Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

3D Photogrammetric Modelling for Digital Twin Development: Accuracy Assessment Using UAV Multi-Altitude Imaging

Centre of Studies for Surveying Science and Geomatics, Faculty of Built Environment, Universiti Teknologi MARA, Shah Alam, 40450, Selangor, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Khairul Nizam Tahar. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative Applications and Developments in Geomatics Technology)

Revue Internationale de Géomatique 2026, 35, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.32604/rig.2026.070991

Received 29 July 2025; Accepted 04 December 2025; Issue published 19 January 2026

Abstract

The use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in photogrammetry has grown rapidly due to enhanced flight stability, high-resolution imaging, and advanced Structure from Motion (SfM) algorithms. This study investigates the potential of UAVs as a cost-effective alternative to Terrestrial Laser Scanners (TLS) for 3D building reconstruction. A 3D model of Bangunan Sarjana was generated in Agisoft Metashape Professional v.2.0.2 using 492 aerial images captured at flying altitudes of 40, 50, and 60 m. Ground control points were established using GNSS (RTK-VRS), and Total Station measurements were employed for accuracy validation. The results indicate that the 60 m flight produced the most accurate reconstruction, with a maximum dimensional deviation of 0.051 m. These findings demonstrate that UAV photogrammetry can achieve centimetre-level accuracy in building modelling while significantly reducing costs and operational effort. The study highlights the integration of SfM processing with UAV technology as a practical and efficient method for spatial data acquisition, supporting applications in urban planning, digital twin development, and heritage documentation.Keywords

Recent advances in digital documentation have demonstrated the combined potential of Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS) and photogrammetry for generating dense point clouds, 3D mesh models, deformation analyses, orthogonal projections, and sectional studies [1]. However, TLS workflows remain complex: registration, filtering, and meshing can accumulate errors that compromise geometric accuracy, while hardware limitations and large data volumes present operational challenges [2,3].

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) augmented with photogrammetry offer a flexible alternative, providing high-resolution imagery, improved flight stability, and autonomous route execution [4–8]. When combined with Structure-from-Motion (SfM) algorithms and deep learning techniques, UAV photogrammetry enables automated feature extraction, robust image matching, and efficient 3D reconstruction workflows [9–11]. Flight altitude significantly influences geometric and textural accuracy. Lower altitudes generally yield higher point-cloud fidelity and better structural or vegetation measurements, while higher altitudes improve coverage but may reduce precision [12–15].

Beyond conventional mapping, UAV photogrammetry can support Digital Twin development, which are dynamic, high-fidelity 3D replicas of physical assets or environments that enable real-time monitoring, simulation, and decision-making. UAV-derived 2D orthophotos and 3D models serve as the geometric and textural foundation for these Digital Twins, offering a cost-effective and adaptable alternative to TLS for architectural and environmental surveys [16–18].

Building on these insights, this study investigates the trade-off between efficiency and geometric accuracy in UAV-based photogrammetry. High-resolution 3D models of the Bangunan Sarjana building were generated at multiple flight altitudes, and their accuracy was evaluated against on-site measurements. This study provides guidance for optimal UAV flight planning and contributes to the broader implementation of UAV-enabled Digital Twins for architectural and infrastructure monitoring.

The methodological framework employed in this study is divided into four systematic phases, beginning with the preliminary study. This initial phase includes defining the research location specifically, the Bangunan Sarjana building and selecting appropriate software tools and UAV systems for data acquisition and processing. Considerations at this stage include software compatibility with photogrammetric algorithms, hardware capabilities, and computational requirements necessary for handling large datasets efficiently.

The second phase entails data acquisition, involving site visits and the execution of UAV flight plans. Flights are conducted at varying altitudes to assess the impact of flight height on model accuracy. Camera calibration and mission planning are performed prior to image capture to ensure optimal data quality, with attention given to overlap ratios, ground sampling distance (GSD), and lighting conditions. These parameters are essential for the success of downstream deep learning models used in image alignment and feature recognition.

In the data processing phase, the collected imagery is processed using photogrammetric software that automates point cloud generation, mesh creation, and texture mapping. Multi-View Stereo (MVS) techniques are applied to improve image correspondence, reduce noise, and accelerate processing time. The output of this phase is a detailed 3D model of the Bangunan Sarjana building that captures its geometric and textural attributes with high precision.

The final stage, results and analysis, focuses on evaluating the accuracy of the generated 3D model. This includes comparing the UAV-derived model with actual field measurements and reference data to assess spatial fidelity. Accuracy metrics such as Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and deviation analysis are applied to quantify model performance. Furthermore, the model is visualized using rendering and analysis tools to facilitate interpretation and support decision-making in urban documentation and architectural applications. Detailed discussions of each phase and additional results are presented in the following sections.

(a) Hardware

A DJI Phantom 4 Pro UAV was employed for aerial data collection due to its high image quality and stable flight performance. Flight missions were planned using the DJI GO 4 application, allowing pre-programmed autonomous flights to ensure consistent image capture. Circular orbit or Point of Interest (POI) flight paths were used to maintain a constant distance from the building façade, ensuring uniform coverage from all viewing angles. Flights at 40, 50, and 60 m were used to evaluate the influence of flight height on model accuracy and image resolution. Corresponding POI radius values of 5, 7, and 9 m were applied to maintain proper image scale and minimize occlusions. A gimbal tilt angle of 45° was selected to optimize façade and roof visibility. Forward and side overlaps of approximately 80% and 70% were maintained to meet photogrammetric accuracy standards, producing Ground Sampling Distances (GSD) of 1.05 cm/pixel (40 m), 1.31 cm/pixel (50 m), and 1.57 cm/pixel (60 m).

High-precision Ground Control Points (GCPs) were collected using CHC LandStar 7 with Real-Time Kinematic and Virtual Reference Station (RTK-VRS) technology. A fixed base station connected to the RTK network allowed real-time coordinate corrections during GCP collection. Post-processing of GNSS observations using CHCNAV software further refined positional accuracy. Total station measurements were processed with Topcon Tools to verify GCP coordinates through cross-validation.

All spatial data were referenced to the Malaysian Rectified Skew Orthomorphic (MRSO) map projection system, with elevations recorded relative to Mean Sea Level (MSL).

(b) Software

Raw UAV imagery was processed using PhotoModeler and Agisoft Metashape. PhotoModeler was used to calibrate the internal camera parameters, providing a reliable and automated calibration workflow. Agisoft Metashape was employed for image alignment, feature extraction, and 3D reconstruction, generating dense point clouds and textured 3D models. Automated feature matching facilitated robust tie-point extraction and reconstruction workflows suitable for building-scale modeling.

To ensure the accuracy and completeness of the 3D reconstruction, data acquisition combined UAV imagery, GNSS observations, and ground-based measurements.

(a) GNSS Observations

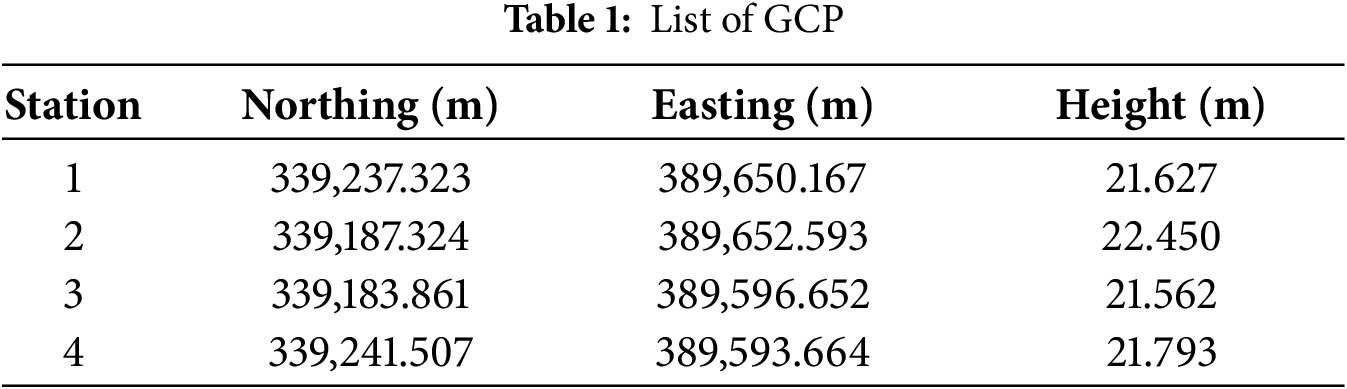

High-precision GCP coordinates were obtained using RTK-VRS techniques (Table 1, Fig. 1). These GCPs served as georeferencing anchors, enhancing the spatial accuracy of the 3D model and providing a benchmark for error assessment.

Figure 1: Location of GCPs in the study area

(b) UAV-Based Aerial Imagery

High-resolution imagery was acquired at 40, 50, and 60 m altitudes to support SfM and Multi-View Stereo (MVS) processing. Circular or POI flight paths ensured consistent camera orientation, maximizing image overlap and minimizing occlusions. Automated waypoint generation allowed repeatable flight trajectories for uniform image acquisition.

(c) Total Station Measurements

Ground truth data of key building elements were collected using a total station to validate the geometric accuracy of UAV-derived 3D models. These measurements were critical in areas where occlusion or complex geometry could limit UAV data quality. The 3D model’s dimensional attributes were compared with terrestrial measurements to evaluate correspondence. Minimal deviation between model-derived and ground-truth dimensions confirmed the reliability of the photogrammetric workflow for detailed structural documentation.

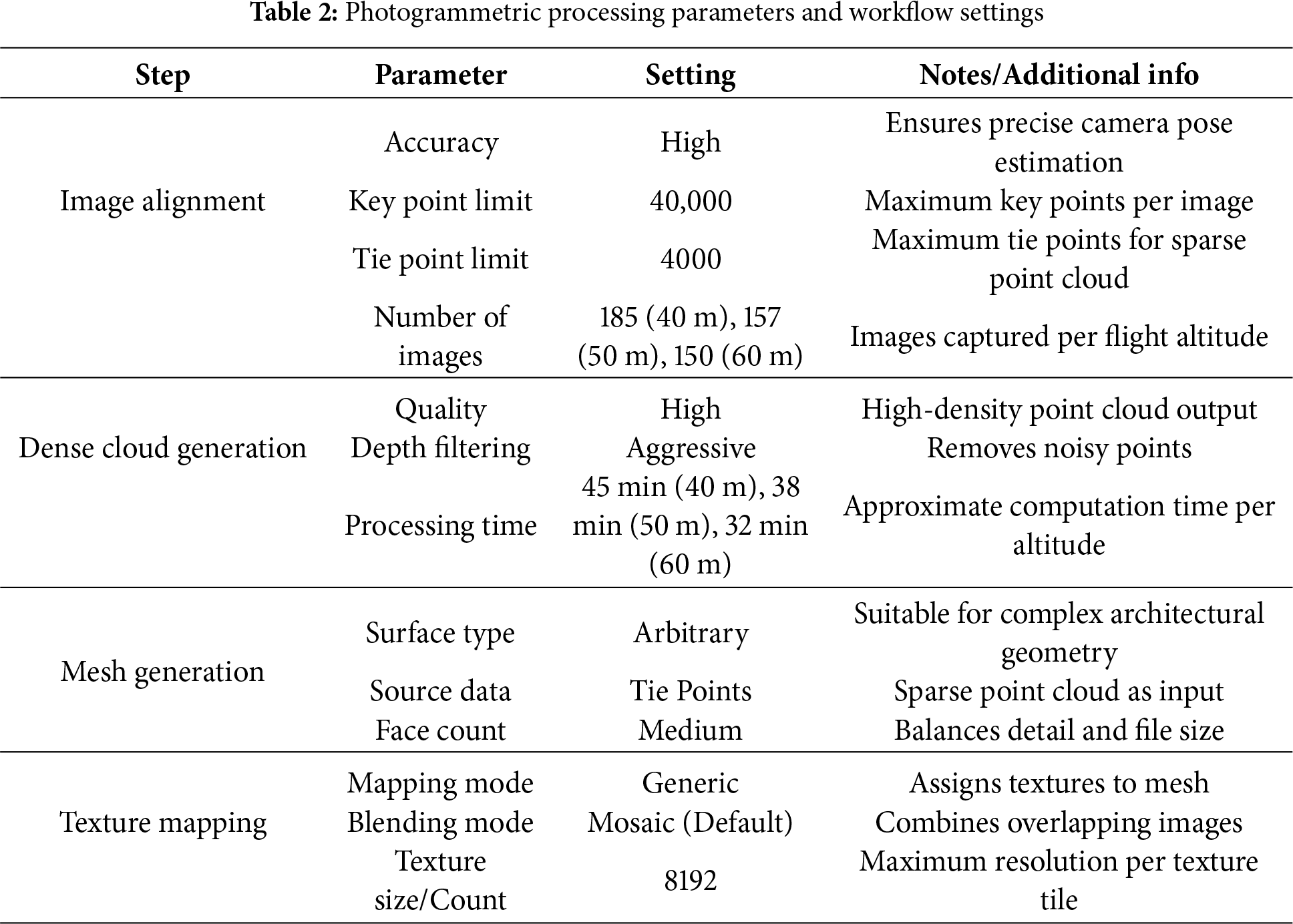

In this study, Agisoft Metashape was employed as the primary photogrammetric software to process aerial imagery captured by unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). The processing parameters, including alignment accuracy, key point limit, and depth filtering mode, were selected based on trial runs and best practices reported in recent UAV photogrammetry literature to achieve an optimal balance between computational efficiency and model precision. The configuration parameters used during each processing stage are summarized in Table 2.

The photogrammetric workflow in Agisoft Metashape successfully reconstructed the spatial configuration of UAV-acquired imagery. The image alignment process produced a sparse point cloud with uniform camera positions, indicating sufficient image overlap and stable bundle adjustment (Fig. 2a). Tie-point extraction was reliable across all altitudes, providing a foundation for dense cloud generation and mesh reconstruction.

Figure 2: Sequential outputs of the photogrammetric processing pipeline: (a) image alignment yielding estimated camera orientations and a sparse tie-point network, (b) dense point cloud generation produced via multi-view stereo reconstruction, (c) surface meshing derived from the densified point cloud, and (d) texture mapping integrating radiometric information onto the triangulated mesh

Dense point clouds were generated to provide detailed geometric representation of the Bangunan Sarjana building (Fig. 2b). The subsequent mesh reconstruction accurately captured architectural features, including the façade and roof elements (Fig. 2c). Texture mapping enhanced visual realism, resulting in a fully textured 3D model that closely represents the physical building (Fig. 2d). These outputs confirm that the photogrammetric workflow preserves both geometric accuracy and visual fidelity.

3D models were reconstructed using UAV imagery captured at 40, 50, and 60 m altitudes, producing datasets with distinct spatial resolutions, ground sampling distances (GSD), and model fidelity. Flight altitude influenced tie-point quality, coverage, and occlusion effects. Lower altitudes (40 m) produced finer geometric detail but increased the number of images and risk of occlusion, whereas higher altitudes (60 m) reduced occlusions and provided consistent tie-point distribution, but slightly decreased geometric resolution.

The 40 m model provided high-detail features for close-up architectural elements; however, some occlusions occurred near roof edges, and mesh continuity was occasionally disrupted by perspective distortion. The 50 m model achieved an optimal balance between GSD, tie-point reliability, and coverage, resulting in smooth surface continuity with minimal occlusions. The 60 m model displayed the clearest overall structural representation, with fewer artifacts and consistent tie-point extraction, although fine roof details were slightly less defined. This underscores the importance of altitude optimization in UAV photogrammetry for producing high-fidelity 3D models and digital twins.

3.1 Geometric Accuracy Analysis

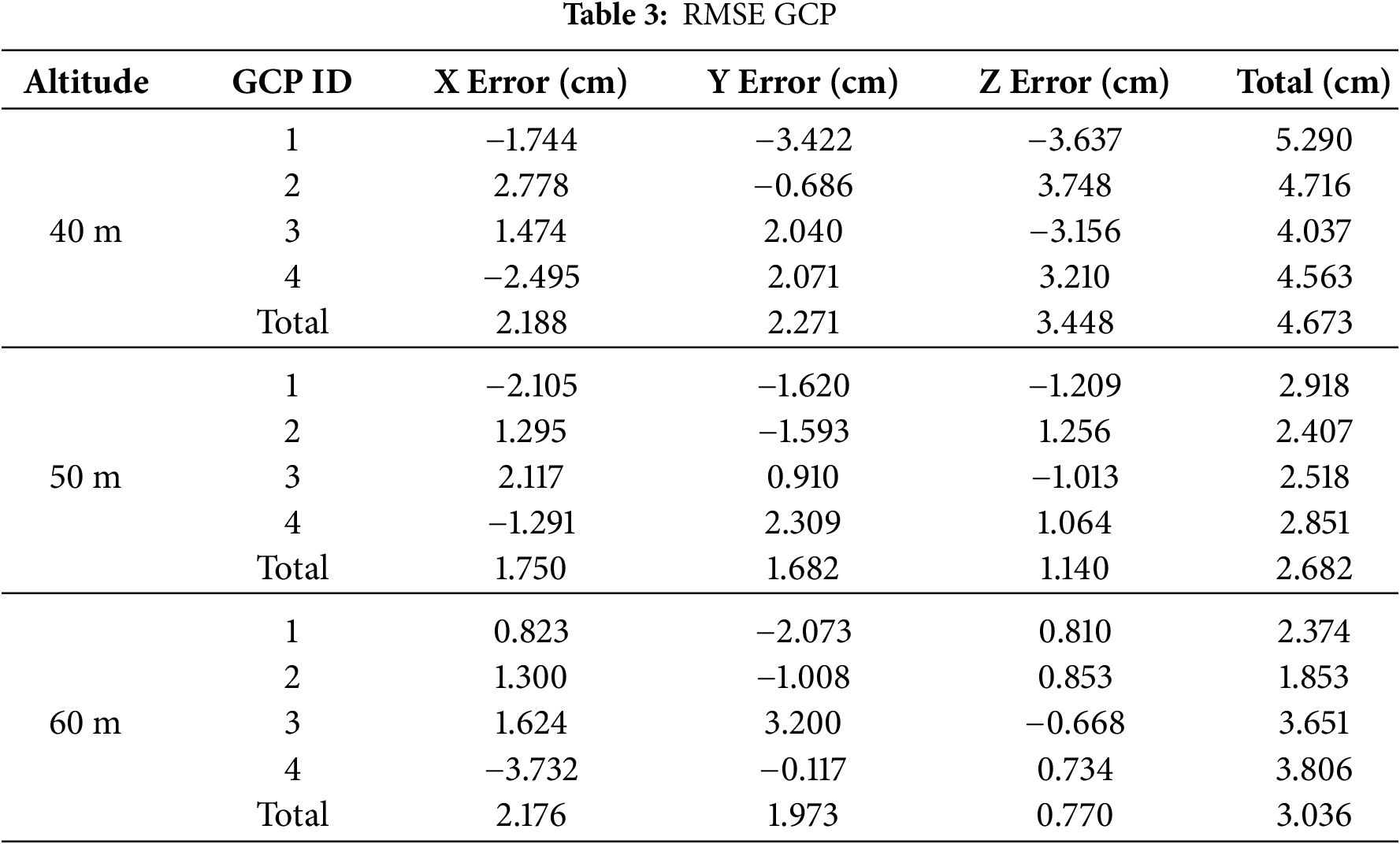

RMSE analysis of Ground Control Points (GCPs) evaluated the accuracy of 3D reconstructions (Table 3). Horizontal (X, Y) RMSE values ranged from 0.018–0.022 m, while vertical (Z) RMSE improved with altitude: 0.034 at 40 m, 0.014 at 50 m, and 0.008 at 60 m. Total RMSE values were 0.046, 0.026, and 0.030 m for 40, 50, and 60 m, respectively, demonstrating sub-decimeter accuracy suitable for architectural documentation, urban mapping, and heritage preservation.

The RMSE trends indicate that higher altitudes reduce vertical error, while horizontal error remains relatively stable. Differences in accuracy among altitudes are largely attributable to variations in GSD and parallax quality, which directly influence tie-point extraction and dense cloud generation. Lower altitudes improve geometric detail but increase image count and processing load, while higher altitudes reduce occlusions but slightly decrease resolution.

Field-based total station measurements were compared with reconstructed 3D model dimensions to evaluate dimensional fidelity. The RMSE between model and field measurements was 0.052 m (40 m), 0.054 m (50 m), and 0.051 m (60 m), confirming sub-centimeter-level accuracy across altitudes. These values align with prior studies ( [19–23]), which reported RMSE ranging from 0.015–0.059 m depending on workflow and sensor setup, validating the reliability of UAV photogrammetry for precise architectural modeling.

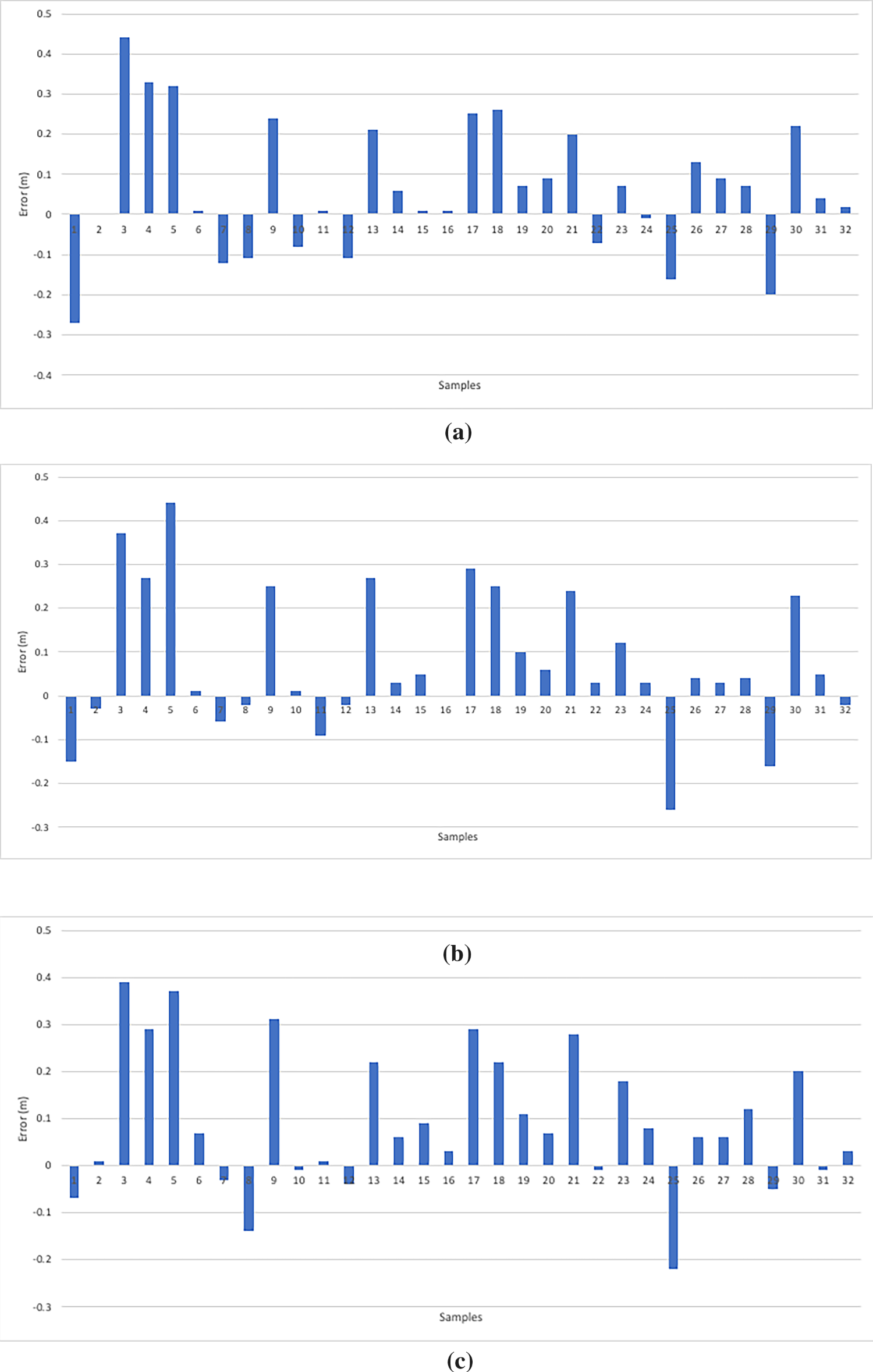

Error distributions (Fig. 3) reveal that maximum positive deviations were +0.44 m (40, 50 m) and +0.39 m (60 m), while minimum negative deviations were −0.27, −0.26, and −0.22 m, respectively. These results confirm that feature matching and surface reconstruction are robust across altitudes, while minor deviations reflect occlusions and perspective distortions.

Figure 3: Error between actual and 3D model; (a) 40 m, (b) 50 m, (c) 60 m

Overall, the findings demonstrate that UAV photogrammetry generates high-fidelity 3D models suitable for architectural documentation, digital twin development, and urban heritage preservation. Flight altitude critically affects GSD, tie-point quality, occlusion, and RMSE, providing practical guidance for UAV survey design. The controlled evaluation on Bangunan Sarjana establishes a baseline for multi-building studies and integration with complementary sensing technologies in future research.

This study confirms that UAV photogrammetry can generate high-precision 3D building models suitable for advanced geospatial applications. Among the tested flight altitudes, 60 m produced the most accurate and structurally consistent model, indicating its suitability for efficient data acquisition and reliable reconstruction. The resulting 3D outputs demonstrate strong potential for Digital Twin development, offering scalability for integration with GIS-based simulations, urban monitoring, and infrastructure analytics. However, the findings are constrained by the single-building scope and ideal weather conditions during data capture, which may limit generalisation across different environments or highly occluded structures. Overall, UAV-based modelling provides a cost-effective and operationally efficient alternative to traditional methods, with clear applicability in engineering surveying, urban planning, heritage documentation, and broader geospatial analysis.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) and Lembaga Jurukur Tanah Malaysia for providing the support and resources necessary to carry out this research. The authors also sincerely thank all individuals who contributed, either directly or indirectly, to the successful completion of this study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, Nur Afikah Juhari and Khairul Nizam Tahar; methodology, Khairul Nizam Tahar; software, Nur Afikah Juhari; validation, Nur Afikah Juhari and Khairul Nizam Tahar; formal analysis, Khairul Nizam Tahar; investigation, Nur Afikah Juhari; resources, Khairul Nizam Tahar; data curation, Khairul Nizam Tahar; writing original draft preparation, Nur Afikah Juhari; writing review and editing, Khairul Nizam Tahar; visualization, Nur Afikah Juhari; supervision, Khairul Nizam Tahar; project administration, Khairul Nizam Tahar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Putra WB, Faisal G, Dewi NIK, Firzal Y. Unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) photogrammetry for heritage building documentation: case study sasaksaat train station, bandung, Indonesia. Int J Environ Archit Soc. 2023;3(2):72–86. doi:10.26418/ijeas.2023.3.02.72-86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Llabani A, Lubonja O. Integrating UAV photogrammetry and terrestrial laser scanning for the 3D surveying of the fortress of bashtova. Wseas Trans Environ Dev. 2024;20:306–15. doi:10.37394/232015.2024.20.30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Conti A, Pagliaricci G, Bonora V, Tucci G. A comparison between terrestrial laser scanning and hand-held mobile mapping for the documentation of built heritage. Int Arch Photogramm Remote Sens Spatial Inf Sci. 2024;48:141–7. doi:10.5194/isprs-archives-xlviii-2-w4-2024-141-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhou M, Li C, Li Z. Extraction of individual tree attributes using ultra-high-density point clouds acquired by low-cost UAV-LiDAR in Eucalyptus plantations. Ann For Sci. 2025;82(1):20. doi:10.1186/s13595-025-01291-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Abujayyab SKM, Almajalid R, Wazirali R, Ahmad R, Taşoğlu E, Karas IR, et al. Integrating object-based and pixel-based segmentation for building footprint extraction from satellite images. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci. 2023;35(10):101802. doi:10.1016/j.jksuci.2023.101802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kovanič Ľ, Topitzer B, Peťovský P, Blišťan P, Gergeľová MB, Blišťanová M. Review of photogrammetric and lidar applications of UAV. Appl Sci. 2023;13(11):6732. doi:10.3390/app13116732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Li S, Tan Y, Zhou Z, Chen P, Li C, Zhou C. Enhancing 3D building reconstruction quality using UAV multi-view photogrammetry and multi-modal large models. Autom Constr. 2026;181(17):106664. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2025.106664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Phojaem T, Dangbut A, Wisutwattanasak P, Janhuaton T, Champahom T, Ratanavaraha V, et al. Evaluating UAV flight parameters for high-accuracy in road accident scene documentation: a planimetric assessment under simulated roadway conditions. ISPRS Int J Geo Inf. 2025;14(9):357. doi:10.3390/ijgi14090357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Pan W, Wang X, Sun Y, Wang J, Li Y, Li S. Karst vegetation coverage detection using UAV multispectral vegetation indices and machine learning algorithm. Plant Methods. 2023;19(1):7. doi:10.1186/s13007-023-00982-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Ikeda H, Bibish B, Fissha Y, Sinaice BB, Toriya H, Adachi T, et al. Advanced UAV photogrammetry for precision 3D modeling in GPS denied inaccessible tunnels. Saf Extreme Environ. 2024;6:269–87. doi:10.1007/s42797-024-00109-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Niu Z, Xia H, Tao P, Ke T. Accuracy assessment of UAV photogrammetry system with RTK measurements for direct georeferencing. ISPRS Ann Photogramm Remote Sens Spatial Inf Sci. 2024;10:169–76. doi:10.5194/isprs-annals-x-1-2024-169-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Stamenković Z, Kešelj K, Kostić M, Aćin V, Tekić D, Ivanišević M, et al. Assessing the impact of UAV flight altitudes on the accuracy of multispectral indices. Contemp Agric. 2024;73(3–4):157–64. doi:10.2478/contagri-2024-0019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Lopes Bento N, Araújo E Silva Ferraz G, Alexandre Pena Barata R, Santos Santana L, Diennevan Souza Barbosa B, Conti L, et al. Overlap influence in images obtained by an unmanned aerial vehicle on a digital terrain model of altimetric precision. Eur J Remote Sens. 2022;55(1):2054028. doi:10.1080/22797254.2022.2054028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Marcello J, Spínola M, Albors L, Marqués F, Rodríguez-Esparragón D, Eugenio F. Performance of individual tree segmentation algorithms in forest ecosystems using UAV LiDAR data. Drones. 2024;8(12):772. doi:10.3390/drones8120772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gu Y, Wang Y, Guo T, Guo C, Wang X, Jiang C, et al. Assessment of the influence of UAV-borne LiDAR scan angle and flight altitude on the estimation of wheat structural metrics with different leaf angle distributions. Comput Electron Agric. 2024;220(1–2):108858. doi:10.1016/j.compag.2024.108858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wang Y, Chew AWZ, Zhang L. Building damage detection from satellite images after natural disasters on extremely imbalanced datasets. Autom Constr. 2022;140(3):104328. doi:10.1016/j.autcon.2022.104328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Dahaghin M, Samadzadegan F, Dadrass Javan F. Precise 3D extraction of building roofs by fusion of UAV-based thermal and visible images. Int J Remote Sens. 2021;42(18):7002–30. doi:10.1080/01431161.2021.1951875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Jati DGP. Uav-based photogrammetry data transformation as a building inspection tool: applicability in mid-high-rise building. J Tek Sipil. 2021;16(2):113–21. doi:10.24002/jts.v16i2.4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Jarahizadeh S, Salehi B. A comparative analysis of UAV photogrammetric software performance for forest 3D modeling: a case study using AgiSoft Photoscan, PIX4DMapper, and DJI Terra. Sensors. 2024;24(1):286. doi:10.3390/s24010286. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Yoon J, Shin H, Kim K, Lee S. CNN- and UAV-based automatic 3D modeling methods for building exterior inspection. Buildings. 2024;14(1):5. doi:10.3390/buildings14010005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hermann M, Weinmann M, Nex F, Stathopoulou EK, Remondino F, Jutzi B, et al. Depth estimation and 3D reconstruction from UAV-borne imagery: evaluation on the UseGeo dataset. ISPRS Open J Photogramm Remote Sens. 2024;13:100065. doi:10.1016/j.ophoto.2024.100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Barba S, Barbarella M, Di Benedetto A, Fiani M, Gujski L, Limongiello M. Accuracy assessment of 3D photogrammetric models from an unmanned aerial vehicle. Drones. 2019;3(4):79. doi:10.3390/drones3040079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Arkalı M, Atik ME. Accuracy assessment of RTK, PPK, and PPP-AR techniques for direct georeferencing in UAV-based photogrammetric mapping. Int Arch Photogramm Remote Sens Spatial Inf Sci. 2025;48:325–30. doi:10.5194/isprs-archives-xlviii-m-6-2025-325-2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools