Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of NPK and Micronutrient Fertilization on Soil Enzyme Activities, Microbial Biomass, and Nutrient Availability

1 Institute of Genetics and Plant Experimental Biology, Uzbekistan Academy of Sciences, Kibray, 111208, Uzbekistan

2 Faculty of Biology, National University of Uzbekistan, Tashkent, 100174, Uzbekistan

3 Division of Microbiology, ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, Pusa, New Delhi, 110012, India

4 Division of Plant Biotechnology, Sher-e-Kashmir University of Agricultural Sciences and Technology of Kashmir, Shalimar, 190025, Jammu and Kashmir, India

5 Division of Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry, ICAR-Indian Agricultural Research Institute, Pusa, New Delhi, 110012, India

6 Academy of Biology and Biotechnology, Southern Federal University, Rostov-on-Don, 100044, Russia

* Corresponding Authors: Dilfuza Jabborova. Email: ; Nasir Mehmood. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Integrated Nutrient Management in Cereal Crops)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2026, 95(1), 8 https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2026.072577

Received 29 August 2025; Accepted 24 December 2025; Issue published 30 January 2026

Abstract

The combined effects of macronutrients (Nitrogen, Phosphorus, and Potassium-N, P, K) and micronutrient fertilization on turmeric yield, soil enzymatic activity, microbial biomass, and nutrient dynamics remains poorly understood, despite their significance for sustainable soil fertility management and optimizing crop productivity across diverse agroecosystems. To investigate, a net house experiment on sandy loam Haplic Chernozem was conducted to 03 fertilizer regimes, viz. N75P50K50 kg ha−1 (T-2), N125P100K100 kg ha−1 (T-3), and N100P75K75 + B3Zn6Fe6 kg ha−1 (T-4). Furthermore, the influence of these treatments was systematically assessed on soil nutrient status (N, P, K), enzymatic activities (alkaline phosphomonoesterase, dehydrogenase, fluorescein diacetate hydrolysis), microbial biomass carbon (MBC) and soil organic carbon (SOC). Balanced fertilization significantly turmeric productivity and soil health. All three fertilizer treatments showed a clear yield increase compared to the unfertilized control. Compared to the control, N75P50K50 kg/ha T-2 increased rhizome number and biomass per plant by 44.7% and 16.3%, respectively, while N100P75K75 + B3Zn6Fe6 kg/ha T-4 further enhanced them by 86.6% and 27.7%. T-3 produced the most significant yield response by increasing the rhizome biomass by 38.0% and rhizome number per plant by 100% compared to the control. The nutrient availability was also substantially improved. T-2 enhanced the soil nitrogen contents by 83.3% with maximum N levels observed in T-3 & T-4. Phosphorus increased by 61.5% in T-3 and 37.3% in T-4, while potassium was enhanced by 12.9% in T-3 relative to the control, respectively. Enzymatic activities were markedly enhanced as T-3 was recorded to improve alkaline phosphomonoesterase (APA), dehydrogenase (DHA) and fluorescein diacetate hydrolysis (FDA) by 50.6%, 37.4%, and 43.4%, where T-4 increased by 32.2%, 30.9%, and 35.9%, respectively compared to control. MBC and SOC also rose significantly, with SOC increased by 13.8% (T-2), 41.6% (T-3), and 47.2% (T-3) relative to control. The result of this study demonstrates that the integrated macro & micronutrient fertilization, particularly T-3 7 T-4 treatments, sustainably enhanced turmeric yield, soil nutrient availability, enzyme activity, microbial biomass, and organic carbon. These findings highlight the critical role of balanced nutrient management in sustaining soil fertility and crop productivity across agroecosystems.Keywords

Sustainable soil fertility management is fundamental for securing crop productivity and preserving the long-term health of agroecosystems. Conventional fertilization practices primarily focus on supplying the essential macronutrients: Nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P), and Potassium (K), which play a central role in plant growth, physiological development, and yield formation [1,2]. However, application of NPK fertilizers is undeniably effective for boosting short-term crop productivity, but it often carries a considerable risk for the long-term sustainability of soil health. Over time, this practice inadvertently causes degradation of soil quality, manifesting as nutrient imbalances, a reduction in microbial diversity and function, and a concerning decline in soil organic carbon stocks (SOC) that collectively drive ecosystem fertility [3,4,5]. Consequently, the contemporary agricultural paradigm advocates for an integrated nutrient management strategy. This strategy recognizes that while NPK provides the primary macronutrients, the incorporation of vital micronutrients is not merely a supplement but also critical for creating a synergistic effect. Studies suggested that this integrated strategy not only improves crop performance [6,7,8,9] but also strengthens the underlying soil biological process that maintains soil vitality and productivity for a resilient and productive agriculture system [10,11,12].

Zinc (Zn) plays an indispensable role as a micronutrient by acting as a vital cofactor for enzymes that drive key processes both in plant and soil microbes, i.e., the decomposition of organic matter and nutrient metabolism [13,14]. The prevalence of Zn deficiency in intensively cultivated soils is therefore a critical issue directly related to crop yield by undermining the efficiency with which crops utilize other nutrients [15]. Addressing Zn deficiency unlocks a positive feedback loop of robust microbial communities contributing towards better soil structure and enhanced nutrient cycling [16]. Furthermore, the increase in plant biomass contributes to the soil, which in turn fuels the accumulation and stabilization of soil organic carbon. This synergistic effect is no longer a theoretical regime and is supported by field studies that consistently demonstrate the integration of Zn in NPK enhanced microbial diversity, higher enzymatic activities, and elevated SOC level as compared to the solo dose of NPK [17,18].

In addition to Zn, a supporting cast of other micronutrients, such as boron (B) and iron (Fe), is also fundamental to microbial processes and overall soil fertility [19]. Boron plays important roles in the synthesis of cell walls, the robust development of the root system, and enabling successful flowering and seed production. When boron is readily available, it creates a ripple effect where plants become more efficient at updating other nutrients, and this vitality in the root zone stimulates increased microbial activity in the rhizosphere [20,21,22]. Conversely, boron deficiency affected the transport of sugars and carbohydrates that directly limit the enzymatic activity involved in nutrient cycling. Supplementing with boron has been reported to actively rejuvenate the soil’s biological health, leading to better soil quality and crop productivity [20,23].

Iron (Fe) constitutes another vital micronutrient that plays a key role in biochemical processes, including chlorophyll synthesis, enzymatic functions, and electron transfer through redox reactions. Its availability in the soil matrix exerts as propound effect on microbial metabolism, particularly by regulating respiration rates and the activity of oxidoreductase enzymes. Subsequently, Fe bioavailability is a determining factor in organic matter decomposition rate and stabilization of SOC [24,25]. The significance of iron management is most apparent in calcareous and alkaline soils, where its bioavailability is markedly limited. Recent research indicates that strategic Fe fertilization in these environments can alter root exudation profiles and stimulate microbial biomass growth, and accelerate the turnover of nutrients [26]. The synergistic ability of micronutrient management is evident when Zn and Fe supplementation is integrated with balanced NPK fertilization. This comprehensive approach addresses the nutritional requirements of both the plant and soil microbial communities, thereby optimizing the soil biochemical environment. This strategy fosters highly efficient nutrient cycling, supports diverse and resilient microbial communities, and directly contributes to the accumulation and preservation of soil organic carbon. The ultimate goal is to build a healthier and more productive soil system for long-term sustainability [27].

Developing sustainable fertilization practices requires a clear understanding of how nutrient combinations affect both soil health and crop performance. With this goal, the present research sets out to evaluate the effects of NPK fertilization supplemented with boron, zinc, and iron (BZnFe) on turmeric production, soil nutrients dynamics (N, P, K), microbial biomass, and soil organic carbon. The study also examined how these factors are interlined using correlation and cluster analyses for the identification of patterns and their relationship.

The research was carried out on sandy loam soil characterized by a slightly alkaline pH, low electrical conductivity, low organic carbon content, and moderate levels of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. The soil also exhibited measurable enzymatic activities, including alkaline phosphatase, fluorescein diacetate (FDA), hydrolytic, and dehydrogenase (DHA), along with microbial biomass carbon, making it suitable for evaluating biological responses for fertilization. We aimed to test the following three hypotheses: (1) NPK and micronutrient fertilization can promote the yield of turmeric; (2) NPK and micronutrient fertilization can improve soil nutrients and soil enzymatic activities; (3) NPK and micronutrient fertilization can interact to improve microbial biomass carbon and soil organic carbon.

The soil used for the study was collected from the field at Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI), Indian Agriculture Research Center (ICAR), New Delhi, India (28°38.184′ N; 77°9.636′ E).

The experimental soil, classified as sandy loam, had the following agrochemical characteristics: pH-8.0, electrical conductivity 0.45 dS/m, soil organic carbon 0.41%, nitrogen 167 kg/ha, phosphorus 40.3 kg/ha, potassium 788 kg/ha [28].

The study was carried out using the Suguna variety of turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) rhizome, a cultivar widely cultivated by local farmers due to its high yield potential and desirable rhizome quality. Rhizomes were procured from the Azadpur Mandi Market, New Delhi, India. Healthy, uniform rhizomes were selected for planting to ensure consistency across treatments. Plants were grown under net house conditions, which provided a controlled environment to minimize the influence of external factors such as pests, diseases, and extreme weather, allowing precise evaluation of the effects of different fertilization regimes. The net house was maintained with standard temperature, humidity, and irrigation management practices to optimize plant growth.

2.1.4 Fertilizer Sources and Treatments

The mineral Salt fertilizers applied in the study included: Urea (NH2)2CO) as a nitrogen source, ammonium dihydrogen phosphate (NH4H2PO4) for phosphorus, potassium chloride (KCI) for potassium, boric acid (H3BO3) for boron, zinc sulfate (ZnSO4), and ferrous sulfate (Fe2SO4) for iron.

Four fertilization treatments were used in the experiment as follows:

T-1: Control (no fertilizers)

T-2: N75P50K50 kg/ha

T-3: N125P100K100 kg/ha

T-4: N100P75K75 + B3Zn6Fe6 kg/ha

2.1.5 Experimental Layout & Sampling

Turmeric rhizomes were planted in March, and the crop was harvested after five months. Soil samples were collected at harvest to evaluate the chemical and biological properties. Each treatment was replicated five times to ensure the reliability of the results.

2.2 Estimation of Soil Nutrients

Soil samples were collected after harvesting the turmeric crop from each experimental pot to assess changes in nutrient availability and soil organic carbon status. In order to obtain a representative sample, five sub-samples were taken from each pot at a depth ranging from 0–30 cm and thoroughly mixed to prepare a final composite sample. This ensured that the analysis reflected the average condition of the soil within each treatment.

The determination of soil organic carbon was carried out using the Walkley-Black carbon (WBC), which involves wet oxidation of organic matter following the procedure as described by Wakley and Black [29]. Available nitrogen in the soil was estimated according to the widely used method of Subbiah and Asija [30]. For estimation of available potassium, 5 g of soil sample was mixed with 25 mL 1 N ammonium acetate solution (NH4OAc) (pH 7.0) and shaken for five minutes to ensure proper extraction of exchangeable potassium. The filtrate was then processed and analyzed as per the method developed by Hanway and Heidel [31]. Similarly, the available phosphorus content in the soil samples was quantified using the Olsen-P method [32], which is considered suitable for soil with neutral to alkaline reaction, such as used in this study.

2.3 Quantification of Enzyme Activities in Soil

The enzymatic activities in soil were assessed using standard procedures. Alkaline phosphatase activity in soil samples was determined following the method of Tabatabai et al. [33]. For each soil, two sets of 1 g soil were placed in conical flasks. One set was used as the control. Then, 0.2 mL toluene and 4 mL of MUB (modified universal buffer) (pH 11) were added, and 1 mL of p-nitrophenyl phosphate solution was added to the other set of samples. These were incubated at 37 C for 1 h. Calcium chloride (1 mL of 0.5 M) and 4 mL of 0.5 M NaOH were added after incubation. Flasks were swirled for a few seconds, and 1 mL of p-nitrophenyl phosphate solution was added to the remaining set of samples. All suspensions were filtered through a Whatman No. 1 filter paper quickly, and the yellow color intensity was measured at 440 nm wavelength. The FDA hydrolytic activity was measured according to the procedure outlined by Green et al. [34]. 0.5 mg of soil was incubated with 25 mL of sodium phosphate (0.06 M; pH 7.6). 0.25 mL of 4.9 mM fluorescein diacetate substrate solution was added to all assay vials. All vials were mixed and incubated in a water bath at 37 C for 2 h. The soil suspension was centrifuged at 8000 rpm for 5 min. The clear supernatant was measured at 490 nm against a reagent blank solution in a spectrophotometer. The DHA, an important indicator of microbial oxidative activity, was measured by the method of Casida et al. [35].

2.4 Determination of Microbial Biomass of Soil

Microbial Biomass Carbon (MBC) in the soil was estimated using the Fumigation-extraction method [36]. Soil samples were subjected to fumigation to release microbial cellulose content, and then the difference in carbon released between fumigated and non-fumigated samples is taken as a measure of the microbial biomass present in the soil.

The experimental data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 20. One way anaysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to assess the significance of siferne among treatments, and Duncan’s multiple range test (DMRT) was applied to compare mean values at a significant level of p ≤ 0.05. In addition, cluster maps were also generated using MetaboAnalyst 6.0 software for visualization of the relationships and patterns among the measured variables.

3.1 Rhizome Number and Biomass of Turmeric

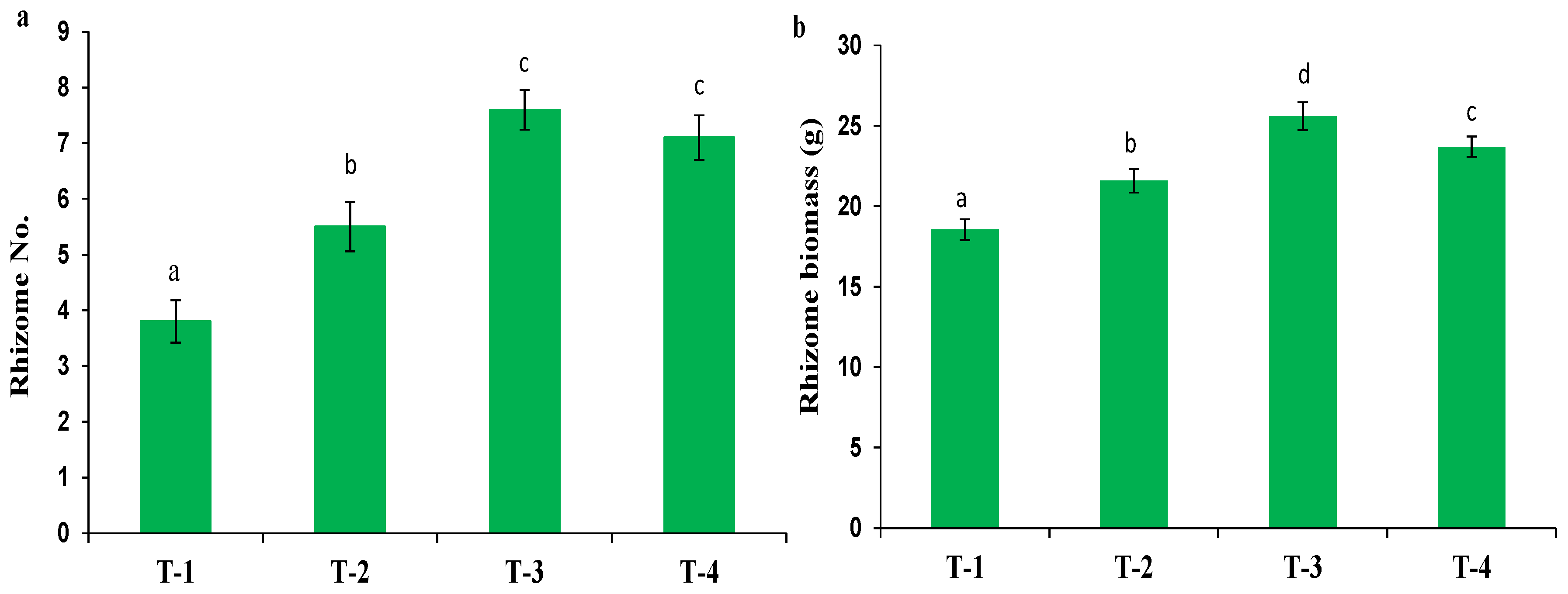

The effects of different fertilization treatments on rhizome number and biomass per plant are illustrated in Fig. 1. As compared to the control treatment, the application of N75P50K50 kg/ha (T-2) led to increased rhizome number by 44.7% and rhizome biomass per plant by 16.3%. A more pronounced effect was observed with the combined application of N100P75K75 + B3Zn6Fe6 kg/ha (T-4), which enhanced rhizome number by 86.6% and rhizome biomass per plant by 27.7% relative to the control. The most significant response, however, was recorded under N125P100K100 kg/ha (T-3), which resulted in 100.0% increase in rhizome number and 38.0% higher rhizome biomass per plant over the control. These results clearly indicate that increasing the nutrient levels in balanced proportions significantly promotes both the rhizome number and turmeric rhizome biomass, highlighting the importance of optimized fertilization for maximum productivity.

Figure 1: Effects of NPK and micronutrient fertilization on rhizome number (a) and rhizome biomass (b) per plant. When applying Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT), different letters ‘a-d’ in the rows indicate that the values are significantly different from each other at p ≤ 0.05.

Soil nitrogen content was significantly influenced by different fertilizer treatments (Table 1). The application of N75P50K50 kg ha−1 (T-2) led to an 83.3% increase in soil nitrogen compared with the unfertilized control. Even greater enhancements were observed with N125P100K100 kg ha−1 (T-3) and N100P75K75 + B3Zn6Fe6 kg ha−1 (T-4), both of which significantly boosted soil nitrogen levels, highlighting the effectiveness of either higher macronutrient applications (T-3) or the integrated macro and micronutrient management (T-4) in improving overall soil nitrogen contents.

The available phosphorus in the soil was also positively affected by the treatments. The N100P75K75 + B3Zn6Fe6 kg ha−1 (T-4) increased phosphorus content by 37.3% in the soil relative to the control. The highest phosphorus content accumulation was recorded under N125P100K100 kg ha−1 (T-3), which significantly enhanced available soil phosphorus by 61.5% compared to the control. Similarly, soil potassium showed marked improvement with treatment N125P100K100 kg ha−1 (T-3), increasing soil potassium content by 12.9% compared to the control. The N100P75K75 + B3Zn6Fe6 kg ha−1 (T-4) increased potassium content by 4.0% in the soil relative to the control. Overall, these results demonstrate that both higher nutrient doses and the combined application of macro and micronutrients substantially enhance soil nutrient availability, contributing to improving soil fertility. The N100P75K75 + B3Zn6Fe6 kg ha−1 (T-4) increased phosphorus content by 37.3% in the soil relative to the control.

Table 1: Effects of NPK and micronutrient fertilization on nutrient availability.

| Treatment | Available N (kg/ha−1) | Available P (kg/ha−1) | Available K (kg/ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-1 | 75.26 ± 2.20a | 48.64 ± 1.88a | 580.83 ± 6.80a |

| T-2 | 137.98 ± 3.05b | 52.92 ± 2.12b | 598.79 ± 7.13a |

| T-3 | 150.52 ± 3.15c | 78.57 ± 3.07d | 656.32 ± 8.10c |

| T-4 | 150.50 ± 2.63c | 66.81 ± 2.36c | 604.35 ± 6.09b |

The results showed that the fertilizer treatments had a pronounced effect on soil enzymatic activities, markedly enhancing them compared to the unfertilized control treatment (Table 2). Significant increases were recorded in key enzymes such as dehydrogenase (DHA), alkaline phosphomonoesterase activity (APA), and fluorescein diacetate hydrolysis (FDA) under the applied treatments. Among them, T-3 and T-4 exhibited the highest enzyme activities. The treatment (T-2) increased the APA by 13.7%, DHA by 25.0% and FDA by 22.0% in soil relative to the control. The most substantial increase in soil enzyme activities was recorded in treatment (T-3), which significantly increased APA by 50.6%, DHA by 37.4% and FDA by 43.4%, compared with the control. Whereas the treatment (T-4) also increased the APA by 32.2%, DHA by 30.9% and FDA by 35.9%, compared with the control. The results demonstrate enhanced microbial function and improved soil biochemical health with the application of a tested proportion of nutrients.

Table 2: Effects of NPK and micronutrient fertilization on soil enzyme activities.

| Treatments | Alkaline Phosphomonoesterase Activity (μg g−1 h−1) | Dehydrogenase Activity (μg g−1 h−1) | Fluorescein Diacetate Hydrolysis Activity (μg g−1 h −1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-1 | 83.25 ± 3.15a | 62.81 ± 2.03a | 55.63 ± 1.87a |

| T-2 | 94.68 ± 2.86b | 78.57 ± 3.11b | 67.89 ± 2.63b |

| T-3 | 125.34 ± 4.91d | 86.35 ± 3.06c | 79.78 ± 3.35c |

| T-4 | 110.09 ± 3.26c | 82.24 ± 2.55c | 75.62 ± 3.18c |

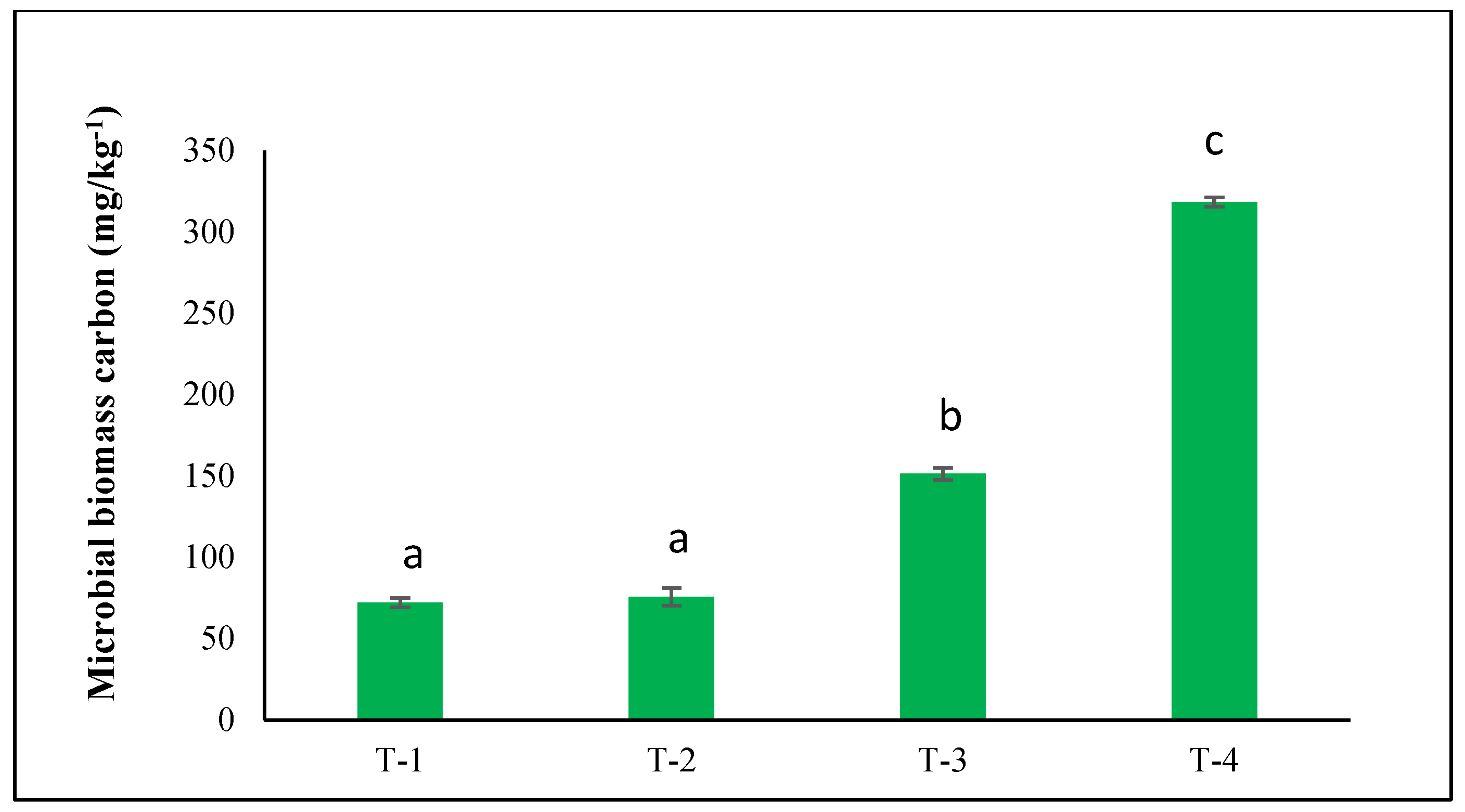

3.4 Microbial Biomass Carbon and Soil Organic Carbon

The analysis of soil biological properties revealed that fertilization treatments significantly enhance microbial biomass carbon (MBC), soil organic carbon (SOC), and enzymatic activity compared with the unfertilized control. MOC exhibited a significant increase under T-3 and T-4 treatments as compared to control soil (Fig. 2). Specifically, the treatment (T-3) elevated MBC, while T-4 showed the highest enhancement, indicating a strong positive response to combined NPK and micronutrients. Increased microbial biomass carbon in soil compared with the control. The increase in microbial biomass carbon was higher in treatment T-4 as compared to the control.

Figure 2: Effects of NPK and micronutrient fertilization on microbial biomass carbon. When applying Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT), different letters ‘a–c’ in the rows indicate that the values are significantly different from each other at p ≤ 0.05.

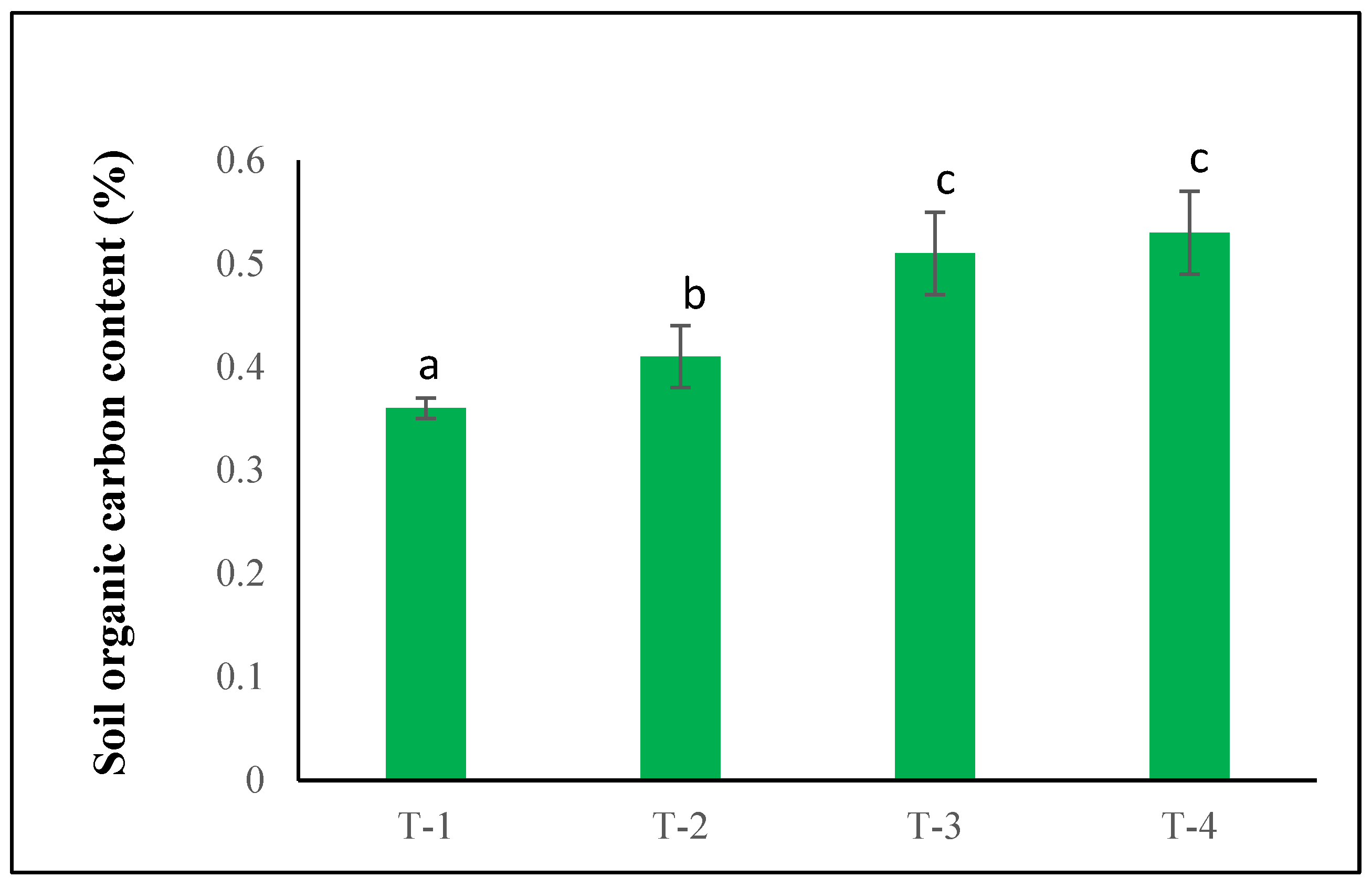

Similarly, soil organic carbon content improved markedly under all fertilizer treatments (Fig. 3). The treatment (T-2) increased SOC by 13.8%, while treatment (T-3) significantly increased the SOC by 41.6% in the soil compared with the control. The highest SOC was recorded under treatment (T-4), which significantly increased SOC by 47.2% compared with the control. The results showed that integrated nutrient management not only stimulates microbial activity but also contributes substantially to soil carbon sequestration. Overall, the results demonstrate that the combined application of NPK and micronutrients (T-3 and T-4) most effectively promotes soil biological health, reflected in higher microbial biomass, elevated organic carbon content, and enhanced enzymatic activity. These improvements underscore the critical role of balanced fertilization in sustaining soil fertility and microbial function.

Figure 3: Effects of NPK and micronutrient fertilization on soil organic carbon content. When applying Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT), different letters ‘a–c’ in the rows indicate that the values are significantly different from each other at p ≤ 0.05.

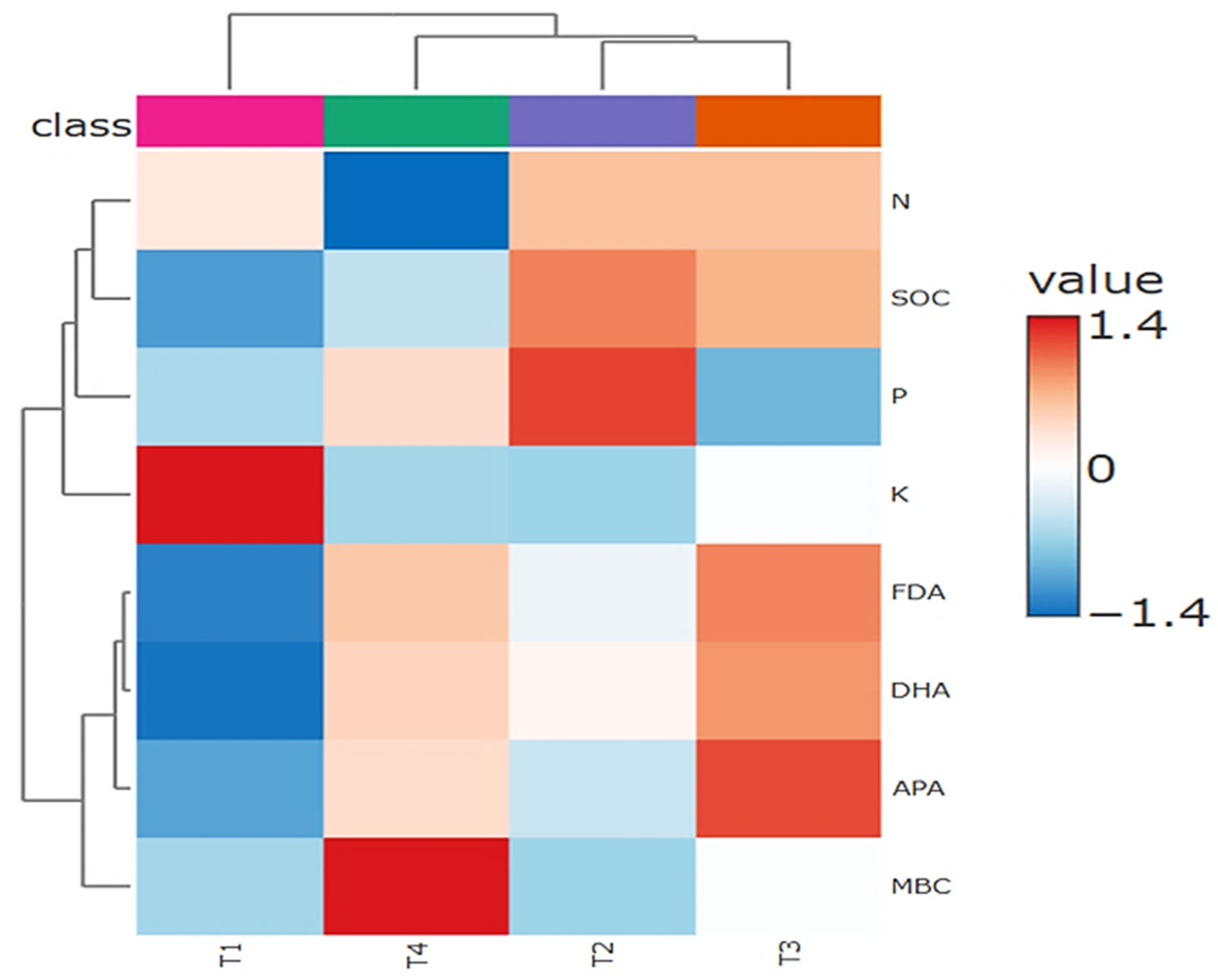

The hierarchical clustering heatmap (Fig. 4) clearly shows distinct treatment effects on soil nutrients, microbial biomass, and enzyme activities. The red color indicates higher (positive) values relative to the mean/average, and the blue color indicates lower (negative) values.

