Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Cytokine fingerprint differences following infection and vaccination – what can we learn from COVID-19?

1

Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel

2

Division of Pulmonary Medicine, Barzilai University Medical Center, Ashkelon, and Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Beer-Sheva, Israel

3

The Institute of Pulmonary Medicine, Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center and Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv,

Israel

4

Medical Office of Southern District, Ministry of Health, Ashkelon, Israel

* Corresponding Author: Shira Cohen Rubin,

European Cytokine Network 2024, 35(1), 13-19. https://doi.org/10.1684/ecn.2024.0494

Accepted 06 February 2024;

Abstract

COVID-19 vaccination and acute infection result in cellular and humoral immune responses with various degrees of protection. While most studies have addressed the difference in humoral response between vaccination and acute infection, studies on the cellular response are scarce. We aimed to evaluate differences in immune response among vaccinated patients versus those who had recovered from COVID-19. Materials and Methods: This was a prospective study in a tertiary medical centre. The vaccinated group included health care workers, who had received a second dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine 30 days ago. The recovered group included adults who had recovered from severe COVID-19 infection (<94% saturation in room air) after 3-6 weeks. Serum anti-spike IgG and cytokine levels were taken at entry to the study. Multivariate linear regression models were applied to assess differences in cytokines, controlling for age, sex, BMI, and smoking status. Results: In total, 39 participants were included in each group. The mean age was 53 ±14 years, and 53% of participants were males. Baseline characteristics were similar between the groups. Based on multivariate analysis, serum levels of IL-6 (β=-0.4, p<0.01), TNFα (β=-0.3, p=0.03), IL-8 (β=-0.3, p=0.01), VCAM-1 (β=-0.2, p<0.144), and MMP-7 (β=-0.6, p<0.01) were lower in the vaccinated group compared to the recovered group. Conversely, serum anti-spike IgG levels were lower among the recovered group (124 vs. 208 pg/mL, p<0.001). No correlation was identified between antibody level and any of the cytokines mentioned above. Conclusions: Recovered COVID-19 patients had higher cytokine levels but lower antibody levels compared to vaccinated participants. Given the differences, these cytokines might be of value for future research in this field.Keywords

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is caused by the highly transmissible novel human pathogen, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection range from asymptomatic infection to fatal disease, and some studies suggest that approximately 32-87% of patients suffer from post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 (PASC), most commonly fatigue and dyspnoea [1–4].

The morbidity and mortality associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection prompted the rapid development of vaccines. In December 2020, two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech’s BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine were granted emergency use authorization by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [5]. After emerging evidence of waning in vaccine effectiveness, the FDA approved the administration of a third vaccine dose, also known as a “booster” shot, given five months after the first two doses [6].

Both SARS-CoV-2 infection and the BNT162b2 vaccine induce cellular and humoral immune responses, with various degrees of protection. Still, there are differences in the immune response between vaccinated and infected patients. For example, unlike following infection, only S1 protein antibodies are produced after vaccination with BNT162b2 since the vaccine does not contain the N protein gene [7]. Regarding COVID-19 infection, several concerns have been raised about the rapid decline of antibodies after viral clearance, particularly in mild cases [8]. However, cellular responses, and specifically T-cell responses, were observed in the majority of people with COVID-19 infection and may be more potent and persistent than the humoral response [9, 10]. The BNT162b2 vaccine also generates significant T-cell responses which could be of interest as a marker of protection [11].

Cytokines are essential for acquired immunity, both cellular and humoral, and play a role in modulating a variety of biological processes [12, 13]. Analyses of cytokine expression have provided valuable insight into some of the immune mechanisms involved in protection and recovery from many infectious agents [14–16]. Both infection- and vaccine-induced changes in serum cytokines have been shown to coincide with activation of T cells and innate cells [17, 18]. These findings suggest that cytokine profiles after viral exposure could potentially serve as biomarkers of immune activation and even yield useful information regarding vaccine efficacy.

In this proof-of-concept study, we aimed to evaluate differences in immune responses between individuals who were either vaccinated or had recovered from COVID-19. By comparing the cytokine and chemokine profiles between these two groups, we hoped to provide a proof-of-concept for their use as a marker of immunity against COVID-19 infection and shed light on the inflammatory cascade in COVID-19 infection and vaccination.

METHODS

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee and Institutional Review Board of Barzilai University Medical Center (No. BRZ-0082-22). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. All participants signed an informed consent form prior to study enrolment. Results are reported according to STROBE statement guidelines.

This prospective observational study was performed in a tertiary medical centre in Southern Israel between 2020-2021 and included two groups of adult participants (≥18 years) who signed an informed consent form:

1. The vaccinated group - health care workers (HCWs) of the Barzilai University Medical Center (BUMC) in Ashkelon who received two doses of the BNT162B2 vaccine, 21 days apart, as a part of the national vaccination program in Israel. All included participants in this group underwent serological tests 30 days after the second dose of the vaccine. HCWs with a confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (based on either positive RT-PCR from nasopharyngeal swabs, or positive antibodies against the nucleocapsid antigen anti-N), before or during the study, were excluded.

2. The recovered group - patients who had recovered from severe COVID-19 and were treated in the pulmonary outpatient clinic of BUMC afterwards. All included participants in this group had a diagnosis of COVID-19 infection based on positive RT-PCR from a nasopharyngeal swab and underwent a serological test 3-6 weeks after recovery from COVID-19. Severe illness was defined as SpO2 <94% on room air, a ratio of arterial partial pressure of oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) <300 mm Hg, or a respiratory rate >30 breaths/minute (42).

Immunosuppressed patients, patients with autoimmune diseases and participants lacking the necessary socio-demographic information were excluded from the study.

Serum for cytokine level measurement was collected during the serological test, 30 days after the second dose of the vaccine in the vaccinated group and 3-6 weeks after recovery from COVID-19 in the recovered group. At the time of collection, all participants were asked to complete a personal questionnaire which included sociodemographic data and medical history. We collected sociodemographic and anthropometric variables, self-reported smoking status (ever/never), and self-reported chronic conditions (yes/no). Additional information included comorbidities such as immunosuppressive states, chronic kidney disease (CKD), hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), and dyslipidaemia. Cytokine and chemokine levels were measured using the Human Premixed Multi Analyte Kit and the Human HS Cytokine Premixed Kit (both manufactured by R&D Systems, Inc., MN, USA). We measured chitinase 3, matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7), chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), matrix metalloproteinase-12 (MMP-12), thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), vascular cell adhesion protein-1 (VCAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), surfactant protein-D (SP-D), myeloperoxidase (MPO), cancer antigen 15-3 (CA15-3), tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), interleukin-2 (IL-2), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-8 (IL-8), interleukin-10 (IL-10), and interferon gamma (IFNγ). Participants were also tested for COVID-19 S1/S2 IgG type antibodies (Abs) using the Liaison chemiluminescent immunoassay kit (DiaSorin, Saluggia, Italy).

Cytokine levels, measured in pg/mL, and IgG anti-S antibody levels, measured in AU/mL, were documented and compared between the study groups. We also investigated associations and correlations between cytokine levels and antibody results relative to time from vaccine/recovery to measurement.

Descriptive analyses were performed to evaluate the characteristics of each study group and the overall cohort. Continuous variables are presented as mean (± standard deviation) or median (inter-quartile range) for normally and non-normally distribution, respectively. Normality of distribution was evaluated with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables are presented as sum (percentage from total). P values lower than 0.05 were considered significant.

Cytokine and antibody levels were compared between the groups (vaccinated / recovered) using independent T-tests for normally distributed samples and the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed samples.

Multivariate linear regression models were used to detect unique and independent predictors for high levels of each cytokine that showed significant association in univariate analysis. The models included the following variables: patient group, sex, age, BMI, smoking status, and any other significant variables from the univariate analysis. In addition, to account for the difference in time from vaccination/recovery to testing, for cases in which cytokines significantly correlated with time, we included duration (in days) in the multivariate model. Betas and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using these models. Data analysis and statistical procedures were conducted using SPSS 25.0 ® (SPSS, Chicago, IL), MATLAB 2021 ® software.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

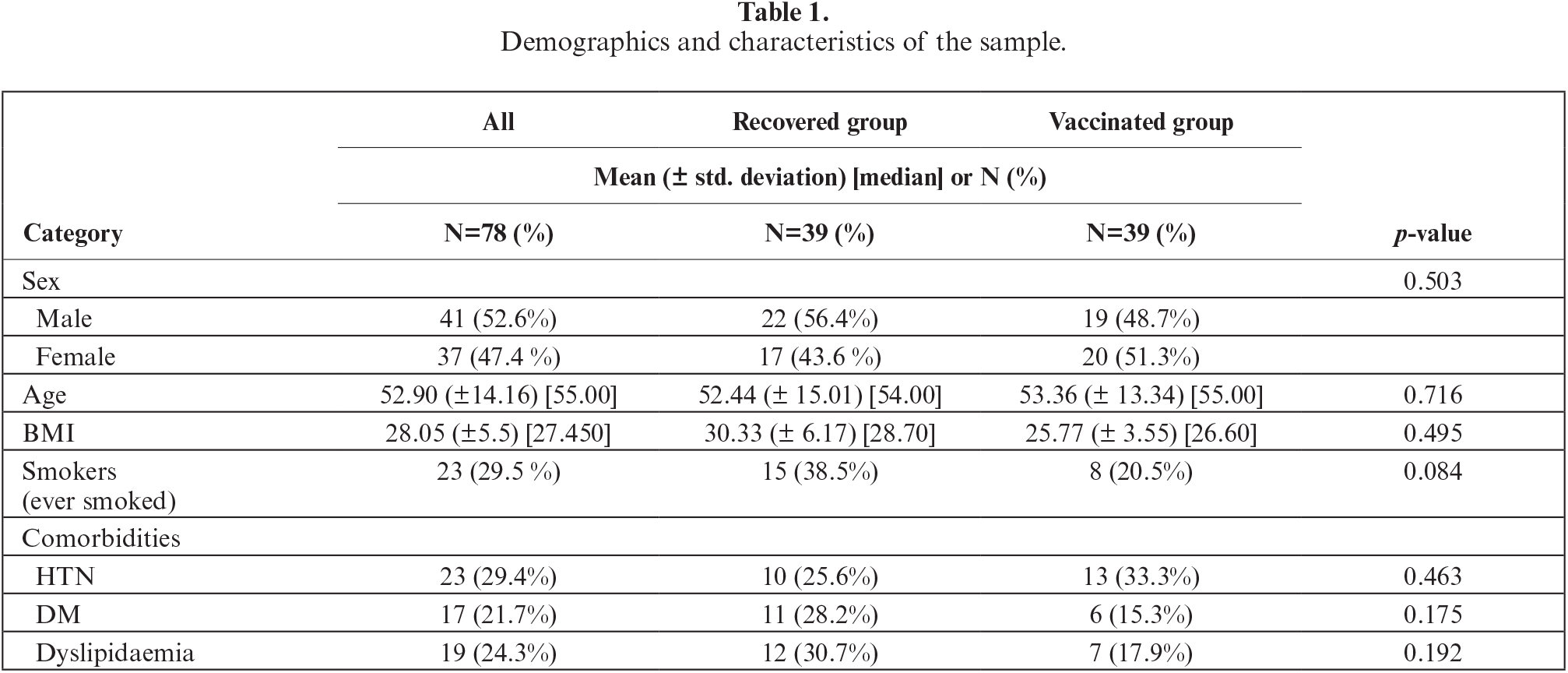

Overall, 39 subjects were included in the vaccinated group and 39 in the recovered group. No participants were excluded. The alpha variant of the virus was found in all participants. The general characteristics of the overall cohort and comparison between the groups are reported in table w. Our study population was relatively young (52.90 ± 14.16 years old) and most were males (41; 53%). The most common comorbidity was hypertension (29.4%). There were no differences in comorbidities between the groups. Of note, none of the patients had chronic kidney disease or chronic respiratory disease. The median time from recovery to laboratory measurements was 32 days (29-38), while the median time from vaccination to laboratory measurements was 29 days (28-30).

Cytokines that did not show any variance in measurement were excluded from this study; this was the case for MPO, CA15-3, and IFNγ due to measuring limitations, and these were excluded from further analysis.

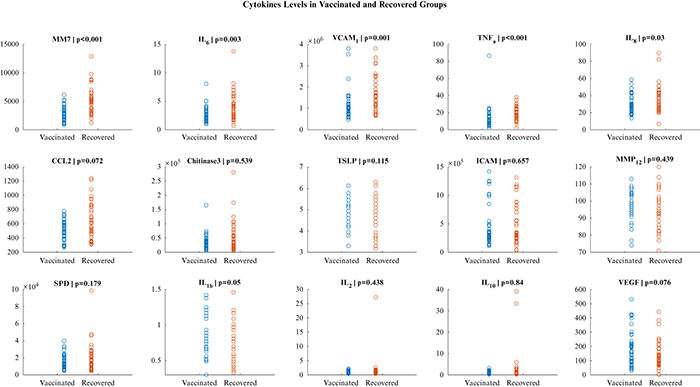

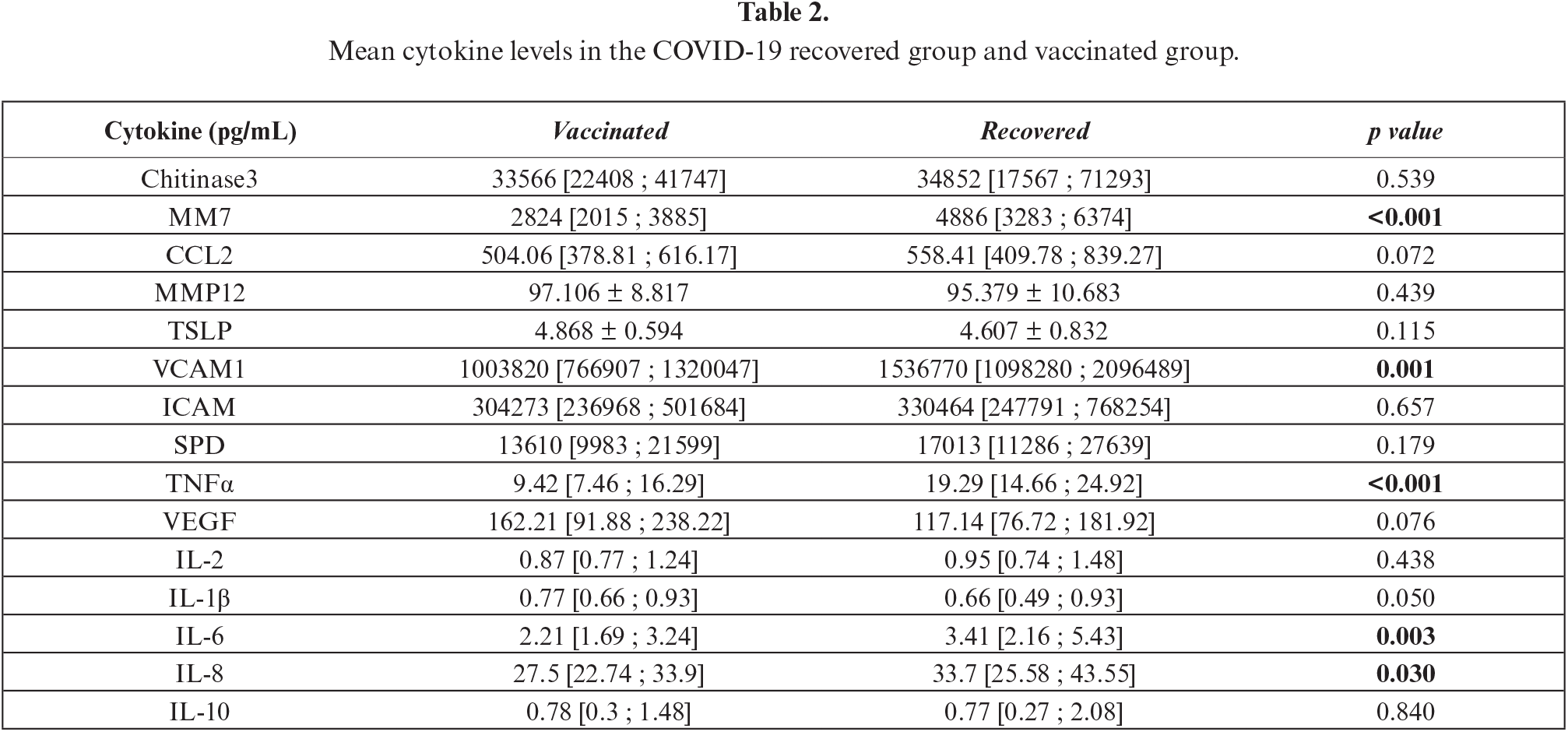

The median cytokine concentrations in each group (vaccinated group and recovered group) are summarized in figure 1 and table 2. Serum levels of MM-7, IL-6, VCAM1, TNFα and IL-8 were significantly higher in the recovered group compared to the vaccinated group. IL-1β levels were higher in the vaccinated group, although only with borderline statistical significance (p=0.05). For all other cytokines, there were no differences in levels between the two groups. Of note, MMP-7, VCAM1, and IL-8 showed significant correlations with time, while this was not the case for TNFα and IL-6.

Figure 1.

Cytokine levels in the vaccinated and recovered group. The vertical axis refers to cytokine level (pg\mL).

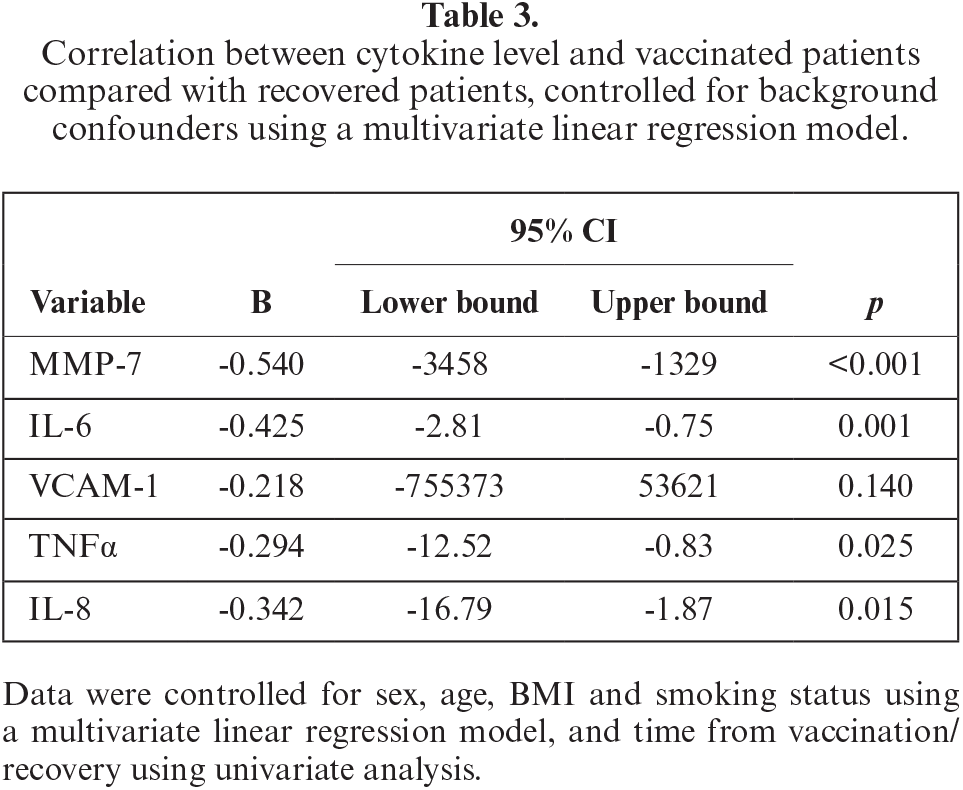

Based on multivariate analysis, recovery from COVID-19 infection was an independent predictor for higher levels of MMP-7, IL-6, VCAM1, TNFα and IL-8 (table 3). The detailed analyses for each cytokine are presented in supplementary tables S1 to S5 in the appendix. We found no other independent predictors among the other variables in the multivariate analyses, including sex, age, BMI, smoking status, and time from vaccination/recovery to measurement.

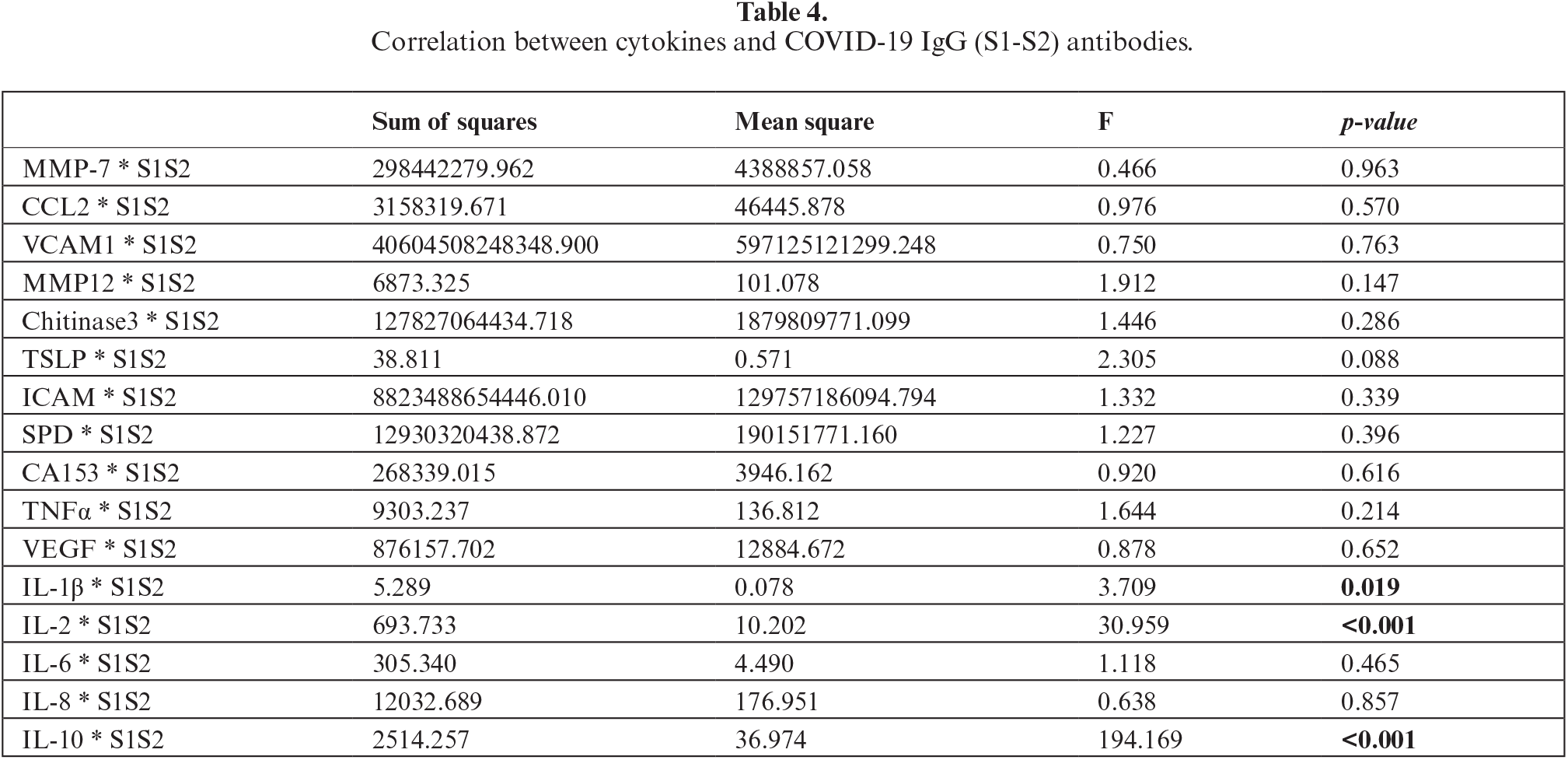

Association between cytokines and COVID-19 IgG (S1-S2) antibody

When comparing the mean anti-COVID-19 IgG (S1-S2) levels of each group, we found higher levels of IgG S1-S2 in the vaccinated group (208 vs. 124 pg/mL; p<0.001). In addition, antibody levels exhibited a negative correlation with time to measurement (r=-0.46, p<0.01). After adjusting for time to measurement using a multivariate linear regression, the difference between groups remained significant (Beta=0.422, p<0.01).

As seen in table 4, IL-1β, IL-2 and IL-10 exhibited positive correlations with anti-COVID-19 IgG (p=0.019, p<0.001, p<0.001, respectively). As mentioned above, these cytokines were not found to be significantly different between the two study groups. Moreover, in a sub-analysis of the study cohort divided by group (vaccinated and recovered group), we did not find any additional associations between antibody and cytokine level.

DISCUSSION

The COVID-19 outbreak highlighted the importance of vaccination for controlling the spread of viral infections [19]. Vaccines had an immense effect on disease spread and severity [20, 21]. A number of studies have noted the potential of measuring cytokine levels as indicators of cell-mediated immunity and protection from infection by different infectious diseases [15, 22]. Several studies have evaluated the immune response to COVID-19 natural infection and to vaccination. The majority have focused on the humoral response, which is more readily measurable [23–25], while the dynamics of cell-mediated immunity has been less commonly described. Thus, in this proof-of-concept study, we compared cytokine and COVID-19 antibody levels in recovered and vaccinated individuals to evaluate the differences in immune responses between those two groups.

We found that serum levels of IL-6, TNFα, IL-8, VCAM-1, and MMP-7 were higher in the recovered group compared to the vaccinated group, independent of other baseline characteristics. IL-6, TNFα, and IL-8 are pro-inflammatory mediators that play crucial roles in the immune response against viral infection and in other inflammatory diseases [15, 23, 26]. IL-6 mobilizes immune cells to the site of infection and promotes the production of virus-specific antibodies [26]. TNFα and IL-8 are chemotactic factors that promote the recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes to the site of infection [28]. Cell adhesion molecules, like VCAM-1, allow immune cells to attach to infected cells and destroy them [29]. As a matrix metalloproteinase, MMP-7 breaks down infected cells, promoting their elimination [30]. Together, these cytokines work to activate and coordinate the immune response against viral infections, ultimately helping to eliminate the virus from the body during infection.

A possible explanation for the differences we found in this study lies in the cytokine response to COVID-19 compared with COVID-19 vaccination. COVID-19 natural infection results in exposure of the upper airway epithelium to the virus, promoting the local immune response. Inflammation begins when the virus replicating in local macrophages, resulting in apoptosis. Macrophages and T cells that release inflammatory cytokines are activated by Toll-like receptor ligands, such as liposaccharide (LPS), DNA, RNA, and other microbial components [31]. Consequently, patients with severe COVID-19 have considerably higher blood levels of IL-2, IL-6, TNFα, IL-1, IL-10, IFNγ, IL-8/CXCL8, and CXCL10/IP-10, leading to a more pronounced inflammatory state (“cytokine storm”), resulting in detrimental prognosis [32]. Experimental models have demonstrated that COVID-19 exposure generates a significant induction of monocyte- and neutrophil-associated chemokines (CCL2 and CCL8, and CXCL2 and CXCL8, respectively), further supporting the mentioned hypothesis [33]. Still, like COVID-19 infection, vaccines induce both cellular and humoral responses, with mixed reports on the dominant factor between them [34, 35]. A study by Wang et al. analysed the immune response after vaccination and showed a strong correlation among cytokines at 40 days after the second vaccine that waned over time [36]. Therefore, although the magnitude of cytokine dynamics after vaccination may be of smaller magnitude compared with that of recovered patients, it should not be ignored as a point of interest in future research.

In contrast to cytokine levels, serum anti-spike IgG levels were lower among the recovered group compared to the vaccinated group, even after adjustment for time to serum measurement. Despite lower antibody response rates in COVID-19 recovered patients in previous studies, both prior infection and vaccination have been shown to be effective in preventing COVID-19 infection 45 days after viral exposure [37, 38]. These results emphasize the assumption that the type of immune response generated by the vaccine and natural infection differ. As a result, specific cytokines might prove to be of added value alongside antibody levels, although this could not be directly concluded from our findings.

This study has several limitations. The sample size was relatively small, and thus its outcomes should be considered as a proof of concept for further studies to explore. We compared vaccinated HCWs with recovered patients from the general population. Therefore, the study population might not appropriately represent the parent population, which could affect the generalizability of our results. Furthermore, it is possible that patients who chose to visit the pulmonary clinic were those with remaining symptoms, which could have created a selection bias. Additionally, it is important to consider that there may be individual differences in how the immune system responds to natural infection versus vaccination. This could have led to variation in the levels of inflammatory markers and other immune responses between individuals, regardless of whether they were vaccinated or had natural infection. Finally, follow-up measurements of cytokine and antibody levels were not obtained, therefore we were unable to examine their dynamics in both groups or evaluate the association between cytokines and clinical outcomes, both of which should be the aim of future studies in this field.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this study is among the few comparing cytokine and antibody responses after COVID-19 vaccination and infection. We found discordant responses between the groups, with higher cytokine levels among the recovered group and higher antibody levels in the vaccinated group. This research may pave the way for further studies focusing on cytokine profiles following vaccination and recovery, as possible markers with added value.

DISCLOSURE

Financial support: none. Conflicts of interest: none.

Author Contributions: S.C.R and A.B.S. conceived and designed the study. S.C.R., N.Z. and A.B.S. drafted the manuscript. S.C.R., N.Z., O.F., and E.G. performed data analysis. O.W., A.B, R.G.V., and N.B. performed data acquisition. A.B.S. supervised the project. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Data Availability Statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article. Acknowledgments: None.

Participated in this study as part of the requirements for graduation from the Goldman Medical School at the Faculty of Health Sciences, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel.

REFERENCES

1. Carlos del R, Collins LF, Malani P. Long-term health consequences of COVID-19. JAMA 2020;324:1723. [Google Scholar]

2. Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med 2021;27:601-15. [Google Scholar]

3. National Institutes of Health. COVID-19 treatment guidelines. clinical spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Available at https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/overview/clinical-spectrum. Accessed May 27th, 2023 [Google Scholar]

4. Singh SJ, Baldwin MM, Daynes E, et al. Respiratory sequelae of COVID-19: pulmonary and extrapulmonary origins, and approaches to clinical care and rehabilitation Lancet. Respir Med 2023;11:709-25. [Google Scholar]

5. Commissioner, Office of the“FDA takes key action in fight against COVID-19 by issuing emergency use authorization for first COVID-19 vaccine” FDA FDA 2020https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-takes-key-action-fight-against-covid-19-issuing-emergency-use-authorization-first-covid-19 [Google Scholar]

6. Barda N, Dagan N, Cohen C, et al. Effectiveness of a third dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine for preventing severe outcomes in Israel: an observational study. Lancet 2021;398:2093-100. [Google Scholar]

7. Bartuzi Z, Rosada T, Ukleja-Sokołowska N, et al. Assessment of the post-SARS-CoV-2 vaccination response depending on the epidemiological status, demographic parameters and levels of selected cytokines in medical personnel. Adv Dermatol Allergol 2022;39:913-22. [Google Scholar]

8. Ibarrondo FJ, Fulcher JA, Goodman-Meza D, et al. Rapid decay of anti–SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in persons with mild Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1085-7. [Google Scholar]

9. Altmann DM, Boyton RJ. SARS-CoV-2 T-cell immunity: specificity, function, durability, and role in protection. Sci Immunol 2020;5:eabd6160. [Google Scholar]

10. Zuo J, Dowell AC, Pearce H, et al. Robust SARS-CoV-2-specific T-cell immunity is maintained at 6 months following primary infection. Nat Immun 2021;22:620-6. [Google Scholar]

11. Sahin U, Muik A, Derhovanessian E, et al. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and TH1 T-cell responses. Nature 2020;586:594-9. [Google Scholar]

12. Bramhachari. Dynamics of immune activation in viral diseases (1st ed. 2020.). Singapore: Springer, 2020 [Google Scholar]

13. Braciale TJ, Hahn YS. Immunity to viruses. Immunol Rev 2013;255:5. [Google Scholar]

14. Thiel V, Weber F. Interferon and cytokine responses to SARS-coronavirus infection. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2008;19:121-32. [Google Scholar]

15. Sladkova T, Kostolansky F. The role of cytokines in the immune response to influenza A virus infection. Acta Virol 2006;50:151. [Google Scholar]

16. Porichis F, Kaufmann DE. HIV-specific CD4 T cells and immune control of viral replication. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2011;6:174. [Google Scholar]

17. Kohler S, Bethke N, Böthe M, et al. The early cellular signatures of protective immunity induced by live viral vaccination. Eur J Immunol 2012;42:2363-73. [Google Scholar]

18. Biron CA. Role of early cytokines, including alpha and beta interferons (IFN-α\βin innate and adaptive immune responses to viral infections. InSeminars in Immunology 1998;10:383-90Academic Press [Google Scholar]

19. Mohammed I, Nauman A, Paul P, et al. The efficacy and effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines in reducing infection, severity, hospitalization, and mortality: a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022;18:2027160. [Google Scholar]

20. Freund O, Tau L, Weiss TE, et al. Associations of vaccine status with characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized severe COVID-19 patients in the booster era. PloS One 2022;17:e0268050. [Google Scholar]

21. Bar-On YM, Goldberg Y, Mandel M. Protection by a fourth dose of BNT162b2 against Omicron in Israel. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1712-20. [Google Scholar]

22. Ramakrishnan A, Althoff KNLopez JA. ColesCL, Bream JH. Differential serum cytokine responses to inactivated and live attenuated seasonal influenza vaccines. Cytokine 2012;60:661-6. [Google Scholar]

23. Siracusano G, Pastori C, Lopalco L. Humoral immune responses in COVID-19 patients: a window on the state of the art. Front Immunol 2020;11:1049. [Google Scholar]

24. Velazquez-Salinas L, Verdugo-Rodriguez A, Rodriguez LL, Borca MV. The role of interleukin 6 during viral infections. Front Microbiol 2019;10:1057. [Google Scholar]

25. Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med 2021;27:1205-11. [Google Scholar]

26. Hunter CA, Jones SA. IL-6 as a keystone cytokine in health and disease. Nat Immun 2015;16:448-57. [Google Scholar]

27. Baggiolini M. Chemokines and leukocyte traffic. Nature 1998;392:565-8. [Google Scholar]

28. Iademarco MF, McQuillan JJ, Rosen GD, Dean DC. Characterization of the promoter for vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1). J Biol Chem 1992;267:16323-9. [Google Scholar]

29. Elkington PT, O’kane CM, Friedland JS. The paradox of matrix metalloproteinases in infectious disease. Clin Exp Immunol 2005;142:12-20. [Google Scholar]

30. Silva MJ, Ribeiro LR, Gouveia MI, et al. Hyperinflammatory response in COVID-19: a systematic review. Viruses 2023;15:553. [Google Scholar]

31. Nishitsuji H, Iwahori S, Ohmori M, Shimotohno K, Murata T. Ubiquitination of SARS-CoV-2 NSP6 and ORF7a Facilitates NF-κB Activation. MBio 2022;13:e00971-22. [Google Scholar]

32. Heo JY, Seo YB, Kim EJ, et al. COVID-19 vaccine type-dependent differences in immunogenicity and inflammatory response: BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19. Front Immunol 202213. [Google Scholar]

33. Boechat JL, Chora I, Morais A, Delgado L. The immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 immunopathology–current perspectives. Pulmonology 2021;27:423-37. [Google Scholar]

34. Goel RR, Painter MM, Apostolidis SA, et al. mRNA vaccines induce durable immune memory to SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern. Science 2021;374:abm0829. [Google Scholar]

35. Koutsakos M, Reynaldi A, Lee WS, et al. SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infection induces rapid memory and de novo T cell responses. Immunity 2023;56:879-892.e4. [Google Scholar]

36. Wang C, Yang S, Duan L, et al. Adaptive immune responses and cytokine immune profiles in humans following prime and boost vaccination with the SARS-CoV-2 CoronaVac vaccine. Virol J 2022;19:223. [Google Scholar]

37. Freund O, Breslavsky A, Fried S, et al. Interactions and clinical implications of serological and respiratory variables 3 months after acute COVID-19. Clin Exp Med 2023;21:1-8. [Google Scholar]

38. Ioannou GN, Bohnert AS, O’Hare AM, et al. Effectiveness of mRNA COVID-19 vaccine boosters against infection, hospitalization, and death: a target trial emulation in the Omicron (B. 1.1. 529) Variant Era. Ann Intern Med 2022;175:1693-706. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools