Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Nanoparticles and Phytohormonal Synergy in Plants: Sustainable Agriculture Approach

1 Department of Horticulture, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, 60800, Pakistan

2 Department of Soil Science, The University of Agriculture, Dera Ismail Khan, 29220, Pakistan

3 Plant Production Department (Horticulture—Medicinal and Aromatic Plants), Faculty of Agriculture (Saba Basha), Alexandria University, Alexandria, 21531, Egypt

4 Department of Agriculture-Horticulture, Faculty of Environmental Protection, University of Oradea, Oradea, 671768, Romania

5 Department of Horticulture, The University of Agriculture, Dera Ismail Khan, 29220, Pakistan

* Corresponding Author: Riaz Ahmad. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Emerging Insights into Phytohormonal Crosstalk in Plant Stress Tolerance)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(9), 2631-2648. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.069474

Received 24 June 2025; Accepted 03 September 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

The production of crops is badly affected by climate change globally. Mitigation of adverse effects of climate change is in need of time through different management practices such as developing tolerant genetic resources, hormonal applications to boost defense systems, nanoparticles, and balanced fertilization. The nano-hormonal synergy had the potential to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change by modulation of morpho-physiological and biochemical activities. Plant growth, yield, and quality can be enhanced with the supplementation of nano-hormonal interactions. Therefore, the current study explores the synergy between nanoparticles and phytohormonal use. The nanoparticles, even in low concentrations, had an excellent capability to improve the endogenous hormones contributing to the regulation of plant responses under stress conditions. Nano-hormonal interaction improved the plant tolerance against climate change by activation of signaling molecules and the plant defense system. Nano-hormonal contact triggers several enzymic and non-enzymatic activities that can scavenge toxic substances generated within the plants. The reduction in electrolyte leakage, malondialdehyde (MDA), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was due to the supplementation of nano-hormonal exchange. The optimum production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is necessary for normal plant growth and various developmental processes. However, the overproduction of ROS can be eliminated with nano-hormonal synergy. However, inappropriate applications can cause phytotoxicity such as germination inhibition, root malformation, and chlorosis. The optimum doses can vary depending on the kind of crop and stress conditions. The nano-hormonal interface is beneficial for crop growth, yield, and quality. Moreover, these are also effective in repairing plants damaged from adverse climatic conditions. Hence, these are effective for sustainable agriculture production.Keywords

Climate change is drastically reducing the productivity of crops. Biotic and abiotic stressors occur from variation in climate change. The variation in climate change may occur due to abrupt changes in temperature, irregular rainfall, nutrient deficiency, and drought conditions. Urbanization, industrialization, extensive mining, rapid population growth, and bombardment of chemicals in farming are also causes of global warming and further climate change [1]. Plants are more sensitive to abiotic stresses (salinity, temperature extremes, drought, and heavy metals), which adversely affect the productivity of crops [2]. Plant stress reactions are very complicated when subjected to adverse climatic conditions [3]. However, several pathways contribute to the tolerance of plants by signaling molecules coordination and cellular compartments [4]. The plant’s reaction is based on the kind, duration, and severity of occurred stress [5]. To counteract stress reactions and enhance tolerance, plants respond to abiotic challenges by activating early stress-signaling systems [6,7]. Calcium, phospholipids, reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitric oxide (NO), and several protein kinases, spread signals when a plant is subjected to adverse conditions [8]. Plant stress tolerance improved by inhibition of energy-intensive activities. Moreover, SnRk1 kinases alter the expression of about 1000 stress-responsive genes, aiding in the restoration of homeostasis. This makes it possible for plants to tolerate abiotic stressors [9]. Moreover, plant defensive responses comprising the stomata closure during drought stress are primarily signaled by plant hormones, i.e., abscisic acid (ABA) and ethylene [5]. These stress-signaling pathways trigger transcription factors, which in turn trigger various stress-response genes to combat the severity of stress conditions in plants [5].

The optimum ROS generation in plants is necessary for sufficient plant growth and various developmental processes. Irregular and higher ROS generation greater than optimum need may injure the plants by causing oxidative injury. Oxidative stress occurs in plants due to the overproduction of ROS within the cell compartments. Moreover, physiological impairments in plants are also due to oxidative damage [10]. Regardless of the stress, damage to photosynthetic systems and membrane peroxidation have been recognized in many plants. Therefore, scavenging ROS through the activation of antioxidant molecules is the primary focus of plant defense systems [11]. The numerous plants have been shown to exhibit decreased phenol and flavonoid synthesis under abiotic stress conditions. Significant levels of phytochelatin were mostly found in response to metal toxicity. The regulation of osmolyte generation is also supportive of improving plant tolerance against adverse conditions [12]. Hence, regulation of proline activation in plants can be effective to mitigate the adverse climatic conditions. The activation of antioxidant enzymes to eliminate the ROS molecules is another significant metabolic alteration. Antioxidant enzymes aid plants in surviving oxidative stress by scavenging of ROS in excess. Abiotic stress mitigation is essential for excellent crop production [12].

Abiotic stress tolerance in crops is effectively boosted with various management techniques comprising the use of nanotechnology, organic amendments, microorganisms, and phytohormone supplements [13,14]. The capability of plants to withstand abiotic stress may be enhanced by all of these management techniques. Crop yield can be increased by cultivating resistant germplasm [15]. Thus, one of the essential strategies for the production of tolerant germplasm with an emphasis on increased yield and superior quality is the selection, assessment, and detection of tolerant genetic resources. Agricultural farming has become more sustainable with the advancements of nanotechnology [16]. Because of their reduced size, larger surface area, improved mobility, and increased porosity, nanoparticles have made remarkable contributions to agriculture farming [17–19]. These nanoparticles could increase plant growth and yield because of their small size [20]. Nanoparticles (NPs) are gaining more attention from plant researchers because of their notable performance, affordability, and climate-friendly features [21]. Higher concentrations beyond the threshold had negative impacts on growth and yield because of toxicity, but the best usage of nanoparticles is for adequate growth and yield [22]. However, several factors, including crop variety, stress level, cultural customs, and climate in the growing locations, influence the selection of nanoparticles [23]. The higher tolerance level to abiotic stress conditions is important for plants to be productive with appropriate fruit quality. Plant productivity is being disrupted by the impairment of physiological and biochemical processes due to unfavorable climatic circumstances. The regulation of morpho-physiological and biochemical processes is necessary for sufficient plant growth and yield. The interactive findings of nanoparticles and phytohormones are necessary for sustainable agriculture. Therefore, the present work aims to explore the interaction of nanoparticles and phytohormones and their impact on plant growth, yield, and quality.

2 Impact of Nanoparticles on Plant Health and Production

Nanotechnology is an emerging way to mitigate the adverse effects of climate change [24]. The plants might strengthen tolerance against abiotic stress conditions through the interaction of nanoparticles. Enhancing plant tolerance mechanisms to abiotic stress is one way that nanotechnology promises to boost crop productivity. Nanotechnology is an effective way to develop and produce crops in modern agriculture. Nanoparticles can be applied to organic agriculture, postharvest management, agri-food production, nano-agrochemicals, plant genetic advancement through nanoparticles-mediated gene transfer, and organic agriculture [25]. Nanotechnology has become more and more reliant in several sectors recently because of its many potential uses, cost-effectiveness, environmental benefits, and durability. The application of nano-pesticides and nano-fertilizers has increased the agricultural output. The commercial crops have benefited from the efficient uptake of nutrients from the soil, particularly nano fertilizers (urea-doped calcium phosphate), which have also helped to maintain crop growth and productivity and promote sustainable agriculture [26]. Madanayake et al. [27] used a urea-hydroxyapatite-montmorillonite nanohybrid composite to observe the gradual release of nitrogen. The use of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles had a major impact on radish plant germination characteristics and crop yield [28]. Many uses for nanotechnology in soil and water remediation have improved food output and quality. Furthermore, because nanotechnology is environmentally friendly, its application greatly lessens the negative impacts of chemicals on crops and the environmental damage that agriculture causes [29]. NPs have had a positive impact on the metabolism of seeds and plants, along with growth promotion. The beneficial properties of NPs’ tiny size enable them to more effectively penetrate biological barriers in plants and treat plant stressors such as heat and salt stress, as well as stress brought on by heavy metals [30]. Nanoparticles had excellent potential to modulate physiological activities in plants that occur due to stress conditions.

The distinctive shape, adjustable pore size, and strong reactivity with increased surface area of nanoparticles improved their efficacy when supplemented on plants under either normal or stress conditions [31]. NPs are thought to be a useful and promising technique for controlling crop productivity and overcoming present and upcoming constraints on agricultural production by strengthening plant tolerance against abiotic stresses. Moreover, NPs have a moderating influence on drought stress by triggering physiological and biochemical regulation and controlling the expression of genes linked to plant response and tolerance. The primary mechanisms by which NPs reduce osmotic stress brought on by water scarcity are improved root growth, upregulation of aquaporins, altered intracellular water metabolism, accumulation of compatible solutes, and ionic homeostasis. NPs also increase the photosynthetic activity of drought-induced plants. NPs mitigate oxidative stress and lessen leaf water loss brought on by ABA buildup through stomatal closure by lowering ROS and triggering the antioxidant defense system [31].

Temperature extremes (heat and cold) occur because climate change has disturbed the productivity of crops. Nanoparticles are effective for the mitigation of temperature stress [32]. Plant growth can be improved with the supplementation of nanoparticles. Nanoparticle in varying quantities to mitigate the adverse effects occurring from heat stress can enhance plant growth even under drought stress [33]. Plants may experience oxidative harm due to nanoparticles’ phytotoxicity. Hence, the optimum dose of nanoparticles is effective, which may vary from one crop to another and also depends on duration and types of stress. The optimum dose of nanoparticles improved the plant defense system against temperature stress by activation of the antioxidant defense system. NPs repaired the membrane leakage by reducing the overgeneration of ROS, MDA, and H2O2 within the cell compartments. Heat shock proteins (HSP70 and HSP90) are regulated by supplementation of NPs [34]. Heat stress can be regulated with nanoparticles by regulating of stomata mechanism in plants [33].

Salt toxicity drastically reduced the plant growth and production. NPs can mitigate the adverse effects of salt toxicity by altering physiological and biochemical activities in millet [35]. Nanoparticles and plant interaction showed a significant impact on crop productivity [36]. NPs have been shown by Zulfiqar and Ashraf [37] to support plant growth and development under salt stress. Enhancing plant nutrition may be significantly impacted by NPs’ effects on nutrient absorption, transport, and ultimate allocation [38]. One of the most important elements for plant resistance to salt stress has been identified as the high K+/Na+ ratio, which is disturbed by salt toxicity. However, an ionic imbalance disturbed the plant growth and development. The osmotic potential of the plant is regulated, which in turn improves plant development under salt stress by supplementation of NPs [39]. Farhangi-Abriz and Torabian [40] privilege that raising the concentration of K+ in the leaves and nano-SiO2 improved the growth of soybean seedlings under salt stress. Moreover, a reduction in the uptake of Na+ in excess was also recorded with NPs application.

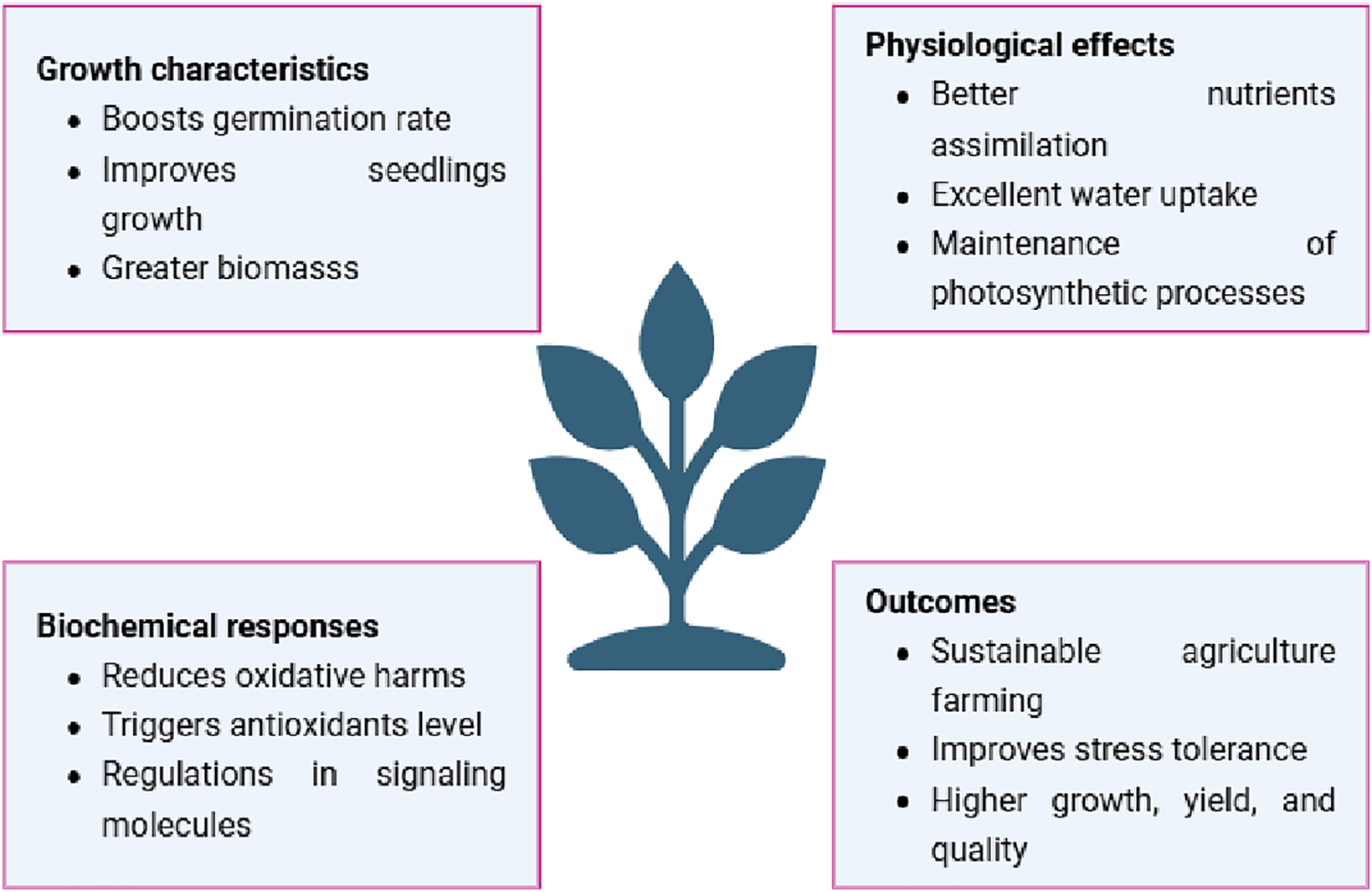

Metal toxicity is dangerous for plants and human health. Urbanization and industrial effluents are major causes of metal toxicity in soil and plants. The optimum dose of metals is necessary for sufficient plant growth, while their excess causes toxicity because it increases oxidative harm in cell compartments. Nanoparticles are an emerging technology to cope with metal toxicity in plants. Nanoparticle remediation is extremely effective, environmentally benign, and free of hazardous byproducts as compared to chemical remediation, which relies on the kinetic pace of the reaction, and bioremediation, which is more time-consuming and microbe-dependent. Nanotechnology is becoming more and more attractive across a range of industries because of its capacity for coping and sustainable competitiveness. The application of nano-pesticides and nano-fertilizers has led to a rise in the use of nanotechnology in agriculture [41]. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (Zn-NPs) were applied to lessen phytotoxicity in rice. There were notable reductions in the rates of arsenic (As) and cadmium (Cd) accumulation [42]. The application of Iron nanoparticles (Fe-NPs) to rice plants was studied by Bidi et al. [12] because immobilization of As in the cell walls and vacuoles improved the accumulation of the chelating agents and strengthened the glyoxalase system and antioxidant enzymes. Moreover, Fe-NPs inhibited the uptake of As in radish by activation of antioxidant capacity with a decrease in guaiacol peroxidase [43]. When copper nanoparticles (Cu-NPs) were applied to lettuce, Wang et al. [44] found a significant decrease in As along with a rise in plant biomass and antioxidant activity. Mitigation of metal toxicity with different nanoparticles is an effective strategy for sustainable agriculture practices (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Impact of nanoparticles on plant growth, yield, and quality

It is predicted that more than 200 million tons of commercial fertilizer are used annually to meet 3 billion tons of crop production. The need for agricultural output cannot be met sustainably by relying solely on commercial fertilizers [45]. Numerous efficient methods are being used to lessen nutrient loss and degradation of soil and groundwater including nano-fertilizers (NFs) supplementation. NFs are covered in nanoparticles that improve the efficiency of nutrient usage by regulating nutrient release based on plant needs [31]. Nanotechnology is widely applied in agricultural activities with the use of either nanoparticles or nano-capsules in slow-release fertilizers (SRFs). Although the rate of release is regulated, the nutrient release in SRFs is slower than usual. SRFs are only marginally soluble in water and can be broken down by microbial activity. A greater nutrient utilization efficiency is indicated by enhanced plant nutrient uptake and decreased nutrient loss [46].

3 Contribution of Phytohormones in Plant Stress Reactions

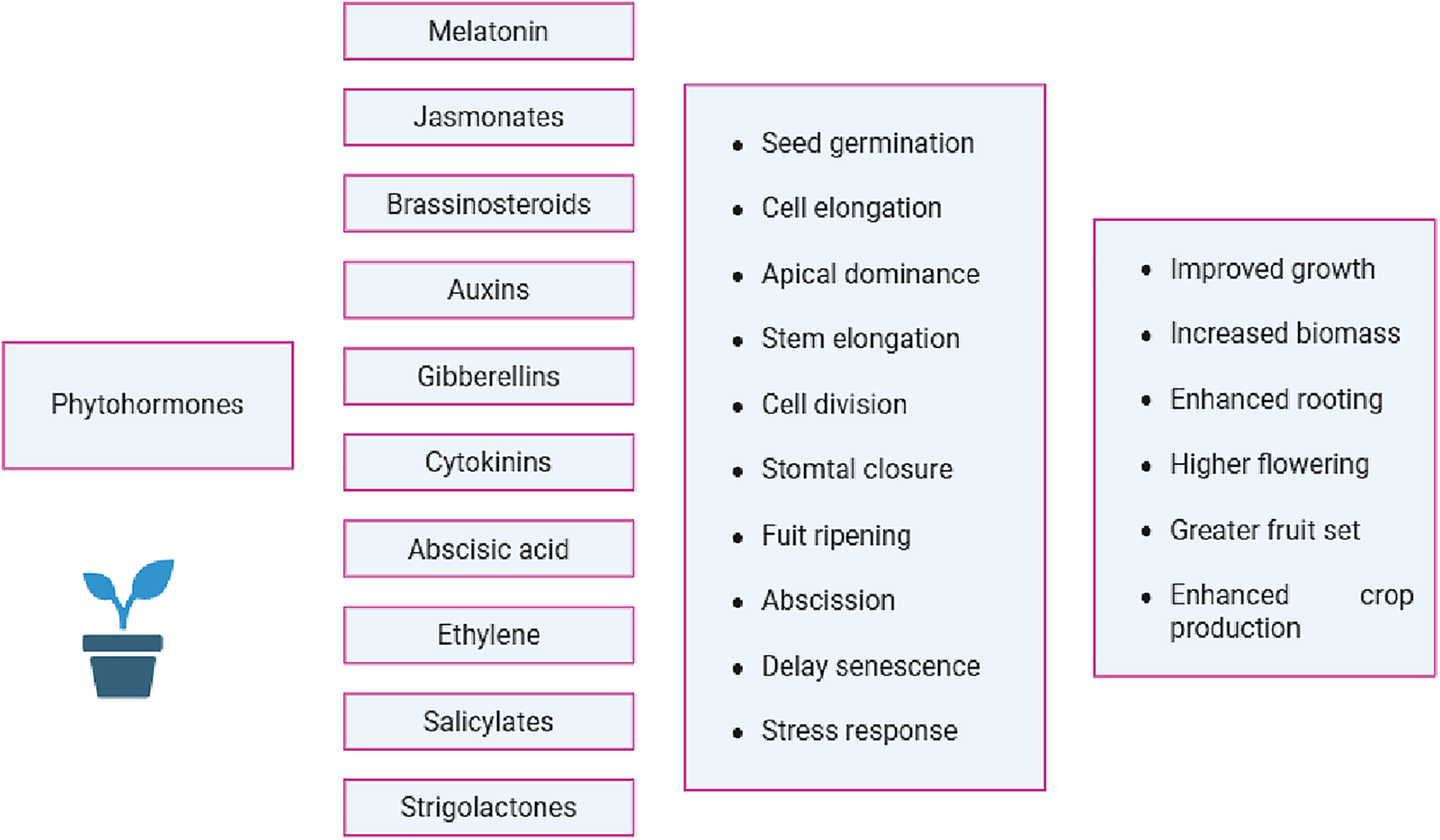

Phytohormones are effective tactics to enhance the climate-resilience in plants, focusing on growth and yield attributes [47]. Moreover, phytohormones are a novel and environmentally friendly way to increase plants’ resistance to abiotic stress in vegetables [48]. Similarly, Saini et al. [49] privilege that phytohormones are chemical mediators that plants make and that regulate environmental stressors by growing, maturing, and responding. Phytohormones are essential for the abiotic stress response by managing several signaling pathways [50]. Furthermore, they contribute to the neglect of numerous internal and external signals, which results in notable changes in seed germination rate and plant growth. The role of phytohormones as signaling molecules in abiotic stress tolerance has been studied by several plant researchers [48,50]. Horticultural crops use jasmonates as a defense against environmental stressors. These are especially helpful for horticultural crops that can tolerate harsh climatic conditions (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Impact of various phytohormones on crop growth and production

Jasmonates can be used to lessen environmental risks [51]. Plant defense mechanisms have evolved to accommodate environmental challenges, such as flooding in peppers [52]. Jasmonates offer an excellent crop defense mechanism in farming under harsh climatic regions [53]. Jasmonic acid regulates the defense system in melons subjected to abiotic stress conditions [54]. Different concentrations of phytohormones regulate the gene expression under normal and stress conditions for sufficient plant growth and many developmental processes [48]. Jasmonic acid foliar spraying improved crops’ tolerance to salt stress [55]. Jasmonic acid has the potential to reduce oxidative harm in plants caused by abiotic stress. Jasmonic acid had the potential to reduce the movement of salts from roots to other plant parts. Hence, jasmonic acid is an excellent treatment for the reduction of oxidative harm in stressed plants [56].

Nitric oxide (NO) is an important phytohormone and signaling molecule contributing to the tolerance of plants subjected to adverse climatic conditions. It is contributing to improving several plant traits such as flowering, fruiting, stomatal regulation, seed dormancy, seed germination, and seedling growth under normal and stressed conditions [57]. Sodium nitroprusside (SNP) is an excellent NO contributor for plants that can decrease the detrimental effects of ROS on plant growth by increasing the activity of antioxidant enzymes [58]. NO spraying is important for the enhancement of plants’ resistance to salt toxicity in various crops, i.e., tomato [59], pepper [60], and eggplant [61]. Furthermore, it was found to help tolerance mechanisms in higher-growing plants grown in harsh environments [62].

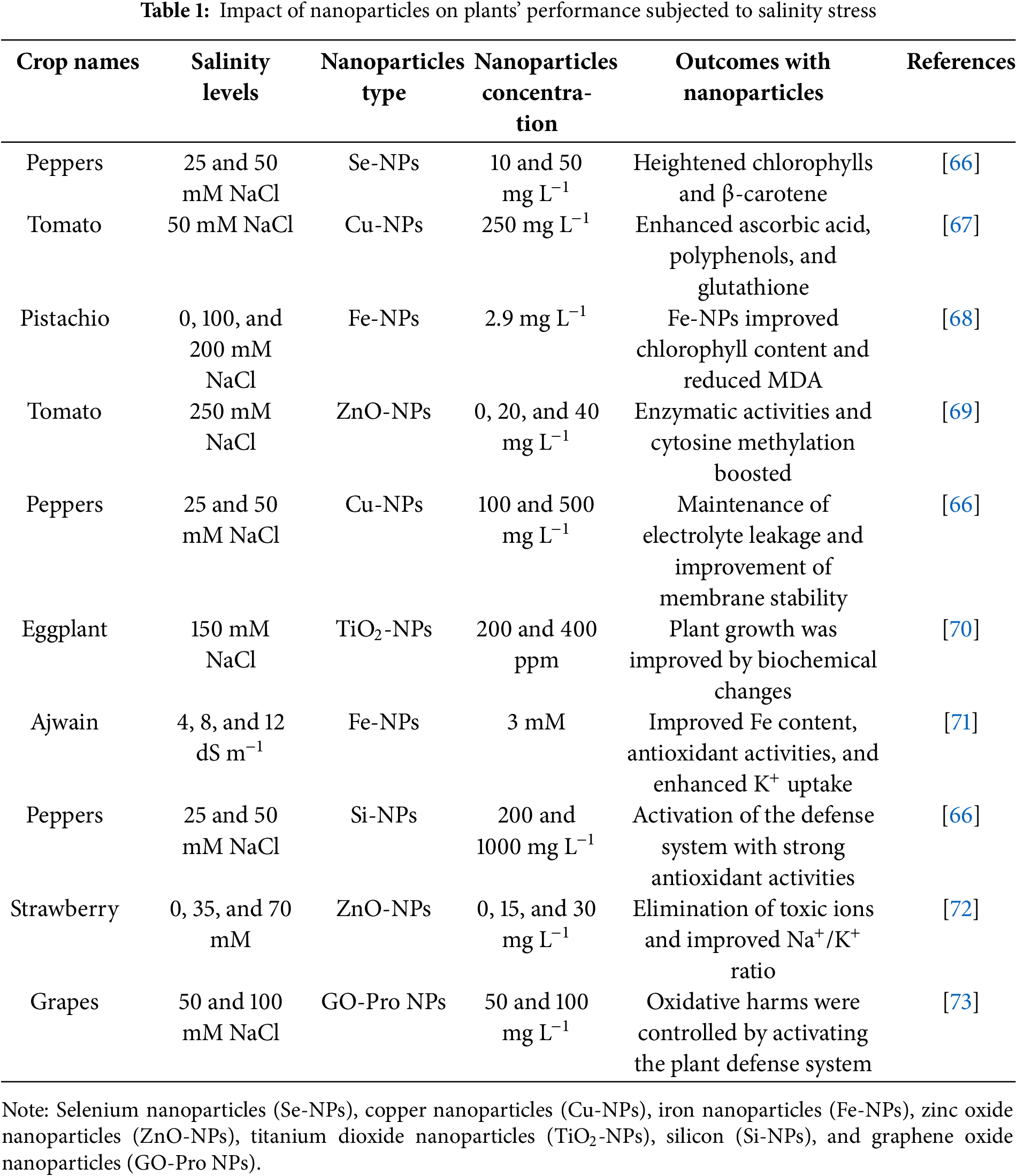

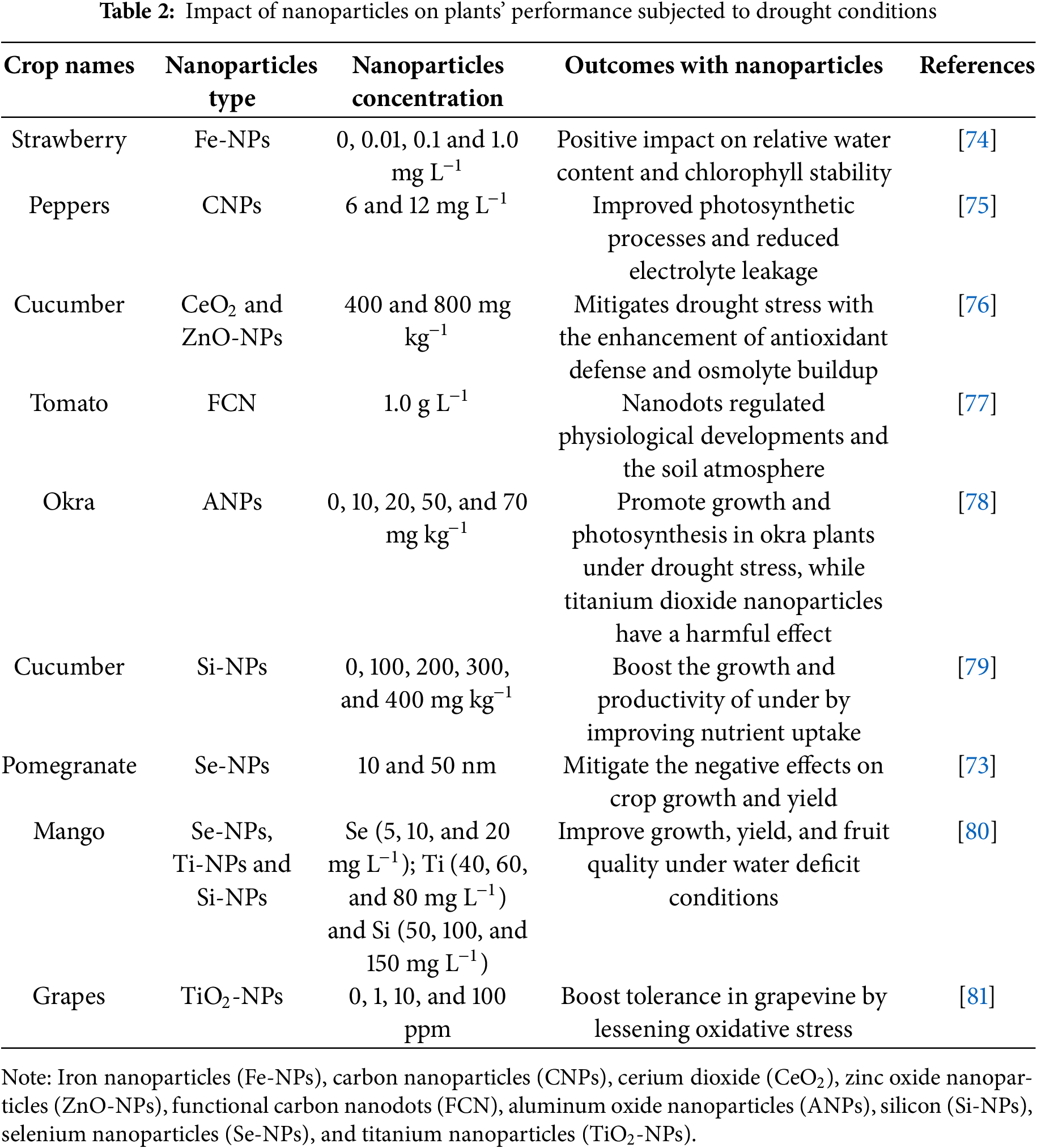

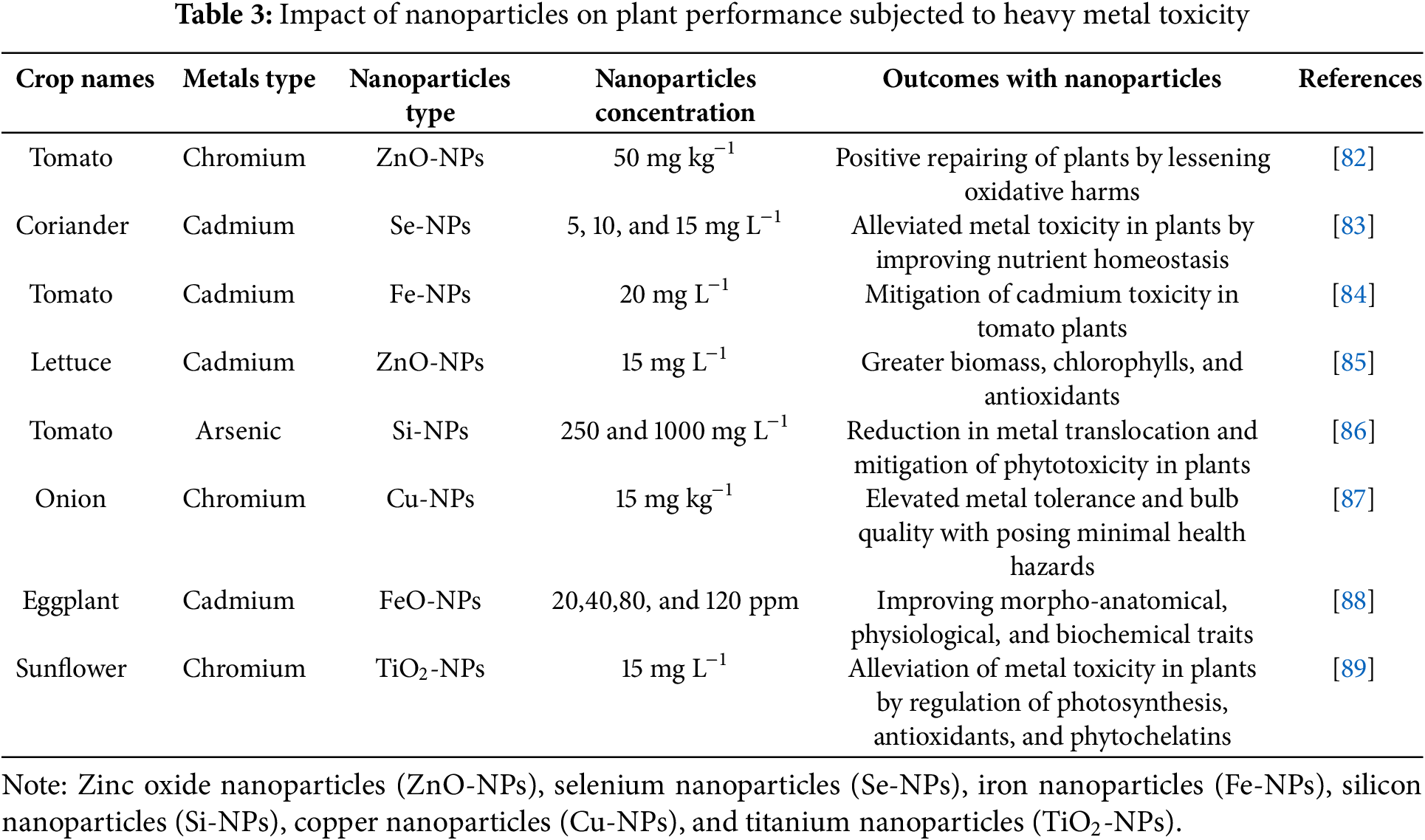

Abiotic stress tolerance can be enhanced with brassinosteroid supplementation [47]. Brassinosteroid application may increase ABA levels and lessen the negative consequences that occur in plants subjected to water deficit conditions [63]. Drought stress can be mitigated with the supplementation of brassinosteroids by reducing toxic substances generated within the cell compartments. Activation of the plant defense system was also noted by application of brassinosteroids, which further scavenges toxic and over-generated ROS in peppers [64]. Moreover, a study on tomatoes demonstrates that increasing endogenous brassinosteroids enhances drought resistance while reducing oxidative harm and lipid peroxidation. The study also found that tomato drought resistance was negatively impacted by BRI1 upregulation, indicating that variations in the brassinosteroid pathway may either boost or decrease stress tolerance and emphasizing the complex interactions between brassinosteroids and stressors [65]. Hence, BRs are necessary phytohormones to combat the adverse effects of abiotic stress conditions. The nanoparticles improve plant growth, yield, and antioxidants defense system subjected to salinity stress (Table 1), drought stress (Table 2), and metal stress (Table 3).

Melatonin effectively mitigates the adverse effects of abiotic stresses in plants. Melatonin improved the nutritional condition and shielded the sugar beet photosynthetic system. Furthermore, in cabbage treated with exogenous melatonin application, there was a documented downregulation of free radical formation as well as an elevation of antioxidant potential and osmotic adaptability [90]. Furthermore, Zhang et al. [91] found that the application of melatonin promoted anthocyanin production in lemons. The application of melatonin to spinach resulted in a significant delay in leaf chlorosis within a week of storage, as well as a sustained rise in soluble sugars, proteins, total flavonoids, phenols, and vitamin C [92]. Applying melatonin (100 μ mol L−1) to cucumber plants has been shown to significantly increase free proline, soluble protein, and vitamin C in addition to reducing the chilling damage index, respiration intensity, MDA contents, electrolyte leakage in tissues, ROS levels, and weight loss rate [93]. Melatonin (100 μM L−1) had a very effective effect on the mitigation of drought stress in tomato [94]. Exogenous melatonin reduces salt damage in rosemary plants [95].

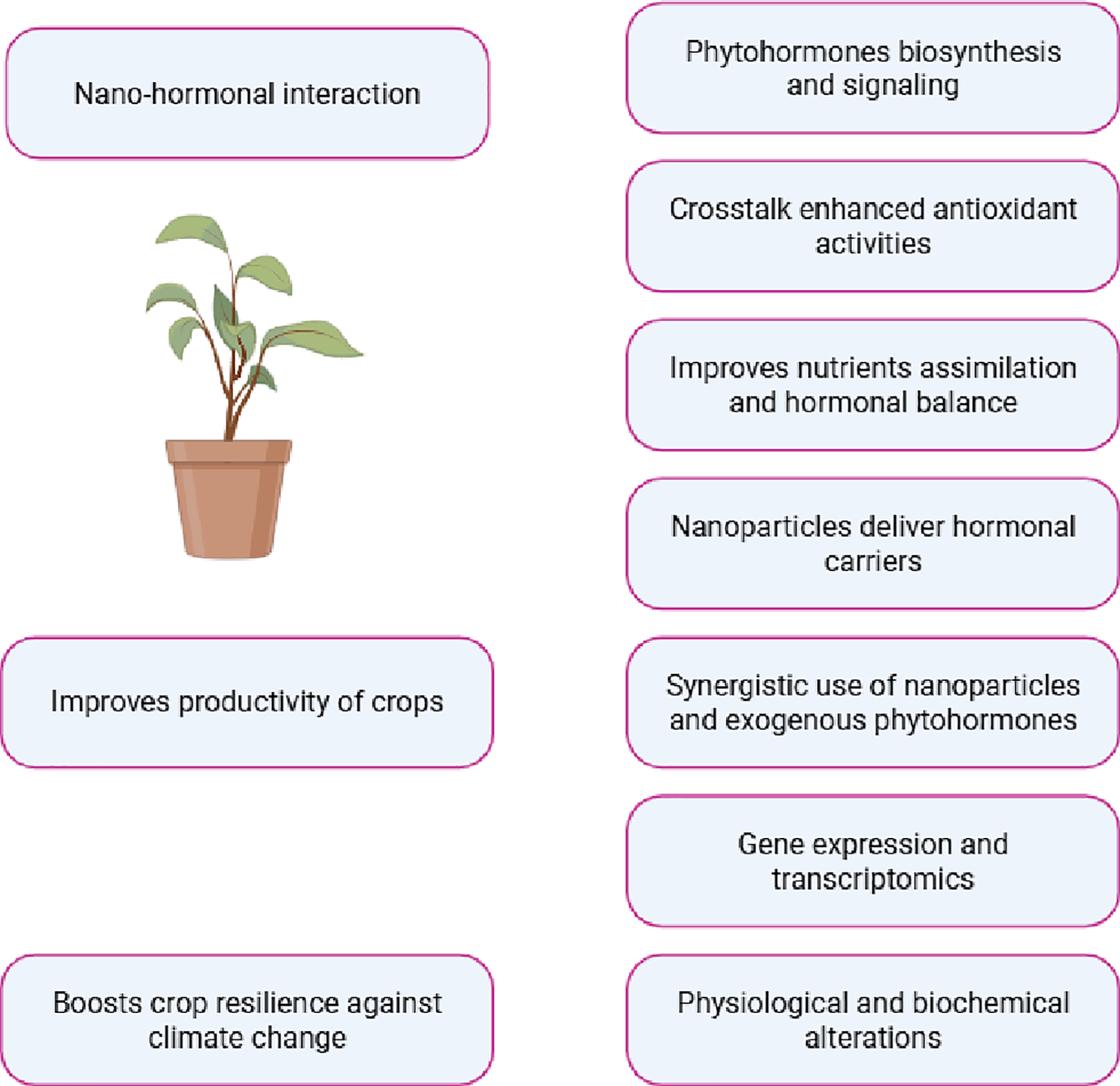

4 Nano-Hormonal Relations toward Resilient Crops against Climate Change

Plant defense responses are controlled by the regulation of signaling molecules with supplementation of nano-hormonal relations (Fig. 3). It is necessary for the sufficient growth of plants to explore nano-hormonal relations, either antagonistic or synergistic. Nanoparticles and phytohormones interact to regulate the stress signaling molecules effectively for proper plant growth under stressed plants [96]. However, reactions mediated by nanoparticles depend on many factors such as nanoparticle type and level, the plant species, and stress type and duration [97]. The important relationships between plant growth hormones and nanoparticles were explored by some plant researchers [98]. The application of nano-selenium caused modifications in phytohormones through NO signaling [99]. They have proposed that hormonal changes, particularly ethylene and auxin, under nano-Se exposure are indicated by the inhibition of xylem tissue differentiation, stem bending, inhibition of primary root development, and appearance of adventitious roots. Further research into nanoparticle-mediated phytohormonal changes at the molecular level is advised in the future. These signaling molecules are tightly linked to the regulation of plant development under biotic and abiotic stress. Moreover, there is a clear connection between the modification of plant hormone pools and the physiological performance of the plants [100]. It is crucial to characterize the metabolism and signaling of plant hormones to fully understand the regulatory networks that function under environmental stress. Many phytohormones contribute to the activation of the defense system in stressed plants by regulating signaling molecules. Plant hormone levels and functions are thought to be a key indicator of plant tolerance against toxicity [101].

Figure 3: Interaction between nanoparticles and phytohormones improves crop production

Plant hormones and nanoparticle exposure can interact either synergistic or an antagonistic way, which is important for plants to respond to stress. Plant hormones, being adaptable regulators of plant growth and development, offer an unknown area for research on interactions between plants and nanoparticles [102]. Plant hormones auxin and cytokinin primarily control the impacts of metallic nanoparticle exposure, which can either positively or negatively impact plant growth depending on concentration. Arabidopsis is exposed to metal oxide-based nanoparticles; its hormonal profile and physiological state are connected [103]. Moreover, ZnO-NPs improve different phytohormones such as cytokinin, auxin, and ABA concentrations in plants under adverse conditions [104]. The levels of cytokinin and cytokinin phosphatase, their active precursor, were upregulated to the mild ZnO-NP concentration in Arabidopsis. The graphene oxide nanomaterial can play a part in controlling mustard root growth through interactions between several plant growth hormones [98].

Numerous studies conducted over the past few decades have demonstrated the regulatory function of nanoparticles in plants under stressed conditions. However, limited research demonstrated that employing nanomaterials to modify various phytohormone production and signaling could alleviate environmental constraints. The production of ROS is a crucial mechanism that controls plant defensive responses and development. Both biotic and abiotic stressors disrupt the equilibrium between the production and elimination of ROS in plants, which is maintained under typical metabolic circumstances. Several phytohormones, i.e., ethylene, ABA, brassinosteroids, and jasmonates, regulate ROS applied at optimal concentration [105]. ZnO-NPs treatment also had adverse effects on indole acetic acid level in root apices of Arabidopsis [102]. Similarly, Sun et al. [105] studied that Ag-NPs enter into the plant cells and tissues through plasmodesmata and disrupt auxin’s and its receptor’s ability to bind. However, Wei et al. [106] found that root tips of Arabidopsis treated with TiO2 nanoparticles accumulated more auxin. Moreover, nano-titania has demonstrated the ability to regulate gibberellin production and signaling at the gene level [107]. The floral transition between the vegetative and reproductive phases of plant growth is a crucial event for controlling plant production and evasion of abiotic stress, which gibberellin regulates [108].

The effect of carbon nanoparticles on the Arabidopsis blooming and photomorphogenesis processes was examined by Kumar et al. [109]. Genes linked to the cytokinin-mediated signaling system were shown to be increased in Arabidopsis when exposed to titania and cerium nanoparticles [110]. Nanoparticles have an impact on plants’ endogenous salicylic acid content. Arabidopsis leaves showed a significant increase in salicylic acid content when subjected to ZnO-NPs [103]. Jasmonic acid controls stomatal opening and shutting, the buildup of amino acids that resemble isoleucine and methionine, soluble sugars, and the activation of the antioxidant defense system [111,112]. A thin-walled carbon nanotubes (CNTs) significantly decreased the concentration of brassinosteroids in plant roots and shoots, which inhibits plant tolerance, demonstrating the phytotoxicity of CNTs in rice [112].

Nanoparticles of Fe3O4 and ZnO upregulated auxin and cytokinin pathways to boost plant growth [113]. Iron nanoparticles encourage drought tolerance because of drought-responsive gene expression (GmERD1) in soybean [114]. ZnO nanoparticles improve gene expression (HsfA1a and HDA3) associated with auxin and cytokinin pathways in tomato, which further improved cell division, elongation, and differentiation [115]. Generally, many plant hormones (auxins, abscisic acid, and gibberellins) were stimulated with nanoparticles by regulation of calcium ions and ROS [116–118]. Nanoparticles of zinc and silver contribute to the upregulation of genes linked with cytokinins and auxins signaling under adverse climatic conditions. Moreover, these are effective for the promotion of root and shoot growth [118–120]. Jasmonic acid transporters cleanse heavy metals through ATP-Binding Cassette-G transporter subfamily of green plant species [121,122].

Crop production drastically reduced because of fluctuations in climate change. The abrupt changes in climatic conditions, i.e., temperature extremes, irregular rainfall, water deficit conditions, water logging, nutrient deficiency, soil contamination, and wind speed are disturbing the production of crops. Therefore, management approaches are necessary to combat stress conditions for proper plant growth and development. The relation between nanoparticles and phytohormones is an effective approach to enhance tolerance in plants against adverse climatic conditions by modulation of morpho-physiological, biochemical, and molecular interventions. Joint efforts of policymakers, farmers, and researchers are required to ensure sustainable vegetable production.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Hafiza Muniba Din Muhammad, Mohamed A. A. Ahmed, and Alina-Stefania Stanciu designed and wrote the paper, Safina Naz, Zarina Bibi, and Riaz Ahmad reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The availability of data is not applicable and all the required data is included within the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Quintarelli V, Ben Hassine M, Radicetti E, Stazi SR, Bratti A, Allevato E, et al. Advances in nanotechnology for sustainable agriculture: a review of climate change mitigation. Sustainability. 2024;16(21):9280. doi:10.3390/su16219280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zandalinas SI, Fritschi FB, Mittler R. Global warming, climate change, and environmental pollution: recipe for a multifactorial stress combination disaster. Trends Plant Sci. 2021;26(6):588–99. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2021.02.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Zhang H, Zhu J, Gong Z, Zhu JK. Abiotic stress responses in plants. Nat Rev Genetic. 2021;23(2):104–19. doi:10.1038/s41576-021-00413-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Marothia D, Kaur N, Kumar Pati P. Abiotic stress responses in plants: current knowledge and future prospects. In: Abiotic stress in plants. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2021. p. 1–18. doi:10.5772/intechopen.93824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Rahim HU, Ali W, Uddin M, Ahmad S, Khan K, Bibi H, et al. Abiotic stresses in soils, their effects on plants, and mitigation strategies: a literature review. Chem Ecol. 2025;41(4):552–85. doi:10.1080/02757540.2024.2439830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Molassiotis A, Fotopoulos V. Oxidative and nitrosative signaling in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 2011;6(2):210–4. doi:10.4161/psb.6.2.14878. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Mohanta TK, Bashir T, Hashem A, Abd Allah EF, Khan AL, Al-Harrasi AS. Early events in plant abiotic stress signaling: interplay between calcium, reactive oxygen species and phytohormones. J Plant Growth Regul. 2018;37(4):1033–49. doi:10.1007/s00344-018-9833-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang H, Zhao Y, Zhu JK. Thriving under stress: how plants balance growth and the stress response. Dev Cell. 2020;55(5):529–43. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2020.10.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Thapa B, Shrestha A. Protein metabolism in plants to survive against abiotic stress. In: Plant defense mechanisms. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2022. doi:10.5772/intechopen.102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ahmad R, Sabir MU. Vanadium stress mitigants in plants: from laboratory to field implications. J Hort Sci Technol. 2023;6:16–24. doi:10.46653/jhst23062016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sachdev S, Ahmad S. Role of nanomaterials in regulating oxidative stress in plants. In: Nanobiotechnology. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2021. p. 305–26. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-73606-4_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Bidi H, Fallah H, Niknejad Y, Barari Tari D. Iron oxide nanoparticles alleviate arsenic phytotoxicity in rice by improving iron uptake, oxidative stress tolerance and diminishing arsenic accumulation. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;163(7):348–57. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.04.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Collins D, Luxton T, Kumar N, Shah S, Walker VK, Shah V. Assessing the impact of copper and zinc oxide nanoparticles on soil: a field study. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e42663. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042663. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Sario DL, Boeri P, Matus JT, Pizzio GA. Plant biostimulants to enhance abiotic stress resilience in crops. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(3):1129. doi:10.3390/ijms26031129. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Fideghelli C, Vitellozzi F, Grassi F, Sartori A. Characterization and evaluation of fruit germplasm for a sustainable use. Acta Hortic. 2003;598(598):153–60. doi:10.17660/actahortic.2003.598.22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Haq IU. Harnessing nanotechnology for superior fruit crop quality and yield enhancement. Trends Anim Plant Sci. 2024;4:74–81. doi:10.62324/taps/2024.049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Su Y, Ashworth VETM, Geitner NK, Wiesner MR, Ginnan N, Rolshausen P, et al. Delivery, fate, and mobility of silver nanoparticles in Citrus trees. ACS Nano. 2020;14(3):2966–81. doi:10.1021/acsnano.9b07733. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Singh A, Tiwari S, Pandey J, Lata C, Singh IK. Role of nanoparticles in crop improvement and abiotic stress management. J Biotechnol. 2021;337(11):57–70. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2021.06.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Hayat F, Khanum F, Li J, Iqbal S, Khan U, Javed HU, et al. Nanoparticles and their potential role in plant adaptation to abiotic stress in horticultural crops: a review. Sci Hortic. 2023;321:112285. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sharma S, Singh SS, Bahuguna A, Yadav B, Barthwal A, Nandan R, et al. Nanotechnology: an efficient tool in plant nutrition management. In: Ecosystem services: types, management and benefits. Hauppauge, NY, USA: Nova Science Publishers, Inc.; 2022. p. 165–88. [Google Scholar]

21. Shahid M, Ullah UN, Khan WS, Saeed S, Razzaq K. Application of nanotechnology for insect pests management: a review. J Innov Sci. 2021;7(1):28–39. doi:10.17582/journal.jis/2021/7.1.28.39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. El-Saadony MT, Saad AM, Soliman SM, Salem HM, Desoky EM, Babalghith AO, et al. Role of nanoparticles in enhancing crop tolerance to abiotic stress: a comprehensive review. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:946717. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.946717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Soni S, Jha AB, Dubey RS, Sharma P. Nano wonders in agriculture: unveiling the potential of nanoparticles to boost crop resilience to salinity stress. Sci Total Environ. 2024;925(1):171433. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.171433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Chausali N, Saxena J, Prasad R. Nanotechnology as a sustainable approach for combating the environmental effects of climate change. J Agric Food Res. 2023;12(10):100541. doi:10.1016/j.jafr.2023.100541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Javaid A, Hameed S, Li L, Zhang Z, Zhang B, Rahman MU. Can nanotechnology and genomics innovations trigger agricultural revolution and sustainable development? Function Integr Genom. 2024;24(6):216. doi:10.1007/s10142-024-01485-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Tiwari P. Nanotechnologies and sustainable agriculture for food and nutraceutical production: an update. In: Plant and nanoparticles. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2022. p. 315–37. doi:10.1007/978-981-19-2503-0_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Madanayake NH, Adassooriya NM, Salim N. The effect of hydroxyapatite nanoparticles on Raphanus sativus with respect to seedling growth and two plant metabolites. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag. 2021;15(1–3):100404. doi:10.1016/j.enmm.2020.100404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Altabbaa S, Mann NA, Chauhan N, Utkarsh K, Thakur N, Mahmoud GAE. Era connecting nanotechnology with agricultural sustainability: issues and challenges. Nanotechnol Environ Eng. 2022;8(2):481–98. doi:10.1007/s41204-022-00289-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Upadhayay VK, Chitara MK, Mishra D, Jha MN, Jaiswal A, Kumari G, et al. Synergistic impact of nanomaterials and plant probiotics in agriculture: a tale of two-way strategy for long-term sustainability. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1133968. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1133968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Seleiman MF, Almutairi KF, Alotaibi M, Shami A, Alhammad BA, Battaglia ML. Nano-fertilization as an emerging fertilization technique: why can modern agriculture benefit from its use? Plants. 2020;10(1):2. doi:10.3390/plants10010002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Aghdam MTB, Mohammadi H, Ghorbanpour M. Effects of nanoparticulate anatase titanium dioxide on physiological and biochemical performance of Linum usitatissimum (Linaceae) under well-watered and drought stress conditions. Brazilian J Bot. 2015;39(1):139–46. doi:10.1007/s40415-015-0227-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Ali S, Mehmood A, Khan N. Uptake, translocation, and consequences of nanomaterials on plant growth and stress adaptation. J Nanomater. 2021;2021(2):1–17. doi:10.1155/2021/6677616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Shafqat W, Jaskani MJ, Maqbool R, Chattha WS, Ali Z, Naqvi SA, et al. Heat shock protein and aquaporin expression enhance water conserving behavior of citrus under water deficits and high temperature conditions. Environ Exp Bot. 2021;181:104270. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2020.104270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Iqbal M, Raja NI, Mashwani ZU, Hussain M, Ejaz M, Yasmeen F. Effect of silver nanoparticles on growth of wheat under heat stress. Iran J Sci Technol. 2019;43(2):387–95. doi:10.1007/s40995-017-0417-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Khan I, Raza MA, Awan SA, Shah GA, Rizwan M, Ali B, et al. Amelioration of salt induced toxicity in pearl millet by seed priming with silver nanoparticles (AgNPsthe oxidative damage, antioxidant enzymes and ions uptake are major determinants of salt tolerant capacity. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020;156(1):221–32. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.09.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Tripathi DK, Shweta, Singh S, Singh S, Pandey R, Singh VP, et al. An overview on manufactured nanoparticles in plants: uptake, translocation, accumulation and phytotoxicity. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017;110(1):2–12. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.07.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Zulfiqar F, Ashraf M. Nanoparticles potentially mediate salt stress tolerance in plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;160(7141):257–68. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.01.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Kopittke PM, Lombi E, Wang P, Schjoerring JK, Husted S. Nanomaterials as fertilizers for improving plant mineral nutrition and environmental outcomes. Environ Sci Nano. 2019;6(12):3513–24. doi:10.1039/c9en00971j. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Tahjib-UI-Arif M, Sohag A, Afrin S, Bashar K, Afrin T, Mahamud AGM, et al. Differential response of sugar beet to long-term mild to severe salinity in a soil-pot culture. Agriculture. 2019;9(10):223. doi:10.3390/agriculture9100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Farhangi-Abriz S, Torabian S. Nano-silicon alters antioxidant activities of soybean seedlings under salt toxicity. Protoplasm. 2018;255(3):953–62. doi:10.1007/s00709-017-1202-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Farooqi ZH, Akram MW, Begum R, Wu W, Irfan A. Inorganic nanoparticles for reduction of hexavalent chromium: physicochemical aspects. J Hazardous Mat. 2021;402:123535. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Ma X, Sharifan H, Dou F, Sun W. Simultaneous reduction of arsenic (As) and cadmium (Cd) accumulation in rice by zinc oxide nanoparticles. Chem Eng J. 2020;384:123802. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2019.123802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Shabnam N, Kim M, Kim H. Iron (III) oxide nanoparticles alleviate arsenic induced stunting in Vigna radiata. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2019;183:109496. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.109496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Wang Y, Lin Y, Xu Y, Yin Y, Guo H, Du W. Divergence in response of lettuce (var. Ramosa Hort.) to copper oxide nanoparticles/microparticles as potential agricultural fertilizer. Environ Pollut Bioavailab. 2019;31(1):80–4. doi:10.1080/26395940.2019.1578187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Usman M, Farooq M, Wakeel A, Nawaz A, Cheema SA, Rehman HU, et al. Nanotechnology in agriculture: current status, challenges and future opportunities. Sci Total Environ. 2020;721:137778. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Rahman MH, Haque KMS, Khan MZH. A review on application of controlled released fertilizers influencing the sustainable agricultural production: a cleaner production process. Environ Technol Innov. 2021;23(5):101697. doi:10.1016/j.eti.2021.101697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Bajguz A, Hayat S. Effects of brassinosteroids on the plant responses to environmental stresses. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2009;47(1):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2008.10.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Muhammad HMD, Naz S, Lal MK, Tiwari RK, Ahmad R, Nawaz MA, et al. Melatonin in business with abiotic stresses in vegetable crops. Sci Hortic. 2024;324(7):112594. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Saini S, Kaur N, Pati PK. Phytohormones: key players in the modulation of heavy metal stress tolerance in plants. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;223(1):112578. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112578. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Podlešáková K, Ugena L, Spíchal L, Doležal K, De Diego N. Phytohormones and polyamines regulate plant stress responses by altering GABA pathway. New Biotechnol. 2019;48(144):53–65. doi:10.1016/j.nbt.2018.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Raza A, Charagh S, Zahid Z, Mubarik MS, Javed R, Siddiqui MH, et al. Jasmonic acid: a key frontier in conferring abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2021;40(8):1513–41. doi:10.1007/s00299-020-02614-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Ge YX, Zhang LJ, Li FH, Chen ZB, Wang C, Yao Y, et al. Relationship between jasmonic acid accumulation and senescence in drought-stress. Afr J Agric Res. 2010;5:1978–83. [Google Scholar]

53. Ruan J, Zhou Y, Zhou M, Yan J, Khurshid M, Weng W, et al. Jasmonic acid signaling pathway in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(10):2479. doi:10.3390/ijms20102479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Xing Q, Liao J, Cao S, Li M, Lv T, Qi H. CmLOX10 positively regulates drought tolerance through jasmonic acid-mediated stomatal closure in oriental melon (Cucumis melo var. makuwa Makino). Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–14. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-74550-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Cohen Y. Local and systemic protection against phytophthora infestans induced in potato and tomato plants by jasmonic acid and jasmonic methyl ester. Phytopathology. 1993;83(10):1054–62. doi:10.1094/phyto-83-1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Munné-Bosch S, Weiler EW, Alegre L, Müller M, Düchting P, Falk J. α-tocopherol may influence cellular signaling by modulating jasmonic acid levels in plants. Planta. 2006;225(3):681–91. doi:10.1007/s00425-006-0375-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Hawrylak-Nowak B. Beneficial effects of exogenous selenium in cucumber seedlings subjected to salt stress. Biol Trace Element Res. 2009;132(1-3):259–69. doi:10.1007/s12011-009-8402-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Majeed S, Nawaz F, Naeem M, Ashraf MY, Ejaz S, Ahmad KS, et al. Nitric oxide regulates water status and associated enzymatic pathways to inhibit nutrients imbalance in maize (Zea mays L.) under drought stress. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2020;155:147–60. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.07.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Ahmad P, Ahanger AM, Nasser Alyemeni M, Wijaya L, Alam P, Ashraf M. Mitigation of sodium chloride toxicity in Solanum lycopersicum L. by supplementation of jasmonic acid and nitric oxide. J Plant Interact. 2018;13(1):64–72. doi:10.1080/17429145.2017.1420830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Shams M, Ekinci M, Ors S, Turan M, Agar G, Kul R, et al. Nitric oxide mitigates salt stress effects of pepper seedlings by altering nutrient uptake, enzyme activity and osmolyte accumulation. Physiol Mol Biol Plant. 2019;25(5):1149–61. doi:10.1007/s12298-019-00692-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Özdamar FÖ, Furtana GB, Tıpırdamaz R, Duman H. H2O2 and NO mitigate salt stress by regulating antioxidant enzymes in in two eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) genotypes. Soil Stud. 2022;11:1–6. doi:10.21657/topraksu.977238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Manai J, Kalai T, Gouia H, Corpas FJ. Exogenous nitric oxide (NO) ameliorates salinity-induced oxidative stress in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) plants. J Soil Sci Plant Nut. 2014;14(2):433–46. doi:10.4067/s0718-95162014005000034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Kaya C, Ashraf M, Alyemeni MN, Ahmad P. The role of nitrate reductase in brassinosteroid-induced endogenous nitric oxide generation to improve cadmium stress tolerance of pepper plants by upregulating the ascorbate-glutathione cycle. Ecotoxicol Environ Safety. 2020;196(1):110483. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Samancıoğlu A, Kocaçınar F, Demirkıran AR, Korkmaz A. Enhancing water stress tolerance in pepper at seedling stage by 24-epibrassinolid (EBL) applications. Acta Hort. 2014;1142(1142):109–416. doi:10.17660/actahortic.2016.1142.62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Lv J, Zong XF, Ahmad SA, Wu X, Wu C, Li YP, et al. Alteration in morpho-physiological attributes of Leymus chinensis (Trin.) Tzvelev by exogenous application of brassinolide under varying levels of drought stress. Chil J Agric Res. 2020;80(1):61–71. doi:10.4067/s0718-58392020000100061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. González-García Y, Cárdenas-Álvarez C, Cadenas-Pliego G, Benavides-Mendoza A, Cabrera-De-La-Fuente M, Sandoval-Rangel A, et al. Effect of three nanoparticles (Se, Si and Cu) on the bioactive compounds of bell pepper fruits under saline stress. Plants. 2021;10(2):217. doi:10.3390/plants10020217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Pérez-Labrada F, López-Vargas ER, Ortega-Ortiz H, Cadenas-Pliego G, Benavides-Mendoza A, Juárez-Maldonado A. Responses of tomato plants under saline stress to foliar application of copper nanoparticles. Plants. 2019;8(6):151. doi:10.3390/plants8060151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Sepaskhah AR, Maftoun M, Karimian N. Growth and chemical composition of pistachio as affected by salinity and applied iron. J Hort Sci. 1985;60(1):115–21. doi:10.1080/14620316.1985.11515609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Hosseinpour A, Haliloglu K, Tolga Cinisli K, Ozkan G, Ozturk HI, Pour-Aboughadareh A, et al. Application of zinc oxide nanoparticles and plant growth promoting bacteria reduces genetic impairment under salt stress in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L ‘Linda’). Agriculture. 2020;10(11):521. doi:10.3390/agriculture10110521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Khalid MF, Jawaid MZ, Nawaz M, Shakoor RA, Ahmed T. Employing titanium dioxide nanoparticles as biostimulant against salinity: improving antioxidative defense and reactive oxygen species balancing in eggplant seedlings. Antioxidants. 2024;13(10):1209. doi:10.3390/antiox13101209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Abdoli S, Ghassemi-Golezani K, Alizadeh-Salteh S. Responses of ajowan (Trachyspermum ammi L.) to exogenous salicylic acid and iron oxide nanoparticles under salt stress. Environ Sci Poll Res. 2020;27(29):36939–53. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-09453-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Zeid IMA, Mohamed FH, Metwali EM. Responses of two strawberry cultivars to NaCl-induced salt stress under the influence of ZnO nanoparticles. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2023;30(4):103623. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2023.103623. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Zahedi SM, Abolhassani M, Hadian-Deljou M, Feyzi H, Akbari A, Rasouli F, et al. Proline-functionalized graphene oxide nanoparticles (GO-Pro NPsa new engineered nanoparticle to ameliorate salinity stress on grape (Vitis vinifera L. cv Sultana). Plant Stress. 2023;7(1):100128. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2022.100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Öztürk ES, Mutluay KM, Karaer M, Gültaş HT. The effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticle applications on seedling development in water-stressed strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa ‘Albion’) plants. Appl Fruit Sci. 2025;67(2):1–9. doi:10.1007/s10341-025-01299-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Alluqmani SM, Alabdallah NM. Exogenous application of carbon nanoparticles alleviates drought stress by regulating water status, chlorophyll fluorescence, osmoprotectants, and antioxidant enzyme activity in Capsicum annumn L. Environ Sci Poll Res. 2023;30(20):57423–33. doi:10.1007/s11356-023-26606-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Zhao L, Peralta-Videa JR, Rico CM, Hernandez-Viezcas JA, Sun Y, Niu G, et al. CeO2 and ZnO nanoparticles change the nutritional qualities of cucumber (Cucumis sativus). J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(13):2752–9. doi:10.1021/jf405476u. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Chen Q, Cao X, Nie X, Li Y, Liang T, Ci L. Alleviation role of functional carbon nanodots for tomato growth and soil environment under drought stress. J Hazard Mater. 2022;423:127260. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Wang J, Xu J, Xie R, Chen N, Yang M, Tian X, et al. Effects of nano oxide particles on the growth and photosynthetic characteristics of okra plant under water deficiency. Folia Hortic. 2024;36(3):449–61. doi:10.2478/fhort-2024-0029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Alsaeedi A, El-Ramady H, Alshaal T, El-Garawany M, Elhawat N, Al-Otaibi A. Silica nanoparticles boost growth and productivity of cucumber under water deficit and salinity stresses by balancing nutrients uptake. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;139(12):1–10. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.03.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Almutairi KF, Górnik K, Awad RM, Ayoub A, Abada HS, Mosa WF. Influence of selenium, titanium, and silicon nanoparticles on the growth, yield, and fruit quality of mango under drought conditions. Horticulturae. 2023;9(11):1231. doi:10.3390/horticulturae9111231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Daler S, Kaya O, Korkmaz N, Kılıç T, Karadağ A, Hatterman-Valenti H. Titanium nanoparticles (TiO2-NPs) as catalysts for enhancing drought tolerance in grapevine saplings. Horticulturae. 2024;10(10):1103. doi:10.3390/horticulturae10101103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Sharma S, Raja V, Bhat AH, Kumar N, Alsahli AA, Ahmad P. Innovative strategies for alleviating chromium toxicity in tomato plants using melatonin functionalized zinc oxide nanoparticles. Sci Hortic. 2025;341:113930. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2024.113930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Sardar R, Ahmed S, Shah AA, Yasin NA. Selenium nanoparticles reduced cadmium uptake, regulated nutritional homeostasis and antioxidative system in Coriandrum sativum grown in cadmium toxic conditions. Chemosphere. 2022;287(26):132332. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.132332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Rahmatizadeh R, Arvin SMJ, Jamei R, Mozaffari H, Nejhad RF. Response of tomato plants to interaction effects of magnetic (Fe3O4) nanoparticles and cadmium stress. J Plant Interact. 2019;14(1):474–81. doi:10.1080/17429145.2019.1626922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Gao F, Zhang X, Zhang J, Li J, Niu T, Tang C, et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles improve lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) plant tolerance to cadmium by stimulating antioxidant defense, enhancing lignin content and reducing the metal accumulation and translocation. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1015745. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1015745. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. González-Moscoso M, Juárez-Maldonado A, Cadenas-Pliego G, Meza-Figueroa D, SenGupta B, Martínez-Villegas N. Silicon nanoparticles decrease arsenic translocation and mitigate phytotoxicity in tomato plants. Environ Sci Poll Res. 2022;29(23):1–17. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-17665-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Naseem Z, Naveed M, Asif M, Alamri S, Nawaz S, Siddiqui MH, et al. Enhancing chromium resistance and bulb quality in onion (Allium cepa L.) through copper nanoparticles and possible health risk. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):777. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-05460-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Gatasheh MK, Shah AA, Noreen Z, Usman S, Shaffique S. FeONPs alleviate cadmium toxicity in Solanum melongena through improved morpho-anatomical and physiological attributes, along with oxidative stress and antioxidant defense regulations. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):742. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-05464-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Kumar D, Dhankher OP, Tripathi RD, Seth CS. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles potentially regulate the mechanism(s) for photosynthetic attributes, genotoxicity, antioxidants defense machinery, and phytochelatins synthesis in relation to hexavalent chromium toxicity in Helianthus annuus L. J Hazard Mat. 2023;454(1):131418. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.131418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Zhang P, Liu L, Wang X, Wang Z, Zhang H, Chen J, et al. Beneficial effects of exogenous melatonin on overcoming salt stress in sugar beets (Beta vulgaris L.). Plants. 2021;10(5):886. doi:10.3390/plants10050886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Zhang YP, Zhu XH, Ding HD, Yang SJ, Chen YY. Foliar application of 24-epibrassinolide alleviates high-temperature-induced inhibition of photosynthesis in seedlings of two melon cultivars. Photosynthetica. 2013;51(3):341–9. doi:10.1007/s11099-013-0031-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Turfan N. The effects of exogenous melatonin application on growth rate parameters and bioactive compounds of some spinach cultivars (Spinacia oleracea L.) grown under winter conditions. Appl Ecol Environ Res. 2023;21(2):1535. doi:10.15666/aeer/2102_15331547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Liu Q, Xin D, Xi L, Gu T, Jia Z, Zhang B, et al. Novel applications of exogenous melatonin on cold stress mitigation in postharvest cucumbers. J Agric Food Res. 2022;10(1):100459. doi:10.1016/j.jafr.2022.100459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Liu J, Wang W, Wang L, Sun Y. Exogenous melatonin improves seedling health index and drought tolerance in tomato. Plant Growth Regul. 2015;77(3):317–26. doi:10.1007/s10725-015-0066-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Mohamadi M, Karimi M. Effect of exogenous melatonin on growth, electrolyte leakage and antioxidant enzyme activity in rosemary under salinity stress. J Plant Process Funct. 2020;9:59–65. [Google Scholar]

96. Verma V, Ravindran P, Kumar PP. Plant hormone-mediated regulation of stress responses. BMC Plant Biol. 2016;16(1):1–10. doi:10.1186/s12870-016-0771-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Yue L, Ma C, Zhan X, White JC, Xing B. Molecular mechanisms of maize seedling response to La2O3 NP exposure: water uptake, aquaporin gene expression and signal transduction. Environ Sci Nano. 2017;4(4):843–55. doi:10.1039/c6en00487c. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Xie L, Chen F, Du H, Zhang X, Wang X, Yao G, et al. Graphene oxide and indole-3-acetic acid cotreatment regulates the root growth of Brassica napus L. via multiple phytohormone pathways. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):1–12. doi:10.1186/s12870-020-2308-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Samynathan R, Venkidasamy B, Ramya K, Muthuramalingam P, Shin H, Kumari PS, et al. A recent update on the impact of nano-selenium on plant growth, metabolism, and stress tolerance. Plants. 2023;12(4):853. doi:10.3390/plants12040853. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Xiao Z, Yue L, Wang C, Chen F, Ding Y, Liu Y, et al. Downregulation of the photosynthetic machinery and carbon storage signaling pathways mediate La2O3 nanoparticle toxicity on radish taproot formation. J Hazard Mater. 2021;411:124971. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Yang J, Cao W, Rui Y. Interactions between nanoparticles and plants: phytotoxicity and defense mechanisms. J Plant Interact. 2017;12(1):158–69. doi:10.1080/17429145.2017.1310944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Vinkovic T, Novak O, Strnad M, Goessler W, Jurasin DD, Parađikovic N, et al. Cytokinin response in pepper plants (Capsicum annuum L.) exposed to silver nanoparticles. Environ Res. 2017;156(3):10–8. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2017.03.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Vankova R, Landa P, Podlipna R, Dobrev PI, Prerostova S, Langhansova L, et al. ZnO nanoparticle effects on hormonal pools in Arabidopsis thaliana. Sci Total Environ. 2017;593:535–42. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.03.160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. Manzoor M, Korolev K, Ahmad R. Zinc oxide nanoparticles: abiotic stress tolerance in fruit crops focusing on sustainable production. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2025;94(5):1401. doi:10.32604/phyton.2025.063930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Sun J, Wang L, Li S, Yin L, Huang J, Chen C. Toxicity of silver nanoparticles to Arabidopsis: inhibition of root gravitropism by interfering with auxin pathway. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2017;36(10):2773–80. doi:10.1002/etc.3833. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Wei J, Zou Y, Li P, Yuan X. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles promote root growth by interfering with auxin pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2020;89(4):883–91. doi:10.32604/phyton.2020.010973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

107. Tumburu L, Andersen CP, Rygiewicz PT, Reichman JR. Phenotypic and genomic responses to titanium dioxide and cerium oxide nanoparticles in Arabidopsis germinants. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2014;34(1):70–83. doi:10.1002/etc.2756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Boss PK, Bastow RM, Mylne JS, Dean C. Multiple pathways in the decision to flower: enabling, promoting, and resetting. Plant Cell. 2004;16(suppl_1):18–31. doi:10.1105/tpc.015958. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Kumar A, Singh A, Panigrahy M, Sahoo PK, Panigrahi KC. Carbon nanoparticles influence photomorphogenesis and flowering time in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 2018;37(6):901–12. doi:10.1007/s00299-018-2277-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Wang J, Song L, Gong X, Xu J, Li M. Functions of jasmonic acid in plant regulation and response to abiotic stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4):1446. doi:10.3390/ijms21041446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Mazaheri-Tirani M, Dayani S. Growth, flowering and physiological response of Trachyspermum ammi L. to zinc oxide micro-and nanoparticles. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2022;69(1):14. doi:10.1134/s1021443722010125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

112. Hao Y, Yu F, Lv R, Ma C, Zhang Z, Rui Y, et al. Carbon nanotubes filled with different ferromagnetic alloys affect the growth and development of rice seedlings by changing the C:N ratio and plant hormones concentrations. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157264. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0157264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Landa P. Positive effects of metallic nanoparticles on plants: overview of involved mechanisms. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;161(3):12–24. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.01.039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Linh TM, Mai NC, Hoe PT, Lien LQ, Ban NK, Hien LTT, et al. Metal-based nanoparticles enhance drought tolerance in soybean. J Nanomat. 2020;2020(1):1–13. doi:10.1155/2020/4056563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

115. Pejam F, Ardebili ZO, Ladan-Moghadam A, Danaee E. Zinc oxide nanoparticles mediated substantial physiological and molecular changes in tomato. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0248778. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0248778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Khalid F, Rasheed Y, Ashraf H, Asif K, Maqsood MF, Shahbaz M, et al. Nanoparticle-mediated phytohormone interplay: advancing plant resilience to abiotic stresses. J Crop Health. 2025;77(2):56. doi:10.1007/s10343-025-01121-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

117. Marslin G, Sheeba CJ, Franklin G. Nanoparticles alter secondary metabolism in plants via ROS Burst. Front Plant Sci. 2017;19:8. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00832. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Tripathi D, Singh M, Pandey-Rai S. Crosstalk of nanoparticles and phytohormones regulate plant growth and metabolism under abiotic and biotic stress. Plant Stress. 2022;6(15):100107. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2022.100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

119. Pandya P, Kumar S, Sakure AA, Rafaliya R, Patil GB. Zinc oxide nanopriming elevates wheat drought tolerance by inducing stress-responsive genes and physio-biochemical changes. Curr Plant Biol. 2023;35(1):100292. doi:10.1016/j.cpb.2023.100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

120. Kandil EE, Lamlom SF, Gheith ES, Javed T, Ghareeb RY, Abdelsalam NR, et al. Biofortification of maize growth, productivity and quality using nano-silver, silicon and zinc particles with different irrigation intervals. J Agric Sci. 2023;161(3):339–55. doi:10.1017/S0021859623000345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

121. Ilyas T, Shahid M, Shafi Z, Aijaz SA, Wasiullah. Molecular mechanisms of methyl jasmonate (MeJAs)-mediated detoxification of heavy metals (HMs) in agricultural crops: an interactive review. South Afr J Bot. 2025;177(3):139–59. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2024.11.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

122. Ansari WA, Shahid M, Shafi Z, Farah MA, Ilyas T, Al-Anazi KM, et al. NO and melatonin interplay augment Cd-tolerance mechanism in eggplants: ROS detoxification and regulation of gene expression. Physiol Plant. 2025;177(1):e70130. doi:10.1111/ppl.70130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools