Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Determination and assessing the role of serum calcium, vitamin D, ferritin, and uric acid levels on prostate cancer risk

1 Department of Biostatistics & Medical Informatics, School of Medicine, Istanbul Medipol University, İstanbul, 34810, Turkey

2 Department of Evidence for Population Health Unit, School of Epidemiology and Health Sciences, The University of Manchester, Manchester, M13 9PL, UK

3 Department of Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Istanbul Atlas University, Istanbul, 34405, Turkey

4 Department of Biostatistics & Medical Informatics, School of Medicine, Istanbul Medipol University, Istanbul, 34810, Turkey

5 Department of Radiology, Medipol School of Medicine, Istanbul Medipol University, Istanbul, 34810, Turkey

* Corresponding Authors: Abdulbari Bener. Email: ,

,

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Prostate Cancer: Biomarkers, Diagnosis and Treatment)

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(5), 401-409. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.067184

Received 26 April 2025; Accepted 23 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Objectives: The evidence remains insufficient and controversial for evaluating modifiable parameters—such as vitamin D, calcium, ferritin, and uric acid—as preclinical biomarkers to contribute to the prevention and early diagnosis of prostate cancer, a disease with a prevalence of up to 10%–20% in men over 50 and strongly associated with environmental factors including diet (high in fat and red meat), obesity, physical inactivity, and carcinogen exposure. This study aims to investigate the potential biomarker role of vitamin D, calcium, ferritin, and uric acids in reducing the risk of prostate cancer (PCa). Methods: The case-control design was employed, involving 496 PCa cases and 496 controls aged 35 and above. Data collection included sociodemographic details, radiological findings, clinical history, and biochemical markers. Results: Advanced age, cigarette and hookah use, alcohol consumption, processed food intake, chemical exposure, obesity, poor dietary habits, stress, and reduced sleep duration were more prevalent in the PCa group (p < 0.05). Symptoms such as hematuria, anemia, infections, and fatigue were significantly increased (p < 0.001). Hypocalcemia (p < 0.001), vitamin D deficiency (p < 0.001), elevated uric acid levels (p < 0.001), increased ferritin (p = 0.005), and elevated systolic blood pressure (p = 0.004) were identified as key risk factors. Conclusion: The current study suggests that vitamin D, calcium, ferritin, and uric acids may serve as promising biomarkers for the detection of PCa. The rising incidence of PCa could be attributed to lifestyle, environmental, and hereditary factors, nutrition, alcohol consumption, hookah use, and cigarette smoking.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileProstate cancer (PCa) is the second most frequently diagnosed cancer in men, with nearly one million new cases reported annually worldwide.1 Several studies have identified that dietary patterns, consumption of dairy products, meat, vegetables, milk, cheese, smoking, obesity, alcohol use, physical activity and vigorous exercise, body mass index (BMI), and sedentary lifestyle as well-established risk factors for PCa.1–5 Due to the complex nature of the Western diet, which comprises a variety of factors, it is challenging to isolate which specific components contribute to the development of PCa. Over the past 50 years, a rise in early-onset PCa, defined as diagnoses before the age of 50, has been noted globally.1–4

Increased serum vitamin D levels have been linked to a reduced risk of PCa.5,6 Additionally, vitamin D supplementation may slow the progression of PCa or induce apoptosis in PCa cells.5–7 However, conflicting results in the literature make this topic highly debated. It is known that both vitamin D and calcium may reduce PCa incidence by regulating cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis.8–12 While some studies suggest that higher vitamin D levels are protective against PCa, and calcium intake plays a role in reducing the risk of both breast and PCa11–13, few interventional studies have explored the relationship between these factors and PCa specifically.12–14 Despite numerous epidemiological investigations into the connection between vitamin D and PCa risk, the findings remain inconclusive, likely due to variability in results from different case-control studies.14–18

Previous reviews on PCa have focused on specific risk factors such as lifestyle, iron, obesity, physical inactivity, dietary fiber intake, red meat consumption, and hereditary PCa.5,19 In addition, Vitamin D deficiency at the time of diagnosis has been investigated and associated with poorer overall survival, and even insufficiency may promote PCa development.1,5,8,12,15 To date, few case-control studies have thoroughly explored the potential role of vitamin D, calcium, ferritin, and uric acid in the development of PCa. Therefore, clinical evidence regarding the preventive effects of supplementation with these factors in PCa remains inconclusive.

Ferritin stores intracellular iron, preventing free iron ions, which cause the Fenton reaction, from causing oxidative stress and DNA damage. Furthermore, ferritin acts as an inflammatory acute-phase reactant, preventing inflammation in the tumor microenvironment.20 Dysfunction of ferritinophagy induces tumorigenesis through iron buildup, lipid peroxidation, and ferroptosis.21 The positive correlation between high serum ferritin levels and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) strengthens the potential of ferritin to be used as a complementary biomarker in diagnostic and prognostic evaluations of the PSA test.22 Moreover, serum levels of uric acid, the final product of purine metabolism, have been observed to be either low or high in PCa patients. Low levels mean that the body’s ability to fight off free radicals is lower and inflammation is higher. High levels, on the other hand, may cause chronic inflammation and help cells grow by blocking activin signaling.23 The finding that probenecid, a urate inhibitor, enhances cell proliferation in vitro suggests that elevated uric acid levels may facilitate the proliferation of prostate cancer cells.24 These mechanisms elevate ferritin and uric acid to clinically significant positions as both biomarkers and therapeutic targets.

The primary aim of this study is to investigate whether vitamin D, calcium, ferritin, and uric acids serve as beneficial biomarkers in preventing PCa.

This study is based on a case-control design involving male participants aged over 40 years who presented to the oncology, urology, and general outpatient clinics of Istanbul Medipol University Hospitals, Istanbul Haseki Training and Research Hospital, Prof. Dr. Cemil Taşcıoğlu City Hospital, and SSK Okmeydanı Hospital between April 24, 2023, and October 20, 2024. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and received approval from the Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine, Istanbul Medipol University (Corporate Registration No. and Ethics Approval No. E-10840098-772.02-2646).

The expected prevalence and sample size in the control group (p = 0.05) were calculated based on the assumed odds ratio (OR = 2), 95% confidence interval (CI), and 80% statistical power. The total estimated sample size, with a 1:1 enrollment of participants, was 1300. A total of 996 individuals participated in the study by giving informed consent, meaning that 76.6% of those invited responded to the study.

The control group consisted of men within the same age range (±3 years) who presented to urology and internal medicine outpatient clinics without any clinical, laboratory, or radiographic findings of PCa and without a history of the disease. Matching was primarily based on age (age 40+), but the case and control groups were also similar in terms of body mass index, comorbidities, and sociodemographic background to reduce the influence of potential external factors.

A comprehensive questionnaire was used to assess a wide range of socio-demographic and lifestyle variables, including family history, age, body mass index, tobacco and alcohol consumption, hookah use, general dietary practices, dairy consumption, physical activity. A pilot sample of 100 participants was used to test the questionnaire’s content validity, face validity, and reliability. The results showed that the questionnaire was quite valid and could be repeated (kappa = 0.85).

Radiological and clinical exams, Vitamin D levels, and other biochemical evaluations

The study evaluated biochemical markers, including testing for systolic and diastolic blood pressure. We used a competitive radioimmunoassay (RIA) for 25-hydroxy vitamin D to find out how much vitamin D was in the serum. This was done using the DiaSorin method, as described in earlier studies.5,6,16,17 For patient evaluations, we did a digital rectal exam, an MRI, a PET/CT scan, and a PSA test. We used a 1.5 Tesla General Electric Signa Voyager Premium Edition (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) for the MRI scans and the General Electric Logic S8 XDclear system (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) for the ultrasonography (USG) tests.

The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used. Student’s t-test was used to determine the significance of differences between the mean values of two continuous variables. Chi-square analysis was used to examine differences in proportions of categorical variables between two or more groups. OR and 95% CI were calculated using the Mantel-Haenszel test. Stepwise logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify the most significant predictors of malignancy, with malignancy as the dependent variable. We used the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) method for multivariable logistic regression analysis to find out the best predictors for the diagnosis of PCa as the dependent variable. The best lambda value for penalizing variables was determined by a 5-fold cross-validation method. The level p < 0.05 was considered as the cut-off value for significance.

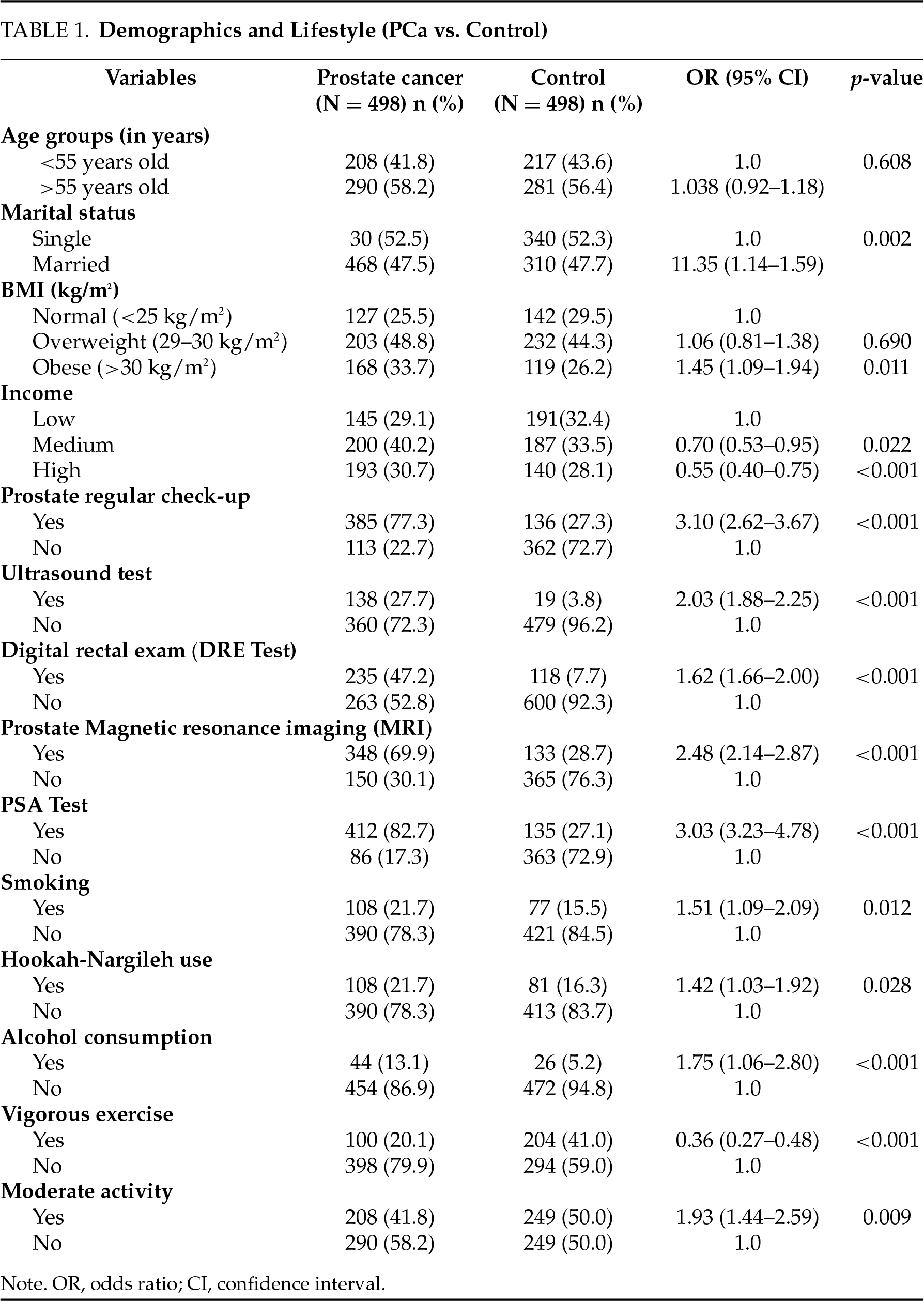

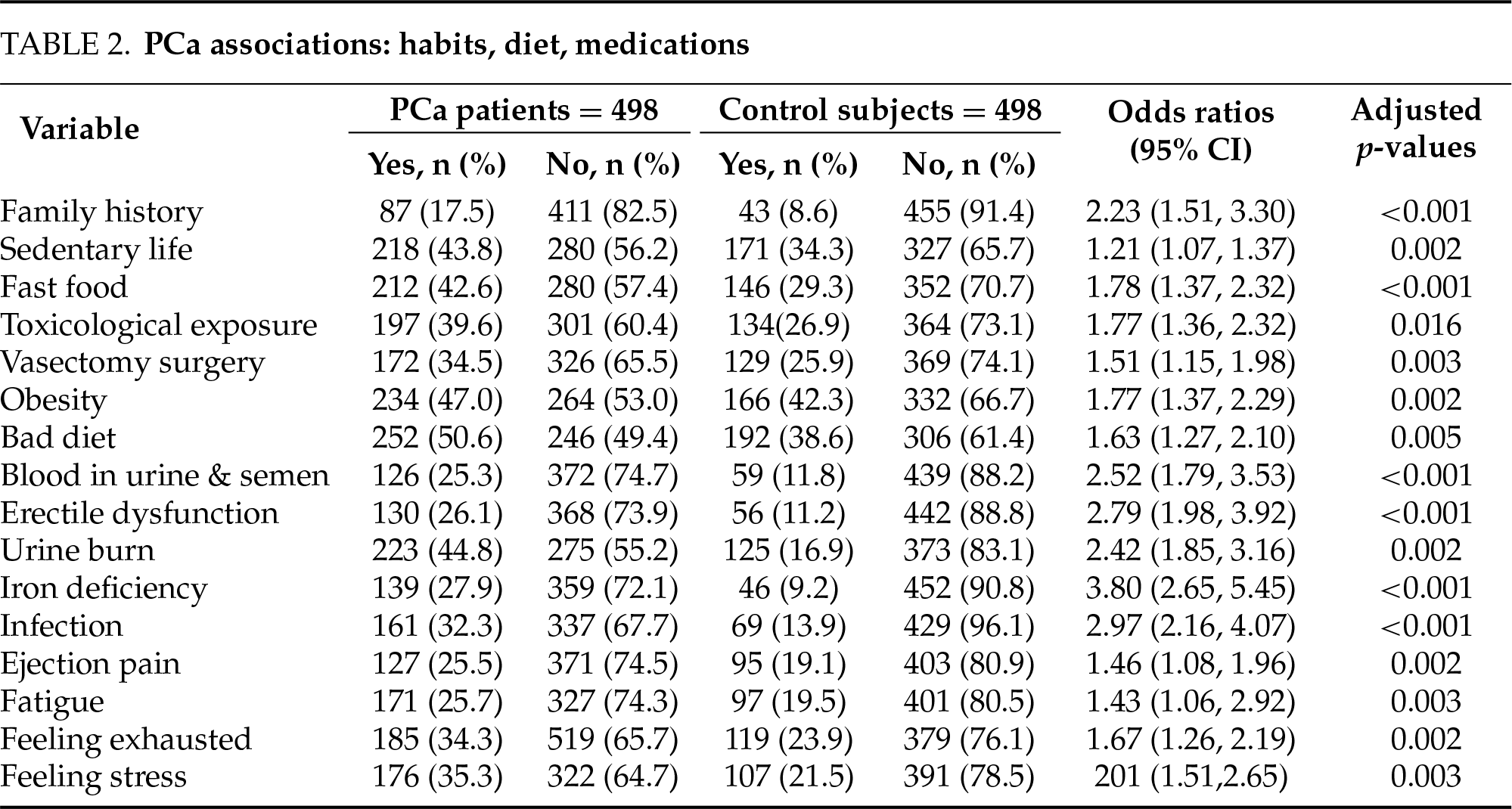

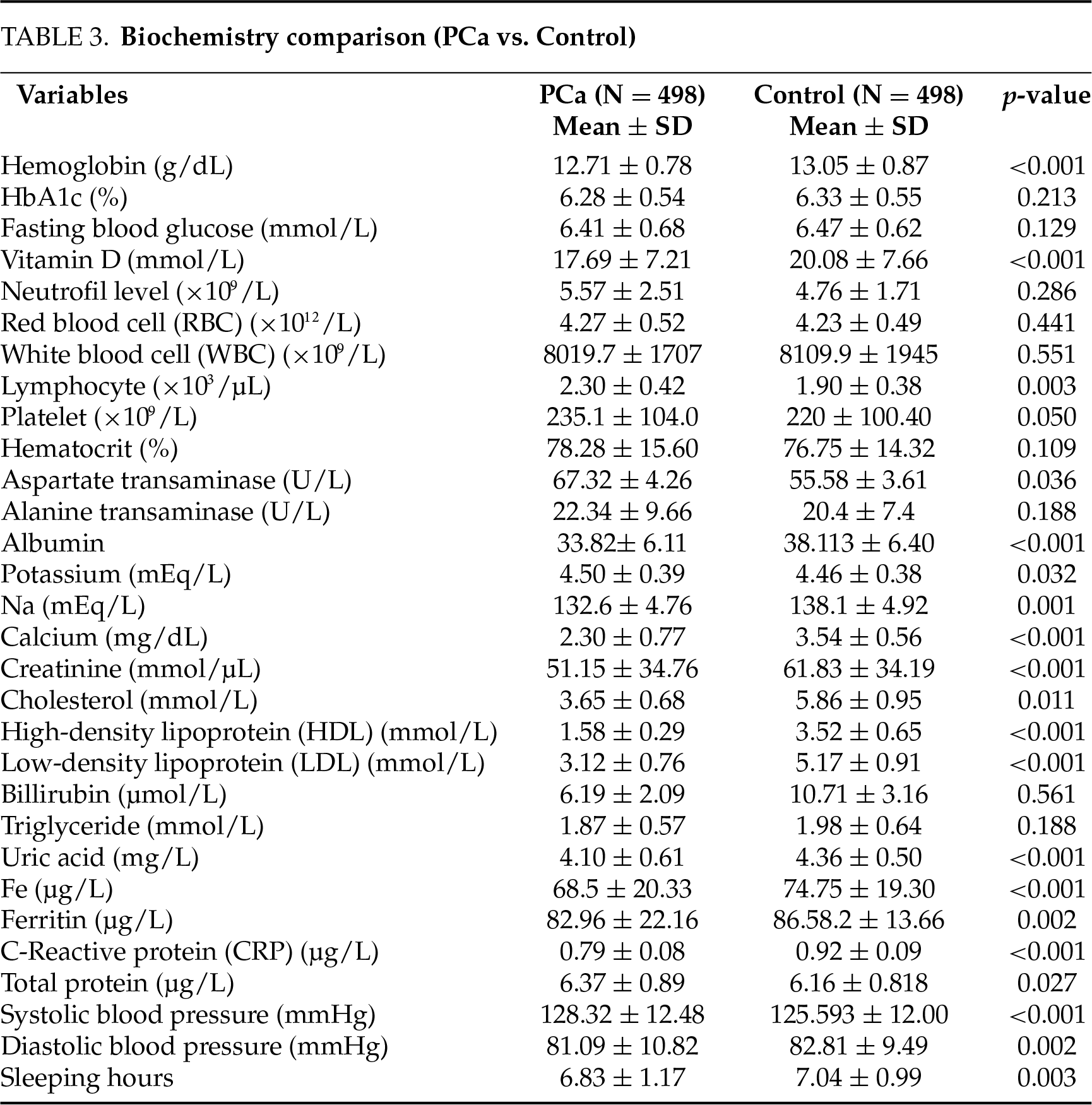

This study conducted a comprehensive comparison between PCa patients and a control group in terms of socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle habits, symptoms, and biochemical parameters. The results showed that there were big disparities between the two groups (Tables 1–4).

In terms of socio-demographic and clinical care habits, the PCa group showed significantly higher rates of regular prostate examinations (77.3% vs. 27.3%, OR = 3.10, p < 0.001), PSA testing (82.7% vs. 27.1%, OR = 3.03, p < 0.001), digital rectal examination (47.2% vs. 7.7%, OR = 1.62, p < 0.001), MRI utilization (69.9% vs. 28.7%, OR = 2.48, p < 0.001), and ultrasonography (27.7% vs. 3.8%, OR = 2.03, p < 0.001) (Table 1). Additionally, smoking (21.7% vs. 15.5%, OR = 1.51, p = 0.012), hookah use (21.7% vs. 16.3%, OR = 1.42, p = 0.028), and alcohol consumption (13.1% vs. 5.2%, OR = 1.75, p < 0.001) were more prevalent in the PCa group (Table 1). These findings underscore the critical role of lifestyle habits and healthcare utilization in PCa risk.

In terms of lifestyle and symptoms, sedentary behavior (OR = 1.21, p = 0.002), fast food consumption (OR = 1.78, p < 0.001), exposure to chemical toxins (OR = 1.77, p = 0.016), obesity (47.0% vs. 42.3%, OR = 1.77, p = 0.002), bad diet (50.6% vs. 38.6%, OR = 1.63, p = 0.005), and history of vasectomy (34.5% vs. 25.9%, OR = 1.51, p = 0.003) were significantly more frequent in PCa patients (Table 2). Moreover, blood in semen and urine (25.3% vs. 11.8%, OR = 2.52, p < 0.001), erectile dysfunction (26.1% vs. 11.2%, OR = 2.79, p < 0.001), urine burn (44.8% vs. 16.9%, OR = 2.42, p = 0.002), iron deficiency (27.9% vs. 9.2%, OR = 3.80, p < 0.001), infections (32.3% vs. 13.9%, OR = 2.97, p < 0.001), ejaculation pain, fatigue, and stress were also significantly more common in the PCa group (Table 2). These results highlight the impact of lifestyle factors on symptomatic presentations in PCa.

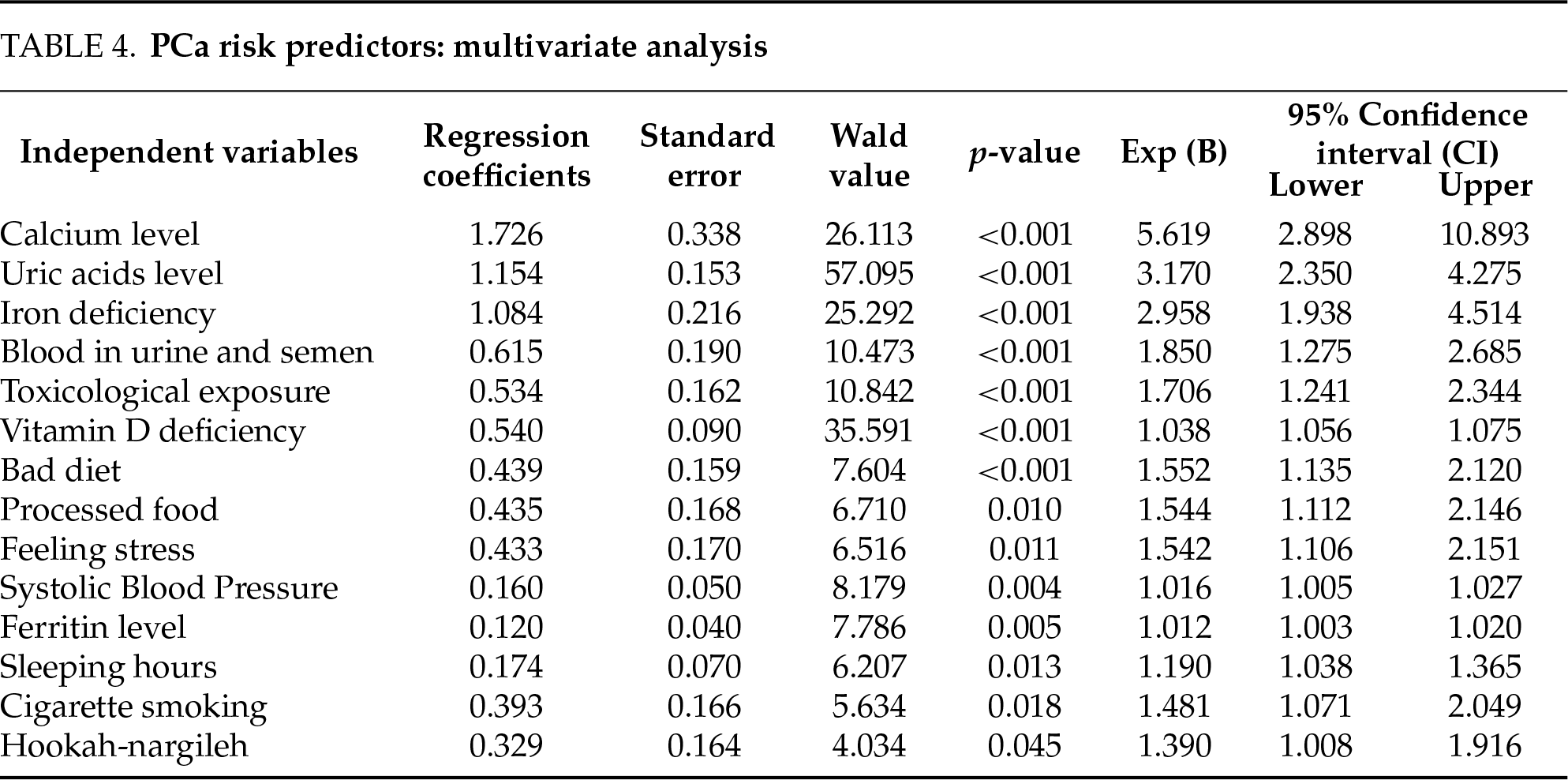

Significantly lower levels of vitamin D (17.69 ± 7.21 mmol/L vs. 20.08 ± 7.66 mmol/L, p < 0.001) and calcium (2.30 ± 0.77 mg/dL vs. 3.54 ± 0.56 mg/dL, p < 0.001) were determined in the PCa group (Table 3). Multivariate regression analysis identified vitamin D deficiency (p < 0.001) as one of the strongest risk factors for PCa (OR = 5.62, 95% CI: 2.90–10.89, p < 0.001) (Table 4). These findings indicate that vitamin D and calcium have important roles in cell cycle, apoptosis, and tumor suppression mechanisms for cancer cell development.

In contrast, ferritin (82.96 ± 22.16 µg/L vs. 86.58 ± 13.66 µg/L, p = 0.002) and uric acid (4.10 ± 0.61 mg/L vs. 4.36 ± 0.50 mg/L, p < 0.001) (Table 3) were significantly higher in the PCa group. High ferritin may contribute to tumor progression through oxidative stress and inflammation in the tumor microenvironment, while increased uric acid levels may aggravate chronic inflammation. Multivariate analysis showed that uric acid (OR = 3.17, 95% CI: 2.35–4.27, p < 0.001) and ferritin (OR = 1.012, 95% CI: 1.003–1.020, p = 0.005) were independent risk factors for PCa risk (Table 4).

Hematologically, hemoglobin levels (12.71 ± 0.78 g/dL vs. 13.05 ± 0.87 g/dL, p < 0.001) and the prevalence of iron deficiency (27.9% vs. 9.2%, OR = 3.80, p < 0.001) were significantly lower in the PCa group, whereas lymphocyte (2.30 ± 0.42 × 103/µL vs. 1.90 ± 0.38 × 103/µL, p = 0.003) were increased. These significant differences in sodium and cholesterol (total, HDL, LDL) levels explain the changes in immune response and metabolic processes associated with PCa development (Table 3). Decreased sleep duration (6.83 ± 1.17 h vs. 7.04 ± 0.99 h, p = 0.003) and increased systolic blood pressure (128.32 ± 12.48 mmHg vs. 125.59 ± 12.00 mmHg, p < 0.001) were identified in PCa patients (Table 3). These factors contribute to chronic stress and metabolic derangement and contribute to an increased risk of PCa. Finally, besides biological and environmental factors, lifestyle-related elements, including sedentary behavior, processed food intake, chemical exposure, obesity, smoking, and hookah use, were significantly associated with increased PCa risk (Table 4). Accordingly, promoting healthy lifestyle habits is essential in PCa prevention strategies. Table 4 presents the multivariate stepwise regression analysis that identified several key risk factors for PCaLow calcium levels (p < 0.001), high uric acid levels (p < 0.001), iron deficiency (p < 0.001), blood in urine and semen (p < 0.001), toxicological exposure (p < 0.001), vitamin D deficiency (p < 0.001), bed diet (p < 0.001), processed food intake (p = 0.010), stress (p = 0.011), systolic blood pressure (p = 0.004), high ferritin levels (p = 0.005), sleep hours (p = 0.013), smoking (p = 0.018), and hookah use (p = 0.045) were found to be significant predictors. These factors are considered to be the main biological, environmental, and lifestyle determinants of prostate cancer risk.

This study found significant differences in biochemistry and lifestyle between PCa patients and controls. Vitamin D deficiency, low calcium levels, high ferritin levels, and high uric acid levels were shown to be significant risk factors for PCa. Multivariate analysis confirmed that decreased serum vitamin D and calcium levels were significant independent risk factors, while increased ferritin and uric acid levels were independent indicators of PCa risk. The present findings highlight the critical role of oxidative stress and inflammation in PCa pathogenesis, suggesting that vitamin D, serum calcium, mineral metabolism disorders, ferritin, and uric acid may be potential biomarkers for the early diagnosis and treatment of PCa.

Dietary habits, consumption of dairy and meat products, vegetable intake, smoking, obesity, alcohol use, physical activity, body mass index (BMI), and a sedentary lifestyle are well-documented risk factors for prostate cancer in the current research.1–5 Findings indicate that lifestyle factors are strongly associated with PCa risk. Smoking, hookah smoking, alcohol consumption, and poor dietary habits were more prevalent among PCa patients. Our findings are consistent with studies indicating alcohol and cigarette consumption as known risk factors for PCa.19,25–27 As with other cancers, PCa risk increases dose-dependently with duration and intensity of smoking. Furthermore, alcohol and hookah consumption contribute to carcinogenesis by disrupting metabolic processes and immune function. While many studies have shown a negative correlation between PCa risk and physical activity2,26–29, this study failed to find a statistically significant association. This gap may arise from differences in the measurement of various forms of physical activity (e.g., occupational vs. leisure). Dietary patterns also showed significant effects: fast food consumption and obesity were more prevalent among PCa patients, aligning with prior literature.19,26–29

High serum vitamin D levels have previously been shown to reduce PCa risk6,7, and vitamin D supplementation has been reported to slow the progression of PCa cells or induce apoptosis in cancer cells.6,7 The active form of vitamin D (calcitriol) has been reported to inhibit proliferative signals such as c-Myc and cyclin D/CDK complexes by increasing cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors such as p21 and p27 through the nuclear vitamin D receptor (VDR) and the retinoid X receptor (RXR) complex.8,9,30 Furthermore, calcitriol promotes apoptosis by increasing Bax, Bad, and caspase-3 levels and decreasing Bcl-2 levels.9–11,31 Vitamin D also downregulates p38 MAPK signaling by inhibiting NF-κB and IL-6/COX-2 pathways, increasing MKP-5 levels, and causing anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting prostaglandin.9,12,32 Calcitriol controls CaSR and TRPC6 channels, which inhibit the growth and proliferation of cells via calcium.12,33 These dose-dependent effects of calcitriol regulate calcium signaling pathways, thereby promoting cell cycle, apoptosis, inflammation, and protective effects against PCa.

Ferritin, an iron storage protein, binds free ionic iron and inhibits the Fenton reaction. This reduces oxidative stress and ultimately prevents DNA damage.20 Furthermore, ferritin, acting as an acute-phase reactant, acts as a marker of inflammation in the tumor microenvironment. Alterations in ferritin levels due to disruption of the ferritin cycle induce lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis, contributing to tumor growth.21 Ferritin levels are positively correlated with PSA and are considered a potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker.22 Furthermore, ferritin is associated with hematological markers; low ferritin levels in prostate cancer patients have been linked to iron dysregulation and anemia, as shown in other studies.34

Uric acid is the end product of purine metabolism and plays a dual role in cancer biology. Low levels are associated with increased oxidative stress and decreased antioxidant activity, while high levels increase inflammation and proliferation.23 Uric acid uptake via membrane-mediated GLUT9 promotes growth in PCa cells via activin A.23 Furthermore, elevated uric acid contributes to cell proliferation and tumorigenesis.24 Although elevated uric acid levels are associated with PCa risk, some localized PCa cases exhibit systemic inflammation and low uric acid levels.35 Therefore, exogenous factors should also be considered in their contribution to tumor development.

In this study, serum vitamin D (p < 0.001) and calcium levels (p < 0.001) were significantly lower, while ferritin (p = 0.002) and uric acid levels (p < 0.001) were significantly higher in the PCa group. These biochemical abnormalities may be early indicators of PCa. Multivariate regression analyses confirmed that vitamin D deficiency and hypocalcemia are independent risk factors, and elevated ferritin and uric acid levels further increase the risk. In addition, the decrease in bilirubin levels in PCa patients suggests that systemic antioxidant defenses are disrupted, considering that bilirubin is an antioxidant.

The first limitation of this study is its observational approach, which precludes establishing causal links between biochemical markers and PCa; therefore, the findings should be considered correlational, and further research is needed to clarify causality. Second, because biochemical measurements were performed at only two time points, longitudinal assessment of changes during tumor growth is limited. Third, because patient selection was made and not all patients were included, a sampling bias may exist. Fourth, it should be considered that clinical assessment and PCa test classification errors could potentially influence data interpretation. Nevertheless, our large sample size makes our results more useful for others. Future studies should more comprehensively investigate the causal relationships between lifestyle factors and biochemical markers and develop personalized preventive and therapeutic strategies based on these findings.

In conclusion, low serum calcium and 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels have been recognized as independent variables that significantly increase the risk of prostate cancer. High uric acid and ferritin levels accelerate tumor growth by causing oxidative stress and inflammation, which in turn contribute to the risk of PCa. Our findings suggest that high uric acid, ferritin levels, and impaired vitamin D and calcium metabolism in PCa may be potential biomarkers for early diagnosis and risk assessment. Monitoring these biochemical markers in diagnosis and prognosis may aid in the development of personalized preventive and treatment plans, taking into account external factors.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the ethical approval and support provided by Istanbul Medipol University, specifically the Medipol School of Medicine.

Funding Statement

The authors declared that the present study has received no financial support.

Author Contributions

Abdulbari Bener: Study design and conceptualization, data curation & supervision, formal analysis and validation, writing—original draft review & editing and approval of final manuscript; Ünsal Veli Üstündağ: Study design and conceptualization, data curation, writing—original draft review & editing and approval of final manuscript; Emir Barışık: Study design and conceptualization, data curation & supervision, writing—original draft review & editing and approval of final manuscript; Cem Cahit Barışık: Study design and conceptualization, data curation & supervision, writing—original draft review & editing and approval of final manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. The data sets used or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Istanbul Medipol University Faculty of Medicine (Institutional Registration No. and Ethical Approval No. E-10840098-772.02-2646). It was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964), and written and verbal patient consent was obtained.

Informed Consent

All data published here are under the consent for publication. Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials

The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/cju.2025.067184/s1.

References

1. Ballon-Landa E, Parsons JK. Nutrition, physical activity, and lifestyle factors in prostate cancer prevention. Curr Opin Urol 2018;28(1):55–61. doi:10.1097/MOU.0000000000000460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Lopez Fontana CM, Recalde Rincon GM, Messina Lombino D, Uvilla Recupero AL, Pérez Elizalde RF, López Laur JD. Body mass index and diet affect prostate cancer development. Actas Urol Esp 2009;33:741–746. doi:10.1016/s0210-4806(09)74225-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Rawla P. Epidemiology of prostate cancer. World J Oncol 2019;10:63–89. doi:10.14740/wjon1191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Mahmoodi M, Gabal BC, Mohammadi F et al. The association between healthy and unhealthy dietary indices with prostate cancer risk: a case-control study. J Health Popul Nutr 2024;43(1):90. doi:10.1186/s41043-024-00578-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Kim MH, Yoo S, Choo MS, Cho MC, Son H, Jeong H. The role of the serum 25-OH vitamin D level on detecting prostate cancer in men with elevated prostate-specific antigen levels. Sci Rep 2022;12(1):14089. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-17563-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Campbell RA, Li J, Malone L, Levy DA. Correlative analysis of vitamin D and omega-3 fatty acid intake in men on active surveillance for prostate cancer. Urology 2021;155:110–116. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2021.04.050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Rowland GW, Schwartz GG, John EM, Ingles SA. Protective effects of low calcium intake and low calcium absorption vitamin D receptor genotype in the California Collaborative Prostate Cancer Study. Can Epidem Biomarkers Prev 2013;22(1):16–24. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0922-T. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. El-attar AZ, Hussein S, Salama MFA et al. Vitamin D receptor polymorphism and prostate cancer prognosis. Curr Urol 2022;16(4):246–255. doi:10.1097/CU9.0000000000000141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Vanhevel J, Verlinden L, Doms S, Wildiers H, Verstuyf A. The role of vitamin D in breast cancer risk and progression. Endocr-Relat Cancer 2022;29(2):R33–R55. doi:10.1530/erc-21-0182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Dallavalasa S, Tulimilli SV, Bettada VG et al. Vitamin D in cancer prevention and treatment: a review of epidemiological, preclinical, and cellular studies. Cancers 2024;16(18):3211. doi:10.3390/cancers16183211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Krajewski W, Dzięgała M, Kołodziej A, Dembowski J, Zdrojowy R. Vitamin D and urological cancers. Cent European J Urol 2016;69(2):139–147. doi:10.5173/ceju.2016.784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Mordan-McCombs S, Valrance M, Zinser G, Tenniswood M, Welsh J. Calcium, vitamin D and the vitamin D receptor: impact on prostate and breast cancer in preclinical models. Nutr Rev 2007;65(8 Pt 2):S131–S133. doi:10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.tb00341.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. A prospective study of calcium intake and incident and fatal prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15(2):203–210. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0586. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. McGrowder D, Tulloch-Reid MK, Coard KCM et al. Deficiency at diagnosis increases all-cause and prostate cancer-specific mortality in jamaican men. Cancer Cont 2022;29:10732748221131225. doi:10.1177/10732748221131225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Seraphin G, Rieger S, Hewison M, Capobianco E, Lisse TS. The impact of vitamin D on cancer: a mini review. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2023;231:106308. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2023.106308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Bener A, Öztürk AE, Barisik CC, Agan AF, Day AS. Assessing the impact of serum calcium, 25-hydroxy vitamin D, ferritin, and uric acid levels on colorectal cancer risk. J Clin Med Res 2024 Oct;16(10):483–490. doi:10.14740/jocmr5296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Bener A, Al-Hamaq AOAA, Zughaier SM, Öztürk M, Ömer A. Assessment of the role of serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D level on coronary heart disease risk with stratification among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Angiology 2021;72(1):86–92. doi:10.1177/0003319720951411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Matsushita M, Fujita K, Nonomura N. Influence of diet and nutrition on prostate cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21(4):1447. doi:10.3390/ijms21041447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Pacheco S, Pacheco F, Zapata G et al. Food habits, lifestyle factors, and risk of prostate cancer in central argentina: a case control study involving self-motivated health behavior modifications after diagnosis. Nutrients 2016 Jul 9;8(7):419. doi:10.3390/nu8070419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Vela D. Iron metabolism in prostate cancer; from basic science to new therapeutic strategies. Front Oncol 2018;8:547. doi:10.3389/fonc.2018.00547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Wang J, Wu N, Peng M et al. Ferritinophagy: research advance and clinical significance in cancers. Cell Death Disc 2023;9(1):463. doi:10.1038/s41420-023-01753-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Wang X, An P, Zeng J et al. Serum ferritin in combination with prostate-specific antigen improves predictive accuracy for prostate cancer. Oncotarget 2017;8(11):17862. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.14977. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Sangkop F, Singh G, Rodrigues E, Gold E, Bahn A. Uric acid: a modulator of prostate cells and activin sensitivity. Molec Cellul Biochem 2016;414(1):187–199. doi:10.1007/s11010-016-2671-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Uwada J, Mukai S, Terada N et al. Pleiotropic effects of probenecid on three-dimensional cultures of prostate cancer cells. Life Sci 2021;278:119554. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Macke AJ, Petrosyan A. Alcohol and prostate cancer: time to draw conclusions. Biomolecules 2022;12(3):375. doi:10.3390/biom12030375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Kawada T. Lifestyles, health habits, and prostate cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2020;146(6):1623–1624. doi:10.1007/s00432-019-02871-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Sawada N, Inoue M, Iwasaki M et al. Alcohol and smoking and subsequent risk of prostate cancer in Japanese men: the Japan Public Health Center-based prospective study. Int J Cancer 2014;134(4):971–978. doi:10.1002/ijc.28423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Yang M, Kenfield SA, Van Blarigan EL et al. Dietary patterns after prostate cancer diagnosis in relation to disease-specific and total mortality. Cancer Prev Res 2015;8:545–551. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.capr-14-0442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Er V, Lane JA, Martin RM et al. Adherence to dietary and lifestyle recommendations and prostate cancer risk in the prostate testing for cancer and treatment trial. Canc Epidem Biomark Prev 2014;23:2066–2077. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.epi-14-0322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Kawa S, Nikaido T, Aoki Y et al. Vitamin D analogues up-regulate p21 and p27 during growth inhibition of pancreatic cancer cell lines. Br J Cancer 1997;76(7):884–889. doi:10.1038/bjc.1997.479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Valle MS, Russo C, Malaguarnera L. Protective role of vitamin D against oxidative stress in diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2021;37(8):e3447. doi:10.1002/dmrr.3447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Liu W, Zhang L, Xu HJ et al. The anti-inflammatory effects of vitamin D in tumorigenesis. Int J Mol Sci 2018;19(9):2736. doi:10.3390/ijms19092736. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Ardura JA, Alvarez-Carrion L, Gutierrez-Rojas I, Alonso V. Role of calcium signaling in prostate cancer progression: effects on cancer hallmarks and bone metastatic mechanisms. Cancers 2020;12(5):1071. doi:10.3390/cancers12051071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Wu F-J, Li I-H, Chien W-C et al. Androgen deprivation therapy and the risk of iron-deficiency anemia among patients with prostate cancer: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open 2020;10(3):e034202. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Singh S, Jaiswal S, Faujdar G, Priyadarshi S. Comparison of serum uric acid levels between localised prostate cancer patients and a control group. Urologia 2024 May;91(2):320–325. doi:10.1177/03915603241228892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools