Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

VMFD: Virtual Meetings Fatigue Detector Using Eye Polygon Area and Dlib Shape Indicator

1 Key Laboratory for Ubiquitous Network and Service Software, School of Software, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian, 116024, China

2 College of Engineering, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, 11533, Saudi Arabia

3 Institute of Human-Centred Computing (HCC), Graz University of Technology, Inffeldgasse 16c, Graz, 8010, Austria

4 School of Computing, Gachon University, Seongnam-si, 13120, Republic of Korea

5 Faculty of Engineering, Uni de Moncton, Moncton, NB E1A3E9, Canada

6 School of Electrical Engineering, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, 2006, South Africa

7 Research Unit, International Institute of Technology and Management (IITG), Av. Grandes Ecoles, Libreville, BP 1989, Gabon

* Corresponding Authors: Sghaier Guizani. Email: ; Ateeq Ur Rehman. Email:

Computers, Materials & Continua 2026, 86(3), 25 https://doi.org/10.32604/cmc.2025.071254

Received 03 August 2025; Accepted 06 October 2025; Issue published 12 January 2026

Abstract

Numerous sectors, such as education, the IT sector, and corporate organizations, transitioned to virtual meetings after the COVID-19 crisis. Organizations now seek to assess participants’ fatigue levels in online meetings to remain competitive. Instructors cannot effectively monitor every individual in a virtual environment, which raises significant concerns about participant fatigue. Our proposed system monitors fatigue, identifying attentive and drowsy individuals throughout the online session. We leverage Dlib’s pre-trained facial landmark detector and focus on the eye landmarks only, offering a more detailed analysis for predicting eye opening and closing of the eyes, rather than focusing on the entire face. We introduce an Eye Polygon Area (EPA) formula, which computes eye activity from Dlib eye landmarks by measuring the polygonal area of the eye opening. Unlike the Eye Aspect Ratio (EAR), which relies on a single distance ratio, EPA adapts to different eye shapes (round, narrow, or wide), providing a more reliable measure for fatigue detection. The VMFD system issues a warning if a participant remains in a fatigued condition for 36 consecutive frames. The proposed technology is tested under multiple scenarios, including low- to high-lighting conditions (50–1400 lux) and both with and without glasses. This study builds an OpenCV application in Python, evaluated using the iBUG 300-W dataset, achieving 97.5% accuracy in detecting active participants. We compare VMFD with conventional methods relying on the EAR and show that the EPA technique performs significantly better.Keywords

A team of professionals might be seen convening around a conference table, engaging with a presentation and subsequently conducting a thorough analysis of projects before the year 2020. However, in 2020, the outbreak of the Coronavirus pandemic led to a substantial deviation from traditional office culture, prompting a transition for most sectors to a virtual environment, which persisted even after the pandemic [1]. People have gradually evolved into digital natives because of the extensive use of online meetings, chats, and screen-sharing devices. In today’s academic world, many researchers and educators are leveraging the benefits of virtual meetings with their students [2,3]. The requirement to organize remote conferences for students utilizing video calling, whiteboards, screen sharing, recording, and numerous other tools is a key feature that aligns with virtual meetings.

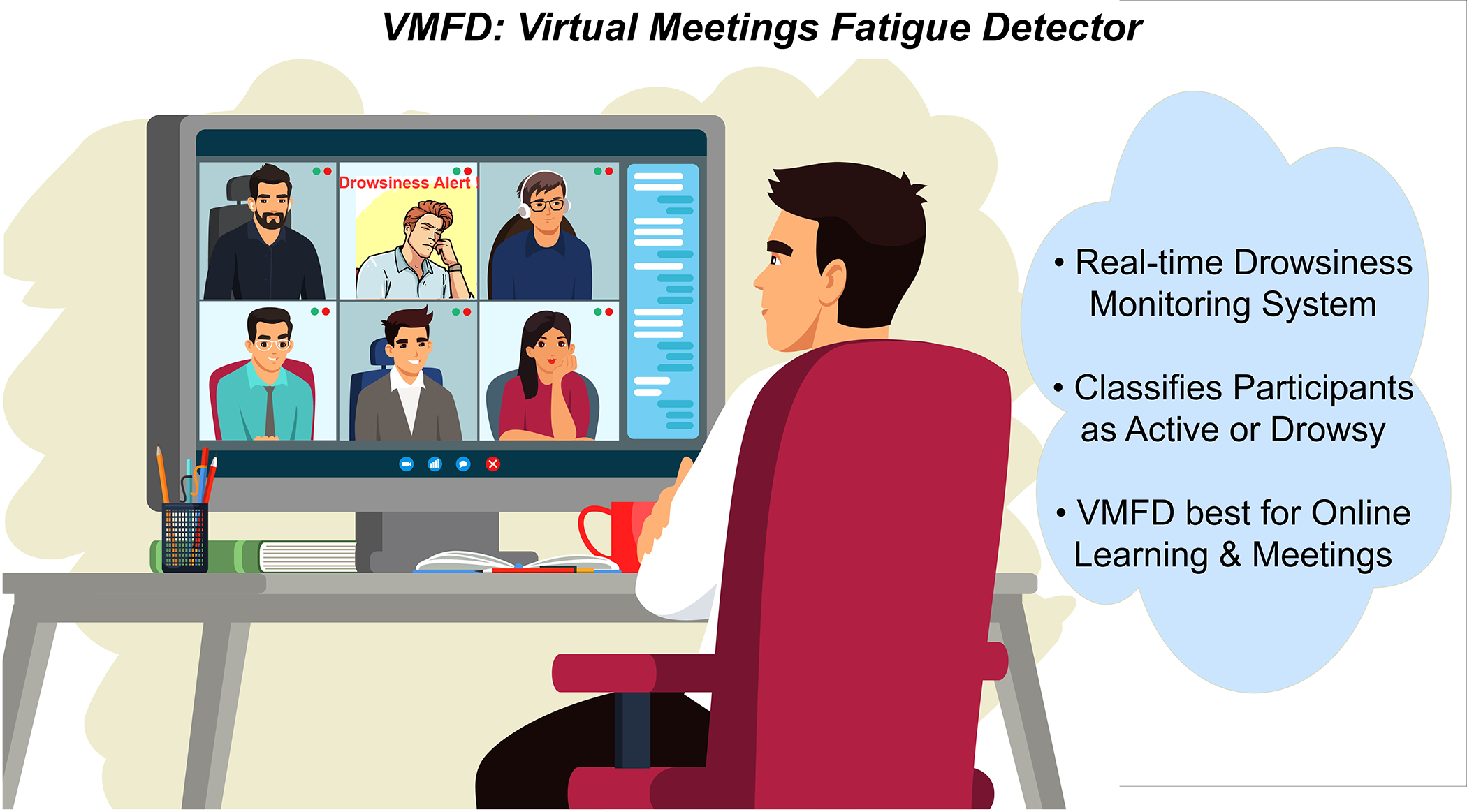

In this research, we focus on online meetings, specifically analyzing the active and inactive state of the participants as shown in Fig. 1. During virtual meeting, the participant must remain attentive. Adequate rest is a fundamental necessity, as fatigue can impede the participants learning abilities. Lack of sleep makes the body weak and unintentionally, it makes the person lose concentration which leads to subpar performance. Several studies rely on traditional machine learning approaches to classify engagement and fatigue. The researcher has focused on developing software that helps participants stay attentive during virtual meetings. Technology has enabled educators to monitor the activities of their students and their participation in online classrooms as part of the global initiative to enhance education [4]. This study investigates attention to the geometric angles of student faces collected using learning devices. Support Vector Machines (SVM), K-Nearest Neighbor, and Random Forest are machine learning techniques that have successfully classified active and inactive students. The results suggested that the proposed model attained a high accuracy level of 90% through a random forest classifier. Additionally, using 35 points on the face as landmarks, they plotted 26 angles using machine learning methods.

Figure 1: System detects active and drowsy participants in online meetings

Another stream of research uses facial landmark–based methods, often relying on the EAR. Numerous instances exist where organizations implement facial landmark algorithms for eye blink detection beyond academic settings. There is a research that suggets an approach for measuring drowsiness in assembly activities by calculating the EAR, operator posture, and the duration of operation [5]. The study is made easier by creating and recording assembly activities from top, side, and front angles. The frontal view facilitates the examination of the person’s eyes to assess drowsiness. They employed the calculation of EAR and detected drowsiness through 30 consecutive frames per second (FPS). In addition to login verification, Eblink secures login passwords, card information, and identifying details [6]. The data are encrypted to mitigate the risk of leakage. Unlocking encrypted data requires blinking. A proper eye blink count unlocks and displays the information.

More recent works apply computer vision and deep learning frameworks for engagement detection. The facial analysis algorithms on webcam footage to track the engagement levels of students in e-learning represents an innovative strategy [7]. Daza et al. trained, analyzed, and compared their system with the public mEBAL2 database collected in an e-learning environment. OpenFace and GAST-Net frameworks are employed to detect faces and postures in online lectures [8]. Afterwards, they used this data to extract areas around the eyes and mouth, the angle of sight, the shoulder, and the neck. XGBoost and random forest have been trained to identify online lecture disruptions. This research demonstrates a computer vision system that uses Dlib face landmarks and You Only Look Once (YOLO) models to detect students’ aberrant behavior during tests [9]. The system identifies objects, faces, sideways staring, hand, and mouth movements, and cellphone use.

Although numerous approaches for fatigue detection in virtual environments have been developed, most rely on conventional metrics such as the EAR or on full-face landmark analysis. These methods suffer from several limitations: (i) their accuracy decreases in challenging scenarios such as low illumination or when participants wear glasses; (ii) they are sensitive to variations in eye geometry, since EAR uses only linear distance ratios and does not generalize well to different eye shapes; and (iii) they often require processing of the entire facial region, which increases computational complexity without necessarily improving detection accuracy. These drawbacks motivated our work. The proposed EPA captures the polygonal eye-opening area using only local eye landmarks, enabling the system to remain robust across different eye shapes, and participant variations while reducing computational cost.

Virtual meetings are becoming increasingly common in both academics and industry these days. This study aims to develop a system that can identify when participants are fatigued, to prevent them from becoming too sedentary. This study focuses on individuals who wear glasses and participate in meetings under low light conditions, rather than examining typical meeting scenarios. This paper has rigorously examined the proposed system across all possible scenarios. This paper ultimately contrasts the proposed system with a state-of-the-art system. This paper makes the following contributions.

1. The main objective is to create an EPA function that the proposed system can utilize for real-time video processing. The EPA approach outperforms the conventional eye aspect ratio calculation when it comes to determining the eye region.

2. This research primarily focuses on the area surrounding the eyes. The system utilizes dlib to detect facial landmarks that serve as possible boundaries for the eyes, while the EPA method is implemented to determine the eye region. The system issues a warning if the eyes fail to recognize an active condition for 36 consecutive frames.

3. This paper rigorously evaluates the proposed system across a comprehensive range of scenarios, including meetings conducted in low light and participants who wear glasses. To achieve the proposed system goal, an OpenCV application has been developed that detects participants’ fatigue with 97.5% accuracy.

The following is the structure of the paper: Section 2 outlines the literature, and Section 3 describes the proposed methodology. Section 4 discusses the experimental outcomes of the designed system. The concluding Section 5 wraps up the paper and offers direction for future research in light of the identified limitations.

Analysts have proposed many strategies for detecting students fatigue using various algorithms [10]. Students exhibit a favorable disposition and engage actively in online learning; the findings of this study aids educators in enhancing online classroom instruction for their students [11]. The studies detect face regions to evaluate the fatigue of participants in the virtual meetings [12]. Most of the researchers has alerted the participents by combining the mouth and ocular features to warn of tiredness [13,14]. There is an alternate method for identifying learning tiredness in students that uses optical and infrared images [15]. The results of the tests demonstrated that the accuracy rate of each system differs depending on the environment in which it tested. Online meetings are becoming increasingly popular in industries outside of academia due to the considerable savings in travel costs and time when compared to in-person gatherings.

The eye blinking influences the electrical potential produced by the movement of the eyelid when electrodes are worn [16]. Electrooculography (EOG) is a widely recognized phenomenon due to its ability to operate at a high frame rate. The potential distribution between the EOG electrodes measured the natural blinking of the eye [17]. Researchers have employed various electrodes positioned near the eye to monitor blinking, specifically utilizing EOG signal [18]. The researcher performed experiments using electrodes and employing the facial landmark technique [19]. The accuracy rate achieved was 92.33% with facial landmarks, in contrast to a 91.68% rate obtained through electroencephalogram (EEG).

Online class participation is categorized using SVM that gave results with 72.4% accuracy [20]. Researchers designed a system utilizing machine learning techniques to monitor students’ tiredness in real-time [21]. This study presents an approach to monitor students’ slumbering, secretive cellphone use, and distraction in online classrooms using a time series analysis of eye movement data obtained from a Dlib-based facial landmark detection model [22]. This study presents and develops an attention recognition technique that uses gaze orientation analysis in time to help students better manage their own learning, make online learning more successful, and provide insight into how each student learns. Similarly, deep learning-based invigilation systems have been proposed to detect suspicious behaviors during examinations such as head movements or whispering using models like Faster Region-based Convolutional Neural Network and Multi-task Cascaded Convolutional Neural Network (MTCNN), achieving over 98% testing accuracy in real-time scenarios [23].

Fatigue detection plays a critical role in enhancing precautions across various domains, including transportation and healthcare [24]. This research introduces an ongoing system developed for the detection of tiredness, utilizing the EAR alongside facial landmark detection methodologies [25]. The suggested application captured the students’s real-time video [26–28]. The video frame provided an EAR using facial landmarks to determine students drowsiness based on a threshold. The Dlib library employed the inherent face identifier based on oriented gradient changes. The suggested method for predicting student engagement in online classes utilizes three types of behavior based on real-time video feed assessment, including facial expressions, head movement, and eye blink frequency [29].

Recently, video advertisements are disseminated across various online websites and watched by countless audiences globally. Major companies assess the appeal and buying goal of their advertisements by examining the facial reactions of participants who participated online to view the promotional materials from their homes or workplaces. A researcher presents a framework for tracking viewer engagement during online advertisements by analyzing facial expressions, head orientation, and eye direction [30]. Seeing faces in meetings is essential for effectively generating innovative solutions involving several team members [31]. Two sections of the given research determine how focused students are when learning online [32]. In the first part, they build an algorithm to count the number of times an eye blinks and how long each blink lasts. In the second part, they deal with emotion recognition.

Although numerous approaches have been developed for drowsiness and fatigue detection in virtual settings, most rely heavily on traditional geometric models such as the EAR and combine facial features like the mouth and eyes. These methods often suffer from reduced accuracy in non-ideal environments such as low-light conditions or when participants wear glasses. Moreover, existing systems typically analyze the full facial structure, which increases computational complexity without necessarily improving precision.

Several studies have proposed adaptive thresholds or hybrid models to enhance online engagement monitoring, yet these methods are not robust across diverse scenarios or do not offer lightweight solutions for real-time application. Additionally, while some prior works have explored machine learning classifiers for engagement recognition, few have integrated precise region-specific metrics such as the EPA derived from Dlib facial landmarks.

This research addresses these gaps by introducing a lightweight, eye-focused metric EPA that enables robust fatigue detection even in challenging visual conditions. The VMFD system is distinguished by its adaptability to users wearing glasses, performance under low-light scenarios, and accurate detection using only eye-region data, significantly reducing the need for full-face processing. Furthermore, the system has been validated across diverse real-world scenarios, unlike many prior studies that rely solely on controlled datasets.

Most previous research papers focused on facial landmark detection and eye aspect ratio [33,34,28]. Furthermore, the main goal of this study is to build an EPA function and use it to forecast eye regions in continuous video. The “Dlib shape predictor” is a Dlib library component used for facial landmark detection in this research. It works by detecting and localizing key facial landmarks, such as the corners of the eyes, nose, and mouth, in images or video frames. The proposed system uses the Dlib shape predictor in Python by first loading a pre-trained facial landmark detection model. This model is provided a file as “shape_predictor_68_face_landmarks.dat”. Additionally, this research uses the dlib.shape_predictor class to create an instance of the shape predictor by passing the path to the pre-trained model file as an argument. After creating the face shape predictor object, the proposed system uses it to detect facial landmarks in video frames by calling its predict() method, and passing the video frame as input. This method returns a collection of points representing the locations of the detected facial landmarks.

The methodology of VMFD is structured around three core elements. First, we implement a novel EPA function, derived from 12 eye landmarks, which replaces the conventional EAR. Second, the system leverages Dlib’s shape predictor focused on the eye region only, enabling a real-time fatigue detection process where a 36-frame threshold triggers a warning. Third, to validate robustness, we design experiments across multiple conditions including low to high light environments and participants with and without glasses. These contributions form the foundation of the following subsections, where dataset choice, camera setup, EPA computation, and system implementation details are described.

The methodology of VMFD follows a step-by-step flow, beginning with dataset overview, followed by system setup, model training with hyperparameters, EPA calculation, and finally the alert mechanism.

Different types of data sets have been employed to train different frameworks; in this study, the iBUG 300–W dataset is employed for experimental purposes [35–37]. This dataset has 68 distinct spots marked on the face, and each point defines x and y coordinate values. The iBUG 300–W dataset contains 7764 photos, and researchers annotated 68 locations on certain pictures in the collection with extraordinary attention to detail. The proposed system model has been trained on 6211 photos and, after that, utilized the rest of the 1553 photos for testing purposes. The 68 pair points on the face can be predicted by any model trained on the iBUG 300–W, and any face feature can be constrained. The goal is to localize the eye region’s position solely rather than the entire face. This increases accuracy while also quickening model calculations and operations. We selected iBUG 300-W over other available datasets because it provides large-scale, in-the-wild facial images with variability in pose, illumination, and occlusion (e.g., glasses). This diversity ensures better generalization of the proposed system to real-world meeting scenarios. After selecting the dataset, the next step involves describing the hardware and camera setup used for real-time implementation.

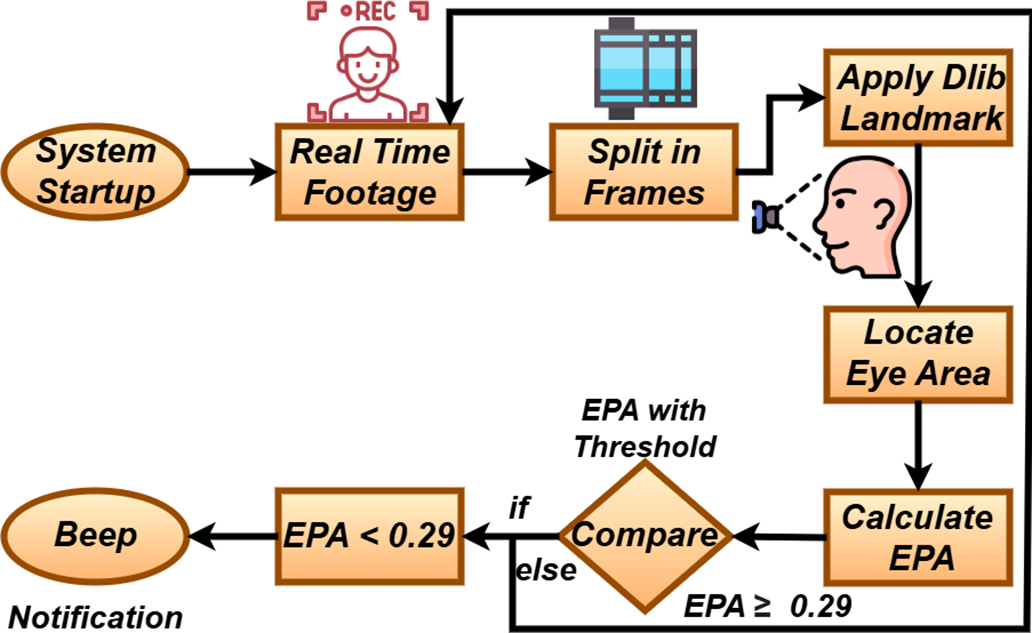

Python is used to create the system. The framework uses the built-in 6MP webcam of an HP ProBook 440 G5 laptop, a cost effective and reliable camera, to capture live footage. The camera utilizes a resolution of six megapixels while maintaining image clarity. The efficacy of the fatigue detection system is initially evaluated on a Dell Vostro 14 3468 personal computer equipped with a 7th generation Core i7 processor operating at 2.70 GHz, 8 GB RAM, and a 500 GB hard drive. As previously said, the camera captures an image in a few seconds. A frame-by-frame montage is used in this real-time video. The quantity of frames that occur in a second is called FPS. Assuming that a second is divided into 24 frames, the camera’s FPS is 24. It indicates a sleepiness-detecting system that takes 1.5 s to sound an alarm. The technology designed to detect inactivity necessitated 36 successive frames of a fatigued person before triggering an alarm. The VMFD system is hardware-independent since it relies only on frame-based processing. It can be generalized to other cameras with different FPS by proportionally adjusting the frame threshold (1.5 s of continuous closure, independent of FPS). Thus, the method is not restricted to a specific device. The current VMFD system assumes single-participant monitoring under frontal face conditions. While we validated robustness across lighting variations (50–1400 lux), with/without glasses, and on different laptop cameras, the present version does not explicitly address large head movements, partial occlusions (e.g., hand over face, hair), or multi-participant scenarios. These cases are acknowledged as limitations and are highlighted in the future work section. Fig. 2 demonstrates the workflow of the system. With the system hardware and camera defined, we now explain the model training process and the hyperparameters used to fine-tune Dlib for eye landmark detection.

Figure 2: Workflow of the virtual meetings fatigue detection system

3.3 Core Notion of Model Training

This study aims to predict the location of the eyes rather than the entire face. Performing computations and operations on a subset of a set is a more straightforward approach than conducting them on the entire set. We use the Dlib facial landmark predictor and select the 12 eye-region points. Thus, we constrain all computations to these eye landmarks rather than processing all 68 face landmarks. This approach leverages Dlib’s pre-trained detector to identify ocular landmarks and then applies our analysis exclusively to those points, enabling the calculation of the proposed EPA for improved drowsiness detection. The model that has been developed predicts the location of the eye region with simplicity after training on iBUG-300-W dataset. During the training of the Dlib shape predictor for the eye region, the proposed system has been tuned with hyperparameters. The value of the hyperparameter called cascade_depth is directly proportional to the accuracy rate of facial landmarks drawn on the face. The cascade_depth 13 has contoured the face accurately. The oversampling_amount hyperparameter solved the problem of data augmentation caused by the Dlib. The num_threads hyperparameter has trained the model quickly. These hyperparameters are chosen empirically during model tuning on the iBUG 300-W dataset. A cascade depth of 13 provided stable landmark fitting without overfitting, oversampling_amount improved robustness by augmenting underrepresented samples, and num_threads has set to fully utilize available CPU cores for faster training. This configuration balanced accuracy and efficiency, achieving optimal eye landmark detection for EPA calculation.

It is important to note that the Dlib shape predictor is based on an ensemble of regression trees rather than a neural network. Therefore, concepts such as training epochs, stochastic optimizers, and conventional learning rates are not directly applicable. Instead, hyperparameters like cascade_depth = 13, oversampling_amount = 300, and nu = 0.05 serve roles analogous to epochs and learning rate in boosting frameworks. These parameters, tuned empirically on the iBUG 300-W dataset, governed model accuracy and efficiency and ensured optimal eye landmark detection. Once the model training and hyperparameter tuning are completed, the next stage is locating the eye boundary to support EPA calculation.

3.4 Process of Locating Eye Boundary

In real-time video, the box represents the coordinates of the face’s border area. To observe how it sets limits of face, consider four credits of rectangle. The first one is related to the upper bound, which is defined by the rectangular box’s initial y-coordinate value. The initial x-coordinate value defines the left corner of the rectangular box as the second credential. In contrast, the rectangular box’s height is the third credential, and the last and the fourth credential is the rectangular box’s width. The dataset contains a rectangular component with 68 points corresponding to the (x, y) coordinates of the facial landmark predictor. Each part component is assigned three credits. The first is the name of a distinct anatomical feature on the face, the second is a number of the x-coordinate at the specified point, and the last and third credit is the numerical representation of the y-coordinate. The framework is created with Python’s built-in functions. Command-line options are parsed using the argparse parsing module of Python. The parsing component has been sent as an argument, and the argparse function parses it using the command-line parameter. The framework requires two command-line parameters, processed as input and output. A 68–point XML file is used as the input command-line option.

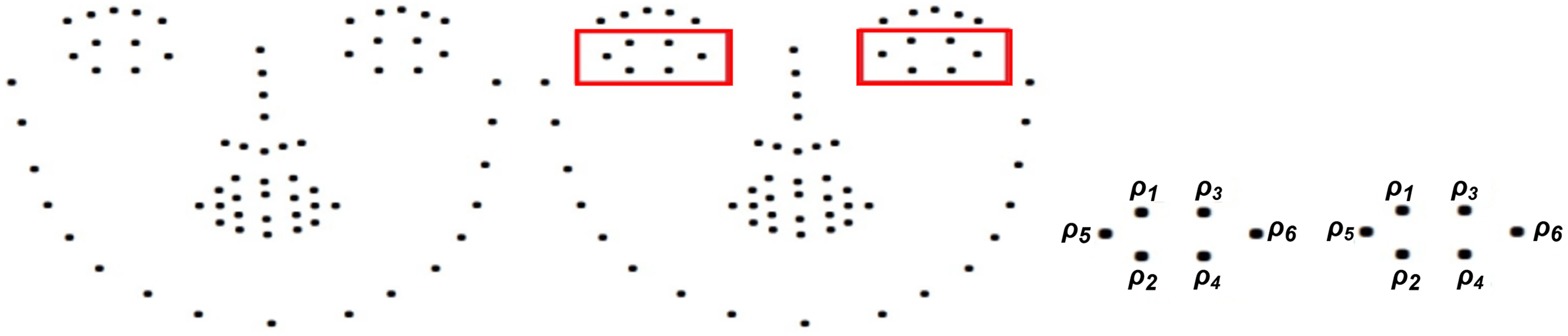

The identification of facial landmarks encompasses a total of 68 distinct points located on various regions of the face. The eye region comprises 12 out of the total 68 landmarks. The six points about the right eye and the remaining six points indicate the precise position of the left eye. The list of landmarks is modified using argparse, and then the parsing technique is applied to extract twelve points situated around the eye region. Upon implementing Python’s argparse function, the resulting command-line option includes an additional XML file that contains solely twelve eye points. The re library in Python is utilized for tasks such as pattern recognition and sequence comparisons in matching regular expressions. The input comprises 68 XML files that contain facial landmarks. Utilizing the Python package for regular expressions, iterate through the rows and verify whether the present row comprises a segment component. Further parsing is required in the presence of a segment component. The attribute name is derived from this section.

Subsequently, it is imperative to devise a shape indicator to delimit the scope of observation for the presence of the name within the facial landmark. If the condition mentioned above holds, the designated row shall be incorporated into the resultant file. Conversely, if the condition is not met, the specified name shall be omitted as it does not meet the necessary criteria. If a segment component is absent, the appropriate action would be to return the line to the XML file. Additionally, the training and testing procedures are conducted solely on a novel file containing 12 eye region pair points, in contrast to the complete facial dataset provided by the iBUG 300–W (68 pair points facial landmark). Identify the left and right eye segments after extracting the ocular region. Once an eye has been located, the next step is to determine if it is opened or closed and what condition it is in. It takes the camera a few seconds to first start capturing images. The camera then records the person’s motion and frames the point at which the framework starts.

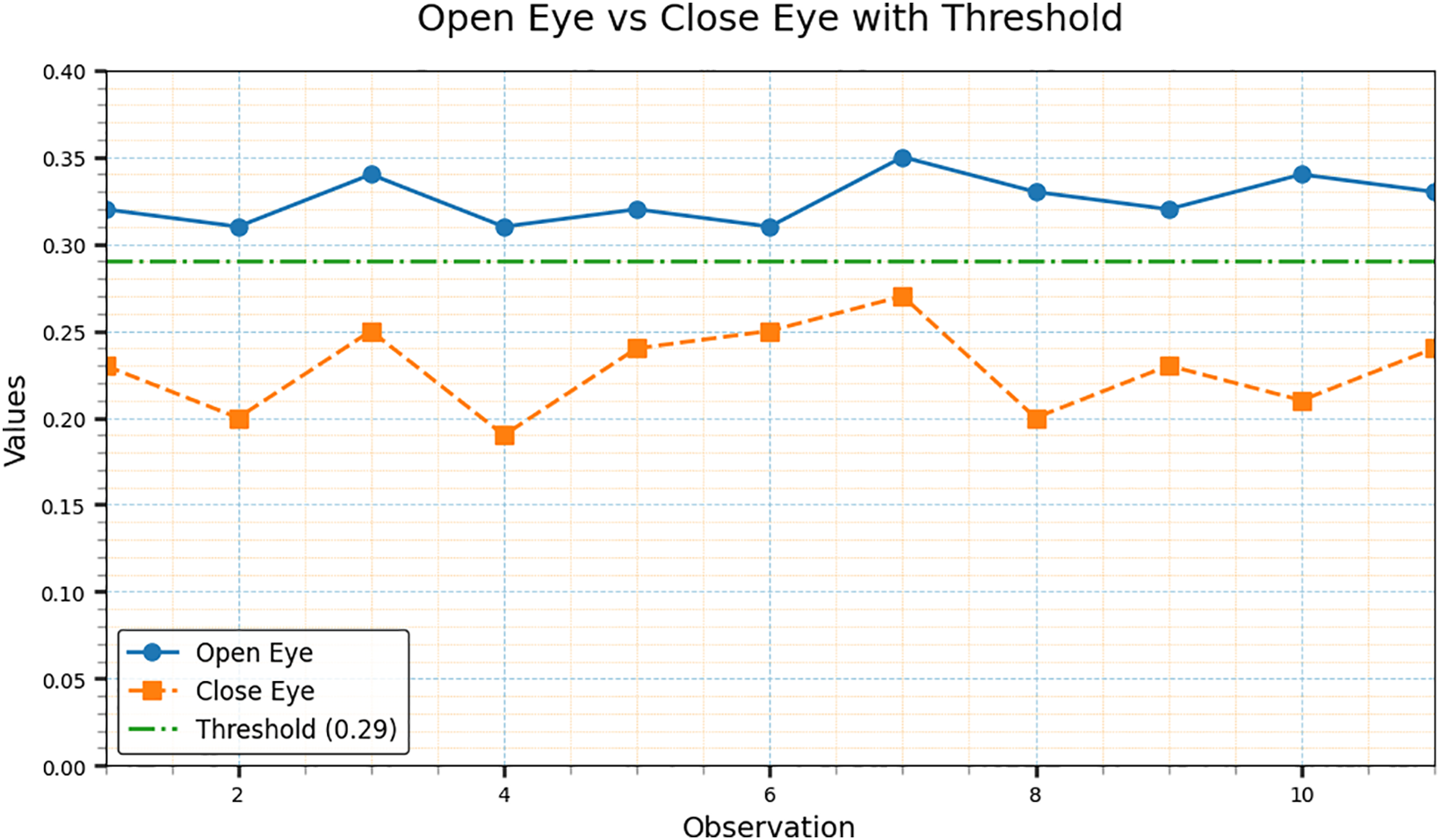

The system marked landmarks on the face of the person after detecting it, intending to evaluate the person’s degree of inactivity in class. For the EPA, this paper defines a set of comparison thresholds. We selected 0.29 as threshold which is determined during the evaluation step. Different cutoff values in the range of 0.25 to 0.35 are tested, and 0.29 provided the most stable balance between correctly detecting fatigue and minimizing false alarms. The sleepy detection method activates if the EPA hits below a particular point of 0.29. The EPA must fall below a specific threshold to reach 0.29 for the person to be considered sleepy. The threshold value is chosen after the inspection is finished, and it may be one of several values. It depends on the place and how the threshold is calculated. The framework is constantly on guard if it recognizes the eye close in 36 consecutive frames. The EPA determines the proportions of the distances between the vertical polygon area and the horizontal line. The method of computing EPA is characterized by the function “def eye–polygon–area”. Fig. 3 shows the facial landmark indicator. The shoelace formula, generally referred to as the surveyor’s formula, is a mathematical approach used to calculate the area of a polygon when the vertices are defined as (

Figure 3: A total of 68 facial points are identified, along with the required points, which include 12 specific eye points

In this context, m represents the count of vertices, specifically 4 for a vertical polygon area and 2 for a horizontal line. The horizontal eye points (

We compute the horizontal coordinates at the corners of the eyes utilizing the distance formula as indicated in Eq. (3).

Calculate the ratio of vertical polygon

The EPA integrates a greater emphasis on geometric interpretation, substituting the conventional eye aspect distance formula. The geometric calculation of EPA addresses general variations in eye shapes during blinking, rendering the EPA more adaptable than the conventional linear distance formula. This formula quantifies the extent of eye openness, with lower values indicating closure. After computing the EPA values from the eye landmarks, the system integrates an alert mechanism to notify users when fatigue is detected.

3.5 Alert/Beep Notification Procedure of the System

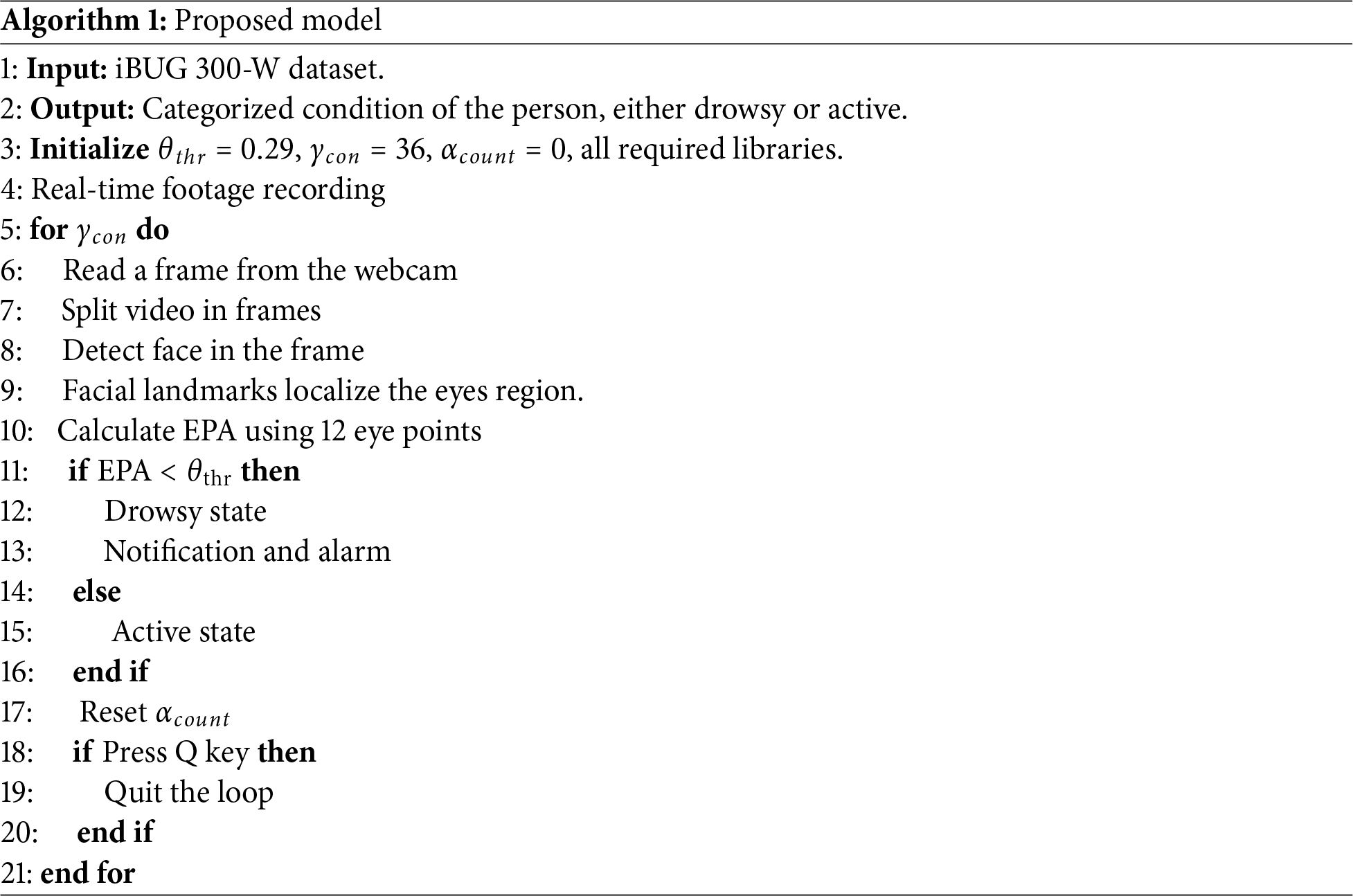

The Thread class is utilized for the alert system regarding drowsiness. The proposed system incorporates the Thread class. The Thread class facilitates efficient code execution in response to an alarm activation, minimizing any potential respite and delay. A library built on Python has been utilized for the alert system to enable the playback of an mp3 file. The playground function necessitates one parameter, specifically the path to an mp3 file and pip facilitates the installation of the playground library. Algorithm 1 illustrates the overall VMFD system.

4 Experimental Outcomes of Designed System

4.1 Performance Evaluation across Scenarios

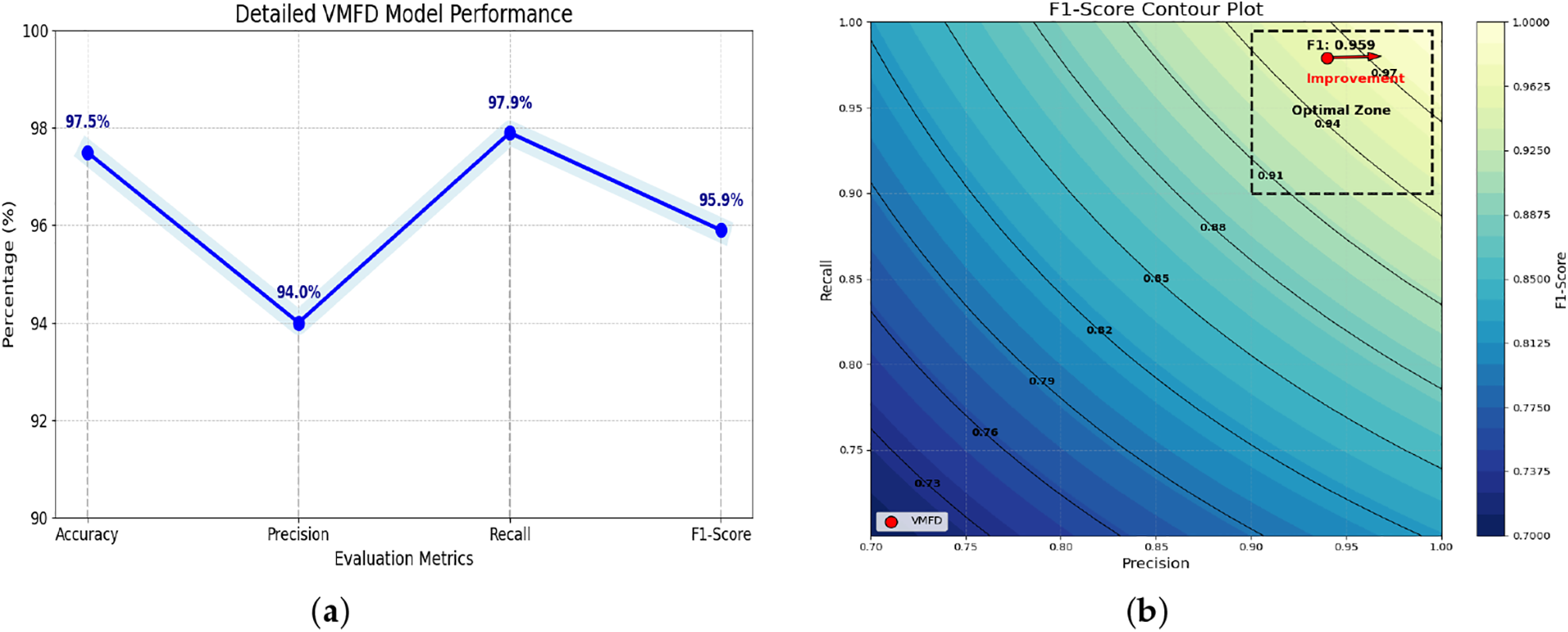

The training and testing of VMFD system are conducted using a publicly available 300-W dataset, while system evaluation involved non-invasive experiments with 61 voluntary participants (31 men, 30 women) aged 18 to 45 years, mainly students and colleagues. The VMFD model demonstrated a high accuracy rate of 97.5%, indicating its capability to accurately predict outcomes and provide significant classification accuracy between active and inactive participants. The model achieved 94% precision, indicating that the system can accurately recognize positive instances while minimizing false positives. The recall value of 97.9% indicates that the model is proficient in accurately identifying true positive cases. However, the last 95.9% of the F1-Score confirms that the overall model is robust and reliable for classifying active and inactive participants. The experimental result/output of the research is shown below in Fig. 4a. Fig. 4b illustrates the F1-Score contour plot, utilized to exhibit the appropriate ratio between precision and recall that VMFD attains. The optimal zone region is located in the upper right corner of the plot. The performance reaches optimal levels here, characterized by a high F1 score, contingent upon elevated prediction and recall values. The red arrow with a dotted tail indicates the performance point, while the dashed black box represents the optimal performance region. This area demonstrates that the system not only achieves high accuracy but also maintains a reliable ratio between false positives and false negatives. This contour plotting shows that the VMFD model is performing close to its peak efficiency. These results are consistent with other machine learning-based classification systems, such as those that integrate random forest classifiers with data augmentation strategies to enhance robustness and minimize misclassifications in imbalanced scenarios.

Figure 4: Experimental evaluation of VMFD: (a) Detailed VMFD model performance using four evaluation metrics; (b) F1-Score contour plot

We present a plot of the EPA values for 11 participants from the evaluation set, illustrating their EPA values during active and inactive states. In Fig. 5, the straight line indicates the threshold, while the circular dotted line reflects the ratio of the eye being opened, and the rectangular dotted line indicates the closed eye. As seen in the pictorial representation, the system sounded an alarm when the value of closed eye line in the illustration fell below the threshold line.

Figure 5: Open v/s closed eye polygon area values from the evaluation group

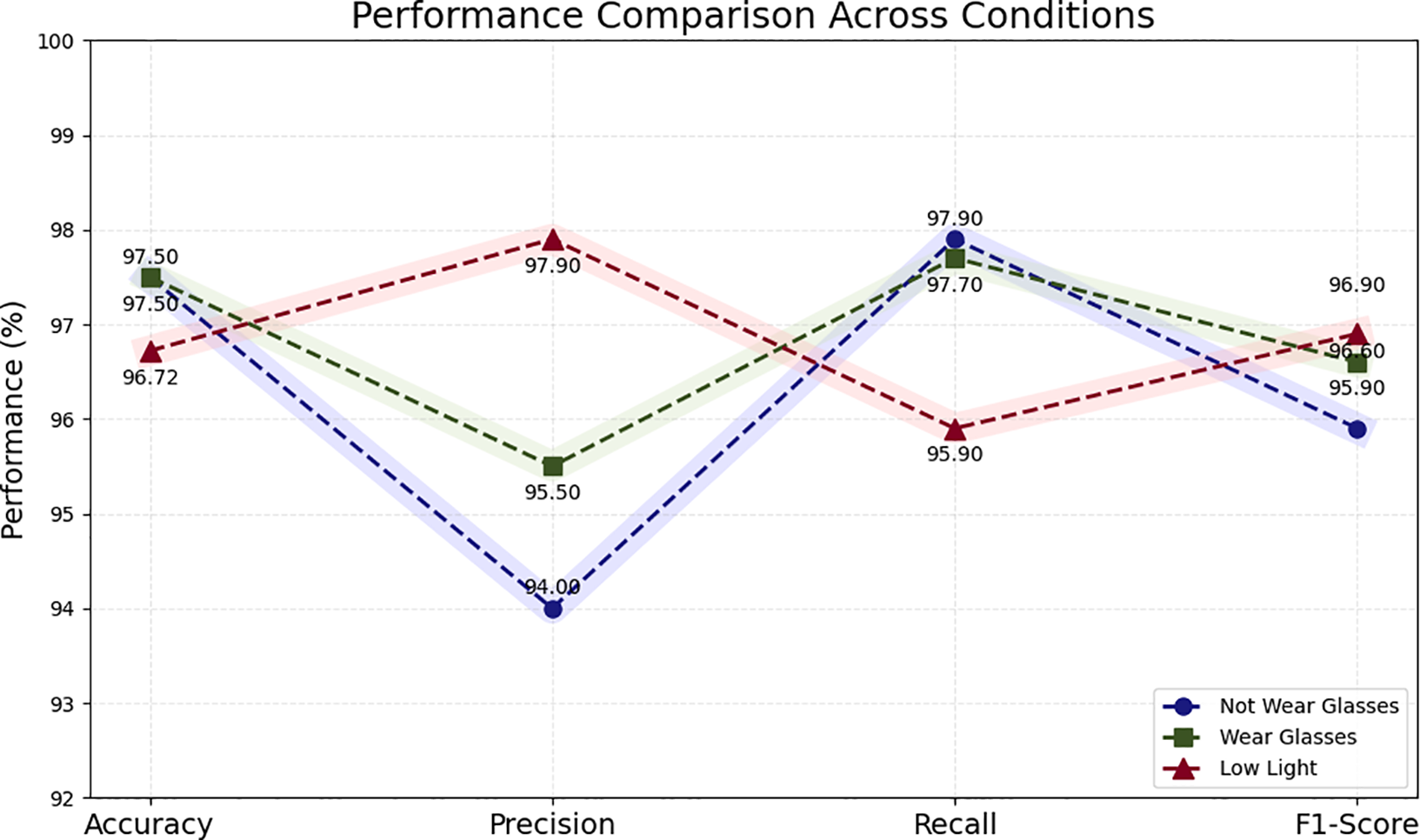

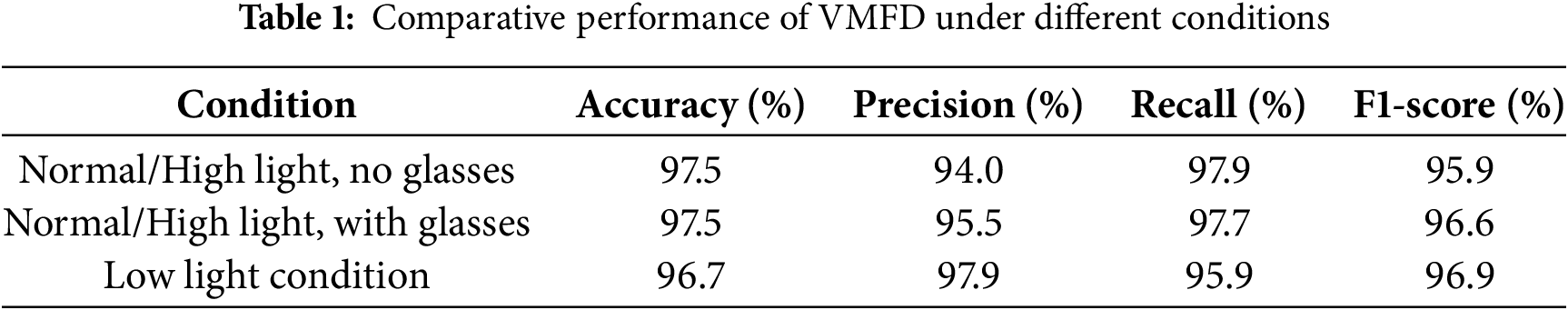

The proposed system has undergone a comprehensive range of tests, encompassing all conceivable scenarios. The individuals who did not wear glasses are also evaluated. The framework’s most significant achievement is the detection of tiredness in glasses wearers. The technique has been tested on 63 people and achieved 97.5% accuracy. The model proved to be 95.5% precise, showing that the system can detect positive cases with little to no false positives. The model’s ability to correctly identify true positive cases is demonstrated by its recall value of 97.7%. However, the entire model’s robustness and dependability in differentiating between actively involved and non-engaged participants wearing glasses is validated by the final 96.6% of the F1-Score. These results confirm the relevance of effective facial landmark-based detection approaches, such as those leveraging the Haar Cascade and Viola-Jones methods for robust face and eye detection in challenging conditions [38]. This research also tests people in low-light conditions. The proposed framework’s greatest accomplishment is detecting persons’ fatigue in low light. The method has been tested on 61 people; among these participants, 58 are correctly identified, and claimed an accuracy of 96.67% for the proposed drowsiness system. The results of the experiment, which include three cases: participants who do not wear glasses, participants who wear glasses, and system performance in low light conditions, can be compared in the Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Performance comparison of VMFD across three different cases

The active states naturally occurred more frequently than inactive states during evaluation, precision, recall, and F1-score are reported alongside accuracy to ensure fair assessment of both classes. As shown in Table 1, the VMFD system demonstrates consistently high precision, recall, and F1-scores across all testing conditions.

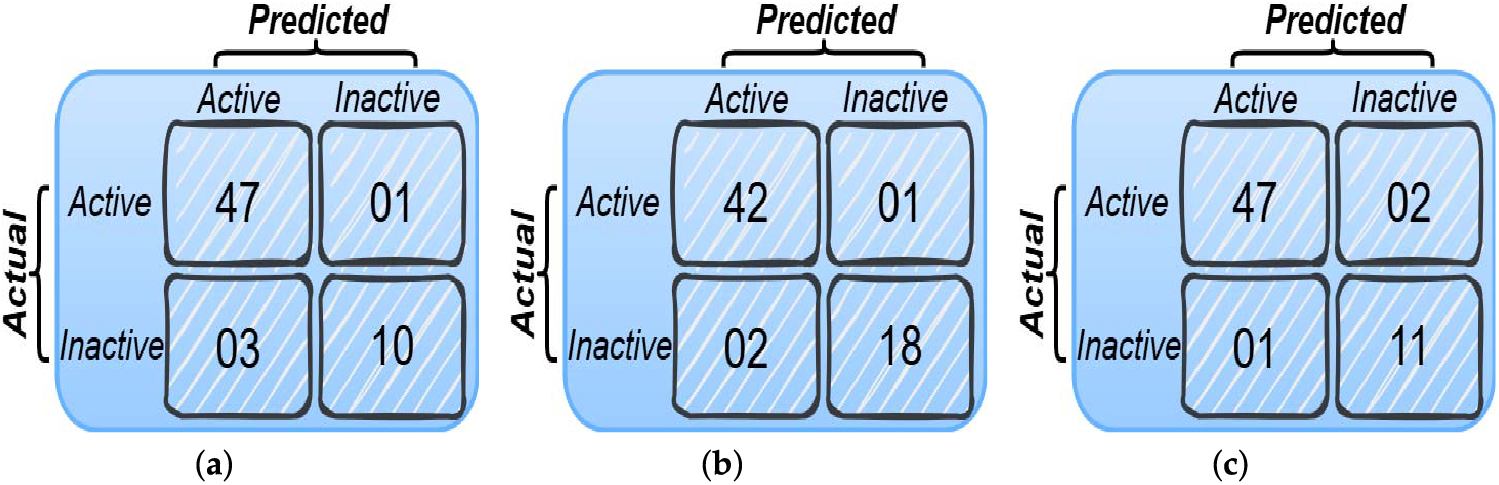

Fig. 7a–c shows the confusion matrices for three evaluation scenarios: (a) participants not wearing glasses, (b) participants wearing glasses, and (c) low-light testing conditions.

Figure 7: Confusion matrices for three evaluation scenarios: (a) participants not wearing glasses; (b) participants wearing glasses; and (c) low-light testing conditions

To further validate the robustness of the reported accuracies, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are computed using the Wilson score method. For the without-glasses group, the 95% CI is [89.1%, 99.1%], indicating that the true accuracy lies within this range with high confidence. Similarly, the with-glasses group achieved a 95% CI of [89.1%, 99.1%], confirming comparable reliability across eyewear variations. For the low-light condition, the 95% CI is [86.5%, 98.3%]. These results provide statistical evidence that VMFD performs significantly above chance across different scenarios.

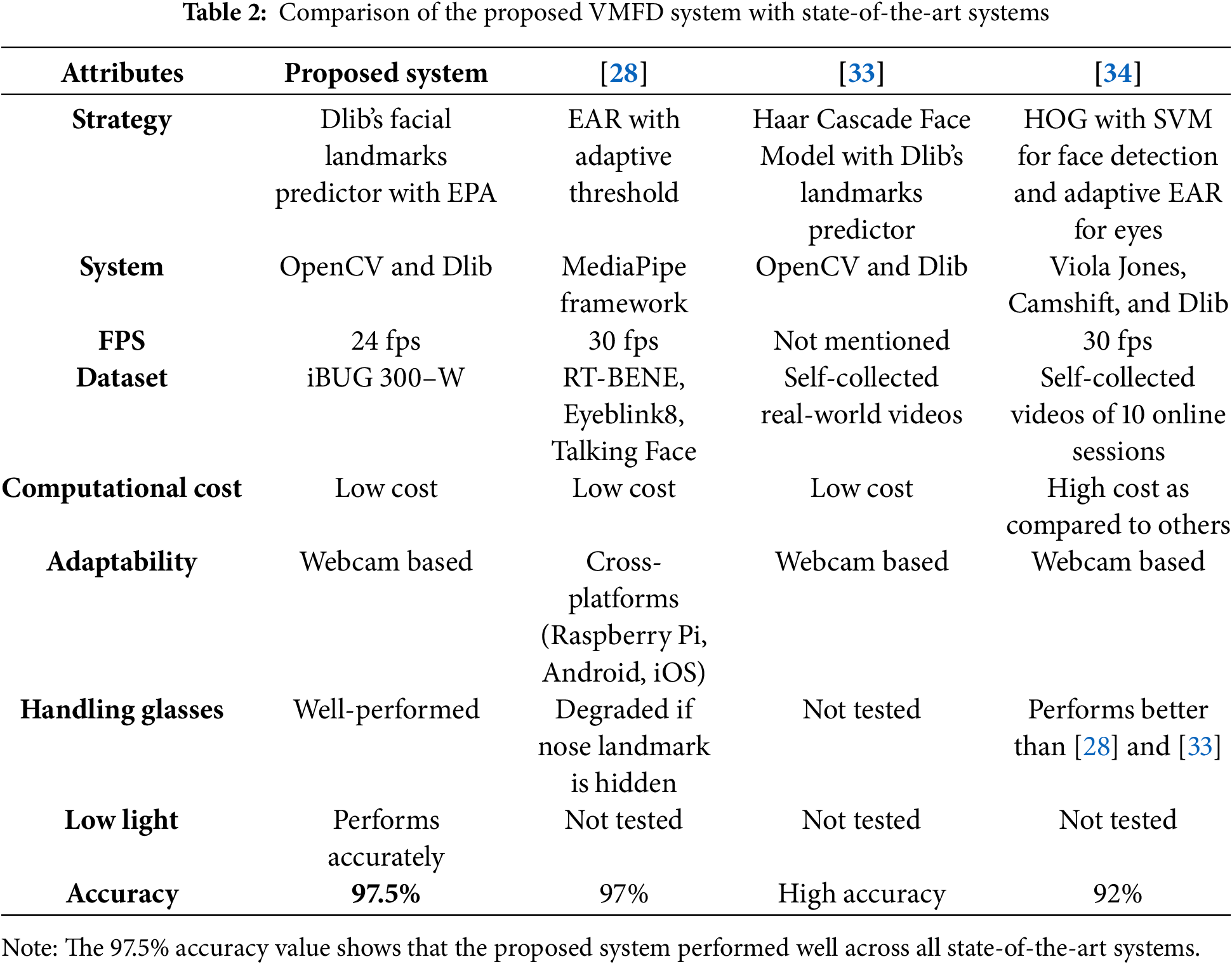

4.2 Comparison with State-of-the-Art Systems

In this section, this paper compares the proposed system with three contemporary systems, as presented in Table 2. The first system is the “Efficient Online Engagement Analytics Algorithm Toolkit That Can Run on Edge [28]”, the second system is “Introducing an Efficient Approach for Real-Time Online Learning Engagement Detection [33]”, and the third system is “An Adaptive System for Predicting Student Attentiveness in Online Classrooms [34]”. We note that the compared systems report results under different frame rates (24 to 30 fps), and one study [33] did not specify FPS. Since our VMFD system triggers fatigue detection based on time duration (1.5 s) rather than a fixed frame count, FPS differences do not affect the comparability of detection accuracy. However, this distinction is acknowledged for completeness. The VMFD is trained and evaluated using the iBUG 300-W dataset, whereas several compared studies relied on self-collected datasets. Benchmark datasets like iBUG 300-W are generally more standardized and less noisy, which may favor performance. To mitigate this limitation, we also validated VMFD under real-world meeting conditions with varying lighting (50–1400 lux) and with/without glasses, demonstrating robustness beyond the benchmark.

The proposed VMFD system employs Dlib’s facial landmarks predictor in conjunction with a novel EPA metric to effectively recognize facial expressions and monitor eye states—specifically, whether the eyes are open or closed. A low-cost HP ProBook 440 G5 laptop camera was used to capture real-time video data for analysis. The system positions the camera in front of participants to continuously track eye movement, and it emits an audible beep and notification upon detecting signs of drowsiness based on EPA thresholds. The system was evaluated under a variety of real-world conditions and compared against three state-of-the-art approaches that utilize EAR, Haar Cascade face detection, and histogram of oriented gradients with SVM classifiers.

The VMFD approach demonstrated superior performance, particularly in challenging environments such as low-light settings and when participants wore glasses. The system achieved a high accuracy rate of 97.5%, validating its robustness and reliability for real-time fatigue detection during virtual meetings. We also recognize that individual variability, such as cultural differences in eye-contact behavior or medical conditions affecting eye movement, may influence fatigue detection, and this represents a limitation of the current study. Finally, while this study evaluated VMFD on individual participants, its lightweight design suggests that the system can be scaled to monitor larger groups in virtual meetings, which we plan to validate in future work.

Despite its promising results, the current system is based exclusively on facial expressions and eye movements, which may limit its effectiveness for individuals exhibiting non-typical fatigue patterns or physiological deviations. To enhance generalizability and reliability, future research will focus on adopting multimodal techniques. In particular, we plan to integrate voice tone analysis alongside visual data to improve fatigue detection accuracy. In this study, the evaluation group consisted predominantly of Asian participants; in future work, we plan to extend testing to more diverse demographic groups to further validate generalizability. Although this study utilized the iBUG 300-W benchmark dataset, future work will include evaluations on larger, self-collected datasets to strengthen the comparison with real-world conditions and further validate the generalizability of VMFD. Future work will also address individual variability by evaluating VMFD across diverse participants, including those with cultural eye-contact differences and medical conditions affecting eye behavior.

Beyond visual cues, vocal characteristics may also provide reliable indicators of fatigue. In particular, features such as pitch variability, speaking rate, loudness, and pause patterns are known to change when individuals become fatigued (e.g., speech often becomes more monotone, slower, and interspersed with longer pauses). In future work, we plan to investigate these vocal features as complementary signals to the proposed visual EPA-based approach, aiming to improve robustness across different meeting conditions. Moreover, the sole reliance on camera-based monitoring introduces certain limitations, including blind spots and privacy concerns. To mitigate these issues, future iterations of the VMFD system will explore the incorporation of acoustic sensors to complement visual cues, enabling a more holistic and privacy-conscious assessment of user engagement and fatigue. We also plan to investigate the scalability of VMFD in larger group settings, ensuring that the system maintains accuracy and efficiency when monitoring multiple participants simultaneously. Future work will extend VMFD to unconstrained conditions by incorporating head-pose tracking, occlusion-robust detection, and multi-participant monitoring capabilities. Future experiments will include older participants to account for age-related differences in fatigue patterns and eye dynamics.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: No funding involved.

Author Contributions: Hafsa Sidaq and Lei Wang contributed equally to the conceptualization, methodology, and implementation of the study. Sghaier Guizani provided supervision, project administration, and critical revisions. Hussain Haider contributed to the literature review and assisted in interpreting the experimental results. Ateeq Ur Rehman contributed to formal analysis and manuscript review. Habib Hamam provided overall guidance, and final manuscript approval. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The 300-W dataset used in this study is publicly available and can be accessed at https://www.ibug.doc.ic.ac.uk/resources/300-W_IMAVIS (accessed on 1 July 2025).

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hosseinkashi Y, Tankelevitch L, Pool J, Cutler R, Madan C. Meeting effectiveness and inclusiveness: large-scale measurement, identification of key features, and prediction in real-world remote meetings. Proc ACM Human-Comput Interact. 2024;8(CSCW1):1–39. doi:10.1145/3637370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Erna N, Genisa RAA, Muslaini F, Suhartini T. The effectiveness of media zoom meetings as online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. ELT-Lectura. 2022;9(1):48–55. doi:10.31849/elt-lectura.v9i1.9108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kapur D. The role of google classroom and google meeting on learning effectiveness. Siber Int J Educat Technol (SIJET). 2023;1(1):8–16. doi:10.38035/sijet.v1i1.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Gopinathan RN, Sherly E. Fostering learning with facial insights: geometrical approach to real-time learner engagement detection. In: 2024 IEEE 9th International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT); 2024 Apr 5–7; Pune, India. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

5. Alfavo-Viquez D, Zamora-Hernandez MA, Azorín-López J, Garcia-Rodriguez J. Visual analysis of fatigue in Industry 4.0. Int J Adv Manufact Technol. 2024;133(1):959–70. doi:10.1007/s00170-023-12506-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Chuah WH, Chong SC, Chong LY. The assistance of eye blink detection for two-factor authentication. J Inform Web Eng. 2023;2(2):111–21. [Google Scholar]

7. Daza R, Gomez LF, Fierrez J, Morales A, Tolosana R, Ortega-Garcia J. DeepFace-attention: multimodal face biometrics for attention estimation with application to e-learning. IEEE Access. 2024;12:111343–59. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3437291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Betto I, Hatano R, Nishiyama H. Distraction detection of lectures in e-learning using machine learning based on human facial features and postural information. Artif Life Robot. 2023;28(1):166–74. doi:10.1007/s10015-022-00809-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Alkhalisy MAE, Abid SH. The detection of students’ abnormal behavior in online exams using facial landmarks in conjunction with the YOLOv5 models. Iraqi J Comput Inform. 2023;49(1):22–9. doi:10.25195/ijci.v49i1.380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Hossain MN, Long ZA, Seid N. Emotion detection through facial expressions for determining students’ concentration level in E-learning platform. In: International Congress on Information and Communication Technology. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 517–30. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-3556-3_42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Watson C, Templet T, Leigh G, Broussard L, Gillis L. Student and faculty perceptions of effectiveness of online teaching modalities. Nurse Educ Today. 2023;120:105651. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Saleem S, Shiney J, Shan BP, Mishra VK. Face recognition using facial features. Mater Today Proc. 2023;80(1):3857–62. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2021.07.402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Abdolhosseinzadeh A, Montazer GA. Real time detection of learner fatigue in e-learning environments through the combination of eye and mouth features. In: 2024 11th International and the 17th National Conference on E-Learning and E-Teaching (ICeLeT); 2024 Feb 27–29; Isfahan, Iran. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

14. Rawat S, Rodrigues M, Sheregar P, Wagaskar KA, Tripathy AK. Computer vision based hybrid classroom attention monitoring. In: 2024 IEEE International Conference on Information Technology, Electronics and Intelligent Communication Systems (ICITEICS); 2024 Jun 28–29; Bangalore, India. p. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

15. Sun Y. Method for detecting student classroom learning fatigue based on optical and infrared images. In: 2023 IEEE 6th International Conference on Knowledge Innovation and Invention (ICKII); 2023 Aug 11–13; Sapporo, Japan. p. 474–8. [Google Scholar]

16. Wang J, Ayas S, Zhang J, Wen X, He D, Donmez B. Towards generalizable drowsiness monitoring with physiological sensors: a preliminary study. arXiv:2506.06360. 2025. [Google Scholar]

17. Sun W, Wang Y, Hu B, Wang Q. Exploration of eye fatigue detection features and algorithm based on eye-tracking signal. Electronics. 2024;13(10):1798. doi:10.3390/electronics13101798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kołodziej M, Tarnowski P, Sawicki DJ, Majkowski A, Rak RJ, Bala A, et al. Fatigue detection caused by office work with the use of EOG signal. IEEE Sensors Journal. 2020;20(24):15213–23. doi:10.1109/jsen.2020.3012404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Gupta S, Kumar P, Tekchandani R. Artificial intelligence based cognitive state prediction in an e-learning environment using multimodal data. Multimed Tools Appl. 2024;83:64467–98. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-18021-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Uçar MU, Özdemir E. Recognizing students and detecting student engagement with real-time image processing. Electronics. 2022;11(9):1500. doi:10.3390/electronics11091500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Borikar D, Dighorikar H, Ashtikar S, Bajaj I, Gupta S. Real-time drowsiness detection system for student tracking using machine learning. Int J Next-Generat Comput. 2023;l(1):28–34. doi:10.47164/ijngc.v14i1.992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang M, Zhao Q, Li J, Liu T. Research on hidden mind-wandering detection algorithm for online classroom based on temporal analysis of eye gaze direction. In: International Conference on Intelligent Computing. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 188–96. [Google Scholar]

23. Mahmood F, Arshad J, Othman MTB, Hayat MF, Bhatti N, Jaffery MH, et al. Implementation of an intelligent exam supervision system using deep learning algorithms. Sensors. 2022;22(17):6389. doi:10.3390/s22176389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Samy S, Gedam VV, Karthick S, Sudarsan JS, Anupama CG, Ghosal S, et al. The drowsy driver detection for accident mitigation using facial recognition system. Life Cycle Reliab Safety Eng. 2025;14:299–311. doi:10.1007/s41872-025-00314-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Dhankhar U, Abhinav, Pathak A, Zeeshan, Jha JK. A computer vision based approach for real-time drowsiness detection using eye aspect ratio analysis. In: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Emerging Applications of Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning and Cybersecurity (EAAIMCS). Balrampur, India: AIJR Publisher; 2025. p. 28–34. [Google Scholar]

26. Youwei L. Real-time eye blink detection using general cameras: a facial landmarks approach. Int Sci J Eng Agric. 2023 Oct 1;2(5):1–8. [cited 2025 Oct 16]. Available from: https://isg-journal.com/isjea/article/view/505. [Google Scholar]

27. Kuwahara A, Nishikawa K, Hirakawa R, Kawano H, Nakatoh Y. Eye fatigue estimation using blink detection based on Eye Aspect Ratio Mapping (EARM). Cognit Robot. 2022;2(2):50–9. doi:10.1016/j.cogr.2022.01.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Thiha S, Rajasekera J. Efficient online engagement analytics algorithm toolkit that can run on edge. Algorithms. 2023;16(2):86. doi:10.3390/a16020086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Gupta S, Kumar P, Tekchandani R. A multimodal facial cues based engagement detection system in e-learning context using deep learning approach. Multimed Tools Appl. 2023;82(18):28589–615. doi:10.1007/s11042-023-14392-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Bishay M, Page G, Emad W, Mavadati M. Monitoring viewer attention during online ads. In: European Conference on Computer Vision. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2024. p. 349–65. [Google Scholar]

31. Bonfert M, Reinschluessel AV, Putze S, Lai Y, Alexandrovsky D, Malaka R, et al. Seeing the faces is so important—Experiences from online team meetings on commercial virtual reality platforms. Front Virtual Real. 2023;3:945791. doi:10.3389/frvir.2022.945791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Villegas-Ch W, García-Ortiz J, Urbina-Camacho I, Mera-Navarrete A. Proposal for a system for the identification of the concentration of students who attend online educational models. Computers. 2023;12(4):74. doi:10.3390/computers12040074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Banik P, Molla A, Sohan M. Introducing an efficient approach for real-time online learning engagement detection. In: Proceedings of the APQN Academic Conference (AAC 2023)—Anthology of APQN Academic Conference 2023. Dhaka, Bangladesh: APQN; 2023. p. 73–80. [Google Scholar]

34. Gupta B, Sharma R, Bansal R, Soni GK, Negi P, Purdhani P. An adaptive system for predicting student attentiveness in online classrooms. Indonesian J Elect Eng Comput Sci. 2023;31(2):1136–46. doi:10.11591/ijeecs.v31.i2.pp1136-1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Sagonas C, Tzimiropoulos G, Zafeiriou S, Pantic M. 300 faces in-the-wild challenge: the first facial landmark localization challenge. In: 2013 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops; 2013 Dec 2–8; Sydney, NSW, Australia. p. 397–403. [Google Scholar]

36. Sagonas C, Tzimiropoulos G, Zafeiriou S, Pantic M. A semi-automatic methodology for facial landmark annotation. In: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops; 2013 Jun 23–28; Portland, OR, USA. p. 896–903. [Google Scholar]

37. Sagonas C, Antonakos E, Tzimiropoulos G, Zafeiriou S, Pantic M. 300 faces in-the-wild challenge: database and results. Image Vis Comput. 2016;47:3–18. doi:10.1016/j.imavis.2016.01.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Sridhar P, Chithaluru P, Kumar S, Cheikhrouhou O, Hamam H. An enhanced haar cascade face detection schema for gender recognition. In: 2023 International Conference on Smart Computing and Application (ICSCA); 2023 Feb 5–6; Hail, Saudi Arabia. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools