Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Assessing the Hematological Cancer Stem Cell Landscape to Improve Immunotherapy Clinical Decisions

1 Laboratory of Pharmacology, School of Pharmacy, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, 54124, Greece

2 Department of Health Sciences, School of Life and Health Sciences, University of Nicosia, Nicosia, CY-1700, Cyprus

3 Department of Medicine, School of Health Sciences, Democritus University of Thrace, Alexandroupolis, 68100, Greece

4 School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, 54124, Greece

* Corresponding Authors: Sotirios Charalampos Diamantoudis. Email: ,

; Ioannis S. Vizirianakis. Email:

,

# These authors contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Stem Cells Therapy in Health and Disease)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(10), 1799-1858. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.067216

Received 27 April 2025; Accepted 28 July 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

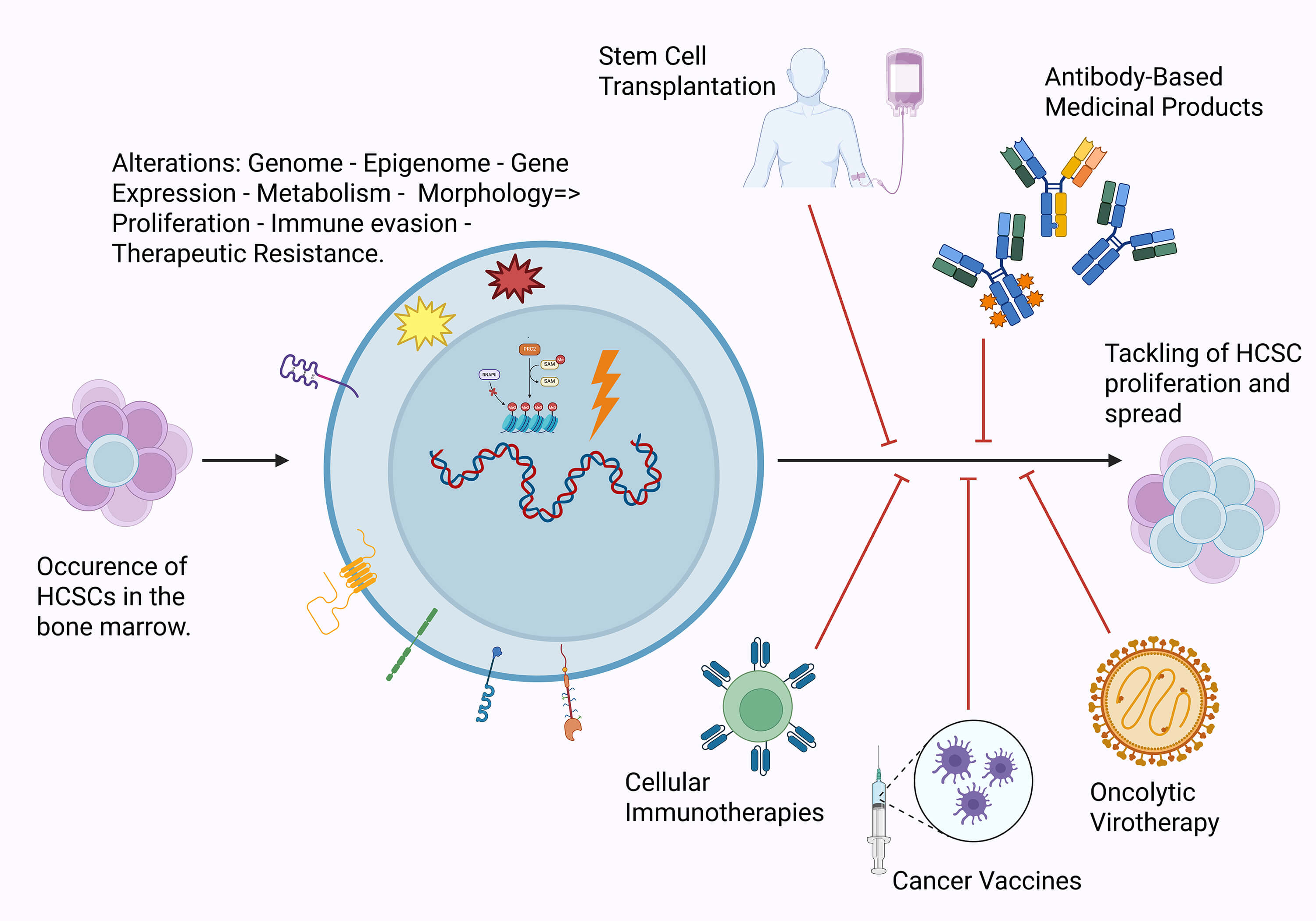

Hematological cancer stem cells (HCSCs) is a subpopulation of cells within hematological cancers that, through their characteristics, enhance malignancy and render their therapy more challenging. By uncovering the underlying mechanisms behind characteristic properties such as self-renewal, immune evasion, and conventional therapy resistance, as well as the major differences between other cancers and physiological cells, new and alternative targets can be assessed for use in existing and novel immunotherapeutic interventions. Through the evaluation of the existing literature, one can realize that there have already been several studies addressing the use of stem cell transplantation (SCT), monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), cell therapies, cancer vaccines, and oncolytic viruses, with varying degrees of success. As such, this study aims to combine existing information and clinical evidence to assess and bring to the spotlight targets related to HCSCs that can be considered for the improvement of therapeutic interventions.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Hematological cancers is a trending topic within modern oncology. Epidemiologic evidence addressing the period between 1990 and 2019 indicates an increase in the global prevalence of malignancies of the blood. Although this is highly concerning, the extent of the threat of this type of disease appears to be decreasing, as evident by the downward trend of the Age-Standardized Death Rate [1]. A plausible explanation for this phenomenon is the therapeutic methods applied within modern medicine that are characterized by the ever-increasing sophistication, targeting capabilities, safety, and effectiveness. These traits are allowed mostly on the basis of a better understanding of the exact pathophysiological mechanisms and advancements in the discovery, manufacturing, and application of more advanced medicinal products that have occurred in recent years. Nonetheless, the fact that blood cancers remain a huge burden for global health serves as a reminder that there is still plenty of room for research within the field.

There are several categories of blood cancers based on the affected cell types and other pathological evidence. Among those, there are leukaemias, which primarily affect the bone marrow and its capacity to produce functioning blood cells, and lymphomas, which originate in the lymphatic system. Additional categories include myelomas, which affect the plasma cells, myelodysplastic syndromes, and myeloproliferative neoplasms [2]. Additional classification under each category can be carried out by considering the timeline of the disease progression, origins and causes, affected cell populations, and other related pathological evidence. Out of these, leukemias (mostly acute) [3] seem to be at the focal point as they are the most prevalent ones in pediatric patients and, to an extent, contribute to the life years lost to cancer [4]. It is important to note that hematological cancer classification continuously evolves following advancements in detection and diagnosis techniques involving omics technologies [5–7].

Cancer stem cells (CSCs), also referred to as hematological/hematopoietic cancer stem cells (HCSCs), or leukemic stem cells (LSCs) in the context of the respective diseases, seem to have a special role in the pathophysiology and therapy of hematological cancers as they appear to be major drivers behind proliferation, immune evasion, therapy resistance, metastatic potential, and relapse [8,9]. CSCs’ relationship with blood cancers dates to the discovery and characterization of CSCs, also known as tumor initiating cells (TICs), in 1994, from a population of leukemic cells derived from a patient with acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). Those leukemic cells were the ones to be first characterized as LSCs and their characteristics/capabilities that, included, amongst others, seemingly unlimited proliferation, have sparked scientific interest ever since [10]. The origins of cancer stem cells are a complex topic that falls under the scope of many disciplines. Although there is extensive research still being conducted, evidence suggests that CSCs may occur from previously physiological stem cells or other types further into the differentiation process such as progenitors or fully differentiated cells. Nonetheless, it is accepted that the key identifying factors of CSCs are the markers they express and the behavior [11].

Granted, the burden of hematological malignancies on the life and the wellbeing of affected patients, with reflections into the society and the economy, and the ever-expanding need for impactful targets, it is important to address the role of HCSCs and the therapeutic value that can be extracted from their targeting.

2 Pathophysiology of the HCSCs

HCSCs possess a distinct set of properties that are crucial for their involvement in hematological cancers, enabling them to maintain tumor heterogeneity and drive disease progression [12]. Foremost among these, HCSCs exhibit key characteristics such as self-renewal, which allows them to sustain the hematological cancer cell (HCC) population, differentiation into various types of hematopoietic cells, and proliferation [13]. These traits are linked to several adverse consequences, including treatment resistance, tumor relapse, and metastatic spread [14]. Notably, these characteristics enable HCSCs to persist in the body, evade therapies, and contribute to the progression and recurrence of hematological malignancies such as leukaemia, making them a critical and promising target for therapeutic strategies aimed at improving patient outcomes [15]. Indeed, it has been found that LSCs, in the context of leukemia, exhibit a quiescent phenotype, which makes them resistant to conventional chemotherapy treatments that target rapidly dividing cells [16]. In addition to the aforementioned properties, HCSCs, as described in the following sections, exhibit genetic and epigenetic modifications, alterations in the programming of various signaling pathways, and distinct metabolic and phenotypic profiles compared to normal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) [17]. These differences make them key players in the progression and relapse of hematological malignancies.

Chromosomal abnormalities and gene mutations are key drivers of the transformation of HSCs into HCSCs, primarily promoting uncontrolled proliferation and impairing normal differentiation. In leukaemia, these genetic alterations occur in hematopoietic stem or progenitor cells, leading to the initiation of leukemogenesis and the disruption of normal blood cell development [18]. According to recent findings, the recurrent genetic mutations observed in leukaemia stem cells include genes such as NPM1, DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A), FLT3, RUNX1, and Ten-eleven translocation 2 (TET2), which are among the most frequently mutated [19]. Furthermore, mutations are commonly observed in genes like isocitrate dehydrogenase 1/2 (IDH1/2), KIT, NRAS, Wilms tumor 1 (WT1), TP53, protein tyrosine phosphatase non-receptor type 11 (PTPN11), U2 small nuclear RNA auxiliary factor 1 (U2AF1), structural maintenance of chromosomes 1A (SMC1A), structural maintenance of chromosomes 3 (SMC3), stromal antigen 2 (STAG2), RAD21, ASXL1/2, and enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) [20,21]. In addition to these changes, other genetic alterations, including chromosomal abnormalities (both numerical and structural), copy number variations (CNVs), uniparental isodisomies (UPDs), small insertions or deletions (indels), and single nucleotide variants (SNVs), also occur in HSCs [22]. Notably, gene fusions resulting from chromosomal translocations are a notable feature, with examples including RUNX1-ETO, PML-RARA, and various MLL fusions involving multiple partner genes [23]. Among the most critical genetic alterations driving the transformation of HSCs into cancerous stem cells are chromosomal abnormalities such as alterations in the 3q26 and 11q23 region [18,23]. Transcription factors like RUNX1 and CBFB are frequently targeted by translocations, including RUNX1::RUNX1T1 and CBFB::MYH11, as revealed through cytogenetic studies. Recurrent cytogenetic changes, including the loss of chromosomes −5/5q and −7/7q, the gain of chromosome +8, deletions in 17p [24] and specific translocations like t(7;12)(q36;p13) [25], further illustrate the genetic instability that underlies the development of hematologic malignancies. Acquired chromosomal abnormalities (aCNAs) and uniparental disomies (UPDs) such as del(2q33.3), del(3p14.2), del(4q22.1), UPD(13q), and del(17p13) are recurrently observed in HCSCs at relapse. Deletions like del(12p13) are linked to complex karyotypes and poor prognosis, while UPD(13q) and TP53 deletions in HCSCs at relapse are associated with therapy resistance and poor survival outcomes [22].

In HSCs, intracellular mechanisms that drive malignant transformation are rooted in not only genetic, but also epigenetic alterations. These changes disrupt normal gene expression and cellular function, enhancing the fitness of these cells and paving the way for their progression into malignancy. Epigenetic modifications, in particular, play a critical role in this process by dysregulating the transcription and translation of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Key mechanisms include alterations in histone modifications, abnormal DNA methylation patterns, and post-transcriptional control by non-coding RNAs such as lncRNAs and miRNAs [23]. In blood malignancies, histone modifications found on promoters are frequently enriched with H3K27me3, either individually or alongside H3K4me3, forming what are known as bivalent states [26]. These histone marks are inversely associated with DNA methylation and transcriptional activity. H3K27me3 is typically connected to promoter hypermethylation and gene repression in HSCs [27], whereas H3K4me3 is linked to reduced promoter methylation and increased gene expression [26].

Regarding non-coding RNAs, the lncRNA Xist (X-inactive specific transcript) plays a pivotal role in HSCs. Xist is known for its ability to recruit the polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) complex to target genes, leading to transcriptional silencing [28]. Its tumor-suppressive function is particularly significant in hematological cancers. Studies have shown that deletion of Xist in HSCs results in the development of myeloproliferative neoplasm and myelodysplastic syndrome (MPN/MDS) with full penetrance [29], highlighting its critical role in maintaining normal epigenetic regulation and preventing malignant transformation. Another lncRNA, eRNA LED (lncRNA activator of enhancer domains), regulates the expression of the P21 tumor suppressor by activating its enhancer. This process is often disrupted in blood cancers, including leukaemia and lymphoma, where LED is inactivated in HSCs through promoter methylation, leading to the loss of its tumor-suppressive activity [30]. At the same time, another study emphasized the role of miR-125b overexpression in the bone marrow, which contributed to the development of a myeloproliferative disorder that may eventually progress to myeloid leukaemia. In HSCs, the analysis of the miRNA signature revealed elevated levels of miR-101, miR-126, miR-99a, miR-135, and miR-20—a pattern also observed in megakaryoblastic leukemic cells [31].

Besides genetic and epigenetic modifications, the reprogramming of key signaling pathways in HCSCs plays a pivotal role in shaping their biology and paving the way for therapeutic strategies aimed at exploiting these alterations, particularly in the context of immunotherapy. One of the most extensively studied signaling pathways in leukaemia, particularly in chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML), but also in other cancers, is the nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) pathway [32]. The NF-κB pathway is a key transcriptional regulator in cancer progression, promoting cell growth, survival, metastasis, and chemotherapy resistance [32,33]. It is activated by cytokines and growth factors, which trigger the inhibitor of kappa B kinase (IKK) complex, leading to the phosphorylation and degradation of inhibitor of kappa B-alpha (IκB-α). This releases the p65/p50 complex, allowing it to activate target genes. The non-canonical pathway, involving p52 and NF-kappa B inducing kinase (NIK), also regulates cellular processes such as growth, apoptosis resistance, migration, and angiogenesis [33]. Beyond its involvement in CML bulk cells, NF-κB is involved in LSCs, where it contributes to their survival by promoting the secretion of transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [34,35]. Among the various pathways that regulate stem cell maintenance, the Hedgehog (HH) signaling pathway definitely plays a critical part. The HH signaling pathway is a tightly regulated network of ligands, receptors, co-regulators, signaling molecules, and transcription factors, which has been found to be deregulated in a variety of hematological cancers, including CML [36], multiple myeloma (MM) [37], chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) [38], B-cell non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) [39], AML [40], and T cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (T-ALL) [41]. The Hedgehog homologues Indian (IHH), Desert (DHH), and Sonic (SHH) bind to the receptor Patched (Ptc), promoting cell proliferation and survival. While DHH and IHH are deregulated in various tumors, SHH signaling is specifically altered in CML, by downstream β-catenin signaling, and leukaemia progenitor cells, making it a potential target for eliminating CML stem cells while preserving normal HSCs [32,42]. Another major stem cell signaling pathway, able to regulate HCSCs behavior, is the WNT pathway. Normally essential for HSCs homeostasis [43], aberrant WNT signaling in HCSCs promotes self-renewal, therapy resistance, and disease progression [44]. In AML, chromosomal translocations like AML1-ETO activate WNT, enhancing proliferation and adverse outcomes [45]. Similarly, in CML, increased nuclear β-catenin supports HCSCs survival and self-renewal [46], while HCSCs seem to be resistant to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) [47]. In ALL, elevated β-catenin and WNT ligands like WNT16 drive proliferation in T-ALL and B-ALL subtypes [44]. These insights highlight WNT as a therapeutic target to eliminate CSCs while sparing normal HSCs. Dysregulation of the Notch signaling pathway has been found to be an additional characteristic for HCSCs, particularly in T-ALL and AML [48]. In T-ALL, activating Notch1 mutations enhance self-renewal and leukaemia-initiating cell (LIC) function, driving clonal expansion and disease progression [49,50]. LICs rely on Notch signaling and interactions with the microenvironment (e.g., DLL1 ligands) for survival and resistance, while Notch inhibition reduces LIC activity and extends survival [51]. In AML, Notch signaling is often inactive in HCSCs (CD34+/CD38−), promoting limited differentiation and increased malignancy [52].

2.1.4 Phenotypic and Metabolic Alterations and Comparison with HSCs

HCSCs share key features with normal HSCs, including the expression of phenotypic marker CD34 and the absence of CD38 and lineage markers such as glycophorin A, CD66, CD59, CD29, CD19, CD16, CD14, CD3 and CD2 [15]. However, their antigen expression varies among different leukaemia types. In AML, HCSCs show altered expression of CD25, CD33, CD44, CD47, CD52, CD90, CD96, CD117, CD123, CD133, TIM-3, and CLL1 [53] which may result from defects in differentiation, as these cells fail to mature. In contrast, in CML HCSCs exhibit changes in CD25, CD26, IL1-RAP [53,54], yet they retain the ability to fully mature. In ALL, CD19−CD10− CD34+ cells have been recognized as long-term proliferating progenitors with the potential to initiate tumor formation. Additionally, other markers such as CD34−Lin+CD38+, CXCR4+, CD34+CD38−CD71−HLA−DR−, CD244, CD34+CD38−CD123+ and TIM-3+ have been associated with leukaemia stem cells, highlighting their diversity and key role in leukaemia progression [55]. In cancer, however, it is worth mentioning that the expression of surface markers can show considerable variability, both between different patients and even within the same patient as the disease progresses [56].

At the same time, researchers have studied HCSCs from an alternative perspective, focusing on their metabolic properties in comparison to normal HCSs. It is known that in eukaryotic cells, the majority of ATP is produced through the Krebs Cycle and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). However, in HSCs, OXPHOS activity, mitochondrial content, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) remain low [57]. Particularly, HSCs generally prioritize glycolysis as their main energy production pathway, as demonstrated in various studies [58–60]. Interestingly, their dependence on glycolysis seems to vary depending on their functional state: primed HSCs, which are closer to differentiation, rely heavily on glycolysis, while quiescent HSCs remain in a dormant state, display higher mitochondrial membrane potential and increased lysosomal activity, indicating a shift towards mitochondrial metabolism [57].

On the other hand, LSCs exhibit greater mitochondrial mass but reduced spare respiratory capacity for OXPHOS compared to normal HSCs in primary human AML; This reduced spare capacity likely contributes to the increased susceptibility of LSCs to disruptions in OXPHOS activity [61]. CML stem cells, in contrast, demonstrate elevated OXPHOS activity and intensified catabolism of TCA cycle metabolites, which may also contribute to the diminished spare capacity observed in LSCs. Notably, in LSCs from CML patients, there is evidence of substantial expression of genes linked to OXPHOS, higher ROS levels, increased mitochondrial mass, significant reliance on mitochondrial respiration, and enhanced fatty acid metabolism [9,57]. This metabolic signature includes also a reduced mitochondrial transmembrane potential and heightened oxygen consumption, highlighting the centrality of OXPHOS [62].

Importantly, the OXPHOS phenotype is linked to resistance to chemotherapy and targeted therapies in HCSCs. In CML, LSCs resistant to BCR-ABL-targeted therapies have been shown to exhibit an OXPHOS phenotype [63]. The regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis, a critical factor for maintaining OXPHOS activity, is predominantly governed by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1α) [64]. In LSCs, elevated OXPHOS activity is modulated by the spleen tyrosine kinase and adrenomedullin–calcitonin receptor-like receptor axis [65]. Alongside glycolysis and OXPHOS, lipid metabolism has also emerged as a focal point in CSC metabolism study [66]. Mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation (FAO) plays a pivotal role in sustaining CSC survival and proliferation by alleviating oxidative stress through NADPH production. Furthermore, FAO generates critical metabolic intermediates like acetyl-CoA and NADH, which support ATP generation [67], while LSCs, and normal HSCs rely on FAO to meet their energy requirements [68,69].

2.2 Tumor Microenvironment (TME) in Hematologic Cancers

In hematologic cancers from Hodgkin lymphoma (HL), NHL, and MM to various leukaemias and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), malignant clones arise in specific niches, mainly in lymphoid structures or bone marrow (BM). Unlike solid tumors, which are embedded in a dense extracellular matrix, hematologic malignancies rely on a more dynamic microenvironment where a variety of stromal and immune cells, as well as secreted molecules, influence the course of the disease. The bone marrow serves as more than just a structural framework. It is a specialized hub of stromal elements, immune subsets, and regulatory signals, all capable of either constraining or fostering tumor survival and expansion. In this environment, a small but critical subgroup—HCSCs—utilizes these supportive factors, enabling the cells to become multidrug-resistant and perpetuate the disease (even when the bulk tumor is diminished) [70].

Bone Marrow

Hematopoietic stem cells in physiological conditions are typically found in the bone marrow. Once a neoplastic clone emerges, HCSCs can take advantage of this marrow niche by using adhesion pathways and local cytokines. These signals work together to shield cancerous stem cells from being eliminated by the immune system or medical treatments [71]. This protective effect is partly mediated by interactions with myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) which can be monocytic or granulocytic and exude molecules such as arginase-1, inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), and ROS, all of which sap T cell or NK cell effectiveness [72].

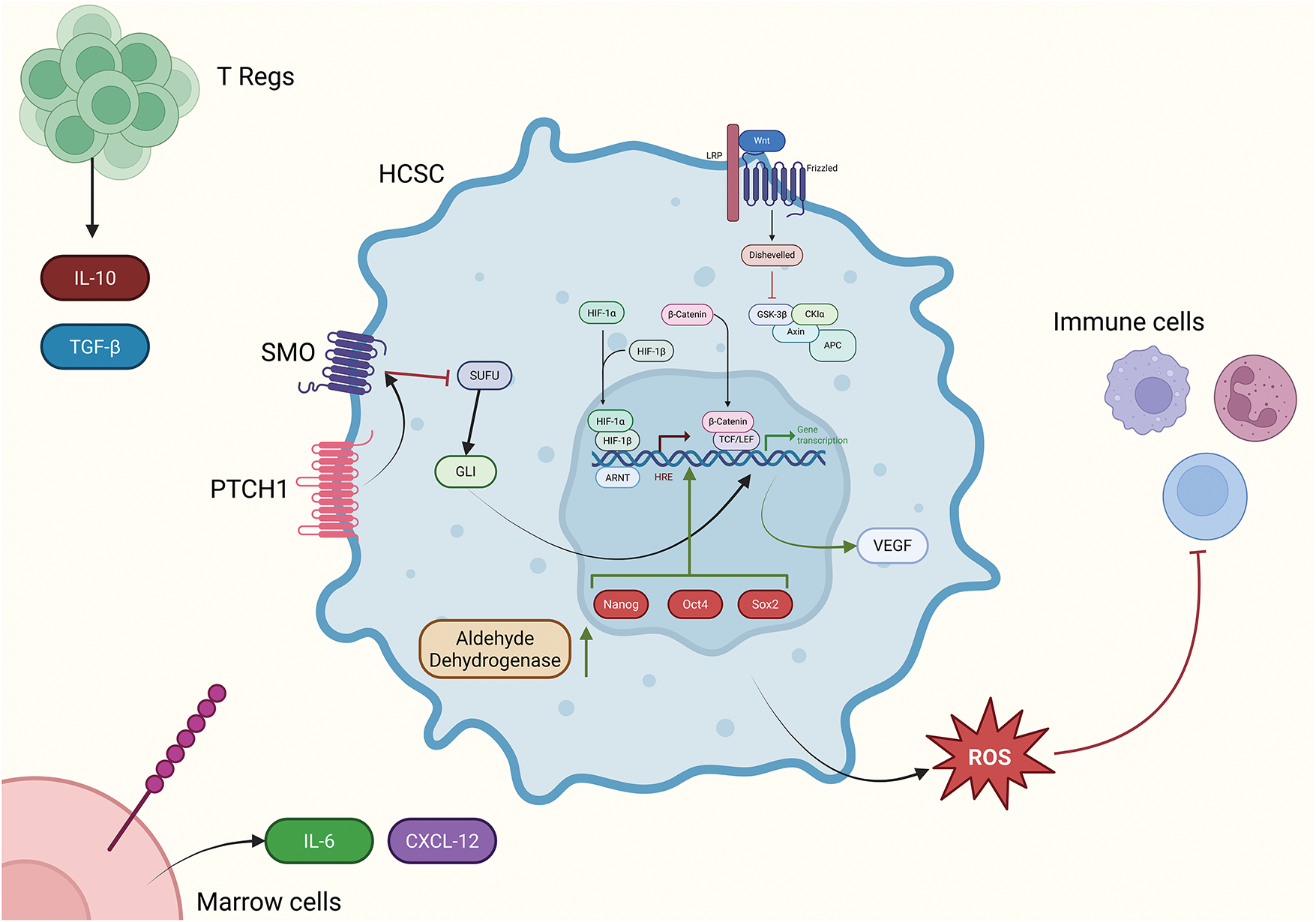

Additionally, regulatory T cells (Tregs) can become a factor to consider by producing interleukin-10 (IL-10) (that suppresses the adoptive immune response and antigen presentation and enhances cancer growth, immune evasion, and MDSC activity) and TGF-β, with similar effects to IL-10 on immunity, and therefore weakening cytotoxic responses, essentially providing a protective microenvironment for HCSCs. Tregs are more frequent in B-cell NHL, such as follicular lymphoma (FL) or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Importantly, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and Stromal cells secrete C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12) (CXCR4 ligand), as well as more IL-6 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). These actions facilitate plasma cells (PCs) homing into BM. The reciprocal interactions between PCs and MSCs drive MM progression and favor the accumulation of chemo resistant malignant PCs. Moreover, by producing adhesion cues (e.g., vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) linking up with VLA-4), they give malignant stem cells a resilient scaffold and keep them from undergoing apoptosis [73,74]. As illustrated in Fig. 1, immune cells within the TME can either suppress or promote tumorigenesis, depending on the context and cancer type.

Figure 1: Illustration of key intracellular pathways including Wnt (top right), HIF-1, and Hedgehog that assist HCSCs to survive and thrive in the microenvironment. Those pathways, along with the upregulation of Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 embryonic transcription factors lead to the transcription/upregulation of key genes related to this phenomenon. In combination with that, the enrichment of the microenvironment with IL-10 and TGF-β by Tregs, and IL-6 and CXCL-12 by bone marrow cells that also provide anchors for HCSCs to latch on withing the bone marrow, assist the viability and immune evasion of the HCSCs, which also dampen the immune response by excreting ROS and other reactive species. The image was created using the platform biorender.com (accessed on 24 June 2025)

Lymphoid Organs

The surrounding environment, known as the TME, plays a significant role in the pathogenesis of HL. It shapes the interactions between immune cells and malignant cells, thereby influencing disease progression. In organs of great importance to the lifecycle of blood cells, including the spleen and lymph nodes, malignant cells exploit their environment to facilitate their growth and survival. In certain regions, immune system components and diverse biochemical signals collaborate to facilitate the survival and proliferation of malignant cells. For instance, while T cells—key players in the immune response—are commonly found in HL tumors, they often fail to attack the cancer effectively. This is because Hodgkin Reed Sternberg (HRS) cells, the malignant cells in HL, release substances like IL-10 and TGF-β. These molecules weaken T cells, redirecting them into roles that support the tumor, such as turning to Tregs. At the same time, the more aggressive, cancer-fighting T cells become too exhausted to function effectively. One key driver of this dysfunction is the overproduction of PD-L1 by HRS cells. PD-L1 binds to PD-1 receptors on T cells, essentially turning them off and worsening their exhaustion. HRS cells also release IL-10, which prompts nearby T cells to produce CD40L—a molecule that strengthens interactions between T cells and cancer cells, further promoting tumor growth [75].

The tumor growth cycle is heavily reliant on a feedback loop involving the protein interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4), which is crucial for cellular survival and proliferation. In HL, interactions with CD40L elevate IRF4 levels, equipping malignant cells with the requisite energy and resources for prolonged proliferation. This equilibrium is tenuous—when growth-inhibiting signals are triggered, IRF4 levels diminish, illustrating the necessity for tumors to meticulously manage their own proliferation. Comparable patterns are observed in other lymphomas, such as DLBCL. Alterations in the IL-10 receptor genes can confer a survival advantage to cancer cells, facilitating their growth more efficiently [76].

These immunosuppressive microenvironments serve as sanctuaries for HCSCs, catering to their survival during therapies and permitting them to remain dormant until cancer recurrence. These stem-like cells remain dormant, poised to reactivate the illness long after the primary tumor has been diminished via treatment. This underscores the critical need to therapeutically target and dismantle these protective niches to prevent cancer recurrence.

2.2.2 Signaling and Interactions Leading to HCSC Proliferation

HCSCs are sustained by a network of intrinsic signaling pathways and extrinsic interactions that collectively promote their self-renewal, proliferation, and drug resistance. The Notch signaling pathway operates as a regulatory mechanism, transmitting essential directives that enable HCSCs to persist. Activating this route enhances the resistance of HCSCs to therapies and improves their capacity for self-renewal and proliferation [48]. The Hedgehog signaling pathway offers critical regulatory signals that improve HCSC defense against chemotherapeutic drugs. Especially beneficial in multiple myeloma, it facilitates immune evasion and imparts chemoresistance [77]. β-Catenin is essential in modulating gene expression that promotes HCSC survival and confers resistance to standard therapy. This renders HCSCs very robust, allowing their persistence despite therapeutic efforts [78]. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) signaling functions as a contingency mechanism for HCSCs, enabling them to evade the apoptosis generally induced by therapies. This indicates that even when treatment attempts to eradicate them, HCSCs persist and remain safeguarded [79]. The detoxification of chemotherapeutic drugs and the preservation of stemness characteristics in HCSCs are facilitated by aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) and retinoic acid receptor alpha 2 (RARα2). These factors promote ongoing self-renewal and provide resistance to apoptosis [80]. MDSCs decrease T cell function, hence suppressing anticancer immunological responses and enabling HCSCs to avoid immune monitoring. The immunosuppressive milieu impedes the effectiveness of treatment approaches aimed at HCSCs [81]. HCSC survival is facilitated by the establishment of an immunosuppressive environment by Tregs, which reduce immunological activation. This inhibition reduces immune-mediated elimination, thereby promoting the proliferation of HCSCs [82]. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) facilitate tumor advancement by altering immune responses and aiding in the maintenance of HSCs. They create an immunosuppressive environment that promotes HCSC survival and proliferation [83]. Stromal cells offer structural and metabolic support that promotes the survival and multiplication of HSCs. They secrete factors and extracellular matrix components that support HCSC survival and proliferation.

2.2.3 Microenvironmental Conditions

HCSCs are directed by significant internal signals, although their activity is profoundly affected by their microenvironment in the bone marrow or lymphoid organs. In malignancies such as HL, NHL, MM, leukaemias, and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS), the microenvironment engenders four primary traits that collectively enable HCSCs to withstand therapies and endure for extended periods. Cancer cell proliferation in marrow or lymphoid locations results in areas of reduced oxygen levels. Stabilized hypoxia inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1α) enhances VEGF production, facilitating the formation of new, often irregular blood vessels. In multiple myeloma, extremely hypoxic bone lesions enhance the Hedgehog or Wnt pathways, hence reinforcing the “stem-like” population. Lymphoma cells in nodal “hotspots” utilize moderate hypoxia to upregulate pro-survival genes [84]. Even minor increases in MDSCs might disrupt the immunological equilibrium, favoring HCSCs and inhibiting T and NK cytotoxic activities through iNOS, arginase-1, and ROS. Tregs provide a low-inflammation environment by secreting IL-10 and TGF-β, allowing the hematopoietic stem population to flourish. This synergy is prevalent in advanced HL and NHL, as well as in acute and chronic leukaemias [85]. Specialized cells inside the bone marrow stroma provide cytokines (e.g., IL-6, CXCL12) and adhesion ligands such as VCAM-1, creating a protective interface with hematopoietic stem cells. Adhesion molecules, including the likes of VLA-4 and VCAM-1, facilitate the anchoring of malignant stem cells inside the marrow or lymphoid compartment. This anchoring establishes a “safe harbor” effect and reduces exposure to detrimental chemotherapeutic concentrations. Certain HCSCs have elevated aldehyde dehydrogenase activity, facilitating the breakdown of harmful chemotherapeutic metabolites and imparting drug tolerance. Under stress, embryonic transcription factors such as Nanog, Oct4, and Sox2 may be increased. In conjunction with RARα2 signals, these substances can direct malignant clones towards a quasi-stem cell state, hence promoting prolonged self-renewal [86]. In total, these environmental factors—hypoxia, immunosuppressive cellular populations, protective stroma, and metabolic adaptability—establish a niche that enables HCSCs to persist despite pharmacological treatment. Understanding and treating these macro-level circumstances is critical for obtaining permanent remissions in hematologic malignancies, as even modest clusters of these “stem-like” cells can reactivate the disease.

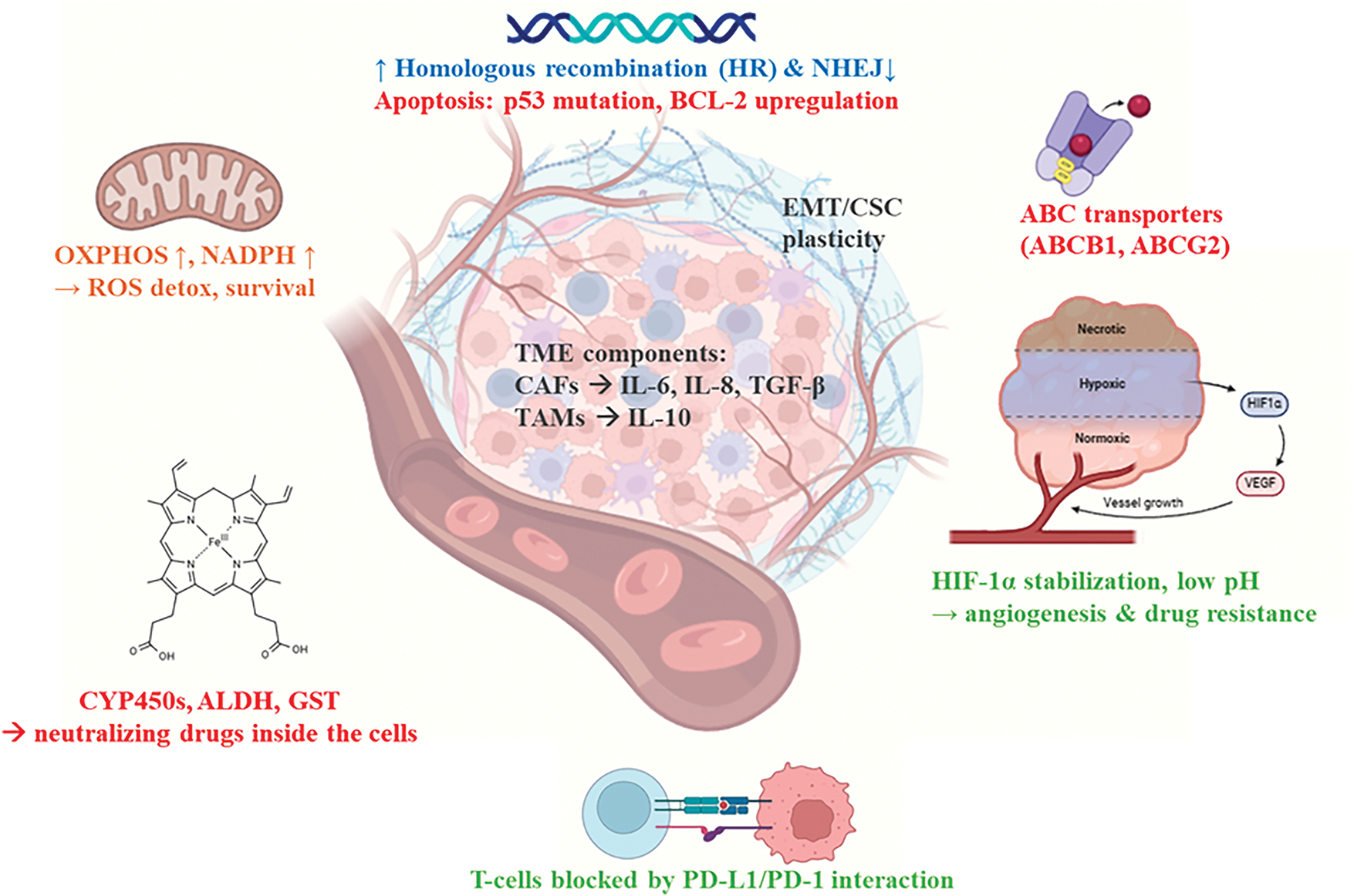

2.3 HCCs Properties Conferring to Therapy Resistance

Therapeutic resistance remains one of the major hindrances in cancer therapy. Almost all surgical, in the case of solid tumors, and treatment interventions, like chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and irradiation-have failed at some point to affect the metabolism or growth of these cancers, due to the intrinsic or acquired mechanisms in relation to the treatment. As can be seen in Fig. 2, the mechanism of the development of resistance is based on the interplay of genetic, epigenetic, metabolic, and microenvironmental factors that help HCCs survive.

Figure 2: Mechanisms of tumor cell therapy resistance. Therapy resistance in tumors arises from a convergence of genetic, epigenetic, metabolic, and microenvironmental adaptations. Tumor cells enhance DNA repair via upregulated homologous recombination (HR) and downregulated non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), while evading apoptosis through p53 mutations and BCL-2 overexpression. Phenotypic plasticity, including epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and acquisition of cancer stem cell (CSC) traits, facilitates survival under therapeutic pressure and promotes DTP states. Drug efflux is mediated by overexpression of ABC transporters (ABCB1, ABCG2), while detoxification enzymes (e.g., ALDH, CYP450) inactivate chemotherapeutics. Metabolic reprogramming, characterized by elevated oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and NADPH production, supports redox balance and resistance. The TME—comprising cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), and hypoxic niches—contributes to resistance through secretion of IL-6, IL-8, TGF-β, IL-10, and stabilization of HIF-1α. Immune evasion is reinforced by PD-L1/PD-1-mediated suppression of cytotoxic T cell activity. The image was created using the platform biorender.com (accessed on 23 June 2025)

2.3.1 Genetic and Epigenetic Resistance

Mutations and chromosomal aberrations are key intrinsic genetic factors involved in inducing resistance. This includes point mutations, copy number alterations, and chromosomal translocations involving oncogenes, tumor suppressors, and machinery for DNA repair pathways [87]. Driver mutations in genes such as epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and oncogenes BRAF or KRAS induce a carcinogenic state and confer resistance to malignant cells against kinase inhibitors. Genomic instability promotes heterogeneity inside the tumor and further leads to the development of subclones with mutations that confer resistance. For example, in melanoma, a subpopulation of CD271 cells has been identified as having tumor-initiating capacity, showing how diverse subclones contribute to tumor propagation and escape from immune surveillance [88].

In addition to genetic mutations, histone modifications and methylation of DNA are important for gene expression. These changes could induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which is related to invasiveness and drug resistance, activate drug resistance genes, or silence genes that inhibit tumors. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs) are examples of the gene regulation from the non-coding RNAs in altering resistance and survival gene networks [89].

2.3.2 Cellular Plasticity and HCSCs

Tumor cell plasticity-or the capability of cancer cells to change phenotypically in response to external stimuli or therapeutic pressure-is one of the most dynamic mechanisms of resistance. It encompasses such phenomena as EMT, transdifferentiation, mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET), and acquisition of the characteristics of HCSCs [90]. Plastic tumor cells are reversible in entering a drug-tolerant persister (DTP) state characterized by dormancy, low proliferation, and survival under drug treatment. For example, acquisition of mesenchymal characteristics such as invasiveness and motility, along with resistance to apoptosis, could be facilitated by EMT among epithelial cells. Signaling pathways like TGF-β, WNT, and Notch regulate transcription factors such as Snail, Slug, Twist, and Zeb1/2 which orchestrate EMT. Partially EMT cells therefore have a hybrid phenotype that strikes a compromise between adaptation and survival, increasing their resistance to therapy [91]. Moreover, it is noted that much of therapeutic resistance, metastasis, and recurrence can be directly related to the formation of HCSCs; the subpopulation within a malignancy able to self-renew and repopulate it. HCSCs stay inactive and resistant to therapies aiming at fast-dividing cells. High efflux pumps of drugs and efficient DNA repair mechanisms also characterize these cells [89].

2.3.3 Microenvironmental Influences and Immune Evasion

Cancer cell activity and adaptive resistance are largely determined by the TME. The TME encompasses stromal cells—such as cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs)—blood vessels, extracellular matrix, immunological cells (T lymphocytes, TAMs), and an assortment of cytokines and chemokines. These supportive cells also act to protect cancer cells from therapeutic interventions [92,93].

CAFs secrete factors such as IL-6, IL-8, TGF-β, TGF-α, and TGF-β, enhancing the stemness of malignant cells, promoting EMT, and inhibiting immune reactions. In other words, CAFs can enhance resistance and promote the survival of HCCs by inducing the NF-κB and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) activation pathways. This escape from immune surveillance is largely dependent on the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines associated with the M2-like phenotype in TAMs [93]. The downregulation of major histocompatibility complex I (MHC-I), attenuated antigen presentation, and the upregulation of different immunological checkpoints are all aspects that render the immunosuppressive nature of the TME. These phenomena promote immune tolerance and diminish T cell recognition [94]. Besides this, hypoxia and low pH within the TME also promote angiogenesis, invasiveness, and altered drug penetration [95].

2.3.4 Metabolic Reprogramming and Plasticity

In order to proliferate and adapt to nutrient- and oxygen-deprived environments of the TME, cancer cells undergo metabolic reprogramming. On one hand, this adaptation enhances survival, and, on the other, it leads to treatment resistance. Through the Warburg effect or aerobic glycolysis, cancer cells can fast-track the generation of metabolic intermediates, even in the presence of oxygen. However, in drug-resistant cells, OXPHOS is often favored over glycolysis.

Notably, doxorubicin treatment of glioblastoma causes poly(morpho)nuclear giant cells (PGCs) to emerge with a distinct metabolic signature. These PGCs help survive under stress via activating pathways for scavenging ROS, producing NADPH, and OXPHOS. Inhibition of either OXPHOS or NADPH-producing pathways interrupts the function of PGCs, consequently sensitizing tumors to chemotherapy. It is this metabolic flexibility—or metabolic plasticity—that allows cancer cells to switch between modes of energy production and resist drug-induced stress. This flexibility is further supported by metabolic crosstalk among stromal and tumor cells [96].

2.3.5 Drug Efflux, Detoxification, and Sequestration

In addition, one classical pathway of resistance is the reduction in intracellular drug concentration. Cancer cells can increase the activity of efflux pumps such as ABCB1 (P-glycoprotein), ABCG2, and ABCC1, to vigorously remove their therapeutic agents from the cell, while simultaneously decreasing the intake of drug transporters [97]. These transporters are frequently overexpressed in CSCs, and most likely in HCSCs, and differentiated tumor cells, thereby contributing to the establishment of the multidrug resistance (MDR) phenotype. Tumors may also inactivate drugs intracellularly by the overexpression of mechanisms of detoxification, such as cytochrome P450s, glutathione S-transferase, and aldehyde dehydrogenases (ALDH) [98]. The cytotoxic efficacy of many conventional treatments is compromised once resistant subclones show a significantly high expression of these enzymes. Furthermore, drug sequestration in intracellular storage compartments, along with impaired activation of prodrugs—such as the loss of deoxycytidine kinase (DCK) in cytarabine resistane—are among the leading factors for chemotherapy failure [99].

2.3.6 Enhanced DNA Repair and Apoptosis Resistance

Most of cancer treatments act by inducing apoptosis and causing DNA damage. However, resistant cells usually tend to employ superior DNA repair mechanisms along with evasion from programmed cell death. In response to DNA damage caused by cancer therapies like radiation and chemotherapy repair via upregulating the pathways of non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homologous recombination (HR) repair [100]. Beyond enhanced DNA repair, survival favors in the same way by mutations of the tumor suppressor gene, p53, overexpression of anti-apoptotic proteins like BCL-2, and inhibiting pro-apoptotic signaling pathways. This resistance is further intensified by the close interplay between these evasion strategies and the characteristics of CSC and EMT phenotypes [101].

2.3.7 Strategies to Overcome Resistance

Integrated therapeutic strategies targeting multiple pathways are essential to overcome therapy resistance. One such promising strategy of combination therapy would include the coupling of drug TKIs to alternate bypass pathway inhibitors against multiple resistance mechanisms [102]. Moreover, blocking immunological checkpoints or reprogramming the TME [92], inhibiting OXPHOS in resistant cancers [98], and focusing on EMT or CSC pathways. Another emerging approach involves the use of nanoparticles to deliver siRNAs to silence resistance genes or circumvent efflux pumps would be an optimistic approach. Personalized medicine will be critical in personalizing treatments and improving patient outcomes through pharmacogenomic profiling and markers of resistance [89].

3 Immunotherapeutic Strategies

Given the importance of the role that HCSCs play in the proliferation, therapy resistance, and, most importantly, in the relapse of the malignancy [103], identifying the exact ways that HCSCs can be addressed via immunotherapeutic means is crucial in applying more efficient and effective therapies in the clinic. There are several targets related to HCSCs already identified and put into use in preclinical and clinical settings under the context of immunotherapy. It can be said that one of the most direct immunotherapeutic strategies is the targeting of cytokine-related pathways. Such interventions include the micromolecular inhibition of CXCR1/2 which is a receptor of IL-8 and the inhibition of the pathway hosted by IL-6 [12]. However, one of the greatest challenges in this endeavor is the identification of markers characteristic to HCSCs, to minimize the off-target effects and, thereafter the adverse events and maximize treatment outcomes. Common targets include the ones displayed on the surface of the cells by themselves, such as the ones previously mentioned, or via human leukocyte antigen (HLA) proteins [104], with an example being the PR1 epitope, although they are usually downregulated in the HCSCs, to escape immune surveillance. In the following paragraphs, exploitable targets, as well as therapeutic interventions, and future directions will be analyzed. It is important to note, as noticed later in the text, and literature in general, that the most effective way to prevent relapses by eliminating as many HCSCs as possible is the targeting of multiple markers simultaneously, mostly due to the plasticity of the targets, as a mechanism of resistance [105].

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is an intervention used for several disorders of the blood, including malignant and non-malignant ones. Its therapeutic utilization in haematologic cancer therapy is based upon the graft vs. tumor (GVT) effect, which is enhanced by conditioning regimens that weakens the HCCs and generates an inflammatory environment [106]. Both autologous and, especially, allogeneic [107,108], stem cell transplantation have proven themselves useful for the long-term improvement of the health and quality of life of hematological cancer patients [109,110]. These outcomes are further supported by recent advancements in donor–recipient matching, conditioning protocols, cell engineering, and patient eligibility assessment [111,112].

Sources of stem cells include the bone marrow, peripheral blood and the umbilical cord [106]. To minimize the risk of graft vs. host disease (GVHD), the patient’s cells are preferable to be used. In this context, induced pluripotent stem cells, originating from differentiated tissue cells that are undergone reprogramming via viral infection with alterations with transformations involving the SOX2, MYC, OCT4, and KLF4 genes, or very small embryonic-like stem cells (VSELSCs) originating from progenitor gametes and transformed in vitro into HSCs, can be utilized [113]. It’s important to consider that one of the major factors behind clinical results of transplantation is also the type of malignancy as different response rates and other metrics are expected for different diseases [114]. Notably, MSCs seem to be quite relevant in the context of HCSC elimination as they have demonstrated enhanced homing and interaction with HCSCs, along with regulation of metastasis and treatment resistance, and the ability to reconstruct the patient’s hematopoietic capabilities after the damages caused by the malignancy and the treatment [115].

Despite its track record, HSCT faces several challenges in clinical implementation, especially in cancer care, including GVHD which is related to the rejection of the graft by the patient’s immune system. Within the main factors to be blamed are listed the activity of T cells of the host and alloreactive T cells of the graft, as well as the chance of relapse of the malignancy resulted by the successful fightback of the graft by the specific form of GVT, graft vs. leukemia (GVL). GVHD and GVL have been proven to be independent from one another. To combat the former, immunosuppressive therapy, such as anti-T cell therapy and the more targeted depletion of alloreactive T cells can be utilized whilst in the latter, sufficient clearage of the malignancy is required to ensure the minimal risk of relapses. However, there is a fine balance between the two approaches, and their effects, say for immunosuppression and immune induction, that needs to be achieved. Additional methods to overcome maximize efficacy include the HLA matching between the donor and the recipient of the graft, the use of cord blood that allows for greater freedom in HLA matching and targeted therapies that minimize the effects on physiological cells whilst addressing the malignant ones [116].

Given that stem cells are considered to underline the characteristic onset, aggressiveness and treatment resistance of many malignancies [117], as well their capability to initiate relapse [104], they have set themselves as one of the prime targets in hematological cancer therapy, particularly in the context of stem cell transplantation. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is considered an intervention that directly targets hematological cancer stem cells (HCSCs), thereby addressing some of the limitations associated with conventional therapies such as chemotherapy [118]. However, transplantation is best combined with conditioning, maintenance, and salvage therapies as minimal residual therapy is a major driver of relapse and an indicator of progression [119]. An example of maintenance therapy addressing residual HCSCs is the use of TKIs such as multi-kinase inhibitor Sorafenib [120] and Hedgehog signaling inhibitor Glasdegib [121]. To ensure the minimization of the risk of relapse, proper measures, such as flow cytometry and other immunochemical techniques as well as other methods based on the different characteristics of HCSCs, need to be taken to avoid any contamination of the autograft in autologous HSCT, as new tumor sited might evolve [122–125].

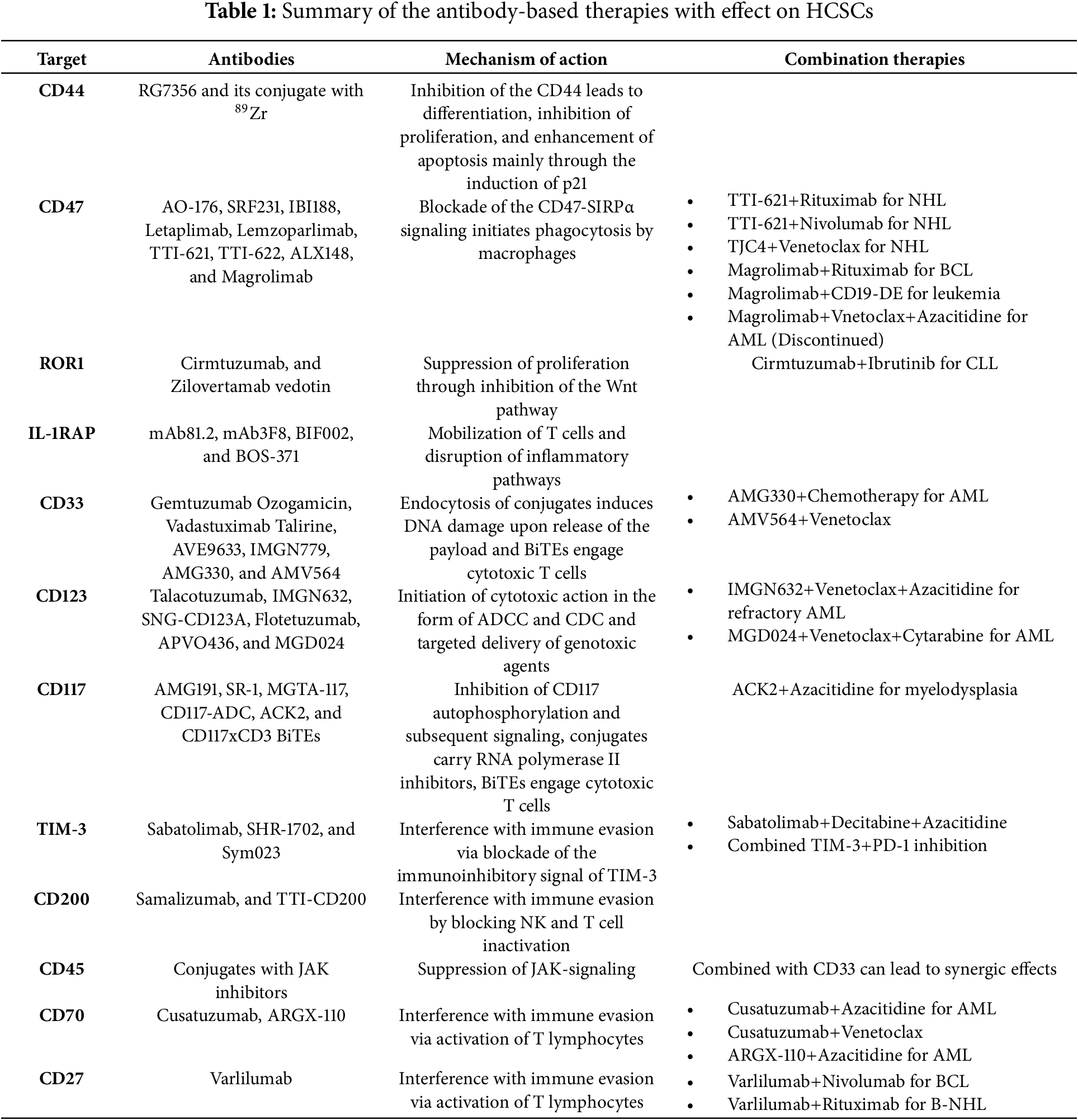

3.2 Antibody-Based Interventions

Antibody-based medicinal products are widely applied in the field of oncology. There are several ways they can be classified based on their structure, their targets and other properties. For the purposes of this study, relevant antibody-based products are addressed based on the targeted molecule. Similar clarification is followed in the summarizing Table 1 and Fig. 3.

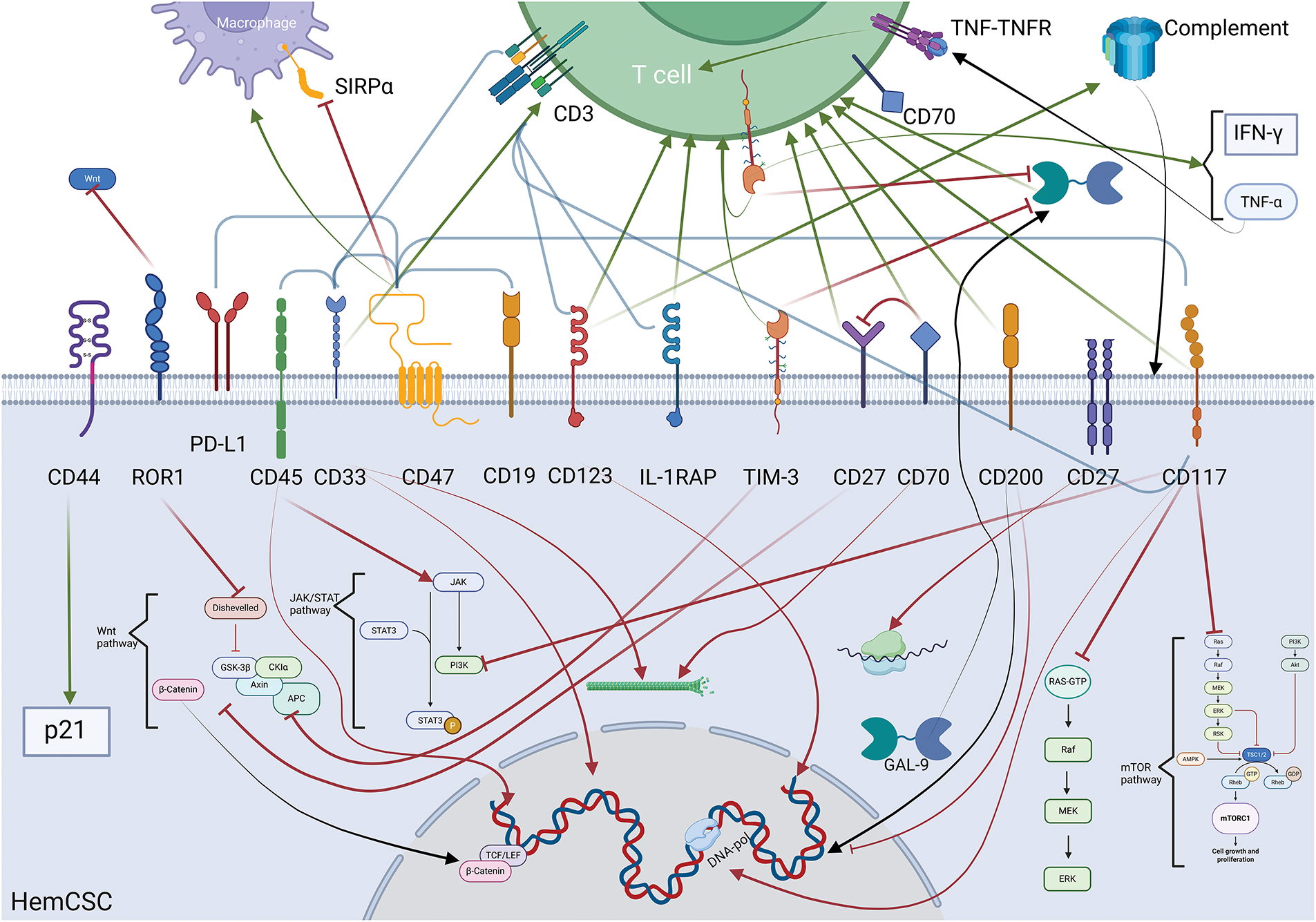

Figure 3: Illustration concentrating and summarizing all biochemical mechanisms and the intermolecular relationships initiated by the inhibition of the corresponding molecules. The bottom half of the image represents the intracellular space of a HCSC and the top one the extracellular space. The green arrows represent activation/upregulation whilst the red ones represent inhibition (flat tip for inhibition stemming from the targeting of the molecule, pointy tip for action associated with the delivery of the payload of a conjugate). The black arrows represent movement of biomolecules within the cell leading to gene transcription when terminating in the nucleus, extracellularization in the case of GAL-9, or assembly in the case of the complementary. The brackets indicate the existence of a bispecific targeting antibody for the molecules at each end. In the extracellular space, a T cell represents the effects of the interventions on the adaptive immune system. The image was created using the platform biorender.com (accessed on 07 April 2025)

Given CD44’s importance in several processes sustaining HCSCs, the antileukemic action of anti-CD44 mAbs appears as no surprise. These inhibitors mostly affect hinder HCSC’s stemness and proliferation [126], most likely due to the imminent cell cycle arrest in the G0/G1 through the enhancement of p21 expression, and of apoptotic capabilities [127]. Targeting CD44 can also be done with conjugated antibodies. The recombinant antibody RG7356 has shown positive safety and tolerability indications after a phase 1 study involving dosages ≤2400 mg every other week or ≤1200 mg weekly or twice weekly [128]. Additionally, the conjugated form of this antibody with the radioisotope 89Zr has been tested only for solid tumors on animal models [129]. Results show it has shown selective cytotoxicity on leukemic cells, specifically B-cell ones, whilst in an early stage in its development [130], highlighting the potential for clinical applications. However, despite all the hopes, the fact that CD44 can also be found in significant levels on CD8+ Natural Killer (NK) cells is a major concern regarding the toxicity and adverse effects that accompany the use of such inhibitors [131].

The presence of CD47, also known as “the don’t eat me signal”, or macrophage checkpoint inhibitor due to its signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) interaction-initiated activity, on the surface of multiple of chemoresistant hematological malignancies [132–134] is a marker of unfavorable prognosis [135]. Hence, it is reasonable to be assumed as a viable target for engineered antibodies, especially in the context of allogenic stem cell transplant [136].

Early Evidence on the Activity of Anti-CD74 Antibodies

In vitro testing of AO-176 has demonstrated effectiveness against multiple myeloma, T-acute lymphocytic leukemia and B lymphoma cell lines that were also added in mice as xenografts and SRF231 in MM, DLBCL, and Burkitt’s Lymphoma [137]. Similarly, in vitro and in vivo testing of IBI188, a biosimilar to Rituximab, an anti-CD20 antibody, indicated that its use can induce phagocytic activity through the blockade of the CD47-SIRP-α pathway in CHO-hCD47 (CD47 expressing Chinese Hamster Ovary cells used in translational studies for their robust growth, genetic modification), Raji (used to simulate Burkitt’s lymphoma cell line), and MDA-MB-231 (representing breast cancer) cell lines, along with inflammation, and activity of macrophages in Raji cells and in vivo conditions and that its activity further enhanced when combined with anti-VEGF antibodies [138]. Additional monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that have shown promising results and tolerable toxicity, mostly comprising of grade I and II adverse events, in early clinical trials are Letaplimab and Lemzoparlimab, as well as the fusion products of SIRPα, as an IgV domain, and an Fc domain, to facilitate phagocytic function, TTI-621, TTI-622, and ALX148, with the latest showing exceptional affinity to CD47 and elevated pharmacokinetic properties by utilizing neonatal Fc receptors.

Combination Therapies and CD47 Targeting

Clinical trials have evaluated the efficacy of TTI-621 in combination with rituximab or nivolumab against NHL with encouraging results as overall response rate (ORR) was 23% with rituximab whilst for HL the rate was 50% with nivolumab [139]. Synergistic effects on phagocytosis were also pbserved with the combination of anti-CD47 antibody TJC4 and Bcl2 inhibitor Venetoclax in B-cell NHL. This synergy was attributed to venetoclax-induced extracellular exposure of phosphatidylserine, a known promoter of phagocytosis, derived from the latter’s pharmacological activity. The experiments suggesting this effect were carried out by Li et al. on OCI-LY-8 (representing human B-cell lymphoma), SU-DHL-6 and SU-DHL-16 (representing large cell lymphoma), U2932 (representing B cell lymphoma), and Raji cell lines as well as on NOD-SCID mice bearing malignant cells derived from cell lines or patient biopsies [137].

Combination therapies targeting additional immune checkpoints have also been explored. For example, Rituximab in combination with Magrolimab in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma achieved a 50% objective response rate, with most adverse events being grade 1 or grade 2 in severity [140]. Magrolimab was also used in tandem with the CD19-DE antibody, tailor-made for enhanced phagocytosis with the result of increasing the latter’s activity, when compared to anti-CD19 monotherapy, when tested in vivo for both adult and pediatric leukemias [141]. CD47 targeting antibody Magrilomab had showcased in its early development the increased efficacy of combination therapies with CD47 inhibitors and molecules such as azacitidine compared to monotherapies using just the latter [142]. However, despite the promising results in early clinical trials showcasing tolerability and efficacy in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome [143] and AML [144], the Phase III (ENHANCE-3) trial testing Magrolimab with Venetoclax and Azacitidine in AML patients [145] had to be early discontinued upon intervention from the United States Food & Drug Administration based on the “demonstrated futility and increased risk of death” [146] arising concerns around the targeting of CD47 and related combination therapies. Similar concerns were also in the spotlight after the poor performance indicators of CC-90002 were published [137].

Bispecific Antibodies Targeting CD47

There have already been clinical trials carried out testing the bispecificTG-1801 antibody targeting CD47 and CD19 along with Rituximab against B-cell lymphoma with positive results regarding efficacy, as there was clinical activity noted, and limited toxicity as there were noted anticipated adverse events including anemia, headache, abdominal pain, fatigue and thrombocytopenia, however, with limited statistical power due to relatively low enrolment [147]. Furthermore, there are TG-1801 (CD47xCD19), IMM0306, HuNb1-Rituximab and RTX-CD47 (CD47xCD20), HMBD004 (CD47xCD33) and IBI322 (CD47xPD-L1) bispecific antibodies under testing at several stages in their development cycle [137].

Challenges Related to C47 Targeting

Nonetheless, there are several issues regarding the targeting of CD47 with biomolecules. On-target toxicity is the primary concern as said antibodies also target physiological cells displaying CD47 with effects such as anemia, mostly caused by the activity of the Fc domain. Additionally, SIRPα monomers that act as agonists and SIRPα antibodies can only be used as adjuvant therapies at best, with the latter being coupled with the concern of targeting neural cells as well [148]. HCCs can also promote resistance mechanisms against CD47 targeted therapy as they can enhance the production of CD47 and/or other antiphagocytic molecules [149]. Besides the shortcomings, there is reason to hope that CD47 can prove itself as one of the most significant immune checkpoint targets once the issues of therapeutic effectiveness and toxicity have been overcome and more robust data have been collected [150].

ROR1 is a tyrosine kinase, located almost exclusively on CSCs, including HCSCs, whose ligand is Wnt5a. Its proliferative and pro-metastatic role has made it a prime target for mAbs such as Cirmtuzumab which has been used against CLL. Early-phase clinical trials revealed that Cirmtuzumab could limit cancer progression with relative safety, with an elevated possibility of stemness return. Despite this discouraging result, preclinical studies assessing its combination with tyrosine kinase inhibitor Ibrutinib had shown better results [133]. Additionally, the antibody-drug conjugate Zilovertamab vedotin that targets ROR1, delivers the small molecule auristatin E and is assessed for mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), DLBCL, and CLL with positive indications, in a small pool of subjects [151]. ROR1 represents an interesting yet untapped full potential target as there are still monoclonal as well as bispecific antibodies in development [152–154].

IL-1RAP is a facilitator in the transduction of the pro-inflammatory signal of the interleukins IL-1α&β and is widely expressed in and serves as a marker for HCSCs, unlike physiological blood cells [155]. The majority of anti-IL-1RAP antibodies used against hematological malignancies have been only assessed preclinically. Several examples include the testing of polyclonal rabbit-originated antibodies against aggressive and TKI resistant CML cells. Results on AML cells originating from patients were also susceptible to the action of the mAb81.2 & mAb3F8 antibodies [156]. Zhang et al. also tested IL-1RAPxCD3 Bispecific T Cell Engager (BiTE) antibodies BIF002 and concluded that in both in vitro and in vivo models they led to T cell activation and proliferation with their activity being mostly directed against HCSCs [157]. West et al. have also tested BOS-371 humanized mAb and noted high affinity to its target and strong activity against leukemic cells, both in vitro and in vivo settings as there was a decreased burden [158].

From a clinical perspective, CD33 appears to be a very appealing target as its levels can serve as a prognosis in AML, as it has been negatively correlated with overall survival [159]. Additionally, it is stated that CD33 is expressed in normally differentiated hematologic cells, leukemic cells and HCSCs, but not on normal hematologic stem cells, thus, to an extent, sparing the patient’s capacity to regain functional hematopoiesis post treatment [160].

Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin

Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin is an antibody-drug conjugate that had been granted accelerated approval by the United States Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) at the beginning of the 21st century. It had to re-enter the market in 2017 after a brief ban due to prior concerns over safety and efficacy, with the latter being partially due to limited conjugation between the antibody and calicheamicin hydrazide as the former does not have a significant antineoplastic effect. After reviewing its characteristics, it was deemed applicable in the therapy of AML patients. The mechanism of action of Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin includes internalization of the conjugate upon binding with the CD33 molecule and, upon release of calicheamicin hydrazide within the lysosome, the interaction of the small molecule with the genetic material causing cell cycle arrest and/or cell death by apoptosis. Resistance can be developed by the function of members of the ABC transporter family, P-glycoprotein, and other drug transporters as well as induction of anti-apoptotic mechanisms. Notable adverse effects of its use include hepatic veno-occlusive disease and sinusoidal obstructive syndrome along with other significant hematological adverse effects and minor ones rendering its use demanding careful and extensive oversight [161,162]. Thereafter, there is a clear demand for the development of additional therapies.

Other Anti-CD33 Conjugates and Design Optimization

Regarding the design, it has been noted by Godwin et al. that proximal, as to the membrane, targeting of CD33 can deliver greater cytotoxic effects such as more effective T cell engagement. As such, targeting the C2 domain of the molecule, a proximal target present at all CD33 molecules occurring in leukemic cells, is a promising method [163]. Additional conjugates include Vadastuximab Talirine carrying pyrrolobenzodiazepine, DNA cross-linkage causing factor, AVE9633, carrying a derivative of Maytansine that inhibits tubulin, and IMGN779, a carrier of novel alkylating agents indolinobenzodiazeprine pseudo dimers [160]. As for conjugates’ design, there is a major significance in the aspects of low-weight molecules used such as the pyrrolobenzodiazepine dimer’s superiority over calicheamicin in MDR-positive cells, as well as the linker. It shall be noted that the resulting conjugate in this study of Han et al. showed concerning toxicity against bone marrow in primates and its use involved more risk than the CD123 analogue [164]. Taking the matter a step further, there is clinical evidence of tolerability and relative manageability of AML of CD33 targeting IL-2 in the form of a fusion protein with an antibody in post-transplant patients [165].

Bispecific Antibodies Targeting CD33

There is also a great amount of interest in the investigation of bispecific engager antibodies. An example of this type of antibody is AMG330, targeting CD33/CD3 which despite showing adequate triggering of T cells in vitro [166] and therefore potential for application in the therapy of AML, a Phase I escalation trial, toxicity was noted before the maximum tolerable dose was reached as there were significant adverse effects including cytokine release syndrome, including grade 3/4 and rash [167]. Another CD33/CD3 bispecific antibody, AMV564, has been reported to have significant immunostimulatory effects [168], with induction of protective immunity [169], in preclinical testing. A phase Ia testing with mostly elderly participants with secondary AML and previous recipients of chemotherapy has been conducted. Early evidence suggests that AMV564 can be a tolerable and effective medicine as there was, in the majority of the patients, response to the treatment of AML [170]. In the same context, AMG673 had not so encouraging evidence as 2/3 of the patients discontinued due to disease progression of AML, half of them had experienced cytokine release syndrome and a third had serious adverse events whilst a third of them experienced a decrease in blasts. Another strategy utilizing bispecific antibodies is CD33/CD16 to stimulate NK cells against neoplastic ones had shown significant stimulation in vitro of the former in both high and low concentrations of CD33-bearing malignant cells of ALL and AML pediatric patients [171,172].

As previously mentioned, CD123 is a marker abundant in LSCs in AML, cells related to B-ALL, and MDS. Its prevalence has shown an increasing trend during disease progression, in 20% of patients with CML with no differential in the levels between children and adults [173]. Besides the clear increase in malignant cells, CD123’s coding gene seems to be well preserved [174]. As such, an interesting aspect is the engineering of allogenic hematological stem cells (Allo-HSCs) to display CD123 markers with differentiated epitopes, even by one amino acid, for them to be spared from CD123 targeted immunotherapeutic interventions, therefore increasing the latter’s efficiency and reducing related adverse reactions originating from on-target toxicity, should they be deemed to be used in tandem [175,176].

Talacotuzumab

Talacotuzumab is a mAb targeting CD123 that involves antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) and (compliment dependent cytotoxicity) CDC has an inapplicable risk/benefit profile as a monotherapy against myelogenous malignancies [177]. In a phase 2/3 multicenter clinical study assessing the superiority of combination therapy including Talacotuzumab+decitabine vs. decitabine alone in patients with AML, refractory in phase A of the trial and untreated with ineligibility for hematological stem cell transplantation and chemotherapy has concluded that there was no clinical superiority in efficacy metrics and therefore early pause of enrollment and termination of Talacotuzumab treatment [178].

Anti-CD33 Conjugates

As with the rest of the molecules mentioned above, antibody-drug conjugates appear to be an appealing solution. IMGN632, also known as Pivekimab sunirine, is a conjugate containing, similarly to anti-CD33 conjugates, alkylating agent indolinobenzodiazepine pseudodimer via cleavable peptide linkage. Phase I studies of this medication conducted on 12 patients with relapsed/refractory AML or blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm (BPDCN) indicated no severe toxicity at the dosage of 0.18 mg/kg with mild symptoms such as tachycardia, fever, chills, and intestinal disorders related to infusion and treatment-related events mattered the gastrointestinal, and cardiovascular as well as the blood [179]. There are additional ongoing trials assessing the safety and efficacy of IMGN632 [180]. Assessment of combination therapy including IMGN632, Azacitidine and Venetoclax in relapsed/refractory AML has suggested dose-related efficacy of the regiment with adverse events including febrile neutropenia, hypophosphatemia, dyspnea and pneumonia [181]. Overall, early clinical trials have led to the suggestion of a dosage for IMGN632 of 0.045 mg/kg one time every 3 weeks for phase 2 trials onwards [182]. An additional conjugate in the preclinical phase is SNG-CD123A used for the targeted action of pyrrolobenzodiazepine dimer [174]. However, resistance to CD123 targeting molecules can be obtained via downregulation of CD123 expression, as observed by Gulati et al. in their study using antibody conjugate Targaxofusp against blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm [183]. Despite this, Targaxofusp has demonstrated its effectiveness and, in general, a tolerable profile in clinical trials [184]. Preclinical evidence has also indicated effectiveness in pediatric ALL specimens [185].

Bispecific Antibodies Targeting CD47

Bispecific antibodies have also been investigated. Flotetuzumab is a bispecific antibody targeting CD123 and CD3. Despite early indications of safety and effectiveness over chemotherapy-resistant leukemias [186], its development has been discontinued by its sponsor. Early clinical trials have concluded an enhanced risk of grade </=2 cytokine release syndrome. Escalation/Expansion studies of APVO436, also a bispecific targeting the same markers, have resulted in Grade 3 or more treatment-related adverse events including anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and sepsis in about half of the participants [187]. The minimum anticipated biological effect has been reported to be 0.3 to 60 μg, which falls below the maximum tolerated dose with results being delivered to about a fifth of the patients, most of whom had failed in prior interventions [188]. MGD024, an altered version of Flotezumab with less affinity to CD3 and containing a mutated IgG domain with the aim of half-life increase through the function of the neonatal Fc receptors had shown reduced cytokine release when studied in rodents hosting human AML cells, and, therefore, reduced effectiveness compared to Flotezumab. However, combination therapy with Venetoclax and Cytarabine seemed to have enhanced cytotoxic activity [189]. MGD024 has been through early clinical development [190]. Finally, by introducing a SIRPα domain in an anti-CD123 antibody, Tahk et al. managed to increase phagocytosis of AML cells via mechanisms described in the corresponding section about CD47 [191].

CD117 is an important target as it caters to the need for selective targeting of HCSCs [192]. Studies suggest that the optimal therapeutic value of anti-CD117 antibodies is the conditioning of the bone marrow for a CD34+ enriched graft transplant, as evident in mouse studies, where they have been reported to act against physiological and myelodysplastic syndrome stem cells [193]. However, conditioning has traditionally been occupied by interventions such as cytotoxic chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

CD117 Blocking Antibodies

The antibodies AMG191 and SR-1, which block the interaction of CD117 with the stem cell factor (SCF) and its autophosphorylation [193,194] have been tested on immunocompetent primates with favorable outcomes consistent with the ones reported on mice [195]. Taking advantage of this positive trend, there have also been early clinical trials conducted on small groups of human immunodeficient patients which have shown safety and efficacy [196]. Combination therapies have also been considered as the parallel use of azacitidine and ACK2 has delivered efficacy in the context of bone marrow clearance and myelodysplastic stem cells [197].

Anti-CD117 Conjugates

Conjugates against CD117 have also been developed. MGTA-117 is a conjugate containing RNA polymerase II inhibitor amanitin that has been relatively successfully tested on murine models for bone marrow conditioning for graft receival. At a single dose of up to 10 mg/kg or a multi-dose of 3 mg/kg four times a day, there was tolerability and effectiveness as most grafted human cells were selectively eliminated [198]. Preliminary evidence of MGTA-117 Phase 1/2 clinical trials with a small number of participants, until the dose of 0.02 mg/kg has deemed safe the conjugate in the trial as no treatment-related adverse events were noticed, besides grade 1 alanine and aspartate aminotransferase. Effectiveness was assessed through the binding to CD117+ cells, the effect on erythropoietic stem cells, and clinical results [199]. Another conjugate, CD117-ADC carrying streptavidin–saporin had shown dose-dependent results, with a range from 0.3–1.5 mg/kg, in mice as depletion of stem cells was noted with the subsequent successful engraftment of allogenic transplants. Mature cells were spared from cytotoxic activity and, thus, as much as possible, immune capabilities remained [200].

Bispecific Antibodies Targeting CD117

Most bispecific antibodies targeting CD117 are designed with T cell engagement in mind as they also include compartments with CD3 affinity. In the context of bone marrow clearance, it has been realized that greater cytotoxicity is needed, to such an extent that T cell recruitment is rendered necessary [201]. CD117xCD3 bispecific T cell engagers (BiTEs) have shown targeted efficacy by inducing T cell proliferation and activation as well as cytotoxicity and the resulting halt of disease progression and reduction in preclinical in vivo and in vitro testing. Cell lines with positive results include HL60, MOLM14 [201], TF-1 [202], CD117+ HeLa, physiological hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells [203] highlighting their use in the treatment of AML. Additionally, a combination approach involving a CD71 aptamer and monomethyl auristatin F (MMAF) in a bispecific antibody format has also been evaluated, showing no observed toxicity in AML bone marrow samples [204].

Galectin-9 (GAL-9) is a molecule synthesized by HCSCs, among other types of physiological and malignant cells as well, crucial for immune evasion through the binding to its receptor TIM-3 and the subsequent reduction of stemness and apoptosis of T-helper 1 and the CD8+ lymphocytes that infiltrate the tumor, possible reduction of activation of dendritic cells, and reduction of activity and interferon gamma IFN-γ excretion by NK cells. Besides the dampening of the immune response, this loop has also been suggested to induce the proliferation of the AML cells in an autocrine manner through the activation of the NF-kB and β-catenin pathways [205,206]. It is then easily considered that the presence of cancer cells, especially on HCSCs, is a major player in the process of proliferation, disease progression, adverse outcomes, and the overall aggressiveness of the malignancy. Targeting TIM-3 utilizing antibodies not only increases the response of the elements of adoptive therapy through the revival of exhausted CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, evidenced by the increased excretion of immunomodulatory cytokines TNF-α and IFN-γ, but also directly limits the extent of the HCSCs’ activity and viability [207]. Besides T cells, antibody-mediated TIM-3 blockade had initiated significant NK cell activation against multiple myeloma (MM) cells in vitro, evident by the increase in proinflammatory cytokines concentration and the amount of apoptotic MM cells. In vivo testing resulted in reduced tumor burden in mice as was noticed by the decreased tumor size [208].

Sabatolimab

Sabatolimab, also known as MBG453, is a mAb used for TIM-3 blockade and that is under clinical development, having reached phase 2 at a dosage of 800 mg every 4 weeks or 600 mg every 3 weeks or 400 mg every 2 weeks. Its high affinity with TIM-3 grants it the capability of initiating similar effects as noted before in AML cells, including cytokine increase, blockade, as well as phagocytosis of marked cells [209]. Additional antibodies clinically assessed are SHR-1702 for MDS and Sym023 for lymphomas [210]. Clinical trials have demonstrated the anti-TIM-3 antibodies’ relative safety and efficacy in patients with leukaemias and solid tumors. Focusing on hematological malignancies, the combined intervention of sabatolimab with a hypomethylating agent had shown no greater incidence of Grade>/=3 adverse events than monotherapy with the hypomethylating agent in patients with high-grade MDS and AML. However, greater efficacy was observed in patients with MDS as they displayed higher overall response rates (ORRs), progressive free survival (PFS) and allowance to undergo HSCT. In a similar study studying the same diseases and interventions, high epidemiological metrics in a two-year span with ORR nearing 70%. Generally, it is considered that the addition of those antibodies into the intervention is not likely to lead to an increased risk of already ongoing therapies. Additionally, more positive results have been recorded for carriers of mutations related to less favorable outcomes [211]. Escalation trials typically include the dosages of 240, 400 and 800 mg of sabatolimab + 20 mg/m2 of decitabine intravenously (IV) in the first 5 days + 75 mg/m2 of azacitidine subcutaneously (SC) in the first 7 days per 28 days. Typical adverse events include conditions related to low numbers of blood cells such as thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, anemia, and pneumonia [212,213].

TIM-3 and PD-1 Tandem Inhibition

There appears to be a significant interplay between PD-1 and TIM-3 pathways, as there are several studies investigating whether both molecules are present on the surface of exhausted cytotoxic effector lymphocytes. Although it achieved a significant increase in survivability, tandem blockade of these molecules in mice had improved other metrics, suggesting a delay in disease progression through the reactivation of exhausted T cells in CML models. However, the evidence is not universally consistent. Some studies have challenged this proposed synergy, reporting that CD8+ T cell activation was either inadequate or failed at all due to the lack of significant CLL cell clearance in vitro [214–217].

CD200’s abundance in numerous cancer types, especially the ones of the blood [218], is catalytical to immune evasion and cancer proliferation. As an immune checkpoint molecule, CD200 bearing HCSCs are rendered capable of evading T & NK cell cytotoxicity, by hindering their metabolism and promoting cell death, leading to proliferation and rapid progression of the malignancy [219]. It’s important to recognize that, although there have been antibodies developed against CD200, as analyzed later in this paragraph, their efficacy can be compromised from the additional role facilitated by its cleavable parts located at its intracellular and extracellular domains. Whilst the intracellular part can translocate to the nucleus and act as a transcription factor for oncogenic genes, the extracellular part can initiate cell death on distant NK cells, generating questions about the extent of the efficacy of the idea of using antibodies against CD200 [220].

Samalizumab is an anti-CD 200 mAb that is evidently generally tolerable in Phase I escalation trials from 50 to 600 mg/m2 with no maximum tolerated dose (MTD) being reached and with mild adverse events being reported. Response metrics indicated 1 overall response case, 16 stable disease cases and 5 progressive disease cases, out of 23 participants. 14 of those participants had shown tumor decrease [221]. Another mAb TTI-CD200 was assessed in vitro and in vivo at 20 mg/kg. In vitro testing including macrophages and T cells has indicated efficacy against CD 200high leukemic cells, measured by the increase in IL-2 concentration, whilst minimal effect was observed on normal cells that were not expressing CD 200 at this rate. Studies on grafted mice had returned delay of disease progression, extension of survival, and decrease of engrafted human malignant cells [222]. Similar targeted cytotoxic effects were also noted in the study of Rastogi et al. using K562 (representing CML) cell lines and NOD-SCID IL2Rγ(-/-) (NSG) immunodeficient mice engrafted with blasts [223].

In the investigated literature, CD45 therapy has been associated with the use of conjugates in combination with HCST in the interest of conditioning. As CD45 tyrosine phosphatase is abundant in HCSCs and T cells, and, as such, its targeting can be implicated as “striking two birds with one stone” in avoiding GVHD that can lead to rejection [224]. Conjugates that involve Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors such as baricitinib, are effective in the conditioning of mice’s bone marrow as their transplantation was characterized as stable with minimal related adverse conditions, the most major one being GVHD [225]. The conjugate’s targeted activity, like most conjugates, only happens upon its internalization and release of the payload within the lysosome. CD45 conjugates have also been preclinically studied in vitro carrying pyrrolobenzodiazepine [226]. Based also on the information provided in Section 3.2.5, tandem inhibition of CD33 and CD45 has been a lucrative approach for the elimination of AML cells and blasts through the increased internalization and effectiveness of the former, facilitated by the latter [227].