Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Salicylic Acid-Elicited Alkaloid Accumulation in Pinellia ternata Microtubers: Cytotoxicity and Transcriptomic Analysis

1 Anhui Provincial Engineering Laboratory for Efficient Utilization of Featured Resource Plants, Key Laboratory of Resource Plant Biology of Anhui Province, College of Life Sciences, Huaibei Normal University, Huaibei, 235000, China

2 Huaibei Key Laboratory of Efficient Cultivation and Utilization of Resource Plants, College of Life Sciences, Huaibei Normal University, Huaibei, 235000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Fenglan Zhao. Email: ; Yongbo Duan. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2026, 95(1), 20 https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2026.074434

Received 11 October 2025; Accepted 30 December 2025; Issue published 30 January 2026

Abstract

As its tuberous alkaloids induce valuable pharmacological effects, Pinellia ternata has considerable clinical value. However, its production currently fails to meet its demand. In vitro microtuber culture, combined with salicylic acid (SA) elicitation, may provide an effective alternative to traditional field production. In this study, an in vitro P. ternata microtuber induction system was developed and used to evaluate SA-induced elicitation of alkaloid accumulation. The quality of in vitro microtubers was assessed by total alkaloid measurement, a cytotoxicity assay, and transcriptomic analysis. With or without SA treatment, P. ternata microtuber induction was achieved within 60 d using petiole-derived explants, with a microtuber proliferation rate of approximately 17 microtubers per explant. The total alkaloid content of in vitro microtubers elicited with 100 μM SA was equivalent to that of field-grown tubers, while those not treated with SA contained lower alkaloid content. The cytotoxicity assay showed preliminary cytotoxic effects of SA-treated microtubers against the breast cancer cell line SUM159, comparable to field-grown tubers. Transcriptomic analysis revealed many differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in SA-treated in vitro microtubers. Six and twelve DEGs were annotated to the tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloid pathway and the isoquinoline alkaloid pathway, respectively. RT-qPCR confirmed that the genes encoding spermidine synthase (c64642_g1), hyoscyamine (6S)-dioxygenase (c62620_g1), catechol oxidase (c61704_g3), monoamine oxidase (c65996_g3), and aspartate transaminase (c71069_g1) were significantly induced by SA. This study advances the production of P. ternata microtubers without field cultivation and provides considerable genetic information regarding SA-promoted alkaloid accumulation in P. ternata.Keywords

Pinelliae Rhizoma (PR) is the dried tuber of Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) from the family Araceae. It has a long history of use in Traditional Chinese Medicine, Japanese Kampo, Korean medicine, and the native medicines of various Southeast Asian countries [1]. The typical prescriptions of PR included “Banxia Houpu Decoction”, “Sho-seiryu-to”, “Kakkon-to”, and “Choto-san” [2,3]. PR is particularly rich in bioactive chemical constituents, with over 200 already identified [4]. Among them, alkaloids have been predominantly studied owing to their well-documented anti-inflammatory, anticancer, antiviral, and molluscicidal activities [5,6]. Moreover, PR is also an important constituent of the traditional Chinese formulas for treating the recently emerged COVID-19 [7,8,9]. Its broad clinical efficacies have driven the rise of PR into the top 10 most frequently utilized bulk traditional Chinese medicines.

According to China Customs statistics, the average annual demand for PR has increased to over 1800 t in recent years. However, PR production from both wild and cultivated sources is currently just nearly 500 t, dramatically insufficient to meet the market demand [10], and the gap between supply and demand has only continued to widen in recent years. The limiting factors mainly include low contents of important bioactive compounds [11,12], “sprout tumble” caused by abiotic stress [13,14,15,16], and high labor costs owing to the inadequacy of mechanized harvesting technology [17]. Thus, the development of new alternatives to field cultivation is critical for PR production.

In vitro culture techniques, including microtuber induction, provide a controlled and efficient system for studying secondary metabolite biosynthesis and optimizing alkaloid production [18]. Pinellia ternata microtuber induction has been explored by various research groups [19,20,21,22]. However, reported changes in bioactive compounds in microtubers are inconsistent, with some studies showing lower contents while others indicate similar content levels compared with field grown tubers. Thus, elicitation with exogenous regulators offers a promising prospect to overcoming the low alkaloid content of these in vitro propagated micro-tubers [23]. Salicylic acid (SA) is among the plant growth regulators that regulate multiple physiological and metabolic processes of plants [24,25]. Recently, SA has been applied to regulate the production of bioactive compounds in P. ternata, using suspension cells [11] or in vitro microtubers [12] as materials. Although induced accumulation of alkaloids has been observed, the specific genes involved in regulating the biosynthesis of these compounds merit further investigation.

Accordingly, this study aimed to assess the cytotoxic activity of SA-elicited microtubers and identify key candidate genes associated with SA-induced alkaloid accumulation through transcriptomic analysis. These findings have the potential to enable the sustainable production of P. ternata resources without continued reliance on field cultivation.

Pinellia ternata plants were pot-cultivated in commercial nutrient soil (turf:coir:sandy loam:vermiculite:perlite ratio of 5:3:1:1 [v:v:v:v], Huaian Zhonghe Agriculture Co., Ltd., Huaian, China) at the Anhui Provincial Engineering Laboratory for Efficient Utilization of Featured Resource Plants, Huaibei, China. The plants were cultivated for approximately 4–6 weeks until they had reached the three-leaf stage. During this cultivation period, the culture environment was controlled at 23°C, with a 16-h light/8-h dark photoperiod and a light intensity of 35 μmol photons m−2 s−1.

The human breast cancer cell line SUM159 and the non-malignant human breast epithelial cell line MCF-10A utilized in this research were preserved in liquid nitrogen.

The ephedrine standard used in this work was the product of the National Institutes for Food and Drug Control (Beijing, China). Unless otherwise noted, all other reagents were obtained from Sigma (Saint Louis, MO, USA).

2.2 Induction of In Vitro Microtubers and SA Treatment

Aseptic plantlets were established following our previously published method [12]. Briefly, petioles of potted P. ternata plants were surface-disinfected and inserted upright into Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium [26] supplemented with 3% sucrose and 0.7% agar. These materials were then maintained at 23 ± 1°C under a 16-h photoperiod provided by cool-white fluorescent light (Shanghai Jiafeng Articles for Horticulture Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The plantlets were regenerated within approximately four weeks under these conditions.

Fifteen approximately 1-cm-long petiole fragments were placed into each flask containing 100 mL of standard liquid MS medium supplemented with 0.5 mg·L−1 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP), 0.5 mg·L−1 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D), and 1.0 mg·L−1 indole-3-acetic acid (IAA). To investigate whether SA treatment affects the formation and growth of microtubers, SA was added to the culture system at a final concentration of 100 μM—a concentration that had been previously reported to optimally induce alkaloid accumulation [12]; cultures maintained without SA supplementation served as the control group. SA was added to the liquid medium at the beginning of microtuber induction (day 0), and the medium was refreshed every two weeks to maintain the 100 μM SA concentration. The elicitation period was maintained for 60 days. The materials were then cultured at 100 r·min−1 and 23 ± 1°C under a 10-h photoperiod with irradiance of 35-μmol photons m−2 s−1.

Microtubers formed after 30 d of culture without SA treatment were then collected for elicitation treatment to investigate SA-elicited alkaloid biosynthesis. The treatment was performed by incubating microtubers in liquid MS medium supplemented with 100 μM SA. Microtubers cultured without SA treatment were used as control materials. The microtubers were collected at days 0, 5, 10, 15, and 20 of elicitation, designated as T0, T5, T10, T15, and T20, respectively. A portion of the tubers was dried at 60°C for alkaloid analysis and a cytotoxicity assay using cancerous and healthy cell lines, and the remaining samples were stored at −80°C for transcriptomic or qRT-PCR analysis.

2.3 Quantification of Alkaloid Contents of In Vitro P. ternata Tubers

Both in vitro induced microtubers and field-grown tubers were used as experimental materials for alkaloid determination. The in vitro microtubers treated with SA or not (as the control treatment) were collected after 15 d of elicitation. The field-grown tubers were harvested from potted P. ternata plants after six months of cultivation in the greenhouse facilities of Anhui Provincial Engineering Laboratory for Efficient Utilization of Featured Resource Plants.

One hundred grams of dried sample powder of each sample was weighed into a 25-mL glass tube, to which were added 0.5 mL of stronger ammonia water and then 10 mL of chloroform. The mixture was incubated at 4°C for 3 h, ultrasonic-extracted for 1 h, and centrifuged at 1000× g, and the resulting supernatant was then collected. The precipitation was extracted again with 10 mL of chloroform. The two supernatants were combined and vacuum-dried in a Concentrator plus (Eppendorf AG, Hamburg, German). The precipitate was redissolved in 2 mL of ethanol. Total alkaloids were determined by spectrophotometry as previously described [11], with ephedrine used as a reference for normalization of alkaloid content. Ephedrine was selected as the reference standard because it is a representative alkaloid commonly detected in P. ternata (Duan et al., 2019), and the compound also has well-established analytical methods for its spectrophotometric quantification. Although pinelline A and guanosine are also known alkaloids in P. ternata, pinelline A standard is unavailable, and guanosine is a purine nucleoside with substantial differences from the major alkaloids in P. ternata, as indicated by previous studies (Duan et al., 2019; Guo et al., 2022). A follow-up dose–response experiment was conducted with SA concentrations of 50, 100, and 150 μM, and sampling was conducted on days 5, 10, 15, and 20. Total alkaloid content was determined to infer the optimal SA concentration and elicitation time.

Ephedrine content was determined using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) following the method described by Duan et al. (2019). A calibration curve was constructed using standard solutions (0.1–100 μg·mL−1), and caffeine was used as an internal standard. Method validation included evaluation of linearity (R2 > 0.99), precision (RSD < 5%), and recovery (85–115%).

The cytotoxic activities of alkaloids derived from in vitro P. ternata microtubers at day 15 of elicitation, and field-grown tubers at 6 months of standard cultivation were evaluated according to the method described by Meng et al. [27]. The human breast cancer cell line SUM159 was challenged with P. ternata extracts, with 3 nM doxorubicin hydrochloride used as a positive control [28]. The non-malignant human breast epithelial cell line MCF-10A was used as control material for the calculation of the selectivity index (SI = IC50 of MCF-10A/IC50 of SUM159). Each extract was diluted to different concentrations (5, 25, 50, and 100 μg·mL−1 for SUM159). Using a blank volume lacking extract as a control, the cell sensitivity at 42 h after treatment was assayed using the (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) method. The cytotoxic activity was calculated as the percentage of viable cells in treatments relative to the blank control (which was deemed as 100%). Cytotoxicity dosing was normalized to the dry weight of the tubers. Extracts were prepared from three independent batches of tubers, and batch-to-batch consistency was confirmed by measuring both total alkaloid content (RSD < 4%) and ephedrine content (RSD < 5%). Each treatment comprised three biological replicates and three technical replicates, and the data are presented as mean ± SD values.

2.5 RNA Extraction, Illumina Sequencing, and De Novo Assembly

As the contents of total alkaloids and various alkaloid compounds did not change during the growth of microtubers within 20 days [12], only the SA-elicited samples T0, T5, T10, T15, and T20 were subjected to transcriptomic analysis. Each sample consisted of two biological replicates. The microtubers were ground in liquid nitrogen, and 200 mg of each sample pooled from three replicates was subjected to RNA isolation using the Trizol method (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). RNA integrity was evaluated using the NanoDrop2000C instrument (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA) and agarose electrophoresis. Then, mRNA was purified using oligo (dT) magnetic beads and sheared into approximately 250-bp fragments for sequencing library construction. The cDNA libraries were sequenced by Benagen Technology Co. (Wuhan, China) using the HiSeq4000 platform (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The RNA-Seq reads were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Short Read Archive (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/) under accession number PRJNA1297976.

Each sample included two biological replicates, and differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014) with library-size normalization and independent filtering. Dispersion estimates were adjusted using a parametric fit, and multiple-testing correction was applied using the Benjamini–Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate (FDR). Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified according to their expression levels at thresholds of FDR < 0.01 and |log2(fold change)| ≥ 1.

The raw data of ten RNA sequencing reads were filtered by removing the adaptor sequences, duplicated sequences, ambiguous reads (with ‘N’ bases), and low-quality reads. The yielded clean reads were then assembled using the Trinity assembly program with the default parameters [29]. The clean reads were assembled to generate contigs, which were then clustered to yield unigenes by using TGICL software [30].

2.6 Functional Annotation and Analysis of Differentially Expressed Genes

Functional annotation was performed by searching public databases, including the NCBI non-redundant (nr) nucleotide (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Swiss-Prot (http://www.expasy.ch/sprot), Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/COG/), and Pfam (http://pfam.xfam.org/) databases, using BLASTX (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) with an E value threshold of 1e−5 [31]. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) annotations were applied to the transcriptomic data to obtain functional classifications for the transcripts. The transcript abundances were quantified according to their fragments per kb per million mapped reads (FPKM) values, setting a threshold for significance at FDR < 0.01 and |log2(fold change)| ≥ 1 for identification of differentially expressed genes DEGs.

2.7 Expression Analysis of Candidate Genes

The primer sequences used for amplification of candidate gene transcripts are listed in Supplementary Table S1. RT-qPCR was performed using the ABI7500 fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with a SYBR® Premix ExTaq™ Kit (Takara, Dalian, China). The P. ternata ribosomal 18S RNA gene was evaluated as an internal control for normalization of gene expression levels. Three biological replicates and three technical replicates were analyzed for each gene and sample. The 2−ΔΔCT method was used to calculate the relative gene expression [32].

For in vitro tissue culture, each treatment comprised 30 explants (n = 30) and three biological replicates. The data are presented as mean ± SD values. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to test the significance of differences between various treatments using SPSS Version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Duncan’s multiple range test was used for post-hoc comparisons to control the family-wise error rate (FWER) at α = 0.05. The assumptions of normality and homogeneity of the variance of the data were tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test and Levene’s test, respectively. No data transformations were needed as neither assumption was violated.

3.1 Enhanced In Vitro P. ternata Microtuber Proliferation

An in vitro microtuber induction system was established in P. ternata within 60 d, using tender petioles as starting culture materials (Fig. 1A,B). Both ends of the petioles began to expand one week into liquid culture, and tuber-like tissues formed by day 15. Thereafter, the tissues grew quickly, with the biomass having increased by 6-, 9-, and 27-fold at days 30, 45, and 60, respectively, compared to the biomass at day 15 (Fig. 1C). Microtuber formation began at approximately day 30, and the microtuber number reached approximately 17 per explant after another 30 d of culture (Fig. 1D). SA application did not affect microtuber initiation, as indicated by both the biomass and number of microtubers yielded (Fig. 1C,D). This system supports the efficient induction and proliferation of P. ternata microtubers in vitro whether or not SA is used.

Figure 1: Establishment of a microtuber induction system with a high proliferation rate. (A), Induction of in vitro microtubers by shaking petioles in 50 mL of liquid Murashige and Skoog medium (per flask) containing 0.5 mg·L−1 6-benzylaminopurine, 0.5 mg·L−1 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, and 1.0 mg·L−1 indole-3-acetic acid. Each flask was shaken on a reciprocating shaker at 100 r·min−1 under a 10-h photoperiod with irradiance of 35 μmol photons m−2s−1 at 23 ± 1°C. (B), Magnified presentation of cultures corresponding to the time-points shown in (A). (C), Fresh weight of each petiole explant with or without SA elicitation at each time-point. (D), The numbers of microtubers with or without SA elicitation recorded at each time-point. Different lowercase letters above bars indicate a significant difference among the treatments based on one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05).

3.2 SA Elicited Alkaloid Accumulation and Boosted Cytotoxic Activities

Since SA application did not affect the initiation or growth of in vitro P. ternata tubers, whether it regulates alkaloid accumulation during tuber growth was next investigated, with field-grown tubers utilized for comparison. The in vitro induced microtubers and field-grown tubers had similar appearances, through their surface colors differed (Fig. 2A). The total alkaloid content of control in vitro microtubers was 0.09 mg·g−1 DW, lower than that of field-grown tubers (p < 0.05). However, when 100 μM SA was added to elicit alkaloid production, the total alkaloid content increased by 2.2 fold, such that it was not significantly different from that of field-grown tubers (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2B). HPLC analysis indicated that the ephedrine content of SA-elicited microtubers (0.051 mg·g−1 DW) was significantly higher than that of non-elicited microtubers (0.029 mg·g−1 DW) (p < 0.05) but comparable to that of field-grown tubers (0.048 mg·g−1 DW) (p > 0.05) (Fig. 2C). The follow-up dose–response experiment confirmed that 100 μM SA was the optimal concentration for alkaloid induction, and the maximum alkaloid accumulation was observed on day 15 of elicitation (Supplementary Table S2), which is consistent with previous findings [12].

The cytotoxicity assay showed an effective inhibition of SUM159 cells challenged with P. ternata tuber extracts (Fig. 2D). The viability of treated SUM159 cells showed a pattern that corresponded well with the alkaloid content of the extracts (Fig. 2E), as indicated by a comparison with the positive control of doxorubicin hydrochloride treatment. For the 5 μg·mL−1 extracts, no difference in cell viability was observed among the three extract sources (p > 0.05). However, when higher extract concentrations (25–100 μg·mL−1) were applied, extracts from SA-elicited in vitro microtubers induced a stronger reduction of cell viability, comparable to that induced by extracts from field-grown tubers (p > 0.05), but greater than that of extracts from in vitro microtubers cultured without SA elicitation (p < 0.05). Seventy-percent ethanol (the extraction solvent) was used as a negative control, with the same volume as the maximum extract concentration (100 μg·mL−1), and no cytotoxicity was observed (cell viability > 95%).

The mean IC50 of SA-elicited microtuber extract against SUM159 cells was 37.5 μg·mL−1 (95% CI, 33.6–39.8 μg·mL−1), comparable to that of field-grown tuber extract (mean IC50 = 36.4 μg·mL−1; 95% CI, 34.1–39.0 μg·mL−1), and lower than that of non-elicited microtuber extract (mean IC50 = 50.6 μg·mL−1; 95% CI, 46.5–54.6 μg·mL−1). The IC50 value for normal MCF-10A breast epithelial cells was 236.3 μg·mL−1 (Fig. 2F), yielding a selectivity index (SI) of 6.3. Thus, the total alkaloids from SA-elicited microtubers had substantial selectivity for tumor cells over normal cells, supporting their potential as a lead compound for antitumor drug development.

Thus, in vitro induction of microtubers, together with SA elicitation, can be used to produce P. ternata materials similar to field-grown tubers in terms of their key bioactive compounds.

Figure 2: Total alkaloids and cytotoxicity of in vitro induced microtubers and field-grown tubers of Pinellia ternata. (A), Images of in vitro induced and field-grown tubers before and after drying. (B), Total alkaloids in dried tubers (mg·g−1 DW). (C), Ephedrine content in dried tubers (mg·g−1 DW), in vitro microtubers were elicited with 100 μM SA or maintained in control conditions for 15 days. (D), Images of SUM159 cells captured at 42 h after incubation; scale bar, 50 μm. (E), Cell viability of SUM159 cells at 42 h after the addition of extracts of various concentrations, with blank and solvent ethanol used as negative controls and doxorubicin hydrochloride used as a positive control. Data are shown as mean ± SD values (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the treatments for each concentration based on one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05). (F), Cell viability of normal MCF-10A breast epithelial cells at 42 h after the addition of SA-elicited in vitro tuber extracts of various concentrations, with blank and solvent ethanol treatments again used as negative controls and doxorubicin hydrochloride treatment again used as a positive control. Data are shown as mean ± SD values (n = 3). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the treatments for each concentration based on one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05).

3.3 De Novo Assembly of Transcriptome and Identification of DEGs

To identify candidate genes involved in alkaloid accumulation that were promoted with SA, the transcriptomes of in vitro microtubers at different time-points were analyzed. The total reads for each sample ranged between 29,047,350 and 32,163,270, and the total bases ranged between 4,357,102,500 and 4,856,653,770 (Table S3). A total of 44.40 Gb clean reads were obtained after adaptor removal, filtering, and quality control of the raw reads. The Q20 value was >90% across all samples, while the GC percentage was 51.52%. After splicing raw reads and removing short contigs (<200 bp), in total, 150,110 transcripts, including 78,576 unigenes, were obtained, with N50 = 1104 bp for transcripts and N50 = 1082 bp for unigenes, respectively. The unigene distribution is shown in Fig. S1. The high-quality transcriptome data were thus found to satisfy the requirements for subsequent analyses. The clean data were then annotated by blasting them against six public databases: Blast-hit, Pfam, GO, eggnog, TmHMM, and SignalP (Table S4). Among the 78,576 transcripts, 45,316 were annotated in total, accounting for 57.67% of all assembled transcripts.

Compared with the control (T0), 1879, 3516, 1584, and 1368 DEGs were identified in SA-elicited in vitro microtubers at days 5, 10, 15, and 20, respectively. GO analysis is used to categorize genes according to three main classifications: biological process, cellular component, and molecular function (Fig. 3). Among biological processes, the most common annotations of DEGs included biosynthetic process, nitrogenous compound metabolism, and stress response. Among cellular components, the DEG annotations were mainly concentrated within cell, intracellular, and organelle. Among molecular functions, the major classifications of DEG annotations included ion binding, DNA binding, and oxidoreductase activity. Thus, these DEGs were determined to be involved in cell growth and secondary metabolism. In particular, the DEGs involved in nitrogenous compound metabolism are likely to play key roles in alkaloid accumulation, as alkaloids are nitrogen-containing compounds.

Figure 3: Gene Ontology classification of unigenes.

In the KEGG analysis, a total of 614 unigenes were annotated to 31 KEGG pathways. Of them, 116 unigenes are involved in carbohydrate metabolism, and 89 are involved in signal transduction. Other annotated unigenes were determined to be mainly concentrated in lipid metabolism, global and overview maps, and amino acid metabolism. Additionally, 26 differentially expressed genes were found to be enriched for metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides annotation, 33 enriched for biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites annotation, and 41 enriched for endocrine system annotation (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Metabolic pathways of differentially expressed genes.

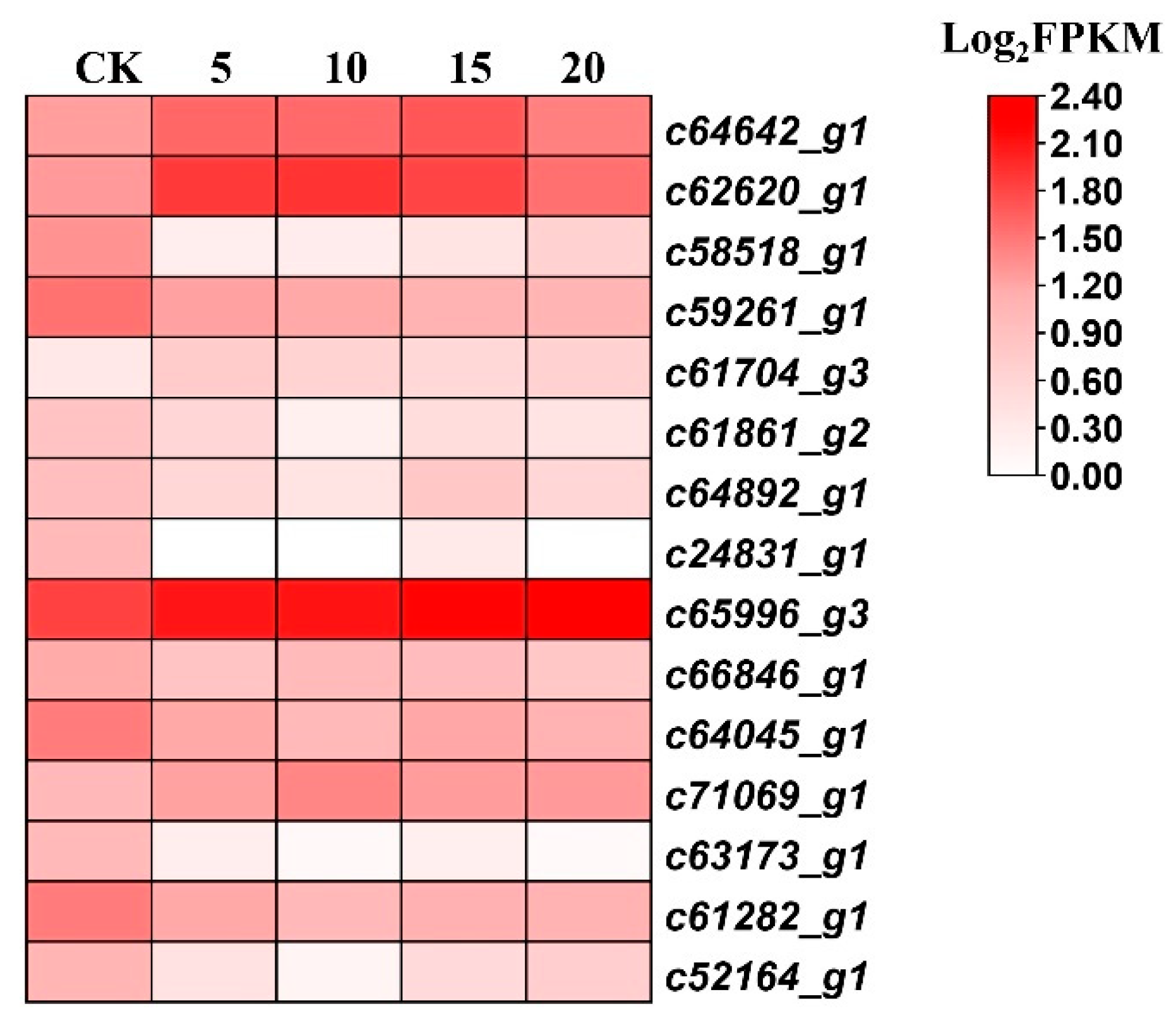

3.4 Identification of DEGs Associated with Alkaloid Biosynthesis

To identify the specific genes associated with alkaloid biosynthesis in P. ternata treated with SA, three KEGG pathways, i.e., the tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloid (map 00960), isoquinoline alkaloid (map 00950), and indole (map 00901) pathways, were analyzed. Six and twelve DEGs were annotated to the tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloid pathway, and isoquinoline alkaloid pathway, respectively (Table S5 and Table S6; Fig. 5). However, no DEGs were observed to have annotations corresponding to the indole pathway.

In the tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloid pathway, the DEGs were annotated as encoding spermidine synthase (EC: 2.5.1.44, 1 gene), hyoscyamine (6S)-dioxygenase (EC: 1.14.11.11, 1 gene), lysine decarboxylase (EC: 4.1.1.18, 2 genes), and tyrosine transaminase (EC: 2.6.1.5, 2 genes). The spermidine synthase gene (c64642_g1) was upregulated by over two fold throughout all time-points assayed. The hyoscyamine (6S)-dioxygenase gene (c62620_g1) was induced by 4.2, 4.5, 3.6, and 1.9 fold at days 5, 10, 15, and 20, respectively, while two tyrosine transaminase genes (c63173_g1 and c61282_g1) were both downregulated across all time points.

Among DEGs annotated to the isoquinoline alkaloid pathway included genes that encode catechol oxidase (EC: 1.10.3.1, 3 genes), monoamine oxidase (EC: 1.4.3.4, 1 gene), N-methylcoclaurine 3′-hydroxylase (EC: 1.14.14.102, 1 gene), tyrosine-dopa oxidase (EC: 1.14.18.1, 1 gene), (S)-tetrahydroprotoberberine N-methyltransferase (EC: 2.1.1.122, 1 gene), and aspartate transaminase (EC: 2.6.1.1, 1 gene). The genes encoding catechol oxidase (c61704_g3), monoamine oxidase (c65996_g3), and aspartate transaminase (c71069_g1) were significantly upregulated throughout all time points, while the other DEGs were consistently downregulated.

Figure 5: Heatmap of the expression profile for differentially expressed genes (DEGs) involved in the alkaloid biosynthesis response pathway. c64642_g1, spermidine synthase; c62620_g1, hyoscyamine (6S)-dioxygenase; c58518_g1, lysine decarboxylase; c59261_g1, lysine decarboxylase; c61704_g3, catechol oxidase; c61861_g2, catechol oxidase; c64892_g1, catechol oxidase; c24831_g1, reticuline oxidase; c65996_g3, monoamine oxidase; c66846_g1, N-methylcoclaurine 3′-hydroxylase; c64045_g1, (S)-tetrahydroprotoberberine N-methyltransferase; c71069_g1, aspartate transaminase, c63713_g1, tyrosine transaminase; c61282_g1, tyrosine transaminase; c52164_g1, (S)-norcoclaurine synthase; FPKM, fragments per kb per million mapped reads.

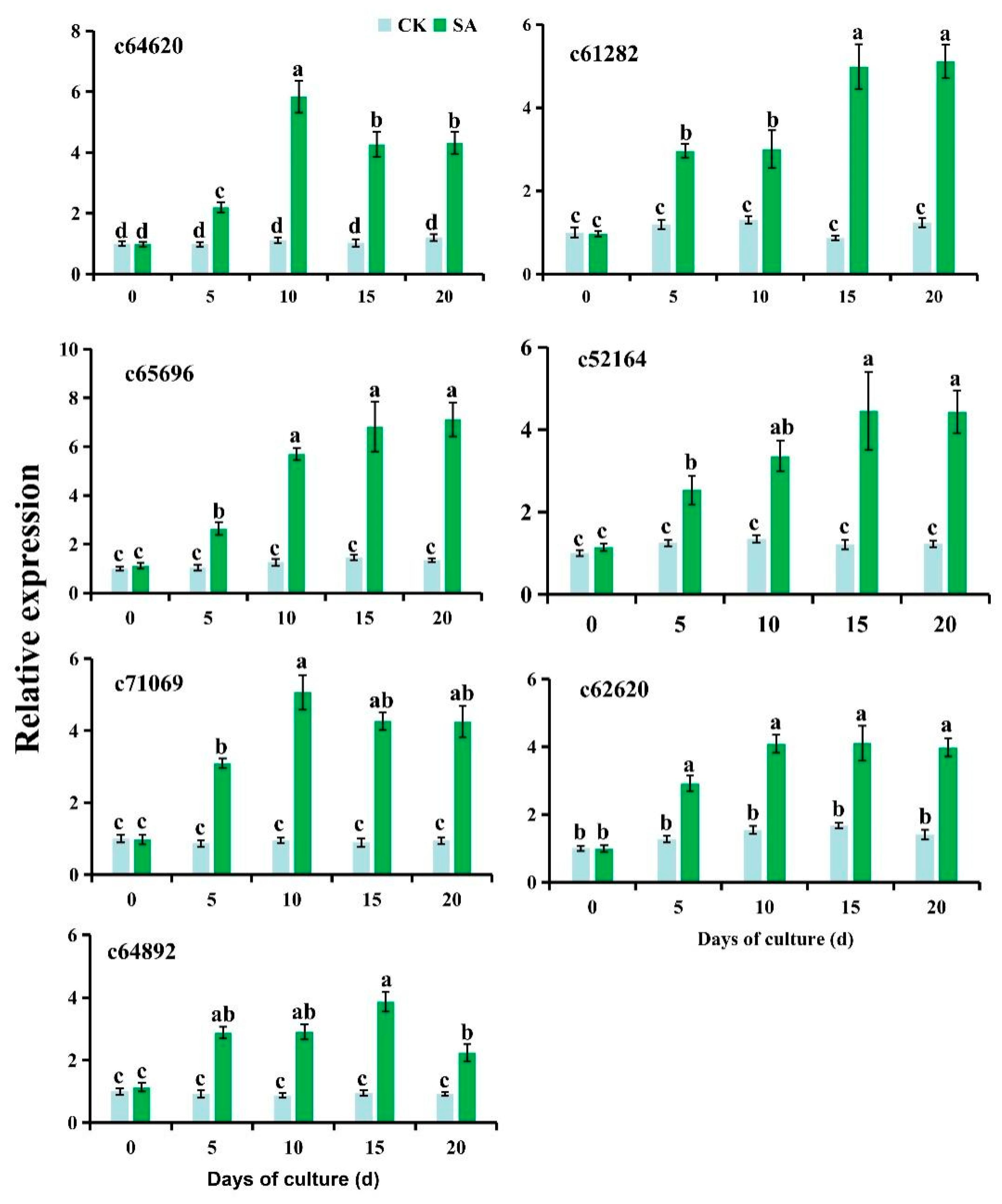

As a follow-up to the transcriptomic analysis detailed above, the genes involved in the tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloid pathway (ko00960) and the isoquinoline alkaloid pathway (ko00950) were quantified via RT-qPCR (Fig. 6). All seven genes were upregulated throughout the whole SA treatment experiment (p < 0.05), but their expression levels did not change significantly over the 20 days of culture without SA, exhibiting strong consistency with transcriptomic profiles. Thus, the RT-qPCR results supported the reliability of the transcriptomic data.

Figure 6: RT-qPCR results of differentially expressed genes involved in alkaloid biosynthesis. c64642_g1, spermidine synthase; c61282_g1, tyrosine transaminase; c65996_g3, monoamine oxidase; c71069_g1, aspartate transaminase; c64892_g1, catechol oxidase; c62620_g1, hyoscyamine (6S)-dioxygenase; c52164_g1, (S)-norcoclaurine synthase. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the treatments for each gene based on one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05).

An efficient in vitro microtuber induction system for P. ternata was established via liquid culture using tender petiole segments as explants, achieving a high microtuber proliferation rate. Under SA elicitation, the in vitro P. ternata microtubers were induced to be equivalent to similarly sized field-grown tubers in terms of their key bioactive compounds, as indicated by both alkaloid measurement and cytotoxicity analysis. Additionally, transcriptomic analysis revealed the genes involved in SA response and alkaloid biosynthesis.

In vitro induction of P. ternata microtubers is a potential approach to resolving the problems of both its currently shrinking cultivation acreage and the expanding gap between its supply and demand. In recent years, induction techniques and quality evaluation of in vitro P. ternata microtubers have been studied [12,19,21,22]. These studies have reported that in vitro induced microtubers can indeed accumulate alkaloids effectively. However, the proliferation rates of the previously reported induction systems are usually lower, with an explant producing only one or several microtubers. When solely MS medium without plant growth regulators was used to induce microtubers, P. ternata plantlets can be readily generated [12]. However, plantlet growth is not expected when inducing microtubers. In the present study, 0.5 mg·L−1 BAP, 0.5 mg·L−1 2,4-D, and 1.0 mg·L−1 IAA were added to the liquid culture medium; multiple microtubers were successfully induced under this treatment, and plantlet growth was successfully inhibited. The mass propagation of microtubers can thus be achieved within 60 d, but the total alkaloid content was lower than that of similarly sized field-grown tubers. Therefore, using an elicitor to enhance alkaloid content is necessary. SA is commonly used for alkaloid induction [25,33,34], though it is not effective for all plant species [35]. Based on our previous results [12], 100 μM SA was incorporated to elicit the accumulation of alkaloids, and the content of total alkaloids of in vitro P. ternata microtubers was thus increased to a level comparable to that of field-grown tubers. To evaluate the efficacy of in vitro P. ternata microtubers, a cytotoxicity assay was also performed with the commonly used triple-negative breast cancer cell line SUM159, a highly metastatic line [36]. As anticipated, SA-elicited microtuber extracts showed efficient inhibition against breast cancer cells, equivalent to that of the field-grown tubers.

To further reveal how SA application can promote alkaloid accumulation, a comparative transcriptomic analysis was conducted. Compared with the control in vitro microtubers, over 1000 DEGs were observed at each time-point under SA elicitation, with 3516 DEGs at day 10 of treatment in particular. As ephedrine has been known to accumulate within in vitro microtubers under SA elicitation [12], DEGs involved in the biosynthesis of other alkaloids were investigated. However, among the three common alkaloid biosynthesis pathways, no DEGs were mapped to the indole alkaloid pathway (00901). This supports the results of Guo et al. [37], who used exogenous brassinolide to induce alkaloid accumulation in P. ternata. The present results suggest that P. ternata indole alkaloid biosynthesis specifically does not respond to SA treatment.

The expression of a series of genes was found to be associated with the tropane, piperidine, and pyridine alkaloid pathway and the isoquinoline alkaloid pathway. Spermidine synthase (SPDS) catalyzes the conversion of putrescine to spermidine, further generating spermidine alkaloids through the action of decarboxylated S-adenosylmethionine (dc-SAM), a universal cofactor of aminopropyltransferases, as a donor of the aminopropyl moiety [38,39]. In the present study, the expression of the gene encoding spermidine synthase (c64642_g1) was significantly induced by SA, suggesting that SA may elicit the accumulation of spermidine alkaloids. Hyoscyamine (6S)-dioxygenase is a key enzyme catalyzing tropane alkaloid biosynthesis [40]. The hyoscyamine (6S)-dioxygenase gene (c62620_g1) exhibited over 5-fold induction by SA throughout the whole elicitation treatment, suggesting that the protein encoded by this gene plays a key role in alkaloid accumulation in P. ternata in vitro microtubers treated with SA. However, the DEGs encoding lysine decarboxylase (c58518_g1 and c59261_g1) and tyrosine transaminase (c63173_g1 and c61282_g1) were all downregulated by SA treatment. Lysine decarboxylase catalyzes Lys decarboxylation to generate cadaverine, the first step in quinolizidine alkaloid biosynthesis [41,42]. Tyrosine transaminase is a rate-limiting enzyme in the tyrosine metabolism pathway [43]. The downregulation of genes encoding these two enzymes implies that SA-elicited alkaloid synthesis is not attributable to lysine and tyrosine metabolism in the tropane alkaloid pathway. For isoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis, the genes encoding catechol oxidase (c61704_g3), monoamine oxidase (c65996_g3), and aspartate transaminase (c71069_g1) were significantly induced by SA treatment. Catechol oxidase, monoamine oxidase, and aspartate transaminase are three crucial enzymes in the isoquinoline alkaloid pathway [44,45,46]. The present results suggest that these three genes may be involved in the alkaloid accumulation of in vitro P. ternata microtubers treated with SA. As shown in Table S7, the current study differs from previous research [12,37,47] in that it integrated a plant growth regulator-optimized microtuber induction system, component-level chemical validation, time-resolved transcriptomics, and comprehensive cytotoxicity assessment, which strengthens the practical application value of SA-elicited microtubers.

For medicinal plants, such tissue culture systems must be scaled up to the commercial level for effective production, and their efficiency, in terms of both yield and bioactive compounds, also requires further validation [48,49,50]. Though the present microtuber induction system has been successfully developed and tested in P. ternata, whether it could be efficiently implemented in large-scale production should be evaluated in future research.

An induction system of in vitro P. ternata microtubers was developed and applied to generate microtubers, which, when subjected to SA treatment, were found to be equivalent to field-grown tubers in terms of both their total alkaloid content and their cytotoxicity to cancer cells. The SA-elicited alkaloid accumulation can be attributed to the altered expressions of genes encoding alkaloid synthases. These results may facilitate the production of high-quality P. ternata microtubers without field cultivation.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Key Project of Natural Science Research for Colleges and Universities in Anhui Province (2024AH051661; 2023AH050345) and Excellent Scientific Research and Innovation Team of University in Anhui Province (2022AH010029).

Author Contributions: Xiaoqing Jiang: methodology, validation, data curation. Pengchong Li: methodology, validation, data curation. Hongchuang Liu: methodology. Wenjie Dong: data curation. Wenjing Liu: data curation. Di Wu: data curation. Jianping Xue: supervision, funding acquisition. Fenglan Zhao: methodology, investigation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, writing—original draft preparation. Yongbo Duan: conceptualization, supervision, visualization, writing—original draft preparation, project administration, writing—reviewing and editing, funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data will be made available on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not Applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2026.074434/s1.

References

1. Mao R , He Z . Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Breit: a review of its germplasm resources, genetic diversity and active components. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020; 263: 113252. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2020.113252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang YB , Huang PQ , Du YY , Yin XB , Dong XX , Ni J . Analysis and consideration based on first classical prescriptions. Chin J Chin Mater Med. 2019; 44( 11): 2191– 6. doi:10.19540/j.cnki.cjcmm.20190115.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Li A , Cao LX . Research progress on the efficacy and compatibility of Pinellia ternata. Fron Med Sci Res. 2022; 4( 12): 28– 34. doi:10.25236/FMSR.2022.041205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bai J , Qi J , Yang L , Wang Z , Wang R , Shi Y . A comprehensive review on ethnopharmacological, phytochemical, pharmacological and toxicological evaluation, and quality control of Pinellia ternata (Thunb.) Breit. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022; 298: 115650. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2022.115650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang J , Morris-Natschke SL , Ma D , Shang XF , Yang CJ , Liu YQ , et al. Biologically active indolizidine alkaloids. Med Res Rev. 2021; 41( 2): 928– 60. doi:10.1002/med.21747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Chen C , Sun Y , Wang Z , Huang Z , Zou Y , Yang F , et al. Pinellia genus: a systematic review of active ingredients, pharmacological effects and action mechanism, toxicological evaluation, and multi-omics application. Gene. 2023; 870: 147426. doi:10.1016/j.gene.2023.147426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Huang K , Zhang P , Zhang Z , Youn JY , Wang C , Zhang H , et al. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) in the treatment of COVID-19 and other viral infections: efficacies and mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther. 2021; 225: 107843. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Huang YX , Li NF , Li CY , Zheng FP , Yao XY , Lin BH , et al. Clinical features and effectiveness of Chinese medicine in patients with COVID-19 from overseas: a retrospective study in Xiamen, China. Front Public Health. 2022; 10: 1038017. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.1038017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ng CWW , Touyon L , Bordoloi S . Influence of biochar on improving hydrological and nutrient status of two decomposed soils for yield of medicinal plant—Pinellia ternata. J Hydrol Hydromech. 2023; 71( 2): 156– 68. doi:10.2478/johh-2023-0008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang J , Tan XH . Research progress on Pinellia ternata. Chin J Inf TCM. 2010; 5: 104– 6. [Google Scholar]

11. Duan YB , Lu F , Cui TT , Zhao FL , Teng JT , Sheng W , et al. Effects of abiotic elicitors MeJA and SA on alkaloids accumulation and related enzymes metabolism in Pinellia ternata suspension cell cultures. Chin J Inf TCM. 2017; 24( 1): 87– 90. [Google Scholar]

12. Duan Y , Zhang H , Meng X , Huang M , Zhang Z , Huang C , et al. Accumulation of salicylic acid-elicited alkaloid compounds in in vitro cultured Pinellia ternata microtubers and expression profiling of genes associated with benzoic acid-derived alkaloid biosynthesis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2019; 139( 2): 317– 25. doi:10.1007/s11240-019-01685-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Eguchi T , Tanaka H , Yoshida S , Matsuoka K . Temperature effects on the yield and quality of the medicinal plant Pinellia ternata Breit. Environ Control Biol. 2019; 57( 3): 83– 5. doi:10.2525/ecb.57.83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Juneidi S , Gao Z , Yin H , Makunga NP , Chen W , Hu S , et al. Breaking the summer dormancy of Pinellia ternata by introducing a heat tolerance receptor-like kinase ERECTA gene. Front Plant Sci. 2020; 11: 780. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.00780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ma G , Zhang M , Xu J , Zhou W , Cao L . Transcriptomic analysis of short-term heat stress response in Pinellia ternata provided novel insights into the improved thermotolerance by spermidine and melatonin. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020; 202: 110877. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang H , Zhang Z , Xiong Y , Shi J , Chen C , Pan Y , et al. Stearic acid desaturase gene negatively regulates the thermotolerance of Pinellia ternata by modifying the saturated levels of fatty acids. Ind Crops Prod. 2021; 166: 113490. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Liu CJ , Shi LR , Yang XP , Zhang J , Zhu HD . Development status and prospect of mechanized Pinellia harvesting. For Mach Woodwork Equip. 2022; 50( 5): 9– 13. doi:10.13279/j.cnki.fmwe.2022.0078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Pandey H , Misra V , Sharma A , Chatterjee B , Sutradhar M , Kumar R , et al. Interventions of plant tissue culture techniques and genome editing in medicinally important spice crops. Med Plant Biol. 2025; 4: e023. doi:10.48130/mpb-0025-0019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Liu Y , Liang Z , Liu J . Use of protocorm-like bodies for studying alkaloid metabolism in Pinellia ternata. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2010; 100( 1): 83– 9. doi:10.1007/s11240-009-9622-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Liu Y , Liang Z , Zhang Y . Induction and in vitro alkaloid yield of calluses and protocorm-like bodies (PLBs) from Pinellia ternata. Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2010; 46( 3): 239– 45. doi:10.1007/s11627-009-9268-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Jie EY , Ryu YB , Choi SA , Ahn MS , Liu JR , Min SR , et al. Mass propagation of microtubers from suspension cultures of Pinellia ternata cells and quantitative analysis of succinic acid in Pinellia tubers. Plant Biotechnol Rep. 2015; 9( 5): 331– 8. doi:10.1007/s11816-015-0369-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kim YG , Komakech R , Eun C , Youn L , Kyoung L , Hyun K , et al. Mass production of Pinellia ternata multiple egg-shaped micro-tubers (MESMT) through optimized growth conditions for use in ethnomedicine. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2020; 140( 1): 173– 84. doi:10.1007/s11240-019-01720-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Tang D , Yan R , Sun Y , Kai G , Chen K , Li J . Material basis, effect, and mechanism of ethanol extract of Pinellia ternata tubers on oxidative stress-induced cell senescence. Phytomedicine. 2020; 77: 153275. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Li A , Sun X , Liu L . Action of salicylic acid on plant growth. Front Plant Sci. 2022; 13: 878076. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.878076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kaya C , Ugurlar F , Ashraf M , Ahmad P . Salicylic acid interacts with other plant growth regulators and signal molecules in response to stressful environments in plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2023; 196: 431– 43. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2023.02.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Murashige T , Skoog F . A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962; 15( 3): 473– 97. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Meng X , Mu F , Zhang Z , Wu X , Gao T , Zhao F , et al. Cytotoxic, clonal fidelity, and antioxidant evaluation of in vitro propagated Vitex negundo var. cannabifolia. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2021; 146( 3): 473– 82. doi:10.1007/s11240-021-02080-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Luo H , Zhou Z , Huang S , Ma M , Zhao M , Tang L , et al. CHFR regulates chemoresistance in triple-negative breast cancer through destabilizing ZEB1. Cell Death Dis. 2021; 12( 9): 820. doi:10.1038/s41419-021-04114-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Haas BJ , Papanicolaou A , Yassour M , Grabherr M , Blood PD , Bowden J , et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat Protoc. 2013; 8( 8): 1494– 512. doi:10.1038/nprot.2013.084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Pertea G , Huang X , Liang F , Antonescu V , Sultana R , Karamycheva S , et al. TIGR gene indices clustering tools (TGICL): a software system for fast clustering of large EST datasets. Bioinformatics. 2003; 19( 5): 651– 2. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhao F , Sun M , Zhang W , Jiang C , Teng J , Sheng W , et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis of roots, stems and leaves of Isodon amethystoides reveals candidate genes involved in Wangzaozins biosynthesis. BMC Plant Biol. 2018; 18( 1): 272. doi:10.1186/s12870-018-1505-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Pfaffl MW . A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001; 29( 9): e45. doi:10.1093/nar/29.9.e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Bastías DA , Alejandra Martínez-Ghersa M , Newman JA , Card SD , Mace WJ , Gundel PE . The plant hormone salicylic acid interacts with the mechanism of anti-herbivory conferred by fungal endophytes in grasses. Plant Cell Environ. 2018; 41( 2): 395– 405. doi:10.1111/pce.13102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Naeini MS , Naghavi MR , Bihamta MR , Sabokdast M , Salehi M . Production of some benzylisoquinoline alkaloids in Papaver armeniacum L. hairy root cultures elicited with salicylic acid and methyl jasmonate. Vitro Cell Dev Biol Plant. 2021; 57( 2): 261– 71. doi:10.1007/s11627-020-10123-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang M , Zhao Y , Yang C , Shi H . The combination of transcriptome and metabolome reveals the molecular mechanism by which topping and salicylic acid treatment affect the synthesis of alkaloids in Nicotiana tabacum L. Life. 2022; 15( 1): 147– 59. doi:10.1080/26895293.2022.2025915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Bourang S , Jahanbakhsh Godehkahriz S , Noruzpour M , Asghari Zakaria R , Granados-Principal S . Anticancer properties of copolymer nanoparticles loaded with Foeniculum vulgare derivatives in Hs578T and SUM159 cancer cell lines. Cancer Nanotechnol. 2025; 16( 1): 17. doi:10.1186/s12645-025-00318-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Guo C , Chen Y , Wu D , Du Y , Wang M , Liu C , et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals an essential role of exogenous brassinolide on the alkaloid biosynthesis pathway in Pinellia ternata. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23( 18): 10898. doi:10.3390/ijms231810898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Chavez BG , Srinivasan P , Glockzin K , Kim N , Montero Estrada O , Jirschitzka J , et al. Elucidation of tropane alkaloid biosynthesis in Erythroxylum coca using a microbial pathway discovery platform. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022; 119( 49): e2215372119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2215372119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Shi YJ , Zhang J , Wang YW , Ding K , Yan Y , Xia CY , et al. The untapped potential of spermidine alkaloids: sources, structures, bioactivities and syntheses. Eur J Med Chem. 2022; 240: 114600. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. De la Cruz IM , Hallab A , Olivares Pinto U , Tapia López R , Velázquez Márquez S , Piñero D , et al. Genomic signatures of the evolution of defence against its natural enemies in the poisonous and medicinal plant Datura stramonium (Solanaceae). Sci Rep. 2021; 11( 1): 882. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79194-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Bunsupa S , Katayama K , Ikeura E , Oikawa A , Toyooka K , Saito K , et al. Lysine decarboxylase catalyzes the first step of quinolizidine alkaloid biosynthesis and coevolved with alkaloid production in Leguminosae. Plant Cell. 2012; 24( 3): 1202– 16. doi:10.1105/tpc.112.095885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Shimizu Y , Rai A , Okawa Y , Tomatsu H , Sato M , Kera K , et al. Metabolic diversification of nitrogen-containing metabolites by the expression of a heterologous lysine decarboxylase gene in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2019; 100( 3): 505– 21. doi:10.1111/tpj.14454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Zhong M , Zhang L , Yu H , Liao J , Jiang Y , Chai S , et al. Identification and characterization of a novel tyrosine aminotransferase gene (SmTAT3-2) promotes the biosynthesis of phenolic acids in Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024; 254( 2): 127858. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Plazas E , Hagenow S , Avila Murillo M , Stark H , Cuca LE . Isoquinoline alkaloids from the roots of Zanthoxylum rigidum as multi-target inhibitors of cholinesterase, monoamine oxidase A and Aβ1-42 aggregation. Bioorg Chem. 2020; 98: 103722. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2020.103722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Singh S , Pathak N , Fatima E , Negi AS . Plant isoquinoline alkaloids: advances in the chemistry and biology of berberine. Eur J Med Chem. 2021; 226: 113839. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Liao J , Wei X , Tao K , Deng G , Shu J , Qiao Q , et al. Phenoloxidases: catechol oxidase—the temporary employer and laccase—the rising star of vascular plants. Hortic Res. 2023; 10( 7): uhad102. doi:10.1093/hr/uhad102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Bo C , Su C , Teng J , Sheng W , Xue T , Zhu Y , et al. Transcriptome profiling reveals differential gene expression during the process of microtuber formation in Pinellia ternata. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24( 14): 11604. doi:10.3390/ijms241411604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Mahanta M , Gantait S . Trends in plant tissue culture and genetic improvement of gerbera. Hortic Plant J. 2025; 11( 3): 974– 88. doi:10.1016/j.hpj.2024.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Yi M , Hu S , Tian C , Chen B , Hu G , Liu Y , et al. Chlorine dioxide enhanced cuttage efficiency in chrysanthemum via accumulating tryptophan and derived auxin. Ind Crops Prod. 2024; 222: 119660. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.119660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Shi WJ , Wu Y , Zhang L . Decoding and designing: Promising routes to tailor-made herbs. Sci Tradit Chin Med. 2025; 3( 2): 194– 7. doi:10.1097/st9.0000000000000065 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools