Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Endothelial and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in COPD Pathophysiology: Focus on Homocysteine–L-Carnitine Interplay

1 Department of Faculty Therapy named after Prof. V.Ya. Garmash, Ryazan State Medical University, Ryazan, 390026, Russia

2 Department of Biological Chemistry, Ryazan State Medical University, Ryazan, 390026, Russia

3 Faculty of Medicine, Ryazan State Medical University, Ryazan, 390026, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Eduard Belskikh. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Mechanisms Driving COPD, Atherosclerosis, and Cardiovascular Disease: From Pathogenesis to Therapeutic Innovations)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(11), 2093-2123. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.069272

Received 19 June 2025; Accepted 05 September 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

Elevated homocysteine is a clinically relevant metabolic signal in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Higher circulating levels track with oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, mitochondrial impairment, and pulmonary vascular remodeling, rise with disease severity, and may contribute to the excess cardiovascular risk—although effect sizes and causality remain uncertain. This review centers on the homocysteine–carnitine relationship in COPD pathophysiology. Carnitine deficiency, prevalent in COPD, can worsen mitochondrial bioenergetics, promote accumulation of acyl intermediates, and reduce nitric oxide bioavailability via endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling (eNOS). Conversely, restoring carnitine status in experimental and early clinical settings has been associated with lower homocysteine, improved nitric oxide signaling, and attenuation of vascular remodeling, suggesting a reciprocal link rather than a one-way pathway. We review existing evidence on various COPD phenotypes and severities, delineate mechanisms that connect homocysteine, carnitine metabolism, mitochondria, redox balance and eNOS uncoupling, and evaluate therapeutic strategies—ranging from lowering homocysteine with B-group vitamins to integrated approaches that also support mitochondrial function and redox homeostasis, including targeted carnitine supplementation. The role of L-carnitine as a potential therapeutic agent for lowering homocysteine and improving mitochondrial and vascular function warrants further investigation, as it may help slow the progression of COPD and its related comorbidities.Keywords

1.1 Clinical-Epidemiological and Genetic Underpinnings for Studying the Role of Hyperhomocysteinemia in Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Research into the role of homocysteine has intensified over recent decades, primarily because of this amino acid’s putative involvement in the development of endothelial dysfunction and, consequently, cardiovascular disease. Early investigations established that higher plasma concentrations of homocysteine correlate with adverse cardiovascular outcomes and atherogenesis [1]. Historically, this association was first noted in patients with congenital defects of homocysteine metabolism who developed premature atherosclerosis, leading to the recognition of hyperhomocysteinemia as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular pathologies. Interest in hyperhomocysteinemia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease emerged relatively recently: a seminal study by Andersson and colleagues in 2001 first demonstrated elevated homocysteine concentrations (17.9 ± 6.7 micromoles per liter in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and 14.1 ± 4.9 micromoles per liter in the comparator group without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), which were linked to oxidative stress within the airways [2]. Subsequently, a prospective study by Kai and colleagues in 2006 showed that higher homocysteine levels, even within the reference range, were associated with an accelerated annual decline in forced expiratory volume in one second in smokers, underscoring the biomarker’s prognostic significance [3]. A large cross-sectional analysis by Seemungal and colleagues in 2007 confirmed a dose-dependent relationship between circulating homocysteine and both chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity and C-reactive protein concentrations, expanding the concept of systemic inflammation as an intermediary mechanism [4]. Further observational cohort data from Nunomiya and colleagues in 2013 demonstrated that hyperhomocysteinemia predicts accelerated loss of lung function even among healthy smokers, thereby strengthening causal inference [5]. To date, a meta-analysis by Zinellu and colleagues in 2022 has synthesized nine studies and confirmed a consistent association between elevated homocysteine and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which may partially account for the high cardiovascular risk in this patient population [6–8].

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease has become a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Contemporary epidemiological evidence indicates that millions of individuals are affected by this debilitating condition, with substantial economic and social consequences [9,10]. Beyond persistent airflow limitation and chronic inflammation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is characterized by pronounced systemic manifestations, among which vascular and endothelial dysfunction play central roles [11,12]. Impaired pulmonary microcirculation—resulting in reduced tissue perfusion and the development of pulmonary hypertension—contributes materially to disease progression and to the heightened cardiovascular risk observed in these patients [12].

The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease defines chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a heterogeneous pulmonary condition—that is, not a single isolated disease but a clinical continuum in which chronic respiratory symptoms coexist with multiple systemic disturbances, with the cumulative burden of comorbid conditions exerting a major influence on prognosis [12,13]. Recent updates by the Global Initiative emphasize this perspective by dedicating an entire chapter to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbidities and adding new sections on cardiovascular risk, dysbiosis, pulmonary hypertension, and treatable traits, thereby elevating comorbid conditions to distinct therapeutic targets [12,13].

Against this background, hyperhomocysteinemia appears to be a promising yet insufficiently explored metabolic hub. Elevated homocysteine has been shown to be associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, increased oxidative stress, and cellular energy deficits in endothelial cells, myocytes, and neurons, creating a common substrate for a wide spectrum of disorders—atherosclerosis, systemic and pulmonary hypertension, progressive renal dysfunction, sarcopenia, osteoporosis, depression, and cognitive impairment—precisely the conditions highlighted by the Global Initiative as the most frequent and clinically consequential in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [12,14,15]. Accordingly, hyperhomocysteinemia aligns well with the contemporary conception of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a state with extensive systemic manifestations and may be considered an underappreciated therapeutic point of intervention—one that is not addressed by standard bronchodilator or anti-inflammatory regimens.

The meta-analysis by Zinellu and colleagues confirmed a robust association between homocysteine concentration and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity, offering a partial explanation for the elevated cardiovascular risk in this cohort [6], while broader epidemiological reviews underscore the role of hyperhomocysteinemia as an independent driver of atherothrombosis and systemic inflammation [15]. Despite this, standard pharmacotherapy—including combinations of long-acting beta-2 agonists with long-acting muscarinic antagonists, inhaled glucocorticosteroids, selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors, acetylcysteine, macrolide antibiotics, and long-term oxygen therapy—has been scarcely investigated with respect to its impact on homocysteine concentrations in serum or tissues.

In this context, reduction of homocysteine with L-carnitine appears promising. Experimental models demonstrate that carnitine attenuates methionine-induced hyperhomocysteinemia and normalizes mitochondrial parameters [16]. In clinical settings, the addition of 2 g per day of carnitine to a rehabilitation program improved exercise tolerance and respiratory muscle strength in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and more recent evidence points to the possibility of targeted correction of muscle dysfunction and metabolic status [17,18]. Furthermore, propionyl-L-carnitine has been shown to improve microcirculation and endothelial function in individuals with critical limb ischemia, indirectly supporting its potential relevance to the vascular complications of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [19]. An elevated homocysteine concentration may therefore represent an accessible leverage point for individualized metabolic therapy aimed at interrupting the cascade of mitochondrial and endothelial dysfunction that underlies multimorbidity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, with carnitine and its derivatives as plausible candidates for such intervention—an approach that warrants confirmation in randomized trials.

1.2 Metabolism and Mechanisms of Homocysteine Elevation in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

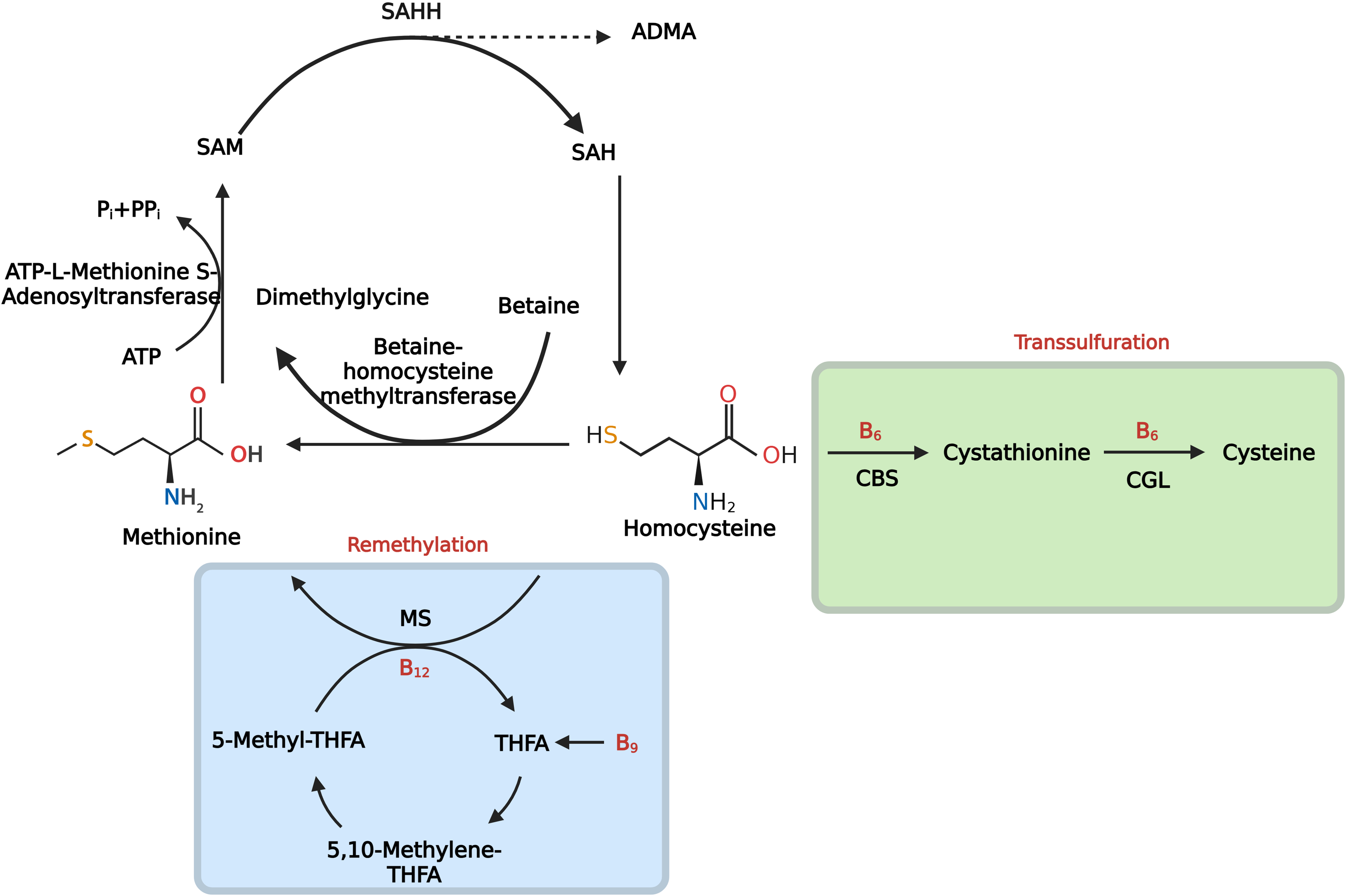

The metabolism of homocysteine proceeds predominantly through two interrelated pathways. In the remethylation pathway, homocysteine is converted back to methionine with the participation of key enzymes such as methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and methionine synthase reductase, both of which depend on B-group vitamins—folate and vitamin B12 [7]. In parallel, the transsulfuration pathway irreversibly converts homocysteine to cystathionine via cystathionine β-synthase, for which vitamin B6 serves as the coenzyme [20]. The general scheme of methionine metabolism is presented in Fig. 1. Under physiological conditions, the plasma concentration of homocysteine is approximately 5–15 μmol/L; values above this range are termed hyperhomocysteinemia and are clinically classified as mild (15–30 μmol/L), moderate (30–100 μmol/L), and severe (>100 μmol/L) [21].

Figure 1: Methionine cycle. Homocysteine (Hcy) is produced from S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) by SAH hydrolase (SAHH). Note: Hcy is either remethylated to methionine by (1) methionine synthase (MS), which uses 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (5-MTHF) as the methyl donor and requires vitamin B12, or (2) betaine–homocysteine methyltransferase (BHMT), which uses betaine and generates dimethylglycine; methionine is then adenylated by methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT) to S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), the universal methyl donor. Alternatively, Hcy enters transsulfuration, where cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) condenses Hcy with serine to cystathionine, and cystathionine γ-lyase (CGL) converts it to cysteine; both steps require vitamin B6. SAH, the product of methyltransferase reactions, is a competitive inhibitor of methyltransferases. Thus, accumulation of Hcy and/or SAH lowers the SAM:SAH ratio and impairs cellular methylation. The scheme also shows the generation of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) by protein arginine methylation, an endogenous inhibitor of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)—particularly with exposure to tobacco smoke and other inhaled oxidants—depletion of folate and vitamin B12, together with oxidative/nitrosative injury, reduces methionine synthase activity and attenuates the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine, whereas inflammation- and redox-driven suppression of cystathionine β-synthase restricts the transsulfuration pathway. Abbreviations: SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; SAH, S-adenosylhomocysteine; SAHH, SAH hydrolase; ADMA, asymmetric dimethylarginine; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; Pi/PPi, inorganic phosphate/pyrophosphate; MAT, methionine adenosyltransferase; BHMT, betaine–homocysteine methyltransferase; MS, methionine synthase; B12, vitamin B12 (cobalamin); B9, folate; THF/THFA, tetrahydrofolate; 5-MTHF, 5-methyltetrahydrofolate; 5,10-MTHF, 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate; B6, vitamin B6 (pyridoxal-5′-phosphate); CBS, cystathionine β-synthase; CGL, cystathionine γ-lyase; Hcy, homocysteine; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Figure created with BioRender.com. Belskikh, E. (2025) https://BioRender.com/dl0fqq7 (accessed on 04 September 2025)

The mechanisms underlying homocysteine accumulation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are multilayered and begin with nutrition-related imbalances induced by inhaled toxicants. Chronic smokers have repeatedly been shown to exhibit depletion of folate and vitamin B12 accompanied by increases in plasma homocysteine; the deficiency has been attributed both to reduced intestinal absorption under the influence of smoke constituents and to accelerated oxidative degradation of folate/cobalamin coenzymes due to excess free radicals in the systemic circulation [22]. Similar deficiencies have been described with passive smoking, which supports a direct influence of tobacco aerosols—rather than dietary behavior alone—on the vitamin pool and, indirectly, on homocysteine metabolism [22].

At a second level, inactivation of key metabolic enzymes contributes to hyperhomocysteinemia. Nitrosative stress and oxidative damage to cobalamin lead to a post-translational loss of methionine synthase activity, thereby blocking the return of homocysteine to the methionine cycle; this has been demonstrated in human cellular systems and in experimental animal models [23]. In parallel, inflammatory mediators and shifts in redox potential suppress cystathionine β-synthase, constraining transsulfuration and the conversion of homocysteine to cysteine, which further sustains its accumulation [24].

Beyond smoking, analogous biochemical perturbations occur with other inhalational exposures. Population-based studies indicate that short-term increases in concentrations of fine particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter of 2.5 μm or less and of black carbon are associated with rises in serum homocysteine among non-smokers [25]. This association persists after adjustment for diet and vitamin status, indicating a general mechanism mediated by oxidative stress [23–25]. For chronic obstructive pulmonary disease associated with exposure to biomass smoke or cooking-related emissions—which may involve mechanisms of injury that differ in important respects from those of tobacco smoke—no studies assessing homocysteine concentrations could be identified, precluding comparison of the severity of hyperhomocysteinemia with that observed in smokers.

Thus, current data on the role of hyperhomocysteinemia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease derive predominantly from studies of smokers; the influence of alternative aerosol exposures, as well as the relationship between homocysteine concentration and morphofunctional phenotypes of the disease, remains insufficiently characterized. Prospective cohort investigations with detailed stratification of inhalational exposure sources, screening of vitamin status, and concurrent assessment of methionine synthase and cystathionine β-synthase activities in clinical and experimental models appear to be promising directions.

1.3 Unresolved Questions and Directions for Further Research on Hyperhomocysteinemia in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Despite a growing number of observational studies, substantial gaps remain. First, most data have been obtained in active smokers; the impact of alternative sources of aerosol stress (biomass fuel, occupational pollutants, urban pollution) on homocysteine metabolism in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease has not been compared systematically [26]. Second, promising hypotheses—for example, damage to vitamin-binding proteins by free radicals or the role of heavy metals in the inactivation of methionine synthase and cystathionine β-synthase—have been confirmed only in vitro and require in vivo validation [27]. Finally, it remains unclear whether the concentration of homocysteine correlates with specific clinical and morphologic phenotypes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (emphysema, bronchitic phenotype, exacerbation frequency) and whether it predicts the response to phenotype-specific therapy. Available evidence is limited to experimental models and a few clinical reports [27,28]. Prospective multicenter studies that incorporate stratification of exposure sources, detailed assessment of nutritional status, and the use of markers of mitochondrial function appear to be the most promising direction for addressing these gaps.

Despite considerable evidence linking elevated homocysteine concentration to cardiovascular morbidity, significant uncertainties persist regarding the precise role of hyperhomocysteinemia in the context of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. This is particularly relevant to endothelial dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—a state characterized by an imbalance among prothrombotic, proinflammatory, vasoconstrictive, and vasodilatory factors, which is now regarded as a key element in the pathogenesis of vascular complications in this disease [29–31]. The pulmonary circulation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is affected not only by reduced blood flow and oxygen delivery but also by heightened susceptibility to oxidative stress and secondary mitochondrial dysfunction, which hyperhomocysteinemia can exacerbate through the induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS), reduction of nitric oxide bioavailability, and activation of inflammatory cascades [14,21,30,31].

Contemporary studies report conflicting results regarding the effectiveness of therapies aimed at lowering homocysteine concentration, including the administration of B-group vitamins. A large randomized, controlled trial (HOPE-2) did not demonstrate a reduction in composite cardiovascular outcomes despite a 25% decrease in homocysteine, whereas meta-analyses show improvements in biochemical markers and endothelial function only in selected patient subgroups [32]. This underscores the complex role of homocysteine in the comorbid pathology of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Observational studies indicate that higher homocysteine concentrations correlate with greater disease severity and worse prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, predicting a more rapid decline in forced expiratory volume in one second and a higher frequency of exacerbations [28,33]. However, there is still no coherent model that describes how hyperhomocysteinemia leads to vascular remodeling and to endothelial and mitochondrial injury; existing data are limited to in vitro experiments and review articles emphasizing the role of disrupted hydrogen sulfide signaling and mitochondrial dysfunction [14,28].

Genetic variability adds further complexity: the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism and low concentrations of B-group vitamins modify the influence of homocysteine and exacerbate metabolic disturbances in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [34,35].

Understanding the reasons for the limited efficacy of current homocysteine-lowering therapies and the impact of long-term vitamin interventions on vascular outcomes remains a critically important task for future research, as supported by clinical studies [34,36,37]. Prospective multicenter investigations with careful stratification of aerosol exposure sources, consideration of genetic variants of homocysteine metabolism, and application of markers of mitochondrial function appear to be the most promising approach to filling these gaps.

The objective of this review is to analyze contemporary literature on the role of homocysteine in the pathogenesis of endothelial and mitochondrial dysfunction as a key mediator of comorbid vascular pathology in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. In doing so, we aim to delineate the foundations for future research directed toward the development of mitochondria-oriented metabolic therapy to reduce vascular comorbid conditions in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. This review will address the following aspects: the clinical significance of elevated homocysteine in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; the molecular mechanisms linking hyperhomocysteinemia to endothelial and mitochondrial dysfunction and to alterations in L-carnitine levels; and research perspectives on L-carnitine as a therapeutic agent capable of correcting secondary mitochondrial and endothelial dysfunction and indirectly influencing multiple comorbid disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

2 Major Mechanisms of Endothelial Dysfunction in HHcy

2.1 Impairment of the Synthesis and Action of Nitric Oxide (NO)

It is likely that one of the most important molecules maintaining the homeostasis of the vascular wall is nitric oxide. The principal mechanism of action of nitric oxide is binding to soluble guanylyl cyclase, which promotes the formation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate, followed by activation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate–dependent proteins (protein kinases, cation channels, and phosphodiesterases) and downstream signaling targets [38]. Activation of this nitric oxide–dependent signaling cascade results in vasodilation and attenuates prothrombotic, proinflammatory, and proliferative activity in both the endothelium and vascular smooth muscle cells [39].

Nitric oxide is produced by a family of enzymes known as nitric oxide synthases. Several isoforms are distinguished: neuronal and endothelial isoforms, which are constitutively expressed, and an inducible isoform. Despite differences in tissue specificity and expression context, the nitric oxide synthase isoforms share a common structural organization (oxygenase and reductase domains) and a common catalytic mechanism. The substrate is L-arginine, which in the presence of the cosubstrates molecular oxygen and reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate is converted by nitric oxide synthase to nitric oxide and L-citrulline. The reaction is activated upon binding of calmodulin and requires the cofactors flavin adenine dinucleotide, flavin mononucleotide, and tetrahydrobiopterin [39].

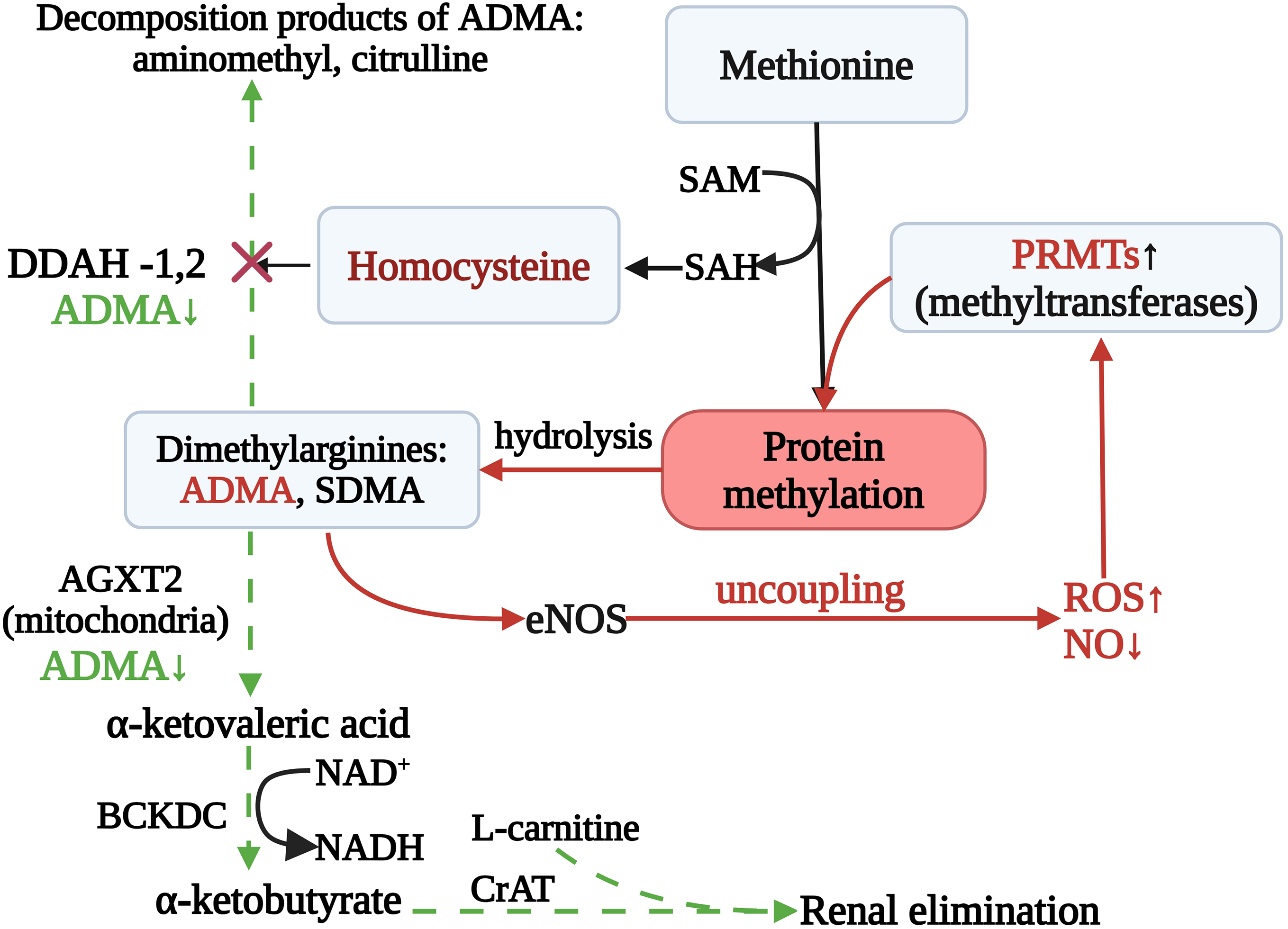

One mechanism of endothelial dysfunction in the setting of elevated homocysteine is impairment of the synthesis and action of nitric oxide. Impaired synthesis can arise through several routes that affect key elements of the reaction. A brief schematic is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Impairment of Synthesis of Nitric Oxide: Carnitine-Mediated Rescue of NO Synthesis and Homocysteine Clearance. Note: Elevated homocysteine (Hcy) diverts methyl-group flux (SAM/SAH) toward PRMT-driven protein arginine methylation, increasing asymmetric/symmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA/SDMA). In parallel, Hcy suppresses DDAH-1/2, causing ADMA accumulation that competitively inhibits eNOS and promotes uncoupling (↑ROS, ↓NO). ADMA can be removed by DDAH-mediated hydrolysis and by mitochondrial AGXT2 transamination to α-ketoacid derivatives (e.g., DMGV/DMGB) that are oxidized by BCKDC. Presumably, L-carnitine, via CPT II, facilitates conversion of these acyl-CoA intermediates to acylcarnitines with efflux and renal elimination, thereby helping to lower the ADMA/Hcy burden, favor eNOS re-coupling, and mitigate adverse effects of hyperhomocysteinemia. Abbreviations: SAM, S-adenosylmethionine; SAH, S-adenosylhomocysteine; ADMA, asymmetric NG,NG-dimethylarginine; SDMA, symmetric NG,N′G-dimethylarginine; PRMTs, protein arginine methyltransferases; DDAH-1/2, NG,NG-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase isoforms 1 and 2; AGXT2, alanine–glyoxylate aminotransferase 2; BCKDC, branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex; CrAT, carnitine O-acetyltransferase; eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; NO, nitric oxide; ROS, reactive oxygen species. Figure created with BioRender.com. Belskikh, E. (2025) https://BioRender.com/s85mlix (accessed on 04 September 2025)

With sustained elevation of homocysteine, the function of transmembrane cation transport systems is disrupted, which can reduce the cellular uptake of L-arginine. One such system is the cationic amino acid transporter 1 (CAT-1), the expression of which also decreases at high homocysteine concentrations [40]. Homocysteine interferes with cation transport principally by suppressing cationic amino acid transporter 1, which mediates sodium-independent L-arginine transport (the y+ system) in endothelial cells. Exposure to pathophysiological homocysteine concentrations (approximately 500–2500 micromoles per liter) for twenty-four hours reduces cationic amino acid transporter 1 expression by 25–30 percent, directly diminishing L-arginine flux and indirectly constraining nitric oxide synthesis by endothelial nitric oxide synthase, thereby impairing vasodilation [40]. Pathophysiologically, this has been linked to oxidative and nitrosative stress that damages plasma-membrane proteins and alters transcription of SLC7A1, which encodes cationic amino acid transporter 1. Thus, hyperhomocysteinemia disrupts L-arginine transport into the cell, potentially reducing nitric oxide production [40].

Deficiency of L-arginine can lead to uncoupling of nitric oxide synthase, in which the oxygenase and reductase domains cease to operate in a coordinated manner. In this state, rather than producing nitric oxide, the enzyme favors the generation of peroxynitrite (ONOO−) [41]. Peroxynitrite formation is further amplified under conditions of oxidative stress induced by homocysteine—the mechanisms of which will be discussed below. Peroxynitrite, in turn, decreases the availability of tetrahydrobiopterin, an essential cofactor for nitric oxide synthesis [41,42]. Consequently, L-arginine deficiency and homocysteine-induced oxidative stress impair nitric oxide synthase function and reduce nitric oxide output.

Another important molecular alteration in hyperhomocysteinemia is the accumulation of asymmetric dimethylarginine, an endogenous competitive inhibitor of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Under normal conditions, asymmetric dimethylarginine is hydrolyzed by dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase, but hyperhomocysteinemia suppresses dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase activity—likely through oxidation of critical sulfhydryl groups—leading to accumulation of asymmetric dimethylarginine and further inhibition of nitric oxide generation. Simultaneously, hyperhomocysteinemia induces oxidative stress that oxidizes tetrahydrobiopterin, an indispensable cofactor stabilizing the endothelial nitric oxide synthase dimer; depletion of tetrahydrobiopterin is a principal trigger of enzyme uncoupling, shifting the enzyme toward electron leak, further increasing superoxide production, and perpetuating redox imbalance [42,43].

S-glutathionylation represents an additional mechanism acting on endothelial nitric oxide synthase—a post-translational modification by glutathione. This modification alters the conformation of the enzyme by conjugating glutathione to cysteine residues within the reductase domain, effectively switching the enzyme from nitric oxide synthesis to superoxide generation. The consequence is twofold: reduced synthesis of nitric oxide and increased production of reactive oxygen species [44]. The propensity for S-glutathionylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase increases under oxidative stress driven by elevated homocysteine. The combined effects of diminished L-arginine transport due to down-regulation of cationic amino acid transporter 1, accumulation of asymmetric dimethylarginine owing to reduced dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase activity, oxidation and depletion of tetrahydrobiopterin, and aberrant S-glutathionylation markedly reduce the bioavailability of nitric oxide and disrupt the regulation of vascular tone.

Finally, even nitric oxide that is synthesized under conditions of hyperhomocysteinemia may rapidly lose biological activity owing to destruction of the molecule itself. Under oxidative stress and nitric oxide synthase uncoupling, nitric oxide reacts with the superoxide anion to form peroxynitrite. This not only reduces nitric oxide availability and impairs endothelial function but also further destabilizes redox homeostasis through accumulation of peroxidizing species [43,45].

Experimental evidence from in vitro endothelial-cell models, from animals maintained on methionine-enriched diets (apolipoprotein E knockout mice), and from clinical observations in patients with hyperhomocysteinemia supports a role for homocysteine-mediated nitric oxide deficiency. For example, addition of tetrahydrobiopterin to the culture medium restores vasorelaxation and reduces superoxide production in human umbilical vein endothelial cells treated with homocysteine [46], while a hypermethionine diet accelerates atherosclerotic remodeling and oxidative stress in apolipoprotein E–deficient mice [47]. In patients with chronic hyperhomocysteinemia, reduced bioavailability of tetrahydrobiopterin is associated with impaired coronary dilation, whereas exogenous tetrahydrobiopterin partially restores endothelial function [47].

It has been shown that high doses of folic acid increase intracellular tetrahydrobiopterin and restore endothelial nitric oxide synthase–dependent vasodilation [48]. Agents that improve L-arginine transport via cationic amino acid transporter 1 or increase the activity of dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase reduce endogenous inhibitors of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (asymmetric dimethylarginine) and enhance nitric oxide synthesis [44,48]. These findings point to the promise of combination strategies aimed at restoring arginine transport, promoting degradation of asymmetric dimethylarginine, and re-coupling endothelial nitric oxide synthase subunits as potential points of intervention to correct vascular dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease–associated hyperhomocysteinemia.

In summary, hyperhomocysteinemia impairs the synthesis and decreases the bioavailability of nitric oxide in the endothelium through multiple mechanisms. Elevated homocysteine reduces cellular L-arginine transport by diminishing the activity of cationic amino acid transporter 1, thereby limiting substrate supply for endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Concurrently, hyperhomocysteinemia-induced oxidative stress oxidizes and depletes tetrahydrobiopterin, an essential cofactor for proper enzyme function, which leads to uncoupling of the enzyme and a shift from nitric oxide synthesis toward superoxide generation. Hyperhomocysteinemia also suppresses dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase activity, causing accumulation of asymmetric dimethylarginine—an endogenous competitive inhibitor of the enzyme—and further lowering nitric oxide production. Under these same conditions, S-glutathionylation of the enzyme promotes electron leak and increases the formation of reactive oxygen species. Nitric oxide already synthesized is more rapidly inactivated through reaction with superoxide to form peroxynitrite, which in turn further depletes tetrahydrobiopterin and sustains redox imbalance. The combined effects of substrate deficiency, enzyme inhibition, cofactor depletion, and accelerated nitric oxide destruction result in a marked reduction of nitric oxide bioavailability and consequent endothelial dysfunction.

2.2 Mechanisms of Mitochondrial Dysfunction Induced by Homocysteine

Contemporary concepts of the pathogenesis of hyperhomocysteinemia do not overlook the issue of mitochondrial dysfunction under conditions of elevated homocysteine production [49]. Increased homocysteine concentrations correlate with disruption of mitochondrial dynamics and with bioenergetic insufficiency across diverse pathological states, including neurodegenerative diseases and cardiovascular disorders [49,50]. The mechanisms linking mitochondrial abnormalities to hyperhomocysteinemia may include disturbances of mitochondrial fission and fusion, increased permeability of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, reduced activity of respiratory chain enzymes (complexes I through III), and increased generation of reactive oxygen species, ultimately leading to a hypoenergetic cellular state [50,51].

One principal mechanism involves an imbalance between mitochondrial fission and fusion. In hyperhomocysteinemia, proteins that regulate fission, such as dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), become excessively activated, resulting in excessive mitochondrial fragmentation. This imbalance not only disrupts mitochondrial networks but may also reflect early events of apoptosis [49].

It is believed that mitochondria lack specific transporters for homocysteine, although they possess a transporter for S-adenosylmethionine. Entry of homocysteine may occur in the form of sulfate species via glutamate transporters [49,50]. Experiments in yeast cells have shown that exposure to homocysteine or to its precursor S-adenosylhomocysteine (but not to S-adenosylmethionine) induces changes in mitochondrial membrane potential, enhances mitochondrial fragmentation, and activates genes governing mitochondrial fission (FIS1 and DNM1), which is consistent with adaptive removal of damaged mitochondria in hyperhomocysteinemia [51]. Similar alterations may also indicate initiation of early apoptosis.

In rats subjected to ischemia–reperfusion injury in the setting of hyperhomocysteinemia, pronounced oxidative stress and apoptosis via the extracellular signal–regulated kinase 1/2 pathway have been observed [32]. In another investigation, oxidative stress was identified as a key mediator of homocysteine-induced mitochondrial damage in cerebral ischemia, involving hyperactivation of the mitochondrial form of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 [52–57]. Collectively, several studies highlight the interaction between hyperhomocysteinemia and hypoxia in driving mitochondrial dysfunction [55].

Another critically important aspect of mitochondrial dysfunction in hyperhomocysteinemia is the increased permeability of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Although the precise molecular identity of this pore remains a matter of debate—many investigators implicate subunits of the F0F1 adenosine triphosphate synthase—there is consensus that pore opening is triggered by mitochondrial calcium overload and oxidative stress [58]. Opening of the pore results in loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential, impairment of adenosine triphosphate synthesis, and release of proapoptotic factors such as cytochrome c, thereby initiating cell-death cascades [58,59].

Homocysteine also affects expression of genes encoded by mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid. Methylation of the heavy strand of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid increases and the copy number of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid decreases, leading to reduced expression of key enzymes of oxidative phosphorylation [60]. Within the cell, excess homocysteine is rapidly converted to S-adenosylhomocysteine—a potent competitive inhibitor of deoxyribonucleic acid methyltransferase 1. S-adenosylhomocysteine impedes methylation of both nuclear and mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acids: deoxyribonucleic acid methyltransferase 1 contains a mitochondrial targeting signal and, when S-adenosylhomocysteine accumulates, loses catalytic activity within the mitochondrial matrix. The result is hypomethylation of the regulatory D-loop region of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid, dysregulation of transcription of oxidative-phosphorylation genes, and increased mitochondrial generation of reactive oxygen species, which exacerbates tissue energy deficiency [61]. Supplementation with B-group vitamins—both to replenish the pool of mitochondrial cofactors and to facilitate homocysteine clearance—improves mitochondrial function [62].

The effects of homocysteine are dose- and time-dependent. With moderate hyperhomocysteinemia, activities of tricarboxylic-acid-cycle enzymes (for example, succinate dehydrogenase, complex II, and isocitrate dehydrogenase) increase; during acute exposure to homocysteine, antioxidant cascades under the control of nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (including catalase, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione peroxidase) are activated; and with chronic exposure, activity of cytosolic superoxide dismutase is enhanced, reflecting early phases of cellular adaptation [63].

An additional mechanism of mitochondrial dysfunction is homocysteine-induced conformational modification of proteins—homocysteinylation. This may occur as N-homocysteinylation of lysine residues or S-homocysteinylation through disulfide-bond formation with cysteine residues [64]. Cytochrome c is particularly susceptible to this modification, especially under hypoxic conditions [65]. The altered structure of cytochrome c increases its peroxidase-like activity [66].

Hyperhomocysteinemia also adversely affects the electron transport chain. Enzymatic activities of complexes I through III decline as a consequence of oxidative modifications and altered mitochondrial dynamics, resulting in diminished adenosine triphosphate synthesis and further accumulation of reactive oxygen species [67]. An additional layer of mitochondrial injury arises from epigenetic alterations at the level of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid. Evidence indicates that hyperhomocysteinemia induces hypermethylation of the heavy strand and reduces the copy number of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid, suppressing expression of key oxidative-phosphorylation enzymes and promoting a hypoenergetic state [67].

Moreover, hyperhomocysteinemia appears to influence mitochondrial substrate utilization. The efficiency of β-oxidation of fatty acids declines, and alterations in carnitine-dependent metabolism are observed, further compromising mitochondrial energy production [68,69]. Experimental models employing yeast cells and rodents demonstrate that exposure to homocysteine or to its precursor S-adenosylhomocysteine promotes mitochondrial fragmentation, up-regulation of fission genes (for example, FIS1 and DNM1), and disruption of the inner mitochondrial-membrane potential [52].

Supplementation with B-group vitamins has been shown to replenish mitochondrial cofactors and accelerate homocysteine clearance, thereby improving mitochondrial functions. Overall, the combined effects of disturbed mitodynamics, opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, inhibition of electron transport, changes in mitochondrial-deoxyribonucleic-acid methylation, and disordered substrate oxidation converge to undermine mitochondrial integrity and function in hyperhomocysteinemia, thereby aggravating vascular dysfunction [35].

In sum, hyperhomocysteinemia is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction manifested by altered mitochondrial dynamics (a shift toward fission with hyperactivation of dynamin-related protein 1 and network fragmentation), increased permeability of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore under conditions of calcium overload and oxidative stress, suppression of complexes I through III of the respiratory chain, and heightened production of reactive oxygen species, collectively establishing a hypoenergetic cellular state. Additional features include epigenetic changes in mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid (hypermethylation of the heavy strand and reduced copy number) with suppression of expression of key oxidative-phosphorylation enzymes, as well as impaired substrate supply (reduced efficiency of β-oxidation of fatty acids and alterations in carnitine-dependent metabolism). Post-translational protein modifications of the N- and S-homocysteinylation type make a substantial contribution, notably modification of cytochrome c with increased peroxidase-like activity, which amplifies proapoptotic shifts. The effects are dose- and time-dependent: at early or moderate stages, adaptive responses are possible (activation of tricarboxylic-acid-cycle enzymes and antioxidant pathways under nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2), whereas with chronic or severe hyperhomocysteinemia, dysfunction of the electron-transport chain, opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, and apoptosis predominate; interaction with hypoxia (including extracellular signal–regulated kinase 1/2– and mitochondrial signal-transducer-and-activator-of-transcription-3–dependent pathways) intensifies injury. Experimental data from yeast to rodents confirm the universality of these mechanisms (fragmentation, up-regulation of FIS1 and DNM1, and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential). Partial correction is achievable through lowering homocysteine and replenishing cofactors (B-group vitamins); however, restoration of energetic homeostasis is often incomplete. The net result is the convergence of abnormalities in mitochondrial dynamics, permeability, the electron-transport chain, epigenetic regulation, and substrate metabolism into a sustained reduction of bioenergetic capacity and amplification of apoptosis, which may contribute to the development of chronic vascular and neurodegenerative pathology in hyperhomocysteinemia.

2.3 Induction of Oxidative Stress via NADPH Oxidases and Mitochondria, Leading to the Depletion of Antioxidant Systems

It is evident that homocysteine, mitochondrial metabolism, and oxidative stress are tightly interrelated, and that this interplay makes a major contribution to the development of endothelial dysfunction. A key initiating event in oxidative stress during hyperhomocysteinemia is the effect on the expression of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases—a family of enzymes that generate reactive oxygen species by oxidizing reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate according to the reaction:

NADPH + 2 O2 ↔ NADP+ + 2 O2− + H+

Elevated concentrations of homocysteine have been shown to increase the expression of several oxidase isoforms—principally isoform 2 and isoform 4—in endothelial cells, thereby establishing an early and potent source of reactive oxygen species. Superoxide generated by the oxidase not only reacts directly with nitric oxide, reducing its bioavailability, but also triggers further production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria, by xanthine oxidase, and by uncoupled nitric oxide synthase [69].

Concurrently, hyperhomocysteinemia suppresses antioxidant defenses: it reduces the expression and activity of glutathione peroxidase-1, thereby impairing the detoxification of hydrogen peroxide [60]. It also inhibits thioredoxin, disrupting the reduction of disulfide bonds in proteins and promotes S-thiolation of proteins by homocysteine, which frequently leads to dysfunction of endothelial proteins [60].

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidases, initially defined by their microbicidal ROS production in phagocytes, are now recognized as a multigene family with cell-type–specific expression and regulation. In the vasculature, and particularly under conditions of endothelial dysfunction, elevated homocysteine induces NOX-dependent oxidative signaling in endothelial cells by upregulating and/or recruiting NOX2 and NOX4, thereby initiating superoxide generation and loss of NO bioavailability [67,68]. Once initiated, this process can be sustained independently of homocysteine itself through cross-activation of other sources of reactive oxygen species. In particular, superoxide formed by the oxidase promotes mitochondrial ROS production, activates xanthine oxidase, and contributes to uncoupling of nitric oxide synthase, thereby intensifying oxidative stress [69].

Beyond the initiation of reactive oxygen species production, homocysteine also impairs intracellular antioxidant systems. One key antioxidant enzyme, glutathione peroxidase-1, reduces hydrogen peroxide using glutathione as an electron donor [70]. In hyperhomocysteinemia, glutathione peroxidase-1 function is suppressed at both the expression level and the level of enzymatic activity [71]. Another target is thioredoxin, a protein capable of directly neutralizing reactive oxygen species and of restoring disulfide bonds in oxidized proteins [72]. Concentrations of thioredoxin have been shown to decline in hyperhomocysteinemia, further weakening antioxidant defenses [70–73]. In addition, homocysteine—analogous to glutathione—can participate in S-thiolation of proteins by forming disulfide bonds with protein thiols [74]. In principle, such modification might be protective by shielding reactive thiols from irreversible oxidation; however, as with S-glutathionylation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, S-homocysteinylation frequently results in functional inactivation of key endothelial proteins, thereby aggravating vascular dysfunction [73].

Crosstalk between oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species establishes a self-amplifying loop. Superoxide generated by the oxidase promotes mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species by perturbing components of the electron-transport chain and by facilitating transient increases in mitochondrial permeability, which further amplifies oxidative stress [75–78]. This redox imbalance exacerbates endothelial injury. A series of in vitro experiments in human umbilical vein endothelial cells and models of hypermethionine diets in rodents demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of the oxidase (for example, with apocynin or with peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists) or enhancement of antioxidant defenses (overexpression of superoxide dismutase and catalase) markedly attenuates homocysteine-induced oxidative stress, restores the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and improves vasorelaxation [67]. These findings support a central role for nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases and mitochondria in the amplification of reactive oxygen species during hyperhomocysteinemia and provide a rationale for therapeutically targeting the oxidases in combination with mitochondria-directed antioxidants.

In summary, hyperhomocysteinemia initiates and sustains oxidative stress by increasing the activity of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases, with consequent hyperproduction of superoxide anion that directly inactivates nitric oxide and activates secondary sources of reactive oxygen species—mitochondria, xanthine oxidase, and uncoupled nitric oxide synthase. Parallel suppression of the antioxidant system (reduced expression and activity of glutathione peroxidase-1 and thioredoxin) and S-thiolation of proteins worsen the redox imbalance and disrupt enzymatic regulatory circuits. Cross-activation of oxidase-dependent and mitochondria-dependent pathways generates a self-perpetuating cycle involving dysfunction of electron-transport-chain components and transient increases in mitochondrial permeability, leading to sustained accumulation of reactive oxygen species. The combined effect is reduced bioavailability of nitric oxide, exacerbation of endothelial dysfunction, and stabilization of a pro-oxidant phenotype even as homocysteine concentrations fluctuate. These mechanistic links justify the therapeutic strategy of simultaneously targeting nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases and strengthening antioxidant defenses to correct the vascular consequences of hyperhomocysteinemia.

2.4 Apoptosis and Alternative Cell Death Pathways

Excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and weakening of antioxidant defenses in hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy) critically contribute to endothelial cell injury and death. Reactive oxygen species directly damage proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, thereby disrupting cellular structural integrity and function [77,78]. In the endothelium, such damage can activate several programmed cell-death pathways. The intrinsic (mitochondrial) apoptotic pathway is initiated when reactive oxygen species increase mitochondrial membrane permeability and promote the release of cytochrome c into the cytosol; cytochrome c then participates in apoptosome assembly and the subsequent activation of the caspase cascade [78]. In parallel, the extrinsic (receptor-mediated) pathway is initiated when oxidative stress in HHcy up-regulates death receptors on the endothelial cell surface, such as Fas, tumor necrosis factor receptor 1, and tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptors. Ligand binding to these receptors activates caspase-8 and propagates downstream caspase activation, culminating in apoptosis [79]. Elevated homocysteine concentrations can sensitize cells to Fas-mediated apoptosis through induction of oxidative stress, which may increase Fas expression, and through suppression of protein kinase B (Akt) activity—mechanisms that likely contribute to endothelial injury [79,80]. Increased ROS production also reduces the activity of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMP) [80], which correlates with accumulation of microRNA-30b under high homocysteine exposure and supports a potential link between HHcy and microRNA-30b–induced apoptosis [81].

Data from multiple organismal models indicate that hyperhomocysteinemia systemically disrupts autophagy. These disturbances may be mediated by epigenetic mechanisms, particularly during prolonged exposure to elevated homocysteine. Hyperhomocysteinemia directly promotes endoplasmic reticulum stress (ER stress), impairing protein folding and activating the unfolded protein response (UPR), which ultimately causes mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis via caspase-3 activation [82]. Sensors of endoplasmic reticulum stress, including protein kinase R–like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK), inositol-requiring enzyme-1 alpha (IRE1α), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), are activated in response to protein misfolding and oxidative damage, inducing proapoptotic signaling through both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent mechanisms. Homocysteine has been shown to specifically activate the IRE1α pathway, thereby linking metabolic imbalance to endothelial apoptosis [79–83].

Beyond classical apoptosis, oxidative stress in HHcy can trigger alternative modes of cell death. By activating endoplasmic reticulum stress, homocysteine enhances formation of endoplasmic-reticulum–mitochondrial contact sites, which increases calcium transfer into mitochondria. The resulting calcium overload, mitochondrial dysfunction, and augmented ROS generation jointly activate the NLR family pyrin domain–containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome. Concurrently, endoplasmic reticulum stress via the PERK/eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha (eIF2α)/C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) pathway directly stimulates NLRP3 expression. Activation of NLRP3 leads to maturation of caspase-1, which in turn activates interleukin-1β and interleukin-18, culminating in pyroptosis—a highly inflammatory form of programmed cell death. Hyperhomocysteinemia also induces overexpression of high-mobility group box 1 (HMGB1), which is released during pyroptosis and activates Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and the receptor for advanced glycation end-products (RAGE), promoting release of proinflammatory cytokines and cellular lysis [84,85]. Parthanatos is characterized by hyperactivation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) secondary to extensive deoxyribonucleic acid damage and leads to translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) from mitochondria to the nucleus, resulting in caspase-independent cell death [85].

Finally, ferroptosis—driven by accumulation of reactive oxygen species and iron-dependent lipid peroxidation—may also contribute [86,87]. Ferrous iron reacts with hydrogen peroxide to generate hydroxyl radicals, causing uncontrolled lipid peroxidation and disruption of membrane integrity [88,89]. In parallel, homocysteine inhibits β-catenin signaling, which ordinarily supports cellular homeostasis and transcriptionally activates glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4). Dysregulation of the β-catenin/GPX4 axis thereby amplifies iron-dependent lipid peroxidation and triggers ferroptosis. Homocysteine can also impair other protective pathways, such as the cystine/glutamate antiporter system—a key regulator of cellular redox homeostasis mechanistically linked to GPX4-dependent ferroptosis—thus exacerbating oxidative stress [88–90].

Taken together, the potential for ROS-mediated damage, disruption of mitochondrial integrity, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and activation of diverse cell-death pathways in HHcy underscores the multifactorial nature of endothelial cell loss observed in cardiovascular pathology under conditions of HHcy. In vitro endothelial-cell models and animal studies consistently demonstrate increased markers of apoptosis and alternative death programs during HHcy, correlating with vascular dysfunction in clinical settings.

Moreover, homocysteine induces neutrophil extracellular trap formation (NETosis) through calcium-dependent activation (extracellular signal–regulated kinase 1/2/peptidyl arginine deiminase 4) and oxidative stress (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase/mitochondrial reactive oxygen species), an effect amplified by hyperglycemia [90,91]. Activated platelets (via P-selectin and integrins) and cytokines (interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor alpha) create a vicious inflammatory cycle, culminating in neutrophil extracellular traps with procoagulant activity [91]. This framework explains the increased thrombosis observed in hyperhomocysteinemia, particularly in the presence of metabolic disturbances, and provides a rationale for therapies employing antioxidants, calcium-channel blockers, and deoxyribonuclease.

In summary, during hyperhomocysteinemia oxidative stress activates intrinsic mitochondrial, receptor-mediated, and endoplasmic reticulum stress–linked apoptosis, as well as alternative cell-death pathways. The combination of these mechanisms intensifies endothelial injury, compromises functional integrity, and accelerates progression of vascular pathology.

2.5 Inflammatory Activation of the Endothelium

Elevated homocysteine concentrations play a substantial role in initiating and sustaining a proinflammatory phenotype of the vascular endothelium. Hyperhomocysteinemia induces up-regulation of key adhesion molecules—intercellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and E-selectin—which facilitate the tethering and firm adhesion of circulating monocytes and neutrophils to the endothelial surface [92]. The enhanced leukocyte–endothelium interaction constitutes the earliest stage of vascular inflammation and promotes the establishment of a proinflammatory microenvironment.

The fundamental mechanism is tightly linked to oxidative stress. Increased homocysteine promotes the production of reactive oxygen species by up-regulating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases and by disrupting mitochondrial function. This, in turn, activates redox-sensitive transcription factors such as nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) [93]. Activation of NF-κB triggers a cascade of proinflammatory gene expression, including the cytokines interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and interleukin-18 [94]. This inflammatory milieu not only augments adhesion-molecule expression but also stimulates proliferation and migration of vascular smooth-muscle cells, thereby exacerbating vascular remodelling.

Another dimension by which hyperhomocysteinemia amplifies inflammation is modulation of other mediators, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha further activates NF-κB and induces additional expression of adhesion molecules, establishing a vicious cycle in which inflammation is both a cause and a consequence of endothelial dysfunction [95]. In addition, proinflammatory modifications induced by hyperhomocysteinemia—such as protein homocysteinylation—may alter intracellular signalling pathways and potentiate immune-cell recruitment, although the precise mechanisms require further clarification.

Integration of these pathways has been demonstrated across a wide spectrum of experimental systems, from endothelial-cell cultures to animal studies and clinical observations. For example, patients with hyperhomocysteinemia frequently exhibit elevated plasma concentrations of adhesion molecules and cytokines, which correlate with reduced flow-mediated dilation and increased cardiovascular risk [96].

In sum, hyperhomocysteinemia initiates a self-reinforcing circuit of inflammatory endothelial activation: excess reactive oxygen species derived from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase isoforms 2 and 4 and from dysfunctional mitochondria activate NF-κB, leading to coordinated up-regulation of adhesion molecules (intercellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and E-selectin) and proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and interleukin-18). Tumor necrosis factor-alpha then amplifies this circuit, stabilising adhesion-molecule expression and sustaining NF-κB-dependent transcription. Against this background, protein homocysteinylation likely fine-tunes signalling pathways and immune-cell recruitment, consolidating the inflammatory phenotype. The net effect is a shift of the endothelium toward a state of high adhesiveness and proinflammatory secretion, clinically associated with reduced flow-mediated dilation and heightened cardiovascular risk. This schema emerges as a missing link between homocysteine-driven metabolic imbalance and persistent vascular inflammation.

2.6 Association of Endothelial Dysfunction and Mitochondrial Pathology

Mitochondrial dysfunction and endothelial dysfunction are tightly interrelated in hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy): disturbances of mitochondrial homeostasis further exacerbate vascular injury. Mitochondria are a principal source of ROS, especially at complexes I and III of the electron-transport chain, and under HHcy dysregulation of oxidative phosphorylation leads to excessive mitochondrial ROS production [97]. Elevated mitochondrial ROS not only directly intensifies oxidative stress but also promotes uncoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) with a consequent reduction in nitric oxide bioavailability, establishing a deleterious feedback loop that impairs vascular function [98].

A critical feature of mitochondrial pathology in HHcy is dysregulation of calcium homeostasis. Excess cytosolic Ca²+ may be sequestered by mitochondria, triggering opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP). Although the precise molecular identity of mPTP remains debated—with current hypotheses implicating adenosine triphosphate synthase components and regulatory proteins—its opening precipitates collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential, loss of adenosine triphosphate production, and initiation of apoptotic cascades [81,90]. Accordingly, mPTP opening is associated with the release of proapoptotic factors such as cytochrome c, which further promotes endothelial apoptosis and vascular dysfunction.

At the genomic level, HHcy induces significant epigenetic modifications of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid (mtDNA). Increased methylation of the heavy strand and a reduced mtDNA copy number have been reported, changes that adversely affect the expression of key oxidative-phosphorylation enzymes. Such epigenetic reprogramming contributes to a global hypoenergetic state and diminishes the mitochondrial capacity to meet cellular energy demands [35]. In addition, HHcy has been reported to impair the efficiency of β-oxidation of fatty acids via disturbances of carnitine metabolism, thereby compounding deficits in mitochondrial energy production [59,99,100].

Recent studies in endothelial-cell models in vitro and in animal experiments have shown that interventions aimed at restoring mitochondrial function—for example, B-vitamin supplementation to enhance homocysteine clearance and replenish the cofactor pool—can partially reverse these mitochondrial abnormalities [62,75]. These findings underscore the bidirectional linkage between mitochondrial dysfunction and endothelial status. Indeed, mitochondrial injury not only augments ROS production and apoptosis but also disrupts calcium signaling and energy metabolism—processes that are critical for maintaining endothelial integrity.

Thus, in hyperhomocysteinemia, mitochondria become a central node that closes the pathological loop between oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction. Dysregulation of oxidative phosphorylation at respiratory-chain complexes increases ROS generation, which reduces nitric oxide bioavailability. Reduced nitric oxide, in turn, worsens vascular dysfunction and further promotes ROS production. In parallel, Ca²+ overload initiates mPTP opening, collapse of the mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), adenosine triphosphate deficiency, and apoptotic cascades, thereby aggravating endothelial injury. At the genomic level, hypermethylation and copy-number loss of mtDNA suppress expression of oxidative-phosphorylation enzymes, while disturbances in carnitine-dependent β-oxidation further constrain energy supply. Collectively, these links constitute a self-sustaining circuit in which mitochondrial ROS drive nitric oxide deficiency, which mediates vascular dysfunction and—via ischemia—feeds back to increase ROS formation, helping to explain the persistence of an inflammatory endothelial phenotype in HHcy. The partial reversibility observed with targeted restoration of mitochondrial function, including enhanced homocysteine clearance and cofactor repletion, highlights mitochondria as a key therapeutic axis for breaking this cycle.

3 Clinical Consequences Hyperhomocysteinemia for COPD

3.1 Hyperhomocysteinemia as a Metabolic Trigger for Inflammation

The magnitude and architecture of hyperhomocysteinemia effects may vary according to the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotype and modifying factors. In the bronchitic phenotype—characterized by more pronounced airway inflammation, hypersecretion, and frequent exacerbations—the association of hyperhomocysteinemia with endothelial activation, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase–dependent oxidative stress, and matrix-metalloproteinase–mediated degradation of the extracellular matrix is likely stronger, consistent with a more pronounced inflammatory–matrix component of remodeling [101–103]. In the emphysematous phenotype, parenchymal destruction and reduction of the capillary bed predominate, and the contribution of hyperhomocysteinemia appears to be realized mainly through mitochondrial dysfunction, nitric oxide deficiency, and hypoxic vasoreactivity against a background of reduced diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide, which may be associated with disproportionate pulmonary hypertension in a subset of patients [104]. A distinct pulmonary-vascular phenotype with more severe pulmonary hypertension may experience an additional modifying effect of hyperhomocysteinemia through amplification of redox stress and endothelial dysfunction, independent of the degree of airflow obstruction [105]. The magnitude of influence in each subgroup is further modified by nutritional status (folate, vitamin B12), smoking, comorbidities, and genetic variants of homocysteine metabolism (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, cystathionine β-synthase), which supports personalized risk stratification and targeted interventions [106].

It must be emphasized that interpretation of the evidence requires consideration of limitations: a substantial portion of mechanistic data derives from cellular and animal models, whereas clinical studies are often observational and vulnerable to confounding and reverse causation; Mendelian randomization partially mitigates these risks but requires rigorous validation of instruments and control of pleiotropy [8]. In light of the foregoing, translationally justified targets include sources of reactive oxygen species (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases), maintenance of endothelial nitric oxide synthase coupling (including provision of tetrahydrobiopterin), enhancement of antioxidant and mitochondrial pathways, and correction of homocysteine metabolism; evaluation of the clinical utility of such approaches calls for prospective cohorts with repeated homocysteine measurements and randomized trials stratified by chronic obstructive pulmonary disease phenotypes, with hard vascular endpoints (mean pulmonary arterial pressure, pulmonary vascular resistance, right ventricular function, flow-mediated dilation, and morphometry of the vascular wall).

In sum, hyperhomocysteinemia is a modifiable metabolic trigger that is converted—through redox disturbances, mitochondrial dysfunction, and inflammation—into vascular remodeling and pulmonary hypertension in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; successful translation will require phenotype-oriented stratification and causal testing in well-designed interventional studies.

3.2 Vascular Remodeling and Pulmonary Hypertension Due to Hyperhomocysteinemia

In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, vascular pathology arises from a linked cascade of disturbances: reduced bioavailability of nitric oxide, persistent oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction lead to endothelial dysfunction, which is followed by remodeling of the vascular wall and an increase in pulmonary vascular resistance with the development of pulmonary hypertension [105–107]. Hyperhomocysteinemia and carnitine deficiency play leading roles in initiating this circuit; notably, carnitine deficiency in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease acts as an independent modifier of mitochondrial metabolism and endothelial nitric oxide synthase signaling, distinguishing this nosological entity from classical cardiovascular and neurological conditions [32,108–110].

Carnitine insufficiency—a characteristic component of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—impairs fatty acid transport into mitochondria, causes accumulation of acyl-carnitine intermediates, and increases mitochondrial reactive oxygen species [100,108–110]. This lowers endothelial energy supply and disrupts coupling between heat-shock protein 90 and endothelial nitric oxide synthase, thereby promoting enzyme uncoupling and a decline in nitric oxide production [110–112]. Thus, carnitine deficiency not only amplifies oxidative stress but also directly interferes with endothelial nitric oxide synthase signaling, potentiating the effect of hyperhomocysteinemia within the pulmonary vasculature [112].

Redox activation of nuclear factor kappa-B during hyperhomocysteinemia induces expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and E-selectin, as well as the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha, thereby sustaining leukocyte adhesion and chronic inflammation [113,114]. At the same time, activity of matrix metalloproteinases—chiefly matrix metalloproteinase-9—increases, accelerating degradation of collagen and elastin and raising vascular-wall stiffness [115]. In the pulmonary circulation, these processes manifest as increased pulmonary vascular resistance, development of pulmonary hypertension, and deterioration of flow-mediated dilation.

From a therapeutic and translational perspective, isolated lowering of homocysteine with B-group vitamins yields inconsistent vascular effects, consistent with the multifactorial nature of the disturbance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [106]. Combined strategies appear promising: correction of hyperhomocysteinemia (folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12) together with targeting of reactive-oxygen-species sources (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidases) and restoration of mitochondrial function using L-carnitine or its derivatives, which can reduce mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and re-establish endothelial nitric oxide-synthase physiological function [112]. Demonstration of clinical benefit will require prospective cohorts with repeated homocysteine measurements and randomized trials stratified by phenotype, employing hard vascular endpoints (mean pulmonary arterial pressure, pulmonary vascular resistance, right ventricular function, flow-mediated dilation, and vascular-wall morphometry) and accounting for the limitations of causal inference in observational studies; genetic instruments (Mendelian randomization) are useful when supported by rigorous validation and control of pleiotropy.

In summary, in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hyperhomocysteinemia and carnitine deficiency establish a mutually reinforcing circuit of redox disturbance, mitochondrial dysfunction, and defective endothelial nitric oxide synthase signaling that converts endothelial dysfunction into a phenotype of pulmonary vascular remodeling and pulmonary hypertension. Breaking this circuit will require phenotype-oriented, combined correction of both homocysteine metabolism and carnitine-dependent mitochondrial function.

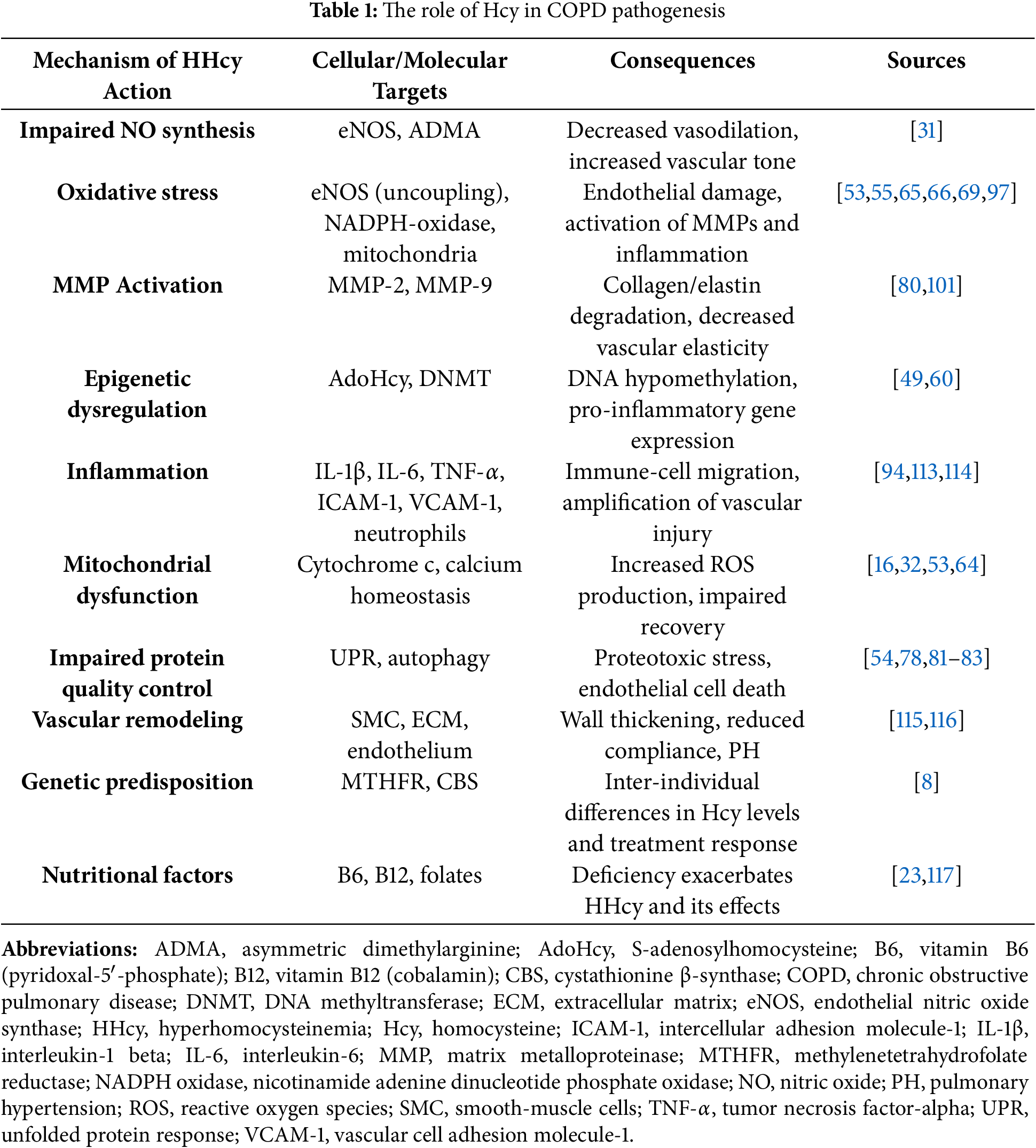

3.3 Contribution of Hyperhomocysteinemia to Pathogenetic Mechanisms of COPD Progression

Below is a summary table integrating the key pathogenic links through which hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy) mediates the progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). For each mechanism, the most studied cellular/molecular targets, typical consequences of their activation, and selected primary sources are indicated (Table 1; numbers in brackets refer to references).

Summarizing these factors, hyperhomocysteinemia can be viewed as an important modifier of the classic causal drivers of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—tobacco smoke, chronic hypoxia, and systemic inflammation. Elevated homocysteine disrupts the endothelial balance of nitric oxide: direct inhibition of endothelial nitric oxide synthase combined with increases in asymmetric dimethylarginine reduces the vasodilatory capacity of the pulmonary circulation, elevates pulmonary vascular resistance, and thereby contributes to the development of pulmonary hypertension [115,116]. Concurrently, endothelial nitric oxide synthase “uncoupling” and activation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase initiate excessive fluxes of reactive oxygen species, amplifying lipid peroxidation, mitochondrial injury, and premature endothelial cellular senescence [31,53,54,97].

Reactive-oxygen-species–driven signaling activates matrix metalloproteinases, accelerating degradation of collagen and elastin in the vascular and alveolar walls, which is accompanied by reduced elasticity of the pulmonary parenchyma and thickening of the vascular media [101,115]. An additional tier of regulation operates at the epigenetic level: intracellular accumulation of S-adenosylhomocysteine inhibits deoxyribonucleic acid methyltransferases, inducing hypomethylation of promoters of proinflammatory genes such as nuclear factor kappa-B, cyclin A, and phosphatase and tensin homolog, thereby stabilizing a long-lasting proinflammatory phenotype in endothelial and smooth-muscle cells [49,60,94]. Against this epigenetic backdrop, homocysteine enhances expression of interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha, intercellular adhesion molecule-1, and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, increasing adhesion and transendothelial migration of neutrophils and aggravating chronic inflammation of the bronchopulmonary system [4,29,92].

In addition, HHcy initiates endoplasmic reticulum stress and activates the unfolded protein response. Through the inositol-requiring enzyme-1 alpha/activating transcription factor 4 axis, this stress induces endothelial apoptosis and up-regulates vascular endothelial growth factor, thereby promoting pathological neovascularization and remodeling of the bronchial wall [118]. The cumulative impact of these mechanisms is expressed as vascular remodeling: proliferation of smooth-muscle cells, excessive deposition of extracellular matrix, and reduced nitric oxide bioavailability lead to persistent wall thickening, loss of compliance, and progressive pulmonary hypertension, which clinically correlate with a more rapid decline in forced expiratory volume in one second and an increased frequency of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [105–107].

Finally, the severity and therapeutic modifiability of HHcy are influenced by genetic and nutritional factors. The methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase C677T polymorphism, as well as variants in cystathionine β-synthase, predispose to higher baseline homocysteine and to weaker responses to folate therapy [8]. Deficiency of vitamins B6, B12, and folates—characteristic of the cachectic phenotype of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—further elevates homocysteine concentrations; short-term repletion of these vitamins lowers its level, but it has not yet been demonstrated that such correction materially affects the trajectory of forced expiratory volume in one second or the frequency of exacerbations, underscoring the need for large, long-term randomized trials.

Thus, hyperhomocysteinemia integrates vascular–metabolic, epigenetic, and inflammatory stimuli, intensifying remodeling of the pulmonary parenchyma and vasculature and thereby accelerating the progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Targeted intervention along this pathway—from the recoupling of endothelial nitric oxide synthase and selective inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases to the reduction of homocysteine with folates while accounting for methylenetetrahydrofolate-reductase genotype—represents a promising direction for personalized therapy that requires further clinico-translational confirmation.

4 L-Carnitine-Centered Strategies for Hyperhomocysteinemia in COPD: Mechanistic Rationale and Future Directions

Elevated homocysteine concentrations are associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and are also observed in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Moreover, a close correlation has been established between the circulating homocysteine concentration and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease severity, underscoring the potential of this measure as a diagnostic marker [6,36,119]. Conversely, several factors predispose to the development of hyperhomocysteinemia, including cigarette smoking, low concentrations of vitamins B12 and folates, and markers of systemic inflammation. Irritant exposures such as tobacco smoke induce oxidative stress by activating macrophages and airway epithelial cells, leading to the release of proinflammatory mediators [113,114]. In addition, a high homocysteine concentration serves as an independent marker of complications of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—for example, thrombophilia [120]—which highlights the need to predict hyperhomocysteinemia in such patients. Analysis of polymorphisms in genes involved in homocysteine metabolism (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase, cystathionine β-synthase, methionine synthase reductase) can identify high-risk groups and personalize nutritional interventions, thereby optimizing management strategies for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Promising therapeutic directions center on correcting of metabolic pathways, including the use of B-group vitamins (folate, vitamin B12, vitamin B6) to normalize homocysteine, tetrahydrobiopterin to restore endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity [23,32,36,121], L-carnitine and its derivatives to improve mitochondrial function [19,110,112], mitochondrial protection with stabilizers of the mitochondrial membrane potential (cyclosporin A) [57], modulators of calcium homeostasis (inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor blockers) [122], stimulators of mitochondrial biogenesis (resveratrol), antioxidant therapy using nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase inhibitors, agents of the glutathione system, and mitochondria-targeted antioxidants (coenzyme Q10) [123]. Anti-inflammatory strategies include blockade of the NLRP3 inflammasome [124], inhibition of proinflammatory cytokines, modulation of nuclear factor kappa-B signaling, and vascular protection by administering nitric oxide donors (L-arginine), inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases, and agonists of the nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 pathway [125]. It should also be recognized that therapy requires personalization, for which genetic testing (methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase and cystathionine β-synthase polymorphisms), biomarker assessment (homocysteine, asymmetric dimethylarginine, reactive oxygen species, inflammatory markers), consideration of disease phenotype (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with or without cardiovascular complications), and other approaches can be applied.

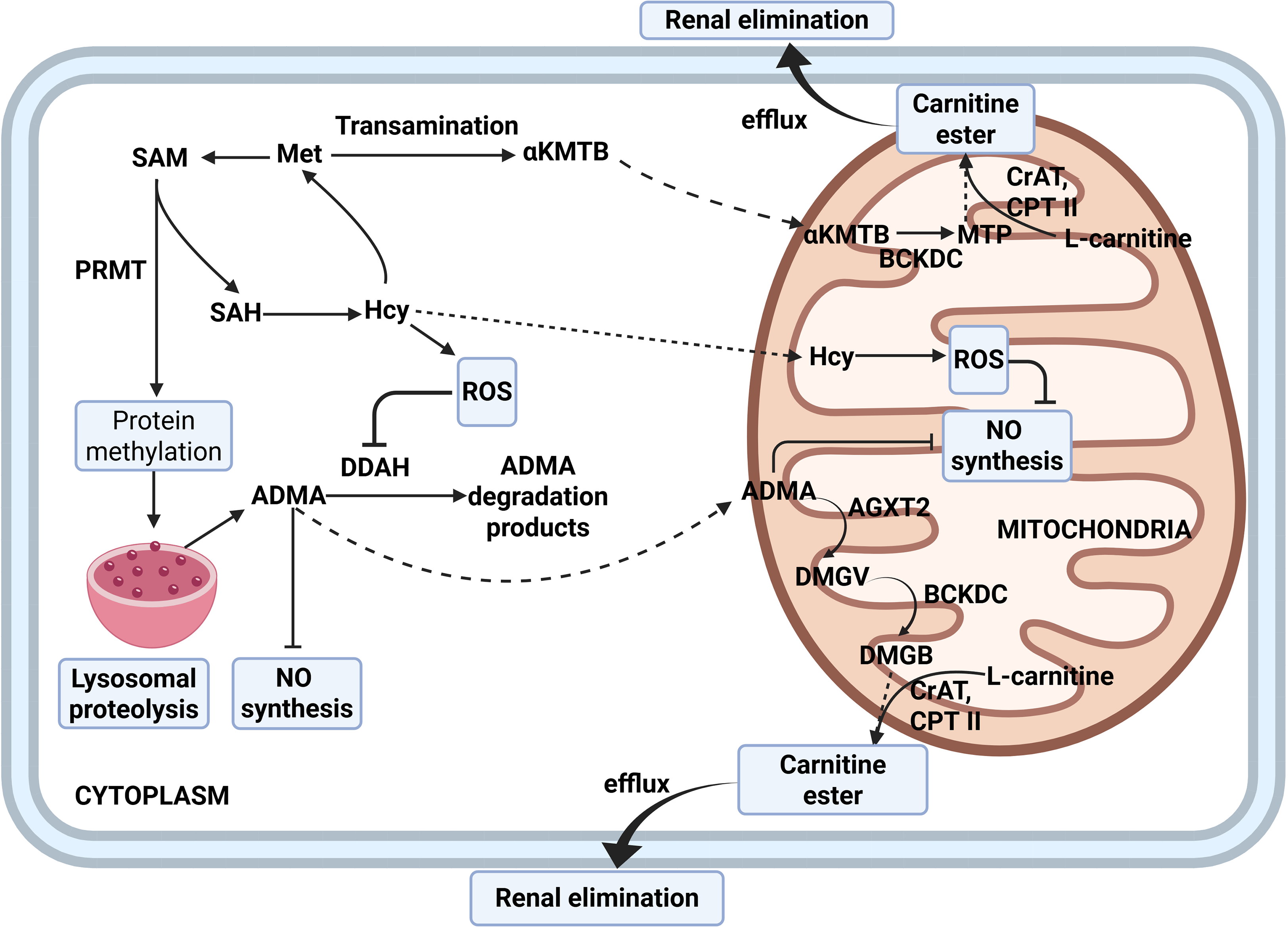

Given the growing evidence that L-carnitine not only supports mitochondrial bioenergetics but also lowers homocysteine concentration, future studies in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease should evaluate the efficacy of adding L-carnitine as a targeted intervention to reduce circulating homocysteine and preserve endothelial nitric oxide signaling. In experimental models of methionine overload, exogenous L-carnitine prevented the rise in serum homocysteine—presumably through formation and renal excretion of short-chain acylcarnitines—and this was accompanied by preservation of nitric oxide metabolites and increased activity of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase in the heart, liver, and epididymis [126,127]. Furthermore, strong inverse correlations (r ≈ −0.7) between total carnitine and homocysteine concentrations in both serum and mitochondrial fractions support a protective role of carnitine under conditions of hyperhomocysteinemia [16,127]. In line with these observations, across diverse experimental models characterized by elevated pulmonary pressures, L-carnitine and its derivatives have been associated with improved endothelial function, which includes higher eNOS expression and NO bioavailability, and attenuation of pulmonary hypertension—findings that suggest potential benefit in COPD but warrant confirmation in further studies [128,129]. A schematic summary of these L-carnitine effects is shown in Fig. 3.