Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Crucial Role of NAD+ in Mitochondrial Metabolic Regulation

1 Department of Neurology, The Agnes Ginges Center for Human Neurogenetics, Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical Center, Jerusalem, 9112001, Israel

2 Faculty of Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Ein Kerem, Jerusalem, 9112102, Israel

* Corresponding Author: Kumudesh Mishra. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Exploring Mitochondria: Unraveling Structure, Function, and Implications in Health and Disease)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(7), 1101-1123. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.061725

Received 02 December 2024; Accepted 18 April 2025; Issue published 25 July 2025

Abstract

Mitochondria are central organelles in cellular metabolism, orchestrating energy production, biosynthetic pathways, and signaling networks. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) and its reduced form (NADH) are essential for mitochondrial metabolism, functioning both as redox coenzymes and as signaling agents that help regulate cellular balance. Thus, while its major role is in energy production, NAD+ is widely recognized as a metabolic cofactor and also serves as a substrate for various enzymes involved in cellular signaling, like sirtuins (SIRTs), poly (ADP-ribosyl) polymerases (PARPs), mono (ADP-ribosyl) transferases, and CD38. Sirtuins, a family of NAD+-dependent deacetylases, are critical in this regulatory network. SIRT3 removes acetyl groups from and enhances the activity of key enzymes that participate in fatty acid breakdown, the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, and the electron transport chain (etc), thereby enhancing mitochondrial efficiency and energy production. Mitochondrial NAD+ biosynthesis involves multiple pathways, including the de novo synthesis from tryptophan via the kynurenine and the salvage pathway, which recycles nicotinamide back to NAD+. Moreover, NAD+ concentrations influence mitochondrial dynamics such as fusion, fission, and mitophagy, which are essential for preserving mitochondrial integrity and function. NAD+ also modulates the balance between glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation, influencing the metabolic flexibility of cells. During NAD+ depletion, mainly in metabolic disorders, cells often shift towards anaerobic glycolysis, reducing ATP production efficiency and increasing lactate production. This metabolic shift is associated with various pathophysiological conditions, including insulin resistance, neurodegeneration, and muscle wasting. This review explores the multifaceted functions of NAD+ in regulating mitochondrial metabolism. It highlights the underlying causes and pathological outcomes of disrupted NAD+ metabolism while exploring potential therapeutic targets and treatment strategies.Keywords

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) plays a crucial role as a coenzyme in various cellular metabolic processes, and contributes to redox processes and energy metabolism by transporting electrons and hydrogen ions. It also functions as a substrate for enzymes that regulate DNA repair, gene expression, and signal transduction [1]. NAD+ serves a dual function, acting both as a cofactor in metabolism and as a mediator in cellular signaling, making it indispensable for maintaining cellular homeostasis, growth, and survival [2]. Numerous mitochondrial processes depend on NAD+ and its phosphorylated form, NADP. These redox reactions involve the reversible exchange of a hydride ion on the nicotinamide group of NAD(P), enabling the interconversion between their oxidized (NAD+, NADP) and reduced (NADH, NADPH) states of the nucleotides. NAD+ plays a crucial role in metabolic pathways, cycling between its reduced (NADH) and oxidized (NAD+) forms to shuttle electrons and protons during reactions like glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation. During catabolic reactions, NAD+ accepts electrons, forming NADH, which drives ATP production in mitochondria and helps regulate the cellular NAD+/NADH balance, a key indicator of metabolic status. Meanwhile, its phosphorylated form, NADPH, is essential for anabolic pathways, like fatty acid and cholesterol biosynthesis [3,4]. NAD+ functions as a key substrate for various enzymes that participate in posttranslational modifications, notably poly-ADP ribose polymerases (PARPs), cyclic ADP ribose synthases (CD38/CD157), and sirtuins participate in DNA repair, calcium signaling, and cellular metabolism regulation, respectively [5–9]. There are seven isoforms of Sirtuin (SIRT1–7), which are NAD+ dependent proteins that deacylate lysine residues in histones and various cellular proteins, distributed across different subcellular locations. Reversible acylation affects various cellular pathways, influencing protein properties like subcellular localization, enzyme activity, and protein interactions, and plays an important role in regulating many cellular functions [10–12]. PARP enzymes are NAD+ consuming enzymes primarily involved in DNA repair, with additional roles in various cellular processes. PARP1 and PARP2 are the main isoforms responsible for most cellular PARP activity and have been the primary focus of research [5,6]. The dependence of key metabolic enzymes on NAD+ levels offers a promising avenue to modulate their activity for potential health benefits. This possibility has driven increasing interest in NAD+ metabolism over the past decade, highlighting the therapeutic potential of NAD+ boosting strategies. Disruptions in NAD+ homeostasis can impair cell signaling and mitochondrial function, and lead to the development of various conditions, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer. Mitochondria generate the majority of cellular ATP in the inner membrane through the electron transport chain (etc) and ATP synthase. The tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and fatty acid oxidation are essential metabolic pathways that occur within the mitochondrial matrix. Additionally, NAD+ is integral to amino acid breakdown, ketone body synthesis, heme production, the urea cycle, and calcium regulation. Given the central role of mitochondria in energy metabolism and the consequences of their dysfunction, understanding the mechanisms that sustain mitochondrial health is critical. This review explores how NAD+ influences mitochondrial activity and considers its potential as a therapeutic approach for treating different diseases.

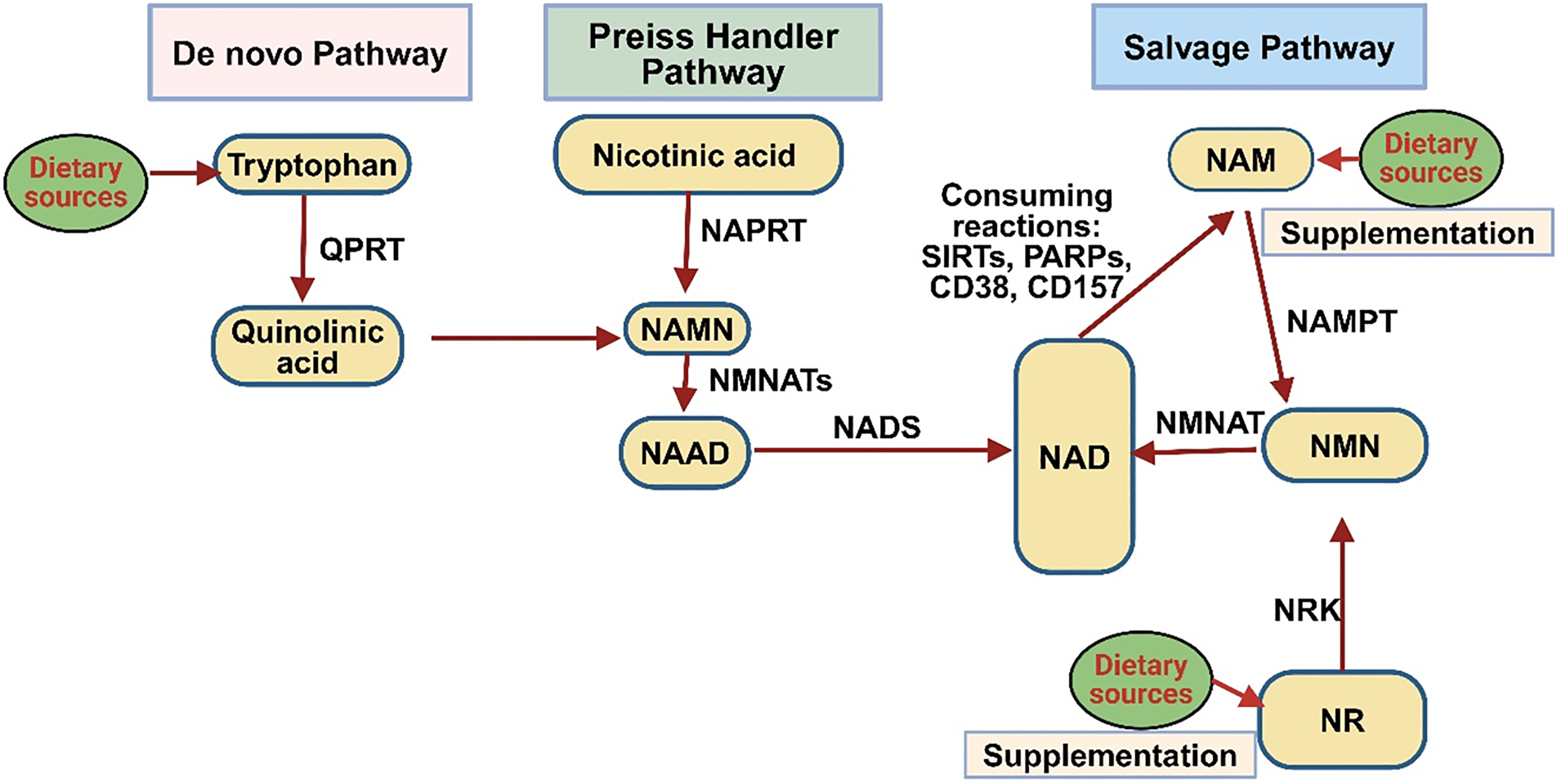

2 NAD+ Biosynthesis and Substrates

In mammals, NAD+ is synthesized via two primary routes: de novo and salvage pathways. These processes rely on four key substrates: the amino acid l-tryptophan (Trp), Vitamin B3 (nicotinic acid, NA), nicotinamide (NAM), and nicotinamide riboside (NR) [13–16] (Fig. 1). In the de novo pathway, NAD+ synthesis begins with the tryptophan (Trp), a dietary amino acid, which undergoes catalytic conversion to N-formylkynurenine. In this initial step, catalysis takes place by either indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) or tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), which serves as the first rate-limiting reaction. Through a sequence of four enzymatic processes, N-formylkynurenine is converted to α-amino-β-carboxymuconate-ε-semialdehyde (ACMS). Due to its inherent instability, ACMS, either by complete enzymatic oxidation or non-enzymatic cyclization, produces quinolinic acid. The second key step in the pathway is the enzymatic conversion of quinolinic acid into nicotinic acid mononucleotide (NAMN) by quinolinate phosphoribosyl transferase (QPRT). NAMN is then converted into nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide (NAAD) through the action of one of three isoforms of nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyl transferase (NMNAT). In humans, NMNAT1 is primarily located in the nucleus, whereas NMNAT2 is in the Golgi complex and cytosol, and NMNAT3 is present in both the mitochondria and cytosol [17]. The last step of the de novo pathway is the amidation of NAAD by NAD synthase (NADS) [18]. Though this pathway provides only a small portion of the total NAD+ pool, it plays a significant role in pellagra, a condition caused by a deficiency in tryptophan (Trp) and nicotinamide (NAM), typically due to inadequate dietary intake. It leads to symptoms such as diarrhea, dermatitis, and dementia, and can be fatal if left untreated. However, the condition can be effectively managed through supplementation with tryptophan or niacin (NA, NAM, or NR). In mammals, the primary source of NAD+ is the salvage pathway, also known as the Preiss-Handler pathway, which utilizes dietary niacin as its key precursor.

Figure 1: NAD+ biosynthesis pathway in a mammalian cell. The salvage pathway recycles NAD+ from NAM, a byproduct of NAD+ consumer enzymes like sirtuins, PARPs, and CD38. Nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase (NAPRT) converts NAM to nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), which NMNAT then converts into NAD+. NR feeds into this pathway via NRK, which converts NR to NMN. Quinolinic acid (QA) is formed by conversion of tryptophan, then NAMN by QAPRT in the de novo pathway. Conversion of NA and NAR to NAMN via NAPRT and NRK, respectively, takes place in the Preiss-Handler pathway. NMNAT enzymes play a central role across all pathways, converting NMN or NAMN into NAD+ or its precursors. NADS finalizes the process by converting NAAD+ to NAD+ (created with BioRender.com)

NA transforms NAMN through the catalytic action of the enzyme nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase (NAPRT). Following this step, NAMN is converted into NAD+ through a sequence of reactions facilitated by the enzymes NMNAT and NADS. Simultaneously, NAM and NR are converted into nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) with the help of enzymes nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) and nicotinamide riboside kinase (NRK). NMN is then transformed into NAD+ through the action of NMNAT [19]. Sirtuins are NAD+-dependent enzymes essential for regulating metabolism, stress adaptation, aging, and circadian rhythms. These enzymes are distributed across distinct areas within the cell: SIRT1, SIRT6, and SIRT7 are primarily found in the nucleus; SIRT3, SIRT4, and SIRT5 reside within the mitochondria; while SIRT1, SIRT2, and SIRT5 are present in the cytoplasm. Sirtuins actively influence various cellular pathways. Under normal physiological conditions, SIRT1 and SIRT2 together utilize approximately one-third of the cell’s total NAD+. Their activity, influenced by NAD+ levels, rises during fasting and calorie restriction, with SIRT1 and SIRT2 consuming significant NAD+ under basal conditions [12,20,21]. SIRT1 also drives NAD+ oscillations via the NAMPT salvage pathway, linking sirtuins to circadian rhythms [22–24]. Primarily known for deacetylating lysine residues, sirtuins also catalyze modifications like succinylation and ADP-ribosylation [25]. Nuclear sirtuins aid DNA repair and genomic stability [20], while mitochondrial sirtuins regulate mitochondrial function, with SIRT1 enhancing biogenesis and mitophagy [20]. SIRT1 plays a role in promoting the formation of new mitochondria by removing acetyl groups from the transcriptional co-activator peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ co-activator 1α (PGC-1α), a key regulator of energy metabolism, and also facilitates the removal of damaged mitochondria through mitophagy. Through these functions, SIRT1 plays a vital role in preserving mitochondrial quality [26–28]. SIRT7, a recently identified sirtuin, is primarily localized in the nucleolus and is abundantly expressed in the blood, bone marrow, liver, spleen, and testes [29]. Its enzymatic activity primarily involves NAD+ dependent deacetylation but also includes desuccinylase, defatty-acylase, debutyrylase, deglutarylase, decrotonylase, and NAD+ independent RNA deacetylase (ac4C) activities [30–34]. The human PARP family consists of 17 distinct enzymes, which exhibit either poly- or mono-ADP-ribosylation activity, functioning as important regulators of various cellular processes. In this process, NAD+ is split into NAM and ADP-ribose, with ADP-ribose forming polymers through PARylation, catalyzed by PARP enzymes [35]. Within this group, PARP1, PARP2, and PARP3 are located in the nucleus and play critical roles in the DNA repair process. Notably, PARP1 accounts for nearly 90% of the total PARP activity initiated in response to DNA damage [6,36]. Upon activation, PARP1 attaches ADP-ribose polymers to itself, histones, and various target proteins by PARylation, recruiting DNA repair machinery to damage sites [37]. PARP1 is a major consumer of NAD+, linking its activation to decreased NAD+ levels and inhibited SIRT1 activity. This competition between PARP1 and SIRT1 for NAD+, driven by PARP1’s higher affinity and catalytic efficiency, affects cellular metabolism, particularly during DNA damage [38,39]. Elevated PARP1 activity is associated with aging and pathologies such as xeroderma pigmentosum, progeroid syndromes, and Cockayne syndrome [40–43]. Studies showed that PARP inhibitors or mice lacking PARP1/2 have revealed elevated NAD+ levels, boosted SIRT1 activity, better mitochondrial performance, and resistance to insulin insensitivity and obesity caused by a high-fat diet [43–45]. While PARP2 shares similar roles with PARP1, contributing ~10% of total PARP activity, and PARP3 also aids DNA repair, their influence on NAD+ homeostasis and metabolism is less pronounced [46,47]. The roles of other PARPs (PARP4–PARP17) remain largely unexplored but are likely minor in NAD+ regulation. Focusing on PARPs, particularly PARP1, presents a potential approach for addressing the age-associated decrease in NAD+ levels and the related dysfunctions. CD38 and CD157 are multifunctional surface enzymes that exhibit both ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity and glycohydrolase properties, enabling them to participate in a variety of cellular signaling pathways. CD38 mainly breaks down NAD+ to produce nicotinamide (NAM) and ADP-ribose, in addition to synthesizing cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR), a key Ca2+-mobilizing messenger [48]. Under acidic conditions, CD38 catalyzes a base-exchange reaction, forming NAAD(P) by substituting NAM in NAD(P) with NA. These metabolites, along with cADPR, play crucial roles in Ca²+ signaling and cellular processes like immune activation and metabolism [49,50]. CD38 also uses NMN as a substrate, while CD157 consumes NR, suggesting potential for targeted inhibition of these enzymes to enhance NAD+ precursor efficiency, particularly in aging [51,52]. CD38 is a transmembrane protein that is upregulated during inflammation, whereas CD157 is a GPI-anchored protein present in hematopoietic and various other tissues. Beyond enzymatic roles, both act as cell receptors [53]. CD38 interacts with CD31, affecting immune cell movement and actively contributing to the proliferation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia [54]. It also supports antimicrobial defense, possibly by restricting bacterial access to NAD+. CD157 plays a role in the movement of neutrophils and monocytes by interacting with integrins and the scrapie-responsive gene 1 (SCRG1). This interaction supports the renewal and differentiation of stem cells [55]. However, its functions in cellular biology and aging remain underexplored.

A significant portion of the cellular NAD+ pool is localized within mitochondria. In isolated mitochondria, NAD+ serves as a substrate in the synthesis of mono-ADP-ribosylation and cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR), activated under oxidative stress [56]. Reduced forms like NADPH, however, are not involved in these signaling pathways. The localization of enzymes responsible for NAD+ metabolism, whether within the mitochondrial matrix or on the outer mitochondrial membrane, remains debated. Under normal conditions, mitochondrial matrix NAD+ levels remain stable and are unaffected by cytosolic ATP variations. Studies show that calcium (Ca2+) addition depletes mitochondrial NAD+ via permeability transition pore (PTP) opening, a process linked to increased ion permeability, matrix swelling, and mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) collapse [57,58]. PTP opening releases NAD+ into the intermembrane space, where reactive oxygen species (ROS) and oxidative conditions enhance its hydrolysis by NADase [59]. This disruption further oxidizes pyridine nucleotides and uncouples oxidative phosphorylation. After PTP opening, NAD+ undergoes degradation, recovery, or signaling pathways. Degradation yields metabolites like ADP-ribose and AMP, which cannot be resynthesized into NAD+. Recovery may involve ATP generation from ADP-ribose, while signaling pathways include ADP-ribosylation and cADPR synthesis. Transient PTP opening may also facilitate NAD+ flux across the inner mitochondrial membrane, contributing to mitochondrial NAD+ turnover [60,61].

4 Role of NAD+ in Metabolism and Mitochondria Dysfunction

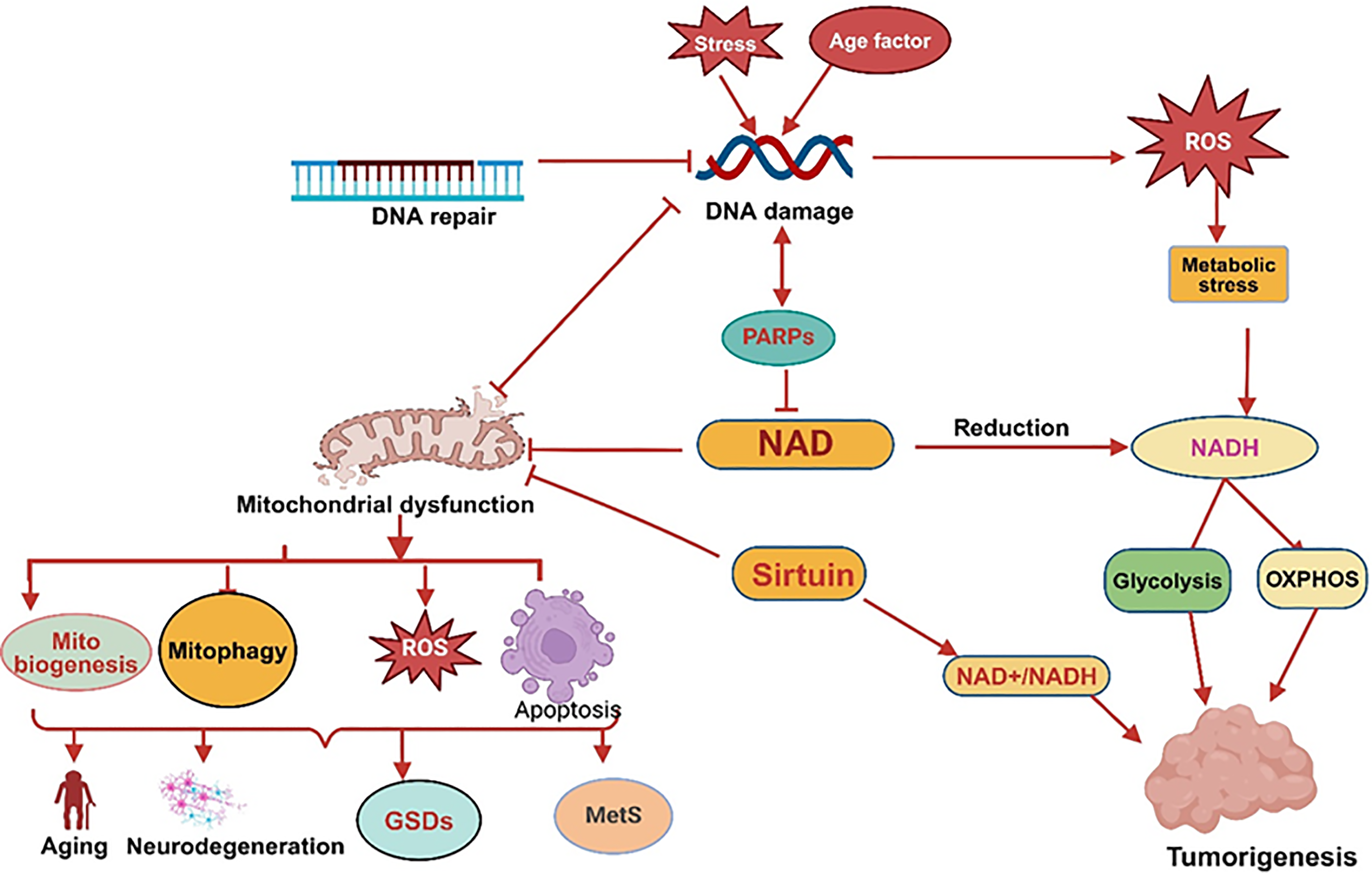

NAD+ and its metabolites, such as NADP, NADH, and NADPH, are essential in controlling cellular metabolic processes and the generation of energy. Serving as a cofactor in various redox reactions, NAD+ facilitates metabolic processes in specific compartments, such as glycolysis in the cytosol and the TCA cycle, oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), fatty acid breakdown, and amino acid degradation in the mitochondria. In glycolysis, NAD+ is converted to NADH through the action of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), facilitating the transformation of glucose into pyruvate [62]. Inside the mitochondria, during the TCA cycle, NAD+ is converted into NADH at multiple stages as acetyl-CoA undergoes oxidation, resulting in the release of carbon dioxide. NADH generated during metabolism transfers electrons to complex I of the electron transport chain (etc), driving ATP production via oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). The balance between NAD+ and NADH regulates key enzymes, including NAD kinase, GAPDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, and malate dehydrogenase. In contrast, the NADPH/NADP ratio is maintained at high levels in both the cytosol and mitochondria to support a reducing environment. NADP, existing in its oxidized (NADP) or reduced (NADPH) forms, acts as a redox pair, collectively referred to as NADP or NADP(H). NAD kinase (NADK) catalyzes the phosphorylation of NAD+ to form NADP [63]. NADPH is crucial for anabolic processes and protecting cells against oxidative damage. It serves as a cofactor for P450 enzymes that help detoxify harmful compounds, supports glutathione reductase in keeping glutathione in its reduced form during oxidative stress, and provides the necessary substrate for NADPH oxidase, which generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) during immune responses [64,65]. The role of NAD+ is studied in various diseases by using genetically modified mice and through interventions aimed at replenishing NAD+ using its biosynthetic precursors [66,67]. NAD+ is essential for the activation of sirtuins, a family of enzymes that depend on NAD+ to perform deacylase and ADP-ribosyl transferase activities, which are key for maintaining cellular integrity. As NAD+ levels decline with age, sirtuin activity diminishes, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction, redox imbalance, and damage to cellular proteins, lipids, and DNA [68,69]. These alterations lead to chromosomal instability, gene mutations, and the onset of chronic diseases, including cancer [70]. Reduced sirtuin activity is closely linked to age-related disorders, as enzymes such as SIRT1 help slow aging by catalyzing histone deacetylation and controlling important transcription factors [71,72]. Intracellular NAD+ levels are significantly influenced by nutritional and environmental factors. As NAD+ levels go down, sirtuin activity compromises epigenetic chromatin structures and mitochondrial metabolism in our research, we reported that histone H3K27 acetylation can be inhibited by SIRT1 [73] was elevated in the chromatin of glycogen storage disease type 1a (GSD1a) patients’ fibroblasts [74]. This increases ROS production, causing oxidative stress, declined ATP production, and heightened inflammation, further exacerbating cellular injury [75]. Shifts in metabolic activity, which rise during early life and decline with age, correlate with reductions in NAD+, though the precise mechanisms driving this decline remain elusive. The enzyme CD38, a NADase, has been linked to age-related NAD+ depletion and is a promising target for therapies aimed at mitigating age-related diseases [76]. The depletion of nuclear NAD+ accelerates mitochondrial dysfunction, including impairments in OXPHOS [77]. Understanding how declining NAD+ levels interact with oxidative stress, inflammation, and DNA damage is critical to unraveling the molecular basis of aging. Studies increasingly link age-related illnesses and comorbidities to NAD+ dependent metabolic changes. Measuring NAD+ dynamics in vivo may offer valuable insights into redox potential alterations and their connections to aging and associated pathologies (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: NAD+ metabolism imbalance and mitochondrial dysfunction: PARP is activated by stress or aging due to DNA damage, further reduced NAD+ levels and causing mitochondrial dysfunction, which disturb mitochondrial biogenesis, mitophagy, apoptosis and increased ROS resulting aging, neurodegeneration, glycogen storage disorders (GSDs) and metabolic syndromes (MetS). Disturbance in Sirtuins activity decreases NAD+/NADH level, causes mitochondrial dysfunction, and promotes tumorigenesis (created with BioRender.com)

5 NAD+ Metabolism Imbalance and Disorders

Excessive body weight, insulin dysfunction, elevated blood pressure, and irregular lipid profiles are major contributors to the development of metabolic disorders such as type 2 diabetes (T2D) and heart-related diseases [71,78]. The concentration of NAD+ regulates the activity of enzymes involved in various energy metabolism pathways, which in turn influences a wide array of downstream cellular functions. Regulating the intracellular NAD+ levels offers a promising therapeutic approach for treating metabolic syndrome and related conditions [79]. High NADH levels can induce reductive stress, raising cellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) and promoting insulin resistance, insulin insufficiency, and cell damage. Restoring NAD+ levels may help restore redox balance and improve diabetes-related outcomes [80]. Disruptions in SIRT1 signaling, which is regulated by NAD+, are connected to the development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes (T2D), as SIRT1 plays a critical role in positively regulating insulin signaling at multiple levels [81]. NAMPT regulates insulin secretion by synthesizing NAD+ in pancreatic cells. Impaired glucose tolerance in NAMPT(+/−) mice was rescued with NMN, which also improved glucose tolerance and lipid profiles in T2D mice models [82]. In mice with type 2 diabetes, NR demonstrated protective effects on the nervous system by enhancing glucose metabolism, decreasing weight gain and liver fat accumulation, and preventing nerve damage [83]. However, NAD+ precursors like NAM may produce toxic catabolites, especially in diabetes, warranting combinatorial therapies like polyphenols or insulin sensitizers [84]. Under hyperglycemic conditions, increased glucose flux through metabolic pathways leads to NADH overproduction, causing excess ROS and contributing to insulin resistance [85]. Inhibiting mitochondrial complex I with agents like rotenone or NDUFA13 knockdown improved glucose homeostasis and alleviated hyperglycemia by modulating NADH levels and NAD+/NADH ratios [86]. Excess body fat disrupts mitochondrial enzyme function, leads to metabolic inflexibility, and significantly increases the risk of developing type 2 diabetes and heart-related conditions. In adipose tissue, obesity disrupts mitochondrial and NAD+ homeostasis, leading to tissue enlargement and dysfunction in the metabolism of lipid and glucose, which contribute to metabolic disorders [87]. NAD+ biosynthesis in adipose tissue relies on NAMPT expression, which is reduced in obesity [88]. The exact role and physiological relevance of extracellular NAMPT (eNAMPT) are still under discussion. However, a recent preclinical study revealed that its release from adipocytes is controlled by SIRT1-mediated deacetylation, this supports the preservation of NAD+ levels in the hypothalamus by delivering NMN directly to the region [89]. NAMPT deficiency in adipose can lead to tissue fibrosis, reduced plasticity, and impaired mitochondrial respiration [88].

5.2 Glycogen Storage Disorders (GSDs)

GSDs represent a set of genetic disorders resulting from enzyme deficiencies involved in glycogen synthesis or breakdown. Mitochondrial dysfunction can worsen the metabolic disturbances associated with defective glycogen metabolism, contributing to more complex health issues in GSD patients [90]. A study found a reduction in the enzymatic activity of NADH dehydrogenase and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), along with a reduced NAD+/NADH ratio, across all types of GSDs [91]. The reduced activity of hepatic SIRT1/PGC-1α signaling leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, contributing to the onset of hepatocellular adenoma/carcinoma (HCA and HCC) in GSD type Ia [92]. Oxidative stress occurs when ROS accumulate, overwhelming the cell’s antioxidant defenses and causing damage to essential macromolecules, impaired mitochondrial functions, and leading to development of metabolic syndrome (MetS) [75]. The activation of PGC-1α, triggered by elevated AMP levels through AMPK and increased NAD+ via Sirtuin-1, helps alleviate cellular oxidative stress by boosting the production of mitochondrial antioxidant enzymes [93], therefore, PGC-1α is an important therapeutic target in metabolic syndrome (MetS). A study used L-G6pc-/-mice, a model for GSD type 1a, liver-specific deletion of G6Pase-α caused an accumulation of inactive, acetylated PGC-1α and mitochondrial dysfunction. When SIRT1 was overexpressed, it facilitated the deacetylation and activation of PGC-1α, leading to a decrease in acetyl-PGC-1α levels, restored expression of etc., components, and improved mitochondrial complex IV activity. This suggests that the impaired SIRT1-PGC-1α signaling pathway plays a critical role in the mitochondrial dysfunction observed in GSD type 1a [92]. Autophagy or mitophagy is essential for lysosomal glycogen degradation disturbed in GSDs. A study by Cho et al. showed that in adult mice with liver-specific deletion of G6pc, reduced expression of SIRT1 and its downstream target FOXO1 was closely linked to impaired autophagy. Although reactivating the SIRT1 pathway successfully restored autophagic activity, it failed to correct other metabolic defects. This suggests that, in GSD type Ia, multiple signaling pathways beyond SIRT1-driven autophagy are likely compromised [94].

A drop in NAD+ concentrations is a hallmark of the aging process and is linked to the onset of numerous age-associated disorders. This reduction is linked to mitochondrial dysfunction, including reduced mitochondrial DNA integrity, volume, and functionality, often driven by increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation [95,96]. Cellular senescence is a key feature of aging, and the connection between NAD+ metabolism and senescence is multifaceted. Low NAD+ levels can lead to DNA damage accumulation and mitochondrial dysfunction, which may accelerate the onset of senescence [97,98]. Beyond mitochondrial changes, additional mechanisms exacerbate NAD+ depletion with age. One key contributor is the heightened function of enzymes that utilize NAD+, mainly PARP1 and sirtuins like SIRT1 [99,100]. SIRT7 plays a crucial role in preserving physiological balance and protecting against aging by ensuring genomic integrity. A decrease in SIRT7 disrupts metabolic stability, hastens aging, and raises the risk of age-related diseases such as cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disorders, pulmonary and kidney diseases, inflammation, and cancer [29]. PARP1 is essential for maintaining DNA integrity through repair processes by recruiting repair proteins to sites of damage [101,102]. However, chronic activation of PARP1 triggered by DNA damage or inflammation rapidly depletes cellular NAD+ stores. This reduction in NAD+ suppresses SIRT1 activity, leading to increased acetylation of PGC-1α and decreased mitochondrial transcriptional factor A (TFAM) levels, impairing mitochondrial biogenesis and function [103]. Together, these changes amplify cellular dysfunction, DNA damage, and age-related diseases. Additional factors contributing to NAD+ decline include increased CD38 expression, circadian rhythm disruption that lowers NAMPT expression, and persistent PARP activation due to chronic metabolic stress or inflammation [51,104,105]. Encouragingly, studies reported that inhibiting PARP1 activity can restore NAD+ levels and improve mitochondrial function. In experimental models, inhibiting PARP1 pharmacologically or deleting it genetically increases mitochondrial content and oxidative metabolism, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target [36,41,42,45]. Strategies to replenish NAD+ levels, such as NAD+ precursor supplements like NR or NMN, have shown promising benefits [18]. Supplementing with NR boosts NAD+ concentrations and enhances mitochondrial performance, and provides protection against metabolic disorders [18,106]. These effects are partly mediated by sirtuin activation, particularly SIRT1 and SIRT3. For instance, NR increases superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) expression through SIRT1 activation, promoting FOXO1 deacetylation and activity. Additionally, NR promotes the activation of mitochondrial genes, supports the renewal of muscle stem cells, helps postpone aging-related decline in neural and melanocyte stem cell populations, and promotes lifespan extension in mice [13,107,108]. It also restores the function of intestinal stem cells (ISCs), aiding tissue repair and mitigating age-related decline in gut health [109]. Similarly, NMN supplementation counters age-associated physiological decline by improving energy metabolism, enhancing insulin sensitivity, and optimizing lipid profiles. NMN has been shown to restore mitochondrial oxidative capacity, increase capillary density, and support vascular health in aged models, further demonstrating its potential as an anti-aging therapy [110–112].

5.4 Neurodegenerative Disorders

Mitochondrial dysfunction in neurons plays a key role in the progression of age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Aging accelerates the generation and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) caused oxidative stress leading to DNA damage and compromised mitochondrial function [113]. In disorders linked to NAD+ depletion, therapeutic strategies such as NAD+ precursor supplementation, PARP inhibitors (PARPi), or sirtuin activators show potential for restoring mitochondrial function, enhancing neuronal health, and improving cognitive outcomes [114,115]. Axonal degeneration, a hallmark of numerous neurological diseases, plays a pivotal role in disease progression and survival. Delaying this process could significantly mitigate disease severity. Activation of sterile alpha and TIR motif-containing protein 1 (SARM1) leads to axon breakdown by locally depleting NAD+ within the nerve fibers. In contrast, overexpression of NMNAT1 effectively blocks this pathway, preserving axons by preventing SARM1-mediated NAD+ depletion [116]. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is an advanced neurodegenerative disorder marked by cognitive decline and memory impairement due to loss in function of neurons, pathological sign is the accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ) protein, forming plaques that disrupt neurotransmission, cause synaptic loss, and drive cognitive deficits [117]. Therapeutic strategies targeting mitochondria show promise in alleviating AD pathology [118,119]. Elevated NAD+ levels reduce Aβ oligomer toxicity, improve cognitive function, and prevent neuronal death in experimental models [120]. NAD+ precursors, such as NMN and NR, have demonstrated neuroprotective effects. NMN reduces mitochondrial dysfunction, Aβ production, synaptic loss, and JNK pathway activation, while NR decreases amyloid plaques, enhances synaptic plasticity, improves cognitive function, and repairs DNA damage in preclinical studies [121,122]. Niacin deficiency, linked to aging and dementia, may contribute to AD progression and offer protection by lowering both serum and cellular cholesterol concentration [123]. Nicotinamide (NAM) has shown additional benefits, such as reducing tau phosphorylation, restoring cognition, and alleviating oxidative stress in AD models. A study ex vivo reported, treatment with NAM decreased ROS, lipid peroxidation, and oxidation of protein while improving the mitochondrial ability to maintain redox balance in rat synaptosomes exposed to A(1e42) [124,125]. Inhibiting CD38, an NAD+ consuming enzyme, also holds potential. CD38 deletion reduces Aβ plaque burden and improves spatial learning in AD mouse models [126]. Parkinson’s disease (PD) is marked by characterized by the progressive loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra, leading to dopamine depletion in the striatum and motor symptoms such as bradykinesia [127–129]. Metabolic imbalances, including a significant reduction in the NAD+/NADH and NAD+/NADP ratios (niacin index), are commonly observed in PD [130]. Supplementation of Niacin has demonstrated potential in managing PD symptoms. Low-dose niacin effectively modulated the niacin index and G-protein coupled receptor 109A (GPR109A), improving motor and cognitive functions without adverse effects [131]. Nicotinamide (NAM) has been shown to exert both protective and harmful effects on the nervous system in PD. NAM supplementation addressed the mitochondrial loss of function in PD models of Parkin and PINK1, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic approach [132]. Furthermore, Nicotinamide riboside (NR) enhanced mitochondrial performance in neurons generated from stem cells of patients with PD, prevented motor deficits, and protected dopaminergic neurons in fruit fly models [133].

Cancer cells primarily depend on aerobic glycolysis instead of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), exhibiting heightened glucose uptake and glycolytic activity, with lowered activity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase enzyme, leading to a diminished transformation of pyruvate into acetyl-CoA [134], recent studies, however, has indicated that oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) is elevated in some cancer types [135,136]. Elevated NAD+ levels enhance anaerobic glycolysis by stimulating the activity of GAPDH and LDH, thereby supporting cancer cell proliferation [137]. Overexpression of NAMPT and increased NAD+ level observed in several cancers which promote cancer cell survival [138]. The oncogene c-MYC plays a pivotal role in regulating NAMPT expression, promoting glycolysis and lactate production, and driving the Warburg effect. Inhibitors targeting NAMPT deplete NAD+ levels, disrupting key metabolic processes including glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and OXPHOS, resulting in the proliferation of cancer cell retardation [139,140]. NAD+ plays an important role in controlling cellular energy generation, maintaining genomic integrity, supporting DNA maintenance mechanisms, and facilitating intracellular signaling [141]. Adequate NAD+ can counter early malignant changes by promoting repair, stress adaptation, halting cell division, and triggering programmed cell death, thereby maintaining genomic stability and preventing mutations and the development of cancer. Conversely, in the context of cancer development and therapy, elevated NAD+ concentrations can promote malignancy by supporting growth, drug resistance, and sustained cellular function, while decreased NAD+ level may reduce DNA damage caused by oncogenes and hinder tumor development [142,143]. Sirtuins play a crucial role in both cancer development and prevention by regulating genes that are involved in DNA repair and cellular maintenance [144]. SIRT1 activity is influenced by the NAD+/NADH ratio; AMPK boosts SIRT1 activity by increasing cellular NAD+ levels, leading to the deacetylation and regulation of downstream targets. On the other hand, Reduced NAD+ availability impairs SIRT1 activity, limiting its capacity to deacetylate key tumor suppressors like p53, thereby disrupting crucial functions such as halting cell division, initiating programmed cell death, and promoting cellular self-digestion [145,146]. Excessive use of intracellular NAD+ by PARP enzymes diminishes its accessibility for sirtuins, compromising the deacetylation of critical tumor suppressors such as p53 [147], its mutations can drive the proliferation of cancer cells by enabling them to thrive in environments with limited nutrients. SIRT2 and SIRT3 function as key regulators that help prevent tumor formation. SIRT2 acts as a tumor suppressor by maintaining chromosomal integrity during cell division, controlling the microtubule structure, enhancing FOXO-mediated DNA binding and gene activation, and protecting cells from oxidative damage by boosting antioxidant enzymes like manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), glutathione peroxidase, and catalase [148–150]. SIRT3 reduces ROS by activating antioxidant defenses through MnSOD and regulating HIF-1 [151,152]. Low levels of Nicotinamide (NAM), serves as NAD+ precursors, support SIRT1 function, whereas buildup of NAM can inhibit SIRT1 activity, potentially leading to adverse effects [153]. SIRT2 overexpressed in gastric cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma and in other cancers also [154–156], boosts production of NADPH and stimulates leukemia cell growth by deacetylation and activation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) [157].

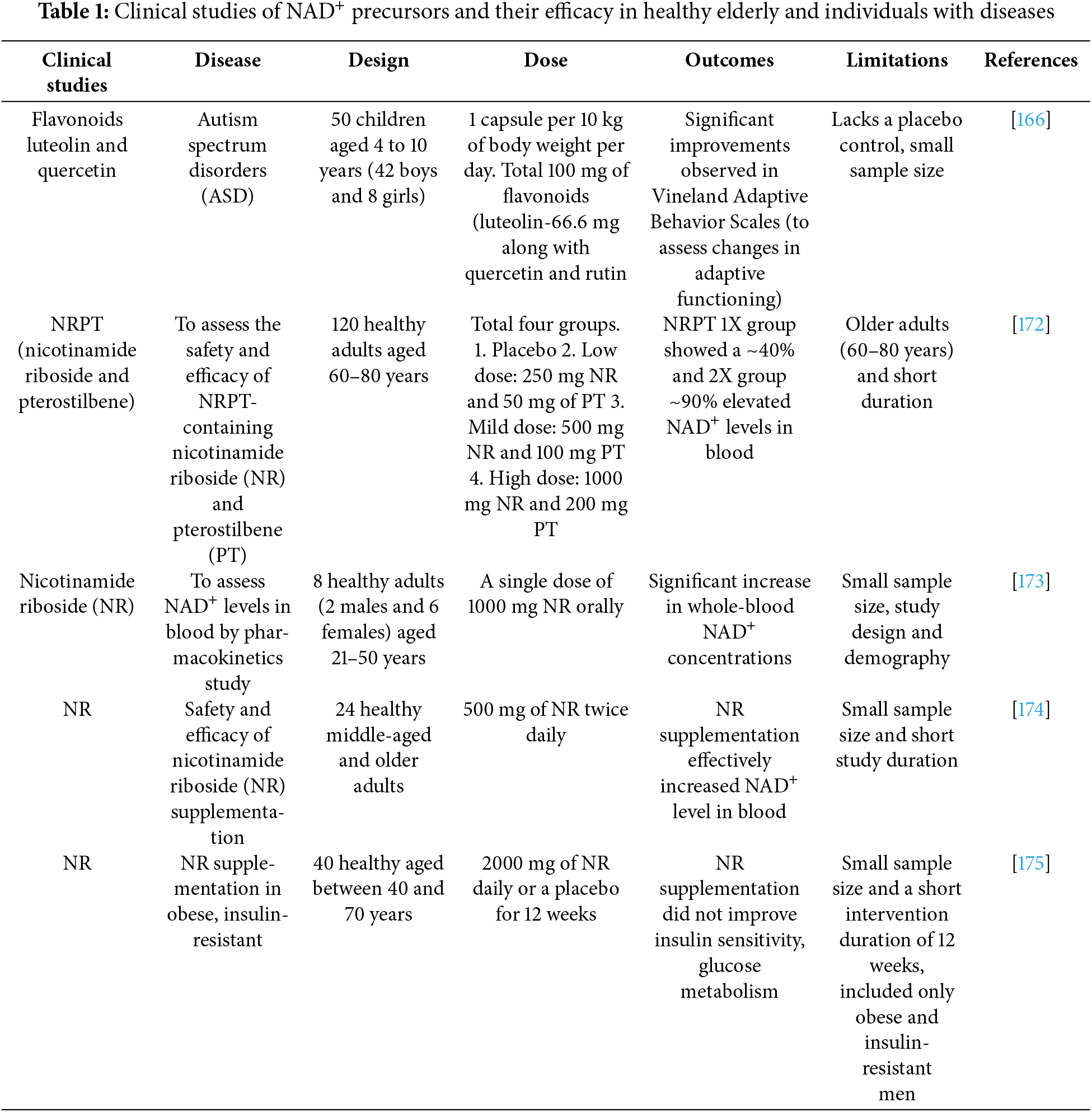

6 Therapeutic Options and Future Direction

Cumulative findings from extensive preclinical and clinical investigations have shed light on the multifaceted roles of NAD+ and its dependent enzymes in regulating aging processes, synaptic remodeling, neurodegeneration, and tumorigenesis. Although NAD+ precursor supplementation is a common strategy to elevate NAD+ levels, its effectiveness may be influenced by factors such as inconsistent cell uptake, chemical stability, appropriate dosing, and the risk of adverse effects. Song et al. (2023) recently summarized the negative outcomes associated with high NAM (nicotinamide) doses, highlighting that elevated NAM can disrupt genomic stability, deplete cellular methyl reserves, and contribute to insulin resistance due to the buildup of methylated NAM derivatives [112]. Modulating the enzymes and pathways responsible for NAD+ degradation has emerged as a highly promising approach in current therapeutic research. In particular, the inhibition of crucial enzymes like PARPs and NADases, including CD38 and CD157, is gaining significant attention, offers significant potential for treating age-related diseases linked to declining NAD+ levels. PARP1 inhibitors like olaparib and rucaparib are widely used either in combination with chemotherapy or as standalone treatments for cancer. These agents increase tumor susceptibility to DNA damage but are constrained by their toxicity [158,159]. Studies showed SIRT7 levels and activity decline in various tissues with aging, making it a promising therapeutic target for promoting longevity [160–162]. On the other hand, CD38, a key NADase in mammals, plays a major role in the reduction of NAD+ levels with age, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target. Several CD38 inhibitors are either available or under development, with some demonstrating its ability in vivo enhancement of NAD+ levels. For example, the natural flavonoid apigenin enhances NAD+ concentrations in human cells and mouse liver, helping to regulate glucose and lipid balance in obese mice model [163]. Apigenin has been reported to downregulate expression of CD38, resulting in an increased NAD+/NADH ratio and promoting SIRT3-dependent antioxidant defense within the mitochondria of diabetic rat kidneys [164]. Similarly, Luteolinidin, another flavonoid known to inhibit CD38, elevates NAD+ levels and offers protective effects to the heart.and endothelial tissues with ischemic myocardial condition in mice [165], Luteolin was found to reduce symptoms of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in a study involving 50 children aged 4 to 10 years (42 boys and 8 girls) with autism. The children were administered luteolin at a dose of 100 mg per capsule, with one capsule given 10 kg/body weight every day with food [166]. Moreover, 4-aminoquinoline derivatives, including compound 78c, act as CD38 inhibitors and effectively raise NAD+ concentrations in the muscle, liver, and heart tissues of mice. In aged mice, 78c mitigates age-related NAD+ decline, improves metabolic function, reduces DNA damage, and enhances muscle performance [167,168]. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a common liver disease caused by the deposition of fat and the condition advancing to liver cirrhosis over time, hepatocellular carcinoma, cardiovascular complications, chronic kidney disease, and other systemic manifestations. CD38 plays a key role in regulating Sirtuin 1 activity, thereby influencing inflammatory responses [169]. In a study, treatment with 78c was shown to improve glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in NAFLD CD38 KO mice model [76]. Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) possess the unique ability to both replicate themselves and maintain their population over time, generating identical stem cells, and for differentiation into various blood cell lineages, encompassing both myeloid and lymphoid cells. However, the regenerative capacity of HSCs declines with age. In a recent study, 24-month-old wild-type mice were treated with 78c for 8 weeks, resulting in an increase in NAD+ levels in HSCs [170]. Numerous clinical studies have investigated the impact of NR supplementation on human health (Table 1). Initial studies demonstrated that NR increases the level of NAD+ in blood plasma and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [171]. Nicotinamide riboside (NR) supplementation was also found to elevate NAAD levels in PBMC. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study reported NRPT, a formulation combining NR with pterostilbene (PT), in 120 healthy individuals aged 60 to 80 years. Participants were assigned to three groups: placebo, standard (1X), or double-dose (2X) of NRPT, and received daily supplementation for eight weeks. The results demonstrated a significant, dose-dependent increased NAD+ levels in blood with supplementation of NRPT. An increase of approximately 40% in NAD+ levels was observed in the standard (1X) and about 90% in the double dose (2X) of the NRPT group after 4 weeks, compared to both the placebo and baseline [172]. A PK study, conducted with eight healthy participants, investigated the oral administration of NR across varying doses over nine days. The dosing regimen began with daily dose of 250 mg for the first two days, thereafter 250 mg two times a day on 3rd and 4th day, on days five and six doses increased up to 500 mg twice daily, and finally ended with 1000 mg two times a day on 7th and 8th day of the study. On the 9th day of the study, participants underwent a whole day PK analysis after receiving a single dose of 1000 mg NR. Results from the study suggest NR enhances NAD+ levels and shows promise as a therapeutic option for addressing mitochondrial dysfunction [173]. In a study, a total of 24 healthy older adults (11 males and 13 females) were included. After chronic NR supplementation, systolic blood pressure and arterial stiffness were observed to be lowered, while acute NR supplementation improved exercise performance [174]. A 12-week trial in obese men (BMI > 30, ages 40–70) found no adverse events but observed no improvements in insulin sensitivity or glucose metabolism after 1000 mg NR supplementation twice daily or placebo [175]. Our group evaluated the effect of GHF201, a glycogen reducing compound and potential therapeutic agent for GSDs, in GSD1a patients’ primary fibroblasts cells and L-G6pc-/-knockout mouse model. GHF201 has been shown to enhance oxygen consumption rate (OCR), mitochondrial ATP generation, lysosomal activity, and autophagy. It has been observed that fibroblasts from various GSD1a patients exhibit significant inhibition of key transcriptional regulators, such as PGC1α and transcription factor EB (TFEB), which govern mitochondrial biogenesis and lysosomal function, respectively. Additionally, the metabolic axis involving pAMPK-SIRT1-NAD+/NADH is notably suppressed, alongside elevated SIRT1-inhibitable histone H3K27 acetylation in chromatin within these fibroblasts. Treatment with GHF201 effectively reduced the heightened histone acetylation. Furthermore, GHF201 demonstrated its therapeutic benefits beyond patient-derived fibroblasts, alleviating GSD1a-related symptoms in a liver-specific inducible mouse model. This included reductions in liver glycogen and G6P levels, alongside increases in liver and serum glucose concentrations [74]. There remain unresolved questions surrounding the pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, tissue targeting, optimal dosing, and long-term safety associated with sustained elevation of NAD+ levels through supplementation, whether using NAD+-consuming enzymes’ precursors or inhibitors. All NAD+ precursors including NMN, NAM, NR, NA, and tryptophan, have been shown to enhance intracellular NAD+ levels; but their suitability for human use remains unclear. These precursors, naturally present in foods, differ in potency, biosynthetic pathways, and enzymatic preferences, which influence their efficacy [64]. Further research is necessary to gain deeper insights into the subcellular localization, tissue targeting, and effectiveness of NAD+ level enhancement in humans. While NAD+ precursors are typically well-tolerated, their prolonged use raises questions about safety. Moreover, further clinical studies are crucial to comprehensively determine their safety and potential therapeutic benefits in combating aging, as well as a range of neurological and metabolic conditions. The future of NAD+ research in mitochondrial metabolic regulation is promising and diverse. Age-related NAD+ decline is closely associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and metabolic diseases. Future studies should investigate how NAD+ modulation influences mitochondrial quality control, mitophagy, and biogenesis. Additionally, sirtuins (SIRT1, SIRT3, SIRT5) play a key role in deacetylating metabolic enzymes and regulating mitochondrial function. Research will further explore how NAD+ supplementation can selectively activate sirtuins to enhance mitochondrial metabolism. The relationship between NAD+, ROS, and antioxidant defense mechanisms across different cell types and disease states remains a crucial area of study. Given that many cancers exhibit altered NAD+ metabolism, future investigations will assess how targeting NAD+ biosynthesis impacts tumor growth, immune responses, and metabolic adaptability. Furthermore, NAD+-based therapies hold potential when combined with chemotherapy or immunotherapy to improve clinical outcomes. Developing non-invasive techniques to monitor NAD+ levels in real time will be a priority, providing better insights into metabolic status in diseases such as diabetes, neurodegeneration, and cancer.

NAD+ is a vital regulator of mitochondrial metabolism, essential for energy production, redox balance, and cellular adaptation. NAD+ alternates between its oxidized and reduced forms (NADH) to facilitate the process of glycolysis, the TCA cycle, and the OXPHOS, ensuring mitochondrial membrane potential and efficient energy generation. Dysregulated NAD+ levels impair these processes, contributing to metabolic inflexibility and mitochondrial dysfunction, hallmarks of aging and metabolic diseases. Beyond energy metabolism, NAD+ influences mitochondrial biogenesis, dynamics, and quality control via NAD+ dependent enzymes like sirtuins. SIRT1 and SIRT3 enhance mitochondrial function by regulating key metabolic pathways, promoting fatty acid oxidation, antioxidant defenses, and stress resilience. NAD+ also supports autophagy and mitophagy, crucial for clearing damaged mitochondria and maintaining cellular health under metabolic stress. Reduced NAD+ levels, common with aging, disrupt inter-organellar communication, gene regulation, and DNA repair, exacerbating cellular dysfunction. Therapeutic strategies, including NAD+ precursors like nicotinamide riboside and inhibitors of NAD+ consuming enzymes, show promise in restoring mitochondrial health. However, the dual role of NAD+ in cellular health and disease, such as cancer, necessitates precise interventions. In summary, NAD+ is pivotal for mitochondrial and systemic metabolic health, offering a promising target for treating mitochondrial-related disorders while requiring careful therapeutic optimization.

Acknowledgement: We would like to acknowledge the Golda Meir Foundation Hebrew University of Jerusalem, fellowship awarded to Kumudesh Mishra for his postdoctoral work.

Funding Statement: A fellowship support from the Golda Meir Fellowship Fund, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Kumudesh Mishra and Or Kakhlon; data collection: Kumudesh Mishra; draft manuscript preparation: Kumudesh Mishra; review and editing: Or Kakhlon. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing does not apply to this article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| NAD+ | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide oxidized |

| NADH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide reduced |

| NADP+ | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidized |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate reduced |

| OXPHOS | Oxidative phosphorylation |

| ETC | Electron transport chain |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| Trp | l-tryptophan |

| NA | Nicotinic acid |

| NAM | Nicotinamide |

| NR | Nicotinamide riboside |

| NMN | Nicotinamide mononucleotide |

| NAAD | Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide |

| NMNAT | Nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase |

| NAPT | Nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase |

| NAMPT | Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase |

| NRK | Nicotinamide riboside kinase |

| AMPK | Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase |

| PGC-1α | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha |

| FOXO1 | Forkhead box protein O1 |

| PARPs | Poly-ADP ribose polymerases |

| IDO | Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase |

| TDO | Tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase |

| ACMS | α-amino-β-carboxymuconate-ε-semialdehyde |

| QPRT | Quinolinate phosphoribosyl transferase |

| NADS | NAD synthase |

| NAPRT | Nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase |

| NMN | Nicotinamide Mononucleotide |

| QA | Quinolinic acid |

| SCRG1 | Scrapie-responsive gene 1 |

| PTP | Permeability transition pore |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GSD | Glycogen storage disease |

| TFAM | Mitochondrial transcriptional factor A |

| SOD2 | Superoxide dismutase 2 |

| ISCs | Intestinal stem cells |

| SARM1 | Sterile alpha and TIR motif-containing 1 |

| GPR109A | G-protein coupled receptor 109A |

| MnSOD | Manganese superoxide dismutase |

| G6PD | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| ASD | Autism spectrum disorders |

| NAFLD | Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease |

| OCR | Oxygen consumption rate |

| TFEB | Transcription factor EB |

References

1. Katsyuba E, Auwerx J. Modulating NAD+ metabolism, from bench to bedside. EMBO J. 2017;36(18):2670–83. doi:10.15252/embj.201797135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Kane AE, Sinclair DA. Sirtuins and NAD+ in the development and treatment of metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Circ Res. 2018;123(7):868–85. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Yang Y, Sauve AA. NAD+ metabolism: bioenergetics, signaling and manipulation for therapy. Biochim Et Biophys Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2016;1864(12):1787–800. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2016.06.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Katsyuba E, Romani M, Hofer D, Auwerx J. NAD+ homeostasis in health and disease. Nat Metab. 2020;2(1):9–31. doi:10.1038/s42255-019-0161-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Gupte R, Liu Z, Kraus WL. PARPs and ADP-ribosylation: recent advances linking molecular functions to biological outcomes. Genes Dev. 2017;31(2):101–26. doi:10.1101/gad.291518.116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Alemasova EE, Lavrik OI. Poly (ADP-ribosyl) ation by PARP1: reaction mechanism and regulatory proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(8):3811–27. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Lee HC. Cyclic ADP-ribose and nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) as messengers for calcium mobilization. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(38):31633–40. doi:10.1074/jbc.R112.349464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Lee HC, Zhao YJ. Resolving the topological enigma in Ca2+ signaling by cyclic ADP-ribose and NAADP. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(52):19831–43. doi:10.1074/jbc.REV119.009635. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. De Flora A, Zocchi E, Guida L, Franco L, Bruzzone S. Autocrine and paracrine calcium signaling by the CD38/NAD+/cyclic ADP-ribose system. Ann New York Acad Sci. 2004;1028(1):176–91. doi:10.1196/annals.1322.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang Y, He J, Liao M, Hu M, Li W, Ouyang H, et al. An overview of Sirtuins as potential therapeutic target: structure, function and modulators. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;161:48–77. doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.10.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Wu QJ, Zhang TN, Chen HH, Yu XF, Lv JL, Liu YY, et al. The Sirtuin family in health and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):402. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-01257-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Osborne B, Bentley NL, Montgomery MK, Turner N. The role of mitochondrial sirtuins in health and disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;100:164–74. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Biţă A, Scorei IR, Ciocîlteu MV, Nicolaescu OE, Pîrvu AS, Bejenaru LE, et al. Nicotinamide riboside, a promising Vitamin B3 derivative for healthy aging and longevity: current research and perspectives. Molecules. 2023;28(16):6078. doi:10.3390/molecules28166078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Srivastava S. Emerging therapeutic roles for NAD+ metabolism in mitochondrial and age-related disorders. Clin Transl Med. 2016;5:1–11. doi:10.1186/s40169-016-0104-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Dölle C, Hvidsten Skoge R, VanLinden RM, Ziegler M. NAD biosynthesis in humans-enzymes, metabolites and therapeutic aspects. Curr Top Med Chem. 2013;13(23):2907–17. doi:10.2174/15680266113136660206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Feoep TO. Pathways and subcellular compartmentation of NAD biosynthesis in human cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(24):21767–78. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.213298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Mayer PR, Huang N, Dewey CM, Dries DR, Zhang H, Yu G. Expression, localization, and biochemical characterization of nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferase 2. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(51):40387–96. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.178913. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Cantó C, Menzies KJ, Auwerx J. NAD+ metabolism and the control of energy homeostasis: a balancing act between mitochondria and the nucleus. Cell Metab. 2015;22(1):31–53. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Elhassan YS, Philp AA, Lavery GG. Targeting NAD+ in metabolic disease: new insights into an old molecule. J Endocr Soc. 2017;1(7):816–35. doi:10.1210/js.2017-00092. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Carrico C, Meyer JG, He W, Gibson BW, Verdin E. The mitochondrial acylome emerges: proteomics, regulation by sirtuins, and metabolic and disease implications. Cell Metab. 2018;27(3):497–512. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.01.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. He W, Newman JC, Wang MZ, Ho L, Verdin E. Mitochondrial sirtuins: regulators of protein acylation and metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23(9):467–76. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2012.07.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Masri S, Sassone-Corsi P. Sirtuins and the circadian clock: bridging chromatin and metabolism. Sci Signal. 2014;7(342):re6. doi:10.1126/scisignal.2005685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Imai SI. “Clocks” in the NAD World: NAD as a metabolic oscillator for the regulation of metabolism and aging. Biochim Et Biophys Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2010;1804(8):1584–90. doi:10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.10.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Nakahata Y, Sahar S, Astarita G, Kaluzova M, Sassone-Corsi P. Circadian control of the NAD+ salvage pathway by CLOCK-SIRT1. Science. 2009;324(5927):654–7. doi:10.1126/science.1170803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Choudhary C, Weinert BT, Nishida Y, Verdin E, Mann M. The growing landscape of lysine acetylation links metabolism and cell signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2014;15(8):536–50. doi:10.1038/nrm3841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Song SB, Park JS, Jang SY, Hwang ES. Nicotinamide treatment facilitates mitochondrial fission through Drp1 activation mediated by SIRT1-induced changes in cellular levels of cAMP and Ca2+. Cells. 2021;10(3):612. doi:10.3390/cells10030612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Jang SY, Kang HT, Hwang ES. Nicotinamide-induced mitophagy: event mediated by high NAD+/NADH ratio and SIRT1 protein activation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(23):19304–14. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.363747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Song SB, Jang SY, Kang HT, Wei B, Jeoun UW, Yoon GS, et al. Modulation of mitochondrial membrane potential and ROS generation by nicotinamide in a manner independent of SIRT1 and mitophagy. Mol Cells. 2017;40(7):503–14. doi:10.14348/molcells.2017.0081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Raza U, Tang X, Liu Z, Liu B. SIRT7: the seventh key to unlocking the mystery of aging. Physiol Rev. 2024;104(1):253–80. doi:10.1152/physrev.00044.2022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Barber MF, Michishita-Kioi E, Xi Y, Tasselli L, Kioi M, Moqtaderi Z, et al. SIRT7 links H3K18 deacetylation to maintenance of oncogenic transformation. Nature. 2012;487(7405):114–8. doi:10.1038/nature11043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Blank MF, Grummt I. The seven faces of SIRT7. Transcription. 2017;8(2):67–74. doi:10.1080/21541264.2016.1276658. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Bao X, Liu Z, Zhang W, Gladysz K, Fung YME, Tian G, et al. Glutarylation of histone H4 lysine 91 regulates chromatin dynamics. Mol Cell. 2019;76(4):660–75.e9. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2019.08.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Yu AQ, Wang J, Jiang ST, Yuan LQ, Ma HY, Hu YM, et al. SIRT7-induced PHF5A decrotonylation regulates aging progress through alternative splicing-mediated downregulation of CDK2. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:710479. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.710479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Kudrin P, Meierhofer D, Vågbø CB, Ørom UAV. Nuclear RNA-acetylation can be erased by the deacetylase SIRT7. bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2021.04.06.438707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Lüscher B, Ahel I, Altmeyer M, Ashworth A, Bai P, Chang P, et al. ADP-ribosyltransferases, an update on function and nomenclature. FEBS J. 2022;289(23):7399–410. doi:10.1111/febs.16142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Bai P, Nagy L, Fodor T, Liaudet L, Pacher P. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases as modulators of mitochondrial activity. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26(2):75–83. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2014.11.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Ray Chaudhuri A, Nussenzweig A. The multifaceted roles of PARP1 in DNA repair and chromatin remodelling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017;18(10):610–21. doi:10.1038/nrm.2017.53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Vida A, Márton J, Mikó E, Bai P. Metabolic roles of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases. In: Seminars in cell & developmental biology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2017. [Google Scholar]

39. Cantó C, Sauve AA, Bai P. Crosstalk between poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase and sirtuin enzymes. Mol Asp Med. 2013;34(6):1168–201. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2013.01.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Szántó M, Bai P. The role of ADP-ribose metabolism in metabolic regulation, adipose tissue differentiation, and metabolism. Genes Dev. 2020;34(5–6):321–40. doi:10.1101/gad.334284.119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Guo S, Zhang S, Zhuang Y, Xie F, Wang R, Kong X, et al. Muscle PARP1 inhibition extends lifespan through AMPKα PARylation and activation in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2023;120(13):e2213857120. doi:10.1073/pnas.2213857120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Pirinen E, Canto C, Jo YS, Morato L, Zhang H, Menzies KJ, et al. Pharmacological Inhibition of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerases improves fitness and mitochondrial function in skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 2014;19(6):1034–41. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2014.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Scheibye-Knudsen M, Mitchell SJ, Fang EF, Iyama T, Ward T, Wang J, et al. A high-fat diet and NAD+ activate SIRT1 to rescue premature aging in cockayne syndrome. Cell Metab. 2014;20(5):840–55. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2014.10.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Gariani K, Ryu D, Menzies KJ, Yi HS, Stein S, Zhang H, et al. Inhibiting poly ADP-ribosylation increases fatty acid oxidation and protects against fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2017;66(1):132–41. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.08.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Bai P, Cantó C, Oudart H, Brunyánszki A, Cen Y, Thomas C, et al. PARP-1 inhibition increases mitochondrial metabolism through SIRT1 activation. Cell Metab. 2011;13(4):461–8. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Gui B, Gui F, Takai T, Feng C, Bai X, Fazli L, et al. Selective targeting of PARP-2 inhibits androgen receptor signaling and prostate cancer growth through disruption of FOXA1 function. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2019;116(29):14573–82. doi:10.1073/pnas.1908547116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Van Beek L, McClay É, Patel S, Schimpl M, Spagnolo L, Maia de Oliveira T. PARP power: a structural perspective on PARP1, PARP2, and PARP3 in DNA damage repair and nucleosome remodelling. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(10):5112. doi:10.3390/ijms22105112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Lee HC. MESSENGER the cyclic ADP-ribose/NAADP/CD38-signaling pathway: past and present. Messenger. 2012;1(1):16–33. [Google Scholar]

49. Zhang B, Watt JM, Cordiglieri C, Dammermann W, Mahon MF, Flügel A, et al. Small molecule antagonists of NAADP-induced Ca2+ release in T-lymphocytes suggest potential therapeutic agents for autoimmune disease. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):16775. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-34917-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Yu P, Liu Z, Yu X, Ye P, Liu H, Xue X, et al. Direct gating of the TRPM2 channel by cADPR via specific interactions with the ADPR binding pocket. Cell Rep. 2019;27(12):3684–95, e4. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Camacho-Pereira J, Tarragó MG, Chini CC, Nin V, Escande C, Warner GM, et al. CD38 dictates age-related NAD decline and mitochondrial dysfunction through an SIRT3-dependent mechanism. Cell Metab. 2016;23(6):1127–39. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Covarrubias AJ, Kale A, Perrone R, Lopez-Dominguez JA, Pisco AO, Kasler HG, et al. Senescent cells promote tissue NAD+ decline during ageing via the activation of CD38+ macrophages. Nat Metab. 2020;2(11):1265–83. doi:10.1038/s42255-020-00305-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Malavasi F, Deaglio S, Ferrero E, Funaro A, Sancho J, Ausiello CM, et al. CD38 and CD157 as receptors of the immune system: a bridge between innate and adaptive immunity. Mol Med. 2006;12:334–41. doi:10.2119/2006-00094.Malavasi. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Deaglio S, Aydin S, Grand MM, Vaisitti T, Bergui L, D’Arena G, et al. CD38/CD31 interactions activate genetic pathways leading to proliferation and migration in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Mol Med. 2010;16:87–91. doi:10.2119/molmed.2009.00146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Ortolan E, Augeri S, Fissolo G, Musso I, Funaro A. CD157: from immunoregulatory protein to potential therapeutic target. Immunol Lett. 2019;205:59–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

56. Migaud ME, Ziegler M, Baur JA. Regulation of and challenges in targeting NAD+ metabolism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2024;25(10):822–40. doi:10.1038/s41580-024-00752-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Wong R, Steenbergen C, Murphy E. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore and calcium handling. Mitochondrial Bioenerg Methods Protoc. 2012;810:235–42. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-382-0_15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Morciano G, Giorgi C, Bonora M, Punzetti S, Pavasini R, Wieckowski MR, et al. Molecular identity of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its role in ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;78:142–53. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.08.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Ellerby LM, Bredesen DE. Measurement of cellular oxidation, reactive oxygen species, and antioxidant enzymes during apoptosis. Vol. 322. In: Methods in enzymology. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2000. p. 413–21. [Google Scholar]

60. Li W, Sauve AA. NAD+ content and its role in mitochondria. Mitochondrial Regul Methods Protoc. 2015;1241:39–48. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-1875-1_4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Stein LR, Imai SI. The dynamic regulation of NAD metabolism in mitochondria. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23(9):420–8. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2012.06.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Nicholls C, Li H, Liu JP. GAPDH: a common enzyme with uncommon functions. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2012;39(8):674–9. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05599.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Kim H, Fu Z, Yang Z, Song Z, Yumnamcha T, Sun S, et al. The mitochondrial NAD kinase functions as a major metabolic regulator upon increased energy demand. Mol Metab. 2022;64:101562. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2022.101562. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Strømland Ø, Niere M, Nikiforov AA, VanLinden MR, Heiland I, Ziegler M. Keeping the balance in NAD metabolism. Biochem Soc Trans. 2019;47(1):119–30. doi:10.1042/BST20180417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Kulikova V, Gromyko D, Nikiforov A. The regulatory role of NAD in human and animal cells. Biochemistry. 2018;83:800–12. doi:10.1134/S0006297918070040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Reiten OK, Wilvang MA, Mitchell SJ, Hu Z, Fang EF. Preclinical and clinical evidence of NAD+ precursors in health, disease, and ageing. Mech Ageing Dev. 2021;199:111567. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2021.111567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Yoshino J, Baur JA, Imai SI. NAD+ intermediates: the biology and therapeutic potential of NMN and NR. Cell Metab. 2018;27(3):513–28. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2017.11.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Wang H, Sun Y, Pi C, Yu X, Gao X, Zhang C, et al. Nicotinamide mononucleotide supplementation improves mitochondrial dysfunction and rescues cellular senescence by NAD+/SIRT3 pathway in mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(23):14739. doi:10.3390/ijms232314739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Zhang H, Ryu D, Wu Y, Gariani K, Wang X, Luan P, et al. NAD+ repletion improves mitochondrial and stem cell function and enhances life span in mice. Science. 2016;352(6292):1436–43. doi:10.1126/science.aaf2693. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Bakhoum SF, Compton DA. Chromosomal instability and cancer: a complex relationship with therapeutic potential. J Clin Investig. 2012;122(4):1138–43. doi: 10.1172/JCI59954. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Lee SH, Lee JH, Lee HY, Min KJ. Sirtuin signaling in cellular senescence and aging. BMB Rep. 2019;52(1):24. doi:10.5483/BMBRep.2019.52.1.290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Chen C, Zhou M, Ge Y, Wang X. SIRT1 and aging related signaling pathways. Mech Ageing Dev. 2020;187:111215. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2020.111215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Umemoto T, Johansson A, Ahmad SAI, Hashimoto M, Kubota S, Kikuchi K, et al. ATP citrate lyase controls hematopoietic stem cell fate and supports bone marrow regeneration. EMBO J. 2022;41(8):e109463. doi:10.15252/embj.2021109463. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Sprecher U, D’Souza J, Mishra K, Canella Miliano A, Mithieux G, Rajas F, et al. Disease-associated programming of cell memory in glycogen storage disorder type 1a. bioRxiv. 2023. doi:10.1101/2023.02.20.529109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Raut SK, Khullar M. Oxidative stress in metabolic diseases: current scenario and therapeutic relevance. Mol Cell Biochem. 2023;478(1):185–96. doi:10.1007/s11010-022-04496-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Tarragó MG, Chini CC, Kanamori KS, Warner GM, Caride A, de Oliveira GC, et al. A potent and specific CD38 inhibitor ameliorates age-related metabolic dysfunction by reversing tissue NAD+ decline. Cell Metab. 2018;27(5):1081–95, e10. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2018.03.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Hill S, Van Remmen H. Mitochondrial stress signaling in longevity: a new role for mitochondrial function in aging. Redox Biol. 2014;2:936–44. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2014.07.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Neeland IJ, Lim S, Tchernof A, Gastaldelli A, Rangaswami J, Ndumele CE, et al. Metabolic syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

79. Okabe K, Yaku K, Tobe K, Nakagawa T. Implications of altered NAD metabolism in metabolic disorders. J Biomed Sci. 2019;26(1):34. doi:10.1186/s12929-019-0527-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Yan LJ. NADH/NAD+ redox imbalance and diabetic kidney disease. Biomolecules. 2021;14,11(5):730. doi: 10.3390/biom11050730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Kitada M, Ogura Y, Monno I, Koya D. Sirtuins and type 2 diabetes: role in inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial function. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:187. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Revollo JR, Körner A, Mills KF, Satoh A, Wang T, Garten A, et al. Nampt/PBEF/visfatin regulates insulin secretion in β cells as a systemic NAD biosynthetic enzyme. Cell Metab. 2007;6(5):363–75. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2007.09.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Trammell SA, Weidemann BJ, Chadda A, Yorek MS, Holmes A, Coppey LJ, et al. Nicotinamide riboside opposes type 2 diabetes and neuropathy in mice. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):26933. doi:10.1038/srep26933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Fan L, Cacicedo JM, Ido Y. Impaired nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) metabolism in diabetes and diabetic tissues: implications for nicotinamide-related compound treatment. J Diabetes Investig. 2020;11(6):1403–19. doi:10.1111/jdi.13303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Wu J, Jin Z, Zheng H, Yan LJ. Sources and implications of NADH/NAD+ redox imbalance in diabetes and its complications. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes Targets Ther. 2016;9:145–53. doi:10.2147/DMSO.S106087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Hou WL, Yin J, Alimujiang M, Yu XY, Ai LG, Bao YQ, et al. Inhibition of mitochondrial complex I improves glucose metabolism independently of AMPK activation. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22(2):1316–28. doi:10.1111/jcmm.13432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Porter LC, Franczyk MP, Pietka T, Yamaguchi S, Lin JB, Sasaki Y, et al. NAD+-dependent deacetylase SIRT3 in adipocytes is dispensable for maintaining normal adipose tissue mitochondrial function and whole body metabolism. Am J Physiol-Endocrinol Metab. 2018;315(4):E520–30. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00057.2018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Nielsen KN, Peics J, Ma T, Karavaeva I, Dall M, Chubanava S, et al. NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis is indispensable for adipose tissue plasticity and development of obesity. Mol Metab. 2018;11:178–88. doi:10.1016/j.molmet.2018.02.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Yang L, Shen J, Liu C, Kuang Z, Tang Y, Qian Z, et al. Nicotine rebalances NAD+ homeostasis and improves aging-related symptoms in male mice by enhancing NAMPT activity. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):900. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-36543-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Mishra K, Kakhlon O. Mitochondrial dysfunction in glycogen storage disorders (GSDs). Biomolecules. 2024;14(9):1096. doi:10.3390/biom14091096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Kurbatova O, Surkov A, Namazova-Baranova L, Polyakova S, Miroshkina L, Semenova G, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in children with hepatic forms of glycogen storage disease. Ann Russ Acad Med Sci. 2014;69(7–8):78–84. doi:10.15690/vramn.v69i7-8.1112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Cho JH, Kim GY, Mansfield BC, Chou JY. Sirtuin signaling controls mitochondrial function in glycogen storage disease type Ia. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2018;41:997–1006. doi:10.1007/s10545-018-0192-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Carling D, Viollet B. Beyond energy homeostasis: the expanding role of AMP-activated protein kinase in regulating metabolism. Cell Metab. 2015;21(6):799–804. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.05.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Cho JH, Kim GY, Pan CJ, Anduaga J, Choi EJ, Mansfield BC, et al. Downregulation of SIRT1 signaling underlies hepatic autophagy impairment in glycogen storage disease type Ia. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(5):e1006819. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006819. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Lautrup S, Hou Y, Fang EF, Bohr VA. Roles of NAD+ in Health and Aging. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2024;14(1):a041193. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a041193. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Peluso A, Damgaard MV, Mori MA, Treebak JT. Age-dependent decline of NAD+—universal truth or confounded consensus? Nutrients. 2021;14(1):101. doi:10.3390/nu14010101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Chini CCS, Cordeiro HS, Tran NLK, Chini EN. NAD metabolism: role in senescence regulation and aging. Aging Cell. 2024;23(1):e13920. doi:10.1111/acel.13920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Covarrubias AJ, Perrone R, Grozio A, Verdin E. NAD+ metabolism and its roles in cellular processes during ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22(2):119–41. doi:10.1038/s41580-020-00313-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Yuan Y, Cruzat VF, Newsholme P, Cheng J, Chen Y, Lu Y. Regulation of SIRT1 in aging: roles in mitochondrial function and biogenesis. Mech Ageing Dev. 2016;155:10–21. doi:10.1016/j.mad.2016.02.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Xu C, Wang L, Fozouni P, Evjen G, Chandra V, Jiang J, et al. SIRT1 is downregulated by autophagy in senescence and ageing. Nat Cell Biol. 2020;22(10):1170–9. doi:10.1038/s41556-020-00579-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Maynard S, Fang EF, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Croteau DL, Bohr VA. DNA damage, DNA repair, aging, and neurodegeneration. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5(10):a025130. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a025130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Welch G, Tsai LH. Mechanisms of DNA damage-mediated neurotoxicity in neurodegenerative disease. EMBO Rep. 2022;23(6):e54217. doi:10.15252/embr.202154217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Chen Z, Tao S, Li X, Yao Q. Resistin destroys mitochondrial biogenesis by inhibiting the PGC-1α/NRF1/TFAM signaling pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;504(1):13–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.08.027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Mouchiroud L, Houtkooper RH, Moullan N, Katsyuba E, Ryu D, Cantó C, et al. The NAD+/sirtuin pathway modulates longevity through activation of mitochondrial UPR and FOXO signaling. Cell. 2013;154(2):430–41. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Poljsak B, Milisav I. NAD+ as the link between oxidative stress, inflammation, caloric restriction, exercise, DNA repair, longevity, and health span. Rejuvenation Res. 2016;19(5):406–13. doi:10.1089/rej.2015.1767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Cantó C, Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Youn DY, Oosterveer MH, Cen Y, et al. The NAD+ precursor nicotinamide riboside enhances oxidative metabolism and protects against high-fat diet-induced obesity. Cell Metab. 2012;15(6):838–47. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Han X, Bao X, Lou Q, Xie X, Zhang M, Zhou S, et al. Nicotinamide riboside exerts protective effect against aging-induced NAFLD-like hepatic dysfunction in mice. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7568. doi:10.7717/peerj.7568. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Sun X, Cao B, Naval-Sanchez M, Pham T, Sun YBY, Williams B, et al. Nicotinamide riboside attenuates age-associated metabolic and functional changes in hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2665. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22863-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Igarashi M, Miura M, Williams E, Jaksch F, Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, et al. NAD+ supplementation rejuvenates aged gut adult stem cells. Aging Cell. 2019;18(3):e12935. doi:10.1111/acel.12935. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Nadeeshani H, Li J, Ying T, Zhang B, Lu J. Nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) as an anti-aging health product-promises and safety concerns. J Adv Res. 2022;37:267–78. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2021.08.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Soma M, Lalam SK. The role of nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) in anti-aging, longevity, and its potential for treating chronic conditions. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49(10):9737–48. doi:10.1007/s11033-022-07459-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Song Q, Zhou X, Xu K, Liu S, Zhu X, Yang J. The safety and anti-ageing effects of nicotinamide mononucleotide in human clinical trials: an update. Adv Nutr. 2023;14(6):1416–35. doi:10.1016/j.advnut.2023.08.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Hassan W, Noreen H, Rehman S, Kamal MA, da Rocha JB. Association of oxidative stress with neurological disorders. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2022;20(6):1046–72. doi:10.2174/1570159X19666211111141246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Lautrup S, Sinclair DA, Mattson MP, Fang EF. NAD+ in brain aging and neurodegenerative disorders. Cell Metab. 2019;30(4):630–55. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2019.09.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]