Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Data-Driven Systematic Review of the Metaverse in Transportation: Current Research, Computational Modeling, and Future Trends

1 Centre of Mathematics, Universidade do Minho, Braga, 4710-057, Portugal

2 School of Industrial Engineering, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Valparaíso, 2362807, Chile

3 Instituto Sistemas Complejos de Ingeniería, Santiago, 8320000, Chile

* Corresponding Author: Victor Leiva. Email:

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 144(2), 1481-1543. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.067992

Received 18 May 2025; Accepted 21 July 2025; Issue published 31 August 2025

Abstract

Metaverse technologies are increasingly promoted as game-changers in transport planning, connected-autonomous mobility, and immersive traveler services. However, the field lacks a systematic review of what has been achieved, where critical technical gaps remain, and where future deployments should be integrated. Using a transparent protocol-driven screening process, we reviewed 1589 records and retained 101 peer-reviewed journal and conference articles (2021–2025) that explicitly frame their contributions within a transport-oriented metaverse. Our review reveals a predominantly exploratory evidence base. Among the 101 studies reviewed, 17 (16.8%) apply fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making, 36 (35.6%) feature digital-twin visualizations or simulation-based testbeds, 9 (8.9%) present hardware-in-the-loop or field pilots, and only 4 (4.0%) report performance metrics such as latency, throughput, or safety under realistic network conditions. Over time, the literature evolves from early conceptual sketches (2021–2022) through simulation-centered frameworks (2023) to nascent engineering prototypes (2024–2025). To clarify persistent gaps, we synthesize findings into four foundational layers—geometry and rendering, distributed synchronization, cryptographic integrity, and human factors—enumerating essential algorithms (homogeneous transforms, Lamport clocks, Raft consensus, Merkle proofs, sweep-and-prune collision culling, Q-learning, and real-time ergonomic feedback loops). A worked bus-fleet prototype illustrates how blockchain-based ticketing, reinforcement learning-optimized traffic signals, and extended reality dispatch can be integrated into a live digital twin. This prototype is supported by a three-phase rollout strategy. Advancing the transport metaverse from blueprint to operation requires open data schemas, reproducible edge–cloud performance benchmarks, cross-disciplinary cyber-physical threat models, and city-scale sandboxes that apply their mathematical foundations in real-world settings.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe term metaverse was popularized by the 1992 science-fiction novel “Snow Crash”, in which an always-on, three-dimensional (3D) cyberspace is accessed through personal terminals and head-mounted displays [1]. While multi-user virtual environments predate that novel, the term provided a concise label that has since gained widespread use—often applied loosely—to describe large-scale shared digital environments.

The rebranding of Facebook Inc. as Meta in 2021 [2] reignited academic and industrial interest in the technological and societal implications of such ecosystems [3–5]. Today, the metaverse is commonly framed as the convergence of immersive 3D interaction, real-time communication, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven personalization, and blockchain-based digital economies [6]. Unlike a traditional virtual reality (VR) application or a stand-alone digital twin (DT), the metaverse is expected to be persistent, decentralized, and interoperable. It should support synchronous interactions among geographically distributed users via extended reality (XR) interfaces, haptic devices, and cryptographically secured assets [3,4]. Nonetheless, there is no universally accepted definition in the literature about the metaverse.

Some sources emphasize the immersive and social dimensions of the metaverse [7–9], while others examine decentralized applications [10] and Tokenized economies based on distributed ledger technologies [11]. Related work explores maturity models [12], terminology harmonization [13], and cross-disciplinary syntheses [14]. Further links include explainable AI [15] and surveys on conceptual boundaries [16], culminating in proposals for governance in decentralized ecosystems [17].

The metaverse here refers to environments with: (i) persistency—continuing and evolving independently of individual users; (ii) large-scale real-time multi-user interaction; (iii) immersive user experience (UX) via extended reality (XR), haptics, and high-fidelity rendering; and (iv) distributed architectures supporting ownership, asset management, and governance through consensus—serving as scope and inclusion criteria for this review.

Technologies from the intelligent transportation systems (ITS) domain underpin adaptive signal control, real-time traffic monitoring, predictive maintenance, and decentralized payment platforms [18–21]. Within this domain, the metaverse is emerging as the next integrative layer, offering DTs for urban planning, scenario-based training for autonomous vehicle (AV) validation, and XR interfaces that enhance traveler safety and interaction. The anticipated benefits could include reduced crash risk, lower operational costs, and improved passenger engagement.

Two recent surveys help to frame the state of metaverse-enabled transport and the work that remains to be done. In [22], a broad technology map for ITS is offered, whereas the uses of bibliometric methods [23] to trace publication trends and thematic clusters in XR mobility research are presented in [24]. Neither survey explores the mathematical and decision-analytic foundations required for large-scale, real-time, and economically viable deployments, thereby identifying a gap in the literature and signaling future trends. To address this gap, the present study makes the following contributions:

(i) Foundational synthesis—We distil the computational building blocks supporting a transport metaverse, that is, homogeneous

(ii) Decision-analytic integration—We reconcile soft-computing fuzzy multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) with the hard real-time constraints of live XR twins, indicating where and when each technique is appropriate.

(iii) Operational gap analysis—Drawing on a corpus of 101 peer-reviewed articles (2021–2025) identified through the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) protocol [25], we quantify how often latency, throughput, safety, and human-factor metrics are reported and expose four persistent shortfalls, namely interoperability, reproducible benchmarking, security modeling, and large-scale validation.

(iv) Actionable frameworks—We introduce three artefacts that connect architecture to readiness, say, the validated XR–AV cycle, the layered XR-mobility stack, and a four-phase strategic agenda for city-scale pilots, none of which appear in previous reviews.

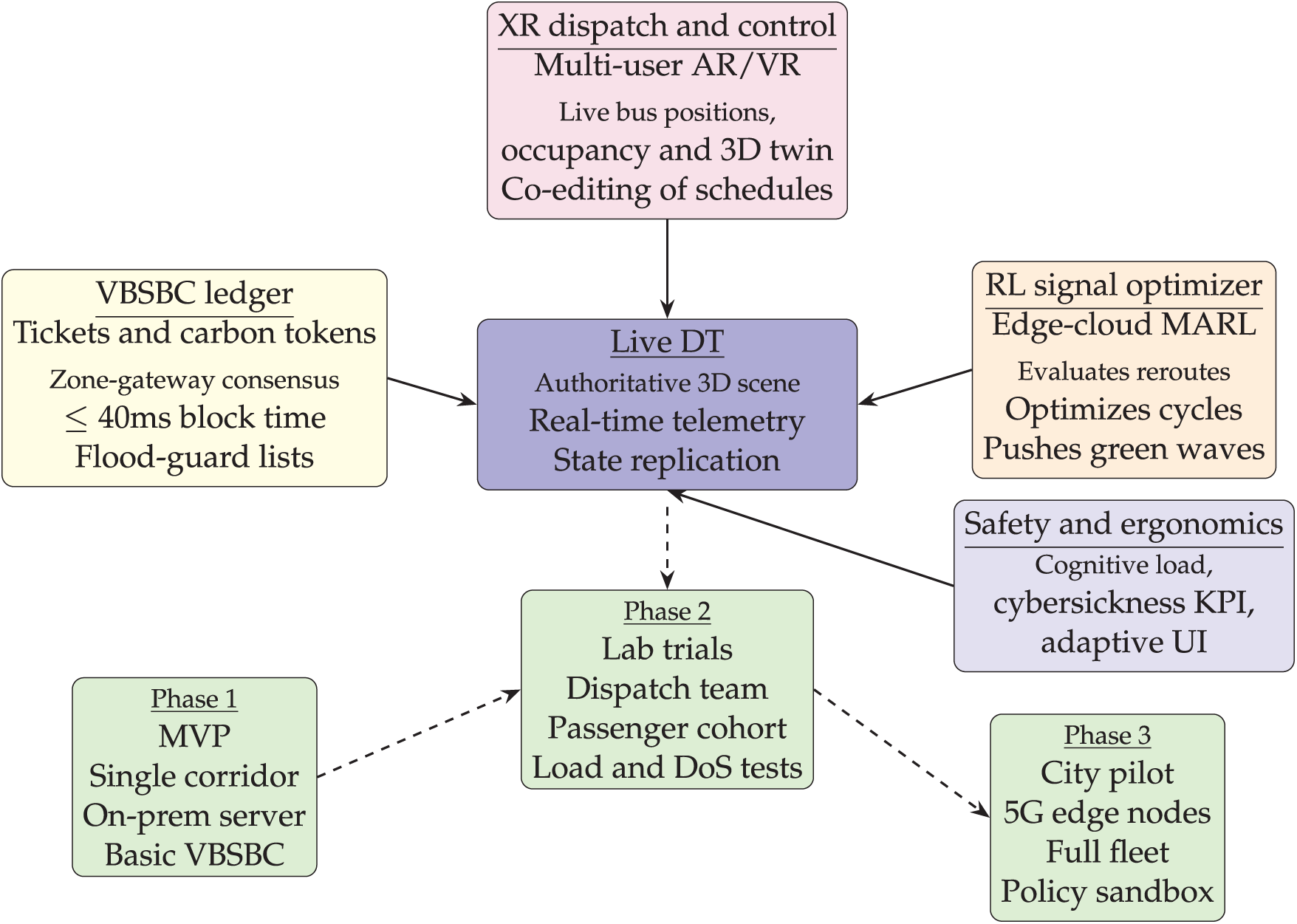

(v) Conceptual prototype—A worked bus-fleet case study shows how blockchain ticketing, reinforcement learning (RL) signal control, and multi-user XR dispatch can be fused inside a live DT, complete with rollout key performance indicators (KPIs).

Guided by these contributions, the article addresses the following five research questions (RQ):

RQ1 What computational architectures and core technologies are required for a persistent real-time metaverse in ITS?

RQ2 How can fuzzy-logic MCDM and related decision-analytic tools be reconciled with the hard real-time constraints of such ITSs?

RQ3 Which transport domains (aviation, maritime, rail, and road) stand to benefit most, and what functional requirements do they impose?

RQ4 What technical, human-factor, and regulatory barriers currently hinder real-world adoption, and how might these be mitigated?

RQ5 Which gaps and future directions could align XR with AI, fifth-/sixth-generation mobile networks (5G/6G) and edge–cloud ecosystems to support sustainable business models?

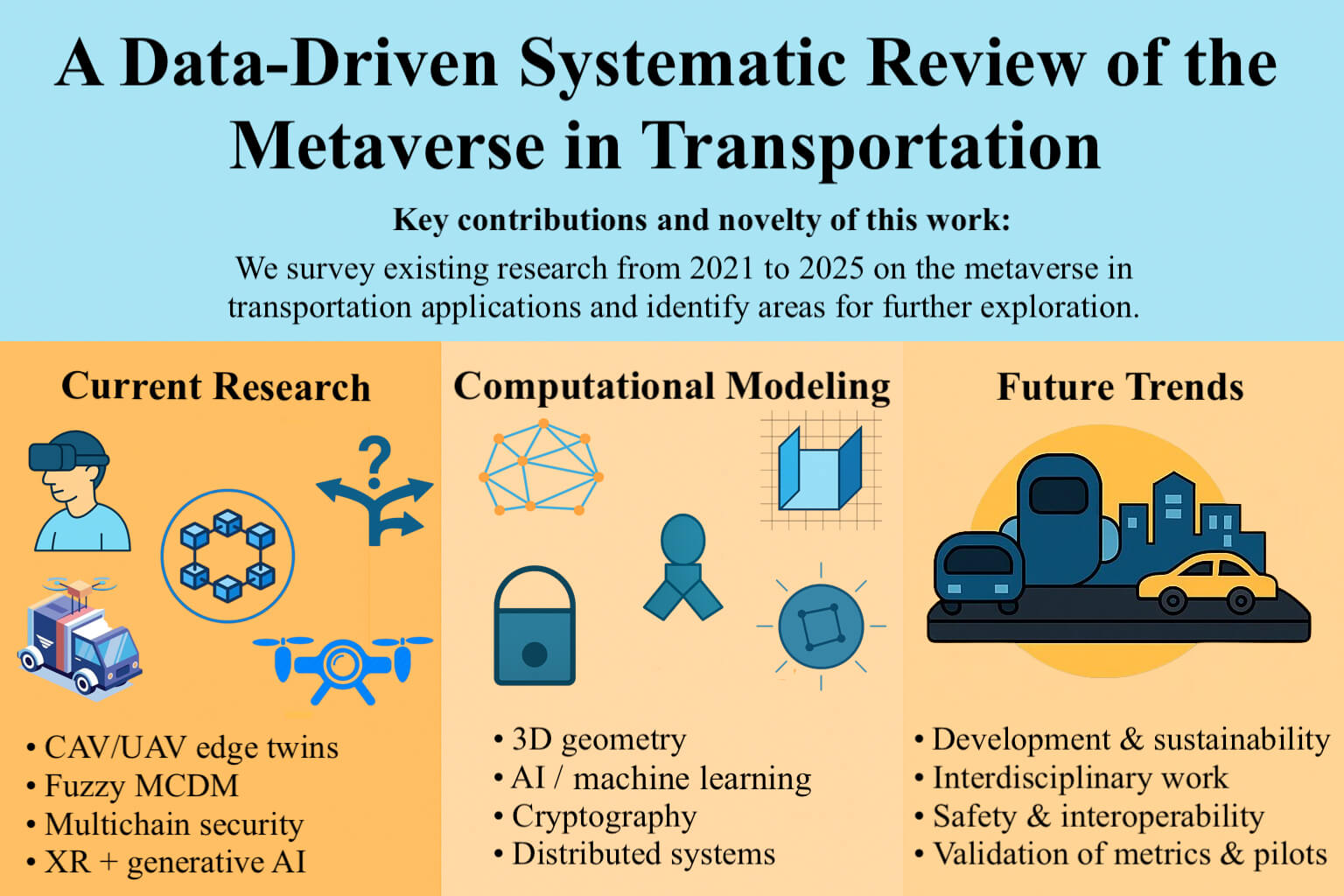

With these questions in mind, we now turn to the organization of the article. The remainder of the article is structured as follows. Section 2 details the systematic-review protocol and analytical tools. In Section 3, we revisit the mathematical and computational principles underlying metaverse platforms. In Section 4, transport-specific applications published between 2021 and 2025 are synthesized. Lessons from extra-transport pilots are summarized in Section 5. Section 6 translates the identified gaps into guidelines for empirical evaluation. In Section 7, we conclude this article with a roadmap toward human-centered, scalable and ethically aligned metaverse deployments in transportation. Appendix A presents a list of acronyms used throughout the article. Key studies from 2021 to 2025 are detailed in Appendices B–E. The PRISMA checklist associated with this review is provided as supplementary material. Fig. 1 summarizes the roadmap of the study.

Figure 1: Summary—The diagram starts with the mathematical foundations of the metaverse (3D rendering, distributed systems, cryptography, AI/ML, human factors), which support the latest transportation applications such as connected autonomous vehicle (CAV)/UAV edge twins, XR with generative-AI content, fuzzy MCDM evaluation and multichain security layers. We highlight key gaps: missing field-scale metrics, limited interoperability, and no unified threat model. The roadmap and future steps call for interdisciplinary pilots, open standards, formal safety/security checks, and robust empirical validation

This section details the search, screening, and selection procedures that underpin the review.

2.1 Context and Search Strategy

The Web of Science (WoS, by Clarivate Analytics) and Scopus (by Elsevier) databases were queried on 16 June 2025. Only peer-reviewed journal articles or conference articles were considered. A record had to contain the term “metaverse” together with at least one transport-related keyword covering road, rail, air, maritime, logistics, micromobility, CAV, ITS, or traffic control. The Boolean string entered verbatim in both databases was structured as follows:

“metaverse” AND (

transport* OR mobility OR vehicle* OR automotive

OR “intelligent transportation system*” OR ITS

OR “autonomous driving” OR “autonomous vehicle*”

OR “connected vehicle*” OR CAV

OR “public transport*” OR “public transit” OR “mass transit”

OR rail* OR railway

OR “air transport*” OR aviation OR aircraft

OR maritime OR “marine transport*” OR shipping OR port

OR freight OR logistics

OR “ride-hailing” OR “ride sharing” OR “shared mobility”

OR “car sharing” OR micromobility OR scooter* OR “bicycle sharing”

OR “intersection management” OR “traffic signal*” OR “traffic management”)

These multidisciplinary databases were selected for their broad coverage of engineering, computer-science and management outlets, reducing the risk of database bias.

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

An article was included if it met the following criteria:

(i) It treated the metaverse as a central construct.

(ii) It addressed transport in at least one mode (road, rail, air or maritime).

(iii) It examined technical foundations (for example 3D rendering, blockchain, distributed computing) or practical transport applications (for example logistics, DTs).

(iv) It incorporated, or could be linked to, data-driven, machine-learning (ML) or other computational methods.

(v) It was indexed in WoS or Scopus with a verifiable digital object identifier (DOI).

An article was excluded if it met the following criteria:

(i) It mentioned the metaverse only as a generic trend.

(ii) It discussed virtual reality or DTs without connecting them to metaverse principles.

(iii) It focused solely on sociological or macro-economic aspects with no transport tie-in.

(iv) It lacked any data-driven or computational component.

(v) It was not peer-reviewed or had no DOI.

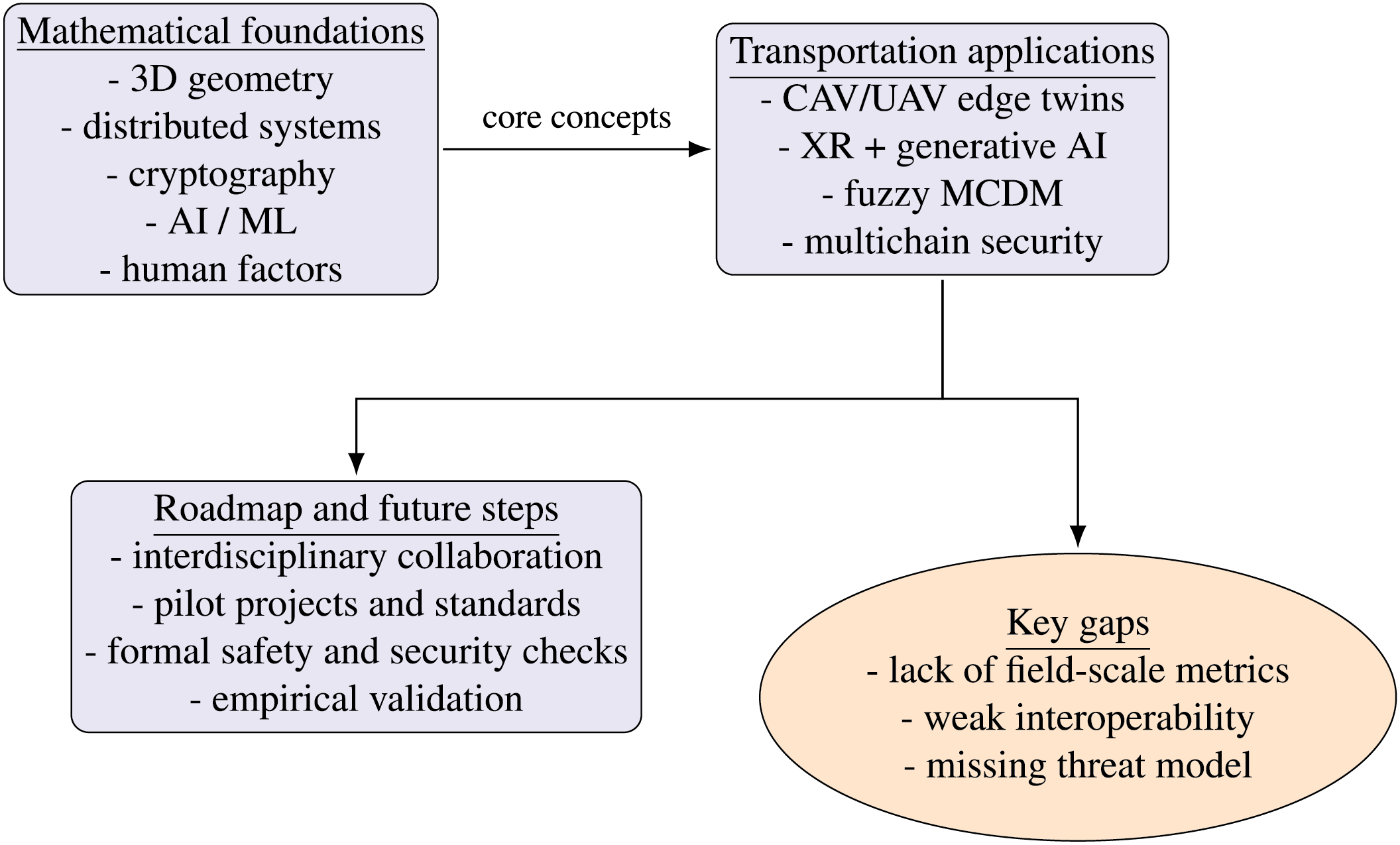

Screening followed the PRISMA protocol (see completed checklist in Supplementary Materials). Fig. 2 summarizes the four selection stages—identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion—leading to the final corpus of 101 articles. Duplicates were removed automatically using R software with DOI and fuzzy-title matching algorithms. Two reviewers then applied the eligibility rules independently, resolving disagreements by discussion before full-text assessment. Detailed data extraction from the full texts was conducted manually by two reviewers using a predefined extraction form, with discrepancies resolved through discussion. No automation tools were used at this stage. The results are described as follows:

Figure 2: PRISMA-style flow diagram for corpus construction

• Identification (1589 records)—The query returned 1000 WoS records and 589 Scopus records (total

• Deduplication (1298)—Automated DOI and title matching removed 291 duplicates, resulting in 1298 unique records.

• Language filter (1270)—Only English-language documents were retained (28 non-English articles were excluded).

• Title/keyword/abstract screening (192)—Two reviewers independently applied the inclusion/exclusion rules (requiring transport focus and substantive—not rhetorical—use of metaverse). The Cohen

• Eligibility re-check (101)—Full texts were reviewed. Ninety-one items were excluded due to: (i) use of metaverse only as a visionary label, (ii) focus on pure VR/AR without metaverse infrastructure, or (iii) lack of scientific peer review. The final corpus consists of 101 articles published between 2021 and 2025.

The resulting 101-article dataset underpins the longitudinal analyses in Sections 4.1–4.4 and Appendices A–D. All intermediate datasets (raw exports, deduplicated set, screened subset, and final corpus) are openly available on GitHub to ensure full reproducibility (https://github.com/cila-a11y/cv (accessed on 20 July 2025)).

3 Mathematical Foundations of the Metaverse

In this section, we present the core mathematical and computational principles underlying metaverse systems. The mathematical underpinnings of the metaverse span multiple areas, including 3D computer graphics, distributed systems, cryptography, AI, and human-computer interaction. While each of these areas relies on distinct theoretical models, they converge to enable the creation of immersive and persistent virtual worlds. This section outlines the key mathematical principles that form the foundation of the metaverse, explaining not only the relevant equations but also their necessity and application in practical scenarios.

3.1 3D Geometry and Computer Graphics

One of the most immediate aspects of entering the metaverse is the ability to visualize and interact with a real-time 3D environment. The mathematical framework that supports these experiences is grounded in linear algebra, computational geometry, and optics, providing the tools needed for high-fidelity rendering at every frame.

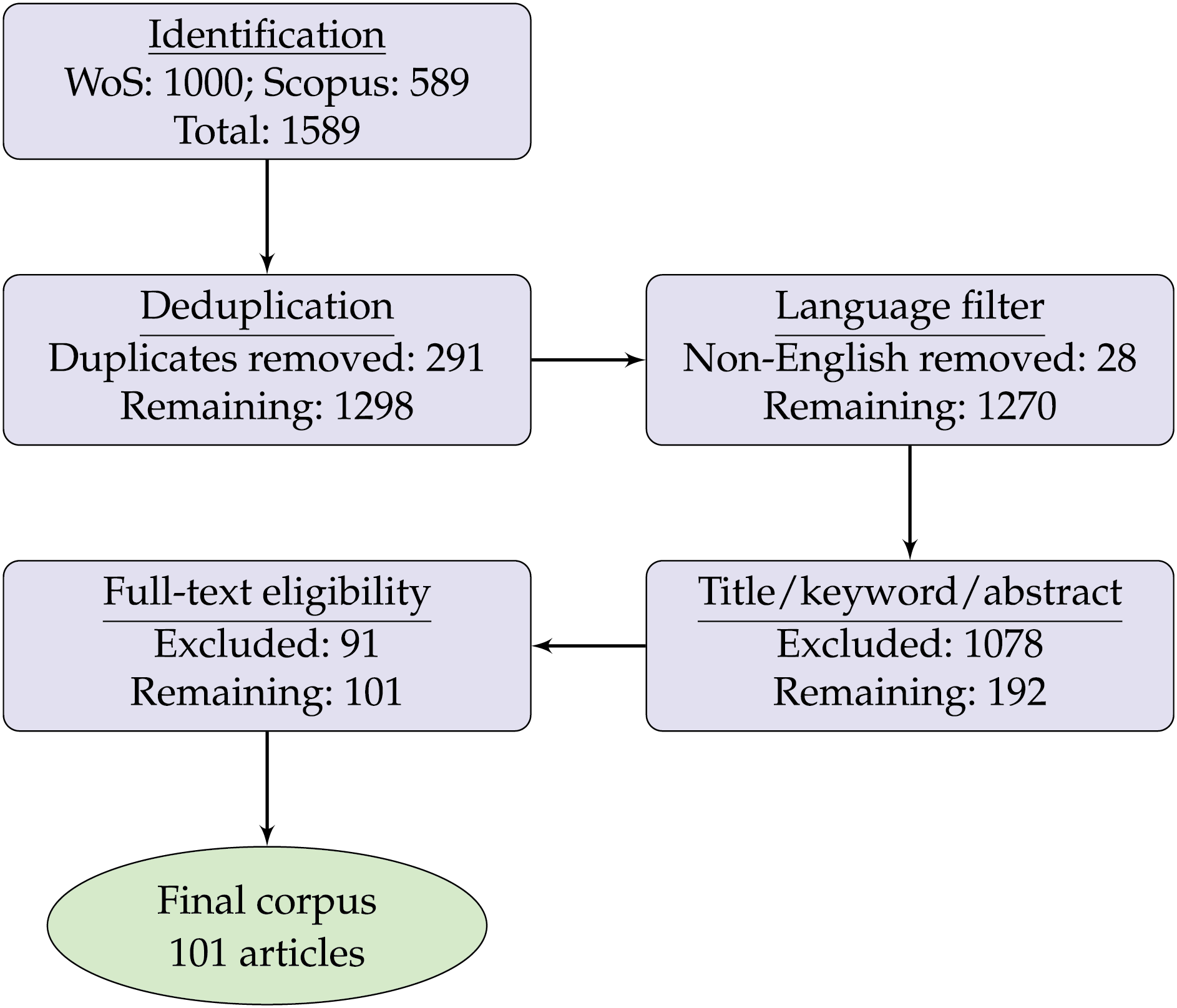

To position and manipulate objects in a virtual scene, we rely on the three elementary transformations —rotation, translation and scaling—which are detailed as follows:

(i) Rotation adjusts an object’s orientation about one or more axes (such as steering a vehicle in a driving simulator).

(ii) Translation moves an object from one spatial location to another (such as the displacement of an avatar across a landscape).

(iii) Scaling changes the size of an object while preserving its shape (such as resizing environmental assets procedurally).

These transformations are most often encoded in

where

In large-scale virtual worlds—whether for buildings, avatars, or props—consistent spatial behavior is paramount. Matrix and quaternion algebra furnish the deterministic, graphics processing unit (GPU)-friendly operations that make real-time positioning and motion possible. Fig. 3 illustrates the three basic two-dimension (2D) transformations. In homogeneous coordinates the same algebra extends directly to 3D.

Figure 3: Basic 2D transformations (rotation, translation, and scaling)

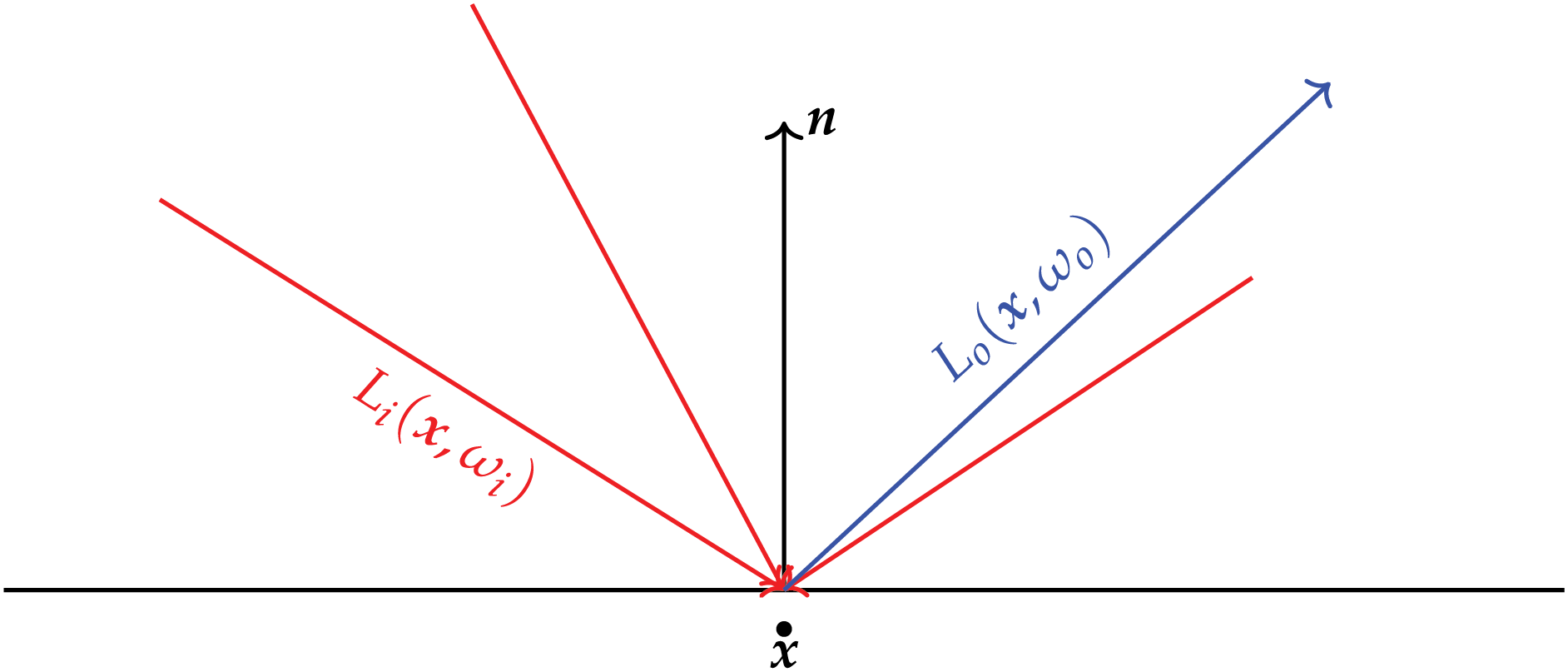

Realistic lighting is essential for users to perceive shapes, distances, and materials convincingly. A unifying description of light transport is provided by the rendering equation, given by

where

The integral given in (1) is over the hemisphere

Strict evaluation of the formulation presented in (1) is expensive. Real-time engines therefore combine fast rasterization with hardware-accelerated ray tracing, denoising filters and pre-computed illumination to strike a balance between physical accuracy and interactive frame rates. Fig. 4 displays multiple incoming radiance directions contributing to the outgoing radiance.

Figure 4: Plot of the multiple incoming radiance directions

3.2 Collision Detection and Surface Management

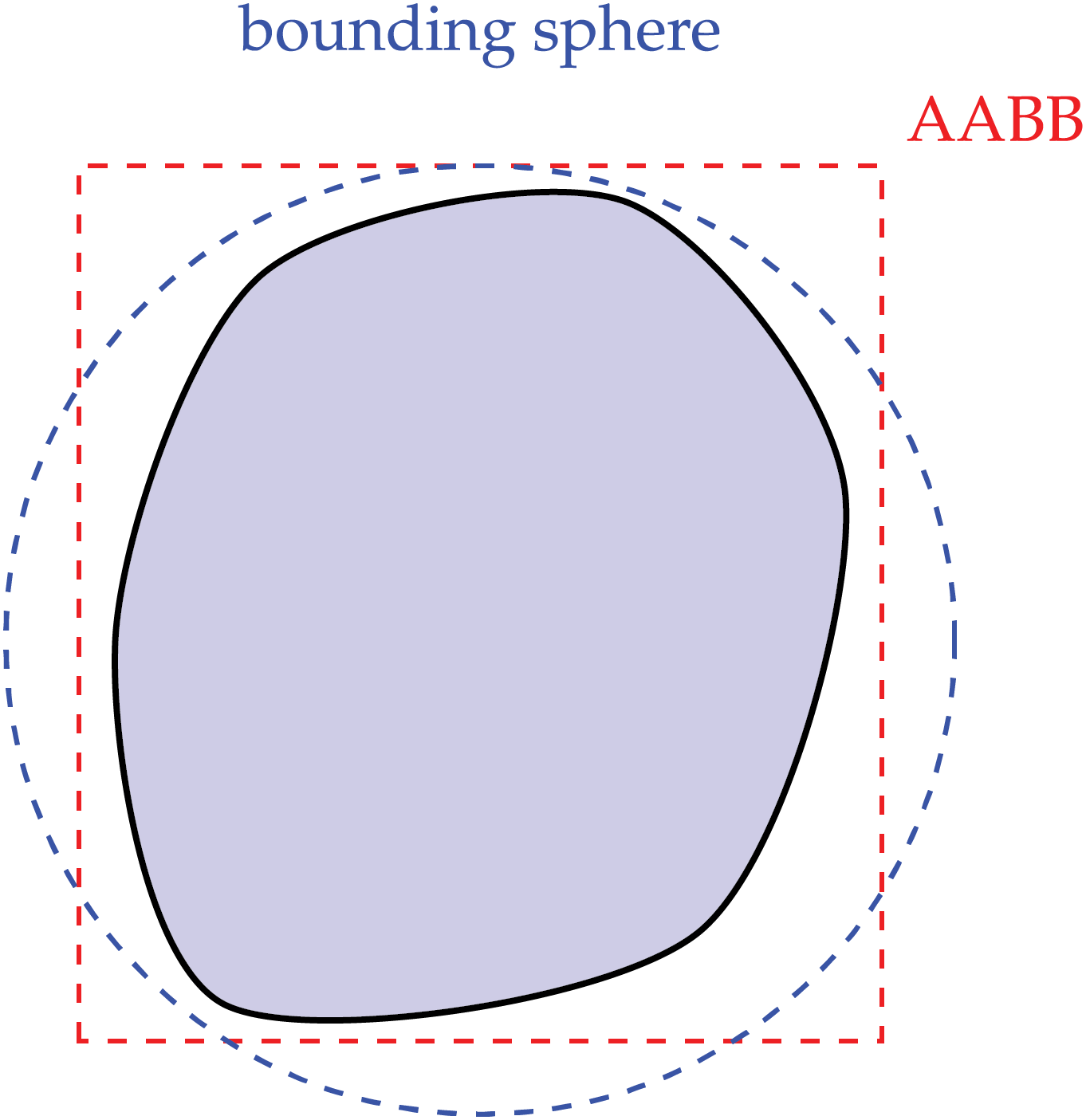

A second cornerstone of any interactive world is collision detection, which guarantees that avatars and objects behave in a physically plausible manner. Two classes of computational-geometry tools are ubiquitous and detailed as follows:

(i) Bounding volumes—Simple shapes, most commonly axis-aligned bounding boxes (AABBs), whose faces are parallel to the global axes, or bounding spheres, that allow extremely fast intersection tests.

(ii) Voronoi diagrams and convex hulls—Data structures that help to approximate object extents and accelerate proximity queries.

Without such tools, objects could interpenetrate and break the user’s sense of presence. Efficient algorithms keep the physics subsystem interactive and affordable, as in the book [31] on real-time collision detection to prevent interpenetration in virtual environments.

Fig. 5 depicts how an irregular 2D silhouette can be enclosed by an AABB (dashed red rectangle) or by the smallest circle that contains it (dashed blue line). Exactly the same logic carries over to 3D, where a complex polygonal mesh is wrapped in a rectangular box aligned with the x-y-z axes or a sphere centered at the object centroid. Because the mathematics for testing two AABBs or two spheres for overlap is constant-time, these coarse volumes form the bedrock of the broad phase of the collision detection, quickly discarding pairs that are provably disjoint.

Figure 5: Plot of irregular 2D object enclosed by two bounding volumes: an AABB and a bounding sphere

Beyond collision handling, visually convincing scenes rely on the following two additional geometry-processing steps:

(i) Surface parameterization—The mapping of a 3D surface to a 2D texture domain so that image data (textures) can be painted or sampled efficiently.

(ii) Subdivision—The adaptive refinement of meshes that adds detail only where the camera demands it, balancing fidelity against throughput.

These two steps ensure stable physics and high visual fidelity in large-scale real-time metaverse environments.

Efficient mesh generation and simplification algorithms further enable the rendering of large-scale virtual environments with minimal overhead, by distributing the computational load either on the central processing unit (CPU) or offloading it to the GPU, depending on the task [32]. In short, without the mathematical principles of transformations, illumination, collision management, and surface generation, a seamless virtual universe would be impossible. Concretely, these principles achieve the following:

• They maintain spatial coherence as users traverse the scene.

• They enhance realism through reflections, shadows and material responses.

• They prevent interpenetration by means of bounding-volume checks followed by narrow-phase polygon tests.

• They automate content creation for the ever-expanding landscapes of the metaverse.

To handle tens of thousands of objects, modern engines employ sweep-and-prune (also called sort-and-sweep) [33]. Instead of naively examining all

A single-axis sweep maintains an active set

After broad-phase culling, advanced polygon-level collision detection methods—such as the Gilbert—Johnson–Keerthi (GJK) algorithm, the separating axis theorem (SAT), or bounding volume (BV) hierarchies—are applied to the reduced set of candidate pairs. These methods ensure that frame times remain within the strict latency budgets required by immersive metaverse applications.

The next subsections explore how these computational models are distributed across global networks and how cryptographic protocols provide the foundation for secure digital ownership and transactions within these persistent virtual environments.

3.3 Distributed Systems and Synchronization Protocols in the Metaverse

A hallmark of any metaverse platform is its ability to sustain simultaneous and persistent interaction among geographically dispersed participants. Unlike single-player simulations, the metaverse must maintain one coherent world state across a federation of servers and heterogeneous clients in the presence of variable network delay, high user concurrency, and partial failures. This invokes traditional results from distributed-systems theory. We first revisit logical-clock ordering and then outline how large clusters agree on world updates through consensus.

In a distributed setting there is no physically shared timer that can order events—a hardware clock cannot be read instantaneously, nor can it be kept exactly in synchrony across machines. Suppose Avatar A opens a door while Avatar B grabs an object. If replicas disagree on which action happened first, the global state can diverge (for example, two users might own the same unique item).

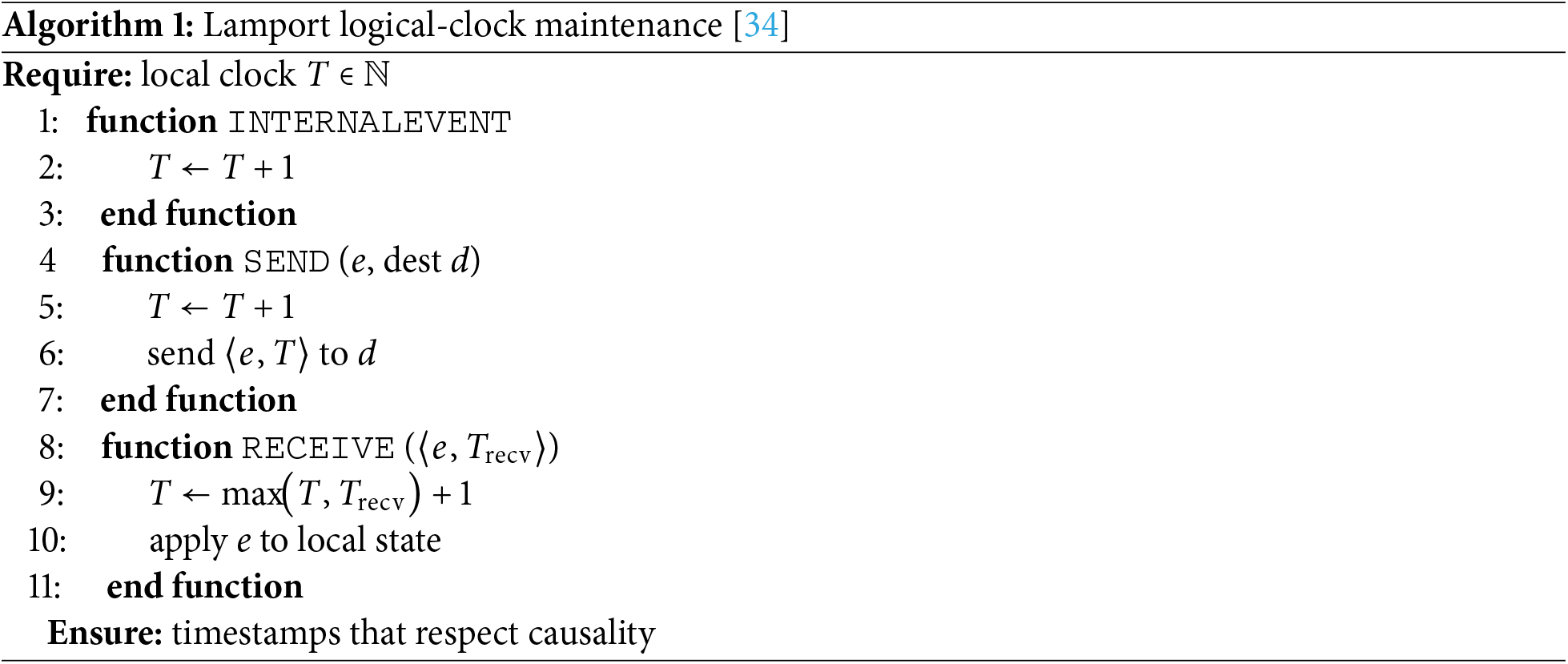

The Lamport logical clock [34] assigns an integer timestamp

While logical clocks prevent blatant inconsistencies by preserving causal order, they are insufficient to resolve concurrent conflicts—cases where two or more actions occur independently and have no defined causal relationship. Resolving such conflicts requires consensus mechanisms that can determine a single agreed-upon sequence of events across distributed replicas.

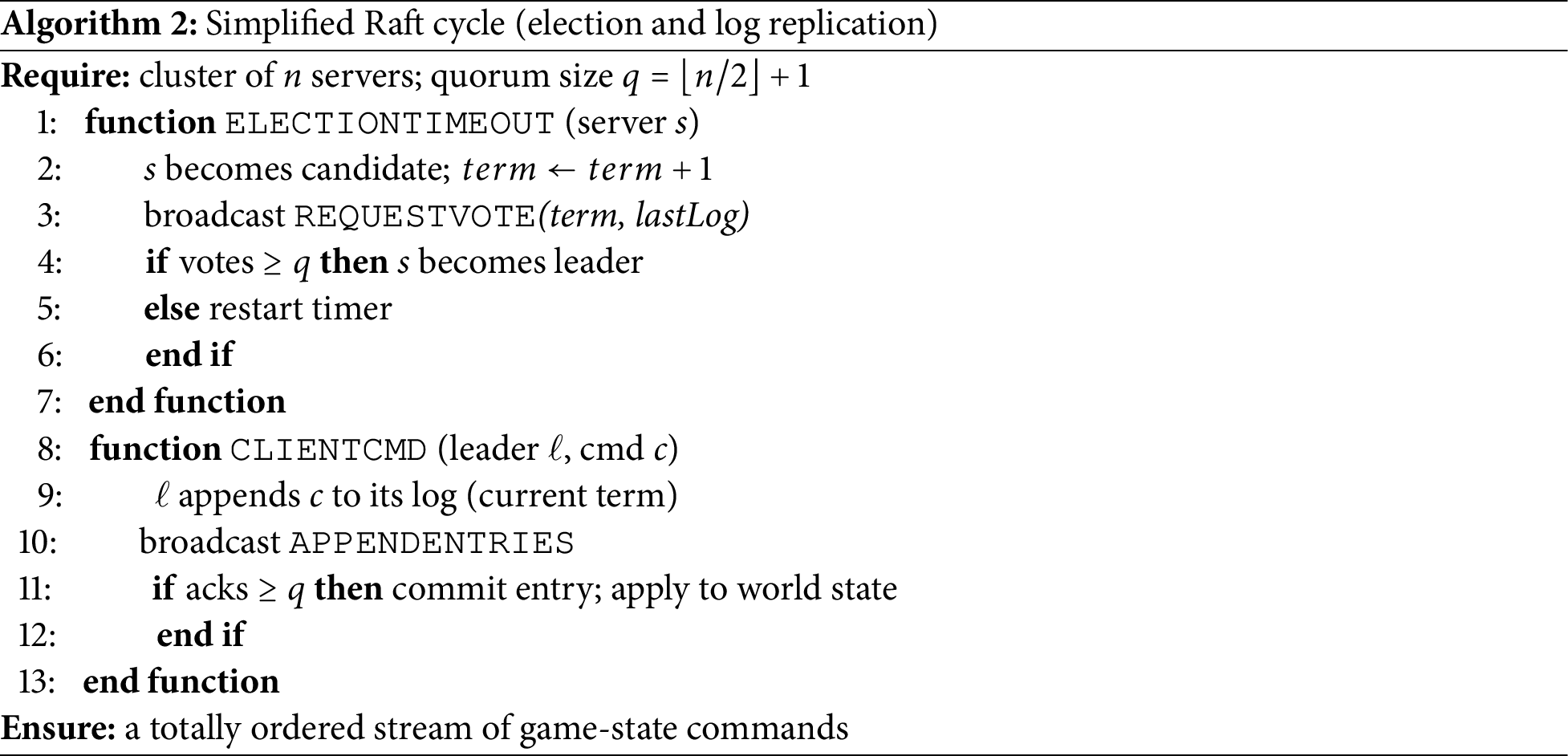

Consensus protocols are designed to ensure that a group of distributed replicas agrees on a consistent sequence of state updates, even in the presence of message loss or node failures. One widely adopted protocol, named Raft [35], models each server as a replicated state machine and provides formal guarantees of safety.

These guarantees include the log matching property (ensuring identical logs for committed entries), leader completeness (the leader contains all committed entries), and state machine safety (no two servers apply different commands at the same log index).

In the event of a leader failure, the remaining nodes hold a new election to select a successor, allowing the system to resume operation without violating consistency. This mechanism ensures eventual consistency from the perspective of clients or users—such as players in immersive environments—who observe a coherent and stable world state despite underlying network asynchrony or transient faults. Algorithm 2 sketches one election/replication round.

Modern metaverses may span thousands of shards or regions. A naive all-to-all consensus is infeasible. Hence, practical systems adopt hierarchical or sharded consensus, that is, each shard runs Raft (or a Byzantine-fault-tolerant analogue) locally, while a higher tier coordinates cross-shard transfers (such as avatar teleportation, global auctions). If a shard leader crashes, clients in that region endure only a brief hiccup, whereas the remainder of the world continues uninterrupted.

Metaverse back-ends must process millions of messages per second at sub-100-ms end-to-end latency. Queueing theory and network calculus supply the analytic tools needed as stated as follows:

• Markov and Poisson models approximate arrival processes, letting operators predict queue lengths and waiting times.

• The Little law given by

• Worst-case bounds from network calculus yield hard latency guarantees, ensuring that critical updates (such as collision events) meet service-level objectives [36].

Without careful load balancing and bandwidth allocation, overload-induced lag would shatter immersion.

Logical clocks provide causality; consensus protocols provide authority; and queueing models provide predictability. Together they form the mathematical and algorithmic substrate of the large-scale, low-latency, and fault-tolerant metaverse.

The metaverse continuously ingests large streams of data from users (for instance, movements, gestures, chat messages) and system sensors (for example, environmental changes, AI agent behaviors). To extract meaningful patterns in real time, complex event processing (CEP) applies automata and streaming algorithms to detect trends. Note that CEP is a computational technique that continuously monitors event streams to identify patterns or anomalies in real time. Pattern recognition identifies sequences of events (such as a gathering of players in a virtual space), and trigger mechanisms can initiate adaptive behaviors (for instance, spawning a new non-player character when a player enters a restricted area) [37].

Thus, CEP enables dynamic responsive worlds. It can detect increases in user density within a particular location and dynamically adjust rendering parameters to balance performance or initiate event-driven story elements based on player actions. Together, the CEP-based mathematical principles yield a scalable, synchronized, and interactive metaverse, where users worldwide can seamlessly engage in a shared digital experience.

3.4 Blockchain and Cryptography

Metaverse platforms increasingly embed digital assets—from plots of virtual land to bespoke avatar items and Tokenized currencies. For users to own, transfer and verify these assets without trusting a single authority, the underlying infrastructure must combine modern cryptography with decentralized-ledger technology.

Secure transactions rely on asymmetric schemes, such as Rivest-Shamir-Adleman and elliptic-curve cryptography, whose security rests on number-theoretic hardness assumptions (such as integer factorization or discrete logarithms). These schemes support the following two primitives indispensable to a metaverse economy:

(i) Digital signatures authenticate asset transfers, preventing impersonation and replay attacks [38].

(ii) Key exchange establishes end-to-end encrypted channels for private negotiations or in-world payments.

Whereas logical clocks and crash-fault consensus keep a server cluster consistent (see Section 3.3), an open metaverse must also tolerate untrusted or pseudonymous participants. To address the need for tolerating untrusted or pseudonymous participants in an open metaverse, blockchains transform the consensus problem into an incentive-compatible game, stated as follows:

• Proof of work—Miners expend computational resources to solve hash-preimage puzzles. Markov-chain models quantify fork probability and chain-growth rates in adversarial settings [39].

• Proof of stake—Validators lock tokens as collateral, with a weighted often verifiably-random function selecting the next block proposer, reducing energy cost while preserving Sybil resistance.

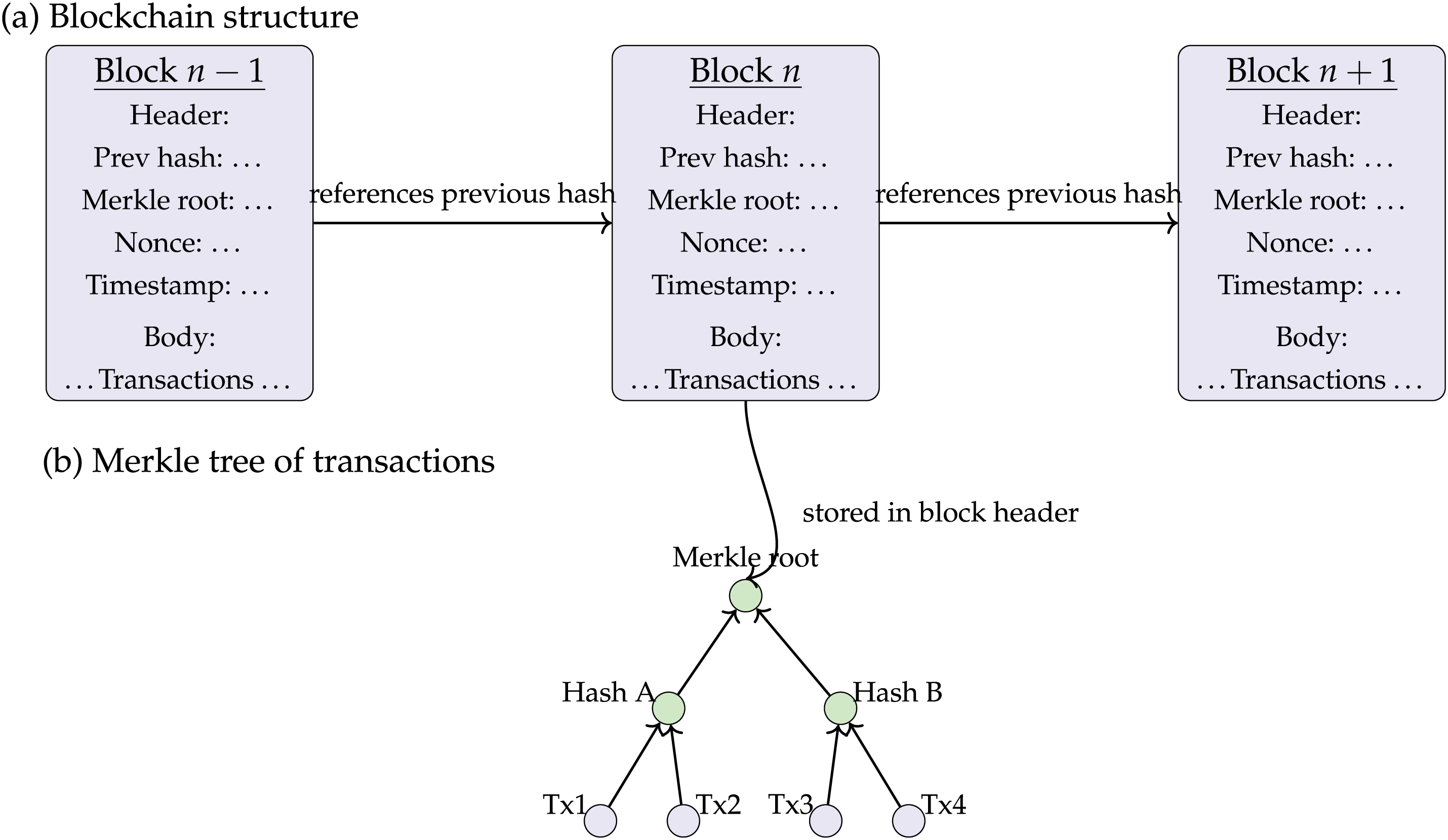

A Merkle tree hashes transactions pairwise up the levels until a single Merkle root is obtained, where the root is placed in the block header. To prove inclusion of a transaction

Public-key signatures bind asset ownership to user identities, blockchains enforce a tamper-evident ledger, and Merkle proofs allow lightweight yet trustless verification. These three aspects provide the cryptographic backbone that lets millions of users trade and showcase scarce digital artefacts in an open metaverse—all without relinquishing control to a central gatekeeper. Fig. 6 shows a diagram of consecutive blockchain blocks, each containing a header, with previous hash, Merkle root, timestamp, etc., and a body of transactions, as well as a Merkle tree where transactions (Tx1–Tx4) are hashed pairwise up to the Merkle root stored in the block header.

Figure 6: Schematic diagram of (a) an blockchain structure and (b) Merkle tree of transactions

Whenever a metaverse platform aims to provide trustless verification, provable scarcity, and liquid tradable assets, these cryptographic foundations become indispensable. By securing user identities, transactions, and asset uniqueness, blockchain and cryptography form the mathematical backbone for robust digital economies within immersive multi-user virtual environments.

3.5 Artificial Intelligence and Behavioral Modeling

Metaverse requires realistic and responsive virtual worlds, where autonomous agents, such as non-player characters (NPCs) and AI-driven entities, interact with personalized UXs. These worlds—capable of simulating lifelike settings and adapting to user behavior—are termed immersive environments. Four key AI domains support them: RL, natural language processing (NLP), computer vision (CV), and procedural content generation (PCG). These domains provide the mathematical and algorithmic basis for agent behavior, dialog, perception, and automated content creation. Thus, AI is essential to the design of immersive metaverse environments.

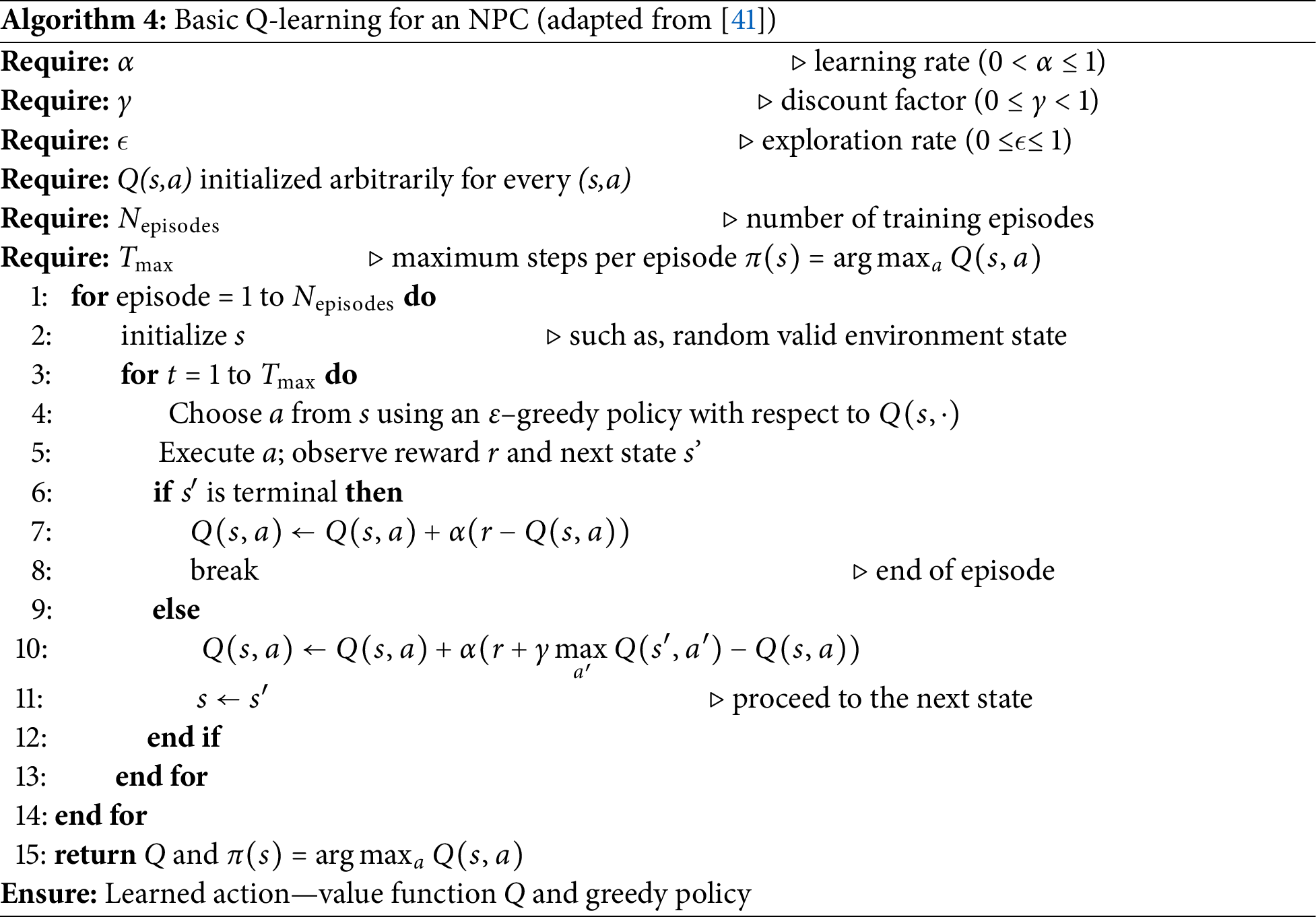

RL enables virtual agents to learn optimal behaviors through trial and error in simulated settings. This learning process involves making decisions based on environmental feedback, where agents observe the outcomes of their actions and adjust their strategies over time. To formally represent this interaction, the environment is typically modeled as a Markov decision process, defined by the tuple

A widely used algorithm within RL is Q-learning, which enables agents to estimate the value of state-action pairs through experience. A simplified update rule for Q-learning is given by

where

By repeatedly applying the Q-learning update rule, agents continuously refine the function Q based on observed rewards

For instance, an NPC acting as a city bus driver in a metaverse simulation could learn to optimize passenger satisfaction by balancing timely arrivals (

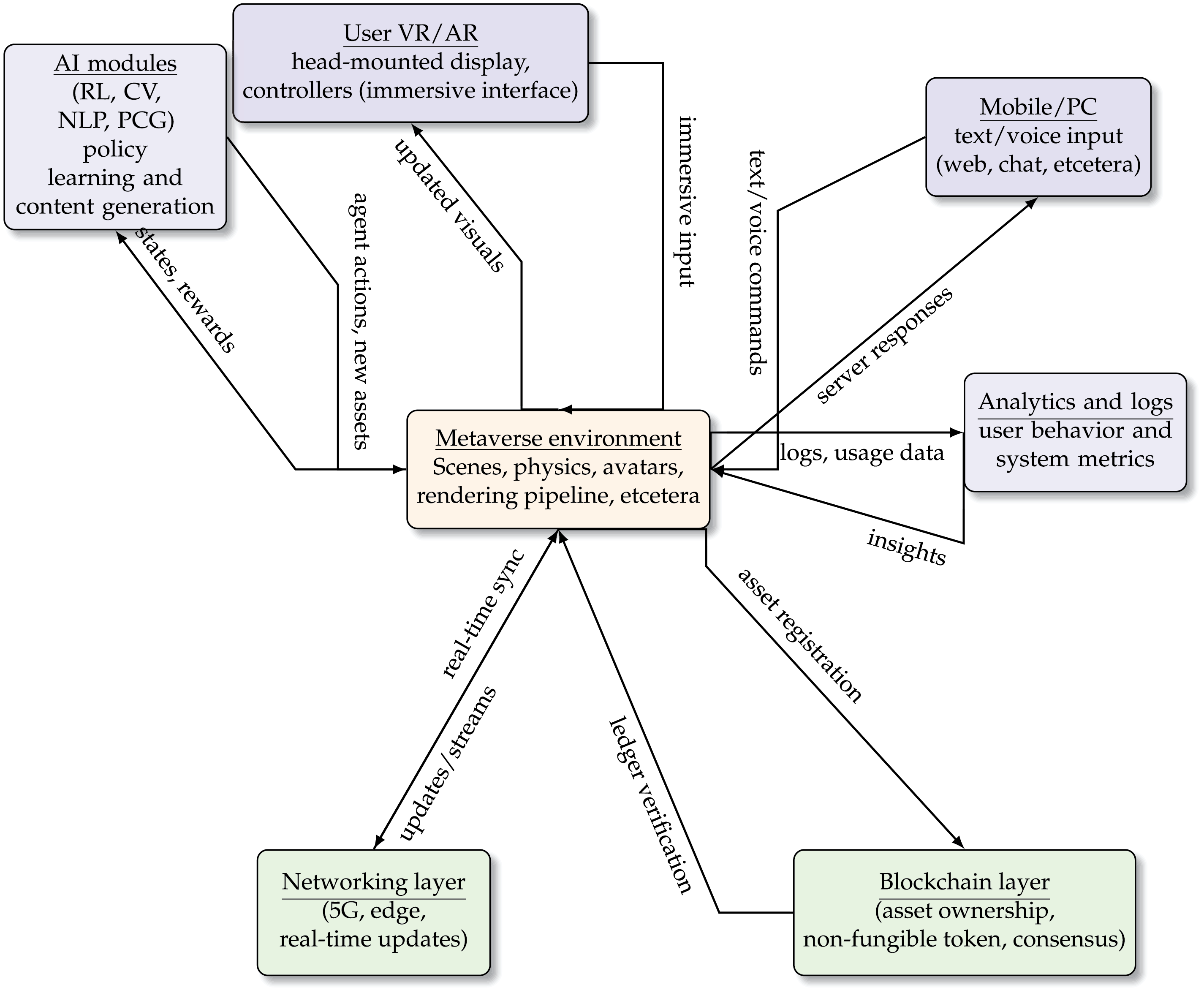

The core AI components—RL, NLP, CV, and PCG—intersect with graphics, cryptography, and networking to support real-time world updates, secure asset control, and immersive interactions. As illustrated in Fig. 7, the metaverse environment synchronizes state changes across distributed servers, while these AI components process incoming events to personalize UXs and maintain world consistency. The AI modules operate in conjunction with the networking and blockchain layers to enable responsive interactions, secure asset management, and dynamic updates to virtual worlds.

Figure 7: Flowchart depicting high-level interactions among user devices, AI modules, and the metaverse environment

An integrated multi-layer architecture emerges from the interplay between AI, communication systems, and decentralized infrastructure. This architecture forms the backbone of modern metaverse ecosystems—technological frameworks that combine AI, distributed computing, and immersive media to support scalable and adaptive virtual societies. This layered architecture also supports extensibility and interoperability, allowing modular integration across heterogeneous platforms. The above-mentioned core AI components also interface seamlessly with the cryptographic and distributed layers, laying the foundation for personalized, secure, and scalable digital societies within the metaverse.

3.6 Human Factors, Perception, and Ergonomics

Metaverse environments must account for human perceptual and cognitive limitations to ensure usability and sustained immersion. Research in human-computer interaction provides mathematical and computational models for perception, ergonomics, and user comfort, which guide the development of experiences that remain both engaging and tolerable during extended interaction sessions.

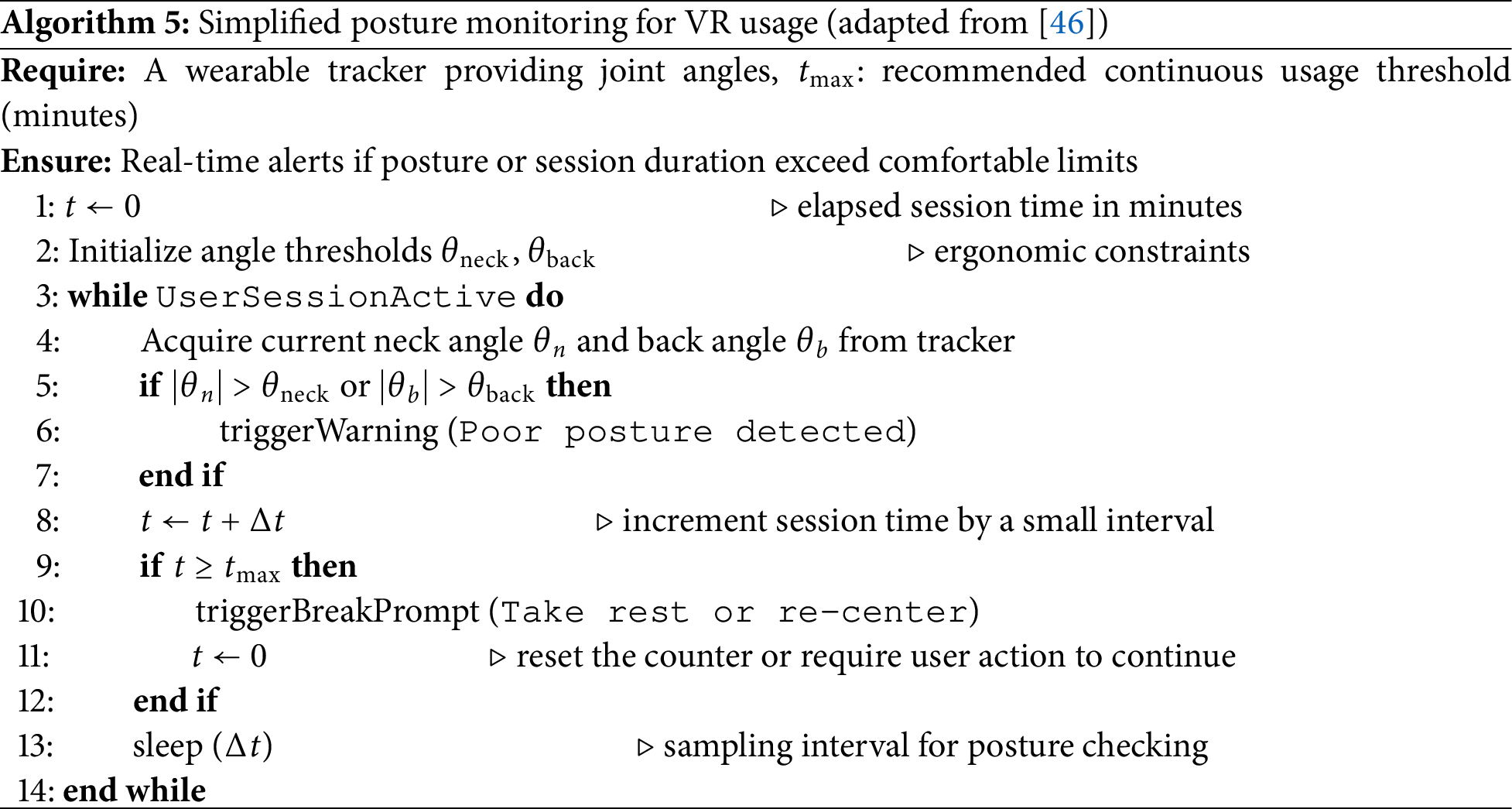

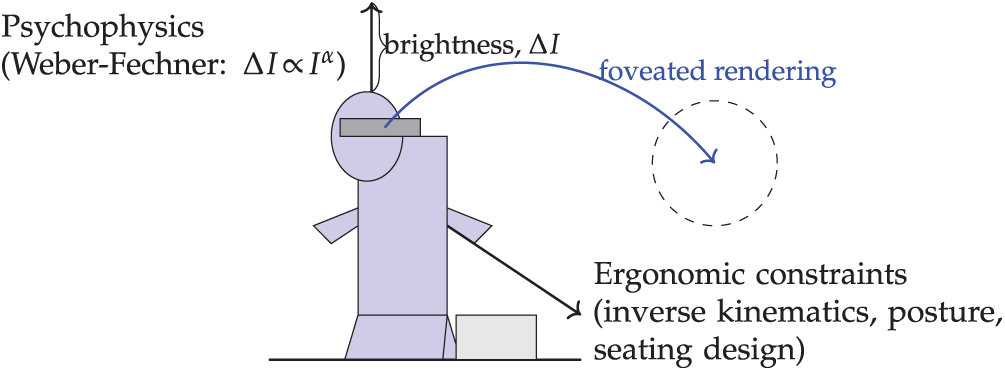

Psychophysical principles, such as the Weber-Fechner and the Stevens power laws, model how changes in physical stimuli correspond to perceived differences in intensity [45]. These laws enable the adjustment of sensory cues (for example, brightness or haptic feedback) to match human perceptual thresholds. Likewise, methods from biomechanics—such as inverse kinematics and load analysis—help to mitigate fatigue and simulator sickness by keeping user posture and movement within ergonomic limits [46].

In parallel, eye-tracking techniques and foveated rendering algorithms exploit the non-uniform distribution of photoreceptors in the human retina to dynamically allocate resolution. These approaches allow high-resolution rendering only in the user’s focal region [47], thereby reducing computational demand without sacrificing visual fidelity.

To illustrate, Algorithm 5 presents a simplified procedure for real-time ergonomic monitoring, which estimates user discomfort risk based on basic posture angles and session duration.

As shown in Fig. 8, accounting for human-centered design principles—such as ergonomics, perceptual realism, and the cognitive load—ensures that metaverse experiences remain immersive yet physically and mentally sustainable.

Figure 8: Simplified scheme of key human factors in metaverse environments of a VR user setup with components ergonomic constraints and inverse kinematics (black arrow), eye tracking and foveated rendering (blue arrow and dashed circle), psychophysical principles like the Weber-Fechner law (brace and vertical arrow), and a support structure (gray rectangle)

In transportation applications, poorly aligned ergonomic setups can result in user discomfort, delayed reactions, or reduced perceived realism, ultimately affecting the validity and credibility of simulations. Therefore, integrating human factors is essential not only for usability, but also for the safety, reliability, and long-term scalability of metaverse-based transportation systems.

3.7 Transition to Applied Computational Modeling

In summary, the mathematical and computational foundations detailed in Sections 3.1–3.6 form a cohesive theoretical toolkit for designing immersive, secure, and AI-driven virtual environments. These foundations include RL, perceptual modeling, decentralized synchronization, and user-centered interaction design—each playing a critical role in enabling core metaverse functionality. However, applying this theoretical toolkit at scale in real-world transportation scenarios presents additional challenges, such as performance constraints, algorithmic complexity, resource management, and multi-agent coordination. In Section 6, we explore how these foundations are embedded within computational modeling frameworks that support large-scale, real-time metaverse applications.

4 Analysis of Metaverse Studies in Transportation

This section reviews how the metaverse concept has been employed in transportation research from 2021 to 2025. Although our search query (see Section 2.1) did not restrict by publication year, every article that met our inclusion criteria (see Section 2.2) was published in or after 2021. The discussion is Organized chronologically to highlight the main domains addressed, the methodological repertoire adopted and the trajectory from conceptual proposals to engineering-oriented deployments.

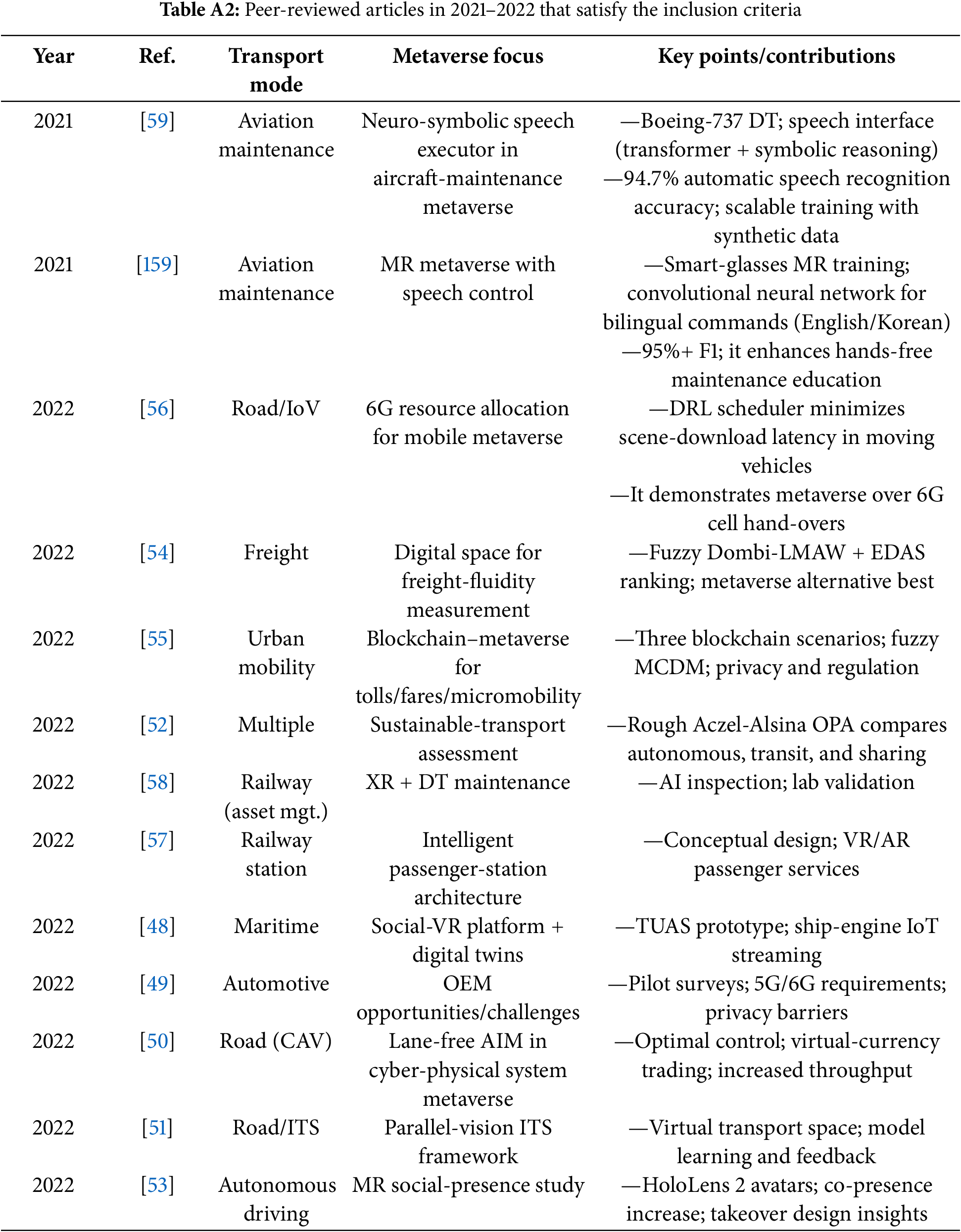

Thirteen peer-reviewed articles meet the 2021–2022 inclusion criteria (see Appendix B): two from 2021—both focused on the aviation maintenance domain—and eleven from 2022, which jointly expand the scope to include freight logistics, urban and shared mobility, public transport, railway operations, maritime collaboration, road-based ITS, and automotive services offered by original equipment manufacturers (OEMs).

Building upon the established areas of freight, urban mobility, sharing-economy logistics, and railway maintenance, 2022 studies extend metaverse applications in transportation as follows:

• Maritime remote collaboration through a social-VR DT platform for ship-engine maintenance [48].

• Automotive design and customer experience, outlining OEM opportunities, 5G/6G requirements, and privacy barriers [49].

• Road CAV ITS frameworks that couple lane-free intersection management [50] and parallel-vision learning loops [51].

• Public-transport and shared-mobility sustainability via rough Aczel-Alsina priority aggregation (OPA) to rank metro, bus, ride-share and AV scenarios [52].

• A mixed-reality (MR) user study on social presence in autonomous driving [53].

MCDM dominates early-stage appraisal tasks, such as those addressed using the Dombi-norm logarithmic mean aggregation weighting (LMAW) combined with evaluation based on distance from average solution (EDAS) [54,55], and the rough Aczel-Alsina ordered OPA method [52]. However, the corpus reveals a diverse range of metaverse methodologies in transportation detailed as follows:

• Deep RL for 6G resource scheduling in in-vehicle metaverse scenes [56].

• Cyber-physical-social (CPS) optimal control combined with virtual-currency trading is used for lane-free autonomous intersection management (AIM) [50].

• A parallel-vision pipeline linking virtual traffic space and iterative model learning [51].

• A lab-controlled MR experiment that quantifies social-presence metrics in automated driving [53].

• Conceptual architecture studies for intelligent passenger stations [57] and XR-enabled railway asset management [58].

Across the corpus, authors position metaverse integration as a lever for efficiency, transparency, and resilience in transportation as follows:

• Freight and urban mobility articles emphasize blockchain-enabled traceability and decentralized payment/toll models.

• Public-transport and shared-mobility studies use fuzzy MCDM to expose trade-offs between cost, sustainability and user acceptance.

• Maritime and railway works highlight DT-assisted maintenance and remote collaboration.

• Road-CAV investigations demonstrate throughput gains and fairness in lane-free junctions, while MR user studies reveal how avatar co-presence shapes driver experience.

Several articles move beyond theory to tangible artefacts—including three implementations: the Turku University of Applied Sciences (TUAS) maritime test-bed [48], the lane-free AIM simulator [50], and the transformer-driven Boeing 737 DT for speech-assisted maintenance [59]. These implementations exemplify early-stage prototypes that mark a first step toward human-in-the-loop validation.

Persistent issues involve the real-time twin synchronization, interoperable data schemas, quality of service (QoS) guarantees for multi-user interaction XR, and scalable edge/cloud off-loading. Addressing these gaps requires standardized reference architectures and cross-sector demonstrators—especially for under-represented modes (such as aviation outside maintenance training).

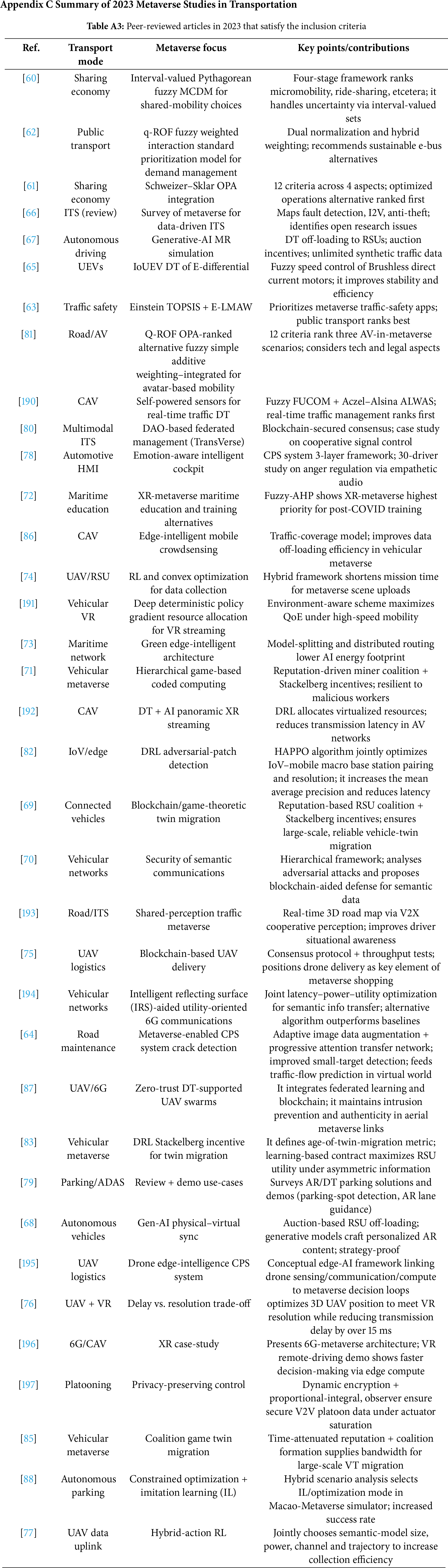

Thirty-six articles published in 2023 (see Appendix C) explicitly frame their contributions around the metaverse in transportation. The portfolio is markedly broader than in 2022, spanning strategic decision-support, edge-cloud implementation frameworks, and human-factor evaluations. The 2023 corpus of the metaverse in transportation includes the following:

• Shared-mobility and micromobility platforms [60,61].

• Public-transport demand management [62].

• Traffic-safety analytics and road-maintenance crack detection [63,64].

• DT control of unmanned electric vehicles (UEV) [65],

• Comprehensive reviews of metaverse-enabled ITS [66].

• Autonomous-driving simulation and physical–virtual synchronization powered by generative AI [67,68].

• Vehicular-metaverse operations such as twin migration, crowdsensing, coded computing and security [69–71].

• Maritime XR training and green edge-intelligent ship networks [72,73].

• Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-centric logistics, sensing, and VR streaming [74–77].

• Automotive human–machine interface (HMI) applications, such as emotion-aware cockpits and AR parking guidance [78,79].

• Cross-modal governance frameworks such as decentralized autonomous organization (DAO)-based TransVerse [80].

Fuzzy MCDM retains a strong presence—using interval-valued Pythagorean fuzzy sets [60], q-ROF models [81], Einstein-technique for order of preference by similarity to ideal solution (TOPSIS) [63], and Schweizer–Sklar OPA [61]. Nonetheless, the methodological palette of the metaverse in transportation has diversified markedly as follows:

• Deep RL (DRL) dominates operation-level optimization—such as hybrid-action trajectory and power control for UAV semantic uplinks [77], heterogeneous-agent proximal policy optimization (HAPPO)-driven adversarial-patch defense in edge internet of vehicles (IoV) [82], and Stackelberg-learning incentives for vehicle-twin migration [83].

• Generative AI and diffusion models appear in autonomous-driving simulators [67] and physical–virtual content generation [68].

• Blockchain, DAO, and reputation mechanisms secure consensus, crowdsourcing, and logistics streams, including pandemic-era transit data [75,80,84].

• Game-theoretic formulations—coalition formation, Stackelberg, and hierarchical games—optimize resource allocation and coded computing [71,85].

Three macro-trends characterize the 2023 literature of the metaverse in transportation and are detailed as follows:

(i) Edge intelligence and twin migration—Multiple studies design roadside unit (RSU)- or UAV-based edge frameworks that migrate vehicle or road twins in real time while balancing latency, energy, and security constraints [69,86].

(ii) Generative-AI augmentation—Diffusion and large-language models (LLM) are adopted to craft limitless training scenes and personalized AR/head-up display (HUD) content, signaling a shift from static DT to adaptive user-centric metaverses [67,68].

(iii) Convergence of governance and security layers—DAO federations, zero-trust architectures, and multi-chain reputation systems emerge as recurring enablers of trustworthy transportation metaverses [70,87].

Most works rely on simulated scenarios or small prototypes (such as the Macao autonomous-parking simulator [88]). However, an increasing number report hardware test-beds or field data (such as self-powered crack-detection sensors [64] and UAV VR trials [76]). This indicates an evolution from the theoretical focus of 2022 towards high-fidelity, data-driven demonstrators.

Between 2022 and 2023, the research agenda progressed from strategic design-oriented models to operational demonstrators that fuse edge intelligence, blockchain-based governance, and generative AI. Fuzzy MCDM remains indispensable for early-stage option appraisal, but is now complemented by deep RL (DRL), cooperative game theory, and multi-chain security protocols to support real-time decision-making in dynamic transport settings.

The next milestone is the deployment of large-scale pilots with interoperable architectures capable of validating performance, safety, and user acceptance across multiple transport modes.

Our updated query retrieved 38 peer-reviewed articles that explicitly frame their contributions around metaverse applications in transportation (see Appendix D).

Compared to the conceptual sketches of 2022 and the simulation-focused prototypes of 2023, the 2024 literature marks a clear shift toward engineering-oriented deployments—including real DT test beds, on-board 6G trials, AI-generated synthetic datasets, and blockchain-secured platforms.

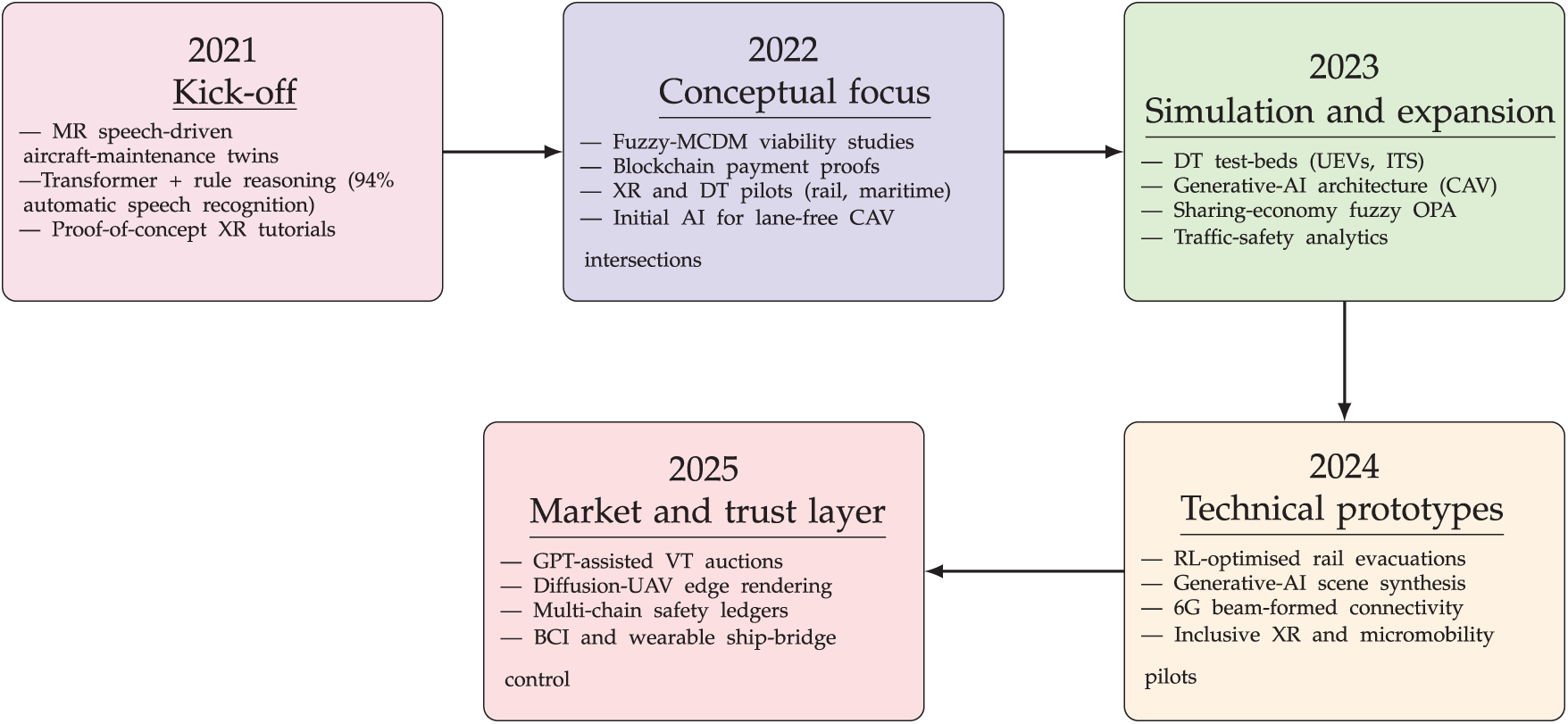

Fig. 9 shows the five-year progression of metaverse research in transportation from the 2021 kick-off (aviation XR pilots) through conceptual work (2022), simulation frameworks (2023), and engineering prototypes (2024) to market-oriented, and trust-centered solutions (2025).

Figure 9: Timeline of five-year progression of metaverse research in transportation from 2021 to 2025

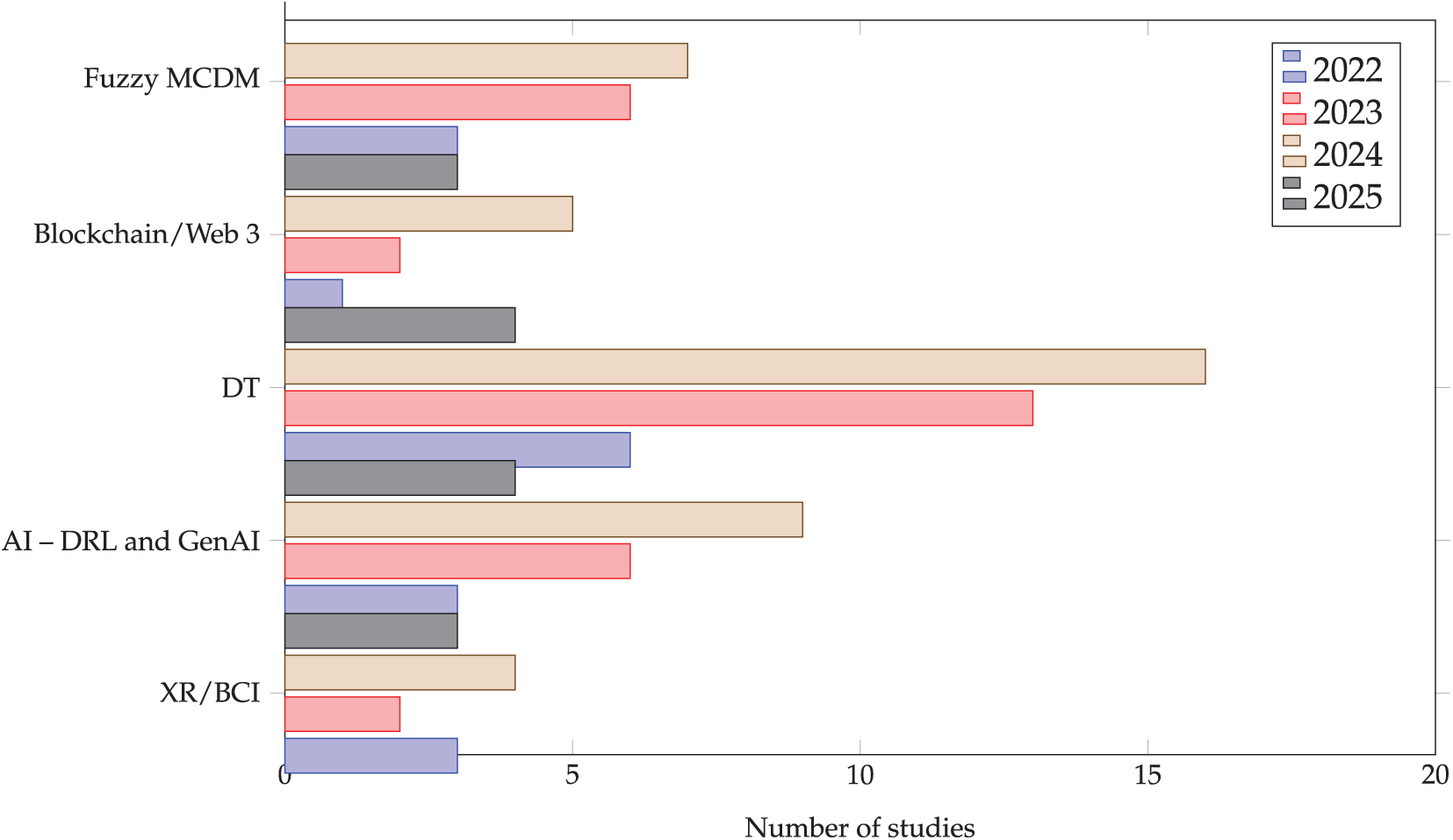

Fig. 10 shows the distribution of methods used in transportation studies based on the metaverse from 2022 to 2025.

Figure 10: Bar plot of the distribution of methods used in transportation studies based on the metaverse from 2022 to 2025, where each article is counted under its dominant method; totals therefore match the 101-article corpus rather than the raw sum of tags

The 2024 corpus covers an unprecedented mix of transport modes, business layers, and governance settings within the metaverse, detailed as follows:

• Urban mobility, micromobility, and ride-sharing—Such as blockchain-enabled e-tolling and fare design models, evaluated through several fuzzy MCDM variants, including cubic fuzzy, q-Rung orthopair fuzzy (q-ROF), constrained q-Rung orthopair fuzzy (CQ-ROF), and picture Yager fuzzy (PYF) sets [89–93], along with a resilience analysis of ride-sharing behavior [94].

• Road-CAV operations and in-vehicle metaverse—Such as joint sensing/off-loading [95], radiance-field compression [96], spatio-temporal back-door attacks [97], freshness-aware UAV relaying [98], quality of information (QoI)-aware UAV crowdsensing [99], diffusion vision transformer (DVIT) inference [100], VR-streamed platooning [101], multi-agent deep RL (MADRL) pseudonym management [102], multichain false data injection attack (FDIA) defense [103], reputation-guided practical Byzantine fault tolerance (PBFT) consensus [104], zero-trust split-learning attacks [105], auction-based synchronization incentives [106], and augmented reality (AR) meta-testing for critical scenarios [107].

• Rail and station environments—Such as generative AI DT creation [108], proximal policy optimization (PPO)-based evacuation in Krung Thep Aphiwat [109], and reconfigurable massive multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) for high-speed trains [110].

• Traffic perception and safety analytics—Such as meta-physical vision acceleration using the meta-intelligent traffic vision framework (MITVF) [111], the privacy-preserving MetaPed anomaly data set [112], in-car XR quality of experience (QoE) surveys [113], and an NVIDIA omniverse-based multi-simulation survey [114].

• Inclusive and human-centric transport—Such as science-fiction prototyping for passengers with disabilities [115], LLM-enhanced metaverse racing education [116], and foresight/design-futures toolkits for vehicle metaverses [117].

• Supply chain and logistics—Such as the architecture-blockchain-cloud/edge-DT-extended reality (ABCDE) digital-technology stack [118], and the BlockTwins traceability framework [119].

• Governance, public services, and cross-modal foundations—Such as a low-code public-sector chatbot that integrates local-transport queries [120], comprehensive ITS technology and security reviews [121], a foundation-model agenda for parallel driving [122], and an omniverse state-of-practice survey [114].

Fuzzy MCDM remains a staple for early-stage appraisal, now in richer forms, such as cubic-picture complex proportional assessment (COPRAS) [89], trigonometric full consistency method (FUCOM) integrated with the combined compromise solution (CoCoSo) [90], Fermatean ordinal consistency ratio analysis (OCRA) [123], Pythagorean multi-step consensus group decision making [93], and constrained q-Rung orthopair fuzzy set-based (CQ-ROFS) step-wise weight assessment ratio analysis (SWARA) combined with additive ratio assessment and optimal weights (AROMAN) [91]. However, the dominant focus of the metaverse in transportation is towards AI-centered engineering, detailed as follows:

• Deep and multi-agent RL (MARL), including PPO and MADRL, combined with graph neural networks (MARL+GNN)—where GNN is graph neural network—applied to evacuation, pseudonym management, VR streaming, and quality of information (QoI) sensing [99,101,102,109].

• Generative and diffusion models used for code-generated railway DTs, edge inference, and radiance-field video compression [96,100,108].

• Blockchain and multichain security—ranging from lightweight FDIA hashing [103] to reputation-guided PBFT [104] and zero-trust split learning [105].

• 6G semantic communication and millimetre-wave (mmWave) beamforming [124], as well as UAV-assisted fronthaul/backhaul for more than 60 immersive rail users [110].

• Design foresight and governance—including science-fiction prototyping [115] and structured forecasting and backcasting methods for vehicular metaverses [117].

The key advances in the metaverse for transportation in 2024 are the following:

• Scalable connectivity—Reconfigurable massive MIMO systems and UAV relays sustain multi-gigabit-per-second (Gbps) links for immersive rail and aerial DTs [110].

• Data efficiency and freshness—Radiance-field encoding reduces connected and CAV uplink volume by approximately 80% [96], with the MetaPed dataset augmenting rare pedestrian events without compromising privacy [112].

• Security and trust—Multichain hashing neutralizes FDIA within milliseconds [103], reputation-based PBFT reduces latency at the edge [104], and zero-trust split-learning attacks are formally analyzed and mitigated [105].

• Human-centered inclusivity—Assistive robotics and metaverse co-design tools rank highest in evaluations by travelers with disabilities [115], where in-vehicle XR QoE gaps and standardization issues are systematically mapped [113].

• Design foresight and governance—The ABCDE stack and BlockTwins traceability framework provide foundational blueprints for supply chain applications, while low-code public-sector chatbots demonstrate accessible entry points for metaverse services [118,120].

Collectively, the 2024 studies exhibit a maturing toolkit that fuses fuzzy decision analytics, AI-driven modeling, real-time edge/cloud DT, and high-throughput wireless networks. They also introduce forecasting, design-futures, and governance frameworks that prepare the ground for large-scale interoperable pilots. The next decisive step is to couple these vertical successes under common ontologies and standards—turning today mode-specific demonstrators into a fully integrated transportation metaverse.

The 2025 corpus (see Appendix E) comprises 14 articles that take the metaverse as a pivotal construct for transportation research and deployment. Two high-level observations from the 2025 metaverse studies on transportation are as follows:

(i) The thematic scope widens well beyond the road-and-rail focus of earlier years to embrace civil aviation, maritime bridge operations, national port ecosystems, urban innovation hubs, multi-modal logistics, and non-terrestrial corridors that couple Low Earth Orbit (LEO) satellites and UAVs.

(ii) Several studies move from proof-of-concept prototypes to market-oriented service models—such as auctions assisted by generative pre-trained transformers (GPT), multi-chain ledgers, and reputation-driven incentive markets—signaling an incipient commercial maturation of metaverse thinking.

The 2025 domains and use cases of metaverse in transportation are the following:

• CAV—GPT-driven Dutch auctions for VT migration [125], adaptive AR off-loading [126], UAV-assisted diffusion rendering and caching [127], split-DRL VT migration [128], DAO-based safe-lane advisory in the transverse metaverse [80], poisoning-attack defense for semantic internet-of-things (IoT) [129], and multi-chain analytics for drunk-driving detection [130].

• Non-terrestrial and remote corridors—LEO-UAV hierarchical caching extends immersive services to rural highways [131].

• Maritime and ports—A triboelectric watch enables gesture-based ship-bridge control [132] and a readiness matrix prioritizes Spanish port metaverse adoption [133].

• Civil aviation—A technology review maps XR/DT/AI/blockchain enablers for sustainable smart airports [134].

• Urban innovation hubs and logistics—An open DT framework for city mobility [135] and a seven-element agenda for logistics/supply-chain metaverses [136].

• Human factors—A brain-computer-interface (BCI) framework for immersive racing twins [137].

The methodological trends of 2025 metaverse studies in transportation are the following:

• Foundation and LLM—A GPT-enhanced DRL auctioneer shortens bidding clocks and lifts social welfare [125].

• Generative and diffusion models—UAV-swarm diffusion rendering underpins energy-efficient metaverse streaming [127].

• Hierarchical/split DRL—Multi-agent split DRL cuts VT-migration latency and model size [128], whereas MADRL synchronizes LEO-UAV caches [131].

• Blockchain and multi-chain security—Ledgers shield V2DT streams [130], subjective-logic reputation scores drive incentives that curb data poisoning [129], and DAO governance steers lane-advisory services [80].

• Wearable and BCI sensing—A self-powered watch achieves 96% gesture recognition accuracy [132] and modular electroencephalography (EEG)—VR—haptic integration yields

The emerging insights from the 2025 metaverse studies in transportation are as follows:

• Economics and incentives—Auction-based VT marketplaces [125] and double-auction UAV-vehicle exchanges [127] showcase scalable pricing.

• Resilience and trust—Reputation-guided defenses [129], multi-chain ledgers [130] and DAO governance [80] mitigate security risks.

• Edge-space convergence—Coupling UAVs with LEO satellites expands immersive coverage to sparsely served corridors [131].

• Human-centric interfaces—Wearable triboelectric sensors and BCI gateways hint at gesture- and neural-intent control of tomorrow’s metaverse transport systems.

Collectively, the 2025 literature drives the metaverse agenda in transportation toward three mutually reinforcing goals: (i) economic sustainability via incentive-compatible auctions and double auctions; (ii) computational scalability through split/hierarchical DRL and diffusion-based rendering; and (iii) operational trust enabled by multi-chain ledgers and subjective reputation models.

The next milestone is cross-modal integration—linking aviation, maritime, road, and logistics twins under shared ontologies, governance and edge-space infrastructure—to transform today’s isolated pilots into a fully interoperable transportation metaverse.

4.6 Fuzzy Logic as an Uncertainty-Handling Tool

Only 17 out of the 101 surveyed articles on the transportation metaverse in Appendices B–E (16.8%) adopt MCDM or related fuzzy-set techniques. Although numerically a minority, these articles all address problems where stakeholders must prioritize alternatives under linguistic or data-scarce uncertainty—precisely the context in which traditional deterministic optimization is weakest.

Freight-fluidity assessment is carried out via Dombi-norm weighting [54], blockchain-enabled urban-mobility choices [55], interval-valued Pythagorean fuzzy set ranking for shared mobility [60], traffic-safety metrics based on the Einstein-weighted TOPSIS [63], cubic picture fuzzy COPRAS for e-toll evaluation [89], fuzzy-trigonometric FUCOM-CoCoSo for urban alternatives [90], Pythagorean fuzzy sets with Wasserstein distance for sharing-economy platforms [93], and CQ-ROFS SWARA-AROMAN for blockchain prioritization [91]. Even in 2025, fuzzy reasoning resurfaces in the seven-element logistics service capability measurement (LSCM) framework [136], showing continued, albeit niche, relevance.

Introduced in [138], fuzzy sets map vague terms (for example, moderate latency and high congestion) to membership degrees in

• Imprecise inputs—Such as driver comfort, passenger satisfaction, or sensor reliability on lossy links.

• Multi-objective trade-offs—Such as throughput vs. energy, safety vs. cost, where crisp thresholds are unrealistic.

• Real-time heuristics—Providing soft state labels, such as

Fuzzy logic is not a core pillar of the transportation metaverse like 3D graphics or cryptographic consensus. This logic is a cross-cutting analytics layer that can carry out the following:

(i) To weigh competing KPIs during DT calibration.

(ii) To offer graded trust levels in Web 3.0 asset transfers.

(iii) To feed linguistically meaningful certainty scores to AI services.

Most fuzzy-based studies remain simulation-centric. Future work on fuzzy methods within transportation metaverse applications should: (i) calibrate membership functions with field data, (ii) embed fuzzy inference in edge/XR middleware, and (iii) harmonize rule bases across agencies to ensure inter-platform interoperability.

The remainder of the article broadens the lens to the overarching challenges of scaling, securing, and governing a truly multimodal transportation metaverse.

4.7 Discussion and Research Implications

The chronological review (see Appendices B–E) shows a clear evolution in transportation metaverse studies as follows:

• 2022 (conceptual groundwork)—Proof-of-concept DT, fuzzy-MCDM assessments, and blockchain payment prototypes.

• 2023 (high-fidelity simulation)—Richer twin test beds, first generative-AI pipelines, and RL-driven traffic-safety analytics.

• 2024 (engineering pilots)—RL-optimized rail evacuations, mmWave and 6G connectivity trials, as well as inclusive XR or micromobility demos.

• 2025 (towards deployment at scale)—Incentive-aligned resource markets [125], diffusion-based edge rendering [127], hierarchical satellite caching [131], Web 3.0 security frameworks [130], split-DRL migration of vehicle twins [128], triboelectric wearables for ship-bridge control [132], and a port-readiness matrix for metaverse governance [133].

Recent work on the metaverse in transportation delivers: (i) economic sustainability via auction-theoretic or game-theoretic incentives; (ii) computational scalability through split/hierarchical DRL, diffusion rendering, and non-terrestrial content caching; and (iii) operational trust using multi-chain ledgers and reputation-driven security.

Although the last three years have produced a handful of field-level demonstrations of metaverse technology in transport—such as a motorway traffic DT in Geneva that streams 1-min sensor updates to a live simulation [139], a blockchain-based mobility-as-a-service ticketing platform validated under high-concurrency load [140], and a deterministic multi-user XR platform for cooperative driving scenarios over 6G testbeds [141]—the majority of published work remains constrained to simulation or laboratory settings. Large cross-modal pilots that fuse aviation, maritime, road, and logistics twins under a shared ontology are still the exception. Key obstacles to the use of the metaverse in transportation include the following:

• Scalability—High-fidelity 3D twins struggle to handle scenarios where dozens of XR users, millisecond-level edge inference, and centimetre-level positioning must coexist.

• Security and privacy—Recent transport pilots already report poisoning-attack threats [129] and zero-trust split-learning vulnerabilities [105]. However, a sector-wide baseline for defense is still lacking.

• Standardization—Without open data schemas, application programming interface (API) gateways, and safety envelopes, mode-specific demonstrators risk becoming isolated silos—even promising initiatives such as the MetaCities open DT framework (ODTF) still target only a single urban domain [135].

• Empirical validation—Notable prototypes (Thai rail-station evacuation [109], BCI-driving twin [137], and mobility-as-a-service—MaaS—blockchain ticketing [140]) remain limited to controlled corridors or test fleets, while longitudinal evidence in live city-scale operation is rare.

Long-duration XR sessions induce cognitive load and cybersickness [142,143], while multi-user enterprise studies underline the importance of workload-balanced interfaces and clear task distribution [144,145]. Translating these findings into transportation requires validated in-situ metrics for driver assistance, dispatcher workstations, and passenger services.

Bridging the gap between mathematical rigour and full deployment therefore calls for the following aspects:

• Interoperability frameworks—Open DT ontologies capable of unifying road, rail, air, and maritime data streams.

• Regulatory sandboxes—Controlled environments that align privacy law, liability, and spectrum allocation with multi-user XR logistics.

• Real-world pilots—Instrumented fleets, stations or port terminals in which complete metaverse stacks run under live traffic, heterogeneous networks, and genuine human-in-the-loop conditions.

• Human-centered metrics—Standardized scales for XR comfort, cognitive workload, and trust, linked in real time to adaptive twin control.

A recent commentary even labels comprehensive metaverse adoption in transport as a mission impossible [146], citing physical constraints and the digital divide. Our synthesis partly concurs that meaningful progress hinges on holistic trials combining connectivity, computation, governance, and ergonomics. Without that convergence, the metaverse risks remain an impressive but fragmented set of mode-specific experiments.

5 Lessons from Real-World Metaverse Pilots

Metaverse technologies have moved from conceptual models to real-world deployments in sectors such as manufacturing, healthcare, education, and, more recently, transportation. This section reviews pilot projects across these sectors to identify transferable practices and architectural patterns common across domains.

5.1 Empirical Pilots across Sectors

Metaverse prototypes have already delivered tangible gains across diverse domains such as manufacturing, healthcare, and education. Typical outcomes include reduced task times, fewer operational errors, and higher user engagement, the evidence for which is summarized in Table 1.

The transport sector is now beginning to showcase pilots that have a level of technical depth comparable to that observed in other sectors. Two pilot cases from 2023 and 2025 span the key layers of the metaverse-transport stack and are described as follows:

(i) Sensing and DT—The microscopic twin of the A1/A40 motorway in Geneva is updated minute-by-minute from 35 loop detectors, maintaining a GEH error

(ii) Economic orchestration—A MaaS platform built on the Hyperledger Fabric blockchain framework processes approximately 100 transactions

Although still isolated, these pilots demonstrate that critical goals (latency

(i) Twins connected to live data—Synchronizing simulations with real data telemetry ensures minute-by-minute fidelity.

(ii) Consensus or blockchain for trust—It avoids single points of failure in ticketing, carbon accounting, or vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) communication.

(iii) AI in decision-making—Traffic optimization, twin migration, and XR resource allocation require sub-second inference.

(iv) Systematic UX measurement—Human impact (cybersickness, cognitive load, satisfaction) ultimately drives large-scale adoption.

These principles offer a pragmatic roadmap for mobility consortia aiming to evolve from isolated demonstrations to interoperable metaverses at urban or continental scale.

These pilots confirm the technical feasibility of core metaverse components such as real-time sensor integration and scalable consensus mechanisms. Building on this foundation, we now examine how immersive technologies have been adopted in sector-specific applications—beginning with training and maintenance in manufacturing and aerospace.

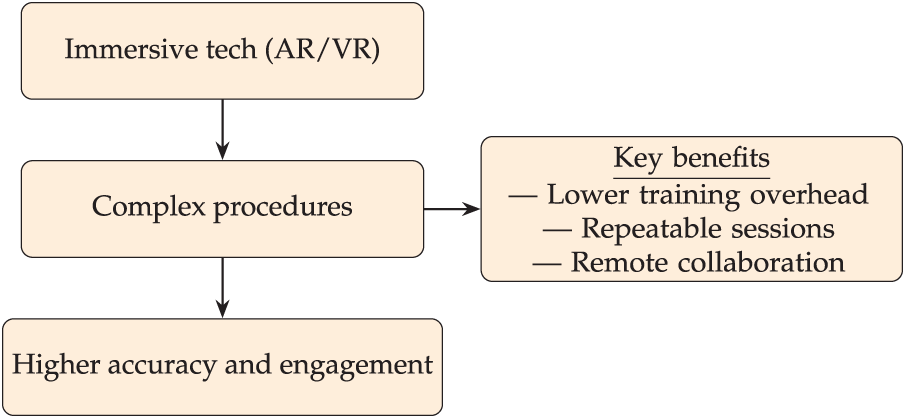

5.2 Immersive Training and AR-Assisted Maintenance

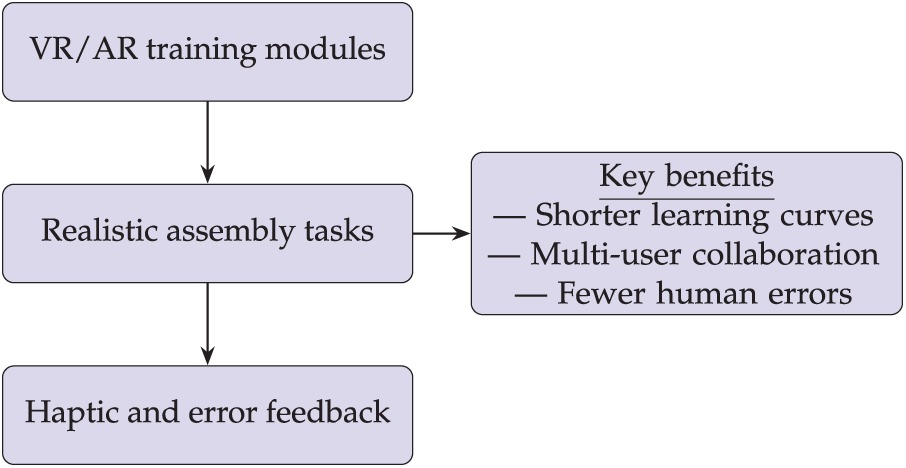

A broad body of pilot studies confirms that VR/AR can improve technical training and support procedures in industrial contexts. In manufacturing and aerospace, VR/AR-based training systems have been shown to reduce learning curves by exposing trainees to realistic assembly and maintenance scenarios involving detailed 3D models [147,156]. When bandwidth management and state synchronization are carefully engineered, these systems—which combine head-mounted displays, real-time rendering engines, and networked DTs—can also support the real-time multi-user collaboration [157]. Furthermore, the integration of haptic feedback and real-time error detection can enhance engagement and knowledge retention [158].

These benefits are further reinforced by the evidence compiled in Table 1 (rows manufacturing, maintenance, and manufacturing analytics). For instance, an AR-assisted assembly-guidance system that combined optical see-through AR with RFID achieved a 32% reduction in assembly time and a 27% decrease in errors [147]. Similarly, an AR platform designed to support the psychomotor phase of torque-sequence tasks led to a 25% reduction in overall task completion time and a 15% decrease in NASA-TLX workload [148]. More recently, a pervasive AR dashboard for shop-floor monitoring demonstrated that, after an acclimatization period, engineers completed repeated diagnostic tasks 47% faster, with 58% eventually preferred the hands-free HoloLens interface over a tablet [149]. The sequence of steps involved in these three AR industrial applications is summarized in Fig. 11, which highlights the key stages and observed benefits of AR use in operational contexts.

Figure 11: XR-assisted industrial training and maintenance: lessons readily transferable to transport-fleet servicing

Although these three applications originated outside the transport sector, early pilots within transportation reveal a similar trajectory. Procedures such as MR maintenance for Boeing 737 systems [159] and XR-based rail asset inspection twins [58] have demonstrated comparable improvements in hands-free operation and fault-detection accuracy. Adapting these procedures to bus-fleet maintenance or station upkeep would involve overlaying live sensor data and procedural guidance directly onto vehicles or infrastructure.

5.3 Digital Twins in Manufacturing and Design

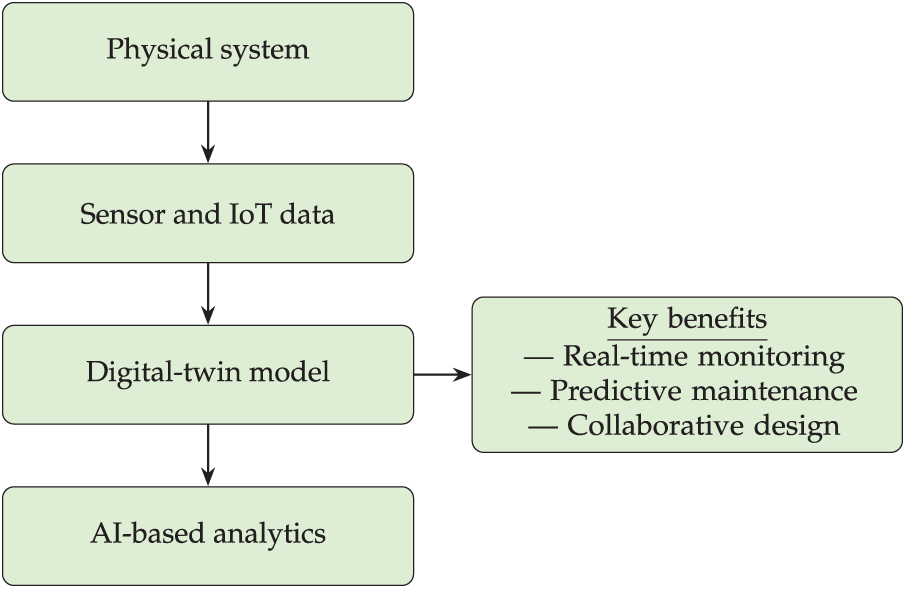

Beyond operational support, DTs have become central to large-scale industrial simulation and systems engineering. In manufacturing and product-design contexts, real-time DT architectures have reached maturity levels that transport applications are only now beginning to explore.

Pioneering studies show that it is now feasible to stream live IoT telemetry into multi-physics simulators that drive photo-realistic 3D replicas of physical assets [160], to co-create persistent virtual workspaces, enabling engineers, operators, and suppliers to simultaneously edit the same model through interoperable data layers [161], and to embed AI services for predictive maintenance and anomaly detection directly within the twin, boosting responsiveness and decision quality [162].

Evidence from the pilots (Table 1) reinforces these gains. For example, integrating real-time IoT data with simulation analytics increased production line throughput by 8% and enabled bottleneck identification in under ten seconds [154]. A human-centric twin for educational campuses similarly improved energy efficiency and occupant comfort through user-adaptive visual layers [163].

Transport-sector analogues are beginning to emerge. Deutsche Bahn and Siemens have deployed Omniverse/Xcelerator twins to model 5700 stations and 33,000 km of railway track in real-time. A Geneva motorway pilot continuously updates a micro-simulation every minute using live traffic sensors [139], while several studies on CAVs use deterministic twins for sub-second congestion forecasting [164]. Although these initiatives remain isolated, they confirm that the factory-style pipeline of sensor data

Fig. 12 generalizes this architecture. Substituting the physical system with a rail corridor, depot, or highway segment merely changes the data source: telemetry is fed into a simulator, short-horizon forecasts are generated, and actionable insights are delivered to dispatchers or maintenance crews via AR overlays. DT architectures form the structural backbone of real-time industrial environments. Beyond design and maintenance, immersive technologies have also gained traction in fields where human interaction and training are paramount, notably healthcare and education.

Figure 12: Canonical DT pipeline. An identical loop can support rail corridors or motorway segments by replacing the physical data source

5.4 Healthcare and Education Pilots

Outside industry, pilot studies in healthcare and education confirm that immersive media deliver measurable real-world benefits (rows Healthcare and Education in Table 1). For example, in robotic-assisted orthopaedics, an AR head-up display maintained surgeons’ attention on the operative field without compromising cut quality or increasing procedure time [151]. Self-guided VR exposure therapy reduced social anxiety symptoms without requiring continuous therapist supervision [165].

Educational studies mirror this pattern: AR-enhanced mannequins increased auscultation accuracy by up to 56 percentage points (

These findings suggest that immersive systems can: (i) scale expert knowledge beyond individual mentors, (ii) sustain high user engagement, and (iii) deliver repeatable, self-paced training. Transport operators can leverage these principles: XR modules for drivers, dispatchers, or technicians can reduce supervision demands while preserving training fidelity.

A generic training workflow applicable to healthcare and education is outlined in Fig. 13. This workflow also translates directly to driver-assistance drills, passenger safety briefings, and depot-maintenance tutorials.

Figure 13: Typical AR/VR training loop already validated in healthcare and education—directly transferable to transport operations

These results highlight how immersive technologies can enhance skill acquisition and knowledge retention in highly structured learning contexts. Yet their potential extends further—beyond training rooms and operating theatres—to reshape the day-to-day experiences of passengers and end users.

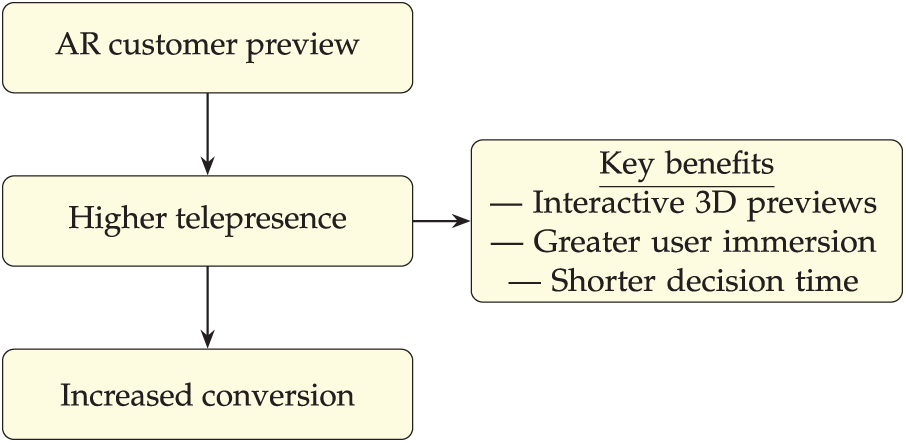

5.5 Retail and User Experience

Immersive technologies extend beyond back-office analytics or professional training, transforming customer-facing interactions. A large-scale retail study conducted in the furniture sector compared a smartphone-based AR app to the traditional 2D web interface. The AR application not only enhanced perceived telepresence by an average of 1.2 points on a Likert scale but also increased purchase intention by 17% [153] (see Table 1). Additionally, the same study revealed a notable decrease of about 38% in perceived intrusiveness when using the AR application, calculated from reported mean values (Web interface: 4.08, AR app: 2.52). This reduction suggests that well-designed AR overlays effectively inform users without overwhelming them.

Integrating AR and VR into mobility platforms—such as allowing passengers to preview seat layouts, luggage compartments, or station amenities—can enhance user confidence during the decision-making process, potentially increasing revenue conversion rates. The reduced intrusiveness observed in retail AR applications is particularly relevant for scenarios involving crowded terminals or in-vehicle interfaces, where excessive information could otherwise lead to user discomfort.

Fig. 14 summarizes the corresponding interaction loop, highlighting its applicability to immersive route visualizations, interactive ticketing processes, and onboard amenity previews within the future MaaS solutions.

Figure 14: Retail-style XR funnel: the same interaction loop can support seat-map previews, AR wayfinding, or in-vehicle amenity selection

5.6 Implications for Transportation

The evidence reviewed in the previous sections—drawn from both cross-domain pilots (manufacturing, healthcare, retail) and the first field demonstrations inside transport (such as motorway DT [139], blockchain MaaS pilots [140], deterministic XR co-driving over 6G citeYu2023)—highlights four capability blocks that are ready for transfer to mobility-centric metaverse deployments:

• Real-time sensor integration: live IoT streams can feed DTs with sub-second latency, as shown in factory analytics [154] and the Geneva motorway pilot [139].

• Scalable multi-user collaboration: persistent XR workspaces already support synchronous design in BIM [145] and cooperative driving scenarios on 6G testbeds [141], suggesting that dispatchers, controllers and depot crews can share a common transport twin.

• XR-based training and system modeling: high-fidelity simulators improve procedural accuracy in orthopaedics [151], industrial assembly [166], and aircraft maintenance [159]; the same workflow is applicable to traffic-control or fleet-maintenance tasks.

• Enhanced UX and engagement: contextual AR previews raise telepresence and purchase intention in e-commerce [153]. An analogous 3D preview of seat layouts, first/last-mile links or real-time crowd density could boost passenger satisfaction and willingness to pay.

These studies demonstrate that carefully engineered immersive systems can enhance efficiency, safety and user satisfaction—core objectives for public-transport stakeholders. To achieve these gains at city scale, operators and regulators must still agree on open data schemas, edge/cloud-based reference architectures and validated human-factor metrics; otherwise, the sector continues to accumulate isolated proofs of concept rather than interoperable, production networks.

6 Toward Empirical Metaverse Studies in Transportation

Despite growing interest in metaverse technologies [13], our review shows a persistent reliance on simulation-based or purely conceptual work in the transportation literature [146]. In order to bridge the gap between theoretical discussion and real-world deployments, in this section, we propose key considerations for designing and conducting empirical studies [3,9].

6.1 Pilot Architectures and Implementation Protocols

An effective pilot project for a metaverse-enabled transportation system should integrate the following architectural layers:

• Hybrid cloud and edge infrastructure—Leverage a combination of edge servers (for example, roadside units, on-board computers) and cloud data centers to ensure low-latency processing near users [167,168] while offloading high-capacity tasks (such as complex 3D rendering) to powerful cloud servers [16,169]. Edge deployments reduce round-trip time, as demonstrated in VR streaming studies that highlight the latency benefits of placing processing closer to users [170], and enable distributed computing resources [11].

• Distributed consensus and synchronization—If blockchain or distributed ledgers are used for asset ownership (such as digital tickets, freight documentation), implement a consensus protocol (such as Proof of Stake or Raft) that can handle real-time transactions without bottlenecks [3,171]. Robust blockchain layers secure user interactions in a metaverse-based transport scenario [172], while modular architectures ensure adaptivity [117]. Moreover, maintaining consistency among multiple servers requires logical clocks or vector timestamps. For smaller-scale deployments, a Lamport clock update mechanism can suffice to order events consistently in a distributed environment, as illustrated in Algorithm 1 of Section 3. If block inclusion proofs are necessary, a Merkle-tree-based verification (Algorithm 3) can efficiently confirm transactions or ownership records without downloading entire block data.

• Cross-platform XR support—It ensures compatibility with multiple augmented and VR devices (headsets, AR glasses, mobile AR) [173,174] to capture diverse user demographics. Evaluate trade-offs in rendering fidelity vs. hardware constraints [175,176]. These XR training modules could enhance operator performance, improve safety awareness, and reduce onboarding time for new personnel. This may include XR-based training modules for drivers or operators, aimed at improving safety awareness and shortening onboarding times [177].

A reference architecture could consist of the following:

• Local edge nodes (for example, roadside 5G/6G units) to process sensor data from vehicles or infrastructure [169].

• A cloud-based real-time simulation engine (for example, using a platform like Unity, Unreal Engine, or Omniverse) for 3D scene management [6,178].

• A permissioned or public blockchain for recording user interactions, digital asset ownership, or micropayments (fares, tolls) [11,171].

6.2 Performance Metrics and Data Collection

Baseline figures for latency, usability, and transaction throughput is now available from both cross-domain pilots (Table 1) and the first transport-sector demonstrations (such as the Geneva motorway twin [139] and a 6G multi-user XR testbed [141]). Building on those benchmarks, the transport prototypes should be instrumented with the following quantitative indicators:

• Latency—Measure the end-to-end delay between a user action and its visual or haptic response under realistic network conditions [139,167,175].

• Throughput (transactions

• QoE—Collect presence, usability, and simulator-sickness scores to link technical performance with perceived immersion [176].

• Bandwidth consumption—Monitor edge-to-cloud traffic during peak commuter periods to expose bottlenecks and define cost envelopes, as emphasized by edge-based VR delivery scenarios showing bandwidth constraints and optimization strategies [167,170].

• Scalability tests—Execute stress runs that progressively increase the number of concurrent avatars or connected vehicles; recent XR pilots sustain approximately 120 Hz at city-block scale over 6G links [66,141].

6.3 Importance of Computational Modeling and Algorithmic Frameworks

As outlined in Section 3, the metaverse relies on a set of geometric, distributed-systems, cryptographic, and AI-driven techniques. However, translating these techniques into working pilots demands robust computational modeling capable of handling dynamic, uncertain, or incomplete data—similar in structure to those found in financial and censored-response contexts [179,180]—beyond basic scenario testing. Key dimensions include the following:

• Algorithmic complexity and scalability—As user counts rise, naive