Figure 4: Hierarchical clustering heatmap showing soil nutrient status and enzyme activities under different treatments (T1, T2, T3, and T4).

The dendrogram at the top divides the treatments into two main groups based on similarity in soil biochemical properties. Across the four treatments (T1, T2, T3, and T4), clear patterns emerged in both nutrient availability (N, P, K, and SOC) and biological indicators (FDA, DHA, APA, and MBC). Treatment T4 was characterized by markedly elevated levels of soil K, SOC, APA, and MBC. This suggests a healthy, nutrient-rich soil and microbial biomass. In contrast, T4 exhibited a comparatively lower N content, suggesting possible imbalances or enhanced uptake by the crop. Treatment T3 showed consistently higher values for FDA, DHA, and APA, reflecting robust overall enzymatic activity and soil microbial functioning. Treatment T2 exhibited moderate increases in P and enzyme activities, placing it between the high-performing T3/T4 and the relatively lower-performing T-1, with consistently low values across the treatments, including K, FDA, DHA, APA, and MBC, indicating poorer soil health and less biological activity.

The analysis also revealed interesting relationships between the soil properties themselves. Potassium, enzyme activities (FDA, DHA, APA), and microbial biomass are all grouped, suggesting they are closely linked. Nitrogen and soil organic carbon formed their own separate group, meaning they responded to the treatments with different responses. Overall, the clustering analysis demonstrated that integrated management practices (as in T3 and T4) significantly enhanced and boosted soil nutrient status and microbial indicators compared to the control.

In agricultural systems, the application of NPK fertilizers plays a pivotal role in improving and sustaining soil fertility by directly supplying essential nutrients and indirectly stimulating soil biological processes in the rhizosphere. In the present study, plots receiving NPK treatments exhibited improved availability of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium compared with unfertilized or poorly managed plots. These results are consistent with earlier research findings where balanced NPK fertilization significantly enhanced nutrient uptake, soil fertility, and crop productivity [37]. Verma et al. [7] reported that a nutrient level of 120:60:120 kg NPK/ha was optimum for the growth and yield of turmeric in the Katyur Valley of the western Himalayan region of Uttarakhand. Srinivasan et al. [6] reported that the integration of inorganic fertilizers (50% N + full dose of P and K, i.e., 30–50–120 kg NPK ha−1) and organic manure (20.0 t ha−1 FYM + Bacillus megaterium var. phosphaticum) markedly improved soil and crop performance in terms of its quality, rhizome yield, and nutrient uptake in turmeric. Such edidences underscireis the broader consequences that nutiernts balanced fertilization strategies are essential for sustaining soil productivity. Beyond chemical nutrients, NPK fertilization can also promote soil biological health. Our study found that adequate nutrient supply stimulates root growth and rhizome number, which in turn support microbial biomass carbon (MBC) by providing more substrates for microbial communities. Several studies showing intergrated nutireint management or combined organic and inorganic fertilization significantly elevate MBC and soil enzymatic activities in agricultural soils [8,9,38]. These inputs, coupled with improved microbial activity, contribute to the accumulation and stabilization of organic carbon in the soil matrix [17,37]. Recent field experiments have confirmed that balanced NPK fertilization combined with good residue management enhances SOC sequestration and overall soil quality [39,40]. Overall, these findings align with current literature demonstrating that balanced NPK fertilization not only improves nutrient availability (N, P, K) but also enhances microbial biomass and contributes to building soil organic carbon [41]. Such integrated improvements in chemical and biological indicators are essential for maintaining long term soil fertility and sustainable crop production.

The combined application of NPK with BZnFe markedly improved soil nutrient status and biological properties, demonstrating the synergistic effect of balanced macro- and micronutrient management. Treatments receiving NPK + BZnFe exhibited higher concentrations of available N, P, and K compared with plots receiving only NPK or no fertilizer. This can be attributed to the enhanced nutrient use efficiency provided by zinc, which plays a key role in root development and enzymatic activation, thereby facilitating nutrient uptake [42]. Recent studies confirm that Zn fortification in fertilization programs significantly improves nutrient cycling and crop nutrient acquisition [15]. Zinc acts as a cofactor for many microbial enzymes, and its adequate supply creates a favorable environment for microbial proliferation [43]. These findings align with recent literature emphasizing the need for integrated nutrient management strategies, including micronutrients, to sustain soil productivity and resilience in modern agroecosystems [15].

The hierarchical clustering analysis highlighted clear differences in soil biological and chemical responses among the four treatments, grouping them into three distinct clusters. This pattern reflects the strong influence of management practices on soil fertility indicators and microbial functioning. T1, which clustered alone in Group I with consistently negative responses, exhibited the lowest values for K, FDA, DHA, APA, and MBC. T4, forming Group II as a stand-alone cluster, demonstrated markedly positive responses, with significant increases in K, SOC, APA, and MBC. T2 and T3, grouped in Cluster III, showed moderately positive to highly positive responses. Their elevated en-zyme activities (FDA, DHA, APA) and improved P levels indicate active nutrient turnover and a healthier soil environment compared with T1. These findings align with studies reporting that integrated nutrient management or bio-organic amendments significantly enhance soil enzyme activities and microbial biomass [44]. The slightly greater enzyme activity observed in T3 compared with T2 may reflect differences in amendment type or application rate, suggesting that subtle adjustments in management can influence soil biological properties.

The results of the study emphasize that treatments enhancing soil organic matter and promoting microbial activity (T4 and the T2–T3 cluster) contribute most effectively to improved soil quality. The correlation analysis provides important insight into the functional relationships among soil chemical and biological parameters under the tested treatments. The strong positive associations observed among microbial biomass carbon (MBC), soil organic carbon (SOC), acid phosphatase activity (APA), dehydrogenase activity (DHA), and fluorescein diacetate hydrolysis (FDA) indicate that these biological indicators are closely coupled with soil organic matter dynamics. The tight clustering of these variables suggests that management practices that improve SOC are likely to simultaneously enhance soil enzymatic functioning and microbial activity, which is consistent with findings from mineral and organic amendment studies [8,41,45].

Phosphorus (P) showed a mixed pattern. Its positive correlations with APA and FDA highlight its critical role in enzymatic processes, particularly in P mineralization and availability [46]. The intermediate behavior of P underscores its pivotal role in linking these clusters. These findings reinforce the view that integrated nutrient management is essential not only for immediate crop productivity but also for maintaining soil health and resilience under modern agricultural intensification [47]. Several studies have reported that fertilization with nutrient sources significantly enhances turmeric yield by increasing nutrient availability, promoting vegetative growth, and stimulating rhizome development [48,49].

Higher macronutrient application (N125P100K100 kg ha−1) and integrated macro- and micronutrient treatments (N100P75K75 + B3Zn6Fe6 kg ha−1) significantly enhanced soil nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium contents compared with the unfertilized control, confirming their effectiveness in sustaining nutrient supply. The N125P100K100 kg/ha produced the greatest improvements in rhizome biomass (38.0%) and rhizome number (100.0%) over the control. N100P75K75 + B3Zn6Fe6 kg/ha also substantially enhanced rhizome turmeric productivity in terms of rhizome growth, underlining the benefits of integrating micronutrients with the macronutrient fertilization. Overall, the findings confirm that balanced and integrated nutrient management not only optimizes soil chemical and biological properties but also enhances turmeric yield potential. Such strategies provide a sustainable pathway for maintaining soil productivity and improving agricultural efficiency.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Dilfuza Jabborova and Khurshid Sulaymanov; methodology, writing—review and editing, Muzafar Jabborov; software, Nayan Ahmed; validation, Dilfuza Jabborova, Tatiana Minkina, and Olga Biryukova; formal analysis, Nasir Mehmood; writing—review and editing, Dilfuza Jabborova, Tatiana Minkina, and Vishnu D. Rajput; investigation, Dilfuza Jabborova and Khurshid Sulaymanov. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declared no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wang H , Yang Y , Yao C , Feng Y , Wang H , Kong Y , et al. The correct combination and balance of macronutrients nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium promote plant yield and quality through enzymatic and antioxidant activities in potato. J Plant Growth Regul. 2024; 43( 12): 4716– 34. doi:10.1007/s00344-024-11428-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sai R , Paswan S . Influence of higher levels of NPK fertilizers on growth, yield, and profitability of three potato varieties in Surma, Bajhang, Nepal. Heliyon. 2024; 10( 14): e34601. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ashraf MN , Hu C , Wu L , Duan Y , Zhang W , Aziz T , et al. Soil and microbial biomass stoichiometry regulate soil organic carbon and nitrogen mineralization in rice-wheat rotation subjected to long-term fertilization. J Soils Sediments. 2020; 20( 8): 3103– 13. doi:10.1007/s11368-020-02642-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Adhikari G , Bhattacharyya KG . Correlation of soil organic carbon and nutrients (NPK) to soil mineralogy, texture, aggregation, and land use pattern. Environ Monit Assess. 2015; 187( 11): 735. doi:10.1007/s10661-015-4932-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kumari M , Sheoran S , Prakash D , Yadav DB , Yadav PK , Jat MK , et al. Long-term application of organic manures and chemical fertilizers improve the organic carbon and microbiological properties of soil under pearl millet-wheat cropping system in North-Western India. Heliyon. 2024; 10( 3): e25333. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e25333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Srinivasan V , Thankamani CK , Dinesh R , Kandiannan K , Zachariah TJ , Leela NK , et al. Nutrient management systems in turmeric: effects on soil quality, rhizome yield and quality. Ind Crops Prod. 2016; 85: 241– 50. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.03.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Verma PPS , Padalia RC , Singh V , Kumar A , Agri B . Effect of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium levels on growth and yield of turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) Under the Katyur valley of western Himalayan region of Uttarakhand. J Med Plants Stud. 2012; 7: 117– 22. [Google Scholar]

8. Selim MM . Introduction to the integrated nutrient management strategies and their contribution to yield and soil properties. Int J Agron. 2020; 2020: 2821678. doi:10.1155/2020/2821678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ayamba BE , Abaidoo RC , Opoku A , Ewusi-Mensah N . Mechanisms for nutrient interactions from organic amendments and mineral fertilizer inputs under cropping systems: a review. PeerJ. 2023; 11: e15135. doi:10.7717/peerj.15135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Noulas C , Torabian S , Qin R . Crop nutrient requirements and advanced fertilizer management strategies. Agronomy. 2023; 13( 8): 2017. doi:10.3390/agronomy13082017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Paramesh V , Mohan Kumar R , Rajanna GA , Gowda S , Nath AJ , Madival Y , et al. Integrated nutrient management for improving crop yields, soil properties, and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2023; 7: 1173258. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2023.1173258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Dash U , Gupta B , Bhardwaj DR , Sharma P , Kumar D , Chauhan A , et al. Tree spacings and nutrient sources effect on turmeric yield, quality, bio-economics and soil fertility in a poplar-based agroforestry system in Indian Himalayas. Agrofor Syst. 2024; 98( 4): 911– 31. doi:10.1007/s10457-024-00962-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Chernikova N , Chaplygin V , Minkina T , Mandzhieva S , Shmaraeva A , Kravchenko E , et al. Fractional composition of Cd, Pb, and Zn in medicinal plants at the impact territories of a coal-fired power station. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2025; 32( 29): 17670– 82. doi:10.1007/s11356-025-36718-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Minkina T , Bauer T , Khroniuk O , Kravchenko E , Pinsky D , Barakhov A , et al. Adsorption of Pb, Ni and Zn by coastal soils: isothermal models and kinetics analysis. Eurasian J Soil Sci Ejss. 2025; 14( 1): 67– 78. doi:10.18393/ejss.1579168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Cakmak I , Kutman UB . Agronomic biofortification of cereals with zinc: a review. Eur J Soil Sci. 2018; 69( 1): 172– 80. doi:10.1111/ejss.12437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Rusan MJ , Lubani R . A Combined application of compost and mineral fertilization enhances plant growth and soil fertility in calcareous clay loam soils. Eurasian J Soil Sci Ejss. 2025; 14( 3): 231– 9. doi:10.18393/ejss.1683715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Imran . Integration of organic, inorganic and bio fertilizer, improve maize-wheat system productivity and soil nutrients. J Plant Nutr. 2024; 47( 15): 2494– 510. doi:10.1080/01904167.2024.2354190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Acharya M , Chhetri S , Acharya P , Adhikari RK . Growth and yield response of spring maize to zinc and boron combined with NPK in Banke district, Nepal. Agric Dev J. 2025; 18: 49– 67. doi:10.3126/adj.v18i1.82088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Venkateswarlu M , Rallapalli S , Singh A , Chalapathi GSS , Kumar S , Katpatal YB , et al. Macro and micronutrient based soil fertility zonation using fuzzy logic and geospatial techniques. Sci Rep. 2025; 15( 1): 26772. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-12184-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Shireen F , Nawaz MA , Chen C , Zhang Q , Zheng Z , Sohail H , et al. Boron: functions and approaches to enhance its availability in plants for sustainable agriculture. Int J Mol Sci. 2018; 19( 7): 1856. doi:10.3390/ijms19071856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hayat F , Ashraf M , Aziz A , Hussain S , Arif MS , Akhtar N . Boron nutrition with NPs and H3BO3 to change its fractionation in soil and wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) productivity under alkaline calcareous conditions. J Plant Nutr. 2025; 48( 19): 3451– 66. doi:10.1080/01904167.2025.2515267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tanveer M , Mahmood A , Alawadi HFN , Adiba A , Javaid MM , Khan BA , et al. Impact of boron on Glycine max L. to mitigate salt stress by modulating the morpho-physiological and biochemical responses. BMC Plant Biol. 2025; 25( 1): 286. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-06037-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kohli SK , Kaur H , Khanna K , Handa N , Bhardwaj R , Rinklebe J , et al. Boron in plants: uptake, deficiency and biological potential. Plant Growth Regul. 2023; 100( 2): 267– 82. doi:10.1007/s10725-022-00844-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kobayashi T , Nishizawa NK . Iron uptake, translocation, and regulation in higher plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2012; 63: 131– 52. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bhat MA , Mishra AK , Shah SN , Bhat MA , Jan S , Rahman S , et al. Soil and mineral nutrients in plant health: a prospective study of iron and phosphorus in the growth and development of plants. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024; 46( 6): 5194– 222. doi:10.3390/cimb46060312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zuluaga MYA , Cardarelli M , Rouphael Y , Cesco S , Pii Y , Colla G . Iron nutrition in agriculture: from synthetic chelates to biochelates. Sci Hortic. 2023; 312: 111833. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.111833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Rakshit R , Patra AK , Purakayastha TJ , Singh RD , Pathak H , Dhar S . Super-optimal NPK along with foliar iron application influences bioavailability of iron and zinc of wheat. Proc Natl Acad Sci Ind Sect B Biol Sci. 2016; 86( 1): 159– 64. doi:10.1007/s40011-014-0428-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Jabborova D , Annapurna K , Choudhary R , Bhowmik SN , Desouky SE , Selim S , et al. Interactive impact of biochar and arbuscular mycorrhizal on root morphology, physiological properties of fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) and soil enzymatic activities. Agronomy. 2021; 11( 11): 2341. doi:10.3390/agronomy11112341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Walkley A . A critical examination of a rapid method for determining organic carbon in soils—effect of variations in digestion conditions and of inorganic soil constituents. Soil Sci. 1947; 63( 4): 251– 64. doi:10.1097/00010694-194704000-00001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Subbiah BV , Asija GL . A rapid procedure for the estimation of available nitrogen in soils. Curr Sci. 1956; 25: 518– 22. [Google Scholar]

31. Hanway JJ , Heidel H . Soil analysis methods as used in Iowa State College, Soil Testing Laboratory. Iowa Agric. 1952; 54: 1– 31. [Google Scholar]

32. Olsen S , Cole C , Watanabe F , Dean L . Estimation of available phosphorus in soils by extraction with sodium bicarbonate. Washington, DC, USA: U.S. Department of Agriculture; 1954. [Google Scholar]

33. Tabatabai MA , Bremner JM . Use of p-nitrophenyl phosphate for assay of soil phosphatase activity. Soil Biol Biochem. 1969; 1( 4): 301– 7. doi:10.1016/0038-0717(69)90012-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Green VS , Stott DE , Diack M . Assay for fluorescein diacetate hydrolytic activity: optimization for soil samples. Soil Biol Biochem. 2006; 38( 4): 693– 701. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.06.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Casida LE Jr , Klein DA , Santoro T . Soil dehydrogenase activity. Soil Sci. 1964; 98( 6): 371– 6. doi:10.1097/00010694-196412000-00004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Jenkinson DS , Powlson DS . The effects of biocidal treatments on metabolism in soil—V: a method for measuring soil biomass. Soil Biol Biochem. 1976; 8( 3): 209– 13. doi:10.1016/0038-0717(76)90005-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang H , Zhai H , Zan R , Tian Y , Ma X , Ji H , et al. Balanced fertilization improves crop production and soil organic carbon sequestration in a wheat-maize planting system in the North China Plain. Plants. 2025; 14( 6): 838. doi:10.3390/plants14060838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ashraf MN , Gao J , Wu L , Mustafa A , Waqas A , Aziz T , et al. Soil microbial biomass and extracellular enzyme–mediated mineralization potentials of carbon and nitrogen under long-term fertilization (>30 years) in a rice–rice cropping system. J Soils Sediments. 2021; 21( 12): 3789– 800. doi:10.1007/s11368-021-03048-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Šimon T , Madaras M , Mayerová M , Kunzová E . Soil organic carbon dynamics in the long-term field experiments with contrasting crop rotations. Agriculture. 2024; 14( 6): 818. doi:10.3390/agriculture14060818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Ramteke P , Gabhane V , Kadu P , Kharche V , Jadhao S , Turkhede A , et al. Long-term nutrient management effects on organic carbon fractions and carbon sequestration in Typic Haplusterts soils of Central India. Soil Use Manag. 2024; 40: e12950. doi:10.1111/sum.12950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Ullah S , Raza MM , Abbas T , Guan X , Zhou W , He P . Responses of soil microbial communities and enzyme activities under nitrogen addition in fluvo-aquic and black soil of North China. Front Microbiol. 2023; 14: 1249471. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1249471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Cakmak I . Enrichment of cereal grains with zinc: agronomic or genetic biofortification? Plant Soil. 2008; 302( 1): 1– 17. doi:10.1007/s11104-007-9466-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Jalal A , Júnior EF , Teixeira Filho MCM . Interaction of zinc mineral nutrition and plant growth-promoting bacteria in tropical agricultural systems: a review. Plants. 2024; 13( 5): 571. doi:10.3390/plants13050571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Tang Y , Nian L , Zhao X , Li J , Wang Z , Dong L . Bio-organic fertilizer application enhances silage maize yield by regulating soil physicochemical and microbial properties. Microorganisms. 2025; 13( 5): 959. doi:10.3390/microorganisms13050959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Gul S , Whalen JK , Thomas BW , Sachdeva V , Deng H . Physico-chemical properties and microbial responses in biochar-amended soils: mechanisms and future directions. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2015; 206: 46– 59. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2015.03.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Margalef O , Sardans J , Fernández-Martínez M , Molowny-Horas R , Janssens IA , Ciais P , et al. Global patterns of phosphatase activity in natural soils. Sci Rep. 2017; 7( 1): 1337. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01418-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Place F , Barrett CB , Freeman HA , Ramisch JJ , Vanlauwe B . Prospects for integrated soil fertility management using organic and inorganic inputs: evidence from smallholder African agricultural systems. Food Policy. 2003; 28( 4): 365– 78. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2003.08.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Amante G . Growth and yield response of turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) to NPSB and urea fertilizer in Yeki district, southwest Ethiopia. Int J Food Agric Nat Resour. 2025; 6( 1): 100– 5. doi:10.46676/ij-fanres.v6i1.470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Liao W , Wang H , Fan H , Chen J , Yin L , Cai X , et al. Nutrient and biomass dynamics for dual-organ yield in turmeric (Curcuma longa L.). PeerJ. 2025; 13: e19933. doi:10.7717/peerj.19933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools