Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Cancer Stem Cells; More Cancer or Stem?

Laboratory of Epigenetic regulation of hematopoiesis, National Medical Research Center for Hematology, Moscow, 125167, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Dmitriy Vladimirovich Karpenko. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Exploring the Role of Cancer Stem Cells)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(5), 743-765. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.062791

Received 27 December 2024; Accepted 21 February 2025; Issue published 27 May 2025

Abstract

Cancer is a highly heterogeneous pathology that poses a significant threat to millions of lives worldwide. In recent decades, there has been a substantial advancement in our understanding of the mechanisms underlying oncogenesis. Contemporary models now take into account the intricate interplay between cancer cells, immune cells, and other non-pathological cells during oncogenesis. The identification of small subpopulations of cancer stem cells has emerged as a crucial area of research, as these cells have been associated with cancer progression and resistance to various therapeutic interventions. The ability to distinguish between cancer stem cells and non-pathological stem cells is paramount for effective diagnostics and treatment. The stem state is associated with a cell’s ability to survive under harmful conditions. Evidence has recently emerged that non-pathological stem cells possess immune privileges. The ability of stem cells to evade surveillance of the immune system could be utilized by oncogenesis. This is of particular significance due to the rising role of anti-cancer immune therapies. Moreover, the immune privileges of stem cells could be exploited by cancer before any treatment, emphasizing the importance of their integration into cancer models. This review elucidates the functional comparison of cancer stem cells with non-pathological stem cells and the associated challenges in diagnostics and treatment.Keywords

Cancer is a major concern in the field of modern medicine. While significant advances have been made in the treatment of specific cancers, the global burden remains substantial, with millions of people afflicted [1,2]. Cancer is defined as the uncontrolled growth of cells, resulting in the disruption of normal tissue and organ function and without treatment leading to severe symptoms and death [3–5]. The molecular mechanisms that underpin this process and lead to the transformation of normal cells into cancerous ones have been the focus of significant research [6–9]. The development of cancer is contingent on the origin of cancer precursors, the presence of diverse cell subtypes, and the interplay between cancer and non-cancer cells, which can be either competitive, cooperative, or supportive [5,10–12]. While in some cases, cancer is presented by the homogeneous or clonal subpopulation of cancer cells, there are cases with significant heterogeneity in subpopulations of cells, which may include cancer stem cells (CSCs) [13–16]. The targeting of different cells in different microenvironments requires different approaches. While there exist unspecific strategies to target common differences among cancer cells, there is a growing body of approaches to treat cancer according to markers specific to a particular cancer type [17–20].

This review is devoted to the issue of CSCs about non-pathological stem cells (npSCs). The first report identifying CSCs was published in 1997, and since then, the subject has been significantly elucidated; yet, we are still far from complete understanding [14,21–23]. The presence of CSCs has been associated with refraction, metastasis, relapses, and overall poor prognosis [22,24–26]. CSCs bear case-specific genomic alterations of cancer cells, yet they also exhibit characteristics of stem cells. The efficiency of therapeutic targeting of CSCs is a major concern. Radiation, chemotherapy, and immune therapy could be ineffective against CSCs, and this could be a manifestation of the stem state itself [27–30]. In a recent article, it was proposed that the common functions and properties of stem cells, in conjunction with their microenvironment and regulatory mechanisms, could be recognized as a stem system [31]. The stem system is not limited to stem cell subpopulation but includes other cells required for the proper tissue support by renewing a pool of differentiated cells, a response to a regeneration request, and modulation of an activity of the immune system. Integration of immune modulation function into stem cell properties leads to the conclusion that such immune modulatory stem cells should be regarded as a specialized component of the immune system. The earlier suggested idea of the close relationship between the immune system and the stem system functions [31] has been further developed to explain the evolutionary link between attributes of immune modulatory stem cells [32]. The question of whether CSCs are also part of the stem system and to what extent remains unresolved. Recent studies demonstrated the immune privileges of npSCs [33–36]. We managed to strengthen the results of our group [35] by the demonstration of immune privileges of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in immunized recipients, with the results of the last study currently available as a preprint [37]. The ability of MSCs to survive and maintain functionality following transplantation, despite targeted immunization, differs from the immune privileges observed in conventional sites such as the brain or eye [38,39]. New data demonstrate similarities between MSCs and CSCs in their ability to evade immune surveillance [40,41]. In consideration of the significance of the transition to the mesenchymal state in the context of CSC regulation, it is imperative to take into account the strong immune privileges exhibited by MSCs in models of CSCs. This also gives rise to the question of the similarity between CSCs and npSCs in the context of functionality.

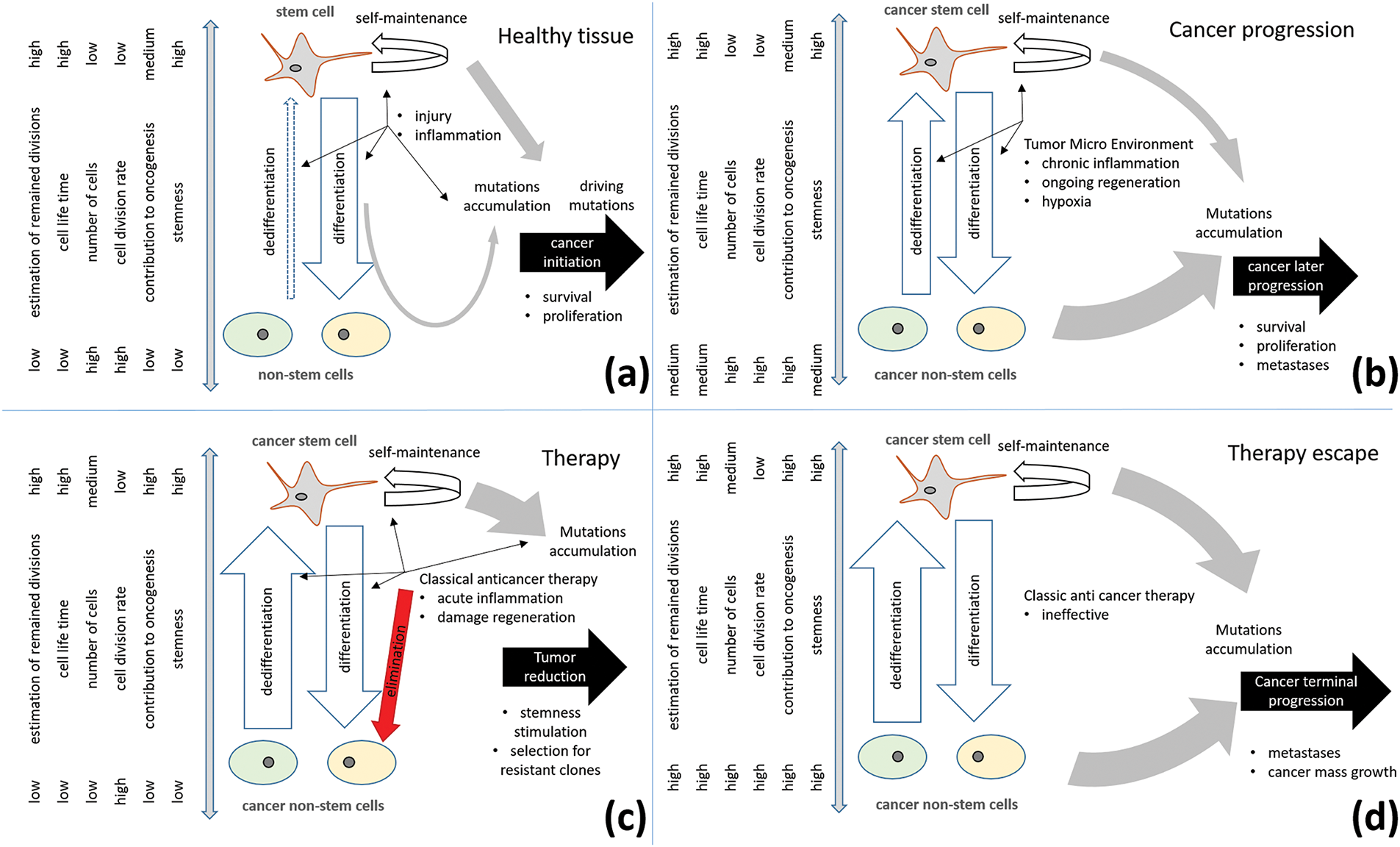

The transformation of precursor cells into cancer cells can occur in a variety of ways [5,8]. Mutations can be caused by various factors, including stochastic events, smoking, diet, irradiation, infection, inflammation, and other internal dysregulations [7,8,42]. Genetic and epigenetic alterations contribute to cancer evolution [43]. Driving mutations often initiate a process of secondary mutations that lead to malignancy [44–46]. Manifestation of cancer can occur through the actions of differentiated cells, while less differentiated cells can be a source of problems [47–49]. The population of undifferentiated cancer cells can form teratomas [50,51]. In contrast to normal tissue supported by the stem system, differentiated cancer cells can, in certain cases, function independently, while in others, cooperation and high heterogeneity are observed [12]. During the early stages of oncogenesis, quiescent stem cells have been shown to persist for extended periods of time, whereas their progeny do not, suggesting that stem cells may play a significant role in the accumulation of pro-oncogenic mutations [52], see Fig. 1a. In the later stages of cancer progression, stem-like cells that undergo slow division are statistically less successful in terms of cancer evolution in comparison to their progeny, which undergoes more frequent divisions [53]. This observation supports the hypothesis that such CSCs are more likely to arise from a process of dedifferentiation rather than being the original source of cancer, see Fig. 1b. Similar to normal tissues, the cancer microenvironment plays an important role in supporting cancer and CSCs as well as in their evolution before and after therapy [54–57]. Cancer cells could be stimulated to dedifferentiate [53,58,59]. This could be a direct induction or a result of competition in dysregulated conditions within the cancerous environment.

Figure 1: Role of cancer stem cells in cancer progression. (a) In healthy tissue, long-living stem cells are the main sources and keepers of oncogenic mutations; (b) In advanced cancer stages, cancer non-stem cells with upregulated proliferation and mechanisms of survival provide significant contributions to cancer progress. Dedifferentiation stimulated by the tumor microenvironment enhances stem cell turnover and cancer progression; (c) Classic anticancer therapy eliminates cancer non-stem cells, induced damage, and inflammation can further stimulate cancer stem cell selection; (d) Therapy escape can occur due to therapy-induced stimulation and selection for resistant properties of cancer stem cells and their resistant clones

Dedifferentiation of non-pathological cells has been observed in various tissues [60–63]. The Yamanaka cocktail, which comprises the transcription factors, has been shown to transform differentiated cells into induced pluripotent stem cells [64–67]. Another factor that has been identified as inducing stemness in cultivated cells is hypoxia [68–71]. It has been observed that the stem niche is characterized by hypoxia [72–75]. The cancer microenvironment has also been shown to be characterized by hypoxia [76–79], and it has been hypothesized that this could be one of the key mechanisms for reprogramming cancer cells towards CSCs [80–83]. Glycolysis and other factors have also been posited as contributors to the case-dependent reprogramming [84–88]. Dedifferentiation has also been observed in vivo for differentiated non-pathological cells induced by stress [61,89,90]. Of particular interest is the observation that stem cells limit the number of dedifferentiating cells [91,92]. Chronic inflammation in normal tissue may induce extended activation of stem cells and their exhaustion [93,94]. At least for some tissues, stem cell balance could be considered dynamic, and in cancer tissues, it can contribute to faster CSC turnover [95]. Furthermore, stress induced by therapy activation of the regeneration program can also lead to dedifferentiation and cancer progression [57,96,97], see Fig. 1c,d. Due to the diversity of cancer pathology, it is difficult to consider only one way.

It is important to acknowledge the existence of diverse oncogenic strategies, where the development of CSCs is an optional event. There is evidence of collaboration between different cancer clones [12,98,99]. The diversification of roles among cancer subclones can contribute to the accelerated progression of the pathology as a whole [100]. Furthermore, metastases can be formed clonally by migrating cells [101]. The demonstration of immune privileges in the field of npSCs provides vital information for understanding the evolutionary advantages of stemness for CSCs in the course of oncogenesis [33–36].

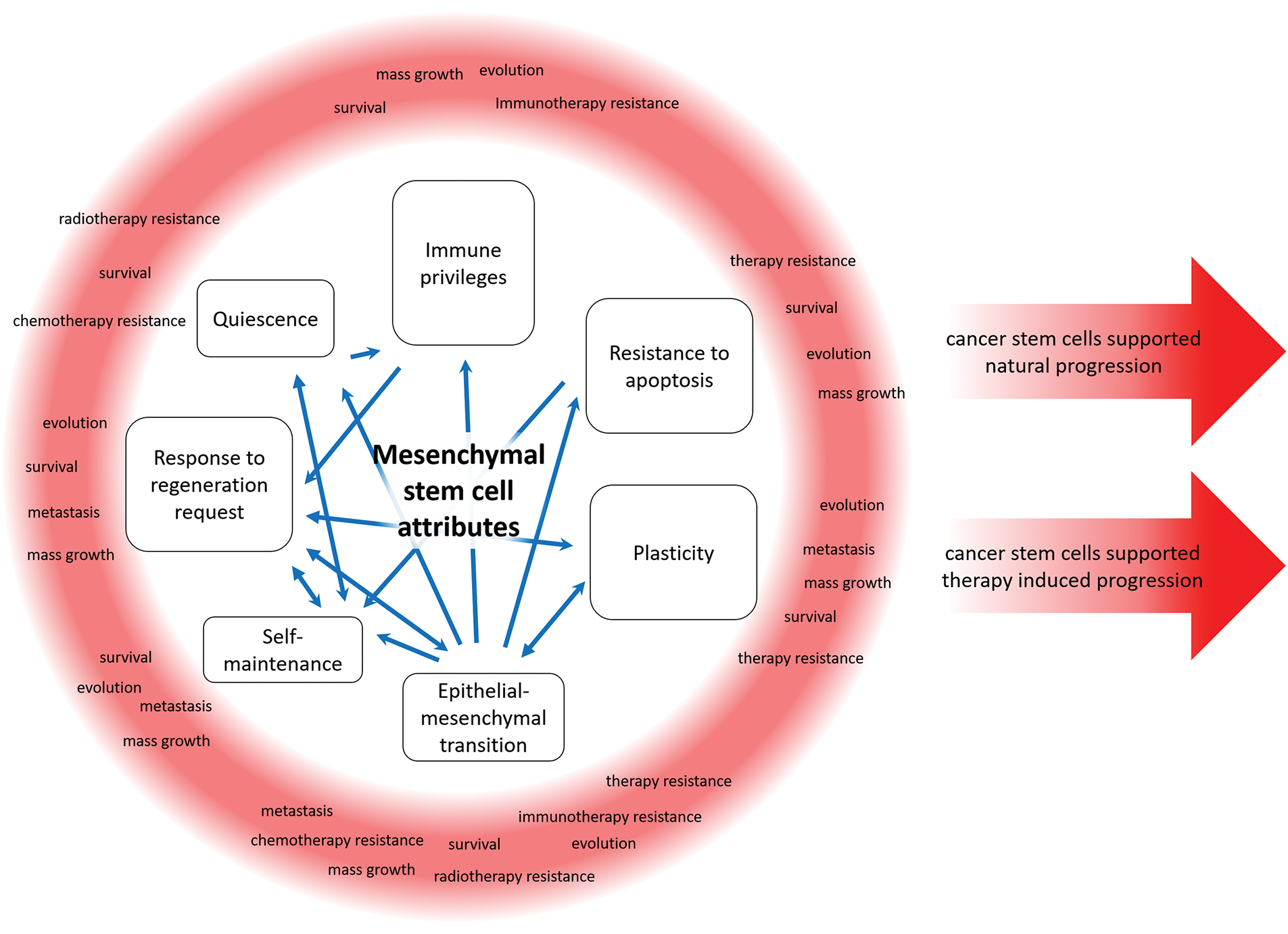

The formation of metastases, the support of the pool of differentiated cancer cells, and the preservation of cancer tissue can be considered functions of CSCs [102]. It is noteworthy that these functions are not required by evolution. These functions are analogous to those of npSCs. While CSCs possess a corrupted genetic program, their stem state and properties can be analogous to those of npSCs. The prevailing concept is that the stem program might be analogous across diverse stem cells, including CSCs [31,103]. This program is responsible for supporting organ and tissue renewal, responding to reparative demand, and forming mutual regulation with the immune system [31,103]. It is important to note that significant diversity in the organization of the stem system exists in different tissues [103,104]. A comparison of CSCs and npSCs, accounting for their own diversity, would be complicated. The present review will therefore focus on the subpopulation of quiescent, immune-privileged stem cells and the traits with which they are associated, see Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Cancer stem cells can utilize the functions of a non-pathological stem cell for cancer progression in native conditions and under therapeutic pressure

Immune privileges provide an ability to evade the action of suppressive immune surveillance, which otherwise would eliminate cells without immune privileges [31]. The immune privileges of cancer cells and CSCs represent a significant concern for the field of oncology [41]. Immune therapy involves the development of approaches aimed at targeting specific markers on cancer cells, with the ability to evade immunity acting as a natural barrier [105–107]. Evidence suggests that CSCs can survive and maintain functionality for extended periods within the host, eradicating differentiated cancer cells [40,41]. The existing literature outlines an intricate network comprising diverse molecular mechanisms and specialized immune cells [41,108–110]. In contrast, the literature on the immune privileges of npSCs remains comparatively limited. Nonetheless, evidence suggests immune privileges for hair follicle and muscle stem cells, as well as for hematopoietic and mesenchymal stem cells [33–36]. The significance of quiescence and T-regulatory lymphocytes has been demonstrated [33,34]. It is important to note that MSCs evade the immune system not only through passive mechanisms but also by actively interacting with immune cells, thereby reprogramming them according to the molecular environment [111–114]. This emphasizes the ability of the stem system to regulate the immune system [115]. It has been suggested that the immune privileges of stem cells result from the regulation required for proper control of autoimmunity and regeneration [31]. In a recent study, we demonstrated that GFP+ MSCs can survive in the transplantats for 6 weeks and preserve functionality despite GFP preliminary immunization; these data are presented as a preprint [37]. We posited that this capacity is analogous to that of CSCs, as they are capable of survival while their progeny are being eradicated [40,41]. Furthermore, it is evident that immune privileges exhibit variation in ocular and cerebral regions, where the entire tissue is protected, yet impairment or immunization results in a substantial diminution of immune privileges [38,39]. The similarity of CSCs and MSCs suggests the presence of shared underlying mechanisms. The hypothesis that immune privileges could be a property of quiescent stem cells is reinforced by a number of studies [33–35,41]. In this context, it can be hypothesized that, in certain cases, the immune privileges exhibited by CSCs may be a manifestation of their stem state, which could be exhibited in conjunction with other stem properties, thereby providing benefits that contribute to survival [31].

Self-maintenance is defined as the capacity of stem cells to sustain their own population [104]. In contrast to differentiated cells, which exhibit limited proliferative potential, stem cells possess the ability to generate differentiated progeny and their own copy in asymmetric cell division [116]. A notable capacity is that of dedifferentiation, whereby certain cells have been observed to regain stem cell characteristics [63,117]. It is important to note that although dedifferentiation and self-maintenance are not synonymous, they contribute to the maintenance of the stem cell population. The distinction between these phenomena, which are intricately linked, may require rigorous lineage-tracing experiments [118]. Dedifferentiation has been observed in transit-amplifying cells, which are closely related to the progeny of stem cells and in differentiated cells [61,95,119]. In vitro cultivation of cells with transcription factors can stimulate dedifferentiation into stem cells, also referred to as induced pluripotent stem cells [67,120–122]. The ability to dedifferentiate is considered one of the mechanisms for transformation towards CSCs and therefore their maintenance [53,58]. The capacity for self-maintenance is considered a hallmark of CSCs in the context of persistent pathology [123,124].

It is noteworthy that while the cells belonging to the CSC population are quiescent, their progeny exhibit active proliferation [125]. Quiescence has been observed in both normal and cancer stem cells [126,127]. However, it is important to note that dormancy is also exhibited by non-stem cells, which underscores the necessity to avoid the interchangeable use of these terms [128]. Quiescence can be considered the inverse of proliferation, yet it is associated with challenges in treatment [125,129,130]. Quiescence and dormancy are mechanisms that enable cells to evade the action of the immune system or other environmental insults, thereby providing a survival advantage [41,129]. In addition to its role in evolution, quiescence provides a natural safeguard against the damaging effects of irradiation and chemotherapy [129,131]. Quiescence is essential for npSCs maintenance and functioning [132–134]. The results associating quiescence with immune privileges in stem cells further emphasize the significance of elucidation of associated mechanisms [33].

Stem cells have been demonstrated to possess a heightened capacity to survive within damaged tissues and to inhibit apoptosis [135,136]. This ability is also of key significance for CSCs [137–139]. The transition to a stem state is regarded as a mechanism of resistance to intracellular cytotoxic mechanisms and induction [28,138,140,141]. ATP-binding cassette transporters, including the multidrug resistance transporter 1 and the breast cancer resistance protein, are among the protective mechanisms of CSCs and npSCs [137,142–144]. Furthermore, enhanced activity of the DNA repair mechanism has been observed in CSCs [27,145]. DNA reparation is also elevated in stem cells [146,147]. Additional resistance could be acquired from external mechanisms accounting for other cells [148,149].

3.5 Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is defined as a cellular transition in which a cell changes from an epithelial to a mesenchymal phenotype, resulting in an increased capacity for motility and the acquisition of stem cell characteristics [150–152]. The transition to a mesenchymal state has been shown to weaken cell-to-cell contacts [153]. The development of cancer is associated with a reduction in the dependency of cancer cells on their niche environment [104,154]. This observation could be indicative of the potential impact of EMT on cancer development. However, it should be noted that the mechanisms of EMT vary depending on the tissue type and can occur alongside the development of CSCs [153,155]. Furthermore, EMT has been demonstrated to contribute to metastasis [156–159]. EMT is associated with invading cells but could be unnecessary for metastase formation, yet cooperation with EMT cells supports the metastasizing process [160–162]. The ability of cells to form metastases and to migrate could be associated with CSCs [163–165]. Furthermore, EMT has been demonstrated to depend on other cell subpopulations, including non-pathological cells stromal, and immune cells [166]. EMT is regarded as a pivotal process in the migration of npSCs [153,167]. The migration and repopulation of hematopoietic territory is well documented in the case of hematopoietic stem cells [168–170]. Migration of MSCs occurs during embryogenesis, where MSCs migrate from the neural crest to developing tissues [171]. The migration of satellite-muscle stem cells from the dermomyotome during embryogenesis is also required for proper development [172]. In adult organisms, migration of MSCs and other stem cells has also been demonstrated, particularly in response to tissue damage signals [173–177]. EMT and migration are important for the proper functioning of stem cells and tissue regeneration.

Plasticity is defined as the ability of cells to modify their phenotype through genetic or epigenetic alterations [178,179]. This phenomenon can be achieved through diverse mechanisms, with one such example being dysregulated differentiation in oncological contexts [179–181]. Plasticity is regarded as a mechanism that fosters cancer cell diversity and an ability to evade therapy [124,140,182,183]. Hypoxia and inflammation have been observed to stimulate the fusion of cancer cells, although this event is rare it contributes to plasticity [184–186]. Furthermore, fusion with MSCs has been shown to result in cells with increased stemness [187,188]. It is important to note that cell fusion is not exclusively a pathological process; it is essential during fetal growth and regeneration [189–191]. The capacity to differentiate into various subtypes is a hallmark of npSCs [104,192]. In non-pathological differentiated cells, plasticity can be triggered by injury or inflammation [91,117]. Cancer cells can be induced to increase stemness as a consequence of anti-cancer therapy [57,96,97]. Despite the capacity of CSCs to undergo epigenetic changes, genomic instability is widely regarded as a significant contributing factor to cancer evolution [193].

3.7 Response to Regeneration Request

Regeneration represents a pivotal function of the stem system [31,104]. The activation of stem cells in response to damage has been observed not only at the site of damage but also in distant tissues [175,194,195]. The regeneration of tissue is required at the site of damage, and the directed migration of stem cells towards such areas is demonstrated, controlled by SDF-1/CXCR4, S1P–S1PR2, and other signals [176,177,196]. The introduction of pathogens often results in tissue damage, necessitating the simultaneous activation of inflammation and regeneration [197]. These processes are mutually interconnected forming regulation with the complex bidirectional signaling, requiring timely and proper tuning [198,199]. The process of inflammation has been shown to stimulate regeneration, which in turn contributes to the inhibition of inflammation [113,200]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that, in the area of damage, the stimulation of differentiated cells can induce their plasticity and dedifferentiation [117]. The tumor microenvironment has been shown to be associated with ongoing regeneration, continuously stimulating cancer cells and possibly contributing to their transformation towards CSCs [117,201]. CSCs stimulated by hypoxia in damaged tissue contribute to angiogenesis, which is of particular significance in solid tumors [202]. A similar regulatory mechanism has been observed in MSCs [203,204]. Stress induced by therapy or inflammation could also contribute to cancer progression [42,97,205]. Induced damage, inflammation, and regeneration are essential for tissue maintenance, but in the case of the cancer microenvironment, they become a serious threat contributing to cancer progression.

Cancer is defined as a proliferative disorder that leads to uncontrolled growth of cancer cells. The nature of cancer can vary significantly depending on the tissue of origin and the presence of functional dysregulations [18,206–208]. There are markers that provide information for prognoses and the selection of the most appropriate strategy for treating a given cancer case [18,209–211]. As emphasized, cancer is presented as heterotrophic populations of cells, and different markers could be associated with different subpopulations [212–215]. To facilitate effective diagnostics, it is imperative to identify case-specific CSCs. The existence of shared functions and mechanisms among CSCs suggests the potential for the development of universal markers, as evidenced by the research on Oct4, Nanog, and Sox2 [124]. A significant number of studies have been undertaken to identify markers not only for CSCs but also for npSCs [215–218]. Distinguishing CSCs from npSCs residing in cancer tissue requires neat protocols [219]. Moreover, a small proportion of stem cells poses a considerable challenge in terms of their identification and study. In our previous study, we identified one MSC for approximately 10,000 cells in a bone marrow sample, a number consistent with other reports [35,220,221]. While there are a number of markers to classify stem cells, they differ depending on a particular study and a research group [216,222–224]. For instance, we suggested nestin as a potential marker associated with stem cells and immune privileges [35]. The existing literature supports the hypothesis that nestin is expressed in CSCs; however, it is also expressed in some non-stem cells, suggesting that it may not be a perfect marker [225,226]. There is a debate in the scientific community about whether multipotent stem cells identified by different markers could represent stem cells with common functionality [222]. However, further research is required to elucidate the functions of differences in stem cell identification [163,227]. The regulation of npSCs is a complex network in which the normal functionality of each mechanism can be disturbed in several ways, thus explaining the complicated understanding of the pathophysiology of CSCs. The identification of CSCs is complicated by dysregulated cancer microenvironments [228–231]. The presence of markers for CSCs varies according to the specific type of cancer and the associated conditions, forming a constantly updating list [19,232–234]. The testing of multiple marker sets is a more extensive process that requires a greater quantity of biological materials. The abundance of CSC markers can be applied to prognosis [235–238]. However, the proportion of CSCs may be low [239,240]. Distinguishing a small subpopulation from a general pool of cells requires appropriate protocols. Bulk analysis for expression, mutations, or other markers would not be sufficient. CSCs can be recognized by methods that distinguish individual cells. Multicolor flow cytometry to target CSC markers or single-cell sequencing utilizing high-throughput technology are appropriate approaches. Regardless of the method employed for CSC diagnostics, the low proportion of cells implies that only a proportion of the acquired data would be relevant to potential CSCs. Consequently, larger biological samples should be considered to obtain sufficient data for CSC analysis. While enriching samples by targeting CSC markers could be advantageous, a substantial volume of biological material would be required. The process of in vitro cell expansion would incur greater costs due to the consumption of time and materials, moreover, it could result in alterations to the subject of study. The plasticity and evolution of cancer present additional challenges for diagnostics, necessitating consideration of not only the stationary condition but also the evolving process [53,183,241]. New events can occur in a natural course of disease and as a reaction to therapy [57,96,97,242]. The migration of individual cancer cells through the body is challenging to detect prior to the formation of metastases. Individual quiescent CSCs can persist for extended periods before relapse [243–246]. These factors naturally create a barrier to the routine diagnostics of CSCs in a clinical setting, with CSCs being the focus of intensive research in experimental contexts. The challenges posed by factors such as the low number of CSCs and their plasticity cannot be overcome by the technology of observation. The persistence of these barriers to the diagnostics of CSCs in a clinical setting can be predicted over an extended period.

Conventional cancer treatment protocols may prove ineffective in eradicating CSCs. Surgery has been demonstrated to facilitate the extraction of cancer cells, including CSCs [247]. However, this approach is only effective for solid tumors and only if the CSCs have not migrated through the body before surgery [248,249]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that surgery can induce the transformation of disseminated cancer cells into CSCs [96]. Radiation and chemotherapy target actively dividing cancer cells, but these approaches are ineffective against quiescent CSCs [27,28,131,250]. While certain therapeutic approaches have been successful in treating specific cancer cases, they have encountered challenges in addressing CSCs, which exhibit heightened drug and apoptosis resistance [138,141,165,251]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that chemotherapy and radiation can induce the transformation of cells into CSCs and stimulate therapy-resistant metastases [97,242]. Strong stress can induce a pro-tumorigenic state in non-cancer cells within the tumor microenvironment [56,219,252]. Furthermore, CSCs have been shown to evade targeted therapy, which is capable of suppressing most cancer cells [253]. Antiangiogenic therapies directed at suppressing tumor growth may cause hypoxia-induced metastatic spread [79]. Recent years have seen a proliferation of approaches to cancer treatment that harness immune mechanisms [254,255]. Immune therapy, which aims to modulate immune checkpoints and cells, has proven to be an effective cancer treatment [256]. Chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell therapy is an approach that involves genetic modification of cytotoxic lymphocytes to direct them to a desired target via the introduction of a chimeric T-cell receptor [257]. CSCs have been demonstrated to have immune privileges, accounting not just for a single immune dysregulation, but for the complex network providing robust protection specific to npSCs [29,30,41,109]. Another problem is the plasticity of cancer and CSCs, which allows the survival of pathologic cells after initially effective treatment [138]. Furthermore, the similarity of molecular mechanisms and signatures of CSCs and npSCs enables CSCs not only to evade therapy but also to render effective anti-CSC treatment risky for npSCs [216].

CSCs are notoriously difficult to eradicate and have the capacity to induce relapses, thus prompting the temptation to designate cases of successful cancer treatment as CSC-free. Indeed, the advent of progress in treatment has led to the successful management of certain cancer types, with the potential for CSCs to be absent in some cases of cancer. However, reports from organ transplantations have highlighted a risk of cancer transmission from donors in long remission [243]. While the probability of this occurrence is minimal, there is evidence to suggest the potential for cancer cells or CSCs to persist in patients who are in remission [243]. Furthermore, there have been instances where cancer has been diagnosed following an unrelated death [244]. This observation suggests the possibility of an underestimation of the total number of people with cancer and CSCs, as many may not survive long enough to receive a diagnosis.

The challenges associated with the treatment of CSCs have given rise to the development of novel approaches aimed at overcoming the resistant profile of CSCs. Despite the challenges associated with the clinical diagnostics of rare subpopulations of CSCs, there has been a notable increase in the number of studies dedicated to the treatment of CSCs. One such example is adaptive treatment, where the restriction of tumor growth is achieved, resulting in enhanced survival outcomes when compared to higher-dose treatments [258,259]. Therapy can be applied to induce differentiation in leukemic cells [260]. Treatment can be aimed at the metabolic reprogramming of CSCs [84,261]. The drug can be targeted to quiescent CSCs [262]. The use of cytotoxic drugs has been proposed as a targeted approach, with the marker of stem cells LGR5 being a potential target [263]. CSCs can also be metabolically labeled for subsequent targeted ablation [264]. The strategy aimed at disrupting WNT signaling can suppress stem cell function in tumors [265]. The use of engineered high-density lipoprotein-mimetic nanoparticles for the delivery of sonic hedgehog inhibitors through the blood-brain barrier to medulloblastoma CSCs has also been proposed [266]. The injection of miR-7-5p mimics has been shown to reduce stemness and radioresistance in the xenograft model of colorectal cancer [267].

CSCs have been observed to produce differentiated cancer cells, which in turn have the capacity to dedifferentiate from CSCs. The elimination of both subpopulations is imperative for the successful treatment of cancer. In this regard, novel strategies combining individual approaches are being developed and tested. It has been demonstrated that the inhibition of the CSC marker aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1 in combination with gemcitabine chemotherapy results in significant suppression of breast tumor growth [268]. A combination of a programmed death-ligand 1 inhibitor and a dendritic cell-based vaccine targeting CSCs following surgical excision has been shown to result in prolonged survival and reduced local tumor relapse [269]. The targeting of combinations of CSC markers by triplebodies or chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cells is a potential avenue for future research [270,271].

The presented examples of CSC treatment are merely a fraction of the reported and ongoing studies in this field. The advent of novel methodologies has enabled the extension of treatment to a greater number of patients, yielding enhanced outcomes; however, a comprehensive grasp of the underlying mechanisms remains elusive. A similar situation pertains to the understanding of the physiology of npSCs. The capacity to distinguish between CSCs and npSCs is critical for effective diagnostics and therapeutic intervention. Furthermore, it is important to note that npSCs functions are mirrored by CSCs in the course of oncogenesis. The challenges associated with the control and elimination of CSCs by diverse therapeutic approaches may be attributed to the multiple protective mechanisms inherent to the stem state. Demonstrating the presence of significant immune privileges in npSCs is particularly important when considering the growing number of anti-cancer immune therapies. A comprehensive understanding of the complex mechanisms underlying stem and immune regulation is critical for the related models and development of effective therapy.

The question of whether cancer stem cells are more stem or cancer cells does not have a universal answer. The regulation of stem cells is a dynamic process determined by multiple factors that form a complex network. The identification of markers that definitively distinguish stem cells is challenging, and the temporal dynamics of these markers during cellular transformation remain to be fully elucidated. Furthermore, the transition from a stem cell to a differentiated progenitor cell is not a unidirectional process. Further research is necessary to comprehensively understand the physiology of both CSCs and npSCs, and to establish a basis for comparison. Nevertheless, the question requires an answer for proper diagnostics and treatment in particular cases. The issue is further complicated by constant evolution in the process of oncogenesis, which allows for retrospective case consideration only. This situation underscores the conclusion that, while distinctions may exist between CSCs and npSCs, the current technological limitations preclude reliable distinction, particularly within the context of routine clinical practice. The npSCs regulation serves as a foundation for the regulation of CSCs, with details being of particular significance, especially in the context of immune modulation and immune privileges. The continuous improvement of technologies and tools will undoubtedly inspire further intensive studies to elucidate the yet-to-be-defined details of stem system regulation. Elucidation of such details is of benefit to cancer treatment and therefore requires more attention.

Acknowledgement: The author thanks Inna Zhurova for editing the language.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this review.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| CSC | Cancer stem cell |

| npSC | Non-pathological stem cell |

| MSC | Mesenchymal stem cell |

| EMT | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

References

1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. doi:10.3322/caac.21660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Schwartz SM. Epidemiology of cancer. Clin Chem. 2024;70(1):140–9. doi:10.1093/clinchem/hvad202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Diori Karidio I, Sanlier SH. Reviewing cancer’s biology: an eclectic approach. J Egypt Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;33(1):1–17. doi:10.1186/s43046-021-00088-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Cairns J. Mutation selection and the natural history of cancer. Nature. 1975;255(5505):197–200. doi:10.1038/255197a0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Nowell PC. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science. 1976;194(4260):23–8. doi:10.1126/science.959840. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Marongiu F, Cheri S, Laconi E. Cell competition, cooperation, and cancer. Neoplasia. 2021;23(10):1029–36. doi:10.1016/j.neo.2021.08.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Wu S, Powers S, Zhu W, Hannun YA. Substantial contribution of extrinsic risk factors to cancer development. Nature. 2016;529(7584):43–7. doi:10.1038/nature16166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Greaves M, Maley CC. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature. 2012;481(7381):306–13. doi:10.1038/nature10762. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Lippman SM, Hawk ET. Cancer prevention: from 1727 to milestones of the past 100 years. Cancer Res. 2009;69(13):5269–84. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1750. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Hanahan D, Coussens LM. Accessories to the crime: functions of cells recruited to the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(3):309–22. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Mateo F, Meca-Cortés Ó, Celià-Terrassa T, Fernández Y, Abasolo I, Sánchez-Cid L, et al. SPARC mediates metastatic cooperation between CSC and non-CSC prostate cancer cell subpopulations. Mol Cancer. 2014;13(1):646. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-13-237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Capp JP, Thomas F, Marusyk A, Dujon M, Tissot A, Gatenby S, et al. The paradox of cooperation among selfish cancer cells. Evol Appl. 2023;16(7):1239–56. doi:10.1111/eva.13571. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Imodoye SO, Adedokun KA, Bello IO. From complexity to clarity: unravelling tumor heterogeneity through the lens of tumor microenvironment for innovative cancer therapy. Histochem Cell Biol. 2024;161(4):299–323. doi:10.1007/s00418-023-02258-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3(7):730–7. doi:10.1038/nm0797-730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Dagogo-Jack I, Shaw AT. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;15(2):81–94. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Kapoor-Narula U, Lenka N. Cancer stem cells and tumor heterogeneity: deciphering the role in tumor progression and metastasis. Cytokine. 2022;157(aad3680):155968. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2022.155968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wang H, Meng Q, Qian J, Li M, Gu C, Yang Y. Review: RNA-based diagnostic markers discovery and therapeutic targets development in cancer. Pharmacol Ther. 2022;234(211–224):108123. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2022.108123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Saeed RF, Awan UA, Saeed S, Mumtaz S, Akhtar N, Aslam S. Targeted therapy and personalized medicine. Cancer Treat Res. 2023;185:177–205. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-27156-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Walcher L, Kistenmacher AK, Suo H, Kitte R, Dluczek S, Strauß A, et al. Cancer stem cells—origins and biomarkers: perspectives for targeted personalized therapies. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1280. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.01280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Shen Y, Zhang Y, Xue W, Yue Z. DbMCS: a database for exploring the mutation markers of anti-cancer drug sensitivity. IEEE J Biomed Heal Informatics. 2021;25(11):4229–37. doi:10.1109/JBHI.2021.3100424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Shaikh MV, Custers S, Anand A, Miletic P, Venugopal C, Singh SK. Cancer stem cells: current challenges and future perspectives. Methods Mol Biol. 2024;2777:1–18. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-3730-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chu X, Tian W, Ning J, Xiao G, Zhou Y, Wang Z, et al. Cancer stem cells: advances in knowledge and implications for cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):170. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01851-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Lim JR, Mouawad J, Gorton OK, Bubb WA, Kwan AH. Cancer stem cell characteristics and their potential as therapeutic targets. Med Oncol. 2021;38(7):1–12. doi:10.1007/s12032-021-01524-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zahra MH, Nawara HM, Hassan G, Afify SM, Seno A, Seno M. Cancer stem cells contribute to drug resistance in multiple different ways. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2022;1393:125–39. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-12974-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Dzobo K, Senthebane DA, Ganz C, Thomford NE, Wonkam A, Dandara C. Advances in therapeutic targeting of cancer stem cells within the tumor microenvironment: an updated review. Cells. 2020;9(8):1–38. doi:10.3390/cells9081896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Osum M, Kalkan R. Cancer stem cells and their therapeutic usage. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2023;1436:69–85. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-41688-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, Hao Y, Shi Q, Hjelmeland AB, et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature. 2006;444(7120):756–60. doi:10.1038/nature05236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Shafee N, Smith CR, Wei S, Kim Y, Mills GB, Hortobagyi GN, et al. Cancer stem cells contribute to cisplatin resistance in Brca1/P53-mediated mouse mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2008;68(9):3243–50. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Wang B, Wang Q, Wang Z, Jiang J, Yu SC, Ping YF, et al. Metastatic consequences of immune escape from NK cell cytotoxicity by human breast cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2014;74(20):5746–57. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2563. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Gholami A. Cancer stem cell-derived exosomes in CD8+ T cell exhaustion. Int Immunopharmacol. 2024;137(1):112509. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2024.112509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Karpenko DV. Immune privileges as a result of mutual regulation of immune and stem systems. Biochemistry. 2023;88(11):1818–31. doi:10.1134/S0006297923110123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Karpenko DV. Immune modulatory stem cells represent a significant component of the immune system. Front Immunol. 2025;16:1543495. doi:10.3389/FIMMU.2025.1543495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Agudo J, Park ES, Rose SA, Alibo E, Sweeney R, Dhainaut M, et al. Quiescent tissue stem cells evade immune surveillance. Immunity. 2018;48(2):271–85.e5. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2018.02.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Hirata Y, Furuhashi K, Ishii H, Li HW, Pinho S, Ding L, et al. CD150 high bone marrow tregs maintain hematopoietic stem cell quiescence and immune privilege via adenosine. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;22(3):445–53.e5. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2018.01.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Karpenko D, Kapranov N, Bigildeev A. Nestin-GFP transgene labels immunoprivileged bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells in the model of ectopic foci formation. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:993056. doi:10.3389/fcell.2022.993056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Kuroda Y, Oguma Y, Hall K, Dezawa M. Endogenous reparative pluripotent muse cells with a unique immune privilege system: hint at a new strategy for controlling acute and chronic inflammation. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1027961. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.1027961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Karpenko DV, Kapranov NM, Bigildeev AE. Strong immune privileges of MSC and other Nes-GFP+ progenitors in bone marrow of transgenic mice. 2024. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-5103170/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Medawar PB. Immunity to homologous grafted skin; the fate of skin homografts. Br J Exp Pathol. 1948;29:58–69. [Google Scholar]

39. Wang X, Wang T, Lam E, Alvarez D, Sun Y. Ocular vascular diseases: from retinal immune privilege to inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(15):12090. doi:10.3390/ijms241512090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. You Y, Li Y, Li M, Lei M, Wu M, Qu Y, et al. Ovarian cancer stem cells promote tumour immune privilege and invasion via CCL5 and regulatory T cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2018;191(1):60–73. doi:10.1111/cei.13044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Galassi C, Musella M, Manduca N, Maccafeo E, Sistigu A. The immune privilege of cancer stem cells: a key to understanding tumor immune escape and therapy failure. Cells. 2021;10(9):2361. doi:10.3390/cells10092361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Afify SM, Hassan G, Seno A, Seno M. Cancer-inducing niche: the force of chronic inflammation. Br J Cancer. 2022;127(2):193–201. doi:10.1038/s41416-022-01775-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Jamal-Hanjani M, Wilson GA, McGranahan N, Birkbak NJ, Watkins TBK, Veeriah S, et al. Tracking the evolution of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(22):2109–21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1616288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339(6127):1546–58. doi:10.1126/science.1235122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Swanton C, McGranahan N, Starrett GJ, Harris RS. APOBEC enzymes: mutagenic fuel for cancer evolution and heterogeneity. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(7):704–12. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Hiley C, de Bruin EC, McGranahan N, Swanton C. Deciphering intratumor heterogeneity and temporal acquisition of driver events to refine precision medicine. Genome Biol. 2014;15(8):453. doi:10.1186/s13059-014-0453-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Riemke P, Czeh M, Fischer J, Walter C, Ghani S, Zepper M, et al. Myeloid leukemia with transdifferentiation plasticity developing from T-cell progenitors. EMBO J. 2016;35(22):2399–416. doi:10.15252/embj.201693927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Ben-Porath I, Thomson MW, Carey VJ, Ge R, Bell GW, Regev A, et al. An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat Genet. 2008;40(5):499–507. doi:10.1038/ng.127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Michor F, Hughes TP, Iwasa Y, Branford S, Shah NP, Sawyers CL et al. Dynamics of chronic myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2005;435(7046):1267–70. doi:10.1038/nature03669. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Saleh M, Bhosale P, Menias CO, Ramalingam P, Jensen C, Iyer R, et al. Ovarian teratomas: clinical features, imaging findings and management. Abdom Radiol. 2021;46(6):2293–307. doi:10.1007/s00261-020-02873-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Kleinsmithf LJ, Plerce GBJr. Multipotentiality of single embryonal carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1964;24:1544–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

52. López-Lázaro M. The stem cell division theory of cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;123(2):95–113. doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.01.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Chaffer CL, Weinberg RA. How does multistep tumorigenesis really proceed? Cancer Discov. 2015;5(1):22–4. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0788. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Ju F, Atyah MM, Horstmann N, Gul S, Vago R, Bruns CJ, et al. Characteristics of the cancer stem cell niche and therapeutic strategies. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):233. doi:10.1186/s13287-022-02904-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Tanabe S. Microenvironment of cancer stem cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2022;1393:103–24. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-12974-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Nicolas AM, Pesic M, Engel E, Ziegler PK, Diefenhardt M, Kennel KB, et al. Inflammatory fibroblasts mediate resistance to neoadjuvant therapy in rectal cancer. Cancer Cell. 2022;40(2):168–84.e13. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2022.01.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Cui Zhou D, Jayasinghe RG, Chen S, Herndon JM, Iglesia MD, Navale P, et al. Spatially restricted drivers and transitional cell populations cooperate with the microenvironment in untreated and chemo-resistant pancreatic cancer. Nat Genet. 2022;54(9):1390–405. doi:10.1038/s41588-022-01157-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Gupta PB, Pastushenko I, Skibinski A, Blanpain C, Kuperwasser C. Phenotypic plasticity: driver of cancer initiation, progression, and therapy resistance. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;24(1):65–78. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2018.11.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Pan Z, Zhang M, Zhang F, Pan H, Li Y, Shao Y, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics unveils the dedifferentiation mechanism of lung adenocarcinoma stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(1):482. doi:10.3390/ijms24010482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Liu Y, Chen YG. Intestinal epithelial plasticity and regeneration via cell dedifferentiation. Cell Regen. 2020;9(1):14. doi:10.1186/s13619-020-00053-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Zhao C, Shen J, Lu Y, Ni H, Xiang M, Xie Y. Dedifferentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells upon vessel injury. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;144(4):113691. doi:10.1016/J.INTIMP.2024.113691. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Lin TY, Gerber T, Taniguchi-Sugiura Y, Murawala P, Hermann S, Grosser L, et al. Fibroblast dedifferentiation as a determinant of successful regeneration. Dev Cell. 2021;56(10):1541–51.e6. doi:10.1016/J.DEVCEL.2021.04.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Lodestijn SC, van Neerven SM, Vermeulen L, Bijlsma MF. Stem cells in the exocrine pancreas during homeostasis, injury, and cancer. Cancers. 2021;13(13):3295. doi:10.3390/CANCERS13133295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Aboul-Soud MAM, Alzahrani AJ, Mahmoud A. Induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSCs)-roles in regenerative therapies, disease modelling and drug screening. Cells. 2021;10(9):2319. doi:10.3390/CELLS10092319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Adegunsoye A, Gonzales NM, Gilad Y. Induced pluripotent stem cells in disease biology and the evidence for their in vitro utility. Annu Rev Genet. 2023;57(1):341–60. doi:10.1146/ANNUREV-GENET-022123-090319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Cai Z, Zhu M, Xu L, Wang Y, Xu Y, Yim WY, et al. Directed differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells to heart valve cells. Circulation. 2024;149(18):1435–56. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.065143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Aoi T, Yae K, Nakagawa M, Ichisaka T, Okita K, Takahashi K, et al. Generation of pluripotent stem cells from adult mouse liver and stomach cells. Science. 2008;321(5889):699–702. doi:10.1126/science.1154884. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Ratushnyy AY, Rudimova YV, Buravkova LB. Replicative senescence and expression of autophagy genes in mesenchymal stromal cells. Biochemistry (Moscow). 2020;85:1169–77. doi:10.1134/S0006297920100053/FIGURES/5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Fojtík P, Beckerová D, Holomková K, Šenfluk M, Rotrekl V. Both hypoxia-inducible factor 1 and MAPK signaling pathway attenuate PI3K/AKT via suppression of reactive oxygen species in human pluripotent stem cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;8:607444. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.607444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Yasan GT, Gunel-Ozcan A. Hypoxia and hypoxia mimetic agents as potential priming approaches to empower mesenchymal stem cells. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2024;19(1):33–54. doi:10.2174/1574888X18666230113143234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Liu Y, Ren L, Li M, Zheng B. The effects of hypoxia-preconditioned dental stem cell-derived secretome on tissue regeneration. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2024;31(1):44–60. doi:10.1089/ten.teb.2024.0054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Ferrer A, Roser CT, El-Far MH, Savanur VH, Eljarrah A, Gergues M, et al. Hypoxia-mediated changes in bone marrow microenvironment in breast cancer dormancy. Cancer Lett. 2020;488:9–17. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2020.05.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Ma M. Role of hypoxia in mesenchymal stem cells from dental pulp: influence, mechanism and application. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2024;82(2):535–47. doi:10.1007/s12013-024-01274-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Zhang S, Chan RWS, Ng EHY, Yeung WSB. Hypoxia regulates the self-renewal of endometrial mesenchymal stromal/stem-like cells via notch signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):4613. doi:10.3390/ijms23094613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Kubota Y, Takubo K, Suda T. Bone marrow long label-retaining cells reside in the sinusoidal hypoxic niche. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366(2):335–9. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.086. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Liu D, Zhu H, Cheng L, Li R, Ma X, Wang J, et al. Hypoxia-induced galectin-8 maintains stemness in glioma stem cells via autophagy regulation. Neuro Oncol. 2024;26(5):872–88. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noad264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Papale M, Buccarelli M, Mollinari C, Russo MA, Pallini R, Ricci-Vitiani L, et al. Hypoxia, inflammation and necrosis as determinants of glioblastoma cancer stem cells progression. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(8):2660. doi:10.3390/ijms21082660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Shi T, Zhu J, Zhang X, Mao X. The role of hypoxia and cancer stem cells in development of glioblastoma. Cancers. 2023;15(9):2613. doi:10.3390/cancers15092613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Lu X, Kang Y. Hypoxia and hypoxia-inducible factors: master regulators of metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(24):5928–35. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Abd GM, Laird MC, Ku JC, Li Y. Hypoxia-induced cancer cell reprogramming: a review on how cancer stem cells arise. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1227884. doi:10.3389/fonc.2023.1227884. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Kim H, Lin Q, Glazer PM, Yun Z. The hypoxic tumor microenvironment in vivo selects the cancer stem cell fate of breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2018;20(1):16. doi:10.1186/S13058-018-0944-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Emami Nejad A, Najafgholian S, Rostami A, Sistani A, Shojaeifar S, Esparvarinha M, et al. The role of hypoxia in the tumor microenvironment and development of cancer stem cell: a novel approach to developing treatment. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21(1):1–26. doi:10.1186/S12935-020-01719-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Yun Z, Lin Q. Hypoxia and regulation of cancer cell stemness. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;772:41–53. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-5915-6_2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Stouras I, Vasileiou M, Kanatas PF, Tziona E, Tsianava C, Theocharis S. Metabolic profiles of cancer stem cells and normal stem cells and their therapeutic significance. Cells. 2023;12(23):2686. doi:10.3390/CELLS12232686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123(3191):309–14. doi:10.1126/SCIENCE.123.3191.309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Zu XL, Guppy M. Cancer metabolism: facts, fantasy, and fiction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;313(3):459–65. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Gatenby RA, Gillies RJ. Why do cancers have high aerobic glycolysis? Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(11):891–9. doi:10.1038/nrc1478. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Xing Y, Zhao S, Zhou BP, Mi J. Metabolic reprogramming of the tumour microenvironment. FEBS J. 2015;282(20):3892–8. doi:10.1111/febs.13402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Li L, Cui L, Lin P, Liu Z, Bao S, Ma X, et al. Kupffer-cell-derived IL-6 is repurposed for hepatocyte dedifferentiation via activating progenitor genes from injury-specific enhancers. Cell Stem Cell. 2023;30(3):283–99.e9. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2023.01.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Cheng YY, Gregorich Z, Prajnamitra RP, Lundy DJ, Ma TY, Huang YH, et al. Metabolic changes associated with cardiomyocyte dedifferentiation enable adult mammalian cardiac regeneration. Circulation. 2022;146(25):1950–67. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.061960. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Tata PR, Mou H, Pardo-Saganta A, Zhao R, Prabhu M, Law BM, et al. Dedifferentiation of committed epithelial cells into stem cells in vivo. Nature. 2013;503(7475):218–23. doi:10.1038/NATURE12777. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Tian H, Biehs B, Warming S, Leong KG, Rangell L, Klein OD, et al. A reserve stem cell population in small intestine renders Lgr5-positive cells dispensable. Nature. 2011;478(7368):255–9. doi:10.1038/NATURE10408. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Haller S, Kapuria S, Riley RR, O’Leary MN, Schreiber KH, Andersen JK, et al. MTORC1 activation during repeated regeneration impairs somatic stem cell maintenance. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21(6):806–18.e5. doi:10.1016/J.STEM.2017.11.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Menéndez-Gutiérrez MP, Porcuna J, Nayak R, Paredes A, Niu H, Núñez V, et al. Retinoid X receptor promotes hematopoietic stem cell fitness and quiescence and preserves hematopoietic homeostasis. Blood. 2023;141(6):592–608. doi:10.1182/BLOOD.2022016832. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Cancedda R, Mastrogiacomo M. Transit amplifying cells (TACsa still not fully understood cell population. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11:1189225. doi:10.3389/FBIOE.2023.1189225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Govaert KM, Emmink BL, Nijkamp MW, Cheung ZJ, Steller EJA, Fatrai S, et al. Hypoxia after liver surgery imposes an aggressive cancer stem cell phenotype on residual tumor cells. Ann Surg. 2014;259(4):750–9. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e318295c160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. D’Alterio C, Scala S, Sozzi G, Roz L, Bertolini G. Paradoxical effects of chemotherapy on tumor relapse and metastasis promotion. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;60(1):351–61. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.08.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Cleary AS, Leonard TL, Gestl SA, Gunther EJ. Tumour cell heterogeneity maintained by cooperating subclones in wnt-driven mammary cancers. Nature. 2014;508(7494):113–7. doi:10.1038/nature13187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Maddipati R, Stanger BZ. Pancreatic cancer metastases harbor evidence of polyclonality. Cancer Discov. 2015;5(10):1086–97. doi:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Martín-Pardillos A, Valls Chiva Á, Bande Vargas G, Hurtado Blanco P, Piñeiro Cid R, Guijarro PJ, et al. The role of clonal communication and heterogeneity in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):666. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5883-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Naffar-Abu Amara S, Kuiken HJ, Selfors LM, Butler T, Leung ML, Leung CT, et al. Transient commensal clonal interactions can drive tumor metastasis. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5799. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19584-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Batlle E, Clevers H. Cancer stem cells revisited. Nat Med. 2017;23(10):1124–34. doi:10.1038/nm.4409. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Clevers H, Watt FM. Defining adult stem cells by function, not by phenotype. Annu Rev Biochem. 2018;87(1):1015–27. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-062917-012341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Beumer J, Clevers H. Hallmarks of stemness in mammalian tissues. Cell Stem Cell. 2024;31(1):7–24. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2023.12.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Li YR, Halladay T, Yang L. Immune evasion in cell-based immunotherapy: unraveling challenges and novel strategies. J Biomed Sci. 2024;31(1):5. doi:10.1186/s12929-024-00998-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Goddard ET, Linde MH, Srivastava S, Klug G, Shabaneh TB, Iannone S, et al. Immune evasion of dormant disseminated tumor cells is due to their scarcity and can be overcome by T cell immunotherapies. Cancer Cell. 2024;42(1):119–34.e12. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2023.12.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Dianat-Moghadam H, Mahari A, Salahlou R, Khalili M, Azizi M, Sadeghzadeh H. Immune evader cancer stem cells direct the perspective approaches to cancer immunotherapy. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):150. doi:10.1186/s13287-022-02829-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Chulpanova DS, Rizvanov AA, Solovyeva VV. The role of cancer stem cells and their extracellular vesicles in the modulation of the antitumor immunity. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24(1):395. doi:10.3390/ijms24010395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Wu B, Shi X, Jiang M, Liu H. Cross-talk between cancer stem cells and immune cells: potential therapeutic targets in the tumor immune microenvironment. Mol Cancer. 2023;22(1):1–22. doi:10.1186/s12943-023-01748-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Marzban H, Pedram N, Amini P, Gholampour Y, Saranjam N, Moradi S, et al. Immunobiology of cancer stem cells and their immunoevasion mechanisms. Mol Biol Reports. 2023;50(11):9559–73. doi:10.1007/s11033-023-08768-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Sergeant E, Buysse M, Devos T, Sprangers B. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells in kidney transplant recipients: the next big thing? Blood Rev. 2021;45:100718. doi:10.1016/j.blre.2020.100718. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Raicevic G, Rouas R, Najar M, Stordeur P, Id Boufker H, Bron D, et al. Inflammation modifies the pattern and the function of toll-like receptors expressed by human mesenchymal stromal cells. Hum Immunol. 2010;71(3):235–44. doi:10.1016/j.humimm.2009.12.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. López-García L, Castro-Manrreza ME. TNF-α and IFN-γ participate in improving the immunoregulatory capacity of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells: importance of cell-cell contact and extracellular vesicles. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(17):9531. doi:10.3390/ijms22179531. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Liao Y, Li G, Zhang X, Huang W, Xie D, Dai G, et al. Cardiac Nestin+ mesenchymal stromal cells enhance healing of ischemic heart through periostin-mediated M2 macrophage polarization. Mol Ther. 2020;28(3):855–73. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.01.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Markov A, Thangavelu L, Aravindhan S, Zekiy AO, Jarahian M, Chartrand MS, et al. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells as a valuable source for the treatment of immune-mediated disorders. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12(1):192. doi:10.1186/s13287-021-02265-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Bolkent S. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of asymmetric stem cell division in tissue homeostasis. Genes Cells. 2024;29(12):1099–110. doi:10.1111/GTC.13172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Guo YJ, Wu WN, Yang X, Fu XB. Dedifferentiation and in vivo reprogramming of committed cells in wound repair (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2022;26(6):369. doi:10.3892/MMR.2022.12886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Sun Q, Lee W, Hu H, Ogawa T, De Leon S, Katehis I, et al. Dedifferentiation maintains melanocyte stem cells in a dynamic niche. Nature. 2023;616(7958):774–82. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-05960-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Bernabé-Rubio M, Ali S, Bhosale PG, Goss G, Mobasseri SA, Tapia-Rojo R, et al. Myc-dependent dedifferentiation of Gata6+ epidermal cells resembles reversal of terminal differentiation. Nat Cell Biol. 2023;25(10):1426–38. doi:10.1038/S41556-023-01234-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Fus-Kujawa A, Mendrek B, Trybus A, Bajdak-Rusinek K, Stepien KL, Sieron AL. Potential of induced pluripotent stem cells for use in gene therapy: history, molecular bases, and medical perspectives. Biomolecules. 2021;11(5):699. doi:10.3390/BIOM11050699. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Liu G, David BT, Trawczynski M, Fessler RG. Advances in pluripotent stem cells: history, mechanisms, technologies, and applications. Stem Cell Rev Reports. 2020;16(1):3–32. doi:10.1007/S12015-019-09935-X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Ilic D, Ogilvie C. Pluripotent stem cells in clinical setting-new developments and overview of current status. Stem Cells. 2022;40(9):791–801. doi:10.1093/STMCLS/SXAC040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Horne GA, Copland M. Approaches for targeting self-renewal pathways in cancer stem cells: implications for hematological treatments. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2017;12(5):465–74. doi:10.1080/17460441.2017.1303477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Gu A, Yuan J, Wills M, Kasper S. Prostate cancer cells with stem cell characteristics reconstitute the original human tumor in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67(10):4807–15. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Lee SH, Reed-Newman T, Anant S, Ramasamy TS. Regulatory role of quiescence in the biological function of cancer stem cells. Stem Cell Rev Reports. 2020;16(6):1185–207. doi:10.1007/S12015-020-10031-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. Kunisaki Y, Bruns I, Scheiermann C, Ahmed J, Pinho S, Zhang D, et al. Arteriolar niches maintain haematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Nature. 2013;502(7473):637–43. doi:10.1038/nature12612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Dias IB, Bouma HR, Henning RH. Unraveling the big sleep: molecular aspects of stem cell dormancy and hibernation. Front Physiol. 2021;12:624950. doi:10.3389/fphys.2021.624950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Phan TG, Croucher PI. The dormant cancer cell life cycle. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(7):398–411. doi:10.1038/s41568-020-0263-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

129. Francescangeli F, De Angelis ML, Rossi R, Cuccu A, Giuliani A, De Maria R, et al. Dormancy, stemness, and therapy resistance: interconnected players in cancer evolution. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2023;42(4):197–215. doi:10.1007/s10555-023-10092-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

130. Paul R, Dorsey JF, Fan Y. Cell plasticity, senescence, and quiescence in cancer stem cells: biological and therapeutic implications. Pharmacol Ther. 2021;231(38):107985. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107985. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

131. Guan Y, Hogge DE. Proliferative status of primitive hematopoietic progenitors from patients with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML). Leukemia. 2000;14(12):2135–41. doi:10.1038/sj.leu.2401975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

132. Urbaìn N, Cheung TH. Stem cell quiescence: the challenging path to activation. Development. 2021;148(3):dev165084. doi:10.1242/dev.165084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

133. Huang T, Song X, Xu D, Tiek D, Goenka A, Wu B, et al. Stem cell programs in cancer initiation, progression, and therapy resistance. Theranostics. 2020;10(19):8721–43. doi:10.7150/thno.41648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

134. de Morree A, Rando TA. Regulation of adult stem cell quiescence and its functions in the maintenance of tissue integrity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24(5):334–54. doi:10.1038/s41580-022-00568-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

135. Chen Z, Xia X, Yao M, Yang Y, Ao X, Zhang Z, et al. The dual role of mesenchymal stem cells in apoptosis regulation. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(4):250. doi:10.1038/s41419-024-06620-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

136. Wen Z, Mai Z, Zhu X, Wu T, Chen Y, Geng D, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes ameliorate cardiomyocyte apoptosis in hypoxic conditions through MicroRNA144 by targeting the PTEN/AKT pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11(1):36. doi:10.1186/s13287-020-1563-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

137. Li Y, Wang Z, Ajani JA, Song S. Drug resistance and cancer stem cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2021;19(1):19. doi:10.1186/s12964-020-00627-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

138. Ramirez M, Rajaram S, Steininger RJ, Osipchuk D, Roth MA, Morinishi LS, et al. Diverse drug-resistance mechanisms can emerge from drug-tolerant cancer persister cells. Nat Commun. 2016;7(1):10690. doi:10.1038/ncomms10690. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

139. Rezayatmand H, Razmkhah M, Razeghian-Jahromi I. Drug resistance in cancer therapy: the pandora’s box of cancer stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13(1):181. doi:10.1186/s13287-022-02856-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

140. Deng S, Wang C, Wang Y, Xu Y, Li X, Johnson NA, et al. Ectopic JAK-STAT activation enables the transition to a stem-like and multilineage state conferring AR-targeted therapy resistance. Nat Cancer. 2022;3(9):1071–87. doi:10.1038/s43018-022-00431-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

141. Raha D, Wilson TR, Peng J, Peterson D, Yue P, Evangelista M, et al. The cancer stem cell marker aldehyde dehydrogenase is required to maintain a drug-tolerant tumor cell subpopulation. Cancer Res. 2014;74(13):3579–90. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3456. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

142. Wulf GG, Wang RY, Kuehnle I, Weidner D, Marini F, Brenner MK, et al. A leukemic stem cell with intrinsic drug efflux capacity in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2001;98(4):1166–73. doi:10.1182/BLOOD.V98.4.1166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

143. Goodell MA, Brose K, Paradis G, Conner AS, Mulligan RC. Isolation and functional properties of murine hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. J Exp Med. 1996;183(4):1797–806. doi:10.1084/JEM.183.4.1797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

144. Hirschmann-Jax C, Foster AE, Wulf GG, Nuchtern JG, Jax TW, Gobel U, et al. A distinct “side population” of cells with high drug efflux capacity in human tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(39):14228–33. doi:10.1073/PNAS.0400067101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

145. Skvortsov S, Debbage P, Lukas P, Skvortsova I. Crosstalk between DNA repair and cancer stem cell (CSC) associated intracellular pathways. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015;31(2):36–42. doi:10.1016/J.SEMCANCER.2014.06.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

146. Squillaro T, Alessio N, Di Bernardo G, Özcan S, Peluso G, Galderisi U. Stem cells and DNA repair capacity: muse stem cells are among the best performers. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1103:103–13. doi:10.1007/978-4-431-56847-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

147. Alessio N, Squillaro T, özcan S, Di Bernardo G, Venditti M, Melone M, et al. Stress and stem cells: adult muse cells tolerate extensive genotoxic stimuli better than mesenchymal stromal cells. Oncotarget. 2018;9(27):19328–41. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.25039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

148. Del Vecchio V, Rehman A, Panda SK, Torsiello M, Marigliano M, Nicoletti MM, et al. Mitochondrial transfer from adipose stem cells to breast cancer cells drives multi-drug resistance. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2024;43(1):166. doi:10.1186/s13046-024-03087-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

149. Sabol RA, Villela VA, Denys A, Freeman BT, Hartono AB, Wise RM, et al. Obesity-altered adipose stem cells promote radiation resistance of estrogen receptor positive breast cancer through paracrine signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(8):2722. doi:10.3390/ijms21082722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

150. Hollier BG, Evans K, Mani SA. The epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cells: a coalition against cancer therapies. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2009;14(1):29–43. doi:10.1007/s10911-009-9110-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

151. Wilson MM, Weinberg RA, Lees JA, Guen VJ. Emerging mechanisms by which EMT programs control stemness. Trends Cancer. 2020;6(9):775–80. doi:10.1016/j.trecan.2020.03.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

152. Guen VJ, Chavarria TE, Kröger C, Ye X, Weinberg RA, Lees JA. EMT programs promote basal mammary stem cell and tumor-initiating cell stemness by inducing primary ciliogenesis and hedgehog signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(49):E10532–39. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711534114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

153. Campbell K, Casanova J. A common framework for EMT and collective cell migration. Development. 2016;143(23):4291–300. doi:10.1242/dev.139071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

154. Fujii M, Shimokawa M, Date S, Takano A, Matano M, Nanki K, et al. A colorectal tumor organoid library demonstrates progressive loss of niche factor requirements during tumorigenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18(6):827–38. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2016.04.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

155. Nieto MA, Huang RYYJ, Jackson RAA, Thiery JPP. EMT: 2016. Cell. 2016;166(1):21–45. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.06.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

156. Saxena K, Jolly MK, Balamurugan K. Hypoxia, partial EMT and collective migration: emerging culprits in metastasis. Transl Oncol. 2020;13(11):100845. doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

157. Pastushenko I, Blanpain C. EMT transition states during tumor progression and metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2019;29(3):212–26. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2018.12.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

158. Brabletz T, Kalluri R, Nieto MA, Weinberg RA. EMT in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18(2):128–34. doi:10.1038/nrc.2017.118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

159. Kalantari E, Taheri T, Fata S, Abolhasani M, Mehrazma M, Madjd Z, et al. Significant co-expression of putative cancer stem cell markers, EpCAM and CD166, correlates with tumor stage and invasive behavior in colorectal cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2022;20(1):15. doi:10.1186/s12957-021-02469-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

160. Tsuji T, Ibaragi S, Shima K, Hu MG, Katsurano M, Sasaki A, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by growth suppressor P12CDK2-AP1 promotes tumor cell local invasion but suppresses distant colony growth. Cancer Res. 2008;68(24):10377–86. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

161. Celià-Terrassa T, Meca-Cortés Ó, Mateo F, De Paz AM, Rubio N, Arnal-Estapé A, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition can suppress major attributes of human epithelial tumor-initiating cells. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(5):1849–68. doi:10.1172/JCI59218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

162. Chapman A, del Ama LF, Ferguson J, Kamarashev J, Wellbrock C, Hurlstone A. Heterogeneous tumor subpopulations cooperate to drive invasion. Cell Rep. 2014;8(3):688–95. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

163. Kong D, Banerjee S, Ahmad A, Li Y, Wang Z, Sethi S, et al. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition is mechanistically linked with stem cell signatures in prostate cancer cells. PLoS One. 2010;5(8):e12445. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

164. Zhang Y, Weinberg RA. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cancer: complexity and opportunities. Front Med. 2018;12(4):361–73. doi:10.1007/s11684-018-0656-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

165. Hermann PC, Huber SL, Herrler T, Aicher A, Ellwart JW, Guba M, et al. Distinct populations of cancer stem cells determine tumor growth and metastatic activity in human pancreatic cancer. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1(3):313–23. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2007.06.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

166. Pastushenko I, Brisebarre A, Sifrim A, Fioramonti M, Revenco T, Boumahdi S, et al. Identification of the tumour transition states occurring during EMT. Nature. 2018;556(7702):463–8. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0040-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

167. Yoshida S, Kato T, Kato Y. EMT involved in migration of stem/progenitor cells for pituitary development and regeneration. J Clin Med. 2016;5(4):43. doi:10.3390/jcm5040043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

168. Amsel S, Dell ES. Bone marrow repopulation of subcutaneously grafted mouse femurs. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1971;138(2):550–2. doi:10.3181/00379727-138-35938. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

169. Tavassoli M, Crosby WH. Transplantation of marrow to extramedullary sites. Science. 1968;161(3836):54–6. doi:10.1126/science.161.3836.54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

170. Balassa K, Danby R, Rocha V. Haematopoietic stem cell transplants: principles and indications. Br J Hosp Med. 2019;80(1):33–9. doi:10.12968/hmed.2019.80.1.33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

171. Isern J, García-García A, Martín AM, Arranz L, Martín-Pérez D, Torroja C, et al. The neural crest is a source of mesenchymal stem cells with specialized hematopoietic stem cell niche function. Elife. 2014;3:3696. doi:10.7554/ELIFE.03696. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

172. Bentzinger CF, Wang YX, Rudnicki MA. Building muscle: molecular regulation of myogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(2):a008342. doi:10.1101/CSHPERSPECT.A008342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

173. Ishido M, Kasuga N. In situ real-time imaging of the satellite cells in rat intact and injured soleus muscles using quantum dots. Histochem Cell Biol. 2011;135(1):21–6. doi:10.1007/S00418-010-0767-X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

174. Sato T, Wakao S, Kushida Y, Tatsumi K, Kitada M, Abe T, et al. A novel type of stem cells double-positive for SSEA-3 and CD45 in human peripheral blood. Cell Transplant. 2020;29(9):096368972092357. doi:10.1177/0963689720923574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

175. Mansilla E, Marín GH, Drago H, Sturla F, Salas E, Gardiner C, et al. Bloodstream cells phenotypically identical to human mesenchymal bone marrow stem cells circulate in large amounts under the influence of acute large skin damage: new evidence for their use in regenerative medicine. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(3):967–9. doi:10.1016/J.TRANSPROCEED.2006.02.053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

176. Yamada Y, Wakao S, Kushida Y, Minatoguchi S, Mikami A, Higashi K, et al. S1P-S1PR2 axis mediates homing of muse cells into damaged heart for long-lasting tissue repair and functional recovery after acute myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2018;122(8):1069–83. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

177. Peyvandi AA, Roozbahany NA, Peyvandi H, Abbaszadeh HA, Majdinasab N, Faridan M, et al. Critical role of SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling pathway in stem cell homing in the deafened rat cochlea after acoustic trauma. Neural Regen Res. 2018;13(1):154–60. doi:10.4103/1673-5374.224382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

178. Pérez-González A, Bévant K, Blanpain C. Cancer cell plasticity during tumor progression, metastasis and response to therapy. Nat Cancer. 2023;4(8):1063–82. doi:10.1038/s43018-023-00595-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]