Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Planting Years Drive Structural and Functional Shifts in the Rhizosphere Bacterial Microbiome of Zanthoxylum bungeanum

1 Gansu Academy of Forestry Sciences, Lanzhou, 730030, China

2 College of Forestry, Gansu Agricultural University, Lanzhou, 730070, China

* Corresponding Author: Jun-Ying Zhao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Biodiversity (Cultivated and Wild Flora) and Its Utility in Plant Breeding)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(9), 2815-2838. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.069196

Received 17 June 2025; Accepted 29 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

This study investigated the effects of planting duration (1, 5, 10 and 15 years) on soil properties, bacterial community diversity, and function in the rhizosphere of Zanthoxylum bungeanum. We employed Illumina high-throughput sequencing and PICRUSt2 functional prediction to analyze the structure and functional potential of rhizosphere soil bacterial communities. The Mantel test and redundancy analysis were used to identify physicochemical factors influencing bacterial community structure and function. The results indicated significant differences in rhizosphere soil physicochemical properties across planting years: the content of organic matter, alkaline hydrolyzable nitrogen in the soil, as well as the activity of invertase, urease, and alkaline phosphatase initially increased and then decreased, while available potassium, Olsen-phosphorus content, and peroxidase activity continued to increase. However, bacterial alpha diversity (Chao1 and Shannon indices) and the number of amplicon sequence variants increased continuously with planting duration. Principal coordinate analysis and Adonis tests revealed that the planting year significantly influenced the bacterial community structure (p < 0.05). The phyla Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Acidobacteriota and Chloroflexi collectively constituted 56.7% to 71.2% of the relative abundance, representing the dominant taxa. PICRUSt2 predictions indicated key functional categories (cellular processes, metabolism, genetic information processing, and environmental information processing) each exceeding 10% relative abundance. BugBase analysis revealed a progressive increase in aerobic and oxidative stress-tolerant bacteria and a decrease in anaerobic and potentially pathogenic bacteria. Differential indicator species analysis identified Firmicutes, Planctomycetes, Methylomirabilota and Actinobacteriota as key discriminators for the 1-, 5-, 10- and 15-year stages, respectively. Organic matter, alkaline phosphatase, soil pH, and available phosphorus were the primary physicochemical drivers of bacterial communities. Notably, soil organic matter significantly influenced both the community structure (p < 0.05) and predicted metabolic functions (p < 0.05). In conclusion, prolonged planting duration significantly enhanced rhizosphere microbial diversity and functional gene abundance in Z. bungeanum while driving the structural succession of bacterial communities dominated by Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Acidobacteriota, and Chloroflexi. This ecological shift, characterized by increased aerobic/oxidative-stress taxa and decreased anaerobic/pathogenic bacteria, was primarily regulated by soil organic matter, a key driver shaping both community structure and metabolic functions, ultimately improving soil microecological health.Keywords

Soil microorganisms are integral components of ecosystems and play a pivotal role in maintaining forest ecosystem functions and soil nutrient cycling [1]. The diversity and composition of soil microbial communities are highly sensitive to environmental changes [2], particularly to factors such as precipitation, temperature, soil pH, and nutrient availability [3]. Consequently, microbial community attributes are key indicators of soil quality and health. Vegetation significantly influences the diversity and composition of soil bacterial communities by altering the physicochemical properties of soil [4]. Furthermore, in healthy soils, a diverse and structurally stable microbial community ensures the proper functioning of its constituent functional groups, ultimately enhancing plant productivity [5].

The composition and diversity of soil microbial communities undergo dynamic shifts over time [3]. Previous studies have confirmed that forest planting duration significantly influences microbial community composition and diversity. As planting years increase, the abundance, community structure, and diversity of rhizosphere microorganisms undergo marked changes [6]. Studies have indicated that divergent responses among plant species and rhizobacterial diversity in Swietenia macrophylla increase with planting time [7], whereas in peonies, both the abundance and diversity of rhizosphere bacteria decline with longer planting duration [8]. Furthermore, soil characteristics such as nutrient status and enzyme activity drive changes in soil microbial community composition and diversity [9]. A study by Ye et al. [10] on Torreya grandis rhizosphere soil microorganisms revealed that although planting duration did not significantly affect bacterial diversity, it significantly altered microbial community composition. Furthermore, planting duration, C/N ratio, total soil nitrogen, and organic matter content were the key drivers shaping the rhizosphere microbial community structure. These findings underscore the pronounced plant species specificity in the response of rhizosphere bacterial communities to planting time. Therefore, the planting duration of Z. bungeanum may shape the composition and diversity of soil microbial communities by altering the rhizosphere soil properties. An in-depth analysis of the rhizosphere bacterial community composition and diversity across different planting ages will help elucidate the response mechanisms of soil bacteria to forest planting duration and environmental factors, which are crucial for promoting sustainable development in economic forest management.

The Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture in Gansu Province is a major production area for Zanthoxylum bungeanum in China. In recent years, the local Z. bungeanum cultivation area has expanded rapidly, and it has emerged as the primary economic forest crop in the prefecture. However, increasing planting duration (particularly under semi-natural cultivation) combined with extensive management practices has led to increasingly prominent issues of declining quality and productivity of Z. bungeanum in the region [11]. Extensive research has demonstrated that increasing tree-planting duration reduces soil microbial diversity and diminishes the abundance of key functional microbial groups. Consequently, these alterations lower soil productivity and increase disease incidence [12], severely compromising the ecological and economic benefits of trees. Currently, the mechanisms by which planting duration affects bacterial diversity and community composition in Z. bungeanum rhizosphere soil remain unclear.

Therefore, this study employed high-throughput sequencing to analyze the diversity and composition of rhizosphere soil microbial communities in Z. bungeanum across different planting durations. By integrating soil physicochemical properties and enzyme activity data, we explored the correlations between the microbial community structure and soil environmental factors. The results aimed to clarify the drivers of rhizosphere microbial community evolution and provide a scientific foundation for the sustainable management of Z. bungeanum industry in the Linxia Prefecture.

2 Overview of the Research Area

The research area is located in Lujia Village, Lianhua Town, Linxia County, Gansu Province (102°41′–103°40′ E, 34°57′–36°12′ N). Situated at an elevation of 1700 m, it experiences a typical continental monsoon climate characterized by distinct seasonal variations: dry winters and springs and humid summers and autumns. The region receives an average annual rainfall of 385 mm, has a mean annual temperature of 6.8°C, and enjoys a frost-free period of approximately 170 days.

3.1 Sample Collection and Processing

Conduct field investigation and soil sample collection in Lujia Village, Lianhua Town, Linxia County, Linxia Prefecture, Gansu Province, China in June 2023, survey plots were established in artificially planted Z. bungeanum stands of different ages (1, 5, 10, and 15 years) using a spatial rather than a temporal approach. The site conditions were consistent across the designated plots (RS1, RS5, RS10 and RS15). Rhizosphere soil samples were collected within a 50 cm radius of each trunk from four cardinal directions (east, west, south, and north). Within each age class, the plants were grouped into three replicate sampling areas. Rhizosphere soil was collected as previously described [13]. Soil from the four directions around each sampled plant was combined into an equal composite sample. Subsequently, composites from the 3 replicate plants within each age group were pooled to form a single representative sample per age group, yielding a total of 12 samples. The samples were transported to the laboratory in insulated containers with ice packs. Large rocks and plant debris were removed with sterile tweezers. One portion of each sample was sieved (2 mm) and stored at −80°C for bacterial diversity analysis, while the remaining portion was air-dried and sieved (1 mm) for physicochemical property assessment.

3.2 Determination of Soil Physical and Chemical Properties

The chemical properties of the soil were assessed using the methods outlined in the agricultural soil analysis [14]. The organic matter content was measured using the potassium dichromate oxidation-ferrous sulfate titration method, alkali hydrolyzed nitrogen (AN) content was evaluated using the alkaline hydrolysis diffusion method, available phosphorus (AP) content was determined using the Olsen method, available potassium (AK) content was measured using the flame photometry method, and soil pH value was assessed using the potentiometric method.

3.3 Determination of Soil Enzyme Activity

Soil enzyme activities were determined according to the methods outlined in a previous study [15]. Peroxidase (POD) activity was assessed using the potassium permanganate titration method, while invertase (IE) and cellulase (CL) activities were evaluated using the 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid colorimetric method. Urease (UE) activity was measured using the phenol-sodium hypochlorite colorimetric method and alkaline phosphatase (AKP) activity was determined using the disodium phenyl phosphate colorimetric method.

3.4 DNA Extraction and High-Throughput Amplicon Sequencing

Total soil DNA was extracted from 1.0 g of the frozen soil samples using a soil DNA extraction kit (MP Biomedicals, 116560200, Irvine, CA, USA). High throughput sequencing of rhizosphere soil bacteria using Illumina MiSeq platform from Lianchuang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Hang Zhou, China). The V3-V4 region of 16S rDNA, amplified with primers 341F (5′-CCTACGGGNGGCGCGCAG-3′) and 805R (5′-GACTACHVGGTATCTAATCC-3′), was subjected to sequencing analysis. Raw sequencing data were processed using the Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology2 (QIIME2, version 2019.4) software. Paired-end reads were assigned to the respective samples based on unique barcodes and were subsequently truncated by removing the barcodes and primer sequences. Amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) were generated by clustering high-quality sequences using the DADA2 pipeline in QIIME2.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare the significance of soil chemical properties, bacterial community diversity, and taxonomic composition across different planting durations using Tukey’s least significant difference test. Statistical significance was asset at p < 0.05. The species composition of different groups and common unique species was assessed using Venn diagrams analyzed with the “VennDiagram” package in R version 3.6.1. Alpha diversity was measured by calculating the Shannon and Chao1 indices using QIIME2 software. Beta diversity differences based on Bray–Curtis distance were visualized and quantified using principal coordinate analysis and permutational multivariate ANOVA (PERMANOVA). The relative abundance of functional genes in the samples was compared with Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database information using PICRUSt2 software in R version 4.2. The correlation between differences in bacterial community structure and functional gene differences was analyzed using Mantel tests from the vegan package in R software. Redundancy analysis (RDA) was performed using Canoco 5 software to investigate the key physicochemical factors affecting soil bacterial classes and functional genes, followed by an Envfit test for validation purposes. To further confirm the species that positively responded to planting years, a heatmap analysis was used to characterize the dominant strains under different planting durations/years/time periods. Mantel tests and Pearson correlation analyses were conducted using the linkET package in R version 4.0.2 to simultaneously examine the drivers influencing microbial community composition at both the phylum and class levels. Random forest algorithms were used to study the roles of these factors in microbial community assembly [16].

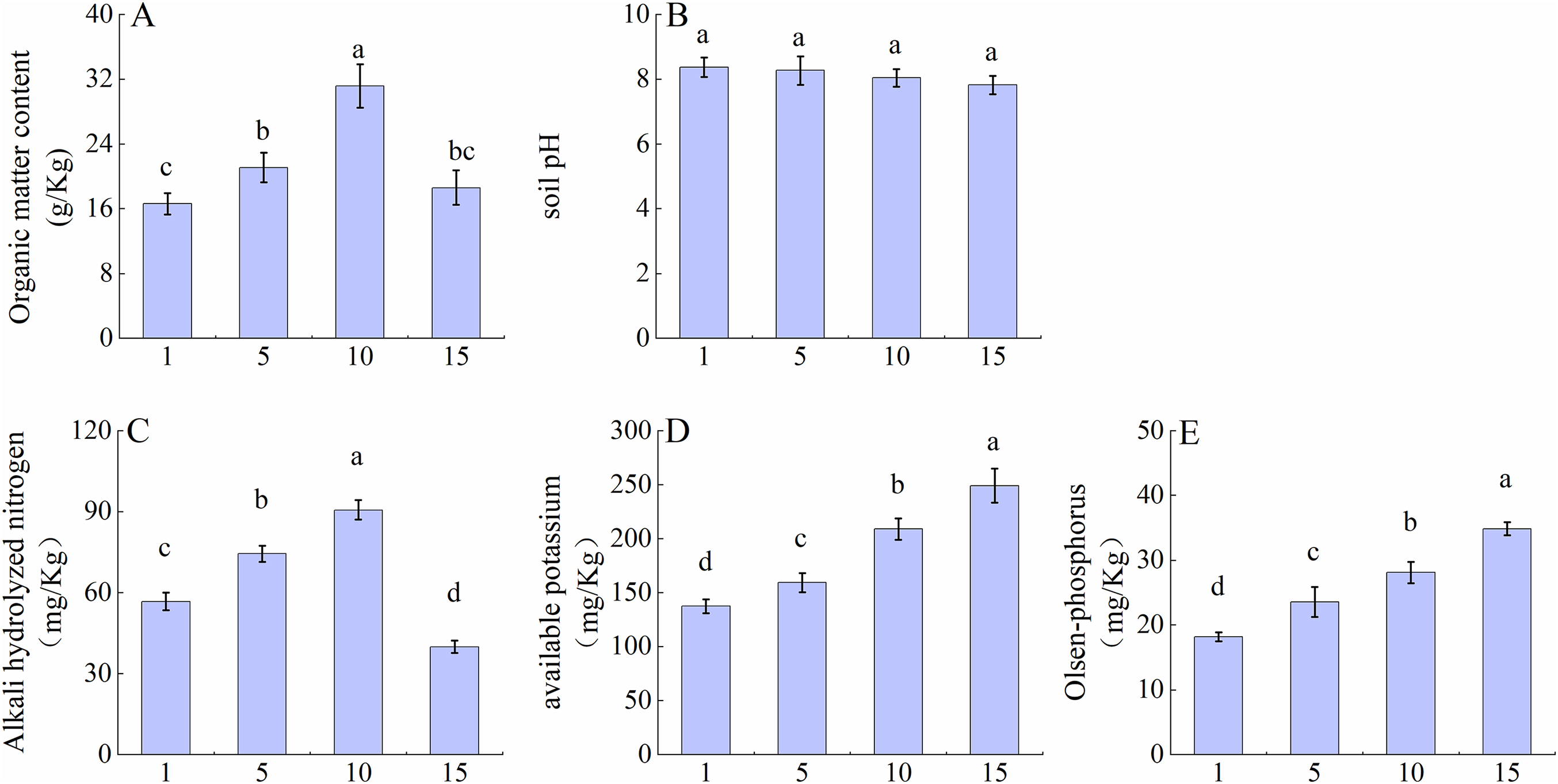

4.1 Changes in Soil pH and Nutrient Content in Z. bungeanum Rhizosphere in Different Planting Years

A single-factor ANOVA was conducted to examine the pH and nutrient content of Z. bungeanum rhizosphere soil across different planting years, revealing significant differences in organic matter, AN, AP, and AK content among the planting years (p < 0.05). No significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed in the pH (Fig. 1B). According to Fig. 1A,C, there was a trend of initially increasing and then decreasing levels of organic matter and An with the increasing planting years. The peak values were reached at year 10, which were 1.88 times higher than those at year 1 for organic matter and 1.60 times higher than those at year 15 for AN. From Fig. 1D,E, it can be observed that the content of AP and AK showed a continuous upward trend, reaching its highest point at 15 years, which was significantly higher than that at the other stages.

Figure 1: Changes in pH value and nutrient content of the rhizosphere soil of Z. bungeanum in different planting years. (A) organic matter content; (B) soil pH; (C) alkali hydrolyzed nitrogen content; (D) available potassium content; (E) Olsen-phosphorus content. Results are presented as mean values with standard errors (n = 3) ± SE. Different lowercase letters ‘a–d’ indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) between different planting years

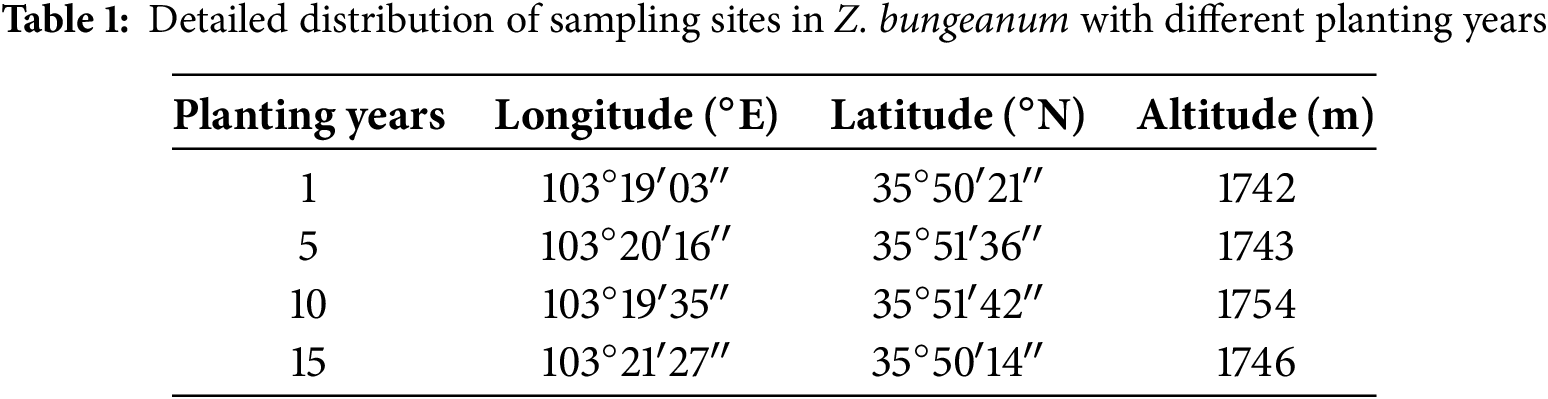

4.2 Differences in Enzyme Activity in the Rhizosphere Soil of Z. bungeanum with Different Planting Years

A single-factor ANOVA was conducted to examine POD, IE, UE, AKP, and CL activities in the rhizosphere soil of Z. bungeanum plants grown for different years. The results showed significant differences (p < 0.05). Table 1 shows that POD activity increased continuously with planting time, reaching a maximum value at 15 years, which was 2.89 times higher than that at year 1. IE, UE, and AKP activities initially increased and then decreased, peaking at 10 years and significantly surpassing those at both 1 and 15 years by factors of 1.28, 1.45, and 1.10, respectively, compared with the activity levels observed at year 1; similarly, they were higher by factors of 1.24, 1.41, and l.20, respectively, compared with the activity levels observed at year 15. The activity level of CL remained unchanged over the period from year 1 to 15 (Table 2).

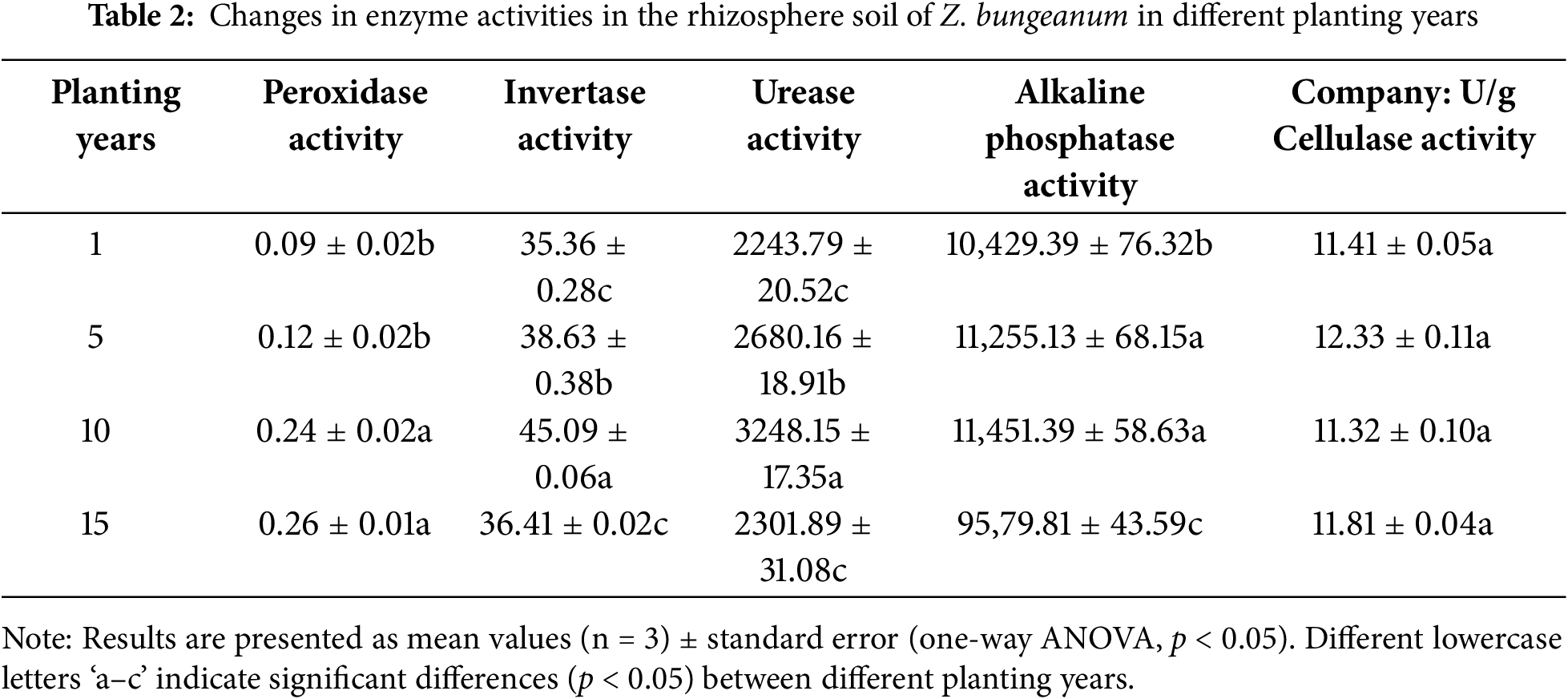

4.3 Analysis of ASVs between Planting Years

Twelve soil samples were processed with a minimum sample sequence number of 44,412, resulting in the identification of 25,592 ASVs by clustering at a similarity threshold >97%. The sequencing coverage for each sample exceeded 99.72%, indicating that the obtained sequence information adequately represented the true status of soil bacteria in the study area.

The Venn diagram in Fig. 2 compares the bacterial ASVs detected in Z. bungeanum rhizosphere across different planting years. From Fig. 2B, it is evident that RS10 and RS15 exhibited significantly higher numbers of ASVs than RS5 and RS1. Among these samples, only 3.11% of ASVs were shared, suggesting substantial differences in the rhizosphere bacterial community composition between the different planting years. In pairwise comparisons among these four samples, the smaller was the difference in planting years, the higher was the consistency of the soil bacterial communities; conversely, as the difference in planting years increased, the consistency decreased. Notably, both RS15 and RS10 had significantly higher numbers of ASVs than RS5 and RS1. Specifically, compared with RS1, the number of ASVs in RS10 and RS15 increased by 2017 and 3061, respectively. The unique ASV counts in RS1, RS5, RS10, and RS15 were 1666, 1531, 3087, and 3477, respectively (Fig. 2A). RS15 had the highest unique bacterial group, whereas RS1 has the lowest, accounting for total ASV of 26.32% and 12.61%, respectively.

Figure 2: Venn diagram illustrating the bacterial composition in the rhizosphere soil of Z. bungeanum across different years of cultivation. (A) the number of ASVs shared and unique to each sample; (B) the number of ASVs for each sample. RS1: planting for 1 year, RS5: planting for 5 year, RS10: planting for 10 year, RS15: planting for 15 year. Different letters ‘a–c’ indicate significant differences in data between groups (p < 0.05)

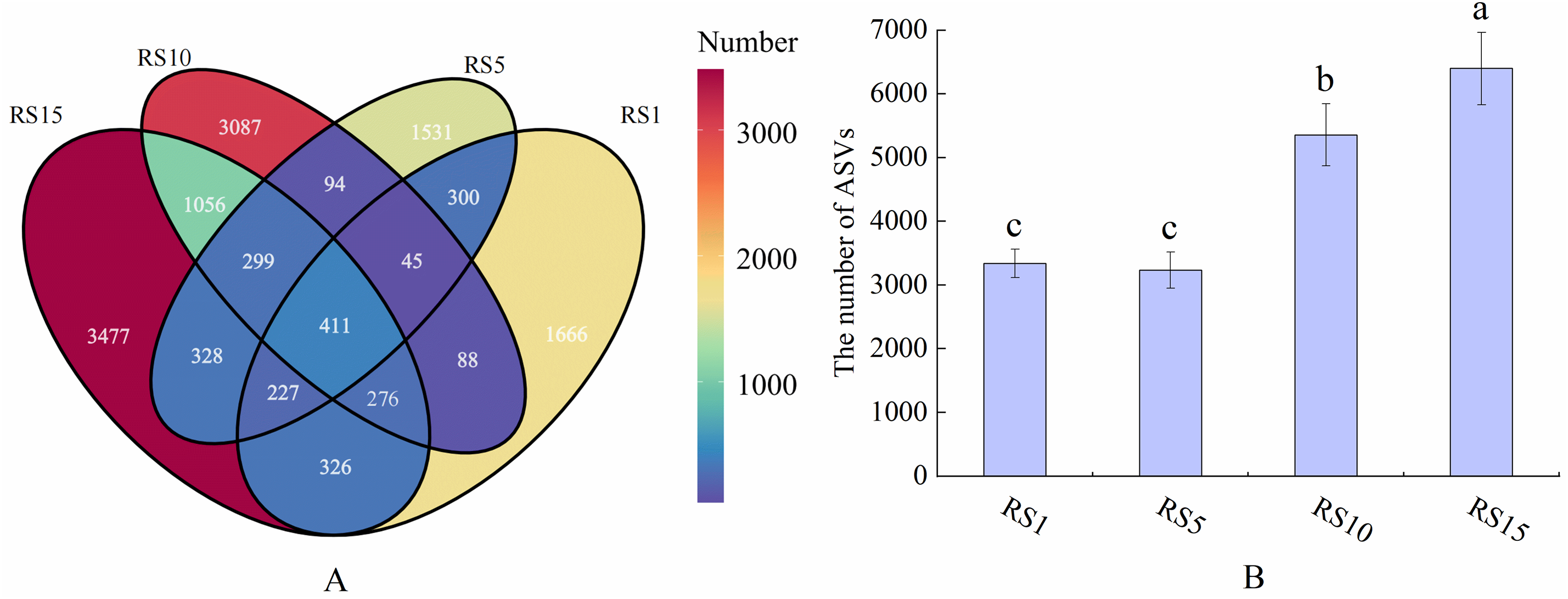

4.4 Diversity Analysis of Rhizosphere Bacterial Communities under Different Planting Years

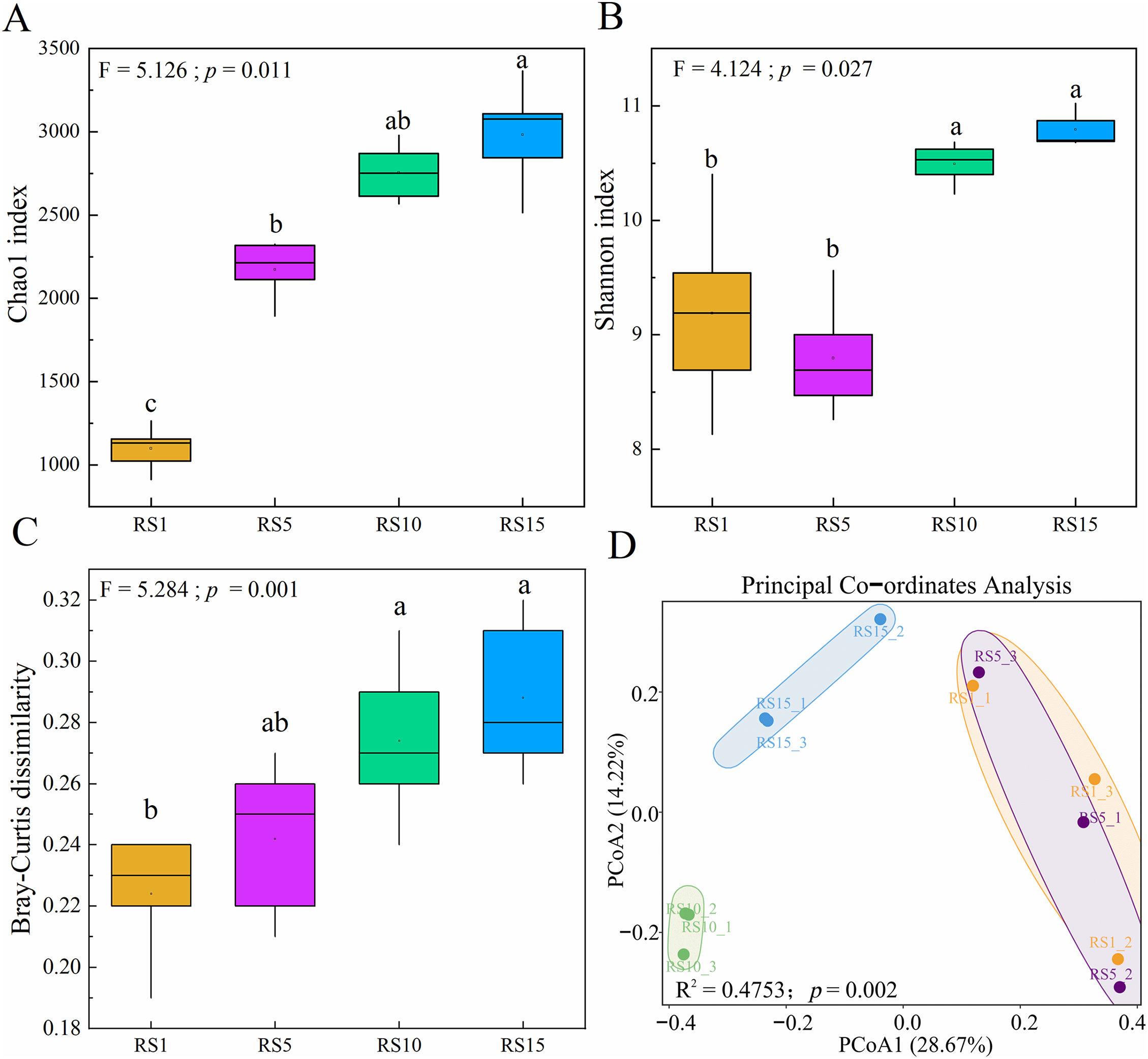

From Fig. 3A,B, it is evident that the Chao1 index (a richness index) in RS15 exhibited a significantly higher value compared with that in RS1 and RS5, with increases of 1.61 and 0.33 times, respectively. The Shannon index (diversity index) of RS15 and RS10 was significantly higher than that of RS1 and RS5 (p < 0 05). In terms of β-diversity, there was an increasing trend in bacterial community β-diversity with longer planting years (Fig. 3C). Principal coordinate analysis based on the Bray-Curtis distance algorithm revealed the spatial separation of rhizosphere soil bacterial communities in different planting years (excluding RS1 and RS5) (Fig. 3D). The principal component axes PC1 and PC2 explained 28.67% and 14.22% of the variation in the bacterial community structure, respectively. Furthermore, the Adonis test revealed significant differences in the rhizosphere bacterial community structure among Z. bungeanum plants with varying planting years (R2 = 0.475, p = 0.002). As the duration of planting increased, the biological replicates became more closely clustered and the distances between different groups increased, indicating a significant impact of planting duration on rhizosphere bacterial communities.

Figure 3: Diversity of bacterial communities in Z. bungeanum across different planting years. (A,B) Boxplot displayed the differences in the Chaol index and Shannon index of bacterial communities under different planting years. (C) The pairwise Bray-Curtis dissimilarity of bacterial communities under different planting years. Different letters ‘a–c’ represent significant differences (p < 0.05) among groups according to the least significant difference (LSD) test. (D) Principal-coordinate analysis (PCoA) of bacterial communities based on Bray-Curtis distances, different colors represent different groups, with points of the same color indicating different samples within a group. The same group is displayed in a circular chart format according to the 95% confidence interval

4.5 Analysis of Soil Bacterial Community Structure in Rhizosphere of Z. bungeanum with Different Planting Years Based on Classification Status

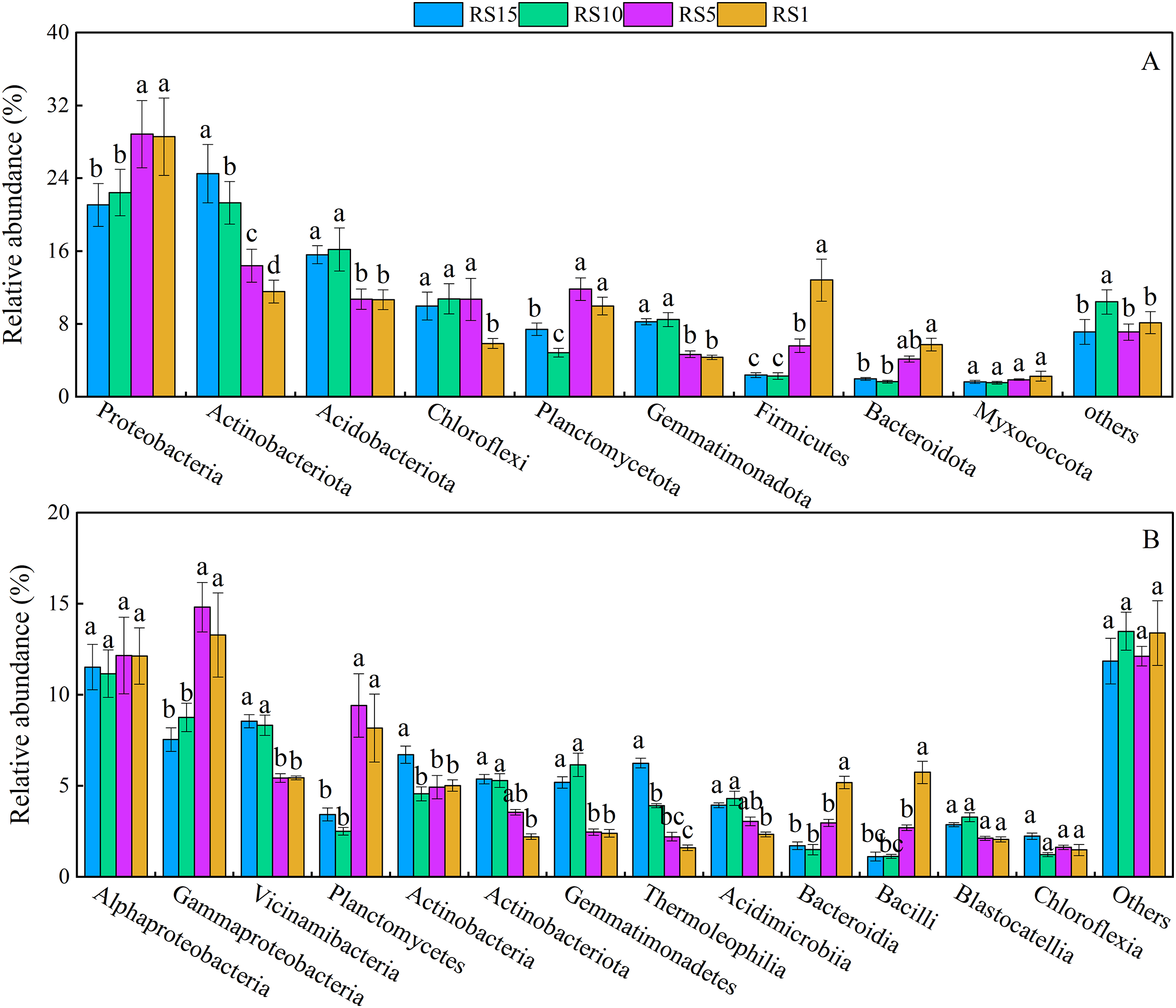

The composition of the rhizosphere bacterial communities remained consistent across different planting years, but there were variations in the relative abundance. A total of 50 phyla, 150 classes, 326 orders, 531 families, and 1095 genera of bacteria were detected in all soil samples. Nine phyla of soil bacteria had a relative abundance ≥1%, while those with a relative abundance <1% were grouped into others. The abundance of each phylum varied at different stages (Fig. 4A). Proteobacteria (from 28.57% to 21.07%), Actinobacteria (from 11.56% to 24.52%), Acidobacteriota (from 10.68% to 15.61%), and Chloroflexi (from 5.86% to 9.98%) accounted for 56.67%–71.18% of the total bacterial relative abundance and were the dominant soil bacterial species. The relative abundance of Proteobacteria was significantly higher in RS1 and RS5 than in RS10 and RS15, and the relative abundance of Actinobacteria in RS15 was significantly higher than that in RS1, RS5, and RS10 by 2.12, 1.70, and 1.15 times, respectively. The relative abundance of Acidobacteriota was significantly higher in RS15 and RS10 than in RS1 and RS5, while the relative abundance of Chloroflexi was significantly lower in RS1 than in others (p < 0.05). Additionally, Planctomycota, Gemmatimonadota, Firmicutes, Bacteroidota, and Myxococota accounted for a total of 18.86%–35.18% of rhizosphere soil bacteria across RS1 to RS15, making them the main bacterial phyla present. Among these phyla, the relative abundance of Gemmatimonadota was significantly higher in RS15 and RS10 than in RS5 and RS1, whereas the abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroidota in RS1 was significantly higher than that in RS10 and RS15 (p < 0.05).

Figure 4: Composition of bacterial communities in Z. bungeanum across different planting years. (A) The relative abundance (%) of more than 1% dominant bacterial at the phylum level. (B) The relative abundance (%) of more than 1% dominant bacterial at the class level. Different letters ‘a–d’ represent significant differences (p < 0.05) among groups according to the least significant difference (LSD) test

Bacterial classes with an average relative abundance of <1% were combined into “Others,” while there were 13 classified bacterial classes with an abundance of ≥1%. The relative abundance of Gammaproteobacteria within the phylum Proteobacteria in RS1 increased significantly by 5.74% compared with that in RS15, Planctomycetes within the phylum Planctomycetota in RS1 increased significantly by 4.74% compared with that in RS15, Bacteroidia within the phylum Bacteroidota in RS1 increased significantly by 3.47% compared with that in RS15, and Bacilli within the phylum Firmicutes in RS1 increased significantly by 4.62% compared with that in RS15. In contrast, the relative abundance of Actinobacteriota within the phylum Actinobacteriota in RS1 decreased significantly by 3.16% relative to that in RS15, and Gemmatimonadetes within the phylum Gemmatimonadota in RS1 decreased significantly by 2.80% (Fig. 4B).

4.6 Effect of Bacterial Function in the Rhizosphere Soil of Z. bungeanum with Different Planting Years

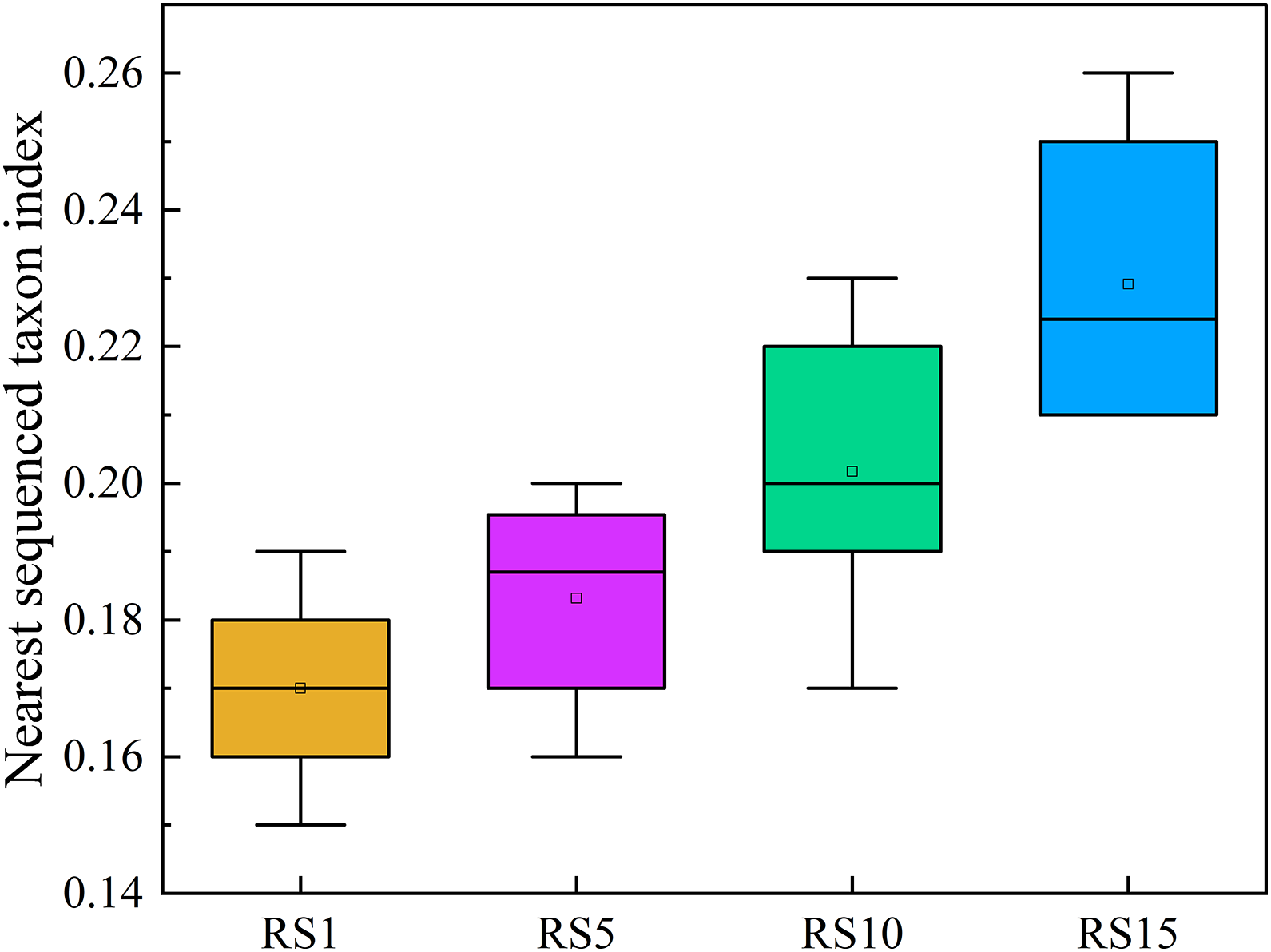

Based on the 16S rRNA marker gene feature sequence, PICRUSt2 was used to predict the function of bacterial ASVs in the rhizosphere soil of different planting years of Z. bungeanum. The abundance of the KEGG Orthology for each sample was determined and statistically analyzed. The weighted NSTI evaluates the weighted average distance between the sequences in each sample and the genes measured in known databases. The smaller the NSTI value, the higher the degree of matching between the predicted microbial composition in the sample and the known database. The NSTI for predicting bacterial function in the rhizosphere soil of different tree ages is shown in Fig. 5. The NSTI of samples 1a, 5a, 10a, and 20a was 0.15–0.19, 0.16–0.20, 0.17–0.23, and 0.21–0.26, respectively (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: NSTI of picrust predictive functional profiling

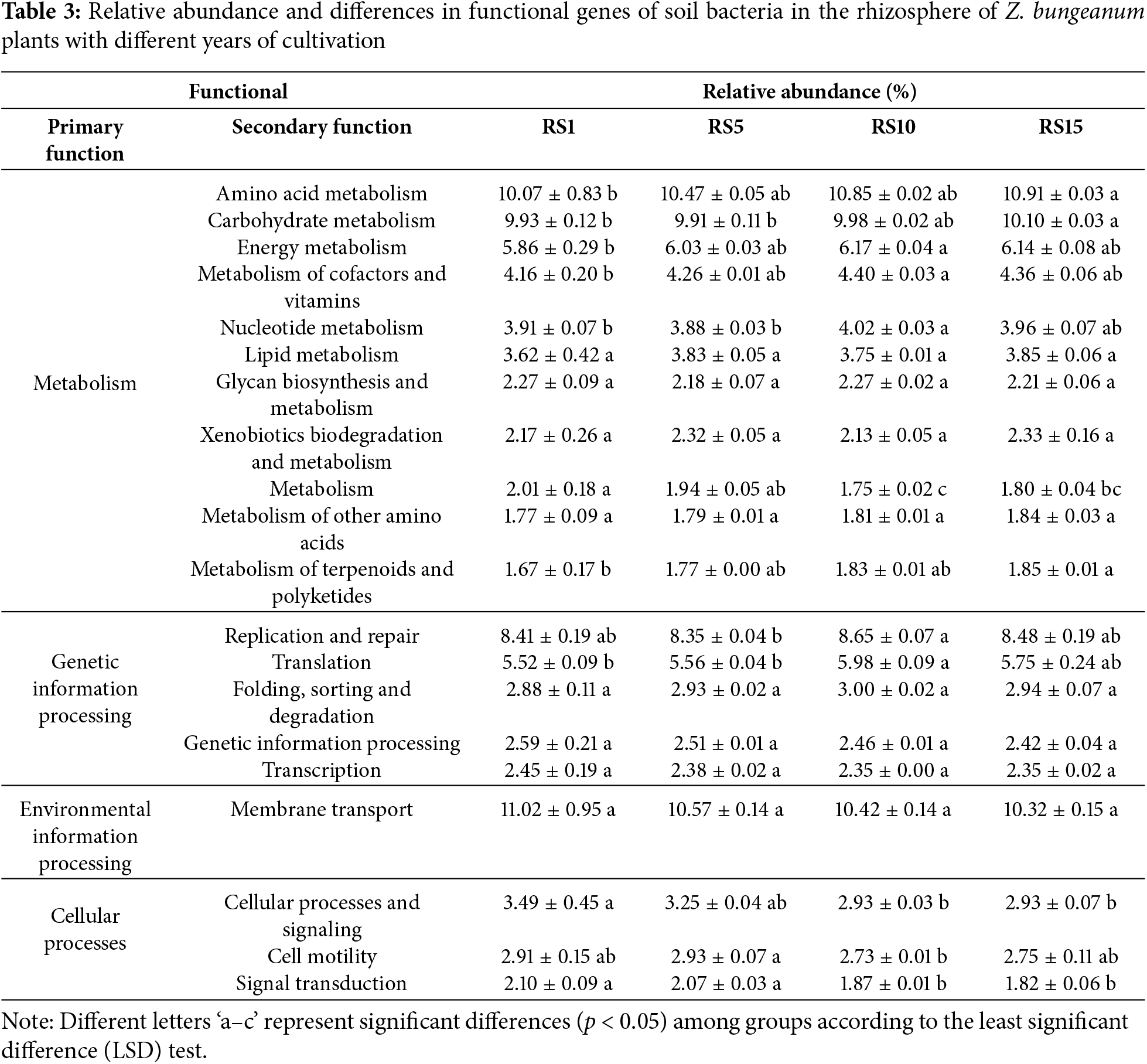

A comparison with the KEGG database revealed seven categories of primary metabolic pathway functions, among which the functions with relative abundances >1% were as follows: metabolism (47.45%), genetic information processing (21.86%), environmental information processing (11.02%), and cellular processes (8.51%) (Table 3). In addition, the bacterial community distributed across seven metabolic pathways revealed 40 secondary functions, with 20 having a relative abundance >1%. Amino acid metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, replication and repair, and membrane transport were identified as the main functional groups among the soil bacteria. The relative abundance of amino acid metabolism, carbohydrate metabolism, terpenoids, and polyketides metabolism in the rhizosphere soil bacteria of RS15 was significantly higher than that in the rhizosphere soil bacteria of RS1; however, cellular processes and signaling functions showed significantly lower abundance in RS15 than that in RS1 (p < 0.05). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in the relative abundance of other functions among the rhizosphere soil bacteria in the different planting years of Z. bungeanum.

Pearson’s correlation analysis indicated (Table 4) that there was a significant correlation between the relative abundance changes of secondary functional genes in the rhizosphere soil bacteria of Z. bungeanum and those of phyla Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteota, Bacteroidota, Chloroflexi, Firmicutes and Gemmatimonadota. This suggests that these bacterial groups may have a crucial effect on the function of rhizosphere soil bacteria associated with Z. bungeanum.

4.7 Bug BASE Bacterial Phenotype Prediction Analysis

The predicted bacterial phenotype of BugBase indicated that aerobic bacteria exhibited an upward trend with increasing planting years. The abundance of aerobic bacteria in RS15 was 1.5 times higher than that in RS1. In contrast, anaerobic bacteria displayed a downward trend, with Acidobacteria playing a dominant role owing to the differences in Planctomycetes abundance. Pathogenic potential bacteria showed a decreasing trend with increasing planting years; their abundance in RS15 was significantly lower than that in RS1, accounting for only 71.43% of the total abundance. This decrease was primarily driven by Proteobacteria and Acidobacteria. Bacterial resistance to oxidative stress was greater in 10a and 15a than in 1a and 5a; specifically, the abundance of stress-tolerant bacteria in RS15 was 1.3 times that in RS1 (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Phenotypic relative abundance (A) and composition of aerobic (B), anaerobic (C), potentially pathogenic (D), and stress-tolerant (E) bacteria in rhizosphere soil of different planting years. Different letters ‘a–c’ represent significant differences (p < 0.05) among groups according to the least significant difference (LSD) test

4.8 Influence of Physicochemical Properties of the Rhizosphere Soil of Z. bungeanum with Different Planting Years on the Bacterial Community Structure and Metabolic Function

4.8.1 Influence of Physicochemical Properties of the Rhizosphere Soil of Z. bungeanum with Different Planting Years on Major Bacterial Phyla

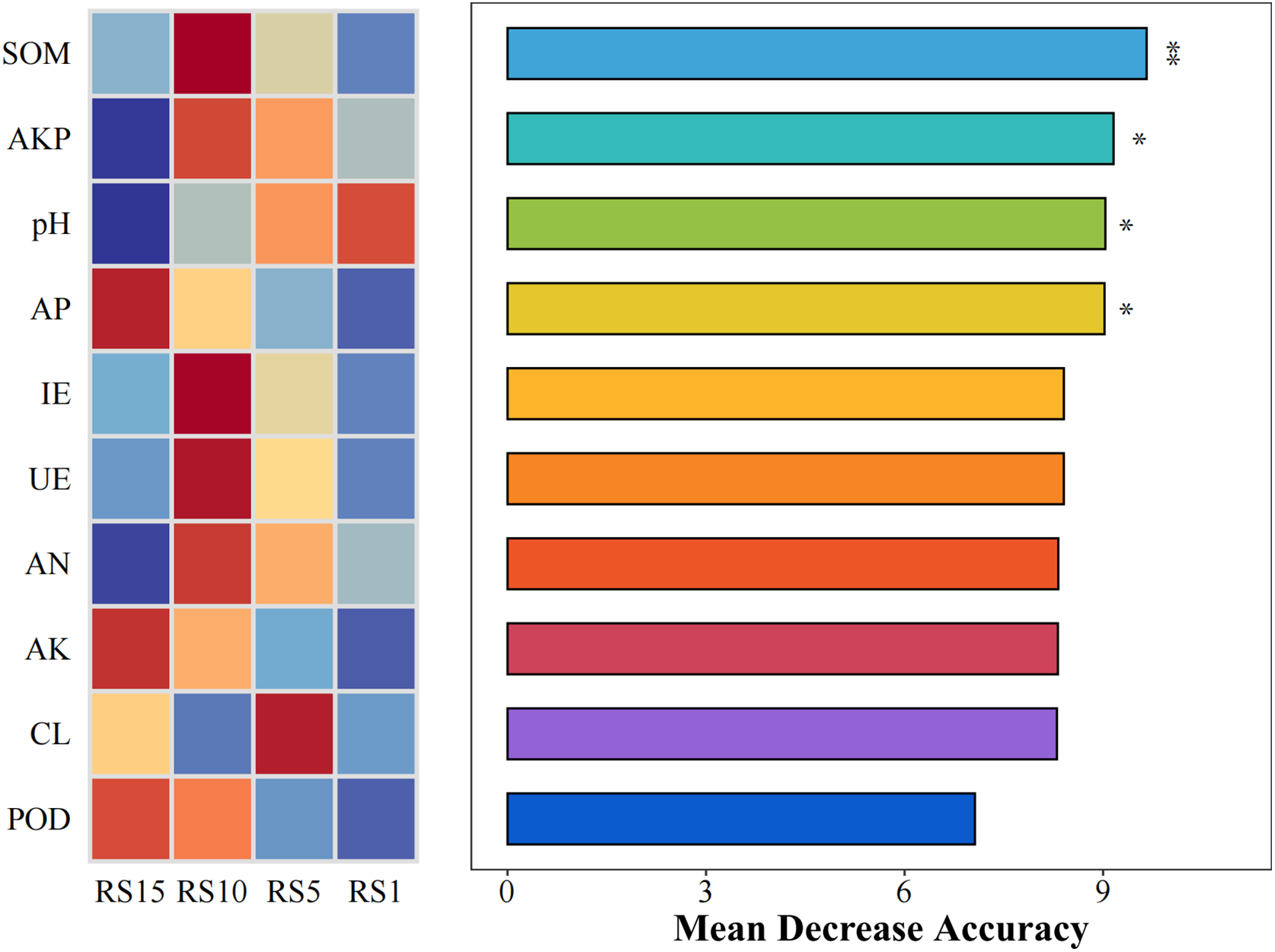

To further explore the potential patterns of bacterial changes over the years of Z. bungeanum cultivation, indicator species analysis (Fig. 7A) revealed that Firmicutes was the differential indicator species at year 1, Planctomycetota at 5 years, Methylomirabilota at 10 years, and Actinobacteriota at 15 years. The relative abundance chart (Fig. 7B) also confirmed that as the planting years increased, the relative abundance of Firmicutes was the highest at year 1, Planctomycetes was particularly prominent at 5 years, and the relative abundance of Methylomirabilota and Actinobacteriota was higher at 10 and 15 years compared with other years.

Figure 7: Differences in bacterial phylum levels in the rhizosphere soil of different planting years of Z. bungeanum indicate heatmap analysis (A) and relative abundance chart (B)

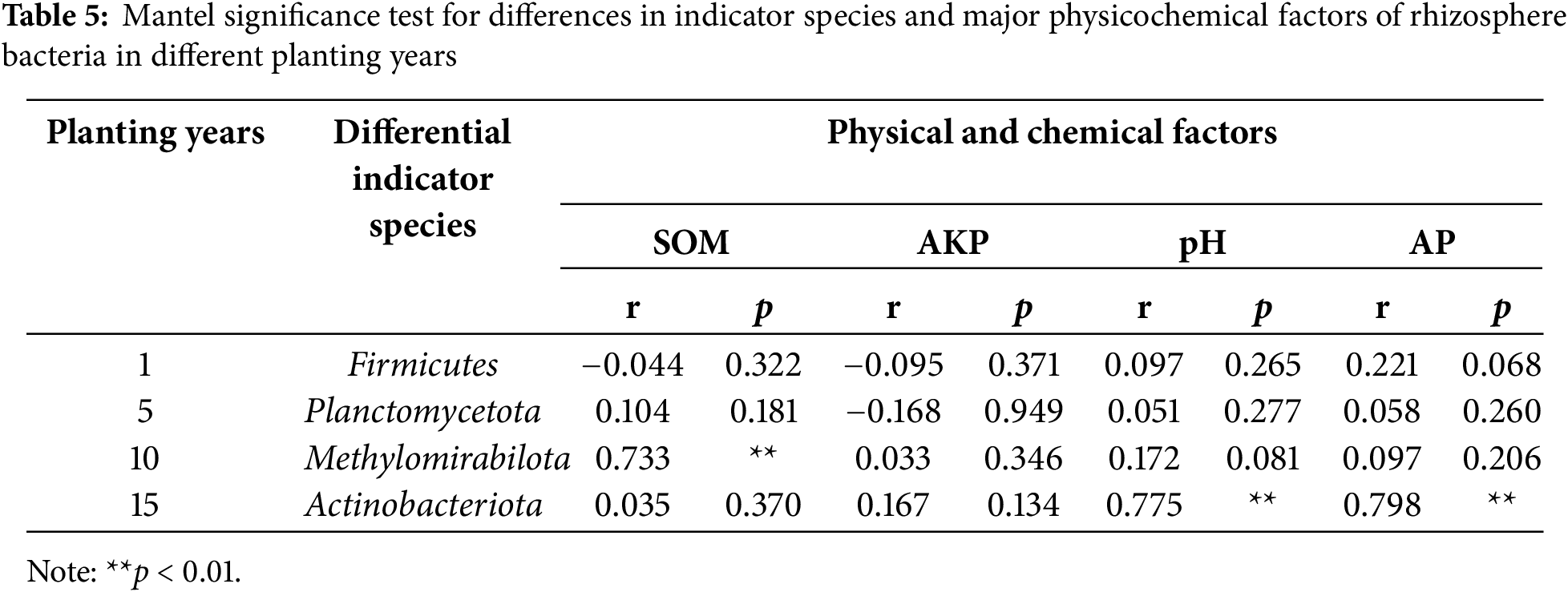

The main physicochemical factors affecting the indicator species of soil bacteria in the rhizosphere soil of Z. bungeanum with different planting years were explored using Mantel test correlation analysis. This analysis used the relative abundance distance matrix (Bray–Curtis) of indicator species from different planting years in the study area, as well as the Euclidean distance matrix of soil physicochemical parameters. The results indicated that the indicator species Firmicutes (RS1) was correlated with AP and AK (p > 0.05); Planctomycetota (RS5) was correlated with POD (p > 0.05); Methylomirabilota (RS10) was significantly correlated with soil organic matter (SOM), AN, pH, POD, IE, and UE; and Actinobacteriota (RS15) was significantly correlated with AP, AK, pH, and POD (p < 0.05) (Fig. 8). Random forest analysis showed that SOM, AKP, pH, and AP were key predictive factors for bacterial community assembly in the rhizosphere soil of Z. bungeanum in different planting years (Fig. 9). As shown in Table 5, there is a highly significant positive correlation between Methylomirabilota and SOM; Actinobacteriota was significantly positively correlated with pH and AP (p < 0.01).

Figure 8: Correlation analysis between abiotic and biotic factors and the microbial community. Pairwise comparisons between factors are shown ina color gradient. Mantel tests for the correlations between factors and microbial community compositionat the dominant phylum levels (Pearson’s correlations, permutations = 9999). Abbreviations: SOM, soil organic carbon; AKP, alkaline phosphatase; pH, soil pH value; AP, available phosphorus; IE, Invertase; UE, urease; AN, available nitrogen; AK, available potassium; CL, cellulase; POD, peroxidase

Figure 9: Random forests determined the role of plant diversity and soil properties in the bacterial communities’ assembly. Abbreviations: SOM, soil organic carbon; AKP, alkaline phosphatase; pH, soil pH value; AP, available phosphorus; IE, Invertase; UE, urease; AN, available nitrogen; AK, available potassium; CL, cellulase; POD, peroxidase. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01)

4.8.2 Influence of Physicochemical Properties of the Rhizosphere Soil of Z. bungeanum with Different Planting Years on Major Bacterial Classes

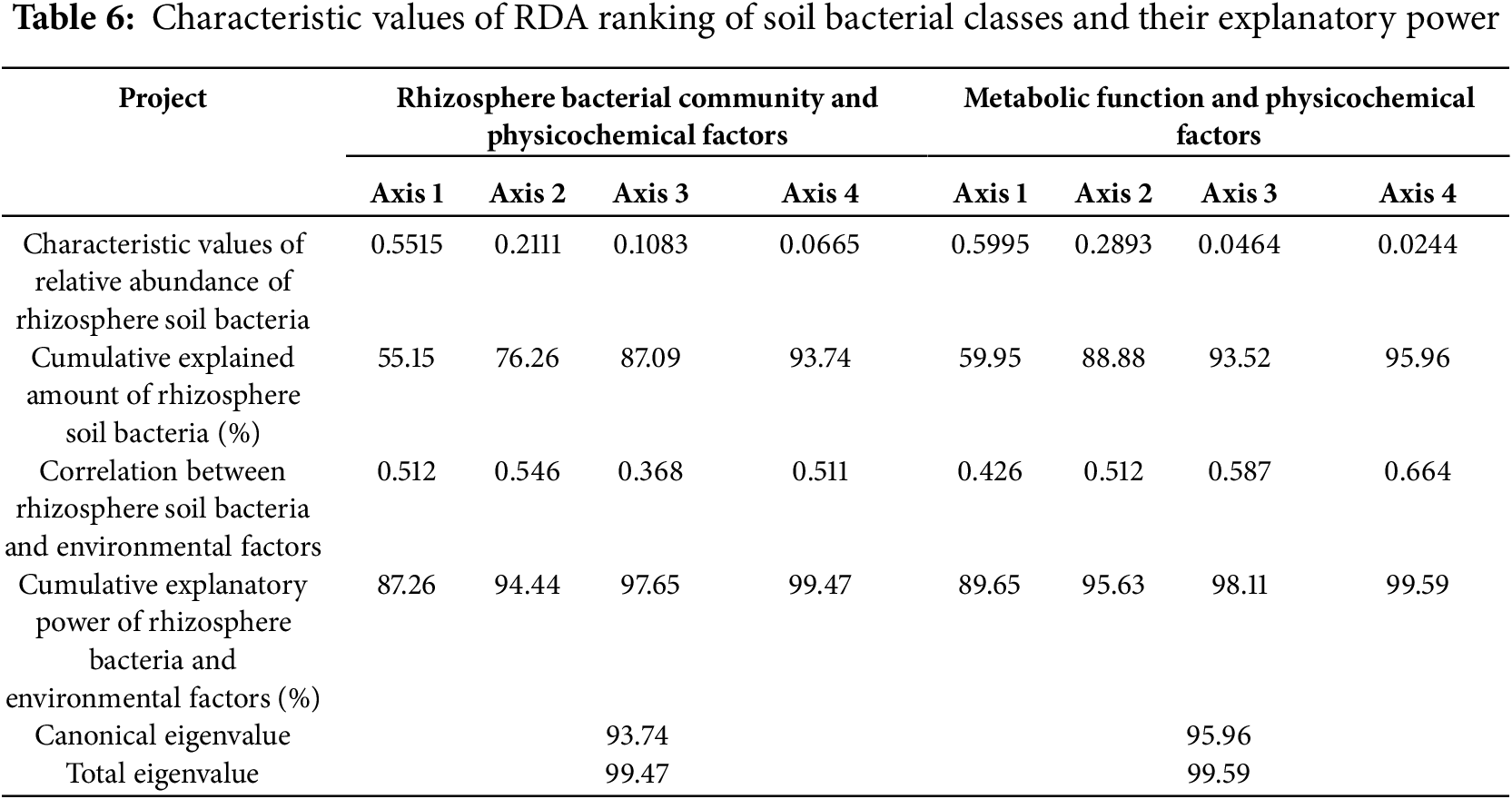

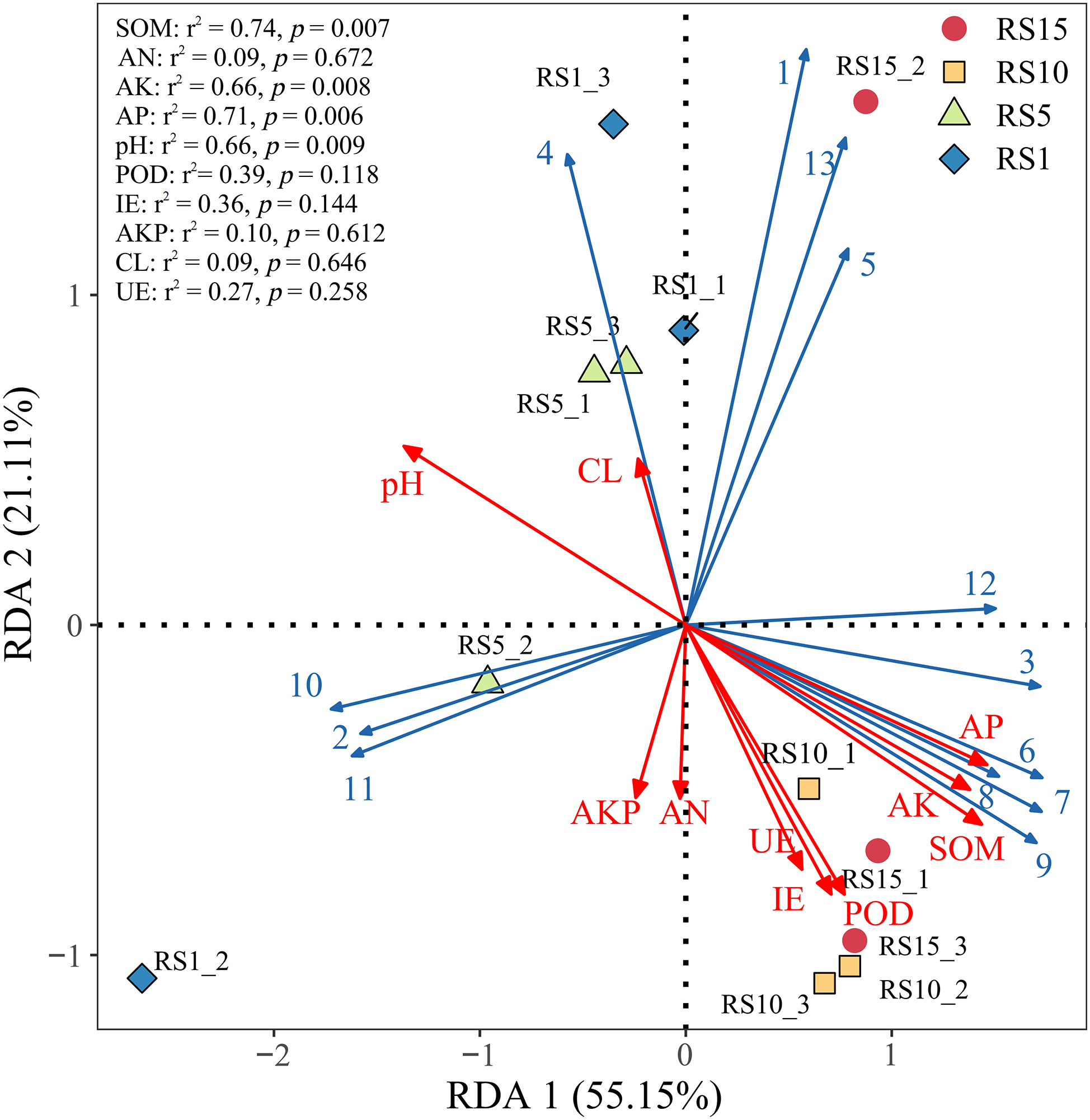

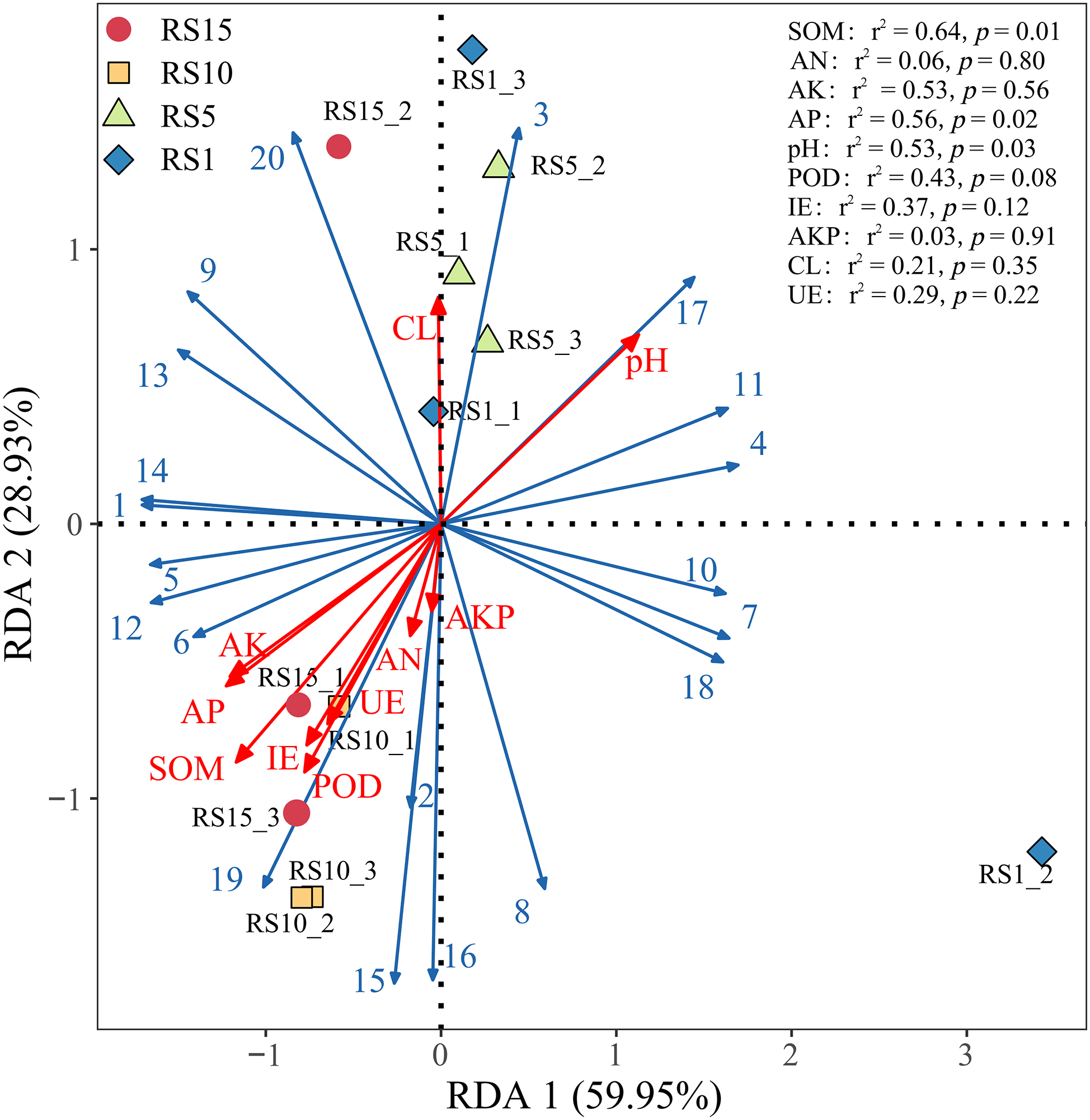

To further investigate the main environmental factors that affect the structure of soil bacterial communities in the rhizosphere soil of Z. bungeanum, detrended correspondence analysis was conducted on soil bacterial classes with a relative abundance of ≥1% in the study area. Because the maximum value of the ordination axis was 2.1, RDA was performed using the relative abundances of the main soil bacterial classes as response variables and soil physicochemical indicators as the explanatory variables. The results indicated that the first and second sorting axes have explanatory powers of 55.15% and 21.11%, respectively, mainly determined by the first sorting axis, and the correlation coefficients between the first and second axes and soil physicochemical factors were 0.512 and 0.546, respectively, with a cumulative explanatory power of 94.55%, indicating that these two axes can better reflect the relationship between soil bacterial community structure and physicochemical factors (Table 6). Fig. 10 shows that Vicinamibacteria, Actinobacteriota, Gemmatimonadetes, Thermoleophilia, Acidimicrobiia, and Blastocatellia were positively correlated with SOM and AP, but negatively correlated with other classes. The Envfit test showed that both SOM and AP significantly affected the community structure of the bacterial class (p < 0.01), with contribution rates of 74% and 71%, respectively.

Figure 10: Redundancy analysis (RDA) of soil bacterial class level and physicochemical factors. Each point represents a sample, and the closer the distance between two points, the higher the similarity in community structure between the two samples. Arrows denote different influencing factors. An acute angle between the influencing factors (factors and samples) indicates a positive correlation, while an obtuse angle indicates a negative correlation. The longer the ray, the greater the effect of the factor. The position of the projection point on the arrow of the sample approximately represents the numerical magnitude of the factor in the corresponding sample. RS1, RS1: planting for 1 year, RS5: planting for 5 year, RS10: planting for 10 year, RS15: planting for 15 year. Abbreviations: SOM, soil organic carbon; AKP, alkaline phosphatase; pH, soil pH value; AP, available phosphorus; IE, Invertase; UE, urease; AN, available nitrogen; AK, available potassium; CL, cellulase; POD, peroxidase. Blue solid line: soil dominance class. 1, Alphaproteobacteria; 2, Gammaproteobacteria; 3, Vicinamibacteria; 4, Planctomycetes; 5, Actinobacteria; 6, Actinobacteriota; 7, Gemmatimonadetes; 8, Thermoleophilia; 9, Acidimicrobiia; 10, Bacteroidia; 11, Bacilli; 12, Blastocatellia; 13, Chloroflexi

4.8.3 Effect of Physicochemical Properties of the Rhizosphere Soil of Z. bungeanum with Different Planting Years on the Relative Abundance of Metabolic Functions

RDA indicated that the metabolism of amino acids and carbohydrates in soil bacteria was positively correlated with the physicochemical properties of the rhizosphere soil (excluding pH and CL), while the replication and repair functions in genetic information processing were positively correlated with soil physicochemical properties (excluding pH and CL). Membrane transport in environmental information processing was negatively correlated with the physicochemical factors of soil (excluding pH and AKP) (Fig. 11). The Envfit test showed that soil organic matter had a significant effect on community bacterial function in the rhizosphere soil (p < 0.01), with a contribution rate of up to 64%.

Figure 11: Redundancy analysis (RDA) of soil bacterial metabolic functional genes and physicochemical factors. Each point represents a sample, and the closer the distance between two points, the higher the similarity in community structure between the two samples. Arrows denote different influencing factors. An acute angle between the influencing factors (factors and samples) indicates a positive correlation, while an obtuse angle indicates a negative correlation. The longer the ray, the greater the effect of the factor. The position of the projection point on the arrow of the sample approximately represents the numerical magnitude of the factor in the corresponding sample. RS1, RS1: planting for 1 year, RS5: planting for 5 year, RS10: planting for 10 year, RS15: planting for 15 year. Abbreviations: SOM, soil organic carbon; AKP, alkaline phosphatase; pH, soil pH value; AP, available phosphorus; IE, Invertase; UE, urease; AN, available nitrogen; AK, available potassium; CL, cellulase; POD, peroxidase. Blue solid line: bacterial function in rhizosphere soil. 1, Amino Acid Metabolism; 2, Carbohydrate Metabolism; 3, Cell Motility; 4, Cellular Processes and Signaling; 5, Energy Metabolism; 6, Folding, Sorting and Degradation; 7, Genetic Information Processing; 8, Glycan Biosynthesis and Metabolism; 9, Lipid Metabolism; 10, Membrane Transport; 11, Metabolism; 12, Metabolism of Cofactors and Vitamins; 13, Metabolism of Other Amino Acids; 14, Metabolism of Terpenoids and Polyketides; 15, Nucleotide Metabolism; 16, Replication and Repair; 17, Signal Transduction; 18, Transcription; 19, Translation; 20, Xenobiotics Biodegradation and Metabolism

5.1 Effect of Planting Years of Z. bungeanum on the Physicochemical Properties of Rhizosphere Soil

Plants obtain essential growth materials from the soil through their root systems, while simultaneously releasing photosynthetic byproducts into the surrounding soil as root exudates or decomposed roots. The composition and concentration of these substances fluctuate in response to external environmental changes, thereby influencing plant growth and development [17]. This study observed an initial increase followed by a decrease in organic matter and AN content in the rhizosphere soil of Z. bungeanum with increasing planting years, which is consistent with the findings reported by Jiao et al. [18], but this result differs from that reported by Liu et al. [19]. These discrepancies may be attributed to variations in Z. bungeanum management practices, including planting density [20], intercropping patterns [21], and the application of organic fertilizers, all of which influence the physicochemical properties of rhizosphere soil. Additionally, this may be associated with the vigorous growth phase of plants during this period, resulting in increased root activity and reduced nutrient accumulation. Some studies have found that long-term continuous cultivation may lead to a decrease in soil nutrient availability [10] but may also result in cumulative benefits in terms of soil nutrient increase. For instance, Wang et al. [22] discovered significantly higher levels of AP and AK in the rhizosphere soil of Rehmannia glutinosa under continuous cropping than in the preceding crop and wild soils. This finding is in agreement with the findings of the present study, which may be due to the fact that acids, phytase and other substances secreted by Z. bungeanum root system play a key role in nutrient transformation process. Acids can lower the pH of rhizospheret soil, thereby increasing the solubility of certain nutrients. Phytase can break down phytic acid into inositol and phosphoric acid, releasing phosphorus that can be absorbed and utilized by plant, and these processes help to increase the amount of effective phosphorus and potassium in soil, which promotes the growth of Z. bungeanum [13]. The pH measurement results also showed that with the increase of planting years, pH value changed from weakly alkaline to weakly acidic, which is consistent with the findings of Liao et al. [23] and Jiao et al. [18]. In addition, correlation analysis also shows that pH value of rhizosphere soil is significantly negatively correlated with AP and AK content, which jointly supports the possibility of this mechanism.

Soil enzymes primarily originate from soil microorganisms, and the cultivation of crops over time can influence the quantity and diversity of these microorganisms, resulting in changes in soil enzyme activity. Soil enzyme activity can indirectly reflect or predict the transformation of certain nutrients and evolution of soil fertility [24]. In present study, POD activity in rhizosphere soil of Z. bungeanum increased continuously with years of planting, which may reflect the increased adaptation of Z. bungeanum to soil environment as well as its ability to detoxify harmful substances. This may reduce the accumulation of harmful substances, such as phenolic acids formed after plant decomposition, thereby lowering the risk of toxic effects on rhizosphere soil microorganisms [17]. The activities of IE, UE, and AKP are closely linked to organic matter transformation, nitrogen supply capacity, and organic phosphorus decomposition, respectively. In this study, correlation analysis revealed that IE activity has a highly significant or significant positive correlation with SOM content, IE with AN content, and AKP with AP content. Interestingly, the activities of IE, UE and AKP significantly decreased after 10 years, corresponding with changes in SOM and AN, which is consistent with the findings of Liu et al. [19]. This indicates that soil nutrient cycling is inhibited, which may lead to the slowing down of decomposition rate of SOM, insufficient supply of nitrogen and reduced effectiveness of phosphorus, thus affecting the growth of plants, which may be related to the changes in structure of soil microbial communities caused by long-term continuous cropping [25].

CL is a crucial indicator of carbon cycling rates in the soil, and its activity is influenced by nitrogen and phosphorus levels. Research indicated that CL activity increases with the age of walnut forests [26], whereas in apple orchards, it initially increases before declining [27]. However, we found no significant change in CL activity with increasing in years of Z. bungeanum cultivation. This suggests that CL activity responds differently to various factors, such as plant type, soil nutrients, microorganisms, vegetation, fertilization, and cultivation methods; thus, further investigation is necessary.

5.2 Effect of Planting Years on Bacterial Diversity and Community Structure in Rhizosphere Soil

The diversity and community structure of soil bacteria in the rhizosphere are highly complex and are influenced by factors such as fertilization management practices, forest age, soil type, plant species and planting duration. These factors result in dynamic changes in the bacterial population structure [18,28]. This study found that the planting years significantly affected the alpha diversity of bacteria in the rhizosphere soil of Z. bungeanum, which increased with the increase of planting years. These findings align with those of Wei et al. [29] regarding the relationship between different breeding years of grape plantations and the soil microbial community structure. The diversity trend observed in the soil microbial community structure gradually increased with the extended breeding years of Chinese fir plantations. This may be related to the presence of root exudates in plants. Z. bungeanum is a typical allelopathic plant, and as the years of cultivation increase, the allelochemicals in its roots change, which may induce, attract, promote, or inhibit microorganisms, thereby affecting microbial diversity [30].

Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria and Acidobacteria were the dominant bacterial phyla (Fig. 4A), which is consistent with other forest soils [31,32]. In the present study, there were significantly different bacterial community compositions in different planting years (Fig. 4A,B). Different species appear in rhizosphere soil in different planting years owing to plants rhizosphere selectivity and varying preferences for bacteria at different stages. Firmicutes were identified as differential indicator species in the rhizosphere soil of 1-year-old Z. bungeanum, which may be related to the relatively high levels of organic matter and other nutrients in the rhizosphere soil of Z. bungeanum during its early developmental stages, which attract species such as fermenting and nitrogen-fixing bacteria [33]. This is consistent with the mechanism of reciprocal plant-microbe selection, in which the developmental stage of plants influences the assembly of microbial communities through nutrient-driven reciprocal interactions [34]. Planctomycetes have a unique cellular structure and lifestyle and play an important role in nutrient cycling [35]. In the rhizosphere soil of 5-year-old Z. bungeanum, we observed a shift in the differential indicator species to Planctomycetes. This may be due to the increase in planting years and photosynthetic products secreted by root system. This affects the propensity of different species to utilize the resource, leading to oxygenic photosynthesis and consequently the enrichment of a phylum of floxigenic molds that can survive in anoxic environments that utilize nitrite and oxidized ammonium ions [36]. This mechanism highlights selective screening and resource-driven microbial enrichment in the roots [37]. Methylomirabilota was a differential indicator species for 10a rhizosphere soils, and correlation analyses showed that its abundance was significantly correlated (p < 0.05) with the alkaline dissolved nitrogen content, consistent with the results of He et al. [38]. This may be related to the over-application of nitrogen or nitrate fertilizers during the 10a period, which provided favorable conditions for its reproduction [39]. Overapplication of nitrogen may have increased competition for resources in favor of microorganisms adapted to high-nitrogen environments, suggesting reciprocal selection between the root system and bacteria mediated by fertilization practices [40]. Actinobacteria decompose SOM, promote carbon cycling, and support plant growth [41]. In the present study, the relative abundance of Actinobacteria gradually increased with the increasing years of planting and served as a differential indicator species in the 15-year old rhizosphere soil. This may be due to the continuous accumulation of complex compounds such as cellulose and lignin as well as root secretions in the soil, which provide more nutrient resources for the growth and reproduction of Actinobacteria, which is consistent with the findings of Cui et al. [42]. This optimizes soil nutrient cycling and microbial stability to maintain sustained plant growth [43]. This analysis suggests that plant-microbe reciprocal selection and inter-root selective screening play key roles in shaping bacterial community structure and function, and that factors such as cropping year, nutrient availability and plant physiology drive these dynamic processes [44]. Future research should focus on elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying these interactions and explore strategies for utilizing microbial communities in sustainable agricultural practices.

5.3 Prediction of Bacterial Functional Genes in the Rhizosphere Soil of Z. bungeanum

Soil microorganisms play a crucial role in the decomposition of organic matter and the transformation of soil nutrients through their metabolic activities [45]. Metabolism is the primary function of soil bacterial communities during biogeochemical cycles [46]. In this study, the relative abundance of metabolic functions of soil bacteria in the rhizosphere soil of Z. bungeanum exceeded 48%, which was closely related to key functions such as carbohydrate metabolism, nitrogen fixation, and phosphorus solubilization. These functions promote nitrogen and phosphorus absorption by Z. bungeanum roots. Amino acid metabolism facilitates nitrogen cycling through deamination and transamination, providing nutritional conditions for bacterial survival and reproduction. Certain metabolic processes enhance plant growth and development by producing antibiotics, growth hormones, and antibacterial proteins [46]. Furthermore, significant differences were observed in the relative abundances of these metabolic functions among rhizosphere soil bacteria across different planting years, indicating that the planting years had a significant impact on the metabolic capacity of soil bacteria. Although PICRUSt2 functional prediction can be used to analyze bacterial function, it lacks gene data support, which presents certain limitations. Future research should explore the relationship between rhizosphere bacteria and planting years more comprehensively by integrating metagenomic technologies.

BugBase predictions for rhizosphere soils in different planting years indicated a general upward trend in the abundance of aerobic bacteria, whereas anaerobic bacteria exhibited a downward trend. Both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria in the rhizosphere include members of the phyla Planctomycetes and Acidobacteria, with varying abundance in different planting years. This variability may be linked to the preference of Acidobacteria for anaerobic and microaerophilic environments, as lower pH values in the rhizosphere promote the growth of certain subgroups of Acidobacteria. However, Acidobacteria cannot survive well in the rhizosphere under nutrient-rich conditions [47]. In contrast, Planctomycetes encompass obligate aerobic genera, such as Mortierella, and anaerobic ammonium oxidation genera, such as Candidatus Brocadia, which can thrive in diverse oxygen environments. Consequently, there were differences in the composition of anaerobic and aerobic bacteria across different years. This study suggests that Z. bungeanum is susceptible to pathogen infection during its initial development because of the high proportion of pathogenic bacteria present during the early stages. However, this vulnerability may decrease with increasing planting years, as the number of oxidative stress-tolerant bacteria increases, thereby enhancing the resistance of Z. bungeanum to pathogens. It is widely accepted that members of the phyla Acidobacteria and Nitrospirales are non-pathogenic; hence, it can be inferred that the potentially pathogenic bacteria affecting Z. bungeanum originate from the phylum Proteobacteria [13]. Research has demonstrated that Actinobacteria can withstand pressure and resist pathogenic infections [48]. In this study, Actinobacteria emerged as the dominant taxonomic group among the stress-tolerant microorganisms, with its abundance steadily increasing over the planting years, indicating its significant role in facilitating the adaptation of Z. bungeanum to environmental stress.

5.4 Relationship between Bacterial Community and Functional Genes in the Rhizosphere Soil of Z. bungeanum and Physicochemical Factors

The soil environment, which acts as a habitat for microorganisms, significantly influences microbial diversity and community structure. The determinants of the rhizosphere microbial community can vary across different growth stages or regions of the same plant. Numerous studies have reported that soil physicochemical properties are important factors affecting the composition of soil bacterial communities [49]. For instance, Tang et al. [50] identified key environmental factors affecting the soil bacterial community structure in pecan plantations, including soil type and the pH, available phosphorus content, electrical conductivity, soil moisture and ammonium nitrogen contents. Liao et al. [23] discovered that pH, AP, AK, and polyphenol oxidase activity are the primary factors influencing the rhizosphere soil bacterial community of Z. bungeanum in Maoxian County. This study revealed that organic matter, AKP, pH, and AP content are the key factors influencing the bacterial community structure of Z. bungeanum rhizosphere soil in Linxia. SOM, as a key energy source, directly shapes microbial community structure and function, and its activity and diversity are regulated by the availability of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus [51]. Conversely, soil microbial communities are vital for sustaining soil fertility because they play an essential role in regulating the cycling of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus in soils. Random forest and RDA also indicated that SOM was the most significant physicochemical factor affecting the community structure of soil bacteria at the phylum and class levels. Wang et al. [47] found that a decrease in bacterial diversity in the rhizosphere soils of forage on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau led to a 30.4% reduction in the potential for carbon utilization. Soil pH is one of the main factors affecting the structure and function of soil bacterial communities [52]. There are significant differences in the composition of bacterial communities under different pH conditions [53]. For example, in soils where chemical fertilizers have been applied for a long period of time, changes in pH can lead to the enrichment of specific bacterial taxa, thereby altering the community structure [54]. The significant negative correlation between rhizosphere soil pH and AP content in the present study is consistent with the findings of Ibrahim and Ikhajiagbe et al. [55]. This may be because the effectiveness of phosphorus is reduced under acidic conditions, which in turn affects the rhizosphere bacterial community in peppercorns. Therefore, clarifying the relationship between soil environment and changes in the microbial community structure is crucial for scientifically evaluating the stability and systematicity of soil ecosystems, while also positively impacting Z. bungeanum cultivation.

The composition of the soil bacterial community is significantly influenced by the metabolic functions of soil bacteria. Pearson correlation analysis revealed a significant correlation between the changes in the relative abundance of secondary metabolic function genes in the rhizosphere soil bacteria of Z. bungeanum and the changes in the relative abundance of Acidobacteriota, Actinobacteriota, and Bacteroidota, which is consistent with the findings of Li et al. [56]. Pold and DeAngelis [57] suggested that soil microorganisms exhibit functional redundancy, indicating that community functions do not change with variations in microbial diversity and structure. However, Liang et al. [58] found that habitat changes lead to increased soil bacterial diversity and alterations in community structure, which play crucial roles in maintaining community functional stability. In the present study, significant differences were observed in the abundance of secondary metabolism functional genes among certain rhizosphere soil bacteria across different planting years, suggesting that planting duration affects the composition of bacterial secondary metabolites. Further investigation is needed to explore the relationship between this observation and changes in the bacterial community structure over time due to planting years. Currently, there is limited research on the intrinsic relationships and mechanisms through which Z. bungeanum affects the soil microbial community structure and metabolic functional genes. Future studies should delve deeper into how Z. bungeanum shapes the soil microbial community structure and fulfills its specific functions.

Planting duration significantly influenced the physicochemical properties, bacterial community composition, and diversity of Z. bungeanum rhizosphere soil. Bacterial diversity increased progressively with the stand age. The predominant phyla were Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Acidobacteriota, and Chloroflexi. Amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism were the primary metabolic functions of bacteria in Z. bungeanum rhizosphere soil, and the relative abundance of functional genes increased significantly as the planting duration increased. The community structure of rhizosphere soil bacteria was mainly influenced by organic matter content, AKP activity, AP content, and pH. Among these factors, organic matter had the most significant impact on the phylum and class levels, as well as metabolic functions. Based on the key role of SOM in shaping bacterial communities and metabolic functions, appropriate cultivation and management measures should be adopted for Z. bungeanum plantations with longer planting years, such as applying decomposed compost and covering crops with legumes. By maintaining a certain SOM content, the soil microbial community structure and function of Z. bungeanum plantations can be improved, and soil quality can be enhanced to promote the healthy growth of Z. bungeanum trees over longer planting years.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank the staff at Hangzhou Lianchuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd., for advice on the data analysis.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by Forestry and Grassland Science and Technology Innovation Project (LCKJCX2022001) from Forestry and Grassland Bureau of Gansu Province’s.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: De Zhang and Jun-Ying Zhao; data acquisition: De Zhang and Tong Zhao; data analysis: De Zhang and Yuan-Zu Ji; design of methodology: De Zhang and Jun-Ying Zhao; writing and editing: De Zhang and Jun-Ying Zhao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data are contained within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zeng J, Liu X, Song L, Lin X, Zhang H, Shen C, et al. Nitrogen fertilization directly affects soil bacterial diversity and indirectly affects bacterial community composition. Soil Biol Biochem. 2016;92:41–9. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2015.09.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Vieira S, Sikorski J, Dietz S, Herz K, Schrumpf M, Bruelheide H, et al. Drivers of the composition of active rhizosphere bacterial communities in temperate grasslands. ISME J. 2020;14(2):463–75. doi:10.1038/s41396-019-0543-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Zhou Z, Wang C, Luo Y. Meta-analysis of the impacts of global change factors on soil microbial diversity and functionality. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):3072. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-16881-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Deng J, Bai X, Zhou Y, Zhu W, Yin Y. Variations of soil microbial communities accompanied by different vegetation restoration in an open-cut iron mining area. Sci Total Environ. 2020;704:135243. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Oldroyd GED, Leyser O. A plant’s diet, surviving in a variable nutrient environment. Science. 2020;368(6486):eaba0196. doi:10.1126/science.aba0196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Xie C, Song P, Zhang Z, Gong Q, Wu J, Sun Z. Change patterns of understory vegetation diversity and rhizosphere soil microbial community structure in a chronosequence of Phellodendron chinense plantations. Forests. 2025;16(8):1298. doi:10.3390/f16081298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Trujillo-Elisea FI, Labrín-Sotomayor NY, Becerra-Lucio PA, Becerra-Lucio AA, Martínez-Heredia JE, Chávez-Bárcenas AT, et al. Plant growth and microbiota structural effects of rhizobacteria inoculation on mahogany (Swietenia macrophylla king [Meliaceae]) under nursery conditions. Forests. 2022;13(10):1742. doi:10.3390/f13101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li Y, Liu Z, Yang L, Yang X, Shi Y, Li X, et al. Analysis of changes in herbaceous peony growth and soil microbial diversity in different growing and replanting years based on high-throughput sequencing. Horticulturae. 2023;9(2):220. doi:10.3390/horticulturae9020220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Pan J, Guo Q, Li H, Luo S, Zhang Y, Yao S, et al. Dynamics of soil nutrients, microbial community structure, enzymatic activity, and their relationships along a chronosequence of Pinus massoniana plantations. Forests. 2021;12(3):376. doi:10.3390/f12030376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ye W, Li YC, Yu WW, Ye XM, Qian YT, Dai WS. Microbial biodiversity in rhizospheric soil of Torreya grandis ‘Merrillii’ relative to cultivation history. Ying Yong Sheng Tai Xue Bao. 2018;29(11):3783–92. doi:10.13287/j.1001-9332.201811.034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Wang F. Development status and countermeasures of Zanthoxylum bungeanum industry in Linxia prefecture. Agric Sci-Technol Inf. 2020;16:55–8. (In Chinese). doi:10.6046/zrzyyg.2021112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Xiong W, Zhao Q, Zhao J, Xun W, Li R, Zhang R, et al. Different continuous cropping spans significantly affect microbial community membership and structure in a vanilla-grown soil as revealed by deep pyrosequencing. Microb Ecol. 2015;70(1):209–18. doi:10.1007/s00248-014-0516-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Yang R, Li J, Long J, Liao HK, Wang X, Li YR. Structural characteristics of bacterial community in rhizosphere soil of Zanthoxylum bungeamun in different planting years in karst areas of Guizhou. Ecol Environ Sci. 2021;30(1):81–91. (In Chinese). doi:10.16258/j.cnki.1674-5906.2021.01.0010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wilke BM. Determination of chemical and physical soil properties. In: Monitoring and assessing soil bioremediation. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2005. p. 47–95. doi:10.1007/3-540-28904-6_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Margenot AJ, Nakayama Y, Parikh SJ. Methodological recommendations for optimizing assays of enzyme activities in soil samples. Soil Biol Biochem. 2018;125:350–60. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.11.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sloan WT, Lunn M, Woodcock S, Head IM, Nee S, Curtis TP. Quantifying the roles of immigration and chance in shaping prokaryote community structure. Environ Microbiol. 2006;8(4):732–40. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00956.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wu L, Weston LA, Zhu S, Zhou X. Rhizosphere interactions: root exudates and the rhizosphere microbiome. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1281010. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1281010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Jiao JH, Fu X, Zhang S, Liu W, Zhou JJ, Wu XY, et al. Physiochemical properties and microorganism community structure of Zanthoxylum bungeanum rhizosphere soil in different planting years. J Northwest A F Univ. 2023;38:156–65. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/i.issn.1001-7461.2023.04.20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Liu JJ, He J, Chen W, Wang B, Wang XJ, Shen QL, et al. Effects of continuous cropping of Zanthoxylum bungeanum on soil chemical properties and enzyme activities. Mol Plant Breed. 2019;17:7545–50. (In Chinese). doi:10.13271/j.mpb.017.007545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Duan A, Lei J, Hu X, Zhang J, Du H, Zhang X, et al. Effects of planting density on soil bulk density, pH and nutrients of unthinned Chinese fir mature stands in south subtropical region of China. Forests. 2019;10(4):351. doi:10.3390/f10040351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chen C, Liu W, Wu J, Jiang X, Zhu X. Can intercropping with the cash crop help improve the soil physico-chemical properties of rubber plantations? Geoderma. 2019;335:149–60. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.08.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wang B, Lu Y, Li W, He S, Lin R, Qu P, et al. Effects of the continuous cropping of Amomum villosum on rhizosphere soil physicochemical properties, enzyme activities, and microbial communities. Agronomy. 2022;12(10):2548. doi:10.3390/agronomy12102548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liao LB, Shi FS, Zhang NN, Chen XX, Bu HH, Sun FY, et al. Effects of different planting years on rhizosphere soil physiochemical properties and microbial community of Zanthoxylum bungeanum. Bull Bot Res. 2022;42:466–74. (In Chinese). doi:10.7525/j.issn.1673-5102.2022.03.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Bebber DP, Richards VR. A meta-analysis of the effect of organic and mineral fertilizers on soil microbial diversity. Appl Soil Ecol. 2022;175:104450. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2022.104450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhao X, Zhang X, Li Z, Wang B, Zhang T, Wan P. Development of root rot in Zanthoxylum bungeanum is closely linked to changes in soil microbial communities, enzyme activities, and physicochemical factors. Glob Ecol Conserv. 2024;55:e03249. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2024.e03249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Luan H, Liu Y, Huang S, Qiao W, Chen J, Guo T, et al. Successive walnut plantations alter soil carbon quantity and quality by modifying microbial communities and enzyme activities. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:953552. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.953552. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Gao C, Li C, Zhang L, Guo H, Li Q, Kou Z, et al. The influence of soil depth and tree age on soil enzyme activities and stoichiometry in apple orchards. Appl Soil Ecol. 2024;202:105600. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2024.105600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Xu M, Jian J, Wang J, Zhang Z, Yang G, Han X, et al. Response of root nutrient resorption strategies to rhizosphere soil microbial nutrient utilization along Robinia pseudoacacia plantation chronosequence. For Ecol Manage. 2021;489:119053. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wei C, Liu S, Li Q, He J, Sun Z, Pan X. Diversity analysis of vineyards soil bacterial community in different planting years at eastern foot of Helan Mountain. Ningxia Rhizosphere. 2023;25:100650. doi:10.1016/j.rhisph.2022.100650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Lan X, Du H, Peng W, Liu Y, Fang Z, Song T. Functional diversity of the soil culturable microbial community in eucalyptus plantations of different ages in Guangxi, South China. Forests. 2019;10(12):1083. doi:10.3390/f10121083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Qiu Z, Shi C, Zhao M, Wang K, Zhang M, Wang T, et al. Improving effects of afforestation with different forest types on soil nutrients and bacterial community in barren hills of North China. Sustainability. 2022;14(3):1202. doi:10.3390/su14031202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wei H, Peng C, Yang B, Song H, Li Q, Jiang L, et al. Contrasting soil bacterial community, diversity, and function in two forests in China. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1693. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01693. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Balasubramanian VK, Jansson C, Baker SE, Ahkami AH. Molecular mechanisms of plant-microbe interactions in the rhizosphere as targets for improving plant productivity. In: Rhizosphere biology: interactions between microbes and plants. Singapore: Springer; 2020. p. 295–338. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-6125-2_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Bakker MG, Schlatter DC, Otto-Hanson L, Kinkel LL. Diffuse symbioses: roles of plant-plant, plant-microbe and microbe-microbe interactions in structuring the soil microbiome. Mol Ecol. 2014;23(6):1571–83. doi:10.1111/mec.12571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Bulgarelli D, Schlaeppi K, Spaepen S, Ver Loren van Themaat E, Schulze-Lefert P. Structure and functions of the bacterial microbiota of plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2013;64:807–38. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Luo J, Zhang Z, Hou Y, Diao F, Hao B, Bao Z, et al. Exploring microbial resource of different rhizocompartments of dominant plants along the salinity gradient around the hypersaline lake ejinur. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:698479. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.698479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang Y, Zhan J, Ma C, Liu W, Huang H, Yu H, et al. Root-associated bacterial microbiome shaped by root selective effects benefits phytostabilization by Athyrium wardii (Hook.). Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2024;269:115739. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2023.115739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. He C, Liu J, Wang R, Li Y, Zheng Q, Jiao F, et al. Metagenomic evidence for the microbial transformation of carboxyl-rich alicyclic molecules: a long-term macrocosm experiment. Water Res. 2022;216:118281. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2022.118281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Ma L, Li Y, Wei J, Li Z, Li H, Li Y, et al. The long-term application of controlled-release nitrogen fertilizer maintains a more stable bacterial community and nitrogen cycling functions than common urea in fluvo-aquic soil. Agronomy. 2024;14(1):7. doi:10.3390/agronomy14010007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Jiang N, Wei K, Pu J, Zhang Y, Xie H, Bao H, et al. Effects of the reduction in chemical fertilizers on soil phosphatases encoding genes (phoD and phoX) under crop residue mulching. Appl Soil Ecol. 2022;175:104428. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2022.104428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Jutakanoke R, Intaravicha N, Charoensuksai P, Mhuantong W, Boonnorat J, Sichaem J, et al. Alleviation of soil acidification and modification of soil bacterial community by biochar derived from water hyacinth Eichhornia crassipes. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):397. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-27557-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Cui H, Mo C, Chen P, Lan R, He C, Lin J, et al. Impact of rhizosphere priming on soil organic carbon dynamics: insights from the perspective of carbon fractions. Appl Soil Ecol. 2023;189:104982. doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2023.104982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Yan W, Yuan MM, Wang S, Sorensen PO, Wen T, Xu Y, et al. Microbial community dynamics in the soil-root continuum are linked with plant species turnover during secondary succession. ISME Commun. 2025;5(1):ycaf012. doi:10.1093/ismeco/ycaf012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Mulani R, Mehta K, Saraf M, Goswami D. Decoding the mojo of plant-growth-promoting microbiomes. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol. 2021;115:101687. doi:10.1016/j.pmpp.2021.101687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ye Z, Wang J, Li J, Zhang C, Liu G, Dong Q. Ecoenzymatic stoichiometry reflects the regulation of microbial carbon and nitrogen limitation on soil nitrogen cycling potential in arid agriculture ecosystems. J Soils Sediments. 2022;22(4):1228–41. doi:10.1007/s11368-022-03142-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ding YP, Du YJ, Gao GL, Zhang Y, Cao HY, Zhu BB, et al. Soil bacterial community structure and functional prediction of Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica plantations in the Hulun Buir Sandy Land. Acta Ecol Sin. 2021;41(10):4131–9. doi:10.5846/stxb202005251335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Wang GH, Liu JJ, Yu ZH, Wang XZ, Jin J, Liu XB. Research progress of acidobacteria ecology in soils. Biotech Bul. 2016;32:14–20. (In Chinese). doi:10.13560/j.cnki.biotech.bull.1985.2016.02.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. de Vries FT, Griffiths RI, Knight CG, Nicolitch O, Williams A. Harnessing rhizosphere microbiomes for drought-resilient crop production. Science. 2020;368(6488):270–4. doi:10.1126/science.aaz5192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Pei Z, Eichenberg D, Bruelheide H, Kröber W, Kühn P, Li Y, et al. Soil and tree species traits both shape soil microbial communities during early growth of Chinese subtropical forests. Soil Biol Biochem. 2016;96:180–90. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2016.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Tang Y, Liu J, Bao J, Chu G, Peng F. Soil type influences rhizosphere bacterial community assemblies of pecan plantations, a case study of Eastern China. Forests. 2022;13(3):363. doi:10.3390/f13030363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Wang Q, Chai Q, Dou X, Zhao C, Yin W, Li H, et al. Soil microorganisms in agricultural fields and agronomic regulation pathways. Agronomy. 2024;14(4):669. doi:10.3390/agronomy14040669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Zhou X, Tahvanainen T, Malard L, Chen L, Pérez-Pérez J, Berninger F. Global analysis of soil bacterial genera and diversity in response to pH. Soil Biol Biochem. 2024;198:109552. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2024.109552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Xiang J, Gu J, Wang G, Bol R, Yao L, Fang Y, et al. Soil pH controls the structure and diversity of bacterial communities along elevational gradients on Huangshan, China. Eur J Soil Biol. 2024;120:103586. doi:10.1016/j.ejsobi.2023.103586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Zhang Y, Shen H, He X, Thomas BW, Lupwayi NZ, Hao X, et al. Fertilization shapes bacterial community structure by alteration of soil pH. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1325. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.01325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Ibrahim MS, Ikhajiagbe B. Effects of plant growth promoting bacteria (PGPB) rhizo-inoculation on soil physico-chemical, bacterial community structure and root colonization of rice (Oryza sativa l. var. faro 44) grown in ferruginous ultisol conditions. Sci World J. 2024;19(3):894–9. doi:10.4314/swj.v19i3.38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Li K, Lin H, Han M, Yang L. Soil metagenomics reveals the effect of nitrogen on soil microbial communities and nitrogen-cycle functional genes in the rhizosphere of Panax ginseng. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1411073. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1411073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Pold G, DeAngelis K. Up against the wall: the effects of climate warming on soil microbial diversity and the potential for feedbacks to the carbon cycle. Diversity. 2013;5(2):409–25. doi:10.3390/d5020409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Liang Y, Xiao X, Nuccio EE, Yuan M, Zhang N, Xue K, et al. Differentiation strategies of soil rare and abundant microbial taxa in response to changing climatic regimes. Environ Microbiol. 2020;22(4):1327–40. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.14945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools