Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Soil Temperature and Moisture as Key Determinants of SPAD Values in Greenhouse-Grown Cucumber in Qatar

1 College of Engineering and Technology, University of Doha for Science and Technology, Doha, 24449, Qatar

2 Department of Agriculture, Hazara University Mansehra, Mansehra, 21120, Pakistan

3 College of Computer and Information Technology, University of Doha for Science and Technology, Doha, 24449, Qatar

4 Al Sulaiteen Agricultural Research Study and Training Center, Umm Salal Ali, Farm No 301, Doha, P.O. Box 8588, Qatar

* Corresponding Author: Fahim Ullah Khan. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Influence of Biotic and Abiotic Stresses Signals on Plants and their Performance at Different Environments)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(9), 2911-2925. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.064239

Received 09 February 2025; Accepted 28 March 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

This study aimed to explore the relationship between Soil-Plant Analysis Development (SPAD) values and key environmental factors in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) cultivation in a greenhouse. SPAD values, indicative of chlorophyll content, reflect plant health and productivity. The analysis revealed strong positive correlations between SPAD values and both indoor light intensity (ILI, r = 0.59, p < 0.001) and outdoor light intensity (OLI, r = 0.62, p < 0.001), suggesting that higher light intensities were associated with enhanced SPAD values. In contrast, significant negative correlations were found between SPAD values and soil temperature at 15–30 cm depth (ST1530, r = −0.47, p < 0.001) and volumetric soil moisture content at the same depth (SM1530, r = −0.52, p < 0.001), with higher soil temperatures (e.g., 28°C) and excessive moisture (e.g., 25%) leading to reduced SPAD values. Multiple regression analysis identified ST1530 and SM1530 as significant negative predictors of SPAD, with coefficients of −0.97 (p = 0.05) and −0.34 (p = 0.05), respectively, suggesting that increases in soil temperature and moisture result in lower SPAD values. Indoor light intensity (e.g., 600–800 μmol/m2/s) emerged as a significant positive contributor, with a coefficient of 0.01 (p < 0.001), highlighting its role in promoting chlorophyll synthesis. Additionally, relative humidity (r = 0.27, p < 0.01) showed a positive, although less pronounced, association with SPAD. These results underscore the importance of both direct and indirect environmental factors in influencing SPAD variability and, by extension, plant health and productivity in cucumber cultivation.Keywords

Given the fact that they provide quick, non-destructive, and on-the-spot evaluations of the plant’s health, handheld instruments, such as SPAD (soil-plant analysis development) chlorophyll meters are useful precision agriculture tools [1]. They provide immediate feedback, enabling farmers to make informed decisions regarding crop management. Due to their ease of use, portability, and accuracy, the SPAD meters are commonly used in greenhouse crop management. For example, the chlorophyll content of a plant’s leaves is critical for photosynthesis and is closely linked to a plant’s active growth. Consequently, SPAD values serve as reliable indicators of plant health, allowing for real-time assessments of plant growth and overall vigor.

Research has consistently shown a significant correlation between SPAD readings and leaf propagation across various crops, affirming the utility of SPAD meters in optimizing fertilization practices [2]. However, the effective use of SPAD values in agricultural management is influenced by a range of environmental factors, necessitating a thorough understanding of these interactions. Studies have indicated that light intensity, soil temperature, and moisture levels significantly impact chlorophyll synthesis and, by extension, SPAD readings [3,4]. For example, optimal light conditions can enhance photosynthesis and chlorophyll production, while extreme temperatures can inhibit these processes, leading to reduced SPAD values [5,6]. Additionally, moisture levels play a critical role in plant health; excessive soil moisture can impede root function and nutrient uptake, adversely affecting chlorophyll content [7]. Given these complexities, a comprehensive understanding of how environmental factors influence SPAD values is vital for accurate assessments of plant health.

Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) was selected for this study due to its global importance as a widely cultivated greenhouse crop and its sensitivity to environmental conditions, making it an ideal candidate for analyzing the interaction between SPAD values and microclimatic factors. Cucumbers thrive under well-defined conditions, including optimal soil temperatures ranging from 21°C to 30°C, with ideal growth occurring between 24°C and 29°C [8]. Additionally, light intensity plays a crucial role in cucumber development, with studies indicating that photosynthetic photon flux densities (PPFDs) between 200 and 600 μmol·m−2·s−1 significantly enhance growth and productivity [9]. These microclimate requirements align with the greenhouse conditions observed during the study, where mean soil temperatures of 28.50°C at 15 cm and 27.95°C at 30 cm depth provided favorable conditions for cucumber growth. The crop’s reliance on precise environmental regulation highlights the importance of investigating how SPAD values interact with these variables to assess plant health and productivity. In the context of Qatar, where agriculture is predominantly conducted in controlled greenhouse environments due to harsh climatic conditions, understanding the role of SPAD values is particularly significant. High temperatures, intense solar radiation, and limited water resources pose unique challenges for crop production, necessitating precise management of environmental variables to optimize plant health. The ability of SPAD meters to provide real-time assessments of chlorophyll content is highly relevant for ensuring efficient nutrient use and irrigation scheduling in Qatar’s greenhouse agriculture. This makes SPAD technology an essential tool for improving crop productivity and sustainability in arid regions.

Despite the wealth of research surrounding SPAD values and their relationship with plant health, a significant knowledge gap persists regarding the multifactorial influences of environmental conditions on these readings. This gap is particularly pronounced in controlled environments such as greenhouses, where optimizing conditions for crop growth is essential. Previous studies conducted in arid and semi-arid regions have explored the impact of environmental variables on SPAD readings, revealing significant interactions between temperature extremes, soil moisture deficits, and chlorophyll content. For instance, research on greenhouse crops in arid climates has demonstrated that prolonged exposure to high temperatures can reduce chlorophyll stability, leading to lower SPAD values, while optimized irrigation strategies can mitigate these effects [10,11]. Similarly, studies in semi-arid regions have shown that soil water availability is a key determinant of SPAD variability, with water-deficient conditions leading to stress-induced reductions in leaf chlorophyll [12]. However, these findings have largely focused on specific environmental stressors rather than an integrated assessment of multiple variables within greenhouse settings. Additionally, the impact of temperature fluctuations and varying humidity levels on greenhouse plant physiology remains insufficiently explored. High temperatures can accelerate transpiration and increase plant water loss, leading to stomatal closure and reduced CO2 assimilation, which subsequently affects chlorophyll synthesis and SPAD readings. Similarly, humidity variations influence leaf water potential and nutrient uptake, which are crucial for maintaining chlorophyll stability. Understanding these physiological responses is essential for optimizing greenhouse environmental management to enhance crop health and productivity. Soil temperature also plays a crucial role in plant growth by affecting nutrient availability and root respiration, both of which are critical for cucumber development. Higher soil temperatures can enhance microbial activity and nutrient mineralization, improving nutrient uptake, whereas excessively high temperatures can impair root function and limit nutrient absorption [13,14]. These interactions underscore the importance of considering soil temperature dynamics when interpreting SPAD values in greenhouse crops.

Furthermore, recent research highlights the critical role of plant hormones and molecular signaling in regulating stress responses in greenhouse crops. Salicylic acid, in particular, has been identified as a key molecule that enhances plant defense mechanisms under abiotic stress conditions, including water deficit. A study by [15] demonstrated that salicylic acid application in Allium hirtifolium stimulates various defense pathways, promoting antioxidant activity and osmotic regulation to mitigate stress-induced damage. These findings underscore the importance of hormonal signaling in maintaining chlorophyll stability and optimizing photosynthetic efficiency under fluctuating environmental conditions. Integrating knowledge of hormonal regulation with SPAD assessments can provide a more comprehensive approach to managing plant health in controlled environments. There is a pressing need for further investigation into how easily measurable environmental variables interact with SPAD values to impact plant health and productivity. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for refining crop management strategies and enhancing the efficacy of SPAD technology in agricultural practice.

This study has bridged these gaps by investigating the relationship between SPAD values and various environmental factors, including light intensity, soil temperature, soil volumetric water content, air temperature, and humidity that affect crop growth in greenhouse settings. By examining these interactions, the objectives of this research were to develop guidelines for the optimal use of SPAD meters in greenhouse environments and to enhance the interpretation of the plant leaf’s SPAD values with plant health. Ultimately, this work contributes to the literature about the use of precision agriculture technologies and sustainable crop production in controlled environments.

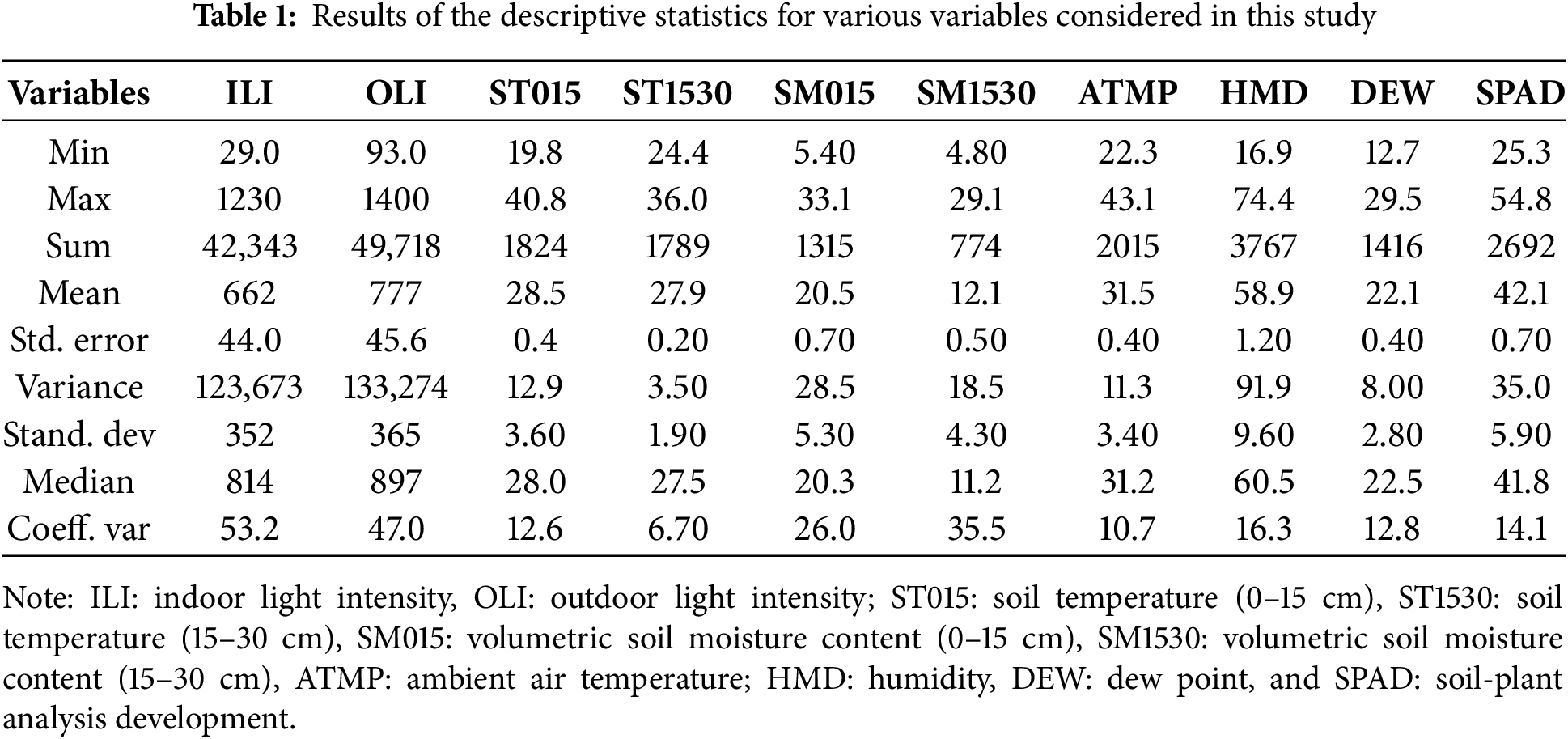

According to the results of descriptive statistics (Table 1), the ILI recorded a minimum of 29 μmol m−2 s−1 and a maximum of 1230 μmol m−2 s−1, while OLI ranged from 93 μmol m−2 s−1 to 1400 μmol m−2 s−1. The average ILI was 661.61 μmol m−2 s−1, which was approximately 15% lower than the outdoor average of OLI (776.84 μmol m−2 s−1), reflecting the importance of supplemental lighting in the greenhouse. The high standard deviations for both indoor (351.67) and outdoor (365.07) light intensities indicated considerable variability, likely influenced by factors such as cloud cover and greenhouse shading. Soil temperature measurements revealed a minimum of 19.8°C and a maximum of 40.8°C at a depth of 15 cm, while temperatures at 30 cm ranged from 24.4°C to 36°C. The mean soil temperatures were 28.50°C at 15 cm and 27.95°C at 30 cm, suggesting favorable conditions for cucumber growth. The standard deviations of 3.60°C for the shallower depth and 1.86°C for the deeper depth indicate relatively stable soil temperatures, particularly at 30 cm. Volumetric water content was measured at 15 cm and 30 cm depths, showing a range from 5.4% to 33.1% at 15 cm and from 4.8% to 29.1% at 30 cm. The mean values of 20.55% at 15 cm and 12.10% at 30 cm indicate that moisture levels were adequate for cucumber growth, although variability was greater at the surface depth. The ambient temperature ranged from 22.3°C to 43.1°C, with a mean of 31.48°C, highlighting potential heat stress. Relative humidity varied from 16.9% to 74.4%, averaging 58.86%, which is essential for understanding moisture balance and transpiration rates. The dew point values ranged from 12.7°C to 29.5°C, with an average of 22.12°C, indicating the potential for condensation and disease risks.

SPAD values, indicative of chlorophyll content and thus plant health, varied between 25.3 and 54.8, with a mean of 42.1 (Table 1). The standard deviation of SPAD readings (5.91) suggests moderate variability in chlorophyll levels among the plants, likely influenced by differing environmental conditions throughout the growing season. The distribution characteristics reveal slight left skewness for most variables, suggesting that most measurements clustered toward the lower end with a few higher outliers. The kurtosis values, especially for soil temperature and humidity, indicate higher peaks in the distributions, suggesting the presence of extreme values. Overall, these descriptive statistics underscore the complex interplay of environmental factors affecting cucumber growth in the greenhouse. The variability observed in light intensity, soil temperature, water content, ambient conditions, and chlorophyll readings emphasizes the necessity for precise environmental control to optimize cucumber cultivation. Understanding these parameters provides a robust foundation for further analysis and modeling aimed at enhancing agricultural practices in greenhouse settings.

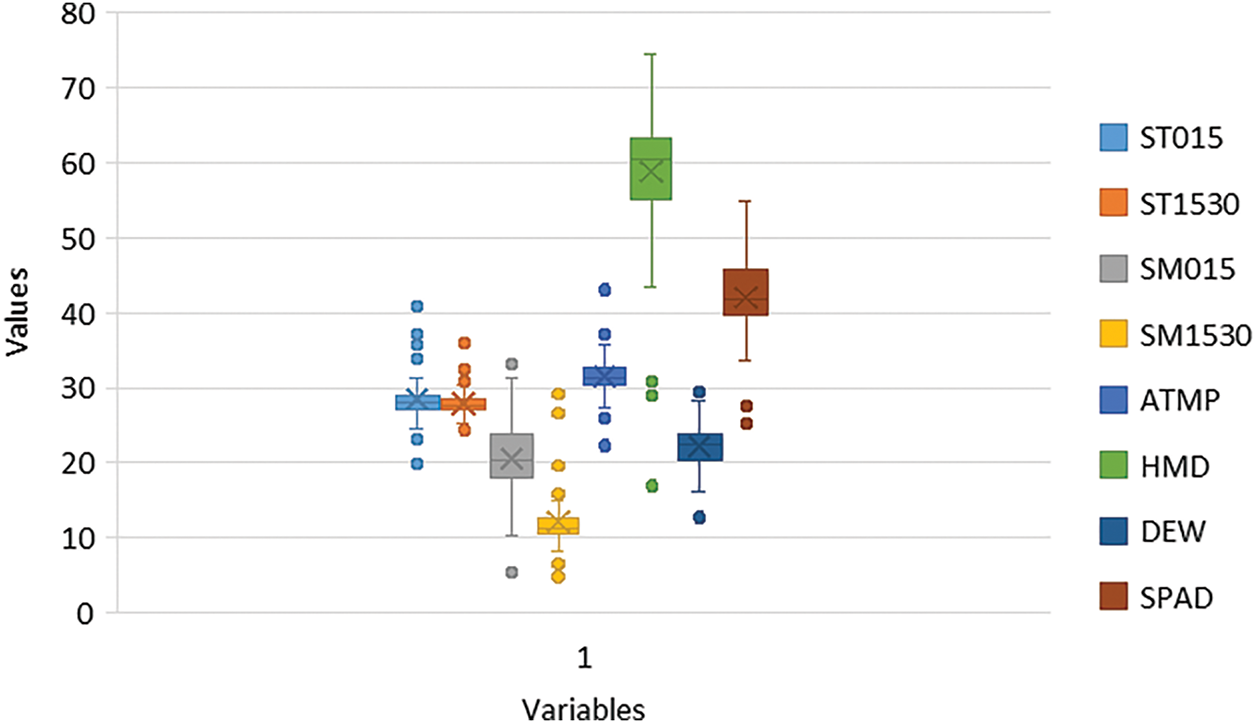

Fig. 1 presents a comparative analysis of SPAD values, soil moisture content at various depths (0–15 cm and 15–30 cm), and dew point measurements under different treatment conditions. The figure highlights significant variations in these parameters, suggesting differential responses of plant physiological traits and soil moisture dynamics to the applied treatments. The observed fluctuations in SPAD values reflect variations in chlorophyll content and potential stress levels, while differences in soil moisture and dew point indicate the impact of environmental and management factors on soil water availability and microclimatic conditions.

Figure 1: Box plot showing the distribution of SPAD values in relation to different environmental variables

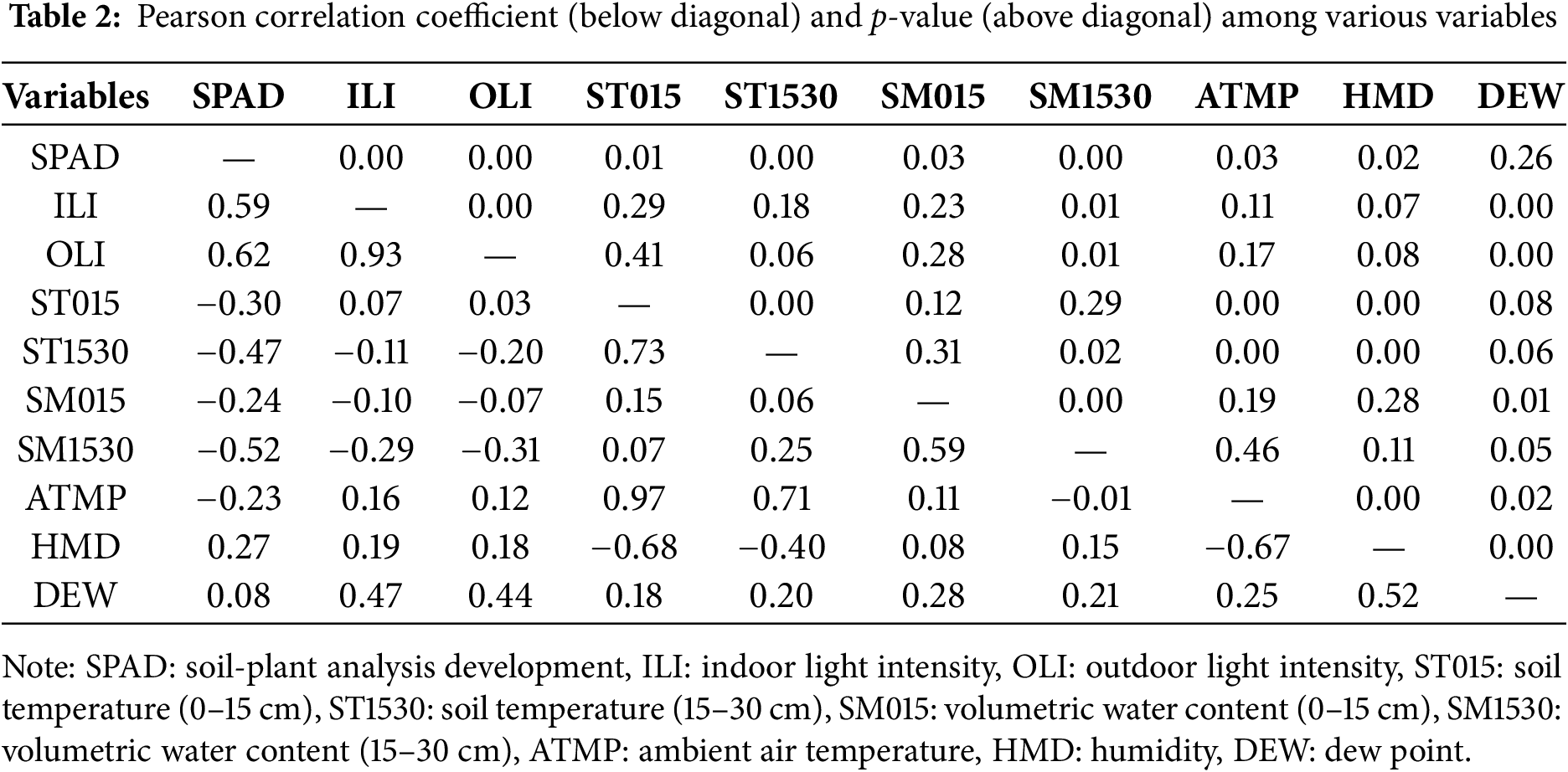

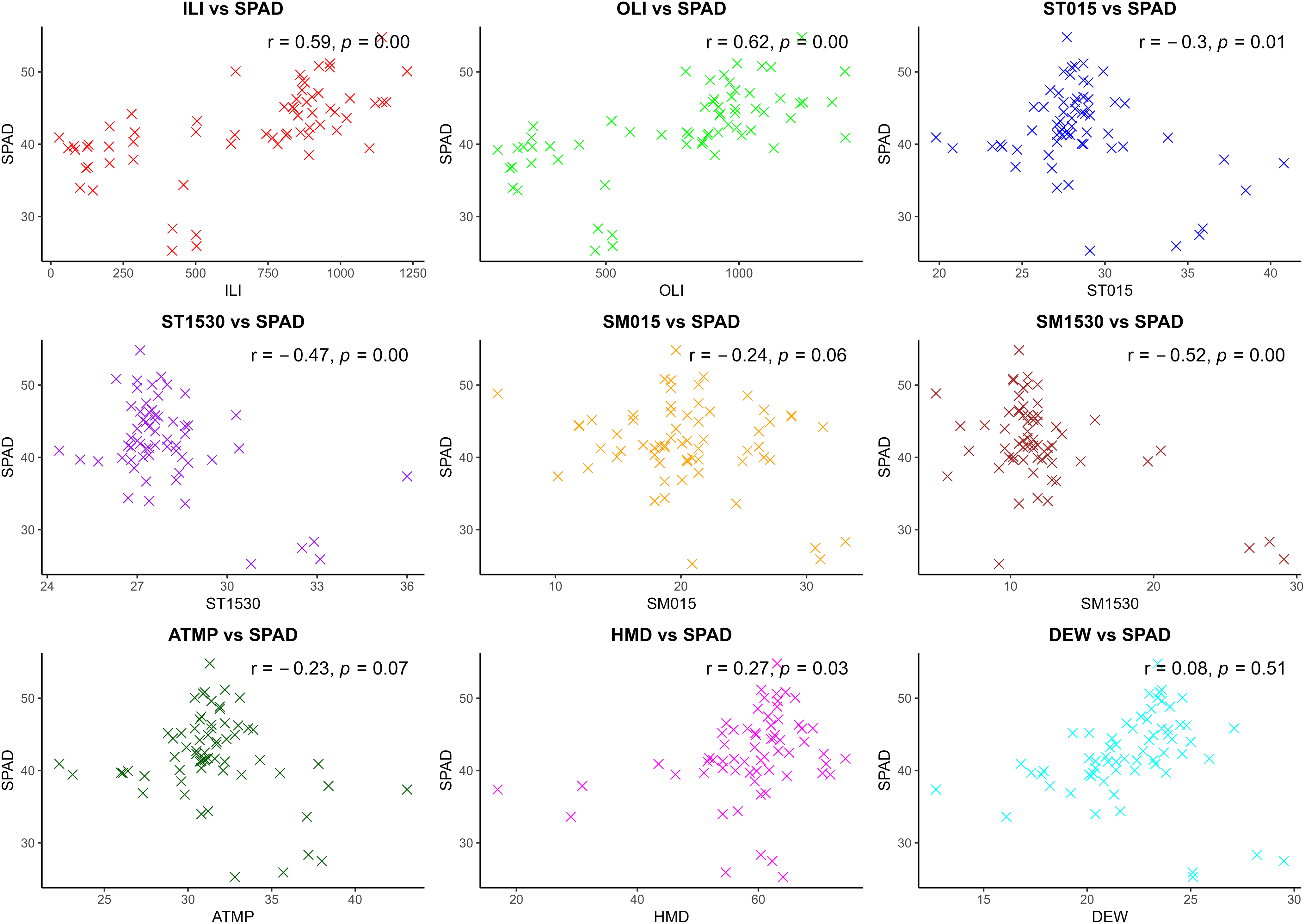

Table 2 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients among various variables in the study, while Fig. 2 illustrates the correlation of different factors with SPAD values only. The correlation analysis revealed strong positive associations between SPAD and both ILI and OLI, with coefficients of 0.59 (p < 0.001) and 0.62 (p < 0.001), respectively. This indicates that higher light intensity correlates with increased SPAD readings. Conversely, a moderate negative correlation was observed with soil temperature at a depth of 15–30 cm (ST1530), showing a Pearson correlation coefficient (r) value of −0.47 (p < 0.001), suggesting that rising soil temperatures are linked to decreasing SPAD values. The correlation with ST015 was minimal (r = −0.30, p = 0.07).

Figure 2: Scatterplot showing correlation coefficient of SPAD (soil-plant analysis development) content with ILI (indoor light intensity), OLI (outdoor light intensity), ST015 (soil temperature: 0–15 cm), ST1530 (soil temperature: 15–30 cm), SM015 (volumetric water content: 0–15 cm), SM1530 (volumetric soil moisture content: 15–30 cm), ATMP (ambient air temperature), HMD (humidity), DEW (dew point), and r (Pearson coefficient of correlation)

Negative correlations were also significant for volumetric water content, particularly SM1530 (r = −0.52, p < 0.001). A weak negative correlation was found with SM015 (r = −0.24, p = 0.19). The analysis of air temperature revealed a weak negative correlation with SPAD (r = −0.23, p = 0.19), suggesting no meaningful relationship. A moderate positive correlation was observed between SPAD and humidity (r = 0.27, p < 0.01), indicating that increased humidity levels relate to higher SPAD readings. The correlation with dew point was weak (r = 0.08, p = 0.39), suggesting no significant association. Overall, the most substantial associations with SPAD were with the light intensity variables, while negative correlations were noted with soil temperature and volumetric water content, particularly SM1530. Other variables, such as air temperature and dew point, displayed weak or negligible relationships with SPAD, emphasizing that leaf indices are more reliable indicators of SPAD compared to the other environmental factors assessed.

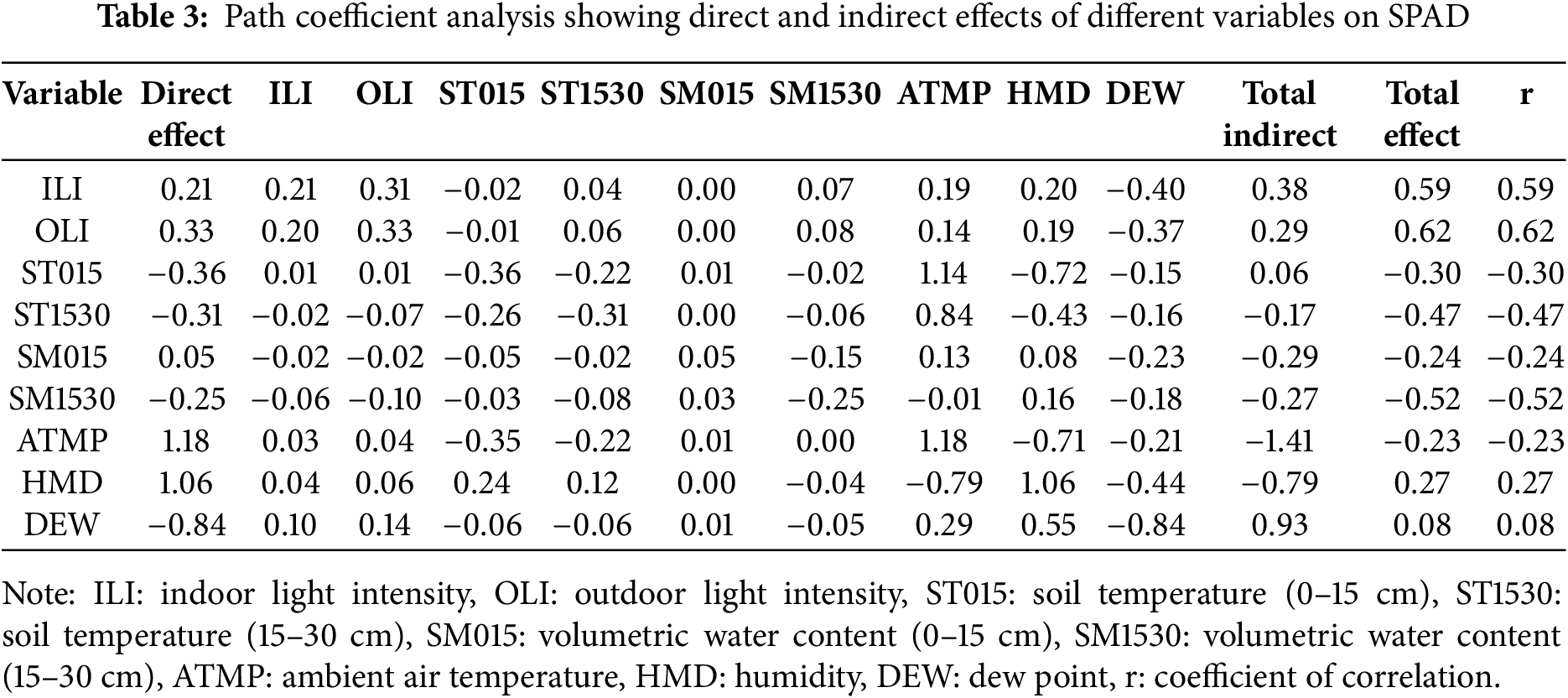

Table 3 shows the values of direct and indirect effects of different variables on SPAD. The path coefficient analysis provided insights into the direct and indirect impacts of various environmental and physiological variables on SPAD. The results indicated that both ILI and OLI had significant direct effects on SPAD, with coefficients of 0.21 and 0.33, respectively. Their total effects were enhanced by their indirect effects, resulting in total effects of 0.59 and 0.62. This demonstrates that these indices serve as strong predictors of SPAD values. In contrast, soil temperature measurements, ST015 and ST1530, exhibited negative direct effects on SPAD, with coefficients of −0.36 and −0.31, respectively. The total effects for these variables were also negative, at −0.30 and −0.47, reinforcing their negative influence on SPAD. Volumetric water content exhibited weak direct effects on SPAD values, with SM015 showing a direct effect of 0.05 and SM1530 showing a direct effect of −0.25. However, the total effects differed, with SM015 exhibiting a slightly negative total effect of −0.24 and SM1530 showing a stronger negative total effect of −0.52. This indicates that variations in volumetric soil moisture at different depths influence SPAD values differently. The data reveal that lower volumetric water content (SM) at 15–30 cm (mean SM1530 = 12.1%) compared to 0–15 cm (mean SM015 = 20.5%) is associated with lower SPAD values. These results highlight the importance of maintaining adequate volumetric soil moisture, particularly at shallower depths, to support higher SPAD readings and, by extension, plant health. Ambient air temperature (ATMP) and humidity (HMD) showed strong direct effects, with coefficients of 1.18 and 1.06, respectively. However, the total indirect effect of ATMP was −1.41, indicating that indirect pathways significantly mitigate its positive influence, while HMD had a positive total effect of 0.27. Dew point (DEW) presented a negative direct effect on SPAD (−0.84) but had a total effect of 0.08, suggesting a complex relationship where higher dew points do not significantly support SPAD readings. Overall, the path coefficient analysis emphasizes the importance of light intensity as primary predictors of SPAD, while also highlighting the adverse effects of soil temperature and certain aspects of water content. Air temperature and humidity emerged as crucial variables with strong positive impacts on SPAD, albeit moderated by their indirect effects. This analysis offers a comprehensive understanding of how various factors interact to influence SPAD values, highlighting the necessity of considering both direct and indirect pathways in future studies

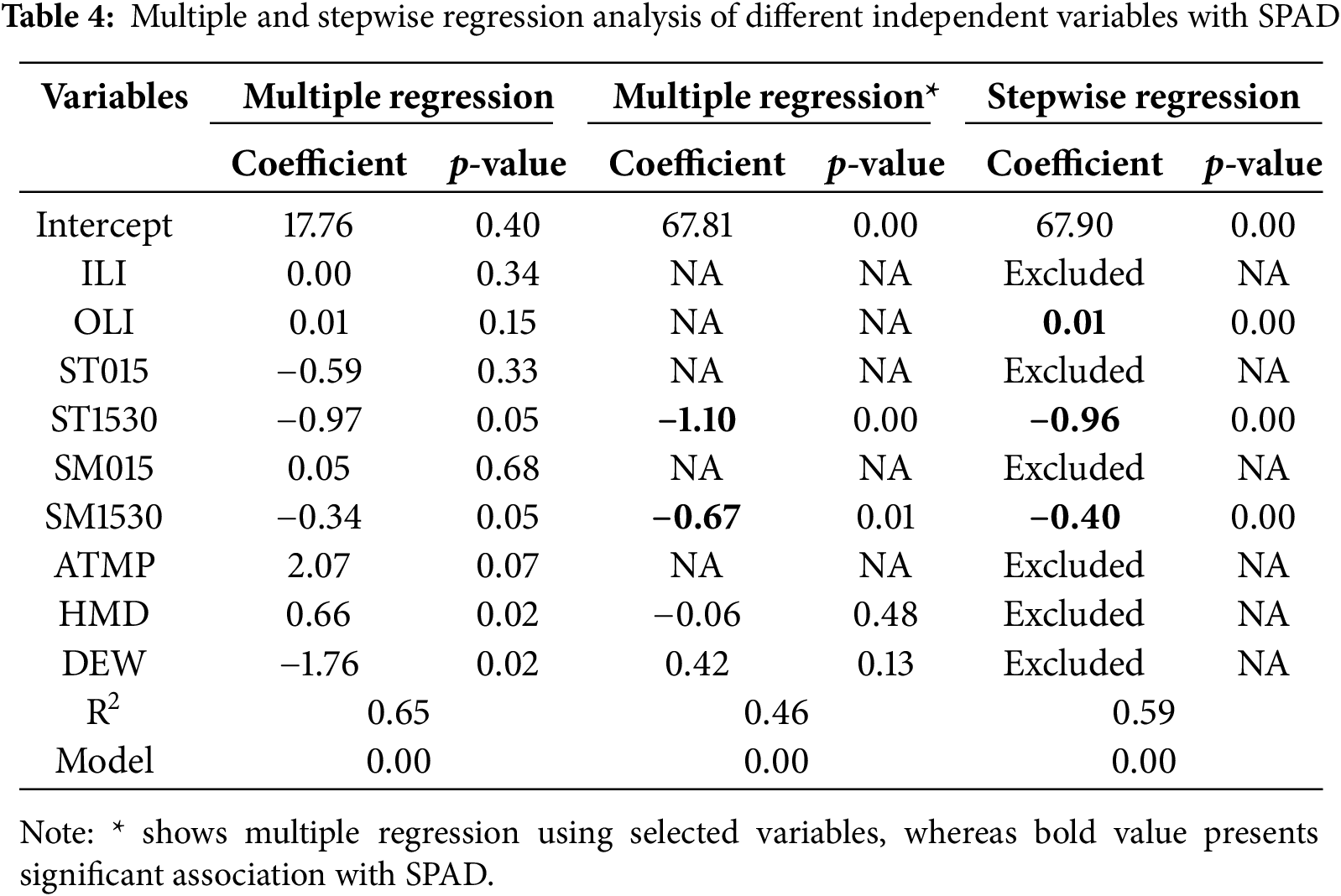

Results of the multiple, stepwise, and linear regression analyses on the selected variables are presented in Tables 4 and 5.

2.5 Multiple Regression Analysis

Table 4 presents regression analysis aimed to clarify the relationships between independent variables and SPAD values by employing multiple regression and stepwise regression methods to identify significant predictors. The initial multiple regression analysis, which included all evaluated variables, yielded an intercept of 17.8 with a p-value of 0.40, suggesting that the model was not a significant predictor of SPAD values. Among the independent variables, only ST1530 showed a significant negative relationship with SPAD, indicated by a coefficient of −0.97 (p = 0.05). This suggests that higher soil temperature in the 15–30 cm range correlates with lower SPAD readings, reinforcing earlier findings. SM1530 also exhibited a significant negative coefficient of −0.34 (p = 0.05), indicating a link between increased volumetric water content in the same soil layer and lower SPAD values. The remaining variables—ILI, ST015, SM015, ATMP, HMD, and DEW—did not show significant coefficients in this model, implying they may not meaningfully contribute to SPAD prediction within this full model context.

A refined multiple regression analysis was conducted using only those variables that demonstrated significant associations in the initial analysis (Table 4). The intercept increased significantly to 67.8 (p < 0.001), indicating a better fit for the data. In this refined model, ST1530 maintained its significant negative coefficient at −1.10 (p < 0.001), emphasizing its detrimental effect on SPAD. The negative effect of SM1530 was also evident, with a coefficient of −0.67 (p = 0.01), suggesting that higher volumetric soil moisture is associated with lower SPAD values. Notably, ILI was excluded from this model, indicating it may have a mediated effect through other factors or that it lacks a direct influence when accounting for ST1530 and SM1530.

2.6 Stepwise Regression Analysis

In the stepwise regression analysis given in Table 4, OLI emerged as a significant positive predictor of SPAD, with a coefficient of 0.01 (p < 0.001). This suggests that higher outdoor light intensity correlates with increased SPAD values, reinforcing the idea that greater light exposure contributes to enhanced chlorophyll content and higher SPAD readings. The stepwise analysis also confirmed the negative roles of ST1530 and SM1530, with coefficients of −0.96 (p < 0.001) and −0.40 (p < 0.001), respectively. The overall coefficient of regression (R2) values indicated that the full multiple regression model accounted for 65% of the variance in SPAD values, while the refined model explained 46% of the variance. The stepwise model provided greater clarity regarding predictive capabilities, accounting for 59% of the variance in SPAD. These results suggest that while a significant portion of SPAD variability is attributed to the included variables, unexplained variance may be due to unmeasured factors or interactions among variables. In summary, the results highlight ST1530 and SM1530 as critical negative predictors of SPAD, while OLI emerges as a positive contributor. These results highlight the complex interactions between environmental variables and emphasise the importance of considering both direct and indirect effects on SPAD variability. Further investigations into additional factors or their interactions may enhance our understanding of the determinants of SPAD values in future studies.

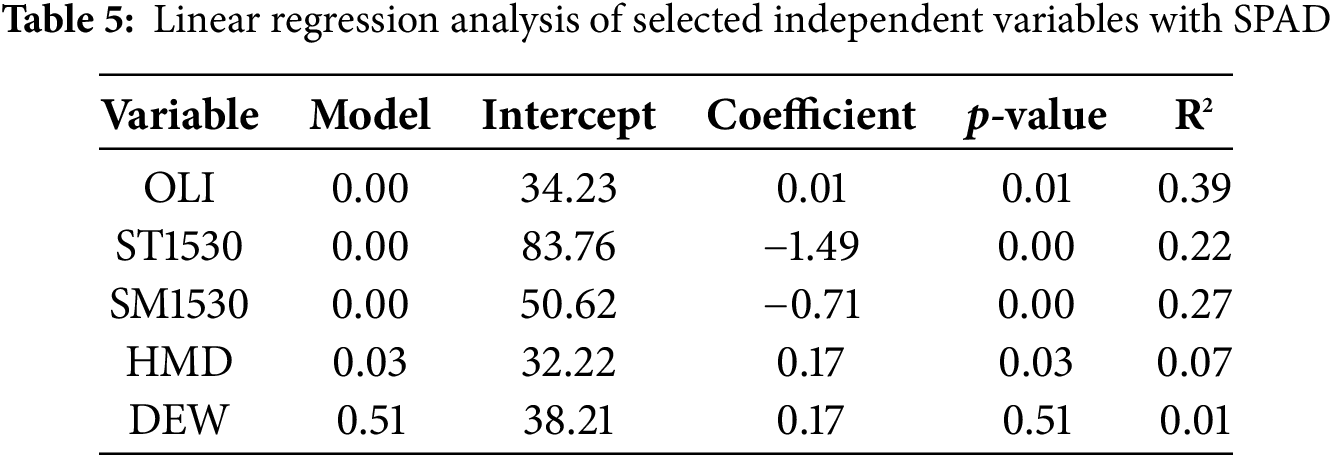

2.7 Linear Regression Analysis

The linear regression analysis focused on selected independent variables that previously showed significant associations with SPAD in the multiple regression analysis (Table 5). The results indicate that OLI had an intercept of 34.2 and a coefficient of 0.01, yielding a p-value of 0.39, suggesting no significant independent effect on SPAD when considered alone. Despite its lack of significance here, its prior inclusion in the multiple regression suggests some level of association dependent on other variables. In contrast, ST1530 demonstrated a substantial and significant negative coefficient of −1.49 (p < 0.001), with an intercept of 83.8, indicating that each unit increase in ST1530 correlates with a decrease of approximately 1.49 units in SPAD values. This reinforces the conclusion that soil temperatures in the 15–30 cm range adversely affect leaf chlorophyll content. The R2 value for this model was 0.22, suggesting a moderate level of predictive power for ST1530. SM1530 also revealed a significant negative coefficient of −0.71 (p < 0.001), with an intercept of 50.6, indicating that increased volumetric water content in the 15–30 cm soil layer corresponds to decreased SPAD values. The R2 value for SM1530 was 0.27, signifying its importance in explaining SPAD variability.

Humidity exhibited an interceptive value of 32.2 and a coefficient of 0.17 (p = 0.03), indicating a positive and statistically significant relationship with SPAD, suggesting that higher humidity is associated with increased SPAD values. However, the relatively low R2 value of 0.07 indicates that HMD explains only a small fraction of the variance in SPAD. Lastly, DEW showed an intercept of 38.2 and a coefficient of 0.17, but with a p-value of 0.51, indicating no significant association with SPAD. Overall, the linear regression analysis highlights the significant negative impacts of ST1530 and SM1530 on SPAD while also noting the positive association of HMD. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the factors influencing leaf chlorophyll content in the studied context.

This study comprehensively evaluates the impact of various environmental variables on SPAD values, a crucial indicator of chlorophyll content in greenhouse-cultivated cucumbers in Qatar. The findings emphasize that light intensity, soil temperature, and volumetric water content are vital determinants of SPAD readings, thereby reflecting plant health and potential yield. The robust positive correlations identified between SPAD values and both indoor and outdoor light intensity underscore the essential role of light in chlorophyll production. Prior research supports the premise that increased light availability directly enhances chlorophyll synthesis, which in turn improves photosynthetic activity [3,4]. In Qatar, where greenhouse environments can optimize light conditions, it is critical to implement effective light management strategies. These strategies can significantly improve crop performance and yield, as noted in studies by Haque et al. [10] and Ji et al. [11]. Moreover, the role of specific light wavelengths, particularly in the red and blue spectra, has been shown to influence chlorophyll synthesis and overall plant growth, indicating that fine-tuning light conditions can yield even greater benefits [12].

In contrast, the negative correlation between SPAD values and soil temperature at depths of 0–15 cm (ST015) highlights the detrimental effects of higher surface soil temperatures on chlorophyll synthesis. This observation is consistent with existing literature, which indicates that elevated soil temperatures at the surface can impair chlorophyll biosynthesis, resulting in reduced SPAD measurements [5,6]. High surface temperatures can lead to thermal stress, negatively impacting a plant’s photosynthetic efficiency and overall metabolic functions. Given the extreme climate conditions in Qatar, farmers could adopt practical mitigation strategies such as the use of reflective mulching materials, which help lower soil temperatures by reducing heat absorption. Additionally, integrating shade netting over greenhouse structures can further regulate soil temperature while ensuring adequate light penetration for photosynthesis. These practices not only regulate soil temperatures but also contribute to improved water retention and reduced evaporation rates, further benefiting plant health [13,14].

The observed negative relationship between SPAD values and lower volumetric water content (VWC), especially at the 15–30 cm soil layer (SM1530), raises significant concerns regarding moisture management in greenhouse settings. Sub-optimal volumetric soil moisture levels at this depth can create conditions detrimental to plant water uptake, leading to reduced chlorophyll content and impaired plant growth [7,16]. Research has shown that insufficient soil moisture can hinder nutrient transport and root function, thereby stunting plant growth [17]. To mitigate this, precision irrigation systems such as drip irrigation and soil moisture sensors can be employed. Drip irrigation, in particular, ensures consistent and localized water delivery, optimizing soil moisture levels while preventing water wastage. Additionally, deficit irrigation strategies tailored to greenhouse conditions can be explored to maximize water-use efficiency while maintaining adequate hydration for cucumber plants. Thus, the implementation of precise irrigation practices that maintain optimal soil moisture levels is critical for promoting healthy cucumber growth. Techniques such as drip irrigation can provide controlled moisture delivery, ensuring adequate hydration while avoiding both waterlogging and drought stress [18].

Furthermore, the weak negative correlation between air temperature and SPAD values, in conjunction with the moderate positive relationship with humidity, illustrates the intricate interplay of these environmental factors. Elevated air temperatures can impose significant stress on plant systems, potentially leading to reduced chlorophyll content and impaired growth. Conversely, increased humidity may enhance photosynthesis and promote plant vigor by mitigating water loss through transpiration [19]. However, excessive humidity can also increase disease susceptibility in cucumbers, necessitating controlled ventilation systems. The use of automated ventilation and evaporative cooling can help regulate greenhouse humidity levels, ensuring optimal plant growth while minimizing the risk of fungal infections. This dual effect underscores the necessity of advanced climate control systems within greenhouse environments, which are essential for optimizing both temperature and humidity levels to create ideal growing conditions [20].

The absence of a significant association between dew point and SPAD values could reflect the stable moisture conditions characteristic of controlled greenhouse environments. Such stability reduces the variability typically observed in open field studies, where environmental conditions fluctuate more dramatically [21]. Controlled environments facilitate consistent growth conditions, corroborating findings from Li et al. [22] that emphasize the predictability of crop responses in managed settings. This consistency is crucial for optimizing growth parameters and maximizing crop yields. Considering these findings, it is evident that future research should explore the multifaceted interactions among these environmental variables to further enhance our understanding of their combined effects on SPAD values and overall plant health. Experimental studies could investigate the interactions between light intensity and soil temperature, or between moisture levels and air temperature, to provide more nuanced insights into how these factors influence chlorophyll content in cucumbers. Moreover, research focusing on the integration of AI-driven climate control technologies could provide innovative solutions for dynamically adjusting greenhouse conditions to maintain optimal plant health and productivity. Additionally, research focusing on the impact of varying light wavelengths on chlorophyll synthesis, especially in controlled environments, could yield valuable information for optimizing greenhouse cultivation practices [23,24].

Moreover, considering the rapidly changing climate and its potential effects on greenhouse agriculture, investigations into how climate variability impacts these relationships will be essential. Understanding these dynamics will enable growers to adapt their practices to ensure sustainable production in the face of environmental challenges [25]. The integration of advanced technologies, such as precision agriculture tools and data analytics, can also enhance decision-making processes regarding environmental control, ultimately leading to more efficient greenhouse operations. By combining real-time environmental monitoring with predictive modeling, farmers can proactively adjust factors such as irrigation and shading to optimize SPAD values and overall plant growth.

In summary, the findings of this research shed light on the complex interactions among environmental factors influencing SPAD values in greenhouse cucumbers. While light intensity emerged as a key predictor, the detrimental effects of soil temperature and volumetric water content warrant further investigation. By exploring the combined effects of these variables, future studies can provide deeper insights into optimizing SPAD values and improving crop productivity in greenhouse settings. Overall, this research provides important insights into the complex interactions that affect leaf chlorophyll content, paving the way for further studies on how different environmental factors and their interrelations influence plant health. By implementing tailored environmental management strategies such as optimized irrigation, shading, and climate control, greenhouse growers in Qatar can significantly improve cucumber yield and sustainability. Future research should explore additional variables that may affect SPAD and investigate potential interactions among them. The findings of this study have practical implications for agricultural practices and environmental management strategies aimed at optimizing plant health, ultimately contributing to enhanced sustainability and productivity in agricultural systems.

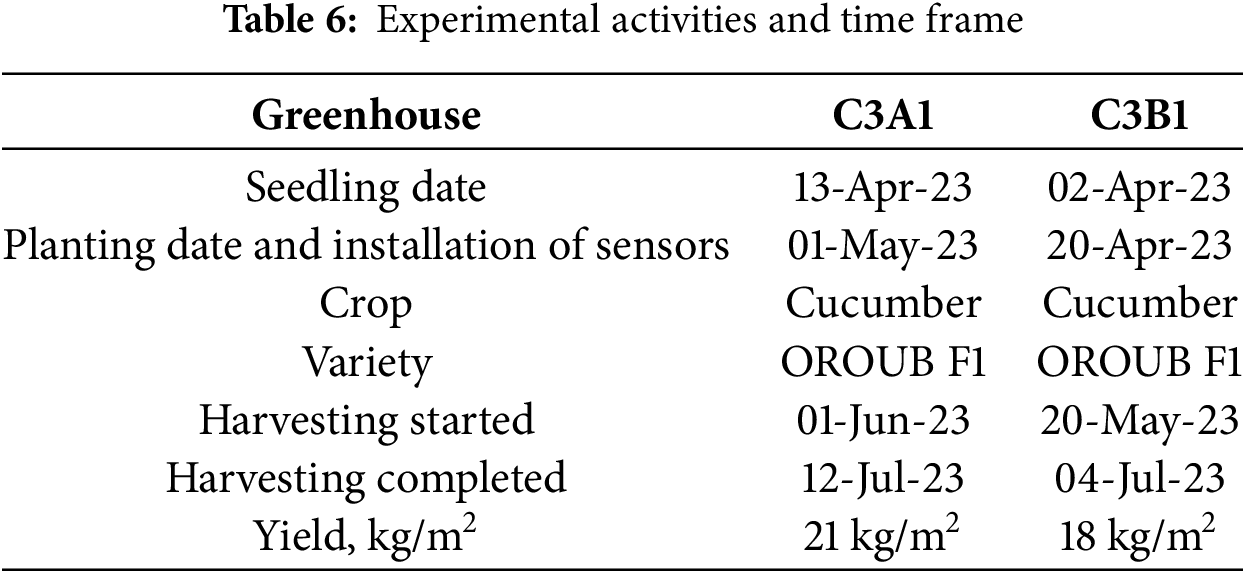

This study investigated the relationship between SPAD values and various environmental factors affecting cucumber growth in a greenhouse setting at the Al-Sulaiteen Agricultural Research, Studies, and Training Center (SARSTC), Qatar. The primary objective was to understand how different environmental parameters influence SPAD readings and to develop predictive models for optimizing cucumber growth. The cucumber plant (Cucumis sativus L.) was chosen as a test crop due to its widespread cultivation and economic importance to local food production and Qatar’s food security initiatives. The cucumber variety used in this study was OROUB F1. The seeds were purchased from the local market in Qatar. Experiments were conducted in two greenhouses, designated as C3-A1 and C3-B1, at SARSTC (25°28′6″ N, 51°22′40.4″ E), Umm Salal Ali, Qatar. These greenhouses were equipped with an automated cooling and humidity control system, utilizing wet pads and exhaust fans to maintain optimal conditions for plant growth. Data collection began in the first week of April 2023 and continued until the end of the growing season in the second week of July 2023. Other information about the experimental setups is given in Table 6.

4.1 Experimental Preparation and Sensor Installation

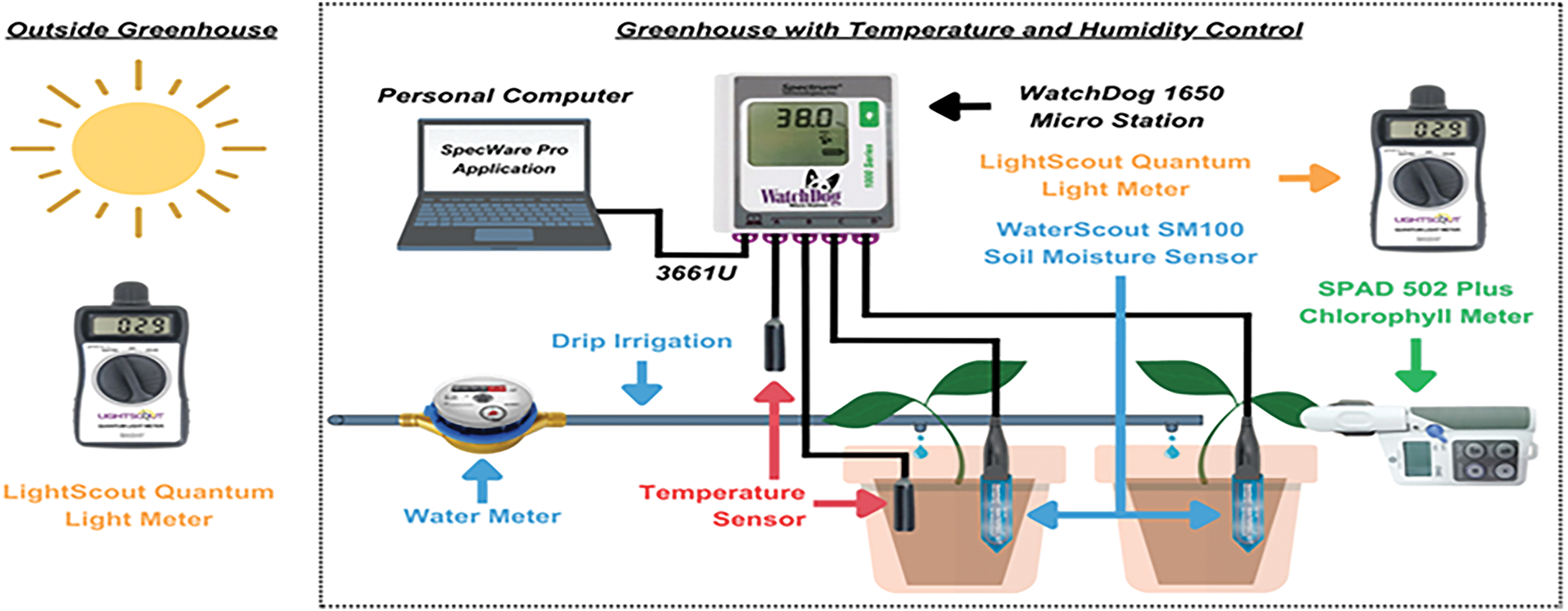

Cucumber seeds were planted in sterilized growing substrate and germinated under control artificial lighting. Seedlings progressed through their developmental stages within seedling chambers before being transplanted into the greenhouses at the seven-leaf stage. The seedlings were grown in a coco peat-based substrate, which provided a well-aerated and moisture-retentive medium for optimal root development. In the greenhouse, a mini weather station was installed centrally in both greenhouses to monitor environmental conditions, including relative humidity, dew point, ambient air temperature, and soil moisture content (Fig. 3). This location minimized the effects of walls, wet pads, exhaust fans, and greenhouse entrances on the measurements. Soil moisture sensors were installed in two representative plant pots, while a thermal sensor was placed in the soil of one pot for root zone temperature, and another was suspended at a height of 1.5 m for ambient air temperature. To improve accuracy, sensors were calibrated before installation using a standard reference method. There was a total of 20 experimental units, ensuring sufficient replication in each greenhouse to minimize experimental error. Data collection was performed weekly, with SPAD readings and environmental data being recorded simultaneously. Irrigation was managed based on real-time soil moisture data collected from sensors. When soil moisture levels dropped below the target range of 65–75% of field capacity, automated drip irrigation was triggered to restore optimal moisture levels. The volume of water applied was variable, adjusted dynamically based on sensor feedback to prevent water stress or over-irrigation. The cooling system, consisting of wet pads and exhaust fans, operated automatically based on temperature and humidity thresholds. When greenhouse temperatures exceeded 28°C or relative humidity levels dropped below the optimal range, the system activated to maintain favorable conditions for cucumber growth.

Figure 3: Experimental setup and mini weather station to record multiple parameters

A WatchDog 1650 Micro Station (Spectrum Technologies, 3600 Thayer Court, Aurora, IL 60,504), with a built-in data logger was installed and configured to collect and record readings from the external sensors attached to its 4 different ports. It also has built-in internal sensors for temperature and relative humidity. The diagram in Fig. 3 shows the wiring setup of the WatchDog 1650 Micro Station and four sensors placed in both greenhouses. Before deployment, all sensors were validated for accuracy by comparing their readings with a reference instrument. For this experiment, ports A and B of the WatchDog 1650 Micro Station had two external temperature sensors (A-series external (soil) temp sensor) used for ambient air and plant root zone temperature data. The resistance-based external temperature sensors were used to measure air and soil temperatures. For ambient temperature measurement, the sensor was installed in the middle area of the greenhouse at a height of 1.5 m. To monitor the soil temperature and soil moisture contents, the respective sensors were buried in the plant pots of soil at the known depths (0–15 and 15–30 cm). While a single sensor was used per pot, this setup reflects the variation expected across the experimental units. The placement of the sensors at different depths and positions ensures that the measurements are representative of the overall conditions. Additionally, with regulated environmental conditions, the potential for significant variation between pots was minimized, and the data from the selected pots were used to estimate conditions across the greenhouses. Targeted volumetric soil moisture levels were maintained at 60–70% of field capacity, and soil temperatures were kept within the optimal range for cucumber growth, around 25–30°C. The data were periodically downloaded on a laptop that had the SpecWare Pro software application installed via a data transmission cable (3661U).

4.2 Measurement of Light Intensity and SPAD Values

The Quantum Light Meter (Spectrum Technologies, 3600 Thayer Court, Aurora, IL 60,504) was used to measure light intensity both outdoors (OLI) and indoors (ILI), positioned at canopy height. The Light Scout Quantum Light Meter was calibrated to display Photosynthetic Photon Flux Density (PPFD), which was measured in units of μmol m−2 s−1 (the number of photons, in units of micromoles, striking an area one meter square each second). The SPAD502 Plus Chlorophyll Meter is a handheld meter used for measuring the amount of chlorophyll by using leaves as measurement samples to determine the overall condition of a plant’s health (Spectrum Technologies, 2019). To determine the relative amount of chlorophyll in the plant, the SPAD-502 Plus measures the absorbance of leaves in two wavelength regions: red and near-infrared region (Konica Minolta, 2009). The meter can output an indexed chlorophyll content reading in the range of −9.9 to 199.9. Measurements were taken on fully expanded leaves at the midpoint of the leaf blade, avoiding the midrib. To minimize variation, all SPAD readings were taken at the same time of the day, under consistent light conditions. Ten readings per plant were averaged to get a representative value.

Data collected were subjected to statistical analysis using the software package R, with a significance level set at 0.05 for all statistical tests. The analyses included descriptive statistics to measure the mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum values for each parameter to collect a summary of the data. For correlation analysis, Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to determine the strength and direction of the relationship between SPAD values and each environmental factor. Multiple regression analysis was conducted to identify the most significant environmental factors affecting SPAD values. This included (i) a full model incorporating all environmental variables, (ii) a reduced model with only the variables that showed significant associations with SPAD values, and stepwise regression analysis to identify the best-fitting model through a systematic selection of variables. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) was used as the model selection criterion to determine the best-fitting model, ensuring an optimal balance between model complexity and goodness-of-fit. To ensure robustness, models were validated using cross-validation techniques, including leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV). Additionally, path coefficient analysis was employed to quantify the direct and indirect effects of each environmental factor on SPAD values, providing insights into the pathways through which these variables impact chlorophyll content. Further, for simple linear regression, individual simple linear regressions were conducted for each environmental variable with SPAD values to understand their direct impact. This analysis helped illustrate how each environmental factor relates to SPAD values, providing a clearer understanding of their effects. This comprehensive methodology facilitated a detailed investigation into how environmental factors influence cucumber growth and SPAD values, aiming to optimize conditions for enhanced crop performance in greenhouse settings.

This study identifies key environmental factors influencing SPAD values, which serve as indicators of leaf chlorophyll content. First, light intensity (both indoor and outdoor) emerged as a strong positive predictor of SPAD, reinforcing the importance of optimized lighting for enhancing chlorophyll synthesis. Second, soil temperature at 15–30 cm depth (ST1530) and volumetric soil moisture at the same depth (SM1530) were identified as significant negative predictors, indicating that excessive heat and suboptimal moisture levels can impair chlorophyll content. Third, the combined use of correlation, path coefficient, and regression analyses highlights the direct and indirect effects of these variables, demonstrating the need for integrated environmental management strategies.

Future research should expand these findings by testing different crop species to determine whether similar environmental influences apply across various plant types. Additionally, the integration of advanced monitoring technologies such as remote sensing, IoT-based climate control systems, and AI-driven predictive models could enhance real-time data collection and decision-making, further improving crop management in controlled environments.

Acknowledgement: Al Sulaiteen Agricultural Research Study and Training Center, Umm Salal Ali, Farm No 301, P.O. Box 8588, Doha, Qatar, provided experimental support for this study.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by QRDI, grant number UREP29-185-1-031.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, Farhat Abbas, Salem Al-Naemi and Awni Al-Otoom; methodology, Farhat Abbas and Ahmed T. Moustafa; software, Farhat Abbas and Fahim Ullah Khan; validation, Farhat Abbas, Salem Al-Naemi and Awni Al-Otoom; formal analysis, Fahim Ullah Khan; investigation, Farhat Abbas, Khaled Shami and Ahmed T. Moustafa; resources, Khaled Shami, Ahmed T. Moustafa and Farhat Abbas; data curation, Farhat Abbas, Fahim Ullah Khan and Ahmed T. Moustafa; writing—original draft preparation, Fahim Ullah Khan and Farhat Abbas; writing—review and editing, Farhat Abbas and Salem Al-Naemi; Awni Al-Otoom, Khaled Shami and Fahim Ullah Khan; visualization, Fahim Ullah Khan; supervision, Farhat Abbas; project administration, Farhat Abbas; funding acquisition, Farhat Abbas, Khaled Shami and Ahmed T. Moustafa. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Uddling J, Gelang-Alfredsson J, Piikki K, Pleijel H. Evaluating the relationship between leaf chlorophyll concentration and SPAD-502 chlorophyll meter readings. Photosynth Res. 2007;91(1):37–46. doi:10.1007/s11120-006-9077-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Trawczyński C. Assessment of the nutrition of potato plants with nitrogen according to the NNI test and SPAD indicator. J Elem. 2019;24(2):687–700. [Google Scholar]

3. Singh MC, Singh JP, Pandey SK, Mahay D, Shrivastva V. Factors affecting the performance of greenhouse cucumber cultivation—a review. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2017;6(10):2304–23. doi:10.20546/ijcmas.2017.610.273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Song J, Meng Q, Du W, He D. Effects of light quality on growth and development of cucumber seedlings in controlled environment. Int J Agric Biol Eng. 2017;10(3):312–8. [Google Scholar]

5. Liu H, Yuan B, Hu X, Yin C. Drip irrigation enhances water use efficiency without losses in cucumber yield and economic benefits in greenhouses in North China. Irrig Sci. 2022;40(2):135–49. doi:10.1007/s00271-021-00756-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mondal S, Ghosal S, Barua R. Impact of elevated soil and air temperature on plants growth, yield and physiological interaction: a critical review. Sci Agric. 2016;14(3):293–305. [Google Scholar]

7. Alomran AM, Louki II. Impact of irrigation systems on water saving and yield of greenhouse and open field cucumber production in Saudi Arabia. Agric Water Manag. 2024;302(7):108974. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2024.108974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Purdue University Extension. Check soil temperatures before planting cucumbers in a high tunnel. [cited 2025 May 1]. Available from: https://vegcropshotline.org/article/check-soil-temperatures-before-planting-cucumbers-in-a-high-tunnel. [Google Scholar]

9. Kim S, Park M, Lee T. Optimizing growth conditions for grafted cucumber seedlings in plant factories. Sustainability. 2023;15(5). [Google Scholar]

10. Haque M, Hasanuzzaman M, Rahman M. Morpho-physiology and yield of cucumber (Cucumis sativa) under varying light intensity. Acad J Plant Sci. 2009;2(3):154–7. [Google Scholar]

11. Ji F, Wei S, Liu N, Xu L, Yang P. Growth of cucumber seedlings in different varieties as affected by light environment. Int J Agric Biol Eng. 2020;13(5):73–8. doi:10.25165/j.ijabe.20201305.5566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Jin D, Su X, Li Y, Shi M, Yang B, Wan W, et al. Effect of red and blue light on cucumber seedlings grown in a plant factory. Horticulturae. 2023;9(2):124. doi:10.3390/horticulturae9020124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zou H, Wang C, Yu J, Huang D, Yang R, Wang R. Eliminating greenhouse heat stress with transparent radiative cooling film. Cell Rep Phys Sci. 2023;4(8):101539. doi:10.1016/j.xcrp.2023.101539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Odhiambo MO, Wang XC, de Antonio PIJ, Shi YY, Zhao B. Effects of root-zone temperature on growth, chlorophyll fluorescence characteristics and chlorophyll content of greenhouse pepper plants grown under cold stress in Southern China. Russ Agricult Sci. 2018;44(5):426–33. doi:10.3103/s1068367418050130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yousefvand P, Sohrabi Y, Heidari G, Weisany W, Mastinu A. Salicylic acid stimulates defense systems in Allium hirtifolium grown under water deficit stress. Molecules. 2022;27(10):3083. doi:10.3390/molecules27103083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Nam Y-I, Woo Y-H, Lee K-H. Effects of soil moisture and chemical application on low temperature stress of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) seedling. J Bio Environ Control. 2006;15(4):377–84. [Google Scholar]

17. Shah F, Wu W. Soil and crop management strategies to ensure higher crop productivity within sustainable environments. Sustainability. 2019;11(5):1485. doi:10.3390/su11051485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Beyaert RP, Roy RC, Ball Coelho BR. Irrigation and fertilizer management effects on processing cucumber productivity and water use efficiency. Can J Plant Sci. 2007;87(2):355–62. doi:10.4141/p06-012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Amin B, Atif MJ, Wang X, Meng H, Ghani MI, Ali M, et al. Effect of low temperature and high humidity stress on physiology of cucumber at different leaf stages. Plant Biol. 2021;23(5):785–96. doi:10.1111/plb.13276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang M, Yan T, Wang W, Jia X, Wang J, Klemeš JJ. Energy-saving design and control strategy towards modern sustainable greenhouse: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2022;164(9):112602. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kokieva GE, Trofimova VS, Fedorov IR. Greenhouse microclimate control. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2020;1001(1):12136. [Google Scholar]

22. Li H, Jin X, Shan W, Han B, Zhou Y, Tittonell P. Optimizing agricultural management in China for soil greenhouse gas emissions and yield balance: a regional heterogeneity perspective. J Clean Prod. 2024;452(Suppl. 1):142255. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.142255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ptushenko OS, Ptushenko VV, Solovchenko AE. Spectrum of light as a determinant of plant functioning: a historical perspective. Life. 2020;10(3):25. doi:10.3390/life10030025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Ouzounis T, Rosenqvist E, Ottosen CO. Spectral effects of artificial light on plant physiology and secondary metabolism: a review. HortScience. 2015;50(8):1128–35. doi:10.21273/hortsci.50.8.1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Raza A, Razzaq A, Mehmood SS, Zou X, Zhang X, Lv Y, et al. Impact of climate change on crops adaptation and strategies to tackle its outcome: a review. Plants. 2019;8(2):34. doi:10.3390/plants8020034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools