Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Mini Review on Plant Immune System Dynamics: Modern Insights into Biotic and Abiotic Stress

1 School of Agriculture, Lovely Professional University, Phagwara, 144411, India

2 Institute of Agricultural Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, 221005, India

* Corresponding Author: Shweta Meshram. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plants Abiotic and Biotic Stresses: from Characterization to Development of Sustainable Control Strategies)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(8), 2285-2312. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.067814

Received 13 May 2025; Accepted 15 August 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

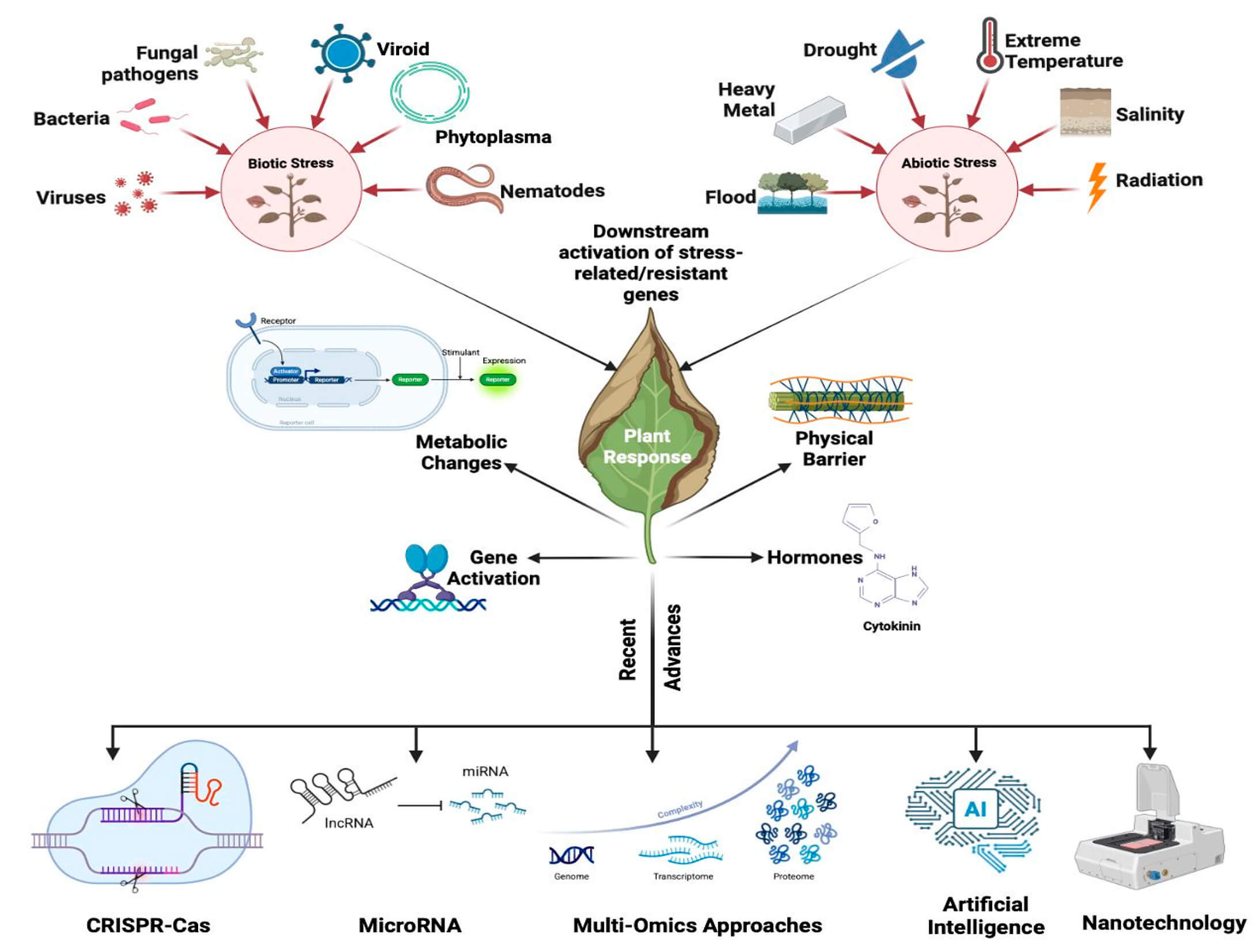

Plants are under constant exposure to varied biotic and abiotic stresses, which significantly affect their growth, productivity, and survival. Biotic stress, caused by pathogens, and abiotic stress, including drought, salinity, extreme temperatures, and heavy metals, activate overlapping yet distinct immune pathways. These are comprised of morphological barriers, hormonal signaling, and the induction of stress-responsive genes through complex pathways mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS), phytohormones, and secondary metabolites. Abiotic stress triggers organelle-mediated retrograde signaling from organelles like chloroplasts and mitochondria, which causes unfolded protein responses and the regulation of cellular homeostasis. Simultaneously, biotic stress activates both PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI) and effector-triggered immunity (ETI), mediated by salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET). This review aims to provide an integrated overview of plant immune responses to multiple stressors, with emphasis on molecular crosstalk and recent technological interventions. A systematic literature search was conducted using the Scopus database, covering studies published between 2010 and 2025. Advances in CRISPR-Cas genome editing, RNA interference, omics technologies, nanotechnology, and artificial intelligence have improved our knowledge of plant stress physiology and facilitated the design of resilient crop varieties. Despite these advances, the integration of immune signals under simultaneous biotic and abiotic stress remains poorly understood, particularly at tissue-specific and cellular levels. Additionally, practical challenges persist in delivery methods, regulatory hurdles, and long-term field validation. With the escalation of climate change, understanding the complex crosstalk between stress signalling pathways is essential for maintaining sustainable agriculture and global food security. Future directions point toward real-time monitoring tools, such as single-cell omics and spatial transcriptomics, to fine-tune immune responses and support precision crop improvement.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Plants are exposed to a range of biotic and abiotic stresses throughout their life cycle. Biotic stresses, such as pathogens, and competition for resources from other organisms are, whereas abiotic stresses include drought, salinity, high temperature, and starvation for nutrients. Plants have developed a range of signalling pathways and behavioural changes to counteract these stresses so that they may survive and reproduce under hostile conditions. The plant immune system, which is activated upon perception of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), is one of the primary signalling pathways that are involved in plant defence against biotic stress. The plant immune system consists of a network of receptor proteins, signalling pathways, and defence responses such as biosynthesis of reactive oxygen species (ROS), phytohormones, and secondary metabolites. These defence mechanisms can help plants resist pathogens [1,2]. Besides biotic stress, plants also encounter abiotic stresses such as Drought stress. For instance, it can create water deficits in plant tissues, leading to reduced photosynthesis, wilting, and ultimately plant death. Plants have evolved several mechanisms of adaptation to drought stress, such as stomatal closure, osmo-protectantsynthesis, and root architecture modification for enhanced water uptake [3,4].

Plants, however, respond through signalling pathways, undergo behavioural modifications against the stress. For example, during drought stress, some plants show alterations in their growth habits, like reduced stem elongation and enhanced root development [1]. Likewise, in response to nutrient deficiency, some plants alter their root architecture, like increased root branching [2]. The study of plant signalling and behaviour under biotic and abiotic stress is a fast-emerging topic with substantial implications for crop improvement and sustainable agriculture [1,5].

In this review, we aim to systematically synthesize and critically evaluate recent advances in understanding plant immunity and its responses against biotic and abiotic stresses, using a comprehensive bibliometric analysis. The key objectives in this study include (i) research landscape surrounding plant stresses and their immunity through literature network visualization, (ii) highlight the structural and physiological adaptations in plants that mediate stress tolerance, (iii) dissect the biochemical and molecular mechanisms underlying plant responses to different stresses, and (iv) to explore the intersection of cutting-edge developments such as CRISPR-Cas, microRNAs (miRNAs), omics, artificial intelligence (AI), and nanotechnology in enhancing plant immunity. This review intends to provide a holistic and updated view on how plants orchestrate multi-layered defense strategies in the face of complex environmental challenges.

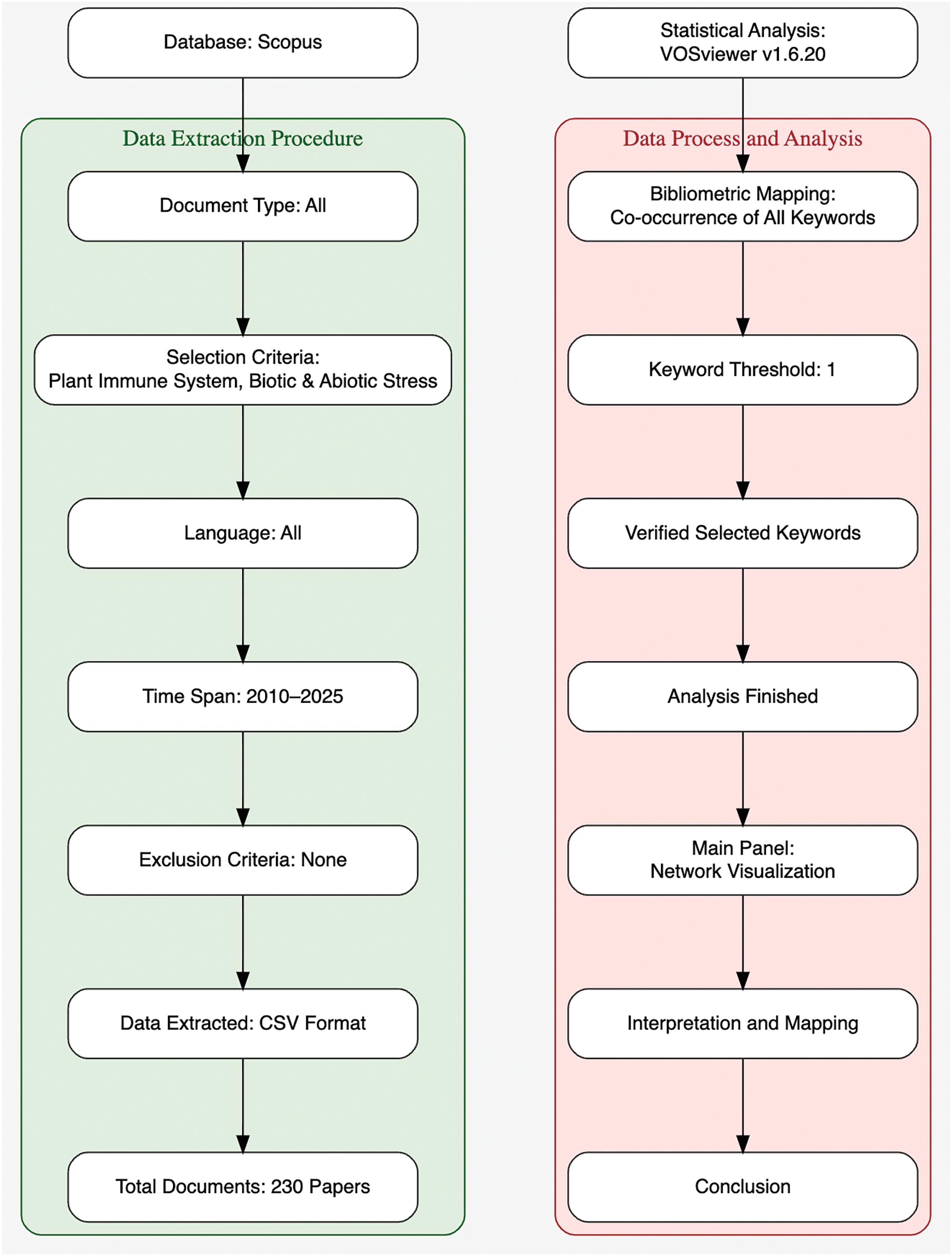

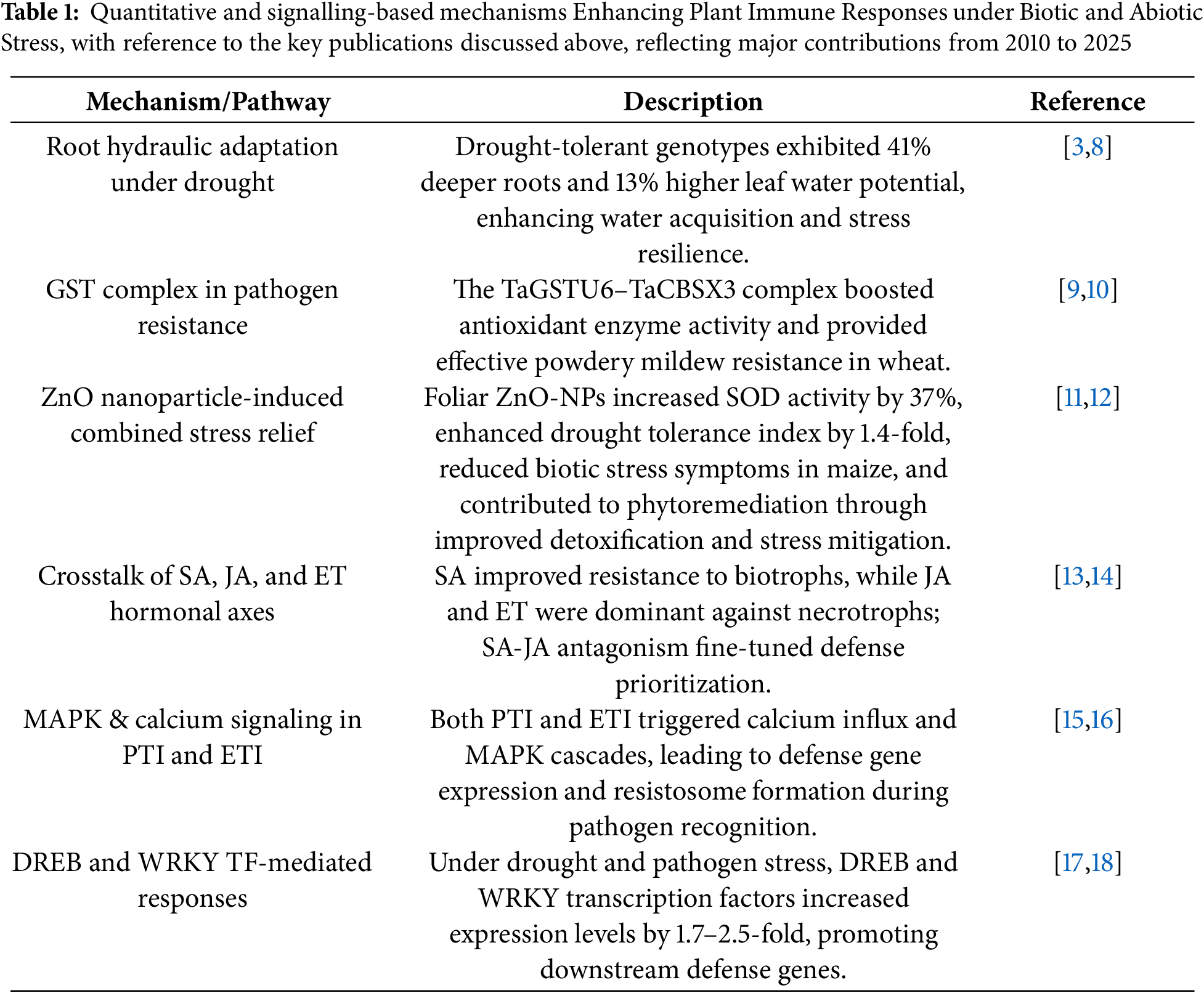

The systemic literature survey using key words “Plant Immune System” and “Biotic and Abiotic Stress” was performed using the Scopus database to assess the significance of current research in this field (Figs. 1 and 2). The literature search provided 230 findings in the last fifteen years, spanning from 2010 to 2025. This includes 103 (44.78%) research articles, 84 (36.52%) review articles, 33 (14.34%) book chapters, 3 (1.30%) books, and 7 (3.04%) others. Among all the papers published thus far, 10 were published in 2025, with 6 originating from India. The recent articles underscore the evolving and dynamic nature of research in Plant stress responses and defence mechanisms. Interestingly, Hossain et al. [6] documented the application of non-immunogenic circular RNA (circRNA) as a targeted gene regulatory tool in plants, whereas Mir et al. [7] emphasized information regarding functions of Salicylic acid (SA), Jasmonic Acid (JA), and ethylene (ET) in Plant-Pathogen interactions. A notable increase in publications between 2017 and 2018 was noted, with an increase from 7 to 25 documents. This trend was maintained year after year and peaked at a remarkable level of 39 documents being published in the year 2024. This consistent increase not only indicates the heightened scientific and academic interest in plant immunity but also the worldwide desperation to comprehend and counteract the effects of biotic and abiotic stress agents on plant systems.

Figure 1: Methodological framework for bibliometric analysis of literature related to the Plant Immune System and associated stress responses. This flowchart illustrates the comprehensive two-phase methodology adopted in the study

Figure 2: A bibliometric analysis of publications related to plant immunity under biotic and abiotic stress (2010–2025), showing trends in research volume, publication types, and regional contributions. A significant increase was observed after 2017, reflecting the growing interest in stress physiology

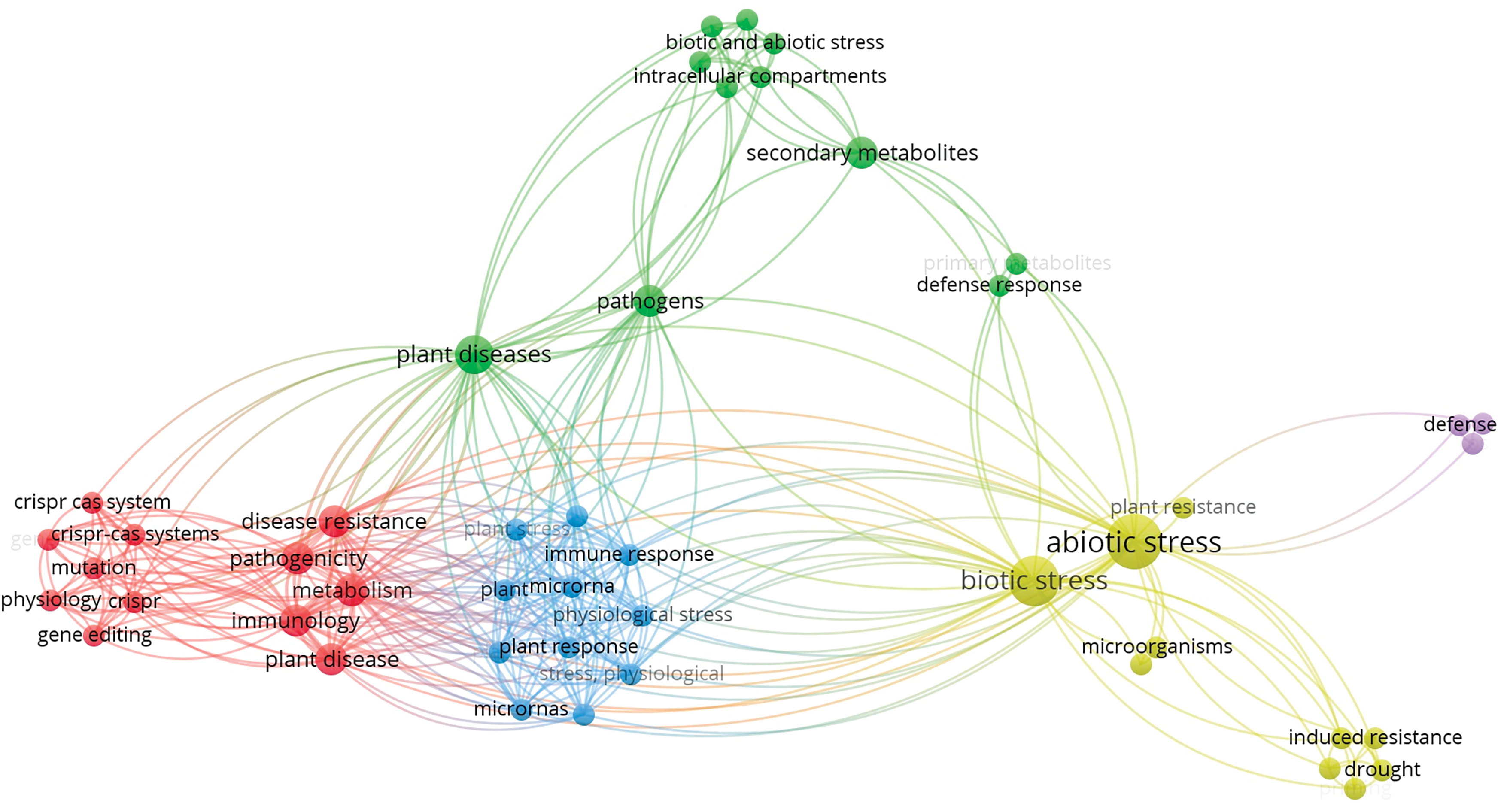

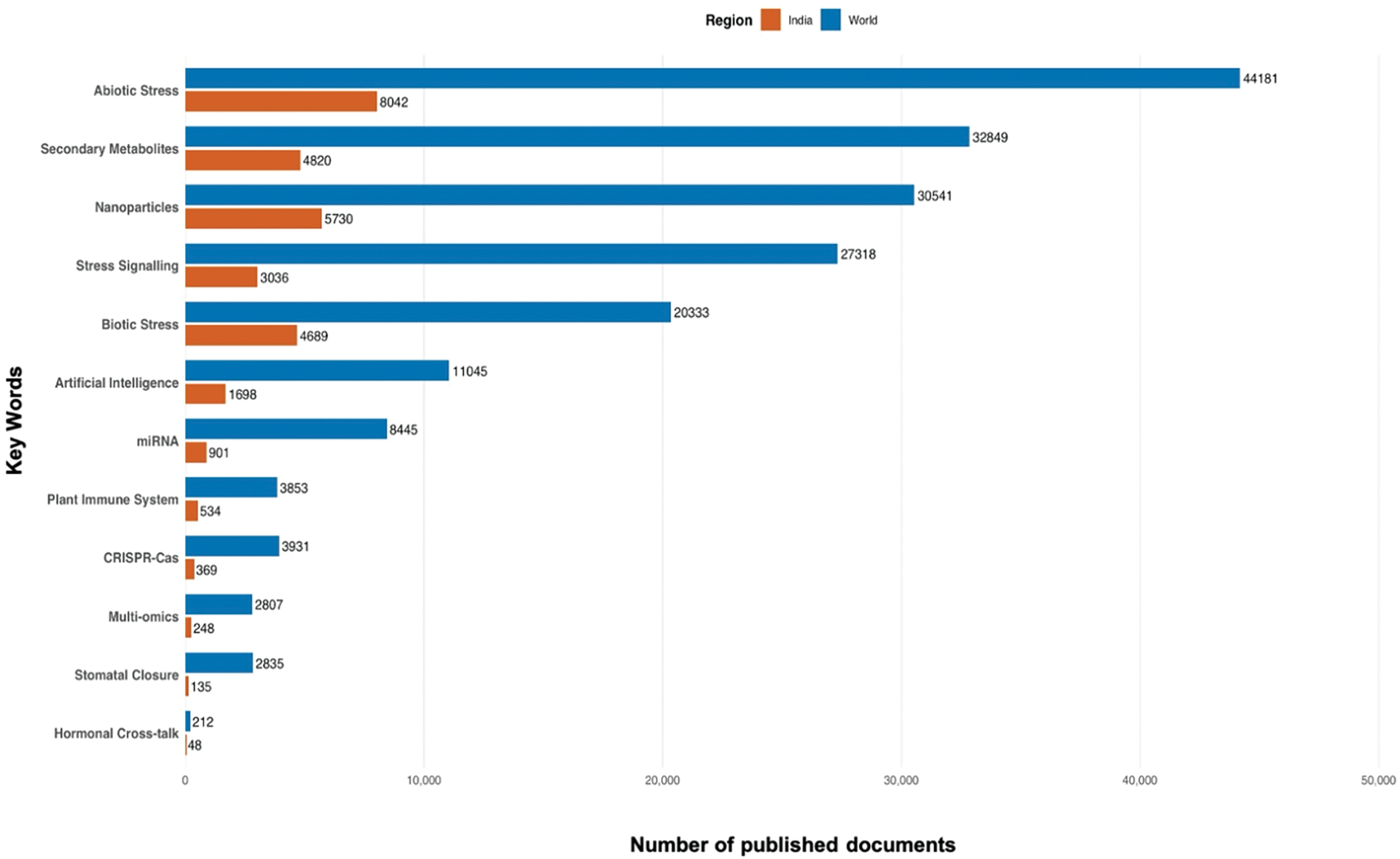

The graphical analysis of keyword-specific publication trends between the years 2010 and 2025 (Fig. 3) provides useful information regarding research priorities in the “Agricultural and Biological Sciences” discipline. As illustrated in Fig. 3, Abiotic Stress and Biotic Stress are the study areas that dominate the literature, together representing the highest number of publications globally (44,181 and 20,333, respectively) and in India (8042 and 4689, respectively). Terms like Secondary Metabolites, Stress Signalling, and Nanoparticles also express intense global research activity, implying their pivotal position in plant biology and mechanisms of stress responses. India’s contribution, while proportionally smaller, follows the global trend of emerging topics like CRISPR-Cas, miRNA, Multi-omics, and Artificial Intelligence, reflecting a growing interest in advanced molecular and computational technologies in plant science. Notably, subdomains like Hormonal Cross-talk and Stomatal Closure have comparatively small publication numbers, perhaps indicating niche or underdeveloped subdomains. This distribution reflects both India’s increasing scientific presence and the thematic shift towards incorporating molecular and computational tools in plant stress studies. Relying on the published documents shown above (Figs. 2 and 3), the subsequent data (Table 1) identifies the contributions of prime sources and fields of research, as well as their thematic visibility within the discipline.

Figure 3: Comparative analysis of Scopus-indexed publications (2010–2025) in the field of Agricultural and Biological Sciences, highlighting keyword-specific research trends globally and in India. Keywords are arranged in descending order based on total publications (World + India)

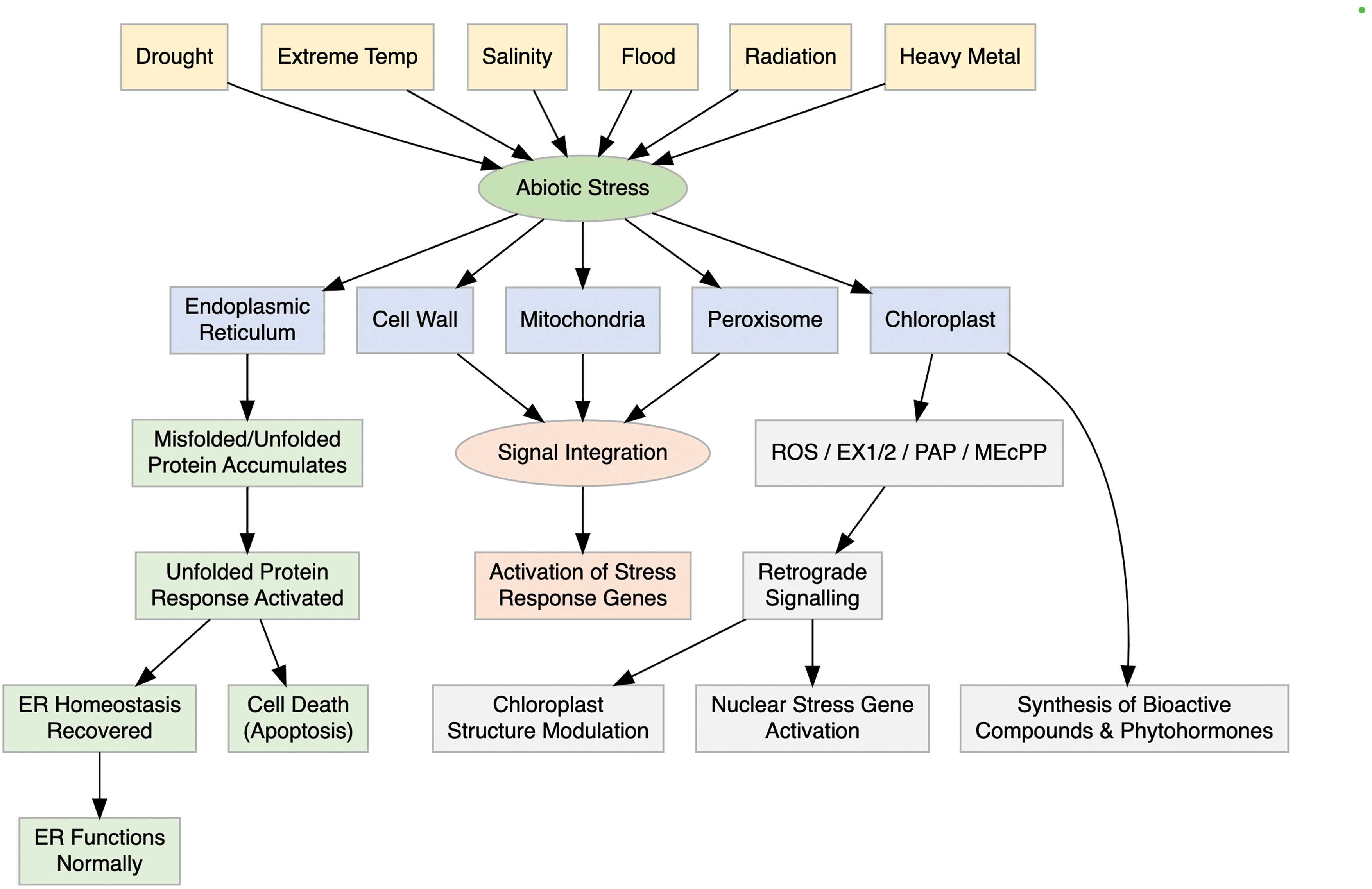

Abiotic stress in plants results from abrupt environmental changes like high or low temperatures, drought, salinity, radiation, and heavy metal toxicity, which severely affect plant growth and productivity [19]. It is widely accepted that such stress inhibits the internal metabolism of plant constituents, hampering critical physiological and biochemical processes. These interruptions may give rise to detectable development hindrances, primarily in delicate crop plants, displaying inhibited flowering, seed production inhibition, or senescence leading to premature flowering [20]. The stress-resistant crop species adjust sequentially by invoking a series of defence techniques. The crop plants counter adversity by the promotion of antioxidant enzymes, adjusting the hormone signaling system, and enforcing stress-regulating genes and cascades of molecular signal pathways. These tightly coordinated mechanisms aid in restoring cellular homeostasis and preserving metabolic stability under stress [21,22]. It is essential to understand these coordinated physiological and morphological responses, especially when plants encounter superimposing abiotic and biotic stress conditions. These stress leads to various cellular, physiological, and morphological changes in plants mediated by an array of signalling systems (Fig. 4) [23].

Figure 4: Schematic representation of organelle specific sensing and signaling pathways in plants under abiotic stress. The diagram highlights how chloroplasts, mitochondria, peroxisomes, and the nucleus coordinate to perceive stress signals and activate appropriate gene expression responses through integrated signaling networks

2.1 Intra Cellular Stress Signalling

Organelle stress perception and signaling in plants entails complex communication between different cellular compartments. Although stress signals tend to be sensed at the cell membrane, they may also arise from internal structures such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), chloroplasts, mitochondria, peroxisomes, and the cell wall. Stress induces protein misfolding in the ER, which elicits unfolded protein responses (UPR) through membrane-associated transcription factors (bZIP17, bZIP28) and RNA splicing processes regulated by IRE1 and bZIP60 [24]. Autophagy can be induced by short-term stress; However, prolong stress can cause cell death and necrosis [25]. Mitochondria and peroxisomes, aside from their metabolic functions, are involved in retrograde signalling through reactive oxygen species (ROS) and stress-related metabolites [26]. Mitochondrial component mutations, such as that of the DEXH box RNA helicase or complex I, cause ROS accumulation and defective ABA and cold stresses [14]. Chloroplasts also perceive environmental changes, emitting ROS and phytohormones, and interact with the nucleus through retrograde signals to modulate gene expression and ensure cellular homeostasis [27,28].

Recent studies have shown that coordination between organelle-specific and systemic responses is mediated by shared signaling molecules and transcriptional regulators. For example, transcription factors like ANAC017 and ABI4 are mobilized downstream of mitochondrial and chloroplast signals, respectively, to control nuclear stress-responsive genes [26]. Additionally, ROS generated in chloroplasts or mitochondria can trigger systemic acquired acclimation (SAA), a process involving calcium waves, redox signals, and mobile peptides such as SAL1-PAP (3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphate), which integrates chloroplast stress signals with nuclear responses [14]. These overlapping signaling networks ensure integrated stress perception, response fine-tuning, and maintenance of cellular homeostasis under abiotic stress.

2.2 Abiotic Stress and Disease Triangle Interaction

Plant interactions mediated by abiotic stress involve complex cross-talk among various physiological, biochemical, and molecular processes. Abiotic stress in the form of drought, salinity, or temperature can influence overall plant metabolism, hormonal balance alterations, and weaken defense responses, altering the ability of plants to cope with pathogens as well as other components of the environment [29,30]. These interactions, however, result in either increased susceptibility or increased defence depending on stress intensity and duration. These dynamic responses are essential to understand in deciphering plant adaptability under conditions of multifactorial stress [31,32].

Plant defence against drought stress involves complex cellular responses and adaptations to reduce damage and maintain water balance. Stomatal closure reduces transpiration, while osmo-protectants like proline and glycine betaine aid in osmotic adjustment [33]. Antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX) detoxify reactive oxygen species (ROS). Abscisic acid (ABA) regulates stomatal closure and expression of stress responsive genes [34]. Transcription factors like Drought Responsive Element Binding (DREB) proteins and ABA-Responsive Element Binding Proteins (AREBs) activate drought-related genes. Root architecture changes, including deeper rooting, improve water uptake. Aquaporins (AQPs) enhance water transport across membranes [35]. Stress from drought mediated exacerbation of infection is best described by Macrophominaphaseolina pathogenesis, the etiologic agent of charcoal rot in common bean. Drought was reported to have a greater severe impact on certain wilt and root-rot diseases [34]. Epigenetic changes like DNA methylation influence drought memory. Protective proteins such as Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA) proteins and Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs) stabilize cellular structures [29,36]. These responses collectively increase plant resilience under drought stress.

2.2.2 Temperature and Pathogen Behaviour

Temperature stress alters pathogen activities, for example, activating dormant pathogens and shifting disease distribution. High temperatures may weaken resistance (R) gene-mediated defences and hypersensitive response (HR), increasing disease susceptibility [37]. However, certain R genes like Sr21, Sr13, and Yr36 retain or enhance resistance under heat. Temperature-induced alternative splicing of R genes can influence defence outcomes [38]. Salicylic acid (SA) responses can be suppressed by abscisic acid (ABA) during heat stress but are maintained in young tissues via GH3.12 regulation [39,40]. Cold stress sometimes boosts resistance through SA pathways, as seen in Arabidopsis. Heat may enhance susceptibility to viruses like TYLCV in tomato, but in some cases, it improves resistance, such as in tobacco against TSWV [41]. The receptor-like kinase TaXa21 and transcription factors like TaWRKY76 mediate heat-induced resistance in wheat [29]. Pathogen behaviour and host defence often depend on stress severity, duration, and plant development stage; therefore, temperature is a crucial factor in the disease triangle and serves link between abiotic and biotic stress.

Salinity stress impacts plant physiology by promoting salt accumulation, especially in leaves, through transpiration. It predisposes roots to higher colonization by pathogens like Phytophthora spp. [42]. Studies show abscisic acid (ABA) marker genes are consistently activated in all root cell layers under salt stress, indicating a universal stress response [43]. While the ABA response appears to be conserved, studies in salt-tolerant halophytes indicate a more balanced interaction between ABA and CK, suggesting species-specific adaptations that could guide genetic improvement [44]. The ABA-CK balance is key in modulating plant adaptation to salinity and pathogen resistance [29]. Experimental setups separate stress and infection phases to better study their effects. Similar kinase and ABA signalling mechanisms are activated under salinity, heat, and drought stresses. While field data is lacking, controlled studies reveal that salinity stress dynamically interacts with plant immune responses, especially in root–pathogen systems.

Biotic stresses are often included living organisms like different microbes—fungi, bacteria, viruses, and nematodes which attack the plants and also cause yield loss by reducing plant health and productivity [45,46]. For instance, Fusarium wilt, aphid and mite infestation, and root-knot nematodes, all of which cause several challenges by stunting growth, yellowing, reduced photosynthesis, and sap loss, lead to the death of the plant [46]. These biotic stresses are responsible for 20%–40% of annual crop yield losses worldwide, especially by the fungal pathogens, being highly destructive [45,46]. The emergence of new pathogen races and pesticide-resistant pests, climate change, and human activities pose current threats to agriculture [47]. In response, plants exert defense strategies such as hypersensitive responses (HR), hormonal cross-talk, and systemic acquired resistance (SAR) to resist invasion [45,47].

3.1 Double-Layer Immune System in Plants

In nature, plants exhibit a two-tiered immune system, which is Pattern-Triggered Immunity (PTI) and Effector-Triggered Immunity (ETI), that coordinately operate to protect themselves against invading pathogens [16]. PTI serves as the first line of defence and is triggered when plasma membrane-localized Pattern Recognition Receptors (PRRs), along with co-receptors mainly receptor-like kinases (RLKs) and receptor-like proteins (RLPs) that detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), microbe associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), or damage associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [48,49]. Within the cell, resistance proteins such as NLRs (Nucleotide-binding domain and Leucine-rich Repeat proteins) detect pathogen-derived effectors, prompting a cascade of defence reactions, often more intense than those seen in the initial immune phase [15]. This interaction will lead to the downstream reactions, including resistosome formation, calcium influx, MAPK cascades, and programmed cell death [15,16]. Although the zigzag model has historically portrayed PTI and ETI as distinct, emerging research reveals significant overlap and integration between the two, with ETI often reinforcing PTI when it is compromised [50,51].

Recent research has shifted away from the traditional linear perspective, uncovering a complex web of interactions and signaling overlaps between PTI and ETI [16]. These two immune layers, once considered separate, are now understood to be deeply interconnected—both activating shared downstream responses like MAPK signalling, ROS burst, and defense gene expression [16]. Recent evidence suggests that ETI often enhances PTI responses, especially in cases in which PAMP detection is inhibited by pathogenic effectors, while PTI lays the groundwork for a stronger and more rapid ETI response, blurring the boundary and suggesting a more integrated immune network [16,52]. At the molecular level, both PTI and ETI converge on shared signaling components such as MPK3, MPK6, and MPK4, and co-activate transcription factors like WRKYs, CBP60g, and SARD1, creating a positive feedback loop that reinforces defense signaling [16]. Additionally, EDS1-PAD4-ADR1 and NDR1-dependent modules serve as key integration hubs facilitating signal relay from both PRRs and NLRs, especially in dicot plants like Arabidopsis thaliana [53]. Though core signaling elements are conserved, species-specific variations exist—e.g., in rice, PTI and ETI appear more modular, with less crosstalk between PRR and NLR networks than in Arabidopsis [24]. This evolving view paints a more unified and dynamic picture of plant immunity—one that challenges the stepwise “zigzag” model and instead highlights the importance of coordinated activation for effective pathogen resistance [16].

3.2 Different Mitigation Strategies Plants Adapted

a. Ascorbate and Glutathione

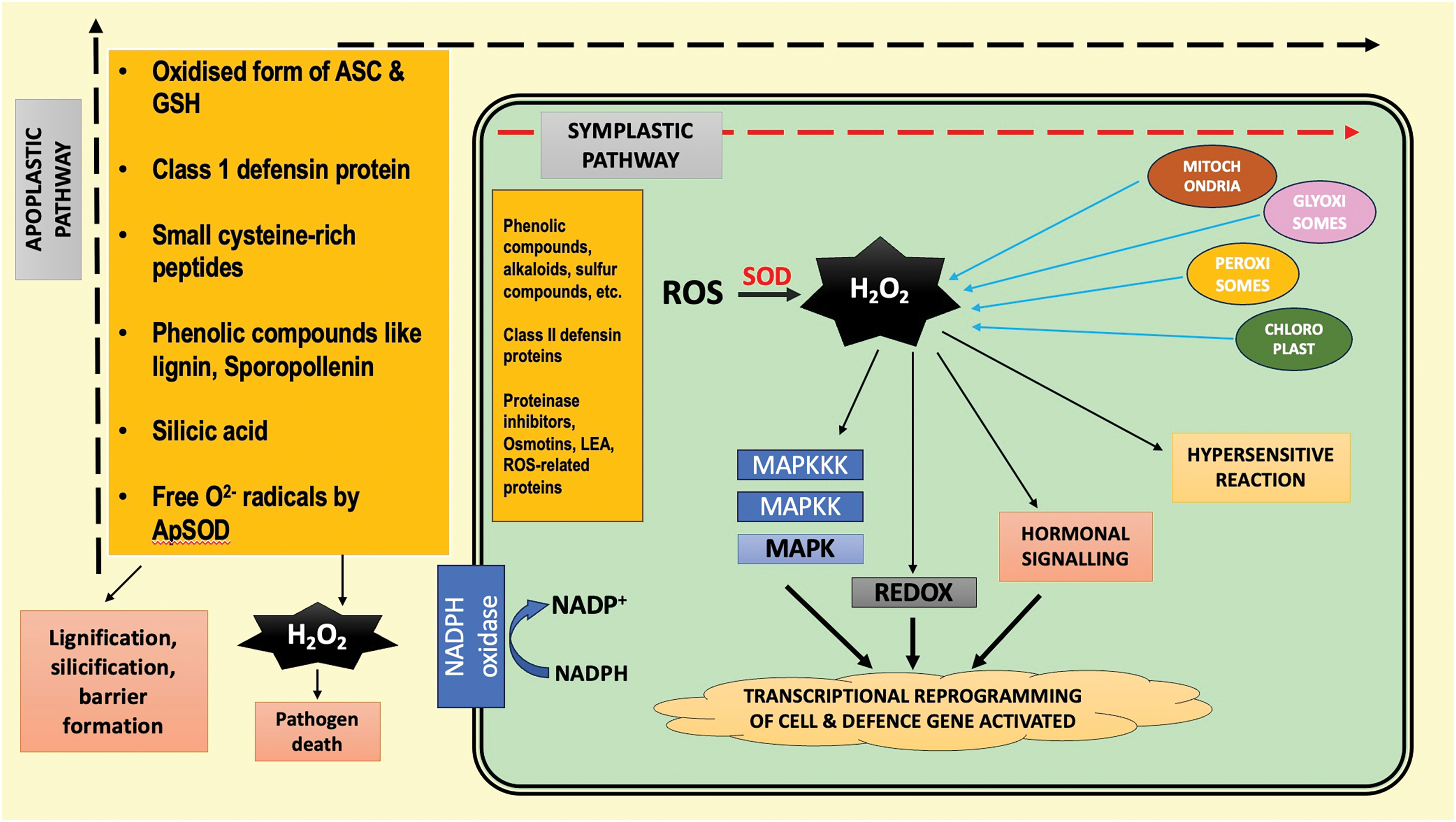

Ascorbate (ASC), the most abundant water-soluble antioxidant present in the apoplast, the space outside the cell membrane, which helps in mitigating the biotic and abiotic stress [38,54,55]. This ASC efficiently scavenges ROS generated by enzymatic and non-enzymatic reactions under stress conditions (Fig. 5) [55]. Under biotic stress, antioxidants fine-tune ROS levels to support defense signaling and localized cell death, whereas under abiotic stress, they act mainly to detoxify excess ROS and protect against widespread oxidative damage. Their function varies by tissue, with heightened roles in sensitive sites like leaves and reproductive organs [56,57].

Figure 5: Coordination of apoplastic and symplastic pathways in plant defense through reactive oxygen species (ROS). In the apoplast, ROS, antioxidants, phenolics, and defensins reinforce cell walls and inhibit pathogens. In the symplast, organelles generate ROS that trigger MAPK cascades, redox, and hormone signaling, leading to defense gene activation and hypersensitive response

In one study, it was found that tomato seed priming with ASC has improved germination rates as well as triggered defence mechanisms against wilt disease [45]. Similarly, in Arassbidopsis thaliana, a lack of ASC has been linked to increased resistance against Pseudomonas syringae infections and aphid attacks, emphasizing a complex role for this antioxidant in plant-pathogen interactions [51]. It is mostly found in an oxidised form, and its redox state depends mostly on the cytoplasmic ASC-dehydroascorbate (DHA) balance [58]. Within the cell, ASC is regulated through a combination of biosynthesis of several key enzymes, including ascorbate peroxidase (APx), monodehydroascorbate reductase (MDHAR), dehydroascorbate reductase (DHAR), and glutathione reductase (GR), and recycling, primarily via the ASC–glutathione cycle [55].

Another key antioxidant found in apoplastic space of plant cells is Glutathione (GSH), but in less amounts [58]. GSH is crucial to strengthening the defence against biotrophic fungi [59]. When oxidised to GSSG, glutathione is transported back into the cytoplasm, where it is returned to its reduced form by GR using NADPH as a reducing agent [59,60]. Together, ASC and GSH work to maintain cellular redox homeostasis and help initiate immune responses. However, much remains to be discovered about how these molecules are transported and regulated within plant tissues [60].

b. Defensins & Small Peptides

In addition to the ASC and GSH, to combat against different biotic stresses, plants have produced defensins and defensin-like proteins, small cysteine-rich peptides [61,62]. In the apoplastic space, these Class I defensins are synthesised in the cytoplasm and interact with negatively charged microbial membranes, inducing ROS accumulation and disrupting pathogen cell membranes [63].

Moreover, defensins and related peptides like systemin enhance the local and systemic defence responses by acting as endogenous danger signals, released upon stress [64]. These peptides also function as novel messengers in intercellular and long-distance signalling [61,65,66]. Thus, as a part of plant defence strategies through membrane-targeted action, signalling roles, and activation of defence pathways, defensins and related peptides form a key part of it.

c. Secondary Metabolites

Plants produce a wide range of secondary metabolites like phenolic compounds, polyphenols, and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) to defend against microbial pathogens [58,67,68]. These compounds are both free phenolics and polymeric forms such as lignin and sporopollenin, which strengthen physical barriers and resist enzymatic degradation [69–71].

The most abundant polyphenol in nature is Lignin, which crosslinks with cell wall carbohydrates to form rigid structures that hinder pathogen invasion and support antioxidant activity [67]. Enhanced lignification, along with cutin, suberin, and Casparian strip formation, has been linked to strengthening resistance against biotic invaders [15,72,73]. The thickness of the cell wall also depends on silicic acid, which stops the infection from spreading farther. For example, in potatoes and paddy, the lignification and silicification of epidermal cells provide defence against Streptomyces scabies and Pyricularia oryzae, respectively. This kind of cutinolytic enzyme’s activity in Fusarium solani isolates and the aggressiveness of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. pisi on pea stems are directly correlated with this, suggesting that pathogens that are unable to break down the cuticle at the site of penetration are excluded [74].

Moreover, VOCs in the apoplast can mitigate oxidative stress by scavenging reactive gases like ozone, protecting internal tissues from oxidative damage [75,76]. Although the multi-functional secondary metabolites can develop stress responses more cost-effectively, their synthesis and limited regeneration capacity, especially for wall-bound polymers like lignin, may divert energy from growth [71,77]. However, their pre-existing presence in the apoplast allows plants to rapidly counteract biotic stress, minimising cellular damage without immediate dependence on new biosynthesis [68,71].

d. Enzymatic Activities

To mitigate different biotic stresses, several enzymes are produced to act in the plant defence system, among which class III apoplastic peroxidases form a prominent family. These enzymes facilitate a range of redox reactions through hydroxylic and peroxidative cycles. These are synthesised in the cell, glycosylated via the ER–Golgi pathway, and secreted into the apoplast through N-terminal signal peptides [61,78]. The diverse members of this enzyme family have multifunctionality, with roles spanning cell wall modification, involvement in hormone-mediated development, and detoxification of reactive compounds [78].

Peroxidases (Prxs) play a vital role in helping plants fend off pathogens and cope with oxidative stress, acting as a frontline defence in various stress conditions [78]. One of their key functions is the detoxification of harmful compounds like ozone and sulfite, particularly within the apoplastic space where such molecules often accumulate [78].

Working alongside NADPH oxidase, which is embedded in the plasma membrane, Prxs participate in generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), including superoxide radicals (O2−). These radicals are swiftly converted into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by the enzyme superoxide dismutase (SOD), a process crucial for oxidative signalling and antimicrobial action [61]. Beyond their toxic effects on pathogens, these ROS are central to broader signalling networks that coordinate plant-wide responses to stress [79,80]. Notably, NADPH oxidase has recently been found to play a role in maintaining a balanced microbial population on leaves in Arabidopsis thaliana, highlighting its dual function in immunity and homeostasis [80,81].

Some case studies reinforce this importance. In sweet potato, Prx activity spikes in response to sulfur dioxide exposure, suggesting a protective role against airborne pollutants [82]. Similarly, in Arabidopsis thaliana, peroxidase 34 (At3G49120) is strongly induced under sulfite stress, indicating gene-level regulation during stress adaptation [83]. Another interesting finding comes from Baillie et al. [84], who showed that apoplastic Prxs can oxidize sulfite into sulfate when H2O2 and phenolic compounds are present—creating a chemical shield that protects plant tissues. Despite this growing body of knowledge, we still lack a full understanding of the genetic and molecular controls that govern how peroxidases and NADPH oxidase function under diverse stress conditions [78,79].

a. Chemical Antioxidants

When apoplastic defenses fail, intracellular ROS produced in organelles like chloroplasts, mitochondria, peroxisomes, and the cytosol must be detoxified to prevent cellular damage [58,85]. H2O2 is neutralized without depleting ASC/GSH, as their oxidized forms (DHA and GSSG) are regenerated enzymatically (Fig. 5) [55]. ASC is primarily synthesized via the D-mannose/L-galactose pathway, which is light and phosphate-dependent [55]. GSH is produced in the cytosol and chloroplasts and requires sulfur, nitrogen, and ATP [59], with limited knowledge on its transporters [86]. GSSG is also sequestered into vacuoles via ABC transporters to maintain redox balance [87].

Subcellular detoxification of ROS is primarily carried out by enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APx), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), peroxiredoxins (Prrxs), and thioredoxins (Trx), which neutralize ROS directly at their sites of production [59,85]. This immediate detoxification minimises oxidative damage. However, these processes demand significant metabolic resources and energy for enzyme and metabolite synthesis. Additionally, excessive ROS removal can disrupt the cellular redox homeostasis, potentially affecting the function and regulation of redox-sensitive proteins involved in vital metabolic pathways [88,89]. Although SOD efficiently converts superoxide radicals (O2•−) into less reactive forms, it simultaneously generates hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which itself is a harmful [85].

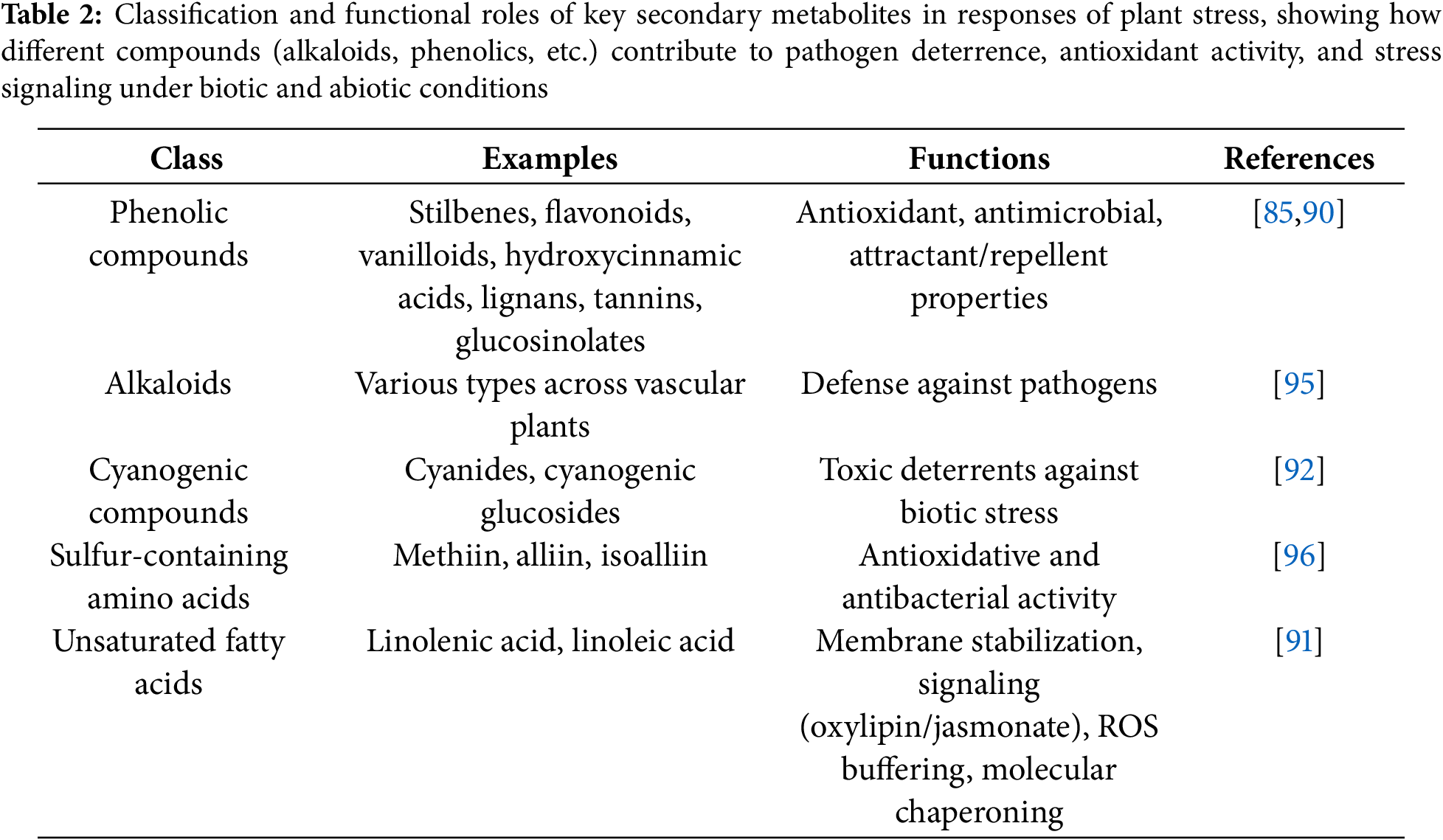

b. Secondary Metabolite Production

Plants yield an enormous diversity of secondary metabolites that are crucial components of resistance against biotic as well as abiotic stresses. Among these, the most common ones are phenolic compounds, which have a multifunctional role owing to their antioxidant and antimicrobial activities [85]. Apart from immediate alleviation of stress, most of these compounds act as attractants or repellents, which affect plant interactions with a wide variety of organisms [90].

Other secondary metabolite classes, such as the alkaloids, cyanogenic glucosides, sulfur amino acids, and unsaturated fatty acids, are involved in stress alleviation via various mechanisms. These are the mitigation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), regulation of membrane dynamics, and involvement in signalling pathways like oxylipin and jasmonate biosynthesis [91,92].

Although secondary metabolite production is a powerful plant defence strategy, it is metabolically expensive. Unlike enzymatic antioxidants like ASC and GSH, the polymerisation of phenolic compounds following oxidation often renders them biologically inactive, making their use less reversible and energetically more demanding [93]. Plant vacuoles serve as key storage compartments for these defence metabolites, allowing for regulated release during stress responses [94]. A brief summary of these compounds and their stress-related functions is presented in Table 2.

c. Defensins and Small Peptides

Defensins and related peptides act in the symplast to counter a broad range of biotic and abiotic stresses [97]. They are expressed across plant tissues and stages, with roles in antimicrobial defence and heavy metal tolerance [98,99]. Class II defensins possess C-terminal prodomains enabling vacuolar targeting through energy-dependent endocytosis [74]. Other peptides like cyclotides, thionins, and snakins also contribute to pathogen defence [65].

While generally non-toxic, overexpression can impair cell growth, fertility, and morphology [100]. Regeneration and trafficking of oxidised defensins remain poorly understood, especially in woody species [99]. Some microbes, including Sinorhizobium meliloti, can evade edefensin activity, highlighting potential limitations [99,100].

d. Defence Proteins

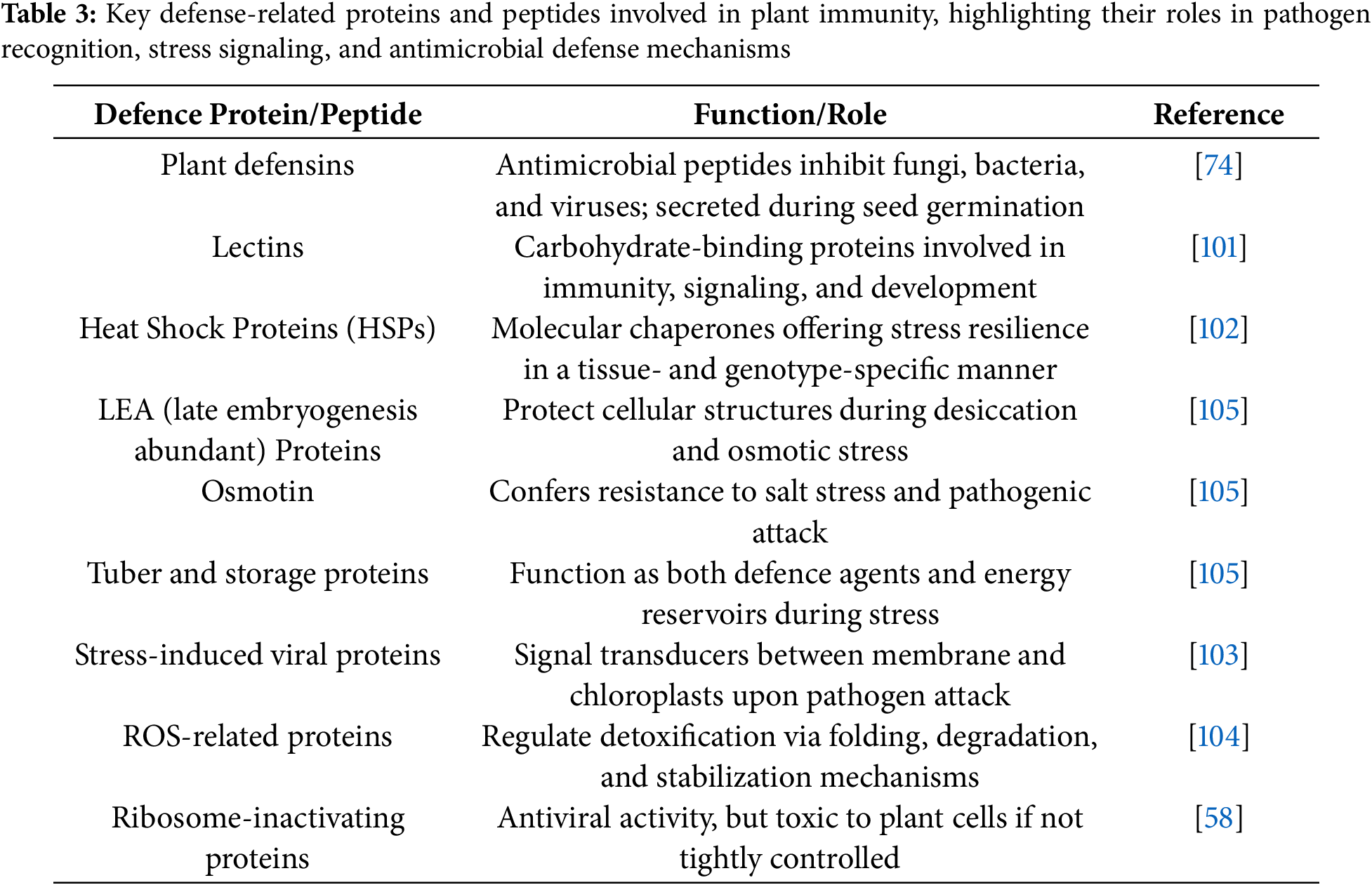

Plants produce small cysteine-rich peptides known as plant defensins that play a crucial antimicrobial role, showing activity against fungi, bacteria, and viruses by functioning as proteinase inhibitors, polygalacturonase inhibitors, ribosome-inactivating proteins, and lectins [58]. Certain defense-related proteins interfere with the nutrition and development of invading pathogens, effectively boosting the plant’s resistance to infection [74]. Among these, defensins are particularly noteworthy. During seed germination, their concentrations surge; although they make up just 0.5% of the total protein content in ungerminated radish seeds, they account for as much as 30% of the secreted proteins once germination begins, forming a protective antimicrobial barrier around the emerging radicle [74]. Defensins are also widely distributed across a range of plant species and tissues, including seeds of cereals, legumes, and solanaceous crops, as well as in outer layers of flowers, leaves, and tubers [74]. Lectins, first identified in seeds, have since been found throughout many plant organs. These proteins bind to carbohydrates inside vacuoles and play multiple roles, from defence and development to stress signalling and gene regulation [101]. Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs) form another essential group. These molecular chaperones assist in protein folding and protection under stress and show variation based on tissue type and plant genotype. Still, their full range of actions, particularly in sensing stress and relocating within cells, is not fully understood [102]. Recently, researchers have uncovered a novel signalling pathway where certain viral proteins relocate from the plasma membrane to the chloroplasts when a pathogen is detected. This discovery suggests a defence signalling system that bridges cellular compartments [103]. Moreover, specific protein–protein interactions involved in ROS detoxification, such as those regulating protein stability, folding, and breakdown, are emerging as crucial elements in plant defence, though these mechanisms are still underexplored [104]. A brief summary of these proteins and their functions is provided in Table 3.

Despite their effectiveness, defence proteins come at a cost. They require substantial metabolic energy, and some, like lectins and ribosome-inactivating proteins, can be toxic to the plant itself if their production or localisation is not tightly controlled [101]. Since protein synthesis is one of the most energy-consuming processes in plant cells, its regulation becomes even more critical during stressful conditions [77].

3.2.3 Defence at Whole Plant Level/Organ Level

a. Stomatal Closure

Stomatal closure is an important and quick defence response in plants against biotic stress, i.e., pathogen attack, by developing an immediate physical barrier that restricts microbial invasion via leaf stomata, a critical element of the innate immune response of the plant. This turgor loss is controlled primarily by abscisic acid (ABA) and modulated by complex signalling cascades that include turgor loss-inducing reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitric oxide (NO), and calcium ions, which together cause turgor loss in guard cells and stomatal closure. Hormonal cross-talk with salicylic acid (SA) and jasmonic acid (JA) also reinforces downstream defence signalling [24,106,107]. A prominent example is found in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), where rapid stomatal closure is triggered upon recognition of the bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae, effectively restricting its entry and proliferation. This early response is further accompanied by enhanced photorespiration and the synthesis of antimicrobial compounds, contributing to sustained defence [106]. Similarly, in Arabidopsis thaliana, pathogen perception induces stomatal closure as part of a well-conserved innate immune mechanism, underscoring the evolutionary significance of stomatal regulation in plant-pathogen interactions [24,106,107].

b. Structural Modifications and Barrier Formation

Plants acquire a variety of structural defence mechanisms at the organ and entire-plant level to limit pathogen invasion. They include deposition of wax on aerial surfaces, which is a hydrophobic barrier that hinders microbial adhesion and penetration. In Triticum aestivum (wheat), the increased accumulation of cuticular wax is linked to resistance towards powdery mildew and aphid attack [108]. In the same way, it has been theorized that the inability of germ tubes to penetrate the thicker cuticles of mature leaves is why Taphrina deformans is limited to infecting freshly unfurled young leaves. The cuticle of linseed serves as a defence against Melampsoralini [74].

Another prominent defence is tylose formation, where parenchyma cells intrude into xylem vessels, thereby blocking pathogen movement through the vasculature. This has been extensively documented in Vitis vinifera (grapevine) in response to Xylella fastidiosa, the causal agent of Pierce’s disease [108].

Cork layer formation is an additional structural modification that involves suberized tissue development around infection sites, effectively isolating infected zones. Some instances of cork layer production due to infection include necrotic lesions on tobacco caused by the tobacco mosaic virus, potato tuber disease caused by Rhizoctonia sp., potato scabies caused by Streptomyces scabies, and soft rot of potatoes caused by Rhizopus spp. [74]. Similarly, in Solanum tuberosum (potato), cork layers restrict the spread of Phytophthora infestans lesions [109].

Likewise, epidermal thickening enhances mechanical strength, reducing pathogen ingress. In Oryza sativa (rice), this has been correlated with improved resistance to the rice blast fungus [110]. The hard outer epidermal cells with a thick cuticle have been linked to disease resistance in Barberry species infected with Puccinia graminis tritici [74].

The formation of abscission layers represents a controlled shedding of infected or compromised tissues. Around the infection site, an abscission layer is made up of a space between the leaf’s healthy and diseased cells. Due to the breakdown of the parenchymatous tissue’s central layer. The infection spreads when the diseased area gradually shrivels, dies, and sloughs off. The development of an abscission layer shields the pathogen’s attack on the healthy leaf tissue [74]. For example, Closterosporium carpophylum on peach leaves and Xanthomonas pruni on pomegranate leaves [74]. In citrus species, abscission layers develop at the base of infected leaves to limit the spread of citrus canker [109]. Trichomes, which are specialised epidermal outgrowths, contribute to defence by creating a physical barrier and secreting toxic or sticky substances. Glandular trichomes in Solanum lycopersicum (tomato) deter whiteflies and thrips through mechanical hindrance and chemical defence [108].

Lastly, gum deposition at infection or wound sites is a strategy to entrap invading pathogens and seal damaged tissues. In Prunus dulcis (almond), gum exudation in response to fungal attack helps restrict pathogen spread [108].

c. Hypersensitive Response

The hypersensitive response (HR) is an extremely effective and widespread immune strategy that plants deploy to combat biotrophic pathogens by inducing rapid, localised cell death at and around the infection site [111]. This localised programmed cell death is activated upon recognition of specific pathogen-derived elicitors, ensuring that infected cells are sacrificed to halt the spread of the invader [111]. The HR is typically initiated only in incompatible host-pathogen combinations, i.e., when the plant can recognise and respond to the pathogen through its immune receptors [112].

The cell death observed in HR is a highly regulated one involving a cascade of signalling molecules like reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitric oxide (NO), ion fluxes, and proteases across various cellular compartments [113]. These biochemical changes not only kill the infected cells but also activate defence-related genes in surrounding tissues [113]. As a result, the HR helps restrict the movement of pathogens like viruses, fungi, and nematodes within plant tissues [111].

Historically, the HR was first described when necrotic mesophyll cells were observed in resistant cultivars of Bromus spp. and wheat infected by rust fungi, leading to the coining of the term “hypersensitivity” in 1915 by Stakman [114]. Stakman noted that the stronger the cultivar’s resistance, the faster the host cell collapses and the sooner the fungal growth is arrested [112,114].

In many cases, the HR contributes not only to host resistance but also to non-host resistance, where entire plant species are resistant to a particular pathogen [114]. Once activated, this response can also lead to systemic acquired resistance (SAR), a prolonged, whole-plant immune state that enhances resistance against future pathogen attacks [115]. SAR is marked by long-distance signalling from the infection site to uninfected tissues and often involves salicylic acid accumulation [115]. Plant activators, such as chemicals that mimic pathogen signals, can artificially induce SAR, offering long-lasting protection with less toxicity than traditional pesticides [112,114].

Despite its protective nature, the HR is metabolically costly and must be tightly regulated. It is suppressed under non-disease conditions or once the stress is relieved to prevent unintended cell death [116]. The response is also temperature-sensitive and light-dependent, adding further complexity to its regulation [116,117]. Interestingly, while the HR enhances resistance, it often leads to a decline in photosynthetic activity at the affected site, potentially causing growth retardation [111,113]. However, plants may counterbalance this by increasing photosynthesis in nearby tissues, allowing for compensatory metabolic recovery [118].

Ultimately, the success of HR as a defence mechanism is influenced by the nutritional needs of the pathogen and the timing, location, and strength of the host response [112,114]. In certain plant-pathogen interactions, HR is most beneficial in the early stages of infection, helping the plant contain the threat before it establishes itself [111].

d. Hormonal Cross-Talk

Hormonal crosstalk is responsible for how plants organize their immune response upon pathogen attack [13]. The three main signalling molecules, salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET), do not act alone but instead speak to each other in complex patterns, with some supporting each other, while others counter or balance depending on the nature of the threat [119]. Usually, SA appears to be more involved in defense against biotrophic pathogens that feed on living tissue, whereas JA and ET are more activated when the plant is faced with necrotrophs that kill plant cells where they attack [13]. The antagonism between SA-JA enables the plant to make rapid choices regarding which defence approach to prioritize, to customize the response based on the type of invader it’s confronting [13,119].

This hormonal communication doesn’t happen at just one level. It spans gene activity, protein function, and even the regulation of hormone production and breakdown, forming a multi-layered regulatory network [119]. Within JA signalling, for instance, transcription factors like MYC2 and ORA59 act as key regulators. These proteins influence how strongly and specifically defence genes are turned on or off during a threat [13,120].

In addition to the primary hormones, there are also other hormones like abscisic acid (ABA), auxins, gibberellins, and cytokinins that also have functions—usually in the background to regulate growth and defense, particularly when the plant is experiencing both environmental stress and disease pressure simultaneously [120]. Knowledge of these hormonal interactions provides us with an even closer glance at the plant’s capacity to adjust its immunity, and how complex and responsive plant defence mechanisms can be [13,120]. Building on this, the relationship between SA, JA, and ET differs between different plant species and simultaneous biotic/abiotic stress. For example, in Arabidopsis thaliana, SA induces biotroph resistance through NPR1-dependent modes, while JA and ET synergistically control PDF1.2 expression for necrotroph defense via MYC2, EIN3, and EIL1. The mutual inhibition enables high-fidelity immune prioritization [121,122]. Contrarily, in Oryza sativa, JA–Ile induces the OsbHLH148–OsJAZ–OsCOI1 module under drought, while MeJA accumulation enhances under incompatible fungal infection, with evidence of stress- and compatibility-dependent regulation [121]. These illustrations show how crosstalk amongst hormones is not just multi-layered but also context- and species-specific, allowing for specific responses to intricate environmental stimuli.

3.2.4 Communication in the Environment

Strigolactone Production through Root Exudates

Arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi exist in the ground in a latent spore state, which activates when it senses specific host-derived cues from plant root exudates [123,124]. Among the most significant compounds exuded by plants upon phosphate starvation is strigolactone, a hormone produced upon the regulation network of phosphate starvation that has a central role to play in the initiation of symbiotic communication [125]. Strigolactones, not only induce germination of AM fungal spores and strong hyphal branching, also the increased exudation can inadvertently stimulate parasitic weed germination, e.g., Striga, invoking ecological hazards and trade-offs in breeding for increased strigolactone exudation [123]. In reply, the fungus releases chito-oligosaccharides and lipo-chito-oligosaccharides, together referred to as Myc factors, which are the main signalling molecules for this symbiotic interaction [126]. These Myc factors are perceived by plant receptors and activate the common symbiotic signalling pathway (CSSP), a conserved molecular route also essential for legume-rhizobia nodulation [126]. A pivotal event in CSSP activation is high-frequency nuclear calcium (Ca2+) spiking, which triggers the expression of transcription factors responsible for cellular reprogramming that enables symbiosis [124].

Additionally, the plant receptor Dwarf14-like is required for the successful establishment of AM symbiosis, suggesting a convergence of hormonal and symbiotic signalling routes [124]. As the fungal hyphae reach the root surface, they develop hyphopodia, specialised structures that initiate contact with the rhizodermal cells [123]. Upon contact, the plant forms a pre-penetration apparatus, a cellular structure that guides fungal entry and facilitates safe intracellular colonization [123]. Once inside the root cortex, fungal hyphae penetrate cortical cells and differentiate into arbuscules, highly branched structures that remain separated from the plant cytoplasm by the peri-arbuscular membrane, the site of reciprocal nutrient exchange [124]. This intimate chemical communication, initiated by strigolactones, underpins a successful symbiosis that enhances nutrient acquisition and boosts plant immunity against various biotic stresses by priming defence signalling and suppressing pathogen development [123].

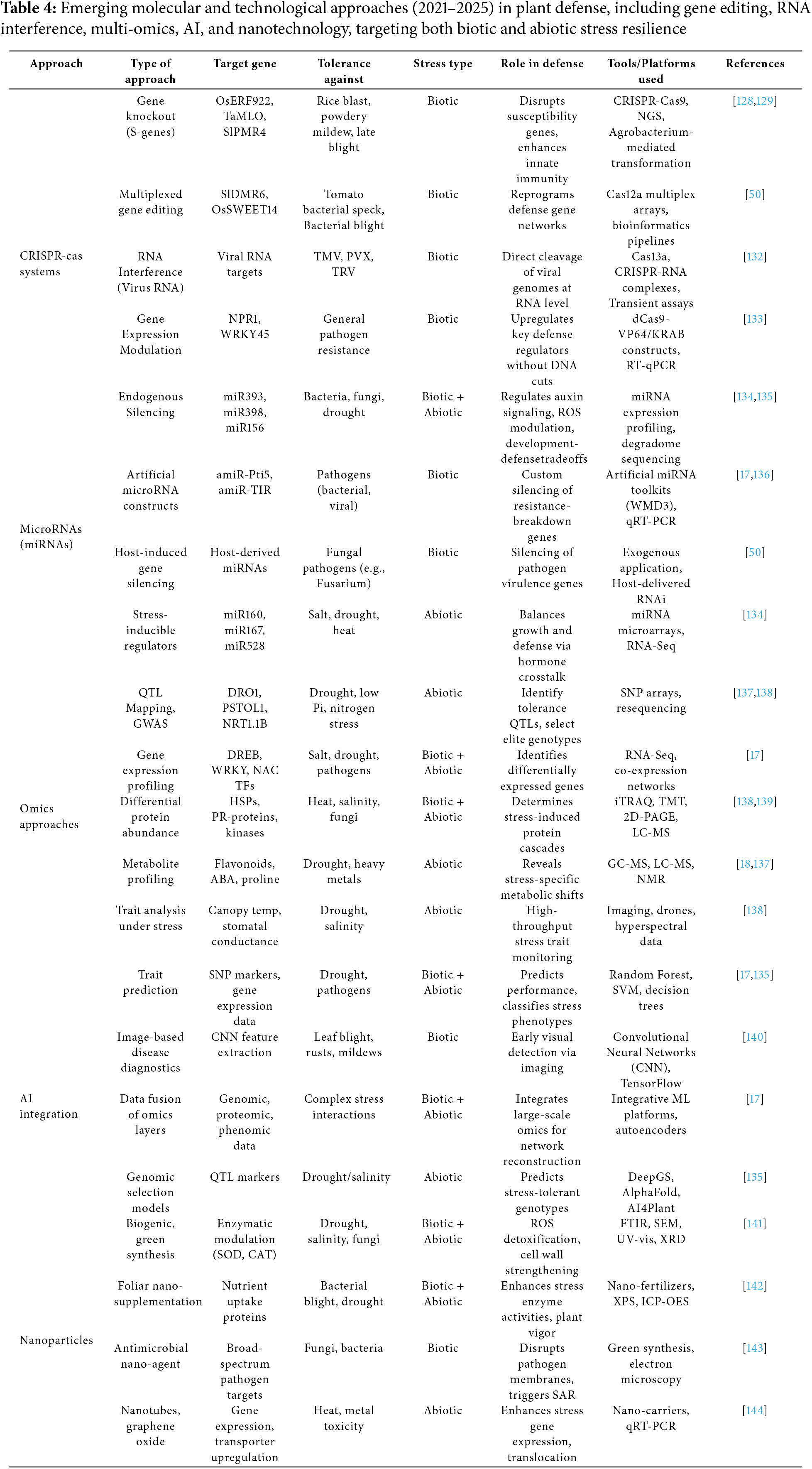

4 Recent Advances into Plant Defense

Recent advances in molecular biology and genomics have identified and characterized several key genes and proteins involved in plant defense against pathogens [127]. Understanding the functions of these genes and proteins is essential for developing new strategies to enhance plant resistance to pathogens and improve crop yields. The following is a description of some of the most significant advancements (Table 4).

CRISPR-Cas tools are now a revolutionizing tool in plant functional genomics and defense strategy design. First derived from prokaryotic immune systems, CRISPR tools have branched out from simple gene-editing tools to high-precision technologies with multiplexing, gene regulation, and RNA targeting function. CRISPR-Cas9 has also been widely applied to knockout susceptibility (S) genes such as OsERF922 in rice and TaMLO in wheat, thereby making them resistant to fungal disease-causing pathogens such as Magnaporthe oryzae and Blumeria graminis, respectively [128,129]. Although CRISPR-Cas9 technology has shown tremendous potential in crop improvement, the literature currently tends to ignore vital scientific and practical hurdles that affect its real-world application. Some of the main challenges are off-target mutations, inefficient editing, and redundancy in polyploid or intricate genomes. In addition, practical considerations like inefficient delivery mechanisms, regulatory ambiguity, and field performance and long-term stability of edited traits need to be overcome for effective agricultural utilization [130,131].

More recently, using a crRNA processing capacity and staggered DNA cuts, Cas12a (Cpf1) provides enhanced multiplexing capacity. This has let scientists simultaneously edit gene families or regulatory pathways, as shown by tomato and rice resistance pathways [50]. The RNA-targeting Cas13 system has also significantly advanced toward eradicating RNA viruses, including PVX and TMV, using post-transcriptional gene silencing [132]. Based on dead Cas9 (dCas9) with transcriptional effectors, CRISpena and CRISpeni tools also enable changes in gene expression without producing double-stranded breaks. These tools also help to balance defense and yield by changing stress-related genes such as WRKY45 and NPR1 [133].

Essential post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression, miRNAs also contribute in plant defense responses. These ~21-nt molecules control hormone signaling, stress perception and immune memory, and as well as fine-tune the expression of important defense regulators [17,136]. For instance, miR393 targets auxin receptors (TIR1/AFBs), so suppressing auxin signaling during pathogen attack and giving immune responses top priority [145]. Known to affect developmental genes reprogrammed under stress as well as antioxidant systems, miR398 and miR156 Stress-inducible miRNAs such as miR160 and miR167 also coordinate auxin-cytokinin crosstalk, so enabling plants to withstand salinity and drought [134].

Developed to silence particular pathogen virulence factors are synthetic and artificial miRNA (amiRNA) constructs. Host-induced gene silencing (HIGS) offers targeted and environmentally sound resistance strategies [136]. Although host-derived miRNAs have shown promise in silencing pathogen genes via cross-kingdom RNA interference, a mechanism demonstrated in Fusarium-infected plants [50,145], several challenges limit their real-world application. Stable expression of miRNAs in the field is problematic, as transgene silencing and environmental variability can reduce effectiveness. Additionally, precise delivery and uptake mechanisms between host and pathogen remain poorly understood, and off-target effects—where plant miRNAs inadvertently silence non-target genes—raise safety concerns [146].

Plant defense research has evolved from single-gene systems to comprehensive approaches. These combined techniques (transcriptomics, genomics, proteomics, phenomics, and metabolomics) clarify complex and multifarious stress-response pathways to find ideal candidate genes and biomarkers [18,137]. Stress tolerance loci such as DRO1 and PSTOL1 for drought and phosphorus shortage respectively have been identified by genomic approaches including GWAS and QTL mapping [137]. Transcriptomics and RNA-Seq [138] have helped in map profiling in response to pathogen attacks, salinity, and other stresses, allowing the identification of transcription factors including DREB, NAC, and WRKY [17,18].

Under biotic stress, proteomics—especially with iTRAQ and TMT helps to clarify protein function and post-translational modifications including those of PRs and HSPs [138]. Complementing these results are metabolomics, which find stress-induced bioactive compounds including ABA, phytoalexins, and flavonoids [138]. Deep learning and machine learning help integrated omics analysis to identify metabolic bottlenecks, build gene regulatory networks, and project phenotypic outcomes under stress [135]. While multi-omics approaches offer powerful insights into plant-pathogen interactions and stress responses, their field translation is limited by high cost, data integration complexity, and environmental variability that may obscure lab-derived signatures. Scalability and interpretability across diverse genotypes remain key hurdles.

Plant defense researches are being revolutionized by the interaction of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning. These approachess enable automated phenotyping, support trait prediction, and allow thorough omics dataset analysis [134]. Analyzing genotype data and transcriptome allows advanced and updated computational approaches more especially, random forests and support vector machines to predict stress tolerance [134]. Advanced methods using convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have become indispensable tools for diagnosing plant diseases through image analysis, so offering instantaneous insights on the distribution and intensity of pathogens [17,140].

Moreover, AI greatly helps to integrate multi-omics data for systems biology modeling. While AI accelerates data analysis and trait prediction in plant stress research, real-world application is constrained by limited high-quality field data, model overfitting, and challenges in generalizing across environments and species. Integration with biological validation remains a key bottleneck.

Nanotechnology has brought fresh ideas for controlling plant stress. By changing redox state and increasing food intake, biogenic selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) and zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) have showed potential in improving stress tolerance [141]. Particularly SeNPsneutralizers, regulating enzymes such as catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD), hence enhancing drought and salinity resistance [144]. Strong antibacterial action of AgNPs makes them interesting foliar sprays against bacterial and fungal infections [143]. Development of carbon-based nanoparticles, including graphene oxide and nanotubes as nano-carriers for stress-responsive gene delivery and hormone control [144] is underway. These nano-enabled technologies offer a focused and sustainable means to increase crop resilience while reducing environmental impact.

Somerecent studies shows, the application of selenium nanoparticles (Se-NPs) significantly enhances drought tolerance in grapevine saplings by activating antioxidant defenses, increasing proline accumulation, and promoting overall plant growth [11]. In another study, foliar application of Cu-NPs (250 mg/L) in tomato plants combined with salt stress increased fruit antioxidant content and reduced oxidative damage [147]. In rice, nano-silicon (SiO2-NPs) enhanced salt tolerance by increasing chlorophyll content, grain filling, and potassium ion retention, while simultaneously reducing malondialdehyde (MDA) levels and ion toxicity [11]. These results show the potential of nanoparticles in plant protection and stress mangement, although long term field trials and biosafety assurance remains a possibility of further studies.

Although nanoparticles show promising for targeted delivery and stress management in plants, their field application faces challenges such as potential toxicity, environmental contamination, and inconsistency under variable field conditions. Regulatory and safety concerns also limit widespread adoption.

5 Conclusion and Future Prospects

The complex immune signaling network that regulates plant response to biotic, abiotic, and combined stress emphasizes key regulatory pathways and molecular convergence points. Bibliometric trends from 2010 to 2025 indicate a growing research focus, with the highest number of publications (39) in 2024, and a dominance of studies on biotic and abiotic stress. Integrating recent advances in gene editing, microRNAs, omics, nanotechnology, and AI, the study presents how plants coordinate defense responses across molecular and physiological levels. These approaches enable targeted stress resilience without compromising growth. However, the dynamic interaction of immune signals under combined stress remains insufficiently understood, especially at cellular and tissue-specific scales. While these innovations have strong potential, their commercial application is still challenged by due to delivery systems, regulatory frameworks, and scalability. Future progress relies on real-time monitoring tools such as single-cell omics, spatial transcriptomics, and smart delivery systems to fine-tune plant immunity. Integrating these tools with predictive models will be a key component for developing stress resilient crops to ensure sustainable agriculture during a changing climate.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Malini Ray and Sanchari Burman equally contributed to literature review and manuscript drafting. Malini Ray and Sanchari Burman conducted the bibliometric analysis and figure preparation. Shweta Meshram conceptualized, coordinated, and finalized the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Maffei ME, Arimura GI, Mithöfer A. Natural elicitors, effectors and modulators of plant responses. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29(11):1288–303. doi:10.1039/c2np20053h. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Benjamin G, Pandharikar G, Frendo P. Salicylic acid in plant symbioses: beyond plant pathogen interactions. Biology. 2022;11(6):861. doi:10.3390/biology11060861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Mohammadi AS, Zahra N, HajiaghaeiKamrani M, AsgariLajayer B, Nobaharan K, Astatkie T, et al. Role of root hydraulics in plant drought tolerance. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;42(10):6228–43. doi:10.1007/s00344-022-10807-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ansari MM, Bisht N, Singh T, Chauhan PS. Symphony of survival: insights into cross-talk mechanisms in plants, bacteria, and fungi for strengthening plant immune responses. Microbiol Res. 2024;285(1):127762. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2024.127762. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Swarna R, Jinu J, Dheeraj C, Talwar HS. Salinity stress in pearl millet: from physiological to molecular responses. In: Pearl Millet in the 21st Century. Singapore: Springer; 2024. p. 361–94. doi:10.1007/978-981-99-5890-0_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Hossain M, Pfafenrot C, Nasfi S, Sede A, Imani J, Šečić E, et al. Designer circRNAGFP reduces GFP-abundance in Arabidopsis protoplasts in a sequence-specific manner, independent of RNAi pathways. Plant Cell Rep. 2025;44(6):1–14. doi:10.1007/s00299-025-03512-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Mir ZA, Ali S, Manzoor S, Sharma D, Sharma D, Tyagi A, et al. Plant defense hormones: thermoregulation and their role in plant adaptive immunity. J Plant Growth Regul. 2025;44(6):2689–706. doi:10.1007/s00344-024-11620-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Gao Y, Lynch JP. Reduced crown root number improves water acquisition under water deficit stress in maize (Zea mays L.). J Exp Bot. 2016;67(15):4545–57. doi:10.1093/jxb/erw243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Lin C, Zhang Z, Zhang Z, Long Y, Shen X, Zhang J, et al. The role of glutathione S-transferase in the regulation of plant growth, and responses to environmental stresses. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2025;94(3):583–601. doi:10.32604/phyton.2025.063086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang Q, Guo J, Jin P, Guo M, Guo J, Cheng P, et al. Glutathione S-transferase interactions enhance wheat resistance to powdery mildew but not wheat stripe rust. Plant Physiol. 2022;190(2):1418–39. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiac326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Jalil A, Munir M, Alqahtani N, Alyas T, Ahmad M, Bashir S, et al. Enhancing plant resilience to biotic and abiotic stresses through exogenously applied nanoparticles: a comprehensive review of effects and mechanism. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2025;94(2):281–302. doi:10.32604/phyton.2025.061534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Bisht S, Sharma V, Kumari N. Biosynthesized hematite nanoparticles mitigate drought stress by regulating nitrogen metabolism and biological nitrogen fixation in Trigonella foenum-graecum. Plant Stress. 2022;6(1):100112. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2022.100112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yu J, Feng Q, Zhou L, Pang B, Zuo D, Hu M, et al. Development, identification, and gene expression profiles of an apetalous Brassica juncea derived from interspecific hybridization. Res Square. 2023. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3114018/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. He J, Duan Y, Hua D, Fan G, Wang L, Liu Y, et al. DEXH box RNA helicase-mediated mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in Arabidopsis mediates crosstalk between abscisic acid and auxin signaling. Plant Cell. 2012;24(5):1815–33. doi:10.1105/tpc.112.098707. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Chen A, Liu T, Wang Z, Chen X. Plant root suberin: a layer of defence against biotic and abiotic stresses. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1056008. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1056008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ngou BP, Ding P, Jones JD. Thirty years of resistance: zig-zag through the plant immune system. Plant Cell. 2022;34(5):1447–78. doi:10.1093/plcell/koac041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Murmu S, Sinha D, Chaurasia H, Sharma S, Das R, Jha GK, et al. A review of artificial intelligence-assisted omics techniques in plant defense: current trends and future directions. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1292054. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1292054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Erpen L, Devi HS, Grosser JW, Dutt M. Potential use of the DREB/ERF, MYB, NAC and WRKY transcription factors to improve abiotic and biotic stress in transgenic plants. Plant Cell, Tissue Organ Culture (PCTOC). 2018;132(1):1–25. doi:10.1007/s11240-017-1320-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yadav S, Modi P, Dave A, Vijapura A, Patel D, Patel M. Effect of abiotic stress on crops. Sustainable Crop Production. 2020;3(17):5–16. doi:10.5772/intechopen.88434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yeshi K, Crayn D, Ritmejerytė E, Wangchuk P. Plant secondary metabolites produced in response to abiotic stresses has potential application in pharmaceutical product development. Molecules. 2022;27(1):313. doi:10.3390/molecules27010313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Gamalero E, Glick BR. Recent advances in bacterial amelioration of plant drought and salt stress. Biology. 2022;11(3):437. doi:10.3390/biology11030437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Dresselhaus T, Hückelhoven R. Biotic and abiotic stress responses in crop plants. Agronomy. 2018;8(11):267. doi:10.3390/agronomy8110267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Sachdev S, Ansari SA, Ansari MI, Fujita M, Hasanuzzaman M. Abiotic stress and reactive oxygen species: generation, signaling, and defense mechanisms. Antioxidants. 2021;10(2):277. doi:10.3390/antiox10020277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Liu JX, Howell SH. Managing the protein folding demands in the endoplasmic reticulum of plants. New Phytol. 2016;211(2):418–28. doi:10.1111/nph.13915. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Howell SH. Endoplasmic reticulum stress responses in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2013;64(1):477–99. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Ng S, De Clercq I, Van Aken O, Law SR, Ivanova A, Willems P, et al. Anterograde and retrograde regulation of nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial proteins during growth, development, and stress. Mol Plant. 2014;7(7):1075–93. doi:10.1093/mp/ssu037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Mignolet-Spruyt L, Xu E, Idänheimo N, Hoeberichts FA, Mühlenbock P, Brosché M, et al. Spreading the news: subcellular and organellar reactive oxygen species production and signalling. J Exp Bot. 2016;67(13):3831–44. doi:10.1093/jxb/erw080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zhu JK. Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell. 2016;167(2):313–24. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Dixit S, Sivalingam PN, Baskaran RM, Senthil-Kumar M, Ghosh PK. Plant responses to concurrent abiotic and biotic stress: unravelling physiological and morphological mechanisms. Plant Physiol Rep. 2014;29(1):6–17. doi:10.1007/s40502-023-00766-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Sharma V, Mohammed SA, Devi N, Vats G, Tuli HS, Saini AK, et al. Unveiling the dynamic relationship of viruses and/or symbiotic bacteria with plant resilience in abiotic stress. Stress Biol. 2024;4(1):10. doi:10.1007/s44154-023-00126-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Valim H. Long-term effects of the circadian clock on plant fitness in the face of abiotic and biotic stress [Ph.D. thesis]. Jena, Germany: Friedrich Schiller University Jena; 2020. [Google Scholar]

32. Muthuramalingam P, Muthamil S, Shilpha J, Venkatramanan V, Priya A, Kim J, et al. Molecular insights into Abiotic stresses in Mango. Plants. 2023;12(10):1939. doi:10.3390/plants12101939. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Abobatta WF. Plant responses and tolerance to combined salt and drought stress. In: Salt and drought stress tolerance in plants: signaling networks and adaptive mechanisms. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2020. p. 17–52. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-40277-8_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Mayek-PÉrez N, GarcÍa-Espinosa R, LÓpez-CastaÑeda C, Acosta-Gallegos JA, Simpson J. Water relations, histopathology and growth of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) during pathogenesis of Macrophomina phaseolina under drought stress. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2002;60(4):185–95. doi:10.1006/pmpp.2001.0388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Shivaraj SM, Sharma Y, Chaudhary J, Rajora N, Sharma S, Thakral V, et al. Dynamic role of aquaporin transport system under drought stress in plants. Environ Exp Bot. 2021;184(1):104367. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Cohen SP, Leach JE. Abiotic and biotic stresses induce a core transcriptome response in rice. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):6273. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-42731-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Yang C. The regulation of intrinsic signaling in Brassica napus defending against Leptosphaeria maculans. [Ph.D. thesis]. Winnipeg, MB, Canada: The University of Manitoba; 2021. [Google Scholar]

38. Negeri A, Wang GF, Benavente L, Kibiti CM, Chaikam V, Johal G, et al. Characterization of temperature and light effects on the defense response phenotypes associated with the maize Rp1-D21autoactive resistance gene. BMC Plant Biol. 2013;13(1):106. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-13-106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Rivero RM, Mittler R, Blumwald E, Zandalinas SI. Developing climate-resilient crops: improving plant tolerance to stress combination. Plant J. 2022;109(2):373–89. doi:10.1111/tpj.15483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Mathura SR, Sutton F, Bowrin V. Genome-wide identification, characterization, and expression analysis of the sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas [L.] Lam.) ARF, Aux/IAA, GH3, and SAUR gene families. BMC Plant Biol. 2023;23(1):622. doi:10.1186/s12870-023-04598-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Prasad A, Sett S, Prasad M. Plant-virus-abiotic stress interactions: a complex interplay. Environ Exp Bot. 2022;199:104869. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2022.104869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ray RV. Effects of pathogens and disease on plant physiology. In: Agrios’ plant pathology. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2024. p. 63–92. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-822429-8.00002-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ahmad M, Abdul Aziz M, Sabeem M, Kutty MS, Sivasankaran SK, Brini F, et al. Date palm transcriptome analysis provides new insights on changes in response to high salt stress of colonized roots with the endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1400215. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1400215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Yu Y, Li Y, Yan Z, Duan X. The role of cytokinins in plant under salt stress. J Plant Growth Regul. 2022;41(6):2279–91. doi:10.1007/s00344-021-10441-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Singh P, Singh J, Ray S, Rajput RS, Vaishnav A, Singh RK, et al. Seed biopriming with antagonistic microbes and ascorbic acid induce resistance in tomato against Fusarium wilt. Microbiol Res. 2020;237(2):126482. doi:10.1016/j.micres.2020.126482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Chahal GK, Ghai M, Kaur J. Stress mechanisms and adaptations in plants. J Pharmacognosy Phytochem. 2022;11(2):109–14. doi:10.22271/phyto.2022.v11.i2b.14365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Kumar J, Murali-Baskaran RK, Jain SK, Sivalingam PN, Mallikarjuna J, Kumar V, et al. Emerging and re-emerging biotic stresses of agricultural crops in India and novel tools for their better management. Curr Sci. 2021;121(1):26–36. doi:10.18520/cs/v121/i1/26-36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Wang P, Si H, Li C, Xu Z, Guo H, Jin S, et al. Plant genetic transformation: achievements, current status and future prospects. Plant Biotechnol J. 2025;23(6):2034–58. doi:10.1111/pbi.70028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Wang W, Feng B, Zhou JM, Tang D. Plant immune signaling: advancing on two frontiers. J Integr Plant Biol. 2020;62(1):2–24. doi:10.1111/jipb.12898. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Ding T, Li W, Li F, Ren M, Wang W. Key regulators in plant responses to abiotic and biotic stresses via endogenous and cross-kingdom mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(2):1154. doi:10.3390/ijms25021154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Chiquito-Contreras CJ, Meza-Menchaca T, Guzmán-López O, Vásquez EC, Ricaño-Rodríguez J. Molecular insights into plant-microbe interactions: a comprehensive review of key mechanisms. Front Biosci-Elite. 2024;16(1):9. doi:10.31083/j.fbe1601009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Ngou BP, Ahn HK, Ding P, Jones JD. Mutual potentiation of plant immunity by cell-surface and intracellular receptors. Nature. 2021;592(7852):110–5. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03315-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Tian S, Liu B, Shen Y, Cao S, Lai Y, Lu G, et al. Unraveling the molecular mechanisms of tomatoes’ defense against Botrytis cinerea: insights from transcriptome analysis of micro-tom and regular tomato varieties. Plants. 2023;12(16):2965. doi:10.3390/plants12162965. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Podgorska A, Burian M, Szal B. Extra-cellular but extra-ordinarily important for cells: apoplastic reactive oxygen species metabolism. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1353. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.01353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Foyer CH, Kyndt T, Hancock RD. Vitamin C in plants: novel concepts, new perspectives, and outstanding issues. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2020b;32(7):463–85. doi:10.1089/ars.2019.7819. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Gill SS, Tuteja N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48(12):909–30. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Sahu PK, Jayalakshmi K, Tilgam J, Gupta A, Nagaraju Y, Kumar A, et al. ROS generated from biotic stress: effects on plants and alleviation by endophytic microbes. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1042936. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1042936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Du B, Haensch R, Alfarraj S, Rennenberg H. Strategies of plants to overcome abiotic and biotic stresses. Biol Rev. 2024;99(4):1524–36. doi:10.1111/brv.13079. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Zechmann B. Subcellular roles of glutathione in mediating plant defence during biotic stress. Plants. 2020;9(9):1067. doi:10.3390/plants9091067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Foyer CH, Noctor G. Ascorbate and glutathione: the heart of the redox hub. Plant Physiol. 2011;155(1):2–18. doi:10.1104/pp.110.167569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Farvardin A, González-Hernández AI, Llorens E, García-Agustín P, Scalschi L, Vicedo B. The apoplast: a key player in plant survival. Antioxidants. 2020;9(7):604. doi:10.3390/antiox9070604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Mammari N, Krier Y, Albert Q, Devocelle M, Varbanov M, OEMONOM. Plant-derived antimicrobial peptides as potential antiviral agents in systemic viral infections. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14(8):774. doi:10.3390/ph14080774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Sher Khan R, Iqbal A, Malak R, Shehryar K, Attia S, Ahmed T, et al. Plant defensins: types, mechanism of action and prospects of genetic engineering for enhanced disease resistance in plants. 3 Biotech. 2019;9(5):192. doi:10.1007/s13205-019-1725-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Zhang H, Zhang H, Lin J. Systemin-mediated long-distance systemic defense responses. New Phytol. 2020;226(6):1573–82. doi:10.1111/nph.16495. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Parisi K, Shafee TM, Quimbar P, van der Weerden NL, Bleackley MR, Anderson MA. The evolution, function and mechanisms of action for plant defensins. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2019;88(5967):107–18. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.02.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Takahashi F, Shinozaki K. Long-distance signaling in plant stress response. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2019;47:106–11. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2018.10.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Cesarino I. Structural features and regulation of lignin deposited upon biotic and abiotic stresses. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2019;56:209–14. doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2018.12.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Erb M, Kliebenstein DJ. Plant secondary metabolites as defenses, regulators, and primary metabolites: the blurred functional trichotomy. Plant Physiol. 2020;184(1):39–52. doi:10.1104/pp.20.00433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. BrglezMojzer E, Knez Hrnčič M, Skerget M, Knez Z, Bren U. Polyphenols: extraction methods, antioxidative action, bioavailability and anticarcinogenic effects. Molecules. 2016;21(7):901. doi:10.3390/molecules21070901. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Oliver MJ, Farrant JM, Hilhorst HWM, Mundree S, Williams B, Bewley JD. Desiccation tolerance: avoiding cellular damage during drying and rehydration. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2020;71(1):435–60. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-071219-105542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Wolf S. Cell wall signaling in plant development and defense. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2022;73(1):323–53. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-102820-095312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Asare MO, Szakova J, Tlustos P. The fate of secondary metabolites in plants growing on Cd-, As-, and Pb-contaminated soils—a comprehensive review. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023;30(5):11378–98. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-24776-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Xu H, Liu P, Wang C, Wu S, Dong C, Lin Q, et al. Transcriptional networks regulating suberin and lignin in endodermis link development and ABA response. Plant Physiol. 2022;190(2):1165–81. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiac298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Shekhada HA, Bhaliya CM, Padsala JJ, Joshi RL. Pathogen defense mechanism in plants. In: Sharma S, Arsia SK, Kaur A, Poorvasandhya R, Dhaka S, editors. Modern approaches in plant pathology. 1st ed. New Delhi, India: Elite Publishing House; 2023. 83 p. [Google Scholar]

75. Simpraga M, Ghimire RP, Van Der Straeten D, Blande JD, Kasurinen A, Sorvari J, et al. Unravelling the functions of biogenic volatiles in boreal and temperate forest ecosystems. Eur J For Res. 2019;138(5):763–87. doi:10.1007/s10342-019-01213-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Wedow JM, Ainsworth EA, Li S. Plant biochemistry influences tropospheric ozone formation, destruction, deposition, and response. Trends Biochem Sci. 2021;46(12):992–1002. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2021.06.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Nelson CJ, Millar AH. Protein turnover in plant biology. Nat Plants. 2015;1(3):1–7. doi:10.1038/nplants.2015.17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Kidwai M, Ahmad IZ, Chakrabarty D. Class III peroxidase: an indispensable enzyme for biotic/abiotic stress tolerance and a potent candidate for crop improvement. Plant Cell Rep. 2020;39(11):1381–93. doi:10.1007/s00299-020-02588-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Hu CH, Wang PQ, Zhang PP, Nie XM, Li BB, Tai L, et al. NADPH oxidases: the vital performers and center hubs during plant growth and signaling. Cells. 2020;9(2):437. doi:10.3390/cells9020437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Pfeilmeier S, Petti GC, Bortfeld-Miller M, Daniel B, Field CM, Sunagawa S, et al. The plant NADPH oxidase RBOHD is required for microbiota homeostasis in leaves. Nat Microbiol. 2021;6(7):852–64. doi:10.1038/s41564-021-00929-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Zhang S, Zhang L, Zou H, Qiu L, Zheng Y, Yang D, et al. Effects of light on secondary metabolite biosynthesis in medicinal plants. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:781236. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.781236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Singh A. Impact of air pollutants on plant metabolism and antioxidant machinery. In: Air pollution and environmental health. Singapore: Springer; 2020. p. 57–86. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-3481-2_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]