Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Cross-Talk between Next-Generation Probiotics and the Immune System

1 Laboratory of Metagenomics and Food Biotechnology, Voronezh State University of Engineering Technologies, Voronezh, 394036, Russia

2 Department of Genetics, Cytology and Bioengineering, Voronezh State University, Voronezh, 394018, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Mikhail Syromyatnikov. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Inflammation and Immune Regulation: From Genotoxicity to Apoptosis)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(9), 1573-1603. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.065311

Received 10 March 2025; Accepted 06 June 2025; Issue published 25 September 2025

Abstract

The gut microbiome is a complex community of microorganisms that plays a direct role in the health of both the gastrointestinal tract and the entire body. Numerous factors influence the abundance and diversity of gut microbiota. Microbial imbalance can contribute to disease development. Probiotics are biologically active supplements with promising properties that have high therapeutic potential. Currently, there is a tendency to switch from classic probiotic microorganisms represented by lactic acid bacteria to next-generation probiotics due to their unique ability to influence the human immune system. New-generation probiotics include bacteria such as Akkermansia muciniphila, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Bacteroides sp., Prevotella sp., Roseburia sp., and Eubacterium sp. Next-generation probiotics can affect host immune cells by secreting various substances, such as butyrate in F. prausnitzii, or through interaction with Toll-like receptors of intestinal epithelial cells, such as A. muciniphila. Studying the role of next-generation probiotics in immune regulation is a promising area of research. This study describes the interactions of next-generation probiotics with the immune system. Understanding the mechanisms of such interactions will improve the treatment of various diseases.Keywords

Human gut microbiota is a diverse community of symbiotic microorganisms whose metabolites influence host homeostasis [1]. Substances produced by intestinal bacteria have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, thereby promoting health. However, these processes can also lead to the formation of dangerous neurotoxins, carcinogens, and immunotoxins can be formed [2]. Consequently, alterations in the gut microbiota can provoke the development of serious diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease, obesity, diabetes mellitus, and others [3–5].

The use of probiotics helps maintain the balance of gut microbiota by producing various functional factors that adapt bacteria to changing host conditions [6]. Probiotics have promising properties that meet the nutritional and therapeutic needs of humans [7].

For a long time, the main traditional probiotic organisms were strains of the genera Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium. They were obtained as a result of isolation from fecal microbiota or fermented dairy products, which explains their main function—the production of lactic acid [8]. Currently, there is a tendency to move away from classical probiotic microorganisms represented by lactic acid bacteria (LAB) cultures in favor of new-generation probiotics (NGP) [9,10]. This development became possible due to the active introduction and use of the whole-genome sequencing technique, as well as cultivation methods that made it possible to identify beneficial anaerobic microorganisms of the human gut microbiome. Despite the proven effectiveness of traditional probiotics, NGPs are potentially considered more suitable for the human intestinal microbiome and have a number of advantages. It is assumed that their use will allow moving to a new level in matters of targeted therapy of many diseases [11].

New probiotic agents include Roseburia intestinalis, Eubacterium hallii, Akkermansia muciniphila, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Christensenella minuta, Prevotella copri, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Parabacteroides goldsteinii, and Bacteroides fragilis [12,13]. They participate in the synthesis of folic acid, serotonin, and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including butyrate, which helps maintain the immune balance in the body [14].

NGPs meet all the criteria for probiotics, but their clinical efficacy requires further validation. Therefore, many opportunities are opening up for studying new probiotic agents and their role in strengthening human health and immunity. Of particular interest is the study of the effect of new-generation probiotic bacteria on the immune system for the purpose of correcting dysbiosis and treating inflammatory bowel diseases, which could significantly improve the treatment of various somatic diseases [15].

2 The Immune System of the Gut

The gut environment is a holistic ecosystem populated by a diverse variety of microorganisms [16]. Their membrane is often enriched with flagella, pili, surface proteins, lipoteichoic acid, and polysaccharides, which are believed to facilitate initial adherence to intestinal epithelial cells. In vitro studies have proposed that these structures facilitate the formation of specific bonds with cell receptors. They provide a signaling function by activating the synthesis of cytokines, blocking apoptotic processes in the cell, and thus reducing inflammation. Probiotic candidates like B. thetaiotaomicron and A. muciniphila have been shown in murine models and ex vivo organoid systems to modulate epithelial barrier properties and mucin expression [17].

Gastrointestinal epithelial cells are among the main components of immunity [18]. For example, goblet cells of the epithelium secrete mucus, which has a barrier function, separating the structural layer and the microbiota. This barrier isolates immune cells from the bacterial and fungal communities of microorganisms, preventing spontaneous immune responses [19]. The mucous membrane separating the intestinal epithelium and microflora is structurally represented by glycocalyx, which is produced by mucinogenic cells [20]. In its structure, gut mucin is represented by a glycoprotein of the second subtype: MUC2 [21]. A direct relationship has been observed in Muc2–knockout mice, where deficiency leads to colitis, though generalization to human disease should be approached cautiously [22]. Thus, the mucous layer ensures the integrity of the cellular structures of the gastrointestinal tract, with its volume reaching an average of 5 L [23].

The protective function of the epithelium is regulated by the physical barrier to pathogen attachment, provided by mucus, as well as Paneth cells, which produce antimicrobial peptides, including lysozymes, ribonucleases, cathelicidins, 14β-glycosidases, α/βdefensins, and C-type lectins [23,24]. Paneth cells are specialized cells of the small intestinal epithelium, but they can also be found in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract—in the large intestine and stomach. Synthesis of antimicrobial peptides by Paneth cells occurs when the pathogen interacts with Toll-like receptors (TLRs) of epithelial cells [25]. Human defensin-5 (HD-5), produced by Paneth cells, affects the microbial composition of the intestine. For instance, a study on mice found that transgenic individuals with HD-5 are resistant to the action of pathogenic strains of S. typhimurium [26].

Therefore, intestinal epithelial cells help protect the body from the effects of various pathogenic microorganisms. At the same time, disturbances in the structure of the epithelium lead to the activation of inflammatory processes in the body [27]. It has been established that a large number of internal and external factors (dietary habits, lifestyle, and environment of a person, genetic potential of the body) participate in the pathogenesis of intestinal disorders; however, intestinal microflora dysbiosis is the determining cause of the development of human diseases [28].

The immune function of gut epithelial cells is realized due to their ability to produce a large number of mediators, which include cytokines, chemokines, and antimicrobial peptides [29]. The gastrointestinal tract is rich in cells of the human immune system, which include intraepithelial lymphocytes γδ and αβ, retinoic acid receptor-related orphan receptors (RORs), lymphoid tissue inducers (LTI), and innate immune cells NKP46T [23]. Immune responses of epithelial cells are evolutionarily formed reactions of the body to the effects of pathogenic microflora [30]. In vitro co-culture experiments have suggested that inflammatory processes in the body and developed immunological tolerance can influence the activation or suppression of cellular T-helpers (Th1, Th2, Th17), regulatory T-cells (Treg), cytotoxic CD8+ T-cells, natural killer T-cells (NKT), and γδ T-cells under the influence of new probiotic bacteria and their metabolites (Fig. 1) [31].

Figure 1: Immune response induced by a next-generation probiotic against a pathogen. New generation probiotics promote activation of immune cells of the host organism. Metabolic products produced by NGPs, through LTI and RORs, affect the epithelium of the intestinal tract. T-helpers, T-cells, and NKP46T induced by the new generation probiotic suppress the growth of the pathogenic organism and deactivate its metabolic products. Abbreviations: RORs—receptor-related orphan receptors, LTI—lymphoid tissue inducers, NKP46T—innate immune cells

For example, studies show that probiotic strains of E. coli activate inflammatory processes in the body due to the action of recognition molecules: TLRs and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domains (NODs). Thus, biochemical reactions of TLRs stimulate myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MYD88) and TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), which, in turn, activate nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/c-Jun-NH2-kinase (JNK)/p38. These reactions promote the production of cytokines that activate the inflammatory response of cells [32]. The most studied receptors of the intestinal immune system are TLRs. TLRs are capable of recognizing specific structures of viral and bacterial infectious agents. Thus, TLR-4 is highly sensitive to lipopolysaccharides, TLR-5 to bacterial flagellin, and TLR-9 recognizes CpG islands of DNA [33,34]. Toll-like receptors not only induce a cellular immune response to pathogens, but are also capable of exerting a healing effect on damaged intestinal epithelial cells. For example, it was found that knocked-out genes responsible for the synthesis of TLR9, TLR4, and TLR2 demonstrated good susceptibility to the development of colitis induced by dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) [23].

3 Effect of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii on the Host Immune System

Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is a gram-positive, rod-shaped bacterium belonging to the Firmicutes phylum. The commensal bacterium has been detected in the gastrointestinal tract of healthy adults, where the overall average population size varies within 5% [35]. In addition to humans, F. prausnitzii is an obligatory component of the gut microbiome of animals. A decrease in its abundancehas been associated with dysbacteriosis in combination with various immune-mediated chronic diseases [36–38].

The interaction between gut epithelial cells and commensal bacteria metabolites in vitro and animal models is recognized by Toll-like receptors, which may maintain homeostasis and trigger immune responses [39]. When the F. prausnitzii levels in the microbiome are reduced, inflammatory defenses are often weakened. This occurs through the inactivation of proinflammatory cytokines and stimulates the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines production, including those blocking the activation of nuclear factor kB (NF-κB) [40,41]. Quévrain and colleagues demonstrated that the anti-inflammatory bioactive molecule MAM from F. prausnitzii can suppress NF-κB in epithelial cell culture [42].

To study the mechanisms of interaction and the role of fecal bacteria in maintaining intestinal immunity, the morphophysiological model gut epithelium-microbe-immune (GuMI) microphysiological system was studied. Co-cultivation of F. prausnitzii with antigen-presenting cells (APC) and CD4+ naive T cells allowed us to establish the significance of each element for immunity in the development of inflammatory diseases. Analysis of various combinations of cultivation established the leading role of CD4+ naive T cells in enhancing the secretion of cytokines, including IL-8, and reducing TLR transcription in the intestinal epithelium. The GuMI-APC model with F. prausnitzii was characterized by an increased level of transcription of proinflammatory genes (TLR1 and IFNA1) in colon cells relative to the GuMI-APC model without probiotic bacteria [43].

The effect of the new probiotic agent on the innate and acquired immunity of humans can be both direct and indirect. By triggering a cascade of reactions, F. prausnitzii suppresses the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines [44]. The anti-inflammatory effects exerted on the body are achieved through changes in lymphocyte populations synthesizing cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), interferon gamma γ (IFNγ), nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), interleukin (IL-4, IL-13, IL-17, IL-22, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10) [45,46]. A special role is given to F. prausnitzii due to its ability to produce butyrate, which acts as the main source of energy for epithelial cells and regulates the activity of intestinal T cells [47,48]. The molecular mechanisms of action of F. prausnitzii on gut immune cells are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Mechanisms of action of F. prausnitzii on gut immune cells. F. prausnitzii produces butyrate, which acts on dendritic cells of the intestinal immune system. Butyrate activates the differentiation of T cells into IL, IFN, TNF, and TGF. Abbreviations: IL—interleukins, IFN—interferons, TNF—tumor necrosis factor, TGF—transforming growth factor

Salicylic acid, formed during glucose fermentation, in experimental models acts as an anti-inflammatory agent that promotes differentiation of immune cells and may help maintain immune homeostasis [49]. N-butyrate, synthesized by bacteria, blocks NF-κB signaling and regulates differentiation of Treg cells in the gut mucosa [50–52]. The main sources of butyrate during intestinal inflammation are believed to be F. prausnitzii and Lachnospiraceae [53,54]. Inflammation provokes a decrease in the number of these bacteria in the gut microbiome [55–57]. In the case of impaired mucin absorption by F. prausnitzii, the level of N-butyrate synthesized in cells decreases. This preclinical murine finding is confirmed by experiments on mice that received mucin as a supplement, which led to an overall increase in the level of butyrate, RORgt+Treg cells, and IgA-producing cells [58].

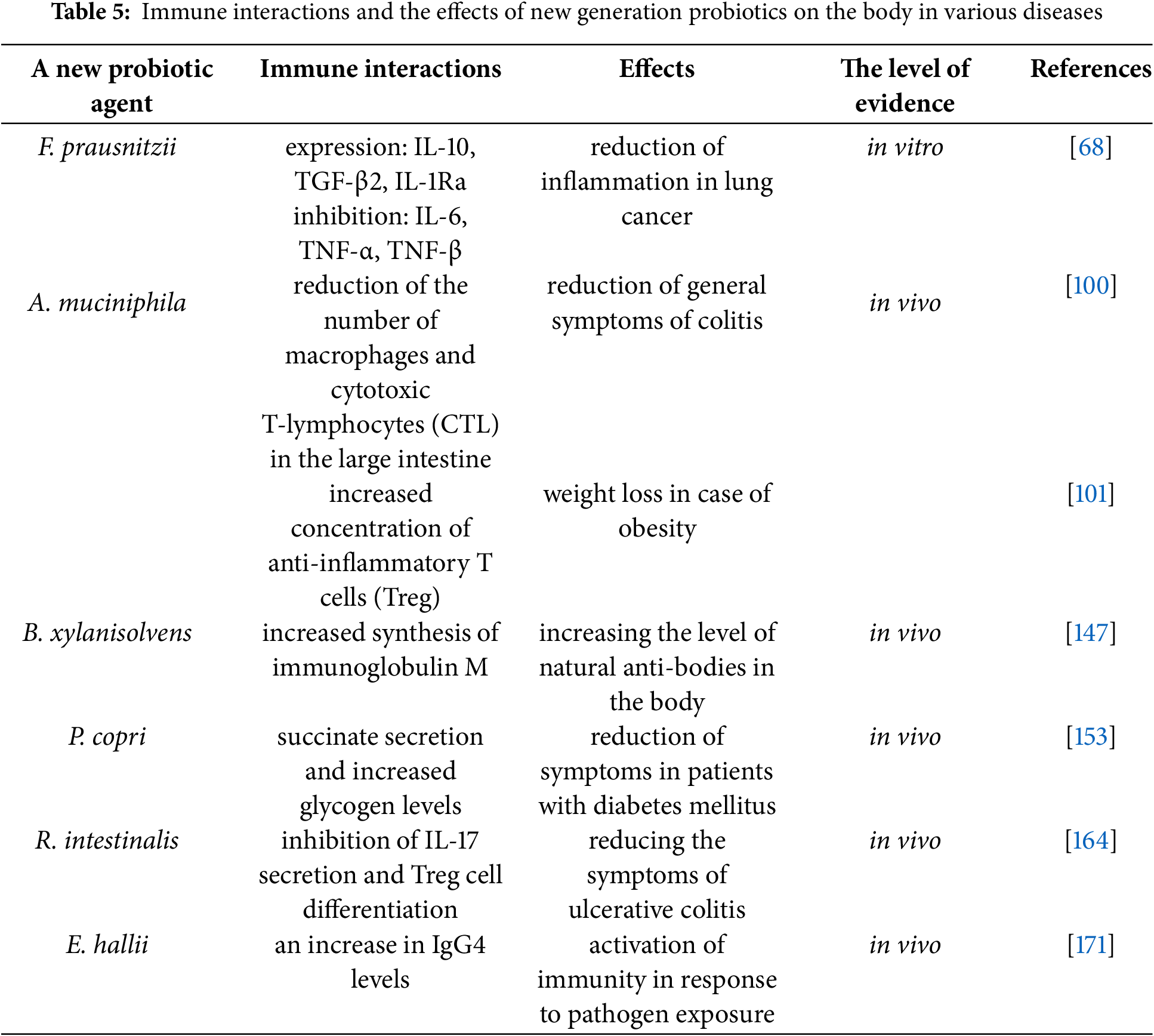

F. prausnitzii stimulates the production of ovalbumin-specific T cells and suppresses IFN-γ-producing T cells. In vitro studies suggest that due to its ability to induce IL-10 secretion by dendritic cells F. prausnitzii can be considered as a therapeutic agent in the treatment of obesity in humans and animals [59,60], and their expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells contributes to anti-inflammatory effects in colitis mice models [39]. A decrease in CD45+ inflammation in adipose tissues was demonstrated, accompanied by an increase in the expression of the hormone adiponectin in visceral adipose tissues [61]. Administration of F. prausnitzii in mice with autoimmune rheumatoid arthritis led to a decrease in IL–17–producing immune cells. Such regulation of the systemic immune cell population contributed to changes in the concentration of short-chain fatty acids in the gut microbiome of mice and alleviated disease symptoms [62].

Multiple studies have shown that the reference strain F. prausnitzii A2-165 exhibits immunomodulatory effects in vitro and in vivo in ulcerative colitis models [63]. Using HT-29 (human colon cancer cell line) and PBMC (peripheral blood mononuclear cells) cell models, it was possible to establish the ability of new probiotic strains to induce an immune response in response to the disease. All studied strains suppressed TNF–α–stimulated interleukin-8 production, while only two isolates (CNCM I-4543 and CNCM I-4573) stimulated IL-10 production in PBMCs [64]. The extracellular matrix of the F. prausnitzii HTF-F strain in cell culture promotes the manifestation of immunomodulatory action through TLR2-mediated modulation of IL-12 and IL-10 synthesis in human monocyte dendritic cells [49].

Regulatory DP8α Treg cells have the ability to identify the F. prausnitzii symbiont. This relationship indicates their induction by this probiotic bacterium [65]. A positive correlation was found between F. prausnitzii-reactive DP8α Treg cells and the amount of these probiotic bacteria in Crohn’s disease. The abundance of these cells is found in the lymphoid tissue of the colon of a healthy person, which produces immunocompetent cells. The lower the content of F. prausnitzii in the blood and fecal microbiota, the lower the number of CCR6+CXCR6+DP8α Treg populations identified in the body [66].

Blockade of the immune synapse modulators CTLA4 and PD-1 contributed to the deterioration of the condition of mice with autoimmune colitis. The introduction of F. prausnitzii in tumor-bearing murine models contributed to the alleviation of symptoms and activation of antitumor immunity, which was induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). The obtained results confirmed the theory of the high potential of F. prausnitzii in reducing the toxicity of immunotherapy in the development of cancer [67].

Despite the fact that the dynamics of F. prausnitzii in the intestine is usually associated with inflammatory bowel diseases, the role of this bacterium in the development of cancer has been shown. Scientists have found that F. prausnitzii is able to control the mechanisms that trigger the expression of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. On the basis of an in vitro the lung cancer cell line, it was demonstrated that the expression of IL-10, TGF-β2, and IL-1Ra was increased while IL-6, TNF-α, and TNF-β were decreased. Such an increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines and suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines had a positive effect on the course of the disease [68]. According to recent data, F. prausnitzii might serve as a preventive agent for breast cancer. A decrease in the level of Faecalibacterium could indicate the onset of carcinogenic processes. Suppression of IL-6 secretion and JAK2 phosphorylation in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line was observed after the introduction of F. prausnitzii supernatant, suggesting a potential antitumor mechanism. This antitumor effect of the probiotic could be associated with the presence of a putative mechanism in the bacterium that inhibits the IL-6/STAT3 pathway [69]. The direction and intensity of cancer development are thought to be determined by modulations of the body’s immune response, particularly the balance between regulatory T cells and effector subsets. In the case of a low content of CD8+ T cells and elevated Treg frequencies, preliminary evidence suggests that the likelihood of an unfavorable outcome of cancer development increases [70].

The immune response to the tumor has been reported to be enhanced by the introduction of F. prausnitzii into the stomach of patients, which leads to a rise in the number of CD8+ T cells in the blood [71]. Butyrate produced by bacteria inhibits the activity of histone deacetylase (HDAC) in tumor cells, potentially triggering a cascade of reactions leading to the activation of CTL and regulatory T cells CD4+, FoxP3+. In addition, mechanisms aimed at blocking the tumor are activated, including apoptosis and stimulation of CTL. Cells located near the tumor appear to exhibit increased cytotoxic T-killer activity, which might enhance the suppression of immune checkpoints [72].

Table 1 shows the main effects of F. prausnitzii on intestinal immune cells.

The effectiveness of melanoma immunotherapy was assessed in relation to the composition of the intestinal microbiome of patients. It was found that the genes of F. prausnitzii, together with two other bacteria (Bifidobacterium adolescentis and Eubacterium rectale), can be used as functional biomarkers. They mediate the production of molecules that stimulate the activation of the immune system. F. prausnitzii accounted for about 70% of all functions effective for immunotherapy, which may indicate a key role of F. prausnitzii in the treatment process [73].

4 Effects of Akkermansia muciniphila on the Host Immune System

Akkermansia muciniphila is a novel probiotic microorganism, first identified in 2004 by Muriel Derrien from human feces [74]. It is a Gram-negative, non-motile, non-endospore-forming bacterium of elliptical shape, belonging to the phylum Verrucomicrobia. A. muciniphila uses monosaccharides, such as mucin derivatives (galactose and fructose) for growth. It has been reported that in the gut of a healthy person, the content of A. muciniphila varies from 1% to 5% of the total number of microorganisms [3].

To date, a number of studies have been published suggesting that mucin-degrading probiotic strains of A. muciniphila might influence immunity [75–77]. Degradation of A. muciniphila mucin can be carried out through signaling pathways mediated by tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interferons (IF), and interleukins (IL) [78]. A decrease in the concentrations of IL-4 and IL-10, with a simultaneous increase in TNF-α and IFN-γ, leads to activation of A. muciniphila proliferation in the gut. After therapy with a new generation probiotic, an increase in the concentration of 2-arachidonoylglycerol was recorded, which stimulates a decrease in inflammation processes [79,80].

Close symbiotic relationships between the gut microbiota and the human body determine the healthy physiology of the gastrointestinal tract, as well as the level of susceptibility of the host organism to pathogens. Microbiota and intestinal epithelial cells help regulate anti-inflammatory processes, forming a timely immune response, thereby displacing pathogenic organisms [81].

The body’s immune response to the activity of A. muciniphila is formed through the interaction of bacterial cells and their metabolic products with the immune cells of the epithelium, as well as the lymphoid tissue of the gastrointestinal tract [82]. It was found that the metabolites of the gut microbiome can be recognized by TLRs of immune cells. This, in turn, triggers immune response reactions in the body and leads to either homeostasis or imbalance in the gut environment [83]. A. muciniphila is able to regulate the thickness of the mucous layer due to the tight junction protein zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), occludin, and claudin [84]. For example, a study has proposed a link between A. muciniphila and the activity of genes responsible for the synthesis of proteins involved in the formation of intercellular junctions (ZO-1, integrin-β1, and E-cadherin) [85]. The probiotic bacterium directly affects goblet cells of the epithelium, which leads to an increase in the expression of the gene responsible for the synthesis of mucin [86]. It has been established that A. muciniphila prevents metabolic endotoxinemia [80].

The study of the influence of the new probiotic microorganism A. muciniphila on the organisms of animals and humans allowed to revealed the role of the bacterium in the regulation of the immune response and activation of inflammatory processes in the cell. A. muciniphila has an immunomodulatory effect on the host organism. Experiments on mice have demonstrated that A. muciniphila frequently colonizes the cecum. At the same time, the analysis of transcripts allowed for registration of the growth of expression of genes responsible for immune responses and cellular differentiation [78]. Interestingly, both live and dead bacterial cultures can have regulatory functions. A study on mice demonstrated that the oral administration of pasteurized cultures of A. muciniphila decreased the level of IL-6, IL-1β, IFN-γ, IFN-β, and IL-10 [87].

Protection and homeostasis of the intestinal mucosa are possible due to the activity of immunoglobulins, in particular, immunoglobulin A (IgA) [88]. It has been reported in murine models that intake of A. muciniphila promotes activation of T-cell responses in mice. Thus, probiotic intake is hypothesized to be associated with the induction of a T cell response independent of follicular T cells [89]. An in vitro study has shown that blood mononuclear cells treated with live and pasteurized cultures of A. muciniphila produced anti- and pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukins (IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10) and tumor necrosis factors (TNF-α) [90].

Short-chain fatty acids produced by A. muciniphila are able to exert a direct effect on the level of gene transcription. A murine study identified A. muciniphila metabolites in the ileum that appear to affect the expression of transcription factors and genes of short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) metabolism [91]. It was suggested that β-carboline alkaloid harmaline (HAL), produced by A. muciniphila, has a regulatory effect on primary conjugation in cells, and also suppresses systemic inflammation induced by NF-κB [92]. A. muciniphila is able to affect the immortalized cell line of human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (Caco-2 cells), suppressing their function. Thus, it is able to exert an inhibitory effect on Clostridioides difficile RT001 [93].

A. muciniphila is able to influence the metabolism of the host organism through special so-called open active molecules located on the outer membrane of the bacterium. The A. muciniphila membrane contains proteins thought to activate host immune signaling. The most common outer membrane protein is believed to be secretin, along with type IV pili [94]. The outer membrane of the bacterial cell of A. muciniphila contains the Amuc_1100 protein in its structure, which is involved in pili formation [95]. Cell assays have shown that it can activate the NF-κB pathway by activating Toll-like receptors TLR2 and TLR4, which may strengthen the intestinal barrier [76,77,90]. A phospholipid that engages TLR2–TLR1 heterodimers was isolated from the cell membrane of A. muciniphila, which demonstrated immunomodulatory activity in cellular tests [96]. The membrane phospholipid of A. muciniphila activates the expression of proinflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNFα, reducing the activation threshold of dendritic cells, due to which the regulation of immunity in the body occurs [97]. The research group headed by Ottman isolated the MucT protein from the membrane of A. muciniphila. MucT is involved in the formation of the body’s immune response, and also regulates the permeability of the intestinal epithelium [77,90]. The membrane protein of A. muciniphila Amuc_1434 enhances the expression of tumor protein 53 (p53) by blocking the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle. Amuc_1434 reduces the membrane potential of mitochondria, possibly inducing ROS-mediated apoptosis [98]. TLR receptors of gut epithelial and endothelial cells recognize bacterial agents and trigger immune responses in the host organism [76,99]. Fig. 3 shows the main mechanisms of interaction between the host organism’s immune system and the new probiotic microorganism A. muciniphila.

Figure 3: Mechanisms of interaction between the host immune system and the novel probiotic microorganism A. muciniphila. A. muciniphila membrane proteins Amuc1100, Amuc1434 interact with Toll-like receptors of intestinal epithelial cells. They activate the differentiation of immune system cells. Abbreviations: Amuc—membrane protein of A. muciniphila, TLR—toll-like receptor, P53—tumor protein 53, NF-κB—nuclear transcription factor

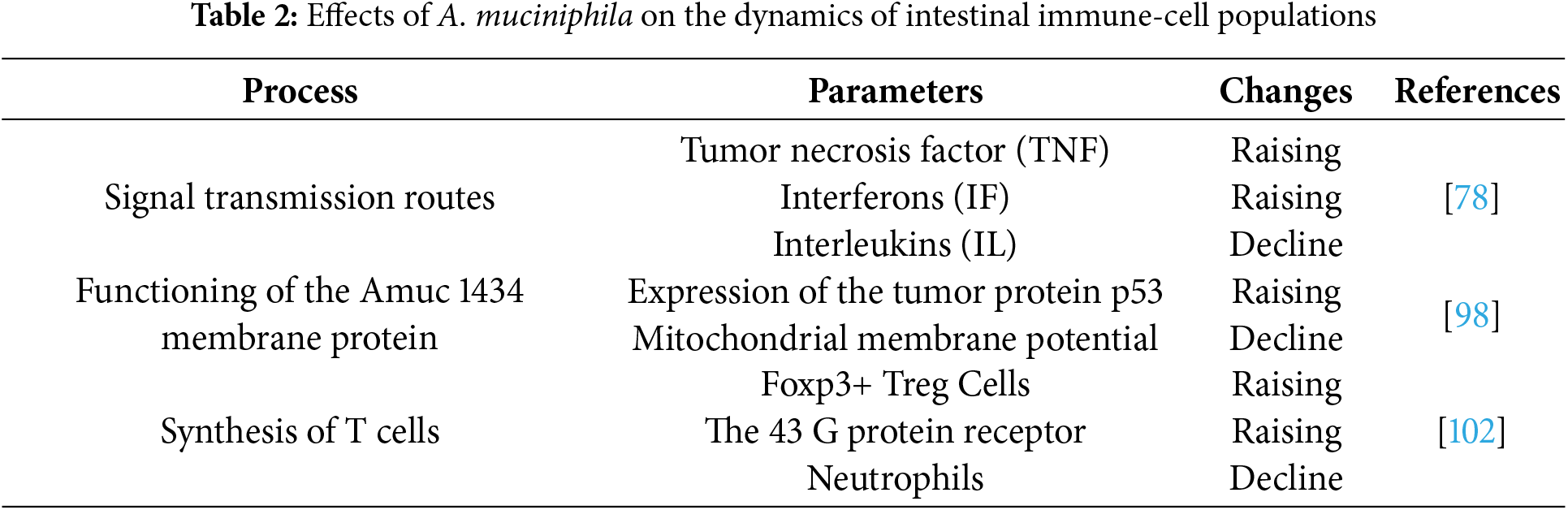

A. muciniphila is known to reduce the number of macrophages and cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTL) in the colon, which helps reduce overall colitis symptoms [100]. A study on mice fed a high-fat diet showed an increase in the concentration of anti-inflammatory T cells (Treg) [101]. An increase in the concentration of short-chain fatty acids (acetate, isobutyrate, valeric, and isovaleric acids) contributes to an increase in the level of Tregs in the gut. A. muciniphila activates the G protein-coupled receptor: GPR41 and GPR43, which leads to stimulation of Foxp3+ Tregs in the colon [102]. A. muciniphila promotes the growth of B cells in the mesenteric lymph nodes, while the overall population of T cells and neutrophils decreases [103]. It has been reported that administration of the novel probiotic agent A. muciniphila stimulates IgG1 production and antigen-specific T-cell responses in mice, leading to differentiation of T cells and T follicular helper cells [89]. Table 2 shows the effects of A. muciniphila on the dynamics of intestinal immune-cell populations.

A. muciniphila secretes diacylphosphatidylethanolamine, which is an active component structurally represented by two branched chains (a15:0-i15:0 PE). It is capable of activating the secretion of TNF-α and IL-6 indirectly via TLR2-TLR1 heterodimers [96]. It should be taken into account that, despite the large contribution of A. muciniphila to the formation of the immune response in the host organism, the anti-inflammatory role of this bacterium appears to be context-dependent and warrants further investigation [104]. At the same time, A. muciniphila is involved in the formation of gut homeostasis [77].

A study has suggested a potential role of A. muciniphila in immune responses of the colon in ulcerative colitis. A new probiotic agent may engage Treg RORγt via the TLR4 receptor. Tregs are a highly stable line of regulatory T cells with enhanced anti-inflammatory and immune properties [105]. It has been established that A. muciniphila has a stimulating effect on the proliferation of stem cells. Undifferentiated cells restore damaged areas of the epithelium and are also involved in the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which helps maintain the integrity of the intestinal mucosa [106,107]. In this regard, A. muciniphila is able to activate adaptive cellular immune responses directly associated with T and B cells [108].

5 Effects of Bacteroides spp. on the Host Immune System

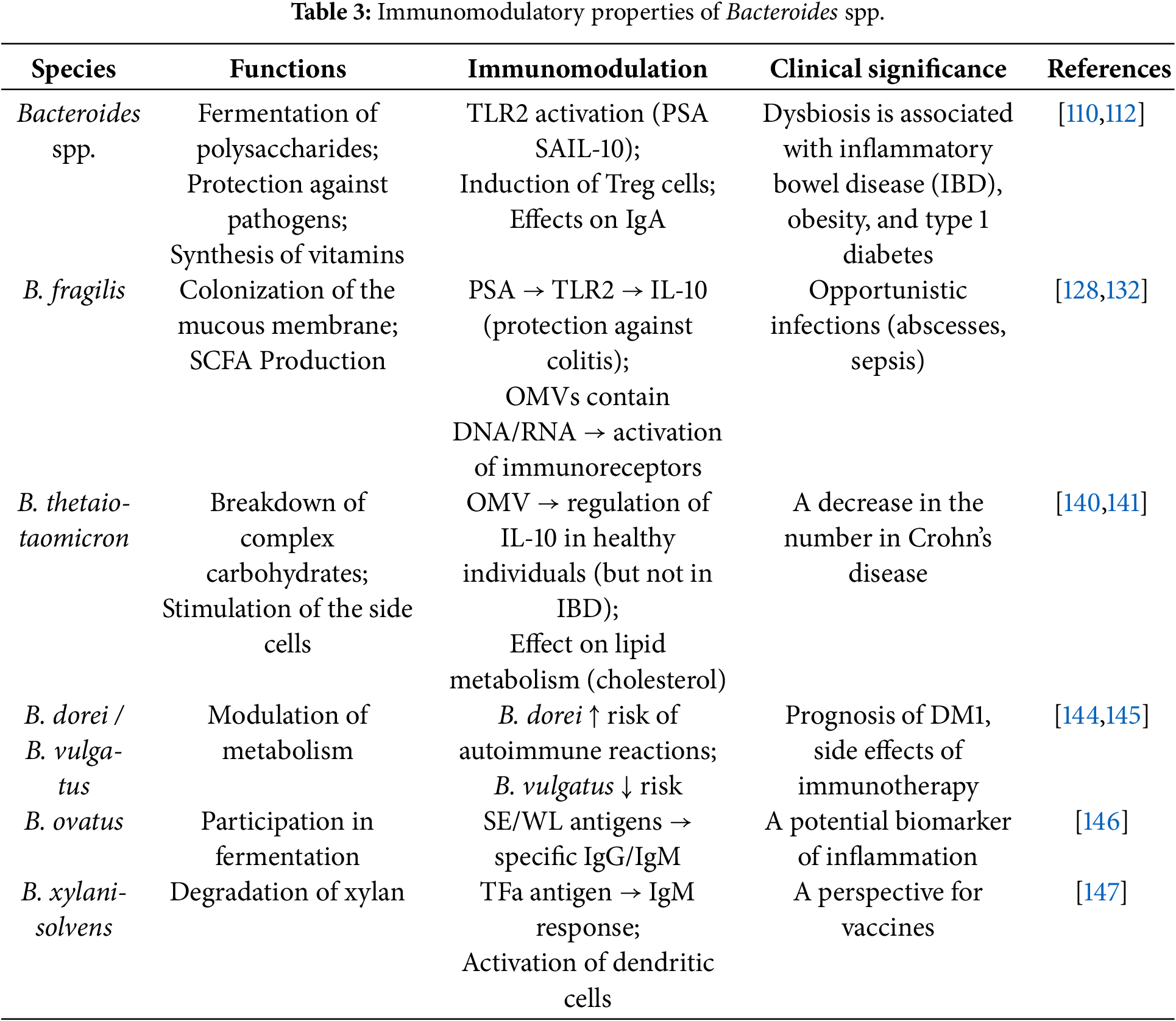

The genus Bacteroides is considered one of the most common taxa in the gastrointestinal tract [109]. Bacteroides species are estimated to comprise approximately 25% of the total microbial mass in the colon [110]. The prevalence of Bacteroides spp. in the gut of adults depends on various factors, mainly diet, environment, and antibiotic use [111].

Members of the genus Bacteroides are commensal microorganisms that may supply nutrients to other microbes and confer protection against pathogens [112]. It has been shown that the symbiotic functions of Bacteroides spp. are influenced by mucin-type O-glycans, which directly determine the interaction of the microorganism with host tissues.

Bacteroides spp. secrete antimicrobial toxins via ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABC exporters), which actively release diffusible toxins into the environment of target microbes [113].

Gram-negative bacteria are known to produce outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) packaged in a lipid bilayer that protects them from physical, chemical, and biological degradation in the gastrointestinal tract [114,115], and contains virulence mediators [116], and components of the bacterial outer membrane, including lipopolysaccharides and outer membrane proteins [117]. Bacteria appear to use extracellular vesicles to deliver toxins to host cells, which can alter their homeostasis and cause cytopathic effects [118]. Epithelial and myeloid cells recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns present in OMVs and trigger innate immune signals, resulting in the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines [119]. OMVs can also induce adaptive immune responses by activating T and B cells [120]. Studies indicate that outer membrane vesicles may be the primary route of bacterial species coupling to host cells and tissues, which is characterized by a number of functional features such as genetic transfer, antimicrobial protection, biofilm formation, and nutrient uptake [121]. Recipient bacteria are capable of breaking down complex substances such as polysaccharides, lipids, and proteins into monosaccharides, peptides, fatty acids, and amino acids using proteases, lipid hydrolases, and glycosidases contained within outer membrane vesicles [122]. Bacteroides spp. are reported to dominate EV export, particularly B. fragilis and B. thetaiotaomicron [123,124].

B. fragilis is an obligate anaerobic gram-negative microorganism [125]. B. fragilis is thought to be a key commensal comprising 1-2% of the healthy gut microbiota [126]. However, physical trauma, inflammation, or surgery can disrupt the integrity of the mucosa, and B. fragilis can spread into the bloodstream or surrounding tissues, which can lead to infection [127].

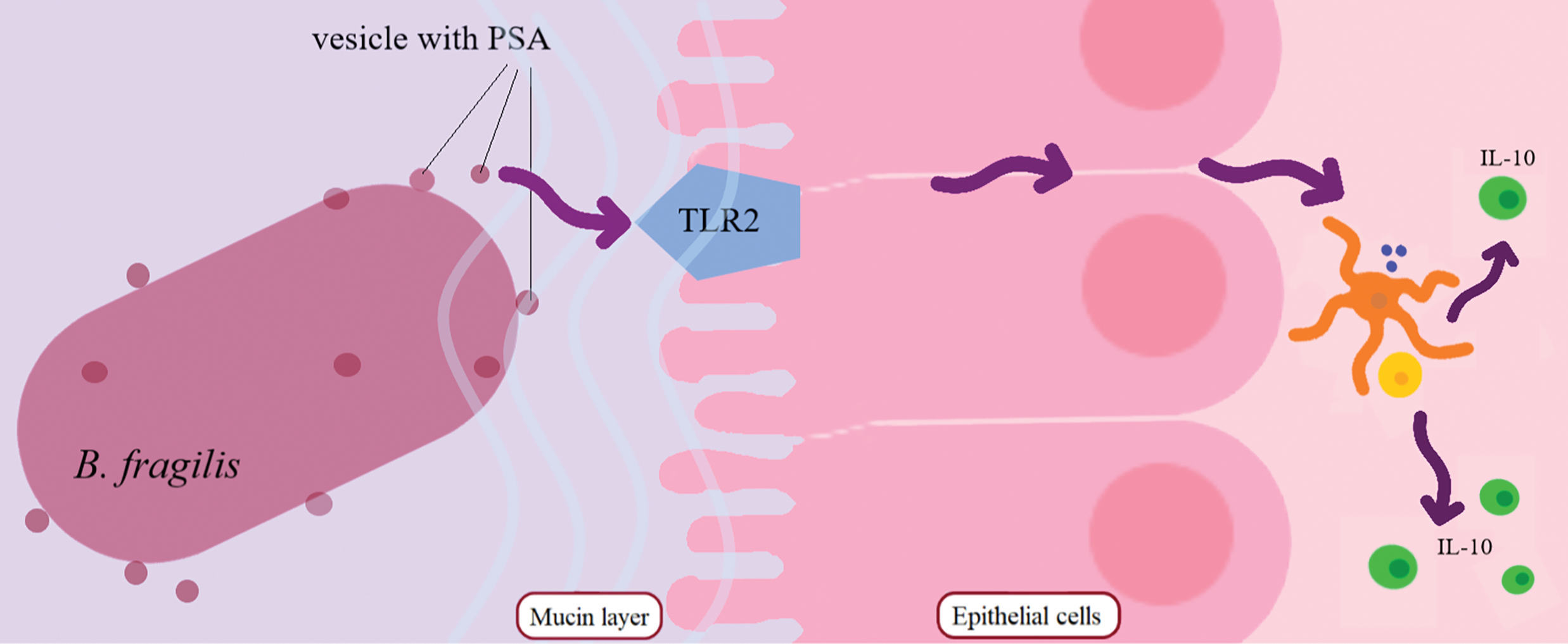

B. fragilis is able to modulate host immunity by inducing IL-10 production via its polysaccharide A (PSA) capsule binding to TLR2 [128]. Murine models have indicated that B. fragilis outer membrane vesicles contain PSA and are able to modulate host immunity through TLR2 activation and IL-10 secretion, resulting in protection against colitis [129,130]. Moreover, B. fragilis outer membrane vesicles contain a number of components, including polysaccharides [129], proteins [122,131], and lipopolysaccharides [122], which also contribute to the production of proinflammatory cytokines and activation of the adaptive immune response (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Mechanism of IL-10 production under the influence of TLR2 activation by PSA vesicle. B. fragilis secretes PSA vesicles that activate intestinal immune cells via epithelial Toll-like receptors. Differentiation of dendritic cells into IL-10 occurs. Abbreviations: PSA—polysaccharide A, TLR-2—toll-like receptor 2, IL-10—interleukin 10

The type and amount of biological cargo associated with outer membrane vesicles of B. fragilis were studied, and their ability to activate host innate immunoreceptors was determined [132]. The data obtained indicated that outer membrane vesicles contain peptide glycans, DNA, and RNA. Moreover, RNA is present at ten times the level of DNA, which gives an idea of the biological cargo in the vesicles of this bacterium. RNA associated with bacterial membrane vesicles obtained from pathogens is characterized by the ability to activate innate immune receptors upon entering host cells [133]. Members of the genus Bacteroides are also capable of secreting antimicrobial toxins. The secretion into the environment is based on the use of various transporters, such as, for example, ABC exporters [113].

B. thetaiotaomicron is a Gram-negative microorganism that is a common representative of the gut microbiota of humans and animals [16,134]. B. thetaiotaomicron is involved in the processes of nutrient absorption, provides a barrier function by influencing mucus secretion and goblet cell development [135,136], and is also a powerful immunomodulatory component of the gut microbiome [137–139].

B. thetaiotaomicron outer membrane vesicles have been shown to play a key role in regulating the immune response to microbiota components in healthy individuals; however, in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), B. thetaiotaomicron outer membrane vesicles do not induce IL-10 production by dendritic cells [140]. Moreover, in the blood of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases, B. thetaiotaomicron outer membrane vesicles induce a lower proportion of IL-10-expressing dendritic cells overall, and a reduction in colonic CD103+ dendritic cells has been noted.

B. thetaiotaomicron influences the host’s immune response, including through the lipid profile, participating in metabolic processes associated with lipid metabolism, which can affect the level of cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood [141]. The level of T cells, B cells, and other components of the immune system is reported to change under the influence of B. thetaiotaomicron, which is also reflected in blood tests. Moreover, by introducing B. thetaiotaomicron into the mouse gut, researchers isolated T cells reactive to this bacterium [142]. It was found that T cells can also react to two other types of bacteria from the genus Bacteroides, and a putative T-cell–activating peptide was reported via genetic screening.. Changes in the level of C-reactive protein (CRP) in the blood can also be a consequence of being in the B. thetaiotaomicron microbiota and is a marker of the presence of an inflammatory process, which is also associated with an immunomodulatory function [143].

The presence of other Bacteroides species, such as B. dorei and B. vulgatus, may predict the risk of immune-related adverse events in melanoma patients receiving immune checkpoint blockade. B. dorei was associated with a high risk of potentially life-threatening immune-related adverse events, whereas B. vulgatus was associated with a reduced risk [144]. The study also highlights the potential for using the microbiome to personalize treatment and reduce the adverse effects of immunotherapy.

The mechanism of influence of B. dorei and B. vulgatus on the immune system and their possible connection with the development of autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) has been formulated [145]. Increased numbers of these species in children at high risk of T1DM may serve as a biomarker for predicting autoimmune reactions. Moreover, changes in diet, as well as the use of antibiotics, can affect the abundance of these bacteria, which highlights their role in the regulation of the immune response.

The potential impact of B. ovatus on the immune response is supported by the fact that in a study [146], fractions of B. ovatus antigens, particularly SE (surface-exposed) and WL (located in the cell wall), exhibit different serological specificities and reactivity, indicating immunomodulatory effects. Results of hemagglutination tests and assays performed using different fractions show the importance of these antigens in interactions with the immune system, as well as their response to various chemical treatments.

B. xylanisolvens may elicit a specific IgM response against TFα antigen. Four groups of people with different doses of B. xylanisolvens, including a placebo group, were analyzed, and it was found that the increase in the level of antibodies to TFαR does not directly depend on the dose of bacteria [147]. It is also known that dendritic cells play a key role in initiating the immune response, capturing antigens from the gut microbiota, and presenting them on their surface. In this study, it was shown that the TFα antigen on B. xylanisolvens is not only processed and presented on dendritic cells, but also does this more effectively on mature dendritic cells, which indicates specific binding of the antigen, and not random attachment. Table 3 shows the main immunomodulatory properties of Bacteroides spp.

6 The Influence of Bacteria of the Genera Prevotella, Roseburia, and Eubacterium on the Immune System

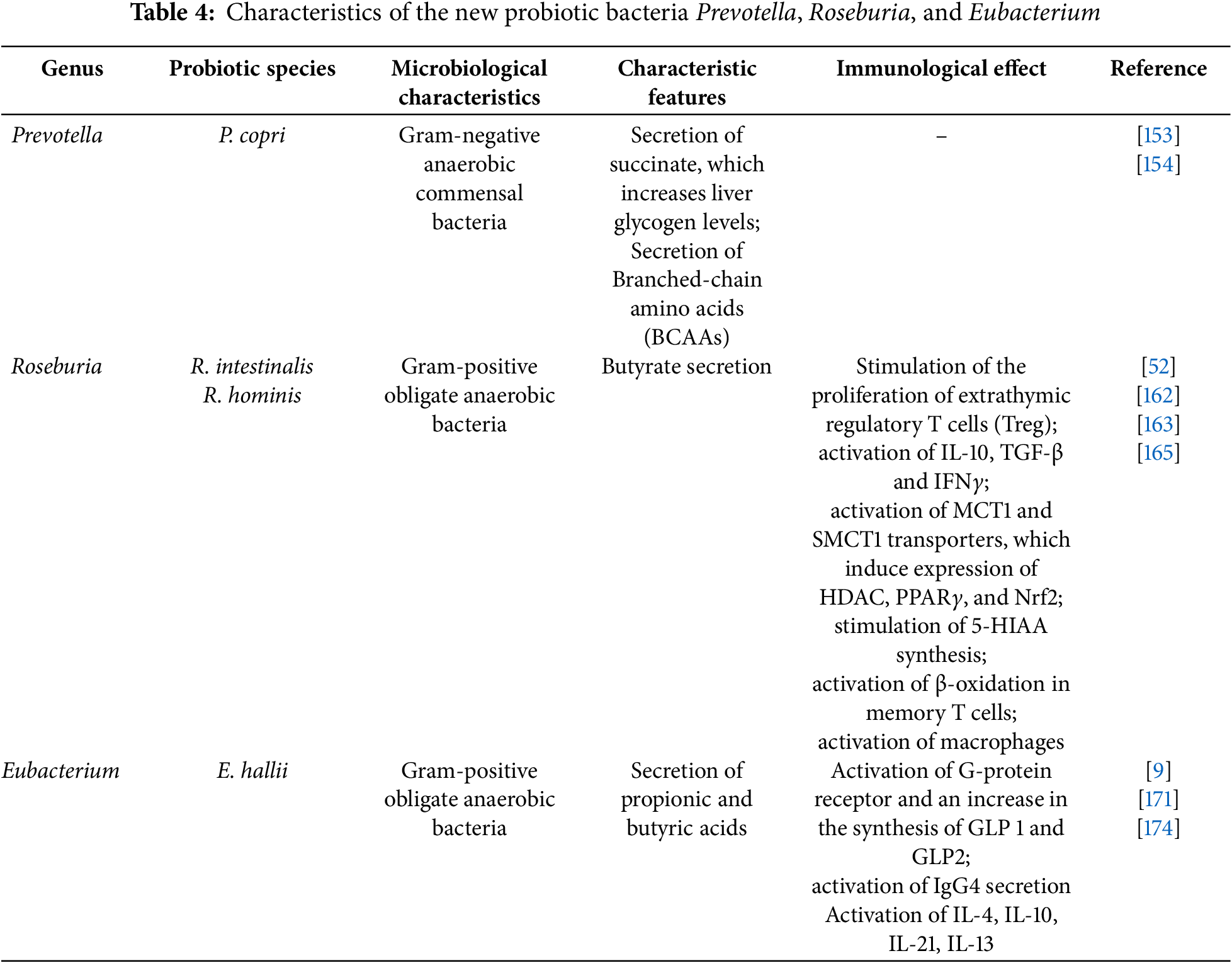

In addition to members of the genera Faecalibacterium, Akkermansia, and Bacteroides, some bacterial strains of Prevotella, Roseburia, and Eubacterium are also recognized as promising new-generation probiotics. Their unique properties include participation in both proinflammatoryand anti-inflammatory immune reactions, as well as the incorporation of microorganism waste products in metabolism, thereby exerting a positive effect on the host organism [148].

Prevotella bacteria are Gram-negative anaerobic commensal microorganisms belonging to the phylum Bacteroidetes [149]. These microorganisms are among the most common bacterial taxa in the human intestine [11]. Several strains of the genus Prevotella are known to be associated with the development of opportunistic infections, such as anaerobic pneumonia [150–152]. However, the species Prevotella copri has demonstrated potential as a promising next-generation probiotic microorganism [148]. P. copri is often identified in humans with plant-based diets rich in fiber, and is therefore traditionally considered a beneficial microorganism [148].

Despite the lack of direct evidence for immunomodulatory properties of P. copri in humans, it is capable of exerting a direct effect on the level of glycogen in the liver (increasing it) due to the secretion of succinate, which is a product of the breakdown of dietary fiber in the gastrointestinal tract. Thus, P. copri may help correct symptoms in patients with diabetes mellitus by ensuring glucose homeostasis through gluconeogenesis in the intestine [153].

It is also known that P. copri is therapeutically effective against prediabetic syndromes, and in cases of already formed diabetes, on the contrary, the bacterium promotes the development of greater glucose tolerance, leading to ischemic heart disease. This may be attributed to its capacity to enhance the biosynthesis of Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) [154]. A number of studies have been reported that have proven the clinical effectiveness of taking Prevotella bacteria on body mass index and blood cholesterol levels [155–158].

The genus Roseburia is represented by Gram-positive, obligate anaerobic, rod-shaped bacteria considered core members of the commensal microflora of the human intestinal tract. Being producers of butyrate, acetate, and propionate, they directly affect intestinal motility and immune function [159]. It is known that Roseburia intestinalis and its metabolitebutyrate have demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects in mice colitis models through cytokine secretion [160]. A relationship was established between the numerical ratio of members of the genus Roseburia abundance and depression in humans. Patients with diagnosed mental disorders showed decreased Roseburia levels [161]. In this regard, the use of a new probiotic drug consisting of Roseburia strains can have a positive effect on the body, which indicates the possibility of using strains as a therapeutic agent.

It has been established that representatives of the genus Roseburia, such as R. intestinalis, affect the immune system of the host organism by producing butyrate. Butyrate is an intermediary for the proliferation of extrathymic regulatory Treg due to the conserved noncoding sequence 1 (CNS1) [52]. Extrathymic differentiation of Treg promotes the activation of IL-10, TGF-β, and IFNγ. It has been experimentally confirmed that bacterial butyrate affects the differentiation of Treg cells, which are directly associated with the regulation of intestinal homeostasis [162].

The immune signaling pathways mediated by butyrate, a metabolite secreted by R. intestinalis, have been studied. Butyrate affects specific receptors GPR41, GPR43, and GPR109a, which promote the activation of monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) and sodium-coupled monocarboxylate transporter 1 (SMCT1) transporters, which trigger the expression of HDAC, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ), and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) genes. This cascade of reactions affects energy metabolism and the total concentration of metabolites in the blood advanced glycation end-products, lipopolysaccharide, and hydroxybutyrate (AGE, LPS, BHB) [163].

In studies on mice with ulcerative colitis, it was found that a probiotic preparation consisting of R. intestinalis has an inhibitory effect on the secretion of IL-17 in the body of animals, and also leads to the differentiation of Treg cells [164]. It was demonstrated that butyrate is able to stimulate the synthesis of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), which in regulatory B cells (Breg) is able to bind to aryl hydrocarbon receptors (AhR), thus participating in the immune response of the body. Butyrate has been observed to promote β-oxidation in memory T cells in vitro and in animal models, suggesting potential regulatory effects on gut macrophages due to the enzyme histone deacetylase [165].

A study has demonstrated that the ability of R. hominis strengthens the intestinal barrier by stimulating regulatory T cell expansion [166]. This regulation occurs through flagellin/TLR5, which in turn stimulates innate lymphoid cells type 3 (ILC3) and IL-22 [167]. Mouse studies suggest that R. intestinalis is also capable of inducing the secretion of IL-22, while reducing the production of IL-17 and IFNγ [108].

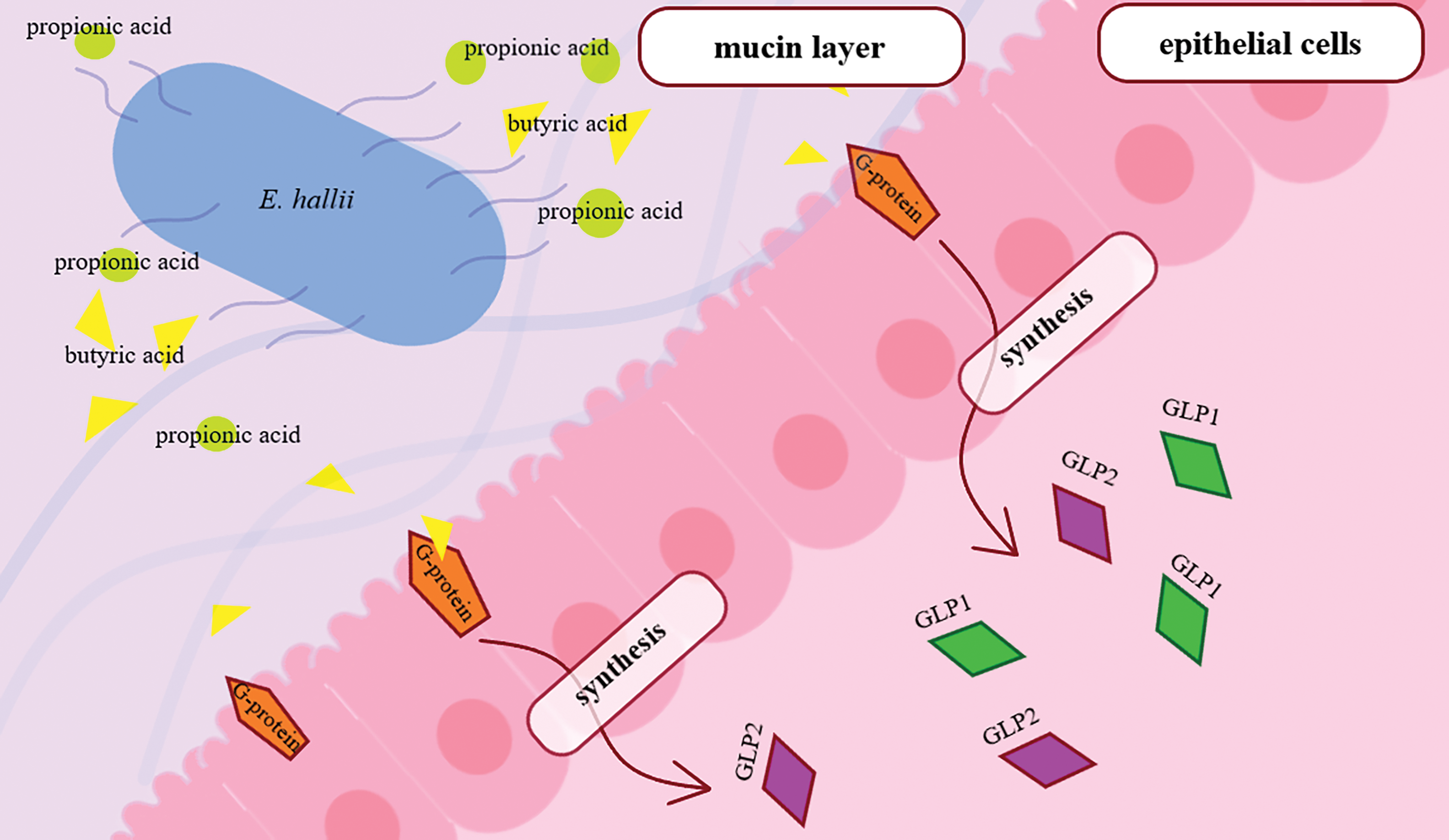

Eubacterium hallii is considered a potential probiotic drug due to its ability to synthesize short-chain fatty acids (propionic and butyric), which are important in maintaining gut homeostasis [9]. This Gram-positive obligate anaerobe uses various sugars and organic acids as an energy source [53]. In a healthy gut, the number of E. hallii is about 3%, and a change in this indicator indicates various inflammatory reactions leading to a decrease in mucus production, proliferation, and differentiation of enterocytes, as well as a general deterioration in the condition of cells [168]. E. hallii metabolism of butyric acid promotes activation of the G-protein receptor and increased synthesis of glucagon-like peptide (GLP1 and GLP2), which directly affects the protective function of the gut. At the same time, there is no effect on body weight, which can be used as an effective means of increasing insulin sensitivity [9]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus has been shown to be associated with decreased levels of the Eubacterium hallii group in the gut microbiome [169], and the use of E. hallii as a therapeutic agent has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity in patients (Fig. 5) [170].

Figure 5: Induction of GLP1 and GLP2 synthesis by E. hallii in the intestine. Propionic and butyric acids secreted by E. hallii activate the synthesis of GLP1 and GLP2 via G-protein. Abbreviations: GLP1, GLP2—glucagon-like peptide 1, glucagon-like peptide 2

The study of the role of E. hallii in maintaining gut immunity is still being explored and represents a promising topic for further scientific investigation. Currently, a correlation has been observed between the number of Eubacterium hallii-group bacteria and immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4), which is involved in the manifestation of immunity in response to pathogen penetration. A decrease in the level of IgG4 accompanies the development of difficult-to-treat diseases of the liver and pancreas [171]. For example, in chronic autoimmune inflammation of the thyroid gland with lymphocytic infiltration, an increase in Eubacterium hallii-group has been reported, along with Blautia and Ruminococcus torques [172]. This may be related to the role of short-chain fatty acids in the process of transformation of Th0 cells into Th2 cells, which are responsible for the synthesis of IL-4 [173]. In addition, correlations were found between IL-4, IL-10, IL-21, IL-13, and B-cell activating factors with IgG4 production [174]. In the case of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy driven by proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 cells, the gut microbiome of patients was dominated by the Eubacterium hallii-group, in contrast to the healthy sample [175,176]. The main characteristics of members of these bacterial genera are presented in Table 4.

7 The Effect of New Generation Probiotics on MicroRNA Content, the Gut-Brain Axis, and Their Re-lationship to the Immune System

New-generation probiotics such as Akkermansia muciniphila, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Bacteroides sp., Prevotella sp., Roseburia sp., and Eubacterium sp. have been suggested to influence not only the composition of the microbiome but also gene expression, potentially through mechanisms related to microRNAs (miRNAs) [177], and can affect their synthesis and regulation in host cells [178]. MicroRNAs are small noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression by participating in various cellular processes, including inflammatory reactions, apoptosis, and metabolism [179]. The relationship between probiotics and microRNAs has gained attention in the context of antibiotic resistance and chronic inflammatory diseases, highlighting potential for the development of new therapeutic strategies [180].

New-generation probiotics may modulate immune responses by stimulating cytokine production (e.g., IL-10, TGF-β), which has been linked to the regulation of inflammation-related microRNAs [181]. Thus, A. muciniphila has been reported to influence the expression of miR-143/145, which may promote synthesis of cell-junction proteins and barrier restoration during inflammation [182], while Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is associated with miR-3120-3p, Roseburia spp. have shown correlations with a broader set of microRNAs, including miR-3120-3p, miR-6529-5p, and neuroprotective miR-124-3p [183], as well as miR-155, and miR-146a, which control TLR signaling. These molecules packaged in exosomes are able to cross the blood-brain barrier, influencing central-nervous-system processes [184,185]. Probiotics also affect the balance of T-helper cells (Th17/Treg) through the regulation of microRNAs such as miR-21, which reduces systemic inflammation [186]. For example, Akkermansia muciniphila is associated with the suppression of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 [187]. Prevotella spp. primarily activate type-2 T helper (Th2) cells, promoting IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 production-hallmarks of the Th2 response [188,189]. The metabolism of short-chain fatty acids, produced by certain bacterial strains, is considered one of the mechanisms of the effect of probiotics on microRNAs [190]. For example, the ability to suppress histone deacetylase affects the epigenetic regulation of microRNAs, as well as the activation of GPR41/GPR43 receptors, modulating the expression of miR-29b associated with glucose metabolism [191].

New generation probiotics have a significant effect on the connection between the gut and the brain, as well as on the immune system as a whole [192]. Effects on the level of neurotransmitters [193], such as serotonin, 95% of which is synthesized in the intestine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [194], affect psychological behavior [195]. The interaction of the microbiota with the central nervous system can lead to changes in inflammatory processes, which is important for mental health [196]. Probiotics have been shown in preclinical studies to reduce levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which may have a protective effect on the brain [197].

Immune modulation may also occur through the regulation of microglial activity by new-generation probiotics, the immune cells of the brain. For example, metabolites of short-chain fatty acids produced by bacteria reduce neuroinflammation through interaction with GPR41/GPR43 receptors, which is critically important in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases [198].

Modulation of the gut-brain axis may also be mediated through endocrine signals based on the ability of new generation probiotics to influence the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA), reducing cortisol levels and stress-induced damage to neurons [199].

The interaction of probiotics with the immune system is to strengthen the intestinal barrier, preventing the translocation of pathogens and lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which provoke systemic inflammation [200], possibly through the stimulation of IgA, which protects the intestinal mucosa [201]. SCFAs produced by NGPs induce the differentiation of T-regulatory cells that suppress autoimmune reactions [202].

8 Clinical Use, Safety, and Regulatory Status of New Generation Probiotics

New-generation probiotics are being investigated for potential applications in both veterinary medicine and human healthcare [203]. Currently, the open databases Scopus, Web of Science, and PubMed have published papers studying new-generation probiotics both in vitro and in vivo. For example, Zhang described a number of clinical trials on the use of A. muciniphila in the treatment of ulcerative colitis [204]. There is a well-known review of positive health outcomes using A. muciniphila–based probiotics in animal and human obesity models [205]. In addition, it has been clinically established that administration of a new probiotic drug F. prausnitzii may influence intestinal microbiome diversity following antibiotic therapy [206]. Table 5 shows the main aspects of immune interactions and the effects that new generation probiotics have on the body in various diseases.

However, there are limitations to the use of probiotic microorganisms, particularly due to ongoing challenges in evaluating their safety and regulatory aspects of their production. Testing probiotic safety, alongside investigating their mechanisms of action in humans and animals, remains a key research objective [207–209]. Classical approaches to studying the safety of probiotics are considered to be the so-called phenotypic assessment of the body, which includes the analysis of virulence factors, as well as acquired mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. The development of sequencing technologies has enabled genome-level safety evaluation of probiotics [210]. The main limitations that cast doubt on the safety of using probiotics were the variety of unclassified strains and the possibility of adverse interactions with host microflora. However, an integrated genetic–phenotypic approaches have been proposed to help mitigate these concerns [211]. The regulatory framework governing the production and use of probiotic drugs does not have an international status, while each country has its own probiotic production and usage regulations [212]. The International Scientific Association of Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) has developed a document that contains information on the short- and long-term risks of using probiotics. Short-term factors indicate that probiotic strains must be assessed for antibiotic resistance, while microbiome profiling is not required. Long-term monitoring evaluates risk–benefit ratios and includes clinical trials in vulnerable populations, such as the elderly and children [213].

The diversity of the gut microbiome directly affects human health. An imbalance in the microbial community leads to the dominance of pathogenic microbiota and the development of various diseases. Probiotics may help maintain the balance of gut microbiota by producing various functional factors that adapt bacteria to changing conditions of the body. Lactic acid bacteria have long been used as probiotics. However, advances in molecular genetic methods have made it possible to identify a number of bacterial taxa of the human gut with probiotic potential. These microorganisms are classified as new-generation probiotics based on emerging research. New probiotic agents include Roseburia intestinalis, Eubacterium hallii, Akkermansia muciniphila, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Christensenella minuta, Prevotella copri, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Parabacteroides goldsteinii, and Bacteroides fragilis. They have been reported to contribute to the synthesis of folic acid, serotonin, and short-chain fatty acids, including butyrate. These substances have immunomodulatory effects by activating the synthesis of biologically active molecules. Metabolites of probiotic bacteria contribute to the formation of specific bonds with cell receptors. They are thought to play a signaling role by activating cytokine synthesis, inhibiting apoptotic processes within cells, and consequently reducing inflammation. In this regard, the study of the role of new-generation probiotics in maintaining the human immune system represents a promising area for future investigation. The limitations of this manuscript include the exclusion of literature from non-indexed databases, the reliance on a substantial number of sources older than five years, and the limited review of practical experiences with the use of next-generation probiotics in disease treatment. This is largely attributable to the limited practical experience with next-generation probiotics (NGPs) in randomized controlled trials, as well as the insufficient data on potential side effects associated with their use. Large-scale studies in this field are essential for addressing critical issues such as optimal dosage, treatment regimens, the choice between monocultures or combinations of probiotic strains, routes of administration, and the organ-specific effects of probiotics. Nevertheless, the study will allow us to better understand the prospects for using new-generation probiotics in the prevention and treatment of various human diseases.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The research was carried out at the expense of a grant from the Russian Science Foundation No. 24-24-20036, https://rscf.ru/project/24-24-20036 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Mikhail Syromyatnikov; draft manuscript preparation: Mariya Gladkikh, Ekaterina Nesterova and Polina Morozova; review and editing: Mikhail Syromyatnikov, Shima Kazemzadeh; supervision: Mikhail Syromyatnikov and Olga Korneeva. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Qiu P, Ishimoto T, Fu L, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Liu Y. The gut microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:733992. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2022.733992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Canfora EE, Meex RCR, Venema K, Blaak EE. Gut microbial metabolites in obesity, NAFLD and T2DM. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15(5):261–73. doi:10.1038/s41574-019-0156-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Liu BN, Liu XT, Liang ZH, Wang JH. Gut microbiota in obesity. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(25):3837–50. doi:10.3748/wjg.v27.i25.3837. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Stecher B. The roles of inflammation, nutrient availability and the commensal microbiota in enteric pathogen infection. Microbiol Spectr. 2015;3(3). doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.MBP-0008-2014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Mejía-Caballero A, Salas-Villagrán VA, Jiménez-Serna A, Farrés A. Challenges in the production and use of probiotics as therapeuticals in cancer treatment or prevention. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2021;48(9–10):kuab052. doi:10.1093/jimb/kuab052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Gul S, Durante-Mangoni E. Unraveling the puzzle: health benefits of probiotics—a comprehensive review. J Clin Med. 2024;13(5):1436. doi:10.3390/jcm13051436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Singh RP, Shadan A, Ma Y. Biotechnological applications of probiotics: a multifarious weapon to disease and metabolic abnormality. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2022;14(6):1184–210. doi:10.1007/s12602-022-09992-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Vera-Santander VE, Hernandez-Figueroa RH, Jimenez-Munguia MT, Mani-Lopez E, Lopez-Malo A. Health benefits of consuming foods with bacterial probiotics, postbiotics, and their metabolites: a review. Molecules. 2023;28(3):1230. doi:10.3390/molecules28031230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Al-Fakhrany OM, Elekhnawy E. Next-generation probiotics: the upcoming biotherapeutics. Mol Biol Rep. 2024;51(1):505. doi:10.1007/s11033-024-09398-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Kazmierczak-Siedlecka K, Skonieczna-Zydecka K, Hupp T, Duchnowska R, Marek-Trzonkowska N, Połom K. Next-generation probiotics—do they open new therapeutic strategies for cancer patients? Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1):2035659. doi:10.1080/19490976.2022.2035659. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. De Filippis F, Esposito A, Ercolini D. Outlook on next-generation probiotics from the human gut. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79(2):76. doi:10.1007/s00018-021-04080-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Dudik B, Kinova Sepova H, Greifova G, Bilka F, Bilkova A. Next generation probiotics: an overview of the most promising candidates. Epidemiol Mikrobiol Imunol. 2022;71(1):48–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

13. Kumari M, Singh P, Nataraj BH, Kokkiligadda A, Naithani H, Azmal Ali S, et al. Fostering next-generation probiotics in human gut by targeted dietary modulation: an emerging perspective. Food Res Int. 2021;150(PtA):110716. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2021.110716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Parada Venegas D, la Fuente MK De, Landskron G, González MJ, Quera R, Dijkstra G, et al. Short Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs)-mediated gut epithelial and immune regulation and its relevance for inflammatory bowel diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:277. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Sionek B, Szydłowska A, Zielinska D, Neffe-Skocińska K, Kołozyn-Krajewska D. Beneficial bacteria isolated from food in relation to the next generation of probiotics. Microorganisms. 2023;11(7):1714. doi:10.3390/microorganisms11071714. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Kuziel GA, Rakoff-Nahoum S. The gut microbiome. Curr Biol. 2022;32(6):R257–R264. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.02.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Liu Q, Yu Z, Tian F, Zhao J, Zhang H, Zhai Q, et al. Surface components and metabolites of probiotics for regulation of intestinal epithelial barrier. Microb Cell Fact. 2020;19(1):23. doi:10.1186/s12934-020-1289-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Amimo JO, Raev SA, Chepngeno J, Mainga AO, Guo Y, Saif L, et al. Rotavirus interactions with host intestinal epithelial cells. Front Immunol. 2021;12:793841. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.793841. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Ohland CL, Macnaughton WK. Probiotic bacteria and intestinal epithelial barrier function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298(6):G807–19. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00243.2009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. McGuckin MA, Lindén SK, Sutton P, Florin TH. Mucin dynamics and enteric pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9(4):265–78. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Luis AS, Hansson GC. Intestinal mucus and their glycans: a habitat for thriving microbiota. Cell Host Microbe. 2023;31(7):1087–100. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2023.05.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Melhem H, Regan-Komito D, Niess JH. Mucins dynamics in physiological and pathological conditions. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(24):13642. doi:10.3390/ijms222413642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Giorgetti G, Brandimarte G, Fabiocchi F, Ricci S, Flamini P, Sandri G, et al. Interactions between innate immunity, microbiota, and probiotics. J Immunol Res. 2015;2015(4):501361. doi:10.1155/2015/501361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Rumio C, Besusso D, Palazzo M, Selleri S, Sfondrini L, Dubini F, et al. Degranulation of paneth cells via toll-like receptor 9. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(2):373–81. doi:10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63304-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Rumio C, Sommariva M, Sfondrini L, Palazzo M, Morelli D, Viganò L, et al. Induction of Paneth cell degranulation by orally administered Toll-like receptor ligands. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227(3):1107–13. doi:10.1002/jcp.22830. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Salzman NH, Ghosh D, Huttner KM, Paterson Y, Bevins CL. Protection against enteric salmonellosis in transgenic mice expressing a human intestinal defensin. Nature. 2003;422(6931):522–6. doi:10.1038/nature01520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Mohammad S, Thiemermann C. Role of metabolic endotoxemia in systemic inflammation and potential interventions. Front Immunol. 2021;11:594150. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.594150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Quaglio AEV, Grillo TG, De Oliveira ECS, Di Stasi LC, Sassaki LY. Gut microbiota, inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28(30):4053–60. doi:10.3748/wjg.v28.i30.4053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Chen Y, Cui W, Li X, Yang H. Interaction between commensal bacteria, immune response and the intestinal barrier in inflammatory bowel disease. Front Immunol. 2021;12:761981. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.761981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124(4):783–801. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Bhutta NK, Xu X, Jian C, Wang Y, Liu Y, Sun J, et al. Gut microbiota mediated T cells regulation and autoimmune diseases. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1477187. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2024.1477187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Lebeer S, Vanderleyden J, De Keersmaecker SC. Host interactions of probiotic bacterial surface molecules: comparison with commensals and pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8(3):171–84. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118(2):229–41. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Lee J, Mo JH, Katakura K, Alkalay I, Rucker AN, Liu YT, et al. Maintenance of colonic homeostasis by distinctive apical TLR9 signalling in intestinal epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(12):1327–36. doi:10.1038/ncb1500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Hold GL, Schwiertz A, Aminov RI, Blaut M, Flint HJ. Oligonucleotide probes that detect quantitatively significant groups of butyrate-producing bacteria in human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69(7):4320–4. doi:10.1128/aem.69.7.4320-4324.2003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Díaz-Rizzolo DA, Kostov B, López-Siles M, Serra A, Colungo C, González-de-Paz L, et al. Healthy dietary pattern and their corresponding gut microbiota profile are linked to a lower risk of type 2 diabetes, independent of the presence of obesity. Clin Nutr. 2020;39(2):524–32. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2019.02.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Aschard H, Laville V, Tchetgen ET, Knights D, Imhann F, Seksik P, et al. Genetic effects on the commensal microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease patients. PLoS Genet. 2019;15(3):e1008018. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1008018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Effendi RMRA, Anshory M, Kalim H, Dwiyana RF, Suwarsa O, Pardo LM, et al. Akkermansia muciniphila and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in immune-related diseases. Microorganisms. 2022;10(12):2382. doi:10.3390/microorganisms10122382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Rabiei N, Ahmadi Badi S, Ettehad Marvasti F, Nejad Sattari T, Vaziri F, Siadat SD. Induction effects of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and its extracellular vesicles on toll-like receptor signaling pathway gene expression and cytokine level in human intestinal epithelial cells. Cytokine. 2019;121(3):154718. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2019.05.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, Lakhdari O, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Gratadoux JJ, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(43):16731–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804812105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Zhang M, Qiu X, Zhang H, Yang X, Hong N, Yang Y, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii inhibits interleukin-17 to ameliorate colorectal colitis in rats. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109146. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Quévrain E, Maubert MA, Michon C, Chain F, Marquant R, Tailhades J, et al. Identification of an anti-inflammatory protein from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a commensal bacterium deficient in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2016;65(3):415–25. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Zhang J, Huang YJ, Trapecar M, Wright C, Schneider K, Kemmitt J, et al. An immune-competent human gut microphysiological system enables inflammation-modulation by Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 2024;10(1):31. doi:10.1038/s41522-024-00501-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Tanes C, Walker EM, Slisarenko N, Gerrets GL, Grasperge BF, Qin X, et al. Gut microbiome changes associated with epithelial barrier damage and systemic inflammation during antiretroviral therapy of chronic SIV infection. Viruses. 2021;13(8):1567. doi:10.3390/v13081567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Hardy H, Harris J, Lyon E, Beal J, Foey AD. Probiotics, prebiotics and immunomodulation of gut mucosal defences: homeostasis and immunopathology. Nutrients. 2013;5(6):1869–912. doi:10.3390/nu5061869. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Saleh M, Elson CO. Experimental inflammatory bowel disease: insights into the host-microbiota dialog. Immunity. 2011;34(3):293–302. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Miquel S, Leclerc M, Martin R, Chain F, Lenoir M, Raguideau S, et al. Identification of metabolic signatures linked to anti-inflammatory effects of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. mBio. 2015;6(2):e00300–15. doi:10.1128/mBio.00300-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Hamer HM, Jonkers DM, Bast A, Vanhoutvin SA, Fischer MA, Kodde A, et al. Butyrate modulates oxidative stress in the colonic mucosa of healthy humans. Clin Nutr. 2009;28(1):88–93. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2008.11.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Fatima SN, Akhtar S, Shahid SM, Sajjad A, Bibi A. Effect of salicylic acid supplementation on blood glucose, lipid profile and electrolyte homeostasis in gentamicin sulphate induced nephrotoxicity. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2021;34(3):1075–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

50. Yin L, Laevsky G, Giardina C. Butyrate suppression of colonocyte NF-κB activation and cellular proteasome activity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(48):44641–46. doi:10.1074/jbc.M105170200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504(7480):446–50. doi:10.1038/nature12721. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, Dikiy S, van der Veeken J, deRoos P, et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013;504(7480):451–5. doi:10.1038/nature12726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Barcenilla A, Pryde SE, Martin JC, Duncan SH, Stewart CS, Henderson C, et al. Phylogenetic relationships of butyrate-producing bacteria from the human gut. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66(4):1654–61. doi:10.1128/AEM.66.4.1654-1661.2000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Louis P, Duncan SH, McCrae SI, Millar J, Jackson MS, Flint HJ. Restricted distribution of the butyrate kinase pathway among butyrate-producing bacteria from the human colon. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(7):2099–106. doi:10.1128/JB.186.7.2099-2106.2004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Frank DN, Amand AL, Feldman RA, Boedeker EC, Harpaz N, Pace NR. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial community imbalances in human inflammatory bowel diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(34):13780–185. doi:10.1073/pnas.0706625104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Fujimoto T, Imaeda H, Takahashi K, Kasumi E, Bamba S, Fujiyama Y. Decreased abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in the gut microbiota of Crohn’s disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(4):613–9. doi:10.1111/jgh.12073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Machiels K, Joossens M, Sabino J, Preter V, Arijs I, Eeckhaut V. A decrease of the butyrate-producing species Roseburia hominis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii defines dysbiosis in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2014;63(8):1275–83. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304833. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Yamada T, Hino S, Iijima H, Genda T, Aoki R, Nagata R, et al. Mucin O-glycans facilitate symbiosynthesis to maintain gut immune homeostasis. eBioMedicine. 2019;48:513–25. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.09.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Rossi O, van Berkel LA, Chain F, Tanweer Khan M, Taverne N, Sokol H, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii A2-165 has a high capacity to induce IL-10 in human and murine dendritic cells and modulates T cell responses. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):18507. doi:10.1038/srep18507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Yang M, Wang J-H, Shin J-H, Lee D, Lee S-N, Seo J-G, et al. Pharmaceutical efficacy of novel human-origin Faecalibacterium prausnitzii strains on high-fat-diet-induced obesity and associated metabolic disorders in mice. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1220044. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1220044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Munukka E, Rintala A, Toivonen R, Nylund M, Yang B, Takanen A, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii treatment improves hepatic health and reduces adipose tissue inflammation in high-fat fed mice. ISME J. 2017;11(7):1667–79. doi:10.1038/ismej.2017.24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Moon J, Lee AR, Kim H, Jhun J, Lee SY, Choi JW, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii alleviates inflammatory arthritis and regulates IL-17 production, short chain fatty acids, and the intestinal microbial flora in experimental mouse model for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2023;25(1):130. doi:10.1186/s13075-023-03118-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Martín R, Chain F, Miquel S, Lu J, Gratadoux JJ, Sokol H, et al. The commensal bacterium Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is protective in DNBS-induced chronic moderate and severe colitis models. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(3):417–30. doi:10.1097/01.MIB.0000440815.76627.64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Martín R, Miquel S, Benevides L, Bridonneau C, Robert V, Hudault S, et al. Functional characterization of novel Faecalibacterium prausnitzii strains isolated from healthy volunteers: a step forward in the use of F. prausnitzii as a next-generation probiotic. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1226. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.01226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Godefroy E, Barbé L, Le Moullac-Vaidye B, Rocher J, Breiman A, Leuillet S, et al. Microbiota-induced regulatory T cells associate with FUT2-dependent susceptibility to rotavirus gastroenteritis. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1123803. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1123803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Touch S, Godefroy E, Rolhion N, Danne C, Oeuvray C, Straube M, et al. Human CD4+CD8α+ Tregs induced by Faecalibacterium prausnitzii protect against intestinal inflammation. JCI Insight. 2022;7(12):e154722. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.154722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Gao Y, Xu P, Sun D, Jiang Y, Lin XL, Han T, et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii abrogates intestinal toxicity and promotes tumor immunity to increase the efficacy of dual CTLA4 and PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Cancer Res. 2023;83(22):3710–25. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-0605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Jafari B, Khavari Nejad RA, Vaziri F, Siadad SD. Evaluation of the effects of extracellular vesicles derived from Faecalibacterium prausnitzii on lung cancer cell line. Biologia. 2019;74(7):889–98. doi:10.2478/s11756-019-00229-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Ma J, Sun L, Liu Y, Ren H, Shen Y, Bi F, et al. Alter between gut bacteria and blood metabolites and the anti-tumor effects of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in breast cancer. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20(1):82. doi:10.1186/s12866-020-01739-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Kareva I. Metabolism and gut microbiota in cancer immunoediting, CD8/Treg ratios, immune cell homeostasis, and cancer (immuno)therapy: concise review. Stem Cells. 2019;37(10):1273–80. doi:10.1002/stem.3051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Guo J, Meng F, Hu R, Chen L, Chang J, Zhao K, et al. Inhibition of the NF-κB/HIF-1α signaling pathway in colorectal cancer by tyrosol: a gut microbiota-derived metabolite. J Immunother Cancer. 2024;12(9):e008831. doi:10.1136/jitc-2024-008831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Verhoef JI, Klont E, van Overveld FJ, Rijkers GT. The long and winding road of faecal microbiota transplants to targeted intervention for improvement of immune checkpoint inhibition therapy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2023;23(11):1179–91. doi:10.1080/14737140.2023.2262765. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Olekhnovich EI, Ivanov AB, Babkina AA, Sokolov AA, Ulyantsev VI, Fedorov DE, et al. Consistent stool metagenomic biomarkers associated with the response to melanoma immunotherapy. mSystems. 2023;8(2):e0102322. doi:10.1128/msystems.01023-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Derrien M, Vaughan EE, Plugge CM, de Vos WM. Akkermansia muciniphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a human intestinal mucin-degrading bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54(Pt5):1469–76. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02873-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Iwaza R, Wasfy RM, Dubourg G, Raoult D, Lagier J-C. Akkermansia muciniphila: the state of the art, 18 years after its first discovery. Front Gastroenterol. 2022;1:1024393. doi:10.3389/fgstr.2022.1024393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Plovier H, Everard A, Druart C, Depommier C, Van Hul M, Geurts L, et al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2017;23(1):107–13. doi:10.1038/nm.4236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Ottman N, Davids M, Suarez-Diez M, Boeren S, Schaap PJ, Martins Dos Santos VAP, et al. Genome-scale model and omics analysis of metabolic capacities of Akkermansia muciniphila reveal a preferential mucin-degrading lifestyle. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83(18):e01014–17. doi:10.1128/AEM.01014-17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Gu Z-Y, Pei W-L, Zhang Y, Zhu J, Li L, Zhang Z. Akkermansia muciniphila in inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;134(23):2841–3. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000001829. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Hryhorowicz S, Kaczmarek-Ryś M, Zielińska A, Scott RJ, Słomski R, Pławski A. Endocannabinoid system as a promising therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel disease—a systematic review. Front Immunol. 2021;12:790803. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.790803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, Ouwerkerk JP, Druart C, Bindels LB, et al. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(22):9066–71. doi:10.1073/pnas.1219451110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]