Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Role of NETosis in the Pathogenesis of Respiratory Diseases: Molecular Mechanisms and Emerging Insights

Research Division of Food Functionality, Korea Food Research Institute (KFRI), Wanju, 55365, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: GUN-DONG KIM. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: NETs: A Decade of Pathological Insights and Future Therapeutic Horizons)

BIOCELL 2026, 50(1), 6 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.073781

Received 25 September 2025; Accepted 30 October 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation or NETosis is a specialized innate immune process in which neutrophils release chromatin fibers decorated with histones and antimicrobial proteins. Although pivotal for pathogen clearance, aberrant NETosis has emerged as a critical modulator of acute and chronic respiratory pathologies, including acute respiratory distress syndrome, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Dysregulated NET release exacerbates airway inflammation by inducing epithelial injury, mucus hypersecretion, and the recruitment of inflammatory leukocytes, thereby accelerating tissue remodeling and functional decline. Mechanistically, NETosis is governed by peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 (PADI4)-mediated histone citrullination, NADPH oxidase-dependent reactive oxygen species production, mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming, and activation of toll-like receptors and inflammasomes. These molecular events perpetuate inflammation and prevent its resolution. Emerging evidence indicates that natural bioactive compounds, such as flavonoids, terpenoids, and polyphenols, attenuate NETosis by modulating oxidative stress, inhibiting PADI4 activation, or suppressing downstream pro-inflammatory cascades. Collectively, these findings highlight the therapeutic potential of targeting NETosis to mitigate neutrophil-driven airway pathology. This review aims to comprehensively synthesize recent mechanistic insights into NETosis and to delineate how modulation of NET formation contributes to the prevention and treatment of inflammatory respiratory diseases.Keywords

Neutrophils serve as critical effectors of innate immunity, executing diverse antimicrobial functions, including phagocytosis, degranulation, and release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) through a specialized form of cell death termed NETosis [1,2]. During this process, neutrophils extrude chromatin structures decorated with histones, neutrophil elastase (NE), and myeloperoxidase (MPO), which function to entrap and neutralize invading pathogens [1,3]. The induction of NETosis is orchestrated by a set of interconnected molecular events, most notably the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via NADPH oxidase (NOX)-and peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 (PADI4)-mediated histone citrullination, which leads to chromatin decondensation and subsequent nuclear envelope breakdown [4,5]. The release of decondensed chromatin complexes, either through suicidal or vital NETosis, reflects a finely tuned balance between host defense and tissue damage [6]. Recent studies have revealed that although NETs and the process of NETosis are classically associated with neutrophils, extracellular trap formation is not restricted to neutrophils [7]. Similar DNA release structures have been observed in other innate immune cells, including macrophages, monocytes, mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils, and extracellular DNA release has also been reported in subsets of lymphocytes [8]. In addition to NETosis, a variety of regulated cell death programs such as apoptosis, necrosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, and ferroptosis have been identified as alternative mechanisms driving extracellular release of nuclear material [9]. These processes, while contributing to host defense and pathogen clearance, can simultaneously induce epithelial and endothelial injury and exacerbate tissue inflammation and damage, thereby amplifying immune-mediated pathology [10].

Although NETosis contributes to microbial clearance, dysregulated or excessive NET release has emerged as a pivotal driver of immunopathology in respiratory diseases [11]. In acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), excessive neutrophil infiltration and NET accumulation disrupt the alveolar capillary integrity, amplify inflammation, and promote microthrombosis [12–14]. Similarly, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and severe neutrophilic asthma are characterized by NET-enriched airway secretions that exacerbate epithelial injury, mucus hypersecretion, and impair mucociliary clearance, thereby accelerating airway obstruction and remodeling [15–17]. In severe pneumonia and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), elevated NETosis markers such as circulating cell-free DNA, MPO-DNA complexes, and citrullinated histone H3 are correlated with disease severity and poor outcomes [18–20]. Similarly, NET-driven immunothrombosis, characterized by NET-rich microthrombi in the pulmonary vasculature, is now considered a hallmark of severe COVID-19 [21]. Notably, in COVID-19–associated ARDS, NET-driven immunothrombosis and cytokine storm responses directly contribute to multi-organ failure [22]. Collectively, these findings highlight the complex role of NETosis as both a defensive and a pathogenic mechanism in diverse pulmonary disorders.

Given the central role of NETosis in respiratory disease pathogenesis, recent studies have focused on the therapeutic potential of natural bioactive compounds in attenuating this process [23]. Phytochemicals, such as flavonoids, terpenoids, and polyphenols, have been shown to inhibit ROS production, suppress PADI4 activity, and modulate downstream inflammatory signaling cascades, thereby reducing NET release and mitigating tissue damage [23–25]. These natural products, with their intrinsic antioxidant and immunomodulatory properties, represent promising adjunctive strategies for counteracting neutrophil-driven pathologies [26,27]. Targeting NETosis may provide novel avenues for the prevention and treatment of acute, chronic, and infectious respiratory disorders. The objective of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the molecular mechanisms driving NETosis in the lung, to delineate its pathological contributions across acute and chronic respiratory diseases, and to highlight recent advances in NET-targeted and NET-modulating therapeutic approaches with translational potential.

2 Molecular Mechanisms and Triggers of NETosis

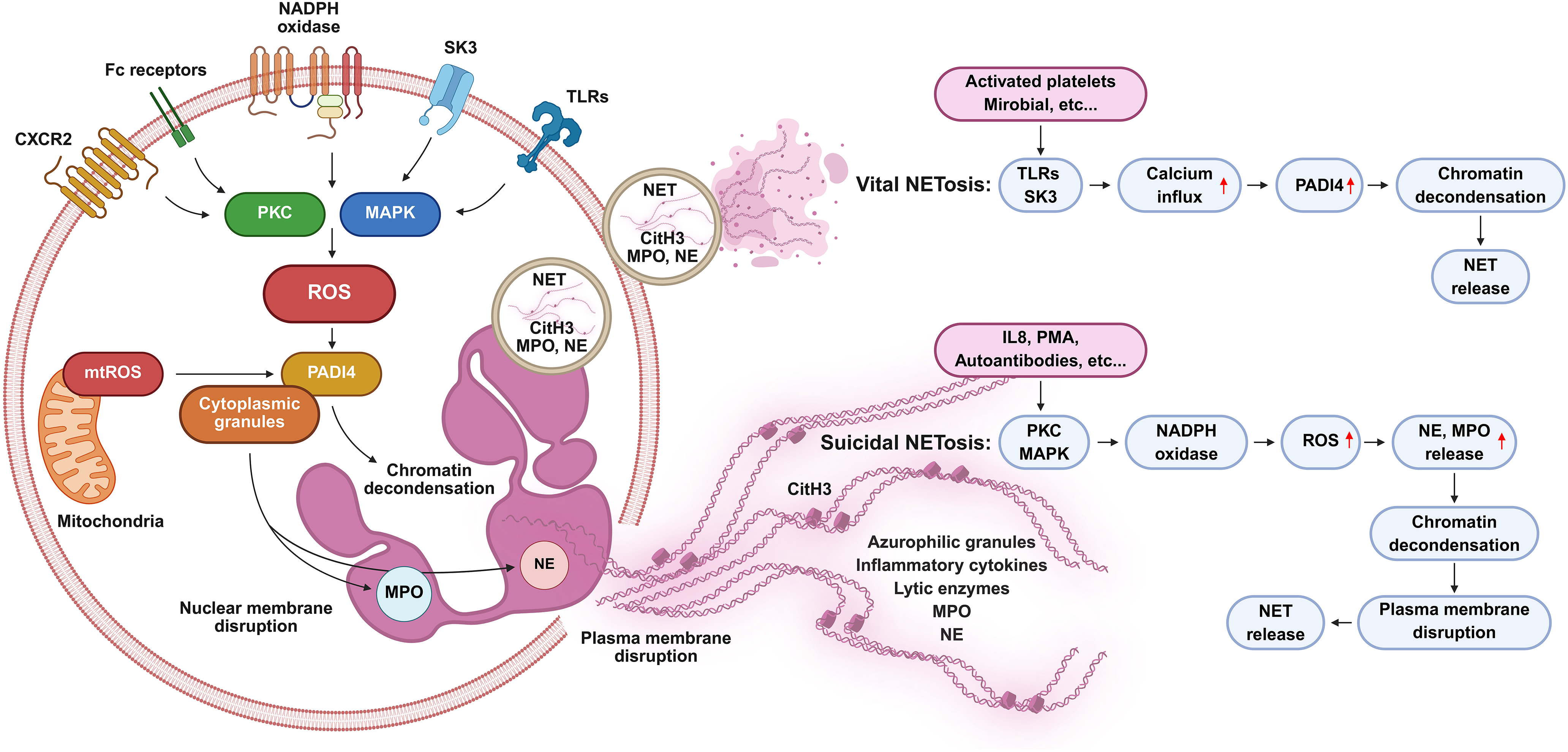

NETosis proceeds through at least three mechanistically distinct pathways [28]. The former, termed suicidal or classical NETosis, relies on the generation of ROS by NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2) [29,30]. ROS drives chromatin decondensation and nuclear envelope rupture, culminating in cell lysis and the release of NETs. The second form, vital NETosis, enables neutrophils to release NETs while remaining viable, thereby preserving critical effector functions such as phagocytosis and chemotaxis [31]. The third variant, mitochondrial NETosis, involves the extrusion of mitochondrial DNA rather than nuclear DNA, typically under ROS-low conditions and sterile inflammatory stimuli [32] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Overview of the mechanisms and types of NETosis. Suicidal NETosis is induced by stimuli such as phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, autoantibodies, and interleukin 8 and typically unfolds over several hours. Protein kinase C- and mitogen-activated protein kinase-driven nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase activation enhances reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, which promotes peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 (PADI4) activation through small-conductance calcium-activated potassium 3 channel-mediated Ca2+ influx, leading to histone citrullination and chromatin decondensation. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase translocate to the nucleus, driving nuclear envelope breakdown and release of protein-decorated chromatin through membrane rupture, culminating in neutrophil death. Vital NETosis occurs within minutes in response to Staphylococcus aureus via toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and Escherichia coli through TLR4, directly or indirectly via TLR4-activated platelets. PADI4 is activated independently of ROS, citrullinated histone H3 facilitates chromatin remodeling, and protein-coated DNA is exported via vesicular trafficking, enabling neutrophils to remain viable and retain effector functions. Citrullinated histone H3: CitH3; CXC motif chemokine receptor 2: CXCR2; fragment crystallizable region: Fc; interleukin 8: IL8; mitogen-activated protein kinase: MAPK; myeloperoxidase: MPO; mitochondrial reactive oxygen species: mtROS; nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate: NADPH; neutrophil elastase: NE; neutrophil extracellular trap: NET; peptidyl arginine deiminase 4: PADI4; protein kinase C: PKC; phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate: PMA; reactive oxygen species: ROS; small-conductance calcium-activated potassium 3 channel: SK3; toll-like receptor: TLR. Created with BioRender.com

NETosis can be initiated by a wide range of triggers, including microbial pathogens, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), immune complexes, pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL) 8 and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), and sterile tissue injury. These signals are detected by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), particularly toll-like receptors (TLRs), which activate intracellular signaling cascades that converge upon chromatin decondensation and enzyme release. A central regulator of this process is PADI4, which catalyzes the citrullination of histones H3 and H4, leading to weakened histone–DNA interactions and consequent chromatin relaxation [33]. The indispensability of PADI4 has been demonstrated in PADI4-deficient mice that fail to form NETs in response to conventional stimuli. Granular enzymes further reinforce this process: NE migrates to the nucleus to cleave histones, whereas MPO promotes oxidative modification and nuclear disruption [4,34].

PRRs, including TLR4 (which senses bacterial lipopolysaccharide), TLR7/8 (which detects viral single-stranded RNA), and TLR9 (which recognizes unmethylated CpG DNA), activate myeloid differentiation primary response 88-dependent pathways that converge on the NETosis machinery [35]. Gasdermin D, a pore-forming protein traditionally associated with pyroptosis, mediates membrane permeabilization and final extrusion of NETs, suggesting a mechanistic overlap among distinct cell death pathways [36]. In addition, calcium signaling plays a crucial role, as calcium ionophores can trigger NOX-independent NETosis and drive the release of mitochondrial DNA, a pathway of particular relevance in sterile inflammatory contexts [37]. Although NETosis protects against microbial invaders, its excessive or persistent activation drives collateral tissue damage, thrombosis, and autoimmunity, underscoring its dual role as a guardian of host defense and a mediator of pathological inflammation [38].

3 Lung-Specific Molecular Mechanisms of NETosis

The lung microenvironment has unique anatomical and physiological conditions that profoundly influence NET formation and function. The alveolar niche is highly oxygenated, favoring ROS-dependent pathways that drive classical NETosis [39]. Surfactant proteins, particularly surfactant protein D (SP-D), exert context-dependent effects on neutrophil activation, either promoting or suppressing NET release depending on the surrounding inflammatory milieu [40]. Constant exposure of the respiratory tract to inhaled pathogens, allergens, and pollutants provides abundant stimuli such as bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), viral RNA, and particulate matter (PM), which readily trigger NETosis [41–43].

Alveolar epithelial cells are key amplifiers of NET-driven inflammation. When injured by NET-derived histones and proteases, they secrete cytokines such as IL1β, IL6, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor, which recruit additional neutrophils and perpetuate a self-sustaining inflammatory loop [44,45]. Normally, alveolar macrophages help resolve inflammation by clearing NETs via phagocytosis and deoxyribonuclease (DNase) secretion [46]. However, in chronic airway diseases, such as COPD and severe asthma, macrophage clearance capacity is impaired, resulting in persistent NET accumulation [47]. In pulmonary fibrosis, NETs promote the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and fibroblast activation, linking innate immune dysregulation to fibrotic remodeling [48].

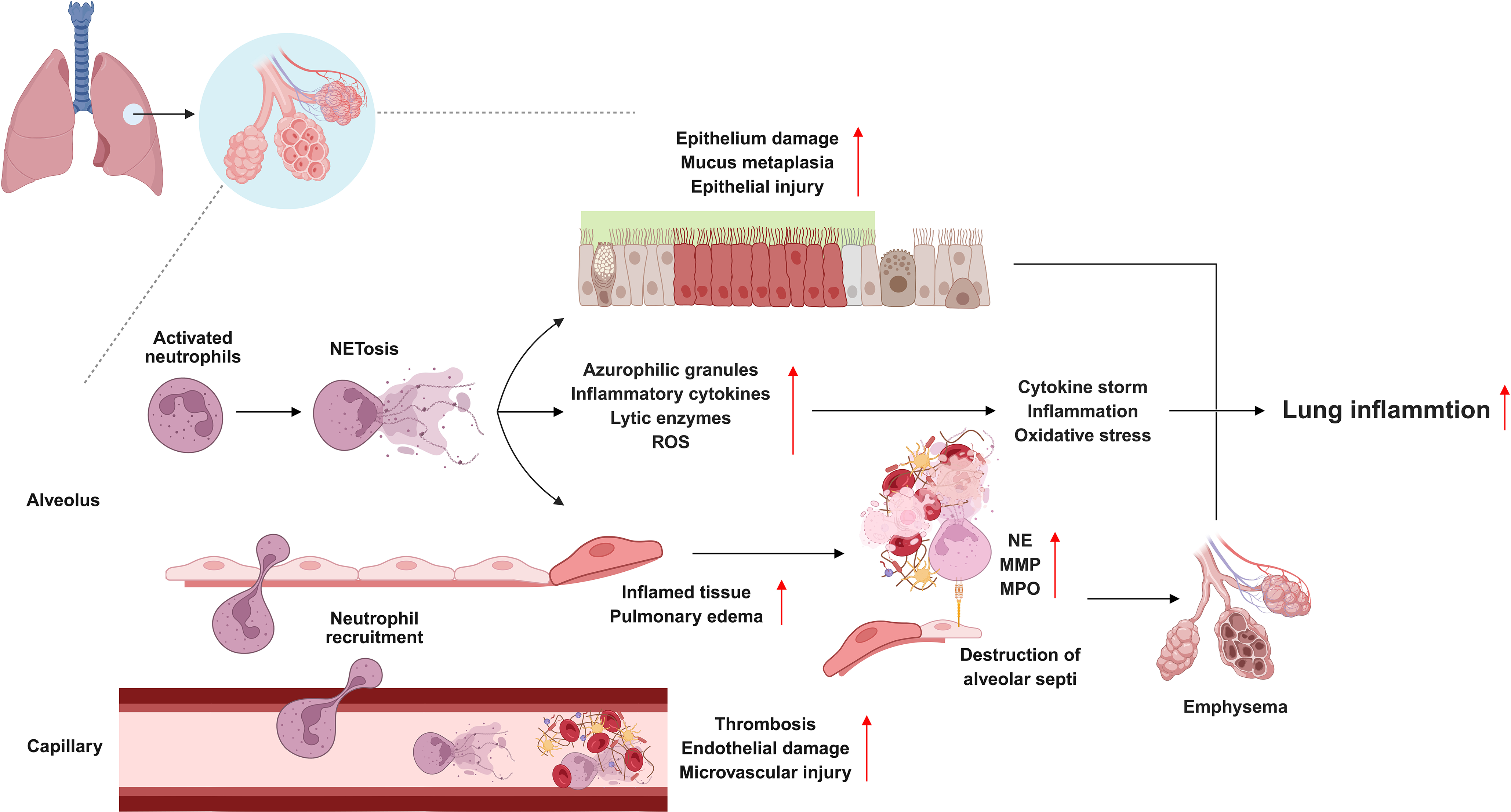

Pulmonary vasculature is also highly vulnerable to NET-mediated injuries. NET-associated histones damage endothelial cells, increase vascular permeability, and contribute to edema and microvascular thrombosis [49]. Immunothrombosis, which is often observed in ARDS and COVID-19, is strongly associated with NET-rich microthrombi that obstruct the pulmonary circulation and impair gas exchange [22]. Environmental factors such as cigarette smoke, PM, and ozone exacerbate NET formation by inducing oxidative stress and calcium flux in neutrophils, thereby reducing the activation threshold for NETosis [50,51]. Collectively, these lung-specific features underscore why dysregulated NETosis is particularly destructive in respiratory diseases (Fig. 2). The interplay between oxygen-rich conditions, surfactant modulation, impaired clearance mechanisms, vascular fragility, and environmental insults amplifies NET-driven injury and chronic remodeling.

Figure 2: Pathological roles of NETosis in pulmonary diseases. Although neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) are essential for host defense, their dysregulated accumulation promotes pulmonary pathology. In acute respiratory distress syndrome, NETs compromise endothelial integrity, drive immunothrombosis, and amplify cytokine release, thereby worsening alveolar damage. In chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, persistent NET formation sustains neutrophilic inflammation, impairs mucociliary clearance, increases oxidative stress, emphysema, and accelerates airway remodeling. In coronavirus disease 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2-induced NETosis augments endothelial injury, microvascular thrombosis, and systemic inflammation, leading to respiratory failure. Enzymes such as peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 critically regulate NET generation, highlighting NETosis as a convergent mechanism that links inflammation, thrombosis, and tissue injury across diverse pulmonary disorders. Matrix metalloproteinase: MMP; myeloperoxidase: MPO; neutrophil elastase: NE; reactive oxygen species: ROS. Created with BioRender.com

4 NETosis in Acute Respiratory Diseases

Acute respiratory diseases, such as ARDS, severe bacterial or fungal pneumonia, and viral infections, including influenza and COVID-19, are characterized by an abrupt onset of overwhelming inflammation, massive neutrophil recruitment into the airspaces, and profound disruption of the alveolar-capillary barrier. In this context, the balance between protective host defense and collateral tissue injury is particularly fragile. Neutrophils, as the first responders, release a spectrum of antimicrobial mediators; however, when excessively activated, they undergo uncontrolled NETosis, which significantly aggravates pulmonary pathology.

NETs contribute to alveolar-capillary barrier dysfunction through multiple mechanisms. Histones embedded within NETs exert direct cytotoxic effects on epithelial and endothelial cells, whereas protease-mediated extracellular matrix degradation weakens their structural integrity [34,44]. The DNA backbone of NETs increases mucus viscosity, impairs mucociliary clearance, and physically obstructs small airways, thereby worsening hypoxemia [52,53]. In addition, NET-associated proteases and oxidants amplify epithelial permeability, resulting in the leakage of protein-rich edema fluid into the alveolar space, a hallmark of ARDS [54]. NET-derived histones also act as potent danger signals that stimulate resident macrophages and epithelial cells, driving a vicious cycle of cytokine release, neutrophil influx, and NETosis.

Viral infections, particularly those caused by COVID-19, illustrate the pathological duality of NETosis. Although NETs can immobilize and neutralize viral particles, excessive NET accumulation in the alveolar spaces and pulmonary vasculature promotes immunothrombosis, leading to diffuse microvascular occlusion and impaired gas exchange [22]. Clinical studies have consistently demonstrated elevated NET biomarkers, such as cell-free DNA, MPO-DNA complexes, and citrullinated histones, in the plasma and tracheal aspirates of patients with severe ARDS or COVID-19, with levels closely associated with poor prognosis [55].

Thus, in acute respiratory diseases, NETosis emerges not only as a defensive mechanism but also as a central driver of pathology, linking exaggerated innate immune responses to tissue injury, alveolar flooding, and vascular thrombosis. This dual role underscores the growing interest in therapeutic strategies that target NET formation or accelerate NET clearance as adjunctive approaches for ARDS, pneumonia, and viral respiratory syndrome.

NET formation has emerged as a central mediator of acute lung injury and ARDS by coupling direct epithelial and endothelial injury with thromboinflammatory cascades [22,56,57]. Mechanistically, PADI4-dependent histone citrullination promotes chromatin decondensation and NET release. Citrullinated histone H3 functions as both a biomarker and DAMP that activates inflammasomes and caspase-1 to amplify alveolar inflammation and cell death [58–60]. NET structural components, including extracellular DNA histones and neutrophil proteases, disrupt the alveolar-capillary barrier, increase vascular permeability, and serve as scaffolds for platelet binding and thrombus formation, thereby driving immunothrombosis in severe ARDS and COVID-19 [22,59,60]. Upstream drivers identified across experimental and clinical studies include excessive neutrophil recruitment via CXCL8 gradients, delayed neutrophil apoptosis, platelet–neutrophil interactions, and NLR family pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome activation, which synergizes with PADI4 to potentiate NETosis under both infectious and sterile insults [58,61,62]. Therapeutic strategies supported by these reports include extracellular DNase to degrade NET DNA, PADI4 inhibition to block NET biogenesis, neutralization of circulating histones, inhibition of neutrophil elastase and MPO, and adjunctive approaches targeting platelet activation and inflammasomes [22,63–65]. Collectively, these studies advocate precision-guided interventions that combine NET-directed agents with antithrombotic and anti-inflammatory modalities, and emphasize the urgent need for standardized NET biomarkers to stratify ARDS endotypes for targeted therapy.

4.2 Viral Pneumonia and COVID-19

Viral respiratory infections are potent inducers of NETosis. SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, triggers excessive NET formation that correlates with disease severity and mortality [54,55]. Elevated NET levels are consistently detected in tracheal aspirates, plasma, and autopsy lung samples from patients with COVID-19 [57]. Mechanistically, viral proteins, such as the spike glycoprotein, directly activate neutrophils, further promoting NETosis [66]. NETs in COVID-19 are implicated in alveolar injury, amplification of cytokine storms, and thrombotic complications, such as pulmonary embolism [22,67]. Therapeutic interventions, including DNase I and anti-inflammatory agents, are currently being investigated for their efficacy against COVID-19-associated ARDS [68].

4.3 Bacterial and Fungal Pneumonia

NET formation is a rapid frontline response to bacterial pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus and to fungal pathogens, including Aspergillus fumigatus, where NETs entrap and restrict microbial spread while decorating DNA scaffolds with histones and granular proteases that possess direct microbicidal activity [39,69,70]. Pathogens have evolved countermeasures, notably secreting nucleases that cleave the DNA backbone of NETs, thereby enabling immune evasion and persistence in the alveolar space [71,72]. NET accumulation within infected airspaces amplifies oxidative stress, protease activity, and DAMP signaling, resulting in epithelial injury, airway occlusion, and impaired mucociliary clearance, exacerbating lung damage beyond the benefits of microbial containment [1,70,73]. In certain fungal infections, NETs are indispensable for restraining large hyphal structures, yet they can paradoxically hinder effective clearance and exacerbate collateral tissue injury in immunocompromised hosts infected with Aspergillus or Pneumocystis [69,73,74]. Mechanistically, PADI4-dependent histone citrullination, integrin and complement receptor engagement, platelet-neutrophil interactions, and lipid mediators such as leukotriene B4 (LTB4) orchestrate NETosis and determine whether the response is protective or pathological [1,74–76]. Translationally, candidate interventions supported by these studies include extracellular DNases to dismantle NET scaffolds, PADI4 inhibition to block NET biogenesis, neutralization of cytotoxic histones, inhibition of neutrophil elastase and MPO, blockade of pathogen nucleases to preserve NET function, and modulation of upstream signals, such as LTB4 or platelet activation, to rebalance host defense and limit tissue injury [71,74,77,78]. Collectively, these observations demonstrate the precise strategies that preserve NET antimicrobial function while preventing excessive NET-mediated lung injury in bacterial and fungal pneumonia.

5 NETosis in Chronic Respiratory Diseases

Chronic respiratory diseases, most notably COPD and asthma, represent a major global health challenge and account for substantial morbidity, mortality, and healthcare expenditure [79,80]. Unlike acute conditions, which are characterized by transient yet intense inflammatory responses, chronic airway diseases are characterized by persistent, self-perpetuating inflammation that drives progressive tissue remodeling and irreversible impairment of lung function. Neutrophils are consistently enriched in the airways of patients with severe COPD and specific asthma phenotypes, which highlights their central role in disease chronicity [81,82]. Within this context, NETosis has emerged not only as an antimicrobial defense mechanism but also as a critical pathogenic driver that sustains inflammation, accelerates structural damage, and amplifies airway remodeling over time.

COPD is one of the most prevalent chronic respiratory conditions worldwide, with neutrophilic inflammation representing a defining hallmark of COPD pathophysiology. Sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid from patients with COPD consistently demonstrate elevated levels of NET-derived markers, including extracellular DNA, MPO-DNA complexes, and citrullinated histones, which are correlated with disease severity and exacerbation frequency [1,47]. NETs in COPD are not passive byproducts of inflammation but are active contributors to structural lung damage [83]. The extracellular DNA scaffold of NETs increases mucus viscosity and impairs mucociliary clearance, creating a permissive niche for bacterial colonization by pathogens such as Hemophilus influenzae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [84]. These microbes persist within NET-rich microenvironments, fueling recurrent exacerbations and amplifying airway injuries.

Proteolytic enzymes embedded in NETs and NE degrade extracellular matrix components such as elastin and collagen, leading to alveolar wall destruction and emphysematous changes. MPO and ROS exacerbate oxidative stress and epithelial injury, further compromising the alveolar structure [85]. Cigarette smoke, the primary risk factor for COPD, primes neutrophils for exaggerated NET release and disrupts clearance mechanisms by inhibiting the macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of NETs [86]. Collectively, these processes establish a self-reinforcing cycle in which environmental insults and microbial persistence perpetuate NET-driven inflammation, tissue destruction, and progressive airflow limitation.

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease traditionally associated with eosinophilic inflammation and Th2 cytokines. However, growing evidence highlights the involvement of neutrophils and NETosis, particularly in severe and corticosteroid-resistant phenotypes [87,88]. In these patients, neutrophils infiltrate the airway lumen and undergo robust NET release, which directly contributes to epithelial damage and goblet cell hyperplasia [89]. NET-derived histones and proteases are cytotoxic to bronchial epithelial cells and cause barrier dysfunction, increased susceptibility to allergens, and microbial invasion. The DNA-protein framework of NETs further enhances mucus gel viscosity, contributing to the formation of dense obstructive sputum plugs that characterize severe asthma [88].

In addition to causing structural damage, NETs function as DAMPs that engage TLRs and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in epithelial cells and macrophages [88]. This activation results in enhanced secretion of IL1β and IL18, fueling a feed-forward inflammatory loop. Elevated levels of IL17A and IL8 are commonly observed in neutrophilic asthma, sustain neutrophil recruitment and NET formation, and exacerbate airway inflammation [45,90]. Clinically, this endotype is associated with poor responsiveness to inhaled corticosteroids and frequent exacerbations, highlighting the urgent need for therapies that specifically target neutrophil- and NET-driven inflammation [91]. Experimental evidence indicates that interventions aimed at inhibiting NETosis or promoting NET clearance can attenuate airway inflammation and reduce the frequency or severity of neutrophilic asthma exacerbation, suggesting a potential therapeutic role for this challenging endotype.

Pulmonary tuberculosis, caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis), is a chronic infectious disease in which the pathogen actively induces the formation of NETs [92,93]. During infection, neutrophils undergo NETosis, releasing DNA decorated with granule-derived enzymes and antimicrobial proteins [93]. These NETs are closely associated with tuberculosis pathogenesis, serving as extracellular scaffolds that may facilitate M. tuberculosis survival and propagation [94]. The bacterium triggers neutrophil necrosis in an ESX-1-dependent manner, while ROS produced by neutrophils further promotes this necrotic process [95]. Moreover, type I interferons exacerbate pulmonary inflammation and NETosis, aggravating disease progression in susceptible hosts [96,97]. M. tuberculosis infection potently triggers NETosis in circulating neutrophils, whereas low-density neutrophils exhibit a markedly reduced ability to form NETs, indicating functional divergence within the neutrophil population [98]. Pharmacological inhibition with the cell-permeable NE inhibitor MeOSuc-AAPV-cmk effectively attenuates M. tuberculosis-induced NETosis but does not interfere with PMA-stimulated NET release, implying that these stimuli engage distinct molecular signaling pathways governing NET formation [92]. Elevated levels of circulating NETs have been observed in patients with active or relapsing tuberculosis, correlating with extensive tissue damage and impaired lung function [99]. Excessive NET release contributes to acute lung injury and caseating granulomatous pathology by promoting epithelial and endothelial cell death, inflammatory cytokine production, and immunothrombosis [100,101]. Notably, NET formation, although induced by M. tuberculosis, is often insufficient to effectively kill the pathogen [102]. Targeting neutrophils and NETosis thus represents a promising host-directed therapeutic approach that may enhance antibiotic efficacy, shorten treatment duration, and mitigate disease-associated pathology [103]. Such interventions could also provide valuable biomarkers for monitoring disease progression and therapeutic response in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis.

6 Therapeutic Targeting of NETosis

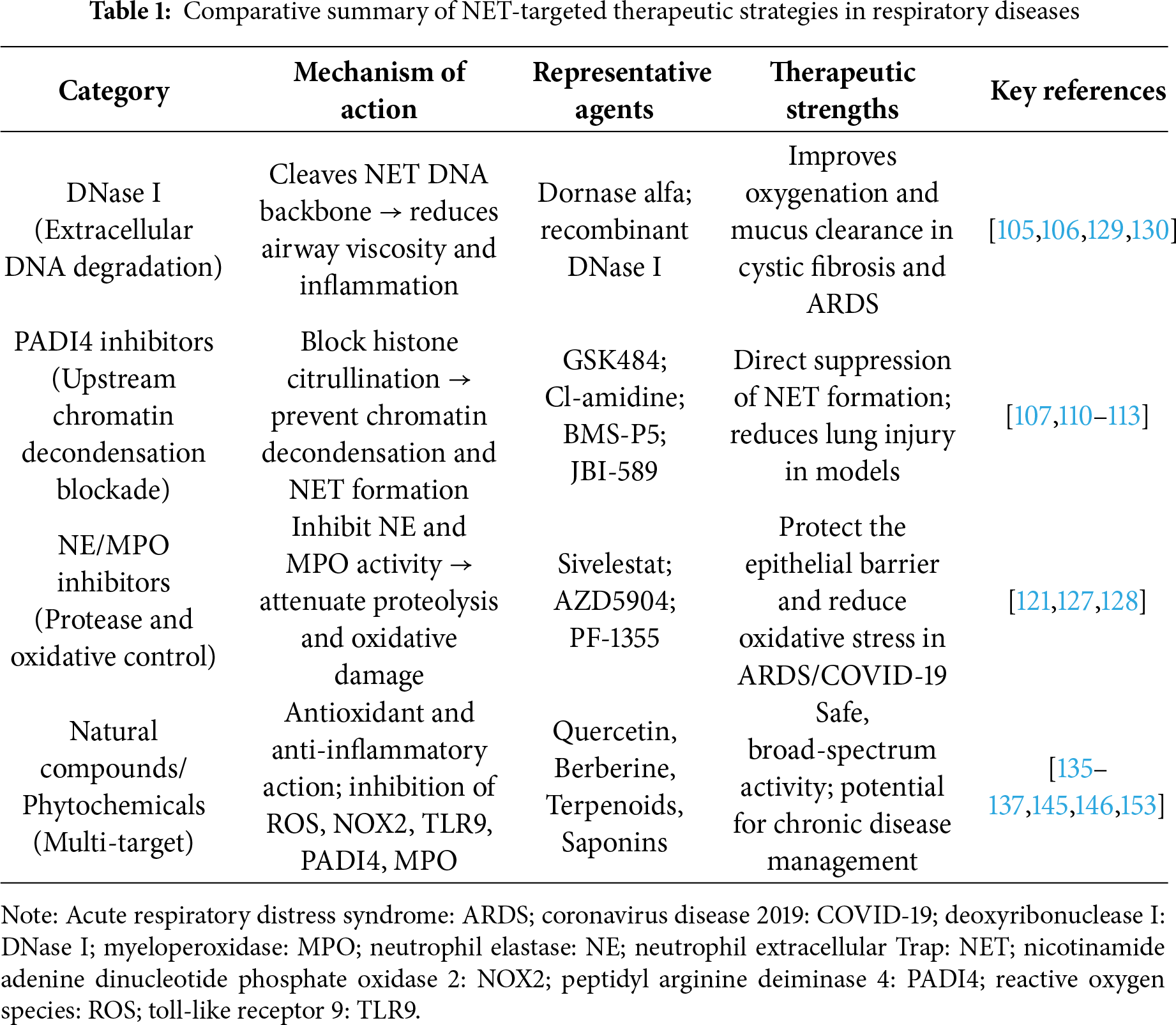

Given the substantial contribution of NETosis to the pathology of respiratory diseases, therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating NET formation, enhancing NET degradation, and neutralizing NET components have attracted considerable interest. With several advances in clinical evaluations, these interventions can be broadly classified into three major categories: biologics (e.g., DNase I), pharmacological inhibitors (e.g., PADI4, NE, and MPO inhibitors, as well as upstream pathway modulators), and natural compounds (phytochemicals with multi-target anti-inflammatory activity). The following subsections discuss representative examples of each category (Table 1).

DNase I, an endonuclease that cleaves extracellular DNA, has been clinically approved to reduce mucus viscosity in cystic fibrosis [104]. DNase I has also been explored in ARDS and COVID-19 [105]. Early-phase studies suggested that aerosolized or intravenous DNase reduces NET burden markers, including cell-free DNA and MPO-DNA complexes, and improves oxygenation, although the results remain inconsistent. For instance, in patients with COVID-19, adjunctive DNase therapy has been associated with reductions in inflammatory biomarkers and improvements in clinical scores; however, large-scale randomized trials are needed to establish survival benefits [106]. A key limitation of DNase therapy is that it dismantles the DNA scaffold, but does not neutralize histones or proteases, highlighting the need for combination approaches.

PADI4 has been established as a linchpin enzyme for NET biogenesis through catalytic histone citrullination that drives chromatin decondensation and extracellular trap extrusion [33,107,108]. Genetic ablation or pharmacological blockade of PADI4 robustly prevents stimulus-induced NET formation in human and murine neutrophils, thereby attenuating downstream tissue injury in multiple disease models, highlighting PADI4 as a tractable therapeutic node [107–109]. Small-molecule covalent inhibitors, such as haloacetamidine derivatives and peptidomimetics, have demonstrated proof-of-concept NET suppression in vitro and in vivo, whereas next-generation selective inhibitors, including GSK484, BMS-P5, and JBI-589, have achieved improved potency, selectivity, and oral bioavailability with disease-modifying effects in oncology, autoimmunity, and lung injury models [110–113]. Structure-activity relationship studies and recent medicinal chemistry efforts have produced heterocyclic scaffolds and phenylboronic acid-modified constructs that enhance tumor targeting and minimize off-target PAD isoform inhibition, thereby improving safety margins [114–116]. Mechanistic adjuncts to direct PADI4 inhibition encompass upstream modulation of calcium signaling, ROS, and inflammasome pathways that converge on PADI4 activation and NETosis and downstream neutralization of NET effectors, such as extracellular histones, neutrophil elastase, and MPO, to limit cytotoxic sequelae [62,109,117,118]. Therefore, translational strategies prioritize selective PADI4 inhibitors combined with scaffold-degrading enzymes, histone neutralizers, or anti-platelet and anti-inflammasome agents to preserve the antimicrobial host defense while preventing immunothrombosis and organ injury [14,119,120].

NET formation is orchestrated by an integrated program in which PADI4-dependent histone citrullination, proteolytic processing by NE, and oxidative chemistry driven by MPO converge to promote chromatin decondensation and extracellular chromatin extrusion [4,34,121]. Genetic PADI4 ablation or selective pharmacological blockade prevents stimulus-induced citrullination and robustly reduces NET biogenesis in both human and murine systems, providing proof of principle that PADI4 is a tractable molecular node for NET inhibition [121,122]. Complementary strategies target the effector enzymes that remodel chromatin and decorate the NET scaffold; inhibition of NE by small molecules such as sivelestat or newer covalent and non-covalent inhibitors curtails NE translocation to the nucleus and abrogates NET release in endotoxemia and lung injury models while improving survival and tissue integrity [121,123,124]. MPO inhibition similarly suppresses NET formation by limiting hypochlorous acid and MPO-processed reactive species that synergize with NE to drive chromatin relaxation and protease activation. MPO blockade has shown benefits in preclinical models of inflammatory and thrombotic injury [4,125,126]. Additionally, MPO inhibitors, such as AZD5904 and PF-1355, have demonstrated preclinical efficacy in reducing oxidative stress and NET formation in lung injury models, with some candidates progressing toward clinical evaluation [127,128]. Mechanistic studies have revealed that NE and MPO act both sequentially and within a multiprotein complex to regulate actin dynamics, granule fusion, and nuclear pore remodeling, thereby defining multiple actionable points for intervention [34,126]. Translationally, the literature advocates combination regimens that pair selective PADI4 inhibitors with NE or MPO antagonists or DNA-degrading enzymes to dismantle established NETs, thereby preserving antimicrobial host defense while minimizing protease- and histone-mediated tissue toxicity [122,129,130]. Similarly, Kim et al. established a lung-homing nanoliposome system co-encapsulating sivelestat and DNase I, both inhibitors of excessive NET formation, together with 25-hydroxycholesterol, a bioactive oxysterol with potent anti-inflammatory properties. This combinatorial formulation effectively attenuated pathological lung injury and improved early respiratory function in a murine model of ARDS, while also reducing excessive neutrophil infiltration and mitigating systemic inflammatory response syndrome [131]. Furthermore, a recent study introduced a self-regulated microgel-based nanocarrier incorporating Nexinhib20, which is activated by NE, designed to achieve targeted drug delivery to lower-airway neutrophils. This system enhanced delivery efficiency and locally suppressed neutrophil recruitment, degranulation, and inflammatory signaling, representing a novel platform for precision control of NET-associated inflammation [132]. Collectively, these advances highlight a promising nanotherapeutic paradigm in which liposomal or microgel-based carriers are engineered to selectively augment the efficacy and specificity of NET-modulatory agents, including NE and MPO inhibitors, while enabling combinatorial control of multiple inflammatory pathways. Such strategies may provide an innovative therapeutic framework for the management and treatment of diverse respiratory disorders driven by dysregulated NET formation.

6.4 Targeting Upstream Signaling Pathways

Interventions directed at upstream pathways of NETosis include inhibitors of TLRs, NOX2, and inflammasomes [62,133,134]. TLR antagonists block pathogen or DAMP-induced NET release, whereas NOX2 inhibitors prevent ROS-dependent chromatin decondensation. Agents targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome may indirectly attenuate NETosis by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine release. Although most of these strategies remain in the experimental or early translational stages, they highlight new avenues for therapeutic development.

6.5 Natural Compounds and Phytochemicals

An increasing body of evidence supports the role of natural bioactive compounds in modulating NETosis. Derived from plants, dietary sources, and traditional medicines, these compounds often possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that directly and indirectly suppress NET formation. Their relative safety and accessibility make them attractive adjunct options for both acute and chronic lung diseases.

Flavonoids exert a multifaceted inhibition of NETosis through concerted antioxidant, enzyme-modulatory, and signaling-interfering actions that target both the initiation and effector phases of NET biogenesis. The primary axis of activity is the suppression of reactive oxygen species production, which is central to many NETosis programs. By scavenging ROS and attenuating NOX activity, flavonoids reduce the oxidative drive required for neutrophil elastase translocation and chromatin decondensation, thereby limiting NET release [135–137]. Closely linked to antioxidant effects is direct inhibition of MPO, which decreases hypochlorous acid generation and MPO-mediated propagation of oxidative damage; quercetin and related flavonols have repeatedly demonstrated dose-dependent inhibition of MPO enzymatic activity and hypochlorous acid scavenging in vitro, providing a mechanistic basis for NET attenuation [34,136,138]. Complementary to MPO targeting, several flavonoids inhibit neutrophil elastase activity or prevent its nuclear relocalization, thereby interrupting the proteolytic chromatin remodeling essential for NET formation; catecholic flavonoids and certain glycosides produced low micromolar IC50s against NE in biochemical assays and reduced NET output in cellular models [121,138].

Beyond direct enzyme antagonism, flavonoids also modulate signaling nodes upstream of PADI4 activation and histone citrullination. By blunting calcium flux, inhibiting MAPK and PI3K/Akt cascades, and reducing proinflammatory cytokine production, flavonoids lower PADI4 activation thresholds, thus reducing histone citrullination and chromatin relaxation central to NETosis [23,121,137,139]. Specific compounds, such as quercetin, luteolin, apigenin, and structurally related derivatives, also interfere with platelet-neutrophil crosstalk and LTB4 signaling, which drive excessive neutrophil recruitment and a pro-NETotic microenvironment in infected and sterile lung injury [139].

Systemic or inhaled flavonoid formulations can be paired with DNase to dismantle preformed NET scaffolds, or combined with selective PADI4 inhibitors to block de novo NET biogenesis, thereby preserving antimicrobial function while reducing tissue toxicity [140,141]. Nanoparticle delivery platforms that directly improve pulmonary bioavailability and target neutrophils have been proposed to overcome flavonoid bioavailability limitations and concentrate activity at the sites of NET-mediated injury [141,142]. Safety and efficacy readouts in the highest impact reports recommend rigorous evaluation of stimulus specificity since antioxidant or protease inhibition may impair host defense against certain pathogens; accordingly, preclinical models that assess microbial clearance alongside tissue protection are essential [126,139,143].

Growing evidence indicates that terpenoids and saponins are critical phytochemical classes with the capacity to modulate extracellular trap formation in neutrophils, thereby attenuating the pathogenesis of respiratory diseases. Triterpenoid saponins exhibit broad anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties by downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL1β, IL6, and TNFα, by suppressing COX-derived prostaglandin E2, and by interfering with NFκB signaling, effects that converge on the reduction of NET-driven inflammation [144,145]. Terpenoids demonstrate similar multi-targeted actions as they inhibit NFκB and MAPK activation, constrain NOX activity, and suppress ROS production, which collectively dampen NOX-dependent NETosis and limit collateral tissue damage in pulmonary models [145,146]. A representative example is the total terpenoids of Celastrus orbiculatus, which significantly reduce PMA-induced NOX activation and ROS generation, resulting in marked inhibition of NET release in vitro [147]. These findings highlight the direct ability of terpenoids to interfere with upstream drivers of NETosis and suggest a mechanistic basis for their protective effects against inflammatory lung disorders.

Preclinical investigations have further demonstrated that saponins extracted from medicinal plants, such as Platycodon grandiflorus, suppress nitric oxide and pro-inflammatory mediators in LPS-challenged models, thereby mitigating neutrophil activation and NET-associated airway inflammation [148,149]. Interestingly, saponins are not uniformly inhibitory, as exemplified by saikosaponin A, which enhances NET formation and bactericidal activity, suggesting a context-dependent duality that may strengthen antimicrobial defense under infectious stress but could also exacerbate tissue injury when dysregulated [150]. This dual functionality underscores the need to discriminate between the inhibitory and stimulatory saponin subtypes to develop therapeutic interventions.

At the molecular level, both terpenoids and saponins converge on several key checkpoints in NETosis, including the regulation of NOX-derived ROS, inhibition of PADI4-mediated histone citrullination, reduction of MPO and neutrophil elastase activity, and suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome activation [137,139,144,147]. These mechanisms are complemented by the antioxidant and autophagy-modulating capacities of these phytochemicals, which collectively restore the balance between protective host defenses and detrimental neutrophil-driven tissue damage. Thus, terpenoids and saponins have emerged as promising candidates for therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating NETosis in respiratory diseases. Their capacity to integrate anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties with direct suppression of NET formation establishes them as multidimensional regulators of neutrophil biology. Although most of the evidence remains confined to preclinical and in vitro models, these data provide a compelling rationale for advancing selected terpenoid and saponin derivatives toward translational development. A rigorous evaluation of compound specificity, pharmacokinetics, and delivery platforms is required to fully harness their therapeutic potential and establish clinically relevant interventions that restore neutrophil homeostasis and mitigate the destructive consequences of uncontrolled NETosis in pulmonary disease [137,145,151].

6.5.3 Alkaloids and Other Phytochemicals

Several prototypical plant alkaloids modulate NET formation by acting on the discrete molecular nodes of the NETosis program. Berberine, an isoquinoline alkaloid, reduces NET release in cellular and preclinical models by suppressing ROS generation and interfering with NE-associated chromatin processing, which are mechanisms that correlate with decreased macrophage pyroptosis and lower alveolar inflammation in the lung injury paradigms [152,153]. Warifteine, an alkaloid purified from Cissampelos sympodialis, blocks NET production without impairing neutrophil oxidative burst in vitro, indicating that certain alkaloids can selectively uncouple NET extrusion from upstream activation signals, thus preserving antimicrobial oxidative functions and preventing excessive extracellular trap release [154]. In addition, sulforaphane, a dietary isothiocyanate found in cruciferous vegetables, activates nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2-dependent antioxidant pathways, reduces oxidative stress, and indirectly limits NET release [155,156]. Ali et al. showed that 6-gingerol, a principal bioactive component of Zingiber officinale, suppresses NETosis and reduces circulating plasma NET levels in both murine autoimmune disease models and human cohort subjects [157]. Beyond their direct effects on neutrophils, alkaloids exert ancillary effects that constrain NETosis in the lung microenvironment [158]. Alkaloid-mediated inhibition of NFκB and MAPK signaling downregulates proinflammatory cytokines, including IL1β and IL6, thus reducing paracrine NET-inducing stimuli [139]. Antioxidant properties of several alkaloids reduce the cellular redox potential required for NOX-dependent NETosis [159]. Additional actions include the attenuation of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and enhancement of NET clearance by phagocytes, both of which restore resolution pathways and limit sustained neutrophil-driven tissue damage [159]. Collectively, these phytochemicals illustrate that dietary and plant-based agents may serve as preventive or adjunctive strategies against neutrophil-driven airway inflammation.

Natural bioactive compounds often possess complex polycyclic structures and multiple chiral centers, resulting in low oral bioavailability and posing challenges for scalable synthesis [160]. Limited absorption and rapid metabolism can prevent these compounds from reaching therapeutic concentrations in target tissues, while variability in source material and extraction methods complicates standardization and may constrain clinical efficacy [161]. To address these limitations, advanced formulation strategies that enhance solubility, stability, and bioavailability are critical. The compositional complexity of natural products also complicates mechanistic understanding and single-target drug development. In the context of NETosis, therapeutic strategies should focus on modulating excessive NET formation while preserving essential host defense, rather than pursuing complete inhibition. Innovative delivery platforms, such as cell-mediated nanoparticle drug delivery systems, can improve tissue targeting and overcome bioavailability constraints, thereby maximizing the translational potential of natural product-derived NET modulators.

7 Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Over the past decade, NETs have been recognized as pivotal mediators of host defense and immunopathology. Dysregulated NETosis exerts profound pathological consequences in the lungs, where fragile structures are continuously exposed to pathogens and environmental stressors. Acute conditions such as ARDS, severe pneumonia, and COVID-19 exemplify the dual role of NETs as they entrap microbes; however, their excessive accumulation disrupts the alveolar-capillary barrier, obstructs the airways, and promotes immunothrombosis. In chronic diseases, such as COPD and severe asthma, unresolved NETosis perpetuates a self-sustaining inflammatory loop, resulting in epithelial injury, mucus hypersecretion, and irreversible airway remodeling.

NET-derived biomarkers detectable in plasma, sputum, and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid correlate with disease severity and clinical outcomes, underscoring their potential as diagnostic and prognostic indicators. However, its translation into clinical practice remains limited and requires standardized assays, cross-cohort validation, and a clear distinction between protective and pathological NETs. The therapeutic targeting of NETosis is still in its infancy. DNase I remains the most advanced clinical candidate; however, its inability to neutralize histones and proteases underscores the necessity of combination strategies. PADI4 inhibitors, blockade of NE and MPO, and immunomodulatory biologics represent promising avenues, whereas natural compounds such as flavonoids, polyphenols, and terpenoids provide safe and pleiotropic alternatives that warrant deeper exploration.

In conclusion, NETosis embodies a double-edged sword in respiratory disease as it is indispensable for antimicrobial defense but causes profound tissue damage when dysregulated. The therapeutic modulation of this process in a context-dependent manner holds great promise for transforming the management of both acute and chronic lung disorders. By integrating mechanistic insights into translational innovation, NET-targeted interventions have emerged as powerful and novel strategies for the prevention and treatment of respiratory diseases.

In the future, several priorities should guide the field. Precision medicine approaches are essential to leverage NET biomarkers for patient stratification, particularly in patients with neutrophilic endotypes or thromboinflammatory complications. Combination therapies that integrate NET-targeted interventions with anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, or anticoagulant modalities are likely to maximize efficacy while minimizing collateral effects. Novel therapeutic modalities, including nanotechnology-based delivery systems, engineered DNase variants, RNA-based approaches, and single-cell transcriptomic analysis, may enhance both efficacy and safety. System-level investigations are equally important to elucidate how NETs interact with adaptive immunity, microbiome dynamics, and systemic complications beyond the lungs, thereby providing a holistic framework for future therapeutic development.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Main Research Program (E0210202-05) of the Korea Food Research Institute (KFRI), funded by the Korean Ministry of Science and ICT.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Seungil Kim and Gun-Dong Kim; writing—original draft preparation, Seungil Kim and Gun-Dong Kim; writing—review and editing, Seungil Kim and Gun-Dong Kim; data curation, Seungil Kim and Gun-Dong Kim. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Vorobjeva NV, Chernyak BV. NETosis: molecular mechanisms, role in physiology and pathology. Biochemistry. 2020;85(10):1178–90. doi:10.1134/S0006297920100065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Thiam HR, Wong SL, Wagner DD, Waterman CM. Cellular mechanisms of NETosis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2020;36(1):191–218. doi:10.1146/annurev-cellbio-020520-111016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Kapoor D, Shukla D. Neutrophil extracellular traps and their possible implications in ocular herpes infection. Pathogens. 2023;12(2):209. doi:10.3390/pathogens12020209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Metzler KD, Fuchs TA, Nauseef WM, Reumaux D, Roesler J, Schulze I, et al. Myeloperoxidase is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation: implications for innate immunity. Blood. 2011;117(3):953–9. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-06-290171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Thiam HR, Wong SL, Qiu R, Kittisopikul M, Vahabikashi A, Goldman AE, et al. NETosis proceeds by cytoskeleton and endomembrane disassembly and PAD4-mediated chromatin decondensation and nuclear envelope rupture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(13):7326–37. doi:10.1073/pnas.1909546117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Papayannopoulos V, Zychlinsky A. NETs: a new strategy for using old weapons. Trends Immunol. 2009;30(11):513–21. doi:10.1016/j.it.2009.07.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Huang SU, O’Sullivan KM. The expanding role of extracellular traps in inflammation and autoimmunity: the new players in casting dark webs. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(7):3793. doi:10.3390/ijms23073793. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Conceição-Silva F, Reis CSM, De Luca PM, Leite-Silva J, Santiago MA, Morrot A, et al. The immune system throws its traps: cells and their extracellular traps in disease and protection. Cells. 2021;10(8):1891. doi:10.3390/cells10081891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ma Q, Steiger S. Neutrophils and extracellular traps in crystal-associated diseases. Trends Mol Med. 2024;30(9):809–23. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2024.05.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Wan A, Chen D. The multifaceted roles of neutrophil death in COPD and lung cancer. J Respir Biol Transl Med. 2025;2(1):10022. doi:10.70322/jrbtm.2024.10022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. King PT, Dousha L. Neutrophil extracellular traps and respiratory disease. J Clin Med. 2024;13(8):2390. doi:10.3390/jcm13082390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Li H, Li Y, Song C, Hu Y, Dai M, Liu B, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps augmented alveolar macrophage pyroptosis via AIM2 inflammasome activation in LPS-induced ALI/ARDS. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:4839–58. doi:10.2147/JIR.S321513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Zhou X, Jin J, Lv T, Song Y. A narrative review: the role of NETs in acute respiratory distress syndrome/acute lung injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(3):1464. doi:10.3390/ijms25031464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Liu X, Li T, Chen H, Yuan L, Ao H. Role and intervention of PAD4 in NETs in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Respir Res. 2024;25(1):63. doi:10.1186/s12931-024-02676-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Uddin M, Watz H, Malmgren A, Pedersen F. NETopathic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and severe asthma. Front Immunol. 2019;10:47. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Chen J, Wang T, Li X, Gao L, Wang K, Cheng M, et al. DNA of neutrophil extracellular traps promote NF-κB-dependent autoimmunity via cGAS/TLR9 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):163. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01881-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Gál Z, Gézsi A, Pállinger É, Visnovitz T, Nagy A, Kiss A, et al. Plasma neutrophil extracellular trap level is modified by disease severity and inhaled corticosteroids in chronic inflammatory lung diseases. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):4320. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-61253-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang Y, Li Y, Sun N, Tang H, Ye J, Liu Y, et al. NETosis is critical in patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1051140. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.1051140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Huckriede J, Anderberg SB, Morales A, de Vries F, Hultström M, Bergqvist A, et al. Evolution of NETosis markers and DAMPs have prognostic value in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):15701. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-95209-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395(10234):1417–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Zhu Y, Chen X, Liu X. NETosis and neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19: immunothrombosis and beyond. Front Immunol. 2022;13:838011. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.838011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Middleton EA, He XY, Denorme F, Campbell RA, Ng D, Salvatore SP, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to immunothrombosis in COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. Blood. 2020;136(10):1169–79. doi:10.1182/blood.2020007008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Askarizadeh F, Karav S, Sahebkar A. Phytochemicals as modulators of NETosis: a comprehensive review on their mechanisms and therapeutic potential. Phytother Res. 2025;39(8):3545–77. doi:10.1002/ptr.70025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Liu Y, Qu Y, Liu C, Zhang D, Xu B, Wan Y, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps: potential targets for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with traditional Chinese medicine and natural products. Phytother Res. 2024;38(11):5067–87. doi:10.1002/ptr.8311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Liu R, Zhang J, Rodrigues Lima F, Zeng J, Nian Q. Targeting neutrophil extracellular traps: a novel strategy in hematologic malignancies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;173(6):116334. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Manoj H, Gomes SM, Thimmappa PY, Nagareddy PR, Jamora C, Joshi MB. Cytokine signalling in formation of neutrophil extracellular traps: implications for health and diseases. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2025;81:27–39. doi:10.1016/j.cytogfr.2024.12.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Gierlikowska B, Stachura A, Gierlikowski W, Demkow U. The impact of cytokines on neutrophils’ phagocytosis and NET formation during sepsis—a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(9):5076. doi:10.3390/ijms23095076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Gao F, Peng H, Gou R, Zhou Y, Ren S, Li F. Exploring neutrophil extracellular traps: mechanisms of immune regulation and future therapeutic potential. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2025;14(1):80. doi:10.1186/s40164-025-00670-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Pieterse E, Rother N, Yanginlar C, Gerretsen J, Boeltz S, Munoz LE, et al. Cleaved N-terminal histone tails distinguish between NADPH oxidase (NOX)-dependent and NOX-independent pathways of neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(12):1790–8. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Douda DN, Yip L, Khan MA, Grasemann H, Palaniyar N. Akt is essential to induce NADPH-dependent NETosis and to switch the neutrophil death to apoptosis. Blood. 2014;123(4):597–600. doi:10.1182/blood-2013-09-526707. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Pilsczek FH, Salina D, Poon KKH, Fahey C, Yipp BG, Sibley CD, et al. A novel mechanism of rapid nuclear neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol. 2010;185(12):7413–25. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1000675. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Yousefi S, Mihalache C, Kozlowski E, Schmid I, Simon HU. Viable neutrophils release mitochondrial DNA to form neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16(11):1438–44. doi:10.1038/cdd.2009.96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Li P, Li M, Lindberg MR, Kennett MJ, Xiong N, Wang Y. PAD4 is essential for antibacterial innate immunity mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med. 2010;207(9):1853–62. doi:10.1084/jem.20100239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Papayannopoulos V, Metzler KD, Hakkim A, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2010;191(3):677–91. doi:10.1083/jcb.201006052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Chen T, Li Y, Sun R, Hu H, Liu Y, Herrmann M, et al. Receptor-mediated NETosis on neutrophils. Front Immunol. 2021;12:775267. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.775267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Sollberger G, Choidas A, Burn GL, Habenberger P, Di Lucrezia R, Kordes S, et al. Gasdermin D plays a vital role in the generation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Sci Immunol. 2018;3(26):eaar6689. doi:10.1126/sciimmunol.aar6689. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Douda DN, Khan MA, Grasemann H, Palaniyar N. SK3 channel and mitochondrial ROS mediate NADPH oxidase-independent NETosis induced by calcium influx. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(9):2817–22. doi:10.1073/pnas.1414055112. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Papayannopoulos V. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(2):134–47. doi:10.1038/nri.2017.105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Wang H, Kim SJ, Lei Y, Wang S, Wang H, Huang H, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in homeostasis and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):235. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01933-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Arroyo R, Khan MA, Echaide M, Pérez-Gil J, Palaniyar N. SP-D attenuates LPS-induced formation of human neutrophil extracellular traps (NETsprotecting pulmonary surfactant inactivation by NETs. Commun Biol. 2019;2(1):470. doi:10.1038/s42003-019-0662-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Malavez-Cajigas SJ, Marini-Martinez FI, Lacourt-Ventura M, Rosario-Pacheco KJ, Ortiz-Perez NM, Velazquez-Perez B, et al. HL-60 cells as a valuable model to study LPS-induced neutrophil extracellular traps release. Heliyon. 2024;10(16):e36386. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e36386. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Muraro SP, De Souza GF, Gallo SW, Da Silva BK, De Oliveira SD, Vinolo MAR, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus induces the classical ROS-dependent NETosis through PAD-4 and necroptosis pathways activation. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14166. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-32576-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Valderrama A, Ortiz-Hernández P, Agraz-Cibrián JM, Tabares-Guevara JH, Gómez DM, Zambrano-Zaragoza JF, et al. Particulate matter (PM10) induces in vitro activation of human neutrophils, and lung histopathological alterations in a mouse model. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):7581. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-11553-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Saffarzadeh M, Juenemann C, Queisser MA, Lochnit G, Barreto G, Galuska SP, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps directly induce epithelial and endothelial cell death: a predominant role of histones. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32366. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Hudock KM, Collins MS, Imbrogno M, Snowball J, Kramer EL, Brewington JJ, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps activate IL-8 and IL-1 expression in human bronchial epithelia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2020;319(1):L137–47. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00144.2019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Farrera C, Fadeel B. Macrophage clearance of neutrophil extracellular traps is a silent process. J Immunol. 2013;191(5):2647–56. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1300436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Grabcanovic-Musija F, Obermayer A, Stoiber W, Krautgartner WD, Steinbacher P, Winterberg N, et al. Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation characterises stable and exacerbated COPD and correlates with airflow limitation. Respir Res. 2015;16(1):59. doi:10.1186/s12931-015-0221-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Yan S, Li M, Liu B, Ma Z, Yang Q. Neutrophil extracellular traps and pulmonary fibrosis: an update. J Inflamm. 2023;20(1):2. doi:10.1186/s12950-023-00329-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, Schatzberg D, Monestier M, Myers DDJr, et al. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(36):15880–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.1005743107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Hosseinzadeh A, Thompson PR, Segal BH, Urban CF. Nicotine induces neutrophil extracellular traps. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;100(5):1105–12. doi:10.1189/jlb.3AB0815-379RR. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Xu H, He X, Zhang B, Li M, Zhu Y, Wang T, et al. Low-level ambient ozone exposure associated with neutrophil extracellular traps and pro-atherothrombotic biomarkers in healthy adults. Atherosclerosis. 2024;395:117509. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2024.117509. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Fuchs HJ, Borowitz DS, Christiansen DH, Morris EM, Nash ML, Ramsey BW, et al. Effect of aerosolized recombinant human DNase on exacerbations of respiratory symptoms and on pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(10):637–42. doi:10.1056/NEJM199409083311003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Shen K, Zhang M, Zhao R, Li Y, Li C, Hou X, et al. Eosinophil extracellular traps in asthma: implications for pathogenesis and therapy. Respir Res. 2023;24(1):231. doi:10.1186/s12931-023-02504-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Narasaraju T, Yang E, Samy RP, Ng HH, Poh WP, Liew AA, et al. Excessive neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to acute lung injury of influenza pneumonitis. Am J Pathol. 2011;179(1):199–210. doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Zuo Y, Yalavarthi S, Shi H, Gockman K, Zuo M, Madison JA, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19. JCI Insight. 2020;5(11):e138999. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.138999. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Lefrançais E, Mallavia B, Zhuo H, Calfee CS, Looney MR. Maladaptive role of neutrophil extracellular traps in pathogen-induced lung injury. JCI Insight. 2018;3(3):e98178. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.98178. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Radermecker C, Detrembleur N, Guiot J, Cavalier E, Henket M, d’Emal C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps infiltrate the lung airway, interstitial, and vascular compartments in severe COVID-19. J Exp Med. 2020;217(12):e20201012. doi:10.1084/jem.20201012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Cesta MC, Zippoli M, Marsiglia C, Gavioli EM, Cremonesi G, Khan A, et al. Neutrophil activation and neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in COVID-19 ARDS and immunothrombosis. Eur J Immunol. 2023;53(1):2250010. doi:10.1002/eji.202250010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Liu S, Su X, Pan P, Zhang L, Hu Y, Tan H, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps are indirectly triggered by lipopolysaccharide and contribute to acute lung injury. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):37252. doi:10.1038/srep37252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Qu M, Chen Z, Qiu Z, Nan K, Wang Y, Shi Y, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps-triggered impaired autophagic flux via METTL3 underlies sepsis-associated acute lung injury. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8(1):375. doi:10.1038/s41420-022-01166-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Song C, Li H, Mao Z, Peng L, Liu B, Lin F, et al. Delayed neutrophil apoptosis may enhance NET formation in ARDS. Respir Res. 2022;23(1):155. doi:10.1186/s12931-022-02065-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Münzer P, Negro R, Fukui S, di Meglio L, Aymonnier K, Chu L, et al. NLRP3 inflammasome assembly in neutrophils is supported by PAD4 and promotes NETosis under sterile conditions. Front Immunol. 2021;12:683803. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.683803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Li Y, Liu Z, Liu B, Zhao T, Chong W, Wang Y, et al. Citrullinated histone H3: a novel target for the treatment of sepsis. Surgery. 2014;156(2):229–34. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2014.04.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Fetz AE, Neeli I, Buddington KK, Read RW, Smeltzer MP, Radic MZ, et al. Localized delivery of Cl-amidine from electrospun polydioxanone templates to regulate acute neutrophil NETosis: a preliminary evaluation of the PAD4 inhibitor for tissue engineering. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:289. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Park HH, Park W, Lee YY, Kim H, Seo HS, Choi DW, et al. Bioinspired DNase-I-coated melanin-like nanospheres for modulation of infection-associated NETosis dysregulation. Adv Sci. 2020;7(23):2001940. doi:10.1002/advs.202001940. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Arcanjo A, Logullo J, Menezes CCB, de Souza Carvalho Giangiarulo TC, dos Reis MC, de Castro GMM, et al. The emerging role of neutrophil extracellular traps in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (COVID-19). Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):19630. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-76781-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Leppkes M, Knopf J, Naschberger E, Lindemann A, Singh J, Herrmann I, et al. Vascular occlusion by neutrophil extracellular traps in COVID-19. eBioMedicine. 2020;58:102925. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102925. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Fisher J, Mohanty T, Karlsson CAQ, Khademi SMH, Malmström E, Frigyesi A, et al. Proteome profiling of recombinant DNase therapy in reducing NETs and aiding recovery in COVID-19 patients. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2021;20:100113. doi:10.1016/j.mcpro.2021.100113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Liang C, Lian N, Li M. The emerging role of neutrophil extracellular traps in fungal infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:900895. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2022.900895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Sanders NL, Martin IMC, Sharma A, Jones MR, Quinton LJ, Bosmann M, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps as an exacerbating factor in bacterial pneumonia. Infect Immun. 2022;90(3):e00491–21. doi:10.1128/IAI.00491-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Tran TM, MacIntyre A, Hawes M, Allen C. Escaping underground nets: extracellular DNases degrade plant extracellular traps and contribute to virulence of the plant pathogenic bacterium Ralstonia solanacearum. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(6):e1005686. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Sharma P, Garg N, Sharma A, Capalash N, Singh R. Nucleases of bacterial pathogens as virulence factors, therapeutic targets and diagnostic markers. Int J Med Microbiol. 2019;309(8):151354. doi:10.1016/j.ijmm.2019.151354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Alflen A, Aranda Lopez P, Hartmann AK, Maxeiner J, Bosmann M, Sharma A, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps impair fungal clearance in a mouse model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Immunobiology. 2020;225(1):151867. doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2019.11.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Zhou Y, Deng S, Du C, Zhang L, Li L, Liu Y, et al. Leukotriene B4-induced neutrophil extracellular traps impede the clearance of Pneumocystis. Eur J Immunol. 2024;54(5):e2350779. doi:10.1002/eji.202350779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Silva JC, Rodrigues NC, Thompson-Souza GA, Muniz VDS, Neves JS, Figueiredo RT. Mac-1 triggers neutrophil DNA extracellular trap formation to Aspergillus fumigatus independently of PAD4 histone citrullination. J Leukoc Biol. 2020;107(1):69–83. doi:10.1002/JLB.4A0119-009RR. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Clark HL, Abbondante S, Minns MS, Greenberg EN, Sun Y, Pearlman E. Protein deiminase 4 and CR3 regulate Aspergillus fumigatus and β-glucan-induced neutrophil extracellular trap formation, but hyphal killing is dependent only on CR3. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1182. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Qu G, Al Ribeiro H, Solomon AL, Sordo Vieira L, Goddard Y, Diodati NG, et al. The heme scavenger hemopexin protects against lung injury during aspergillosis by mitigating release of neutrophil extracellular traps. JCI Insight. 2025;10(10):e189151. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.189151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Tsukasaki Y, Prasad N, Vellingiri V, Mehta D, Malik A. Highly motile neutrophil cytoplast ameliorate bacterial pneumonia. J Immunol. 2024;212(1):0827–6240. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.212.supp.0827.6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Safiri S, Carson-Chahhoud K, Noori M, Nejadghaderi SA, Sullman MJM, Ahmadian Heris J, et al. Burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its attributable risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ. 2022;378:e069679. doi:10.1136/bmj-2021-069679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Wang X, Gou A, Wang J, Li J, Gou C. Global trends and future projections of COPD burden under low-temperature risk: a 1990-2041 analysis based on GBD 2021. BMC Pulm Med. 2025;25(1):403. doi:10.1186/s12890-025-03811-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Hoenderdos K, Condliffe A. The neutrophil in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2013;48(5):531–9. doi:10.1165/rcmb.2012-0492tr. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Wenzel SE, Schwartz LB, Langmack EL, Halliday JL, Trudeau JB, Gibbs RL, et al. Evidence that severe asthma can be divided pathologically into two inflammatory subtypes with distinct physiologic and clinical characteristics. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(3):1001–8. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.160.3.9812110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Abdo M, Uddin M, Goldmann T, Marwitz S, Bahmer T, Holz O, et al. Raised sputum extracellular DNA confers lung function impairment and poor symptom control in an exacerbation-susceptible phenotype of neutrophilic asthma. Respir Res. 2021;22(1):167. doi:10.1186/s12931-021-01759-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Dicker AJ, Crichton ML, Pumphrey EG, Cassidy AJ, Suarez-Cuartin G, Sibila O, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps are associated with disease severity and microbiota diversity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(1):117–27. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2017.04.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Haegens A, Vernooy JHJ, Heeringa P, Mossman BT, Wouters EFM. Myeloperoxidase modulates lung epithelial responses to pro-inflammatory agents. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(2):252–60. doi:10.1183/09031936.00029307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Qiu SL, Zhang H, Tang QY, Bai J, He ZY, Zhang JQ, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps induced by cigarette smoke activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Thorax. 2017;72(12):1084–93. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209887. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Poto R, Shamji M, Marone G, Durham SR, Scadding GW, Varricchi G. Neutrophil extracellular traps in asthma: friends or foes? Cells. 2022;11(21):3521. doi:10.3390/cells11213521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Lachowicz-Scroggins ME, Dunican EM, Charbit AR, Raymond W, Looney MR, Peters MC, et al. Extracellular DNA, neutrophil extracellular traps, and inflammasome activation in severe asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199(9):1076–85. doi:10.1164/rccm.201810-1869oc. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Xiang J, Cui M, Zhang Y. Neutrophil extracellular traps and neutrophilic asthma. Respir Med. 2025;245:108150. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2025.108150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Al-Ramli W, Préfontaine D, Chouiali F, Martin JG, Olivenstein R, Lemière C, et al. TH17-associated cytokines (IL-17A and IL-17F) in severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(5):1185–7. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.02.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Green RH, Brightling CE, Woltmann G, Parker D, Wardlaw AJ, Pavord ID. Analysis of induced sputum in adults with asthma: identification of subgroup with isolated sputum neutrophilia and poor response to inhaled corticosteroids. Thorax. 2002;57(10):875–9. doi:10.1136/thorax.57.10.875. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Braian C, Hogea V, Stendahl O. Mycobacterium tuberculosis—induced neutrophil extracellular traps activate human macrophages. J Innate Immun. 2013;5(6):591–602. doi:10.1159/000348676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Chowdhury CS, Kinsella RL, McNehlan ME, Naik SK, Lane DS, Talukdar P, et al. Type I IFN-mediated NET release promotes Mycobacterium tuberculosis replication and is associated with granuloma caseation. Cell Host Microbe. 2024;32(12):2092–111. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2024.11.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Cardona PJ. The progress of therapeutic vaccination with regard to tuberculosis. Front Microbiol. 2016;7(612):1536. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2016.01536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Dallenga T, Repnik U, Corleis B, Eich J, Reimer R, Griffiths GW, et al. Tuberculosis-induced necrosis of infected neutrophils promotes bacterial growth following phagocytosis by macrophages. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;22(4):519–30. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2017.09.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Mayer Bridwell AE. mSphere of influence: the key role of neutrophils in tuberculosis and type 2 diabetes comorbidity. mSphere. 2021;6(3):e00251–21. doi:10.1128/mSphere.00251-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Moreira-Teixeira L, Stimpson PJ, Stavropoulos E, Hadebe S, Chakravarty P, Ioannou M, et al. Type I IFN exacerbates disease in tuberculosis-susceptible mice by inducing neutrophil-mediated lung inflammation and NETosis. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5566. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19412-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. La Manna MP, Orlando V, Paraboschi EM, Tamburini B, Di Carlo P, Cascio A, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis drives expansion of low-density neutrophils equipped with regulatory activities. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2761. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.02761. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Zlatar L, Knopf J, Singh J, Wang H, Muñoz-Becerra M, Herrmann I, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps characterize caseating granulomas. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(7):548. doi:10.1038/s41419-024-06892-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Gopal R, Monin L, Torres D, Slight S, Mehra S, McKenna KC, et al. S100A8/A9 proteins mediate neutrophilic inflammation and lung pathology during tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(9):1137–46. doi:10.1164/rccm.201304-0803OC. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Pan T, Woo L. A crucial role of neutrophil extracellular traps in pulmonary infectious diseases. Chin Med J Pulm Crit Care Med. 2024;2(1):34–41. doi:10.1016/j.pccm.2023.10.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Ramos-Kichik V, Mondragón-Flores R, Mondragón-Castelán M, Gonzalez-Pozos S, Muñiz-Hernandez S, Rojas-Espinosa O, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps are induced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis. 2009;89(1):29–37. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2008.09.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Dallenga T, Linnemann L, Paudyal B, Repnik U, Griffiths G, Schaible UE. Targeting neutrophils for host-directed therapy to treat tuberculosis. Int J Med Microbiol. 2018;308(1):142–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijmm.2017.10.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Mahri S, Wilms T, Hagedorm P, Guichard MJ, Vanvarenberg K, Dumoulin M, et al. Nebulization of PEGylated recombinant human deoxyribonuclease I using vibrating membrane nebulizers: a technical feasibility study. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2023;189(6):106522. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2023.106522. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Holliday ZM, Earhart AP, Alnijoumi MM, Krvavac A, Allen LH, Schrum AG. Non-randomized trial of dornase Alfa for acute respiratory distress syndrome secondary to covid-19. Front Immunol. 2021;12:714833. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.714833. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Porter JC, Inshaw J, Solis VJ, Denneny E, Evans R, Temkin MI, et al. Anti-inflammatory therapy with nebulized dornase Alfa for severe COVID-19 pneumonia: a randomized unblinded trial. eLife. 2024;12:RP87030. doi:10.7554/eLife.87030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Lewis HD, Liddle J, Coote JE, Atkinson SJ, Barker MD, Bax BD, et al. Inhibition of PAD4 activity is sufficient to disrupt mouse and human NET formation. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11(3):189–91. doi:10.1038/nchembio.1735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Zhu YP, Speir M, Tan Z, Lee JC, Nowell CJ, Chen AA, et al. NET formation is a default epigenetic program controlled by PAD4 in apoptotic neutrophils. Sci Adv. 2023;9(51):eadj1397. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adj1397. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Tatsiy O, McDonald PP. Physiological stimuli induce PAD4-dependent, ROS-independent NETosis, with early and late events controlled by discrete signaling pathways. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2036. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Li M, Lin C, Deng H, Strnad J, Bernabei L, Vogl DT, et al. A novel peptidylarginine deiminase 4 (PAD4) inhibitor BMS-P5 blocks formation of neutrophil extracellular traps and delays progression of multiple myeloma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2020;19(7):1530–8. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-19-1020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Deng H, Lin C, Garcia-Gerique L, Fu S, Cruz Z, Bonner EE, et al. A novel selective inhibitor JBI-589 targets PAD4-mediated neutrophil migration to suppress tumor progression. Cancer Res. 2022;82(19):3561–72. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-4045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]