Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

PpCSC1, a Novel ERD4 Ortholog from Physcomitrium patens, Plays a Negative Role in Salt Stress Tolerance

1 Key Laboratory of Microbiological Metrology, Measurement & Bio-product Quality Security, State Administration for Market Regulation, College of Life Sciences, China Jiliang University, 258 Xueyuan Street, Hangzhou, 310018, China

2 College of Life Sciences, Capital Normal University, 105 West Third Ring North Road, Beijing, 100048, China

* Corresponding Authors: Sheng Teng. Email: ; Yikun He. Email:

; Fang Bao. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Responses to Abiotic Stress Mechanisms)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2026, 95(1), 13 https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.073817

Received 26 September 2025; Accepted 15 December 2025; Issue published 30 January 2026

Abstract

ERD4 proteins, members of the early responsive-to-dehydration family, act as plasma membrane ion channels that contribute to ion homeostasis and modulate plant response to abiotic stresses. However, the functions of ERD4 homologs in non-vascular species remain largely unexplored. Here, we characterized an ERD4 family homolog in Physcomitrium patens (Hedw.) Mitt., PpCSC1 (Calcium-permeable Stress-responsive Cation Channel 1), and investigated its role in salt stress response. PpCSC1 localized to the plasma membrane and functioned as a non-selective cation channel permeable to Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+. Under salt treatment, PpCSC1 transcripts were markedly downregulated, whereas overexpression lines exhibited enhanced salt sensitivity. Ion content analysis further revealed reduced K+ accumulation, lowered K+/Na+ ratios, and elevated Mg2+ levels, collectively disrupting ionic homeostasis and impairing salt tolerance. Transcriptional regulation analysis revealed that the C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factor PpSTOP2 directly activated PpCSC1 expression. Notably, PpSTOP2 knockout plants displayed reduced PpCSC1 mRNA accumulation and improved salt tolerance. Together, these findings indicate that PpCSC1 is a plasma membrane-localized cation channel that negatively regulates salt tolerance by disturbing ion balance, and that its regulation by PpSTOP2 integrates upstream signaling with downstream physiological responses. This work provides new insight into how non-selective ion channels shape stress adaptation in early land plants.Keywords

Plants are constantly exposed to various abiotic stresses, including drought, high salinity, osmotic fluctuations, and low temperature, which disrupt cellular ion balance and metabolic homeostasis, impair photosynthesis and growth, and can ultimately result in plant death [1,2,3,4]. To address these challenges, plants have developed sophisticated membrane-associated perception and signaling systems that rapidly activate stress-response pathways [5,6,7,8,9]. Among these, ion channels that directly sense osmotic changes and initiate downstream signaling events play a central role in the early stages of abiotic stress responses [10,11,12,13].

In Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh, 16 dehydration-responsive genes were originally identified and designated as early-responsive to dehydration (ERD) genes [14,15]. Among them, ERD4 encodes a multi-pass transmembrane protein that contains the highly conserved DUF221 domain (Pfam accession: 02714), a motif commonly found in stress-related ion channels [16,17,18,19]. ERD4 proteins, such as OSCA1 (Reduced Hyperosmolality-Induced [Ca2+]i Increase 1) and AtCSC1 (Calcium-permeable Stress-responsive Cation Channel 1), function as osmosensitive ion channels that mediate rapid Ca2+ influx under hyperosmotic stress [16,17]. However, AtCSC1 conducts not only Ca2+, but also other cations, including Na+ and K+ [17]. Structural studies on OSCA channels have demonstrated that they form lipid-gated homodimeric pores and share features with mechanosensitive ion channels [20,21,22,23]. Functionally, the rapid activation of OSCA1 under osmotic stress triggers Ca2+ signaling waves that regulate stomatal closure, root architecture adjustment, and transcriptional reprogramming [16].

In angiosperms, ERD4 homologs have been implicated in enhancing abiotic stress tolerance. For example, ZmERD4 in Zea mays L. is constitutively expressed in various tissues and is strongly induced by drought, salinity, and ABA treatment, but not by cold stress. Heterologous overexpression of ZmERD4 in A. thaliana enhances tolerance to drought and salt [24]. Similarly, BjERD4 from Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. is stress-inducible and exhibits RNA-binding activity, suggesting a potential role in post-transcriptional regulation during stress responses [18].

Despite these advances, the functions of ERD4 homologs in non-vascular plants remain largely unknown. Physcomitrium patens (Hedw.) Mitt., a model bryophyte, exhibits physiological traits of early land plants and demonstrates remarkable tolerance to drought, salinity, osmotic, and cold stress [25,26,27,28]. In response to salinity, P. patens activates a coordinated defense program that includes ion transporters such as PpENA1, PpSOS1, PpNHAD1, and PpHAK1/2, which help maintain K+/Na+ homeostasis [29,30,31,32,33], along with ROS-scavenging enzymes like PpAKR1A, which enhance antioxidative capacity [34,35]. Additionally, several regulators, including PpCIPK1, PpAOX, PpCKX1, AP2/ERF transcription factors, PpLEA3, and PpSARK, enhance salt adaptation in P. patens by promoting ion homeostasis, stabilizing mitochondrial redox balance, improving developmental and dehydration tolerance, controlling chloroplast division, enhancing osmotic and oxidative protection, and activating ABA-dependent signaling [36,37,38,39,40,41]. Together, these findings suggest that P. patens possesses a highly integrated network of ionic, redox, and transcriptional regulation for abiotic stress adaptation, highlighting its value as a model for understanding ERD4 function and the evolutionary origins of salt-stress tolerance in early land plants.

In parallel with membrane-mediated signaling, transcriptional regulators also play central roles in plant stress responses. Among them, STOP1 (Sensitive to Proton Rhizotoxicity 1), a C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factor in A. thaliana, is essential for tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses, particularly aluminum toxicity and low-pH conditions in acid soils [42,43,44]. STOP1 directly activates key transporter genes, such as ALMT1, MATE, and ALS3, which mediate organic acid efflux and facilitate detoxification [45,46,47,48]. STOP1-like proteins in Oryza sativa L. and other species perform similar functions in regulating responses to aluminum toxicity and low pH [49,50,51,52,53]. These findings highlight how plants integrate transcriptional regulation and membrane-based mechanisms to maintain ion homeostasis under stress conditions.

Here, we identified and characterized a novel ERD4 homolog from P. patens, designated PpCSC1. The encoded protein localizes to the plasma membrane and functions as a non-selective cation channel. Functional analyses revealed that overexpression of PpCSC1 disrupts ion balance, lowers the K+/Na+ ratio, and reduces salt tolerance, suggesting a negative regulatory role in salt stress adaptation. Moreover, we identified the transcription factor PpSTOP2 as an upstream activator of PpCSC1. Loss of PpSTOP2 suppressed PpCSC1 expression and enhanced salt tolerance under salt stress. Together, our findings reveal a regulatory module in which PpCSC1, controlled by PpSTOP2, acts as a negative regulator of salt tolerance in moss. This study expands the functional understanding of ERD4 proteins in basal land plants and provides new insights into membrane-mediated sensing and signaling mechanisms during abiotic stress.

2.1 Plant Materials and Stress Treatments

Physcomitrium patens (Hedwig) ecotype ‘Gransden 2004’ was used as the wild-type strain. Protonema tissues were propagated axenically on solid BCD medium supplemented with 0.5% (w/v) glucose and 1 mmol L−1 CaCl2, under a 16 h light/8 h dark cycle at 25°C with a light intensity of 50 µmol m−2 s−1 [54,55,56]. For analyzing the transcript levels of PpCSC1 and PpSTOP2 under salt stress, five-day-old protonemata were transferred to BCD medium containing 350 mmol L−1 NaCl and harvested at 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, or 24 h. Based on existing literature [28,36,57] and our preliminary results, five-day-old protonemata were grown on BCD medium containing 350 mmol L−1 or 500 mmol L−1 NaCl for 4 days to assess growth performance. The two concentrations were selected to provide gene-specific insights: 350 mmol L−1 NaCl allows visualization of the growth phenotype in PpCSC1-overexpressing lines, whereas 500 mmol L−1 NaCl is suitable for evaluating the function of PpSTOP2 under more severe salt stress. This experimental design enables a focused investigation of the distinct contributions of these genes to salt stress adaptation.

2.2 Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from plant tissues using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), and contaminating genomic DNA was removed by gDNA Eraser (Takara Bio, Dalian, China). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara, China). The P. patens tubulin gene was used as the internal reference (forward primer: GAGTTCACGGAAGCGGAGAG; reverse primer: TCCTCCAGATCCTCCTCATA). Transcript levels were quantified using the SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM Kit (Takara Bio, Dalian, China) on an ABI 7500 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems). The primers used for qRT-PCR were as follows: PpCSC1 forward CGGACCTACAGGATTCGCTAA and reverse ATCTCCAGCACTGCAACGAAG; PpSTOP2 forward GCCAATGTACAGAAGCAAGCCTA and reverse ATTCATCATCTGACTACTGAGCT. Relative expression values were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method [58,59], with three independent biological replicates.

For CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis of PpSTOP2, a 20-bp guide RNA (crRNA: TTGAGGGCAATGCTGTAGCC) targeting the first exon was designed using the CRISPOR V1 web tool based on the P. patens genome Phytozome V9 (http://crispor.tefor.net/crispor.py) [60]. The sgRNA, driven by the P. patens U3/U6 promoter, was fused with the Streptococcus pyogenes tracrRNA scaffold (Fabien Nogué) and cloned into the pUC57 backbone. The sgRNA plasmid, along with a Cas9 expression construct (Sp-hCas9) and pBNRF (Fabien Nogué), was introduced into P. patens protoplasts via PEG-mediated transformation.

The full-length coding sequence of PpCSC1 was amplified from wild-type cDNA (primers: forward ATGACGGCAACTGGGGCTT; reverse GAGAGCATGGAACTCCTCTGTGC) and inserted downstream of the rice Actin2 promoter in the binary vector pTFH15.3 to create an overexpression construct. For promoter activity assays, a 2.0-kb upstream fragment of PpCSC1 was cloned into pTFH15.3-GUS vector using SpeI/AscI restriction sites to generate the PpCSC1pro::GUS construct.

2.4 Transformation of P. patens

Protoplast transformation was carried out following established PEG-mediated protocols [35]. Regenerated protoplasts were initially cultivated on BCD medium for 7 days and then transferred to selection plates containing G418 (25 mg L−1 for overexpression and fusion GUS transgenic lines; 50 mg L−1 for CRISPR/Cas9-based editing). Resistant colonies were subcultured on non-selective medium for recovery. The integration of exogenous DNA into the genomic DNA of stable transformants was verified by genomic PCR following the manufacturer’s protocols, while CRISPR-induced mutations were confirmed by sequencing of the target locus.

2.5 Histochemical Analysis of GUS Activity

Transgenic lines carrying PpCSC1pro::GUS were stained for β-glucuronidase activity using a commercial staining buffer (Sbjbio, Nanjing, China). Protonemata (5 days) and gametophores (21 days) were incubated at 37°C for 10–12 h, washed in water for 10–60 min, and cleared in 70% ethanol. Staining was examined using Zeiss Axio Imager M2 (protonema) and Axio Zoom V16 (gametophore) microscopes [46]. Data were obtained from at least three independent lines showing consistent patterns.

2.6 Transient Transformation of A. thaliana Protoplasts

Transient expression in A. thaliana mesophyll protoplasts was carried out as described [61]. Reporter plasmids (PpCSC1-LUC and Ubi-GU) were co-transformed with effector plasmids using PEG-mediated transformation. After 12 h of incubation, protoplasts were lysed and clarified by centrifugation at 20,000× g. Luciferase activity was normalized to GUS activity (relative LUC = LUC/GUS). Data represent four biological replicates.

For subcellular localization, PpCSC1-EGFP was introduced into protoplasts and fluorescence was observed after 12 h using a Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope (Stuttgart, Germany). Two independent experiments showed consistent GFP localization patterns.

2.7 Determination of Total Chlorophyll Content

Fresh tissues were homogenized in 10 mL of extraction buffer (acetone: ethanol: Milli-Q water = 4.5:4.5:1). Absorbance at 645 nm and 663 nm was measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer. Chlorophyll concentrations were estimated using previously described equations [35].

2.8 Cation Content Determination

Five-day-old protonemal cultures of P. patens were transferred to BCD medium supplemented with 350 mmol L−1 NaCl for three days. The material was rinsed thoroughly with deionized water, then dried to constant mass at 98°C for 2–3 days. The dried samples were ground into a fine powder using mortar and pestle. Approximately 100 mg samples were digested with concentrated nitric acid, and ion concentrations were quantified by ICP-MS (Capital Normal University, Beijing, China).

The full-length coding sequence of PpCSC1 was inserted into the pGEMHE expression plasmid for functional assays. Linearized plasmids (1 µg each) were used as templates for in vitro transcription with the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 kit (Ambion, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Austin, TX, USA), following the supplier’s standard protocol to produce capped cRNAs. Defolliculated Xenopus laevis oocytes, after removal of follicle cells, were microinjected with approximately 23 ng of cRNA per cell and then maintained in ND96 buffer at 18°C for four days before current recordings. Electrophysiological measurements were performed using the two-electrode voltage-clamp (TEVC) technique with a TEV-200 amplifier (Dagan Corp., Minneapolis, MN, USA). Data acquisition was performed using a Digidata 1440A interface coupled with pCLAMP 10.2 software (Molecular Devices/Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA, USA), with cells held at −60 mV. During recording, Xenopus laevis oocytes were continuously bathed in ND96 buffer containing 96 mmol L−1 NaCl, 2 mmol L−1 KCl, 1 mmol L−1 MgCl2, 1.8 mmol L−1 CaCl2, and 10 mmol L−1 HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.5 with NaOH, at ambient temperature. To test cation selectivity, NaCl in the external solution was equimolarly substituted with either KCl, CaCl2 or MgCl2.

3.1 Phylogenetic Analysis of PpCSC1 within the Bryophyte ERD4 Family

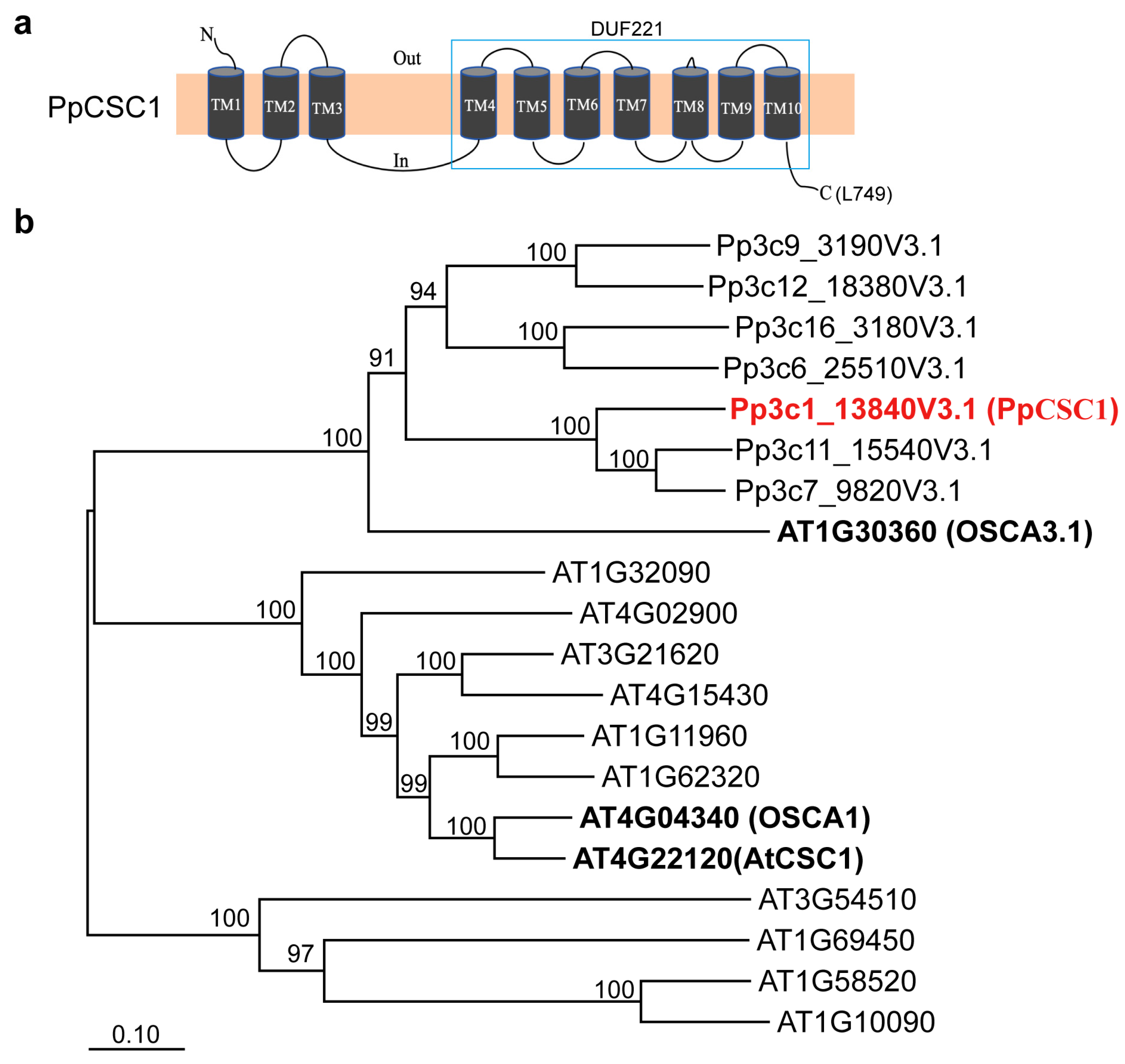

Similar to A. thaliana AtCSC1 and OSCA1 [16,17,20], the moss ERD4 homolog PpCSC1 encodes a protein of 749 amino acids. TMHMM-2.0 prediction (https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/service.php?TMHMM-2.0) indicated that PpCSC1 contains ten transmembrane domains (Fig. 1a), with domains 4–10 forming the conserved DUF221 domain. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that moss ERD4 homologs form a distinct evolutionary clade, with PpCSC1 showing high sequence similarity to A. thaliana OSCA family member OSCA3.1 (Fig. 1b).

Figure 1: Phylogenic analysis of PpCSC1 and its orthologous in bryophytes. (a) The predicted membrane topology and protein structure of PpCSC1. Transmembrane domains (TM) and the predicted pore-forming region are indicated. (b) Phylogenetic tree of ERD4 orthologs from P. patens and A. thaliana. Bootstrap support values (1000 replicates) are shown next to branches, and the scale bar represents the number of substitutions per site.

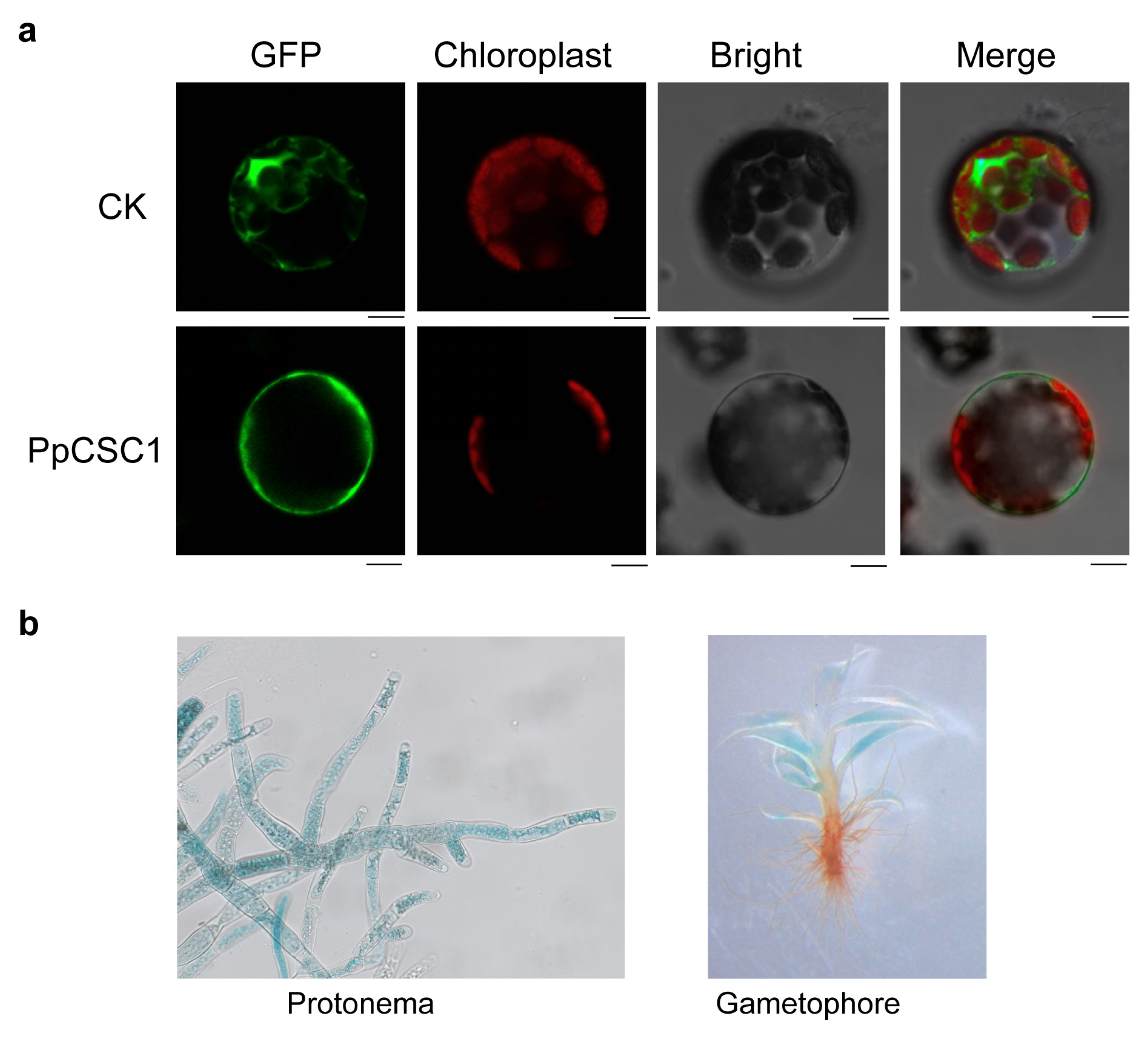

3.2 The PpCSC1 Protein Localizes in the Plasma Membrane

Subcellular localization was examined using a transient expression system in A. thaliana protoplast. The PpCSC1–GFP fusion protein exhibited a strong GFP signal at the plasma membrane (Fig. 2a).

Expression pattern was further assessed using ProPpCSC1::GUS reporter plants. GUS staining indicated predominant expression in protonemal tissues and in the central region of gametophyte leaves (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2: The subcellular localization and tissue specificity of PpCSC1 protein. (a) Subcellular localization of PpCSC1–GFP in A. thaliana protoplasts. From left to right: GFP fluorescence (green), chloroplast autofluorescence (red), bright-field (BF), and the merged image combining GFP, chloroplast, and BF signals. Images represent single confocal optical sections. Scale bar = 10 µm. (b) Tissue-specific expression patterns of PpCSC1::GUS in protonema (left) and gametophyte (right).

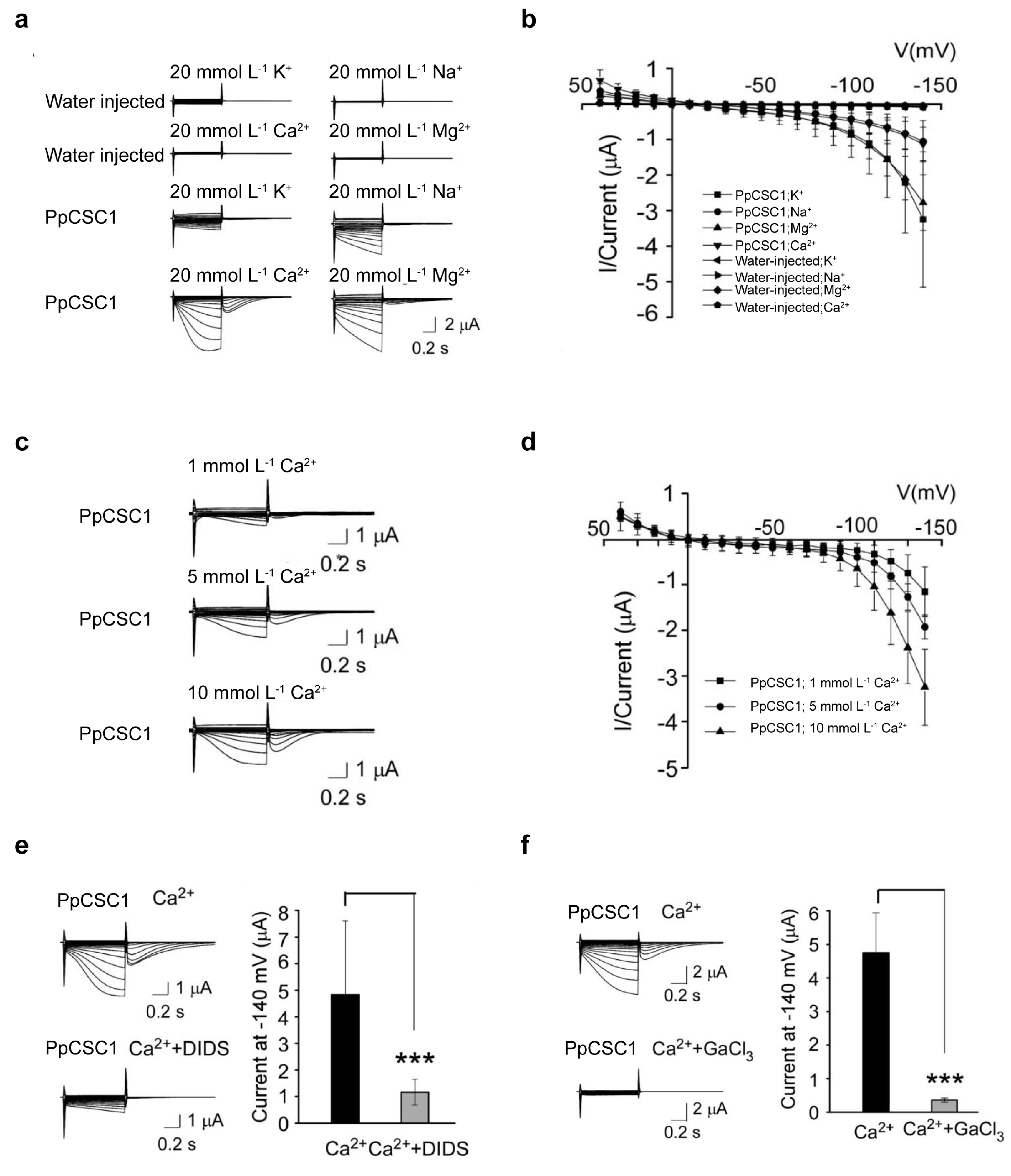

3.3 PpCSC1 Exhibits Cation Transport Activity

Since ERD4 family members in A. thaliana have been reported to function as osmosensitive cation channels [16,17,20,21], we investigated whether PpCSC1 exhibits similar activity using two-electrode voltage-clamp (TEVC) recording in the Xenopus laevis oocytes heterologous expression system. We replaced ND96 solution with 20 mmol L−1 NaCl, KCl, CaCl2, or MgCl2. Robust inward currents were detected in all conditions (Fig. 3a,b), demonstrating that PpCSC1 conducts multiple cations and functions as a non-selective cation channel.

We next investigated whether extracellular Ca2+ influences PpCSC1 activity. Perfusion with increasing Ca2+ concentrations (1, 5, and 10 mmol L−1) enhanced current amplitudes in a dose-dependent manner, accompanied by shifts in reversal potentials (Fig. 3c,d), indicating Ca2+-dependent regulation. Notably, prominent tail currents were observed in Ca2+-containing buffers, and these were attenuated by the Cl− channel blocker DIDS (0.1 mM) (Fig. 3e), consistent with activation of endogenous Ca2+-activated chloride channels (CACC). Furthermore, treatment with the Ca2+ channel inhibitor GaCl3 strongly suppressed PpCSC1-mediated currents (Fig. 3f), confirming that its channel activity depends on external Ca2+.

Figure 3: Electrophysiological characteristics of PpCSC1 in Xenopus laevis oocytes. (a, b) Representative whole-cell currents recorded from Xenopus laevis oocytes expressing PpCSC1 in solutions containing 20 mmol L−1 K+, Na+, Ca2+, or Mg2+, with water-injected oocytes used as controls. (c, d) Electrophysiological signals recorded from Xenopus laevi oocytes expressing PpCSC1, perfused with 1, 5 or 10 mmol L−1 Ca2+. Water-injected oocytes served as controls. (e) Tail currents observed in PpCSC1-expressing Xenopus laevis oocytes in 20 mmol L−1 CaCl2, with or without the Cl− channel blocker DIDS. (f) Currents recorded from fifteen PpCSC1-expressing Xenopus laevi oocytes in 20 mmol L−1 CaCl2 with or without GaCl3 treatment. The current-voltage curves were plotted using GraphPad Prism. Values are shown as means ± SD of fifteen oocytes. Asterisks indicate significant difference between the conditions with and without inhibitor treatment, as determined by Student’s t-test (***p < 0.001).

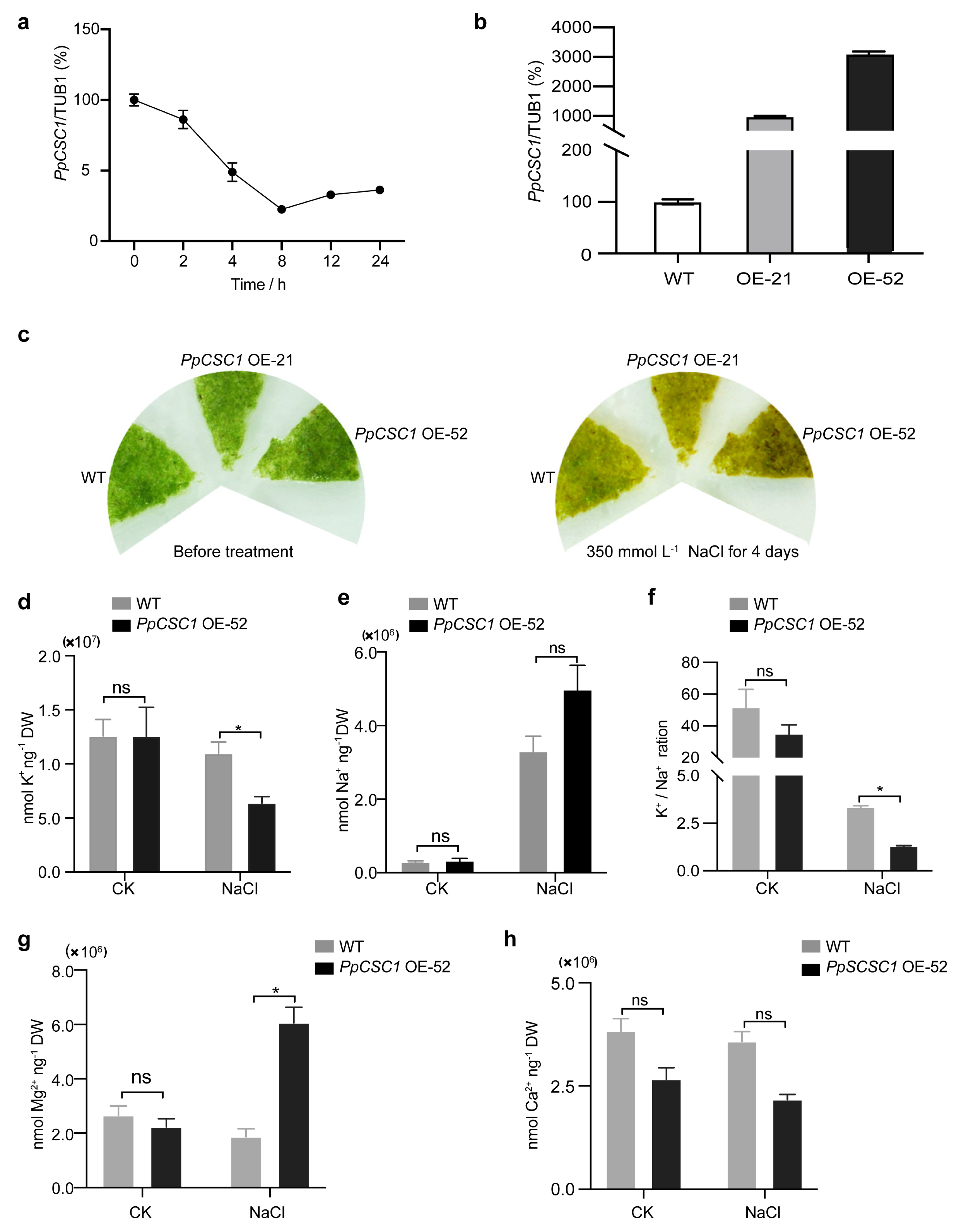

3.4 PpCSC1 Negatively Regulates Salt Tolerance in P. patens

To investigate the role of PpCSC1 in abiotic stress tolerance, we first examined its transcriptional response to NaCl stress by qRT-PCR. In five-day-old protonemata, PpCSC1 transcript levels progressively declined following NaCl treatment, reaching the lowest level at 8 h, and then partially recovered to one-third of the initial level at 24 h (Fig. 4a).

Further functional analysis was conducted by generating PpCSC1-overexpression (OE) lines, in which the coding sequence was placed under a strong promoter (Fig. 4b). After treatment with 350 mmol L−1 NaCl for 4 days, both wild-type (WT) and OE protonemata exhibited growth inhibition, whereas OE line with higher transcript levels exhibited more severe bleaching and browning (Fig. 4c), indicating reduced salt tolerance.

Ion content analysis revealed that, after 350 mmol L−1 NaCl treatment, K+ levels were significantly lower in the OE line than in WT (Fig. 4d), while Na+ content showed no significant difference (Fig. 4e). Consequently, the K+/Na+ ratio in the OE line was markedly decreased (Fig. 4f). The OE line also accumulated significantly more Mg2+ than the WT (Fig. 4g), while Ca2+ content remained unchanged (Fig. 4h).

Together, these results demonstrate that overexpression of PpCSC1 disrupts ion homeostasis under salt stress, leading to K+ loss and Mg2+ accumulation, which impairs salt tolerance.

Figure 4: PpCSC1 negatively regulates salt tolerance in P. patens. (a) Relative mRNA levels of PpCSC1 after salt treatment. Five-day-old WT protonema were exposed to 350 mmol L−1 NaCl for 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h. Transcript levels were normalized to TUB1 as the internal control, with the expression level at 0 h set as the baseline (100%). Relative expression is presented as percentage values relative to the 0 h time point. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three biological replicates. (b) Transcription levels of PpCSC1 in overexpression (OE) transgenic lines. Transcript levels were normalized to TUB1, with WT expression set as the baseline (100%). Relative expression is presented as percentage values relative to WT. Standard deviation was derived from three biological replicates. (c) Phenotypic analysis of PpCSC1 OE plants under salt stress. Representative images show five-day-old protonemata before treatment and after 4 days of exposure to 350 mmol L−1 NaCl. (d-h) Cation contents in the PpCSC1 OE plant under 350 mmol L−1 NaCl stress. After 3 days of NaCl treatment, K+ content (d), Na+ content (e), K+/Na+ contents (f), Mg2+ content (g) and Ca2+ content (h) were measured. Values are shown as means ± SD from three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate significant difference between WT and OE transgenic plant, as determined by Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05). ‘ns’ indicates no significant difference.

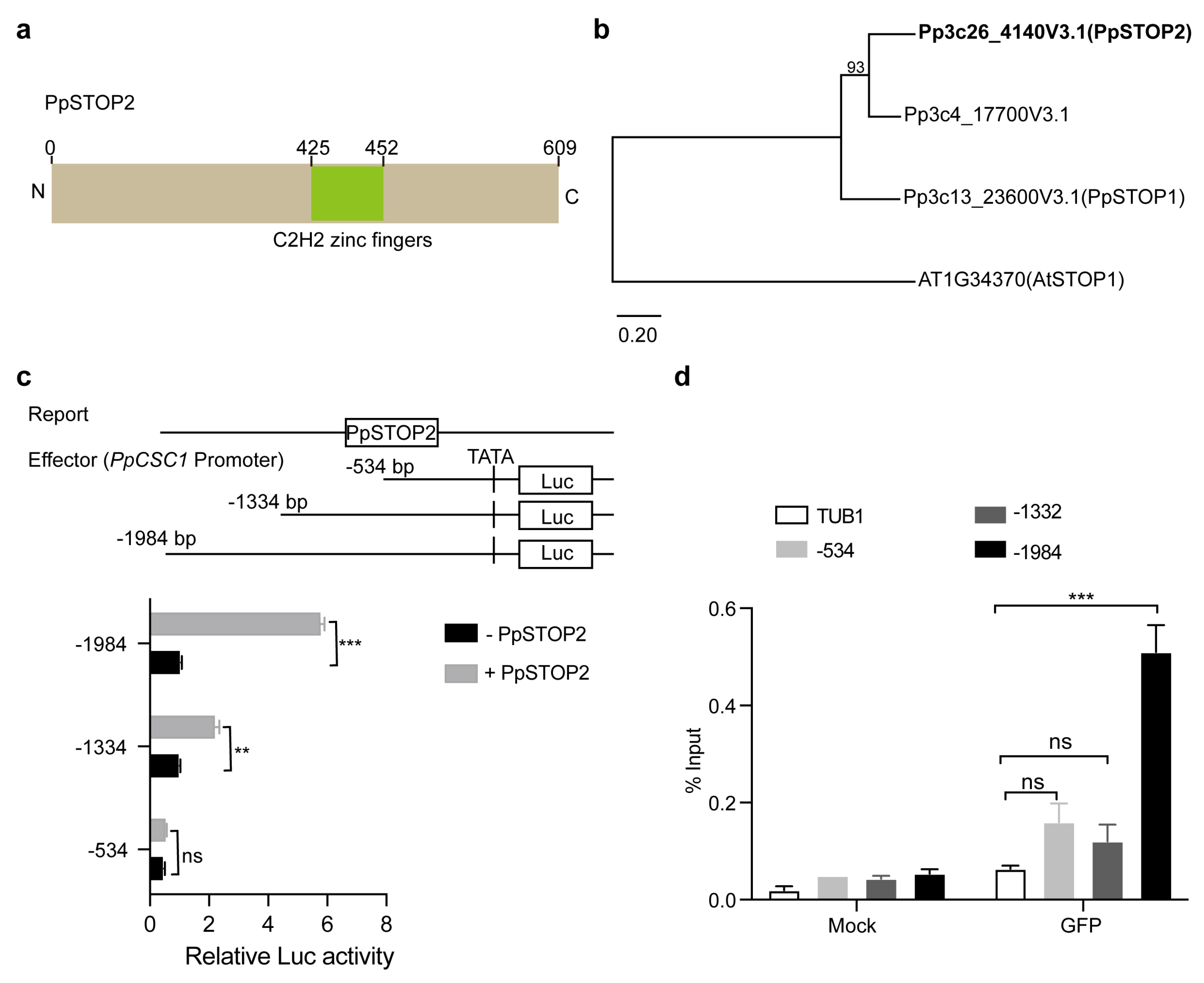

3.5 PpCSC1 is Transcriptionally Regulated by PpSTOP2

We employed a gene interaction and co-expression network centered on PpCSC1 to identify its upstream regulators. This approach identified a C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factor PpSTOP2 as a strong regulatory candidate. Phylogenetic and sequence analyses revealed that PpSTOP2 is a 609-amino acid protein and the moss homolog of PpSTOP1 (Fig. 5a,b).

The regulatory influence of PpSTOP2 on PpCSC1 was examined using dual-luciferase (LUC) reporter assays in A. thaliana protoplasts. Effector constructs containing progressive deletions of the PpCSC1 promoter (−534, −1334, and −1984 bp upstream of the transcription start site) were co-transformed with a 35S::PpSTOP2 reporter plasmid. The strongest induction of LUC activity occurred only when the −1334 to −1984 bp promoter region was present (Fig. 5c). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-qPCR) further confirmed that PpSTOP2 is specifically enriched at the −1334 to −1984 bp region of the PpCSC1 promoter (Fig. 5d). Together, these results indicate that PpSTOP2 regulates PpCSC1 transcription by directly binding to the −1334 to −1984 bp promoter fragment.

Figure 5: Regulation of PpCSC1 by the transcription factor PpSTOP2. (a) Predicted domain architecture of PpSTOP2. The positions of the C2H2 zinc finger motifs are indicated. (b) Phylogenetic tree of PpSTOP orthologs in P. patens. Maximum-likelihood analysis was performed using the PpSTOP1 family. Bootstrap support values (1000 replicates) are shown next to branches, and the scale bar represents the number of substitutions per site. (c) Transcriptional activation assay of PpCSC1 by PpSTOP2. A schematic of the pPpCSC1::LUC reporter and PpSTOP2 effectors (top). The PpCSC1 promoter was divided into three fragments: −1 to −1984 bp (−1984), −1 to −1334 bp (−1334), and −1 to −534 bp (−534). LUC activity was used to evaluate transcriptional activation, with GUS as a control. (d) ChIP-qPCR validation of PpSTOP2 binding to the PpCSC1 promoter. Promoter structure and corresponding amplified fragments analyzed are shown in (c). ChIP assays were performed using anti-GFP antibody, with GFP as the antibody control and the PpTubulin promoter (TuB1) as a negative control. The values are shown as means ± SD of three repeats. Asterisks indicate significant difference between wild-type and other genetic materials, as determined by Student’s t-test (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). ‘ns’ indicates no significant difference.

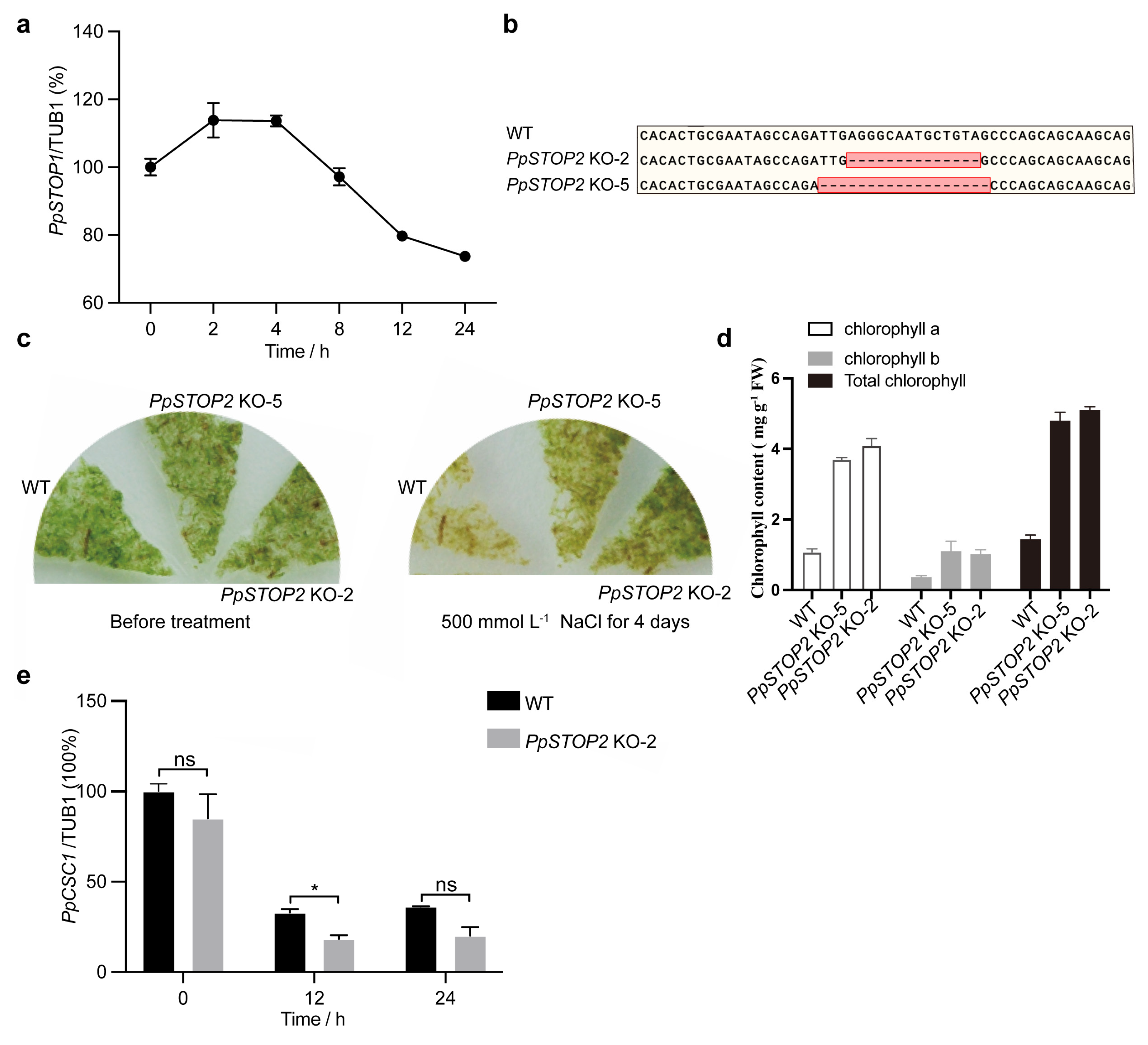

3.6 PpSTOP2 Negatively Influences Salt Tolerance

The expression dynamics of PpSTOP2 under NaCl stress were analyzed by qRT-PCR. In five-day-old protonemata, PpSTOP2 expression was transiently induced at 2–4 h and subsequently declined (Fig. 6a).

Further functional characterization was carried out by generating PpSTOP2 knockout (KO) mutants using CRISPR/Cas9 (Fig. 6b). After 4 days of exposure to 500 mmol L−1 NaCl, wild-type protonemata displayed severe bleaching, whereas PpSTOP2 KO lines retained green tissue and continued to grow (Fig. 6c). Consistent with this phenotype, chlorophyll content remained significantly higher in PpSTOP2 KO lines under salt stress (Fig. 6d), indicating that loss of PpSTOP2 enhances salt tolerance. Given this phenotype, we next examined whether PpSTOP2 regulates PpCSC1 transcription in vivo. qRT-PCR analysis revealed that PpCSC1 transcript levels were consistently lower in PpSTOP2 KO than in WT protonemata at 12 and 24 h after NaCl treatment (Fig. 6e). Together, these results suggest that PpSTOP2 positively regulates PpCSC1 expression, thereby compromising salt tolerance in P. patens.

Figure 6: PpSTOP2 negatively regulates salt resistance in P. patens. (a) Relative mRNA levels of PpSTOP2 after salt treatment. Five-day-old WT protonema were subjected to 350 mmol L−1 NaCl treatment for 0, 2, 4, 8, 12, and 24 h respectively. (b) Partial genomic sequences of WT and PpSTOP2 alleles. (c) Representative photograph of PpSTOP2 KO and WT plants on BCD media with 500 mmol L−1 NaCl for 4 days. (d) Total chlorophyll contents of WT and PpSTOP2 KO protonema after 500 mmol L−1 NaCl treatment for 4 days (e) Relative mRNA levels of PpCSC1. Five-day-old WT protonema and PpSTOP2 KO-2 were treated with 500 mmol L−1 NaCl treatment. Transcript levels were normalized to TUB1 as the internal control, with the expression level at 0 h set as the baseline (100%). Relative expression was presented as percentage values relative to the 0-h time point. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three biological replicates. The values are shown as means ± SD of three repeats. Asterisks indicate significant difference between wild-type and other genetic materials, as determined by Student’s t-test (*p < 0.05). ‘ns’ indicates no significant difference.

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that bryophyte ERD4 homologs form distinct subclades within the OSCA/AtCSC family, separate from angiosperm homologs (Fig. 1b). This divergence likely predates the emergence of vascular plants, indicating that ERD4 diversification occurred early in land plant evolution. Despite this evolutionary separation, bryophyte ERD4 homologs, including PpCSC1, retain the conserved DUF221 domain characteristic of the ERD4 family, supporting their structural homology with OSCA proteins in vascular plants. The presence of multiple ERD4 homologs in P. patens further suggests potential functional redundancy, which may obscure phenotypes in single-gene knockout lines. Therefore, comprehensive analyses that integrate expression profiling, subcellular localization, and ion selectivity will be necessary to elucidate the distinct functions of each family member.

Functionally, our electrophysiological and physiological analyses demonstrate that PpCSC1 acts as a non-selective cation channel permeable to Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Mg2+. Unlike vascular plant OSCAs, which positively contribute to stress adaptation by initiating Ca2+ signaling [16,17,62]. PpCSC1 functions as a negative regulator of salt tolerance (Fig. 4). Overexpression of PpCSC1 decreases the K+/Na+ ratio, perturbs ionic balance, and inhibits growth under salinity stress, implying that channel activity must be tightly constrained in moss to avoid maladaptive ion fluxes. This distinct physiological role emphasizes the expanded diversity of ion selectivity within ERD4 family: whereas vascular homologs predominantly link osmotic perception to Ca2+-based signaling, PpCSC1 primarily modulates bulk cation fluxes, highlighting functional diversification of ERD4 proteins in land plants.

In Arabidopsis thaliana, ERD4 homologs such as OSCA1, OSCA3.1, and AtCSC1 act as mechanosensitive channels whose activation depends on membrane tension or osmotic fluctuations [16,17,62]. By contrast, overexpression of PpCSC1 in Xenopus laevis oocytes produces substantial basal currents in the absence of mechanical stimulation, suggesting that the channel has an intrinsic ion-conducting capacity. This phenomenon is more likely a consequence of protein overexpression in the heterologous system rather than a reflection of its physiological behavior, and thus does not exclude the mechanosensitive nature of PpCSC1. In its native P. patens cellular context, activation of PpCSC1 is more likely to depend on mechanical signals, such as osmotic stress or membrane stretching, with its precise regulatory mechanisms remaining to be elucidated. Moreover, the lipid composition of the moss plasma membrane and potential interacting proteins may be critical for constraining or fine-tuning channel activity. Taken together, these findings indicate that while ERD4 channels are conserved in ion selectivity and mechanosensitivity, their regulatory modes have diversified among plant lineages, reflecting evolutionary adaptation to distinct cellular and ecological contexts.

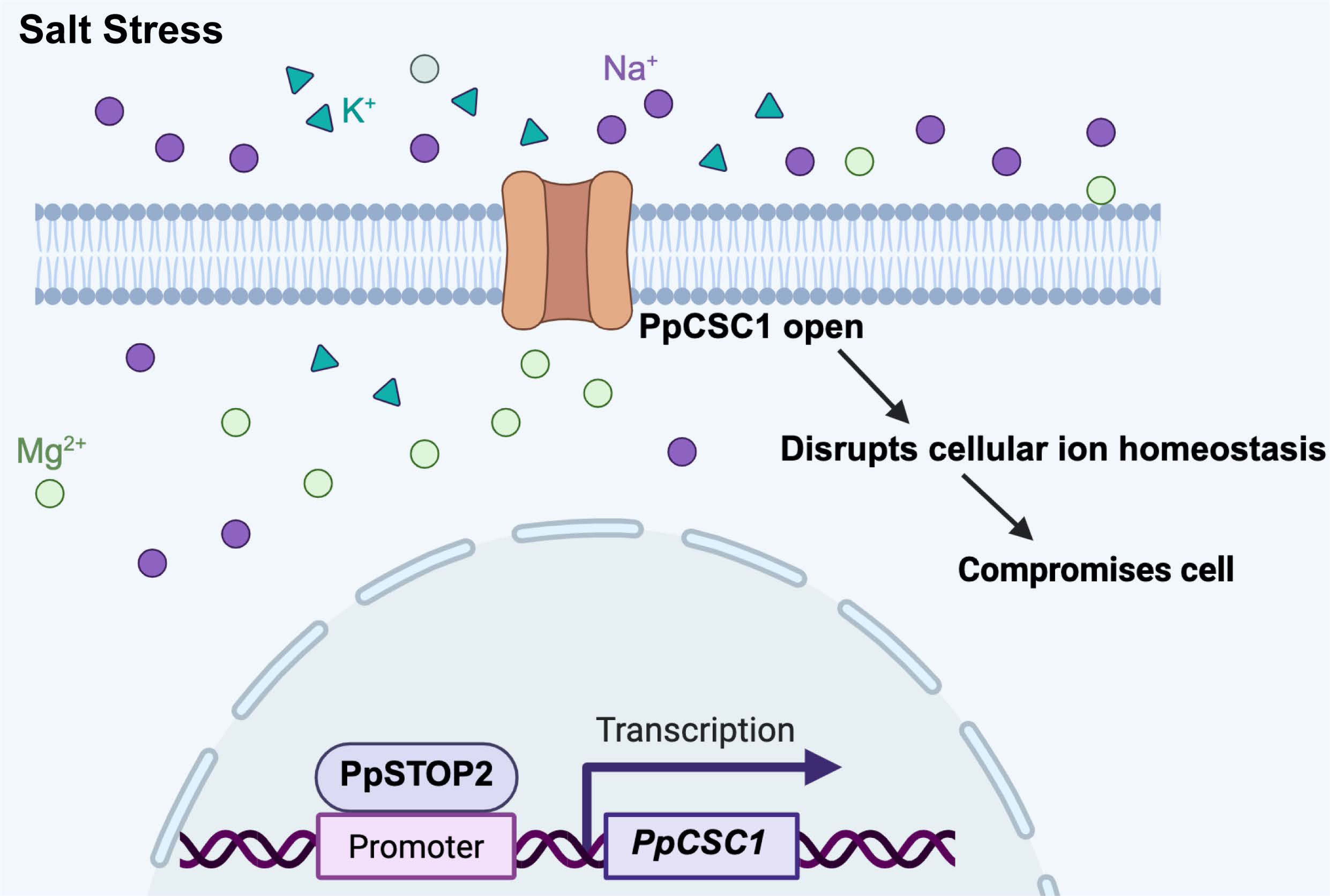

This physiological gating constraint is complemented by transcriptional regulation through PpSTOP2. PpSTOP2 activates PpCSC1 expression and displays biphasic dynamics under salt stress: rapid induction during the early phase, followed by strong repression (Fig. 6a). This feedback ensures transient channel activation for signaling while preventing prolonged cation influx and associated ionic toxicity. By contrast, in angiosperms such as A. thaliana and O. sativa, STOP1-like factors (AtSTOP1, OsART1) exhibit stable expression and protein activity under acid or aluminum stress, sustaining downstream transporter activation (e.g., ALMT1, MATE, ALS3) to promote detoxification [24,27,45,51]. Thus, whereas vascular plants rely on transcriptional activation of transporter pathways, mosses employ a dual-layered regulatory system-mechanosensitive gating at the protein level and biphasic transcriptional control at the gene level-to fine-tune channel activity (Fig. 7).

Collectively, these findings highlight a fundamental divergence in stress adaptation strategies between bryophytes and vascular plants. Bryophytes achieve tolerance primarily by restricting channel activity to maintain ionic homeostasis, whereas vascular plants enhance tolerance by sustaining activation through stable transcriptional programs. This divergence likely reflects fundamental differences in vacuolar capacity, tissue complexity, and ion compartmentalization between early and advanced land plants. The discovery of the PpSTOP2-PpCSC1 regulatory module not only broadens the functional landscape of ERD4 protein but also underscores the evolutionary plasticity of transcriptional and post-translational control in stress signaling. Future studies should determine whether other moss ERD4 paralogs act redundantly or divergently in abiotic stress responses, and how their functions integrate with Ca2+-based signaling pathways typical of vascular ERD4 protein.

Figure 7: Model of the PpSTOP2-PpCSC1 regulatory module under salt stress. Under salt stress, the transcription factor PpSTOP2 binds to the promoter of PpCSC1 and activates its transcription. The resulting PpCSC1 protein localizes to the plasma membrane and functions as a non-selective cation channel permeable to Na+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+. When PpCSC1 channels open, excessive cation flux reduces the K+/Na+ ratio, disrupts cellular ion homeostasis, and ultimately impaires cellular function and reduced stress tolerance.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31970658 and No. 32400208), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. LD24C130002 and No. LQN25C020001), and the Scientific Research Foundation of China Jiliang University.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: Fang Bao, Yikun He, and Lu Chen conceived and designed the research and wrote the manuscript. Sheng Teng provided critical analyses and revised the manuscript. Lu Chen performed most of the experiments and contributed to manuscript editing. Legong Li and Zhijie Ren carried out the voltage-clamp experiments. Guangmin Zhao performed the ChIP-qPCR assays. Xuan He optimized the CRISPR/Cas9 system for PpSTOP2 knockout in Physcomitrium patens. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ma L , Liu X , Lv W , Yang Y . Molecular mechanisms of plant responses to salt stress. Front Plant Sci. 2022; 13: 934877. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.934877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhao S , Zhang Q , Liu M , Zhou H , Ma C , Wang P . Regulation of plant responses to salt stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2021; 22( 9): 4609. doi:10.3390/ijms22094609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Slama I , Abdelly C , Bouchereau A , Flowers T , Savoure A . Diversity, distribution and roles of osmoprotective compounds accumulated in halophytes under abiotic stress. Ann Bot. 2015; 115( 3): 433– 47. doi:10.1093/aob/mcu239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Munns R , Tester M . Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008; 59: 651– 81. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhou H , Shi H , Yang Y , Feng X , Chen X , Xiao F , et al. Insights into plant salt stress signaling and tolerance. J Genet Genomics. 2024; 51( 1): 16– 34. doi:10.1016/j.jgg.2023.08.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yu Z , Duan X , Luo L , Dai S , Ding Z , Xia G . How plant hormones mediate salt stress responses. Trends Plant Sci. 2020; 25( 11): 1117– 30. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2020.06.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhu JK . Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell Rep. 2016; 167: 313– 24. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhu JK . Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2002; 53: 247– 73. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.091401.143329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Joshi S , Nath J , Singh AK , Pareek A , Joshi R . Ion transporters and their regulatory signal transduction mechanisms for salinity tolerance in plants. Physiol Plant. 2022; 174( 3): e13702. doi:10.1111/ppl.13702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zuo Y , Abbas A , Dauda SO , Chen C , Bose J , Donovan-Mak M , et al. Function of key ion channels in abiotic stresses and stomatal dynamics. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2025; 220: 109574. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2025.109574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Liu L , Li X , Wang C , Ni Y , Liu X . The role of chloride channels in plant responses to NaCl. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 25( 1): 19. doi:10.3390/ijms25010019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mostofa MG , Rahman MM , Ghosh TK , Kabir AH , Abdelrahman M , Rahman Khan MA , et al. Potassium in plant physiological adaptation to abiotic stresses. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2022; 186: 279– 89. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2022.07.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Amin I , Rasool S , Mir MA , Wani W , Masoodi KZ , Ahmad P . Ion homeostasis for salinity tolerance in plants: a molecular approach. Physiol Plant. 2021; 171( 4): 578– 94. doi:10.1111/ppl.13185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Taji T , Seki M , Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K , Kamada H , Giraudat J , Shinozaki K . Mapping of 25 drought-inducible genes, RD and ERD, in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 1999; 40( 1): 119– 23. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a029469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kiyosue T , Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K , Shinozaki K . Cloning of cDNAs for genes that are early-responsive to dehydration stress (ERDs) in Arabidopsis thaliana L.: identification of three ERDs as HSP cognate genes. Plant Mol Biol. 1994; 25( 5): 791– 8. doi:10.1007/BF00028874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yuan F , Yang H , Xue Y , Kong D , Ye R , Li CJ , et al. OSCA1 mediates osmotic-stress-evoked Ca2+ increases vital for osmosensing in Arabidopsis. Nature. 2014; 514( 7522): 367– 71. doi:10.1038/nature13593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hou C , Tian W , Kleist T , He K , Garcia V , Bai F , et al. DUF221 proteins are a family of osmosensitive calcium-permeable cation channels conserved across eukaryotes. Cell Res. 2014; 24: 632– 5. doi:10.1038/cr.2014.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Rai A , Suprasanna P , D’Souza SF , Kumar V . Membrane topology and predicted RNA-binding function of the ‘early responsive to dehydration (ERD4)’ plant protein. PLoS One. 2012; 7( 3): e32658. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jaroszewski L , Li Z , Krishna SS , Bakolitsa C , Wooley J , Deacon AM , et al. Exploration of uncharted regions of the protein universe. PLoS Biol. 2009; 7: e1000205. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1000205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Shan Y , Zhang M , Chen M , Guo X , Li Y , Zhang M , et al. Activation mechanisms of dimeric mechanosensitive OSCA/TMEM63 channels. Nat Commun. 2024; 15( 1): 7504. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-51800-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Han Y , Zhou Z , Jin R , Dai F , Ge Y , Ju XS , et al. Mechanical activation opens a lipid-lined pore in OSCA ion channels. Nature. 2024; 628( 8009): 910– 8. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07256-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang M , Wang D , Kang Y , Wu JX , Yao F , Pan CF , et al. Structure of the mechanosensitive OSCA channels. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2018; 25( 9): 850– 8. doi:10.1038/s41594-018-0117-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang M , Shan Y , Cox CD , Pei D . A mechanical-coupling mechanism in OSCA/TMEM63 channel mechanosensitivity. Nat Commun. 2023; 14( 1): 3943. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39688-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Liu Y , Li H , Shi Y , Song Y , Wang T , Li Y . A maize early responsive to dehydration gene, ZmERD4, provides enhanced drought and salt tolerance in arabidopsis. Plant Mol Biol Report. 2009; 27( 4): 542– 8. doi:10.1007/s11105-009-0119-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Rensing SA , Goffinet B , Meyberg R , Wu SZ , Bezanilla M . The Moss Physcomitrium (Physcomitrella) patens: a model organism for non-seed plants. Plant Cell. 2020; 32( 5): 1361– 76. doi:10.1105/tpc.19.00828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang XQ , Yang PF , Liu Z , Liu WZ , Hu Y , Chen H , et al. Exploring the mechanism of Physcomitrella patens desiccation tolerance through a proteomic strategy. Plant Physiol. 2009; 149( 4): 1739– 50. doi:10.1104/pp.108.131714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Saavedra L , Svensson J , Carballo V , Izmendi D , Welin B , Vidal S . A dehydrin gene in Physcomitrella patens is required for salt and osmotic stress tolerance. Plant J. 2006; 45: 237– 49. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02603.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Frank W , Ratnadewi D , Reski R . Physcomitrella patens is highly tolerant against drought, salt and osmotic stress. Planta. 2005; 220( 3): 384– 94. doi:10.1007/s00425-004-1351-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Haro R , Fraile-Escanciano A , González-Melendi P , Rodríguez-Navarro A . The potassium transporters HAK2 and HAK3 localize to endomembranes in Physcomitrella patens. HAK2 is required in some stress conditions. Plant Cell Physiol. 2013; 54( 9): 1441– 54. doi:10.1093/pcp/pct097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Oh DH , Ali A , Yun DJ , Bressan RA , Jin JB . SOS1 and AtHKT1;1 transporters mediate long-distance Na+ transport in Arabidopsis. Plant Signal Behav. 2010; 5( 8): 1034– 6. doi:10.3390/ijms20051085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Fraile-Escanciano A , Kamisugi Y , Cuming AC , Rodríguez-Navarro A , Benito B . The SOS1 transporter of Physcomitrella patens mediates sodium efflux in planta. New Phytol. 2010; 188( 3): 750– 61. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03405.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Fraile-Escanciano A , Garciadeblás B , Rodríguez-Navarro A , Benito B . Role of ENA ATPase in Na+ efflux at high pH in bryophytes. Plant Mol Biol. 2009; 71( 6): 599– 608. doi:10.1007/s11103-009-9543-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Barrero-Gil J , Rodríguez-Navarro A , Benito B . Cloning of the PpNHAD1 transporter of Physcomitrella patens, a chloroplast transporter highly conserved in photosynthetic eukaryotic organisms. J Exp Bot. 2007; 58( 11): 2839– 49. doi:10.1093/jxb/erm094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Koochak H , Ludwig-Muller J . Physcomitrium patens mutants in auxin conjugating GH3 proteins show salt stress tolerance but auxin homeostasis is not involved in regulation of oxidative stress factors. Plants. 2021; 10( 7): 1398. doi:10.3390/plants10071398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Chen L , Bao F , Tang S , Zuo E , Lv Q , Zhang DY , et al. PpAKR1A, a novel Aldo-Keto reductase from Physcomitrella Patens, plays a positive role in salt stress. Int J Mol Sci. 2019; 20( 22): 5723. doi:10.3390/ijms20225723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Xiao F , Li XC , He JX , Zhao JF , Wu GC , Gong QY , et al. Protein kinase PpCIPK1 modulates plant salt tolerance in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Mol Biol. 2021; 105( 6): 685– 96. doi:10.1007/s11103-021-01120-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Hyoung SJ , Cho SH , Chung JH , So WM , Cui MH , Shin JS . Cytokinin oxidase PpCKX1 plays regulatory roles in development and enhances dehydration and salt tolerance in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell Rep. 2020; 39( 3): 419– 30. doi:10.1007/s00299-019-02500-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Do TH , Pongthai P , Ariyarathne M , Teh OK , Fujita T . AP2/ERF transcription factors regulate salt-induced chloroplast division in the moss Physcomitrella patens. J Plant Res. 2020; 133( 4): 537– 48. doi:10.1007/s10265-020-01195-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Li P , Yang H , Liu GJ , Ma WZ , Li CH , Huo HQ , et al. PpSARK regulates moss senescence and salt tolerance through ABA related pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2018; 19( 9): 2609. doi:10.3390/ijms19092609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Du J , Wang L , Zhang XC , Xiao X , Wang F , Lin PL , et al. Heterologous expression of two Physcomitrella patens group 3 late embryogenesis abundant protein (LEA3) genes confers salinity tolerance in arabidopsis. J Plant Biol. 2016; 59( 2): 182– 93. doi:10.1007/s12374-016-0565-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Saavedra L , Balbi V , Dove SK , Hiwatashi YJ , Mikami K , Marianne Sommarin M . Characterization of phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinases from the moss Physcomitrella patens: PpPIPK1 and PpPIPK2. Plant Cell Physiol. 2009; 50( 3): 595– 609. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcp018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Sadhukhan A , Kobayashi Y , Iuchi S , Koyama H . Synergistic and antagonistic pleiotropy of STOP1 in stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2021; 26( 10): 1014– 22. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2021.06.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Huang CF , Ma Y . Aluminum resistance in plants: a critical review focusing on STOP1. Plant Commun. 2025; 6( 2): 101200. doi:10.1016/j.xplc.2024.101200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Li X , Tian Y . STOP1 and STOP1-like proteins, key transcription factors to cope with acid soil syndrome. Front Plant Sci. 2023; 14: 1200139. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1200139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Fan N , Li XB , Xie WX , Wei X , Fang Q , Huang CF . Modulation of external and internal aluminum resistance by ALS3-dependent STAR1-mediated promotion of STOP1 degradation. New Phytol. 2024; 244( 2): 511– 27. doi:10.1111/nph.19985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Silva-Navas J , Salvador N , Del Pozo JC , Benito C , Gallego FJ . The rye transcription factor ScSTOP1 regulates the tolerance to aluminum by activating the ALMT1 transporter. Plant Sci. 2021; 310: 110951. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2021.110951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Sawaki Y , Iuchi S , Kobayashi Y , Kobayashi Y , Ikka T , Sakurai N , et al. STOP1 regulates multiple genes that protect arabidopsis from proton and aluminum toxicities. Plant Physiol. 2009; 150( 1): 281– 94. doi:10.1104/pp.108.134700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Liu J , Magalhaes JV , Shaff J , Kochian LV . Aluminum-activated citrate and malate transporters from the MATE and ALMT families function independently to confer Arabidopsis aluminum tolerance. Plant J. 2009; 57( 3): 389– 99. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03696.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Huang S , Gao J , You J , Liang Y , Guan K , Yan SQ , et al. Identification of STOP1-like proteins associated with aluminum tolerance in sweet sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.). Front Plant Sci. 2018; 9: 258. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.00258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Che J , Tsutsui T , Yokosho K , Yamaji N , Ma JF . Functional characterization of an aluminum (Al)-inducible transcription factor, ART2, revealed a different pathway for Al tolerance in rice. New Phytol. 2018; 220( 1): 209– 18. doi:10.1111/nph.15252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Yamaji N , Huang CF , Nagao S , Yano M , Sato Y , Nagamura Y , et al. A zinc finger transcription factor ART1 regulates multiple genes implicated in aluminum tolerance in rice. Plant Cell. 2009; 21( 10): 3339– 49. doi:10.1105/tpc.109.070771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Magalhaes JV , Liu J , Guimaraes CT , Lana UG , Alves VM , Wang YH , et al. A gene in the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family confers aluminum tolerance in sorghum. Nat Genet. 2007; 39( 9): 1156– 61. doi:10.1038/ng2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Furukawa J , Yamaji N , Wang H , Mitani N , Murata Y , Sato K , et al. An aluminum-activated citrate transporter in barley. Plant Cell Physiol. 2007; 48( 8): 1081– 91. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcm091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Ćosić MV , Božović DP , Jadranin B , Vujičić MM , Sabovljević AD , Sabovljević MS . Axenic cultivation of bryophytes: growth media composition. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2025; 160( 2): 276217461. doi:10.1007/s11240-024-02957-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Wang X , Zhou S , Chen L , Quatrano RS , He YK . Phospho-proteomic analysis of developmental reprogramming in the moss Physcomitrella patens. J Proteomics. 2014; 108: 284– 94. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2014.05.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Cove DJ , Perroud PF , Charron AJ , McDaniel SF , Khandelwal A , Quatrano RS . The moss Physcomitrella patens: a novel model system for plant development and genomic studies. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2009; 2009: 115. doi:10.1101/pdb.emo115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Wu GC , Li S , Li XC , Liu YH , Zhao SS , Liu BH , et al. A Functional Alternative Oxidase Modulates Plant Salt Tolerance in Physcomitrella patens. Plant Cell Physiol. 2019; 60( 8): 1829– 41. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcz099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Rao XY , Huang XL , Zhou ZC , Lin X . An improvement of the 2−ΔΔCt method for quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction data analysis. Biostat Bioinforma Biomath. 2013; 3( 3): 71– 85. [Google Scholar]

59. Livak KJ , Schmittgen TD . Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt method. Methods. 2001; 25( 4): 402– 8. doi:10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Lopez-Obando M , Hoffmann H , Géry C , Guyon-Debast A , Téoulé E , Rameau C , et al. G3 genes genom. Simple and Efficient targeting of multiple genes through CRISPR-Cas9 in Physcomitrella patens. Genetica. 2016; 6: 3647– 53. doi:10.1534/g3.116.033266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Abel S , Theologis A . Transient transformation of Arabidopsis leaf protoplasts: a versatile experimental system to study gene expression. Plant J. 1994; 5( 3): 421– 7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313x.1994.00421.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Pei S , Tao Q , Li W , Qi G , Wang B , Wang Y , et al. Osmosensor-mediated control of Ca2+ spiking in pollen germination. Nature. 2024; 629: 1118– 25. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07445-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools