Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Agro-Climatic Suitability of Purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.) under Abiotic Stress in Semiarid—Arid Zone in North America

1 Programa Institucional de Doctorado en Ciencias Agropecuarias y Forestales, Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Gómez Palacio, Durango, 35111, Mexico

2 Departamento de Agricultura y Ganadería, Universidad de Sonora, Blvd. Luis Encinas S/N Col, Centro, Hermosillo, Sonora, 83000, Mexico

3 Facultad de Agricultura y Zootecnia, Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango, Km 35 Carretera Gómez Palacio-Tlahualilo, Ejido Venecia, Gómez Palacio, Durango, 35111, Mexico

* Corresponding Author: José Luis García-Hernández. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2026, 95(1), 14 https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.075449

Received 01 November 2025; Accepted 22 December 2025; Issue published 30 January 2026

Abstract

To ensure the efficient use of resources, particularly in water-scarce arid and semi-arid regions where abiotic stress threatens food security, assessing soil and climate suitability for specific crops is crucial. Simultaneously, food production must align with sustainable development goals by minimizing negative environmental impacts. Therefore, establishing agro-climatic suitability using a spatiotemporal approach is essential. This involves three key steps: first, determining the climatically appropriate months based on the species’ requirements (temporal suitability), and second, establishing the soil suitability of specific plots (spatial suitability). Following this, quantifying crop evapotranspiration allows for optimized water use. This study used climatic and soil variables from diverse data sources to characterize the study area. Subsequently, suitability classes for Portulaca oleracea were determined based on existing literature. Our analysis concerning temporal suitability revealed that June and July are the optimal months for sowing this species in all of the municipalities. Spatially, approximately 30% of the agricultural land use of the study area exhibits a highly suitable class in most municipalities. Both dimensions, the temporal and the spatially, were validated through Chi square (χ2) Goodness-of-Fit test and the χ2 test of independence, respectively. Consequently, for a one-month production cycle during periods of high suitability, estimated evapotranspiration values are between 210 and 245 mm. In brief, the study area demonstrates favorable agro-climatic conditions for P. oleracea cultivation in specific months of the year according to parameters used, with potential in a large proportion of agricultural land and achievable water requirements.Keywords

Food security must adhere to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [1]. Therefore, food production systems should adopt more efficient agricultural practices for natural resource preservation. That could be interpreted from different perspectives, but the proposal here consists of producing food according to the agro-climatic characteristics of the agricultural production regions to maximize food production [2]. This idea becomes more pressing for arid and semi-arid areas, since they face greater challenges, i.e., droughts, warm temperatures, and soil degradation, while 44% of the world’s population’s food is produced in these climatic regions of the planet [3,4,5].

As a case study, this research is focused on North America, particularly in the municipalities of the “Comarca Lagunera” from Coahuila de Zaragoza and Durango, both North Central states of Mexico, which are characterized, according to the Aridity Index (AI), by arid (0.051–0.201) and semi-arid (0.201–0.501) ecosystems. This AI is derived from the ratio of precipitation to evapotranspiration. Arid and semi-arid classifications are determined by the predominance of evapotranspiration over precipitation [6]. These localities are known as the primary source of protein in the country due to forage, milk, and poultry production; for that, it is of national interest to increase the resilience of local agro-ecosystems and thereby reduce the uncertainty around the agri-food sector [7]. Therefore, reorienting the local production system is a priority for the municipalities in the aforementioned area, which are known for lacking practices aligned with the SDGs, such as unregulated aggregation of organic matter, deep water irrigation, and high levels of fertilizers and pesticides [8].

On the other hand, the current agricultural vocation is predominantly forage; these crops are expected to be affected in the coming decades due to climate change [7,8,9]. For example, the study area included in this research is expected to experience a decrease in agro-climatic suitability for the most relevant crops, such as maize, alfalfa, sorghum, oats, and cotton, according to the Global Agro-Ecological Zone (GAEZ) from FAO. For instance, the cotton crop is facing a decrease in its cultivation recently, from 78,000 ha−1 in 2019 to 6800 ha−1 in 2024 (SIAP). This information increases the necessity of projections for future scenarios. The GAEZ platform utilized an ENSEMBLE, which is a complex climate model created generated from individual models, to reduce uncertainty in projections. This information is available for the following Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs): SSP126, SSP370, and SSP585, and for the periods 2021–2040, 2041–2060, 2061–2080, and 2081–2100 [9,10].

Consequently, considering climate change scenarios, food and economic security are actually facing uncertainties, while the negative impact is prognosticated to be major due to increases in temperatures, pests, and water demand for crops. Therefore, the planning of the production system of arid and semi-arid regions is a must for the public and private sectors [5]. That requires exploration of alternative crops primarily, and, secondly, the utilization of these crops with agro-climatic suitability. Such an effort is necessary to reduce the uncertainty in the agri-food sector related to the climatic and soil requirements of selected species. Principally, tolerance for warm temperatures and slightly saline soils/water as limiting factors of the study area [6,8,11].

In respect to agro-climatic methodologies determination, there is not specific methodology; in reality, several approaches exist, but these lack a temporal perspective from a monthly examination view. Specifically, these methodologies do not take into account monthly climate variability, which affects crop suitability in this context, nor do they consider water requirements based on reference evapotranspiration [9,12]. Both previous points are critical in arid and semi-arid regions because two severe adverse conditions become worse: lower water availability and warm temperatures [6]. Methodologies commonly use temperature and precipitation, with temperature identified as the most important factor for agro-ecological zoning, accounting for 75% of the variance explained in a study conducted in Iran [13,14]. The regional context is of vital importance when assessing the limitations and suitability of crops. As a result, the climatic parameters utilized may vary. Additionally, indices derived from these parameters, such as temperature or precipitation, can be employed, including the Palmer Drought Severity Index or the AI [6,14,15].

For all of the above, it is a priority of our study to consider the most pressing challenges of the study area: water scarcity, groundwater with high salt concentration, warm temperatures, and poor soil fertility (i.e., slightly saline conditions); all of this points to challenges faced by farmers in arid and semiarid regions of Northern Mexico [8,16]. The environment in which P. oleracea (purslane) thrives is significant, as this plant is considered a xerophyte and halophyte, emerging as an alternative due to its tolerance to drought and salinity, which is facilitated by its C4-CAM metabolism [17]. Purslane is adapted to the climate and soil conditions of the region because it is native. This species has valuable nutraceutical components, such as omega-3, carotenoids, and betalains [18]; additionally, it has greater economic appeal than traditional crops. One of the reasons is that harvests for this species permit productions since 23 days after sowing during the spring-summer cycle, although its life cycle is completed in 50–65 days (from sowing until seed production) [17,18,19,20,21].

There is a knowledge gap regarding the specific agro-climatic context of Northern Mexico, particularly in the “Comarca Lagunera” region, which lacks a comprehensive assessment of P. oleracea’s temporal and spatial suitability, despite this species being native to the study area [19]. For that, this research aims to address this knowledge gap by utilizing bibliographic data and databases: (1) mapping the spatial distribution of agricultural suitability for its cultivation according to geodatabases, (2) determining the optimal sowing periods for P. oleracea in the region using meteorological information (temperatures) no older than 5 years, as the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) [15] recommends, and daily light integral (DLI), and (3) establishishing the water requirement of the crop in the vegetative development phenological stage (at 30 days after sowing) and considering the proportion covered by rainfall. By providing detailed information on the temporal, spatial, and water requirements of this species, this study seeks to offer farmers in Northern Mexico a viable and productive alternative crop option.

The study area comprised the La Laguna metropolitan area (also named Comarca Lagunera), a region in northern Mexico, specifically the municipalities of Francisco I. Madero (FIM), Matamoros (M), Torreón (T), Gómez Palacio (GP), and Lerdo (L). Furthermore, Tlahualilo de Zaragoza (TZ) and San Pedro de las Colonias (SP) were incorporated to account for regional spatial contiguity because in total, the municipalities selected make up approximately 70% of the agricultural land area of Irrigation District 017 [22].

These municipalities are characterized by arid and semi-arid climates with an annual average precipitation of 220 mm. They are situated at an average elevation of 1114 m above sea level (masl) [6]. Despite these conditions, the region boasts a substantial agricultural sector, with approximately 140,000 hectares under annual cultivation featuring calcareous and slightly saline soils. Irrigation is primarily sourced from dams and groundwater extraction, the latter being notably impacted by the presence of heavy metals, salts, and nitrates [8].

Additionally, a persistent drought is affecting the Lázaro Cárdenas and Francisco Zarco dams; the absence of rain has severely curtailed cultivation for the current year, 2025. This water scarcity underscores the urgent need to transition towards drought-salinity-tolerant crops with shorter production cycles than long-duration forages traditionally grown.

For spatial zoning, edaphic variables were collected from geospatial databases; in particular, pH and electrical conductivity (EC) [16,23]. Both datasets had a pixel size of 250 m, and the data was extracted in QGIS 3.34.0 using vector maps of the study area developed by INEGI [24]. It is noted that the edaphic parameters utilized were sourced from different monitoring periods. This approach was necessary due to data availability limitations. However, the data remains relevant as soil pH is considered a low-variability parameter over the short term, and regional salinity levels demonstrate long-term stability in the absence of major hydrological shifts, allowing both datasets to accurately reflect the representative edaphic conditions influencing P. oleracea suitability [16].

These variables were selected because previous studies conducted in the region indicated the importance of both variables in favoring the presence of wild P. oleracea (statistically significant) in the study region when using stepwise regression [19].

Subsequently, the soil suitability of the crop was determined specifically for the agricultural land use [25]. In this way, suitability classes were determined considering the pH and EC ranges reported in the literature. Using QGIS 3.34, reclassification per table was performed in original geodatabases: the highly suitable class received value 2, moderately suitable 1, and non-suitable 0 (Table 1).

Then, Eq. (1) was used in the raster calculator. Finally, the suitability map was generated with the corresponding classification, as mentioned in the last paragraph.

Monthly data on average maximum temperature, average temperature, and average minimum temperature for the period 2019–2023 were collected from municipal meteorological stations (Table 2) [27]. A short period was chosen in accordance with the “guide to climatological practices” established by WMO [15], which states that “the most recent 5 to 10 year period of record has as much predictive value as a 30-year record”, and the Agri-food and Fisheries Information Service (SIAP by its Spanish acronym) methodology [28]. Then, the monthly mean and standard error were quantified for the previously mentioned variables in Minitab (Version 19).

Table 2: Meteorological stations per municipality used in this study [27].

| Municipality | State | Geographical Coordinates | Station Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Francisco I.-Madero | Coahuila de Zaragoza | 26.4825° N −103.0352778° W | Acatita |

| Gomez Palacio | Durango | 25.81388889° N −103.5741667° W | C.B.T.A. 101 Gómez Palacio |

| Lerdo | Durango | 25.50555556° N −103.6538889° W | C.B.T.A. 047 Lerdo |

| Matamoros | Coahuila de Zaragoza | 25.52777778° N −103.2280556° W | Matamoros |

| San Pedro | Coahuila de Zaragoza | 25.75722222° N −102.9955556° W | San pedro |

| Tlahualilo | Durango | 26.14° N −103.7591667° W | Cartagena |

| Torreon | Coahuila de Zaragoza | 25.54222222° N −103.4691667° W | Presa coyote |

The radiation data were obtained with spatial resolution of around 1 km2 [29]. It was extracted using QGIS 3.34.0 through vector maps of the study area developed by INEGI [24]. Solar radiation was then converted to daily light integral (DLI) [30]. The mean monthly photoperiod reported for latitude 24° was used as a standard [31].

Reclassification of climatic variables used in this study was assigned following the same instructions as the Spatial Zoning methodology (Table 3).

Table 3: Classes of temporal suitability for P. oleracea with ranges for each class according to bibliographic data.

Consequently, the monthly mean and standard error of the DLI were calculated per municipality. Finally, classes were established based on the suitability of P. oleracea according to the requirements compiled in the literature.

2.4 Evapotranspiration of P. oleracea

With respect to monthly reference evapotranspiration (ETo), it was extracted from a geospatial database (with a pixel size of around 1 km2) via QGIS 3.34.0 using vector maps of the study area [24,35]. Subsequently, crop evapotranspiration (ETc) was calculated using ETo (per municipality for each month) and the crop coefficient (Kc) (Table 4), a dimensionless value that accounts for the combined influence of the specific crop characteristics, such as stem height, root length, leaves, or development stage, and the averaged effects of water evaporation from the soil [35,36,37].

For the quantification of evapotranspiration of P. oleracea per month for each municipality, it was necessary to determine a period according to the development phenological stage of the crop at 30 days after sowing. This study used a 30-day sowing and harvest cycle to make smooth estimations. Precipitation was obtained from CONAGUA meteorological stations. It was taken into account to determine the proportion of P. oleracea evapotranspiration covered by rainfed means [27]. This objective was achieved by estimating the percentage of evapotranspiration covered by precipitation per month for each municipality.

Table 4: Crop coefficient (Kc) of P. oleracea by assumed phases expressed in days according to FAO Guidelines [38].

| Kc Initial | Kc Mid | |

|---|---|---|

| 0.9 | 1.4 | |

| Days | 20 | 10 |

2.5 Model Validation for Spatial and Temporal Dimensions

Occurrence points of P. oleracea were obtained from GBIF for the country of Mexico [39]. Later, the points within the study area were extracted in QGIS 3.34.0 through vector maps of the study area developed by INEGI [24].

For spatial model validation, the Chi-Square (χ2) Goodness-of-Fit test was employed because it examines the conformity of a unidimensional observed frequency distribution, that is, the P. oleracea field occurrences, with the theoretical distribution, the spatial model’s prediction [40]. The analysis focused on the two most relevant categories, moderately suitable and highly suitable, due to the nonexistence of occurrence points in the non-suitable category.

For temporal model validation, the χ2 test of independence was utilized. This test is necessary to assess the relationship between two distinct categorical variables: the suitability classes (non-suitable, slightly, moderately, and highly suitable) and the season (spring, summer, and autumn-winter). This test determines if the distribution of suitability classes is dependent on the season [40]. To ensure the validity of the χ2 approximation, the months of autumn and winter were grouped into a single category (autumn-winter) due to low expected counts. The final analysis used a contingency table of three rows and four columns. Cramer’s V was performed for determination of strength of association [41].

3.1 Agro-Climatic Requirements of P. oleracea

Soil and climate requirements for P. oleracea were recompiled according to several studies (Table 5). From this information, the classes of soil and climatic requirements were selected, correspondingly for the spatial and temporal dimensions. As can be seen, this species tolerates conditions that could be stressful for other crops commonly used, i.e., warm temperatures and slightly saline conditions or more (>2 ds m−1) [17,20]. In this context, the farmers’ adoption of P. oleracea is promising under scenarios with increasing abiotic stress for plants; consequently, it’s important to construct food production systems for food security and national sovereignty [18].

Table 5: Agro-climatic requirements of P. oleracea from bibliographic data.

3.2 Spatial Suitability of P. oleracea

Slightly saline conditions prevail in the soils of the study area; the municipalities of San Pedro de las Colonias (SP), Matamoros (M), Lerdo (L), and Tlahualilo de Zaragoza (TZ) have 99% of the agricultural surface with salinity in the range of 2–4 ds m−1 for the year 2016. Meanwhile, Francisco I. Madero (FIM), Torreon (T), and Gomez Palacio (GP) contain 98% [16].

Additionally, the pH of the agricultural surface of the municipalities showed a homogeneous behavior (Table 6) [23]. Although pH values are distributed between 6.5 and 8.9 for the entire surface, the major proportion of agricultural surface is located between 8.1 and 8.5 for all of the municipalities.

Table 6: pH of agricultural surface expressed in proportion per municipality. Elaborated with data from WoSIS [23].

| Municipality | 7.7 (%) | 7.8 (%) | 7.9 (%) | 8 (%) | 8.1 (%) | 8.2 (%) | 8.3 (%) | 8.4 (%) | 8.5 (%) | 8.6 (%) | 8.7 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Pedro | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.19 | 1.76 | 6.88 | 20.09 | 42.41 | 24.38 | 4.08 | 0.18 | 0.02 |

| Torreón | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.34 | 3.77 | 21.90 | 50.07 | 19.81 | 3.77 | 0.34 | 0.00 |

| Matamoros | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 6.23 | 23.24 | 50.95 | 18.30 | 0.59 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Francisco I. Madero | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.63 | 5.10 | 17.21 | 38.39 | 30.16 | 8.26 | 0.18 | 0.00 |

| Tlahualilo | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 1.57 | 12.34 | 32.88 | 35.14 | 16.23 | 1.80 | 0.00 |

| Lerdo | 0.09 | 0.66 | 1.18 | 4.45 | 17.22 | 42.00 | 30.63 | 3.59 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Gómez Palacio | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.87 | 5.76 | 18.40 | 42.63 | 27.77 | 4.43 | 0.13 | 0.00 |

In depth, a pH of 8.3 presents the highest proportion of agricultural surface for SP, T, M, FIM, and GP soils, while a pH of 8.4 predominates in TZ, and a pH of 8.2 in L. The rest of the soils are mainly distributed between pH values of 8.2 and 8.4.

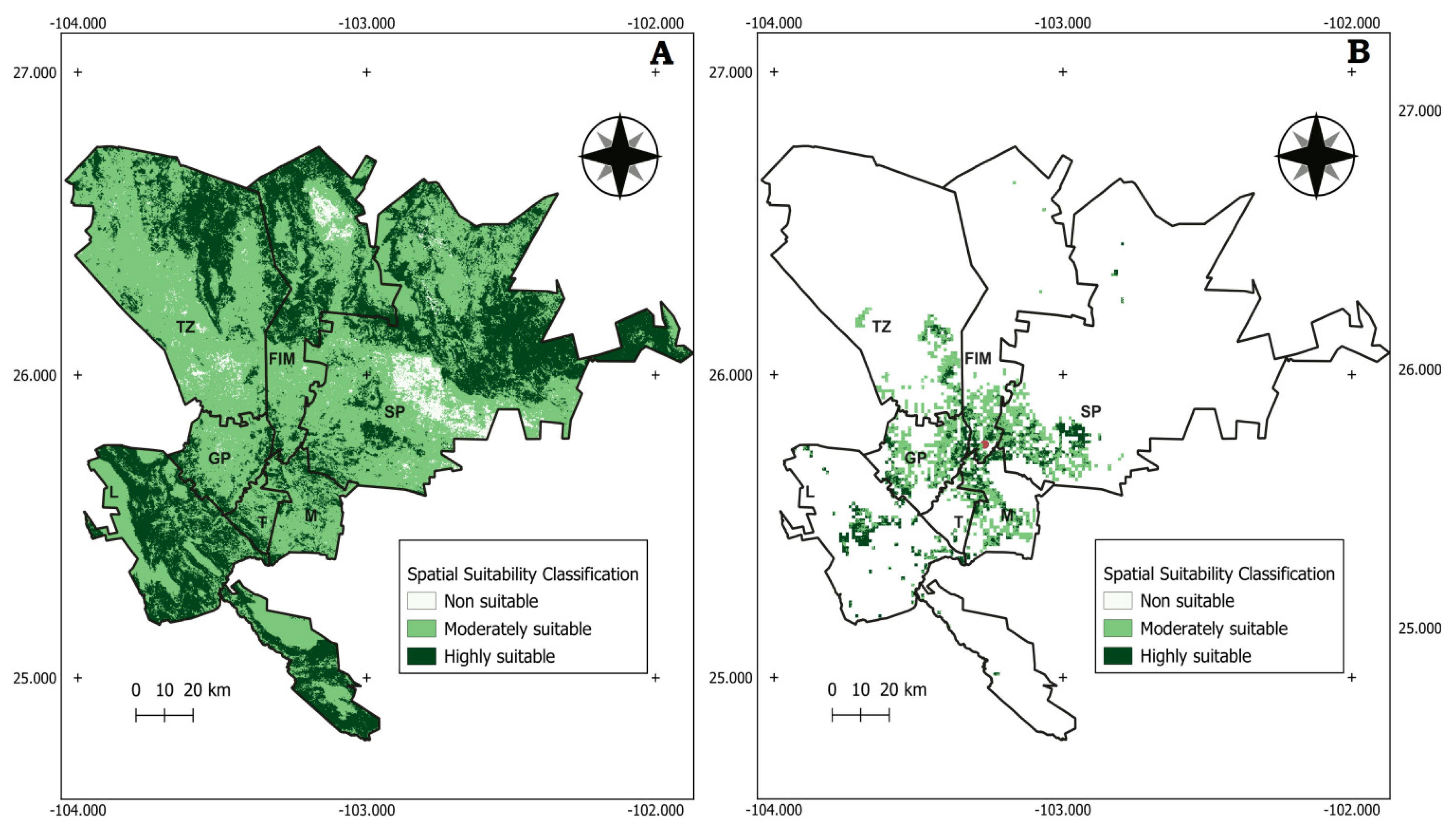

Based on the degree of salinity and pH of the soils, the spatial suitability was determined for all of the surface of the municipalities (Fig. 1A); but the relevant information indicates that the proportion of the agricultural land in the localities is mainly grouped in the highly and moderately suitable classes (Fig. 1B). Regarding the highly suitable class, GP contains 25%, L 64%, TZ 14%, FIM 24%, M 30%, T 27%, and SP 29%. In the moderately suitable category, GP has 74%, L 36%, TZ 84%, FIM 76%, M 69%, T 73%, and SP 71%. On the other hand, the non-suitable class reaches 2% in TZ, while GP and T present 1%, and the rest of the municipalities 0%.

The model validation was carried out through the Chi-Square (χ2) Goodness-of-Fit test, which indicated that the calculated χ2 was less than the critical value (1.0833 < 3.841); so, the null hypothesis was not rejected [40]. Therefore, the spatial dimension demonstrates a good fit, as the observed distribution of P. oleracea occurrences did not significantly deviate from the distribution predicted by the suitability map.

Figure 1: Edaphic suitability of P. oleracea in agricultural land use in the municipalities of the study area. (A) Entirely surface. (B). Agricultural land use. Maps generated from pH and salinity geodatabases [16,23]. Where FIM: Francisco I. Madero, GP: Gómez Palacio, L: Lerdo, M: Matamoros, SP: San Pedro, TZ: Tlahualilo, T: Torreón.

3.3 Temporal Suitability of P. oleracea

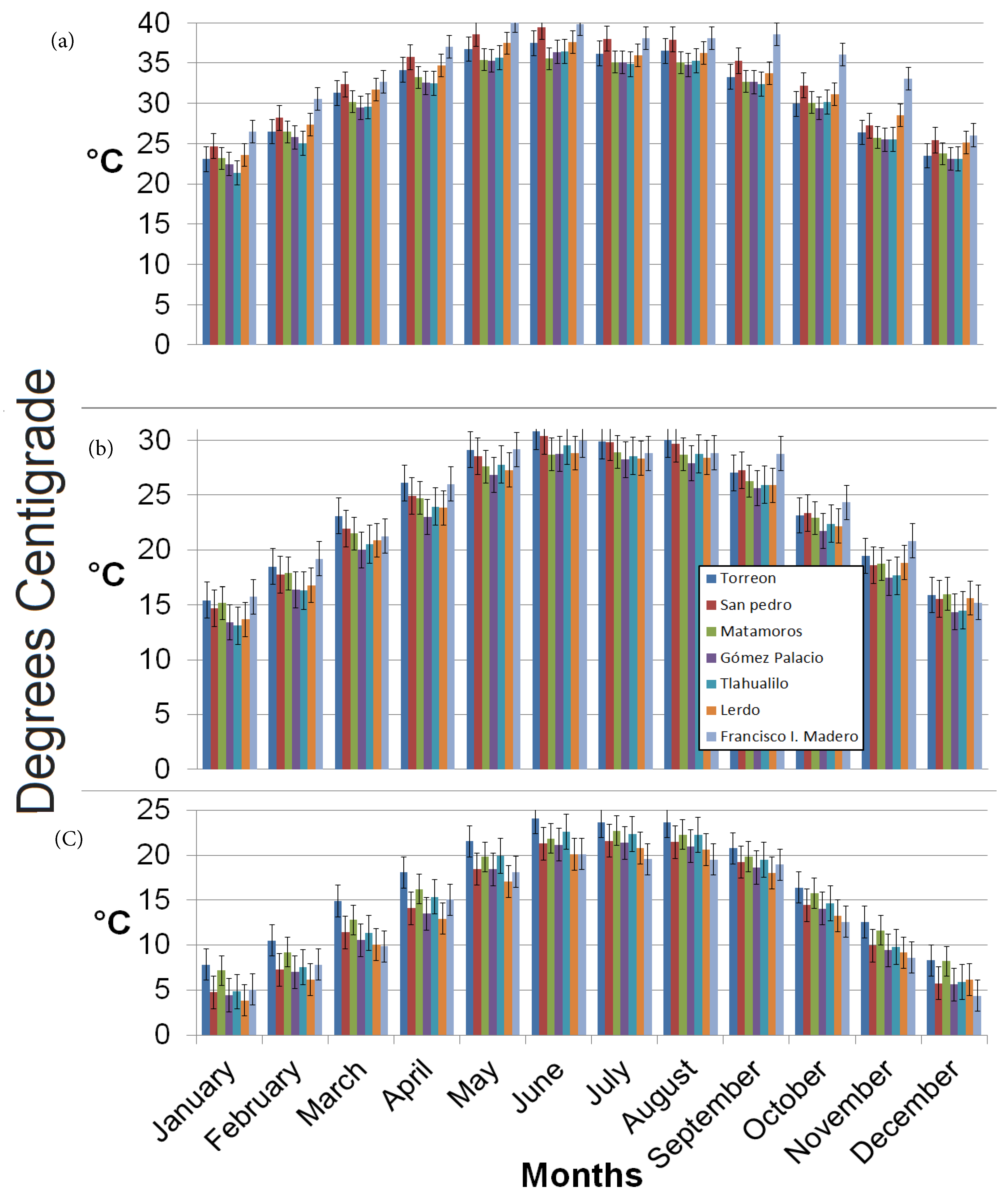

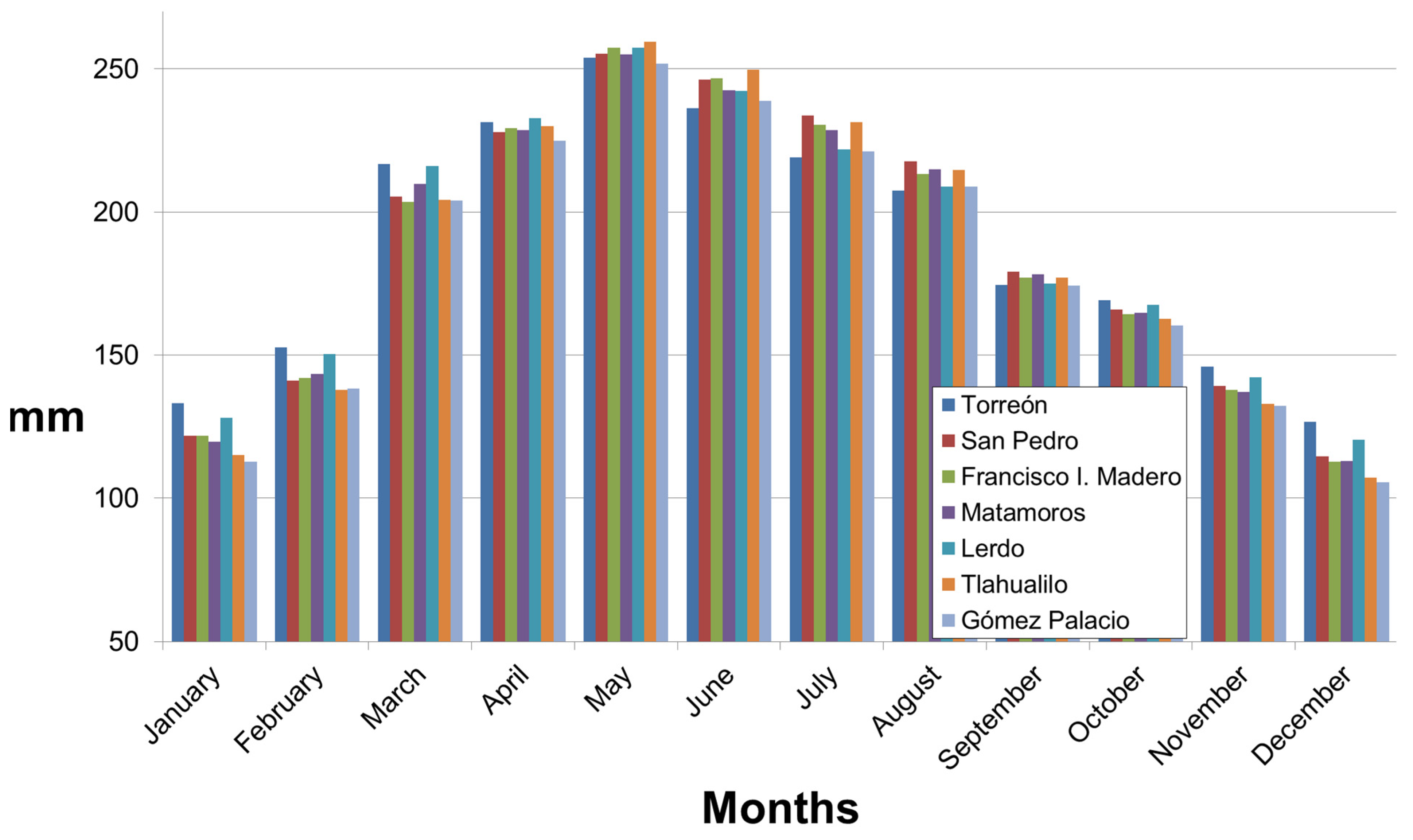

In Fig. 2 (a, b, and c correspondingly), we observe the behavior of the maximum average, average, and minimum average temperatures for the time period considered in the study. Winter oscillates within an average temperature of 15°C, while in the spring months, the average temperature is around 20°C and culminates closer to 30 with maximums near 40°C. Summer begins in the same way, which later drops the temperature to 26°C with maximums of 33°C, representing the period of agricultural production in the region.

Figure 2: Monthly mean temperatures for the period 2019–2023 per municipality. (a) maximum temperature. (b) mean temperature. (c) minimum temperature. The meteorological stations at CONAGUA provided the data [27].

To provide guidance on the stability of temperatures between the months used, it is important to observe the standard error, which allows interpretation of the variation [15]. Regarding the months that allow germination and development of the P. oleracea, either highly or moderately suitable according to temporal suitability, the monthly standard error is uniform, with most of the values <1.5°C.

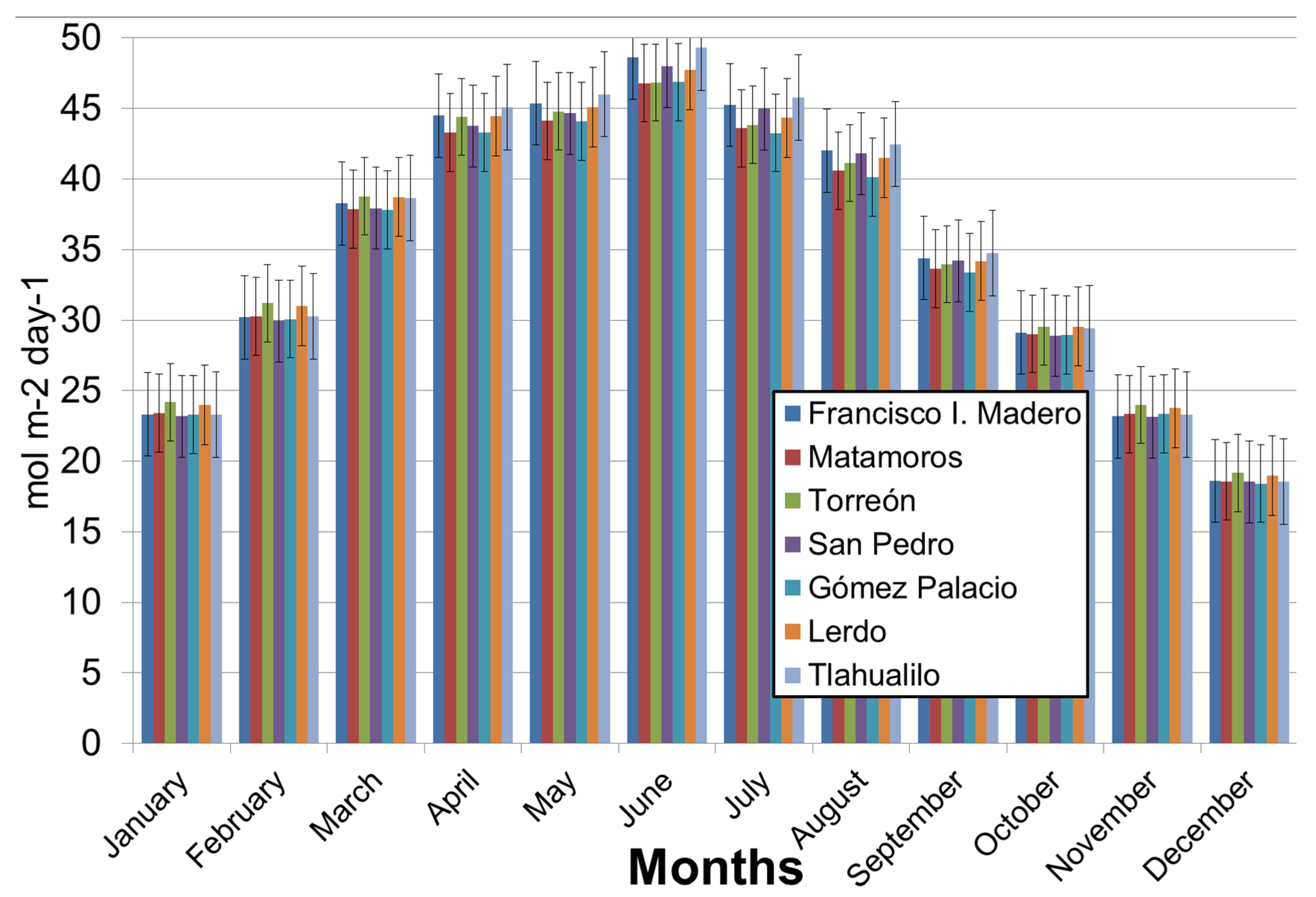

Fig. 3 displays values for the daily light integral (DLI). Which suggests that the spring-summer months range from 35 to values close to 50 mol m−2 day−1 in June, mainly; while the standard error presented this indicates that all of the municipalities don’t exceed a variation of 0.035 mol m−2 day−1 in any month, in other words, they are highly homogeneous values for each locality [29]. For the previous reason, considering the DLI values of each municipality and the P. oleracea requirements [33,34], all of the municipalities have appropriate DLI conditions for sowing of this crop, except in December.

Figure 3: Monthly mean DLI in mol m−2 day−1 per municipalities with the corresponding standard error. Both prepared with data from WorldClim [29].

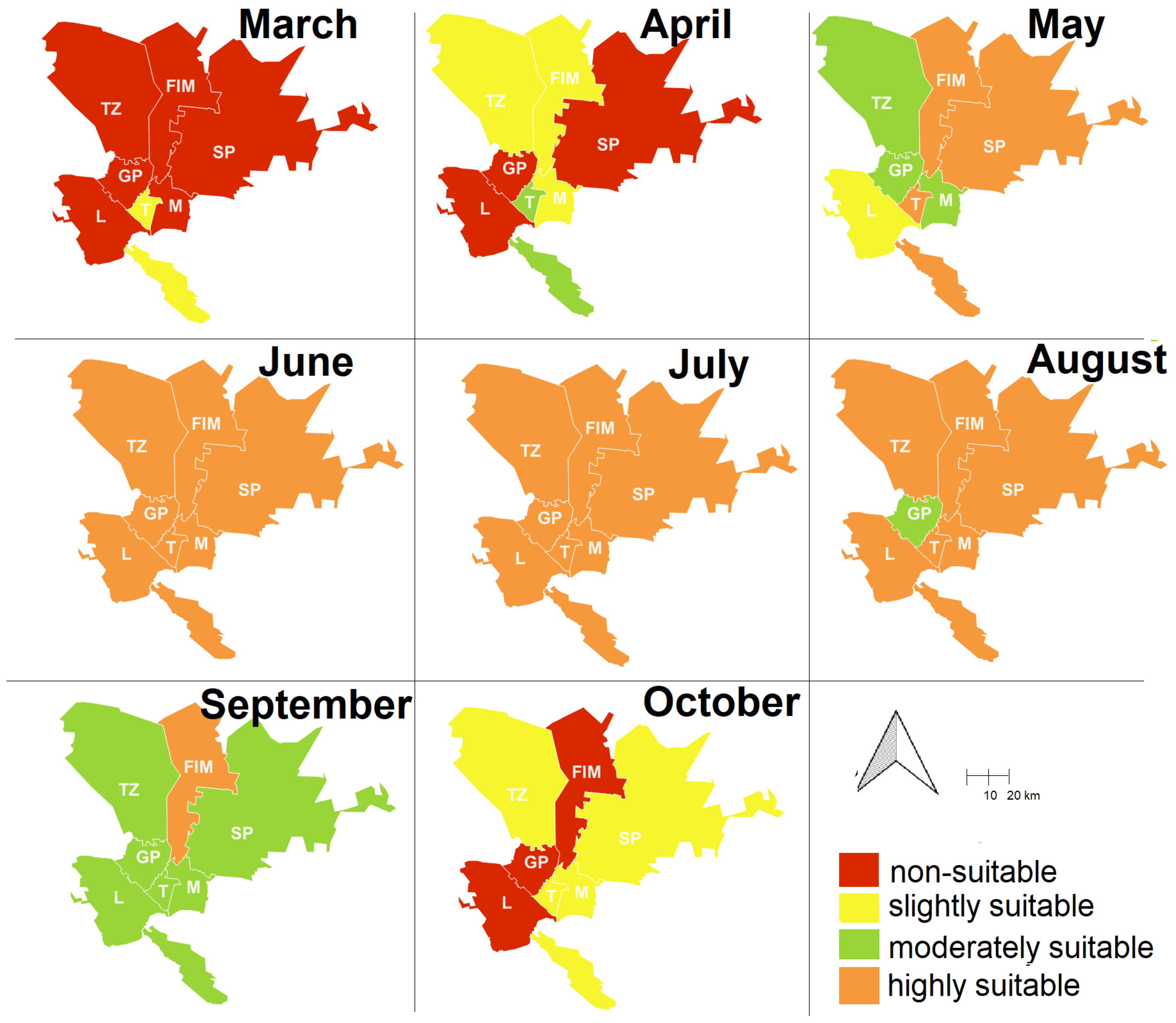

In the case of temporal suitability, it was found that there are slight variations between the municipalities of the study area (Fig. 4). FIM stands out with 41% of the months with highly suitable conditions, followed by SP and T with 33%, while L, M, and TZ have 25% and GP has 16%. Regarding moderately suitable conditions, GP has 33% of the months in this class, T, M, and TZ with 16%, followed by SP and L with 8%.

The most suitable months for raising P. oleracea are June and July; these months present highly suitable conditions for P. oleracea sowing in all of the municipalities of the study area. On the other hand, periods from January to March and November to December are non-suitable due to cooler temperatures.

Additionally, the acceptable period of time for P. oleracea utilization encompasses from April until October, affected principally by municipalities’ temperature variations. In this period, the suitability of this species fluctuates depending on mean and minimum temperatures, with slightly suitable conditions in April and October, while May and September have moderately suitable classifications.

The model validation was carried out through the χ2 test of independence, which indicated that the calculated χ2 was greater than the critical value (27.15 > 12.592); so, the null hypothesis was rejected [40]. Therefore, the temporal dimension shows a relationship strength of 0.59 according to Cramér’s V [41], indicating a strong association between the aptitude category and the season. As a result, P. oleracea ocurrence depends on the season; that is, the highly suitable category is statistically associated with the species’ main growing season.

Figure 4: Monthly temporal suitability of P. oleracea per municipality according to temperatures from CONAGUA and DLI from WorldClim [27,29]. Where, FIM: Francisco I. Madero, GP: Gómez Palacio, L: Lerdo, M: Matamoros, SP: San Pedro, TZ: Tlahualilo, and T: Torreón.

3.4 Evapotranspiration of P. oleracea

Concerning the evapotranspiration determination of P. oleracea, the months that were classified as slightly and moderately suitable classes in the temporal dimension are April and October for the first class, and May and September for the second class; most of the municipalities present crop evapotranspiration rates of 225, 170, 250, and 175 mm, respectively. On the other hand, the months categorized as highly suitable—June, July, and August—show rates of 245, 225, and 210 mm, respectively, as seen in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Evapotranspiration of P. oleracea per month and municipality estimated from ETo and Kc [35,36].

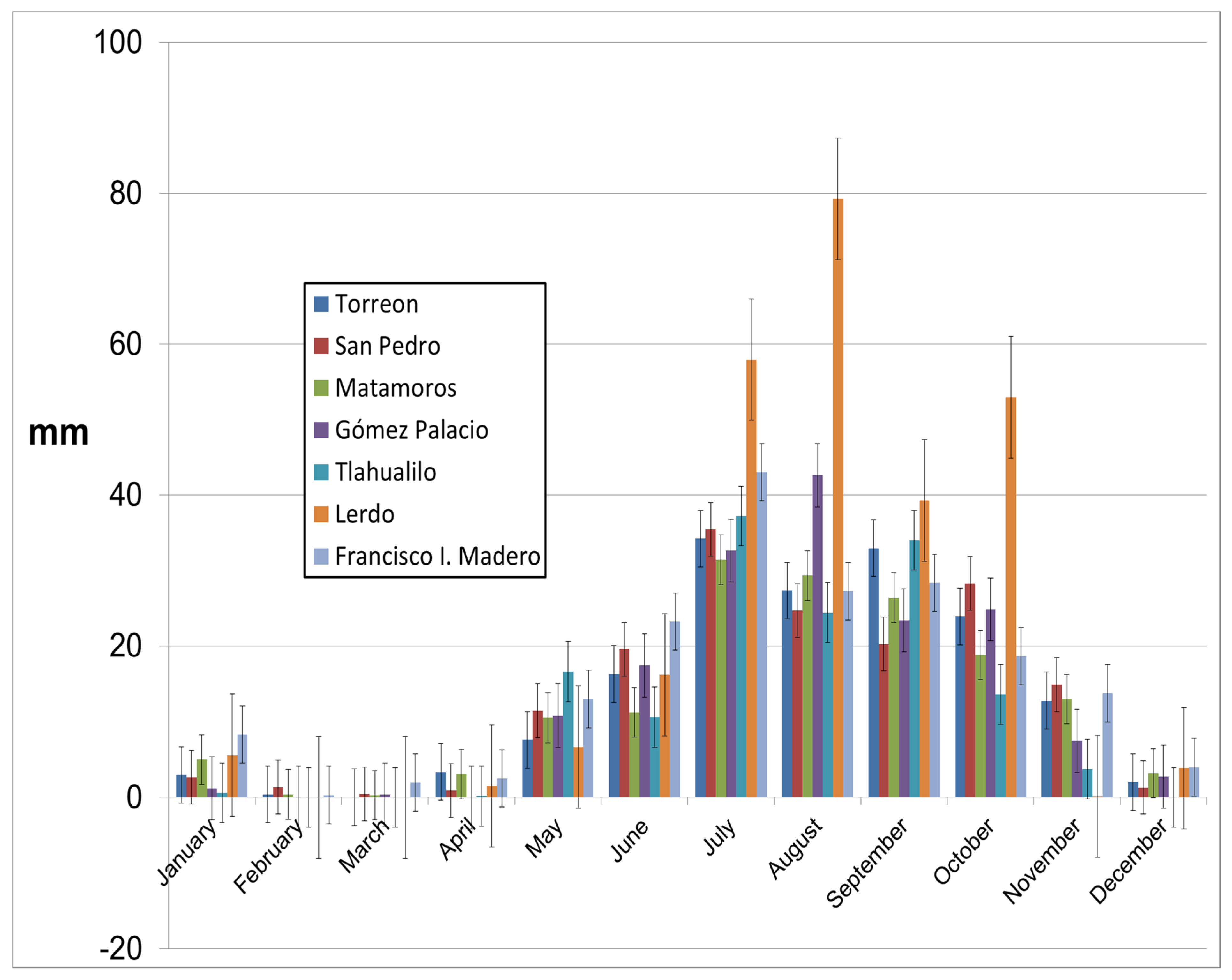

In the case of precipitation, Fig. 6 shows the monthly precipitation by municipality with the corresponding standard error. Derived from this data, the annual mean precipitation was estimated, and its average is 170 mm for the entire study area; therefore, it is not possible to produce this crop by rainfed means. Additionally, the average precipitation appears to be slightly lower than the 200–220 mm reported during the period 1970–2000 in another study [6].

At the municipal level, L receives the highest annual precipitation with 263 mm, while the rest of the municipalities receive between 140 and 170 mm [27]. Meanwhile, the standard error of this study indicates high variation for all locations, with values up to 42, as observed in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Monthly mean precipitation for the period 2019–2023 per month and municipality This information is derived from the meteorological data provided by CONAGUA [27].

As can be seen in Table 7, the potential proportion of water covered by precipitation is relatively low following FAO ECOCROP data [42]. Regarding the months classified as slightly and moderately suitable according to temporal suitability, no municipality exceeds 2% in April; subsequently, the average rises to 3% in May. However, in September, T, FIM, M, and TZ meet the 15% to 20% threshold, while L reaches 23%.

On the other hand, the months classified as highly suitable begin with values below 10% for June in all of the municipalities. Then, these range from 14% to 18% in July, with the exception of L reaching 26%. In August, L and GP stand out with 38% and 20%, respectively, while the remaining municipalities range between 11% and 13%.

Table 7: Proportion of water demand covered by precipitation per month and municipality. The table has been elaborated by taking into account the mean precipitations from CONAGUA meteorological data for the period 2019–2023 [27].

| Municipalities | Months | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan. | Feb. | Mar. | Apr. | May | Jun. | Jul. | Aug. | Sep. | Oct. | Nov. | Dec. | |

| T | 2.23 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 1.46 | 3.01 | 6.90 | 15.61 | 13.19 | 18.90 | 14.13 | 8.76 | 1.60 |

| SP | 2.17 | 0.96 | 0.22 | 0.40 | 4.48 | 7.96 | 15.17 | 11.34 | 11.31 | 17.03 | 10.72 | 1.16 |

| FIM | 6.85 | 0.23 | 0.98 | 1.09 | 5.05 | 9.42 | 18.66 | 12.78 | 16.01 | 11.36 | 9.99 | 3.55 |

| M | 4.18 | 0.28 | 0.14 | 1.36 | 4.12 | 4.63 | 13.75 | 13.64 | 14.81 | 11.41 | 9.49 | 2.84 |

| L | 4.36 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.66 | 2.59 | 6.69 | 26.12 | 37.94 | 22.43 | 31.60 | 0.12 | 3.21 |

| TZ | 0.52 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.09 | 6.39 | 4.24 | 16.08 | 11.36 | 19.20 | 8.36 | 2.82 | 0.00 |

| GP | 1.06 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.00 | 4.29 | 7.29 | 14.74 | 20.40 | 13.43 | 15.47 | 5.64 | 2.61 |

4.1 Agro-Climatic Requirements of P. oleracea

Agro-climatic studies must consider the most limiting factors of the studied region; with this, crops with background research about tolerance for these limiting factors should be explored [5]. P. oleracea appears achievable according to the agro-climatic components of the study area, commonly present in arid and semi-arid zones [6,16,35]. Regarding FAO methodology [38], it may not be suitable for every region’s situation, primarily due to the monthly variations in climatic variables such as potential evapotranspiration, precipitation, and temperatures. For the previous reason, the proposed methodology for agro-ecological zoning has three sections: the first, spatial suitability, which is based on pH and electrical conductivity for soil conditions; the second, temperatures and DLI for temporal suitability; and the third, water requirements according to crop evapotranspiration (ETc) in the study area. This information would increase the efficiency of food production systems [1,2]. Consequently, field experiments should be carried out to verify the theoric results of agro-climatic studies [3].

4.2 Spatial Suitability of P. oleracea

As previously mentioned, slightly saline conditions predominate in the study area. The irrigation district, where the municipalities of the study area represent 77% of the cultivable surface, reports 43,000 ha−1 of agricultural land within the range of 2 to 4 dS m−1 [43]. The data suggests that the salinization of the region’s soils may have intensified in recent years due to groundwater irrigation, which has led to higher salt concentrations recently reported in the range of 0–332 mM equivalent of NaCl [11].

For that reason, it is time-sensitive to adopt tolerant crops. Efforts have already been made in the past to revalue the agricultural sector of the region using native drought-tolerant plants, but adoption of alternatives is lacking for farmers [44]; such as Macaw palm in Argentina [45]. Additionally, salinity tolerance is another of the most attractive characteristics of P. oleracea because it can develop up to 30 ds m−1, activating CAM photosynthesis [17].

Regarding electrical conductivity, the increase in each ds m−1 linearly decreases P. oleracea dry matter by 2% for stem, 0.9% for leaves, and 2.41% for roots [18]. Nevertheless, considering the salinity concentration that generates statistically significant damage in yield (fresh or dry weight) differs according to studies, some authors suggest 6.3 ds m−1 [46]; others showed 7.5 ds m−1 or 20 ds m−1 [25,47]; and yet another study found no difference between values from 0 to 1 M [48].

Focusing specifically on the P. oleracea response within the study area, a soil electrical conductivity of 4 dS m−1 appears to favor the wild growth of this species compared to areas with lower salt concentrations [19]. It is important to acknowledge that the salinity-drought tolerance varies among the different ecotypes or cultivars examined in related studies. Nevertheless, practices such as the application of biostimulants are available to enhance its overall resilience [49].

Concerning pH, P. oleracea adapts to a wide pH range, developing in acidic and alkaline environments [21]. However, the probability of occurrence of this species within the interest area suggests that it is favored with linear increase of pH from 7.6 to 8.2 [19]. Agricultural soils within the study area predominate these values; therefore, crop sowing appears appropriate [23].

This study aims to suggest that agro-ecological zoning methodologies may vary depending on the region and the specific crop. Examples include using temperatures, precipitations, and the International Soil Classification System for coffee in Chiapas, Mexico [14]. Another study used climatic-topographic-soil parameters for chickpeas in Iran [13]. Other authors utilized rainfall and temperature data for macaw palm in Argentina, as well as temperature, precipitation, and frost-free days for castor bean [45,50]. Various efforts have been made to present alternatives appropriate to the conditions of particular regions, including semi-dry zones in northern Mexico and arid regions [44,51]. With all of this, future research should prioritize the particularities of each region and crop, and the scientific methodologies for agro-climatic suitability determination must be based on pluralistic epistemological approaches.

4.3 Temporal Suitability of P. oleracea

Regarding temporal suitability, P. oleracea exhibits a wide tolerance range for temperature [20]. This temperature tolerance is a highly important factor for crop viability; satisfying the temperature requirements alone can account for 75% of the variation in crop suitability within agro-ecological zones [13].

However, the temporal dimension of suitability must be analyzed using trends over shorter periods to allow for greater flexibility in food production systems, moving away from the static conception of agro-ecological zoning [15]. The observed rate of temperature increase in past periods may exacerbate the effects of climate change. Therefore, agro-ecological zoning studies must be performed continuously to adapt to these evolving conditions [2].

Additionally, it is important to point out that temperature is continuously rising; a global study reported a standard deviation of 0.019°C for the entire arid surface of the planet and an annual increase in temperature of 0.039°C for the arid regions of North America considering data from 1979 to 2018 [4]. This variable plays a fundamental role in plant development and optimizing germination. As evidence, it was shown that P. oleracea can germinate between 12 and 15°C; however, it does not exceed 45% emergence, while at 18°C it reaches 90% [32]. This is similar to other authors, who suggest that germination is maximized in the range of 20–30°C, preferably at 28°C with 88% success [21].

Furthermore, it was reported that the optimal DLI for P. oleracea is 20.73 in contrast to 10.36 mol m−2 day−1 [33]. Another study found a positive linear relationship between DLI and fresh weight accumulation at values of 8.64–11.52–14.4–17.28 mol m−2 day−1 [34]. For this reason, the optimal DLI requirement demanded for this crop is within the normal optimal levels for vegetables, that is, between 10 and 25 mol m−2 day−1 [30]. Based on the above, all months of the year, except December, have the DLI required by P. oleracea [29].

4.4 Evapotranspiration of P. oleracea

In general, almost all of the municipalities in every month present high values of standard error for precipitations. This implies a lack of homogeneity in monthly rainfall. As a result, it is impossible to produce P. oleracea under rainfed conditions. This must consider drought periods that regularly affect this zone, resulting in water scarcity. Along with this, it is estimated that precipitation will continue to decrease in the arid zones of the planet at a rate of −0.075 mm month−1 year−1 and a standard deviation of 0.244 [4]. For the previous reason, the water crop requirements must be supplied from other sources of water, i.e., dam water or groundwater, like any other crop used in the region [7]. Therefore, P. oleracea can be harvested 23 days after sowing, despite being annual [47]. This feature opens the opportunity to consider this species in short production cycles, as proposed in our research. However, precise quantification of the necessary water requirement, defined by ETc, would facilitate accurate irrigation layer application [31,37]. For that reason, water requirements should be estimated using agro-climatic suitability approaches for an approximation of these parameters, principally in arid and semiarid zones.

The municipalities of “Comarca Lagunera” have suitable soil and climate conditions for sowing P. oleracea according to the parameters used in this study. The Chi-Square (χ2) test of independence validates the temporal dimension, which indicates that sowing should be carried out mainly in the months of June and July, with high suitability considering the phenological cycle of P. oleracea. Regarding spatial suitability, the χ2 Goodness-of-Fit test confirms that this species can be established in around 99% of the agricultural land use of the region, with approximately 30% within the highly suitable class. However, estimated evapotranspiration indicates that this crop faces limitations in water supply, so adopting it requires considering the availability of dam water or groundwater, which makes water use efficiency a priority.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Aaron David Lugo-Palacios; methodology, Aaron David Lugo-Palacios and Urbano Nava-Camberos; software, Aaron David Lugo-Palacios; validation, César Omar Montoya-García and Ignacio Orona-Castillo; formal analysis, Aaron David Lugo-Palacios and José Luis García-Hernández; investigation, Aaron David Lugo-Palacios, César Omar Montoya-García resources and José Luis García-Hernández; data curation, José Luis García-Hernández and Aaron David Lugo-Palacios; writing—original draft preparation, Aaron David Lugo-Palacios; writing—review and editing, Edgar Omar Rueda-Puente and José Luis García-Hernández; visualization, José Luis García-Hernández; supervision, Edgar Omar Rueda-Puente; project administration, José Luis García-Hernández and Edgar Omar Rueda-Puente. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Viana CM , Freire D , Abrantes P , Rocha J , Pereira P . Agricultural land systems importance for supporting food security and sustainable development goals: a systematic review. Sci Total Environ. 2022; 806( Pt 3): 150718. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.150718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Trnka M , Balek J , Brázdil R , Dubrovský M , Eitzinger J , Hlavinka P , et al. Observed changes in the agro-climatic zones in the Czech Republic between 1961 and 2019. Plant Soil Environ. 2021; 67( 3): 154– 63. doi:10.17221/327/2020-pse. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Sosa-Yañez LC , López-Ahumada GA , García-Hernández JL , Sosa-Yañez LC , López-Ahumada GA , García-Hernández JL . Gradiente de humedad en el comportamiento agronómico del centeno cultivado en ambiente de zonas áridas. Ecosistemas Y Recur Agropecu. 2024; 11( 2): e4052. (In Spain). [Google Scholar]

4. Daramola MT , Xu M . Recent changes in global dryland temperature and precipitation. Int J Climatol. 2022; 42( 2): 1267– 82. doi:10.1002/joc.7301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Karimian Z , Farashi A . Predicting the potential habitat of Russian-Olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia) in urban landscapes. Ital J Agrometeorol. 2021;( 1): 3– 19. doi:10.36253/ijam-1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. de Jesús Correa-Islas J , Romero-Padilla JM , Pérez-Rodríguez P , Vázquez-Alarcón A . Application of geostatistical models for aridity scenarios in northern Mexico. Atmósfera. 2023; 37: 233– 44. doi:10.20937/atm.53103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. SAGARPA (Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación) . La Comarca Lagunera, primer lugar en producción de leche, carne de ave y forrajes. 2016 [cited 2025 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.gob.mx/agricultura. [Google Scholar]

8. Torres-Martínez JA , Mora A , Mahlknecht J , Daesslé LW , Cervantes-Avilés PA , Ledesma-Ruiz R . Estimation of nitrate pollution sources and transformations in groundwater of an intensive livestock-agricultural area (Comarca Lagunera), combining major ions, stable isotopes and MixSIAR model. Environ Pollut. 2021; 269: 115445. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. FAO & IIASA. Global Agroecological Zoning version 5 (GAEZ v5) model documentation. 2025 [cited 2025 Dec 5]. Available from: http://github.com/un-fao. [Google Scholar]

10. Wang J , Zhao L , Hao M , Wang N , Wen QH , Mei FJ , et al. Climate suitability determines optimal yielding of dryland maize: a validation on timely sowing as an ancient wisdom. Field Crops Res. 2025; 328: 109920. doi:10.1016/j.fcr.2025.109920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Cauich-Kau D , Castro-Larragoitia J , Cardona Benavides A , García-Arreola ME , García-Vargas GG . An adapted groundwater quality index including toxicological critical pollutants. Groundw Sustain Dev. 2025; 28: 101401. doi:10.1016/j.gsd.2024.101401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Araya A , Keesstra SD , Stroosnijder L . A new agro-climatic classification for crop suitability zoning in northern semi-arid Ethiopia. Agric For Meteor. 2010; 150( 7–8): 1057– 64. doi:10.1016/j.agrformet.2010.04.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Sharafi S . Predicting Iran’s future agro-climate variability and coherence using zonation? Based PCA. Ital J Agrometeorol. 2023;( 2): 17– 30. doi:10.36253/ijam-1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Suárez Venero GM , Avendaño Arrazate CH , Hernández Ramos MA , Rodríguez Larramendi LA , Estrada de los Santos P , Salas Marina MÁ . Zonificación edafoclimática del cultivo de cacao en el estado Chiapas. Remexca. 2021; 12( 4): 629– 41. (In Spain). doi:10.29312/remexca.v12i4.2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. WMO (World Meteorological Organization). Guide to climatological practices WMO-No. 100. Geneva, Switzerland: World Meteorological Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

16. Ivushkin K , Bartholomeus H , Bregt AK , Pulatov A , Kempen B , de Sousa L . Global mapping of soil salinity change. Remote Sens Environ. 2019; 231: 111260. doi:10.1016/j.rse.2019.111260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Hnilickova H , Kraus K , Vachova P , Hnilicka F . Salinity stress affects photosynthesis, malondialdehyde formation, and proline content in Portulaca oleracea L. Plants. 2021; 10( 5): 845. doi:10.3390/plants10050845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yazdani-Biouki R , Karimi M , Soltangheisi A . Purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.) salt tolerance assessment. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2023; 69( 4): 250– 9. doi:10.1080/00380768.2023.2212696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Segura-Castruita MÁ , Yescas-Coronado P , Orozco-Vidal JA , Fortis-Hernández M , Preciado-Rangel P , Montemayor-Trejo JA . Distribución espacial de la probabilidad de ocurrencia de verdolaga silvestre (Portulaca oleracea L.) en la Región Lagunera de Coahuila, México. Investig Y Cienc De La Univ Autónoma De Aguascalientes. 2018;( 74): 10– 6. doi:10.33064/iycuaa2018741716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Leguizamon ES , Ferrari G . Requerimientos germinativos y modelización de la emergencia de Portulaca oleracea L. (Verdolaga). Rev De Investig De La FacDe CiencAgrar-UNR. 2006; 6( 9): 25– 37. [Google Scholar]

21. Kaur H , Kaur N , Bhullar MS . Germination ecology and management of Portulaca oleracea L.—a weed of summer vegetable crops in Punjab. Agric Res J. 2021; 58( 1): 51– 9. doi:10.5958/2395-146x.2021.00007.7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. SIAP (Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera) . Anuario Estadístico de la Producción Agrícola. [cited 2025 Jan 5]. Available from: https://nube.agricultura.gob.mx/cierre_agricola/. [Google Scholar]

23. Batjes NH , Calisto L , de Sousa LM . Providing quality-assessed and standardised soil data to support global mapping and modelling (WoSIS snapshot 2023). Earth Syst Sci Data. 2024; 16( 10): 4735– 65. doi:10.5194/essd-16-4735-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. INEGI . División política municipal. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad; 2022 [cited 2024 Dec 5]. Available from: http://geoportal.conabio.gob.mx/metadatos/doc/html/mun22gw.html. [Google Scholar]

25. SIAP (Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera) . Frontera agrícola serie II. 2016 [cited 2025 Jan 5]. Available from: http://datamx.io. [Google Scholar]

26. Franco JA , Cros V , Vicente MJ , Martínez-Sánchez JJ . Effects of salinity on the germination, growth, and nitrate contents of purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.) cultivated under different climatic conditions. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol. 2011; 86( 1): 1– 6. doi:10.1080/14620316.2011.11512716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. CONAGUA . Información Estadística Climatológica. 2024 [cited 2024 Dec 5]. Available from: https://smn.conagua.gob.mx/es/climatologia/informacion-climatologica/informacion-estadistica-climatologica. [Google Scholar]

28. SIAP. Aptitud agroclimática del frijol en México ciclo agrícola otoño invierno. Mexico City, Mexico: Ciudad de México: Servicio de Información Agroalimentaria y Pesquera; 2019 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. 30 p. Available from: http://frijol.gob.mx. [Google Scholar]

29. Fick SE , Hijmans RJ . WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int J Climatol. 2017; 37( 12): 4302– 15. doi:10.1002/joc.5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jung A , Szabó D , Varga Z , Pék Z , Vohland M , Sipos L . Spatially scaled and customised daily light integral maps for horticulture lighting design. NJAS Impact Agric Life Sci. 2024; 96( 1): 2349522. doi:10.1080/27685241.2024.2349522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Allen R , Raes D , Pereira L , Raes D , Smith M . Crop evapotranspiration-Guidelines for computing crop water requirements. FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. Fao Rome. 1998;( 56): 300. [Google Scholar]

32. Nikolić N , Ghirardelli A , Schiavon M , Masin R . Effects of the salinity-temperature interaction on seed germination and early seedling development: a comparative study of crop and weed species. BMC Plant Biol. 2023; 23( 1): 446. doi:10.1186/s12870-023-04465-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. He J , Gan JHS , Qin L . Productivity, photosynthetic light-use efficiency, nitrogen metabolism and nutritional quality of C4 halophyte Portulaca oleracea L. grown indoors under different light intensities and durations. Front Plant Sci. 2023; 14: 1106394. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1106394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kudirka G , Viršilė A , Laužikė K , Sutulienė R , Samuolienė G . Photosynthetic photon flux density effects on Portulaca olearacea in controlled-environment agriculture. Plants. 2023; 12( 20): 3622. doi:10.3390/plants12203622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zomer RJ , Xu J , Trabucco A . Version 3 of the global aridity index and potential evapotranspiration database. Sci Data. 2022; 9( 1): 409. doi:10.1038/s41597-022-01493-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Miri Z , Khashei-Siuki A , Salari A . The estimation of evapotranspiration and crop coefficient of purslane herb plant in Shiraz. Water Irrig Manag. 2021; 11( 3): 451– 60. [Google Scholar]

37. Pereira LS , Mota M , Raziei T , Paredes P . Water requirements and crop coefficients of edible, spicy and medicinal herbs and vegetables; a review aimed at supporting plant and water management. Irrig Sci. 2024; 42( 6): 1199– 228. doi:10.1007/s00271-024-00960-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. FAO . Agro-ecological zoning: Guidelines (No. 73). Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 1998 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: http://www.fao.org. [Google Scholar]

39. GBIF.org. GBIF Occurrence Download [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Jan 5]. Available from: https://www.gbif.org/occurrence/download/0021485-251120083545085. [Google Scholar]

40. Nihan ST . Karl pearsons chi-square tests. Educ Res Rev. 2020; 15( 9): 575– 80. doi:10.5897/err2019.3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. McHugh ML . The Chi-square test of independence. Biochem Med. 2013; 23( 2): 143– 9. doi:10.11613/bm.2013.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. FAO ECOCROP . Database of crop constraints and characteristics. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 1998 [cited 2025 Jan 1]. Available from: http://gaez.fao.org/ecocrop. [Google Scholar]

43. Santamaría-César J , Figueroa-Viramontes U , Medina-Morales Ma del C . Productividad de la alfalfa en condiciones de salinidad en el distrito de riego 017, comarca lagunera. Terra. 2004; 22( 3): 343– 9. [Google Scholar]

44. Martinez-Burciaga OU , Castillo-Quiroz D , Mares-Arreola O . Caracterización y Selección de Sitios Para Plantaciones de Lechuguilla (Agave lechuguilla Torr.) en el Estado de Coahuila. Mexico City, Mexico: Distrito Federal: Instituto Nacional de Invest igaciones Forest ales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias; 2011. 26 p. [Google Scholar]

45. Falasca S , Ulberich A , Pitta-Alvarez S . Development of agro-climatic zoning model to delimit the potential growing areas for macaw palm (Acrocomia aculeata). Theor Appl Climatol. 2017; 129( 3): 1321– 33. doi:10.1007/s00704-016-1850-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Tanji KK , Kielen NC . Agricultural drainage water management in arid and semi-arid areas. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; 2002. [Google Scholar]

47. Bekmirzaev G , Ouddane B , Beltrao J , Khamidov M , Fujii Y , Sugiyama A . Effects of salinity on the macro- and micronutrient contents of a halophytic plant species (Portulaca oleracea L.). Land. 2021; 10( 5): 481. doi:10.3390/land10050481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Guevara-Olivar BK , Gómez-Merino FC , Ruíz-Posadas LDM , Fernández-Pavía YL , Escalante-Estrada JA , Trejo-Téllez LI . Morphological, biochemical and nutritional variations in a Mexican purslane (Portulaca oleracea L.) variety exposed to salt stress during the vegetative stage. Not Bot Horti Agrobo. 2024; 52( 2): 13434. doi:10.15835/nbha52213434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Alhawsa Z , Jalal R , Asiri N . Enhancing salt stress tolerance in Portulaca oleracea L. using Ascophyllum nodosum biostimulant. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2025; 94( 4): 1319– 37. doi:10.32604/phyton.2025.061918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Falasca SL , Ulberich AC , Ulberich E . Developing an agro-climatic zoning model to determine potential production areas for castor bean (Ricinus communis L.). Ind Crops Prod. 2012; 40: 185– 91. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.02.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Castorena EVG , Gómez GAR , Solorio CAO . The agricultural potential of a region with semi-dry, warm and temperate subhumid climate diversity through agroecological zoning. Sustainability. 2023; 15( 12): 9491. doi:10.3390/su15129491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools