Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Tetramethylpyrazine Alleviates Pancreatitis Progression by Regulating Inflammation and Autophagy through the YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB Axis

General Surgery Department, The First Hospital of Yulin, No. 59, Wenhua Road, Suide County, Yulin, 718000, China

* Corresponding Author: Yang Liu. Email:

BIOCELL 2025, 49(10), 1985-2006. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.069527

Received 25 June 2025; Accepted 29 August 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

Background: Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a serious gastrointestinal disorder. Tetramethylpyrazine (TMP), a bioactive alkaloid extracted from Ligusticum chuanxiong, exhibits various pharmacological effects, but its protective mechanisms against AP remain unclear. This study aimed to investigate the protective effects and underlying mechanisms of TMP in AP. Methods: The study utilized Cerulein (CER) to model pancreatitis across experimental systems. Cellular responses were characterized through functional assays (CCK-8 viability, EdU proliferation, Transwell migration, flow cytometric apoptosis, Fluo-3/AM calcium imaging) and inflammatory profiling (ELISA for trypsin, CRP, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6). Autophagy was monitored via mRFP-GFP-LC3 flux and LysoTracker staining, with parallel LDH measurements. Mechanistic studies examined autophagy-related proteins (LAMP-1, p62, LC3) and YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB signaling intermediates by Western blot, supported by YAP genetic manipulation. In vivo assessments included HE-stained histology, TUNEL apoptosis detection, and MPO-based neutrophil evaluation. Results: TMP dose-dependently improved CER-induced cell viability and ATP levels, inhibited cell apoptosis, reduced Ca2+ concentration, LDH release, and inflammatory responses (trypsin, CRP, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and NLRP3). TMP also upregulated LAMP-1 protein expression, downregulating p62, Beclin-1, Atg5, LC3 protein levels, promoting autophagosome-lysosome fusion, and enhancing lysosomal activity, thus alleviating pancreatic damage. Additionally, TMP inhibited YAP, RIPK1, and NF-κB p65 phosphorylation, with YAP knockdown enhancing TMP effects while YAP overexpression partially counteracted TMP actions. In the rat AP model, TMP significantly improved tissue pathological changes, reduced inflammatory infiltration and cell apoptosis, decreased serum inflammatory marker levels, and inhibited YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB axis activation. Conclusion: This study reveals that TMP alleviates AP progression by inhibiting YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB axis activation, achieving dual effects of anti-inflammation and promoting autophagy.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a frequently occurring condition involving inflammation of the pancreas, primarily caused by damage to its acinar cells, abnormal pancreatic enzyme activation, and intense inflammatory response, with clinical manifestations including upper abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, and fever [1,2]. Recent studies indicate a rising global prevalence of AP, with an estimated annual incidence ranging from 13 to 45 cases per 100,000 individuals [3,4]. Although the majority of AP patients experience mild symptoms, roughly 15%–20% develop Severe AP (SAP), which can trigger widespread inflammation, organ dysfunction, and death in 20%–30% of cases [5]. The high incidence, high mortality, and high treatment costs of SAP impose a heavy burden on patients and healthcare systems; therefore, in-depth research on its pathogenesis and the identification of effective therapeutic strategies have significant clinical implications.

AP progression is fundamentally driven by inflammation. Early-phase acinar cell damage induces Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) and other cytokine release, activating inflammatory pathways that attract immune cells (neutrophils/macrophages), leading to amplified pancreatic damage [6]. Autophagy, as an important cellular homeostasis regulatory mechanism, maintains cellular homeostasis by clearing damaged organelles and protein aggregates [7]. In AP models, autophagy flux obstruction is commonly observed, manifested as autophagosome accumulation with decreased autolysosomes, elevated LC3 and p62 protein levels, and decreased lysosomal activity. This autophagy flux blockade leads to insufficient ATP, triggering secretory disorders and abnormal zymogen accumulation, further aggravating pancreatitis symptoms [8]. Emerging evidence highlights autophagy’s regulatory function in AP pathogenesis, where miR-20b-5p enhances autophagic activity to suppress inflammation and apoptosis, ultimately mitigating SAP severity [9]. Therefore, simultaneously targeting inflammatory responses and restoring autophagy flux may become a novel therapeutic strategy for alleviating AP progression.

The Yes-associated protein (YAP), a key downstream mediator of the Hippo pathway, has been implicated in the pathogenesis of multiple disorders [10]. Notably, preclinical investigations have demonstrated marked YAP overexpression in experimental murine models of pancreatitis [11], and upregulating YAP to inhibit autophagy can aggravate pancreatic cell inflammation [12]. Modulation of YAP1 expression demonstrates therapeutic potential, as its downregulation suppresses pancreatic stellate cell activation, thereby attenuating chronic pancreatic inflammation and fibrotic progression [13]. Furthermore, emerging evidence highlights the critical involvement of RIPK1 and NF-κB pathways in inflammatory cascades, where their pharmacological inhibition markedly ameliorates AP-associated tissue damage [14,15]. The latest research indicates that the YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB axis has significant importance in regulating inflammation and autophagy processes [16], suggesting that this signaling axis may become a potential target for AP treatment.

Tetramethylpyrazine (TMP) is an alkaloid extracted from the Chinese herb Ligusticum chuanxiong, possessing various pharmacological effects including vasodilation, microcirculation improvement, anti-inflammation, antioxidation, and anti-apoptosis [17]. Previous studies have reported that TMP can inhibit the release of inflammatory cytokines and apoptosis in pancreatic cells, as well as alleviate histopathological damage in pancreatic tissue [18]. Additionally, TMP restores impaired autophagy flux via YAP1-NRF2-P62 signaling, thereby reducing acute kidney injury [19]. In recent years, the role of the YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB signaling axis in inflammatory responses and cell death has attracted increasing attention; however, its specific mechanisms in acute pancreatitis remain unclear. More importantly, to date, there have been no studies reporting pharmacological modulation of this signaling axis to intervene in the progression of acute pancreatitis. Based on the research background described above, this study hypothesizes that TMP may regulate the activity of YAP, thereby affecting the downstream RIPK1-NF-κB signaling axis. By inhibiting excessive inflammatory responses in pancreatic acinar cells while restoring protective autophagic flux, TMP may ultimately act synergistically to alleviate the pathological progression of pancreatitis. This study intends to employ a combination of in vivo and in vitro experiments, first confirming the therapeutic effect of TMP in caerulein (CER)-induced AP cell and mouse models. Furthermore, by integrating techniques such as molecular biology, cell biology, and gene knockdown/overexpression, we will thoroughly investigate whether TMP modulates inflammation and autophagy through the YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB axis to attenuate the progression of pancreatitis, thereby providing new insights and targets for the development of novel AP therapeutics.

Rat pancreatic exocrine cell line AR42J (ZKCC, ZKCC62173, Beijing, China) was cultured in Kaighn’s Modification of Ham’s F-12 Medium (F12K, ZKCC, ZKCC809444) containing 20% FBS (Gibco, 10100147, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (MCE, HY-K1006, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) at 37°C with 5% CO2. For in vitro pancreatitis induction, AR42J cells were exposed to 100 nM cerulein (CER, purity: 99.97%, MCE, HY-A0190) for 24 h. The CER stock solution was initially prepared in PBS and subsequently diluted to the working concentration using complete culture medium [20]. No mycoplasma contamination was detected during the experimental period.

2.2 siRNA and Plasmid Transfection

siRNA targeting YAP (si-YAP, 5′-GGUUGAGUGUCACCUACAA-3′) and corresponding negative control (si-NC, 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′), as well as YAP overexpression plasmid (oe-YAP, constructed using pcDNA 3.1 vector) and corresponding negative control (oe-NC) were provided by Sangon Biotech company (Shanghai, China). AR42J cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well. When the cell confluence reached 60%–70%, transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher, L3000150, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One hour prior to transfection, the medium was replaced with Optimized Minimum Essential Medium (Opti-MEM, Sigma, M0325, St Louis, MO, USA). siRNA or overexpression plasmids were dissolved in Opti-MEM, mixed with the transfection reagent, and then added dropwise to the cell culture medium. The cells were then incubated in an incubator. 6 h after transfection, the medium was replaced with fresh F12K medium. Transfection efficiency was assessed 48 h later.

To investigate the effects and mechanisms of TMP on a CER-induced in vitro pancreatitis cell model, the following groups were established: control group, CER model group, and CER + TMP (25, 50, 100 μM) groups. In the TMP treatment groups, cells were co-treated with TMP (purity: 98%, Sigma, 183938) and 100 nM CER for 24 h, after which the cells were collected for subsequent experiments.

To further investigate the molecular mechanism of YAP in TMP’s protective effects, YAP low-expression and overexpression cell models were established through siRNA knockdown or plasmid overexpression methods, respectively, with corresponding control groups: si-NC, si-YAP (transfected with YAP-targeting siRNA), oe-NC, and oe-YAP (transfected with the YAP overexpression plasmid). After verifying transfection efficiency, combined treatment groups were established: CER + TMP100 + si-NC (100 μM TMP and 100 nM CER co-treatment, with negative control siRNA transfection), CER + TMP100 + si-YAP (TMP and CER co-treatment, with YAP-targeting siRNA transfection), CER + TMP100 + oe-NC (TMP and CER co-treatment, with empty vector transfection), and CER + TMP100 + oe-YAP (TMP and CER co-treatment, with YAP overexpression plasmid transfection).

Cell proliferation was evaluated with a CCK-8 assay kit (Vazyme, A311-01, Nanjing, China). AR42J cells were resuspended and slowly loaded into the sample wells of cell counting plates. For cytotoxicity assessment, AR42J cells (5 × 104/well) were seeded in 96-well plates and exposed to varying TMP concentrations (0, 10, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 μM) for 24 h. To evaluate cytoprotective effects, parallel cultures were co-treated with 100 nM CER and TMP (0, 10, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400 μM) for 24 h. Cellular viability was determined by CCK-8 assay, involving 2.5 h incubation with 10 μL reagent followed by absorbance measurement at 450 nm.

This study used the 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) method to detect AR42J cell proliferation activity. After the aforementioned treatments, cells from each group were labeled with 10 μM EdU (Beyotime, C0078S, Shanghai, China) for 2 h, fixed with 4% PFA, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Beyotime, ST1723), followed by adding the Click reaction solution and incubating in the dark for 30 min, and DAPI (Beyotime, C1002) counterstaining of nuclei. Finally, EdU-positive cell ratios were observed and calculated using a fluorescence microscope (Eclipse Ti2, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) to assess cell proliferation.

2.6 Flow Cytometry Detection of Cell Apoptosis

Following treatments, cells underwent three PBS washes before trypsinization (Solarbio, T1360, Beijing, China). The cell suspension was prepared in binding buffer and stained with 5 μL Annexin V-FITC (Solarbio, CA1020) for 5 min at room temperature, followed by the addition of propidium iodide (PI, Solarbio, CA1020). After 5 min incubation on ice, samples were immediately analyzed using an Attune NxT flow cytometer (Thermo) to determine apoptosis rates within 30 min post-staining.

Cell migration was evaluated using 8.0 μm pore Transwell chambers (Corning, New York, USA). Briefly, treated AR42J cells (2 × 105 cells/200 μL serum-free F12K medium) were seeded in the upper chamber, while the lower chamber contained 600 μL complete medium with 10% FBS as chemoattractant. Following 24 h incubation, non-migratory cells were removed from the upper membrane surface. Migrated cells on the lower surface were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (15 min). Cell migration was evaluated by counting the number of migrated cells in five randomly selected fields on the lower surface of the Transwell membrane. The migration rate was expressed as the average number of migrated cells per field, and the results were presented as mean ± standard deviation.

2.8 Ca2+ Concentration Detection

Intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured using Fluo-3/AM (Beyotime, Y240853). AR42J cells were cultured in confocal dishes, treated according to experimental groups for 24 h, then washed with PBS and loaded with 3 μM Fluo-3/AM (37°C, 30 min, dark). After removing extracellular probe with Ca2+-free HBSS (Sigma, H6648), cells were incubated in HBSS (room temperature, 30 min, dark) for complete probe hydrolysis. Stain the cell nuclei with DAPI for 5 min, observe the intracellular Ca2+ fluorescence intensity using a confocal microscope (SP8, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), and analyze using ImageJ 1.54 software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

2.9 mRFP-GFP-LC3 Tandem Lentivirus

The mRFP-GFP-LC3 tandem fluorescent reporter lentivirus (Hanbio, Shanghai, China) was used to transfect AR42J cells for monitoring autophagic flux. AR42J cells were plated at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well in confocal imaging dishes. After cell attachment, mRFP-GFP-LC3 lentivirus was added at an MOI of 20, along with 5 μg/mL polybrene (Sigma, S2667) to enhance transfection efficiency. Following 24 h incubation, the medium was refreshed and cells were maintained for another 48 h to achieve optimal reporter gene expression. Subsequently, the cells were treated according to experimental groups for 24 h, followed by fixation, washing, and mounting with anti-fluorescence quenching mounting medium containing Hoechst 33342 (Beyotime, P0133). GFP and mRFP were observed using a confocal microscope (FV3000, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Yellow dots (co-localization of GFP and mRFP) represent autophagosomes, while orange-red dots (mRFP signal only) represent autolysosomes.

Lysosomal activity in AR42J cells was evaluated using LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Invitrogen, L7528, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Following 24 h experimental treatments, cells underwent two washes with pre-warmed serum-free medium before incubation with 100 nM LysoTracker Red DND-99 (37°C, 30 min, dark). Subsequently, washed gently twice with serum-free medium, and incubate with Hoechst stain (Beyotime, C1025) at room temperature for 10 min. Centrifuge the cells at 4°C, 400× g for 3 min, discard the supernatant, and wash the cells twice with PBS. Lysosomes in live cells were observed using a confocal laser scanning microscope with an excitation wavelength of 577 nm and an emission wavelength of 590 nm. The lysosomal activity of cells in each group was analyzed using ImageJ software.

Male SD rats (6–8 weeks old, 200–220 g) were obtained from Slaccas-Shanghai Lab Animal Ltd. (Shanghai, China). They were maintained in controlled environmental conditions (22 ± 2°C, 55 ± 5% humidity) with a 12 h photoperiod and ad libitum access to food and water. All animal procedures were conducted in compliance with institutional ethical guidelines following approval by the First Hospital of Yulin Animal Ethics Committee (Ethical approval number: 20230097). Animals were randomly assigned to different experimental groups using a random number table. All outcome assessments were performed by investigators blinded to the group allocations.

The rats were randomly divided into three groups (n = 6): Sham group: Intraperitoneal injection of saline at the same frequency as the AP model group. AP model group (CER group): Intraperitoneal injection of 50 μg/kg CER once per hour for a total of seven injections [21]; TMP treatment group (CER + TMP group): Pre-treatment with intraperitoneal injection of TMP at a dose of 300 mg/kg, starting 3 h before the first CER injection, followed by CER injections as per the model protocol. The experiment lasted approximately 10–12 h, during which the rats were regularly monitored. After the experiment, the rats were anesthetized with 3% pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg) (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., TT019325G, Shanghai, China), and blood samples were collected. The rats were then euthanized, and the pancreatic tissues were rapidly isolated. Briefly, the abdominal cavity was opened under sterile conditions, and the pancreas was carefully separated from the surrounding tissues using sterile surgical instruments to avoid contamination and tissue damage. Part of the pancreatic tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for histological analysis, while the remaining tissue was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and subsequently stored at −80°C for biochemical and molecular biological analyses.

2.12 Hematoxylin-Eosin (HE) and TUNEL Staining

Firstly, the fixed pancreatic tissues from rats were dehydrated, cleared, and embedded in paraffin, followed by sectioning (5 μm) and mounting onto slides. After deparaffinization and hydration, HE staining was performed using a standard HE staining kit (Solarbio, G1120). Hematoxylin staining was performed for 10 min, followed by differentiation with differentiation solution for 30 s and eosin staining for 1 min. After dehydration and clearing, the sections were mounted with neutral balsam (Solarbio, G8590). The stained sections were observed under a microscope (BX53, Olympus), where nuclei appeared blue, cytoplasm appeared pink, and structural features such as pancreatic acini, ducts, and stroma were clearly displayed. Two pathologists, blinded to the grouping, randomly selected five fields of view and scored pancreatic tissue for edema, inflammatory cell infiltration, and acinar cell necrosis (0–3 points) [22], and also assigned a pancreatic pathological score (0–5 points).

Apoptotic cells were detected using a commercial TUNEL assay kit (Solarbio, T2130). Briefly, deparaffinized tissue sections underwent antigen retrieval with proteinase K (15 min), followed by TUNEL reagent incubation (37°C, 60 min, humidified chamber). After POD-conjugate treatment (37°C, 30 min), DAB chromogenic development was performed with hematoxylin counterstaining. The apoptotic index was quantified as the percentage of TUNEL+ cells in five random high-power fields.

Serum was isolated from clotted blood samples through centrifugation (1000× g, 15 min, 4°C; 5424R, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) following 30 min room temperature coagulation. After specific treatments described in Section 2.3, AR42J cells were collected and subjected to ultrasonic disruption for 3 min. The cell suspension was then centrifuged at 12,000× g for 15 min to pellet the cells at the bottom of the tube. Subsequently, 120 μL of supernatant from each well (5 × 104 cells per well) was carefully collected and transferred to corresponding positions in a new 96-well plate for further analysis. A microplate reader (Rayto, RT-6100, Shenzhen, China) was preheated for 30 min, and commercial kits were used to measure the levels of amylase (BC0615), lipase (BC2345), and ATP (BC0305) in the supernatants of AR42J cells and rat serum at wavelengths of 540, 710, and 340 nm, respectively (all kits from Solarbio).

2.14 Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Commercial ELISA kits were used to measure the levels of trypsin (MBS765078, MyBioSource, Los Angeles, CA, USA), C-reactive protein (CRP, MBS494518, MyBioSource), TNF-α (SEKR-0009, Solarbio), Interleukin 1 Beta (IL-1β, SEKR-0002, Solarbio), and Interleukin 6 (IL-6, SEKR-0005, Solarbio) in AR42J cell culture supernatants or rat serum. Before detection, the cell supernatants, rat serum, and reagents from the kits were slowly thawed to room temperature. According to the manufacturer’s protocol, samples were loaded into 96-well plates pre-coated with washing and detection buffers. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, diluted antibodies were added and incubated for another hour. Enzyme conjugates were then added and incubated for 30 min, followed by TMB color development for 15 min. The reaction was terminated with stop solution, followed by absorbance measurement at 450 nm using a microplate reader (RT-6100, Rayto).

2.15 Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Assay

Cellular damage was evaluated by measuring LDH activity using a commercial kit (Beyotime, C0016). Briefly, AR42J cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells per well and subjected to specific treatments. 60 μL aliquots of AR42J cell supernatants or rat serum were mixed with equal volumes of LDH reagent in 96-well plates, followed by 30 min incubation (room temperature, dark). Absorbance readings were obtained at 490 nm using a BioTek Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek, Hercules, CA, USA).

Immunofluorescence staining was performed on paraffin-embedded pancreatic sections. Following deparaffinization and antigen retrieval (citrate buffer, pH 6.0, microwave), samples were treated with 3% H2O2 (Aladdin, H433857, Shanghai, China) to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Non-specific binding was blocked with 5% goat serum/0.1% Triton X-100 (1 h, RT). Primary antibodies against MPO (1:100, Abcam, ab208670, Cambridge, UK), LC3 (1:100, CST, #12741, Danvers, Massachusetts, USA), and p62 (1:400, CST, #23214) were applied overnight at 4°C. After washing, Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500, 488/594, A-11034/A-11012, Invitrogen; RT, 1 h) and DAPI (RT, 5 min) were used for detection. Slides were imaged by confocal microscopy and analyzed with ImageJ.

Protein extraction and immunoblotting were performed as follows: AR42J cells or pancreatic tissues were homogenized in ice-cold RIPA buffer (Beyotime, 89900) supplemented with protease/phosphatase inhibitors (Beyotime, P1045). Lysates were centrifuged (12,000× g, 15 min, 4°C) and supernatants were quantified using BCA assay. Equal protein amounts (30–50 μg) were denatured (95°C, 5 min), separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to PVDF membranes (Vazyme, E801/E802). After blocking (5% BSA, 1 h), membranes were probed overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against: p-YAP (1:1000, #4911), YAP (1:1000, #4912), p-RIPK1 (1:1000, #53286), RIPK1 (1:1000, #3493), NF-κB p-p65 (1:1000, #3033), NF-κB p65 (1:1000, #8242), p62 (1:1000, #5114), Beclin-1 (1:1000, #3738), Atg5 (1:1000, #12994), LC3 (1:1000, #2775), and β-Actin (1:1000, #4967), all purchased from CST. LAMP-1 (1 µg/mL, ab13523), TNF-α (1:1000, ab307164), IL-1β (1:1000, ab283818), IL-6 (1:1000, ab259341), and NLRP3 (1:1000, ab263899) were purchased from Abcam.

Following PBST washes, membranes were probed with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000, ab288151, Abcam) for 1 h at room temperature. ECL reagent was used for visualization, and images were captured using a gel imaging system (Tanon 5200, Shanghai, China). Protein band quantification was performed using ImageJ, with β-actin serving as the loading control for data normalization.

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism 9.0 (San Diego, CA, USA) and presented as mean ± SD. Intergroup comparisons were made using two-tailed Student’s t-test (two groups) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test (multiple groups), with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

3.1 TMP Ameliorates CER-Induced Reduction in AR42J Cell Viability and Apoptosis

The results of the CCK-8 assay showed that TMP exhibited no significant cytotoxicity at concentrations of 0, 10, 25, 50, and 100 μM. However, within the concentration range of 200, 400, 800, and 1600 μM, TMP inhibited cell viability in a dose-dependent manner (from 95.12% to 42.71%), with the most pronounced inhibitory effect observed at 1600 μM (Fig. 1A). Based on these findings, the protective effects of TMP on CER-induced AR42J cell injury were further examined. TMP at concentrations of 25, 50, and 100 μM significantly ameliorated the CER (100 nM)-induced reduction in cell viability (from 75.23% to 95.31%), while 200 and 400 μM concentrations showed inhibitory effects (Fig. 1B). Therefore, subsequent experiments employed 25, 50, and 100 μM as low, medium, and high concentration gradients of TMP for further investigation.

Figure 1: TMP ameliorates CER-induced reduction in AR42J cell viability and apoptosis. (A) Cell viability assessed by CCK-8 assay after treatment with varying TMP doses (0, 10, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600 μM). (B) TMP (0, 10, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400 μM) rescued CER-impaired cell viability; these doses were chosen for further experiments. (C,D) Proliferation of AR42J cells measured by EdU assay. Scale bar: 50 μm. (E,F) Migratory capacity evaluated via Transwell assay. Scale bar: 100 μm. (G,H) Apoptosis rates analyzed by flow cytometry. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation from three separate trials

Experimental groups included Control, CER, and CER combined with different concentrations of TMP (25, 50, 100 μM). EdU assays demonstrated that CER treatment significantly suppressed AR42J cell proliferation (the proportion of EdU-positive cells decreased from 30.67% to 10.00%), whereas TMP treatment notably restored proliferative activity in a dose-dependent manner (from 15.67% to 27.33%) (Fig. 1C,D). This protective effect was also confirmed in cell migration assays. Transwell migration assays revealed that CER treatment markedly reduced cell migration ability (the migration rate decreased from 68.33% to 23.00%) (Fig. 1E,F), while TMP intervention dose-dependently enhanced AR42J cell migration (from 32.00% to 63.00%). Further flow cytometry analysis showed that CER significantly promoted apoptosis (the apoptosis rate increased from 13.51% to 49.03%) (Fig. 1G,H), whereas TMP exhibited pronounced anti-apoptotic effects (17.25%). Collectively, these results indicate that TMP effectively mitigates CER-induced reductions in AR42J cell viability, proliferation inhibition, migration impairment, and increased apoptosis, without significantly enhancing normal cell functions.

3.2 TMP Ameliorates CER-Induced Inflammation in AR42J Cells

Using the Fluo-3/AM fluorescent probe, it was found that CER treatment significantly increased intracellular Ca2+ concentration in AR42J cells (Fig. 2A,B), whereas TMP intervention dose-dependently and markedly reduced this abnormal Ca2+ elevation. Biochemical assays further assessed characteristic markers of pancreatitis. Lipase and amylase levels were significantly elevated in CER-treated cells (Lipase, 1352.33 U/L; Amylase: 660.00 U/L), and TMP treatment dose-dependently inhibited their activities (Lipase: 819 U/L; Amylase: 354.00 U/L) (Fig. 2C,D). ELISA results confirmed that TMP significantly suppressed CER-induced secretion of trypsin (1706.00 pg/mL), CRP (914.00 ng/mL) (Fig. 2E,F), and pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α (62.67 pg/mL), IL-1β (135.00 pg/mL), and IL-6 (103.33 pg/mL) (Fig. 2G–I). Western blot analysis demonstrated that TMP dose-dependently downregulated the protein expression levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and the NLRP3 inflammasome in AR42J cells (Fig. 2J–N). These systematic assessments not only validated the CER-induced inflammatory model but also comprehensively revealed that TMP exerts anti-inflammatory effects through multiple mechanisms, including regulation of calcium homeostasis, inhibition of aberrant digestive enzyme activation, and downregulation of inflammatory cytokine expression.

Figure 2: TMP ameliorates CER-induced inflammation in AR42J cells. (A,B) Intracellular Ca2+ levels were measured using Fluo-3/AM to assess TMP’s effect on CER-triggered inflammation. Scale bar: 100 μm. (C,D) Amylase and lipase levels in cell supernatants were quantified. (E–I) ELISA analysis of trypsin, CRP, TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 in supernatants to evaluate inflammatory responses. (J–N) Western blotting of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and NLRP3 to explore TMP’s anti-inflammatory mechanism in the pancreatitis model. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation from three separate trials

3.3 TMP Improves CER-Induced Autophagic Flux in AR42J Cells

Autophagic flux changes were initially monitored using the mRFP-GFP-LC3 dual fluorescence system (Fig. 3A). The results showed that the number of AR42J cells expressing GFP-LC3+ and mRFP-LC3+ (autophagosomes) significantly increased in the CER treatment group (Fig. 3B), while the number of AR42J cells expressing mRFP-LC3+ (autolysosomes) significantly decreased (Fig. 3C), indicating that CER induced a notable autophagic flux blockage. It is noteworthy that after TMP intervention, as the drug concentration increased, the number of autophagosomes gradually decreased while lysosomes increased, suggesting that TMP can dose-dependently promote the fusion of autophagosomes and lysosomes, thereby restoring autophagic flux.

Figure 3: TMP improves CER-induced autophagic flux in AR42J cells. (A–C) mRFP-GFP-LC3 transfection assessed TMP’s effect on CER-induced autophagic flux. Scale bar: 50 μm. (D,E) LysoTracker Red evaluated lysosomal activity. Scale bar: 50 μm. (F) LDH release measured cell injury. (G) ATP levels in AR42J cells from each group were measured using an ATP detection kit. (H–M) Western blot analyzed LAMP-1, p62, Beclin-1, Atg5 and LC3 expression. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation from three separate trials

To further validate this finding, LysoTracker Red fluorescent probe was used to assess lysosomal activity in AR42J cells. The results demonstrated a significant reduction in lysosome numbers in the CER-treated group compared to controls (Fig. 3D,E), whereas TMP intervention significantly increased lysosome numbers, with high-dose TMP restoring lysosome counts close to control levels. Regarding cell injury and energy metabolism, CER treatment significantly increased LDH release and decreased ATP (15.33 nmol/mg) levels (Fig. 3F,G). TMP intervention dose-dependently reduced LDH release and elevated ATP (38.33 nmol/mg) levels.

Western blot analysis revealed that CER treatment significantly upregulated the expression of p62, Beclin-1, Atg5, and LC3 proteins, accompanied by downregulation of the lysosomal marker protein LAMP-1 (Fig. 3H–M). After TMP intervention, LC3 and p62 protein levels decreased dose-dependently, while LAMP-1 expression was significantly upregulated, further confirming that TMP effectively improves the autophagy-lysosome pathway function. Additionally, TMP markedly downregulated the expression of autophagy-related proteins Beclin-1 and Atg5, indicating that it may restore autophagic homeostasis by modulating the initiation phase of autophagy. These results demonstrate that TMP promotes autophagosome-lysosome fusion, enhances lysosomal activity, and improves cellular energy metabolism, thereby effectively alleviating CER-induced autophagic dysfunction and cellular injury, ultimately restoring autophagic flux.

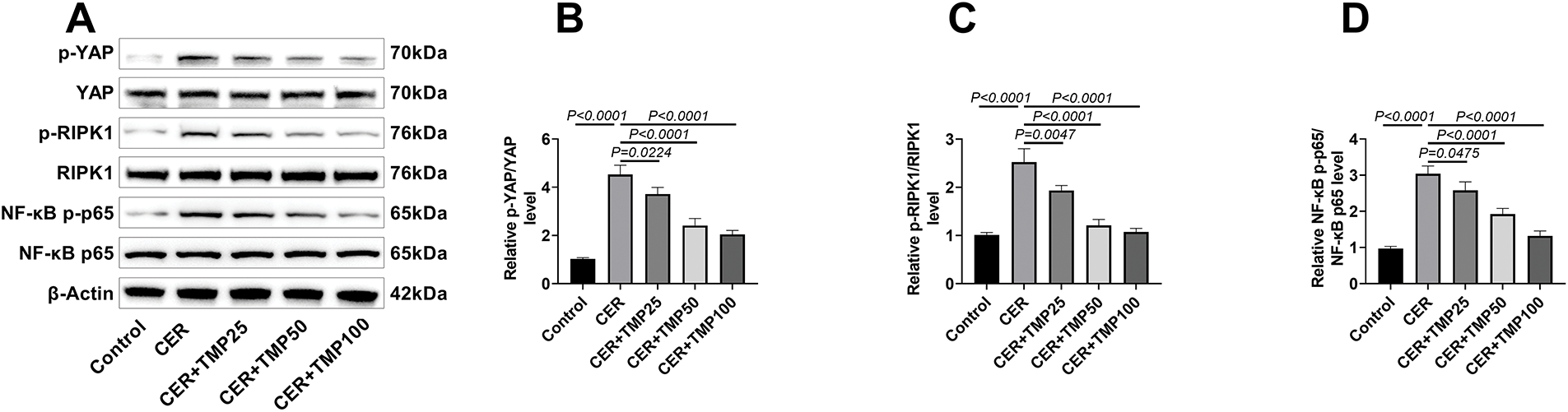

3.4 TMP Regulates the YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB Axis

Western blot analysis confirmed CER-induced phosphorylation of YAP, RIPK1 and NF-κB p65 in AR42J cells (Fig. 4A–D), indicating pathway activation. TMP intervention markedly inhibited the phosphorylation of these key signaling molecules, with the 100 μM TMP treatment group exhibiting the most pronounced inhibitory effect.

Figure 4: TMP regulates the YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB axis. (A–D) Western blot analysis was performed to detect the phosphorylation and total protein expression levels of key proteins in the YAP/RIPK1/NF-κB signaling pathway (including p-YAP/YAP, p-RIPK1/RIPK1, NF-κB p-p65/p65) in CER-induced AR42J cells, elucidating the molecular mechanism by which TMP modulates this signaling pathway. (E–H) YAP gene knockdown and overexpression AR42J cell models were constructed using siRNA interference (si-NC, si-YAP groups) and plasmid transfection (oe-NC, oe-YAP groups), respectively. The results showed that the p-YAP/YAP ratio in the si-YAP group was significantly lower than that in the si-NC group, while the p-YAP/YAP ratio in the oe-YAP group was significantly higher than that in the oe-NC group, indicating that the cell models were successfully constructed. (I–L) Western blot analysis of key proteins in the YAP/RIPK1/NF-κB signaling pathway (p-YAP/YAP, p-RIPK1/RIPK1, NF-κB p-p65/p65) was conducted across different treatment groups (Control, CER, CER + TMP100, CER + TMP100 + si-NC, CER + TMP100 + si-YAP, CER + TMP100 + oe-NC, CER + TMP100 + oe-YAP) in AR42J cells, revealing the central regulatory role of YAP in this pathway. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation from three separate trials

YAP knockdown and overexpression AR42J cell models were established using RNA interference and plasmid transfection techniques, respectively. Western blot results showed that compared to the si-NC control group, the p-YAP/YAP ratio in si-YAP transfected AR42J cells was significantly decreased, confirming successful YAP knockdown (Fig. 4E,F). Conversely, the p-YAP/YAP ratio was significantly increased in the oe-YAP overexpression group compared to the oe-NC control group (Fig. 4G,H).

Based on these successfully constructed cell models, it was further found that in YAP knockdown AR42J cells, TMP’s inhibitory effects on phosphorylation of YAP, RIPK1, and NF-κB p65 were more pronounced than those in the CER + TMP100 + si-NC group; whereas YAP overexpression partially reversed TMP’s inhibitory effects on these phosphorylations (Fig. 4I–L). Moreover, there were no significant differences in the p-YAP/YAP, p-RIPK1/RIPK1, and NF-κB p-p65/NF-κB p65 ratios among the CER + TMP 100 + si-NC, CER + TMP 100 + oe-NC, and CER + TMP 100 groups. These data not only confirm the central regulatory role of YAP in this signaling pathway but also reveal the molecular mechanism by which TMP exerts its anti-inflammatory effects by targeting the YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB signaling axis.

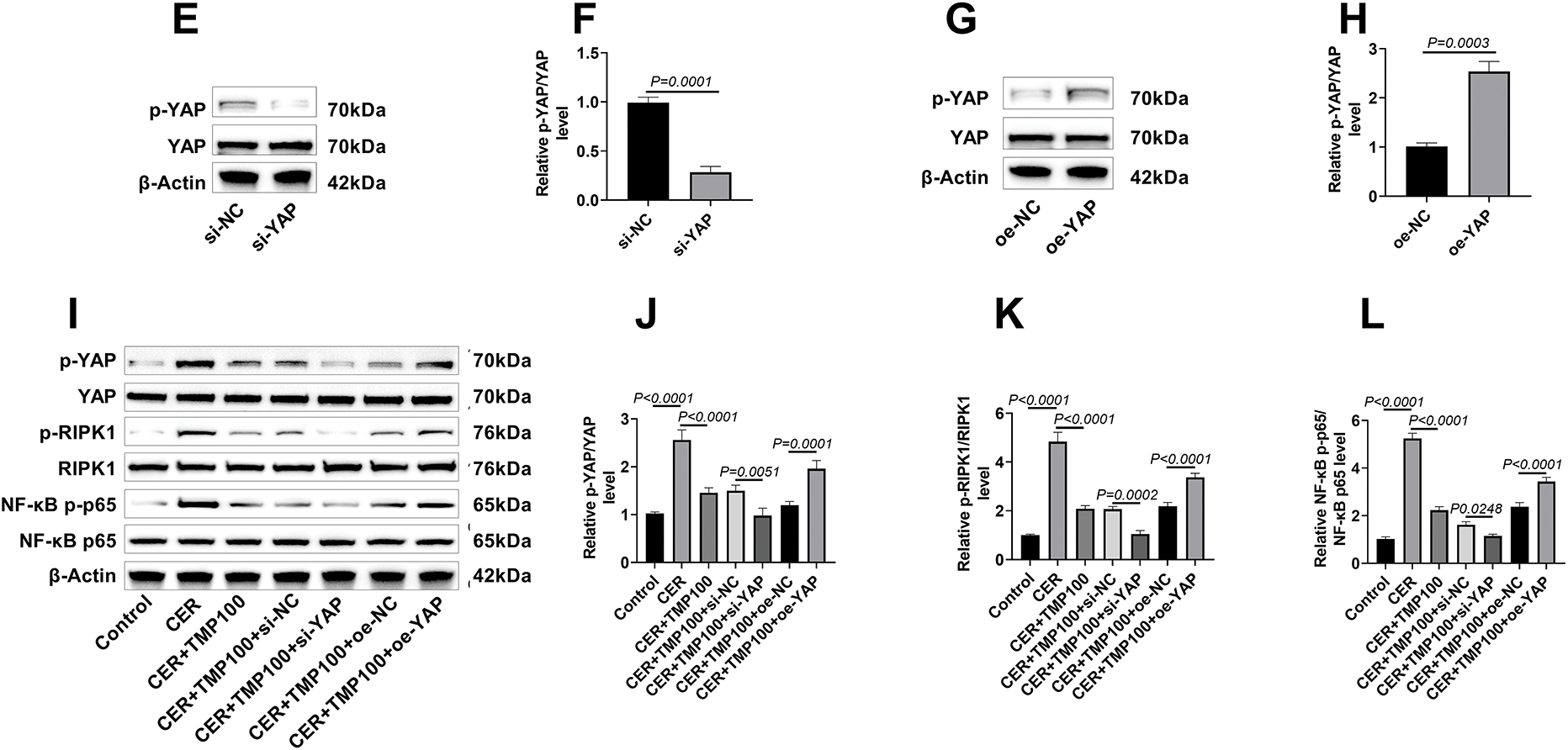

3.5 TMP Alleviates Pancreatic Injury, Pancreatic Enzyme Activation, and Improves Pancreatitis Symptoms in Rats

Histopathological analysis showed that the CER model group exhibited typical pathological features of AP (Fig. 5A–E): marked disorganization of acinar structure, significant widening of interlobular spaces, extensive infiltration of neutrophils and monocytes in the stroma, with some acinar cells showing nuclear fragmentation and dissolution accompanied by lipid vacuole formation. Compared with the model group, TMP-treated rats exhibited significantly improved pathological changes in pancreatic tissue, with more intact acinar structures, markedly reduced inflammatory cell infiltration, and significantly attenuated cell necrosis, indicating that TMP alleviates pancreatic injury in rats (Fig. 5A–E).

Figure 5: TMP alleviates pancreatic injury, pancreatic enzyme activation, and improves pancreatitis symptoms in rats. (A–E) Rats (n = 6/group) were divided into Sham, AP, and AP + TMP groups. HE staining was used to detect the histological changes in the pancreatic tissue of mice in each group. Edema, inflammation, necrosis, and pancreatic pathology were scored to assess the protective effect of TMP in the in vivo mouse model of pancreatitis. Scale bar: 100 μm. (F,G) TUNEL staining evaluated pancreatic apoptosis. Scale bar: 50 μm. (H) Serum LDH levels in rats were measured to analyze the protective effect of TMP against cell injury in the pancreatitis model. (I,J) Serum amylase and lipase activities were measured to evaluate TMP’s effect on pancreatic enzyme regulation in AP rats. (K,L) ELISA was performed to detect serum trypsin and CRP levels, analyzing the molecular-level impact of TMP on inflammatory responses in pancreatic tissue of the pancreatitis rat model. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation from three separate trials

The CER model group exhibited significantly increased apoptotic cell counts (apoptosis rate: 43.32%) in pancreatic tissues compared to Sham controls (apoptosis rate: 6.85%), as demonstrated by TUNEL staining, while TMP administration effectively attenuated this apoptotic response (apoptosis rate: 18.17%) (Fig. 5F,G). Biochemical analyses revealed substantial elevation of LDH activity in the CER group, which was significantly ameliorated by TMP treatment (Fig. 5H). Detection of pancreatic injury markers showed that serum amylase (1226.83 U/L) and lipase (382.67 U/L) levels were significantly elevated in the CER model group. After TMP intervention, these levels decreased markedly (amylase: 887.33 U/L; lipase: 277.67 U/L) (Fig. 5I,J). Furthermore, the CER model displayed significantly elevated serum trypsin (8455.17 pg/mL) and CRP (3377.00 ng/mL) concentrations relative to Sham controls, both of which were significantly reduced by TMP treatment (trypsin: 3600.83 pg/mL; CRP: 1958.83 ng/mL) (Fig. 5K,L). These results collectively demonstrate that TMP effectively mitigates the pathological damage and clinical symptoms of AP through a multi-targeted mechanism, including inhibition of aberrant pancreatic enzyme activation, attenuation of inflammatory responses, and reduction of cell apoptosis.

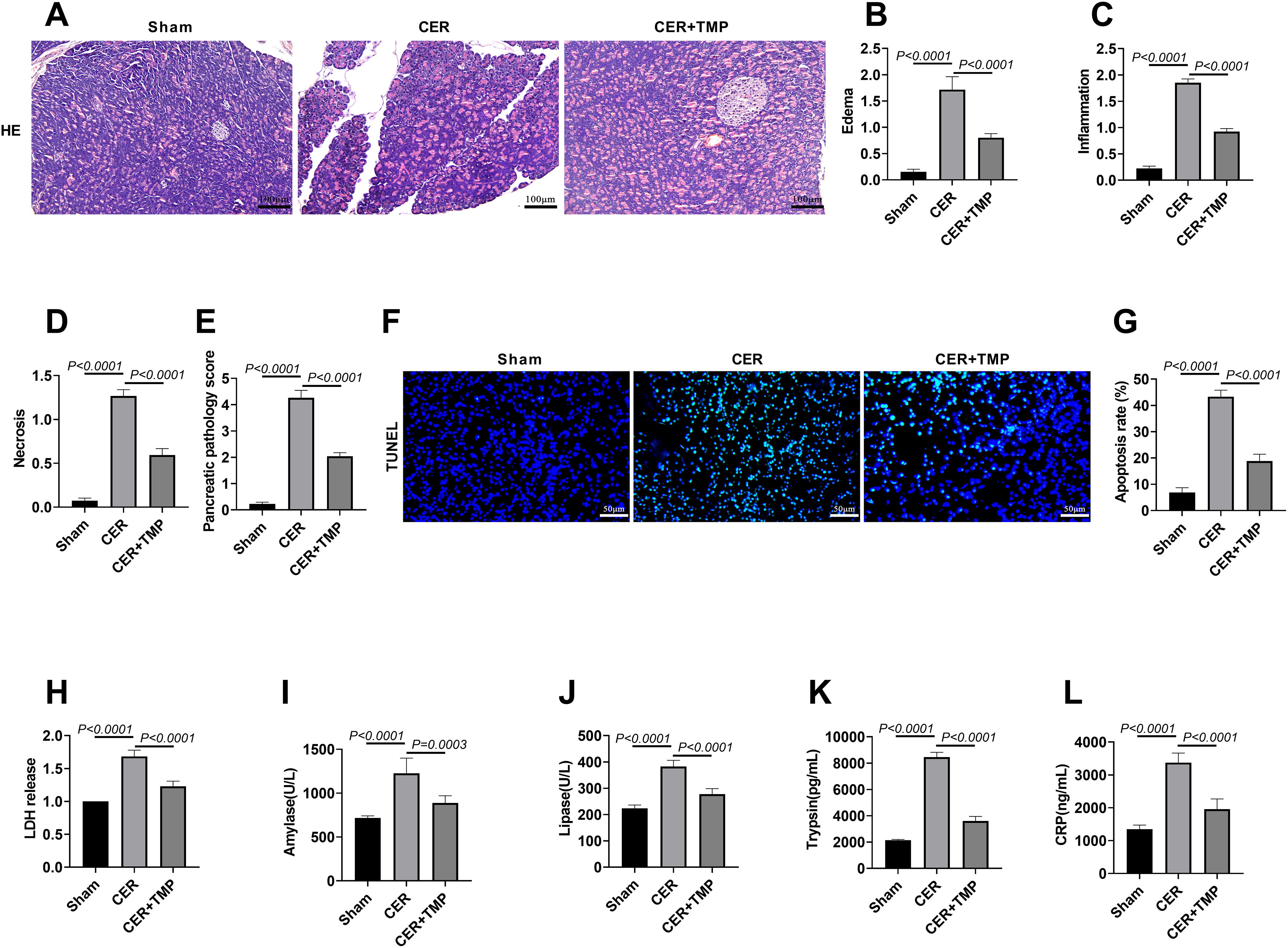

3.6 TMP Mediates the YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB Axis to Regulate Inflammation and Autophagy, Improving AP in Rats

Western blot demonstrated that the ratios of p-YAP/YAP, p-RIPK1/RIPK1, and NF-κB p-p65/NF-κB p65 were significantly elevated in pancreatic tissues of the CER model group, indicating aberrant activation of the YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB signaling pathway (Fig. 6A–D). TMP treatment significantly suppressed the phosphorylation levels of these key signaling molecules. MPO, a specific marker of neutrophil activation [23], was assessed by immunofluorescence, revealing a marked increase in MPO-positive cells in the pancreatic tissue of the CER model group (19.67%). TMP treatment significantly reduced the number of MPO-positive cells (8.00%), indicating inhibition of neutrophil infiltration (Fig. 6E,F).

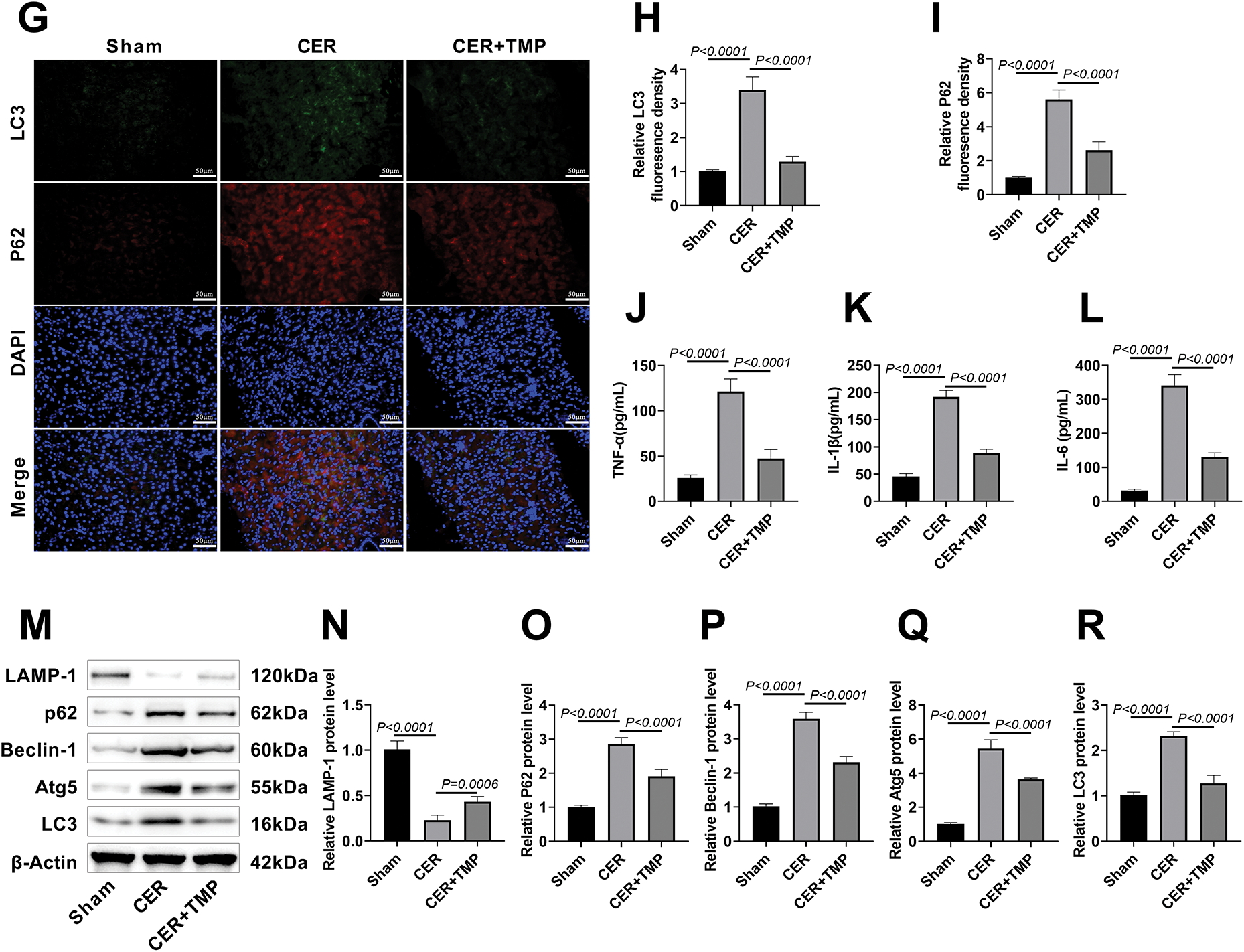

Figure 6: TMP mediates the YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB axis to regulate inflammation and autophagy, improving AP in rats. (A–D) Western blotting assessed p-YAP/YAP, p-RIPK1/RIPK1, and p-p65/p65 expression in pancreatic tissues to evaluate TMP’s regulation of the YAP/RIPK1/NF-κB axis. (E,F) Immunofluorescence was used to assess MPO expression in pancreatic tissues of rats from each group, analyzing the impact of TMP on inflammatory infiltration in pancreatic tissue. Scale bar: 50 μm. (G–I) LC3 and p62 immunofluorescence in pancreatic tissues assessed TMP’s effects on autophagy in pancreatitis rats. Scale bar: 50 μm. (J–L) Serum TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 levels measured by ELISA evaluated TMP’s anti-inflammatory effects. (M–R) Western blot analysis of LAMP-1, p62, Beclin-1, Atg5, and LC3 examined TMP’s regulation of autophagy in pancreatitis. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation from three separate trials

Immunofluorescence further showed that the expression levels of autophagy markers LC3 and p62 were significantly increased in the pancreatic tissues of CER model rats (Fig. 6G–I), suggesting autophagic flux obstruction. Serum inflammatory cytokine assays revealed significantly elevated levels of TNF-α (121.17 pg/mL), IL-1β (191.67 pg/mL), and IL-6 (341.17 pg/mL) in the CER model group (Fig. 6J–L), with the excessive release of these pro-inflammatory factors being critical to pancreatitis progression [24]. Further analysis through Western blot results revealed that the expression of p62, Beclin-1, Atg5, and LC3 proteins was significantly increased in the CER model group, while the expression of the lysosomal marker protein LAMP-1 was downregulated (Fig. 6M–R). TMP intervention significantly improved the above-mentioned abnormal indicators. These results suggest that TMP may improve rat AP by regulating inflammation and autophagy through the inhibition of YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB axis activation.

AP is a common inflammatory disease of the digestive system, characterized primarily by acinar cell injury, abnormal activation of pancreatic enzymes, amplification of inflammatory cascades, and autophagic dysfunction [25,26]. In this study, CER-induced AR42J cell and rat models of AP were established to systematically investigate the protective effects of TMP against pancreatitis. The results demonstrated that CER treatment significantly reduced AR42J cell viability, suppressed proliferation and migration capabilities, and increased apoptosis rate and intracellular Ca2+ concentration. TMP intervention dose-dependently enhanced cell viability, restored proliferation and migration, inhibited apoptosis, and lowered intracellular Ca2+ levels post-CER treatment. During AP pathogenesis, various factors such as gallstones, alcohol, and hyperlipidemia can induce calcium overload within pancreatic acinar cells, triggering aberrant activation of pancreatic zymogens, a critical event in AP development [27,28]. Calcium ions, as essential second messengers, when abnormally elevated, activate multiple proteases and phospholipases, leading to membrane damage, mitochondrial dysfunction, ATP depletion, and ultimately cell death [29]. Recent studies suggest that TMP maintains cellular energy metabolism and membrane integrity by modulating redox status and mitochondrial function, which may underlie its ability to enhance cell viability [30]. In a model of brain microvascular endothelial cell (BMEC) injury induced by OGD/R, studies have found that TMP treatment can significantly alleviate Ca2+ overload in BMECs, maintain cellular calcium homeostasis, and thereby mitigate cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury [31]. On the other hand, in acute pancreatitis, elevated calcium ion concentrations inhibit the activation of transcription factor EB (TFEB), which depends on low intracellular calcium levels, resulting in autophagy-lysosomal dysfunction and exacerbating cellular stress [32]. In summary, TMP exerts significant protective effects in the treatment of pancreatitis by regulating cellular calcium homeostasis, proliferation, viability, migration, invasion, and apoptosis through multiple pathways. Notably, low (25 μM) and medium (50 μM) doses of TMP showed significant protective effects on AR42J cells, with the highest efficacy observed at 100 μM, whereas supra-high doses (200 and 400 μM) exhibited cytotoxicity. Previous studies have shown that treatment of rat aortic endothelial cells (RAECs) with TMP at concentrations above 400 μM inhibits cell viability [33]. These findings provide important dosage reference for the clinical application of TMP.

In vivo, CER-induced rat AP models exhibited typical pathological features including disrupted acinar structure, widened interlobular spaces, extensive inflammatory cell infiltration, nuclear fragmentation and dissolution of some acinar cells accompanied by lipid vacuole formation. While inflammatory cell infiltration represents an immune response to tissue injury, excessive inflammation exacerbates tissue damage [34]. TMP treatment significantly ameliorated these pathological changes, preserving acinar integrity and markedly reducing inflammatory infiltration. Furthermore, TMP markedly decreased apoptotic cell numbers in pancreatic tissue and reduced serum LDH activity as well as amylase, lipase, trypsin, and CRP levels. Previous studies have shown that TMP can inhibit the release of inflammatory cytokines from pancreatic cells, regulate islet microcirculation, and promote acinar cell apoptosis, thereby alleviating pancreatitis [35,36]. In summary, TMP may slow the progression of pancreatitis by maintaining cell membrane integrity, inhibiting acinar cell injury and abnormal zymogen activation, blocking protease cascade reactions, and reducing systemic inflammatory responses.

Studies have demonstrated that abnormal elevation of calcium levels in pancreatic acinar cells is a key trigger of inflammatory responses. Calcium overload activates inflammatory signaling pathways such as NF-κB and MAPK, promoting production and release of inflammatory cytokines, thereby creating a vicious cycle [37]. In this study, TMP intervention dose-dependently reduced these inflammatory markers. Western blot analysis further confirmed that TMP significantly downregulated protein expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and the NLRP3 inflammasome in AR42J cells. The NLRP3 inflammasome, a multiprotein complex, activates caspase-1 and promotes maturation and release of IL-1β and IL-18, playing a key role in various inflammatory diseases [38]. In studies on AP, Zhang et al. found that exogenous β-hydroxybutyrate (β-OHB) supplementation can reduce the levels of TNFα, IL6, and IL12b in the pancreas, thereby alleviating the inflammatory response and mitigating the severity of AP [39]. Additionally, Du et al. have found that in the CER mouse model, overexpression of MiR-26a can inhibit the levels of serum amylase, lipase, IL-6, and NLRP3, thereby alleviating AP [40]. These findings suggest that TMP suppresses inflammation through multiple mechanisms, including regulation of calcium homeostasis, inhibition of aberrant digestive enzyme activation, and downregulation of inflammatory cytokines and inflammasome expression. In vivo, MPO immunofluorescence staining revealed a significant increase in MPO-positive cells in pancreatic tissue of CER model rats, indicative of extensive neutrophil infiltration—a hallmark of AP-associated inflammation. MPO, a neutrophil-specific peroxidase, generates reactive oxygen species and hypochlorous acid, exerting potent bactericidal effects; however, its overactivation leads to tissue damage [41]. TMP treatment significantly reduced MPO-positive cell numbers, demonstrating effective inhibition of neutrophil infiltration.

This study employed the mRFP-GFP-LC3 dual fluorescence system to analyze TMP’s regulation of autophagic flux in CER-induced AR42J cells. Results showed significant autophagosome accumulation and lysosome reduction in CER-treated cells, confirming autophagic flux blockade. With increasing TMP concentrations, autophagosomes decreased while lysosomes increased dose-dependently, indicating TMP promotes autophagosome-lysosome fusion and effectively restores autophagic flux. Autophagic flux blockade is a prominent feature in AP models, characterized by autophagosome accumulation alongside decreased autolysosomes, elevated LC3 and p62 protein levels, and reduced lysosomal activity [42]. Such blockade leads to ATP deficiency, secretory dysfunction, and abnormal zymogen accumulation, further aggravating pancreatitis symptoms [43]. LysoTracker Red staining further validated these findings, showing significantly reduced lysosome numbers in CER-treated cells, which were markedly increased by TMP, with high-dose TMP restoring lysosome counts near control levels, confirming TMP enhances lysosomal activity to promote autophagic flux.

At the molecular level, Western blot revealed CER treatment significantly upregulated p62, Beclin-1, Atg5, and LC3 protein expression, accompanied by downregulation of lysosomal marker LAMP-1. TMP intervention dose-dependently decreased LC3 and p62 levels while significantly upregulating LAMP-1, confirming TMP’s efficacy in restoring autophagy-lysosome pathway function. Additionally, TMP markedly downregulated Beclin-1 and Atg5 expression, indicating possible restoration of autophagic homeostasis via modulation of autophagy initiation. In vivo immunofluorescence and Western blot results showed TMP significantly reduced LC3 and p62 expression in CER-induced rat pancreatitis models, further confirming its regulatory effect on autophagic flux. LC3 is a key protein in autophagosome formation, with conversion from LC3-I to LC3-II marking autophagy activation [44]. p62 serves as an autophagy substrate degraded during autophagy; its accumulation indicates autophagic flux inhibition [45]. Beclin-1 and Atg5 are critical proteins in autophagy initiation and elongation, involved in autophagosome formation [46]. LAMP-1, a major lysosomal membrane glycoprotein, maintains lysosomal integrity and function [47]. These changes suggest enhanced autophagy initiation but impaired autophagic flux completion, leading to p62 and LC3 accumulation.

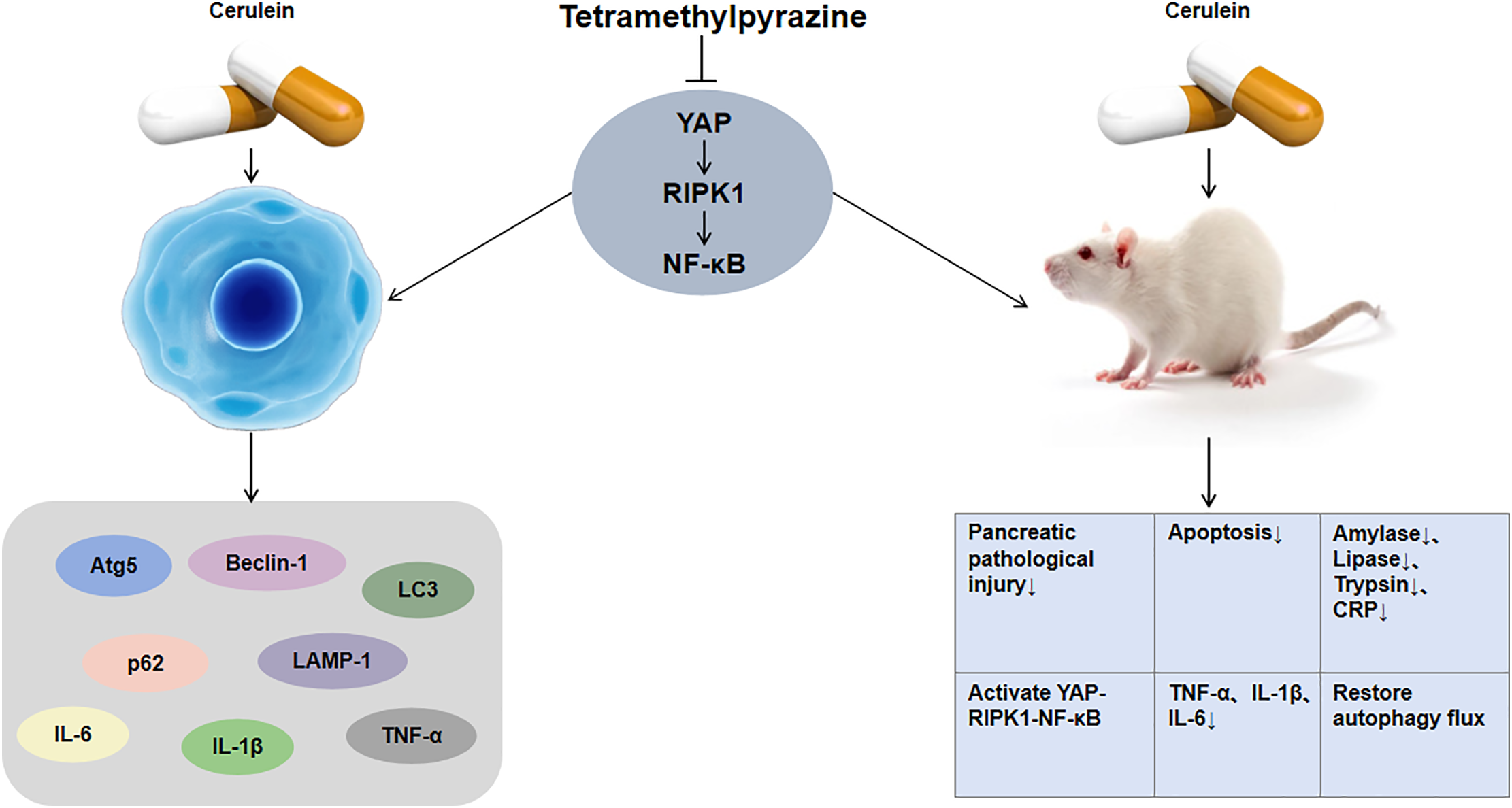

Western blot showed CER treatment significantly increased phosphorylation of YAP, RIPK1, and NF-κB p65 in AR42J cells, while TMP effectively inhibited these phosphorylation events. Using YAP knockdown and overexpression cell models, YAP knockdown enhanced TMP’s inhibitory effects, whereas YAP overexpression attenuated TMP’s efficacy, confirming YAP’s central role in this pathway. Importantly, in vivo experiments revealed that YAP, as an upstream regulator of this signaling axis, promotes RIPK1 and NF-κB phosphorylation, activating inflammation and inhibiting autophagic flux. YAP, a core Hippo pathway effector, regulates proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation, and mediates tissue injury/repair [48,49]. RIPK1, a multifunctional kinase, modulates inflammatory targets such as NF-κB and regulates cell death, inflammation, and autophagy [50,51]. Studies indicate the RIPK1/NF-κB axis plays a key role in AP pathogenesis; RIPK1 inhibition significantly reduces pancreatic tissue damage and inflammatory mediator release, exerting protective effects [52]. In preclinical models (AR42J cells and rat AP models), TMP exerts both anti-inflammatory effects and promotes autophagic flux by inhibiting the phosphorylation of YAP, which in turn suppresses the activation of RIPK1 and NF-κB (Fig. 7). This discovery provides a novel theoretical basis for TMP treatment of pancreatitis and offers new insights for developing YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB axis-targeted therapeutic strategies. With the advancement of technology, nanotechnology has indeed demonstrated tremendous potential in the field of disease treatment [53]. Nanomaterials can improve drug bioavailability, enhance imaging, and exert anti-inflammatory and antioxidative stress effects, thereby offering the prospect of more efficient and precise therapeutic strategies. Therefore, integrating nanotechnology with molecular targeted therapy may provide broader prospects for the precise treatment of diseases.

Figure 7: Mechanistic diagram illustrating TMP regulation of the YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB signaling axis

However, this study still has certain limitations. First, our findings are based solely on preclinical models, including AR42J cells and rat AP models, without involving long-term or chronic models, and further clinical validation is required. In addition, the effects of TMP on upstream regulators of the YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB axis, as well as its protective roles in various pancreatitis models, have not been fully investigated and warrant further exploration in future studies. Moreover, the limited sample size and the lack of inflammation- or autophagy-positive controls also represent important limitations of this study. These issues should be addressed in future research to further strengthen the reliability and comprehensiveness of our findings.

TMP exerts therapeutic effects in pancreatitis by targeting and inhibiting YAP phosphorylation, thereby blocking downstream activation of the RIPK1/NF-κB axis. This not only significantly suppresses inflammatory responses but also promotes restoration of autophagic flux, effectively alleviating acinar cell injury and improving pancreatic histopathology, ultimately mitigating pancreatitis progression. This study provides a new theoretical foundation for TMP application in pancreatitis treatment and offers novel strategies for developing therapies targeting the YAP-RIPK1-NF-κB axis.

Acknowledgement: None

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contribution: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Hong Wu, Yang Liu; data collection: Hong Wu, Yang Liu; analysis and interpretation of results: Hong Wu, Yang Liu; draft manuscript preparation: Yang Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author, upon request.

Ethic Approval: All animal procedures were conducted in compliance with institutional ethical guidelines following approval by the First Hospital of Yulin Animal Ethics Committee (Ethical approval number: 20230097).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | Full name |

| TMP | Tetramethylpyrazine |

| MPO | Myeloperoxidase |

| AP | Acute Pancreatitis |

| CCK-8 | Cell Counting Kit-8 |

| EdU | 5-Ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha |

| IL-1β | Interleukin 1 Beta |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| LAMP-1 | Lysosomal-Associated Membrane Protein 1 |

| p62 | Sequestosome 1 |

| LC3 | Microtubule-Associated Protein 1A/1B-Light Chain 3 |

| TUNEL | Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling |

| MPO | Myeloperoxidase |

| YAP | Yes-Associated Protein |

| RIPK1 | Receptor-Interacting Protein Kinase 1 |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| NLRP3 | NOD-Like Receptor Family Pyrin Domain Containing 3 |

| ATP | Adenosine Triphosphate |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| MOI | Multiplicity of Infection |

| RAECs | Rat aortic endothelial cells |

| β-OHB | β-hydroxybutyrate |

| BMEC | Brain microvascular endothelial cell |

| TFEB | Transcription factor EB |

| OGD/R | Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation/Reoxygenation |

References

1. Szatmary P, Grammatikopoulos T, Cai W, Huang W, Mukherjee R, Halloran C, et al. Acute pancreatitis: diagnosis and treatment. Drugs. 2022;82(12):1251–76. doi:10.1007/s40265-022-01766-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Baeza-Zapata AA, García-Compeán D, Jaquez-Quintana JO. Acute pancreatitis in elderly patients. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(6):1736–40. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.06.081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Iannuzzi JP, King JA, Leong JH, Quan J, Windsor JW, Tanyingoh D, et al. Global incidence of acute pancreatitis is increasing over time: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2022;162(1):122–34. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2021.09.043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Xu Q, Fu X, Xiu Z, Yang H, Men X, Liu M, et al. Interleukin-22 alleviates arginine-induced pancreatic acinar cell injury via the regulation of intracellular vesicle transport system: evidence from proteomic analysis. Exp Ther Med. 2023;26(6):578. doi:10.3892/etm.2023.12277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Heckler M, Hackert T, Hu K, Halloran CM, Büchler MW, Neoptolemos JP. Severe acute pancreatitis: surgical indications and treatment. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021;406(3):521–35. doi:10.1007/s00423-020-01944-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Liu D, Wen L, Wang Z, Hai Y, Yang D, Zhang Y, et al. The mechanism of lung and intestinal injury in acute pancreatitis: a review. Front Med. 2022;9:904078. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.904078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang R, Zhu Z, Ma Y, Tang T, Wu J, Huang F, et al. Rhizoma Alismatis decoction improved mitochondrial dysfunction to alleviate SASP by enhancing autophagy flux and apoptosis in hyperlipidemia acute pancreatitis. Phytomedicine. 2024;129:155629. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2024.155629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Voronina S, Chvanov M, De Faveri F, Mayer U, Wileman T, Criddle D, et al. Autophagy, acute pancreatitis and the metamorphoses of a trypsinogen-activating organelle. Cells. 2022;11(16). doi:10.3390/cells11162514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Tang GX, Yang MS, Xiang KM, Yang BC, Liu ZL, Zhao SP. miR-20b-5p modulates inflammation, apoptosis and angiogenesis in severe acute pancreatitis through autophagy by targeting AKT3. Autoimmunity. 2021;54(7):460–70. doi:10.1080/08916934.2021.1953484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Cunningham R, Hansen CG. The Hippo pathway in cancer: YAP/TAZ and TEAD as therapeutic targets in cancer. Clin Sci. 2022;136(3):197–222. doi:10.1042/CS20201474. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Tan Q, Xiang C, Zhang H, Yuan Y, Gong S, Zheng Z, et al. YAP promotes fibrosis by regulating macrophage to myofibroblast transdifferentiation and M2 polarization in chronic pancreatitis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;148:114087. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2025.114087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Deng J, Song Z, Li X, Shi H, Huang S, Tang L. Role of lncRNAs in acute pancreatitis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Front Genet. 2023;14:1257552. doi:10.3389/fgene.2023.1257552. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Almanzar VMD, Shah K, LaComb JF, Mojumdar A, Patel HR, Cheung J, et al. 5-FU-miR-15a inhibits activation of pancreatic stellate cells by reducing YAP1 and BCL-2 levels in vitro. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(4). doi:10.3390/ijms24043954. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. An Y, Tu Z, Wang A, Gou W, Yu H, Wang X, et al. Qingyi decoction and its active ingredients ameliorate acute pancreatitis by regulating acinar cells and macrophages via NF-κB/NLRP3/Caspase-1 pathways. Phytomedicine. 2025;139:156424. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2025.156424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Yao J, Luo Y, Liu X, Wu P, Wang Y, Liu Y, et al. Inhibition of necroptosis in acute pancreatitis: screening for RIPK1 inhibitors. Processes. 2022;10(11):2260. doi:10.3390/pr10112260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Pan C, Hao X, Deng X, Lu F, Liu J, Hou W, et al. The roles of Hippo/YAP signaling pathway in physical therapy. Cell Death Discov. 2024;10(1):197. doi:10.1038/s41420-024-01972-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Lin J, Wang Q, Zhou S, Xu S, Yao K. Tetramethylpyrazine: a review on its mechanisms and functions. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;150:113005. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Li H, Gao Y, Huang M, Zhang H, Wu Q, Huang Y, et al. Tetramethylpyrazine alleviates acute pancreatitis inflammation by inhibiting pyroptosis via the NRF2 pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2025;16:1557681. doi:10.3389/fphar.2025.1557681. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Song Z, Hei TK, Gong X. Tetramethylpyrazine attenuates sodium arsenite-induced acute kidney injury by improving the autophagic flux blockade via a YAP1-Nrf2-p62-dependent mechanism. Int J Biol Sci. 2025;21(3):1158–73. doi:10.7150/ijbs.104107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Ye Z, Cheng L, Xuan Y, Yu K, Li J, Gu H. Chlorogenic acid alleviates the development of severe acute pancreatitis by inhibiting NLPR3 Inflammasome activation via Nrf2/HO-1 signaling. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;151:114335. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2025.114335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Lim ST, Zhao X, Liu S, Zhang W, Tan Y, Mullappilly N, et al. LRG1 inhibition promotes acute pancreatitis recovery by inducing cholecystokinin Type 1 receptor expression via Akt. Theranostics. 2025;15(10):4247–69. doi:10.7150/thno.110116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Li B, Wu J, Bao J, Han X, Shen S, Ye X, et al. Activation of α7nACh receptor protects against acute pancreatitis through enhancing TFEB-regulated autophagy. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866(12):165971. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.165971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Hayden H, Ibrahim N, Klopf J, Zagrapan B, Mauracher LM, Hell L, et al. ELISA detection of MPO-DNA complexes in human plasma is error-prone and yields limited information on neutrophil extracellular traps formed in vivo. PLoS One. 2021;16(4):e0250265. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0250265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Sternby H, Hartman H, Thorlacius H, Regnér S. The initial course of IL1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12, IFN-γ and TNF-α with regard to severity grade in acute pancreatitis. Biomolecules. 2021;11(4):591. doi:10.3390/biom11040591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kong L, Deng J, Zhou X, Cai B, Zhang B, Chen X, et al. Sitagliptin activates the p62-Keap1-Nrf2 signalling pathway to alleviate oxidative stress and excessive autophagy in severe acute pancreatitis-related acute lung injury. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(10):928. doi:10.1038/s41419-021-04227-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Mederos MA, Reber HA, Girgis MD. Acute pancreatitis: a review. JAMA. 2021;325(4):382–90. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.20317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Zheng Z, Ding YX, Qu YX, Cao F, Li F. A narrative review of acute pancreatitis and its diagnosis, pathogenetic mechanism, and management. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(1):69. doi:10.21037/atm-20-4802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Walkowska J, Zielinska N, Karauda P, Tubbs RS, Kurtys K, Olewnik Ł. The pancreas and known factors of acute pancreatitis. J Clin Med. 2022;11(19):5565. doi:10.3390/jcm11195565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Szabó V, Csákány-Papp N, Görög M, Madácsy T, Varga Á., Kiss A, et al. Orai1 calcium channel inhibition prevents progression of chronic pancreatitis. JCI Insight. 2023;8(13). doi:10.1172/jci.insight.167645. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Feng F, Xu DQ, Yue SJ, Chen YY, Tang YP. Neuroprotection by tetramethylpyrazine and its synthesized analogues for central nervous system diseases: a review. Mol Biol Rep. 2024;51(1):159. doi:10.1007/s11033-023-09068-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Liu Y, Yang G, Cui W, Zhang Y, Liang X. Regulatory mechanisms of tetramethylpyrazine on central nervous system diseases: a review. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:948600. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.948600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Oh SJ, Park K, Sonn SK, Oh GT, Lee MS. Pancreatic β-cell mitophagy as an adaptive response to metabolic stress and the underlying mechanism that involves lysosomal Ca2+ release. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55(9):1922–32. doi:10.1038/s12276-023-01055-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Ai J, Zheng J. Tetramethylpyrazine promotes osteo-angiogenesis during bone fracture repair. J Orthop Surg Res. 2025;20(1):58. doi:10.1186/s13018-024-05371-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Jiang N, Li Z, Luo Y, Jiang L, Zhang G, Yang Q, et al. Emodin ameliorates acute pancreatitis-induced lung injury by suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated neutrophil recruitment. Exp Ther Med. 2021;22(2):857. doi:10.3892/etm.2021.10289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Xu X, Wu L, Lu ZQ, Xia P, Zhu XP, Gao X. Effects of tetramethylpyrazine phosphate on pancreatic islet microcirculation in SD rats. J Endocrinol Invest. 2018;41(4):411–9. doi:10.1007/s40618-017-0748-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Chen J, Chen J, Wang X, Wang C, Cao W, Zhao Y, et al. Ligustrazine alleviates acute pancreatitis by accelerating acinar cell apoptosis at early phase via the suppression of p38 and Erk MAPK pathways. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;82:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2016.04.048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Petersen OH, Gerasimenko JV, Gerasimenko OV, Gryshchenko O, Peng S. The roles of calcium and ATP in the physiology and pathology of the exocrine pancreas. Physiol Rev. 2021;101(4):1691–744. doi:10.1152/physrev.00003.2021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Fujimura K, Karasawa T, Komada T, Yamada N, Mizushina Y, Baatarjav C, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome-driven IL-1β and IL-18 contribute to lipopolysaccharide-induced septic cardiomyopathy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2023;180:58–68. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2023.05.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zhang L, Shi J, Du D, Niu N, Liu S, Yang X, et al. Ketogenesis acts as an endogenous protective programme to restrain inflammatory macrophage activation during acute pancreatitis. eBioMedicine. 2022;78:103959. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Du W, Liu G, Shi N, Tang D, Ferdek PE, Jakubowska MA, et al. A microRNA checkpoint for Ca2+ signaling and overload in acute pancreatitis. Mol Ther. 2022;30(4):1754–74. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.01.033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Lin W, Chen H, Chen X, Guo C. The roles of neutrophil-derived myeloperoxidase (MPO) in diseases: the new progress. Antioxidants. 2024;13(1):132. doi:10.3390/antiox13010132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Zhu L, Xu Y, Lei J. Molecular mechanism and potential role of mitophagy in acute pancreatitis. Mol Med. 2024;30(1):136. doi:10.1186/s10020-024-00903-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Ding WX, Ma X, Kim S, Wang S, Ni HM. Recent insights about autophagy in pancreatitis. eGastroenterology. 2024;2(2):e100057. doi:10.1136/egastro-2023-100057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Ding R, Liu Z, Tan J, Sun B. Advanced oxidation protein products mediate human keratinocytes apoptosis by inducing cell autophagy through the mTOR-Beclin-1 pathway. Cell Biochem Funct. 2022;40(8):880–7. doi:10.1002/cbf.3749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Huang X, Zhang J, Yao J, Mi N, Yang A. Phase separation of p62: roles and regulations in autophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 2025;24:9. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2025.01.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Cao Z, Tian K, Ran Y, Zhou H, Zhou L, Ding Y, et al. Beclin-1: a therapeutic target at the intersection of autophagy, immunotherapy, and cancer treatment. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1506426. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1506426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Liu W, Wang Y, Liu S, Zhang X, Cao X, Jiang M. E3 ubiquitin ligase RNF13 suppresses TLR lysosomal degradation by promoting LAMP-1 proteasomal degradation. Adv Sci. 2024;11(32):e2309560. doi:10.1002/advs.202309560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Deng F, Wu Z, Zou F, Wang S, Wang X. The hippo-YAP/TAZ signaling pathway in intestinal self-renewal and regeneration after injury. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:894737. doi:10.3389/fcell.2022.894737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Islam R, Hong Z. YAP/TAZ as mechanobiological signaling pathway in cardiovascular physiological regulation and pathogenesis. Mechanobiol Med. 2024;2(4):100085. doi:10.1016/j.mbm.2024.100085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Rojas-Rivera D, Beltrán S, Muñoz-Carvajal F, Ahumada-Montalva P, Abarzúa L, Gomez L, et al. The autophagy protein RUBCNL/PACER represses RIPK1 kinase-dependent apoptosis and necroptosis. Autophagy. 2024;20(11):2444–59. doi:10.1080/15548627.2024.2367923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Lee YM, Vucic D. The role of autophagy in RIP1 mediated cell death and intestinal inflammation. Adv Immunol. 2024;163:1–20. doi:10.1016/bs.ai.2024.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Li H, Wu D, Zhang H, Li P. New insights into regulatory cell death and acute pancreatitis. Heliyon. 2023;9(7):e18036. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e18036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Kapoor DU, Garg R, Saini PK, Gaur M, Prajapati BG. Nanomedicine breakthrough: cyclodextrin-based nano sponges revolutionizing cancer treatment. Nano-Struct Nano-Objects. 2024;40:101358. doi:10.1016/j.nanoso.2024.101358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools