Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of Childhood Maltreatment on Subjective Well-Being: The Multiple Mediating Roles of Shyness and Emotion Regulation Strategies

1

School of Education, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, 410081, China

2

Center of Mental Health Education, Linli No. 1 Middle School, Changde, 415299, China

* Corresponding Authors: Ce Sun. Email: ; Huazhan Yin. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Exploring the Impact of School Bullying, Aggression and Childhood Trauma in the Digital Age: Influencing Factors, Interventions, and Prevention Methods)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(3), 347-361. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.059151

Received 29 September 2024; Accepted 17 December 2024; Issue published 31 March 2025

Abstract

Objectives: The statistics from World Health Organization show a high incidence of childhood maltreatment which has a negative impact on the development of middle school students; for this reason, it is necessary to investigate the potential harms of childhood maltreatment. This study aimed to explore the direct negative consequences of childhood maltreatment on subjective well-being as well as the mediating roles of shyness and emotion regulation strategies. Methods: A random cluster sampling survey was conducted among 1021 Chinese middle school students (male 49.2%, female 50.8%). The Subjective Well-Being Scale (SWLS), The Positive affect and Negative affect scale (PANAS), and The Childhood Trauma were adopted Questionnaire-28 item Short Form (CTQ-SF), the Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale (RCBS), and the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ) for data collection. SPSS PROCESS macros were used for data analysis. Results: The findings demonstrated that: (a) childhood maltreatment was negatively correlated with subjective well-being (r = −0.482, p < 0.001); (b) shyness (β = −0.141, 95% CI = [−0.190, −0.097]) and the two emotion regulation strategies, namely cognitive reappraisal (β = −0.120, 95% CI = [−0.167,−0.079]) and expression suppression (β = −0.034, 95% CI = [−0.063, −0.010]), partially mediated the association between childhood maltreatment and subjective well-being separately; (c) shyness and the two emotion regulation strategies partially mediated the relationship between childhood maltreatment and subjective well-being in a sequential pattern (β = −0.026, 95% CI = [−0.041,−0.015]; β = −0.022, 95% CI = [−0.035, −0.012]). Conclusion: These findings provide new perspectives and strategies to understand and deal with children’s mental health problems. It shows that the intervention of shyness and emotion regulation strategies in adolescents is of great significance to improve individual subjective happiness.Keywords

The World Health Organization’s 2020 report indicated that approximately 50% of children aged 2 to 17 experience violence each year. Nearly 300 million children aged 2 to 4 are subjected to violent discipline by caregivers, and one in three children is affected by emotional violence [1]. Childhood maltreatment (CM) not only leads to physical harm and increases suicidal ideation [2,3] but it also results in long-term psychiatric disorders [4,5]. Additionally, there are inter-generational effects, as children of maltreated mothers exhibit more problematic behaviors [6,7]. CM also incurs significant economic costs, with an annual expenditure of $209 billion for countries in the Asia-Pacific region, which is equivalent to 2% of the region’s GDP [1].

Given the impact of CM on subjective well-being (SWB), it is crucial to explore strategies that mitigate its adverse effects while promoting positive experiences. Early childhood experiences significantly shape an individual’s SWB [8], with those who have experienced CM tending to report lower life satisfaction [9]. SWB is influenced by a combination of internal and external factors for middle school students, with an interactive relationship between them, as suggested by the top-down and bottom-up theories of SWB [10]. These theories propose that individuals’ responses to events are shaped by their subjective perceptions and involve cognitive processes that flow from higher-level cognitive functions to more immediate reactions. Further research is necessary to fully understand how internal factors interact with immediate, bottom-up events to influence SWB [11]. Among the micro-systems crucial to middle school students’ development [12], the family plays a particularly significant role, with family cohesion being a key external factors affecting students’ SWB. Among various influences such as life events, activities, personality traits, biological factors, and family economic status [11], temperament has a more profound impact on SWB than external experiences. SWB is also influenced by individual attributional styles and extraversion, along with their associated constructs. A study [13] highlighted the close link between neuroticism, extraversion and shyness. Middle school students with higher levels of shyness are more likely to be overlooked by both teachers and peers. However, not all shy middle school students face health issues; a significant contributing factor is emotion regulation. Li et al. [14] found that shyness affects emotional self-efficacy, which in turn impacts SWB. It is clear that the SWB of shy individuals can be influenced by their emotional experiences and the strategies they use to regulate them. Shyness, along with internal factors such as emotion regulation strategies and external factors such as CM, collectively influence an individual’s SWB. Despite numerous studies exploring the relationship between CM, SWB, shyness, and emotion regulation strategies, the potential correlation among these four factors has been overlooked.

In summary, the aim of this study was to investigate the causal relationship between CM and SWB among middle school students.

1.1 Childhood Maltreatment and Subjective Well-Being

CM encompasses various forms of physical and/or emotional abuse, sexual exploitation, neglect, and inadequate care, as well as commercial or other forms of exploitation that result in actual or potential harm to a child’s health, survival, development, or dignity within the context of a relationship characterized by responsibility, trust, or power dynamics [15]. This primarily occurs within the family system before the age of 18 [16]. The main types of CM include emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect [17].

Research findings indicated a significant impact of CM on adolescents’ SWB [18]. Individuals who have experienced CM exhibit higher levels of psychological distress and lower levels of SWB [19,20]. Furthermore, adverse childhood experiences have lasting effects on life satisfaction in adulthood [21]. Emotional abuse and neglect may exacerbate tendencies toward experiential avoidance [22], while the co-occurrence of emotional abuse with other forms of maltreatment can severely compromise an individual’s psychological resilience [23].

1.2 The Mediating Role of Shyness

Shyness is characterized by a predisposition to experience discomfort or anxiety in unfamiliar or evaluative social situations, often accompanied by an heightened awareness of others’ attention, evaluation, or expectations [24]. According to the theory of symbolic interaction, individuals who have suffered from childhood trauma are more likely to develop negative self-cognition [25] and are more likely to form shyness personality trait. Studies have confirmed that those who have suffered adverse experiences tend to exhibit higher levels of shyness [26]. Furthermore, the social adaptation model of shyness suggests that [11] shy individuals, when approaching or entering social situations, often anticipate poor performance and feel ill-equipped to handle the challenges that arise. The fearful anticipation reduces their sense of security and also leads to social avoidance behaviors, such as being less inclined to initiate conversations [27,28], which over time can decrease life satisfaction. Additionally, shy individuals are more prone to self-deprecation and lower self-efficacy [29,30]. Chen et al. found that adolescents who experience shyness tend to underperform academically [31]. These cumulative experiences can lead to increased negative emotions, adversely affecting life satisfaction, positive emotions, and ultimately well-being [32]. Finally, the biopsychosocial model [33] posits that childhood trauma impacts the biological, psychological, and social aspects of an individual. CM can lead to hippocampal degeneration and elevated cortisol levels, which have lasting psychological effects and can damage social functions to varying degrees. This propensity for negative self-perception further affects an individual’s SWB [34].

1.3 The Mediating Role of Emotion Regulation Strategies

Emotion regulation is the process by which individuals manage their emotional state, including the selection of emotions experienced, the timing of their emotion emergence, and the modulation of how these emotions are felt and expressed. This process involves five key aspects: emotion selection, emotion modification, attention deployment, cognitive reappraisal, and response regulation [35]. Cognitive reappraisal (CR) and expression suppression (ES) are the primary strategies used in emotion regulation. CR is an antecedent-focused strategy that occurs early in the emotion generation process, involving cognitive reevaluation of potentially emotionally evocative situations to reduce emotional responses. In contrast, ES is a response-focused strategy that is later adopted in the emotion generation process and primarily involves inhibiting ongoing emotional expressions [36].

The emotion regulation process model suggests that individuals’ mental experiences of life events differ based on their chosen emotion regulation strategies [36]. When confronted with adverse situations, individuals who choose positive emotion regulation strategies enhance their positive emotional experiences, fostering positive psychological encounters and promoting constructive behaviors [37,38]. Abnormal emotion regulation can be a consequence of CM [39], potentially impairing the capacity to use adaptive regulation strategies [40]. Individuals who have experienced childhood trauma or stressful events are more likely to employ maladaptive emotion regulation strategies like ES instead of adaptive ones such as CR, which can lead to a depressed mood [31,41–43].

According to the global interaction theory [44], individual behavior development is influenced by the interaction between individual and environmental factors. There is an interaction between CM (environmental factors) and selected emotion regulation strategies (individual factors) that affects the SWB of middle school students. Empirical studies showed that individuals who have suffered CM are more likely to develop depression, anxiety, and other negative emotions. Emotion regulation strategies are significant predictors of SWB. A tendency towards ES predicts lower SWB, while a tendency towards CR has the opposite effect [45,46]. CR plays a key role in mitigating the effects of early life adversity and promoting SWB [47]. However, adults who have experienced significant childhood adversity may use ES as a maladaptive emotion regulation strategy [48], exacerbating the impacts of their childhood adversity experiences [49]. Some studies suggested that while expressing emotions does not immediately boost mood, it can ultimately lead to higher life satisfaction [50]. Over time, ES can lead to emotional overcrowding and reduce an individual’s SWB.

In summary, CM significantly influences the selection of emotional strategies. Various forms of adversity, even those less severe than abuse and neglect, also have a substantial impact on emotional processing, particularly among children with shy traits. In response to CM, individuals adopt diverse emotion regulation strategies, leading to variations in SWB.

1.4 The Multiple Mediating Model

The top-down and bottom-up theories [11] highlight that external environment and internal factors jointly influence individual’s SWB. CM, as a life experience, is an external influencing factor, while shyness and emotion regulation strategies are internal influencing factors. Studies have shown that shyness is a significant predictor of the direct or indirect use of emotion regulation strategies, which can affect an individual’s emotional experience and lead to increased levels of negative emotions, such as social anxiety [51]. According to research on shyness, individuals with high levels of shyness tend to hesitate when expressing emotions, with this difficulty increasing proportionally to their levels of shyness [14]. Consequently, shy individuals may be more inclined to use suppression strategies to handle their emotions. The combination of shyness and inhibition can also lead to rigidity in young people’s behavior patterns, affecting their ability to adapt effectively to social environments and academic demands [52]. Shy middle school students may adopt negative emotion regulation strategies to temporarily suppress their negative emotions in uncomfortable environments, only for these emotions to resurface once they leave, subsequently affecting their happiness levels. Heshmati et al. [22] found that shy girls allocate more cognitive resources to problem-solving during private conversations. Shy individuals show difficulty in using CR, with one prominent manifestation being that negative self-evaluation leads to increased social anxiety [53]. As a result, shy individuals struggle to maintain positive thinking in adverse situations, increasing the likelihood of experiencing negative emotions and decreasing life satisfaction, which ultimately affects well-being. Furthermore, according to the complex trauma theory [54], childhood abuse is one of the types of complex trauma that can impact the psychological and emotional aspects of an individual, leading to emotional, behavioral, and cognitive dysregulation that affects interactions with others, etc. Shy individuals mainly show emotional and behavioral withdrawal. Finally, shyness is closely related to the use of emotion regulation strategies, which can influence behavior and SWB by promoting effective emotion management or improving emotional ability [14,27]. Therefore, emotion regulation strategies may sever as an important mediating factor between shyness and other variables, thus establishing a chain mediation mechanism between CM and SWB.

The present study aims to examine a conceptual model that seeks to enhance our understanding of the relationship between CM and SWB. In this model, we hypothesize that CM has a negative impact on SWB. Additionally, we propose that shyness and two emotion regulation strategies (CR and ES) mediate this relationship. Drawing from the existing literature, our hypotheses are as follows:

H1: CM negatively influences SWB;

H2: Shyness and the two emotion regulation strategies serve as indirect pathways linking CM to SWB;

H3: The mediating roles of shyness and the two emotion regulation strategies contribute to the indirect effect of CM on SWB.

A random cluster sample was taken from a middle school in Hunan Province, China, and questionnaires were distributed by class. A total of 1083 questionnaires were sent out. After eliminating invalid data such as incorrect filling, missing filling, and regular answering, 1021 questionnaires were valid, with an effective rate of 94.28%. The study included 1021 samples, of which 502 were males (49.5%) and 236 were females (50.5%). The age range of 12 to 15 years old. In terms of origin of students, 566 (55.4%) came from towns and 455 (44.6%) came from cities.

Sample Inclusion Criteria were as follows: (i) aged 12–15 years old; (ii) middle school students reading (iii) able to complete the questionnaire independently or with the help of the investigator; (iv) able to understand the questionnaire entries. Exclusion criteria included: (i) accurate repetition of answers; (ii) incomplete responses; (iii) physical disability; (iv) brain damage/mental retardation; and (v) impairment in vision, hearing, or speech.

The Subjective Well Being Scale (SWLS), developed by Diener et al. [55], consists of 5 items (such as, “ My life is ideal.”, “I am satisfied with my life.”) which are rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Different choices represent different degrees of satisfaction with the described situation. Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.848, indicating that the scale has good reliability.

The Positive affect and Negative affect scale (PANAS), revised by Qiu et al. [56] consists of 18 items (such as, “active”, “ashamed”) which are scored using a five-point scale with 1 representing ‘none or very mild’ and 5 representing ‘very strong’. There are nine items with words describing positive emotions and nine items describing negative emotions. Cronbach’s α in this study was 0.839, indicating that the scale has good reliability.

The SWLS and PANAS scales were combined to measure SWB in this study. The total SWB score, which was calculated by adding and subtracting the standard scores of life satisfaction, positive emotions, and negative emotions, represents an individual’s level of SWB. The higher the score, the higher the level of SWB. This calculation is based on the research methods used by Sheldon et al. [57] and Thrash et al. [58].

The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-28 item Short Form (CTQ-SF), revised by Zhao et al. [59], consists of 28 items (such as, “No one at home cared about my hunger.”, “I had someone to look after me and protect me.”). The questionnaire includes five sub-scales: emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional neglect, and physical neglect. The items are rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), with higher total scores implying higher levels of CM for the individual. In this study, Cronbach’s α was 0.819, indicating good reliability of this scale.

The Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale (RCBS), developed by Cheek et al. [24], contains 13 items(such as, “I feel nervous when I’m around people I don’t know very well.”, “I’m pretty bad at social things.”). The items are rated on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (extremely inconsistent) to 5 (highly consistent). A higher score implies a greater degree of shyness, and a total score that is higher than 34 will be judged shy. The scale was first introduced to China by one of Chinese scholars Xiang et al. [60], and proved to have good reliability among college students. The scale in this study has good reliability, as indicated by Cronbach’s α was 0.834.

2.2.4 Emotional Regulation Strategies

The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), a 10-question instrument developed by Gross [36] and revised by Wang et al. [61], measures emotion regulation strategies (such as, “I will not show my emotions.”, “I control my emotions by changing the way I think about the situation.”). The items are rated on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree), which involves two specific strategies, namely CR and ES. The scores on each dimension can be used to determine a person’s propensity to employ that strategy, with higher scores on a given dimension suggesting the inclination to use the corresponding emotion regulation strategy more frequently. The scale has good reliability in this study, as indicated by Cronbach’s α, which were 0.789 and 0.677 for the CR and ES strategies, respectively.

Sampling began with contacting the teacher and introducing the purpose of the study. Next, the teacher distributed the study introduction and consent form to the child’s parents before the study began. Written informed consent has obtained from the child’s parents. In addition, voluntary participation and confidentiality of responses were emphasized. All data were collected by the researcher who went to the class to issue questionnaires. The study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Hunan Normal University (IRB No. 2022495).

Age, gender, place of residence was controlled for in the correlation analysis.

SPSS 23.0 and PROCESS macros were employed to analyze the data gathered in this study. The subsequent statistical analyses were carried out as follows: (1) The Harman single-factor test was utilized to analyze common method bias. (2) SPSS 23.0 was adopted for the reliability and validity tests as well as the correlation analysis of variables. (3) Regression analysis was employed to examine the relationship between CM and SWB. The standardized regression coefficient β indicates the magnitude of the relationship between them. (4) The PROCESS macro (Model 81) developed by Hayes was used to test whether there are mediating effects among variables and whether these mediating effects reach the requisite level of statistical significance. The bootstrap method for bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) was adopted to calculate indirect effects. If the 95% CI does not encompass 0, it indicates a significant mediating effect [62]. A p-value < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

In this study, the self-report scale was used to measure each variable. In order to exclude the influence of common method bias on the research results, the Harman single-factor test was used for testing. This method requires the first-factor explanation rate to be less than 40%. The statistical results showed that the explanation rate of the first common factor to the total variation was 15.37%, so there was no serious common method bias.

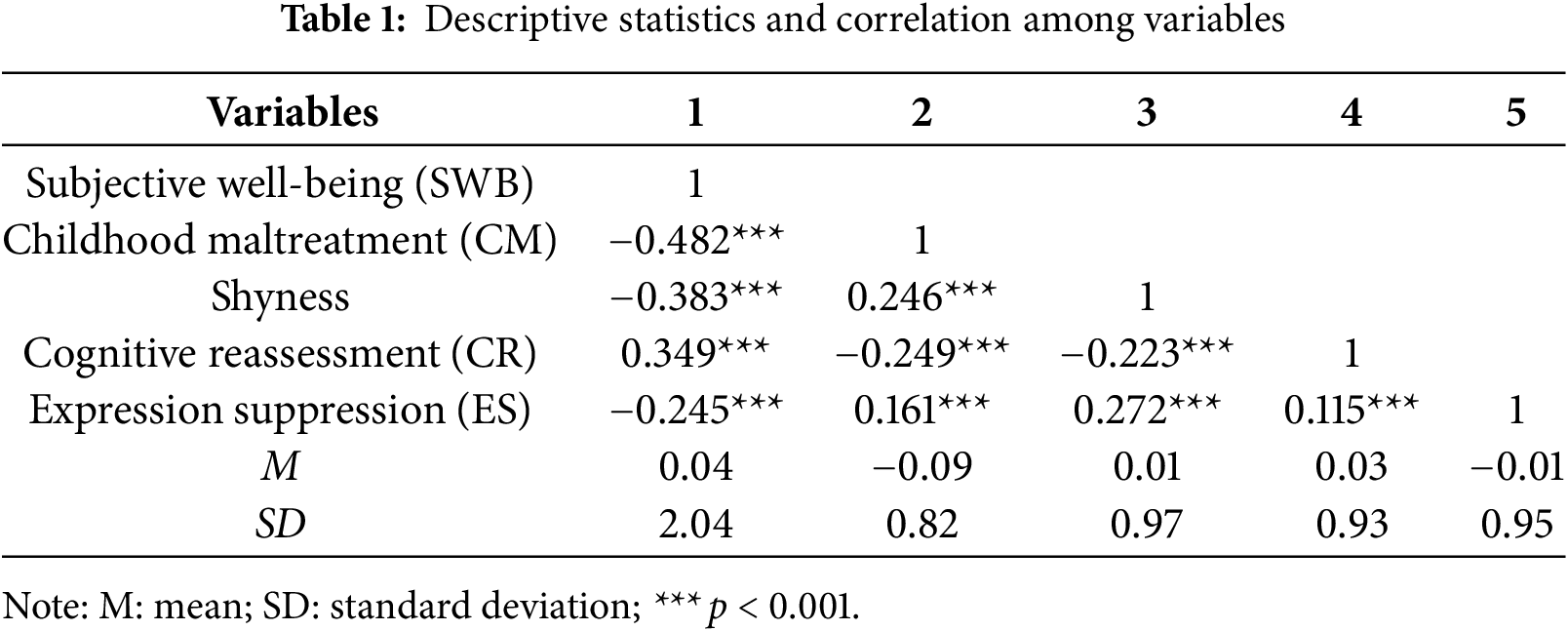

3.2 Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Correlation analysis was conducted for each variable, and the results were shown in Table 1. There was a significant correlation between CM, CR, shyness, ES, and SWB (r = −0.482, −0.383, −0.249, −0.223, −0.245, 0.115, 0.161, 0.246, 0.272, 0.349, p < 0.001).

3.3 Multiple Intermediary Model

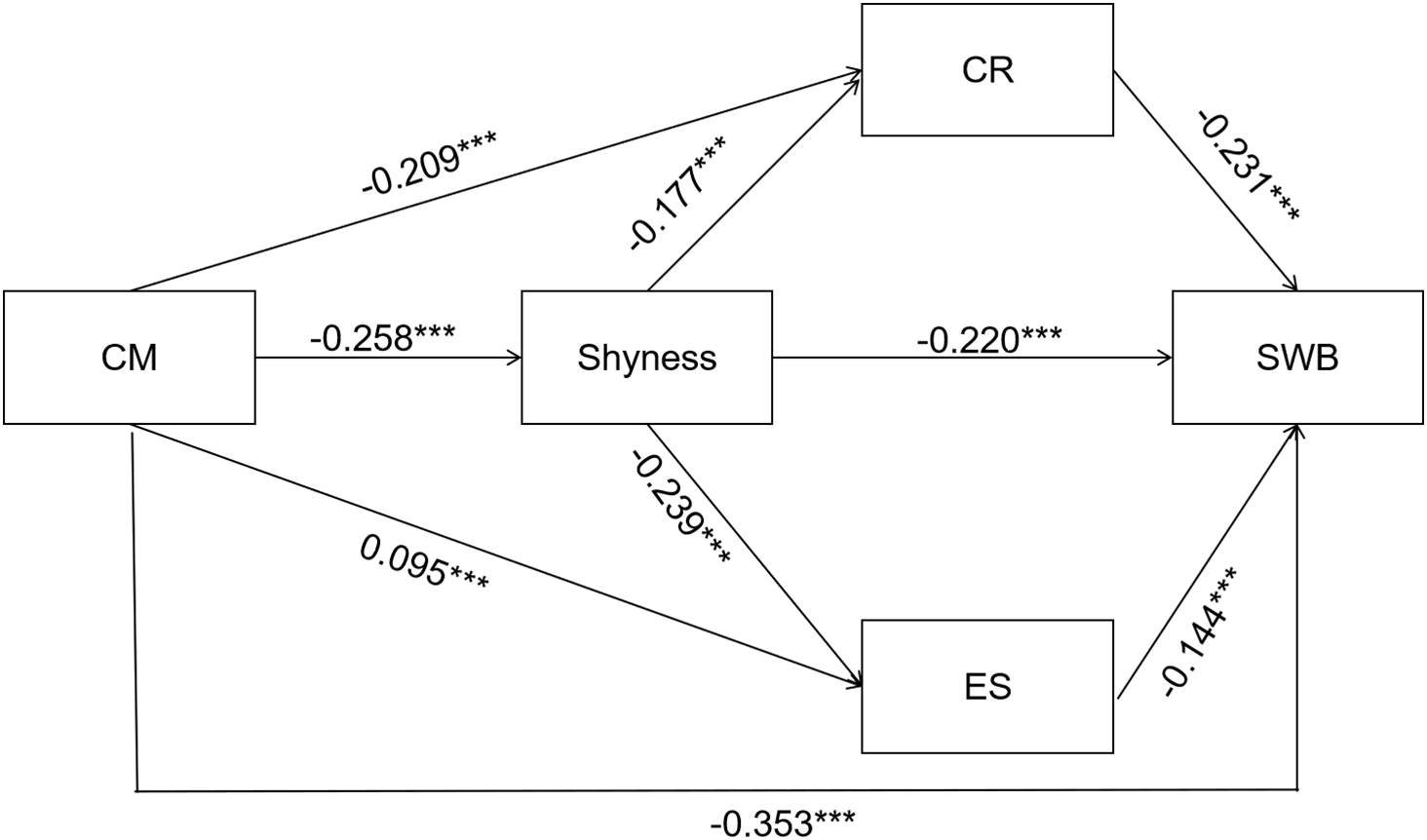

We tested the multiple mediation model with shyness and two emotion regulation strategies (CR and ES) as mediators between SWB and CM. The bootstrap was set for 5000 times with a 95% confidence interval.

The results of the analysis were shown in Fig. 1. Controlling for other variables, CM had a significant positive effect on shyness and ES (β = 0.258, p < 0.001; β = 0.095, p < 0.01), a negative effects on CR and SWB (β = −0.209, p < 0.001; β = −0.353, p < 0.001), shyness had a significant negative effect on CR and SWB (β = −0.177, p = < 0.001; β = −0.220, p < 0.001) and a significant positive effect on ES (β = 0.239, p < 0.001); CR had a significant positive effect on SWB (β = 0.231, p < 0.001) while ES had a significant negative effect on SWB ( β = −0.144, p < 0.001).

Figure 1: The multiple mediation model.

Note: Path values are the path coefficients. CM: childhood maltreatment, CR: cognitive reappraisal, ES: expressive suppression, SWB: subjective well-being. ***p < 0.001.

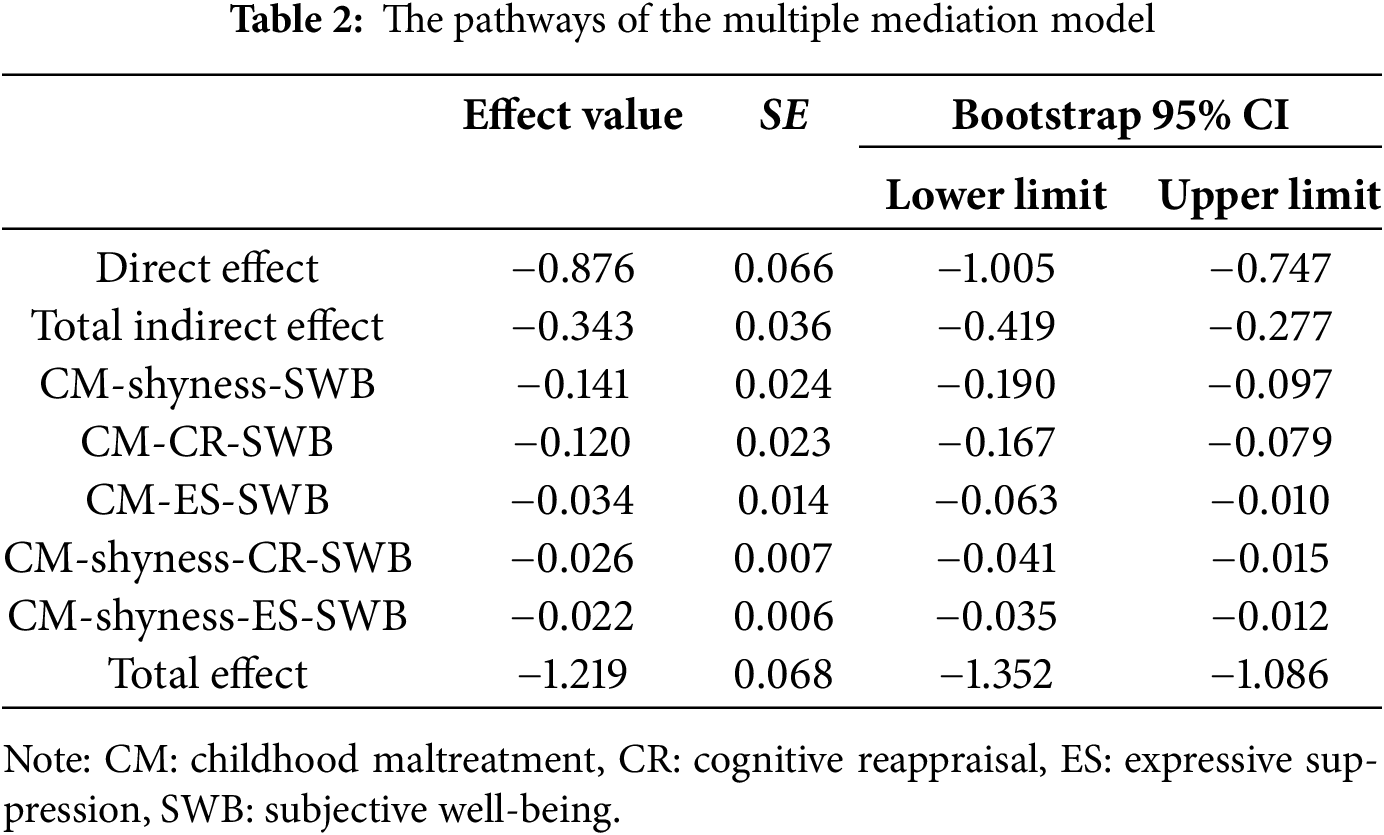

The results of the analysis in Table 2 indicated that the total effect of CM on SWB was −1.219 (95% CI = [−1.352, −1.086]). The overall effect between the two variables was significant. The direct effect of CM on SWB was −0.876 (95% CI = [−1.005, −0.747]), and the correlation between them was significant. A total of five indirect effects were verified in this study: First, CM—shyness—SWB (95% CI = [−0.190, −0.097]), which suggested that the mediating effect of shyness was significant. Second, CM—CR—SWB (95% CI = [−0.167, −0.079]), which indicated that the mediating effect of CR was significant. Third, CM—ES—SWB (95% CI = [−0.063, −0.010]), which showed that the mediating effect of ES was also significant. Fourth, CM—shyness—CR—SWB (95% CI = [−0.041, −0.015]), which meant that the chain mediating effect of shyness and CR was significant. Fifth, CM—shyness—ES—SWB (95% CI = [−0.035, −0.012]), which showed that the chain mediating effect of shyness and ES was significant as well.

This study found that CM was significantly negatively correlated with SWB and was an effective predictor of SWB. In other words, middle school students who had experienced higher levels of CM were more likely to perceive lower SWB, which supported H1 and was consistent with previous research [63]. Individuals who had experienced maltreatment tended to report reduced life satisfaction, increased negative emotions, and fewer positive emotions [64]. CM could have affected an individual’s healthy physical and mental development. Individuals with abuse experiences were more likely to have self-injuries and higher feelings of shame and psychological vulnerability [65], which also meant that individuals found it more difficult to bear the pressure of life, experienced more negative emotions, and were more prone to psychological breakdown in later life. These negative emotions hindered the psychological growth of middle school teenagers in the critical period of self-knowledge development. As a result, these students may have had greater difficulty coping with life pressures and experienced more negative emotions as they entered adulthood, making them more prone to psychological breakdown, which led to the decline of SWB [5].

Based on the significant correlation between CM, shyness, and SWB, we further explored the internal mechanism of these variables, and the results supported H2. The results indicated that middle school students who had experienced more CM were more likely to develop shy personalities, which subsequently affected their SWB. Adolescence is a critical period for individual development, where emotions, thinking, and abilities gradually develop and mature. Research suggested that CM might have impacted brain development, particularly in the right frontal lobe of the brain, and was associated with higher levels of shyness in such populations [66]. Additionally, the social adaptation model [11] emphasizes the interaction between environmental and individual factors, which affects the level of individual adaptation and can lead to maladjustment. Shy individuals often show negative cognition and emotions in social interactions, are sensitive to negative evaluations from others, and tend to assume that others’ evaluations of them are negative. These cognitive and emotional states can affect an individual’s ability to socialize and increase the risk of social anxiety [67]. Previous studies had also found that higher levels of shyness are associated with lower quality of friendships among middle school students’ peers [66]. According to China’s 2022 compulsory education curriculum standards [68], middle school students spent approximately seven hours in school, highlighting the importance of adaptability for students. Extroverted students tended to be more popular with their peers, while introverted students might face more social challenges, which added additional interpersonal pressure on shy middle school students. At the same time, academic achievement was the primary responsibility of secondary school students, and research by D’Agostino et al. [69] showed that introverted students faced greater academic pressure and were more likely to experience negative emotions such as exam anxiety and fear of failure in exams [70]. Therefore, in this environment, shy middle school students may be more prone to experiencing higher levels negative emotions and consequently exhibit lower SWB.

Secondly, the findings further revealed the differences in emotional regulation strategies among middle school students with higher levels of CM. Specifically, those who experienced more severe abuse in childhood tended to use ES strategies more frequently and CR strategies less frequently, which ultimately led to lower levels of SWB. For individuals with a high degree of childhood adversity, ES is more likely to cause maladjustment because it may lead to the continuous accumulation and strengthening of emotions within individuals, thereby increasing the risk of depression, anxiety, and other negative psychological symptoms [71]. This phenomenon is also consistent with the holistic interaction theory [44], which emphasizes the continuous interaction between the psychological and biological factors of the individual and the social, cultural, and physical factors of the environment. Individuals who experienced CM may choose different emotional regulation strategies to influence their SWB. Therefore, understanding the predictive value of emotion regulation strategies on the mental health of individuals facing adverse life events is critical to improving SWB [48].

Finally, in this study, by constructing a chain mediation model, we found that shyness and emotion regulation strategies are two important factors affecting SWB. The study found that middle school students who experienced CM tended to exhibit higher levels of shyness and more frequent use of ES, while CR use was relatively low. These findings supported H3 and were consistent with previous findings [41,42]. According to the complex trauma theory [54], traumatic experiences (such as physical abuse and psychological abuse) may lead to the failure of key developmental tasks in many areas of the individual due to the lack of coping ability of children and adolescents in the developmental stage, and the impact on individual development can be exacerbated over time. There are differences in the influence of emotion regulation strategies on SWB, especially for individuals who tend to use CR, as they have higher SWB compared to those who use ES. This may be because individuals who have experienced CM often have difficulty talking about the abuse experience, feel shame, and fear negative evaluation [72], which are all major manifestations of shyness [73]. Individuals with a higher degree of shyness have a higher degree of expression inhibition, and long-term inhibition tends to produce greater psychological pressure and difficulty in emotional relief, thus affecting their SWB [74]. According to the top-down and bottom-up theories, individual internal factors and external factors jointly determine an individual’s SWB. CM as an external factor, and shyness and emotion regulation, as internal factors, interact with each other and affect the level of SWB of middle school students [10].

In summary, this study has revealed the mechanism between CM, shyness, emotion regulation strategies, and SWB. It was found that shyness and emotion regulation strategies act mediators between CM and SWB. According to the risk enhancement model [75], shyness is characterized by high sensitivity, insecurity, and alertness, which leads individuals to use ES as a coping mechanism. This heightened sensitivity to CM reduces their SWB. Therefore, shyness influences an individual’s vulnerability to CM. Additionally, adaptive emotion regulation strategies can deepen the negative emotions resulting from CM, further impacting SWB [76]. This suggests that emotion regulation strategies are not only crucial for individuals to cope with CM, but also play a significant role in their long-term mental health and well-being. By employing effective emotion regulation strategies, it may be possible to enhance the SWB of individuals who have experienced CM.

5 Recommendations for Prevention and Intervention of Adolescent Mental Health

Firstly, society must pay greater attention to the mental health issues faced by adolescents. The findings reveal the wide range of childhood abuse, encompassing not only physical abuse but also various other forms. By raising public awareness of this issue, we can encourage families and communities to take childhood abuse seriously, thereby reducing its occurrence and promoting further research and practices that benefit the mental health of adolescents. Secondly, the study provides significant reference for school education. A comprehensive understanding of the characteristics and severity of shyness in middle school students is crucial in identifying and addressing the needs of shy adolescents. With this information, teachers can better comprehend the requirements of shy students and implement personalized teaching strategies. Additionally, the study offers valuable resources for social workers, educators, and parents to effectively support middle school students who have experienced CM, thereby enhancing their SWB, mental health, and overall quality of life. Lastly, in the field of psychotherapy, the study proposes a set of practical group intervention programs suitable for junior high school students. Effective interventions for shyness can not only help individuals overcome psychological barriers, improve self-confidence, and enhance SWB, but also have a positive impact on their healthy growth and development. Simultaneously, these interventions can improve adolescents’ social skills, enhance interpersonal relationships, and positively influence family and social dynamics.

6 Limitations and Future Prospects

Although this study held significant practical significance, it did have some limitations, primarily in the following three aspects: Firstly, the generalization of the research findings: This study focused on middle school students in Hunan Province, China, and the results may not be applicable to other student populations or regions. The applicability of this research model to other groups needs to be verified and supplemented. Future studies could compare the results of multiple studies conducted on different populations to explore the influence of socio-cultural and economic factors on the outcomes. Secondly, in terms of research methods, this study utilized a cross-sectional research design, making it challenging to establish a causal relationship between childhood abuse and subjective well-being. Future studies could employ longitudinal or follow-up designs to further investigate the relationship model among various variables. Thirdly, regarding the measurement of various variables, this study primarily relied on self-reporting scales, which heavily rely on students’ recall and self-assessment. Consequently, there may be recall bias, social expectations, self-protection, and other factors that could impact the quality of the data. Future studies may include physiological indicators in the measurement standards to obtain more objective research results.

The present study aimed to examine the impact of CM, shyness, and emotion regulation strategies (CR and ES) on SWB. Individually and sequentially, shyness along with both emotion regulation strategies were found to mediate the relationship between CM and SWB. Consequently, this analysis enables us to provide recommendations for corresponding intervention or prevention programs that can mitigate the detrimental effects of CM and enhance the SWB of middle school students.

Acknowledgement: We thank all the students and parents who participated in the test.

Funding Statement: Funded by the scientific research project of Hunan Department of Education (23A0098).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Dan Li, Huazhan Yin; data collection: Jiayu Chen, Biyu Jiang; analysis and interpretation of results: Ce Sun, Jiayu Chen; draft manuscript preparation: Ce Sun, Jiayu Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hunan Normal University (IRB No. 2022495). All participants in the study signed informed consent forms.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. World Health Organization. UN Children’s Fund, UN Educational SaCO. In: Global status report on preventing violence against children 2020: executive summary. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 2024 Nov 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240004191. [Google Scholar]

2. Li L, Chen YM, Liu ZH. Shyness and self-disclosure among college students: the mediating role of psychological security and its gender difference. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(9):6003–13. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-01099-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. van Bentum JS, Sijbrandij M, Saueressig F, Huibers MJH. The association between childhood maltreatment and suicidal intrusions: a cross-sectional study. J Trauma Stress. 2022;35(4):1273–81. doi:10.1002/jts.22821. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Teicher MH, Ohashi K, Khan A. Additional insights into the relationship between brain network architecture and susceptibility and resilience to the psychiatric sequelae of childhood maltreatment. Advers Resil Sci. 2020;1(1):49–64. doi:10.1007/s42844-020-00002-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Liu JB, Lin XJ, Shen YM, Zhou YY, He YQ, Meng TT, et al. Epidemiology of childhood trauma and analysis of influencing factors in psychiatric disorders among Chinese adolescents: a cross-sectional study. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(19–20):NP17960–78. doi:10.1177/08862605211039244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Abrams M, Chronos A, Grdinic MM. Childhood abuse and sadomasochism: new insights. Sexologies. 2022;31(3):240–59. doi:10.1016/j.sexol.2021.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wang DF, Deng QJ, Ross B, Wang M, Liu ZN, Wang HH, et al. Mental health characteristics and their associations with childhood trauma among subgroups of people living with HIV in China. BMC Psychiat. 2022;22(1):13. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03658-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Nikolova M, Nikolaev BN. Family matters: the effects of parental unemployment in early childhood and adolescence on subjective well-being later in life. J Econ Behav Organ. 2021;181(1):312–31. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2018.05.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kalyon A, Yazici H. The role of childhood abuse and neglect experiences in predicting satisfaction with life among university students: comparisons based on gender and psychological problems. J Higher Educ Sci. 2020;10(3):573. doi:10.5961/jhes.2020.417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychol Bull. 1999;125(2):276–301. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychol Bull. 1984;95(3):542–75. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. In: Handbook of child psychology. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2007. p. 793–828. [Google Scholar]

13. Kwiatkowska MM, Rogoza R. Shy teens and their peers: shyness in respect to basic personality traits and social relations. J Res Pers. 2019;79:130–42. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2019.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Li CN, Wang Y, Liu M, Sun CC, Yang Y. Shyness and subjective well-being in Chinese adolescents: self-efficacy beliefs as mediators. J Child Fam Stud. 2020;29(12):3470–80. doi:10.1007/s10826-020-01823-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. World Health Organization. Research GFfH. In: Report of the consultation on child abuse prevention. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999. p. 29–31. [cited 2024 Nov 10]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/65900. [Google Scholar]

16. American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children. Child Maltreatment Guidelines. New York: APSAC; 2016 [cited 2024 Nov 10]. Available from: https://apsac.org/practice-guidelines/. [Google Scholar]

17. Bernstein DP, Ahluvalia T, Pogge D, Handelsman L. Validity of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire in an adolescent psychiatric population. J Am Acad Child Adolescent Psychiat. 1997;36(3):340–8. doi:10.1097/00004583-199703000-00012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Kwan CK, Kwok S. The impact of childhood emotional abuse on adolescents’ subjective happiness: the mediating role of emotional intelligence. Appl Res Qual Life. 2021;16(6):2387–401. doi:10.1007/s11482-021-09916-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Spinhoven P, Elzinga BM, Van Hemert AM, de Rooij M, Penninx BW. Childhood maltreatment, maladaptive personality types and level and course of psychological distress: a six-year longitudinal study. J Affect Disord. 2016;191:100–8. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Hu YQ, Zeng ZH, Peng LY, Zhan L, Liu SJ, Ouyang XY, et al. The effect of childhood maltreatment on college students’ depression symptoms: the mediating role of subjective well-being and the moderating role of MAOA gene rs6323 polymorphism. Eur J Dev Psychol. 2022;19(3):438–57. doi:10.1080/17405629.2021.1928491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Mosley-Johnson E, Garacci E, Wagner N, Mendez C, Williams JS, Egede LE. Assessing the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and life satisfaction, psychological well-being, and social well-being: United States Longitudinal Cohort 1995–2014. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(4):907–14. doi:10.1007/s11136-018-2054-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Heshmati R, Azmoodeh S, Caltabiano ML. Pathway linking different types of childhood trauma to somatic symptoms in a subclinical sample of female college students the mediating role of experiential avoidance. J Nervous Mental Disease. 2021;209(7):497–504. doi:10.1097/nmd.0000000000001323. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Nishimi K, Choi KW, Davis KA, Powers A, Bradley B, Dunn EC. Features of childhood maltreatment and resilience capacity in adulthood: results from a large community-based sample. J Trauma Stress. 2020;33(5):665–76. doi:10.1002/jts.22543. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Cheek J, Buss AH. Shyness and sociability. J Personality Soc Psychol. 1981;41(2):330–9. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.41.2.330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Brownfield D, Thompson K. Self-concept and delinquency: the effects of reflected appraisals by parent and peers. Western Criminol Rev. 2005;6(1):22–9. [Google Scholar]

26. Luo XM, He H, Pan YG. Influence of rough parenting on fear of negative evaluation of vocational college students in Guizhou and its mediating factors. China J Health Psychol. 2022;30(2):266–71. doi:10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2022.02.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Hipson WE, Coplan RJ, Seguin DG. Active emotion regulation mediates links between shyness and social adjustment in preschool. Soc Dev. 2019;28(4):893–907. doi:10.1111/sode.12372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Chen J, Lin TJ, Anderman LH, Paul N, Ha SY. The role of friendships in shy students’ dialogue patterns during small group discussions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2021;67(4–5):102021. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2021.102021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang LL, Eggum-Wilkens ND. Correlates of shyness and unsociability during early adolescence in urban and rural China. J Early Adolescence. 2018;38(3):408–21. doi:10.1177/0272431616670993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Bober A, Gajewska E, Czaprowska A, Swiatek AH, Szczesniak M. Impact of shyness on self-esteem: the mediating effect of self-presentation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(1):230. doi:10.3390/ijerph19010230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Chen MA, Fagundes CP. Childhood maltreatment, emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms during spousal bereavement. Child Abuse Neglect. 2022;128(4):105618. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Satici SA. Facebook addiction and subjective well-being: a study of the mediating role of shyness and loneliness. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2019;17(1):41–55. doi:10.1007/s11469-017-9862-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Brasfield CR. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder: Marsha M. Linehan: Guilford Press, New York (1993). xvii + 558 pp. $39.50. Behav Res Ther. 1994;32(8):899. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(94)90183-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Watters ER, Martin G. Health outcomes following childhood maltreatment: an examination of the biopsychosocial model. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7–8):596–606. doi:10.1177/08982643211003783. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Gross JJ. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Rev General Psychol. 1998;2(3):271–99. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Gross JJ. Emotion regulation in adulthood: timing is everything. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2001;10(6):214–9. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yan CP. The regulation and recognition of the individuals with depression inclination in sad and happy images. Adv Psychol. 2021;11(10):2389–94. doi:10.12677/AP.2021.1110272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Xu D. The relationship between distress tolerance and anxiety in adolescents: the mediating role of emotion regulation strategies. Adv Psychol. 2023;13(3):1293–302. doi:10.12677/AP.2023.133155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Vajda A, Láng A. Emotional abuse, neglect in eating disorders and their relationship with emotion regulation. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci. 2014;131:386–90. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.04.135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Wooten W, Laubaucher C, George GC, Heyn SA, Herringa RJ. The impact of childhood maltreatment on adaptive emotion regulation strategies. Child Abuse Neglect. 2022;125(2):105494. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Wu ZJ, Huebner ES, Hills KJ, Valois RF. Mediating effects of emotion regulation strategies in the relations between stressful life events and life satisfaction in a longitudinal sample of early adolescents. J Sch Psychol. 2018;70(2):16–26. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2018.06.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Weindl D, Knefel M, Glück T, Lueger-Schuster B. Emotion regulation strategies, self-esteem, and anger in adult survivors of childhood maltreatment in foster care settings. Eur J Trauma Dissoc. 2020;4(4):100163. doi:10.1016/j.ejtd.2020.100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Dimanova P, Borbás R, Schnider CB, Fehlbaum LV, Raschle NM. Prefrontal cortical thickness, emotion regulation strategy use and COVID-19 mental health. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2022;17(10):877–89. doi:10.1093/scan/nsac018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Magnusson D, Stattin H. Person-context interaction theories. In: Handbook of child psychology: theoretical models of human development. 5th ed. Vol. 1. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1998. p. 685–759. [Google Scholar]

45. Kobylinska D, Zajenkowski M, Lewczuk K, Jankowski KS, Marchlewska M. The mediational role of emotion regulation in the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(6):4098–111. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-00861-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Lin ZZ. Emotion regulation strategies and sense of life meaning: the chain-mediating role of gratitude and subjective wellbeing. Front Psychol. 2022;13:810591. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2022.810591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Vally Z, Ahmed K. Emotion regulation strategies and psychological wellbeing: examining cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression in an Emirati college sample. Neurol, Psychiatry Brain Res. 2020;38:27–32. [Google Scholar]

48. McCullen JR, Counts CJ, John-Henderson NA. Childhood adversity and emotion regulation strategies as predictors of psychological stress and mental health in American Indian adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Emotion. 2023;23(3):805–13. doi:10.1037/emo0001106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Kalia V, Knauft K. Emotion regulation strategies modulate the effect of adverse childhood experiences on perceived chronic stress with implications for cognitive flexibility. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0235412. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0235412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Lee S, Kim B. Cognitive and emotional processes and life satisfaction of Korean Adults with childhood abuse experience according to the level of emotional expressiveness. Psychol Rep. 2022;125(4):1957–76. doi:10.1177/00332941211012622. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Kong X, Brook CA, Li J, Li Y, Schmidt LA. Shyness subtypes and associations with social anxiety: a comparison study of Canadian and Chinese children. Dev Sci. 2024;27(5):e13369. doi:10.1111/desc.13369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Sette S, Hipson WE, Zava F, Baumgartner E, Coplan RJ. Linking shyness with social and school adjustment in early childhood: the moderating role of inhibitory control. Early Educ Dev. 2018;29(5):675–90. doi:10.1080/10409289.2017.1422230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Blöte AW, Miers AC, Van den Bos E, Westenberg PM. Negative social self-cognitions: how shyness may lead to social anxiety. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2019;63(2):9–15. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2019.05.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Herman JL. Complex PTSD: a syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1992;5(3):377–91. doi:10.1002/jts.2490050305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 1985;49(1):71–5. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Qiu L, Zheng X, Wang YF. Revision of the positive affect and negative affect scale. Chin J Appl Psychol. 2008;14(3):249–54+68. [Google Scholar]

57. Sheldon KM, Elliot AJ. Goal striving, need satisfaction, and longitudinal well-being: the self-concordance model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;76(3):482–97. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.76.3.482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Thrash TM, Elliot AJ, Maruskin LA, Cassidy SE. Inspiration and the promotion of well-being: tests of causality and mediation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2010;98(3):488–506. doi:10.1037/a0017906. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Zhao XF, Zhang YL, Li LF, Zhou YF, Yang SC. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of childhood trauma questionnaire. Chin J Clin Rehabil. 2005;9(20):105–7. doi:10.3321/j.issn:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Xiang BH, Ren LJ, Zhou Y, Liu JS. Psychometric properties of cheek and buss shyness scale in Chinese college student. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2018;26(2):268–71. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.02.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Wang L, Liu H, Li Z. Reliability and validity of emotion regulation questionnaire Chinese revised version. China J Health Psychol. 2007;15(6):503–5. doi:10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2007.06.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

63. Badr HE, Naser J, Al-Zaabi A, Al-Saeedi A, Al-Munefi K, Al-Houli S, et al. Childhood maltreatment: a predictor of mental health problems among adolescents and young adults. Child Abuse Neglect. 2018;80(1):161–71. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Xiang YH, Yuan R, Zhao JX. Childhood maltreatment and life satisfaction in adulthood: the mediating effect of emotional intelligence, positive affect and negative affect. J Health Psychol. 2020;26(13):2460–9. doi:10.1177/135910532091438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Iorfa SK, Effiong JE, Apejoye A, Johri T, Isaiah US, Eche GO, et al. Silent screams: listening to and making meaning from the voices of abused children. Child Care Health Dev. 2022;48(5):702–7. doi:10.1111/cch.12975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Lahat A, Tang A, Tanaka M, Van Lieshout RJ, MacMillan HL, Schmidt LA. Longitudinal associations among child maltreatment, resting frontal electroencephalogram asymmetry, and adolescent shyness. Child Dev. 2018;89(3):746–57. doi:10.1111/cdev.13060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Li L, Han L, Gao FQ, Chen YM. The role of negative cognitive processing bias in the relation between shyness and self-disclosure among college students. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2021;29(6):1260–5. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2021.06.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Education Mo. Notice of the ministry of education on printing and distributing the compulsory education curriculum plan and curriculum standards. China: MoEotPsRo; 2022. [Google Scholar]

69. D’Agostino A, Schirripa Spagnolo F, Salvati N. Studying the relationship between anxiety and school achievement: evidence from PISA data. Stat Methods Appl. 2022;31(1):1–20. doi:10.1007/s10260-021-00563-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Bayram Özdemir S, Cheah CSL, Coplan RJ. Processes and conditions underlying the link between shyness and school adjustment among Turkish children. Br J Dev Psychol. 2017;35(2):218–36. doi:10.1111/bjdp.12158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Amstadter AB, Vernon LL. A preliminary examination of thought suppression, emotion regulation, and coping in a trauma exposed sample. J Aggress Maltreat Trauma. 2008;17(3):279–95. doi:10.1080/10926770802403236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Brophy K, Brähler E, Hinz A, Schmidt S, Körner A. The role of self-compassion in the relationship between attachment, depression, and quality of life. J Affect Disord. 2020;260(6):45–52. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Henderson LN, Zimbardo PG. Shyness as a clinical condition: the stanford model. Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. [Google Scholar]

74. Zhao X, Feng ZN, Shang PF, Jin G. Shyness and emotion regulation strategies: the mediating role of emotion regulation self-efficacy. Chin J Clin Psychol. 2016;24(4):717–20. doi:10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2016.04.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Luthar SS, Crossman EJ, Small PJ. Resilience and Adversity. In: Handbook of Child Psychology and Developmental Science. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2015. p. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

76. Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity. Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiat. 1985;147(6):598–611. doi:10.1192/bjp.147.6.598. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools