Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Performance of fluorescence in situ hybridization in detecting lower versus upper tract urothelial carcinoma

1 Department of Urology, Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, 430071, China

2 Institute of Urology, Wuhan University, Wuhan, 430071, China

3 Hubei Key Laboratory of Urological Diseases, Wuhan, 430071, China

4 Hubei Clinical Research Center for Laparoscopic/Endoscopic Urologic Surgery, Wuhan, 430071, China

5 Hubei Medical Quality Control Center for Laparoscopic/Endoscopic Urologic Surgery, Wuhan, 430071, China

* Corresponding Author: Song Xu. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(6), 579-588. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.063069

Received 03 January 2025; Accepted 01 July 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Background: Many studies have evaluated the performance of fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in detecting urothelial carcinoma, while few of them compared it in detecting bladder cancer (BC) vs. upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC). This study aimed to determine and compare the FISH performance in detecting BC and UTUC. Methods: Data of patients with suspected urothelial carcinoma (UC) who accepted FISH from January 2021 to April 2023 were retrieved. The sensitivity and specificity of FISH in detecting BC and UTUC were determined and compared. Results: A total of 145 BC, 62 UTUC, and 170 non-UC patients were included. No significant differences existed between BC and UTUC cohorts in FISH sensitivity (46.2% vs. 51.6%, p = 0.476) and specificity (100% vs. 95.8%, p = 0.271). FISH sensitivity was significantly higher in high-grade vs. low-grade BC and increased gradually from Ta to ≥T2 group. It was also higher in patients with multiple or large tumors or older age. Similar tendencies were observed in UTUC. FISH sensitivity was higher in BC vs. UTUC in detecting T1 or ≥T2 tumors (p < 0.05). Multivariate analysis confirmed the tumor stage and the patient’s age as predictors of FISH results in BC. Conclusions: FISH demonstrated overall similar sensitivity and specificity in detecting BC vs. UTUC, while the sensitivity was higher in BC for T1 or ≥T2 tumors. FISH was more sensitive in detecting more invasive or advanced tumors. The tumor stage and the patient’s age were predictors of the FISH result in BC.Keywords

Bladder cancer (BC) and upper tract urothelial carcinoma (UTUC) account for 90%−95% and 5%−10%, respectively, of urothelial carcinoma (UC).1,2 Urinary cytology is generally accepted for the diagnosis of UC with good specificity but low sensitivity. Numerous urinary molecular markers were developed to improve sensitivity, and some have been approved for clinical use.3 The multitarget fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is applied to detect chromosomal aberrations correlated with UC from exfoliated urothelial cells, mainly targeting the aneuploidy of chromosomes 3, 7, and 17 and the loss of 9p21.4 In most cases, FISH was found to be superior to urinary cytology in sensitivity in detecting UC, with no significant loss of specificity.5–7 However, few studies compared its performance in detecting BC vs. UTUC.8 Hence, this study aimed to determine and compare the performance of voided urine FISH in detecting BC and UTUC. The predictive factors of the FISH result were also explored. This study hypothesized that the diagnostic yield of FISH might be better in detecting BC vs. UTUC since a higher quantity of shedding tumor cells could be achieved in BC cases.

Ethical approval was achieved by the institutional review board of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (approval No. Kelun2021125). Data of patients who accepted the FISH test from January 2021 to April 2023 were retrieved from the hospital information system. Two major groups of UC and non-UC patients were identified. The UC group included patients with pathologically confirmed BC or UTUC through resection or biopsy of lesions. Patients were excluded if no confirmed pathological results could be obtained or in cases of conditions other than UC. The non-UC group included patients with no UC disease. It comprised two categories of patients: first, patients examined for various reasons (e.g., clinical symptoms, medical examination) and suspected BC or UTUC were observed in imaging (mainly CT urography) and/or endoscopy, while the diagnosis was finally excluded; second, patients examined for gross hematuria with no significant findings in both imaging and endoscopy. All patients accepted the FISH test before the invasive operation during the same hospital stay.

FISH sensitivity was determined in the UC group, which was calculated by dividing the number of FISH-positive patients by the total number of the group. FISH specificity was determined on the non-UC group, which was calculated by dividing the number of FISH-negative patients by the total number of the group. Comparisons between BC and UTUC were performed. Further subgroup analysis was performed by the clinicopathological characteristics of patients. The predictive factors of the FISH result were also explored. In addition, the ability of the separate probes in detecting aberrant cells was analyzed in FISH-positive UC patients.

Approximately 200 mL of fresh morning urine was collected and sent for processing within 2−3 h. The urine sample was divided into several 50 mL centrifuge tubes and then centrifuged using the TDZ5-WS centrifuge (Hunan Saite Xiangyi Centrifuge Instrument Co., Ltd., Changsha, China) at 2000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was removed. The sediment was collected into a centrifuge tube and mixed with 5 mL of hypotonic solution of potassium chloride before incubation at 37°C for 20 min. After fixing with 3:1 methanol: glacial acetic acid, the cells were spotted on glass slides and heated at 56°C for 2 h. The slides were washed with 2× saline sodium citrate (SSC) and then incubated in a pepsin solution (0.02 mg/mL) at 37°C for 10 min. After being washed in 2× SSC, the slides were dehydrated in 75%, 85%, and 100% ethanol for 2 min each and then air dried. The probe mix (Catalog number: F01008-00) (Beijing GP Medical Technologies, Ltd., Beijing, China) which contained three centromere-specific probes (CSP) for chromosomes 3, 7, and 17, and a gene locus-specific probe (GLP) for the locus 9p21 (P16) was added on the slides, which were then covered with glass coverslips and rubber sealed. Denaturation was performed at 75°C for 5 min, followed by hybridization overnight at 42°C. The slides were then washed separately in 0.3% and 0.1% Nonidet P-40 (octylphenoxypolyethoxyethanol) and dehydrated in 75%, 85%, and 100% ethanol. After air drying, the slides were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Beijing GP Medical Technologies, Ltd., Beijing, China) and coverslipped. Finally, the slides were placed in the dark for 10−20 min and then observed using an Olympus BX51 fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) under the 100× oil objective.

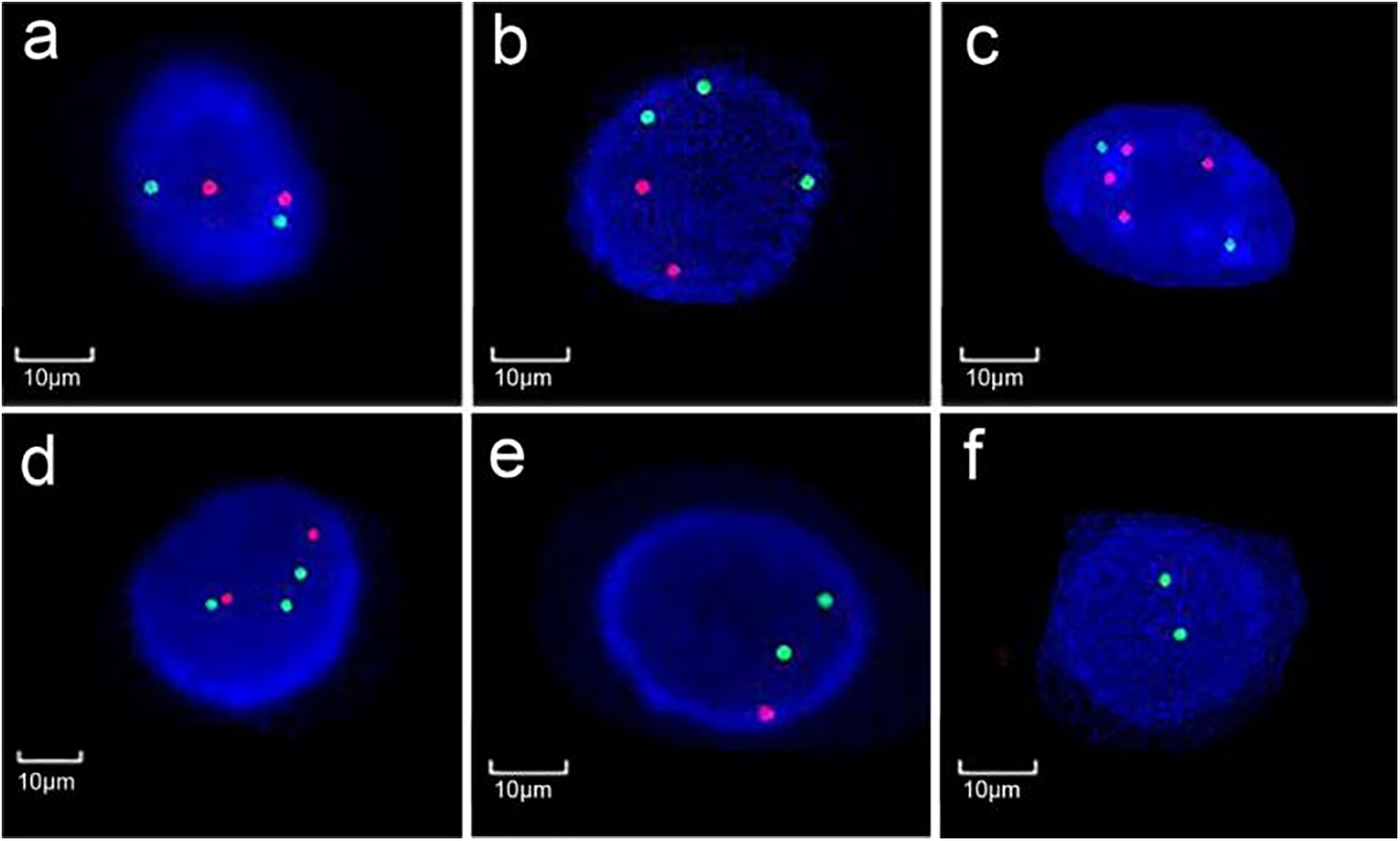

The probe mix was composed of two combinations of probes, i.e., the CSP3/CSP7 and the CSP17/GLP P16, with the labeled colors of green/red for each combination. The normal signal pattern thus included two red and two green signals in a nucleus under fluorescence microscopy using a certain filter set. Abnormality was identified in the case of the increase or loss of signals, and the increased copies 3–5 of chromosomes 3, 7, and 17 are commonly seen in the case of UC (Figure 1). According to the manufacturer’s suggestion, one hundred cells were analyzed, and the percentage of cells with abnormal signals on the target chromosomes was recorded. The cutoff values were set as 10% for aneuploidy of chromosomes 3, 7, and 17 and 15% for heterozygous deletion of P16. Positivity was considered if the cutoff values of two or more chromosomes were exceeded or a single cutoff value was exceeded but with multiple patterns of abnormality. Homozygous deletion of P16 in more than 10% of cells was also an indication of positivity. The cutoff values suggested by the manufacturer were determined in healthy controls based on the Gaussian model. They were set as the mean+3×standard deviation of the percentage of abnormal cells in control individuals.9

FIGURE 1. Different signal patterns on CSP3 (green)/CSP7 (red) or CSP17 (green)/GLP P16 (red). (a) normal diploidy of chromosomes 3 and 7; (b) polyploidy of chromosome 3, (c) 7, and (d) 17; (e) heterozygous and (f) homozygous deletion of P16 (Magnification: ×1000)

Some cautions were made to ensure the quality of the test. For example, the collection of adequate fresh morning urine and the timely processing of the sample, strict adherence to the protocol, including precise control of time and solution temperature; storage of excess cell sediments for possible retests; and prioritized analysis in large cells with irregular nuclei. In case of insufficient cell count or unsatisfactory signal intensity, the test would be redone. The tests were performed by a technologist and a second expert would be consulted in case of doubts. The conclusion would be made after discussion.

Statistical analysis was performed using R version 4.3.1. The packages of “autoReg” version 0.3.3 and “MatchIt” version 4.7.0 were used, and Pearson’s Chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare rates between groups as appropriate. A “Bonferroni” method was used for p-value adjustment for multiple comparisons. A propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was also performed to compare FISH sensitivity between BC and UTUC cohorts. Univariate and multivariate logistic regressions were used to determine predictors of the FISH result with the odds ratio (OR) calculated. The percentage of aberrant cells detected by the separate probes was compared using either a Wilcoxon rank sum test or an analysis of variance, depending on the number of subgroups stratified. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05.

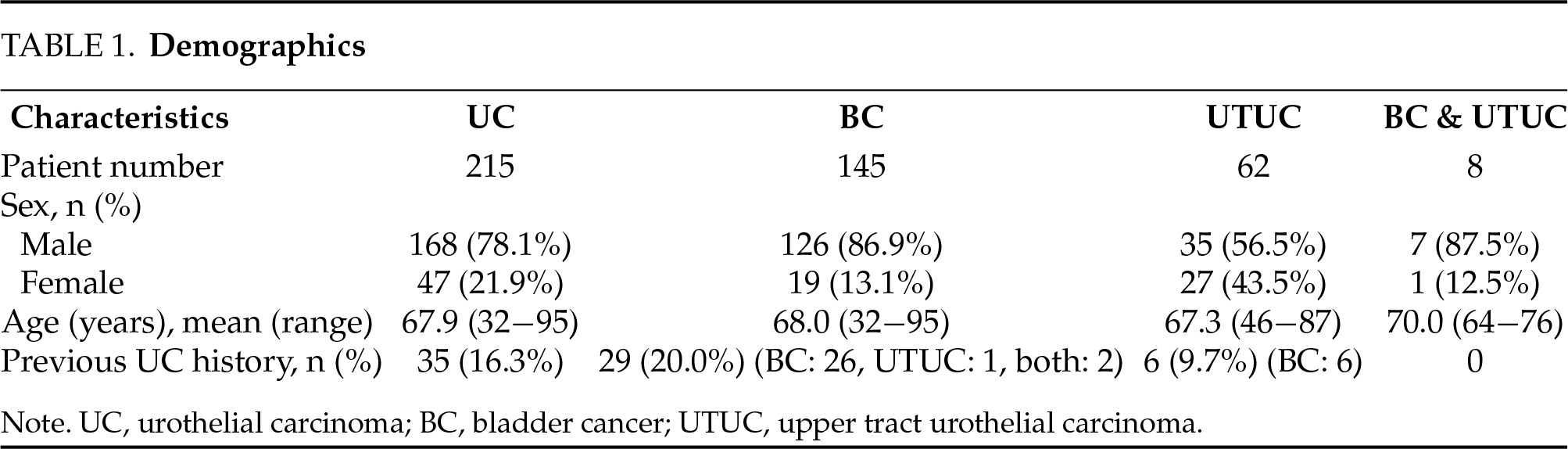

A total of 215 patients with UC were included, including 145 BC, 62 UTUC, and 8 cases with both diseases (Table 1). No significant difference in the patient age was observed between the BC and UTUC cohorts (p = 0.691). Most BC patients (86.2%) accepted transurethral resection of bladder tumors, and most UTUC patients (82.3%) accepted radical nephroureterectomy.

A total of 170 non-UC patients were included, including 49 patients with suspicious BC, 72 patients with suspicious UTUC, and 49 cases assessed for hematuria with no significant findings.

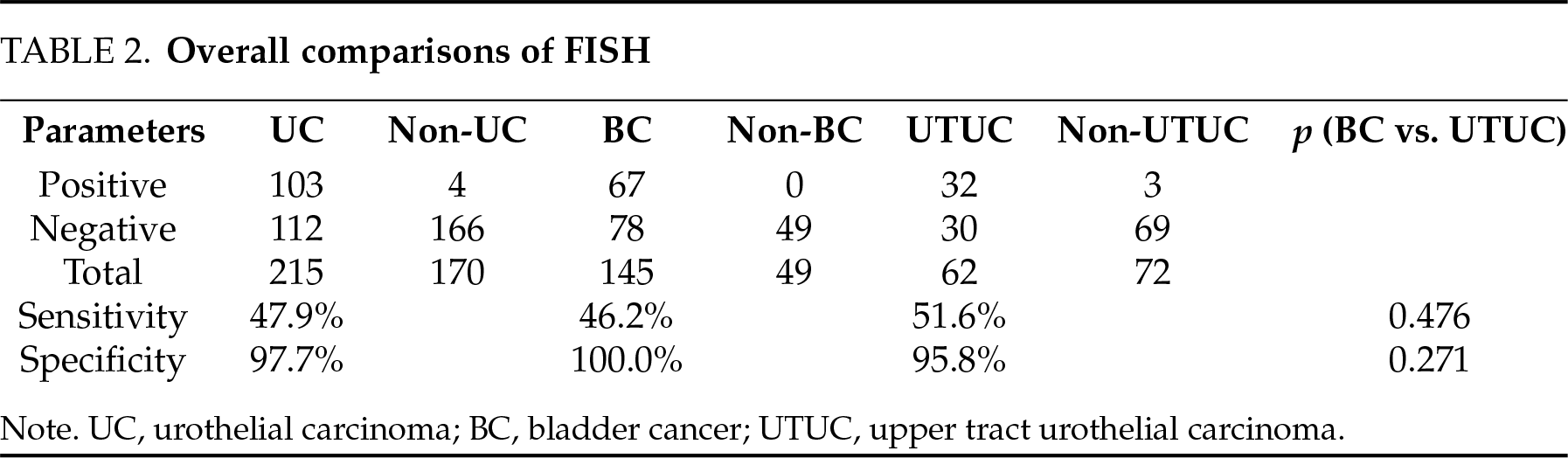

The sensitivity and specificity of FISH in detecting UC were 47.9% and 97.7%, respectively. No significant differences were determined between BC and UTUC in both measures (Table 2).

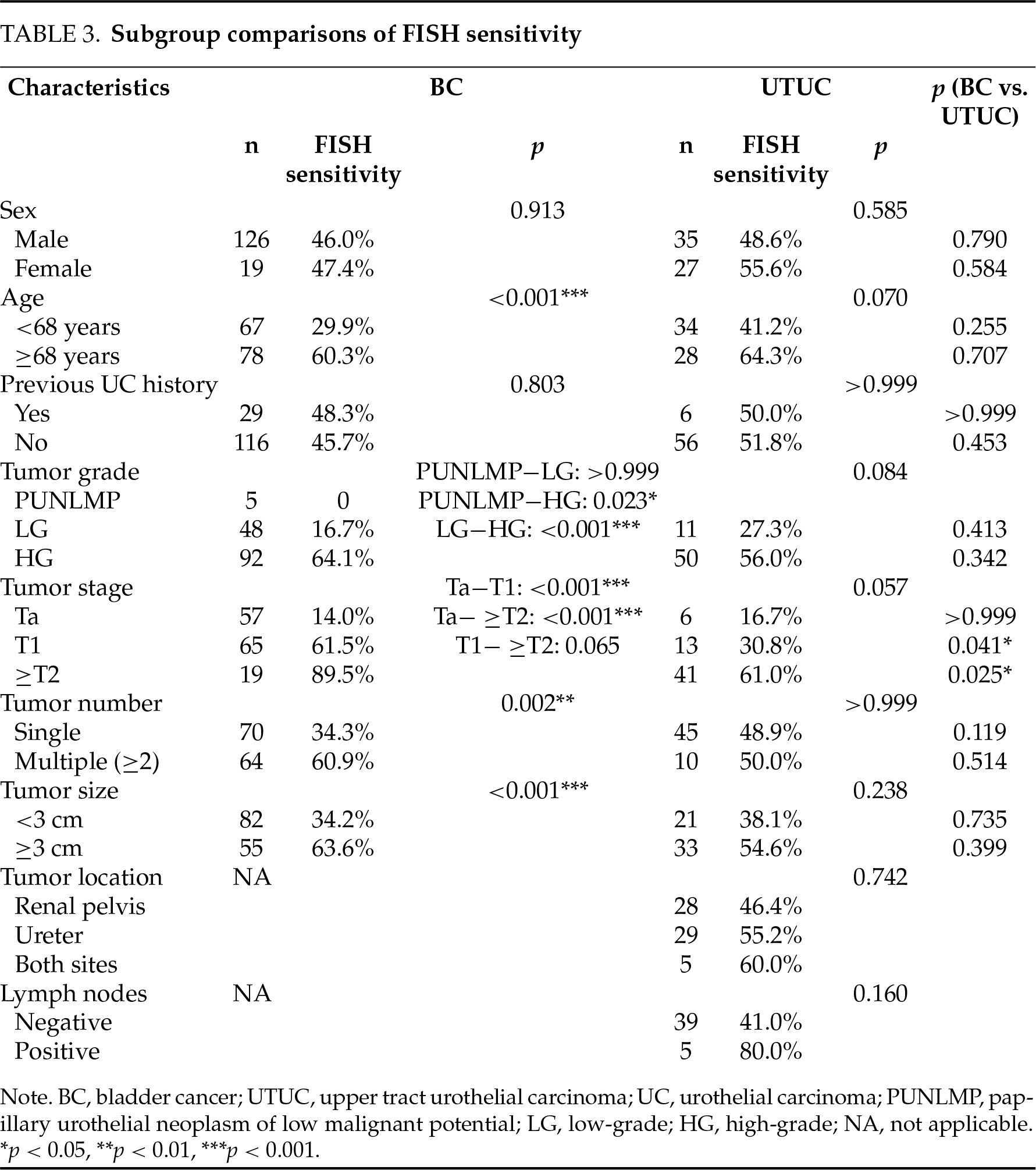

In the BC cohort, FISH sensitivity was significantly higher in patients with tumors of high grade, advanced stages, multiplicity, and large size, and also in patients with older age. Similar tendencies were observed in the UTUC cohort, while significance was only achieved in the comparison of the ≤T1 vs. the ≥T2 group. FISH sensitivity was significantly higher in BC vs. UTUC cohort in detecting T1 or ≥T2 tumors (Table 3). A 1:1 PSM analysis was performed to compare FISH sensitivity between BC and UTUC cohorts using the factors of sex, age, previous UC history, as well as the size, number, grade, and stage of tumors as covariates. Each cohort comprised 53 patients after matching, and the FISH sensitivity was 52.8% in BC vs. 47.2% in UTUC (p = 0.56).

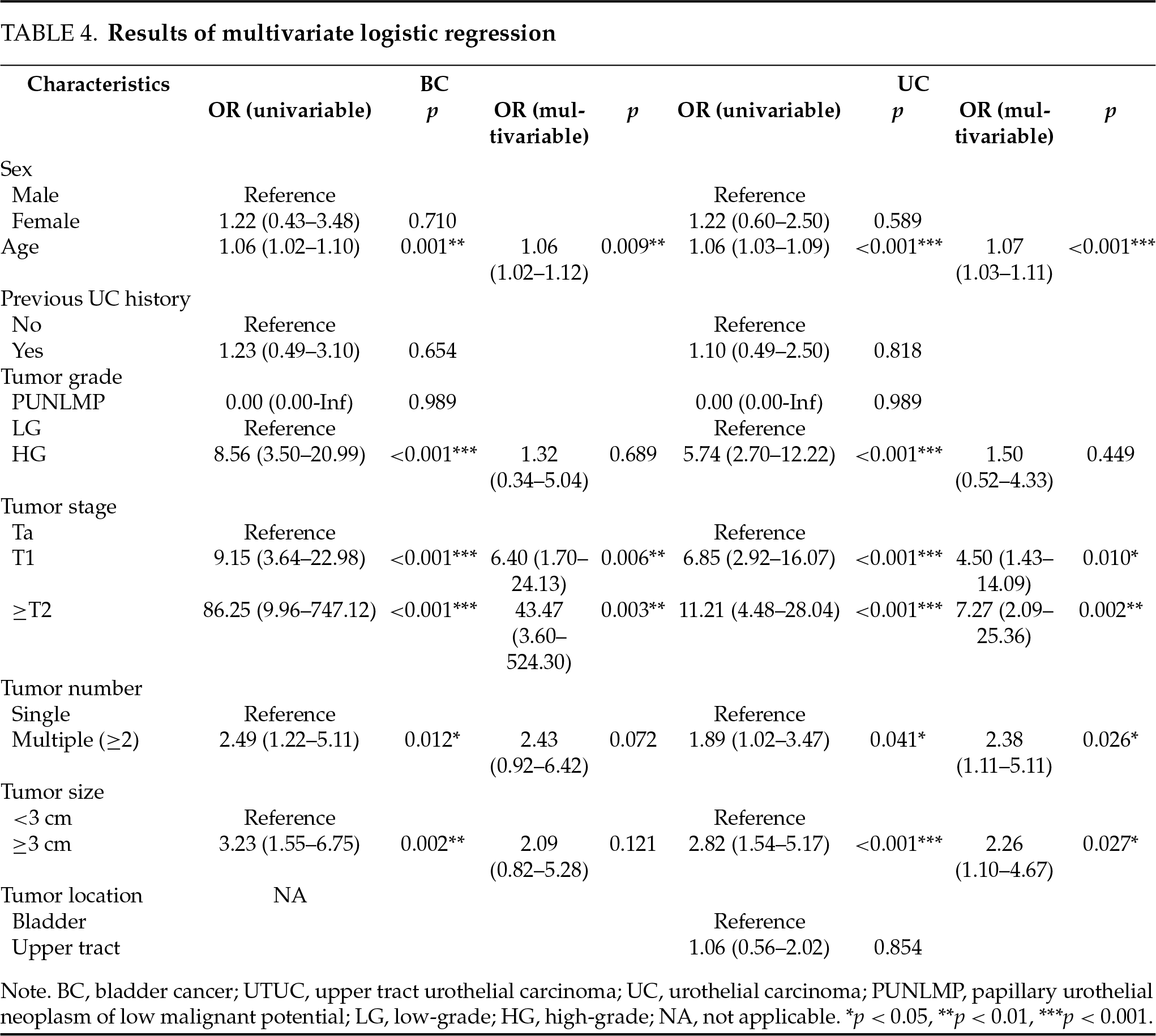

In BC, the tumor grade, stage, number, and size, as well as the patient age, were associated with the FISH results in univariate logistic regression, while only the T1 and ≥T2 stages and the patient age were proven to be predictors of FISH positivity in multivariate analysis. No corresponding predictors were determined in the UTUC cohort. When combining the data of BC and UTUC, the T1 and ≥T2 stages, the tumor multiplicity, the large tumor size, and the patient age were determined to be independent predictors of FISH positivity (Table 4).

Performance of probes in FISH-positive UC cases

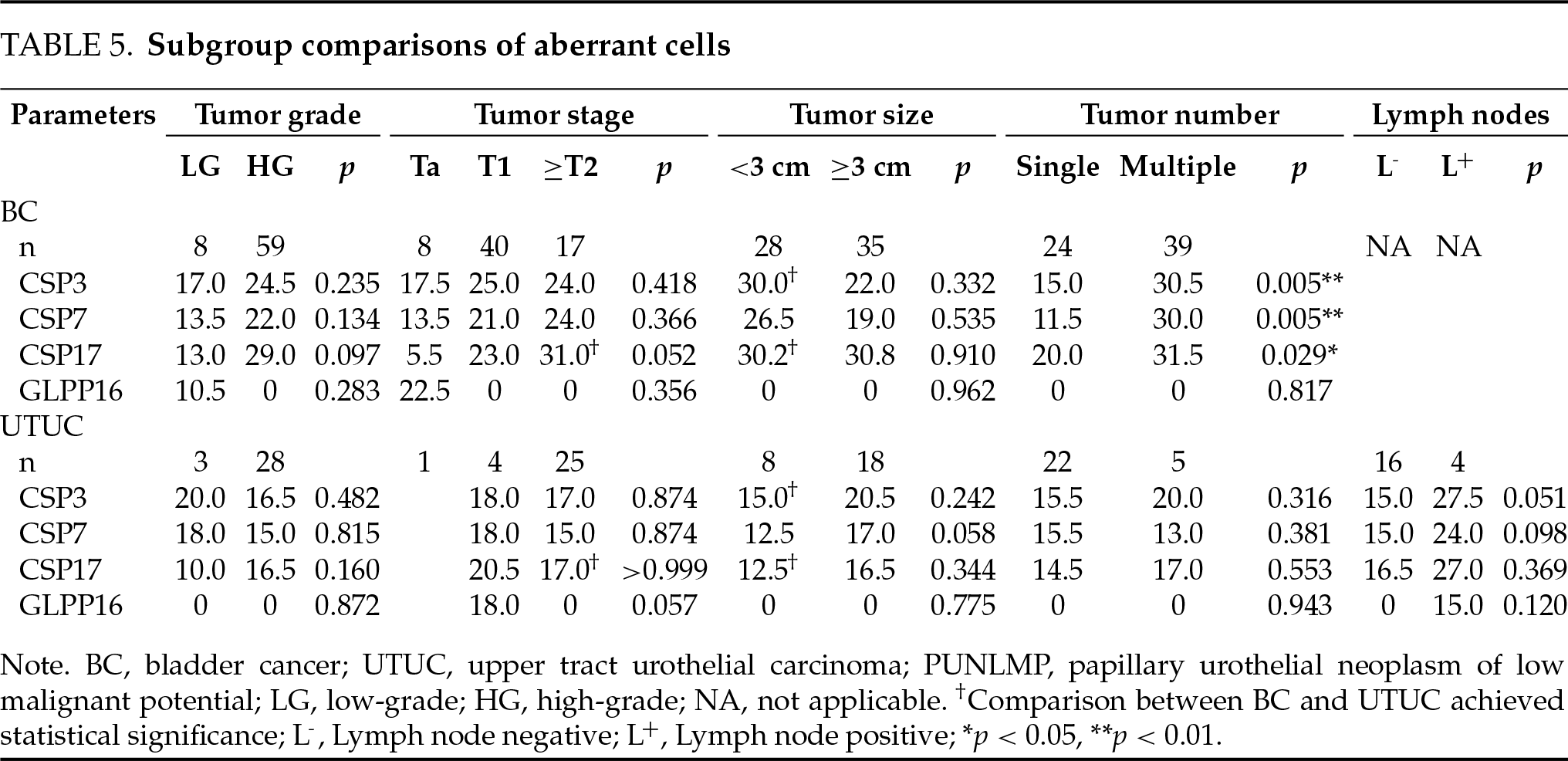

More aberrant cells seemed to be detected in BC vs. UTUC cohort by CSP3 (median 24.0 vs. 17.5), CPS7 (20.5 vs. 15.5), and CSP17 (26.0 vs. 16.0), although statistical significance was not achieved. The difference was not observed on GLP P16 (both median 0). In subgroup analysis, CSP3 detected more aberrant cells in BC vs. UTUC for small tumors, and CSP17 detected more for small tumors and ≥T2 tumors (p < 0.05). The three CSPs detected more aberrant cells in patients with multiple tumors in BC (p < 0.05) (Table 5).

This study aimed to determine and compare the FISH performance in detecting BC and UTUC. The predictive factors of the FISH result were also explored.

FISH demonstrated moderate sensitivity and good specificity in detecting UC in our series. FISH sensitivity and specificity in detecting UC varied from 54.9% to 83.6% and 73.5% to 100%, respectively, in some previous reports 6,10,11, and the specific values were 27.3%−82.7% and 69.9%−100% for BC 12,13, and 51.9%−100% and 78%−97.8 % for UTUC, respectively.14,15 Our results stayed in the ranges with a relatively low level of sensitivity and a high level of specificity. We did not perform FISH regularly for all suspicious UCs. In fact, it was often omitted for patients with relatively clear tumors in imaging or endoscopy, which may impact the sensitivity result. The FISH result may also be influenced by the subjectivity of technicians, the sampling method, the sample processing quality, and the evaluation criteria.16 In addition, not all UCs, regardless of the stage, have chromosomal alterations that could be detected by FISH. Lavery et al. performed FISH on 16 pathology samples of BC and revealed 5 (31%) negatives.17 The evaluation criteria may differ in different studies, and the manufacturer-recommended criteria were often questioned and modified by researchers to improve results.18

The stratified FISH sensitivity in our study seemed lower than that of previous reports in many cases, while the overall specificity favored our results. Yu et al. determined the FISH sensitivity of 12.5% and 94.4% in detecting non-muscle-invasive and muscle-invasive UTUC, respectively. The former was lower, while the latter was higher than our results.19 Lavery et al. used intraoperative bladder-washed urine for FISH in detecting BC and determined the sensitivity of 25% and 73% for low-grade and high-grade tumors, respectively, and 63% and 74% for ≤T1 and ≥T2 tumors, respectively. Each was higher than that of our results, except for the ≥T2 group. The overall specificity was relatively low at 72%.17 Nagai et al. determined a sensitivity of 27.3% in 40 suspected BC patients with major Ta tumors.13 Pycha et al. performed FISH using selective upper tract urine, the sensitivity was 84.6% and 100% for low-grade and high-grade UTUC, respectively. The overall specificity was 81.8%.8 Caution should be taken to the finding that FISH may also be positive in some carcinomas of non-urothelial lineages.20 Overall, large discrepancies existed in previous reports with differences in patient number and characteristics, urine sampling method, positivity criteria, etc., which render direct comparisons difficult.

An overall similar sensitivity or specificity was achieved in detecting BC vs. UTUC. However, the sensitivity was higher in BC for T1 or ≥T2 tumors. Most patients in the UTUC cohort had ≥T2 tumors, while Ta and T1 tumors accounted for most cases in the BC cohort. More aberrant cells seemed to be obtained in FISH-positive cases of BC vs. UTUC on CSP3, CSP7, and CSP17, although statistical significance was not achieved. In subgroup analysis, CSP3 detected more aberrant cells in BC for small tumors, and CSP17 detected more for small tumors and ≥T2 tumors. These results support our hypothesis that the diagnostic yield with FISH may be better in detecting BC vs. UTUC, since a higher quantity of shedding tumor cells could be achieved in BC cases. Furthermore, in case of severe upper tract obstruction caused by tumors, the yield of exfoliated cells may decrease further.19 Invasive approaches to obtain washing, brushing, or passively collecting urine from the upper urinary tract may improve detection, while it should be considered against the additional suffering, risk, and cost. Modification of the positivity criteria for better applicability in UTUC may be explored. Timely and correct sample processing, together with standardized protocol and quality control measures, should be adhered to ensure the quality of the test.18 Lin et al. determined a higher FISH sensitivity in BC vs. UTUC (84.6% vs. 73.7%) with relatively limited patient numbers, and no stratified analysis was available.21 Gomella et al. determined an overall comparable FISH sensitivity of 50.0% vs. 51.9% in detecting BC vs. UTUC, which was similar to our finding, while the specificity was lower. In addition, FISH was performed within 6 months of endoscopic evaluation, which rendered it an anticipatory instead of a diagnostic test.10 Freund et al. demonstrated the feasibility of FISH for the detection of UTUC using 1 mL of passively collected upper tract urine.22

FISH sensitivity was higher for more invasive or advanced tumors. The sensitivity was significantly higher in BC of high grade, advanced T stages, multiplicity, or large size. This is easy to understand since more shedding cells or cells with more chromosomal aberrations could be achieved in these cases. FISH sensitivity was also higher in older patients with BC, and it may share the same reason as mentioned above. Multivariate analysis confirmed the T1 and ≥T2 stages as well as the older patient age as predictors of FISH positivity in BC. When combining the data of BC and UTUC, the tumor multiplicity and the large tumor size were determined to be additional adverse predictors. The high-grade tumor was identified as an independent predictor of FISH positivity in the study of Nagai et al.13 Chen et al. found that the CSP7/CSP17 positivity was correlated with tumor stage, size, and number, as well as patient age, in patients with low-grade non-muscle-invasive BC (NMIBC).23 FISH was also used to predict the pathological stage and grade of UTUC after surgery.15,24

More aberrant cells seemed to be detected in more advanced tumors in FISH-positive UC cases. The three CSPs had more positive findings in BC of high grade, advanced stages, and multiplicity, with statistical significance achieved regarding tumor multiplicity. Most cases had no abnormality on GLP P16. The deletion of P16 was reported to occur frequently in the early stages of BC, while high-grade or invasive disease accounted for the most in our series, especially in UTUC.3 Lodde et al. identified the loss of 9p21 as the most frequent aberration in their series, which was mainly composed of patients with Ta NMIBC.25 Sharan et al. observed that the chromosome 3 polysomy was statistically significant in differentiating muscle-invasive from muscle-free high-grade UC and low-grade UC cases.26 In the study of Diao et al., the positivity of CSP3, CSP7, and CSP17 was found to be associated with muscular invasion of BC, and CSP7 positivity was identified as an independent predictor of this. P16 locus loss was identified in 22% of the cohort.27 Similarly, Xu et al. only identified 24% of UTUC cases with 9p21 loss, and it was more commonly seen in Ta and low-grade tumors. They also observed that the higher polysomy correlated with the state of a higher-grade or higher-stage tumor.28 Guan et al. declared that the P16 genetic aberrations of Chinese UTUC patients might be lower than those of patients from Western countries.29 Current commercial FISH kits generally adopt the four probes as mentioned above, while some researchers questioned their optimality and tried to locate more specific chromosomes for the detection of UC.30

This study presents some limitations. The retrospective nature may introduce bias and the issue of a lack of standardization. For example, FISH was performed based on physicians’ discretion and could be omitted if the diagnosis was clear in imaging or endoscopy. The risk of selection bias may exist for the inclusion of non-UC patients. In addition, the patient number in the UTUC cohort was relatively small, which may restrict the statistical power. The positivity criteria of FISH applied in the study were relatively stringent, which may increase the specificity at the sacrifice of sensitivity. Nonetheless, our series was relatively homogeneous with histologically confirmed UC and effective FISH results before surgery during the same hospital stay. It provided detailed stratified data for comparisons between BC and UTUC, which were not available in previous reports. Prospective studies would be needed to further clarify the issue.

FISH demonstrated overall similar sensitivity and specificity in detecting BC vs. UTUC, while the sensitivity was higher in BC for T1 or ≥T2 tumors. FISH was more sensitive in detecting more invasive or advanced tumors. The T1 and ≥T2 stages and the older patient age were predictors of FISH positivity in BC. The tumor multiplicity and the large tumor size were additional predictors in UC. More aberrant cells could be yielded in FISH-positive cases of BC vs. UTUC and in FISH-positive cases of UC with more advanced tumors.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author Contributions

Song Xu: Protocol development, Data collection and management, Data analysis, Manuscript writing and editing. Mengxin Lu: Data collection, Data analysis, Manuscript writing. Zhonghua Yang: Data collection, Administrative support. Hang Zheng: Protocol development, Manuscript editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the institutional review board of Zhongnan Hospital of Wuhan University (approval No. Kelun2021125) and was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Individual consent for this retrospective study was waived.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2025. CA Cancer J Clin 2025;75:10–45. doi:10.3322/caac.21871. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. European Association of Urology. EAU guidelines on non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (TaT1 and CIS). [cited 2025 Jun 15]. Available from: https://uroweb.org/guidelines/non-muscle-invasive-bladder-cancer. [Google Scholar]

3. La Maestra S, Benvenuti M, D’Agostini F, Micale RT. Comet-FISH analysis of urothelial cells. A screening opportunity for bladder cancer? Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2023;23(8):653–663. doi:10.1080/14737159.2023.2227381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zheng J, Lu S, Huang Y et al. Preoperative fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis as a predictor of tumor recurrence in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: a bi-institutional study. J Transl Med 2023;21(1):685. doi:10.1186/s12967-023-04528-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Kavcic N, Peric I, Zagorac A, Kokalj Vokac N. Clinical evaluation of two non-invasive genetic tests for detection and monitoring of urothelial carcinoma: validation of UroVysion and Xpert Bladder Cancer Detection Test. Front Genet 2022;13:839598. doi:10.3389/fgene.2022.839598. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Shang D, Liu Y, Xu X, Chen Z, Wang D. Diagnostic value comparison of CellDetect, fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISHand cytology in urothelial carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int 2021;21(1):465. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-472514/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Carmona O, Kleinmann N, Zilberman DE, Dotan ZA, Shvero A. Do urine cytology and FISH analysis have a role in the follow-up protocol of upper tract urothelial carcinoma? Clin Genitourin Cancer 2024;22(1):98–105. doi:10.1016/j.clgc.2023.10.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Pycha S, Trenti E, Mian C et al. Diagnostic value of Xpert® BC Detection, Bladder Epicheck®, Urovysion® FISH and cytology in the detection of upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. World J Urol 2023;41(5):1323–1328. doi:10.1007/s00345-023-04350-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Sun J-J, Wu Y, Lu Y-M et al. Immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization can inform the differential diagnosis of low-grade noninvasive urothelial carcinoma with an inverted growth pattern and inverted urothelial papilloma. PLoS One 2015;10(7):e0133530. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Gomella LG, Mann MJ, Cleary RC et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) in the diagnosis of bladder and upper tract urothelial carcinoma: the largest single-institution experience to date. Can J Urol 2017;24(1):8620–8626. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2016.02.976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Thuzar M, Flowers A, Takei H. Optimizing UroVysion fluorescence in-situ hybridization reflex testing in atypical urothelial cell diagnosis: a comprehensive cytomorphological analysis. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2024;54(6):837–844. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

12. Zhou L, Yang K, Li X et al. Application of fluorescence in situ hybridization in the detection of bladder transitional-cell carcinoma: A multi-center clinical study based on Chinese population. Asian J Urol 2019;6(1):114–121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

13. Nagai T, Okamura T, Yanase T et al. Examination of diagnostic accuracy of UroVysion fluorescence in situ hybridization for bladder cancer in a single community of Japanese hospital patients. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2019;20(4):1271–1273. doi:10.31557/apjcp.2019.20.4.1271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Mian C, Mazzoleni G, Vikoler S et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridisation in the diagnosis of upper urinary tract tumours. Eur Urol 2010;58(2):288–292. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2010.04.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Su X, Hao H, Li X et al. Fluorescence in situ hybridization status of voided urine predicts invasive and high-grade upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017;8(16):26106–26111. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.15344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zheng W, Lin T, Chen Z et al. The role of fluorescence in situ hybridization in the surveillance of non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Diagnostics 2022;12(8):2005. doi:10.3390/diagnostics12082005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Lavery HJ, Zaharieva B, McFaddin A, Heerema N, Pohar KS. A prospective comparison of UroVysion FISH and urine cytology in bladder cancer detection. BMC Cancer 2017;17(1):247. doi:10.1186/s12885-017-3227-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Nagai T, Naiki T, Etani T et al. UroVysion fluorescence in situ hybridization in urothelial carcinoma: a narrative review and future perspectives. Transl Androl Urol 2021;10(4):1908–1917. doi:10.21037/tau-20-1207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Yu J, Xiong H, Wei C, Cui Z, Jin X, Zhang J. Utility of fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis for detecting upper urinary tract-urothelial carcinoma. J Cancer Res Ther 2017;13(4):647–650. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

20. Ke C, Liu X, Wan J, Hu Z, Yang C. UroVysion™ fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) possibly has a high positive rate in carcinoma of non-urothelial lineages. Front Mol Biosci 2023;10:1250442. doi:10.3389/fmolb.2023.1250442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Lin T, Liu Z, Liu L et al. Prospective evaluation of fluorescence in situ hybridization for diagnosing urothelial carcinoma. Oncol Lett 2017;13(5):3928–3934. doi:10.3892/ol.2017.5926. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Freund JE, Liem EIML, Savci-Heijink CD, de Reijke TM. Fluorescence in situ hybridization in 1 mL of selective urine for the detection of upper tract urothelial carcinoma: a feasibility study. Med Oncol 2019;36(1):10. doi:10.1007/s12032-018-1237-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Chen Y, Tao B, Peng Y et al. Utility of Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to sub-classify low-grade urothelial carcinoma for prognostication. Med Sci Monit 2017;23:3161–3167. doi:10.12659/msm.902481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Xu B, Zhang J-E, Ye L, Yuan C-W. Evaluation of the diagnostic efficiency of voided urine fluorescence in situ hybridization for predicting the pathology of preoperative low-risk upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Front Oncol 2023;13:1225428. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1225428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Lodde M, Mian C, Mayr R et al. Recurrence and progression in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer: Prognostic models including multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization molecular grading. Int J Urol 2014;21(10):968–972. doi:10.1111/iju.12509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Sharan KC, Srinivasan R, Uppal R et al. Utility of UroVysion fluorescence in situ hybridization in improving the diagnostic performance of urine cytology. Acta Cytol 2024;68(5):423–435. doi:10.1159/000540070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Diao X, Cai J, Zheng J et al. Association of chromosome 7 aneuploidy measured by fluorescence in situ hybridization assay with muscular invasion in bladder cancer. Cancer Commun 2020;40(4):167–180. doi:10.1002/cac2.12017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Xu C, Zeng Q, Hou J et al. Utility of a modality combining FISH and cytology in upper tract urothelial carcinoma detection in voided urine samples of Chinese patients. Urology 2011;77(3):636–641. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2010.07.498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Guan B, Du Y, Su X et al. Positive urinary fluorescence in situ hybridization indicates poor prognosis in patients with upper tract urothelial carcinoma. Oncotarget 2018;9(18):14652–14660. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.24007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Anderson T, Hartman S, Dunn W et al. Technical comparison of Abbott’s UroVysion® and Biocare’s CytoFISH urine fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assays. Cancer Cell Int 2023;23(1):314. doi:10.1186/s12935-023-03156-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools