Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

RP3-340N1.2 Knockdown Suppresses Proliferation and Migration by Downregulating IL-6 in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer

1 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Binzhou Medical University, Yantai, 264003, China

2 School of Science, Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, Suzhou, 215123, China

* Corresponding Authors: Fei Jiao. Email: ; Yun-Fei Yan. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

BIOCELL 2026, 50(1), 10 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.068322

Received 26 May 2025; Accepted 23 September 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

Objectives: Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) remains a leading cause of cancer-related mortality, with limited understanding of lncRNA-driven mechanisms in tumor progression. This study aimed to identify differentially expressed lncRNAs in NSCLC tissues and elucidate the functional role of the significantly upregulated RP3-340N1.2 in promoting malignancy. Methods: RNA sequencing was used to screen dysregulated lncRNAs. RP3-340N1.2 was functionally characterized via gain/loss-of-function assays in NSCLC cells, assessing proliferation, migration, and macrophage polarization. Mechanisms of interleukin 6 (IL-6) regulation were explored using cytokine profiling, Actinomycin D assays, and RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP) assays to study RP3-340N1.2 interactions with zinc finger CCCH-type containing 12A (ZC3H12A) and IL-6 mRNA. Results: RP3-340N1.2 was upregulated in NSCLC tissues and cells. Functional assays demonstrated that RP3-340N1.2 knockdown suppressed NSCLC cell proliferation/migration and reduced macrophage polarization toward tumor-associated phenotypes. Mechanistically, RP3-340N1.2 knockdown promoted IL-6 mRNA degradation, as supported by reduced IL-6 levels and accelerated mRNA decay. Further RIP assays revealed that RP3-340N1.2 interacts with ZC3H12A, an RNA-binding protein previously reported to degrade IL-6 mRNA, and that RP3-340N1.2 knockdown enhanced ZC3H12A binding to IL-6 mRNA. Consequently, RP3-340N1.2 knockdown in carcinoma cells attenuated IL-6-mediated tumor-promoting effects, including tumor cell proliferation and migration. Importantly, these effects were observed not only in a direct carcinoma cell culturing system but also when carcinoma cells were exposed to conditioned medium from co-culturing RP3-340N1.2-knockdown tumor cells and macrophages. Conclusion: RP3-340N1.2 drives NSCLC malignancy by stabilizing IL-6 mRNA; its inhibition offers a potential therapeutic strategy to disrupt tumor-promoting interactions.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileAbbreviations

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| lncRNAs | Long noncoding RNAs |

| TKIs | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

| ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| ceRNAs | Competitive endogenous RNAs |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| CCK-8 | Cell Counting Kit-8 |

| TAM | Tumor-associated macrophage |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| CM | Conditioned medium |

| RIP | RNA Binding Protein Immunoprecipitation |

| EMT | Epithelial-mesenchymal transition |

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the principal histological subtype of lung malignancies, accounts for 80%–85% of all primary lung cancer diagnoses globally [1,2]. Current therapeutic strategies for NSCLC adhere to a multimodal framework, integrating surgical resection, radiotherapy, and systemic therapies (e.g., tyrosine kinase inhibitors [TKIs], immune checkpoint inhibitors [ICIs], and combination regimens) [3,4]. Despite these advancements, NSCLC persists as the leading cause of cancer-related mortality, contributing to 80%–90% of lung cancer deaths, with a 5-year overall survival rate of approximately 22% across all disease stages [5,6]. This clinical burden underscores the critical need to identify novel therapeutic targets and strategies to improve clinical outcomes. Recent genomic dissections of lung carcinomas have revealed numerous potential targets, among which non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have emerged as promising candidates for diagnostic and therapeutic exploitation [7].

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs), emerge as critical regulators of both intracellular and intercellular signaling networks in lung cancer. These molecules coordinate cellular signaling pathways to modulate a variety of biological processes, such as proliferation, migration, and apoptosis, thereby influencing tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic responsiveness [8]. Among these ncRNAs, lncRNAs exhibit remarkable diversity in both their molecular sizes and functional repertoires, particularly in the pathogenesis of NSCLC [9]. The functional versatility of lncRNAs in NSCLC is manifested through several pivotal mechanisms: firstly, acting as ceRNAs, lncRNAs sponge miRNAs via complementary base-pairing, thereby preventing miRNA-mediated mRNA repression and indirectly upregulating miRNA-targeted genes; secondly, lncRNAs modulate the chromatin landscape by recruiting chromatin-modifying enzymes or complexes to specific genomic loci, contributing to the epigenetic regulation of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Thirdly, lncRNAs function as molecular scaffolds that coordinate the assembly of multi-protein complexes at gene regulatory regions, enabling precise tuning of transcriptional programs in response to pro-tumorigenic or anti-tumorigenic signals; lastly, through direct protein-RNA interactions, lncRNAs regulate protein function by modulating their activity, stability, or localization and adding a post-translational regulatory dimension to cellular process control in NSCLC [10–12]. Central to the functional execution of these lncRNA-mediated mechanisms are RNA-binding proteins (RBPs). RBPs, characterized by conserved structural domains such as zinc-finger motifs and K-Homology domains, possess the intrinsic ability to bind lncRNAs with high specificity and affinity [13]. Through these interactions, RBPs participate in diverse aspects of lncRNA biology, including transcription initiation, RNA editing, stability maintenance, and subcellular localization [14]. The interplay between lncRNAs and their binding RBPs thus constitutes a sophisticated regulatory network that profoundly impacts NSCLC pathogenesis.

LncRNAs exert pivotal roles in both oncogenic and tumor-suppressive signaling pathways. In addition to modulating key cellular processes such as proliferation, apoptosis, metastasis, and angiogenesis, certain lncRNAs further shape the intricate tumor microenvironment (TME) [15,16]. The regulatory axis of lncRNAs typically targets effector molecules that are integral to the pathogenesis of carcinomas. Interleukins (ILs), a class of key cytokines, have traditionally been associated with immune cell communication. However, accumulating evidence indicates that tumor cells also secrete ILs across various cancer types [17,18]. This aberrant production of ILs by tumor cells significantly influences the dynamic interplay between the tumor and the host immune system. Among these ILs, several have emerged as promising therapeutic targets in cancer treatment, with interleukin-6 (IL-6) being particularly noteworthy. IL-6 exerts a pro-oncogenic effect during tumor development, notably by reshaping the TME [19]. Actually, strategies aimed at blocking IL-6 expression, its receptors, or its associated signaling pathways have been explored in clinical trials for cancer therapy [20]. Given that tumor cells constitute one of the primary sources of IL-6, targeting lncRNAs that promote IL-6 expression in carcinoma cells represents a potential therapeutic approach [21,22].

NSCLC progression is critically influenced by lncRNAs that modulate tumor-stromal interactions through cytokine networks. While RNA sequencing has identified numerous dysregulated lncRNAs in NSCLC, their functional roles in shaping the TME remain poorly characterized. This study focuses on RP3-340N1.2, a previously uncharacterized lncRNA significantly upregulated in NSCLC tissues compared to adjacent normal lung epithelium. We hypothesized that RP3-340N1.2 promotes NSCLC malignancy by regulating the secretion of pro-tumorigenic cytokines, particularly IL-6, which is known to drive M2-like tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) polarization and immunosuppression. Furthermore, given emerging evidence that lncRNAs can act as competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) to modulate mRNA stability, we investigated whether RP3-340N1.2 influences IL-6 availability through direct interaction with RNA-binding proteins involved in cytokine regulation.

The specific objectives of this study were to: (1) validate the differential expression of RP3-340N1.2 in NSCLC, (2) determine its functional impact on tumor cell proliferation/migration and macrophage polarization, and (3) elucidate the molecular mechanism underlying its cytokine-mediated effects on tumor-TME crosstalk.

The 21 pairs of NSCLC tissues and the matched para-carcinoma tissue specimens used in this experiment were all collected from Yantaishan Hospital, Affiliated to Binzhou Medical University, and were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Binzhou Medical University. The approval number for patients’ sample was 2021-102.

2.2 Cell Culture and Treatment

Human lung adenocarcinoma cell lines (A549, NCI-H1975, H1299, and PC9), human bronchial epithelial cell line (BEAS-2B), and human monocyte cell line THP-1 were obtained from Shanghai Institute of Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China. Take 1 μL of the cell culture supernatant, add it to the reaction system of the Mycoplasma Rapid Test Kit (CA1082, Solarbio, Beijing, China), and incubate it at 60°C for 1 h. After 1 h, if the solution turns blue, it indicates that there is no mycoplasma contamination in the cells. The cells have been tested and showed no mycoplasma contamination.

These cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, C11875500BT, Waltham, MA, USA) medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 16140071) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15140122), and all cells were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Inoculate 100 μL of cell suspension (5 × 105 cells/mL) into a six-well plate (Corning Incorporated, 3516, New York, NY, USA) and use it for subsequent experiments upon reaching approximately 70% confluence. According to the manufacturer’s instructions, pcDNA3.1, pcDNA3.1-IL-6, si-NC (sense: 5′UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT′3, antisense: 5′ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT3′), and si-RP3-340N1.2 (sense: 5′GCUACCCAGUACAAGAUAUTT3′, antisense: 5′AUAUCUUGUACUGGUAGCTT3′) (Shanghai GenePharma Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) were transfected into A549 and H1975 cells using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). The cDNA sequence of IL-6 has been attached to the additional files. After 48 h, the cells were collected for subsequent experiments or preparation of conditioned medium. THP-1 cells were induced with 100 ng/mL Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (Merck KGaA, P8139, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 24 h to obtain M0 macrophages, and the obtained M0 macrophages were treated with IL-4 and IL-13 (20 ng/mL) for 48 h to activate them to the M2 phenotype.

2.3 Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 15596026CN). For miRNA isolation, the mirVana™ miRNA Isolation Kit (Ambion, AM1560, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was employed according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Polyadenylation of miRNAs was performed using poly(A) polymerase (New England Biolabs, M0276S, Ipswich, MA, USA). Reverse transcription of RNA into cDNA was carried out with the PrimeScript™ RT Reagent Kit (Takara Bio, RR047A, Shiga, Japan). qRT-PCR was conducted using TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II (RR820L, Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan) on a CFX96 Touch™ Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Relative expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH and U6 serving as endogenous controls for mRNA and miRNA, respectively. The primers (Human) used are shown in Table 1.

2.4 Preparation of Conditional Medium

The cell culture supernatant of different treatment groups was collected, centrifuged at 4980× g (Eppendorf, 5810, Hamburg, Germany) for 10 min, filtered through a 0.2-μm filter, and subpackaged for storage at −80°C, which was used as conditioned medium in subsequent experiments.

Cells were collected 48 h after transfection and seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 2000 cells per well. Every 24 h, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution (Beyotime, C0038, Shanghai, China) was added to each well and incubated for 2 h. Subsequently, Optical density (OD) values were measured at 450 nm using an enzyme-labeler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, N17646, Multiskan Skyhigh). A549 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 4000 cells per well, and incubated with different medium conditions for 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, respectively. Finally, cell viability was measured.

The cells were digested and counted, then suspended in serum-free medium (2 × 105/mL) (Thermo Scientific, 12633020). 100 μL cell suspension was added to the upper chamber of Transwell, and 600 μL of RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 20% FBS or conditioned medium was added to the lower chamber according to the follow-up experiments. After 24 h of culture, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Beyotime, P0099, Shanghai, China), stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Beyotime, Y268091, Shanghai, China), and the migrated cells were imaged and counted using a Leica DM2500 microscope (Leica Microsystems, DM2500, Wetzlar, Germany).

The cells were inoculated in a six-well plate at a density of 500 cells per well and cultured under different conditioned media, changing the medium every three days. After 14 days of culture, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Beyotime, P0099, Shanghai, China) for 30 min, stained with 0.1% crystal violet (Beyotime, Y268091, Shanghai, China) for 5 min, and then observed and counted.

2.8 Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

The CY3-conjugated RP3-340N1.2 FISH probe (Shanghai GenePharma, F40124, Gemma Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was ordered from Gemma Pharmaceutical Technology (Shanghai, China). The cells were seeded at 5 × 104 per-well in a six-well plate (Corning Incorporated, 3516, New York, NY, USA) and analyzed using a fluorescent in situ hybridization kit (Shanghai GenePharma, F40111, Gemma Pharmaceutical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) when the confluence rate reached 60%.

2.9 In Vivo Xenograft Tumor Models

This prospective controlled intervention study compares tumor growth between two groups of BALB/c nude mice (5 weeks old, male, SPF grade) to evaluate the tumorigenic effects of A549 cells. Each group comprises 5 mice, with a control group included to isolate treatment effects. Sample size determination is based on pre-experimental data (tumor volume CV ≤ 20%) and statistical power analysis (α = 0.05, β = 0.2), ensuring detection of ≥30% tumor volume differences. Mice are stratified by initial weight (18–22 g) and randomly assigned via random number tables to groups, with ear tags for identification. Mice are purchased from Nanjing Mairuisi Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China and housed in sterile barrier systems under controlled conditions (22°C–24°C, 40%–60% humidity, 12 h light/dark cycle) with ad libitum access to sterile feed and water. A 7-day acclimatization period precedes experimentation. A549 cells are suspended in cold PBS (1 × 108 cells/mL), mixed 1:1 with Corning Matrigel, and injected subcutaneously (0.1 mL/mouse, 5 × 106 cells) into the dorsal region under isoflurane anesthesia. Post-injection analgesia (0.3 mg/kg medetomidine) is administered. Tumor dimensions (length/width) are measured every 3 days using digital calipers (precision 0.1 mm) by blinded researchers. Volume is calculated as volume = length × width2 × 0.5 cm3. At week 3, mice are euthanized via CO2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation. Tumors are excised, weighed (precision 0.001 g), and recorded. Data are analyzed using SPSS 26.0. (International Business Machines Corporation, Armonk, New York, NY, USA) Tumor volume trends are assessed via repeated-measures ANOVA, while tumor weights are compared using independent t-tests. Results are reported as mean ± SD with 95% confidence intervals and Cohen’s d effect sizes. Statistical significance is set at p < 0.05. The protocol is approved by the Ethics Committee of Binzhou Medical University (2022-390) and adheres to the 3R principles. Humane endpoints are enforced, with daily monitoring of animal well-being (weight, behavior, signs of distress). Environmental enrichment (nesting materials, hiding spots) is provided to minimize stress. Raw data (weight, tumor volume) are archived in institutional databases for peer review. Limitations include a single-center design, necessitating multi-center validation. No conflicts of interest are declared.

2.10 Immunofluorescence (IF) Assay

The tissues were placed in 4% paraformaldehyde and fixed for 24 h. Then, paraffin embedding and sectioning were performed. The tissue sections were successively treated with dewaxing and hydration procedures. Antigens were retrieved using a citric acid antigen retrieval solution (pH 6.0), and unmasks antigenic epitopes obscured by formalin fixation, enabling antibody binding through heat-or enzyme-mediated disruption of protein cross-links in tissue sections. After retrieval, the sections were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (Beyotime, ST023, Shanghai, China) at room temperature for 1 h. The diluted CD206 antibody (1:400, 18704-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) was then added to the tissue sections and incubated overnight at 4°C. The sections were washed with PBS and then incubated with Alexa Fluor™ 594 Micro Protein Labeling Reagent (1:500, A20181 and A30008, Thermo Fisher Scientific) in the dark for 1 h. After a 5-min incubation with DAPI (Beyotime, C1002, Shanghai, China), the sections were mounted with an anti-quenching agent. Finally, imaging was performed using a German LEICA fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany).

M0 macrophages were incubated with different conditioned media for a co-culture period of 48 h. The macrophages were collected and then fixed and permeabilized by the Fixed membrane buffer solution (Thermo Scientific, 88-8824-00). Subsequently, they were incubated with 0.6 μg/mL APC-conjugated human anti-CD206 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 17-2069-42, 1:50) in the dark at 4°C for 40 min. After washing the cells three times with 1X cell membrane permeabilization solution, the proportion of CD206-positive cells was analyzed on a BD C6 plus flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, 660517, San Jose, CA, USA).

A549 cells were treated with 8-Chloroadenosine (APExBIO, B7667, Houston, TX, USA). Cells were collected at 0, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2 h, and RNA was extracted. Finally, IL-6 mRNA expression was detected by qRT-PCR.

The supernatant of A549 cells in different treatment groups was collected, and IL-6 concentration in the supernatant of cell culture was determined by a human IL-6 ELISA kit (Elabscience, E-EL-H0149, Wuhan, China). Each group had 3 parallel wells, and the experiment was repeated 3 times.

2.14 RNA Immunoprecipitation (RIP)

The cells were resuspended in a lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and RNase inhibitors (P0101, GeneSeed, Guangzhou, China) and lysed on ice for 10 min. 5 μg of anti-ZC3H12A (sc-515275, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) or anti-IgG (B900620, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) was added to Protein A + G magnetic beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 88802) and incubated for 2 h. After incubation, the cell lysates were incubated with the antibody-coupled magnetic beads at 4°C for 12 h. The RNA bound to the magnetic beads was eluted and reverse transcribed into cDNA. Finally, the analysis was performed by qRT-PCR.

The cell precipitate was re-suspended using RIPA lysis buffer (P0013B, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), lysed on ice for 30 min, and centrifuged at 14,938× g (Eppendorf, 5810, Hamburg, Germany) for 10 min to obtain the supernatant. The proteins were isolated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a PVDF (Polyvinylidene Fluoride) (MilliporeSigma, IPVH00010, Darmstadt, Germany) membrane, which was blocked in 5% skim milk at room temperature for 2 h. The incubation time of the primary antibody was overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies used in Western blotting were as follows: ZC3H12A (K106615P, 1:1000, Solarbio, Beijing, China), Arg1 (93668T, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA, USA), GAPDH (Bioworld, AP0063, 1:5000, Dublin, OH, USA). After washing with TBST, the membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Bioworld, BS20241-Y, 1:5000) or HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse (Bioworld, BS20242-Y, 1:5000) secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature.

To identify RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) that may interact with the long non-coding RNA RP3-340N1.2, we employed an integrated bioinformatics prediction strategy. First, potential binding proteins of the RP3-340N1.2 sequence were predicted using three major prediction tools: RBPsuit (http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/RBPsuite/ (accessed on 25 May 2025)), RBPmap (http://rbpmap.technion.ac.il/ (accessed on 25 May 2025)), and catRAPID (http://service.tartaglialab.com/page/catrapid_group (accessed on 25 May 2025)), leveraging their respective algorithmic strengths. To enhance the reliability of the predictions, the potential binding proteins identified by the three tools were intersected to obtain a high-confidence candidate RBP list. Subsequently, Gene Ontology (GO) functional annotation and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis were performed on this candidate set. Notably, we identified the protein ZC3H12A, which is associated with IL-6 mRNA degradation, among the candidate RBPs. To validate the biological authenticity of this interaction, we further conducted RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) experiments.

All experimental data were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The statistical significance of the difference between the two groups was analyzed by Student’s t-test or two-way ANOVA. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

3.1 Long Noncoding RNA (LncRNA) RP3-340N1.2 Levels Are Significantly Upregulated in NSCLC Tissue and Cell Lines

To characterize the landscape of aberrantly expressed lncRNAs in NSCLC, we conducted RNA sequencing on three tumor-adjacent paired NSCLC tissues. Sample similarity was assessed by calculating Pearson correlation coefficients of lncRNA expression profiles. The resulting correlation matrices demonstrated robust co-expression patterns among lncRNAs in both tumor pairs and matched adjacent non-tumor pairs. (Fig. 1a). This RNA sequencing analysis identified a total of 114 lncRNAs, whose expression patterns were visualized in a heatmap to compare differential expression between NSCLC tissues and adjacent para-carcinoma tissues. This clustering analysis confirmed distinct expression profiles that distinguished NSCLC tissues from their matched normal counterparts. (Fig. 1b). Through the application of stringent selection criteria (fold change ≥ 2 and Padjust < 0.05), a total of 43 significantly upregulated and 34 downregulated lncRNAs were identified. Notably, among the upregulated lncRNAs, RP3-340N1.2 demonstrated a log2 fold change of 6.67 (CA read-count/PARA read-count) as visualized in Fig. 1c. To further validate the expression profile of RP3-340N1.2 in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), we analyzed data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), encompassing 483 primary carcinoma tissue samples and 347 matched healthy control samples. This analysis confirmed a statistically significant upregulation of RP3-340N1.2 in NSCLC tissues compared to normal controls, as illustrated in Fig. 1d. Complementary validation was performed using 21 paired NSCLC tissue samples collected in-house. Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis revealed consistently elevated RP3-340N1.2 expression levels in lung carcinoma tissues relative to adjacent para-carcinoma tissues. This differential expression pattern was corroborated by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) detection in three representative paired-NSCLC tissue sections, as shown in Fig. 1e,f. Furthermore, comparative analysis across cell lines demonstrated marked overexpression of RP3-340N1.2 in multiple NSCLC-derived cell lines (A549, H1975, H1299, PC-9) when benchmarked against the non-malignant bronchial epithelial cell line BEAS-2B (Fig. 1g). Subcellular fractionation studies confirmed that RP3-340N1.2 predominantly localizes to the cytoplasm (Fig. 1h). Collectively, these findings strongly suggest that RP3-340N1.2 may play a pivotal pathophysiological role in NSCLC tumorigenesis.

Figure 1: RP3-340N1.2 levels are significantly upregulated in NSCLC tissue and cell lines. (a) Pearson correlation matrix of lncRNAs expression in 3 NSCLC tissues and paired normal tissues; (b) clustering heatmap of 114 lncRNAs identified in RNA sequencing; (c) volcanoplot of relative expression of lncRNAs; (d) relative expression of RP3-340N1.2 in 483 lung adenocarcinoma tissues and 347 normal tissues from TCGA; Mann–Whitney U test; (e) qRT-PCR analysis of RP3-340N1.2 levels in NSCLC tissues and corresponding para-carcinoma tissues (n = 21). Data are expressed as median (interquartile range); Mann–Whitney U test; (f) FISH analysis of RP3-340N1.2 level in 3 NSCLC tissues and the corresponding para-carcinoma tissues, CA: carcinoma; PA: para-carcinoma; Scale bar = 125 μm; (g) qRT-PCR analysis of RP3-340N1.2 levels in A549, H1975, H1299, PC9 and BEAS-2B cells; ANOVA test; (h) the subcellular localization of RP3-340N1.2 in A549 cells and H1975 cells was performed with FISH. Nuclei were stained blue (DAPI) and RP3-340N1.2 was stained red (Cy3). Scale bar = 50 μm. Data are expressed as mean ± SD for triplicate experiments, ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, &&p < 0.01, @@p < 0.01

3.2 RP3-340N1.2 Knockdown Resulted in Attenuation of Cell Proliferation and Migration

To further elucidate the specific functions of RP3-340N1.2 in lung carcinoma, we synthesized interference RNA as si-RP3-340N1.2. After transfection of si-RP3-340N1.2 into A549 or H1975 cells, the expression of RP3-340N1.2 was significantly attenuated. (Fig. 2a). Initially, we assessed the potential impact of RP3-340N1.2 on cell proliferation through the CCK8 assays. The results showed that si-RP3-340N1.2 treatment could significantly suppress A549 or H1975 cell proliferation compared with the negative control (NC) (Fig. 2b). By conducting a colony formation assay, we observed that transfection with si-RP3-340N1.2 resulted in a statistically significant reduction in the number of colonies formed compared to NC treatment in both A549 and H1975 cell lines (Fig. 2c). To investigate the potential involvement of RP3-340N1.2 in tumor cell migration, we also performed transwell migration assays. The results indicated that treatment with si-RP3-340N1.2 significantly attenuated the migration of A549 and H1975 cells compared with the NC group (Fig. 2d). To examine the potential influence of RP3-340N1.2 overexpression on the carcinogenic process, we generated a pcDNA3.1-RP3-340N1.2 expression vector and subsequently transfected it into A549 and H1975 lung cancer cell lines to achieve overexpression of RP3-340N1.2. (Fig. 2e). However, no statistically significant difference was observed in cell proliferation or migration capabilities between cells treated with pcDNA3.1-RP3-340N1.2 and those treated with pcDNA3.1 (Fig. 2f–h). To further investigate the effect of si-RP3-340N1.2 on tumor growth in vivo, we established a xenograft tumor model by subcutaneously or orthotopically injecting nude mice with A549 lung cancer cells that had been previously transfected with either si-RP3-340N1.2 or NC, ensuring strict adherence to animal welfare protocols and ethical guidelines. The volume of the xenografted tumors was quantitatively assessed every 3 days. After one month, the mice were euthanized and sacrificed. The excised tumor specimens were photographed and examined. The resulting tumors derived from A549 cells that had been transfected with si-RP3-340N1.2 exhibited a statistically significant decrease in both volumetric dimensions and mass, as measured by caliper-based volumetric calculations and precision weighing, respectively, when compared to tumors originating from cells transfected with NC (Fig. 2i). These data indicate that RP3-340N1.2 knockdown has an anti-oncogenic capability in lung carcinoma.

Figure 2: RP3-340N1.2 knockdown resulted in attenuation of cell proliferation and migration. (a) qRT-PCR analysis of RP3-340N1.2 level in A549 cells and H1975 cells with transfection of si-RP3-340N1.2 or negative control (NC); Student’s t-test, n = 3; (b) cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay of A549 cells and H1975 cells in 96 h post-transfection of si-RP3-340N1.2 or NC; ANOVA test; (c) colony formation assay of A549 cells and H1975 cells in 48 h post-transfection of si-RP3-340N1.2 or NC; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (d) transwell migration assay of A549 cells and H1975 cells at 24 h post-transfection of si-RP3-340N1.2 or NC; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (e) qRT-PCR analysis of RP3-340N1.2 level in A549 cells and H1975 cells with transfection of pcDNA3.1-RP3-340N1.2 or pcDNA3.1; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (f) cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay of A549 cells and H1975 cells in 96 h post-transfection of pcDNA3.1-RP3-340N1.2 or pcDNA3.1; ANOVA test; (g) colony formation assay of A549 cells and H1975 cells in 48 h post-transfection of pcDNA3.1-RP3-340N1.2 or pcDNA3.1; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (h) Transwell migration assay of A549 cells and H1975 cells at 24 h post-transfection of pcDNA3.1-RP3-340N1.2 or pcDNA3.1; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (i) images of xenograft formed by A549 cells treated by si-RP3-340N1.2 or NC, quantitative analysis of xenograft volume growth (ANOVA test) and tumor weight (Student’s t-test), n = 5. Data are expressed as mean ± SD for triplicate experiments, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, nsp > 0.05

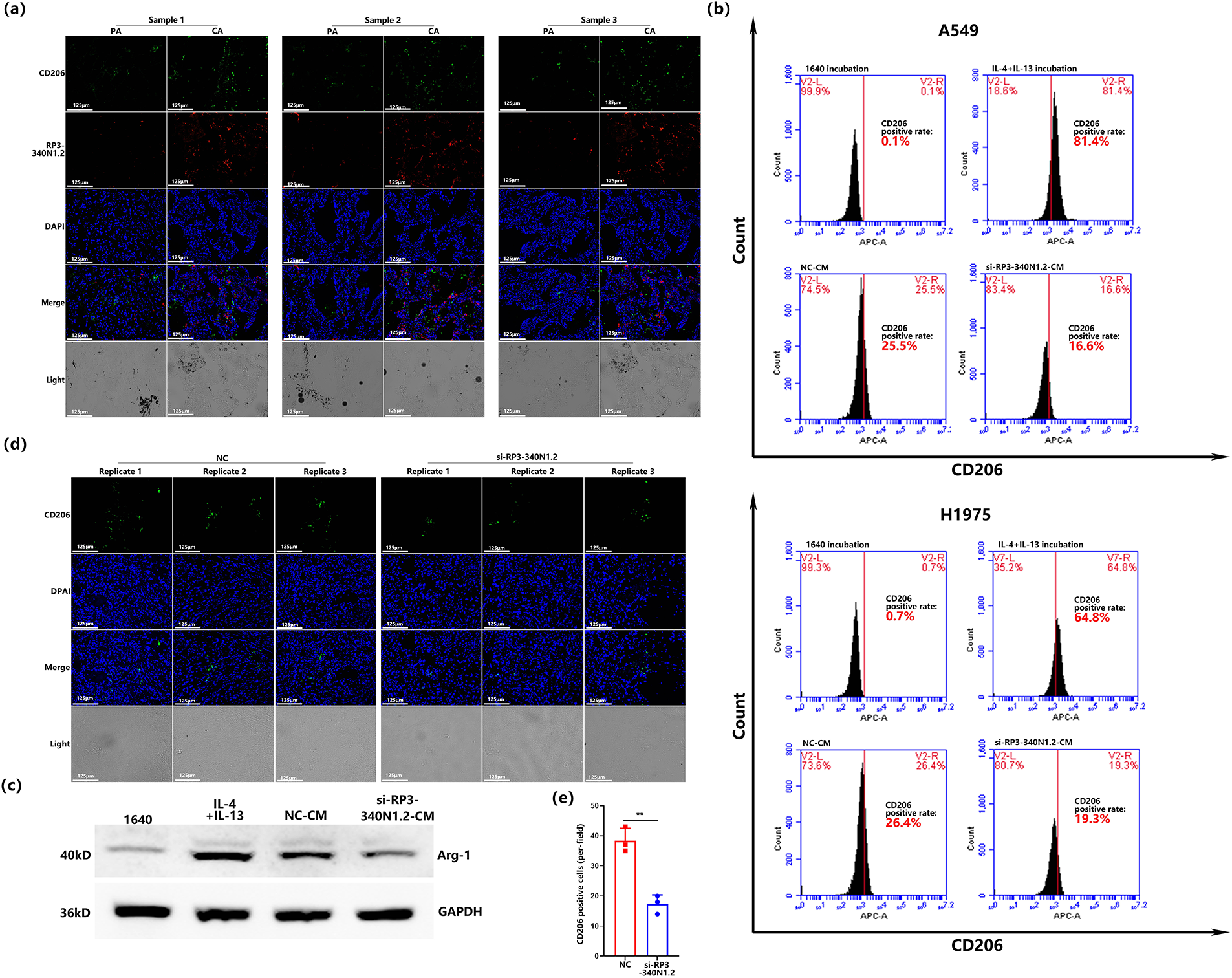

3.3 RP3-340N1.2 Knockdown Blocks the TAMs Polarization in Lung Carcinoma

Based on the evidence presented herein, RP3-340N1.2 exhibits oncogenic potential within the context of lung carcinoma pathogenesis. Nonetheless, its overexpression in lung carcinoma cells does not appear to directly facilitate the progression of carcinogenesis. Drawing from this insight, we hypothesized that RP3-340N1.2 may augment the malignancy of lung tumors through dual mechanisms: (1) by promoting oncogenic processes within carcinoma cells, and (2) by modulating the tumor microenvironment (TME). Given the pivotal involvement of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) in shaping TME, our initial investigation focused on comparing the expression of the TAM marker CD206 in lung carcinoma tissues to the para-carcinoma counterparts [23,24]. Through double stain immunofluorescence analysis targeting both CD206 and RP3-340N1.2, we observed a significant upregulation in the expression levels of these two markers within lung carcinoma tissue relative to the control tissue. Notably, despite this concurrent upregulation, there was almost no colocalized staining of CD206 and RP3-340N1.2 within the analyzed tissue samples (n = 3) (Fig. 3a). Subsequently, we aimed to examine the potential influence of RP3-340N1.2 expression in carcinoma cells on CD206 expression levels in macrophages. After inducing THP-1 monocytes into M0 macrophages, the M0 macrophages were subsequently cultured in various specialized conditioned mediums for an additional 48-h. Subsequent to this culture phase, the expression levels of CD206 on the macrophage surface were evaluated via flow cytometry. The experimental design incorporated four distinct conditioned medium groups: (1) RPMI 1640 medium, which served as the negative control; (2) the positively control medium formulated by supplementing RPMI 1640 with interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interleukin-13 (IL-13); (3) NC-CM, a conditioned medium derived from A549 transfected NC; and (4) si-RP3-340N1.2-CM, a conditioned medium obtained from A549 cells subjected to transfection with si-RP3-340N1.2. As demonstrated by the results, M0 macrophages cultured in NC-CM yielded to CD206+ macrophage percentage of 25.5%. While si-RP3-340N1.2-CM resulted in a 16.6% CD206+ cell population. Following the identical experimental protocol as previously outlined, we performed the experiment utilizing conditioned medium sourced from H1975 cells. As expected, the si-RP3-340N1.2-CM precipitated a significant reduction in the percentage of CD206+ macrophages compared with the NC-CM. The flow cytometry experiment was repeated three times and statistical analysis was conducted. (Figs. 3b and S1a,b). In addition to CD206, Arginase-1 (Arg-1) is widely recognized as a canonical marker of TAM polarization, where it critically coordinates immunosuppressive, tissue-repair and remodeling functions within TME [25]. Therefore, we cultured M0 macrophages with the conditioned mediums from A549 described as before, and then detected the Arg-1 expression in macrophage by western blot and its quantification. The results revealed that si-RP3-340N1.2-CM incubation resulted in attenuation of Arg-1 expression compared with NC-CM (Figs. 3c and S1c). Furthermore, we conducted an examination of CD206 expression in xenograft tumors via immunofluorescence analysis and observed that transfection with si-RP3-340N1.2 in xenografts effectively diminished CD206 expression levels (Fig. 3d,e). Collectively, these results suggest that RP3-340N1.2 may play a role in promoting M2 macrophage polarization within the context of lung carcinoma.

Figure 3: RP3-340N1.2 knockdown blocks the TAMs polarization in lung carcinoma. (a) immunofluorescence co- staining analysis of CD206 and RP3-340N1.2 level in 3 NSCLC tissues and the corresponding para-carcinoma tissues, CA: carcinoma; PA: para-carcinoma; Scale bar = 125 μm; (b) flow cytometry analysis of CD206 staining in macrophages treated with conditioned media derived from A549 and H1975 cells with 4 different treatment methods; (c) western blot analysis of Arg-1 in macrophages treated with conditioned media derived from A549 cells with 4 different treatment methods; (d) FISH analysis of CD206 in xenografts from cells with transfection of si-RP3-340N1.2 or NC; (e) quantitative graph of CD206 in xenografts from cells with transfection of si-RP3-340N1.2 or NC. Student’s t-test, n = 3. Data are expressed as mean ± SD for triplicate experiments, **p < 0.01

3.4 RP3-340N1.2 Knockdown Accelerates the Degradation of IL-6 mRNA Mediated by ZC3H12A

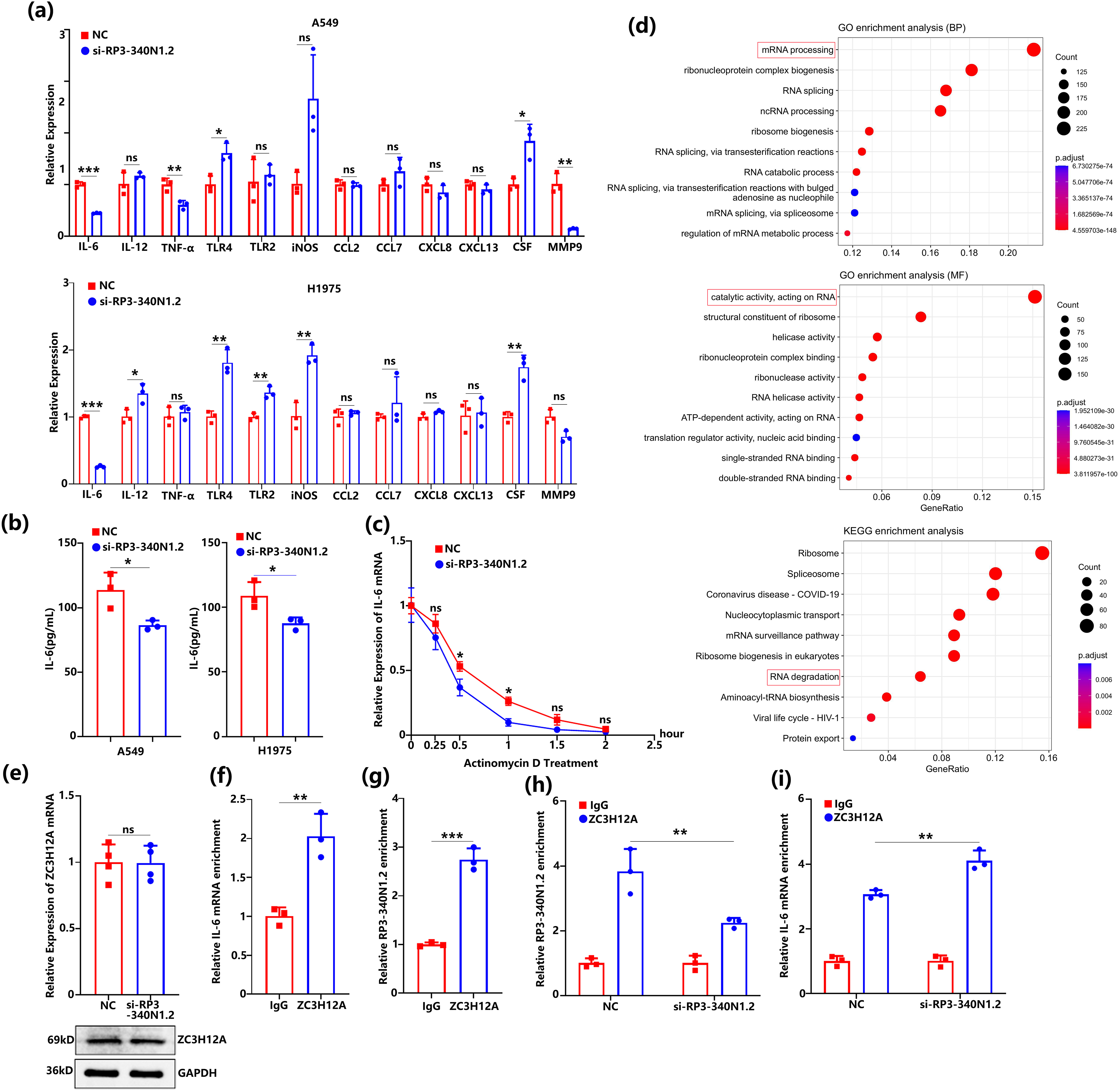

Based on the above data, RP3-340N1.2 within carcinoma cells exhibited the capacity to modulate the conditioned medium, thereby participating in the progression of carcinogenesis. Motivated by these findings, we conducted an investigation into the expression profiles of several pivotal cytokines associated with TAM polarization. Among the cytokines examined via qRT-PCR, IL-6 emerged as the only cytokine exhibiting significant downregulation in both A549 and H1975 cell lines following transfection with si-RP3-340N1.2 (Fig. 4a). To validate these findings, we further assessed the levels of IL-6 secreted into the culture medium by A549 and H1975 cells using ELISA. The results confirmed that si-RP3-340N1.2 transfection significantly attenuates IL-6 expression in lung carcinoma cells (Fig. 4b). To elucidate the underlying mechanism by which si-RP3-340N1.2 reduces IL-6 expression, we firstly employed the actinomycin D assay to evaluate the degradation of IL-6 mRNA. The findings revealed that si-RP3-340N1.2 transfection was able to accelerate the degradation of IL-6 mRNA (Fig. 4c). Subsequently, we used RBPsuit, RBPmap, and catRAPID to predict the potential RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) interacting with RP3-340N1.2, followed by analyzing the candidate proteins through Wei Sheng Xin Platform (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis demonstrated that several of these proteins are implicated in RNA processing and function as enzymes acting on RNA. Furthermore, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis indicated that certain binding proteins of RP3-340N1.2 are involved in mRNA degradation (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4: RP3-340N1.2 knockdown accelerates the degradation of IL-6 mRNA mediated by ZC3H12A. (a) qRT-PCR analysis of several cytokines in A549 cells and H1975 cells with transfection of si-RP3-340N1.2 or NC; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (b) ELISA analysis of IL-6 in culture medium from A549 cells and H1975 cells with transfection of si-RP3-340N1.2 or NC; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (c) actinomycin D assay evaluating the existence of IL-6mRNA in A549 cells in 2 h; ANOVA test; (d) GO and KEGG analysis of potential binding protein of RP3-340N1.2; (e) qRT-PCR and western blot analysis of ZC3H12A in A549 cells with transfection of si-RP3-340N1.2 or NC; Student’s t-test, n = 4; (f) RIP assay analysis of IL-6 mRNA enrichment in A549 cells; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (g) RIP assay analysis of RP3-340N1.2 enrichment in A549 cells; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (h) RIP assay analysis of RP3-340N1.2 enrichment in A549 cells with transfection of si-RP3-340N1.2 or NC; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (i) RIP assay analysis of IL-6 mRNA enrichment in A549 cells with transfection of si-RP3-340N1.2 or NC; Student’s t-test, n = 3. Data are expressed as mean ± SD for triplicate experiments, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, nsp > 0.05

It has previously been reported that ZC3H12A, an RNA-binding protein, plays a regulatory role in promoting the degradation of IL-6 mRNA [26]. To further investigate the relationship between RP3-340N1.2 and IL-6 mRNA regulation mediated by ZC3H12A, we initially examined the expression levels of ZC3H12A in si-RP3-340N1.2 transfected A549 cells using qRT-PCR and western blot analysis. Our results demonstrated thatthe suppression of RP3-340N1.2 did not significantly alter the expression of ZC3H12A at either the mRNA or protein level (Figs. 4e and S1d). This finding suggests that the regulatory effects of RP3-340N1.2 on IL-6 mRNA stability are unlikely to be mediated through direct modulation of ZC3H12A expression. Given these observations, we sought to elucidate whether RP3-340N1.2 could involve the degradation of IL-6 mRNA by binding to ZC3H12A. To this end, we subsequently performed RIP assays to determine whether RP3-340N1.2 interacts with ZC3H12A and whether this interaction is associated with the degradation of IL-6 mRNA. Our RIP assay results revealed a significant enrichment of both IL-6 mRNA and RP3-340N1.2 in the ZC3H12A immunoprecipitants compared to the IgG control (Fig. 4f,g), indicating a direct or indirect association between ZC3H12A and these RNA molecules. Next, we conducted additional RIP assays in A549 cells transfected with si-RP3-340N1.2. As expected, suppress of RP3-340N1.2 led to a marked reduction in the enrichment of RP3-340N1.2 by ZC3H12A (Fig. 4h). More critically, we observed a significant increase in the enrichment of IL-6 mRNA by ZC3H12A in the presence of si-RP3-340N1.2 compared to the NC transfection (Fig. 4i). These findings suggest that RP3-340N1.2 may indeed play a role in facilitating the ZC3H12A-mediated degradation of IL-6 mRNA, potentially by modulating the interaction between ZC3H12A and its target RNA substrates.

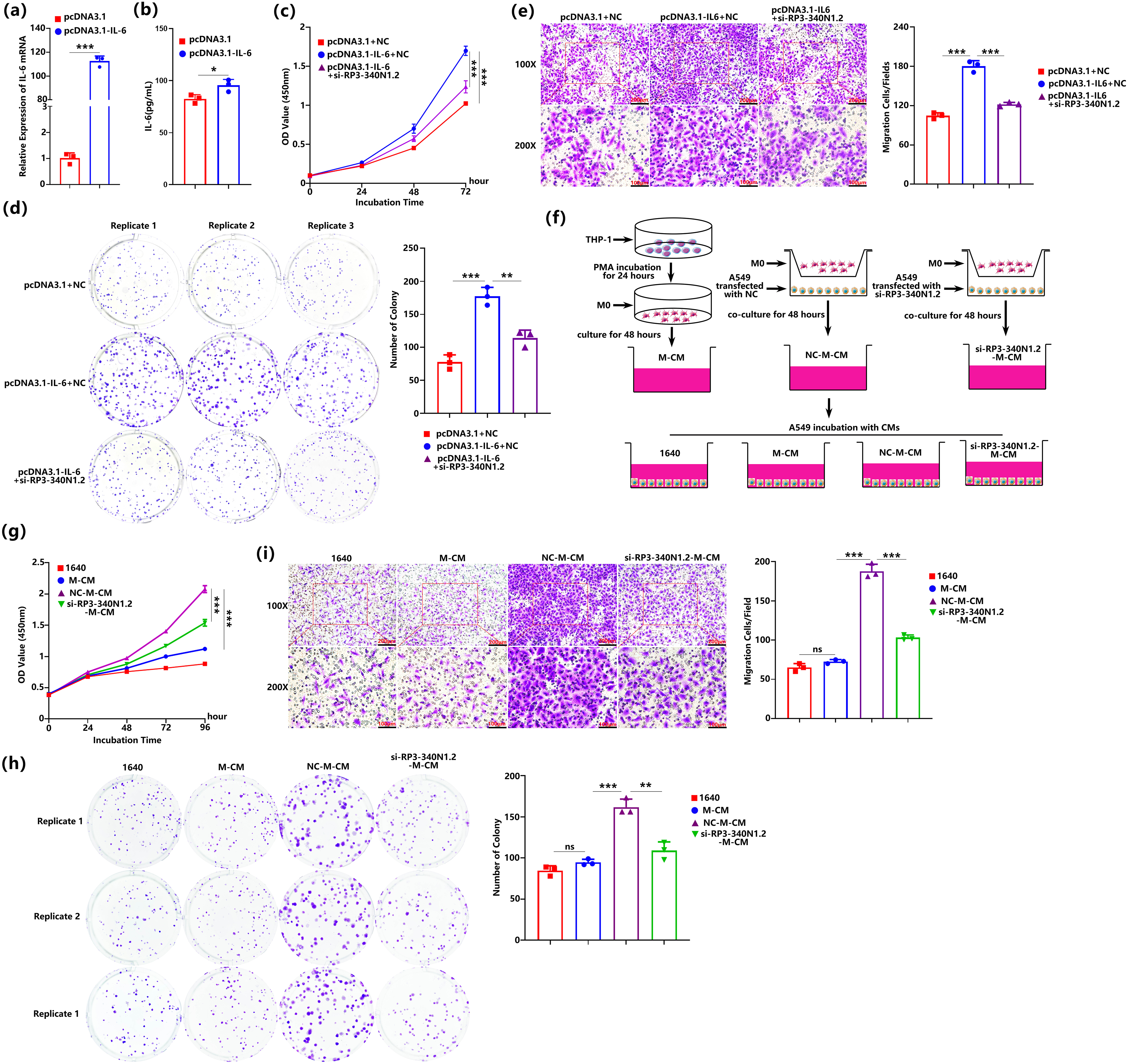

3.5 RP3-340N1.2 Knockdown Not Only Alleviates the Oncogenic Effects Mediated by IL-6 in Carcinoma Cells But Also Exerts Tumor-Suppressive Activities via Conditioned Medium from Co-Culture of Macrophage and Carcinoma Cells

The above data indicate that RP3-340N1.2 knockdown demonstrates anti-oncogenic properties by inhibiting the proliferation and migration capabilities of lung carcinoma cells. Furthermore, this suppression of RP3-340N1.2 is associated with the facilitation of IL-6 mRNA degradation. To investigate the potential of RP3-340N1.2 knockdown in attenuating the oncogenic properties of IL-6, we initially generated a pcDNA3.1-IL-6 overexpression vector to induce overexpression of IL-6 in A549 cells. Subsequent analysis revealed a significant elevation of both intracellular IL-6 mRNA levels and extracellular IL-6 secretion into the culture supernatant (Fig. 5a,b). Following functional experiments utilizing CCK-8 assay demonstrated that overexpression of IL-6 induced a significant increase in the proliferative capacity of A549 cells, which could be alleviated by administration of si-RP3340N1.2 (Fig. 5c). Consistent with these findings, IL-6 overexpression also enhanced the colony-forming potential of A549 cells, whereas treatment with si-RP3-340N1.2 partially attenuated this enhanced colony-forming capability (Fig. 5d). To further elucidate the role of RP3-340N1.2 in IL-6-induced cellular migration, we conducted transwell migration assays, of which the results demonstrated that A549 cells co-transfected with pcDNA3.1-IL-6 and NC exhibited a significantly enhanced migratory capacity when compared to cells transfected with only NC. In contrast, transfection with si-RP3-340N1.2 effectively alleviated the enhancement in cell migration observed upon overexpression of IL-6 (Fig. 5e).

Figure 5: RP3-340N1.2 knockdown not only alleviates the oncogenic effects mediated by IL-6 in carcinoma cells but also exerts tumor-suppressive activities via conditioned medium from co-culture of macrophage and carcinoma cells. (a) qRT-PCR analysis of IL-6 mRNA in A549 cells with transfection of pcDNA3.1-IL-6 or pcDNA3.1; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (b) ELISA analysis of IL-6 in culture medium from A549 cells with transfection of pcDNA3.1-IL-6 or pcDNA3.1; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (c) CCK-8 assay of A549 cells in 72 h post-transfection of pcDNA3.1 + NC, pcDNA3.1-IL-6 + NC or pcDNA3.1-IL-6 + si-RP3-340N1.2; ANOVA test; (d) colony formation assay of A549 cells in 48 h post-transfection of pcDNA3.1 + NC, pcDNA3.1-IL-6 + NC or pcDNA3.1-IL-6 + si-RP3-340N1.2; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (e) transwell migration assay of A549 cells 24 h post-transfection of pcDNA3.1 + NC, pcDNA3.1-IL-6 + NC or pcDNA3.1-IL-6 + si-RP3-340N1.2; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (f) schematic flow diagram of the production process for four different conditioned mediums; (g) CCK-8 assay of A549 cells cultured by 4 different conditioned mediums; ANOVA test; (h) colony formation assay of A549 cells cultured in 4 different conditioned mediums; Student’s t-test, n = 3; (i) transwell migration assay of A549 cells cultured in 4 different conditioned mediums; Student’s t-test, n = 3. Data are expressed as mean ± SD for triplicate experiments, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, nsp > 0.05

The above data indicate that the conditioned medium derived from A549 cells subjected to RP3-340N1.2 knockdown exhibits the capacity to inhibit the polarization of macrophages toward a TAM phenotype. Drawing upon these observations, we hypothesize that the decrease of RP3-340N1.2 expression in A549 cells may exert a significant influence on the malignant progression of A549 by modulating the polarization of TAMs. To verify the proposed hypothesis, we systematically prepared distinct conditioned medium (CM) for the cultivation of A549 cells. Specifically, si-RP3-340N1.2-M-CM was generated through a co-culture system wherein M0-polarized macrophages were cocultured with A549 cells transfected with si-RP3-340N1.2 for 48 h. This co-culture medium was harvested followed by condensation and mixing with same volume 1640 medium. NC-M-CM was derived from a parallel co-culture experiment involving M0 macrophages and A549 cells transfected NC. Additionally, M-CM was obtained by incubating M0 macrophages alone (Fig. 5f). Subsequently, we conducted an evaluation of the proliferative potential, colony-forming efficiency, and migratory capacity of A549 cells when cultured in various conditioned medium. Our findings revealed that, when compared to cells incubated with M-CM, those exposed to NC-M-CM exhibited a significant enhancement in proliferation, colony formation, and migration. Moreover, our data further demonstrated that si-RP3-340N1.2-M-CM incubation was effective in attenuating the proliferative, colony-forming, and migratory advantages conferred by NC-M-CM exposure (Fig. 5g–i). This observation strongly suggests that the RP3-340N1.2 knockdown not only counteracts the oncogenic effects that mediated by IL-6 but also actively promotes tumor-suppressive activities, potentially through the modulation of soluble factors secreted by TAMs.

In the present study, we initiated our investigation by conducting RNA sequencing to identify differentially expressed lncRNAs in NSCLC. Among the dysregulated lncRNAs detected, RP3-340N1.2 was found to be significantly upregulated. Functional assays revealed that knockdown of RP3-340N1.2 effectively suppressed the proliferative and migratory capacities of tumor cells. Notably, while overexpression of RP3-340N1.2 did not enhance these malignant phenotypes, an intriguing observation was made regarding its influence on the TME. Specifically, conditioned medium derived from NSCLC cells subjected to RP3-340N1.2 knockdown exhibited a diminished capacity to induce macrophage polarization toward the TAM phenotype. This finding prompted us to explore the mechanistic basis underlying this phenomenon. Given the critical role of cytokines in modulating macrophage function and TME dynamics, we hypothesized that RP3-340N1.2 might regulate the secretory profile of tumor cells, thereby influencing macrophage behavior. Through targeted screening, we identified IL-6 as a key cytokine whose expression was markedly downregulated following RP3-340N1.2 knockdown. IL-6 is a well-established pro-inflammatory cytokine implicated in promoting tumor progression, angiogenesis, and immunosuppression within the TME. The reduction in IL-6 secretion by RP3-340N1.2-knockdown tumor cells likely accounts for the observed attenuation of TAM polarization, as IL-6 is a potent inducer of the M2-like phenotype characteristic of TAMs. To further validate the functional significance of these findings, we employed co-culture systems comprising RP3-340N1.2-knockdown tumor cells and macrophages. Consistent with our hypothesis, these co-cultures demonstrated a significant suppression of cancer-promoting processes, including tumor cell proliferation and migration, as well as a shift in macrophage polarization away from the pro-tumorigenic TAM phenotype. These results collectively underscore the pivotal role of RP3-340N1.2 in complicated cross-talk between tumor cells and the TME, particularly through its regulation of cytokine secretion.

The investigation into the functional roles and underlying molecular mechanisms of lncRNAs within the tumor formation and advancement has remained a central focus in lncRNA-tumor research.

In the present study, we observed a marked upregulation of RP3-340N1.2 expression in NSCLC tissues and established cancer cell lines (A549, H1975, PC9, and H1299). Functional analyses revealed that siRNA-mediated knockdown of RP3-340N1.2 in A549 and H1975 cells significantly attenuated tumor cell proliferation and migratory capacity in vitro. In contrast, overexpression of RP3-340N1.2 in these same NSCLC cell lines (A549 and H1975) failed to produce statistically significant alterations in either proliferation or migratory phenotypes under identical experimental conditions. In addition, qRT-PCR analysis revealed a striking elevation of RP3-340N1.2 levels in NSCLC tissues, with expression nearly tenfold higher than that observed in adjacent non-cancerous tissues. Remarkably, the expression of RP3-340N1.2 in lung cancer cell lines exhibited an even more significant increase, surpassing that in bronchial epithelial cell lines by several hundredfold. These findings collectively suggest that, among the diverse potential mechanisms through which RP3-340N1.2 may exert its biological effects, its participation as a substrate in an enzymatic reaction that is subject to saturation kinetics might represent the predominant mode of action [27]. Our findings provide strong support for the hypothesis. RP3-340N1.2 was found to be involved in the post-transcriptional regulation of IL-6 mRNA stability, with ZC3H12A emerging as a pivotal regulator in this process.

ZC3H12A, an RNA-binding protein, functions as a critical modulator in both innate and adaptive immune responses, exerting profound influences on post-transcriptional immune regulation [28,29]. One of its well-documented functions is the mediation of IL-6 mRNA degradation. Our study has unveiled an additional layer of IL-6 mRNA degrading complexity by demonstrating that, apart from its interaction with IL-6 mRNA, ZC3H12A also binds to RP3-340N1.2. Critically, the knockdown of RP3-340N1.2 expression in tumor cells resulted in a significant elevation of ZC3H12A binding to IL-6 mRNA, ultimately accelerating its degradation rate. This observation implies a potential competitive binding relationship between RP3-340N1.2 and IL-6 mRNA for ZC3H12A binding sites. Despite existing studies having partially elucidated the structural features of ZC3H12A, particularly its zinc finger domains, which are indispensable for its binding to the 3′-UTR of IL-6 mRNA [30,31]. However, we did not observe ZC3H12A-mediated degradation of RP3-340N1.2, nor did we identify critical sequence in RP3-340N1.2 mediating its interaction with ZC3H12A. These limitations underscore the necessity for further investigations to elucidate the regulatory mechanism between RP3-340N1.2 and ZC3H12A.

Current treatment paradigms for NSCLC have evolved to prioritize precision medicine strategies, encompassing targeted therapies (e.g., EGFR/ALK inhibitors) and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which have significantly improved outcomes for patients with actionable genetic alterations [7]. However, therapeutic resistance and tumor heterogeneity continue to pose substantial challenges, necessitating the exploration of novel molecular targets. Emerging evidence highlights the potential of anti-angiogenic approaches, as exemplified by Ornidazole’s demonstrated efficacy in suppressing NSCLC progression through VEGFA/VEGFR2 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway inhibition. Within this context, IL-6 emerges as a pivotal effector molecule in the regulatory axis investigated in this study. Numerous prior studies have demonstrated that IL-6 exerts critical regulatory functions within the TME [32], including promoting endothelial cell proliferation and migration to induce angiogenesis; facilitating extracellular matrix (ECM) degradation to accelerate tumor cell motility; and inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which endows tumor cells with stem cell-like properties [33]. These EMT-driven alterations enhance metastatic dissemination capacity, self-renewal potential at primary tumor sites, and the ability to generate secondary tumors [34]. Our findings further confirmed that IL-6 was capable of promoting the polarization of macrophage toward a pro-tumoral phenotype. We observed that when RP3-340N1.2 was knocked down in tumor cells, the conditioned medium derived from these cells exhibited significantly reduced capacity to induce macrophage M2 polarization compared to NC groups. Notably, among various cytokines analyzed, IL-6 expression was markedly suppressed following RP3-340N1.2 knockdown, as supported by both reduced mRNA levels in tumor cells and diminished secretion into the extracellular culture medium. As a key altered component in the conditioned medium, IL-6 likely synergizes with other secreted factors to modulate macrophage polarization. To further validate the role of IL-6, we performed IL-6 overexpression experiments in tumor cells, which significantly enhanced their proliferative and migratory capacities. More critically, the conditioned medium obtained from the coculture system exhibited a markedly augmented tumor-promoting capacity. This conditioned medium, when utilized to culture tumor cells, is capable of significantly enhancing the malignant phenotype of these tumor cells. Conversely, RP3-340N1.2 knockdown abolished these tumor-aggravating effects, demonstrating its dual regulatory impact on both tumor cells and their microenvironment. Although this study identified IL-6 as a critical mediator in RP3-340N1.2-mediated tumor regulation, it did not investigate the combined effects of exogenous IL-6 supplementation and RP3-340N1.2 knockdown on tumor cells and their microenvironment. Consequently, the study cannot definitively conclude whether IL-6 serves as the primary downstream effector of RP3-340N1.2. As a component of the complex regulatory network involving long non-coding RNAs, the multifaceted role of RP3-340N1.2 in tumorigenesis and tumor progression warrants further comprehensive investigation.

Current treatment paradigms for NSCLC have evolved to prioritize precision medicine strategies, encompassing targeted therapies (e.g., EGFR/ALK inhibitors) and immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), which have significantly improved outcomes for patients with actionable genetic alterations [7]. However, therapeutic resistance and tumor heterogeneity continue to pose substantial challenges, necessitating the exploration of novel molecular targets. Emerging evidence highlights the potential of anti-angiogenic approaches, as exemplified by Ornidazole’s demonstrated efficacy in suppressing NSCLC progression through VEGFA/VEGFR2 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway inhibition [35]. This study addresses critical limitations in the current understanding of NSCLC pathogenesis by bridging gaps in the regulatory mechanisms of IL-6-driven malignancy. While prior research has established the IL-6 signaling axis as a pivotal driver of NSCLC progression, the upstream regulatory networks—particularly those involving lncRNA-mediated mRNA stability control—have remained underexplored. Our work elucidates how RP3-340N1.2 knockdown enhances ZC3H12A-dependent IL-6 mRNA degradation, thereby disrupting tumor-promoting interactions between cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment. This mechanism not only resolves ambiguities in how lncRNAs interact with RNA-binding proteins like ZC3H12A to regulate mRNA stability in cancer but also overcomes therapeutic challenges associated with direct IL-6 inhibition, such as off-target effects or resistance, by proposing a novel strategy that indirectly modulates IL-6 signaling through lncRNA targeting. By clarifying this molecular pathway linking lncRNA dysregulation to tumor-promoting signaling, our findings provide a potential foundation for precision therapeutic interventions aimed at inhibiting tumor aggressiveness in NSCLC.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81702296).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yun-Fei Yan and Fei Jiao; methodology, Hang Zhang and Meng-yuan Chu; software, Guohui Lv and Xuhang Liu; validation, You-Jie Li, Hang Zhang and Meng-yuan Chu; formal analysis, Hang Zhang; resources, You-Jie Li; data curation, Yun-Fei Yan and Meng-yuan Chu; writing—original draft preparation, Yun-Fei Yan; writing—review and editing, Fei Jiao and Hang Zhang; visualization, Guohui Lv; supervision, You-Jie Li; funding acquisition, Yun-Fei Yan and Fei Jiao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated during this study are included either in the article or in the additional files.

Ethics Approval: The tissues used in this experiment were all collected from Yantaishan Hospital, Affiliated to Binzhou Medical University, and were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Binzhou Medical University. The approval number for patients’ samples was 2021-102. The animal experiment used in this experiment was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Binzhou Medical University. The approval number was 2022-390.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/biocell.2025.068322/s1.

References

1. Sorin M, Prosty C, Ghaleb L, Nie K, Katergi K, Shahzad MH, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy for NSCLC: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2024;10(5):621–33. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2024.0057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Alexander M, Kim SY, Cheng H. Update 2020: management of non-small cell lung cancer. Lung. 2020;198(6):897–907. doi:10.1007/s00408-020-00407-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Herbst RS, Morgensztern D, Boshoff C. The biology and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2018;553(7689):446–54. doi:10.1038/nature25183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Jonna S, Subramaniam DS. Molecular diagnostics and targeted therapies in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLCan update. Discov Med. 2019;27(148):167–70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Chen P, Liu Y, Wen Y, Zhou C. Non-small cell lung cancer in China. Cancer Commun. 2022;42(10):937–70. [Google Scholar]

6. Wang M, Herbst RS, Boshoff C. Toward personalized treatment approaches for non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med. 2021;27(8):1345–56. doi:10.1038/s41591-021-01450-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Meyer ML, Fitzgerald BG, Paz-Ares L, Cappuzzo F, Janne PA, Peters S, et al. New promises and challenges in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2024;404(10454):803–22. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(24)01029-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Hu Q, Ma H, Chen H, Zhang Z, Xue Q. LncRNA in tumorigenesis of non-small-cell lung cancer: from bench to bedside. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8(1):359. doi:10.1038/s41420-022-01157-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ginn L, Shi L, Montagna M, Garofalo M. LncRNAs in non-small-cell lung cancer. Noncoding RNA. 2020;6(3):25. doi:10.3390/ncrna6030025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Chen LL, Kim VN. Small and long non-coding RNAs: past present, and future. Cell. 2024;187(23):6451–85. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.10.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Palazzo AF, Koonin EV. Functional long non-coding RNAs evolve from junk transcripts. Cell. 2020;183(5):1151–61. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kopp F, Mendell JT. Functional classification and experimental dissection of long noncoding RNAs. Cell. 2018;172(3):393–407. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Mikhaleva S, Lemke EA. Beyond the transport function of import receptors: what’s all the fus about? Cell. 2018;173(3):549–53. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Ripin N, Parker R. Formation function, and pathology of RNP granules. Cell. 2023;186(22):4737–56. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2023.09.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Gugnoni M, Kashyap MK, Wary KK, Ciarrocchi A. lncRNAs: the unexpected link between protein synthesis and cancer adaptation. Mol Cancer. 2025;24(1):38. doi:10.1186/s12943-025-02236-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Roy D, Bhattacharya B, Chakravarti R, Singh P, Arya M, Kundu A, et al. LncRNAs in oncogenic microenvironment: from threat to therapy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024;12:1423279. doi:10.3389/fcell.2024.1423279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Guo Y, Xu F, Lu T, Duan Z, Zhang Z. Interleukin-6 signaling pathway in targeted therapy for cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(7):904–10. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.04.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Liao C, Yu Z, Guo W, Liu Q, Wu Y, Li Y, et al. Prognostic value of circulating inflammatory factors in non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Biomark. 2014;14(6):469–81. doi:10.3233/cbm-140423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Wang L, Cheng Q. APOBEC-1 complementation factor: from RNA binding to cancer. Cancer Control. 2024;31:10732748241284952. doi:10.1177/10732748241284952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Chen C, Yin H, Zhang Y, Chen H, Xu J, Ren L. Plasma D-dimer and interleukin-6 are associated with treatment response and progression-free survival in advanced NSCLC patients on anti-PD-1 therapy. Cancer Med. 2023;12(15):15831–40. doi:10.1002/cam4.6222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Wu J, Gao FX, Wang C, Qin M, Han F, Xu T, et al. IL-6 and IL-8 secreted by tumour cells impair the function of NK cells via the STAT3 pathway in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):321. doi:10.1186/s13046-019-1310-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhou M, Na R, Lai S, Guo Y, Shi J, Nie J, et al. The present roles and future perspectives of Interleukin-6 in biliary tract cancer. Cytokine. 2023;169:156271. doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2023.156271. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Kloosterman DJ, Akkari L. Macrophages at the interface of the co-evolving cancer ecosystem. Cell. 2023;186(8):1627–51. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2023.02.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Larionova I, Tuguzbaeva G, Ponomaryova A, Stakheyeva M, Cherdyntseva N, Pavlov V, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages in human breast, colorectal, lung ovarian and prostate cancers. Front Oncol. 2020;10:566511. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.566511. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zhou D, Huang C, Lin Z, Zhan S, Kong L, Fang C, et al. Macrophage polarization and function with emphasis on the evolving roles of coordinated regulation of cellular signaling pathways. Cell Signal. 2014;26(2):192–7. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.11.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Matsushita K, Takeuchi O, Standley DM, Kumagai Y, Kawagoe T, Miyake T, et al. Zc3h12a is an RNase essential for controlling immune responses by regulating mRNA decay. Nature. 2009;458(7242):1185–90. doi:10.1038/nature07924. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Sondergaard JN, Sommerauer C, Atanasoai I, Hinte LC, Geng K, Guiducci G, et al. CCT3-LINC00326 axis regulates hepatocarcinogenic lipid metabolism. Gut. 2022;71(10):2081–92. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Uehata T, Takeuchi O. Post-transcriptional regulation of immunological responses by Regnase-1-related RNases. Int Immunol. 2021;33(12):859–65. doi:10.1093/intimm/dxab048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Wang R, Sun S, Wang Z, Xu X, Jiang T, Liu H, et al. MCPIP1 promotes cell proliferation, migration and angiogenesis of glioma via VEGFA-mediated ERK pathway. Exp Cell Res. 2022;418(1):113267. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2022.113267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Cifuentes RA, Cruz-Tapias P, Rojas-Villarraga A, Anaya JM. ZC3H12A (MCPIP1molecular characteristics and clinical implications. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411(23–24):1862–8. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2010.08.033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Xu J, Peng W, Sun Y, Wang X, Xu Y, Li X, et al. Structural study of MCPIP1 N-terminal conserved domain reveals a PIN-like RNase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(14):6957–65. doi:10.1093/nar/gks359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Thuya WL, Cao Y, Ho PC, Wong AL, Wang L, Zhou J, et al. Insights into IL-6/JAK/STAT3 signaling in the tumor microenvironment: implications for cancer therapy. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2025;85(1):26–42. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2025.01.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Yuan H, Qiu Y, Mei Z, Liu J, Wang L, Zhang K, et al. Cancer stem cells and tumor-associated macrophages: interactions and therapeutic opportunities. Cancer Lett. 2025;624:217737. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2025.217737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Liao L, Wang YX, Fan SS, Hu YY, Wang XC, Zhang X. The role and clinical significance of tumor-associated macrophages in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of lung cancer. Front Oncol. 2025;15:1571583. doi:10.3389/fonc.2025.1571583. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Evyapan G, Senturk NC, Celik IS. Ornidazole inhibits the angiogenesis and migration abilities of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) via downregulation of VEGFA/VEGFR2/NRP-1 and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2024;82(4):3277–85. doi:10.1007/s12013-024-01358-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools