Open Access

Open Access

MINI REVIEW

Exogenous and Endogenous Virus Infection and Pollutants Drive Neuronal Cell Senescence and Alzheimer’s Disease

Department of Experimental, Diagnostic and Specialty Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Bologna, Bologna, 40123, Italy

* Corresponding Author: Federico Licastro. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies for Neurodegenerative Diseases)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(6), 981-989. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.062303

Received 15 December 2024; Accepted 27 March 2025; Issue published 24 June 2025

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease causing the most frequent form of dementia in old age. AD etiology is still uncertain and deposition of abnormal proteins in the brain along with chronic neuroinflammation have been suggested as pathogenic mechanisms of neuronal death. Infections by exogenous neurotropic virus, endogenous retrovirus reactivation, infections by other microbes, and air pollutants may either induce neurodegeneration or activate brain inflammation. Up to 8% of the human genome has a retroviral origin. These ancient retroviruses, also called human endogenous retroviruses, are associated with a clinical history of several neurodegenerative diseases. Under persistent stress, such as chronic infections and inflammation, neurons, and microglia cells may enter a state of division inactivation called cell senescence. Senescent cells are resistant to apoptosis and can release pro-inflammatory molecules promoting the functional decline of tissues and organs and also activate silent viruses. Infections and mutations induced by pollutants can lead to the expression of different endogenous retroviruses, which may contribute to several different diseases, including AD-associated neurodegeneration. Here I discuss that infection by exogenous pathogen, activation of endogenous retrovirus or retrotransposons and pollutants might induce neuronal senescence and cause persistent brain neurodegeneration. Therefore, cell senescence appears to be an emerging mechanism that might contribute to AD neurodegeneration. Finally, treatment of AD patients with senolytic drugs, e.g., compounds able to kill senescent cells, might show a positive effect on AD progression.Keywords

Neurodegenerative disorders affecting the brain or spinal cord, are associated with neuronal loss and neuroinflammation, which lead to a progressive decline in cognitive and/or motor functions [1].

Sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an age-related neurodegenerative disease and amyloid protein deposits and neurofibrillary tangles are considered pathology hallmarks of the AD brain [2]. However, these abnormal proteins also accumulate in the brain of the elderly without cognitive impairment [3] and the disease’ s etiology is still under investigation.

Cellular senescence (CS) has been suggested as an emerging mechanism associated with different neurological diseases. In fact, under persistent stress, neurons, and astroglia cells may enter an abnormal cell function characterized by inactivation of cellular division, resistance to apoptosis, and secretion of pro-inflammatory molecules, i.e., the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Senescent cells promote tissue functional decline and have been recently involved in neurodegeneration and dementia [4].

This mini-review discusses the role of different factors such as virus infections, endogenous retrovirus activation, and environmental pollutants in brain senescence and neurodegenerative alterations associated with AD.

2 Brain Infection and Senescence

Human Herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) has been implicated in AD [5]. Viruses of the Herpes family enter frequent cycles of reactivation and latency, persistently activate immune responses, and are neurotropic pathogens. However, the host immune system usually is not able to completely eradicate these pathogens. We have previously reported that these neurotropic microbes might play a role in microglia activation of genetically susceptible elderly and promote neurodegenerative mechanisms [6].

It is important to note that the monomeric form of amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide, found in the AD amyloid plaques, shows antimicrobial activity against several microorganisms [7]. Moreover, monomeric Aβ peptides share functional activity with different antimicrobial peptides produced by natural immunity [7].

We reported that some antimicrobial defenses of innate immunity were impaired in the brains of AD patients and that these immune disorders might contribute to neuronal damage [8].

Several reports show that virus infection can also induce CS. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) latent infection has been reported to induce senescence of the immune system, the impairment of immune responses to other pathogens, and the decrease of vaccination efficacy [9]. It has also been shown that the prevalence of CMV infection is up to 91% in 80-year-old adults; the infection by this virus contributes to immune memory inflation and is associated with increased age-related mortality risk and unhealthy aging [10].

Accordingly, HSV-1 recurrent infections increase neuronal aging in mice [11].

A different neurotropic retrovirus, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can induce microglia senescence and this cell alteration contributes to the neurodegeneration [12] observed during the clinical history of this disease.

Recently, the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic, has been shown to induce CS and the SASP release, as a stress response from the virus-infected cells [13].

As shown from the results above, it is possible to conclude that virus infection, either in the persistent or latent forms, induces CS and may accelerate tissue aging and brain neurodegeneration.

These notions are reinforced by other data showing that antiviral therapy in CMV-infected mice reverses immune senescence during the viral latent phase [14].

3 Transposable Elements and Endogenous Retroviruses

Transposable elements (TSE), transposons and retrotransposons, are DNA fragments moving within the genome and active retrotransposons replicate by RNA intermediates via reverse transcriptase. TSE produces complementary DNAs which are thereafter inserted into chromosomes [15].

Up to 8% of the human genome has a retroviral origin. These ancient retroviruses, also called human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs), invaded the germ line of our primate ancestor, thereafter, they were integrated into the human genome [15].

Retrotransposon activity is responsible for the amplification of these integrated endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) [16]. Most HERV genes contain deletions or nonsense mutations and therefore, are silent. However, it is of interest that some ERVs maintained some functions and acted as immune gene enhancers [17]. In this contest is important to note that few of these ERVs retained an infectious capacity. Abnormal activity of HERV has been reported in some neurological diseases. Increased activation of HERV-K has been described in human amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [18]. Moreover, abnormal HERV-W activity has been reported in patients with multiple sclerosis [19].

As we suggested elsewhere, abnormal ERV activity in the human brain might represent a further mechanistic and pathogenic link with brain aging and pathology associated with AD [20].

Moreover, we have also hypothesized that infectious agents such as exogenous neurotropic viruses, other human pathogens, and air pollutants might cause retrotransposon mutations and ERV activation by inducing the brain’ s temporary immune responses and inflammation [20].

As shown in a murine cell line model, infection with a virus of the Herpes family induced an increased expression of ERV [21]. HERV activity can also be induced by different pathogens since peripheral blood leukocyte infection by coxsackie virus-B promoted increased levels of the HERV-W ENV mRNA [22]. Several TSE can be indeed activated by multiple environmental factors such as chemicals and exogenous viruses and by intrinsic factors such as hormones, cellular co-factors, aging-associated processes, epigenetic modification, and radiation [23].

It is of interest that the expression of the HERV-W family, peaks in old adults [24]; therefore, it appears to be a genetic characteristic of aging.

Moreover, aged tissues commonly show decreased proliferation and low functional capabilities, increased apoptosis resistance, high levels of inflammatory mediators, and accumulation of senescent cells [23].

Data concerning the activation of retrotransposons and ERV in CS are scanty. However, mice injected with an HIV antigen (rVpr) showed an elevated copy number of long interspersed element−1 in the heart genome. rVpr injections also increased the number of heart senescent cells positive for the senescence-associated β-galactosidase marker and induced heart fibrosis [25].

Elevated HERV-K ENV protein levels (HML-2) were found in senescent cell culture supernatants and the addition of these soluble factors to younger cells induced their senescence, while the concomitant treatment with anti-ENV antibodies blocked the expression of the senescent phenotype [26].

Retrotransposons activation has been reported to induce interferon-1 and inflammatory cytokine production by the nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) pathway [27]. Moreover, a progressive increase in retrotransposon transcript levels, such as ERVs appears to be associated with aging, CS, inflammation, and neurodegeneration [27].

Increased or inappropriate HERV expression is also associated with the aging phenotype and several age-related diseases. For instance, the retrotransposon expression level was found elevated in brain samples from ALS or frontotemporal dementia (FTD) [28,29].

It is of interest that HERV-K expression or the addition of its ENV protein induces neurite retraction in cultures of human neurons [27]. It has been shown that transgenic mice over-expressing pan-neuronal HERV-K envelop glycoprotein (ENV) showed progressive motor dysfunction, motor cortex neuronal loss, muscular atrophy, and neurodegeneration of the spinal cord [30]. ERVs produce dsRNAs which can induce antiviral response by the viral RNA sensors such as those of the Toll-like receptor family [27].

TSE activation in AD appears to be a consequence of pathological tau and differential retrotransposon expression correlates with the tau deposition in the brain [31].

It has been suggested that the tau-induced retrotransposon activation also generates cDNA that integrates into genomic DNA, causing a novel somatic insertion [27]. On the other hand, a genomic DNA insertion failure by inducing DNA double-strand breaks may cause genomic instability and innate immune activation [24]. Recently, an accurate estimation of HERV expression at specific loci identified 698 differentially expressed HERVs in AD brains in comparison with control brains [32].

Unlike transmissible prion diseases, ALS and FTD are not infectious pathologies and injection of aggregated Tar-DNA-binding protein (TDP-43) is not sufficient to cause those diseases. The missing component to sustain the disease progression might be the inappropriate ERV expression. Therefore, TDP-43 proteinopathy and inappropriate ERV expression may act as mutually reinforcing neurodegenerative processes [33].

4 Pollutants and Brain-Damaging Factors

Pollutants, such as particulates and other derivatives from oil combustion, can induce many neurological alterations and affect brain functioning since exposure to air pollutants is associated with amyloid-β pathology in older adults and increases cognitive decline and AD risk [34]. It has been suggested that pollutant exposure and AD risk may be affected by the gero exposome during early life exposure [35] and the induction of epigenetics modifications [36]. We have previously suggested that environmental pollutants can abnormally activate retrotransposons and ERVs in the human brain [20]. Therefore, cell insults by several pollutants, by inappropriately activating HERVs, may contribute to CS, age-associated chronic and neurodegenerative diseases.

Insults such as cellular abnormal tau accumulation, environmental mutagens, and virus infection may induce changes in nuclear and genomic architecture and may cause CS or accelerate tissue senescence by disrupting retrotransposon silencing mechanisms and activating HERVs. This notion is supported by data showing that in human senescent cells, HERVs were transcribed to produce retrovirus-like particles which transformed young cells into senescent cells [37].

Therefore, infections and mutations can induce differential HERV expression, which may contribute to neurodegeneration and chronic inflammation and lead to different human diseases [37].

Exogenous virus infection, as well as environmental pollutants, may either directly induce neurodegeneration and by activating HERV promote neuronal senescence and brain inflammation. Both pathways may contribute to brain lesions associated with dementia and other neurological diseases.

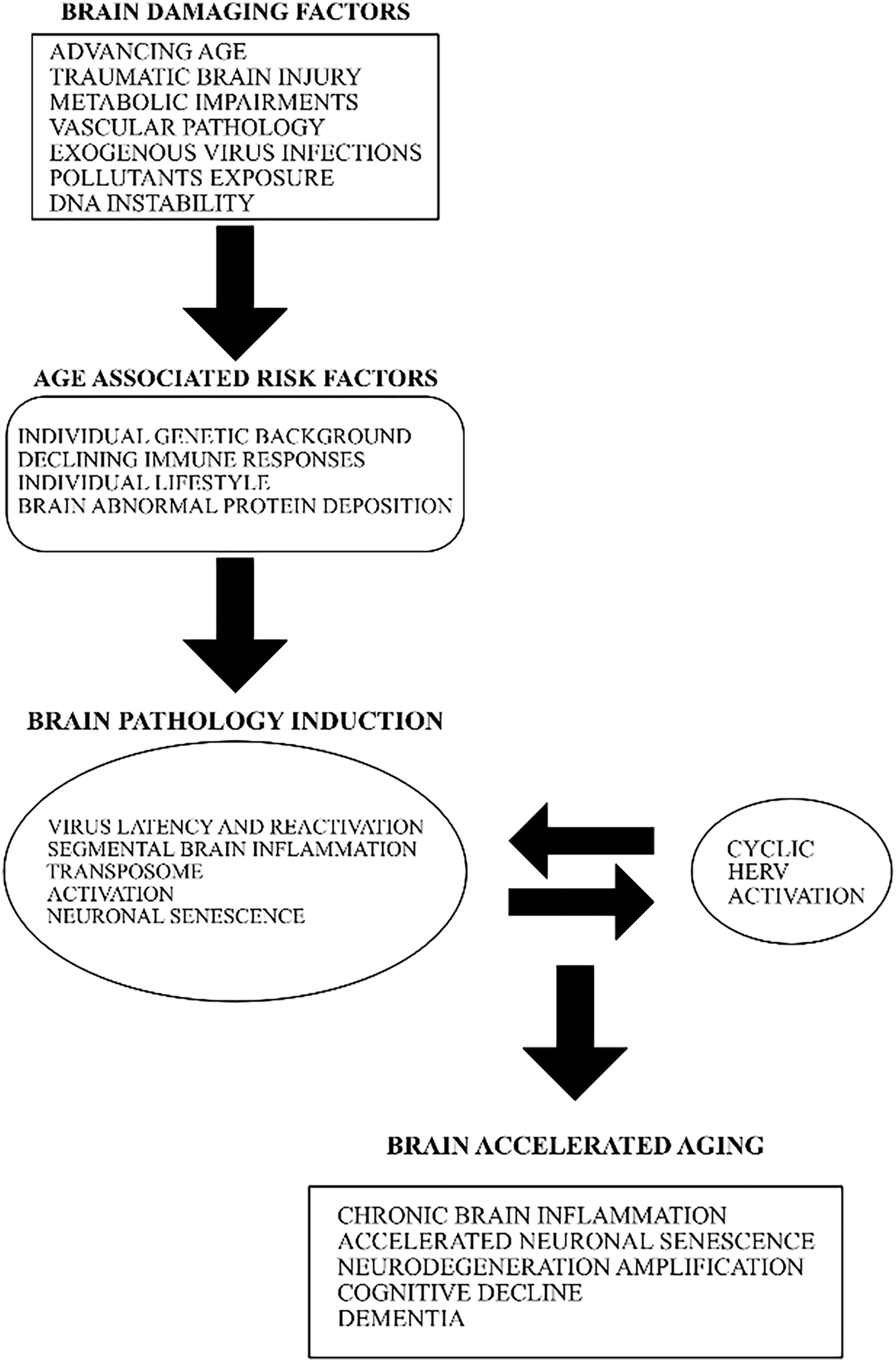

Several external and lifestyle factors may contribute to complex mechanisms involved in brain aging and to the vicious and self-sustained circle leading to brain damage and cognitive decline, as summarized in Fig. 1. In conclusion, virus infections or pollution may start a neurodegenerative feedback cycle by activating HERVs, CS, and neuroinflammation which in turn induce additional neuronal loss and with time the onset of clinical disease. Notions presented in this paper are supported by recent data showing that in an in vitro tissue culture model the traumatic brain injury reactivates silent virus such as HSV-1 [38].

Figure 1: The involvement of diverse age-associated risk factors with exogenous virus infections and HERV abnormal activation in the induction of neurodegenerative processes and AD

AD is a complex disease and several different causative factors may play a role in its beginning and progression, as described in Fig. 1. However, these factors may converge in three major pathways: (1) the reactivation of silent intracellular pathogens; (2) the increased genomic instability induced by TSE inappropriate activation; (3) the persistent activation of brain HERVs. These three pathways might induce early or accelerated neuronal CS and start irreversible brain neurodegenerative alterations.

Several other factors (Fig. 1) such as age, metabolic alterations, vascular pathology, individual genetic background, or lifestyle may contribute to modulate brain senescence and neurodegeneration associated with AD.

As discussed above, CS plays a role in neurodegenerative diseases and modulation of senescence may affect brain aging [39]. It is of interest that CS is susceptible to drug treatments and several compounds able to induce apoptosis of senescent cells, named senolytics, have been discovered [39]. Other molecules, called xenomorphic drugs, can modulate the SASP and reduce the inflammatory components of CS [40]. Some senolytic drugs have been shown to decrease brain CS and cognitive impairment in rats [41].

Moreover, clinical trials of some chronic diseases using senolytic compounds are in progress. Treatment of AD patients with a senolytic drug, as reported in ongoing clinical trials, induced modulation of the disease’ s markers in both plasma and cerebrospinal fluid [42,43].

Recently, senescence microglia has been described in a mouse model of AD, and treatment with a senolytic compound decreased senescent microglia, improved cognitive performances, and reduced brain inflammation [44]. Therefore, new therapeutic opportunities for AD and other brain degenerative diseases by modulating CS are emerging on the clinical horizon. Future investigations will show whether modulation of CS might influence the expression of HERVs and their effects on aging and age-associated chronic diseases. Finally, reducing pollutant exposure and protecting from virus infections or reactivation may decrease brain insults, diminish the risk of abnormal retrotransposons and HERV activation, and decelerate the CS of neuronal and microglial cells.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| Aβ | Amyloid-β |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| CMV | Cytomegalovirus |

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| CS | Cell senescence |

| ENV | Envelop glycoprotein of HERV-W |

| ERV | Endogenous retrovirus |

| FTD | Frontotemporal dementia |

| HERV | Human endogenous retrovirus |

| HIV | Human immune deficiency virus |

| HML-2 | HERV-k subtype 2 |

| HSV-1 | Human herpes simplex virus-1 |

| NF-kB | Nuclear factor-kB |

| SASP | Senescence-associated secretory phenotype |

| SARS-Cov-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 |

| TDP-43 | Tar-DNA binding protein-43 |

| TSE | Transposable element |

References

1. Milo R, Korczyn AD, Manouchehri N, Stüve O. The temporal and casual causal relationship between inflammation and neurodegenerazion neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2020;26(8):876–86. doi:10.1177/1352458519886943. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Sun Z, Kwon JS, Ren Y, Chen S, Walker CK, Lu X, et al. Modelling late-onset Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology via direct neuronal reprogramming. Science. 2024;385(6708):adl2992. doi:10.1126/science.adl2992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Roberts RO, Aakre JA, Kremers WK, Vassilaki M, Knopman DS, Mielke MM, et al. Prevalence and outcomes of amyloid positivity among persons without dementia in a longitudinal, population-based setting. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(8):970–9. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.0629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Saez-Atienzar S, Masliah E. Cellular senescence and Alzheimer disease: the egg and the chicken scenario. Nat Neurosci Rev. 2020;21:435–44. doi:10.1038/s41583-020-0325-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Itzhaki RF, Golde TE, Heneka MT, Readhead B. Do infections have a role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease? Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16(4):193–7. doi:10.1038/s41582-020-0323-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Porcellini E, Carbone I, Ianni M, Licastro F. Alzheimer’s disease gene signature says: beware of brain viral infections. Immun Ageing. 2010;7:1–6. doi:10.1186/1742-4933-7-16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Soscia SJ, Kirby JE, Washicosky KJ, Tucker SM, Ingelsson M, Hyman B, et al. The Alzheimer’s disease-associated amyloid beta-protein is an antimicrobial peptide. PLoS One. 2010;5(3):e9505. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Romagnoli M, Porcellini E, Carbone I, Veerhuis R, Licastro F. Impaired innate immunity mechanisms in the brain of Alzheimer’s bisease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(3):1126. doi:10.3390/ijms21031126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Mekker A, Vincent S, Tchang VS, Haeberli L, Oxenius A, Trkola A, et al. Immune senescence: relative contributions of age and cytomegalovirus infection. PLoS Pathogen. 2012;8:1–17. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Heath JJ, Grant MD. The immune response against human cytomegalovirus links cellular to systemic senescence. Cells. 2020;9(3):766. doi:10.3390/cells9030766. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Napoletani G, Protto V, Marcocci ME, Nencioni L, Palamara AT, De Chiara G. Recurrent herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection modulates neuronal aging marks in in vitro and in vivo models. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(12):6279. doi:10.3390/ijms22126279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Natalie C, Chen NC, Andrea T, Partridge AT, Sell C, Torres C, et al. Fate of microglia during HIV-1 Infection: from activation to senescence? Glia. 2017;65(3):431–46. doi:10.1002/glia.23081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Lee S, Yu Y, Trimpert J, Benthani F, Mairhofer M, Richter-Pechanska P, et al. Virus-induced senescence is a driver and therapeutic target in COVID-19. Nature. 2021;599(7884):283–9. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03995-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Beswick M, Pachnio A, Lauder SA, Sweet C, Mossa PA. Antiviral therapy can reverse the development of immune senescence in elderly mice with latent cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol. 2013;87(2):779–89. doi:10.1128/JVI.02427-12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Kury P, Nath A, Creange A, Dolei A, Marche P, Gold J, et al. Human endogenous retroviruses in neurological diseases. Trends Mol Med. 2018;24:379–94. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2018.02.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Belshaw R, Pereira V, Katzourakis A, Talbot G, Paces J, Burt A, et al. Long-term reinfection of the human genome by endogenous retroviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4894–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0307800101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Grandi N, Tramontano E. Human endogenous retroviruses are ancient acquired elements still shaping innate immune responses. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2039. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Douville R, Liu J, Rothstein J, Nath A. Identification of active loci of a human endogenous retrovirus in neurons of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:141–51. doi:10.1002/ana.22149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Antony JM, van Marle G, Opii W, Butterfield DA, Mallet F, Yong VW, et al. Human endogenous retrovirus glycoprotein-mediated induction of redox reactants causes oligodendrocyte death and demyelination. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1088–95. doi:10.1038/nn1319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Licastro F, Porcellini E. Activation of endogenous retrovirus, brain infections and environmental insults in neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(14):7263. doi:10.3390/ijms22147263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Sutkowski N, Conrad B, Thorley-Lawson DA, Huber BT. Epstein-Barr virus transactivates the human endogenous retrovirus HERV-K18 that encodes a superantigen. Immunity. 2001;15:579–89. doi:10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00210-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Dechaumes A, Bertin A, Sane F, Levet S, Varghese J, Charvet B, et al. Coxsackievirus-B4 infection can induce the expression of human endogenous retrovirus W in primary cells. Microorganisms. 2020;8(9):1335. doi:10.3390/microorganisms8091335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. da Silva A, Guedes BLM, Santos SN, Correa GF, Nardy A, Nali LHS, et al. Beyond pathogens: the intriguing genetic legacy of endogenous retroviruses in host physiology. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1379962. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2024.1379962. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Balestrieri E, Pica F, Matteucci C, Zenobi R, Sorrentino R, Argaw-Denboba A, et al. Transcriptional activity of human endogenous retroviruses in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:e164529. doi:10.1155/2015/164529. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Ueno M, Matsunaga A, Teratake Y, Ishizaka Y. Retrotransposition and senescence in mouse heart tissue by viral protein R of human immunodeficiency virus-1. Exp Mol Pathol. 2020;114:104433. doi:10.1016/j.yexmp.2020.104433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Liu X, Liu Z, Wu Z, Ren J, Fan Y, Sun L, et al. Resurrection of endogenous retroviruses during aging reinforces senescence. Cell. 2023;186:287–304. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.12.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Frost B, Dubnau J. The role of retrotransposons and endogenous retroviruses in age-dependent neurodegenerative disorders. Ann Rev Neurosci. 2024;47:123–43. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-082823-020615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Prudencio M, Gonzales PK, Cook CN, Gendron TF, Daughrity LM, Song Y, et al. Repetitive element transcripts are elevated in the brain of C9orf72 ALS/FTLD patients. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(17):3421–31. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddx233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Tam OH, Rozhkov NV, Shaw R, Kim D, Hubbard I, Fennessey S, et al. Postmortem cortex samples identify distinct molecular subtypes of ALS: retrotransposon activation, oxidative stress, and activated glia. Cell Rep. 2019;29(5):1164–77. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2019.09.066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Li W, Lee MH, Henderson L, Tyagi R, Bachani M, Steiner J, et al. Human endogenous retrovirus-K contributes to motor neuron disease. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(307):307ra153. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aac8201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Guo C, Jeong HH, Hsieh YC, Klein HU, Bennett DA, De Jager PL, et al. Tau activates transposable elements in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Rep. 2018;23(10):2874–80. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Dawson T, Rentia U, Sanford J, Cruchaga C, Kauwe JSK, Crandall KA. Locus specific endogenous retroviral expression associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2023;15:1186470. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2023.1186470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Chang YH, Dubnau J. Endogenous retroviruses and TDP-43 proteinopathy form a sustaining feedback driving intercellular spread of Drosophila neurodegeneration. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):966. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-36649-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Iaccarinbo L, La Joie R, Lesman-Segev OH, Lee E, Hanna L, Allen IE, et al. Association between ambient air pollution and amyloid positron emission tomography positivity in older adults with cognitive impairment. JAMA Neurol. 2021;78:197–207. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.3962. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Finch CE, Thorwald MA. Inhaled pollutants of the gero-exposome and later-life health. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2024;79(7):glae107. doi:10.1093/gerona/glae107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Migliore L, Coppedè F. Gene-environment interactions in Alzheimer disease: the emerging role of epigenetics. Nat Rev Neurol. 2022;18:643–60. doi:10.1038/s41582-022-00714-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Dopkins N, Nixon DF. Activation of human endogenous retroviruses and its physiological consequences. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25:212–22. doi:10.1038/s41580-023-00674-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Cairns DM, Smiley BM, Smiley JA, Khorsandian Y, Kelly M, Itzhaki RF, et al. Repetitive injury induces phenotypes associated with Alzheimer’s disease by reactivating HSV-1 in a human brain tissue model. Sci Signal. 2025;18(868):eado6430. doi:10.1126/scisignal.ado6430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Richardson M, Richardson DR. Pharmacological targeting of senescence with senolytics as a new therapeutic strategy for neurodegeneration. Mol Pharmacol. 2024;105(2):64–74. doi:10.1124/molpharm.123.000803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Di Micco R, Krizhanovsky V, Baker D, d’Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence in ageing: from mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:75–95. doi:10.1038/s41580-020-00314-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Wang C, Kang Y, Liu P, Liu W, Chen W, Hayashi T, et al. Combined use of dasatinib and quercetin alleviates overtraining-induced deficits in learning and memory through eliminating senescent cells and reducing apoptotic cells in rat hippocampus. Behav Brain Res. 2023;440:114260. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2022.114260. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Gonzales MM, Garbarino VR, Kautz TF, Palavicini JP, Lopez-Cruzan M, Dehkordi SK, et al. Senolytic therapy in mild Alzheimer’s disease: a phase 1 feasibility trial. Nat Med. 2023;29(10):2481–8. doi:10.1038/s41591-023-02543-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Garbarino VR, Palavicini JO, Melendez J, Barthelemy N, He Y, Kautz TF, et al. Evaluation of exploratory fluid biomarker results from a phase 1 senolytic trial in mild Alzheimer’s disease. Res Sq. 2024. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3994894/v1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Rachmian N, Medina S, Cherqui U, Akiva H, Deitch D, Edilbi D, et al. Identification of senescent, TREM2-expressing microglia in aging and Alzheimer’s disease model mouse brain. Nat Neurosci. 2024;27(6):1116–24. doi:10.1038/s41593-024-01620-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools