Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Acalypha gaumeri: Antifungal Activity of Three Populations under Edaphic and Seasonal Variations and Ex-Situ Propagation

1 Departamento de Ecología Tropical, Campus de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, SECIHTI−Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán, Mérida, 97000, Yucatán, México

2 Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, A.C., Mérida, 97205, Yucatán, México

3 Instituto de Agroindustrias, Universidad Tecnológica de la Mixteca, Huajuapan de León, Oaxaca, 69000, Oaxaca, México

4 Laboratorio de Fitopatología, Campus Conkal, Tecnológico Nacional de México, Conkal, 97345, Yucatán, México

* Corresponding Authors: Jairo Cristóbal-Alejo. Email: ; Marcela Gamboa-Angulo. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Functional Plant Extracts and Bioactive Metabolites)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(9), 2839-2853. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.066682

Received 15 April 2025; Accepted 10 June 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

In the search for new alternatives to control tropical fungal pathogens, the ethanol extracts (EEs) from Acalypha gaumeri (Euphorbiaceae) roots showed antifungal properties against several tropical fungal phytopathogens. A. gaumeri is classified as endemic to the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico, an area with distinct rainy, drought and northern seasons. The present study evaluated the antifungal activity of three wild populations of A. gaumeri collected quarterly in different seasons during one year against Alternaria chrysanthemi, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, and Pseudocercospora fijiensis and explored their ex-situ propagation. The highest activity was shown by the EE from the Tinum wild population during the rainy season against A. chrysanthemi, C. gloeosporioides, and P. fijiensis with MIC values of 500–1000 μg/mL, followed by Yaxcaba populations during the rainy season and Kiuic and Tinum from November against A. chrysanthemi and P. fijiensis 1000 and 500 μg/mL, respectively. The propagation of A. gaumeri was more effective through medium cuttings, showing 96% with 0.06% auxin indolbutyric acid, whereas only 51% of seeds germinated. The results indicated that seasonal changes and edaphic conditions in the three populations influence the antifungal efficacy of the extracts from A. gaumeri roots. This study enhances the knowledge of the biology and sustainable management of the A. gaumeri plant and advances the development of a biorational product to control tropical fungal diseases.Keywords

Fungal infections are responsible for about 70%–80% of the losses in agricultural production brought on by microbial diseases [1]. The phytopathogenic fungi Alternaria chrysanthemi, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, and Pseudocercospora fijiensis (before Mycosphaerella fijiensis M. Morelet) causing plant diseases such as leaf blight in chrysanthemum, anthracnose in tropical fruit and black leaf streak (black sigatoka) on banana, respectively [2–4]. These fungi are responsible for significant losses in crops, so their main control strategy is chemical products [2–4]. Therefore, looking for more environmentally friendly control strategies for plant diseases is essential [1]. In this respect, in vitro antifungal studies of ethanol extracts from leaves, stems, and roots from Acalypha gaumeri Pax & Hoffm. (mayan name Sak ch’ilib tuux) were evaluated against four plant pathogenic fungi. Only the root extract demonstrated the capacity to inhibit the mycelial growth of A. tagetica, C. gloeosporioides, and Fusarium oxysporum to a greater extent [5]. In a separate study, the ethanol root extract from A. gaumeri demonstrated an antifungal effect against A. chrysanthemi, Corynespora cassiicola, Curvularia sp., and Helminthosporium sp. [6]. The root aqueous extract was observed to effectively control A. chrysanthemi, the causal agent of the leaf blight in Chrysanthemum morifolium, in a field setting [7]. Acalypha species have generally been tested against several human bacterial pathogens and fungi. The extract of A. indica was effective against Aspergillus flavus, A. niger, C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and P. chrysogenum [8]; leaf extract of A. indica showed effect on A. alternata [9]; while Acalypha cuspidata and Acalypha subviscida shown activity on A. alternata [10]. The ethanol root extract from A. gaumeri demonstrated efficacy against the root-knot nematode Meloidogyne incognita [11]. Additionally, the foliar ethanol and aqueous extracts resulted in mortality among the eggs and nymphs of the insect Bemisia tabaci [12]. Conversely, the plant material for these studies was collected from a wild population in the Kiuic Reserve in Yucatan. There are no ecological, phytochemical, or other studies on A. gaumeri, much less on the A. gaumeri populations or the influence of seasonal changes and soils on the antifungal activity of this species.

A tropical climate distinguishes the Yucatan Peninsula, where the distribution of precipitation over a year allows for the division of the peninsula into three seasons: The first season, which begins in November and ends in February, is distinguished by the onset of drought, with intermittent, short showers known as “nortes”. The second season, from March to May, is characterized by prolonged drought. The last season, from June to October, is marked by rain [13] The biological activities and biosynthesis of metabolites by organisms may vary depending on the environmental conditions [14]. For example, drought conditions expose plants to various environmental factors, including temperature variations, light levels, and soil types [15,16]. The influence of drought and rainy seasons on the development and accumulation of bioactive substances in plants has been the subject of several studies [17–20]. Other studies have investigated the impact of salinity and soil fertility on plant development [21–23]. Nevertheless, no studies have examined the effects of seasonal fluctuations and soil characteristics on the antifungal activity of A. gaumeri. Accordingly, the present study selected three wild populations of A. gaumeri exhibiting disparate edaphic conditions in the Yucatan state.

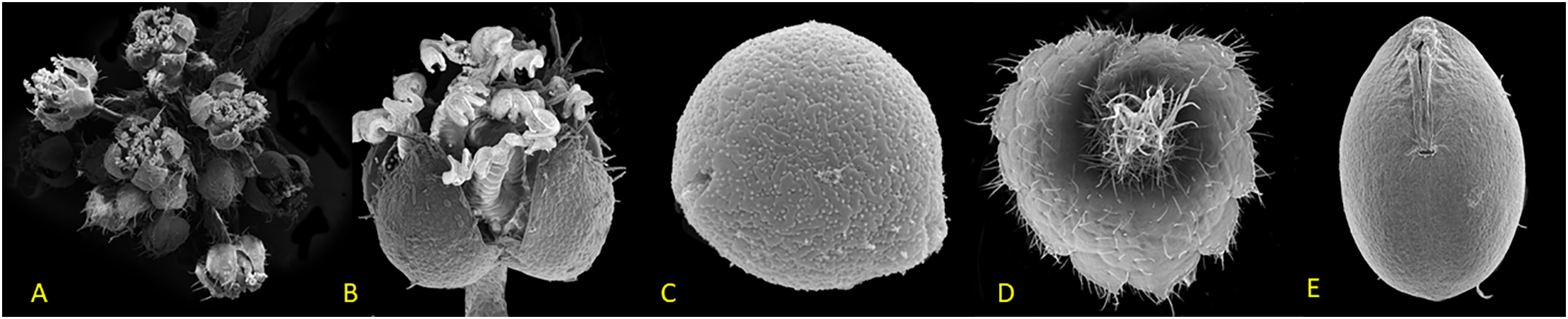

The Acalypha gaumeri plant is a terrestrial shrub belonging to the Euphorbiaceae family. This species is dioecious, meaning it has staminate male flowers on small spikes and solitary pistillate female flowers on distinct individuals. This species represents one of the 154 endemic plants from the Yucatan Peninsula Biotic Province (Fig. 1), which is classified as near threatened with nine populations registered [24–26].

Figure 1: Scanning electron microscope images of Acalypha gaumeri: (A) male inflorescence, (B) male flower, (C) pollen, (D) female flower, (E) seed

The remarkable efficacy of A. gaumeri, both in vitro and in natural settings, and its restricted geographic range underscores the imperative necessity to cultivate this species through propagation and nursery culturing to guarantee its long-term conservation and sustainable use.

This study aimed to ascertain the antifungal activity of three selected wild populations of A. gaumeri from the Yucatan state with different edaphic conditions and seasonal variation during one year and to explore their propagation by cuttings and seeds.

2.1 Collection Sites of Plant Material

The plant material was collected in wild populations of Acalypha gaumeri, Kiuic, Oxkutzcab (22°24′ N and 23°33′ W), Tinum (20°38′ N and 88°27′ W), and Tixcacaltuyub, Yaxcabá (20°25′ N and 88°55′ W) in the Yucatan Peninsula. These sites were selected by consulting the herbarium of the Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán and the Missouri Botanical Garden, USA. The data gathered were mapped from the various sites and populations to obtain the environmental, climatic, and edaphic variables using the cartographic base of García and Secaira [27], and Hijmans et al. [28].

The A. gaumeri root samples (n = 15 plants) were collected quarterly (February, May, August and November) from the three sites during 2011. The roots were washed and subjected to a three-day drying process at a temperature not exceeding 50°C in a lamplight oven, after which they were fragmented using a blade mill with a 5 mm cutting diameter (Brabender, Duisburg, Gemany).

2.2 Preparation of Extracts and Alkaloid Test

The plant material (20 g) was extracted with ethanol distiled in the labortory (150 mL, three times) at room temperature for 24 h. Subsequently, the solvent was removed under vacuum in a rotary evaporator at 40°C until the solvent had evaporated entirely. The resulting ethanol extracts (EEs) were stored in the dark at 4°C until required for use [6].

2.2.2 Dragendorff Test by Thin-Layer Chromatography

Each EE (1 μL) was applied in a chromatographic plate of aluminium impregnated with silica gel 60 F254 of 0.25 mm (E.M. Merck DC-Alufolien thickness). The plates were eluted with butanol: acetic acid: water (7:1:2, v/v) system revealed under UV light λ of 264, 365 nm, and Dragendorff reagent. The spots were registered as reference front (Rf) [29].

2.3 Antifungal Bioassay by Microdilution Assay

The inhibition of spore germination (ISG) of the EEs was evaluated using the 96-well microdilution bioassay against A. chrysanthemi E.G. Simmons and Crosier, strain CICY004 (GenBank MH846127); C. gloeosporioides (Penz.) Penz. and Sacc., strain CG4; and P. fijiensis CIRAD 1233 (IMI 392976) [6,7,26].

The spore suspension of the phytopathogens was obtained following a seven-day growth period in malt extract medium at 18°C ± 2°C in darkness for A. chrysanthemi and P. fijiensis; on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 23°C ± 2°C in natural light for C. gloeosporioides, respectively. Subsequently, the spores were extracted using a sterile slide, filtered, and adjusted to 5 × 104 spores/mL for A. chrysanthemi and C. gloeosporioides, and 2 × 105 spores/mL for M. fijiensis, employing a hemocytometer [6,7,30].

The extracts (80 μg/μL) were evaluated at final concentrations of 1000, 500 and 250 μg/mL against A. chrysanthemi and C. gloeosporioides; and 500, 250 and 125 μg/mL against P. fijiensis. The positive control used was Amphotericin B (4 μg/mL) and medium RPMI-1640 + 40% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO); while the negative control consisted of RPMI-1640 + 2.5% DMSO and 2.5% RPMI-1640. All samples were subjected to three replicates. The experiment was conducted under controlled conditions at 25°C ± 2°C with a 16/8 light/dark cycle. Following 96 h, the ISG readings for each phytopathogen were recorded per the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards [31], with certain modifications. The data were converted to percentages, and the results were reported as growth inhibition (GI) using Abbott’s formula. The percentage of growth inhibition (GI) in the control group was subtracted from the percentage of GI in the treatment group. This value was then divided by the percentage of GI in the control group to obtain the final rate of GI: [(% GI in control − % GI in treatment)/% GI in control × 100]. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of each extract was also determined.

Statistical Analysis

Multivariate and one-way analyses were performed on the percentage data for mycelial growth inhibition. Since normality criteria were not met, transformations were performed using the arcsine function to homogenize variations. Means were compared using the Bonferroni method (p ≤ 0.05) SPSS version 18 for Windows was used [32].

Plant material was obtained from field samples in Yaxcabá, Yucatán and their leaves were removed from the cuttings before transfer to the Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán nursery. The cuttings, measuring approximately 15 cm in length, were obtained from three sections: the basal, middle, and distal regions. Each cutting, comprised of a minimum of five buds, was treated with indolebutyric acid (IBA, Raizone*-Plus®, Villa Guerrero, México) at a concentration of 0.06%, and control treatments consisted of A. gaumeri cuttings from each layer without IBA [33]. A total of 30 units were utilized in this experiment, with five replicates per treatment. Each replicate consisted of six cuttings planted in polystyrene trays containing a 1:2:1 commercial Cosmopeat® (Puebla, México) soil-agro-lite substrate and maintained at 35°C ± 2°C and 64% ± 7.8% humidity. The response variable was determined 60 days after the initiation of the experimental treatments. The percentage of rooted cuttings (PRC) was estimated using the following formula: PRC = (number of rooted cuttings/total number of cuttings) × 100.

Statistical Analysis

A completely randomized experimental design was used, and a one-way analysis of variance was performed on the data obtained after transformation using the arcsine function of propagation by cutting. Comparisons of means were performed using the Tukey method (p ≤ 0.05). SPSS version 18 for Windows was used.

The seeds were obtained from plants from the Yaxcabá population cultivated in a glasshouse. Seedling traps were placed on fruiting branches to collect the seeds. The seeds were subjected to shade drying at room temperature for three days, after which they were stored at 20°C until required for use. One hundred seeds were treated with a 2.5% Benomyl solution for 20 min to prevent the presence of fungi. Following a drying period of one h, the seeds were sown in polystyrene trays of approximately 1–2 cm, with a substrate comprising a 1:2:1 ratio of Cosmopeat®-soil-agro-lite. The germination trays were covered with transparent plastic to ensure optimal humidity and facilitate light penetration. The number of germinated seeds was counted weekly to assess their viability. The percentage of germinated seeds was recorded 40 days after sowing. The following equation was used to calculate the germination percentage: GP = (number of germinated seeds/total number of seeds tested) × 100.

2.5 Scanning Electron Microscopy Sample Preparation

This study uses a scanning electron microscope (JSM 6360LV Jeol, Tokyo, Japan) for morphological observations. The samples were first dehydrated in 70% alcohol for one week. After that, the samples were loaded into the chamber of Tousimis Samdri 795, MD, USA, for critical point. Finally, the specimens were sputter-coated with palladium (Denton vacuum desk II sputter, Denton, TX, USA) for 60 s to render the surface conductive without compromising the fine surface microstructure.

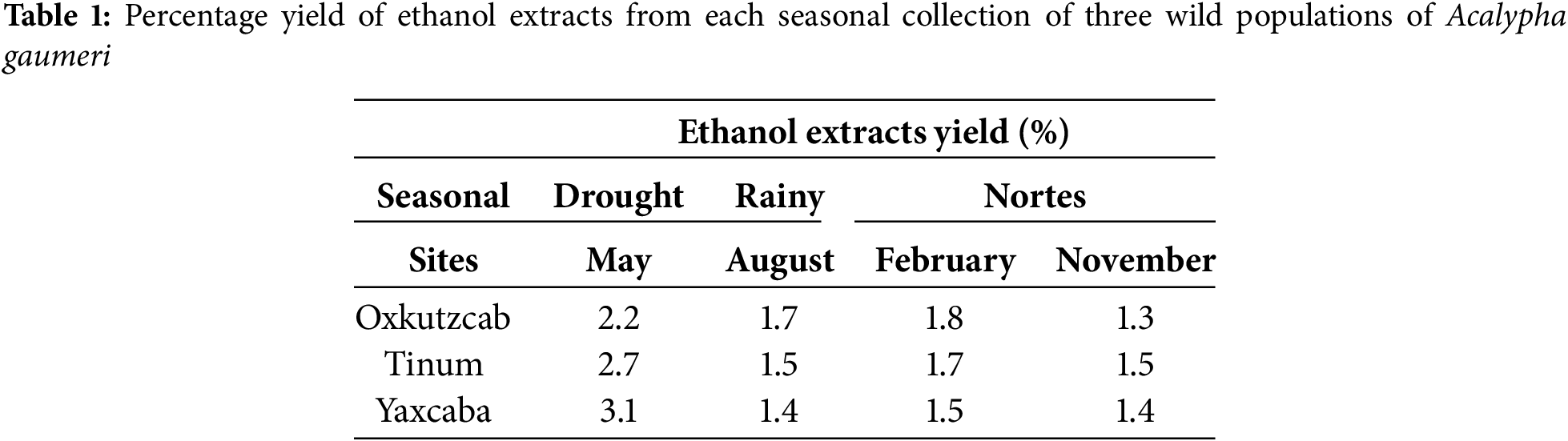

3.1 Yields of Ethanol Extracts from A. gaumeri Roots

The EEs of the four collections demonstrated comparable yields among the three populations. During the drought season, the highest yield of 2.2% to 3.1% was observed in the EEs of the three wild populations compared to the other two seasons (Table 1).

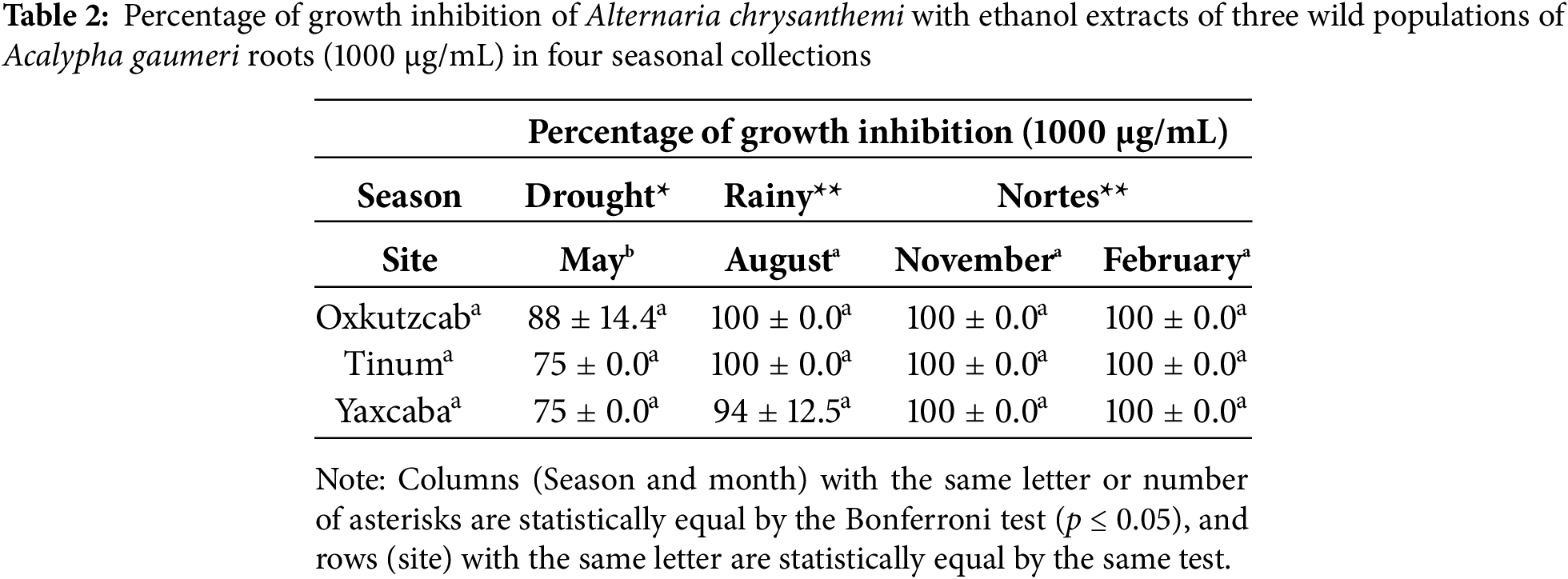

The antifungal activity of 12 EEs from A. gaumeri roots against A. chrysanthemi showed a statistically significant difference between seasons was observed (p ≤ 0.01). However, no statistical difference was found between populations (Table 2). The three A. gaumeri wild populations exhibited high efficacy against A. chrysanthemi, with GI values of ≥75% at 1000 μg/mL. The EEs obtained from the collections during the rainy season and at the beginning of the drought season exhibited the highest antifungal activity against this pathogen (GI = 94%–100%), with no significant difference between the two periods. During the drought period, the antifungal activity was slightly reduced (GI = 75%–88%).

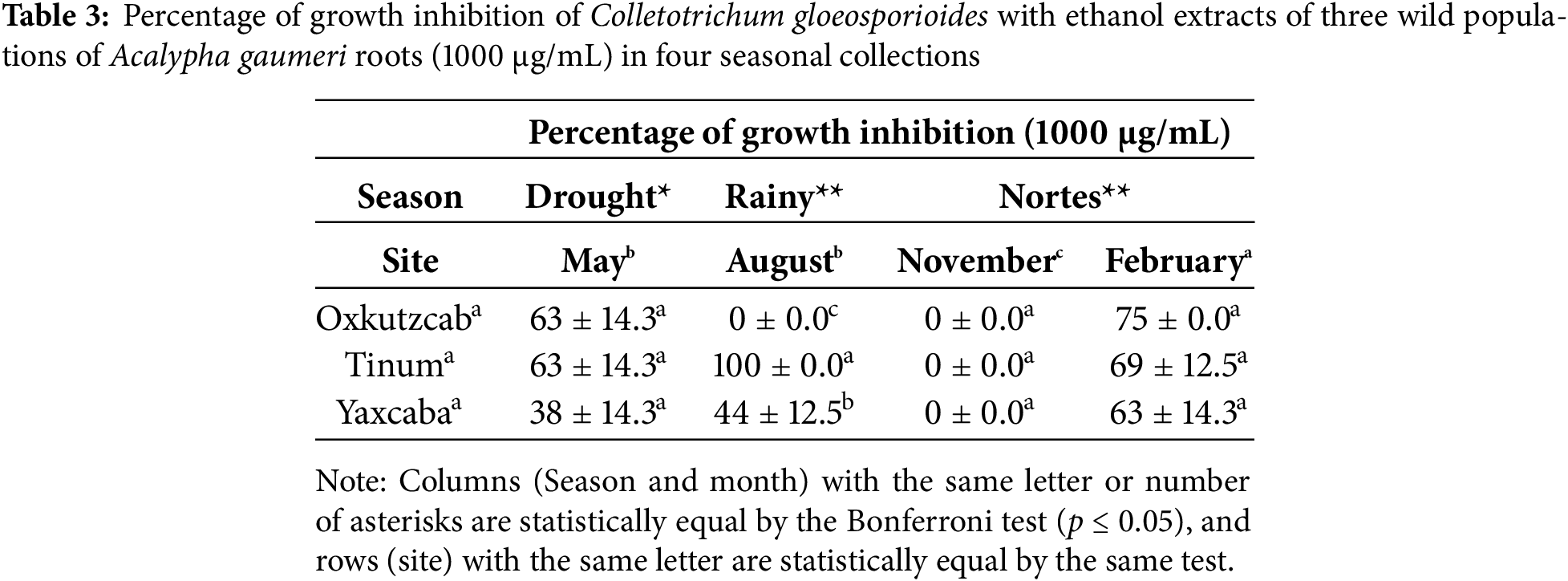

3.2.2 Colletrotrichum Gloeosporioides

The results of the statistical analysis indicated significant differences (p ≤ 0.01) between the percentage of GI of C. gloeosporioides with the EEs from A. gaumeri roots of the three wild populations at different seasons of the year at 1000 μg/mL (Table 3). The EEs of the Tinum wild population showed the highest percentages of GI against C. gloeosporioides across all three seasons (63%–100%), except for November. The variance of the collections permitted the separation of the EEs of February, which exhibited the highest percentages of GI in all wild populations against C. gloeosporioides (63%–75%) (p ≤ 0.01). No antifungal activity was observed during November with the EEs of the three wild populations.

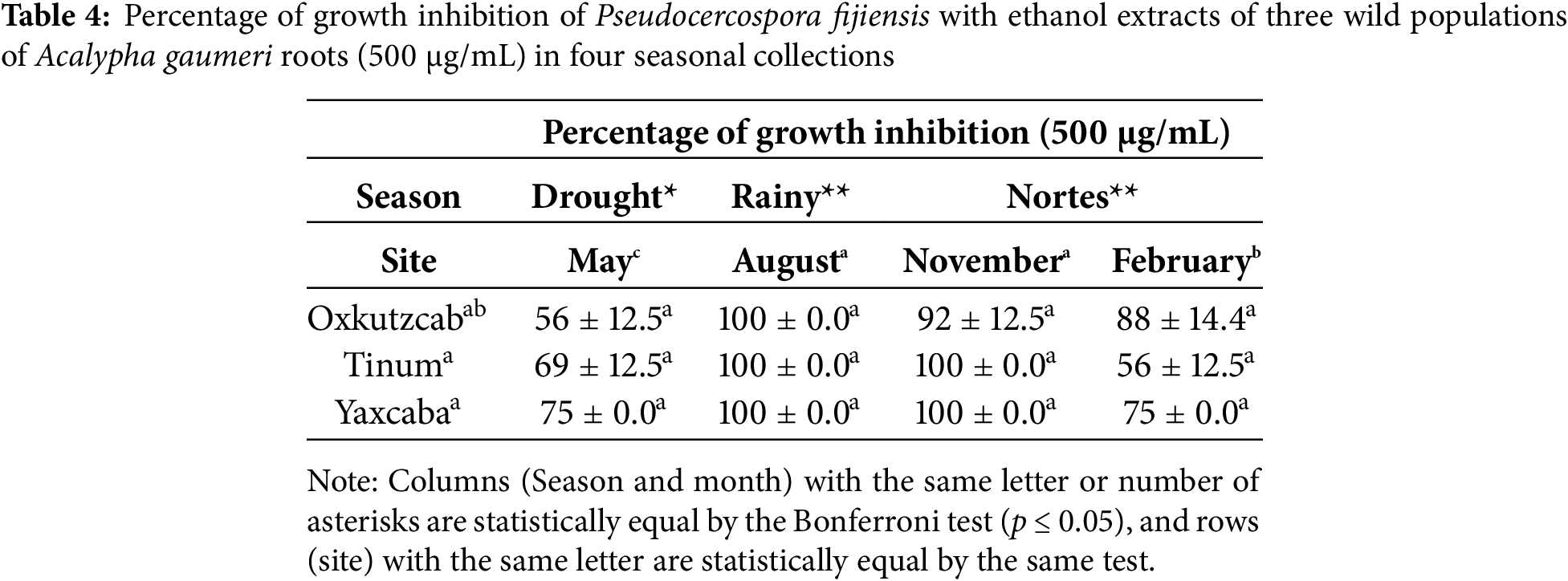

3.2.3 Pseudocercospora fijiensis

The analysis of variance with the 12 EEs obtained from the roots of A. gaumeri revealed a statistically significant difference between collections, seasons and populations (p ≤ 0.01). The EEs collected from all wild populations during the rainy season demonstrated lethal activity at 500 μg/mL against P. fijiensis, with a statistically significant difference between all seasons (p ≤ 0.01). The EEs obtained in the August and November collections showed percentages of 92%–100% of GI values against P. fijiensis in all populations at a concentration of 500 μg/mL. The variance test between populations indicated that the EEs of roots from A. gaumeri exhibited high antifungal activity against P. fijiensis in the collections obtained from Yaxcabá, with inhibition percentages ranging from 75% to 100% at a concentration of 500 μg/mL (Table 4).

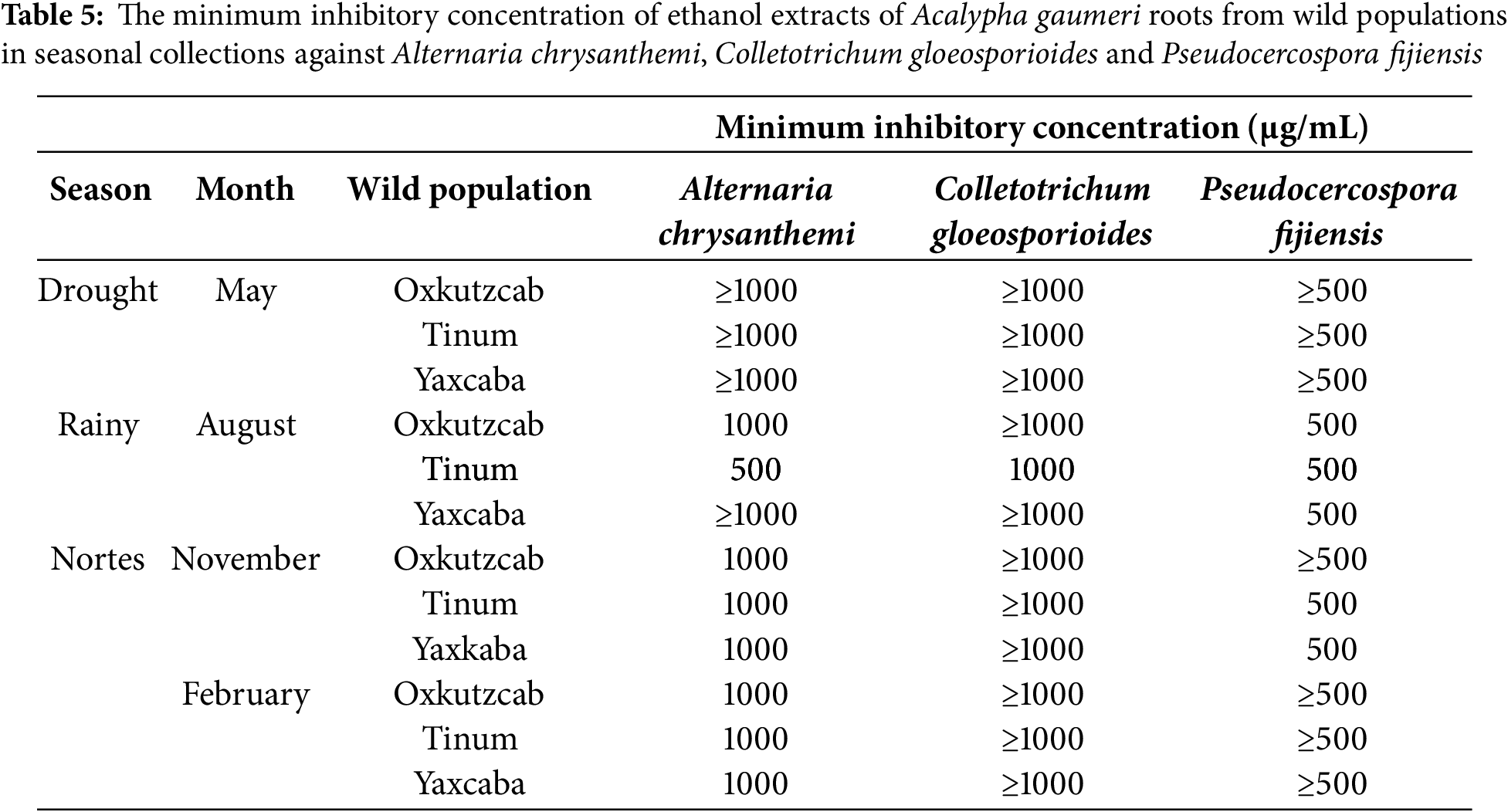

3.3 MICs of Ethanol Extracts of Acalypha gaumeri Roots from Wild Populations

The EE of A. gaumeri roots from the wild population of Tinum during the rainy season showed the lowest MICs against the three phytopathogens, with values of 500 μg/mL against A. chrysanthemi, P. fijiensis, and 1000 μg/mL against C. gloeosporioides. The same MIC values against P. fijiensis were observed with extracts from the three populations collected during the rainy season and from the wild populations of Tinum and Yaxcaba in February (Table 5).

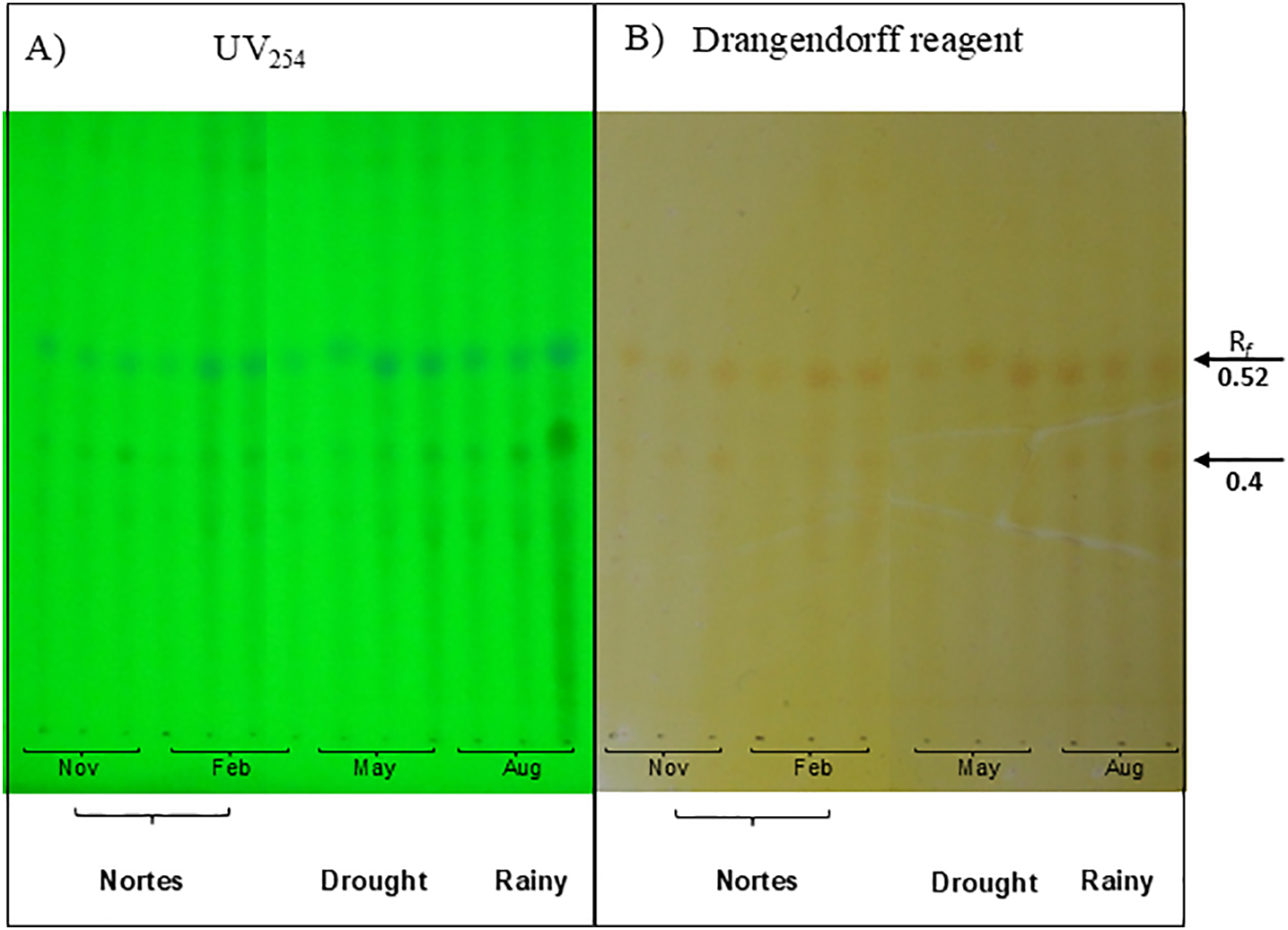

3.4 Alkaloids from Roots of A. gaumeri

The Dragendorff tests revealed the presence of nitrogenous compounds in the active EEs from the A. gumeri roots collected in the three populations and the different seasonal collects. TLC analysis revealed a similar chromatographic profile with several alkaloidal components, including two principal components at Rf values of 0.52 and 0.4, which absorbed at a UV wavelength of 254 nm (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Chemical profile of the nitrogenous extracts of Acalypha gaumeri in a system: n-butanol:acetic acid:water 7:1:2. (A) chromatographic plate revealed in phosphomolybdic acid. (B) chromatographic plate revealed with Dragendorff

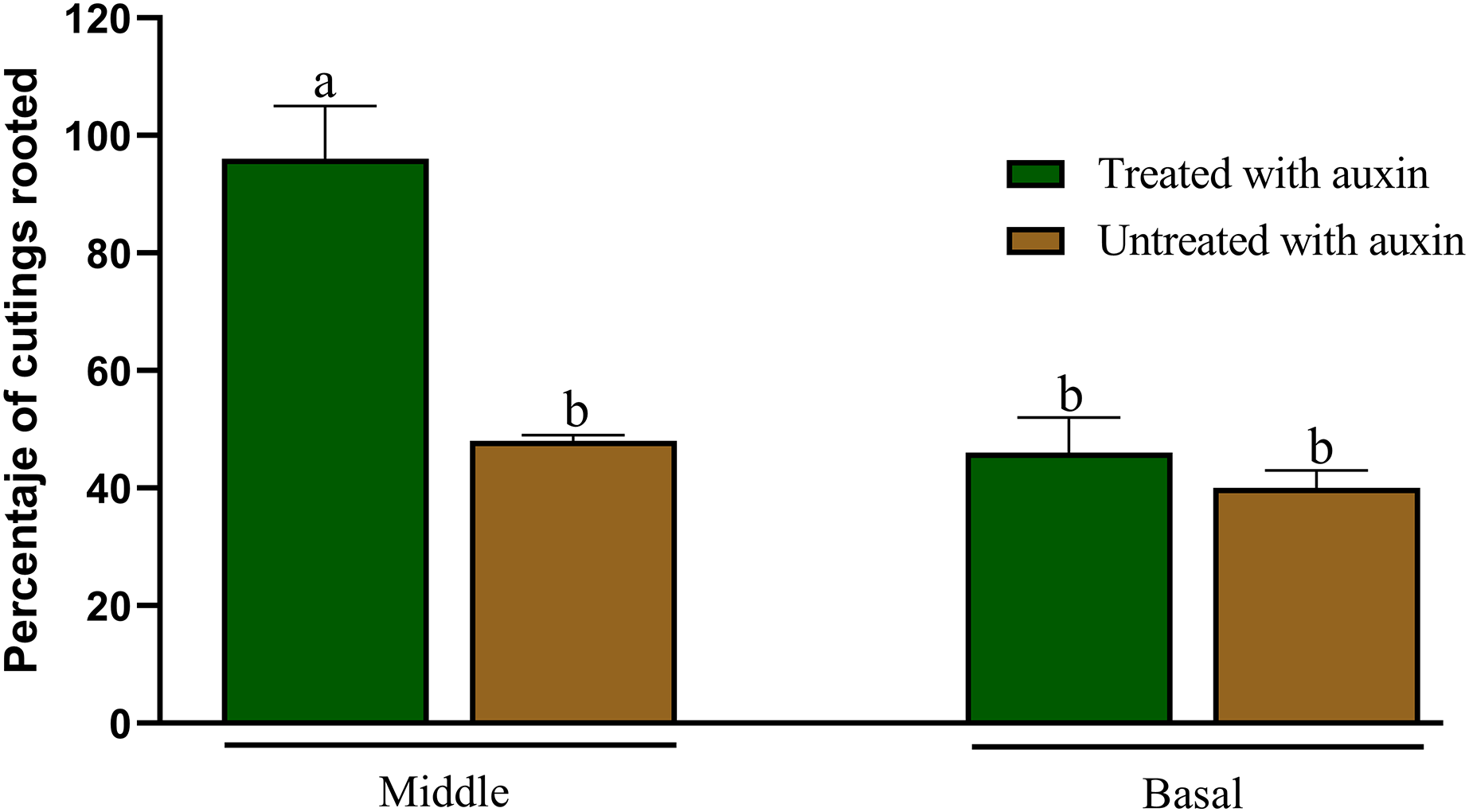

3.5 Propagation by Cuttings of Acalypha gaumeri

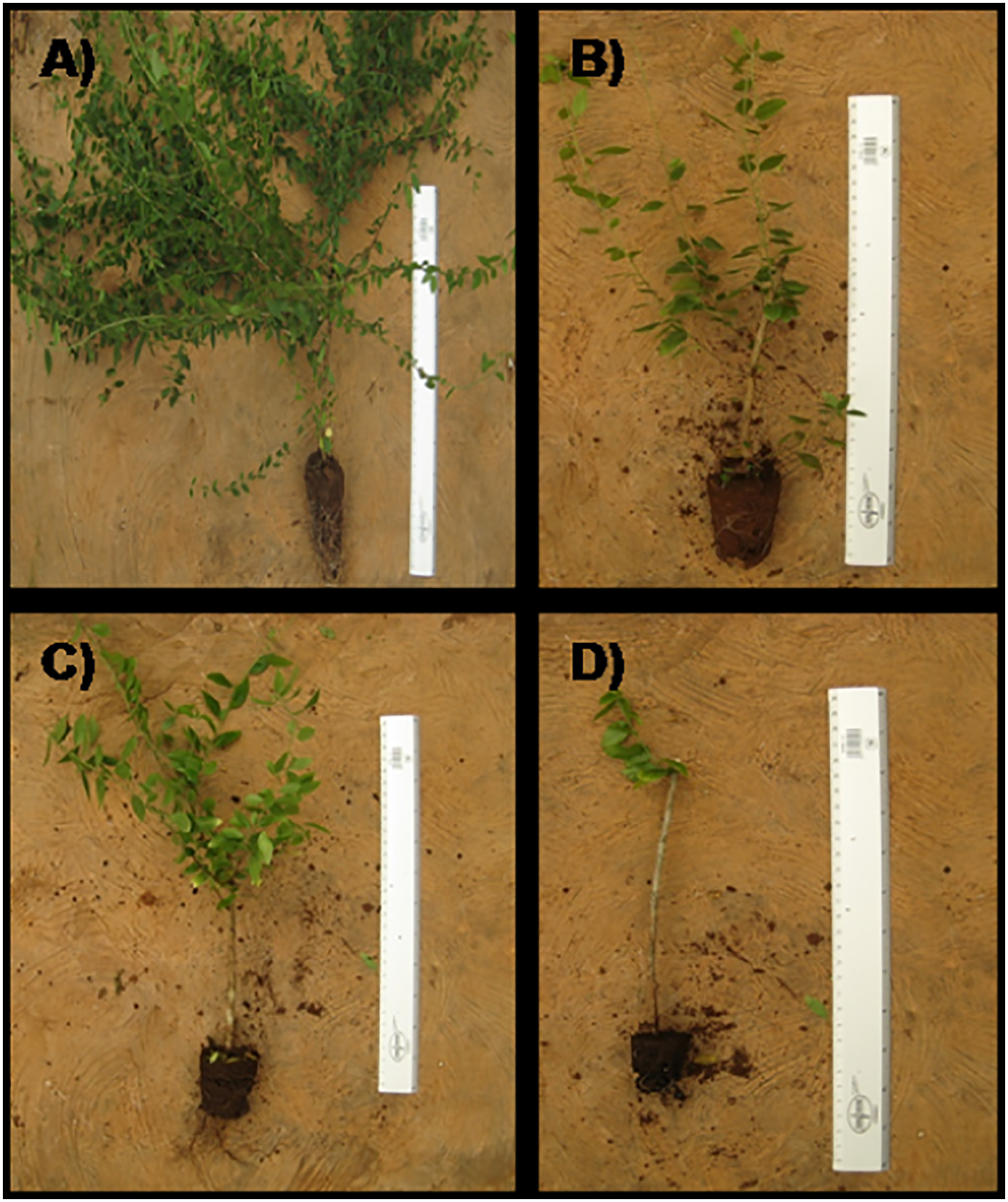

Statistical analyses revealed significant differences (p ≤ 0.01) in rooting percentage between the treatments after 30 days. The highest rooting percentage (96%) was observed in cuttings from the middle layer of the plant when treated with 0.06% auxin (AIB). Without auxin, rooting viability declined to 47% (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Percentage of rooting of cuttings from the middle and basal part of Acalypha gaumeri branches with and without auxins. According to Tukey’s test, different letters determine significant differences at p < 0.05

No statistically significant differences (p = 0.05) in rooting were observed when cuttings from the basal part were treated with or without AIB, with a 48% and 40% success rate, respectively (Fig. 4). Cuttings from the distal part exhibited signs of wilting and mortality after 15 days.

Figure 4: Cuttings of Acalypha gaumeri after 60 days. (A) middle part with auxins. (B) middle part without auxins. (C) basal part with auxins. (D) basal part without auxins

This is the first seasonal study to examine the antifungal activity of A. gaumeri in three distinct wild populations from Oxkutzcab, Tinum and Yaxcaba and to elucidate the impact of seasonal variation. This research contributes to the knowledge regarding the wild populations of A. gaumeri in Yucatan, an endemic species to the Yucatan Peninsula. The study zone is characterized by mid-deciduous and sub-caducifolious forests in a warm, sub-humid climate, with a mean annual temperature exceeding 22°C and the coldest monthly temperature exceeding 18°C [27,28]. The climate type is classified as Awo for Oxkutzcab and Aw1(x′) for Tinum and Yaxcaba, with annual precipitation of 1224, 1133 and 1033 mm, respectively; and the soil types are leptosol-vertisol, rendzina, and cambisol, respectively [27,28].

At least one of the ethanol extracts from A. gaumeri showed antifungal activity against the three plant pathogens tested, dependent on edaphic and seasonal conditions of wild populations. All EEs showed antifungal effects against A. chrysanthemi and P. fijiensis (GI = 56%–100%), and six EEs (50%) inhibited C. gloeosporioides (GI = 38%–100%). The lowest MICs against the three pathogenic fungi were shown by the EEs of the wild Tinum population during the rainy season (August). This effect on the fungal pathogens was similar to that found with the essential oils from leaves of Eucalyptus tereticornis (Myrtaceae) collected during the rainy, summer and winter seasons, exhibited good growth inhibition against Magnaporthe grisea (100%), Rhizoctonia solani (100%), R. bataticola (60%–82%) and F. oxysporum (100%) to 2% (w/v) [34]. In the Yucatán state (Mexico), other studies using the methanol extract from Petiveria alliaceae (Petiveriaceae) stems collected during the rainy season showed the lowest LC50 of 33.3–78.9 μg/mL against three gastrointestinal nematodes of domestic animals [35]. Also, during June (rainy season), the methanol extract from Tridax procumbis root (Asteraceae) contained the highest amount of (3S)-16,17-didehydrofalcarinol, a polyacetilene with antiparasitic activity against Leishmania mexicana [36]. The elevated humidity levels have been observed to stimulate the growth of microorganisms, significantly influencing the production of secondary metabolites in plants and their associated biological activities [37].

The opposite was during the early drought (November), when no antifungal activity was observed in the EEs from the three A. gaumeri root wild populations tested against C. gloeosporioides and drought (may) season, with the low effect on A. chrysanthemi (GI = 75%–88%) and P. fijiensis (GI = 56%–75%). Contrary to the above mentioned, the extracts of Annona purpurea (Annonaceae) roots obtained during the drought season (April) exhibited the most pronounced inhibitory activity against C. gloeosporioides, Curvularia lunata, and F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici at 250 μg/mL [18]. The hexane and ethyl acetate fractions from the pulp of Vitex mollis (Lamiaceae) collected from April to August were effective against C. gloeosporioides with MIC values of 20 and 30 mg/L, respectively [38]. A water deficit may stimulate the production of secondary metabolites; however, a prolonged water deficit may have a detrimental impact [39].

This study demonstrated that different strains exhibited varying sensitivity to the A. gaumeri extract. The A. chrysanthemi strain displayed high sensitivity to all 12 EEs. In contrast, the EEs from the Oxkutzcab and Tinum populations demonstrated the lowest activity against P. fijiensis during May and February, respectively. The C. gloeosporioides strain exhibited differential sensitivity to the EEs from diverse populations and seasonal variations. Other studies have indicated that secondary metabolite levels may be influenced by factors such as soil composition and nutrient stress [21,23].

On the other hand, this is the first report of antifungal activity of A. gaumeri against P. fijiensis, the causal agent of black Sigatoka leaf spots disease in bananas (Musa spp.). In the control of P. fijiensis some plant extracts and their mixtures are reported. In vitro activity in the control of P. fijiensis, the methanol and dichloromethane extracts from Piper pesaresanum (Piperaceae) showed the highest inhibition of the ascospore germination (96% and 100%, respectively) and mycelial radial growth (100% and 78%, respectively) at 1000 mg/L [40]. The botanical fermented aqueous mixture contained Allium sativum (bulbs), Acorus calamus (rhizome and leaves), Tagetes erecta (flowers), Zingiber officinale (rhizome), Azadirachta indica (bark and leaves), Curcuma longa (rhizome) and Gliricidia sepium (leaves) showed inhibition mycelial growth of 86.9% in vitro level and reduced significantly the disease severity index to 39.7 compared with the unsprayed control to 43.88 to 67.77 within 28 days [41]. Foliar ethanol extracts from Heliotropium indicum-Ricinus communis mixture showed anti fungal potential against black sigatoka after the fourth application on plantain [42]. Our contribution expands the antifungal action spectra of A. gaumeri roots, further A. chrysanthemi, A. tagetica, C. gloeosporioides, C. cassiicola, Curvularia sp., F. oxysporum, and Helminthosporium sp. [5,6] and now on P. fijiensis.

Among approximately 570 species belonging to the Acalypha genus, 12 species have been reported against any human pathogenic fungi [43–46] or the yeasts Candida albicans, Cryptococcus spp. and Malassezia furufur [47]. These species include Acalypha alnifolia, A. communis, A. diversifolia, A. fructicosa, A. godseffiana [43,45], A. hispida, A. integrifolia, A. manniana, A. monostachya, A. ornata, [43–46], and A. wilkesiana [43,47]. However, against fungal phytopathogens, the dichloromethane extract from the aerial part of A. diversifolia showed MIC values of 1 mg/mL against F. solani (ATCC 11712) [48]. The crude extracts of Acalypha cuspidata and Acalypha subviscida showed MIC values 12.50 mg/mL and 8.51 mg/mL for inhibiting fungal growth of A. alternata [10]. Also, leaf extract of A. indica at 5% concentration caused inhibition of mycelial growth of A. alternata (37.52%) [9]. The extract from A. indica was in vivo tested against Colletotrichum capsici, the causal agent of anthracnose on chilli fruit, which exhibited a slight antifungal effect [49]. Therefore, the ethanol extract from the roots of A. gaumeri has a broad antifungal spectrum against phytopathogens, which is enriched [5,6].

With regard to population dynamics, documented intra- and inter-population differences in biological activity and, consequently, in secondary metabolism have been observed. The environmental and soil conditions of each site exert an influence on these differences. To illustrate, the interpopulation variability of Inula helenium L. (Asteraceae) in the quantity of phenolics and antioxidant activity exhibited notable variation among the different populations [50]. In a single population of Cistus ladanifer L. growing under similar conditions, the analyses of flavonoids and diterpenes from the leaves of 100 individuals revealed quantitative variation, allowing the detection of four chemotypes. This intra-population variation indicates that external environmental factors influence the metabolism of these compounds but may also vary between individuals [51]. This could explain the variation in the antifungal activity of the EEs from A. gaumeri from Tinum population.

Alkaloidal compounds were detected in all EEs from A. gaumeri. In the Acalypha genus, there have been reports of the occurrence of alkaloids such as acalyphin [52], acalyphamide, aurantiamide, succinimide [43], flindersine [53], epiacalyphin, noracalyphin, epinoracalyphin, ar-acalyphidone, acalyphin amide and epiacalyphin amide cycloside [54]. More recently, 2-amino-3-carboxymuconic acid semialdehyde, N-acetyl-L-phenylalanine [55], 1-phenyl-3,5,7-trimethyl-4,5,6,7-tetrahydropyrazolo(3,4-B)(1,4)diazepine, 1H-1,2,4-triazole, indolizine, methyl-2-oxo-1H,5H,6H,7H-cyclopenta[B] pyridine-3-carboxylate, 3-methyl-2-henylindole, furazano[3,4-β]pyrazin-5(4H)-one, 1H-isoindole-1,3(2H)-dione, quinolinamine, benzenesulfonamide, allylamine, benzamide and indolizine [56] were identified. To date, there is no evidence that these compounds possess antifungal properties. Preliminary purification and identification studies of the active principles of A. gaumeri are ongoing.

This study presents the first report on A. gaumeri propagation, an endemic plant species from the Yucatan Peninsula biodiversity with antifungal potential. Among the approximately 570 species of Acalypha genus, A. hispida [57], A. herzogiana [58], and A. wilkesiana [59] are ornamental plants and widely propagated by cuttings. The middle cuttings propagation of A. gaumeri exhibits greater responsiveness to treatment with the IBA hormone, displaying a higher number of ramifications and superior root vigour compared to those originating from the basal part, which is more lignified. Similar results were reported for A. wilkesiana with IBA at 2000 mg/L, increased root number in herbaceous cuttings [59] and Passiflora edulis cuttings [60]. These findings corroborate the hypothesis proposed by Hanson [61], who suggested that cuttings with a lower degree of lignification respond better to the effect of IBA. These data showed that A. gaumeri can be readily propagated by cuttings with IBA, so this method could be used for its sustainability. The sexual propagation of A. gaumeri through seed was less efficient, and previous research indicates the existence of a notable physiological dormancy in seeds belonging to the genus Acalypha [62]. Therefore, alternative seed treatment strategies should be evaluated to increase the germination percentage. The antifungal efficacy of A. gaumeri species is the focus of continuous study, with particular emphasis on its effectiveness when used in conjunction with ex-situ propagated plants.

The antifungal activity of A. gaumeri roots is subject to stimulation by seasonal variations, soil growth conditions, and pathogen sensitivity. The population of Tinum growing in rendzine soil under high humidity conditions produced compounds lethal to all three plant pathogens tested. A. gaumeri broadens its spectrum of antifungal activity by inhibiting P. fijiensis. The three populations of A. gaumeri biosynthetised alkaloidal compounds in all seasons. However, the results obtained are from an annual analysis, so it would be important to monitor antifungal activity for several years since environmental conditions currently change annually due to climate change. For this reason, it is important to establish a propagation method that allows the control of optimal conditions for harvesting the plant with the highest amount of antifungal compounds. In this sense, propagation of A. gaumeri by cuttings using IBA is very efficient. The findings of the present study contribute to the existing knowledge regarding the management of A. gaumeri, a wild endemic species with considerable potential for utilization as a natural product in agricultural applications in the near future.

Acknowledgement: We thank Irma L. Medina Baizabal from CICY for her valuable technical assistance in the laboratory and Sergio Pérez, Miriam Juan-Qui and Narcedalia Gamboa-Angulo, CICY library staff. Arely A. Vargas-Díaz thanks to proyecto CIR/027/2024.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by Secihti project PDCPN-2015-266, México.

Author Contributions: All authors contributed to the study conceptualization and design; Methodology: Arely A. Vargas-Díaz; Formal analysis and investigation: Arely A. Vargas-Díaz and Marcela Gamboa-Angulo; MEB experimental data: Silvia Andrade-Canto; Writing—original draft preparation: Arely A. Vargas-Díaz and Marcela Gamboa-Angulo; Supervisión: Marcela Gamboa-Angulo, Jairo Cristóbal-Alejo, Beatriz Hernández-Carlos and Daisy Pérez-Brito; Resources: Marcela Gamboa-Angulo; Funding acquisition: Marcela Gamboa-Angulo; Writing—review and editing: Marcela Gamboa-Angulo, Jairo Cristóbal-Alejo, Beatriz Hernández-Carlos and Daisy Pérez-Brito. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support this study are available from the corresponding author, Marcela Gamboa-Angulo, upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Deresa EM, Diriba TF. Phytochemicals as alternative fungicides for controlling plant diseases: a comprehensive review of their efficacy, commercial representatives, advantages, challenges for adoption, and possible solutions. Heliyon. 2023;9(3):e13810. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Fullerton RA, Casonato SG. The infection of the fruit of ‘Cavendish’ banana by Pseudocercospora fijiensis, cause of black leaf streak (black Sigatoka). Eur J Plant Pathol. 2019;155(3):779–87. doi:10.1007/s10658-019-01807-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Couoh EV, Briceno MAS, Alejo JC, Sánchez E, Suárez JMT. Diagnóstico y alternativas de manejo químico del tizón foliar (Alternaria chrysanthemi Simmons and Croisier) del crisanthemo (Chrysanthemum morifoliumRamat.) Kitamura in Yucatán, México. Rev Mex Fitopatol. 2005;23:49–56. (In Spain). [Google Scholar]

4. Zakaria L. Diversity of Colletotrichum species associated with anthracnose disease in tropical fruit crops—a review. Agriculture. 2021;11(4):297. doi:10.3390/agriculture11040297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gamboa-Angulo MM, Cristóbal-Alejo J, Medina-Baizabal IL, Chí-Romero F, Méndez-González R, Simá-Polanco P, et al. Antifungal properties of selected plants from the Yucatan peninsula. Mexico World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;24(9):1955–9. doi:10.1007/s11274-008-9658-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Vargas-Díaz AA, Gamboa-Angulo M, Medina-Baizabal IL, Pérez Brito D, Alejo JC, Ruiz Sánchez E. Evaluación de extractos de plantas nativas yucatecas contra Alternaria chrysanthemi y espectro de actividad antifúngica de Acalypha gaumeri. Rev Mex Fitopatol. 2014;32:1–11. (In Spain). [Google Scholar]

7. Vargas-Díaz AA, Cristóbal-Alejo J, Canto-Canché B, Gamboa-Angulo MM. Aqueous extracts from Acalypha gaumeri and Bonellia flammea for leaf blight control in Chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum morifolium). Rev Mex De Fitopatol Mex J Phytopathol. 2021;40(1):40–58. doi:10.18781/r.mex.fit.2109-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chekuri S, Lingfa L, Panjala S, Sai Bindu KC, Anupalli RR. Acalypha indica L.—an important medicinal plant: a brief review of its pharmacological properties and restorative potential. Eur J Med Plants. 2020;31(11):1–10. doi:10.9734/ejmp/2020/v31i1130294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ahmad L, Pathak N. Antifungal potential of plant extracts against seed-borne fungi isolated from barley seeds (Hordeum vulgare L.). J Plant Pathol Microbiol. 2016;7(5):5–8. doi:10.4172/2157-7471.1000350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Lira-de León KI, Ramírez-Mares MV, Sánchez-López V, Ramírez-Lepe M, Salas-Coronado R, Santos-Sánchez NF, et al. Effect of crude plant extracts from some oaxacan flora on two deleterious fungal phytopathogens and extract compatibility with a biofertilizer strain. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:383. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2014.00383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Cristóbal-Alejo J, Tun-Suárez JM, Moguel-Catzín S, Marbán-Mendoza N, Medina-Baizabal L, Sima-Polanco P, et al. In vitro sensitivity of Meloidogyne incognita to extracts from native Yucatecan plants. Nematropica. 2006;36:89–97. [Google Scholar]

12. Ruiz-Sanchez E, Cruz-Estrada A, Gamboa-Angulo M, Bórges-Argáez R. Insecticidal effects of plant extracts on immature whitefly Bemisia tabaci Genn. (Hemiptera: aleyroideae). Electron J Biotechnol. 2013;16(1):6. doi:10.2225/vol16-issue1-fulltext-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Schmitter-Soto JJ, Comín FA, Escobar-Briones E, Herrera-Silveira J, Alcocer J, Suárez-Morales E, et al. Hydrogeochemical and biological characteristics of cenotes in the Yucatan Peninsula (SE Mexico). Hydrobiologia. 2002;467(1):215–28. doi:10.1023/a:1014923217206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Li Y, Kong D, Fu Y, Sussman MR, Wu H. The effect of developmental and environmental factors on secondary metabolites in medicinal plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020;148(6):80–9. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.01.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Prinsloo G, Nogemane N. The effects of season and water availability on chemical composition, secondary metabolites and biological activity in plants. Phytochem Rev. 2018;17(4):889–902. doi:10.1007/s11101-018-9567-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Shi Y, Yang L, Yu M, Li Z, Ke Z, Qian X, et al. Seasonal variation influences flavonoid biosynthesis path and content, and antioxidant activity of metabolites in Tetrastigma hemsleyanum Diels & Gilg. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0265954. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0265954. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Botha LE, Prinsloo G, Deutschländer MS. Variations in the accumulation of three secondary metabolites in Euclea undulata Thunb. var. myrtina as a function of seasonal changes. S Afr N J Bot. 2018;117:34–40. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2018.04.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. De-la-Cruz-Chacón I, Riley-Saldaña CA, Arrollo-Gómez S, Sancristóbal-Domínguez TJ, Castro-Moreno M, González-Esquinca AR. Spatio-temporal variation of alkaloids in Annona purpurea and the associated influence on their antifungal activity. Chem Biodivers. 2019;16(2):e1800284. doi:10.1002/cbdv.201800284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Dias ALB, Batista HRF, Sousa WC, Bailão EFLC, Rocha JD, Sperandio EM, et al. Psidium myrtoides O. Berg fruit and leaves: physicochemical characteristics, antifungal activity and chemical composition of their essential oils in different seasons. Nat Prod Res. 2022;36(4):1043–7. doi:10.1080/14786419.2020.1844689. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Saunier A, Greff S, Blande JD, Lecareux C, Baldy V, Fernandez C, et al. Amplified drought and seasonal cycle modulate Quercus pubescens leaf metabolome. Metabolites. 2022;12(4):307. doi:10.3390/metabo12040307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Bhat BA, Islam ST, Ali A, Sheikh BA, Tariq L, Islam SU, et al. Role of micronutrients in secondary metabolism of plants. In: Aftab T, Hakeem KR, editors. Plant micronutrients. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. p. 311–29. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-49856-6_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Bistgani ZE, Hashemi M, Dacosta M, Craker L, Maggi F, Morshedloo MR. Effect of salinity stress on the physiological characteristics, phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of Thymus vulgaris L. and Thymus daenensis Celak. Ind Crops Prod. 2019;135:311–20. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.04.055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Pant P, Pandey S, Dall’acqua S. The influence of environmental conditions on secondary metabolites in medicinal plants: a literature review. Chem Biodivers. 2021;18(11):e2100345. doi:10.1002/cbdv.202100345. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Carnevali Fernández-Concha G, Ramírez-Morillo I, Pérez-Sarabia JE, Tapia-Muñoz JL, Estrada Medina H, Cetzal-Ix W, et al. Assessing the risk of extinction of vascular plants endemic to the Yucatán peninsula biotic province by means of distributional data. Annals. 2021;106:424–57. doi:10.3417/2021661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Duno De Stefano R, Aguilar-Canché M, Carnevali Fernández-Concha G, Ramírez-Morillo I, Tapia-Muñoz JL, Reyes-Palomeque G, et al. Seasonally flooded Coquinal: typifying a particular plant association in the northern Yucatan peninsula. Mexico Bot Sci. 2024;102(2):513–33. doi:10.17129/botsci.3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Flora de la Península de Yucatán [Internet]. [cited 2025 May 24]. Available from: https://www.cicy.mx/sitios/flora%20digital/ficha_virtual.php?especie=1297. [Google Scholar]

27. García G, Secaira F. A vision for the future: cartography of the Maya, Zoque and Olmec forests. Pronatura Península de Yucatán-the nature conservancy. San José, Costa Rica: Nature Conservation Association; 2006. 41 p. (In Spain). [Google Scholar]

28. Hijmans RJ, Cameron SE, Parra JL, Jones PG, Jarvis A. Very high resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol. 2005;25(15):1965–78. doi:10.1002/joc.1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Stahl E. Thin-layer chromatography: a laboratory handbook. 2nd ed. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1969. 1041 p. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-88488-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Rodríguez-García CM, Ruiz-Ruiz JC, Peraza-Echeverría L, Peraza-Sánchez SR, Torres-Tapia LW, Pérez-Brito D, et al. Antioxidant, antihypertensive, anti-hyperglycemic, and antimicrobial activity of aqueous extracts from twelve native plants of the Yucatan coast. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213493. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0213493. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. CLSI M44. Method for antifungal disk diffusion susceptibility testing of yeasts. In: Clinical and laboratory standards institute. 3rd ed. Wayne, PA, USA; 2018. doi:10.1007/978-1-59745-134-5_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. SPSS Inc. IBM Corp. Statistical package for the social sciences statistics, windows, versión 18.0 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 9]. Available from: https://www.ibm.com/mx-es/products/spss-statistics. [Google Scholar]

33. Cruz-Estrada A, Ruiz-Sánchez E, Baizabal IM, Balam-Uc E, Gamboa-Angulo M. Effect of Eugenia winzerlingii extracts on Bemisia tabaci and evaluation of its nursery propagation. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2019;88(2):161–70. doi:10.32604/phyton.2019.05809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Khaiper M, Poonia PK, Redhu I, Verma P, Sheokand RN, Nasir M, et al. Chemical composition, antifungal and antioxidant properties of seasonal variation in Eucalyptus tereticornis leaves of essential oil. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;222(3):119669. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.119669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Janett Flota-Burgos G, Alberto Rosado-Aguilar Jé, Iván Rodríguez-Vivas R, Borges-Argáez Río, Gamboa-Angulo M, Martínez-Ortiz-de-Montellano C. Anthelmintic activity of petiveria alliacea, bursera simaruba y casearia corymbosa collected in two seasons on ancylostoma caninum, haemonchus placei and cyathostomins. Act Sci Vet Sci. 2020;2(12):12–24. doi:10.31080/asvs.2020.02.0113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Larqué-García H, Torres-Tapia LW, Vera-Ku M, Gamboa-León R, Novelo-Castilla S, Coral-Martínez TI, et al. Quantitative seasonal variation of the falcarinol-type polyacetylene (3S)-16,17-didehydrofalcarinol and its spatial tissue distribution in Tridax procumbens. Phytochem Anal. 2020;31(2):183–90. doi:10.1002/pca.2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Gershenzon J. Changes in the levels of plant secondary metabolites under water and nutrient stress. In: Timmermann BN, Steelink C, Loewus FA, editors. Phytochemical adaptations to stress. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1984. p. 273–320. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-1206-2_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. López-Velázquez JG, Delgado-Vargas F, Ayón-Reyna LE, López-Angulo G, Bautista-Baños S, Uriarte-Gastelum YG, et al. Postharvest application of partitioned plant extracts from Sinaloa, Mexico for controlling papaya pathogenic fungus Colletotrichum gloeosporioides. J Plant Pathol. 2021;103(3):831–42. doi:10.1007/s42161-021-00838-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Cheng L, Han M, Yang LM, Li Y, Sun Z, Zhang T. Changes in the physiological characteristics and baicalin biosynthesis metabolism of Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi under drought stress. Ind Crops Prod. 2018;122(9):473–82. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.06.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Niño J, Correa YM, Mosquera OM. In vitro evaluation of Colombian plant extracts against Black Sigatoka (Mycosphaerella fijiensis Morelet). Arch Phytopathol Plant Prot. 2011;44(8):791–803. doi:10.1080/03235401003672939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Dissanayake M, Herath H, Jayasekara HM, Abeywickrame PD. Efficacy of botanical mixture and fungicides to combat sigatoka disease in banana cultivation. Asian J Mycol. 2023;6:26–35. doi:10.5943/ajom/6/2/2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Vargas Hernández JL, Rodríguez D, Sanabria ME, Hernández J. Effect of three plant extracts on plantain black sigatoka (Musa AAB cv Harton). Rev UDO Agrícola. 2009;9:182–90. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

43. Seebaluck R, Gurib-Fakim A, Mahomoodally F. Medicinal plants from the genus Acalypha (Euphorbiaceae)—a review of their ethnopharmacology and phytochemistry. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015;159(2):137–57. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Thambiraj J. Study of antimicrobial activity of the folklore medicinal plant, Acalypha fruticosa Forssk. Kongunadu Res J. 2017;4(2):57–60. doi:10.26524/krj203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Asekunowo AK, Ashafa AOT, Okoh OO, Asekun OT, Familoni OB. Evaluation of phytochemical constituents and antifungal properties of different solvent extracts of the leaf of Acalypha godseffiana. Mull Arg Uni Lagos J Basic Med Sci. 2017;5:14–20. [Google Scholar]

46. Seebaluck-Sandoram R, Lall N, Fibrich B, Van Staden AB, Mahomoodally F. Antibiotic-potentiating activity, phytochemical profile, and cytotoxicity of Acalypha integrifolia Willd (Euphorbiaceae). J Herb Med. 2018;11(2):53–9. doi:10.1016/j.hermed.2017.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Sherifat KO, Itohan AM, Adeola SO, Adeola KM, Aderemi OL. Anti-fungal activity of Acalypha wilkesiana: a preliminary study of fungal isolates of clinical significance. Afr J Infect Dis. 2022;16(1):21–30. doi:10.21010/ajid.v16i1.4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Niño J, Mosquera OM, Correa YM. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of crude plant extracts from Colombian biodiversity. Rev Biol Trop. 2012;60(4):1535–42. doi:10.15517/rbt.v60i4.2071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Chaurasiya U, Solanki MK, Patel S. Medicinal plant extracts enhanced the shelf life of chilli fruits against the anthracnose disease through defense modulation. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2023;107(9):104604. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2023.104604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Zlatić N, Jakovljević D, Stanković M. Temporal, plant part, and interpopulation variability of secondary metabolites and antioxidant activity of Inula helenium L. Plants. 2019;8(6):179. doi:10.3390/plants8060179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Valares Masa C, Alías Gallego JC, Chaves Lobón N, Sosa Díaz T. Intra-population variation of secondary metabolites in Cistus ladanifer L. Molecules. 2016;21(7):945. doi:10.3390/molecules21070945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Nahrstedt A, Kant JD, Wray V. Acalyphin, a cyanogenic glucoside from Acalypha indica. Phytochemistry. 1982;21(1):101–5. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(82)80022-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Taufiq-Yap YH, Peh TH, Ee GCL, Rahmani M. Chemical investigation of Acalypha indica (Euphorbiaceae). Orient J Chem. 2000;16:249–51. [Google Scholar]

54. Hungeling M, Lechtenberg M, Fronczek FR, Nahrstedt A. Cyanogenic and non-cyanogenic pyridone glucosides from Acalypha indica (Euphorbiaceae). Phytochemistry. 2009;70(2):270–7. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.12.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Fadhila SI, Hayati EK, Rafi M, Sabarudin A. Effect of ethanol-water concentration as extraction solvent on antioxidant activity of Acalypha indica. Al-Kim J Ilmu Kim Dan Terap. 2023;10(2):133–42. doi:10.15575/ak.v10i2.30081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Odion EE, Odiete AA, Eravweroso CO. Identification of alkaloids from the methanol leaf extract of Acalypha wilkesiana using HPLC/GC-MS. Niger J Pharm. 2024;58(1):25–32. doi:10.51412/psnnjp.2024.03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Rifnas LM, Vidanapathirana NP, Silva TD, Dahanayake N, Subasinghe S, Weerasinghe SS, et al. Vegetative propagation of Acalypha hispida through cuttings with different types of media. Inter J Minor Fruits Med Aromatic Plants. 2021;7(2):89–94. doi:10.53552/ijmfmap.2021.v07ii02.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Steinmann VW, Levin GA. Acalypha herzogiana (Euphorbiaceaethe correct name for an intriguing and commonly cultivated species. Brittonia. 2011;63(4):500–4. doi:10.1007/s12228-011-9181-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Fernandes Sarkis L, Fernandes Guareschi R, Almeida dos Santos C, Sebastião de Paula Araujo J, dos Santos Rosa de Oliveira V, Cândido da Silva Rodrigues G. Production of Acalypha wilkesiana seedlings using stem cuttings. Comun Sci. 2022;13:e3665. doi:10.14295/cs.v13.3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Bakir MA, Saddam HA. Effect of cutting type and IBA concentration on propagation of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis Sims). Hortic Res J. 2023;1(3):81–8. doi:10.21608/hrj.2023.321775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Hanson CK. The effects of indobutyric acid on rooting Lovell and Nemaguard peach cuttings. HortScience. 1978;13(3S):374. doi:10.21273/hortsci.13.3s.321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Gupta S, Bandopadhyay A. Overcoming seed dormancy of Acalypha indica L. (Euphorbiaceaean important medicinal plant. Indian J Plant Sci. 2013;2:72–9. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools