Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

How I do it: percutaneous cystolitholapaxy for bladder stones with complex lower urinary tract anatomy

Department of Urology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN 55905, USA

* Corresponding Author: Kevin Koo. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(4), 325-333. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.064255

Received 10 February 2025; Accepted 29 April 2025; Issue published 29 August 2025

Abstract

While cystolitholapaxy for bladder stones is commonly performed using a transurethral approach, large or complex stone burdens in patients with complex lower urinary tract anatomy may make this inefficient or infeasible. Percutaneous cystolitholapaxy is a safe, effective, minimally invasive alternative for diverse indications, including patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia, urethral stricture disease, closed bladder neck, continent catheterized channel, or other urinary diversion. In this article, we review the indications for and advantages of percutaneous cystolitholapaxy and describe our step-by-step technique for this procedure, including representative imaging and favored equipment. We also discuss preoperative and postoperative considerations, management of potential complications, strategies to optimize clinical outcomes and patient safety, and comparisons with transurethral approaches. Finally, we report outcomes from our institutional series of percutaneous cystolitholapaxy cases to highlight the safety and efficacy of the procedure.Keywords

Surgical treatment of bladder stones has evolved from open cystolithotomy to endoscopic approaches. While transurethral cystolitholapaxy (TUCL) is the most common operation, percutaneous cystolitholapaxy (PCCL) is an effective alternative for specific scenarios.

PCCL mirrors the technical framework for percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) and involves percutaneous bladder access to create a cystostomy tract. This may be performed with ultrasound/fluoroscopic guidance or direct vision following bladder access. Dilation of the cystostomy tract then permits the use of various lithotripsy modalities and direct stone evacuation.

The earliest published reports of PCCL date back to 1988 and 1991,1,2 wherein ultrasonic lithotripsy via rigid nephroscope was used to treat pediatric bladder stones. Ikari et al. subsequently published a series of 36 patients treated with percutaneous ultrasonic lithotripsy with difficult urethral access due to BPH or urethral stricture, reporting an 89% success rate.3 In 1996, Van Savage et al. published a series of 10 pediatric patients with a history of bladder augmentation and limited urethral access treated with stone aspiration or electrohydraulic lithotripsy.4 All patients achieved stone clearance, with a mean hospitalization of <1 day.

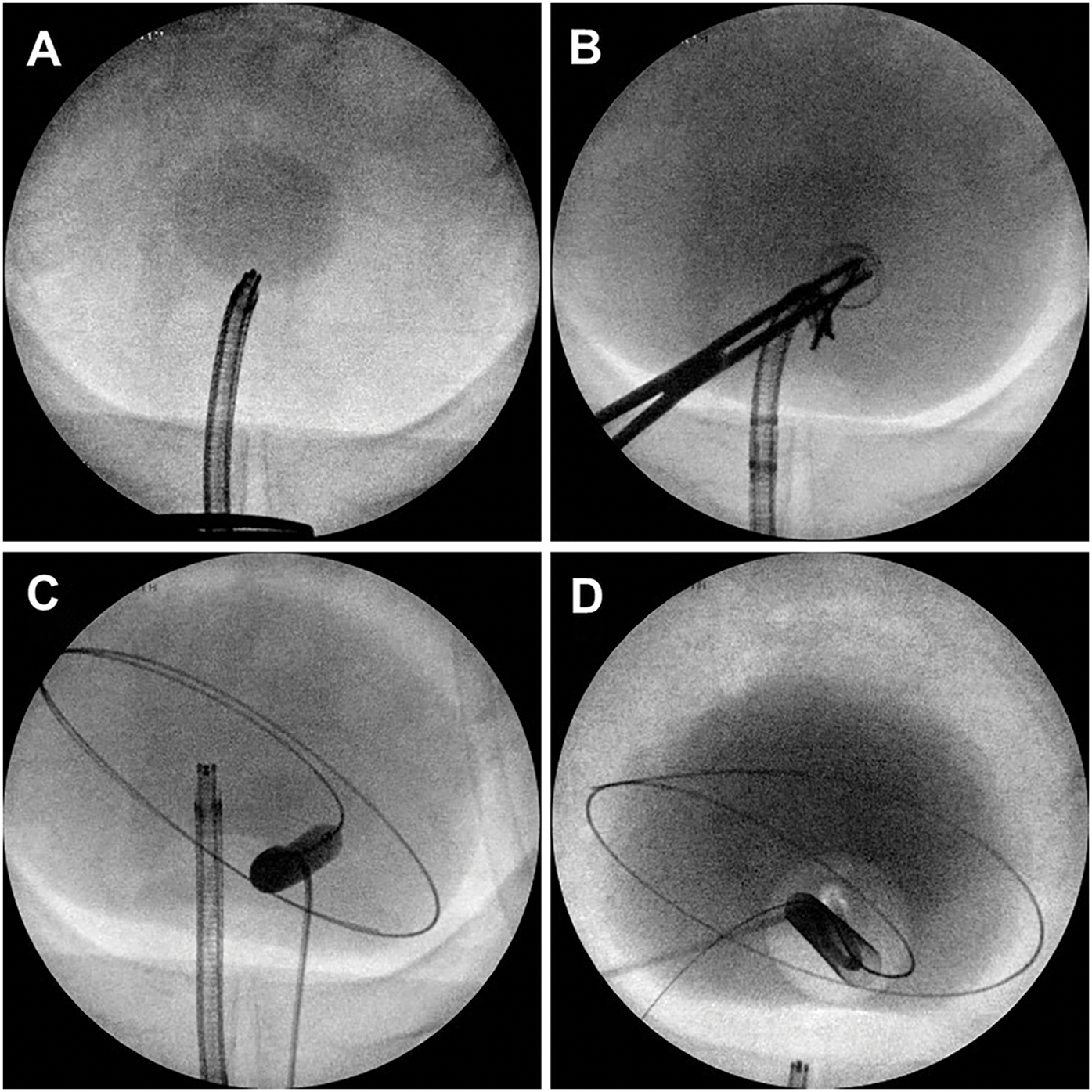

The primary indication for PCCL is difficult, delicate, or dead-end urethral access (Table 1). One important population is patients with a history of major reconstruction for neurogenic bladder or congenital anomalies. Many such patients have bladder augmentation using bowel, often with a catheterizable channel. In patients who also underwent bladder closure, urethral access is infeasible. Furthermore, manipulation of large-bore instruments through a catheterizable channel is preferably avoided due to the potential for mechanical trauma, leading to channel stenosis or disruption of the continence mechanism. Unfortunately, these patients are predisposed to bladder stones due to bowel mucus and incomplete emptying. PCCL provides an efficient route for stone removal while protecting the channel.

Additional patients with complex urethral access include those with severe benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) or urethral strictures. Incomplete emptying secondary to these processes predisposes to stone formation. However, passing rigid instruments per urethra may be challenging due to bladder neck angulation and may increase the risk of postoperative incontinence. An analogous concern exists in patients with radiation damage to the urethra or bladder neck, which may predispose to dystrophic calcification.

The pediatric urethra may not accommodate large-bore rigid instruments to facilitate efficient stone evacuation. A smaller urethral diameter may also increase the risk of urethral injury and subsequent stricture formation following transurethral procedures.

Laser lithotripsy through a flexible endoscope may be a reasonable alternative for many of the indications above. However, the extraction of stone fragments or irrigation of stone debris may add considerable operative time and risk trauma to the urethra or channel. The choice of percutaneous vs. transurethral approach in these cases should be individualized based on the degree of stone burden, patient anatomy, navigability of the urethra or channel, and importance of complete stone clearance (i.e., infection stones, stagnant urine in a continent reservoir).

Finally, all patients with large multi-centimeter stone burdens, including those secondary to calcified extruded mesh or other foreign bodies, can be considered for PCCL due to the direct trajectory onto the stone and the ability to use large-bore instruments for efficient lithotripsy. Open cystolitholapaxy remains an option for large stones, but catheter duration, operative time, and hospitalization appear to favor endoscopic approaches;5 small-incision techniques may mitigate these disadvantages in well-selected patients.

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, IRB #24-010902. Informed consent has been waived.

Patients typically present with bladder stones diagnosed on cystoscopy, ultrasound, or computed tomography (CT) scan. Pertinent history includes bladder augmentation, state of the bladder neck, history of urethral or bladder neck stricture, BPH, and bladder outlet procedures, and prior pelvic radiation. For patients who catheterize routinely, the size of the catheter and the anatomy of the catheterized channel are relevant considerations. Finally, the reversibility of anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy should be considered.

Additional imaging is obtained selectively. Office cystoscopy can evaluate the feasibility of urethral access and assess for strictures, calcification, and prostate configuration. Prostate sizing may be helpful with severe BPH, and a pre-operative CT scan can assess the safety of percutaneous access. This is especially relevant in those with a history of bladder reconstruction or other complex abdominal surgery. Specific anatomic considerations include bowel or other structures anterior to the bladder, the position of catheterizable channels or fecal diversions, and other barriers that may constrain a safe percutaneous access window.

We routinely obtain a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and urine culture prior to surgery. Positive urine cultures should be treated with culture-directed antibiotics. Patients are instructed to hold any therapeutic anticoagulation, with bridging if indicated, according to the relevant guidelines.

PCCL can be performed in either the supine or dorsal lithotomy position. The surgeon typically stands at the side of the table opposite the surgeon’s dominant hand. Thus, right-handed surgeons would stand on the patient’s left. The assistant may stand on the opposite side of the table for supine positioning or between the patient’s legs for dorsal lithotomy. We typically position female patients in dorsal lithotomy when performing concomitant cystoscopic urethral access.

We shave the suprapubic area from the base of the penis or mons to just below the umbilicus. Chlorhexidine is used for sterile preparation from the umbilicus to the upper thighs, with povidone/iodine used to prep the genitalia and urethral meatus if urethral access is planned.

We use a PCNL drape with a pouch connected to suction on the surgeon side for supine, and a lithotomy drape with the window opened to include the suprapubic access site for dorsal lithotomy. Using an adhesive drape such as 3M Steri-Drape™ or applying 3M Ioban™ tape around the drape window assists with directing irrigation fluid to the suction pouch.

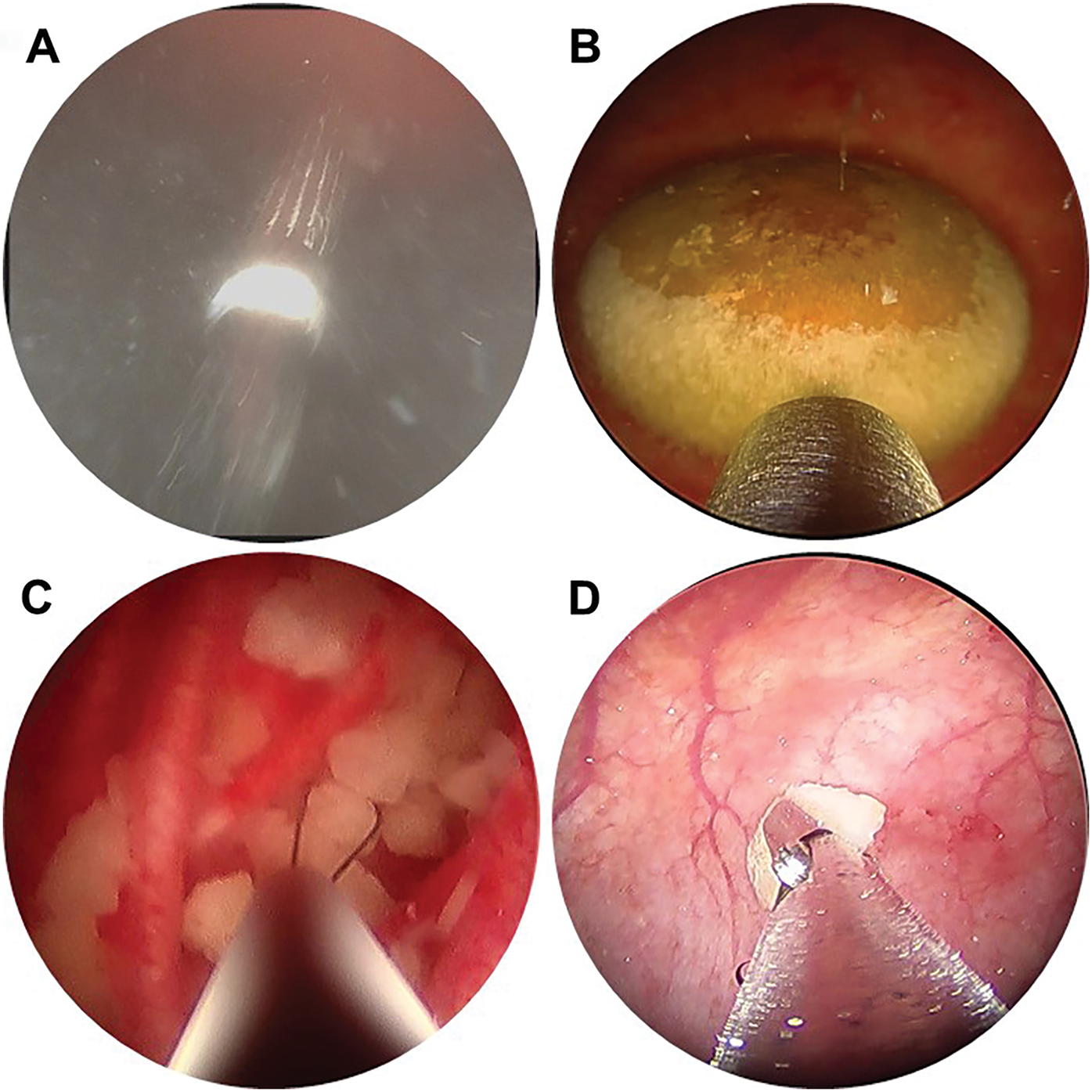

Table 2 summarizes our typical equipment for PCCL. If transurethral endoscopy is planned and/or percutaneous access is to be performed under direct vision, then separating equipment for the transurethral and percutaneous portions of the case on two sterile tables may be helpful.

Prophylactic antibiotics should be administered within 1 h before the procedure. In patients with negative preoperative urine culture, we typically give a single dose of cefazolin or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, consistent with antimicrobial prophylaxis guidelines for clean-contaminated lower tract procedures.6 We perform PCCL under general anesthesia, although spinal anesthesia could be considered for high-risk patients.

Percutaneous bladder access may be performed under direct vision with a flexible cystoscope or with imaging guidance. In patients with catheterizable channels, we prefer to obtain access under direct vision with a flexible ureteroscope, which can safely traverse the channel. The bladder is inspected, noting the position of the ureteral orifices, the dependent locations of the stones, and any visible distinction between native urothelium and bowel in patients with augmentation cystoplasty. The access site is selected based on anatomic considerations and pre-operative imaging, favorable trajectory onto the stone, and puncturing native bladder tissue.

Alternatively, a catheter can be placed into the bladder to backfill with either saline for blind or ultrasound-guided puncture or radiopaque contrast for fluoroscopic puncture. The access site is generally chosen 2 fingerbreadths above the pubic symphysis to remain extraperitoneal. We typically obtain access at the midline, but a lateral site may be preferred if dictated by distorted anatomy or to avoid a catheterizable channel or bowel diversion.

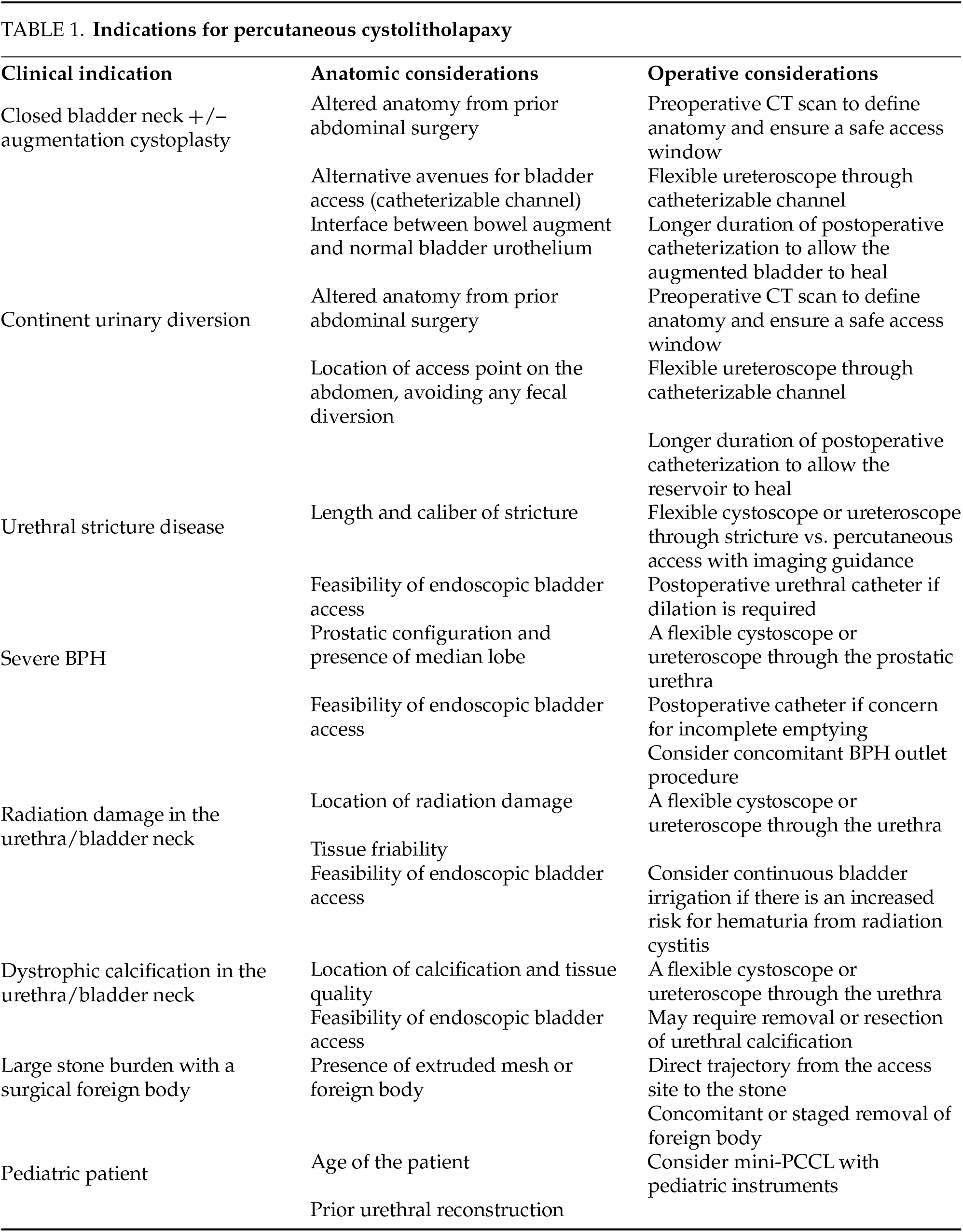

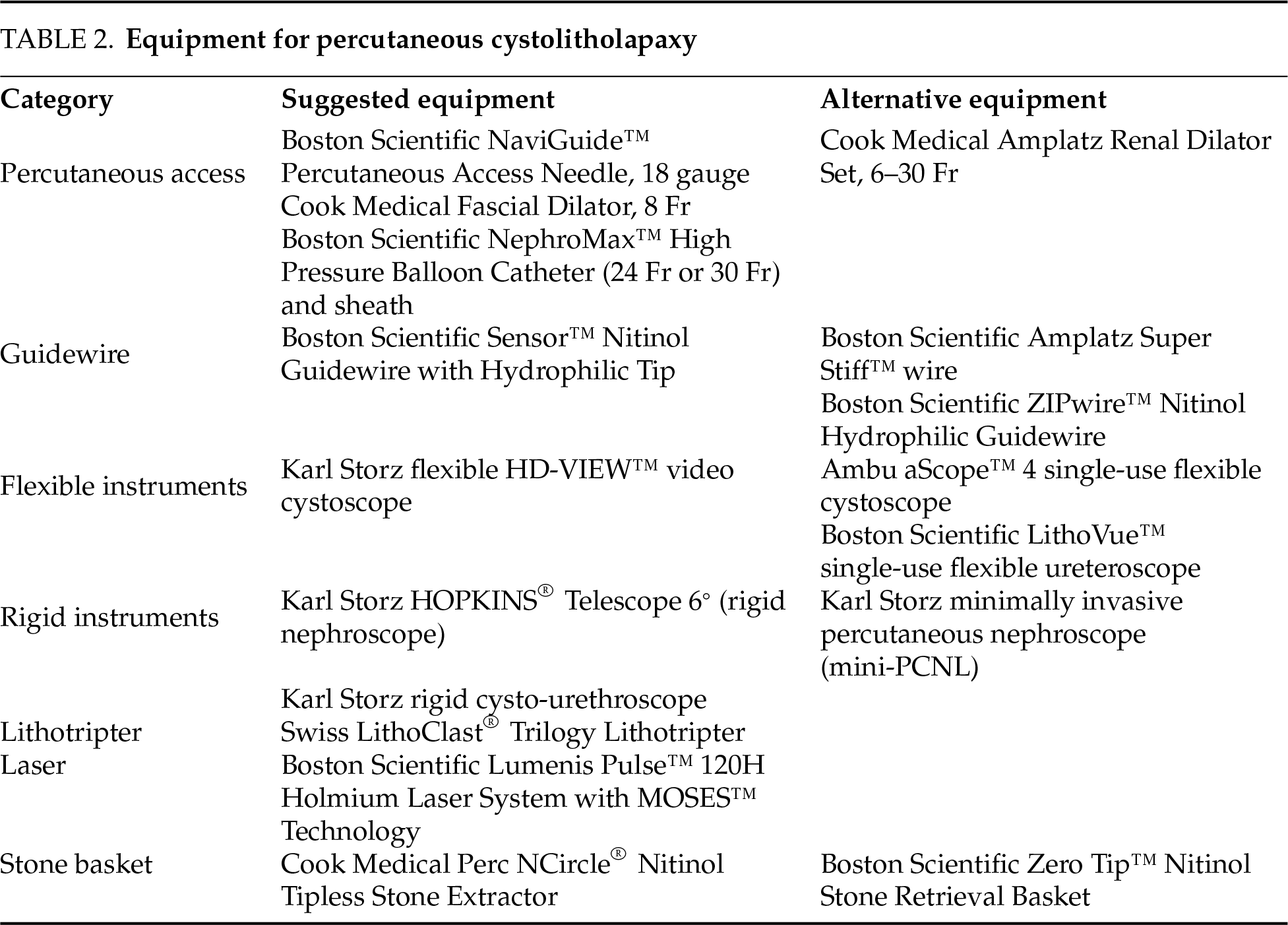

The technique for initial access mirrors percutaneous renal access. Scout fluoroscopy can confirm the stone position (Figure 1A). We perform the initial puncture using a percutaneous access needle (Boston Scientific NaviGuide™ Percutaneous Access Needle, 18 gauge). A bull’s eye technique facilitates a midline suprapubic puncture directly over the stone (Figure 1B). Successful bladder entry should yield urine return through the hollow needle. Two guidewires are passed and curled in the bladder. The safety wire is secured to the drape. If the access is performed under vision, needle entry and wire passage may be confirmed directly (Figure 2A). In patients with a pre-existing suprapubic tube (SPT), a guidewire may be directed through or alongside the catheter to obtain access. Performing a cystogram through the SPT may help confirm the wire position.

Figure 1: Intraoperative fluoroscopic cystography demonstrating (A) large bladder stone, (B) percutaneous needle access using bull’s eye technique, (C) balloon dilation of cystostomy tract, (D) final cystogram following suprapubic catheter placement

Figure 2: Intraoperative endoscopy demonstrating (A) percutaneous needle puncture under direct vision, (B) bladder stone with Swiss LithoClast® Trilogy lithotripter probe, (C) basket extraction of stone fragments, (D) extraction of stone fragments using grasping forceps

Once bladder access is achieved, the cystostomy tract is sequentially dilated. We typically pass an 8 Fr fascial dilator followed by a 24 Fr or 30 Fr dilation balloon (Boston Scientific NephroMax™ High-Pressure Balloon Catheter). The balloon is dilated with contrast so that it can be visualized under fluoroscopy during inflation (Figure 1C), and any “waisting” indicative of incomplete dilation is revealed. In patients with a chronic SPT, fascial fibrosis may preclude successful balloon dilation, and manual dilation with sequential Amplatz dilators may be required. Once complete dilation is achieved, an access sheath is advanced over the balloon into the bladder to establish the cystostomy tract. The balloon is deflated and removed, maintaining the safety wire outside the sheath. A rigid nephroscope with a parallel eyepiece is advanced into the bladder to confirm appropriate trajectory to the stones.

In select cases, the tract may be dilated to a smaller diameter (≤18 Fr), analogous to a mini-PCNL. Typically, the small decrease in morbidity is outweighed by the efficiency of using a rigid nephroscope and combination lithotripter through a standard 24–30 Fr tract to evacuate large stones. One specific indication for a “mini-PCCL” would be a patient with limited stone burden but a closed bladder neck and continent catheterizable channel, where percutaneous access is the only available approach.

Various devices can be used for stone fragmentation and evacuation. We generally prefer the Swiss LithoClast® Trilogy, as the combination of ballistic and ultrasound energy and suction evacuation facilitates highly efficient stone removal (Figure 2B). Smaller stones or residual fragments may be extracted using a basket such as the Cook Medical Perc NCircle® basket (Figure 2C) or grasping forceps (Figure 2D). When patient anatomy allows, advancing a flexible cystoscope or ureteroscope per urethra or catheterizable channel helps locate residual fragments and relocate them for treatment via the percutaneous tract. Stone fragments may be collected for composition analysis. In patients with recurrent or elevated infection risk, we obtain a bacterial and/or fungal culture of stone material.

Exit and postoperative considerations

We perform a cystogram following stone treatment to rule out intraperitoneal extravasation (Figure 1D). There are several options for bladder drainage postoperatively. We generally leave a 14 Fr urethral Foley or a 16 Fr SPT for 5–7 days. However, no optimal duration or route of bladder catheterization has been established and thus may be directed by surgeon preference and patient anatomy.

For patients who void spontaneously per urethra, leaving a SPT capped allows the patient to void immediately after surgery, and uncapping the SPT in case of retention. An SPT can also be placed on tension to tamponade residual bleeding from the access tract if present. For patients with an augmented bladder or bowel diversion, we favor leaving the SPT for 2 weeks to allow the bowel segment adequate time to heal. Patients with a channel may continue to catheterize as usual during this time.

The access sheath is removed over a wire in case reentry is required. Holding several minutes of manual pressure over the puncture site may help achieve hemostasis. We inject a solution of 1% lidocaine and 0.25% bupivacaine along the cystostomy tract and incision for local anesthesia. The incision is then closed, and the catheter may be irrigated to ensure clear urine output.

We perform PCCL either as an outpatient surgery or with overnight observation, depending on the patient’s comorbidities, duration and complexity of the case, and concern for postoperative infection. Incisional pain is typically managed with acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and opioids are seldom necessary.

Post-PCCL urinary infections can be treated with culture-directed antibiotic therapy. Bladder stone culture, if obtained, may help guide antibiotic selection. In patients with a history of urinary retention, a longer duration of catheterization to ensure maximal bladder emptying can be considered. Septic infections are infrequent but should be treated with broad-spectrum empiric antibiotic therapy, fluid resuscitation, and bladder decompression.

Uncontrolled hemorrhage is the most common serious complication requiring active management. Bleeding due to urothelial injury during lithotripsy can be identified during inspection of the bladder before completion of the procedure. If necessary, electrocautery may be used for the fulguration of bleeding sites.

Following sheath removal and cystostomy closure, postoperative hemorrhage is often from the cystostomy tract. If an SPT was inserted, the first step is to fill the balloon to 20 mL and place the SPT on traction to provide tamponade. Continuous bladder irrigation (CBI) can be initiated using the SPT for inflow and a urethral catheter for outflow if patient anatomy allows. However, CBI may not be effective for tract site bleeding. We would advise a low threshold to return to the operating room for clot evacuation and fulguration if there is no significant improvement in hematuria and/or clinical signs of continued hemorrhage within 24 h.

Complications due to intraoperative injury are uncommon. Endoscopic orientation of the lower tract anatomy from a suprapubic trajectory may be less familiar to urologists, so care must be taken to identify and avoid the ureteral orifices during tract dilation, lithotripsy, and suction evacuation. Suction injury may result in transient edema that can obstruct ureteral drainage, so ureteral stent placement should be considered if there is any concern for injury. Care should also be taken at the posterior bladder wall, as inadvertent loss of control of the lithotripter can cause perforation and even rectal injury.

Bladder perforation is also uncommon but may be more likely to occur in patients with chronic bladder outlet obstruction and trabeculation. Performing a final cystogram prior to closure can help identify potential perforation. Most cases of intraperitoneal perforation will require open cystorrhaphy, thus underscoring the importance of extraperitoneal puncture during initial access.

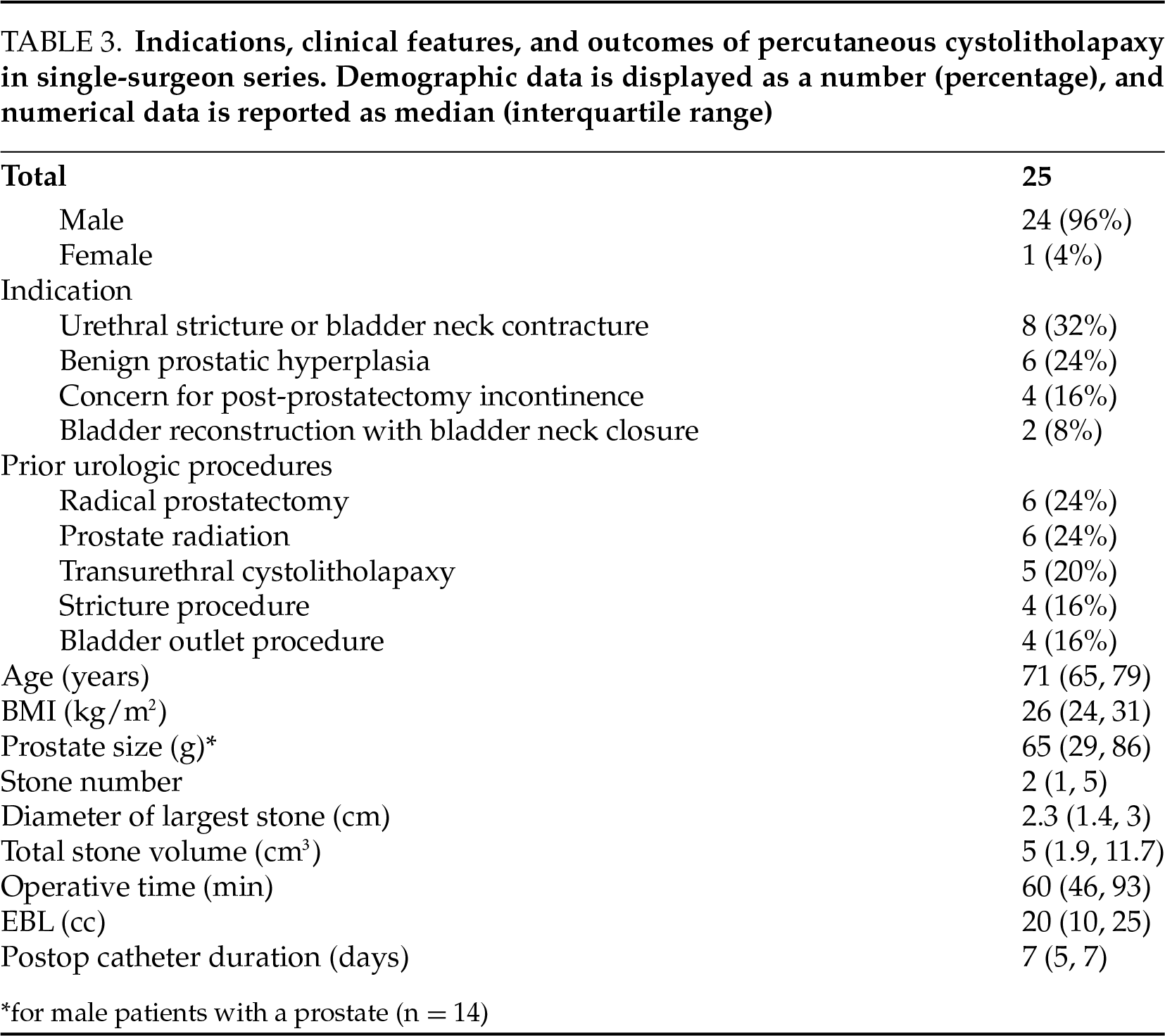

After obtaining institutional review board approval, a retrospective chart review was performed of consecutive PCCL cases performed by a single surgeon from 2020 to 2024. Indications, clinical characteristics, and outcomes are shown in Table 3. Notably, the stone-free rate was 96%—only one patient with a 900 cm3 stone required a staged open cystolithotomy. Median operative time was 60 min, 12 patients (48%) were discharged the day of surgery, and 10 patients (40%) were discharged following <24-h observation. Five patients experienced Clavien I/II complications within 30 days, and 2 patients experienced a Clavien III complication (ongoing hemorrhage requiring operative clot evacuation in both cases).

PCCL is an important technique in the stone surgeon’s arsenal to manage bladder stones in patients with complex anatomy. It has been shown to be safe and efficacious across three decades of utilization. Two studies of patients with bladder augmentation who underwent PCCL using a similar technique to that described here showed stone-free rates of 90%–95%, inpatient stays of 1.1–1.3 days, and no major complications.7,8 A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) randomized 100 boys <14 years old to TUCL vs. PCCL.9 Patients with neurogenic bladder, bladder augmentation, and urethral stricture were notably excluded. They found no significant difference in stone-free rate or hospital stay, and PCCL had a significantly shorter operative time (13 vs. 22 min).

Two systematic reviews were conducted to inform the European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines for bladder stone treatment.10 Donaldson et al. performed a systematic review and meta-analysis that included 4 RCTs comparing TUCL to PCCL.5 Notably, studies investigating patients with bladder augmentation were excluded. They found no difference in stone-free rate, unplanned procedures, major complications, or retreatment rate. TUCL had lower pain scores and hospital stays by 0.8 days. TUCL had a faster operative time when a nephroscope was utilized (−10 min) but a longer operative time with a cystoscope (+13 min). A subsequent systematic review focusing on pediatric patients included 4 retrospective studies comparing TUCL and PCCL.11 Similarly, there was no difference in stone free rate, unplanned procedures, recurrence, catheter duration, or complications. There was no significant difference in urethral stricture rate, but the authors note that the overall incidence of strictures was higher in the TUCL group. Overall, both studies found comparable stone free rates between TUCL, PCCL, and open cystolitholapaxy, with endoscopic approaches displaying shorter operative time, hospital stay, and catheter duration. Ultimately, the EAU guidelines recommend TUCL for most adults with bladder stones, which is similar to our practice. However, PCCL is the preferred procedure when TUCL is infeasible due to anatomy or unfavorable due to stone burden, as well as in children with a high risk of urethral stricture (i.e., young age, urethral reconstruction, spinal cord injury).10

After treating the bladder stone itself, it is imperative to address the root cause of stone formation. Primary/endemic bladder stones are rare in developed nations, where the most common cause is outlet obstruction from BPH. Studies have supported the safety and efficacy of concomitant cystolitholapaxy and prostate resection or enucleation,12,13 although the procedures may be staged if preferred. As single-port simple prostatectomy has been increasingly described, concomitant or stand-alone single-port cystolithotomy represents a fascinating technique for future study. In patients with bladder augmentation, regular bladder irrigations to reduce urinary stasis and evacuate debris and stone matrix have been shown to decrease stone recurrence rate.14,15 Patients with calcified extruded mesh or other foreign bodies as a nidus of stone formation should undergo concomitant or staged foreign body removal.

Finally, PCCL is an excellent procedure for educating trainees on the fundamental techniques of percutaneous endoscopic surgery. PCCL mimics nearly all the steps of PCNL, including access, scope handling, and lithotripsy. The capacious nature of the bladder and lower overall vascularity compared to the kidney reduces the risk of serious hemorrhage and allows trainees to gain universal percutaneous endoscopic surgical skills in a lower-risk environment.

Percutaneous cystolitholapaxy is a safe and efficient procedure to treat large or challenging bladder stones in patients with complex lower urinary tract anatomy. The procedure incorporates well-established techniques for percutaneous urinary surgery and can be adapted for patients with bladder outlet or urethral obstruction, urinary diversion, or abdominopelvic reconstruction. It may be performed in the outpatient setting and can be combined with procedures to address the underlying etiology of bladder stones, including BPH treatment, urethral stricture repair, or foreign body removal.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific external funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Matthew S. Lee, Kevin Koo; methodology, Matthew S. Lee, Kevin Koo; formal analysis, Matthew S. Lee, Trey R. Sledge; investigation, Matthew S. Lee, Trey R. Sledge, Kevin Koo; resources, Amanda K. Seyer, Robert Qi, Kevin Koo; data curation, Matthew S. Lee, Trey R. Sledge, Amanda K. Seyer, Robert Qi; writing—original draft preparation, Matthew S. Lee; writing—review and editing, Matthew S. Lee, Trey R. Sledge, Amanda K. Seyer, Robert Qi, Kevin Koo; visualization, Matthew S. Lee, Kevin Koo; supervision, Kevin Koo; project administration, Matthew S. Lee, Kevin Koo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Kevin Koo, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, IRB #24-010902. Informed consent has been waived.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study. Kevin Koo received royalties from UpToDate, Inc. outside the scope of this study.

References

1. Gopalakrishnan G, Bhaskar P, Jehangir E. Suprapubic lithotripsy. Br J Urol 1988;62(4):389. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.1988.tb04379.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Hakeem H, Aman HM. Percutaneous cystolithotripsy. J Endourol 1991;5(4):307–310. doi:10.1089/end.1991.5.307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ikari O, Netto NR, D’ancona CAL, Palma PCR. Percutaneous treatment of bladder stones. J Urol 1993;149(6):1499–1500. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(17)36426-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Van Savage JG, Khoury AE, McLorie GA, Churchill BM. Percutaneous vacuum vesicolithotomy under direct vision: a new technique. J Urol 1996;156(2 SUPPL. 1):706–708. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)65791-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Donaldson JF, Ruhayel Y, Skolarikos A et al. Treatment of bladder stones in adults and children: a systematic review and meta-analysis on behalf of the european association of urology urolithiasis guideline panel. Eur Urol 2019;76(3):352–367. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2019.06.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Lightner DJ, Wymer K, Sanchez J, Kavoussi L. Best practice statement on urologic procedures and antimicrobial prophylaxis. J Urol 2020;203(2):351–356. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000000509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Breda A, Mossanen M, Leppert J, Harper J, Schulam PG, Churchill B. Percutaneous cystolithotomy for calculi in reconstructed bladders: initial UCLA experience. J Urol 2010;183(5):1989–1993. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2010.01.033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Burns R, Hardesty J, Schmidt J et al. Percutaneous cystolitholapaxy is safe and effective in adult patients with lower urinary tract reconstruction utilizing bowel. Urology 2023;178:37–41. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2023.04.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Shahat AA, Kamel AA, Taha TM et al. A randomised trial comparing transurethral to percutaneous cystolithotripsy in boys. BJU Int 2022;130(2):254–261. doi:10.1111/bju.15693. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Skolarikos A, Jung H, Neisius A et al. EAU guidelines on urolithiasis: bladder stones. [Internet]; 2024. [cited 2025 Apr 28]. Available from: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/urolithiasis/chapter/bladder-stones. [Google Scholar]

11. Davis NF, Donaldson JF, Shepherd R et al. Treatment outcomes of bladder stones in children with intact bladders in developing countries: a systematic review of >1000 cases on behalf of the European Association of Urology Bladder Stones Guideline panel. J Pediatr Urol 2022;18(2):132–140. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2022.01.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Gao BM, Saadat S, Choi EJH, Jiang J, Das AK. How I do it: holmium laser cystolitholapaxy and enucleation of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia. Can J Urol 2024;31(3):11904–11907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

13. Romero-Otero J, García González L, García-Gómez B et al. Analysis of holmium laser enucleation of the prostate in a high-volume center: the impact of concomitant holmium laser cystolitholapaxy. J Endourol 2019;33(7):564–569. doi:10.1089/end.2019.0019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Hensle TW, Bingham J, Lam J, Shabsigh A. Preventing reservoir calculi after augmentation cystoplasty and continent urinary diversion: the influence of an irrigation protocol. BJU Int 2004;93(4):585–587. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2003.04664.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Husmann DA. Long-term complications following bladder augmentations in patients with spina bifida: bladder calculi, perforation of the augmented bladder and upper tract deterioration. Transl Androl Urol 2016;5(1):3–11. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.12.06. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools