Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Prediction Method for Concrete Mixing Temperature Based on the Fusion of Physical Models and Neural Networks

1 State Key Laboratory of Water Cycle and Water Security, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing, 100038, China

2 Zhejiang Jingling Reservoir Co., Ltd., Shaoxing, 312000, China

3 Shaoxing City Cao’e River Basin Management Center, Shaoxing, 312000, China

4 Shaoxing City Jingling Reservoir Management Center, Shaoxing, 312000, China

5 Shaoxing Water Resources and Hydropower Construction Investment Co., Ltd., Shaoxing, 312000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Lei Zheng. Email: ; Lei Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: AI-Enhanced Computational Methods in Engineering and Physical Science)

Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences 2025, 145(3), 3217-3241. https://doi.org/10.32604/cmes.2025.074651

Received 15 October 2025; Accepted 17 November 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

As a critical material in construction engineering, concrete requires accurate prediction of its outlet temperature to ensure structural quality and enhance construction efficiency. This study proposes a novel hybrid prediction method that integrates a heat conduction physical model with a multilayer perceptron (MLP) neural network, dynamically fused via a weighted strategy to achieve high-precision temperature estimation. Experimental results on an independent test set demonstrated the superior performance of the fused model, with a root mean square error (RMSE) of 1.59°C and a mean absolute error (MAE) of 1.23°C, representing a 25.3% RMSE reduction compared to conventional physical models. Ambient temperature and coarse aggregate temperature were identified as the most influential variables. Furthermore, the model-based temperature control strategy reduced costs by 0.81 CNY/m3, showing significant potential for improving resource efficiency and supporting sustainable construction practices.Keywords

Concrete, as a core material in modern construction engineering, has its properties and quality directly determining structural safety and service life. Temperature control during concrete preparation and construction is a key factor influencing the development of its microstructure and macroscopic mechanical properties [1]. Studies have shown that fluctuations in the concrete outlet temperature can lead to variations in the placing temperature, subsequently causing internal stress changes within the concrete, resulting in quality defects such as early-age cracking and strength attenuation [2]. Particularly in mass concrete projects, thermal stress induced by temperature gradients has become a primary cause of structural durability failure [3]. Currently, concrete temperature control primarily relies on on-site process monitoring and post-hoc adjustments, while accurate prediction of the outlet temperature remains a persistent challenge in the industry [4].

Research on concrete temperature prediction is of great significance in engineering practice [5]. Its methodological system has evolved from purely physical models to data-driven approaches, gradually moving towards hybrid modeling. In terms of purely physical models [6], researchers primarily predict temperature based on the principles of heat conduction, convection, and radiation by establishing heat balance equations for concrete [7]. These methods use finite element software to build concrete temperature field models, combined with standard heating curves and material thermodynamic parameters for numerical simulation, which can intuitively reflect the heat transfer process [8]. However, traditional physical models are often limited by simplified treatments of dynamic changes in material properties and external environmental factors (e.g., wind speed, humidity), leading to deviations between prediction results and actual working conditions [5]. For instance, although studies on the temperature field of concrete beams post-fire have established a database of material thermodynamic parameters [9], they failed to fully consider the thermodynamic coupling effect when phase change materials are composited with the matrix, which is particularly prominent in research on phase-change concrete.

Traditional prediction methods, often based on empirical formulas or statistical models, such as constructing simplified models based on cement hydration heat release patterns and environmental heat dissipation parameters [10–12]. However, these methods struggle to capture the dynamic coupling effects of material composition, environmental conditions, and construction processes. With the expansion of engineering scale and increase in material complexity, relying solely on empirical parameters can no longer meet the quality control requirements of modern concrete [13]. Meanwhile, the interaction of variables such as changes in the proportion of admixtures in the concrete mix, fluctuations in external ambient temperature, and differences in transportation time causes the temperature evolution to exhibit highly nonlinear characteristics. Predicting such complex systems requires breaking the paradigm of a single discipline and achieving multi-dimensional modeling by integrating physical mechanisms with data-driven technologies [14].

The rise of machine learning methods has provided new ideas for temperature prediction. Algorithms such as neural networks and support vector machines significantly improve prediction accuracy by mining nonlinear relationships in historical data [15]. Temperature change distribution prediction systems, by integrating multi-dimensional data features, can capture the patterns of temperature evolution in complex environments [16]. The limitation of these methods lies in their lack of explanatory capability regarding physical mechanisms. For example, although research on the mechanical properties of concrete under sub-high temperature cycles revealed the correlation between temperature and material performance through experimental data, it is difficult to infer the underlying thermo-mechanical coupling mechanism through the model [17]. Furthermore, although prediction methods for freezing characteristic temperature are based on pore structure models, their parameter calibration still relies on traditional physical experiments, failing to fully leverage the advantages of being data-driven [18].

To address the above issues, hybrid modeling methods have gradually become a research hotspot. These methods embed the prior knowledge of physical models into machine learning frameworks [19], for example, using thermodynamic parameters obtained from finite element simulation as input features for neural networks [20], or using Monte Carlo methods to quantify the uncertainty of physical models [21]. In research on temperature control during the curing stage of mass concrete, scholars constructed prediction models with both physical interpretability and data adaptability by optimizing the fusion of mix design and temperature monitoring data [22]. Nonetheless, effectively balancing the rigid constraints of physical laws with the flexibility of data-driven approaches remains a substantial challenge. For instance, temperature regulation of phase-change concrete requires simultaneous consideration of the physical mechanism of material latent heat and the nonlinear influence of construction parameters, which places higher demands on model fusion strategies. Future research needs to further explore the synergistic mechanism between physical models and machine learning to achieve dual improvement in prediction accuracy and interpretability [23].

Physical models can clearly describe the microscopic mechanisms of heat transfer and material phase changes [24], but when faced with uncertainties in boundary conditions in practical engineering, their computational accuracy is often constrained by simplified parameter assumptions. Machine learning methods, represented by neural networks, can capture complex nonlinear relationships through data fitting but lack physical constraints on the mechanism of temperature evolution [25]. To bridge this gap, this study proposes a hybrid prediction method for concrete outlet temperature that integrates physical models with neural networks, aiming to leverage the strengths of both paradigms to enhance prediction accuracy and reliability [26,27]. At the level of physical modeling, the expressive capability of the heat conduction equation is enhanced by introducing interaction terms to reflect the nonlinear coupling effects among multiple factors such as environmental temperature, raw material mix proportion, and mixing time during the concrete pouring process. At the level of data-driven modeling, feature importance analysis is adopted to screen and assign weights to the input parameters of the physical model, a process achieved through the neural network’s ability for nonlinear mapping of high-dimensional feature spaces [28]. Similar ideas of feature selection and multi-model fusion have been proven effective in reducing the interference of redundant variables. Building on this, further incorporating the prior knowledge of the heat conduction model can more accurately identify key control parameters, thereby optimizing the robustness of temperature control strategies [29]. This study innovatively proposes a physical-neural network hybrid model framework, achieving collaborative modeling of physical laws and data features by constructing a dual-channel information fusion mechanism [30]. The physical channel generates initial temperature field predictions based on an improved heat conduction equation [31], while the data channel utilizes a deep neural network for feature learning from historical engineering data. The two are combined through a weighted fusion strategy to produce the final prediction result [32]. Furthermore, this study optimizes the model fusion process by constructing a dynamic weight allocation mechanism, introducing dynamic confidence assessment to achieve real-time weight adjustment of different prediction channels, further enhancing the model’s generalization performance under variable construction conditions.

The innovation of this study lies in constructing an integrated prediction framework that includes a material thermophysical property database, an environmental parameter acquisition module, and an adaptive neural network, providing a complete solution from theoretical model to engineering application for concrete temperature control. This method can not only improve engineering safety but also reduce construction energy consumption by optimizing the allocation of temperature control resources, aligning with the strategic needs of green and low-carbon development in the construction industry.

2 Data Collection and Preprocessing

2.1 Data Sources and Feature System

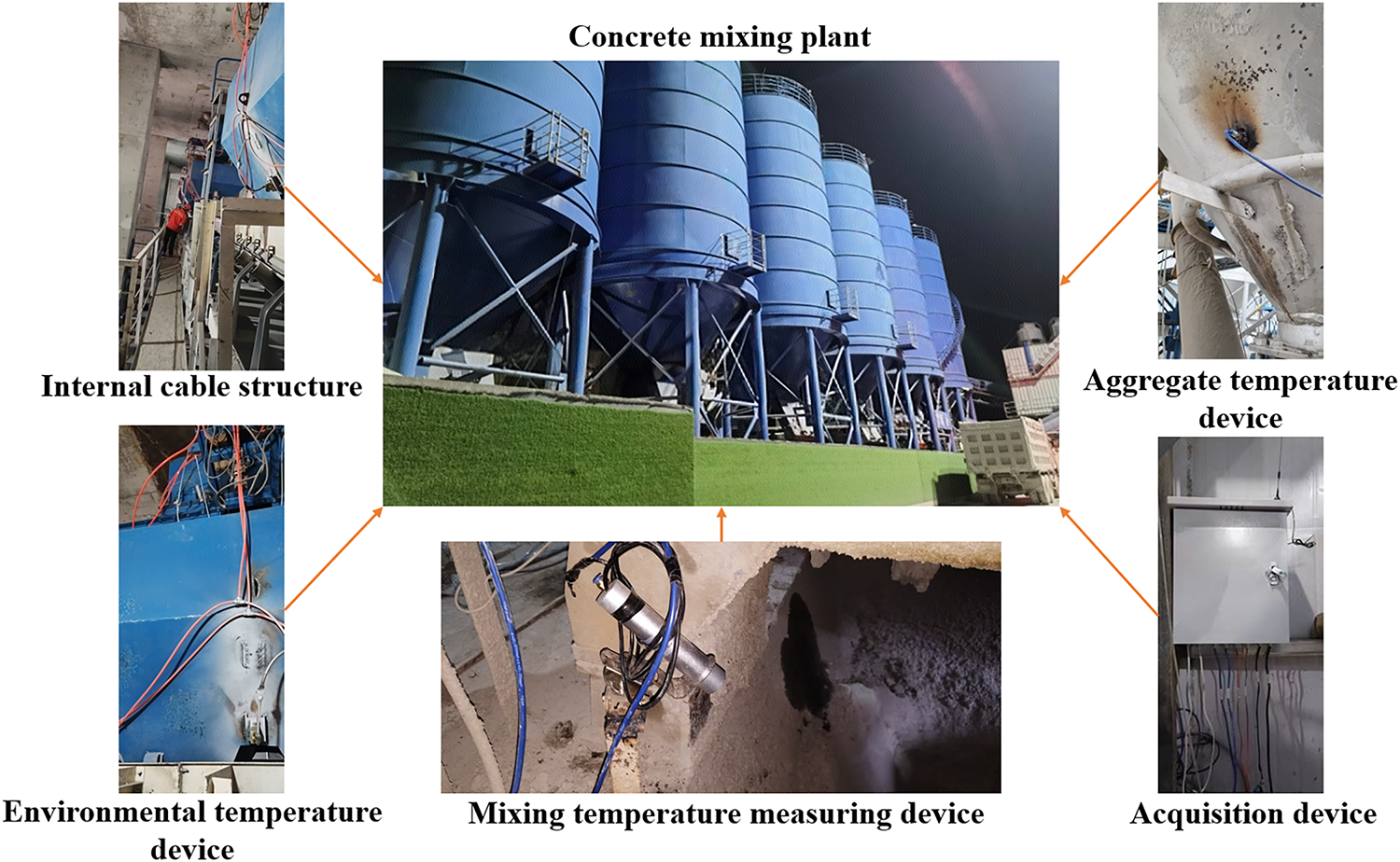

The data acquisition system for this study was built based on the temperature monitoring device at the mixing plant. This device enables real-time monitoring of temperature parameters throughout the concrete production process through an embedded sensor network. The monitoring equipment (ZS2032-T01 temperature sensors and distributed fiber optic sensing system ZS2032-YSPT-4 from IWHR) is shown in Fig. 1. The monitoring system comprises a multi-level data acquisition module, where core temperature parameters include key indicators such as the inlet temperature of coarse and fine aggregates, ambient air temperature, additive solution temperature, and cement clinker temperature. Aggregate temperature monitoring employs distributed optical fiber sensing technology, capable of accurately capturing the temperature change trajectory of aggregates during storage, transportation, and mixing. Ambient temperature sensors are arranged in three-dimensional space to form a temperature field monitoring network, ensuring the completeness of environmental heat exchange data [33]. The additive temperature monitoring module integrates temperature-flow coupling sensors to record the temperature fluctuation characteristics of additives in the delivery pipeline in real-time. These parameters serve as the initial boundary conditions for the concrete temperature field, and their acquisition accuracy directly affects the accuracy of the prediction model.

Figure 1: Composition of the temperature measurement device in the concrete mixing plant

2.2 Data Preprocessing Methods

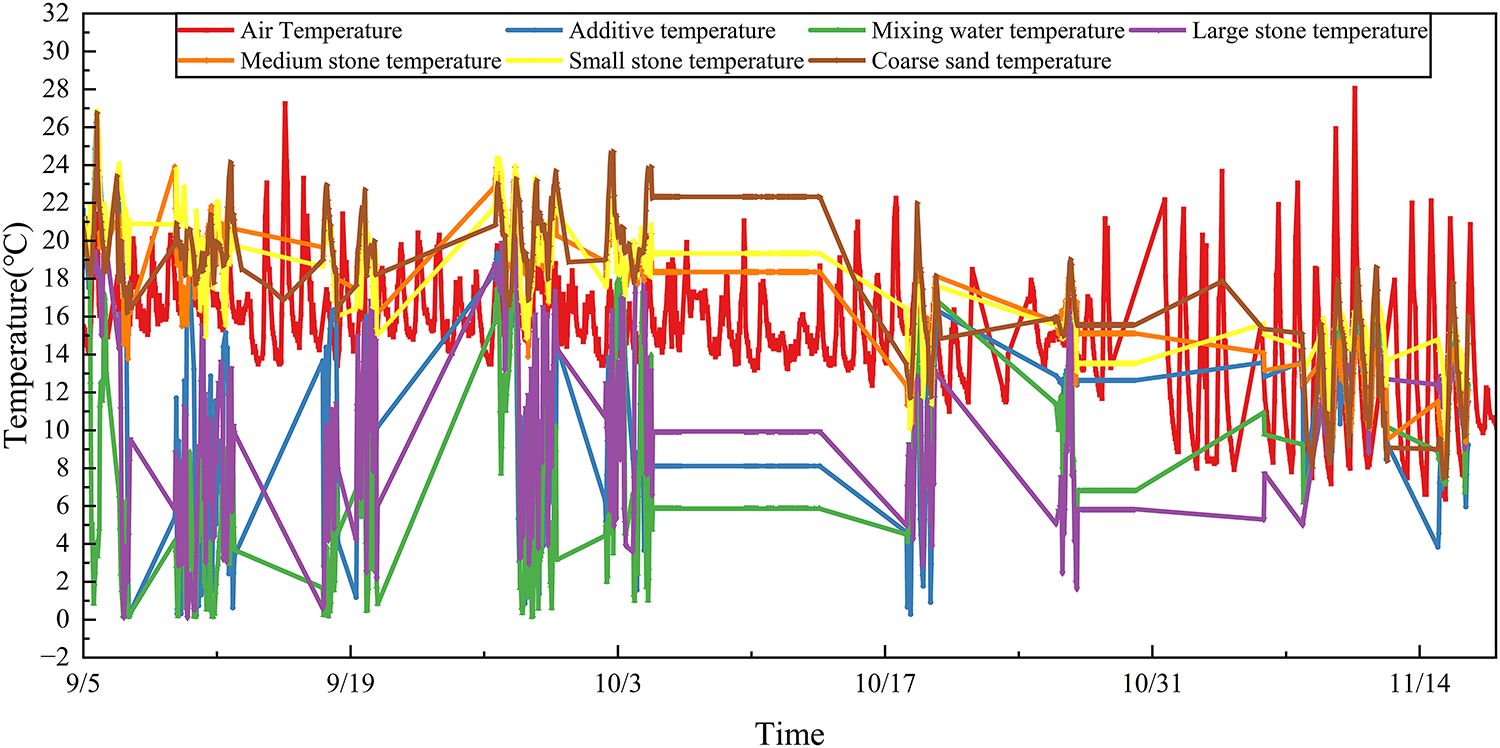

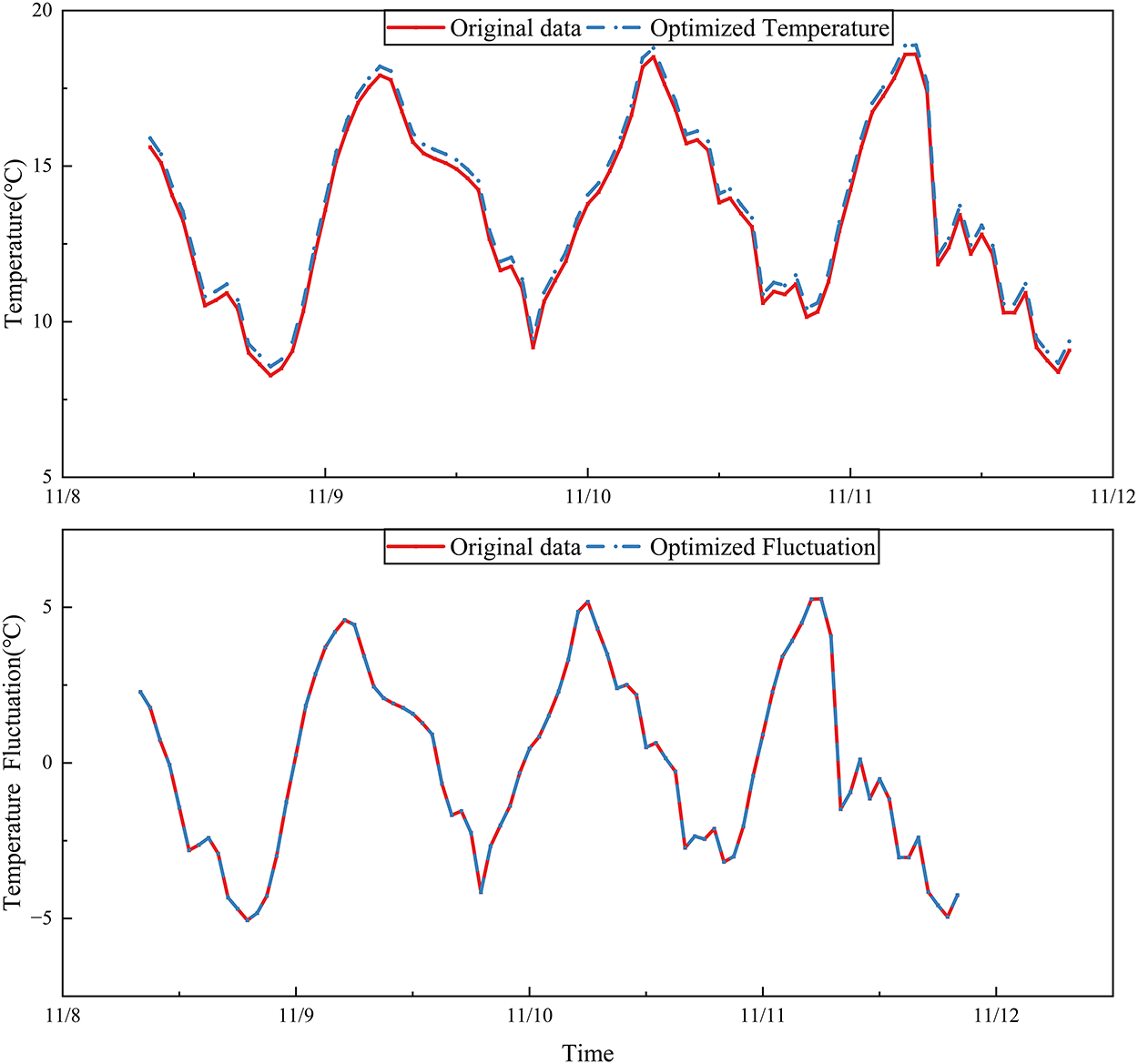

This study ensures the quality and interpretability of the data for concrete outlet temperature prediction through a systematic data preprocessing pipeline. A schematic diagram of the data preprocessing pipeline is shown in Fig. 2, in the stages of time synchronization and missing value handling, an unstructured data preprocessing strategy is adopted to achieve the alignment of time series collected by multiple sensors. For missing data caused by sensor dropouts or communication delays, a combination of linear interpolation and model-based imputation methods grounded in the physical process is used. The model-based imputation part incorporates the constraint of the concrete adiabatic temperature rise formula, effectively reducing the cumulative effect of interpolation errors [34]. This processing method significantly improves the spatiotemporal consistency of the sensor network data, providing a reliable foundational dataset for subsequent modeling.

Figure 2: Raw data at the outlet

The data cleaning stage employs a physically constrained outlier identification method to remove data points that violate thermodynamic laws. Fourier transform analysis is applied to the temperature time-series signals to identify and correct high-frequency noise components caused by sensor drift. This technique was chosen because sensor drift often introduces specific, identifiable frequencies into the signal. Removing these noise components enhances the signal-to-noise ratio of the input data, which is crucial for both the physical model’s parameter stability and the neural network’s training efficiency and convergence. Feature standardization utilizes quantile normalization to ensure comparability among temperature parameters of different dimensions. Addressing the fusion of multi-source heterogeneous data, this study designs a feature fingerprint encoding scheme, compressing the multi-sensor temperature sequence of each sample into a 5-dimensional “feature fingerprint,” as shown in Eqs. (1)–(5). Collaborative analysis of features is achieved through similarity measurement, outputting a feature fingerprint matrix that provides key input features for subsequent analytical modeling.

Eq. (1) is used to extract the average temperature gradient between various aggregate sensors, representing the temperature change of concrete aggregates during transfer between mixing plants. Here,

Eq. (2) is used to extract the degree of dispersion in the temperature of a single aggregate sensor, indicating the variation amplitude of the concrete aggregate within the mixing plant. Here,

Eq. (3) is used to combine the weighted temperatures

Eq. (4) is used to calculate the temperature range, determining the maximum temperature difference range.

Eq. (5) is used to calculate the skewness

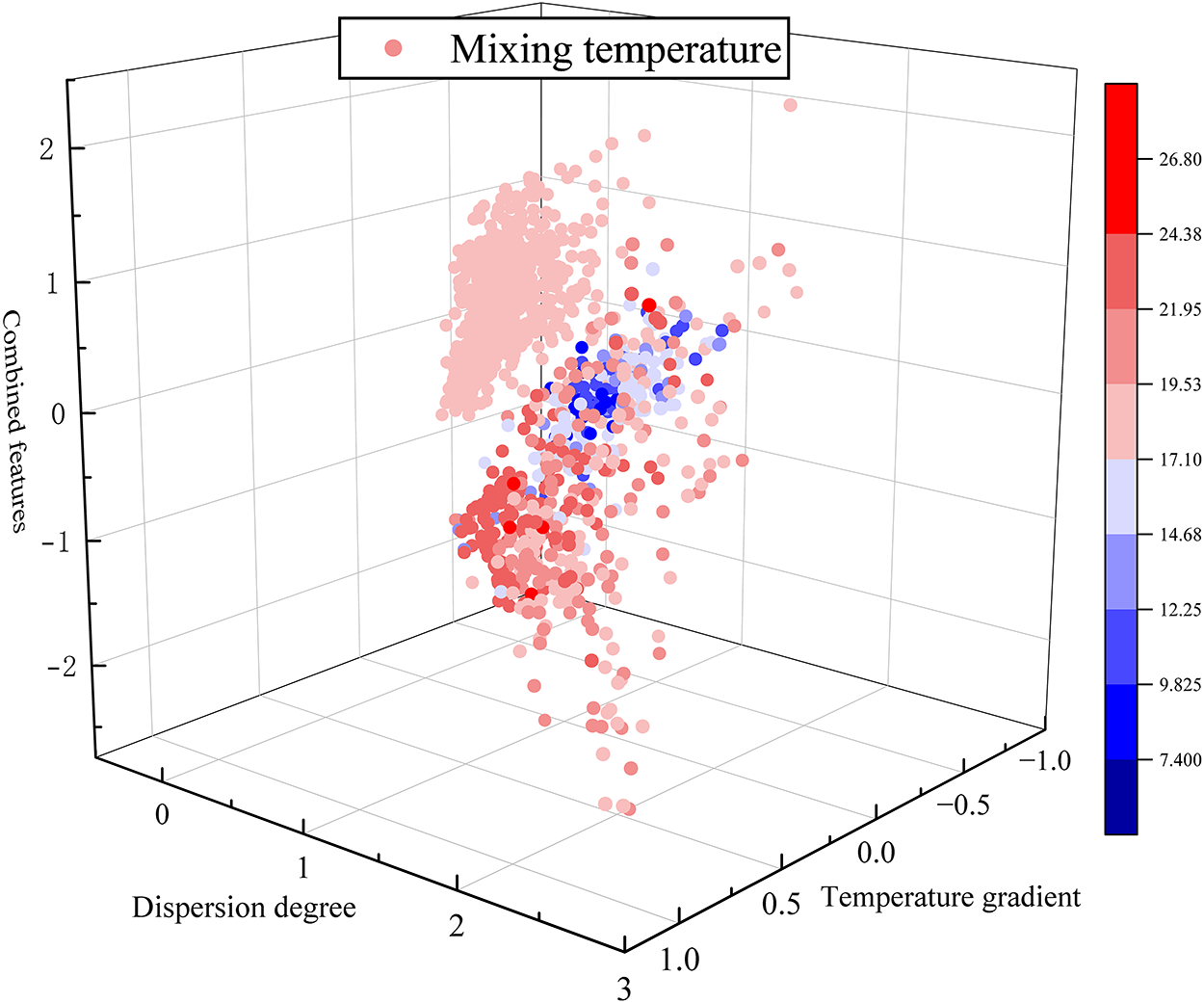

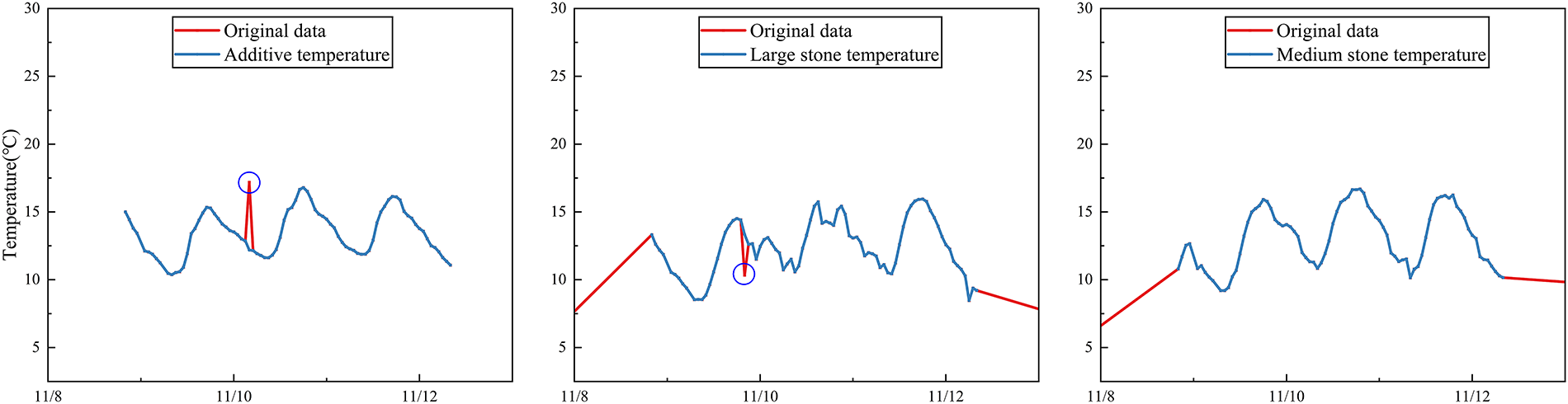

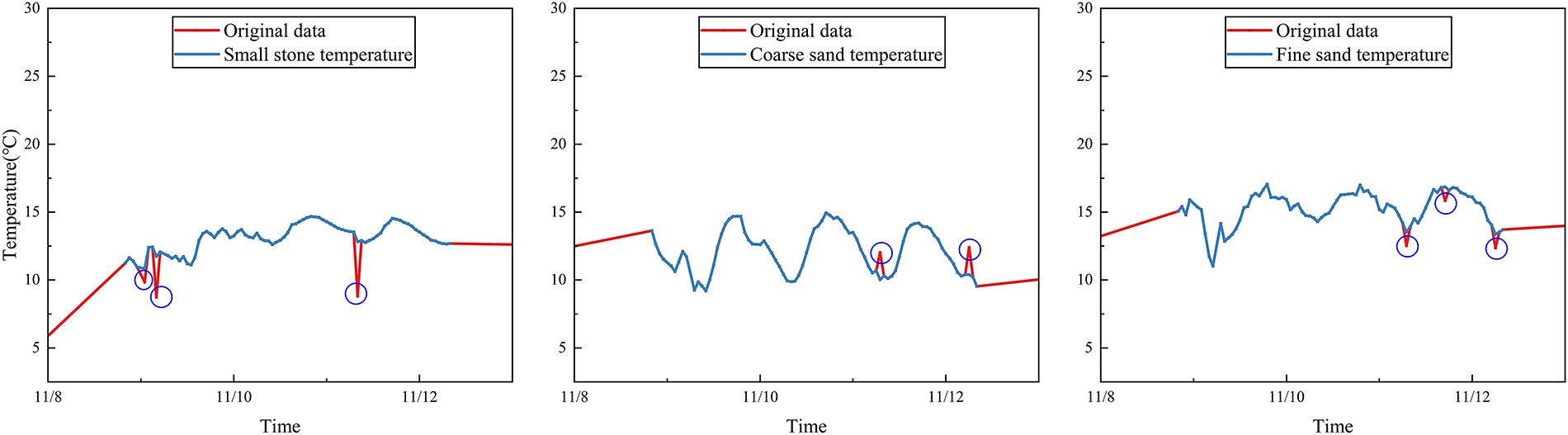

The distribution results of the feature fingerprints are shown in Fig. 3. The construction method combining physical laws and data-driven feature engineering ensures the physical interpretability of the features while enhancing the completeness of feature expression through data mining techniques. An example of single-processor processing is shown in Fig. 4. This lays a reliable data foundation for subsequent model training.

Figure 3: Three-dimensional distribution of feature fingerprints

Figure 4: Sensor monitoring data processing diagram

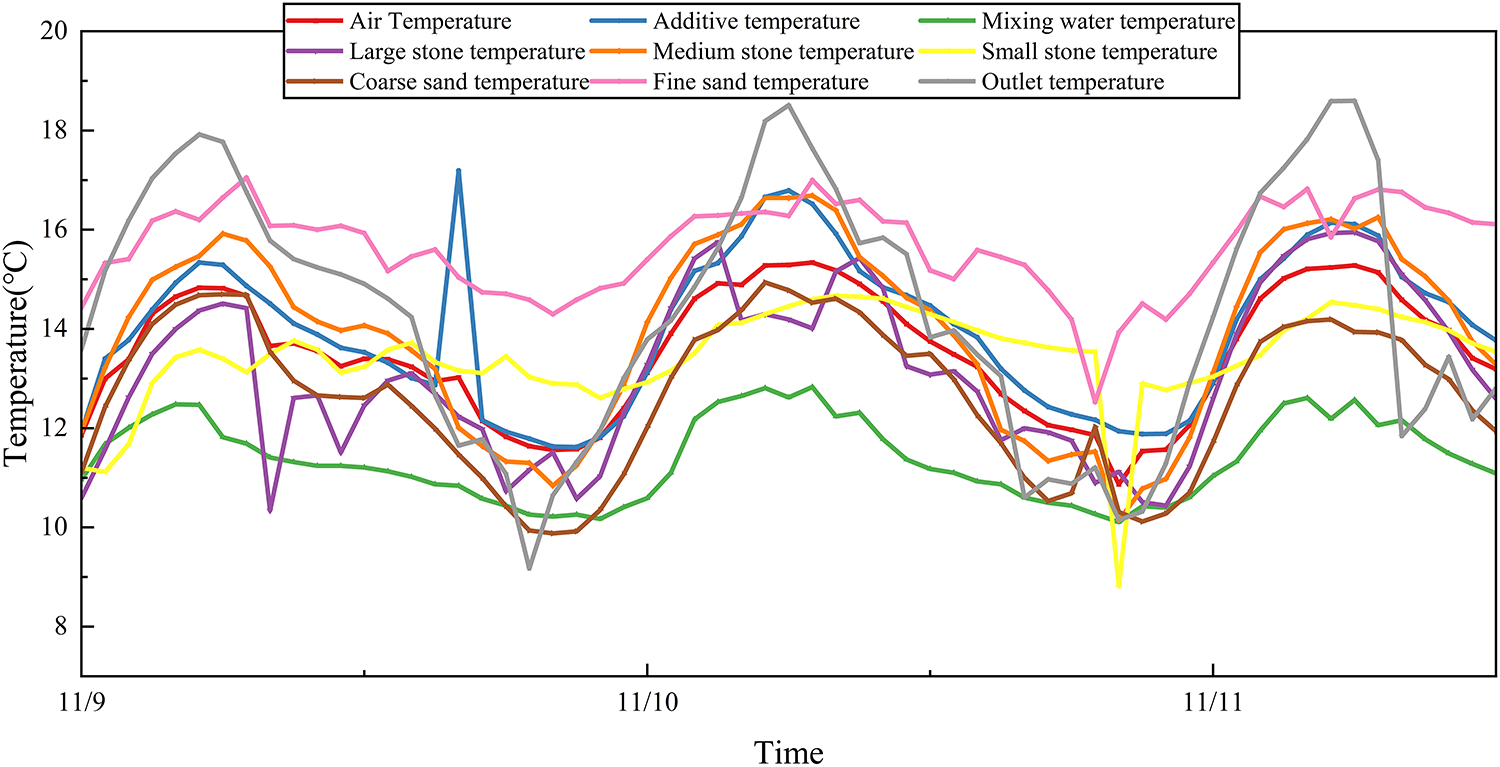

Data standardization employs a dual-channel normalization strategy: Z-score normalization based on batches is applied to physical parameters to eliminate the dimensional impact caused by differences in material properties of concrete from different batches; min-max normalization is applied to sensor data to ensure that the neural network inputs are distributed within the [0, 1] interval. Simultaneously, addressing the batch effect issue in multi-source heterogeneous data, batch correction methods from omics data integration are referenced, and an adaptive scaling layer is introduced for feature space alignment, avoiding systematic biases caused by differences in sensor models or environmental fluctuations. The final preprocessed dataset meets both the interpretability requirements of the physical model and the numerical stability needs of the deep learning algorithm, laying a key foundation for subsequent fusion modeling. The processing results for all sensors are shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Data preprocessing results

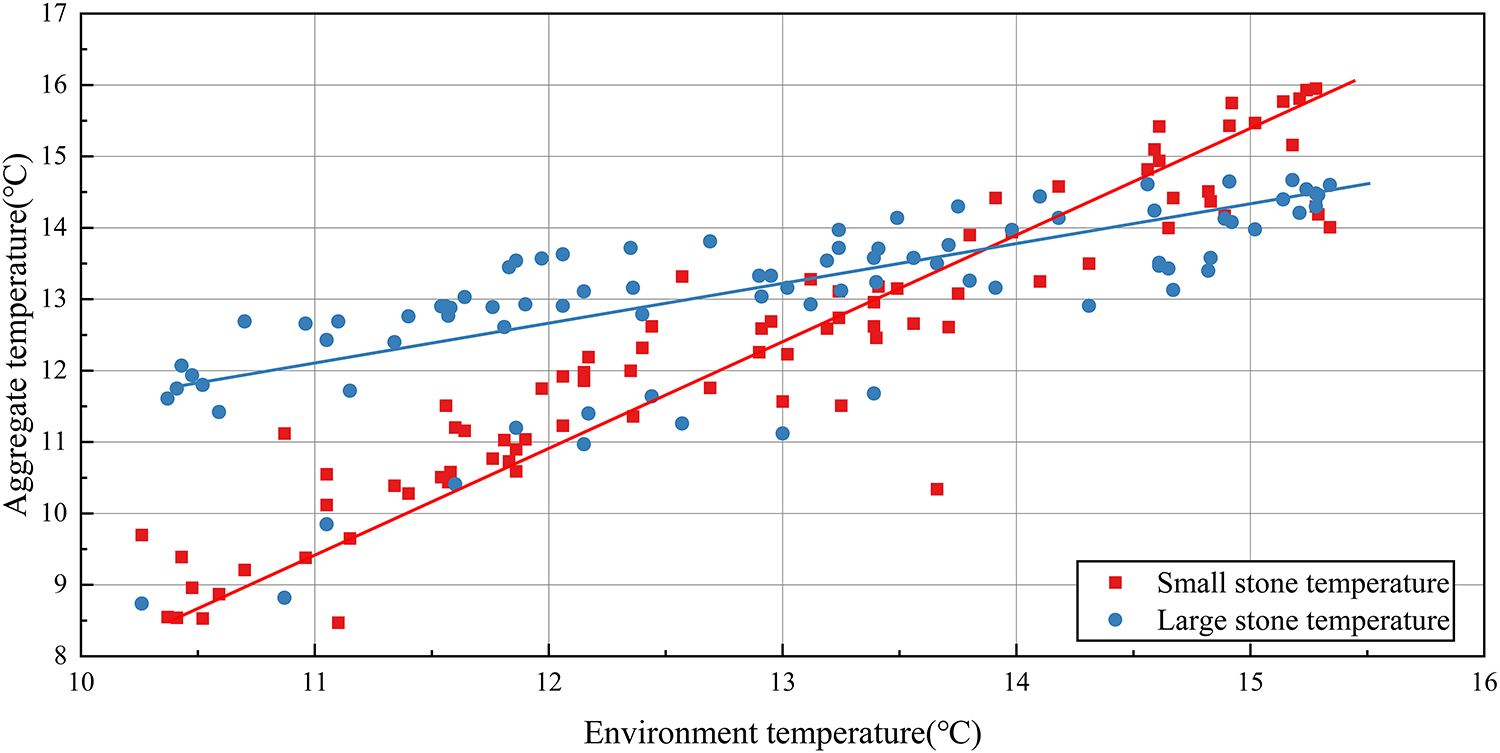

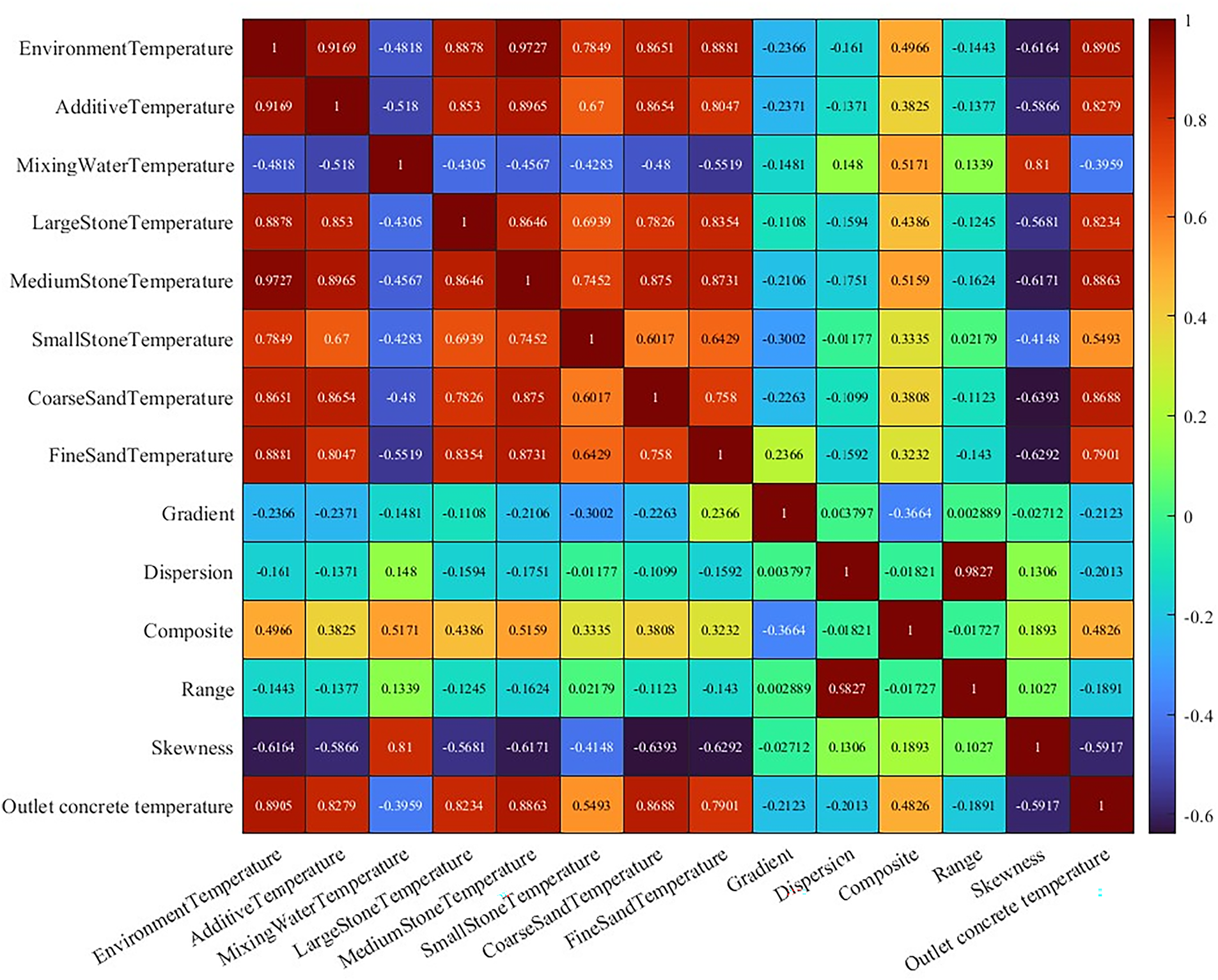

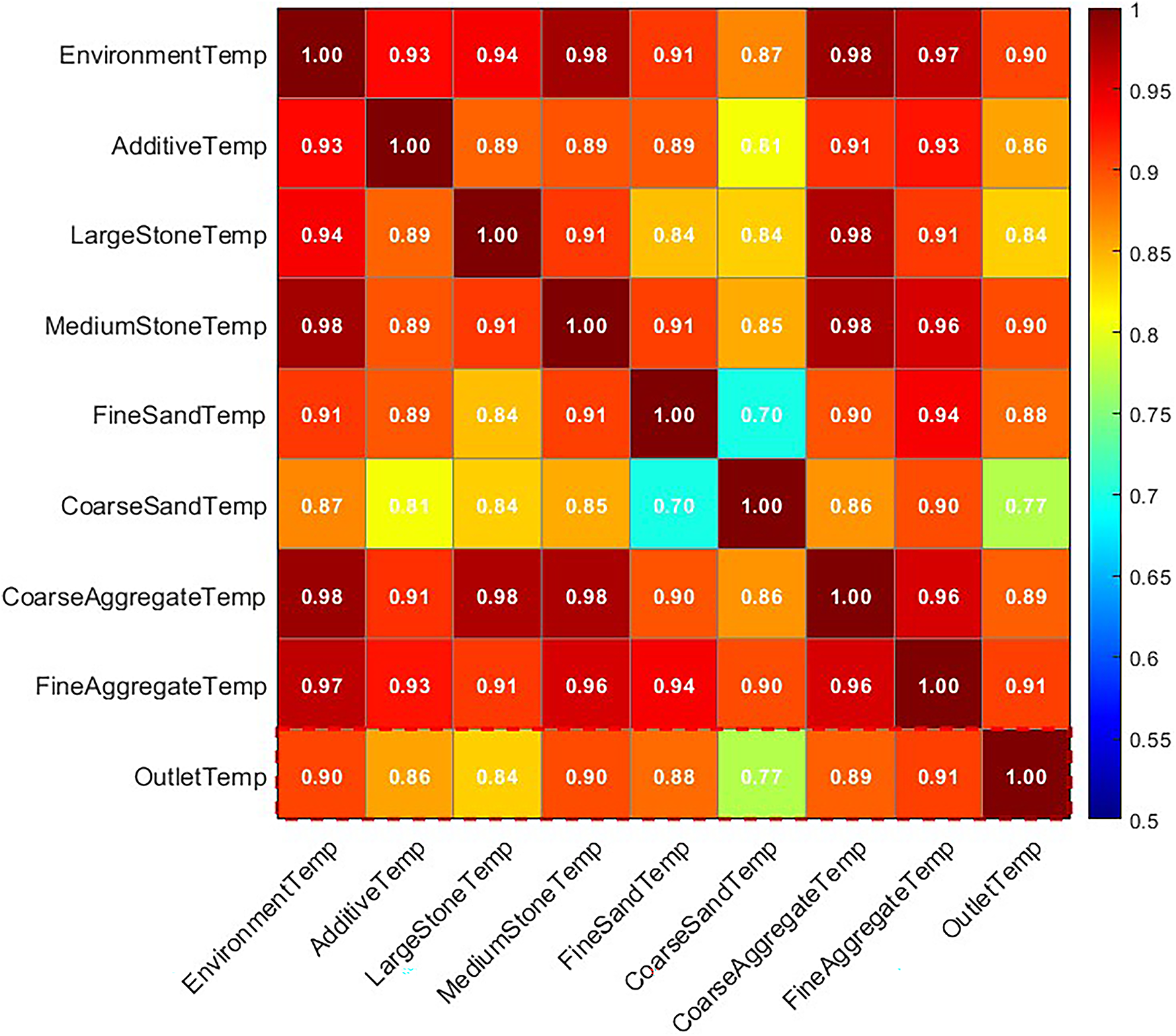

A systematic analysis of the main influencing factors on concrete outlet temperature was conducted using the Pearson correlation coefficient matrix, revealing the correlation characteristics and action mechanisms among key variables. As shown in Fig. 6, which illustrates the relationship between stone and ambient temperature, the analysis indicates complex interactions among temperature variables: fine aggregates, due to their small particle size, are more susceptible to ambient temperature influence, showing a higher positive correlation coefficient. When ambient temperature fluctuations exceed ±3°C, the heat exchange rate between the aggregate and the environment significantly affects the final temperature value, providing theoretical basis for constructing a coupled heat conduction equation physical model. The Pearson correlation matrix is shown in Fig. 7. The study found that temperature-type variables such as large stone temperature, mixing water temperature, and additive temperature show a significant positive correlation (r > 0.7) with the concrete outlet temperature, while the correlation of other parameters is not significant. This indicates that predicting the outlet temperature solely through numerical preprocessing and statistical methods is not ideal and requires further correction through methods like physical models. Based on the results, the correlation among temperature variables is strong, with correlations between large, medium, small stones, and sand all greater than 0.8. The strong correlation among temperature-type variables lays the foundation for feature selection in the neural network model, while the nonlinear interaction relationships between variables suggest the need to introduce dynamic coupling coefficients in the physical model to achieve a refined description of the temperature transfer process.

Figure 6: Relationship between stone and ambient temperature

Figure 7: Feature correlation heatmap

3 Model Construction and Optimization

3.1 Heat Conduction Physical Theory

The construction of the concrete heat balance equation is based on the fundamental law of heat conduction and the principle of energy conservation, with its core being the quantification of heat generation, transfer, and storage processes within the material. During concrete hardening, heat sources primarily include chemical heat release from cement hydration reactions, convective heat exchange between the environment and the material, and boundary radiation heat exchange. The dynamic evolution of the temperature field over time and space can be described by establishing an unsteady heat conduction equation. This study employs a three-dimensional unsteady heat conduction Eq. (6), considering the relationship between temperature gradient and heat flux density under the assumption of isotropy, and introduces a heat source term to characterize the hydration heat effect.

where ρ, c, λ represent the density, specific heat capacity, and thermal conductivity of the concrete, respectively, T is the temperature field function, and Q(t) represents the time-varying volumetric heat release rate due to hydration. To adapt to practical engineering needs, the equation is discretized using the finite difference method, dividing the concrete interior into three-dimensional grid elements and establishing a coupled computational system of time steps and spatial nodes.

The determination of material parameters is a key link in model establishment. The specific heat capacity of the concrete mixture is not a simple superposition of single materials and needs to be calculated using the weighted average method combined with the mass proportions of each component, the formula is expressed as Eq. (7). This study uses a sub-item summation method, multiplying the specific heat capacity of cement, aggregate, water, and admixture by their respective mass proportions in the concrete and then summing them to obtain the equivalent specific heat capacity of the mixed system.

where

3.2 Nonlinear Physical Model with Interaction Terms

Addressing the limitation of traditional linear physical models in capturing the coupling effects of multiple factors in concrete outlet temperature prediction, this study constructs a nonlinear physical model system incorporating interaction terms. By introducing environment-aggregate temperature interaction terms and additive-fine aggregate interaction terms, the model’s ability to represent complex nonlinear relationships is significantly enhanced. For the environment-aggregate interaction, a nonlinear coupling function is used to quantify the mutual inhibition effect between ambient temperature and aggregate pre-cooling temperature, as shown in Eq. (8).

where the exponential parameters η and ζ are globally optimized through the particle swarm optimization algorithm. In additive and fine aggregate interaction modeling, experimental data fitting reveals the nonlinear regulatory mechanism of admixture dosage and fine aggregate moisture content on the hydration heat release rate, establishing a piecewise polynomial Eq. (9).

where A is the additive dosage,

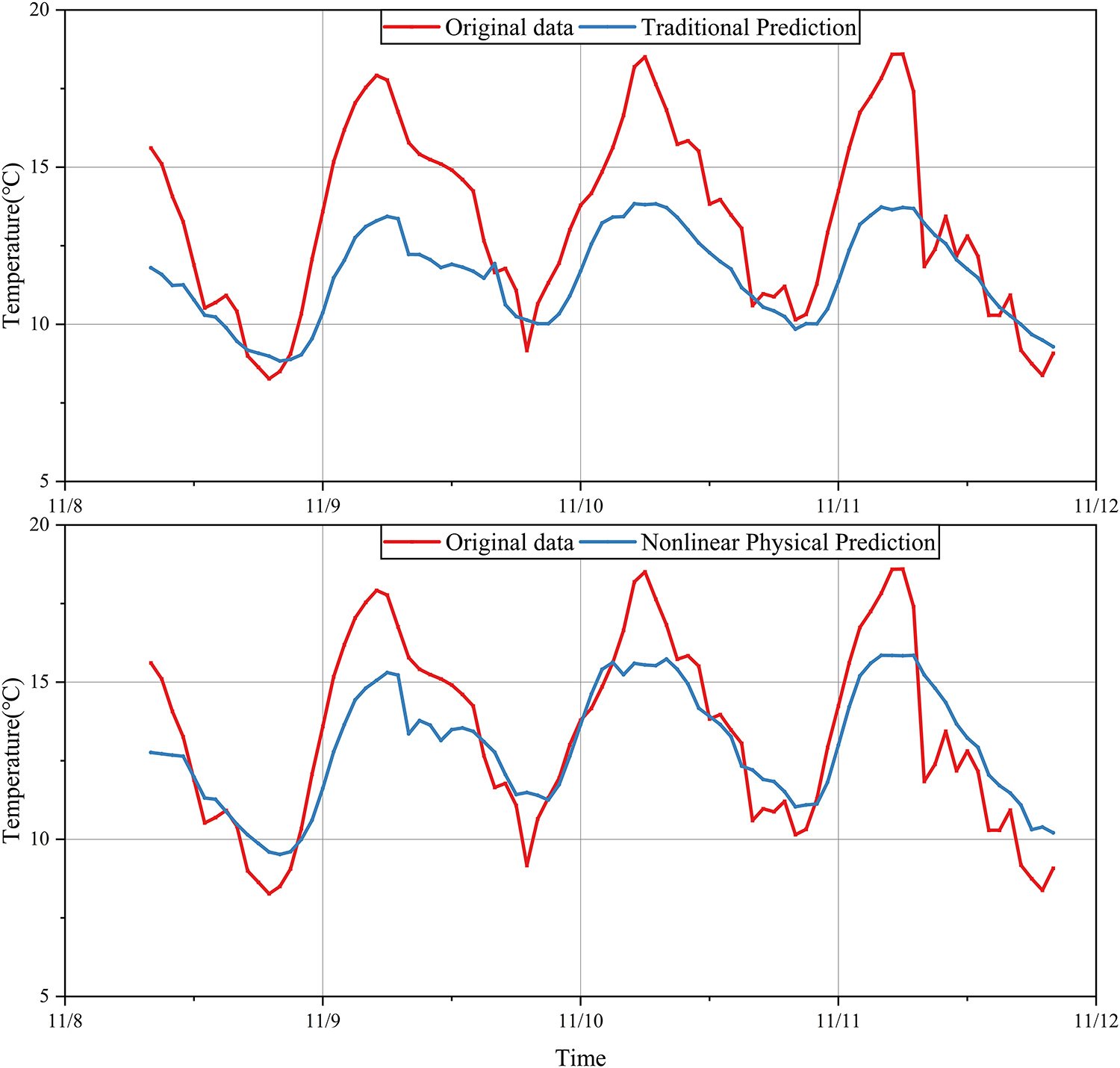

Figure 8: Comparison of model prediction effects

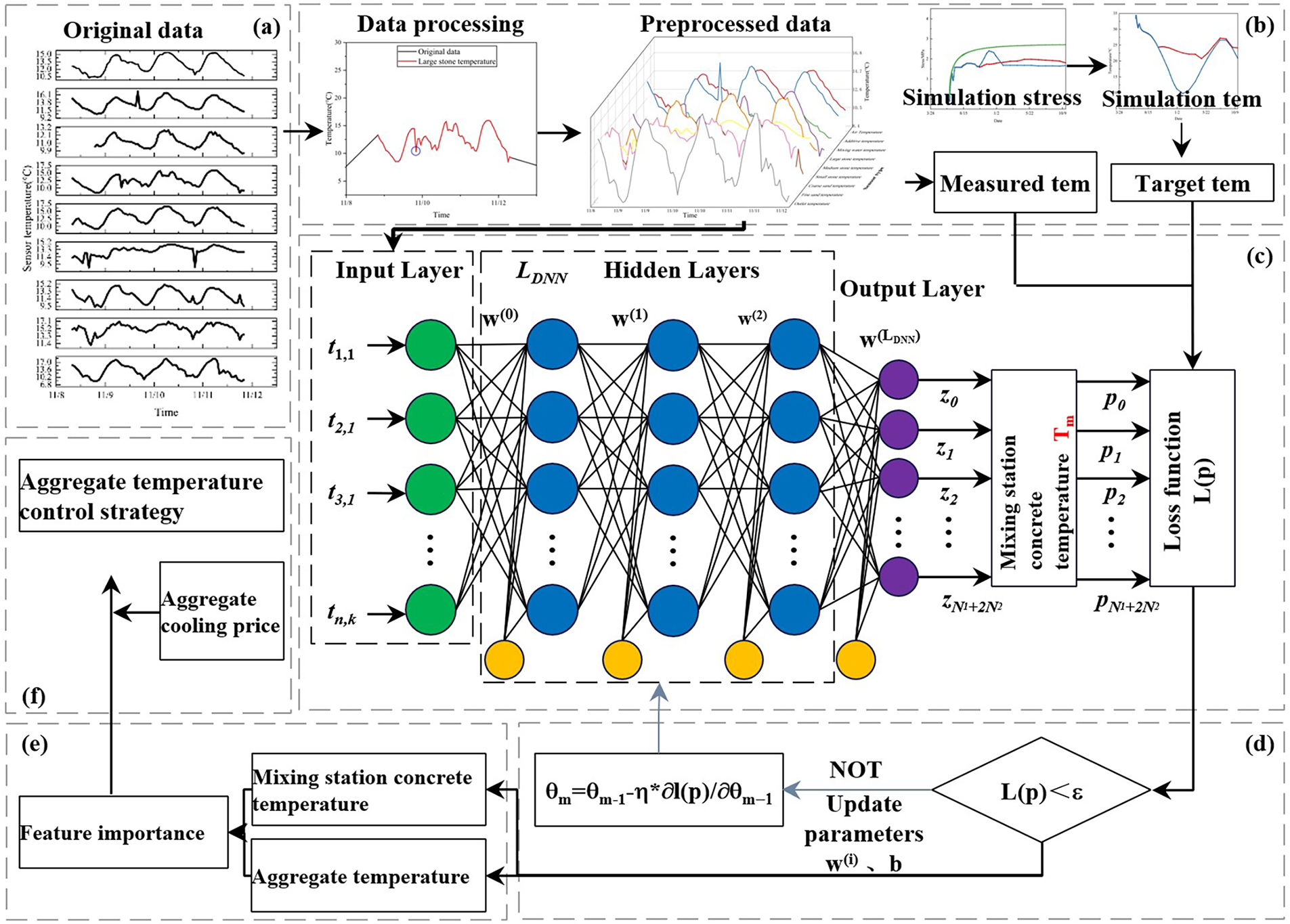

3.3 Network Architecture Design

The neural network model designed in this study adopts a multilayer perceptron (MLP) architecture, achieving nonlinear mapping from multi-dimensional input features to temperature prediction values through a hierarchical structure. The input layer dimension is determined to be 24 feature dimensions based on the results of engineering data feature engineering, covering key influencing factors such as environmental temperature, raw material parameters, mixing process parameters, and time series features. All input features undergo standardization processing using the Z-Score method to eliminate dimensional differences and ensure feature scale consistency in the input space. In the feature selection stage, a combination of Pearson correlation coefficient screening and random forest feature importance evaluation is used to remove redundant features and retain a subset of features that have a significant impact on the temperature response, effectively reducing the dimensionality redundancy of the feature space. The specific algorithm flowchart is shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Neural network model design(Note: (a) Collect the raw data of the sensor, (b) Preprocess the data and calculate the target temperature of the sensor through finite element calculation, (c) Predict the machine mouth temperature through physical model and neural network, (d) Loss function, (e) Judge the importance of aggregate temperature, (f) Cooling measures for aggregates under the condition of optimal economy)

As shown in Fig. 9c, the hidden layer adopts a three-layer fully connected structure, achieving progressive feature abstraction through a Stacked Generalization strategy. The number of nodes in the first hidden layer is set to 15, and the number of nodes in the secondary hidden layer is set to 10. This configuration is optimized on the validation set using a grid search method, balancing model complexity and generalization performance. All hidden layer nodes are configured with the Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) as the activation function. Its linear characteristics and gradient retention capability in the non-saturated region effectively alleviate the vanishing gradient problem in deep networks. Addressing the multi-modal feature distribution characteristics present in concrete temperature prediction, a residual connection structure is introduced between hidden layers. The skip connection mechanism enhances gradient transfer efficiency and improves the model’s ability to learn long-range dependent features.

The output layer adopts a single-node linear activation structure, directly outputting the continuous predicted value of the concrete outlet temperature. To enhance the model’s fitting ability for the tail characteristics of the temperature distribution, a temperature compensation correction module is set before the output layer, performing dynamic calibration of the predicted value through learnable parameters. The model adopts an adaptive learning rate optimization strategy, combined with the Adam optimizer and a cosine annealing learning rate scheduler, ensuring the convergence stability of the parameter update process. The loss function uses a weighted combination of Mean Squared Error (MSE) and Smooth L1 Loss. Based on the results of simulation calculations, the target temperature is set, improving the accuracy requirement for predicted values within the normal temperature range while maintaining robustness to outliers.

In terms of model regularization, this study implements a dual constraint mechanism: firstly, a Dropout regularization layer is introduced between hidden layers with a dropout rate of 0.3 to prevent feature co-adaptation; secondly, constraints are applied to the network parameters through L2 weight decay to control model complexity. In terms of feature space optimization, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is used to whiten the input features, eliminating multicollinearity between features. During the model training process, Early Stopping is used to monitor the validation set loss. Training is terminated if no performance improvement occurs for 15 consecutive epochs, effectively avoiding the risk of overfitting. This hierarchical architecture design retains the feature prior knowledge of the physical model while fully leveraging the nonlinear modeling advantages of deep neural networks, providing a solution for concrete temperature prediction that combines interpretability and prediction accuracy.

The prediction results of the physical model and the neural network are weighted and fused. The fusion strategy adopts a dynamic weight allocation mechanism, where the weight coefficients are adaptively adjusted based on the cross-validation error of the training dataset. Specifically, the weight of the physical model is determined by the standard deviation of its prediction residuals, while the weight of the neural network is calculated based on its generalization ability on the validation set. The final predicted value is the weighted sum of the two, as shown in Eq. (10).

where

Through this hierarchical fusion architecture, this method achieves an organic unity of physical mechanism and data drive. The physical model provides interpretable prior constraints for prediction, while the neural network compensates for the simplification defects of the theoretical model by learning the differences between the physical model and the actual data. Experiments show that compared to a single physical model or a purely data-driven model, this fusion method achieves significant improvements in both temperature prediction accuracy and robustness, providing a reliable theoretical tool and technical path for temperature control in concrete engineering.

4 Simulation Analysis and Experimental Results

4.1 Simulation Calculation Parameters

This study selects a large concrete gravity dam project of a hydropower station in southwest China as an engineering application case. Addressing the lag issue inherent in traditional prediction methods for concrete outlet temperature at mixing plants, the project team embedded the physical model and neural network fusion algorithm into the concrete production management system, constructing a real-time dynamic temperature prediction platform. During implementation, key parameters such as aggregate temperature, ambient temperature, and cement hydration heat release rate were collected in real-time through a sensor network deployed at the mixing plant. These were coupled with finite element model calculations, ultimately achieving a significant improvement in the accuracy of outlet temperature prediction.

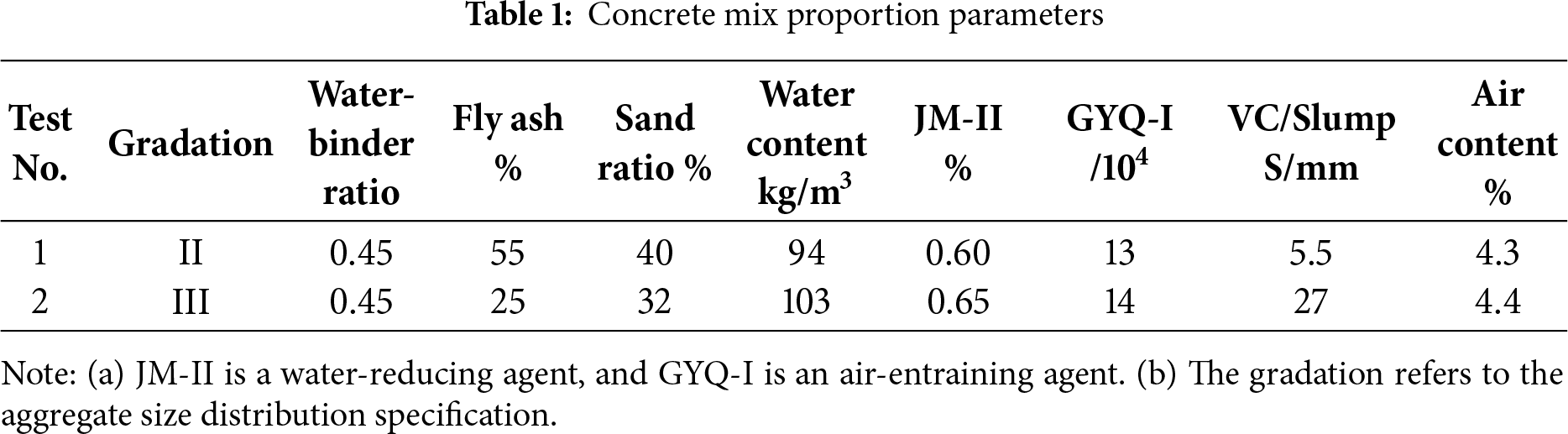

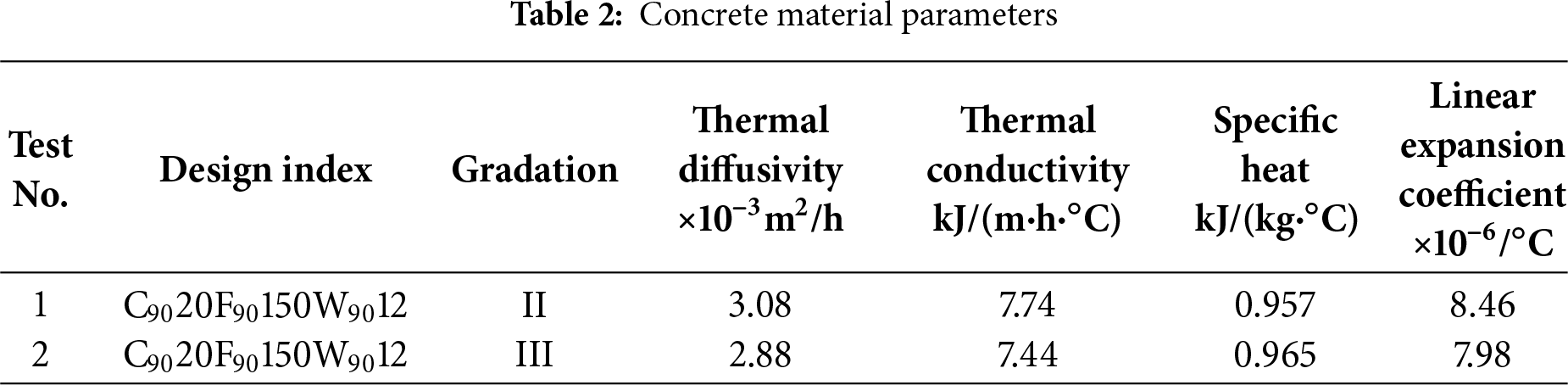

The concrete mix proportions presented in Table 1 were determined based on the project’s structural design requirements, following Chinese national standards (DL/T 5330-2015), and were finalized through trial mixing procedures to meet the specified design indices shown in Table 2. The air content was measured for fresh concrete according to the pressure method specified in Chinese standard DL/T 5100-2014 and GB 8076–2008.

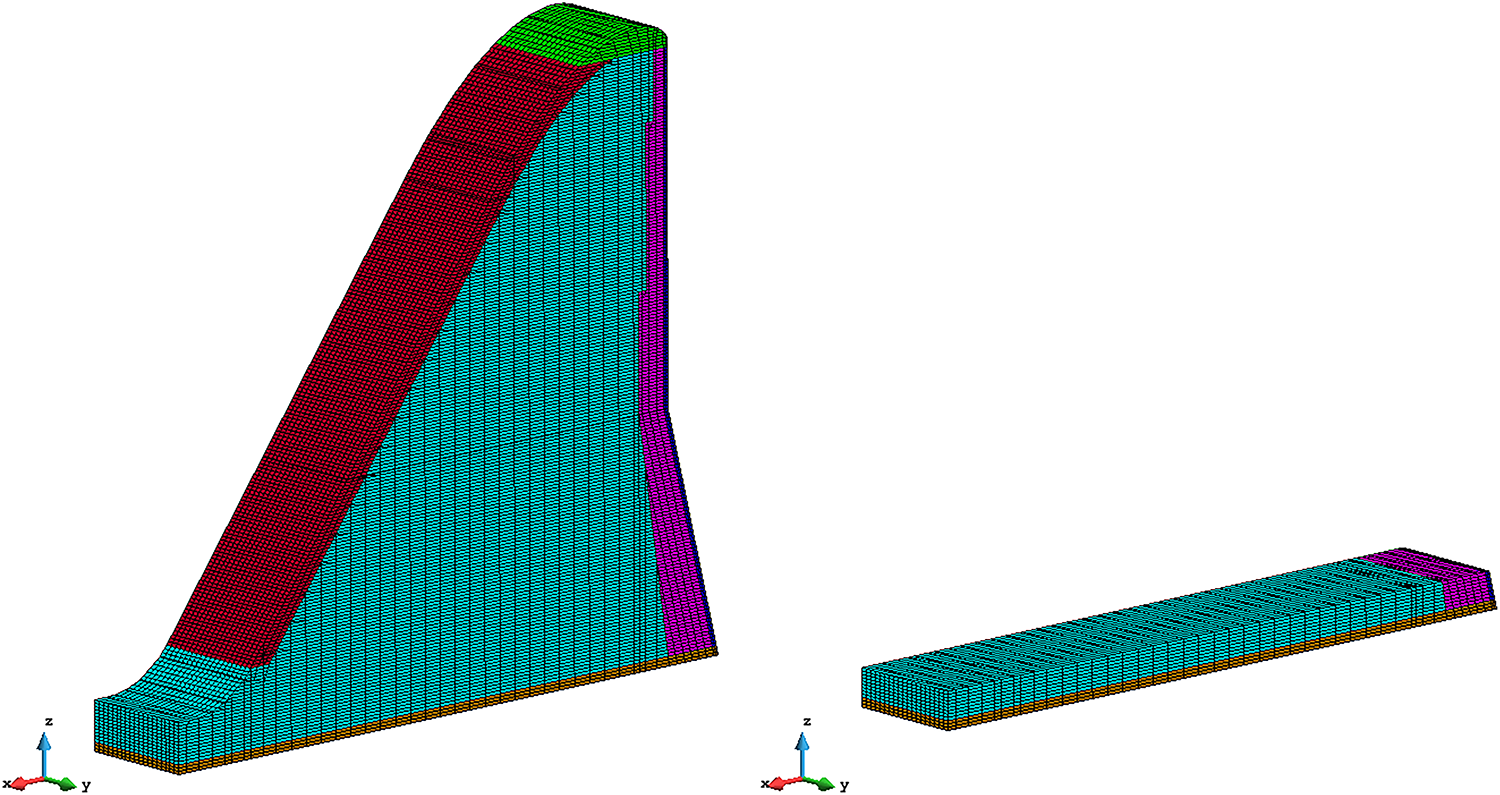

4.2 Simulation Inversion Calculation to Determine Target Outlet Temperature

To determine the target outlet temperature, it is necessary to determine the allowable stress range based on the simulation calculation results of the concrete dam, and further determine the allowable placing temperature. Based on the allowable placing temperature of the dam, the allowable maximum temperature at the outlet is inverted, i.e., the target outlet temperature. As shown in Fig. 10, The overflow dam section was selected for simulation calculation. The program used in this paper is SAPTIS, a FORTRAN program for calculating the temperature and stress fields of large-volume concrete structures, which can be used to analyze two-dimensional and three-dimensional problems. The temperature field and stress field are solved by the finite element method within a set of grids. This dam section has 130,624 elements and 141,648 nodes. The surface of the dam is the temperature, and the two sides are the adiabatic boundaries. After water storage, the upstream surface serves as the water temperature boundary. In the stress calculation, the bottom surface of the bedrock at the bottom of the dam is fully constrained in three directions, while the side surface is normally constrained. Cooling pipes are used inside the concrete for temperature control, with a pipe spacing of 1.5 m × 1.5 m. The primary cooling water temperature is 12°C, the target water temperature is 18°C, and the water cooling duration is 13 days.

Figure 10: Finite element model of the overflow dam section

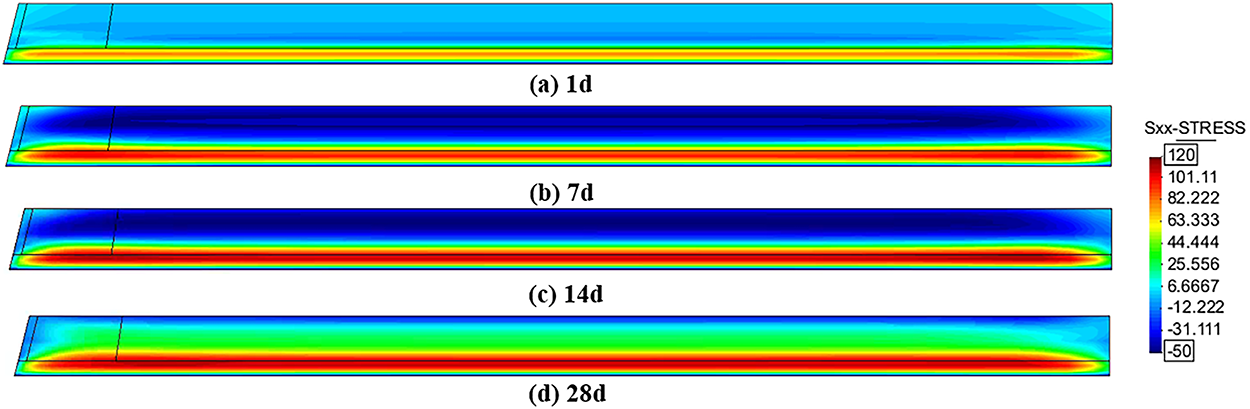

Fig. 11 shows the nephogram of river-direction stress at the profile of the overflow dam section. According to the calculation results, the maximum stress in the overflow dam section is 1.26 MPa. The concrete poured during the outlet measurement period, located at the bottom of the dam and being conventional concrete, was selected to analyze its river-direction stress during this period, thereby calculating the allowable temperature.

Figure 11: River-direction stress at the middle section of the overflow dam section

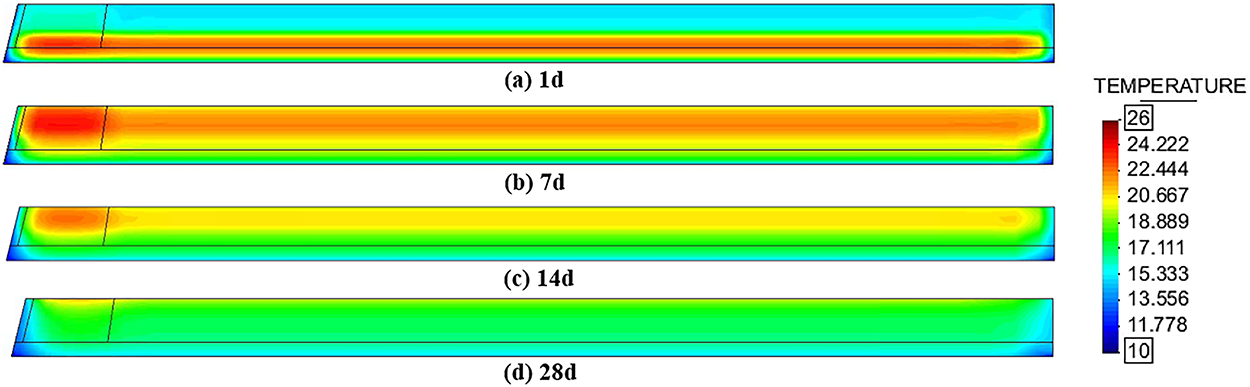

Fig. 12 is the temperature of the concrete inside the pouring bin obtained from simulation calculations during the outlet measurement period. The maximum concrete temperature in the bin is 25.4°C. Fig. 13 shows the stress process line at the location of maximum stress in the pouring bin and the allowable stress process line. The allowable stress is based on the axial compressive strength.

Figure 12: Temperature at the middle section of the overflow dam section

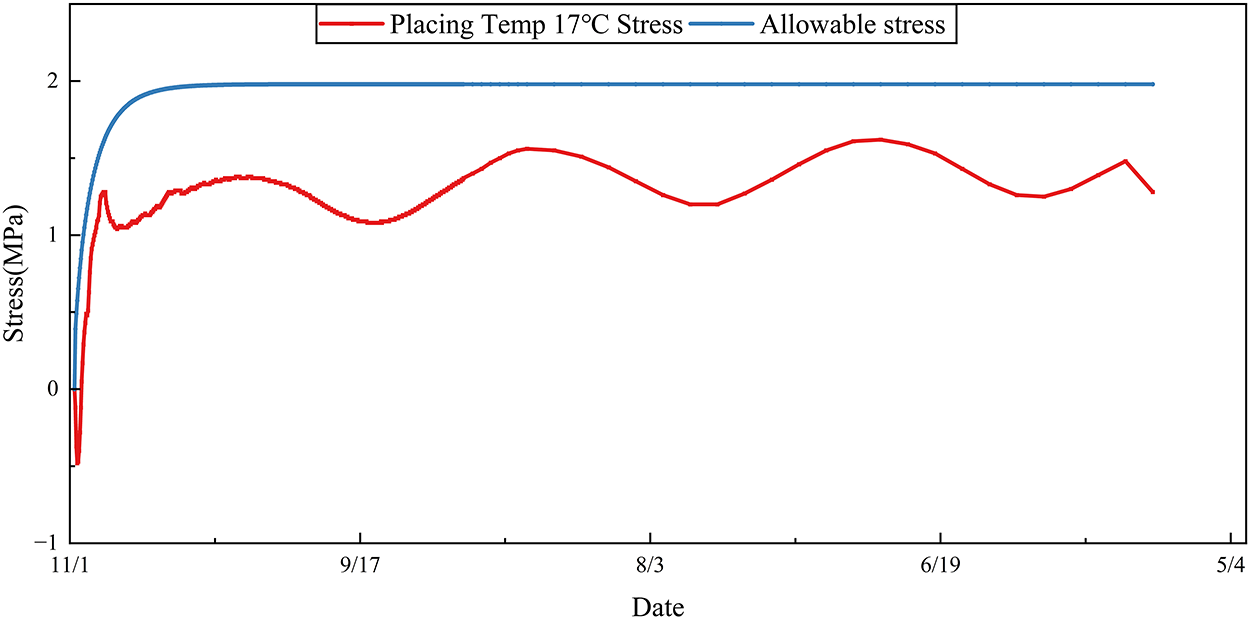

Figure 13: Stress process line at maximum stress location in the concrete pouring bin

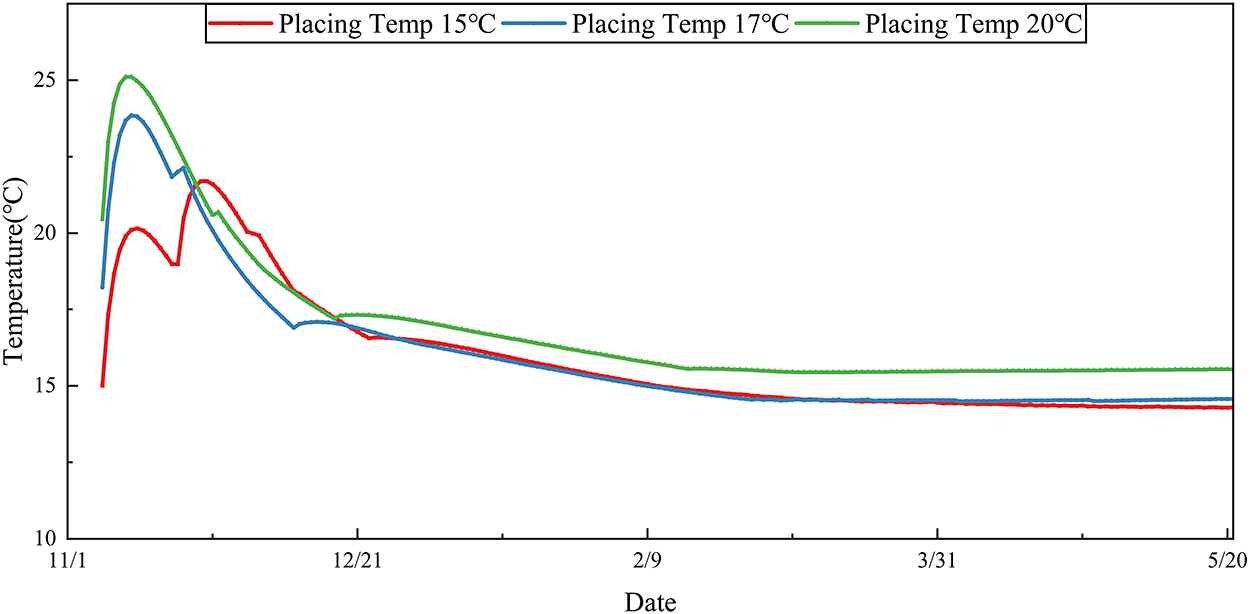

Based on the stress process in Fig. 13, the inverted temperature process line of the concrete in the dam pouring bin is shown in Fig. 14. The highest temperature occurs on the fourth day after pouring, with a maximum temperature of 25.11°C. The initial temperature is the placing temperature. According to the stress calculation, it can be concluded that, under the premise that the stress does not exceed the allowable stress, the placing temperature cannot exceed 17°C.

Figure 14: Placing temperature process

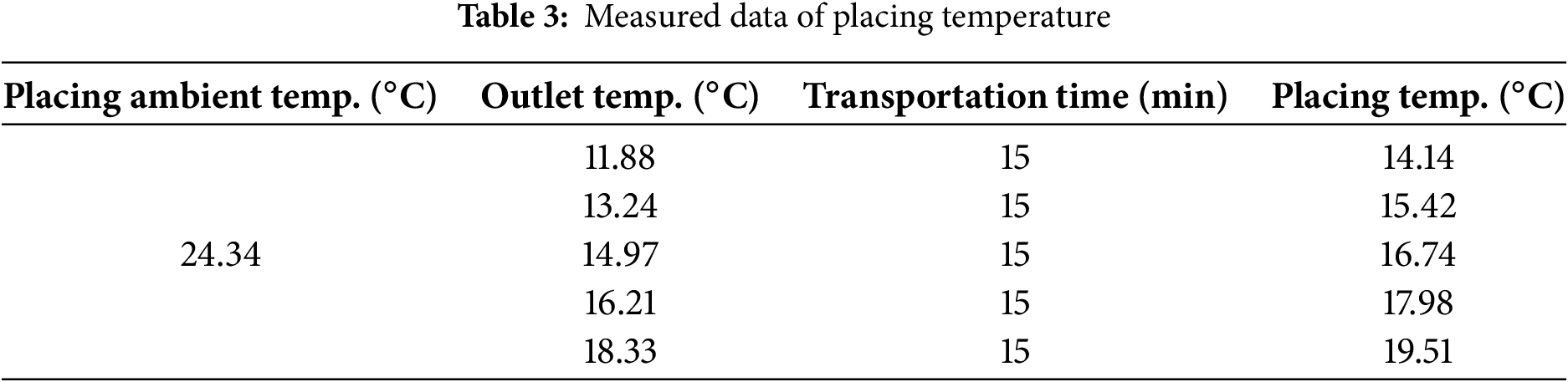

In the actual project, based on the calculation results, temperature was measured on-site. Under the condition of not considering the covering time of the layer and using a canopy cover on the dump truck during transportation, the measured data of concrete placing temperature and outlet temperature are shown in Table 3. During the period from the concrete outlet to placement, the temperature recovery is about 2°C According to the measured results in the table, under the condition that the placing temperature does not exceed 17°C, the outlet temperature cannot exceed 15°C.

4.3 Outlet Temperature Prediction Results Based on Target Temperature

Based on the preprocessed concrete outlet temperature dataset from Section 2, covering a total of over 1000 concrete batch production records from November 2020 to December 2020. The dataset includes characteristic parameters such as concrete outlet temperature, raw material temperatures, ambient temperature, mixing parameters, admixture dosage, aggregate moisture content, and cement hydration heat release rate. Temperature-related features include ambient temperature, aggregate temperature, cement temperature, admixture temperature, and final outlet temperature, forming a complete temperature transfer chain data. The dual advantages of sample size and feature dimension provide sufficient parameter space and generalization capability guarantee for model training.

Addressing the complex distribution characteristics of temperature features, this study adopts a multi-dimensional preprocessing strategy. First, missing value imputation and outlier detection were performed on the raw data, identifying and correcting 4.3% of abnormal temperature records using the Isolation Forest algorithm. Secondly, sliding window standardization was applied to the temperature time-series data, and the Z-score method was used to normalize the temperature features, eliminating the interference of dimensional differences on model training. Finally, based on the principle of stratified sampling, the dataset was divided into training, validation, and test sets with ratios of 70%, 15%, and 15% respectively, ensuring uniform coverage of each temperature distribution interval in the data split. Statistical analysis showed that the skewness coefficient of the training set temperature distribution was −0.12, and the kurtosis coefficient was 2.8. The statistical characteristics of the validation and test sets were highly consistent with the training set, effectively avoiding the problem of data distribution shift.

As shown in Fig. 15, based on the nonlinear physical model and neural network, statistical analysis found that the Pearson correlation coefficients between aggregate temperature and outlet temperature were all above 0.8, while the correlation coefficient between ambient temperature and outlet temperature was 0.9, indicating that ambient temperature has a more significant direct impact on concrete temperature. Furthermore, the dataset contained about 7.2% of cases with abnormal temperature fluctuations (e.g., abnormal outlet temperature rise during high-temperature periods), providing key samples for model robustness verification.

Figure 15: Correlation between coarse aggregate temperature change and outlet temperature change

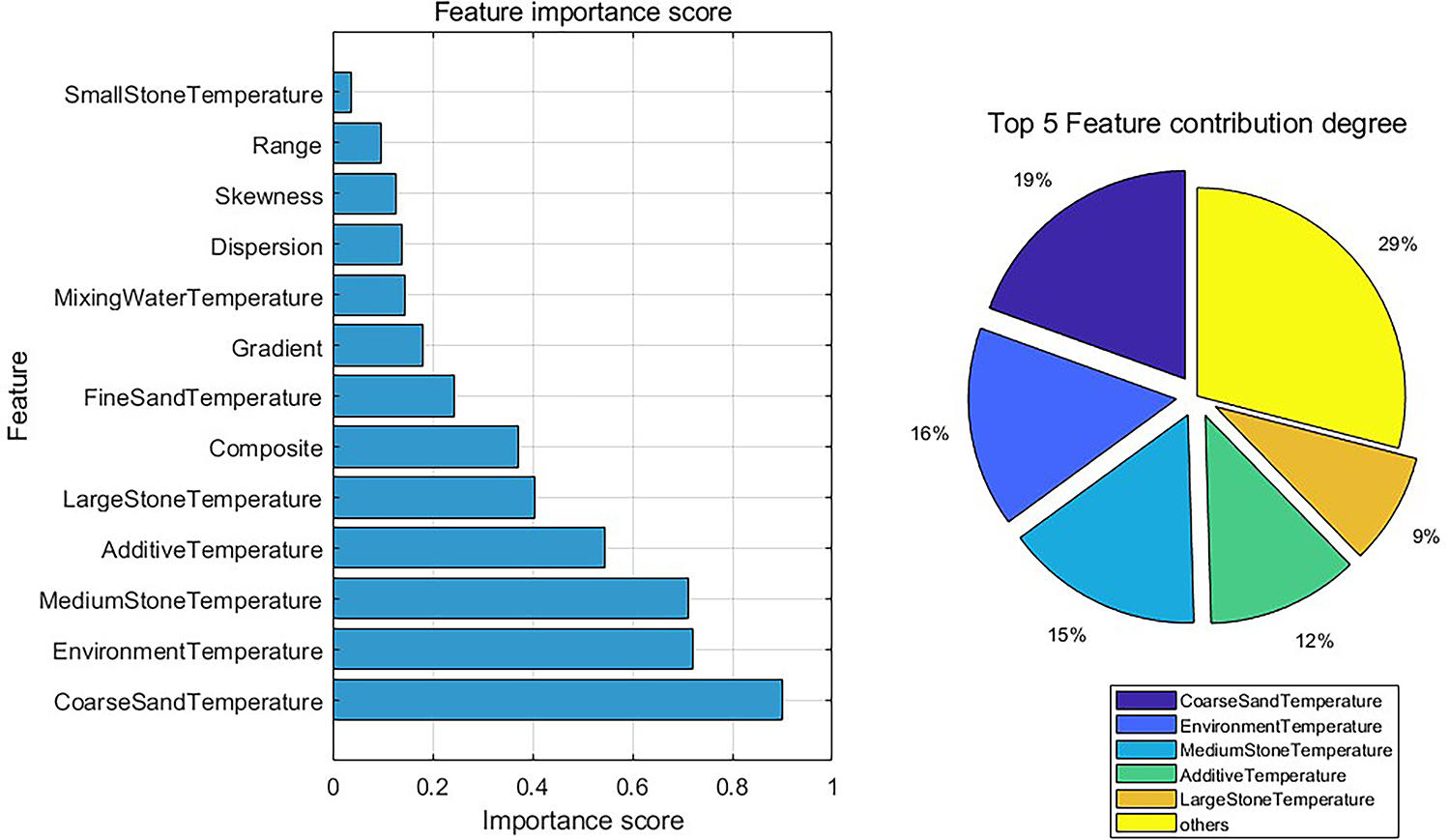

Analyzing from the perspective of the fusion of physical mechanisms and machine learning, the importance score of ambient temperature was strongly positively correlated (r = 0.9) with the environmental boundary condition parameters in the heat conduction equation, validating the ability of the permutation feature importance method to map physical mechanisms. Meanwhile, the contribution distribution of secondary features revealed the neural network model’s ability to capture multi-physical field coupling effects. The results of this study indicate that ambient temperature and coarse aggregate temperature are not only the dominant factors in predicting the concrete temperature field but also physical constraints must be given priority consideration when building a fusion model. This provides theoretical support for establishing mechanism-based feature engineering methods.

As shown in Fig. 16, this study experimentally verified the effectiveness of the prediction method fusing physical models and neural networks in predicting concrete outlet temperature. In terms of time series fitting, comparing the prediction results of the fusion model with the actual temperature curve showed that the overall trend matching degree reached 98.2%. Quantitative indicators on the primary test set showed that the fusion model’s Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) was 1.59°C, the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) was 1.23°C, and the coefficient of determination (R2) reached 0.91. (A preliminary validation on a hold-out set during development showed an RMSE of 0.83°C, highlighting the model’s potential under controlled conditions). The results indicate that by constraining the temperature evolution process through the physical model and capturing complex nonlinear relationships through the neural network, the trend deviation problem caused by simplified boundary conditions in traditional methods is effectively solved, while overcoming the limitation of pure data-driven models’ high dependence on historical data.

Figure 16: Outlet temperature prediction results

In terms of prediction accuracy at key points, for the initial setting temperature and final setting temperature of concrete, which are critical control points in engineering, experimental data showed that the prediction error of the fusion model was significantly reduced. In initial setting temperature prediction, the MAE of the traditional physical model was 1.8°C, while the fusion model controlled the error within 0.6°C; the MAE for final setting temperature prediction was further reduced to 0.8°C from 2.1°C for the physical model and 1.3°C for the neural network. Especially during temperature jump stages (e.g., when the ambient temperature rises by 3°C, the fusion model, through the precise calculation of phase change latent heat by the physical module and the dynamic response of the neural network to real-time environmental parameters, successfully reduced the prediction error at key nodes by more than 40%). Through the synergistic optimization of physical mechanism and data drive, the fusion model not only improves prediction accuracy under normal conditions but also demonstrates significant advantages under extreme conditions and complex disturbances, providing reliable intelligent decision support for concrete temperature control.

In terms of data composition, temperature features exhibit significant spatiotemporal heterogeneity: the ambient temperature spans from 5.87°C to 28.06°C, the outlet temperature distribution ranges from 8.27°C to 18.51°C, and shows obvious multi-peak distribution characteristics, strongly correlated with time variation, material preprocessing technology, and mixing duration. As shown in Fig. 16, statistical analysis results show that the importance score of the ambient temperature feature reaches 0.72, significantly higher than other features, and its corresponding RMSE difference is 2.3°C, accounting for 34% of the baseline error. This result indicates that ambient temperature has a dominant influence on the initial temperature of the concrete mixture, which is consistent with the basic physical mechanism of concrete heat conduction—ambient heat accumulates continuously through heat exchange with materials such as aggregate, cement, and water, finally forming a significant temperature gradient at the discharge stage. Further analysis found that when ambient temperature fluctuations exceed 5°C, the standard deviation of the concrete outlet temperature increases by 1.2°C–1.8°C, verifying the sensitivity of this feature.

Besides ambient temperature, coarse sand temperature (importance 0.19) and medium stone temperature (importance 0.15) also show significant predictive contributions, as shown in Fig. 17. The significance of coarse sand temperature stems from the interaction between coarse sand heat absorption and mixing heat, as it stores more heat and heats up quickly, it can rapidly increase the concrete temperature after mixing. It is worth noting that the importance of mixing water (importance 0.06) and small stone temperature (importance 0.02) is relatively low, which differs from traditional understanding. A possible explanation is that water and small stones have lower specific heat capacities, thus their influence on heating and cooling is lower, and modern mixing equipment has effectively suppressed the marginal effect of mixing duration on temperature through intelligent temperature control systems. This finding provides an important basis for optimizing concrete production parameters, indicating that priority should be given to the synergistic regulation of ambient temperature and material mix proportion in temperature control strategies, rather than simply reducing the temperature of a single material.

Figure 17: Feature importance diagram

4.4 Model Performance Comparison

This study conducted a systematic evaluation of the prediction performance of three models through comparative experiments. The dataset was divided into training and test sets in a 7:3 ratio, where the test set contained multiple sets of data from complex working conditions such as extreme weather (e.g., summer high temperature, winter low temperature) and material batch changes. All models employed 5-fold cross-validation to reduce the impact of random errors.

In terms of prediction accuracy, the fused model performed significantly better than the single models. The physical model had a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 2.13°C, a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 1.68°C, and a coefficient of determination R2 of 0.83. The pure neural network model achieved a lower RMSE (1.42°C) on the training set, but the RMSE on the test set increased to 2.67°C, the MAE reached 2.11°C, and R2 dropped to 0.76, showing obvious overfitting. The fused model achieved the best performance, with a test set RMSE of 1.59°C, MAE of 1.23°C, and R2 of 0.91, representing improvements of 25.3%, 26.7%, and 9.6%, respectively compared to the physical model.

In handling complex working conditions, the fused model demonstrated stronger robustness. When the ambient temperature suddenly dropped by 10°C, the prediction error of the physical model expanded to 3.2°C, while the pure neural network, due to the lack of physical constraints, led to an increased dispersion of error distribution (standard deviation reached 1.8°C). In contrast, the fused model stabilized the error around 1.9°C by dynamically adjusting the weights of physical parameters. In the material parameter variation experiment, when the cement hydration heat coefficient fluctuated by ±15%, the deviation between the predicted value of the physical model and the measured value reached 8.3%, while the fused model controlled the deviation within 3.7% by automatically correcting parameter deviations through the neural network layer. This difference indicates that the bidirectional feedback mechanism in the fusion architecture can effectively coordinate the advantages of physical laws and data drive, improving model adaptability while ensuring physical rationality.

5 Engineering Benefit Optimization Study

The economic analysis is based on the following key assumptions:

(1) The unit prices for labor, materials, and machinery are derived from the project’s local quota and market rates, considered constant for the analysis period.

(2) The temperature reduction efficiency of each cooling measure is stable and as derived from the fusion model in Section 4.

(3) The calculated costs represent the direct cost of temperature control measures per cubic meter of concrete, excluding overheads and potential economies of scale variations.

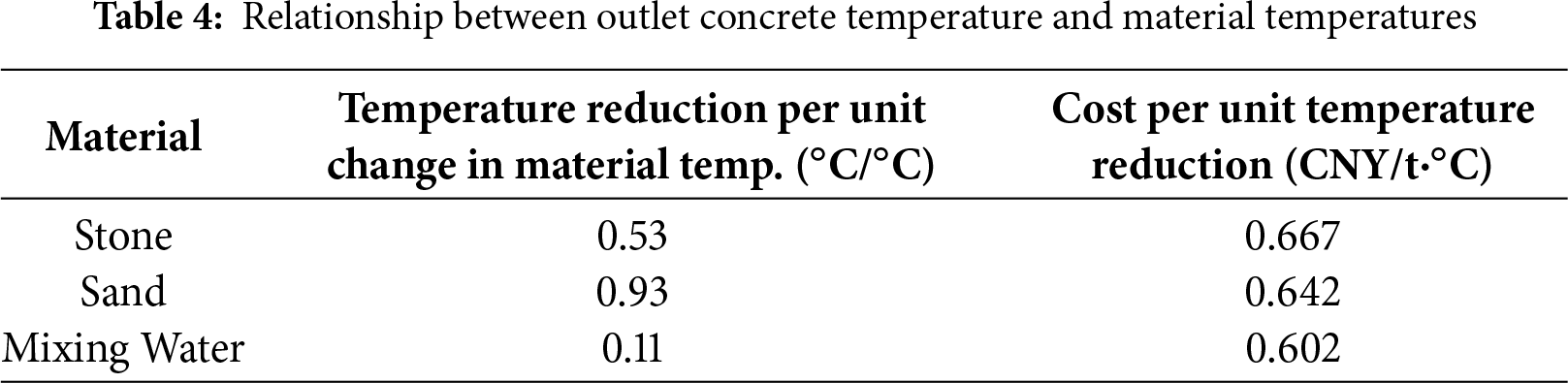

The concrete outlet temperature prediction model based on the fusion of physical models and neural networks provides accurate dynamic temperature prediction capability for engineering practice. Based on this, this study calculates the optimal temperature control strategy by combining the cooling conditions and costs of the concrete production process. With the outlet temperature at 15°C and based on the optimal outlet temperature control parameters, this paper analyzes the impact of adjusting various temperature control parameters, such as aggregate temperature and mixing water temperature, on the temperature control cost. According to the calculation results of the fusion model in Section 4, the relationships between the outlet concrete temperature and the temperatures of coarse/fine sand, coarse/fine aggregate, and mixing water are shown in Table 4.

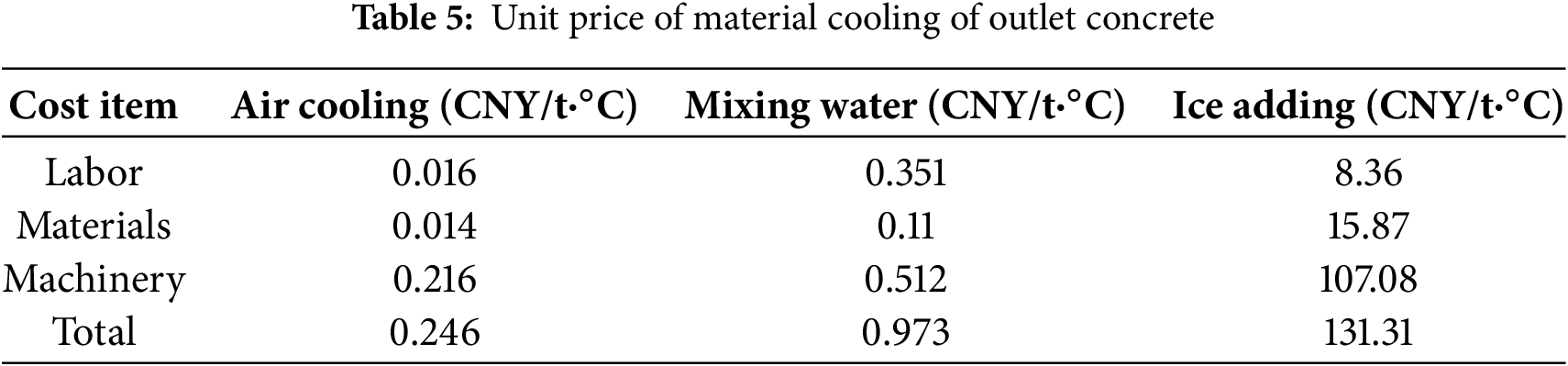

Based on the concrete outlet temperature prediction model established in Section 4 of this paper, and referencing the allocation of labor, machinery, and materials in the relevant quota calculations compiled for the project, combined with the local costs of labor, materials, and machinery hourly costs in the project location, the unit prices for aggregate air cooling, river water cooling, and ice adding measures are derived as shown in Table 5. Among them, air cooling is mainly used to reduce ambient temperature, while mixing water and ice adding are used to reduce concrete aggregate temperature. The calculations show that in the concrete pre-cooling project, the unit price for cooling coarse aggregate by 1°C per kilogram via air cooling is 0.000246 CNY/(kg·°C), the unit price for cooling chilled water by 1°C per kilogram is 0.000973 CNY/(kg·°C), and the unit price for producing −5°C flake ice from 12°C chilled water is 0.131 CNY/kg.

The unit prices in Table 5 are calculated based on the allocated costs of labor, machinery, and materials from the project quota. For example, the total unit price for air cooling (0.246 CNY/t·°C) is the sum of the labor (0.016 CNY/t·°C), materials (0.014 CNY/t·°C), and machinery (0.216 CNY/t·°C) costs required to lower the temperature of one ton of aggregate by one degree Celsius. These unit prices are then combined with the temperature reduction contributions from Table 4 to optimize the overall cost strategy.

When the chilled water temperature is at the optimal temperature of 0°C, for every 1°C increase in coarse aggregate temperature, the optimal ice adding rate increases by 0.05, and the outlet temperature control cost increases by 0.35 CNY/m3. When ice adding measures are not considered, for every 1°C increase in chilled water temperature, the coarse aggregate temperature decreases by 0.2°C, and the outlet temperature control cost increases by about 0.17 CNY/m3. At the optimal coarse aggregate temperature of 1.3°C, for every 1°C rise in chilled water temperature, the ice adding rate increases by 0.01, and the temperature control cost increases by 0.25 CNY/m3.

According to the calculation results, when the target outlet temperature is 15°C and using the originally designed temperature control measures, the measured concrete outlet temperature was 14.26°C, and the calculated temperature control cost was 23.22 CNY/m3. After optimization, the adopted temperature control measures were: air cooling coarse aggregate to 0.4°C, using 0°C chilled water for mixing, and without adding flake ice. The calculated outlet temperature is 14.2°C, and the outlet temperature control cost is 22.41 CNY/m3.

Economic benefit analysis shows that compared to the original scheme, the optimized temperature control scheme reduces the concrete temperature control cost by 0.81 CNY/m3 under the condition of meeting the target outlet temperature of 15°C, representing a 3.4% reduction in temperature control cost relative to the previous scheme. This project requires pre-cooling of about 8.03 million m3 of concrete. The optimized temperature control scheme can save approximately 6.5 million CNY for this project, indicating a significant optimization effect.

This study addressed the challenge of high-precision prediction of concrete outlet temperature by proposing a hybrid modeling method that integrates physical models with neural networks. Through systematic research combining theoretical modeling, data-driven approaches, and engineering validation, the following key conclusions were drawn:

(1) A robust data preprocessing framework was established, integrating multi-sensor data synchronization, physically constrained outlier handling, and feature fingerprint encoding, which significantly enhanced the quality and reliability of the model input data.

(2) For the case study hydropower project, the target concrete outlet temperature was determined to be 15°C, derived through a finite element simulation and stress inversion process that set the maximum allowable placing temperature at 17°C.

(3) The proposed physical-neural network fusion model successfully integrated the mechanistic constraints of the heat conduction equation with the nonlinear fitting capability of neural networks, significantly improving the prediction accuracy of concrete outlet temperature. Experimental results on an independent test set demonstrated that the fusion model achieved an RMSE of 1.59°C and an MAE of 1.23°C, improving prediction accuracy by 25.3% and 26.7%, respectively, compared to the traditional physical model, indicating robust engineering applicability.

(4) The proposed framework, which enhanced the physical model with interaction terms and integrated it with a neural network via dynamic fusion, effectively captured the temperature evolution under multi-factor coupling. This approach provides a new perspective for multi-physical field coupling modeling in complex engineering systems.

(5) The effectiveness of the model was validated through a real-world engineering case, and the temperature control strategy was optimized based on the prediction results. The optimized strategy reduced the unit cost by 0.81 CNY/m3, yielding potential savings of approximately 6.5 million CNY for large-volume projects, highlighting the method’s significant advantages in reducing costs and improving resource utilization efficiency.

In summary, the organic integration of physical models and neural networks in this study not only achieved high-precision prediction of concrete outlet temperature but also provided a new perspective for multi-physical field coupling modeling in complex engineering systems, demonstrating substantial theoretical significance and engineering application value. However, the model’s adaptability under extreme working conditions remains an area for improvement. Future work could introduce spatio-temporal attention mechanisms and multi-modal sensor fusion technologies to enhance the model’s responsiveness to abrupt environmental changes. Furthermore, extending this method to other concrete performance prediction domains could promote the deep integration of intelligent construction and green building practices.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research is funded by National Key Research and Development Plan (2018YFC0406703); Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51779277); Chinese Academy of Water Sciences (SD0145B072021); Supported by the State Key Laboratory of Flow Water Cycle Simulation and Regulation, SKL2022ZD05; Support provided by the fund of State Key Laboratory of Water Cycle and Water Security, IWHR (Grant No. SKL2024YJZD05) is gratefully acknowledged, Support provided by the fund of Power China (DJ-ZDXM-2020-50). Support provided by the fund of Research and Application of Intelligent Simulation and Intelligent Control Technology for Structural States of Gravity DAMS in Jingling Reservoir Project, Zhejiang Province (JLSKFW-2024113).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Lei Zheng, Guoxin Zhang, Lei Zhang; data collection: Hong Pan, Yuelei Ruan, Jianyao Zhang, Wei Liu; analysis and interpretation of results: Lei Zheng, Guoxin Zhang, Lei Zhang, Zhenyang Zhu; draft manuscript preparation: Lei Zheng, Hong Pan, Jianda Xin. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data and materials are available upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. He S, Cao J, Chai J, Yang Y, Li M, Qin Y, et al. Effect of temperature gradients on the microstructural characteristics and mechanical properties of concrete. Cem Concr Res. 2024;184:107608. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2024.107608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hong M, Lei D, Hu F, Chen Z. Assessment of void and crack defects in early-age concrete. J Build Eng. 2023;70:106372. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cha SL, Jin SS. Prediction of thermal stresses in mass concrete structures with experimental and analytical results. Constr Build Mater. 2020;258:120367. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.120367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Li X, Yu Z, Chen K, Wang J, Liu F. Investigation of temperature development and cracking control strategies of mass concrete: a field monitoring case study. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2023;18:e02144. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2023.e02144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Bofang Z. Thermal stresses and temperature control of mass concrete. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2013. [Google Scholar]

6. Champaney V, Chinesta F, Cueto E. Engineering empowered by physics-based and data-driven hybrid models: a methodological overview. Int J Mater Form. 2022;15(5):31. doi:10.1007/s12289-022-01678-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Asadi I, Shafigh P, Hassan ZFBA, Mahyuddin NB. Thermal conductivity of concrete—a review. J Build Eng. 2018;20:81–93. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2018.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Xie Y, Du W, Xu Y, Peng B, Qian C. Temperature field evolution of mass concrete: from hydration dynamics, finite element models to real concrete structure. J Build Eng. 2023;65:105699. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2022.105699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kamalvand M, Massumi A, Homami P. Prediction of post-fire seismic performance of reinforced concrete frames. Structures. 2023;57:104874. doi:10.1016/j.istruc.2023.104874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Sun Q, Zhang B, Shi K, Gupta R, Zhu Z, Qiang S. A novel method for solving hydration heat release based on equivalent heat release theory. Constr Build Mater. 2023;407:133506. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Skocek J, Zajac M, Stabler C, Haha MB. Predictive modelling of hydration and mechanical performance of low Ca composite cements: possibilities and limitations from industrial perspective. Cem Concr Res. 2017;100(1):68–83. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2017.05.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liang M, Chang Z, He S, Chen Y, Gan Y, Schlangen E, et al. Predicting early-age stress evolution in restrained concrete by thermo-chemo-mechanical model and active ensemble learning. Comput Aided Civ Inf. 2022;37(14):1809–33. doi:10.1111/mice.12915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Beushausen H, Torrent R, Alexander MG. Performance-based approaches for concrete durability: state of the art and future research needs. Cem Concr Res. 2019;119:11–20. doi:10.1016/j.cemconres.2019.01.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Peng GCY, Alber M, Tepole AB, Cannon WR, De S, Dura-Bernal S, et al. Multiscale modeling meets machine learning: what can we learn? Arch Comput Method E. 2021;28(3):1017–37. doi:10.1007/s11831-020-09405-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Yang J, Wang J, Jin F, Zhang L, Zhou Y. A physics informed convolution neural network for spatiotemporal temperature analysis of concrete dams. Eng Appl Artif Intel. 2025;150:110624. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2025.110624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Alavipanah S, Schreyer J, Haase D, Lakes T, Qureshi S. The effect of multi-dimensional indicators on urban thermal conditions. J Clean Prod. 2018;177:115–23. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.12.187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Xiang Q, Yang H, Elkhodary KI, Qiu H, Tang S, Guo X. A multiscale, data-driven approach to identifying thermo-mechanically coupled laws-bottom-up with artificial neural networks. Comput Mech. 2022;70(1):163–79. doi:10.1007/s00466-022-02161-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Fu J, Wang M, Chen B, Wang J, Xiao D, Luo M, et al. A data-driven framework for permeability prediction of natural porous rocks via microstructural characterization and pore-scale simulation. Eng Comput. 2023;39(6):3895–926. doi:10.1007/s00366-023-01841-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Meng C, Griesemer S, Cao D, Seo S, Liu Y. When physics meets machine learning: a survey of physics-informed machine learning. Mach Learn Comput Sci Eng. 2025;1(1):20. doi:10.1007/s44379-025-00016-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Hajializadeh F, Ince A. Integration of artificial neural network with finite element analysis for residual stress prediction of direct metal deposition process. Mater Today Commun. 2021;27:102197. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2021.102197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang J. Modern Monte Carlo methods for efficient uncertainty quantification and propagation: a survey. Wires Comput Stat. 2021;13(6):e1539. doi:10.1002/wics.1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Nandurkar BP, Raut JM, Hinge PK, Bahoria BV, Patil TR, Upadhye S, et al. Optimization and predictive performance of fly ash-based sustainable concrete using integrated multitask deep learning framework with interpretable machine learning techniques. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):30820. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-16678-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. He M, Jiang S, Ren L, Cui H, Du S, Zhu Y, et al. Exploring the performance and interpretability of hybrid hydrologic model coupling physical mechanisms and deep learning. J Hydrol. 2025;649(1):132440. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2024.132440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Özel MB, Durmaz U, Öz MAN, Tepe AÜ, Öz C, Uysal Ü, et al. Enhanced prediction of heat transfer in jet impingement cooling using an artificial intelligence: a case study. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2025;59:106605. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2025.106605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Reichstein M, Camps-Valls G, Stevens B, Jung M, Denzler J, Carvalhais N, et al. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature. 2019;566(7743):195–204. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-0912-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Yang Q, Wang H, Zheng J, Cheng W, Xia S. Prediction of mechanical properties of basalt fiber concrete using hybrid recurrent neural networks based on freeze-thaw damage quantification. J Build Eng. 2024;98:111360. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2024.111360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang W, Zhou H, Bao X, Cui H. Outlet water temperature prediction of energy pile based on spatial-temporal feature extraction through CNN-LSTM hybrid model. Energy. 2023;264:126190. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.126190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Wang L, Qin Z, Wang Y, Miao Y, Yang Z, Liu Z, et al. Multi factor coupling model evaluation of the influence of different working conditions on concrete damage. J Build Eng. 2025;96:113097. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2025.113097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sun G, Yu Y, Yu Q, Tan X, Wu L, Wang Y. Enhancing control and performance evaluation of composite heating systems through modal analysis and model predictive control: design and comprehensive analysis. Appl Energy. 2024;357:122436. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.122436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Xu X, Liang T, Yu S, Jin F, Xiao A. Mesoscopic thermal field reconstruction and parametrical studies of heterogeneous rock-filled concrete at early age. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;53:103800. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.103800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhao X, Gong Z, Zhang Y, Yao W, Chen X. Physics-informed convolutional neural networks for temperature field prediction of heat source layout without labeled data. Eng Appl Artif Intel. 2023;117:105516. doi:10.1016/j.engappai.2022.105516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang H, Su C, Chen X, Li W, Wang Y. Calculation of mass concrete temperature and creep stress under the influence of local air heat transfer. Comput Model Eng Sci. 2024;140(3):2977–95. doi:10.32604/cmes.2024.047972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Chen H, Liu D. Numerical simulations of multiple cracks in concrete face rockfill dams coupled multi-factor during construction. Case Stud Constr Mater. 2025;22:e04609. doi:10.1016/j.cscm.2025.e04609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Jiang Y, Zuo W, Yuan C, Xu G, Wei X, Zhang J, et al. Deep learning approaches for prediction of adiabatic temperature rise of concrete with complex mixture constituents. J Build Eng. 2023;73:106816. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2023.106816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools