Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Role of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps in Periodontitis Pathogenesis: A Systematic Review of Ex Vivo Studies

1 Department of Periodontics, School of Dentistry, University of Granada, Granada, 18071, Spain

2 Research Intern, Department of Periodontics, School of Dentistry, University of Granada, Granada, 18071, Spain

* Corresponding Author: Marco Bonilla. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: NETs: A Decade of Pathological Insights and Future Therapeutic Horizons)

BIOCELL 2026, 50(2), 6 https://doi.org/10.32604/biocell.2025.073576

Received 21 September 2025; Accepted 07 November 2025; Issue published 14 February 2026

Abstract

Objectives: Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) have emerged as critical effectors in immune defense but also as potential drivers of tissue damage in chronic inflammatory diseases. Their role in periodontitis, a highly prevalent condition characterized by dysregulated host–microbe interactions, remains incompletely defined. This systematic review aimed to synthesize, for the first time, ex vivo human evidence on the presence, activity, and clinical significance of NETs in periodontitis. Methods: A comprehensive search of Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus was conducted up to August 2025. Eligible studies included ex vivo human investigations assessing NETs or NET markers in gingival tissues, gingival crevicular fluid, saliva, blood, or biofilms from patients with periodontitis. Study selection, data extraction, and risk-of-bias assessment were conducted in duplicate, and the protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD420251109174). Results: Seventeen studies met the inclusion criteria. NET markers such as citrullinated histone H3 (CitH3), myeloperoxidase (MPO), and neutrophil elastase were consistently elevated in periodontitis samples compared with controls. Several studies reported a reduction in NET levels or improved NET degradation following periodontal therapy. NETs were also implicated in biofilm stability and in systemic associations with rheumatoid arthritis and chronic kidney disease. However, heterogeneity in methodologies, small sample sizes, and inconsistent marker use limited comparability across studies. Conclusions: Ex vivo evidence indicates that aberrant NET formation and impaired clearance contribute to periodontal inflammation and tissue destruction. Nonetheless, methodological variability and risk of bias constrain definitive conclusions. Standardization of detection methods, consensus on marker panels, and exploration of neutrophil subsets and systemic confounders are essential to establish NETs as reliable biomarkers and therapeutic targets in periodontitis.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FilePeriodontitis is a chronic multifactorial disease characterized by the destruction of the supporting tissues of the teeth and remains a leading cause of tooth loss worldwide. Its pathogenesis is the result of a dysbiotic microbial challenge interacting with a susceptible host, giving rise to a dysregulated and non-resolving immune-inflammatory response that leads to tissue breakdown [1]. Within this framework, neutrophils are the most abundant immune cells recruited to the gingiva and act as the first line of defense at the oral barrier. Their presence is indispensable, as illustrated by severe early-onset forms of periodontitis observed in congenital neutrophil deficiencies such as leukocyte adhesion deficiency type I or Papillon–Lefèvre syndrome [2]. However, excessive or dysregulated neutrophil activity is equally detrimental, fueling a cycle of chronic inflammation and dysbiosis that drives periodontal tissue destruction [3].

The dual role of neutrophils in periodontal health and disease has become increasingly evident. While functional neutrophils are essential for immune surveillance and microbial control, their hyperactivation, priming, or impaired clearance contribute to a proinflammatory state. Aging further exacerbates this imbalance, as senescent neutrophils display altered chemotaxis, reduced antimicrobial activity, and dysregulated Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation, a phenomenon contributing to “inflammaging” and increased susceptibility to periodontitis [4]. These insights place neutrophils at the crossroads of periodontal and systemic inflammation, underlining their importance in both local disease pathogenesis and broader comorbidities.

A key effector mechanism of neutrophils is the formation of Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). These structures—composed of decondensed chromatin decorated with histones and granular proteins such as neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase (MPO) are released during a process termed NETosis. Initially described as an antimicrobial strategy, NETs have been recognized as molecules capable of both protective and harmful effects. On the one hand, they entrap and neutralize pathogens; on the other, excessive or persistent NETs can damage host tissues, impair healing, and contribute to chronic inflammatory disorders, including systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and cardiovascular disease [5,6].

In the context of periodontal disease, NETs have been detected in the gingival and systemic compartments and are thought to contribute to the chronic inflammatory milieu characteristic of periodontitis. However, existing studies vary widely in design, sample type, and methodological approaches, and their findings have not been comprehensively integrated.

Despite growing interest in this topic, no systematic review has yet synthesized the available ex vivo human evidence on NETs in periodontitis. The null hypothesis was that NETs are not significantly associated with the pathogenesis or clinical expression of periodontitis. Therefore, the aim of the present review was to critically appraise and summarize the ex vivo human data concerning NETs in periodontitis.

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [7]. The protocol defined eligibility criteria, search strategy, study selection, data extraction, and risk-of-bias assessment, which was registered in the PROSPERO database (ID: CRD420251109174). The PRISMA 2020 checklist is provided as Supplementary Material S1.

The research question was structured according to the PICOS framework:

• Population (P): Human participants diagnosed with periodontitis, irrespective of disease stage or grade, as well as healthy controls, when included for comparison.

• Intervention/Exposure (I): Assessment of NETs or markers of NETosis in oral or systemic samples.

• Comparison (C): Healthy participants, gingivitis patients, or baseline/pre-treatment conditions.

• Outcomes (O): Detection, quantification, or characterization of NETs (e.g., extracellular DNA, citrullinated histones, MPO-DNA complexes, neutrophil elastase, NET-associated imaging).

• Study design (S): Ex vivo human studies (including tissue, gingival crevicular fluid, saliva, blood, or biofilm samples).

2.2 Eligibility and Exclusion Criteria

Exclusion criteria were: (i) in vitro cell culture studies, even if using human cells; (ii) animal studies; (iii) narrative or systematic reviews, case reports, conference abstracts, and letters; and (iv) studies not reporting original ex vivo data on NETs in periodontitis. In addition, eligible studies were required to include human-derived ex vivo samples (e.g., gingival tissue, gingival crevicular fluid, saliva, etc.) obtained from individuals diagnosed with periodontitis. Analyses had to be conducted outside the organism, ensuring a true ex vivo design. Studies addressing systemic or syndromic conditions were considered eligible only when they contained distinct subgroups of participants with periodontitis but without the systemic disorder, and when those subgroup data could be clearly distinguished and analysed separately.

2.3 Information Sources and Search Strategy

A comprehensive electronic search was performed in Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus up to August 2025. The search strategy combined medical subject headings (MeSH) and free-text terms related to “neutrophil extracellular traps”, “NETosis”, and “periodontitis”. Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were used in various combinations. No date restrictions were applied, and only studies published in English were considered. Reference lists of relevant articles were also screened manually to identify additional eligible studies, and a hand search was conducted in the Grey literature to identify any possible relevant articles that could not be obtained via electronic search. The detailed search strategies are provided as Supplementary Material S2.

Two independent researchers (SMA and MB) screened the titles of articles obtained from duplication-free data. Abstracts of articles were accessed if it could not be decided whether to be included or not as a result of the title review. Moreover, in cases where insufficient information was obtained from the abstracts, a full-text assessment of the studies was performed in terms of eligibility criteria. Where any discrepancies occurred, a third researcher (FM) was consulted to make the conclusive decision, and disagreements between the researchers were discussed until a consensus was reached.

Data extraction was independently performed by two reviewers (SMA and MB) using a standardized form. Extracted variables included: author and year of publication, study population, sample type (gingival tissue, gingival crevicular fluid [GCF], saliva, blood, biofilm), methods for NET detection, specific NET markers assessed, and main findings. All researchers have approved the final version of the extracted data, followed by the resolution of disagreements.

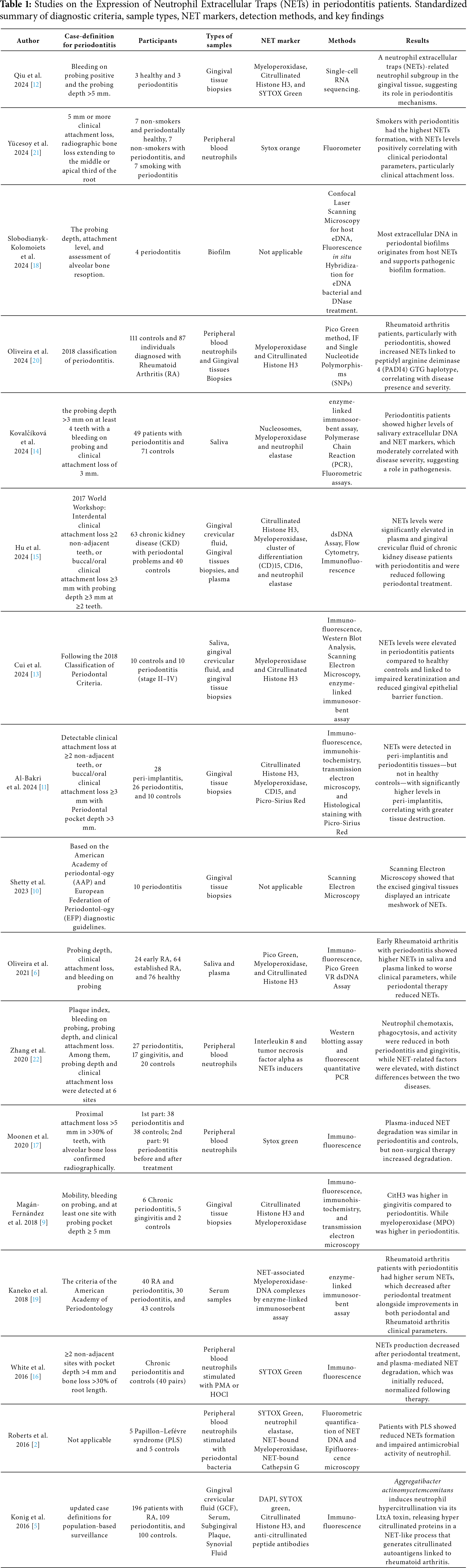

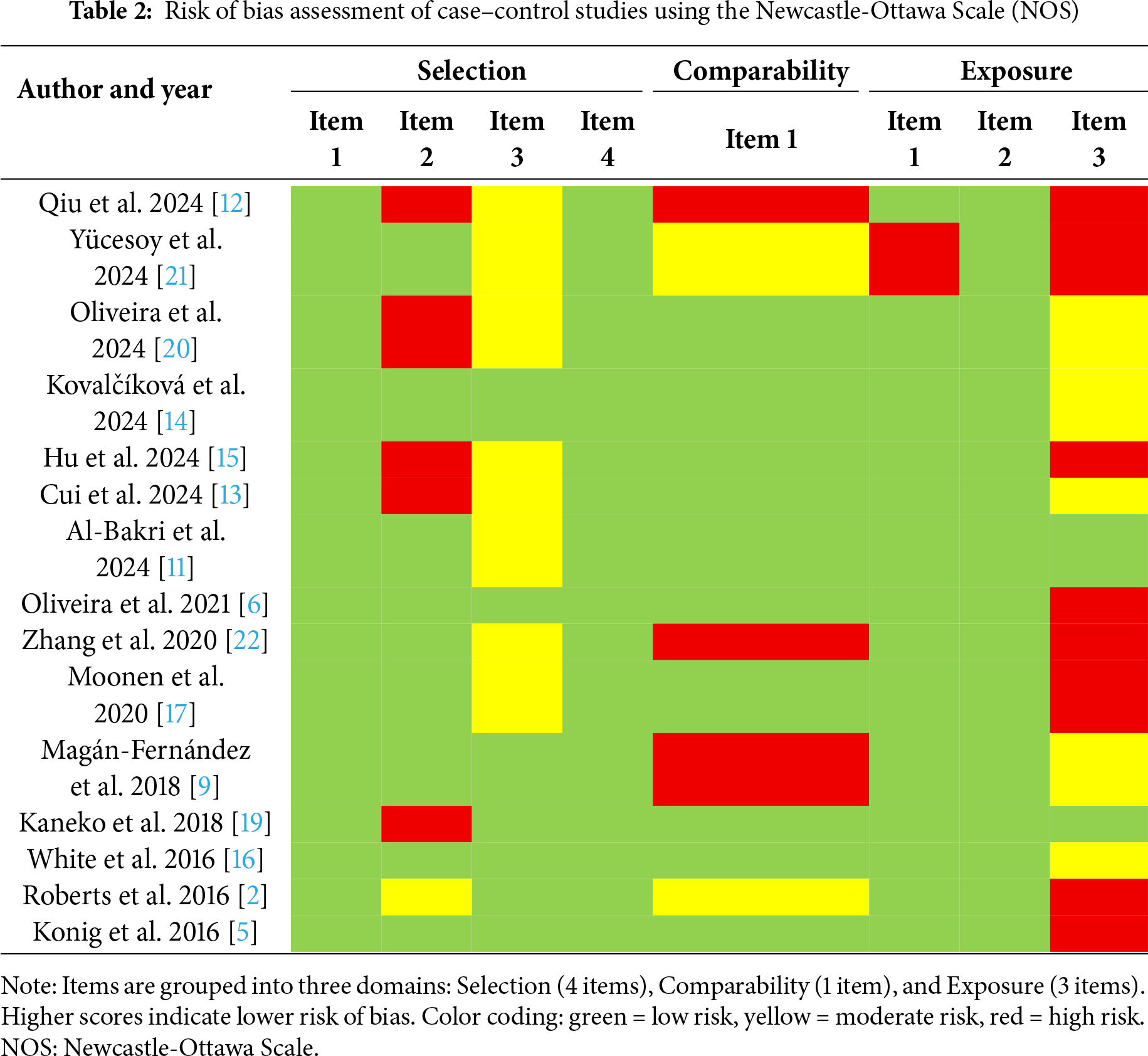

Two researchers (SMA and MB) independently performed the quality assessment of the selected studies, and consensus was reached in case of discrepancies. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was applied for the case–control studies [8], while the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist was used for the case series [9]. Domains were scored as green (low risk), yellow (moderate risk), or red (high risk). Total scores ≥7 indicated low risk of bias, while scores <7 were considered high risk.

3.1 Results of the Literature Search

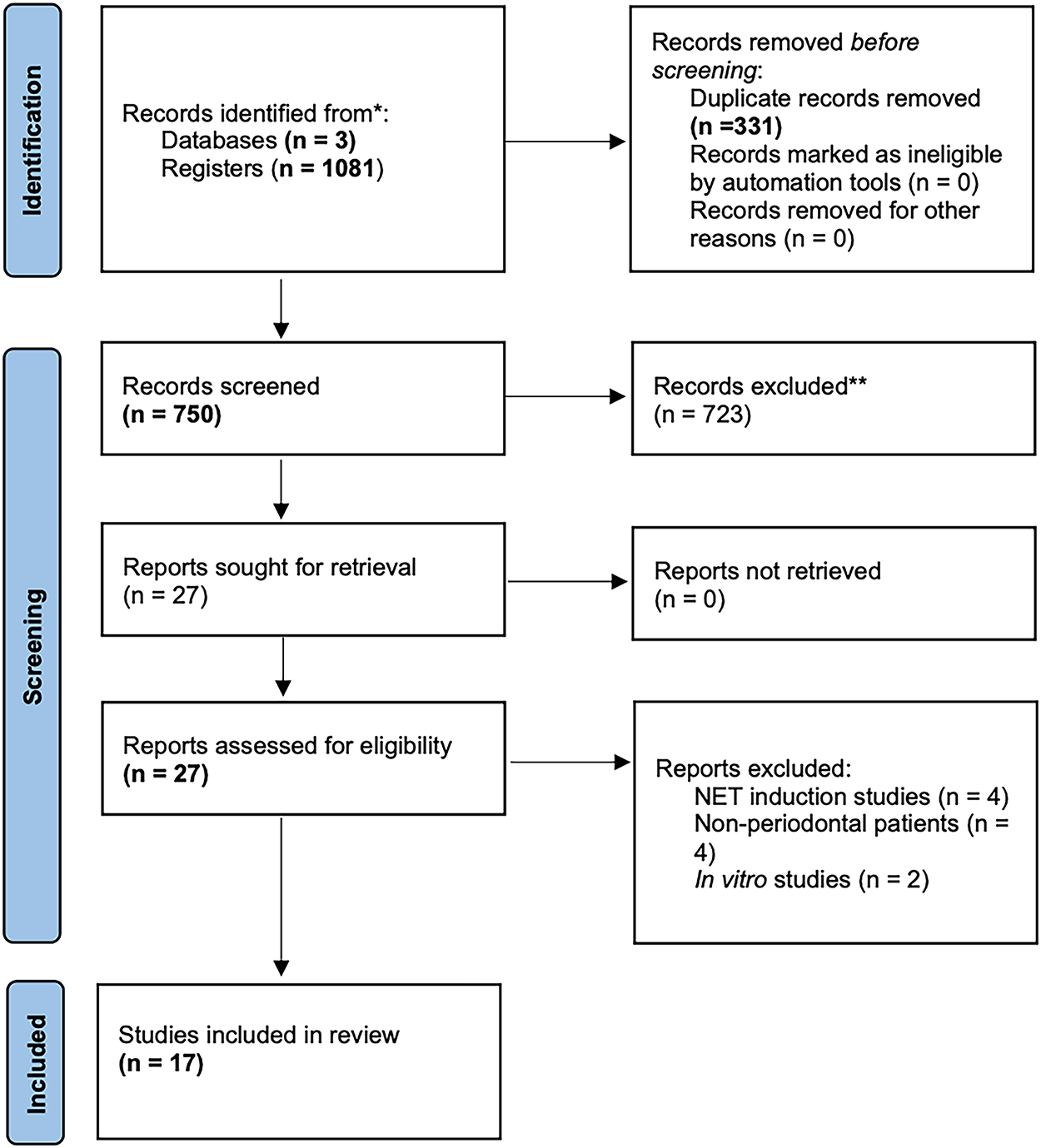

Following an online database search, 1081 records were retrieved. After removal of duplicates (n = 331), 750 records were screened at the title and abstract level. 17 articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the qualitative synthesis, presented in Table 1 [2,5,6,9–23]. Among the 17 included articles, two studies [2,5] involved mixed populations with systemic conditions. For these, only data referring to the periodontitis subgroups without systemic involvement were extracted and analyzed to preserve the homogeneity of the review. The study selection process is summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: PRISMA 2020 systematic review flowchart

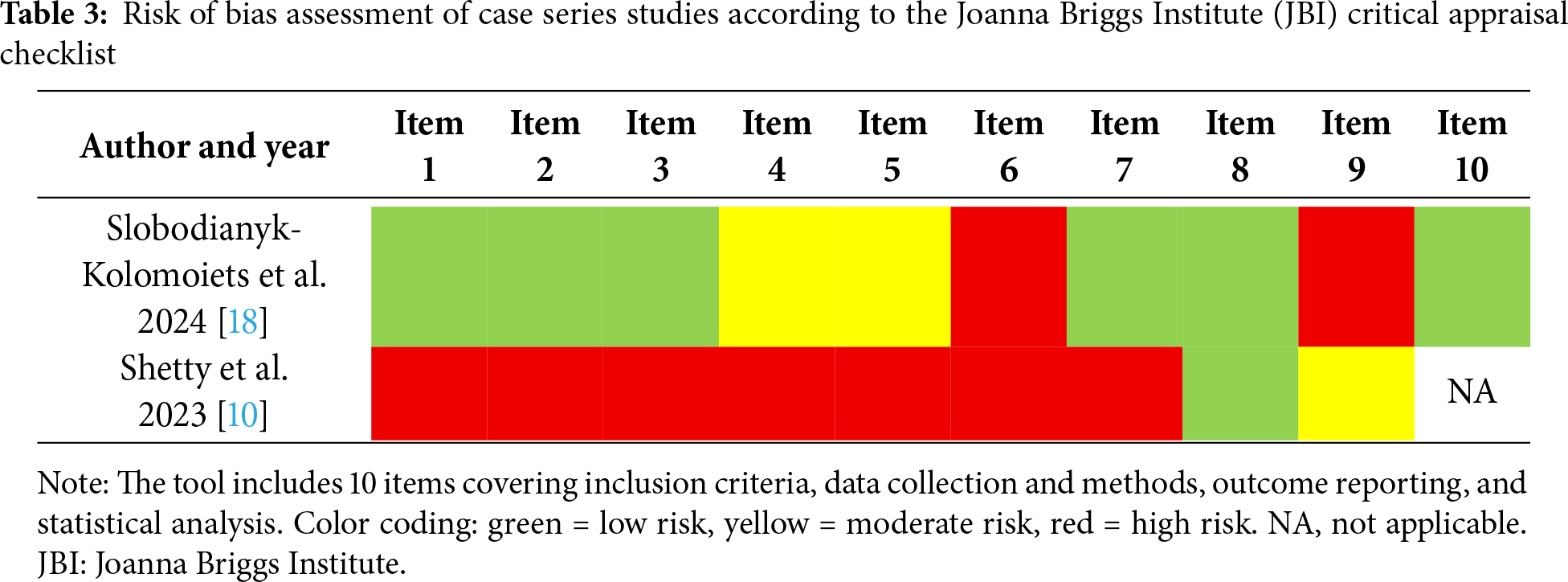

Sample sizes ranged from small pilot studies (<10 participants) to large cohorts (>100 participants), encompassing diverse ex vivo models. Gingival tissue was the most frequently analyzed sample (seven studies), followed by peripheral blood (six studies), saliva, and GCF. Table 1 presents standardized details for all included studies, including diagnostic criteria, sample type, NET markers, detection methods, and main outcomes. Across studies, NET markers such as citrullinated histone H3 (CitH3), MPO, neutrophil elastase (NE), and extracellular DNA were consistently elevated in periodontitis compared with healthy or gingivitis controls. Smoking and systemic comorbidities tended to amplify NET formation, correlating with greater clinical attachment loss.

Synthesis of Findings across Studies

The collective evidence from the 17 included ex vivo studies revealed a consistent pattern of upregulated NET formation or accumulation in periodontitis. Gingival tissue biopsies demonstrated increased CitH3 and MPO expression in diseased sites compared with healthy controls [9–11], confirming local NET deposition within inflamed tissues. GCF analyses showed elevated extracellular DNA and NET-associated proteins (CitH3, MPO, NE), which frequently declined after non-surgical periodontal therapy [15–17,19]. Saliva-based studies reported higher nucleosome and MPO concentrations correlating with probing depth and attachment loss [14]. Peripheral blood and plasma investigations revealed augmented NET release or reduced degradation capacity, both of which improved post-therapy [16,17]. Finally, biofilm studies identified host-derived NET DNA as a structural scaffold supporting pathogenic biofilm persistence [18].

Although the direction of findings was consistent, some variability emerged regarding CitH3 and MPO expression, potentially reflecting differences in disease stage, sampling site, or methodological approach (e.g., immunofluorescence [IF] vs. ELISA vs. microscopy). Collectively, these results indicate that NET dysregulation represents a unifying mechanism linking local periodontal inflammation, tissue destruction, and systemic immune responses.

Building upon the synthesis above, the methodological quality of the included studies was generally moderate. Most case–control designs achieved adequate scores in the Selection and Exposure domains, while Comparability was more frequently limited due to insufficient adjustment for confounders. Some studies presented unclear risk in participant selection and exposure ascertainment. Regarding case series, evaluated with the JBI tool, the risk of bias was generally moderate to high. The detailed results of the risk of bias assessment are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

This systematic review synthesizes, for the first time, the current body of ex vivo human evidence from 17 studies investigating the presence, activity, and clinical significance of NETs in periodontitis. The null hypothesis that NETs are not significantly associated with the pathogenesis or clinical expression of periodontitis is rejected. The collective findings provide a compelling narrative of NET dysregulation as a central feature of the disease, revealing a consistent pattern of aberrant NET formation and impaired clearance across a diverse array of biological samples. Crucially, the dynamic nature of this involvement is underscored by multiple studies demonstrating that successful periodontal therapy reduces NET levels or restores NET degradation capacity [15–17,19], positioning NETosis not merely as a static marker but as a responsive participant in the disease process.

4.1 The Dual Role of NETs: From Host Defense to Tissue Destruction

NETs exert a fundamentally dualistic effect within the periodontal microenvironment, embodying the paradox of neutrophil function in periodontitis. On one hand, they play an indispensable beneficial role in host defense by physically containing bacterial spread and creating a high-localized concentration of antimicrobial peptides that contribute to the elimination of periodontal pathogens [23]. This protective function represents the evolutionary rationale for NETosis and likely maintains periodontal homeostasis in health or mild inflammation. However, the synthesized evidence from the 17 reviewed studies demonstrates that in established periodontitis, this equilibrium is lost. The persistent microbial challenge and inflammatory milieu drive a transition where NETosis shifts from a protective mechanism to a pathogenic one [23]. The consistent finding of elevated NET markers across gingival tissues [9–12], GCF [13,15], and saliva [15] in periodontitis patients compared to controls indicates a state of sustained NET activation that exceeds physiological levels.

4.2 Synthesis of Evidence and Consistency across Compartments

The 17 included studies, despite their methodological diversity, present a remarkably coherent picture of NET involvement across different biological compartments. Gingival tissue biopsies provided direct histopathological evidence, with studies uniformly demonstrating intense immunostaining for CitH3 and MPO within the inflammatory infiltrate [9–12]. Complementing these findings, fluid-based analyses revealed elevated NET components in GCF and saliva that frequently correlated with clinical parameters of disease severity [13–15]. Perhaps most significantly, peripheral blood studies revealed a systemic neutrophil phenotype characterized by both enhanced NET release and impaired degradation capacity [16,17]. This dual defect—increased production and decreased clearance—creates conditions ideal for NET accumulation. The improvement in these parameters following periodontal therapy directly links clinical intervention to restored neutrophil homeostasis and suggests that systemic neutrophil dysregulation is driven by the periodontal inflammatory burden.

4.3 Analysis of Heterogeneity and Methodological Challenges

A critical finding of this review is the considerable methodological heterogeneity that characterizes the current literature. The included studies utilized diverse sample sources, detection techniques, and target NET markers. Immunofluorescence, while the most frequently employed technique, was used in only eight studies with substantial variation in antibody panels and protocols. This heterogeneity is not merely academic but has real consequences for interpretation. For instance, the conflicting findings regarding CitH3 levels between studies [5,9] may reflect genuine biological differences across disease stages or technical variations in detection sensitivity. Similarly, the focus on different NET components (DNA, histones, granular enzymes) across studies likely captures distinct aspects of the NETosis process, complicating direct comparisons. This variability underscores the urgent need for standardization in NET research, particularly as protocols and reagents for NET quantification in oral fluids like saliva and GCF become increasingly available.

4.4 NETs as Active Drivers of Periodontal Pathogenesis

Beyond their mere presence, the synthesized evidence positions NETs as active contributors to tissue destruction through multiple mechanisms. First, NET-derived DNA contributes to biofilm architecture by acting as a structural scaffold [18,24], creating a vicious cycle where neutrophils fortify the very biofilms they aim to eliminate. Second, NET-associated proteases, including MPO and elastase, degrade extracellular matrix components [9,25] and disrupt epithelial barrier function [26], representing direct pathways for tissue breakdown.

Third, NETs directly drive bone destruction through Interleukins (IL)-17/T helper cell (Th)17 pathway activation. Emerging evidence from mechanistic studies demonstrates that extracellular histones within NETs serve as key pathogenic factors that trigger IL-17-mediated osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. This pathway appears independent of microbiome alterations, positioning NETs as primary instigators of periodontal immunopathology rather than secondary responders [27,28].

This mechanism may be particularly relevant to the net bone loss characteristic of periodontitis. Fourth, the impaired clearance of NETs emerges as a critical pathogenic factor. Under physiological conditions, NETs are degraded by DNases and cleared by phagocytes [29], but in periodontitis, these mechanisms appear impaired [30]. The persistence of non-degraded NETs has been associated with the onset of immune disorders [31], perpetuating inflammation through continuous presentation of immunostimulatory molecules.

4.5 Molecular Mechanisms and Citrullination Pathways

The molecular underpinnings of NETosis in periodontitis involve sophisticated interactions with periodontal pathogens. NET formation depends on calcium influx and activation of peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 (PAD4) [32], a key enzyme in histone citrullination. Periodontopathogens like Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans actively manipulate this machinery [33,34], with the latter inducing hypercitrullination via its leukotoxin A [5]. This pathogen-induced citrullination generates citrullinated autoantigens that may breach immune tolerance. Beyond histones, the citrullination of neutrophil-derived chemokines like small inducible cytokine subfamily B (Cys-X-Cys), member 10 (CXCL10) can promote an immunosuppressive microenvironment and hamper microbial clearance [35], creating conditions favorable for chronic infection. The finding that polymorphisms in peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 (PADI4) modulate NET formation in periodontitis patients with rheumatoid arthritis [20] provides genetic evidence for the importance of this pathway in connecting oral infection to systemic autoimmunity.

4.6 Systemic Implications and the Oral-Gut-Brain Axis

The reviewed studies compellingly implicate NETs as a plausible biological link between periodontitis and systemic comorbidities. In patients with rheumatoid arthritis or chronic kidney disease, circulating NET levels increase in the presence of periodontitis and decline after periodontal therapy [36,37]. This pattern suggests that periodontal inflammation contributes to the systemic NET burden in these conditions. The connection may extend beyond traditional systemic diseases through the emerging concept of the Oral-Gut-Brain axis [38]. Periodontitis-associated oral dysbiosis can alter gut microbiome composition, triggering low-grade inflammation that amplifies systemic immune activation and potentially NETosis. This bidirectional communication allows oral bacteria and their products to reach distant sites, creating a dysbiotic inflammatory cycle that perpetuates systemic neutrophil activation and tissue destruction [38]. The implication is that NET dysregulation in periodontitis may have far-reaching consequences beyond the oral cavity.

However, this systematic review is subject to several limitations. The most significant constraint lies in the considerable methodological heterogeneity across the included studies, which varied substantially in sample sources (gingival tissue, GCF, saliva, peripheral blood), detection techniques (IF, ELISA, Western blot), and the specific NET markers analyzed (CitH3, MPO, NE, extracellular DNA). This variability precluded meta-analysis and complicated direct comparison of findings across studies. Furthermore, many studies featured small sample sizes and insufficient adjustment for key confounding factors known to influence NETosis, including smoking status, hyperglycemia, and systemic oxidative stress. The predominance of case-control designs limits causal inference, as the observed NET dysregulation could be either a cause or consequence of periodontal inflammation. Additionally, the lack of neutrophil-specific markers in some tissue-based studies raises the possibility of misidentifying macrophage extracellular traps as NETs.

In conclusion, ex vivo evidence indicates that aberrant NET formation and impaired clearance contribute to periodontal inflammation and tissue destruction. However, the current body of research remains limited, and the direct mechanistic role of NETs in periodontitis pathogenesis is not yet fully defined. Future studies with standardized methodologies and robust clinical correlations are essential to clarify whether NETs can serve not only as markers of disease activity but also as potential targets for innovative therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Marco Bonilla, Francisco Mesa; data collection: Antonio Magan-Fernández, Sarmad Muayad Rasheed Al-Bakri; analysis and interpretation of results: Marco Bonilla, Francisco Mesa, Antonio Magan-Fernández; draft manuscript preparation: Sarmad Muayad Rasheed Al-Bakri, Antonio Magan-Fernández, Francisco Mesa, Marco Bonilla. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/biocell.2025.073576/s1. Supplementary Material S1: The PRISMA 2020 checklist. Supplementary Material S2: The detailed search strategies.

References

1. Uriarte SM, Hajishengallis G. Neutrophils in the periodontium: interactions with pathogens and roles in tissue homeostasis and inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2023;314(1):93–110. doi:10.1111/imr.13152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Roberts H, White P, Dias I, McKaig S, Veeramachaneni R, Thakker N, et al. Characterization of neutrophil function in Papillon-Lefevre syndrome. J Leukoc Biol. 2016;100(2):433–44. doi:10.1189/jlb.5a1015-489r. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Liu S, Chen Y, Jiang Y, Du J, Guo L, Xu J, et al. The bidirectional effect of neutrophils on periodontitis model in mice: a systematic review. Oral Dis. 2024;30(5):2865–75. doi:10.1111/odi.14803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wang Z, Saxena A, Yan W, Uriarte SM, Siqueira R, Li X. The impact of aging on neutrophil functions and the contribution to periodontitis. Int J Oral Sci. 2025;17(1):10. doi:10.1038/s41368-024-00332-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Konig MF, Abusleme L, Reinholdt J, Palmer RJ, Teles RP, Sampson K, et al. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans-induced hypercitrullination links periodontal infection to autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(369):369ra176. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aaj1921. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Oliveira SR, de Arruda JAA, Schneider AH, Carvalho VF, Machado CC, Correa JD, et al. Are neutrophil extracellular traps the link for the cross-talk between periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis physiopathology? Rheumatology. 2021;61(1):174–84. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keab289. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):89. doi:10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa, ON, Canada: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2000. [Google Scholar]

9. Magan-Fernandez A, O’Valle F, Abadia-Molina F, Munoz R, Puga-Guil P, Mesa F. Characterization and comparison of neutrophil extracellular traps in gingival samples of periodontitis and gingivitis: a pilot study. J Periodontal Res. 2019;54(3):218–24. doi:10.1111/jre.12621. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Shetty S, Srigiri SK, Shetty K. The potential role of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETS) in periodontal disease—a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) study. Aims Mol Sci. 2023;10(3):205–12. doi:10.3934/molsci.2023014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Al-Bakri SMR, Magan-Fernandez A, Galindo-Moreno P, O’Valle F, Martin-Morales N, Padial-Molina M, et al. Detection and comparison of neutrophil extracellular traps in tissue samples of peri-implantitis, periodontitis, and healthy patients: a pilot study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2024;26(3):631–41. doi:10.1111/cid.13325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Qiu W, Guo R, Yu H, Chen X, Chen Z, Ding D, et al. Single-cell atlas of human gingiva unveils a NETs-related neutrophil subpopulation regulating periodontal immunity. J Adv Res. 2025;72(4):287–301. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2024.07.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Cui Y, Yang Y, Zheng J, Ma H, Han X, Liao C, et al. Elevated neutrophil extracellular trap levels in periodontitis: implications for keratinization and barrier function in gingival epithelium. J Clin Periodontol. 2024;51(9):1210–21. doi:10.1111/jcpe.14025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Kovalcikova AG, Novak B, Roshko O, Kovalova E, Pastorek M, Vlkova B, et al. Extracellular DNA and markers of neutrophil extracellular traps in saliva from patients with periodontitis—a case-control study. J Clin Med. 2024;13(2):468. doi:10.3390/jcm13020468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Hu S, Yang R, Yang W, Tang J, Yu W, Zhao D, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in the cross-talk between periodontitis and chronic kidney disease. BMC Oral Health. 2024;24(1):1357. doi:10.1186/s12903-024-05071-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. White P, Sakellari D, Roberts H, Risafi I, Ling M, Cooper P, et al. Peripheral blood neutrophil extracellular trap production and degradation in chronic periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43(12):1041–9. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Moonen CG, Buurma KG, Faruque MR, Balta MG, Liefferink E, Bizzarro S, et al. Periodontal therapy increases neutrophil extracellular trap degradation. Innate Immun. 2020;26(5):331–40. doi:10.1177/1753425919889392. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Slobodianyk-Kolomoiets M, Khlebas S, Mazur I, Rudnieva K, Potochilova V, Iungin O, et al. Extracellular host DNA contributes to pathogenic biofilm formation during periodontitis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1374817. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2024.1374817. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Kaneko C, Kobayashi T, Ito S, Sugita N, Murasawa A, Nakazono K, et al. Circulating levels of carbamylated protein and neutrophil extracellular traps are associated with periodontitis severity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot case-control study. PLoS One. 2018;13(2):e0192365. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0192365. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Oliveira SR, de Arruda JAA, Schneider AH, Bemquerer LM, de Souza RMS, Barbim P, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis: contribution of PADI4 gene polymorphisms. J Clin Periodontol. 2024;51(4):452–63. doi:10.1111/jcpe.13921. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Yücesoy G, Olgun E, Yıldız K, Göksuluk MB. Evaluation of neutrophil extracellular trap formation on smokers and non-smokers with periodontitis. Meandros Med Dent J. 2024;25(2):195–208. [Google Scholar]

22. Zhang F, Yang X, Jia S. Characteristics of neutrophil extracellular traps in patients with periodontitis and gingivitis. Braz Oral Res. 2020;34(1):e015. doi:10.1590/1807-3107bor-2020.vol34.0015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Retter A, Singer M, Annane D. "The NET effect": neutrophil extracellular traps—a potential key component of the dysregulated host immune response in sepsis. Crit Care. 2025;29(1):59. doi:10.1186/s13054-025-05283-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Hawkins CL, Davies MJ. Role of myeloperoxidase and oxidant formation in the extracellular environment in inflammation-induced tissue damage. Free Radic Biol Med. 2021;172(13):633–51. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2021.07.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Keskin M, Kompuinen J, Harmankaya İ, Karaçetin D, Nissilä V, Gürsoy M, et al. Oral cavity calprotectin and lactoferrin levels in relation to radiotherapy. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2022;44(10):4439–46. doi:10.3390/cimb44100304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Hiyoshi T, Domon H, Maekawa T, Tamura H, Isono T, Hirayama S, et al. Neutrophil elastase aggravates periodontitis by disrupting gingival epithelial barrier via cleaving cell adhesion molecules. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):8159. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-12358-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Lu F, Verleg SMNE, Groven RVM, Poeze M, van Griensven M, Blokhuis TJ. Is there a role for N1-N2 neutrophil phenotypes in bone regeneration? A systematic review. Bone. 2024;181(117021):117021. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2024.117021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Azzouz D, Khan MA, Palaniyar N. ROS induces NETosis by oxidizing DNA and initiating DNA repair. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7(1):113. doi:10.1038/s41420-021-00491-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Demkow U. Molecular mechanisms of neutrophil extracellular trap (NETs) degradation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(5):4896. doi:10.3390/ijms24054896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Vitkov L, Knopf J, Krunić J, Schauer C, Schoen J, Minnich B, et al. Periodontitis-derived dark-NETs in severe Covid-19. Front Immunol. 2022;13:872695. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.872695. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Hakkim A, Furnrohr BG, Amann K, Laube B, Abed UA, Brinkmann V, et al. Impairment of neutrophil extracellular trap degradation is associated with lupus nephritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(21):9813–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.0909927107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wang H, Kim SJ, Lei Y, Wang S, Wang H, Huang H, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps in homeostasis and disease. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):235. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01933-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Chen J, Tong Y, Zhu Q, Gao L, Sun Y. Neutrophil extracellular traps induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide modulate inflammatory responses via a Ca2+-dependent pathway. Arch Oral Biol. 2022;141(6):105467–7. doi:10.1016/j.archoralbio.2022.105467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Engström M, Eriksson K, Lee L, Hermansson M, Johansson A, Nicholas AP, et al. Increased citrullination and expression of peptidylarginine deiminases independently of P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans in gingival tissue of patients with periodontitis. J Transl Med. 2018;16(1):214. doi:10.1186/s12967-018-1588-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Bonilla M, Martín-Morales N, Gálvez-Rueda R, Raya-Álvarez E, Mesa F. Impact of protein citrullination by periodontal pathobionts on oral and systemic health: a systematic review of preclinical and clinical studies. J Clin Med. 2024;13(22):6831. doi:10.3390/jcm13226831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Shahbaz M, Al-Maleki AR, Cheah CW, Aziz J, Bartold PM, Vaithilingam RD. Connecting the dots: NETosis and the periodontitis-rheumatoid arthritis nexus. Int J Rheum Dis. 2024;27(11):e15415. doi:10.1111/1756-185x.15415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Irwandi RA, Chiesa ST, Hajishengallis G, Papayannopoulos V, Deanfield JE, D’Aiuto F. The roles of neutrophils linking periodontitis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. Front Immunol. 2022;13:915081. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.915081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Sansores-España LD, Melgar-Rodríguez S, Olivares-Sagredo K, Cafferata EA, Martínez-Aguilar VM, Vernal R, et al. Oral-Gut-Brain axis in experimental models of periodontitis: associating gut dysbiosis with neurodegenerative diseases. Front Aging. 2021;2:781582. doi:10.3389/fragi.2021.781582. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools