Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Exacerbated Cellular Senescence in Human Dopaminergic Neurons along with an Increase in LRRK2 Kinase Activity

1 InAm Neuroscience Research Center, Wonkwang University, Sanbon Medical Center, Sanbon-Ro, Gunpo-Si, 15865, Republic of Korea

2 Stem Cell Convergence Research Center, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB), Daejeon-Si, 34141, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Functional Genomics, KRIBB School of Bioscience, University of Science and Technology, Daejeon-Si, 34113, Republic of Korea

4 Paik Institute for Clinical Research, College of Medicine, Inje University, Busan-Si, 47392, Republic of Korea

5 Department of Convergence Biomedical Science, College of Medicine, Inje University, Busan-Si, 47392, Republic of Korea

6 Department of Neurology, Wonkwang University, Sanbon-ro, Gunpo-Si, 15865, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Dong Hwan Ho. Email: ; Ilhong Son. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: LRRK2 and Alpha-Synucleinopathy: Molecular Mechanisms in Neuroinflammation and Parkinson's Disease)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(7), 1225-1244. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.065486

Received 14 March 2025; Accepted 21 May 2025; Issue published 25 July 2025

Abstract

Background: Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a common neurodegenerative disease, characterized by symptoms like tremors, muscle rigidity, and slow movement. The main cause of these symptoms is the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in a brain area called the substantia nigra. Various genetic and environmental factors contribute to this neuronal loss. Once symptoms of PD begin, they worsen with age, which also impacts several critical cellular processes. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) is a gene associated with PD. Certain mutations in LRRK2, such as G2019S, increase its activity, disrupting cellular mechanisms necessary for healthy neuron function, including autophagy and lysosomal activity. Exposure to rotenone (RTN) promotes LRRK2 activity in neurons and contributes to cellular senescence and α-syn accumulation. Methods: In this study, human dopaminergic progenitor cells were reprogrammed to study the effects of RTN with the co-treatment of LRRK2 inhibitor on cellular senescence. We measured the cellular senescence using quantifying proteins of senescence markers, such as p53, p21, Rb, phosphorylated Rb, and β-galatocidase, and the enzymatic activity of senescence-associated β-galatocidase. And we estimated the levels of accumulated α-synuclein (α-syn), which is increased via the impaired autophagy-lysosomal pathway by cellular senescence. Then, we evaluated the association of the G2019S LRRK2 mutation and senescence-associated β-galatocidase and the levels of accumulated or secreted α-syn, and the neuroinflammatory responses mediated by the secreted α-syn in rat primary microglia were determined using the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Results: RTN raised senescence markers and affected the phosphorylation of Rab10, a substrate of LRRK2. The inhibiting agent MLI2 reduced these senescence markers and Rab10 phosphorylations. Additionally, RTN increased α-syn levels in the neurons, while MLI2 aided in degrading it. When focusing on cells from PD patients with the G2019S mutation, an increase in cellular senescence and release of α-syn was observed, provoking neuroinflammation. Treatment with the LRRK2 inhibitor MLI2 decreased both cellular senescence and α-syn secretion, thereby mitigating inflammatory responses. Conclusion: Overall, inhibiting LRRK2 may provide a beneficial strategy for managing PD.Keywords

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease worldwide. The main symptoms of PD are characterized by abnormal spontaneous movements and postural disturbances, including tremors, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability. The loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta is a major pathological hallmark of PD and is the primary cause of its motor symptoms [1]. Various genetic and environmental factors contribute to dopaminergic neuron degeneration [2,3]; however, neuroinflammation caused by reactive microglia or astrocytes plays a crucial role in mediating neuronal loss [4]. Recent studies have reported that a lack of neurotrophic factors increases the vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons to cellular stress [5]. Once PD symptoms appear, they progressively worsen with age. Aging plays a pivotal role in most neurodegenerative diseases by altering critical cellular processes essential for survival [6]. One such process is cellular senescence—an irreversible aging-related state distinct from quiescence [7]. Cellular senescence in dopaminergic neurons leads to impaired lysosomal function, promoting the accumulation of α-synuclein (α-syn) within cells [8]. The aggregation of α-syn is a major molecular hallmark of PD pathology, and its propagation through brain tissue via neuron-to-neuron and neuron-to-astroglia interactions is closely linked to disease progression [9,10].

Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), a causative gene of PD, exhibits increased penetrance with aging in sporadic PD patients. The mutants of LRRK2, including G2019S, R1441C/G/H, and I2020T, have been extensively studied because these variants are associated with enhanced LRRK2 kinase activity [11]. As LRRK2 kinase activity increases, several cellular mechanisms essential for maintaining homeostasis, such as autophagy [12], vesicle trafficking [13], lysosomal function [14], mitochondrial membrane potential [15], and programmed cell death [16], become disrupted in dopaminergic neurons. Additionally, LRRK2 kinase activity is implicated in the activation of microglia and astrocytes, processes that are also closely linked to cellular senescence. In our previous study, rotenone (RTN) increased LRRK2 kinase activity in the human neuroblastoma cell line SH-SY5Y upon differentiation into dopaminergic neurons using retinoic acid. Simultaneously, RTN treatment induced cellular senescence, lysosomal dysfunction, and autophagic accumulation, thereby exacerbating α-syn deposition. Notably, treatment with an LRRK2 kinase inhibitor rescued RTN-induced LRRK2 kinase activation, mitigated cellular senescence, restored autophagy-lysosome pathway function, and promoted α-syn degradation [8]. We observed similar findings in rat primary cortical neurons and the mouse midbrain, confirming that LRRK2 kinase inhibition modulates these RTN-mediated cellular processes across multiple models. Here, we sought to reproduce the effects of LRRK2 kinase activity modulation by RTN in induced human dopaminergic neurons (iDP-neurons) and investigate whether iDP-neurons reprogrammed from fibroblasts of a G2019S LRRK2 patient—harboring the kinase-enhancing mutation—exhibit increased cellular senescence and α-syn accumulation. Furthermore, we examined whether LRRK2 kinase inhibition could rescue cellular senescence and α-synucleinopathy in this system.

2.1 Cell Culture and Drug Treatment

All human fibroblast cell lines used in this study were obtained by Dr. Janghwan Kim from the Coriell Institute (Camden, NJ, USA) [17]. To generate induced human dopaminergic progenitor (iDP) cells, human fibroblast cells were reprogrammed using AG02261 (RRID: CVCL_0D99; WT LRRK2) and ND38262 (RRID: CVCL_EZ26; G2019S LRRK2) cell lines. The cells were cultured in human neural reprogramming medium, which consisted of a 1:1 mixture of advanced Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM)/F-12 (12634-010; Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and Neurobasal medium (21103-049; Gibco). The medium was supplemented with 0.05% AlbuMAX (11020-021; Gibco), 1× N2 (17502-048; Gibco), 1× B27 without Vitamin A (12587-010; Gibco), 2× GlutaMAX (35050; Gibco), 3.0 μM CHIR99021 (4423; Tocris, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and 0.5 μM A83-01 (2939; Tocris) at 37°C with 5% carbon dioxide. Additionally, the culture medium contained 50 μg/mL 2-phospho-L-ascorbic acid (49752; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 200 μg/mL sonic hedgehog (SHH, 464-SH-200; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and 100 μg/mL fibroblast growth factor 8 (FGF8, 100-25; Peprotech, Cranbury, NJ, USA). For neuronal differentiation, iDP cells (4 × 105 cells per well) were plated onto 12-well plates (30012; SPL, Pocheon-si, Republic of Korea) and cultivated in neuronal differentiation medium, which consisted of DMEM/F-12 (11330-032; Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with B27 without Vitamin A, 50 μg/mL 2-phospho-L-ascorbic acid, 20 ng/mL brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF, 450-02; Peprotech), 20 ng/mL glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF, 450-10; Peprotech), and 0.5 mM dibutyryl-cAMP (dbcAMP, CN125-100; Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, USA). During the cultivation of iDP cells or the differentiation of neurons, there were no mycoplasma contaminations. For experiments involving RTN and MLI2, an LRRK2 kinase inhibitor, differentiated iDP-neurons were maintained for 21 days with media changes every other day to reproduce the iDP-neuron in the previous study [17]. RTN (200 nM) or MLI2 (300 nM) was simultaneously added to the neuronal differentiation medium and administered to iDP-neurons for 3 days to harvest cells before cell death by RTN. To investigate the effect of the LRRK2 kinase inhibitor on G2019S LRRK2 iDP-neurons, 300 nM MLI2 or vehicle (DMSO) was mixed with the neuronal differentiation medium and replaced every other day for 21 days. Although it varies depending on the cells and culture conditions, MLI-2 shows toxicity at high concentrations, such as 1 μM; the concentration was set at 300 nM, with the understanding that it is treated with RTN simultaneously. Furthermore, we administered 300 nM MLI-2 to avoid similar toxic effects along with the long-term treatment. However, to ensure a definitive effect, MLI-2 was treated at higher concentrations than the initial report, which described the drug’s Inhibitory Concentration 50 at 0.76 to 3.4 nM [18].

2.2 Preparation of Fibrillar α-Syn

EndoClear™ (Franca, Brazil) human recombinant α-syn protein (Anaspec, AS-55555-1000) was purchased and reconstituted according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Recombinant α-syn (2 μg/mL) was incubated at 37°C for 21 days under continuous rotation at 300 rpm to induce fibril formation using a shaking incubator (SI-600R, Jeiotech, Deajon, Republic of Korea). Following incubation, the heterogeneous α-syn mixture was subjected to ultracentrifugation at 100,000× g for 1 h at 4°C. The fibrillar α-syn was collected as a pellet after centrifugation. The concentration of fibrils was then determined using an α-syn enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

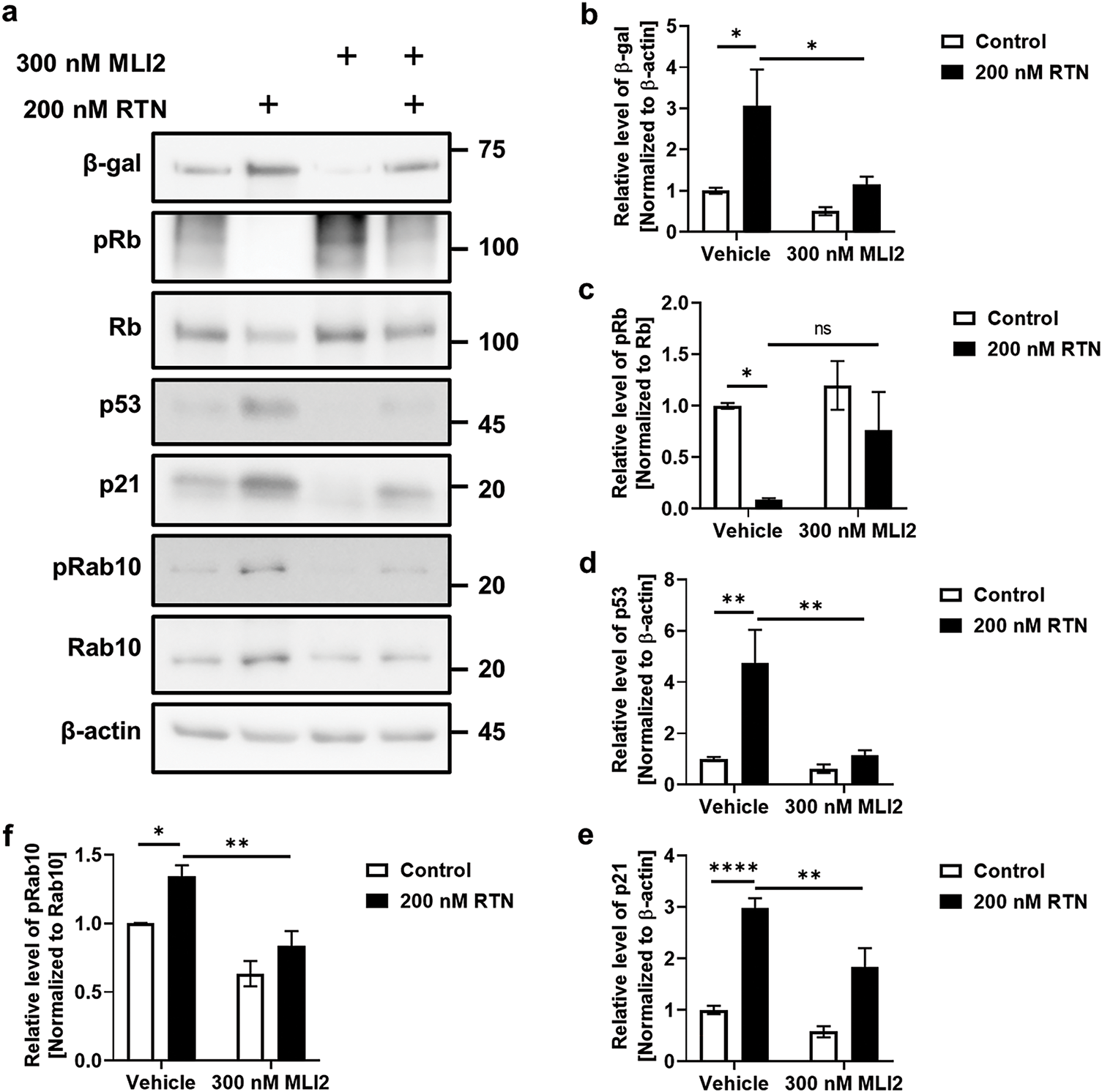

Protein quantification was performed as follows: First, cells were washed twice with Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (DPBS; LB001-02; Welgene, Gyeongsan-si, Republic of Korea) at 4°C. The cells were then harvested using 4× Laemmli sample buffer, reducing agent (L1100-001; GenDEPOT, Katy, TX, USA), and 1× sample buffer diluted with sterile water. Samples were sonicated for 20 s at 10% amplification frequency using a sonicator (VCX 130; Sonics & Materials, Inc., Newtown, CT, USA) and subsequently boiled at 95°C for 5 min. Each sample was loaded onto a 4%–20% MINI-PROTEAN® TGX Precast Protein Gel, 15-well (15 μL; 4561096; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and subjected to electrophoresis at 100 V for 100 min. Following electrophoresis, proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (10600004; Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis at 300 mA for 80 min. The membranes were then blocked with 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) for 30 min at room temperature (RT). Primary antibodies (listed in Table 1) were diluted in 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in TBST and incubated with the membranes overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed three times with TBST before incubation with secondary antibodies (Table 1) for an hour at RT. The primary antibodies were administered at an initial ratio of 1:1000, while the secondary antibodies were administered at an initial ratio of 1:5000. Immunoreactive signals were developed using Luminata Crescendo Western horseradish peroxidase (HRP; WBLUR0500; Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA). Protein bands were visualized using a MicroChemi 4.2 camera (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

2.4 The Measurement of Lysosomal Activity

We seeded iDP-neurons differentiated for one week onto 96-well dark plates and differentiated them for another two weeks. After simultaneously treatment with 200 nM rotenone and 300 nM MLi-2 for 3 days, 500 nM LysoSensor™ Blue DND-167 (L7533, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was added without fixation, and analyzed with Flexstation 3 (Molecular Device, San Jose, CA, USA)) at 375 nm excitation and 425 nm emission wavelengths..

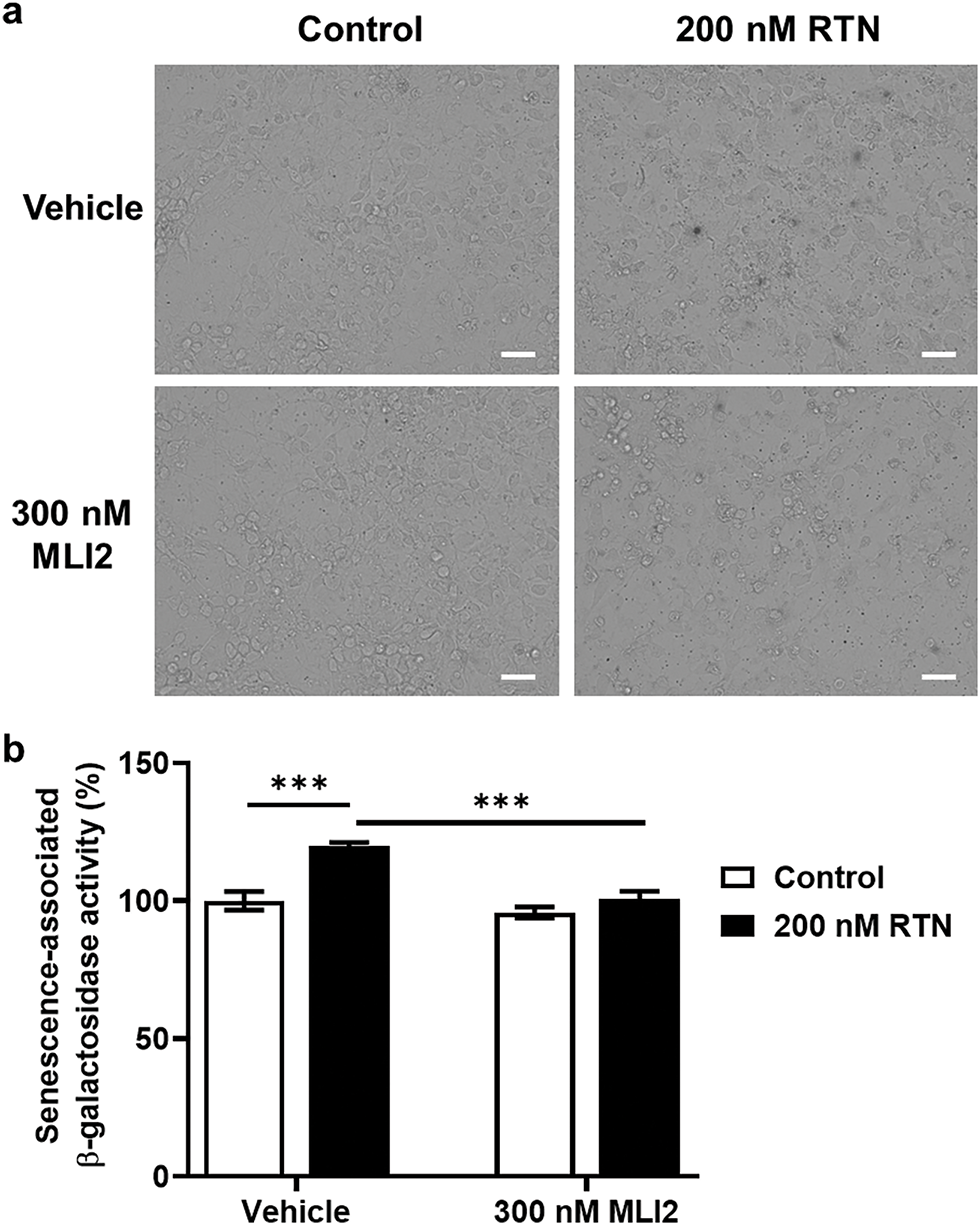

2.5 Senescence-Associated β-Gal Activity Staining

The SA β-gal activity was assessed using the Senescence β-gal Staining Kit (9860; Cell Signaling Technology), following the manufacturer’s instructions. All images were captured using the EVOS M7000 microscope (AMF7000HCA; Thermo Fisher Scientific). For image analysis, co-treatment images involving RTN and MLI2 were processed using ImageJ 1.52a (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, ND, USA), applying the Alcian Blue & Haematoxylin vector in Color Deconvolution 2. Similarly, images of WT, G2019S, and vehicle or MLI2-treated samples were analyzed by applying the Astra Blue and Fuchsin vectors in Color Deconvolution 2 of ImageJ.

2.6 Total and Fibril α-Syn ELISA

After collecting the culture media, iDP-neurons were washed twice with DPBS. Crude extracts of iDP-neurons were prepared using M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent (78503, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 1× Xpert Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Solution (P3100; GenDepot, Katy, TX, USA) and 1× Xpert Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail Solution (P3200; GenDepot). Both culture media and crude extracts were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C using Combi514R (Hanil Scientific Inc., Gimpo, Republic of Korea). The resulting supernatants were analyzed using ELISA, previously established in our laboratory, to detect total and fibrillar α-syn using two pairs of antibodies (Table 2) [19].

2.7 Concentration of Culture Media

To prepare iDP-neuron culture media for application to primary mouse microglia, the culture medium was concentrated to 5× the original volume and subsequently washed five times with equal volumes of DMEM/F-12 (LM002-04; Welgene). Concentration was performed using 10K filter tubes (Microsep Advance Centrifugal Devices with Omega Membrane—10K, MCP010C41; Pall, Port Washington, NY, USA). Following concentration and washing, the 5× concentrated culture medium was collected in 2.0 mL Eppendorf tubes (MCT-200-C; Axygen, Union City, CA, USA) and stored in a deep freezer. Before use, the concentrated medium was freshly diluted in the culture media for rat primary microglia to achieve a 1× concentration level.

2.8 Rat Primary Microglia Isolation

The rats at embryonic day 15 (Sprague Dawley; 37 females, 23 males) were purchased from Hanna Biotech (Pyeontaek-si, Republic of Korea). Primary microglia and astrocyte cultures were initiated using cortices isolated from fetal rat brains at embryonic day 17 of 12 females via euthanizing by carbon dioxide. The cortices were dissected and enzymatically dissociated by incubating in 0.25% trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) with phenol red (25200056; Gibco) and bovine pancreatic deoxyribonuclease I (DN-25-100MG; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min. The cells were dissociated using pipetting, and cell debris and myelin were removed by centrifugation at 200× g for 10 min at room temperature. The resulting cell suspension was filtered through a nylon mesh and seeded into T75 culture flasks (11090; SPL). The flasks were maintained in DMEM/F-12 (LM002-04; Welgene) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; BFS-1000; T&I, Chuncheon-si, Republic of Korea) and 1× antibiotic-antimycotic. After one week, cells were detached using TrypLE™ Express enzyme (1×) without phenol red (12604013; Gibco) and replated into T75 flasks for further expansion. After two weeks, microglia were selectively detached by gentle tapping. Subsequently, 5 × 105 primary mouse microglia were seeded into 12-well plates (30012; SPL) for experimental procedures. The following day, iDP-neuron culture media was added to microglial cultures and incubated for 24 h. Cells and culture media were then harvested for subsequent analyses.

To measure pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, culture media from rat primary microglia were harvested by centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C using Combi514R. The levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) were quantified using ELISA MAX™ Deluxe Set Rat TNF-α (438204; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) and iNOS ELISA Kit (MBS723326; MyBiosource, San Diego, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a Synergy 2 microplate reader (Biotek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

Senescence-associated β-gal activity staining intensities were analyzed using ImageJ (RRID: SCR_003070, Ver. 1.52a, National Institutes of Health, LOCI, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA) with the Color Deconvolution 2 plug-in [20]. Western blot protein quantification from nitrocellulose membranes was performed using Multi Gauge V 3.0 (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan). All datasets were analyzed and visualized using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The methods and significance of all statistical analyses are described in the figure legends.

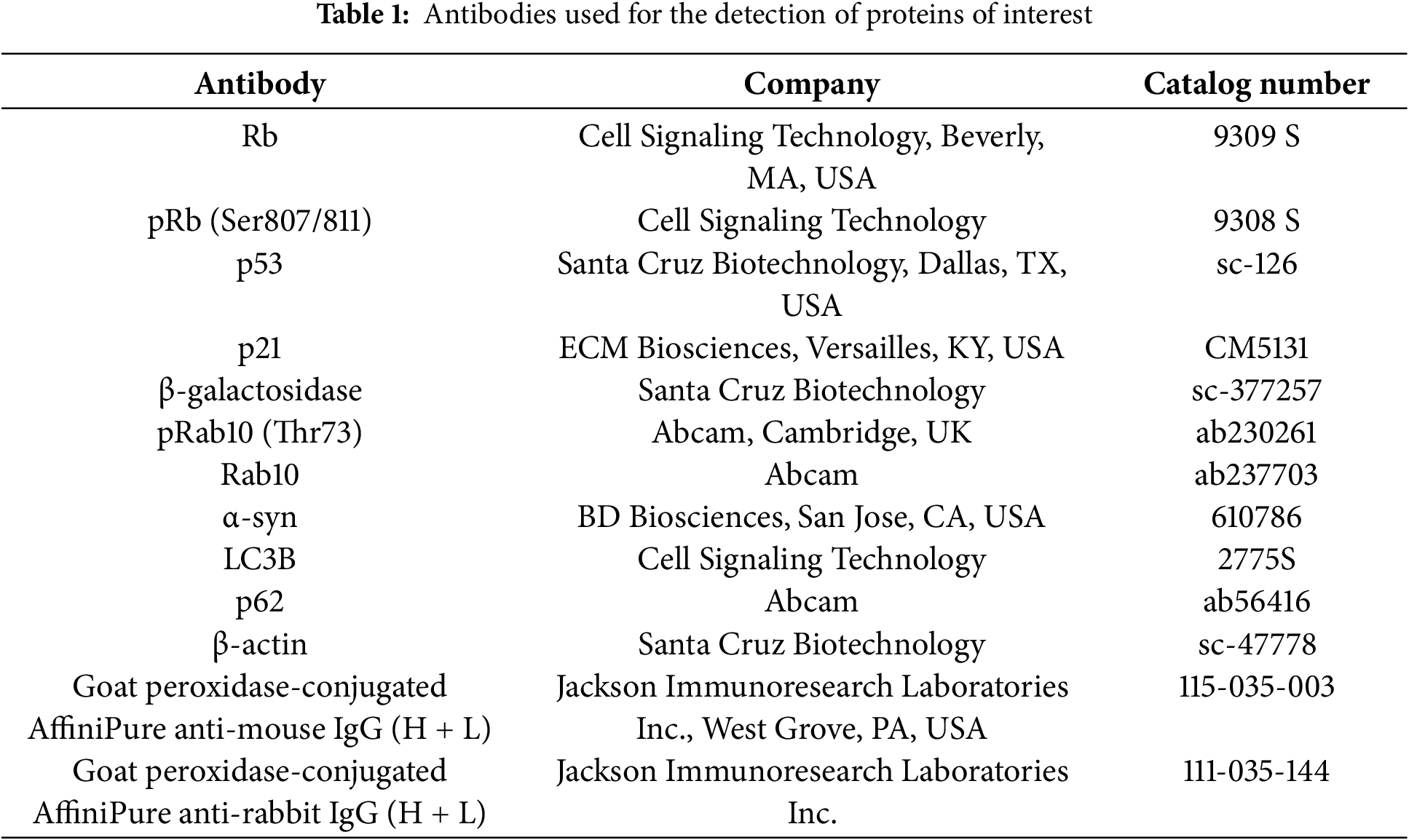

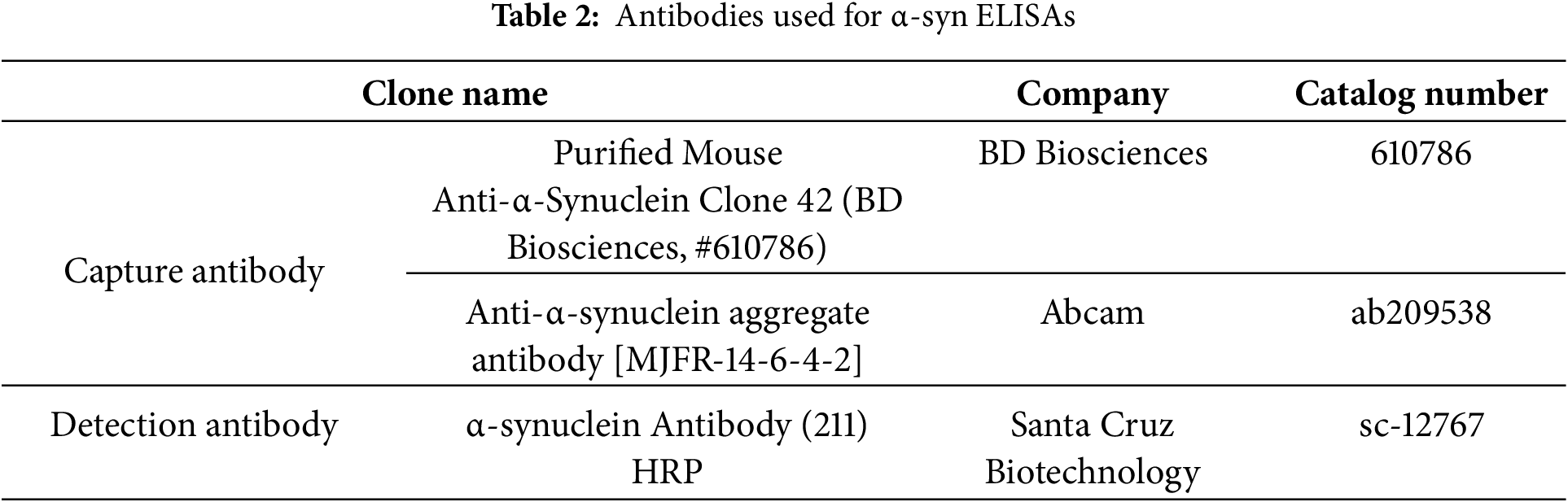

3.1 Rontenone Mediates Cellular Senescence via LRRK2 Kinase Activation

Our previous study demonstrated that the elevation of LRRK2 kinase activity by RTN in differentiated SH-SY5Y cells, rat primary cortical neurons, and the mouse midbrain exacerbated cellular senescence [8]. Additionally, treatment with an LRRK2 kinase inhibitor mitigated RTN-induced cellular senescence. However, whether cellular senescence is directly influenced by RTN-mediated LRRK2 kinase activity or LRRK2 kinase inhibition in an authentic human dopaminergic neuron remains unclear. To address this, we cultured reprogrammed human dopaminergic progenitor cells and differentiated them into iDP-neurons. RTN treatment significantly elevated cellular senescence markers, including an increase in beta-galactosidase (β-gal), p53, and p21, along with a decrease in the phosphorylation of retinoblastoma protein (Rb) (Fig. 1a–e). Furthermore, Rab10, a well-established LRRK2 kinase substrate, exhibited significantly increased phosphorylation following RTN treatment (Fig. 1a,f). Notably, treatment with the LRRK2 kinase inhibitor MLI2 rescued RTN-mediated cellular senescence and concurrently inhibited Rab10 phosphorylation (Fig. 1). Additionally, RTN-induced activation of senescence-associated β-gal was reversed by MLI2 treatment (Fig. 2). Collectively, these findings suggest that RTN is a crucial environmental factor that promotes cellular senescence via LRRK2 kinase activity in multiple models, including iDP-neurons, the mouse midbrain, rat primary cortical neurons, and secondary human cell lines. Moreover, LRRK2 kinase inhibition represents a potential therapeutic strategy for individuals exposed to environmental toxins.

Figure 1: Induction of cellular senescence via LRRK2 kinase activation by rotenone and its amelioration by LRRK2 kinase. Inhibition of RTN-mediated cellular senescence was assessed in iDP-neurons, and the effect of LRRK2 kinase inhibition by MLI2 was examined. (a) Western blot analysis was performed to evaluate the effects of RTN and MLI2 on cellular senescence markers and LRRK2 kinase activity. (b–e) Densitometry quantification of cellular senescence marker proteins, including β-gal (b), phosphorylated Rb (pRb) and total Rb (c), p53 (d), and p21 (e), was performed and plotted as a graphical representation. (f) Changes in LRRK2 kinase activity following RTN and MLI2 treatment were determined by measuring phosphorylated Rab10 (pRab10) levels normalized to total Rab10. Cells were treated with 200 nM RTN or 300 nM MLI2 for 72 h. N = 6 (duplicates per N); statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis. Significance levels: ns, not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001

Figure 2: Senescence-associated β-gal staining and LRRK2 kinase activity modulation by RTN or MLI2. Senescence-associated β-gal activity was assessed following RTN or MLI2 treatment. (a) X-gal staining was performed to visualize senescence-associated β-gal activity, with arrowheads indicating stained cells. White bar = 15 μm. (b) Quantification of β-gal activity was plotted as a graphical representation. Cells were treated with 200 nM RTN or 300 nM MLI2 for 72 h. N = 6 (one image per N); statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis. Significance level: ***p < 0.001

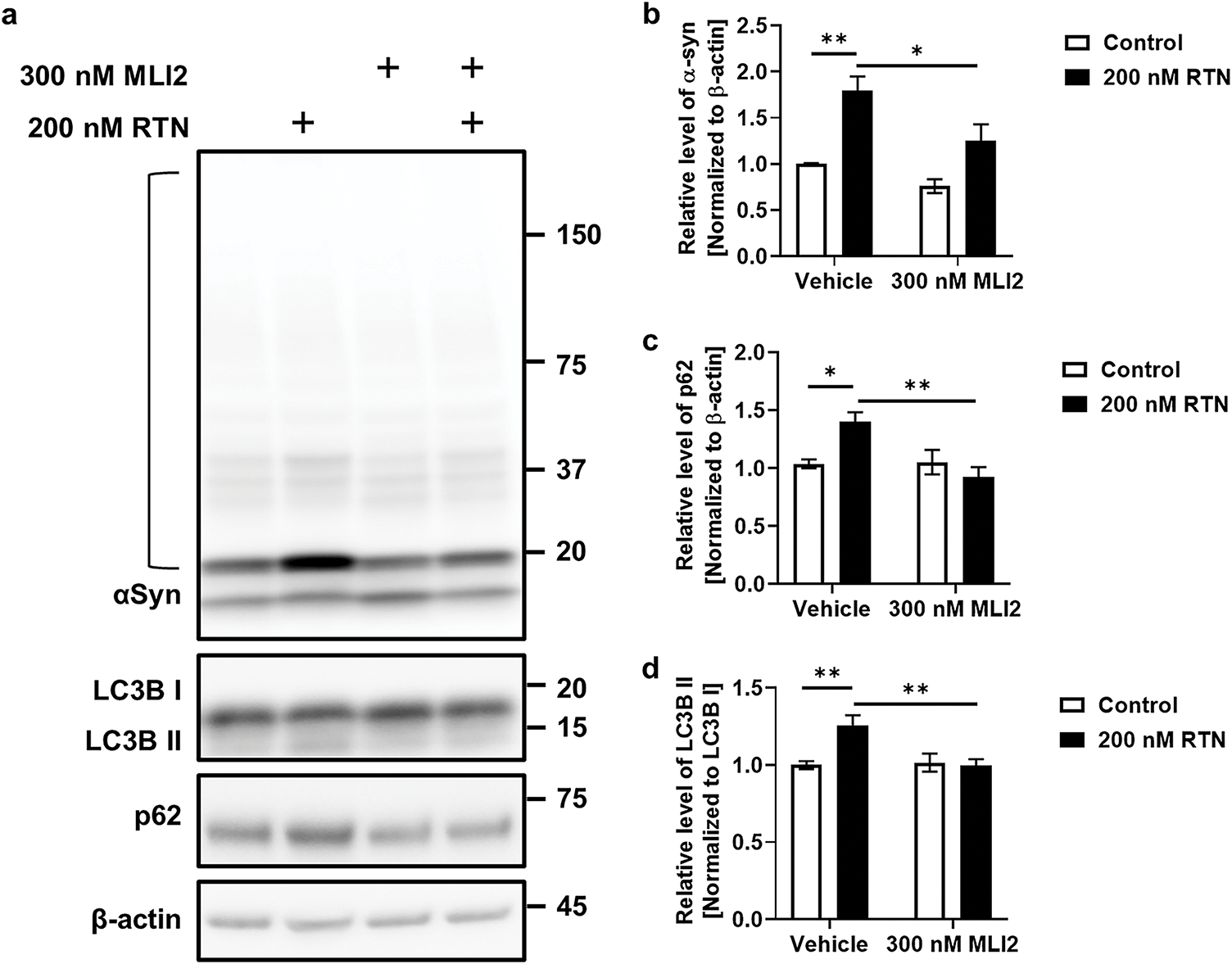

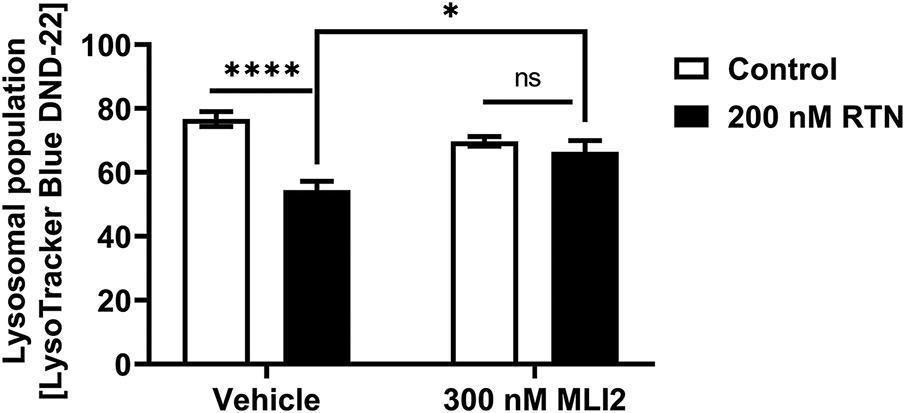

3.2 Rotenone-Mediated Cellular Senescence Increases Accumulation of α-Syn

The accumulation of α-syn was previously shown to be enhanced by LRRK2-mediated cellular senescence in our earlier studies [8,21]. Here, we investigated whether RTN induces α-syn accumulation and whether MLI2 treatment facilitates α-syn clearance in iDP-neurons. We found that fibrillar α-syn significantly accumulated in iDP-neurons following RTN treatment, whereas MLI2 treatment effectively degraded α-syn fibrils (Fig. 3a,b). This accumulation was speculated to be due to abnormalities in the degradation mechanism of aggregates known to be primarily degraded by autophagy, and p62 and LC3B, key markers of this mechanism, were investigated. p62 is a selective autophagy receptor that recognizes ubiquitinated cargo and links it to the autophagosome by binding to LC3B on the autophagosome membrane [22]. The cleavage of pro-LC3B by Atg4 generates LC3B-I, which is then modified to its membrane-associated form (LC3B-II), a crucial step for its incorporation into the autophagosome and interaction with p62, thereby facilitating the engulfment and degradation of specific cellular components; both p62 and LC3B-II are eventually degraded within the autolysosome, making p62 degradation a marker of autophagic flux and the conversion of LC3B-I to LC3B-II an indicator of autophagosome formation [23]. RTN increased the expression of p62/sequestosome-1, which was subsequently reduced by MLI2 treatment. Similarly, LC3B-II accumulation was elevated by RTN and attenuated by MLI2 (Fig. 3a,c,d). These results were observed without blocking the autophagy-lysosome flux by treating with bafilomycin A1. In a previous study, we performed the experiment under similar conditions using SH-SY5Y cells differentiated into dopaminergic neurons by treating them with retinoic acid for 7 days, and the accumulation of LC3II and p62 coincided with the decrease in the active lysosomes exhibiting low pH [8], suggesting that this similar result of low lysosomal activity in iDP-neuron would support the decrease in the autophagy-lysosome pathway (Fig. A1). These findings suggest that RTN-induced LRRK2 kinase upregulation promotes α-syn accumulation and aggregation in dopaminergic neurons. Furthermore, treatment with LRRK2 kinase inhibitors may enhance the degradation and clearance of α-syn. α-Syn would exist as monomers, dimers, tetramers, or small oligomers in cells, and in this study, we did not identify any conformational species or strains of α-syn, as our approach was to use artificial fibrils composed of recombinant alpha-synuclein to investigate the accumulation of alpha-synuclein aggregates as a consequence of cellular aging via an autophagic failure. Furthermore, it was not possible because the alpha-synuclein fibrils we processed are more likely than other α-syn conformers to aggregate fibrillar structure due to seeding effects as reported in previous studies [24,25], and the amount of endogenous α-syn already present is too small to identify these structures by an immunoblot, and there are no structure-specific antibodies available to identify them.

Figure 3: Clearance of RTN-induced α-synuclein accumulation via LRRK2 kinase inhibition. The effect of LRRK2 kinase inhibition on α-syn clearance was assessed following RTN and MLI2 treatment. (a) Western blot analysis was performed on cells treated with 100 nM fibrillar α-syn, along with 200 nM RTN or 300 nM MLI2 for 72 h. (b–d) Accumulated α-syn fibrils were measured in each lane (open bracket). Quantification of α-syn accumulation (b), p62 levels (c), and the LC3B-II/LC3B-I ratio (d) was plotted as graphical representations. N = 6 (duplicates per N); statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis. Significance levels: *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01

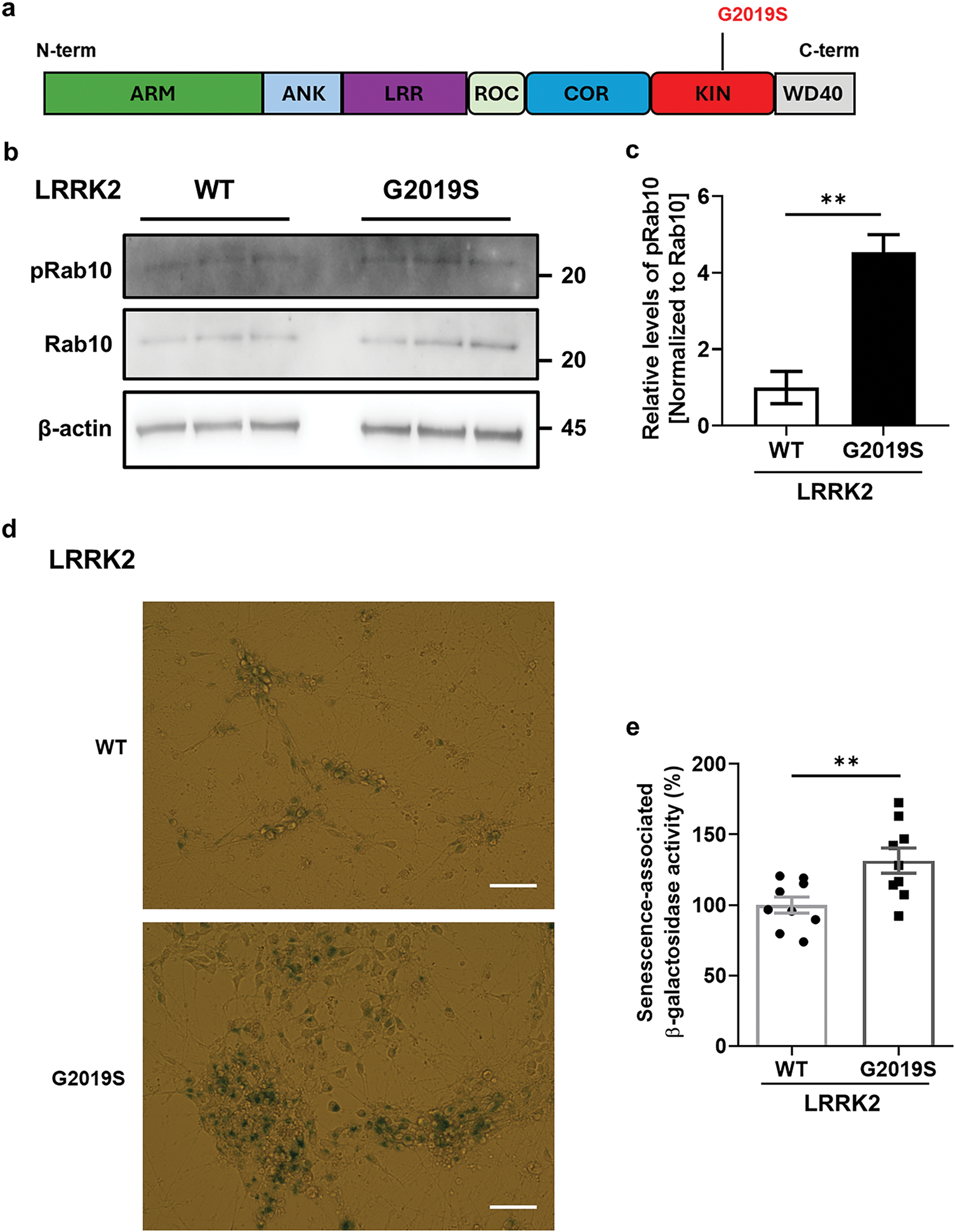

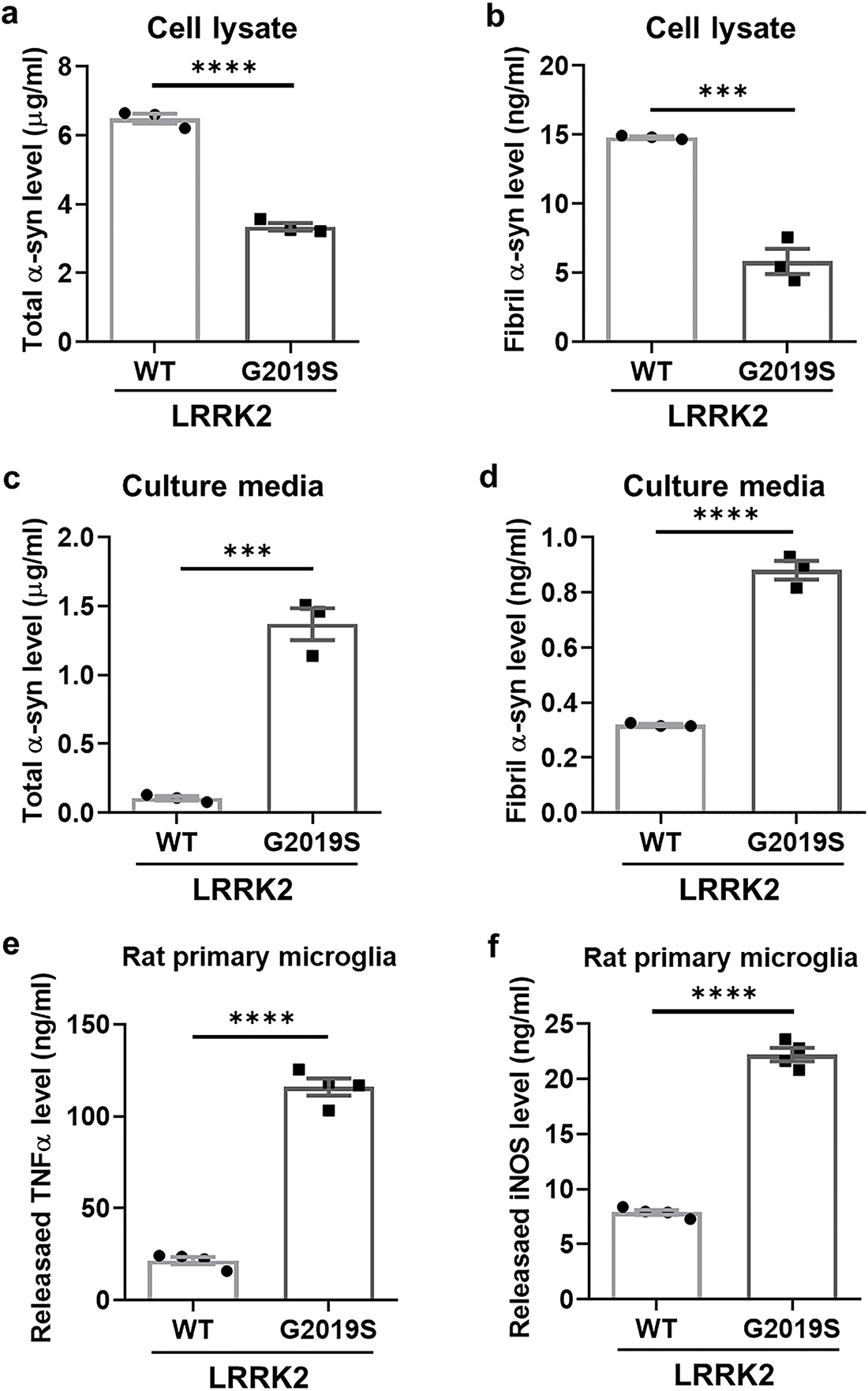

3.3 G2019S LRRK2 Mutant Increases Cellular Senescence and α-Syn Secretion

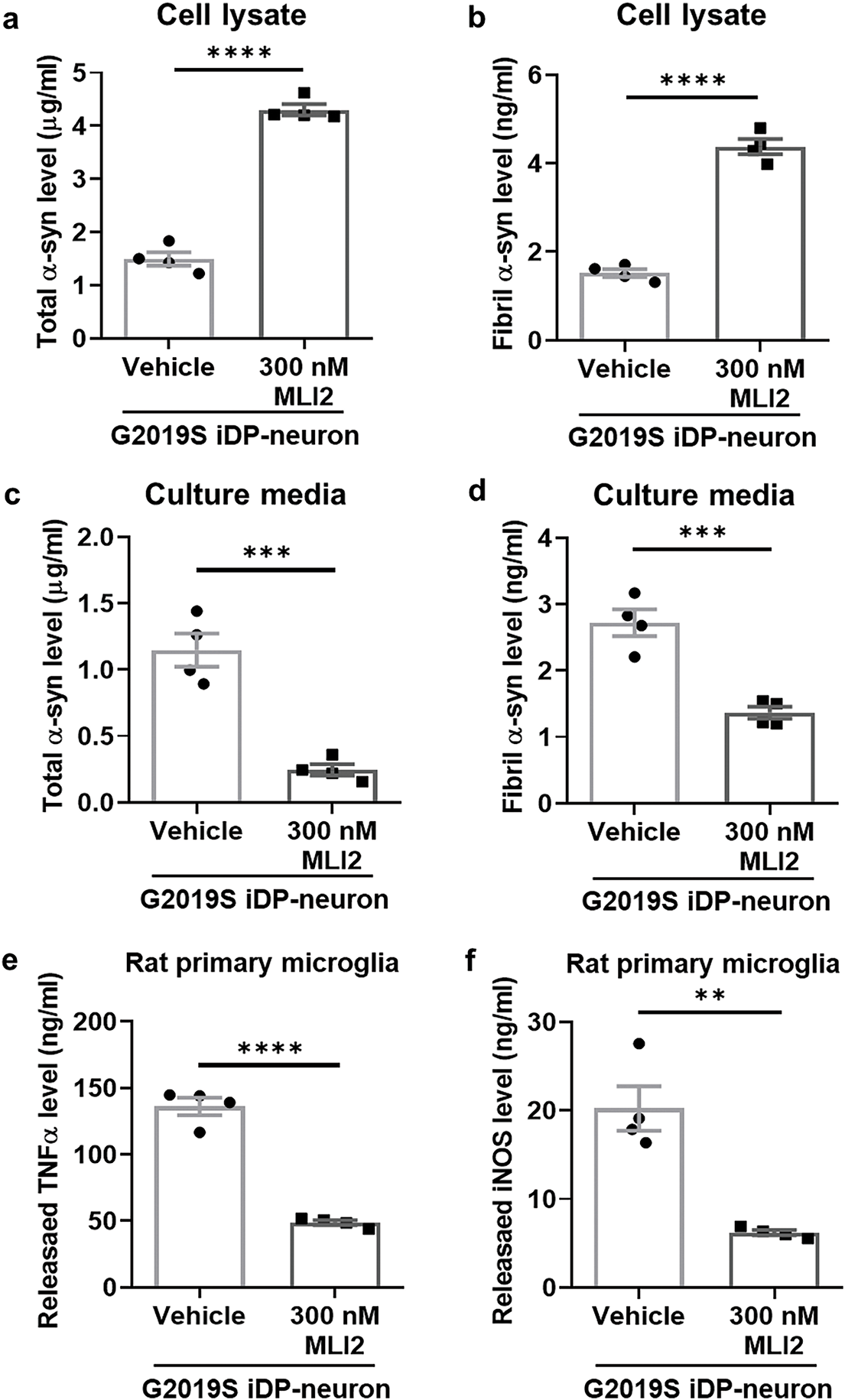

To verify the effect of LRRK2 kinase activity on cellular senescence, we used iDP-neurons derived from PD patients’ fibroblasts carrying the G2019S LRRK2 mutation (G2019S). The phosphorylation of Rab10, a direct LRRK2 kinase substrate, was significantly increased in G2019S iDP-neurons (Fig. 4a,b). Additionally, senescence-associated β-gal activity was distinctly elevated in G2019S iDP-neurons (Fig. 4c,d). To determine whether G2019S enhances α-syn accumulation in iDP-neurons, we performed an α-syn enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), capable of quantifying both intracellular and secreted total and fibrillar α-syn, as established in our previous study. Surprisingly, intracellular levels of both total and fibrillar α-syn were decreased in G2019S iDP-neurons (Fig. 5a,b), whereas the secretion of both total and fibrillar α-syn was dramatically increased in G2019S iDP-neurons (Fig. 5c,d). Previous studies have demonstrated that extracellular α-syn plays a role in neuroinflammation by interacting with microglial receptors, such as toll-like receptor 2 and toll-like receptor 4 [26,27]. Therefore, we investigated whether fibrillar α-syn secreted from G2019S iDP-neurons could stimulate microglial neuroinflammatory responses. To eliminate potential confounding effects from iDP-neuron culture media, we concentrated the conditioned medium before applying it to microglial cultures. We observed that the increased secretion of fibrillar α-syn from G2019S iDP-neurons strongly induced the release of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNFα and inducible iNOS, in rat primary microglia (Fig. 5e,f). However, the phosphorylated or tetrameric form of alpha-synuclein could not be analyzed because it was well below measurable levels. Taken together, these findings suggest that the endogenous G2019S LRRK2 mutation promotes the secretion rather than the intracellular accumulation of fibrillar α-syn in iDP-neurons, leading to the stimulation of neuroinflammatory responses.

Figure 4: Elevation of cellular senescence by kinase activation of G2019S LRRK2 in iDP-neurons. (a) LRRK2’s modular structure includes N-terminal Armadillo (ARM) and Ankyrin (ANK) repeats for protein interactions, followed by the Leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain. The central ROC GTPase domain is coupled with the unique COR domain, and the core kinase domain (KIN) phosphorylates substrates. These domains collaboratively govern LRRK2’s diverse cellular functions, impacting processes relevant to neuronal health and PD pathology. The G2019S mutation specifically changes the amino acid at position 2019 from glycine to serine, and it resides within the kinase domain. (b,c) Western blot analysis of cell lysates was performed to determine whether the kinase activity of G2019S LRRK2 was elevated compared to WT LRRK2, as indicated by Rab10 phosphorylation levels. N = 4 (duplicates per N); statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired Student’s t-test, **p < 0.01. (d,e) Senescence-associated β-gal activity was assessed using X-gal staining, and quantification was plotted as a graphical representation. White bar = 30 μm. N = 3 (3 images per N); unpaired Student’s t-test, **p < 0.01

Figure 5: Enhanced secretion of α-synuclein in G2019S LRRK2 iDP-neurons leading to neuroinflammation. (a,b) Cell lysates were analyzed using ELISA to quantify the levels of total α-syn and fibrillar α-syn. (c,d) Culture media from iDP-neurons were collected and subjected to ELISA to measure total α-syn and fibrillar α-syn levels. (e,f) Concentrated culture media, after washing with DMEM/F-12, were applied to rat primary microglia for 24 h, and cytokine levels were quantified using ELISA for TNFα and iNOS. N = 3 (duplicates per N); statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired Student’s t-test. Significance levels: ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001

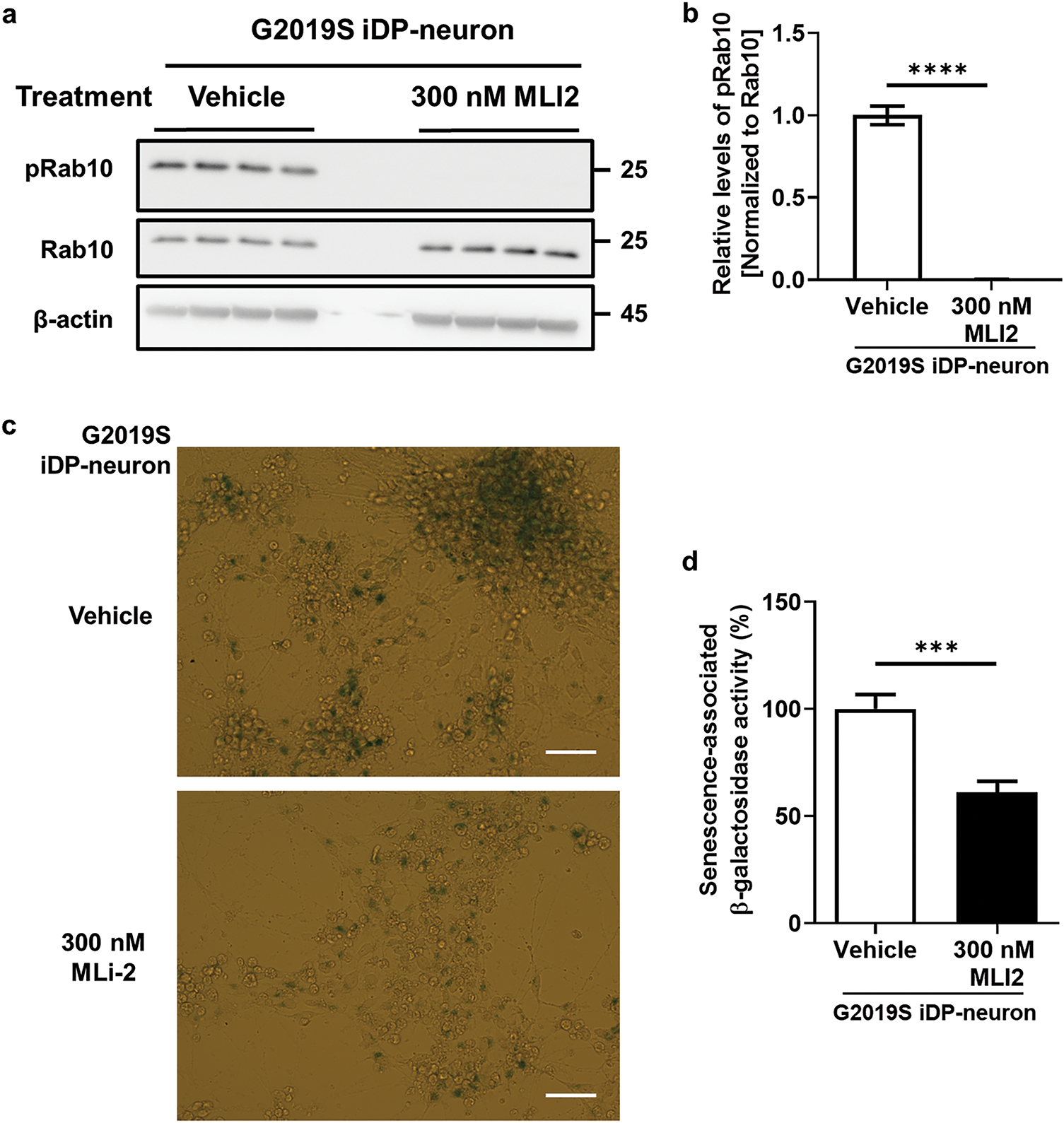

3.4 LRRK2 Kinase Inhibition Attenuates Cellular Senescence and α-Syn Release

To further elucidate the role of LRRK2 kinase activity in cellular senescence and neuroinflammation, we treated G2019S iDP-neurons with MLI2, a selective LRRK2 kinase inhibitor. MLI2 treatment significantly reduced the phosphorylation of Rab10 in iDP-neurons (Fig. 6a,b) and markedly decreased senescence-associated β-gal activity (Fig. 6c,d). Moreover, MLI2 treatment reversed α-syn accumulation, restoring levels comparable to those observed in wild-type (WT) iDP-neurons (Fig. 7a,b). Simultaneously, MLI2 treatment significantly alleviated α-syn secretion in G2019S iDP-neurons (Fig. 7c,d). To ensure that residual MLI2 in the conditioned media did not confound our results, we thoroughly washed and concentrated the media prior to subsequent experiments. Additionally, MLI2-treated G2019S iDP-neurons’ conditioned media suppressed the release of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNFα and iNOS, compared to vehicle-treated G2019S iDP-neurons (Fig. 7e,f). Collectively, these findings suggest that LRRK2 kinase inhibition is a potential therapeutic strategy for PD, as it mitigates cellular senescence and attenuates α-syn-mediated neuroinflammation.

Figure 6: Recovery of cellular senescence by LRRK2 kinase inhibition in G2019S LRRK2 iDP-neurons. iDP-neurons carrying the G2019S LRRK2 mutation were cultivated and differentiated in the presence of DMSO (vehicle) or 300 nM MLI2 for 21 days. (a,b) LRRK2 kinase activity was assessed by measuring Rab10 phosphorylation levels using western blot analysis. N = 4 (duplicates per N); statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired Student’s t-test, ****p < 0.0001. (c,d) Senescence-associated β-gal activity was quantified following X-gal staining, and the results were plotted as a graphical representation. White bar = 30 μm. N = 3 (3 images per N); unpaired Student’s t-test, ***p < 0.001

Figure 7: Mitigation of neuroinflammation by reducing α-synuclein release via LRRK2 kinase inhibition in G2019S LRRK2 iDP-neurons. (a,b) Cell lysates were analyzed using ELISA to quantify total α-syn (a) and fibrillar α-syn (b). (c,d) Culture media from iDP-neurons were collected, and the levels of total α-syn (c) and fibrillar α-syn (d) were measured using ELISA. (e,f) Concentrated culture media from iDP-neurons were applied to rat primary microglia for 24 h, and the release levels of TNFα (e) and iNOS (f) were quantified using ELISA. N = 4 (duplicates per N); statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired Student’s t-test. Significance levels: **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001

Studies have shown that LRRK2 kinase activity is altered via cellular stresses, particularly under conditions of oxidative stress induced by RTN [8,16,28]. Our previous studies demonstrated that treatment with an LRRK2 kinase inhibitor mitigates cellular senescence and reduces the accumulation of α-syn [8,21]. However, the effect of LRRK2 on cellular senescence in human dopaminergic neurons is not the sole pathomechanism underlying PD. Although LRRK2 phosphorylation in human dopaminergic neurons has been shown to modulate cellular senescence (Figs. 1,2,4,6), elucidating the precise mechanisms underlying the observed increase in α-syn secretion rather than intracellular accumulation in G2019S LRRK2 mutant neurons remains challenging (Figs. 5a–d and 7a–d). LRRK2 has emerged as a critical regulator within the complex pathophysiology of PD, a progressive neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the selective loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra. Encoded by the LRRK2 gene, this large multi-domain protein is involved in an intricate network of cellular processes. While its precise physiological functions continue to be meticulously investigated, LRRK2 is known to participate in several crucial pathways, including vesicular trafficking, autophagy, mitochondrial homeostasis, and neuroinflammatory signaling. Disruptions to these pathways, particularly those arising from pathogenic LRRK2 mutations, are thought to be central to PD pathogenesis.

One of the key roles of LRRK2 is its regulatory influence on vesicle trafficking, a process essential for the coordinated movement of membrane-bound vesicles that transport proteins, lipids, and other vital molecules within the cell’s intracellular network [13]. The tightly regulated formation, trafficking, and fusion of these vesicles are critical for fundamental cellular functions, including intercellular communication, nutrient uptake, and organelle homeostasis [29]. LRRK2 has been shown to regulate specific aspects of vesicular transport through the phosphorylation of members of the Rab protein family, particularly those involved in endocytic pathways, which mediate the internalization and processing of extracellular substances [30,31]. Disruptions in LRRK2’s regulatory control over vesicle trafficking have been linked to impaired protein sorting, the accumulation of misfolded proteins, and heightened cellular stress [32,33]. The interaction between LRRK2-mediated cellular senescence and vesicle trafficking may play a key role in modulating the secretion of fibrillar α-syn in G2019S LRRK2 mutant neurons. Notably, the enhanced release of pathological α-syn observed in G2019S LRRK2 mutant neurons contributes to the exacerbation of neuroinflammatory responses (Figs. 5e,f and 7e,f).

Beyond its role in vesicle trafficking, LRRK2 is also implicated in maintaining protein quality control through autophagy, the cell’s intrinsic recycling and degradation system [12]. Autophagy plays a crucial role in clearing damaged proteins, organelles, and other cellular debris, thereby preserving cellular homeostasis and preventing the accumulation of toxic substances, including dysfunctional mitochondria [34]. LRRK2 is thought to regulate various stages of autophagy, from autophagosome formation to autolysosome maturation and degradation [35,36]. Pathogenic LRRK2 mutations have been shown to impair autophagy, leading to defective clearance of cellular waste products, which in turn contributes to cellular stress and neurodegeneration [37,38]. While the role of LRRK2 in these processes is becoming increasingly evident, the precise mechanisms underlying the selective vulnerability of dopamine neurons in PD remain an area of intense investigation. Current hypotheses suggest a multifaceted interplay between vesicle trafficking disruptions and impaired autophagy, which collectively trigger a cascade of events leading to neuronal degeneration [39,40]. Although it has been hypothesized that LRRK2 kinase activity accelerates accumulation, the findings of this study indicate that G2019S LRRK2 mutant neurons preferentially secrete α-syn into the extracellular space rather than accumulating it intracellularly (Figs. 5a–d and 7a–d). In this study, dopamine neurons were cultured and differentiated for 21 days; however, if the experiment were extended to mimic the prolonged pathological environment of the human midbrain, α-syn accumulation might intensify and eventually surpass the rate of secretion. Lysosomal dysfunction due to LRRK2 mutations significantly impacts the autophagic process, in which cellular debris is delivered to lysosomes for degradation [14]. Lysosomes are essential organelles responsible for breaking down and recycling various macromolecules, including proteins, lipids, and cellular debris. These organelles contain a diverse array of hydrolytic enzymes that facilitate the degradation of biomolecules, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis [41]. Impaired autophagy leads to the accumulation of damaged mitochondria and other cellular waste, contributing to cellular stress and neuronal death [42]. In PD, lysosomes play a critical role in degrading misfolded α-syn [43]. Given previous findings that lysosomal accumulation of α-syn can lead to its release through an unconventional secretory pathway [44,45]. One potential mechanism for the secretion of α-syn could be via the GTP-binding protein, Rab35. It has been demonstrated in previous studies that the G2019S mutation causes a significant release of α-syn from neurons, leading to its propagation and the progression of PD [32]. Or it is plausible that cells may adopt a strategy of releasing accumulated α-syn in order to counteract with cellular stress [46]. However, under prolonged pathological conditions, the concomitant accumulation of α-syn and upregulation of LRRK2 kinase activity may overwhelm these compensatory mechanisms, ultimately disrupting cellular homeostasis and accelerating PD progression.

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the study of senescent microglia and their implications in neurodegenerative diseases [47]. Microglia, the resident immune cells of the brain, play a pivotal role in maintaining homeostasis and responding to neuronal damage [48]. However, with aging, these cells can enter a state of senescence, leading to impaired function and an increased propensity to contribute to inflammation and tissue damage. Senescent microglia are characterized by a loss of their normal surveillance functions and an enhanced secretion of pro-inflammatory factors, collectively known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) [49]. This chronic pro-inflammatory environment is particularly detrimental in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and PD, where inflammation plays a key role in disease progression. In AD, senescent microglia have been shown to exacerbate the accumulation of amyloid-beta and tau proteins, which are pathological hallmarks of the disease [50]. Similarly, in PD, senescent microglia contribute to the buildup of α-syn, further promoting neuronal damage [51]. The role of senescent microglia in neurodegeneration underscores the potential of targeting these cells for therapeutic intervention. One promising approach is the use of senolytic drugs, which selectively eliminate senescent cells. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that senolytics can reduce neuroinflammation and improve cognitive function in animal models of AD [52]. Cellular senescence in microglia is strongly associated with LRRK2-induced neuroinflammation, suggesting that LRRK2 kinase inhibitors may exert senolytic-like effects [8]. However, the precise role of this relationship in PD progression remains unclear and warrants further investigation. Understanding this mechanism may provide additional evidence for LRRK2 phosphorylation inhibitors as a potential therapeutic strategy in PD.

The identification of LRRK2 as a key factor in PD has significantly advanced our understanding of the disease’s pathogenesis and has opened new therapeutic avenues. Current research efforts are focused on developing LRRK2-targeting drugs with the goal of slowing or even halting PD progression. Inhibitors of LRRK2 kinase activity are actively being investigated as potential therapeutic agents. However, further research into the complex biological functions of LRRK2 is essential for the development of more targeted and effective treatments for this debilitating disease. A deeper understanding of the precise mechanisms by which LRRK2 contributes to PD pathology will not only enhance our knowledge of the disease but also facilitate the design of novel therapeutic strategies that could ultimately alleviate the burden of PD for affected individuals.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by a grant from the Korean Fund for Regenerative Medicine (KFRM), which is funded by the Korean government’s Ministry of Science and ICT and the Ministry of Health & Welfare (23A0102L1 to Janghwan Kim) and by KRIBB Research Initiative Program (KGM5362521 to Janghwan Kim). This study was also supported by a grant from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), which is funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) of the Korean government (RS-2023-NR077070 to Sung Woo Park).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Dong Hwan Ho; methodology, Dong Hwan Ho, Minhyung Lee, Mi Kyoung Seo, Janghwan Kim; validation, Dong Hwan Ho; formal analysis, Dong Hwan Ho, Hyejung Kim; investigation, Dong Hwan Ho, Daleum Nam; resources, Janghwan Kim, Ilhong Son; data curation, Dong Hwan Ho; writing—original draft preparation, Dong Hwan Ho; writing—review and editing, Ilhong Son; visualization, Dong Hwan Ho; supervision, Janghwan Kim, Ilhong Son; project administration, Janghwan Kim, Sung Woo Park, Ilhong Son; funding acquisition, Sung Woo Park, Janghwan Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, Dong Hwan Ho, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: For reprogramming purposes, the use of human fibroblast was exempted from IRB review by Public Institutional Review Board Designated by Ministry of Health and Welfare (P01-201802-31-001). All experimental procedures were conducted following the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals for scientific purposes, with protocols approved by the Committee for Animal Experimentation and the Institutional Animal Laboratory Review Board of Inje Medical College (approval no. 2023-007, approval date: 27 March 2023).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| α-syn | Alpha-synuclein |

| LRRK2 | Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 |

| iDP-neuron | Induced-human dopaminergic neuron |

| RTN | Rotenone |

| β-gal | Beta-galactosidase |

| TLR2 | Toll-like receptor 2 |

| TLR4 | Toll-like receptor 4 |

| TNFα | Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| iNOS | Inducible nitric oxide species |

Appendix A

Figure A1: The changes of active lysosome population by LRRK2 kinase activity in iDP-neurons. The active lysosomes, which are associated with acidic conditions, were stained with LysoSensor Blue DND-167, and its intensity was measured at 373 nm excitation and 425 nm emission wavelengths. N = 12 (duplicates per N); statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post hoc analysis. Significance levels: ns, not significant; *p < 0.05; ****p < 0.0001

References

1. Mhyre TR, Boyd JT, Hamill RW, Maguire-Zeiss KA. Parkinson’s disease. Subcell Biochem. 2012;65(50):389–455. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5416-4_16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Cherian A, Divya KP, Vijayaraghavan A. Parkinson’s disease—genetic cause. Curr Opin Neurol. 2023;36(4):292–301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

3. Nandipati S, Litvan I. Environmental exposures and Parkinson’s disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(9):881. doi:10.3390/ijerph13090881. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Tansey MG, Wallings RL, Houser MC, Herrick MK, Keating CE, Joers V. Inflammation and immune dysfunction in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22(11):657–73. doi:10.1038/s41577-022-00684-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Bondarenko O, Saarma M. Neurotrophic factors in Parkinson’s disease: clinical trials, open challenges and nanoparticle-mediated delivery to the brain. Front Cell Neurosci. 2021;15:682597. doi:10.3389/fncel.2021.682597. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Trist BG, Hare DJ, Double KL. Oxidative stress in the aging substantia nigra and the etiology of Parkinson’s disease. Aging Cell. 2019;18(6):e13031. doi:10.1111/acel.13031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Regulski MJ. Cellular senescence: what, why, and how. Wounds. 2017;29(6):168–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

8. Ho DH, Nam D, Seo MK, Park SW, Seol W, Son I. LRRK2 kinase inhibitor rejuvenates oxidative stress-induced cellular senescence in neuronal cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:9969842. doi:10.1155/2021/9969842. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Hijaz BA, Volpicelli-Daley LA. Initiation and propagation of α-synuclein aggregation in the nervous system. Mol Neurodegener. 2020;15(1):19. doi:10.1186/s13024-020-00368-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Huang J, Ding J, Wang X, Gu C, He Y, Li Y, et al. Transfer of neuron-derived α-synuclein to astrocytes induces neuroinflammation and blood-brain barrier damage after methamphetamine exposure: involving the regulation of nuclear receptor-associated protein 1. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;106:247–61. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2022.09.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Sosero YL, Gan-Or Z. LRRK2 and Parkinson’s disease: from genetics to targeted therapy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2023;10(6):850–64. doi:10.1002/acn3.51776. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Ho DH, Kim H, Nam D, Sim H, Kim J, Kim HG, et al. LRRK2 impairs autophagy by mediating phosphorylation of leucyl-tRNA synthetase. Cell Biochem Funct. 2018;36(8):431–42. doi:10.1002/cbf.3364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Bae EJ, Lee SJ. The LRRK2-RAB axis in regulation of vesicle trafficking and α-synuclein propagation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866(3):165632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Eguchi T, Sakurai M, Wang Y, Saito C, Yoshii G, Wileman T, et al. The V-ATPase-ATG16L1 axis recruits LRRK2 to facilitate the lysosomal stress response. J Cell Biol. 2024;223(3):e202302067. doi:10.1101/2023.10.13.562167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Singh F, Prescott AR, Rosewell P, Ball G, Reith AD, Ganley IG. Pharmacological rescue of impaired mitophagy in Parkinson’s disease-related LRRK2 G2019S knock-in mice. eLife. 2021;10:e67604. doi:10.7554/elife.67604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Quintero-Espinosa DA, Sanchez-Hernandez S, Velez-Pardo C, Martin F, Jimenez-Del-Rio M. LRRK2 knockout confers resistance in HEK-293 cells to rotenone-induced oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, and apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(13):10474. doi:10.1016/j.ibneur.2023.08.933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lee M, Sim H, Ahn H, Ha J, Baek A, Jeon YJ, et al. Direct reprogramming to human induced neuronal progenitors from fibroblasts of familial and sporadic Parkinson’s disease patients. Int J Stem Cells. 2019;12(3):474–83. doi:10.15283/ijsc19075. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Fell MJ, Mirescu C, Basu K, Cheewatrakoolpong B, DeMong DE, Ellis JM, et al. MLi-2, a potent, selective, and centrally active compound for exploring the therapeutic potential and safety of LRRK2 kinase inhibition. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2015;355(3):397–409. doi:10.1124/jpet.115.227587. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Nam D, Lee JY, Lee M, Kim J, Seol W, Son I, et al. Detection and assessment of α-synuclein oligomers in the urine of Parkinson’s disease patients. J Park Dis. 2020;10(3):981–91. doi:10.3233/jpd-201983. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Landini G, Martinelli G, Piccinini F. Colour deconvolution: stain unmixing in histological imaging. Bioinformatics. 2020;37(10):1485–7. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa847. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Ho DH, Seol W, Son I. Upregulation of the p53-p21 pathway by G2019S LRRK2 contributes to the cellular senescence and accumulation of α-synuclein. Cell Cycle. 2019;18(4):467–75. doi:10.1080/15384101.2019.1577666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Lippai M, Lőw P. The role of the selective adaptor p62 and ubiquitin-like proteins in autophagy. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:832704. doi:10.1155/2014/832704. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Jiang P, Mizushima N. LC3- and p62-based biochemical methods for the analysis of autophagy progression in mammalian cells. Methods. 2015;75:13–8. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.11.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Ardah MT, Ghanem SS, Abdulla SA, Lv G, Emara MM, Paleologou KE, et al. Inhibition of alpha-synuclein seeded fibril formation and toxicity by herbal medicinal extracts. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020;20(1):73. doi:10.1186/s12906-020-2849-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Mahul-Mellier AL, Vercruysse F, Maco B, Ait-Bouziad N, De Roo M, Muller D, et al. Fibril growth and seeding capacity play key roles in α-synuclein-mediated apoptotic cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22(12):2107–22. doi:10.1038/cdd.2015.79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Ho DH, Nam D, Seo M, Park SW, Seol W, Son I. LRRK2 inhibition mitigates the neuroinflammation caused by TLR2-specific α-synuclein and alleviates neuroinflammation-derived dopaminergic Neuronal Loss. Cells. 2022;11(5):861. doi:10.3390/cells11050861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Hughes CD, Choi ML, Ryten M, Hopkins L, Drews A, Botía JA, et al. Picomolar concentrations of oligomeric alpha-synuclein sensitizes TLR4 to play an initiating role in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;137(1):103–20. doi:10.1007/s00401-018-1907-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Mendivil-Perez M, Velez-Pardo C, Jimenez-Del-Rio M. Neuroprotective effect of the LRRK2 kinase inhibitor PF-06447475 in human nerve-like differentiated cells exposed to oxidative stress stimuli: implications for Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem Res. 2016;41(10):2675–92. doi:10.1007/s11064-016-1982-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. García-Cazorla A, Oyarzábal A, Saudubray J-M, Martinelli D, Dionisi-Vici C. Genetic disorders of cellular trafficking. Trends Genet. 2022;38(7):724–51. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2022.02.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Yun HJ, Kim H, Ga I, Oh H, Ho DH, Kim J, et al. An early endosome regulator, Rab5b, is an LRRK2 kinase substrate. J Biochem. 2015;157(6):485–95. doi:10.1093/jb/mvv005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Madero-Pérez J, Fdez E, Fernández B, Lara Ordóñez AJ, Blanca Ramírez M, Gómez-Suaga P, et al. Parkinson disease-associated mutations in LRRK2 cause centrosomal defects via Rab8a phosphorylation. Mol Neurodegener. 2018;13:1–22. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2017.07.604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Bae EJ, Kim DK, Kim C, Mante M, Adame A, Rockenstein E, et al. LRRK2 kinase regulates α-synuclein propagation via RAB35 phosphorylation. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):3465. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05958-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Purlyte E, Dhekne HS, Sarhan AR, Gomez R, Lis P, Wightman M, et al. Rab29 activation of the Parkinson’s disease-associated LRRK2 kinase. EMBO J. 2018;37(1):1–18. doi:10.15252/embj.201798099. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Gómez-Virgilio L, Silva-Lucero MD, Flores-Morelos DS, Gallardo-Nieto J, Lopez-Toledo G, Abarca-Fernandez AM, et al. Autophagy: a key regulator of homeostasis and disease: an overview of molecular mechanisms and modulators. Cells. 2022;11(15):2262. doi:10.3390/cells11152262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Dou D, Smith EM, Evans CS, Boecker CA, Holzbaur ELF. Regulatory imbalance between LRRK2 kinase, PPM1H phosphatase, and ARF6 GTPase disrupts the axonal transport of autophagosomes. Cell Rep. 2023;42(5):112448. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112448. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Boecker CA, Goldsmith J, Dou D, Cajka GG, Holzbaur ELF. Increased LRRK2 kinase activity alters neuronal autophagy by disrupting the axonal transport of autophagosomes. Curr Biol. 2021;31(10):2140–54. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2021.02.061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Obergasteiger J, Frapporti G, Lamonaca G, Pizzi S, Picard A, Lavdas AA, et al. Kinase inhibition of G2019S-LRRK2 enhances autolysosome formation and function to reduce endogenous alpha-synuclein intracellular inclusions. Cell Death Discov. 2020;6(1):45. doi:10.1038/s41420-020-0279-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Chen ML, Wu RM. Homozygous mutation of the LRRK2 ROC domain as a novel genetic model of parkinsonism. J Biomed Sci. 2022;29(1):60. doi:10.1186/s12929-022-00844-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Boecker CA. The role of LRRK2 in intracellular organelle dynamics. J Mol Biol. 2023;435(12):167998. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2023.167998. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Roosen DA, Cookson MR. LRRK2 at the interface of autophagosomes, endosomes and lysosomes. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11(1):73. doi:10.1186/s13024-016-0140-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Trivedi PC, Bartlett JJ, Pulinilkunnil T. Lysosomal biology and function: modern view of cellular debris bin. Cells. 2020;9(5):1131. doi:10.3390/cells9051131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Ferrari V, Tedesco B, Cozzi M, Chierichetti M, Casarotto E, Pramaggiore P, et al. Lysosome quality control in health and neurodegenerative diseases. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2024;29(1):116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

43. Guiney SJ, Adlard PA, Lei P, Mawal CH, Bush AI, Finkelstein DI, et al. Fibrillar α-synuclein toxicity depends on functional lysosomes. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(51):17497–513. doi:10.1074/jbc.ra120.013428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Burbidge K, Rademacher DJ, Mattick J, Zack S, Grillini A, Bousset L, et al. LGALS3 (galectin 3) mediates an unconventional secretion of SNCA/α-synuclein in response to lysosomal membrane damage by the autophagic-lysosomal pathway in human midbrain dopamine neurons. Autophagy. 2022;18(5):1020–48. doi:10.1080/15548627.2021.1967615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Xie YX, Naseri NN, Fels J, Kharel P, Na Y, Lane D, et al. Lysosomal exocytosis releases pathogenic α-synuclein species from neurons in synucleinopathy models. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):4918. doi:10.1101/2021.04.10.439302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Fussi N, Höllerhage M, Chakroun T, Nykänen NP, Rösler TW, Koeglsperger T, et al. Exosomal secretion of α-synuclein as protective mechanism after upstream blockage of macroautophagy. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(7):757. doi:10.1038/s41419-018-0816-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Rim C, You MJ, Nahm M, Kwon MS. Emerging role of senescent microglia in brain aging-related neurodegenerative diseases. Transl Neurodegener. 2024;13(1):10. doi:10.1186/s40035-024-00402-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Colonna M, Butovsky O. Microglia function in the central nervous system during health and neurodegeneration. Annu Rev Immunol. 2017;35(1):441–68. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-051116-052358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Greenwood EK, Brown DR. Senescent microglia: the key to the ageing brain? Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):4402. doi:10.3390/ijms22094402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Zhu J, Wu C, Yang L. Cellular senescence in Alzheimer’s disease: from physiology to pathology. Transl Neurodegener. 2024;13(1):55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

51. Bae EJ, Choi M, Kim JT, Kim DK, Jung MK, Kim C, et al. TNF-α promotes α-synuclein propagation through stimulation of senescence-associated lysosomal exocytosis. Exp Mol Med. 2022;54(6):788–800. doi:10.1038/s12276-022-00789-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Gonzales MM, Garbarino VR, Kautz T, Palavicini JP, Lopez-Cruzan M, Dehkordi SK, et al. Senolytic therapy to modulate the progression of Alzheimer’s disease (SToMP-AD)—outcomes from the first clinical trial of senolytic therapy for Alzheimer’s disease. Res Sq. 2023. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-2809973/v1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools