Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Cryotherapy for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer—preliminary results in an animal model

1 Department of Urology, Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa, 3109601, Israel

2 Faculty of Medicine, Technion, Haifa, 3525433, Israel

3 VESSI Medical, Nesher, 368847, Israel

* Corresponding Author: Azik Hoffman. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(5), 423-432. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.064740

Received 22 February 2025; Accepted 11 August 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Initial treatment for Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer (NMIBC) has remained mostly unchanged in recent decades. Cryotherapy with CO2 has been commonly used in medicine for many years. In this study, we present the results of a pre-clinical study aimed at developing a novel cryoablation device to treat superficial low-grade bladder lesions. Methods: Following initial technical and developmental studies, a rigid cryotherapy device was developed. A technical and efficacy assessment was conducted utilizing the porcine model. Overall, twenty-six ablation areas (up to four per animal) were evaluated. Following an initial routine cystoscopy, the bladder irrigation medium was replaced with CO2 insufflation, and each area was treated with 2 cycles (15 s each) of direct liquid CO2 spraying. After five days, the bladder epithelium was harvested for pathological evaluation. Results: No bladder perforation was noted on pathology. The initial efficacy and usability of the device were demonstrated. Pathological evaluation of treated tissue morphology revealed focal mucosal edema and necrosis with associated surrounding reactive fibrosis, with penetration depths ranging from 0.5 to 4 mm, without profound muscularis propria damage. Conclusions: Initial results suggest the safety and feasibility of cryotherapy utilizing CO2 spraying. Pathological analysis confirms its potential in treating non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. Ongoing clinical studies aim to validate these results in human subjects, offering a potential paradigm shift in non-muscle invasive bladder treatment.Keywords

Non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) accounts for 75% of new bladder cancers. Current destructive treatment options have not significantly changed in several decades, and typically involve transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) followed by intravesical therapy with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) or Chemotherapy agents. The treatment is tailored based on the patient’s risk stratification (low, intermediate, or high-risk) according to guidelines published by the American Urological Association (AUA) and the European Association of Urology (EAU).1,2 TURBT remains the standard treatment for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer. However, patients should be counseled on potential risks as overall complication rates range from 5% to 20%, and 8.4% of patients experiencing more than one complication, including 3.3% having Clavien-Dindo grade 3 complications such as bleeding (14.1%) and bladder perforation (4.7%).3 These risks become a significant consideration as NMIBC often has a high rate of recurrence, despite current treatments.4,5

Cryotherapy, also known as cryosurgery or cryoablation, produces extreme cold to freeze and destroy cancer cells by utilizing liquid nitrogen or argon gas. For external tumors, liquid nitrogen is applied directly. For internal tumors, a probe is usually inserted directly into the tumor to deliver the freezing agent. Cryotherapy is utilized in various cancers, including skin cancer, liver, lung, bone, kidney, and prostate. For external cancerous lesions such as skin cancer, liquid nitrogen is applied directly using a cotton swab or spray, while internal tumors are treated by inserting the cryoprobes by ultrasound or CT guidance.6 Most treatments involve a freezing and thawing process, which is repeated several times to ensure cell death. The benefits of cryosurgery include a minimally invasive procedure in most cases, which is traditionally performed under local anesthesia, requires shorter hospital stays, and can be repeated if necessary. Additionally, this emerging treatment does not preclude surgery if needed later on and can be combined with other treatments aimed at eradicating cancerous lesions.

Recent publications support the use of cryotherapy in bladder cancer in specific clinical scenarios. Percutaneous cryotherapy has been evaluated for metastatic bladder cancer. A study involving twenty-three patients demonstrated that this approach could reduce complications such as hematuria, urinary irritation, and pain within a short period post-procedure, with a progression-free survival (PFS) of 14 ± 8 months. This suggests that percutaneous cryotherapy may be a safe and effective option in metastatic bladder cancer management.7 Endoscopic balloon cryoablation (EBCA) combined with transurethral resection (TUR) has also been investigated. A Phase 2, multicenter, randomized controlled trial compared EBCA with a single instillation of pirarubicin after TUR. The study found that EBCA had a higher local control rate (91.5% vs. 76.5%) and better recurrence-free and progression-free survival compared to the control group, indicating that EBCA is a promising adjuvant therapy for NMIBC.8

Cryoablation as an adjuvant therapy to transurethral resection has also been explored in a pilot study, proving it is feasible and safe, with no significant serious complications such as bladder perforation. The study reported a median follow-up of 9 months, in which tumor recurrence was observed in three patients, with only one recurrence at the primary tumor site. This suggests that cryoablation can effectively eliminate residual tumors post-TUR.9 These preliminary reports demonstrate improved local control rates and progression-free survival, supporting the drive to explore cryotherapy as a novel approach to improve outcomes while reducing the burden of treatment for patients.

While cryotherapy offers a promising alternative treatment for certain bladder cancers, its effectiveness can vary depending on the type and stage of cancer. Recently, an endoscopic approach to treat bladder cancer using EBCA has been reported.8 This first-in-human trial offered treatment of the cancerous lesions by transurethral resection, followed by EBRA or a single pirarubucin instillation (SI). Local control rates were 91.5% in the TUR-EBCA group compared with 76.5% in the TUR-SI arm (risk difference: 15%, 95% CI [3, 27%], p < 0.001). Despite some concern that EBCA devices could not reach the lesion’s base or cover the entire lesion surface, these results support the role of cryotherapy in selected bladder cancer lesions.

When compared with alternative bladder-sparing approaches, CO2 cryotherapy demonstrates several distinct advantages. Unlike photodynamic therapy, which requires photosensitizer administration and causes prolonged skin photosensitivity, CO2 cryotherapy offers a single-session treatment without systemic side effects. Compared to radiofrequency ablation, which carries higher procedural pain and hematuria risks (25%–35%), cryotherapy provides more precise depth control with minimal bleeding risk, making it particularly suitable for anticoagulated patients. Chemohyperthermia necessitates multiple treatment sessions with chemical cystitis occurring in up to 45% of patients, whereas CO2 cryotherapy can be completed in one session.

The basic mechanism is to decrease the mucosa temperature to form ice at the extracellular and intracellular levels. The cytotoxic effects of CO2 cryotherapy operate through distinct cellular and molecular pathways that induce both immediate necrosis and delayed apoptosis in bladder cancer cells. During the freezing phase, intracellular ice crystal formation causes direct mechanical disruption of organelles and cell membranes, leading to immediate necrotic cell death in the central treatment zone.10 Concurrently, the rapid temperature drop activates cold-shock proteins (CSPs) such as RNA-binding motif protein 3 (RBM3) and Cold-inducible RNA-binding protein (CIRP), which destabilize mRNA secondary structures and impair protein synthesis.11 In the peripheral zone where temperatures reach −20°C to −40°C, sublethally injured cells undergo membrane phase transitions with phospholipid rearrangement and ion channel dysfunction, resulting in calcium homeostasis disruption. This calcium dysregulation triggers mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening, cytochrome c release, and subsequent activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3, the executioners of the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. Additionally, CO2-induced cellular stress activates the p53 pathway, enhancing p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) and phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate-induced protein 1 (PMAIP1) expression, which further promotes mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization. During the thawing phase, reperfusion injury generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause oxidative damage to cellular components and trigger the ASK1-JNK/p38 stress response pathway, culminating in secondary apoptotic waves 24–72 h after initial treatment.6 This offers an opportunity to treat superficial bladder mucosa lesions while sparing deeper bladder wall layers. The main challenges adopting this commonly used treatment for bladder cancer include accessibility into the bladder wall, humidity inside the closed bladder tapering visibility, and possibly pressure build-up during the treatment procedure. Additionally, there is the challenge of delivering the liquid CO2 close enough to the lesion, ensuring proper coverage and constant visualization of the borders, while sparing unaffected healthy urothelium and ureteral orifices.

Vessi Medical© (Nesher, Israel) developed a novel surface cryotherapy device aimed to address all these clinical issues, being able to apply cryospray at a temperature of minus 78°C to the urinary bladder epithelium while ensuring low bladder pressure during the procedure to treat superficial NMIBC and prevent deep layer collateral damage, as usually seen in low-grade NMIBC patients treated with recurrent resections.

In this study, we suggest a novel approach to utilizing cryotherapy to treat superficial bladder cancer. Surface spray cryotherapy is being used by dermatologists and gynecologists extensively, and it is highly effective in destroying surface lesions. We developed a surface cryotherapy device to treat NMIBC lesions while replacing the fluids used during TURBT with a CO2 environment inside the bladder. We report the results of a preliminary study aimed at demonstrating the safety and efficacy of this method in an animal model.

Following regulatory approval, the study was performed in a certified Biotech lab, following the Food and Drug Administration Code of Federal Regulations 21 (Section 58—Good Laboratory Practice for Nonclinical Laboratory Studies). The study was approved by the Israeli Ministry of Health’s Council for experiments on animal subjects (Approval No. IL-19-2-73).

Seven healthy Sus scrofa domestica young female porcine 2-month-old, weighing 21–23 kg, were selected as experimental subjects based on their urinary bladder histology similarity to a healthy human bladder in volume and layer thickness, as the expected depth of bladder wall layers is 1–3 mm for lamina propria and 3.5–16 mm for muscularis propria.12 This animal model was also selected as the porcine is a well-known experimental animal, and the porcine bladder wall has similar stretch and expansion properties compared to humans.13

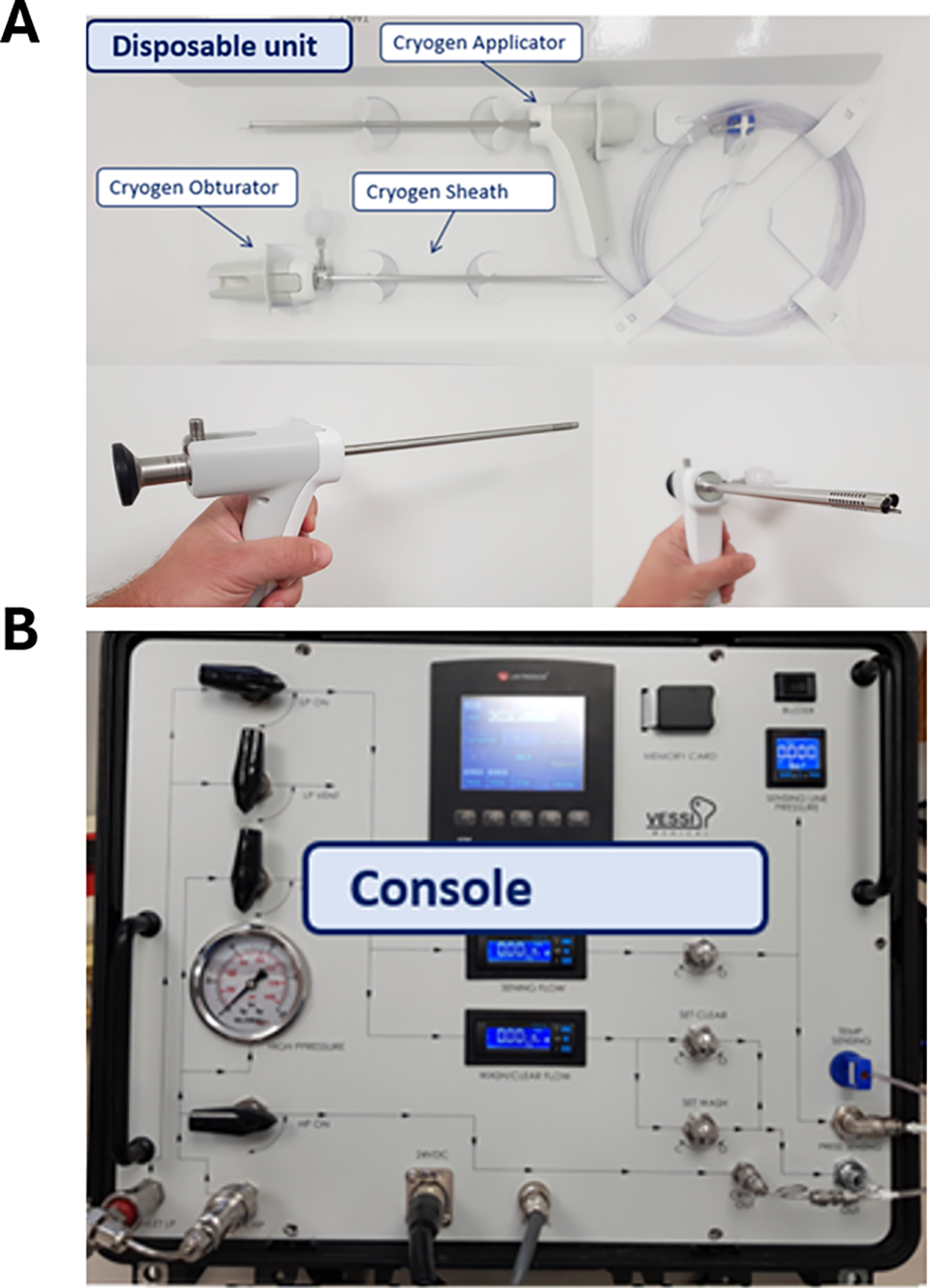

The Frigus System (Figure 1) uses compressed liquid carbon dioxide (CO2). It produces a freezing effect through a phase transition and Joule Thomson (JT) expansion. The device system is comprised of a disposable sterile single-use kit which includes a cryo-device, a sheath, and an obturator, and is controlled by a Console.

FIGURE 1. The frigus system. Frigus single-use (A) kit and (B) console

The cryo-device is inserted into the bladder through a dedicated sheath, along with a cystoscope, thus allowing the device to be properly placed inside the bladder and perform the ablation under direct visualization. The system operates by spraying CO2 fluid from an external source attached to the cryo-device and connected to the system through the console. The CO2 flows through the cryo-device and onto the tissue surface lesions while evacuating expanding CO2 during and between treatment sessions. The console controls the flow and regulates the pressure of the CO2.

CO2 was selected as the optimal cryogen for bladder tissue ablation after careful consideration of available alternatives. While liquid nitrogen and argon achieve lower temperatures (−160°C to −190°C vs. CO2’s −70°C to −80°C),10 CO2 offers several advantages specific to bladder applications. The moderate freezing rate of CO2 allows for more controlled tissue freezing, which is critical in the thin-walled bladder, where excessive freezing could lead to perforation. When applied as a spray, CO2 produces uniform surface freezing with predictable depth of penetration, which aligns with the typical treatment requirements for non-muscle invasive bladder tumors. Safety considerations also favored CO2, as it has a lower expansion ratio compared to liquid nitrogen or argon, reducing the risk of gas-related complications during endoscopic application. Our selection of CO2 as the cryogen of choice for bladder tissue cryoablation represents a carefully considered balance between ablative efficacy and safety. The moderate freezing temperature, controlled tissue penetration depth, favorable safety profile, and practical delivery considerations make CO2 particularly well-suited for the unique challenges of endoscopic bladder tissue ablation. This approach allows us to target the superficial layers of the bladder wall where most pathologies of interest reside, while minimizing the risk of full-thickness injury that could lead to serious complications such as perforation, fistula formation, or thermal injury to adjacent pelvic structures.

Cryotherapy protocol (duration of freezing, thawing, and repetition) was determined based on previously published data, stressing the need for repetitive freezing to achieve a proper response.10,14 Extensive tissue damage occurs in temperatures of −20°C to −30°C when repetitive freeze-thaw cycles are used, and permanent cell damage and death occur. Normal cells are more likely to survive at the borders of the treated area at the 0°C-isotherm line. Additionally, cells can supercool to −10°C and remain viable once the temperature returns to normal, allowing high chances of cell survival around the treatment area and preventing collateral damage. When taking into consideration normal human12 and porcine13 bladder wall thickness, the following depth-related temperature limits were set for this trial: in a depth of 0–0.5 mm: temperature below −20°C, 0.5 to 1.0 mm: temperature below −10°C, and in a depth over 2.0 mm: temperature above 0°C.

Following a proper period of animal acclimatization, the animals were sedated and put in a standard lithotomy position. Urinary bladder direct visualization and Frigus device insertion were performed using 4 mm 30-degree rigid optics throw a dedicated sheath (Figure 1). Next, the urinary bladder was emptied of urine and irrigation fluid and filled with CO2 administered through the Frigus device. As a sufficient CO2 volume was inserted, allowing for bladder expansion and proper bladder mucosa visualization, three to four treatment areas in each animal were selected at different bladder areas (base, lateral walls, and dome). Each area, measuring 0.5–1 cm in diameter, was treated with up to three cycles of cryoablation. Each treatment cycle included 15 s of active freezing and 15 s of passive thawing. During the ablation procedure, temperature and pressure were measured by the console. The cryoprobe’s CO2 flow was monitored during the entire procedure. Following treatment, the animals were monitored for 5 days. Additionally, a questionnaire rating the ease of insertion, device manipulation, bladder navigation, sheath smoothness, and general concept was evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale questionnaire (1-Unacceptable, 5-Excellent).

After 5 days of observation, in which the animals were examined for irregular signs (Fever, pain, gaiting, stress, stereotypic behavior, infection, weight loss, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, and hematuria), the animals were euthanized, the abdominal organs were examined, and the urinary bladder was harvested and sent for histological evaluation.

Bladder wall samples were placed into 4% formalin for fixation, embedded in paraffin, and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) following a routine pathological practice. A pathologist recorded comprehensive descriptions of any cellular damage (thermal and nonthermal) in the treated bladder area and non-treated areas, reporting the extent and shape of treatment-related damage in the treated areas of the bladder. Histological processing (embedding, sectioning of tissues, and preparation of slides) was performed by Patholab Laboratories, Nes Ziona, Israel.

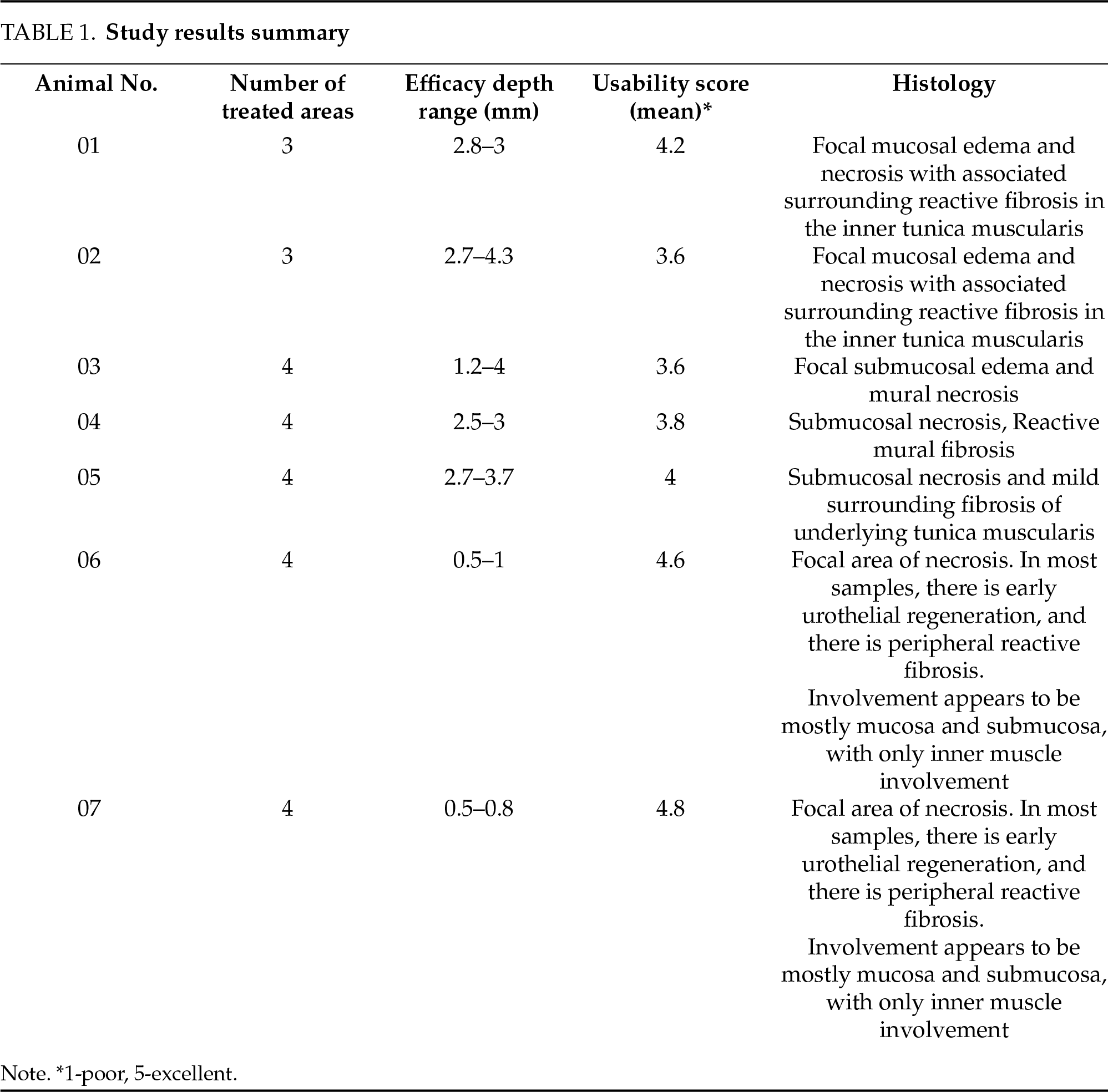

Histological reports of each animal are summarized in Table 1. Cross-sectional histological pictures of the bladder tissue are shown in Figure 2.

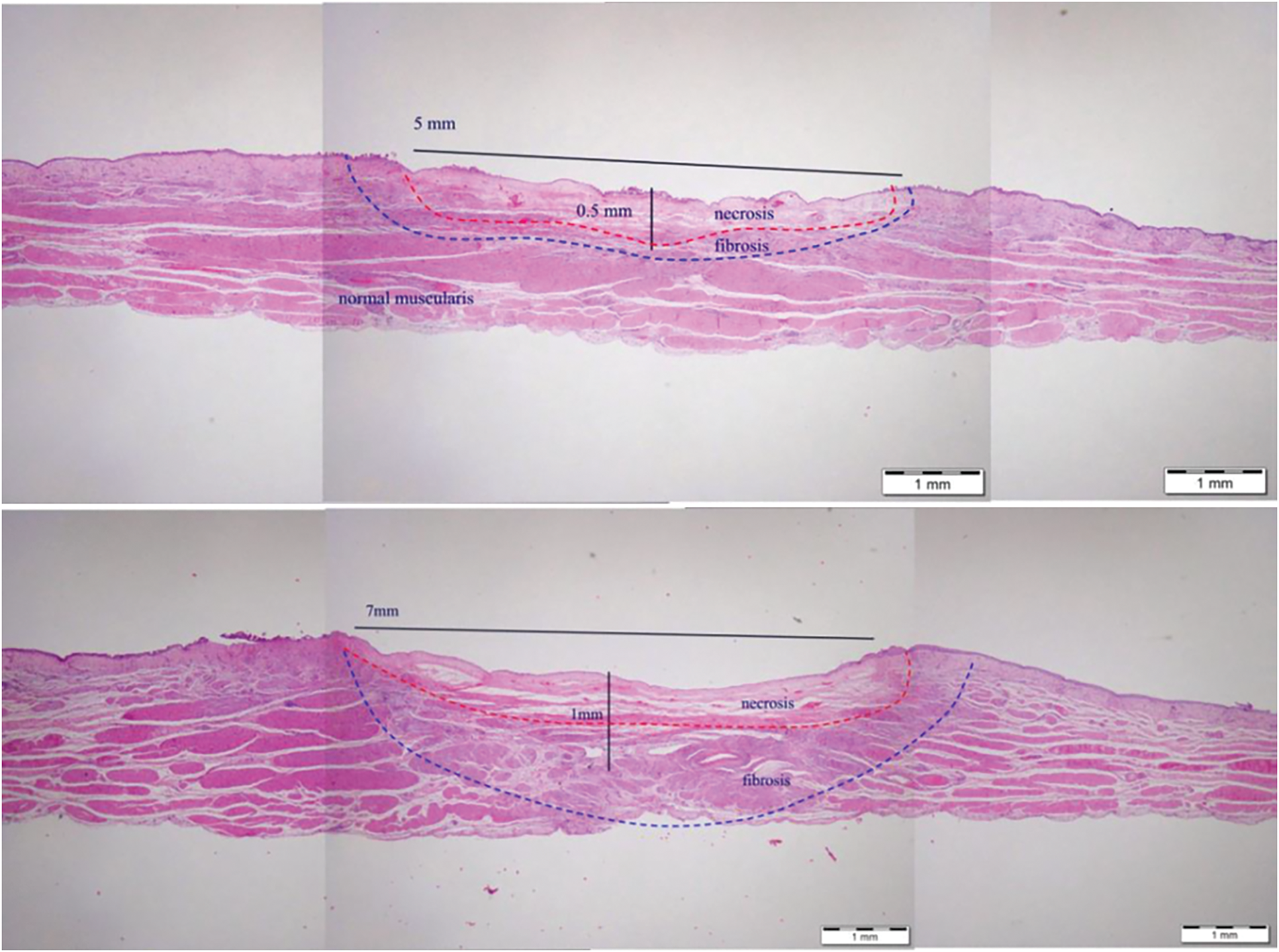

FIGURE 2. Typical cross-section histology of bladder wall

Overall, twenty-six areas of cryotherapy were evaluated. No sign of bladder perforation nor any adverse events were noted, as all animals remained healthy after treatment. Regular urination without any sign of infection or hematuria was reported. The histology of urinary bladder tissue revealed thermal cell damage confined to the intended treated area, while no surrounding tissue was damaged, and no deep layer damage or bladder perforation was observed.

Cross-sectional bladder wall histological images are illustrated in Figure 2. In general, the treated area consisted of focal mucosal edema and necrosis with associated surrounding reactive fibrosis. There was occasional focal mineralization in the areas of necrosis. Variations in the depth of necrosis were noted, which might be associated with anatomical variation in the depth of bladder wall layers.

The observed variability in CO2 cryotherapy-induced necrosis depth (0.5–4 mm) stems from multiple factors affecting clinical outcomes. Anatomical variations in bladder wall thickness and regional vascularity may influence treatment penetration. Our analysis revealed that spray distance from tissue, treatment duration, and methodological considerations in tissue processing, including fixation method, further affect depth measure.

The CO2 pressure during the procedure was recorded, as well as the urologist’s subjective response regarding the device’s usability and maneuverability in a CO2 environment. The trial results per animal are summarized in Table 1. Maximal CO2 pressure during the procedure was below 60 cm H2O, and ambient temperature was above 0°C in all animals, meeting the predetermined safety points. Cell damage depth ranged from 0.5 to 4.3 mm, with mucosal necrosis and only mild inner layers fibrosis without deep muscular layers damage.

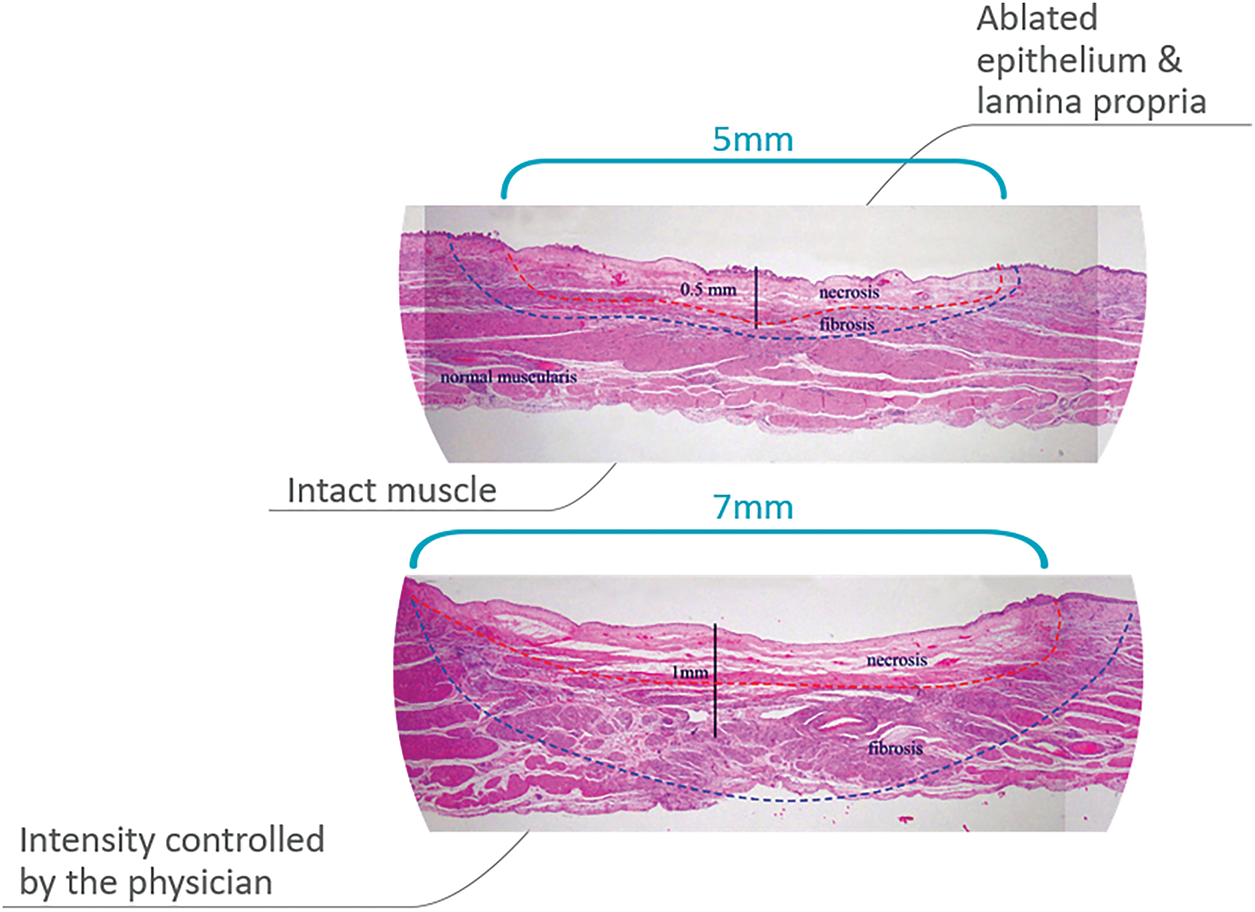

Cryotherapy was administered by a urologist, who also evaluated its usability. A mean usability score of 4 (range 3.8–4.8) on a 5-point Likert scale of 1 to 5 (1 poor, 5 excellent) was recorded, representing ease of use. Bladder mucosa visualization in a CO2 environment during and between cryo cycles was also scored and reported as excellent (data not shown). The treatment intensity during the procedure was controlled by the urologist by repeating cryotherapy treatment at the same site. The safety mechanism was set to stop the treatment cycle as the temperature or pressure reached the safety point, but the urologist was allowed to end the treatment cycle before reaching this point, to reduce the depth of tissue response as needed. This treatment feature is demonstrated in Figure 3, showing two different treatment intensities, resulting in different penetration depths without affecting the muscularis propria or causing bladder perforation.

FIGURE 3. Tissue ablation in two different treatment intensities

The concept of cryospray inside the bladder following a temporary replacement of the environment with CO2 represents a paradigm shift. While being a novel concept in treating bladder cancer, it imitates a well-established office-based treatment method to treat low-risk papillary lesions in other organs, such as the skin. Previously published attempts to utilize cryotherapy to treat bladder cancer involved the application of an EBCA under direct visualization into the lesion,8 aiming to eradicate residual bladder cancer immediately following transurethral resection and reduce recurrences by producing an ice ball at the base of the resected lesions (−100°C in a depth of 15–20 mm in two treatment cycles). Most patients had deep tumor resection before treatment, and 72% of the patients had T1 or T2a bladder cancer lesions. Despite this deep cryo treatment, no bladder perforation was noted. In contrast, the Frigus system is aimed at treating superficial bladder lesions in an office setting as a stand-alone procedure under local anesthesia and therefore is expected to decrease the risk of perforation, as demonstrated in this trial.

As described in Figure 3, the treatment modality is set to allow only maximal treatment time (15 s) per cycle within a preset low CO2 pressure controlled by a safety mechanism that stops the cryospray once a pressure buildup is measured. Maintaining low pressure allows the urologist to control the depth of the cryo effect and repeat treatments as needed.

Other investigational cryo treatments of the bladder require a similar patient setup as transurethral resection in terms of operating room resources, anesthesia, and occasionally temporary catheter placement following the procedure. The described cryospray method will allow an office-based procedure, reducing the treatment cost.

As mentioned, the concept of utilizing cryospray in a closed and humid environment inside the urinary bladder poses a challenge. The Frigus system allows a balanced low-pressure CO2 environment during the procedure while maintaining an excellent visualization for the urologist. Since most urologists are accustomed to performing the TUR procedure while the bladder is filled with irrigation fluid, the CO2 environment could be unfamiliar. Our preclinical work identified several manageable challenges when replacing traditional fluid irrigation with CO2 during bladder procedures. Effective gas management requires a dual-channel system for simultaneous instillation and evacuation. While CO2 provides superior visualization by eliminating fluid-related artifacts, it presents different mucosal appearances requiring operator adaptation. Concerns about systemic CO2 absorption appear minimal as intact urothelium provides an effective diffusion barrier. Technical implementation necessitates modest equipment modifications, including gas-tight seals, calibrated flow regulators, and integration with existing cystoscopic systems. These considerations, while important for clinical translation, do not present substantial barriers to adoption based on our preliminary testing and early first-in-human experience. Human studies utilizing this system are underway to evaluate this aspect.

The Frigus system is currently considered an investigational device. This preliminary study is set to determine the cryotherapy settings based on common cryo-biology theory and practice. The main goal was to prove the device’s ability to ablate the proper bladder wall layer (mainly mucosa, submucosa, and muscularis mucosa) without extensive muscularis propria damage. Initially, in-vivo animal studies performed before this study using two cryo-cycles with an activation time of 10–30 s per cycle demonstrated necrosis and fibrosis at a depth of 1–8 mm as the cryo tip was placed 5 to 10 mm away from the target. This is expected to prevent irreversible tissue damage to the underlying muscularis propria layer, which could cause damage to physiological bladder contraction. As most urologists are used to treating superficial non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, whether by fulguration or resection in a liquid environment utilizing saline irrigation, the concept of cryotherapy in a CO2 environment, while maintaining proper distance from the target area to ensure adequate temperature on one hand and maintaining visibility is required. High scores on visibility and maneuverability evaluations during the procedure, alongside the ease of Frigus system use, as measured during this study, may therefore have a significant impact on future utilization of this device. To maintain proper visibility, a thermocouple sensor was added near the optics’ lens aimed at preventing frost accumulation on the lens when temperatures drop to 0°C. An additional safety mechanism was to prevent bladder pressure from reaching more than 6–10 cm H2O above baseline at the end of filling, as normal bladder pressure is 5–20 cm H2O in the supine position but could reach 30–50 cm H2O while standing.15 An additional concern raised in previously published cryotherapy treatment modalities is the quality of transurethral resection of the tumor before cryotherapy, affecting treatment results.16 Since our suggested method of treatment involves directly applying the cryospray on the lesion and the ability to cover additional margins around, we believe this would translate to a favorable result when clinically evaluated in the future.

CO2 cryotherapy shows promise for combination with established NMIBC treatments to enhance efficacy and reduce recurrence. Cryoablation induces immunomodulatory effects through tumor antigen and Damage-Associated Mollecular Patterns (DAMPs) release, potentially creating synergy with immunotherapeutic agents like BCG. The disruption of cellular membranes following cryotherapy may increase the permeability and uptake of intravesical chemotherapeutic agents such as mitomycin C, enabling “cryo-enhanced drug delivery” that could maintain efficacy at lower chemotherapy doses. Additionally, controlled CO2 cryoablation may temporarily disrupt the glycosaminoglycan layer, overcoming a significant barrier to drug penetration in bladder tissue. Future trials should evaluate sequential protocols of cryotherapy followed by immediate instillation of therapeutic agents to optimize this approach for NMIBC management.

Additionally, incorporating molecular biomarkers such as CYFRA 21.1, ERCC1, p53, FGFR3, and TATI into the clinical assessment of bladder cancer could enhance the selection criteria for cryoablation candidates. For instance, tumors with FGFR3 mutations, typically associated with low-grade, non-invasive phenotypes, may respond favorably to localized therapies like cryoablation. Conversely, elevated TATI or mutated p53, which suggest more aggressive disease behavior, could indicate the need for adjunct systemic treatment or closer post-procedural surveillance. Tailoring cryoablation strategies based on these biomarkers may not only improve oncologic outcomes but also refine patient stratification for minimally invasive interventions.17

The porcine model offers excellent anatomical and physiological similarities to human bladders, including comparable wall thickness, similar stratified organization of tissue layers, analogous vascular network distribution, and comparable urothelial barrier function. However, we acknowledge several important interspecies differences that influence clinical translation. Porcine tissue demonstrates accelerated healing kinetics, with the inflammatory peak occurring 24–48 h earlier than in humans and neovascularization rates approximately 25%–30% faster. Porcine bladder tissue exhibits 15%–20% greater elasticity than human tissue, potentially affecting thermal conductivity during freezing and mechanical response to freeze-thaw cycles. Age-related differences are also significant, as our young porcine (4–6 months) have less collagen cross-linking, higher regenerative capacity, and lower baseline fibrosis than the elderly human population typically requiring intervention. This interspecies difference should be considered when translating to a clinical setting.

We recognize that the five-day observation period represents a limitation of this study. Longer-term follow-up is necessary to fully characterize tissue response, including fibrosis progression, urothelial regeneration patterns, and potential effects on bladder contractility. A separate study with extended observation is currently underway, which will provide comprehensive data on long-term tissue response and functional outcomes. These findings will be presented in a subsequent publication to complement the acute and subacute safety profile established in the current study.

In summary, this initial animal model study demonstrates the usability of the Frigus system in terms of device design, manipulation, and ability to empty the bladder of urine and replace it with CO2, creating a workspace and allowing proper maneuverability to all areas of the bladder with proper visibility. A future study is set to explore the efficacy of the Frigus system in treating recurrent low grade bladder cancer while maintaining similar safety outcomes. While our current study establishes the feasibility and the initial safety profile in the acute and subacute period of CO2 cryotherapy in normal bladder tissue, evaluation of oncologic efficacy will be addressed through future clinical investigations

Surface cryotherapy is a potential paradigm shift in the treatment of superficial bladder cancer. The tissue response to the cryo spray can be seen in real-time, allowing the assessment of the tissue destruction. Visualization is excellent and is not affected by the cryo spray at all the procedure stages. Histological results demonstrated the efficacy of tissue destruction and safety since there was no bladder perforation or bleeding. Depth of destruction was directly correlated and controlled by the time of exposure to the cryo spray. These encouraging preliminary results may allow us to proceed to first-in-human clinical trials, which were recently approved by regulatory authorities and are underway.

Acknowledgement

We wish to acknowledge the support of Dr. Michal Sudak and the Vessi Research and Development team for their administrative and technical assistance in the device development.

Funding Statement

The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Gilad E. Amiel, Eyal Kochavi; data collection, analysis, and interpretation of results: Azik Hoffman, Eyal Kochavi; draft manuscript preparation: Azik Hoffman. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Azik Hoffman, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Israeli Ministry of Health’s Council for experiments on animal subjects, approval number: IL-19-2-73.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Holzbeierlein J, Bixler BR, Buckley DI et al. Treatment of non-metastatic muscle-invasive bladder cancer: AUA/ASCO/SUO guideline (2017; Amended 2020, 2024). J Urology 2024;212(1):3–10. doi:10.1097/ju.0000000000003981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Babjuk M, Burger M, Capoun O et al. European association of urology guidelines on non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (Ta, T1, and Carcinoma in situ). Eur Urol 2022 Jan;81(1):75–94. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2021.08.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Poletajew S, Krajewski W, Gajewska D et al. Prediction of the risk of surgical complications in patients undergoing monopolar transurethral resection of bladder tumor—a prospective multicentre observational study. Arch Med Sci 2019;16(4):863–870. doi:10.5114/aoms.2019.88430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. McNall S, Hooper K, Sullivan T, Rieger-Christ K, Clements M. Treatment modalities for non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: an updated review. Cancers 2024;16(10):1843. doi:10.3390/cancers16101843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Sharma V, Chamie K, Schoenberg M et al. Natural history of multiple recurrences in intermediate-risk non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: lessons from a prospective cohort. Urology 2023;173:134–141. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2022.12.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. National Cancer Institute. Cryosurgery to treat cancer. National Institutes of Health; 2021 [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/types/surgery/cryosurgery. [Google Scholar]

7. Liang Z, Fei Y, Lizhi N et al. Percutaneous cryotherapy for metastatic bladder cancer: experience with 23 patients. Cryobiology 2014;68(1):79–83. doi:10.1016/j.cryobiol.2013.12.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Xu C, Jiang S, Zou L et al. Endoscopic balloon cryoablation plus transurethral resection for bladder cancer: a phase 2, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Cancer 2023;129(3):415–425. doi:10.1002/cncr.34563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Liu S, Zhang L, Zou L, Wen H, Ding Q, Jiang H. The feasibility and safety of cryoablation as an adjuvant therapy with transurethral resection of bladder tumor: a pilot study. Cryobiology 2016;73(2):257–260 doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2016.07.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Baust GJ, Gage AA. The molecular basis of cryosurgery. BJU Int 2005;95:1187–1191 doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2005.05502.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Zhu X, Bührer C, Wellmann S. Cold-inducible proteins CIRP and RBM3, a unique couple with activities far beyond the cold. Cell Mol Life Sci 2016;73:3839–3859. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2253-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Cheng L, Neumann RM, Scherer BG et al. Tumor size predicts the survival of patients with pathologic stage T2 bladder carcinoma: a critical evaluation of the depth of muscle invasion. Cancer 1999;85(12):2638–2647 doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19990615)85:12<2638::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-v. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Trostorf R, Morales-Orcajo E, Siebert T, Böl M. Location- and layer-dependent biomechanical and microstructural characterization of the porcine urinary bladder wall. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2021;115(2):104275. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2020.104275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Baust JG, Gage AA, Baust JM. Principles of cryoablation. In: Dermatological cryosurgery and cryotherapy. London, UK: Springer; 2016. p. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

15. Mahfouz W, Al Afraa T, Campeau L, Corcos J. Normal urodynamic parameters in women: part II—invasive urodynamics. Int Urogynecol J 2012;23(3):269–277. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1585-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ho MD, Modi PK. Novel cryotherapy in non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Cancer 2023;129(3):333–334. doi:10.1002/cncr.34560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Matuszczak M, Salagierski M. Diagnostic and prognostic potential of biomarkers CYFRA 21. 1, ERCC1, p53, FGFR3 and TATI in bladder cancers. Int J Mol Sci 2020 May 9;21(9):3360. doi:10.3390/ijms21093360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools