Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Influence of Aviation Kerosene-Diesel Blending Ratios on Ignition Behavior and Spray Dynamics

1 Mechanical Electrical Management Department, China Coast Guard Academy, Ningbo, 315801, China

2 College of Power and Energy Engineering, Harbin Engineering University, Harbin, 150001, China

3 College of Power Engineering, Navy University of Engineering, Wuhan, 430030, China

* Corresponding Author: Hailong Chen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Model-Based Approaches in Fluid Mechanics: From Theory to industrial Applications)

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(10), 2527-2538. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.069569

Received 26 June 2025; Accepted 19 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

Modifications in fuel spray characteristics fundamentally influence fuel–air mixing dynamics in diesel engines, thereby significantly affecting combustion performance and emission profiles. This study explores the operational behavior of RP-5 aviation kerosene/diesel blended fuels in marine diesel engines. A spray visualization platform based on Mie scattering technology was developed to comparatively analyze the spray characteristics, ignition behavior, and soot emissions of RP-5 aviation kerosene, conventional-35# diesel, and their blends at varying mixing ratios (D100H0, D90H10, D70H30, D50H50, D30H70, D0H100). The findings demonstrate that, under constant injection pressure, aviation kerosene combustion results in a more uniform temperature field, characterized by lower core flame temperatures, broader high-temperature regions, and reduced soot concentrations with spatially homogeneous distribution and no pronounced peaks. In terms of spray dynamics, increasing the proportion of aviation kerosene leads to a marked widening of the spray cone angle. Meanwhile, spray penetration length exhibits a non-monotonic trend—initially decreasing and subsequently increasing—as the kerosene blending ratio rises.Keywords

In recent years, with the advancement of battlefield fuel unification and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UVA) Technology, research on the application of aviation kerosene in piston engines has increased significantly [1]. Since the 1960s, the U.S. Army has conducted feasibility studies on using jet fuel (military aviation fuel designated as JP-8 in the U.S. and allied nations [2]) as diesel engine fuel [3,4,5].

Pickett [6], Lee [7], and others discovered that JP-8 aviation kerosene has lower density, shorter spray penetration, and larger spray cone angle compared to diesel. These properties may reduce combustion efficiency and exacerbate HC emissions in diesel engines. Bayindir et al. [8] directly applied JP-8 aviation kerosene in diesel engines but observed severe wear issues in fuel injection systems due to its low viscosity and density, along with significant cycle-to-cycle variations under engine operating conditions. Kook et al. [9] compared the spray and combustion characteristics of diesel and JP-8 in a constant-volume combustion chamber, revealing similar spray penetration distances but longer ignition delays for aviation kerosene due to its lower cetane number.

Recently, Extensive research has conducted on research on RP-3 aviation kerosene applications in diesel engines, revealing substantial differences in spray, ignition, combustion, and emission characteristics compared to foreign aviation fuels like JP-8 [10]. Zhang et al. [11] calculated auto-ignition points and ignition delay times for RP-3 under low-pressure conditions. Shi et al. [12] investigated spray ignition characteristics of RP-3/No. 0 diesel blends at low ambient temperatures using Mie scattering and direct photography, demonstrating that such blended fuels (wide-cut fuels [13]) improve cold-start performance.

Liu et al. [14] conducted combustion experiments in shock tubes and constant-volume combustion chambers to characterize RP-3 properties, developing a novel surrogate fuel. Wang et al. [15] studied the spray, combustion, and engine performance of RP-3 in diesel engines, revealing increased spray cone angles, reduced penetration distances, and decreased Sauter Mean Diameter (SMD), indicating enhanced atomization quality [16]. This supports RP-3’s viability as an emergency alternative fuel for heavy-duty vehicles.

While existing literature indicates considerable global research on fuel standardization, fundamental investigations specifically targeting the spray, ignition, combustion, and emission properties of RP-5 aviation kerosene/diesel blended fuels are limited. This study utilizes an electrically-heated constant volume combustion vessel to examine the ignition, soot production, and spray characteristics of RP-5/diesel blends. The combination of RP-5 jet fuel’s high volatility with -35# diesel’s enhanced low-temperature flow properties markedly improves cold-start capability and combustion efficiency in marine engines. Additionally, the blend’s lower carbon content reduces smoke emissions. These outcomes provide theoretical support and optimization strategies for subsequent analysis of RP-5/diesel blend combustion and emission performance in unmodified diesel engines.

2 Experimental Setup and Methodology

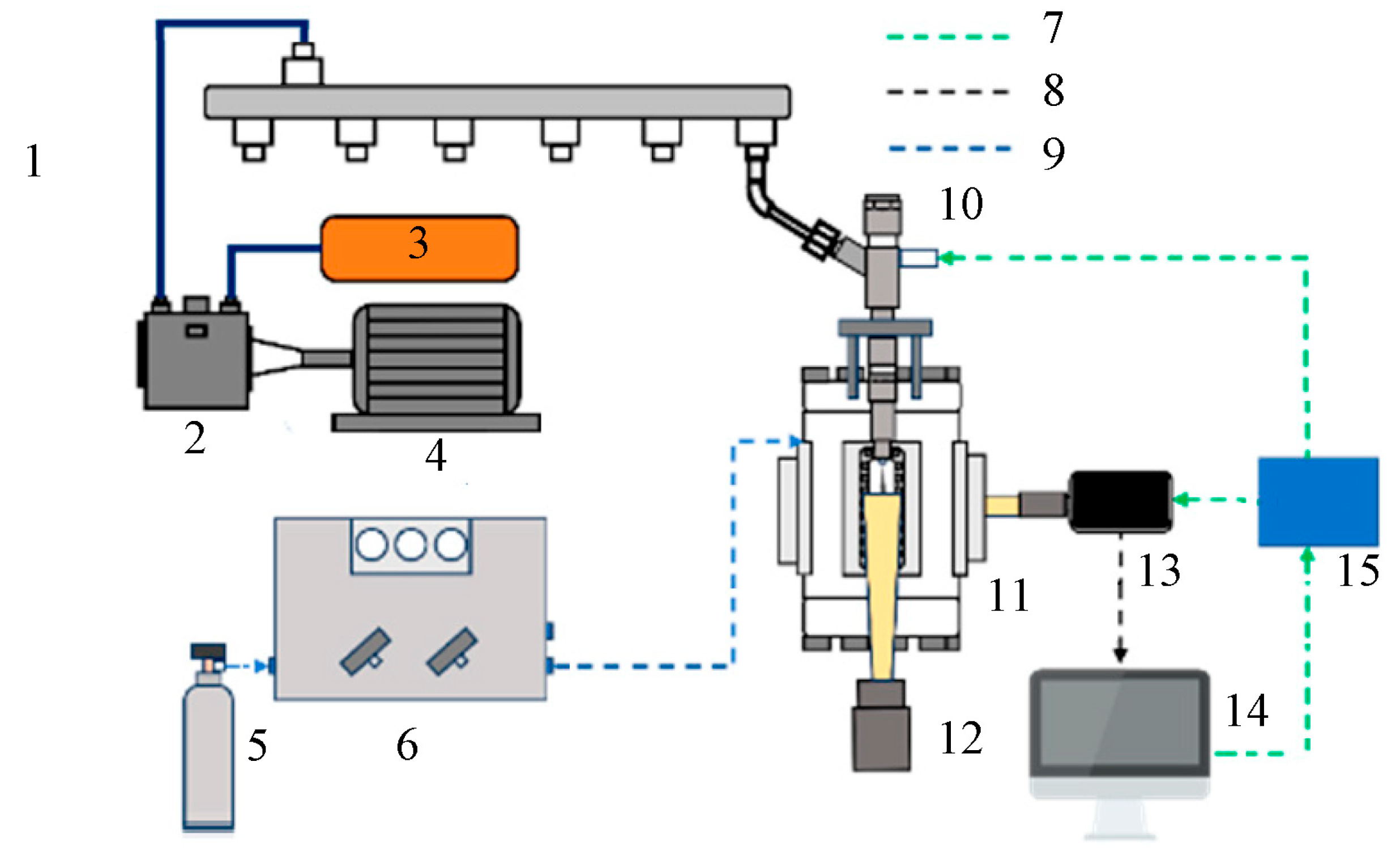

The study was conducted on a fuel spray characterization test rig. The experimental apparatus comprises a constant-volume combustion chamber (CVCC) system, fuel supply system, control system, illumination source, and image acquisition/processing system. The complete test system is shown in Fig. 1.

As depicted in Fig. 1, the constant-volume combustion chamber (CVCC) incorporates a cylindrical cavity with electrical heating elements integrated into its base. Laterally positioned gas exchange ports connect the intake manifold to a high-pressure gas supply, regulated by pneumatic solenoid valves for chamber pressure control. A transient pressure sensor (e.g., Kistler 601C) and K-type thermocouple are mounted within the cavity to record pressure and temperature during experiments, achieving measurement accuracies of 0.1 MPa and ±1°C, respectively, across all test conditions. The chamber maintains high-temperature/high-pressure environments (300–900 K; 0.1–10 MPa) through high-power electrical heating, demonstrating exceptional thermal homogeneity (>95%), operational stability (±0.5% fluctuation), and repeatability (RSD < 1.5%) [17]. Spray development, combustion events, and soot formation captured by high-speed cameras (e.g., Phantom) are processed using MATLAB algorithms [18], with simultaneous quantification of macroscopic spray characteristics through parametric image analysis.

Figure 1: Constant-volume combustion chamber (CVCC) test system. 1—High-Pressure Common Rail; 2—Fuel Pump; 3—Fuel Tank; 4—Motor; 5—High-Pressure Gas Cylinder; 6—Intake and Exhaust Control System; 7—Signal Trigger Channel; 8—Data Acquisition Channel; 9—Gas Channel; 10—Injector; 11—Constant Volume Chamber; 12—LED Light; 13—High-Speed Camera; 14—Computer; 15—Timing Synchronization Microprocessor.

The technical specifications of major components in the fuel spray characterization test platform are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: The technical specifications of major components in the fuel spray characterization test platform.

| Component | Technical Parameter |

|---|---|

| Constant-Volume Chamber | Bore: 320 mm; Volume: 32 L; Viewport: 220 × 110 mm; Max Temp: <1000 K; Max Pressure: <20 MPa |

| Optical Viewport | Sapphire Glass |

| High-Speed Camera | Photron Fastcam SA-X2; Telecentric lens |

| Ambient Gas | N2; Air |

| LED Light Source | SH-100D-W |

| High-Pressure Common Rail | Pressure Range: 40–200 MPa; Accuracy: 0.1 MPa |

The experiment employed aviation kerosene RP-5 and -35# diesel as base fuels, with their physicochemical properties presented in Table 2.

Table 2: Key physicochemical properties of RP-5 aviation kerosene and -35# diesel.

| Parameter | RP-5 Aviation Kerosene | -35# Diesel |

|---|---|---|

| Density ρ (kg/m3, 20°C) | 811.7 | 820–850 |

| Kinematic Viscosity ν (m2/s, 20°C) | 2.115 | 3.8 |

| Cetane Number | 46.5 | >51 |

| Net Heating Value (MJ/kg) | 43.51 | 42–44 |

| Surface Tension (N/m, 40°C) | 22.6 | 25–35 |

| Latent Heat of Vaporization (KJ/kg) | 427.6 | 250–300 |

| Oxygen Content (%) | 7.31 | 0 |

Blends of -35# diesel and RP-5 aviation kerosene were prepared at volumetric fractions of 0%, 10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 100% kerosene, designated as D100H0, D90H10, D70H30, D50H50, D30H70, and D0H100, respectively. Spray characterization employed a high-pressure common-rail fuel injection system representative of marine diesel engines, with the experimental matrix detailed in Table 3.

Table 3: Experimental scheme.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of Nozzle Holes | 7 |

| Nozzle Hole Diameter (mm) | 0.31 |

| Injection Duration (ms) | 2 |

| Injection Pressure (MPa) | 80, 100, 120 |

| Ambient Density (kg·m−3) | 15, 20 |

| Ambient Temperature (K) | 300 (Cold), 800 (Hot) |

3 Ignition and Soot Characteristics Analysis

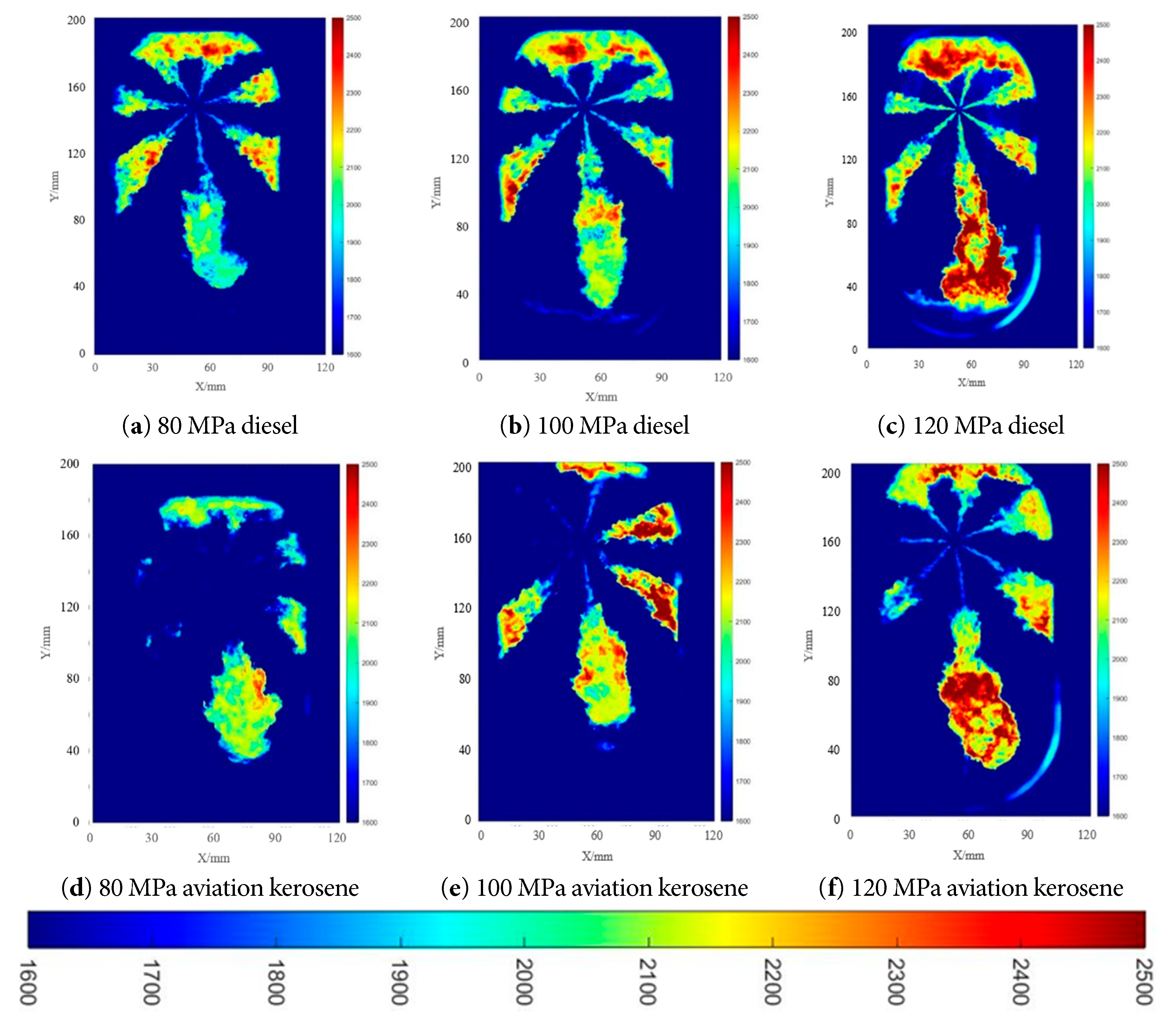

Fig. 2 depicts combustion flame temperature and flow field distributions under the following test parameters: 2 ms injection pulse width, 800 K ambient temperature, 4.85 MPa back pressure (20 kg/m3 density), and varied injection pressures (80/100/120 MPa). The temperature color scale (K) is positioned at right.

Figure 2: Temperature flow field diagram of aviation kerosene and diesel flame area.

Fig. 2 reveals the following observations:

- (1)Combustion images of diesel and aviation kerosene exhibit consistent variation patterns across different injection pressures. Diesel combustion displays distinct thermal stratification, with higher temperatures concentrated in narrow flame cores predominantly located downstream of the spray. This results from diesel’s elevated cetane number enhancing auto-ignition propensity, promoting intense combustion. Concurrently, its heavier distillation range reduces evaporation rates, causing non-uniform fuel-air mixing.

- (2)RP-5 aviation kerosene combustion exhibits improved temperature homogeneity, with lower peak temperatures in the flame core and broader high-temperature zones. Given the established mechanism where high-temperature oxygen-rich conditions promote NOx formation, RP-5’s extended high-temperature distribution potentially elevates NOx emissions in practical applications. This behavior results from kerosene’s rapid evaporation rate enhancing fuel-air mixing, establishing quasi-premixed combustion. Additionally, its low aromaticity suppresses localized high-temperature region formation.

3.2 Soot Characterization and Analysis

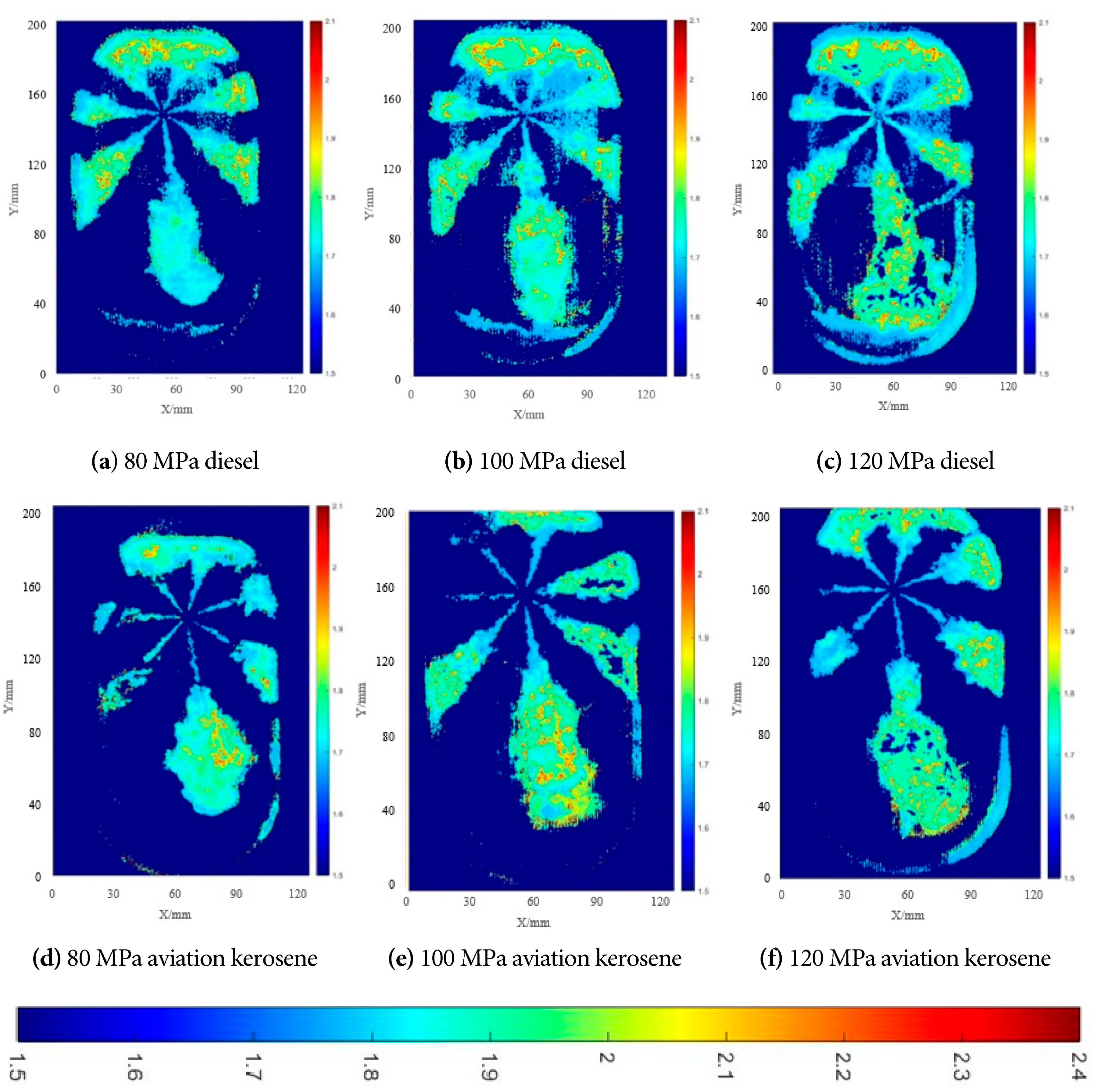

Fig. 3 presents KL factor distributions for aviation kerosene and diesel, with the KL scale positioned at right [19].

Figure 3: KL factor distribution of aviation kerosene and diesel.

Key observations from Fig. 3:

- (1)Aviation kerosene exhibits lower soot concentrations with a more uniform distribution and no distinct peaks. This is primarily attributed to its fuel characteristics: a predominance of paraffinic hydrocarbons, low aromatic content, lower viscosity, lower boiling point, and reduced surface tension. These properties result in finer, more uniformly distributed droplets during atomization, achieving a larger spray surface area. Additionally, aviation kerosene demonstrates superior ligament formation, evaporation, atomization, and spray dispersion capabilities compared to diesel, evidenced by a wider spray cone angle and greater penetration distance. This promotes thorough fuel-air mixing, effectively suppressing the formation of soot precursors.

- (2)Diesel fuel exhibits significantly higher soot concentrations with a non-uniform distribution, featuring localized zones of elevated concentration. This is primarily due to its high aromatic hydrocarbon content, which is prone to pyrolysis under high-temperature, oxygen-deficient conditions and subsequent conversion into soot. Concurrently, diesel’s higher surface tension impedes atomization compared to aviation kerosene. This, poorer atomization coupled with localized inhomogeneous fuel-air mixing, exacerbates soot formation.

4 Spray Characteristics Analysis

4.1 Effect of Blend Ratio on Spray Penetration

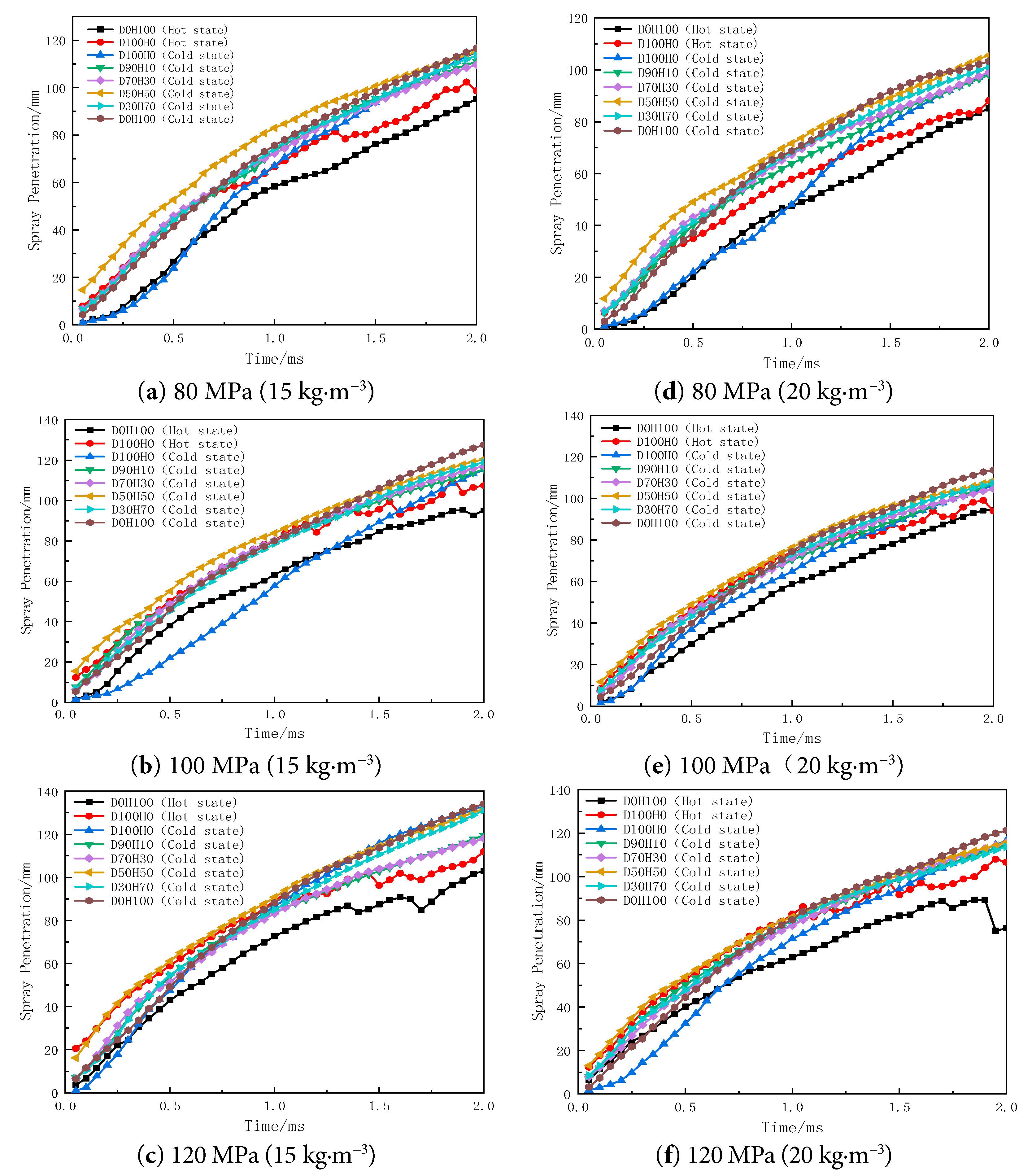

Fig. 4 shows the spray penetration distance curve changes of fuels with different blend ratios under the conditions of spray pulse width of 2 ms, spray hole diameter of 0.31 mm, and environmental densities of 15 kg·m−3 and 20 kg·m−3.

Figure 4: Variation of spray penetration curves with blend ratios.

As evidenced in Fig. 4:

- (1)Under constant ambient density and injection pressure conditions, the spray penetration of blended fuels consistently exceeds that of pure diesel and aviation kerosene under hot conditions. This discrepancy arises due to the higher viscosity of the fuels under cold conditions, which is substantially greater than that of pure diesel and aviation kerosene under elevated temperatures. The high-viscosity blended fuels generate droplets with greater initial momentum during the primary atomization stage and are more prone to maintaining a continuous liquid core. Conversely, under hot conditions, the abrupt decrease in fuel viscosity and enhanced volatility lead to rapid droplet evaporation and dispersion, accompanied by a swift loss of momentum, resulting in markedly reduced penetration. Consequently, the spray penetration of blended fuels under cold conditions surpasses that of pure diesel and aviation kerosene under hot conditions. Additionally, owing to its lower latent heat of vaporization, viscosity, and surface tension, aviation kerosene is more susceptible to thermal breakup and atomization, experiencing a more pronounced reduction in penetration. As a result, its penetration under hot conditions becomes shorter than that of diesel.

- (2)The spray penetration of diesel-jet fuel blends exhibits a “decrease followed by an increase” trend with increasing jet fuel blending ratio. Specifically: At an ambient density of 15 kg/m3 and an injection pressure of 80 MPa, the spray penetration decreases by 3.9% as the jet fuel ratio increases from 0% to 30%, but increases by 4.8% as the ratio further rises from 50% to 100%. At injection pressures of 100 MPa and 120 MPa, the spray penetration decreases by 0.69% and 6.5%, respectively, over the 0% to 30% jet fuel ratio range, while it increases by 7.2% and 5.8%, respectively, over the 50% to 100% range. At an ambient density of 20 kg/m3, the spray penetration is slightly reduced compared to the value at 15 kg/m3, although this reduction is not significant. This minor decrease occurs because increasing ambient density raises the injection resistance, thereby shortening the penetration distance; however, at higher injection pressures, this increase in injection resistance does not lead to a significant reduction in penetration distance. Similarly, at an ambient density of 20 kg/m3, the spray penetration of the blended fuels also exhibits the “decrease followed by an increase” trend with increasing jet fuel blending ratio.

Similarly, at an ambient density of 20 kg/m3, the spray penetration of the blended fuel first decreases and then increases with a higher proportion of aviation kerosene. This non-monotonic trend stems from the distinct physicochemical properties of diesel and aviation kerosene. As indicated by Eq. (1) [20,21], aviation kerosene exhibits lower density and viscosity, resulting in reduced flow resistance loss, greater momentum in the fuel jet, and higher injection velocity compared to diesel. As injection pressure rises, the lower density of aviation kerosene leads to a more pronounced increase in injection velocity under elevated pressure conditions.

When the proportion of aviation kerosene exceeds 50%, the continued reduction in diesel content leads to a further decline in the viscosity of the blended fuel. This lower viscosity effectively reduces flow resistance at the nozzle, approaching the ideal flow characteristics of pure aviation kerosene. As a result, the kinetic energy conversion efficiency during injection improves, leading to an increase in injection velocity. Concurrently, the higher kerosene ratio reduces the density of the blended fuel, which, according to Eq. (1), further elevates the injection velocity. Under the combined effect of these factors, the droplet momentum of the fuel spray is significantly enhanced, resulting in a noticeable increase in spray penetration. This stronger spray promotes a more intense velocity field near the jet and enhances vortex formation in the near-wall region, thereby improving air entrainment and fuel–air mixing quality, which contributes to more efficient combustion.

4.2 Effect of Blend Ratio on Spray Cone Angle

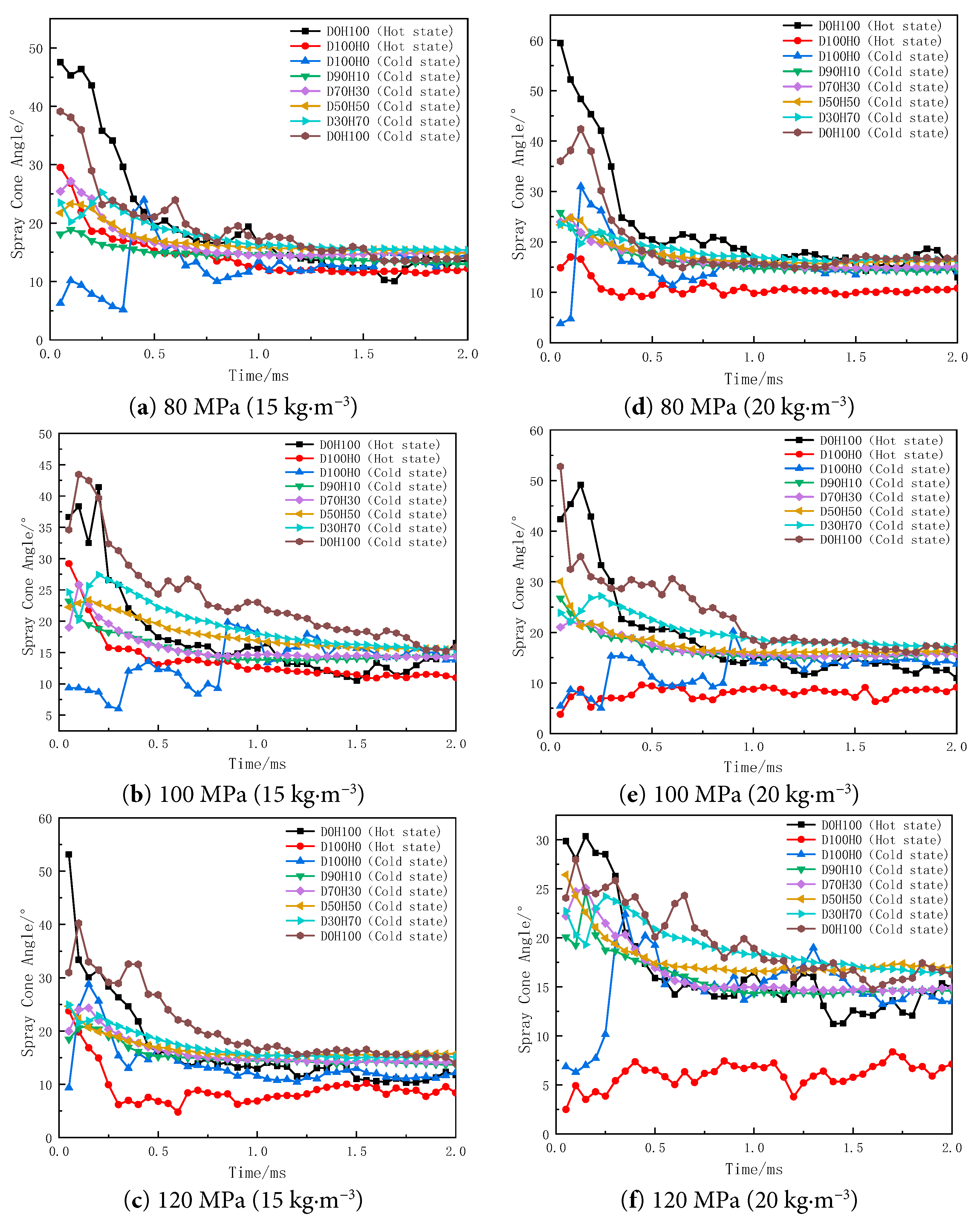

Fig. 5 illustrates the variations in spray cone angle curves for different blending ratios of -35# diesel and aviation kerosene under conditions of 2 ms injection pulse width, 0.31 mm nozzle diameter, and ambient densities of 15 kg/m3 and 20 kg/m3.

Figure 5: Variation of spray cone angle curves at different blend ratios.

As shown in Fig. 5:

- (1)Under cold conditions, with constant ambient density and injection pressure, the spray cone angle of the blended fuel increases with a higher aviation kerosene blending ratio. This is primarily due to the reduced viscosity, lower surface tension, and decreased density of the blend as kerosene content rises, which collectively enhance atomization and increase injection velocity. Moreover, the lower viscosity promotes cavitation within the nozzle, intensifying turbulent disturbances at the exit and further improving atomization. This facilitates droplet dispersion and leads to a wider spray cone angle. These factors also contribute to a broader distribution of high-temperature zones in the cylinder during aviation kerosene combustion, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Ultimately, the combined effects result in a significant increase in the spray cone angle—by approximately 3.5°—with rising aviation kerosene content.

- (2)Under hot conditions, the spray cone angle of aviation kerosene is significantly larger than that of diesel. This is attributed to its lower viscosity, reduced surface tension, and smaller latent heat of vaporization compared to diesel. These properties promote the formation of finer droplets under high-temperature conditions, enhance momentum exchange with the ambient air, and facilitate more pronounced radial expansion of the spray—thereby increasing the spray cone angle.

- (3)As the injection pressure increases, the spray cone angles of both diesel and aviation kerosene exhibit a corresponding expansion. This trend results from the elevated injection velocity at higher pressures (ranging from 80 MPa to 120 MPa), which intensifies turbulent kinetic energy in the spray jet. The enhanced turbulence promotes interaction between the fuel droplets and the ambient air, facilitating greater radial dispersion and consequently leading to an increase in the spray cone angle.

A comparative study of RP-5 aviation kerosene and -35# diesel reveals notable differences in ignition behavior, soot formation, and spray characteristics. Further investigation into their blended fuels demonstrates significant variations in spray penetration and droplet dispersion patterns. These distinctions in spray attributes stem from fundamental differences in the physicochemical properties between aviation kerosene and diesel. Moreover, the blending ratio of aviation kerosene exerts a far more pronounced influence on the spray cone angle than on the spray penetration.

- (1)Under identical injection pressure conditions, aviation kerosene exhibits a more uniform temperature distribution during combustion, with a lower flame core temperature and a broader high-temperature region. Significant differences are observed in the KL distributions between aviation kerosene and diesel: the former shows lower soot concentration, more uniform dispersion, and the absence of distinct peak values. Owing to substantial differences in physicochemical properties, the spray characteristics of the two fuels differ markedly. Furthermore, the blending ratio of aviation kerosene has a more pronounced influence on the spray cone angle than on the spray penetration.

- (2)Under cold conditions with an injection duration of 2 ms, a nozzle orifice diameter of 0.31 mm, and ambient densities of 15 and 20 kg/m3, the spray cone angle of aviation kerosene is significantly larger than that of diesel under both cold and hot conditions. Moreover, as the injection pressure increases from 80 MPa to 120 MPa, the spray cone angles of both diesel and aviation kerosene show a consistent increasing trend.

- (3)As the aviation kerosene blending ratio increases and injection pressure rises from 80 MPa to 120 MPa, the spray penetration of the blended fuel exhibits an initial decrease followed by an increase under both ambient densities of 15 and 20 kg/m3. Meanwhile, the spray cone angle increases progressively with higher kerosene content.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This work is supported by Innovation Research Project for the training of high-level scientific and technological talents (Technical expert talents) of the Armed Police Force ZZKY20222415, Research and Innovation Team in Marine Propulsion Technology, China Coast Guard Academy.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Hailong Chen, Guanzhen Tao; data collection: Hailong Chen, Guanzhen Tao; analysis and interpretation of results: Hailong Chen, Daijun Wei; draft manuscript preparation: Hailong Chen, Guanzhen Tao, Guangyao Ouyang; fuel property parameter detection and fuel ratio: Hailong Chen, Guanzhen Tao. All authors reviewed theresults and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhang C , Luo L , Chen W , Yang F , Luo G , Xu J . Experimental investigation on the performance of an aviation piston engine fueled with Bio-Jet fuel prepared via thermochemical conversion of triglyceride. Energies. 2022; 15( 9): 3246. doi:10.3390/en15093246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Luning Prak DJ , Simms GR , Dickerson T , McDaniel A , Cowart JS . Formulation of 7-component surrogate mixtures for military jet fuel and testing in diesel engine. ACS Omega. 2022; 7( 2): 2275– 85. doi:10.1021/acsomega.1c05904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Labeckas G , Slavinskas S . Comparative evaluation of the combustion process and emissions of a diesel engine operating on the cetane improver 2-Ethylhexyl nitrate doped rapeseed oil and aviation JP-8 fuel. Energy Convers Manag X. 2021; 11( 18–19): 100106. doi:10.1016/j.ecmx.2021.100106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wang J , Zhang Q , Zhang Y , Yu L , Zhou D , Lu X , et al. Comparative study of ignition characteristics and engine performance of RP-3 kerosene and diesel under compression ignition condition. J Automob Eng. 2024; 238( 5): 999– 1013. doi:10.1177/09544070221146349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ardebili SMS , Babagiray M , Aytav E , Can Ö , Boroiu AA . Multi-objective optimization of DI diesel engine performance and emission parameters fueled with Jet-Al-Diesel blends. Energy. 2022; 242: 122997. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2021.122997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Pickett LM , Hoogterp L . Fundamental spray and combustion measurements of JP-8 at diesel conditions. SAE Int J Commer Veh. 2008; 1( 1): 108– 18. doi:10.4271/2008-01-1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lee JW , Bae CS . Application of JP-8 in a heavy duty diesel engine. Fuel. 2011; 90( 5): 1762– 70. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2011.01.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Bayındır H , Işık MZ , Argunhan Z , Yücel HL , Aydın H . Combustion, performance and emissions of a diesel power generator fueled with biodiesel-kerosene and biodiesel-kerosene-diesel blends. Energy. 2017; 123: 241– 51. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2017.01.153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kook S , Pickett LM . Liquid length and vapor penetration of conventional, Fischer-Tropsch, coal-derived, and surrogate fuel sprays at high-temperature and high pressure ambient conditions. Fuel. 2012; 93: 539– 48. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2011.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Song Y , Shen W , Bai S , Li S , Liang X , Shao J , et al. Modeling combustion chemistry of China aviation kerosene (RP-3) through the HyChem approach. Combust Flame. 2025; 280: 114339. doi:10.1016/j.combustflame.2025.114339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang P , Wang XH , Wang J , Wang D , Wang J . Auto-ignition characteristics of RP 3 kerosene under low pressure. J Saf Environ. 2024; 24( 2): 545– 50. doi:10.13637/j.issn.1009-6094.2022.2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shi Z , Lee CF , Wu H , Wu Y , Zhang L , Liu F . Optical diagnostics of low temperature ignition and combustion characteristics of diesel/kerosene blends under cold-start conditions. Appl Energy. 2019; 251: 113307. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.113307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang J , Yu W , Chen JKB . Influence of diesel-rocket Propellant-3 wide distillation blended fuels on combustion and particle emissions of a diesel engine. J Energy Eng. 2021; 147( 6): 4021053. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)EY.1943-7897.0000783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Liu J , Hu E , Zeng W , Zheng W . A new surrogate fuel for emulating the physical and chemical properties of RP 3 kerosene. Fuel. 2020; 259: 116210. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Wang X , Li R , Li Q , Zhao W , Yu W . Simulation on combustion of high power vehicle diesel engine fuelled with jet fuel. Sci Technol Eng. 2016; 16( 22): 207– 12. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-1815.2016.22.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. An Q , Zhu J , Wang J , Wang Y , Gao C . Combustion and emission characteristics of diesel engine fueled with alternative fuel blends. J Combust Sci Technol. 2014; 20( 3): 270– 5. (In Chinese). doi:10.11715/rskxjs.R201309002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lee J , Lee J , Chu S , Choi H , Min K . Emission reduction potential in a light-duty diesel engine fueled by JP-8. Energy. 2015; 89: 92– 9. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2015.07.060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wang Z , Wu S , Huang Y , Chen Y , Shi S , Cheng X , et al. Evaporation and ignition characteristics of water emulsified diesel under conventional and low temperature combustion conditions. Energies. 2017; 10( 8): 1– 14. doi:10.3390/en10081109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chembedu G , Manu PV . Investigation of performance and emissions of a diesel engine fueled with preheated blends of diesel-watermelon seed biodiesel-isopentanol-turmeric oil. Process Saf Environ Prot. 2025; 196: 106863. doi:10.1016/j.psep.2025.106863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Özgünoğlu M , Mouokue G , Oevermann M , Bensow RE . Numerical investigation of cavitation erosion in high-pressure fuel injector in the presence of surface deviations. Fuel. 2025; 386: 134174. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2024.134174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li Z , Zhou Y , Cheng XLQ . Flow and spray characteristics of a gas-liquid pintle injector under backpressure environment. Phys Fluids. 2024; 36: 043314. doi:10.1063/5.0201668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools