Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of the 9/11 Terrorist Attacks on Family Narratives and Family Systems

1 Department of Psychiatry, The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX 75390, USA

2 School of Nursing, Boise State University, Boise, ID 83725, USA

3Private Practice, Tampa, FL 33617, USA

* Corresponding Author: Cesar E. Montelongo Hernandez. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Safeguarding the Mental Health of Disaster Survivors and Frontline Healthcare Workers During Pandemics)

International Journal of Mental Health Promotion 2025, 27(6), 737-752. https://doi.org/10.32604/ijmhp.2025.065317

Received 10 March 2025; Accepted 27 May 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

Background: Disaster mental health outcomes of individuals may be affected by the families they inhabit, with effects rippling through the entire family system. Existing research on the experience of children in disasters has typically been limited to examining single individuals or, at most, family dyads. Research is needed to explore interactions within families as a whole, including interactions among multiple family members, as well as with community entities in a broad systems approach with dynamic analysis of family systems over time. The purpose of this study was to combine quantitative and qualitative data using structured diagnostic interviews and accompanying open-ended narratives of family members (spouses and children) of survivors of the 9/11 attacks. Methods: This study examined 60 members in 25 families of employees affected by the 9/11 attacks on New York City’s World Trade Center, using a mixed methods approach, collecting quantitative data using full assessments of psychiatric disorders and qualitative data from detailed personal disaster narratives. The employees were a highly 9/11 trauma-exposed group, with about one-fourth developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The employees’ exposures and PTSD did not regularly appear to propagate straightforwardly to psychopathology in their spouses or children. Based on the impact of disaster experience, 4 illustrative families were selected for narrative and family systems analyses. Results: Qualitative analysis of their narratives suggested distinct family system patterns or archetypes that may reflect different ways that families cope with disaster. Conclusion: Findings suggest that family systems and family dynamics may influence not only disaster trauma-exposed members but also other family members in supporting one another and coping with the disaster, with interactions with outside community influences adding further complexity. This information may help guide disaster response efforts to provide psychosocial support targeted to specific family patterns.Keywords

Disasters in general are well known to result in serious and widespread negative mental health consequences, and this is especially true of terrorism in particular. An important and comprehensive review of urban terrorism that broadly encompassed urban, economic, and governmental issues, and security, counterterrorism, and health among terrorism survivors in general, affirmed the psychological effects of terrorism as significant and long-lasting [1].

The relevant research has primarily focused on disaster survivors [2] and secondarily on exposed disaster responders [3] as well as on other specialty groups, such as rural women [4], family business owners [5], healthcare workers [6–8], and teachers [9]. This research has been largely limited to studies of individual spouses and children of disaster survivors. The experiences of families in disasters have also been studied. However, it has particularly concentrated on psychiatric disorders, especially posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and information relevant to designing treatment and predicting mental health outcomes [10]. Much of this research has suffered from methodological shortcomings, especially mixing disaster-exposed and unexposed family members, use of nondiagnostic self-report brief symptom screening tools instead of diagnostic instruments, and conducting cross-sectional post-disaster assessment without regard to pre-disaster characteristics [11]. Inconsistent data collection methods have further limited the ability to compare across studies. The findings of quantitative studies are informative, but qualitative studies should not be overlooked. Qualitative studies have been included in this literature overview because of their ability to provide rich, in-depth accounts of the experiences of disaster survivors, although one review described their methodological quality to be substandard [10].

Research on spouses and children exposed to disasters has largely been limited to the study of individual family members. These studies have typically collected data from mothers [12,13] on their perceptions of their parenting abilities or their child’s mental health; others have conducted separate interviews with children directly [13–15]. Research data collected from a single family member, such as the mother, represents a source of reporting bias, as maternal psychopathology may influence perceptions of their children’s reactions to disaster. Most disaster mental health studies examining relationships across family members have been further limited to the exploration of family dyads, usually a parent and child [16,17]. Disaster mental health studies of other types of relational dyads have also included partners of first responders and couples [18,19]. Even among these studies, research on terrorist disasters has been largely lacking. Research examining the mental health effects of disasters on families requires the inclusion of the perspectives both parents and children and of both partners to best understand the effects of disaster experience within intrafamily dyads. Previous studies of families in disasters, in a wide international literature, have largely concerned natural disasters, with a recent emphasis on the COVID-19 pandemic. However, research on the effects of terrorist disasters on families in particular is needed.

Much can potentially be learned about families’ experiences of disaster by examining family members who may have been exposed to disaster trauma only indirectly through a trauma-exposed member. Disaster experience and mental health outcomes of such individuals may differ from those directly exposed and may affect and be affected by the families they inhabit, with effects rippling through the entire family system.

Research is needed on multiple members of the same families studied together after a disaster. The disaster mental outcomes of various family members are shaped by the relationships among the many members of families, with effects that are likely to increase exponentially with the inclusion of all members. Additionally, consideration of the family unit as a whole adds further complexity to understanding the effects of disasters on individuals and relationships within families. Finally, consideration of relationships of both family members and the family unit with outside community entities can complete family system models in the context of disasters.

Observations of the disaster experience over time within families (starting with pre-disaster characteristics) are needed to elucidate the dynamic processes through which families experience disaster together and their subsequent progression through processes that promote recovery [20,21]. Qualitative inductive methods are ideal for this type of investigation, but this type of approach is remarkably missing in the published literature on disaster mental health outcomes within families [20]. For example, a review of published research on families affected by the 11 September 2001 (9/11), terrorist attacks found only a very small number of qualitative studies, the majority of which were conducted by a single research group [22].

Specific recommendations have been made to address the methodological limitations of family disaster mental health research through conceptualization and examination of the responses of families as a system [18]. This requires moving beyond a focus on individuals in isolation from their families to explore the interactions within families as a whole [23], with an examination of multiple family informants whose perspectives and trajectories interrelate to support or impede the processes of healing after disasters. Triangulation of data from multiple family informants is a valuable component of this analysis. An additional methodological enhancement is to investigate how family members and family systems interact in the broader social and community environment (e.g., schools, workplaces, religious institutions, and mental health services). Such broad examination of interactions of individuals, families, and the external environment all together in family systems can address existing gaps in understanding of disaster-related psychopathology and dysfunction, which in turn can point to new directions for developing effective family therapy and community interventions [11,20].

Providing data for this study to address the gaps in research knowledge reviewed above, a sample of 25 families was studied as part of a larger investigation of 379 employees of businesses affected by the 9/11 attacks on New York City’s World Trade Center. This disaster was of unprecedented magnitude, with destruction, and fatalities. The employee sample included many members who were highly exposed to 9/11 trauma, of whom more than one-third developed PTSD [24]. For this family sub-study, a mixed methods approach was applied with a collection of quantitative data with full assessments of psychiatric disorders before and after the disaster to the present time, and also qualitative data consisting of detailed personal disaster narratives, accompanied by 4 illustrative family case reports. The combination of these methods in a single study permitted a comprehensive examination of disaster experiences and perceptions not only of individuals but also across multiple family member relationships and within the family unit, as well as with the community. This study therefore advances the field’s methodology through the use of a systems approach with dynamic analysis of family systems over time to address the research question: How do families as a whole respond to such extreme events in a larger context and how do individuals’ interactions within family structures and with factors of outside systems and communities relate to the family response as a whole?

In the original 9/11 study, structured diagnostic interviews were conducted with a volunteer sample of 379 employees from 8 businesses affected by the 9/11 terrorist attacks on New York City’s World Trade Center (WTC), approximately 3 years after the 9/11 attacks, with follow-up interviews 6 years post-disaster. Details about the employee sample, research methods, and findings of the larger study can be found in a previously published article [24]. The sample for this family study was selected from the original study’s participants and interviewed at approximately 3 years post-disaster. A volunteer subsample of 25 employees (hereinafter referred to as probands) was invited to participate in the family sub-study, including their spouses (and significant others) and both adult and minor children. The family sample included 25 probands, 18 spouses/partners, and 17 children, for a total of 60 members of 25 families. Some families had >1 child participating (2 children in 2 families and 3 children in 1 family), resulting in child participants connected to 13 probands. Of the 18 participating spouses, 6 were connected to participating children, and 12 had no children interviewed. All children in the study were in families with proband parent interviews. Ten of the 17 participating children, from 7 families, had no spouse of their parent proband interviewed. Child interviews were conducted in 6 families with and 7 families without spouse interviews. In sum, 7 families had both spouse and child interviews, and the remaining 18 families had only spouse or child interviews in addition to the proband. No information was collected about how many spouses/partners and children in the families of the 25 proband parents did not participate in the family sub-study.

The probands in this study were all interviewed at 3 years after the disaster; spouses were interviewed at either 3 (n = 7) or 6 (n = 11) years and children were interviewed at 6 years. Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was provided by Washington University (approval #02-041 and #00-0922) and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (approval #092010-006 and #052011-079), and all written informed consent was provided by adult participants and assent by minor children. Like the probands, the spouses and children were interviewed with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS) for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) [25]. The DIS provided pre-disaster, post-disaster, and incident (new since the disaster) psychiatric diagnoses for PTSD, major depressive disorder (MDD), panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and alcohol and drug use disorders, by keying the initial onset and most recent symptoms of the disorder in relation to the date of the disaster. The DIS diagnostic modules were limited for family members: the drug use disorder section was not administered to spouses or children, and the panic and GAD sections were not administered to minor children. A variable representing any diagnosis was generated for proband parents and their spouses, but not for the children because it would not be equivalent without representation of some diagnoses. Spouses and children also had variables created to represent pre-disaster, post-disaster, and incident diagnoses.

The Disaster Supplement [26] part of the interviews provided additional qualitative information through open-ended questions, including personal reactions to the disaster, detailed descriptions of disaster trauma exposures, allowing classification of exposures into criterion A (the trauma exposure criterion) for the diagnosis of PTSD, treatment received, and other life difficulties and circumstances. The interviews were administered in private by mental health professionals formally trained on the use of these instruments for this study. The interviews lasted approximately 1.5–2.5 h. Responses to open-ended questions were recorded by the interviewers by hand. Interviewer training emphasized the importance of verbatim and complete documentation of responses.

The quantitative data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Summary data were generated separately for probands, their spouses, and their children for variables including demographic characteristics (sex, age, race/ethnicity, education, marital status), 9/11 trauma exposures (direct, witnessed, and indirect for classification of disaster trauma using DSM-IV criteria for PTSD), and pre-disaster, post-disaster, and incident psychiatric diagnoses. Categorical variables are presented using counts and proportions, and continuous variables with means, standard deviations (SDs), medians, and ranges. For comparison of proband characteristics in the family sub-study with those of the original study’s larger sample, chi-squared analysis was used for dichotomous variables, substituting Fisher’s exact tests for instances of expected cell sizes <5, and t-tests were used for continuous variables, substituting Satterthwaite analysis for instances of inequality of variances based on Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances. The alpha level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

The qualitative data analysis used text responses to open-ended questions about the participants’ disaster experiences, emotional responses, perspectives on their disaster experience, coping methods, and interactions with other family members and external systems. External systems were defined as any institution or organization outside of the family identified in any interview, including psychotherapy and psychiatric care, work and school environments, community, and faith or religion. The qualitative methods follow the recommendations of Padgett’s seminal textbook on qualitative research [27]. Analysis was conducted using a phenomenological approach, incorporating elements of qualitative systems dynamic modeling [28], focusing on the disaster experience of family members in the context of post-disaster response. Analysis of the family system used an iterative approach. One author identified relationships between individuals and various systems, a second independently verified the existence of the relationship within the data and identified areas of differences, and then these 2 authors reconciled these differences. Once this process was completed, an interpretation was made of the family structures identified, and then the family systems presented here were verified by an additional team member.

Based on variables of interest reflecting disaster impact, including 9/11 trauma exposures and their members’ psychopathology, 4 families were selected for presentation of an in-depth description of their individual member and family characteristics and for application of family narratives and family systems analyses. Detailed descriptions of these families and the disaster-related experiences of their participating members (presented in text) were assembled through inspection and narrative analysis of open-ended responses. For family systems analysis, open-ended responses were examined for statements describing interactions with other family members and with external systems. Also, because many narratives mentioned the family as a whole, a system category labelled “family as collective” was identified.

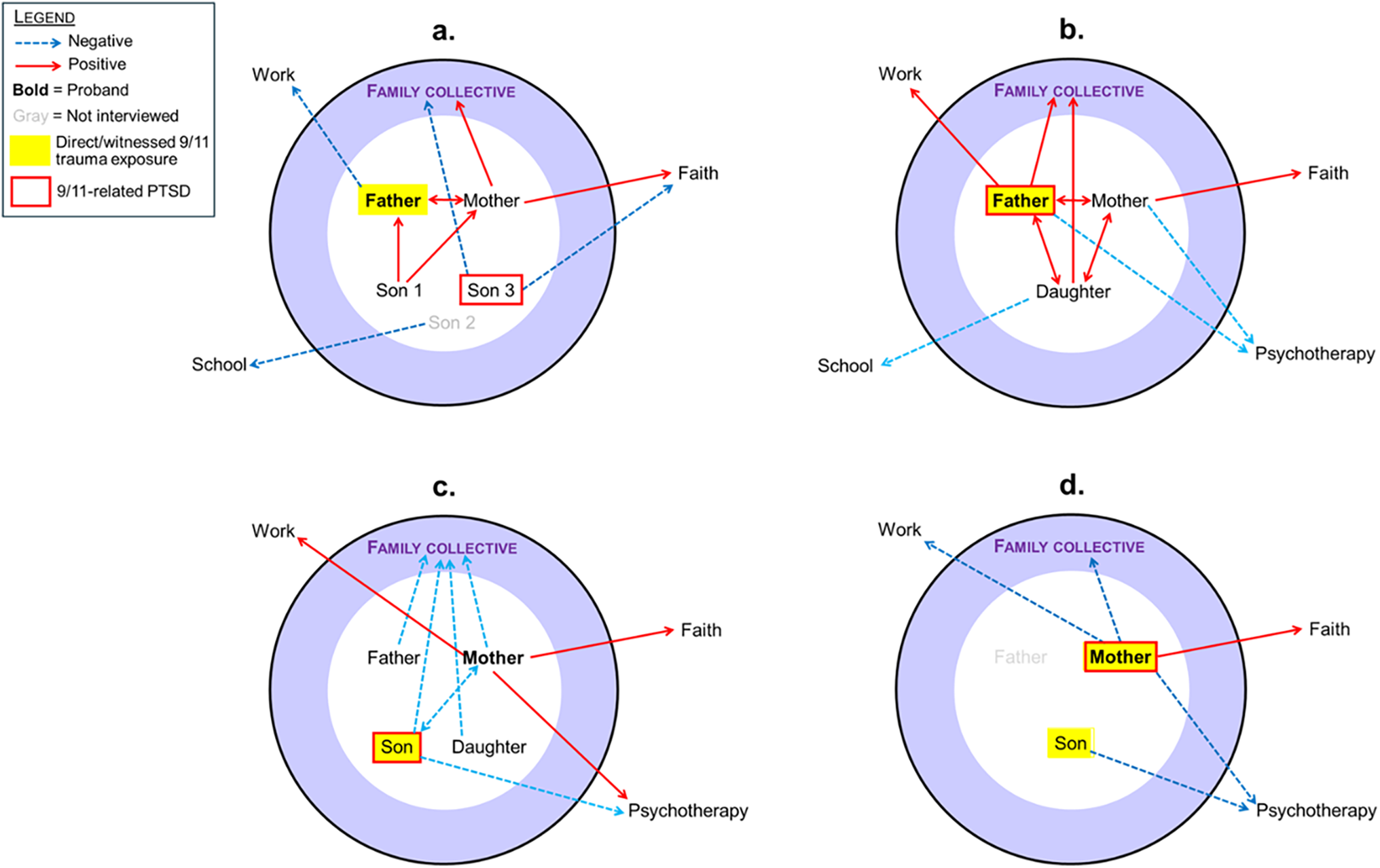

Statements referring to each system by individual members were identified for each family by 2 raters (Cesar E. Montelongo Hernandez and David E. Pollio) and designated as either positive or negative using a consensus process. This decision process included re-examination of individual interviews as a whole for context, with depiction of family global patterns with labels summarizing the family response, again based on raters’ consensus. Relationships between family members and with external systems were mapped into separate figures for each family (see Fig. 1). Family units are represented within a circle confined by a black outline, and the outer shaded section of the circle represents the family collective. The family members are represented with designations for 9/11 direct/witnessed trauma exposures and PTSD. Relationships among family members, the family collective, and external systems are indicated by arrows connecting them. The conceptualization of these family representations in the figure panels follows Bronfenbrenner’s classic figure on modeling systems theory [23]. This process led to the identification of distinct family system archetypes that may reflect different ways that families cope with disaster.

Figure 1: Illustrative family systems. (a) Outside negative; (b) family centered; (c) family negative; (d) uninvolved family

This study was not preregistered. Data and analysis code for this study are not available.

The only demographic difference between the 25 probands in this family sub-study and the rest of the sample of 379 employees of affected businesses was a higher proportion married (80% vs. 49%; χ2 = 8.73, df = 1, p = 0.003). There were no differences in 9/11 trauma exposure variables or psychiatric disorders.

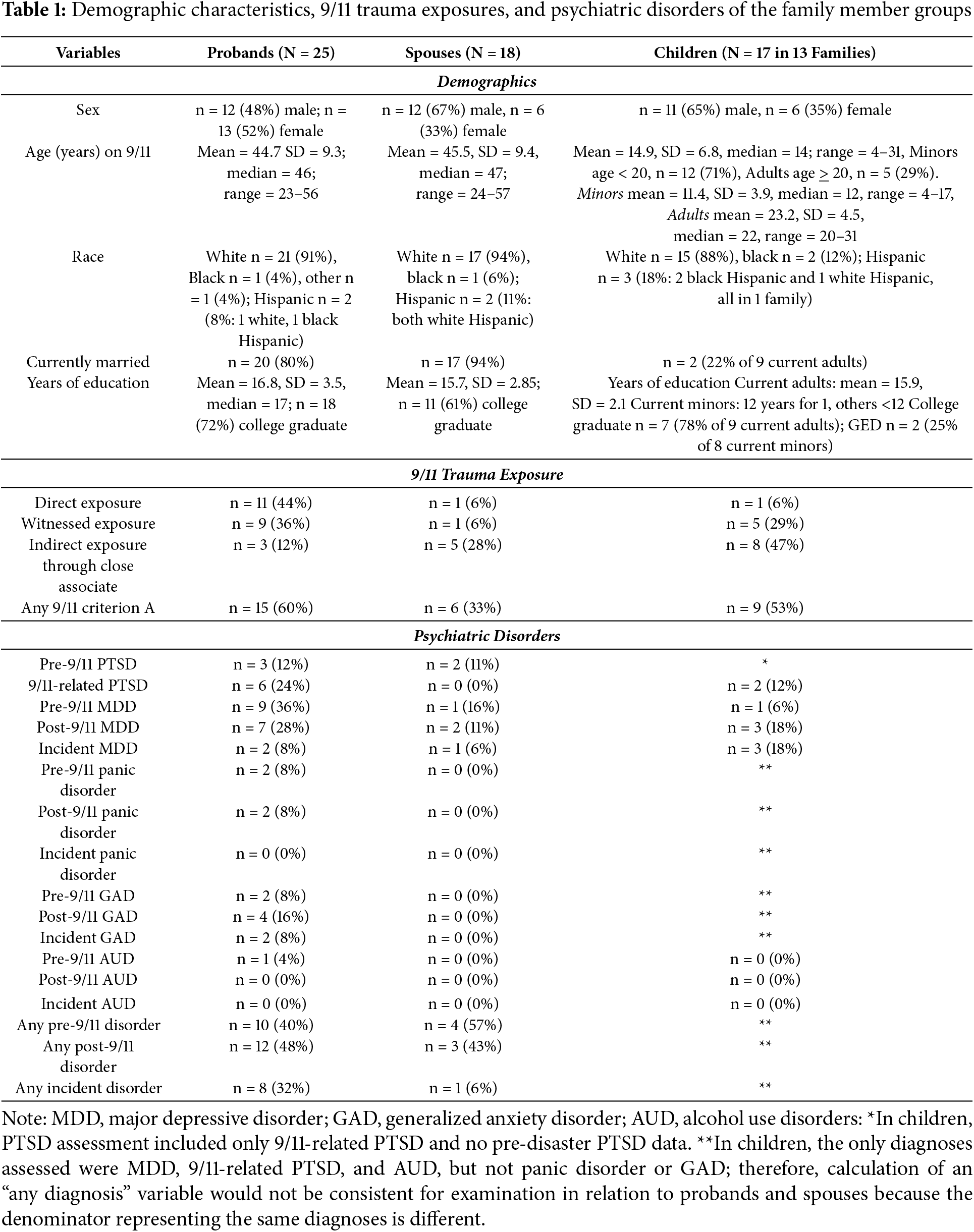

Table 1 shows demographic characteristics, disaster trauma exposures, and psychiatric disorders for the family member groups (N = 60 members of 25 families). The 25 probands were approximately equal in proportions by sex; both spouses and children were about two-thirds male. The children in these families included 12 minors (<20 years old) on 9/11 and 5 adult children (>20 years old) on 9/11.

Nearly one-half of the 25 probands had direct 9/11 trauma exposure (including 6 in the WTC towers), and more than one-third witnessed 9/11 exposure. Of the spouses, 1 had direct 9/11 trauma exposure (none in the WTC towers); one-third had any 9/11 trauma exposure, predominantly indirect through loved ones. More than half of the child family members had any 9/11 trauma exposure, also predominantly indirect exposures.

About one-fourth of the probands developed 9/11-related PTSD. More than one-third had a pre-disaster disorder (mostly MDD), nearly one-half had a post-disaster disorder (mostly MDD, and nearly one-third had an incident disorder (largely PTSD, because most of the post-disaster MDD was pre-existing). Among spouses, none developed disaster-related PTSD, but 1 developed an incident disorder after the disaster. Of the children, 2 developed PTSD and 3 developed an incident disorder.

Based on the impact of disaster experience (9/11 trauma exposures and post-disaster psychopathology), 4 illustrative families were selected for narrative and family systems analyses. The text below details these findings.

3.2.1 Family 1: Outside Negative (See Fig. 1a)

The proband father in this family was a married middle-aged upper-level manager of a consulting company, who was in his office on an upper floor of the south tower, above the strike zone, on 9/11. Because the first plane had already hit the north tower, south tower employees were instructed to evacuate, which the father and others did by the stairs. After he had descended about 25 stories, an overhead announcement proclaimed that the tower they were in was undamaged and that people should return to their offices. A coworker with him started having a panic attack and entered the express elevator to continue evacuating. He felt compelled to accompany her outside instead of returning upstairs. He considered this a “fluke” of random luck enabling his survival. As he was exiting his tower’s ground floor, the second plane struck his tower. He walked from Manhattan to his home. Cell phone service was incapacitated. He was first able to contact his family on a landline around noon, but was not physically reunited with his family until late afternoon. One-half of his co-workers perished in the attacks, including his boss and all the coworkers who returned to their offices after the announcement. The father did not have any pre-disaster psychopathology and did not develop any post-disaster disorder. He did not seek or obtain psychiatric treatment. The father described himself as “very upset” initially, with considerable survival guilt, and now partly recovered from the experience. The father was not emotionally ready to return to work when he did. His wife expressed that his coworkers did not seem sensitive or sympathetic, or supportive enough regarding his 9/11 experience and feelings.

The mother, a teacher, was in a high school outside Manhattan in view of the towers. She had no personal direct exposure to 9/11 trauma. She did not have any pre-disaster psychiatric illness and did not develop any post-disaster psychiatric disorder. She said the 9/11 attacks made her “very upset”, but she felt she had recovered. She did not seek formal assistance for her feelings. Her main sources of support were her family and friends, along with her Catholic faith. In the end, she felt that 9/11 made her feel “stronger and more unflappable”, yet she also mentioned that she feels the disaster made the whole family anxious at times when official threat levels increased.

This couple had 3 sons whose ages ranged from late teens to mid-20s on 9/11. Two of the sons (son 1, the oldest, and son 3, the youngest) were interviewed for this sub-study.

The oldest son was employed as a computer technician at a high school outside Manhattan on 9/11. He had no direct 9/11 trauma exposure and did not have pre-disaster or post-disaster psychopathology. When he first heard about his father’s 9/11 experience and that he had survived, he “jumped for joy”. However, he also felt conflicted and overwhelmed thinking about the multitudes of people killed and profoundly affected. He increased the amount of time he spent with his family after the 9/11 attacks, finding it helpful to talk with his father about 9/11. He did not observe any long-lasting changes in himself or family members related to 9/11.

The youngest son, a junior in the high school where his mother taught, was at school that morning (At the time of his interview, he was in graduate school). He had no direct or witnessed 9/11 trauma exposure; he learned of the attacks from a school nurse. The oldest brother arrived in a car to rescue him and his mother. On the way home, he saw the massive cloud of smoke over lower Manhattan, and “the severity of the situation sank in”. He later saw news footage of the towers collapsing and feared that his father must have died in the attacks and that his body would never be recovered. Later, he felt very guilty over his thoughts of his father’s demise, and his religious “faith went out the window”. He remained fearful all day with a sense of “impending doom”.

Although he had no pre-disaster psychopathology, the youngest son developed 9/11-related PTSD but no other post-disaster disorder. He felt the 9/11 attacks had severely affected him psychologically and created an “unwanted benchmark” in his life, but he was not interested in treatment for his condition. His symptoms began immediately after 9/11 and lasted 4 months, preventing him from doing his homework. He was so upset that he did not attend sports practice for 2 weeks, for which he was removed from the team. He felt this too profoundly affected him, and he harbored negative feelings toward the school. He wanted to talk to his parents and siblings about 9/11, but did not because he felt it would be too difficult and probably not helpful. However, he stated that he and all his family members have good relationships, although the 9/11 attacks caused substantial family disruptions. He felt that the family dynamic with his brothers was “changed”. He grew distant from them immediately after 9/11 and found solace in television and comedy. He lamented that he and his family had been “forgotten” because of public focus on victims who died and not recognizing the suffering of the survivors.

To summarize, this first family archetype is labelled Outside Negative because most connections of this family to the outside world were either oppositional or nonexistent, providing little support. Instead, this family’s dynamic is generally structured with an internal focus on the family collective and relationships within family members. This type of family, therefore, had to depend on healing predominantly through internal cohesion among family members. This family eventually formed a cohesive family narrative, which helped soothe feelings of upset and survivor guilt.

3.2.2 Family 2: Family Centered (See Fig. 1b)

The proband father was a married middle-aged employee of a consulting company on the upper floors of the south tower above the strike zone on 9/11. When the first plane hit the north tower, he was in transit to work. The second plane struck his tower shortly after he exited the subway station at the base of his tower. The lights flickered, he smelled jet fuel, and he “immediately knew his office was not there anymore”. He tried to evacuate the building, hugging the walls to avoid confrontation with potential terrorists, fearing being killed. On a ferry to home, he had direct views of flames and smoke rising and debris falling from the towers. Half of his co-workers perished in the attacks. Although he did not have any pre-disaster psychiatric illness, he developed PTSD, which lasted for 2 years, and no other post-disaster disorders. Before 9/11, he regularly drank 1 alcoholic drink per day and used cannabis and hallucinogens recreationally. After 9/11, he increased his alcohol consumption to as much as 7 drinks per day and increased his cannabis consumption, but subsequently returned to his pre-9/11 usage of alcohol and cannabis. He used cannabis and pain medications for sleep temporarily. He gained weight from coping through eating. He attended 3 counseling sessions provided by his workplace, but discontinued because he felt it was “totally useless” and that the provider was unqualified. He did not feel he had sufficient opportunities to discuss his 9/11 experience. His main sources of support were friends and relatives and his work. He reported that he felt less comfortable and less tolerant toward Muslims after 9/11.

The mother, a scientist, was at home on her day off work. When a relative notified her of the unfolding events, she “freaked” and continuously tried unsuccessfully to reach her husband by cell phone. She did not learn of his survival until hours later when notified by a second-hand informant. She was initially very upset about the attacks, and longstanding fears prevented her from going near the site. She had a history of pre-9/11 depressive symptoms but did not develop PTSD or the other new psychopathology. She declined referral to mental health care. She coped through praying and with support from family and friends. She stated that the 9/11 attacks made her and her husband more loving and better able to express their emotions.

The daughter was a college student in her early 20s in a nearby state on 9/11. A close friend awakened her from sleep and alerted her to the attacks, and together they watched live news coverage of the event, seeing the plane hitting the tower where her father worked. Although her mother did not know of the father’s status, she called the daughter and told her that her father was all right, to protect her emotionally. The daughter was reunited with her father that evening. She had no history of any pre-disaster psychiatric disorder and did not develop PTSD or any other psychopathology. Her scholastic performance suffered, however. She felt that her peers and teachers outside of the NYC area did not understand the depth of the situation. She said that since 9/11, she had become more patient and valued her family more. She was impressed that her parents were highly affected by 9/11, and that losing several close colleagues and attending many funerals was especially hard on her father. She noted that her parents had become much more prejudiced and more “leery of certain ethnicities” since 9/11.

To summarize, this second archetype is labeled as Family Centered, because this type of family is strongly focused inward. All 3 members had positive relationships with the family collective, with the experience of 9/11 further strengthening their bonds. The family was portrayed as happy and living normally. The outside world was a secondary positive influence through connections with work and faith communities (although negative toward school and community members of different ethnicities) after 9/11. The family viewed the outside world as static, providing little nurturance for family reconciliation and healing, with no connection to mental health services. Unlike the outside negative family, which created its family narrative largely in opposition to the outside world, this family focused on supporting its family members within the internal family structure, particularly directed toward the perceived vulnerable daughter.

3.2.3 Family 3: Family Negative (See Fig. 1c)

The proband mother was a married middle-aged upper manager at a consulting company on the upper floors of south tower on 9/11, above the strike zone. That morning, she was flying to another state. She was not able to contact family for many hours to inform them that she was safe. She was unable to return home for 5 days. Many of her coworkers and others she knew were killed. She did not have a history of any pre-disaster psychiatric illness and did not develop any post-disaster psychiatric disorder. Although she felt very upset about the attacks, this improved with time, and she felt happy with her job, with even better job performance after the attacks. Her main concern was with her 6th-grade son, who was at school just 5 blocks from the WTC where he witnessed the attacks and subsequently developed PTSD and MDD. She attended therapy with him, and she also saw a psychologist weekly for herself for a year. Her strong Catholic faith helped her cope. After 9/11, she felt able to put things in perspective and no longer allowed small things to bother her. She reported feelings of fear and prejudice toward Middle Easterners after 9/11.

The father, a middle-aged married copy editor, passed under the WTC via subway to his workplace outside Manhattan, later seeing the towers burning and eventually collapsing from his office window. He was unable to contact family until late that evening to inform them that he was safe, feeling very guilty about not connecting with his son and daughter sooner. The father had no pre-disaster psychiatric illness and did not develop any post-disaster disorder. He described himself as coping well with the disaster, but expressed concern over his son’s PTSD and depression and his daughter’s emotional upset over 9/11. He said his children do not communicate well with their parents, and the family does not discuss the 9/11 attacks. He alluded to family problems, especially between his wife and son, and said that he serves as a family peacemaker.

A 6th-grade son was in school 5 blocks from the WTC on 9/11. He did not see anything until the school was evacuated, at which time he saw people falling from the towers and the towers collapsing. The son thought his mother was in the WTC, and he didn’t know if his father was there too because his train to work runs under the WTC. It was late in the day before he heard that both parents were safe. Although he had no pre-existing psychopathology, he developed PTSD and MDD, which persisted for 4 years. The mother did not think her son did well after the attacks. She had him see a psychiatrist weekly for 2 years, but he disliked treatment and did not disclose his feelings to the psychiatrist. He also rejected his parents’ attempts to talk with him about 9/11, finding his mother’s efforts to reach out to him to be unsatisfactory. He began to play violent video games and entertained plans to become a Navy SEAL so he could kill people; he lost interest in sports and other activities. At the time of his interview, the son had completed high school and was feeling better adjusted.

To summarize, the third archetype is labelled Family Negative, because of the extensive array of negative and functionally ineffective relationships between members and with the family collective. The parents were unable to connect satisfactorily with the emotional needs of their son, who rejected their attempts to talk about 9/11, and the daughter was also withdrawn from the family initially. Thus, family members functioned as essentially separate identities with unrelated behaviors in this family with poor communication, which did not promote mutual family support. Despite all these family difficulties, the family members, apparently lacking awareness, portrayed the family as a whole weathering the disaster experience well. This family was eventually able to engage somewhat with external systems (through work, faith, and mental health treatment), which may have helped enable this family’s journey to healing.

3.2.4 Family 4: Uninvolved Family (See Fig. 1d)

The proband mother was a married middle-aged upper manager for a consulting company and was in her office on the upper floors of the south tower, above the strike zone, on 9/11. After the first plane hit the north tower, she evacuated to the outside, where she witnessed the second plane strike her tower. She saw buildings burning and people falling from buildings. She felt in immediate danger of being hit by debris and thought she might be killed. Many of her coworkers died on 9/11. Although she had no pre-disaster psychiatric illness, she developed 9/11-related PTSD immediately after the disaster and was still symptomatic at the time of the interview, without other post-disaster disorders. After 9/11, her smoking temporarily increased from 1/2 to 1–1/2 packs per day. She increased gambling, had a new onset of teeth grinding in her sleep, and cried easily after 9/11. She participated in a workplace debriefing intervention, which she found helpful, and she saw a psychologist once, which was not helpful. Her main coping was through resuming her daily routine as much as possible; however, she felt she had returned to work before being psychologically ready, and her workplace expected her to move on emotionally too soon. She attended Jewish services weekly and felt that her religious faith was strengthened after 9/11. She said she had lower levels of trust and comfort with people who were different from her after 9/11.

Neither the mother nor the son in this family discussed the 9/11 experience of the father, who was not interviewed for this study. They indicated that he was not exposed to danger in the attacks and was not much affected.

The son, an only child in this family, a 30-something-year-old worker in commodities commerce, was in his office on 9/11 at a company located a block from the north tower. He did not see either plane hitting the towers, at first thinking the first plane striking the tower was an accident, but realized it was intentional when the second plane arrived. He witnessed buildings burning and people falling from the buildings, yet he did not feel his life was endangered. Before the towers collapsed, he left for home, traveling first by ferry and then by subway. He did not learn that his mother was safe until mid-afternoon that day. He did not have any pre-disaster psychiatric illness and did not develop any post-disaster disorder. He expressed profuse anger about 9/11 and the loss of 6 of his friends in the attacks. Although initially very upset, he rejected mental health care. He had only limited discussions with his parents about 9/11 as they “keep things inside”, and he did not really know how they were affected or whether his mother was even in her office during the attacks. He described no sources of personal support or coping. He said he now felt completely recovered, and that 9/11 ultimately caused no problems or disruption in his family.

To summarize, the fourth archetype is labeled Uninvolved Family, because of the largely absent and negative relations between the family members with the family collective, and with external entities. The family members in this family archetype were remarkably emotionally unaware and unsupportive of how the others were doing, and uncommunicative, even though they had notable reactions. Family members portrayed the family’s dynamics as having no long-term impact from the disaster, which may simply reflect their minimal mutual engagement present even before 9/11. Years later, the family still did not discuss the events of 9/11 or their emotions. Communicating feelings and lending support to one another may not have been options in this uninvolved family without severely adjusting the established family dynamics. Furthermore, there was little positive family connection to external community support aside from the mother’s positive faith connection. The main response to the emotional pain and suffering in this family seems to have been to deny that there were problems or that the 9/11 attacks had affected the family.

This study combined quantitative and qualitative data using structured diagnostic interviews and accompanying open-ended narratives of family members (spouses and children) of 25 employees of businesses affected by the 9/11 attacks. Using mixed methods and a systems approach to data analysis, this study contributes new insights toward understanding the role of family dynamics in mental health outcomes after disasters.

The probands in this study’s families were highly 9/11 trauma-exposed, and although few of their spouses or children had direct or witnessed exposures, more than one-fourth of the spouses and nearly one-half of the children were indirectly exposed through a loved one. It could be speculated that the finding of nearly one-fourth of probands developing 9/11-related PTSD suggests the potential for individuals with 9/11 trauma exposures and disaster-related psychopathology to affect and be affected by family members. Investigation of such possibilities would require collection of more detailed data to conduct definitive multivariate model testing of all the relevant variables to examine various potential relationships. In these data, proband exposures and PTSD did not regularly appear to propagate straightforwardly to psychopathology in their spouses or children. This finding suggests that family relationships in the post-disaster setting likely consist of multi-component interactions operating simultaneously within family systems and with outside connections. The qualitative data illuminated detailed disaster mental health dynamics of family systems.

This study’s findings are not unintuitive based on published results from prior research. Consistent with this study’s findings, parents and children have been found to affect one another [16]. Additionally, consistent with the current study’s findings, mental health interventions have been found to be important to families affected by disasters in recent research [9,29] and reviews and commentaries [10,30–32], including articles specific to children [33,34]. External resources found in the literature that reflect this study’s findings are the utility of spiritual/religious resources [4,7], social connectedness [2,7,12,30], and organizational efforts in the community [6,8], specifically including the workplace [10] and schools [12,34].

Although the family systems examined in this study do not strictly generalize, they do point to some potential ways that families may respond to disaster, labelled herein as “archetypal” family system responses. Not all families can be expected to be the same, as revealed by the distinct family archetypes observed in this study. Evident patterns of typical post-disaster family systems came into focus with in-depth analysis of 4 illustrative families, based on how individual family members experienced the disaster and how families interacted with factors internal and external to them. The existence and further development of effective communication skills also varied across the family archetypes. Whether families remained static or developed new dynamics appeared to relate to healing within members or across the system.

Engaging with or ignoring the outside world also likely affected family responses in various ways. Family dynamics before the disaster and how those dynamics changed or failed to change constituted important features of family responses. These archetypes exemplify dimensions of family system dynamics that include both negative interactions that might be linked to psychopathology and positive interactions that might reflect resilience and positive coping. The former could be targeted for treatment, and the latter nurtured in family interventions. For example, therapy might focus on strengthening the family collective as well as developing healthier interactions within family member dyads to provide greater support and family healing. Problems connecting with and benefiting from therapy, illustrated by some family members in this study, suggest the need for efforts to improve the acceptability and utility of therapy for these members. Several external resources that might be utilized to help these families navigate their difficult circumstances appear from these data to include existing faith communities and work and school environments that could be leveraged, such as through special programs targeting their post-disaster social support needs. These findings very much reflect the conclusion of Tekin and colleagues in their study of hurricane survivors, emphasizing the need to include resources beyond the individual level [12]. These illustrative families by no means represent the only possible family constellations, but they are noteworthy examples of a starting place to inform consideration of the effects of disaster on family systems beyond the typical focus on individuals.

Central to the inherent value of this study is its use of both quantitative and qualitative data. Its scope transcended single individuals and dyads within families to examine relationships among multiple family members and with external community factors, using a broad family systems perspective. Structured diagnostic interviews provided full assessment of established diagnostic criteria for PTSD, MDD, and other selected psychiatric disorders, both before and after the disaster [24]. This sample consisted of families of highly trauma-exposed employees, with nearly one-half directly exposed to 9/11 trauma, including 24% who were in the towers during the attacks.

A limitation of this study’s volunteer sample is that it may have introduced selection bias by underrepresenting individuals on both ends of the spectrum: those with psychopathology who avoided research participation and those unmotivated to participate because of feeling unaffected by the disaster. This potential bias is possibly reflected in the predominantly Caucasian, married, and well-educated study sample’s demographics, which may not represent all families. Because the sample was relatively small (60 members in 25 families), the findings may not generalize. The 4 illustrative families were selected for indicators of 9/11 impact, and thus, their experience may be more intense than in other families. The timing of the interviews was not uniform (3–6 years post disaster), potentially adding artifactual imprecision.

This study’s findings suggest that family systems and family dynamics may influence not only how the disaster trauma-exposed member but also other family members cope with the disaster experience and support one another in their journey toward healing. This information may help guide disaster response efforts to provide psychosocial support to disaster trauma-exposed families. Families may respond in different identifiable patterns, which may suggest potential opportunities for tailoring interventions for different family archetypes. Clinicians and other disaster responders need to be sensitive to the different ways in which family members interact with each other, and to how families and individual family members interact with outside systems, in developing intervention strategies. In functional and supportive families, relationships within and outside of the family can represent opportunities for intervention for the directly exposed member and for other affected members.

Family systems clearly represent an unrealized, but important, potential part of developing disaster response strategies. While not all individuals have supportive or even intact families, families that are engaged and communicate effectively represent a potentially important opportunity for promoting positive outcomes. Intervening at the family level presents an opening for mutual support that can benefit all members. An intriguing opportunity for developing disaster responses might be in incorporating multiple families as a means of mutual support, perhaps through multifamily group interventions. Multifamily groups, particularly in problem-solving and educational psychoeducation models, have a long history of effective interventions for supporting family members with a variety of clinical issues.

Additional research is needed to further examine family dynamics in disaster mental health beyond the beginnings of the family archetypes presented here. This can help determine whether these patterns generalize across families and different disasters, as well as identify the likely existence of other archetypes of family dynamics responding to disasters. Prospective longitudinal studies of disaster-affected families proceeding from immediately post-disaster through time are needed to understand the evolution of individual and family coping and the role that family dynamics play at various points in this process. The traditional definition of family could use further exploration to include nonconventional families that are defined by affective bonds but not necessarily biological ties. Such “families” may represent equally fruitful directions for mutual support, further informing disaster interventions. Minimally, the findings from this study demonstrate the need to examine systems beyond the individual as potential avenues for improving clinical responses to disaster victims. Finally, as an understanding of the role that family dynamics plays in supporting individuals and families advances, intervention research is needed using this knowledge to add to our toolkit of effective disaster interventions.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Grant MH68853 and the National Memorial Institute for the Prevention of Terrorism (MIPT) and Office of State and Local Government Coordination and Preparedness, US Department of Homeland Security MIPT106-113-2000-020.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Carol S. North, David E. Pollio; methodology, Carol S. North, David E. Pollio; data managements, Carol S. North; qualitative analysis validation, Cesar E. Montelongo Hernandez, Carol S. North, David E. Pollio; formal qualitative analysis, Cesar E. Montelongo Hernandez, Carol S. North, David E. Pollio; investigation, Cesar E. Montelongo Hernandez, Carol S. North, E. Whitney Pollio, David E. Pollio; resources, Carol S. North; data curation, Cesar E. Montelongo Hernandez, Carol S. North, David E. Pollio; writing—original draft preparation, Cesar E. Montelongo Hernandez, Carol S. North, E. Whitney Pollio, David E. Pollio; writing—review and editing, Cesar E. Montelongo Hernandez, Carol S. North, E. Whitney Pollio, David E. Pollio; visualization, Cesar E. Montelongo Hernandez, Carol S. North, E. Whitney Pollio, David E. Pollio; supervision, Carol S. North, David E. Pollio; project administration, Carol S. North, David E. Pollio. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was provided by Washington University (approval #02-041 and #00-0922) and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (approval #092010-006 and #052011-079), and all written informed consent was provided by adult participants and assent by minor children.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mirza MNEE, Rana IA. A systematic review of urban terrorism literature: root causes, thematic trends, and future directions. J Saf Sci Resil. 2024;5(3):249–65. doi:10.1016/j.jnlssr.2024.03.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mao W, Agyapong VIO. The role of social determinants in mental health and resilience after disasters: implications for public health policy and practice. Front Public Health. 2021;9:658528. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.658528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Umeda M, Chiba R, Sasaki M, Agustini EN, Mashino S. A literature review on psychosocial support for disaster responders: qualitative synthesis with recommended actions for protecting and promoting the mental health of responders. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(6):2011. doi:10.3390/ijerph17062011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Yoosefi Lebni J, Khorami F, Ebadi Fard Azar F, Khosravi B, Safari H, Ziapour A. Experiences of rural women with damages resulting from an earthquake in Iran: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):625. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-08752-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Schwaiger K, Zehrer A, Braun B. Organizational resilience in hospitality family businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative approach. Tour Rev. 2021;77(1):163–76. doi:10.1108/tr-01-2021-0035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Abdi A, Vaisi-Raygani A, Najafi B, Saidi H, Moradi K. Reflecting on the challenges encountered by nurses at the great Kermanshah earthquake: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(1):90. doi:10.1186/s12912-021-00605-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Salik H, Şahin M, Uslu Ö. Experiences of nurses providing care to individuals in earthquake-affected areas of Eastern Turkey: a phenomenological study. J Community Health Nurs. 2024;41(2):110–22. doi:10.1080/07370016.2023.2285964. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Scrymgeour GC, Smith L, Maxwell H, Paton D. Nurses working in healthcare facilities during natural disasters: a qualitative enquiry. Int Nurs Rev. 2020;67(3):427–35. doi:10.1111/inr.12614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Parrott E, Lomeli-Rodriguez M, Burgess R, Rahman A, Direzkia Y, Joffe H. The role of teachers in fostering resilience after a disaster in Indonesia. Sch Ment Health. 2025;17(1):118–36. doi:10.1007/s12310-024-09709-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. May K, Van Hooff M, Doherty M, Iannos M. Experiences and perceptions of family members of emergency first responders with post-traumatic stress disorder: a qualitative systematic review. JBI Evid Synth. 2023;21(4):629–68. doi:10.11124/jbies-21-00433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Pfefferbaum B, Simic Z, North CS. Parent-reported child reactions to the September 11, 2001 world trade center attacks (New York USA) in relation to parent post-disaster psychopathology three years after the event. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2018;33(5):558–64. doi:10.1017/s1049023x18000869. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Tekin S, Burrows K, Billings J, Waters M, Lowe SR. Psychosocial resources underlying disaster survivors’ posttraumatic stress symptom trajectories: insight from in-depth interviews with mothers who survived Hurricane Katrina. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2023;14(2):2211355. doi:10.1080/20008066.2023.2211355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Gökalp K, Kemer AS. Mothers’ and children’s thoughts on COVID-19: a qualitative study. J Pediatr Nurs. 2022;67(6):38–43. doi:10.1016/j.pedn.2022.07.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Niazi IUHK, Rana IA, Arshad HSH, Lodhi RH, Najam FA, Jamshed A. Psychological resilience of children in a multi-hazard environment: an index-based approach. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022;83(1):103397. doi:10.1016/j.ijdrr.2022.103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kaplan V, Düken ME, Kaya R, Alkasaby M. The impact of Kahramanmaraş (2023) earthquake on adolescents: exploring psychological impact, suicide possibility and future expectations. Glob Ment Health Camb Engl. 2024;11:e115. doi:10.1017/gmh.2024.90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Felix ED, Afifi TD, Horan SM, Meskunas H, Garber A. Why family communication matters: the role of co-rumination and topic avoidance in understanding post-disaster mental health. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2020;48(11):1511–24. doi:10.1007/s10802-020-00688-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Russell BS, Hutchison M, Tambling R, Tomkunas AJ, Horton AL. Initial challenges of caregiving during COVID-19: caregiver burden, mental health, and the parent-child relationship. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2020;51(5):671–82. doi:10.1007/s10578-020-01037-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Beitin BK, Allen KR. Resilience in Arab American couples after September 11, 2001: a systems perspective. J Marital Fam Ther. 2005;31(3):251–67. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2005.tb01567.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Cohan CL, Cole SW, Schoen R. Divorce following the September 11 terrorist attacks. J Soc Pers Relatsh. 2009;26(4):512–30. doi:10.1177/0265407509351043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bauwens J. Losing a family member in an act of terror: a review from the qualitative grey literature on the long-term affects of September 11, 2001. Clin Soc Work J. 2017;45(2):146–58. doi:10.1007/s10615-017-0621-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Webb EK, Stevens JS, Ely TD, Lebois LAM, van Rooij SJH, Bruce SE, et al. Neighborhood resources associated with psychological trajectories and neural reactivity to reward after trauma. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81(11):1090–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

22. Randle E, Pollio E, Pollio D, North C. Qualitative investigation of effects of 9/11 attacks on individuals working in or near the world trade center. Dir Psychiatry. 2018;38(3):165–71. [Google Scholar]

23. Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design [Internet]. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press; 1979 [cited 2025 Jan 18]. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv26071r6. [Google Scholar]

24. North CS, Pollio DE, Smith RP, King RV, Pandya A, Surís AM, et al. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder among employees of New York City companies affected by the September 11, 2001 attacks on the world trade center. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2011;5(S2):S205–13. doi:10.1001/dmp.2011.50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Robins L, Cottler L, Bucholz K, Compton W. Diagnostic interview schedule for DSM-IV (DIS-IV). St. Louis, MO, USA: Washington University; 1995. 145 p. [Google Scholar]

26. North CS, Pfefferbaum B, Robins L, Smith EM. The disaster supplement to the diagnostic interview schedule for DSM-IV (DIS-IV/DS). St. Louis, MO, USA: Washington University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

27. Padgett DK. Qualitative methods in social work research. Los Angeles, CA, USA: SAGE Publications; 2016. 353 p. [Google Scholar]

28. Luna-Reyes LF, Andersen DL. Collecting and analyzing qualitative data for system dynamics: methods and models. Syst Dyn Rev. 2003;19(4):271–96. doi:10.1002/sdr.280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhuang X, Li Q, Liu S, Mo J. Forbearance coping, community resilience, family resilience and mental health during the post-pandemic in China: a moderated mediation model. Psychiatry Investig. 2024;21(12):1349–59. doi:10.30773/pi.2024.0162. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Saeed SA, Gargano SP. Natural disasters and mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry Abingdon Engl. 2022;34(1):16–25. [Google Scholar]

31. Danese A, Smith P, Chitsabesan P, Dubicka B. Child and adolescent mental health amidst emergencies and disasters. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2020;216(3):159–62. doi:10.1192/bjp.2019.244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Hsieh KY, Kao WT, Li DJ, Lu WC, Tsai KY, Chen WJ, et al. Mental health in biological disasters: from SARS to COVID-19. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;67(5):576–86. doi:10.1177/0020764020944200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Stark AM, White AE, Rotter NS, Basu A. Shifting from survival to supporting resilience in children and families in the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons for informing U.S. mental health priorities. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(S1):S133–5. doi:10.1037/tra0000781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Pfefferbaum B. Challenges for child mental health raised by school closure and home confinement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2021;23(10):65. doi:10.1007/s11920-021-01279-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools