Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

AI-Driven Approaches to Utilization of Multi-Omics Data for Personalized Diagnosis and Treatment of Cancer: A Comprehensive Review

1 Department of Computer Science, Faculty of Computing and Information Technology, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 21589, Saudi Arabia

2 Centre of Research Excellence in Artificial Intelligence and Data Science, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 21589, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Somayah Albaradei. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advanced Computational Intelligence Techniques, Uncertain Knowledge Processing and Multi-Attribute Group Decision-Making Methods Applied in Modeling of Medical Diagnosis and Prognosis)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 2937-2970. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.072584

Received 30 August 2025; Accepted 07 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

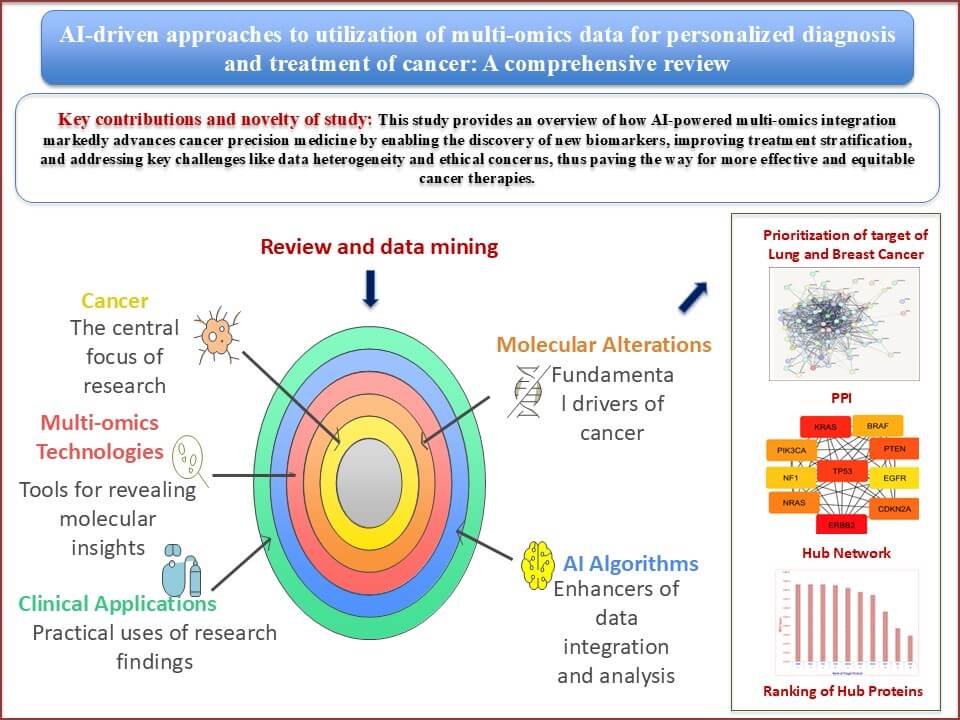

Cancer deaths and new cases worldwide are projected to rise by 47% by 2040, with transitioning countries experiencing an even higher increase of up to 95%. Tumor severity is profoundly influenced by the timing, accuracy, and stage of diagnosis, which directly impacts clinical decision-making. Various biological entities, including genes, proteins, mRNAs, miRNAs, and metabolites, contribute to cancer development. The emergence of multi-omics technologies has transformed cancer research by revealing molecular alterations across multiple biological layers. This integrative approach supports the notion that cancer is fundamentally driven by such alterations, enabling the discovery of molecular signatures for precision oncology. This review explores the role of AI-driven multi-omics analyses in cancer medicine, emphasizing their potential to identify novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets, enhance understanding of Tumor biology, and address integration challenges in clinical workflows. Network biology analyzes identified ERBB2, KRAS, and TP53 as top hub genes in lung cancer based on Maximal Clique Centrality (MCC) scores. In contrast, TP53, ERBB2, ESR1, MYC, and BRCA1 emerged as central regulators in breast cancer, linked to cell proliferation, hormonal signaling, and genomic stability. The review also discusses how specific Artificial Intelligence (AI) algorithms can streamline the integration of heterogeneous datasets, facilitate the interpretation of the tumor microenvironment, and support data-driven clinical strategies.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

About 10.0 million cancer deaths and 19.3 million new cases of cancer are reported to have occurred globally in 2020. By 2040, the expected instances of cancer worldwide will be 28.4 million, rising 47% from 2020. Compared to transition countries, which are expecting a 32% increase to 56%, transitioning countries are expected to experience a higher increase of 95% [1]. Tumor severity is largely determined by the timing, accuracy, and staging of cancer diagnosis, all of which have an impact on clinical decision-making and results [2]. Cancers may initially develop in the lung, breast, or kidney, and their development can have a variety of phenotypic characteristics, including cell surface markers and genetic alterations such as tumor suppressor protein (p53) [3], phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) [4], estrogen receptor (ER) [5]. Malignancies can also vary in growth rate and apoptosis depending on the cancer microenvironment, blood supply, and aggressiveness [6]. It is the result of various biological entities, genes, proteins, mRNAs, miRNAs, metabolites, etc., behaving improperly and changing on a global level.

There is an exponential rise in complexity that coincides with the information transfer from DNA to RNA to protein. The four nucleotides that make up the genome’s genetic code are mostly static, but during the transcription process, which turns genes into RNAs, temporal dynamics are introduced. The transcriptome is an extremely dynamic entity because it is orchestrated to regulate gene expression temporally in response to extracellular, environmental, and developmental signals through gene-regulatory networks [7]. The transcriptome becomes more complicated as a result of temporal dynamics and alternative splicing. Even more intricate information coding systems involve mRNAs, such as the translation process, in which mRNAs code for proteins made up of 20 amino acids. Following synthesis, proteins can fold into a wide variety of conformations, which are determined by the initial amino acid sequences and chemically induced post-translational modifications (PTMs) of amino acid residues. Numerous PTMs, including phosphorylation, acetylation, and glycosylation, occur in proteins and can have an immediate impact on their structure and function. Furthermore, proteins can be found in a variety of subcellular locations, including the cytoplasm, the nucleus, the endoplasmic reticulum, and the cell membrane. In contrast, mRNAs are synthesized in the nucleus and translated in the cytoplasm. The proteome is incredibly complicated as a result of all these events [8].

Taking into account that the omics data listed above are the direct result of several bio-entities, they can be regarded as “primary” sorts of omics data. Other non-canonical types of omics data, like immunomics, microbiome data, and multiplex family history data, are rare and fall outside of the “primary” categories of omics data. The original omics data and additional non-omics biological information are integrated to create this non-canonical data. The heterogeneity, volume, and intricate relationships among the data make this integration a difficult task [9]. AI offers a plethora of opportunities for developing useful models for non-canonical data processing.

A number of databases, such as ICGC (International Cancer Genome Consortium) and TCGA, are expanding quickly to handle multi-omics data [10]. Humans lack the capacity to analyze this vast amount of data with sufficient speed. Many traditional statistical techniques are limited in their application by the high dimensionality of omics data and the small sample size. Conversely, the quickly developing field of artificial intelligence (AI) in computer science provides sophisticated analytical techniques with predictive powers. Biologists and computer scientists must successfully collaborate in order to analyze and interpret multi-omics data. In a short period of time, AI has significantly improved this crucial field of oncology, often outperforming human specialists and offering additional benefits like automation and scalability [11]. AI includes machine learning (ML) as a subfield. ML is the study of computer programs that automatically learn from past experiences. The program completes some tasks at first, evaluates its performance, accumulates experience, and then applies what it has learned to the other assignments to provide better results [12].

In order to distinguish significant data from noise, computational techniques and methods are required. Deep learning (DL), a subset of AI, is well-suited to handle heterogeneous and unstructured data because it is adaptable and has a strong tendency to identify high-dimensional, non-linear associations in multi-modal data [13,14]. The focus of AI has moved from theoretical study to practical applications in recent years. All phases of cancer care, including early risk assessment and prevention, screening, diagnosis, response evaluation, prognosis prediction, and formulation of the final treatment plan, have experienced the successful application of AI [14]. Clinical medicine with AI support can benefit from better management choices, which will ultimately advance precision medicine.

AI-driven multi-omics analysis has the ability to identify novel targets and biomarkers to maximize treatment effects, in addition to significantly advancing our understanding of cancer biology [15]. Current multi-omics technologies for cancer precision medicine are highlighted in this study, along with a workflow for integrated analysis of multi-omics and other modality data. The most recent developments in AI-based multi-omics tumor profiling are then thoroughly reviewed, with an emphasis on how these technologies are applied to cancer diagnosis, classification, early cancer detection, response evaluation, and prognosis prediction. Lastly, the logistical challenges of multi-omics analysis based on AI are explored, along with potential future applications in cancer personalized diagnosis and treatments. Table 1 summarizes the diverse AI-based approaches in multi-omics data analysis across various biological domains.

The present study explores the transformative potential of AI-driven multi-omics integration in cancer precision medicine. It covers how artificial intelligence algorithms enhance the analysis of complex, heterogeneous biological datasets—ranging from genomics and transcriptomics to proteomics and metabolomics—to uncover novel biomarkers, therapeutic targets, and disease signatures. Emphasizing applications in both breast and lung cancers, the review also highlights how network biology and hub gene analysis can deepen understanding of cancer pathophysiology. Ultimately, it underscores the critical role of AI in bridging the gap between big data and actionable clinical strategies.

3 Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Cancer Multi-Omics

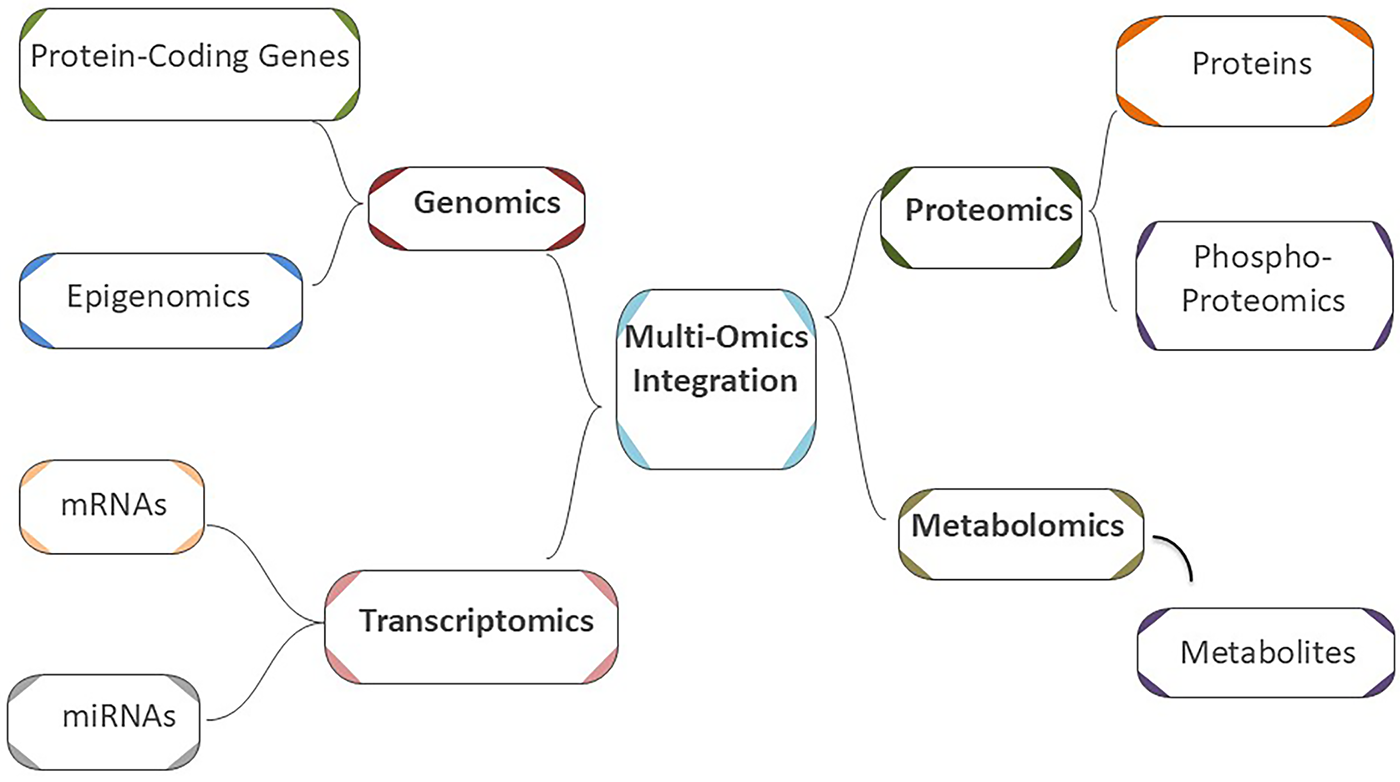

Approximately 20,000 proteins [39], 20,000–22,000 protein-coding genes [40], 30,000 mRNAs [41], 2300 miRNAs [42], and 114,100 metabolites [43] have been identified in the human body, in that order. Many kinds of biological “omics” data are generated by thorough analysis of these bio-entities. Many genes (genomics and epigenomics), proteins (proteomics and phospho-proteomics), RNAs (RNA transcriptomics), miRNAs (miRNA transcriptomics), and metabolites (metabolomics) from the same individuals can now be profiled globally owing to technological advancements [44–46].

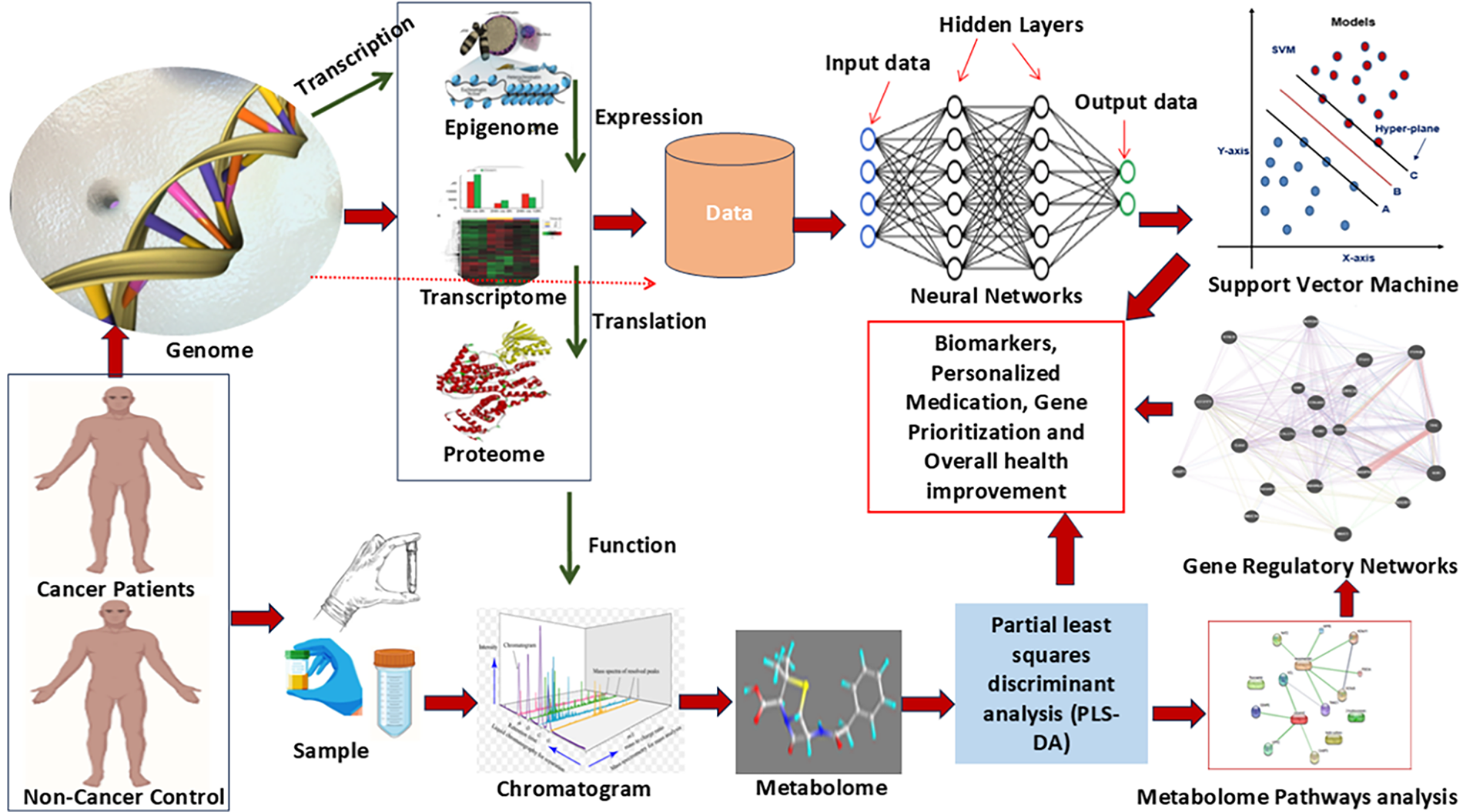

Consequently, new avenues for the study and treatment of diverse diseases can be opened by analyzing and assessing biological samples at each omics research area or by connecting the dots between the resulting data and analyzing them in a multi-omics field [47]. The present approach in oncology research centers on the idea that cancer is inevitably caused by molecular alterations at several biological layers [48]. Therefore, omics techniques have been able to offer comprehensive insights into the mechanisms underlying cancer (Fig. 1), which could assist in discovering the molecular signature of the disease [49].

Figure 1: Schematic representation of a multi-omics approach for cancer research and diagnosis

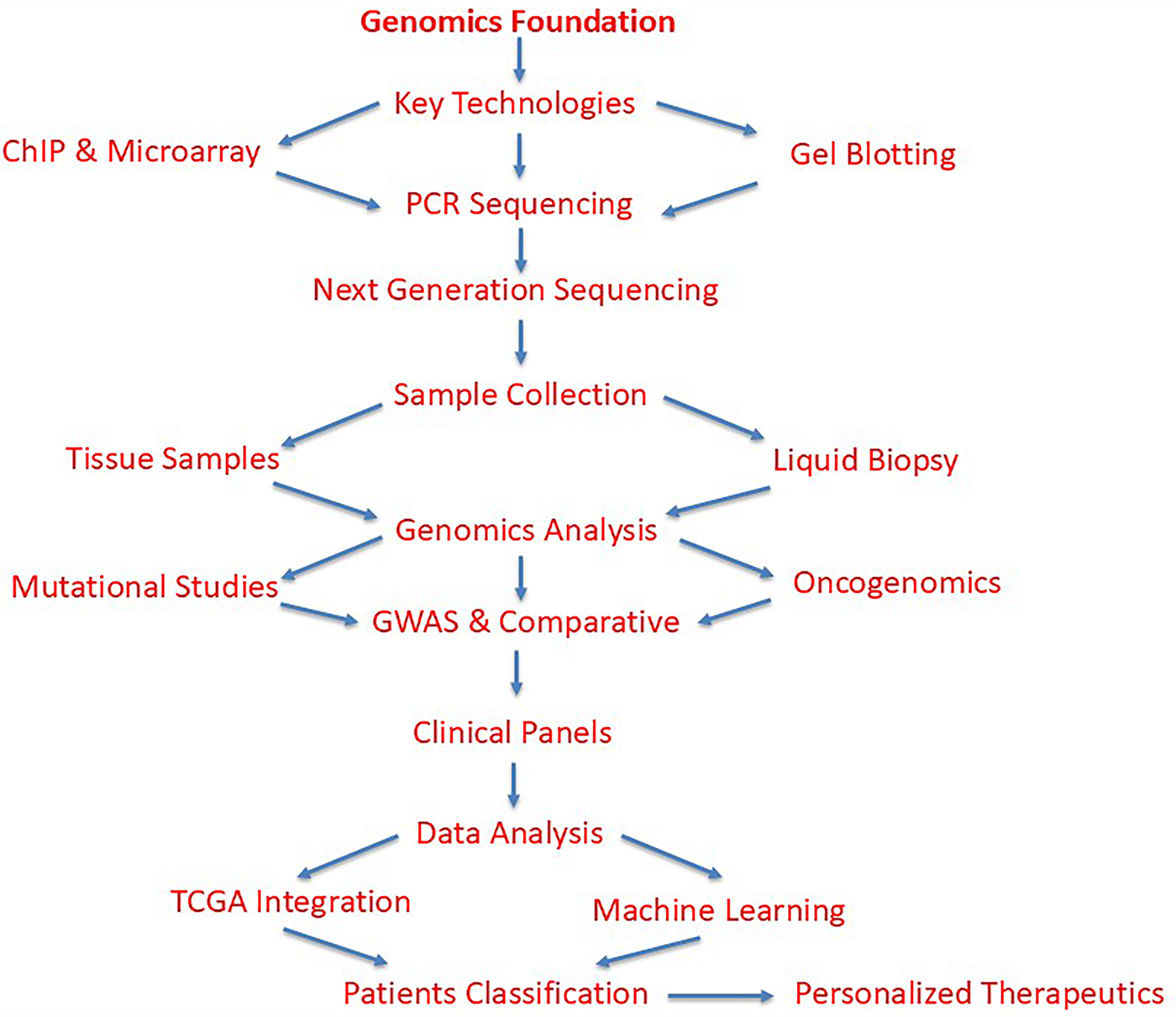

Amongst the omics branches, genomics is the most fundamental. In principle, the field of genomics can offer comprehensive insights into the structure, function, and relationships between genes and their products in an organism, in addition to genome mapping and editing. However, its significance increases when the pathology of diseases is traced through genes and associated modifications. Thus, deciphering different facets of diseases can be accomplished with the use of technologies, including chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) test, DNA microarray, gel electrophoresis, blotting, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and DNA sequencing [49].

Cancer genomics, to define it specifically, is the study of genetic anomalies associated with the cancer process, which, remarkably, has a significant impact on personalized cancer treatment [50]. Identification of cancer-specific molecular signatures and mechanisms underlying cancer at the genomic level not only improves the field of genomics science and related technologies but may also aid in managing cancer from early detection to treatment [51]. This is because changes and mutations at the genome level are one of the inseparable facts of cancer. In this sense, DNA sequencing technologies have provided new molecular insights for research by revealing the mysteries of genetic coding in an organism [52].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is becoming widely used as a useful technique for discovering more about a tumor’s genomic composition. A thorough profile of the tumor can be obtained by concurrently sequencing millions of DNA fragments in a single sample in order to identify a variety of abnormalities. The use of NGS for clinical applications has increased significantly as a result of the thorough detection of aberrations as well as advances in cost, sequencing chemistry, pipeline study, dependability, and data analysis [53]. Mutation signature studies, or “mutational landscape studies,” are studies that identify patterns among millions of mutations detected by NGS. These studies focus on identifying recurring patterns in mutations caused by specific processes, such as UV light, smoking, or DNA repair deficiencies [54]. NGS also analyzes genome-wide association studies, variable frequency analysis, comparative genomic studies, oncogenomic studies, and population genomics to study evolution and demographic history [55].

Cancer panels are made especially to reliably identify somatic mutations that are clinically significant. For assessment of cancer risk, germline mutations in cancer-predisposing genes such as BRCA1/2, have been identified as well [56]. The Oncomine Dx Target Test, Praxis Extended RAS Panel, MSK-IMPACT, and Foundation One CDx are among the oncology-related NGS-based panels which are authorized by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017 [57]. The FDA’s recent clearance of NTRK gene fusions for tumor-agnostic indications expands the clinical application of NGS (FDA approval for larotrectinib). Considering that liquid biopsy is non-invasive, it holds considerable potential. Liquid biopsy has been shown in numerous trials to be useful for drug-response monitoring, cancer diagnosis, and prognosis. Tumor DNA is frequently obtained via circulating tumor cells (CTCs), which are discharged from the tumor and enter the vascular system, exosomes, which are vesicles generated from cells, and cell-free DNA (cfDNA) released by dying tumor cells. Crucially, multiple research teams have demonstrated that NGS-sequencing protocols may be adjusted to reach sensitivity levels that are comparable to traditional sequencing processes [58]. However, clinical trials are currently needed to confirm this before the approach can be implemented in medical applications.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project demonstrates how NGS analysis can help with patient classification and the identification of new carcinogenic pathways. This knowledge has been utilized to clarify oncogenic pathways that are functionally significant for many types of tumors [59]. Machine learning techniques such as support vector machines (SVMs), random forest (RF), or gradient boosting algorithms could have been applied in a recent study [60] to classify data or predict outcomes, revealing the regulatory role of F-box/WD repeat-containing protein 7 (Fbw7) in cancer cell oxidative metabolism [61]. Molecular subgroups discovered through pan-cancer research also contribute to therapeutic personalization and enhance patient survival [62]. The flow chart of the genomics approach has been given in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Comprehensive workflow of genomics-based methodology in cancer research and diagnosis. The flowchart illustrates the systematic approach starting from genomics foundation through core technologies (ChIP, DNA microarray, gel electrophoresis, blotting, PCR, and DNA sequencing) to NGS as the central analytical platform. Sample acquisition includes both traditional tissue samples and liquid biopsy approaches. Genomic analyses encompass mutational landscape studies, genome-wide association studies (GWAS), comparative genomics, oncogenomics, and population genomics. Data integration through The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project and machine learning algorithms (support vector machines, random forest, gradient boosting) enables patient classification, therapeutic personalization, improved survival outcomes, and identification of novel carcinogenic pathways

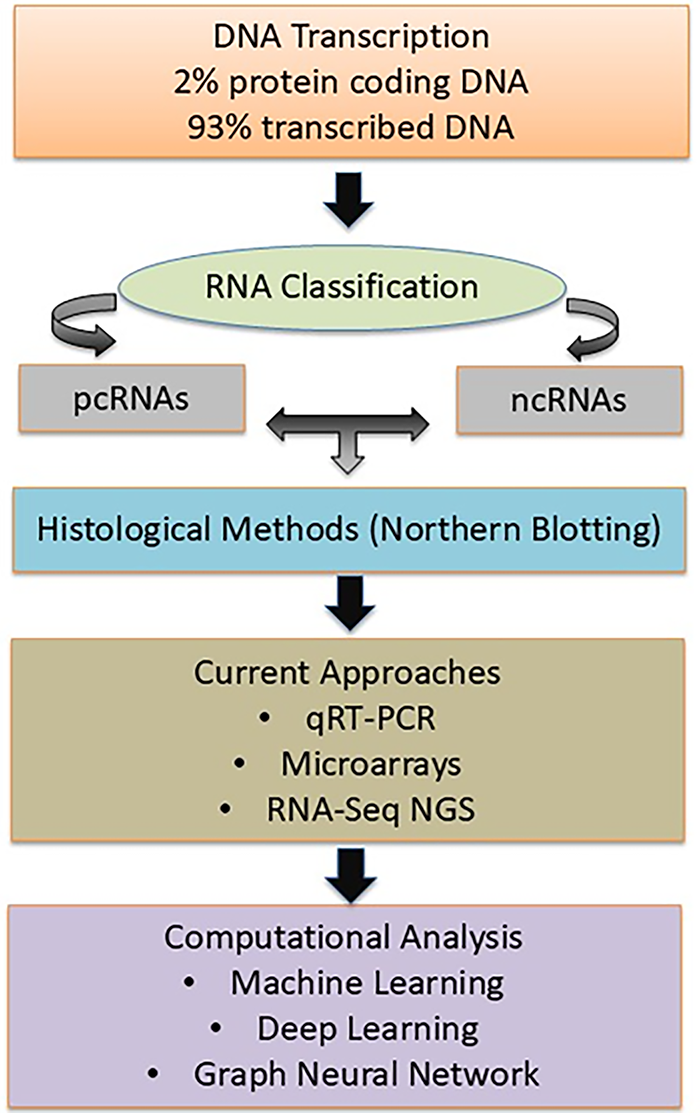

Research reveals that only 2% of human DNA is translated into protein-coding RNA (pcRNA), whereas 93% of DNA is transcribed into RNA [63]. Once these RNA molecules reach their mature state, they participate in translation and specify the amino acid sequence of the protein. The remaining portion of the human transcriptome is composed of non-coding RNA (ncRNA). Among those that have been identified so far are ribosomal RNA (rRNA), transfer RNA (tRNA), micro-RNA (miRNA), small interfering RNA (siRNA), PIWI-interacting RNA (piRNA), small nuclear RNA (snRNA), small nucleolar RNA (snoRNA), extra-cellular RNA (exRNA), guide RNA (gRNA), small Cajal body-specific RNA (scaRNA), circular RNA (circRNA), long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), which includes X-inactive specific transcript (XIST) and HOX Transcript Antisense RNA (HOTAIR) [64]. They differ significantly from one another in terms of their cellular functions. Certain non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have catalytic activities, such as tRNA and rRNA synthesis, whereas other ncRNAs, such as miRNA, snRNA, and snoRNA, are engaged in mRNA regulation [65]. Each of the ncRNA types listed above could play a significant role in oncogenesis. Furthermore, new kinds of RNAs that were not known before are constantly being found—largely as a result of contemporary technologies. Transcriptome cognition could be improved by carefully examining the roles of RNAs and developing novel techniques.

Several approaches have been developed to identify each RNA’s function in the transcriptome, or collection of all RNAs, in human disorders. Northern blotting is a classical method used for the detection and quantification of specific mRNA transcripts, serving as one of the earliest approaches for examining gene expression patterns in the human transcriptome [66]. This laborious technique analyzes a maximum of several gene transcripts simultaneously using gene-specific DNA probes that are hybridized to the RNA [67]. Later, more advanced techniques for transcriptome analysis emerged based on complementary probe hybridization [68]. In the field of cancer transcriptomics, three primary approaches may currently be identified: the use of probe hybridization in a large-scale quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and microarrays, and the most recent advancement in NGS technology, RNA-Seq [69]. Deep Learning is used for gene expression prediction, transcript quantification, and disease state classification, while Machine Learning is used for feature selection, clustering, and dimensionality reduction [70]. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are used to analyze transcript annotations, identify non-coding RNAs, and interpret gene regulatory elements in gene transcripts [71]. The flow chart of the transcriptomics workflow is given in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: The flowchart now presents the transcriptomics workflow with enhanced visual clarity, showing the progression from DNA transcription (2% pcRNA, 93% transcribed RNA) through RNA classification, analytical methods (Northern blotting → qRT-PCR/Microarrays → RNA-Seq), computational approaches (ML, Deep Learning, GNNs), and final applications in cancer research

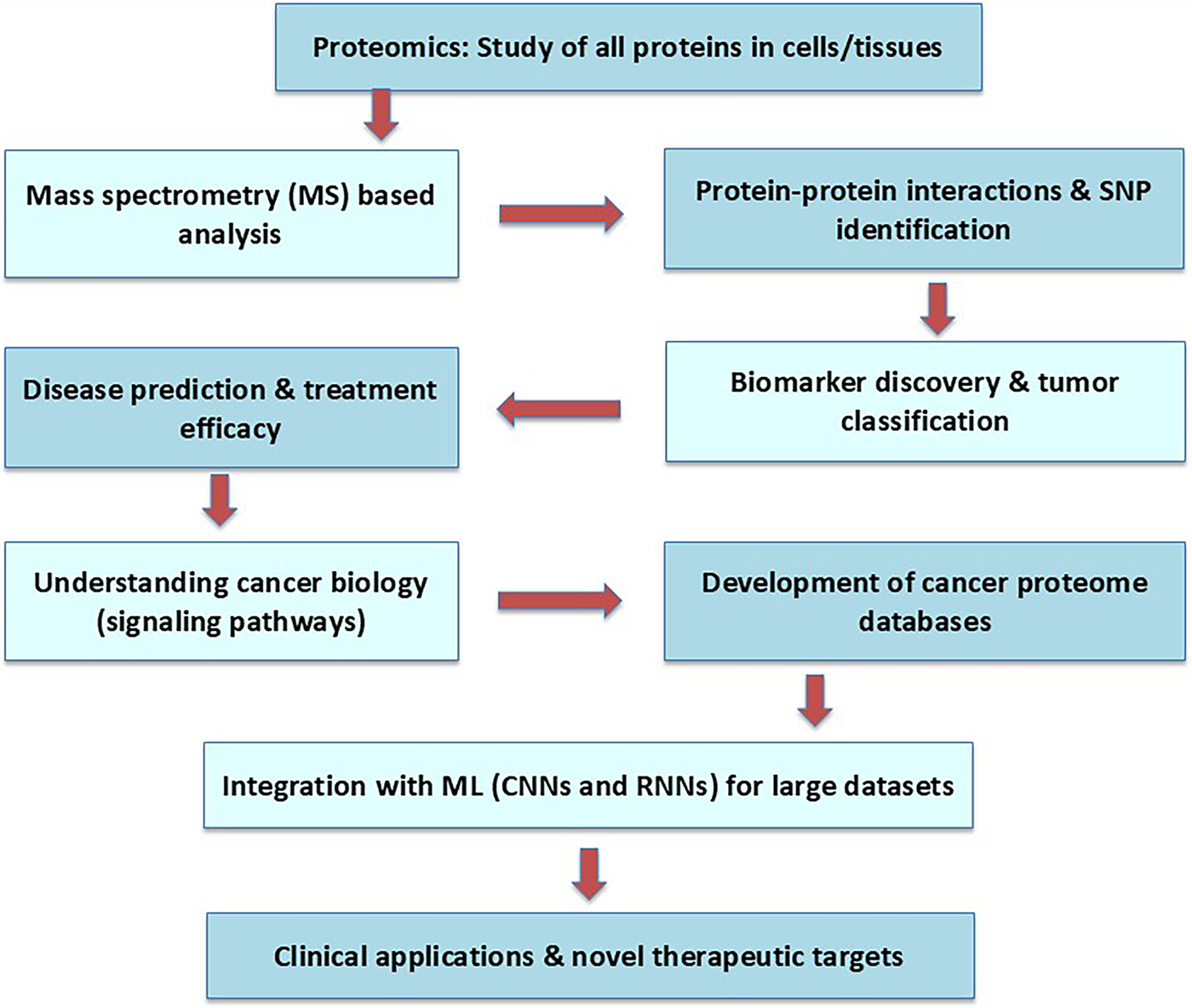

The study of all the proteins expressed in a cell, tissue, or individual is known as proteomics. Large-scale protein analysis has now gained widespread usage thanks to the development of mass spectrometry (MS) based protein analysis technologies [72]. The MS information gathered from such jobs can be utilized to diagnose and forecast illnesses, understand the mechanisms behind diseases, assist in the development of new drugs, and give the building blocks for biological discovery [73,74]. Significant advancements have been achieved in the identification of novel therapeutic targets and clinically relevant biomarkers with the development of proteomics technology and its application to a variety of diseases, including cancer [75].

Proteomics techniques such as protein-protein interactions and identification of single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNPs) enable the identification of biomarkers and protein expression patterns, aiding in tumor classification, disease prediction, and treatment efficacy [76,77]. Proteomics approaches have also been applied to better understand the basic biology of cancer, including how tumor cells alter their signaling pathways and how different pathways can be targeted for cancer therapy [78]. Consequently, enormous data sets have been gathered and combined with clinical and molecular biology data about cancer to develop cancer proteome databases.

Recently, emphasis has been placed on using Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) to analyze large cancer proteome datasets and to overcome data complexity and heterogeneity from diverse sources. Shen et al. [79] analyzed the TCGA, National Institute of Health, Medical Research, and AMC databases for mutant genes related to vascular invasion, using the Boruta algorithm. Mutations linked to vascular invasion were found in ten different genes. This work supports the idea that ML is useful, even if it has not yet been established whether this mutation can be used for clinical prediction. The working pipeline of proteomics is given in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: The working flowchart of proteomics starts with a set of proteins and a cell for the specific therapeutics

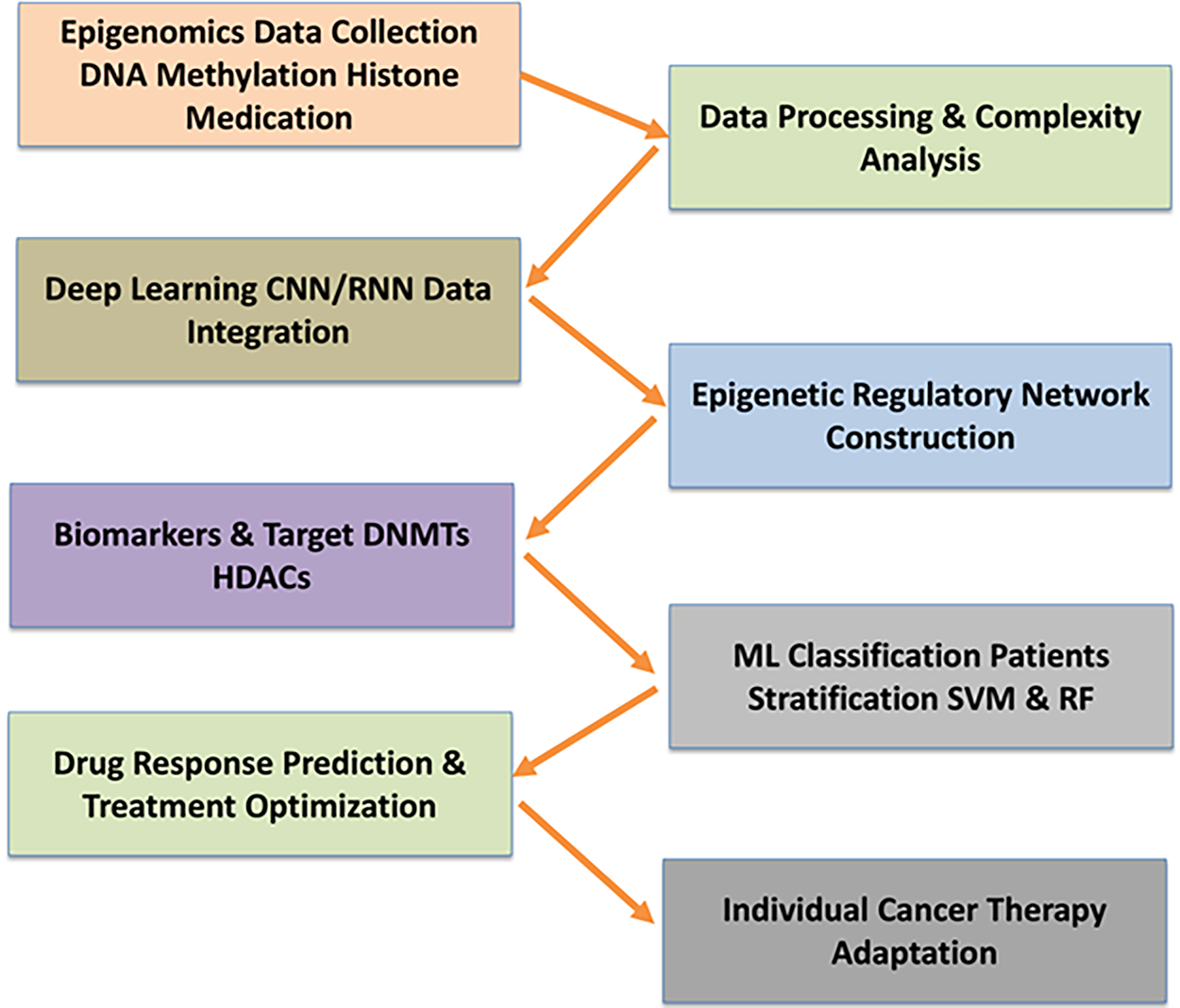

The study of the complete set of epigenetic modifications (chemical alterations) on a cell’s genetic material is referred to as epigenomics. These modifications do not alter the DNA sequence but affect gene expression [80]. According to Castilho et al. [81], these modifications are key players in tumor initiation, progression, and response to the treatment of cancer patients. The advancement in epigenetics-based treatments triggers novel therapeutic targets and optimization of strategies for cancer patients [82]. The massive complexity of epigenomic data poses the main challenges in screening relevant biomarkers and therapeutic targets of cancer [83]. CNNs and RNNs are utilized to integrate epigenomic data [84]. In addition, “epigenetic regulatory networks (ERNs)” are more comprehensive to drug resistance and disease progression states. CNNs are widely accepted algorithms to predict chromatin accessibility from DNA methylation data that revealed gene expression regulation in various cancer types [85]. These targets are involved in epigenetic modifications, viz., “DNA methyltransferases and histone deacetylases”.

Vougas et al. [86] stated that ML is the specific framework that has been shown to accurately predict drug responses to therapies such as epigenetic inhibitors in clinical settings. Supervised learning approaches like RF and SVM are renowned algorithms utilized for the classification of cancer types through epigenetic markers such as DNA methylation and histone modification patterns analysis [87]. SVMs have a greater impact on the characterization of tumor subtypes and forecasting patient outcomes by unique epigenomic profiles of individuals [88]. This enables oncologists to tailor treatment plans, avoiding ineffective therapies and minimizing the drug’s adverse effects [89]. The working flowchart of epigenomics has been depicted in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: The illustration of an integrative workflow for epigenomics-based cancer biomarker and therapeutic target discovery. Epigenomic data, including DNA methylation and histone modifications, are first collected and processed. Deep learning algorithms such as CNNs and RNNs enable the integration and interpretation of complex datasets, supporting the construction of epigenetic regulatory networks (ERNs) for comprehensive analysis of drug resistance and disease progression. Machine learning methods (SVM and RF) are employed to classify cancer types, stratify patients, and predict drug responses, enabling the identification of clinically relevant biomarkers and optimization of individualized treatment strategies

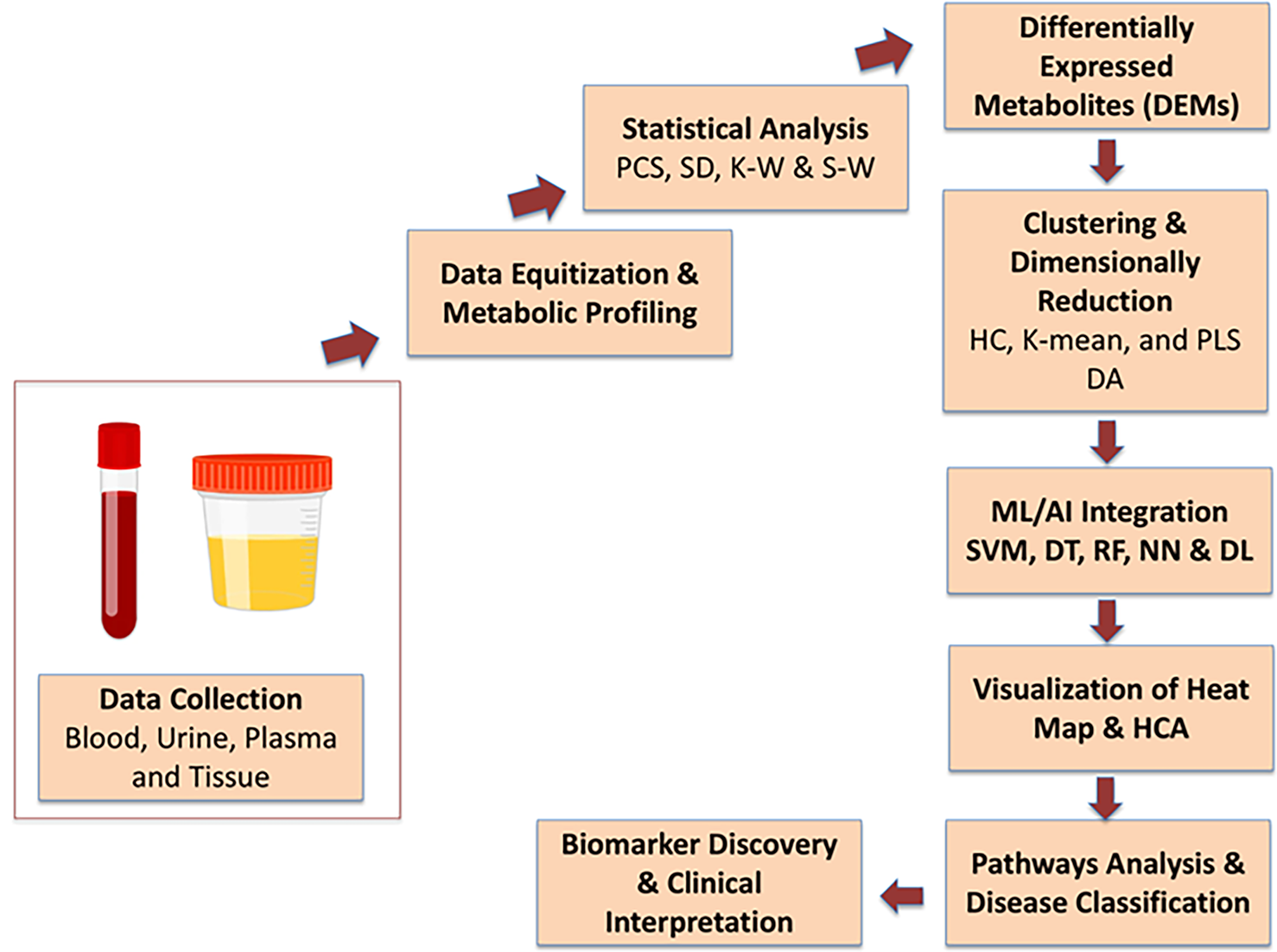

The metabolomics of blood, urine, tissue, plasma, and other body samples provide a promising avenue for early diagnosis and improved care of cancer-associated persons [90]. A mixed approach of metabolomics and AI accelerates the diagnosis and therapeutic process of cancer patients. In actuality, metabolomics is a novel approach that enables ML and statistical modeling to comprehensively understand the pathophysiological processes of cancer disease via accessing the network pathways analysis [91]. Metabolomics produces extensive datasets containing hundreds to thousands of metabolites with intricate relationships. AI, designed to replicate human intelligence, offers exceptional potential for analyzing large-scale metabolomic data [90]. ML algorithms such as SVM, decision trees (DT), RF, neural networks (NN), and deep learning (DL) also offer advanced proficiencies for the management of large, complex metabolite datasets [92]. The principal component analysis (PCA), mean ± standard deviation (SD), and some other tests like the Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney non-parametric test are used to identify differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs) in cancer patients compared to non-cancer patients (control) [93,94]. The clustering methods, such as hierarchical and k-means clustering, provide significant metabolic features of these DEMs [95]. Partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA) is also popular for metabolic features of differentially expressed metabolites [96]. The supervised, multivariate analysis dimensionality reduction maximizes covariance relationships between intensities of similar metabolic features of DEMs. To visualize and characterize the differences between two groups in the abundance of potential biomarkers, the hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) algorithm is used to make a heat map [97]. These identified metabolites are utilized for disease classification, metabolic pathway analysis, and biomarker discovery [92]. Further, deep learning methods like CNNs and RNNs are increasingly used for classifying cancer diseases based on specified metabolomic features [98]. The flow chart of metabolomics study has been given in Fig. 6, and graphical illustration of AI-driven multi-omics approaches for cancer study has been illustrated in Fig. 7.

Figure 6: Flowchart depicting the metabolomics-based workflow for cancer diagnosis and biomarker discovery, integrating sample collection, statistical and clustering analyses, machine learning, and pathway analysis for differential metabolite profiling and clinical interpretation

Figure 7: An integrated multi-omics and machine learning framework for cancer biomarker discovery and personalized medicine. Genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data are derived from cancer and non-cancer samples, followed by chromatographic profiling and pathway analysis. Gene regulatory networks are constructed, and machine learning models such as neural networks and support vector machines (SVMs) are employed for data integration. This approach enables biomarker identification, gene prioritization, and the development of personalized therapeutic strategies

4 AI-Based Big Data Integration in Oncology

Precision oncology focuses on the accurate identification and targeting of specific tumor cells by leveraging molecular profiling, particularly genetic and proteomic signatures. It integrates personalized cancer genomic data and clinical signatures from electronic health records through computational databases [99]. AI plays a vital role in managing and analyzing high-throughput data generated by NGS, which is central to modern cancer diagnostics and treatment design. NGS facilitates early detection, mutation profiling, and biomarker identification. Recent advances include third-generation sequencing platforms such as PacBio RS and Oxford Nanopore, which enable rapid and long-read sequencing without complex library preparation [100].

In oncology, AI approaches are increasingly used to handle Big Data, enabling analysis and interpretation of complex, large-scale datasets. These include ML for cancer progression prediction, SVM for diagnostic classification, DL for high-resolution imaging tasks, CNNs for medical image extraction, natural language processing (NLP) for clinical decision support, reinforcement learning for treatment optimization, GNNs for biological network analysis, and federated learning for secure, collaborative data analysis [101]. Collectively, these AI technologies support precision oncology by extracting actionable insights from vast and diverse cancer datasets.

Technically, for data handling, AI algorithms are designed to integrate heterogeneous data types—such as genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, radiologic, and clinical datasets—into unified models for actionable predictions. Supervised learning models, like random forests and logistic regression, are used for gene mutation classification and therapy response prediction, while unsupervised methods such as hierarchical clustering and t-SNE assist in molecular subtyping and biomarker discovery. CNNs have proven effective in histopathological image analysis for tumor grading and subtype identification, whereas RNNs and transformers are being applied in longitudinal data modeling from electronic health records. Furthermore, ensemble learning methods improve robustness by combining outputs from multiple models, and explainable AI (XAI) tools like SHAP and LIME are increasingly used to interpret model predictions, making them more transparent and clinically relevant. Together, these AI-powered frameworks enhance the precision, scalability, and interpretability of oncological data analysis. AI techniques are being used in oncology to handle big data, including machine learning for cancer progression prediction, SVM for diagnosis and prognosis, DL for imaging tasks, CNNs for medical image extraction, Natural Language Processing for clinical decision-making, reinforcement learning for treatment optimization, Graph Neural Networks for understanding biological interaction networks, and Federated Learning for collaborative analysis of distributed datasets. These techniques help researchers and clinicians tackle the complexity of cancer data, driving advancements in personalized medicine and precision oncology [101].

An essential part of the diagnostic process is assessing the aggressiveness and the advanced stage of the cancer. This is known as cancer staging and grading. Treatment decisions, such as selecting between aggressive treatment comprising radiation, surgery, and chemotherapy and cautious waiting, might be influenced by staging [102]. The Gleason score, which combines two scores to determine the frequency of tumor cells in two different areas on a slide, is used to stage prostate cancer. When it comes to predicting Gleason scores from histopathology images of prostate tumors, DNNs have demonstrated encouraging preliminary results [103]. In order to train and test a DNN (Inception-V3) and k-nearest-neighbor classifier–based model to predict Gleason scores, Nagpal and colleagues used WSI for H&E-stained prostatectomy tissues [103]. When comparing the Gleason scores generated from their model (0.70) to those assessed by a panel of 29 independent pathologists (0.61), the researchers found an enhanced prediction accuracy. Radiological images can also be used for cancer staging. Zhou et al. [104] achieved an AUC of 0.83 using a deep learning strategy based on SENet and DenseNet to predict grade (high versus low) from MRI images of patients with liver cancer. Overall, these studies show that AI can be used to stage cancer in a promising way; although modest AUC, reported performance was on par with that of qualified professionals.

Genomic profiles and other non-imaging data are increasingly being employed for staging and diagnosis. Tumor subtype classification and cancer diagnosis are possible using information from NGS, including whole-exome, whole-genome, and targeted panels; transcription profiles from RNA-seq, microarray, and miRNAs; and methylation profiles. These platforms give highly multidimensional data (10,000 genes can be examined simultaneously); thus, statistical or ML techniques are needed to use them for cancer classification [105]. Since the early 2000s, when ML techniques like clustering, support vector machines, and artificial neural networks were applied to microarray-based expression profiles for cancer classification and subtype, ML has been used for cancer diagnosis and staging from molecular data. Both omics technologies and ML algorithm advancements have progressed over time. Capper et al. [106] showed that the prediction accuracies for the difficult-to-diagnose subclasses of central nervous system malignancies can be markedly enhanced by a random forest classifier that is exclusively trained on tumor DNA methylation profiles (AUC, 0.99). Their subclass predictions for 139 patients did not match pathologists’ diagnoses; however, follow-up of those select cases indicated that about 93% of those mismatched cases were, in fact, accurately predicted by the model [106]. In order to categorize tissues into either of the 12 TCGA cancer types or healthy tissues acquired from the 1000 Genomes Project, Sun and colleagues developed and used a DNN to genomic point mutations [107]. This is an example of how deep learning approaches are being used. The classifier performed poorly in a multiclass classification task to simultaneously distinguish all 12 cancer types (AUC, 0.70), but it was able to distinguish between healthy and tumor tissue with high accuracy (AUC, 0.94), having been trained on the most common cancer-specific point mutations derived from whole-exome sequencing profiles. This study demonstrated the difficulty in accurately classifying cancers based on mutation data; this difficulty may be attributed to intratumor heterogeneity, low tumor purity, and the occurrence of common mutations among various cancer types. However, the study also demonstrates that comparable models that evaluate cancer using genomic data may be used to analyze genomic profiles from other sources, including cell-free DNA (cfDNA).

6 Prioritization of Hub Genes by AI and ML

Gene lists associated with the most prevalent subtypes of lung and breast cancer were retrieved from public databases like GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) and Ensembl (https://proteinensemble.org/). Protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks were constructed using the STRING database (v12.0) (https://string-db.org/), applied a confidence score threshold of ≥0.7 was applied to ensure high-quality interactions [108]. The resulting networks were imported into Cytoscape (v3.9.1) for topological analysis. Key hub genes were identified using network parameters such as degree, betweenness centrality, and clustering coefficient via the CytoHubba plugin, helping prioritize critical molecular targets for further investigation [108].

6.1 Identification of Key Hub Genes in Lung Cancer Network Using MCC Algorithm

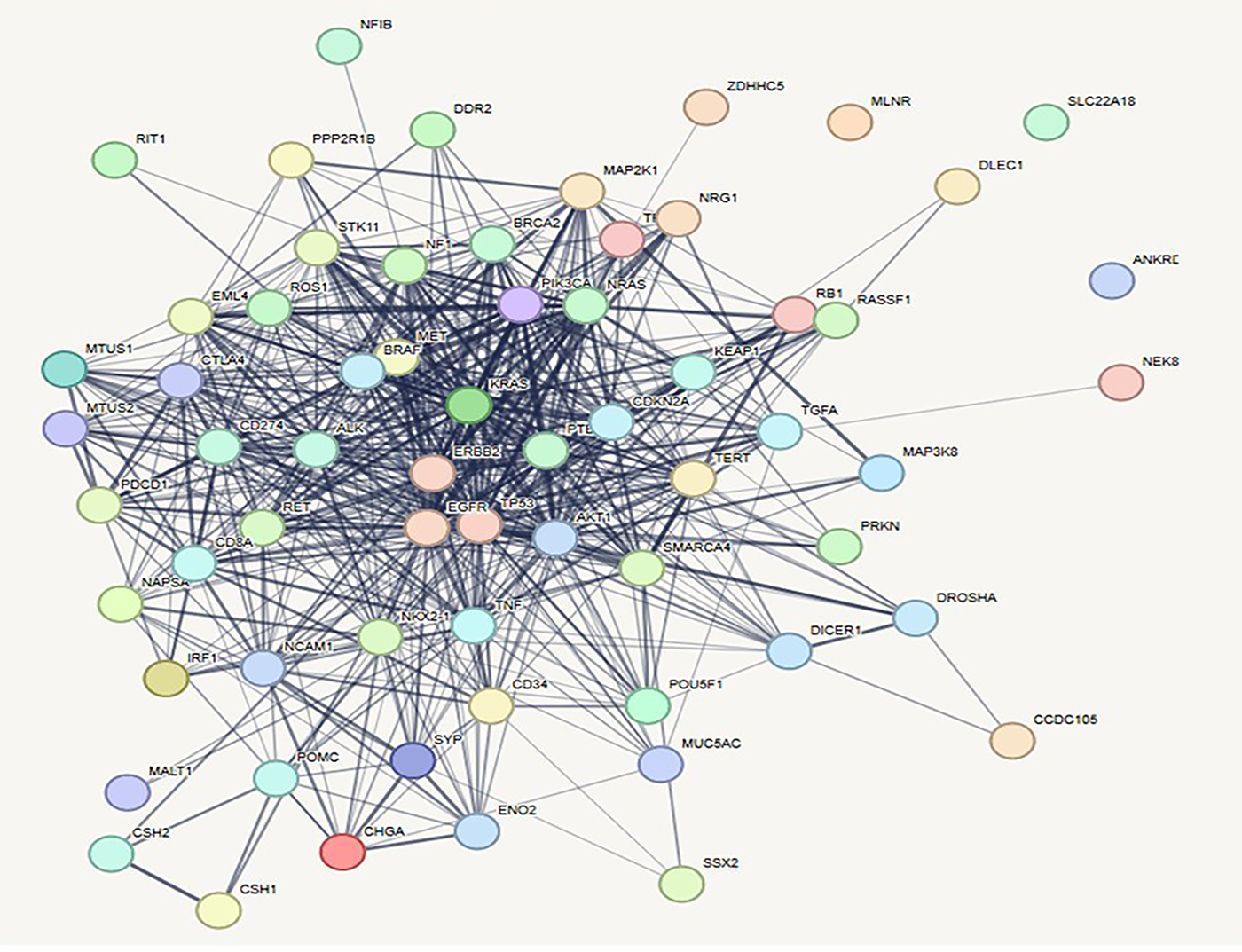

The curated gene interaction network for lung cancer was constructed using the STRING database and further analyzed its topological properties. The resulting network comprised 61 nodes and 603 edges, indicating a densely interconnected system [109]. The average number of neighbors was 19.770, reflecting high interactivity among the genes. The network diameter was calculated as 4, and the network radius was 2, suggesting a compact structure with relatively short paths between nodes [110]. The characteristic path length stood at 1.783, supporting efficient communication across the network. The clustering coefficient was notably high at 0.700, indicative of a strong modular organization [111]. Moreover, the network density was 0.330, while network heterogeneity and centralization were 0.665 and 0.504, respectively (Fig. 8), highlighting the presence of hub genes and centralized regulation. The entire network was fully connected with only one connected component, and the analysis was computationally efficient, taking just 0.127 s. These metrics underline the biological relevance and robustness of the lung cancer gene network in capturing key molecular interactions.

Figure 8: Prioritization of key genes in lung cancer using protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks and CytoHubba plugin. [A] PPI network of lung cancer-associated genes constructed using STRING and visualized in Cytoscape, illustrating complex molecular interactions

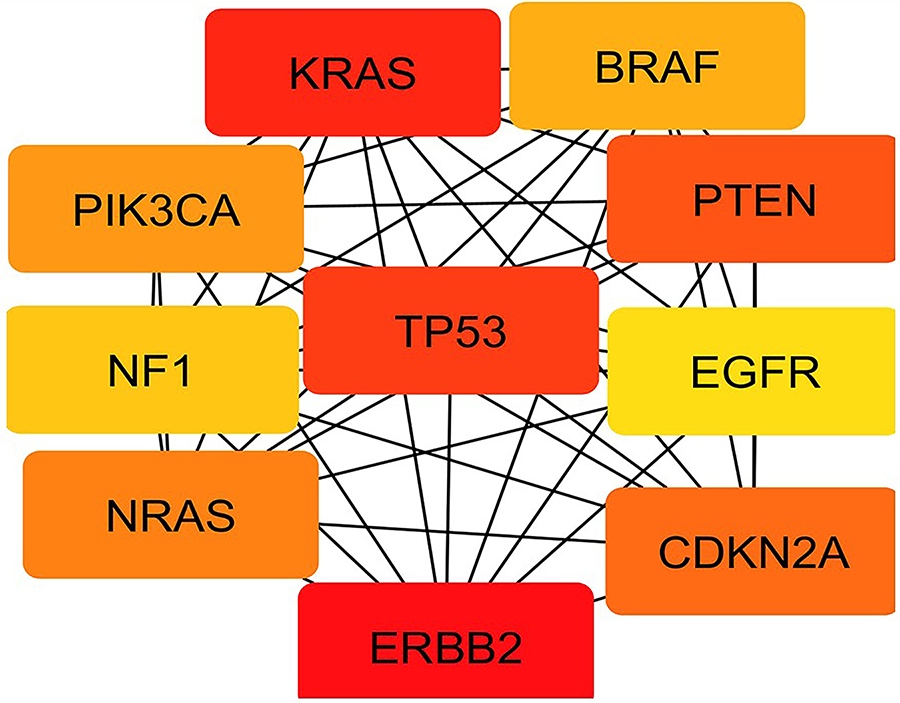

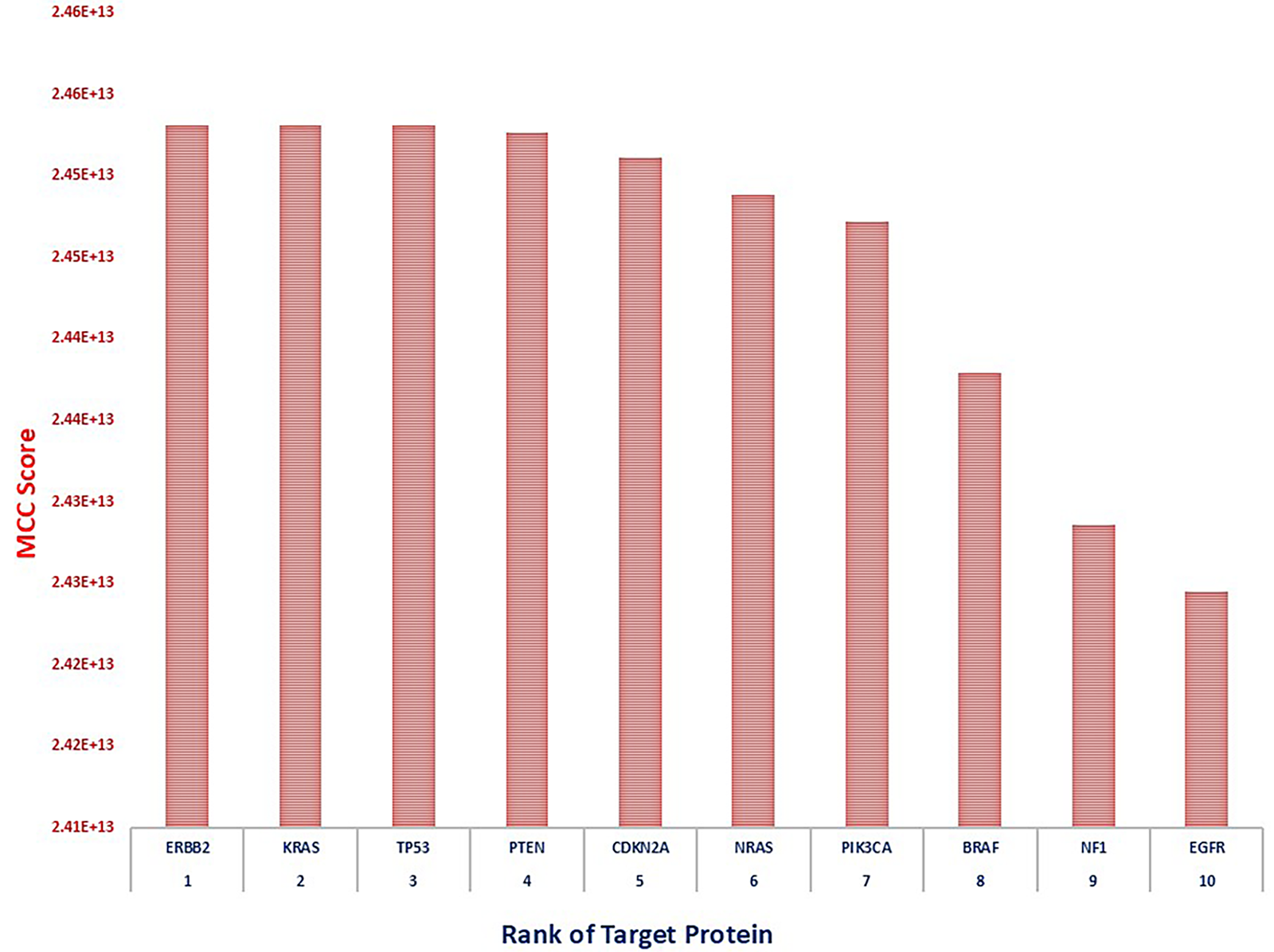

To identify the most appropriate target within the lung cancer-associated protein-protein interaction (PPI) network, the Maximal Clique Centrality (MCC) algorithm was utilized via the CytoHubba module in Cytoscape [108]. The MCC method effectively detects highly interconnected nodes that are likely to play essential biological roles in disease progression. Among the top-ranked genes, ERBB2, KRAS, and TP53 were identified as the leading hub nodes, each attaining a peak MCC score of 2.45 × 1013. These genes are well-established oncogenic drivers in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with ERBB2 and KRAS mediating aberrant receptor tyrosine kinase and RAS/MAPK pathway signaling, respectively. The tumor suppressor TP53, frequently mutated in lung malignancies, underscores its central regulatory function in genomic surveillance and cell cycle control [112].

Other significant hub genes included PTEN, CDKN2A, NRAS, and PIK3CA, all scoring equivalently (2.45 × 1013) and representing key modulators of PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling and cell proliferation checkpoints. Genes such as BRAF and NF1, scoring slightly lower (2.44–2.43 × 1013), further emphasize the RAS/RAF axis as a major oncogenic pathway in lung cancer biology [113]. EGFR, although ranked 10th with an MCC score of 2.42 × 1013, remains clinically relevant due to its role in tyrosine kinase inhibitor-targeted therapies. This prioritized gene set, derived through network topology analysis, provides a focused list of candidates for functional validation and therapeutic targeting, highlighting critical molecular drivers underpinning lung cancer development and progression. The pictorial representation of hub protein network and graph of rankings of lung cancer has been given in Figs. 9 and 10, respectively.

Figure 9: Top 10 hub genes identified using the Maximal Clique Centrality (MCC) algorithm in CytoHubba, highlighting TP53, KRAS, EGFR, and ERBB2 as central regulators in PPI of lung cancer

Figure 10: Bar plot representing CytoHubba scores of the top-ranked genes, with ERBB2 showing the highest interaction score, indicating its critical role in lung cancer pathogenesis

6.2 Identification of Key Hub Genes in Breast Cancer Network Using MCC Algorithm

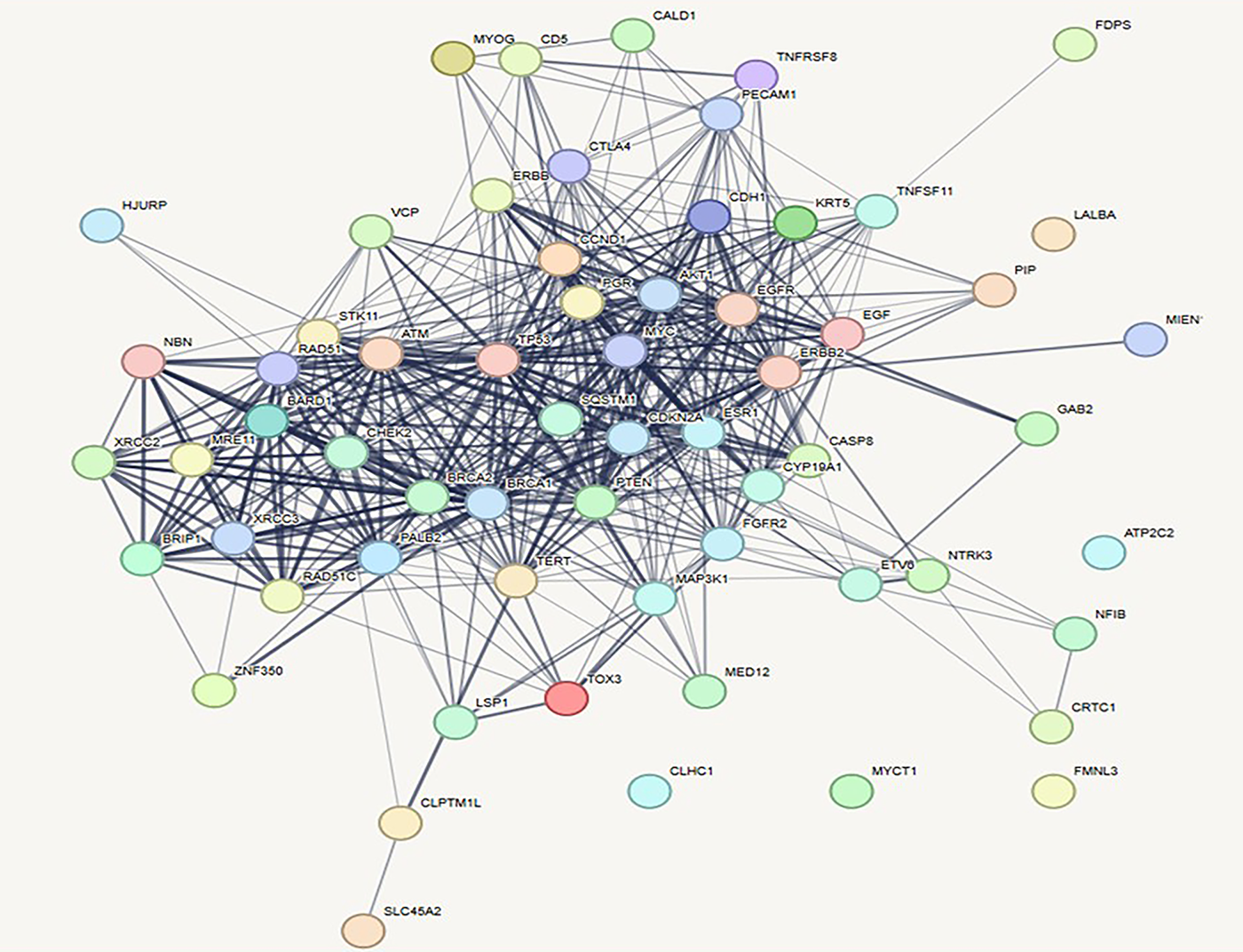

The constructed breast cancer gene interaction network comprises a total of 57 nodes and 507 edges, indicating a densely connected structure. The average number of neighbors per node is approximately 17.789, reflecting a high degree of interaction among the genes. The network displays a diameter of 5 and a radius of 3, suggesting relatively short paths between the most distant nodes and a compact overall structure [108]. The characteristic path length is 1.837, further supporting the idea of efficient communication within the network. A high clustering coefficient of 0.678 indicates strong modularity and the presence of tightly connected gene clusters [111]. The network density is 0.318, signifying a moderate level of overall connectivity. With a heterogeneity score of 0.637 and a centralization of 0.504, the network demonstrates a balanced distribution of node degrees and the presence of key hub genes (Fig. 11). The entire network forms a single connected component, and the analysis was completed in just 0.101 s, highlighting both the cohesiveness and computational efficiency of the analysis.

Figure 11: Prioritization of key genes in breast cancer using protein–protein interaction (PPI) networks and CytoHubba plugin. PPI network of breast cancer-related genes constructed using STRING and visualized in Cytoscape, showing intricate molecular interactions among cancer-associated proteins

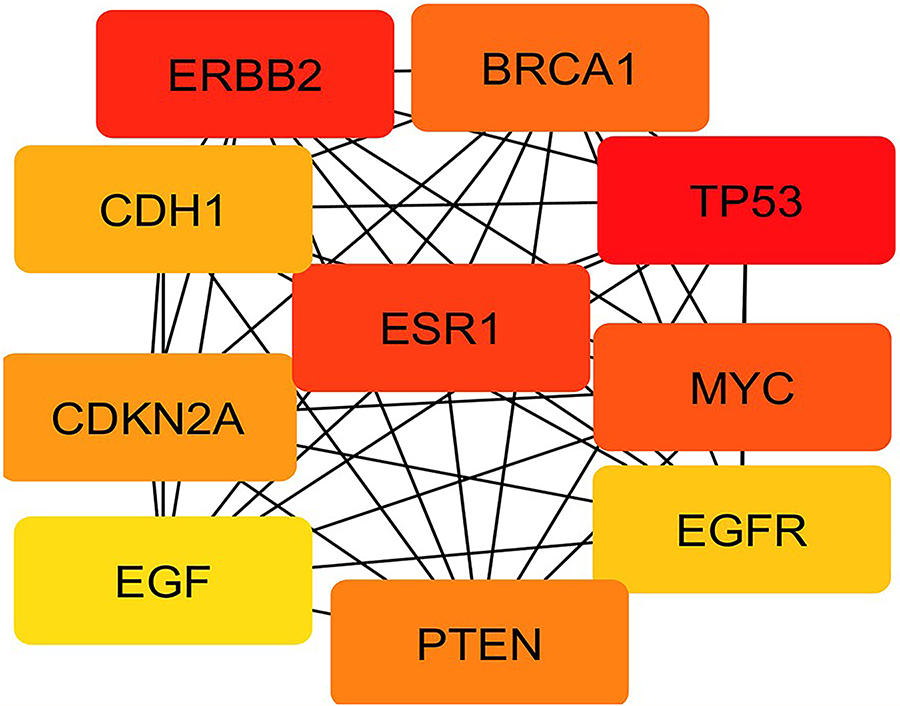

The present study elucidated the central molecular drivers in the PPI network of breast cancer. We employed the MCC algorithm—a highly sensitive topological method integrated within the CytoHubba plugin in Cytoscape. The analysis identified the top 10 hub genes based on their MCC scores, which represent their topological importance in the network architecture.

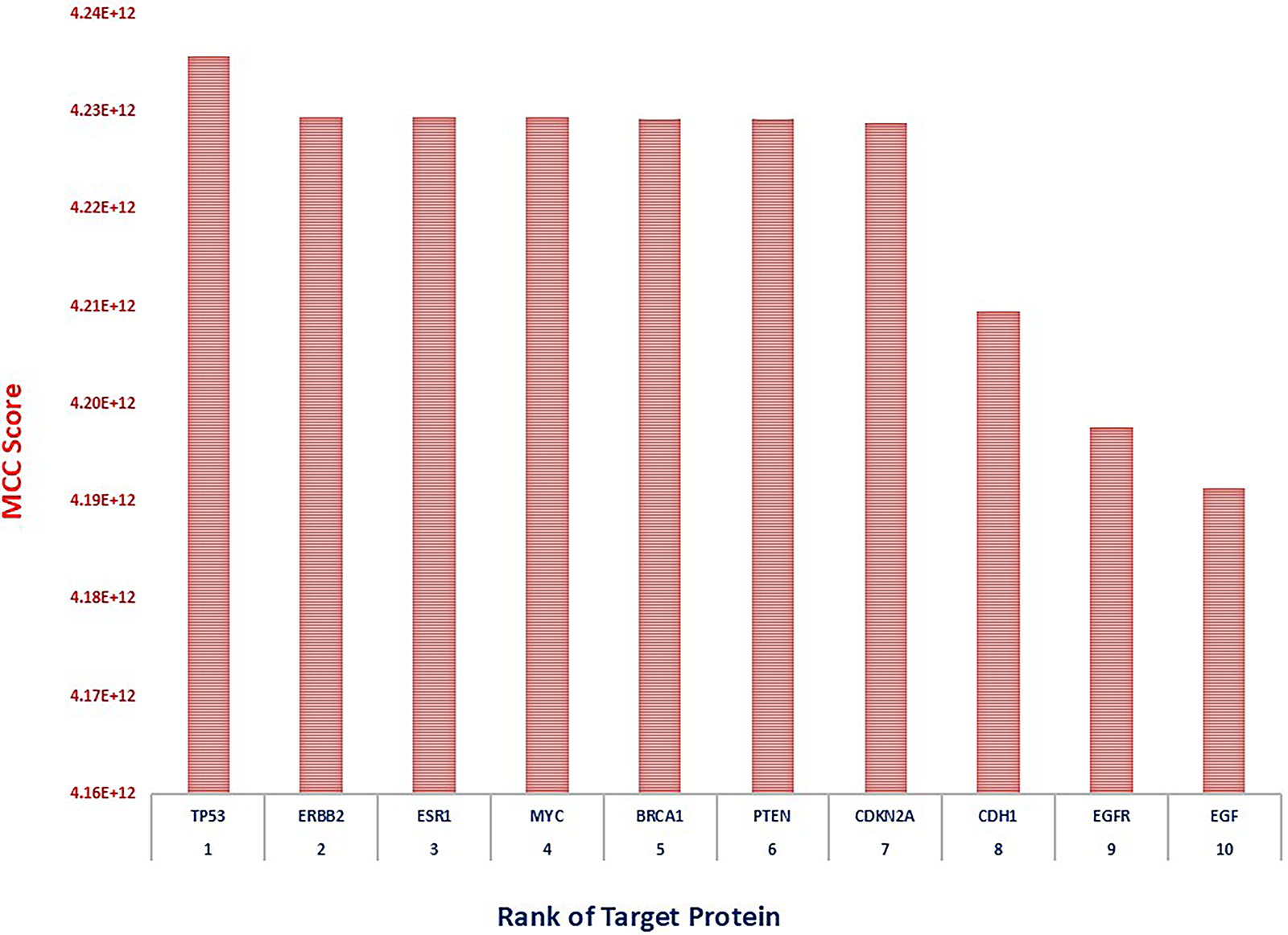

The gene TP53 emerged as the most prominent hub, exhibiting the highest MCC score of 4.24 × 1012, indicating its critical regulatory role in tumor suppression and DNA damage response. Following TP53, ERBB2, ESR1, MYC, and BRCA1 showed equally high MCC scores (~4.23 × 1012), reflecting their pivotal involvement in hormonal signaling, cell proliferation, and genomic integrity—hallmarks of breast cancer pathophysiology. Genes such as PTEN and CDKN2A, both tumor suppressors, also scored highly, emphasizing their functional significance in cell cycle control and apoptosis [114]. CDH1, known for its role in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), and EGFR and EGF, key mediators of growth factor signaling, rounded out the list with slightly lower but still substantial MCC scores (~4.19–4.21 × 1012), suggesting their contributory role in breast cancer progression and metastasis. TP53, ERBB2, ESR1, MYC, and BRCA1 showed equally high MCC scores (~4.23 × 1012), reflecting their pivotal involvement in hormonal signaling, cell proliferation, and genomic integrity—hallmarks of breast cancer pathophysiology. This ranking provides a robust framework for prioritizing target genes for downstream functional validation and highlights potential biomarkers and therapeutic targets in breast cancer.

The pictorial representation of hub protein network and graph of rankings of lung cancer has been given in Figs. 12 and 13, respectively.

Figure 12: Top 10 hub genes identified through the Maximal Clique Centrality (MCC) algorithm in CytoHubba, with TP53, ERBB2, and ESR1 emerging as central regulatory nodes. TP53 is the most influential gene in the network, followed by ERBB2 and ESR1, highlighting their potential roles in breast cancer pathogenesis and therapeutic targeting

Figure 13: Bar plot of hub gene scores, indicating TP53 as the most influential gene in the network, followed by ERBB2 and ESR1, highlighting their potential roles in breast cancer pathogenesis and therapeutic targeting

AI enables computers and robots to perform tasks that would otherwise be impossible, including developing drug formulations, assisting with clinical diagnostics and robotic surgery, collecting medical statistical databases, and understanding the cellular structure of diseases like cancer. AI has both a virtual and a real impact on medicine. The virtual component, which is dependent on DL information management tools, can assist the doctor in making precise decisions by interpreting the information dataset for electronic health records. A mathematical algorithm is used by DL to enhance experience-based learning. Nonetheless, robotically assisted surgery and nanorobotic applications for precise medication distribution can benefit from the physical AI system [115]. The application of DL and logistic data mining to clinical diagnostics gives medical professionals more cognitive ability and helps them make accurate treatment decisions. The scientific community widely embraced AI after IBM Big Blue, an AI-based computer, ultimately defeated “Gary Kasparov,” the world chess champion, on 11 May 1997. AI is currently able to handle difficult problems, including biologically complicated ones. It has been applied to robotic heart valve repair surgery, gynecological illnesses, prostatectomies, and other related procedures. In the future, it is anticipated to play a major role in the fight against cancer [116]. The primary categories of ML algorithms are (i) Supervised learning, which estimates algorithms using prior data; (ii) Unsupervised learning, which uncovers hidden patterns without labelled responses; and (iii) Reinforcement learning, which uses a series of rewards or penalties for the action it requires, similar to a video game model. The application of AI in medicine has expanded with the discoveries made in genetics and molecular medicine through information management and computational biology algorithms. An important advancement in the identification of therapeutic targets has reportedly been made using an unsupervised protein-protein interaction algorithm [117]. Through the use of an evolutionary integrated algorithm, novel DNA variations have been found as early-stage risk factors for specific human illnesses, such as cancer [118]. The application of advanced medical technology, such as “care bots” that monitor patients’ vital signs in real time, especially for elderly patients, and help surgeons perform surgery, is the physical branch of AI in medicine [119]. AI has the capability to completely alter healthcare and make procedures safer, more precise, and quicker. The therapeutic influence of AI in medical radiography has been examined using sizable datasets that are updated on a regular basis. The AI-based clinical assessment service “National Health Service” (NHS 24) in Scotland, which is based on the DL NHS 111 algorithm, is currently undergoing clinical testing in order to provide phone calls for the community’s minor health issues [120]. In a similar vein, “Babylon Health,” another online healthcare provider, uses semantic web technologies to deliver complementary digital services that enhance clinical outcomes. The purpose of the semantic web is to enable automated comprehension of online data [121]. The methodology of logic-based reasoning has been suggested to produce important outcomes in the pharmaceutical industry.

With computational support, a vast amount of data linked to genetics, microbiology, and imaging may be systematically collected and handled for individualized treatment. More advancements are required to phase out the predicted error in the supervised and unsupervised AI tool development, which is still in its early stages [122]. It has been found that the support vector machine algorithm and causal probabilistic network tools are highly accurate in identifying the carcinogenesis associated with infections and are suggested as appropriate therapy approaches [123]. Clinical researchers are now focusing on large-scale ML algorithms, which are thought to enable computers to learn from massive pharmaceutical big data at an industrial scale. This could lead to the rapid and low-cost discovery of new drugs through the use of supercomputers and machine-learning tools similar to those used in self-driving cars. The Exascale Compound Activity Prediction Engine (ExCAPE) project is a big data analytics chemogenomic research project that targets a biological protein in in silico models utilizing chemical compounds. It is financed by the European funding program Horizon 2020. The goal is to create extensive chemogenomics datasets from reliable sources (PubChem and ChEMBL) in order to forecast gene expression and protein interactions for large-scale pharmaceutical firms [124]. ExCAPE is a scalable ML model created for managing complicated information at an industrial scale. It is particularly useful in the pharmaceutical business, where it is used to predict the biological activity of compounds and their interactions at the protein level [124]. Nevertheless, a number of intricate cellular constraints must be addressed at a scalable level using algorithms, and it is anticipated that this project will grow further by accelerating an ML-based supercomputer for rapid drug discovery. AI-assisted medication design and microfluidic drug manufacturing are examples of recent developments in medicine [125]. Applying trained DL-derived ML models to databases of pharmaceutical businesses has been shown to outperform all comparative practice techniques [126].

Personalized Medication

Cancer patients have more chances of alteration and variability in therapeutic approaches and medication due to their pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) behaviors. AI triggers and facilitates the drug development process of personalized treatment approaches through prioritized therapeutic targets [127]. Dlamini et al. [128] have advocated the integration of AI-driven tools utilized for the early detection and precision of risk through biomarkers in the cancer disease of any individual. It offers a personalized diagnostic tool for more precise and non-invasive techniques than orthodox diagnostic methods such as biopsies [129]. Liquid biopsies have been used to analyze “Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA)” and other epigenetic markers in the bloodstream. The analysis of DNA methylation patterns in ctDNA and AI models detects more prioritized cancer-specific changes even at early stages [130]. Foser et al. [131] have observed that the high sensitivity and specificity of liquid biopsy models were found with an AI-driven approach to screening in colorectal, lung, and breast cancer. The integration of omics data with clinical vital tests and environmental factors, a deep learning model differentiates the type of cancers, viz., melanoma, prostate, and breast cancer [132]. In addition to NGS and high-resolution medical imaging, powered by AI, is improving cancer diagnostics and prognosis predictions. However, with continuous advancement, ongoing innovation, and technological progress, the future of AI and precision oncology holds significant promise [128].

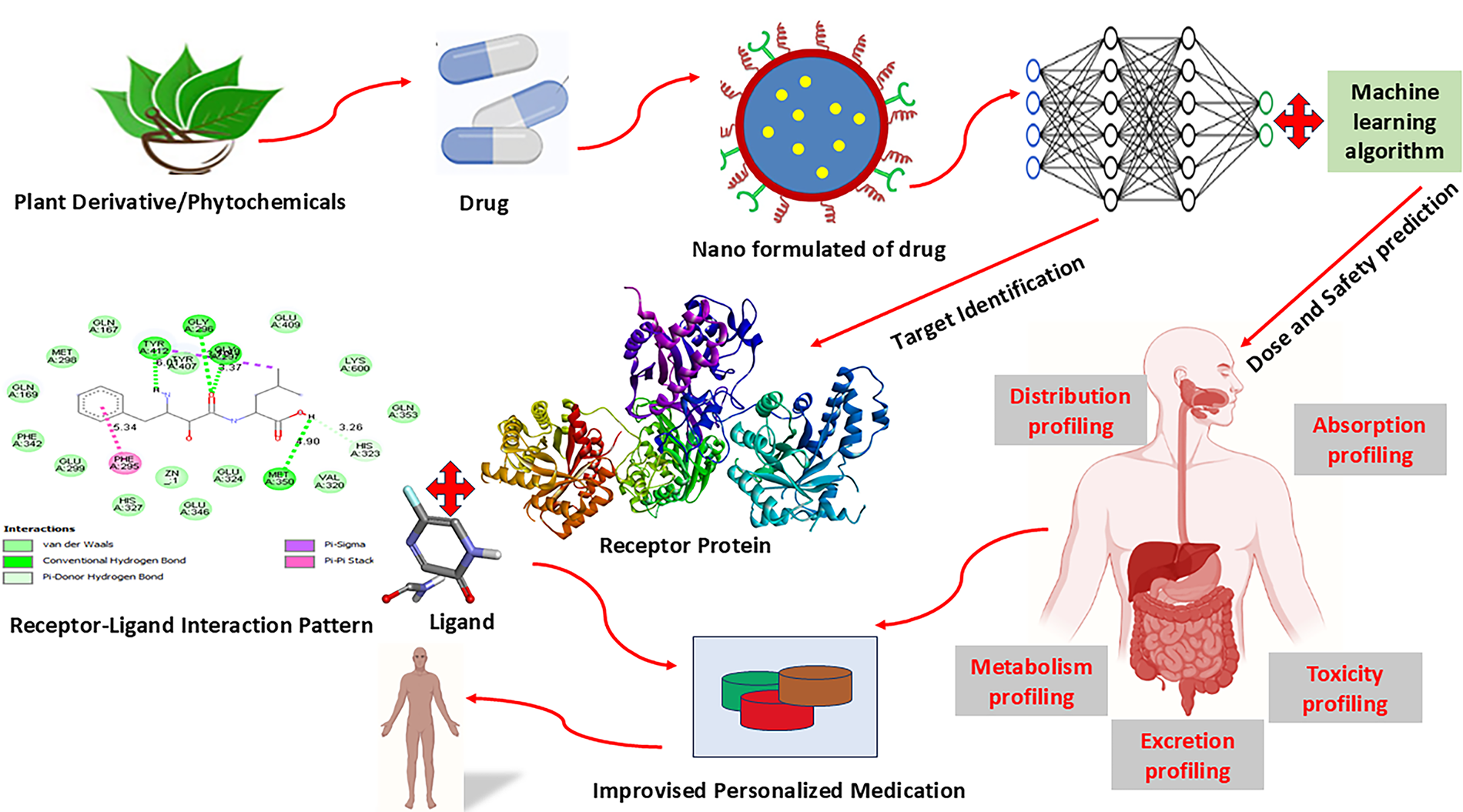

The various ML algorithms are integrated into the pathways analysis tools for prioritization of gene targets [133]. This integrative approach enhances the understanding of the underlying biology, revealing comprehensive insights into the disease mechanisms. Further, it helps individual metabolic profiles to develop personalized treatment strategies based on specific altered metabolic pathways of the patient. It provides power to metabolomics that can be utilized in precision medicine to optimize therapeutic interventions and improve patient outcomes [134]. The details of the personalized medicine developmental pipeline have been illustrated in Fig. 14.

Figure 14: Schematic workflow for AI-assisted personalized drug development using phytochemicals and nanomedicine. Plant-derived phytochemicals or conventional drugs are nano-formulated to enhance bioavailability and targeted delivery. These nano-drugs undergo target identification through receptor-ligand interaction modeling, followed by molecular docking and protein–ligand interaction analysis. Machine learning algorithms are applied to predict optimal dose and safety profiles. Comprehensive pharmacokinetic profiling—including absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET)—supports the design of improvised, personalized therapeutic regimens for enhanced clinical outcomes

8 AI Implementation and Treatment for Cancer

Multidrug resistance is a basic component that presents a significant therapeutic problem and is crucial to the management of disease outcomes. Finding new genes and biological mechanisms that cause medication resistance can help with this. These genes and pathways are usually good options for developing and finding new drugs. Additionally, a number of epigenetic changes may also contribute to drug resistance [128]. For example, it has been demonstrated that treatment resistance develops in ovarian and breast tumors that are positive for the estrogen receptor. It is anticipated that between 30 and 55 per cent of metastatic receptor-positive subtypes in breast cancer develop secondary resistance to therapy after receiving neoadjuvant aromatase inhibitor treatment. The existence of mutant ESR1 is thought to be the cause of the drug resistance. Mutations in the ligand-binding domain of ER, mutant ESR1 in circulating tumor DNA, and the activation of PI3K/mTOR pathways are attributable to ESR1 acquired secondary resistance, according to mutation analysis, RNA sequencing data collected from NGS, and bioinformatic analysis. Because of the tumor’s aggressive biology, the disease’s progression, recurrence, and metastasis, it has been observed that ESR1-related cancers typically have a poor prognosis [135]. ESR1 mutations are a crucial biomarker for managing ER+ breast tumors, since they can predict prognosis and change available therapy options. In a similar vein, mutations or altered gene expressions have been linked to the development of drug resistance to chemotherapy in more than 50% of relapsed patients with advanced ovarian cancer. Most patients with advanced ovarian cancer recur within two years due to the development of drug resistance, and the standard treatment strategy involves surgery followed by neoadjuvant chemotherapy. In individuals with advanced illness, neoadjuvant chemotherapy is associated with resistance to platinum-based treatment [136]. Apoptosis to avoid drug-induced cytotoxicity, tumor migration, drug metabolism, enhanced DNA repair, and activation of molecular pathways that promote tumor angiogenesis are some of the molecular mechanisms that lead to drug resistance [137]. P-glycoprotein, the p53 pathway, the mismatched DNA repair process, and multidrug resistance-associated protein are the proposed molecular pathways that cause drug resistance in ovarian cancer.

In a recent study, Meng et al. [138] identified the molecular pathways responsible for ovarian cancer drug resistance. The research demonstrated that dual oxidase maturation factor 1 (DUOXA1) is overexpressed in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer cells. The overexpression of this gene results in a higher generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which in turn maintains the activation of the ATR-Chk1 pathway and causes resistance to treatments based on platinum. The ATR-Chk1 pathway will be hampered by ROS inhibition, which will also reverse acquired drug resistance. This data was collected by RNA-sequencing and quantitative high-throughput combinational screening (qHTCS) based on NGS technology [138]. Aberrant RNA splicing signatures can also be found by RNA sequencing using NGS. Drug resistance can be counteracted and used as an advantage by focusing on the splice variants that increase drug resistance. Appropriate screening to find critical candidate biomarkers that can evade these molecular processes would advance our understanding of medication resistance and enhance the treatment plan for the best possible results. In research that revealed 46% of patients needed adjustments to their cancer management, Mody et al. [139] emphasized the significance of precision oncology in cancer therapy. Both DNA and RNA from a cohort of patients with solid tumors and relapsed and refractory hematological malignancies were sequenced using NGS technology. Leukemia and lymphoma were among the hematological malignancies in this group; on the other hand, brain, neuroblastoma, sarcoma, renal, liver, and ovarian cancers were among the solid tumor types. 10% of the patients in this cohort needed genetic counseling to assess future risk, and 15% of the patients needed modifications to their cancer therapy [139]. Their results made clear how important precision oncology is for better patient outcomes and clinical decision-making. In the management of cancer, metastatic tumors pose a significant challenge, especially when they are recurrent and have developed resistance to treatment. Robinson et al. [140] used integrated sequencing of DNA and RNA to show the mutational landscape of many metastatic tumors. Through the use of NGS, they were able to identify critical germline mutations, gene fusions, and complementary RNA transcriptional signatures of crucial molecular pathways that are very prevalent in a number of significant cancers, including ovarian, breast, colorectal, prostate, brain, and pancreatic cancer. Researchers also found predictive biomarkers for immune treatment for metastatic tumors using their precision oncology approach [140]. In light of the sequencing data, the patient’s treatment plans were modified, underscoring the significance of precision oncology in the treatment and management of cancer. NGS profiling of cancer genomes clarifies the molecular pathways linked to medication resistance and allows for the identification of genetic abnormalities. Finding these biomarkers will help with the development of new treatments that will enhance the prognosis for cancer treatment.

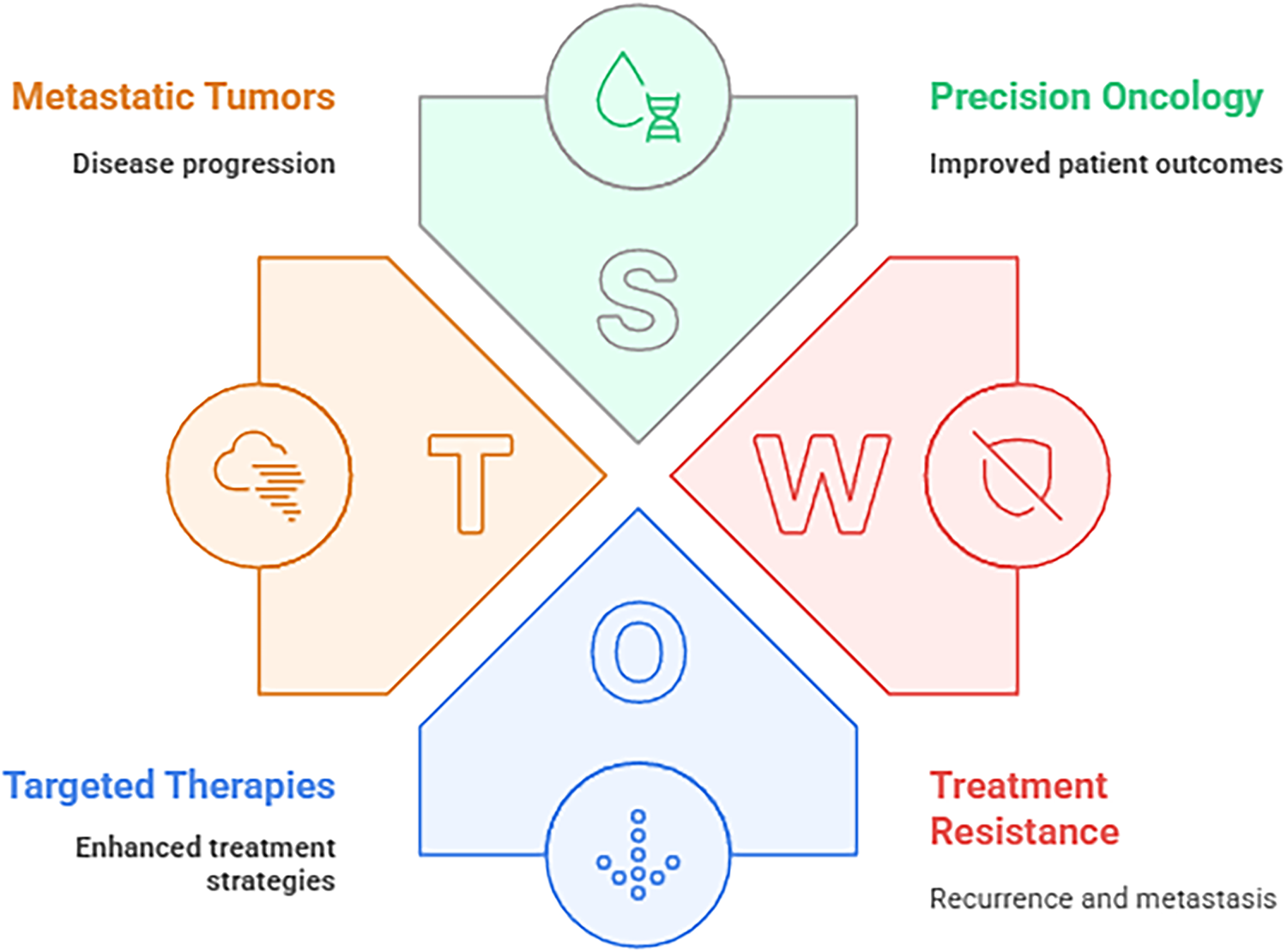

The IBM Watson for Oncology support system is another recent advancement in AI that uses algorithms to suggest treatments to help clinicians make decisions. In order to offer a dependable foundation for precision medicine and individualized patient care, IBM Watson for Oncology was created. The Watson for Oncology platform has proven effective in determining therapy regimens for breast [141], gastric [142], and non-small-cell lung cancer [143], despite some contradictory findings. The Watson for Oncology system’s dependability for therapy suggestions for gastric cancer was proven by [142]. The study demonstrated agreement between the medical team’s suggestions and those made by the Watson for Oncology system. Similar outcomes for metastatic non-small-cell lung tumors were reported by [143], who also found an 85.16% concordance between the medical team and the Watson for Oncology system. They underlined that the AI system helped the medical staff make decisions about therapy in a timely, accurate, and efficient manner [143]. According to their research, the AI system may be further enhanced with localized medical programs and is especially helpful in low-resource settings. The graphical illustration of SWOT analysis for cancer therapies is shown in Fig. 15.

Figure 15: The SWOT analysis of contemporary oncology frameworks, highlighting key elements such as metastatic tumor progression, targeted therapy enhancement, precision oncology for improved patient outcomes, and challenges of treatment resistance including recurrence and metastasis

8.2 Therapeutic Target Discovery

The traditional process of discovering and developing new drugs is frequently an expensive and time-consuming process [144,145]. The increasing availability of big cancer datasets, both public and commercial, coupled with the affordability of various NGS and imaging technologies, has resulted in a surge of interest in utilizing AI to optimize this process. To address each element in the drug discovery spectrum, researchers create models that use a variety of information. Using a one-class support vector machine (AUC, 0.88) [146], for instance, integrated clinical data with gene expression patterns and protein–protein interaction networks to produce characteristics that potentially predict possible therapeutic targets in liver cancer. López-Cortés and colleagues [147] integrated multiple cancer databases, including PharmGKB, Cancer Genome Interpreter, and TCGA, among others, in a deep learning-based classification approach specific to breast cancer. They predicted proteins associated with breast cancer pathogenesis and reported several promising candidates to pursue as biomarkers or drug targets [148]. Researchers can now use hundreds of loss-of-function screen datasets from the DepMap Consortium to test a wide range of AI techniques [149]. For instance, using both gene-specific and cell line-specific data, the ECLIPSE ML approach uses the DepMap data to suggest cancer-specific therapeutic targets. Chen and associates have discovered that proteomics data, more especially reverse-phase protein array data, are highly predictive of cancer cell line dependencies after looking at a broad range of molecular characteristics from DepMap data [36]. This discovery highlights how versatile AI is in terms of its ability to identify the kinds of experimental data that are most relevant to a predictive model, in addition to predicting treatment targets.

Massively parallel sequencing of DNA and RNA simultaneously is made possible by high-throughput screening, which also produces massive datasets. This allows for the detection of both cancer-specific transcriptome alterations, such as alternative splicing, and pathogenic mutations. A complex biological process called alternative splicing is essential for controlling the expression of several genes that are involved in DNA repair, angiogenesis, adhesion, invasion, and cell division. Cancer cells are characterized by these functions.

In triple-negative, luminal, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) breast cancer, novel subtype-specific splice variants in important genes such as LARP1, CDK4, ADD3, and PHLPP2 were found using RNA sequencing in a study by [150]. Targeting these cancer-specific isoforms with therapeutic techniques can lead to successful clinical outcomes. For example, there is a correlation between advanced gastric cancer and higher levels of CD44v6, while lower levels of CD44v6 are linked to prostate cancer. Similarly, different isoform expression levels can predict metastasis. The isoform CD44v10 is linked to pancreatic cancer [151]. RNA sequencing can be used to identify cancer-specific splice variants, which are becoming popular targets for the development of novel drugs.

9 Challenges and Future Direction with AI

The availability and cost-effectiveness of collecting omics data are increasing due to technological advancements. Analysts will undoubtedly benefit from the data’s availability since it will present more chances to consider other viewpoints. While the outcome is encouraging, further efforts must be made to identify the underlying causes associated with a specific phenotype. Given the diversity of the data, this endeavor is undoubtedly difficult. We have talked about the putative biomarkers that have previously been discovered by a number of researchers in this article. These results are still sporadic, though [12]. Further research is necessary before these results can be applied to patients. Research in the field of multi-omics data analysis is still in its infancy. It’s an exciting field of study that’s expanding quickly. There is a great deal of room for improvement, particularly when related data like radiomics is incorporated. The constraints of traditional pathology can be transcended by AI-driven radiomics data analysis. Regarding tumor classification for precision medicine, radiomic characteristics can be used as a complement to or alternative to primary omics data [138,152]. A new perspective can be added to the research by integrating a number of additional aspects, such as lifestyle choices and environmental impacts.

Because ML cannot resolve the causal inference issue on its own, doctors, biologists, and computational analysts must work together [153]. The biologists analyze the primary specimens obtained by healthcare professionals through experimental methods, while the analysts analyze them through computer means. After the biologists have provided justification, the retrieved data is then returned to the medical professionals. Interdisciplinary information must be fluidly communicated within such a workflow to produce useful results for multi-omics analysis.

This study underscores the significant advancements brought about by AI-driven multi-omics technologies in cancer diagnosis, staging, and therapy, where integration of diverse, complex datasets has facilitated the discovery of novel biomarkers and personalized treatment strategies. Despite the transformative potential of these approaches, challenges such as data heterogeneity, model interpretability, infrastructure demands, and regulatory complexities continue to hamper widespread clinical adoption and risk exacerbating disparities in cancer care.

The study also addressing these limitations through transparent AI models, enhanced data standardization, and equitable access frameworks will be crucial for realizing the full promise of AI-powered precision oncology. Continued research must focus on bridging technological innovation with clinical workflow integration to ensure effective translation into patient-centered cancer management.

Furthermore, the future of AI-driven precision oncology hinges on the development of more transparent and interpretable models that can seamlessly integrate into clinical workflows. Present review emphasizing ethical AI use, equitable access, and robust validation will be essential to harnessing AI’s full potential in improving patient outcomes globally. Collaborative efforts across disciplines and continued innovation in algorithm design and multi-omics data integration promise to propel oncology into a new era of personalized medicine with greater accuracy, efficiency, and inclusivity.

Acknowledgement: The project was funded by KAU Endowment (WAQF) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks WAQF and the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) for technical and financial support.

Funding Statement: The project was funded by KAU Endowment (WAQF) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. doi:10.3322/caac.21660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Albaradei S, Thafar M, Alsaedi A, Van Neste C, Gojobori T, Essack M, et al. Machine learning and deep learning methods that use omics data for metastasis prediction. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2021;19:5008–18. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2021.09.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Benitez DA, Cumplido-Laso G, Olivera-Gómez M, Del Valle-Del Pino N, Díaz-Pizarro A, Mulero-Navarro S, et al. p53 genetics and biology in lung carcinomas: insights, implications and clinical applications. Biomedicines. 2024;12(7):1453. doi:10.3390/biomedicines12071453. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Álvarez-Garcia V, Tawil Y, Wise HM, Leslie NR. Mechanisms of PTEN loss in cancer: it’s all about diversity. Semin Cancer Biol. 2019;59(56):66–79. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.02.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Verfaillie T, Garg AD, Agostinis P. Targeting ER stress induced apoptosis and inflammation in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2013;332(2):249–64. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2010.07.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Neophytou CM, Panagi M, Stylianopoulos T, Papageorgis P. The role of tumor microenvironment in cancer metastasis: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cancers. 2053 2021;13(9):2053. doi:10.3390/cancers13092053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Marku M, Pancaldi V. From time-series transcriptomics to gene regulatory networks: a review on inference methods. PLoS Comput Biol. 2023;19(8):e1011254. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1011254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Chakraborty S, Hosen MI, Ahmed M, Shekhar HU. Onco-multi-OMICS approach: a new frontier in cancer research. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018(1):9836256. doi:10.1155/2018/9836256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. López de Maturana E, Alonso L, Alarcón P, Martín-Antoniano IA, Pineda S, Piorno L, et al. Challenges in the integration of omics and non-omics data. Genes. 2019;10(3):238. doi:10.3390/genes10030238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Pettini F, Visibelli A, Cicaloni V, Iovinelli D, Spiga O. Multi-omics model applied to cancer genetics. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(11):5751. doi:10.3390/ijms22115751. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Vobugari N, Raja V, Sethi U, Gandhi K, Raja K, Surani SR. Advancements in oncology with artificial intelligence—a review article. Cancers. 2022;14(5):1349. doi:10.3390/cancers14051349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Biswas N, Chakrabarti S. Artificial intelligence (AI)-based systems biology approaches in multi-omics data analysis of cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:588221. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.588221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Esteva A, Robicquet A, Ramsundar B, Kuleshov V, DePristo M, Chou K, et al. A guide to deep learning in healthcare. Nat Med. 2019;25(1):24–9. doi:10.1038/s41591-018-0316-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Kann BH, Hosny A, Aerts HJWL. Artificial intelligence for clinical oncology. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(7):916–27. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2021.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. He L, Bulanova D, Oikkonen J, Häkkinen A, Zhang K, Zheng S, et al. Network-guided identification of cancer-selective combinatorial therapies in ovarian cancer. Brief Bioinform. 2021;22(6):bbab272. doi:10.1093/bib/bbab272. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Maniruzzaman M, Jahanur Rahman M, Ahammed B, Abedin MM, Suri HS, Biswas M, et al. Statistical characterization and classification of colon microarray gene expression data using multiple machine learning paradigms. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2019;176(3):173–93. doi:10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.04.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Vural S, Wang X, Guda C. Classification of breast cancer patients using somatic mutation profiles and machine learning approaches. BMC Syst Biol. 2016;10(Suppl 3):62. doi:10.1186/s12918-016-0306-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zauderer MG, Martin A, Egger J, Rizvi H, Offin M, Rimner A, et al. The use of a next-generation sequencing-derived machine-learning risk-prediction model (OncoCast-MPM) for malignant pleural mesothelioma: a retrospective study. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3(9):e565–76. doi:10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00104-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Lee SI, Celik S, Logsdon BA, Lundberg SM, Martins TJ, Oehler VG, et al. A machine learning approach to integrate big data for precision medicine in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):42. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02465-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Gumaei A, Sammouda R, Al-Rakhami M, AlSalman H, El-Zaart A. Feature selection with ensemble learning for prostate cancer diagnosis from microarray gene expression. Health Inform J. 2021;27(1):1460458221989402. doi:10.1177/1460458221989402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Baran Y, Bercovich A, Sebe-Pedros A, Lubling Y, Giladi A, Chomsky E, et al. MetaCell: analysis of single-cell RNA-seq data using K-NN graph partitions. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):206. doi:10.1186/s13059-019-1812-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Bottaci L, Drew PJ, Hartley JE, Hadfield MB, Farouk R, Lee PW, et al. Artificial neural networks applied to outcome prediction for colorectal cancer patients in separate institutions. Lancet. 1997;350(9076):469–72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)11196-X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wang Y, Wang D, Ye X, Wang Y, Yin Y, Jin Y. A tree ensemble-based two-stage model for advanced-stage colorectal cancer survival prediction. Inf Sci. 2019;474(1):106–24. doi:10.1016/j.ins.2018.09.046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhu L, Luo W, Su M, Wei H, Wei J, Zhang X, et al. Comparison between artificial neural network and Cox regression model in predicting the survival rate of gastric cancer patients. Biomed Rep. 2013;1(5):757–60. doi:10.3892/br.2013.140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Biglarian A, Hajizadeh E, Kazemnejad A, Zali MR. Application of artificial neural network in predicting the survival rate of gastric cancer patients. Iran J Public Health. 2011;40(2):80–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

26. Wang J, Zhanghuang C, Jin L, Zhang Z, Tan X, Mi T, et al. Development and validation of a nomogram to predict cancer-specific survival in elderly patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma: a population-based study. BMC Geriatr. 2022;22(1):736. doi:10.1186/s12877-022-03430-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Lu Y, Yu Q, Gao Y, Zhou Y, Liu G, Dong Q, et al. Identification of metastatic lymph nodes in MR imaging with faster region-based convolutional neural networks. Cancer Res. 2018;78(17):5135–43. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Haenssle HA, Fink C, Schneiderbauer R, Toberer F, Buhl T, Blum A, et al. Man against machine: diagnostic performance of a deep learning convolutional neural network for dermoscopic melanoma recognition in comparison to 58 dermatologists. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(8):1836–42. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdy166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Ribli D, Horváth A, Unger Z, Pollner P, Csabai I. Detecting and classifying lesions in mammograms with Deep Learning. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):4165. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-22437-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Park K, Ali A, Kim D, An Y, Kim M, Shin H. Robust predictive model for evaluating breast cancer survivability. Eng Appl Artif Intell. 2013;26(9):2194–205. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2013.06.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Jović S, Miljković M, Ivanović M, Šaranović M, Arsić M. Prostate cancer probability prediction by machine learning technique. Cancer Invest. 2017;35(10):647–51. doi:10.1080/07357907.2017.1406496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Kuo RJ, Huang MH, Cheng WC, Lin CC, Wu YH. Application of a two-stage fuzzy neural network to a prostate cancer prognosis system. Artif Intell Med. 2015;63(2):119–33. doi:10.1016/j.artmed.2014.12.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Chaturvedi P, Jhamb A, Vanani M, Nemade V. Prediction and classification of lung cancer using machine learning techniques. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2021;1099(1):012059. [Google Scholar]

34. Hasnain Z, Mason J, Gill K, Miranda G, Gill IS, Kuhn P, et al. Machine learning models for predicting post-cystectomy recurrence and survival in bladder cancer patients. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0210976. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0210976. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Karsan A, Eigl BJ, Flibotte S, Gelmon K, Switzer P, Hassell P, et al. Analytical and preanalytical biases in serum proteomic pattern analysis for breast cancer diagnosis. Clin Chem. 2005;51(8):1525–8. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2005.050708. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Chen MM, Li J, Mills GB, Liang H. Predicting cancer cell line dependencies from the protein expression data of reverse-phase protein arrays. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4(4):357–66. doi:10.1200/CCI.19.00144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Murata T, Yanagisawa T, Kurihara T, Kaneko M, Ota S, Enomoto A, et al. Salivary metabolomics with alternative decision tree-based machine learning methods for breast cancer discrimination. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;177(3):591–601. doi:10.1007/s10549-019-05330-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Alakwaa FM, Chaudhary K, Garmire LX. Deep learning accurately predicts estrogen receptor status in breast cancer metabolomics data. J Proteome Res. 2018;17(1):337–47. doi:10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00595. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Ponomarenko EA, Poverennaya EV, Ilgisonis EV, Pyatnitskiy MA, Kopylov AT, Zgoda VG, et al. The size of the human proteome: the width and depth. Int J Anal Chem. 2016;2016:7436849. doi:10.1155/2016/7436849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Piovesan A, Antonaros F, Vitale L, Strippoli P, Pelleri MC, Caracausi M. Human protein-coding genes and gene feature statistics in 2019. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12(1):315. doi:10.1186/s13104-019-4343-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Ziats MN, Rennert OM. Aberrant expression of long noncoding RNAs in autistic brain. J Mol Neurosci. 2013;49(3):589–93. doi:10.1007/s12031-012-9880-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Alles J, Fehlmann T, Fischer U, Backes C, Galata V, Minet M, et al. An estimate of the total number of true human miRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(7):3353–64. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Wishart DS, Feunang YD, Marcu A, Guo AC, Liang K, Vázquez-Fresno R, et al. HMDB 4.0: the human metabolome database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D608–17. doi:10.1093/nar/gkx1089. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Arjmand B, Alavi-Moghadam S, Parhizkar-Roudsari P, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Tayanloo-Beik A, Goodarzi P, et al. Metabolomics signatures of SARS-CoV-2 infection, stem cells in tissue differentiation, regulation and disease. In: Cell biology and translational medicine. Vol. 15. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2021. p. 45–59. doi:10.1007/5584_2021_674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Hu C, Jia W. Multi-omics profiling: the way toward precision medicine in metabolic diseases. J Mol Cell Biol. 2021;13(8):576–93. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjab051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Tayanloo-Beik A, Roudsari PP, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Biglar M, Tabatabaei-Malazy O, Arjmand B, et al. Diabetes and heart failure: multi-omics approaches. Front Physiol. 2021;12:705424. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.705424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Shahrajabian MH, Sun W. Survey on multi-omics, and multi-omics data analysis, integration and application. Curr Pharm Anal. 2023;19(4):267–81. doi:10.2174/1573412919666230406100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Pecorino L. Molecular biology of cancer: mechanisms, targets, and therapeutics. New York, NU, USA: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

49. Arjmand B, Hamidpour SK, Tayanloo-Beik A, Goodarzi P, Aghayan HR, Adibi H, et al. Machine learning: a new prospect in multi-omics data analysis of cancer. Front Genet. 2022;13:824451. doi:10.3389/fgene.2022.824451. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Mardis ER. The impact of next-generation sequencing on cancer genomics: from discovery to clinic. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2019;9(9):a036269. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a036269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Shukla AK, Neeru, Kumar A. A chemoinformatics study to prioritization of anticancer orally active lead compounds of pearl millet against adhesion G protein-coupled receptor. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2025;334(2):125960. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2025.125960. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Kamble MA, Jha SK, Sabale PM. Discovering the genetic code: investigating gene expression analysis and genomic sequencing. In: Deep learning and computer vision: models and biomedical applications. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2025. p. 47–61. doi:10.1007/978-981-96-1285-7_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Vestergaard LK, Oliveira DNP, Høgdall CK, Høgdall EV. Next generation sequencing technology in the clinic and its challenges. Cancers. 2021;13(8):1751. doi:10.3390/cancers13081751. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]