Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Parkinson’s Disease: Is Impaired Deuterium Depleted Nutrient Supply by Gut Microbes a Primary Factor?

1 Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA

2Private Practice, Greg Nigh, LLC, Westerly, RI 02891, USA

3 Laboratory of Molecular Biology and Immunology, Department of Pharmacy, University of Patras, Rio-Patras, 26500, Greece

4 Department of Research and Development, Nasco AD Biotechnology Laboratory, Piraeus, 18536, Greece

* Corresponding Author: Stephanie Seneff. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Cellular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches in Protein Misfolding Diseases)

BIOCELL 2025, 49(9), 1545-1572. https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.066687

Received 15 April 2025; Accepted 10 June 2025; Issue published 25 September 2025

Abstract

Deuterium is a heavy isotope of hydrogen, with an extra neutron, endowing it with unique biophysical and biochemical properties compared to hydrogen. The ATPase pumps in the mitochondria depend upon proton motive force to catalyze the reaction that produces ATP. Deuterons disrupt the pumps, inducing excessive reactive oxygen species and decreased ATP synthesis. The aim of this review is to develop a theory that mitochondrial dysfunction due to deuterium overload, systemically, is a primary cause of Parkinson’s disease (PD). The gut microbes supply deuterium-depleted short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) to the colonocytes, particularly butyrate, and an insufficient supply of butyrate may be a primary driver behind mitochondrial dysfunction in the gut, an early factor in PD. Indeed, low gut butyrate is a characteristic feature of PD. Mitochondrial dysfunction is a factor in many diseases, including all neurodegenerative diseases. Biological organisms have devised sophisticated strategies for protecting the ATPase pumps from deuterium overload. One such strategy may involve capturing deuterons in bis-allylic carbon atoms present in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in cardiolipin. Cardiolipin uniquely localizes to the inner membrane of the intermembrane space, tightly integrated into ATPase proteins. Bis-allylic carbon atoms can capture and retain deuterium, and, interestingly, deuterium doping in PUFAs can quench the chain reaction that causes massive damage upon lipid peroxidation. Neuronal cardiolipin is especially rich in docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), a PUFA with five bis-allylic carbon atoms. Upon excessive oxidative stress, cardiolipin migrates to the outer membrane, where it interacts with α-synuclein (α-syn), the amyloidogenic protein that accumulates as fibrils in Lewy bodies in association with PD. Such interaction leads to pore formation and the launch of an apoptotic cascade. α-syn misfolding likely begins in the gut, and misfolded α-syn travels along nerve fibers, particularly the vagus nerve, to reach the brainstem nuclei, where it can seed misfolding of α-syn molecules already present there. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the gut may be a primary factor in PD, and low-deuterium nutrients may be therapeutic.Keywords

It has been said that all disease begins in the gut, and the evidence is quite compelling that this is the case for Parkinson’s disease (PD) [1]. It is also widely accepted that mitochondrial dysfunction is a common factor in most, if not all, chronic diseases, and the evidence is overwhelming that mitochondrial dysfunction plays an important role in PD [2]. In this paper, we review the evidence in support of these two claims, focusing on PD, but we take it one step further, by proposing that excess deuterium in the mitochondrial ATPase pumps is a primary factor in mitochondrial dysfunction, and that this is the initial step in the cascade of events that eventually leads to PD.

Deuterium is a heavy isotope of hydrogen, containing an extra neutron in addition to the proton and electron in hydrogen. Its physical and chemical properties differ substantially from those of hydrogen, which poses challenges to biological organisms. Deuterium is present everywhere in nature, found at a concentration of one in 155 parts per million in seawater. Theoretical considerations have led to the strong hypothesis that deuterium is highly disruptive in the ATP synthase (ATPase) pumps that drive the synthesis of ATP in mitochondria [3].

Deuterium concentrations vary among different cellular compartments in an organism, with higher levels found in collagen in the extracellular matrix and much lower levels within organelles, especially the mitochondria [4]. Interestingly, various foods have differing concentrations of deuterium, with a general rule-of-thumb being that carbohydrates have more deuterium than proteins, and fats have the least amount (as low as 110 parts per million (ppm)) [5]. Some water sources have substantially reduced deuterium levels, particularly glacier melt water, because deuterium tends to stay behind in the solid crystals of ice [6]. Antarctic glacier water can be as low as 90 ppm.

The gut microbiome plays an essential role in supplying deuterium-depleted (deupleted) nutrients to the host, most evident as the short-chain fatty acid butyrate that is the preferred nutrient source of the colonocytes [7]. Butyrate is synthesized from acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), which, in turn, is produced by acetogenic microbes from carbon dioxide and hydrogen gas. The hydrogen gas is provided by hydrogenogenic microbes, and it has been shown experimentally that it is severely depleted in deuterium, with levels down to only 20% of the levels in the medium [8], likely due in part to deuterium’s tendency to stay with the liquid phase and in part due to a high deuterium kinetic isotope effect (KIE) in the hydrogenase enzymes that synthesize it, which can be as high as 43 in an acidic environment [9]. An elevated pH in the gut favors the synthesis of propionate at the expense of butyrate [10]. Butyrate has many beneficial effects, including maintaining healthy tight junctions in the gut lining, increasing the synthesis of sulfomucins, reducing hydrogen-peroxide induced DNA damage, and increasing glutathione levels [11]. Butyrate also acts as a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, protecting from inflammation by attenuating excessive production of histamines released through mast cell activation [12,13]. Post-mortem studies on PD brains showed significantly increased levels of histamines in the putamen, substantia nigra, and globus pallidus, critical areas of the brain that control motor behavior [14].

D-β-hydroxybutyrate (DβHB) is the most abundant ketone body produced by the liver in response to caloric restriction or fasting. It circulates throughout the vasculature, so it is available to the neurons in the brain as a deupleted nutrient. It is derived from the short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), especially butyrate, that are produced by the gut microbes. In a mouse model of PD induced by the neurotoxin 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP), the infusion of DβHB alleviated symptoms [15]. The infusion of DβHB in mice partially protects against dopaminergic neurodegeneration and motor deficits induced by MPTP [16].

PD is strongly associated with the accumulation of Lewy bodies (filamentous aggregates) in the brain, especially in the substantia nigra. It was first determined nearly three decades ago that the dominant protein fibrils in Lewy bodies are α-synuclein (α-syn) [17], an amyloidogenic protein whose normal function is unclear [18]. In initially germ-free mice that overexpress α-syn, gut microbial colonization was found to be required for motor deficits, microglia activation, and α-syn-related pathology. Remarkably, when these mice were colonized with gut microbes from patients with PD, their physical impairments were enhanced compared to colonization from healthy subjects [19].

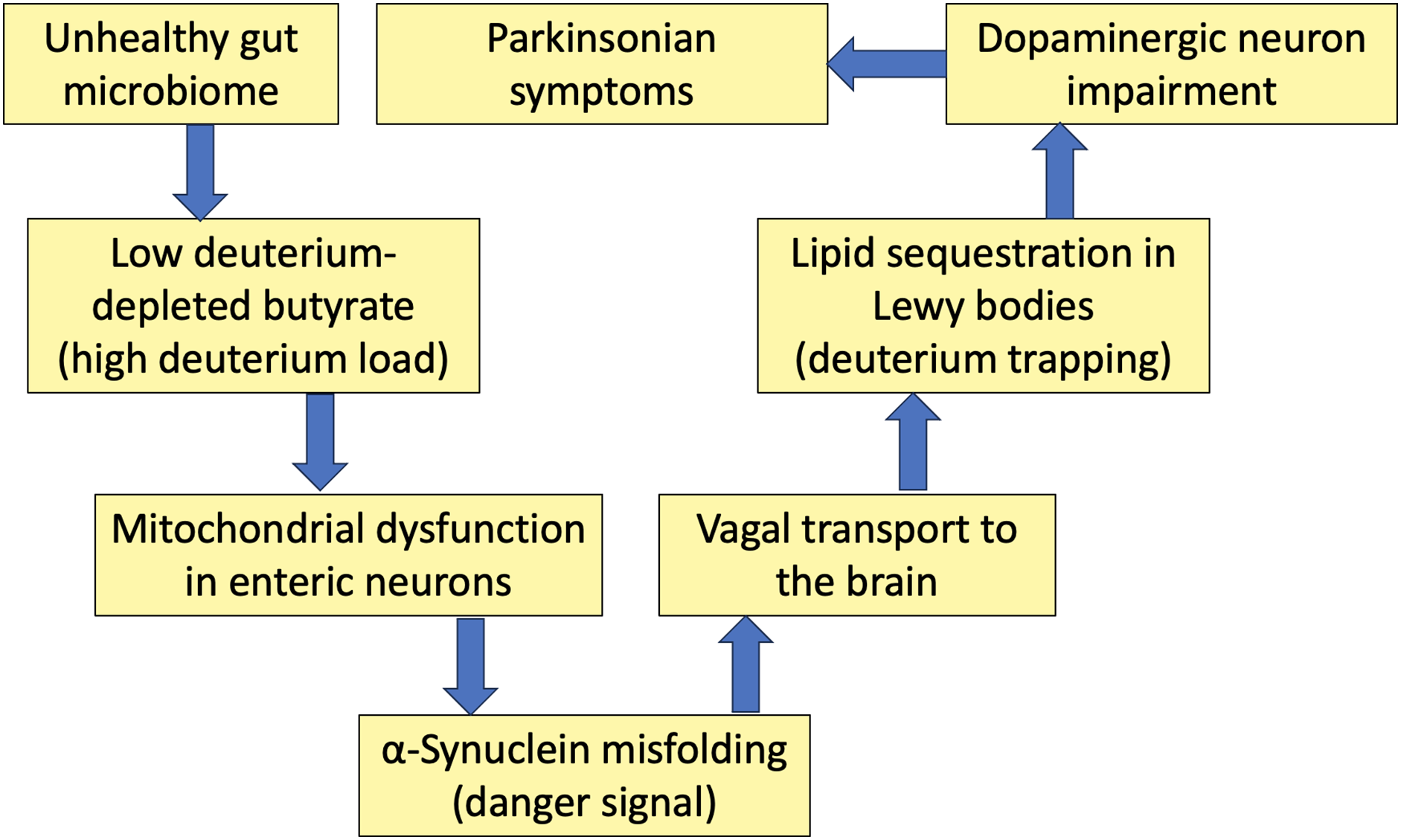

In the remainder of this paper, we will develop a theory that the primary cause of PD is excessive deuterium in the mitochondria, systemically. An early sign of PD is constipation, which reflects gut dysbiosis, with insufficient butyrate production being a major factor. Under stressful conditions, gut microbes release proteins that can seed α-syn misfolding in the gut. Misfolded α-syn is transported along the vagus nerve to the brainstem nuclei, where it seeds misfolding of α-syn molecules already present in neurons. The phospholipid cardiolipin plays a major role in the pathology, but it is also essential in its function to trap deuterium and sequester it in the mitochondria. Cardiolipin is synthesized in the mitochondrial matrix and embedded in the inner membrane of the intermembrane space, tightly coupled with proteins associated with proton transport across the membrane. We hypothesize that the bis-allylic carbon atoms in cardiolipin serve as deuterium traps to help keep deuterium from reaching the ATPase pumps. A bis-allylic carbon is a carbon atom that is adjacent to two carbon-carbon double bonds (alkenes), and it is known to be highly reactive. Cardiolipin migrates to the outer membrane under conditions of high oxidative stress, and this allows it to interact with α-syn, facilitating the opening up of pores in the mitochondrial membrane that can launch an apoptotic cascade reaction. This process may allow the cells to clear mitochondria that are overloaded with deuterium and even allow the brain tissue to clear entire cells that have been too damaged as a consequence of excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) released from multiple dysfunctional mitochondria. The mitochondrial membrane fragments containing highly deuterated cardiolipin are trapped in the Lewy bodies along with α-syn. Thus, the Lewy bodies may serve as a mechanism to sequester deuterium, reducing the deuterium burden in the brain. A schematic of this pathological progression is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Schematic of a sequence of events that unfold due to deuterium overload in the mitochondria, ultimately leading to Parkinsonian symptoms. A disrupted microbiome leads to butyrate deficiency in the gut, which causes mitochondrial dysfunction in enteric neurons, inducing α-synuclein misfolding. The vagus nerve supports the transport of misfolded α-synuclein to the brain. Lipids in the brain trap deuterium, which then gets incorporated into Lewy bodies formed as fibril deposits containing α-synuclein. It is the defective mitochondria in the dopaminergic neurons that are the initiating factor inducing Parkinsonian symptoms

2 Hydrogen Gas Recycling in the Gut and the Competition among Bacterial Strains

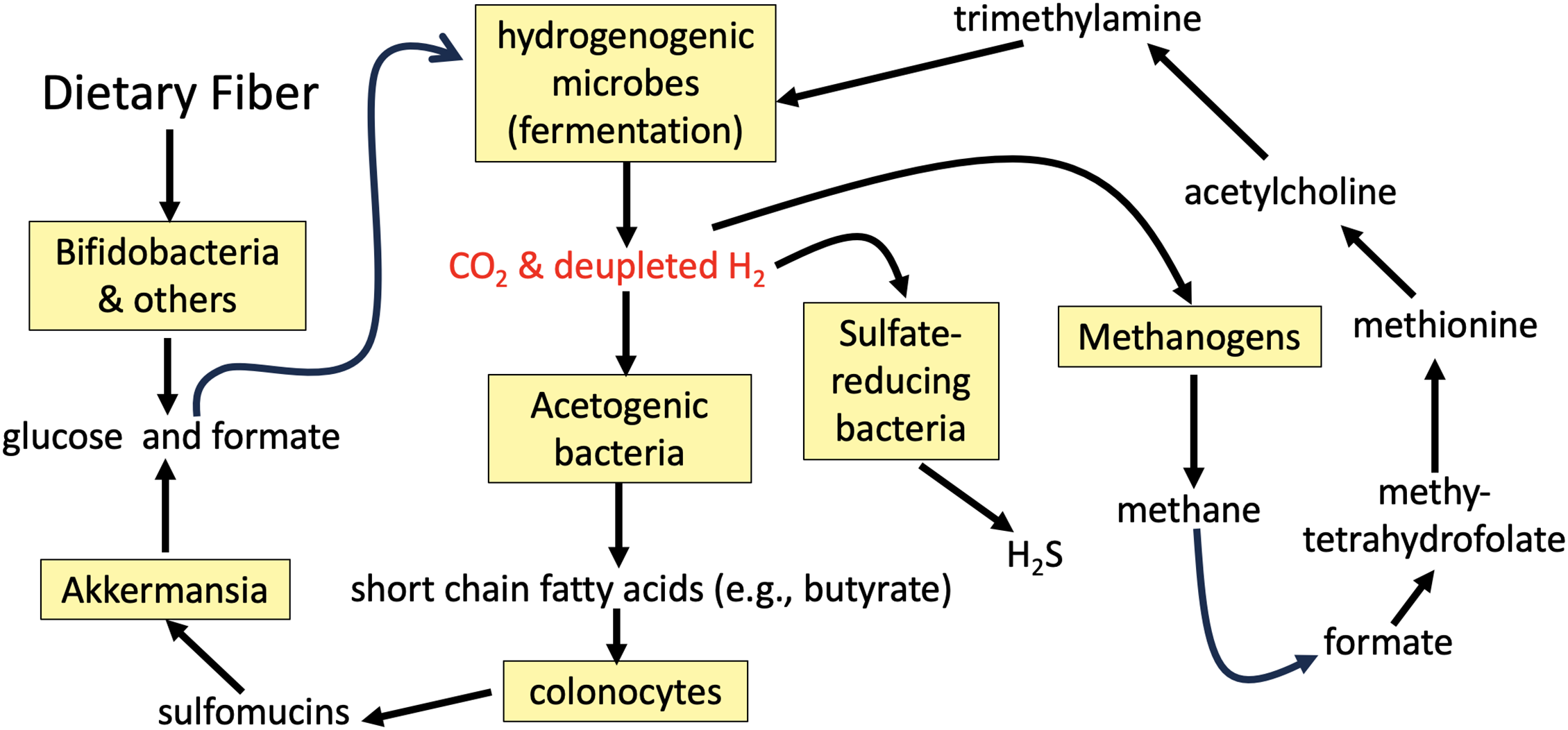

The fermentation process in the gut that constantly recycles hydrogen gas is essential for producing SCFAs, especially butyrate, which is the primary fuel for the colonocytes. Fig. 2 schematizes the various pathways that involve multiple species of gut microbes that are involved in recycling hydrogen gas. An in vitro study cocultured three bacterial species that compete for hydrogen gas in their reductive metabolism, with the goal of understanding how they compete for the hydrogen gas. Blautia hydrogenotrophica reduces carbon dioxide to acetate (a precursor to butyrate), Desulfovibrio piger reduces sulfate to hydrogen sulfide gas (H2S), and Methanobrevibacter smithii is a methanogen that produces methane gas as the product. One of their findings was that, in the late phase of incubation, the Desulfovibrio strain inhibited the growth of both the methanogen and the acetogen. Furthermore, the researchers found that high sulfide concentrations inhibited methanogenesis [20].

Figure 2: Schematic of the pathways involving diverse gut microbial species that center on recycling of deupleted hydrogen gas back into organic matter. Methanogens and sulfate reducing bacteria compete with acetogens for the hydrogen gas, which they all use as a reducing agent. Akkermansia spp. support a recycling back to hydrogenogenic microbes for further deuterium scrubbing. Methanogens produce methane gas that is used to supply a methyl group to synthesize methionine, the universal methyl donor. Methionine is the source of the methyl groups in trimethylamine that are metabolized by certain microbes in a second recycling step

Sulfomucins are high molecular weight sulfated glycoproteins that are constantly recycled in the gut, produced by specialized colonocytes called goblet cells, and consumed by certain bacterial species, such as Akkermansia spp. They play an essential role as a thick protective layer that forms the front line of innate host defense against pathogens and noxious substances [21]. A defective mucus barrier in the colon due to insufficient sulfomucins leads to inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). There are statistically significant correlations between genetic defects linked to PD and those linked to IBD [22].

A seminal article published in 2022 studied the progression of disease in 165 PD patients and, in parallel, tracked the relative abundance of four genera of bacteria (Fusicatenibacter, Faecalibacterium, Blautia, and Akkermansia) over a two-year period. Patients harboring an overabundance of Akkermansia spp. (which consume sulfomucins as their sole nutrient source) and a deficiency in the other three species (all of which produce SCFAs) showed accelerated rates of disease progression. These authors wrote: “Decreases of short-chain fatty acid-producing genera, Fusicatenibacter, Faecalibacterium, and Blautia, as well as an increase of mucin-degrading genus Akkermansia, predicted accelerated disease progression” [23].

It has been shown experimentally that excessive H2S in the gut promotes the breakdown of sulfomucins [24]. Desulfovibrio strains are the most predominant sulfate-reducing bacteria in the gut. As an opportunistic pathobiont, they are a primary source of excess H2S production in the setting of both intestinal and extra-intestinal diseases [25]. A study on 20 PD patients and 20 controls revealed that the patients had higher levels of Desulfovibrio species in their guts, and that the concentration of Desulfovibrio species correlated with disease severity [26]. A follow-on paper proposed that H2S induces the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria, which could be the trigger leading to α-syn misfolding in the gut [27]. H2S is implicated in several different inflammatory conditions, including pancreatitis, sepsis, joint inflammation, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [28].

3 The Gut-Brain Axis and the Role of the Gut Microbiome in Human Disease

Arthur I Kendall’s seminal 1909 article titled “Some observations on the study of the intestinal bacteria” in many ways marks the beginning of the idea of the intestinal bacteria as an object of unique scientific inquiry. It offered many prescient observations about what is now referred to as the human gastrointestinal microbiome (henceforth “the microbiome”), and this article laid the foundations for many of the discoveries that followed [29]. For over a century now, and especially in the past decade, the microbiome has been the object of intensive research and discovery.

The recognition of two-way neural communication between the gut and the brain was the first of now dozens of “gut-[organ] axes” to be identified. A review by Aziz and Thomas (1998) was one of the first to explicitly use the phrase “gut-brain axis”, describing what was known regarding the afferent and efferent signaling via the vagus nerve that modulates and coordinates activity at both ends of the axis [30]. Less than a decade later, Gill et al. (2006) brought the study of the microbiome into the age of genetics by cataloguing the genetic diversity contained within the microbiome, beginning with its wide range of metabolic products, including glycans, amino acids, isoprenoids, and others that support overall health [31].

Since that time, a more complex set of communication channels between the microbiome and the brain has been documented. Specifically, the role this axis can play in the development and progression of neurological diseases has been elucidated and entails at least three communication pathways between the microbiome and the brain: neural, immune, and neuroendocrine [32]. The microbiome produces a wide range of molecules that have both a direct and a secondary effect on the health and function of the brain. Most prominently, this includes the neurotransmitters gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), acetylcholine, histamine, serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, as well as the SCFAs butyrate, acetate, and propionate [33].

Also, of significant relevance to neurological disease generally and PD specifically, nearly all preganglionic projections of the vagus nerve throughout the gastrointestinal tract stain positive for α-syn [34]. Sensory cells of the gut mucosa express α-syn, and it has been demonstrated experimentally in transgenic mice that α-syn fibril-templating activity in the intestinal epithelium transferred to the vagus nerve and dorsal motor nucleus (DMN) [35]. A paper published in 2024 demonstrated in a transgenic mouse model that α-syn and tau co-pathology were initially observed in the gut, but then subsequently propagated to the DMN and the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and then spread to other brain regions. Truncal vagotomy and α-syn deficiency suppressed spreading to the brain [36]. A study by Pan-Montojo et al. (2012) involved exposing the intestinal epithelium of mice to the environmental toxin rotenone. This chemical exposure induced mesenteric neurons to secrete α-syn, which was then taken up by presynaptic neurites of the vagus nerve [37]. Ahn et al. (2019) demonstrated that this same environmental toxin led to α-syn misfolding and, most importantly, its aggregation and retrograde transport to the brain via the vagus nerve [38].

It is not just environmental toxins that have been shown to induce misfolding of α-syn in the gut. Kim et al. (2016) showed that endotoxins produced by bacteria commonly inhabiting the gut in the context of the dysbiosis associated with PD can also induce misfolding of α-syn into its pathogenic conformation, creating fibrils with self-propagating properties [39]. A 2003 study found that PD patients have increased gastrointestinal membrane permeability concurrent with elevated markers of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) exposure relative to healthy controls. This enhanced permeability, combined with the enhanced LPS production, creates a “perfect storm” scenario for misfolded α-syn to be produced by endothelial cells, translocate from mesenteric neurons to the vagus nerve, and subsequently migrate via the vagus nerve to regions of the brain strongly correlated with the etiology of PD, such as the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve (DMV) [40].

α-syn is also found in splenocytes and has been found to play an important functional role in both the maturation of immune cells and the regulation of inflammation. In a mouse model of PD, lack of α-syn in the spleen leads to underproduction of both CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes and a profound reduction in circulating CD4+ lymphocytes. Conversely, its presence plays a key role in regulating both the number and localization of lymphocytes within the spleen [41]. Alam et al. described the important immunoregulatory role α-syn plays in response to gastrointestinal inflammation initiated by bacterial LPS, infections, or gastrointestinal (GI) barrier disruption. Should any or all of these insults become chronic, α-syn can be chronically induced, leading to its aggregation, which is characteristic of PD [42].

In a study relevant to this process, Karikari et al. injected mutated α-syn into the brains of mice and documented both the inflammatory cytokine profiles and lymphocyte activation that evolved subsequent to that injection. They specifically noted splenic lymphocytes, which targeted antigenic peptides within α-syn [43]. It is not unreasonable to posit a pathological feedback loop that involves a chronic insult (infectious, toxic, etc.) which leads to chronic inflammation, which leads to α-syn overproduction, which leads to immune activation against α-syn, all of which leads to α-syn misfolding and aggregation and its subsequent transport to the brain via the vagus nerve.

Bacteria of the microbiome are known to generate metabolites that interact with and promote the misfolding and aggregation of α-syn. For example, E. coli produces a protein called curli, shown by Sampson et al. (2020) to interact with α-syn, acting as a template for its misfolding and aggregation [44]. Similarly, endotoxins generated by a range of pathogenic bacteria that can inhabit the microbiome have been shown to induce conformational changes in α-syn, changes which go on to induce a range of amyloid-associated diseases in a mouse model, including PD, Lewy body dementia, and multiple system atrophy [39].

Of particular interest in this regard is the role of the SCFA butyrate, produced by a wide range of bacteria in the microbiome. It is known that individuals with PD have a high incidence of dysbiosis. Interestingly, this manifests as an overabundance of eubiotic species of bacteria such as those of Lactobacillus, Akkermansia, Hungatella, and Bifidobacterium, and a concurrent depletion of butyrate-producing bacterial species, including those of Roseburia, Fusicatenibacter, Blautia, Anaerostipes (Lachnospiraceae family), and Faecalibacterium (Ruminococcaceae family) [45]. Multiple studies have consistently found low fecal levels of SCFAs in association with PD [46–49]. Tan et al. (2021) noted that low SCFAs in PD were significantly associated with poorer cognition and low body mass index. Low butyrate levels, in particular, were correlated with postural instability and lower gait scores [47].

Butyrate acts as both an anti-inflammatory and immune modulating molecule, helping maintain the integrity of the intestinal epithelium and thus reducing the immune activation that can result from intestinal permeability [50]. It is perhaps not surprising that supplementation with oral butyrate in individuals with PD has been shown to reduce both motor- and non-motor deficits commonly present in those with the disease [51].

Histone hypoacetylation is a feature of neurodegenerative disease, and therefore HDAC inhibitors are being explored for their potential to treat neurodegenerative diseases [52]. Intriguingly, α-syn, when localized to the nucleus, inhibits histone acetylation [53]. Nuclear localization of α-syn induces DNA damage of hippocampal neurons in mice, causing cognitive and motor defects, which may be due in part to decreased histone acetylation [54]. Acting as an inhibitor of HDACs, butyrate is expected to be protective against neurodegenerative diseases [12].

The protective impact of microbiome-produced butyrate and the detrimental impact of microbiome-provoked misfolding of α-syn represent the dichotomous role the gut-brain axis can have on neurological functioning and disease initiation and progression. Throughout this paper, we will explore the role of this axis in much greater detail, as it pertains to the etiology of PD.

4 Parkinson’s Disease, Constipation, Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth, and Methane Gas

There have been many papers published attempting to characterize the gut microbiome in association with PD, often with inconsistent results. However, one significant pattern is constipation associated with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) [55,56]. High levels of methane in the breath are a common feature of both SIBO and constipation [57,58]. An overabundant methanogenic population consumes hydrogen gas and reduces its bioavailability for butyrate production. In a large population study, SIBO was detected in one in four PD patients, and it predicted worse motor function [59]. One study found 54% of PD patients suffered from SIBO, whereas only 8% of the control population was affected [60]. Constipation is a common early sign of PD [55], and, independent of PD, the severity of constipation is strongly correlated with the amount of methane in the gut [56,58].

A review paper analyzing 26 studies on the characteristics of the gut microbiome in association with PD identified the genera Faecalibacterium, Blautia, and Fusicatenibacter as being under-populated in PD in at least three of the reports [61]. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is the most abundant bacterium in the healthy human gut, normally making up more than 5% of the total bacterial species population. It is the primary producer of butyrate, and it is low in association with many gut disorders, including IBD, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and coeliac disease [62,63]. Under anoxic conditions, hydrogen gas is a common product of carbohydrate fermentation. Two of the bacterial genera that were listed as deficient, Blautia and Fusicatenibacter, are strict anaerobes, and Fusicatenibacter spp. are known for their role in fermenting sugars. Blautia spp. primarily ferment glucose, but various strains can also ferment a variety of other sugars, including sucrose, fructose, lactose, maltose, rhamnose, and raffinose. A major product of fermentation by Blautia spp. is acetate, which is a precursor to butyrate [64].

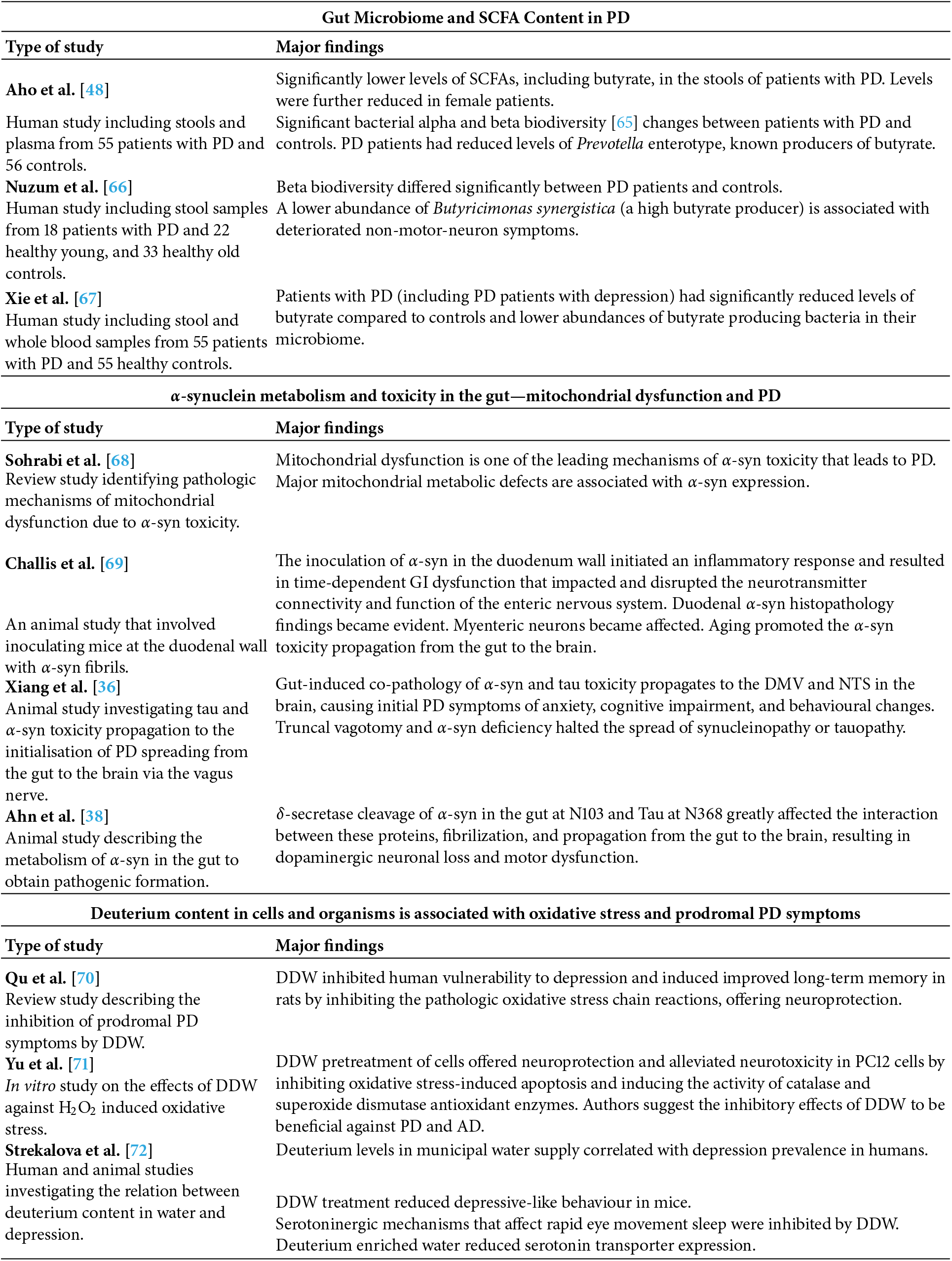

Table 1 summarizes findings among several recent publications that show links between PD and gut microbiome imbalances associated with butyrate deficiency, as well as α-syn transfer to the brain via the vagus nerve, a role for mitochondrial dysfunction, and the benefits of deuterium depleted water (DDW) as a therapy.

{\leftskip0pt\rightskip0pt plus1fill}p{#1}}?> {\leftskip0pt plus1fill\rightskip0pt plus1fill}p{#1}}?>Given the findings of the studies presented in Table 1, it would be reasonable to suggest a future clinical study to evaluate the levels of deuterium content in the organism in relation to prodromal symptoms and/or severity of PD conditions. For example, the levels of deuterium in the organism (e.g., in the saliva) could be tracked concurrently with interventions such as butyrate supplementation, increased dietary fiber, probiotic or prebiotic supplements, or fecal transplants, in patients with PD.

5 α-Synuclein, Deuterated PUFAs, Dopamine, and Parkinson’s Disease

PD is the second most common neurodegenerative disease in the world, and it is projected to become the second leading cause of death worldwide by 2040, surpassing cancer-related deaths [73]. It is characterized by intracellular accumulations of Lewy bodies in the cytoplasm of dopaminergic neurons, primarily composed of α-syn fibrils [74]. α-syn is a 140-residue intrinsically disordered protein expressed primarily in the substantia nigra, and its aggregation is a strong feature of PD [75].

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a core feature of PD. In post-mortem studies, defects in complex I, complex II, and even complex IV have been found in multiple brain regions in association with PD [76] (and references therein). The neurotransmitter dopamine plays an important role in the etiology of PD, likely through its oxidation to toxic metabolites such as 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL) under conditions of oxidative stress. Dopamine expression may be a key vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons, which are especially susceptible to apoptosis compared to other neuron types. α-syn binds to DOPAL, and it has been shown experimentally that such binding can cause suppression of chaperone-mediated autophagy, which is critical for lysosomal degradation not only of α-syn but also of multiple other proteins and of damaged mitochondria [77,78]. Defective autophagy could lead to impaired mitophagy and the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria, resulting in apoptosis [79,80].

Interestingly, deuterated PUFAs have become a topic of interest for their potential therapeutic value in treating neurodegenerative disease [81–83]. Bis-allylic carbon atoms have the characteristic feature that each of the carbon atoms that they bind to (left and right) is double-bonded to the other carbon in the chain (-C=C-C*-C=C-). The n-3 fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and DHA, have 4 and 5 bis-allylic carbon atoms, respectively. These carbon atoms are especially amenable to deuteration, and, once deuterated, they almost never let go of the deuterium atom [84].

Remarkably, deuterated PUFAs can quench the chain reaction that occurs when PUFAs are exposed to reactive oxygen. This chain reaction yields highly reactive aldehyde species such as malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (4-HNE), which are known for their ability to damage neurons. They form adducts with the amino acids in critical proteins, including enzymes involved in neurotransmitter metabolism, synaptic plasticity, and stress response pathways [85]. These reactive aldehydes play an important role in neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and PD, diseases of the eye, hearing loss, and cancer [85]. It has been argued that there may be a natural mechanism operating under inflammatory conditions, causing a peroxidation reaction cascade whereby the gradual accumulation of deuterated bis-allylic carbons eventually induces the synthesis of anti-inflammatory resolvins and arrests the inflammatory cascade [86]. It is the number of bis-allylic carbon atoms in a lipid that determine its susceptibility to free-radical-mediated peroxidation. Lipid peroxidation increases exponentially with the number of bis-allylic carbon atoms, but this may also mean an exponential increase in the ability to trap deuterium [87].

4-HNE has been shown experimentally to induce aggregation of α-syn into a toxic form, and a key mechanism is the formation of an adduct to Histidine-50 (His50) in the protein [88]. Acidic conditions increase the rate of formation of toxic oligomers induced by HNE [89]. These oligomers can seed amyloidogenesis of monomeric α-syn. When neuronal cells are treated in vitro with HNE, both the translocation of α-syn into vesicles and its release from cells were increased, facilitating cell-to-cell transfer [90]. His50 is highly significant in α-syn, and its mutation to other amino acids drastically changes the protein’s behavior. Substitution with glutamine, aspartate, or alanine promotes α-syn aggregation, whereas substitution with a positively charged amino acid, such as arginine, suppresses aggregation. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies revealed that substitution by glutamine causes an increase in the flexibility of the C-terminal region, mediating long range effects. This may be a key first step towards misfolding [91]. These results also imply that acidification of α-syn would make it more prone to misfold, due to the fact that histidine would be protonated under low pH conditions. Remarkably, photo-oxidation of His50 in α-syn protects the protein from fibrillization [92].

In multiple studies, reduction in the activity of mitochondrial complex I in the brain, muscles, and platelets has been clearly associated with PD (see [93,94] and references therein). Exposure to toxic molecules that act as complex I inhibitors, such as the pesticide rotenone, have been shown to be causal in PD. Rotenone exposure to rats caused dopaminergic degeneration, associated with the formation of α-syn positive nigral inclusions. Brains of PD patients show evidence of oxidative stress, including decreased levels of reduced glutathione and oxidative modifications to DNA, lipids and proteins. Impaired complex I activity enhances ROS formation. It is the oxidative stress caused by complex I impairment, more than the loss of ATP, that causes dopaminergic degeneration [95].

It may be significant that two major enzymes involved in dopamine metabolism have very high deuterium KIEs. Dopamine β hydroxylase is the enzyme that converts dopamine to epinephrine, playing a vital role in regulating neurotransmitters that affect mood, attention, and learning. It is localized to the synaptic vesicles of sympathetic neurons, in close proximity to α-syn, which binds to synaptic vesicles. It has a very high deuterium KIE for abstraction of a proton from the dopamine ring, estimated to be around 11.0 [96]. The enzyme also reduces dioxygen to water, and this water molecule would be deupleted due to the high KIE. The other proton in the water molecule comes from ascorbate, which carries deupleted protons derived from nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) [97].

Monoamine oxidase, a flavin-dependent enzyme, is localized to the outer mitochondrial membrane, and it metabolizes many neurotransmitters, including dopamine, serotonin, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and others, as well as dietary amines. It has a large deuterium KIE ranging from 7 to 14 [98], and it therefore produces deupleted hydrogen peroxide as a by-product. Glutathione peroxidase, highly expressed in the mitochondria, can then convert the hydrogen peroxide to deupleted metabolic water, contributing two more deupleted protons. Thus, the metabolism of dopamine in the mitochondria serves to replenish deupleted water in the intermembrane space.

Perhaps surprisingly, excessive monoamine oxidase activity can result in suppression of electron transport. Glutathione disulfide (GSSG), the product of glutathione peroxidase, reacts spontaneously with thiol groups in proteins, forming protein-mixed disulfides, in a reaction catalyzed by thiol-transferases or thioredoxins. Multiple mitochondrial proteins, including succinate dehydrogenase, NADH dehydrogenase, ATPase, isocitrate dehydrogenase, and succinate-supported mitochondrial electron transport, are suppressed through this mechanism. This may be the primary mechanism by which excess dopamine becomes neurotoxic [99]. A high ratio of oxidized to reduced glutathione is a strong indicator of insufficient antioxidant defenses, but it may also imply overproduction of reactive oxygen because of impaired oxidative phosphorylation, which could be due to deuterium toxicity. Thus, monoamine oxidase works both to restore deupleted water and to suppress the enzymes that fuel the ATPase pumps, generating too much reactive oxygen when deuterium levels are high.

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors are a common pharmaceutical class that treats depression [100]. Geographically, the rates of depression have been shown to be highly correlated with the amount of deuterium in the municipal drinking water, in a study that analyzed data from the 50 states of the United States [72]. Overexpression of monoamine oxidase may be a mechanism used by the neurons to restore deupleted water in the intermembrane space when deuterium levels are elevated. Suppressing its activity will increase the availability of neurotransmitters for mood regulation but may also impair the ability to resolve the deuterium problem in the mitochondria, leading to a worse outcome in the long run. These drugs have serious, even life-threatening, adverse reactions caused by excessive accumulation of serotonin in the synapse, especially when they are combined with serotonin reuptake inhibitors [101].

6 Cardiolipin and ATP Synthase

Cardiolipin (CL) is a structurally unique dimeric phospholipid localized primarily in the inner mitochondrial membrane, where it is required for optimal mitochondrial function [102]. Cardiolipin’s cone-like shape facilitates high curvature in the membrane, which is necessary to form the cristae. Peroxidation of cardiolipin, modifications in its lipid content, and a loss of cardiolipin have all been associated with ischemia, hypothyroidism, aging, and heart failure [102].

The presence of cardiolipin is critical for the supramolecular organization of ATP synthase. ATP synthase readily dimerizes, and the dimers are then organized into rows of dimers running along the high-curvature edges of the disc-shaped cristae that form the inner membrane of the intermembrane space. In a study involving mitochondria that were isolated from the flight muscles of Drosophila, the authors were able to examine the role of cardiolipin in the morphology of ATP synthase by comparing mutants that completely lacked cardiolipin with normal controls. These mutants suffered from severe mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to cardiac insufficiency, motor weakness, and early death. Close examination of their ATP synthase molecules revealed that many of them remained as monomers, and their density at the high-curvature regions was reduced by half. The assembly into neatly packed rows of dimers was also disrupted. They concluded that cardiolipin and ATP synthase collaborate to stabilize the high-curvature folds in the inner membrane [103].

It was known already in 1990 that bovine ATP synthase has a high affinity to cardiolipin, but not to other lipid moieties [104]. A more recent study on the structure of bovine ATPase has revealed some interesting details regarding the role of cardiolipin. Wedge structures in the membrane domains of each monomer in the ATPase dimer allow the monomer-monomer interfaces to pivot during catalysis. These wedge structures are filled with lipids, specifically, three molecules of cardiolipin as well as two other phospholipids, which may also be cardiolipins, but this has not been resolved [105]. It is conceivable that the highly unsaturated DHA in these cardiolipin molecules plays a role in trapping deuterium as it comes through the ATPase pumps, to protect ATPase from deuterium toxicity [86].

Cardiolipin is synthesized at and is localized mainly to the inner membrane of the intermembrane space of mitochondria, where it typically constitutes 10%–20% of the lipids [94]. Although generally in lesser amounts, cardiolipin is also found in the outer membrane of mitochondria, and migration to the outer membrane is an early event in apoptosis [106,107]. Intriguingly, the brains of α-syn knock-out mice have 22% reduced levels of cardiolipin compared to controls, which is associated with impaired activity of the electron transport chain [108].

Cardiolipin plays an essential role not only in mammalian ATPase, but also in the distinctly different ATPase synthesized by one-celled organisms. In a study on the unusual ATPase synthesized by a photosynthetic one-celled organism, Euglena gracilis, the authors were able to identify 37 lipid molecules associated with the ATPase near the proton channel region at the interface between the dimers, of which 25 were cardiolipin molecules [109].

7 Cardiolipin, α-Synuclein, Mitochondrial Pore Formation, and Apoptosis

When cardiolipin gets oxidized, it redistributes from the inner mitochondrial membrane to the outer membrane. An important source of stress is ROS produced by complex II. Oxidized cardiolipin exposed to the cytosol mediates apoptosis, in part by facilitating pore formation in the mitochondrial membrane [110]. High levels of cardiolipin in mito-mimetic lipid bilayers promote pore formation in the presence of α-syn. Pore formation in mitochondria due to α-syn leads to organelle swelling and the release of cytochrome c and the launch of the apoptotic death cascade [111]. It is likely that, at least in neurons, α-syn plays a vital role in mitochondrial death, and, perhaps ultimately, cell death when too many mitochondria expose cardiolipin on their outer membrane.

A study on the distribution of α-syn within the cell as a function of pH revealed a remarkable inverse relationship between pH and the amount of α-syn that localized to the outer mitochondrial membrane. The authors confirmed that it is cardiolipin that draws α-syn to the outer membranes of the mitochondria. Remarkably, cardiolipin is able to buffer synucleinopathy by drawing α-syn monomers out of preformed fibrils and soluble oligomers [111]. It is conceivable that these released monomers are then incorporated one-by-one into a pore-forming membrane-penetrating configuration of α-syn oligomers, expanding pore size to eventually induce the apoptotic pathway.

The interaction of α-syn with negatively charged phospholipids in membranes promotes the adoption of an α-helical structure that facilitates its entry into the membrane [112]. In 2020, Gilmozzi et al. published a paper which claimed that the interaction of cardiolipin with α-syn is a critical factor in PD. Following membrane binding, α-syn undergoes a transformation from random coils to a helical structure in its N-terminal region. α-syn preferentially binds to membranes with a lipid composition characterized by high negative charge and high curvature, both of which are classic features of cardiolipin [113]. Artificial membranes containing cardiolipin are fragmented by the small oligomeric form of α-syn in vitro [114]. The amount of α-syn localized to the mitochondria of substantia nigra neurons increases dramatically in PD [115].

It is widely believed that apoptosis of dopaminergic neurons drives the progression of PD. Apoptosis is triggered by the interaction between two proteins in the mitochondrial outer membrane, BAX and BAK (protein members of the bcl-2 family), to induce pore formation and trigger cytochrome c release and subsequent programmed cell death. BAK constitutively localizes to the mitochondrial outer membrane. By contrast, BAX normally localizes to the cytoplasm, but, upon activation, translocates to the mitochondria, oligomerizes, and causes outer membrane permeabilization, leading to the release of cytochrome c and other proteins [116,117].

A study published in 2024 examined the crucial role of cardiolipin in initiating a destructive inflammatory pathway responsible for severe cardiac damage resulting from endotoxemia. They showed that oxidation of cardiolipin led to its externalization to the outer membrane, where it induced oligomerization of the N-terminal fragment of Gasdermin D (GSDMD-N) and pore formation in the mitochondria. This step even precedes the BAX/BAK activity [110].

A theoretical study utilizing the STRING database and rigid-body-docking analyses via the ClusPro software found strong evidence that α-syn interacts with BAX. They proposed that the binding of α-syn to BAX could be the initiating event leading to apoptotic signaling via a conformational change in BAX. They also suggested that, triggered by stress, α-syn binding to BAX blocks binding of the anti-apoptotic protein BCL2L1, causing uninhibited pro-apoptotic action of BAX [118].

8 Cardiolipin’s Role in Mitophagy Is Complex

The natural pesticide rotenone inhibits mitochondrial complex I, disrupting the electron transport chain and causing mitochondrial dysfunction. Subcutaneous infusion of rotenone into rats induces Parkinsonian-like symptoms [119]. Rotenone exposure to primary cortical neurons caused a ten-fold increase in the amount of cardiolipin in the outer membrane. Knock-down of the scramblase enzyme that translocates cardiolipin from the inner to the outer membrane not only prevented the increase in outer membrane cardiolipin but also inhibited autophagic delivery of mitochondria to lysosomes. Further investigation revealed that externalized cardiolipin interacts with the autophagy protein LC3 to mediate the clearance of defective mitochondria. The authors concluded that cardiolipin presence in the outer membrane is a signal for the recognition of injured or dysfunctional mitochondria to facilitate their removal [120].

It appears that misfolded α-syn interferes with the clearance of damaged mitochondria. In 2023 and 2024, a team of researchers published two scientific studies that used “light-induced protein aggregation” (LIPA) as a tool to induce α-syn aggregation, and they were then able to monitor the impact on mitochondria. They discovered that the aggregated α-syn molecules interacted dynamically with the mitochondria, triggering their depolarization, which then led to translocation of cardiolipin from the inner membrane to the outer membrane. This was associated with lower ATP production and mitochondrial fragmentation [121,122]. They wrote: “Overall, our findings suggest that the dynamic interaction between LIPA-α-syn aggregates and mitochondria induces mitochondrial alterations which favor cardiolipin externalization and mitophagy” [122].

However, these authors also pointed out that α-syn can compete with the autophagy protein LC3 for binding to cardiolipin, which might work to prevent mitophagy [123]. Bayati et al. wrote in a paper published in 2024: “The inclusions formed in DA [dopaminergic] neurons space contain a medley of organelles, membranous fragments, filaments, lysosomes, autolysosomes and mitochondria” [124]. A plausible explanation is that α-syn together with fragmented mitochondrial membranes containing heavily deuterated cardiolipin due to extreme levels of oxidative stress could coprecipitate into Lewy bodies, securing the deuterium atoms, as well as entire unhealthy mitochondria, well away from other healthy mitochondria.

Ischemic and reperfused rat heart mitochondria have been found to have significantly reduced activity of complex I compared with controls. This was shown to be associated with reduced amounts of cardiolipin. Production of hydrogen peroxide increased on reperfusion, and it was suspected that this caused peroxidation of cardiolipin leading to its loss. Remarkably, they could restore the activity of complex I by adding exogenous cardiolipin, but not peroxidized cardiolipin or other phospholipids [125].

Acyl-coenzyme A:lyso-cardiolipin acyltransferase-1 (ALCAT1), is an enzyme that catalyzes the remodeling of cardiolipin by increasing the levels of DHA and arachidonic acid (AA) in the cardiolipin molecule at the expense of shorter, less unsaturated fatty acids such as linoleic acid. DHA is highly vulnerable to oxidative stress, but it also has five bis-allylic carbon atoms that can permanently trap deuterium [86]. While it seems very surprising that biological mechanisms would increase the risk of exposure to highly polyunsaturated fatty acids to reactive oxygen under conditions when reactive oxygen is abundant, it makes sense if the purpose is to sequester excess deuterium.

Parkin is a ubiquitin ligase that facilitates mitochondrial clearance via mitophagy. Genetic mutations in Parkin are associated with familial PD, believed to be due to the accumulation of defective mitochondria that failed to be cleared [126]. In a mouse model of PD, increased ALCAT1 expression was shown to suppress both Parkin expression and Parkin association with mitochondria, leading to disrupted mitochondrial clearance [127]. This is likely due to the increased presence, due to ALCAT1 overexpression, of PUFAs that induce excessive reactive oxygen due to widespread lipid peroxidation. Under conditions of high oxidative stress, dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1) binds to cardiolipin in the outer mitochondrial membrane to induce mitochondrial fission. A Drp1-cardiolipin-binding motif is essential for stress-induced mitochondrial fission [128]. Following mitochondrial depolarization, both Drp1 and Parkin are co-recruited to mitochondria [129]. Drp1 is one of the proteins targeted for ubiquitination by Parkin. Thus, the suppression of Parkin’s availability to clear defective mitochondria through ALCAT1 overexpression, while Drp1 is being recruited to the membrane, should lead to excessive fragmentation of defective mitochondria and impaired clearance.

Elongation of Very Long Chain Fatty Acids 5 (Elovl5) is an enzyme that is involved in the elongation of long-chain fatty acids, especially PUFAs, and it is crucial for the synthesis of AA and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). RNA sequencing analyses of downregulated enzymes in liver tissue from mice with a defective version of Elovl5 found significant decreases in expression of proteins involved in complexes I and III of the respiratory chain and ATP synthase, as well as Pink1, which regulates mitophagy, and an enzyme that relays electrons from various mitochondrial flavoenzymes to the respiratory chain, essential for fatty acid beta oxidation. Furthermore, overall amounts of cardiolipins in the liver were decreased, and there was a significant increase in the percentage of cardiolipin molecules containing shorter and less unsaturated fatty acids. These mice suffered from metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) [130].

9 Lewy Bodies and Lipid Deposits

Lewy bodies (LB) are abnormal protein deposits that accumulate within neurons and contain an abundance of α-syn, and they are a well-established feature of PD [131]. Light microscopy imaging of LB obtained postmortem from brains of five patients with PD revealed the presence of membranes of fragmented mitochondria in the center of the inclusions, as well as “disc-like and tubulovesicular structures” reminiscent of mitochondrial remnants [131]. These authors wrote: “Our findings of mitochondria around and within LB, many of which appear distorted and clustered together or in a damaged state, indicate potential mitochondrial instability or dysfunction in disease-affected neurons” [132]. We speculate that the deuterium-enriched cardiolipin originating in the inner membrane, after having helped to quench the chain reaction cascade in lipid peroxidation in the mitochondrion, is then captured in the Lewy bodies along with α-syn as a way to sequester deuterium to lower the deuterium burden in the mitochondrial ATPase pumps. In fact, it has been claimed that PD may be better thought of as a lipidopathy rather than a proteinopathy [133]. α-syn rapidly forms stable multimers in the presence of vesicles containing long chain PUFAs, including AA and DHA, and this occurs at physiological concentrations of both molecules [134].

While Lewy bodies are clearly associated with neurodegenerative diseases, it has not been proven that the Lewy bodies themselves are toxic. In fact, on the contrary, a study examining the brains postmortem of patients suffering from Lewy body dementia found that the neurons that contained Lewy bodies were healthier in terms of complex I activity compared to neurons that did not have Lewy bodies. At the end of the abstract, these authors wrote: “One could speculate that Lewy bodies may provide a mechanism to encapsulate damaged mitochondria and/or α-synuclein oligomers, thus protecting neurons from their cytotoxic effects” [135].

10 The Fine Regulation of Mature Cardiolipin Fatty Acid Content and Parkinson’s Disease

The mature cardiolipins have a diverse fatty acid content, which is found primarily during de novo synthesis, the primary construction phase, but it is overwhelmingly modified during remodeling stages (for review, see [136]). Cardiolipin remodeling is a process where cardiolipin undergoes post-synthetic modifications to alter its fatty acyl composition. During remodeling stages, significant changes to the final acyl composition are performed that cannot be attributed to the initial functions of cardiolipin synthase and other phosphatidyl transferases, which operate during de novo synthesis. The final molecular composition of cardiolipin is important for its relation to disease. Particularly for PD, important interactions take place between the mature cardiolipin molecular species and α-syn.

The research group of CE Ellis et al. has discovered that animals with complete loss of α-syn expression, i.e., (Snca−/−) mice, show a total of 22% reduction of cardiolipin content in mitochondria. Moreover, the molecular species of cardiolipin encountered in the genetically ablated animals were also altered in their acyl composition. An overall 51% increase in saturated fatty acids (FA) and a 25% reduction in essential n-6, but not in the n-3, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) content in the acyl groups of these cardiolipin species was observed. Moreover, solely the content of phosphatidylglycerol (and not of other brain phospholipids), which is the immediate precursor of cardiolipin and the substrate of cardiolipin synthase during de novo synthesis, was also found to be reduced by 23% [108].

The paradox in these findings is that the shortage of n-6 PUFAs in the absence of α-syn production would be expected to be beneficial for the brain, since n-6 PUFAs and their derivatives, namely linoleic acid and arachidonic acid-lipid mediators, associate strongly with inflammation in the brain, depression, and AD [137]. Nevertheless, in the α-syn deprived mice described above, the detected cardiolipin molecular species were linked to characteristic abnormalities in the mitochondrial membrane properties. This was accompanied with a significant and specific reduction in the respiratory chain I/III chain activity, which is highly correlated with the development of PD [138]. α-syn levels are increased after hypoxia, e.g., due to cellular injury, and, surprisingly, its elevation can boost mitochondrial function and integrity [139]. This could be because it facilitates the clearance of defective mitochondria.

On the other hand, when α-syn is expressed in yeast or human cells in in vitro models, another lipid-fatty acid homeostatic dysregulation occurs. During α-syn overexpression, oleic acid (OA, C18:1n6) diglycerides and triglycerides are increased, and this increase potentiates α-syn toxicity in these models. The key over-expressed enzyme under these conditions was the OA-generating enzyme stearoyl-CoA-desaturase [140]. Ablation of this enzyme’s activity reversed α-syn’s induction of neuronal toxicity.

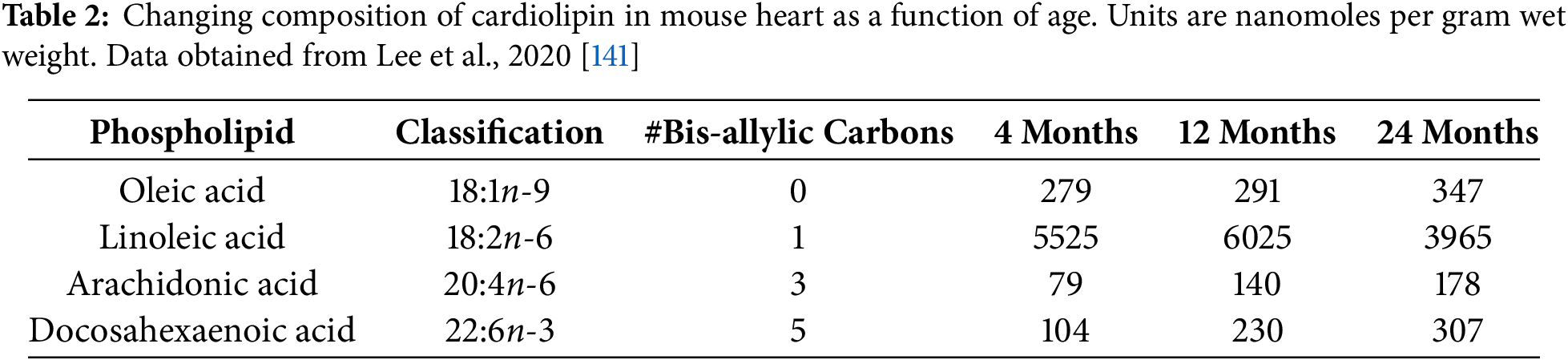

In rats, aging increases the number of highly unsaturated fatty acids in cardiolipin. Linoleic acid (LA, C18:2n6) is the dominant phospholipid in cardiolipin in mouse heart. Cardiolipin readily incorporates dietary LA into its acyl groups during the remodeling phase. This is considered to be the standard mature acylated composition of this unique lipid post de novo synthesis. However, during aging, the acylation and incorporation of LA into mature cardiolipin acyl groups decreases significantly, whereas the acylation of OA increases. Moreover, with aging, the incorporation of DHA (22:6n-3), as well as that of AA (20:4n-6) into mature cardiolipin acyl groups increases significantly [141]. As these researchers have found, however, although the acylation of DHA and AA into mature cardiolipin increases with aging, the pool of these PUFAs located in cell glycerophospholipids does not show significant variation with aging (i.e., they remain relatively high). This means that the increased acylations of DHA and AA in cardiolipin with aging are not due to their increased availability for conjugation to its mature structure. Furthermore, it has been shown that α-syn toxicity increases with aging, and this associates with the development of PD [142].

One of the main factors that contributes to the development of PD with aging is the inhibition of autophagy. It may be that DHA contributes to that inhibitory activity of autophagy in PD during aging. Cancer researchers have discovered that DHA can be therapeutic in prostate cancer patients, due to its ability to suppress autophagy [143]. Impaired autophagy is a strong feature of PD, and this may be a primary factor in the accumulation of misfolded α-syn [144]. The increased availability of bis-allylic carbon atoms in AA, and especially DHA, may be a significant feature that leads to their enrichment with aging (see Table 2).

The composition of cardiolipin in the brain is strikingly different from that in the heart. In brain tissues, LA is found in very low concentrations compared to the concentrations of OA, DHA and AA. Also, the majority of LA crossing the blood-brain barrier immediately sustains β-oxidation, which will thus disable the incorporation of LA into the acyl groups of cardiolipin [145]. In these respects, brain tissue possesses unique conditions that specify the final structure of mature cardiolipin molecular species. The tremendous increase in the number of available bis-allylic carbon atoms due to rich incorporation of AA and DHA may be an essential aspect that greatly facilitates deuterium trapping. Thus, due to the increase in OA and DHA availability, the brain is more prone to α-syn toxicity compared to other tissues such as the heart, where LA will be adequately available for conjugation to cardiolipin acyl groups during remodeling.

Enzymes that facilitate the translocation of cardiolipin from the inner to the outer leaflets of mitochondrial membranes for remodeling to occur can play a significant role in the α-syn toxicity mechanisms occurring in PD. During the translocation of cardiolipin and for the remodeling of its acyl groups to occur, the enzymes phospholipid scramblases are involved. Scramblases have also been shown to control the mitochondrial apoptotic response by promoting the accumulation of mature cardiolipin. Apart from their role in the mitochondrial membrane translocation-remodeling phase of cardiolipin, scramblase-3 has been shown additionally to influence cardiolipin de novo synthesis by potently increasing the expression and activity of cardiolipin synthase, thus also enabling its resynthesis [146].

Another lipid scramblase, namely TMEM16F, that also acts as an ion channel, has been shown to be implicated in α-syn spread of toxicity in neurons [147]. When TMEM16F was not expressed in neurons, there was limited pathologic α-syn cell-to-cell spread, and this was attributed to the reduction of autophagosome levels and not to the overall concentration of pathologic α-syn levels. Since the presence and interaction of cardiolipin is evident in autophagosome formations [148], it would be reasonable to assume that, in the absence of TMEM16F scramblase, the toxicity of neuronal death by apoptosis is bypassed, preventing the spread of pathologic α-syn from cell to cell.

In patients with PD, DHA is present at high levels in brain areas where α-syn inclusions are present. Animal models have shown that DHA induces the formation of α-syn oligomers. In fact, amyloid-like fibrils are formed when the ratio of α-syn to DHA is 1 to 10. The fibrils are distinct in morphology from fibrils formed from α-syn alone, and they have a less packed structure [149]. This strongly implies that the DHA molecules are embedded in the fibrils. When the ratio is increased to 1 to 50, stable oligomers are formed instead of fibrils. DHA also induces methionine oxidations in α-syn, likely due to peroxidation cascades following oxidative stress. Methionine oxidation acts as a scavenger of ROS, playing a protective role [149].

In summary, it seems that there is a certain preference in the mature structure of cardiolipin (which is enriched with DHA and AA) that may need further investigation for its association with the development of PD. Other studies have shown that alterations in cardiolipin metabolism associate with neurological defects [102]. Both stages of de novo synthesis and final cardiolipin remodeling are influenced by α-syn. Cardiolipin-α-syn pathologic interactions are defined by activation of enzymes like cardiolipin synthase, OA-generating enzyme stearoyl-CoA-desaturase, and scramblases. The brain tissue has optimum conditions for neurodegeneration due to the deprivation of LA, which promotes the conjugation of OA and DHA to the acyl groups of mature cardiolipin. Finally, the presence of α-syn clearly defines the final composition of PUFAs in the mature structure of cardiolipin. Aging can be a contributing factor that influences mature cardiolipin PUFA composition to trigger PD pathology.

11 Lifestyle Changes to Protect from PD

A simple but powerful strategy for preventing or treating PD, which is also protective against many other health issues, is to consume mainly organic whole foods, with abundant fiber-rich foods, probiotics, and healthy fats, while making time to be outdoors in the sunlight and exercising every day.

A large-cohort dietary study of low-socioeconomic American adults revealed a significant increase in all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and gastrointestinal cancer-related mortality associated with a dietary profile that promotes the growth of sulfur-metabolizing gut bacteria. Specifically, the study results suggest that a beneficial diet is one that is rich in high-fiber foods such as fruits, vegetables, grains, nuts, and legumes, as well as fermented dairy products and tea, and relatively low in processed meats, high-energy drinks, alcohol, and fried potatoes [150].

One can reduce deuterium levels from the diet by favoring fats over carbohydrates. Starchy foods such as flour, sugar, and potatoes tend to be relatively high in deuterium, compared to fats, especially animal-based fats. Butter, pork lard, and beef fat are consistently low in deuterium, at around 115–125 parts per million, whereas foods high in carbohydrates generally have levels above 140 parts per million. Butter is especially beneficial because it is also a good source of butyrate. Seed oils and animal-based proteins fall in the middle range between these two food groups [151].

An important consideration is exposure to toxic pesticides used in food production. Rotenone is a natural, broad-spectrum insecticide that is also toxic to fish. It suppresses mitochondrial complex I, and it has been used to induce PD in animal studies of the disease [152]. Paraquat, a toxic water-soluble herbicide widely used worldwide, has also been linked to PD in animal studies [153]. Consuming only certified organic foods would minimize exposure to these chemicals.

It is likely beneficial to take deuterium depleted water (DDW) on a regular basis, both to prevent and to treat PD. The PC12 tumor cell line has become a popular choice for research in PD, because these cells synthesize, store, and release dopamine. An in vitro study on PC12 cells evaluating the potential for DDW to protect from PD showed that it attenuated apoptosis induced by H2O2 exposure, reduced reactive oxygen species, and increased the activity of the protective enzymes catalase and CuZn-superoxide dismutase [71].

A long review paper published in 2024 provides a detailed analysis of the myriad ways in which the gut microbiome communicates with glial cells in the brain, impacting neurodevelopment, social behavior, and neurodegenerative diseases. The paper concludes with suggestions for promoting brain health through therapeutics, including prebiotics, probiotics, and fecal transplantation, that can potentially restore the integrity of the intestinal barrier, the blood-brain barrier, and the meninges. It remains a research question regarding which microbial species to include in probiotics, and whether the microbes can survive the harsh conditions in the stomach [154]. However, these are exciting areas where new research to optimize these interventions may lead to significant advances in our ability to treat neurodegenerative diseases.

We have written elsewhere that specific nutrients, including PUFAs, lutein, carotenes, heme, and others, are uniquely structured to entrap ambient deuterium and facilitate its excretion [86]. This model predicts that supplementation with these nutrients will increase stool deuterium concentration—likely more significantly in PD patients than in healthy controls—as well as reduce the risk of PD-symptom onset and severity, an idea that could be tested both in pre-clinical models and ultimately in clinical trials. In fact, our model fits very well with the evidence brought forth in the excellent review by Loh et al., which provides a comprehensive overview of the beneficial impact of some of these same nutrients [154].

Regular aerobic exercise has the potential to prevent prodromal conditions that can lead to the development of PD [155]. Animal studies have shown that, during Parkinsonism, exercise helps to evoke adaptive neuroplasticity in the basal ganglia [156]. Vitamin D has been shown to play a significant role in mitochondrial health [157]. Spending more time outdoors in the sunlight to promote vitamin D synthesis in the skin decreases the risk of PD [158].

For nearly three decades, α-synuclein has been recognized as playing a primary etiological role in the development and progression of PD. However, the role that α-syn plays, both in health and in PD progression, is widely acknowledged to require further investigation. In this study, we have proposed that one vital role of α-syn is to sequester deuterium-enriched fatty acids that are created specifically within the mitochondria of neurons in the brain. These fatty acids are themselves uniquely structured and positioned via cardiolipin on the inner membrane of the intermembrane space to capture and trap ambient deuterons as they pass through the ATPase pumps, thus preventing them from interfering with the energy-producing capacity of the cell. Furthermore, the long chain PUFAs in neuronal cardiolipin that have captured deuterium are later utilized in both the inner and outer membranes of the mitochondria to quench the peroxidation chain reaction that is fueled by bis-allylic carbon atoms in the undeuterated PUFAs, thus protecting the cell from the severe consequences of further oxidative damage.

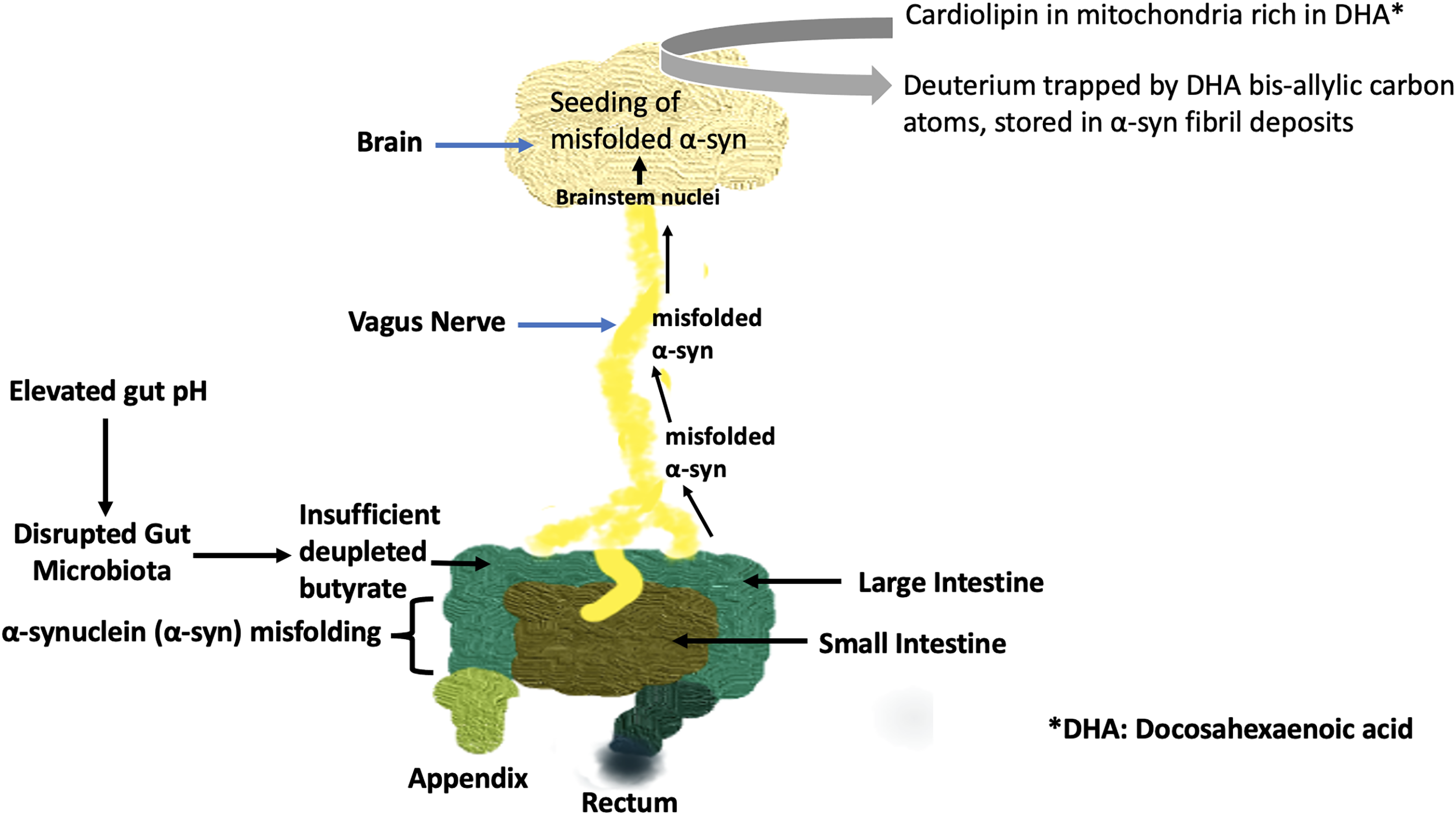

The model we have proposed here places α-syn within the larger network of systemic deuterium homeostasis in the body. In this model, the microbiome plays a fundamental role by supplying—or failing to supply—deuterium-depleted butyrate to both the gut and the brain. Butyrate plays a unique role in protecting neurons from oxidative damage. The lack of butyrate and the concurrent rise in ROS act as a danger signal. The conditions creating this signal, i.e., dysbiosis of the microbiome, contain all the elements necessary to initiate α-syn misfolding in the enteric nervous system. The gut-brain axis then shuttles misfolded α-syn to the brain via the vagus nerve to initiate PD pathology. Fig. 3 summarizes our hypothetical but strongly supported conception of the pathology that ultimately leads to PD.

Figure 3: Schematic of the pathological processes involving the gut microbiome, the vagus nerve, and the brain, which over time can lead to Parkinson’s disease. Elevated gut pH impairs butyrate supply to the colon. Misfolded α-syn is transported to the brain via the vagus nerve to seed further misfolding of α-syn already present in the brain. Cardiolipin, when present on the outer membrane of mitochondria, causes α-syn to form pores in the mitochondrial membrane, inducing apoptosis. Deuterium, trapped by bis-allylic carbon atoms in DHA present in cardiolipin, becomes incorporated into fibril deposits in Lewy bodies, protecting the surrounding cells from deuterium overload

In many ways, PD has been recognized as an increasingly complex medical mystery since its initial recognition. Further clinical studies that focus on microbiome diversity and/or SCFA supplementation, while tracking deuterium content in body fluids, will help to elucidate our hypothesis. It is our hope that this model, through rigorous testing and validation, can ultimately offer renewed hope for the millions of patients and family members struggling with this tragic disease.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded in part by Quanta Computer, Inc., in Tanyuan, Taiwan, under contract number 6950759, as part of the AIR project.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Stephanie Seneff, Greg Nigh, Anthony M. Kyriakopoulos. Analysis and interpretation of results: Stephanie Seneff, Greg Nigh, Anthony M. Kyriakopoulos. Draft manuscript preparation: Stephanie Seneff, Greg Nigh, Anthony M. Kyriakopoulos. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| 4-HNE | 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal |

| AA | Arachidonic acid |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ALCAT1 | Acyl-coenzyme A:lyso-cardiolipin acyltransferase-1 |

| ATPase | ATP synthase |

| CL | Cardiolipin |

| DDW | Deuterium depleted water |

| DHA | Docosahexaenoic acid |

| DMN | Dorsal motor nucleus |

| DMV | Dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus nerve |

| DOPAL | 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde |

| Drp1 | Dynamin-related protein 1 |

| DβHB | D-β-hydroxybutyrate |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| EPA | Eicosapentaenoic acid |

| Elovl5 | Elongation of very long chain fatty acids 5 |

| FA | Fatty acids |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| GSDMD-N | N-terminal fragment of gasdermin D |

| GSSG | Glutathione disulfide |

| H2S | Hydrogen sulfide gas |

| HDAC | Histone deacetylase |

| His50 | Histidine-50 |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| IBS | Irritable bowel syndrome |

| KIE | Kinetic isotope effect |

| LA | Linoleic acid |

| LB | Lewy bodies |

| LIPA | Light-induced protein aggregation |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MASH | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| MPTP | 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine |

| NADPH | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate |

| NTS | Nucleus tractus solitarius |

| OA | Oleic acid |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PUFAs | Poly-unsaturated fatty acids |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SCFAs | Short chain fatty acids |

| SIBO | Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth |

| acetyl-CoA | Acetyl coenzyme A |

| deupleted | Deuterium-depleted |

| ppm | Parts per million |

| α-syn | α-synuclein |

References

1. Liddle RA. Parkinson’s disease from the gut. Brain Res. 2018;1693(Pt B):201–6. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2018.01.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Henrich MT, Oertel WH, Surmeier DJ, Geibl FF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease—a key disease hallmark with therapeutic potential. Mol Neurodegener. 2023;18(1):83. doi:10.1186/s13024-023-00676-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Olgun A. Biological effects of deuteronation: aTP synthase as an example. Theor Biol Med Model. 2007;4(1):9. doi:10.1186/1742-4682-4-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Boros LG, Seneff S, Túri M, Palcsu L, Zubarev RA. Active involvement of compartmental, inter- and intramolecular deuterium disequilibrium in adaptive biology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121(37):e2412390121. doi:10.1073/pnas.2412390121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Korchinsky N, Davis AM, Boros LG. Nutritional deuterium depletion and health: a scoping review. Metabolomics. 2024;20(6):117. doi:10.1007/s11306-024-02173-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Ekaykin AA, Lipenkov VY, Kozachek AV, Vladimirova DO. Stable water isotopic composition of the Antarctic subglacial Lake Vostok: implications for understanding the lake’s hydrology. Isotopes Environ Health Stud. 2016;52(4–5):468–76. doi:10.1080/10256016.2015.1129327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Pryde SE, Duncan SH, Hold GL, Stewart CS, Flint HJ. The microbiology of butyrate formation in the human colon. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;217(2):133–9. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11467.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Krichevsky MI, Friedman I, Newell MF, Sisler FD. Deuterium fractionation during molecular hydrogen formation in marine pseudomonad. J Biol Chem. 1961;236(9):252–5. doi:10.1016/s0021-9258(18)64032-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Greene BL, Wu CH, McTernan PM, Adams MW, Dyer RB. Proton-coupled electron transfer dynamics in the catalytic mechanism of a [NiFe]-hydrogenase. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(13):45584566. doi:10.1021/jacs.5b01791. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Walker AW, Duncan SH, McWilliam Leitch EC, Child MW, Flint HJ. pH and peptide supply can radically alter bacterial populations and short-chain fatty acid ratios within microbial communities from the human colon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(7):3692–700. doi:10.1128/AEM.71.7.3692-3700.2005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Canani RB, Costanzo MD, Leone L, Pedata M, Meli R, Calignano A. Potential beneficial effects of butyrate in intestinal and extraintestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(12):1519–28. doi:10.3748/wjg.v17.i12.1519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Pedersen SS, Ingerslev LR, Olsen M, Prause M, Billestrup N. Butyrate functions as a histone deacetylase inhibitor to protect pancreatic beta cells from IL-1-induced dysfunction. FEBS J. 2024;291(3):566–83. doi:10.1111/febs.17005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Folkerts J, Redegeld F, Folkerts G, Blokhuis B, van den Berg MPM, de Bruijn MJW, et al. Butyrate inhibits human mast cell activation via epigenetic regulation of FcRI-mediated signaling. Allergy. 2020;75(8):1966–78. doi:10.1111/all.14254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Rinne JO, Anichtchik OV, Eriksson KS, Kaslin J, Tuomisto L, Kalimo H, et al. Increased brain histamine levels in Parkinson’s disease but not in multiple system atrophy. J Neurochem. 2002;81(5):954–60. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00871.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Przedborski S, Tieu K, Perier C, Vila M. MPTP as a mitochondrial neurotoxic model of Parkinson’s disease. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2004;36(4):375–9. doi:10.1023/B:JOBB.0000041771.66775.d5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Tieu K, Perier C, Caspersen C, Teismann P, Wu DC, Yan SD, et al. D-beta-hydroxybutyrate rescues mitochondrial respiration and mitigates features of Parkinson disease. J Clin Investig. 2003;112(6):892–901. doi:10.1172/JCI18797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388(6645):839–40. doi:10.1038/42166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Xu L, Pu J. Alpha-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease: from pathogenetic dysfunction to potential clinical application. Parkinsons Dis. 2016;2016(4):1720621. doi:10.1155/2016/1720621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Sampson TR, Debelius JW, Thron T, Janssen S, Shastri GG, Ilhan ZE, et al. Gut microbiota regulate motor deficits and neuroinflammation in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell. 2016;167(6):1469–80.e12. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Wang T, Leibrock N, Plugge CM, Smidt H, Zoetendal EG. In vitro interactions between Blautia hydrogenotrophica, Desulfovibrio piger and Methanobrevibacter smithii under hydrogenotrophic conditions. Gut Microbes. 2023;15(2):2261784. doi:10.1080/19490976.2023.2261784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cornick S, Tawiah A, Chadee K. Roles and regulation of the mucus barrier in the gut. Tissue Barriers. 2015;3(1–2):e982426. doi:10.4161/21688370.2014.982426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Kang X, Ploner A, Wang Y, Ludvigsson JF, Williams DM, Pedersen NL, et al. Genetic overlap between Parkinson’s disease and inflammatory bowel disease. Brain Commun. 2023;5(1):fcad002. doi:10.1093/braincomms/fcad002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Nishiwaki H, Ito M, Hamaguchi T, Maeda T, Kashihara K, Tsuboi Y, et al. Short chain fatty acids-producing and mucin-degrading intestinal bacteria predict the progression of early Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2022;8(1):65. doi:10.1038/s41531-022-00328-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Ijssennagger N, van der Meer R, van Mil SWC. Sulfide as a mucus barrier-breaker in inflammatory bowel disease? Trends Mol Med. 2016;22(3):190–9. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2016.01.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Singh SB, Carroll-Portillo A, Lin HC. Desulfovibrio in the gut: the enemy within? Microorganisms. 2023;11(7):1772. doi:10.3390/microorganisms11071772. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Murros KE, Huynh VA, Takala TM, Saris PEJ. Desulfovibrio bacteria are associated with Parkinson’s disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:652617. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2021.652617. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Murros KE. Hydrogen sulfide produced by gut bacteria may induce Parkinson’s disease. Cells. 2022;11(6):978. doi:10.3390/cells11060978. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Bhatia M. Role of hydrogen sulfide in the pathology of inflammation. Scientifica. 2012;2012(3):159680. doi:10.6064/2012/159680. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Kendall AI. Some observations on the study of the intestinal bacteria. J Biol. 1909;6(6):499–507. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)91596-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Aziz Q, Thompson DG. Brain-gut axis in health and disease. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(3):559–78. doi:10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70540-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Gill SR, Pop M, Deboy RT, Eckburg PB, Turnbaugh PJ, Samuel BS, et al. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science. 2006;312(5778):1355–9. doi:10.1126/science.1124234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Lu S, Zhao Q, Guan Y, Sun Z, Li W, Guo S, et al. The communication mechanism of the gut-brain axis and its effect on central nervous system diseases: a systematic review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;178(1):117207. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2024.117207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. He Y, Wang K, Su N, Yuan C, Zhang N, Hu X, et al. Microbiota-gut-brain axis in health and neurological disease: interactions between gut microbiota and the nervous system. J Cell Mol Med. 2024;28(18):e70099. doi:10.1111/jcmm.70099. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Phillips RJ, Walter GC, Wilder SL, Baronowsky EA, Powley TL. Alpha-synuclein-immunopositive myenteric neurons and vagal preganglionic terminals: autonomic pathway implicated in Parkinson’s disease? Neuroscience. 2008;153(3):733–50. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Chandra R, Sokratian A, Chavez KR, King S, Swain SM, Snyder JC, et al. Gut mucosal cells transfer α-synuclein to the vagus nerve. JCI Insight. 2023;8(23):e172192. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.172192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Xiang J, Tang J, Kang F, Ye J, Cui Y, Zhang Z, et al. Gut-induced alpha-Synuclein and Tau propagation initiate Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease co-pathology and behavior impairments. Neuron. 2024;112(21):3585–601.e5. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2024.08.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Pan-Montojo F, Schwarz M, Winkler C, Arnhold M, O’Sullivan GA, Pal A, et al. Environmental toxins trigger Parkinson’s disease-like progression via increased alpha-synuclein release from enteric neurons in mice. Sci Rep. 2012;2(1):898. doi:10.1038/srep00898. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Ahn EH, Kang SS, Liu X, Chen G, Zhang Z, Chandrasekharan B, et al. Initiation of Parkinson’s disease from gut to brain by δ-secretase. Cell Res. 2020;30(1):70–87. doi:10.1038/s41422-019-0241-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]