as Zea mays and Ipomoea, loss of a single MYB gene can cause notable phenotypic changes, including pigmentation loss [62,123].

Addressing this complexity requires integrative systems biology approaches that combine transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic datasets. These strategies can identify MYB regulators with pleiotropic functions, for example, SmMYB75 in eggplant enhances anthocyanin biosynthesis and abiotic stress tolerance [115]. Similarly, FeR2R3-MYB in buckwheat coordinates pigmentation with drought adaptation, highlighting how non-model species can inform multi-trait improvement strategies [59]. However, the translation of these findings is frequently constrained by limited transformation protocols in minor or underutilized crops.

Technological limitations further constrain progress. Conventional transgenic approaches for MYB functional validation are time-intensive and lack scalability [124]. Emerging CRISPR-Cas9-based tools, including activation/repression systems [125,126], provide potential alternatives for high-throughput screening and precise editing of MYB genes. However, field validation remains essential to assess MYB-driven traits under realistic agronomic conditions. For example, although FeR2R3-MYB confers drought resilience in controlled environments, its effectiveness in field settings must be verified [59]. To accelerate its application, a multidisciplinary framework is essential. This includes integrating MYB-focused research with plant breeding programs, high-throughput phenotyping platforms, and regulatory systems to facilitate the deployment of engineered crops. The increasing frequency of compound abiotic stresses, such as simultaneous drought, heat, and salinity, underscores the need to identify MYBs with broad-spectrum resilience. Candidates such as MdMYB4 in apple [127] or GmMYB68 in soybean [128], which balance stress tolerance with productivity, represent potential targets.

A strategic roadmap is proposed to bridge existing knowledge gaps and translate MYB research into real-world agricultural solutions. Central to this strategy is the expansion of genomic databases for understudied crops, using advanced sequencing technologies such as long-read sequencing and pangenomics to identify novel regulatory mechanisms. We propose a dual-axis prioritization framework: (1) conserved nodes (ABA-responsive MYBs such as AtMYB44 or OsMYB3R-2), which regulate stress pathways across species, and (2) species-specific adaptors (flavonoid-activating MYBs such as CsMYB75 in tea or SmMYB75 in eggplant) that fine-tune metabolic responses. As highlighted in Section 4, PTMs (MPK4-mediated phosphorylation of AtMYB75) frequently regulate conserved nodes, whereas species-specific adaptors such as CsMYB75 in tea evolve distinct regulatory mechanisms to meet ecological demands [107]. To comprehensively elucidate these networks, multi-omics integration is essential, particularly under combinatorial stress conditions, to identify key regulators with dual roles in defense and yield optimization.

High-throughput CRISPR systems can further accelerate gene functional discovery and trait manipulation, exceeding traditional transgenic methods. However, agronomic relevance must remain a priority, with MYB-engineered traits validated in the field through collaboration with breeders, agronomists, and farmers. Finally, stakeholder engagement is vital to ensure regulatory alignment and public trust in biotechnological innovations. These interconnected initiatives will facilitate the transformation of MYB research into scalable, sustainable, and climate-resilient agricultural solutions.

MYB TFs have emerged as key regulators of plant growth, development, secondary metabolism, and stress responses, underscoring their functional diversity and evolutionary importance across various plant species. This review highlights the multifaceted roles of MYBs, from regulating flavonoid and anthocyanin biosynthesis to enhancing abiotic stress tolerance and influencing tissue differentiation. Advancements in genomic and transcriptomic technologies have provided invaluable insights into MYB-mediated regulatory networks, particularly in major crops such as maize, cotton, and soybean, as well as underrepresented species such as buckwheat and tea plants. Despite these advancements, notable gaps remain in understanding the complex interplay between MYBs and other TFs, hormonal signaling pathways, and stress-adaptive mechanisms. Addressing these gaps through innovative approaches such as CRISPR-Cas9 and systems biology will enhance our understanding of MYB functionality as well as accelerate the development of genetically engineered crops with improved resilience and productivity. The applications of MYBs extend beyond fundamental plant biology to practical implications in agricultural biotechnology, providing solutions for sustainable farming practices and food security amidst global climate challenges. By integrating MYB research with interdisciplinary initiatives, future studies can lay the foundation for effective advancements in crop improvement and environmental adaptation, making MYBs essential tools for a sustainable agricultural future.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (Grant No. FRGS/1/2023/STG03/UM/02/2) and Universiti Malaya RU Grant (RU002-2025B).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Boon Chin Tan; draft manuscript preparation: Imene Tatar Caliskan, George Dzorgbenya Ametefe, Aziz Caliskan, Su-Ee Lau, Yvonne Jing Mei Liew, Nur Kusaira Khairul Ikram, and Boon Chin Tan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhang D, Zhou H, Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Feng X, et al. Diverse roles of MYB transcription factors in plants. J Integr Plant Biol. 2025;64(3):539–62. doi:10.1111/jipb.13869. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Hajheidari M, Huang SSC. Elucidating the biology of transcription factor-DNA interaction for accurate identification of cis-regulatory elements. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2022;68:102232. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2022.102232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Schmitz RJ, Grotewold E, Stam M. Cis-regulatory sequences in plants: their importance, discovery, and future challenges. Plant Cell. 2022;34(2):718–41. doi:10.1093/plcell/koab281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Sun M, Xiao X, Khan KS, Lyu J, Yu J. Characterization and functions of Myeloblastosis (MYB) transcription factors in cucurbit crops. Plant Sci. 2024;348(5):112235. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2024.112235. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Kang L, Teng Y, Cen Q, Fang Y, Tian Q, Zhang X, et al. Genome-wide identification of R2R3-MYB transcription factor and expression analysis under abiotic stress in rice. Plants. 2022;11(15):1928. doi:10.3390/plants11151928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Oh JE, Kwon Y, Kim JH, Noh H, Hong SW, Lee H. A dual role for MYB60 in stomatal regulation and root growth of Arabidopsis thaliana under drought stress. Plant Mol Biol. 2011;77(1):91–103. doi:10.1007/s11103-011-9796-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Seo PJ, Xiang F, Qiao M, Park JY, Lee YN, Kim SG, et al. The MYB96 transcription factor mediates abscisic acid signaling during drought stress response in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2009;151(1):275–89. doi:10.1104/pp.109.144220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Xu Z, Yang Q, Feng K, Yu X, Xiong A. DcMYB113, a root-specific R2R3-MYB, conditions anthocyanin biosynthesis and modification in carrot. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020;18(7):1585–97. doi:10.1111/pbi.13325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Jian L, Kang K, Choi Y, Suh MC, Paek N. Mutation of OsMYB60 reduces rice resilience to drought stress by attenuating cuticular wax biosynthesis. Plant J. 2022;112(2):339–51. doi:10.1111/tpj.15947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Sukumaran S, Lethin J, Liu X, Pelc J, Zeng P, Hassan S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of MYB transcription factors in the wheat genome and their roles in salt stress response. Cells. 2023;12(10):1431. doi:10.3390/cells12101431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Arce-Rodríguez ML, Martínez O, Ochoa-Alejo N. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the MYB transcription factor gene family in chili pepper (Capsicum spp.). Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(5):1–24. doi:10.3390/ijms22052229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Cao Y, Li K, Li Y, Zhao X, Wang L. MYB transcription factors as regulators of secondary metabolism in plants. Biology. 2020;9(3):61. doi:10.3390/biology9030061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Ma Z, Zhong Y. Functions of MYB transcription factors response and tolerance to abiotic stresses in plants. Biochem Mol Biol Forthcoming. 2025. doi:10.20944/preprints202501.0491.v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Du H, Yang SS, Liang Z, Feng BR, Liu L, Huang YB, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the MYB transcription factor superfamily in soybean. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12(1):1–22. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-12-106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ma D, Constabel CP. MYB repressors as regulators of phenylpropanoid metabolism in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2019;24(3):275–89. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2018.12.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Kajla M, Roy A, Singh IK, Singh A. Regulation of the regulators: transcription factors controlling biosynthesis of plant secondary metabolites during biotic stresses and their regulation by miRNAs. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1126567. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1126567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang Y, Xu Y, Huang D, Xing W, Wu B. Research progress on the MYB transcription factors in tropical fruit. Trop Plants. 2022;1(1):1–15. doi:10.48130/TP-2022-0005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ogata K, Morikawa S, Nakamura H, Sekikawa A, Inoue T, Kanai H, et al. Solution structure of a specific DNA complex of the Myb DNA-binding domain with cooperative recognition helices. Cell. 1994;79(4):639–48. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(94)90549-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Li LX, Wei ZZ, Zhou ZL, Zhao DL, Tang J, Yang F, et al. A single amino acid mutant in the EAR motif of IbMYB44.2 reduced the inhibition of anthocyanin accumulation in the purple-fleshed sweetpotato. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;167:410–9. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.08.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Zhou M, Sun Z, Ding M, Logacheva MD, Kreft I, Wang D, et al. FtSAD2 and FtJAZ1 regulate activity of the FtMYB11 transcription repressor of the phenylpropanoid pathway in Fagopyrum tataricum. New Phytol. 2017;216(3):814–28. doi:10.1111/nph.14692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Chouhan R, Rai G, Gandhi SG. Plant transcription factors and flavonoid metabolism. In: Plant transcription factors. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. p. 219–31. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-90613-5.00001-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Liu J, Wang J, Wang M, Zhao J, Zheng Y, Zhang T, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the R2R3-MYB gene family in Fragaria × ananassa and its function identification during anthocyanins biosynthesis in pink-flowered strawberry. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:702160. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.702160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Li W, Li P, Chen H, Zhong J, Liang X, Wei Y, et al. Overexpression of a Fragaria vesca 1R-MYB transcription factor gene (FvMYB114) increases salt and cold tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6):5261. doi:10.3390/ijms24065261. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Du H, Wang YB, Xie Y, Liang Z, Jiang SJ, Zhang SS, et al. Genome-wide identification and evolutionary and expression analyses of MYB-related genes in land plants. DNA Res. 2013;20(5):437–48. doi:10.1093/dnares/dst021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Liu Z, Li J, Li S, Song Q, Miao M, Fan T, et al. The 1R-MYB transcription factor SlMYB1L modulates drought tolerance via an ABA-dependent pathway in tomato. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2025;222(6):109721. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2025.109721. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Pesch M, Schultheiß I, Klopffleisch K, Uhrig JF, Koegl M, Clemen CS, et al. TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA1 and GLABRA1 compete for binding to GLABRA3 in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2015;168(2):584–97. doi:10.1104/pp.15.00328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Stracke R, Werber M, Weisshaar B. The R2R3-MYB gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2001;4(5):447–56. doi:10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00199-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Tan L, Ijaz U, Salih H, Cheng Z, Htet NNW, Ge Y, et al. Genome-wide identification and comparative analysis of MYB transcription factor family in Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana. Plants. 2020;9(4):413. doi:10.3390/plants9040413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Hernández-Hernández B, Tapia-López R, Ambrose BA, Vasco A. R2R3-MYB gene evolution in plants, incorporating ferns into the story. Int J Plant Sci. 2021;182(1):1–8. doi:10.1086/710579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wu Y, Wen J, Xia Y, Zhang L, Du H. Evolution and functional diversification of R2R3-MYB transcription factors in plants. Hortic Res. 2022;9:uhac058. doi:10.1093/hr/uhac058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Cao Y, Xie L, Ma Y, Ren C, Xing M, Fu Z, et al. PpMYB15 and PpMYBF1 transcription factors are involved in regulating flavonol biosynthesis in peach fruit. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;67(2):644–52. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.8b04810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Czemmel S, Stracke R, Weisshaar B, Cordon N, Harris NN, Walker AR, et al. The grapevine R2R3-MYB transcription factor VvMYBF1 regulates flavonol synthesis in developing grape berries. Plant Physiol. 2009;151(3):1513–30. doi:10.1104/pp.109.142059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Wang H, Zhang H, Yang Y, Li M, Zhang Y, Liu J, et al. The control of red colour by a family of MYB transcription factors in octoploid strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) fruits. Plant Biotechnol J. 2020;18(5):1169–84. doi:10.1111/pbi.13282. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. An JP, Li R, Qu FJ, You CX, Wang XF, Hao YJ. R2R3-MYB transcription factor MdMYB23 is involved in the cold tolerance and proanthocyanidin accumulation in apple. Plant J. 2018;96(3):562–77. doi:10.1111/tpj.14050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Höll J, Vannozzi A, Czemmel S, Donofrio C, Walker AR, Rausch T, et al. The R2R3-MYB transcription factors MYB14 and MYB15 regulate stilbene biosynthesis in Vitis vinifera. Plant Cell. 2013;25(10):4135–49. doi:10.1105/tpc.113.117127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Takos AM, Jaffé FW, Jacob SR, Bogs J, Robinson SP, Walker AR. Light-induced expression of a MYB gene regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples. Plant Physiol. 2006;142(3):1216–32. doi:10.1104/pp.106.088104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Zeng Q, Liu H, Chu X, Niu Y, Wang C, Markov GV, et al. Independent evolution of the MYB family in brown algae. Front Genet. 2022;12:811993. doi:10.3389/fgene.2021.811993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Dai X, Xu Y, Ma Q, Xu W, Wang T, Xue Y, et al. Overexpression of an R1R2R3 MYB Gene, OsMYB3R-2, increases tolerance to freezing, drought, and salt stress in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;143(4):1739–51. doi:10.1104/pp.106.094532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Ma Q, Dai X, Xu Y, Guo J, Liu Y, Chen N, et al. Enhanced tolerance to chilling stress in OsMYB3R-2 transgenic rice is mediated by alteration in cell cycle and ectopic expression of stress genes. Plant Physiol. 2009;150(1):244–56. doi:10.1104/pp.108.133454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Salih H, Gong W, He S, Sun G, Sun J, Du X. Genome-wide characterization and expression analysis of MYB transcription factors in Gossypium hirsutum. BMC Genet. 2016;17(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/s12863-016-0436-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Katiyar A, Smita S, Lenka SK, Rajwanshi R, Chinnusamy V, Bansal KC. Genome-wide classification and expression analysis of MYB transcription factor families in rice and Arabidopsis. BMC Genom. 2012;13(1):1–9. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-13-544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Thiedig K, Weisshaar B, Stracke R. Functional and evolutionary analysis of the Arabidopsis 4R-MYB protein SNAPc4 as part of the SNAP complex. Plant Physiol. 2021;185(3):1002–20. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiaa067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Liu X, Yu W, Zhang X, Wang G, Cao F, Cheng H. Identification and expression analysis under abiotic stress of the R2R3-MYB genes in Ginkgo biloba L. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2017;23(3):503–16. doi:10.1007/s12298-017-0436-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Qin B, Fan SL, Yu HY, Lu YX, Wang LF. HBMYB44, a rubber tree MYB transcription factor with versatile functions in modulating multiple phytohormone signaling and abiotic stress responses. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:893896. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.893896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zhuang Y, Lian W, Tang X, Qi G, Wang D, Chai G, et al. MYB42 inhibits hypocotyl cell elongation by coordinating brassinosteroid homeostasis and signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Ann Bot. 2022;129(4):403–13. doi:10.1093/aob/mcab152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Xie Y, Bao C, Chen P, Cao F, Liu X, Geng D, et al. Abscisic acid homeostasis is mediated by feedback regulation of MdMYB88 and MdMYB124. J Exp Bot. 2020;72(2):592–607. doi:10.1093/jxb/eraa449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]