Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Donor-gifted nephrolithiasis: case-based analysis and comparative study

1 Department of Urology, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Winston Salem, NC 27101, USA

2 Chicago Medical School, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, IL 60064, USA

3 College of Medicine, Northeast Ohio Medical University, Rootstown, OH 44272, USA

4 Campbell School of Osteopathic Medicine, Lillington, NC 27546, USA

5 Section of Transplantation, Department of General Surgery, Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center, Winston Salem, NC 27157, USA

6 University of Alabama Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294, USA

* Corresponding Author: Maxwell Sandberg. Email:

Canadian Journal of Urology 2025, 32(6), 633-641. https://doi.org/10.32604/cju.2025.069091

Received 14 June 2025; Accepted 04 September 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

Objectives: Donor-gifted nephrolithiasis—the presence of a stone in a donor kidney at the time of transplantation—is rare. Research is limited, and no consensus high-quality evidence guidelines exist, leaving selection criteria and management to individual provider discretion. We aimed to estimate the frequency and analyze patient and graft outcomes of deceased donor (DD) transplant recipients with stones in their kidneys at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. Methods: All DD renal transplants or patients receiving most of their care postoperatively after DD renal transplantation at our institution from 1979 to 2025 were reviewed. Stones were considered donor-gifted if discovered during transplantation or on imaging within two weeks of the transplant date. Patient, stone, and graft outcomes were followed over time. Stone size on imaging was compared between patients who were treated versus surveyed for their donor-gifted stones using an independent samples t-test. Results: Of 4723 patients who underwent DD renal transplant, eight were found to have a graft with stones at transplant (0.2%). The median stone size was 8 mm. Three (38%) patients underwent treatment for stones, and five (62%) underwent surveillance. Two (25%) patients experienced graft failure, and one of these patients received stone treatment. Conclusions: The frequency of donor-gifted nephrolithiasis is extremely low in DD transplant patients. Despite a small sample set, these results demonstrate favorable outcomes and provide support for the feasibility of intentionally performing DD renal transplantation in grafts with known stones.Keywords

Donor-gifted (graft) nephrolithiasis refers to one or more calculi in the donor kidney at the time of transplantation. This finding is distinctly different from de novo stone formation, which occurs post-transplant. Previously, the acceptance of donor kidneys with stones was a relative, if not absolute, contraindication to deceased donor kidney transplantation (DDKT).1 However, good outcomes in living donor transplants using kidneys with stones and in those who develop stones after transplantation support using deceased donor kidneys containing stones.2 Despite this, many consider the presence of stones in a deceased donor kidney to still preclude transplantation. A need exists then, to further investigate the prevalence and effect of stones in donor transplant allografts at the time of transplantation.

1–2% of patients undergoing DDKT develop stones in their grafts, and approximately 0.2% will form bladder stones.3–5 Prior literature has shown that low serum calcium, elevated lymphocyte counts, hypercalciuria, hyperoxaluria, and recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) are risk factors for the development of nephrolithiasis postoperatively in a transplant graft after allograft transplantation.4,6,7 Interestingly, there is also some data to support stone formation being associated with prolonged graft survival.4 Although somewhat limited, there is some data on gifted stones in living donor kidney transplants. Bin Mohamed Ebrahim et al. studied 432 living donor transplant recipients, of which there was just one stone related event over nearly two years follow-up.8 Additionally, while a significant portion of their study had glomerular filtration rates <60, no significant difference was seen compared to living donor recipients without a gifted stone. Arpali et al. also studied over 1400 living donor nephrectomy patients, noting stones to be found incidentally in approximately 3% of cases.9 No stone related events were noted over a 10-year median follow-up time. It appears then, that in living donor patients who receive an allograft with a stone, outcomes are favorable and transplantation feasible in most instances. However, there is a paucity of information regarding the frequency of donor-gifted stones and their subsequent impact on transplant outcomes for DDKTs.

There are no standard guidelines for imaging deceased donor kidneys prior to using them for transplantation. When such stones are identified, recommendations for utilization of these kidneys vary. As of 2005, the Amsterdam Forum suggested acceptance for a graft with a stone <15 mm in greatest dimension.10 Other international organizations have guidelines that vary regarding imaging modality, size, and number of stones.1 Such variability and lack of evidence-based guidelines have left the decision to proceed with transplantation in such cases up to the discretion of the respective transplantation center. Consequently, in the past 15 years, the acceptance of kidneys with stones has become more common.11,12 With over 90,000 people awaiting renal transplant in the United States, discarding such kidneys could have a negative impact on those awaiting renal transplantation.13,14

There is a paucity of information regarding clinical outcomes for proceeding with renal transplantation using deceased donor kidneys with stones. This had led to a lack of standardized management protocols for such cases. This study aimed to estimate the frequency of donor-gifted nephrolithiasis in DDKTs at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center and analyze clinical outcomes.

This was a retrospective analysis of all DDKTs performed at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center from 1979 to 2025. The study was approved by the Atrium Health Wake Forest Baptist Institutional Review Board (IRB00093774). The electronic medical record (EMR) was utilized to collect donor and recipient demographic data. Living donor kidney transplant patients were excluded from analysis as were patients who formed bladder stones Patients were considered to have a renal graft with stones at the time of transplantation (donor-gifted) if it was either documented in the transplant operative note and/or by imaging before or within two weeks from the date of transplantation. Ureteral anastomosis was performed via extravesical ureteroneocystostomy with absorbable suture. Pre-transplant imaging on donor kidneys was not routinely employed, but some DDKTs did have this done, which was at the discretion of the providers involved in the procurement and transplant but there was not a specific year in the study window where this practice began to be utilized. Intraoperative ultrasound and ex vivo pyeloscopy were not utilized for stone identification. Patients typically undergo graft ultrasonography within 24 h of transplantation and if there is suspicion of stones, or another imaging study which included computerized tomography (CT) scan imaging in many. UTIs were diagnosed based on presence of symptoms and urine culture with >105 colony-forming units/high-powered field.

In all cases of donor-gifted stones, urology consultation was obtained, and stone management was formulated by the urologist and the transplant team. All patients with donor-gifted stones underwent periodic follow-up graft imaging after transplantation with a minimum interval of one year. Specific timing of imaging was not standardized, but most often occurred at two-to-three-month intervals after the date of DDKT with ultrasound. All patients had at least one ultrasound or CT scan of their graft within their most recent year of follow-up. Graft failure was defined as when a patient’s allograft was nonfunctioning requiring them to be placed back on long-term dialysis. Patient management strategies were divided into either surveillance versus surgical intervention, all of which was percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) plus antegrade ureteroscopy. The reasons for surgical intervention were based on stone location and presence of hydronephrosis on graft ultrasound, with lesser consideration to stone size. Stone size on imaging was compared between surveyed and treated patients using independent samples t-test. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

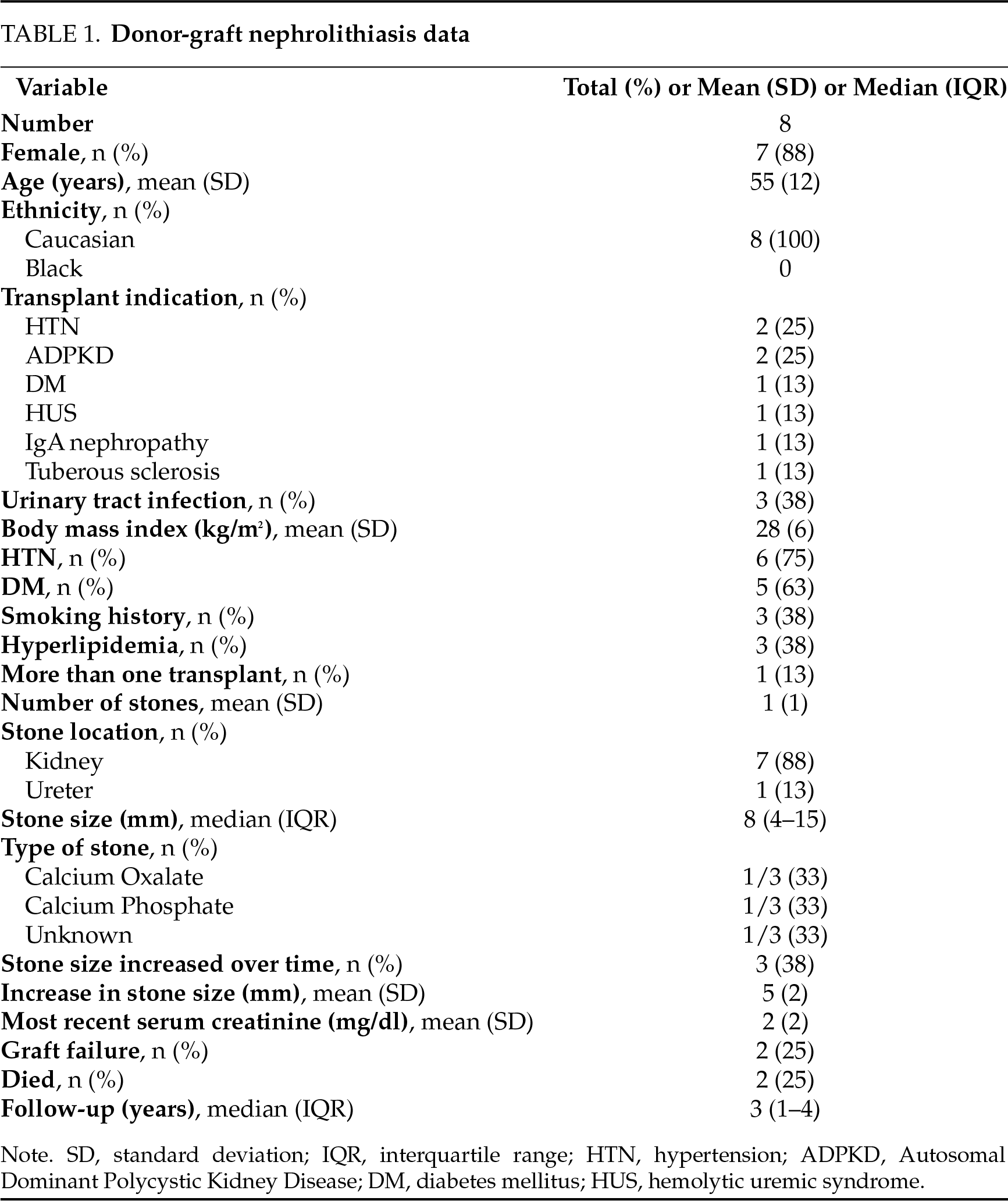

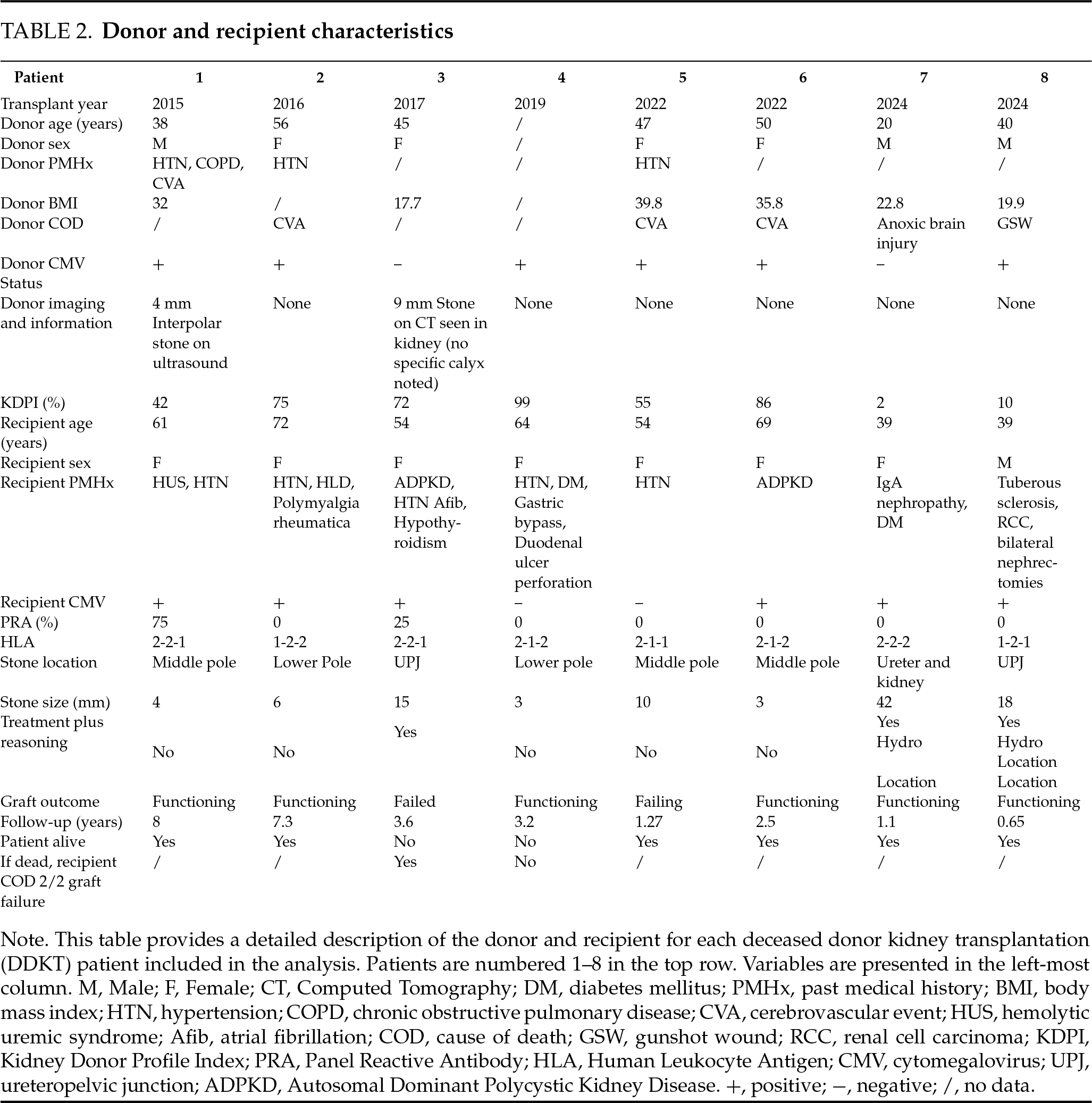

From 1979–2025, a total of 4793 DDKT recipients were reviewed in the study who underwent primary DDKT at our institution. Only eight patients were found to have received a renal graft with stones at the time of transplantation (0.2%; Table 1). Full details on each donor and recipient are detailed in Table 2. There were two (25%) patients whose stones were seen preoperatively on CT or ultrasound of the donor graft and six (75%) patients whose stones were seen on postoperative ultrasound. No patients had stones that were identified intraoperatively during their DDKT. There were two (25%) patients with a stone at the ureteropelvic junction, three (38%) with a stone in the lower pole of the transplant kidney, two (25%) with a stone in the middle pole of the kidney, and one (13%) with stones in the middle ureter and kidney (unspecified site). For patients with a donor-gifted stone, the mean age at the time of DDKT was 56 years old, with one (13%) male and seven (87%) females. The date of transplantation for patients with donor-gifted nephrolithiasis ranged from January 2016 to November 2024, and the median follow-up was three years post-transplant. All patients (100%) were Caucasian with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 28 kg/m2. Overall, six (75%) patients had hypertension, five (63%) had diabetes mellitus, and three (38%) had hyperlipidemia. Two (25%) patients underwent renal transplant for Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD), one (13%) for diabetes, two (25%) for hypertension, one for hemolytic uremic syndrome (13%), one (13%) for IgA nephropathy, and one (13%) for Tuberous Sclerosis. One patient had multiple renal transplants. There were six (75%) patients whose stones were identified at the time of primary renal transplantation, and two (25%) were not seen at the time of surgery but were identified on routine ultrasonography within 2 weeks of transplantation. The median size of the stones identified was 8 mm. Three (38%) patients had stones that increased in size over time based on serial imaging. One patient (17%) had a stone recurrence after being stone-free in the study window, and this patient underwent treatment initially not surveillance. There were three (38%) patients who underwent stone removal: stone composition was available on two of these patients which was calcium oxalate in one and calcium phosphate in the other. There was one patient whose graft failed during the follow-up period. Two (25%) patients died during the study at a mean time of three years following DDKT, but not from stone related complications. One (50%) of these patients underwent stone removal.

As noted, three (38%) patients underwent treatment for their donor-gifted nephrolithiasis, and five (63%) underwent surveillance. The reasons for surgical intervention were based on stone location and presence of hydronephrosis on graft ultrasound, with lesser consideration to stone size. All treated stones were either at the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ; N = 2) or within the ureter (N = 1), and two (67%) patients had associated allograft hydronephrosis after transplant prior to stone removal. No patients who underwent stone treatment were symptomatic from their stone. A difference in the mean size of stones at identification was observed between surveyed (5 mm) and treated (2.5 cm) patients (p = 0.027). One (20%) patient in the surveyed group was confirmed to have passed their stones spontaneously but the stone was not captured. One (33%) of the three treated patients had stone recurrence on follow-up imaging. Three (60%) patients undergoing surveillance developed a UTI during follow-up, and none in the treatment group. Most recent serum creatinine was not significantly different between surveyed and treated patients (p > 0.05). Two (25%) patients experienced graft failure, and one (50%) was a patient that underwent stone treatment.

Donor-gifted lithiasis is a rare occurrence in DDKT which may present some challenges. Transplanted kidneys are denervated, so patients are often asymptomatic, and clinical presentation may be incidental or occult. Allografts are usually single renal units, so obstruction demands more immediate intervention. In addition, recipients are immunosuppressed and may have a higher susceptibility to infection.15 If detected prior to transplant, the most common management is ex vivo ureteroscopy and escalation to ex vivo pyelotomy as needed following explantation of the kidney from the donor.15 At our institution, we do not perform this practice. Additional studies have reported to placement of JJ stents intraoperatively during renal transplantation to allow for spontaneous passage of stones once transplanted.16 Olsburgh et al.17 and Vasdev et al.18 have also both described harvesting the opposite kidney, without any stone burden, leaving the donor with the stone bearing kidney left in place.19 However, this is not a viable strategy for DDKTs. There are multiple approaches for the management of donor-gifted nephrolithiasis discovered post-transplant including observation, retrograde ureteroscopy, percutaneous nephrolithotomy, shock wave lithotripsy (SWL), open surgery, and standard laparoscopic or robotic assisted surgery for stone removal.15,20–22 Management is dictated by stone size, stone position, clinical findings, and risk for adverse stone related outcomes. The literature shows a diverse range of management strategies, many of which are viable options for donor-gifted calculi from DDKTs. In our analysis, stone location most often dictated whether a patient received intervention, along with allograft hydronephrosis. Size was a consideration, but not the primary director of therapeutic intervention. In addition to intervention though, our data provide support for observation with no intervention at all after transplant.

In this study, we reviewed the frequency of donor-gifted nephrolithiasis at our institution over a significant period with over 4000 DDKTs. Our frequency was quite low (0.2%). Liu et al. reported that out of 580 diseased renal donors, 14 had stones in 17 kidneys. Thus, if we assume that 1160 kidneys were harvested, the frequency for each respective renal unit would be 1.5%.23 They performed ex-vivo pyelotomy and stone removal in the 17 stone containing kidneys with adequate outcomes in all. The difference in stone prevalence could be attributable to dissimilarity in the respective donor pools. One of the multiple issues with the current research landscape regarding donor-gifted calculi is that the overwhelming majority of studies focus on living donor pools, excluding DDKTs. Prevalence of stones in living donor series ranges from ~3–10%.19,24–26

We exclusively focused on deceased donor kidney transplants, knowing that there was a window of opportunity to provide valuable information on an understudied topic. This is of even more relevance given that approximately 75% percent of all transplants in the United States each year are DDKTs and worldwide it is estimated the around 61% of all kidney transplants are DDKTs.14,27 However, it is worth discussing living donor transplantation with gifted nephrolithiasis, as more information is readily available. Yao et al. performed a meta-analysis on living donor nephrolithiasis, noting incidental stones were seen in 5.8% of all cases.28 The mean stone size was only 3.6 mm in this study, whereas our mean stone size was 12 mm. Further, nearly 7% of cases ended up having the contralateral stone-free kidney transplanted rather than the initially planned graft with stones.28 In all instances of DDKT with stones in our cohort, the transplant proceeded as planned. Only a single stone-related event was reported with overall excellent graft outcomes by Yao et al. Likewise, we too did not see stone-related events in the DDKT cohort presented. Given that the incidence of nephrolithiasis is 6–12% in the general population, one may expect a greater rate of events after transplantation in stone gifted transplants.29 Ganesan et al. performed an analysis of stone formation in renal transplant patients, concluding the rate of stone-related events to be 7.8 per 1000 person years in the transplant population and around 2% within three years post-transplant.30 The causes for this are likely multifactorial, but may be related to closer follow-up patients in the transplant population often have.

We had very limited information on stone composition in our study, however the data we did have showed all calcium-based stones, whether that be calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate. The literature has shown that calcium-based stones are the most common stones in transplant recipients, which is similar to the general population.31 In the past, our research group has also found calcium-based stones to be the most common type of stone in de novo calculi formation after renal transplant.4 Likewise, calcium-based stones have been shown to be the most common type of bladder stones that form in renal transplant recipients.5 Ultimately, we feel one would expect the types of gifted stones from DDKT to reflect the fact that calcium-based stones are the most common in the general population.

Some centers elect to not use disease donor kidneys containing stones for renal transplantation. Our results and those of Liu et al. suggest good renal transplantation outcome using such kidneys.23 Our results illustrate that this may be possible with the stones left in situ. We are aware of very few studies assessing utilization of deceased donor kidneys containing small stones that were left in place. Sierra et al. reviewed 38 renal transplants with donor-gifted stones, of which 22 were DDKT.32 All 22 patients underwent renal transplant with the stones left in situ in this analysis. Interestingly, 10 patients were noted to have initial delayed graft function, but only one had ultimate graft failure requiring dialysis, not from a stone related event. There was one stone related event which was pyelonephritis, five months after DDKT and four patients required stone surgical intervention after transplant, which included one case of SWL, one case of flexible ureteroscopy, and two cases of PCNL.32 Additionally, Yin et al. compared two groups of patients in which living donor kidneys containing stones less than 5 mm in size were utilized.33 In 63 patients, ex-vivo stone removal was performed, and stones were left in place in 56 patients. The mean follow-up was 75.5 months. function was better in the stone removal group while stone events and occurrence of UTI were higher in the surveillance cohort.33

While the small body of literature seems to favor transplantation of deceased donor kidneys with stones, we recognize there are counterpoints worth considering. Tan et al. performed a review of 520 deceased donor kidney transplants from 2016–2020.34 They compared donor kidneys without stones, kidneys without stones but where the donor had stones prior to transplant, and donor kidneys with stones that were transplanted. The rate of delayed graft function was 7.5%, but was not significantly different between each grouping analyzed.34 No difference was observed in one year allograft survival nor overall patient survival rates either.34 Notably though, allografts transplanted with stones in them had a greater serum creatinine at most recent follow-up and lower glomerular filtration rate. Moreover, in Tan et al.’s study there were four instances of confirmed urolithiasis development in the cohort postoperatively, and this significantly favored patients who also received a graft with stones in it.34 In our cohort, most recent serum creatinine was not significantly different between surveyed and treated patients. Further, there was one instance of stone recurrence. We do not feel we have enough information in this case series to adequately conclude that patients with a deceased donor kidney and nephrolithiasis have a greater propensity to form stones, it certainly is a possibility.

There are several limitations in our study to consider. This is a single-center study, which limits the generalizability to other transplant centers. We estimated the frequency of donor-gifted nephrolithiasis in DDKT’s at out center, but we recognize that this may better reflect our institution’s donor selection strategy more than a true frequency. It is likely that many potential donors with nephrolithiasis were excluded from donation and thus, the frequency we present is not a perfect number. While the lengthy time period we collected data over is a strength, technological advancements over the same time period that have occurred including renal imaging may confound our results. The retrospective study design also relies on the EMR, which we cannot be certain is fully accurate which may result in an under-reporting of donor-gifted stones. Additionally, we have a very small sample set to analyze, which limits the generalizability of our conclusions. Nevertheless, this is likely unavoidable given how rare DDKT gifted calculi are, as we analyzed over 4000 transplants. One way to overcome this would be multi-institutional collaboration. Strengths of this paper as noted above are the lengthy time frame and high number of DDKTs studied. Further, comparison of surveyed patients and those with an intervention is very rare to find in the literature, and makes this paper more unique. The focus on DDKTs is also important to recognize, given how little of the literature addresses this patient population and instead focuses on living donor transplants. It is this particular point that we would like to emphasize the most, and call for additional investigation to validate these claims.

Our study demonstrates that the frequency of donor-gifted stones in deceased donor kidneys is quite low at our institution. An exact frequency likely remains elusive for DDKTs due to different screening protocols, transplantation protocols, and the asymptomatic nature of nephrolithiasis in many transplant patients. It is our goal that this manuscript adds to the small body of literature on DDKT gifted stone prevalence, but we call for additional population-wide study on this important question. Additionally, adequate outcomes can be achieved when using such kidneys. A multitude of treatment options exist for removal of stones both during and after transplantation. However, even in selected cases where small stones are left in place, we observed reasonably good graft function. Nevertheless, we recognize additional factors need to be accounted for like stone size, patient history, and the like before making a decision on leaving the stone in place versus early treatment. In our case series though, the outcomes for patients undergoing DDKT with a gifted stone were adequate. Thus, we call for additional investigation towards consensus guidelines on the use of DDKTs with stones, and consideration of endorsing such kidneys for deceased donor renal transplantation as this would help overcome the existent organ shortage. Donor-gifted nephrolithiasis is an understudied topic, both in the domain of urology and transplant surgery. We hope this paper guides the way for further research into this important phenomenon.

Acknowledgement

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Maxwell Sandberg, Mark Xu, Randall Bissette, Jacob Malakismail, Niara East, Robenson Nguyen, Jackson Nowatzke, Robert Stratta, Dean Assimos, Colin Kleinguetl; Methodology: Maxwell Sandberg, Robert Stratta, Dean Assimos, Colin Kleinguetl; Software: Maxwell Sandberg; Validation: Maxwell Sandberg, Robert Stratta, Dean Assimos, Colin Kleinguetl; Formal analysis: Maxwell Sandberg; Investigation: Maxwell Sandberg, Mark Xu, Randall Bissette, Jacob Malakismail, Niara East, Robenson Nguyen, Jackson Nowatzke, Robert Stratta, Dean Assimos, Colin Kleinguetl; Resources: Maxwell Sandberg, Mark Xu, Randall Bissette, Jacob Malakismail, Niara East, Robenson Nguyen, Jackson Nowatzke, Robert Stratta, Dean Assimos, Colin Kleinguetl; Data curation: Maxwell Sandberg, Mark Xu, Randall Bissette, Jacob Malakismail, Niara East, Robenson Nguyen, Jackson Nowatzke, Robert Stratta, Dean Assimos, Colin Kleinguetl; Writing—original draft: Maxwell Sandberg, Dean Assimos; Writing—editing and review: Maxwell Sandberg, Mark Xu, Randall Bissette, Jacob Malakismail, Niara East, Robenson Nguyen, Jackson Nowatzke, Robert Stratta, Dean Assimos, Colin Kleinguetl; Visualization: Maxwell Sandberg, Mark Xu, Randall Bissette, Jacob Malakismail, Niara East, Robenson Nguyen, Jackson Nowatzke, Robert Stratta, Dean Assimos, Colin Kleinguetl; Supervision: Colin Kleinguetl, Dean Assimos, Robert Stratta; Project administration: Maxwell Sandberg. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The data used in this manuscript is not publicly available but is available in de-identified format upon reasonable request to the corresponding author

Ethics Approval

The Wake Forest Baptist Institutional Review Board approved this IRB (IRB00093774) on 8 February 2023. Informed consent was waived for this study as no direct patient interaction was required.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Tatapudi VS, Goldfarb DS. Differences in national and international guidelines regarding use of kidney stone formers as living kidney donors. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2019;28(2):140–147. doi:10.1097/MNH.0000000000000480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Sierra A, Castillo C, Carbonell E et al. Living donor-gifted allograft lithiasis: surgical experience after bench surgery stone removal and follow-up. Urolithiasis 2023;51(1):91. doi:10.1007/s00240-023-01463-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Cheungpasitporn W, Thongprayoon C, Mao MA et al. Incidence of kidney stones in kidney transplant recipients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Transplant 2016;6(4):790–797. doi:10.5500/wjt.v6.i4.790. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Sandberg M, Cohen A, Escott M et al. Renal transplant nephrolithiasis: presentation, management and follow-up with control comparisons. BJUI Compass 2024;5(10):1048–1055. doi:10.1002/bco2.436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Sandberg M, Cohen A, Escott M et al. Bladder stones in renal transplant patients: presentation, management, and follow-up. Urol Int 2024;108(5):399–405. doi:10.1159/000539091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Harraz AM, Zahran MH, Kamal AI et al. Contemporary management of renal transplant recipients with de novo urolithiasis: a single institution experience and review of the literature. Exp Clin Transplant 2017;15(3):277–281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

7. Kim H, Cheigh JS, Ham HW. Urinary stones following renal transplantation. Korean J Intern Med 2001;16(2):118–122. doi:10.3904/kjim.2001.16.2.118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Bin Mohamed Ebrahim ME, Singla A, Yao J et al. Outcomes of live renal donors with a history of nephrolithiasis; A systematic review. Transplant Rev 2023;37(1):100746. doi:10.1016/j.trre.2022.100746. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Arpali E, Karatas C, Akyollu B, Sal O, Kiremit MC, Kocak B. P.205: the kidney donors with nephrolithiasis: is it safe? Transplantation 2024;108(9S). doi:10.1097/01.tp.0001067660.86985.5a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Delmonico F, Council of the Transplantation Society. A report of the amsterdam forum on the care of the live kidney donor: data and medical guidelines. Transplantation 2005;79(6 Suppl):S53–S66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

11. Mandelbrot DA, Pavlakis M, Danovitch GM et al. The medical evaluation of living kidney donors: a survey of US transplant centers. Am J Transplant 2007;7(10):2333–2343. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01932.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Jan MY, Sharfuddin A, Mujtaba M et al. Living donor gifted lithiasis: long-term outcomes in recipients. Transplant Proc 2021;53(3):1091–1094. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2021.01.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Kidney Disease Statistics for the United States. National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive Health. [cited 2025 May 25]. Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/kidney-disease. [Google Scholar]

14. Lentine KL, Smith JM, Lyden GR et al. Annual data report: kidney. Am J Transplant 2023;25(2S1):S22–S137. doi:10.1016/j.ajt.2025.01.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Klingler HC, Kramer G, Lodde M, Marberger M. Urolithiasis in allograft kidneys. Urology 2002;59(3):344–348. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01575-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ganpule A, Vyas JB, Sheladia C et al. Management of urolithiasis in live-related kidney donors. J Endourol 2013;27(2):245–250. doi:10.1089/end.2012.0320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Olsburgh J, Thomas K, Wong K et al. Incidental renal stones in potential live kidney donors: prevalence, assessment and donation, including role of ex vivo ureteroscopy. BJU Int 2013;111(5):784–792. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11572.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Vasdev N, Moir J, Dosani MT et al. Endourological management of urolithiasis in donor kidneys prior to renal transplant. ISRN Urol 2011;2011(3):242690. doi:10.5402/2011/242690. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Harraz AM, Kamal AI, Shokeir AA. Urolithiasis in renal transplant donors and recipients: an update. Int J Surg 2016;36(Pt D):693–697. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.11.032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Bhadauria RP, Ahlawat R, Kumar RV, Srinadh ES, Banerjee GK, Bhandari M. Donor-gifted allograft lithiasis: extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy with over table module using the Lithostar Plus. Urol Int 1995;55(1):51–55. doi:10.1159/000282750. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Jin Z, Lai J, Zhang J. A case of a transplanted kidney with an orthotopic kidney stone. J Surg Case Rep 2024;2024(8):rjae445. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjae445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Lu HF, Shekarriz B, Stoller ML. Donor-gifted allograft urolithiasis: early percutaneous management. Urology 2002;59(1):25–27. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01490-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Liu L, Li G, Zhang P et al. Ex vivo removal of stones in donor kidneys by pyelotomy prior to renal transplantation: a single-center case series. Transl Androl Urol 2022;11(6):814–820. doi:10.21037/tau-22-335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Thomas S, Lam N, Welk B et al. Risk of kidney stones with surgical intervention in living kidney donors. Am J Transplant 2013;13(11):2935–2944. doi:10.1111/ajt.12446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kim IK, Tan JC, Lapasia J, Elihu A, Busque S, Melcher ML. Incidental kidney stones: a single center experience with kidney donor selection. Clin Transplant 2012;26(4):558–563. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01567.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Lorenz EC, Lieske JC, Vrtiska TJ et al. Clinical characteristics of potential kidney donors with asymptomatic kidney stones. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2011;26(8):2695–2700. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfq769. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. WHO-ONT. Global observatory on donation and transplant. [cited 2025 Jul 1]. Available from: https://www.transplant-observatory.org/. [Google Scholar]

28. Yao J, Tovmassian D, Lau H et al. Live kidney donor allograft lithiasis: a systematic review of stone related morbidity in donors. Transplantation 2020;104(S3):S240. doi:10.1097/01.tp.0000699652.01627.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Lieske JC, Peña de la Vega LS, Slezak JM et al. Renal stone epidemiology in Rochester, Minnesota: an update. Kidney Int 2006;69(4):760–764. doi:10.1038/sj.ki.5000150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Ganesan C, Holmes M, Liu S et al. Kidney stone events after kidney transplant in the united states. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2023;18(6):777–784. doi:10.2215/CJN.0000000000000176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Shearya F, Algethamy M, Ahmed S, Algehany W, Alshahrani M, Shaheen F. Urolithiasis in a deceased donor kidney transplant recipient: case report. Exp Clin Transplant 2021;19(12):1341–1344. doi:10.6002/ect.2021.0329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Sierra A, Etcheverry B, Alvarez-Maestro M et al. Management of deceased and living kidney donor with lithiasis: a multicenter retrospective study on behalf of the renal transplant group of the Spanish urological association. J Nephrol 2024;37(6):1621–1630. doi:10.1007/s40620-024-01960-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Yin S, Tang Y, Zhu M et al. Ex vivo surgical removal versus conservative management of small asymptomatic kidney stones in living donors and long-term kidney transplant outcomes. Transplantation 2025;109(3):e175–e183. doi:10.1097/TP.0000000000005146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Tan L, Song L, Xie Y et al. Short-term outcome of kidney transplantation from deceased donors with nephrolithiasis. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban 2022;47(9):1217–1226. doi:10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2022.220311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools